Title: Twenty-Five Years in the Black Belt

Author: William James Edwards

Release date: January 23, 2010 [eBook #31055]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bryan Ness, Stephanie Eason, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. (This

book was produced from scanned images of public domain

material from the Google Print project.)

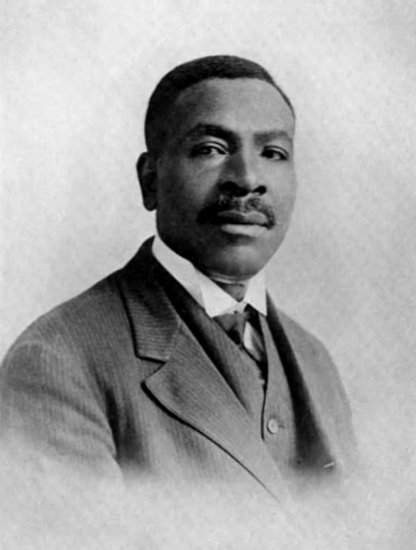

William J. Edwards

| chapter | page | ||

| 1. | Childhood Days | 1 | |

| 2. | Shadows | 7 | |

| 3. | A Ray of Light | 13 | |

| 4. | Life at Tuskegee | 18 | |

| 5. | Reconnoitering | 26 | |

| 6. | Founding the Snow Hill School | 35 | |

| 7. | Small Beginnings | 37 | |

| 8. | Campaigning for Funds in the North | 43 | |

| 9. | Results | 49 | |

| 10. | Origin of the Jeanes Fund | 54 | |

| 11. | Appreciation | 56 | |

| 12. | Graduates and Ex-Students | 63 | |

| 13. | The Solution of the Negro Problem | 77 | |

| 14. | The Greatest Menace of the South | 86 | |

| 15. | The Negro Exodus | 94 | |

| 16. | The Negro and the Public Schools of the South | 100 | |

| 17. | Where Lies the Negro’s Opportunity? | 104 | |

| 18. | School Problems of a Tuskegee Graduate | 109 | |

| 19. | Benefits Wrought by Hardships | 115 | |

| 20. | The Negro and the World War | 120 | |

| Appendix | 127 |

| William J. Edwards | Frontispiece | |||

| Uncle Charles Lee and His Home in the Black Belt | Facing | Page | 32 | |

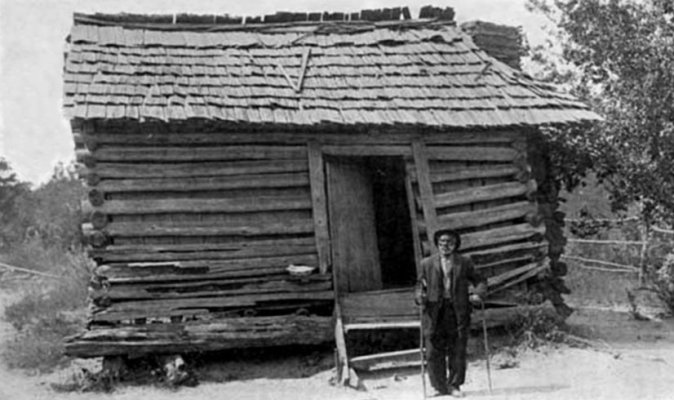

| First Trustees of Snow Hill and Two of Their Wives | “ | “ | 36 | |

| Partial View of Snow Hill Institute | “ | “ | 48 | |

| A New Type of Home in the Black Belt | “ | “ | 52 | |

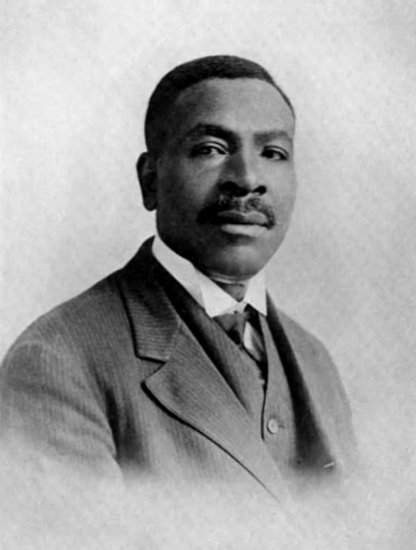

| Typical Log Cabin in the Black Belt | “ | “ | 60 | |

| Home of a Snow Hill Graduate | “ | “ | 60 | |

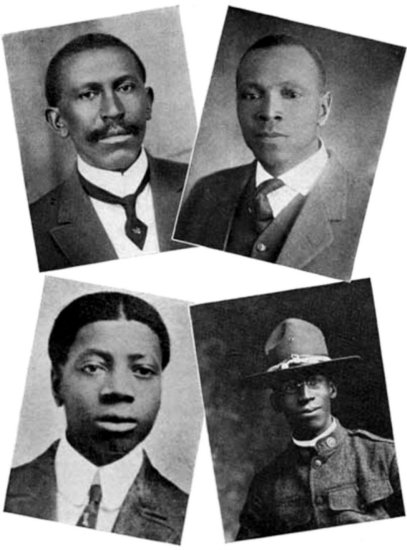

| Graduates of Snow Hill Institute | “ | “ | 72 | |

| Teachers of Snow Hill Institute | “ | “ | 100 | |

In bringing this book before the public, it is my hope that the friends of the Snow Hill School and all who are interested in Negro Education may become more familiar with the problems and difficulties that confront those who labor for the future of a race. I have had to endure endless hardships during these twenty-five years, in order that thousands of poor negro youths might receive an industrial education,—boys and girls who might have gone into that demoralized class that is a disgrace to any people and that these friends may continue their interest in not only Snow Hill but all the schools of the South that are seeking to make better citizens of our people. I also hope that the interest may be sustained until the State and Nation realize that it is profitable to educate the black child as well as the white.

To me, these have been twenty-five years of self denial, of self sacrifice, of deprivation, even of suffering, but when I think of the results, I am still encouraged to go on; when I think of the work that Mr. McDuffie is doing at Laurinburg, N. C., Brown at Richmond, Ala., Knight at Evergreen, Ala., Mitchell at W. Butler, Ala., Carmichael at Perdue Hill, Ala., Brister at Selma, Ala., and hundreds of others, I feel that the sacrifice has not been in vain, so I continue believing[Pg xii] that after all the great heart of the American people is on the right side. I think that to-day, the Negro faces the dawn,—not the twilight,—the morning,—not the evening.

In my passionate desire to hasten that time and with the crying needs of my race at heart, I choose this opportunity for making an appeal in their behalf.

“Lord, and what shall this man do?” (John 21.)

Man is a relative being and should be thus considered. The status of my brother then will always serve as a standard of value by which my own conduct can be measured; by his standard mine may become either high or low, broad or narrow, deep or shallow. This is the theory that underlies all humanitarian work. This is the great dynamic force of the Christian life.

No question is being asked by the American people more earnestly today than this one: “Lord, What shall this man, the Negro, do,—this black man upon whom centuries of ignorance have left their marks?” He has made a faithful slave, a courageous soldier, and when trained and educated, an industrious and law-abiding citizen, yet he is troubled on every side. What shall he do? Uneducated, undisciplined, untrained, he is often ferocious or dangerous; he makes a criminal of the lowest type for he is the product of ignorance.

Crime has increased in proportion as educational privileges have been withdrawn. This brings the Negro face to face with a most dangerous criminal force. What shall this man do? It is true that the white man is further up on the ladder of civilization than the Negro, but the Negro desires to climb and has made rapid strides, according to his chances.

[Pg xiii]Christ’s answer to Peter was, “What is that to thee, follow thou Me.” John’s future welfare evidently depended upon Peter’s ability to follow Christ. So the future work and welfare of the Negro in the Black-Belt of the South depend largely upon the Christian work of the southern white man. The Negro needs justice and mercy from the courts of the land and asks for equal rights in educational opportunities.

We admit that there is a difference between the white man and the Negro, but the difference is not as great as was the difference between Christ and His disciples. We admit that the white man is above the Negro, but not so high as was Christ above His disciples. The very fact that Christ was superior to His disciples served to Him as a reason why He should minister unto them. The superiority of the white man to his black brother can only be shown by the white man’s willingness to minister unto him. Lord, what shall this black man do?

Many great problems confront the people of the rural South, namely, this Negro Problem and the problem of sufficient labor supply. In a practical way I wish to consider the relation of the Negro to the labor problem of the rural South. It is a fact that today many of the best farms of the South have been turned into pastures because of the lack of labor; other farms have been sold, and still others are growing up in weeds because there is no one to till them. This condition obtains in a very marked degree in almost every southern state. Certainly in most of the Agricultural Sections.

Before investigating the cause of this condition, men[Pg xiv] of influence and power have hastened to proclaim through the press and otherwise, that the responsibility rests upon the Negro. They say that the Negro is lazy, worthless, criminal and will not work and therefore they are compelled to have immigrants to work these fields. That there are lazy, worthless and criminal Negroes, we do not deny, but we do deny that as a race they are such.

The facts are these: first, the South, unlike other sections of the country, has not had thousands of immigrants to come into her borders year after year to do her work, but has depended solely upon the increase in her native population for this purpose. This increase has not kept pace with the marvellous growth and development of that section, hence, the cry for labor. Second, scarcity of labor in that section is due in part, to ignorance and a false idea of real freedom. Men with such ideas do not work long in any one place, but rove from section to section and work enough to keep themselves living. This labor is not only unprofitable to the individual, but is not satisfactory to the employers. Third, the labor trouble in the rural South is due mostly to the way in which the landlords and merchants treat their tenants and customers.

The great mass of Negroes in the South either rent the lands or work them on shares. This rent varies according to the kind of crops that are made. If the tenant makes a good crop this year, he must expect to pay more rent the next year, or his farm will be rented to another at higher figures. Of course, the Negroes are ignorant and are unable to keep their own accounts. Sometimes these Negro farmers pay as much[Pg xv] as 50%, 75% and 100% on the goods and provisions which they consume during the year.

This method of renting lands and selling goods according to the condition of the crops, is repeated year after year. I know ignorant farmers who have been working under these conditions for twenty-five and thirty years, who have never been able to get more than $15 or $20 in any one year during this period. These are not worthless and shiftless Negroes, but persons who work hard from Monday morning until Saturday night. As a rule, they are on their farms at sunrise, and remain there until sunset. They have their dinners brought to them in the fields. I have seen small families grow into large ones under these conditions. I have also seen infants grow to manhood under same. Now, these people who have been working in this way for twenty-five and thirty years are becoming discouraged. When you ask them why they do not ditch, fertilize, and improve their farms, their answer is, that if they do this, the next year they will either have to pay more rent or hunt another home for themselves.

It seems to be the policy of the landlords and the merchants of the rural South to keep their tenants and customers in debt. It is this abominable method of the landlords and tenants of the rural South more than anything else, that has caused many of the best farming lands there to be turned into pastures, others to be sold at sheriff sale, and still others to be growing up in weeds. Another menace is loss of fertility of the soil.

The problem is, how can we stop these people from[Pg xvi] leaving the country for the cities and other places of public works and again reclaim these waste fields? It was once thought that the places of these Negroes could be supplied by immigrants from foreign countries, but this hope is now almost abandoned. In fact, the few immigrants who have gone into that section have, in many instances, been oppressed almost as much as the Negroes, many have gone to other parts of the country or have returned to their homes. So we find ourselves face to face with large and fertile agricultural areas in the South with no labor to till them.

The remedy of these evils lies in the Negro himself. He is best suited to the work, best adapted to the climate, and understands the southern white man better than anyone else. Furthermore, he knows the white man; knows his disposition and inclinations, and therefore, knows what is so called his place. He feels that justice is wanting in the courts of the South and he therefore tries to avoid all troubles. Most of all, he prays for a chance to work and educate his children. He labors and waits thus patiently because he has faith in the American people. He believes that ere long the righteous indignation of this people will be aroused and like the great wave of prohibition, will sweep this country from center to circumference, and then every man will be awarded according to his several abilities.

These waste places can be reclaimed and the guttered hills made to blossom, only by giving the Negro a common education combined with religious, moral and industrial training and the opportunity to at least[Pg xvii] own his home, if not the land he cultivates. The Negro must be taught to believe that the farmer can become prosperous and independent; that he can own his home and educate his children in the country. If he can, and he can be taught these things, in less than ten years, every available farm in the rural South will be occupied.

WILLIAM J. EDWARDS.

All that I know of my ancestors was told to me by my people. I learned from my grandfather on my mother’s side that the family came to Alabama from South Carolina. He told me that his mother was owned by the Wrumphs who lived in South Carolina, but his father belonged to another family. For some cause, the Wrumphs decided to move from South Carolina to Alabama; this caused his mother and father to be separated, as his father remained in South Carolina. The new home was near the village of Snow Hill. This must have been in the Thirties when my grandfather was quite a little child. He had no hope of ever seeing his father again, but his father worked at nights and in that way earned enough money to purchase his freedom from his master. So after four or five years he succeeded in buying his own freedom from his master and started out for Alabama. When he arrived at Snow Hill, he found his family, and Mr. Wrumphs at once hired him as a driver. He remained with his family until his death, which[Pg 2] occurred during the war. At his death one of his sons, George, was appointed to take his place as driver.

As I now remember, my grandfather told me that his mother’s name was Phoebe and that she lived until the close of the war. My grandfather married a woman by the name of Rachael and she belonged to a family by the name of Sigh. His wife’s mother came directly from Africa and spoke the African language. It is said that when she became angry no one could understand what she said. Her owner allowed her to do much as she pleased.

My grandfather had ten children, my mother being the oldest girl. She married my father during the war and, as nearly as I can remember, he told me that it was in 1864. Three children were born to them and I was the youngest; there was a girl and another boy.

I know little of my father’s people, excepting that he repeatedly told me that they came from South Carolina. So it is, that while I can trace my ancestry back to my great-grandparents on my mother’s side, I can learn nothing beyond my grandparents on my father’s side. My grandfather was a local preacher and could read quite well. Just how he obtained this knowledge, I have never been able to learn. He had the confidence and respect of the best white and colored people in the community and sometimes he would journey eight or ten miles to preach. Many times at these meetings there were nearly as many whites as colored people in the audience. He was indeed a grand old man. His name was James and his father’s name was Michael. So after freedom he took the name of James Carmichael.

[Pg 3]One of the saddest things about slavery was the separation of families. Very often I come across men who tell me that they were sold from Virginia, South Carolina or North Carolina, and that they had large families in those states. Since their emancipation, many of these have returned to their former states in search of their families, and while some have succeeded in finding them, there are those who have not been able to find any trace of their families and have come back again to die.

Sometimes we hear people attempt to apologize for slavery, but slavery at its best was hard and cruel. Often the old slaves tell me of their bitter experience. Even today, there are everywhere in the South many ex-slaves who lived their best days before and during the civil war. Many of these men and women found themselves alone at the close of the war, having been sold away from their families while they were slaves.

I was born at Snow Hill, Wilcox County, Alabama, September 12th, 1869, three-quarters of a mile east of where Snow Hill Institute now stands. My mother died September 9th, 1870, at which time I lacked three days of being one year old. From all I can learn my mother was very religious. She was a great praying woman and almost at every meeting held in the neighborhood she would be called upon to pray. In fact, she was sent for miles around to pray at these meetings. My mother’s death left my father with three children, I being the youngest. He succeeded in getting his mother, who was cooking for her white people in Selma, Alabama, to come and take us in charge. My name was Ulyses Grant Edwards, but my [Pg 4]grandmother, who had been with white people since emancipation, changed my name to William. I afterward added to this my grandfather’s name of James.

My father went away to work and I remained with my grandmother. We lived about one mile from the “quarter,”—that is, the collection of slaves’ cabins. We had about three acres of ground cleared around our cabin and my grandmother and I farmed. I do not know how old I was when I began working, for I have been a farm hand ever since I could remember anything. We usually made one bale of cotton each year and about twenty-five or thirty bushels of corn. Sometimes my grandfather would do our plowing and at other times,—as we had no stock,—my grandmother and I worked out for others to get our plowing done.

In the summer time it was the custom for little Negro boys to wear only one garment, a shirt. Sometimes, however, my grandmother would be unable to get one for me and in that case she would take a crocus sack or corn sack and put two holes in it for my arms and one for my head. In putting on a sack shirt for the first time the sensation was extremely irritating. It seemed as if a thousand pins were sticking me all at once, but after a few days it would become all right and I could wear it comfortably. For several summers this was my only garment.

Sometimes we would raise a pig during the summer to kill in the winter and sometimes we had a cow to milk. At such times we had plenty to eat, but at other times we had neither a pig nor a cow and then we had hard times in the way of getting something to eat.[Pg 5] Some days our only diet was corn-bread and corn coffee.

When I was old enough, I was sent to school for two or three months each winter. Here again I had a hard time, as we usually carried our dinner in a little tin bucket. Sometimes I had nothing but bread and when recess came for dinner, I went away by myself and ate my bread and drank water. As long as I could keep out of the way of the other children, no one was the wiser and I did not mind it, but some of the children began to watch me and in that way found that I had nothing but bread, and when they told the others, they would laugh and make fun of me. This would make me feel badly and sometimes I cried, but I did not stop school for this. My one desire was to learn to read the Bible for my old grandmother, who like my mother, was very religious. At last I was able to read the Bible for her. She would listen for hours and too, she would sing such songs as, “Roll, Jordan Roll.”

Saturdays were mill days and I had to take the corn on my shoulder and go to the mill, which was four or five miles away. It always took me from four to five hours to make this trip, as I had to stop by the way several times to rest.

By this time my brother and sister were large enough to do good work on the farm. My grandfather and grandmother for whom they were working, now desired to take them wholly from my old grandmother. The Justice of the Peace said that the children might decide the matter. My brother chose to go to my grandfather’s but my sister came back home with the grandmother who had reared us from[Pg 6] infants. Of course, I did not go to court, because they all knew that there was no chance of my leaving my grandmother.

In the early spring of 1880 while on one of my trips to the mill the thought dawned upon me that my grandmother was very old and must soon die. I cried all the way to the mill and back. I could not see how I would live after she was gone. I did not tell anybody why I was crying. On a June night, she became severely ill and died. All she said to us during her illness was: “Children, I have been waiting for this hour a long time.”

After the death of my grandmother, her daughter Marina Rivers, who was herself a widow and well on in years, came to live with us that year. I soon learned to love her as I had my grandmother and never once thought of leaving her for my mother’s people. We gathered the crop that fall and when all was over, my father, whom I had not seen for five or six years, came to carry my sister and myself to Selma, where he was staying. The thought of going to the city filled me with joy and the time to go could not come too soon for me.

We arrived in Selma several days before Christmas. Here everything was strange to me, as I had never been in a city before. I did not know any one and it was not long before I was crying to return to Snow Hill. My father gave me to understand then, that Selma was my home now and that I should not be permitted to return to Snow Hill. He said that he was going to put me in school when the New Year came, but when the time came nothing was said about school. He gave us little care and often we were in need of food and clothes.

After spending a few weeks doing nothing, I went out one day to hunt for work and succeeded in getting a job at the compress, where they reduced the size of a bale of cotton by one-half and clipped the tires. My job was to straighten out the bent tires. I got twenty-five cents a day for this. That week I made one dollar and fifty cents. This was the most money I had ever had. I spent almost all of it for provisions and that night my sister cooked a great supper. Finally, my father said that he would save my wages for me, but if he did he has it still, as I never have seen any that he collected.

I had not been in Selma long before I was taken ill. That misfortune changed my whole life. I had no[Pg 8] medical attendance and suffered greatly. Sometimes I prayed and sometimes I cried. The news reached Snow Hill that I was sick and not being cared for. As soon as she could, my aunt Rina came to Selma for me and carried me home.

On my return to Snow Hill I was sick and emaciated, but few people welcomed me. Many tried to discourage my aunt for bringing me back. They gave me about three months to live. I was glad to be at home again and had the consolation of knowing that should I die I would be buried in the old burying ground.

I was unable at the time to do any work on the farm, so I was put to the task of raising chickens. I took personal interest in the little chicks. I had a name for each one of them. I would follow them around the yard and see them work for their food. When I was weary of this I would go to an old deserted cabin nearby, taking a few old books and the Bible; there unmolested I would spend hours at a time reading the Bible and pondering over the books. One of the books was an old Davies’ Practical Arithmetic. Nothing gave me more pleasure than working out new sums for the first time. I kept up this practice until I had read the New Testament through several times and had worked every problem in the arithmetic. In addition to this I would gather up wood and carry it home for the people to cook with.

My aunt and her daughter were very poor and had to work each day for what they could get to eat. It pained me because I could not go out and work for something to eat as I had done in Selma. I never ate[Pg 9] a full meal although my aunt and her daughter insisted upon my doing so; I felt that I had no right to eat up what they had worked so hard to get, while I was doing nothing that was worth while. My aunt’s daughter had a son who was one month older than I; he was well grown for his age and always was the picture of health. We all lived in a one-room cabin and there were three beds in it, besides it was the kitchen and dining-room as well. My aunt and her daughter wanted me to sleep at nights with their boy, but he objected, so I would not force myself upon him. I asked them to give me one or two old quilts and I would spread these upon the floor of the cabin at night for my bed. I would get up early and roll them up and store them away in some dark corner of the cabin until the next night. I slept in this manner for several years.

After I had been at home for several months and my condition did not improve, my aunt went about begging people for nickels and dimes to take me to the local physician. I think she raised about three dollars in this way and succeeded in getting a doctor to treat me, but he gave my aunt to understand that she had to pay cash for each treatment.

I shall never forget one Sunday when a great many of the neighbors came to our home, they began telling my aunt what they would do with me if they were in her place. At the time I was in the back-yard watching the chicks. Some one said that she should send me to the poorhouse, others said that she had done so much for me, it was time that some of my other people should take me and share in the burden, while others[Pg 10] said that I should be driven away and go wherever I could find shelter. I was so offended at hearing this that I hobbled down the hill and there under a pine tree, which now stands, I prayed for an hour or more for God to let me die. After this prayer I lay down, folded my arms and closed my eyes, to see if my prayer would be answered. After waiting for awhile I finally decided to get up and I felt better then than I had felt for several months. I have made many prayers since then, but never since have I prayed to die.

None of the solicitations and advices from our good friends could change my aunt’s attitude towards me. In fact, she was more determined now than ever to care for me. The next year she rented a little patch and worked it as best she could and that fall she cleared a little money. As the local physician had done me no good, she took me to Dr. George Keyser who lived in the town of Richmond, eight or ten miles away. Dr. Keyser had the reputation of being the best physician in that section of the state and people would come for twenty-five and thirty miles around to be treated by him. But we had also heard that he was a man who would not treat any one without having his money down. As I remember, my aunt paid him five dollars on the first visit and each time after that she would send whatever she could get. I used to borrow a mule from one of the neighbors to ride to see him. Sometimes when my medicine gave out and I had to go without any money, I would pray to God the whole distance that he might soften the doctor’s heart so that he would let me have my medicine. I don’t know[Pg 11] whether my prayers were needed or not, but I do know that the doctor always treated me kindly and finally he told me that I could be treated whenever my medicine gave out, money or no money. He treated me in this way until the early fall of ’84 when he told my aunt that I needed an operation and she must try and get me a place to stay nearby so that he could see me daily. After looking around she found on the doctor’s place an old fellow-servant, that is, an old lady who belonged to the same man my aunt did in slavery time. Her name was Lucy George; she was near the age of my aunt, and had never been married. They were indeed glad to meet and she readily consented to take me to her little cabin where she lived alone. The doctor visited his plantation two or three times a week and usually came to see me. He operated on me twice during my stay there.

“In 1888 the subject of this sketch, W. J. Edwards, was sent to me by his aunt, Rina Rivers, for medical treatment. He had been sick for several months from scrofula and it had affected the bone of his left arm (hinneras) near the elbow joint, and the heel bone (os calcis) of his left foot. It was with much difficulty and pain that he walked at all.

The boy was kind, courteous and polite to every one, white and colored, and all sympathized with him in his great affliction, and manifested their sympathy in a very substantial way, by sending him many good things to eat. This enabled me to build up his general health.

I had to remove the dead bone (necrosed bone) from his arm and heel many times. He always stood the operation patiently and manifested so great a desire to get well, I kept him near me a long time and patiently watched his case.

After four years’ treatment his heel cured up nicely, and he was enabled to walk very well, and the following fall he picked cotton. With prudence, care and close application to cotton picking, he saved money enough to very nearly pay his medical account, and his fare to Booker Washington’s School at Tuskegee, Alabama.

The work of this pupil of Booker Washington,—carried on under [Pg 12]adverse circumstances,—is worthy of emulation. He has, and is now, doing much good work for his race. He has won the confidence and esteem of all the white and colored citizens of this section of the country. He is a remarkable man, a great benefactor to his race, and it affords me great pleasure to testify as to his history and character. Mr. R. O. Simpson, on whose plantation he lived and who aided him materially,—is one of the Trustees of his Institute.”

George W. Keyser, M. D.

Richmond, Dallas County, Alabama.

For three months after my first operation I could not walk. My aunt would come from Snow Hill once a week to bring my rations and to see how I was getting along. I always cried when she went home.

During my first month’s stay on the doctor’s place, “Aunt Lucy” George with whom I lived, was at home most of the time, but when the cotton season came on, she had to go to the doctor’s field, which was a mile away, to pick cotton. This left me alone for five days in the week. “Aunt Lucy” would get up early and prepare her breakfast, take her lunch to the field with her, and would not return until night. She would also leave me something to eat, and I could crawl about the house and get such other things as I needed.

The first few days that I was alone were the most miserable days of my life. I tried to walk, but fainted once or twice at these attempts, so I had to be contented with crawling. Soon, however, I began crawling about the yard. I found several red ants’ nests within about twenty or twenty-five yards of the house, and soon made friends of the ants. I would crawl from nest to nest and watch them do their work. I became so interested in them that I would spend the[Pg 14] whole day watching and following them about the yard. I would be anxious for the nights to pass that I might return to them the next day.

I found that the ants worked by classes. One class would bring out the dirt, another would go out in search of food, another would take away the dead, another would over look those that worked, and still another class, though few in numbers, would come out and look around and then return. These had much larger heads than the average. Some few, however, with great heads, would come out once or twice a day. I never learned what their business was, as they did not seem to do much of anything. They very seldom went more than a few inches from the nests. I noticed, too, that those that went in search of food and failed to get it, would come back to the nests and stand around and consult with the guards and then would return. They did this several times. Sometimes they would go away and get into the weeds and rest awhile. However, when they saw others coming, they would start out again. Sometimes, after making several trips without success, I would give them crumbs of bread, and they would hasten away to their nests. They never hesitated when they had food, but would run right in. This was great fun for me, and I spent most of the remainder of my time in this manner.

This was during the fall of ’84. By the first week in December I had recovered sufficiently to be able to walk very well with a stick and could do a little work. I then returned to Snow Hill with my aunt, and, though I was anxious to return home, I hated very much to leave my little friends. I got home in time to make toy wagons for my Christmas money.

[Pg 15]The following year, although far from being well, I could do a little work on my aunt’s farm. I ought not to call it a farm, because it was only a few acres which she rented from one of the tenants on Mr. Simpson’s plantation. The habit of sub-renting was very prevalent on this plantation. A tenant with one mule would rent twenty-five acres, if he had two mules he would rent fifty acres. Now in order to get work done on his farm, he would sub-rent four or five acres, to some one who would do this work for him. It was in this way that my aunt could get land to work. We usually made on these few acres about twenty bushels of corn and sometimes a half a bale or a whole bale of cotton.

Having to work for our plowing and to pay the rent of the land, we had but little chance to do much work for ourselves. We very seldom had enough to eat. Some days we would work from the rising of the sun until dark without anything but water. Then my aunt would go out among the neighbors in the evening and borrow a little corn meal or get a little on condition that she would work to pay for it the next day. While my aunt would go to hunt for the bread I would go out and beg for some milk from some of our friends. I would always add water to my milk to make it go a long way. This bread and half-water-and-milk constituted our supper for many nights.

In spite of these hard times I always found time to study my books. Sometimes I borrowed books from the boys and girls who had them. We were too poor to buy oil so I would go to the woods and get a kind of pine that we called light-wood. This would make[Pg 16] an excellent light and I could study some nights until twelve o’clock. When the blackberries, peaches, apples and plums were ripe, we fared better, as these grew wild and we could have a plenty of them to eat. As the season came for the corn to mature, we would sometimes make a meal of green corn. When the corn became too hard for us to use in this way, we used to make a grater out of an old piece of tin and would grate the corn and make meal of it in this way until it was hard enough to go to the mill.

When the cotton picking season came on we could pick cotton for the neighbors and in that way could have a plenty to eat. They paid fifty cents a hundred pounds for picking cotton. I sometimes picked two hundred pounds a day, but by picking at night, I occasionally got almost three hundred. We children thought it great fun to go into the swamps at night to pick cotton. We would go at seven o’clock in the evening and spend the whole night in the cotton fields. When we got sleepy we would lie down in the cotton row with our cotton sacks under our heads. We would sleep a few hours and get up and begin picking again. In the swamps at night the owls and frogs made plenty of music for us. Such was my life for several years.

During all these years the one thing uppermost in my mind was the desire to attend some school, but I could not see how I would ever be able to do so. I had heard much of Talladega College, the school at Normal and the state school at Montgomery, but board at these schools was from seven to eight dollars per month and this had to be paid in cash. This, of[Pg 17] course, would keep me out, as I could never see how I could get so much money.

It was during the month of August ’87 that I first heard of Tuskegee. There was a revival meeting going on at one of the churches at Snow Hill. I was determined to visit this meeting. I did not have suitable clothes, neither did I have any shoes, so my people told me that I would not be able to attend church.

I had not been to church in seven years, and I was very anxious to hear some preaching. Notices were sent out that on a Wednesday night a Presiding Elder would speak. This man had the reputation of being a great preacher. All of our people prepared early, and went to church. When I thought the services had begun, I too went. Though I was far from being well, I did not have much trouble in reaching there. I did not go in, however, but went around to the rear of the church. The building was a large, box-like cottage, and contained many cracks. One could hear as well on the outside as on the inside. I stood directly behind the pulpit and heard all that the preacher said.

At the close of his sermon he spoke of the school at Tuskegee, where, he said, poor boys and girls could go without money and without price, and work for an education. From that night I decided to go to Tuskegee. Before the meeting closed, I returned home, and when the others got there, I was in my place fast asleep. I wrote Mr. Washington the next day, and he sent me a catalogue immediately.

In the fall of ’87 I told my aunt that I wanted to go to Tuskegee the next year, and that in addition to her little farm, I wanted to rent an acre of land and work it for that purpose. She encouraged me in this idea and said that she wished so much that she could do something for me that was worth while, but she was poor and could do but little, as she was now well advanced in years. She said, however, that she would help me to work my patch.

About this time I learned that my brother Washington, who had been away for a number of years, was living at Hazen, Alabama, about fifty miles northeast of Snow Hill. He was working in the bridge-gang on a railroad and was making good money. I learned also that my father and sister had died several years before. Now as there were but two of us, and I was cripple, I thought that I would write my brother and get him to help me go to Tuskegee. So I started out for Hazen and reached there after two days’ journey on foot. My brother did not seem to care for me and gave me no encouragement whatever. This was a sore disappointment to me and I did not remain there more than a few days. I returned to Snow Hill very much discouraged, but the warmth with which my old[Pg 19] aunt greeted and welcomed me back home, helped me much.

Soon we were all busy getting ready to plant our little farms. That year there were four of us still living in the one room log cabin, my aunt, her daughter, her grandson and myself. Each of us had a little farm. About mid-summer when our provisions had given out, my aunt’s daughter and her son mortgaged their crops for something to eat, and wanted that we should do the same, but I would not agree to do so. This, of course, made it hard for me to get anything to eat. My cousin and her son were perfectly willing that their mother and grandmother should share in their provisions, but would see to it that I got none. I did not think hard of them for this, because I felt that I had no right to what they had. I continued to live on water and bread, and sometimes I would get a little milk from the neighbors as I had formerly done. I asked them, however, if I might have the water in which they boiled their vegetables whenever they had a boiled dinner. We called this water “pot liquor.” Of course, they readily consented to this and sometimes I would get enough of this liquor to last me two or three days. In fact, I was poorly nourished all the time.

About this time someone came through the county selling clocks, on condition that we pay for them later in the fall. I objected to this but the other members of the family over-ruled my objections and the clock was bought on the condition stated above. The clock cost $12 and each of us agreed to pay $3.00 each. When the time came to pay for this clock no one had[Pg 20] any money, and so I paid what I had saved to prepare myself for Tuskegee. I thought now that I would never get to that school as I had spent most of my money in paying for a worthless clock. However, I picked cotton day and night for almost two weeks, and succeeded in making all the money back which I had spent for the clock. I was now able to finish paying Dr. Keyser and get a few clothes and start for Tuskegee. For a long time the people in the quarter did not believe that I was going, and many tried to discourage me. Had it not been for my aunt’s encouraging words and sincere efforts, I believe that I could not have overcome the efforts of others to keep me from going. When, however, they all found that I was determined to go, they all became my friends and each would give me a nickel or a dime to help me off.

The night before I left for Tuskegee, one of the neighbors told me that while he did not have anything to give me, he had a contract to get a cord of wood to the woodyard for the train by six o’clock the next morning and if I would take his team and haul it, he would give me one dollar for my services. I agreed to do it and at two o’clock the next morning I was at his home hitching up the team to haul the wood. I had to go about two miles for the wood and there was a very heavy frost that morning. By five o’clock I had hauled the wood and had the team back to my neighbor’s home waiting for my dollar. I thought this to be the coldest morning that I had ever experienced up to that time. I then got my few things together and was off for school.

I reached Tuskegee the first day of ’89. I found[Pg 21] things there very strange indeed. Hundreds of students were going to and fro. Some were playing football, others were having band practice, and still others were going around doing nothing, as the first day of the New Year was a holiday. I was placed with a crowd of boys from Pensacola, Fla. I learned afterwards that they were the roughest boys in school. They made it very unpleasant for me, so much so that I decided to return home. In going back to the office I met Mr. Washington for the first time. He wanted to know why I was not satisfied, and after I told him my troubles, he said that he would remedy them. I was deeply impressed with him and from that day to this, I loved him as a father. He changed my room and I found a crowd of very congenial boys.

The next ordeal through which I was to pass, was going into the dining-room and using knives and forks, but I avoided all humiliation by simply watching. I have made it a rule of my life to never be the first to try new things, nor the last to lay old ones aside.

After supper, I was worried about sleeping. I had heard the boys talking about night shirts and I knew I had none; in fact, I did not know their purpose. So when time came to retire, one of the boys in my room who had several, gave me one, then I was undecided just whether it was to go over my day shirt or over my undershirt, but I did not want to ask how it should be worn, so I decided to sit up until some one had gone to bed and by watching him I knew I would learn just how to use mine. In this way I came through all right. The habit of using the tooth-brush was not so hard.

[Pg 22]The next day the regular routine work of the school began and I was given my examination. I took examination for the B-Middle class. This is the second year normal. Miss Annie C. Hawley of Portland, Maine, who was then a teacher there, gave me the examination. I made the class in all of the subjects except grammar. Of this subject I knew absolutely nothing. I did not know what a sentence was. I could not tell the subject from the predicate, so I was put back two years into what is called the A-Prep. class.

After my examination I was assigned to my work. I was placed in the tin shop, which was then being placed as one of the industries, under Mr. Lewis Adams. I was the first student to work in this shop, but it did not take two days to learn that I could never be a tinsmith. Next I was assigned to the printing office, but here too I found that I could never become a printer; so finally, I was put on the farm and there I remained during my whole stay at Tuskegee. The farm manager at that time, Mr. C. W. Green, had charge of the brick-yard, poultry, dairy, landscape gardening, horticulture, as well as the general farm and truck-farm. I worked some in all of these departments and enjoyed my work immensely. I considered the work in the brick-yard as being the hardest of all and that was the only work which I could not do without suffering great pain because of my physical condition. Still I was willing to endure suffering if by so doing I could obtain an education.

I did not go to night school because I was given extra work, such as keeping the clocks on the campus regulated and making fires in the girls’ buildings, and[Pg 23] too, they had a system of electric bells which were used for the passing of classes, and I kept these in order. In this way I worked enough each month to pay my board and stay in day school. Of course, I did not have, or get any money for my work, but I did not worry about that. Miss Maggie Murray (afterwards Mrs. Washington) kept me well supplied with clothes from the supply of second hand garments which came to the school from northern friends.

The remainder of the time that I was at Tuskegee was spent in practically the same way that I have already described. Many of the students would complain about the food, but the fact that I was getting three regular meals a day was enough for me. And too, I was now sleeping in a bed, something that I seldom had done.

When burning bricks they would pay students cash for working at night, and it was by this work that I got a little money now and then. It usually takes from seven to eight days to burn a kiln of brick and sometimes I would work every night until the kiln had been burned.

The one thing that made the deepest impression on me while at Tuskegee was Mr. Washington’s Sunday evening talks to the students. He used to tell us that after getting our education we should return to our homes and there help the people. He said that the people were supporting Tuskegee in order that we might be able to help the masses of our people. I could understand every word he said, and too, I felt always that he was talking directly to me. These talks of Dr. Washington’s changed the course of my[Pg 24] whole life and they are responsible for my being at the Snow Hill School today.

It was when I reached the senior class that I came in personal touch with Dr. Washington, as he taught that class in two or three subjects. Here I could study him as I was never able to do before. He had a thorough grasp upon all subjects he taught and would accept nothing but the same from his students.

As the time was nearing for my graduation, I was deeply worried about my Commencement suit. All of the other members of the class were sending home for their suits or for the money with which to get them, but I knew that my aunt was not able to help me, so I was at a loss to know where I should get mine. Finally, I decided to write to Mr. R. O. Simpson of Furman, Alabama, the man on whose plantation I was reared, and ask him to loan me fifteen dollars. I prayed during the entire time it took me to write the letter and when I had sealed it I prayed over it again. In two days’ time I had an answer with the fifteen dollars. So all of my troubles and worries were banished and I proceeded to get ready for Commencement. I graduated second, with a class of twenty, on May 17, 1893. Our class motto was “Deeds Not Words.”

The morning of May 18th found me packing my few clothes in an old trunk which one of the young men had given me, and getting ready to return to Snow Hill. All the while I was thinking of what I could do to live up to this new training which I had received at Tuskegee, and above all, how could I make good our class motto: “Deeds Not Words.”[Pg 25] Although it has been now well nigh 25 years since my graduation, those words still ring in my ears: “Deeds Not Words.” I should like so to live that when the summons come for me to join Dr. Washington in the Great Beyond, these words might be written as an epitaph on my tomb:

“Deeds Not Words.”

When I returned from Tuskegee on the 19th of May, 1893, I found my old aunt, her daughter and her grandson still living in the one-room log cabin in which I had left them four and a half years before. Their condition was much the same as when I left them. My first work was to build another end, a log pen, to the one room cabin; this gave us two rooms, something we never had before. As it was too late for me to pitch a crop, I worked with them until their crop was clean of weeds and then I went from farm to farm in the neighborhood, helping all the farmers that I could. The only pay I received was three meals a day wherever I worked. I usually worked from one to three days on each farm. All the while I was making a close study of the people’s condition. I continued working in this way until I was convinced that I had a thorough knowledge of their condition. I then ventured to carry the investigation into other sections of Wilcox County and the adjoining counties. I visited most of the places in the counties of Monroe, Butler, Dallas and Lowndes. These constitute most of the Black Belt counties of the State. I made the entire journey on foot.

It was a bright beautiful morning in July when I[Pg 27] started from my home, a log cabin. More than two hundred Negroes were in the nearby fields plowing corn, hoeing cotton and singing those beautiful songs often referred to as plantation melodies: “I am going to roll in my Jesus’ arms,” “O, Freedom,” and “Before I’d be a Slave, I’d be carried to my Grave.” With the beautiful fields of corn and cotton outstretched before me, and the shimmering brook like a silver thread twining its way through the golden meadows, and then through verdant fields, giving water to thousands of creatures as it passed, I felt that the earth was truly clothed in His beauty and the fulness of His glory.

But I had scarcely gone beyond the limits of the field when I came to a thick undergrowth of pines. Here we saw old pieces of timber and two posts. “This marks the old cotton-gin house,” said Uncle Jim, my companion, and then his countenance grew sad; after a sigh, he said: “I have seen many a Negro whipped within an inch of his life at these posts. I have seen them whipped so badly that they had to be carried away in wagons. Many never did recover.”

From this our road led first up-hill, then down, and finally through a stretch of woods until we reached Carlowville. This was once the most aristocratic village of the Southern part of Dallas County. Perhaps no one who owned less than a hundred slaves was able to secure a home within its borders. Here still are to be seen stately mansions and among the names of the owners are those of Lyde, Lee, Wrumph, Bibb, Youngblood and Reynolds. Many of these mansions have been partly rebuilt and remodeled to[Pg 28] conform to modern styles of architecture, while others have been deserted and are now fast decaying. Usually the original families have sold out or many have died out.

In Carlowville stands the largest white church in Dallas or Wilcox Counties. It has a seating capacity of 1,000, excluding the balcony, which during slavery was used exclusively for the Negroes of the families attending.

Our stay in Carlowville was necessarily short, as the evening sun was low and the nearest place for lodging was two miles ahead. Before reaching this place we came to a large one-room log cabin, 30 by 36 feet on the road-side, with a double door and three holes for windows cut in the sides. There was no chimney nor anything to show that the room could be heated in cold weather. This was the Hopewell Baptist Church. Here five hundred members congregated one Sunday in each month and spent the entire day in eating, shouting, and praising God for His goodness toward the children of men. Here also the three months’ school was taught during the winter. A few hundred yards beyond this church brought us to the home of a Deacon Jones. He was living in the house occupied by the overseer of the plantation during slavery. It was customary for Deacon Jones to care for strangers who chanced to come into the community, especially for the preachers and teachers. So here we found rest. At supper Deacon Jones told of the many preachers he had entertained and their fondness for chicken.

After supper I spent some time in trying to find[Pg 29] out the real condition of the people in this section. Mr. Jones told me how for ten years he had been trying to buy some land, and had been kept from it more than once, but that he was still hopeful of getting the right deeds for the land for which he had paid. He also told of many families who had recently moved into this community. These newcomers had made a good start for the year and had promising crops, but they were compelled to mortgage their growing crops in order to get “advances” for the year.

When asked of the schools, he said that there were more than five hundred children of school age in his township, but not more than two hundred of these had attended school the previous winter, and most of these for a period not longer than six weeks. He also said that the people were very indifferent as to the necessity of schoolhouses and churches. Quite a few who cleared a little money the previous year had spent it all in buying whiskey, in gambling, in buying cheap jewelry, and for other useless articles. After spending two hours in such talk, I retired for the evening. Thus ended the first day of my search for first-hand information.

Instead of going farther northward, we turned our course westward for the town of Tilden, which is only eight miles west of Snow Hill. The road from Carlowville to Tilden is somewhat hilly, but a very pleasant one, and for miles the large oak trees formed an almost perfect arch.

On reaching Tilden we learned that there would be a union meeting of two churches that night. I decided that this would give me an opportunity to study the[Pg 30] religious life of these people for myself. The members of churches number one and number two assembled at their respective places at eight o’clock. The members of church number two had a short praise service and formed a line of procession to march to church number one. All the women of the congregation had their heads bound in pieces of white cloth, and they sang peculiar songs as they marched. When the members of church number two were within a few hundred yards of the church number one, the singing then alternated, and finally, when the members of church number two came to church number one, they marched around this church three times before entering it.

After entering the church, six sermons were preached to the two congregations by six different ministers, and at least three of these could not read a word in the Bible. Each minister occupied at least one hour. Their texts were as often taken from Webster’s blue-back speller as from the Bible, and sometimes this would be held upside down. It was about two o’clock in the morning when the services were concluded. Here, again, we found no school-houses, and the three months’ school had been taught in one of the little churches.

The next day we started for Camden, a distance of sixteen miles. This section between Tilden and Camden is perhaps the most fertile section of land in the State of Alabama. Taking a southwest course from Tilden, I crossed into Wilcox County again, where I saw acres of corn and miles of cotton, all being cultivated by Negroes.

[Pg 31]The evening was far advanced when we reached Camden, but having been there before, we had no difficulty in securing lodging. Camden is the seat of Wilcox County, and has a population of about three thousand. The most costly buildings of the town were the courthouse and jail, and these occupied the most conspicuous places. Here great crowds of Negroes would gather on Saturdays to spend their earnings of the week for a fine breakfast or dinner on the following Sunday, or for useless trivialities.

On Saturday evenings, on the roads leading to and from Camden, as from other towns, could be seen groups of Negroes gambling here and there, and buying and selling whiskey. As the county had voted against licensing whiskey-selling, this was a violation of the law, and often the commission merchant, a Negro, was imprisoned for the offense, while those who supplied him went free.

In Camden I found one Negro school-house; this was a box-like cottage, 20 by 16 feet, and was supposed to seat more than one hundred students. This school, like those taught in the churches, was opened only three months in the year.

After a two days’ stay in Camden, I next visited Miller’s Ferry on the Alabama River, twelve miles west of Camden. The road from Camden is one of the best roads in the State, and for miles and miles one could see nothing but cotton and corn.

At Miller’s Ferry a Negro school-house of ample proportions had been built on Judge Henderson’s plantation. Here the school ran several months in the year, and the colored people in the community[Pg 32] were prosperous and showed a remarkable degree of intelligence. Their church was as attractive as their school-house.

Judge Henderson was for twelve years Probate Judge of Wilcox County. He proved to be one of the best judges this county has ever had, and even unto this day he is admired by all, both white and black, rich and poor, for his honesty, integrity, and high sense of justice.

From Judge Henderson’s place we traveled southward to Rockwest, a distance of more than fifteen miles. During this journey hundreds of Negroes were seen at work in the corn and cotton fields. These people were almost wholly ignorant, as they had neither schools nor teachers, and their ministers were almost wholly illiterate. At Rockwest I found a very intelligent colored man, Mr. Darrington, who had attended school at Selma for a few years. He owned his home and ran a small grocery. He told of the hardships with which he had to contend in building up his business, and of the almost hopeless condition of the Negroes about there. He said that they usually made money each year, but that they did not know how to keep it. The merchants would induce them to buy buggies, machines, clocks, etc., but would never encourage them to buy homes. We were very much pleased with the reception which Mr. Darrington gave us, and felt very much like putting into practice our State motto, “Here We Rest,” at his home, but our objective point for the day was Fatama, sixteen miles away.

UNCLE CHARLES LEE AND HIS HOME IN THE BLACK BELT

On our journey that afternoon we saw hundreds of [Pg 33]Negro one-room log cabins. Some of these were located in the dense swamps and some on the hills, while others were miles away from the public road. Most of these people had never seen a locomotive.

We reached Fatama about seven o’clock that night, and here for the first time we were compelled to divide our crowd in order to get a night’s lodging. Each of us had to spend the night in a one-room cabin. It was my privilege to spend the night with Uncle Jake, a jovial old man, a local celebrity. After telling him of our weary journey, he immediately made preparation for me to retire. This was done by cutting off my bed from the remainder of the cabin by hanging up a sheet on a screen. While somewhat inconvenient, my rest that night was pleasant, and the next morning found me very much refreshed and ready for another day’s journey. Our company assembled at Uncle Jake’s for breakfast, after which we started for Pineapple.

We found the condition of the Negroes between Fatama and Pineapple much the same as that of those we had seen the previous day. No school-house was to be seen, but occasionally we would see a church at the cross-roads. We reached Pineapple late in the afternoon.

From Pineapple we went to Greenville, and from Greenville to Fort Deposit, and from Fort Deposit we returned to Snow Hill, after having traveled a distance of 157 miles and visiting four counties.

In three of these counties there was a colored population of 42,810 between the ages of five and twenty years, and a white population of 7,608 of the same[Pg 34] ages. The Negro school population of Wilcox and the seven adjoining counties was 11,623. Speaking of public schools in the sense that educators use the term, the colored people in this section had none. Of course, there were so-called public schools here and there, running from three to five months in the year and paying the teachers from $7.50 to $18 per month.

Our trip through this section revealed the following facts: (1) That while many opportunities were denied our people, they abused many privileges; (2) that there was a colored population, in this section visited, of more than 200,000 and a school population of 85,499; (3) that the people were ignorant and superstitious; (4) that the teachers and preachers for the most part, were of the same condition; (5) that there were no public or private libraries and reading-rooms to which they had access; (6) that, strictly speaking, there were no public schools and only one private one. Now, what can be expected of any people in such a condition? Can the blind lead the blind? They could not in the days of old, and it is not likely that they can now.

After this trip through the “Black Belt” I was more convinced than ever before of the great need of an Industrial School in the very midst of these people; a school that would correct the erroneous ideas the people held of education; a school that would put most stress upon the things which the people were most likely to have to do with through life; a school that would endeavor to make education practical rather than theoretical; a school that would train men and women to be good workers, good leaders, good husbands, good wives, and finally train them to be fit citizens of the State and proper subjects for the Kingdom of God.

With this idea the Snow Hill Normal and Industrial Institute was started twenty-five years ago in an old dilapidated one-room log cabin with one teacher and three students, with no State appropriation, and without any church or society responsible for one dollar of its expenses. Aside from this unfortunate state of affairs, the condition of the people was miserable. This was due partly to poor crops and partly to bad management on their part.

In many instances the tenants were not only unable to pay their debts, but were also unable to pay their rents. In a few cases the landlords had to provide at their own expense provisions for their tenants. This[Pg 36] was simply another way of establishing soup-houses on the plantations. The idea of buying land was foreign to all of them, and there were not more than twenty acres of land owned by the colored people in this whole neighborhood. The churches and schools were practically closed, while crime and immorality were rampant. The carrying of men and women to the chain-gang was a frequent occurrence. These people believed that the end of education was to free their children from manual labor.

They were much opposed to industrial education. When the school was started, many of the parents came to school and forbade our “working” their children, stating as their objection that their children had been working all their lives and that they did not mean to send them to school to learn to work. Not only did they forbid our having their children work, but many took their children out of school rather than allow them to do so. A good deal of this opposition was kept up by illiterate preachers and incompetent teachers, who had not had any particular training for their profession. In fact, ninety-eight per cent of them had attended no school. We continued, however, to keep the “Industrial Plank” in our platform, and year after year some industry was added until we now have fourteen industries in constant operation. Agriculture is the foremost and basic industry of the institution. We do this because we are in a farming section and ninety-five per cent of the people depend upon agriculture for a livelihood.

FIRST TRUSTEES OF SNOW HILL AND TWO OF THEIR WIVES

The early years of the school were indeed trying ones. There are however in all communities persons whose hearts are in the right place. I found it so in this case, for while there were many who opposed the industrial idea, there were those who stood for it and held up our arms. I refer to that noble class of old colored men who always seek for truth. The men who stood so loyally by me in the founding of the school were Messrs. Frank Warren, Willis McCants, Ellis Johnson, John Thomas, Isaac Johnson, Tom Johnson and P. J. Gaines. These men and their wives were ready at every call. They gave suppers, fairs and picnics as well as other entertainments to raise money for the school. Not only would they help in the raising of money, but they would come to the school and work for days without thinking of any pay for their work. When we got ready to put up a new building, we would have what we called a house-raising and would invite all the men in the neighborhood to come out and help us. On these days the wives of these men would compete with each other to see who could bring out the best basket.

At the end of the first school year it was clearly seen that we needed two assistant teachers; but the[Pg 38] question that puzzled us was, where could they work. We had only one room and none of us had the money to buy the lumber needed. But there was a saw-mill near by and finally I sought work at this mill with the understanding that I would take my pay in lumber if the people would agree to feed me. This they readily consented to do. So I worked during May, June, July and August at the saw-mill and took my wages in lumber. This enabled us to get sufficient material to erect two of the rooms of our present Training Building. The following October we opened school with three teachers and 150 students. These two teachers had graduated at Tuskegee with me in ’93. They were Misses Ophelia Clopton and Rosa Bradford. They spent four years in the work here and we never had two teachers who did more for the old people in the community and who were loved more by them.

In the fall of ’95 Mr. Barnes, who was also a member of the class of ’93, joined us, and has been connected with the school since then except for two years which he spent in Boston.

In the fall of ’96 another one of our class-mates, Julius Webster, a carpenter, joined in our work here. We now had five teachers, all of Tuskegee and all class-mates. I can never forget these old people and these early teachers, for we all shared our many sorrows and our few joys. No work was too hard for us and no sacrifice was too great.

Another Tuskegee student was with us almost from the beginning. While Mr. Rivers did not graduate from the Academic Department at Tuskegee, he finished his trade, Agriculture, there. Mr. Rivers has[Pg 39] had charge of our farm off and on since ’95. I should say to his credit that he is in charge today and last year he made the best crop the school has ever made.

Thus far, I have spoken of the assistance given me by the colored people and teachers, but no chapter about the founding of Snow Hill Institute would be complete without a mention of Mr. R. O. Simpson, the white man on whose plantation I was reared. Mr. Simpson must have known me from my birth. I well remember that in ’78 and ’79 he used to stop by to see my old grandmother when riding over his plantation. I think that my grandmother prepared meals for him on some of these visits to the plantation. I also remember that after the death of grandmother, when I was sick and living with my aunt Rina, some days he would see me lying on the roadside and would toss me a coin.

On my return from Tuskegee I found Mr. Simpson deeply interested in the welfare of my people; in fact, it seemed as if he was looking for some one to start an industrial school upon his place. We had many talks together. When he found out that I had returned to cast my lot with my people, he seemed highly pleased and said that he would give a few acres for the school if I thought I could use it to advantage. I decided that this was my opportunity and told him that I could. He first gave seven acres, and then thirty-three, and finally sixty more, making in all one hundred acres that he gave the school. In later years we bought one-half of his plantation, making in all nearly two thousand acres. While all of the white people in Snow Hill have been friendly towards the[Pg 40] work, I have found Mr. Simpson and his entire family to be our particular friends and I have yet to go to them for a favor and be refused.

One of the cardinal points in Dr. Washington’s Sunday evening talks to the students and teachers at Tuskegee was that they should buy homes of their own. I felt that the best way to teach the people to get a home was for me to own one myself. I thought that it would be useless for me to talk to them about buying homes as long as I did not have one for myself, so I secured a home.

After the school was thoroughly planted and I had bought and paid for my home, we began to encourage the people to buy homes. This was done through several agencies, the Negro Farmers Conference, the Workers Conference and the Black-Belt Improvement Society. The aim of this Society is clearly set forth in its constitution, a part of which is as follows:

(1) This society shall be known as the Black Belt Improvement Society. Its object shall be the general uplift of the people of the Black Belt of Alabama; to make them better morally, mentally, spiritually, and financially.

(2) It shall further be the object of the Black Belt Improvement Society as far as possible, to eliminate the credit system from our social fabric; to stimulate in all members the desire to raise, as far as possible, all their food supplies at home, and pay cash for whatever may be purchased at the stores.

(3) To bring about a system of co-operation in the purchase of what supplies cannot be raised at home wherever it can be done to advantage.

[Pg 41](4) To discuss topics of interest to the communities in which the various societies may be organized, and topics relating to the general welfare of the race, and especially to farmers.

(5) To teach the people to practice the strictest economy, and especially to obtain and diffuse such information among farmers as shall lead to the improvement and diversification of crops, in order to create in farmers a desire for homes and better home conditions, and to stimulate a love for labor in both old and young. Each local organization may offer small prizes for the cleanest and best-kept house, the best pea-patch, and the best ear of corn, etc.

(6) To aid each other in sickness and in death; for this purpose a fee of ten cents will be collected from each member every month and held sacred to be used for no other purpose whatever.

(7) It shall be one of the great objects of this society to stimulate its members to acquire homes, and urge those who already possess homes to improve and beautify them.

(8) To urge our members to purchase only the things that are absolutely necessary.

(9) To exert our every effort to obliterate those evils which tend to destroy our character and our homes, such as intemperance, gambling, and social impurity.

(10) To refrain from spending money and time foolishly or in unprofitable ways; to take an interest in the care of our highways, in the paying of our taxes and the education of our children; to plant shade trees, repair our yard fences, and in general, as far as [Pg 42]possible, bring our home life up to the highest standard of civilization.

This Society has standing committees on Government, on Education, on Business, on Housekeeping, on Labor, and on Farming. The chairman of each of these committees holds monthly meetings in the various communities, at which time various topics pertaining to the welfare and uplift of the people are discussed. As a result of these meetings the people return to their homes with new inspiration. The meetings are doing good in the communities where they are being held, and our sincere hope is that such meetings may be extended. It is the aim of the school and of its several organizations, to reach the ills that most retard the Negroes of the rural South. The articles of our simple constitution go to the very bottom of the conditions.

Thus it will be seen that the work of the class-room is only a small part of what we are trying to do for the uplift of the Negro people in the Black Belt.

The matter of raising money for undenominational schools in the South is no easy task, and right here I ought to state just why I preferred to have such a school. Our people in the rural South are mostly Baptists and Methodists, and of course the denominations have their schools, located in certain cities. While no one is barred from these schools, it is a fact that undue influence is exerted upon the pupils to make them become members of the church that supports the school. This is not only true of the Methodist and Baptist schools, but is also true of all denominational schools in the South. I did not like that and our people do not like to have any one influence their children to join churches other than the one of their choice. We may shut our eyes to this truth, but the fact remains that Methodists do not want their children to be persuaded to join some other church, neither do the Baptists want theirs taken away from them.

Now, I wanted that my school should be free from such “isms.” I wanted a school for all the Negroes, thoroughly religious in its spirit, but entirely undenominational. For twenty-five years now we have adhered strictly to this policy. Many times when all[Pg 44] was dark and there seemed to be no way, some of these denominations would come and offer me the money to run the work, provided I would accept their faith. But this I have never done, I had rather that the work should die than to sell my principle for money. I repeat that raising money for such a school is a hard task. I have never been particularly interested as to the choice of the church that my students make, but I have been profoundly interested in their finding salvation.

A great many people to whom I appeal for aid from time to time, tell me that they give all their alms through their church. But in spite of all this, I feel that the kind of schools most needed for our people, should be broad and not narrow, deep and not shallow.

After winning the approval of the people in the community, both black and white, and getting whatever help I could from them, my thoughts turned towards the North for means to run the work. My first attempt was in March, ’97. I got as far as Washington, D. C., and saw the Inauguration of President McKinley, and then I returned home.

The following June Dr. Washington wrote me to come to Tuskegee so as to accompany the Tuskegee Quartet North that summer. It must not be understood that I was one of the singers; that was not my good fortune. I was to tell what Tuskegee had done for me and was to show in turn what I was trying to do for my people. Dr. Washington reasoned in this way I would have a chance to meet some of the best people of the country and thereby gain support for my work. There was to be no collection taken for[Pg 45] Snow Hill, but those who became interested would often come up after the meetings and give me something for my work.

We left Tuskegee about the first of July. We spent most of the month of July in the southeastern part of Massachusetts, known as the Cape and South Shore. We had meetings at most of the churches and resorts in that section. Dr. Washington himself met us at the most prominent places.

In August we came to Boston and from there went up the North Shore. This was my first visit to Boston and it was here that I met Miss Susan D. Messinger and her brother William S. Messinger. Their home was at 81 Walnut Avenue, Roxbury, Mass. Miss Messinger had been an abolitionist. Both she and her brother were deeply interested in the welfare of my people. They listened attentively to my story and from that day became my best friends.

Although I have been going North now for twenty years, I have never met such welcome as was shown me at their home. I think I have never met such Christ-like people anywhere. It was largely through Miss Messinger’s appeals in the “Transcript” that the people of Boston and New England learned of our work at the Snow Hill Institute. Through her appeals from time to time, we raised much money for our school. I cannot, in words, express the valuable aid these people gave us in our work. Sometimes when I had worked hard all day with poor results, I would go to their home in the evening discouraged and low-spirited, but would always find there a hearty welcome and a word of cheer. I would always leave[Pg 46] with new zeal and fresh courage. Their home has been to me a home now for twenty years and although they are now dead, I never go to Boston but that I find time to go out to Mt. Auburn and put a fresh flower on their graves. The old home is lonely now, but the Messinger spirit still abides there in the person of Mr. Reed, their nephew. I still receive from him the hearty welcome and support that they used to give in days of old.

Another friend whom I met that summer was Mrs. J. S. Howe of Brookline (now Mrs. Herman F. Vickery). She became interested in our work through Miss Messinger and from that time to this her interest has steadily grown. Had it not been for the encouragement and aid received from the Messingers and Mrs. Howe on this trip, I am sure that I should have given up the struggle.

After leaving Boston, the Tuskegee singers went up the North Shore and on to the Isles of Shoals. There we had a very good meeting, and as Mr. Washington could not be present, I was the principal speaker. The people were greatly interested in what I said and although we took up a good collection for Tuskegee, my private collection was equally large. This the leader of the quartet did not like. It was the duty of this man who was a teacher at Tuskegee, to speak as well as myself, but for some reason he did not like to do it and would always shirk it when he could. But after this meeting he cut off my support and when we reached Portsmouth, he told me that I was dividing the interest and that he could not use me further on that trip. Of course, what little money I had been[Pg 47] getting I had sent to the school, so I was almost penniless when he turned me off. I ought to say, however, that he gave me my fare back to Boston. I reached Boston that night about eight o’clock with no money and nowhere to go, but finally, I went to the place where we had stopped when the quartet was in Boston and I found R. W. Taylor, who at the time was financial agent in the North for Tuskegee. He saw that I was discouraged and insisted that I tell him why I had come back to Boston. When he had learned the facts he told his landlady to provide lodging and board for me at his expense until I could do better.