Title: From Paris to New York by Land

Author: Harry De Windt

Release date: July 8, 2008 [eBook #26007]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Steven desJardins and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THOMAS NELSON & SONS

LONDON, EDINBURGH, DUBLIN AND NEW YORK

Many who read the following account of our long land journey will not unnaturally ask: "What was the object of this stupendous voyage, or the reward to be gained by this apparently unnecessary risk of life and endurance of hardships?"

I would reply that my primary purpose was to ascertain the feasibility of constructing a railway to connect the chief cities of France and America, Paris and New York. The European Press was at the time of our departure largely interested in this question, which fact induced the proprietors of the Daily Express of London, the Journal of Paris, and the New York World to contribute towards the expenses of the expedition. Another reason is one with which I fancy most Englishmen will readily sympathise—viz., the feat had never before been performed, and my first attempt to accomplish it in 1896 (with New York as the starting-point) had failed half way on the Siberian shores of Bering Straits.

The invaluable assistance rendered by the United States Government in the despatch of a revenue cutter to our relief on the Siberian coast is duly acknowledged in another portion of this volume, but I would here express my sincere thanks to the "Compagnie Internationale des Wagonslits" for furnishing the expedition[Pg viii] with a free pass from Paris to the city of Irkutsk, in Eastern Siberia. In America the "Southern Pacific" and "Wabash" Lines extended the same courtesies, thus enabling us to travel free of cost across the United States, as guests of two of the most luxurious railways in the world.

45 Avenue Kléber, Paris,

October 1903.

| PART I.—EUROPE AND ASIA | ||

| I. | THROUGH EUROPE. THE TRANS-SIBERIAN RAILWAY. | 15 |

| II. | THE PARIS OF SIBERIA | 28 |

| III. | THE GREAT LENA POST-ROAD | 41 |

| IV. | THE CITY OF THE YAKUTE | 68 |

| V. | THE LAND OF DESOLATION | 92 |

| VI. | VERKHOYANSK | 109 |

| VII. | THROUGH DARKEST SIBERIA | 122 |

| VIII. | AN ARCTIC INFERNO | 148 |

| IX. | THE LOWER KOLYMA RIVER | 171 |

| X. | A CRUEL COAST | 183 |

| XI. | IN THE ARCTIC | 203 |

| XII. | AMONG THE TCHUKTCHIS | 221 |

| XIII. | AMONG THE TCHUKTCHIS (contd.) | 239 |

| PART II.—AMERICA. | ||

| XIV. | ACROSS BERING STRAITS—CAPE PRINCE OF WALES | 257 |

| XV. | AN ARCTIC CITY | 274 |

| XVI. | A RIVER OF GOLD | 286 |

| XVII. | DAWSON | 304 |

| XVIII. | THE UPPER YUKON AND LEWES RIVERS. THE WHITE PASS RAILWAY | 323 |

| XIX. | THE FRANCO-AMERICAN RAILWAY—SKAGWAY—NEW YORK | 340 |

| PART III.—APPENDICES. | ||

| I. | APPROXIMATE TABLE OF DISTANCES, PARIS TO NEW YORK | 361 |

| II. | LIST OF POST STATIONS BETWEEN IRKUTSK AND YAKUTSK | 363 |

| III. | REINDEER STATIONS BETWEEN YAKUTSK AND VERKHOYANSK | 368 |

| IV. | YAKUTE SETTLEMENTS BETWEEN VERKHOYANSK AND SREDNI-KOLYMSK | 370 |

| V. | SETTLEMENTS ON KOLYMA RIVER BETWEEN SREDNI-KOLYMSK AND NIJNI-KOLYMSK | 372 |

| VI. | A SHORT GLOSSARY OF YAKUTE WORDS | 373 |

| VII. | GLOSSARY OF VARIOUS DIALECTS IN USE AMONGST THE TCHUKTCHIS INHABITING THE COASTS OF N.E. SIBERIA | 375 |

| VIII. | METEOROLOGICAL RECORD OF THE DE WINDT EXPEDITION | 377 |

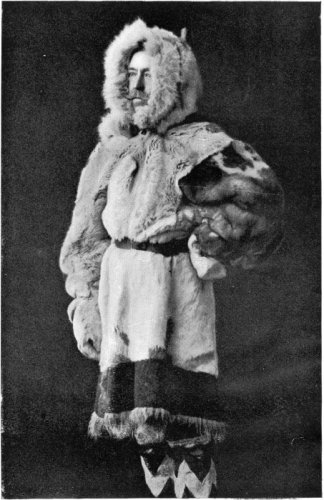

| HARRY DE WINDT | Frontispiece |

| POOR YAKUTES | Facing page 64 |

| THE CHIEF OF POLICE, VERKHOYANSK | 97 |

| A VISITOR | 128 |

| CAPE DESPAIR | 193 |

| TENESKIN'S DAUGHTERS | 224 |

| ESKIMO GIRLS | 289 |

| CONSTRUCTING THE WHITE PASS RAILWAY | 320 |

The success of my recent land expedition from Paris to New York is largely due to the fact that I had previously essayed the feat in 1896 and failed, for the experience gained on that journey was well worth the price I paid for it. On that occasion I attempted the voyage in an opposite direction—viz., from America to France, but only half the distance was covered. Alaska was then almost unexplored and the now populous Klondike region only sparsely peopled by poverty-stricken and unfriendly Indians. After many dangers and difficulties, Alaska was crossed in safety, and we managed to reach the Siberian shores of Bering Straits only to meet with dire disaster at the hands of the natives of that coast. For no sooner had the American revenue cutter which landed us steamed away than our stores were seized by the villainous chief of the village (one Koari), who informed us that[Pg 16] we were virtually his prisoners, and that the dog-sleds which, during the presence of the Government vessel, he had glibly promised to furnish, existed only in this old rascal's fertile imagination. The situation was, to say the least, unpleasant, for the summer was far advanced and the ice already gathering in Bering Straits. Most of the whalers had left the Arctic for the southward, and our rescue seemed almost impossible until the following year. When a month here had passed away, harsh treatment and disgusting food had reduced us to a condition of hopeless despair. I was attacked by scurvy and a painful skin disease, while Harding, my companion, contracted a complaint peculiar to the Tchuktchis, which has to this day baffled the wisest London and Paris physicians. Fortunately we possessed a small silk Union Jack, which was nailed to an old whale rib on the beach (for there was no wood), much to the amusement of the natives. But the laugh was on our side when, the very next morning, a sail appeared on the horizon. Nearer and nearer came the vessel, scudding close-reefed before a gale which had raised a mountainous sea. Would they see our signal? Would the skipper dare to lay-to in such tempestuous weather, hemmed in as he was by the treacherous ice? Had we known, however, at the time that the staunch little Belvedere was commanded by the late Capt. Joseph Whiteside, of New Bedford, we should have been spared many moments, which seemed hours, of intense anxiety. Without a thought of his own safety, or a valuable cargo of whales representing many thousands of pounds,[Pg 17] this gallant sailor stood boldly in shore, launched a boat, which, after a scuffle with the natives and a scramble over floating ice, we managed to reach, and hauled us aboard the little whaler, more dead than alive. A month later we were in San Francisco, far from the fair French city we had hoped to reach, but sincerely grateful for our preservation. For twenty-four hours after our rescue no ship could have neared that ice-bound coast, and we could scarcely have survived, amidst such surroundings, until the following spring.

A glance at a map will show the route which I had intended to pursue in 1896, although, as this land journey has never before been accomplished (or even attempted), I was unable to benefit by the experience of previous explorers. From New York we travelled to Vancouver, thence across the now famous Chilkoot Pass to the Great Lakes and down the Yukon River to the sea, crossing Bering Straits in an American revenue cutter to the Siberian settlement of melancholy memory. From here I hoped to reach the nearest Russian outpost, Anadyrsk, by dog-sled, proceeding thence along the western shores of the Okhotsk Sea to Okhotsk and Yakutsk. The latter is within a couple of thousand miles of civilisation, a comparatively easy stage in this land of stupendous distances. Had I been able on this occasion to reach Anadyrsk, I could, all being well, have pushed on to Yakutsk, for Cossacks carry a mail, once a year, between the two places. But the connecting link between that miserable Tchuktchi village and Anadyrsk was missing, and so we had to submit to the will of fate.

[Pg 18]Follow now on a map my itinerary upon the last occasion, starting from Paris to Moscow, and continuing from Moscow to Irkutsk by the Trans-Siberian Railway. Here we strike in a north-easterly direction to Yakutsk by means of horse-sleighs. Reindeer-sleighs are procured at Yakutsk, and we then steer a north-westerly course to Verkhoyansk. From Verkhoyansk we again proceed (still with reindeer) in a north-easterly direction to the tiny political settlement of Sredni-Kolymsk, where we discard our deer (for there is no more moss) and take to dog-sleds. A journey of nearly two months, travelling almost due east, brings us to East Cape Bering Straits, the north-easternmost point of Asia, and practically half way from Paris to our destination.

From here the journey is fairly easy, for the beaten tracks of Alaska now entail no great hardships. Remote Eskimo settlements like that at Cape Prince of Wales are naturally as primitive as those on the Siberian side, but once Nome City is reached, the traveller may proceed (in summer) to New York solely by the aid of steam.

I shall not weary the reader with details of my preparations. Suffice it to say that, although the minutest care and attention were lavished on the organisation of our food-supply, lack of transport in the Far North compelled me to abandon most of our provisions and trust to luck for our larder, which was therefore frequently very meagrely stocked. Indeed, more than once we were within measurable distance of starvation, but this was the more unavoidable in so far as, even at Moscow, I was compelled to abandon several cases of pro[Pg 19]visions on account of a telegram received from the Governor-General of Siberia. The message informed me that reindeer were scarce, dogs yet more so, and that, unless the expedition travelled very light, it could not possibly hope to reach even the shores of the Arctic Ocean, to say nothing of Bering Straits. Nevertheless, even at the outset of the journey I was blamed, and that by totally inexperienced persons, for abandoning stores so early in the day; a certain British merchant in Moscow expressing surprise that I should have "made such an egregious error" as to leave any provisions behind. I fancy most explorers have met this type of individual—the self-complacent Briton, who, being located for business or other purposes in a foreign or colonial city, never leaves it, and yet poses as an authority on the entire country, however vast, in which he temporarily resides. I can recall one of these immovable fixtures in India, who had never stirred from Bombay save in a P. and O. liner, but who was good enough to advise me how to travel through Central Baluchistan, a country which I had recently explored with some success! The Moscow wiseacre was perhaps unaware that during hard seasons in Arctic Siberia the outfit of an expedition must be strictly limited to the carrying capacity of dogs and reindeer. However, this gentleman's ignorance was perhaps excusable, seeing that his experience of Russian travel had been solely gleaned in a railway car between Moscow and the German frontier. I am told that the same individual severely criticised me for not travelling through Siberia in summer, thereby[Pg 20] avoiding the severe hardships arising from intense cold. He was, of course, unaware that during the open season the entire tract of country north-east of Yakutsk is practically impassable owing to thousands of square miles of swamp and hundreds of shallow lakes which can only be crossed in a frozen condition on a dog-sled. Even the natives of these regions never attempt to travel between the months of May and September.

Paris is my home, and I am not ashamed to own that, like most Parisians, I suffer, when abroad, from a nostalgia of the Boulevards that a traveller were perhaps better without. It was therefore as well that our departure for New York took place on a dreary December day, when the beautiful city lay listless and despondent, swept by a wintry gale and lashed by gusts of driving sleet. The sky was sunless, the deserted thoroughfares rivers of mud mournfully reflecting bars of electric light from either side of the street. As my cab splashed wearily up the Rue Lafayette I thought that I had never seen such a picture of desolation. And yet it were better, perhaps, to remember Paris thus, than to yearn through the long Arctic night for the pleasant hours I had learned to love so well here in leafy June. Bright days of sunshine and pleasure in and around the "Ville Lumière!" cool, starlit nights at Armenonville and Saint Cloud! Should I ever enjoy them again?

"The De Windt Expedition" left Paris on December 19, 1901. Preliminary notices of the journey in the French Press had attracted considerable notice in Paris, and a small crowd of journalists[Pg 21] and others had assembled at the Gare du Nord to wish us God-speed. We were three in number—myself, the Vicomte de Clinchamp (a young Frenchman who acted as photographer), and George Harding, my faithful companion on many previous expeditions. The "Nord Express" was on the point of departure, but a stirrup-cup was insisted upon by some of De Clinchamp's enthusiastic compatriots, and an adjournment was made to the Buffet, where good wishes were expressed for our safety and success. After a hearty farewell the train steamed out of the station amidst ringing cheers, which plainly told me that Paris as well as London contained true friends who would pray for our welfare in the frozen North and welcome our safe return to "La Belle France."

Moscow was reached three days later, and here commenced the first of a series of minor but harassing delays which relentlessly pursued me throughout the Asiatic portion of the journey. While alighting from the train I was suddenly seized with such severe internal pains, accompanied by faintness and nausea, that on arrival at the Slaviansky Bazar (the best Hotel, by the way, in the place), I was carried to bed. The attack was inexplicable. Harding, ever a pessimist, suggested appendicitis, and a physician was hastily summoned. The medicine-man gravely shook his head: "You are very ill," he said, and I did not dispute the fact. "Can it be appendicitis?" I asked anxiously. "Appendicitis," replied the Doctor; "what is that? I never heard of the disease!"

Morning brought me some relief, and with a not[Pg 22] unnatural distrust of Russian medical methods, I resolved to return at once to Berlin and consult Professor Bergmann. To abandon the journey was now out of the question, but our medicine-chest was up-to-date and I could at any rate ask the famous surgeon how to treat the dread disease should it declare itself in the wilds of Siberia. The next morning saw me back in Berlin, and by midday my mind was at rest. I was suffering from a simple rupture of long standing, but hitherto quiescent, which only required rest and proper treatment for at least a fortnight. "Then it must be in the train," I said, explaining the situation and the priceless value of time. So, after some discussion, I departed with the Professor's good wishes, which, however, were conveyed with an ominous shake of the head.

Two days later I arrived in Moscow, only to be confronted by another difficulty: our rifles, revolvers and ammunition had been seized at the Russian frontier, and at least a fortnight must elapse before we could obtain them. Moscow fortunately boasts of an excellent gun-maker, and I was able to replace our armoury with English weapons, though, of course, at a ruinous expense. But time was too precious to waste. We had now but a little over four months in which to reach Bering Straits, for by the middle of May the bays and estuaries of the Arctic begin to break up, and open water might mean imprisonment (and worse) on these desolate shores throughout the entire summer. So I purchased revolvers, two rifles and a fowling-piece at about five times their usual cost,[Pg 23] and hoped that our troubles were over, at least for the present. I should add that the arms had left London six weeks previously, and that I was furnished with a special permit to introduce them into the country. But Russian methods are peculiar, and fortunately unique, I was unaware before our departure of the fact that if a gun is consigned direct from its English maker to a gunsmith in Russia it goes through without any trouble whatsoever. Otherwise, it may take six months or more to reach its destination.

The New Year was passed in Moscow, and a gloomy one it was. From an historical and picturesque point of view the city is intensely interesting, but otherwise it is a dull, dreary place. Russian cities, not excepting Petersburg, generally are, although the English novelist generally depicts them as oases of luxurious splendour, where love and Nihilism meet one at every turn, and where palaces, diamonds and silver sleigh-bells play an important part, to say nothing of that journalistic trump card, the Secret Police! I wish one of these imaginative scribes could spend a winter evening (as I have so often done) in a stuffy hotel reading-room, with a Times five days old, wondering whether the Russians will ever provide a theatre sufficiently attractive to tempt a stranger out of doors after nightfall. In summer it is less dismal; there are gardens and restaurants, dancing gipsies and Hungarian Tziganes, but even then the entertainment is generally so poor, and the surroundings so tawdry, that one is glad to leave them at an early hour and go sadly to bed.

[Pg 24]The distance from Moscow to Irkutsk is a little under 4000 English miles, the first-class fare a little over a hundred roubles (or about £12), which, considering the journey occupies nine days or more, is reasonable enough. There are, or were, two trains a week,—the "State" and Wagonlits expresses, which run alternately. The former is a Government train, inferior in every respect to the latter, which is quite as luxurious in its service and appointments as the trains run by the same company in Europe.

At 10 P.M., on January 4, we left Moscow, in a blinding snowstorm, a mild foretaste of the Arctic blizzards to come, which would be experienced without the advantage of a warm and well-lit compartment to view them from. For this train was truly an ambulant palace of luxury. An excellent restaurant, a library, pianos, baths, and last, but not least, a spacious and well-furnished compartment with every comfort, electric and otherwise (and without fellow travellers), rendered this first "étape" of our great land journey one to recall in after days with a longing regret. But we had nearly a fortnight of pleasant travel before us and resolved to make the most of it. Fortunately the train was not crowded. Some cavalry officers bound for Manchuria, three or four Siberian merchants and their families, and a few Tartars of the better class. The officers were capital fellows, full of life and gaiety (Russian officers generally are), the merchants and their women-folk sociable and musically inclined. Nearly every one spoke French, and the time passed pleasantly enough, for although the[Pg 25] days were terribly monotonous, evenings enlivened by music and cards, followed by cheery little suppers towards the small hours, almost atoned for their hours of boredom.

Nevertheless, I cannot recommend this railway journey, even as far as Irkutsk, to those on pleasure bent, for the Trans-Siberian is no tourist line, notwithstanding the alluring advertisements which periodically appear during the holiday season. Climatically the journey is a delightful one in winter time, for Siberia is then at its best—not the Siberia of the English dramatist: howling blizzards, chained convicts, wolves and the knout, but a smiling land of promise and plenty even under its limitless mantle of snow. The landscape is dreary, of course, but most days you have the blue cloudless sky and dazzling sunshine, so often sought in vain on the Riviera. At mid-day your sunlit compartment is often too warm to be pleasant, when outside it is 10° below zero. But the air is too dry and bracing for discomfort, although the pleasant breeze we are enjoying here will presently be torturing unhappy mortals in London in the shape of a boisterous and biting east wind. On the other hand, the monotony after a time becomes almost unbearable. All day long the eye rests vacantly upon a dreary white plain, alternating with green belts of woodland, while occasionally the train plunges into dense dark pine forest only to emerge again upon the same eternal "plateau" of silence and snow. Now and again we pass a village, a brown blur on the limitless white, rarely a town, a few wooden houses clustering around a green[Pg 26] dome and gilt crosses, but it is all very mournful and depressing, especially to one fresh from Europe. This train has one advantage, there is no rattle or roar about it, as it steals like a silent ghost across the desolate steppes. As a cure for insomnia it would be invaluable, and we therefore sleep a good deal, but most of the day is passed in the restaurant. Here the military element is generally engrossed in an interminable game of Vint[1] (during the process of which a Jew civilian is mercilessly rooked), but our piano is a godsend and most Russian women are born musicians. So after déjeuner we join the fair sex, who beguile the hours with Glinka and Tchaikovsky until they can play and sing no more. By the way, no one ever knows the time of day and no one particularly wants to. Petersburg time is kept throughout the journey and the result is obvious. We occasionally find ourselves lunching at breakfast time and dining when we should have supped, but who cares? although in any other clime bottled beer at 8 A.M. might have unpleasant results.

[1] Russian whist.

The Ural Mountains (which are merely downs) are crossed. Here the stations are built with some attempt at coquetry, for the district teems with mineral wealth, and in summer is much frequented by fashionable pleasure-seekers and invalids, for there are baths and waters in the neighbourhood. One station reminds me of Homburg or Wiesbaden with its gay restaurant, flower-stall, and a little shop for the sale of trinkets in silver and malachite, and the precious stones found in this region[Pg 27]—Alexandrites, garnets and amethysts. But beyond the Urals we are once more lost in the desolate plains across which the train crawls softly and silently at the rate of about ten miles an hour. I know of only one slower railway in the world, that from Jaffa to Jerusalem, where I have seen children leap on and off the car-steps of the train while in motion, and the driver alight, without actually stopping his engine, to gather wildflowers! We cross the great Obi and Yenisei rivers over magnificent bridges of iron and Finnish granite, which cost millions of roubles to construct. Krasnoyarsk is passed by night, but its glittering array of electric lights suggests a city many times the size of the tiny town I passed through in a tarantass while travelling in 1887 from Pekin to Paris. So the days crawl wearily away. Passengers come and passengers go, but this train, like the brook, goes on for ever. Although the travelling was luxurious I can honestly say that this was the most wearisome portion of the entire journey. But all things must have an end, even on the Trans-Siberian Railway, and on the tenth day out from Moscow we reach (unconsciously) our destination—Irkutsk. For it is two o'clock in the morning and we are aroused from pleasant dreams in a warm and cosy bed to embark upon a drive of about three miles through wind and snow in an open droshky. But we are now in Eastern Siberia, and comfort will soon be a thing of the past.

We arrived in Irkutsk on the eve of the Russian New Year, when business throughout the Empire comes to a standstill, and revelry amongst all classes reigns supreme. It was, therefore, useless to think of resuming our journey for at least a week, for sleighs must be procured, to say nothing of that important document, a special letter of recommendation, which I was to receive from the Governor-General of Siberia. But a resplendent aide-de-camp called at the hotel and regretfully informed me that State and social functions would keep his Excellency fully occupied for several days. It was hopeless, he added, to think of getting sleighs built while vodka was running like water amongst the people. So there was nothing for it but to await the end of the festival with patience, without which commodity no traveller should ever dream of visiting Asiatic Russia. He is otherwise apt to become a raving lunatic.

Irkutsk has several so-called hotels, the only one in any way habitable being the "Hotel Metropole," a name which has become suggestive of gold-laced porters and gilded halls. It was, therefore, rather[Pg 29] a shock to enter a noisome den, suggestive of a Whitechapel slum, although its prices equalled those of the Carlton in Pall Mall. The house was new but jerry-built, reeked of drains, and swarmed with vermin. Having kept us shivering for half an hour in the cold, a sleepy, shock-headed lad with guttering candle appeared and led the way to a dark and ill-smelling sleeping-apartment. The latter contained an iron bedstead (an unknown luxury here a decade ago), but relays of guests had evidently used the crumpled sheets and grimy pillows. Bathroom and washstand were supplied by a rusty brass tap, placed, pro bono publico, in the corridor. Our meals in the restaurant were inferior to those of a fifth-rate gargotte. And this was the best hotel in the "Paris of Siberia," as enthusiastic Siberians have christened their capital.

Irkutsk now has a population of over 80,000. It stands on a peninsular formed by the confluence of two rivers, the clear and swiftly-flowing Angará (which rises in Lake Baikal to join the river Yenisei just below Yeniseisk), and the small and unimportant Irkut river. It is an unfinished, slipshod city, a strange mixture of squalor and grandeur, with tortuous, ill-paved streets, where the wayfarer looks instinctively for the "No-thoroughfare" board. There is one long straggling main street with fairly good shops and buildings, but beyond this Irkutsk remains much the same dull, dreary-looking place that I remember in the early nineties, before the railway had aroused the town from its slumber of centuries. Even now, the place is absolutely primitive and uncivilised, from an European point of view,[Pg 30] and the yellow Chinese and beady-eyed Tartars who throng the business quarters are quite in keeping with the Oriental filth around, unredeemed by the usual Eastern colour and romance. On fine mornings the Market Place presents a curious and interesting appearance, for here you may see the Celestial in flowery silk elbowing the fur-clad Yakute and Bokhara shaking hands with Japan. The Irkutsk district is peopled by the Buriates, who originally came from Trans-Baikalia, but who have now become more Russianised than any other Siberian race. The Buriat dialect is a kind of patois composed of Mongolian and Chinese; the religion Buddhism. About every fourth Buriat becomes a Lama, and takes vows of celibacy. They are thrifty, industrious people, ordinarily of an honest, hospitable disposition, who number, perhaps, 300,000 in all. This is probably the most civilised aboriginal race in Siberia, and many Buriates now wear European dress, and are employed as Government officials.

The climate of Irkutsk is fairly good; not nearly so cold in winter as many places on the same latitude; the summers are pleasant and equable; but the fall of the year is generally unhealthy, dense fogs occasioning a good deal of pulmonary disease and rheumatism. The city, too, is so execrably drained that severe epidemics occasionally occur during the summer months, but in winter the dry cold air acts as a powerful disinfectant. In spring-time, when the river Angará is swollen by the break-up of the ice, inundations are frequent, and sometimes cause great destruction to life and property. Winter is, therefore, the pleasantest season here, for during[Pg 31] dry warm weather the clouds of black gritty dust are unbearable, especially on windy days. Indeed, the dust here is almost worse than in Pekin, where the natives say that it will work its way through a watch-glass, no exaggeration, as I can, from personal experience, testify.

There was little enough to do here during our five days of enforced inactivity, and time crawled away with exasperating slowness, the more so that the waste of every hour was lessening our chance of success. But although harassed myself by anxiety, I managed to conceal the fact from de Clinchamp, whose Gallic nature was proof against ennui, and who managed to find friends and amusement even in this dismal city. In summer we might have killed time by an excursion to Lake Baikal,[2] for I retain very pleasant recollections of a week passed, some years since, on the pine-clad margin of this the largest lake in Asia, sixty-six times the area of the Lake of Geneva. Now its wintry shores and frozen waters possessed no attraction, save, perhaps, the ice-breaker used by the Trans-Siberian Railway to carry passengers across the lake, a passage of about twenty miles. But even the ice-breaker had met with an accident, and was temporarily disabled. So there was literally nothing to do but to linger as long as possible over the midday meal in the dingy little restaurant, and then to stroll aimlessly[Pg 32] up and down the "Bolshaya," the main thoroughfare aforementioned, until dusk. This is the fashionable drive of the city, which on bright days presented an almost animated appearance. There is no lack of money in Irkutsk, for gold-mining millionaires abound, and I generally spent the afternoon watching the cavalcade of well-appointed sleighs dashing, with a merry clash of bells, up and down the crowded street, and sauntering amongst the groups of well-dressed women and brilliant uniforms, until darkness drove me back to our unsavoury quarters at the Metropole. My companions generally patronised the skating rink, a sign of advancing civilisation, for ten years ago there was not a pair of skates to be found throughout the length and breadth of Siberia. Thus passed our days, and the evenings were even longer and more wearisome. Once we visited the Opera, a new and beautifully-decorated house, but the performance was execrable, and "La Dame de Chez Maxim" unrecognisable in Russian dress. There were also other so-called places of amusement, which blazed with electric light from dusk till dawn, where refreshments were served at little wooden tables while painted harridans from Hamburg cackled suggestive songs to the accompaniment of a cracked piano. In these establishments we used to see the local millionaires (and there are many) taking their pleasure expensively, but sadly enough, amidst surroundings that would disgrace a dive in San Francisco. The company was generally very mixed, soldiers and flashily-dressed cocottes being alone distinguishable, by their costume, from the rest of the audience. For although[Pg 33] the Siberian woman of the better class has learnt of late years to dress well, wealth makes no difference to the garb of mankind. All of the latter have the same dirty, unkempt appearance; all wear the same suit of shiny black, rusty high boots, and a shabby slouch-hat or peaked cap. Furs alone denote the difference of station, sable or blue fox denoting the mercantile Crœsus, astrachan or sheep-skin his clerk. Otherwise all the men look (indoors) as though they had slept in their clothes, which, by the way, is not improbable, for on one occasion I stayed with an Irkutsk Vanderbilt who lived in palatial style. His house was a dream of beauty and millions had been lavished on its ornamentation. Priceless pictures and objets d'art, a Paris chef, horses and carriages from London, and covered gardens of rare orchids and exotics. No expense had been spared to render life luxurious in this land of dirt and discomfort. Even my host's bedroom was daintily furnished, à la Louis XV., by a French upholsterer. And yet he slept every night, fully dressed, on three chairs! There is no accounting for tastes—in Siberia!

[2] "Lake Baikal is about twenty miles from Irkutsk. It is 420 miles in length, its breadth varying from ten to sixty miles. Its average depth is rarely less than 819 ft., but in parts the ground has been touched only at 4500 ft. The natives believe it to be unfathomable."—"Side Lights on Siberia," by J. Y. Simpson.

Although the "Bolshaya," in which most of the café chantants are situated, is bright with electric light, the back streets of the city are lit by flickering oil-lamps, and here the stranger must almost grope his way about after dark. If wise he will stay at home, for robbery and even murder are of frequent occurrence. A large proportion of the population here consists of time-expired convicts, many of whom haunt the night-houses in quest of prey. During our short stay a woman was murdered one night[Pg 34] within a few yards of our hotel, and a man was stabbed to death in broad daylight on the busy "Bolshaya." The Chief of Police told me that there is an average of a murder a day every year within the precincts of the city, and warned us not to walk out unarmed after dark. There was no incentive to drive, for the Irkutsk cab, or droshky, is a terrible machine, something like a hoodless bath-chair, springless, and constructed to hold two persons (at a pinch) besides the driver. There is no guard-rail, and it was sometimes no easy matter to cling on as the vehicle bumped and bounded, generally at full gallop, along the rough, uneven streets.

Three days elapsed before the business of the city was resumed and I was able to turn my attention to the purchase of sleighs. Fur coats and felt boots we were already provided with, but I had determined to obtain the Arctic kit destined to protect us from the intense cold north of Yakutsk from the fur merchants of that place. Finally, when the fumes of vodka had evaporated, at least a dozen sleigh-builders invaded my bedroom early one morning, for the Irkutsk papers had published our needs. The whole day was passed in driving about to the various workshops and examining sleighs, some of which appeared to have been constructed about the same period as the Ark. It was not easy to make a selection from the score of ramshackle kibitkas which were hauled out for my inspection, especially as I had a very faint notion of the kind of sleigh required for the work in hand. Fortunately, my friend the Chief of Police, white with rage[Pg 35] and blazing with orders, burst into a yard as I was concluding the purchase of a venerable vehicle, which bore a striking resemblance to Napoleon's travelling carriage at Madame Tussaud's, and which would probably have come to pieces during the first stage.

"Son of a dog," furiously cried the official to the trembling coach-builder, "don't you know that this gentleman wishes to go to Yakutsk, and you are trying to swindle him into buying a 'Bolshaya' coupé!" And in less than a minute I was being whirled away towards the Police Station, where a number of the peculiar sleighs required for this journey are kept on hand for the convenience of travellers.

"That man is an infernal scoundrel," said the Chief of Police, when told that Napoleon's barouche was to have cost me 150 roubles. "I will give you a couple of good Yakute sleighs for half the money. You can only use them on the Lena." And when I saw the primitive contrivances in question I no longer marvelled at their low price.

Let me describe the comfortless conveyance in which we accomplished the first two thousand miles of the journey across Siberia. A Yakute sleigh has a pair of runners, but otherwise totally differs from any other sleigh in the wide world. Imagine a sack of coarse matting about four feet deep suspended from a frame of rough wooden poles in a horizontal triangle, which also forms a seat for the driver. Into this bag the traveller first lowers his luggage, then his mattress, pillows, and furs, and finally enters himself, lying at full length upon his belongings. There is a thick felt apron which can be pulled[Pg 36] completely over its occupant at night-time or in stormy weather. This sounds warm and comfortable, but is precisely the reverse, for after a few hours the porous felt becomes saturated with moisture (formed by bodily warmth and external cold), rendering the traveller's heavy garments damp and chilly for the remainder of the journey. There is nothing to prevent the Koshma, as this covering is called (Cauchemar would be a better name!), from resting upon the face during sleep, and frost-bitten features are the natural result. So far, therefore, as comfort is concerned a Yakute sleigh is capable of some improvement, for, even in fine weather, the occupant must raise himself up on his elbows to see anything but the sky above him, while in storms the damp, heavy covering casts him into outer darkness. Under the most favourable circumstances little is seen of the country travelled through, but, as the Chief of Police consolingly remarked, "Between here and Yakutsk there is nothing to see!"

Provisions were the next consideration, and these were obtained from a well-appointed store on the "Bolshaya." We now had but a dozen cases of condensed foods, &c., left, and these I wished to keep intact, if possible, for use in the Arctic regions. On the Lena road the post-houses were only from thirty to forty miles apart, but as they only provide hot water and black bread for the use of travellers, I laid in a good supply of canned meats, sardines, and tea to carry us comfortably, at any rate, through the first stage of the journey. With months of desolation before us our English tobacco was too precious[Pg 37] to smoke in civilisation, so a few hundred Russian cigarettes were added to the list.

At last came the welcome news that the Governor-General would grant us an interview. Accompanied by an aide-de-camp, we drove to the Palace on the banks of the Angará, and were ushered into the presence of the Tsar's Viceroy, who governs a district about the size of Europe. General Panteleyéff was a middle-aged man, with white moustache, light blue eyes, and a spare athletic figure, displayed to advantage by a smart dark green uniform. The General is a personal friend of the Emperor, and the cross of St. Andrew and a tunic covered with various orders bore witness to their wearer's distinguished career. He received me most cordially, and asked many questions regarding the land-journey, which had apparently aroused considerable interest in Russian official circles. The General, however, had no great faith in the proposed line to connect his country with the New World.

"We have our hands too full in the Far East for the next century," he said, with a smile, "to meddle with Arctic railways."

His Excellency assured me of every assistance as far as Nijni-Kolymsk, the most remote Cossack outpost on the shores of the Polar Sea, on ordinary occasions a year's journey from St. Petersburg. "Beyond Kolymsk," he added, "I fear I cannot help you. The Tchuktchi region is nominally under my control, but even our own officials rarely venture for any distance into that desolate country. But you will first have to reach Nijni-Kolymsk, and even that is a voyage that few Russians would care to[Pg 38] undertake; and beyond Nijni-Kolymsk you will have yet another two thousand miles to Bering Straits. Great Heavens! what a terrible journey! But you English are a wonderful people!" Here a secretary entered the apartment with a document, which the Governor rapidly scanned and then signed.

"Your Imperial passport," he said, placing the paper in my hand, "which will ensure civility and assistance from all officials you may meet as far as the Kolyma river. Beyond that you must rely upon yourselves and the goodwill of the natives, if you ever find them! May God preserve you all."

So saying, with a hearty shake of the hand, the General touched a bell, the aide-de-camp appeared, and I was re-conducted to my sleigh, rejoicing that nothing could now retard our departure. Amongst other privileges the passport ensured immediate relays of horses at the post-stations. As there are no less than one hundred and twenty-two of these (from fifteen to twenty-five miles apart) between Irkutsk and Yakutsk, and as the ordinary traveller is invariably delayed by extortionate postmasters, this clause was of the utmost importance. In many other ways also the document was a priceless one, and without it we could scarcely have reached the shores of America.

It may be that I have unduly underrated the attractions of Irkutsk to the average public. If so, the reader must remember that every hour of delay here was of importance and meant endless worry and vexation to the leader of an expedition which had not an hour to lose. There is no doubt that Irkutsk must in a few years become a teeming[Pg 39] centre of commercial activity. The social aspects of the place will then no doubt improve under the higher civilisation introduced by a foreign element. The resources of this province are limitless, for the soil has up till now, minerally speaking, only been scratched by idle fingers. Further afield we hear of important discoveries of valuable minerals in Manchuria, while the output of gold in the Lena district has been trebled by modern machinery within the past four years. Coal has also been recently discovered within a short distance of Lake Baikal, and is already being exported in large quantities to the Pacific ports. Irkutsk has, no doubt, a great commercial future, but should I ever return there I shall, personally speaking, be quite satisfied to find a decent hotel. Such an establishment run on modern lines would certainly yield fabulous returns. At present the only available restaurant is that of the grimy and verminous Metropole, and even here the local millionaires cheerfully pay prices for atrocious food and worse wines which would open the eyes of a Ritz.

Perhaps the most pleasant memory which I retain of Irkutsk is a cheery little supper which was given in our honour by a Mr. Koenigswerther and his wife and brother on the eve of our departure. The travellers, who had only arrived that day, were visiting the city on business connected with the purchase of furs, and a chance word dropped in the purest French by Madame at the dinner-table linked our parties inseparably for the remainder of the evening; indeed, until the next day. Madame Koenigswerther, an attractive little Parisienne,[Pg 40] seemed to cast a gleam of sunshine over the gloomy dining-room in which we had partaken of so many melancholy meals. The trip here from Paris had already imbued her with a passion for further exploration, and I verily believe that she would have accompanied the expedition to Yakutsk if not restrained by her less enthusiastic male companions. Bed on such an occasion was not to be thought of, so we visited the theatre and café chantants, ending the evening with a supper at the Metropole (previously ordered by the fur merchants) which proved that money, even in Irkutsk, will convert a culinary bungler into a very passable chef. Our departure for the North took place very early on the morning of January 19, and I have since heard that nothing would induce our merry little hostess to seek her couch until the tingle of our sleigh bells had died out on the frosty air.

"A New York!" she cried, as our horses sprang into their collars and dashed away down the frosty, silent street.

"N'ayéz pas peur! Nous arriverons," answered de Clinchamp, with a cool assurance which at the time excited my envy, if not admiration!

The distance from Irkutsk to Yakutsk is about 2000 English miles, but the post-road by which we travelled during the first stage of the overland journey is, properly speaking, no road at all. After leaving Irkutsk the traveller crosses about 150 miles of well-wooded country, until the upper waters of the Lena river are reached.[3] In winter time the frozen surface of the latter connects the two cities, and there is no other way by land. A double row of pine branches stuck into the snow at short intervals indicate the track, and this is a necessary precaution, as the hot springs of the Upper Lena frequently render the ice treacherous and unsafe. A sharp look-out is, therefore, kept all along the line for overflows, and, when necessary, the road is shifted to avoid them, but notwithstanding these precautions, darkness and drunken drivers often cause fatal accidents. In summer time Yakutsk may be[Pg 42] reached by small steamers plying from Ust-kutsk, on the Lena, about 250 miles by road from Irkutsk. The trip takes about a fortnight down stream, and three weeks in the reverse direction, but sand-bars frequently cause delays, rendered the more irksome by poor accommodation, stifling heat, and clouds of mosquitoes.[4]

[3] The Lena river has an estimated length of not less than 3000 miles. It rises in the Baikal mountains and flows north and east past the towns of Kirensk, Vitimsk, and Olekminsk to Yakutsk, thence it turns to the north-west and enters the Arctic Ocean, forming a wide delta. The Lena receives several large tributaries, viz., the Vitim, about 1400, the Olekma, about 800, and the Aldan, about 1300 miles long.

[4] This must be very slow travelling, for Dobell, the traveller, writes: "When I descended the Lena from Ust-kutsk in the spring of 1816, I was only fourteen days going to Yakutsk in a large flat-bottomed boat."

Most people in England have a very vague idea of the size of Siberia. It is only by actually visiting the country that one can grasp the harassing difficulties due to appalling distances and primitive modes of locomotion, especially when the traveller is bound for the Far North. I will, therefore, endeavour to convey to the reader, as briefly as possible, the area of this land of illimitable space, and cannot do so better than by quoting the graphic description given by the American explorer, Mr. George Kennan.[5] He says: "You can take the whole of the United States of America, from Maine to California and from Lake Superior to the Gulf of Mexico, and set it down in the middle of Siberia without touching anywhere the boundaries of the latter's territory; you can then take Alaska and all the countries of Europe, with the exception of Russia, and fit them into the remaining margin like the pieces of a dissected map. After having thus accommodated all of the United States, including Alaska, and the whole of Europe, except Russia,[Pg 43] you will still have more than 300,000 miles of Siberian territory to spare. In other words, you will still have unoccupied in Siberia an area half as large again as the Empire of Germany." According to the census of 1897 the entire population of Siberia is little more than that of the English metropolis.

[5] "Siberia and the Exile System," by George Kennan.

A couple of Yakute sleighs sufficed for ourselves and entire outfit. I rode with de Clinchamp in the leading vehicle, while Harding and the bulk of the stores followed in the other. At first sight, the Yakute sleigh appears to be a clumsy but comfortable contrivance, but very few miles had been covered before I discovered its unlimited powers of inflicting pain. For this machine does not glide like a well-behaved sleigh, but advances by leaps and bounds that strain every nerve and muscle in the body. In anything like deep, soft snow it generally comes to a standstill, and the combined efforts of men and horses are required to set it going again. However, for the first three or four days, good progress was made at the rate of about 200 versts[6] in the twenty-four hours, for we travelled night and day. There was no incentive to pass the night in the post-houses, which were generally of a filthy description, although luxurious compared to the Yakute Yurtas and Tchuktchi huts awaiting us up North. On the Lena post-road, stages were only from fifteen to thirty miles apart, and with a fresh troika (three horses harnessed abreast) at such short intervals, our rate of speed for the first week was very satisfactory. Between Irkutsk and the river Lena part of the road lies through dense forests, which[Pg 44] are generally infested with runaway convicts, so we kept a sharp look-out and revolvers handy. Only a week before we passed through this region a mail-cart had been held up and its driver murdered, but I fancy news had filtered through that my expedition was well armed, and we therefore reached the Lena unmolested.

[6] A verst is two-thirds of an English mile.

The weather at Irkutsk had been comparatively warm, and we were, therefore, unprepared for the intense cold experienced only forty-eight hours after our departure. Although on the evening of the 19th the thermometer had registered only 10° below zero Fahrenheit, it suddenly sank during the night to 65° below zero, where it remained until the following evening. Oddly enough, a dense mist accompanied the fall of the mercury, rendering the cold infinitely harder to bear. Our drivers declared that this climatic occurrence was most unusual, and the fact remains that this was the lowest temperature recorded during the entire journey south of the Yakute Yurta of Yuk-Takh, several hundred miles north of Yakutsk. There we had to face 75° below zero, but then Yuk-Takh adjoins Verkhoyansk, the coldest place in the world. But the dry frosty air of even this remote settlement inconvenienced me far less than the chilly breeze of a raw November day on the Paris Boulevards with the mercury half a dozen degrees above the freezing-point. On the Lena this Arctic cold only lasted for about eighteen hours, and then slowly rose again, after remaining at about 50° below zero for a couple of days. The severest cold afterwards experienced south of Yakutsk was 51° below zero, and that only upon one occasion. Other[Pg 45]wise it varied from 2° above to 40° below zero, but even that was sufficient to convert our provisions into a granite-like consistency, and at first wearisome delays were occasioned at the post-stations by the thawing out of petrified sardines and tinned soup converted into solid ice. Milk, frozen and cut into cubes, was conveniently carried in a net attached to the sleigh, and this, with tea, was our sole beverage. For a case with a few bottles of Crimean claret, which we had taken to enliven the first portion of the journey, was found when broached to contain nothing but fragments of red ice and broken glass. Even some cognac (for medicinal purposes) was partly frozen in its flask. On the same day de Clinchamp, removing his mits to take a photograph, accidentally touched some metal on the camera, and his fingers were seared as though with a red-hot iron. Perhaps our greatest annoyance on this voyage was the frequent deprivation of tobacco, that heavenly solace on long and trying journeys. For at even 40° below zero nicotine blocks the pipe-stem, and cigar or cigarette freezes firmly to the lips. The moustache also forms a mask of solid ice, and becomes an instrument of torture, so much so that on the third day out on the Lena ours were mercilessly clipped.

The post-houses on this road are, as I have said, luxurious as compared to the accommodation found among the Arctic races of Siberia, but I fancy those accustomed to "roughing it," as the word is generally understood in England, would find even a trip as far as Yakutsk rather a trial. Of course, these establishments vary from the best, which are about on a par with the labourer's cottage in England,[Pg 46] to the worst, which can only be described as dens of filth and squalor. All are built on the same plan. There is one guest-room, a bare carpetless apartment, with a rough wooden bench, a table, and two straight-backed wooden chairs, and the room is heated to suffocation by a huge stove, which occupies a corner of the room. The flimsy plank partition is unpapered, but generally plastered with the cheap, crudely coloured prints sold by pedlars. Some of these depicted events connected with our recent war in South Africa, and it is needless to add that the English troops were invariably depicted in the act of ignominious flight.[7] I purchased one, in which three distinguished British Generals were portrayed upon their knees imploring mercy of Mr. Kruger, and sent it to England, but it never reached its destination. This work of art had been "made in Germany."

[7] I was surprised by the interest displayed by the Russian settlers of this district anent the Boer War. In every village we were eagerly questioned as to how affairs in the Transvaal were progressing.

In every guest-room, however squalid, four objects were never missing: the sacred Ikon, portraits of the Tsar and Tsarina, and a printed copy of the posting rules. On the wall was generally also a bill of fare, in faded ink, which showed how many generations of travellers must have been duped by its tempting list of savoury dishes. I never could ascertain whether these had ever really existed in the far distant past, or whether the notice was a poor joke on the part of the proprietor. In any case, the menu we found was always the same: hot water,[Pg 47] sour black bread, and (very rarely) eggs of venerable exterior, for although the inmates of these stations presumably indulge occasionally in meat, no amount of bribery would induce them to produce it for our benefit. Vermin was everywhere; night and day it crawled gaily over the walls and ceiling, about our bodies, and into our very food, and, although the subject did not interest us, a naturalist would have delighted in the ever-changing varieties of insect life. Of the latter, cockroaches were, I think, the most objectionable, for they can inflict a nasty poisonous bite. Oddly enough, throughout Siberia I never saw a rat, although mice seem to swarm in every building, old or new, which we entered. The Lena post-house has a characteristic odour of unwashed humanity, old sheep-skins and stale tobacco. Occasionally, this subtle blend includes a whiff of the cow-shed, which generally means that one or more of its youthful occupants have been carried indoors out of the cold. In winter there is no ventilation whatsoever, save when the heavy felt-lined door is opened and an icy blast rushes in to be instantly converted by the stifling heat into a dense mass of steam. Indoors it was seldom under 80° Fahrenheit, and although divested of heavy furs we would invariably awaken from a sleep of, perhaps, a couple of hours, drenched with perspiration, in which state we would once more face the pitiless cold. In England such extremes of temperature, experienced day after day, would probably kill the strongest man outright, but here they made no appreciable difference in our bodily health.

It was no doubt rough travelling along the Lena,[Pg 48] and yet the pleasures of the journey far outweighed its ills. Before reaching the river our way lay across vast deserts of snow, with no objects visible save, at rare intervals, some tiny village almost buried in the drifts, its dark roofs peeping out here and there, and appearing at a distance like pieces of charcoal laid on a piece of white cotton-wool. Beyond these nothing but the single telegraph wire which connects Yakutsk with civilisation. Coated with rime it used to stand out like a jewelled thread against the dazzling sky, which merged imperceptibly from darkest sapphire overhead to tenderest turquoise on the horizon. Who can describe the delights of a sleigh journey under such conditions, or realise, in imagination, the charm and novelty of a wild gallop over leagues of snow behind game little Siberian horses, tearing along to the clash of yoke-bells at the rate of twenty miles an hour! In anything but a Yakute sleigh we should have been in an earthly paradise.

And on fine evenings, pleasanter still was it to lie in the sleigh snugly wrapped in furs, and watch the inky sky powdered with stars—Ursa Major (now almost overhead) sprawling its glittering shape across the heavens, and the little Pleiades twinkling like a diamond spray against dark velvet. At times I could make out every lonely peak and valley in the lunar world, and even distinguish far-away Polaris twinkling dimly over the earth's great mystery. The stars are never really seen in misty Europe.

But a week, ten days, elapses and so little progress is made in the alarming total of mileage that the heart sinks at the mere thought of the stupend[Pg 49]ous distance before us. Few villages are passed and these are invariably alike. A row of ramshackle huts; at one extremity the post-house with black and white verst post, at the other a rough palisade of logs about twenty feet high, enclosing a space from which a grey column of smoke rises lazily into the frosty air. The building is invisible, but it generally contains one or more unhappy exiles wending slowly towards a place of exile. Every village between Irkutsk and Yakutsk has its Balogan, or resting-place for political offenders, but in the Far North beyond the Arctic Circle prison bars become superfluous. Nature has taken their place.

There can be no doubt that, for monotony, this journey is unequalled. After a few days surrounding objects seemed to float by in a vague dream. Only the "scroop" of the runners and jingle of the sleigh-bells seemed to be hammered into the brain, for all eternity. And yet, even the bells in their own way were a godsend, for they were changed (with the yoke) at every station, and I liked to think that every one of the hundred and twenty-two stages were accompanied by a different tune! There were other drawbacks to complete enjoyment. On the whole, the weather was still and clear, but occasionally the sky would darken, down would come the snow, and we would flounder about, sometimes for hours, lost in the drifts. Logs frozen into the river, fissures in the ice, and other causes rendered upsets of almost daily occurrence, but it was generally soft falling. I remarked that as we proceeded further north the post-horses became wilder and more unmanageable, and it was often more than the drivers[Pg 50] could do to hold them. Twice our sleigh was run away with, and once de Clinchamp and myself were thrown with unpleasant force on to hard black ice. On another occasion the troika started off while the driver was altering the harness, and went like the wind before we could clamber on to the box, seize the reins, and stop them. The unfortunate yemstchik[8] was dragged with them, and I expected to find the poor fellow a mangled corpse, but we pulled him out from under his team badly cut and bruised, but otherwise little the worse for the accident. He had clung like grim death to the pole, or the heavy sleigh must have crushed him.

[8] Driver.

During daylight we could afford to laugh at such trifles, but at night time it was a different matter. To tear through the darkness at a breakneck pace at the mercy of three wild, unbroken horses required some nerve, especially when lying under the koshma as helpless as a sardine in a soldered tin. For the first few days overflows were a constant menace, especially at night when sleep under the apron was out of the question, for any moment might mean a plunge through the ice into the cold dark waters of the Lena. I generally had a clasp-knife ready to slash asunder, at a moment's notice, the ropes which secured the apron to the sleigh. After a time I could lie in the dark and tell with unerring precision whether the sleigh was gliding over the river or the land, and whether, in the former case, the ice was black and sound or that dread element, water, was rippling against the runners. If so, out came the clasp-knife, and there was no more koshma for that night.[Pg 51] During the first week we frequently passed places where hot springs had broken through the ice. One or two of these holes were quite near the track, and might well, on a dark night, have brought the expedition to an untimely end.

Talking of ice, we noticed a curious phenomenon in connection with it while journeying down the Lena. On clear sunny days the frozen surface of the river would appear to be sloping downwards at a perceptible gradient in the direction in which we were travelling; occasionally it would almost seem as though we were descending a fairly steep hill, had not the unrelaxed efforts of our teams suggested the optical delusion which, as long ago as 1828, was observed by Erman the explorer, who wrote: "I am disposed to think that this phenomenon was connected with the glistening and distortion of distant objects which I remarked not only in this part of the valley, but frequently also on the following days. This proved that the air was ascending from the ice and therefore that the lower strata were lighter than those above in which the eye was placed. Under such circumstances a plane perfectly horizontal and level in fact would appear depressed towards the horizon, or, in other words, it would seem to slope downwards." Scientists must determine whether this be the correct explanation of this strange deception of nature, which was often noticeable on the Lena, although we never observed it elsewhere.

We reached Ust-kutsk (the first town of any importance) on the sixth day. This place figures largely on most English maps, but it is little more than an overgrown village. A church with apple-[Pg 52]green dome and gilt crosses, a score of neat houses clustered around the dwelling of an ispravnik,[9] perhaps a couple of stores for the sale of clothing and provisions, and a cleaner post-house than usual: such is a "town" on the banks of the Lena. With the exception of Ust-kutsk there are only three, Kirensk, Vitimsk, and Olekminsk, places of such little general interest that they are chiefly associated in my mind with the four square meals we were able to obtain during those three weeks of incessant travel. At Ust-kutsk, for instance, we refreshed the inner man with a steaming bowl of schtchi or cabbage soup followed by the tough and greasy chunks of meat that had been boiled in it, and the meal tasted delicious after nearly a week on black bread, an occasional salt fish and dubious eggs. Our own provisions were so hopelessly frozen that we seldom wasted the time necessary to thaw them out into an eatable condition.

[9] An official who combines the duties of Mayor and Chief of Police.

There are salt-mines near Ust-kutsk from which about 50,000 poods[10] are annually exported throughout the Lena province, and the forests around here contain valuable timber, but agriculture did not seem so prosperous here as in the districts to the north and south. Oddly enough the cultivation of the land seemed to improve as we progressed northward, as far as Yakutsk, where, as the reader will presently see, the most modern methods of farming have been successfully adopted by a very peculiar and interesting class of people.

I was told that during the navigation season, from June until the latter end of September, Ust-kutsk is a busy place on account of the weekly arrival and departure of the river steamers. But lying silent and still in the icy grip of winter, this appeared to me to be the most desolate spot I had ever set eyes upon. And we left it without regret, notwithstanding that a darkening sky and threatening snow-flakes accompanied our departure, and the cold and hunger of the past few days had considerably lowered the high spirits in which we had left Irkutsk. Up till now monotony had been the worst evil to bear. In summer time the river as far as Yakutsk is highly cultivated, and smiling villages and fertile fields can be discerned from the deck of a steamer, but in winter, from a sleigh, nothing is visible day after day, week after week, but an unvarying procession of lime-stone, pine-clad cliffs, which completely shut out any scenery which may lie beyond them, and between which the bleak and frozen flood lies as inert and motionless as a corpse. Even at Ust-kutsk, nearly 3000 miles from the Arctic Ocean, the stream is as broad as an arm of the sea, which enhances the general impression of gloom and desolation. But in this world everything is comparative, and we little dreamt, when reviling the Lena, that a time was coming when we should look back even upon this apparently earthly Erebus as a whirlpool of gaiety.

When we left Ust-kutsk at about 3 P.M. night was falling fast, a proceeding which scattered snow-flakes followed with such vigour that only a few versts had been covered when we were brought to a[Pg 54] standstill by a dense snowstorm, which, with a northerly gale, rapidly assumed the proportions of a blizzard. Providence has mercifully ordained that a high wind seldom, if ever, accompanies a very low temperature or on this occasion (and many others) we should have fared badly. But here and in the Arctic a fall of the glass was invariably accompanied by a rise of the thermometer, and vice versâ. During this, our first storm, it was only eight degrees below zero, and even then it was impossible to face the wind for more than a few moments at a time, for it penetrated our heavy fur coats as though they had been of crêpe-de-chine, and cut into the face like the lash of a cat-o'-nine-tails. I had never experienced such a gale (although it was nothing to those we afterwards encountered), for the wind seemed to blow from all points of the compass at once as we blundered blindly along through the deep snow, pushing and hauling at the sleighs as well as our numbed hands and cumbersome garments would permit. So blinding was the snow we couldn't see a yard ahead; so fierce the wind we could scarcely stand up to it. Suddenly both teams gave a wild plunge which sent us sprawling on our faces, and when I regained my feet the sleighs were upset and the horses, snorting with terror, were up to their girths in a snow-drift. I then gave up all hopes of reaching a station that night. For over an hour we worked like galley-slaves, and suddenly when we had finally got things partly righted, the wind dropped as if by magic, and one or two stars peeped out overhead. The rapidity with which the weather can change in these[Pg 55] regions is simply marvellous. We often left a post-house in clear weather, and, less than an hour after, were fighting our way in the teeth of a gale and heavy snow. An hour later and stillness would again reign, and the sun be shining as before! We now quickly took advantage of the lull to push on, and in a few hours were rewarded by the glimmering lights of a post-house. We had reached the village of Yakurimsk and, being fairly exhausted by the cold and hard work, I resolved to stay here the night. This was our first experience of frost-bite (both faces and hands suffered severely), which is not actually painful until circulation returns, and care must then be taken not to approach a fire. I have always found that snow, vigorously rubbed on the frozen part, is the best remedy. The stage between Ust-kutsk and Yakurimsk was a short one, only about eighteen versts, but it took us six hours to make it. When we awoke next morning bright sunshine was streaming into the guest-room, which was older and filthier than usual. But it possessed a cracked and cloudy looking-glass which dimly reflected three countenances swollen and discoloured beyond recognition. For we had neglected to anoint our faces with grease (Lanoline is the best), but after this experience never neglected this essential precaution.

The postmaster at Yakurimsk, a decrepit Pole of benign but unwashed exterior, informed me that the woods around his village swarmed with bears, and that on payment of a few roubles for beaters he could ensure us a good day's sport. But although the offer was tempting I did not feel justi[Pg 56]fied in risking the delay. Wolves had also been numerous, but had, as usual, confined their attacks to pigs and cattle. Before visiting Siberia I had the usual fallacious notion concerning the aggressiveness of this meek and much maligned animal. I remember, in my early youth, a coloured plate depicting a snow scene and a sleigh being hotly pursued at full gallop by a pack of hungry and savage-looking wolves. In the sleigh was a Cossack pale with terror, with a baby in his teeth and a pistol in each hand. I fancy that, in riper years, I must have unconsciously based my estimate of the wolf's ferocity on this illustration, for I have now crossed Siberia four times without being attacked, or even meeting any one who had been molested. The only wolf which ever crossed my path was a haggard mangy-looking specimen, which, at first sight, I took for a half-starved dog. We met in a lonely wood near Krasnoyarsk in Western Siberia, but, as soon as he caught sight of me, the brute turned and ran for his life!

Our drivers and horses were exchanged at every station so that the severe work of the previous night did not retard our progress after leaving Yakurimsk. The weather was fine and we made good headway until the 28th, on the afternoon of which day we reached the second town of Kirensk. A few miles above the latter the Lena makes a wide détour of fifty to sixty miles and the post-road is laid overland in a straight line to avoid it. It was a relief to exchange, if only for a few hours, that eternal vista of lime-stone and pines for a more extended view. The Kirensk mountains are here crossed, a[Pg 57] range which, although of no great altitude, is precipitous and thickly wooded, so much so that in places the sleighs could scarcely pass between the trees. The climb was severe, but a lovely view over hundreds of miles of country amply rewarded our exertions. The glorious panorama of mountain, stream, and woodland stretching away on all sides to the horizon, intersected by the silvery Lena, was after the flat and dismal river scenery like a draught of clear spring water to one parched with thirst. Overhead a network of rime-coated branches sparkled against the blue with a bright and almost unnatural effect that reminded one of a Christmas card. A steep and difficult descent brought us to the plains again, and after a pleasant drive through forests of pine and cedar interspersed with mountain ash and a pretty red-berried shrub of which I ignore the name, we arrived, almost sorry that the short land trip was over, at Kirensk.

Although not the largest, this is the prettiest and cleanest-looking town on the Lena. Perhaps our favourable impressions of the place were partly due to the dazzling sunshine and still, delicious air. Dull skies and a fog would, perhaps, have made a world of difference; but as, under existing conditions, Kirensk afforded us the only interval of real rest and enjoyment on the Lena, we were proportionately grateful. And it was almost a pleasure to walk through the neat streets, with their gaily-painted houses and two or three really fine stores, where any article from a ship's anchor to a gramophone seemed to be on sale. A few mercantile houses and a busy little dockyard, with[Pg 58] a couple of river-steamers in course of construction, explained the prosperous appearance of this attractive little town, which contrasted cheerfully with all others which we saw in Siberia. The inn was quite in keeping with its surroundings, and perhaps a longer time than was absolutely necessary was passed there, for déjeuner was served, not in the usual dark fusty room reeking with foul odours, but in a bright, cheerful little apartment with comfortable furniture and a table set with a white cloth and spotless china by a window overlooking the river. There was a mechanical organ, too, which enlivened us with "La Marseillaise" and "Loin du Pays" as a pretty waiting-maid in Russian costume served us with some excellent cutlets and an omelette, which were washed down with a bottle of Crimean wine. These culinary details may appear trifles to the reader, but they had already become matters of moment to us. And the sun shone so brightly that the claret glowed like a ruby in the glass as we drank to the success of the expedition and our friends in far-away France and England. And so susceptible is man to the influence of his surroundings that for one fleeting hour New York seemed no distance away to speak of!

After leaving Kirensk the horses were harnessed gusem or tandem fashion, for it is here necessary to leave the river and travel along its shores where the roadway becomes a mere track three or four feet wide through the forests. As our sleighs were unusually broad, this caused some trouble, and once or twice trees had to be felled before we could pro[Pg 59]ceed. When Vitimsk was reached, on February 2, the drivers there flatly refused to embark upon a stage until the breadth of our sleighs had been reduced by at least one-third. Fortunately the weather changed for the worse, and snowstorms and a stiff Northern gale would have greatly impeded us, so that the lost time was not so precious as it might have been. There is no inn at Vitimsk, but the post-house was clean and comfortable, and the ispravnik, on reading the Governor's letter, also placed his house and services at my disposal, but I only availed myself of the latter to hasten the alteration to the sleighs. The only wheelwright in Vitimsk being an incorrigible drunkard, this operation would, under ordinary circumstances, have occupied at least a week; under the watchful eye of the stern official it was finished in forty-eight hours. Politically, I am a Radical, but I am bound to admit that there are circumstances under which an autocratic form of Government has its advantages.

Until Vitimsk was reached we had met but few travellers during our journey down the Lena, certainly under a score in all, which was fortunate, considering the limited accommodation en route. But at Vitimsk I was destined to come across not only an Englishman but a personal friend. The meeting, on both sides, was totally unexpected, and as on the evening of our arrival I watched a sleigh drive up through the blinding storm and a shapeless bundle of furs emerge from it and stagger into the post-house, I little dreamt that the newcomer was one with whom I had passed many a pleasant[Pg 60] hour in the realms of civilisation. The recognition was not mutual, for a week of real Siberian travel will render any man unrecognisable. "Pardon, M'sieu," began the stranger, and I at once recognised the familiar British accent; "Je reste ici seulement une heure." "Faites, monsieur," was my reply. But as I spoke the fur-clad giant looked up from the valise he was unstrapping and regarded me curiously. "Well, I'm d——d," he said, after a long pause, "if it isn't Harry de Windt." But Talbot Clifton had to reveal his identity, for months of hardship and privation, followed by a dangerous illness, had so altered his appearance that I doubt if even his mother would have recognised her son in that post-house at Vitimsk. Clifton had already passed a year among the Eskimo on the Northern coast of the American continent, when, in the summer of 1901, he descended the Lena as far as its delta on the Arctic Ocean. Here he remained for several months, living with the natives and accompanying them on their fishing and shooting expeditions. In the fall of the year he returned to Yakutsk, where he contracted a chill which developed into double pneumonia, and nearly cost him his life. My friend, who was now on his way home to England, had only bad news for us. The reindeer to the north of Yakutsk were so scarce and so weak that he had only just managed to struggle back there from Bulun, on the delta, a trifling trip compared to the journey we were about to undertake. Moreover, the mountain passes south of Verkhoyansk were blocked with snow, and, even if deer were obtainable, we might be detained on[Pg 61] the wrong side of the range for days, or even weeks. All things considered, I would rather not have met Clifton at this juncture, for his gloomy predictions seemed to sink into the hearts of my companions—and remain there. However, a pleasant evening was passed with the assistance of tobacco and a villainous mixture, which my friend concocted with fiery vodka and some wild berries, and called punch. I doubt if, before this notable occasion, Vitimsk had ever contained (at the same time) two Englishmen, a Frenchman, and the writer, who may claim to be a little of both.

Talbot Clifton left early the next day, and before sunset the sleighs were finished and we were once more on the road. From Vitimsk I despatched telegrams to the Governor of Yakutsk and the London Daily Express, and was surprised at the moderate charges for transmission. Of course, the messages had to be written in Russian, but they were sent through at five and ten kopeks a word respectively.[11]

[11] A kopek is the one-hundredth part of a rouble; the value of the latter is about 2s. 1d.

Vitimsk is, perhaps, less uninteresting than other towns on the Lena, for two reasons. It is the centre of a large and important gold-mining district, and the finest sables in the world are found in its immediate neighbourhood. Up till four years ago the gold was worked in a very desultory way, but machinery was introduced in 1898, and last year an already large output was trebled. This district is said to be richer than Klondike, but only Russian subjects may work the gold.

[Pg 62]Olekminsk (pronounced "Alokminsk") was now our objective point. I shall not weary the reader with the details of this stage, for he is probably already too familiar, as we were at this juncture, with the physical and social aspects of travel on the Lena. Suffice it to say that a considerable portion of the journey was accomplished through dense forests, during which the sleighs were upset on an average twice a day by refractory teams, and that the filthiest post-houses and worst weather we had yet experienced added to the discomfort of the trip. Blizzards, too, were now of frequent occurrence, and once we were lost for nearly eighteen hours in the drifts and suffered severely from cold and hunger. Nearing Yakutsk travellers became more numerous, and we met some strange types of humanity. Two of these, travelling together, are stamped upon my memory. They consisted of an elderly, bewigged, and powdered little Italian, his German wife, a much-berouged lady of large proportions and flaxen hair, with a poodle. We met them at midnight in a post-house, where they had annexed every available inch of sleeping space the tiny hut afforded.