Title: Two Little Confederates

Author: Thomas Nelson Page

Release date: September 29, 2008 [eBook #26725]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Diane Monico, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Diane Monico,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS

BY THOMAS NELSON PAGE

Tommy Trot's Visit to Santa Claus

Santa Claus's Partner

A Captured Santa Claus

Among the Camps

Two Little Confederates

The Page Story Book

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

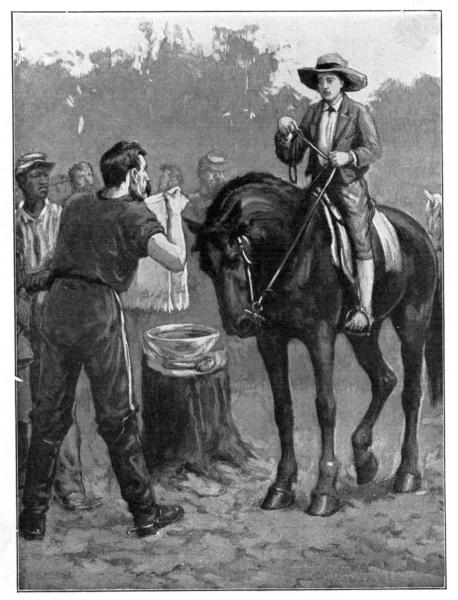

"I'M IN COMMAND," SAID THE GENTLEMAN, SMILING

AT HIM OVER THE TOWEL.

"I'M IN COMMAND," SAID THE GENTLEMAN, SMILING

AT HIM OVER THE TOWEL.

Copyright, 1888, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

Copyright, 1916, by

THOMAS NELSON PAGE

Printed in the United States of America

| "I'm in command," said the gentleman, smiling at him over the towel | Frontispiece |

| page | |

| The old man walked up to the door, and standing on one side, flung it open | 29 |

| "Gentlemen, marsters, don't teck my horses, ef you please," said Uncle Balla | 69 |

| Frank and Willy capture a member of the conscript-guard | 95 |

| The boy faced his captor, who held a strap in one hand | 129 |

| "Look! Look! They are running. They are beating our men!" exclaimed the boys | 143 |

| The boys sell their cakes to the Yankees | 159 |

| Some of the servants came back to their old home | 167 |

The "Two Little Confederates" lived at Oakland. It was not a handsome place, as modern ideas go, but down in Old Virginia, where the standard was different from the later one, it passed in old times as one of the best plantations in all that region. The boys thought it the greatest place in the world, of course excepting Richmond, where they had been one year to the fair, and had seen a man pull fire out of his mouth, and do other wonderful things. It was quite secluded. It lay, it is true, right between two of the county roads, the Court-house Road being on one side, and on the other the great "Mountain Road," down which the large covered wagons with six horses and jingling bells used to go; but the lodge lay this side of the one, and "the big woods," where the boys shot squirrels, and hunted 'possums and coons, and which reached to the edge of "Holetown," stretched between the house and the other, so that the big gate-post where the semi-weekly mail was left by the[Pg 2] mail-rider each Tuesday and Friday afternoon was a long walk, even by the near cut through the woods. The railroad was ten miles away by the road. There was a nearer way, only about half the distance, by which the negroes used to walk and which during the war, after all the horses were gone, the boys, too, learned to travel; but before that, the road by Trinity Church and Honeyman's Bridge was the only route, and the other was simply a dim bridle-path, and the "horseshoe-ford" was known to the initiated alone.

The mansion itself was known on the plantation as "the great-house," to distinguish it from all the other houses on the place, of which there were many. It had as many wings as the angels in the vision of Ezekiel.

These additions had been made, some in one generation, some in another, as the size of the family required; and finally, when there was no side of the original structure to which another wing could be joined, a separate building had been erected on the edge of the yard which was called "The Office," and was used as such, as well as for a lodging-place by the young men of the family. The privilege of sleeping in the Office was highly esteemed, for, like the toga virilis, it marked the entrance upon manhood of the youths who were fortunate enough to enjoy it. There smoking was admissible, there the guns were kept in the corner, and there the dogs were allowed to[Pg 3] sleep at the feet of their young masters, or in bed with them, if they preferred it.

In one of the rooms in this building the boys went to school whilst small, and another they looked forward to having as their own when they should be old enough to be elevated to the coveted dignity of sleeping in the Office. Hugh already slept there, and gave himself airs in proportion; but Hugh they regarded as a very aged person; not as old, it was true, as their cousins who came down from college at Christmas, and who, at the first outbreak of war, all rushed into the army; but each of these was in the boys' eyes a Methuselah. Hugh had his own horse and the double-barrelled gun, and when a fellow got those there was little material difference between him and other men, even if he did have to go to the academy,—which was really something like going to school.

The boys were Frank and Willy; Frank being the eldest. They went by several names on the place. Their mother called them her "little men," with much pride; Uncle Balla spoke of them as "them chillern," which generally implied something of reproach; and Lucy Ann, who had been taken into the house to "run after" them when they were little boys, always coupled their names as "Frank 'n' Willy." Peter and Cole did the same when their mistress was not by.[Pg 4]

When there first began to be talk at Oakland about the war, the boys thought it would be a dreadful thing; their principal ideas about war being formed from an intimate acquaintance with the Bible and its accounts of the wars of the Children of Israel, in which men, women and children were invariably put to the sword. This gave a vivid conception of its horrors.

One evening, in the midst of a discussion about the approaching crisis, Willy astonished the company, who were discussing the merits of probable leaders of the Union armies, by suddenly announcing that he'd "bet they didn't have any general who could beat Joab."

Up to the time of the war, the boys had led a very uneventful, but a very pleasant life. They used to go hunting with Hugh, their older brother, when he would let them go, and after the cows with Peter and Cole. Old Balla, the driver, was their boon comrade and adviser, and taught them to make whips, and traps for hares and birds, as he had taught them to ride and to cobble shoes.

He lived alone (for his wife had been set free years before, and lived in Philadelphia). His room over "the old kitchen" was the boys' play-room when he would permit them to come in. There were so many odds and ends in it that it was a delightful place.

Then the boys played blindman's-buff in the house, or hide-and-seek about the yard or garden, or upstairs[Pg 5] in their den, a narrow alcove at the top of the house.

The little willow-shadowed creek, that ran through the meadow behind the barn, was one of their haunts. They fished in it for minnows and little perch; they made dams and bathed in it; and sometimes they played pirates upon its waters.

Once they made an extended search up and down its banks for any fragments of Pharaoh's chariots which might have been washed up so high; but that was when they were younger and did not have much sense.[Pg 6]

There was great excitement at Oakland during the John Brown raid, and the boys' grandmother used to pray for him and Cook, whose pictures were in the papers.

The boys became soldiers, and drilled punctiliously with guns which they got Uncle Balla to make for them. Frank was the captain, Willy the first lieutenant, and a dozen or more little negroes composed the rank and file, Peter and Cole being trusted file-closers.

A little later they found their sympathies all on the side of peace and the preservation of the Union. Their uncle was for keeping the Union unbroken, and ran for the Convention against Colonel Richards, who was the chief officer of the militia in the county, and was as blood-thirsty as Tamerlane, who reared the pyramid of skulls, and as hungry for military renown as the great Napoleon, about whom the boys had read.

There was immense excitement in the county over the election. Though the boys' mother had made them add to their prayers a petition that their Uncle William might[Pg 7] win, and that he might secure the blessings of peace; and, though at family prayers, night and morning, the same petition was presented, the boys' uncle was beaten at the polls by a large majority. And then they knew there was bound to be war, and that it must be very wicked. They almost felt the "invader's heel," and the invaders were invariably spoken of as "cruel," and the heel was described as of "iron," and was always mentioned as engaged in the act of crushing. They would have been terribly alarmed at this cruel invasion had they not been reassured by the general belief of the community that one Southerner could whip ten Yankees, and that, collectively, the South could drive back the North with pop-guns. When the war actually broke out, the boys were the most enthusiastic of rebels, and the troops in Camp Lee did not drill more continuously nor industriously.

Their father, who had been a Whig and opposed secession until the very last, on Virginia's seceding, finally cast his lot with his people, and joined an infantry company; and Uncle William raised and equipped an artillery company, of which he was chosen captain; but the infantry was too tame and the artillery too ponderous to suit the boys.

They were taken to see the drill of the county troop of cavalry, with its prancing horses and clanging sabres. It was commanded by a cousin; and from that moment they[Pg 8] were cavalrymen to the core. They flung away their stick-guns in disgust; and Uncle Balla spent two grumbling days fashioning them a stableful of horses with real heads and "sure 'nough" leather bridles.

Once, indeed, a secret attempt was made to utilize the horses and mules which were running in the back pasture; but a premature discovery of the matter ended in such disaster to all concerned that the plan was abandoned, and the boys had to content themselves with their wooden steeds.

The day that the final orders came for their father and uncle to go to Richmond,—from which point they were ordered to "the Peninsula,"—the boys could not understand why every one was suddenly plunged into such distress. Then, next morning, when the soldiers left, the boys could not altogether comprehend it. They thought it was a very fine thing to be allowed to ride Frank and Hun, the two war-horses, with their new, deep army saddles and long bits. They cried when their father and uncle said good-bye, and went away; but it was because their mother looked so pale and ill, and not because they did not think it was all grand. They had no doubt that all would come back soon, for old Uncle Billy, the "head-man," who had been born down in "Little York," where Cornwallis surrendered, had expressed the sentiment of the whole plantation when he declared, as he sat in the[Pg 9] back yard surrounded by an admiring throng and surveyed the two glittering sabres which he had no one but himself to polish, that "Ef them Britishers jest sees dese swodes dee'll run!" The boys tried to explain to him that these were not British, but Yankees,—but he was hard to convince. Even Lucy Ann, who was incurably afraid of everything like a gun or fire-arm, partook of the general fervor, and boasted effusively that she had actually "tetched Marse John's big pistils."

Hugh, who was fifteen, and was permitted to accompany his father to Richmond, was regarded by the boys with a feeling of mingled envy and veneration, which he accepted with dignified complacency.

Frank and Willy soon found that war brought some immunities. The house filled up so with the families of cousins and friends who were refugees that the boys were obliged to sleep in the Office, and thus they felt that, at a bound, they were almost as old as Hugh.

There were the cousins from Gloucester, from the Valley, and families of relatives from Baltimore and New York, who had come south on the declaration of war. Their favorite was their Cousin Belle, whose beauty at once captivated both boys. This was the first time that the boys knew anything of girls, except their own sister, Evelyn; and after a brief period, during which the novelty[Pg 10] gave them pleasure, the inability of the girls to hunt, climb trees, or play knucks, etc., and the additional restraint which their presence imposed, caused them to hold the opinion that "girls were no good."[Pg 11]

In course of time they saw a great deal of "the army,"—which meant the Confederates. The idea that the Yankees could ever get to Oakland never entered any one's head. It was understood that the army lay between Oakland and them, and surely they could never get by the innumerable soldiers who were always passing up one road or the other, and who, day after day and night after night, were coming to be fed, and were rapidly eating up everything that had been left on the place. By the end of the first year they had been coming so long that they made scarcely any difference; but the first time a regiment camped in the neighborhood it created great excitement.

It became known one night that a cavalry regiment, in which were several of their cousins, was encamped at Honeyman's Bridge, and the boys' mother determined to send a supply of provisions for the camp next morning; so several sheep were killed, the smoke-house was opened, and all night long the great fires in the kitchen and wash-house glowed; and even then there was not room, so that a big fire was kindled in the back yard, beside which saddles[Pg 12] of mutton were roasted in the tin kitchens. Everybody was "rushing."

The boys were told that they might go to see the soldiers, and as they had to get off long before daylight, they went to bed early, and left all "the other boys"—that is, Peter and Cole and other colored children—squatting about the fires and trying to help the cooks to pile on wood.

It was hard to leave the exciting scene.

They were very sleepy the next morning; indeed, they seemed scarcely to have fallen asleep when Lucy Ann shook them; but they jumped up without the usual application of cold water in their faces, which Lucy Ann so delighted to make; and in a little while they were out in the yard, where Balla was standing holding three horses,—their mother's riding-horse; another with a side-saddle for their Cousin Belle, whose brother was in the regiment; and one for himself,—and Peter and Cole were holding the carriage-horses for the boys, and several other men were holding mules.

Great hampers covered with white napkins were on the porch, and the savory smell decided the boys not to eat their breakfast, but to wait and take their share with the soldiers.

The roads were so bad that the carriage could not go; and as the boys' mother wished to get the provisions to[Pg 13] the soldiers before they broke camp, they had to set out at once. In a few minutes they were all in the saddle, the boys and their mother and Cousin Belle in front, and Balla and the other servants following close behind, each holding before him a hamper, which looked queer and shadowy as they rode on in the darkness.

The sky, which was filled with stars when they set out, grew white as they splashed along mile after mile through the mud. Then the road became clearer; they could see into the woods, and the sky changed to a rich pink, like the color of peach-blossoms. Their horses were covered with mud up to the saddle-skirts. They turned into a lane only half a mile from the bridge, and, suddenly, a bugle rang out down in the wooded bottom below them, and the boys hardly could be kept from putting their horses to a run, so fearful were they that the soldiers were leaving, and that they should not see them. Their mother, however, told them that this was probably the reveille, or "rising-bell," of the soldiers. She rode on at a good sharp canter, and the boys were diverting themselves over a discussion as to who would act the part of Lucy Ann in waking the regiment of soldiers, when they turned a curve, and at the end of the road, a few hundred yards ahead, stood several horsemen.

"There they are," exclaimed both boys.

"No, that is a picket," said their mother; "gallop on,[Pg 14] Frank, and tell them we are bringing breakfast for the regiment."

Frank dashed ahead, and soon they saw a soldier ride forward to meet him, and, after a few words, return with him to his comrades. Then, while they were still a hundred yards distant, they saw Frank, who had received some directions, start off again toward the bridge, at a hard gallop. The picket had told him to go straight on down the hill, and he would find the camp just the other side of the bridge. He accordingly rode on, feeling very important at being allowed to go alone to the camp on such a mission.

As he reached a turn in the road, just above the river, the whole regiment lay swarming below him among the large trees on the bank of the little stream. The horses were picketed to bushes and stakes, in long rows, the saddles lying on the ground, not far off; and hundreds of men were moving about, some in full uniform and others without coat or vest. A half-dozen wagons with sheets on them stood on one side among the trees, near which several fires were smoking, with men around them.

As Frank clattered up to the bridge, a soldier with a gun on his arm, who had been standing by the railing, walked out to the middle of the bridge.

"Halt! Where are you going in such a hurry, my young man?" he said.[Pg 15]

"I wish to see the colonel," said Frank, repeating as nearly as he could the words the picket had told him.

"What do you want with him?"

Frank was tempted not to tell him; but he was so impatient to deliver his message before the others should arrive, that he told him what he had come for.

"There he is," said the sentinel, pointing to a place among the trees where stood at least five hundred men.

Frank looked, expecting to recognize the colonel by his noble bearing, or splendid uniform, or some striking marks.

"Where?" he asked, in doubt; for while a number of the men were in uniform, he knew these to be privates.

"There," said the sentry, pointing; "by that stump, near the yellow horse-blanket."

Frank looked again. The only man he could fix upon by the description was a young fellow, washing his face in a tin basin, and he felt that this could not be the colonel; but he did not like to appear dull, so he thanked the man and rode on, thinking he would go to the point indicated, and ask some one else to show him the officer.

He felt quite grand as he rode in among the men, who, he thought, would recognize his importance and treat him accordingly; but, as he passed on, instead of paying him the respect he had expected, they began to guy him with all sorts of questions.[Pg 16]

"Hullo, bud, going to jine the cavalry?" asked one. "Which is oldest; you or your horse?" inquired another.

"How's pa—and ma?" "Does your mother know you're out?" asked others. One soldier walked up, and putting his hand on the bridle, proceeded affably to ask him after his health, and that of every member of his family. At first Frank did not understand that they were making fun of him, but it dawned on him when the man asked him solemnly:

"Are there any Yankees around, that you were running away so fast just now?"

"No; if there were I'd never have found you here," said Frank, shortly, in reply; which at once turned the tide in his favor and diverted the ridicule from himself to his teaser, who was seized by some of his comrades and carried off with much laughter and slapping on the back.

"I wish to see Colonel Marshall," said Frank, pushing his way through the group that surrounded him, and riding up to the man who was still occupied at the basin on the stump.

"All right, sir, I'm the man," said the individual, cheerily looking up with his face dripping and rosy from its recent scrubbing.

"You the colonel!" exclaimed Frank, suspicious that he was again being ridiculed, and thinking it impossible that this slim, rosy-faced youngster, who was scarcely stouter[Pg 17] than Hugh, and who was washing in a tin basin, could be the commander of all these soldierly-looking men, many of whom were old enough to be his father.

"Yes, I'm the lieutenant-colonel. I'm in command," said the gentleman, smiling at him over the towel.

Something made Frank understand that this was really the officer, and he gave his message, which was received with many expressions of thanks.

"Won't you get down? Here, Campbell, take this horse, will you?" he called to a soldier, as Frank sprang from his horse. The orderly stepped forward and took the bridle.

"Now, come with me," said the colonel, leading the way. "We must get ready to receive your mother. There are some ladies coming—and breakfast," he called to a group who were engaged in the same occupation he had just ended, and whom Frank knew by instinct to be officers.

The information seemed to electrify the little knot addressed; for they began to rush around, and in a few moments they all were in their uniforms, and surrounding the colonel, who, having brushed his hair with the aid of a little glass hung on a bush, had hurried into his coat and was buckling on his sword and giving orders in a way which at once satisfied Frank that he was every inch a colonel.[Pg 18]

"Now let us go and receive your mother," said he to the boy. As he strode through the camp with his coat tightly buttoned, his soft hat set jauntily on the side of his head, his plumes sweeping over its side, and his sword clattering at his spurred heel, he presented a very different appearance from that which he had made a little before, with his head in a tin basin, and his face covered with lather. In fact, Colonel Marshall was already a noted officer, and before the end of the war he attained still higher rank and reputation.

The colonel met the rest of the party at the bridge, and introduced himself and several officers who soon joined him. The negroes were directed to take the provisions over to the other side of the stream into the camp, and in a little while the whole regiment were enjoying the breakfast. The boys and their mother had at the colonel's request joined his mess, in which was one of their cousins, the brother of their cousin Belle.

The gentlemen could eat scarcely anything, they were so busy attending to the wants of the ladies. The colonel, particularly, waited on their cousin Belle all the time.

As soon as they had finished the colonel left them, and a bugle blew. In a minute all was bustle. Officers were giving orders; horses were saddled and brought out; and by what seemed magic to the boys, the men, who just before were scattered about among the trees laughing and[Pg 19] eating, were standing by their horses all in proper order. The colonel and the officers came and said good-bye.

Again the bugle blew. Every man was in his saddle. A few words by the colonel, followed by other words from the captains, and the column started, turning across the bridge, the feet of the horses thundering on the planks. Then the regiment wound up the hill at a walk, the men singing snatches of a dozen songs of which "The Bonnie Blue Flag," "Lorena," and "Carry Me Back to Old Virginia Shore," were the chief ones.

It seemed to the boys that to be a soldier was the noblest thing on earth; and that this regiment could do anything.[Pg 20]

After this it became a common thing for passing regiments to camp near Oakland, and the fire blazed many a night, cooking for the soldiers, till the chickens were crowing in the morning. The negroes all had hen-houses and raised their own chickens, and when a camp was near them they used to drive a thriving trade on their own account, selling eggs and chickens to the privates while the officers were entertained in the "gret house."

It was thought an honor to furnish food to the soldiers. Every soldier was to the boys a hero, and each young officer might rival Ivanhoe or Cœur de Lion.

It was not a great while, however, before they learned that all soldiers were not like their favorite knights. At any rate, thefts were frequent. The absence of men from the plantations, and the constant passing of strangers made stealing easy; hen-roosts were robbed time after time, and even pigs and sheep were taken without any trace of the thieves. The boys' hen-house, however, which was in the yard, had never been troubled. It was about their only possession, and they took great pride in it.[Pg 21]

One night the boys were fast asleep in their room in the office, with old Bruno and Nick curled up on their sheep-skins on the floor. Hugh was away, so the boys were the only "men" on the place, and felt that they were the protectors of the plantation. The frequent thefts had made every one very suspicious, and the boys had made up their minds to be on the watch, and, if possible, to catch the thief.

The negroes said that the deserters did the stealing.

On the night in question, the boys were sound asleep when old Bruno gave a low growl, and then began walking and sniffing up and down the room. Soon Nick gave a sharp, quick bark.

Frank waked first. He was not startled, for the dogs were in the habit of barking whenever they wished to go out-of-doors. Now, however, they kept it up, and it was in a strain somewhat different from their usual signal.

"What's the matter with you? Go and lie down, Bruno," called Frank. "Hush up, Nick!" But Bruno would not lie down, and Nick would not keep quiet, though at the sound of Frank's voice they felt less responsibility, and contented themselves with a low growling.

After a little while Frank was on the point of dropping off to sleep again, when he heard a sound out in the yard, which at once thoroughly awakened him. He nudged Willy in the side.[Pg 22]

"Willy—Willy, wake up; there's some one moving around outdoors."

"Umm-mm," groaned Willy, turning over and settling himself for another nap.

The sound of a chicken chirping out in fright reached Frank's ear.

"Wake up, Willy!" he called, pinching him hard. "There's some one at the hen-house."

Willy was awake in a second. The boys consulted as to what should be done. Willy was sceptical. He thought Frank had been dreaming, or that it was only Uncle Balla, or "some one" moving about the yard. But a second cackle of warning reached them, and in a minute both boys were out of bed pulling on their clothes with trembling impatience.

"Let's go and wake Uncle Balla," proposed Willy, getting himself all tangled in the legs of his trousers.

"No; I'll tell you what, let's catch him ourselves," suggested Frank.

"All right," assented Willy. "We'll catch him and lock him up; suppose he's got a pistol? your gun maybe won't go off; it doesn't always burst the cap."

"Well, your old musket is loaded, and you can hold him, while I snap the cap at him, and get it ready."

"All right—I can't find my jacket—I'll hold him."

"Where in the world is my hat?" whispered Frank.[Pg 23] "Never mind, it must be in the house. Let's go out the back way. We can get out without his hearing us."

"What shall we do with the dogs? Let's shut them up."

"No, let's take 'em with us. We can keep them quiet and hold 'em in, and they can track him if he gets away."

"All right;" and the boys slowly opened the door, and crept stealthily out, Frank clutching his double-barrelled gun, and Willy hugging a heavy musket which he had found and claimed as one of the prizes of war. It was almost pitch-dark.

They decided that one should take one side of the hen-house, and one the other side (in such a way that if they had to shoot, they would almost certainly shoot one another!) but before they had separated both dogs jerked loose from their hands and dashed away in the darkness, barking furiously.

"There he goes round the garden," shouted Willy, as the sound of footsteps like those of a man running with all his might came from the direction which the dogs had taken.

"Come on," and both started; but, after taking a few steps, they stopped to listen so that they might trace the fugitive.

A faint noise behind them arrested their attention, and Frank tiptoed back toward the hen-house. It was[Pg 24] too dark to see much, but he heard the hen-house door creak, and was conscious even in the darkness that it was being pushed slowly open.

"Here's one, Willy," he shouted, at the same time putting his gun to his shoulder and pulling the trigger. The hammer fell with a sharp "click" just as the door was snatched to with a bang. The cap had failed to explode, or the chicken-eating days of the individual in the hen-house would have ended then and there.

The boys stood for some moments with their guns pointed at the door of the hen-house expecting the person within to attempt to burst out; but the click of the hammer and their hurried conference without, in which it was promptly agreed to let him have both barrels if he appeared, reconciled him to remaining within.

After some time it was decided to go and wake Uncle Balla, and confer with him as to the proper disposition of their captive. Accordingly, Frank went off to obtain help, while Willy remained to watch the hen-house. As Frank left he called back:

"Willy, you take good aim at him, and if he pokes his head out—let him have it!"

This Willy solemnly promised to do.

Frank was hardly out of hearing before Willy was surprised to hear the prisoner call him by name in the[Pg 25] most friendly and familiar manner, although the voice was a strange one.

"Willy, is that you?" called the person inside.

"Yes."

"Where's Frank?"

"Gone to get Uncle Balla."

"Did you see that other fellow?"

"Yes."

"I wish you'd shot him. He brought me here and played a joke on me. He told me this was a house I could sleep in, and shut me up in here,—and blest if I don't b'lieve it's nothin' but a hen-house. Let me out here a minute," he continued, after a pause, cajolingly.

"No, I won't," said Willy firmly, getting his gun ready.

There was a pause, and then from the depths of the hen-house issued the most awful groan:

"Umm! Ummm!! Ummmm!!!"

Willy was frightened.

"Umm! Umm!" was repeated.

"What's the matter with you?" asked Willy, feeling sorry in spite of himself.

"Oh! Oh! Oh! I'm so sick," groaned the man in the hen-house.

"How? What's the matter?"

"That man that fooled me in here gave me something to drink, and it's pizened me; oh! oh! oh! I'm dying."[Pg 26]

It was a horrible groan.

Willy's heart relented. He moved to the door and was just about to open it to look in when a light flashed across the yard from Uncle Balla's house, and he saw him coming with a flaming light-wood knot in his hand.[Pg 27]

Instead of opening the door, therefore, Willy called to the old man, who was leisurely crossing the yard: "Run, Uncle Balla. Quick, run!"

At the call Old Balla and Frank set out as fast as they could.

"What's the matter? Is he done kill de chickens? Is he done got away?" the old man asked, breathlessly.

"No, he's dyin'," shouted Willy.

"Hi! is you shoot him?" asked the old driver.

"No, that other man's poisoned him. He was the robber and he fooled this one," explained Willy, opening the door and peeping anxiously in.

"Go 'long, boy,—now, d'ye ever heah de better o' dat?—dat man's foolin' wid you; jes' tryin' to git yo' to let him out."

"No, he isn't," said Willy; "you ought to have heard him."

But both Balla and Frank were laughing at him, so he felt very shamefaced. He was relieved by hearing another groan.

"Oh, oh, oh! Ah, ah!"[Pg 28]

"You hear that?" he asked, triumphantly.

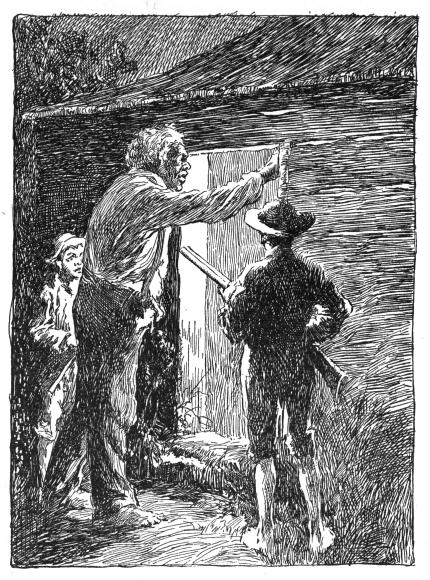

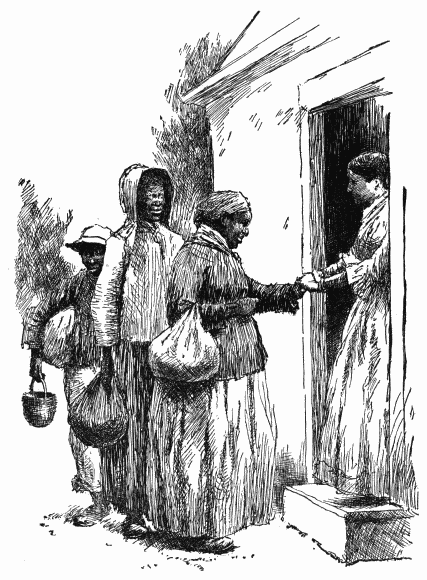

"I boun' I'll see what's the matter with him, the roscol! Stan' right dyah, y' all, an' if he try to run shoot him, but mine you don' hit me," and the old man walked up to the door, and standing on one side flung it open. "What you doin' in dyah after dese chillern's chickens?" he called fiercely.

"Hello, old man, 's 'at you? I's mighty sick," muttered the person within. Old Balla held his torch inside the house, amid a confused cackle and flutter of fowls.

"Well, ef 'tain' a white man, and a soldier at dat!" he exclaimed. "What you doin' heah, robbin' white folks' hen-roos'?" he called, roughly. "Git up off dat groun'; you ain' sick."

"Let me get up, Sergeant,—hic—don't you heah the roll-call?—the tent's mighty dark; what you fool me in here for?" muttered the man inside.

The boys could see that he was stretched out on the floor, apparently asleep, and that he was a soldier in uniform. Balla stepped inside.

"Is he dead?" asked both boys as Balla caught him by the arms, lifted him, and let him fall again limp on the floor.

"Nor, he's dead-drunk," said Balla, picking up an empty flask. "Come on out. Let me see what I gwi' do wid you?" he said, scratching his head.[Pg 29]

THE OLD MAN WALKED UP TO THE DOOR, AND STANDING ON ONE

SIDE FLUNG IT OPEN.

THE OLD MAN WALKED UP TO THE DOOR, AND STANDING ON ONE

SIDE FLUNG IT OPEN.

"I know what I gwi' do wid you. I gwi' lock you up right whar you is."

"Uncle Balla, s'pose he gets well, won't he get out?"

"Ain' I gwi' lock him up? Dat's good from you, who was jes' gwi' let 'im out ef me an' Frank hadn't come up when we did."

Willy stepped back abashed. His heart accused him and told him the charge was true. Still he ventured one more question:

"Hadn't you better take the hens out?"

"Nor; 'tain' no use to teck nuttin' out dyah. Ef he comes to, he know we got 'im, an' he dyahson' trouble nuttin'."

And the old man pushed to the door and fastened the iron hasp over the strong staple. Then, as the lock had been broken, he took a large nail from his pocket and fastened it in the staple with a stout string so that it could not be shaken out. All the time he was working he was talking to the boys, or rather to himself, for their benefit.

"Now, you see ef we don' find him heah in the mornin'! Willy jes' gwi' let you get 'way, but a man got you now, wha'ar' been handlin' horses an' know how to hole 'em in the stalls. I boun' he'll have to butt like a ram to git out dis log hen-house," he said, finally, as he finished tying[Pg 32] the last knot in his string, and gave the door a vigorous rattle to test its strength.

Willy had been too much abashed at his mistake to fully appreciate all of the witticisms over the prisoner, but Frank enjoyed them almost as much as Unc' Balla himself.

"Now y' all go 'long to bed, an' I'll go back an' teck a little nap myself," said he, in parting. "Ef he gits out that hen-house I'll give you ev'y chicken I got. But he am' gwine git out. A man's done fasten him up dyah."

The boys went off to bed, Willy still feeling depressed over his ridiculous mistake. They were soon fast asleep, and if the dogs barked again they did not hear them.

The next thing they knew, Lucy Ann, convulsed with laughter, was telling them a story about Uncle Balla and the man in the hen-house. They jumped up, and pulling on their clothes ran out in the yard, thinking to see the prisoner.

Instead of doing so, they found Uncle Balla standing by the hen-house with a comical look of mystification and chagrin; the roof had been lifted off at one end and not only the prisoner, but every chicken was gone!

The boys were half inclined to cry; Balla's look, however, set them to laughing.

"Unc' Balla, you got to give me every chicken you got, 'cause you said you would," said Willy.[Pg 33]

"Go 'way from heah, boy. Don' pester me when I studyin' to see which way he got out."

"You ain't never had a horse get through the roof before, have you?" said Frank.

"Go 'way from here, I tell you," said the old man, walking around the house, looking at it.

As the boys went back to wash and dress themselves, they heard Balla explaining to Lucy Ann and some of the other servants that "the man them chillern let git away had just come back and tooken out the one he had locked up"; a solution of the mystery he always stoutly insisted upon.

One thing, however, the person's escape effected—it prevented Willy's ever hearing any more of his mistake; but that did not keep him now and then from asking Uncle Balla "if he had fastened his horses well."[Pg 34]

These hens were not the last things stolen from Oakland. Nearly all the men in the country had gone with the army. Indeed, with the exception of a few overseers who remained to work the farms, every man in the neighborhood, between the ages of seventeen and fifty, was in the army. The country was thus left almost wholly unprotected, and it would have been entirely so but for the "Home Guard," as it was called, which was a company composed of young boys and the few old men who remained at home, and who had volunteered for service as a local guard, or police body, for the neighborhood of their homes.

Occasionally, too, later on, a small detachment of men, under a leader known as a "conscript-officer," would come through the country hunting for any men who were subject to the conscript law but who had evaded it, and for deserters who had run away from the army and refused to return.

These two classes of troops, however, stood on a very different footing. The Home Guard was regarded with much respect, for it was composed of those whose extreme[Pg 35] age or youth alone withheld them from active service; and every youngster in its ranks looked upon it as a training school, and was ready to die in defence of his home if need were, and, besides, expected to obtain permission to go into the army "next year."

The conscript-guard, on the other hand, were grown men, and were thought to be shirking the very dangers and hardships into which they were trying to force others.

A few miles from Oakland, on the side toward the mountain road and beyond the big woods, lay a district of virgin forest and old-field pines which, even before the war, had acquired a reputation of an unsavory nature, though its inhabitants were a harmless people. No highways ran through this region, and the only roads which entered it were mere wood-ways, filled with bushes and carpeted with pine-tags; and, being travelled only by the inhabitants, appeared to outsiders "to jes' peter out," as the phrase went. This territory was known by the unpromising name of Holetown.

Its denizens were a peculiar but kindly race known to the boys as "poor white folks," and called by the negroes, with great contempt, "po' white trash." Some of them owned small places in the pines; but the majority were simply tenants. They were an inoffensive people, and their worst vices were intemperance and evasion of the tax-laws.[Pg 36]

They made their living—or rather, they existed—by fishing and hunting; and, to eke it out, attempted the cultivation of little patches of corn and tobacco near their cabins, or in the bottoms where small branches ran into the stream already mentioned.

In appearance they were usually so thin and sallow that one had to look at them twice to see them clearly. At best, they looked vague and illusive.

They were brave enough. At the outbreak of the war nearly all of the men in this community enlisted, thinking, as many others did, that war was more like play than work, and consisted more of resting than of laboring. Although most of them, when in battle, showed the greatest fearlessness, yet the duties of camp soon became irksome to them, and they grew sick of the restraint and drilling of camp-life; so some of them, when refused a furlough, took it, and came home. Others stayed at home after leave had ended, feeling secure in their stretches of pine and swamp, not only from the feeble efforts of the conscript-guard, but from any parties who might be sent in search of them.

In this way it happened, as time went by, that Holetown became known to harbor a number of deserters.

According to the negroes, it was full of them; and many stories were told about glimpses of men dodging behind trees in the big woods, or rushing away through[Pg 37] the underbrush like wild cattle. And, though the grown people doubted whether the negroes had not been startled by some of the hogs, which were quite wild, feeding in the woods, the boys were satisfied that the negroes really had seen deserters.

This became a certainty when there came report after report of these wood-skulkers, and when the conscript-guard, with the brightest of uniforms, rode by with as much show and noise as if on a fox-hunt. Then it became known that deserters were, indeed, infesting the piny district of Holetown, and in considerable numbers.

Some of them, it was said, were pursuing agriculture and all their ordinary vocations as openly as in time of peace, and more industriously. They had a regular code of signals, and nearly every person in the Holetown settlement was in league with them.

When the conscript-guard came along, there would be a rush of tow-headed children through the woods, or some of the women about the cabins would blow a horn lustily; after which not a man could be found in all the district. The horn told just how many men were in the guard, and which path they were following; every member of the troop being honored with a short, quick "toot."

"What are you blowing-that horn for?" sternly asked the guard one morning of an old woman,—old Mrs. Hall[Pg 38] who stood out in front of her little house blowing like Boreas in the pictures.

"Jes' blowin' fur Millindy to come to dinner," she said, sullenly. "Can't y' all let a po' 'ooman call her gals to git some'n' to eat? You got all her boys in d'army, killin' 'em; whyn't yo' go and git kilt some yo'self, 'stidder ridin' 'bout heah tromplin' all over po' folk's chickens?"

When the troop returned in the evening, she was still blowing; "blowin' fur Millindy to come home," she said, with more sharpness than before. But there must have been many Millindys, for horns were sounding all through the settlement.

The deserters, at such times, were said to take to the swamps, and marvellous rumors were abroad of one or more caves, all fitted up, wherein they concealed themselves, like the robbers in the stories the boys were so fond of reading.

After a while thefts of pigs and sheep became so common that they were charged to the deserters.

Finally it grew to be such a pest that the ladies in the neighborhood asked the Home Guard to take action in the matter, and after some delay it became known that this valorous body was going to invade Holetown and capture the deserters or drive them away. Hugh was to accompany them, of course; and he looked very handsome, as well as very important, when he started out on[Pg 39] horseback to join the troop. It was his first active service; and with his trousers in his boots and his pistol in his belt he looked as brave as Julius Cæsar, and quite laughed at his mother's fears for him, as she kissed him good-bye and walked out with him to his horse, which Balla held at the gate.

The boys asked leave to go with him; but Hugh was so scornful over their request, and looked so soldierly as he galloped away with the other men that the boys felt as cheap as possible.[Pg 40]

When the boys went into the house they found that their Aunt Mary had a headache that morning, and, even with the best intentions of doing her duty in teaching them, had been forced to go to bed. Their mother was too much occupied with her charge of providing for a family of over a dozen white persons, and five times as many colored dependents, to give any time to acting as substitute in the school-room, so the boys found themselves with a holiday before them. It seemed vain to try to shoot duck on the creek, and the perch were averse to biting. The boys accordingly determined to take both guns and to set out for a real hunt in the big woods.

They received their mother's permission, and after a lunch was prepared they started in high glee, talking about the squirrels and birds they expected to kill.

Frank had his gun, and Willy had the musket; and both carried a plentiful supply of powder and some tolerably round slugs made from cartridges.

They usually hunted in the part of the woods nearest[Pg 41] the house, and they knew that game was not very abundant there; so, as a good long day was before them, they determined to go over to the other side of the woods.

They accordingly pushed on, taking a path which led through the forest. They went entirely through the big woods without seeing anything but one squirrel, and presently found themselves at the extreme edge of Holetown. They were just grumbling at the lack of game when they heard a distant horn. The sound came from perhaps a mile or more away, but was quite distinct.

"What's that? Somebody fox-hunting?—or is it a dinner-horn?" asked Willy, listening intently.

"It's a horn to warn deserters, that's what 'tis," said Frank, pleased to show his superior knowledge.

"I tell you what to do:—let's go and hunt deserters," said Willy, eagerly.

"All right. Won't that be fun!" and both boys set out down the road toward a point where they knew one of the paths ran into the pine-district, talking of the numbers of prisoners they expected to take.

In an instant they were as alert and eager as young hounds on a trail. They had mapped out a plan before, and they knew exactly what they had to do. Frank was the captain, by right of his being older; and Willy was lieutenant, and was to obey orders. The chief thing that troubled them was that they did not wish to be seen by[Pg 42] any of the women or children about the cabins, for they all knew the boys, because they were accustomed to come to Oakland for supplies; then, too, the boys wished to remain on friendly terms with their neighbors. Another thing worried them. They did not know what to do with their prisoners after they should have captured them. However, they pushed on and soon came to a dim cart-way, which ran at right-angles to the main road and which went into the very heart of Holetown. Here they halted to reconnoitre and to inspect their weapons.

Even from the main road, the track, as it led off through the overhanging woods with thick underbrush of chinquapin bushes, appeared to the boys to have something strange about it, though they had at other times walked it from end to end. Still, they entered boldly, clutching their guns. Willy suggested that they should go in Indian file and that the rear one should step in the other's footprints as the Indians do; but Frank thought it was best to walk abreast, as the Indians walked in their peculiar way only to prevent an enemy who crossed their trail from knowing how many they were; and, so far from it being any disadvantage for the deserters to know their number, it was even better that they should know there were two, so that they would not attack from the rear. Accordingly, keeping abreast, they struck in; each[Pg 43] taking the woods on one side of the road, which he was to watch and for which he was to be responsible.

The farther they went the more indistinct the track became, and the wilder became the surrounding woods. They proceeded with great caution, examining every particularly thick clump of bushes; peeping behind each very large tree; and occasionally even taking a glance up among its boughs; for they had themselves so often planned how, if pursued, they would climb trees and conceal themselves, that they would not have been at all surprised to find a fierce deserter, armed to the teeth, crouching among the branches.

Though they searched carefully every spot where a deserter could possibly lurk, they passed through the oak woods and were deep in the pines without having seen any foe or heard a noise which could possibly proceed from one. A squirrel had daringly leaped from the trunk of a hickory-tree and run into the woods, right before them, stopping impudently to take a good look at them; but they were hunting larger game than squirrels, and they resisted the temptation to take a shot at him,—an exercise of virtue which brought them a distinct feeling of pleasure. They were, however, beginning to be embarrassed as to their next course. They could hear the dogs barking farther on in the pines, and knew they were approaching the vicinity of the settlement; for they had crossed the[Pg 44] little creek which ran through a thicket of elder bushes and "gums," and which marked the boundary of Holetown. Little paths, too, every now and then turned off from the main track and went into the pines, each leading to a cabin or bit of creek-bottom deeper in. They therefore were in a real dilemma concerning what to do; and Willy's suggestion, to eat lunch, was a welcome one. They determined to go a little way into the woods, where they could not be seen, and had just taken the lunch out of the game-bag and were turning into a by-path, when they met a man who was coming along at a slow, lounging walk, and carrying a long single-barrelled shot-gun across his arm.

When first they heard him, they thought he might be a deserter; but when he came nearer they saw that he was simply a countryman out hunting; for his old game-bag (from which peeped a squirrel's tail) was over his shoulder, and he had no weapon at all, excepting that old squirrel-gun.

"Good morning, sir," said both boys, politely.

"Mornin'! What luck y' all had?" he asked good-naturedly, stopping and putting the butt of his gun on the ground, and resting lazily on it, preparatory to a chat.

"We're not hunting; we're hunting deserters."

"Huntin' deserters!" echoed the man with a smile[Pg 45] which broke into a chuckle of amusement as the thought worked its way into his brain. "Ain't you see' none?"

"No," said both boys in a breath, greatly pleased at his friendliness. "Do you know where any are?"

The man scratched his head, seeming to reflect.

"Well, 'pears to me I hearn tell o' some, 'roun' to'des that-a-ways," making a comprehensive sweep of his arm in the direction just opposite to that which the boys were taking. "I seen the conscrip'-guard a little while ago pokin' 'roun' this-a-way; but Lor', that ain' the way to ketch deserters. I knows every foot o' groun' this-a-way, an' ef they was any deserters roun' here I'd be mighty apt to know it."

This announcement was an extinguisher to the boys' hopes. Clearly, they were going in the wrong direction.

"We are just going to eat our lunch," said Frank; "won't you join us?"

Willy added his invitation to his brother's, and their friend politely accepted, suggesting that they should walk back a little way and find a log. This all three did; and in a few minutes they were enjoying the lunch which the boys' mother had provided, while the stranger was telling the boys his views about deserters, which, to say the least, were very original.

"I seen the conscrip'-guard jes' this mornin', ridin' 'round whar they knowd they warn' no deserters, but[Pg 46] ole womens and children," he said with his mouth full. "Whyn't they go whar they knows deserters is?" he asked.

"Where are they? We heard they had a cave down on the river, and we were going there," declared the boys.

"Down on the river?—a cave? Ain' no cave down thar, without it's below Rockett's mill; fur I've hunted and fished ev'y foot o' that river up an' down both sides, an' 'tain' a hole thar, big enough to hide a' ole hyah, I ain' know."

This proof was too conclusive to admit of further argument.

"Why don't you go in the army?" asked Willy, after a brief reflection.

"What? Why don't I go in the army?" repeated the hunter. "Why, I's in the army! You didn' think I warn't in the army, did you?"

The hunter's tone and the expression of his face were so full of surprise that Willy felt deeply mortified at his rudeness, and began at once to stammer something to explain himself.

"I b'longs to Colonel Marshall's regiment," continued the man, "an' I's been home sick on leave o' absence. Got wounded in the leg, an' I's jes' gettin' well. I ain' rightly well enough to go back now, but I's anxious to git back; I'm gwine to-morrow mornin' ef I don' go this evenin'. You see I kin hardly walk now!" and to demonstrate his[Pg 47] lameness, he got up and limped a few yards. "I ain' well yit," he pursued, returning and dropping into his seat on the log, with his face drawn up by the pain the exertion had brought on.

"Let me see your wound. Is it sore now?" asked Willy, moving nearer to the man with a look expressive of mingled curiosity and sympathy.

"You can't see it; it's up heah," said the soldier, touching the upper part of his hip; "an' I got another one heah," he added, placing his hand very gently to his side. "This one's whar a Yankee run me through with his sword. Now, that one was where a piece of shell hit me,—I don't keer nothin' 'bout that," and he opened his shirt and showed a triangular, purple scar on his shoulder.

"You certainly must be a brave soldier," exclaimed both boys, impressed at sight of the scar, their voices softened by fervent admiration.

"Yes, I kep' up with the bes' of 'em," he said, with a pleased smile.

Suddenly a horn began to blow, "toot—toot—toot," as if all the "Millindys" in the world were being summoned. It was so near the boys that it quite startled them.

"That's for the deserters, now," they both exclaimed.

Their friend looked calmly up and down the road, both ways.

"Them rascally conscrip'-guard been tellin' you all[Pg 48] that, to gi' 'em some excuse for keepin' out o' th' army theyselves—that's all. Th' ain' gwine ketch no deserters any whar in all these parts, an' you kin tell 'em so. I'm gwine down thar an' see what that horn's a-blowin' fur; hit's somebody's dinner horn, or somp'n'," he added, rising and taking up his game-bag.

"Can't we go with you?" asked the boys.

"Well, nor, I reckon you better not," he drawled; "thar's some right bad dogs down thar in the pines,—mons'us bad; an' I's gwine cut through the woods an' see ef I can't pick up a squ'rr'l, gwine 'long, for the ole 'ooman's supper, as I got to go 'way to-night or to-morrow; she's mighty poorly."

"Is she poorly much?" asked Willy, greatly concerned. "We'll get mamma to come and see her to-morrow, and bring her some bread."

"Nor, she ain' so sick; that is to say, she jis' poorly and 'sturbed in her mind. She gittin' sort o' old. Here, y' all take these squ'rr'ls," he said, taking the squirrels from his old game-bag and tossing them at Willy's feet. Both boys protested, but he insisted. "Oh, yes; I kin get some mo' fur her.

"Y' all better go home. Well, good-bye, much obliged to you," and he strolled off with his gun in the bend of his arm, leaving the boys to admire and talk over his courage.

They turned back, and had gone about a quarter of a[Pg 49] mile, when they heard a great trampling of horses behind them. They stopped to listen, and in a little while a squadron of cavalry came in sight. The boys stepped to one side of the road to wait for them, eager to tell the important information they had received from their friend, that there were no deserters in that section. In a hurried consultation they agreed not to tell that they had been hunting deserters themselves, as they knew the soldiers would only have a laugh at their expense.

"Hello, boys, what luck?" called the officer in the lead, in a friendly manner.

They told him they had not shot anything; that the squirrels had been given to them; and then both boys inquired:

"You all hunting for deserters?"

"You seen any?" asked the leader, carelessly, while one or two men pressed their horses forward eagerly.

"No, th' ain't any deserters in this direction at all," said the boys, with conviction in their manner.

"How do you know?" asked the officer.

"'Cause a gentleman told us so."

"Who? When? What gentleman?"

"A gentleman who met us a little while ago."

"How long ago? Who was he?"

"Don't know who he was," said Frank.[Pg 50]

"When we were eating our snack," put in Willy, not to be left out.

"How was he dressed? Where was it? What sort of man was he?" eagerly inquired the leading trooper.

The boys proceeded to describe their friend, impressed by the intense interest accorded them by the listeners.

"He was a sort of man with red hair, and wore a pair of gray breeches and an old pair of shoes, and was in his shirt-sleeves." Frank was the spokesman.

"And he had a gun—a long squirrel-gun," added Willy, "and he said he belonged to Colonel Marshall's regiment."

"Why, that's Tim Mills. He's a deserter himself," exclaimed the captain.

"No, he ain't—he ain't any deserter," protested both at once. "He is a mighty brave soldier, and he's been home on a furlough to get well of a wound on his leg where he was shot."

"Yes, and it ain't well yet, but he's going back to his command to-night or to-morrow morning; and he's got another wound in his side where a Yankee ran him through with his sword. We know he ain't any deserter."

"How do you know all this?" asked the officer.

"He told us so himself, just now—a little while ago, that is," said the boys.

The man laughed.[Pg 51]

"Why, he's fooled you to death. That's Tim himself, that's been doing all the devilment about here. He is the worst deserter in the whole gang."

"We saw the wound on his shoulder," declared the boys, still doubting.

"I know it; he's got one there,—that's what I know him by. Which way did he go,—and how long has it been?"

"He went that way, down in the woods; and it's been some time. He's got away now."

The lads by this time were almost convinced of their mistake; but they could not prevent their sympathy from being on the side of their late agreeable companion.

"We'll catch the rascal," declared the leader, very fiercely. "Come on, men,—he can't have gone far;" and he wheeled his horse about and dashed back up the road at a great pace, followed by his men. The boys were half inclined to follow and aid in the capture; but Frank, after a moment's thought, said solemnly:

"No, Willy; an Arab never betrays a man who has eaten his salt. This man has broken bread with us; we cannot give him up. I don't think we ought to have told about him as much as we did."

This was an argument not to be despised.

A little later, as the boys trudged home, they heard the horns blowing again a regular "toot-toot" for "Millindy."[Pg 52] It struck them that supper followed dinner very quickly in Holetown.

When the troop passed by in the evening the men were in very bad humor. They had had a fruitless addition to their ride, and some of them were inclined to say that the boys had never seen any man at all, which the boys thought was pretty silly, as the man had eaten at least two-thirds of their lunch.

Somehow the story got out, and Hugh was very scornful because the boys had given their lunch to a deserter.[Pg 53]

As time went by the condition of things at Oakland changed—as it did everywhere else. The boys' mother, like all the other ladies of the country, was so devoted to the cause that she gave to the soldiers until there was nothing left. After that there was a failure of the crops, and the immediate necessities of the family and the hands on the place were great.

There was no sugar nor coffee nor tea. These luxuries had been given up long before. An attempt was made to manufacture sugar out of the sorghum, or sugar-cane, which was now being cultivated as an experiment; but it proved unsuccessful, and molasses made from the cane was the only sweetening. The boys, however, never liked anything sweetened with molasses, so they gave up everything that had molasses in it. Sassafras tea was tried as a substitute for tea, and a drink made out of parched corn and wheat, of burnt sweet potato and other things, in the place of coffee; but none of them were fit to drink—at least so the boys thought. The wheat crop proved a failure; but the corn turned out very fine, and the boys learned to live on corn bread, as there was no wheat bread.[Pg 54]

The soldiers still came by, and the house was often full of young officers who came to see the boys' cousins. The boys used to ride the horses to and from the stables, and, being perfectly fearless, became very fine riders.

Several times, among the visitors, came the young colonel who had commanded the regiment that had camped at the bridge the first year of the war. It did not seem to the boys that Cousin Belle liked him, for she took much longer to dress when he came; and if there were other officers present she would take very little notice of the colonel.

Both boys were in love with her, and after considerable hesitation had written her a joint letter to tell her so, at which she laughed heartily and kissed them both and called them her sweethearts. But, though they were jealous of several young officers who came from time to time, they felt sorry for the colonel,—their cousin was so mean to him. They were on the best terms with him, and had announced their intention of going into his regiment if only the war should last long enough. When he came there was always a scramble to get his horse; though of all who came to Oakland he rode the wildest horses, as both boys knew by practical experience.

At length the soldiers moved off too far to permit them to come on visits, and things were very dull. So it was for a long while.[Pg 55]

But one evening in May, about sunset, as the boys were playing in the yard, a man came riding through the place on the way to Richmond. His horse showed that he had been riding hard. He asked the nearest way to "Ground-Squirrel Bridge." The Yankees, he said, were coming. It was a raid. He had ridden ahead of them, and had left them about Greenbay depot, which they had set on fire. He was in too great a hurry to stop and get something to eat, and he rode off, leaving much excitement behind him; for Greenbay was only eight miles away, and Oakland lay right between two roads to Richmond, down one or the other of which the party of raiders must certainly pass.

It was the first time the boys ever saw their mother exhibit so much emotion as she then did. She came to the door and called:

"Balla, come here." Her voice sounded to the boys a little strained and troubled, and they ran up the steps and stood by her. Balla came to the portico, and looked up with an air of inquiry. He, too, showed excitement.

"Balla, I want you to know that if you wish to go, you can do so."

"Hi, Mistis——" began Balla, with an air of reproach; but she cut him short and kept on.

"I want you all to know it." She was speaking now so as to be heard by the cook and the maids who were[Pg 56] standing about the yard listening to her. "I want you all to know it—every one on the place! You can go if you wish; but, if you go, you can never come back!"

"Hi, Mistis," broke in Uncle Balla, "whar is I got to go? I wuz born on dis place an' I 'spec' to die here, an' be buried right yonder;" and he turned and pointed up to the dark clumps of trees that marked the graveyard on the hill, a half mile away, where the colored people were buried. "Dat I does," he affirmed positively. "Y' all sticks by us, and we'll stick by you."

"I know I ain't gwine nowhar wid no Yankees or nothin'," said Lucy Ann, in an undertone.

"Dee tell me dee got hoofs and horns," laughed one of the women in the yard.

The boys' mother started to say something further to Balla, but though she opened her lips, she did not speak; she turned suddenly and walked into the house and into her chamber, where she shut the door behind her. The boys thought she was angry, but when they softly followed her a few minutes afterward, she got up hastily from where she had been kneeling beside the bed, and they saw that she had been crying. A murmur under the window called them back to the portico. It had begun to grow dark; but a bright spot was glowing on the horizon, and on this every one's gaze was fixed.

"Where is it, Balla? What is it?" asked the boys'[Pg 57] mother, her voice no longer strained and harsh, but even softer than usual.

"It's the depot, madam. They's burnin' it. That man told me they was burnin' ev'ywhar they went."

"Will they be here to-night?" asked his mistress.

"No, marm; I don' hardly think they will. That man said they couldn't travel more than thirty miles a day; but they'll be plenty of 'em here to-morrow—to breakfast." He gave a nervous sort of laugh.

"Here,—you all come here," said their mistress to the servants. She went to the smoke-house and unlocked it. "Go in there and get down the bacon—take a piece, each of you." A great deal was still left. "Balla, step here." She called him aside and spoke earnestly in an undertone.

"Yes'm, that's so; that's jes' what I wuz gwine do," the boys heard him say.

Their mother sent the boys out. She went and locked herself in her room, but they heard her footsteps as she turned about within, and now and then they heard her opening and shutting drawers and moving chairs.

In a little while she came out.

"Frank, you and Willy go and tell Balla to come to the chamber door. He may be out in the stable."

They dashed out, proud to bear so important a message. They could not find him, but an hour later they[Pg 58] heard him, coming from the stable. He at once went into the house. They rushed into the chamber, where they found the door of the closet open.

"Balla, come in here," called their mother from within. "Have you got them safe?" she asked.

"Yes'm; jes' as safe as they kin be. I want to be 'bout here when they come, or I'd go down an' stay whar they is."

"What is it?" asked the boys.

"Where is the best place to put that?" she said, pointing to a large, strong box in which, they knew, the finest silver was kept; indeed, all excepting what was used every day on the table.

"Well, I declar', Mistis, that's hard to tell," said the old driver, "without it's in the stable."

"They may burn that down."

"That's so; you might bury it under the floor of the smoke-house?"

"I have heard that they always look for silver there," said the boys' mother. "How would it do to bury it in the garden?"

"That's the very place I was gwine name," said Balla, with flattering approval. "They can't burn that down, and if they gwine dig for it then they'll have to dig a long time before they git over that big garden." He stooped and lifted up one end of the box to test its weight.[Pg 59]

"I thought of the other end of the flower-bed, between the big rose-bush and the lilac."

"That's the very place I had in my mind," declared the old man. "They won' never fine it dyah!"

"We know a good place," said the boys both together; "it's a heap better than that. It's where we bury our treasures when we play 'Black-beard the Pirate.'"

"Very well," said their mother; "I don't care to know where it is until after to-morrow, anyhow. I know I can trust you," she added, addressing Balla.

"Yes'm, you know dat," said he, simply. "I'll jes' go an' git my hoe."

"The garden hasn't got a roof to it, has it, Unc' Balla?" asked Willy, quietly.

"Go 'way from here, boy," said the old man, making a sweep at him with his hand. "That boy ain' never done talkin' 'bout that thing yit," he added, with a pleased laugh, to his mistress.

"And you ain't ever given me all those chickens either," responded Willy, forgetting his grammar.

"Oh, well, I'm gwi' do it; ain't you hear me say I'm gwine do it?" he laughed as he went out.

The boys were too excited to get sleepy before the silver was hidden. Their mother told them they might go down into the garden and help Balla, on condition that they would not talk.[Pg 60]

"That's the way we always do when we bury the treasure. Ain't it, Willy?" asked Frank.

"If a man speaks, it's death!" declared Willy, slapping his hand on his side as if to draw a sword, striking a theatrical attitude and speaking in a deep voice.

"Give the 'galleon' to us," said Frank.

"No; be off with you," said their mother.

"That ain't the way," said Frank. "A pirate never digs the hole until he has his treasure at hand. To do so would prove him but a novice; wouldn't it, Willy?"

"Well, I leave it all to you, my little Buccaneers," said their mother, laughing. "I'll take care of the spoons and forks we use every day. I'll just hide them away in a hole somewhere."

The boys started off after Balla with a shout, but remembered their errand and suddenly hushed down to a little squeal of delight at being actually engaged in burying treasure—real silver. It seemed too good to be true, and withal there was a real excitement about it, for how could they know but that some one might watch them from some hiding-place, or might even fire into them as they worked?

They met the old fellow as he was coming from the carriage-house with a hoe and a spade in his hands. He was on his way to the garden in a very straightforward manner, but the boys made him understand that to bury[Pg 61] treasure it was necessary to be particularly secret, and after some little grumbling, Balla humored them.

The difficulty of getting the box of silver out of the house secretly, whilst all the family were up, and the servants were moving about, was so great that this part of the affair had to be carried on in a manner different from the usual programme of pirates of the first water. Even the boys had to admit this; and they yielded to old Balla's advice on this point, but made up for it by additional formality, ceremony, and secrecy in pointing out the spot where the box was to be hid.

Old Balla was quite accustomed to their games and fun—their "pranks," as he called them. He accordingly yielded willingly when they marched him to a point at the lower end of the yard, on the opposite side from the garden, and left him. But he was inclined to give trouble when they both reappeared with a gun, and in a whisper announced that they must march first up the ditch which ran by the spring around the foot of the garden.

"Look here, boys; I ain' got time to fool with you chillern," said the old man. "Ain't you hear your ma tell me she 'pend on me to bury that silver what yo' gran'ma and gran'pa used to eat off o'—an' don' wan' nobody to know nothin' 'bout it? An' y' all comin' here with guns, like you huntin' squ'rr'ls, an' now talkin' 'bout wadin' in the ditch!"[Pg 62]

"But, Unc' Balla, that's the way all buccaneers do," protested Frank.

"Yes, buccaneers always go by water," said Willy.

"And we can stoop in the ditch and come in at the far end of the garden, so nobody can see us," added Frank.

"Bookanear or bookafar,—I's gwine in dat garden and dig a hole wid my hoe, an' I is too ole to be wadin' in a ditch like chillern. I got the misery in my knee now, so bad I'se sca'cely able to stand. I don't know huccome y' all ain't satisfied with the place you' ma an' I done pick, anyways."

This was too serious a mutiny for the boys. So it was finally greed that one gun should be returned to the office, and that they should enter by the gate, after which Balla was to go with the boys by the way they should show him, and see the spot they thought of.

They took him down through the weeds around the garden, crouching under the rose-bushes, and at last stopped at a spot under the slope, completely surrounded by shrubbery.

"Here is the spot," said Frank in a whisper, pointing under one of the bushes.

"It's in a line with the longest limb of the big oak-tree by the gate," added Willy, "and when this locust bush and that cedar grow to be big trees, it will be just half-way between them."[Pg 63]

As this seemed to Balla a very good place, he set to work at once to dig, the two boys helping him as well as they could. It took a great deal longer to dig the hole in the dark than they had expected, and when they got back to the house everything was quiet.

The boys had their hats pulled over their eyes, and had turned their jackets inside out to disguise themselves.

"It's a first-rate place! Ain't it, Unc' Balla?" they said, as they entered the chamber where their mother and aunt were waiting for them.

"Do you think it will do, Balla?" their mother asked.

"Oh, yes, madam; it's far enough, an' they got mighty comical ways to get dyah, wadin' in ditch an' things—it will do. I ain' sho' I kin fin' it ag'in myself." He was not particularly enthusiastic. Now, however, he shouldered the box, with a grunt at its weight, and the party went slowly out through the back door into the dark. The glow of the burning depot was still visible in the west.

Then it was decided that Willy should go before—he said to "reconnoitre," Balla said "to open the gate and lead the way,"—and that Frank should bring up the rear.

They trudged slowly on through the darkness, Frank and Willy watching on every side, old Balla stooping under the weight of the big box.

After they were some distance in the garden they heard, or thought they heard, a sound back at the gate,[Pg 64] but decided that it was nothing but the latch clicking; and they went on down to their hiding place.

In a little while the black box was well settled in the hole, and the dirt was thrown upon it. The replaced earth made something of a mound, which was unfortunate. They had not thought of this; but they covered it with leaves, and agreed that it was so well hidden, the Yankees would never dream of looking there.

"Unc' Balla, where are your horses?" asked one of the boys.

"That's for me to know, an' them to find out what kin," replied the old fellow with a chuckle of satisfaction.

The whole party crept back out of the garden, and the boys were soon dreaming of buccaneers and pirates.[Pg 65]

The boys were not sure that they had even fallen asleep when they heard Lucy Ann call, outside. They turned over to take another nap. She was coming up to the door. No, for it was a man's step, it must be Uncle Balla's; they heard horses trampling and people talking. In a second the door was flung open, and a man strode into the room, followed by one, two, a half-dozen others, all white and all in uniform. They were Yankees. The boys were too frightened to speak. They thought they were arrested for hiding the silver.

"Get up, you lazy little rebels," cried one of the intruders, not unpleasantly. As the boys were not very quick in obeying, being really too frightened to do more than sit up in bed, the man caught the mattress by the end, and lifting it with a jerk emptied them and all the bedclothes out into the middle of the floor in a heap. At this all the other men laughed. A minute more and he had drawn his sword. The boys expected no less than to be immediately killed. They were almost paralyzed. But instead of plunging his sword into them, the man began to stick it into the mattresses and to rip them up; while[Pg 66] others pulled open the drawers of the bureau and pitched the things on the floor.

The boys felt themselves to be in a very exposed and defenceless condition; and Willy, who had become tangled in the bedclothes, and had been a little hurt in falling, now that the strain was somewhat over, began to cry.

In a minute a shadow darkened the doorway and their mother stood in the room.

"Leave the room instantly!" she cried. "Aren't you ashamed to frighten children!"

"We haven't hurt the brats," said the man with the sword good-naturedly.

"Well, you terrify them to death. It's just as bad. Give me those clothes!" and she sprang forward and snatched the boys' clothes from the hands of a man who had taken them up. She flung the suits to the boys, who lost no time in slipping into them.

They had at once recovered their courage in the presence of their mother. She seemed to them, as she braved the intruders, the grandest person they had ever seen. Her face was white, but her eyes were like coals of fire. They were very glad she had never looked or talked so to them.

When they got outdoors the yard was full of soldiers. They were upon the porches, in the entry, and in the house. The smoke-house was open and so were the doors[Pg 67] of all the other outhouses, and now and then a man passed, carrying some article which the boys recognized.

In a little while the soldiers had taken everything they could carry conveniently, and even things which must have caused them some inconvenience. They had secured all the bacon that had been left in the smoke-house, as well as all other eatables they could find. It was a queer sight, to see the fellows sitting on their horses with a ham or a pair of fowls tied to one side of the saddle and an engraving or a package of books, or some ornament, to the other.

A new party of men had by this time come up from the direction of the stables.

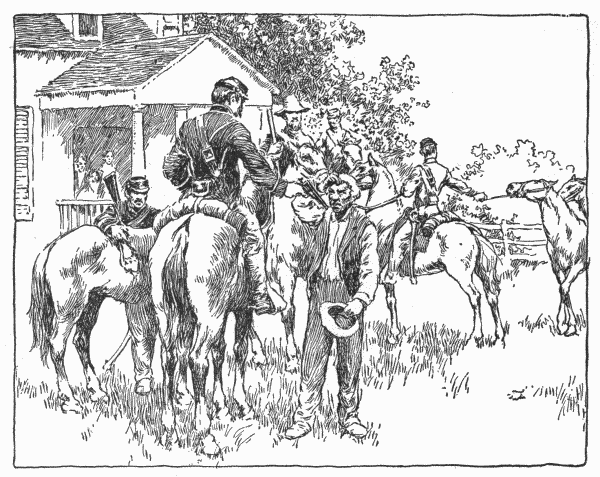

"Old man, come here!" called some of them to Balla, who was standing near expostulating with the men who were about the fire.

"Who?—me?" asked Balla.

"B'ain't you the carriage driver?"

"Ain't I the keridge driver?"

"Yes, you; we know you are, so you need not be lying about it."

"Hi! yes; I the keridge driver. Who say I ain't?"

"Well, where have you hid those horses? Come, we want to know, quick," said the fellow roughly, taking out his pistol in a threatening way.

The old man's eyes grew wide. "Hi! befo' de Lord![Pg 68] Marster, how I know anything of the horses ef they ain't in the stable,—there's where we keep horses!"

"Here, you come with us. We won't have no foolin' 'bout this," said his questioner, seizing him by the shoulder and jerking him angrily around. "If you don't show us pretty quick where those horses are, we'll put a bullet or two into you. March off there!"

He was backed by a half-a-dozen more, but the pistol, which was at old Balla's head, was his most efficient ally.

"Hi! Marster, don't pint dat thing at me that way. I ain't ready to die yit—an' I ain' like dem things, no-ways," protested Balla.

There is no telling how much further his courage could have withstood their threats, for the boys' mother made her appearance. She was about to bid Balla show where the horses were, when a party rode into the yard leading them.

"Hi! there are Bill and John, now," exclaimed the boys, recognizing the black carriage-horses which were being led along.