Captain Mayne Reid

"The Boy Tar"

Chapter One.

My Boy Audience.

My name is Philip Forster, and I am now an old man.

I reside in a quiet little village, that stands upon the sea-shore, at the bottom of a very large bay—one of the largest in our island.

I have styled it a quiet village, and so it really is, though it boasts of being a seaport. There is a little pier or jetty of chiselled granite, alongside which you may usually observe a pair of sloops, about the same number of schooners, and now and then a brig. Big ships cannot come in. But you may always note a large number of boats, either hauled up on the beach, or scudding about the bay, and from this, you may conclude that the village derives its support rather from fishing than commerce. Such in reality is the fact.

It is my native village—the place in which I was born, and where it is my intention to die.

Notwithstanding this, my fellow-villagers know very little about me. They only know me as “Captain Forster,” or more specifically as “The Captain,” this soubriquet being extended to me as the only person in the place entitled to it.

Strictly speaking, I am not entitled to it. I have never been a captain of soldiers, nor have I held that rank in the navy. I have only been the master of a merchant vessel,—in other words, a “skipper.” But the villagers are courteous, and by their politeness I am styled “Captain.”

They know that I live in a pretty cottage about half a mile from the village, up shore; they know that I live alone—for my old housekeeper can scarce be accounted as company; they see me each day pass through the place with my telescope under my arm; they note that I walk out on the pier, and sweep the offing with my glass, and then, perhaps, return home again, or wander for an hour or two along the shore. Beyond these facts, my fellow-villagers know but little of myself, my habits, or my history.

They have a belief among them that I have been a great traveller. They know that I have many books, and that I read much; and they have got it into their heads that I am a wonderful scholar.

I have been a great traveller, and am a great reader, but the simple villagers are mistaken as to my scholarship. In my youth I was denied the advantages of a fine education, and what little literary knowledge I possess has been acquired by self-instruction—hasty and interrupted—during the brief intervals of an active life.

I have said that my fellow-villagers know very little about me, and you are no doubt surprised at this; since among them I began my life, and among them I have declared my intention of ending it. Their ignorance of me is easily explained. I was but twelve years of age when I left home, and for forty years after I never set foot in my native place, nor eyes upon any of its inhabitants.

He must be a famous man who would be remembered after forty years’ absence; and I, scarce a boy at going forth, returned to find myself quite forgotten. Even my parents were scarce remembered. Both had died before I went away from home, and while I was only a mere lad. Besides, my father, who was a mariner by profession, was seldom or never at home, and I remember little else about him, than how I grieved when the news came that his ship was lost, and he with most of his crew were drowned. Alas! my mother did not long survive him; and their death occurring such a long time ago, it is but natural that both should be forgotten among a people with whom they had but slight intercourse. Thus, then, is it explained how I chance to be such a stranger in my native place.

But you are not to suppose that I am lonely or without companions. Though I have ceased to follow my profession of the sea, and returned home to spend the remainder of my days in a quiet, peaceful way, I am by no means of an unsocial disposition or morose habits. On the contrary, I am fond, as I have ever been, of social intercourse; and old man though I be, I take great delight in the society of young people, especially little boys. I can boast, too, that with all these in the village I am a favourite. I spend hours upon hours in helping them to fly their kites, and sail their tiny boats; for I remember how much delight I derived from these pastimes when I was myself a boy.

As I take part in their sports, little do the simple children think that the gentle old man who can so amuse them and himself, has spent most of his life amidst scenes of wild adventure and deadly peril; and yet such has been my history.

There are those in the village, however, who are better acquainted with some chapters from the story of my life—passages of it which they have heard from my own lips, for I am never disinclined to relate to those who may be worthy of hearing it any interesting adventure through which I may have passed; and even in our quiet village I have found an audience that merits the narrator. Schoolboys have been my listeners; for there is a famous school near the village—an “establishment for young gentlemen” it is styled—and it is from this I draw my most attentive auditory.

These boys and I used to meet in our rambles along the shore, and observing my weather-beaten, salt-water look, they fancied that I could tell them tales of wild scenes and strange incidents that I had encountered far over the sea. Our meetings were frequent—almost daily—and soon a friendly acquaintance sprung up between us; until, at their solicitation, I began to relate to them an occasional adventure of my life. Often I may have been observed, seated upon the “bent” grass of the beach, encircled by a crowd of these well-dressed youths, whose parted lips and eager eyes betokened the interest they felt in my narrations.

I am not ashamed to declare that I, too, felt pleasure in this sort of thing: like all old soldiers and sailors, who proverbially delight to “fight their battles o’er again.”

These desultory recitals continued for some time, until one day, as I met my young friends in the ordinary way, only somewhat earlier than common, I saw that there was something unusual in the wind. They mustered stronger than was their wont, and I noticed that one of them—the biggest boy of the crowd—held a folded paper in his hand, upon which I could perceive there was writing.

As I drew near, the paper was placed in my hands without a word being said; and I saw by the superscription that it was directed to myself.

I opened the paper, and soon perceived the nature of its contents. It was a “petition” signed by all the boys present. It ran thus:—

“Dear Captain,—We have been allowed holiday for the whole of to-day; and we know of no way in which we could spend it with so much of pleasure and profit, as by listening to you. We have therefore taken the liberty of asking you to indulge us, by the narration of some remarkable incident that has happened to you. A stirring passage we should prefer, for we know that many of these have befallen you during your adventurous life; but choose whatever one it may be most pleasant for you to relate; and we shall promise to listen attentively, since one and all of us know that it will be an easy thing to keep that promise. And now, dear captain! grant us the favour we ask, and your petitioners shall be for ever grateful.”

Such a polite request could not be refused; and without hesitation I declared my intention to gratify my young friends with a chapter from my life. The chapter chosen was one which I thought would be most interesting to them—as it gave some account of my own boy-life, and of my first voyage to sea—which, from the odd circumstances under which it was made, I have termed a “Voyage in the Dark.”

Seating myself upon the pebbly beach, in full view of the bright sea, and placing my auditory around me, I began.

Chapter Two.

Saved by Swans.

From my earliest days, I was fond of the water—instinctively so. Had I been born a duck, or a water-dog, I could not have liked it better. My father had been a seaman, and his father before him, and grandfather too; so that perhaps I inherited the instinct. Whether or not, my aquatic tastes were as strong as if the water had been my natural element; and I have been told, though I do not myself remember it, that when still but a mere child, it was with difficulty I could be kept out of puddles and ponds. In fact, the first adventure of my life occurred in a pond, and that I remember well. Though it was neither so strange nor so terrible as many adventures that befell me afterwards, still it was rather a curious one, and I shall give you it, as illustrating the early penchant I had for aquatic pursuits. I was but a very little boy at the time, and the odd incident occurring, as it were, at the very threshold of my life, seemed to foreshadow the destiny of my future career—that I was to experience as in reality I have experienced, many vicissitudes and adventures.

I have said I was but a very little boy at the time—just big enough to go about, and just of that age when boys take to sailing paper-boats. I knew how to construct these out of the leaf of an old book, or a piece of a newspaper; and often had I sent them on voyages across the duck-pond, which was my ocean. I may ay, I had got a step beyond the mere paper-boats: with my six months’ stock of pocket-money, which I had saved for the purpose, I had succeeded in purchasing a full-rigged sloop, from an old fisherman, who had “built” her during his hours of leisure. She was only six inches in length of keel, by less than three in breadth of beam, and her tonnage, if registered—which it never was—would have been about half a pound avoirdupois. A small craft you will style her; but at that time, in my eyes, she was as grand as a three-decker.

I esteemed her too large for the duck-pond, and resolved to go in search of a piece of water where she should have more room to exhibit her sailing qualities.

This I soon found in the shape of a very large pond—or lake, I should rather call it—where the water was clear as crystal, and where there was usually a nice light breeze playing over the surface—just strong enough to fill the sails, and drive my little sloop along like a bird on the wing—so that she often crossed the pond before I myself could get round to the other side to receive her into my hands again.

Many a race have I had with my little sloop, in which sometimes she, and sometimes I, proved victorious, according as the wind was favourable or unfavourable to her course.

Now this pretty pond—by the shores of which I used to delight myself, and where I spent many of the happiest hours of my boyhood—was not public property. It was situated in a gentleman’s park, that extended backward from the end of the village, and the pond of course belonged to the owner of the park. He was a kind and liberal gentleman, however, and permitted the villagers to go through his grounds whenever they pleased, and did not object to the boys sailing their boats upon the ornamental water, or even playing cricket in one of his fields, provided they did not act rudely or destroy any of the shrubs or plants that grew along the walks. It was very kind and good of him to allow this freedom; and we, the boys of the village, were sensible of this, and I think on the whole we behaved as if we were so; for I never heard of any damage being done that was deemed worthy of complaint. The park and pond are there still—you all know them?—but the kind gentleman I speak of has long since left this world; for he was an old gentleman, then, and that is sixty years ago.

Upon the little lake, there was at that time a flock of swans—six, if I remember aright—besides other water-fowl of rare kinds. The boys took great delight in feeding these pretty creatures; and it was a common thing for one or other of us to bring pieces of bread, and chuck them to the water-fowl. For my part, I was very fond of this little piece of extravagance; and, whenever I had the opportunity, I came to the lake with my pockets crammed.

The fowls, and especially the swans, under this treatment had grown so tame, that they would eat out of our hands, without exhibiting the slightest fear of us.

There was a particular way of giving them their food, in which we used to take great delight. On one side of the lake, there was a bank that rose three feet or so above the surface of the water. Here the pond was deep, and there was no chance for either the swans, or any other creature, to land at this place without taking to wing. The bank was steep, without either shelf or stair to ascend by. In fact, it rather hung over, than shelved.

At this point we used to meet the swans, that were always ready to come when they saw us; and then, placing the piece of bread in the split end of a rod, and holding it out high above them, we enjoyed the spectacle of the swans stretching up their long necks, and occasionally leaping upward out of the water to snatch it, just as dogs would have done. All this, you will perceive, was rare fun for boys.

Now I come to the promised adventure.

One day, I had proceeded to the pond, carrying my sloop with me as usual. It was at an early hour; and on reaching the ground, I found that none of my companions had yet arrived. I launched my sloop, however; and then walked around the shore to meet her on the opposite side.

There was scarcely a breath of wind, and the sloop sailed slowly. I was therefore in no hurry, but sauntered along at my leisure. On leaving home I had not forgotten the swans, which were my great pets: such favourites, indeed, that I very much fear they induced me on more than one occasion to commit small thefts for them; since the slices of bread with which my pockets were crammed, had been rather surreptitiously obtained from the domestic larder.

Be this as it may, I had brought their allowance along with me; and on reaching the high bank, I halted to give it them.

All six, who knew me well, with proud arching necks and wings slightly elevated, came gliding rapidly across the pond to meet me; and in a few seconds arrived under the bank, where they moved about with upstretched beaks, and eyes eagerly scanning my movements. They knew that I had called them thither to be kind to them.

Having procured a slight sapling, and split it at the end, I placed a piece of bread in the notch, and proceeded to amuse myself with the manoeuvres of the birds.

One piece after another was snatched away from the stick, and I had nearly emptied my pockets, when all at once the sod upon which I was standing gave way under me, and I fell plump into the water.

I fell with a plunge like a large stone, and as I could not swim a stroke, I should have gone to the bottom like one, but it so happened that I came down right in the middle of the swans, who were no doubt taken as much by surprise as myself.

Now it was not through any peculiar presence of mind on my part, but simply from the instinct of self-preservation, which is common to every living creature, that I made an effort to save myself. This I did by throwing out my hands, and endeavouring to seize hold of something, just as drowning men will catch even at straws. But I caught something better than a straw, for I chanced to seize upon the leg of one of the biggest and strongest of the swans, and to that I held on, as if my life depended on my not letting it go.

At the first plunge my eyes and ears had been filled with water, and I was hardly sensible of what I was doing. I could hear a vast splashing and spluttering as the birds scattered away in affright, but in another second of time I had consciousness enough to perceive that I had got hold of the leg of the swan, and was being towed rapidly through the water. I had sense enough to retain my hold; and in less time than I have taken to tell it, I was dragged better than half across the pond, which, after all, was but a short distance. The swan made no attempt to swim, but rather fluttered along the surface, using his wings, and perhaps the leg that was still free, to propel himself forward. Terror, no doubt, had doubled both his strength and his energies, else he could never have towed such a weight, big and strong as he was. How long the affair would have lasted, it is hard to say. Not very long, however. The bird might have kept above water a good while, but I could not have held out much longer. I was every moment being ducked under, the water at each immersion getting into my mouth and nostrils. I was fast losing consciousness, and would soon have been forced to let go.

Just at this crisis, to my great joy, I felt something touch me underneath; some rough object had struck against my knees. It was the stones and gravel at the bottom of the lake; and I perceived that I was now in water of no great depth. The bird, in struggling to escape, had passed over the portion of the lake where it was deep and dangerous, and was now close to the edge, where it shoaled, I did not hesitate a moment; I was only too glad to put an end to the towing match, and therefore released my grasp from the leg of the swan. The bird, thus lightened, immediately took to wing; and, screeching like a wild fowl, rose high into the air.

For myself, I found bottom at once, and after some staggering, and a good deal of sneezing and hiccoughing, I regained my feet; and then wading out, stood once more safe upon terra firma.

I was so badly terrified by the incident that I never thought of looking after my sloop. Leaving her to finish her voyage as she might, I ran away as fast as my legs would carry me, and never made halt or pause till I had reached home and stood with dripping garments in front of the fire.

Chapter Three.

The “Under-Tow.”

You will fancy that the lesson I had thus received should have been a warning to me to keep away from the water. Not so, however. So far as that went, the ducking did me no good, though it proved beneficial in other respects. It taught me the danger of getting into water over one’s depth, which I had before then but little appreciated; and young as I was, I perceived the advantage of being able to swim. The peril from which I had so narrowly escaped, stimulated me to form a resolve, and that was—to learn the art of swimming.

I was encouraged in this resolution by my mother, as also by a letter received from my father, who was then abroad; and in which he gave directions that I should be taught to swim in the best manner. It was just what I desired, and with the intention of becoming a first-rate swimmer, I went about it in right earnest. Once and sometimes twice each day during the warm weather—that is, after school was out—I betook myself to the water, where I might be seen splashing and spluttering about like a young porpoise. Some bigger boys, who had already learnt to swim, gave me a lesson or two; and I soon experienced the delightful sensation of being able to float upon my back without assistance from any one. I well remember how proud I felt on the occasion when I first accomplished this natatorial feat.

And here, young reader, let me advise you by all means to imitate my example, and learn to swim. You know not how soon you may stand in need of a knowledge of this useful art; how soon you may be called upon to practise it perforce. You know not but that sooner or later it may be the means of saving your life.

At the present time, the chances of death by drowning are multiplied far beyond anything of the kind in past ages. Almost everybody now travels across seas, oceans, and upon large rivers, and the number of people who annually risk their lives on the water, voyaging on business, pleasure, or in the way of emigration, is scarce credible. Of these, a proportion—in stormy years a large one—perish by drowning.

I do not mean to assert that a swimmer, even the best, if cast away at a great distance from shore, in mid-Atlantic, for instance, or even in the middle of the English Channel—would have any prospect of swimming to land. That, of course, would be impracticable. But there are often other chances of life being saved, besides that of getting to land. A boat may be reached, a spar, an empty hencoop or barrel; and there are many instances on record of lives having been saved by such slight means. Another vessel, too, may be in sight, may hasten to the scene of the disaster, and the strong swimmer may be still afloat upon her arrival; while those who could not swim, must of course have gone to the bottom.

But you must know that it is neither in the middle of the Atlantic, nor of any great ocean, that most vessels are wrecked and lives are lost. Some are, it is true—when a storm rages with extreme fury, “blowing great guns,” as the seamen phrase it, and blowing a ship almost to atoms. These events, however, are extremely rare, and bear but a small proportion to the number of wrecks that take place within sight of the shore, and frequently upon the beach itself. It is in “castaways” of this kind, that the greatest number of lives are sacrificed, under circumstances when, by a knowledge of the art of swimming, many of them might have been saved. Not a year passes, but there is a record of hundreds of individuals who have been drowned within cable’s length of the shore—ships full of emigrants, soldiers, and sailors, have sunk with all on board, leaving only a few good swimmers survivors of the wreck! Similar “accidents” occur in rivers, scarce two hundred yards in width; and you yourselves are acquainted with the annual drownings, even in the narrow and icy Serpentine!

With these facts before the eyes of the world, you will wonder that the world does not take warning, and at once learn to swim.

It may be wondered, too, that governments do not compel the youth to learn this simple accomplishment; but that indeed is hardly to be wondered at, since the business of governments in all ages has been rather to tax than to teach their people.

It seems to me, however, that it would be a very easy thing for governments to compel all those who travel by ships, to provide themselves with a life-preserver. By this cheap and simple contrivance, I am prepared to show that thousands of lives would be annually saved; and no one would grumble at either the cost or inconvenience of carrying so useful an article.

Governments take special care to tax travellers for a piece of worthless paper, called a passport. Once you have paid for this, it signifies not to them how soon you and your passport go to the bottom of the sea.

Well, young reader, whether it be the desire of your government or not, take a hint from me, and make yourself a good swimmer. Set about it at once—that is, if the weather be warm enough—and don’t miss a day while it continues so. Be a swimmer before you become a man; for when you have reached manhood, you will most probably find neither time, opportunity, nor inclination to practise; besides, you may run many risks of being drowned long before there is hair upon your lip.

For myself, I have had a variety of hair-breadth escapes from drowning. The very element which I loved so dearly, seemed the most desirous of making a victim of me; and I should have deemed it ungrateful, had I not known that the wild billows were unreasoning, irresponsible creatures; and I had too recklessly laid “my hand upon their mane.”

It was but a few weeks after my ducking in the pond, and I had already taken several swimming lessons, when I came very near making my last essay at this aquatic exercise.

It was not in the pond that the incident occurred, for that, being a piece of ornamental water, and private property, as I have told you, was not permitted to be used as a bathing place.

But the people of a sea-shore town need no lake in which to disport themselves. The great salt sea gives them a free bath, and our village had its bathing beach in common with others of its kind. Of course, then, my swimming lessons were taken in salt-water.

The beach which was habitually used by the villagers, had not the best name as a bathing place. It was pretty enough, with yellow sand, white shells, and pebbles; but there was what is termed an “under-tow”—in one particular place stronger than elsewhere; and at times it was a dangerous matter to get within the influence of this “under-tow,” unless the person so exposing himself was a good and strong swimmer.

There was a legend among the villagers, that some one had been drowned by this current; but that was an occurrence of long ago, and had almost ceased to be talked about. There were also one or two more modern instances of bathers being carried out to sea, but finally saved by boats sent after them.

I remember at that time having been struck with a fact relating to these mishaps; and this was, that the older inhabitants of the village, and they who were of most consequence in the place, never liked to talk about them; either shrugging their shoulders and remaining silent, or giving the legends a flat contradiction. Some of them even went so far as to deny the existence of an “under-tow,” while others contented themselves by asserting that it was perfectly harmless. I always noticed, however, that parents would not permit their boys to bathe near the place where the dangerous current was represented to exist.

I never knew the reason why the villagers were so unwilling to acknowledge the “under-tow,” and the truth of the stories connected therewith. That is, I knew it not until long, long afterwards—until I came home again after my forty years of adventure. On my return, I found the same silence and shrugging of the shoulders, although by a generation of villagers altogether different from those I had left behind. And this, too, notwithstanding that several accidents had occurred in my absence, to prove that the “under-tow” did actually exist, and that it was actually dangerous.

But I was then older and better able to reason about men’s motives, and I soon fathomed the mystery. It was this: our village is, as you know, what is called a “watering-place,” and derived some support from visitors who came to it to spend a few weeks of their summer. It is a watering-place upon a small scale, it is true, but were there to be much talk about the “under-tow,” or too much credence given to legends of people who have been drowned by it, it would become a watering-place on a still smaller scale, or might cease to be one altogether. Therefore the less you say of the “under-tow,” the better for your own popularity among the wise men of the village.

Now, my young friends, I have been making a long story about what you will deem a very ordinary adventure, after all. It is simply to end by my telling you that I was drowned by the “under-tow”—actually drowned!

You will say that I could not have been drowned dead, though that is a doubtful point, for, as far as my feelings were concerned, I am certain I should not have known it had I never been restored to life again. No, I should not have felt pain had I been cut into a hundred pieces while I was in that state, nor would I ever have come to life again had it not been for somebody else. That somebody else was a fine young waterman of our village, by name Harry Blew, and to him was I indebted for my second life.

The incident, as I have said, was of the ordinary kind, but I relate it to show how I became acquainted with Harry Blew, whose acquaintance and example had an important influence on my after-life.

I had gone to the beach to bathe as usual, at a point new to me, and where I had not seen many people bathe before. It chanced to be one of the worst places for this “under-tow,” and shortly after entering the water I got into its gripe, and was drawn outward into the open sea, far beyond the distance I could have swum back. As much from terror, that paralysed my strength, as aught else—for I was aware of my danger—I could swim no further, but sank to the bottom like a piece of lead!

I did not know that I had ever come up again. I knew nothing at all about what happened after. I only remembered seeing a boat near me, and a man in it; and then all was dark, and I heard a loud rumbling like thunder in my ears, and my consciousness went out like the snuffing of a candle.

It returned again, thanks to young Harry Blew, and when I knew that I was still alive, I re-opened my eyes, and saw a man kneeling above me, rubbing me all over with his hands, and pushing my belly up under my ribs, and blowing into my mouth, and tickling my nostrils with a feather, and performing a great variety of such antic manoeuvres upon me.

That was Harry Blew bringing me to life again; and as soon as he had partially succeeded, he lifted me up in his arms and carried me home to my mother, who was nearly distracted on receiving me; and then wine was poured down my throat, and hot bricks and bottles were put to my feet, and my nose anointed with hartshorn, and my body rolled in warm blankets, and many other appliances were administered, and many remedies had I to take, before my friends considered the danger to be over, and that I should be likely to live.

But it was all over at length, and in twenty hours’ time I was on my feet again, and as brisk and well as ever.

I had now had my warning of the water, if that could have been of any service. But it was not, as the sequel will show.

Chapter Four.

The Dinghy.

No; the warning was all in vain. Even the narrow escape I had had, did not cure me of my fondness for being on the water, but rather had an opposite effect.

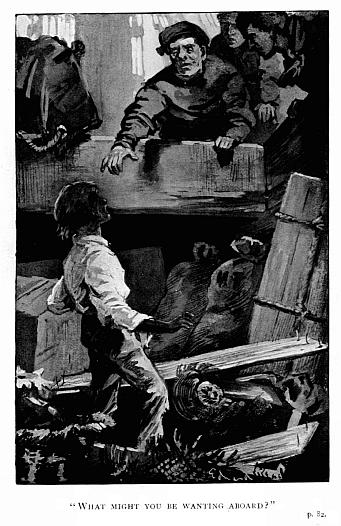

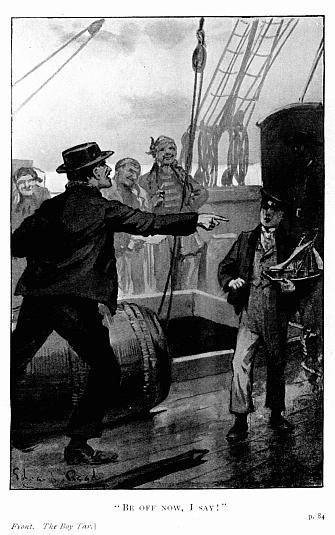

The acquaintance thus singularly formed between the young waterman and myself, soon ripened into a strong feeling of friendship. His name, as I have said, was Harry Blew, and—if I may be allowed to play upon the word—he was “true blue,” for he was gifted with a heart as kind as it was brave. I need hardly add that I grew vastly fond of him, and he appeared to reciprocate the feeling, for he acted towards me from that time forward as if I had saved his life, instead of its being the other way. He took great pains to make me perfect in swimming; and he also taught me the use of the oar; so that in a short time I was able to row in a very creditable manner, and far better than any boy of my age or size. I even attained to such proficiency that I could manage a pair of oars, and pull about without any assistance from my instructor. This I esteemed a great feat, and I was not a little proud when I was entrusted (as was frequently the case) to take the young waterman’s boat from the little cove where he kept her, to some point on the beach where he might be waiting to take up a fare. Perhaps in passing an anchored sloop, or near the beach, where some people might be sauntering, I may have heard remarks made in a sneering tone, such as, “You are a queer chap to be handlin’ a pair o’ oars!” or, “Oh, jimminy! Look at that millikin pin, boys!” And then I could hear other jeers mingled with shouts of laughter. But this did not mortify me in the least. On the contrary, I felt proud to show them that, small as I was, I could propel my craft in the right direction, and perhaps as rapidly as many of them that were even twice my size.

After a time I heard no more of these taunts, unless now and then from some stranger to the place. The people of our village soon learned how well I could manage a boat; and small as I was, they held me in respect—at all events, they no longer jeered at me. Often they would call me the “little waterman,” or the “young sailor,” or still oftener was I known by the name of the “Boy Tar.” It was my father’s design that, like himself, I should follow the sea as a calling; and had he lived to make another voyage, it was his intention to have taken me away with him. I was encouraged, therefore, in these ideas; and moreover, my mother always dressed me in sailor costume of the most approved pattern—blue cloth jacket and trousers, with black silk handkerchief and folding collar. Of all this I was very proud, and it was my costume as much as aught else, that led to my receiving the soubriquet of the “Boy Tar.” This title pleased me best of any, for it was Harry Blew that first bestowed it on me, and from the day that he saved me from drowning, I regarded him as my true friend and protector.

He was at this time rather a prosperous young fellow, himself owner of his boat—nay, better still, he had two boats. One was much bigger than the other—the yawl, as he styled her—and this was the one he mostly used, especially when three or four persons wanted a sail. The lesser boat was a little “dinghy” he had just purchased, and which for convenience he took with him when his fare was only a single passenger, since the labour of rowing it was much less. In the watering season, however, the larger boat was more often required; since parties of pleasure were out every day in it, and at such times the little one lay idle at its moorings. I was then welcome to the use of it for my own pleasure, and could take it when I liked, either by myself or with a companion, if I chose to have one. It became my custom, therefore, after school hours, or indeed whenever I had any spare time, to be off to the dinghy, and rowing it all about the harbour. I was rarely without a companion—for more than one of my schoolfellows relished this sort of thing—and many of them even envied me the fine privilege I had in being almost absolute master of a boat. Of course, whenever I desired company, I had no need to go alone; it was not often that I was so. Some one or other of the boys was my companion on every excursion that was made, and these were almost daily—at least, every day on which the weather was calm enough to allow of it. With such a small cockleshell of a boat, we dared not go out when it was not calm; and with regard to this, I had been duly cautioned by Henry Blew himself. Our excursions only extended to a short distance from the village, usually up the bay, though sometimes down, but I always took care to keep near the shore, and never ventured far out, lest the little boat might be caught in a squall and get me into danger.

As time passed on, however, I grew less timid, and began to feel more at home on the wide water. Then I extended my excursions sometimes as far as a mile from the shore, and thought nothing of it. My friend, the waterman, seeing me on one of these far voyages, repeated his former caution, but it might have had a more salutary effect had I not overheard him, the moment after, observe to one of his companions:—

“Wonderful boy! ain’t he, Bob? Come of the true stock—make the right sort of a sailor, if ever he grows big enough.”

This remark led me to think that I had not much displeased my patron in what I had done; and therefore his caution “to keep close in-shore” produced very little effect on me.

It was not a long time before I quite disobeyed it; and the disobedience, as you shall hear, very nigh cost me my life.

But first let me tell of a circumstance that occurred at this date, and which quite changed the current of my existence. It was a great misfortune that befell me—the loss of both my parents.

I have said that my father was a seaman by profession. He was the master of a ship that traded, I believe, to the colonies of America, and so little was he at home from the time I was old enough to remember, that I scarce recollected him more than just what he was like—and that was a fine, manly, sailor-looking man, with a face bronzed by the weather until it was nearly of a copper colour, but for all that a handsome and cheerful face.

My mother must have thought so too, for from the time that news arrived that his ship was wrecked and he himself drowned, she was never herself again. She seemed to pine away, as if she did not wish to live longer, but was desirous of joining him in the other world. If such were her wishes, it was not long before they were gratified; for in a very few weeks after the terrible news had reached us, my poor mother was carried to her grave.

These were the circumstances that changed the current of my existence. Even my mode of life was no longer the same. I was now an orphan, without means and without a home; for, as my parents had been without any fortune, and subsisted entirely upon the hard earnings of my father’s trade, no provision had been made against such an unexpected event as my brave father’s death, and even my mother had been left almost penniless. Perhaps it was a merciful providence that called her away from a world that to her was no longer a place of enjoyment; and although I long lamented my dear kind mother, in after years I could not help thinking that it was her happier destiny that at that time she had been summoned away. Long, long years it was before I could have done anything to aid or protect her—during the chill cold winter of poverty that must have been her portion.

To me the events brought consequences of the most serious kind. I found a home, it is true, but a very different one from that to which I had all along been used. I was taken to live with an uncle, who, although my mother’s own brother, had none of her tender or affectionate feelings; on the contrary, he was a man of morose disposition and coarse habits, and I soon found that I was but little more cared for than any one of his servants, for I was treated just as they.

My school-days were at an end, for I was no more sent to school from the day I entered my uncle’s house. Not that I was allowed to go about idle. My uncle was a farmer, and soon found a use for me; so that between running after pigs and cattle, and driving the plough horses, or tending upon a flock of sheep, or feeding calves, or a hundred other little matters, I was kept busy from sunrise till sunset of every day in the week. Upon Sundays only was I permitted to rest—not that my uncle was at all religious, but that it was a custom of the place that there should be no work done on the Sabbath. This custom was strictly observed by everybody belonging to the village, and my uncle was compelled to follow the common rule; otherwise, I believe, he would have made Sunday a day of work as well as any other.

My uncle, not having any care for religion, I was not sent to church, but was left free to wander idle about the fields, or indeed wherever I chose to go. You may be sure I did not choose to stop among the hedges and ditches. The blue sea that lay beyond, had far more attractions for me than birds-nesting, or any other rural amusement; and the moment I could escape from the house I was off to my favourite element, either to accompany my friend, Harry Blew, in some of his boating trips, or to get possession of the “dinghy,” and have a row on my own account. Thus, then, were my Sundays passed.

While my mother was living, I had been taught to regard this idle way of spending Sunday as sinful; but the example which I had before me in my uncle’s life, soon led me to form other ideas upon this matter, and I came to regard the Lord’s Day as only differing from any other of the week in its being by far the pleasantest.

One Sunday, however, proved anything but pleasant. So far from it, that it came very near being the most painful as well as the last day of my life—which was once more imperilled by my favourite element—the water.

Chapter Five.

The Reef.

It was Sunday morning, and as fine a one as I can remember. It was in the month of May, and not likely to be otherwise than fine. The sun was shining brightly, and the birds filled the air with joyous music. The thrush and blackbird mingled their strong vigorous voices, with the mellowed trilling of the skylark, and over the fields could be heard almost continuously the call of the cuckoo—now here, now there, as the active creature plied her restless wing from one hedge-tree to another. There was a strong sweet perfume in the air like the scent of almonds, for the white thorn was now expanding its umbels of aromatic flowers, and there was just enough breeze to bear their fragrance throughout the whole atmosphere. The country, with its green hedgerows, its broad fields of young corn, its meadows enamelled with the golden ranunculus and the purple spring orchis both in full flower; the country with its birds’ nests and bird music would have been attractive to most boys of my age, but far more fascination for me was there in that which lay beyond—that calm, glassy surface of a sky-blue colour that shone over the fields, glistening under the rays of the sun like a transparent mirror. That great watery plain was the field upon which I longed to disport myself: far lovelier in my eyes than the rigs of waving corn, or the flower-enamelled mead, its soft ripple more musical to my ear than the songs of thrush or skylark, and even its peculiar smell more grateful to my senses than the perfume of buttercups and roses.

As soon, therefore, as I left my chamber and looked forth upon this smiling, shining sea, I longed to fling myself on its bosom with a yearning which I cannot express. To satisfy this desire, I made all haste to be gone. I did not even wait for a regular breakfast, but was content with a piece of bread and a bowl of milk, which I obtained from the pantry, and having hurriedly swallowed these, I struck out for the beach.

I rather stole away than otherwise, for I had apprehensions that some obstacle might arise to hinder me from gratifying my wishes. Perhaps my uncle might find reason to call me back, and order me to remain about the house; for although he did not object to my roaming idly about the fields, I knew that he did not like the idea of my going upon the water, and once or twice already had forbidden it.

This apprehension, then, caused me to use a little precaution. Instead of going out by the avenue leading direct from the house to the main road that ran along the shore, I went by a back way that would bring me to the beach in a circuitous direction.

I met with no interruption, but succeeded in reaching the water edge without being observed—by any one who had an interest in knowing where I went.

On arriving at the little cove where the young waterman kept his boats, I perceived that the larger one was out, but the dinghy was there at my service. This was just what I wished for, as on that particular day I had formed a design to make a very grand excursion in the little boat. My first act, then, was to get inside and bale out the water which had gathered in the bottom of the dinghy. There was a good deal of water in her, and I concluded from this that she must have lain several days without being used, for she was a craft that did not leak very fast. Fortunately, I found an old tin pan, that was kept on purpose to bale out with, and after scooping away for some ten minutes or a quarter of an hour, I got the little boat dry enough for my purpose. The oars were kept in a shed behind the cottage of the waterman, which stood only a short distance back upon the beach: and these I fetched, as I had often done before, without the necessity of asking leave from any one.

I now entered the dinghy, and having adjusted the thole pins and placed my oars on the rowlocks, I took my seat and pushed off from the shore. My little skiff yielded freely to my stroke, and shot out into the deep water as smoothly as if she had been a fish; and with a heart as light as ever beat in my breast, I pulled away over the bright blue sea. The sea was not only bright and blue, but as calm as a lake. There was hardly so much as a ripple, and so clear was it underneath, I could see the fishes at play down to a depth of several fathoms.

The bed of the sea in our bay is of pure sand of a silvery whiteness; and the smallest objects, even little crabs not so big as a crown-piece, could be distinctly seen gambolling along the bottom, in playful pursuit of one another, or in search of some creatures still smaller than themselves, of which they designed to make their breakfast. I could see “schools” of small herring fry and broad round plaice, and huge turbots, and beautiful green mackerel, and great conger eels as large as boa-constrictors, all engaged in pursuits of pleasure or prey.

It was one of those mornings when the sea is perfectly still, and such as are very rare upon our coasts. It was just the morning for me, for, as I have already said, I had designed a “grand excursion” for the day, and the weather would enable me to carry my design into execution.

You will ask whither was I going? Listen, and you shall hear.

About three miles from the shore, and just visible from it, lay a small islet. It is not exactly correct to say islet. It was but a shoal of rocks—a small patch, apparently about a square pole in dimensions, and rising only a few inches above the surface of the water. This, too, only when the tide was out, for at all other times it was quite covered with the waves; and then there could only be seen a slender staff sticking up out of the water to the height of a few feet, and at the head of this appeared a sort of knob, or lump. Of course the staff had been placed there to point out the shoal in times of high tide, so that the sloops and other small vessels that traded up the bay might not run upon it by mistake, and so get wrecked.

Only when the tide was low, then, was this little islet to be observed from the shore. Usually, it appeared of a jet black colour; but there were other times when it was as white as if covered a foot deep with snow, and then it showed plainer and more attractive. I knew very well what caused this singular metamorphosis in its colour. I knew that the white mantle that covered it was neither more nor less than a vast flock of beautiful sea-fowl, that had settled upon the rocks, either to rest themselves after so much flying, or to search for such small fish or Crustacea as might be left there by the tide.

Now this little spot had long been to me a place of first-rate interest, partly on account of its remote and isolated situation; but more, I fancy, on account of these very birds, for in no other part of the bay had I seen so many of them together. It seemed also to be a favourite place with them; for at the going out of every tide, I observed them gather from all directions, hover around the staff, and then settle down upon the black rocks around it, until the latter were hidden from the view behind the white bodies of the birds. These birds were gulls; but there appeared to be several kinds of them; large ones and small ones, and at different times I had noticed birds of other kinds, such as the great terns and grebes, preening themselves in the same neighbourhood. Of course, from the shore the view one could have of these creatures was a very distant one, and it was difficult to tell to what species they belonged. The largest of them appeared not much bigger than sparrows, and had they not been on the wing, or so many of them together, they might have moved about unnoticed by any one passing along the shore.

I think it was the presence of these birds that had made this remote spot so interesting to me. At a very early age I was fond of all objects of natural history, but particularly of the creatures that have wings, and I believe there are few boys that are not so. There may be sciences and studies of greater importance to mankind, but there is none more refining to the taste or more fascinating to the youthful fancy than the study of nature. Whether it was to get a good look at the birds, or whether from some curiosity about other things I might see upon this little islet, I often wished that I could get to it. Never did I turn my eyes in that direction—and I did so as often as I came near the beach—without feeling a strong wish to get there and explore it from end to end. I knew in my memory the exact shape of it when the tide was lowest, and could at any time have chalked out its profile without looking at it. It was lower at both ends, and rose with a sort of curve towards the middle, like a huge black whale lying along the surface, and the staff, rising from the highest point, looked like a harpoon that was sticking in his back.

That staff, too, I longed to get my hands upon; to see what it was made out of; how high it really was if one were near it, for it only looked about a yard high from the shore; what sort of a thing the knob was on the top, and how the butt was fastened in the ground. Firmly it must have been set; for I had often seen the waves wash up to it during great storms, and the spray driving so high above it, that neither rock, nor staff, nor knob were at all visible.

Ah! many a time had I sighed to visit that attractive spot; but never yet had the opportunity occurred. It was by far too distant for any excursion I had hitherto dared to make—far too dangerous a flight for me to take in the little dinghy; and no one had offered to go with me. Harry Blew had once promised me he would take me—at the same time, he laughed at the desire I expressed to visit such a place. What was it to him? He had often rowed past it and around it, and no doubt landed upon it, and perhaps tied his boat to the staff, while he shot the sea-birds, or fished in the waters beside it; but it had never been my good fortune to accompany him in one of these pleasant excursions. I had been in expectation, however, of doing so; but now these hopes were gone. I could no more get away except on the Sundays; and on these very days my friend was always engaged in his own occupation—for Sundays, above all other days of the week, was the time for sailing parties.

For a long time, then, I had waited in vain; but I now resolved to wait no longer. I had made a bold determination on that very morning; which was, that I should take the dinghy and visit the reef myself. This, then, was the grand excursion on which I was bound, when I removed the little boat from her fastenings, and shot out upon the bosom of the bright blue sea.

Chapter Six.

The Gulls.

I have styled my determination a bold one. True, there was nothing remarkable in the enterprise itself.

I only mean that it was bold for one so young and so little as I was at the time. Three miles rowing would be a good long pull, and that right out into the great deep water almost beyond sight of the shore! I had never been so far before, nor half so far, neither; in fact, never more than a mile from the beach, and in pretty shallow water, too—I mean, while by myself.

With Blew I had been everywhere around the bay; but then, of course, I had nothing to do with the management of the boat; and, trusting to the skill of the young waterman, had no cause to feel afraid.

Alone, the case was different. Everything depended upon myself; and should any accident arise, I should have no one to give me either counsel or assistance.

Indeed, before I had got quite a mile from the shore, I began to reflect that my enterprise was not only a bold but a rash one, and very little would have induced me to turn round and pull back.

It occurred to me, however, that some one might have been watching me from the shore; some boy who was jealous of my prowess as an oarsman—and there were such in our village—and this boy or boys would have seen that I had started for the islet, would easily have divined my reasons for turning back, and would not fail to “twit” me with cowardice. Partly influenced by this thought, and partly because I still had a desire to proceed, I plucked up fresh spirit and rowed on.

When I had got within about half a mile of the shoal, I rested upon my oars, and looked behind me, for in that direction lay the goal I was struggling to reach. I perceived at a glance that the little islet was quite out of the water, as if the tide was at its lowest; but the black stones were not visible on account of the birds that were standing or sitting all over them. It looked as if a flock of swans or white geese were resting upon the shoal; but I knew they were only large gulls, for many of the same kind were wheeling about in the air—some settling down and some rising to take a fresh flight. Even at the distance of half a mile, I could hear their screaming quite distinctly, and I had heard it much further off, so calm was the atmosphere.

I was now the more anxious to proceed on account of the presence of the birds, for I was desirous of getting near them and having a good view of them. I intended to stop again before going too close, in order to watch the movements of these pretty creatures; for many of them were in motion over the shoal, and I could not divine what they were about.

In hopes that they would let me approach near enough to observe them, I rowed gently and silently, dipping the blades of my oars as carefully as a cat would set down her paws.

When I had reached within some two hundred yards of them, I once more lifted the oars above water, and twisted my neck round to look at the birds. I observed that I had not yet alarmed them. Though gulls are rather shy birds, they know pretty well the range of a common fowling-piece, and will rarely trouble themselves to stir from the spot where they are seated until one is just getting within shooting distance. I had no gun, and therefore they had nothing to fear—not much, indeed, even had I possessed one, as I should not have known how to use it. It is probable enough that had they seen a gun they would not have allowed me so near, for white gulls somewhat resemble, black crows in this respect, and can distinguish between a gun and hoe-handle a long way off. Right well do they know the glance of a “shooting-iron.”

I watched the creatures for a long while with great interest; and would have considered myself well rewarded for the exertions I had made in getting there, had I even turned back on the spot and rowed ashore again. The birds that clustered near the stones were all gulls, but there were two kinds, very different in size, and somewhat unlike in colour. One sort had black heads and greyish wings, while the other and larger kind was nearly of a pure white colour. Nothing could exceed the cleanly appearance of both. They looked as if a spot of dirt had never soiled their snowy plumage; and their beautiful red legs shone like branches of the purest coral. I made out that those upon the stones were engaged in various ways. Some ran about evidently in search of food; and this consisted of the small fry of fish that had been left by the receding tide, as well as little crabs, shrimps, lobsters, mussels, and other curious animals of the sea. A great many of the birds merely sat preening their white plumage, of which they appeared to be not a little proud. But although they all looked contented and happy, they were evidently not exempted, any more than other living creatures, from cares and evil passions. This was proved by the fact that more than one terrible quarrel occurred among them while I was looking on, from what cause—unless it was the male birds battling through jealousy—I could not determine. A most captivating sight it was to see those upon the wing engaged in their occupation of fishing; to see them shoot down from a height of more than a hundred yards, disappear with almost silent plunge beneath the blue waves, and after a short interval emerge, bearing their glittering prey in their beaks. Of all the movements of birds, either upon foot or on the wing, I think there is none so interesting to look at as the actions of the fishing gull while engaged in pursuit of his prey. Even the kite is not more graceful in its flight. The sudden turning in his onward course—the momentary pause to fix more accurately the position of his prey—the arrow-like descent—the plunge—the white spray dancing upward, and then the hiatus occasioned by the total disappearance of the winged thunderbolt, until the white object starts forth again above the blue surface—all these points are incomparable to behold. No ingenuity of man, aided by all the elements of air, water, or fire, can produce an exhibition with so fine an effect.

For a good long while I sat in my little boat watching the movements of the gulls; and then, satisfied that I had not made the excursion in vain, I turned myself to carrying out my original design, and landing upon the reef.

The pretty birds kept their places until I had got nearly up to its edge. They seemed to know that I intended them no harm, and did not mistrust me. At all events, they had no fear of a gun, for when they at length arose they winged their way directly over my head, so near that I could almost have struck them down with the oar.

One, that I thought was larger than any of the flock, had been all the time perched in a conspicuous place—on the top of the signal-staff. Perhaps I only fancied him larger on account of the position in which he was placed; but I noticed that before any of the others took to flight, he had shot upward with a screech, as if it were a command for the rest to follow example. Very likely he was either the sentinel or leader of the flock; and this little bit of tactics was no other than I had often seen practised by a flock of crows, when engaged on a pillaging expedition in a field of beans or potatoes.

The departure of the birds appeared to produce a darkening effect upon my spirits. The very sea seemed blacker after they had gone; but this was natural enough, for instead of their white plumage that had filled my eyes, I now looked upon the desolate reef, covered over with loose stones that were as black as if coated with tar. This was only partly what had brought about the change in my feelings. There was another cause. A slight breeze had sprung up, as a cloud passed suddenly over the sun’s disc; and the surface of the water, hitherto smooth and glassy, had grown all at once of a greyish hue by the curling of the little waves.

The reef had a forbidding aspect; but determined to explore it—since I had come so far for that especial purpose—I rowed on till the keel of the dinghy grated upon the rocks.

A little cove presented itself to my view, which I thought would answer my purpose; and heading my prow up into it, I stepped out, and took my way direct towards the staff—that object which for so many years I had looked upon from afar, and with which I had longed to be more intimately acquainted.

Chapter Seven.

Search for a Sea-Urchin.

I soon touched with my hands the interesting piece of wood, and felt as proud at that moment as if it had been the North Pole itself, and I its discoverer. I was not a little surprised at its dimensions, and how much the distance had hitherto deceived me. Viewed from the shore, it looked no bigger than the shaft of a hoe or a hay-fork, and the knob at the top about equal to a fair-sized turnip. No wonder I was a bit astonished to find the staff as thick, and thicker, than my thigh, and the top full larger than my whole body! In fact, it was neither more nor less than a barrel or cask of nine gallons. It was set upon end, the top of the staff being wedged into a hole in the bottom, thus holding it firmly. It was painted white, though this I knew before, for often had I viewed it glistening under the sun, while the shaft below was a dark colour. It may have been black at one time, and had grown discoloured by the weather and the spray of the stormy water, that often lashed all around it, even up to the barrel at the top.

Its height, too, I had miscalculated as much as its thickness. From the land it appeared no taller than an ordinary man; but looking up to it from the shoal, it towered above me like the mast of a sloop. It could not have been less than twelve feet—yes, twelve it was at the very least.

I was equally surprised at the extent of ground that I found above water. I had long fancied that my islet was only a pole or so in size, but I now perceived it was a hundred times that—an acre, or very near. Most of the surface was covered with loose rocks, or “boulders,” from the size of small pebbles to pieces as big as a man’s body, and there were other rocks still larger, but these I perceived were not loose, but half buried, and fast as rocks could be. They were only the projecting ends of great masses that formed the strength of the reef. All, both large ones and small ones, were coated over with a black, slimy substance, and here and there great beds of seaweed, of different kinds, among which I recognised some sorts that were usually cast up on our beach, and passed by the name of “sea-wreck.” With these I had already formed a most intimate acquaintance, for more than one hard day’s work had I done in helping to spread them over my uncle’s land, where they were used as manure for potatoes.

After having satisfied myself with a survey of the tall signal-staff, and guessed at the dimensions of the barrel at the top, I turned away from it, and commenced wandering over the reef. This I did to see if I could find some curious shell or other object that would be worth carrying back with me—something to keep as a memento of this great and hitherto pleasant excursion.

It was not such an easy matter getting about; more difficult than I had imagined. I have said the stones were coated over with a slimy substance, and this made them slippery too. Had they been well soaped, they could not have been smoother to the tread; and before I had proceeded very far, I got a tolerably ugly fall, and several severe scrambles.

I hesitated as to whether I should go farther in that direction, which was to the opposite side from where I had left the boat; but there was a sort of peninsula jutting out from the main part of the reef; and near the end of this I saw what I fancied to be a collection of rare shells, and I was now desirous of possessing some. With this view, then, I kept on.

I had already observed several sorts of shells among the sand that lay between the boulders, some with fish in them, and others opened and bleached. None of these kinds were new to me, for I had seen them all many a time before—even in the potato-field, where they turned up among the wreck. They were only blue mussels, and a sort the farm people called “razors,” and “whelks,” and common “cockle-shells.” I saw no oysters, and I regretted this, for I had grown hungry and could have eaten a dozen or two; but it was not the ground for these. Plenty of little crabs and lobsters there were, but these I did not fancy to eat unless I could have boiled them, and that of course was not possible under the circumstances.

On my way to the front of the peninsula, I looked for “sea-urchin,” but none fell in my way. I had often wished to get a good specimen of this curious shell, but without success. Some of them turned up now and then upon the beach near our village, but they were not allowed to lie long. As they made a pretty ornament for the mantel-shelf, and were rare upon our coast, it was natural they should be prized above the common kinds, and such was in reality the case. This reef being remote, and being seldom visited by any of the boatmen, I was in hopes I should find some upon it, and I was determined to look narrowly for one. With this view I sauntered slowly along, examining every crevice among the rocks, and every water hole that lay within eyeshot of my path.

I had great hopes that I should find something rare upon the peninsula. The glittering forms that had first induced me to turn my steps in that direction, seemed to gleam still brighter as I drew near. For all that, I did not particularly hasten. I had no fear that the shells would walk off into the water. These were houses whose tenants had long since deserted them,  and I knew they would keep their place till I got up; so, under this impression, I continued to go deliberately, searching as I went. I found nothing to my mind until I had reached the peninsula; but then indeed a beautiful object came under my eyes. It was of a dark red colour, round as an orange, and far bigger; but I need not describe what I saw, since every one of you must have seen and admired the shell of the sea-urchin.

and I knew they would keep their place till I got up; so, under this impression, I continued to go deliberately, searching as I went. I found nothing to my mind until I had reached the peninsula; but then indeed a beautiful object came under my eyes. It was of a dark red colour, round as an orange, and far bigger; but I need not describe what I saw, since every one of you must have seen and admired the shell of the sea-urchin.

It was not long before I held it in my hand, and admiring its fine curving outlines, and the curious protuberances that covered them. It was one of the handsomest I had ever seen, and I congratulated myself upon the pretty souvenir it would make of my trip.

For some minutes I kept looking at it, turning it over and over, and peeping into its empty inside—into the smooth white chamber that its tenant had long since evacuated. Yes, some minutes passed before I tired of this manipulation; but at length I remembered the other shells I had noticed, and strode forward to gather them.

Sure enough they were strangers, and fair strangers too. They were of three or four sorts, all new to me; and on this account I filled my pockets with them, and after that both my hands, and then turned round with the intention of going back to the boat.

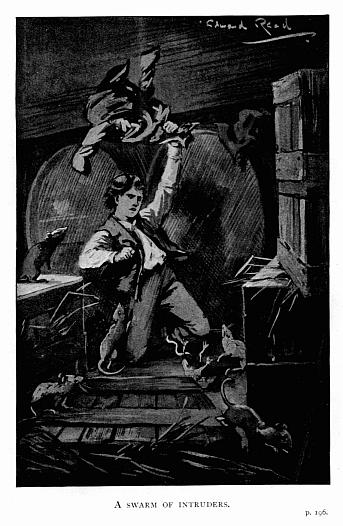

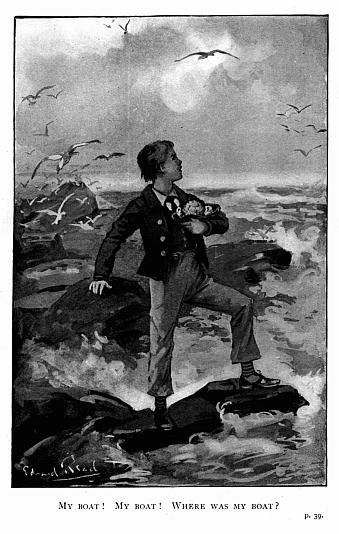

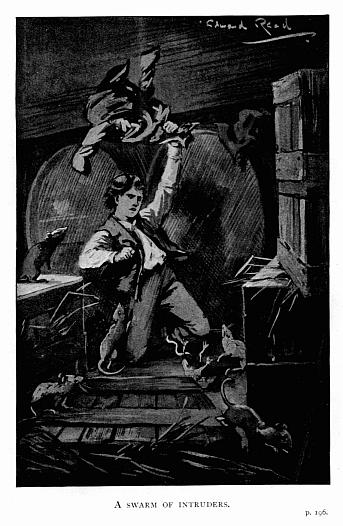

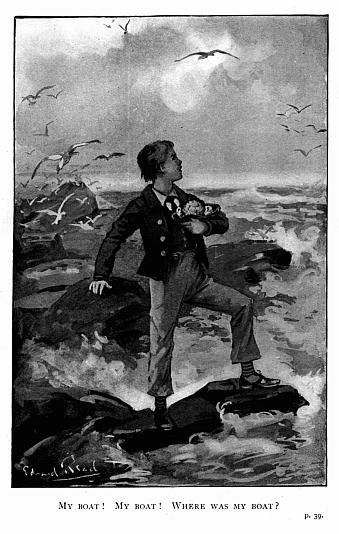

Gracious heaven! what did I see? A sight that caused me to drop my shells, sea-urchin and all, as if they had been pieces of red-hot iron. I dropped them at my feet, and was nigh to falling on top of them, so greatly was I astonished at what I saw. What was it? My boat! my boat! Where was my boat?

Chapter Eight.

Loss of the Dinghy.

It was the boat, then, that had caused me this sudden surprise, or rather alarm, for it speedily came to this. What, you will ask, had happened to the boat? Had she gone to the bottom? Not that; but, what at first appeared almost as bad for me—she had gone away!

When I turned my eyes in the direction I expected to see her, she was not there! The little cove among the rocks was empty.

There was no mystery about the thing. At a glance I comprehended all, since at a glance I saw the boat herself, drifting away outward from the reef. No mystery at all. I had neglected to make the boat fast, had not even taken the rope-hawser ashore; and the breeze, which I now observed had grown fresher, catching upon the sides of the boat, had drifted her out of the cove, and off into the open water.

My first feeling was simply surprise; but in a second or two, this gave way to one of alarm. How was I to recover the boat? How to get her back to the reef? If not successful in this, how then should I reach the shore? Three miles was the shortest distance. I could not swim it even for my life; and I had no hope that any one would come to my rescue. It was not likely that any one upon the shore could see me, or be aware of my situation. Even the little boat would hardly be seen, for I was now aware of how much smaller objects would be rendered at that great distance. The signal-staff had taught me this fact, as well as the reef itself. Rocks that, from the shore, appeared to rise only a foot above the surface, were actually more than a yard. The boat, therefore, would hardly be visible, and neither I nor my perilous situation would be noticed by any one on the shore, unless, indeed, some one might chance to be looking through a glass; but what probability was there of such a thing? None whatever, or the least in the world.

Reflection only increased my uneasiness; for the more I reflected the more certain did it appear to me, that my negligence had placed me in a perilous situation.

For a while my mind was in a state of confusion, and I could not decide upon what course to follow. There was but little choice left me—in fact, I saw no alternative at all—but remain upon the reef. Upon second thoughts, however, an alternative did suggest itself, if I could but succeed in following it. That was to swim out after the boat, and endeavour to regain possession of her. She had not drifted so far away but that I might reach her by swimming. A hundred yards or so she had got from the edge of the islet, but she was still widening the distance between us, and would soon be much farther off.

It was plain, then, that if I intended to take this course, no time was to be lost—not a moment.

What else could I do? If I did not succeed in reaching her, I might set myself down for a troublesome adventure, perhaps perilous too; and this belief nerved me to the attempt.

With all the speed I could make, I stripped off my clothes and flung them upon the rocks. My shoes and stockings followed—even my shirt was thrown aside, lest it might encumber me, and just as if I was going in to have a bathe and a swim, I launched myself upon the water. I had no wading to do. The water was beyond my depth from the very edge of the reef, and I had to swim from the first plunge. Of course, I struck out directly for the boat, and kept on without turning to one side or the other.

I swam as swiftly as I could, but it was a long while before I could perceive that I was coming any nearer to the dinghy. At times, I thought I was not gaining upon her at all, and when the thought occurred to me that she might be going as fast as I was, it filled me with vexation and alarm. Should I not succeed in coming up with her, then it would be a hopeless case indeed. I should have to turn round again and swim back to the reef, or else go to the bottom; for, as already stated, I could no more have reached the shore by swimming than I could have swum across the Atlantic. Though I was now a very good swimmer, and might have done a mile on a pinch, three were far beyond my power, and I could not have made the distance to save my life. Moreover, the boat was not drifting in the direction of the shore, but up the bay, where there was at least ten miles of water before me.

I was getting discouraged in this pursuit, and thought of turning back to the reef, before I might become too exhausted to reach it, when I noticed that the dinghy veered slightly round, and then drifted in a direction oblique to that she had already taken. This arose from a sudden puff of wind which blew from a new quarter. It brought the boat nearer me, and I resolved to make one more effort to reach her.

In this, I at length succeeded; and in a few minutes more, had the satisfaction of laying my hands upon the gunwale of the boat, which enabled me to obtain a little rest after my long swim.

As soon as I had recovered breath, I attempted to climb in over the side; but to my chagrin, the crank little craft sunk under my weight, and turned bottom upwards, as if it had been a washing tub, plunging me under water by the sudden capsize. I rose to the surface, and once more laying my hands upon the boat, climbed up to get astride across the keel; but in this I was also unsuccessful, for losing my balance, I drew the boat so much to one side, that she righted again mouth upwards. This was what I should have desired; but I perceived to my alarm that she was nearly full of water, which she had shipped in turning over. The weight of the water steadied her, so that I was able to draw myself over the gunwale without further difficulty, and got safe enough inside; but I had not been there a second, till I perceived that the boat was sinking! My additional weight was the cause of this, and I saw at once that unless I leaped out again, she would speedily go to the bottom. Perhaps if I had preserved my presence of mind and leaped out again, the boat might still have kept afloat. But what with my fears, and the confusion consequent upon the various duckings I had had, my presence of mind was gone, and I remained standing in the boat up to my knees in the water. I thought of baling her out, but I could find no vessel. The tin pan had disappeared, as well as the oars. The former no doubt had sunk as the boat capsized, and the oars were floating on the water at a great distance off.

In my despair, I commenced baling out the water with my hands; but I had not made half-a-dozen strokes before I felt that she was going down. The next instant she had gone, sinking directly underneath me, and causing me to jump outwards in order to escape from being carried down in the vortex she had made.

I cast one glance upon the spot where she had disappeared. I saw that she was gone for ever; and heading away from the spot, I swam back in the direction of the reef.

Chapter Nine.

The Signal-Staff.

I succeeded in reaching the reef, but not without a tough struggle. As I breasted the water, I felt that there was a current against me—the tide; and this it was, as well as the breeze, that had been drifting the boat away. But I got back to the reef, and there was not a foot to spare. The stroke that brought me up to the edge of the rocks, would have been my last, had no rocks been there; for it would have been the last I could give, so much was I exhausted. Fortunately, my strength had proved equal to the effort; but that was now quite gone, and I lay for some minutes upon the edge of the reef, at the spot where I had crawled out, waiting to recover my breath.

I did not maintain this inactive attitude longer than was necessary. This was not a situation in which to trifle with time; and knowing this, I got to my feet again to see if anything could be done.

Strange enough, I cast my eyes in the direction whence I had just come from the boat. It was rather a mechanical glance, and I scarce know why I should have looked in that particular direction. Perhaps I had some faint hope that the sunken craft might rise to the surface; and I believe some such fancy actually did present itself. I was not permitted to indulge in it, for there was no boat to be seen, nor anything like one. I saw the oars floating far out, but only the oars; and for all the service they could do me, they might as well have gone to the bottom, along with the boat.

I next turned my eyes toward the shore; but nothing was to be seen in that direction, but the low-lying land upon which the village was situated. I could not see any people on shore—in fact, I could hardly distinguish the houses; for, as if to add to the gloom and peril that surrounded me, the sky had become overcast, and along with the clouds a fresh breeze had sprung up.

This was raising the water into waves of considerable height, and these interfered with my view of the beach. Even in bright weather, the distance itself would have hindered me from distinguishing human forms on the shore; for from the reef to the nearest suburb of the village, it was more than three statute miles.

Of course, it would have been of no avail to have cried out for assistance. Even on the calmest day I could not have been heard, and fully understanding this, I held my peace.

There was nothing in sight—neither ship, nor sloop, nor schooner, nor brig—not a boat upon the bay. It was Sunday, and vessels had kept in port. Fishing boats for the same reason were not abroad, and such pleasure boats as belonged to our village had all gone in their usual direction, down the bay, to a celebrated lighthouse there—most likely the boat of Harry Blew among the rest.

There was no sail in sight, either to the north, the south, the east, or the west. The bay appeared deserted, and I felt as much alone as if I had been shut up in my coffin.

I remembered instinctively the dread feeling of loneliness that came over me. I remember that I sank down upon the rocks and wept.

To add to my agony of mind, the sea-birds, probably angry at me for having driven them away from their resting-place and feeding ground, now returned; and hovering over my head in a large flock, screamed in my ears as if they intended to deafen me. At times one or another of them would swoop almost within reach of my hands; and uttering their wild cries, shoot off again, to return next moment with like hideous screams. I began to be afraid that these wild birds might attack me, though I suppose, in their demonstrations they were merely actuated by some instinct of curiosity.

After considering every point that presented itself to my mind, I could think of no plan to pursue, other than to sit down (or stand up, if I liked it better), and wait till some succour should arrive. There was no other course left. Plainly, I could not get away from the islet of myself, and therefore I must needs stay till some one came to fetch me.

But when would that be? It would be the merest chance if any one on shore should turn their eyes in the direction of the reef; and even if they did, they would not recognise my presence there without the aid of a glass. One or two of the watermen had telescopes—this I knew—and Harry Blew had one; but it was not every day that the men used these instruments, and ten chances to one against their pointing them to the reef. What would they be looking for in that direction? No boats ever came or went that way, and vessels passing down or up the bay always gave the shoal a wide berth. My chances, therefore, of being seen from the shore, either with the naked eye or through a glass, were slender enough. But still more slender were the hopes I indulged that some boat or other craft might pass near enough for me to hail it. It was very unlikely, indeed, that any one would be coming in that direction.

It was with very disconsolate feelings, then, that I sat down upon the rock to await the result.

That I should have to remain there till I should be starved I did not anticipate. The prospect did not appear to me so bad as that, and yet such might have been the case, but for one circumstance, which I felt confident would arise to prevent it. This was, that Harry Blew would miss the dinghy and make search for me.

He might not, indeed, miss her before nightfall, because he might not return with his boating party before that time. As soon as night came, however, he would be certain to get home; and then, finding the little boat away from her moorings, he would naturally suspect that I had taken her, for I was the only boy in the village, or man either, who was allowed this privilege. The boat being absent, then, and not even returning at night, Blew would most likely proceed to my uncle’s house; and then the alarm at my unusual absence would lead to a search for me; which I supposed would soon guide them to my actual whereabouts.