Title: Architecture: Classic and Early Christian

Author: T. Roger Smith

John Slater

Release date: August 22, 2009 [eBook #29759]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Sam W. and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

ILLUSTRATED HANDBOOKS OF ART HISTORY

OF ALL AGES

ARCHITECTURE

CLASSIC AND EARLY CHRISTIAN

BY PROFESSOR T. ROGER SMITH, F.R.I.B.A.

AND

JOHN SLATER, B.A., F.R.I.B.A.

THE PARTHENON AT ATHENS, AS IT WAS IN THE TIME OF PERICLES, circa B.C. 438.

ILLUSTRATED HANDBOOKS OF ART HISTORY

Professor of Architecture, University Coll. London

AND

ATRIUM OF A ROMAN MANSION.

LONDON

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE, & RIVINGTON

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188, FLEET STREET

1882.

[All rights reserved.]

LONDON. PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED,

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING CROSS.

This handbook is intended to give such an outline of the Architecture of the Ancient World, and of that of Christendom down to the period of the Crusades, as, without attempting to supply the minute information required by the professional student, may give a general idea of the works of the great building nations of Antiquity and the Early Christian times. Its chief object has been to place information on the subject within the reach of those persons of literary or artistic education who desire to become in some degree acquainted with Architecture. All technicalities which could be dispensed with have been accordingly excluded; and when it has been unavoidable that a technical word or phrase should occur, an explanation has been added either in the text or in the glossary; but as this volume and the companion one on Gothic and Renaissance Architecture are, in effect, two divisions of the same work, it has not been thought necessary to repeat in the glossary given with this part the words explained in that prefixed to the other.

In treating so very wide a field, it has been felt that the chief prominence should be given to that great sequence of architectural styles which form the links of a chain connecting the architecture of modern Europe with the earliest specimens of the art. Egypt, Assyria, and Persia combined to furnish the foundation upon which the splendid architecture of the Greeks was based. [viii] Roman architecture was founded on Greek models with the addition of Etruscan construction, and was for a time universally prevalent. The break-up of the Roman Empire was followed by the appearance of the Basilican, the Byzantine, and the Romanesque phases of Christian art; and, later on, by the Saracenic. These are the styles on which all mediæval and modern European architecture has been based, and these accordingly have furnished the subjects to which the reader’s attention is chiefly directed. Such styles as those of India, China and Japan, which lie quite outside this series, are noticed much more briefly; and some matters—such, for example, as prehistoric architecture—which in a larger treatise it would have been desirable to include, have been entirely left out for want of room.

In treating each style the object has not been to mention every phase of its development, still less every building, but rather to describe the more prominent buildings with some approach to completeness. It is true that much is left unnoticed, for which the student who wishes to pursue the subject further will have to refer to the writings specially devoted to the period or country. But it has been possible to describe a considerable number of typical examples, and to do so in such a manner as, it is hoped, may make some impression on the reader’s mind. Had notices of a much greater number of buildings been compressed into the same space, each must have been so condensed that the volume, though useful as a catalogue for reference, would have, in all probability, become uninteresting, and consequently unserviceable to the class of readers for whom it is intended.

As far as possible mere matters of opinion have been excluded from this handbook. A few of the topics which it has been necessary to approach are subjects on which [ix] high authorities still more or less disagree, and it has been impossible to avoid these in every instance; but, as far as practicable, controverted points have been left untouched. Controversy is unsuited to the province of such a manual as this, in which it is quite sufficient for the authors to deal with the ascertained facts of the history which they have to unfold.

It is not proposed here to refer to the authorities for the various statements made in these pages, but to this rule it is impossible to avoid making one exception. The writers feel bound to acknowledge how much they, in common with all students of the art, are indebted to the patient research, the profound learning, and the admirable skill in marshalling facts displayed by Mr. Fergusson in his various writings. Had it been possible to devote a larger space to Eastern architecture, Pagan and Mohammedan, the indebtedness to him, in a field where he stands all but alone, must of necessity have been still greater.

The earlier chapters of this volume were chiefly written by Mr. Slater, who very kindly consented to assist in the preparation of it; but I am of course, as editor, jointly responsible with him for the contents. The Introduction, Chapters V. to VII., and from Chapter X. to the end, have been written by myself: and if our work shall in any degree assist the reader to understand, and stimulate him to admire, the architecture of the far-off past; above all, if it enables him to appreciate our vast indebtedness to Greek art, and in a lesser degree to the art of other nations who have occupied the stage of the world, the aim which the writers have kept in view will not have been missed.

T. Roger Smith.

University College, London.

May, 1882.

Frieze from Church at Denkendorf.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTION. | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE. | |

| Pyramids. Tombs. Temples. Analysis of Buildings. | 14 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| WEST ASIATIC ARCHITECTURE. | |

| Babylonian. Assyrian. Persian. Analysis of Buildings. | 43 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| ORIENTAL ARCHITECTURE. | |

| Hindu. Chinese and Japanese. | 64 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| GREEK ARCHITECTURE. | |

| Buildings of the Doric Order. | 80 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Buildings of the Ionic and Corinthian Orders. | 102 |

| [xi]CHAPTER VII. | |

| Analysis of Greek Architecture. The Plan. The Walls. The Roof. The Openings. The Columns. The Ornaments. Architectural Character. | 117 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| ETRUSCAN AND ROMAN ARCHITECTURE. | |

| Historical and General Sketch. | 138 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The Buildings of the Romans. Basilicas. Theatres and Amphitheatres. Baths (Thermæ). Bridges and Aqueducts. Commemorative Monuments. Domestic Architecture. | 147 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Analysis of Roman Architecture. The Plan. The Walls. The Roofs. The Openings. The Columns. The Ornaments. Architectural Character. | 182 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| EARLY CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE. | |

| Basilicas in Rome and Italy. | 198 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE. | 210 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| ROMANESQUE ARCHITECTURE. | 222 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| CHRISTIAN ROUND-ARCHED ARCHITECTURE. | |

| Analysis of Basilican, Byzantine, and Romanesque. | 240 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| MOHAMMEDAN ARCHITECTURE. | |

| Egypt, Syria and Palestine, Sicily and Spain, Persia and India. | 252 |

| PAGE | ||

| The Parthenon at Athens, as it was in the time of Pericles, circa B.C. 438. | Frontispiece | |

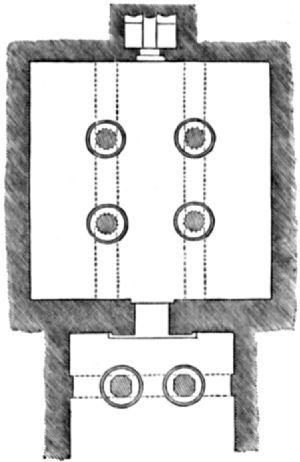

| Atrium of a Roman Mansion. | (on title‑page) | |

| Frieze from Church at Denkendorf. | x | |

| Rock-cut Tomb at Myra, in Lycia. Imitation of Timber Construction in Stone. | xviii | |

| The Temple of Vesta at Tivoli. | xxiv | |

| 1. | Opening spanned by a Lintel. Arch of the Goldsmiths, Rome. | 3 |

| 2. | Opening spanned by a Semicircular Arch. Roman Triumphal Arch at Pola. | 4 |

| 3. | Openings spanned by Pointed Arches. Interior of St. Front, Périgueux, France. | 5 |

| 4. | Temple of Zeus at Olympia. Restored according to Adler. | 8 |

| 5. | Part of the Exterior of the Colosseum, Rome. | 10 |

| 6. | Timber Architecture. Church at Borgund. | 12 |

| 7. | An Egyptian Cornice. | 14 |

| 8. | Section across the Great Pyramid (of Cheops or Suphis). | 17 |

| 9. | Ascending Gallery in the Great Pyramid. | 19 |

| 10. | The Sepulchral Chamber in the Pyramid of Cephren at Gizeh. | 19 |

| 11. | The Construction of the King’s Chamber in the Great Pyramid. | 19 |

| 12. | Imitation of Timber Construction in Stone, from a Tomb at Memphis. | 21 |

| 13. | Imitation of Timber Construction in Stone, from a Tomb at Memphis. | 21 |

| 14. | Plan and Section of the Tomb at Beni-Hassan. | 23 |

| 15. | Rock-cut Façade of the Tomb at Beni-Hassan. | 24 |

| 16. | Ground-plan of the Temple at Karnak. | 26 |

| 17. | The Hypostyle Hall at Karnak, showing the Clerestory. | 27 |

| 18. | Entrance to an Egyptian Temple, showing the Pylons. | 27 |

| [xiii]19. | Plan of the Temple at Edfou. | 30 |

| 20. | Example of one of the Mammisi at Edfou. | 30 |

| 21. | Ground-plan of the Rock-cut Temple at Ipsamboul. | 31 |

| 22. | Section of the Rock-cut Temple at Ipsamboul. | 31 |

| 23. | Egyptian Column with Lotus Bud Capital. | 33 |

| 24. | Egyptian Column with Lotus Flower Capital. | 33 |

| 25. | Palm Capital. | 34 |

| 26. | Sculptured Capital. | 34 |

| 27. | Isis Capital from Denderah. | 35 |

| 28. | Fanciful Column from painted Decoration at Thebes. | 35 |

| 29. | Crowning Cornice and Bead. | 36 |

| 30. | Painted Decoration from Thebes. | 42 |

| 31. | Sculptured Ornament at Nineveh. | 43 |

| 32. | Palace at Khorsabad. Built by King Sargon about 710 B.C. | 48 |

| 33. | Pavement from Khoyunjik. | 51 |

| 34. | Proto-Ionic Column from Assyrian Sculpture. | 53 |

| 34a. | Proto-Ionic Capital from Assyrian Sculpture. | 53 |

| 34b. | Proto-Corinthian Capital from Assyrian Sculpture. | 53 |

| 35. | Tomb of Cyrus. | 54 |

| 35a. | General Plan of the Buildings at Persepolis. | 56 |

| 35b. | Column from Persepolis—East and West Porticoes. | 58 |

| 36. | Column from Persepolis—North Portico. | 58 |

| 37. | The Rock-cut Tomb of Darius. | 60 |

| 38. | Sculptured Ornament at Allahabad. | 64 |

| 39. | Dagoba from Ceylon. | 66 |

| 40. | Chaitya near Poona. | 68 |

| 41. | The Kylas at Ellora. A Rock-cut Monument. | 69 |

| 42. | Plan of the Kylas at Ellora. | 70 |

| 43. | Vimana from Manasara. | 71 |

| 44. | Bracket Capital. | 73 |

| 45. | Column from Ajunta. | 73 |

| 46. | Column from Ellora. | 73 |

| 47. | Column from Ajunta. | 73 |

| 48. | A small Pagoda. | 76 |

| 49. | Greek Honeysuckle Ornament. | 80 |

| 50. | Plan of a small Greek Temple in Antis. | 82 |

| 50a. | Plan of a small Greek Temple. | 83 |

| 51. | Ancient Greek Wall of Unwrought Stone from Samothrace. | 86 |

| [xiv]52. | Plan of the Treasury of Atreus at Mycenæ. | 86 |

| 52a. | Section of the Treasury of Atreus at Mycenæ. | 86 |

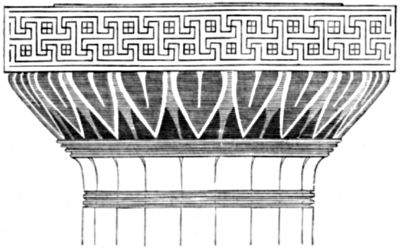

| 53. | Greek Doric Capital from Selinus. | 87 |

| 53a. | Greek Doric Capital from the Theseum. | 87 |

| 53b. | Greek Doric Capital from Samothrace. | 87 |

| 54. | The Ruins of the Parthenon at Athens. | 89 |

| 55. | Plan of the Parthenon. | 90 |

| 56. | The Roof of a Greek Doric Temple, showing the Marble Tiles. | 91 |

| 56a. | Section of the Greek Doric Temple at Pæstum. As restored by Bötticher. | 92 |

| 57. | The Greek Doric Order from the Theseum. | 93 |

| 58. | Plan of a Greek Doric Column. | 94 |

| 59. | The Fillets under a Greek Doric Capital. | 94 |

| 60. | Capital of a Greek Doric Column from Ægina, with Coloured Decoration. | 95 |

| 61. | Section of the Entablature of the Greek Doric Order. | 96 |

| 62. | Plan, looking up, of part of a Greek Doric Peristyle. | 96 |

| 63. | Details of the Triglyph. | 97 |

| 64. | Details of the Mutules. | 97 |

| 65. | Elevation and Section of the Capital of a Greek Anta, with Coloured Decoration. | 99 |

| 66. | Palmette and Honeysuckle. | 102 |

| 67. | Shaft of an Ionic Column, showing the Flutes. | 103 |

| 68. | Ionic Capital. Front Elevation. | 103 |

| 69. | Ionic Capital. Side Elevation. | 103 |

| 70. | The Ionic Order. From Priene, Asia Minor. | 105 |

| 71. | The Ionic Order. From the Erechtheium, Athens. | 106 |

| 72. | North-west View of the Erechtheium, in the time of Pericles. | 107 |

| 73. | Plan of the Erechtheium. | 108 |

| 74. | Ionic Base from the Temple of the Wingless Victory (Nikè Apteros). | 108 |

| 75. | Ionic Base Mouldings from Priene. | 108 |

| 76. | The Corinthian Order. From the Monument of Lysicrates at Athens. | 111 |

| 77. | Corinthian Capital from the Monument of Lysicrates. | 112 |

| 78. | Monument of Lysicrates, as in the time of Pericles. | 113 |

| 79. | Capital of an Anta from Miletus. Side View. | 114 |

| 80. | Restoration of the Greek Theatre of Segesta. | 115 |

| [xv]81. | Capital of an Anta from Miletus. | 117 |

| 82. | Greek Doorway, showing Cornice. | 123 |

| 83. | Greek Doorway. Front View. (From the Erechtheium.) | 123 |

| 84. | The Acanthus Leaf and Stalk. | 128 |

| 85. | The Acanthus Leaf. | 129 |

| 86. | Metope from the Parthenon. Conflict between a Centaur and one of the Lapithæ. | 130 |

| 87. | Mosaic from the Temple of Zeus, Olympia. | 131 |

| 88. | Section of the Portico of the Erechtheium. | 132 |

| 89. | Plan of the Portico of the Erechtheium, looking up. | 132 |

| 90. | Capital of Antæ from the Erechtheium. | 133 |

| 91‑96. | Greek Ornaments in Relief. | 134 |

| 97‑104. | Greek Ornaments in Relief. | 135 |

| 105‑110. | Greek Ornaments in Colour. | 136 |

| 111‑113. | Examples of Honeysuckle Ornament. | 137 |

| 114. | Combination of the Fret, the Egg and Dart, the Bead and Fillet, and the Honeysuckle. | 137 |

| 116‑120. | Examples of the Fret. | 137 |

| 121. | Elevation of an Etruscan Temple (restored from Descriptions only). | 138 |

| 122. | Sepulchre at Corneto. | 140 |

| 123. | The Cloaca Maxima. | 142 |

| 124. | “Incantada” in Salonica. | 147 |

| 125. | The Ionic Order from the Temple of Fortuna Virilis, Rome. | 148 |

| 126. | Roman-Corinthian Temple at Nîmes (Maison Carrée). Probably of the time of Hadrian. | 150 |

| 127. | Ground-plan of the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli. | 151 |

| 128. | The Corinthian Order from the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli. | 152 |

| 129. | The Temple of Vesta at Tivoli. Plan, looking up, and Section of Part of the Peristyle. | 153 |

| 130. | Ground-plan of the Basilica Ulpia, Rome. | 155 |

| 131. | Plan of the Colosseum, Rome. | 157 |

| 132. | The Colosseum. Section and Elevation. | 158 |

| 133. | Plan of the principal Building, Baths of Caracalla, Rome. | 163 |

| 134. | Interior of Santa Maria degli Angeli, Rome. | 165 |

| 135. | The Pantheon, Rome. Ground-plan. | 166 |

| 136. | The Pantheon. Exterior. | 167 |

| [xvi]137. | The Pantheon. Interior. | 168 |

| 138. | The Corinthian Order from the Pantheon. | 169 |

| 139. | The Arch of Constantine, Rome. | 172 |

| 140. | Ground-plan of the House of Pansa, Pompeii. | 176 |

| 141. | Ground-plan of the House of the Tragic Poet, Pompeii. | 177 |

| 142. | The Atrium of a Pompeian House. | 178 |

| 143. | Wall Decoration from Pompeii. | 180 |

| 144. | Carving from the Forum of Nerva, Rome. | 182 |

| 145. | Roman-Corinthian Capital and Base. From the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli. | 188 |

| 145a. | A Roman Composite Capital. | 188 |

| 146. | Part of the Theatre of Marcellus, Rome. Showing the Combination of Columns and Arched Openings. | 190 |

| 147. | From the Ruins of the Forum of Nerva, Rome. Showing the Use of an Attic Story. | 191 |

| 148. | From the Baths of Diocletian, Rome. Showing a fragmentary Entablature at the starting of part of a Vault. | 192 |

| 149. | From the Palace of Diocletian, Spalatro. Showing an Arch springing from a Column. | 192 |

| 150. | Mouldings and Ornaments from various Roman Buildings. | 193 |

| 151. | Roman Carving. An Acanthus Leaf. | 194 |

| 152. | The Egg and Dart Enrichment—Roman. | 194 |

| 153. | Wall-Decoration of (so-called) Arabesque Character from Pompeii. | 195 |

| 154. | Decoration in Relief and Colour of the Vault of a Tomb in the Via Latina, near Rome. | 197 |

| 155. | Basilica Church of San Miniato, Florence. | 198 |

| 156. | Interior of a Basilica at Pompeii. Restored, from Descriptions by various Authors. | 200 |

| 156a. | Basilica, or Early Christian Church, of Sant’ Agnese at Rome. | 202 |

| 157. | Sant’ Apollinare, Ravenna. Part of the Arcade and Apse. | 205 |

| 158. | Apse of the Basilica of San Paolo Fuori le Mura, Rome. | 207 |

| 158a. | Frieze from the Monastery at Fulda. | 210 |

| 159. | Church of Santa Sophia at Constantinople. Longitudinal Section. | 212 |

| 160. | Plan of San Vitale at Ravenna. | 216 |

| 161. | San Vitale at Ravenna. Longitudinal Section. | 216 |

| [xvii]162. | Plan of St. Mark’s at Venice. | 217 |

| 163. | Sculptured Ornament from the Golden Door of Jerusalem. | 219 |

| 164. | Church at Turmanin in Syria. | 220 |

| 165. | Tower of a Russian Church. | 221 |

| 166. | Tower of Earl’s Barton Church. | 223 |

| 167. | Cathedral at Piacenza. | 225 |

| 168. | Vaults of the excavated Roman Baths in the Musée de Cluny, Paris. | 227 |

| 169. | Church of St. Sernin, Toulouse. | 228 |

| 170. | Nave Arcade at St. Sernin, Toulouse. | 229 |

| 171. | Arches in receding Planes at St. Sernin, Toulouse. | 230 |

| 172. | Norman Arches in St. Peter’s Church, Northampton. | 234 |

| 173. | Nave Arcade, Peterborough Cathedral. | 236 |

| 174. | Decorative Arcade from Canterbury Cathedral. | 237 |

| 175. | Hedingham Castle. | 238 |

| 176. | Interior of Hedingham Castle. | 239 |

| 177. | Rounded Arch of Church at Gelnhausen. | 240 |

| 178. | Plan of the Church of the Apostles at Cologne. | 241 |

| 179. | Spire of Spires Cathedral. | 242 |

| 180. | Church at Rosheim. Upper Portion of Façade. | 244 |

| 181. | Cubic Capital. | 246 |

| 182. | Doorway at Tind, Norway. | 247 |

| 183. | Mouldings of Portal of St. James’s Church at Koesfeld. | 248 |

| 184. | Byzantine Basket work Capital from San Michele in Affricisco at Ravenna. | 251 |

| 185. | Arabian Capital. From the Alhambra. | 252 |

| 186. | Horse-shoe Arch. | 254 |

| 187. | Exterior of Santa Sophia, Constantinople. Showing the Minarets added after its Conversion into a Mosque. | 255 |

| 188. | Alhambra. Hall of the Abencerrages. | 257 |

| 189. | Mosque “El Moyed” at Cairo. | 259 |

| 190. | Arabian Wall Decoration. | 260 |

| 191. | Plan of the Sakhra Mosque at Jerusalem. | 261 |

| 192. | Section of the Sakhra Mosque at Jerusalem. | 262 |

| 193. | Doorway in the Alhambra. | 264 |

| 194. | Grand Mosque at Delhi, built by Shah Jehan. | 267 |

| 195. | Entrance to a Moorish Bazaar. | 269 |

Rock-cut Tomb at Myra, in Lycia.

Imitation of Timber Construction in Stone.

Abacus, a square tablet which crowns the capital of the column.

Acanthus, a plant, the foliage of which was imitated in the ornament of the Corinthian capital.

Agora, the place of general assembly in a Greek city.

Alæ (Lat. wings), recesses opening out of the atrium of a Roman house.

Alhambra, the palatial fortress of Granada (from al hamra—the red).

Ambo, a fitting of early Christian churches, very similar to a pulpit.

Amphitheatre, a Roman place of public entertainment in which combats of gladiators, &c., were exhibited.

Antæ, narrow piers used in connection with columns in Greek architecture, for the same purpose as pilasters in Roman.

Arabesque, a style of very light ornamental decoration.

Archaic, primitive, so ancient as to be rude, or at least extremely simple.

Archivolt, the series of mouldings which is carried round an arch.

Arena, the space in the centre of an amphitheatre where the combats, &c., took place.

Arris, a sharp edge.

Astragal, a small round moulding.

Atrium, the main quadrangle in a Roman dwelling-house; also the enclosed court in front of an early Christian basilican church.

Baptistery, a building, or addition to a building, erected for the purposes of celebrating the rite of Christian baptism.

Basement, the lowest story of a building, applied also to the lowest part of an architectural design.

Bas-relief, a piece of sculpture in low relief.

Bird’s-beak, a moulding in Greek architecture, used in the capitals of Antæ.

[xx]Byzantine, the style of Christian architecture which had its origin at Byzantium (Constantinople).

Carceres, in the ancient racecourses, goals and starting-points.

Cartouche, in Egyptian buildings, a hieroglyphic signifying the name of a king or other important person.

Caryatidæ, human figures made to carry an entablature, in lieu of columns in some Classic buildings.

Cavædiam, another name for the atrium of a Roman house.

Cavea, the part of an ancient theatre occupied by the audience.

Cavetto, in Classic architecture, a hollow moulding.

Cella, the principal, often the only, apartment of a Greek or Roman temple.

Chaitya, an Indian temple, or hall of assembly.

Circus, a Roman racecourse.

Cloaca, a sewer or drain.

Columbarium, literally a pigeon-house—a Roman sepulchre built in many compartments.

Columnar, made with columns.

Compluvium, the open space or the middle of the roof of a Roman atrium.

Corona, in the cornices of Greek and Roman architecture, the plain unmoulded feature which is supported by the lower part of the cornice, and on which the crowning mouldings rest.

Cornice, the horizontal series of mouldings crowning the top of a building or the walls of a room.

Cuneiform, of letters in Assyrian inscriptions, wedge-shaped.

Cyclopean, applied to masonry constructed of vast stones, usually not hewn or squared.

Cyma (recta, or reversa), a moulding, in Classic architecture, of an outline partly convex and partly concave.

Dagoba, an Indian tomb of conical shape.

Dentil band, in Classic architecture, a series of small blocks resembling square-shaped teeth.

Domus (Lat.), a house, applied usually to a detached residence.

Dwarf-wall, a very low wall.

Echinus, in Greek Doric architecture, the principal moulding of the capital placed immediately under the abacus.

Entablature, the superstructure—comprising architrave, frieze and cornice—above the columns in Classic architecture.

[xxi]Entasis, in the shaft of a column, a curved outline.

Ephebeum, the large hall in Roman baths in which youths practised gymnastic exercises.

Facia, in Classic architecture, a narrow flat band or face.

Fauces, the passage from the atrium to the peristyle in a Roman house.

Flutes, the small channels which run from top to bottom of the shaft of most columns in Classic architecture.

Forum, the place of general assembly in a Roman city, as the Agora was in a Greek.

Fresco, painting executed upon a plastered wall while the plaster is still wet.

Fret, an ornament made up of squares and L-shaped lines, in use in Greek architecture.

Garth, the central space round which a cloister is carried.

Girder, a beam.

Grouted, said of masonry or brickwork, treated with liquid mortar to fill up all crevices and interstices.

Guttæ, small pendent features in Greek and Roman Doric cornices, resembling rows of wooden pegs.

Hexastyle, of six columns.

Honeysuckle Ornament, a decoration constantly introduced into Assyrian and Greek architecture, founded upon the flower of the honeysuckle.

Horse-shoe Arch, an arch more than a semicircle, and so wider above than at its springing.

Hypostyle, literally “under columns,” but used to mean filled by columns.

Impluvium, the space into which the rain fell in the centre of the atrium of a Roman house.

Insula, a block of building surrounded on all sides by streets, literally an island.

Intercolumniation, the space between two columns.

Keyed, secured closely by interlocking.

Kibla, the most sacred part of a Mohammedan mosque.

Lâts, in Indian architecture, Buddhist inscribed pillars.

[xxii]Mammisi, small Egyptian temples.

Mastaba, the most usual form of Egyptian tomb.

Mausoleum, a magnificent sepulchral monument or tomb. From the tomb erected to Mausolus, by his wife Artemisia, at Halicarnassus, 379 B.C.

Metopes, literally faces, the square spaces between triglyphs in Doric architecture; occasionally applied to the sculptures fitted into these spaces.

Minaret, a slender lofty tower, a usual appendage of a Mohammedan mosque.

Monolith, of one stone.

Mortise, a hollow in a stone or timber to receive a corresponding projection.

Mosque, a Mohammedan place of worship.

Mutule, a feature in a Classic Doric cornice, somewhat resembling the end of a timber beam.

Narthex, in an early Christian church, the space next the entrance.

Obelisk, a tapering stone pillar, a feature of Egyptian architecture.

Opus Alexandrinum, the mosaic work used for floors in Byzantine and Romanesque churches.

Ovolo, a moulding, the profile of which resembles the outline of an egg, used in Classic architecture.

Pendentive, a feature in Byzantine and other domed buildings, employed to enable a circular dome to stand over a square space.

Peristylar, or Peripteral, with columns all round.

Peristylium, or Peristyle, in a Roman house, the inner courtyard; also any space or enclosure with columns all round it.

Piscina, a small basin usually executed in stone and placed within a sculptured niche, fixed at the side of an altar in a church, with a channel to convey away the water poured into it.

Polychromy, the use of decorative colours.

Precincts, the space round a church or religious house, usually enclosed with a wall.

Presbytery, the eastern part of a church, the chancel.

Profile (of a moulding), the outline which it would present if cut across at right angles to its length.

Pronaos, the front portion or vestibule to a temple.

Propylæa, in Greek architecture, a grand portal or state entrance.

[xxiii]Prothyrum, in a Roman house, the porch or entrance.

Pseudo-peripteral, resembling, but not really being peristylar.

Pylon, or Pro-Pylon, the portal or front of an Egyptian temple.

Quadriga, a four-horse chariot.

Romanesque, the style of Christian architecture which was founded on Roman work.

Rotunda, a building circular in plan.

Sacristy, the part of a church where the treasures belonging to the church are preserved.

Shinto Temples, temples (in Japan) devoted to the Shinto religion.

Span, the space over which an arch or a roof extends.

Spina, the central wall of a Roman racecourse.

Stilted, raised, usually applied to an arch when its centre is above the top of the jambs from which it springs.

Struts, props.

Stupa, in Indian architecture, a mound or tope.

Stylobate, a series of steps, usually those leading up to a Classic temple.

Taas, a pagoda.

Tablinum, in a Roman house, the room between the atrium and the peristyle.

Talar, in Assyrian architecture, an open upper story.

Tenoned, fastened with a projection or tenon.

Tesselated, made of small squares of material, applied to coarse mosaic work.

Tetrastyle, with four columns.

Thermæ, the great bathing establishments of the Romans.

Topes, in Indian architecture, artificial mounds.

Trabeated, constructed with a beam or beams, a term usually employed in contrast to arches.

Triclinium, in a Roman house, the dining-room.

Triglyph, the channelled feature in the frieze of the Doric order.

Tumuli, mounds, usually sepulchral.

Typhonia, small Egyptian temples.

Velarium, a great awning.

Vestibule, the outer hall or ante-room.

[xxiv]Volutes, in Classic architecture, the curled ornaments of the Ionic capital.

Voussoirs, the wedge-shaped stones of which arches are made.

N.B. For the explanation of other technical words found in this volume, consult the Glossary given with the companion volume on Gothic and Renaissance Architecture.

The Temple of Vesta at Tivoli.

ARCHITECTURE may be described as building at its best, and when we talk of the architecture of any city or country we mean its best, noblest, or most beautiful buildings; and we imply by the use of the word that these buildings possess merits which entitle them to rank as works of art.

The architecture of the civilised world can be best understood by considering the great buildings of each important nation separately. The features, ornaments, and even forms of ancient buildings differed just as the speech, or at any rate the literature, differed. Each nation wrote in a different language, though the books may have been [2] devoted to the same aims; and precisely in the same way each nation built in a style of its own, even if the buildings may have been similar in the purposes they had to serve. The division of the subject into the architecture of Egypt, Greece, Rome, &c., is therefore the most natural one to follow.

But certain broad groups, rising out of peculiarities of a physical nature, either in the buildings themselves or in the conditions under which they were erected, can hardly fail to be suggested by a general view of the subject. Such, for example, is the fourfold division to which the reader’s attention will now be directed.

All buildings, it will be found, can be classed under one or other of four great divisions, each distinguished by a distinct mode of building, and each also occupying a distinct place in history. The first series embraces the buildings of the Egyptians, the Persians, and the Greeks, and was brought to a pitch of the highest perfection in Greece during the age of Pericles. All the buildings erected in these countries during the many centuries which elapsed from the earliest Egyptian to the latest Greek works, however they may have differed in other respects, agree in this—that the openings, be they doors, or be they spaces between columns, were spanned by beams of wood or lintels of stone (Fig. 1). Hence this architecture is called architecture of the beam, or, in more formal language, trabeated architecture. This mode of covering spaces required that in buildings of solid masonry, where stone or marble lintels were employed, the supports should not be very far apart, and this circumstance led to the frequent use of rows of columns. The architecture of this period is accordingly sometimes called columnar, but it has no exclusive claim to the [3] epithet; the column survived long after the exclusive use of the beam had been superseded, and the term columnar must accordingly be shared with buildings forming part of the succeeding series.

Fig. 1.—Opening spanned by a Lintel. Arch of the Goldsmiths, Rome.

The second great group of buildings is that in which the semicircular arch is introduced into construction, and [4] used either together with the beam, or, as mostly happened, instead of the beam, to span the openings (Fig. 2). This use of the arch began with the Assyrians, and it reappeared in the works of the early Etruscans. The round-arched series of styles embraces the buildings of the Romans from their earliest beginnings to their decay; it also includes the two great schools of Christian architecture which were founded by the Western and the Eastern Church respectively,—namely, the Romanesque, which, originating in Rome, extended itself through Western Europe, and lasted till the time of the Crusades, and the Byzantine, which spread from Constantinople over all the countries in which the Eastern (or Greek) Church flourished, and which continues to our own day.

Fig. 2.—Opening Spanned by a Semicircular Arch. Roman Triumphal Arch at Pola.

Fig. 3.—Openings Spanned by Pointed Arches. Interior of St. Front, Périgueux, France.

The third group of buildings is that in which the pointed arch is employed instead of the semicircular arch to span the openings (Fig. 3). It began with the rise of Mohammedan architecture in the East, and embraces all the buildings of Western Europe, from the time of the First Crusade to the revival of art in the fifteenth century. [6] This great series of buildings constitutes what is known as Pointed, or, more commonly, as Gothic architecture.

The fourth group consists of the buildings erected during or since the Renaissance (i.e. revival) period, and is marked by a return to the styles of past ages or distant countries for the architectural features and ornaments of buildings; and by that luxury, complexity, and ostentation which, with other qualities, are well comprehended under the epithet Modern. This group of buildings forms what is known as Renaissance architecture, and extends from the epoch of the revival of letters in the fifteenth century, to the present day.

The first two of these styles—namely, the architecture of the beam, and that of the round arch—are treated of in this little volume. They occupy those remote times of pagan civilisation which may be conveniently included under the broad term Ancient; and the better known work of the Greeks and Romans—the classic nations—and they extend over the time of the establishment of Christianity down to the close of that dreary period not incorrectly termed the Dark ages. Ancient, Classic, and early Christian architecture is accordingly an appropriate title for the main subjects of this volume, though, for the sake of convenience, some notices of Oriental architecture have been added. Gothic and Renaissance architecture form the subjects of the companion volume.

It may excite surprise that what appears to be so small a difference as that which exists between a beam, a round arch, or a pointed arch, should be employed in order to distinguish three of the four great divisions. But in reality this is no pedantic or arbitrary grouping. The mode in which spaces or openings are covered lies at the root of most of the essential differences between styles of [7] architecture, and the distinction thus drawn is one of a real, not of a fanciful nature.

Every building when reduced to its elements, as will be done in both these volumes, may be considered as made up of its (1) floor or plan, (2) walls, (3) roof, (4) openings, (5) columns, and (6) ornaments, and as marked by its distinctive (7) character, and the student must be prepared to find that the openings are by no means the least important of these elements. In fact, the moment the method of covering openings was changed, it would be easy to show, did space permit, that all the other elements, except the ornaments, were directly affected by the change, and the ornaments indirectly; and we thus find such a correspondence between this index feature and the entire structure as renders this primary division a scientific though a very broad one. The contrast between the trabeated style and the arched style may be well understood by comparing the illustration of the Parthenon which forms our frontispiece, or that of the great temple of Zeus at Olympia (Fig. 4), with the exterior of the Colosseum at Rome (Fig. 5), introduced here for the purposes of this comparison.

Fig. 4.—Temple of Zeus at Olympia. Restored according to Adler.

A division of buildings into such great series as these cannot, however, supersede the more obvious historical and geographical divisions. The architecture of every ancient country was partly the growth of the soil, i.e. adapted to the climate of the country, and the materials found there, and partly the outcome of the national character of its inhabitants, and of such influences as race, colonisation, commerce, or conquest brought to bear upon them. These influences produced strong distinctions between the work of different peoples, especially before the era of the Roman Empire. Since that [9] period of universal dominion all buildings and styles have been influenced more or less by Roman art. We accordingly find the buildings of the most ancient nations separated from each other by strongly marked lines of demarcation, but those since the era of the Empire showing a considerable resemblance to one another. The circumstance that the remains of those buildings only which received the greatest possible attention from their builders have come down to us from any remote antiquity, has perhaps served to accentuate the differences between different styles, for these foremost buildings were not intended to serve the same purpose in all countries. Nothing but tombs and temples have survived in Egypt. Palaces only have been rescued from the decay of Assyrian and Persian cities; and temples, theatres, and places of public assembly are the chief, almost the only remains of architecture in Greece.

A strong contrast between the buildings of different ancient nations rises also from the differing point of view for which they were designed. Thus, in the tombs and, to a large extent, the temples of the Egyptians, we find structures chiefly planned for internal effect; that is to say, intended to be seen by those admitted to the sacred precincts, but only to a limited extent appealing to the admiration of those outside. The buildings of the Greeks, on the other hand, were chiefly designed to please those who examined them from without, and though no doubt some of them, the theatres especially, were from their very nature planned for interior effect, by far the greatest works which Greek art produced were the exteriors of the temples.

Fig. 5.—Part of the Exterior of the Colosseum, Rome. (Now in Ruins.)

The works of the Romans, and, following them, those of almost all Western Christian nations, were designed [11] to unite external and internal effect; but in many cases external was evidently most sought after, and, in the North of Europe, many expedients—such, for example, as towers, high-pitched roofs, and steeples—were introduced into architecture with the express intention of increasing external effect. On the other hand, the Eastern styles, both Mohammedan and Christian, especially when practised in sunny climates, show in many cases a comparative disregard of external effect, and that their architects lavished most of their resources on the interiors of their buildings.

Passing allusions have been made to the influence of climate on architecture; and the student whose attention has been once called to this subject will find many interesting traces of this influence in the designs of buildings erected in various countries. Where the power of the sun is great, flat terraced roofs, which help to keep buildings cool, and thick walls are desirable. Sufficient light is admitted by small windows far apart. Overhanging eaves, or horizontal cornices, are in such a climate the most effective mode of obtaining architectural effect, and accordingly in the styles of all Southern peoples these peculiarities appear. The architecture of Egypt, for example, exhibited them markedly. Where the sun is still powerful, but not so extreme, the terraced roof is generally replaced by a sloping roof, steep enough to throw off water, and larger openings are made for light and air; but the horizontal cornice still remains the most appropriate means of gaining effects of light and shade. This description will apply to the architecture of Italy and Greece. When, however, we pass to Northern countries, where snow has to be encountered, where light is precious, and where the sun is low in the heavens for the [12] greater part of the day, a complete change takes place. Roofs become much steeper, so as to throw off snow. The horizontal cornice is to a large extent disused, but the buttress, the turret, and other vertical features, from which a level sun will cast shadows, begin to appear; and windows are made numerous and spacious. This description applies to Gothic architecture generally—in other words, to the styles which rose in Northern Europe.

Fig. 6.—Timber Architecture. Church at Borgund.

The influence of materials on architecture is also worth notice. Where granite, which is worked with difficulty, [13] is the material obtainable, architecture has invariably been severe and simple; where soft stone is obtainable, exuberance of ornament makes its appearance, in consequence of the material lending itself readily to the carver’s chisel. Where, on the other hand, marble is abundant and good, refinement is to be met with, for no other building material exists in which very delicate mouldings or very slight or slender projections may be employed with the certainty that they will be effective. Where stone is scarce, brick buildings, with many arches, roughly constructed cornices and pilasters, and other peculiarities both of structure and ornamentation, make their appearance, as, for example, in Lombardy and North Germany. Where materials of many colours abound, as is the case, for example, in the volcanic districts of France, polychromy is sought as a means of ornamentation. Lastly, where timber is available, and stone and brick are both scarce, the result is an architecture of which both the forms and the ornamentation are entirely dissimilar to those proper to buildings of stone, marble, or brick, as may be seen by a glance at our illustration of an early Scandinavian church built of timber (Fig. 6), which presents forms appropriate to a timber building as being easily constructed of wood, but which would hardly be suitable to any other material whatever.

Fig. 7.—Egyptian Cornice.

THE origin of Egyptian architecture, like that of Egyptian history, is lost in the mists of antiquity. The remains of all, or almost all, other styles of architecture enable us to trace their rude beginnings, their development, their gradual progress up to a culminating point, and thence their slow but certain decline; but the earliest remains of the constructions of the Egyptians show their skill as builders at the height of its perfection, their architecture highly developed, and their sculpture at its very best, if not indeed at the commencement of its decadence; for some of the statuary of the age of the Pyramids was never surpassed in artistic effect by the work of a later era. It is impossible for us to conceive of such scientific skill as is evidenced in the construction of the great pyramids, or such artistic power as is displayed on the walls of tombs of the same date, or in the statues found in them, as other than the outcome of a vast accumulation of experience, the attainment of which must imply the lapse of very long periods of time since the nation which produced [15] such works emerged from barbarism. It is natural, where so remote an antiquity is in question, that we should feel a great difficulty, if not an impossibility, in fixing exact dates, but the whole tendency of modern exploration and research is rather to push back than to advance the dates of Egyptian chronology, and it is by no means impossible that the dynasties of Manetho, after being derided as apocryphal for centuries, may in the end be accepted as substantially correct. Manetho was an Egyptian priest living in the third century B.C., who wrote a history of his country, which he compiled from the archives of the temples. His work itself is lost, but Josephus quotes extracts from it, and Eusebius and Julius Africanus reproduced his lists, in which the monarchs of Egypt are grouped into thirty-four dynasties. These, however, do not agree with one another, and in many cases it is difficult to reconcile them with the records displayed in the monuments themselves.

The remains with which we are acquainted indicate four distinct periods of great architectural activity in Egyptian history, viz.: (1) the period of the fourth dynasty, when the Great Pyramids were erected (probably 3500 to 3000 B.C.); (2) the period of the twelfth dynasty, to which belong the remains at Beni-Hassan; (3) the period of the eighteenth and nineteenth dynasties, when Thebes was in its glory, which is attested by the ruins of Luxor and Karnak; and (4) the Ptolemaic period, of which there are the remains at Denderah, Edfou, and Philæ. The monuments that remain are almost exclusively tombs and temples. The tombs are, generally speaking, all met with on the east or right bank of the Nile: among them must be classed those grandest and oldest monuments of Egyptian skill, the [16] Pyramids, which appear to have been all designed as royal burying-places. A large number of pyramids have been discovered, but those of Gizeh, near Cairo, are the largest and the best known, and also probably the oldest which can be authenticated.[1] The three largest pyramids are those of Cheops, Cephren, and Mycerinus at Gizeh (or, as the names are more correctly written, Suphis, Sensuphis, and Moscheris or Mencheris). These monarchs all belonged to the fourth dynasty, and the most probable date to be assigned to them is about 3000 B.C. The pyramid of Suphis is the largest, and is the one familiarly known as the Great Pyramid; it has a square base, the side of which is 760 feet long,[2] a height of 484 feet, and an area of 577,600 square feet. In this pyramid the angle of inclination of the sloping sides to the base is 51° 51′, but in no two pyramids is this angle the same. There can be no doubt that these huge monuments were erected each as the tomb of an individual king, whose efforts were directed towards making it everlasting, and the greatest pains were taken to render the access to the burial chamber extremely hard to discover. This accounts for the vast disproportion between the lavish amount of material used for the pyramid and the smallness of the cavity enclosed in it (Fig. 8).

The material employed was limestone cased with syenite (granite from Syene), and the internal passages were lined with granite. The granite of the casing has entirely [17] disappeared, but that employed as linings is still in its place, and so skilfully worked that it would not be possible to introduce even a sheet of paper between the joints.

Fig. 8.—Section across the Great Pyramid (of Cheops or Suphis).

The entrance D to this pyramid of Suphis was at a height of 47 ft. 6 in. above the base, and, as was almost invariably the case, on the north face; from the entrance a passage slopes downward at an angle of 26° 27′ to a chamber cut in the rock at a depth of about 90 feet below the base of the pyramid. This chamber seems to have been intended as a blind, as it was not the place for the deposition [18] of the corpse. From the point in the above described passage—marked A on our illustration of this pyramid—another gallery starts upwards, till it reaches the point C, from which a horizontal passage leads to another small chamber. This is called the Queen’s Chamber, but no reason has been discovered for the name. From this point C the gallery continues upwards till, in the heart of the pyramid, the Royal Chamber, B, is reached. The walls of these chambers and passages are lined with masonry executed in the hardest stone (granite), and with an accuracy of fitting and a truth of surface that can hardly be surpassed. Extreme care seems to have been taken to prevent the great weight overhead from crushing in the galleries and the chamber. The gallery from C upwards is of the form shown in Fig. 9, where each layer of stones projects slightly beyond the one underneath it. Fig. 11 is a section of the chamber itself, and the succession of small chambers shown one above the other was evidently formed for the purpose of distributing the weight of the superincumbent mass. From the point C a narrow well leads almost perpendicularly downwards to a point nearly at the bottom of the first-mentioned gallery; and the purpose to be served by this well was long a subject of debate. The probability is that, after the corpse had been placed in its chamber, the workmen completely blocked up the passage from A to C by allowing large blocks of granite to slide down it, these blocks having been previously prepared and deposited in the larger gallery; the men then let themselves down the well, and by means of the lower gallery made their exit from the pyramid. The entrances to the chamber and to the pyramid itself were formed by huge blocks of stone which exactly fitted into grooves prepared for them with the [20] most beautiful mathematical accuracy. The chief interest attaching to the pyramids lies in their extreme antiquity, and the scientific method of their construction; for their effect upon the spectator is by no means proportionate to their immense mass and the labour bestowed upon them.

Fig. 9.—Ascending Gallery in the Great Pyramid.

Fig. 10.—The Sepulchral Chamber in the Pyramid of Cephren at Gizeh.

Fig. 11.—The Construction of the King’s Chamber in the Great Pyramid.

In the neighbourhood of the pyramids are found a large number of tombs which are supposed to be those of private persons. Their form is generally that of a mastaba or truncated pyramid with sloping walls, and their construction is evidently copied from a fashion of wooden architecture previously existing. The same idea of making an everlasting habitation for the body prevailed as in the case of the pyramids, and stone was therefore the material employed; but the builders seem to have desired to indulge in a decorative style, and as they were totally unable to originate a legitimate stone architecture, we find carved in stone, rounded beams as lintels, grooved posts, and—most curious of all—roofs that are an almost exact copy of the early timber huts when unsquared baulks of timber were laid across side by side to form a covering. Figs. 12 and 13 show this kind of stone-work, which is peculiar to the old dynasties, and seems to have had little influence upon succeeding styles.

A remarkable feature of these early private tombs consists in the paintings with which the walls are decorated, and which vividly portray the ordinary every-day occupations carried on during his lifetime by the person who was destined to be the inmate of the tomb. These paintings are of immense value in enabling us to form an accurate idea of the life of the people at this early age.

Fig. 12.—Imitation of Timber Construction in Stone, from a Tomb at Memphis.

Fig. 13.—Imitation of Timber Construction in Stone, from a Tomb at Memphis.

It may possibly be open to doubt whether the dignified appellation of architecture should be applied to buildings [22] of the kind we have just been describing; but when we come to the series of remains of the twelfth dynasty at Beni-Hassan, in middle Egypt, we meet with the earliest known examples of that most interesting feature of all subsequent styles—the column. Whether the idea of columnar architecture originated with the necessities of quarrying—square piers being left at intervals to support the superincumbent mass of rock as the quarry was gradually driven in—or whether the earliest stone piers were imitations of brickwork or of timber posts, we shall probably never be able to determine accurately, though the former supposition seems the more likely. We have here monuments of a date 1400 years anterior to the earliest known Greek examples, with splendid columns, both exterior and interior, which no reasonable person can doubt are the prototypes of the Greek Doric order. Fig. 14 is a plan with a section, and Fig. 15 an exterior view, of one of these tombs, which, it will be seen, consisted of a portico, a chamber with its roof supported by columns, and a small space at the farther end in which is formed the opening of a sloping passage or well, at the bottom of which the vault for the reception of the body was constructed. The walls of the large chamber are lavishly decorated with scenes of every-day life, and it has even been suggested that these places were not erected originally as tombs, but as dwelling-places, which after death were appropriated as sepulchres.

Section.

Fig. 14.—Plan and Section of the Tomb at Beni-Hassan.

The columns are surmounted by a small square slab, technically called an abacus, and heavy square beams or architraves span the spaces between the columns, while the roof between the architraves has a slightly segmental form. The tombs of the later period, viz. of the eighteenth and nineteenth dynasties, are very different from those of [23] the twelfth dynasty, and present few features of architectural interest, though they are remarkable for their vast extent and the variety of form of their various chambers and galleries. They consist of a series of chambers excavated in the rock, and it appears certain that the tomb was commenced on the accession of each monarch, and was driven farther and farther into the rock during the continuance of his reign till his death, when all work abruptly ceased. All the chambers are profusely decorated with paintings, but of a kind very different from those of the earlier dynasties. Instead of depicting scenes of ordinary life, all the paintings refer to the supposed life after death, and are thus of very great value as a means of determining the religious opinions of the [24] Egyptians at this time. One of the most remarkable of these tombs is that of Manephthah or Sethi I., at Bab-el-Molouk, and known as Belzoni’s tomb, as it was discovered by him; from it was taken the alabaster sarcophagus now in the Soane Museum in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. To this relic a new interest is given by the announcement, while these pages are passing through the press, of the discovery of the mummy of this very Manephthah, with thirty-eight other royal mummies, in the neighbourhood of Thebes.

Fig. 15.—Rock-cut Façade of Tomb at Beni-Hassan.

Of the Ptolemaic period no tombs, except perhaps a few at Alexandria, are known to exist.

It is very doubtful whether any remains of temples of the time of the fourth dynasty—i.e. contemporaneous with the pyramids—exist. One, constructed on a most extraordinary plan, was supposed to have been discovered about a quarter of a century ago, and it was described by [25] Professor Donaldson at the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1861, but later Egyptologists rather incline to the belief that this was a tomb and not a temple, as in one of the chambers of the interior a number of compartments were discovered one above the other which were apparently intended for the reception of bodies. This singular building is close to the Great Sphinx; its plan is cruciform, and there are in the interior a number of rectangular piers of granite supporting very simple architraves, but there are no means of determining what kind of roof covered it in. The walls seem to have been faced on the interior with polished slabs of granite or alabaster, but no sculpture or hieroglyphic inscriptions were found on them to explain the purpose of the building. Leaving this building—which is of a type quite unique—out of the question, Egyptian temples can be generally classed under two heads: (1) the large principal temples, and (2) the small subsidiary ones called Typhonia or Mammisi. Both kinds of temple vary little, if at all, in plan from the time of the twelfth dynasty down to the Roman dominion.

Fig. 16.—Ground-plan of the Palace at Karnak.

The large temples consist almost invariably of an entrance gate flanked on either side by a large mass of masonry, called a pylon, in the shape of a truncated pyramid (Fig. 18). The axis of the ground-plan of these pylons is frequently obliquely inclined to the axis of the plan of the temple itself; and indeed one of the most striking features of Egyptian temples is the lack of regularity and symmetry in their construction. The entrance gives access to a large courtyard, generally ornamented with columns: beyond this, and occasionally approached by steps, is another court, smaller than the first, but much more splendidly adorned with columns and colossi; beyond this [26] again, in the finest examples, occurs what is called the Hypostyle Hall, i.e. a hall with two rows of lofty columns down the centre, and at the sides other rows, more or less in number, of lower columns; the object of this arrangement being that the central portion might be lighted by a kind of clerestory above the roof of the side portions. Fig. 17 shows this arrangement. This hypostyle hall stood with its greatest length transverse to the general axis of the temple, so that it was entered from the side. Beyond it were other chambers, all of small size, the innermost being generally the sanctuary, while the others were probably used as residences by the priests. Homer’s hundred-gated Thebes, which was for so long the capital of Egypt, offers at Karnak and Luxor the finest remains of temples; what is left of the former evidently showing that it must have been one of the most magnificent buildings ever erected in any country. Fig. 16 is a plan of the temple of Karnak, which was about 1200 feet long and 348 feet wide. A is the entrance between the two enormous pylons giving access to a large courtyard, in which is a small detached temple, and another larger one breaking into the courtyard obliquely. A gateway between a second pair of pylons admits to B, the grand Hypostyle Hall, 334 feet by 167 feet. Beyond this are additional gateways with pylons, separated by a sort [28] of gallery, C, in which were two gigantic obelisks; D, another grand hall, is called the Hall of the Caryatides, and beyond is the Hall of the eighteen columns, through which access is gained to a number of smaller halls grouped round the central chamber E. Beyond this is a large courtyard, in the centre of which stood the original sanctuary, which has disappeared down to its foundations, nothing but some broken shafts of columns remaining. At the extreme east is another hall supported partly by columns and partly by square piers, and a second series of pillared courts and chambers. The pylons and buildings generally decrease in height as we proceed from the entrance eastwards. This is due to the fact that, the building grew by successive additions, each one more magnificent than the last, all being added on the side from which the temple was entered, leaving the original sanctuary unchanged and undisturbed.

Fig. 17.—The Hypostyle Hall at Karnak, showing the Clerestory.

Fig. 18.—Entrance to an Egyptian Temple, showing the Pylons.

Besides the buildings shown on the plan there were many other temples to the north, south, and east, entered by pylons and some of them connected together by avenues of sphinxes, obelisks, and colossi, which altogether made up the most wonderful agglomeration of buildings that can be conceived. It must not be imagined that this temple of Karnak, together with the series of connected temples is the result, of one clearly conceived plan; on the contrary, just as has been frequently the case with our own cathedrals and baronial halls, alterations were made here and additions there by successive kings one after the other without much regard to connection or congruity, the only feeling that probably influenced them being that of emulation to excel in size and grandeur the erections of their predecessors, as the largest buildings are almost always of latest date. The original sanctuary, [29] or nucleus of the temple, was built by Usertesen I., the second or third king of the twelfth dynasty. Omenophis, the first king of the Shepherd dynasties, built a temple round the sanctuary, which has disappeared. Thothmes I. built the Hall of the Caryatides and commenced the next Hall of the eighteen columns, which was finished by Thothmes II. Thothmes III. built that portion surrounding the sanctuary, and he also built the courts on the extreme east. The pylon at C was built by Omenophis III., and formed the façade of the temple before the erection of the grand hall. Sethi I. built the Hypostyle Hall, which had probably been originated by Rhamses I., who commenced the pylon west of it. Sethi II. built the small detached temple, and Rhamses III. the intersecting temple. The Bubastites constructed the large front court by building walls round it, and the Ptolemies commenced the huge western pylon. The colonnade in the centre of the court was erected by Tahraka.

Extensive remains of temples exist at Luxor, Edfou (Fig. 19), and Philæ, but it will not be necessary to give a detailed description of them, as, if smaller in size, they are very similar in arrangement to those already described. It should be noticed that all these large temples have the mastaba form, i.e. the outer walls are not perpendicular on the outside, but slope inwards as they rise, thus giving the buildings an air of great solidity.

Fig. 19.—Plan of the Temple at Edfou.

Fig. 20.—Plan of one of the Mammisi at Edfou.

The Mammisi exhibit quite a different form of temple from those previously described, and are generally found in close proximity to the large temples. They are generally erected on a raised terrace, rectangular on plan and nearly twice as long as it was wide, approached by a flight of steps opposite the entrance; they consist of oblong buildings, usually divided by a wall into two [30] chambers, and surrounded on all sides by a colonnade composed of circular columns or square piers placed at intervals, and the whole is roofed in. A dwarf wall is frequently found between the piers and columns, about half the height of the shaft. These temples differ from the larger ones in having their outer walls perpendicular. Fig. 20 [31] is a plan of one of these small temples, and no one can fail to remark the striking likeness to some of the Greek temples; there can indeed be little doubt that this nation borrowed the peristylar form of its temples from the Ancient Egyptians.

Fig. 21.—Ground-plan of the Rock-cut Temple at Ipsamboul.

Fig. 22.—Section of the Rock-cut Temple at Ipsamboul.

Although no rock-cut temples have been discovered in Egypt proper, Nubia is very rich in such remains. The arrangement of these temples hewn out of the rock is closely analogous to that of the detached ones. Figs. 21 and 22 show a plan and section of the [32] largest of the rock-cut temples at Ipsamboul, which consists of two extensive courts, with smaller chambers beyond, all connected by galleries. The roof of the large court is supported by eight huge piers, the faces of which are sculptured into the form of standing colossi, and the entrance is adorned by four splendid seated colossi, 68 ft. 6 in. high. As was the case with the detached temples, it will be noticed that the height of the various chambers decreases towards the extremity of the excavation.

Plan.

Fig. 23.—Egyptian Column with Lotus Bud Capital.

Fig. 24.—Egyptian Column with Lotus Flower Capital.

The constructional system pursued by the Egyptians, which consisted in roofing over spaces with large horizontal blocks of stone, led of necessity to a columnar arrangement in the interiors, as it was impossible to cover large areas without frequent upright supports. Hence the column became the chief means of obtaining effect, and the varieties of form which it exhibits are very numerous. The earliest form is that at Beni-Hassan, which has already been noticed as the prototype of the Doric order. Figs. 23 and 24 are views of two columns of a type more commonly employed. In these the sculptors appear to have imitated as closely as possible the forms of the plant-world around them, as is shown in Fig. 23, which represents a bundle of reeds or lotus stalks, and is the earliest type known of the lotus column, which was afterwards developed into a number of forms, one of which will be observed on turning to our section of the Hypostyle Hall at Karnak (Fig. 17), as employed for the lateral columns. The stalks are bound round with several belts, and the capital is formed by the slightly bulging unopened bud of the flower, above which is a small abacus with the architrave resting upon it: the base is nothing but a low circular plinth. The square piers also have frequently a lotus bud carved on them. At the bottom of the shaft is frequently found [33] a decoration imitated from the sheath of leaves from which the plant springs. As a further development of this capital we have the opened lotus flower of a very graceful bell-like shape, ornamented with a similar sheath-like decoration to that at the base of the shaft (Fig. 24). This decoration was originally painted only, not sculptured, but at a later period we find these sheaths and buds worked in stone. Even more graceful is the palm capital, which also had its leading lines of decoration painted on it at first (Fig. 25), and afterwards sculptured (Fig. 26). At a later period of the style we find the plant forms abandoned, and capitals were formed of a fantastic combination of the head [34] of Isis with a pylon resting upon it (Fig. 27). Considerable ingenuity was exercised in adapting the capitals of the columns to the positions in which they were placed: thus in the hypostyle halls, the lofty central row of columns generally had capitals of the form shown in Fig. 24, as the light here was sufficient to illuminate thoroughly the underside of the overhanging bell; but those columns which were farther removed from the light had their capitals of the unopened bud form, which was narrower at the top than at bottom. In one part of the temple at Karnak is found a very curious capital resembling the open lotus flower inverted. The proportion which the height of Egyptian columns bears to their diameter differs so much in various cases that there was evidently no regular standard adhered to, but as a general rule they have a heavy and massive character. The wall-paintings of the Egyptian buildings show many curious forms of [35] columns (Fig. 28), but we have no reason for thinking that these fantastic shapes were really executed in stone.

Fig. 25.—Palm Capital.

Fig. 26.—Sculptured Capital.

Fig. 27.—Isis Capital from Denderah.

Fig. 28.—Fanciful Column from Painted Decoration at Thebes.

Almost the only sculptured ornaments worked on the exteriors of buildings were the curious astragal or bead at all the angles, and the cornice, which consisted of a very large cavetto, or hollow moulding, surmounted by a fillet. These features are almost invariable from the earliest to the latest period of the style. This cavetto was generally enriched, over the doorways, with an ornament representing a circular boss with a wing at each side of it (Fig. 29).

One other feature of Egyptian architecture which was peculiar to it must be mentioned; namely, the obelisk. [36] Obelisks were nearly always erected in pairs in front of the pylons of the temples, and added to the dignity of the entrance. They were invariably monoliths, slightly tapering in outline, carved with the most perfect accuracy; they must have existed originally in very large numbers. Not a few of these have been transported to Europe, and at least twelve are standing in Rome, one is in Paris, and one in London.

Fig. 29.—Crowning Cornice and Bead.

The most striking features, and the most artistic, in the decoration of Egyptian buildings, are the mural paintings and sculptured pictures, which are found in the most lavish profusion, and which exhibit the highest skill in conventionalising the human figure and other objects.[3] Tombs and temples, columns and obelisks are completely covered with graphic representations of peaceful home pursuits, warlike expeditions and battle scenes, and—though not till a late period—descriptions of ritual and mythological delineations of the supposed spirit-world which the soul has entered after death. These pictures, together with the [37] hieroglyphic inscriptions—which are in themselves a series of pictures—not only relieve the bare wall surface, but, what is far more important, enable us to realise the kind of existence which was led by this ancient people; and as in nearly every case the cartouche (or symbol representing the name) of the monarch under whose reign the building was erected was added, we should be able to fix the dates of the buildings with exactness, were the chronology of the kings made out beyond doubt.

The following description of the manner in which the Egyptian paintings and sculptures were executed—from the pen of Owen Jones—will be read with interest:—“The wall was first chiselled as smooth as possible, the imperfections of the stone were filled up with cement or plaster, and the whole was rubbed smooth and covered with a coloured wash; lines were then ruled perpendicularly and horizontally with red colour, forming squares all over the wall corresponding with the proportions of the figure to be drawn upon it. The subjects of the painting and of the hieroglyphics were then drawn on the wall with a red line, most probably by the priest or chief scribe, or by some inferior artist, from a document divided into similar squares; then came the chief artist, who went over every figure and hieroglyphic with a black line, and a firm and steady hand, giving expression to each curve, deviating here and confirming there the red line. The line thus traced was then followed by the sculptor. The next process was to paint the figure in the prescribed colours.”

Although Egyptian architecture was essentially a trabeated style,—that is to say, a style in which beams or lintels were usually employed to cover openings,—there is strong ground for the belief that the builders of that time [38] were acquainted with the nature of the arch. Dr. Birch mentions a rudimentary arch of the time of the fifth dynasty: at Abydos there are also remains of vaulted tombs of the sixth dynasty; and in a tomb in the neighbourhood of the Pyramids there is an elementary arch of three stones surmounted by a true arch constructed in four courses. The probability is that true brick arches were built at a very early period, but in the construction of their tombs, where heavy masses of superincumbent masonry or rock had to be supported, the Egyptians seem to have been afraid to risk even the remote possibility of their arches decaying; and hence, even when they preserved the form of the arch in masonry, they constructed it with horizontal courses of stones projecting one over the other, and then cut away the lower angles. One dominating idea seems to have influenced them in the whole of their work—esto perpetua was their motto; and though they have been excelled by later peoples in grace and beauty, it is a question whether they have ever been surpassed in the skill with which they adapted their means to the end which they always kept in view.

Floor (technically Plan).—The early rock-cut tombs were, of course, only capable of producing internal effects; their floor presents a series of halls and galleries, varying in size and shape, leading one out of the other, and intended by their contrast or combination to produce architectural effect. To this was added in the later rock-cut tombs a façade to be seen directly in front. Much the same account can be given of the disposition of the [39] built temples. They possess one front, which the spectator approaches, and they are disposed so as to produce varied and impressive interiors, but not to give rise to external display. The supports, such as walls, columns, piers, are all very massive and very close together, so that the only wide open spaces are courtyards.

The circle, or octagon, or other polygonal forms do not appear in the plans of Egyptian buildings; but though all the lines are straight, there is a good deal of irregularity in spacing, walls which face one another are not always parallel, and angles which appear to be right angles very often are not so.

The later buildings extend over much space. The adjuncts to these buildings, especially the avenues of sphinxes, are planned so as to produce an air of stately grandeur, and in them some degree of external effect is aimed at.

The walls are uniformly thick, and often of granite or of stone, though brick is also met with; e.g. some of the smaller pyramids are built entirely of brick. In all probability the walls of domestic buildings were to a great extent of brick, and less thick than those of the temples; hence they have all disappeared.

The surface of walls, even when of granite, was usually plastered with a thin fine plaster, which was covered by the profuse decoration in colour already alluded to.

The walls of the propylons tapered from the base towards the top, and the same thing sometimes occurred in other walls. In almost all cases the stone walls are built of very large blocks, and they show an unrivalled skill in masonry.

The roofing which remains is executed entirely in stone, but not arched or vaulted. The rock-cut tombs, however, as has been stated, contain ceilings of an arched shape, and in some cases forms which seem to be an imitation of timber roofing. The roofing of the Hypostyle Hall at Karnak provides an arrangement for admitting light very similar to the clerestory of Gothic cathedrals.

The openings were all covered by a stone lintel, and consequently were uniformly square-headed. The interspaces between columns were similarly covered, and hence Egyptian architecture has been, and correctly, classed as the first among the styles of trabeated architecture. Window-openings seldom occur.

The columns have been already described to some extent. They are almost always circular in plan, but the shaft is sometimes channelled. They are for the most part of sturdy proportions, but great grace and elegance are shown in the profile given to shafts and capitals. The design of the capitals especially is full of variety, and admirably adapts forms obtained from the vegetable kingdom. The general effect of the Egyptian column, wherever it is used, is that it appears to have, as it really has, a great deal more strength than is required. The fact that the abacus (the square block of stone introduced between the moulded part of the capital and what it carries) is often smaller in width than the diameter of the column aids very much to produce this effect.

Mouldings are very rarely employed; in fact, the large bead running up the angles of the pylons, &c., and a heavy hollow moulding doing duty as a cornice, are all that are usually met with. Sculpture and carving occur occasionally, and are freely introduced in later works, where we sometimes find statues incorporated into the design of the fronts of temples. Decoration in colour, in the shape of hieroglyphic inscriptions and paintings of all sorts, was profusely employed (Figs. 27-30), and is executed with a truth of drawing and a beauty of colouring that have never been surpassed. As has been pointed out, almost every object drawn is partly conventionalised, in the most skilful manner, so as to make it fit its place as a piece of a decorative system.

This is gloomy, and to a certain extent forbidding, owing to the heavy walls and piers and columns, and the great masses supported by them; but when in its freshness and quite uninjured by decay or violence, the exquisite colouring of the walls and ceilings and columns must have added a great deal of beauty: this must have very much diminished the oppressive effect inseparable from such massive construction and from the gloomy darkness of many portions of the buildings. It is also noteworthy that the expenditure of materials and labour is greater in proportion to the effect attained than in any other style. The pyramids are the most conspicuous example of this prodigality. Before condemning this as a defect in the style, it must be remembered that a stability which should defy enemies, earthquakes, and the tooth of time, was far [42] more aimed at than architectural character; and that, had any mode of construction less lavish of material, and less perfect in workmanship, been adopted, the buildings of Egypt might have all disappeared ere this.

Fig. 30.—Painted Decoration from Thebes.

[1] Some Egyptologists incline to the opinion that the pyramid of Saqqára is the most ancient, while others think it much more recent than those of Gizeh.

[2] Strictly speaking, the base is not an exact square, the four sides measuring, according to the Royal Engineers, north, 760 ft. 7·5 in.; south, 761 ft. 8·5 in.; east, 760 ft. 9·5 in.; and west, 764 ft. 1 in.

[3] Conventionalising may be described as representing a part only of the visible qualities or features of an object, omitting the remainder or very slightly indicating them. A black silhouette portrait is an extreme instance of convention, as it displays absolutely nothing but the outline of a profile. For decorative purposes it is almost always necessary to conventionalise to a greater or less extent whatever is represented.

Fig. 31.—Sculptured Ornament at Nineveh.