Title: Library of the World's Best Literature, Ancient and Modern — Volume 07

Editor: Charles Dudley Warner

Hamilton Wright Mabie

Lucia Isabella Gilbert Runkle

George H. Warner

Release date: May 4, 2009 [eBook #28684]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Katherine Ward and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER

EDITOR

HAMILTON WRIGHT MABIE

LUCIA GILBERT RUNKLE

GEORGE HENRY WARNER

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Connoisseur Edition

Vol. VII.

NEW YORK

THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY

Connoisseur Edition

LIMITED TO FIVE HUNDRED COPIES IN HALF RUSSIA

No. 299

Copyright, 1896, by

R. S. Peale and J. A. Hill

All rights reserved

CRAWFORD H. TOY, A.M., LL.D.,

Professor of Hebrew,

Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

THOMAS R. LOUNSBURY, LL.D., L.H.D.,

Professor of English in the Sheffield Scientific School of

Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

WILLIAM M. SLOANE, Ph.D., L.H.D.,

Professor of History and Political Science,

Princeton University, Princeton, N.J.

BRANDER MATTHEWS, A.M., LL.B.,

Professor of Literature,

Columbia University, New York City.

JAMES B. ANGELL, LL.D.,

President of the

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

WILLARD FISKE, A.M., Ph.D.,

Late Professor of the Germanic and Scandinavian Languages

and Literatures,

Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y.

EDWARD S. HOLDEN, A.M., LL.D.,

Director of the Lick Observatory, and Astronomer,

University of California, Berkeley, Cal.

ALCÉE FORTIER, Lit.D.,

Professor of the Romance Languages,

Tulane University, New Orleans, La.

WILLIAM P. TRENT, M.A.,

Dean of the Department of Arts and Sciences, and Professor of

English and History,

University of the South, Sewanee, Tenn.

PAUL SHOREY, Ph.D.,

Professor of Greek and Latin Literature,

University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill.

WILLIAM T. HARRIS, LL.D.,

United States Commissioner of Education,

Bureau of Education, Washington, D.C.

MAURICE FRANCIS EGAN, A.M., LL.D.,

Professor of Literature in the

Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.

| PAGE | |

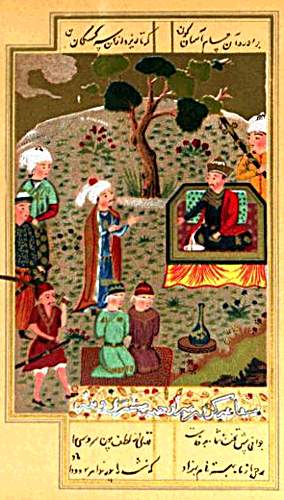

| Persian Manuscript (Colored Plate) | Frontispiece |

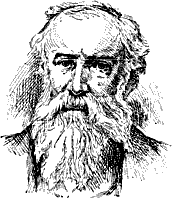

| John Bunyan (Portrait) | 2748 |

| Edmund Burke (Portrait) | 2780 |

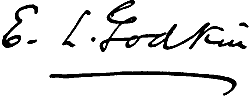

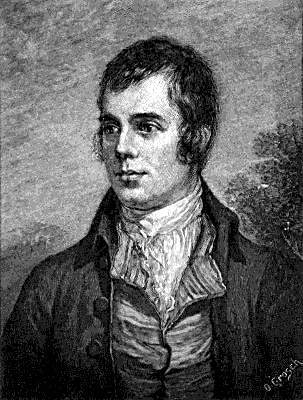

| Robert Burns (Portrait) | 2834 |

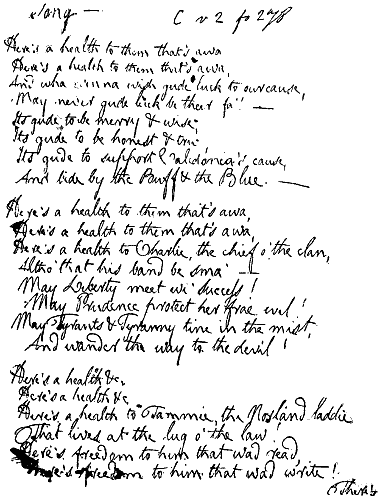

| Burns Manuscript (Facsimile) | 2844 |

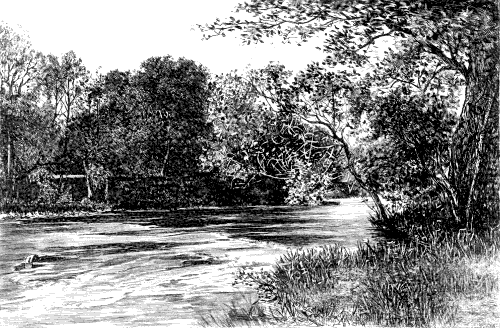

| "Banks and Braes o' Bonnie Doon" (Etching) | 2866 |

| Lord Byron (Portrait) | 2936 |

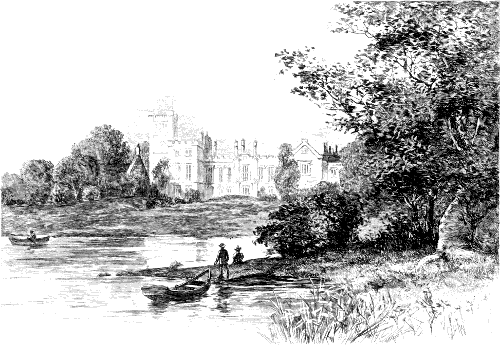

| "Newstead Abbey" (Etching) | 2942 |

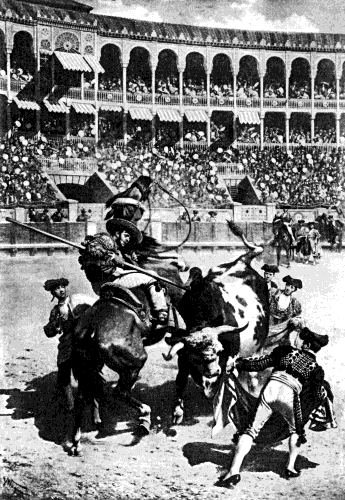

| "The Bull-Fight" (Photogravure) | 3004 |

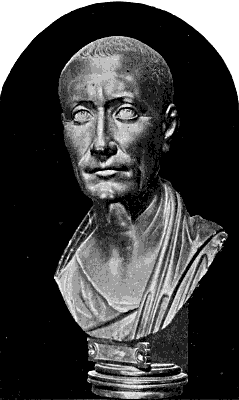

| Julius Cæsar (Portrait) | 3038 |

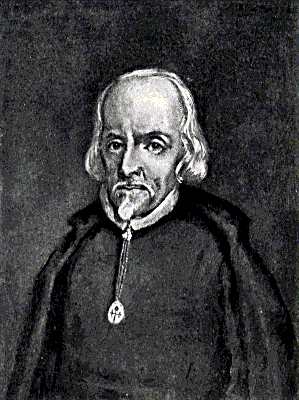

| Calderon (Portrait) | 3072 |

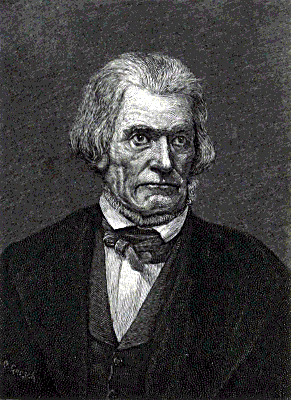

| John Caldwell Calhoun (Portrait) | 3088 |

| Henry Cuyler Bunner |

| Gottfried August Bürger |

| Frances Burney |

| Sir Richard F. Burton |

| Robert Burton |

| John Burroughs |

| Horace Bushnell |

| Samuel Butler |

| George W. Cable |

| Thomas Henry Hall Caine |

(1855-1896)

The position which Henry Cuyler Bunner has come to occupy in the literary annals of our time strengthens as the days pass. If the stream of his genius flowed in gentle rivulets, it traveled as far and spread its fruitful influence as wide as many a statelier river. He was above all things a poet. In his prose as in his verse he has revealed the essential qualities of a poet's nature: he dealt with the life which he saw about him in a spirit of broad humanity and with genial sympathy. When he fashioned the tender triolet on the pitcher of mignonette, or sang of the little red box at Vesey Street, he wrote of what he knew; and his stories, even when embroidered with quaint fancies, tread firmly the American soil of the nineteenth century. But Bunner's realism never concerned itself with the record of trivialities for their own sake. When he portrayed the lower phases of city life, it was the humor of that life he caught, and not its sordidness; its kindliness, and not its brutality. His mind was healthy, and since it was a poet's mind, the point upon which it was so nicely balanced was love: love of the trees and flowers, love of his little brothers in wood and field, love of his country home, love of the vast city in its innumerable aspects; above all, love of his wife, his family, and his friends; and all these outgoings of his heart have found touching expression in his verse. Indeed, this attitude of affectionate kinship with the world has colored all his work; it has made his satire sweet-tempered, given his tales their winning grace, and lent to his poetry its abiding power.

Henry C. Bunner

The work upon which Bunner's fame must rest was all produced within a period of less than fifteen years. He was born in 1855 at Oswego, New York. He came to the city of New York when very young, and received his education there. A brief experience of business life sufficed to make his true vocation clear, and at the age of eighteen he began his literary apprenticeship on the Arcadian. When that periodical passed away, Puck was just struggling into2732 existence, and for the English edition, which was started in 1877, Bunner's services were secured. Half of his short life was spent in editorial connection with that paper. To his wisdom and literary abilities is due in large measure the success which has always attended the enterprise. Bunner had an intimate knowledge of American character and understood the foibles of his countrymen; but he was never cynical, and his satire was without hostility. He despised opportune journalism. His editorials were clear and vigorous; free not from partisanship, but from partisan rancor, and they made for honesty and independence. His firm stand against political corruption, socialistic vagaries, the misguided and often criminal efforts of labor agitators, and all the visionary schemes of diseased minds, has contributed to the stability of sound and self-respecting American citizenship.

Bunner's first decided success in story-telling was 'The Midge,' which appeared in 1886. It is a tale of New York life in the interesting old French quarter of South Fifth Avenue. Again, in 'The Story of a New York House,' he displayed the same quick feeling for the spirit of the place, as it was and is. This tale first appeared in the newly founded Scribner's Magazine, to which he has since been a constant contributor. Here some of his best short stories have been published, including the excellent 'Zadoc Pine,' with its healthy presentation of independent manhood in contest with the oppressive exactions of labor organizations. But Bunner was no believer in stories with a tendency; the conditions which lie at the root of great sociological questions he used as artistic material, never as texts. His stories are distinguished by simplicity of motive; each is related with fine unobtrusive humor and with an underlying pathos, never unduly emphasized. The most popular of his collections of tales is that entitled 'Short Sixes,' which, having first appeared in Puck, were published in book form in 1891. A second volume came out three years later. When the shadow of death had already fallen upon Bunner, a new collection of his sketches was in process of publication: 'Jersey Street and Jersey Lane.' In these, as in the still more recent 'Suburban Sage,' is revealed the same fineness of sympathetic observation in town and country that we have come to associate with Bunner's name. Among his prose writings there remains to be mentioned the series from Puck entitled 'Made in France.' These are an application of the methods of Maupassant to American subjects; they display that wonderful facility in reproducing the flavor of another's style which is exhibited in Bunner's verse in a still more eminent degree. His prose style never attained the perfection of literary finish, but it is easy and direct, free from sentimentality and rhetoric; in the simplicity of his conceptions and the delicacy of his treatment lies its chief charm.

2733 Bunner's verse, on the other hand, shows a complete mastery of form. He was a close student of Horace; he tried successfully the most exacting of exotic verse-forms, and enjoyed the distinction of having written the only English example of the difficult Chant-Royal. Graceful vers de société and bits of witty epigram flowed from him without effort. But it was not to this often dangerous facility that Bunner owed his poetic fame. His tenderness, his quick sympathy with nature, his insight into the human heart, above all, the love and longing that filled his soul, have infused into his perfected rhythms the spirit of universal brotherhood that underlies all genuine poetry. His 'Airs from Arcady' (1884) achieved a success unusual for a volume of poems; and the love lyrics and patriotic songs of his later volume, 'Rowen,' maintain the high level of the earlier book. The great mass of his poems is still buried in the back numbers of the magazines, from which the best are to be rescued in a new volume. If his place is not among the greatest of our time, he has produced a sufficient body of fine verse to rescue his name from oblivion and render his memory dear to all who value the legacy of a sincere and genuine poet. He died on May 11th, 1896, at the age of forty-one.

Copyrighted by Charles Scribner's Sons.

From 'Short Sixes'

When the little seamstress had climbed to her room in the story over the top story of the great brick tenement house in which she lived, she was quite tired out. If you do not understand what a story over a top story is, you must remember that there are no limits to human greed, and2734 hardly any to the height of tenement houses. When the man who owned that seven-story tenement found that he could rent another floor, he found no difficulty in persuading the guardians of our building laws to let him clap another story on the roof, like a cabin on the deck of a ship; and in the southeasterly of the four apartments on this floor the little seamstress lived. You could just see the top of her window from the street—the huge cornice that had capped the original front, and that served as her window-sill now, quite hid all the lower part of the story on top of the top story.

The little seamstress was scarcely thirty years old, but she was such an old-fashioned little body in so many of her looks and ways that I had almost spelled her "sempstress," after the fashion of our grandmothers. She had been a comely body, too; and would have been still, if she had not been thin and pale and anxious-eyed.

She was tired out to-night, because she had been working hard all day for a lady who lived far up in the "New Wards" beyond Harlem River, and after the long journey home she had to climb seven flights of tenement-house stairs. She was too tired, both in body and in mind, to cook the two little chops she had brought home. She would save them for breakfast, she thought. So she made herself a cup of tea on the miniature stove, and ate a slice of dry bread with it. It was too much trouble to make toast.

But after dinner she watered her flowers. She was never too tired for that, and the six pots of geraniums that caught the south sun on the top of the cornice did their best to repay her. Then she sat down in her rocking-chair by the window and looked out. Her eyry was high above all the other buildings, and she could look across some low roofs opposite and see the further end of Tompkins Square, with its sparse spring green showing faintly through the dusk. The eternal roar of the city floated up to her and vaguely troubled her. She was a country girl; and although she had lived for ten years in New York, she had never grown used to that ceaseless murmur. To-night she felt the languor of the new season, as well as the heaviness of physical exhaustion. She was almost too tired to go to bed.

She thought of the hard day done and the hard day to be begun after the night spent on the hard little bed. She thought2735 of the peaceful days in the country, when she taught school in the Massachusetts village where she was born. She thought of a hundred small slights that she had to bear from people better fed than bred. She thought of the sweet green fields that she rarely saw nowadays. She thought of the long journey forth and back that must begin and end her morrow's work, and she wondered if her employer would think to offer to pay her fare. Then she pulled herself together. She must think of more agreeable things or she could not sleep. And as the only agreeable things she had to think about were her flowers, she looked at the garden on top of the cornice.

A peculiar gritting noise made her look down, and she saw a cylindrical object that glittered in the twilight, advancing in an irregular and uncertain manner toward her flower-pots. Looking closer, she saw that it was a pewter beer-mug, which somebody in the next apartment was pushing with a two-foot rule. On top of the beer-mug was a piece of paper, and on this paper was written, in a sprawling, half-formed hand:—

The seamstress started up in terror and shut the window. She remembered that there was a man in the next apartment. She had seen him on the stairs on Sundays. He seemed a grave, decent person; but—he must be drunk. She sat down on her bed all a tremble. Then she reasoned with herself. The man was drunk, that was all. He probably would not annoy her further. And if he did, she had only to retreat to Mrs. Mulvaney's apartment in the rear, and Mr. Mulvaney, who was a highly respectable man and worked in a boiler-shop, would protect her. So, being a poor woman who had already had occasion to excuse—and refuse—two or three "libberties" of like sort, she made up her mind to go to bed like a reasonable seamstress, and she did. She was rewarded, for when her light was out, she could see in the moonlight that the two-foot rule appeared again with one joint bent back, hitched itself into the mug-handle, and withdrew the mug.

The next day was a hard one for the little seamstress, and she hardly thought of the affair of the night before until the same hour had come around again, and she sat once more by2736 her window. Then she smiled at the remembrance. "Poor fellow," she said in her charitable heart, "I've no doubt he's awfully ashamed of it now. Perhaps he was never tipsy before. Perhaps he didn't know there was a lone woman in here to be frightened."

Just then she heard a gritting sound. She looked down. The pewter pot was in front of her, and the two-foot rule was slowly retiring. On the pot was a piece of paper, and on the paper was—

This time the little seamstress shut her window with a bang of indignation. The color rose to her pale cheeks. She thought that she would go down to see the janitor at once. Then she remembered the seven flights of stairs; and she resolved to see the janitor in the morning. Then she went to bed, and saw the mug drawn back just as it had been drawn back the night before.

The morning came, but somehow the seamstress did not care to complain to the janitor. She hated to make trouble—and the janitor might think—and—and—well, if the wretch did it again she would speak to him herself, and that would settle it. And so on the next night, which was a Thursday, the little seamstress sat down by her window, resolved to settle the matter. And she had not sat there long, rocking in the creaking little rocking-chair which she had brought with her from her old home, when the pewter pot hove in sight, with a piece of paper on the top. This time the legend read:—

The seamstress did not quite know whether to laugh or to cry. But she felt that the time had come for speech. She leaned out of her window and addressed the twilight heaven.

"Mr.—Mr.—sir—I—will you please put your head out of the window so that I can speak to you?"

The silence of the other room was undisturbed. The seamstress drew back, blushing. But before she could nerve herself for another attack, a piece of paper appeared on the end of the two-foot rule.2737

What was the little seamstress to do? She stood by the window and thought hard about it. Should she complain to the janitor? But the creature was perfectly respectful. No doubt he meant to be kind. He certainly was kind, to waste these pots of porter on her. She remembered the last time—and the first—that she had drunk porter. It was at home, when she was a young girl, after she had the diphtheria. She remembered how good it was, and how it had given her back her strength. And without one thought of what she was doing, she lifted the pot of porter and took one little reminiscent sip—two little reminiscent sips—and became aware of her utter fall and defeat. She blushed now as she had never blushed before, put the pot down, closed the window, and fled to her bed like a deer to the woods.

And when the porter arrived the next night, bearing the simple appeal—

the little seamstress arose and grasped the pot firmly by the handle, and poured its contents over the earth around her largest geranium. She poured the contents out to the last drop, and then she dropped the pot, and ran back and sat on her bed and cried, with her face hid in her hands.

"Now," she said to herself, "you've done it! And you're just as nasty and hard-hearted and suspicious and mean as—as pusley!" And she wept to think of her hardness of heart. "He will never give me a chance to say 'I am sorry,'" she thought. And really, she might have spoken kindly to the poor man, and told him that she was much obliged to him, but that he really must not ask her to drink porter with him.

"But it's all over and done now," she said to herself as she sat at her window on Saturday night. And then she looked at the cornice, and saw the faithful little pewter pot traveling slowly toward her.

She was conquered. This act of Christian forbearance was too much for her kindly spirit. She read the inscription on the paper,

2738 and she lifted the pot to her lips, which were not half so red as her cheeks, and took a good, hearty, grateful draught.

She sipped in thoughtful silence after this first plunge, and presently she was surprised to find the bottom of the pot in full view. On the table at her side a few pearl buttons were screwed up in a bit of white paper. She untwisted the paper and smoothed it out, and wrote in a tremulous hand—she could write a very neat hand—

This she laid on the top of the pot, and in a moment the bent two-foot rule appeared and drew the mail-carriage home. Then she sat still, enjoying the warm glow of the porter, which seemed to have permeated her entire being with a heat that was not at all like the unpleasant and oppressive heat of the atmosphere, an atmosphere heavy with the spring damp. A gritting on the tin aroused her. A piece of paper lay under her eyes.

Now it is unlikely that in the whole round and range of conversational commonplaces there was one other greeting that could have induced the seamstress to continue the exchange of communications. But this simple and homely phrase touched her country heart. What did "groing weather" matter to the toilers in this waste of brick and mortar? This stranger must be, like herself, a country-bred soul, longing for the new green and the upturned brown mold of the country fields. She took up the paper, and wrote under the first message:—

But that seemed curt: "for—" she added; "for" what? She did not know. At last in desperation she put down "potatoes." The piece of paper was withdrawn, and came back with an addition:—

And when the little seamstress had read this, and grasped the fact that "m-i-s-t" represented the writer's pronunciation of "moist," she laughed softly to herself. A man whose mind at such a time was seriously bent upon potatoes was not a man to be feared. She found a half-sheet of note-paper, and wrote:—

I lived in a small village before I came to New York, but I am afraid I do not know much about farming. Are you a farmer?

The answer came:—

As she read this, the seamstress heard the church clock strike nine.

"Bless me, is it so late?" she cried, and she hurriedly penciled Good Night, thrust the paper out, and closed the window. But a few minutes later, passing by, she saw yet another bit of paper on the cornice, fluttering in the evening breeze. It said only good nite, and after a moment's hesitation, the little seamstress took it in and gave it shelter.

After this they were the best of friends. Every evening the pot appeared, and while the seamstress drank from it at her window, Mr. Smith drank from its twin at his; and notes were exchanged as rapidly as Mr. Smith's early education permitted. They told each other their histories, and Mr. Smith's was one of travel and variety, which he seemed to consider quite a matter of course. He had followed the sea, he had farmed, he had been a logger and a hunter in the Maine woods. Now he was foreman of an East River lumber-yard, and he was prospering. In a year or two he would have enough laid by to go home to Bucksport and buy a share in a ship-building business. All this dribbled out in the course of a jerky but variegated correspondence, in which autobiographic details were mixed with reflections moral and philosophical.

A few samples will give an idea of Mr. Smith's style:—

To which the seamstress replied:—

But Mr. Smith disposed of this subject very briefly:—

2740 Further he vouchsafed:—

The seamstress had taught school one winter, and she could not refrain from making an attempt to reform Mr. Smith's orthography. One evening, in answer to this communication,—

she wrote:—

but she gave up the attempt when he responded:—

The spring wore on, and the summer came, and still the evening drink and the evening correspondence brightened the close of each day for the little seamstress. And the draught of porter put her to sleep each night, giving her a calmer rest than she had ever known during her stay in the noisy city; and it began, moreover, to make a little "meet" for her. And then the thought that she was going to have an hour of pleasant companionship somehow gave her courage to cook and eat her little dinner, however tired she was. The seamstress's cheeks began to blossom with the June roses.

And all this time Mr. Smith kept his vow of silence unbroken, though the seamstress sometimes tempted him with little ejaculations and exclamations to which he might have responded. He was silent and invisible. Only the smoke of his pipe, and the2741 clink of his mug as he set it down on the cornice, told her that a living, material Smith was her correspondent. They never met on the stairs, for their hours of coming and going did not coincide. Once or twice they passed each other in the street—but Mr. Smith looked straight ahead of him about a foot over her head. The little seamstress thought he was a very fine-looking man, with his six feet one and three-quarters and his thick brown beard. Most people would have called him plain.

Once she spoke to him. She was coming home one summer evening, and a gang of corner-loafers stopped her and demanded money to buy beer, as is their custom. Before she had time to be frightened, Mr. Smith appeared,—whence, she knew not,—scattered the gang like chaff, and collaring two of the human hyenas, kicked them, with deliberate, ponderous, alternate kicks, until they writhed in ineffable agony. When he let them crawl away, she turned to him and thanked him warmly, looking very pretty now, with the color in her cheeks. But Mr. Smith answered no word. He stared over her head, grew red in the face, fidgeted nervously, but held his peace until his eyes fell on a rotund Teuton passing by.

"Say, Dutchy!" he roared. The German stood aghast. "I ain't got nothing to write with!" thundered Mr. Smith, looking him in the eye. And then the man of his word passed on his way.

And so the summer went on, and the two correspondents chatted silently from window to window, hid from sight of all the world below by the friendly cornice. And they looked out over the roof and saw the green of Tompkins Square grow darker and dustier as the months went on.

Mr. Smith was given to Sunday trips into the suburbs, and he never came back without a bunch of daisies or black-eyed Susans or, later, asters or golden-rod for the little seamstress. Sometimes, with a sagacity rare in his sex, he brought her a whole plant, with fresh loam for potting.

He gave her also a reel in a bottle, which, he wrote, he had "maid" himself, and some coral, and a dried flying-fish that was something fearful to look upon, with its sword-like fins and its hollow eyes. At first she could not go to sleep with that flying-fish hanging on the wall.

But he surprised the little seamstress very much one cool September evening, when he shoved this letter along the cornice:—

The little seamstress gazed at this letter a long time. Perhaps she was wondering in what Ready Letter-Writer of the last century Mr. Smith had found his form. Perhaps she was amused at the results of his first attempt at punctuation. Perhaps she was thinking of something else, for there were tears in her eyes and a smile on her small mouth.

But it must have been a long time, and Mr. Smith must have grown nervous, for presently another communication came along the line where the top of the cornice was worn smooth. It read:

2743 The little seamstress seized a piece of paper and wrote:—

Then she rose and passed it out to him, leaning out of the window, and their faces met.

Copyright of Keppler and Schwarzmann.

Copyrighted by Charles Scribner's Sons.

Copyrighted by Charles Scribner's Sons.

(1628-1688)

BY REV. EDWIN P. PARKER

John Bunyan, son of Thomas Bunnionn Junr and Margaret Bentley, was born 1628, in the quaint old village of Elstow, one mile southwest of Bedford, near the spot where, three hundred years before, his ancestor William Boynon resided. His father was a poor tinker or "braseyer," and his mother's lineage is unknown. He says,—"I never went to school to Aristotle or Plato, but was brought up at my father's house in a very mean condition, among a company of poor countrymen."

He learned to read and write "according to the rate of other poor men's children"; but soon lost "almost utterly" the little he had learned. Shortly after his mother's death, when he was about seventeen years of age, he served as a soldier for several months, probably in the Parliamentary army. Not long afterward he married a woman as poor as himself, by whose gentle influence he was gradually led into the way of those severe spiritual conflicts and "painful exercises of mind" from which he finally came forth, at great cost, victorious. These religious experiences, vividly described in his 'Grace Abounding,' traceable in the course of his chief Pilgrim, and frequently referred to in his discourses, have been too literally interpreted by some, and too much explained away as unreal by others; but present no special difficulty to those who will but consider Bunyan's own explanations.

From boyhood he had lived a roving and non-religious life, although possessing no little tenderness of conscience. He was neither intemperate nor dishonest; he was not a law-breaker; he explicitly and indignantly declares:—"If all the fornicators and adulterers in England were hanged by the neck till they be dead, John Bunyan would still be alive and well!" The particular sins of which he was guilty, so far as he specifies them, were profane swearing, from which he suddenly ceased at a woman's reproof, and certain sports, innocent enough in themselves, which the prevailing Puritan rigor severely condemned. What, then, of that vague and exceeding sinfulness of which he so bitterly accuses and repents himself? It was that vision of sin, however disproportionate, which a deeply wounded and graciously healed spirit often has, in looking back upon the past from that theological standpoint whence all want of conformity to the perfect law of God seems heinous and dreadful.

"A sinner may be comparatively a little sinner, and sensibly a great one. There are two sorts of greatness in sin: greatness by reason of number; greatness by reason of the horrible nature of sin. In the last sense, he that has but one sin, if such an one could be found, may in his own eyes find himself the biggest sinner in the world."

"Visions of God break the heart, because, by the sight the soul then has of His perfections, it sees its own infinite and unspeakable disproportion."

"The best saints are most sensible of their sins, and most apt to make mountains of their molehills."

Such sentences from Bunyan's own writings—and many like them might be quoted—shed more light upon the much-debated question of his "wickedness" than all that his biographers have written.

In John Gifford, pastor of a little Free Church in Bedford, Bunyan found a wise friend, and in 1653 he joined that church. He soon discovered his gifts among the brethren, and in due time was appointed to the office of a gospel minister, in which he labored with indefatigable industry and zeal, and with ever-increasing fame and success, until his death. His hard personal fortunes between the Restoration of 1660 and the Declaration of Indulgence of 1672, including his imprisonment for twelve years in Bedford Gaol; his subsequent imprisonment in 1675-6, when the first part of the 'Pilgrim's Progress' was probably written; and the arduous engagements of his later and comparatively peaceful years,—must be sought in biographies, the latest and perhaps the best of which is that by Rev. John Brown, minister of the Bunyan Church at Bedford. The statute under which Bunyan suffered is the 35th Eliz., Cap. 1, re-enacted with rigor in the 16th Charles II., Cap. 4, 1662; and the spirit of it appears in the indictment preferred against him:—"that he hath devilishly and perniciously abstained from coming to Church to hear Divine service, and is a common upholder of several unlawful meetings and conventicles, to the great disturbance and distraction of the good subjects of this Kingdom," etc., etc.

The story of Bunyan's life up to the time of his imprisonment, and particularly that of his arrests and examinations before the justices, and also the account of his experiences in prison, should be read in his own most graphic narrative, in the 'Grace Abounding,' which is one of the most precious portions of all autobiographic literature. Bunyan was born and bred, he lived and labored, among the common people, with whom his sympathies were strong and tender, and by whom he was regarded with the utmost veneration and affection. He understood them, and they him. For nearly a century they were almost the only readers of his published writings. They came to call him Bishop Bunyan. His native genius, his great human-heartedness and loving-kindness, his burning zeal and indomitable courage, his racy humor and kindling imagination, all vitalized2749 by the spiritual force which came upon him through the encompassing atmosphere of devout Puritanism, were consecrated to the welfare of his fellow-men. His personal friend, Mr. Doe, describes him as "tall in stature, strong-boned, of a ruddy face, with sparkling eyes, nose well set, mouth moderately large, forehead something high, and his habit always plain and modest." His portrait, painted in 1685, shows a vigorous, kindly face, with mustachios and imperial, and abundance of hair falling in long wavy masses about the neck and shoulders,—more Cavalier-like than Roundhead.

JOHN BUNYAN.

Bunyan was a voluminous writer, and his works, many of them posthumous, are said to equal in number the sixty years of his life. But even the devout and sympathetic critic is compelled to acknowledge the justice of that verdict of time which has consigned most of them to a virtual oblivion. The controversial tracts possess no elements of enduring interest. The doctrinal and spiritual discourses are elaborations of a system of religious thought which long ago "had its day and ceased to be." Yet they contain pithy sentences, homely and pat illustrations, and many a paragraph, rugged or tender, in which one recognizes the stamp of his genius, and an intimation of his remarkable power as a preacher. The best of these discourses, 'The Jerusalem Sinner Saved,' 'Come and Welcome to Jesus Christ,' and 'Light for Them that Sit in Darkness,' while they sparkle here and there with things unique and precious to the Bunyan-curious student, would seem dull and tedious to the general though devout reader. In many a passage we feel, to use his phrase, his "heart-pulling power," no less than the force and felicity of his most original images and analogies; but these passages are little oases in a dry and thirsty land. The 'Life and Death of Mr. Badman' vividly presents certain aspects of English provincial life in that day; but they are repulsive, and the entire work is marred by flat moralizings and coarse, often incredible stories.

The 'Holy War,' which Macaulay said would have been our greatest religious allegory if the 'Pilgrim's Progress' had not been written, has ceased to be much read. The conception of the conquest of the human soul by the irresistible operation of divine force is so foreign to modern thought and faith that Bunyan's similitude no longer seems a verisimilitude. The pages abound with quaint, humorous, and lifelike touches;—as where Diabolus stations at Ear-Gate a guard of deaf men under old Mr. Prejudice, and Unbelief is described as "a nimble jack whom they could never lay hold of";—but as compared with the 'Pilgrim's Progress' the allegory is artificial, its elaboration of analogies is ponderous and tedious, and its characters lack solidity and reality.

All these works, however, exhibit a remarkable command of the mother tongue, a shrewd common-sense and mother wit, a fervid2750 spiritual life, and a wonderful knowledge of the English Bible. They may be likened to more or less submerged wrecks kept from sinking into utter neglect by the bond of authorship which connects them with the one incomparable work which floats, unimpaired by time, on the sea of universal appreciation and favor. Bunyan's unique and secure position in English literature was gained by the 'Pilgrim's Progress,' the first part of which was published in 1678, and the second in 1685.

The broader, freer conception of the pilgrimage—as old in literature as the ninetieth Psalm, apt and fond, as innumerable books show, from De Guileville's 'Le Pelerinage de l'Homme' in the fourteenth century to Patrick's 'Parable' three hundred years later—took sudden possession of Bunyan's imagination while he was in prison, and kindled all his finest powers. Then he undertook, poet-wise, to work out this conception, capable of such diversity of illustration, in a form of literature that has ever been especially congenial to the human mind. Unguided save by his own consecrated genius, unaided by other books than his English Bible and Fox's 'Book of Martyrs,' he proceeded with a simplicity of purpose and felicity of expression, and with a fidelity to nature and life, which gave to his unconsciously artistic story the charm of perfect artlessness as well as the semblance of reality. When Bunyan's lack of learning and culture are considered, and also the comparative dryness of his controversial and didactic writings, this efflorescence of a vital spirit of beauty and of an essentially poetic genius in him seems quite inexplicable. The author's rhymed 'Apology for His Book,' which usually prefaces the 'Pilgrim's Progress,' contains many significant hints as to the way in which he was led to

He had no thought of producing a work of literary excellence; but on the other hand he had not, in writing this book, his customary purpose of spiritual edification. Indeed, he put his multiplying thoughts and fancies aside, lest they should interfere with a more serious and important book which he had in hand!

2751 The words are exceedingly suggestive. In writing so aimlessly—"I knew not what"—to gratify himself by permitting the allegory into which he had suddenly fallen to take possession of him and carry him whithersoever it would, while he wrote out with delight his teeming fancies, was not Bunyan for the first time exercising his genius in a freedom from all theological and other restraint, and so in a surpassing range and power? The dreamer and poet supplanted the preacher and teacher. He yielded to the simple impulse of his genius, gave his imagination full sweep, and so, as never before or elsewhere, soared and sang in what seemed to many of his Puritan friends a questionable freedom and profane inspiration. And yet his song, or story, was not a creation of mere fancy,—

and therefore, we add, it finds its way to the heart of mankind.

Hence the spontaneity of the allegory, its ease and freedom of movement, its unlabored development, its natural and vital enfolding of that old pilgrim idea of human life which had so often bloomed in the literature of all climes and ages, but whose consummate flower appeared in the book of this inspired Puritan tinker-preacher. Hence also the dramatic unity and methodic perfectness of the story. Its byways all lead to its highway; its episodes are as vitally related to the main theme as are the ramifications of a tree to its central stem. The great diversities of experience in the true pilgrims are dominated by one supreme motive. As for the others, they appear incidentally to complete the scenes, and make the world and its life manifold and real. The Pilgrim is a most substantial person, and once well on the way, the characters he meets, the difficulties he encounters, the succor he receives, the scenes in which he mingles, are all, however surprising, most natural. The names, and one might almost say the forms and faces, of Pliable, Obstinate, Faithful, Hopeful, Talkative, Mercy, Great-heart, old Honest, Valiant-for-truth, Feeble-mind, Ready-to-halt, Miss Much-afraid, and many another, are familiar to us all. Indeed, the pilgrimage is our own—in many of its phases at least,—and we have met the people whom Bunyan saw in his dream, and are ourselves they whom he describes. When Dean Stanley began his course of lectures on Ecclesiastical History at Oxford, his opening words were those of the passage where the Pilgrim is taken to the House Beautiful to see "the rarities and histories of that place, both ancient and modern"; and at the end of the same course, wishing to sketch the prospects of Christendom, he quoted the words in which, on leaving the House Beautiful, Christian was shown the distant view of the Delectable Mountains.

2752 But for one glance at Pope and Pagan, there is almost nothing to indicate the writer's ecclesiastical standing. But for here and there a marking of time in prosaic passages which have nothing to do with the story, there is nothing to mar the catholicity of its spirit. Romanists and Protestants, Anglicans and Puritans, Calvinists and Arminians,—all communions and sects have edited and circulated it. It is the completest triumph of truth by fiction in all literature. More than any other human book, it is "a religious bond to the whole of English Christendom." The second part is perhaps inferior to the first, but is richer in incident, and some of its characters—Mercy, old Honest, Valiant-for-truth, and Great-heart, for instance—are exquisitely conceived and presented. Here again the reader will do well to carefully peruse the author's rhymed introduction:—

"Go then, my little Book," he says, "and tell young damsels of Mercy, and old men of plain-hearted old Honest. Tell people of Master Fearing, who was a good man, though much down in spirit. Tell them of Feeble-mind, and Ready-to-halt, and Master Despondency and his daughter, who 'softly went but sure.'

This second part introduces some new scenes, as well as characters and experiences, but with the same broad sympathy and humor; and there are closing descriptions not excelled in power and pathos by anything in the earlier pilgrimage.

In his 'Apology' Bunyan says:—

The idiom of the book is purely English, acquired by a diligent study of the English Bible. It is the simplest, raciest, and most sinewy English to be found in any writer of our language; and Bunyan's amazing use of this Saxon idiom for all the purposes of his story, and the range and freedom of his imaginative genius therein, like certain of Tennyson's 'Idylls,' show it to be an instrument of symphonic capacity and variety. Bunyan's own maxim is a good one:—"Words easy to be understood do often hit the mark, when high and learned ones do only pierce the air."

Of the 'Pilgrim's Progress,' in both its parts, we may say in the words of Milton:—

"These are works that could not be composed by the invocation of Dame Memory and her siren daughters, but by devout prayer to that eternal Spirit who can enrich with all utterance and knowledge, and send out his Seraphim, with the hallowed fire of his altar, to touch and purify the lips of whom he pleases, without reference to station, birth, or education."

Let Bunyan speak for his own book:—

Bunyan died of fever, in the house of a friend, at London, August 12th, 1688, in the sixty-first year of his age. Three of his four children survived him; the blind daughter, for whom he expressed such affectionate solicitude during his imprisonment, died before him. His second wife, Elisabeth, who pleaded for him with so much dignity and feeling before Judge Hale and other justices, died in 1692. In 1661 a recumbent statue was placed on his tomb in Bunhill Fields, and thirteen years later a noble statue was erected in his honor at Bedford. The church at Elstow is enriched with memorial windows presenting scenes from the 'Holy War' and the 'Pilgrim's Progress,' and the Bunyan Meeting-House in Bedford has bronze doors presenting similar scenes.

The great allegory has been translated into almost every language and dialect under the sun. The successive editions of it are almost innumerable; and no other book save the Bible has had an equally large circulation. The verdict of approval stamped upon it at first by the common people, has been fully recognized and accepted by the learned and cultivated.

From the 'Pilgrim's Progress'

But now, in this Valley of Humiliation, poor Christian was hard put to it; for he had gone but a little way before he espied a foul fiend coming over the field to meet him; his name is Apollyon. Then did Christian begin to be afraid, and to cast in his mind whether to go back or to stand his ground: But he considered again that he had no armor for his back, and therefore thought that to turn the back to him might give him the greater advantage with ease to pierce him with his darts. Therefore he resolved to venture and stand his ground; for, thought he, had I no more in mine eye than the saving of my life, 'twould be the best way to stand.

So he went on, and Apollyon met him. Now the monster was hideous to behold: he was clothed with scales like a fish (and they are his pride); he had wings like a dragon, feet like a bear, and out of his belly came fire and smoke; and his mouth was as the mouth of a lion. When he was come up to Christian, he beheld him with a disdainful countenance, and thus began to question with him.

Apollyon—Whence come you? and whither are you bound?

Christian—I am come from the City of Destruction, which is the place of all evil, and am going to the City of Zion.

Apollyon—By this I perceive thou art one of my subjects, for all that country is mine, and I am the prince and god of it. How is it then that thou hast run away from thy King? Were it not that I hope thou mayest do me more service, I would strike thee now at one blow to the ground.

Christian—I was born indeed in your dominions, but your service was hard, and your wages such as a man could not live on, "for the wages of sin is death;" therefore when I was come to years, I did as other considerate persons do—look out, if perhaps I might mend myself.

Apollyon—There is no prince that will thus lightly lose his subjects, neither will I as yet lose thee; but since thou complainest of thy service and wages, be content to go back; what our country will afford, I do here promise to give thee.

Christian—But I have let myself to another, even to the King of Princes, and how can I with fairness go back with thee?

2755 Apollyon—Thou hast done in this according to the proverb, changed a bad for a worse; but it is ordinary for those that have professed themselves his servants, after a while to give him the slip and return again to me: Do thou so too, and all shall be well.

Christian—I have given him my faith, and sworn my allegiance to him: how then can I go back from this, and not be hanged as a traitor?

Apollyon—Thou didst the same to me, and yet I am willing to pass by all, if now thou wilt yet turn again and go back.

Christian—What I promised thee was in my nonage; and besides, I count that the Prince under whose banner now I stand is able to absolve me; yea, and to pardon also what I did as to my compliance with thee: and besides, O thou destroying Apollyon, to speak truth, I like his service, his wages, his servants, his government, his company and country, better than thine; and therefore leave off to persuade me further; I am his servant, and I will follow him.

Apollyon—Consider again when thou art in cool blood, what thou art like to meet with in the way that thou goest. Thou knowest that for the most part his servants come to an ill end, because they are transgressors against me and my ways: How many of them have been put to shameful deaths; and besides, thou countest his service better than mine, whereas he never came yet from the place where he is to deliver any that served him out of our hands; but as for me, how many times, as all the world very well knows, have I delivered, either by power or fraud, those that have faithfully served me, from him and his, though taken by them; and so I will deliver thee.

Christian—His forbearing at present to deliver them is on purpose to try their love, whether they will cleave to him to the end: and as for the ill end thou sayest they come to, that is most glorious in their account; for, for present deliverance, they do not much expect it, for they stay for their glory, and then they shall have it, when their Prince comes in his, and the glory of the angels.

Apollyon—Thou hast already been unfaithful in thy service to him, and how dost thou think to receive wages of him?

Christian—Wherein, O Apollyon, have I been unfaithful to him?

Apollyon—Thou didst faint at first setting out, when thou wast almost choked in the Gulf of Despond; thou didst attempt2756 wrong ways to be rid of thy burden, whereas thou shouldst have stayed till thy Prince had taken it off; thou didst sinfully sleep and lose thy choice thing; thou wast also almost persuaded to go back at the sight of the lions; and when thou talkest of thy journey, and of what thou hast heard and seen, thou art inwardly desirous of vainglory in all that thou sayest or doest.

Christian—All this is true, and much more which thou hast left out; but the Prince whom I serve and honor is merciful, and ready to forgive; but besides, these infirmities possessed me in thy country, for there I sucked them in, and I have groaned under them, been sorry for them, and have obtained pardon of my Prince.

Apollyon—Then Apollyon broke out into grievous rage, saying, I am an enemy to this Prince; I hate his person, his laws and people: I am come out on purpose to withstand thee.

Christian—Apollyon, beware what you do, for I am in the King's highway, the way of holiness, therefore take heed to yourself.

Apollyon—Then Apollyon straddled quite over the whole breadth of the way, and said, I am void of fear in this matter; prepare thyself to die; for I swear by my infernal den, that thou shalt go no further; here will I spill thy soul.

And with that he threw a flaming dart at his breast, but Christian had a shield in his hand, with which he caught it, and so prevented the danger of that.

Then did Christian draw, for he saw 'twas time to bestir him: and Apollyon as fast made at him, throwing darts as thick as hail; by the which, notwithstanding all that Christian could do to avoid it, Apollyon wounded him in his head, his hand, and foot. This made Christian give a little back; Apollyon therefore followed his work amain, and Christian again took courage, and resisted as manfully as he could. This sore combat lasted for above half a day, even till Christian was almost quite spent; for you must know that Christian, by reason of his wounds, must needs grow weaker and weaker.

Then Apollyon, espying his opportunity, began to gather up close to Christian, and wrestling with him, gave him a dreadful fall; and with that Christian's sword flew out of his hand. Then said Apollyon, I am sure of thee now; and with that he had almost pressed him to death, so that Christian began to despair of life: but as God would have it, while Apollyon was fetching2757 of his last blow, thereby to make a full end of this good man, Christian nimbly stretched out his hand for his sword, and caught it, saying, "Rejoice not against me, O mine enemy! when I fall I shall arise;" and with that gave him a deadly thrust, which made him give back, as one that had received his mortal wound; Christian, perceiving that, made at him again, saying, "Nay, in all these things we are more than conquerors through him that loved us." And with that Apollyon spread forth his dragon's wings, and sped him away, that Christian for a season saw him no more.

In this combat no man can imagine, unless he had seen and heard as I did, what yelling and hideous roaring Apollyon made all the time of the fight; he spake like a dragon; and on the other side, what sighs and groans burst from Christian's heart. I never saw him all the while give so much as one pleasant look, till he perceived he had wounded Apollyon with his two-edged sword; then indeed he did smile, and look upward; but 'twas the dreadfulest sight that ever I saw.

So when the battle was over, Christian said, I will here give thanks to him that hath delivered me out of the mouth of the lion, to him that did help me against Apollyon. And so he did, saying:—

Then there came to him a hand, with some of the leaves of the tree of life, the which Christian took, and applied to the wounds that he had received in the battle, and was healed immediately. He also sat down in that place to eat bread, and to drink of the bottle that was given him a little before; so being refreshed, he addressed himself to his journey, with his sword drawn in his hand; for he said, I know not but some other enemy may be at hand. But he met with no other affront from Apollyon quite through this valley.

From the 'Pilgrim's Progress'

They went then till they came to the Delectable Mountains, which mountains belong to the Lord of that Hill of which we have spoken before; so they went up to the mountains, to behold the gardens and orchards, the vineyards and fountains of water; where also they drank, and washed themselves, and did freely eat of the vineyards. Now there were on the tops of these mountains shepherds feeding their flocks, and they stood by the highway side. The pilgrims therefore went to them, and leaning upon their staves (as is common with weary pilgrims, when they stand to talk with any by the way) they asked, Whose delectable mountains are these? And whose be the sheep that feed upon them?

Shepherds—These mountains are "Immanuel's Land," and they are within sight of his city; and the sheep also are his, and he laid down his life for them.

Christian—Is this the way to the Celestial City?

Shepherds—You are just in your way.

Christian—How far is it thither?

Shepherds—Too far for any but those that shall get thither indeed.

Christian—Is the way safe or dangerous?

Shepherds—Safe for those for whom it is to be safe, "but transgressors shall fall therein."

Christian—Is there in this place any relief for pilgrims that are weary and faint in the way?

Shepherds—The lord of these mountains hath given us a charge "not to be forgetful to entertain strangers"; therefore the good of the place is before you.

I saw also in my dream, that when the shepherds perceived that they were wayfaring men, they also put questions to them (to which they made answer as in other places), as, Whence came you? and, How got you into the way? and, By what means have you so persevered therein? For but few of them that begin to come hither do show their face on these mountains. But when the shepherds heard their answers, being pleased therewith, they looked very lovingly upon them, and said, Welcome to the Delectable Mountains.

2759 The shepherds, I say, whose names were Knowledge, Experience, Watchful, and Sincere, took them by the hand, and had them to their tents, and made them partake of that which was ready at present. They said moreover, We would that ye should stay here a while, to be acquainted with us; and yet more to solace yourselves with the good of these delectable mountains. They then told them that they were content to stay; and so they went to their rest that night, because it was very late.

Then I saw in my dream, that in the morning the shepherds called up Christian and Hopeful to walk with them upon the mountains; so they went forth with them, and walked a while, having a pleasant prospect on every side. Then said the shepherds one to another, Shall we show these pilgrims some wonders? So when they had concluded to do it, they had them first to the top of a hill called Error, which was very steep on the furthest side, and bid them look down to the bottom. So Christian and Hopeful looked down, and saw at the bottom several men dashed all to pieces by a fall that they had from the top. Then said Christian, What meaneth this? The shepherds answered, Have you not heard of them that were made to err, by hearkening to Hymeneus and Philetus, as concerning the faith of the resurrection of the body? They answered, Yes. Then said the shepherds, Those that you see lie dashed in pieces at the bottom of this mountain are they; and they have continued to this day unburied (as you see) for an example to others to take heed how they clamber too high, or how they come too near the brink of this mountain.

Then I saw that they had them to the top of another mountain, and the name of that is Caution, and bid them look afar off; which when they did, they perceived, as they thought, several men walking up and down among the tombs that were there; and they perceived that the men were blind, because they stumbled sometimes upon the tombs, and because they could not get out from among them. Then said Christian, What means this?

The shepherds then answered, Did you not see a little below these mountains a stile, that led into a meadow, on the left hand of this way? They answered, Yes. Then said the shepherds, From that stile there goes a path that leads directly to Doubting Castle, which is kept by Giant Despair; and these men (pointing to them among the tombs) came once on pilgrimages as you do2760 now, even till they came to that same stile; and because the right way was rough in that place, and they chose to go out of it into that meadow, and there were taken by Giant Despair and cast into Doubting Castle; where, after they had been awhile kept in the dungeon, he at last did put out their eyes, and led them among those tombs, where he has left them to wander to this very day, that the saying of the wise man might be fulfilled, "He that wandereth out of the way of understanding shall remain in the congregation of the dead." Then Christian and Hopeful looked upon one another, with tears gushing out, but yet said nothing to the shepherds.

Then I saw in my dream that the shepherds had them to another place, in a bottom, where was a door in the side of a hill, and they opened the door, and bid them look in. They looked in therefore, and saw that within it was very dark and smoky; they also thought that they heard there a rumbling noise as of fire, and a cry as of some tormented, and that they smelt the scent of brimstone. Then said Christian, What means this?

The shepherds told them, This is a by-way to hell, a way that hypocrites go in at; namely, such as sell their birthright, with Esau; such as sell their Master, as Judas; such as blaspheme the Gospel, with Alexander; and that lie and dissemble, with Ananias and Sapphira his wife. Then said Hopeful to the shepherds, I perceive that these had on them, even every one, a show of pilgrimage, as we have now: had they not?

Shepherds—Yes, and held it a long time too.

Hopeful—How far might they go on in pilgrimage in their day, since they notwithstanding were thus miserably cast away?

Shepherds—Some further, and some not so far as these mountains.

Then said the pilgrims one to another, We had need to cry to the Strong for strength.

Shepherds—Ay, and you will have need to use it when you have it too.

By this time the pilgrims had a desire to go forwards, and the shepherds a desire they should; so they walked together towards the end of the mountains. Then said the shepherds one to another, Let us here show to the pilgrims the gates of the Celestial City, if they have skill to look through our perspective-glass. The pilgrims then lovingly accepted the motion; so they2761 had them to the top of a high hill, called Clear, and gave them their glass to look.

Then they essayed to look, but the remembrance of that last thing that the shepherds had showed them made their hands shake, by means of which impediment they could not look steadily through the glass; yet they thought they saw something like the gate, and also some of the glory of the place.

From the 'Pilgrim's Progress'

Now while they lay here and waited for the good hour, there was a noise in the town that there was a post come from the Celestial City, with matter of great importance to one Christiana, the wife of Christian the pilgrim. So inquiry was made for her, and the house was found out where she was. So the post presented her with a letter, the contents whereof was, Hail, good woman, I bring thee tidings that the Master calleth for thee, and expecteth that thou shouldest stand in his presence in clothes of immortality, within this ten days.

When he had read this letter to her, he gave her therewith a sure token that he was a true messenger, and was come to bid her make haste to be gone. The token was an arrow with a point sharpened with love, let easily into her heart, which by degrees wrought so effectually with her, that at the time appointed she must be gone.

When Christiana saw that her time was come, and that she was the first of this company that was to go over, she called for Mr. Great-heart her guide, and told him how matters were. So he told her he was heartily glad of the news, and could have been glad had the post come for him. Then she bid that he should give advice how all things should be prepared for her journey. So he told her, saying, Thus and thus it must be, and we that survive will accompany you to the river-side.

Then she called for her children and gave them her blessing, and told them that she yet read with comfort the mark that was set in their foreheads, and was glad to see them with her there, and that they had kept their garments so white. Lastly, she bequeathed to the poor that little she had, and commanded her2762 sons and daughters to be ready against the messenger should come for them.

When she had spoken these words to her guide and to her children, she called for Mr. Valiant-for-truth, and said unto him, Sir, you have in all places showed yourself true-hearted; be faithful unto death, and my King will give you a crown of life. I would also entreat you to have an eye to my children, and if at any time you see them faint, speak comfortably to them. For my daughters, my sons' wives, they have been faithful, and a fulfilling of the promise upon them will be their end. But she gave Mr. Stand-fast a ring.

Then she called for old Mr. Honest and said of him, Behold an Israelite indeed, in whom is no guile. Then said he, I wish you a fair day when you set out for Mount Sion, and shall be glad to see that you go over the river dry-shod. But she answered, Come wet, come dry, I long to be gone, for however the weather is in my journey, I shall have time enough when I come there to sit down and rest me and dry me.

Then came in that good man Mr. Ready-to-halt, to see her. So she said to him, Thy travel hither has been with difficulty, but that will make thy rest the sweeter. But watch and be ready, for at an hour when you think not, the messenger may come.

After him came in Mr. Despondency and his daughter Much-afraid, to whom she said, You ought with thankfulness forever to remember your deliverance from the hands of Giant Despair and out of Doubting Castle. The effect of that mercy is, that you are brought with safety hither. Be ye watchful and cast away fear, be sober and hope to the end.

Then she said to Mr. Feeble-mind, Thou wast delivered from the mouth of Giant Slay-good, that thou mightest live in the light of the living for ever, and see thy King with comfort. Only I advise thee to repent thee of thine aptness to fear and doubt of his goodness before he sends for thee, lest thou shouldest, when he comes, be forced to stand before him for that fault with blushing.

Now the day drew on that Christiana must be gone. So the road was full of people to see her take her journey. But behold, all the banks beyond the river were full of horses and chariots, which were come down from above to accompany her to the city gate. So she came forth and entered the river with a beckon of2763 farewell to those who followed her to the river-side. The last words she was heard to say here was, I come, Lord, to be with thee and bless thee.

So her children and friends returned to their place, for that those that waited for Christiana had carried her out of their sight. So she went and called and entered in at the gate with all the ceremonies of joy that her husband Christian had done before her. At her departure her children wept, but Mr. Great-heart and Mr. Valiant played upon the well-tuned cymbal and harp for joy. So all departed to their respective places.

In process of time there came a post to the town again, and his business was with Mr. Ready-to-halt. So he inquired him out, and said to him, I am come to thee in the name of Him whom thou hast loved and followed, though upon crutches; and my message is to tell thee that he expects thee at his table to sup with him in his kingdom the next day after Easter, wherefore prepare thyself for this journey.

Then he also gave him a token that he was a true messenger, saying, "I have broken thy golden bowl, and loosed thy silver cord."

After this Mr. Ready-to-halt called for his fellow pilgrims, and told them saying, I am sent for, and God shall surely visit you also. So he desired Mr. Valiant to make his will. And because he had nothing to bequeath to them that should survive him but his crutches and his good wishes, therefore thus he said, These crutches I bequeath to my son that shall tread in my steps, with a hundred warm wishes that he may prove better than I have done.

Then he thanked Mr. Great-heart for his conduct and kindness, and so addressed himself to his journey. When he came at the brink of the river he said, Now I shall have no more need of these crutches, since yonder are chariots and horses for me to ride on. The last words he was heard to say were, Welcome, life. So he went his way.

After this Mr. Feeble-mind had tidings brought him that the post sounded his horn at his chamber door. Then he came in and told him, saying, I am come to tell thee that thy Master has need of thee, and that in very little time thou must behold his face in brightness. And take this as a token of the truth of my message, "Those that look out at the windows shall be darkened."

2764 Then Mr. Feeble-mind called for his friends, and told them what errand had been brought unto him, and what token he had received of the truth of the message. Then he said, Since I have nothing to bequeath to any, to what purpose should I make a will? As for my feeble mind, that I will leave behind me, for that I have no need of that in the place whither I go. Nor is it worth bestowing upon the poorest pilgrim; wherefore when I am gone, I desire that you, Mr. Valiant, would bury it in a dung-hill. This done, and the day being come in which he was to depart, he entered the river as the rest. His last words were, Hold out faith and patience. So he went over to the other side.

When days had many of them passed away, Mr. Despondency was sent for. For a post was come, and brought this message to him, Trembling man, these are to summon thee to be ready with thy King by the next Lord's day, to shout for joy for thy deliverance from all thy doubtings.

And said the messenger, That my message is true, take this for a proof; so he gave him "The grasshopper to be a burden unto him." Now Mr. Despondency's daughter, whose name was Much-afraid, said when she heard what was done, that she would go with her father. Then Mr. Despondency said to his friends, Myself and my daughter, you know what we have been, and how troublesomely we have behaved ourselves in every company. My will and my daughter's is, that our desponds and slavish fears be by no man ever received from the day of our departure for ever, for I know that after my death they will offer themselves to others. For to be plain with you, they are ghosts, the which we entertained when we first began to be pilgrims, and could never shake them off after; and they will walk about and seek entertainment of the pilgrims, but for our sakes shut ye the doors upon them.

When the time was come for them to depart, they went to the brink of the river. The last words of Mr. Despondency were, Farewell, night; welcome, day. His daughter went through the river singing, but none could understand what she said.

Then it came to pass a while after, that there was a post in the town that inquired for Mr. Honest.... When the day that he was to be gone was come, he addressed himself to go over the river. Now the river at that time overflowed the banks in some places, but Mr. Honest in his lifetime had spoken to one Good-conscience to meet him there, the which he also did, and2765 lent him his hand, and so helped him over. The last words of Mr. Honest were, Grace reigns. So he left the world.

After this it was noised abroad that Mr. Valiant-for-truth was taken with a summons by the same post as the other, and had this for a token that the summons was true, "That his pitcher was broken at the fountain." When he understood it, he called for his friends, and told them of it. Then said he, I am going to my fathers, and though with great difficulty I am got hither, yet now I do not repent me of all the trouble I have been at to arrive where I am. My sword I give to him that shall succeed me in my pilgrimage, and my courage and skill to him that can get it. My marks and scars I carry with me, to be a witness for me that I have fought his battles who now will be my rewarder. When the day that he must go hence was come, many accompanied him to the river-side, into which as he went he said, Death, where is thy sting? And as he went down deeper he said, Grave, where is thy victory? So he passed over, and all the trumpets sounded for him on the other side.

Then there came forth a summons for Mr. Stand-fast (this Mr. Stand-fast was he that the rest of the pilgrims found upon his knees in the enchanted ground), for the post brought it him open in his hands. The contents whereof were, that he must prepare for a change of life, for his Master was not willing that he should be so far from him any longer. At this Mr. Stand-fast was put into a muse. Nay, said the messenger, you need not doubt of the truth of my message, for here is a token of the truth thereof, "Thy wheel is broken at the cistern." Then he called to him Mr. Great-heart, who was their guide, and said unto him, Sir, although it was not my hap to be much in your good company in the days of my pilgrimage, yet since the time I knew you, you have been profitable to me. When I came from home, I left behind me a wife and five small children: let me entreat you at your return (for I know that you will go and return to your Master's house, in hopes that you may yet be a conductor to more of the holy pilgrims) that you send to my family, and let them be acquainted with all that hath and shall happen unto me. Tell them moreover of my happy arrival to this place, and of the present late blessed condition that I am in. Tell them also of Christian and Christiana his wife, and how she and her children came after her husband. Tell them also of what a happy end she made, and whither she is gone. I have2766 little or nothing to send to my family, except it be prayers and tears for them; of which it will suffice if thou acquaint them, if peradventure they may prevail.

When Mr. Stand-fast had thus set things in order, and the time being come for him to haste him away, he also went down to the river. Now there was a great calm at that time in the river; wherefore Mr. Stand-fast, when he was about half-way in, he stood awhile, and talked to his companions that had waited upon him thither. And he said:—

This river has been a terror to many; yea, the thoughts of it also have often frighted me. But now methinks I stand easy; my foot is fixed upon that upon which the feet of the priests that bare the ark of the covenant stood, while Israel went over this Jordan. The waters indeed are to the palate bitter and to the stomach cold, yet the thought of what I am going to and of the conduct that waits for me on the other side, doth lie as a glowing coal at my heart.

I see myself now at the end of my journey; my toilsome days are ended. I am going now to see that Head that was crowned with thorns, and that Face that was spit upon for me.

I have formerly lived by hearsay and faith, but now I go where I shall live by sight, and shall be with him in whose company I delight myself.

I have loved to hear my Lord spoken of, and wherever I have seen the print of his shoe in the earth, there I have coveted to set my foot too.

His name has been to me as a civet-box, yea, sweeter than all perfumes. His voice to me has been most sweet, and his countenance I have more desired than they that have most desired the light of the sun. His Word I did use to gather for my food, and for antidotes against my faintings. He has held me, and I have kept me from mine iniquities; yea, my steps hath he strengthened in his way.

Now while he was thus in discourse, his countenance changed, his strong man bowed under him, and after he had said, Take me, for I come unto thee, he ceased to be seen of them.

But glorious it was to see how the open region was filled with horses and chariots, with trumpeters and pipers, with singers and players on stringed instruments, to welcome the pilgrims as they went up, and followed one another in at the beautiful gate of the city.

(1747-1794)

The ballad of 'Lenore,' upon which Bürger's fame chiefly rests, was published in 1773. It constituted one of the articles in that declaration of independence which the young poets of the time were formulating, and it was more than a mere coincidence that in the same year Herder wrote his essay on 'Ossian' and the 'Songs of Ancient Peoples,' and Goethe unfurled the banner of a new time in 'Götz von Berlichingen.' The artificial and sentimental trivialities of the pigtail age were superseded almost at a stroke, and the petty formalism under which the literature of Germany was languishing fell about the powdered wigs of its professional representatives. The new impulse came from England. As in France, Rousseau, preaching the gospel of a return to nature, found his texts in English writers, so in Germany the poets who inaugurated the classic age derived their chief inspiration from the wholesome heart of England. It was Shakespeare that inspired Goethe's 'Götz'; Ossian and the old English and Scotch folk-songs were Herder's theme; and Percy's 'Reliques' stimulated and saved the genius of Bürger. This was the movement which, for lack of a better term, has been called the naturalistic. Literature once more took possession of the whole range of human life and experience, descending from her artificial throne to live with peasant and people. These ardent innovators spurned all ancient rules and conventions, and in the first ecstasy of their new-found freedom and unchastened strength it is no wonder that they went too far. Goethe and Schiller learned betimes the salutary lesson of artistic restraint. Bürger never learned it.

Gottfried A. Bürger

Bürger was wholly a child of his time. At the age of twenty-six he wrote 'Lenore,' and his genius never again attained that height. Much may be accomplished in the first outburst of youthful energy; but without the self-control which experience should teach, and without the moral character which is the condition of great achievement, genius rots ere it is ripe; and this was the case with Bürger. We are reminded of Burns. Goethe in his seventy-eighth year said to Eckermann:—"What songs Bürger and Voss have written! Who2768 would say that they are less valuable or less redolent of their native soil than the exquisite songs of Burns?" Like Burns, Bürger was of humble origin; like Burns, he gave passion and impulse the reins and drove to his own destruction; like Burns, he left behind him a body of truly national and popular poetry which is still alive in the mouths of the people.

Bürger was born in the last hour of the year 1747 at Molmerswende. His father was a country clergyman, and he himself was sent to Halle at the age of seventeen to study theology. His wild life there led to his removal to Göttingen, where he took up the study of law. He became a member and afterwards the leader of the famous "Göttinger Dichterbund," and was carried away and for a time rescued from his evil courses by his enthusiasm for Shakespeare and Percy's 'Reliques.' He contributed to the newly established Musenalmanach, and from 1779 until his death in 1794 he was its editor. In 1787 the university conferred an honorary degree upon him, and he was soon afterward made a professor without salary, lecturing on Kantian philosophy and æsthetics. Three times he was married; his days were full of financial struggles and self-wrought misery; there is little in his private life that is creditable to record: a dissolute youth was followed by a misguided manhood, and he died in his forty-seventh year.

It fell to the lot of the young Goethe, then an unknown reviewer, to write for the Frankfurter Gelehrte Anzeigen in November, 1772, a notice of some of Bürger's early poems. "The 'Minnelied' of Mr. Bürger," he says, "is worthy of a better age; and if he has more such happy moments, these efforts of his will be among the most potent influences to render our sentimental poetasters, with their gold-paper Amors and Graces and their elysium of benevolence and philanthropy, utterly forgotten." With such clear vision could Goethe see at the age of twenty-three. But he soon saw also the danger that lay in unbridled freedom. For the best that was in Bürger Goethe retained his admiration to the last, but before he was thirty he felt that their ways had parted. Among the 'Maxims and Reflections' we find this note:—"It is sad to see how an extraordinary man may struggle with his time, with his circumstances, often even with himself, and never prosper. Sad example, Bürger!"

Doubtless German literature owes less to Bürger than English owes to Burns, but it owes much. Bürger revived the ballad form in which so much of the finest German poetry has since been cast. With his lyric gifts and his dramatic power, he infused a life into these splendid poems that has made them a part of the folk-lore of his native land. 'Lenardo und Blandine,' his own favorite, 'Des Pfarrers Tochter von Taubenhain' (The Pastor's Daughter of Taubenhain), 'Das Lied vom braven Mann' (The Song of the Brave2769 Man), 'Die Weiber von Weinsberg' (The Women of Weinsberg), 'Der Kaiser und der Abt' (The Emperor and the Abbot), 'Der Wilde Jäger' (The Wild Huntsman), all belong, like 'Lenore,' to the literary inheritance of the German people. Bürger attempted a translation of the Iliad in iambic blank verse, and a prose translation of 'Macbeth.' To him belongs also the credit of having restored to German literature the long-disused sonnet. His sonnets are among the best in the language, and elicited warm praise from Schiller as "models of their kind." Schiller had written a severe criticism of Bürger's poems, which had inflamed party strife and embittered the last years of Bürger himself; but even Schiller admits that Bürger is as much superior to all his rivals as he is inferior to the ideal he should have striven to attain.

The debt which Bürger owed to English letters was amply repaid. In 'Lenore' he showed Percy's 'Reliques' the compliment of quoting from the ballad of 'Sweet William,' which had supplied him with his theme, the lines:—"Is there any room at your head, Willie, or any room at your feet?" The first literary work of Walter Scott was the translation which he made in 1775 of 'Lenore,' under the title of 'William and Helen'; this was quickly followed by a translation of 'The Wild Huntsman.' Scott's romantic mind received in Bürger's ballads and in Goethe's 'Götz,' which he translated four years later, just the nourishment it craved. It is a curious coincidence that another great romantic writer, Alexandre Dumas, should also have begun his literary career with a translation of 'Lenore.' Bürger was not, however, a man of one poem. He filled two goodly volumes, but the oft-quoted words of his friend Schlegel contain the essential truth:—"'Lenore' will always be Bürger's jewel, the precious ring with which, like the Doge of Venice espousing the sea, he married himself to the folk-song forever."

Walter Scott's Translation of 'Lenore'

Translated by C. T. Brooks: Reprinted from 'Representative German Poems' by the courtesy of Mrs. Charles T. Brooks.

(1729-1797)

BY E. L. GODKIN