Title: The History of Virginia, in Four Parts

Author: Robert Beverley

Release date: June 6, 2010 [eBook #32721]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Julia Miller, Christine Aldridge, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive/American Libraries (http://www.archive.org/details/americana)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/American Libraries. See http://www.archive.org/details/historyofvirgini00beve |

1. Minor punctuation irregularities have been made consistent.

2. Numerous corrections have been made. A complete list is located at the end of the text together with word use variations.

| I. | The History of the first settlement of Virginia, and the government thereof, to the year 1706. |

| II. | The natural productions and conveniences of the country, suited to trade and improvement. |

| III. | The native Indians, their religion, laws and customs, in war and peace. |

| IV. | The present state of the country, as to the polity of the government, and the improvements of the land the 10th of June 1720. |

A native and inhabitant of the place.

REPRINTED FROM THE AUTHOR'S SECOND REVISED EDITION, LONDON, 1722.

WITH AN INTRODUCTION

Author of the Colonial History of Virginia.

[Pg ii]Entered according to act of Congress, in the year 1855, by

J. W. RANDOLPH,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court in and for the Eastern District of Virginia.

H. K. ELLYSON'S STEAM PRESSES, RICHMOND, VA.

History of the first attempts to settle Virginia, before the discovery of Chesapeake bay.

| PAGE. | ||

| §1. | Sir Walter Raleigh obtains letters patent, for making discoveries in America, | 8 |

| 2. | Two ships set out on the discovery, and arrive at Roanoke inlet, | 9 |

| Their account of the country, | 9 | |

| thier account of the natives, | 9 | |

| 3. | Queen Elizabeth names the country of Virginia, | 10 |

| 4. | Sir Richard Greenvile's voyage, | 10 |

| He plans the first colony, under command of Mr. Ralph Lane, | 11 | |

| 5. | The discoveries and accidents of the first colony, | 11 |

| 6. | Their distress by want of provisions, | 12 |

| Sir Francis Drake visits them, | 12 | |

| He gives them a ship and necessaries, | 12 | |

| He takes them away with him, | 12 | |

| 7. | Sir Walter Raleigh and Sir Richard Greenvile, their voyages, | 13 |

| The second settlement made, | 13 | |

| 8. | Mr. John White's expedition, | 13 |

| The first Indian made a Christian there, | 14 | |

| The first child born there of Christian parentage, | 14 | |

| Third settlement, incorporated by the name of the city of Raleigh, in Virginia, | 14 | |

| Mr. White, their governor, sent home to solicit for supplies, | 14 | |

| 9. | John White's second voyage; last attempts to carry them recruits, | 14 |

| His disappointment, | 15 | |

| 10. | Capt. Gosnell's voyage to the coast of Cape Cod, | 15 |

| 11. | The Bristol voyages, | 16 |

| 12. | A London voyage, which discovered New York, | 16 |

Discovery of Chesapeake bay by the corporation of London adventurers; their colony at Jamestown, and proceedings during the government by an elective president and council.

| §13. | The companies of London and Plymouth obtain charters, | 18 |

| 14. | Captain Smith first discovers the capes of Virginia, | 19 |

| 15. | He plants his first colony at Jamestown, | 20 |

| An account of Jamestown island, | 20 | |

| 16. | He sends the ships home, retaining one hundred and eight men to keep possession, | 20 |

| 17. | That colony's mismanagement, | 21[Pg iv] |

| Their misfortunes upon discovery of a supposed gold mine, | 21 | |

| 18. | Their first supplies after settlement, | 22 |

| Their discoveries, and experiments in English grain, | 22 | |

| An attempt of some to desert the colony, | 22 | |

| 19. | The first Christian marriage in that colony, | 23 |

| They make three plantations more, | 23 |

History of the colony after the change of their government, from an elective president to a commissionated governor, until the dissolution of the company.

| §20. | The company get a new grant, and the nomination of the governors in themselves, | 24 |

| They send three governors in equal degree, | 24 | |

| All three going in one ship, are shipwrecked at Bermudas, | 24 | |

| They build there two small cedar vessels, | 24 | |

| 21. | Captain Smith's return to England, | 25 |

| Mismanagements ruin the colony, | 25 | |

| The first massacre and starving time, | 25 | |

| The first occasion of the ill character of Virginia, | 26 | |

| The five hundred men left by Captain Smith reduced to sixty in six months time, | 26 | |

| 22. | The three governors sail from Bermudas, and arrive at Virginia, | 26 |

| 23. | They take off the Christians that remained there, and design, by way of Newfoundland, to return to England, | 27 |

| Lord Delaware arrives and turns them back, | 27 | |

| 24. | Sir Thomas Dale arrives governor, with supplies, | 27 |

| 25. | Sir Thomas Gates arrives governor, | 28 |

| He plants out a new plantation, | 28 | |

| 26. | Pocahontas made prisoner, and married to Mr. Rolfe, | 28 |

| 27. | Peace with the Indians, | 28 |

| 28. | Pocahontas brought to England by Sir Thomas Dale, | 29 |

| 29. | Captain Smith's petition to the queen in her behalf, | 29 |

| 30. | His visit to Pocahontas, | 32 |

| An Indian's account of the people of England, | 32 | |

| 31. | Pocahontas' reception at court, and death, | 33 |

| 32. | Captain Yardley's government, | 34 |

| 33. | Governor Argall's good administration, | 34 |

| 34. | Powhatan's death, and successors, | 34 |

| Peace renewed by the successors, | 34 | |

| 35. | Captain Argall's voyage from Virginia to New England, | 35 |

| 36. | He defeats the French northward of New England, | 35 |

| 37. | An account of those French, | 36 |

| 38. | He also defeats the French in Acadia, | 36 |

| 39. | His return to England, | 36 |

| Sir George Yardley, governor, | 36 | |

| 40. | He resettles the deserted plantation, and held the first assembly, | 36 |

| The method of that assembly, | 37 | |

| 41. | The first negroes carried to Virginia, | 37 |

| 42. | Land apportioned to adventurers, | 37 |

| 43. | A salt work and iron work in Virginia, | 38 |

| 44. | Sir Francis Wyat made governor, | 38 |

| King James, his instructions in care of tobacco, | 38 | |

| Captain Newport's plantation, | 38 | |

| 45. | Inferior courts in each plantation, | 39[Pg v] |

| Too much familiarity with the Indians, | 39 | |

| 46. | The massacre by the Indians, anno 1622, | 39 |

| 47. | The discovery and prevention of it at Jamestown, | 40 |

| 48. | The occasion of the massacre, | 41 |

| 49. | A plot to destroy the Indians, | 42 |

| 50. | The discouraging effects of the massacre, | 43 |

| 51. | The corporation in England are the chief cause of misfortunes in Virginia, | 43 |

| 52. | The company dissolved, and the colony taken into the king's hands, | 44 |

History of the government, from the dissolution of the company to the year 1707.

| §53. | King Charles First establishes the constitution of government, in the methods appointed by the first assembly, | 45 |

| 54. | The ground of the ill settlement of Virginia, | 45 |

| 55. | Lord Baltimore in Virginia, | 46 |

| 56. | Lord Baltimore, proprietor of Maryland, | 46 |

| Maryland named from the queen, | 46 | |

| 57. | Young Lord Baltimore seats Maryland, | 46 |

| Misfortune to Virginia, by making Maryland a distinct government, | 47 | |

| 58. | Great grants and defalcations from Virginia, | 47 |

| 59. | Governor Harvey sent prisoner to England, and by the king remanded back governor again, | 47 |

| 60. | The last Indian massacre, | 48 |

| 61. | A character and account of Oppechancanough, the Indian emperor, | 48 |

| 62. | Sir William Berkeley made governor, | 49 |

| 63. | He takes Oppechancanough prisoner, | 49 |

| Oppechancanough's death, | 50 | |

| 64. | A new peace with the Indians, but the country disturbed by the troubles in England, | 50 |

| 65. | Virginia subdued by the protector, Cromwell, | 50 |

| 66. | He binds the plantations by an act of navigation, | 51 |

| 67. | His jealousy and change of governors in Virginia, | 51 |

| 68. | Upon the death of Matthews, the protector's governor, Sir William Berkeley is chosen by the people, | 52 |

| 69. | He proclaims King Charles II before he was proclaimed in England, | 52 |

| 70. | King Charles II renews Sir William Berkeley's commission, | 52 |

| 71. | Sir William Berkeley makes Colonel Morrison deputy governor, and goes to England, | 53 |

| The king renews the act concerning the plantation, | 53 | |

| 72. | The laws revised, | 53 |

| The church of England established by law, | 53 | |

| 73. | Clergy provided for by law, | 53 |

| 74. | The public charge of the government sustained by law, | 53 |

| 75. | Encouragement of particular manufactures by law, | 54 |

| 76. | The instruction for all ships to enter at Jamestown, used by law, | 54 |

| 77. | Indian affairs settled by law, | 54 |

| 78. | Jamestown encouraged by law, | 54 |

| 79. | Restraints upon sectaries in religion, | 55 |

| 80. | A plot to subvert the government, | 55[Pg vi] |

| 81. | The defeat of the plot, | 55 |

| 82. | An anniversary feast upon that occasion, | 56 |

| 83. | The king commands the building a fort at Jamestown, | 56 |

| 84. | A new restraint on the plantations by act of parliament, | 56 |

| 85. | Endeavors for a stint in planting tobacco, | 56 |

| 86. | Another endeavor at a stint defeated, | 57 |

| 87. | The king sent instructions to build forts, and confine the trade to certain ports, | 57 |

| 88. | The disappointment of those ports, | 58 |

| 89. | Encouragement of manufactures enlarged, | 58 |

| 90. | An attempt to discovery the country backward, | 59 |

| Captain Batt's relation of that discovery, | 59 | |

| 91. | Sir William Berkeley intends to prosecute that discovery in person, | 60 |

| 92. | The grounds of Bacon's rebellion, | 60 |

| Four ingredients thereto, | 61 | |

| 93. | First, the low price of tobacco, | 61 |

| Second, splitting the country into proprieties, | 61 | |

| The country send agents, to complain of the propriety grants, | 61 | |

| 94. | Third, new duties by act in England on the plantations, | 62 |

| 95. | Fourth, disturbances on the land frontiers by the Indians, | 62 |

| First, by the Indians on the head of the bay, | 62 | |

| Second, by the Indians on their own frontiers, | 63 | |

| 96. | The people rise against the Indians, | 63 |

| They choose Nathan Bacon, Jr., for their leader, | 63 | |

| 97. | He heads them, and sends to the governor for a commission, | 64 |

| 98. | He begins his march without a commission, | 64 |

| The governor sends for him, | 65 | |

| 99. | Bacon goes down in a sloop with forty of his men to the governor, | 65 |

| 100. | Goes away in a huff, is pursued and brought back by governor, | 65 |

| 101. | Bacon steals privately out of town, and marches down to the assembly with six hundred of his volunteers, | 65 |

| 102. | The governor, by advice of assembly, signs a commission to Mr. Bacon to be general, | 66 |

| 103. | Bacon being marched away with his men is proclaimed rebel, | 66 |

| 104. | Bacon returns with his forces to Jamestown, | 66 |

| 105. | The governor flies to Accomac, | 66 |

| The people there begin to make terms with him, | 67 | |

| 106. | Bacon holds a convention of gentlemen, | 67 |

| They propose to take an oath to him, | 67 | |

| 107. | The forms of the oath, | 67 |

| 108. | The governor makes head against him, | 69 |

| General Bacon's death, | 69 | |

| 109. | Bacon's followers surrender upon articles, | 69 |

| 110. | The agents compound with the proprietors, | 69 |

| 111. | A new charter to Virginia, | 70 |

| 112. | Soldiers arrive from England, | 70 |

| 113. | The dissolution by Bacon's rebellion, | 70 |

| 114. | Commissioners arrive in Virginia, and Sir William Berkeley returns to England, | 71 |

| 115. | Herbert Jeffreys, esq., governor, concludes peace with Indians, | 71 |

| 116. | Sir Henry Chicheley, deputy governor, builds forts against Indians, | 71 |

| The assembly prohibited the importation of tobacco, | 72 | |

| 117. | Lord Colepepper, governor, | 72 |

| 118. | Lord Colepepper's first assembly, | 72 |

| He passes several obliging acts to the country, | 72 | |

| 119. | He doubles the governor's salary, | 72[Pg vii] |

| 120. | He imposes the perquisite of ship money, | 73 |

| 121. | He, by proclamation, raises the value of Spanish coins, and lowers it again, | 73 |

| 122. | Sir Henry Chicheley, deputy governor, | 74 |

| The plant cutting, | 74 | |

| 123. | Lord Colepepper's second assembly, | 75 |

| He takes away appeals to the assembly, | 75 | |

| 124. | His advantage thereby in the propriety of the Northern Neck, | 76 |

| 125. | He retrenches the new methods of court proceedings, | 77 |

| 126. | He dismantled the forts on the heads of rivers, and appointed rangers in their stead, | 77 |

| 127. | Secretary Spencer, president, | 77 |

| 128. | Lord Effingham, governor, | 77 |

| Some of his extraordinary methods of getting money, | 77 | |

| Complaints against him, | 78 | |

| 129. | Duty on liquors first raised, | 78 |

| 130. | Court of Chancery by Lord Effingham, | 78 |

| 131. | Colonel Bacon, president, | 79 |

| The college designed, | 79 | |

| 132. | Francis Nicholson, lieutenant governor, | 79 |

| He studies popularity, | 79 | |

| The college proposed to him, | 79 | |

| He refuses to call an assembly, | 79 | |

| 133. | He grants a brief to the college, | 79 |

| 134. | The assembly address King William and Queen Mary for a college charter, | 80 |

| The education intended by this college, | 80 | |

| The assembly present the lieutenant governor, | 80 | |

| His method of securing this present, | 80 | |

| 135. | Their majesties grant the charter, | 80 |

| They grant liberally towards the building and endowing of it, | 80 | |

| 136. | The lieutenant governor encourages towns and manufactures, | 80 |

| Gentlemen of the council complain of him and are misused, | 81 | |

| He falls off from the encouragement of the towns and trade, | 81 | |

| 137. | Edmund Andros, governor, | 81 |

| The town law suspended, | 81 | |

| 138. | The project of a post office, | 81 |

| 139. | The college charter arrived, | 81 |

| The college further endowed, and the foundation laid, | 82 | |

| 140. | Sir Edmund Andros encourages manufactures, and regulates the secretary's office, | 82 |

| 141. | A child born in the old age of the parents, | 83 |

| 142. | Francis Nicholson, governor, | 83 |

| His and Colonel Quarrey's memorials against plantations, | 84 | |

| 143. | His zeal for the church and college, | 84 |

| 144. | He removes the general court from Jamestown, | 84 |

| 145. | The taking of the pirate, | 84 |

| 146. | The sham bills of nine hundred pounds for New York, | 86 |

| 147. | Colonel Quarrey's unjust memorials, | 87 |

| 148. | Governor Nott arrived, | 88 |

| 149. | Revisal of the law finished, | 88 |

| 150. | Ports and towns again set on foot, | 88 |

| 151. | Slaves a real estate, | 88 |

| 152. | A house built for the governor, | 88 |

| Governor dies, and the college burnt, | 88 | |

| 153. | Edmond Jennings, esq., president, | 89[Pg viii] |

| 154. | Alexander Spotswood, lieutenant governor, | 89 |

Natural Productions and Conveniences of Virginia in its unimproved state, before the English went thither.

Bounds and Coast of Virginia.

| §1. | Present bounds of Virginia, | 90 |

| 2. | Chesapeake bay, and the sea coast of Virginia, | 91 |

| 3. | What is meant by the word Virginia in this book, | 91 |

Of the Waters.

| §4. | Conveniency of the bay and rivers, | 93 |

| 5. | Springs and fountains descending to the rivers, | 93 |

| 6. | Damage to vessels by the worm, | 94 |

| Ways of avoiding that damage, | 94 |

Earths, and Soils.

| §7. | The soil in general, | 96 |

| River lands—lower, middle and upper, | 96 | |

| 8. | Earths and clays, | 98 |

| Coal, slate and stone, and why not used, | 98 | |

| 9. | Minerals therein, and iron mine formerly wrought upon, | 98 |

| Supposed gold mines lately discovered, | 99 | |

| That this gold mine was the supreme seat of the Indian temples formerly, | 99 | |

| That their chief altar was there also, | 99 | |

| Mr. Whitaker's account of a silver mine, | 99 | |

| 10. | Hills in Virginia, | 100 |

| Springs in the high lands, | 101 |

Wild Fruits.

| §11. | Spontaneous fruits in general, | 102 |

| 12. | Stoned fruits, viz: cherries, plums and persimmons, | 102 |

| 13. | Berries, viz: mulberries, currants, hurts, cranberries, raspberries and strawberries, | 103 |

| 14. | Of nuts, | 104 |

| 15. | Of grapes, | 105 |

| The report of some French vignerons formerly sent in thither, | 107 | |

| 16. | Honey, and the sugar trees, | 107 |

| 17. | Myrtle tree, and myrtle wax, | 108 |

| Hops growing wild, | 109 | |

| 18. | Great variety of seeds, plants and flowers, | 109 |

| Two snake roots, | 109 | |

| Jamestown weed, | 110 | |

| Some curious flowers, | 111 | |

| 19. | Creeping vines bearing fruits, viz: melons, pompions, macocks, gourds, maracocks, and cushaws, | 112[Pg ix] |

| 20. | Other fruits, roots and plants of the Indians, | 114 |

| Several sorts of Indian corn, | 114 | |

| Of potatoes, | 115 | |

| Tobacco, as it was ordered by the Indians, | 116 |

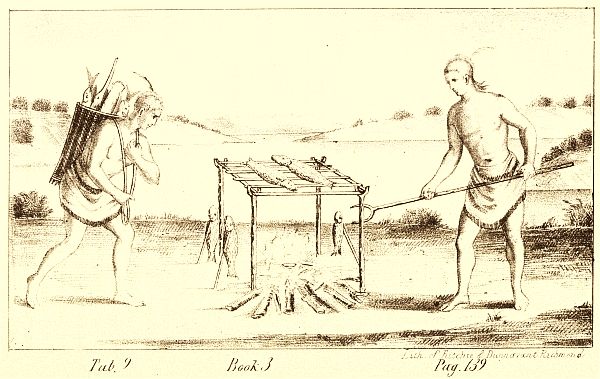

Fish.

| §21. | Great plenty and variety of fish, | 117 |

| Vast shoals of herrings, shad, &c., | 117 | |

| 22. | Continuality of the fishery, | 118 |

| The names of some of the best edible fish, | 118 | |

| The names of some that are not eaten, | 118 | |

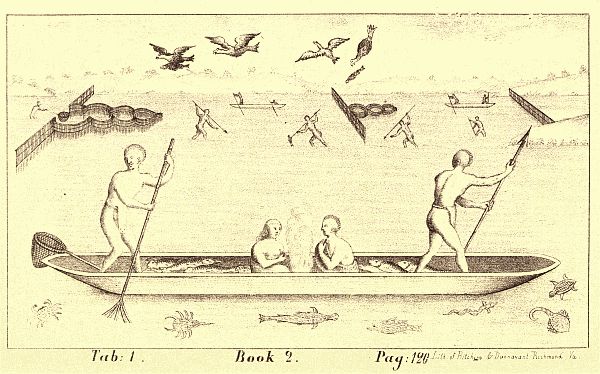

| 23. | Indian children catching fish, | 118 |

| Several inventions of the Indians to take fish, | 119 | |

| 24. | Fishing hawks and bald eagles, | 121 |

| Fish dropped in the orchard, | 121 |

Wild Fowl and Hunted Game.

| §25. | Wild Water Fowl, | 123 |

| 26. | Game in the marshes and watery grounds, | 123 |

| 27. | Game in the highlands and frontiers, | 123 |

| Of the Opossum, | 124 | |

| 28. | Some Indian ways of hunting, | 124 |

| Fire hunting, | 124 | |

| Their hunting quarters, | 125 | |

| 29. | Conclusion, | 126 |

Indians, their Religion, Laws and Customs, in War and Peace.

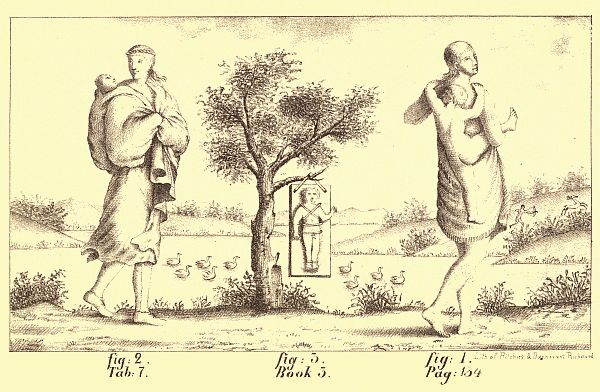

Persons of the Indians, and their Dress.

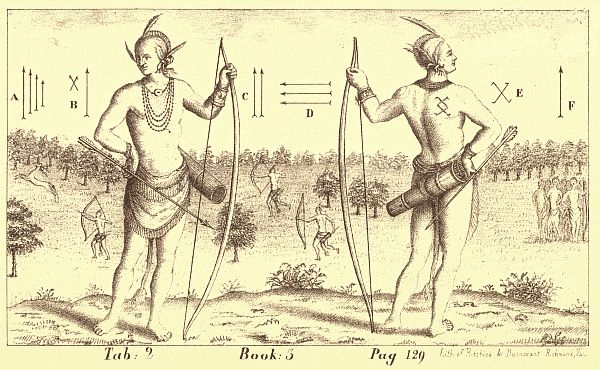

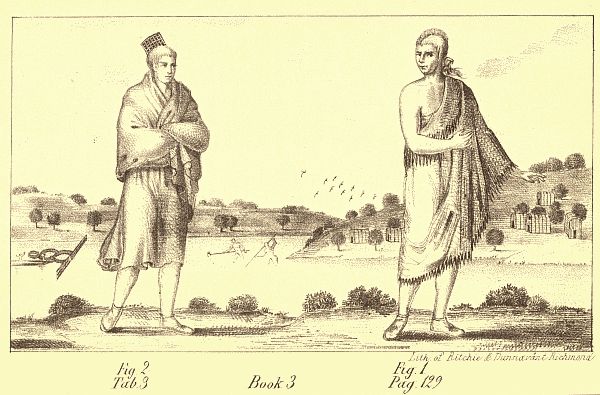

| §1. | Persons of the Indians, their color and shape, | 127 |

| 2. | The cut of their hair, and ornament of their head, | 128 |

| 3. | Of their vesture, | 128 |

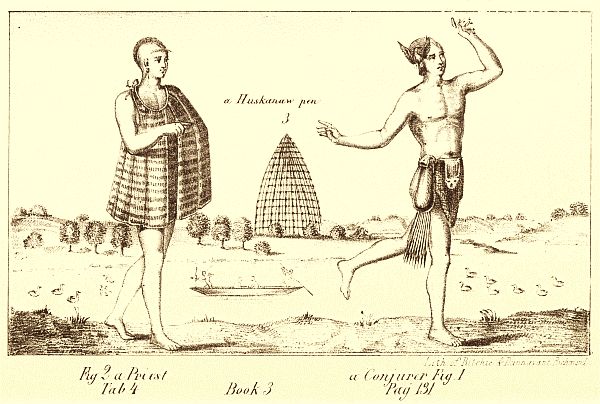

| 4. | Garb peculiar to their priests and conjurors, | 130 |

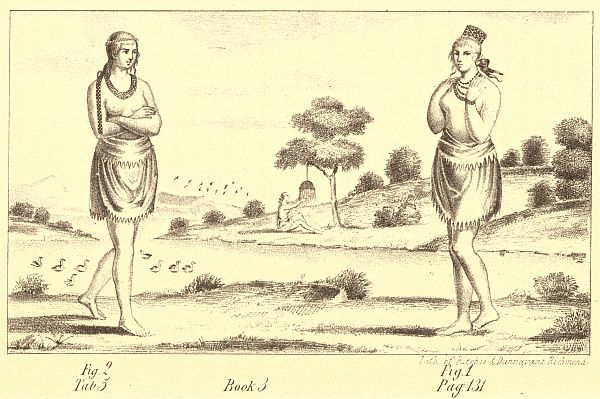

| 5. | Of the women's dress, | 131 |

Matrimony of the Indians, and Management of their Children.

| §6. | Conditions of their marriage, | 133 |

| 7. | Maidens, and the story of their prostitution, | 133 |

| 8. | Management of the young children, | 134 |

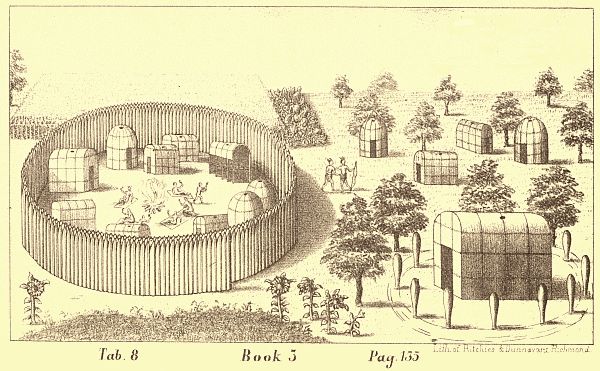

Towns, Building and Fortification of the Indians.

| §9. | Towns and kingdoms of the Indians, | 135 |

| 10. | Manner of their building, | 135 |

| 11. | Their fuel, or firewood, | 136 |

| 12. | Their seats and lodging, | 136[Pg x] |

| 13. | Their fortifications, | 136 |

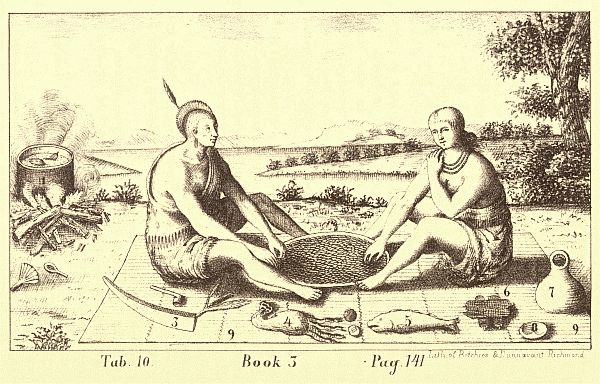

Cookery and Food of the Indians.

| §14. | Their cookery, | 138 |

| 15. | Their several sorts of food, | 139 |

| 16. | Their times of eating, | 140 |

| 17. | Their drink, | 140 |

| 18. | Their ways of dining, | 141 |

Traveling, Reception and entertainment of the Indians.

| §19. | Manner of their traveling, and provision they make for it, | 142 |

| Their way of concealing their course, | 142 | |

| 20. | Manner of their reception of strangers, | 143 |

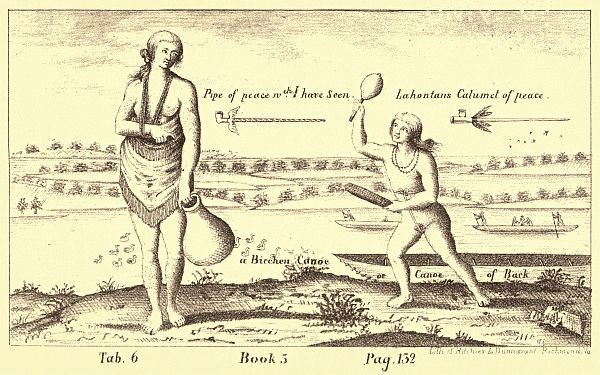

| The pipe of peace, | 143 | |

| 21. | Their entertainment of honorable friends, | 145 |

Learning and Languages of the Indians.

| §22. | That they are without letters, | 147 |

| Their descriptions by hieroglyphics, | 147 | |

| Heraldry and arms of the Indians, | 147 | |

| 23. | That they have different languages, | 148 |

| Their general language, | 148 |

War and Peace of the Indians.

| §24. | Their consultations and war dances, | 149 |

| 25. | Their barbarity upon a victory, | 149 |

| 26. | Descent of the crown, | 150 |

| 27. | Their triumphs for victory, | 150 |

| 28. | Their treaties of peace, and ceremonies upon conclusion of peace, | 151 |

Religion, Worship and Superstitious Customs of the Indians.

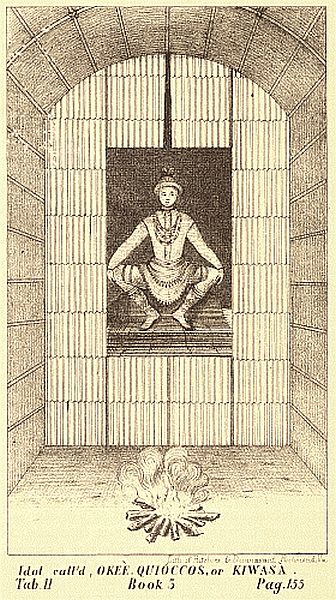

| §29. | Their quioccassan and idol of worship, | 152 |

| 30. | Their notions of God, and worshiping the evil spirit, | 155 |

| 31. | Their pawwawing or conjurations, | 157 |

| 32. | Their huskanawing, | 160 |

| 33. | Reasons of this custom, | 164 |

| 34. | Their offerings and sacrifice, | 165 |

| 35. | Their set feasts, | 165 |

| 36. | Their account of time, | 165 |

| 37. | Their superstition and zealotry, | 166 |

| 38. | Their regard to the priests and magicians, | 167 |

| 39. | Places of their worship and sacrifice, | 168 |

| Their pawcorances or altar stones, | 168 | |

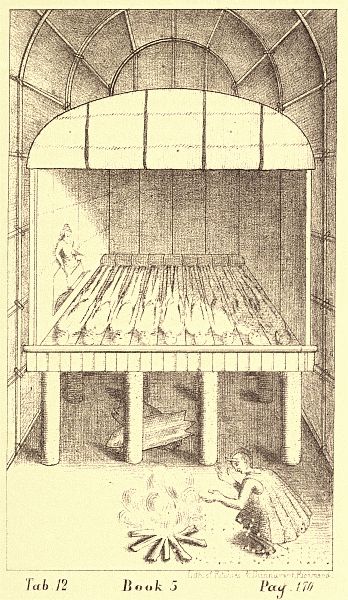

| 40. | Their care of the bodies of their princes after death, | 169 |

Diseases and Cures of the Indians.

| §41. | Their diseases in general, and burning for cure, | 171 |

| Their sucking, scarifying and blistering, | 171 | |

| Priests' secrecy in the virtues of plants, | 171 | |

| Words wisoccan, wighsacan and woghsacan, | 172 | |

| Their physic, and the method of it, | 172 | |

| 42. | Their bagnios or baths, | 172 |

| Their oiling after sweating, | 173 |

Sports and Pastimes of the Indians.

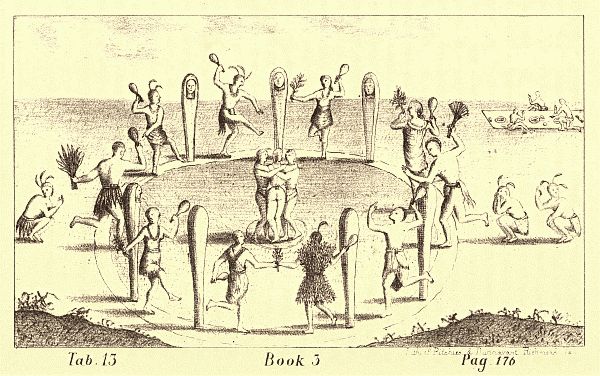

| §43. | Their sports and pastimes in general, | 175 |

| Their singing, | 175 | |

| Their dancing, | 175 | |

| A mask used among them, | 176 | |

| Their musical instruments, | 177 |

Laws, and Authorities of the Indians among one another.

| §44. | Their laws in general, | 178 |

| Their severity and ill manners, | 178 | |

| Their implacable resentments, | 179 | |

| 45. | Their honors, preferments and authorities, | 179 |

| Authority of the priests and conjurers, | 179 | |

| Servants or black boys, | 179 |

Treasure or Riches of the Indians.

| §46. | Indian money and goods, | 180 |

Handicrafts of the Indians.

| §47. | Their lesser crafts, as making bows and arrows, | 182 |

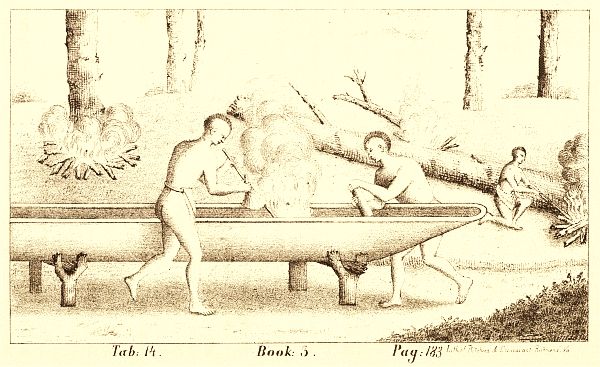

| 48. | Their making canoes, | 182 |

| Their clearing woodland ground, | 183 | |

| 49. | Account of the tributary Indians, | 185 |

Present State of Virginia.

Polity and Government.

Constitution of Government in Virginia.

| §1. | Constitution of government in general, | 186 |

| 2. | Governor, his authority and salary, | 188 |

| 3. | Council and their authority, | 189[Pg xii] |

| 4. | House of burgesses, | 190 |

Sub-Divisions of Virginia.

| §5. | Division of the country, | 192 |

| 6. | Division of the country by necks of land, counties and parishes, | 192 |

| 7. | Division of the country by districts for trade by navigation, | 194 |

Public Offices of Government.

| §8. | General officers as are immediately commissionated from the throne, | 196 |

| Auditor, Receiver General and Secretary, | 196 | |

| Salaries of those officers, | 197 | |

| 9. | Other general officers, | 197 |

| Ecclesiastical commissary and country's treasurer, | 197 | |

| 10. | Other public officers by commission, | 197 |

| Escheators, | 197 | |

| Naval officers and collectors, | 198 | |

| Clerks and sheriffs, | 198 | |

| Surveyors of land and coroners, | 199 | |

| 11. | Other officers without commission, | 199 |

Standing Revenues or Public Funds.

| §12. | Public funds in general, | 200 |

| 13. | Quit rent fund, | 200 |

| 14. | Funds for maintenance of the government, | 201 |

| 15. | Funds for extraordinary occasions, under the disposition of the assembly, | 201 |

| 16. | Revenue granted by the act of assembly to the college, | 202 |

| 17. | Revenue raised by act of parliament in England from the trade there, | 202 |

Levies for Payment of the Public, County and Parish Debts.

| §18. | Several ways of raising money, | 203 |

| Titheables, | 203 | |

| 19. | Public levy, | 203 |

| 20. | County levy, | 204 |

| 21. | Parish levy, | 204 |

Courts of Law in Virginia.

| §22. | Constitution of their courts, | 205 |

| 23. | Several sorts of courts among them, | 206 |

| 24. | General court in particular, and its jurisdiction, | 206 |

| 25. | Times of holding a general court, | 206[Pg xiii] |

| 26. | Officers attending this court, | 206 |

| 27. | Trials by juries and empannelling grand juries, | 207 |

| 28. | Trial of criminals, | 207 |

| 29. | Time of suits, | 208 |

| 30. | Lawyers and pleadings, | 208 |

| 31. | County courts, | 208 |

| 32. | Orphans' courts, | 209 |

Church and Church Affairs.

| §33. | Parishes, | 210 |

| 34. | Churches and chapels in each parish, | 210 |

| 35. | Religion of the country, | 210 |

| 36. | Benefices of the clergy, | 210 |

| 37. | Disposition of parochial affairs, | 211 |

| 38. | Probates, administrations, and marriage licenses, | 212 |

| 39. | Induction of ministers, and precariousness of their livings, | 213 |

Concerning the College.

| §40. | College endowments, | 214 |

| 41. | The college a corporation, | 214 |

| 42. | Governors and visitors of the college in perpetual succession, | 215 |

| 43. | College buildings, | 215 |

| 44. | Boys and schooling, | 215 |

Military Strength in Virginia.

| §45. | Forts and fortifications, | 217 |

| 46. | Listed militia, | 217 |

| 47. | Number of the militia, | 217 |

| 48. | Service of the militia, | 218 |

| 49. | Other particulars of the troops and companies, | 218 |

Servants and Slaves.

| §50. | Distinction between a servant and a slave, | 219 |

| 51. | Work of their servants and slaves, | 219 |

| 52. | Laws in favor of servants, | 220 |

Provision for the Poor, and other Public Charitable Works.

| §53. | Legacy to the poor, | 223 |

| 54. | Parish methods in maintaining their poor, | 223 |

| 55. | Free schools, and schooling of children, | 224 |

Tenure of Lands and Grants.

| §56. | Tenure and patents of their lands, | 225 |

| 57. | Several ways of acquiring grants of land, | 225 |

| 58. | Rights to land, | 225[Pg xiv] |

| 59. | Patents upon survey, | 225 |

| 60. | Grants of lapsed land, | 226 |

| 61. | Grants of escheat land, | 227 |

Liberties and Naturalization of Aliens.

| §62. | Naturalizations, | 228 |

| 63. | French refugees at the Manican town, | 228 |

Currency and Valuation of Coins.

| §64. | Coins current among them, what rates, and why carried from among them to the neighboring plantations, | 230 |

Husbandry and Improvements.

People, Inhabitants of Virginia.

| §65. | First peopling of Virginia, | 231 |

| 66. | First accession of wives to Virginia, | 231 |

| 67. | Other ways by which the country was increased in people, | 232 |

Buildings in Virginia.

| §68. | Public buildings, | 234 |

| 69. | Private buildings, | 235 |

Edibles, Potables and Fuel.

| §70. | Cookery, | 236 |

| 71. | Flesh and fish, | 236 |

| 72. | Bread, | 237 |

| 73. | Their kitchen gardens, | 237 |

| 74. | Their drinks, | 238 |

| 75. | Their fuel, | 238 |

Clothing in Virginia.

| §76. | Clothing, | 239 |

| Slothfulness in handicrafts, | 239 |

Temperature of the Climate, and the Inconveniences attending it.

| §77. | Natural temper and mixture of the air, | 240 |

| 78. | Climate and happy situation of the latitude, | 240 |

| 79. | Occasions of its ill character, | 241[Pg xv] |

| Rural pleasures, | 241 | |

| 80. | Annoyances, or occasions of uneasiness, | 243 |

| Thunders, | 243 | |

| Heat, | 243 | |

| Troublesome insects, | 243 | |

| 81. | Winters, | 250 |

| Sudden changes of the weather, | 251 |

Diseases incident to the Country.

| §82. | Diseases in general, | 252 |

| 83. | Seasoning, | 253 |

| 84. | Cachexia and yaws, | 253 |

| 85. | Gripes, | 253 |

Recreations and Pastimes in Virginia.

| §86. | Diversions in general, | 254 |

| 87. | Deer-hunting, | 254 |

| 88. | Hare-hunting, | 254 |

| 89. | Vermin-hunting, | 255 |

| 90. | Taking wild turkies, | 256 |

| 91. | Fishing, | 256 |

| 92. | Small game, | 256 |

| 93. | Beaver, | 256 |

| 94. | Horse-hunting, | 257 |

| 95. | Hospitality, | 258 |

Natural Product of Virginia, and the Advantages of Husbandry.

| §96. | Fruits, | 259 |

| 97. | Grain, | 261 |

| 98. | Linen, silk and cotton, | 261 |

| 99. | Bees and cattle, | 262 |

| 100. | Usefulness of the woods, | 263 |

| 101. | Indolence of the inhabitants, | 263 |

My first business in the world being among the public records of my country, the active thoughts of my youth put me upon taking notes of the general administration of the government; but with no other design, than the gratification of my own inquisitive mind; these lay by me for many years afterwards, obscure and secret, and would forever have done so, had not the following accident produced them:

In the year 1703, my affairs calling me to England, I was soon after my arrival, complimented by my bookseller with an intimation, that there was prepared for printing a general account of all her majesty's plantations in America, and his desire, that I would overlook it before it was put to the press; I agreed to overlook that part of it which related to Virginia.

Soon after this he brings me about six sheets of paper written, which contained the account of Virginia and Carolina. This it seems was to have answered a part of Mr. Oldmixion's British Empire in America. I very innocently, (when I began to read,) placed pen and paper by me, and made my observations upon the first page, but found it in the sequel so very faulty, and an abridgement only of some accounts that had been printed sixty or seventy years ago; in which also he had chosen the most strange and untrue parts, and left out the more sincere and faithful, so that I laid aside all thoughts of further observations, and gave it only a reading; and my bookseller for answer, that the account was too faulty and too imperfect to be mended; withal telling him, that seeing I had in my junior days taken some notes of the government, which I then had with me in England, I would make him an account of my own country, if I could find time, while I staid in London. And this I should the rather undertake in justice to so fine a country, because it has been so misrepresented to the common people of England, as to make them believe that the servants in Virginia are made to draw in cart and plow as horses and oxen do in England, and that the country turns all people black who go to live there, with other such prodigious phantasms.

Accordingly, before I left London, I gave him a short history of the country, from the first settlement, with an account of its then state; but I would not let him mingle it with Oldmixion's other account of the plantations, because I took them to be all of a piece with those I had seen of Virginia and Carolina, but desired mine to be printed[Pg xviii] by itself. And this I take to be the only reason of that gentleman's reflecting so severely upon me in his book, for I never saw him in my life that I know of.

But concerning that work of his, I may with great truth say, that (notwithstanding his boast of having the assistance of many original papers and memorials that I had not the opportunity of) he nowhere varies from the account that I gave, nor advances anything new of his own, but he commits so many errors, and imposes so many falsities upon the world, To instance some few out of the many:

Page 210, he says that they were near spent with cold, which is impossible in that hot country.

Page 220, he says that Captain Weymouth, in 1605, entered Powhatan river southward of the bay of Chesapeake;——whereas Powhatan river is now called James river, and lies within the mouth of Chesapeake bay some miles, on the west side of it; and Captain Weymouth's voyage was only to Hudson's river, which is in New York, much northward of the capes of Virginia.

Page 236, he jumbles the Potomac and eastern shore Indians as if they lived together, and never quarrelled with the English; whereas the last lived on the east side the great bay of Chesapeake, and the other on the west. The eastern shore Indians never had any quarrel with the English, but the Potomacs used many treacheries and enmities towards us, and joined in the intended general massacre, but by a timely discovery were prevented doing anything.

Page 245, he says that Morrison held an assembly, and procured that body of laws to be made; whereas Morrison only made an abridgement of the laws then in being, and compiled them into a regular body; and this he did by direction of Sir William Berkeley, who, upon his going to England, left Morrison his deputy governor.

Page 248, he says (viz: in Sir William Berkeley's time) the English could send seven thousand men into the field, and have twice as many at home; whereas at this day they cannot do that, and yet have three times as many people in the country as they had then.

By page 251, he seems altogether ignorant of the situation of Virginia, the head of the bay and New York, for he there says:

"When the Indians at the head of the bay traveled to New York, they past, going and coming, by the frontiers of Virginia, and traded with the Virginians, &c.;" whereas the head of the bay is in the common route of the Indians traveling from New York to Virginia, and much about halfway.

Page 255, he says Sir William Berkeley withdrew himself from his government; whereas he went not out of it, for the counties of Accomac and Northampton, to which he retired, when the rebels rose,[Pg xix] were two counties of his government, and only divided from the rest by the bay of Chesapeake.

Page 266, he says, Dr. Thomas Bray went over to be president of the college in Virginia; whereas he was sent to Maryland, as the bishop's commissary there. And Mr. Blair, in the charter to the college, was made president during life, and is still alive. He also says, that all that was subscribed for the college came to nothing; whereas all the subscriptions were in a short time paid in, and expended upon the college, of which two or three stood suit, and were cast.

Page 269, he tells of camels brought by some Guiana ships to Virginia, but had not then heard how they throve with us. I don't know how he should, for there never was any such thing done.

Then his geography of the country is most absurd, notwithstanding the wonderful care he pretends to have of the maps, and his expert knowledge of the new surveys, (page 278) making almost as many faults as descriptions. For instance:

Page 272, Prince George county, which lies all on the southside of James river, he places on the north, and says that part of James City county, and four of the parishes of it, lie on the southside of James river; whereas not one inch of it has so done these sixty years.

Page 273, his account of Williamsburg is most romantic and untrue; and so is his account of the college, page 302, 303.

Page 274, he makes Elizabeth and Warwick counties to lie upon York river; whereas both of them lie upon James river, and neither of them comes near York river.

Page 275, he places King William county above New Kent, and on both sides Pamunkey river; whereas it lies side by side with New Kent, and all on the north side Pamunkey river. He places King and Queen county upon the south of New Kent, at the head of Chickahominy river, which he says rises in it; whereas that county lies north of New Kent from head to foot, and two large rivers and two entire counties are between the head of Chickahominy and King & Queen. Essex, Richmond and Stafford counties, are as much wrong placed.

He says that York and Rappahannock rivers issue out of low marshes, and not from the mountains as the other rivers, which note he has taken from some old maps; but is a false account from my own view, for I was with our present governor at the head spring of both those rivers, and their fountains are in the highest ridge of mountains.

Page 276, he says that the neck of land between Niccocomoco river and the bay, is what goes by the name of the northern neck; whereas it is not above the twentieth part of the northern neck, for that contains all that track of land which is between Rappahannock and Potomac rivers.

[Pg xx]How unfaithful and frontless must such an historian be, who can upon guess work introduce such falsities for truth, and bottom them upon such bold assertions? It would make a book larger than his own to expose his errors, for even the most general offices of the government he misrecites.

Page 298, he says the general court is called the quarter court, and is held every quarter of a year; whereas it never was held but three times a year, tho' it was called a quarter court. When he wrote, it was held but twice a year, as I had wrote in my book, and has not been called a quarter court these seventy-nine years. The county courts were never limited in their jurisdiction to any summons, neither was the sheriff ever a judge in them, as he would have it, but always a ministerial officer to execute their process, &c.

The account that I have given in the following sheets is plain and true, and if it be not written with so much judgment, or in so good a method and style as I could wish, yet in the truth of it I rest fully satisfied. In this edition I have also retrenched such particulars as related only to private transactions, and characters in the historical part, as being too diminutive to be transmitted to posterity, and set down the succession of the governors, with the more general incidents of their government, without reflection upon the private conduct of any person.

The name of Beverley has long been a familiar one in Virginia. It is said that the family may be traced among the records of the town of Beverley in England, as far back as to the time of King John. During the reign of Henry VIII, one of the Beverleys was appointed by the Crown a commissioner for enquiring into the state and condition of the northern monasteries. The family received some grants of church property, and one branch of them settled at Shelby, the other at Beverley, in Yorkshire. In the time of Charles I, John Beverley of Beverley adhered to the cause of royalty, and at the restoration his name appears in the list of those upon whom it was intended to confer the order of the Royal Oak. Robert Beverley of Beverley, the representative of the family, having sold his possessions in that town, removed with a considerable fortune to Virginia, where he purchased extensive tracts of land. He took up his residence in the county of Middlesex. Elected clerk of the House of Burgesses, he continued to hold that office until 1676, the year of Bacon's rebellion, in suppressing which he rendered important services, and by his loyal gallantry won the marked favor of the Governor, Sir William Berkley. In 1682 the discontents of Virginia arose again almost to the pitch of rebellion. Two sessions of the Assembly having been spent in angry and fruitless disputes, between Lord Culpepper, the Governor, and the House of Burgesses, in May of that year, the malcontents in the counties of Gloucester, New Kent and Middlesex, proceeded riotously to cut up the tobacco plants in the beds, especially[Pg 2] the sweet-scented, which was produced nowhere else. Culpepper, the Governor, prevented further waste by patrols of horse. The ringleaders were arrested, and some of them hanged upon a charge of treason. A riot-act was also passed, making plant-cutting high treason, the necessity of which act evinces the illegality of the execution of these unfortunate plant-cutters. The vengeance of the government fell heavily upon Major Robert Beverley, clerk of the House of Burgesses, as the principal instigator of these disturbances. He had before incurred the displeasure of the governor and council, by refusing to deliver up to them copies of the legislative journal, without permission of the Assembly. Thus by a firm adherence to his duty, he drew down upon himself an unrelenting persecution.

In May, 1682, he was committed a prisoner on board the ship, the Duke of York, lying in the Rappahannock river. Ralph Wormley, Matthew Kemp, and Christopher Wormley, were directed to seize the records in Beverley's possession, and to break open doors if necessary. Beverley was afterwards transferred from the Duke of York to the ship Concord, and a guard was set over him. Contriving however to escape from the custody of the sheriff at York, the fugitive was retaken at his own house in Middlesex county, and transported over to the county of Northampton, on the Eastern Shore. Some months afterwards he applied by his attorney, William Fitzhugh, for a writ of habeas corpus, which however was refused. In a short time being again found at large, he was again arrested, and remanded to Northampton. In 1683 new charges were brought against him: 1st. That he had broken open letters addressed to the Secretary's office; 2d. That he had made up the journal, and inserted his Majesty's letter therein, notwithstanding it had been first presented at the time of the prorogation; 3d. That in 1682 he had refused to deliver copies of the journal to the governor and council, saying "he might not do it without leave of his masters."

In May, 1684, Major Robert Beverley was found guilty of high misdemeanors, but judgment being respited, and the prisoner asking pardon on his bended knees, was released upon giving security for his good behavior in the penalty of £2,000. The abject terms in which he now sued for pardon,[Pg 3] form a singular contrast to the constancy of his former resistance, and the once gallant and loyal Beverley, the strenuous partizan of Berkley, thus became the victim of that tyranny which he had once so resolutely defended. He had not however lost the esteem of his countrymen, for in 1685 he was again elected clerk of the Assembly. This body strenuously resisted the negative power claimed by the governor, and passed resolutions complaining strongly of his tyranny. He negatived them, and prorogued the Assembly. James II, indignant at these democratical proceedings, ordered their dissolution, and attributing these disorders mainly to Robert Beverley, their clerk, commanded that he should be incapable of holding any office, and that he should be prosecuted, and that in future the appointment of their clerk should be made by the governor.

In the spring of 1687 Robert Beverley died, the persecuted victim of an oppressive government. Long a distinguished loyalist, he lived to become a sort of patriot martyr. It is thus that in the circle of life extremes meet. He married Catherine Hone of James City, and their children were four sons: Peter, William, Harry, and Robert, (the historian,) and three daughters, who married respectively, William Randolph, eldest son of William Randolph of Turkey Island; Sir John Randolph, his brother, of Williamsburg; and John Robinson. Peter Beverley was appointed clerk of the Assembly in 1691.

In the preface to the first edition of his History of Virginia, published at London 1705, Robert Beverley says of himself: "I am an Indian, and don't pretend to be exact in my language." This intimation may perhaps have been merely playful, but the full and minute account that he has given of the Indians, shows that he took a peculiar interest in that race.

In the preface to the second edition of his history, now republished, he remarks: "My first business in this world being among the public records of my country, the active thoughts of my youth put me upon taking notes of the general administration of the government." He was probably a deputy in his father's office, and perhaps also in that of his brother Peter Beverley. This Peter Beverley was in 1714 promoted[Pg 4] to the place of speaker of the House of Burgesses, and he was subsequently treasurer of the colony. Robert Beverley, the historian, was born in Virginia, and educated in England. He married Ursula, daughter of William Byrd of Westover, on the James river. She lies buried at Jamestown. John Fontaine, son of a Huguenot refugee, having come over from England to Virginia, visited Robert Beverley, the author of this work, in the year 1715, at his residence, near the head of the Mattapony. Here he cultivated several varieties of the grape, native and French, in a vineyard of about three acres, situated upon the side of a hill, from which he made in that year four hundred gallons of wine. He went to very considerable expense in this enterprise, having constructed vaults of a wine press. But Fontaine comparing his method with that used in Spain, deemed it erroneous, and that his vineyard was not rightly managed. The home-made wine Fontaine drank heartily of, and found it good, but he was satisfied by the flavor of it that Beverley did not understand how to make it properly. Beverley lived comfortably, yet although wealthy, had nothing in or about his house but what was actually necessary. He had good beds, but no curtains, and instead of cane chairs used wooden stools. He lived mainly within himself upon the products of his land. He had laid a sort of wager with some of the neighboring planters, he giving them one guinea in hand, and they promising to pay him each ten guineas, if in seven years he should cultivate a vineyard that would yield at one vintage seven hundred gallons of wine. Beverley thereupon paid them down one hundred pounds, and Fontaine entertained no doubt but that in the next year he would win the thousand guineas. Beverley owned a large tract of land at the place of his residence. On Sunday Fontaine accompanied him to his parish church, seven miles distant, where they heard a good sermon from the Rev. M. De Latané, a Frenchman. A son of Beverley accompanied Fontaine in some of his excursions in that neighborhood. On the banks of the Rappahannock, about five miles below the falls, (Fredericksburg,) Fontaine came upon a tract of three thousand acres of land, which Beverley offered him at £7 10s. per hundred acres, and Fontaine would have purchased it, had not Beverley somewhat[Pg 5] singularly insisted upon making a title for nine hundred and ninety-nine years, instead of an absolute fee simple.

On the 20th of August, 1716, Alexander Spotswood, Governor of Virginia, accompanied by John Fontaine, started from Williamsburg on his expedition over the Appalachian mountains, as they were then called. Having crossed the York river at the Brick House, they lodged that night at Chelsea, the seat of Austin Moore, on the Mattapony river, in the county of King William. On the following night they were hospitably entertained by Robert Beverley at his residence. The governor left his chaise there, and mounted his horse for the rest of the journey. Beverley accompanied Spotswood in this exploration. On the 26th of August Spotswood was joined by several gentlemen, two small companies of rangers, and four Meherrin Indians. The gentlemen of the party appear to have been Spotswood, Fontaine, Beverley, Austin Smith, Todd, Dr. Robinson, Taylor, Mason, Brooke, and Captains Clouder and Smith. The whole number of the party, including gentlemen, rangers, pioneers, Indians and servants, was probably about fifty. They had with them a large number of riding and pack-horses, an abundant supply of provisions, and an extraordinary variety of liquors.

The camps were named respectively after the gentlemen of the expedition, and the first one being that of the 29th of August, was named in honor of our historian, Robert Beverley. Here "they made," as Fontaine records in his diary, "great fires, supped and drank good punch." In the preface to this edition of the work, (1722,) Beverley says in reference to this Tramontane expedition, "I was with the present Governor (Spotswood) at the head spring of both those rivers, (the York and the Rappahannock,) and their fountains are in the highest range of mountains." Thus it appears that the historian was one of the celebrated knights of the golden horseshoe.

An Abridgement of the Laws of Virginia, published at London in 1722 is ascribed to Robert Beverley. Filial indignation will naturally account for the acrimony which in his history he exhibits towards Lord Culpepper and Lord Howard of Effingham, who had so persecuted his father, the clerk of the[Pg 6] Assembly, and against Nicholson, who was Effingham's deputy. In his second edition, when time had mitigated his animosities, Beverley omitted some of his accusations against those governors.

The first edition of Beverley's History of Virginia appeared at London in 1705. It was republished in French at Paris in 1707, and in the same year an edition was issued at Amsterdam. The second English edition was published in 1722 at London. The work is dedicated to the Right Honorable Robert Harley, so celebrated both as a statesman and as the patron of letters.

In the title page appear only the initials of the author's name, thus: "R. B. Gent.," whence the blundering historian, Oldmixon, supposed his name to be "Bullock," and in some German catalogues he received the appellation of "Bird." Warden, an American writer, has repeated this last misnomer. Beverley's work is divided into four parts, styled Books, and the fourth book is again divided into two parts.

Of the history, Mr. Jefferson in his "Notes on Virginia" has remarked, that it is "as concise and unsatisfactory as Stith is prolix and tedious." This criticism, however, is only applicable to Beverley's first book, which includes the civil history of the colony; the other three books on "the present state of Virginia" being sufficiently full and satisfactory. Brief as is the summary of history comprised in book first, it was probably quite ample enough for the taste of the readers of Beverley's day. His style of writing is easy, unsophisticated and pleasing, his simplicity of remark sometimes amusing, and the whole work breathes an earnest, downright, hearty, old-fashioned Virginia spirit. His account of the internal affairs of the colony is faithful, and in the main correct, but in regard to events occurring beyond the precincts of Virginia, he is less reliable. The second book treats of the boundary of Virginia, waters, earth and soil, natural products, fish, wild fowl and hunted game. Book third gives a full and minute description of the manners and customs of the Indians, illustrated by Gribelin's engravings. The contents are the persons and dress of the Indians, marriage and management of children, towns, buildings and fortifications, cookery and food, travelling, reception and entertainments, language, war and peace, religion, diseases and remedies,[Pg 7] sports and pastimes, laws and government, money, goods and handicrafts. The fourth book relates to the government of the colony, its sub-divisions, public offices, revenues, taxes, courts, the church, the college of William and Mary, militia, servants and slaves, poor laws, free schools, tenure and conveyance of lands, naturalization and currency, the people, buildings, eatables, drinkables and fuel, climate, diseases, recreations, natural productions, and the advantages of improved husbandry. The closing paragraph is as follows: "Thus they depend upon the liberality of Nature, without endeavoring to improve its gifts by art or industry. They sponge upon the blessings of a warm sun and a fruitful soil, and almost grudge the pains of gathering in the bounties of the earth. I should be ashamed to publish this slothful indolence of my countrymen, but that I hope it will rouse them out of their lethargy, and excite them to make the most of all those happy advantages which Nature has given them, and if it does this, I am sure they will have the goodness to forgive me." Happily, at the present day, Virginia has been aroused from her lethargy, and with energetic efforts is developing her rich resources. It may be hoped that with these material improvements a wider interest in the history of the past may be diffused.

Petersburg, May 30th, 1854.

SHEWING WHAT HAPPENED IN THE FIRST ATTEMPTS TO SETTLE VIRGINIA, BEFORE THE DISCOVERY OF CHESAPEAKE BAY.

The learned and valiant Sir Walter Raleigh, having entertained some deeper and more serious considerations upon the state of the earth than most other men of his time, as may sufficiently appear by his incomparable book, the History of the World, and having laid together the many stories then in Europe concerning America, the native beauty, riches, and value of that part of the world, and the immense profits the Spaniards drew from a small settlement or two thereon made, resolved upon an adventure for farther discoveries.

According to this purpose, in the year of our Lord 1583, he got several men of great value and estate to join in an expedition of this nature, and for their encouragement obtained letters patents from Queen Elizabeth, bearing date the 25th of March, 1584, for turning their discoveries to their own advantage.

[Pg 9]§ 2. In April following they set out two small vessels under the command of Capt. Philip Amidas and Capt. Arthur Barlow, who after a prosperous voyage, anchored at the inlet by Roanoke, at present under the government of North Carolina. They made good profit of the Indian truck, which they bought for things of much inferior value, and returned. Being overpleased with their profits, and finding all things there entirely new and surprising, they gave a very advantageous account of matters, by representing the country so delightful and desirable, so pleasant and plentiful; the climate and air so temperate, sweet, and wholesome; the woods and soil so charming and fruitful; and all other things so agreeable, that paradise itself seemed to be there in its first native lustre.

They gave particular accounts of the variety of good fruits, and some whereof they had never seen the like before; especially, that there were grapes in such abundance as was never known in the world. Stately tall large oaks, and other timber; red cedar, cypress, pines, and other evergreens and sweet woods, for tallness and largeness, exceeding all they had ever heard of; wild fowl, fish, deer, and other game in such plenty and variety, that no epicure could desire more than this new world did seem naturally to afford.

And to make it yet more desirable, they reported the native Indians (which were then the only inhabitants) so affable, kind, and good-natured; so uncultivated in learning, trades, and fashions; so innocent and ignorant of all manner of politics, tricks, and cunning; and so desirous of the company of the English, that they seemed rather to be like soft wax, ready to take an impression, than anyways likely to oppose the settling of the English near them. They represented it as a scene laid open for the good and gracious Queen Elizabeth to propagate the gospel in and extend her dominions over; as if purposely reserved for her majesty by a peculiar direction of providence, that had brought all former adventures in this affair to nothing; and to give a further taste of their discovery, they took with[Pg 10] them in their return for England, two men of the native Indians, named Wanchese and Manteo.

§ 3. Her majesty accordingly took the hint, and espoused the project as far as her present engagements in war with Spain would let her; being so well pleased with the account given, that as the greatest mark of honor she could do the discoverer, she called the country by the name of Virginia, as well for that it was first discovered in her reign, a virgin queen, as it did still seem to retain the virgin purity and plenty of the first creation, and the people their primitive innocence; for they seemed not debauched nor corrupted with those pomps and vanities which had depraved and enslaved the rest of mankind; neither were their hands hardened by labor, nor their minds corrupted by the desire of hoarding up treasure. They were without boundaries to their land, without property in cattle, and seem to have escaped, or rather not to have been concerned in the first curse, of getting their bread by the sweat of their brows, for by their pleasure alone they supplied all their necessities, namely, by fishing, fowling, and hunting; skins being their only clothing, and these, too, five-sixths of the year thrown by; living without labor, and only gathering the fruits of the earth when ripe or fit for use; neither fearing present want, nor solicitous for the future, but daily finding sufficient afresh for their subsistence.

§ 4. This report was backed, nay, much advanced by the vast riches and treasure mentioned in several merchants' letters from Mexico and Peru, to their correspondents in Spain, which letters were taken with their ships and treasure, by some of ours in her majesty's service, in prosecution of the Spanish wars. This was encouragement enough for a new adventure, and set people's invention at work till they had satisfied themselves, and made sufficient essays for the farther discovery of the country. Pursuant whereunto, Sir Richard Greenvile, the chief of Sir Walter Raleigh's associates, having obtained seven sail of ships, well laden with provision, arms, ammunition, and spare men to[Pg 11] make a settlement, set out in person with them early in the spring of the succeeding year to make farther discoveries, taking back the two Indians with him, and according to his wish, in the latter end of May, arrived at the same place where the English had been the year before; there he made a settlement, sowed beans and peas, which he saw come up and grow to admiration while he staid, which was about two months, and having made some little discoveries more in the sound to the southward, and got some treasure in skins, furs, pearl, and other rarities in the country, for things of inconsiderable value, he returned for England, leaving one hundred and eight men upon Roanoke island, under the command of Mr. Ralph Lane, to keep possession.

§ 5. As soon as Sir Richard Greenvile was gone, they, according to order and their own inclination, set themselves earnestly about discovering the country, and ranged about a little too indiscreetly up the rivers, and into the land backward from the rivers, which gave the Indians a jealousy of their meaning; for they cut off several stragglers of them, and had laid designs to destroy the rest, but were happily prevented. This put the English upon the precaution of keeping more within bounds, and not venturing themselves too defenceless abroad, who till then had depended too much upon the natives simplicity and innocence.

After the Indians had done this mischief, they never observed any real faith towards those English; for being naturally suspicious and revengeful themselves, they never thought the English could forgive them; and so by this jealousy, caused by the cowardice of their nature, they were continually doing mischief.

The English, notwithstanding all this, continued their discoveries, but more carefully than they had done before, and kept the Indians in some awe, by threatening them with the return of their companions again with a greater supply of men and goods; and before the cold of the winter became uneasy, they had extended their discoveries near an hundred miles along the seacoast to the northward; but not reaching[Pg 12] the southern cape of Chesapeake bay in Virginia, they had as yet found no good harbor.

§ 6. In this condition they maintained their settlement all the winter, and till August following; but were much distressed for want of provisions, not having learned to gather food, as the Indians did, nor having conveniences like them of taking fish and fowl; besides, being now fallen out with the Indians, they feared to expose themselves to their contempt and cruelty; because they had not received the supply they talked of, and which had been expected in the spring.

All they could do under these distresses, and the despair of the recruits promised them this year, was only to keep a good looking out to seaward, if, perchance, they might find any means of escape, or recruit. And to their great joy and satisfaction in August aforesaid, they happened to espy and make themselves be seen to Sir Francis Drake's fleet, consisting of twenty-three sail, who being sent by her majesty upon the coast of America, in search of the Spanish treasures, had orders from her majesty to take a view of this plantation, and see what assistance and encouragement it wanted: Their first petition to him was to grant them a fresh supply of men and provisions, with a small vessel, and boats to attend them; that so if they should be put to distress for want of relief, they might embark for England. This was as readily granted by Sir Francis Drake, as asked by them; and a ship was appointed them, which ship they began immediately to fit up, and supply plentifully with all manner of stores for a long stay; but while they were adoing this, a great storm arose, and drove that very ship (with some others) from her anchor to sea, and so she was lost for that occasion.

Sir Francis would have given them another ship, but this accident coming on the back of so many hardships which they had undergone, daunted them, and put them upon imagining that Providence was averse to their designs; and now having given over for that year the expectation of their promised supply from England, they consulted together, and agreed to desire Sir Francis Drake to take them along with him, which he did.

[Pg 13]Thus their first intention of settlement fell, after discovering many things of the natural growth of the country, useful for the life of man, and beneficial to trade, they having observed a vast variety of fish, fowl and beasts; fruits, seeds, plants, roots, timber-trees, sweet-woods and gums: They had likewise attained some little knowledge in the language of the Indians, their religion, manners, and ways of correspondence one with another, and been made sensible of their cunning and treachery towards themselves.

§ 7. While these things were thus acting in America, the adventurers in England were providing, though too tediously, to send them recruits. And though it was late before they could dispatch them (for they met with several disappointments, and had many squabbles among themselves); however, at last they provided four good ships, with all manner of recruits suitable for the colony, and Sir Walter Raleigh designed to go in person with them.

Sir Walter got his ship ready first, and fearing the ill consequence of a delay, and the discouragement it might be to those that were left to make a settlement, he set sail by himself. And a fortnight after him Sir Richard Greenvile sailed with the three other ships.

Sir Walter fell in with the land at Cape Hatteras, a little to the southward of the place, where the one hundred and eight men had been settled, and after search not finding them, he returned: However Sir Richard, with his ships, found the place where he had left the men, but entirely deserted, which was at first a great disheartening to him, thinking them all destroyed, because he knew not that Sir Francis Drake had been there and taken them off; but he was a little better satisfied by Manteo's report, that they were not cut off by the Indians, though he could give no good account what was become of them. However, notwithstanding this seeming discouragement, he again left fifty men in the same island of Roanoke, built them houses necessary, gave them two years provision, and returned.

§ 8. The next summer, being Anno 1587, three ships more were sent, under the command of Mr. John White,[Pg 14] who himself was to settle there as governor with more men, and some women, carrying also plentiful recruits of provisions.

In the latter end of July they arrived at Roanoke aforesaid, where they again encountered the uncomfortable news of the loss of these men also; who (as they were informed by Manteo) were secretly set upon by the Indians, some cut off, and the others fled, and not to be heard of, and their place of habitation now all grown up with weeds. However, they repaired the houses on Roanoke, and sat down there again.

The 13th of August they christened Manteo, and styled him Lord of Dassamonpeak, an Indian nation so called, in reward of the fidelity he had shewn to the English from the beginning, who being the first Indian that was made a Christian in that part of the world, I thought it not amiss to remember him.

On the same occasion also may be mentioned the first child there born of Christian parentage, viz: a daughter of Mr. Ananias Dare. She was born the 18th of the same August, upon Roanoke, and, after the name of the country, was christened Virginia.

This seemed to be a settlement prosperously made, being carried on with much zeal and unanimity among themselves. The form of government consisted of a governor and twelve counselors, incorporated by the name of governor and assistants, of the city of Raleigh, in Virginia.

Many nations of the Indians renewed their peace, and made firm leagues with the corporation. The chief men of the English also were so far from being disheartened at the former disappointments, that they disputed for the liberty of remaining on the spot; and by mere constraint compelled Mr. White, their governor, to return for England to negotiate the business of their recruits and supply, as a man the most capable to manage that affair, leaving at his departure one hundred and fifteen in the corporation.

§ 9. It was above two years before Mr. White could obtain any grant of supplies, and then in the latter end of[Pg 15] the year 1589, he set out from Plymouth with three ships, and sailed round by the Western and Caribbee islands, they having hitherto not found any nearer way: for though they were skilled in navigation, and understood the use of the globes, yet did example so much prevail upon them, that they chose to sail a thousand leagues about, rather than attempt a more direct passage.

Towards the middle of August, 1590, they arrived upon the coast, at Cape Hatteras, and went to search upon Roanoke for the people; but found, by letters on the trees, that they were removed to Croatan, one of the islands forming the sound, and southward of Roanoke about twenty leagues, but no sign of distress. Thither they designed to sail to them in their ships; but a storm arising in the meanwhile, lay so hard upon them that their cables broke; they lost three of their anchors, were forced to sea, and so returned home, without ever going near those poor people again for sixteen years following. And it is supposed that the Indians, seeing them forsaken by their country, and unfurnished of their expected supplies, cut them off, for to this day they were never more heard of.

Thus, after all this vast expense and trouble, and the hazard and loss of so many lives, Sir Walter Raleigh, the great projector and furtherer of these discoveries and settlements, being under trouble, all thoughts of farther prosecuting these designs lay dead for about twelve years following.

§ 10. And then, in the year 1602, Captain Gosnell, who had made one in the former adventures, furnished out a small bark from Dartmouth, and set sail in her himself with thirty odd men, designing a more direct course, and not to stand so far to the southward, nor pass by the Caribbee Islands, as all former adventurers had done. He attained his ends in that, but touched upon the coast of America, much to the northward of any of the places where the former adventurers had landed, for he fell first among the islands forming the northern side of Massachusetts bay in New England; but not finding the conveniences that[Pg 16] harbor affords, set sail again southward, and, as he thought, clear of land into the sea, but fell upon the Byte of Cape Cod.

Upon this coast, and a little to the southward, he spent some time in trade with the Indians, and gave names to the islands of Martha's Vineyard and Elizabeth's Isle, which retain the same to this day. Upon Elizabeth's Isle he made an experiment of English grain, and found it spring up and grow to admiration as it had done at Roanoke. Here also his men built huts to shelter them in the night and bad weather, and made good profit by their Indian traffic of furs, skins, &c. And as their pleasure invited them, would visit the main, set receivers, and save the gums and juices distilling from sweet woods, and try and examine the lesser vegetables.

After a month's stay here, they returned for England, as well pleased with the natural beauty and richness of the place they had viewed, as they were with the treasure they had gathered in it: neither had they a head, nor a finger that ached among them all the time.

§ 11. The noise of this short and most profitable of all the former voyages, set the Bristol merchants to work also; who, early in the year 1603, sent two vessels in search of the same place and trade—which vessels fell luckily in with the same land. They followed the same methods Captain Gosnell had done, and having got a rich lading they returned.

§ 12. In the year 1605, a voyage was made from London in a single ship, with which they designed to fall in with the land about the latitude 39°, but the winds put her a little farther northward, and she fell upon the eastern parts of Long Island, (as it is now called, but all went then under the name of Virginia.) Here they trafficked with the Indians, as the others had done before them; made short trials of the soil by English grain, and found the Indians, as in all other places, very fair and courteous at first, till they got more knowledge of the English, and perhaps thought themselves overreached because one bought better pennyworths than another, upon which, afterwards,[Pg 17] they never failed to take revenge as they found their opportunity or advantage. So this company also returned with the ship, having ranged forty miles up Connecticut river, and called the harbor where they rid Penticost harbor, because of their arrival there on Whitsunday.

In all these latter voyages, they never so much as endeavored to come near the place where the first settlement was attempted at Cape Hatteras; neither had they any pity on those poor hundred and fifteen souls settled there in 1587, of whom there had never since been any account, no relief sent to them, nor so much as any enquiry made after them, whether they were dead or alive, till about three years after this, when Chesapeake bay in Virginia was settled, which hitherto had never been seen by any Englishman. So strong was the desire of riches, and so eager the pursuit of a rich trade, that all concern for the lives of their fellow-christians, kindred, neighbors and countrymen, weighed nothing in the comparison, though an enquiry might have been easily made when they were so near them.

CONTAINING AN ACCOUNT OF THE FIRST SETTLEMENT OF CHESAPEAKE BAY, IN VIRGINIA, BY THE CORPORATION OF LONDON ADVENTURERS, AND THEIR PROCEEDINGS DURING THEIR GOVERNMENT BY A PRESIDENT AND COUNCIL ELECTIVE.

§ 13. The merchants of London, Bristol, Exeter, and Plymouth soon perceived what great gains might be made of a trade this way, if it were well managed and colonies could be rightly settled, which was sufficiently evinced by the great profits some ships had made, which had not met with ill accidents. Encouraged by this prospect, they joined together in a petition to King James the First, shewing forth that it would be too much for any single person to attempt the settling of colonies, and to carry on so considerable a trade; they therefore prayed his majesty to incorporate them, and enable them to raise a joint stock for that purpose, and to countenance their undertaking.

His majesty did accordingly grant their petition, and by letters patents, bearing date the 10th of April, 1606, did in one patent incorporate them into two distinct colonies, to make two separate companies, viz: "Sir Thomas Gates, Sir George Summers, knights; Mr. Richard Hackluit, clerk, prebend of Westminster, and Edward Maria Wingfield, esq., adventurers of the city of London, and such others as should be joined unto them of that colony, which should be called the first colony, with liberty to begin their first plantation and seat, at any place upon the coast of Virginia[Pg 19] where they should think fit and convenient, between the degrees of thirty-four and forty-one of northern latitude. And that they should extend their bounds from the said first seat of their plantation and habitation fifty English miles along the seacoast each way, and include all the lands within an hundred miles directly over against the same seacoast, and also back into the main land one hundred miles from the seacoast; and that no other should be permitted or suffered to plant or inhabit behind or on the back of them towards the main land, without the express license of the council of that colony, thereunto in writing first had and obtained. And for the second colony, Thomas Hanham, Rawleigh Gilbert, William Parker, and George Popham, esquires, of the town of Plymouth, and all others who should be joined to them of that colony, with liberty to begin their first plantation and seat at any place upon the coast of Virginia where they should think fit, between the degrees of thirty-eight and forty five of northern latitude, with the like liberties and bounds as the first colony; provided they did not seat within an hundred miles of them."

§ 14. By virtue of this patent, Capt. John Smith was sent by the London company, in December, 1606, on his voyage with three small ships, and a commission was given to him, and to several other gentlemen, to establish a colony, and to govern by a president, to be chosen annually, and council, who should be invested with sufficient authorities and powers. And now all things seemed to promise a plantation in good earnest. Providence seemed likewise very favorable to them, for though they designed only for that part of Virginia where the hundred and fifteen were left, and where there is no security of harbor, yet, after a tedious voyage of passing the old way again, between the Caribbee islands and the main, he, with two of his vessels, luckily fell in with Virginia itself, that part of the continent now so called, anchoring in the mouth of the bay of Chesapeake; and the first place they landed upon was the southern cape of that bay; this they named Cape[Pg 20] Henry, and the northern Cape Charles, in honor of the king's two eldest sons; and the first great river they searched, whose Indian name was Powhatan, they called James river, after the king's own name.

§ 15. Before they would make any settlement here, they made a full search of James river, and then by an unanimous consent pitched upon a peninsula about fifty miles up the river, which, besides the goodness of the soil, was esteemed as most fit, and capable to be made a place both of trade and security, two-thirds thereof being environed by the main river, which affords good anchorage all along, and the other third by a small narrow river, capable of receiving many vessels of an hundred ton, quite up as high as till it meets within thirty yards of the main river again, and where generally in spring tides it overflows into the main river, by which means the land they chose to pitch their town upon has obtained the name of an island. In this back river ships and small vessels may ride lashed to one another, and moored ashore secure from all wind and weather whatsoever.

The town, as well as the river, had the honor to be called by King James' name. The whole island thus enclosed contains about two thousand acres of high land, and several thousands of very good and firm marsh, and is an extraordinary good pasture as any in that country.

By means of the narrow passage, this place was of great security to them from the Indian enemy; and if they had then known of the biting of the worm in the salts, they would have valued this place upon that account also, as being free from that mischief.

§ 16. They were no sooner settled in all this happiness and security, but they fell into jars and dissensions among themselves, by a greedy grasping at the Indian treasure, envying and overreaching one another in that trade.

After five weeks stay before this town, the ships returned home again, leaving one hundred and eight men settled in the form of government before spoken of.

After the ships were gone, the same sort of feuds and[Pg 21] disorders happened continually among them, to the unspeakable damage of the plantation.