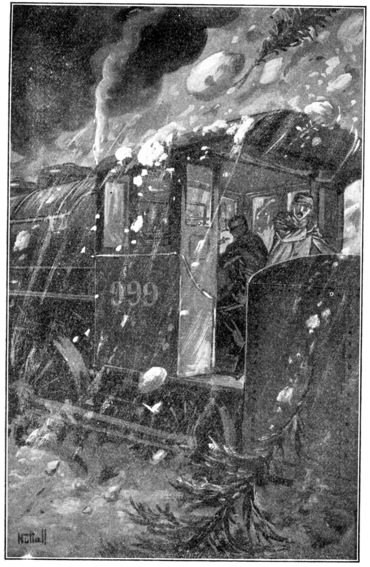

“An Avalanche!” declared Fogg. “Dodge—something’s coming!”

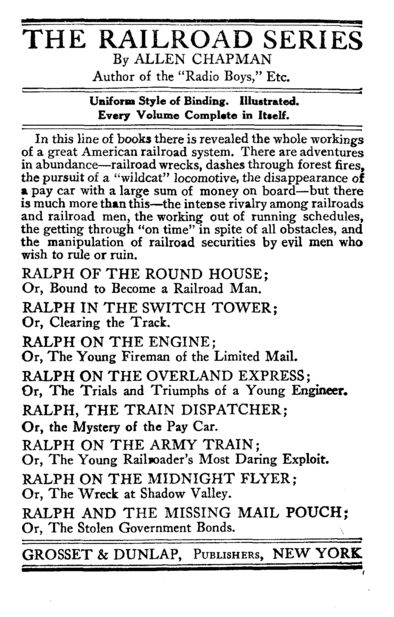

Page 254. Ralph on the Overland Express.

Title: Ralph on the Overland Express; Or, The Trials and Triumphs of a Young Engineer

Author: Allen Chapman

Release date: May 1, 2009 [eBook #28655]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | No. 999 | 1 |

| II. | A Special Passenger | 12 |

| III. | One of the Rules | 22 |

| IV. | A Warning | 35 |

| V. | At Bay | 43 |

| VI. | Four Medals | 51 |

| VII. | Dave Bissell, Train Boy | 60 |

| VIII. | An Astonishing Discovery | 68 |

| IX. | The Light of Home | 76 |

| X. | Fire! | 88 |

| XI. | The Master Mechanic | 95 |

| XII. | A Good Friend | 104 |

| XIII. | The “Black Hand” | 114 |

| XIV. | A Serious Plot | 123 |

| XV. | “The Silvandos” | 129 |

| XVI. | Zeph Dallas and His “Mystery” | 138 |

| XVII. | In Widener’s Gap | 145 |

| XVIII. | At the Semaphore | 153 |

| XIX. | The Boy Who Was Hazed | 160 |

| XX. | “Lord Lionel Montague” | 171 |

| XXI. | Archie Graham’s Invention | 179 |

| XXII. | Ike Slump Again | 188 |

| XXIII. | A Critical Moment | 195 |

| XXIV. | The New Run | 203 |

| XXV. | The Mountain Division | 209 |

| XXVI. | Mystery | 217 |

| XXVII. | The Railroad President | 225 |

| XXVIII. | A Race Against Time | 233 |

| XXIX. | Zeph Dallas Again | 244 |

| XXX. | Snowbound | 254 |

| XXXI. | Conclusion | 264 |

RALPH ON THE OVERLAND EXPRESS

“All aboard.”

Ralph Fairbanks swung into the cab of No. 999 with the lever hooked up for forward motion, and placed a firm hand on the throttle.

It looked as though half the working force of the railroad, and every juvenile friend he had ever known in Stanley Junction, had come down to the little old depot that beautiful summer afternoon to especially celebrate the greatest event in his active railroad career.

Ralph was the youngest engineer in the service of the Great Northern, and there was full reason why he should center attention and interest on this the proudest moment of his life. No. 999 was the crack locomotive of the system, brand new and resplendent. Its headlight was a great glow of crystal, its metal bands and trimmings 2 shone like burnished gold, and its cab was as spick and span and neat as the private office of the division superintendent himself.

No. 999 was out for a trial run—a record run, Ralph hoped to make it. One particular car attached to the rear of the long train was the main object of interest. It was a new car to the road, and its blazoned name suggested an importance out of the ordinary—“China & Japan Mail.”

This car had just come in over a branch section by a short cut from the north. If No. 999 could beat timetable routine half an hour and deliver the mail to the Overland Express at Bridgeport, two hundred miles distant, on time, it would create a new schedule, and meant a good contract for the Great Northern, besides a saving of three hours’ time over the former roundabout trip of the China & Japan Mail.

Ralph had exchanged jolly greetings with his friends up to now. In an instant, however, the sonorous, echoing “All aboard” from the conductor way down the train was a signal for duty, prompt and imperative. The pleasant depot scene faded from the sight and mind of the ambitious young railroader. He turned his strict attention now to the cab interior, as though the locomotive was a thing of life and intelligence. 3

“Let ’er go, Ralph!”

John Griscom, the oldest engineer on the road, off duty, but a privileged character on all occasions, stepped from the gossiping crowd of loungers at a little distance. He swung up into the cab with the expert airiness of long usage. His bluff, hearty face expressed admiration and satisfaction, as his rapid eye took in the cab layout.

“I’ll hold up the tender rail till we get to crossing,” announced Griscom. “Lad, this is front rank service all right, and I’m happy to say that you deserve it.”

“Thank you, Mr. Griscom,” answered Ralph, his face beaming at the handsome compliment. “I don’t forget, though, that you helped some.”

“Oh, so, so,” declared Griscom. “I say, Fogg, you’re named right.”

It was to Lemuel Fogg that Griscom spoke. Fogg was Ralph’s fireman on the present trip. He presented a decided contrast to the brisk, bright engineer of No. 999. He shoveled in the coal with a grim mutter, and slammed the fire door shut with a vicious and unnecessary bang.

“What you getting at?” he growled, with a surly eye on Griscom.

“Fogg—fog, see? foggy, that’s you—and groggy, eh? Sun’s shining—why don’t you take 4 it in? No slouch privilege firing this magnificent king of the road, I’m thinking, and you ought to think so, too.”

“Huh!” snapped Fogg, “it’ll be kid luck, if we get through.”

“Oho! there’s where the shoe pinches, is it?” bantered the old railroad veteran. “Come, be fair, Fogg. You was glad to win your own spurs when you were young.”

“All right, mind the try-out, you hear me!” snorted Fogg ungraciously. “You mind your own business.”

“Say,” shot out Griscom quickly, as he caught a whiff from Fogg’s lips, “you be sure you mind yours—and the rules,” he added, quite sternly, “I advise you not to get too near the furnace.”

“Eh, why not?”

“Your breath might catch fire, that’s why,” announced Griscom bluntly, and turned his back on the disgruntled fireman.

Ralph had not caught this sharp cross-fire of repartee. His mind had been intently fixed on his task. He had started up the locomotive slowly, but now, clearing the depot switches, he pulled the lever a notch or two, watching carefully ahead. As the train rounded a curve to an air line, a series of brave hurrahs along the side 5 of the track sent a thrill of pleasure through Ralph’s frame.

The young engineer had only a fleeting second or two to bestow on a little group, standing at the rear fence of a yard backing down to the tracks. His mother was there, gaily waving a handkerchief. A neighbor joined in the welcome, and half-a-dozen boys and small children with whom Ralph was a rare favorite made the air ring with enthusiastic cheers.

“Friends everywhere, lad,” spoke Griscom in a kindly tone, and then, edging nearer to his prime young favorite, he half-whispered: “Keep your eye on this grouch of a Fogg.”

“Why, you don’t mean anything serious, Mr. Griscom?” inquired Ralph, with a quick glance at the fireman.

“Yes, I do,” proclaimed the old railroader plainly. “He’s got it in for you—it’s the talk of the yards, and he’s in just the right frame of mind to bite off his own nose to spite his face. So long.”

The locomotive had slowed up for crossing signals, and Griscom got to the ground with a careless sail through the air, waved his hand, and Ralph buckled down to real work on No. 999.

He glanced at the schedule sheet and the clock. The gauges were in fine working order. There 6 was not a full head of steam on as yet and the fire box was somewhat over full, but there was a strong draft and a twenty-mile straight run before them, and Ralph felt they could make it easily.

“Don’t choke her too full, Mr. Fogg,” he remarked to the fireman.

“Teach me!” snorted Fogg, and threw another shovelful into the box already crowded, and backed against the tender bar with a surly, defiant face.

Ralph made no retort. Fogg did, indeed, know his business, if he was only minded to attend to it. He was somewhat set and old-fashioned in his ways, and he had grown up in the service from wiper.

Ralph recalled Griscom’s warning. It was not pleasant to run two hundred miles with a grumpy cab comrade. Ralph wished they had given him some other helper. However, he reasoned that even a crack fireman might be proud of a regular run on No. 999, and he did not believe that Fogg would hurt his own chances by any tactics that might delay them.

The landscape drifted by swiftly and more swiftly, as Ralph gave the locomotive full head. A rare enthusiasm and buoyancy came into the situation. There was something fascinating in the breathless rush, the superb power and steadiness 7 of the crack machine, so easy of control that she was a marvel of mechanical genius and perfection.

Like a panorama the scenery flashed by, and in rapid mental panorama Ralph reviewed the glowing and stirring events of his young life, which in a few brief months had carried him from his menial task as an engine wiper up to the present position which he cherished so proudly.

Ralph was a railroader by inheritance as well as predilection. His father had been a pioneer in the beginning of the Great Northern. After he died, through the manipulations of an unworthy village magnate named Gasper Farrington, his widow and son found themselves at the mercy of that heartless schemer, who held a mortgage on their little home.

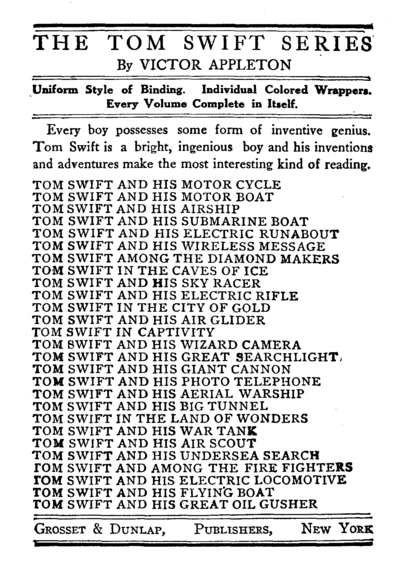

In the first volume of the present series, entitled “Ralph of the Roundhouse,” it was told how Ralph left school to earn a living and help his self-sacrificing mother in her poverty.

Ralph got a job in the roundhouse, and held it, too, despite the malicious efforts of Ike Slump, a ne’er-do-well who tried to undermine him. Ralph became a favorite with the master mechanic of the road through some remarkable railroad service in which he saved the railroad shops from destruction by fire. 8

Step by step Ralph advanced, and the second volume of this series, called “Ralph in the Switch Tower,” showed how manly resolve, and being right and doing right, enabled him to overcome his enemies and compel old Farrington to release the fraudulent mortgage. Incidentally, Ralph made many friends. He assisted a poor waif named Van Sherwin to reach a position of comfort and honor, and was instrumental in aiding a former business partner of his father, one Farwell Gibson, to complete a short line railroad through the woods near Dover.

In the third volume of the present series, entitled “Ralph on the Engine,” was related how our young railroad friend became an active employee of the Great Northern as a fireman. He made some record runs with old John Griscom, the veteran of the road. In that volume was also depicted the ambitious but blundering efforts of Zeph Dallas, a farmer boy who was determined to break into railroading, and there was told as well the grand success of little Limpy Joe, a railroad cripple, who ran a restaurant in an old, dismantled box car.

These and other staunch, loyal friends had rallied around Ralph with all the influence they could exert, when after a creditable examination Ralph was placed on the extra list as an engineer. 9

Van and Zeph had been among the first to congratulate the friend to whom they owed so much, when, after a few months’ service on accomodation runs, it was made known that Ralph had been appointed as engineer of No. 999.

It was Limpy Joe, spending a happy vacation week with motherly, kind-hearted Mrs. Fairbanks, who led the cheering coterie whom Ralph had passed near his home as he left the Junction on his present run.

Of his old-time enemies, Ike Slump and Mort Bemis were in jail, the last Ralph had heard of them. There was a gang in his home town, however, whom Ralph had reason to fear. It was made up of men who had tried to cripple the Great Northern through an unjust strike. A man named Jim Evans had been one of the leaders. Fogg had sympathized with the strikers. Griscom and Ralph had routed the malcontents in a fair, open-handed battle of arguments and blows. Fogg had been reinstated by the road, but he had to go back on the promotion list, and his rancor was intense when he learned that Ralph had been chosen to a position superior to his own.

“They want young blood, the railroad nobs tell it,” the disgruntled fireman had been heard to remark in his favorite tippling place on Railroad Street. “Humph! They’ll have blood, and 10 lots of it, if they trust the lives of passengers and crew to a lot of kindergarten graduates.”

Of all this Ralph was thinking as they covered a clear dash of twenty miles over the best stretch of grading on the road, and with satisfaction he noted that they had gained three minutes on the schedule time. He whistled for a station at which they did not stop, set full speed again as they left the little village behind them, and glanced sharply at Fogg.

The latter had not spoken a word for over half-an-hour. He had gone about his duties in a dogged, sullen fashion that showed the permanency of the grouch with which old John Griscom had charged him. Ralph had made up his mind to leave his cab companion severely alone until he became more reasonable. However, there were some things about Fogg of which the young engineer was bound to take notice, and a new enlightenment came to Ralph’s mind as he now glanced at his helper.

Fogg had slipped clumsily on the tender plate in using the coal rake, and Ralph had marveled at this unusual lack of steadiness of footing. Then, twice he had gone out on the running board on some useless errand, fumbling about in an inexplicable way. His hot, fetid breath crossed Ralph’s face, and the latter arrived at a definite 11 conclusion, and he was sorry for it. Fogg had been “firing up” from a secret bottle ever since they had left the Junction, and his condition was momentarily becoming more serious and alarming.

They were slowing down to a stop at a water tank as Ralph saw Fogg draw back, and under cover of the tender lift a flask to his lips. Then Fogg slipped it under the cushion of his seat as he turned to get some coal.

He dropped the shovel, coal and all, with a wild snort of rage, as turning towards the fire box door he saw Ralph reach over swiftly, grab the half empty bottle from under the cushion, and give it a fling to the road bed, where it was dashed into a thousand pieces.

Blood in his eye, uncontrollable fury in his heart, the irrational fireman, both fists uplifted, made a wild onslaught upon the young engineer.

“You impudent meddler!” he raved. “I’ll smash you!”

“Behave yourself,” said Ralph Fairbanks quietly.

The young engineer simply gave his furious antagonist a push with his free hand. The other hand was on duty, and Ralph’s eyes as well. He succeeded in bringing the locomotive to a stop before Fogg needed any further attention.

The fireman had toppled off his balance and went flat among the coal of the tender. Ralph did not feel at all important over so easily repelling his assailant. Fogg was in practically a helpless condition, and a child could have disturbed his unsteady footing.

With maudlin energy, however, he began to scramble to his feet. All the time he glowered at Ralph, and made dreadful threats of what he was going to do to the youth for “knocking him down.” Fogg managed to pull himself erect, but swayed about a good deal, and then observing that Ralph had the free use of both hands now and 13 was posed on guard to meet any attack he might meditate, the irate fireman stooped and seized a big lump of coal. Ralph could hardly hope to dodge the missile, hemmed in as he was. It was poised for a vicious fling. Just as Fogg’s hand went backwards to aim the projectile, it was seized, the missile was wrested from his grasp, and a strange voice drawled out the words:

“I wouldn’t waste the company’s coal that way, if I were you.”

Ralph with some surprise and considerable interest noted the intruder, who had mounted the tender step just in time to thwart the quarrelsome designs of Lemuel Fogg. As to the fireman, he wheeled about, looked ugly, and then as the newcomer laughed squarely in his face, mumbled some incoherent remark about “two against one,” and “fixing both of them.” Then he climbed up on the tender to direct the water tank spout into place.

“What’s the row here, anyhow?” inquired the intruder, with a pleasant glance at Ralph, and leaning bodily against the fireman’s seat.

Ralph looked him over as a cool specimen, although there was nothing “cheeky” about the intruder. He showed neither the sneakiness nor the effrontery of the professional railroad beat or ride stealer, nothwithstanding the easy, natural 14 way in which he made himself at home in the cab as though he belonged there.

“Glad you happened along,” chirped the newcomer airily. “I’ll keep you company as far as Bridgeport, I guess.”

“Will you, now?” questioned Ralph, with a dubious smile.

The lad he addressed was an open-faced, smart-looking boy. He was well dressed and intelligent, and suggested to Ralph the average college or home boy. Certainly there was nothing about him that indicated that he had to work for a living.

“My name is Clark—Marvin Clark,” continued the intruder.

Ralph nodded and awaited further disclosures.

“My father is President of the Middletown & Western Railroad,” proceeded the stranger.

Ralph did not speak. He smiled slightly, and the keen-eyed intruder noticed this and gave him a sharp look.

“Old racket, eh? Too flimsy?” he propounded with a quizzical but perfectly good-natured grin. “I suppose they play all kinds of official relationships and all that on you fellows, eh?”

“Yes,” said Ralph, “we do hear some pretty extravagant stories.”

“I suppose so,” assented the youth calling himself 15 Marvin Clark. “Well, I don’t want to intrude, but if there’s room for myself and my credentials, I’d rather keep you company than free pass it in the parlor coach. There you are.”

As the boy spoke of “credentials,” he drew an unsealed envelope from his pocket and handed it to Ralph. The latter received it, noting that it bore in one corner the monogram of the Great Northern, with “President’s office—official business” printed under it. He withdrew the enclosure and perused it.

The sheet was a letter head of the Middletown & Western Railroad. It bore on one line in one handwriting the name “Marvin Clark,” and beneath it the words: “For identification,” in another handwriting, and the flourishing signature below “Nathaniel Clark, President.”

In typewriting beneath all this were the words: “Pass on all trains, Marvin Clark,” and below that a date and the name in writing of Mr. Robert Grant, the President of the Great Northern, unmistakably genuine. There were few employees on the road who were not familiar with that signature.

“All right,” said Ralph, refolding the sheet, re-inclosing it in the envelope, and handing it back to the stranger. “I guess that passes you anywhere on the line.” 16

“You see, I’ve got a sort of roaming commission,” explained young Clark buoyantly, as he got comfortably seated on the fireman’s cushion. “No particular use at school, and father wants me to learn railroading. The first step was to run down all the lines and pick up all the information I could. I’ve just got to put in two months at that, and then report to family headquarters my store of practical knowledge. See here.”

Marvin Clark drew a blank from his pocket. Some thirty of its pages he showed to Ralph were filled with memoranda. Thus: “Aug. 22, cattle freight, Upton to Dover. O. K. Simpson, Conductor.” There followed like items, all signed, forming a link of evidence that the boy had been a passenger on all kinds of rolling stock, had visited railroad shops, switch towers, water stations, in fact had inspected about every active department of several railroad lines that connected with the Middletown & Western Railroad.

“That is a pretty pleasant layout, I should say,” remarked Ralph.

“Oh, so, so,” replied Clark indifferently. “Athletics is my stronghold. If I ever get money enough—I mean if I had my own way—I’d train for expert on everything from golf to football.”

“I’m pretty strong in that direction myself,” 17 said Ralph, “but a fellow has to hustle for something to eat.”

“I know what that means,” declared Clark. “Had to help the family by peddling papers—.”

Clark paused and flushed. Ralph wondered at the singular break his visitor had made. A diversion covered the embarassment of the young stranger and caused Ralph to momentarily forget the incident. Fogg had swung back the water spout, set the tender cover, and climbed down into the cab. Then he took the side light signals and went around to the pilot. No. 999 carried two flags there, now to be replaced by lanterns. Fogg came back to the cab rolling up the flags.

“All right,” he announced ungraciously, and hustled Clark to one side without ceremony as the latter abandoned his seat. Ralph gave the starting signal and Clark edged back in the tender out of the way.

The young engineer took a good look at his fireman. The latter was muddled, it was plain to see that, but he went about his duties with a mechanical routine born from long experience. Only once did he lurch towards Ralph and speak to him, or rather hiss out the words.

“You’ll settle with me for your impudence yet, young fellow. You’re a high and mighty, you 18 are, breaking the rules giving your friends a free ride.”

Ralph did not reply. One anxiety kept him devoted to his work—to lose no time. A glance at the clock and schedule showed a ten minutes’ loss, but defective or experimental firing on a new locomotive had been responsible for that, and he counted on making a spurt, once beyond Plympton.

Marvin Clark knew his place, and Ralph liked him for keeping it. The young fellow watched everything going on in the cab in a shrewd, interested fashion, but he neither got in the way of the cross-grained Fogg, nor pestered Ralph with questions.

Plympton was less than five miles ahead just as dusk began to fall. Ralph noticed that his fireman rustled about with a good deal of unnecessary activity. He would fire up to the limit, as if working off some of his vengefulness and malice. Then he went out on the running board, for no earthly reason that Ralph could see, and he made himself generally so conspicuous that young Clark leaned over and said to Ralph.

“What’s the matter with your fireman, anyhow—that is, besides that load he’s got aboard?”

“Oh, he has his cross moods, like all of us, I 19 suppose,” explained Ralph, with affected indifference.

“I wouldn’t take him for a very pleasant comrade at any time,” observed Clark. “It’s a wonder he don’t take a tumble. There he is, hitching around to the pilot. What for, I wonder?”

Ralph was not paying much attention to what the cab passenger was saying. He had made up five minutes, and his quick mind was now planning how he would gain five more, and then double that, to Plympton and beyond it.

He gave the whistle for Plympton, as, shooting a curve, No. 999 drove a clattering pace down the grade with the lights of the station not a quarter-of-a-mile away. They were set for clear tracks, as they should be. Ralph gave the lever a hitch for a rattling dash on ten miles of clear running. Then fairly up to the first station semaphore, he broke out with a cry so sharp and dismayed that young Clark echoed it in questioning excitement.

“The siding!” cried Ralph, with a jerk of the lever—“what’s the meaning of this?”

“Say!” echoed Clark, in a startled tone, “that’s quick and queer!”

What had happened was this: No. 999 going at full speed on clear signals had been sent to a siding and the signals cancelled without a moment’s 20 warning. Under ordinary circumstances, a train thus sidetracked would be under notified control and run down the siding only a short distance. Going at high speed, however, and with a full head of steam on, Ralph realized that, long as the siding was, he would have to work quick and hard to check down the big locomotive before she slid the limit, and stuck her nose deep into the sand hill that blocked the terminus of the rails.

It was quite dark now. The lights of the station flashed by. Both hands in use to check the locomotive and set the air brakes, Ralph leaned slightly from the cab window and peered ahead.

“Shoot the sand!” he cried, almost mechanically.

It was a good thing that the cab passenger was aboard and knew something about the cab equipment. Young Clark reached the side of the engineer’s seat in a nimble spring. His hand located the sand valve without hesitancy.

Ralph uttered a short, sharp gasp. That look ahead had scared him. He was doing all he could to slow down, and was doing magnificently, for the reverse action moved to a charm. Still, he saw that after dashing fully two hundred yards down the siding, the natural momentum 21 would carry the train fully one-third that distance further.

“Any obstruction?” shot out his agile companion, springing to the fireman’s seat, sticking his head out of the window and staring ahead. “Whew! we’re going to hit.”

The speaker saw what Ralph also beheld. Dimly outlined directly in their path was a flat car, and above it, skeletonized against the fading sunset sky, was the framework of a derrick. A repair or construction gondola car was straight ahead of No. 999.

They seemed to be approaching it swiftly and irresistibly. The wheels slid now, fairly locked, there was a marked ease-down, but Ralph saw plainly that, great or small, a collision was inevitable.

“Say, that fireman of yours!” shouted young Clark—“there he goes.”

The locomotive was fairly upon the obstruction now. Ralph stuck to the lever, setting his lips firmly, a little pale, his muscles twitching slightly under the stress of excitement and suspense.

“Zing!” remarked the cool comrade of the young engineer—“we’re there!”

At that moment a flying form shot from the running board of the locomotive. Lemuel Fogg had jumped.

Locomotive No. 999 landed against the bumper of the gondola car with a sharp shock. However, there was no crash of consequence. The headlight radiance now flooded fully the obstruction. Young Clark suddenly shouted:

“Look out!”

The quick-witted, keen-eyed special passenger was certainly getting railroad training so coveted by his magnate father. He saw the fireman shoot through the air in his frightened jump for safety. Lemuel Fogg landed in a muddy ditch at the side of the tracks, up to his knees in water.

The sharp, warning cry of Marvin Clark was not needed to appraise Ralph of the danger that threatened. The jar of the collision had displaced and upset the derrick. Ralph saw it falling slantingly towards them. He pulled the reverse lever, but could not get action quick enough to entirely evade the falling derrick. It grazed the headlight, chopping off one of its metal wings, 23 and striking the pilot crushed in one side of the front fender rails.

The young engineer gave the signal for backing the train, and kept in motion. His purpose was to allay any panic on the part of the passengers, whom he knew must be alarmed by the erratic tactics of the past few moments. Then after thus traversing about half the distance back to the main line, he shut off steam and whistled for instructions.

“Another notch in my education,” observed young Clark with a chuckle—“been waiting to pass examination on a smash up.”

“Oh, this isn’t one,” replied Ralph. His tone was tense, and he showed that he was disturbed. He was too quick a thinker not to at once comprehend the vital issue of the present incident. With Fogg headed down the track towards him from the ditch, trying to overtake the train, and the conductor, lantern in hand, running to learn what had happened, Ralph sized up the situation with decided annoyance.

The action of the station man in giving the free track signal and then at a critical moment shooting the special onto the siding, had something mysterious about it that Ralph could not readily solve. The slight mishap to the locomotive and the smashing of the derrick was not particularly 24 serious, but there would be a report, an investigation, and somebody would be blamed and punished. Ralph wanted to keep a clear slate, and here was a bad break, right at the threshold of his new railroad career.

All he thought of, however, were the delays, all he cared for at this particular moment was to get back to the main tracks on his way for Bridgeport, with a chance to make up lost time. A sudden vague suspicion flashing through his mind added to his mental disquietude: was there a plot to purposely cripple or delay his train, so that he would be defeated in his efforts to make a record run?

“What’s this tangle, Fairbanks?” shouted out the conductor sharply, as he arrived breathless and excited at the side of the cab.

His name was Danforth, and he was a model employee of long experience, always very neat and dressy in appearance and exact and systematic in his work. Any break in routine nettled him, and he spoke quite censuringly to the young engineer, whom, however, he liked greatly.

“I’m all at sea, Mr. Danforth,” confessed Ralph bluntly.

“Any damage?—I see,” muttered the conductor, going forward a few steps and surveying the scratched, bruised face of the locomotive. 25

“There’s a gondola derailed and a derrick smashed where we struck,” reported Ralph. “I acted on my duplicate orders, Mr. Danforth,” he added earnestly, “and had the clear signal almost until I passed it and shot the siding.”

“I don’t understand it at all,” remarked the conductor in a troubled and irritated way. “You had the clear signal, you say?”

“Positively,” answered Ralph.

“Any serious damage ahead?”

“Nothing of consequence.”

“Back slowly, we’ll see the station man about this.”

The conductor mounted to the cab step, and No. 999 backed slowly. As they neared the end of the siding the train was again halted. All down its length heads were thrust from coach windows. There was some excitement and alarm, but the discipline of the train hands and the young engineer’s provision had prevented any semblance of panic.

The conductor, lantern in hand, ran across the tracks to the station. Ralph saw him engaged in vigorous conversation with the man on duty there. The conductor had taken out a memorandum book and was jotting down something. The station man with excited gestures ran inside the depot, and the signal turned to clear tracks. Ralph 26 switched to the main. Then the conductor gave the go ahead signal.

“That’s cool,” observed young Clark. “I should think the conductor would give us an inkling of how all this came about.”

“Oh, we’ll learn soon enough,” said Ralph. “There will have to be an official report on this.”

“I’m curious. Guess I’ll go back and worm out an explanation,” spoke Clark. “I’ll see you with news later.”

As Clark left the cab on one side Fogg came up on the other. He had been looking over the front of the locomotive. Ralph noticed that he did not seem to have suffered any damage from his wild jump beyond a slight shaking up. He was wet and spattered to the waist, however, and had lost his cap.

Lemuel Fogg’s eyes wore a frightened, shifty expression as he stepped to the tender. His face was wretchedly pale, his hands trembled as he proceeded to pile in the coal. Every vestige of unsteadiness and maudlin bravado was gone. He resembled a man who had gazed upon some unexpected danger, and there was a half guiltiness in his manner as if he was responsible for the impending mishap.

The fireman did not speak a word, and Ralph considered that it was no time for discussion or 27 explanations. The injury to the locomotive was comparatively slight, and with a somewhat worried glance at the clock and schedule card the young railroader focussed all his ability and attention upon making up for lost time.

Soon Ralph was so engrossed in his work that he forgot the fireman, young Clark, the accident, everything except that he was driving a mighty steel steed in a race against time, with either the winning post or defeat in view. There was a rare pride in the thought that upon him depended a new railway record. There was a fascinating exhilaration in observing the new king of the road gain steadily half a mile, one mile, two miles, overlapping lost time.

A smile of joy crossed the face of the young engineer, a great aspiration of relief and triumph escaped his lips as No. 999 pulled into Derby two hours later. They were twenty-one minutes ahead of time.

“Mr. Fogg,” shouted Ralph across to the fireman’s seat, “you’re a brick!”

It was the first word that had passed between them since the mishap at the siding, but many a grateful glance had the young engineer cast at his helper. It seemed as if the shake-up at Plympton had shaken all the nonsense out of Lemuel Fogg. Before that it had been evident to Ralph that the 28 fireman was doing all he could to queer the run. He had been slow in firing and then had choked the furnace. His movements had been suspicious and then alarming to Ralph, but since leaving Plympton he had acted like a different person. Ralph knew from practical experience what good firing was, and he had to admit that Fogg had outdone himself in the splendid run of the last one hundred miles. He was therefore fully in earnest when he enthusiastically designated his erratic helper as a “brick.”

It was hard for Fogg to come out from his grumpiness and cross-grained malice quickly. Half resentful, half shamed, he cast a furtive, sullen look at Ralph.

“Humph!” he muttered, “it isn’t any brick that did it—it was the briquettes.”

“The what, Mr. Fogg?” inquired Ralph.

“Them,” and with contemptuous indifference Fogg pointed to a coarse sack lying among the coal. “New-fangled fuel. Master mechanic wanted to make a test.”

“Why, yes, I heard about that,” said Ralph quickly. “Look like baseballs. Full of pitch, oil and sulphur, I understand. They say they urge up the fire.”

“They do, they burn like powder. They are great steam makers, and no question,” observed 29 Fogg. “Won’t do for a regular thing, though.”

“No?” insinuated Ralph attentively, glad to rouse his grouchy helper from his morose mood.

“Not a bit of it.”

“Why not?”

“Used right along, they’d burn out any crown sheet. What’s more, wait till you come to clean up—the whole furnace will be choked with cinders.”

“I see,” nodded Ralph, and just then they rounded near Macon for a fifteen minutes wait.

As Fogg went outside with oil can and waste roll, Mervin Clark came into the cab.

“Glad to get back where it’s home like,” he sang out in his chirp, brisk way. “Say, Engineer Fairbanks, that monument of brass buttons and gold cap braid is the limit. Discipline? why, he works on springs and you have to touch a button to make him act. I had to chum with the brakeman to find out what’s up.”

“Something is up, then?” inquired Ralph a trifle uneasily.

“Oh, quite. The conductor has been writing a ten-page report on the collision. It’s funny, but the station man at Plympton––”

“New man, isn’t he?” inquired Ralph.

“Just transferred to Plympton yesterday mornin’,” explained Clark. “Well, he swears that your 30 front signals were special at the curves and flashed green just as you neared the semaphore.”

“Absurd!” exclaimed Ralph.

“That’s what the conductor says, too,” said Clark. “He told the station agent so. They nearly had a fight. ‘Color blind!’ he told the station agent and challenged him to find green lights on No. 999 if he could. The station man was awfully rattled and worried. He says he knew a special was on the list, but being new to this part of the road he acted on Rule 23 when he saw the green lights. He sticks to that, says that he will positively swear to it. He says he knows some one will be slated, but it won’t be him.”

“What does the conductor say?” inquired Ralph.

“He says Rule 23 doesn’t apply, as the white lights prove. If there was any trickery or any mistake, then it’s up to the fireman, not to the engineer.”

At that moment, happening to glance past Clark, the young engineer caught sight of Lemuel Fogg. The latter, half crouching near a drive wheel, was listening intently. The torch he carried illuminated a pale, twitching face. His eyes were filled with a craven fear, and Ralph tried to imagine what was passing through his mind. 31

There was something mysterious about Fogg’s actions, yet Ralph accepted the theory of the conductor that the station man had made a careless blunder or was color blind.

“You see, it isn’t that the smash up amounts to much,” explained Clark, “but it might have, see?”

“Yes, I see,” replied Ralph thoughtfully.

“Then again,” continued Clark, “the conductor says that it delayed a test run, and there’s a scratched locomotive and a busted construction car.”

“I’m thankful that no one was hurt,” said Ralph earnestly.

When the next start was made, Fogg was taciturn and gloomy-looking, but attended strictly to his duty. Ralph voted him to be a capital fireman when he wanted to be. As an hour after midnight they spurted past Hopeville forty minutes to the good, he could not help shouting over a delighted word of commendation to Fogg.

“I said you were a brick, Mr. Fogg,” he observed. “You’re more than that—you’re a wonder.”

Fogg’s face momentarily lighted up. It looked as if he was half minded to come out of his shell and give some gracious response, but instantly the 32 old sullenness settled down over his face, accompanied by a gloomy manner that Ralph could not analyze. He half believed, however, that Fogg was a pretty good fellow at heart, had started out to queer the run, and was now sorry and ashamed that he had betrayed his weakness for drink.

“Maybe he is genuinely sorry for his tantrums,” reflected Ralph, “and maybe our narrow escape at the siding has sobered him into common sense.”

What the glum and gruff fireman lacked of comradeship, the young passenger made up in jolly good cheer. He was interested in everything going on. He found opportunity to tell Ralph several rattling good stories, full of incident and humor, of his amateur railroad experiences, and the time was whiled away pleasantly for these two acquaintances.

Ralph could not repress a grand, satisfied expression of exultation as No. 999 glided gracefully into the depot at Bridgeport, over forty-seven minutes ahead of time.

The station master and the assistant superintendent of the division came up to the cab instantly, the latter with his watch in his hand.

“Worth waiting for, this, Fairbanks,” he called 33 out cheerily—he was well acquainted with the young railroader, for Ralph had fired freights to this point over the Great Northern once regularly for several weeks. “I’ll send in a bouncing good report with lots of pleasure.”

“Thank you,” said Ralph. “We’ve demonstrated, anyhow.”

“You have, Fairbanks,” returned the official commendingly.

“Only, don’t lay any stress on my part of it,” said Ralph. “Any engineer could run such a superb monarch of the rail as No. 999. If you don’t tell them how much the experiment depended on our good friend, Fogg, here, I will have to, that’s all.”

The fireman flushed. His eyes had a momentary pleased expression, and he glanced at Ralph, really grateful. He almost made a move as if to heartily shake the hand of his unselfish champion.

“You’re too modest, Fairbanks,” laughed the assistant superintendent, “but we’ll boost Fogg, just as he deserves. It’s been a hard, anxious run, I’ll warrant. We’ve got a relief crew coming, so you can get to bed just as soon as you like.”

The passenger coaches were soon emptied of the through passengers. A local engineer, fireman 34 and brakeman took charge of the train to switch the China & Japan Mail car over to another track, ready to hitch on to the Overland express, soon to arrive, sidetrack the other coaches, and take No. 999 to the roundhouse.

Ralph doffed his working clothes, washed up at the tender spigot, and joined Clark, who stood waiting for him on the platform. Fogg, without tidying up, in a sort of tired, indifferent way was already some distance down the platform. Ralph hurried after him.

“Six-fifteen to-night, Mr. Fogg, isn’t it?” spoke Ralph, more to say something than anything else.

“That’s right,” returned Fogg curtly.

“Griscom directed me to a neat, quiet lodging house,” added Ralph. “Won’t you join me?”

“Can’t—got some friends waiting for me,” responded the fireman.

Ralph followed him seriously and sadly with his eyes. Fogg was making for Railroad Row, with its red saloon signs, and Ralph felt sorry for him.

“See here,” spoke Clark, as they walked along together, “headed for a bunk, I suppose?”

“Yes,” answered Ralph. “John Griscom, that’s 36 our veteran engineer, and a rare good friend of mine, told me about a cheap, comfortable lodging house to put up at. It’s some distance from the depot, but I believe I shall go there.”

“Good idea,” approved Clark. “I’ve been in some of those railroad men’s hotels yonder, and they’re not very high toned—nor clean.”

“What’s your program?” inquired Ralph.

“Got to sleep, I suppose, so, if I’m not too much of a bore and it’s pleasing to you, I’ll try the place your friend recommends.”

“I shall be delighted,” answered Ralph.

Within half-an-hour both tired lads tumbled into their beds in rooms adjoining in a private house about half a mile from the depot. Ralph stretched himself luxuriously, as he rested after the turmoil and labor of what he considered the most arduous day in his railroad career.

The young engineer awoke with the bright sun shining in his face and was out of bed in a jiffy. These lay-over days had always been prized by the young railroader, and he planned to put the present one to good use. He went to the closed door communicating with the next room and tapped on it.

“Hey, there!” he hailed briskly, “time to get up,” then, no response coming, he opened the door to find the apartment deserted. 37

“An early bird, it seems,” observed Ralph. “Probably gone for breakfast.”

John Griscom had told Ralph all about the house he was in, and the young engineer soon located the bathroom and took a vigorous cold plunge that made him feel equal to the task of running a double-header special. Ralph had just dressed when Marvin Clark came bustling into the room.

“Twenty minutes for breakfast!” hailed the volatile lad. “I’ve been up an hour.”

“You didn’t take a two hundred mile run, or you wouldn’t be up for four,” challenged Ralph.

“Guess that’s so,” admitted Clark. “Well, here we are. I’ve been out prospecting.”

“What for?” inquired Ralph.

“A good restaurant.”

“Found one?”

“A dandy—wheat cakes with honey, prime country sausages and Mocha, all for twenty cents.”

“Good,” commended Ralph. “We’ll take air line for that right away.”

Clark chattered like a magpie as they proceeded to the street. It was evident that he had taken a great fancy to Ralph. The latter liked him in return. For the son of a wealthy railroad magnate, Clark was decidedly democratic. The 38 one subject he seemed glad to avoid was any reference to his direct family and friends.

He was full of life, and Ralph found him very entertaining. Some bad breaks in grammar showed, indeed, that he had not amounted to much at school. Some of his adventures also suggested that the presence and power of money had not always been at his command. Ralph noticed some inconsistencies in his stories here and there, but Clark rattled on so fast and jumped so briskly from one subject to another, that it was hard work to check him up.

As they reached the porch of the house Clark gave Ralph a deterring touch with his hand.

“Just wait a minute, will you?” he spoke.

“Why what for?” inquired Ralph in some surprise.

“I want to find out something before we go out into the street,” and the speaker glided down the walk to the gate, peered down the street, and then beckoned to his companion.

“Come on,” he hailed. “They’re still there, though,” he added, his tones quite impressive.

“Who is there?” asked Ralph.

“Just dally at the gate here and take a look past the next street corner—near where there’s an alley, see?” 39

“That crowd of boys?” questioned Ralph, following his companion’s direction.

“Yes, that gang of hoodlums,” responded Clark bluntly, “for that is what they are.”

“And how are we interested in them?” inquired Ralph.

“We’re not, but they may become interested in us.”

“Indeed?”

“Mightily, if I don’t mistake my cue,” asserted Clark.

“You are pretty mysterious,” hinted Ralph, half-smiling.

“Well, I’ll explain. Those fellows are laying for you.”

“Laying for me?” repeated Ralph vaguely.

“That’s it.”

“Why? They don’t know me, and I don’t know them.”

“Not much acquainted at Bridgeport, eh?”

“Only casually. I’ve laid over here several times when I was firing on the fast freight. I know a few railroad men, that’s all.”

“Ever hear of Billy Bouncer?”

“I never did.”

“Then I’m the first one to enlighten you. When I went out to find a restaurant I passed that crowd you see. I noticed that they drew together 40 and scanned me pretty closely. Then I heard one of them say, ‘That’s not Fairbanks.’ ‘Yes, it is, didn’t he come out of the place we’re watching?’ said another. ‘Aw, let up,’ spoke a third voice. ‘Billy Bouncer will know, and we don’t want to spoil his game. He’ll be here soon.’”

“That’s strange,” said Ralph musingly.

“What are you going to do about it?” inquired Clark.

“Oh, I’m not at all alarmed,” replied Ralph, “barely interested, that’s all. We’ll walk by the crowd and see if they won’t throw some further light on the subject.”

“Tell you, Fairbanks,” said Clark quite seriously, “I’m putting two and two together.”

“Well,” laughed Ralph, “that makes four—go ahead.”

“More than four—a regular mob. That crowd, as I said, for some reason is laying for you. What’s the answer? They have been put up to it by some one. You know, you told me incidentally that you had some enemies on account of the big boost you’ve got in the service. You said, too, that your friend, Engineer Griscom, warned you on just that point. I haven’t said much so far, but the actions of that grouch fireman of yours, Fogg, looked decidedly queer and suspicious to me.” 41

Ralph made no comment on this. He had his own ideas on the subject, but did not feel warranted in fully expressing them.

“I believe that Fogg started out on your run yesterday to queer it. Why he changed tactics later, I can’t tell. Maybe he was scared by the smash-up on the siding. Anyhow, I never saw such mortal malice in the face of any man as that I saw in his when I came aboard No. 999. This crowd down the street is evidently after you. Some one has put them up to it.”

“Oh, you can’t mean Fogg!” exclaimed Ralph.

“I don’t know,” replied Clark.

“I can’t believe that he would plot against me that far,” declared Ralph.

“A malicious enemy will do anything to reach his ends,” said Clark. “Doesn’t he want you knocked out? Doesn’t he want your place? What would suit his plans better than to have you so mauled and battered, that you couldn’t show up for the return trip to Stanley Junction this afternoon? Are you going past that crowd?”

“I certainly shall not show the white feather by going out of my way,” replied Ralph.

“Well, if that’s your disposition, I’m at your call if they tackle us,” announced Clark.

They proceeded down the street, and Ralph as they advanced had a good view of the crowd, 42 which, according to the views of his companion, was laying in wait for him. There were about fifteen of them, ranging from selfish-faced lads of ten or so up to big, hulking fellows of twenty. They represented the average city gang of idlers and hoodlums. They were hanging around the entrance to the alley as if waiting for some mischief to turn up. Ralph noticed a rustling among them as he was observed. They grouped together. He fancied one or two of them pointed at him, but there was no further indication of belligerent attention as he and Clark approached nearer to the crowd.

“I fancy Billy Bouncer, whoever he is, hasn’t arrived yet,” observed Clark.

Just then one of the mob set up a shout.

“Hi there, Wheels!” he hailed, and some additional jeers went up from his fellows. Their attention seemed directed across the street, and Ralph and Clark glanced thither.

A queer-looking boy about eighteen years of age was proceeding slowly down the pavement. He was stockily built, and had an unusually massive head and great broad shoulders. He was a boy who would be remarked about almost anywhere. His hair was long, and this gave him a somewhat leonine aspect.

The hat of this boy was pushed far back on his head, and his eyes were fixed and his attention apparently deeply absorbed upon an object he held in his hand. This was a thin wooden rod with two cardboard wheels attached to it. These he would blow, causing them to revolve rapidly. Then he would study their gyrations critically, wait till they had run down, and then repeat the maneuver.

His side coat pockets were bulging, one with a lot of papers. From the other protruded what seemed to be a part of a toy, or some real mechanical device having also wheels in its construction. 44

“Well, there’s a queer make-up!” observed Clark in profound surprise.

“He is certainly eccentric in his appearance,” said Ralph. “I wonder who he can be.”

“No, what he can be,” corrected Clark, “for he’s an odd genius of some kind, I’ll wager.”

The object of their interest and curiosity had heard the derisive hail from across the street. He halted dead short, stared around him like a person abruptly aroused from a dream, traced the call to its source, thrust the device with which he had been experimenting into his pocket, and fixing his eyes on his mockers, started across the street. The hoodlum crowd nudged one another, blinked, winked, and looked as if expecting developments of some fun. The object of their derision looked them over in a calculating fashion.

“Did any one here speak to me?” he asked.

“No, Wheels—it was the birdies calling you!” hooted a jocose voice.

“You sort of suggest something, somehow,” drawled the lad in an abstracted, groping way. “Yes, certainly, let me see. What is it? Ah, perhaps I’ve made a memorandum of it.”

The lad poked into several vest pockets. Finally he unearthed a card which seemed to be all written over, and he ran his eye down this. The crowd chuckled at the profound solemnity of his manner. 45

“H’m,” observed the boy designated as “Wheels.” “Let me see. ‘Get shoes mended.’ No, that isn’t it. I have such a bad memory. ‘Order some insulated wire.’ No, that’s for an uptown call. ‘Buy Drummond on Superheated Steam.’ That’s for the bookstore. Ah, here we have it. ‘Kick Jim Scroggins.’ Who’s Jim? Aha! you young villain, I remember you well enough now,” and with an activity which could scarcely be anticipated from so easy-going an individual, Wheels made a dive for a big hulking fellow on the edge of the crowd. He chased him a few feet, and planted a kick that lifted the yelling hoodlum a foot from the ground. Then, calmly taking out a pencil, he crossed off the memorandum—“Kick Jim Scroggins”—gave the crowd a warning glance, and proceeded coolly down the sidewalk, resuming his occupation with the contrivance he had placed in his pocket.

The gang of loafers had drawn back. A sight of the massive arms and sledge hammer fists of the young giant they had derided, and his prompt measures with one of their cronies, dissuaded them from any warlike move.

“Whoop!” commented Clark in an exultant undertone, and he fairly leaned against his companion in a paroxysm of uncontrollable laughter. “Quick, nifty and entertaining, that! Say Engineer 46 Fairbanks, I don’t know who that fellow Wheels is, but I’d be interested and proud to make his acquaintance. Now steam up and air brake ready, while we pass the crossing!”

“Passing the crossing,” as Clark designated it, proved, however, to be no difficult proceeding. The crowd of hoodlums had got a set-back from the boy with the piston-rod arm, it seemed. They scanned Ralph and Clark keenly as they passed by, but made no attempt to either hail or halt them.

“We’ve run the gauntlet this time,” remarked Clark. “Hello—four times!”

The vigilant companion of the young engineer was glancing over his shoulder as he made this sudden and forcible remark.

“Four times what?” inquired Ralph.

“That fireman of yours.”

“Mr. Fogg?”

“Yes.”

“What about him?”

“Say,” replied Clark, edging close to Ralph, “just take a careless backward look, will you? About half the square down on the opposite side of the street you’ll see Fogg.”

“Why such caution and mystery?” propounded Ralph.

“I’ll tell you later. See him?” inquired Clark, 47 as Ralph followed out the suggestion he had made.

Ralph nodded assentingly. He had made out Fogg as Clark had described. The fireman was walking along in the direction they were proceeding. There was something stealthy and sinister in the way in which he kept close to the buildings lining the sidewalk.

“That’s four times I’ve noticed Fogg in this vicinity this morning,” reported Clark. “I discovered him opposite the lodging house when I first came out this morning. When I came back he was skulking in an open entry, next door. When we left the house together I saw him a block away, standing behind a tree. Now he bobs up again.”

“I can’t understand his motive,” said Ralph thoughtfully.

“I can,” declared Clark with emphasis.

“What’s your theory?”

“It’s no theory at all, it’s a dead certainty,” insisted Clark. “Your fireman and that gang of hoodlums hitch together in some way, you mark my words. Well, let it slide for a bit. I’m hungry as a bear, and here’s the restaurant.”

It was a neat and inviting place, and with appetizing zeal the two boys entered and seated themselves at a table and gave their order for wheat 48 cakes with honey and prime country sausages. Just as the waiter brought in the steaming meal, Clark, whose face was toward the street, said:

“Fogg just passed by, and there goes the crowd of boys. I’m thinking they’ll give us a chance to settle our meal, Engineer Fairbanks!”

“All right,” responded Ralph quietly, “if that’s the first task of the day, we’ll be in trim to tackle it with this fine meal as a foundation.”

Their youthful, healthy appetites made a feast of the repast. Clark doubled his order, and Ralph did full credit to all the things set before him.

“I was thinking,” he remarked, as they paid their checks at the cashier’s counter, “that we might put in the day looking around the town.”

“Why, yes,” assented his companion approvingly, “that is, if you’re going to let me keep with you.”

“Why not?” smiled Ralph. “You seem to think I may need a guardian.”

“I’ve got nothing to do but put in the time, and get a signed voucher from you that I did so in actual railroad service and in good company,” explained Clark. “I think I will go back to Stanley Junction on your return run, if it can be arranged.”

“It is arranged already, if you say so,” said 49 Ralph. “We seem to get on together pretty well, and I’m glad to have you with me.”

“Now, that’s handsome, Engineer Fairbanks!” replied Clark. “There’s some moving picture shows in town here, open after ten o’clock, and there’s a mechanics’ library with quite a museum of railroad contrivances. We’ve got time to take it all in. Come on. Unless that crowd stops us, we’ll start the merry program rolling. No one in sight,” the youth continued, as they stepped into the street and he glanced its length in both directions. “Have the enemy deserted the field, or are they lying in ambush for us?”

They linked arms and sauntered down the pavement. They had proceeded nearly two squares, when, passing an alley, both halted summarily.

“Hello! here’s business, I guess,” said Clark, and he and Ralph scanned closely the group they had passed just before the breakfast meal.

The hoodlum gang had suddenly appeared from the alleyway, and forming a circle, surrounded them. There was an addition to their ranks. Ralph noted this instantly. He was a rowdy-looking chunk of a fellow, and the swing of his body, the look on his face and the expression in his eyes showed that he delighted in thinking himself a “tough customer.” Backed by his comrades, who looked vicious and expectant, he 50 marched straight up to Ralph, who did not flinch a particle.

“You look like Fairbanks to me—Fairbanks, the engineer,” he observed, fixing a glance upon Ralph meant to dismay.

“Yes, that is my name,” said Ralph quietly.

“Well,” asserted the big fellow, “I’ve been looking for you, and I’m going to whip the life out of you.”

Marvin Clark stepped promptly forward at the announcement of the overgrown lout, who had signified his intention of whipping the young engineer of No. 999. Clark had told Ralph that athletics was his strong forte. He looked it as he squared firmly before the bully.

“Going to wallop somebody, are you?” spoke Clark cooly. “Watch the system-cylinder”—and the speaker gave to his arms a rotary motion so rapid that it was fairly dizzying, “or piston rods,” and one fist met the bulging breast of the fellow with a force that sent him reeling backwards several feet.

“Hey, there! you keep out of this, if you don’t want to be massacreed!” spoke a voice at Clark’s elbow, and he was seized by several of the rowdy crowd and forced back from the side of Ralph.

“Hands off!” shouted Clark, and he cleared a circle about him with a vigorous sweep of his arms. 52

“Don’t you mix in a fair fight, then,” warned a big fellow in the crowd, threateningly.

“Ah, it’s going to be a fair fight, is it?” demanded Clark.

“Yes, it is.”

“I’ll see to it that it is,” remarked Clark briefly.

The fellow he had dazed with his rapid-fire display of muscle had regained his poise, and was now again facing the young engineer.

“Understand?” he demanded, hunching up his shoulders and staring viciously at Ralph. “I’m Billy Bouncer.”

“Are you?” said Ralph simply.

“I am, and don’t you forget it. I happen to have got a tip from my uncle, John Evans, of Stanley Junction. I guess you know him.”

“I do,” announced Ralph bluntly, “and if you are as mean a specimen of a boy as he is of a man, I’m sorry for you.”

“What?” roared the young ruffian, raising his fists. “Do you see that?” and he put one out, doubled up.

“I do, and it’s mighty dirty, I can tell you.”

“Insult me, do you? I guess you don’t know who I am. Champion, see?—light-weight champion of this burg, and I wear four medals, and here they are,” and Bouncer threw back his coat 53 and vauntingly displayed four gleaming silver discs pinned to his vest.

“If you had four more, big as cartwheels, I don’t see how I would be interested,” observed Ralph.

“You don’t?” yelled Bouncer, hopping mad at failing to dazzle this new opponent with an acquisition that had awed his juvenile cohorts and admirers. “Why, I’ll grind you to powder! Strip.”

With this Bouncer threw off his coat, and there was a scuffle among his minions to secure the honor of holding it.

“I don’t intend to strip,” remarked Ralph, “and I don’t want to strike you, but you’ve got to open a way for myself and my friend to go about our business, or I’ll knock you down.”

“You’ll––Fellows, hear him!” shrieked Bouncer, dancing from foot to foot. “Oh, you mincemeat! up with your fists! It’s business now.”

The young engineer saw that it was impossible to evade a fight. The allusion of Bouncer to Jim Evans was enlightening. It explained the animus of the present attack.

If Lemuel Fogg had been bent on queering the special record run to Bridgeport out of jealousy, Evans, a former boon companion of the fireman, 54 had it in for Ralph on a more malicious basis. The young railroader knew that Evans was capable of any meanness or cruelty to pay him back for causing his arrest as an incendiary during the recent railroad strike on the Great Northern.

There was no doubt but what Evans had advised his graceless nephew of the intended visit of Ralph to Bridgeport. During the strike Evans had maimed railroad men and had been guilty of many other cruel acts of vandalism. Ralph doubted not that the plan was to have his precious nephew “do” him in a way that he would not be able to make the return trip with No. 999.

The young engineer was no pugilist, but he knew how to defend himself, and he very quickly estimated the real fighting caliber of his antagonist. He saw at a glance that Billy Bouncer was made up of bluff and bluster and show. The hoodlum made a great ado of posing and exercising his fists in a scientific way. He was so stuck up over some medal awards at amateur boxing shows, that he was wasting time in displaying his “style.”

“Are you ready?” demanded Bouncer, doing a quickstep and making a picturesque feint at his opponent.

“Let me pass,” said Ralph.

“Wow, when I’ve eaten you up, maybe!” 55

“Since you will have it, then,” observed Ralph quietly, “take that for a starter.”

The young engineer struck out once—only once, but he had calculated the delivery and effect of the blow to a nicety. There was a thud as his fist landed under the jaw of the bully, so quickly and so unexpectedly that the latter did not have time to put up so much as a pretense of a protection.

Back went Billy Bouncer, his teeth rattling, and down went Billy Bouncer on a backward slide. His head struck a loose paving brick. He moaned and closed his eyes.

“Four—medals!” he voiced faintly.

“Come on, Clark,” said Ralph.

He snatched the arm of his new acquaintance and tried to force his way to the alley opening. Thus they proceeded a few feet, but only a few. A hush had fallen over Bouncer’s friends, at the amazing sight of their redoubtable champion gone down in inglorious defeat, but only for a moment. One of the largest boys in the group rallied the disorganized mob.

“Out with your smashers!” he shouted. “Don’t let them get away!”

Ralph pulled, or rather forced his companion back against two steps with an iron railing, leading 56 to the little platform of the alley door of a building fronting on the street.

“No show making a break,” he continued in rapid tones. “Look at the cowards!”

At the call of their new leader, the crowd to its last member whipped out their weapons. They were made of some hard substance like lead, and incased in leather. They were attached to the wrist by a long loop, which enabled their possessors to strike a person at long range, the object of the attack having no chance to resist or defend himself.

“Grab the railing,” ordered Clark, whom Ralph was beginning to recognize as a quick-witted fellow in an emergency. “Now then, keep side by side—any tactics to hold them at bay or drive them off.”

The two friends had secured quite a tactical position, and they proceeded to make the most of it. The mob with angry yells made for them direct. They jostled one another in their eager malice to strike a blow. They crowded close to the steps, and their ugly weapons shot out from all directions.

One of the weapons landed on Ralph’s hand grasping the iron railing, and quite numbed and almost crippled it. A fellow used his weapon as a missile, on purpose or by mistake. At all events, 57 it whirled from his hand through the air, and striking Clark’s cheek, laid it open with quite a ghastly wound. Clark reached over and snatched a slungshot from the grasp of another of the assaulting party. He handed it quickly to his companion.

“Use it for all it’s worth,” he suggested rapidly. “Don’t let them down us, or we’re goners.”

As he spoke, Clark, nettled with pain, balanced himself on the railing and sent both feet flying into the faces of the onpressing mob. These tactics were wholly unexpected by the enemy. One of their number went reeling back, his nose nearly flattened to his face.

“Rush ’em!” shouted the fellow frantically.

Half-a-dozen of his cohorts sprang up the steps. They managed to grab Ralph’s feet. Now it was a pull and a clutch. Ralph realized that if he ever got down into the midst of that surging mob, or under their feet, it would be all over with him.

“It’s all up with us!” gasped Clark with a startled stare down the alley. “Fogg, Lemuel Fogg!”

The heart of the young engineer sank somewhat as he followed the direction of his companion’s glance. Sure enough, the fireman of No. 999 had put in an appearance on the scene.

“He’s coming like a cyclone!” said Clark. 58

Fogg was a rushing whirlwind of motion. He was bareheaded, and he looked wild and uncanny. Somewhere he had picked up a long round clothes pole or the handle to some street worker’s outfit. With this he was making direct for the crowd surrounding Ralph and Clark. Just then a slungshot blow drove the latter to his knees. Two of the crowd tried to kick at his face. Ralph was nerved up to desperate action now. He caught the uplifted foot of one of the vandals and sent him toppling. The other he knocked flat with his fist, but overpowering numbers massed for a headlong rush on the beleaguered refugees.

“Swish—thud! swish!” Half blinded by a blow dealt between the eyes by a hurling slungshot, the young engineer could discern a break in the program, the appearance of a new element that startled and astonished him. He had expected to see the furious Fogg join the mob and aid them in finishing up their dastardly work. Instead, like some madman, Fogg had waded into the ranks of the group, swinging his formidable weapon like a flail. It rose, it fell, it swayed from side to side, and its execution was terrific.

The fireman mowed down the amazed and scattering forces of Billy Bouncer as if they were rows of tenpins. He knocked them flat, and then he kicked them. It was a marvel that he did not 59 cripple some of them, for, his eyes glaring, his muscles bulging to the work, he acted like some fairly irresponsible being.

Within two minutes’ time the last one of the mob had vanished into the street. Flinging the pole away from him, Fogg began looking for his cap, which had blown off his head as he came rushing down the alley at cyclone speed.

Clark stared at the fireman in petrified wonder. Ralph stood overwhelmed with uncertainty and amazement.

“Mr. Fogg, I say, Mr. Fogg!” he cried, running after the fireman and catching at his sleeve, “How—why––”

“Boy,” choked out Lemuel Fogg, turning a pale, twitching face upon Ralph, “don’t say a word to me!”

And then with a queer, clicking sob in his throat, the fireman of No. 999 hastened down the alley looking for his cap.

“I don’t understand it at all,” exclaimed Ralph.

“Mad—decidedly mad,” declared young Clark. “Whew! that was a lively tussle. All the buttons are gone off my vest and one sleeve is torn open clear to the shoulder, and I guess there were only basting threads in that coat of yours, for it’s ripped clear up the back.”

Clark began to pick up some scattered buttons from the ground. His companion, however, was looking down the alley, and he followed Fogg with his eyes until the fireman had disappeared into the street.

“You’re wondering about things,” spoke Clark. “So am I.”

“I’m trying to figure out the puzzle, yes,” admitted the young engineer. “You see, we were both of us wrong, and we have misjudged Mr. Fogg.”

“I don’t know about that,” dissented Ralph’s companion.

“Why, he has helped us, instead of hurt us.” 61

“Yes,” said Clark, “but why? It’s nonsense to say that he didn’t start out on your trip fixed up to put you out of business if he could do it. It is folly, too, to think that he didn’t know that this Billy Bouncer, relative of that old-time enemy of yours back at Stanley Junction, Jim Evans, had put this gang up to beat you. If that wasn’t so, why has he been hanging around here all the morning in a suspicious, mysterious way, and how does he come to swoop down on the mob just in the nick of time.”

“Perhaps he was planning to head off the crowd all the time,” suggested Ralph.

“Not from the very start,” declared Clark positively. “No, sir—I think he has had a fit of remorse, and thought better of having you banged up or crippled.”

“At all events, Fogg has proven a good friend in need, and I shall not forget it soon,” observed Ralph.

When they came out into the street the hoodlum crowd had dispersed. They entered the first tailor shop they came to and soon had their clothing mended up.

“There’s a moving picture show open,” said Clark, after they had again proceeded on their way. “Let’s put in a half-hour or so watching the slides.” 62

This they did. Then they strolled down to the shops, took in the roundhouse, got an early dinner, and went to visit the museum at the Mechanics’ Exchange. This was quite an institution of Bridgeport, and generally interested railroad men. Clark was very agreeable to the proposition made by his companion to look over the place. They found a fine library and a variety of drawings and models, all along railroad lines.

“This suits me exactly,” declared Clark. “I am not and never will be a practical railroader, but I like its variety just the same. Another thing, a fellow learns something. Say, look there.”

The speaker halted his companion by catching his arm abruptly, as they turned into a small reading room after admiring a miniature reproduction in brass of a standard European locomotive.

“Yes, I see,” nodded Ralph, with a slight smile on his face, “our friend, Wheels.”

Both boys studied the eccentric youth they had seen for the first time a few hours previous. He occupied a seat at a desk in a remote corner of the room. Propped up before him was a big volume full of cuts of machinery, and he was taking notes from it. A dozen or more smaller books were piled up on a chair beside him.

Young as he was, there was a profound solemnity 63 and preoccupation in his methods that suggested that he had a very old head on a juvenile pair of shoulders. As Ralph and his companion stood regarding the queer genius, an attendant came up to Wheels. He touched him politely on the shoulder, and as the lad looked up in a dazed, absorbed way, pointed to the clock in the room.

“You told me to inform you when it was two o’clock,” spoke the attendant.

“Did I, now?” said Wheels in a lost, distressed sort of a way. “Dear me, what for, I wonder?” and he passed his hand abstractedly over his forehead. “Ah, I’ll find out.”

He proceeded to draw from his pocket the selfsame memorandum he had consulted in the case of Jim Scroggins. He mumbled over a number of items, and evidently struck the right one at last, for he murmured something about “catch the noon mail with a letter to the patent office,” arose, put on his cap, and hurriedly left the place, blissfully wool-gathering as the fact that noon had come and gone several hours since.

“I’m curious,” observed Clark, and as Wheels left the place he followed the attendant to the library office, and left Ralph to stroll about alone, while he engaged the former in conversation. In about five minutes Clark came back to Ralph with a curious but satisfied smile on his face. 64

“Well, I’ve got his biography,” he announced.

“Whose—Wheels?”

“Yes.”

“Who is he, anyway?” inquired Ralph.

“He thinks he is a young inventor.”

“And is he?”

“That’s an open question. They call him Young Edison around here, and his right name is Archie Graham. His father was an aeronaut who was an expert on airships, got killed in an accident to an aeroplane last year, and left his son some little money. Young Graham has been dabbling in inventions since he was quite young.”

“Did he really ever invent anything of consequence?” asked Ralph.

“The attendant here says that he did. About two years ago he got up a car window catch that made quite a flurry at the shops. It was used with good results, and the Great Northern was about to pay Graham something for the device, when it was learned that while he was bringing it to perfection some one else had run across pretty nearly the same idea.”

“And patented it first?”

“Both abroad and in this country. That of course shut Graham out. All the same, the attendant declares that Graham must have got the idea fully a year before the foreign fellow did.” 65

The boys left the place in a little while and proceeded towards the railroad depot. Ralph had conceived quite a liking for his volatile new acquaintance. Clark had shown himself to be a loyal, resourceful friend, and the young engineer felt that he would miss his genial company if the other did not take the return trip to Stanley Junction. He told Clark this as they reached the depot.

“That so?” smiled the latter. “Well, I’ll go sure if you’re agreeable. I’ve got no particular program to follow out, and I’d like to take in the Junction. Another thing, I’m curious to see how you come out with your friends. There’s that smash-up on the siding at Plympton, too. Something may come up on that where I may be of service to you.”

They found the locomotive, steam up, on one of the depot switches in charge of a special engineer. It lacked over half an hour of leaving time. While Clark hustled about the tender, Ralph donned his working clothes and chattered with the relief engineer. The latter was to run the locomotive to the train, and Ralph walked down the platform to put on the time.

“I’ve stowed my vest in a bunker in the cab,” said Clark, by his side.

“That’s all right,” nodded Ralph. 66

“And I’m going to get some sandwiches and a few bottles of pop for a little midnight lunch.”

“All right,” agreed the young engineer, as his companion started over towards Railroad Row.

Lemuel Fogg had not put in an appearance up to this time, but a few minutes later Ralph saw him in the cab of No. 999, which he had gained by a short cut from the street. As Ralph was looking in the direction of the locomotive, some one came briskly up behind him and gave him a sharp, friendly slap on the shoulder.

“Hello, Ralph Fairbanks!” he hailed.

“Why, Dave Bissell!” said the young railroader, turning to face and shake hands with an old acquaintance. Dave had been a train boy on an accommodation run at Stanley Junction about a year previous, and had graduated into the same line of service on the Overland Limited.

“I’m very glad to see you,” said Ralph; “I hear you’ve got a great run.”

“Famous, Fairbanks!” declared Dave. “I’m hearing some big things about you.”

“You call them big because you remember the Junction and exaggerate home news,” insisted Ralph.

“Maybe so, but I always said you’d be president of the road some time,” began Dave, and then with a start stared hard at young Clark, who appeared 67 at that moment crossing the platform of a stationary coach from the direction of Railroad Row. “Why!” exclaimed Dave, “hey! hi! this way.”

Clark had halted abruptly. His expressive features were a study. As he evidently recognized Dave, his face fell, his eyes betokened a certain consternation, and dropping a package he carried he turned swiftly about, jumped from the platform and disappeared.

“Why” spoke Ralph, considerably surprised, “do you know Marvin Clark?”

“Who?” bolted out Dave bluntly.

“That boy—Marvin Clark.”

“Marvin Clark nothing!” shouted the train boy volubly. “That’s my cousin, Fred Porter, of Earlville.”

The young engineer of No. 999 faced a new mystery, a sharp suspicion darted through his mind. He recalled instantly several queer breaks that the special passenger had made in his conversation.

“Your cousin, is he?” observed Ralph thoughtfully.

“That’s what he is,” affirmed Dave Bissell.

“And his name is Fred Porter?”

“Always has been,” declared Dave. “Why, something up? Humph! I can guess. Bet he’s been up to some of his old tricks. He always was a joker and full of mischief.”

“Tell me more about him,” suggested Ralph.

“Why, there isn’t much to tell,” said Dave. “He and I were raised at Earlville. His parents both died several years ago, and he wandered around a good deal. This is the first I’ve seen of him for over two years.” 69

“Might you not be mistaken—facial resemblance?”

“Not much,” observed Dave staunchly. “Think I don’t recognize my own relatives? Why, didn’t you notice how he acted?”

“Yes, surprised.”

“No, scared,” corrected Dave, “and ran away.”

“Why?” demanded Ralph.

“Well, from your seeming to know him under another name, I should say because he is found out. What game has he been playing on you, Fairbanks?”

“He has done me more good than harm,” evaded Ralph. “I’ve only known him since yesterday.”

“Well, he has run away, that’s certain. That bothers me. Fred Porter was never a sneak or a coward. He was full of jolly mischief and fun, but a better friend no fellow ever had.”

“He struck me that way,” said Ralph. “I hope he’ll come back. There’s my engine coming, and I’ll have to go on duty. Try and find him, Dave, will you?”

“If I can.”

“And if you find him, tell him I must see him before we leave Bridgeport.”

“All right.”

Ralph picked up the lunch package that his odd 70 acquaintance had dropped and moved along the platform to where No. 999 had run. The locomotive was backed to the coaches and the relief engineer stepped to the platform.

“I say,” he projected in an undertone to Ralph, “what’s up with Fogg?”

“Is there anything?” questioned Ralph evasively.

“Dizzy in the headlight and wobbly in the drivers, that’s all,” came the response, with a wink.

Ralph’s heart sank as he entered the cab. Its atmosphere was freighted with the fumes of liquor, and a single glance at the fireman convinced him that Fogg was very far over the line of sobriety. Ralph hardly knew how to take Fogg. The latter nodded briefly and turned away, pretending to occupy himself looking from the cab window. Ralph could not resist the impulse to try and break down the wall of reserve between them. He stepped over to the fireman’s side and placed a gentle hand on his shoulder.

“See here, Fogg,” he said in a friendly tone, “I’ve got to say something or do something to square accounts for your help in routing that crowd this morning.”

“Don’t you speak of it!” shot out the fireman fiercely. “It’s over and done, isn’t it? Let it drop.” 71