Transcriber's Notes:

1. Page scan source:

http://books.google.com/books?pg=PA381&id=12YTAAAAYAAJ#v=onepage&q&f=false

BLACK FOREST

VILLAGE STORIES

BY

Berthold Auerbach

TRANSLATED BY

CHARLES GOEPP

AUTHOR'S EDITION

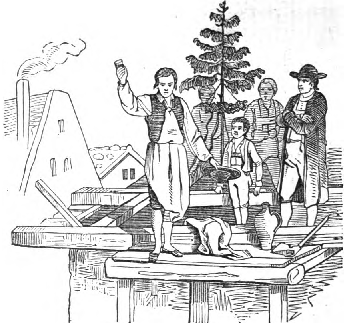

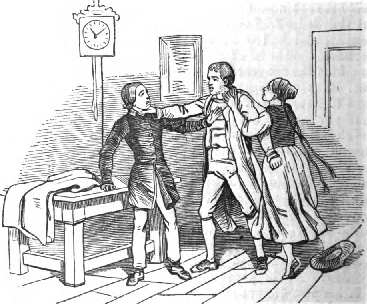

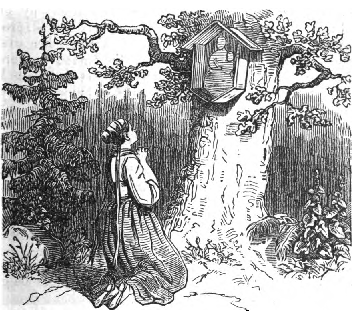

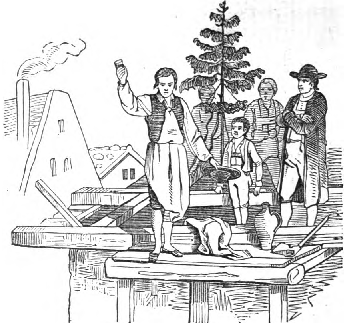

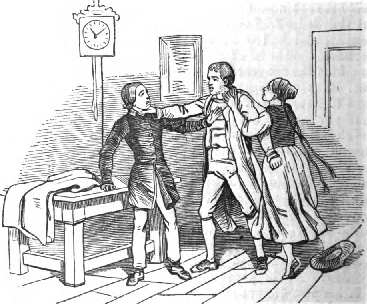

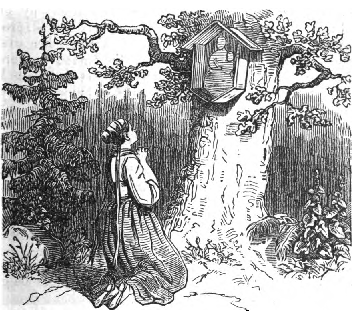

Illustrated with Facsimiles of the original

German Woodcuts.

NEW YORK

LEYPOLDT & HOLT

1869

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1869, by

LEYPOLDT & HOLT,

In the Clerk's office of the District Court of the United States

for the Southern District of New York.

BLACK FOREST

VILLAGE STORIES.

THE GAWK

I see you now, my fine fellow, as large as life, with your

yellow hair

cropped very short, except in the neck, where a long tail remains as if

you had cut yourself after the pattern of a plough-horse. You are

staring straight at me with your broad visage, your great blue goggle

eyes, and your mouth which is never shut. Do you remember the morning

we met in the hollow where the new houses stand now, when you cut me a

willow-twig to make a whistle of? We little thought then that I should

come to pipe the world a song about you when we should be thousands of

miles apart. I remember your costume perfectly, which is not very

surprising, as there is nothing to keep in mind but a shirt, red

suspenders, and a pair of linen pantaloons dyed black to guard against

all contingencies. On Sunday you were more stylish: then you wore a fur

cap with a gold tassel, a blue roundabout with broad buttons, a scarlet

waistcoat, yellow shorts, white stockings, and buckled shoes, like any

other villager; and, besides, you very frequently had a fresh pink

behind your ear. But you were never at ease in all this glory; and I

like you rather better in your plainer garb, myself.

But now, friend gawk, go about your business; there's a good

fellow. It

makes me nervous to tell your story to your face. You need not be

alarmed: I shall say nothing ill of you, though I do speak in the third

person.

The gawk not only had a real name, but a whole pedigree of

them; in the

village he ought to have been called Bart's Bast's1 boy, and he had

been christened Aloys. To please him, we shall stick to this last

designation. He will be glad of it, because, except his mother Maria

and a few of us children, hardly any one used it; all had the impudence

to say "Gawk." On this account he always preferred our society, even

after he was seventeen years old. In out-of-the-way places he would

play leap-frog with us, or let us chase him over the fields; and when

the gawk--I should say, when Aloys--was with us, we were secure against

the attacks of the children at the lime-pit; for the rising generation

of the village was torn by incessant feuds between two hostile parties.

Yet the boys of Aloys' own age were already beginning to feel

their

social position. They congregated every evening, like the grown men,

and marched through the village whistling and singing, or stood at the

tavern-door of the Eagle, by the great wood-yard, and passed jokes with

the girls who went by. But the surest test of a big boy was the

tobacco-pipe. There they would stand with their speckled bone-pipe

bowls, of Ulm manufacture, tipped with silver, and hung with little

silver chains. They generally had them in their mouths unlit; but

occasionally one or the other would beg a live coal from the baker's

maid, and then they smoked with the most joyful faces they knew how to

put on, while their stomachs moaned within them.

Aloys had begun the practice too, but only in secret. One

evening he

mustered up courage to mingle with his fellows, with the point of his

pipe peeping forth from his breast-pocket. One of the boys pulled the

pipe out of his pocket with a yell; Aloys tried to seize it, but it

passed from hand to hand with shouts of laughter, and the more

impatiently he demanded it the less it was forthcoming, until it

disappeared altogether, and every one professed to know nothing of what

had become of it. Aloys began to whimper, which made them laugh still

more; so at last he snatched the cap of the first robber from his head,

and ran with it into the house of Jacob the blacksmith. Then the

capless one brought the pipe, which had been hidden in the wood-yard.

Jacob Bomiller the blacksmith's house was what is called

Aloys'

"go-out." He was always there when not at home, and never at home after

his work was done. Aunt Applon, (Apollonia,) Jacob's wife, was his

cousin; and; besides his own mother and us children, she and her eldest

daughter Mary Ann always called him by his right name. In the morning

he would get up early, and, after having fed and watered his two cows

and his heifer, he always went to Jacob's house and knocked at the door

until Mary Ann opened it. With a simple "Good-morning," he passed

through the stable into the barn. The cattle knew his step, and always

welcomed him with a complacent growl and a turn of the head: he never

stopped to return the compliment, but went into the barn and filled the

cribs of the two oxen and the two cows. He was on particularly good

terms with the roan cow. He had raised her from a calf; and, when he

stood by her and watched her at her morning meal, she often licked his

hands, to the improvement of his toilet. Then he would open the door of

the stable and restore its neatness and good order, often chatting

cosily to the dumb beasts as he made them turn to the right or left.

Not a dunghill in the village was so broad and smooth and with such

clean edges as the one which Aloys built before the house of Jacob the

blacksmith; for a fine dunghill is the greatest ornament to a

villager's door-front in the Black Forest. The next thing he did was to

wash and curry the oxen and cows until you might have seen your face in

their sleek hides. This done, he ran to the pump before the house and

filled the trough with water: the cattle, unchained, ran out to drink;

while he spread fresh straw in their stalls. Thus, by the time that

Mary Ann came to the stable to milk the cows, she found every thing

neat and clean. Often, when a cow was "skittish," and kicked, Aloys

stood by her and laid his hand on her back while Mary Ann milked; but

generally he found something else to do. And when Mary Ann said,

"Aloys, you are a good boy," he never looked up at her, but plied the

stable-broom so vehemently that it threatened to sweep the boulder-stones

out of the floor. In the barn he cut the feed needed for the day; and,

after all the work required in the lower story of the building--which,

in the Black Forest, as is well known, contains what in America is

consigned to the barn and outhouses--was finished, he mounted up-stairs

into the kitchen, carried water, split the kindling-wood, and at last

found his way into the room. Mary Ann brought the soup-bowl, set it on

the table, folded her hands, and, everybody having done the same, spoke

a prayer. All now seated themselves with a "God's blessing." The bowl

was the only dish upon the table, into which every one dipped his spoon,

Aloys often stealing a mouthful from the place where Mary Ann's spoon

usually entered. The deep silence of a solemn rite prevailed at the

table: very rarely was a word spoken. After the meal and another prayer,

Aloys trudged home.

Thus things went on till Aloys reached his nineteenth year,

when, on

New-Year's day, Mary Ann made him a present of a shirt, the hemp of

which she had broken herself, and had spun, bleached, and sewed it. He

was overjoyed, and only regretted that it would not do to walk the

street in shirt-sleeves: though it was bitter cold, he would not have

cared for that in the least; but people would have laughed at him, and

Aloys was daily getting more and more sensitive to people's laughter.

The main cause of this was the old squire's2 new hand who

had come

into the village last harvest.

He was a tall, handsome fellow, with a

bold, dare-devil face appropriately set off with a reddish mustache.

George (for such was his name) was a cavalry soldier, and almost always

wore the cap belonging to his uniform. When he walked up the village of

a Sunday, straight as an arrow, turning out his toes and rattling his

spurs, every thing about him said, as plainly as words could speak, "I

know all the girls are in love with me;" and when he rode his horses

down to Jacob's pump to water them, poor Aloys' heart was ready to

burst as he saw Mary Ann look out of the window. He wished that there

were no such things as milk and butter in the world, so that he too

might be a horse-farmer.

He was a tall, handsome fellow, with a

bold, dare-devil face appropriately set off with a reddish mustache.

George (for such was his name) was a cavalry soldier, and almost always

wore the cap belonging to his uniform. When he walked up the village of

a Sunday, straight as an arrow, turning out his toes and rattling his

spurs, every thing about him said, as plainly as words could speak, "I

know all the girls are in love with me;" and when he rode his horses

down to Jacob's pump to water them, poor Aloys' heart was ready to

burst as he saw Mary Ann look out of the window. He wished that there

were no such things as milk and butter in the world, so that he too

might be a horse-farmer.

Inexperienced as Aloys was, he knew all about the three

classes or

"standings" into which the peasants of the Black Forest are divided.

The cow-farmers are the lowest in the scale: their draught-cattle, in

addition to their labor, must yield them milk and calves. Then come the

ox-farmers, whose beasts, after having served their time, may be

fattened and killed. The horse-farmers are still more fortunate: their

beasts of draught yield neither milk nor meat, and yet eat the best

food and bring the highest prices.

Whether Aloys took the trouble to compare this arrangement

with the

four castes of Egypt, or the three estates of feudalism, is doubtful.

On this New-Year's day, George derived a great advantage from

his

horses. After morning service, he took the squire's daughter and her

playmate Mary Ann sleighing to Impfingen; and, though the heart of poor

Aloys trembled within him, he could not refuse George's request to help

him hitch the horses and try them in the sleigh. He drove about the

village, quite forgetting the poor figure he cut beside the showy

soldier. When the girls were seated, Aloys led the horses a little way,

running beside them until they were fairly started, and then let them

go. George drove down the street, cracking his whip; the horses jingled

their bells; half the commune looked out of their windows; and poor

Aloys stared after them long after they were out of sight; and then

went sadly home, cursing the snow which brought the water to his eyes.

The village seemed to have died out when Mary Ann was not to be in it

for a whole day.

All this winter Aloys was often much cast down. At his

mother's house

the girls frequently assembled to hold their spinning-frolics,--a

custom much resembling our quiltings. They always prefer to hold these

gatherings at the house of a comrade recently married or of a

good-natured widow; elder married men are rather in the way. So the

girls often came to Mother Maria, and the boys dropped in later,

without waiting to be invited. Hitherto Aloys had never troubled

himself about them so long as they left him undisturbed: he had sat in

a corner doing nothing. But now he often said to himself, "Aloys, this

is too bad: you are nineteen years old now, and must begin to put

yourself forward." And then again he would say, "I wish the devil would

carry that George away piecemeal!" George was the object of his

ill-humor, for he had soon obtained a perfect control over the minds of

all the boys, and made them dance to his whistle. He could whistle and

sing and warble and tell stories like a wizard. He taught the boys and

girls all sorts of new songs. The first time he sang the verse,--

"Do thy cheeks with gladness tingle

Where the snows and scarlet mingle?"--

Aloys suddenly rose: he seemed taller than usual; he clenched

his fists

and gnashed his teeth with secret joy. He seemed to draw Mary Ann

toward him with his looks, and to see her for the first time as she

truly was; for, just as the song ran, so she looked.

The girls sat around in a ring, each having her distaff with

the gilt

top before her, to which the hemp was fastened with a colored ribbon;

they moistened the thread with their lips, and twirled the spindle,

which tumbled merrily on the floor. Aloys was always glad to put "a

little moistening," in the shape of some pears or apples, on the table,

and never failed to put the plate near Mary Ann, so that she might help

herself freely.

Early in the winter Aloys took his first courageous step in

right of

his adolescence. Mary Ann had received a fine new distaff set with

pewter. The first time she brought it into the spinning-room and sat

down to her work, Aloys came forward, took hold of it, and repeated the

old rhyme:--

"Good lassie, give me leave,

Let me shake your luck out of this sleeve;

Great goodhap and little goodhap

Into my lassie's lap.

Lassie, why are you so rude?

Your distaff is only of wood;

If it had silver or gold on't,

I'd have made a better rhyme on't."

His voice trembled a little, but he got through without

stammering.

Mary Ann first cast her eyes down with shame and fear lest he should

"balk;" but now she looked at him with beaming eyes. According to

custom, she dropped the spindle and the whirl,3 which Aloys picked

up, and exacted for the spindle the promise of a dumpling, and for the

whirl that of a doughnut. But the best came last. Aloys released the

distaff and received as ransom a hearty kiss. He smacked so loud that

it sounded all over the room, and the other boys envied him sorely. He

sat down quietly in a corner, rubbed his hands, and was contented with

himself and with the world. And so he might have remained to the end of

time, if that marplot of a George had not interfered again.

Mary Ann was the first voice in the church-choir. One evening

George

asked her to sing the song of the "Dark-Brown Maid." She began without

much hesitation, and George fell in with the second voice so finely and

sonorously that all the others who had joined in also lapsed into

silence one by one, and contented themselves with listening to the two

who sang so well. Mary Ann, finding herself unsupported by her

companions, found her voice trembling a little, and nudged her

companions to go on singing; but, as they would not, she took courage,

and sang with much spirit, while George seemed to uphold her as with

strong arms. They sang:--

"Oh, to-morrow I must leave you,

My belovéd dark-brown maid:

Out at the upper gate we travel,

My belovéd dark-brown maid.

"When I march in foreign countries,

Think of me, my dearest one;

With the sparkling glass before you,

Often think how I adore you;

Drink a health to him that's gone.

"Now I load my brace of pistols,

And I fire and blaze away,

For my dark-brown lassie's pleasure;

For she chose me for her treasure,

And she sent the rest away.

"In the blue sky two stars are shining:

Brighter than the moon they glow;

This looks on the dark-brown maiden,

And that looks where I must go.

"I've bought a ribbon for my sabre,

And a nosegay for my hat,

And a kerchief in my keeping,

To restrain my eyes from weeping:

From my love I must depart.

"Now I spur my horse's mettle,

Now I rein him in and wait:

So good-bye, dear dark-brown maiden;

I must ride out at the gate."

When each of the girls had filled four or five spindles, the

table was

pushed into a corner, to clear a space of three or four paces in length

and breadth, on which they took turns in dancing, those who sat singing

the music. When George brought out Mary Ann, he sang his own song,

dancing to it like a spindle: indeed, he did not need much more space

than a spindle, for he used to say that no one was a good waltzer who

could not turn around quickly and safely on a plate. When he stopped at

last,--with a whirl which made the skirts of Mary Ann's wadded dress

rise high above her feet,--she suddenly left him alone, as if afraid of

him, and ran into a corner, where Aloys sat moodily watching the sport.

Taking his hand, she said,--

"Come, Aloys, you must dance."

"Let me alone: you know I can't dance. You only want to make

game of

me."

"You g----" said Mary Ann: she would have said, "you gawk,"

but

suddenly checked herself on seeing that he was more ready to cry than

to laugh. So she said, gently, "No, indeed, I don't want to make game

of you. Come; if you can't dance you must learn it: there is none I

like to dance with better than you."

They tried to waltz; but Aloys threw his feet about as if he

had wooden

shoes on them, so that the others could not sing for laughing.

"I will teach you when nobody is by, Aloys," said Mary Ann,

soothingly.

The girls now lighted their lanterns and went home. Aloys

insisted on

going with them: he would not for all the world have let Mary Ann go

home without him when George was of the company.

In the still, snowy night, the raillery and laughter of the

party were

heard from end to end of the village. Mary Ann alone was silent, and

evidently kept out of George's way.

When the boys had left all the girls at their homes, George

said to

Aloys, "Gawk, you ought to have stayed with Mary Ann to-night."

"You're a rascal," said Aloys, quickly, and ran away. The

others

laughed. George went home alone, warbling so loud and clear that he

must have gladdened the hearts of all who were not sick or asleep.

Next morning, as Mary Ann was milking the cows, Aloys said to

her, "Do

you see, I should just like to poison that George; and if you are a

good girl you must wish him dead ten times over."

Mary Ann agreed with him, but tried to convince him that he

should

endeavor to become just as smart and ready as George was. A bright idea

suddenly struck Aloys. He laughed aloud, threw aside the stiff old

broom and took a more limber one, saying, "Yes: look sharp and you'll

see something." After much reluctance, he yielded to Mary Ann's

solicitations to be "good friends" with George: he could not refuse her

any thing.

It was for this reason alone that Aloys had helped George to

get the

sleigh out, and that the snow made his eyes run over as he watched the

party till they disappeared.

In the twilight Aloys drove his cows to water at Jacob's well.

A knot

of boys had collected there, including George and his old friend, a

Jew, commonly called "Long Hartz's Jake." Mary Ann was looking out of

the window. Aloys was imitating George's walk: he carried himself as

straight as if he had swallowed a ramrod, and kept his arms hanging

down his sides, as if they had been made of wood.

"Gawk," said Jake, "what will you allow me if I get Mary Ann

to marry

you?"

"A good smack on your chops," said Aloys, and drove his cows

away. Mary

Ann closed the sash, while the boys set up a shout of laughter, in

which George's voice was heard above all the others.

Aloys wiped the sweat from his forehead with his sleeve, so

great was

the exertion which the expression of his displeasure had cost him. He

sat for hours on the feed-box of his stable, maturing the plans he had

been meditating.

Aloys had entered his twentieth year, and it was time for him

to pass

the inspection of the recruiting-officers. On the day on which he, with

the others of his age, was to present himself at Horb, the county town,

he came to Mary Ann's house in his Sunday gear, to ask if she wished

him to get any thing for her in town. As he went away, Mary Ann

followed him into the hall, and, turning aside a little, she drew a bit

of blue paper from her breast, which, on being unwrapped, was found to

contain a creutzer.4 "Take it," said she: "there are three crosses on

it. When the shooting stars come at night, there's always a silver bowl

on the ground, and out of those bowls they make this kind of creutzers:

if you have one of them in your pocket you are sure to be in luck. Take

it, and you will draw a high number."5

Aloys took the creutzer; but in crossing the bridge which

leads over

the Necker he put his hand in his pocket, shut his eyes, and threw the

creutzer into the river. "I won't draw a high number: I want to be a

soldier and cut George out," he muttered, between his teeth. His hand

was clenched, and he drew himself up like a king.

At the Angel Hotel the squire waited for the recruits of his

parish;

and when they had all assembled he went with them to the office. The

squire was equally stupid and pretentious. He had been a corporal

formerly, and plumed himself on his "commission:" he loved to treat all

farmers, old and young, as recruits. On the way he said to Aloys,

"Gawk, you will be sure to draw the highest number; and even if you

should draw No. 1 you need not be afraid, for they never can want you

for a soldier."

"Who knows?" said Aloys, saucily. "I may live to be a corporal

yet, as

well as any one: I can read and write as well as another, and the old

corporals haven't swallowed all the wisdom in the world, either."

The squire looked daggers at him.

When Aloys walked up to the wheel, his manner was bold almost

to

provocation. Several papers met his fingers as he thrust his hand in.

He closed his eyes, as if determined not to see what he should draw,

and brought out a ticket. He handed it to the clerk, trembling with

fear of its being a high number. But, when "Number 17" was called, he

shouted so lustily that they had to call him to order.

The boys now bought themselves artificial flowers tied with

red

ribbons, and, after another hearty drink, betook themselves homeward.

Aloys sang and shouted louder than all the others.

At the stile at the upper end of the village the mothers and

many

of the sweethearts of the boys were waiting: Mary Ann was among them

also. Aloys, a little fuddled,--rather by the noise than by the

wine,--walked, not quite steadily, arm-in-arm with the others. This

familiarity had not occurred before; but on the present occasion they

were all brothers. When Aloys' mother saw No. 17 on his cap, she cried,

again and again, "O Lord a' mercy! Lord a' mercy!" Mary Ann took Aloys

aside, and asked, "What has become of my creutzer?" "I have lost it,"

said Aloys; and the falsehood smote him, half unconscious as he was.

The boys now walked down the village, singing, and the mothers

and

sweethearts of those who had probably been "drawn" followed them,

weeping, and wiping their eyes with their aprons.

The "visitation," which was to decide every thing, was still

six weeks

off. His mother took a large lump of butter and a basket full of eggs,

and went to the doctor's. The butter was found to spread very well,

notwithstanding the cold weather, and elicited the assurance that Aloys

would not be made a recruit of; "for," said the conscientious

physician, "Aloys is incapable of military service, at any rate: he

cannot see well at a distance, and that is what makes him so awkward

sometimes."

Aloys gave himself no trouble about all these matters: he was

quite

altered, and swaggered and whistled whenever he went out.

On the day of the visitation, the boys went to town a little

more

soberly and quietly than when the lots were drawn.

When Aloys was called into the visitation-room and ordered to

undress,

he said, saucily, "Spy me out all you can: you will find nothing wrong

about me. I have no blemish: I can be a soldier." His measure being

taken and found to be full, he was entered on the list without delay:

the doctor forgot the short-sightedness, the butter, and the eggs, in

his astonishment at the boldness of Aloys.

But, when the irrevocable step was fairly taken, Aloys

experienced such

a sense of alarm that he could have cried. Still, when his mother met

him on the stone steps of the office, weeping bitterly, his pride

returned; and he said, "Mother, this is not right: you must not cry. I

shall be back in a year, and Xavier can keep things in order very well

while I am gone."

On being assured of their enlistment as soldiers, the boys

began to

drink, sing, and royster more than ever, to make up for the time they

supposed themselves to have lost before.

When Aloys came home, Mary Ann, with tears in her eyes, gave

him a

bunch of rosemary with red ribbons in it, and sewed it to his cap.

Aloys took out his pipe, smoked all the way up the village, and made a

night of it with his comrades.

One hard day more was to be passed,--the day when the recruits

had to

set out for Stuttgart. Aloys went to Jacob's house early, and found

Mary Ann in the stable, where she now had to do all the hard work

without his assistance. Aloys said, "Mary Ann, shake hands." She did

so; and then he added "Promise me you won't get married till I come

back."

"No, indeed, I won't," said she; and then he replied, "There,

that's all:

but stop! give me a kiss for good-bye." She kissed him; and the cows and

oxen looked on in astonishment, as if they knew what was going on.

Aloys patted each of the cows and oxen on the back, and took

leave of

them: they mumbled something indistinctly between their teeth.

George had hitched his horses to the wagon, to give the

recruits a lift

of a few miles. They passed through the village, singing; the baker's

son, Conrad, who blew the clarionet, sat on the wagon with them and

accompanied; the horses walked. On all sides the recruits were stopped

by their friends, who came to shake hands or to share a parting cup.

Mary Ann was looking out of her window, and nodded, smiling.

When they were fairly out of the village, Aloys suddenly

stopped

singing. He looked around him with moistened eyes. Here, on the heath

called the "High Scrub," Mary Ann had bleached the linen of the shirt

he wore: every thread of it now seemed to scorch him. He bade a sad

farewell to every tree and every field. Over near the old heath-turf

was his best field: he had turned the soil so often that he knew every

clod in it. In the adjoining patch he had reaped barley with Mary Ann

that very summer. Farther down, in the Hen's Scratch, was his

clover-piece, which he had sown and was now denied the pleasure of

watching while it grew. Thus he looked around him. As they passed the

stile he was mute. In crossing the bridge he looked down into the

stream: would he have dropped the marked creutzer into it now?

In the town the singing and shouting was resumed; but not till

the

Bildechingen Hill was passed did Aloys breathe freely. His beloved

Nordstetten lay before him, apparently so near that his voice could

have been heard there. He saw the yellow house of George the

blacksmith, and knew that Mary Ann lived in the next house but one. He

swung his cap and began to sing again.

At Herrenberg George left the recruits to pursue their way on

foot. At

parting he inquired of Aloys whether he had any message for Mary Ann.

Aloys reddened. George was the very last person he should have

chosen

for a messenger; and yet a kind message would have escaped his lips if

he had not checked himself. Involuntarily he blurted out, "You needn't

talk to her at all: she can't bear the sight of you, anyhow."

George laughed and drove away.

An important adventure befell the recruits on the road. At the

entrance

of the Boeblingen Forest, which is five miles long, they impressed a

wood-cutter with his team, and compelled him to carry them. Aloys was

the ringleader: he had heard George talk so much of soldiers' pranks

that he could not let an occasion slip of playing one. But when they

had passed through the wood he was also the first to open his leathern

pouch and reimburse the involuntary stage-proprietor.

At the Tuebingen gate of Stuttgart a corporal stood waiting to

receive

them. Several soldiers from Nordstetten had come out to meet their

comrades; and Aloys clenched his teeth as every one of them greeted him

with, "Gawk, how are you?" There was an end of all shouting and singing

now: like dumb sheep the recruits were led into the barracks. Aloys

first expressed a wish to go into the cavalry, as he desired to emulate

George; but, on being told that in that case he would have to go home

again, as the cavalry-training would not begin till fall, he changed

his mind. "I won't go home again until I am a different sort of a

fellow," he said to himself; "and then, if any one undertakes to call

me gawk, I'll gawk him."

So he was enrolled in the fifth infantry regiment, and soon

astonished

all by his intelligence and rapid progress. One misfortune befel him

here also; he received a gypsy for his bedfellow. This gypsy had

a peculiar aversion to soap and water. Aloys was ordered by the

drill-sergeant to take him to the pump every morning and wash him

thoroughly. This was sport at first; but it soon became very irksome:

he would rather have washed the tails of six oxen than the face of the

one gypsy.

Another member of the company was a broken-down painter. He

scented the

spending-money with which Aloys' mother had fitted him out, and soon

undertook to paint him in full uniform, with musket and side-arms, and

with the flag behind him. This made up the whole resemblance: the face

was a face, and nothing more. Under it stood, however, in fine Roman

characters, "Aloys Schorer, Soldier in the Fifth Regiment of Infantry."

Aloys had the picture framed under glass and sent it to his

mother. In

the accompanying letter he wrote,--

"DEAR MOTHER:--Please hang up the picture in the front room,

and let

Mary Ann see it: hang it over the table, but not too near the dovecote;

and, if Mary Ann would like to have the picture, make her a present of

it. And my comrade who painted it says you ought to send me a little

lump of butter and a few yards of hemp-linen for my corporal's wife: we

always call her Corporolla. My comrade also teaches me to dance; and

to-morrow I am going to dance at Haeslach. You needn't pout, Mary Ann:

I am only going to try. And I want Mary Ann to write to me. Has Jacob

all his oxen yet? and hasn't the roan cow calved by this time?

Soldiering isn't much of a business, after all: you get catawampously

tired, and there's no work done when it's over."

The butter came, and was more effective this time: the gypsy

was

saddled upon somebody else. With the butter came a letter written by

the schoolmaster, in which he said,--

"Our Matthew has sent fifty florins from America. He also

writes that

if you had not turned soldier you might have come to him and he would

make you a present of thirty acres of land. Keep yourself straight, and

let nobody lead you astray; for man is easily tempted. Mary Ann seems

to be out of sorts with you,--I don't know why: when she saw your

picture she said it didn't look like you at all."

Aloys smiled when he read this, and said to himself, "All

right. I am

very different from what I was: didn't I say it, Mary Ann,--eh?"

Months passed, until Aloys knew that next Sunday was

harvest-home at

Nordstetten. Through the corporal's intervention, he obtained a

furlough for four days, and permission to go in full uniform, with his

shako on his head and his sword at his side. Oh, with what joy did he

put his "fixings" into his shako and take leave of his corporal!

With all his eagerness, he could not refrain from exchanging a

word

with the sentry at the gate of the barracks and with the one at the

Tuebingen gate. He must needs inform them that he was going home, and

that they must rejoice with him; and his heart melted with pity for his

poor comrades, who were compelled to walk to and fro in a little yard

for two mortal hours, during which time he was cutting down, step by

step, the distance that lay between him and his home.

He never stopped till he got to Boeblingen. Here he ordered a

pint of

wine at the "Waldburg;" but he could not sit quiet in his chair, and

walked away without emptying the glass.

At Nufringen he met Long Hartz's Jake,--the same who had

teased him so.

They shook hands, and Aloys heard much news of home, but not a word of

Mary Ann; and he could not make up his mind to inquire after her.

At Bohndorf he forced himself to rest: it was high time to do

so; for

his heart was beating furiously. Stretched upon a bench, he reflected

how they all would open their eyes on his arrival: then he stood before

the looking-glass, fixed the shako over his left ear, twisted the curl

at the right side of his forehead, and encouraged himself by a nod of

approbation.

It was dusk when he found himself on the heights of

Bildechingen and

once more beheld his native village. He shouted no longer, but stood

calm and firm, laid his hand upon his shako, and greeted his home with

a military salute.

He walked slower and slower, wishing to arrive at night, so as

to

astonish them all in the morning. His house was one of the first in the

village: there was a light in the room; and he tapped at the window,

saying,--

"Isn't Aloys here?"

"Lord a'-mercy!" cried his mother: "a gens-d'armes!"

"No: it's me, mother," said Aloys, taking off his shako as he

entered,

and clasping her hand.

After the first words of welcome were spoken, his mother

expressed her

regret that there was no supper left for him; nevertheless, she went

into the kitchen and fried him some eggs. Aloys stood by her near the

hearth, and told his story. He asked about Mary Ann, and why his

picture was still hanging in the room. His mother answered, "Don't

think any thing more of Mary Ann, I beg and beg of you: she is good for

nothing,--she is indeed!"

"Don't talk anymore about it, mother," said Aloys; "I know

what I

know." His face, tinted by the ruddy glow of the hearth-fire, had a

strange decision and ferocity. His mother was silent until they had

returned to the room, and then she saw with rapture what a fine fellow

her son had become. Every mouthful he swallowed seemed a titbit to her

own palate. Lifting up the shako, she complacently bewailed its

enormous weight.

Aloys rose early in the morning, brushed up his shako,

burnished the

plating of his sword, and the buckler and buttons, more than if he had

been ordered on guard before the staff. At the first sound of the

church-bell he was completely dressed, and at the second bell he walked

into the village.

Two little boys were talking as they passed him.

"Why, that's the gawk, a'n't it?" said one.

"No, it a'n't," said the other.

"Yes, it is," rejoined the first.

Aloys looked at them grimly, and they ran away with their

hymn-books.

Amid the friendly greetings of the villagers he approached the church.

He passed Mary Ann's house; but no one looked out: he looked behind him

again and again as he walked up the hill. The third bell rang, and he

entered the church; Mary Ann was not there: he stood at the door; but

she was not among the late-comers. The singing began, but Mary Ann's

voice was not heard: he would have known it among a thousand. What was

the universal admiration to him now? she did not see him, for whom he

had travelled the long road, and for whom he now stood firm and

straight as a statue. He heard little of the sermon; but, when the

minister pronounced the bans of Mary Ann Bomiller, of Nordstetten, and

George Melzer, of Wiesenstetten, poor Aloys no longer stood like a

statue. His knees knocked under him, and his teeth chattered. He was

the first who left the church. He ran home like a crazy man, threw his

sword and his shako on the floor, hid himself in the hay-loft, and

wept. More than once he thought of hanging himself, but he could not

rise for dejection: all his limbs were palsied. Then he would remember

his poor mother, and sob and cry aloud.

At last his mother came and found him in the hay-loft, cried

with him,

and tried to comfort him. "It was high time they were married," was the

burden of her tale of Mary Ann. He wept long and loud; but at last he

followed his mother like a lamb into the room. Seeing his picture, he

tore it from the wall and dashed it to pieces on the floor. For hours

he sat behind the table and covered his face with his hands. Then

suddenly he rose, whistled a merry tune, and asked for his dinner. He

could not eat, however, but dressed himself, and went into the village.

From the Adler he heard the sound of music and dancing. In passing

Jacob's house, he cast down his eyes, as if he had reason to be

ashamed; but when it was behind him he looked as proud as ever. Having

reported himself and left his passport in the squire's hands, he went

to the ball-room. He looked everywhere for Mary Ann, though he dreaded

nothing more than to meet her. George was there, however. He came up to

Aloys and stretched out his hand, saying, "Comrade, how are you?" Aloys

looked at him as if he would have poisoned him with his eyes, then

turned on his heel without a word of answer. It occurred to him that he

ought to have said, "Comrade! the devil is your comrade, not I;" but it

was too late now.

All the boys and girls now made him drink out of their

glasses; but the

wine tasted of wormwood. He sat down at a table and called for a

"bottle of the best," and drank glass after glass, although it gave him

no pleasure. Mechtilde, the daughter of his cousin Matthew of the Hill,

stood near him, and he asked her to drink with him. She complied very

readily, and remained at his side. Nobody was attentive to her: she had

no sweetheart, and had not danced a round that day, as every one was

constantly dancing with his or her sweetheart, or changing partners

with some other.

"Mechtilde, wouldn't you like to dance?" said Aloys.

"Yes: come, let's try."

She took Aloys by the hand. He rose, put on his gloves, looked

around

the floor as if he had lost something, and then danced to the amazement

of all the company. From politeness he took Mechtilde to a seat after

the dance: by this he imposed a burden on himself, for she did not

budge from his side all the evening. He cared but little for her

conversation, and only pushed the glass toward her occasionally by way

of invitation. His eyes were fixed fiercely on George, who sat not far

from him. When some one asked the latter where Mary Ann was, he said,

laughing, "She is poorly." Aloys bit his pipe till the mouthpiece broke

off, and then spat it out with a "Pah!" which made George look at him

furiously, thinking the exclamation addressed to him. Seeing that Aloys

was quiet, he shrugged his shoulders in derision and began singing bad

songs, which all had pretty much the same burden:--

"A bright boy will run through

Many a shoe;

An old fool will tear

Never a pair."

At midnight Aloys took his sword from the wall to go. George

and his

party now began to sing the "teaser," keeping time with their fists on

the table:--

"Hey, Bob, 'ye goin' home?

'Ye gettin' scared? 'Ye gettin' sick?

Got no money, and can't get tick?

Hey, Bob, 'ye goin' home?"

Aloys turned back with some of his friends and called for two

bottles

more. They now sang songs of their own, while George and his gang were

singing at the other table. George got up and cried, "Gawk, shut up!"

Then Aloys seized a full bottle and hurled it at his head, sprang over

the table, and caught him by the throat. The tables fell down, the

glasses chinked on the floor, the music stopped. For a while all was

still, as if the two were to throttle each other in silence: then

suddenly the room was filled with shouting, whistling, scolding, and

quarrelling. The bystanders interfered; but, according to custom, each

party only restrained the adversary of the party he sided with, so as

to give the latter a chance of drubbing his opponent undisturbed.

Mechtilde held George by the head until his hair came out by handfuls.

The legs of chairs were now broken off, and all hands whacked each

other to their hearts' content. Aloys and George remained as if

fastened together by their teeth. At length Aloys gained his feet, and

threw George down with such violence that he seemed to have broken his

neck, and then kneeled down on him, and would have throttled him had

not the watchman entered and put an end to the row. The musicians were

sent home and the two chief combatants taken to the lock-up.

With his face black and blue, pale and haggard, Aloys left the

village

next day. His furlough had another day to run; but what should he do at

home? He was glad enough to go soldiering again; and nothing would have

pleased him better than a war. The squire had endorsed the story of the

fracas on his passport, and a severe punishment awaited him on his

return. He looked neither to the right nor to the left, but walked away

almost without knowing it, and hoping never to return. At Horb, on

seeing the signpost to Freudenstadt, which is on the way to Strasbourg,

he stopped a long time and thought of deserting to France. Unexpectedly

he found himself addressed by Mechtilde, who asked, "Why, Aloys, are

you going back to Stuttgart already?"

"Yes," he answered, and went on his way. Mechtilde had come

like an

angel from heaven. With a friendly good-bye, they parted.

As he walked, he found himself ever and anon humming the song

he had

heard George sing so long ago, and which now, indeed, suited poor Mary

Ann's case:--

"In a day, in a day,

Pride and beauty fade away.

Do thy checks with gladness tingle

Where the snows and roses mingle?

Oh, the roses all decay!"

At Stuttgart he never said a word to the sentry at the

Tuebingen gate

nor to the one at the barrack-gate. Like a criminal, he hardly raised

his eyes. For eight days he did penance in a dark cell,--the "third

degree" of punishment. At times he became so impatient that he could

have dashed his head against the wall; and then again he would lie for

days and nights half asleep.

When released from prison, he was attached for six weeks to

the class

of culprits who are never permitted to leave the barracks, but are

bound to answer the call at every moment. He now cursed his resolution

to become a soldier, which bound him for six years to the land of his

birth. He would have gone away, far as could be.

One morning his mother Maria came with a letter from Matthew,

in

America. He had sent four hundred florins for Aloys to buy a field

with, or, if he wished to join him, to buy himself clear of the army.

Aloys and Matthew of the Hill, with his wife and eight

children,--Mechtilde among them,--left for America that same autumn.

While at sea he often hummed the curious but well-known old

song, which

he had never understood before:--

"Here, here, here, and here,

The ship is on her way;

There, there, there, and there,

The skipper goes to stay;

When the winds do rave and roar

As though the ship could swim no more,

My thoughts begin to ponder

And wander."

In his last letter from Ohio Aloys writes to his mother:--

"... My heart seems to ache at the thought that I must enjoy

all these

good things alone. I often wish all Nordstetten was here,--old Zahn,

blind Conrad, Shacker of the stone quarry, Soges, Bat of the sour well,

and Maurice of the hungry spring: they ought to be here, all of them,

to eat their fill until they couldn't budge from their seats. What good

does it do me while I am alone here? And then you might all see the

gawk with his four horses in the stable and his ten colts in the field.

If Mary Ann has any trouble, let me know about it, and I will send her

something; but don't let her know from whom it comes. Oh, how I pity

her! Matthew of the Hill lives two miles away. His Mechtilde is a good

worker; but she is no Mary Ann, after all. I do hope she is doing well.

Has she any children? On the way across there was a learned man with us

on the ship,--Dr. Staeberle, of Ulm: he had a globe with him, and he

showed me that when it is day in America it is night in Nordstetten,

and so on. I never thought much about it till now. But when I am in the

field and think, 'What are they doing now in Nordstetten?' I remember

all at once that you are all fast asleep, and Shackerle's John, the

watchman, is singing out, 'Two o'clock, and a cloudy morning.' On

Sunday I can't bear to think that it is Saturday night in Nordstetten.

All ought to have one day at once. Last Sunday was harvest-home in

Nordstetten: I should never forget that, if I were to live a hundred

years. I should like to be in Nordstetten for one hour, just to let the

squire see what a free citizen of America looks like."

THE PIPE OF WAR.

It is a singular story, and yet intimately connected with the

great

events of modern history, or, what is almost the same thing, with the

history of Napoleon. Those were memorable times. Every farmer could see

the whole array of history manœuvre and pass in review beneath his

dormer-window: kings and emperors behaved like play-actors, and,

sometimes assumed a different dress and a different character in every

scene. And all this gorgeous spectacle was at the farmer's service,

costing him nothing but his house and home, and occasionally, perhaps,

his life. My neighbor Hansgeorge was not quite so unlucky,--as the

story will show.

It was in the year 1796. We who live in these piping times of

peace

have no idea of the state of things which then existed: mankind seemed

to have lost their fixed habitations and to be driving each other here

and there at random. The Black Forest saw the Austrians, with their

white coats, in one month, and in the next the French, with their

laughing faces; then the Russians came, with their long beards; and

mixed and mingled with them all were the Bavarians, Wurtembergers, and

Hessians, in every possible uniform. The Black Forest was the open gate

of Germany for the French to enter; it is only ten years since that

Rastatt was placed as a bolt before it.

The marches and counter-marches, retreats and advances,

cannonades and

drum-calls, were enough at times to turn the head of a bear in winter;

and many a head did indeed refuse to remain upon its shoulders. In a

field not far from Baisingen is a hillock as high as a house, which,

they say, contains nothing but dead soldiers,--French and Germans

mixed.

But my neighbor Hansgeorge escaped being a soldier, although a

fine

sturdy fellow, well fit to stand before the king, and the people too,

and just entering his nineteenth year. It happened in this wise.

Wendel, the mason, married a wife from Empfingen, and on the day before

the wedding the bride was packed on a wagon with all her household

goods, her blue chest, her distaff, and her bran-new cradle. Thus she

was conveyed to the village, while the groom's friends rode on

horseback behind, cracking off their pistols from time to time to show

how glad they were. Hansgeorge was among them, and always shot more

than all the others. When the cavalcade had reached the brick-yard,

where the pond is at your right hand and the kiln at your left,

Hansgeorge fired again; but, almost before the pistol went off,

Hansgeorge was heard to shriek with pain. The pistol dropped from his

hand, and he would have fallen from his horse but for Fidele, his

friend, who caught him in his arms.

He had shot off the forefinger of

his right hand, just at the middle joint. Every one came up, eager to

lend assistance; and even Kitty of the brick-kiln came up, and almost

fainted on seeing Hansgeorge's finger just hanging by the skin.

Hansgeorge clenched his teeth and looked steadily at Kitty. He was

carried into the brickmaker's house. Old Jake, the farrier, who knew

how to stop the blood, was sent for in all haste; while another ran to

town for Dr. Erath, the favorite surgeon.

He had shot off the forefinger of

his right hand, just at the middle joint. Every one came up, eager to

lend assistance; and even Kitty of the brick-kiln came up, and almost

fainted on seeing Hansgeorge's finger just hanging by the skin.

Hansgeorge clenched his teeth and looked steadily at Kitty. He was

carried into the brickmaker's house. Old Jake, the farrier, who knew

how to stop the blood, was sent for in all haste; while another ran to

town for Dr. Erath, the favorite surgeon.

When Old Jake came into the room, all were suddenly silent,

and stepped

back, so as to form a sort of avenue, through which he walked toward

the wounded man, who was lying on the bench behind the table. Kitty

alone came forward, and said, "Jake, for God's sake, help Hansgeorge!"

The latter opened his eyes and turned his head toward the speaker, and

when Jake stood before him, mumbling as he touched his hand, the blood

ceased running.

This time, however, it was not Jake's witchcraft which

produced the

result, but another kind of magic. Hansgeorge no sooner heard Kitty's

words than he felt all the blood rush to his heart, and of course the

hemorrhage ceased.

Dr. Erath came and amputated the finger. Hansgeorge bore the

cruel pain

like a hero. As he lay in a fever for hours after, he seemed to see an

angel hovering over him and fanning him. He did not know that Kitty was

driving the flies away, often bringing her hand very near his face:

such neighborhood of a loving hand, even though there be no actual

touch, has marvellous effects, and may well have fashioned the dream in

his wandering brain. Then again he saw a veiled figure: he could never

recall exactly how she looked; but--so curious are our dreams--it had a

finger in its mouth, and smoked tobacco with it, as if it were a pipe:

the blue whiffs rose up from rings of fire.

Kitty observed that the closed lips of Hansgeorge moved in his

sleep.

When he awoke, the first thing he called for was his pipe. He had the

finest pipe in the village; and we must regard it more closely, as it

is destined to play an important part in this history. The head was of

Ulm manufacture, marbleized so that you might fancy the strangest

figures by looking at it. The lid was of silver, shaped like a helmet,

and so bright that you could see your face in it, and that twice

over,--once upside-down and once right side up. At the lower edge also,

as well as at the stock, the head was tipped with silver. A double

silver chain served as the cord, and secured the short stem as well as

the long, crooked, many-jointed mouthpiece. Was not that a splendid

pipe?

When he awoke, the first thing he called for was his pipe. He had the

finest pipe in the village; and we must regard it more closely, as it

is destined to play an important part in this history. The head was of

Ulm manufacture, marbleized so that you might fancy the strangest

figures by looking at it. The lid was of silver, shaped like a helmet,

and so bright that you could see your face in it, and that twice

over,--once upside-down and once right side up. At the lower edge also,

as well as at the stock, the head was tipped with silver. A double

silver chain served as the cord, and secured the short stem as well as

the long, crooked, many-jointed mouthpiece. Was not that a splendid

pipe?

"And who shall dare

To chide him for loving his pipe so fair,"

even as an ancient hero loved his shield?

What vexed Hansgeorge most in the loss of his finger was, that

he could

not fill his pipe without difficulty. Kitty laughed, and scolded him

for his bad taste; but she filled his pipe nevertheless, took a coal

from the fire to light it, and even drew a puff or two herself. She

shook herself, and made a face, as if she was dreadfully disgusted.

Hansgeorge had never liked a pipe better than that which Kitty started

for him.

Although it was the middle of summer, Hansgeorge could not be

taken

home with his wound, and was compelled to stay at the brickmaker's

house. With this the patient was very well content; for, although his

parents came to nurse him, he knew very well that times would come when

he would be alone with Kitty.

The next day was Wendel's wedding; and when the church-bell

rang and

the inevitable wedding-march was played in the village, Hansgeorge

whistled an accompaniment in his bed. After church the band paraded

through the village where the prettiest girls were, or where their

sweethearts lived. The boys and girls joined the procession, which

swelled as it went on: they came to the brickmaker's house also.

Fidele, as George's particular friend, came in with his sweetheart to

take Kitty off to the dance; but she thanked them, pleaded household

duties, and remained at home. Hansgeorge rejoiced greatly at this, and

when they ware alone he said,--

"Kitty, never mind: there'll be another wedding soon, and then

you and

I will dance our best."

"A wedding?" said Kitty, sadly: "who is going to be married?"

"Come here, please," said Hansgeorge, smiling. Kitty

approached, and he

continued:--"I may as well confess it: I shot my finger off on purpose,

because I don't want to be a soldier."

Kitty started back, screaming, and covered her face with her

apron.

"What makes you scream?" said Hansgeorge. "A'n't you glad of

it? You

ought to be, for you are the cause."

"Jesus! Maria! Joseph! No, no! surely I am innocent! Oh,

Hansgeorge,

what a sinful thing you have done! Why, you might have killed yourself!

You are a wild, bad man! I never could live with you; I am afraid of

you."

She would have fled; but Hansgeorge held her with his left

hand. She

tried to tear herself away, turned her back, and gnawed the end of her

apron: Hansgeorge would have given the world for a look, but all his

entreaties were in vain. He let her go, and waited a while to see

whether she would turn round; but, as she did not, he said, with a

faltering voice,--

"Will you be so kind as to fetch my father? I want to go

home."

"No; you know you can't go home: you might get the lockjaw:

Dr. Erath

said you might," returned Kitty,--still without looking at him.

"If you won't fetch anybody, I'll go alone," said Hansgeorge.

Kitty turned and looked on him with tearful eyes, eloquent

with

entreaty and tender solicitude. George took her offered hand, and gazed

long and earnestly into the face of his beloved. It was by no means a

face of regular beauty: it was round, full, and plump; the whole head

formed almost a perfect sphere; the forehead was high and strongly

protruding, the eyes lay deep in their sockets, and the little pug

nose, which had a mocking and bantering expression, and the swelling

cheeks, all proclaimed health and strength, but not delicacy or

refinement. George regarded her in her burning blushes as if she had

been the queen of beauty.

They remained silent for a long time. At last Kitty said,

"Shall I fill

your pipe for you?"

"Yes," said George, and let go her hand.

This proposal of Kitty's was the best offer of reconciliation.

Both

felt it as such, and never exchanged another word on the subject of

their dispute.

In the evening many boys and girls, with flushed cheeks and

sparkling

eyes, came to take Kitty to the dance; but she refused to go.

Hansgeorge smiled. When he asked Kitty to go as a favor to him, she

skipped joyfully away, and soon came back in her holiday gown. Another

difficulty arose, however. With all their good nature, none of the

comers cared to give up their dance and stay with Hansgeorge; and Kitty

had just announced her intention, when, fortunately, old Jake came in.

For a good stoup of wine,--which they promised to send him from the

inn,--he agreed to sit up all night, if necessary.

Hansgeorge had got Dr. Erath to preserve his finger in

alcohol, and

intended to make Kitty a present of it; but, with all her strength of

nerve, the girl dreaded it like a spectre, and could hardly be induced

to touch the phial. As soon as Hansgeorge was able to leave the house,

they went into the garden and buried the finger. Hansgeorge stood by,

lost in thought, while Kitty shovelled the earth upon it. The wrong he

had done his country by making himself unfit to serve it never occurred

to him; but he remembered that a part of the life which was given him

lay there never to rise again. It seemed as if, while full of life, he

were attending his own funeral; and the firm resolve grew in him to

atone for the waste committed of a part of himself by the more

conscientiously husbanding what yet remained. A thought of death

flitted across his mind, and he looked up with mingled sadness and

pleasure to find himself yet spared and the girl of his heart beside

him. Such reflections glimmered somewhat dimly in his soul, and he

said, "Kitty, you are quite right: I committed a great sin. I hope it

will be forgiven me." She embraced and kissed him, and he seemed to

have a foretaste of the absolution yet to come.

had got Dr. Erath to preserve his finger in

alcohol, and

intended to make Kitty a present of it; but, with all her strength of

nerve, the girl dreaded it like a spectre, and could hardly be induced

to touch the phial. As soon as Hansgeorge was able to leave the house,

they went into the garden and buried the finger. Hansgeorge stood by,

lost in thought, while Kitty shovelled the earth upon it. The wrong he

had done his country by making himself unfit to serve it never occurred

to him; but he remembered that a part of the life which was given him

lay there never to rise again. It seemed as if, while full of life, he

were attending his own funeral; and the firm resolve grew in him to

atone for the waste committed of a part of himself by the more

conscientiously husbanding what yet remained. A thought of death

flitted across his mind, and he looked up with mingled sadness and

pleasure to find himself yet spared and the girl of his heart beside

him. Such reflections glimmered somewhat dimly in his soul, and he

said, "Kitty, you are quite right: I committed a great sin. I hope it

will be forgiven me." She embraced and kissed him, and he seemed to

have a foretaste of the absolution yet to come.

One would expect to find in a man a peculiar fondness for the

spot

where a part of his bodily self is buried. As our native country is

doubly dear to us because the bodies of those we love are resting

there,--as the whole earth is revealed in all its holiness when we call

to mind that it is the sepulchre of ages past, that

"all who tread

The earth are but a handful to the tribes

That slumber in its bosom,"--

so must a man who has already surrendered a part of his dust

to become

dust again be attracted by the sacred claims of earth, and often turn

to the resting-place of his unfettered portion.

Thoughts like these, though vaguely conceived, cannot be

supposed to

have taken clear form and shape in such a mind as that of our friend

Hansgeorge. He went to the brickmaker's house every day; but it was in

obedience to the attraction, not of something dead, but of a living

being. But, joyfully as he went, he sometimes came away quite sad and

downhearted; for Kitty seemed intent upon teasing and worrying him. The

first thing she required, and never ceased requiring, was that he

should give up smoking. She never allowed him to kiss her when he had

smoked, and before she would sit near him he was always obliged to hide

his darling pipe. In the brickmaker's room he could not smoke on any

account; and, much as he liked to be there, he always took his way home

again before long. Kitty was not mistaken in often rallying him about

this.

Hansgeorge was greatly vexed at Kitty's pertinacity, and

always came

back to his favorite enjoyment with redoubled zest. It appeared to him

unmanly to submit to a woman's dictation: woman ought to yield, he

thought; and then it must be confessed that it was quite out of his

power to renounce his habit. He tried it once in haying-time for two

days; but he seemed to be fasting all the time: something was missing

constantly. He soon drew forth his pipe again; and, while he held it

complacently between his teeth and struck his flint, he muttered to

himself, "Kitty and all the women in the world may go to the devil

before I'll stop smoking." Here he struck his finger with the steel,

and, shaking the smarting hand, "This is a judgment," thought he; "for

it isn't exactly true, after all."

At last autumn came on, and George was pronounced unfit for

military

service. Some other farmers' boys had imitated his trick by pulling out

their front teeth, so as to make themselves unable to bite open the

cartridges; but the military commission regarded this as intentional

self-mutilation, while that of George, from its serious character, was

pronounced a misfortune. The toothless ones were taken into the carting

and hauling service, and so compelled to go to the wars, after all.

With defective teeth they had to munch the hard rations of the

soldiers' mess; and at last they were made to bite the dust,--which,

indeed, they could have done as well without any teeth at all.

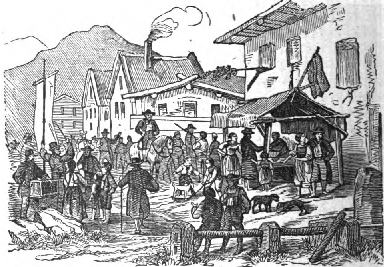

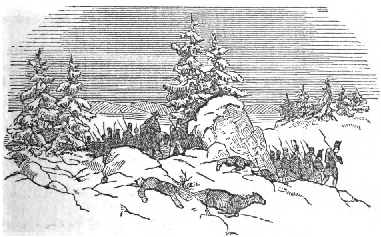

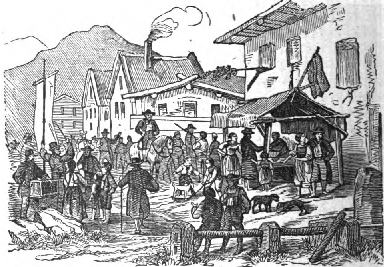

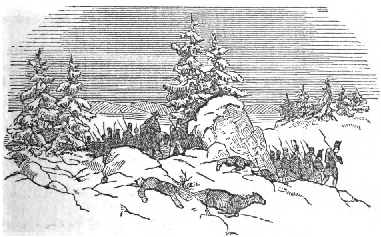

In the beginning of October, the French general Moreau made

good his

famous retreat across the Black Forest. A part of his army passed

through Nordstetten: it was spoken of for several days before. There

was fear and trembling in all the village, and none knew which way to

turn. A hole was dug in every cellar, and every thing valuable

concealed. The girls took off their strings of garnets with the silver

medallions, and drew their silver rings from their fingers, to bury

them. All went unadorned, as if in mourning. The cattle were driven

into a secluded ravine near Eglesthal. The boys and girls looked at

each other sadly when the approaching foe was mentioned: many a young

fellow sought the handle of his knife, which peeped out of his

side-pocket.

The Jews were more unfortunate than any others. Rob a farmer

of every

thing you can carry away, and you must still leave him his field and

his plough; but all the possessions of the Jews are movables,--money

and goods: they, therefore, trembled doubly and trebly. The Jewish

Rabbi--a shrewd and adroit man--hit upon a lucky expedient. He placed a

large barrel of red wine, well inspirited with brandy, before his

house, and a table with bottles and glasses beside it, for the unbidden

guests to regale themselves. The device succeeded to perfection,--the

more so as the French were rather in a hurry.

In fact, the storm passed over, doing much less damage than

was

expected. The villagers collected in large groups to view the passing

troops. The cavalry came first, then a long column of infantry.

Hansgeorge had gone to the brick-yard with his comrades Xavier

and

Fidele: he wished to be near Kitty in case of emergency. The three

stood in the garden before the house, leaning upon the fence,

Hansgeorge calmly smoking his pipe. Kitty looked out of the window and

said, "George, if you'll stop smoking you may come into the house with

your friends."

"Wo are quite comfortable here, thank you," replied

Hansgeorge, sending

up three or four whiffs in quick succession.

On came the cavalry. They rode in entire disorder, each

apparently

occupied with himself alone; and nothing showed that they belonged

together save the common interest manifested in any deviltry undertaken

by any one of them. Several impudently kissed their hands to Kitty,--at

which Hansgeorge grasped his jack-knife and Kitty quickly closed the

sash. The infantry were followed by the forage-wagons and the pitiable

cavalcade of the wounded and dying. This was a wretched sight. One of

them stretched forth a hand which had but four fingers. This curdled

Hansgeorge's blood in his veins: it seemed to him as if he himself were

lying there. The poor sufferer had nothing but a kerchief round his

head, and seemed to shiver with cold. Hansgeorge jumped over the fence,

pulled off his fur cap, and set it on the poor man's head; then he gave

him his leathern purse with all the money in it. The poor fellow made

some signs with his mouth, as if he wished to smoke, and looked

beseechingly at Hansgeorge's pipe; but the latter shook his head. Kitty

brought some bread and some linen, and laid them on the cart. The

maimed warriors looked with pleasure on the blooming lass, and some

made her a military salute and garbled some broken German. No one asked

whether they were friends or foes: the unfortunate and helpless have a

claim on every one.

Another troop of cavalry brought up the rear. Kitty stood at

the window

again, while Hansgeorge and his comrades had returned to their post at

the garden-gate. Suddenly Fidele exclaimed, "Look out: the marauders

are coming."

Two ragged fellows in half-uniform, without saddle or stirrup,

came

galloping up. While yet a few yards off, they stopped and whispered

something to each other, at which one of them was heard to laugh. They

then rode up slowly, the one coming very near the fence. Quick as a

flash he tore the pipe out of Hansgeorge's mouth, and galloped off at

the top of his horse's speed. Putting the still-burning pipe into his

mouth, he puffed away merrily in derision. Hansgeorge held his chin

with both his hands: every tooth seemed to have been torn out of his

jaw. Kitty laughed heartily, crying, "Go get your pipe, Hansgeorge:

I'll let you smoke now."

"I'll get it," said Hansgeorge, breaking a board of the fence

in his

fury. "Come, Fidele, Xavier; let's get our horses out and after them: I

won't let the rascals have my pipe, if I must die for it."

His two comrades went away and took the horses out of the

stable. Kitty

came running over, however, and called Hansgeorge into the house. He

came reluctantly, for he was angry with her for laughing at him; but

she took his hand, trembling, and said, "For God's sake, Hansgeorge,

let the pipe alone. I'll do any thing to please you if you'll only mind

me now. How can you let them kill you for such a good-for-nothing pipe?

Do stay here, I beg of you."

"I won't stay here! I don't care if they do send a bullet

through my

head! What should I stay here for? You never do any thing but tease

me."

"No, no!" cried Kitty, falling upon his neck: "you must stay

here! I

won't let you go."

Hansgeorge felt a strange thrill pass through him; but he

asked,

saucily, "Will you be my wife, then?"

"Yes, yes, I will, Hansgeorge! I will!"

They embraced each other with transport, and Hansgeorge

exclaimed,

"I'll never put a pipe into my mouth again as long as I live: if I do,

I hope I may be----"

"No, no; don't swear, but keep your word: that's much better.

But now

you will stay here, won't you, Hansgeorge? Let the pipe and the

Frenchman go to the devil together."

Xavier and Fidele now came riding up, armed with pitchforks,

and cried,

"Hurry up, Hansgeorge! hurry up!"

"I am not going with you," said Hansgeorge.

"What will you give us if we bring your pipe back?" asked

Fidele.

"You may keep it."

They rode off post-haste down the Empfingen road, Hansgeorge

and Kitty

looking after them. At the little hill by the clay-pit they had nearly

caught up to the marauders; but when the latter found themselves

pursued they turned, brandished their swords, and one of them drew a

pistol. Fidele and Xavier, seeing this, turned round also, and returned

faster than they had come.

From that day Hansgeorge never touched a pipe. Four weeks

later his and

Kitty's banns were read in the church.

One day Hansgeorge went to the brickmaker's: he had come

unperceived,

having taken the back way. He heard Kitty say to some one inside. "So

you are sure it is the same?"

"Of course it is," said the person addressed, whose voice he

recognised

as belonging to Little Red Meyer, a Jewish peddler. "Why, they were

always seen together: for my part, I don't see how he ever made up his

mind to marry anybody else."

"Well," said Kitty, laughingly, "I only want to make him stare

a little

on our wedding-day. So you won't disappoint me, will you?"

"I'll do it as sure as I want to make a hundred thousand

florins."

"But Hansgeorge mustn't hear a word about it."

"Mum's the word," said Little Red Meyer, and took his leave.

Hansgeorge came in rather sheepishly, being ashamed to confess

that he

had been listening. But when they sat closely side by side, he said,

"Kitty, don't let them put any nonsense into your head: it's no such

thing. They once used to say that I was courting the maid at the Eagle,

who is now in Rothweil: don't you believe a bit of it. I wasn't

confirmed then: it was nothing but child's-play."

Kitty pretended to lay great stress on this matter, and put

Hansgeorge

to a world of trouble to clear himself. In the evening he did his best

to pump the whole secret out of Little Red Meyer; but all in vain: his

word was "mum."

Hansgeorge had many things to go through with yet, and, in a

manner, to

run the gauntlet of the whole village. On the Sunday before the

wedding, he, as well as his "playmate" Fidele, adorned their hats and

left arms with red ribbons, and went, thus accoutred, from house to

house, the groom that was to be repeating the following speech at

every call:--"I want you to come to the wedding on Tuesday, at the

Eagle. If we can do the same for you, we will. Be sure to come. Don't

forget. Be sure to come." Thereupon the housewife invariably opened the

table-drawer and brought out a loaf of bread and a knife, saying,

"There! have some bread." Then the intended groom was expected to cut a

piece from the loaf and take it with him. The loss of his forefinger

made Hansgeorge rather awkward at this operation; and many would hurt

his feelings unintentionally by saying, "Why, Hansgeorge, you can't cut

the bread. You oughtn't to get married: you are unfit for service."

Hansgeorge rejoiced greatly when this ordeal was over.

The wedding was celebrated with singing and rejoicing, although there

was no shooting, as it had been strictly forbidden since Hansgeorge's

misfortune.

The dinner was uncommonly merry. Immediately after it, Kitty

slipped

out into the kitchen, and came back with the memorable pipe in her

mouth: no one, at least, could say that it was not the same. Kitty

puffed away a little with a wry face, and then handed it to Hansgeorge,

saying,  "There, take it: you have kept your word like a man, and now

you may smoke as much as you please. I don't mind it a bit."

"There, take it: you have kept your word like a man, and now

you may smoke as much as you please. I don't mind it a bit."

Hansgeorge blushed up to the eyes, but shook his head. "What I

have

said is said, and not a mouse shall bite a crumb off: I'll never smoke

again in all my life. But, Kitty, I may kiss you after you've done

smoking, mayn't I?"

He strained her to his heart, and then confessed, laughing,

that he had

overheard a part of Kitty's talk with Little Red Meyer, and had

supposed they were speaking of the maid at the Eagle. The joke was much

relished by all the company.

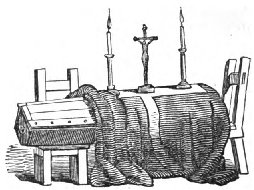

The pipe was hung up in state over the wedding-bed of the

young couple;

and Hansgeorge often points to it in proof of the maxim that love and

resolution will enable a man to overcome any weakness or foible.

Many years are covered by a few short words. Hansgeorge and

Kitty are

venerable grandparents, enjoying a ripe old age in the midst of their

descendants. The pipe is an heirloom in which their five sons have a

common property: not one of them has ever learned to smoke.

MANOR-HOUSE FARMER'S VEFELA.

1.

Not many will divine the orthography of this name in the

Almanac; yet

it is by no means uncommon, and the fate of the poor child who bore it

reminds one strongly of the German story of her afflicted patroness,

the holy St. Genevieve.

Not many will divine the orthography of this name in the

Almanac; yet

it is by no means uncommon, and the fate of the poor child who bore it

reminds one strongly of the German story of her afflicted patroness,

the holy St. Genevieve.

The grandest house in all the village, which has such a broad

front

toward the street that all the wandering journeymen stop there to ask

for a little "assistance," once belonged to Vefela's father: the houses

standing on each side of it were his barns. The father is dead, the

mother is dead, and the children are dead. The grand house is now a

linen-factory. The barns have been altered into houses, and Vefela has

disappeared without a trace.

One thing alone remains, and will probably remain for all time

to come.

Throughout the village the grand house still goes by the name of the

Manor-Farmer's House; for old Zahn, Vefela's father, was called the

Manor-House Farmer. He was not a native of the village, but had moved

there from Baisingen, which is five miles away. Baisingen is one of