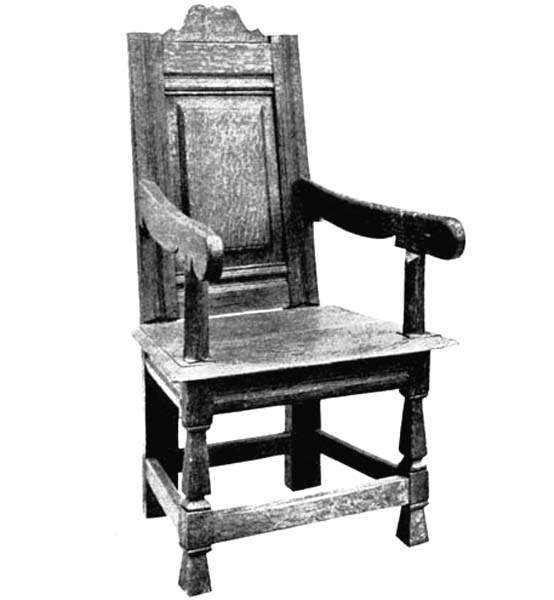

Photo of a group in the U. S. National Museum,

Washington, D. C.

Photo of a group in the U. S. National Museum,

Washington, D. C.Captain John Smith and companions trading with the Indians in Virginia, 1607. The colonists seek corn and furs from the natives in exchange for beads, trinkets, utensils and cloth.

Title: Domestic Life in Virginia in the Seventeenth Century

Author: Annie Lash Jester

Release date: December 10, 2008 [eBook #27482]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Mark C. Orton, Carla Foust, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Mark C. Orton, Carla Foust,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

A Table of Contents has been created for the HTML version.

Illustrations were all placed in the middle of the original book. In this version, the illustrations have been moved beside the relevant section of the text.

Printer errors have been changed, and they are indicated with a mouse-hover and listed at the end. All other inconsistencies are as in the original.

By

Annie Lash Jester

Member, Virginia Historical Society

Virginia 350th Anniversary Celebration Corporation

Williamsburg, Virginia

1957

COPYRIGHT©, 1957 BY

VIRGINIA 350th ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION

CORPORATION, WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA

Jamestown 350th Anniversary

Historical Booklet Number 17

PART I

PART II

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

Successful colonization, contingent upon a stable domestic life, was quickened in Virginia with the coming of the gentlewoman Mrs. Lucy Forest and her maid Ann Burras, who with Mrs. Forest's husband Thomas, arrived in the second supply, 1608, following the planting of the colony at Jamestown, 13 May 1607.

The possibility of finding a source of wealth in the new world, such as the Spanish had found in Mexico and Peru, and the more urgent need of finding a route to the East and securing this through the development of colonies across the seas, had motivated the several expeditions, begun with the unsuccessful settlement at Roanoke Island in 1585. Coupled with these reasons, for colonizing in the new world, was an ever expanding population in England, and the ancient law of entail, which limited possession of large landed estates to the eldest sons; younger sons and the scions of the middle classes were left with exceedingly limited opportunities or means of attaining estates in England, or, for that matter, of ever bettering their condition. Also, if England was to sustain its existing population, the nation must have sources of raw materials other than the dwindling supplies in the land, and it must have also outlets for the wares of the artisans.

Thus, while the hope of wealth in one form or another was a factor in the settlement of Virginia, a prerequisite to attainment, also taken into account by the promoters of expeditions, was the establishment of homes in a new land. Homes would serve as stabilizers for permanent bases, from which could be carried on the trade essential to England's rising position as a leading power.

Notwithstanding hardship, discouragement and sickness, the firm [2]resolution of the English succeeded. Their determination, as shown in their several attempts at colonization, culminated eventually in a colonial homeland, which offered to gentlemen adventurers the lure of the unknown, as well as the prospect of land, and, to the many unemployed craftsmen a demand for their labor and privileges which could not be had by the average man in England.

Withal, the fireside became the bulwark for the great new venture. And, fortunate it was that such a base had been established, for, by the middle of the seventeenth century, many scions of the English upper classes were forced into exile because of the Civil wars, which reached their climax in the beheading of Charles I. A number of the King's loyal subjects found havens in Virginia and not only managed to bring with them some of the family wealth, but also their important connections with the trading enterprises, which gave another impetus to the colonial undertaking.

The silent part of women, ever in the background in the colony, but overseeing orderly households, comforting the men in discouragement and, at the same time carrying on the perpetual cycle of child bearing, was an immeasurable contribution. They braved the unknown to be at the sides of their mates and, as the prospering colony during the passing years of the century increased their responsibilities and burdens, they readily assumed the new tasks. Not least among these was that of household executive: managing servants, seeing that they as well as the family were clothed, fed and attended in their sicknesses, supervising spinning, weaving, garment making and generally maintaining a hub for the operation of plantations ranging from 100 acres to those of several thousands.

To the Englishman, the basis for wealth and position was a large landed estate. News from Virginia had spread the information that great fertile lands, sparsely inhabited by the natives, were available. Thus, valid expectations sent the women thither, some with their husbands, some to join their husbands, some to[3] follow their sweethearts and, by 1620, some to find husbands among the men who were toiling to establish the Colony firmly and longing for the comforts of their own firesides.

The first wedding in Virginia took place in 1608, not long after the arrival of Mrs. Forest and her maid, who, as may be surmised, did not long remain a maid. John Laydon, who had come as a laborer in 1607, took her, a girl fourteen years old, then of marriageable age, for a bride. In 1625, they were living with their four daughters in Elizabeth City Corporation.

The Laydon marriage probably had taken place in the rough little church built at Jamestown within the stockade, which enclosed also the first houses of the settlers along with a guardhouse and a storehouse. The stockade, actually a triangular fort built as protection against the natives, was erected of a succession of upright logs, some twelve feet in height and sharpened to a point. The small buildings within, patterned after the simple homes of the peasantry in England, were built of available material. Beams were cut from the trees in the forests close by, the timbers being held together with pegs. The uprights were interwoven with osiers or stout vines and, on these wattles, was daubed the clay and mud found in the surrounding area, which the colonists had mixed with reeds from the marshes. Coatings of this applied both outside and inside, when dry, made thick, though perhaps fragile walls. Nevertheless, they shut out temporarily, at least, the chill winds and the summer heat. Material for chimneys was not then available, and the colonists made do the ample openings in the roofs thatched with reeds. Sometimes, skins were attached on the outer sides of these openings and flapped over the hole, in a heavy storm, to shut out the rain. Openings for light were closed with sliding panels. Shallow wells within the stockade supplied water, not always unpolluted.

The tinder-like material, with which these first buildings were[4] constructed, together with the open central fires, made them a prey to flames in January, 1608, which shortly were out of control. The reeds, with which the roofs were thatched, merely fed the blaze which spread so rapidly that even the palisades were destroyed. The colonists lost practically everything, including arms, clothing, bedding and provisions held by individuals. Reverend Robert Hunt suffered the loss of his collection of books.

By 1609, a number of women passengers were included among those who departed from England on nine ships, comprising the largest expedition ever sent to Virginia. Reverend Richard Buck brought with him his wife, and although they were among those marooned for nine months on the Bermuda Islands following the wreck there of the Seaventure, both survived the hardships encountered, and established a home at Jamestown and reared a family. Temperance Flowerdieu, aged about fourteen years, arrived in 1609 on the Falcon, but presumably returned to England, shortly to come back, in 1618, as the wife of Sir George Yeardley. Thomas Dunthorne's wife came in the Triall, 1610, and their servant Elizabeth Joones was among those on the Seaventure who eventually reached Virginia in the Patience, 1610. Sisley Jordan, later wife of William Farrar, came in the Swan, 1610.

By the time the second contingent of women had arrived, America's first industry, glass making, had been established and the colonists had built some twenty houses, providing also for themselves a well of "excellent sweet water" within the fort. The conditions of living were somewhat improved. The fragile walls of the church, having begun to crumble, were renewed and a block house was built on the neck of the Island, to which point the savages were permitted to come for trade, but were prohibited from further passage by a garrison kept there. When not otherwise employed, the men spent their time fashioning clapboard and wainscoting from the trees cut from the surrounding forests.[5]

Finding their limited food supplies spoiled by mold or eaten by a horde of rats, the offspring of rodents which arrived also on the first ships, the colonists were forced to the necessity of "living off the country." In the spring they planted some thirty or forty acres hoping for a plentiful crop before midsummer. Also, upon taking an inventory of livestock, they found in all sixty odd pigs, the offspring of three sows which they originally possessed; and some 500 chickens roamed around their habitations, feeding from the countryside. Yet, in order not to tax this supply, sixty or eighty of the colonists were sent down the river to live on oysters and other seafood, obtainable at and near Old Point. Sturgeon was plentiful; in fact, there being a greater supply than could be used, some of the surplus was dried, then pounded, mixed with the roe and sorrel to provide both bread and meat. Also, an edible root called tockwough (tuckahoe, a tuberous plant growing in fresh marshes, with a root similar to that of a potato) was gathered, and after the Indian fashion, pounded into a meal from which bread was made.

In order to conserve their scarce food supply, the colonists sought to acquaint themselves with the use of the native resources. To this end, a number of the settlers were billetted with the Indians. They not only learned to distinguish the edible roots, berries, leafy plants and fruits, and how to prepare them, but found the whereabouts of Indian trails, the location of their villages, and fields where they cultivated corn, beans, and apooke (tobacco).

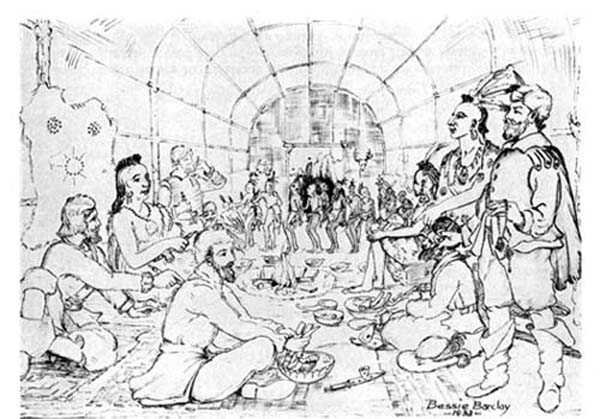

Photo of a group in the U. S. National Museum,

Washington, D. C.

Photo of a group in the U. S. National Museum,

Washington, D. C.Yet, a scarce two years in the wilderness hardly equipped the Englishmen to cope with the altogether new situations which they encountered. Aside from the lack of adequate provisions for the heavy diet in beef, mutton and pork to which they were accustomed in England, there were at least two months of hot,[6] humid weather to which they were not acclimated. Moreover, during this period, the "sickness"—probably malaria and yellow fever from the West Indies and diarrhea from polluted drinking-water—was rampant. Also the hostility of certain of the Indians increased the death toll. Debilitated, discouraged and fearful of the savages, the survivors hovered together at Jamestown. By May 1610, all of their livestock had been consumed, including hogs, hens, goats, sheep and even a horse. Finally, the sixty living began to trade their weapons to the savages in exchange for food.

This was the state of the colony when 150 adventurers—men, women and children—marooned for nine months on the Bermuda Islands after the wreck of the Seaventure, arrived in the Patience and the Deliverance commanded by Sir Thomas Gates and Sir George Somers. The newcomers, who already had passed through a harrowing experience, faced a forlorn situation in the land of their destination; and so their leaders concurred in a decision to return to England. But, Lord De La Warr's timely arrival, with three ships exceedingly well furnished with all necessaries, changed the outlook. Here were not only the means of survival but resources for some stable home life. Several of the women who had sailed in the 1609 expedition reached Jamestown ahead of their shipwrecked husbands, who had accompanied the official party on the Seaventure. Among these were Mrs. Joane Peirce, wife of Captain William Peirce, and their daughter Joane, who arrived at Jamestown, 1609, on the Blessing.

One of Lord De La Warr's first commands ordered the building of a number of houses, since he found the fragile buildings erected of unseasoned timbers, after the fire, already in a state of decay. The roofs of these new dwellings were covered with boards and the sides were fortified against the weather with Indian mats.[7]

The following May, 1611, Sir Thomas Dale reached Jamestown with three ships, men, cattle and provisions for a year. Four months later, six ships under Sir Thomas Gates, who had carried back to England news of the desperate straits of the colony in 1610, arrived with a complement of 300 men, 100 kine and other livestock, with munitions and all manner of provisions.

Dale, a hard taskmaster, in his capacity as Marshal, put the settlers under a military regime and, in requiring a schedule of work for everyone, succeeded in establishing the colony on a firm basis. He ordered at once the repair of the Church, the storehouse and other buildings, adding a munitions house, a building in which to cure sturgeon, a cattle-barn and a stable.

In order to broaden the base of the colony, Dale at once set about seeking a suitable location for a new town, which he located on the neck of land since changed into an island by the Dutch Gap canal, and later known as Farrar's Island. At the site of the projected town, laid out on a seven acre enclosed plat, and called Henrico, he raised watchtowers at four corners, built a wooden church and several storehouses, laid off streets on which frame dwellings were erected, with the first stories, probably the foundations, built of brick. This is the earliest mention of the use of bricks for home building in Virginia. Also, five houses were erected on the banks of the James River, the dwellers agreeing to act as sentinels for approach to the town by water.

The elements, however, favored the new town no more than Jamestown, and the buildings were constantly in need of repair. A hospital was projected for location at the new town and its building begun. At the site, also, a college for the education of the Indians was planned, and iron works were erected at Falling Creek, a portion of the profits from which, under agreement, was to defray the cost of operation of the proposed college. As is well known, the Indians, in an attempt to wipe out the colony in 1622, practically obliterated the town.[8]

Terms agreed upon, in the Virginia Company at the beginning of the settlement, stipulated that there should be no individual assignments of land during the first seven years. The communal plan, under which the colonists lived through these years, was terminated while Dale ruled the colony; a policy was adopted of assigning rights for a hundred acres to every individual who had come to Virginia, before 1616, with the intention of planting (settling). This acreage could be doubled under certain conditions. Those who came, after 1616, were entitled to fifty acres each, provided they paid their own passages. Similarly, each could claim an additional fifty acres in the name of every person whose passage he paid. This was known as the headright system of granting land. Thus, a man with a wife, three children and two servants, was entitled to 350 acres. Not only did these generous provisions, for the acquisition of landed estates, lure settlers to the new world, but they provided a sound base for the beginning of a secure domestic life in the colony.

Unfortunately, there is no complete list of the women who came to Virginia prior to 1616, but, in addition to those heretofore named, the presence of others is recorded. Joane Salford, wife of Robert Salford of Elizabeth City, came by 1611, and Salford's sister Sarah reached Virginia at the same time, or just a year or so later. Susan, wife of John Collins of West and Shirley Hundred, came in the Treasurer, 1613. Elizabeth, wife of Lieutenant Albiano Lupo, came in the George, 1616, and little Susan Old was brought by her cousin Richard Biggs, when she was only two years of age; eight years later she was reported living with the Biggs family in Charles City Corporation. Martha Key was with her husband Thomas by 1616. Rachel Davis joined her husband Captain James Davis before 1616, and their son Thomas later settled in Isle of Wight and Upper Norfolk (Nansemond) Counties, taking out land patents, in the name of his parents as old planters. Mary Flint, wife of Captain Thomas[9] Flint of the area which later became Warwick County, was the widow of Robert Beheathland, who had come to Virginia with the first settlers in 1607. Beheathland's wife arrived some time before 1616 and they had two daughters, Mary and Dorothy, who married and left Virginia descendants. Izabella,—three times married, first to Richard Pace, second, to William Perry and third to George Menefie came to the colony before 1616.

After the first settlement at Jamestown, the Virginia Company recognized that youthful, hearty young men were essential in the new land, in order to cope with the wilderness. Inducements were offered, both in passage across the seas at Company expense, and in supplies and equipment furnished each man. Moreover, by 1616, there was the lure of land at the end of the required seven-year tenure of service and the hope of becoming a planter. Probably, articles of indenture were drawn for these tenants as they were later between colonists and their servants.

The cost of sending and supplying these young men was a considerable sum. Passage alone cost £6 and, together with supplies furnished and freight on them, the total cost of bringing a youth to Virginia amounted to £20. Even if an adventurer paid his own passage he was advised to come with the same "necessaries." In apparel, each needed a Monmouth cap, three falling bands (large loose collars), three shirts, a waistcoat, a suit of canvas (work clothes), a suit of frieze and a suit of cloth, also three pairs of Irish stockings, four pairs of shoes, a pair of garters, a dozen points, a pair of canvas sheets, canvas to make a bed and a bolster, to be filled in Virginia and serving for two men, canvas to make a bed enroute, also for two men, a coarse rug (covering) at sea for two men.

In food the adventurer needed eight bushels of meal, two bushels of peas, eight bushels of oatmeal, a gallon of wine, a gallon of oil and two gallons of vinegar. In armor, he was advised[10] to possess a complete light suit, a musket, a sword, a belt and a bandoleer, twenty pounds of powder and sixty pounds of shot or lead, together with a pistol and goose-shot.

For a group of six men the following tools were deemed essential: five broad-hoes, five narrow-hoes, two broadaxes, five felling-axes, four handsaws, a whipsaw with equipment for filing, two hammers, three shovels, two spades, two augers, six chisels, two piercing tools, three gimlets, two hatchets, two frowes, two handbills, a grindstone, nails of all sorts and two pickaxes.

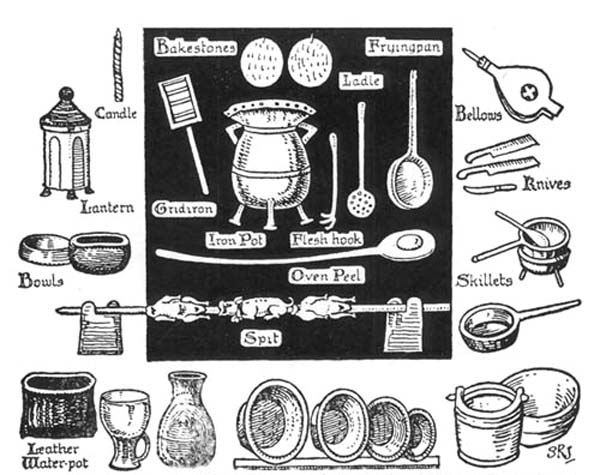

Household utensils to be used by six persons included an iron pot, a kettle, a large frying-pan, a gridiron, two skillets, a spit, platters, dishes and spoons of wood.

There was a charge for sugar, spice and fruit to be supplied on the voyage. Moreover, if the company was made up of a number of persons, they were advised to bring, in addition to the above: nets, hooks and lines for fishing, cheese, kine and goats.

By 1618, the Virginia Company had set aside 3000 acres of land in each of the four corporations, Elizabeth City, James City, Henrico and Charles City, where they settled these young men known as the Company's tenants. Half of the profit from their labors went to the Company to defray costs of Colonial government. However, Governor Sir George Yeardley realized that far too few of these substantial workers, inured to the climate and the wilderness, were satisfied to remain in the Colony. He, forthwith, reported the situation to Sir Edwin Sandys, then Treasurer of the Company, who then proposed that one hundred "maids young and uncorrupt" be sent to the Colony to become wives, stipulating that their passage would be paid by the Company if they married the Company's tenants; otherwise, their passage money should be reimbursed to the Company by the planter-husbands whom they had chosen.

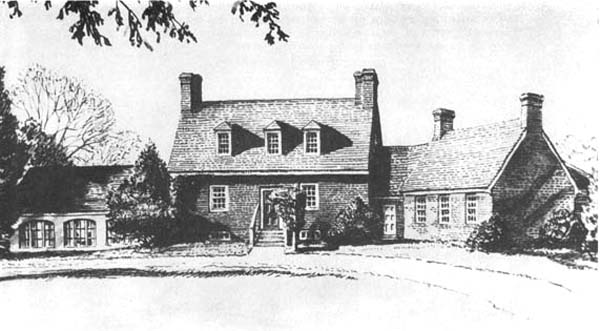

Photo by Flournoy, Virginia State Chamber of Commerce

Photo by Flournoy, Virginia State Chamber of CommerceBy 17 May, 1620, ninety young women had come to the Colony under these arrangements, having embarked in the London Merchant and the Jonathan. The following year, an additional[11] fifty-seven young women came in three ships, the Marmaduke, the Warwick and the Tiger. The Virginia Company reported to Governor Yeardley that "extraordinary diligence" and care had been exercised in the choice of the maids, and that none had been received, who had other than excellent reputations in their communities. They further reported that they had provided "young, handsome and honestly educated maids."

Evidently, there was no problem in arranging marriages, and report went back to England that among the last fifty-seven sent to Virginia, many had been married, before the ships, on which they arrived, had departed from the Colony for the return voyage. But, whom they and the others married is not known, nor are the fates of the 147 young women who came to fill gaps in home life, known. Some were certainly slain in the massacre, others must have died of the sickness soon after coming, for Governor Berkeley later estimated that four out of five persons died, in the early years, shortly after arrival, especially if they came in late spring or summer when the sickness took its toll.

In an effort to reduce the financial burden of colonization resting solely upon the Virginia Company, and at the same time to satisfy some of the shareholders, who were complaining of no profit from their investment, their Council sitting in London, inaugurated a policy of assigning thousands of acres for "particular plantations." These acreages were promised to shareholders and other promoters, who agreed to transport colonists to Virginia and keep them supplied. Usually several promoters joined in assuming the costs of such adventures and, thus, the Company was altogether relieved of the cost and responsibility of settlement. In this category were the plantations at Martin's Hundred, Berkeley, Smith's (Southampton) Hundred and Newport News. Thomas Southey, who outfitted a ship and set out from England with his wife, six children and ten servants, came with great[12] expectations, having indicated his desire that the Company would assign to him a "particular plantation." His ship arrived safely in Virginia but before his hopes were realized, he and three of his children had died. However, one of his surviving daughters was the progenitor of a well known Eastern Shore family.

The settlement of Berkeley Hundred as a "particular plantation" was agreed upon, in 1619, with Captain John Woodliffe. The promoters, one of whom was John Smith of Nibley, England, soon became dissatisfied with Woodliffe's management of the project and revoked his commission, assigning a similar commission to William Tracy. In 1620, Tracy booked fifty colonists, twelve of whom were women, to come over in the Supply. The ship was exceedingly well furnished with necessaries of every description that might be of use in his undertaking. Every item in the cargo on the ship of sixty tons burden is listed from onions to millstones. A resumé will give some idea of the wealth of commodities brought to Virginia in 1620. Among the implements useful for clearing land were pickaxes, felling-axes, squaring-axes, spades, weeding-hoes, scythes, reap-hooks. Grindstones and two French millstones were brought along with 22,500 nails, an anvil and two sieves for making gunpowder.

Material for making garments included linen of several grades, blue linen for facing doublets, dowlas, canvas for sheets and shirts. Ready for use were breeches of russet leather with leather linings, 100 Monmouth caps (round caps without a brim used by soldiers and sailors), 200 pairs of shoes of seven sizes, 100 pairs of knit socks, 100 pairs of Irish stockings, falling-bands, which were the large loose collars that fell about the neck replacing the stiff ruff of the sixteenth century. Accessories included glass beads, buttons, thread, both brown and black, twelve dozen yards of gartering, bone combs, scissors, shears and tailors' shears.

Among the utensils were trenchers (wooden plates or trays), bread-baskets, wooden spoons, porridge dishes, saucers and four dozen platters. For food there was wheat, butter, cheese, white[13] peas, dried malt (probably for making beer), oatmeal, sugar, Irish beef, salted beef, pork and codfish, flitches of bacon, biscuit and a separate item of pap (mush) for indentured servants. Spices brought over included pepper, ginger, cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, mace, and in the dried fruits there were dates, raisins, currants, prunes. A single variety in nuts is listed in a quantity of almonds, certainly a luxury in the colony in 1620.

For the household and various uses on the plantation there were barrels of tar and pitch, six hogsheads of baysalt (i.e. salt evaporated from sea water), 102 pounds of soap, ten gallons of oil, candles, wire candle-holders, lanterns and bellows. There were drugs and physic for the indisposed. Spring planting had not been overlooked for the ship brought a quantity of seeds in parsnips, carrots, cabbage, turnips, lettuce, onions, mustard and garlic.

For protection there were corslets, muskets, swords, lead and powder. Six bandoleers were listed; they were belts with loops holding pierced metal cases which held the matches for firing the powder which set off the charge in guns. The matches mentioned were actually slow burning fuses, as the modern match did not come into use until the nineteenth century.

Tragedy followed closely upon this auspicious second start for Berkeley Hundred. William Tracy was dead by 8 April 1621 and his wife Mary died the same year. Their daughter Joyce, who had married Captain Nathaniel Powell, was slain with her husband in the Indian massacre of 1622. A son Thomas who survived returned to England.

Of the twelve women named in the passenger list of the Supply, Joane Greene failed to make the trip and also, probably, Frances Page, whose husband was reported not to have come with the party, although he was booked. Frances Greville, a young gentlewoman, a cousin of the Tracys, was married by 1621 to young Nathaniel West, son of Lord De La Warr. Shortly becoming a widow, she thereafter married, as his second wife, the cape-mer[14]chant Abraham Peirsey and upon his death, 1626, she became the wife of Captain Samuel Mathews of "Denbigh" on the Warwick River. William Finch, who brought over his wife and daughter Frances, was dead by 1622, and the widow shortly thereafter became the wife of Captain John Flood and the mother of three sons and a daughter. Jane Rowles, with her husband Richard, was slain and, though Joane Coopey and her son Anthony died, the daughter Elizabeth survived. Elizabeth Webb married in Virginia, and Isabel Gifford had been wed to Adam Raymer while the Supply was on the high seas.

As has been previously indicated, all supplies, sent to the Colony during the first ten years, were paid for through the Company's treasury, but so great was the financial burden, particularly since the Colony was not yielding the profit anticipated, that a different arrangement was sought, in 1617. There was organized within the Company a "Society of Particular Adventurers for Traffic with the People of Virginia in Joint Stock." This was known as the Magazine, to which members of the Virginia Company contributed such sums as they were willing to venture. In practice, it was an association of private investors who, upon return of the ship that had been sent stocked to Virginia, divided the profits from the sale of goods and the tobacco returned on the ships, according to their investment in the enterprise.

The first of these ships to arrive in the Colony was the Susan, a vessel of small tonnage, with a cargo restricted to clothing of which the colonists ever stood in great need. Abraham Peirsey was in charge as Cape-Merchant and it was his responsibility also to dispose of the cargo at a price that would bring a profit to the promoters. The exchange, of course, was in tobacco or sassafras, the only two commodities at the time, which could be disposed of in England at a profit. Evidently, Peirsey was successful in his bargaining, for upon his return to England in the[15] Susan, he came back the following year with the second magazine ship, the George, which was delayed five months and in consequence unloaded a damaged cargo. Although during the remainder of the Company's tenure in Virginia, until June 1624, transportation of supplies, supposedly was restricted to the magazine ships, the vessels of private adventurers often reached the Colony with articles which were in the luxury class such as sweetmeats, sack (wine from southern Europe) and strong waters (liquor). The Dutch probably were the chief promoters of this trade, which England sought unsuccessfully to prohibit, as diverting the tobacco trade from the realm and diminishing the royal customs.

The dissolution of the Virginia Company in London, May 1624, left the colony without restriction to independent traders, who shortly began to respond to the colonists' eagerness for supplies from overseas. There is, however, a record of the Colony at the conclusion of the Company's administration taken just ahead of the influx of the accelerated trade.

As the Company was about to be dissolved, Captain John Harvey (later as Sir John Harvey, Governor of Virginia) was sent over to obtain exact information as to the number of people in Virginia, their names, where they lived and what supplies and arms they possessed. The document preserved in the British Public Record Office shows to what degree the planters had spread their homes along both banks of the James River from Henrico to Elizabeth City and Kecoughtan at the confluence of the James River with the Chesapeake Bay (this point now Hampton Roads) and on the Eastern Shore. In addition to the names of all persons living in the colony, the ages of many are given, together with the times of their arrival, and the names of the ships on which they came. Also, those recently deceased are listed.

The 1232 persons living in Virginia, January, 1625, dwelt at[16] twenty-five locations. Several of these were large plantations, such as Peirsey's Hundred, Mr. Treasurer's (George Sandys'), Martin's Hundred, Captain Roger Smith's, Captain Samuel Mathews', Mr. Crowder's, Mr. Blaney's and Newport News, where colonists lived in groups, presumably as employees for the promotion of extensive enterprises. As previously mentioned a number of these colonists at Henrico, James City, Charles City and Elizabeth City were living on the Company's land. Yet, many at this time dwelt upon their own acreages, assigned to them individually in patents of record in a list sent to England the following year. For instance, Lieutenant John Chisman and his brother Edward were living at Kecoughtan on their patent of 200 acres, as was Pharoah Flinton who had been assigned an 150 acre plot, and John Bush with his 300 acres, where he dwelt with his wife, two children and two servants. For protection against the Indians, palisades had been erected at a number of the plantations.

Staples on hand are listed for every household, including corn, peas, beans, oatmeal, fish, the latter both smoked and in brine. Besides, many of the planters owned swine, poultry, goats and cattle. A few luxuries were mentioned such as a flitch of bacon, cheese and oil. For protection, the colonists possessed armor such as had been used in England, but which probably proved to be of little use against the stealthy natives in thickly wooded areas. Nevertheless, there were whole suits of armor, including headpieces, coats of mail and coats of plate and jack-coats (thickly padded jackets). The guns were of various types. Many apparently were of the older design and the charge had to be fired by the application of a fuse; others had been fixed with the more up-to-date firing mechanism attached to the gun. There were also matchlocks, snaphaunce pieces, pistols, swords and hangers (cutlasses). For the larger plantation there were small cannon, called murderers, usually placed at the bow of a ship to prevent boarding, falconets and petronels. The matches mentioned were[17] the slow-burning fuses, kept by a soldier in his bandoleer. Once ignited, these "matches" kept a smouldering fire and could be used again and again. Pirates were accustomed to stick them lighted in their beards and hair, not to give a ferocious look, but for convenience.

Powder and lead also were on hand in many households, for life, on the edge of a wilderness with stealthy Indians frequently lurking about, was hazardous in the extreme. Men who worked in the fields took fowling pieces with them and, at times, armed guards were stationed to be on the lookout, and warn the workers in case of danger.

Among other possessions listed were the houses of the planters, their boats—barks, shallops and skiffs being named—and, at George Sandys' plantation across from Jamestown, a house for silkworms had been framed. The prolific growth of mulberry trees, about the Indian settlements and elsewhere, encouraged the English to conclude that Virginia was an ideal location for development of the silk industry. Greatly encouraged from England, the colonists made earnest efforts, throughout the seventeenth century, to establish the culture and production of silk on a paying basis. However, the lure of profit accruing from the easy tobacco crop, plus the difficulty in obtaining for the Colony skilled silk workers, resulted eventually in the abandonment of the undertaking.

Fearing that their right of assembly, instituted in 1619, would be revoked, the colonists, following the abrogation of the charter of the Virginia Company, opposed the decision of King Charles I, to take over administration of affairs in Virginia, and sent a protest to England, 1625. Nevertheless, facing the inevitable, they acceded to the Royal demands and surrendered the colony to the King. One of the immediate effects of the change in control was a stimulus to trade. So abundant were the supplies brought[18] in by traders, now independent of the requirements formerly placed by the Virginia Company, that the colonists, by 1630, had often become deeply indebted to the English merchants.

An account of a trading voyage to Virginia, a venture in which eight Englishmen joined to send both cargo and indentured servants to the Colony and bring back tobacco, not only conveys an idea of commodities and servants sold for domestic purposes, but projects a picture of life along the estuaries flowing into the Chesapeake Bay, as the ship plied from one plantation wharf to another, selling merchandise and human help, both in demand. The Tristram and Jane of London left England in the late summer or early fall of 1636, arriving in Virginia in time for the fall tobacco crop ready for the market in December. Daniel Hopkinson, merchant, was in charge of the cargo, but dying before the ship's return to England, he requested to be "decently" buried at the Kecoughtan (Elizabeth City) Church.

At five or more ports of call, both cargo and servants were disposed of. There were a number of items in the luxury class, such as sack (white wine from southern Europe), strong waters (drink high in alcoholic content), candy oil (olive oil from the island of Crete, originally known as Candia), sugar, both powdered and loaf, shelled almonds (least in demand among the items), marmalade of quinces, conserves of sloes (plums), of roses and barberries, raisins, Sussex cheese, vinegar, and handkerchiefs. Among the more useful items were: 87 pairs of shoes, 12 suits of clothing, nails of various sizes, of which there appeared to be never enough in the Colony, peas and oatmeal. In addition to these, a shallop, a pair of steelyards (scales), and three fowling pieces were disposed of.

The ship stopped first at Kecoughtan (now Hampton), a populous settlement, having been established by the colonists in 1610, and, here, buried Hopkinson and disposed of some of her cargo of seventy-four white persons who were sold as indentured servants. These persons, before embarking from England, had[19] agreed to serve a term of years, usually seven, in the Colony in return for passage, clothes and supplies, to be furnished them at the conclusion of their service. The major portion of help in the colony, at this period, was of this class, although a few Negroes were brought to Virginia by 1619, and approximately a score are listed in the muster of 1625.

Upon departing from Kecoughtan, the ship retraced a portion of her course in the Chesapeake Bay, and entered Back River, on which the Langley Air Force Base and the laboratories for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics are now located, and from there entered the Old Poquoson River, later termed the Northwest Branch of Back River. This very populous area was readily accessible to the port of Kecoughtan both by water and by land.

Next, the Tristram and Jane discharged cargo and sold servants on the New Poquoson (now Poquoson) River, which flows into the Bay north of Back River. In this latter area, first settled in 1630, patents had been assigned, one including a large acreage to Christopher Calthrope, and it is reasonable to conclude that both commodities and servants were wanted.

From the New Poquoson, the ship sailed across the Chesapeake and traded at Accawmack on the Eastern Shore, and then sailed back towards the mouth of the James River, and entered Chuckatuck Creek and the Nansemond River, where the Gookins, whose father had settled Newport News in 1621, bought two servants. Other ports are not named, but among the purchasers of servants was George Menefie on the James below Jamestown. It is probable that the ship went as far up the River as the mouth of the Appomattox.

Prices paid for the servants were not all the same, and a bonus of fifty acres of land accrued to the planter, if the servant's passage money was added to the purchase price.

Having unloaded the entire cargo, the Tristram and Jane took on tobacco for the return voyage, loading 99 hogsheads or a total[20] of 31,800 pounds. In addition, the partners in the shipping enterprise loaded two hogsheads on the Unity of Isle of Wight, making a total poundage of 32,350.

The America was another of the trading vessels, which made annual voyages to Virginia, between the years 1632 and 1636, and showed a profit, in each of the first three years, of 640 pounds sterling. This was divided among several partners in the enterprise. William Barker was master and part owner of the vessel and made his Virginia headquarters in Norfolk, where brief accounts of the voyages were entered in the Court records, in 1646.

As commodities began to reach Virginia in quantities, tools and building supplies became available, and skilled workers arrived. Thus, homes could be more sturdily built. By 1620, Reverend Richard Buck, who had reached Virginia, 1610, had purchased from William Fairfax the latter's dwelling house located on twelve acres of land in James City. In 1623, William Claiborne was sent to the colony and laid out an area on Jamestown Island known as New Town, where a number of dwellings were erected.

As the colonists had begun to fashion clapboard and wainscoting by 1609, and were using brick made in the Colony by 1612, the houses, built in this newly laid-out area, were far more substantial than the early shelters described. Among those dwelling in New Town, by 1624 were, Richard Stephens, Ralph Hamor, George Menefie, John Chew, Doctor John Pott, Captain John Harvey and Ensign William Spence.

In 1624, John Johnson was ordered by the Court to repair the "late dwelling house" of Spence. References to other houses mentioned are found in the early land patents. Abraham Peirsey, the cape-merchant, directed, in his will dated 1626, that he be buried in his garden, where his new frame house stood. Thomas Dunthorne's house is mentioned, in 1625, and in 1627, Sir[21] George Yeardley noted, in his will of that date, his dwelling house and other houses at Jamestown.

Since the materials are of record, these recently built homes may be envisioned as having been constructed of hewn timbers, covered with clapboard on the exterior, and wainscoting inside. The foundations and chimneys were of brick, which, while not plentiful, was certainly being supplied within the Colony at the period. Clay from the James River shores and the Chickahominy was available, and reeds from the marshes at hand furnished the necessary straw. It is entirely improbable that bricks were at any time brought from England for building purposes. Cargo space on inbound ships was too valuable and supplies too badly needed to fill ships' holds with bricks, especially when materials for making them were so close at hand.

Similar houses were being built in other areas at the same period. Mrs. Rachel Pollentine's house in Warriscoyack (Isle of Wight) is mentioned in 1628. John Bush had two houses at Kecoughtan by 1618.

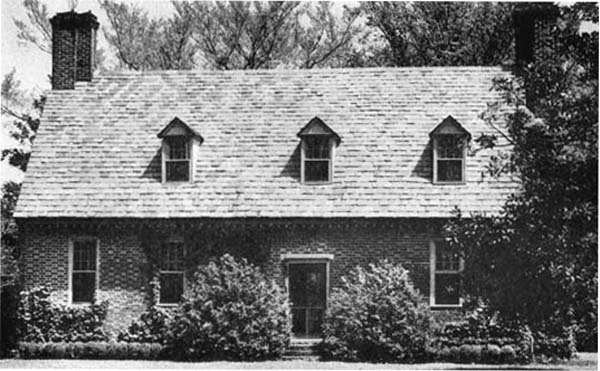

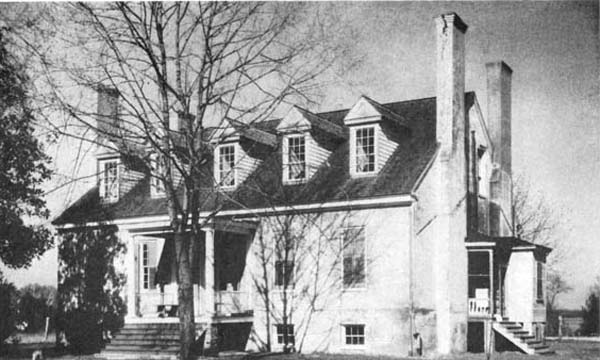

Governor Sir John Harvey reported that Richard Kemp, Secretary of the Colony, had the first brick house built in Virginia, in 1636, and at Jamestown. However, Adam Thoroughgood, who was granted land at Lynnhaven in Lower Norfolk County, is said to have begun construction of his brick house there between 1636 and 1640. This house, which has undergone numerous modifications throughout the years, is believed to be the oldest colonial home now standing in Virginia. Originally, it is believed to have been a one story, single-room house with chimneys at both ends. Access to the loft above was by a ladder-like stairway; the dormer windows were a later addition.

A very early house in Virginia, of which there is a clear Court record, is the brick dwelling of the colonial planter Thomas Warren, located on Smith's Fort Plantation, in Surry County. It is sometimes called the Rolfe House, as the land, on which the[22] house was erected, was a gift from the Indian King to Thomas, son of John Rolfe and Pocahontas.

Photo by Flournoy, Virginia State Chamber of Commerce

Photo by Flournoy, Virginia State Chamber of CommerceThe dwelling-house of Captain Thomas Bernard on Mulberry Island was mentioned in 1641. The Wills family lived in the same area in a brick house during the 1650's, for, in 1659, Henry Jackson bequeathed, to "my widow's eldest son John Wills, the part that belongs to him of my wife's brick house and lands on Mulberry Island."

Before 1627 the first windmill in the colony had been erected and was in operation at Flowerdew Hundred, Governor Yeardley's plantation on the south side of the James River. The more affluent planters like Yeardley, and in keeping with the English customs, maintained homes at the seat of government while operating large plantations on the River not too far distant.

William Peirce, captain of the Governor's guard, had a plantation project on Mulberry Island while he and Mrs. Peirce lived at Jamestown. On a visit to England in 1629, Mrs. Peirce reported, that she had lived for 20 years in the Colony, and from her garden of three or four acres at Jamestown, she had gathered about 100 bushels of figs, and that she could keep a better house in Virginia for three or four hundred pounds a year than in London.

Young Daniel Gookin, probably with his brother John, was living at Newport News in 1633, where their father had established a home called "Marie's Mount," for the Dutch sea-captain Peter deVries recorded that he stopped there over night. The Gookins also maintained a plantation, directly across from Newport News on the Nansemond River, at which point the Tristram and Jane called in 1637.

Richard Kingsmill, who patented land at Archer's Hope, James City, in 1626, planted there a pear orchard, and reported later that he had made from fruit gathered there some forty or fifty butts of perry. In addition to his house at Jamestown, George Menefie maintained a plantation, near Archer's Hope Creek,[23] called "Littletown" where he had orchards of apple, pear, cherry and peach trees, and a flower garden especially noted for its rosemary, thyme and marjoram. Captain Brocas of the Council kept an excellent vineyard on his plantation, in Warwick County, patented in 1638. Richard Bennett, of Nansemond River, developed an apple orchard and, in 1648, reported that he had made from it twenty butts of cider.

About 1625, Captain Samuel Mathews moved his seat from the south side of the James River to a location near Blount Point at the mouth of the Warwick River, and across from Mulberry Island, which later was called "Denbigh." He married, a year or two thereafter, the widow of the cape-merchant Abraham Peirsey. A contemporary writer, in 1648, described Mathews' plantation as a miniature village, at the center of which was the manor-house. On surrounding acreage, hemp and flax were sown, and upon being harvested, the flax was spun and woven into cloth in one of the many outbuildings. At a tan-house, eight shoemakers dressed leather and made shoes. There were negro servants, some of whom worked in the fields while others were taught trades. Barley and wheat, grown at "Denbigh," were reported to have been sold at four shillings per bushel. Some of the cattle raised on the place supplied the dairy while others, kept for slaughtering, supplied meat for out-bound vessels. Mathews also kept swine and poultry. Incidentally, Colonel William Cole acquired "Denbigh" from the Mathews family in the latter part of the seventeenth century. In turn, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, descendants of Cole conveyed the original home site and several hundred acres of the plantation to Richard Young, whose descendants still own a portion of it.

"Greenspring," Governor Berkeley's home about three miles inland from Jamestown, was built of brick soon after 1642, to which additions were made at different times; recent excavations show that it was ninety-seven feet, five inches in length by twenty-four feet, nine inches in width. The rooms on the ground[24] floor, overhung by a colonnade, were in single file with an ell on the north front at the west end. Only the foundations of the structure remain. The ever-flowing spring, from which the plantation took its name, is maintained within a brick enclosure.

"Bacon's Castle," in Surry County, built by Arthur Allen soon after his arrival in Virginia about 1650, passed to his son, Speaker of the House of Burgesses, from whom it was seized by Bacon's followers, 1676, and garrisoned by sympathizers under William Rookings. Bacon is not known to have visited the house, although, since its eventful occupation by his followers, the early Allen home has been known by his name. The cluster chimney is a unique feature of its architecture, as is the gabled end. The bricks were laid in English bond.

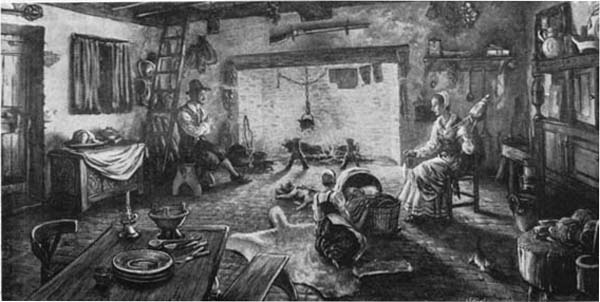

Of the typical frame homes of the seventeenth century, occupied by the average family, not one remains, which can be dated with authority. However, from extant descriptions, it is known that these modest homes for the most part were one-story structures, with a loft above, to which there was access by means of a ladder-like stairway. Dormer windows, added in the eighteenth century to some of the homes, made of the loft a half-story, providing for more comfortable sleeping quarters for the family. There were chimneys at both ends of these early homes, and meals were prepared on the open hearth of the larger fireplace. The early homes apparently had no partitions, but by the middle of the century, some were divided by one partition on the lower floor. Cellars were not practical in the low-lying areas, for in wet weather the water-table is level with the ground. Inland, for the better homes, in the last half of the century, there were cellars, though some of the more modest structures merely had unbricked excavations below for storage purposes. The size of the modest homes varied, in length, between thirty and forty feet and, in width, between eighteen and twenty feet. In 1679, Major Thomas Chamberlaine, of Henrico, contracted for a frame house forty by twenty feet without a cellar. In 1686, Benjamin Branch's[25] brothers built for him "a home twenty feet long" on the family plantation "Kingsland" in Henrico.

When the English transported themselves or were transported to Virginia, they brought with them as much of England as possible in their manners, their customs, their pride in family and race, their laws and their possessions. With something of nostalgia for home, they often named their plantations for the family estates in England, and the locales, in which they settled, for the shires or the communities near their old world homes. They did not seek to create a new race, as did the Spanish in settling Louisiana who designated themselves Criollo, but to remain Englishmen in the new world. To this end they were willing to struggle and overcome a wilderness. In so doing, they sharpened their native acumen, awakened their inherent resourcefulness, and eventually in the eighteenth century, established themselves as a free and independent people.

Their manner of living in Virginia was determined, not so much by design, as by force of circumstances. Available land and tobacco were determining factors in developing large plantations along the main waterways and small plantations in the hinterlands. Self-sufficiency was concomitant with their way of life.

Although, in several acts of the Assembly, the first in 1680, efforts were made by authorities to create towns, establish central warehouses, and so bring the people together, such attempts met with only partial success. Towns that were projected, in 1680, in expectation of developing centers of population, were difficult to promote. Once started, they languished, as did Warwicktown in one of the eight original shires. Except for its ports of entry, such as Jamestown, Norfolk and Kecoughtan, Virginia in the seventeenth century was not adapted to urban living.

Upon arrival in Virginia, the colonists faced a vast forest.[26] Before them in the April sunshine was a massive wall of shimmering green in the stately pines, cedars and holly, intermingled with the freshly unfolded leaves of the venerable oak, walnut, hickory and beech. There were no grassy plains, no open fields, save the garden plots of small tribes of Indians. Clearing the land, in itself, was a tremendous task.

The choice acreage ever in demand by the colonists was, of course, the open land found in and near the Indian villages. Many a land patent later embraced an Indian field. The Company lands in Elizabeth City were the fertile fields of the Kecoughtan Indians, who had been driven from their habitations there, in 1610, after the murder of a colonist, Humphrey Blount. Following the massacre of 1622, the natives were relentlessly driven from their villages and fields—the Warriscoyacks, the Nansemonds, the Chickahominies and in 1630, the Chiskiackes. Then, the white men took over their areas of cleared land.

Photo by Virginia State Library

Photo by Virginia State LibraryHowever, these fields were but small open spaces required by the Englishmen who arrived in increasing numbers. There was a constant operation, in the seventeenth century, of clearing and planting new lands. As help in the white indentured servants was never very plentiful, the planters, finally resorted to an available supply of Negro labor, being peddled along the coast of the Americas, and landed wherever the slaveships could gain entry.

The muster of 1625 shows that many goats had been brought to the Colony by that time. Multiplying, they provided able assistance during the early seventeenth century in thoroughly clearing away the undergrowth, preparatory to cutting down trees and grubbing stumps. Joseph Ham, in the colony by 1633, resorted to these omnivorous quadrupeds in clearing his land. He lived in the New Poquoson area where growth of all kinds is lush. The region, which has its name from the Indian term for lowlands, had afforded the Kecoughtan Indians a rich hunting-ground. Midst tall pines, oak, walnut, cedar, wild cherry,[27] locust, swamp willow, holly, myrtle and persimmon, entangled with grape vines, reaching the tops of trees, and Virginia creeper, game found a haven. Deer, bears, rabbits, squirrel, opossum, raccoon, foxes, weasels, mink, otter and muskrat were sheltered in the thickets and adjacent swamps, while wild ducks and geese made of the marshes, bordering the waterways, a rendezvous for days and weeks on their flights southward. The Bay at hand, and its estuaries, abounded in trout, hogfish, rock, shad, sturgeon and other edible species in season, not to speak of soft-shell crabs, hard-shell crabs, turtles, terrapin, clams and oysters.

Here was food in plenty, but to clear the land for a crop posed a problem to Joseph Ham. He had married a widow with two young children and the family had one servant only—a maid. The heavy work fell to him, but not all of it, for he turned fifty-one goats into the thickets to feast upon the vines and undergrowth. When he died, in 1638, he bequeathed his herd of goats to his stepchildren and to his wife. Although he left other possessions, including a feather bed, two blankets, a rug, a bolster, a warming-pan, a parcel of pewter, three iron pots, two brass kettles, a brass basin, a copper kettle, three pairs of sheets, one dozen napkins, a table-cloth, a looking-glass, a chest, ten barrels of corn and three shoats, along with his plantation, yet the goats had been his first thought. He carefully designated thirty for his stepchildren and twenty-one for his wife. The present may measure the worth of the goats in the early seventeenth century by this scrupulous legacy.

In establishing the colony, the Virginia Company had projected the idea that the people who settled the land would, in a short time, be able to supply their daily needs. In addition, they would ship to England raw materials needed there, and absorb in return articles produced by the English craftsmen, and such imports from foreign lands as were surplus in England. Thus,[28] a brisk trade was anticipated, and did develop, but not in the direction forecast in the beginning.

As the forests were rapidly being depleted in England, wood and wood products were among the greatest needs. Accordingly, report was made in 1624, that, by 1608 and 1609, such woods as cedar, cypress and black walnut had been exported from the Colony, and both clapboard and wainscoting, fashioned in Virginia, had been sent to the Mother Country, along with soap ashes, yielding the necessary potash, an ingredient for soap-making scarce in England. In addition, pitch, tar, iron ore, sturgeon and glass were exported and sassafras, growing wild in Virginia, was in demand in England for tea making. Ere long, of course, the colonists found that tobacco was a lucrative crop, and put their time, attention and efforts in developing a grade of tobacco, which would bring a good price. Inspection before exportation helped in maintaining the standard.

However, in cultivating tobacco, the Virginia planter also promoted assiduously a program of self-sufficiency for his plantation, so that what was needed in daily living was at hand or could be had from a neighbor. Practically every plantation, both large and small, had livestock and produced milk and butter. Sufficient quantities of corn, barley and wheat were grown to supply year-around needs. Very soon the Englishmen abandoned the Indian method of pounding grain into meal for bread-making and established mills on the fresh-water courses and on tidal waters where the dammed streams and the tide furnished water-power. Mill stones were among early shipments to the colony and locations of some of these seventeenth-century mills remain landmarks in Virginia today. Denbigh, on Waters Creek in Warwick County, Chuckatuck in Nansemond, and the headwaters of the Poquoson in York County are among the sites of early mills. John Bates of Skimeno in Upper York County, a large land owner, operated two mills, one on his plantation[29] called "Pease Hill creek mill" and the other, "Okenneck," a water-grist-mill.

Brandy for family use often was distilled on the plantation. While Philip Fisher of the Eastern Shore bequeathed both his mill and his still to his son Thomas, he directed that his son John should have the use of both, the mill to grind his corn and the still "to still his own drink." Beer was made from malt, and cider was produced from apples grown on the plantations.

The remains of an icehouse uncovered during excavations at Jamestown, and dated about the middle of the seventeenth century, is evidence that the colonists cut ice from the ponds nearby, during a freeze, and stored it for use in summer. These cylindrical structures, usually of brick, erected in a shady spot and reinforced at the base with the cooling earth, were packed ten, fifteen or more feet deep with ice, depending on the supply available. In between the layers, straw and reeds were laid, and the arrangement in general preserved the ice even into the very warm months.

Thomas Cocke, of "Pickthorn Farm" and "Malvern Hill," carried on enterprises established by his father, operating at the latter a flour mill, tanneries and looms for making both woolens and linen. For a specimen of linen five ells in length and three-fourths of a yard wide of the first quality, he received an award, in 1695, of 800 pounds of tobacco, offered by the Assembly in 1692. Both Virginia-made stockings and Virginia-made cloth are listed in the Bridger inventory of 1686.

A pottery kiln, uncovered at "Greenspring," and in operation prior to 1675, shows the interest of the Virginia Governor in having earthenware fashioned in the colony for domestic uses. Morgan Jones of Westmoreland County is mentioned as a "potter" in 1674. At the same time, Joseph Copeland of Chuckatuck, in Nansemond County, was fashioning pewter. The handle of a spoon bearing the hallmark of this earliest American pewterer,[30] of whom there is a record, is extant and may be seen at the museum at Jamestown.

Some of the earliest of the colonists were skilled in boatbuilding, the shipwrecked passengers on the Seaventure having constructed, on the Bermuda Islands in 1609, two pinnaces in which they sailed the 700 miles to Virginia in 1610. The Hansfords maintained a boatyard on Felgate's Creek in York County, where they both built and repaired small vessels. On 17 November 1675, John Allen, Augustine Kneaton and William Hobson of Northumberland County agreed to build a sloop of twenty-four feet by the keel for Andrew Pettigrew and deliver it to his plantation, the sloop to be able "to floor [lay flat] nine hogsheads complete."

These brief mentions by no means complete the story of the independent Virginia planter, who acquired the luxuries shipped from England as the proceeds from his tobacco crop permitted, but who generally had at hand the necessities of life regardless of the times.

The progress, from the status of a younger son in England, to that of a landed proprietor in Virginia, is illustrated in the typical case of Christopher Calthrope, third son of Christopher Calthrope Esq. of Blakeney, Norfolk, England. The seniority of two brothers was a limitation upon opportunity for him in England. As a youth of sixteen years of age he was sent to Virginia, in 1622, in company with Lieutenant Thomas Purefoy, the latter named later Commander of Elizabeth City Corporation.

Young Calthrope had been well supplied by his family before leaving England, even bringing with him a quantity of "good liquor" which, while it lasted, added considerably to his popularity. In the name of the family attorney, the young man shortly was assigned land on Waters Creek, in the area now the site of the Mariners Museum of Warwick. In 1628, he also owned land in a choice area near Fort Henry and adjacent to Lieutenant Purefoy in Elizabeth City.

These tracts, however, provided but small plantations, and so when the area along the York River was opened for settlement in 1630, Christopher Calthrope sought land available in large tracts in the adjacent territory, patenting some 1200 acres on the New Poquoson (now Poquoson) River, which flows into the Chesapeake Bay just beyond the mouth of the York. He called his new plantation "Thropland" after the family estate in England. By 1635, a church had been built on his land and New Poquoson Parish (later Charles Parish) was established, the records of which are the earliest extant Parish records in[32] Virginia. As the Parish then embraced the areas on the west side of the river, the Chismans and other families who had settled on Chisman's Creek, sailed over in their sloops or came in their shallops, to worship there on Sundays.

Captain Christopher Calthrope, the Virginia planter, served both York and Elizabeth City in the House of Burgesses during the period, 1644-1660, and also was one of the Commissioners for York County. He was replaced in the latter office, 1661, since he had gone Southward, the designation then for the area, which lay on the southern border of Virginia and the northern boundary of the present state of North Carolina. Vast tracts of land were available there, and Calthrope, still land hungry, acquired acreage in the Nottoway region, on which his great grandson was living in 1756.

Shortly after Calthrope's demise, his widow Anne petitioned the York County Court to grant her administration of his estate, and on 24 April, 1662, she gave bond with very good security in return for her appointment. Six months later the inventory estimated the estate, with several items not then accounted for, at "30,480 pounds of tobacco and casks." The widow, a son and three daughters shared in the estate, which not only included land in York and at the Southward, but possessions in a considerable number.

Both tobacco and corn were raised on the Calthrope land, hives of bees were kept, and a dairy was in operation. To aid the family enterprise there were nine indentured servants, one of whom, Thomas Ragg, later became the husband of Elinor Calthrope.

Four draught oxen did the hauling on the low-lying plantation. Also there were six steers, thirteen milch cows, five heifers, four yearlings and seven calves, the cows obviously supplying the dairy equipped with ten milk trays, a tub and earthenware pan. Three sows, two barrows and four shoats completed the list of livestock.

All other possessions are listed in the "outer room, the chamber[33] and the shedd." These three areas constituted the Calthrope home. In the chamber where the family apparently lived and slept, there were two feather beds, with the usual appurtenances of bolsters, sheets, blankets, valances and curtains, and also a couch bed and a couch. In the outer room, apparently a storeroom, there was, in accordance with the practice of planters to keep a supply of materials on hand, a quantity of piece-goods in dowlas, lockram, dimity, coarse Holland, fine Holland and tufted Holland, osnaburg and kersey, and seventeen ells (45 inches in English measure and 27 inches in Dutch measure) of sheeting, as well as yarn stockings. A limited supply of colored calico, East Indian stuff and Norway stuff are evidence that the English merchantmen, tramping to all parts of the world, brought some of their cargoes from remote areas to Virginia.

Cooking was carried on in the shed, probably a thinly enclosed area, equipped with a large fireplace and attached to the house. Here, there were andirons, racks, a spit, hooks and bellows. Utensils for preparing food included an iron pot, a gridiron, frying-pan, dripping-pan, two brass kettles, a skimmer, a mortar and pestle, and a grater. Pewter-ware and a supply of three dozen napkins and six tablecloths made meals something of an occasion for the family.

Evidently, the Calthrope family had little fear of enemies in their area, from which the Indians had previously been driven away, for they owned but one gun and that was "unfixt," that is, not equipped with a firing mechanism.

James Calthrope, only son of Christopher, inherited his father's plantation, served as Justice of York County and, in his will, proved 1690, bequeathed land to New Poquoson Parish, which evidently was that upon which the church had originally been erected.

The fourth generation of Calthropes in Virginia maintained title to a portion of the York County grant, more than a century and a quarter, after the progenitor of the family came to the col[34]onies. Thus, did the Englishmen reach out across the seas, and plant branches of their families to carry on in the English tradition in the new world.

By 1644, conditions in England had become difficult because of the Civil Wars. In a correspondence with Daniel Llewellyn of Charles City, William Hallom of England wrote: "if these times hold long amongst us we must all faine come to Virginia."

The message sent by Hallom was prophetic, for by 1650, many well-to-do Englishmen, loyal to the Crown, fled to Virginia to escape the wrath of Cromwell's men. Some were so deeply involved politically that they assumed aliases. This was the case of Captain Francis Dade, who, until the Restoration, was known in Virginia as Major John Smith. Many, who came to Virginia during this period, remained. Mrs. Anne Gorsuch, whose husband, a Royalist, was pursued and killed in England, brought seven of her children to Virginia, but on returning to see to her affairs there, died. The children remained and established families in Virginia and Maryland. Daniel Horsmanden later returned to England and died there; however, his daughter Ursula married, as her second husband, William Byrd I and established the well-known Virginia family of that name.

Also, representative of the Royalists who migrated to Virginia was Colonel Joseph Bridger of Isle of Wight County. The date of his coming is unknown, but he appeared in the records as a member of the House of Burgesses, 1657; thus, apparently, he had been in the county several years prior to that time. His tombstone, uncovered at the site of his home plantation, "White Marsh," was removed in the late nineteenth century and placed in the chancel of the Old Brick Church (St. Luke's) in the county.

Colonel Bridger established in Isle of Wight a large mercantile business, trading Virginia tobacco for commodities[35] needed by the colonists. In addition, on several plantations, aggregating in total over 12000 acres, he raised tobacco and cattle, the latter apparently to supply ships departing for England. As a successful business man he shortly rose to prominence in the colony; he was a member of the Commission to adjust the boundary between Maryland and Virginia, 1664, a member of the Council, 1675, and sat on Governor Berkeley's court at "Greenspring," which condemned to death leaders of Bacon's Rebellion. In 1680, he was commander-in-chief of the militia of Isle of Wight, Surry, Lower Norfolk and Upper Norfolk (Nansemond) Counties, with the title of Major General. Evidently, he maintained a close association with Governor Berkeley, for he was a witness to the latter's will, 2 May 1676. His own will, dated 3 August 1683, with a codicil attached less than two months later, together with the inventory of his extensive estate, taken in 1686, provides interesting information as to the manner of living of the Virginia merchant and planter of the latter half of the seventeenth century.

In the settlement, Colonel Bridger's holdings were shared by his wife Hester (Pitt) and six of his seven children. The eldest son was excluded from his inheritance as Colonel Bridger, evidently a martinet with his family as well as in his official capacity, added in the codicil a directive cutting him off with 2000 pounds of tobacco because Joseph Jr. had been disobedient to him and had gone out in "diverse ways." In friendly suits with his brothers, after his father's death, the disinherited son gained possession of a large portion of his rightful heritage.

The family lived on the 850 acre plantation which Colonel Bridger had purchased from Captain Upton. There was on the place a brick house when the Bridger inventory was taken. There were four rooms on the first floor, including the children's chamber and the dining room, with two rooms in an upper story. Also a "new house" is listed in which there were the hall, the parlor and the lower chamber on the first floor, and on the upper floor[36] three rooms and a "gallery" (hall). All rooms and the halls in both houses were fully furnished. In the cellar beneath the new house the family supply of drink was kept. The kitchen with two additional chambers was probably separate from the house.

The mercantile business was carried on from a store, with an outer room, a supply room in the rear and a storeroom above. Also, there was a brick store, probably a warehouse, with storage space above. Merchandise brought from England was unloaded at the landing, where an unusual item of 800 "painting tiles" is listed. These imported tiles became popular, in the latter part of the century, for facing fireplaces and other uses.

A sloop, with a capacity of twenty-eight hogsheads, equipped with "furniture, sails, rigging and ground tackle" is accounted for in the inventory. Tobacco was picked up at the planters' wharfs, as goods shipped from England, through the Bridger agents, Micajah Perry and Thomas Lane, were delivered on the sloop.

Livestock was kept at pasture at the home plantation, at John Cahan's and at "Curowoak," the latter an 8000 acre grant. There were fifty-four head of cattle, and seven calves, these probably for butchering, thirteen cows and five yearlings for dairy supplies; eight oxen were used for heavy hauling, and besides there were nine steers and four bulls. Of old hogs, young hogs, sows, shoats and pigs there were fifty-four and, in addition, seven sheep and fourteen horses.

Colonel Bridger owned 490 ounces of plate (silver) and had on hand, at the time of his death, Spanish money valued at sixty pounds and English money valued at forty-two pounds ten shillings.

In addition to these holdings, obligations due the merchant both in money and tobacco, are recorded, showing the extent of the business he carried on with the planters, who lived for the most part on the James River and its estuaries. Among those indebted to the Bridger estate were Colonel William Byrd for[37] twelve pounds, John Pleasants for five pounds, John Champion for 958 pounds of tobacco, Thomas Pitt for 2000 pounds of tobacco and Colonel Christopher Wormeley in a bill of exchange amounting to eight pounds. Besides, Perry and Lane in London held bills of exchange to Bridger's credit amounting to 654 pounds.

Four indentured servants, with existing terms of service, and thirteen Negroes including two small children, are listed by name in the inventory. A Negro, obviously from the West Indies, was called "Monsieur."

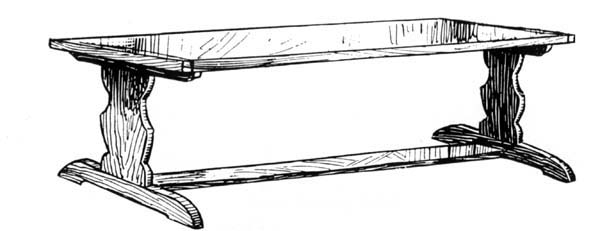

The enumeration of items in the two houses are of interest, as they show the more elaborate type of furnishings, that began to flow into the colony, after the middle of the century. The houses were heated as customary in the seventeenth century by fireplaces, for numerous andirons, either brass or iron, are listed together with tongs and fire-shovels. Numerous candlesticks, some of brass, some of wire and others of silver, illuminated the rooms in the evening. Chairs, rare in the early part of the century, were not scarce by 1686, for they are mentioned as caned, of leather, or covered either with serge or turkey-work, as were several couches. Tables of various sizes, a great looking-glass, a number of chests, several chests of drawers, and pictures were among the furnishings.

The beds were of the usual two types—the bedstead with feather-bedding, bolster and pillows being the more elegant, while the less important folks were assigned flock beds. Both types had curtains and valances, were supplied with blankets and sheets, the latter, either of canvas or Holland, and there were several quilts. The use of rugs mentioned is undetermined, for these often served as covering, or were hung on the walls to keep out the drafts. However, there was a carpet in the "great hall" of the new house, where also stood a clock, and unusual items as, three pairs of steelyards (scales).

There was a plentiful supply of table-linen in cloths and nap[38]kins of various qualities, the diaper linen (damask) being the best. The tableware for the most part was of pewter, some four dozen plates being listed, together with porringer, chafing-dish, fish-plates and pie-plates. Among the silver was a punch bowl, candlesticks, serving dish, several spoons and the cover of a tobacco box.

The family was one of some learning for a parcel of books is listed; and evidently Colonel Bridger was interested in the mysteries of the times, for a book on Witchcraft and another on Astrology are mentioned particularly.

In addition to the planter's usual possession of arms for family protection, in a capacity of high ranking officer of the militia, Colonel Bridger had on hand several guns, a case of pistols and holsters, and a pair of pocket pistols, a hanger (type of cutlass), three rapiers, one with a silver hilt, and ammunition.

Among the interesting items in his possession were a parcel of Virginia-made cloth and fourteen pairs of Virginia stockings. As these were in the home, it is possible that they were made on the plantation.

The size of some of the kitchen utensils and equipment point to a kitchen, with a very large fireplace, occupying an end of the room, where all food was prepared and cooked over the burning coals of a plentiful supply of wood. There were two great copper kettles weighing sixty-one pounds and forty pounds respectively, a brass kettle weighing fifty pounds, and two great andirons weighing 105 pounds, two iron pots weighing forty pounds each, four pot hooks, a heavy mall, three spits and skillets of several sizes. In the room adjoining the kitchen the milk was cared for, as there were eleven milk-pans, an "earthen" pan and three "earthen" butter-pots.

In the cellar was the gentleman's supply of drink, cider for family use, a cask of brandy, a cask of old whiskey, and a malt-mill listed as worn out.

While it is not practicable to mention here all of the goods[39] carried in the store and the storehouse, certain of the items are of special interest, such as materials used for wearing apparel of the period, accessories of dress, utensils and agricultural tools available in Virginia. About twenty different materials of varying qualities were imported from England. They were woven for the most part of flax, hemp or wool, or combinations, with some cotton, not generally in use, but available in a few materials.

Osnaburg, a coarse, heavy linen suitable for work clothes, or for sails, was available in quantities, in brown, for the former and white, for the latter; canvas, a closely woven cloth, of hemp or flax, was used for various purposes and appears to have been of different weights, for often canvas sheets are mentioned, which undoubtedly were of the lighter grade; dowlas, very much in use in the Colony, was a coarse linen made in the north of England and in Scotland, and today replaced in use by calico. Various weights of serge were listed, similar, no doubt, to the serge the present knows, for it was used for suits, coats and dresses. Linsey, a coarse cloth, was made of linen and wool, or occasionally of cotton and wool; kersey, a knit woolen cloth, usually coarse and ribbed, manufactured in England as early as the thirteenth century, was especially for hose; lockram was a sort of a coarse linen or hempen cloth, and penniston, a coarse woolen frieze. Shalloon, a woolen fabric of twill weave was used chiefly for linings; fustian was a cotton and linen cloth, and diaper linen was woven of flax with a raised figure such as in damask, and used chiefly for table-linen.

In addition, the Bridger store had on its shelves, colored calico, a small amount of flannel, some broadcloth, and a small parcel of silk valued at one pound. There was also thread in brown and other colors, knitting-needles, pins, horn-combs, combs made of ivory and knives of various descriptions. For trimming garments, there was guimpe, colored tape, Holland tape and Hamburg, the latter an embroidered edging, buttons, some silk covered. Oth[40]er items included skeins of twine, whalebone, scissors, and 132 pounds of soap.

Among the building supplies were quantities of nails of all sizes, which ever seemed to be in great demand in the Colony. For the field, there were narrow hoes and weeding-hoes, axes of different types, as well as a whipsaw.

For home furnishings, are listed such items as feather bedticks and bolsters, Irish bedticks, plain rugs, matting rugs, the latter showing importations from the Orient to England and thence to the Colony. Also, there were blankets, curtains and valances for tester beds, counterpanes of serge, table-knives with white handles, black handles, and ivory handles; in pewter, the store offered porringers, plates, serving-dishes and candlesticks. Among supplies, in addition to soap and twine, there were fifty-five bushels of salt and a barrel of coarse sugar.