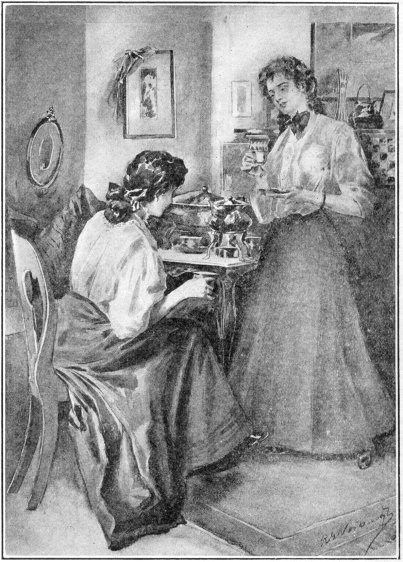

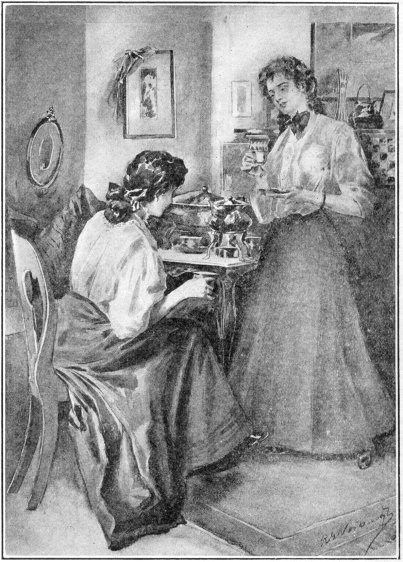

Elizabeth raised her cup to the toast.

Title: Elizabeth Hobart at Exeter Hall

Author: Jean K. Baird

Illustrator: R. G. Vosburgh

Release date: August 10, 2008 [eBook #26258]

Most recently updated: January 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Elizabeth raised her cup to the toast.

ELIZABETH HOBART

AT

EXETER HALL

BY

JEAN K. BAIRD,

AUTHOR OF

“DANNY,” “CASH THREE,” “THE HONOR GIRL,” ETC., ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY R. G. VOSBURGH

THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING COMPANY

New York Akron, Ohio Chicago

COPYRIGHT, 1907

By THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING COMPANY

Contents

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Preparations for School. | 7 |

| II. | The Journey. | 25 |

| III. | The Dinner Episode. | 55 |

| IV. | The Reception. | 81 |

| V. | A Box From Home. | 113 |

| VI. | How “Smiles” Was Scalped. | 143 |

| VII. | Defying the Powers. | 167 |

| VIII. | Midnight Confidences. | 199 |

| IX. | Joe’s Message. | 227 |

| X. | Clouds and Gathering Storms. | 249 |

| XI. | The Proud, Humbled. | 273 |

| XII. | The Seniors Outwitted. | 299 |

| XIII. | Imprisonment. | 323 |

| XIV. | Retaliation. | 339 |

| XV. | Victory. | 361 |

ELIZABETH HOBART AT

EXETER HALL.

Bitumen was what its name suggested. There was soft coal and smoke everywhere. Each day the clothes on the line were flecked with black. The buildings had the dull, dingy look which soot alone can give. The houses sagged on either side of narrow, unpaved streets, where during a rainy period ducks clattered about with their broods, and a few portly pigs led their shoats for a mud bath.

During a summer shower barefooted urchins waded knee-deep in the gutters, their trousers rolled to their thighs. Irish-Americans shot mud balls at black-eyed 8 Italians; Polanders and Slavs together tried the depths of the same puddles; while the little boys of the Russian Fatherland played in a group by themselves at one end of the square.

The houses were not so much homes as places of shelter. Walls painted red were the popular fancy. Although there was room enough, gardens were unknown, while blooming plants were rare enough to cause comment. Each dooryard had its heap of empty cans and pile of ashes. Ill-kempt women stood idly about the doorways, or sat upon unscrubbed steps with dirty babies in their arms.

Bitumen was not a place of poverty. There was plenty of work for the men, and good wages if they chose to earn them. They lacked nothing to eat or wear. Money, so long as it lasted, was spent with a prodigal hand. The Company store kept nothing too good for their palates. Expensive fruits and early vegetables were in demand. The cheap finery bought for the 9 young folk lasted but a few weeks, and was tossed aside by the next “pay day.”

There was one saloon in the place. It did a thriving business in spite of some unseen influence working against it. Its proprietor was one Dennis O’Day, who held the politics of the little town in his palm. He was a little brighter, a little keener and much more unscrupulous than the other men of the place, but he felt at times the force of some one greater than himself, and it was always directed against his business. He perceived it when he received orders that, in fulfillment of the law, he must remove the blinds before his windows, and keep his place open to the public view. He felt it again when he received a legal notice about free lunches, closing hours, and selling to minors. Never once had he stepped beyond the most rigid observance of the law but he was called to account for it. He knew some keen eye was upon him and some one ready to fight him and his business at every turn.

The great blow came when the Club House 10 was established. An empty store-room had been fitted up with chairs and tables and a supply of books and magazines. Here the boys had the liberty of coming to smoke and talk together while Joe Ratowsky served coffee and sandwiches cheaper than O’Day could sell beer.

It was not Ratowsky’s doings. There was some one else behind the scenes who provided the brains and money to keep the business moving. Dennis O’Day meant to find out who that person was and square accounts with him. But for three years he had been no nearer the truth than now. To learn anything from Ratowsky was impossible, for the man had a tied tongue when he chose.

In the midst of all the dirt and squalor there was one touch of dainty hominess and comfort. This was found near Mountain Glen, where the superintendent of the mines lived. The house was an unpretentious wooden building with great porches and big, airy rooms, but the windows shone in the 11 sunlight, the curtains were white as snow, and the worn floors of the porches were always scrubbed.

In front and at the sides of the house was a lawn mowed until it looked like a stretch of moss. Masses of scarlet sage and cannas grew near the house, while at the rear a white-washed fence gleamed white.

The superintendency of the Bitumen mines was not the most desirable position, cutting off, as it did, the man and his family from all congenial companionship. The salary attached was fairly good, quite sufficient to provide a comfortable, if not luxurious, living. The present incumbent had begun his profession with other ambitions than living in a little mining town.

Twenty years before, Mr. Hobart, then newly married, had every prospect of becoming prominent in his profession. He had new theories on mining and mine-explosives. He had brought to perfection a substance to destroy the explosive gas which collects in unused chambers of mines. 12

Just at the time when the mining interests were about to make use of his discovery, his health failed from too close application. He was threatened with consumption, brought about by inhaling poisonous gases. He was ordered from the laboratory into the mountains. The Kettle Creek Mining Company offered him a position at Bitumen, one of the highest soft coal regions in the world. The air was bracing and suited to his physical condition. Confident that a few months would find him restored to health, he accepted. But with each attempted return to lower altitudes the enemy came back, and months passed into years, until he came to look upon Bitumen as the scene for his life work.

Here his only child, Elizabeth, was born. Here she grew into girlhood, knowing no companionship except that of her parents and Miss Hale, a woman past middle age, who, in her youth, had travelled abroad and had spent the greater part of her time in the study of languages and music. She had 13 come to Bitumen with her father for the same reason that had brought Mr. Hobart.

She had a quaint old place just at the edge of town. Here, during the warm weather, she cultivated flowers and vegetables. In her home were unique collections of botanical and geological specimens, books, and music. She found recreation in painting both in oils and water colors, and in plaster-casting.

She paid little attention to dress. Most frequently she might be seen in a gown ten years behind the fashions, driving a dashing span of horses along the rough mountain roads in search of some member of the mission school in which she was interested. Most of the miners were Catholics, but here and there among them she found members of her own church and sought to bring and keep them together. Her appearance might cause a stranger to smile, but when once he heard her cultivated voice, and caught the varying expression of her face, he forgot all else. 14

Miss Hale taught Elizabeth French and music. Few days in recent years had been too cold or stormy to keep her from driving down the rough road to the Hobart home for the sake of the lessons.

The other branches of his daughter’s education, Mr. Hobart took under his own charge. He taught her mathematics as conscientiously as though he expected her to enter his own profession.

This line of work had not been a burden to her. She had her father’s aptitude for study, and took up an original problem in geometry as most girls take up their fancy work.

Elizabeth had no girl friends at Bitumen. Her father was the only really young person she knew, for although in years he was not young, yet in the joy he took in living, he was still a boy. He had the buoyancy of youth and the ability of manhood. No laugh came clearer or more often than his. No one could be dull in his presence.

His daughter took part in his pleasures. 15 She was interested in his work; even his business affairs were not unknown to her. There was one subject, however, with which she was not acquainted. Many times while she was at her books, her parents with Miss Hale were deep in a discussion, which ceased when she joined them.

She had finished her second reading of Cicero, and reviewed all the originals in solid geometry. Her summer suspension of study was about to begin. She was conscious that something of importance to herself was brewing in which she took no part. Miss Hale had made unusual visits and had been closeted with her parents for hours. One day Elizabeth sat studying in an upper room, and from her window she saw Miss Hale drive away. At the same instant her father called, “Elizabeth, Elizabeth!”

She ran down-stairs. Her father and mother stood at the foot looking pleased.

“I know she will be glad,” her mother said.

“Of course she will,” replied her father. 16

She paused on the stairway in wonder. She was very good to look at as she stood so. Her soft hair was drawn loosely back from her face, and hung in a long, fair plait down her back. She was not beautiful, only wholesome looking, with a clear, healthy color, and large, honest eyes. Her dress was a simple, inexpensive shirtwaist suit, but every article about her was in order. There was no sagging of belts, or loose hooks.

Her father held out a book as she came toward them. He was brimming over with joy at the prospect of her delight.

“It is a catalog of Exeter Hall, Elizabeth. That is the school Miss Hale attended. I’ve looked over dozens of catalogs and this pleases your mother and me best. We want you to go in the fall.”

“Oh!” was all she said then, but it was expressive enough to satisfy her parents. She had read stories of schoolgirl life which seemed more like fairy stories than experiences of real girls. 17

“Look it all over, Elizabeth. The course of study is mapped out. We think the classical course suited to you. Your mother and I are going to drive down to the mines. Study the catalog while we are gone and be ready to tell us what you think of it when we come back.”

She needed no second bidding to do this. By the close of the afternoon, she had read and re-read the prospectus. She became so excited she could scarcely sit still. There was one matter which did not fully satisfy her. She had advanced beyond the course at Exeter in some branches and smiled as she read the amount of work laid out in botany for the Middle Class. She had far exceeded that, for she had found and mounted every specimen of plant and flower that grew for miles around Bitumen.

The cost of a year’s schooling was a surprise. Her father and Miss Hale could teach her everything that the course at Exeter included. It seemed foolish to spend so 18 much money when all could be learned at home.

That evening Miss Hale drove over to see how Elizabeth was pleased with the prospect of going away to school. The matter was discussed from all points of view. Then Elizabeth expressed the thought which had come to her while studying the catalog:

“But I have had more work than the Freshman and Middle Classes require. It would not take me long to complete the work for the Senior year. I want to go,—I think I have always wanted to go to school, but it seems such a waste of money. You can teach me more, I can really learn as much at home.”

Her father laughed, “Impossible! The girls at Exeter will teach you more in one term than I can in a year. I do not expect you to be a Senior. I shall be more than satisfied with your entering as a ‘Middler.’ You’ll need plenty of time for extras.”

“Extras? What extras must I take?”

“Chafing-dish cooking and fudge making,” 19 replied Miss Hale, promptly. “It will take a full term for you to find your place among young people, and learn all they will teach you.”

“But they will know no more than I do,” said Elizabeth.

“Perhaps not so much; but what they know will bear no relation to what they teach you. I’m willing to promise that you will learn more from your roommate than you do from any instructor there.”

Elizabeth glanced from one to the other. She failed to understand.

“We will have no more lessons after to-morrow,” said Mrs. Hobart. “Elizabeth and I will begin putting her clothes in order. There will be a great deal to do, for she will need so much more at school than she does at home. We do not wish to hurry.”

“Only eight weeks yet,” said Elizabeth, “I wish I was going next week.”

The day following the work on the outfit for school began. “Plain and simple,” her 20 mother declared it should be. But Elizabeth fairly held her breath as she viewed the beautiful articles laid out to be made.

“This pale blue organdie will do for receptions and any public entertainments you have,” her mother explained. “Every girl at school needs some kind of a simple evening dress. You’ll need a cloth suit for church and shopping. Then, of course, the school dresses.”

Every morning Elizabeth on her way down-stairs to breakfast slipped into the sewing room to view the new dresses. She had never so much as thought, not to say expected, to own a rain coat and bath robe, and a soft eider-down sacque. But there they lay before her. Their existence could not be questioned.

“Do you think the other girls at Exeter will have so much?” she asked of Miss Hale. “I don’t want to look as though I was trying to out-dress anyone.”

“If you find they have less than you, keep some of your good things in your trunk. 21 You do not need to wear them all,” was Miss Hale’s advice. “No doubt they are fixing themselves up, too,” she added.

Elizabeth had never thought of the matter before. Now the mere thinking about it seemed to bring her into relation and sympathy with those hundreds of unknown girls who were, like her, counting each penny in order to spend it to the best advantage, all the while looking forward to the first of September.

It came at last. The big trunk was brought down from the attic. The new dresses were folded and packed. The books which she might need at Exeter were put into a box. The trunk was locked and carried into the lower hall, waiting for the drayman to call for it early the following morning.

At this juncture going away from home changed color. It was no longer something to look forward to with pleasure, but something to dread. Elizabeth was not the only one who felt the coming separation. She 22 noticed through a film of tears that the best linen and china were used, and that her favorite dishes had been prepared for the last home supper.

Despite their feelings, each made an effort to be cheerful. Mr. Hobart told incidents of his own school-days, and rallied Elizabeth on being homesick before she had started.

Afterward, they sat together on the porch. The father and mother talked but Elizabeth sat silent. She was thinking that the next evening would find her far away and among strangers. She dreaded meeting girls who had been reared with others of their age, and who had been in school before, feeling that she would appear very awkward and dull until she learned the ways of school. She half wished that her father would tell her she need not go. She came closer and seating herself on the step below him, rested her head on his knee. “Father, I do not wish to go to Exeter. May I stay home 23 with you and mother? Be a good daddy and say ‘yes.’”

“I shall be good and say ‘no.’ Our little girl must go away to-morrow. I can’t tell you how lonely we shall be, but we have had you so long that we were almost forgetting that you had a life of your own. We must not be selfish, so we send you off, bag and baggage.” Her mother added: “Unless she oversleeps, which I am sure she will unless she goes to bed right away. It is later than I supposed. Come, Elizabeth.”

As she spoke, Joe Ratowsky came across the lawn. In the moonlight, he looked like a great tawny giant. He spoke in English: “Mr. Hobart, that beeznez is no good. He no stay to-morrow. To-day homes he goes quick.”

“Where is his home? Doesn’t he live here?”

“Dennis O’Day, b’gosh, niver. So many as one children he have. Milton, he live.”

“Why doesn’t he bring his family here? I didn’t know the man was married.” 24

“Umh—yes, b’gosh. His girl tall like your girl. He no bring her. He proud like the tivil. Never he tell his girl what he do here—no, b’gosh, he don’t.”

“Well, come in and I will talk the matter over. We can’t do much else than wait.” Then turning to his daughter, “Good-night, Elizabeth, I must talk to Joe now.”

Elizabeth ascended the stair. Joe’s visit had taken her mind from her going away. She wondered what the Pole could have in common with her father. Joe was not even a miner.

Only accommodation trains ran between Bitumen and Exeter. Elizabeth found herself in a motley crowd of passengers. To her right sat a shabbily dressed mother with a sick baby in her arms; back of her was a plain little woman of middle age dressed in a gingham suit and rough straw hat; while before her sat two young women, perhaps a year or two older than herself. They talked loudly enough to attract the attention of those about them. Elizabeth learned that the larger was named Landis, and her companion “Min.”

They were handsomely though showily dressed. Min seemed to be less self-assertive than her companion. Landis evidently had confidence enough for two. She frequently 26 turned to look around, gazing into the faces of her fellow passengers with a self-assurance that in one of her age amounted almost to boldness.

She had been careful to arrange her jacket that its handsome buckle and silk lining were in evidence. She was a girl of large physique, with broad shoulders, which she carried rigidly. This, with the haughty pose of her head, attracted attention to her even in a crowd.

Her companion was as tall, but more slender. It was evident that she looked up to Landis and depended upon her in every emergency. A reader of human nature could have seen at a glance that she was the weaker.

From their conversation, it appeared they knew all places and people of importance along the route. As the train stopped at Westport, Landis viewed the town with critical eye.

“Tacky little hole, isn’t it? I should simply die if I were compelled to live here.” 27

“You would never stand it. You’d run away, Landis, or do something desperate. Isn’t this where the Gleasons live?”

“It used to be. But they live at Gleasonton now. They have a perfectly elegant place there. Of course, it is just their summer home. I’d like to take you down there sometime. I feel like taking the liberty for they are such old friends. They are in Washington during the winter. He’s United States Senator, you know.”

“Have you ever been there to visit them, Landis?”

“How could I, Min? I’ll have to leave all such times until I’ve finished school and have come out. I don’t doubt that Mrs. Gleason will ask me there for my first season. She’s not a society woman. She hasn’t much ability that way, and has sense enough to know it; so she goes in for charity, and temperance work, and all that.”

A suppressed exclamation from the seat behind her caused Elizabeth to look around. She was just in time to see the plainly-dressed 28 woman suppress a laugh. As Elizabeth glanced at her, she was pretending absorption in a magazine, but her lips were yet twitching with amusement.

The baby across the aisle began a low, fretful cry. The mother soothed it as best she could, holding it in her arms, patting it on the back, and trying all manner of devices to keep it quiet. A little boy several years old was on the seat beside her, and the instant the baby began to fret, he set up a distinct and independent howl of his own.

Landis made no attempt to conceal her discomfort.

“How annoying!” she exclaimed in tones that could be heard half the length of the car. “Anything but a crying baby! Why don’t women with babies stay at home? It wouldn’t matter so much if there was a decent train on this road, but one can’t get a Pullman for love or money. If there is anything I despise, it’s traveling with a mixed set. You never know whom you are getting next to.” 29

Her companion agreed, offering her subtle flattery in sympathizing that one of her station should be compelled to mingle with such people.

Again Elizabeth, in her hurried glance, caught a twinkle of amusement in the eyes of the woman back of her. Elizabeth could form no opinion about the girls in the seat ahead. She had no precedent to guide her. All she knew was learned from her parents and Miss Hale.

The train had been advancing at a steady if not rapid rate. They had descended the mountain, and were moving close to its base through a country barren of vegetation and population. There came a sudden jolt,—then a creaking sound as the train gradually slowed and then stopped.

The passengers looked from the window. No station or village was in sight. There was a moment of uneasiness. A few men got up and went to see what the trouble was. An half-hour passed. The restlessness expressed itself in words. Some complained 30 loudly; some grumbled, others walked up and down the aisle, every few moments looking at their watches, while their faces grew more expressive of displeasure and annoyance.

The baby across the way fretted. The little boy cried aloud. The tired mother worried over them until she herself was almost sobbing.

The half-hour lengthened into an hour. Then a trainman entered the car with the unpleasant news that they would be delayed yet longer. The air-brake had failed them, and they must wait until the wreck-train came down from Westport with another car, so it might be an hour before they would be able to proceed.

The girls, Landis and Min, left their places to walk up and down the aisle. Landis looked infinitely bored. She turned to her companion with deprecatory remarks about second-class traveling, where one could not have either a lunch or dinner.

The dinner hour had passed. Some of 31 the travellers who had a day’s journey before them had fortified themselves against hunger with a lunch.

The baby continued crying. The older child clamored loudly for something to eat. Elizabeth crossed the aisle.

“You look tired,” she said to the mother. “Will you trust your baby with me?” She held out her arms, but the child clung closer to its mother while its fretful cry grew louder.

“Perhaps I can persuade her to come,” said Elizabeth, going to her lunch box and returning with an orange. The bright color attracted the child at once. Elizabeth took her in her arms and began walking up and down. The other passengers, absorbed in their lunches or growling at their own discomfort, paid little attention to her.

The little boy continued his pleadings for something to eat. The mother endeavored to call his attention to other matters.

“Have you nothing for him?” asked Elizabeth. 32

The woman’s face flushed at the question. She was a subdued, worn-out little soul whose experience with the world had made her feel that every one was but awaiting an excuse to find fault with her. Her manner as she replied was more apologetic than explanatory.

“No; I hain’t. I counted on being home before noon. My man has a job in the brickyard at Italee, and we’d been there now if the train hadn’t stopped. I was up to Leidy a-buryin’ my mother,” she added, as though she expected that Elizabeth might blame her for being on the train at all.

Landis and Min had gone back to their seats. Hearing this bit of conversation, Landis turned her head to look at Elizabeth and her friend. Judging from her expression, she had no sympathy with a girl like Elizabeth who could hob-nob on a train with a common-looking person like this woman.

Landis turned back to her companion, who had opened a small leather lunch-case and was spreading out napkins on the seat 33 before her. The napkins were of heavy linen with drawnwork borders. The drinking-cup was silver. The lunch was in harmony with its service. There were quantities of dainty sandwiches, olives and pickles, fruits, the choicest bits of roast chicken, slices of meat-loaf, and several varieties of cake and confections. The sight of it was quite enough to make one’s mouth water.

The lady back of them had also opened her lunch. She, too, had heard the conversation between Elizabeth and the woman with the babies. Arising with her lunch in her hand, and a traveling cape over her arm, she came over to where Elizabeth stood with the baby.

“The trainmen tell me we shall have an hour to wait,” she said, addressing them. “I see a pretty little bit of grass out here, not far from the car. There is shade, too. Don’t you think it would be pleasant to sit out there and eat our lunch together? It would be rest from the close car.”

Undoubtedly she was one whose suggestions 34 were followed, as she expected them to be now. Before she had ceased speaking she had the boy in her arms, and was on the way to the door. The mother and Elizabeth with the baby followed.

A narrow green bank lay between the railroad and the creek. A large forest oak stood there, making the one bit of shade within sight. The woman, with the boy in her arms, hurried to this. Spreading out her traveling cape, she put him down upon it, and immediately taking a sandwich from her lunch, placed it in his hands. His cries ceased. He fell to munching the sandwich, at intervals giving expression to his enjoyment.

Elizabeth trudged after with the baby. She had never carried such a burden before, and was surprised to find how heavy the frail little child was. It was all she could do to keep it from slipping from her arms, or jumping out over them. The uncertainty of what its next move would be caused her to clutch it so tightly that her muscles and 35 nerves were at a tension, and she was glad to put it down on the cape also. The mother, with her eyes open wide at this unexpected goodness of strangers, was close at her heels.

“It’s her sleeping time,” she explained. “That’s what makes her fret so.”

“Will she eat a piece of orange?” asked Elizabeth, preparing to remove the rind.

“I don’t know but what she will.”

Elizabeth held it out. The baby knew whether she would or not. Instantly her fingers closed about it, and carried it to her mouth. It was only a few moments until the eyes closed and the child was fast asleep with the bit of orange tight in her hand.

“Your husband works at Italee?” asked the woman of the child’s mother, as she was arranging her lunch for them.

“Yes’m, he works in the brickyard there. We hain’t been there long. I was just up home buryin’ my mother.”

“What is your husband’s name?”

“Koons—Sam Koons. He’s a molder. 36 They pay pretty well there. That’s why we moved. He used to work up at Keating; but it seemed like we’d do better down here.”

“There’s no brickyard at Keating?”

“No; but there’s mines. Sam, he’s a miner, but he’s takin’ up the brick trade.”

“Yes; I see. I do not wonder that you were glad to leave Keating. It surely is a rough place. I have never known a town so reeking with liquor. There’s every inducement there for a man’s going wrong, and none for his going right.”

“Yes’m,” said Mrs. Koons. Her deprecatory, worried expression showed that she appreciated the disadvantages of the place. “That’s what I’ve always told Sam,” she continued in her apologetic, meek voice. “When a man’s trying to do his best and keep sober, there’s them what would come right in his house and ask him to drink. A man may be meanin’ well, and tryin’ to do what’s right, but when the drink’s in his blood, and there’s them what’s coaxin’ him 37 to it, it hain’t much wonder that he gives up. Sam, he’s one of the biggest-hearted men, and a good miner, but he’s no man for standin’ his ground. He’s easy-like to lead. We heard there wasn’t no drinkin’ places about Italee—they wasn’t allowed—so we come.”

“Yes; I’ve heard that Mr. Gleason tried to keep the place free from drink.”

“Yes’m, but folks down there say that the Senator don’t have much to do about that. It’s his wife that does all the bothering. She’s the one that tends to that. Her bein’ a woman and trustin’-like, mebbe, is what makes it easy to deceive her.”

“Oh, they do deceive her, then?”

“Yes’m. There hain’t no drinkin’ places open public-like. A stranger couldn’t go in there and buy a glass of anything; but them what’s known can get pretty much what they want.”

“Someone keeps a speak-easy?”

“Yes’m. Big Bill Kyler gets it every week, and the men get what they want.” 38

“Bill Kyler—um-m,” said the lady. “And where does he get it?”

“Dennis O’Day, the man what owns the brewery and the wholesale house, sells to him. Big Bill drives down in the afternoon and comes home after dark.”

“Each Saturday, you say?” asked the woman.

“Yes’m.”

During the conversation, Elizabeth had also been emptying her lunch-box. She listened eagerly to the conversation between her companions. This Dennis O’Day was the man who was doing all in his power to demoralize Bitumen. She was interested because she knew of him, and moreover, by the feeling that these questions were asked from more than passing curiosity.

“This O’Day is about at the end of his string,” continued the lady. “There are too many people watching him, eager to find him overstepping the letter of the law. I can promise you, Mrs. Koons, that he or his friend, Bill Kyler, will not be long at either 39 Gleasonton or Italee. But come, let us dispose of the lunch while the babies are taking care of themselves.”

She had arranged the repast as daintily as her surroundings would permit. Several discarded railroad ties served as a table. Over these, she had spread napkins. Together the three sat at the improvised table until not a scrap of lunch remained.

“I didn’t know how hungry I was,” said Mrs. Koons. “We have to drive five miles to the station and that gets us up pretty early. An’ by the time I got the children up and dressed and got dressed myself, I hadn’t no time to eat much. I was just settin’ down when pap drove round and told me I should hurry up or we’d miss the train, and I couldn’t miss it, for Sam was expectin’ me to-day. He’s been gettin’ his own meals and he wanted me back home; so I didn’t scarcely finish my coffee. I was expectin’ that I’d be home in time for dinner, and I would if the train hadn’t been late.”

“You can’t get to Italee to-night, then,” 40 said her benefactress. “There’s only one train a day from Gleasonton to Italee and it has gone by this time. They don’t wait on the accommodation.”

“Can’t I? Isn’t there?” Mrs. Koons’ countenance fell. “But I’ve got to get there! There hain’t no one I know in Gleasonton. If it wasn’t for carrying the children, I’d walk. It hain’t more than five miles, and mebbe I’d meet someone going up. The trucks come down pretty often. I’ve got to get there even if I have to walk.” Back of her years of repression, her native independence showed. She had set out to reach Italee, and she meant to. Difficulties like a walk of five miles with two children in her arms might hamper but not deter her.

“Do not worry about that. I get off at Gleasonton, and I’ll get someone to drive you over. The roads are fine now and it will not take long.”

“Yes’m. Oh, thank you! It will be kind of you, I’m sure, for walkin’ with two babies 41 in your arms ain’t very pleasant. Do you live in Gleasonton, ma’am?”

“I’m not living there now. All summer I have been out on the Creighton farm beyond Keating.”

“Hain’t it lonely out there? I’ve driv by. It’s fixed up grand with big porches, and swings, and loads of flowers and all that, but there hain’t a house for miles about. I’d think you’d find it lonely?”

“Not at all. I take my children along, and I’m too busy while I’m there to be lonely.”

“Oh, you’re a married woman then, and have a family of your own. I was a-thinkin’ just that thing when you picked up little Alec here. You had a knack with him that don’t come to a woman unless she’s used to handling young ones. How many children have you? They’re pretty well grown, I suppose.”

Again Elizabeth caught the merry twinkle of amusement in the woman’s eyes. “Really, you may think it strange,” she replied, 42 “when I declare that I really am not certain how many I have. There are so many that, at times, I almost forget their names. None of them are grown up; for when they are, I lose them. They go off into the world—some do well and some do not. One or two remember me; but the others forget that such a person as I ever lived.” It was not in a complaining tone she spoke, rather in a spirit of light-hearted raillery.

Elizabeth smiled. She understood the speaker, but Mrs. Koons did not. Elizabeth had been accustomed to hear Miss Hale speak thus of her mission boys and girls. Miss Hale looked upon them as a little family of which she was the head.

Mrs. Koons was amazed. She had heard, in a misty way, of a woman who had so many children she did not know what to do, but she had never heard of one who had so many that she did not know how many. Yet she supposed that such a thing might be 43 true, and accepted the statement in good faith.

“Pap was tellin’ me when I was home that Senator Gleason had bought the farm, and it was him that fixed it up so grand. Pap says they’ve only Jersey cows on the place,—no common stock—and chickens that they raise for layin’, and some for hatchin’, and some that’s for eatin’. But the Senator don’t never stay up there much. He farms just for fun. But he must work pretty hard to get any fun out of it. I was raised on a farm and stayed there till I was married, and I never saw no fun anywhere about.”

Again the laugh and again the merry twinkle came to her eyes.

“It’s just the way we’re used to. If you had never been on a farm, perhaps you’d think it lots of fun to stay on one for awhile. I’m sure I thoroughly enjoy every minute I spend on the Creighton farm. The days are far too short for me.”

“But perhaps you don’t have no work to 44 do. Gettin’ up early is what makes it hard.”

“I get up at daybreak, and I am busy every moment. I wash and dress and feed a dozen children. I have no moment to myself.”

Suddenly Mrs. Koons seemed to understand. “It’s too bad,” she said sympathetically. “Life’s pretty hard for a woman when she’s a family and has to look out for herself.”

When they had finished their lunch, and began gathering and folding the napkins, Elizabeth observed something which had escaped Mrs. Koons’ notice. The left hand of their unknown companion bore a heavy gold band, undoubtedly a wedding-ring, guarded by a diamond noticeable for its size and brilliance. Her hands, too, were worthy of notice. They were white and soft, showing both good care and skilled manicuring. They were not the hands of one accustomed to manual labor.

As Elizabeth assisted her in clearing away 45 the remains of the lunch, the conversation was directed toward herself.

“You got on the train at Bitumen,” she said. “I took particular notice of you, for there one expects to see only foreigners board the car.”

Elizabeth smiled. She knew how few were the times when an American-born woman or girl ever was seen near the station.

“We are mostly foreigners there,” she replied.

“Don’t you find it dull?”

“I never have so far. But then I never have known any life but that at Bitumen. This is my first trip away from home.” Her companion looked at her keenly. “Expectant schoolgirl” was written from the top of Elizabeth’s fair hair to the soles of her shoes. Her linen traveling dress was conspicuously new, as were her gloves and shoes.

“You are going to school, then?” 46

“Yes; to Exeter Hall.” Elizabeth wondered in her own mind how she knew.

“You’ll like it there. That is, unless you are the exception among girls. I was a student there over thirty years ago. I liked it, I’m sure. And every girl student I’ve ever met, and I meet them by the score, has no voice except to sing its praises.”

“Do you know many of the students there now?”

“I met most of those who were there last year. Some I knew quite well. Of course, the Senior class will not return, and there will be many new students. Those I hope to meet.”

“I’ve never had any girl companions,” said Elizabeth. “I expect to like all the girls.”

Again the smile. She shook her head decidedly in negation at Elizabeth’s remark.

“No; you will not like them all,” she replied. “Exeter Hall is like a little world. We have some fine girls there, but we have, too, some that are petty and selfish. Exeter 47 Hall has sent forth some of the noblest women I have ever known, and it has also sent forth some that simply cumber the earth with their presence.”

“I would think they’d be able to keep that last class out.”

“Perhaps it could be done. But the Hall is for the girls—not the girls for the Hall. Some flighty, irresponsible girls, under the influence of the school, develop into strong characters, and leave there to do good work. But there are always a few who fritter their time, and leave the same as they enter. But even these must be given the opportunity for development, if they are capable of it. You know that is true even in public schools.”

“I know nothing about it,” was the reply. “I never went to school a day in my life.”

“How then, child, do you expect to enter Exeter? The requirements are considerable, and the examinations rigid.”

“I’ve been admitted. Miss Hale and my father taught me. Miss Hale said I was 48 ready for the Middle Class, and they admitted me on her statement.”

“And well they might. They would take Julia Hale’s word for anything. Who that knew her wouldn’t?”

“You know her, then?”

“I was a student at Exeter. That means I know Julia Hale by report, at least. But I was more fortunate than the most of girls. I really met her and knew her well. Your father helped Miss Hale prepare you for school? Who is your father? I do not know your name.”

“Hobart! My father is superintendent of the mines at Bitumen.”

“I’ve heard of him, but I have never met him. He’s doing good work there.”

“Yes,” was the reply. “He hopes by Christmas to have every chamber supported by new props, and an exhaust engine which will pump out the gas and make explosions impossible.”

“I was not thinking of the mines when I said he did good work,” said her companion, 49 and after a pause, “I think it is time we were getting into our car. I would not like the train to pull out without us. Look at the babies! Both asleep. Perhaps I can move them without wakening them.” But already Elizabeth had taken up the baby in her arms and was at the step of the car. As she waited for a trainman to help her on, she caught bits of the conversation between two men who stood on the rear platform of the smoker. They had been discussing the “coal-fields”, and were looking up at the mountain which they had just descended.

“There’s plenty there to supply the country for the next ten years. I wasn’t thinking of the supply when I spoke, but of the possibility of not being able to get it out. You remember how the hard-coal region was tied up for eight months or more.”

“There’s little danger here. The miners are satisfied—”

“Yes—satisfied until an agitator comes their way. If I was the Kettle Creek Mining 50 Company, I’d keep that man out of my community. He’s bound to stir up bad blood.”

“But he’s left the mining business. He’ll not trouble himself.”

“Not unless he sees more money in it. Matters have not been going his way lately. Someone has been dogging his steps, and his business is falling off. You know there’s really little money in that business if a man keeps within the law.”

“Well, I pity that man Hobart if your friend begins his work. Hobart’s a fine fellow, but is not accustomed to deal with men in the underbrush.”

“Hobart will take care of himself. He’s had his eye on—”

At this moment the porter came to her assistance and Elizabeth heard no more. She wondered at their talk, but she was not uneasy. She had unbounded faith in her father, and felt that he would be able to protect and take care of himself under all circumstances. Entering the car, she deposited 51 her sleeping burden on the seat. The others followed with the boy and the wraps.

Landis and Min had finished their lunch. There were several sandwiches, a chicken breast, half a bottle of olives, and cake untouched. This Landis gathered together in a heap in her napkin. She arose and leaned toward the window. As she did so, the lady with whom Elizabeth had been talking touched her on the arm. But it was too late. The contents of the napkin had at that moment gone out the window.

“I beg pardon,” she said, “I was about to ask you not to throw that good lunch away. There’s a woman, a foreigner, with her children in the rear of the coach, who has had nothing to eat.”

“I do not know that it is my place to provide it for her,” cried Landis, with a haughty toss of her head.

“I am sorry that you see the matter in that light,” was the rejoinder. “There are so many little mouths to be fed that I dislike to see good food wasted. Extravagance 52 can be so extreme as to become a sin.”

“I do not know that it is anyone’s affair what I do with my lunch,” was the response.

The woman smiled, not at all affronted by the lack of courtesy shown her.

“I make many things my affairs,” she said sweetly. “I think it my duty when I see a girl as young as you doing what is not right to remind her, in a spirit of love and tenderness, of her error. I am sorry if my suggestion can not be received in the spirit in which it was given.” Then she went back to her place.

From the conversation of the two girls, Elizabeth caught such expressions as “that class of people,” “counting each penny,” “bound down by poverty,” and similar phrases.

The train had started on its way. A half-mile passed before it again slowed up. “This is Gleasonton,” said the lady, arising and coming to Mrs. Koons to assist her with the children. With a farewell nod and 53 smile to Elizabeth, they quitted the car. From the window she saw them try to make their way through the crowd of loafers which had gathered about the platform. Suddenly a young colored boy in snuff-colored suit and high hat appeared. He immediately took charge of the children, and with them in his arms pushed his way to where a carriage stood at the curb, the women following close at his heels.

As the train pulled out, Elizabeth saw them bowling down the country road in a wide-open barouche, with coachman and footman in livery.

It was not long until the trainman called “Exeter!” Elizabeth gathered up her wraps and magazines. She knew that she might expect a carriage from the Hall at the station to meet the students.

Landis and Min had also gathered together their belongings. As the train drew into the station, they were first on the platform.

“There’s Jimmy Jordan!” they cried together, 54 as a young colored boy with an expansive grin came up to take their luggage.

“Jimmy, how’s the Hall?”

Jimmy responded with a grin just a little more expansive than the previous one.

Elizabeth stood close at their side. “Are you from Exeter Hall?” she asked the boy. Having received an answer which she supposed an affirmative, she handed him her checks and the baggage which she carried in her arms. The girls whom the boy had addressed as Miss Kean and Miss Stoner led the way. Elizabeth followed at their heels, and in a few moments the three were being driven rapidly to Exeter Hall.

A drive of several miles through a beautiful country brought them to their destination. Elizabeth was surprised, for neither her father nor mother had prepared her for the beauty of the place; a long stretch of campus, with great forest trees, beyond which were the tennis-courts and athletic fields; then the Hall itself. The original building was a large wooden mansion with wide porches and spacious rooms with low ceilings. But for years this had served as a home for the president of Exeter, the school itself having been removed to the newer buildings of gray stone.

The carriage passed through shaded drives which led to the front entrance. Arm in arm, groups of girls in white gowns 56 were moving about or sat in little groups beneath the trees.

During the drive Elizabeth’s companions had chattered continuously. Elizabeth had paid little attention to them. Her eyes were on the new country about her.

“It must be nearly dinner-time,” exclaimed Landis, as the carriage turned in at the entrance to the campus. “The girls are all out. I hope we’ll be in time to go down with them. But we’ll have to go in and do the ‘polite’ with Miss Morgan.”

“Nora O’Day is back,” exclaimed Miss Kean. “Isn’t that she out there on the campus with Mary Wilson?”

“It can’t be. Mary Wilson and she were never friends.” As she spoke, Landis leaned eagerly from the window to get a view of the campus. “It can’t be Miss O’Day,” she repeated. “She and Mary are not the same style at all.”

“I think Miss O’Day’s swell looking. Don’t you?” 57

“She has plenty of money and knows how to dress,” was the rejoinder.

They had reached the entrance door. Jimmy Jordan, who appeared to be general utility boy, dismounted to open the door for them. Then he led the way into the great hall and on to the office, throwing open the doors before him with energetic officiousness, giving one the impression that he was the most important personage at Exeter Hall.

On entering the office, a woman advanced to shake hands with Miss Stoner and Miss Kean. With a few words of greeting, she dismissed them each with a bunch of jangling keys, and the information that they were to occupy the same rooms as the previous year. Then she turned to Elizabeth. “This is Miss Hobart?” she said, shaking her hand cordially, and drawing her forward to a chair. “Your father wrote me that you would arrive to-day. Jordan,” to the boy who stood grinning at her side, “Miss Wilson is somewhere on the campus. 58 Ask her to step to the office, please. Miss Wilson will be your roommate. She will take charge of you. If you will excuse me, I’ll return to work which claims me.” She turned to her desk and was soon absorbed in correspondence.

Elizabeth was thus given an opportunity to study her. She was a tall woman, so tall and slender that these qualities first impressed those who saw her. Yet later, when one stood beside her, you discovered to your surprise that she was merely the average woman in height. It had been her carriage, her manner of holding her head, which gave the impression of unusual height. One might have thought her critical and stern had it not been that the expression of her eyes, which were gray and unusually large, was gentle and shy. Her well-shaped head was crowned with coils of brown hair touched with gray drawn loosely back from a broad, low forehead. She was a woman who could not pass unobserved in a crowd, yet she was not beautiful. It was that her 59 presence was felt, rather than she herself observed. She had said little to the new student; yet the direct effect of her presence caused Elizabeth to be glad she had come to Exeter.

“Oh, here is Miss Wilson!” Dr. Morgan arose. “Miss Wilson, Miss Hobart will be your roommate. I shall put her in your care.”

The girl extended her hand. She was not nearly so tall as Elizabeth. Her yellow hair without ribbon or comb hung about her ears. She shook her head and flung back her locks like a spirited young horse tossing its mane. Her eyes were brown and dancing and her face was brimming over with fun. Her voice was high pitched and so cheery that her hearers were compelled to believe that she was at that minute having the best time of her life.

“I have been expecting you,” she cried. “I was hoping you would come to-day so that we could get to housekeeping to-morrow, for lessons begin the next day.” 60

She led the way into the hall. Here she stopped to clap her hands in order to call Jimmy’s attention. “Here, Jimmy, take this lady’s checks and bring her trunks up to No. 10. If they are there before we get back from dinner, Jimmy, there’ll be a piece of cake for you.”

Jimmy grinned and rolled his eyes, then swung himself down the hall in search of the baggage.

Miss Wilson never ceased her chatter as they entered the side hallway and mounted the stairs.

“The students must not use the main stairway, except during commencement week, under penalty of death,” she explained. “That’s reserved for the Fac and other Lord-Highs. Here’s our room—quite close to the stairway. A nuisance, you’ll find it. Every girl on her way up or down will drop in to see us. It won’t be because we’re popular, but one can’t help wanting to rest after climbing stairs, and our chairs are particularly easy.” Her voice, as she 61 talked, had a ring of laughter in it which made Elizabeth feel, for the moment, that having your friends love you for your chairs alone was the greatest fun in the world.

She led the way into their apartment. There was a big sitting-room with wide windows overlooking the campus; an open grate with log and gas fixtures, ready for the cooler days of autumn, filled the space between the two windows. From this room a door led to a bedroom devoid of all furnishing except the simple essentials of a sleeping-place.

Miss Wilson drew forward a chair. “Sit here a moment to rest. Let me put your wraps away. I’ll make a guest of you to-day. It isn’t long until dinner-time. We are expected to change our dresses. But Miss Morgan will excuse you to-day as you have just arrived. I think you will like the girls here.”

She chatted on while Elizabeth rested and prepared for dinner. She looked with admiration upon Elizabeth’s linen frock and 62 long braid of smooth hair. “I like the way you braid your mane,” she laughed, giving a toss of her own. “It’s the style of hair I’ve always coveted. A siege of fever a year ago is responsible for my new crop, short and curly. I look forward to the time when I, too, can appear with dignity and a coil of hair about my head.”

“Do you think you could be dignified then?” asked Elizabeth shyly. She was standing in the middle of the bedroom with towel in hand. At her words Miss Wilson tossed her head.

“I’m afraid you will prove like the other girls here. They can not be brought to realize how much such trifles have to do with one’s manner. Short curls bobbing over one’s shoulders and dignity can never go together. But let me put my hair up high and get on a trained skirt and you will see what you will see. People are bound to live up to their clothes. That is why, on general principles, I disapprove of bathing and gym suits. They give the wearer such a sense of 63 freedom.” She laughed again. Elizabeth knew not whether she were serious or joking. She was so effervescing with good humor that her companion had no opportunity for a moment’s dullness or homesickness.

“There’s the ten-minute bell,” she exclaimed, as they returned to the study. “That is our last warning, and gives no one an excuse to be late. You will find Exeter rigid in many ways, Miss Hobart. Miss Morgan is what I call a crank on development of character. She keeps track of the thousand little things that a girl is supposed not to do. In her lectures to us, which she gives twice a semester, she declares that these seeming trifles are neither sins nor crimes in themselves, but getting into the habit of yielding to trifles is detrimental to the development of strong character. Therefore,” at this Miss Wilson drew herself up as tall as possible, and assuming Miss Morgan’s best manner continued, “trifles must be made subservient to us. 64 We must conquer ourselves even in these.” Here Miss Wilson laughed merrily. “Being late; not having your necktie straight; letting your shoes run down at the heel; missing lectures—these, all these, and hundreds more, are trifles.”

There was a hurried knock at the door. Without waiting for an invitation to enter, a young lady came in. Elizabeth’s fear of out-dressing the other girls vanished at the sight of her. The newcomer was a girl of slender physique and delicate, regular features. Her skin was almost olive in hue; her eyes were dark, with brows so heavy and black as to be noticeable. They were too close together and her lips and nostrils too thin to permit her being beautiful. Her dress was handsome and showy. It was of white silk, elaborated with heavy insertions, and transparent yoke and sleeve-caps made it suitable for an evening gown. Her hands were covered with rings scintillating at every gesture. Each movement of her body suggested silk linings and petticoats. 65 Her manner of speaking had a touch of affectation.

“Ah, Miss Wilson, I’m awfully sorry to intrude, but will you be kind enough to hook my waist? I can’t reach the last two hooks on the shoulder. This style of fastening dresses in the back is such a nuisance.”

“Surely,” replied Miss Wilson. Elizabeth was surprised at the change which came to her roommate’s voice. There was neither vivacity nor good humor in it. It was expressive of mere icy courtesy.

“You must bend your knees a little, or I’ll be compelled to get on a chair. You’re so much taller than I.”

The girl complied. Miss Wilson put the refractory hooks to their proper use, then stood quiet. Her guest made some trifling remark as though to continue the conversation; but received no encouragement. Her dark cheeks flushed. “Thank you,” she began hurriedly, “I’m sorry to bother you so.”

“It was no bother,” in the same cold, 66 conventional voice. “I can assist you any time. I understand how difficult it is to get into your clothes when you have no roommate to pull you together.” Then with a smile she turned to Elizabeth. “Come, Miss Hobart, we must not be late for dinner the first evening at Exeter.” So saying, she held open the door, allowing Elizabeth to precede her from the room. Miss Wilson gave no explanation to Elizabeth of her manner toward the girl; neither did she offer an excuse for not introducing her. As they passed the open door, Elizabeth caught a view of this girl’s study. It was more than comfortable. There was a luxury of soft cushions and rich hangings. There were chairs and tables of carved wood.

From all the rooms the students came forth two by two, their tongues flying as they made their way toward the dining-hall. There were frequent stops to greet one another, and a babel of voices expressing pleasure at this reunion. There were handshakes for those who were newcomers, and 67 embraces for old friends. Every one knew every one else or was going through the first process of meeting them.

The olive-skinned girl in the handsome gown came from her room and passed the others. Each girl was careful to nod and bid her good-evening, but none greeted her effusively or even so much as shook hands with her.

Miss Wilson was not lax in courtesy now. Drawing her arm through Elizabeth’s, she came up to the group of girls at the head of the main stairway. “I wish you girls to meet Miss Hobart,” she cried, “so that you may condole with her. She is to room with me this semester.”

“Why this semester?” rejoined a tall girl in the group as she came forward extending her hand. “Why not the year?”

“She may not survive,” said Miss Wilson. “If she’s able to stand me one semester, then she’ll be compelled to stay the year out.”

“I am Anna Cresswell,” continued the 68 tall girl to Elizabeth. “Mary Wilson’s introductions leave much to be desired. She rarely sees fit to mention the names of the people she introduces.”

Miss Stoner and Miss Kean came up at this juncture. They had changed their traveling dresses, and were wearing light challis. They were introduced to Elizabeth, but neither made mention that they had seen each other in the car or had come up in the carriage together. Landis was most demonstrative in greeting Miss Wilson, chiding her for not writing during vacation, and declaring that they must make up for lost time by spending a great many leisure hours together now. Miss Wilson laughed merrily. She had been busy all summer, she said, and had written only to her own people. Elizabeth noticed that she expressed no desire to mortgage her future leisure hours by any promises.

“You busy?” exclaimed Landis. “Now, what were you doing—reading novels, dressing and driving about?” 69

“I should scarcely be content with such a summer, Landis. No; I played nurse-girl to Mrs. Gleason’s large family. I was busy, too. The place was no sinecure, I assure you.”

“Mrs. Gleason—from Gleasonton?” exclaimed Min. “Why, I thought she had no children.”

“She hasn’t—but she adopts them annually. During July and August we had a dozen babies at their home. We went for them in the morning and took them back at night, and I gave each one of them a bath every day.” This last was said triumphantly.

“I’ve heard she was rather—eccentric!” said Landis.

“Don’t you know her?” asked Elizabeth.

“No; I do not—not personally,” was the response, “but we have mutual friends.”

Miss Wilson would have quitted Miss Stoner and Miss Kean here, but was prevented by Landis telling her experience that day in the train, how a woman, a total 70 stranger, had taken her to task for throwing away her lunch.

“She was a common-looking person,” she added. “One could see she belonged to the middle class, and I suppose had been compelled to practice economy, so that my throwing a sandwich away seemed recklessly extravagant.”

“Did you think she was common-looking?” asked Elizabeth. “Her skin was as fine as a baby’s, and her eyes were beautiful. Didn’t you see how expressive they were?”

“No, I didn’t. All I could see was her gingham shirtwaist suit with its prudish white linen cuffs and collar, and her rough straw hat.”

Miss Wilson put her arm through her roommate’s to hurry her.

“Excuse us, girls, if we walk faster; I wish Miss Hobart to meet Nancy. She’s the girl ahead with Anna Cresswell.”

Elizabeth was borne along toward the dining-hall, at the door of which Miss Cresswell and her companion stopped. 71

“Nancy, I wish you and Miss Hobart to meet,” said Miss Wilson, “and I intend that you shall be good friends. Nancy and I were brought up together, and she’s used to me. When you want anyone to sympathize with you because of me, go to Nancy.”

“Her name is Miss Eckdahl,” added Miss Cresswell with a smile.

“But she should have known. Everyone should know Nancy without being told. What is the good of being famous otherwise? If your name goes not abroad, what is the good of being a champion in mathematics or anything else? When I say ‘Nancy,’ the intelligent person should know that I mean—”

“Nancy Hanks,” added the girl herself. “I might be mistaken for the famous trotter.”

So chatting, they entered the dining-hall. Tables set for six each filled the room.

“Miss Cresswell, will you take charge of Elizabeth—I’m going to call you Elizabeth; 72 you don’t look nearly old enough to be Miss Hobart.”

“Yes; come with me, Miss Hobart. Nancy, I presume you and I part here. I shall be surprised if Miss Morgan permits you and Mary to be together much longer.”

She led the way to a table by the window where she seated herself at its head, placing Elizabeth at her right.

“Miss Morgan never allows roommates to sit together at meals,” she explained, “or two girls who have been reared together as Mary and Nancy have. She wishes us to know all the students, and tries to prevent our forming little cliques, as we’re bound to do when we room and eat and study with the same people.”

“But what if you should not like the other people?” asked Elizabeth. “It must be rather unpleasant to sit at meals with someone whom you do not like.”

“That is one of the lessons Miss Morgan is giving us the opportunity of learning. We may discover on close acquaintance that 73 one is more likable than we first supposed; and if that is impossible, then we learn to keep our dislikes to ourselves.”

The dining-hall was rapidly filling. Landis Stoner and Min Kean came in among the last, the former taking her place at Miss Cresswell’s table, sitting beside Elizabeth.

“Why, Anna Cresswell,” she exclaimed, leaning forward, “did Miss Morgan put you at the head of the table?”

“How else should I be here? You surely did not think I came unasked.”

“Oh, no, I spoke without thinking. Of course, you would not come unless she asked you to do so. I was surprised, that was all.”

“Why surprised? You know I am a Senior, and it is customary to give them the head.”

“Oh, yes, of course. But there are Seniors who haven’t been given the head. That is what made me speak.”

Miss Cresswell turned the conversation to other subjects. Elizabeth was the only new 74 student at the table. She felt that some reason other than the one given had caused Miss Stoner to speak as she had. It was not until some days later that she learned that Landis was a Senior. She learned, too, that the girl was ambitious to be first, even in so slight a thing as sitting at the head of a table and playing hostess to five girls, generally of under classes.

“Are you on the second floor again this year, Landis?” asked a little pink-and-white, china-doll girl from the foot of the table.

“Yes, Mame. Min and I have the same rooms as before. The third time is the charm. I presume something good will happen this year.”

“Perhaps Min will get through the preliminaries,” was the rejoinder. “She won’t pull through from any effort she makes herself. If her friends wish to see her graduate, they will be compelled to resort to something. Get her to pick four-leafed clovers and wear them in the toe of her shoe, possibly. 75 That has been known to work where all else fails.”

Landis looked serious at the jest. Her manner grew quite self-assertive as she replied, as though expressing herself quite settled the question. Yet throughout there was an assumed self-deprecatory air, as though she would not have her hearers think she was either maligning her friend or lauding herself too highly in the comparison suggested in her speech.

“Don’t blame Min too much. Some work which would be possible for you or me, is impossible for her. I did not realize until we roomed together what a difference there can be in—in—minds. I could not have believed that any one would consider a theorem or a page of French difficult. But,” with an arch glance, “these past two years have taught me a great deal. I am more sympathetic, and oh so much more thankful that I am—”

“Not as ‘these publicans and sinners,’” finished the girl at the foot. As she spoke, 76 her glance swept over the table to include among “these” all who sat there.

Even Elizabeth, though a stranger, could not suppress a smile.

“Who has No. 12—that big room, the one Miss Watson used to have?” continued Miss Welch, ignoring Landis’ show of vexation at her words. Landis made no attempt to answer, although the question was addressed to her. After a moment’s silence, a little German girl, Elizabeth’s vis-a-vis, replied, “If I have not heard it unright, Fraulein—that is, Miss O’Day in it she will room.”

She blushed prettily as she spoke, half in shyness and half in embarrassment that her German idioms would intrude themselves when she was trying to speak English. She looked up at Miss Cresswell, as though she sought encouragement from her.

“Why, Miss Hirsch, what have you been doing all summer? Spending all your vacation talking English? You have improved wonderfully. Now Fraulein Kronenberg 77 will complain that you are losing your pure German accent.”

“Oh, think you so? It is glad I am. A single German word the whole long summer have I not said. But about the room which on the second floor is; to me it was said Miss O’Day will—will—occupy? it.”

“Who is to room with her?” asked Miss Welch.

“I believe she is to room alone,” said Miss Cresswell.

“Why doesn’t Maud Harris go back with her? They seemed to get along well last fall, and Maud is well enough to enter again!” said Miss Welch.

“Miss Harris with anything could—what you call it?—get along,” said Miss Hirsch.

“My words seem to suggest that Miss O’Day is difficult to get along with. I did not mean that. So far as I know, she has a very even temper, and is more than generous with all her possessions. She isn’t selfish.”

“I can plainly see why Maud has another 78 roommate. Of course you all do. It does seem a little hard.” Here Landis’ manner grew important. Her head was raised, and her lips curled. “But those of us who have a high sense of honor would not care to room with Miss O’Day. I hope I am not narrow-minded, but I feel that all my finer instincts rebel at the thought of——”

“Miss Stoner, if you please, we will drop the subject. Nothing can be gained by carrying it further.” This came from Miss Cresswell. She spoke quietly but her manner and voice was that of one who expected to have her suggestions followed.

Landis tilted her head a little higher, but her face flushed. She was about to tell Miss Cresswell that she would discuss any subject when and where she chose when she remembered suddenly that Miss Cresswell was the head of the table and the one to whom she must pay a certain amount of respect.

The dinner had been brought in. Miss Cresswell served the plates with Maggie, the colored serving-maid, standing at her side. 79 All conversation of a personal nature stopped while the servants were in the room. When the dinner was over, and dessert on the table, the chatter began. As they were about to quit the room, a bell rang. Quiet fell upon them. Dr. Morgan arose from her place at the head table.

She made a few general announcements. Then in her clear, decisive voice continued: “The students will not forget that they are expected to dress for dinner. If you are too indisposed to change your school attire for something fresher, you are too indisposed to come to the dining-hall. But you will bear in mind that this does not mean either dinner or reception gowns. Elaborate and extravagant dressing is not suited to girls in school. Miss O’Day has infringed upon this rule. Consequently she may pass immediately to her apartments, change her gown, and spend the evening in her room, without conversing with anyone. You may be excused, Miss O’Day.”

From a table at a distant part of the 80 room, Miss O’Day arose. As she moved through the room with her head high and eyes straight before her, her shoulders and arms gleamed through their transparent covering, and the rustle of her silken petticoats was audible.

As she disappeared, Dr. Morgan gave the signal for dismissal. The hum of conversation among the students began again, as in little groups they passed to the parlors or to the campus.

“What have you brought to fix up our quarters?” asked Miss Wilson, the day following Elizabeth’s arrival at Exeter. Her trunk and box were in the middle of the study, while she and Miss Wilson stood and looked on as Jimmy Jordan unfastened straps and drew out nails.

“I do not know,” was the reply. “Mother slipped in a whole box of extras. I wondered why she was doing it. She said I would see later. There were cups and spoons, and doilies.”

“Sensible mother,” rejoined Miss Wilson. “She realizes the necessity of frequent spreads in the strenuous life we lead. No doubt we’ll find among your traps a glass or so of jelly, and some preserves. Mothers 82 who have been at school themselves appreciate the situation.”

Elizabeth laughed. She was beginning to understand her roommate’s style of conversation.

Miss Wilson was not one to shirk. Work had no terrors for her. She was never idle, but when she was tired with study she found rest in some other form of occupation. Now, while Elizabeth was unpacking, she assisted her in every way, putting in order bureau drawers, and arranging books.

Elizabeth had depended more or less upon her mother. How much that “more” was greater than that “less” she did not realize until she was alone. Miss Wilson proved her right hand now.

The greater part of the day was spent in arranging their possessions. The pictures which Elizabeth had brought from home were hung; the bright cushions placed at a proper angle on the couch, over which had been placed a covering of gay tapestry. A table had been drawn up near the fireplace. 83

This was a new experience for Elizabeth so she let Miss Wilson take the lead. She watched her arrange the tea-table. The dainty cups and plates, souvenir spoons, sugar bowl and creamer found their proper places. It was a small edition of their dining-table at home. The chafing-dish and swinging kettle with its alcohol lamp were too much for Elizabeth to bear without comment. She must and did ask their purpose.

“I’ll show you in one minute,” said Mary. She took a box of cocoa and a bottle of alcohol from a small cabinet. “I must borrow some cream from Anna Cresswell. I saw her get some this morning. But first I must put this water on to boil.” She did so, then hurried from the room, soon returning with the cream.

After stirring the cream, cocoa and sugar in the cup, she poured on the boiling water. With a few additional manipulations of the spoon, she held out the cup to Elizabeth. “Here, girlie, drink to the prosperity of Exeter Hall in general, and these quarters in 84 particular. May you get along with your roommate better than people generally do, and may all the scraps between you and her be made up before the retiring-bell rings.”

Elizabeth raised her cup to the toast, then drank. “Why, that is fine—and made with such a little fire! I would not have believed it possible.”

“You think that is good?” was the reply. “You will open your eyes when you see what can be done with the chafing-dish,—creamed oysters, fudge, soups of all kinds, Welsh rarebits. I hope, Elizabeth, that you spoke to your mother about boxes. At Exeter, boxes are acceptable at all times.”

“Boxes?” in surprise. “No; I never mentioned the word to her. I didn’t understand that they would be required. The catalog made no mention of them. I know because I looked particularly about the number of napkins and towels required. What do you put in them?”

“I don’t know. It is what you take out of them that makes them valuable. Personally, 85 I prefer roast chicken and cake.”

“Oh!” cried Elizabeth. “How dull I am! But you know that I was never before at any school, and I never knew any girls my own age.”

“They’ll teach you a lot,” was the response.

“You and father agree in that. He says that the students will teach me more than the faculty. But that is one of the things I cannot understand.”

“You will sometime. I wouldn’t bother my head much about it now. What do you think about this Gibson head? It doesn’t fit in here with the other pictures.”

“Let me try it on this side of the room,” Elizabeth replied, placing the picture at a better angle.

So the day progressed in doing a score of little odds and ends of work which have the effect of making boarding-school quarters suggestive of home.

Several weeks later Elizabeth had one lesson in what the girls could teach her, something 86 which was not found between the covers of books. At home, there had always been her mother to pick up after her. She might drop hat, gloves and coat anywhere about the house, and when she needed them, find them in their proper places, dusted, mended and ready for use.

During the first week at Exeter, Mary Wilson unconsciously dropped into her mother’s place in this particular, perhaps because she was a year older than Elizabeth, and had learned this lesson in her own time. Certain it was, when they dressed for dinner, she looked about the bedroom and put in order each article which was out of place, or called Elizabeth’s shortcomings to notice with, “Your dress will muss lying on that chair,” or “Is that your slipper in the study, or did I leave mine there?”

During the month of October, the girls at Exeter gave their first reception. Guests came from all the little towns about, and the Hall was filled with flowers, lights and bright music. 87

Elizabeth and Mary had hurried from the dinner-table to get into their party gowns. Miss Wilson, as a Senior, was one of the reception-committee. Elizabeth was but half-way through with her dressing when Mary had finished.

“There, Elizabeth, I’m done. Look me over and see if my waist is together all right.”

Elizabeth was standing before the mirror, pins between her lips, trying to reduce a refractory bow to submission. She turned to look at her roommate. “Sweet—your dress is beautiful.”

“Thank you,” was the response with a characteristic toss of her head. “With those pins in your mouth you talk like a dialect story. I’m off now. Dr. Morgan wishes the committee to meet in her parlor. I suppose she wants to get our mouths into the ‘papa, potatoes, prunes and prisms’ shape before we meet the guests. I’m sorry I can’t go down with you, Elizabeth. A first reception is so trying. Nancy won’t go 88 down until late. Suppose I ask her to wait for you?”

“That may put her to trouble. I thought of asking Miss O’Day to go with me. She’s just across the hall, and has no one special to go with her since she rooms alone.”

Miss Wilson hesitated a moment, standing in the middle of the doorway. She looked quite serious at the mention of Miss O’Day.

“Miss O’Day might—not like to be bothered. Besides, you do not know her very well. I’ll send Nancy.”

With that she disappeared.

As the gaslight in the bedroom was not satisfactory Elizabeth went into the sitting-room or study, as the students were accustomed to call it, to finish her dressing. Nancy came to the door just as Elizabeth put on the last touches.

“We’ll be late,” she exclaimed. “I think it’s fun to go early and meet all the strangers. Judge Wilson and his friends will be here if the train was on time at Ridgway.”

Elizabeth caught up her fan and handkerchief 89 and started forth. Her attention was claimed by the curious fan Nancy carried.

“It is odd, isn’t it?” exclaimed Nancy, unfurling it. “It is hand-carved. You know the Swedes are famous for that kind of work. This is quite old. My grandfather made it for my grandmother when they were sweethearts over in Sweden.”

Elizabeth looked her surprise at this statement. Her companion noticed her expression.

“You knew, of course, that I was of Swedish birth!”

“No, I did not. I knew that you made your home with Miss Wilson’s family. I took it for granted that you must be a relative.”

“Not the least bit,” was the response, given without a show of embarrassment. “I’m merely a dependent. My father was a Swedish minister, and worked among our people near the Wilson home. When he died, we were left with nothing to live on. Mother did sewing for the Swedish people. 90 I was very strong and quite as able to work as she. So I went to live at the Wilson home where I helped with the little children and also went to school. I grew to love them, and they seemed to really care for me. When I finished the high school, Mrs. Wilson sent me here. I’m to be a teacher after I graduate at Exeter. I always count the Wilson home mine. Each summer I go back there and help with the children while Mrs. Wilson takes a vacation.”

She did not add that she had shown such an aptitude for study, and had proved so efficient and trustworthy that Mrs. Wilson had decided to give her the best advantages to fit her for a profession.

As they passed the open door of the room occupied by Landis Stoner and Min Kean, the voices of the girls came to them. They had evidently taken it for granted that the other students had gone to the parlors and that there wasn’t anyone to hear the conversation.

“Well, for my part, Min,” Landis was 91 saying, “I do not think you look at all well in that blue silk. You look so sallow. You are so much sweeter in your white organdy with your pink sash.”

“But, Landis, I’ve worn it so often.”

“But not here. It will be new to the girls, and it looks perfectly fresh.”

“You said you liked the blue silk when I was buying it.”

“I did and I do yet, but it isn’t suited to you. Now for me, it would be all right, but—”

“I wish you’d come down, Landis. I always have a better time when you are there.”

“How can I? I haven’t a dress for a reception. You simply cannot get a dress made at home fit to wear, and my staying up in the country all summer with you made my going to the city impossible.”

That was all that reached the girls in the hall, and this was forced upon them. Nancy could not forbear a smile. Elizabeth with the guilelessness of an unexperienced 92 child exclaimed, “Why, Landis seems to have so many beautiful clothes. Her father must be very wealthy. Her rings and pins are simply lovely. Isn’t that a diamond she wears?”

“Yes; but it’s Min’s. Landis has been wearing it for the last two years. Min is an only child. She has no mother and her father, who is a millionaire oil-man, allows her to spend what she pleases.”

“Is Landis’ father an oil-man?”

“No, he isn’t,” was the reply.

Elizabeth was learning how much could be said by silence. During her short acquaintance with Landis, the girl had suggested many of the possibilities of her future—a cruise on a private yacht, a year’s study and travel in Europe. She had not said that money was no consideration with her, yet Elizabeth had gained such an impression from her words.

“I am sorry Landis will miss the reception,” she said.

Nancy smiled. “She will not miss it. 93 She enjoys the social side of school life too much to miss anything of this kind. She will be down after awhile.”

“But you heard what she said—that she had nothing fit to wear.”