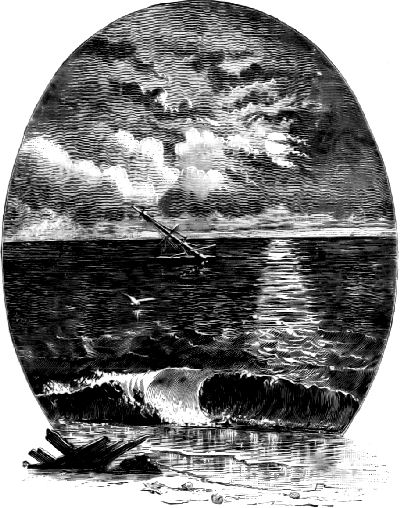

WRECK OF THE CIRCASSIAN.

WRECK OF THE CIRCASSIAN.

Title: Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Vol. 22, November, 1878

Author: Various

Release date: April 10, 2008 [eBook #25030]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Greg Bergquist, and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

OF

POPULAR LITERATURE AND SCIENCE,

NOVEMBER, 1878.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1878, by J.B. Lippincott & Co., in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Transcriber's Note:

Variant spelling, dialect, and unusual punctuation have been retained. A Table of Contents has been created for the HTML version.

CONTENTS

WRECK OF THE CIRCASSIAN.

WRECK OF THE CIRCASSIAN.

IT is not by any means certain what was the name by which Long Island was known to the aboriginal dwellers in its "forest primeval," or indeed 522that they ever had a common name by which to designate it. It seems probable that each tribe bestowed upon it a different name, expressive of the aspect that appeared most striking to its primitive and poetical visitors and occupants. Among so many tribes—the Canarsees (who met Hudson when on September 4, 1609, he anchored in Gravesend Bay), the Rockaways, Nyacks, Merrikokes, Matinecocs, Marsapeagues, Nissaquages, Corchaugs, Setaukets, Secataugs, Montauks, Shinecocs, Patchogues, and Manhansetts, to say nothing of the Pequots and Narragansetts on the northern shore of the Sound—a community of usage in regard to nomenclature could hardly be expected. We accordingly find that one of the old names of the island was Mattenwake, a compound of Mattai, the Delaware for "island." It was also called Paumanacke (the Indian original of the prosaic Long Island), Mattanwake (the Narragansett word for "good" or "pleasant land"), Pamunke and Meitowax. For a name, however, at once beautiful and suggestive, appropriate to an island whose sunny shores are strewn with shells, and recalling Indian feuds and customs, savage ornament and tributes paid in wampum, no name equals that we have chosen—Seawanhaka or Seawanhackee, the "Island of Shells."

No general description will give an adequate idea of its changing beauty and wellnigh infinite variety. Its scenery assumes a thousand different aspects between odoriferous Greenpoint and the solitary grandeur of Montauk. If one could only recall the old stagecoach, and, instead of whirling in a few hours from New York to Sag Harbor, creep slowly along the southern shore, and complete the journey of one hundred and ten miles in two days and a half, as they did fifty years ago, a description of the route would be both easy and interesting. Then the old stage lumbered out of Brooklyn about nine o'clock in the morning, a halt was made at Hempstead for dinner, and at Babylon the passengers slept. Starting early, they arrived in due time at Patchogue, where they breakfasted late, and thereby saved their dinner, and at Quogue, about twenty-four miles farther, they supped and slept. Again making an early start without breakfast, they jogged along to Southampton, where the morning meal was taken, and thus fortified they returned to their seats, and, passing through the beautiful country lying around Water Mill and Bridgehampton, rattled into Sag Harbor—a far different place from the Sag Harbor of to-day—and there dined. Fortunately, the rest of the route remains to us, and we can still "stage it" down the old and beautiful road to Easthampton. A leisurely journey of this description, at an average rate of a fraction less than two miles an hour, and with abundant opportunity of getting out for a brisk walk as the horses dragged their cumbrous load over an occasional sandhill, gave the traveller a chance of seeing the country he passed through. Long Island lay before him like a book, every line of which he could read at leisure. He could wander along the shore of the bay at Babylon, and mayhap meditate upon the beauty of Nature while looking at the moonlight sleeping on the water: he could at Quogue seek his way across the meadows and gaze upon the troubled face of the ocean. We can do so still, but these pleasures are no longer to be counted among the fascinating interludes of continuous travel. They are not the accompaniments of a long journey that gave it a flavor of romance, and made a trip to Sag Harbor and return the employment of an eventful and delightful week.

To adapt ourselves to modern conditions, and as we must view Long Island in sections to appreciate it as a whole, a route may be chosen in which, by using both railroad and stage, we may see even more of it, and that to greater advantage, than the old-time traveller. It is necessary, in the first place, that something should be seen of the northern shore. In character and associations it differs widely from the southern. There is, in the second place, the central section, in avoiding which much of the rural and most placid beauty of the island would be lost. There is, thirdly, the southern523 shore, varied in itself according as the point at which it is viewed lies on the ocean or on the landlocked bays between Hempstead and Mecoc, and extending to the rugged headland of Montauk. We shall thus, by passing from point to point, see as in a panorama all that need now attract our attention in viewing Seawanhaka.

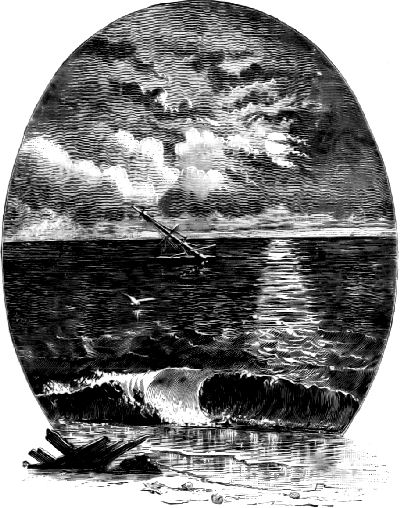

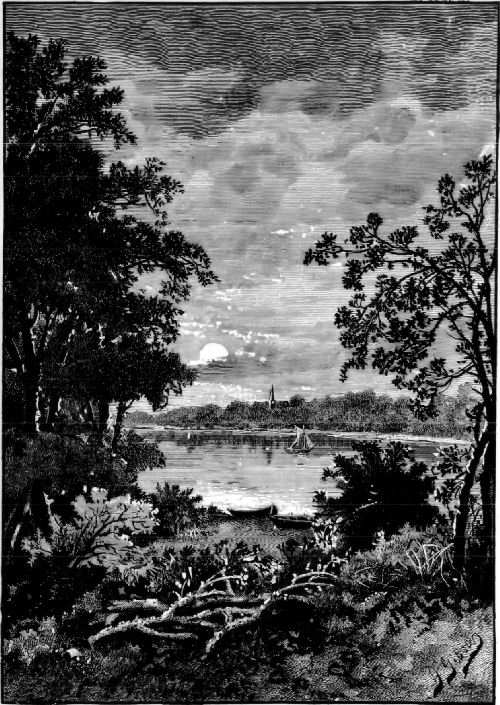

PORT JEFFERSON, FROM CEDAR HILL.

PORT JEFFERSON, FROM CEDAR HILL.

The place which the Indians named Cumsewogue is now mainly distinguished by the cemetery of Cedar Hill. Passing among the graves, we reach the summit, and a wonderful scene bursts upon our view. Looking north toward where the village is nestling in a hollow surrounded by woods, the waters of Port Jefferson Bay are lying without a visible ripple; the sails of the ships passing up and down the Sound gleam in the sun;524 and beyond them, like a hazy line, are the shores of Connecticut. On the left are glimpses of farmhouses, the church-spires of Setauket, and rolling fields alternating with woods. On the right are more woods, bounded far away by the broken shore of the cliff-bound Sound. The wooded peninsula in front that stretches to the north, forming the eastern shore of Port Jefferson Bay, was named by the old Puritan settlers—for what reason it would be hard to divine—Mount Misery. It is now, fortunately, more generally known in the neighborhood by the name of the Strong estate of Oakwood. Sea, shore, woods and valleys make up a picturesque scene of peaceful beauty, and one forgets in the presence of its living charms that the site upon which he stands is within the limits of a city of the dead.

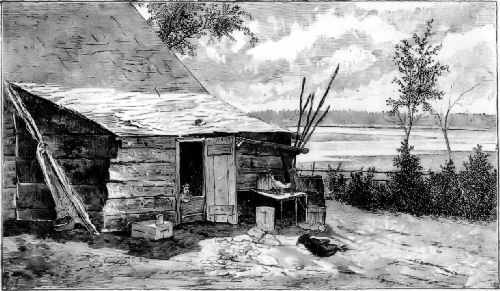

CABIN IN THE WOODS ABOVE POQUOTT.

CABIN IN THE WOODS ABOVE POQUOTT.

We descend into the village—which lies as if in a slumber that has lasted for a century and a half—at the head of the bay. The Indians named the place Souwassett, and the Puritans, in their usual matter-of-fact manner, called it Drowned Meadow. Its present name was adopted about forty years ago, probably in a patriotic mood, and also in the belief that the name it then bore was too unqualified and likely to give rise to unwarrantable prejudices. That there was some truth, if there was neither beauty nor imagination, in the name, is, however, evident from the marsh-lands lying between the village and Dyer's Neck or Poquott, which divides the harbor from that of Setauket on the west. One of the old landmarks of the village, dating from about the first quarter of the last century, is the house built by the Roe family when the settlement was first made. It now forms part of the Townsend house, and is still occupied by collateral descendants of its builder. Accessions to the little colony came slowly. Even the fine harbor could not compensate for the disadvantages of Drowned Meadow for building purposes, and the hillsides are steep and rocky. But about 1797, when it is said there were only half a dozen houses in the village, shipbuilding was begun, and its subsequent rise was comparatively rapid.

Securely though it seems to repose among its wood-crowned hills, it has had at least one exciting episode in its history. During the war of 1812 its shipping suffered considerably at the hands of King George's cruisers, and one night the enemy entered the harbor and captured seven sloops that were lying there at anchor. Otherwise, life at Port Jefferson appears to have been as it is now, unexciting and peaceful. Its attractions are in part those of association, but chiefly those of Nature—its sandy shore, its still woods and its placid bay. It is a place to fly to when the only conception of immediate happiness is to be still, to float idly upon water that has no waves to detract from the perfection of a dream of absolute rest, or to seek shelter and eloquent quiet in deep and shady woods. There are several winding paths that lead up the hilly promontory of Oakwood, and there are clearings upon the high ground swept over by breezes from the Sound where one can look upon rural scenes525 as perfect in their way as imagination can picture.

LAKE RONKONKOMA.

LAKE RONKONKOMA.

To the west of the village, pathways lead through the woods and past many ruined and ruinous cabins. The latter are chiefly occupied by negroes, who enjoy the sweets of liberty in these sequestered nooks. It is questionable if emancipation in any way bettered their condition. The Dutch introduced slaves into Long Island immediately upon settling on its western extremity, but it is said upon good authority—and the fact is a notable one in the history of the island—that slavery never existed there except in name. The work of the farms526 and houses was divided with the utmost impartiality among the nominal slaves and the white men and boys of the household. Possibly, then, there is not only no dark background to the lives of these Port Jefferson negroes, but one that in comfort and happiness is a contrast to the present. One little fellow—a darkling he should be called—peeped out shyly as we passed, and then disappeared in a hut which, though embowered in creeping plants and bushes, did not suggest either comfort or beauty when the trees are bare and the winds of winter are moaning through the woods. Beyond these cabins the path leads to the pebbly and shell-covered shore of Poquott.

To the east of Port Jefferson the shore runs in bolder outline to Orient Point, but within thirty or forty miles to the west there are innumerable points and well-sheltered bays and inlets that give the scenery the same picturesque character that is found at Port Jefferson. It may be taken, in short, as representing the northern side of the island.

When the shore is left a few miles behind the country assumes an entirely different aspect. The roads run through a wide tract covered as far as the eye can see with young timber and brushwood. In places the charred trunks give evidence that it has at no distant period been passed over by a forest-fire. The view to the south is bounded by the low range of hills that runs nearly the entire length of the island. In a hollow in this rising ground, a few miles east of Comac Hills, about two miles north-east of Mount Pleasant and near the eastern continuation of the Comac range, we drop suddenly upon the most charming of the lakes of Long Island—Ronkonkoma. It matters little from which side it is approached or from what point it is viewed—Lake Ronkonkoma is in every way and in every aspect beautiful. Around it on all sides is an undulating country comprising both woodland and farm, and dotted with quaint old houses of the many-gabled order, and a few that affect a certain latter-day primness. The architectural patriarchs and juveniles represent two different orders of things. The first tell of the early colonists of two hundred years ago making their way through the dense woods from the northern shore, and choosing dwellings by the lake where the land was good. The latter tell of later settlers, attracted solely by the beauty and salubrity of the place. There is one house still standing on the east side of the lake, a weather-beaten veteran of a century and a half. It has been in the same family ever since it was built, and if its walls were as eloquent of facts as they are of sentiment, it could no doubt unfold a varied tale. The place has, of course, a history based upon Indian times. Where we now see boats and skiffs, canoes were once paddled, and the lonely seclusion of the lake is said to have made it the theme of many an Indian story. Only one legend now survives. The lake has always been, and is now, well stocked with fish, and it is in places so deep that the Indians thought it unfathomable. With a curious kind of veneration they believed that the Great Spirit brought the fish that swarm in its waters, and kept them under his special care. Even when the whites came upon the scene the red men clung to their superstition, and would not catch nor eat the fish, believing them to be superior beings.

A change has come over the spot since that day. The land near the lake has been partially cleared, but not to such an extent as to divest it of any of its early beauty. A fringe of trees encloses it on all sides except the north, where a narrow belt of sand divides it from a lily pond. It is from that feature, and from the glistening western shore, that the lake was called Ronkonkoma (Sand Pond). At the point where it first bursts upon the traveller from the south it is seen gleaming through the trees like a diamond in a robe of green. Standing upon its margin, we are about fifty feet above the sea, and the cool wind that is rustling among the trees comes fresh from the Great South Bay, seven miles away. To right and left are high tree-covered banks, and to the north across the lake, about a mile off, the white sand is shining like a line of silver. The trees above the eastern527 shore are reflected as in a mirror, and the little boat with its snowy sail is there in duplicate, itself and double.

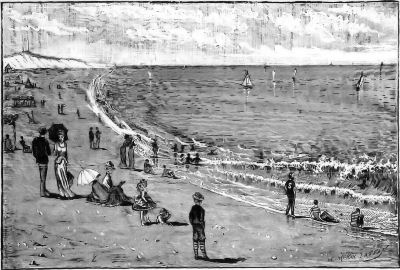

THE BEACH AT FIRE ISLAND.

THE BEACH AT FIRE ISLAND.

But, to be seen at its best, Ronkonkoma should be viewed from one of the higher points along its eastern shore when the sun is sloping down the western sky. One memorable evening this view was so beautiful as to be almost unearthly. The sun had sunk behind a heavy cloud-bank, which it tipped with a dull tawny red. By and by the sky began to change. The cloud sank lower, and lay upon the horizon in a perfectly black mass that threw its shadow upon the landscape. Its lining had deepened in color to a blood-red, and the clouds higher up the arch of the sky were ringed with a rich crimson border. Higher still they shaded off into paler tints, mingled with a copper-like hue that merged in the lighter clouds into gold. Above these were fleecy, rounded fragments of cloud floating over the deep blue like burnished brass upon lapis lazuli; and higher yet, about midway to the zenith, every cloudlet was tinged with pale yellow. Could such a sky be represented on canvas it would be condemned as unnatural—a case of the painter's imagination carrying him beyond the limits of true art. But it was from the reflection in the lake that the scene derived its weird, supernatural character. The shadows lay heavily upon the trees and bank that line the western shore. Upon the edge of the waters, which were so still that not a ripple waved the line drawn upon the white streak of sand, the deep red of the cloud upon the horizon reappeared. Nearer were the graduated tints of crimson, copper, gold, brass and pale yellow, every hue mirrored in the crystal lake with a fidelity so perfect that one was in doubt whether the reality or the reflection were the more gorgeous.

To the east and west of the lake, for twenty miles on either side of it, stretches a pleasant tract, chiefly of rolling woodland, with here and there a farm or garden. Wherever the land has been cleared and brought under cultivation it appears to give ample return to the husbandman. But the least observant traveller can hardly help being struck by the sight of a few fields of apparently healthy grain surrounded by miles of brushwood. It is a mystery not yet satisfactorily solved how within fifty miles of a city like New York so much land should be left unproductive and untilled. All the evidence, both of experiment and of opinion, goes to show that the soil, if not the richest in the world, is far too good to be given528 over to scrubby bushes and luxuriant weeds.

Leaving, however, a question so abstruse, let us turn southward from Yaphank and follow the brook that runs down past Carman's until it empties itself in Fireplace Bay. Again the scenery undergoes a change. Here is neither the broken, picturesque shore of the north nor the inland quietude of Ronkonkoma. Toward the west, beyond our ken, stretches the Great South Bay, far past where the lighthouse of Fire Island can be seen flashing out upon the night. To the south, about three miles distant, are the undulating dunes of the Great South Beach, that like a huge breakwater shuts out the ocean. To the east is the broad promontory lying behind Mastic Point. This is practically the same view upon which we have imagined the traveller by the old-time stage feasting his eyes at the halting-places along the southern shore. At any point between Babylon and the place at which we stand the scenery has the same general character—a picturesque pleasantness devoid of disturbing grandeur. However loudly the ocean may thunder upon the outer shore, the bay seldom changes its dimpling smiles for a rougher aspect, and never wears in wrath the scornful look of the outer deep. A strong wind may sometimes give a little trouble to the yachtsmen whose craft enliven the scene, and lead them to reef their swelling canvas, but the impression carried away from the Great South Bay is decidedly summery—a memory of mingled sunshine and gentle breezes. The shore is generally flat, and is lined with a succession of villages located at intervals of from three to four miles. They are all more or less alike—quiet, healthy places, in which, to all appearances, the inhabitants take life easily.

Five or six miles to the west is Blue Point, of oyster fame, in connection with which a curious tradition is extant. It is said that long ago the oysters disappeared entirely from the bay. The poor people from all the country round were in the habit of raking up the oysters for their own consumption and for sale. In an evil hour the authorities of the town of Brookhaven, to which the beds belong, resolved upon replenishing the town treasury by the imposition of a license upon the poor fishermen. The latter, either unable to meet the demands of the law or bent upon maintaining what appeared to them a natural right, made a counter-resolve upon resistance to its enforcement. The result was a collision, and by dint of armed men and boats the unlicensed fishermen were driven off. Thereafter, curious to relate, not another oyster was taken, and nothing but empty shells filled the unblessed rakes. This state of things lasted until about forty years ago, when it is presumed the grip of the law was relaxed. The poor people, at all events, then again had recourse to the long-deserted beds, and found them covered to the depth of several feet with luscious young oysters.

A number of boats ply between Bellport and the Great South Beach, whither the summer visitors are in the habit of repairing for the purpose of tumbling in the surf on the outside. In one of these, with a fair wind and a skipper acquainted with the numerous shoals, it is very pleasant to sail across the bay, and then turning round Mastic Point to follow the channel connecting the Great South with East Bay, and so to reach Moriches. From that point east the shore is broken up into shallow creeks until Quogue (from quohaug, a clam), an old resort of the citizens of Philadelphia, New York and other cities, is reached. It occupies the neck of land dividing Shinecoc from East Bay, and is the first place after leaving Rockaway, about sixty miles to the west, which has direct communication with the shore of the ocean. The beach there touches the mainland, and then leaves it again to make room for Shinecoc Bay. At the most northerly arm of the latter we come upon a place with a peculiar history and corresponding associations, and there on the adjacent hills of Shinecoc we may pause for a few moments' observation. We are now in the township of Southampton, where, with the exception of Lion Gardiner's settlement upon the529 island still bearing his name, the first English settlement in the State of New York was effected.

Toward both east and west the country stretches away as far as we can see in undulating woods and fields. Had we come by land instead of the bays, we should have passed through a series of four or five little villages, Moriches, Speonk, Good Ground and West Hampton, cozily nestling among the woods—quiet, retired places, given over to peace and agriculture. There is no particularly prominent feature in the landscape. Its charm lies in its harmony, and the ensemble is as nearly perfect as can be imagined. Immediately in front are the knolls and dales above and below Good Ground, and extending down to where the Ponquogue lighthouse stands out in clear outline against the sky. To the south is Shinecoc Bay, and to the north is Peconic Bay, the water that lies between the forks at the eastern end of Long Island. Below us, looking west, is Canoe Place, the name given to the narrow neck of land joining the peninsula that terminates at Montauk to the body of the island. It is the point at which the waters on the north and south come most nearly together, and there, accordingly, as the name implies, was the Indian portage.

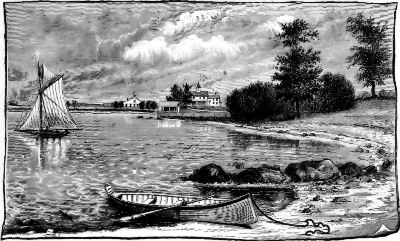

PECONIC BAY, AND RESIDENCE OF CHIEF-JUSTICE DALY.

PECONIC BAY, AND RESIDENCE OF CHIEF-JUSTICE DALY.

Toward the east, across the rising and falling ground and beyond the woods, lies the village of Southampton, where the first settlement in the township was formed. The colonists were chiefly Englishmen, who, having resided for a short time in Lynn, Massachusetts, turned their eyes toward such "pastures new" as Long Island afforded. They first tried to locate themselves in the north-western part of the island, but having been driven out by the Dutch, their second venture led them to North Sea, and thence through the woods to Southampton. They found the land both good and cheap. All that the Indians asked for the district lying between Canoe Place and the eastern limit of the township at Sag Harbor was sixteen coats, threescore bushels of Indian corn and a promise of protection against hostile tribes. Forty-three years afterward the official estimate of the township amounted to about eighty thousand dollars, so that the men of Lynn undoubtedly received good value for their coats and corn.

Their choice of a home is sufficient to place their good judgment above question. There are still existing in the village a few mementos of their presence in the form of weather-stained houses, over which have passed, leaving them untouched, all the vicissitudes of Indian530 times, the Revolutionary War and modern improvement. Time, however, has left its scars upon their fronts. The street leading down toward the shore of the ocean is grass-grown and spacious, and probably differs very little from what it was in the olden time. On the left side stands the Pelletreau house, where Lord Erskine resided during the winter of 1778. On the floor in one of the rooms are certain marks, said to have been made by the axe of the British quartermaster. Others of the old buildings have recently been removed, but those that are left are sufficient to recall the time when, plundered alike by friend and foe, and compelled to maintain its enemy, Southampton yet patriotically contributed its quota of men to the war for independence. There is nothing of the upstart about the place. It reposes in a quiet, dignified present resting upon a long and honorable past, and there is in its attitude and air something that compels one to revert to the latter. Its population partakes of the same character. Although some of the first settlers removed to other places or returned to Lynn, most of the old families took deep root in the soil, and are represented by descendants who live within sight of the primitive dwellings their forefathers reared. Offshoots were, however, thrown off in many directions. Some went down to Cape May, whither the whale-fishing attracted them; others were among the pioneers of the West, and founded colonies at various places in New York State and in Pennsylvania; others took their places among the Argonauts of '49 and sought the gold-fields of California. But still the parent trees stood fast in Southampton.

The appearance of whales off the coast, though now a rare occurrence, was not so in the early days of the town. Among the earliest of its records is a law providing for the cutting up and division of any whales that might be cast up on the shore. At a later day boats were fitted up either to put off in pursuit when a whale was signalled or to cruise along the coast in the whaling season. In the former case, by a usage which extended to the adjoining township of Easthampton, signals were hoisted at fixed stations along the shore, whereupon the boats were dragged down the beach and launched through the surf, while the venturesome crew leaped in, each man taking his own place. How dangerous such a pursuit was can be estimated by any one who will walk to the high ridge of sand running along the beach and look eastward down the long line of breakers that toss their foam-capped heads before a heavy gale. For many miles nothing can be seen but the arching waves dashing themselves upon the sand, as if furious that their course should be checked. The whale has almost entirely deserted its old haunt, but the sea still furnishes many an exciting, and also many a sad, episode in the otherwise uneventful lives of the townsmen. Not a winter passes without some ship or ocean steamer being thrown upon Hampton shore, and often, in spite of the gallantry and exertions of the lifeboatmen, whose stations stand at intervals of five miles, the crews never reach the land until flung up lifeless by the waves.

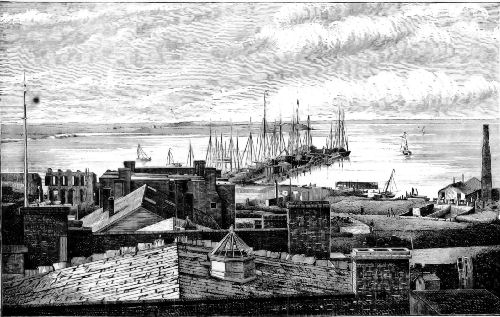

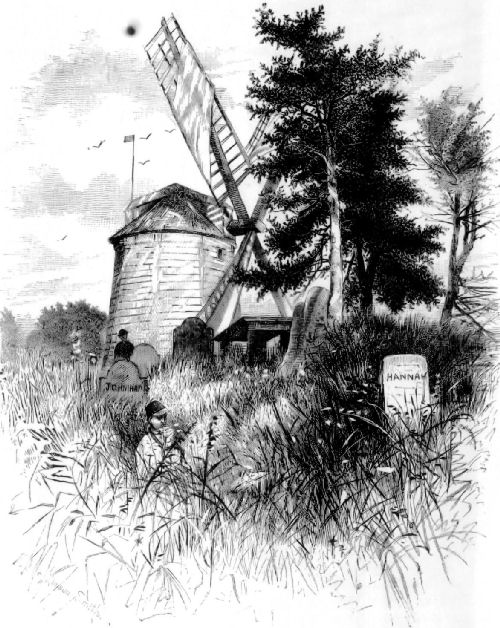

SAG HARBOR.

SAG HARBOR.

Maintaining still an eastward course, we pass Water Mill, lying upon one of the inlets of Mecoc Bay, and hurrying through Bridgehampton arrive at Sag Harbor, the chief port of the peninsula. It is a quiet, interesting town, beautifully situated on a branch of Gardiner's Bay. Across the neck that projects over toward Shelter Island on the north, and beyond the site chosen by Chief-Justice Daly for his residence, lies Peconic Bay. Toward the east stretches the bay, past the lower end of Shelter Island, past Cedar Point, and then away off to where Gardiner's Island is stretching its long arms to the north and south, as if to guard the great haven inside from the ocean storms. A century and a half ago nothing stood upon the spot where the town now stands but a few fishermen's huts. In a short time the settlers were engaged in whale-fishing off the coast, and thereby really laid the foundations of Sag Harbor's future prosperity and wealth. In 1760 three sloops were fitted out to prosecute the fishing531 in the northern seas, and after the war of independence Dr. N. Gardiner and his brother despatched on the same errand the first ship that ever sailed from Sag Harbor. The venture failed, but others succeeded, and in 1847 sixty-three ships were engaged in the business. After that date the decline was fast, and532 now not a single ship of the whole fleet is left. Captain Babcock, the lighthouse-keeper of Montauk, sailed six or seven years ago the brig Myra, the last whaler that left Sag Harbor. His success was not so great that the owners, the Messrs. French, cared to repeat the experiment; so that within twenty years Sag Harbor has fallen from its position as the third or fourth whaling-port in the country to that in which we find it to-day. The gold fever of '49, the discovery of petroleum and the increased expense attending the whale-fishing, all contributed to its decline. It is also claimed for Sag Harbor that Captain Cooper of the Manhattan, sailing from that port, was the first to take a ship into Yeddo.

NEAR EASTHAMPTON.

NEAR EASTHAMPTON.

In and around the town are many evidences of the generally well-to-do condition of its inhabitants, amongst whom are several whose rise to greater wealth was checked by the fall of the whale-fishing. In their homes and those of retired merchant captains are many mementos of long voyages to China, Japan, the Indies, and, in short, to every part of the world. It is singular how interesting,533 as compared with the choicest things to be found in the shops, these porcelains, lacquers, enamels, ivories, fans, silks, weapons and cabinets are. They are the trophies of the Ancient Mariner, who takes some pride in turning over the contents of his shelves, and derive a personal interest from having been with him through the storms he weathered before he brought them safe to port.

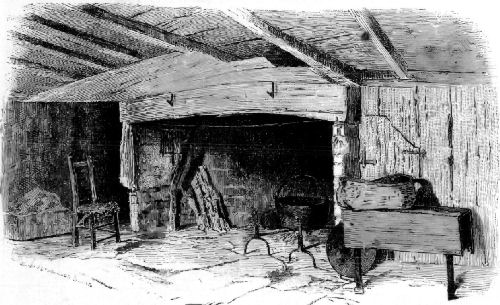

"HOME, SWEET HOME!"—PAYNE'S INTERIOR.

"HOME, SWEET HOME!"—PAYNE'S INTERIOR.

Every part of the town is interesting, and certainly not the least so is the old cemetery. It contains an extensive collection of rude headstones and quaint epitaphs. Here, on a sailor's grave, are engraved the lines—

Rude Boreas' winds and Neptune's waves

Have tossed me to and fro:

By God's decree, you plainly see,

I'm harbored here below.

In Sag Harbor there lived a certain Captain David Hand, who died in 1840 at the age of eighty-one. Here he and his five wives are sleeping, all in a row. The first died in 1791; the second, in 1794; the third, in 1798; the fourth, in 1810; the fifth, in 1835. The gallant captain himself went down while cruising in quest of a sixth. It is upon the grave of the third that the following appears:

Behold, ye living mortals passing by,

How thick the partners of one husband lie.

Vast and unsearchable the ways of God:

Just, but severe, we feel His chastening rod.

The meaning is a little obscure, and it is only the subsequent matrimonial ventures of the captain that assure us he did not mean that the three who had gone were to him as a chastening rod.

Let us now take our station where we can look down upon the town and over the surrounding scene of mingled island, sea and shore, and try to recall some of the thrilling events that give Sag Harbor its historical interest. Two hundred and fifty years ago these bays, now alive with coasting vessels, pleasure craft and an occasional steamer, showed nothing but the canoes of the Manhansetts and Montauketts. In 1637 we might have seen the large canoe of Wyandanch, the sachem of the Montauks, surrounded by those of his tribe, stealing across toward Shelter Island to complete the extermination of the Pequots. In 1699 the ship in which Kidd won his plunder in the southern seas was lying under the island's lee while the famous pirate was burying a part of his booty on its shore. It is said that the proprietor of the island has still in his possession a piece of gold cloth given to his ancestor by Captain Kidd. Soon afterward Gardiner's Island was visited and plundered by Paul534 Williams and some of his buccaneering associates. In 1728 these seas swarmed with the pirates of Spain, and one night in September of that year the crew of a schooner landed upon Gardiner's Island, and for three days it was given up to plunder. The next we see is a British fleet in 1775 sweeping round the arm of the island and coming to anchor in the bay, whence, like the pirates, they sent out parties to plunder Mr. Gardiner's house and farm. Sag Harbor was occupied by British troops, and one evening in 1777 across Peconic Bay from Southold the boat that carried Lieutenant-Colonel Meigs and his patriot companions was sailing. Landing a few miles to the west of the town, they fell upon the British garrison like a midnight thunderbolt. The commander was seized in bed, the shipping and provisions were fired, and Meigs and his men had finished their work and retired before the British soldiers were fully awake. Again, in 1780–81, the British fleet anchored in the bay, and yet again in 1813. In the latter year Commodore Hardy sent a launch and two barges with a hundred men to plunder Sag Harbor, but the project utterly failed. The town was roused, the guns of the fort opened upon the intruders, and then the villagers returned to their slumbers. When peace was restored the bay was ploughed by West Indiamen and whalers, and then, as we have seen, they also vanished. Apart, then, from the beauty of its situation, Sag Harbor has associations and a history that form appreciable items in the list of its attractions; and if its future should be less glowing than its past, it will not be for lack of a healthy and mild climate nor of exceptional advantages of location.

FISHERMAN'S HOUSE NEAR HAMPTON BEACH.

FISHERMAN'S HOUSE NEAR HAMPTON BEACH.

Before leaving the town in quest of Easthampton Village we find ourselves in the township of that name. All these woods and fair fields stretching from the Southampton limit eastward to Montauk, and comprising upward of thirty thousand acres, were in 1648 bought for "20 coats, 24 hoes, 24 hatchets, 24 knives, 24 looking-glasses and 100 muxes." Most of the settlers in the village we are now approaching came from Kent, and memories of their English home led them to give it the name of Maidstone, which was afterward changed to Easthampton. It lies in the midst of a beautiful section of country, full of pretty little pictures of rustic life. The main street is, like that of Southampton, a broad grass-grown avenue lined with stately trees, and as we go down in the direction of the shore we pass a spot interesting to English-speaking people all over the535 world—the birthplace of John Howard Payne, the author of "Home, Sweet Home." It is with a feeling approaching reverence that we look at the old open fireplace, the rafters and walls; and as we emerge and glance up and down the spacious street, and drink in the placid beauty of the scene, the fountain of the poet's inspiration is revealed. Once seen, it is a place for every man to remember all through life, even if "he owed it not his birth." And here the thought recurs that there must be an unusually strong tie between the villagers in all the Hamptons and their homes. The names of many of the old settlers are still met with throughout the entire section from Southampton eastward, so that while Payne was giving expression to a sentiment that is universal in language that the world at large has adopted, his words have also a particular significance in telling us of the atmosphere of sentiment peculiar in its warmth and manifestation to the district in which he was reared.

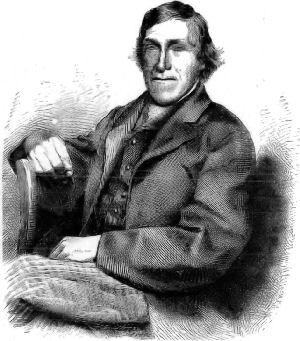

KING SYLVESTER.

KING SYLVESTER.

Our path now lies eastward through the straggling little village of Amagansett, and through the woods beyond which lie Neapeague and Montauk, the "Hilly Land." The quiet repose of village-life is now left behind, and through rapidly-changing scenes we set our faces toward the grandest and most wonderful section of Long Island. For about two miles after leaving Amagansett our route lies through thick woods of young timber, and then we suddenly emerge at a point where the road turns round a spur of the high land we have just passed. On the south is the ocean, in sight of which the road thereafter runs the greater part of the way to the point, and in front, stretching for six or seven miles until it joins the hills of Montauk, is the marshy beach of Neapeague, the "Water Land." As we descend, the sea is hidden by the irregular dunes that lie along the shore, and the dreary expanse extends far before us and off toward the north. Every step leads us to realize more fully the dismal character of the sterile flat. The wagon-wheels alternately grind through the sand and bump into deep puddles in the marsh. There can be no doubt that once this whole tract was overflowed by the sea, and still in heavy storms the waves force their way between the sandhills and lay parts of the beach under water. Meanwhile, however, attention is likely to be diverted from the consideration of the inroads of the sea to the incessant attacks of the insatiate and bloodthirsty mosquitoes. We are here in their very home, and, galled by their furious stinging onslaughts, can recall nothing but Ayres's exclamation:

Cheerless Neapeague! how bounds the heart to gain

The hills that spring beyond thy weary plain!

The busy, bloodthirsty wretches spring in clouds from every swamp. They fill the air, obscure the blue lining of the wagon with their own tawny gray, and would, I verily believe, turn a white horse brown. But the end comes at length, and as we climb the hill bounding the beach on the east the last of the little tormentors disappears. To our left are the Nommonock Hills, and those of Hither Wood rise in front of us. At the point now reached it is well to turn round and view the land we have passed. We can look across from shore to shore, from the ocean breakers on the south to the little harbor of Neapeague on the north, and beyond it to where Gardiner's Island536 lies out in the bay. The conviction grows upon us that where we now stand was once an island, and that the rugged base of Nommonock was once washed by the sea.

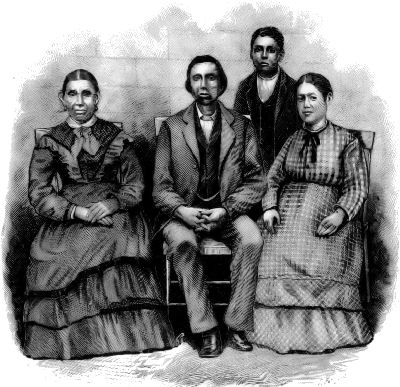

KING DAVID FARO AND FAMILY.

KING DAVID FARO AND FAMILY.

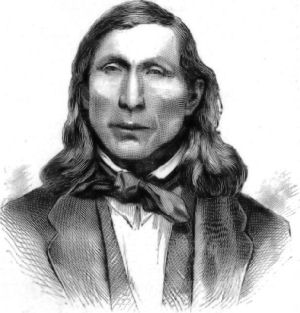

Soon we pass through the Hither Woods, and with them leave behind the last remnant of the forest that formerly covered Montauk. All else, to where Womponomon—the Indian name of the eastern point—juts out into the sea, are hills and rolling downs which rise and fall like the sea when the waves are running "mountains high." Here and there we pass a pond, and often startle the cattle that graze over the greater part of Montauk; and at length pause, spellbound by the view from the hills looking down upon Fort Pond, or Kongonock. The road runs past its southern extremity, where, until the embankment was built, the ocean-surf frequently broke across; and after passing this plain, called Fithian's, we find ourselves a very short distance south of the site of the old Indian village. The hill about halfway between the two ends of the pond on its eastern side was once occupied by an Indian fort, and between it and us lies the valley where were clustered the wigwams of Wyandanch and his tribe. He figures in history as the staunch and often severely-tried ally of the whites, and was the lifelong friend of Lion Gardiner. His warriors were, hyperbolically, "as many as the spires of the grass" until reduced by sickness and battle. The Narragansetts pursued him with an insatiate and vindictive hate, and this peaceful valley was once the scene of a bloody tragedy from which the Montauketts never recovered. Wyandanch had pursued a party of Narragansetts to Block Island, and killed a great number of them. To retaliate, Ninicraft (or Ninigret) invaded Montauk, and on the537 night of the nuptials of the chief's daughter fell upon the village, burned, sacked and slew, and, in spite of Wyandanch's bravery, totally defeated his followers. Among the fallen was the bridegroom, and beside his dead body the invaders found the bride in a stupor of grief. She was hurried away, an unresisting captive, but was ultimately restored to her father by the exertions of Lion Gardiner. In 1659, Wyandanch died from the effects of poison, and with him went out the glory of his tribe. Piece after piece, the lands he had held were ceded to the whites, and the royal line of Faro came to an end. In 1819 "King" Stephen died, and was buried by subscription. His distinctive badge consisted of a yellow ribbon round his hat. After him others reigned, and although the royal family long ago became extinct, the name of king or chief is still retained. The late holder of the title was David Faro, and he reigned over two families, his own and the Fowlers. He will probably be succeeded by his cousin Stephen, an athletic gentleman and a full-blooded Indian, who is said to have walked in one day from Brooklyn to Montauk, and who thinks little of stepping from Montauk to Bridgehampton, thence to Sag Harbor for dinner, and so on back to Montauk. The late chief left a widow and five children. The eldest is a boy named Wyandanch, who occasionally visits the few houses on the peninsula and the nearest villages, selling berries. The queen's mother and the rest of the tribe are basket-makers. The second of David's children is Maggie Arabella, a pleasant-faced girl with thick-set figure; the third and fourth are bright-eyed boys, Samuel Powhattan and Ebenezer Tecumseh; and the fifth is a child of about six months, Sarah Pocahontas. Besides these there are the present king, Stephen, and his son Samuel. King Sylvester preceded David, so that we are in possession of the likenesses of three of the line of sachems. Ephraim Fowler, a son of Sylvester, also survives. Of the other family of Fowlers, there are the husband and wife and their four children, three sons and a daughter. Such, so far as I know, is a complete census of the tribe of Montauketts. Their possessions are small and their way of living rude. Ichabod! Ichabod!

STEPHEN, KING IN POSSE.

STEPHEN, KING IN POSSE.

Returning to the hill overlooking Fort Pond, we are almost due south of Point Culloden. When Montauk throws off entirely its old character and fully assumes the inevitable new, the bay to the west of Culloden will probably be converted by a breakwater into a harbor, and to the north of where we stand it is not unlikely that the snort of the locomotive may yet be heard. Already there are rumors of impending change. With the railroad brought through from Sag Harbor, Fort Pond Bay will be the point of arrival and departure of steamers plying between the island and the New England shore. It is even suggested that the Transatlantic steamers might make it a stopping-place to land mails and passengers. The bay is so deep that vessels of any tonnage could enter it, and it would moreover prove an excellent refuge in stormy weather. When thus brought into more speedy communication with the western part of the island, the lonely grandeur of Montauk will be modified by the inroads of traffic and the things that tell of the far-distant city and its seething mass of jaded humanity. The tens who now seek it will be exchanged for hundreds in quest of the health and vigor that are inhaled with every breath of the fresh salt air.538 There is, it must be admitted, a certain amount of resignation in our view of such a transformation. We wish for no change in Montauk—would not even ask for the iron road to span the waste of Neapeague. All around is beauty—of the sky, of the sea, of lake and land—beauty of wavy outline and delicious color. There is a deep pleasure also in the feeling that we are here away from the world. Care went riding down the wind into the marshes of the Water Land, and we are emancipated from drudgery and routine. The workshop has receded so far from its usual prominence that it is almost out of memory, a thousand miles away. Why should it be brought nearer and Montauk be made a portion of the old, every-day world?

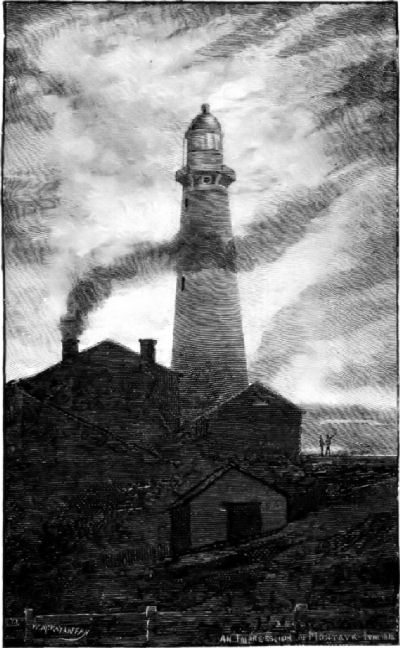

MONTAUK LIGHTHOUSE.

MONTAUK LIGHTHOUSE.

But to turn to the present. To the east of the hill upon which we stand lies Great Pond, the largest sheet of water on Long Island, and across it may be seen the Shagwannock Hills. And now we may return to the point whence we started at the south end of Fort Pond, and resume our drive across the downs. Soon after passing Stratton's, the third house between Neapeague and the point, the road makes a sweeping détour to the south, bringing us nearer to the sea-cliff, and we hastened to reach the lighthouse before the night made the rough track dangerous. The sky was threatening, and had to the west and north-west an aspect ominous of storm. It was on that night that Wallingford was swept almost out of existence by a tornado. Before we arrived at the lighthouse the lightning was playing brilliantly over the dense mass of clouds that overhung the Connecticut shore. Gradually the black bank drifted eastward, and then to the south,539 and as it drew near the rumble of the thunder became more audible. By and by a counter-current of wind seemed to set in toward the south-west, and a part of the huge vapory mass was broken off from the rest and whirled directly overhead. The unceasing roar of the surf was drowned by the thunder, and the540 foam-crested waves that came curling into Turtle Bay were lit up by the glare of the lightning. Toward the east the darting forks of fire seemed now to flash down into the inky sea, and now to throw a baleful and blinding light around the lighthouse. What made the phenomenon singular was that the wind had been blowing a southerly gale all day, and that for a time the motion of the clouds appeared to be entirely independent of the wind. A heavy rainstorm accompanied the thunder, and it was in the midst of this elemental chaos that we first looked out upon the ocean from Womponomon. Soon, however, the heavy cloud passed away to sea, and again

The pale and quiet moon

Makes her calm forehead bare.

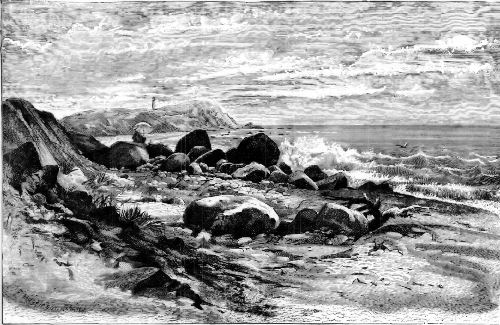

THE CLIFFS OF MONTAUK.

THE CLIFFS OF MONTAUK.

In the morning a dull gray sky hung over the still-vext ocean, and upon its long swell a few fishing craft were riding at anchor. The view from the lighthouse, the lantern of which was presented to the United States by the French government, is worth all and far more than is ever likely to be passed through in reaching it. Block Island lay like a dark mark deepening the horizon-line, and to the south and east were ships passing gallantly out to sea. To the north the view was hazy, and to the west were the hills of Montauk and glimpses of its ponds. Round the point the water was comparatively still, but the long swell was breaking grandly among the boulders on the south. Below the lantern is the room in which the keepers maintain their vigils, listening to the roar of the wind, and occasionally feeling the tower vibrate to such an extent that the lantern ceases its revolutions. This, however, rarely happens. The tower is strongly built of stone and brick, and, although it has seen many a storm since 1795, it is staunch enough to weather many more.

Down under the cliffs, where the "cruel, hungry foam" is dashing among the rocks, the seaward view is grand and awful. In Turtle Bay, as we casually learned, the dead bodies of those shipwrecked farther up the coast generally come ashore, and a ghastly kind of interest attaches to the place. For miles along the shore the same sad tale is being continually told: it is the solemn burden of the sea's loud wail. We heard it at Fire Island; walking along the beach opposite Sayville, we heard it again in the billows that broke over the wreck of the Great Western; it haunted us at Quogue, and rang in our ears on the lovely beach at the Hamptons; it followed us to Amagansett, and within a few miles of the point we can sit in a veritable "graveyard" filled with beams, broken timbers and rusty iron bolts, the rejected spoils of the ocean. For the moment one cannot help sympathizing with the shepherd of the Noctes, who "couldna thole to lieve on the seashore." There is, in truth, something disturbing to the imagination and confusing to the senses in its everlasting thunder. We see it and leave it—perhaps for a month, possibly for a year—and it is hard to realize when we return that throughout the long interval it has never for a single moment been at rest.

But the time comes when we must retrace our steps to the world which seems so far away. Again we roll over the pasture-land, swept by constant winds, sometimes by storms, and long before we reach Neapeague have learned the truth and felt the sentiment that inspired Ayres's lines:

There is no country like Montauk's rude isle.

Strange are its rolling hills, its valleys' smile,

Its trees lone dying in their ancient place,

As if in sorrow for a dying race.

Jennie J. Young.

THE RESULT OF PERCIVAL'S ECONOMY.

JUDITH'S letter lay on the table still. Bertie had not come to claim it, and she had not come home.

Having ascertained these facts, Percival went to his own room, and, finding his tea set ready for him, ate and drank hurriedly, hesitating whether he should go and meet her. Standing by the window he looked out on the darkening street. All vulgarity of detail was lost in the softening dusk, and there was something almost picturesque in the opposite roof, whose outline was delicately drawn on the pale-blue sky. Everything was refined, subdued and shadowy in the tender light, but Percival, gazing, saw no charm in the little twilight picture. Sorrow may be soothed by quiet loveliness, but perplexities absorb all our faculties, and we do not heed the beauty of the world, which is simple and unperplexed. If it is forced upon our notice, the contrast irritates us: it is almost an impertinence. Percival would have been angry had he been called upon to feel the poetry which Bertie had found only a few days before in the bit of houseleek growing on that arid waste of tiles. It is true that in that dim light the houseleek was only a dusky little knob.

Should he go and meet Judith? Should he wait for her? What would she do? Should he go to St. Sylvester's? By the time he could reach the church the choristers would have assembled: would the organist be there? While he doubted what to do his fingers were in his waistcoat pocket, and he incidentally discovered that he had only a shilling and a threepenny-piece in it. He went quickly to the table and struck a light. Since he had enrolled himself as Judith Lisle's true knight, ready to go anywhere or render her any service in her need, it would be as well to be better provided with the sinews of war. He unlocked the little writing-case which stood on a side table.

Percival's carefulness in money matters had helped him very much in his poverty. It seemed the most natural thing in the world to him that, since his income was fixed, his expenditure must be made to fit it. He hardly understood the difficulties of that numerous class of which Bertie was an example—men who consider certain items of expenditure as fixed and unchangeable, let their income be what it may. But Percival had retained one remembrance of his wealthier days, a familiarity with money. People who have been stinted all their lives are accustomed to handle silver and copper, but are anxious about gold and frightened at notes or cheques. Percival, though he was quite conscious of the relative greatness of small sums to his narrow means, retained the old habit of thinking them small, and never bestowed an anxious thought on the little hoard in his desk. As he went to it that evening he remembered with sudden pleasure that there was the money that had been accumulating for some time in readiness for Mrs. Bryant's return. He could borrow from that if need were.

The money was gone.

Percival stood up and stared vaguely round the room. Then, unable to believe in his misfortune, he emptied out the contents of the desk upon the table and tossed them over in a hurried search. A carelessly-folded paper caught his eye as something unfamiliar. He opened it and read:

"Dear Thorne: You were good enough to let me borrow of you once when I was in a scrape. I am in a worse difficulty now, and, as I have not the chance of asking your leave, I've ventured to help myself. You shall have it back again in a few days, with an explanation of this cool proceeding."

"H.L."

Percival threw the letter down, and walked to the window again. It was clear enough now. Bertie had had no need to borrow eight or nine pounds if he were only going out for the day to inquire about a situation as organist. But if a man is running off with a young lady it will not do to have an absolutely empty purse. Even though she may be an heiress, he cannot very well begin by asking her to pay his railway-fare. "It would define the relative positions a little too clearly," thought Percival with a scornful smile.

"Will she hope still?" was his next thought. "It is not utterly impossible, I suppose, that Master Bertie has bolted alone. One couldn't swear he hadn't. Bolted he certainly has, but if she will hope I can't say that I know he has gone with Miss Nash. Though I am sure he has: how else would he undertake to repay me in a few days? Unless that is only a figure of speech."

He suddenly remembered the time when Bertie left his debt unpaid after a similar promise, and he went back to his desk with a new anxiety. His talisman, the half-sovereign which was to have been treasured to his dying day, had shared the fate of the commonplace coins which were destined for Mrs. Bryant and his bootmaker. It was a cruel blow, but Percival saw the absurd side of his misfortune, and laughed aloud in spite of himself.

"My sentiment hasn't prospered: it might just as well have been a three-penny-piece! Ah, well! it would be unreasonable to complain," he reflected, "since Bertie has promised to send my souvenir back again. Very thoughtful of him! It will be a little remembrance of Emmeline Nash when it comes, and not of Judith Lisle: that will be the only difference. Quite unimportant, of course. Upon my word, Lisle went about it in a systematic fashion. Pity he gave his attention to music: a distinguished burglar was lost to society when he turned organist." He took up the paper and glanced at it again. "If I show this to her she will pay his debt, as she did last time; and that she never shall do." He doubled it up and thrust it in with the rest.

A shuffling step in the passage, a knock at the door, and Emma made her appearance: "Miss Lisle has come in, sir."

Percival looked up a little astonished, but he only thanked her in his quiet voice and closed his desk. He turned the key, and waited a moment till Emma should have gone before he obeyed the summons. When, answering Judith's "Come in," he entered the Lisles' room, he found her standing by the window. She turned and looked at him, as if she were not quite certain whom to expect.

"It is I," he said. "Thank you for sending for me."

"Sending for you? I didn't send. But I am glad you came," she added.

She had not sent for him, and Percival remembered that he had passed Lydia Bryant on his way. The message—which, after all, was a mere statement of a fact—was hers. He colored angrily and stood confused: "You did not send? No—I see. I beg your pardon—I misunderstood—"

"It makes no difference," said Judith quickly. "Don't go: I wanted to tell you—" She paused: "I have not been unjust, Mr. Thorne. Mr. Nash has been at Standon Square this afternoon. After he had my telegram he received a letter from Emmeline, and it was as I thought. She is with Bertie."

"With Bertie? And he came here?"

"Yes—to see if it was as Emmeline543 said, that they were married at St. Andrew's last Tuesday."

Percival looked blankly at her: "Married! It isn't possible, is it?"

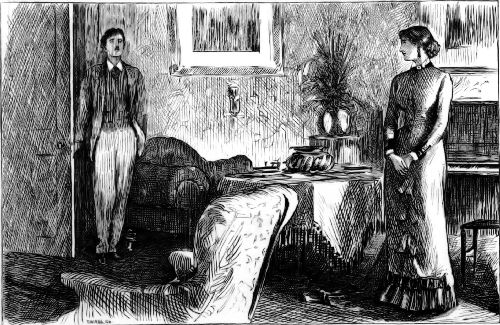

"IT IS I," HE SAID. "THANK YOU FOR SENDING FOR ME."—Page

542.

"IT IS I," HE SAID. "THANK YOU FOR SENDING FOR ME."—Page

542.

"Quite possible," said Judith bitterly. "Standon Square is in St. Andrew's parish, as well as Bellevue street. It seems that Bertie had only to have the banns mumbled over for three Sundays by an old clergyman whom nobody hears in a544 church where nobody goes. It sounds very easy, doesn't it?"

Percival stood for a moment speechless while the cool audacity of Bertie's proceeding filtered slowly into his mind. "But if any one had gone to St. Andrew's?" he said at last.

"That would have ended it, of course. I suppose he would have run away without Emmeline. If I had gone that Sunday when I had arranged to go, for instance. Yes, that would have been very awkward, wouldn't it, Mr. Thorne? Only, you see, Bertie happened to be ill that morning, and I couldn't leave him. You remember you were good enough to go to church with us."

"I remember," said Percival with a scornful smile as he recalled the devoted attention with which he had escorted the young organist to St. Sylvester's.

"He must have enjoyed that walk, I should think," said Judith, still very quietly. Her unopened note was on the table, where she had placed it that morning. She took it up and tore it into a hundred pieces. "You have heard people talk of broken hearts, haven't you?" she said.

"Often," he answered.

"Well, then, Bertie has broken Miss Crawford's. She said this morning that she should never hold up her head again if this were true; and I believe she never will."

"Do you mean she will die of it?" said Thorne, aghast.

"Not directly, perhaps, but I am sure she will die the sooner for it. All her pride in her life's work is gone. She feels that she is disgraced. I could not bear to see her this afternoon, utterly ashamed and humble before that man."

"What did he say?"

"Some things I won't tell you." A quick blush dyed her face. "Naturally, he was angry: he had good reason to be. And when he told her she was past her work, she moaned, poor thing! while the tears rained down her cheeks, and only said, 'God forgive me—yes.'"

Percival could but echo her pity. "Bertie never thought—" he began.

"Never thought? When our trouble came," said Judith, "we had plenty of friends better able to do something for us, but, somehow, they didn't. And when there was the talk of Bertie's coming here, and I remembered her and asked her if she could help me to a situation anywhere in the neighborhood, she wrote to me to come to her at once, and she would do all she could to help Bertie too. I have her letter still. She said she longed to know me for my mother's sake, and was sure she would soon love me for my own. And this afternoon she prayed God she might never see my face again!"

"She thinks you are to blame, then?" said Thorne.

"Yes; and am I not?" was the quick reply. "Ought I not to have known Bertie better? And I did know him: that is the worst of it. I did not expect this, and yet I ought to have been on my guard. He has been my one study from first to last. From the time that he was a little boy—the bonniest little boy that ever was!—my life has been all Bertie. I remember him, with long curls hanging down his back and his gray eyes opened wide, when he stood on tiptoe at the piano and touched the little tunes that he had heard, and looked over his shoulder at me and laughed for pleasure in his music. I can see his little baby-fingers—the little soft fingers I used to kiss—on the keys now.—Oh, Bertie, why didn't you die then?"

She stopped as if checked by a sudden thought, and looked so quickly up at Percival that she caught an answer in his eyes that he would never have uttered.

"Ah, yes, he would have been the same," she said. "He was the same then: I know it. They used to praise me, when I was a child, for giving everything up to Bertie. As if he were not my happiness! And it has been so always. And now I have sacrificed Miss Crawford to Bertie—my dear old friend, my mother's friend, who is worth ten times as much as Bertie ever was or ever will be! Is not this a fine ending of all?"

Percival broke the silence after a moment's pause. "Is it an ending of all?" he said. "Bertie has been very wrong,545 but it has been partly thoughtlessness. He is very young, and if he should do well hereafter may there not even yet be a future to which you may look forward? As for the world, it is not disposed to look on a runaway match of this sort as a crime."

She turned her eyes full upon him, and he stopped.

"Oh, the world!" she said. "The world will consider it a sort of young Lochinvar affair, no doubt. But how much of the young Lochinvar do you think there is about Bertie, Mr. Thorne? You have heard him speak of Emmeline Nash sometimes—not as often nor as freely as he has spoken to me; still, you have heard him. And judging from that, do you believe he is in love with her?"

"Well—no," said Thorne reluctantly. "Hardly that."

"A thousand times no! If by any possibility he had loved her, foolishly, madly, with a passion that blinded him to the cruel wrong he was doing, it would all have been different. I should have blamed him, but in spite of Miss Crawford I should have forgiven him; I should have had hope; he would have been my Bertie still; I should not have despised him. But this is cold and base and horrible: he has simply sold himself for Emmeline's money—sold himself, his smiles and his pretty speeches and his handsome face. And now it is all over."

As Judith spoke Percival understood for the first time what a woman's voice could be. The girl's soul was filled and shaken with passion. She did not cry aloud nor rant, but every accent thrilled through him from head to foot. And it seemed to him that she needed no words—that, had she been speaking in an unknown tongue, the very intonation, the mere sound, the vibration of her voice, would have told him of her wounded heart, her despair, her unavailing sorrow, her bitter shame, so eloquent it was. He did not think all this, but in a passing moment felt it. "I fear it is all too true," he said. "I don't know what to say nor how to help you. Your brother—"

"Don't call him that: he is no brother of mine. Ah yes, God help me, he is my brother; and I think we Lisles bring sorrow to all who are good to us. We have to you, have we not? Don't stay here, Mr. Thorne: don't try to help me. Remember that I am of the same blood as my father, who robbed you—as Bertie, who has been so base."

"And if Judas himself were your brother, what then?" Percival demanded. His voice, in its masculine vigor and fulness, broke forth suddenly, like a strong creature held till then in a leash. "And as for the money, what of that? I am glad it is gone, or I should not have been here to-day."

No, he would not have needed to turn clerk and earn his living. He would not have gone to Brackenhill to confess his poverty. He might never have discovered anything. Most likely he would long since have been Sissy's husband. Sissy seemed far away now. He had loved her—yes. Oh, poor little Sissy, who had clung to him! But what were these new feelings that thronged his heart as he looked at Judith Lisle? He stopped abruptly. What had he said?

Judith too looked at him, and grew suddenly calm and still. "You are very good," she said. "I should have been very lonely to-day if I had not had a friend. It has been a comfort to speak out what I felt, though I'm afraid I've talked foolishly."

"One can't weigh all one's words," said Percival.

"No," she answered; "and I know you will not remember my folly."

"At any rate, I will not forget that you have trusted me. You are tired," he said gently: "you ought to rest. There is nothing to be done to-night."

"Nothing," she answered hopelessly.

"And to-morrow, if there is anything that I can do, you will send for me, will you not?"

She smiled.

"Promise me that," he urged in a tone of authority. "You will?"

"Yes, I promise."

Sometimes, when clouds roll up, black with thunder and rain, to overshadow the heavens and to deluge the earth, between546 their masses you may catch a momentary gleam of blue, faint and infinitely far away, deep, untroubled, most beautiful. Judith had caught such a glimpse that evening as she bade Percival good-night.

CONSEQUENCES.

The story of the elopement was in all the local papers, which seemed for once to be printed on Judith Lisle's heart. It was the latest and most exciting topic of conversation in the neighborhood of Standon Square and St. Sylvester's, and was made doubly interesting by the utter collapse of Mr. Clifton's Easter services, which were to have been something very remarkable indeed. Every one recollected the young organist who was so handsome and who played so divinely. People forgot that his father had failed very disgracefully, and only remembered that Bertie had once been in a much better position. There was a sort of general impression that he was an aristocratic young hero who lived in lofty poverty, and was a genius into the bargain. No one was very precise about it, but Beethoven and Mendelssohn and all those people were likely to find themselves eclipsed some fine morning. Emmeline Nash of course became a heroine to match, vaguely sketched as slim, tall and fair. She had stayed on at Miss Crawford's at an age when a girl's education is generally supposed to be finished, and she had not always gone home for the holidays. These facts were of course the germs of a romance. There was a quarrel with her father, who wished her to marry some one. No one knew who the some one might be, but as he was only a shadowy figure in the background, his name was of no importance. Emmeline and her music-master had fallen in love at first sight; and when the moment came for the girl to return home, to be persecuted by her father's threats and by the attentions of the shadowy lover, her heart had failed her and she had consented to fly with the young musician. As Judith had said, it was a young Lochinvar romance—a boy-and-girl attachment. No one seemed to think much the worse of Bertie. Hardly any one called him a fortune-hunter, for Emmeline's money seemed trivial compared with the wealth that he was supposed to have once possessed. And no one thought anything at all of Judith herself or of Miss Crawford.

It would soon be over and forgotten, but Judith suffered acutely while it lasted. Perhaps it was well that she was forced to think about her own prospects, which were none of the brightest.

"Shall you go to Rookleigh?" Percival asked her a couple of days later.

She shook her head: "No: I'm too proud, I suppose, or too miserable: I can't have my failure here talked over. Aunt Lisle's conversation is full of sharp little pin-pricks, which are all very well when they don't go straight into one's heart."

He saw her lip quiver as she turned her face away. "Where will you go, then?" he asked with gentle persistence. It was partly on his own account, for he feared that a blow was in store for him, and he wanted to know the worst.

"I shall not go anywhere. I shall not leave Brenthill."

The blood seemed to rush strongly to his heart: his veins were full of warm life. She would not leave Brenthill!

"I will stay, at any rate, while Miss Crawford remains here. She will not speak to me, she has forbidden me to attempt to see her, but I cannot go away and leave her here alone. I may not be of any use—I do not suppose I shall be—but while she is here I will not go."

"But if she left?"

"Still, I would not leave Brenthill if I could get any work to do. I feel as if I must stay here, if only to show that I have not gone away with Bertie to live on Emmeline's money. Poor Emmeline! And when he used to talk of my not working any more, and he would provide for me, I thought he meant that he would make a fortune with his opera. What a fool I was!"

"It was a folly to be proud of."

He was rewarded with a faint smile, but the delicate curve of the girl's lips relaxed into sadness all too soon.

The table at her side was strewn with sheets of roughly-blotted music, mixed with others daintily neat, which Judith herself had copied. "His opera," she repeated, laying the leaves in order. "Emmeline will be promoted to the office of critic and admirer now, I suppose. But I think the admiration will be too indiscriminate even for Bertie. Poor Emmeline!"

"What are you going to do with all these?" said Thorne, laying his hand on the papers.

"I am putting them together to send to him. I had a letter this morning, so I know his address now. He seems very hopeful, as usual, and thinks her father will forgive them before long."

"And do you think there is a chance of it?"

"No, I don't. Bertie did not hear what Mr. Nash said that afternoon to Miss Crawford and to me," she replied; and once again the color rushed to her face at the remembrance.

"Miss Lisle," said Percival suddenly, "I am ready to make every allowance for Mr. Nash, but if—"

"Oh, it was nothing. He was angry, as he had reason to be: that was all. And you see I am not used to angry men."

"I should hope not. I wish I had been there."

"And I don't," said Judith softly. "I think you might not have been very patient, and I felt that one ought to be patient for Miss Crawford's sake. Besides, if you had been there I could not have—Bertie writes in capital spirits," she continued with a sudden change of tone. "He wants me to go and join them. He is just the same as ever, only rather proud of himself."

"Proud of himself! In Heaven's name, why?"

"Why, he is only two-and-twenty, and has secured a comfortable income for the rest of his life by his own exertions. Naturally, he is proud of himself." Percival had learned now that Judith never suffered more keenly than when she spoke of Bertie in a jesting tone, and it pained him for her sake. He looked sorrowfully at her. "Mr. Thorne," she went on, "he does not even suspect that what he has done is anything but praiseworthy and rather clever. He does not so much as mention Miss Crawford. And I am haunted by a feeling that we have somehow wronged my mother by wronging her old friend."

Percival did not tell her that he too had had a letter from Bertie. It was in his pocket as he stood there, and when he went away he took it out and read it again.

Bertie was as light-hearted as she had said. He enclosed an order for the money taken from the desk, and hoped Thorne had not wanted it; or, if he had been put to any inconvenience, he must forgive him this once, as he, Lisle, did not suppose he should ever run away in that style again.

"I think the old man will come round without much fuss," Bertie went on. "We have been very penitent—the waste of note-paper before we could get our feelings properly expressed was something frightful; but the money was well laid out, for we have heard from him again, and there is a perceptible softening in the tone of his letter. Emmeline assures me that he is passionately fond of music, and reminds me how anxious he was that she should learn to play. The reasoning does not exactly convince me, but if the old fellow does but imagine that he has a passion for music I will conquer him through that. And if the worst comes to the worst, and he is as stony-hearted as one of his own fossils, we have only to manage for this year, and we must come into our money when Emmeline is twenty-one. But I have no fear. He will relent, and we shall be comfortably settled under the paternal roof long before Christmas.

"What did old Clifton say and do when he found I had bolted? And how did the Easter services go off? Those blessed Easter services that he was in such a state of mind about! Was he548 very savage? Send me as graphic a description as you can.

"Excuse a smudge, but Emmeline and I are bound to do a good deal of hugging and kissing just now—a honeymoon after an elopement is something remarkably sweet, as you may suppose—and her sleeve brushed the wet ink. This particular embrace was on the occasion of her departure to put on her things. We are going out.

"Don't they say that married women always give up their accomplishments? Emmeline is a married woman, therefore Emmeline will give up her music. How soon do you suppose she will begin?"

Half a page more of Bertie's random scribble brought him to a conclusion, but it was not a final one, for he had added a couple of lines: "P.S. Persuade J. to shake herself free of Brenthill as soon as possible: there can be no need for her to work now, thank God! You know it has always been my day-dream and hope to provide for her. You must come and see us too. Come soon, before we go to my father-in-law's. Good-bye: we are off.—P.S. No. 2. No, we are not. E. has forgotten her parasol, and is gone for it. How is Lydia? What did she say when she heard the news? I suppose by this time everybody knows it."

Percival's lip curved with scorn and disgust as he refolded the letter, in which Emmeline, Judith and Lydia jostled each other as they might have done in a bad dream. Then he looked up, being suddenly aware of eyes that were fixed upon him.

Miss Bryant stood in the doorway: "You've heard from him, Mr. Thorne?"

Percival did not choose to answer as if he were in Miss Bryant's secrets and knew as a matter of course that "him" meant Lisle. Neither did he choose to say that he did not know who was intended by the energetic pronoun. He looked back at Lydia politely and inquiringly, as if he awaited further information before he could be expected to reply.

"Oh, you know," said Lydia scornfully. "You have heard from Mr. Bertie Lisle?"

"Yes," Percival acquiesced gravely.

"Well?"

"Well—what, Miss Bryant?"

"What does he say?" Lydia demanded; and when Thorne arched his brows, "Oh, you needn't look as if you thought it wasn't my business. I've a right to ask after him, at any rate, for old acquaintance' sake."

"I'm sorry to hear you take so much interest in him," he rejoined.

"Why? You may keep your sorrow for your own affairs: I'll manage mine. I can take very good care of myself, I assure you, and I won't trouble you to be sorry for me," said Lydia shortly. I do not think she had ever spoken to a young man before and been unconscious that it was a young man to whom she spoke. But she was utterly heedless of Percival as she questioned him, and he perceived it, and preferred this angry mood. "Can't you tell me anything about him?" said the girl. "Is he well—happy?"

"He writes in the best of spirits."

Lydia advanced a step or two: "And is it all true what they are saying? He has married this young lady?"

"Yes, he has married her."

"And do you suppose he cares for her?" said Lydia slowly.

Thome's brows went up again: "Really, Miss Bryant—"

"Because if he does, he has told lies enough: that's all."

("And he isn't a miracle of honor if he doesn't," said Percival.)

"But that's quite likely," Lydia went on, unheeding. "I knew all the time that he didn't mean any good. He thought I believed him, but I didn't—not more than half, anyhow. But when he went away I didn't guess it was for this."

"You knew he was going?" Thorne said.

Lydia half smiled, in conscious superiority.

"You don't seem to have served yourself particularly well by keeping his secrets. You are deceived at last, like the rest."

"Well, if I haven't served myself I've served him," said Lydia. "And I don't know but what I am glad of it. He wasn't as stuck-up and proud as some people. One likes to be looked at and spoken to as if one wasn't dirt under people's feet. And, after all, I don't see that there's any harm done." There were red rims to Lydia's eyes, telling of tears which must surely have been too persistent to pass for tears of joy at the tidings of Bertie's elopement. "I suppose a marriage like that is all right?" she asked with a quick glance.

"Of course—no doubt of it," said Percival very shortly. He had pitied her a moment earlier.

"Ah! I supposed so. But things ain't always all right when people run away. And the money's all right too, is it?"

"Some of it, at any rate," said Thorne, taking a book from the table.

"Wouldn't he be sure to take care of that! And there's more to come if the father likes, isn't there? He'll get that too: see if he doesn't."

"It is to be hoped he will—for Mrs. Lisle's sake. Otherwise, I cannot say I care to discuss his prospects."

"Well," said Lydia after a pause, during which she turned a ring slowly on her finger—"well, I'll wish him all the happiness he deserves."

Percival's lip curved a little: "Miss Bryant, are you absolutely pitiless?"

Lydia's expression was rather blank. "What do you mean? No, I ain't," she said. "I've nothing more to do with him. He hasn't done me any harm, and I won't wish him any. At least, only a little." With which small ebullition of feminine tenderness and spite she fled hurriedly down stairs to shed a few more tears, and left Thorne to write his letter to Lisle. It was brief, and none the sweeter for that recent interview.

"I return the money," Percival wrote, "which you say was so useful to you. I know that what you have sent me is not yours, but your wife's, and I cannot conscientiously say that I think Mrs. Herbert Lisle is indebted to me in any way.

"I have not delivered your message to your sister. I have no wish to insult her in her trouble, and I know she would feel such persuasion a cruel insult, as indeed I think it would be."

Judith at the same time was writing:

"From this time our paths must lie apart. I will never touch a penny of your wife's money. Do not dare to offer me a share of it again. It seems to me that all the shame and sorrow is mine, and you have only the prosperity. Not for the whole world would I change burdens with you.

"Miss Crawford is going to give up her school at once. She will not see or speak to me, for she suspects me of having been your accomplice. And I cannot help blaming myself that I trusted you so foolishly. But I could not have believed that you would have been false to her—our one friend, our mother's friend. Is it possible that you do not see that every one under her roof should have been sacred to you? But what is the use of saying anything now?

"I don't know, after this, how to appeal to you, and I don't want any promises; but if you feel any regret for the pain you have caused, and if you really wish to do anything for me, I entreat you to be good to Emmeline. It is the only favor I will ever ask of you. She is young and weak, poor girl! and she has trusted you utterly. In God's name, do not repay her trust as you have repaid Miss Crawford's and mine!"

Bertie's incredulous amazement was visible in every line of his answer to Percival:

"Are you both cracked—you and Judith—or am I dreaming? I have read your letters a score of times, and I think I understand them less than I did. Here are sweet bells jangled out of tune with a vengeance, and Heaven only knows what all the row is about: I don't.

"Do you suppose a man never made a runaway match before? And how could I do otherwise than as I did? Was I to stop and consult all the old women in the parish about it—ask Miss Crawford's blessing, and get my sister to look out my train for me and pack my portmanteau? Can't you see that I was obliged to deceive you a little?