Title: Criminal Man, According to the Classification of Cesare Lombroso

Author: Gina Lombroso

Commentator: Cesare Lombroso

Release date: September 3, 2009 [eBook #29895]

Most recently updated: January 5, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marilynda Fraser-Cunliffe, Stephanie Eason,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net. (This file was made using scans of

public domain works from the University of Michigan Digital

Libraries.)

1. The Study of Man. By A. C. Haddon.

2. The Groundwork of Science. By St. George Mivart.

3. Rivers of North America. By Israel C. Russell.

4. Earth Sculpture, or; The Origin of Land Forms. By James Geikie.

5. Volcanoes; Their Structure and Significance. By T. G. Bonney.

6. Bacteria. By George Newman.

7. A Book of Whales. By F. E. Beddard.

8. Comparative Physiology of the Brain, etc. By Jacques Loeb.

9. The Stars. By Simon Newcomb.

10. The Basis of Social Relations. By Daniel G. Brinton.

11. Experiments on Animals. By Stephen Paget.

12. Infection and Immunity. By George M. Sternberg.

13. Fatigue. By A. Mosso.

14. Earthquakes. By Clarence E. Dutton.

15. The Nature of Man. By Élie Metchnikoff.

16. Nervous and Mental Hygiene in Health and Disease. By August Forel.

17. The Prolongation of Life. By Élie Metchnikoff.

18. The Solar System. By Charles Lane Poor.

19. Heredity. By J. Arthur Thompson, M.A.

20. Climate. By Robert DeCourcy Ward.

21. Age, Growth, and Death. By Charles S. Minot.

22. The Interpretation of Nature. By C. Lloyd Morgan.

23. Mosquito Life. By Evelyn Groesbeeck Mitchell.

24. Thinking, Feeling, Doing. By E. W. Scripture.

25. The World's Gold. By L. de Launay.

26. The Interpretation of Radium. By F. Soddy.

27. Criminal Man. By Cesare Lombroso.

| PART I.—THE CRIMINAL WORLD | ||

| CHAPTER I | PAGE | |

| The Born Criminal | 3 | |

| Classical and modern schools of penal jurisprudence—Physical anomalies of the born criminal—Senses and functions—Psychology—Intellectual manifestations—The criminal in proverbial sayings. | ||

| CHAPTER II | ||

| The Born Criminal and his Relation to Moral Insanity and Epilepsy | 52 | |

| Identity of born criminals and the morally insane—Analogy of physical and psychic characters, origin and development—Epilepsy—Multiformity of disease—Equivalence of certain forms to criminality—Physical and psychic characters—Cases of moral insanity with latent epileptic phenomena. | ||

| CHAPTER III | ||

| The Insane Criminal | 74 | |

| General forms of criminal insanity, imbecility, melancholia, general paralysis, dementia, monomania—Physical and psychic characters of the mentally deranged—Special forms of criminal insanity—Inebriate lunatics from inebriation—Physical and psychic characters—Specific crimes—Epileptic lunatics—Manifestations—Hysterical lunatics—Physical and functional characters—Psychology. | ||

| [Pg iv] | ||

| CHAPTER IV | ||

| Criminaloids | 100 | |

| Psychology—Tardy adoption of criminal career—Repentance—Confession—Moral sense and affections—Habitual criminals—Juridical criminals—Criminals of passion. | ||

| PART II.—CRIME, ITS ORIGIN, CAUSE, AND CURE | ||

| CHAPTER I | ||

| Origin and Causes of Crime | 125 | |

| Atavistic origin of crime—Criminality in children—Pathological origin of crime—Direct and indirect heredity—Illnesses, intoxications, and traumatism—Alcoholism—Social causes of crime—Education and environment—Atmospheric and climatic influences—Density of population—Imitation—Immigration—Prison life—Economic conditions—Sex—Age. | ||

| CHAPTER II | ||

| The Prevention of Crime | 153 | |

| Preventive institutions for children and young people—Homes for orphans and destitute children—Colonies for unruly youths—Institutions for assisting adults—Salvation Army. | ||

| CHAPTER III | ||

| Methods for the Cure and Repression of Crime | 175 | |

| Juvenile offenders—Children's Courts—Institutions for female offenders—Minor offenders, criminals of passion, political offenders, and criminaloids—Probation system and indeterminate sentence—Reformatories—Penitentiaries—Institutes for habitual criminals—Penal colonies—Institutions for born criminals and the morally insane—Asylums for insane criminals—Capital punishment—Symbiosis. | ||

| [Pg v] | ||

| PART III.—CHARACTERS AND TYPES OF CRIMINALS | ||

| CHAPTER I | ||

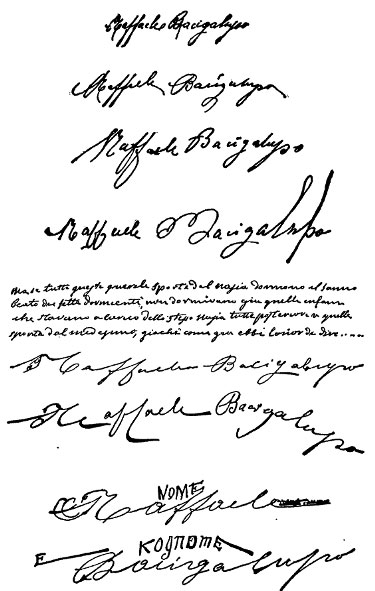

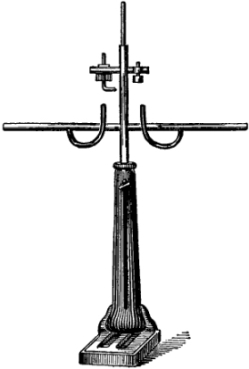

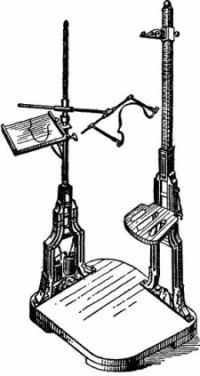

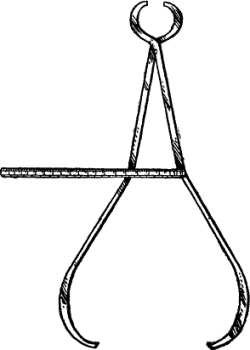

| Examination of Criminals | 219 | |

| Antecedents and psychology—Methods of testing intelligence and emotions—Morbid phenomena—Speech, memory, and handwriting—Clothing—Physical examination—Tests of sensibility and senses—Excretions—Table of anthropological examination of criminals and the insane. | ||

| CHAPTER II | ||

| Summary of Chief Forms of Criminality to Aid in Distinguishing between Criminals and Lunatics and in Detecting Simulations of Insanity | 258 | |

| A few cases showing the practical application of criminal anthropology. | ||

| APPENDIX | ||

| Works of Cesare Lombroso (Briefly Summarised) | ||

| I. | The Man of Genius | 283 |

| II. | Criminal Man | 288 |

| III. | The Female Offender. (In Collaboration with Guglielmo Ferrero.) | 291 |

| IV. | Political Crime. (In Collaboration with Rodolfo Laschi.) | 294 |

| V. | Too Soon: A Criticism of the New Italian Penal Code | 298 |

| VI. | Prison Palimpsests: Studies in Prison Inscriptions | 300 |

| VII. | Ancient and Modern Crimes | 302 |

| VIII. | Diagnostic Methods of Legal Psychiatry | 303 |

| IX. | Anarchists | 305 |

| X. | Lectures on Legal Medicine | 307 |

| XI. | Recent Discoveries in Psychiatry and Criminal Anthropology and the Practical Application of these Sciences | 309 |

| [Pg vi] | ||

| Bibliography of the Chief Works of Cesare Lombroso | 310 | |

| Index | 315 | |

| PAGE | ||

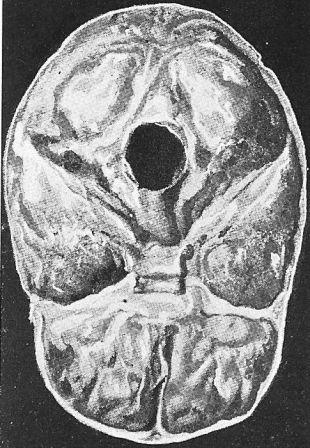

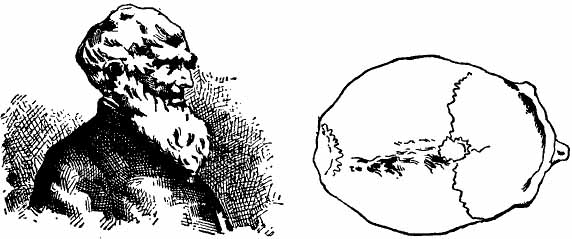

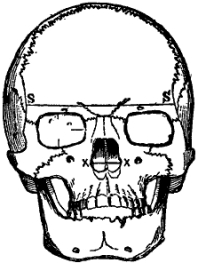

| Fig. 1. | Fossette Occipital | 6 |

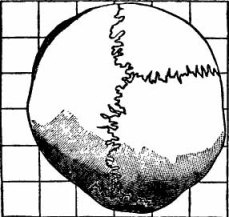

| Fig. 2. | Skull Formation | 11 |

| Fig. 3. | Skull Formation | 11 |

| Fig. 4. | Head of Criminal | 16 |

| Fig. 5. | Head of Criminal | 16 |

| Fig. 6. | Layers of the Frontal Region | 23 |

| Fig. 7. | Figures Made in Prison. Murder of a Sleeping Victim | 32 |

| Fig. 8. | Crucifix Poignard | 32 |

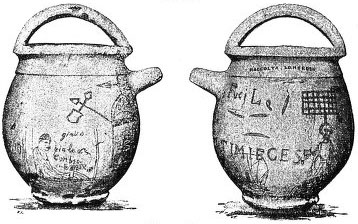

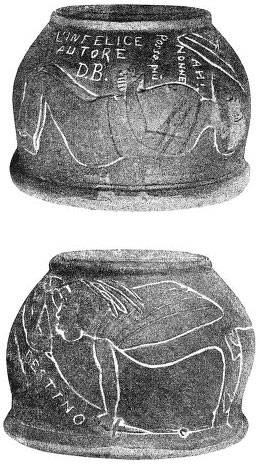

| Fig. 9. | Water-Jugs | 42 |

| Fig. 10. | Drawings in Script. Discovered by De Blasio | 44 |

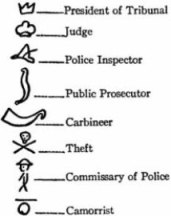

| Fig. 11. | Alphabet. Discovered by De Blasio | 45 |

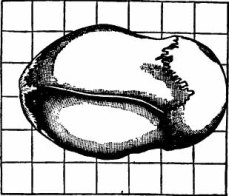

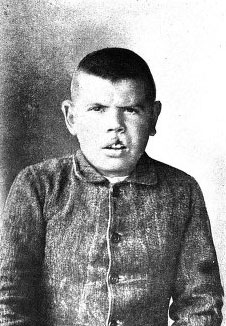

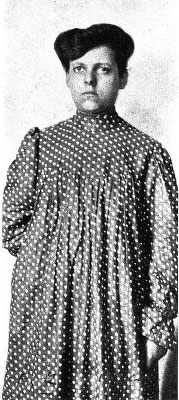

| Fig. 12. | Boy Morally Insane | 56 |

| Fig. 13. | Boy Morally Insane | 56 |

| Fig. 14. | An Epileptic Boy | 60 |

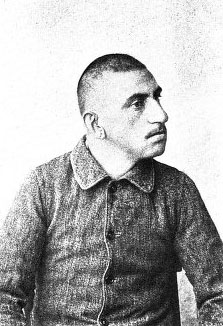

| [Pg viii]Fig. 15. | Fernando. Epileptic | 60 |

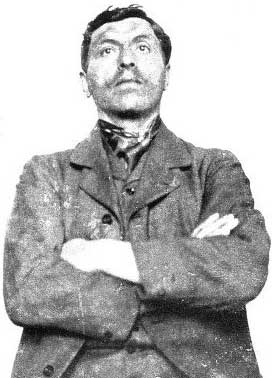

| Fig. 16. | Italian Criminal. A Case of Alcoholism | 82 |

| Fig. 17. | Signatures of Criminals | 163 |

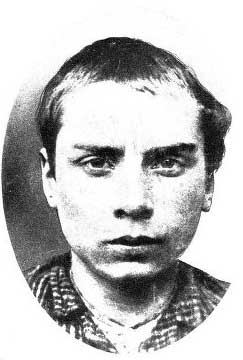

| Fig. 18. | Criminal Girl | 114 |

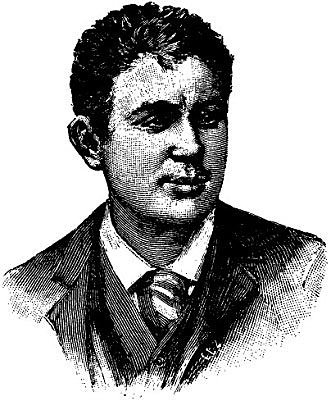

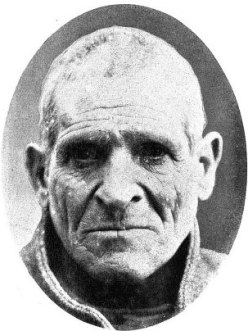

| Fig. 19. | The Brigand Salomone | 114 |

| Fig. 20. | Brigand Gasparone | 166 |

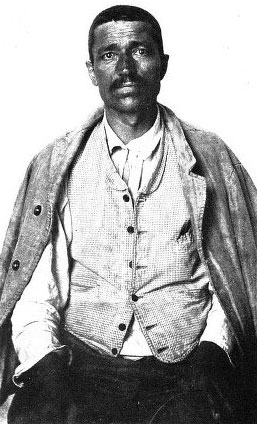

| Fig. 21. | Brigand Caserio | 120 |

| Fig. 22. | Terra-cotta Bowls. Designed by a Criminal | 134 |

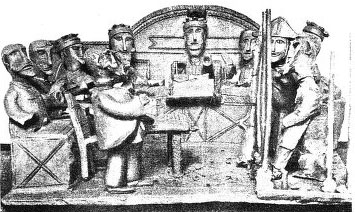

| Fig. 23. | Art Production from Prison | 136 |

| Fig. 24. | A Combat between Brigands and Gendarmes. Designed by a Criminal | 136 |

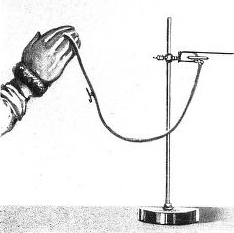

| Fig. 25. | A Volumetric Glove | 224 |

| Fig. 26. | Head of a Criminal. Epileptic | 224 |

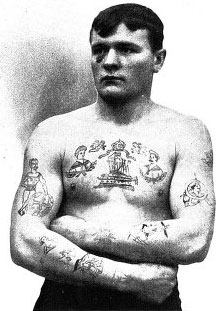

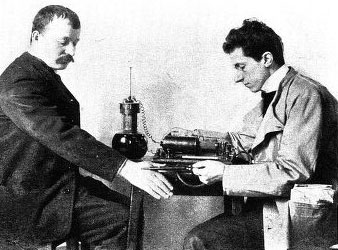

| Fig. 27. | Anton Otto Krauser. Apache | 236 |

| Fig. 28. | A Criminal's Ear | 224 |

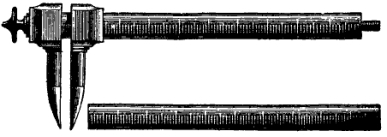

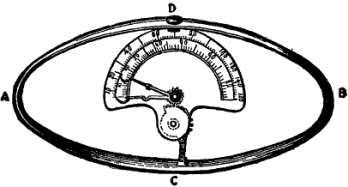

| Fig. 29. | Anthropometer | 237 |

| Fig. 30. | Craniograph Anfossi | 238 |

| Fig. 31. | Pelvimeter | 239 |

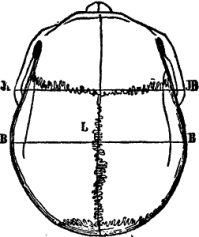

| Fig. 32. | Diagram of Skull | 241 |

| [Pg ix]Fig. 33. | Diagram of Skull | 241 |

| Fig. 34. | Esthesiometer | 245 |

| Fig. 35. | Algometer | 248 |

| Fig. 36. | Campimeter of Landolt (Modified) | 248 |

| Fig. 37. | Diagram Showing Normal Vision | 250 |

| Fig. 38. | Dynamometer | 253 |

| Fig. 39. | Head of an Italian Criminal | 254 |

[Professor Lombroso was able before his death to give his personal attention to the volume prepared by his daughter and collaborator, Gina Lombroso Ferrero (wife of the distinguished historian), in which is presented a summary of the conclusions reached in the great treatise by Lombroso on the causes of criminality and the treatment of criminals. The preparation of the introduction to this volume was the last literary work which the distinguished author found it possible to complete during his final illness.]

It will, perhaps, be of interest to American readers of this book, in which the ideas of the Modern Penal School, set forth in my work, Criminal Man, have been so pithily summed up by my daughter, to learn how the first outlines of this science arose in my mind and gradually took shape in a definite work—how, that is, combated by some, the object of almost fanatical adherence on the part of others, especially in America, where tradition has little hold, the Modern Penal School came into being.

On consulting my memory and the documents relating to my studies on this subject, I find that its two fundamental ideas—that, for instance, which[Pg xii] claims as an essential point the study not of crime in the abstract, but of the criminal himself, in order adequately to deal with the evil effects of his wrong-doing, and that which classifies the congenital criminal as an anomaly, partly pathological and partly atavistic, a revival of the primitive savage—did not suggest themselves to me instantaneously under the spell of a single deep impression, but were the offspring of a series of impressions. The slow and almost unconscious association of these first vague ideas resulted in a new system which, influenced by its origin, has preserved in all its subsequent developments the traces of doubt and indecision, the marks of the travail which attended its birth.

The first idea came to me in 1864, when, as an army doctor, I beguiled my ample leisure with a series of studies on the Italian soldier. From the very beginning I was struck by a characteristic that distinguished the honest soldier from his vicious comrade: the extent to which the latter was tattooed and the indecency of the designs that covered his body. This idea, however, bore no fruit.

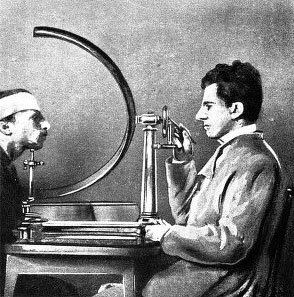

The second inspiration came to me when on one occasion, amid the laughter of my colleagues, I sought to base the study of psychiatry on experimental methods. When in '66, fresh from the atmosphere of clinical experiment, I had begun to study psychi[Pg xiii]atry, I realised how inadequate were the methods hitherto held in esteem, and how necessary it was, in studying the insane, to make the patient, not the disease, the object of attention. In homage to these ideas, I applied to the clinical examination of cases of mental alienation the study of the skull, with measurements and weights, by means of the esthesiometer and craniometer. Reassured by the result of these first steps, I sought to apply this method to the study of criminals—that is, to the differentiation of criminals and lunatics, following the example of a few investigators, such as Thomson and Wilson; but as at that time I had neither criminals nor moral imbeciles available for observation (a remarkable circumstance since I was to make the criminal my starting-point), and as I was skeptical as to the existence of those "moral lunatics" so much insisted on by both French and English authors, whose demonstrations, however, showed a lamentable lack of precision, I was anxious to apply the experimental method to the study of the diversity, rather than the analogy, between lunatics, criminals, and normal individuals. Like him, however, whose lantern lights the road for others, while he himself stumbles in the darkness, this method proved useless for determining the differences between criminals and lunatics, but served instead to[Pg xiv] indicate a new method for the study of penal jurisprudence, a matter to which I had never given serious thought. I began dimly to realise that the a priori studies on crime in the abstract, hitherto pursued by jurists, especially in Italy, with singular acumen, should be superseded by the direct analytical study of the criminal, compared with normal individuals and the insane.

I, therefore, began to study criminals in the Italian prisons, and, amongst others, I made the acquaintance of the famous brigand Vilella. This man possessed such extraordinary agility, that he had been known to scale steep mountain heights bearing a sheep on his shoulders. His cynical effrontery was such that he openly boasted of his crimes. On his death one cold grey November morning, I was deputed to make the post-mortem, and on laying open the skull I found on the occipital part, exactly on the spot where a spine is found in the normal skull, a distinct depression which I named median occipital fossa, because of its situation precisely in the middle of the occiput as in inferior animals, especially rodents. This depression, as in the case of animals, was correlated with the hypertrophy of the vermis, known in birds as the middle cerebellum.

This was not merely an idea, but a revelation. At the sight of that skull, I seemed to see all of a[Pg xv] sudden, lighted up as a vast plain under a flaming sky, the problem of the nature of the criminal—an atavistic being who reproduces in his person the ferocious instincts of primitive humanity and the inferior animals. Thus were explained anatomically the enormous jaws, high cheek-bones, prominent superciliary arches, solitary lines in the palms, extreme size of the orbits, handle-shaped or sessile ears found in criminals, savages, and apes, insensibility to pain, extremely acute sight, tattooing, excessive idleness, love of orgies, and the irresistible craving for evil for its own sake, the desire not only to extinguish life in the victim, but to mutilate the corpse, tear its flesh, and drink its blood.

I was further encouraged in this bold hypothesis by the results of my studies on Verzeni, a criminal convicted of sadism and rape, who showed the cannibalistic instincts of primitive anthropophagists and the ferocity of beasts of prey.

The various parts of the extremely complex problem of criminality were, however, not all solved hereby. The final key was given by another case, that of Misdea, a young soldier of about twenty-one, unintelligent but not vicious. Although subject to epileptic fits, he had served for some years in the army when suddenly, for some trivial cause, he attacked and killed eight of his superior officers and[Pg xvi] comrades. His horrible work accomplished, he fell into a deep slumber, which lasted twelve hours and on awaking appeared to have no recollection of what had happened. Misdea, while representing the most ferocious type of animal, manifested, in addition, all the phenomena of epilepsy, which appeared to be hereditary in all the members of his family. It flashed across my mind that many criminal characteristics not attributable to atavism, such as facial asymmetry, cerebral sclerosis, impulsiveness, instantaneousness, the periodicity of criminal acts, the desire of evil for evil's sake, were morbid characteristics common to epilepsy, mingled with others due to atavism.

Thus were traced the first clinical outlines of my work which had hitherto been entirely anthropological. The clinical outlines confirmed the anthropological contours, and vice versâ; for the greatest criminals showed themselves to be epileptics, and, on the other hand, epileptics manifested the same anomalies as criminals. Finally, it was shown that epilepsy frequently reproduced atavistic characteristics, including even those common to lower animals.

That synthesis which mighty geniuses have often succeeded in creating by one inspiration (but at the risk of errors, for a genius is only human and in[Pg xvii] many cases more fallacious than his fellow-men) was deduced by me gradually from various sources—the study of the normal individual, the lunatic, the criminal, the savage, and finally the child. Thus, by reducing the penal problem to its simplest expression, its solution was rendered easier, just as the study of embryology has in a great measure solved the apparently strange and mysterious riddle of teratology.

But these attempts would have been sterile, had not a solid phalanx of jurists, Russian, German, Hungarian, Italian, and American, fertilised the germ by correcting hasty and one-sided conclusions, suggesting opportune reforms and applications, and, most important of all, applying my ideas on the offender to his individual and social prophylaxis and cure.

Enrico Ferri was the first to perceive that the congenital epileptoid criminal did not form a single species, and that if this class was irretrievably doomed to perdition, crime in others was only a brief spell of insanity, determined by circumstances, passion, or illness. He established new types—the occasional criminal and the criminal by passion,—and transformed the basis of the penal code by asking if it were more just to make laws obey facts instead of altering facts to suit the laws, solely[Pg xviii] in order to avoid troubling the placidity of those who refused to consider this new element in the scientific field. Therefore, putting aside those abstract formulæ for which high talents have panted in vain, like the thirsty traveller at the sight of the desert mirage, the advocates of the Modern School came to the conclusion that sentences should show a decrease in infamy and ferocity proportionate to the increase in length and social safety. In lieu of infamy they substituted a longer period of segregation, and for cases in which alienists were unable to decide between criminality and insanity, they advocated an intermediate institution, in which merciful treatment and social security were alike considered. They also emphasised the importance of certain measures which hitherto had been universally regarded as a pure abstraction or an unattainable desideratum—measures for the prevention of crime by tracing it to its source, divorce laws to diminish adultery, legislation of an anti-alcoholistic tendency to prevent crimes of violence, associations for destitute children, and co-operative associations to check the tendency to theft. Above all, they insisted on those regulations—unfortunately fallen into disuse—which indemnify the victim at the expense of the aggressor, in order that society, having suffered once for the crime, should not be obliged to suffer pecuniarily[Pg xix] for the detention of the offender, solely in homage to a theoretical principle that no one believes in, according to which prison is a kind of baptismal font in whose waters sin of all kinds is washed away.

Thus the edifice of criminal anthropology, circumscribed at first, gradually extended its walls and embraced special studies on homicide, political crime, crimes connected with the banking world, crimes by women, etc.

But the first stone had been scarcely laid when from all quarters of Europe arose those calumnies and misrepresentations which always follow in the train of audacious innovations. We were accused of wishing to proclaim the impunity of crime, of demanding the release of all criminals, of refusing to take into account climatic and racial influences and of asserting that the criminal is a slave eternally chained to his instincts; whereas the Modern School, on the contrary, gave a powerful impetus to the labors of statisticians and sociologists on these very matters. This is clearly shown in the third volume of Criminal Man, which contains a summary of the ideas of modern criminologists and my own.

One nation, however—America,—gave a warm and sympathetic reception to the ideas of the Modern School which they speedily put into practice, with the brilliant results shown by the Reformatory at[Pg xx] Elmira, the Probation System, Juvenile Courts, and the George Junior Republic. They also initiated the practice, now in general use, of anthropological co-operation in every criminal trial of importance.

For this reason, and in view of the fact that America does not possess a complete translation of my works—The Criminal, Male and Female, and Political Crime (translation and distribution being alike difficult on account of the length of these volumes)—I welcome with pleasure this summary, in which the principal points are explained with precision and loving care by my daughter Gina, who has worked with me from childhood, has seen the edifice of my science rise stone upon stone, and has shared in my anxieties, insults, and triumphs; without whose help I might, perhaps, never have witnessed the completion of that edifice, nor the application of its fundamental principles.

A criminal is a man who violates the laws decreed by the State to regulate the relations between its citizens, but the voluminous codes which in past times set forth these laws treat only of crime, never of the criminal. That ignoble multitude whom Dante relegated to the Infernal Regions were consigned by magistrates and judges to the care of gaolers and executioners, who alone deigned to deal with them. The judge, immovable in his doctrine, unshaken by doubts, solemn in all his inviolability and convinced of his wisdom, which no one dared to question, passed sentence without remission according to his whim, and both judge and culprit were equally ignorant of the ultimate effect of the penalties inflicted.

In 1764, the great Italian jurist and economist, Cesare Beccaria first called public attention to those wretched beings, whose confessions (if statements[Pg 4] extorted by torture can thus be called) formed the sole foundation for the trial, the sole guide in the application of the punishment, which was bestowed blindly, without formality, without hearing the defence, exactly as though sentence were being passed on abstract symbols, not on human souls and bodies.

The Classical School of Penal Jurisprudence, of which Beccaria was the founder and Francesco Carrara the greatest and most glorious disciple, aimed only at establishing sound judgments and fixed laws to guide capricious and often undiscerning judges in the application of penalties. In writing his great work, the founder of this School was inspired by the highest of all human sentiments—pity; but although the criminal incidentally receives notice, the writings of this School treat only of the application of the law, not of offenders themselves.

This is the difference between the Classical and the Modern School of Penal Jurisprudence. The Classical School based its doctrines on the assumption that all criminals, except in a few extreme cases, are endowed with intelligence and feelings like normal individuals, and that they commit misdeeds consciously, being prompted thereto by their unrestrained desire for evil. The offence alone was considered,[Pg 5] and on it the whole existing penal system has been founded, the severity of the sentence meted out to the offender being regulated by the gravity of his misdeed.

The Modern, or Positive, School of Penal Jurisprudence, on the contrary, maintains that the anti-social tendencies of criminals are the result of their physical and psychic organisation, which differs essentially from that of normal individuals; and it aims at studying the morphology and various functional phenomena of the criminal with the object of curing, instead of punishing him. The Modern School is therefore founded on a new science, Criminal Anthropology, which may be defined as the Natural History of the Criminal, because it embraces his organic and psychic constitution and social life, just as anthropology does in the case of normal human beings and the different races.

If we examine a number of criminals, we shall find that they exhibit numerous anomalies in the face, skeleton, and various psychic and sensitive functions, so that they strongly resemble primitive races. It was these anomalies that first drew my father's attention to the close relationship between the criminal and the savage and made him suspect that criminal tendencies are of atavistic origin.

When a young doctor at the Asylum in Pavia, he[Pg 6] was requested to make a post-mortem examination on a criminal named Vilella, an Italian Jack the Ripper, who by atrocious crimes had spread terror in the Province of Lombardy. Scarcely had he laid open the skull, when he perceived at the base, on the spot where the internal occipital crest or ridge is found in normal individuals, a small hollow, which he called median occipital fossa (see Fig. 1). This abnormal character was correlated to a still greater anomaly in the cerebellum, the hypertrophy of the vermis, i.e., the spinal cord which separates the cerebellar lobes lying underneath the cerebral hemispheres. This vermis was so enlarged in the case of Vilella, that it almost formed a small, intermediate cerebellum like that found in the lower types of apes, rodents, and birds. This anomaly is very rare among inferior races, with the exception of the South American Indian tribe of the Aymaras of Bolivia and Peru, in whom it is not infrequently found (40%). It is seldom met with in the insane or other degenerates, but later investigations have shown it to be prevalent in criminals.

This discovery was like a flash of light. "At the sight of that skull," says my father, "I seemed to see all at once, standing out clearly illumined as in a vast plain under a flaming sky, the problem of the nature of the criminal, who reproduces in civilised[Pg 7] times characteristics, not only of primitive savages, but of still lower types as far back as the carnivora."

Thus was explained the origin of the enormous jaws, strong canines, prominent zygomæ, and strongly developed orbital arches which he had so frequently remarked in criminals, for these peculiarities are common to carnivores and savages, who tear and devour raw flesh. Thus also it was easy to understand why the span of the arms in criminals so often exceeds the height, for this is a characteristic of apes, whose fore-limbs are used in walking and climbing. The other anomalies exhibited by criminals—the scanty beard as opposed to the general hairiness of the body, prehensile foot, diminished number of lines in the palm of the hand, cheek-pouches, enormous development of the middle incisors and frequent absence of the lateral ones, flattened nose and angular or sugar-loaf form of the skull, common to criminals and apes; the excessive size of the orbits, which, combined with the hooked nose, so often imparts to criminals the aspect of birds of prey, the projection of the lower part of the face and jaws (prognathism) found in negroes and animals, and supernumerary teeth (amounting in some cases to a double row as in snakes) and cranial bones (epactal bone as in the Peruvian Indians): all these characteristics pointed to one conclusion, the[Pg 8] atavistic origin of the criminal, who reproduces physical, psychic, and functional qualities of remote ancestors.

Subsequent research on the part of my father and his disciples showed that other factors besides atavism come into play in determining the criminal type. These are: disease and environment. Later on, the study of innumerable offenders led them to the conclusion that all law-breakers cannot be classed in a single species, for their ranks include very diversified types, who differ not only in their bent towards a particular form of crime, but also in the degree of tenacity and intensity displayed by them in their perverse propensities, so that, in reality, they form a graduated scale leading from the born criminal to the normal individual.

Born criminals form about one third of the mass of offenders, but, though inferior in numbers, they constitute the most important part of the whole criminal army, partly because they are constantly appearing before the public and also because the crimes committed by them are of a peculiarly monstrous character; the other two thirds are composed of criminaloids (minor offenders), occasional and habitual criminals, etc., who do not show such a marked degree of diversity from normal persons.

Let us commence with the born criminal, who as[Pg 9] principal nucleus of the wretched army of law-breakers, naturally manifests the most numerous and salient anomalies.

The median occipital fossa and other abnormal features just enumerated are not the only peculiarities exhibited by this aggravated type of offender. By careful research, my father and others of his School have brought to light many anomalies in bodily organs, and functions both physical and mental, all of which serve to indicate the atavistic and pathological origin of the instinctive criminal.

It would be incompatible with the scope of this summary, were I to give a minute description of the innumerable anomalies discovered in criminals by the Modern School, to attempt to trace such abnormal traits back to their source, or to demonstrate their effect on the organism. This has been done in a very minute fashion in the three volumes of my father's work Criminal Man and his subsequent writings on the same subject, Modern Forms of Crime, Recent Research in Criminal Anthropology, Prison Palimpsests, etc., etc., to which readers desirous of obtaining a more thorough knowledge of the subject should refer.

The present volume will only touch briefly on the principal characteristics of criminals, with the object[Pg 10] of presenting a general outline of the studies of criminologists.

The Head. As the seat of all the greatest disturbances, this part naturally manifests the greatest number of anomalies, which extend from the external conformation of the brain-case to the composition of its contents.

The criminal skull does not exhibit any marked characteristics of size and shape. Generally speaking, it tends to be larger or smaller than the average skull common to the region or country from which the criminal hails. It varies between 1200 and 1600 c.c.; i.e., between 73 and 100 cubic inches, the normal average being 92. This applies also to the cephalic index; that is, the ratio of the maximum width to the maximum length of the skull[1] multiplied by 100, which serves to give a concrete idea of the form of the skull, because the higher the index, the nearer the skull approaches a spherical form, and the lower the index, the more elongated it becomes. The skulls of criminals have no characteristic cephalic index, but tend to an exaggeration of the ethnical type prevalent in their native countries. In regions where dolichocephaly (index less[Pg 11] than 80) abounds, the skulls of criminals show a very low index; if, on the contrary, they are natives of districts where brachycephaly (index 80 or more) prevails, they exhibit a very high index.

|  | |

| Fig. 2 | Fig. 3 |

In 15.5% we find trochocephalous or abnormally round heads (index 91). A very high percentage (nearly double that of normal individuals) have submicrocephalous or small skulls. In other cases the skull is excessively large (macrocephaly) or abnormally small and ill-shaped with a narrow, receding forehead (microcephaly, 0.2%). More rarely the skull is of normal size, but shaped like the keel of a boat (scaphocephaly, 0.1% and subscaphocephaly 6%). (See Fig. 2.) Sometimes the anomalies are still more serious and we find wholly asymmetrical skulls with protuberances on either side (plagiocephaly[Pg 12] 10.9%, see Fig. 3), or terminating in a peak on the bregma or anterior fontanel (acrocephaly, see Fig. 4), or depressed in the middle (cymbocephaly, sphenocephaly). At times, there are crests or grooves along the sutures (11.9%) or the cranial bones are abnormally thick, a characteristic of savage peoples (36.6%) or abnormally thin (8.10%). Other anomalies of importance are the presence of Wormian bones in the sutures of the skull (21.22%), the bone of the Incas already alluded to (4%), and above all, the median occipital fossa. Of great importance also are the prominent frontal sinuses found in 25% (double that of normal individuals), the semicircular line of the temples, which is sometimes so exaggerated that it forms a ridge and is correlated to an excessive development of the temporal muscles, a common characteristic of primates and carnivores. Sometimes the forehead is receding, as in apes (19%), or low and narrow (10%).

The Face. In striking contrast to the narrow forehead and low vault of the skull, the face of the criminal, like those of most animals, is of disproportionate size, a phenomenon intimately connected with the greater development of the senses as compared with that of the nervous centres. Prognathism, the projection of the lower portion of the face beyond the forehead, is found in 45.7% of criminals.[Pg 13] Progeneismus, the projection of the lower teeth and jaw beyond the upper, is found in 38%, whereas among normal persons the proportion is barely 28%. As a natural consequence of this predominance of the lower portion of the face, the orbital arches and zygomæ show a corresponding development (35%) and the size of the jaws is naturally increased, the mean diameter being 103.9 mm. (4.09 inches) as against 93 mm. (3.66 inches) in normal persons. Among criminals 29% have voluminous jaws.

The excessive dimensions of the jaws and cheek-bones admit of other explanations besides the atavistic one of a greater development of the masticatory system. They may have been influenced by the habit of certain gestures, the setting of the teeth or tension of the muscles of the mouth, which accompany violent muscular efforts and are natural to men who form energetic or violent resolves and meditate plans of revenge.

Asymmetry is a common characteristic of the criminal physiognomy. The eyes and ears are frequently situated at different levels and are of unequal size, the nose slants towards one side, etc. This asymmetry, as we shall see later, is connected with marked irregularities in the senses and functions.

The Eye. This window, through which the mind[Pg 14] opens to the outer world, is naturally the centre of many anomalies of a psychic character, hard expression, shifty glance, which are difficult to describe but are, nevertheless, apparent to all observers (see Fig. 4). Side by side with peculiarities of expression, we find many physical anomalies—ptosis, a drooping of the upper eyelid, which gives the eye a half-closed appearance and is frequently unilateral; and strabismus, a want of parallelism between the visual axes, which is insignificant if it arises from errors of refraction, but is very serious if it betokens progressive or congenital diseases of the brain or its membranous coverings. Other anomalies are asymmetry of the iris, which frequently differs in colour from its fellow; oblique eyelids, a Mongolian characteristic, with the edge of the upper eyelid folding inward or a prolongation of the internal fold of the eyelid, which Metchnikoff regards as a persistence of embryonic characters.

The Ear. The external ear is often of large size; occasionally also it is smaller than the ears of normal individuals. Twenty-eight per cent. of criminals have handle-shaped ears standing out from the face as in the chimpanzee: in other cases they are placed at different levels. Frequently too, we find misshapen, flattened ears, devoid of helix, tragus, and anti-tragus, and with a protuberance on the upper[Pg 15] part of the posterior margin (Darwin's tubercle), a relic of the pointed ear characteristic of apes. Anomalies are also found in the lobe, which in some cases adheres too closely to the face, or is of huge size as in the ancient Egyptians; in other cases, the lobe is entirely absent, or is atrophied till the ear assumes a form like that common to apes.

The Nose. This is frequently twisted, up-turned or of a flattened, negroid character in thieves; in murderers, on the contrary, it is often aquiline like the beak of a bird of prey. Not infrequently we meet with the trilobate nose, its tip rising like an isolated peak from the swollen nostrils, a form found among the Akkas, a tribe of pygmies of Central Africa. All these peculiarities have given rise to popular saws, of a character more or less prevalent everywhere.

The Mouth. This part shows perhaps a greater number of anomalies than any other facial organ. We have already alluded to the excessive development of the jaws in criminals. They are sometimes the seat of other abnormal characters,—the lemurine apophysis, a bony elevation at the angle of the jaw, which may easily be recognised externally by passing the hand over the skin; and the canine fossa, a depression in the upper jaw for the attachment of the canine muscle. This muscle, which is strongly[Pg 16] developed in the dog, serves when contracted to draw back the lip leaving the canines exposed.

The lips of violators of women and murderers are fleshy, swollen and protruding, as in negroes. Swindlers have thin, straight lips. Hare-lip is more common in criminals than in normal persons.

The Cheek-pouches. Folds in the flesh of the cheek which recall the pouches of certain species of mammals, are not uncommon in criminals.

The Palate. A central ridge (torus palatinus), more easily felt than seen, may sometimes be found on the palate, or this part may exhibit other peculiarities, a series of cavities and protuberances corresponding to the palatal teeth of reptiles. Another frequent abnormality is cleft palate, a fissure in the palate, due to defective development.

The Teeth. These are specially important, for criminals rarely have normal dentition. The incisors show the greatest number of anomalies. Sometimes both the lateral incisors are absent and the middle ones are of excessive size, a peculiarity which recalls the incisors of rodents. The teeth are frequently striated transversely or set very wide apart (diastema) with gaps on either side of the upper canines into which the lower ones fit, a simian characteristic. In some cases, these spaces[Pg 17] occur between the middle incisors or between these and the lateral ones.

| Fig. 4 | Fig. 5 | |

|  | |

| Head of Criminal (see page 14) | Head of Criminal (see page 18) |

Very often the teeth show a strange uniformity, which recalls the homodontism of the lower vertebrates. In some cases, however, this uniformity is limited to the premolars, which are furnished with tubercles like the molars, a peculiarity of gorillas and orang-outangs. In 4% the canines are very strongly developed, long, sharp, and curving inwardly as in carnivores. Premature caries is common.

The Chin. Generally speaking, this part of the face projects moderately in Europeans. In criminals it is often small and receding, as in children, or else excessively long, short or flat, as in apes.

Wrinkles. Although common to normal individuals, the abundance, variety, and precocity of wrinkles almost invariably manifested by criminals, cannot fail to strike the observer. The following are the most common: horizontal and vertical lines on the forehead, horizontal and circumflex lines at the root of the nose, the so-called crow's-feet on the temple at the outer corners of the eyes, naso-labial wrinkles around the region of the mouth and nose.

The Hair. The hair of the scalp, cheeks and chin, eyebrows, and other parts of the body, shows a number of anomalies. In general it may be said[Pg 18] that in the distribution of hair, criminals of both sexes tend to exhibit characteristics of the opposite sex. Dark hair prevails especially in murderers, and curly and woolly hair in swindlers. Both grey hair and baldness are rare and when found make their appearance later in life than in the case of normal individuals. The beard is scanty and frequently missing altogether. On the other hand, the forehead is often covered with down. The eyebrows are bushy and tend to meet across the nose. Sometimes they grow in a slanting direction and give the face a satyr-like expression (see Fig. 5).

The blemishes peculiar to the delinquent are not only confined to the face and head, but are found in the trunk and limbs.

The Thorax. An increase or decrease in the number of ribs is found in 12% of criminals. This is an atavistic character common to animals and lower or prehistoric human races and contrasts with the numerical uniformity characteristic of civilised mankind.

Polymastia, or the presence of supernumerary nipples (which are generally placed symmetrically below the normal ones as in many mammals) is not an uncommon anomaly. Gynecomastia or hypertrophy of the mammæ is still more frequent in male criminals. In female criminals, on the contrary,[Pg 19] we often find imperfect development or absence of the nipples, a characteristic of monotremata or lowest order of the mammals; or the breasts are flabby and pendent like those of Hottentot women.

The chest is often covered with hair which gives the subject the appearance of an animal.

The Pelvis and Abdomen. The abdomen, pelvis, and reproductive organs sometimes show an inversion of sex-characters. In 42% the sacral canal is uncovered, and in some cases there is a prolongation of the coccyx, which resembles the stump of a tail, sometimes tufted with hair.

The Upper Limbs. One of the most striking and frequent anomalies exhibited by criminals is the excessive length of the arms as compared with the lower limbs, owing to which the span of the arms exceeds the total height, an ape-like character.

Six per cent. exhibit an anomaly which is extremely rare among normal individuals—the olecranon foramen, a perforation in the head of the humerus where it articulates with the ulna. This is normal in the ape and dog and is frequently found in the bones of prehistoric man and in some of the existing inferior races of mankind.

Several abnormal characters, which point to an atavistic origin, are found in the palm and fingers. Supernumerary fingers (polydactylism) or a reduction[Pg 20] in the usual number are not uncommon. Sometimes we find syndactylism, or palmate fingers, a continuation of the interdigital skin to the second phalanx. The length of the fingers varies according to the type of crime to which the individual is addicted. Those guilty of crimes against the person have short, clumsy fingers and especially short thumbs. Long fingers are common to swindlers, thieves, sexual offenders, and pickpockets. The lines on the palmar surfaces of the finger-tips are often of a simple nature as in the anthropoids. The principal lines on the palm are of special significance. Normal persons possess three, two horizontal and one vertical, but in criminals these lines are often reduced to one or two of horizontal or transverse direction, as in apes.

The Lower Limbs. Of a number of criminals examined, 16% showed an unusual development of the third trochanter, a protuberance on the head of the femur where it articulates with the pelvis. This distinctly atavistic character is connected with the position of the hind-limb in quadrupeds.

The Feet. Spaces between the toes like the interdigital spaces of the hand are very common, and in conjunction with the greater mobility of the toes and greater length of the big-toe, produce the prehensile foot, of the quadrumana, which is used for[Pg 21] grasping. The foot is often flat, as in negroes. In the feet, as in the hands, there is frequently a tendency to greater strength or dexterity on the left side, contrary to what happens in normal persons, and this tendency is manifested in many cases where there is no trace of functional and motorial left-handedness.

The Cerebrum and the Cerebellum. The chief and most common anomaly is the prevalence of macroscopic anomalies in the left hemisphere, which are correlated to the sensory and functional left-handedness common to criminals and acquired through illness. The most notable anomaly of the cerebellum is the hypertrophy of the vermis, which represents the middle lobe found in the lower mammals. Anomalies in the cerebral convolutions consist principally of anastomotic folds, the doubling of the fissure of Rolando, the frequent existence of a fourth frontal convolution, the imperfect development of the precuneus (as in many types of apes), etc. Anomalies of a purely pathological character are still more common. These are: adhesions of the meninges, thickening of the pia mater, congestion of the meninges, partial atrophy, centres of softening, seaming of the optic thalami, atrophy of the corpus callosum, etc.

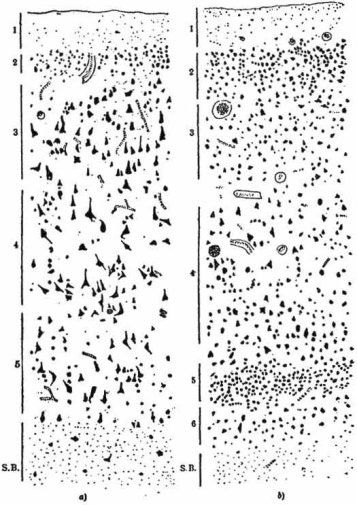

Of great importance, too, are the histological anomalies discovered by Roncoroni in the brains of[Pg 22] criminals and epileptics. In normal individuals the layers of the frontal region are disposed in the following manner:

1. Molecular layer. 2. Superficial layer of small cells. 3. Layer of small pyramidal cells. 4. Deep layer of small nerve cells. 5. Layer of polymorphous cells (see Fig. 6).

In certain animals, the dog, ape, rabbit, ox, and domestic fowl, the superficial layer is frequently non-existent and the deep one is found only to some extent in the ape.

In born criminals and epileptics there is a prevalence of large, pyramidal, and polymorphous cells, whereas in normal individuals small, triangular, and star-shaped cells predominate. Also the transition from the small superficial to the large pyramidal cells is not so regular, and the number of nervous cells is noticeably below the average. Whereas, moreover, in the normally constituted brain, nervous cells are very scarce or entirely absent in the white substance, in the case of born criminals and epileptics they abound in this part of the brain.

The abnormal morphological arrangement described by Roncoroni is probably the anatomical expression of hereditary alterations, and reveals disorders in nervous development which lead to moral insanity or epilepsy according to the gravity of the morbid conditions which give rise to them.

a) Cortical strata of the circumvolutions of the parietal lobes of a normal person.

b) Cortical strata of the circumvolutions of the parietal lobes of a criminal epileptic.

[Pg 24] These anomalies in the limbs, trunk, skull and, above all, in the face, when numerous and marked, constitute what is known to criminal anthropologists as the criminal type, in exactly the same way as the sum of the characters peculiar to cretins form what is called the cretinous type. In neither case have the anomalies an intrinsic importance, since they are neither the cause of the anti-social tendencies of the criminal nor of the mental deficiencies of the cretin. They are the outward and visible signs of a mysterious and complicated process of degeneration, which in the case of the criminal evokes evil impulses that are largely of atavistic origin.

The above-mentioned physiognomical and skeletal anomalies are further supplemented by functional peculiarities, and all these abnormal characteristics converge, as mountain streams to the hollow in the plain, towards a central idea—the atavistic nature of the born criminal.

An examination of the senses and sensibility of criminals gives the following results:

General Sensibility. Tested simply by touching[Pg 25] with the finger, a certain degree of obtuseness is noted. By using an apparatus invented by Du Bois-Reymond and adopted by my father, the degree of sensibility obtained was 49.6 mm. in criminals as against 64.2 mm. in normal individuals. Criminals are more sensitive on the left side, contrary to normal persons, in whom greater sensibility prevails on the right.

Sensibility to Pain. Compared with ordinary individuals, the criminal shows greater insensibility to pain as well as to touch. This obtuseness sometimes reaches complete analgesia or total absence of feeling (16%), a phenomenon never encountered in normal persons. The mean degree of dolorific sensibility in criminals is 34.1 mm. whereas it is rarely lower than 40 mm. in normal individuals. Here again the left-handedness of criminals becomes apparent, 39% showing greater sensibility on the left.

Tactile Sensibility. The distance at which two points applied to the finger-tips are felt separately is more than 4 mm. in 30% of criminals, a degree of obtuseness only found in 4% of normal individuals. Criminals exhibit greater tactile sensibility on the left. Tactile obtuseness varies with the class of crime practised by the individual. While in burglars, swindlers, and assaulters, it is double that of normal[Pg 26] persons, in murderers, violators, and incendiaries it is often four or five times as great.

Sensibility to the Magnet, which scarcely exists in normal persons, is common to a marked degree in criminals (48%).

Meteoric Sensibility. This is far more apparent in criminals and the insane than in normal individuals. With variations of temperature and atmospheric pressure, both criminals and lunatics become agitated and manifest changes of disposition and sensations of various kinds, which are rarely experienced by normal persons.

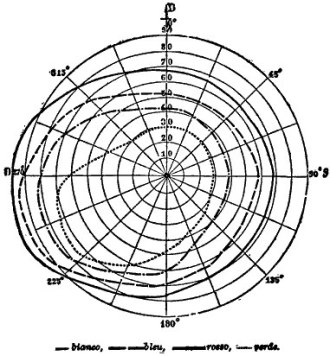

Sight is generally acute, perhaps more so than in ordinary individuals, and in this the criminal resembles the savage. Chromatic sensibility, on the contrary, is decidedly defective, the percentage of colour-blindness being twice that of normal persons. The field of vision is frequently limited by the white and exhibits much stranger anomalies, a special irregularity of outline with deep peripheral scotoma, which we shall see is a special characteristic of the epileptic.

Hearing, Smell, Taste are generally of less than average acuteness in criminals. Cases of complete anosmia and qualitative obtuseness are not uncommon.[2]

[Pg 27]Agility. Criminals are generally agile and preserve this quality even at an advanced age. When over seventy, Vilella sprang like a goat up the steep rocks of his native Calabria, and the celebrated thief "La Vecchia," when quite an old man, escaped from his captors by leaping from a high rampart at Pavia.

Strength. Contrary to what might be expected, tests by means of the dynamometer show that criminals do not usually possess an extraordinary degree of strength. There is frequently a slight difference between the strength of the right and left limbs, but more often ambidexterity, as in children, and a greater degree of strength in the left limbs.

The physical type of the criminal is completed and intensified by his moral and intellectual physiognomy, which furnishes a further proof of his relationship to the savage and epileptic.

Natural Affections. These play an important part in the life of a normally constituted individual and are in fact the raison d'être of his existence, but the criminal rarely, if ever, experiences emotions of this kind and least of all regarding his own kin. On the other hand, he shows exaggerated and abnormal fondness for animals and strangers. La Sola, a female criminal, manifested about as much[Pg 28] affection for her children as if they had been kittens and induced her accomplice to murder a former paramour, who was deeply attached to her; yet she tended the sick and dying with the utmost devotion.

In the place of domestic and social affections, the criminal is dominated by a few absorbing passions: vanity, impulsiveness, desire for revenge, licentiousness.

The ability to discriminate between right and wrong, which is the highest attribute of civilised humanity, is notably lacking in physically and psychically stunted organisms. Many criminals do not realise the immorality of their actions. In French criminal jargon conscience is called "la muette," the thief "l'ami," and "travailler" and "servir" signify to steal. A Milanese thief once remarked to my father: "I don't steal. I only relieve the rich of their superfluous wealth." Lacenaire, speaking of his accomplice Avril, remarked, "I realised at once that we should be able to work together." A thief asked by Ferri what he did when he found the purse stolen by him contained no money, replied, "I call them rogues." The notions of right and wrong appear to be completely inverted in such minds. They seem to think they have a right to[Pg 29] rob and murder and that those who hinder them are acting unfairly. Murderers, especially when actuated by motives of revenge, consider their actions righteous in the extreme.

Repentance and Remorse. We hear a great deal about the remorse of criminals, but those who come into contact with these degenerates realise that they are rarely, if ever, tormented by such feelings. Very few confess their crimes: the greater number deny all guilt in a most strenuous manner and are fond of protesting that they are victims of injustice, calumny, and jealousy. As Despine once remarked with much insight, nothing resembles the sleep of the just more closely than the slumbers of an assassin.

Many criminals, indeed, allege repentance, but generally from hypocritical motives; either because they hope to gain some advantage by working on the feelings of philanthropists, or with a view to escaping, or, at any rate, improving their condition while in prison. Thus Lacenaire, when convicted for the first time, wrote in a moving strain to his friend Vigouroux in order to get money and help from him, "Repentance is the only course left open to me. You may well feel pleased at having turned a man from a path of crime for which he was not intended by nature." A few hours later he committed another theft, and before he died remarked cynically[Pg 30] that he had never experienced remorse. When tried at the Assizes at Pavia, Rognoni pronounced a touching discourse on his repentance and refused the wine brought him in prison for some days because it reminded him of his murdered brother. But he obtained it surreptitiously from his fellow-prisoners, and when one of them grumbled at having to give up his own portion, Rognoni threatened him saying, "I have already murdered four, and shall make no bones about killing a fifth."

Sometimes remorse is advanced by criminals as a palliation of their crimes. Michelieu justified the coup de grace inflicted on his victim by saying, "When I saw her in that state, I felt such terrible remorse that I shot her dead in order not to meet her glance."

Sometimes an appearance of remorse is produced by hallucinations due to alcoholism. Philippe and Lucke imagined they saw the spectres of the persons they had murdered a short time before, but in reality they were suffering from the effects of drink and so little true remorse did they feel that on being sentenced, Philippe remarked, "If they had not sent me to Cayenne, I should have done it again." Generally speaking, what seems to be repentance is only the fear of death or some superstitious dread, which assumes an appearance of remorse, but is devoid of real feeling.

[Pg 31]A typical instance of hypocrisy and cynicism is furnished by the Marquise de Brinvilliers, the notorious poisoner, who succeeded in deceiving the venerable prison-chaplain so completely that he regarded her as a model of penitence, yet in her last moments she wrote to her husband denying her guilt and exhibited lascivious and revengeful feelings.

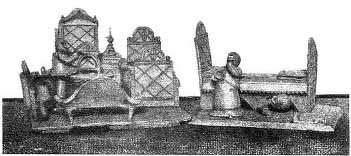

Many criminals, when in prison, model sculptural representations of their crimes with crumbs of bread (see Fig. 7).

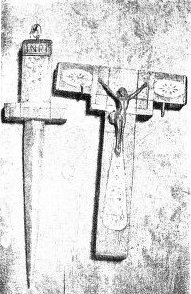

Cynicism. The strongest proof of the total lack of remorse in criminals and their inability to distinguish between good and evil is furnished by the callous way in which they boast of their depraved actions and feign pious sentiments which they do not feel. One criminal humbly entreated to be allowed to retain his own crucifix while in prison. It was subsequently discovered that the sacred image served as a sheath for his dagger (see Fig. 8).

Philippe made the following statement to one of his female companions. "My way of loving women is a very strange one. After enjoying their caresses, I take the greatest delight in strangling them or cutting their throats. Soon you will hear everyone talking about me." Shortly before he murdered his father, Lachaud said to his friends, "This evening I[Pg 32] shall dig a grave and lay my father there to rest eternally."

Sometimes, indeed, a criminal realises dimly the depravity of his actions; he rarely judges them, however, as a normal person would, but seeks to explain and justify them after his own fashion. When asked by the magistrate if he denied having stolen a horse, Ansalone replied, "Surely you do not call that a theft; a leader of brigands could hardly be expected to go on foot!"

Others consider that their actions are less criminal if their intentions were good; like Holland, who murdered to obtain food for his wife and children. Others, again, think themselves excused by the fact that many do worse things with impunity. Any circumstance, the lack or insufficiency of evidence against them or the fact that they are accused of an offence different from the one they have really committed, is seized upon as a mitigation of their guilt, and they always manifest much resentment against those who administer the law. "London thieves," observes Mayhew, "realise that they do wrong, but think that they are no worse than ordinary bankrupts."

The constant perusal of newspaper reports leads criminals to believe that there are a great many rogues in higher circles, and by taking exceptions to[Pg 33] be the rule, they flatter themselves that their own actions are not very reprehensible, because the wealthy are not censured for similar actions.

| Fig. 7 | Fig. 8 | |

|  | |

| Figures made in Prison Murder of a Sleeping Victim Work of a Prisoner (see page 31) | Crucifix Poignard (see page 31) |

These instances show that criminals are not entirely unable to distinguish between right and wrong. Nevertheless, their moral sense is sterile because it is suffocated by passions and the deadening force of habit.

In the cant of Spanish thieves, justice is called "la justa" (the just), and this name is given in French slang to the Assizes, but, as Mayor observes, it may be applied ironically.

In alluding to the unknown author of the crimes committed in reality by himself, the murderer Prévost remarked, "Whoever it is, he is bound to end by the guillotine sooner or later." In such cases, although a sense of truth and justice exists, the desire to act according to it is lacking.

"It is one thing [observes Harwick] to possess a theoretical notion of what is right and wrong, but quite another to act according to it. In order that the knowledge of good should be transformed into an ardent desire for its triumph, as food is converted into chyle and blood, it must be urged to action by elevated sentiments, and these are generally lacking in the criminal. If, on the contrary, good feelings really exist, the individual desires to do right and his convictions are translated into action with the same energy that he displayed in doing wrong."

[Pg 34]A philanthropist once invited a number of young London thieves to a friendly gathering, and it was noticed that the most hardened offenders were greeted with the greatest amount of applause from the company. Nevertheless, when the President requested one of them to change a gold coin outside, and he did not return, those present showed great indignation and anxiety, abusing and threatening their absent companion, whose ultimate return was hailed with genuine relief. In this case, no doubt, envy and vanity played as great a part as a sense of integrity, in the resentment shown at this fancied breach of faith.

In the prisons at Moscow, offences against discipline are dealt with by the offenders' fellow-prisoners. The convict population on the island of San Stefano compiled spontaneously a Draconian code to quell internal discord arising from racial jealousies.

Treachery. This species of morality and justice, which unexpectedly makes its appearance in the midst of a naturally unrighteous community, can only be forced and temporary. When, instead of reaping advantages, interests and passions are injured by acting rightly, these notions of justice, unsustained by innate integrity suddenly fail. Contrary to universal belief, criminals are very prone to[Pg 35] betray their companions and accomplices, and are easily induced to act as informers in the hope of gaining some personal advantage or of injuring those they envy or suspect of treachery towards themselves.

"Many thieves," says Vidocq, "consider it a stroke of luck to be consulted by the police." In fact, Bouscaut, one of a notorious band of malefactors in France, was chiefly instrumental in causing the arrest of the gang; and the brigand Caruso aided the authorities in capturing his former companions.

Vanity. Pride, or rather vanity, and an exaggerated notion of their own importance, which we find in the masses, generally in inverse proportion to real merit, is especially strong in criminals. In the cell occupied by La Gala, the following notice was found in his handwriting: "March 24th. On this date La Gala learnt to knit." Another criminal, Crocco, tried hard to save his brother, "Lest," he said, "my race should die out." Lacenaire was less troubled by the death-sentence than by adverse criticisms of his bad verse and the fear of public contempt. "I do not fear being hated," he is reported to have said, "but I dread being despised—the tempest leaves traces of its passage, but unobserved the humble flower fades."

Thus thieves are loth to confess that they are[Pg 36] guilty of only petty larceny, and are sometimes prompted by vanity to commit more serious robberies. The same false shame is common to fallen women, among whom contempt is incurred, not by excess of depravity but by the failure to command high prices. Grellinier, a petty thief, boasted in court of imaginary offences, with the desire of appearing in the light of a great criminal. The crimes in the haunted castle, attributed by Holmes to himself, were certainly in part inventions. The female poisoner, Buscemi, when writing to her accomplice, signed herself, "Your Lucrezia Borgia."

One of the most frequent causes of modern crime is the desire to gratify personal vanity and to become notorious.

Impulsiveness. This is another and almost pathognomonical characteristic of born criminals, and also, as we shall see later on, of epileptics and the morally insane. That which in ordinary individuals is only an eccentric and fugitive suggestion vanishing as soon as it arises, in the case of abnormal subjects is rapidly translated into action, which, although unconscious, is not the less dangerous. A youth of this impulsive type, returning home one evening flushed with wine, met a peasant leading his ass and cried out, "As I have not come to blows with anyone to-day, I must vent my rage on this beast,"[Pg 37] at the same time drawing his knife and plunging it several times into the poor animal's body (Ladelci, Il Vino, Rome, 1868). Pinel describes a morally insane subject, who was in the habit of giving way to his passions, killing any horses that did not please him and thrashing his political opponents. He even went to the length of throwing a lady down a well, because she ventured to contradict him.

"The most trifling causes [remarks Tamburini, speaking of Sbro...] that stand in the way of his wishes, provoke a fit of rage in which he appears to lose all self-control, like little children, who in resenting any offence show no sense of proportion. The most trivial reasons for disliking anyone awaken in him an irresistible desire to kill the object of his aversion, and if any new blasphemy rises to his lips, he feels constrained to repeat it."

A thief once said to my father: "It is in our very blood. It may be only a pin, but I cannot help taking it, although I am quite ready to give it back to its owner." The pickpocket Bor... confessed that at the age of twelve he had begun to steal in the streets and at school, to the extent of taking things from under his schoolfellows' pillows, and that it was impossible for him to resist stealing, even when his pockets were full. If he had not stolen some article before going to bed, he was unable to sleep, and when midnight struck, he felt obliged to take the first thing that came to his[Pg 38] hand, destroying it frequently as soon as he had appropriated it.

"To give up stealing," said Deham to Lauvergne, "would be like ceasing to exist. Stealing is a passion that burns like love and when I feel the blood seething in my brain and fingers, I think I should be capable of robbing myself, if that were possible." When sentenced to the galleys, he stole the bands from the masts, nails, and copper plates, and he himself fixed the number of lashes he was to receive after each of these exploits, which did not prevent his recommencing stealing directly afterward (Les Forçats, p. 358).

Ponticelli once saw a thief, who was dying of consumption, steal an old slipper from his neighbour and hide it under the bedclothes.

Vindictiveness. Closely allied to this impulsiveness and exaggerated personal vanity, we find an extraordinary thirst for revenge. Lebuc murdered a man who had stolen some matches from him. Baron R... caused the death of a man, because he had failed to order a religious procession to halt under the windows of his palace.

"To see expire the one you hate—

Such is the joy of the gods.

My sole desire is to hate and be avenged."

wrote Lacenaire.

[Pg 39]After a slight dispute with Voit, whose hospitality he had enjoyed, Renaud threw his friend down a well. He was arrested, and when Voit, who had been rescued, pardoned him, he said, "I only regret not having finished him, but when I come out of prison, I will do so." And he kept his word.

The tattooing on the persons of criminals and their writings while in prison are full of solemn oaths of vengeance. A female thief once said, "If it were true that those who refuse to pardon will be damned eternally, I should still withhold my forgiveness."

Cruelty depends on moral and physical insensibility, those incapable of feeling pain being indifferent to the sufferings of others.

The post of executioner was eagerly competed for at the prison of Rochefort. Mammon used to drink the blood of his victims and when this was not to be had, he drank his own. The executioner Jean became so maddened by the sight of blood flowing beneath his lash, that guards were stationed to prevent undue prolongation of the punishment. Dippe wrote: "My chief pleasure is beheading. When I was young, stabbing was my sole pastime."

It has often been observed that the ferocity of women exceeds that of men. Rulfi killed her own niece, whom she detested, by thrusting long pins[Pg 40] into her, and the female brigand Ciclope reproached her lover for murdering his victims too quickly.

Idleness. Like savages, criminals are dominated by an incorrigible laziness, which in certain cases leads them to prefer death from starvation to regular work. This idleness alternates with periods of ferocious impulsiveness, during which they display the greatest energy. Like savages, too, they are passionately fond of alcohol, orgies, and sensual pleasures, which alone rouse them to activity.

Orgies. Those who have observed children absorbed all day long by a game that pleases them, can understand the meaning of these words, spoken by a woman: "Criminals are grown-up children." The love of habitual debauch is so intense that, as soon as thieves have made some great haul or escaped from prison, they return to their haunts to carouse and make merry, in spite of the evident danger of falling once more into the hands of the police.

Gambling. The passion for gambling is so strong that the criminal is always in a penniless condition, no matter how much treasure he has appropriated, and cases of starvation in prison are not unknown, prisoners having sold their rations in order to gratify this vice.

Games. Many primitive and cruel amusements, similar to the pastimes of savages, have been preserved[Pg 41] or reconstructed by criminals. Such are the games known to Italian offenders as "La Patta," in which one of the players tries to avoid being struck while passing his head between two points brought together horizontally by another, who stands with his arms outstretched; and "La Rota," in which the players run in a circle, one behind the other, seeking to escape, by dodging, the blows from a stout stick, aimed at them by one of their companions.

Intelligence is feeble in some and exaggerated in others. Prudence and forethought are generally lacking. A very common characteristic is recklessness, which leads criminals to run the risk of arrest for the sake of being witty, or to leave some blood-stained weapon on the very spot where they have committed a crime, notwithstanding the fact that they have taken a hundred precautions to avoid detection. This same recklessness prompts them, when the danger is scarcely past, to make verses or pictures of their exploits or to tattoo them upon their persons, heedless of consequences.

Zino relates the story of a Sicilian schoolboy, who illustrated his criminal relations with his schoolfellows by a series of sketches in his album. A certain Cavaglia, called "Fusil" robbed and murdered an accomplice and hid the body in a cupboard. He was arrested and in prison decided to commit[Pg 42] suicide a hundred days after the date of his crime, but before doing so, he adorned his water-jug with an account of his misdeed, partly in pictures and partly in writing, as though he desired to raise a monument to himself (see Fig. 9). The clearest and strangest instance of this recklessness was furnished by a photograph discovered by the police, in which, at the risk of arrest and detection, three criminals had had themselves photographed in the very act of committing a murder.

Slang. This is a peculiar jargon used by criminals when speaking among themselves. The syntax and grammatical construction of the language remain unchanged, but the meanings of words are altered, many being formed in the same way as in primitive languages; i.e., an object frequently receives the name of one of its attributes. Thus a kid is called "jumper," death "the lean or cruel one," the soul "the false or shameful one," the body "the veil," the hour "the swift one," the moon "the spy," a purse "the saint," alms "the rogue," a sermon "the tedious one," etc. Many words are formed as among savages, by onomatopoeia, as "tuff" (pistol), "tic" (watch), "guanguana" (sweetheart), "fric frac" (lottery).

[Pg 43]The necessity of eluding police investigations is the reason usually given for the origin of this slang. No doubt it was one of the chief causes, but does not explain the continued use of a jargon which is too well known now to serve this purpose; moreover, it is employed in poems, the object of which is to invite public attention, not to avoid it, and by criminals in their homes where there is no need for secrecy.

Pictography. One of the strangest characteristics of criminals is the tendency to express their ideas pictorially. While in prison, Troppmann painted the scene of his misdeed, for the purpose of showing that it had been committed by others. We have already mentioned the rude illustrations engraved by the murderer Cavaglia on his pitcher, representing his crime, imprisonment, and suicide. Books, crockery, guns, all the utensils criminals have in constant use, serve as a canvas on which to portray their exploits.

From pictography it is but an easy step to hieroglyphics like those used by ancient peoples. The hieroglyphics of criminals are closely allied to their slang, of which in fact they are only a pictorial representation, and, although largely inspired by the necessity for secrecy, show, in addition, evident atavistic tendencies.

De Blasio has explained the meaning of the hieroglyphics used by the "camorristi" (members[Pg 44] of the camorra at Naples), especially when they are in prison. For instance, to indicate the President of the Tribunal, they use a crown with three points; to indicate a judge, the judge's cap (see Fig. 10). The following is a list of some of the hieroglyphics mentioned by De Blasio:

Police Inspector—a hat like those worn by the Italian soldiers who are called Alpini (a helmet with flat top and an upright feather on the left side).

Public Prosecutor—an open-mouthed viper (see Fig. 10).

Carabineer—a bugle.

Theft—a skull and cross-bones.

Commissary of the Police—a dwarf with the three-cornered hat worn by the carabinieri.

Arts and Industries of the Criminal. Although habitual criminals show a strong aversion to any kind of useful labour, in prison and at large, they, nevertheless, apply themselves with great diligence to certain tasks, sometimes of an illegal nature, such as the manufacture of implements to aid them in escaping,[Pg 45] sometimes merely artistic, such as modelling, with breadcrumbs, brickdust, or soap, the figures of persons. Sometimes they make baskets, machines, dominoes, draughts, playing-cards, etc., or form means of communication with their fellow-prisoners and construct weapons for executing their schemes of vengeance. They also devote themselves to eccentric and useless occupations, like the training of animals, such as mice, marmosets, birds, and even fleas (Lattes). This morbid and misguided activity, which frequently shows gleams of talent, might well be utilised for increasing the scope of prison industries.

This personal decoration so often found on great criminals is one of the strangest relics of a former state. It consists of designs, hieroglyphics, and words punctured in the skin by a special and very painful process.

Among primitive peoples, who live in a more or less nude condition, tattooing takes the place of decorations or ornamental garments, and serves as a mark of distinction or rank. When an[Pg 46] Eskimo slays an enemy, he adorns his upper-lip with a couple of blue stripes, and the warriors of Sumatra add a special sign to their decorations for every foe they kill. In Wuhaiva, ladies of noble birth are more extensively tattooed than women of humbler rank. Among the Maoris, tattooing is a species of armorial bearings indicative of noble birth.

According to ancient writers, tattooing was practised by Thracians, Picts, and Celts. Roman soldiers tattooed their arms with the names of their generals, and artisans in the Middle Ages were marked with the insignia of their crafts. In modern times this custom has fallen into disuse among the higher classes and only exists among sailors, soldiers, peasants, and workmen.

Although not exclusively confined to criminals, tattooing is practised by them to a far larger extent than by normal persons: 9% of adult criminals and 40% of minors are tattooed; whereas, in normal persons the proportion is only 0.1%. Recidivists and born criminals, whether thieves or murderers, show the highest percentage of tattooing. Forgers and swindlers are rarely tattooed.

Sometimes tattooing consists of a motto symbolical of the career of the criminal it adorns. Tardieu found on the arm of a sailor who had served various terms of imprisonment, the words, "Pas de chance."[Pg 47] The notorious criminal Malassen was tattooed on the chest with the drawing of a guillotine, under which was written the following prophecy: "J'ai mal commencé, je finirai mal. C'est la fin qui m'attend."

Tattooing frequently bears witness to indecency. Of 142 criminals examined by my father, the tattooing on five showed obscenity of design and position and furnished also a remarkable proof of the insensibility to pain characteristic of criminals, the parts tattooed being the most sensitive of the whole body, and therefore left untouched even by savages.

Another fact worthy of mention is the extent to which criminals are tattooed. Thirty-five out of 378 criminals examined by Lacassagne were decorated literally from head to foot.

In a great many cases, the designs reveal violence of character and a desire for revenge. A Piedmontese sailor, who had perpetrated fraud and murder from motives of revenge, bore on his breast between two daggers, the words: "I swear to revenge myself." Another had written on his forehead, "Death to the middle classes," with the drawing of a dagger underneath. A young Ligurian, the leader of a mutiny in an Italian Reformatory, was tattooed with designs representing all the most important episodes of his life, and the idea of revenge was[Pg 48] paramount. On his right forearm figured two crossed swords, underneath them the initials M. N. (of an intimate friend), and on the inner side, traced longitudinally, the motto: "Death to cowards. Long live our alliance."

Tattooing, as practised by criminals, is a perfect substitute for writing with symbols and hieroglyphics, and they take a keen pleasure in this mode of adorning their skins.

Of atavistic origin, also, is the practice, common to members of the camorra, of branding their sweethearts on the face, not from motives of revenge, but as a sign of proprietorship, like the chiefs of savage tribes, who mark their wives and other belongings; and the form of tattooing called "Paranza," which distinguishes the various bands of malefactors,—the band of the "banner," of the "three arrows," of the "bell-ringer," of the "Carmelites," etc.

All the physical and psychic peculiarities of which we have spoken are found singly in many normal individuals. Moreover, crime is not always the result of degeneration and atavism; and, on the other hand, many persons who are considered perfectly normal are not so in reality. However, in normal individuals, we never find that accumulation[Pg 49] of physical, psychic, functional, and skeletal anomalies in one and the same person, that we do in the case of criminals, among whom also entire freedom from abnormal characteristics is more rare than among ordinary individuals.

Just as a musical theme is the result of a sum of notes, and not of any single note, the criminal type results from the aggregate of these anomalies, which render him strange and terrible, not only to the scientific observer, but to ordinary persons who are capable of an impartial judgment.

Painters and poets, unhampered by false doctrines, divined this type long before it became the subject of a special branch of study. The assassins, executioners, and devils painted by Mantegna, Titian, and Ribera the Spagnoletto embody with marvellous exactitude the characteristics of the born criminal; and the descriptions of great writers, Dante, Shakespeare, Dostoyevsky, and Ibsen, are equally faithful representations, physically and psychically, of this morbid type.

The conclusions of instinctive observers have found expression in many proverbs, which warn the world against the very characteristics we have noted in criminals.