“I’ll hit any trail with you––barring Mexican politics.” [Page 19]

Title: The Treasure Trail: A Romance of the Land of Gold and Sunshine

Author: Marah Ellis Ryan

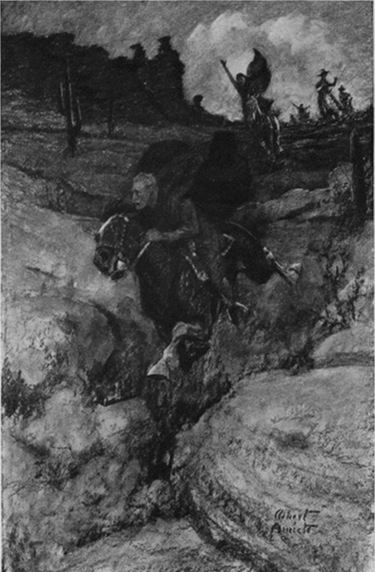

Illustrator: Robert Wesley Amick

Release date: August 15, 2009 [eBook #29694]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

“I’ll hit any trail with you––barring Mexican politics.” [Page 19]

|

The A Romance of the Land of By MARAH ELLIS RYAN

Illustrated Publishers Chicago A. C. McCLURG & CO. 1918 |

Copyright

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1918

Published November, 1918

Copyrighted in Great Britain

To

Kalatoka

of the brown tent

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | KIT AND THE GIRL OF THE LARK CALL | 1 |

| II | THE RED GOLD LEGEND | 15 |

| III | A VERIFIED PROPHECY OF SEÑORITA BILLIE | 54 |

| IV | IN THE ADOBE OF PEDRO VIJIL | 66 |

| V | AN “ADIOS”––AND AFTER | 73 |

| VI | A DEAD MAN UNDER THE COTTONWOODS | 90 |

| VII | IN THE PROVINCE OF ALTAR | 107 |

| VIII | THE SLAVE TRAIL | 124 |

| IX | A MEETING AT YAQUI WELL | 133 |

| X | A MEXICAN EAGLET | 144 |

| XI | GLOOM OF BILLIE | 161 |

| XII | COVERING THE TRAIL | 167 |

| XIII | A WOMAN OF EMERALD EYES | 186 |

| XIV | THE HAWK OF THE SIERRAS | 217 |

| XV | THE “JUDAS” PRAYER AT MESA BLANCA | 230 |

| XVI | THE SECRET OF SOLEDAD CHAPEL | 256 |

| XVII | THE STORY OF DOÑA JOCASTA | 288 |

| XVIII | RAMON ROTIL DECIDES | 300 |

| XIX | THE RETURN OF TULA | 328 |

| XX | EAGLE AND SERPENT | 346 |

| XXI | EACH TO HIS OWN | 360 |

| PAGE | |

| “I’ll hit any trail with you––barring Mexican politics.” | Frontispiece |

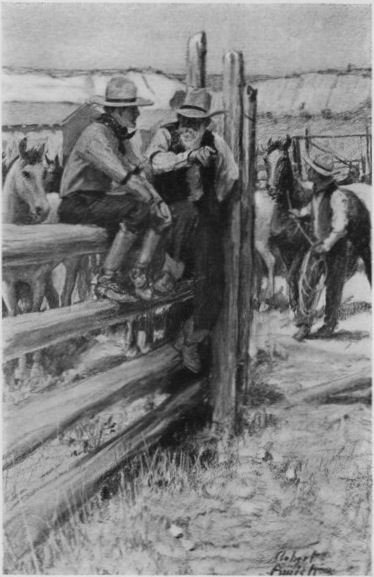

| “You poor kid, you have a hard time with the disreputables you pick up.” | 76 |

| “No, Ramon! No!” she cried, and flung herself between him and his victims. | 280 |

| The Indian girl was steadily gaining on the German. | 356 |

In the shade of Pedro Vijil’s little brown adobe on the Granados rancho, a horseman squatted to repair a broken cinch with strips of rawhide, while his horse––a strong dappled roan with a smutty face––stood near, the rawhide bridle over his head and the quirt trailing the ground.

The horseman’s frame of mind was evidently not of the sweetest, for to Vijil he had expressed himself in forcible Mexican––which is supposed to be Spanish and often isn’t––condemning the luck by which the cinch had gone bad at the wrong time, and as he tinkered he sang softly an old southern ditty:

|

Oh––oh! I’m a good old rebel, |

He varied this musical gem occasionally by whistling the air as he punched holes and wove the rawhide thongs in and out through the spliced leather.

Once he halted in the midst of a strain and lifted his head, listening. Something like an echo of his own notes sounded very close, a mere shadow of a whistle.

Directly over his head was a window, unglazed and wooden barred. A fat brown olla, dripping moisture, almost filled the deep window sill, but the interior was all in shadow. Its one door was closed. The Vijil family was scattered around in the open, most of them under the ramada, and after a frowning moment of mystification the young fellow resumed his task, but in silence.

Then, after a still minute, more than the whisper of a whistle came to him––the subdued sweet call of a meadow lark. It was so sweet it might have been mate to any he had heard on the range that morning.

Only an instant he hesitated, then with equal care he gave the duplicate call, and held his breath to listen––not a sound came back.

“We’ve gone loco, Pardner,” he observed to the smutty-faced roan moving near him. “That jolt from the bay outlaw this morning has jingled my brain pans––we don’t hear birds call us––we only think we do.”

If he had even looked at Pardner he might have been given a sign, for the roan had lifted its head and was staring into the shadows back of the sweating olla.

“Hi, you caballero!”

The words were too clear to be mistaken, the “caballero” stared across to the only people in sight. There was Pedro Vijil sharpening an axe, while Merced, his wife, turned the creaking grindstone for him. The young olive branches of the Vijil family were having fun with a horned toad under the ramada where gourd vines twisted about an ancient grape, and red peppers hung in a gorgeous splash of color. Between that and the blue haze of the far mountains there was no sign of humanity to account for such cheery youthful Americanism as the tone suggested.

“Hi, yourself!” he retorted, “whose ghost are you?”

There was a giggle from the barred window of the adobe.

“I don’t dare say because I am not respectable just now,” replied the voice. “I fell in the ditch and have nothing on but the Sunday shirt of Pedro. I am the funniest looking thing! wish I dared ride home in it to shock them all silly.”

“Why not?” he asked, and again the girlish laugh gave him an odd thrill of comradeship.

“A good enough reason; they’d take Pat from me, and say he wasn’t safe to ride––but he is! My tumble was my own fault for letting them put on that fool English saddle. Never again for me!”

“They are all right for old folks and a pacing pony,” he observed, and again he heard the bubbling laugh.

“Well, Pat is not a pacing pony, not by a long shot; and I’m not old folks––yet!” Then after a little silence, “Haven’t you any curiosity?”

“I reckon there’s none allowed me on this count,” he replied without lifting his head, “between the wooden bars and Pedro’s shirt you certainly put the fences up on me.”

“I’m a damsel in distress waiting for a rescuing knight with a white banner and a milk-white steed––” went on the laughing voice in stilted declamation.

“Sorry, friend, but my cayuse is a roan, and I never carried a white flag yet. You pick the wrong colors.”

Whereupon he began the chanting of a war song, with an eye stealthily on the barred window.

|

Hurrah! Hurrah! For southern rights, hurrah! |

“Oh! I know that!” the voice was now a hail of recognition. “Cap Pike always sings that when he’s a little ‘how-came-ye-so’––and you’re a Johnny Reb!”

“Um! twice removed,” assented the man by the wall, “and you are a raiding Yank who has been landed in one of our fortresses with only one shirt to her back, and that one borrowed.”

He had a momentary vision of two laughing gray eyes beside the olla, and the girl behind the bars laughed until Merced let the grindstone halt while she cast a glance towards the house as if in doubt as to whether three feet of adobe wall and stout bars could serve instead of a dueña to foolish young Americans who chattered according to their foolishness.

There was an interval of silence, and then the girlish voice called again.

“Hi, Johnny Reb!”

“Same to you, Miss Yank.”

“Aren’t you the new Americano from California, for the La Partida rancho?”

“Even so, O wise one of the borrowed garment.” The laugh came to him again.

“Why don’t you ask how I know?” she demanded.

“It is borne in upon me that you are a witch of the desert, or the ghost of a dream, that you see through the adobe wall, and my equally thick skull. Far be it for me to doubt that the gift of second sight is yours, O seventh daughter of a seventh daughter!”

“No such thing! I’m the only one!” came the quick retort, and the young chap in the shade of the adobe shook with silent mirth.

“I see you laughing, Mr. Johnny Reb, you think you caught me that time. But you just halt and listen to me, I’ve a hunch and I’m going to prophesy.”

“I knew you had the gift of second sight!”

“Maybe you won’t believe me, but the hunch is that you––won’t––hold––the job on these ranches!”

“What!” and he turned square around facing the window, then laughed. “That’s the way you mean to get even for the ‘seventh daughter’ guess is it? You think I can’t handle horses?”

“Nix,” was the inelegant reply, “I know you can, for I saw you handle that bay outlaw they ran in on you this morning: seven years old and no wrangler in Pima could ride him. Old Cap Pike said it was a damn shame to put you up against that sun-fisher as an introduction to Granados.”

“Oh! Pike did, did he? Nice and sympathetic of Pike. I reckon he’s the old-time ranger I heard about out at the Junction, reading a red-fire riot to some native sons who were not keen for the cactus trail of the Villistas. That old captain must be a live wire, but he thinks I can’t stick?”

“No-o, that wasn’t Cap Pike, that was my own hunch. Say, are you married?”

“O señorita! this is so sudden!” he spoke in shy reproof, twisting his neckerchief in mock embarrassment, and again Merced looked toward the house because of peals of laughter there.

“You are certainly funny when you do that,” she said after her laughter had quieted down to giggles, “but I wasn’t joking, honest Indian I wasn’t! But how did you come to strike Granados?”

“Me? Well, I ranged over from California to sell a patch of ground I owned in Yuma. Then I hiked over to Nogales on a little pasear and offered to pack a gun and wear a uniform for this Mexican squabble, and the powers that be turned me down because one of my eyes could see farther than the other––that’s no joke––it’s a calamity! I spent all the dinero I had recovering from the shock, and about the time I was getting my sympathetic friends sobered up, Singleton, of Granados, saw us trying out some raw cavalry stock, and bid for my valuable services and I rode over. Any other little detail you’d like to know?”

“N-no, only needed to know it wasn’t Conrad the manager hired you, and I asked if you were married because married men need the work more than single strays. Adolf Conrad got rid of two good American men lately, and fetches over Mexicans from away down Hermosillo way.”

“’Cause why?” asked the man who had ceased pretense of mending the saddle, and was standing with back against the adobe.

“’Cause I don’t know,” came petulant response. “I only had the hunch when I saw you tame that outlaw in the corral. If he pulls wires to lose you, I’ll stop guessing; I’ll know!”

“Very interesting, señorita,” agreed the stranger reflectively. “But if I have a good job, I can’t see how it will give me aid or comfort to know that you’ve acquired knowledge, and stopped guessing. When’s your time up behind the bars?”

“Whenever my clothes get dry enough to fool the dear home folks.”

“You must be a joy to the bosom of your family,” he observed, “also a blessing.”

He heard again the girlish laughter and concluded she could not be over sixteen. There was silence for a space while only the creak of the grindstone cut the stillness. Whoever she was, she had given him a brief illuminating vision of the tactics of Conrad, the manager for the ranches of Granados and La Partida, the latter being the Sonora end of the old Spanish land grant. Even a girl had noted that the rough work had been turned over to a new American from the first circle of the rodeo. He stood there staring out across the sage green to the far purple hills of the Green Springs range.

“You’ve fixed that cinch, what you waiting for?” asked the voice at last, and the young fellow straightened up and lifted the saddle.

“That’s so,” he acknowledged. “But as you whistled to me and the call seemed friendly, it was up to me to halt for orders––from the lady in distress.”

Again he heard the soft laughter and the voice.

“Glad you liked the friendly call, Johnny Reb,” she confessed. “That’s my call. If ever you hear it where there are no larks, you’ll know who it is.”

“Sure,” he agreed, yanking at the cinch, “and I’ll come a lopin’ with the bonnie blue flag, to give aid and succor to the enemy.”

“You will not!” she retorted. “You’ll just whistle back friendly, and be chums. I think my clothes are dry now, and you’d better travel. If you meet anyone looking for a stray maverick, you haven’t seen me.”

“Just as you say. Adios!”

After he had mounted and passed along the corral to the road, he turned in the saddle and looked back. He could see no one in the window of the bars, but there came to him clear and sweet the field bugle of the meadow lark.

He answered it, lifted his sombrero and rode soberly towards the Granados corrals, three miles across the valley. Queer little trick she must be. American girls did not usually ride abroad alone along the border, and certainly did not chum with the Mexicans to the extent of borrowing shirts. Then as he lifted the bridle and Pardner broke into a lope, he noted an elderly horseman jogging along across trail on a little mule. Each eyed the other appraisingly.

“Hello, Bub!” hailed the older man. “My name’s Pike, and you’re the new man from California, hey? Glad to meet you. Hear your name’s Rhodes.”

“I reckon you heard right,” agreed the young chap. “K. Rhodes at your service, sir.”

“Hello! K? K? Does that K stand for Kit?”

“Center shot for you,” assented the other.

“From Tennessee?”

“Now you’re a sort of family historian, I reckon, Mr. Pike,” suggested K. Rhodes. “What’s the excitement?”

“Why you young plantation stray!” and the older man reached for his hand and made use of it pump-handle fashion with a sort of sputtering glee. “Great guns, boy! there was just one K. Rhodes a-top of God’s green earth and we were pardners here in Crook’s day. Hurrah for us! Are you cousin, son, or nephew?”

“My grandfather was with Crook.”

“Sure! I knew it soon as I laid eyes on you and heard your name; that was in the corral with the outlaw Conrad had driven in for you to work, it wa’n’t a square deal to a white man. I was cussin’ mad.”

“So I heard,” and the blue eyes of the other smiled at the memory of the girl’s glib repetition of his discourse. “What’s the great idea? Aside from the fact that he belongs to the white dove, anti-military bunch of sisters, Singleton seems quite white, a nice chap.”

“Yeh, but he’s noways wise at that. He sort of married into the horse game here, wasn’t bred to it. Just knows enough to not try to run it solo. Now this Dolf Conrad does know horses and the horse market, and Granados rancho. He’s shipped more cavalry stock to France than any other outfit in this region. Yes, Conrad knows the business end of the game, but even at that he might not assay as high grade ore. He is mixed up with them too-proud-to-fight clique organized by old maids of both sexes, and to show that he is above all prejudice, political or otherwise, he sure is corraling an extra lot of Mex help this year. I’ve companeros I’d go through hell for, but Conrad’s breed––well, enough said, Bub, but they’re different!” Mr. Pike bit off a chew of black plug, and shook his head ruminatively.

Rhodes looked the old man over as they rode along side by side. He was lean, wiry and probably sixty-five. His hair, worn long, gave him the look of the old-time ranger. He carried no reata and did not look like a ranchman. He had the southern intonation, and his eyes were wonderfully young for the almost snowy hair.

“Belong in the valley, Captain?”

“Belong? Me belong anywhere? Not yet, son,” and he smiled at his own fancy. “Not but what it’s a good enough corner when a man reaches the settlin’ down age. I drift back every so often. This ranch was Fred Bernard’s, and him and me flocked together for quite a spell. Singleton married Bernard’s widow––she’s dead now these seven years. I just drift back every so often to keep track of Bernard’s kid, Billie.”

“I see. Glad to have met you, Captain. Hope we can ride together often enough for me to hear about the old Apache days. This land has fetched out three generations of us, so it surely has some pull! My father came at the end of his race, but I’ve come in time to grow up with the country.”

Captain Pike looked at him and chuckled. K. Rhodes was about twenty-three, tall, almost boyish in figure, but his shoulders and hands suggested strength, and his mouth had little dents of humor at the corners to mitigate the squareness of jaw and the heavy dark brows. His black lashes made the deep blue of his eyes look purple. Young he was, but with a stature and self-reliant manner as witness of the fact that he was fairly grown up already.

“Where’d you learn horses, Bub?”

“Tennessee stock farm, and southern California ranges. Then this neck of the woods seemed calling me, and I trailed over to look after a bit of land in Yuma. I wasted some time trying to break into the army, but they found some eye defect that I don’t know anything about––and don’t more than half believe! I had some dandy prospecting plans after that, but there was no jingling in my pockets––no outfit money, so I hailed Singleton as an angel monoplaned down with the ducats. Yes sir, I had all the dream survey made for a try at some gold trails down here, going to take it up where the rest of the family quit.”

“You mean that, boy?” The old man halted his mule, and spat out the tobacco, staring at Rhodes in eager anticipation.

“I sure do. Reckon I’ve inherited the fever, and can’t settle down to any other thing until I’ve had one try at it. Did do a little placer working in the San Jacinto.”

“And you’re broke?” Mr. Pike’s voice betrayed a keen joy in the prospect.

“Flat,” stated K. Rhodes, eyeing the old gentleman suspiciously, “my horse, saddle, field glass, and gun are the only belongings in sight.”

“Ki-yi!” chirruped his new acquaintance gleefully, “I knew when I got out of the blankets this morning I was to have good luck of some sort, had a ‘hunch.’ You can bet on me, Bub; you’ve struck the right rail, and I’m your friend, your desert companero!”

“Yes, you sound real nice and friendly,” agreed K. Rhodes. “So glad I’m flat broke that you’re having hysterics over it. Typical southern hospitality. Hearty welcome to our city, and so forth, and so forth!”

The old man grinned at him appreciatively. “Lord boy!––I reckon I’ve been waiting around for you about ten year, though I didn’t know what your name would be when you come, and it couldn’t be a better one! We’ll outfit first for the Three Hills of Gold in the desert, and if luck is against us there we’ll strike down into Sonora to have a try after the red gold of El Alisal. I’ve covered some of that ground, but never had a pardner who would stick. They’d beat it because of either the Mexicans or the Indians, but you––say boy! It’s the greatest game in the world and we’ll go to it!”

His young eyes sparkled in his weathered desert face, and more than ten years were cast aside in his enthusiasm. K. Rhodes looked at him askance.

“If I did not have a key to your sane and calm outlining of prospects for the future, I might suspect loco weed or some other dope,” he observed. “But the fact is you must have known that my grandfather in his day went on the trail of the Three Hills of Gold, and left about a dozen different plans on paper for future trips.”

“Know it? Why boy, I went in with him!” shrilled Captain Pike. “Know it? Why, we crawled out half starved, and dried out as a couple of last year’s gourds. We dug roots and were chewing our own boot tops when the Indians found us. Sure, I know it. He went East to raise money for a bigger outfit, but never got back––died there.”

“Yes, then my father gathered up all the plans and specifications and came out with a friend about fifteen years ago,” added Rhodes. “They never got anywhere, but he sort of worked the fever off, bought some land and hit the trail back home. So I’ve been fairly well fed up on your sort of dope, Captain, and when I’ve mended that gone feeling in my pocketbook I may ‘call’ you on the gold trail proposition. Even if you’re bluffing there’ll be no come back; I can listen to a lot of ‘lost mine’ vagaries. It sounds like home sweet home to me!”

“Bluff nothing! we’ll start next week.”

“No we won’t, I’ve got a job and made a promise, got to help clean up the work here for the winter. Promised to take the next load of horses East.”

“That’s a new one,” observed his new friend. “Conrad himself has always gone East with the horses, or sent Brehmen, his secretary. But never mind, Bub, the eastern trip won’t take long. I’ll be devilin’ around getting our outfit and when the chance comes––us for the Three Hills of Gold!”

“It listens well,” agreed K. Rhodes, “cheeriest little pasear I’ve struck in the county. We’ll have some great old powwows, even if we don’t make a cent, and some day you’ll tell me about the mental kinks in the makeup of our Prussian friend, Conrad. He sounds interesting to me.”

Captain Pike uttered a profane and lurid word or two concerning Mr. Conrad, and stated he’d be glad when Billie was of age. Singleton, and therefore Conrad, would only have the management up to that time. Billie would know horses if nothing else, and––Then he interrupted himself and stared back the way he had come.

“I’m a forgetful old fool!” he stated with conviction. “I meandered out to take a look around for her, and I didn’t like the looks of that little dab of a saddle Conrad had put on Pat. You didn’t see anything of her, did you?”

“What does she look like?”

“A slip of a girl who rides like an Indian, rides a black horse.”

“No, I’ve seen no one,” said the young chap truthfully enough. “But who did you say your girl was?”

“You’ll find out if you hold your job long enough for her to be of age,” said Pike darkly. “She’ll be your boss instead of Conrad. It’s Billie Bernard, the owner of Granados and La Partida.”

“Billie?”

“Miss Wilfreda, if you like it better.”

But K. Rhodes said he didn’t. Billie seemed to fit the sort of girl who would garb herself in Pedro’s shirt and whistle at him through the bars of the little window.

It took less than a week for Kit Rhodes to conclude that the girl behind the bars had a true inspiration regarding his own position on her ranches. There was no open hostility to him, yet it was evident that difficulties were cleverly put in his way.

Not by Philip Singleton, the colorless, kindly disposed gentleman of Pike’s description. But by various intangible methods, he was made to feel an outsider by the manager, Conrad, and his more confidential Mexican assistants. They were punctiliously polite, too polite for a horse-ranch outfit. Yet again and again a group of them fell silent when he joined them, and as his work was with the horse herds of La Partida, that part of the great grant which spread over the border into Sonora, he was often camped fifty miles south of the hacienda of Granados, and saw no more of either the old prospector, or the tantalizing girl of the voice and the whistle.

Conrad, however, motored down two or three times concerning horses for eastern shipment, but Rhodes, the new range capitan, puzzled considerably over those flying visits, for, after the long drive through sand and alkali, the attention he gave either herds or outfit was negligible. In fact he scarcely touched at the camp, yet always did some trifling official act coming or going to make record that he had been there.

The Mexicans called him El Aoura, the buzzard, because no man could tell when he would swoop over even the farthest range of La Partida to catch them napping. Yet there was some sort of curious bond between them for there were times when Conrad came north as from a long southern trail, yet the Mexicans were as dumb men if it was referred to.

He was a compactly built, fair man of less than forty, with thin reddish brown hair, brows slanting downward from the base of the nose, and a profile of that curious Teuton type reminiscent of a supercilious hound if one could imagine such an animal with milk-blue eyes and a yellow mustache with spiky turned-up ends.

But Rhodes did not permit any antipathy he might feel towards the man to interfere with his own duties, and he went stolidly about the range work as if in utter forgetfulness of the dark prophecy of the girl.

If he was to lose his new job he did not mean that it should be from inattention, and nothing was too trifling for his notice. He would do the work of a range boss twelve hours out of the day, and then put in extra time on a night ride to the cantina at the south wells of La Partida.

But as the work moved north and the consignment of horses for France made practically complete, old Cap Pike rode down to Granados corrals, and after contemplation of the various activities of Rhodes, climbed up on the corral fence beside him, where the latter was checking off the accepted animals.

“You’re a cheerful idiot for work, Bub,” agreed the old man, “but what the devil do you gain by doing so much of the other fellow’s job? Pancho Martinez wasn’t sick as he played off on you; you’re green to these Mexican tricks.”

“Sure, I’m the original Green from Greenburg,” assented his new companero. “Pancho was only more than usually drunk last night, while I was fresh as a daisy and eager to enlarge my geographic knowledge, also my linguistics, Hi! Pedro! not the sorrel mare! Cut her out!”

“Linguistics?” repeated Pike impatiently.

“Yeh, nice little woman in the cantina at La Partida wells. I am a willing pupil at Spanish love songs, and we get along fine. I am already a howling success at La Paloma, La Golondrina, and a few other sentimental birds.”

“Oh, you are, are you?” queried Pike. “Well, take a warning. You’ll get a knife in your back from her man one of these fine nights, and the song will be Adios, adios amores for you!”

“Nothing doing, Cap! We play malilla for the drinks, and I work it so that he beats me two out of three. I’m so easy I’m not worth watching. Women don’t fancy fools, so I’m safe.”

“Well, I’ll be ‘strafed’ by the Dutch!” Pike stared at the young fellow, frowning in perplexity. “You sure have me puzzled, Bub. Are you a hopeless dunce by training or nature?”

“Natural product,” grinned K. Rhodes cheerfully. “Beauty unadorned. Say Cap, tell me something. What is the attraction for friend Conrad south of La Partida? I seem to run against a stone wall when I try to feel out the natives on that point. Now just what lies south, and whose territory?”

The old man looked at him with a new keenness.

“For your sort of an idiot you’ve blundered on a big interrogation point,” he observed. “Did you meet him down there?”

“No, only heard his voice in the night. It’s not very easy to mistake that velvety blood-puddin’ voice of his, and a team went down to meet him. He seems to go down by another route, railroad I reckon, and comes in by the south ranch. Now just what is south?”

“The ranches of Soledad grant join La Partida, or aim to. There are no maps, and no one here knows how far down over the border the Partida leagues do reach. Soledad was an old mission site, and a fortified hacienda back in the days of Juarez. Its owner was convicted of treason during Diaz’ reign, executed, and the ranches confiscated. It is now in the hands of a Federal politician who is safer in Hermosillo. The revolutionists are thick even among the pacificos up here, but the Federals have the most ammunition, and the gods of war are with the guns.”

“Sure; and who is the Federal politician? No, not that colt, Marcito!”

“Perez, Don José Perez,” stated Pike, giving no heed to corral interpolations. “He claims more leagues than have ever been reckoned or surveyed, took in several Indian rancherias last year when the natives were rounded up and shipped to Yucatan.”

“What?”

“Oh, he is in that slave trade good and plenty! They say he is sore on the Yaquis because he lost a lot of money on a boat load that committed suicide as they were sailing from Guaymas.”

“A boat load of suicides! Now a couple of dozen would sound reasonable, but a boat load–––”

“But it happened to every Indian on the boat, and the boat was full! No one knows how the poor devils decided it, but it was their only escape from slavery, and they went over the side like a school of fish. Men, women, and children from the desert who couldn’t swim a stroke! Talk about nerve––there wasn’t one weakling in that whole outfit, not one! Perez was wild. It lost him sixty dollars a head, American.”

“And that’s the neighbor friend Conrad takes a run down south to see occasionally?”

“Who says so, Bub?”

The two looked at each other, eyes questioning.

“Look here, son,” said Pike, after a little, “I’ll hit any trail with you barring Mexican politics. They all sell each other out as regular as the seasons swing around, and the man north of the line who gets tangled is sure to be victim if he stays in long enough.”

“Oh, I don’t know! We have a statesman or two who flirted with Sonora and came out ahead.”

“I said if he stayed in,” reminded Pike. “Sure we have crooks galore who drift across, play a cut-throat game and skip back to cover. The border is lined with them on both sides. And Conrad–––”

“But Conrad isn’t in politics.”

“N-no. There’s no evidence that he is, but his Mexican friends are. There are men on the Granados now who used to be down on Soledad, and they are the men who make the trips with him to the lower ranch.”

“Tomas Herrara and Chico Domingo?”

“I reckon you’ve sized them up, but remember, Kit, I don’t cross over with you for any political game, and I don’t know a thing!”

“All right, Captain, but don’t raise too loud a howl if I fancy a pasear occasionally to improve my Spanish.”

The old man grumbled direful and profane prophecies as to things likely to happen to students of Spanish love songs in Sonora, and then sat with his head on one side studying Kit ruminatively as he made his notes of the selected stock.

“Ye know Bub, it mightn’t be so bad at that, if you called a halt in time, for one of the lost mine trails calls for Spanish and plenty of it. I’ve got a working knowledge, but the farther you travel into Sonora the less American you will hear, and that lost mine of the old padres is down there along the ranges of Soledad somewhere.”

“Which one of the fifty-seven varieties have you elected to uncover first?” queried Rhodes. “The last time you were confidential about mines I thought the ‘Three Hills of Gold’ were mentioned by you.”

“Sure it was, but since you are on the Sonora end of the ranch, and since you are picking up your ears to learn Sonoran trails, it might be a good time to follow your luck. Say, I’ll bet that every herder who drifts into the cantina at La Partida has heard of the red gold of El Alisal. The Yaquis used to know where it was before so many of them were killed off; reckon it’s lost good and plenty now, but nothing is hid forever and it’s waiting there for some man with the luck.”

“We’re willing,” grinned Kit. “You are a great little old dreamer, Captain. And there is a fair chance I may range down there. I met a chap named Whitely from over toward the Painted Hills north of Altar. Ranch manager, sort of friendly.”

“Sure, Tom Whitely has some stock in a ranch over there––the Mesa Blanca ranch––it joins Soledad on the west. I’ve always aimed to range that way, but the lost mine is closer than the eastern sierras––must be! The trail of the early padres was farther east, and the mine could not well be far from the trail, not more than a day’s journey by mule or burro, and that’s about twenty miles. You see Bub, it was found by a padre who wandered off the trail on the way to a little branch mission, or visita, as they call it, and it was where trees grew, for a big alisal tree––sycamore you know––was near the outcrop of that red gold. Well, that visita was where the padres only visited the heathen for baptism and such things; no church was built there! That’s what tangles the trail for anyone trying to find traces after a hundred years.”

“I reckon it would,” agreed Rhodes. “Think what a hundred years of cactus, sand, and occasional temblors can do to a desert, to say nothing of the playful zephyrs. Why, Cap, the winds could lift a good-sized range of hills and fill the baby rivers with it in that time, for the winds of the desert have a way with them!”

A boy rode out of the whirls of dust, and climbed up on the corral fence where Rhodes was finishing tally of the horses selected for shipment. He was the slender, handsome son of Tomas Herrara of whom they had been speaking.

“It is a letter,” he said, taking a folded paper from his hat. “The Señor Conrad is having the telegraph, and the cars are to be ready for Granados.”

“Right you are, Juanito,” agreed Rhodes. “Tell Señor Conrad I will reach Granados for supper, and that all the stock is in.”

The lad whirled away again, riding joyously north, and Rhodes, after giving final directions to the vaqueros, turned his roan in the same direction.

“Can’t ride back with you, Cap, for I’m taking a little pasear around past Herrara’s rancheria. I want to take a look at that bunch of colts and size up the water there. I’ve a hunch they had better be headed up the other valley to the Green Springs tank till rains come.”

Captain Pike jogged off alone after some audible and highly colored remarks concerning range bosses who assumed the power of the Almighty to be everywhere the same day. Yet as he watched the younger man disappear over the gray-green range he smiled tolerantly for, after all, that sort of a hustler was the right sort of partner for a prospecting trip.

The late afternoon was a golden haze under a metal blue sky; afar to the east, sharp edges of the mountains cut purple zig-zags into the salmon pink of the horizon. The rolling waves of the ranges were bathed in a sea of rest, and now and then a bird on the mesquite along an arroya, or resting on branch of flaring occotilla would give out the foreboding call of the long shadows, for the heart of the day had come and gone, and the cooler air was waking the hidden things from siesta.

Kit Rhodes kept the roan at a steady lope along the cattle trail, drinking in the refreshing sweetness of the lonely ranges after hours of dust and heat and the trampling horse herds of the corrals. Occasionally he broke into songs of the ranges, love songs, death laments, and curious sentimental ditties of love and wars of old England as still crooned in the cabins of southern mountains.

|

I had not long been married, |

The ancient song of the sad bride whose lover proved false in the “low, low lands of Holland” trailed lugubriously along the arroya in a totally irrelevant way, for the singer was not at all sad. He was gaily alert, keen-eyed and watchful, keeping time to the long lope with that dubious versification.

“And they’re at it again pretty close to the ‘low, low lands of Holland,’ Pardner,” he confided to the horse. “And when you and I make a stake you’ll go on pasture, I’ll hit the breeze for Canada or some other seaport, and get one whack at the Boche brown rat on my own if official America is too proud to fight, for

|

Oh-h! oh-h! Oh-h! |

Then, after long stretches of sand dunes, mesquite thickets, occasional wide cañons where zacatan meadows rippled like waves of the sea in the desert air, he swung his horse around a low hill and came in sight of the little adobe of Herrara, a place of straggly enclosures of stakes and wattles, with the corral at the back.

Another rider came over the hill beyond the corral, on a black horse skimming the earth. Rhodes stared and whistled softly as the black without swerving planted its feet and slid down the declivity by the water tank, and then, jumping the fence below, sped to the little ramada before the adobe where its rider slid to the ground amid a deal of barking of dogs and scattering of children.

And although Kit had never seen the rider before, he had no difficulty as to recognition, and on a sudden impulse he whistled the meadow-lark call loudly enough to reach her ears.

She halted at the door, a bundle in her hand, and surveyed the landscape, but failed to see him because he at that moment was back of a clump of towering prickly pear. And she passed on into the shadows of the adobe.

“That’s the disadvantage of being too perfect, Pardner,” he confided to the roan, “she thinks we are a pair of birds.”

He turned at the corner of the corral and rode around it which took him back of the house and out of range from the door, but the dogs set up a ki-yi-ing, and a flock of youngsters scuttled to the corner of the adobe, and stared as children of the far ranges are prone to stare at the passing of a traveler from the longed-for highways of the world.

The barking of the dogs and scampering of the children evidently got on the nerves of the black horse left standing at the vine-covered ramada, for after a puppy had barked joyously at his heels he leaped aside, and once turned around kept on going, trotting around the corral after the roan.

Rhodes saw it but continued on his way, knowing he could pick it up on his return, as the Ojo Verde tank was less than a mile away. A boy under the ramada gave one quick look and then fled, a flash of brown and a red flapping end of a sash, up the cañoncita where the home spring was shadowed by a large mesquite tree.

At first Rhodes turned in the saddle with the idea of assisting in the catching of the black if that was the thing desired, but it evidently was not.

“Now what has that muchacho on his mind that he makes that sort of get-away after nothing and no pursuer in sight? Pardner, I reckon we’ll squander a valuable minute or two and gather in that black.”

He galloped back, caught the wanderer but kept right on without pause to the trickle of water under the flat wide-spreading tree––it was a solitaire, being king of its own domain and the only shade, except the vine-covered ramada, for a mile.

The startled boy made a movement as if to run again as Kit rode up, then halted, fear and fateful resignation changing the childish face to sullenness.

“Buenas tardes, Narcisco.”

“Buenas tardes, señor,” gulped the boy.

“I turned back to catch the horse of the señorita for you,” observed Rhodes. “It is best you tie him when you lead him back, but first give him water. Thirst is perhaps the cause he is restless.”

“Yes señor,” agreed the lad. “At once I will do that.” But he held the horse and did not move from his tracks, and then Rhodes noticed that on the flat rock behind him was a grain sack thrown over something, a brown bottle had rolled a little below it, and the end of a hammer protruded from under the sacking.

Ordinarily Rhodes would have given no heed to any simple ranch utensils gathered under the shadow where work was more endurable, but the fear in the face of the boy fascinated him.

“Think I’ll give Pardner a drink while I am about it,” he decided, and dismounted carelessly. “Got a cup that I can take my share first?”

Narcisco had no cup, only shook his head and swallowed as if the attempt at words was beyond him.

“Well, there is a bottle if it is clean,” and Rhodes strode awkwardly towards it, but his spur caught in the loose mesh of the sacking, and in loosening it he twisted it off the rock.

Narcisco gasped audibly, and Rhodes laughed. He had uncovered a couple of dozen empty whiskey bottles, and a tin pan with some broken glass.

“What you trying to start up here in the cañon, Buddy?” he asked. “Playing saloon-keeper with only the gophers for customers?”

He selected a corked bottle evidently clean, rinsed and drank from it.

“Yes––señor––I am here playing––that is all,” affirmed Narcisco. “At the house Tia Mariana puts us out because there is a new niño––my mother and the new one sleep––and there is no place to make a noise.”

“Oh,” commented Rhodes, “well, let the black have a little water, and lead him out of the way of mine. This gully isn’t wide enough to turn around in.”

Obediently the boy led the black to the sunken barrel catching seepage from the barrel under the drip. Rhodes tossed the sack back to the flat rock and noted an old canvas water bottle beside the heap, it was half full of something––not water, for it was uncorked and the mouth of it a-glitter with shimmering particles like diamond dust, and the same powder was over a white spot on the rock––the lad evidently was playing miller and pounding broken glass into a semblance of meal.

“Funny stunt, that!” he pondered, and, smiling, watched the frightened boy. “Herrara certainly is doing a bit of collecting vino to have a stock of bottles that size, and the poor kid’s nothing else to play with.”

He mounted and rode on, leaving Narcisco to lead the black to his mistress. He could not get out of his mind the fright in the eyes of the boy. Was Herrara a brute to his family, and had Narcisco taken to flight to hide his simple playthings under the mistaken idea that the horseman was his father returned early from the ranges?

That was the only solution Rhodes could find to the problem, though he milled it around in his mind quite a bit. Unless the boy was curiously weak-minded and frightened at the face of a stranger it was the only explanation he could find, yet the boys of Herrara had always struck him as rather bright. In fact Conrad had promoted Juanito to the position of special messenger; he could ride like the wind and never forget a word.

The shadows lengthened as he circled the little cañon of the Ojo Verde and noted the water dripping from the full tanks, ideal for the colt range for three months. He took note that Herrara was not neglecting anything, despite that collection of bottles. There was no wastage and the pipes connecting the tanks were in good condition.

He rode back, care free and content, through the fragrant valley. The cool air was following the lowering sun, and a thin mauve veil was drifting along the hills of mystery in the south; he sang as he rode and then checked the song to listen to the flutelike call of a lark. His lips curved in a smile as he heard it, and with it came the thought of the girl and the barred window of Vijil’s adobe.

She permeated the life of Granados just as the soft veil enwrapped the far hills, and she had seemed almost as far away if not so mysterious. Not once had he crossed her trail, and he heard she was no longer permitted to ride south of the line. The vaqueros commented on this variously according to their own point of view. Some of the Mexicans resented it, and in one way or another her name was mentioned whenever problems of the future were discussed. Singleton was regarded as temporary, and Conrad was a salaried business manager. But on a day to come, the señorita, as her mother’s daughter, would be their mistress, and the older men with families showed content at the thought.

Rhodes never could think of her as the chatelaine of those wide ranges. She was to him the “meadow-lark child” of jests and laughter, heard and remembered but not seen. She was the haunting music of youth meeting him at the gateway of a new land which is yet so old!

Some such vagrant thought drifted through his mind as the sweet calls of the drowsy birds cut the warm silence, now from some graceful palo verde along a barranca and again from the slender pedestal of an occotilla.

“Lucky you, for you get an answer!” he thought whimsically. “Amble along, Pardner, or the night witches get us!”

And then he circled a little at the north of the cañon, and the black horse, champing and fidgeting, was held there across the trail by its rider.

“We are seeing things in broad daylight, Pardner, and there ain’t no such animal,” decided Rhodes, but Pardner whinnied, and the girl threw up her hand.

“This time I am a highwayman, the far-famed terror of the ranges!” she called.

“Sure!” he conceded. “I’ve been thinking quite a while that your term must be about up.”

She laughed at that, and came alongside.

“Didn’t you suppose I might have my time shortened for good behavior?” she asked. “You never even ride our way to see.”

“Me? Why, child, I’m so busy absorbing kultur from your scientific manager that my spare moments for damsels in distress are none too plenty. You sent out nary a call, and how expect the lowest of your serfs to hang around?”

“Serf? That’s good!” she said skeptically. “And say, you must love Conrad about as much as Cap Pike does.”

“And that?”

“Is like a rattlesnake.”

“Don’t know that rattlesnake would be my first choice of comparison,” remarked Rhodes. “Back in Tennessee we have a variety beside which the rattlesnake is a gentleman; a rattlesnake does his best to give warning of intention, but the copperhead never does.”

“Copperhead! that’s funny, for you know Conrad’s hair is just about the color of copper, dusty copper, faded copper––copper with tin filings sifted through.”

“Don’t strain yourself,” laughed Rhodes. “That beautiful blondness makes him mighty attractive to our Mexican cousins.”

“They can have my share,” decided the girl. “I could worry along without him quite awhile. He manages to get rid of all the likeable range men muy pronto.”

Rhodes laughed until she stared at him frowningly, and then the delicious color swept over her face.

“Oh, you!” she said, and Rhodes thought of sweet peas, and pink roses in old southern gardens as her lips strove to be straight, yet curved deliciously. No one had mentioned to him how pretty she was; he had thought of her as a browned tom-boy, but instead she was a shell-pink bud on a slender stem, and wonder of wonders––she rode a side-saddle in Arizona!

She noticed him looking at it.

“Are you going to laugh at that, too?” she demanded.

“Why no, it hadn’t occurred to me. It sort of looks like home to me––our southern girls use them.”

She turned to him with a quick birdlike movement, her gray eyes softened and trusting.

“It was my mother’s saddle, a wedding present from the vaqueros of our ranches when she married my father. I am only beginning to use it, and not so sure of myself as with the one I learned on.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” he observed. “You certainly looked sure when you jumped that fence at Herrara’s.”

She glanced at him quickly, curious, and then smiling.

“And it was you, not the meadow lark! You are too clever!”

“And you didn’t answer, just turned your back on the lonely ranger,” he stated dolefully, but she laughed.

“This doesn’t look it, waiting to go home with you,” she retorted. “Cap Pike has been telling me about you until I feel as if I had known you forever. He says you are his family now, so of course that makes Granados different for you.”

“Why, yes. I’ve been in sight of Granados as much as twice since I struck this neck of the woods. Your manager seems to think my valuable services are indispensable at the southern side of this little world.”

“So that’s the reason? I didn’t know,” she said slowly. “One would have to be a seventh son of a seventh son to understand his queer ways. But you are going along home today, for I am a damsel in distress and need to be escorted.”

“You don’t look distressed, and I’ve an idea you could run away from your escort if you took a notion,” he returned. “But it is my lucky day that I had a hunch for this cañon trail and the Green Springs, and I am happy to tag along.”

They had reached Herrara’s corral and Rhodes glanced up the little gulch to the well. The flat rock there was stripped of the odd collection, and Narcisco stood at the corner of the adobe watching them somberly.

“Buenos tardes!” called the girl. “Take care of the niño as the very treasure of your heart!”

“Sure!” agreed the lad, “Adios, señorita.”

“Why the special guard over the treasure?” asked Rhodes as their horses fell into the long easy lope side by side. “The house seems full and running over, and niñitas to spare.”

“There are never any to spare,” she reminded him, “and this one is doubly precious for it is named for me––together its saint and its two grandmothers! Benicia promised me long ago that whether it was a boy or a girl it would be Billie Bernard Herrara. I was just taking the extra clothes I had Tia Luz make for him––and he is a little black-eyed darling! Soon as he is weaned I’m going to adopt him; I always did want a piccaninny for my own.”

Rhodes guided his horse carefully around a barranca edge, honeycombed by gophers, and then let his eyes rest again on the lustrous confiding eyes, and the rose-leaf lips.

Afterward he told himself that was the moment he began to be bewitched by Billie Bernard.

But what he really said was––“Shoo, child, you’re only a piccaninny yourself!” and they both laughed.

It was quite wonderful how old Captain Pike had managed to serve as a family foundation for their knowledge of each other. There was not a doubt or a barrier between them, they were “home folks” riding from different ways and meeting in the desert, and silently claiming kindred.

The shadows grew long and long under the sun of the old Mexic land, and the high heavens blazed above in yellows and pinks fading into veiled blues and far misty lavenders in the hollows of the hills.

The girl drew a great breath of sheer delight as she waved her hands towards the fire flame in the west where the desert was a trail of golden glory.

“Oh, I am glad––glad I got away!” she said in a hushed half-awed voice. “It never––never could be like this twice and we are seeing it! Look at the moon!”

The white circle in the east was showing through a net of softest purple and the beauty of it caused them to halt.

“Oh, it makes me want to sing, or to say my prayers, or––to cry!” she said, and she blinked tears from her eyes and smiled at him. “I reckon the colors would look the same from the veranda, but all this makes it seem different,” and her gesture took in the wide ranges.

“Sure it does,” he agreed. “One wants to yell, ‘Hurrah for God!’ when a combination like this is spread before the poor meek and lowly of the earth. It is a great stage setting, and makes us humans seem rather inadequate. Why, we can’t even find the right words for it.”

“It makes me feel that I just want to ride on and on, and on through it, no matter which way I was headed.”

“Well, take it from me, señorita, you are headed the right way,” he observed. “Going north is safe, but the blue ranges of the south are walls of danger. The old border line is a good landmark to tie to.”

“Um!” she agreed, “but all the fascinating things and the witchy things, and the mysterious things are down there over the border. I never get real joy riding north.”

“Perhaps because it is not forbidden, Miss Eve.”

Then they laughed again and lifted the bridles, and the horses broke into a steady lope, neck and neck, as the afterglow made the earth radiant and the young faces reflected the glory of it.

“What was that you said about getting away?” he queried. “Did you break jail?”

“Just about. Papa Singleton hid my cross-saddle thinking I would not go far on this one. They have put a ban on my riding south, but I just had to see my Billie Bernard Herrara.”

“And you ran away?”

“N-no. We sneaked away mighty slow and still till we got a mile or two out, and then we certainly burned the wind. Didn’t we, Pat?”

“Well, as range boss of this end of the ranch I reckon I have to herd you home, and tell them to put up the fences,” said Rhodes.

“Yes, you will!” she retorted in derision of this highly improbable suggestion.

“Surest thing you know! Singleton has good reasons for restricting your little pleasure rides to Granados. Just suppose El Gavilan, the Hawk, should cross your trail in Sonora, take a fancy to Pat––for Pat is some caballo!––and gather you in as camp cook?”

“Camp cook?”

“Why, yes; you can cook, can’t you? All girls should know how to cook.”

“What if I do? I have cooked on the camp trips with Cap Pike, but that doesn’t say I’ll ever cook for that wild rebel, Ramon Rotil. Are you trying to frighten me off the ranges?”

“No, only stating the case,” replied Rhodes lighting a cigarette and observing her while appearing not to. “Quite a few of the girls in the revolution camps are as young as you, and many of them are not doing camp work by their own choice.”

“But I––” she began indignantly.

“Oh yes, in time you would be ransomed, and for a few minutes you might think it romantic––the ‘Bandit Bride,’ the ‘Rebel Queen,’ the ‘Girl Guerrilla,’ and all that sort of dope,––but believe me, child, by the time the ransom was paid you would be sure that north of the line was the garden spot of the earth and heaven enough for you, if you could only see it again!”

She gave him one sulky resentful look and dug her heel into Pat. He leaped a length ahead of the roan and started running.

“You can pretend you are El Gavilan after a lark, and see how near you will get!” she called derisively and leaned forward urging the black to his best.

“You glorified gray-eyed lark!” he cried. “Gather her in, Pardner!”

But he rode wide to the side instead of at the heels of Pat and thus they rode neck and neck joyously while he laughed at her intent to leave him behind.

The corrals and long hay ricks of Granados were now in sight, backed by the avenue of palms and streaks of green where the irrigation ditches led water to the outlying fields and orchards.

“El Gavilan!” she called laughingly. “Beat him, Pat,––beat him to the home gate!”

Then out of a fork of the road to the left, an automobile swept to them from a little valley, one man was driving like the wind and another waved and shouted. Rhodes’ eyes assured him that the shouting man was Philip Singleton, and he rode closer to the girl, grasped her bridle, and slowed down his own horse as well as hers.

“You’ll hate me some more for this,” he stated as she tried to jerk loose and failed, “but that yelping windmill is your fond guardian, and he probably thinks I am trying to kidnap you.”

She halted at that, laughing and breathless, and waved her hand to the occupants of the car.

“I can be good as an angel now that I have had my day!” she said. “Hello folks! What’s the excitement?”

The slender man whom Rhodes had termed the yelping windmill, removed his goggles, and glared, hopelessly distressed at the flushed, half-laughing girl.

“Billie––Wilfreda!”

“Now, now, Papa Singleton! Don’t swear, and don’t ever get frightened because I am out of sight.” Then she cast one withering glance at Rhodes, adding,––“and if you engage range bosses like this one no one on Granados will ever get out of sight!”

“The entire house force has been searching for you over two hours. Where have you been?”

“Oh, come along home to supper, and don’t fuss,” she suggested. “Just because you hid my other saddle I went on a little pasear of my own, and I met up with this roan on my way home.”

Rhodes grinned at the way she eliminated the rider of the roan horse, but the driver of the machine was not deceived by the apparent slight. He had seen that half defiant smile of comradeship, and his tone was not nice.

“It is not good business to waste time and men in this way,” he stated flatly. “It would be better that word is left with the right ones when you go over the border to amuse yourself in Sonora.”

The smile went out of the eyes of the girl, and she held her head very erect.

“You and Mr. Rhodes appear to agree perfectly, Mr. Conrad,” she remarked. “He was trying to show me how little chance I would stand against El Gavilan or even the Yaqui slave traders if they ranged up towards the border.”

“Slave traders?” repeated Conrad. “You are making your jokes about that, of course, but the camp followers of the revolution is a different thing;––everywhere they are ranging.”

The girl did not answer, and the car sped on to the ranch house while the two horses cantered along after them, but the joyous freedom of the ride had vanished, lost back there on the ranges when the other minds met them in a clash.

“Say,” observed Rhodes, “I said nothing about Yaqui slave traders. Where did you get that?”

“I heard Conrad and his man Brehman talking of the profits,––sixty pesos a head I think it was. I wonder how they knew?”

Singleton was waiting for them at the entrance to the ranch house, great adobe with a patio eighty feet square in the center. In the old old days it had housed all the vaqueros, but now the ranchmen were divided up on different outlying rancherias and the many rooms of Granados were mostly empty. Conrad, his secretary Brehman, and their cook occupied one corner, while Singleton and Billie and Tia Luz with her brood of helpers occupied the other.

Singleton was not equal to the large hospitality of the old days when the owner of a hacienda was a sort of king, dispensing favors and duties to a small army of retainers. A companionable individual he was glad to meet and chat or smoke with, but if the property had been his own he would have sold every acre and spent the proceeds in some city of the East where a gentleman could get something for his money.

Conrad had halted a moment after Singleton climbed out of the car.

“I sent word to Rhodes to come up from La Partida because of the horse shipment,” he said looking across the level where the two riders were just entering the palm avenue. “Because of that it would seem he is to be my guest, and I have room.”

“Oh, we all have room, more room than anything else,” answered Singleton drearily, “but it will be as Billie says. I see Pike’s nag here, and she always wants Pike.”

The milky blue eyes of Conrad slanted towards Singleton in discreet contempt of the man who allowed a wayward girl to decide the guests or the housing of them. But he turned away.

“The telephone will reach me if there is anything I can do,” he said.

Singleton did not reply. He knew Conrad absolutely disapproved of the range boss being accepted as a family guest. Between Billie and Captain Pike, who was a privileged character, he did not quite see how he could prevent it in the case of Rhodes, although he was honestly so glad to see the girl ride home safe that he would have accepted any guest of the range she suggested.

“Papa Phil,” she said smiling up into his face teasingly, “I’m on my native heath again, so don’t be sulky. And I have a darling new namesake I’ve been making clothes for for a month, and I’ll tell you all about him if you’ll give Mr. Rhodes and me a good supper. He is Cap Pike’s family, and will have the south corner room; please tell Tia Luz.”

And when Billie was like that, and called him “Papa Phil,” and looked up at him with limpid childish eyes, there was never much else to be said.

“I’ll show Rhodes his quarters myself, and you make haste and get your habit off. Luz has been waiting supper an hour. Today’s paper reports a band of bandits running off stock on the Alton ranch, and it is on the Arizona side of the border. That should show you it is no time to ride out of sight of the corrals.”

“Now, now! you know the paper raids aren’t real raids. They’ll have a new one to get excited over tomorrow.”

She ran away to be petted and scolded and prayed for by Tia Luz, who had been her nurse, and was now housekeeper and the privileged one to whom Billie turned for help and sympathy.

“You laugh! but the heart was melting in me with the fear,” she grumbled as she fastened the yellow sash over the white lawn into which Billie had dashed hurriedly. “It is not a joke to be caught in the raiding of Ramon Rotil, or any of the other accursed! Who could think it was south you were riding? I was the one to send them north in the search, every man of them, and Señor Conrad looks knives at me. That man thinks I am a liar, sure he does! and the saints know I was honest and knew nothing.”

“Sure you know nothing, never could and never did, you dear old bag of cotton,” and Billie pinched affectionately the fat arm of Tia Luz and tickled her under her fat chin. “Quick Luzita, and fasten me up. Supper waits, and men are always raving wolves.”

She caught up a string of amber beads and clasped it about her throat as she ran across the patio, and Kit Rhodes halted a moment in the corridor to watch her.

“White and gold and heavenly lovely,” he thought as he rumpled his crisp brown curls meditatively, all forgetful of the earnest attempts he had just made to smooth them decorously with the aid of a damp towel and a pocket comb. “White and gold and a silver spoon, and a back seat for you, Kittie boy!”

Captain Pike emerged from a door at the corner of the patio. He also had damp hair, a shiny face, and a brand-new neckerchief with indigo circles on a white ground.

“Look at this, will you?” he piped gleefully. “Billie’s the greatest child ever! Always something stuck under the pillow like you’d hide candy for a kid, and say,––if any of the outfit would chuck another hombre in my bunk the little lady would raise hell from here to Pinecate, and worse than that there ain’t any this side of the European centers of civilization. Come on in, supper’s ready.”

Rhodes hesitated at the door of the dining room, suddenly conscious of a dusty blouse and a much faded shirt. His spurs clink-clanked as he strode along the tiling of the patio, and in the semi-twilight he felt at home in the ranch house, but one look at the soft glow of the shaded lamps, and the foot deep of Mexican needlework on the table cover, gave him a picture of home such as he had not seen on the ranges.

Singleton was in spotless white linen, the ideal southern ranchman’s home garb, while the mistress of all the enticing picture was in white and gold, and flushing pink as she met the grave appreciative gaze of Rhodes.

“H’lo little Santa Claus,” chirruped Pike. “It’s just the proper caper to set off my manly beauty, so I’m one ahead of Kit who has no one to garnish him for the feast––and it sure smells like some feast!”

“Venison perhaps a trifle overdone, but we hope it won’t disappoint you,” remarked Singleton. “Have this seat, Mr. Rhodes. Captain Pike and Miss Bernard always chum together, and have their own side.”

“Rather,” decided Pike, “and that arrangement reaches back beyond the memory of mere man in this outfit.”

“I should say,” agreed the girl. “Why, he used to have to toss me over his head a certain number of times before I would agree to be strapped in my high chair.”

“Yep, and I carpentered the first one, and it wasn’t so bad at that! Now child, if you will pass the lemons, and Kit will pass the decanter of amber, and someone else will rustle some water, I’ll manufacture a tonic to take the dust out of your throats.”

“Everybody works but father,” laughed Billie as the Chinaman sliced and served the venison, and Tia Luz helped supply all plates, and then took her place quietly at the lower end of the table and poured the strong fragrant coffee.

Rhodes spoke to her in Spanish, and her eyes lit up with kindly appreciation.

“Ah, very good!” she commented amicably. “You are not then too much Americano?”

“Well, yes, I’m about as American as you find them aside from the Apache and Pima and the rest of the tribes.”

“Maybe so, but not gringo,” she persisted. “I am scared of the Apache the same as of El Gavilan, and today my heart was near to stop going at all when we lose señorita and that black horse––and I say a prayer for you to San Antonio when I see you come fetch her home again.”

“Yes, the black horse is valuable,” remarked Billie. “Huh! I might as well be in a convent for all I get to see of the ranges these late days. If anyone would grubstake me, I’d break loose with Cap here and go prospecting for adventures into some of the unnamed ranges.”

“You see!” said Tia Luz. “Is it a wonder I am cold with the fear when she is away from my eyes? I have lived to see the people who go into the desert for adventure, and whose bare bones are all any man looks on again! Beside the mountain wells of Carrizal my own cousin’s husband died; he could not climb to the tank in the hill. There they found him in the moon of Kumaki, which is gray and nothing growing yet.”

“Yes, many’s the salt outfit in the West played out before they reached Tinajas Altas,” said Pike. “I’ve heard curious tales about that place, and the Carrizals as well. Billie’s father nearly cashed in down in the Carrizals, and one of his men did.”

“But that is what I am saying. It was Dario Ruiz,” stated Tia Luz. “Yes, señor, that was the time, and it was for the nameless ranges they went seeking, and for adventures, treasure too; but––his soul to God! it was death Dario was finding on that trail. Your father never would speak one word again of the treasure of that old fable, for Dario found death instead of the red gold, and Dario was compadre to him.”

“The red gold?” and Cap Pike’s eyes were alight with interest. “Why, I was telling Kit about that today, the red gold of El Alisal.”

“Yes, Señor Capitan, once so rich and so red it was a wonder in Spain when the padres are sending it there from the mission of Soledad, and then witches craft, like a cloud, come down and cover that mountain. So is the vein lost again, and it is nearly one hundred years. So how could Dario think to find it when the padres, with all their prayer, never once found the trail?”

“I never heard it was near a mission,” remarked Pike. “Why, if it had a landmark like that there should be no trouble.”

“Yet it is so, and much trouble, also deaths,” stated Tia Luz. “That is how the saying is that the red gold of El Alisal is gold bewitched, for of Soledad not one adobe is now above ground unless it be in the old walls of the hacienda. All is melted into earth again or covered by the ranch house, and it is said the ranch house is also neglected now, and many of its old walls are going.”

“There are still enough left to serve as a very fair fortress,” remarked Singleton. “I was down there two years ago when we bought some herds from Perez, and lost quite a number from lack of water before the vaqueros got them to La Partida wells. It is a long way between water holes over in Altar.”

“Sure,” agreed Pike, “but if the old mine was near a mission, and the mission was near the ranch of Soledad it should not be a great stunt to find it, and there must be water and plenty of it if they do much in cattle.”

“They don’t these days,” said Singleton. “Perez sold a lot rather than risk confiscation, and I heard they did have some raids down there. I thought I had heard most of the lost mine legends of western Sonora, but I never heard of that one, and I never heard that Fred Bernard went looking for it.”

The old woman lifted her brows and shrugged her shoulders with the suggestion that Sonora might hold many secrets from the amicable gentleman. But a little later, in an inquiry from Rhodes she explained.

“See you, señor, Dario Ruiz was compadre of Señor Alfredo Bernard, Americanos not understanding all in that word, and the grandfather of Dario was major-domo of the rancho of Soledad at that time the Apaches are going down and killing the people there. That is when the mine was lost. On the skin of a sheep it was told in writing all about it, and Dario had that skin. Sure he had! It was old and had been buried in the sand, and holes were eaten in it by wild things, but Don Alfredo did read it, and I was hearing the reading of it to Dario Ruiz, but of what use the reading when that mine bewitched itself into hiding?”

“But the writing? Did that bewitch itself away also?” demanded Billie.

“How could I be asking of that when Dario was dead down there in the desert, and his wife, that was my cousin Anita, was crazy wild against Don Alfredo the father of you! Ai, that was a bad time, and Don Alfredo with black silence on him for very sorrow. And never again in his life did he take the Sonora trail for adventures or old treasure. And it is best that you keep to a mind like his mind, señorita. He grew wise, but Dario died for that wisdom, and in Sonora someone always dies before wisdom is found. First it was two priests went to death for that gold, and since that old day many have been going. It is a witchcraft, and no blessing on it!”

“Well, I reckon I’d be willing to cross my fingers, and take the trail if I could get started right,” decided Rhodes. “It certainly sounds alluring.”

“I did go in once,” confessed Pike, “but we had no luck, struck a temporale where a Papago had smallpox, and two dry wells where there should have been water. My working pardner weakened at Paradones and we made tracks for the good old border. That is no trail for a lone white man.”

“But the writing, the writing!” persisted Billie. “Tia Luz, you are a gold mine yourself of stories, but this one you never told, and I am crazy about it! You never forget anything, and the writing you could not,––so we know you have the very words of that writing!”

“Yes, that is true too, for the words were not so many, and where some words had been the wild things had eaten holes. The words said that from the mine of El Alisal the mission of Soledad could be seen. And from the door of Soledad it was one look, one only, to the blue cañoncita where the alisal tree was growing, and water from the gold of the rose washed the roots of that tree.”

“Good God!” muttered Rhodes staring at the old lady who sat nodding her head in emphasis until her jet and gold earrings were all a-twinkle. “It was as easy as that,––yet no one found it?”

“But señor,”––and it was plain to be seen that Doña Luz was enjoying herself hugely as the center of all attention, “the two padres who made that writing met their death at that place––and it was said the barbaros at last killed also the grandfather of Dario, anyway he did die, and the women were afraid to tell even a new padre of that buried writing for the cause that it must have been accursed when it killed all people. That is how it was, and that mission was forsaken after that time. A Spaniard came up from Sinaloa and hunted gold and built Soledad hacienda where that mission had been in that old time, but no one ever found any more of gold than the chickens always are picking, a little here, a little there with a gravel in the craw. No señor, only once the red gold––red as flame––went out of Altar on a mule to the viceroy in Mexico, and the padres never lived to send any more, or see their brothers again. The men who dug that gold dug also their grave. Death goes with it.”

“Ugh!” and Billie shivered slightly, and looked at Rhodes, “don’t you go digging it!”

His eyes met hers across the table. It was only for an instant, and then Billie got very busy with her coffee which she had forgotten.

“Oh, I’d travel with a mascot to ward off evil,” he said. “Would you give me a bead from your string?”

She nodded her head, but did not speak. No one noticed them, for Cap Pike was telling of the old native superstition that the man who first found an ore bed found no good luck for himself, though the next man might make a fortune from it.

“Why,” he continued in evidence, “an Indian who finds even a vein of special clay for pottery doesn’t blaze a trail to it for anyone else. He uses it if he wants it, because his own special guardian god uncovered it for him, but if it is meant for any other man, that other man’s god will lead him to it when the time comes. That is how they reason it out for all the things covered by old Mother Earth. And I reckon the redder the gold the more secret the old barbaros would be about it, for gold is their sun-god medicine, or symbol, or something.”

“With white priests scattered through Sonora for two centuries one would suppose those old superstitions would be pretty well eradicated,” remarked Singleton.

Doña Luz glanced at him as at a child who must be let have his own ideas so long as they were harmless, but Pike laughed.

“Lord love you, Singleton, nothing eradicates superstition from the Indian mind, or any other mind! All the creeds of the earth are built on it, and a lot of the white ones are still alive and going strong! And as for priests, why man, the Indian priests are bred of those tribes, and were here before the white men came from Spain. It’s just about like this: If ‘Me und Gott’ and the U-boats took a notion to come over and put a ball and chain on all of so-called free America, there might be some pacifist mongrels pretend to like it, and just dote on putting gilt on the chain, and kow-towing to that blood-puddin’ gang who are raising hell in Belgium. But would the thoroughbreds like it? Not on your life! Well, don’t you forget there were a lot of thoroughbreds in the Indian clans even if some of their slaves did breed mongrels! And don’t forget that the ships from overseas are dumping more scrub stock on the eastern shores right now than you’ll find in any Indian rancheria either here in Pima or over in Sonora. The American isn’t to blame for all the seventeen dozen creeds they bring over,––whether political or religious, and I reckon that’s about the way the heads of the red clans feel. They are more polite than we are about it, but don’t you think for a moment that the European invasion ever changed religion for the Indian thoroughbred. No sir! He is still close to the earth and the stars, and if he thinks they talk to him––well, they just talk to him, and what they tell him isn’t for you or me to hear,––or to sit in judgment on either, if it comes to that! We are the outsiders.”

“Now, Cap,” said Billie, “I’m going to take it away. It’s too near your elbow, and you have had a double dose for every single one you’ve been handing out! You can take a rest until the others catch up. Tia Luz, give him a cup of coffee good and strong to help get his politics and religion straightened out.”

Pike laughed heartily with the rest of them, and took the coffee.

“All right, dear little Buttercup. Any medicine you hand out is good to me. But say, that dope about hidden ores may not be all Indian at that, for I recollect that mountaineers of Tennessee had the same hunch about coal veins, and an old lead vein where one family went for their ammunition. They could use it and they did, but were mighty sure they’d all be hoodooed if they uncovered it for anyone else, so I reckon that primitive dope does go pretty far back. I’ll bet it was old when Tubal Cain first began scratching around the outcroppings by his lonesomes.”

Conrad sauntered along the corridor and seated himself, flicking idly some leather thongs he had cut out from a green hide with a curved sheath knife rather fine and foreign looking. Singleton called him to come in and have coffee, but he would not enter, pleading his evil-smelling pipe as a reason.

“It can’t beat mine for a downright bachelor equipment,” affirmed Pike, “but I’ve scandalized this outfit enough, or thereabout, and that venison has killed all our appetites until breakfast, so why hang around where ungrateful children swat a man’s dearest hobbies?”

“If you think you’ll get rid of me that way you had better think again,” said Billie. “I don’t mind your old smokes, or any other of your evil ways, so long as you and Tia Luz tell us more bewitched mine stories. Say, Cap, wouldn’t it be great if that old sheepskin was found again, and we’d all outfit for a Sonora pasear, and–––”

“We would not!” decided the old man patting her hair. “You, my lady, will take a pasear to some highbrow finishing school beyond the ranges, and I’ll hit the trail for Yuma in a day or two, but at the present moment you can wind up the music box and start it warbling. That supper sure was so perfect nothing but music will do for a finish!”

The men drifted out in the corridor and settled into the built-in seats of the plazita, though Rhodes remained standing in the portal facing inward to the patio where the girl’s shimmering white dress fluttered in the moonlight beside the shadowy bulk of Tia Luz.

He lit a cigarette and listened for the music box Pike had suggested, but instead he heard guitar strings, and the little ripple of introduction to the old Spanish serenade Vengo a tu ventana, “I come to your window.”

He turned and glanced towards the men who were discussing horse shipments, and possibilities of the Prussian sea raiders sinking transports on the way to France, but decided his part of that discussion could wait until morning.

Tia Luz had lit the lamp in the sala, and the light streamed across the patio where the night moths fluttered about the white oleanders. He smiled in comical self-derision as he noticed the moths, but tossed away the cigarette and followed the light.

When Captain Pike indulged the following morning in sarcastic comment over Kit’s defection, the latter only laughed at him.

“Shirk business? Nothing doing. I was strictly on the job listening to local items on treasure trails instead of powwowing with you all over the latest news reports from the Balkans. Soon as my pocket has a jingle again, I am to get to the French front if little old U. S. won’t give me a home uniform, but in the meantime Doña Luz Moreno is some reporter if she is humored, and I mean to camp alongside every chance I get. She has the woman at the cantina backed off the map, and my future Spanish lessons will be under the wing of Doña Luz. Me for her!”

“Avaricious young scalawag!” grunted Pike. “You’d study African whistles and clicks and clacks if it blazed trail to that lost gold deposit! Say, I sort of held the others out there in front thinking I would let you get acquainted with little Billie, and you waste the time chinning about death in the desert, and dry camps to that black-and-tan talking machine.”

Kit only laughed at him.

“A record breaker of a moon too!” grumbled the old man. “Lord!––lord! at your age I’d crawled over hell on a rotten rail to just sit alongside a girl like Billie––and you pass her up for an old hen with a mustache, and a gold trail!”

Kit Rhodes laughed some more as he got into the saddle and headed for the Granados corral, singing:

|

Oh––I’ll cut off my long yellow hair |

He droned out the doleful and incongruous love ballad of old lands, and old days, for the absurd reason that the youth of the world in his own land beat in his blood, and because in the night time one of the twinkling stars of heaven had dropped down the sky and become a girl of earth who touched a guitar and taught him the words of a Spanish serenade,––in case he should find a Mexican sweetheart along the border!