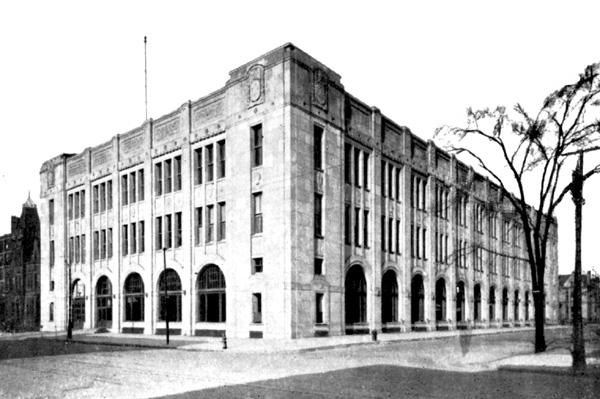

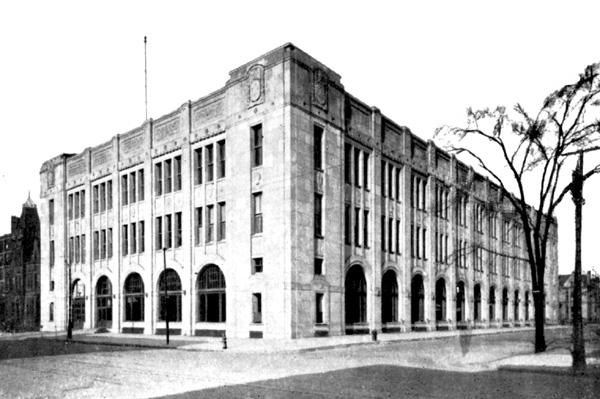

THE HOME OF THE DETROIT NEWS

THE HOME OF THE DETROIT NEWSFort Street, Second Avenue and Lafayette Boulevard

Title: The Style Book of The Detroit News

Author: Detroit news

Editor: A. L. Weeks

Release date: June 27, 2010 [eBook #32997]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Barbara Tozier, Bill Tozier and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

For helpful suggestions the editor is beholden to the style books of the United States Government Printing Office, the Universities of Missouri, Iowa and Montana, the Indianapolis News, the Chicago Herald, and the New York Evening Post; to "Newspaper Writing and Editing," by Willard G. Bleyer; "Newspaper Editing," by Grant M. Hyde; "The Writing of News," by Charles G. Ross; and to the New York Tribune for permission to make applicable to Michigan its digest of the libel laws of New York.

The inscriptions on the building of The News, reprinted in this book in boxes, were written by Prof. Fred N. Scott, of the University of Michigan.

THE HOME OF THE DETROIT NEWS

THE HOME OF THE DETROIT NEWS| Founded by James Edmund Scripps | August 23, 1873 |

| Absorbed the subscription lists of the Detroit Daily Union | July 27, 1876 |

| Established a Sunday edition | Nov. 30, 1884 |

| Sunday News and Sunday Tribune combined as Sunday News-Tribune | October 15, 1893 |

| Daily Tribune merged with The News and discontinued | February 1, 1915 |

| Ground broken for present building | November, 1915 |

| Sunday News-Tribune became The Sunday News | October 14, 1917 |

| The News entered new building | October 15, 1917 |

The

Style Book

OF

The Detroit News

Edited by

A. L. WEEKS

Published and Copyrighted 1918 by

The Evening News Association

Detroit

This edition consists of 1,000 copies, of which this is No. 625

| The Aim of The Detroit News | 1 |

| Instructions to Reporters | 4 |

| Instructions to Copy Readers | 6 |

| Preparing Copy | 7 |

| Leads | 7 |

| Heads | 8 |

| Diction | 14 |

| A. P. Style | 15 |

| Capitalization | 17 |

| Punctuation | 22 |

| Quotations | 23 |

| Nouns | 24 |

| Pronouns | 27 |

| Conjunctions | 28 |

| Verbs | 29 |

| Adverbs | 33 |

| Adjectives | 34 |

| Prepositions | 37 |

| Articles | 38 |

| Numbers | 38 |

| Roman Numerals | 39 |

| Weights and Measures | 40 |

| Abbreviation | 42 |

| Names and Titles | 45 |

| Jew and Hebrew | 46 |

| Church Titles | 48 |

| Compounds | 48 |

| Superfluous Words | 49 |

| Vital Statistics | 50 |

| Spelling | 51 |

| Popular Names of Railroads | 52 |

| Do and Don't | 54 |

| The Cannery | 57 |

| Michigan Institutions | 59 |

| Army and Navy Organization | 60 |

| Dates Often Called For | 62 |

| The Law of Libel | 64 |

| First Three Years of the War | 72 |

| Index | 77 |

Formation of a newspaper's ideals comes through a process of years. The best traditions of the past, blending with hopes of the future, should be the writer's guide for the day. Nov. 1, 1916, the editor-in-chief of The Detroit News, in a letter to the managing editor, wrote his interpretation of the principles under which the staff should work, in striving toward those journalistic ideals to which this paper feels itself dedicated. His summary of the best practices of the profession follows:

The Detroit News should be:

We should work to have the word RELIABLE stamped on every page of the paper.

The place to commence this is with the staff members: First, getting men and women of character to do the writing and editing; and then training them in our way of thinking and handling news and other reading matter.

If you make an error you have two duties to perform—one to the person misrepresented and one to your reading public. Never leave the reader of The News misinformed on any subject. If you wrongfully write that a man has done something that he did not do, or has said something that he did not say, you do him an injustice—that's one. But you also do thousands of readers an injustice, leaving them misinformed as to the character of the man dealt with. Corrections should never be made grudgingly. Always make them cheerfully, fully, and in larger type than the error, if there is any difference.

The American people want to know, to learn, to get information. To quote a writer: "Your opinion is worth no more than your information." Give them your information and let them draw their own conclusions. Comment should enlighten by well marshaled facts, and by telling the readers what relation an act of today has to an act of yesterday. Let them come to their own conclusions as far as possible.

No issue is worth advocating that is not strong enough to withstand all the facts that the opposition to it can throw against it. Our readers should be well informed on both sides of every issue.

[2]Kindly, helpful suggestions will often direct officials in the right, when nagging will make them stay stubbornly on the wrong side. That does not mean that there should be any lack of diligence in watching for, and opposing, intentional criminals.

A staff can be good and strong only by having every part of it strong. The moment it becomes evident that a man, either by force of circumstance or because of his own character, does not fit into our organization, you do him a kindness and do justice to the paper by letting him know, so he can go to a calling in which he can succeed, and will not be in the way of filling the place with a competent man.

No one on the staff should be asked to do anything that will make him think less of himself or the paper.

MAKE THE PAPER GOOD ALL THE WAY THROUGH, so there will not be disappointment on the part of a reporter if his story is not found on the first page, but so he will feel that it must have merit to get into the paper at all. Avoid making it a "front-page paper."

Stories should be brief, but not meager. Tell the story, all of it, in as few words as possible.

Nature makes facts more interesting than any reporter can imagine them. There is an interesting feature in every story, if you will dig it out. If you don't get it, it is because you don't dig deep enough.

The most valuable asset of any paper is its reputation for telling the truth; the only way to have that reputation is to tell the truth. Untruth due to carelessness or excessive imagination injures the paper as much as though intentional.

Everyone with a grievance should be given a respectful and kindly hearing; especial consideration should be given the poor and lowly, who may be less capable of presenting their claims than those more favored in life. A man of prominence and education knows how to get into the office and present his complaint. A washerwoman may come to the door, timidly, haltingly, scarcely knowing what to do, and all the while her complaint may be as just as that of the other complainant, perhaps more so. She should be received kindly and helped to present what she has to say.

Simple, plain language is strongest and best. A man of little education can understand it, while the man of higher education, usually reading a paper in the evening after a day's work, will read it with relish. There is never any need of using big words to show off one's learning. The object of a story or an editorial is to inform or convince; but it is hard to do either if the reader has to study over a big word or an involved sentence. Use plain English all the time. A few readers may understand and appreciate a Latin or French quotation, or one from some other foreign language, but the big mass of our readers are the plain people, and such a quotation would be lost on the majority.

[3]Be fair. Don't let the libel laws be your measure in printing of a story, but let fairness be your measure. If you are fair, you need not worry about libel laws.

Always give the other fellow a hearing. He may be in the wrong, but even that may be a matter of degree. It wouldn't be fair to picture him as all black when there may be mitigating circumstances.

It is not necessary to tell the people that we are honest, or bright, or alert, or that a story appeared exclusively in our paper. If true, the public will find it out. An honest man does not need to advertise his honesty.

Time heals all things but a woman's damaged reputation. Be careful and cautious and fair and decent in dealing with any man's reputation, but be doubly so—and then some—when a woman's name is at stake. Do not by direct statement, jest or careless reference raise a question mark after any woman's name if it can be avoided—and it usually can be. Even if a woman slips, be generous; it may be a crisis in her life. Printing the story may drive her to despair; kindly treatment may leave her with hope. No story is worth ruining a woman's life—or a man's, either.

Keep the paper clean in language and thought. Profane or suggestive words are not necessary. When in doubt, think of a 13-year-old girl reading what you are writing.

Do not look on newspaper work as a "game," of pitilessly printing that on which you are only half informed, for the mere sake of beating some other paper; but take it rather as a serious, constructive work in which you are to use all your energy and diligence to get all the worth-while information for your readers at the earliest possible moment.

When you go after a story, make sure that you get all of it.

Drill yourself into searching for facts; almost anybody can write a story—it takes real brains and resourcefulness to get one.

You are urged to call the city editor for instructions whenever in doubt, and it is a good idea to call as often as possible to keep the office informed and also to get any information on your story that may have come in from other sources.

Before you write or telephone your story, make sure that you have all your facts marshaled in your own mind. A good reporter usually plans his story, lead and details in his head on his way to the office.

NEVER GUESS.

KNOW WHAT YOU ARE WRITING ABOUT.

When you turn in a story KNOW that everything in that story is true—and if you feel there is a statement you can not prove, call your city editor's attention to it.

To color or fake a story is not newspaper work—it is prostitution of the profession of journalism.

Be sure of your sources of information. Never take anything for granted—find out for yourself. You will discover that many persons talk convincingly about things although they have no actual knowledge of the subject under discussion.

Remember always that a newspaper has to prove what it says—and any decent newspaper is eager to.

If you don't know, tell the city editor you don't know. To guess is criminal because nobody can guess with any consistent degree of accuracy. And accuracy should be your guide.

Reporters should study their stories after they are printed, with the realization that any changes made in them were made to better them. Ask why your stories have been changed so your next story will be better through avoidance of the same mistake.

Never be afraid to ask anybody anything.

The mainspring of a good newspaper man is a wholesome curiosity.

The essentials of newspaper writing are accuracy and simplicity. The newspaper is no place for fine writing. Simplicity means directness and conciseness in telling the story as well as an avoidance of hifalutin phrases, obsolete words and involved sentences.

Walt Whitman wrote: "The art of arts, the glory of expression, and the sunshine[5] of the light of letters, is simplicity. Nothing is better than simplicity—nothing can make up for excess or the lack of definiteness."

Every worker on a newspaper knows the value of accuracy. Accuracy is the god before whom all newspaper men bow. If one could analyze the effort put forth in one day in this office, one might discover that perhaps a third of that effort was in an attempt to obtain accuracy. The city directory is the newspaper man's Bible because accuracy is his deity.

The hardest lesson the journalist must learn is the development of the impersonal viewpoint. He must learn to write what he sees and hears, clearly and accurately, with never a tinge of bias. His own views, his personal feelings and his friendships should have nothing to do with what he writes in a story.

The ideal reporter would be a man who could give the public facts about his bitterest enemy even though such facts would make the man he personally hated a hero before the public.

In journalism more than in any other profession does the advice hold good: "Beware of your friends; your enemies will take care of themselves." By this is meant: Learn well the code of ethics which governs your profession, and when any man in the guise of friendship asks you to violate that code, you may say to him, "If you were truly my friend, you would not ask me to do this any more than you would ask a physician as a matter of friendship to perform an illegal operation, or a lawyer to stoop to shyster practices."

Supplying his editors with the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, is the only mission of the reporter, and any man who asks the reporter to deviate from that principle asks that which is dishonest.

Thomas Carlyle: To every writer we might say: Be true, if you would be believed. Let a man but speak forth with genuine earnestness the thought, the emotion, the actual condition of his own heart; and other men, so strangely are we all knit together by the tie of sympathy, must and will give heed to him. In culture, in extent of view, we may stand above the speaker, or below him; but in either case, his words, if they are earnest and sincere, will find some response within us; for in spite of all casual varieties in outward rank or inward, as face answers to face, so does the heart of man to man.

The copy reader's position carries with it larger responsibilities than the position of any other member of the staff. He can mar or ruin a good story; he can redeem the poor story; he can save the reporter from errors of commission or omission in the matter of his story or in the manner of its writing. No matter how accomplished a writer a reporter may be, the copy reader who handles his story can destroy his product. Then, too, it is the function of the copy reader, if he believes that a better story can be written with the same facts as a basis, to suggest to the city editor that the story be rewritten by the reporter, by another reporter or by the copy reader himself. Because a man is reading copy, he should not imagine that he is not to write a story or rewrite one when occasion demands.

Charles G. Ross writes: "His [the copy reader's] work is critical rather than creative. It is destructive so far as errors of grammar, violations of news style and libel are concerned. But if his sense of news is keen, as that of every copy reader should be, he will find abundant opportunity for something more than mechanical deletion and interlineation. He may insert a terse bit of explanation to clear away obscurity, or may add a piquant touch that will redeem a story from dullness. To the degree that he edits news with sympathy and understanding, with a clear perception of news values, his work may be regarded as creative. If, on the other hand, he conceives it his duty to reduce all writing to a dead level of mediocrity * * * * he richly deserves the epithet that is certain to be hurled at the copy reader by the reporter whose fine phrases have been cut out—he is in truth a 'butcher' of copy."

Dr. Willard G. Bleyer writes: "The reading and editing of copy consists of (1) correcting all errors whether in expression or in fact; (2) making the story conform to the style of the newspaper; (3) improving the story in any respect; (4) eliminating libelous matter; (5) marking copy for the printer; (6) writing headlines and subheads."

Said Robert Louis Stevenson to a painter friend: "You painter chaps make lots of studies, don't you? And you don't frame them all and send them to the Salon, do you? You just stick them up on the studio wall for a bit, and presently you tear them up and make more. And you copy Velasquez and Rembrandt and Vandyke and Corot; and from each you learn some little trick of the brush, some obscure little point of technic. And you know damn well that it is the knowledge thus acquired that will enable you later on to deliver your own message with a fine and confident bravado. You are simply learning your metier; and believe me, mon cher, an artist in any line without the metier is just a blind man with a stick. Now, in the literary line I am simply doing what you painter men are doing in the pictorial line—learning the metier."

Use the typewriter. See that the keys are clean. Use triple space. Write on one side of the paper. Do not paste sheets together. Leave wide margins on both sides and at the top. Write your name and a brief description of the story in two or three words at top of first sheet. Number sheets. Never write perpendicularly in the margin. Never divide a word from one page to another, and if possible do not divide a word from one line to the next. Try to make each page end with a completed paragraph to aid the composing room in setting the story in "takes." When necessary to write in long hand, underscore u and overscore n, and print proper names and unusual words. Ring periods or write x to stand for them. When there is a chance that a word intentionally misspelled will be changed by the printer, write Follow Copy in the margin. Indent deeply for paragraphs. Use an end-mark to indicate your story is completed. Avoid interlining by crossing out the sentence you desire to correct and writing it again.

Save time for your office by care in writing and editing. A little thought before setting down a sentence will save you the trouble of rewriting and the copy reader the annoyance of reading untidy copy.

There is generally a better way to begin a story than with A, An, The, It is, There is, There are.

Avoid beginning a story with figures, but when this must be done, then spell out, as: Ten thousand men marched away today.

The comprehensive A. P. lead is generally preferable, but in writing some stories, particularly feature stories, a reporter may find a more effective lead than the sentence or sentences that summarize the story.

Remember that your reader's time may be limited and that if your story begins with a striking sentence, arresting either because of what it says or the manner in which it says it, your story will be read.

He that uses many words for the explaining of any subject doth, like the cuttlefish, hide himself in his own ink.—Anon.

"The head," says Ross, "is an advertisement, and like all good advertisements it should be honest, holding out no promise that the story does not fulfill. It should be based on the facts as set forth in the story and nothing else."

The head should be a bulletin or summary of the important facts, not a mere label.

It is usually best to base the head on the lead of the story. The first deck should tell the most important feature. Every succeeding deck should contribute new information, not merely explain previous statements or repeat them in different language.

The function of the head is to tell the facts, not to give the writer's comment on the facts.

The head for the feature story, the special department, the editorial or the illustration may properly be a title that suggests the material it advertises instead of summarizing it. Indeed, the success of a feature story often depends on its having a head that directs the reader to the story and arouses his curiosity in it without disclosing the most interesting content. Head writers should beware of revealing in the head the surprise of a story, if it has one.

Never turn in a head that you guess will fit. Make sure. Heads that are too long cause delay and confusion.

As a general rule write heads in the present tense.

Principal words should not be repeated. Do not, however, use impossible synonyms, as canine for dog or inn for hotel.

Make every deck complete in itself.

Use articles sparingly. Occasionally they are needed. Observe the difference in meaning between King George Takes Little Liquor and King George Takes a Little Liquor.

Avoid such overworked and awkward words as probe, rap, quiz, Russ.

Never abbreviate President to Pres.

Avoid ending a line with a preposition, an article or a conjunction, as,

Do not divide phrases, as,

[9] Try to make each line of the first deck a unit, as,

Observe that in reading these heads there is a natural pause that comes at the end of the line. The same principle may govern the writing of three-line heads, as,

In the head just written observe that the first line has fewer letters because it contains two W's and an M. Either an M or a W is equal to a letter and a half, and an I and a space are each equal to half a letter. The first line contains 14½ units; the second line contains 15 units; the third line contains 15 units. And yet the first line contains 14 letters and spaces, the second 16, and the third 17.

Every deck should contain a verb, expressed or implied. In this head,

the verb are is understood.

If the subject of the verb in the first deck is not written, it should be the first word of the second deck, as,

Omit all forms of the verb to be whenever possible. This head,

is more effective than this,

[10]Avoid expressions that are awkward because of omission of some form of the verb to be such as this:

Negatives should be avoided. The head should as a rule tell what happened, not what did not happen.

Avoid the word may. The head should as a rule tell what happened, not what is going to take place, perhaps.

Beware of heads that contain words of double meaning, as,

The word nurses may be taken as a noun or a verb.

In this head the first word might be read as a noun or as a verb:

Use as little punctuation as possible in the first deck.

Avoid alliteration.

Use few abbreviations.

Use figures sparingly.

Insert subheads in long stories at intervals of 150 to 200 words. Use at least two subheads or none.

When there is a paragraph ending, The President spoke as follows:, place the subhead before this paragraph and not between it and the quoted matter.

Avoid such makeshift constructions as

Avoid beginning a head with quotation marks because the white space destroys the balance of the head. When it is unavoidable, use single quotation marks.

Avoid heads in which a dash takes the place of says, as,

When this style is necessary, use quotation marks.

It is permissible to make the first deck of a head a quotation without quotation marks, writing the name of the person quoted in full-face caps immediately below the deck. One need seldom resort to this expedient.

[11]Be careful of the present tense in writing of historical events. The head on a story about the legality of Christ's trial should not read,

nor should it read

but it should read

Remember always in writing heads that although a newspaper man seldom reads more than the first deck, deciding by that whether to read the story, many readers of the paper read no more than the head, and for them it should summarize the story, embodying all its salient features.

The most common errors in grammar to be found in copy are in:

The position of correlative conjunctions with relation to the elements they connect.

To gain grace in writing one must either be born with a natural aptitude in the use of words—and such men: Stevenson, Poe, Walter Pater and others, are geniuses—or one must study the writings of these masters of prose and attempt to discover the secret of their success. It is not necessary that a good writer should know rules of grammar, but he must know enough to observe them. A writer may be unable to tell why a dangling participle is faulty English by testing it with a rule, but he may nevertheless avoid such a construction because his ear tells him it is not the best style.

Copies of the best grammars may be found in the office library and should be consulted when reporters and copy readers are in doubt.

In character, in manners, in style and in all things the supreme excellence is simplicity.—Longfellow.[12]

The newspaper writer must beware of two pitfalls in writing: Fine writing and dialect. Stilted English, pompous and high-sounding, is in just as bad taste as garish clothing or pungent perfume. Reporters often give to their stories a wordy and turgid flavor by their refusal to repeat a word, preferring a synonym. One often sees such sentences as this: "The policeman took his pistol away as he was about to shoot at the bluecoat's partner, another officer of the law." This is a quite unnecessary avoidance of the repetition of the word policeman.

Fine writing is quite out of place at all times in a newspaper and is particularly obnoxious when a reporter quotes a person of inferior mentality in polished—or what the reporter thinks are polished—phrases. Things like this shouldn't get into the paper: "It is with poignant grief that I gaze on the torn frame of my dear spouse," said Mrs. Sowikicki, as she stood beside a slab in the morgue.

On the other hand reporters should not try to be funny at the expense of someone inexpert in the use of the language. If a person interviewed uses bad grammar, correct him when you write the story. To make a person say Hadn't ought to of or Hain't got no is not only insulting to that person and to your readers, but is poor comedy.

Dialect must be absolutely accurate if it is used. Finley Peter Dunne can write Irish dialect and not many other persons in America can write as good. Probably no reporter on The News can write it. Dialect that might hurt the feelings of others who speak the same way should not be used. In fact as a general rule: DON'T WRITE DIALECT. The greatest masters of humor, such as Moliere, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Mark Twain, have obtained their best effects by writing their language straightforwardly.

I began to compose by imitating other authors. I admired, and I worked hard to get, a smooth, rich, classic style. The passion I afterwards formed for Heine's prose forced me from this slavery, and taught me to aim at naturalness. I seek now to get back to the utmost simplicity of expression, to disuse the verbosity I tried so hard to acquire, to get the grit of compact, clear truth, if possible, informal and direct. It is very difficult. I should advise any beginner to study the raciest, strongest, best spoken speech and let the printed speech alone; that is to say, to write straight from the thought without bothering about the manner, except to conform to the spirit or genius of the language. I once thought Latinized diction was to be invited; I now think Latinized expression is to be guarded against.—W. D. Howells.

What M. E. Stone says to his correspondents on story writing may be read with profit by any newspaper man. The following is clipped from the monthly bulletin issued by the Associated Press to its correspondents:

A plain statement of fact is the best introduction to a news story. A simple, direct style—which does not mean a wooden style—is always desirable. In the opening sentence it is of particular value.

The news which a story contains is the one thing which entitles it to place in the Associated Press report. It is the news, not the manner of telling the news, on which the story must stand. It is therefore essential to present the vital point at the outset, in such form as will enable the reader to grasp it quickly, clearly and easily. For this purpose there is no acceptable substitute for plain English.

In an effort to make the most vivid and emphatic impression at the opening, objectionable forms of construction often are employed. A highly-colored or strained introduction almost always fails of its purpose of enlisting interest at once, since it tends to divert the attention of the reader from the subject-matter of the story to the writer's manner of telling it. This renders the introduction cloudy and lessens interest instead of stimulating it. Once the main point is established, the well known rules of news writing should be observed.

To say that "'William Brown may obtain a fair trial in Greene County,' Judge Smith so ruled today," is to misstate the facts. It places the Associated Press on record as making a statement made by the court. Use of this and similar introductory sentences which require subsequent qualification is objectionable.

Opening sentences frequently lose directness and clearness because of the effort to crowd too much into them. All that is essential is to cover the vital point, leaving details for subsequent narration.

Introductions must be impartial. It is possible to take almost any given set of statements and present them in such a way as to convey any one of several shades of meaning. This may depend merely on the order of presentation. Associated Press stories must be accurate and accuracy involves not only the truthfulness of individual statements but the co-relation of these statements in such a way as to convey to the reader a fair and unbiased impression of the story as a whole. An account of a court proceeding, a political debate, or any other event which involves conflicting claims or interests, should not be introduced by singling out a particular phase of the story which is limited to one side of the controversy, simply because that is the most striking feature. Such a form of introduction[16] tends to place the emphasis on one side of the case, giving bias to the entire story.

Stereotyped introductions should be avoided. One of the most common is the "When" introduction, as: "Two men were killed when a train struck . . . " etc. "If" and "After" often are used similarly. Inverted sentences are also frequent; as "That the prisoner was guilty was the opinion expressed by . . . " etc. Constant employment of these fixed styles becomes monotonous. Moreover, it is possible to state the facts more simply, directly and effectively without them.

Edward Harlan Webster gives this excellent advice on how to broaden the vocabulary:

Practice is the first aid. Actually get hold of new words and then use them. You will perceive that you will not startle others so much as yourself. Gradually the words will begin to assume a standing in your vocabulary, and before long, they will seem like old friends.

To obtain these words, various practical methods are possible. Here are a few:

1. Find synonyms for words which you have a tendency to overuse.

2. Record words with which you are familiar but you never use—and then "work" them.

3. Make a list of important, unfamiliar words which you hear, or discover in your reading.

4. Listen carefully to the conversations or addresses of educated people.

5. If possible, try to translate from a foreign language. In this way a fine perception of shades of meaning, almost unattainable by any other method, is acquired.

6. Get interested in the dictionary, where you can trace the life history of words.

"Words have a considerable share in exciting ideas of beauty—they affect the mind by raising in it ideas of those things for which custom has appointed them to stand. Words, by their original and pictorial power have great influence over the passions; if we combine them properly, we may give new life and beauty to the simplest object. In painting, we may represent any fine figure we please, but we never can give it those enlivening touches which it may receive from words. For example, we can represent an angel in a picture by drawing a young man winged: but what painting can furnish out anything so grand as the addition of one word—'the angel of the Lord'? Is there any painting more grand and beautiful?"—Edmund Burke.

Capitalize titles preceding names, as, Chief of Detectives Fox, Gen. Bell. Lower-case titles following names, as John Downey, superintendent of police, except these which are capitalized always:

| President | } | |

| Vice-President | } | |

| Cabinet | } | of the United States. |

| Government | } | |

| Administration | } | |

| Supreme Court | } | |

| Governor (of Michigan). | ||

| Lieutenant-Governor (of Michigan). | ||

| Mayor (of Detroit). | ||

| Supreme Court (of Michigan). | ||

| Judges and Justices of all courts of record. | ||

| The names of all courts of record. | ||

| King, Emperor, Czar, Kaiser, Sultan, Viceroy, etc. | ||

| The Crown Prince. | ||

| The Duke of Blank. | ||

| The Prince of Dash. | ||

Do not capitalize former preceding a title, as former Senator Wilson. Former is preferred to ex-.

Capitalize the full names of associations, clubs, societies, companies, etc., as Michigan Equal Suffrage Association, Detroit Club, Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Star Publishing Company. The preceding such a name is not to be capitalized. Do not capitalize association, club, etc., when not attached to a specific name.

Capitalize university, college, academy, etc., when part of a title, as University of Detroit, Olivet College. But do not capitalize when the plural is used, as the state universities of Michigan, Kansas and Ohio.

Capitalize the first word after a colon in giving a list, as, The following were elected: President, William Jones; vice-president, Sam Smith, etc. Try this menu: Rice, milk and fruit. When the colon is used merely to indicate a longer pause than a semicolon, it is not followed by a capital, as, A tire blew out: the car skidded: we were in the ditch.

Capitalize building, hall, house, hotel, theater, hospital, etc., when used with a distinguishing name, as Book Building, Hull House, Cadillac Hotel, Garrick Theater, Harper Hospital.

Capitalize the names of federal and state departments and bureaus, as Department of Agriculture, State Insurance Department, Bureau of Vital Statistics.[18] But lower-case municipal departments, as fire department, water and light department, street department.

Capitalize the names of national legislative bodies, as Congress, House of Representatives or House, Senate, Parliament, Reichstag, Duma, Chamber (France).

Capitalize state legislature and synonymous terms (legislature, assembly, general assembly) only when the Michigan Legislature is meant.

Capitalize the names of all political parties, in this and other countries, as Democratic, Republican, Progressive, Socialist, Liberal, Tory, Union. But do not capitalize these or similar words, or their derivatives, when used in a general sense, as republican form of government, democratic tendencies, socialistic views.

Capitalize pole, island, isthmus, cape, ocean, bay, river, and in general all such geographical terms when used in specific names, as North Pole, South Sea Islands, Cape Hatteras, Hudson Bay, Pacific Ocean, Mississippi River, Isthmus of Panama.

Capitalize county when used in a specific name, as Wayne County.

Capitalize the East, the West, the Middle West, the Orient and other terms used for definite regions; but do not capitalize east, west, etc., when used merely to designate direction or point of compass, as "west of here." Do not capitalize westerner, southerner, western states and other such derivatives.

Capitalize sections of a state, as Upper Peninsula, Western Michigan, etc., but not the northern part of Michigan, etc.

Capitalize, when used with a distinguishing name, ward, precinct, square, garden, park, etc., as First Ward, Eighth Precinct, Cadillac Square, Madison Square Garden, Palmer Park.

Capitalize Jr. and Sr. after a name.

Capitalize room, etc., when followed by a number or letter, as Room 18, Dime Bank Building; Parlor C, Normandie Hotel.

Capitalize distinctive names of localities in cities, as North End, Nob Hill, Back Bay, Happy Hollow.

Capitalize the names of holidays and days observed as holidays by churches, as Fourth of July, Dominion Day, Good Friday, Yom Kippur, Columbus Day, Washington's Birthday.

Capitalize the names of notable events and things, as the Declaration of Independence, the War of 1812, the Revolution, the Reformation, the Civil War, the Battle of the Marne.

Capitalize church when used as a specific name, as North Woodward Methodist Church, First Christian Church. But write: a Methodist church, a Christian church.

Capitalize the names of all religious denominations, as Baptist, Quaker, Mormon, Methodist.

[19]Capitalize names for the Bible, as the Holy Scriptures, the Book of Books. But do not capitalize adjectives derived from such names, as biblical, scriptural.

Capitalize all names and pronouns used for the Deity.

Capitalize the Last Supper, Lord's Prayer, Ten Commandments, Book of Ruth, etc.

Capitalize the names of races and nationalities, as Italian, American, Indian, Gypsy, Caucasian and Negro.

Capitalize titles of specific treaties, laws, bills, etc., as Treaty of Ghent, Eleventh Amendment, Workmen's Compensation Act, Good Roads Bill. But when the reference is general use lower-case, as the good roads legislation of the last congress.

Capitalize such terms as Stars and Stripes, Old Glory, Union Jack, Stars and Bars, etc.

Capitalize U. S. Army and Navy.

Capitalize names of military organizations, as First Regiment, B Company (do not quote letter), National Guard, Grand Army of the Republic, Michigan State Militia, University Cadet Corps (but University cadets).

Capitalize such names as Triple Alliance, Triple Entente, Quadruple Entente, Allies (in the European war).

Capitalize the fanciful titles of cities and states, as the City of the Straits, the Buckeye State.

Capitalize the nicknames of base ball, foot ball and other athletic teams, as Chicago Cubs, Boston Braves, Tigers.

Capitalize epithets affixed to or standing for proper names, as Alexander the Great, the Pretender.

Capitalize the names of stocks in money markets, as Federal Steel, City Railway.

Capitalize college degrees, whether written in full or abbreviated, as Bachelor of Arts, Doctor of Laws, Bachelor of Science in Education: A.B., LL.D., B.S. in Ed.

Capitalize high school when used thus: Central High School (but the high school at Port Huron).

Capitalize, but do not quote, the titles of newspapers and other periodicals, the New York World, the Outlook, the Saturday Evening Post. Do not capitalize the, except The Detroit News.

Capitalize and quote the titles of books, plays, poems, songs, speeches, etc., as "The Scarlet Letter," "Within the Law," "The Man With the Hoe." The beginning a title must be capitalized and included in the quotation. All the principal words—that is, nouns, pronouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs and interjections—are to be capitalized, no matter how short; thus: "The Man Who Would Be King." Other parts of speech—that is, prepositions, conjunctions and articles—are to be capitalized only when they contain four or more letters; thus:[20] at, in, a, for, Between, Through, Into. The same rules apply to capitalization in headlines.

Capitalize adjectives derived from proper nouns, as English, Elizabethan, Germanic, Teutonic. But do not capitalize proper names and derivatives whose original significance has been obscured by long and common usage. Under this head fall such words as india rubber, oriental colors, street arab, pasteurize, macadam, axminster, gatling, paris green, plaster of paris, philippic, socratic, herculean, guillotine, utopia, bohemian, philistine, platonic. When, however, a name is comparatively recent, use capitals, as in Alice blue, Taft roses, Burbank cactus.

Capitalize the particles in French names, as le, la, de, du, when used without a Christian name or title preceding, as Du Maurier. But lower-case when preceded by a name or title, as George du Maurier. The same rule applies to the German von: Field Marshal von Mackensen, but, without Christian name or title, Von Mackensen. Always capitalize Van in Dutch names unless personal preference dictates an exception, as Henry van Dyke.

Capitalize the names of French streets and places, as Rue de la Paix, Place de la Concorde.

Do not capitalize street, avenue, boulevard, place, lane, terrace, way, road, highway, etc., as Ninth street, Boston boulevard, Maryland place, Rosemary lane, Seven Mile road.

Do not capitalize addition, depot, elevator, mine, station, stockyards, etc., as Wabash freight depot, Yellow Dog mine, Union station, Chicago stockyards.

Do not capitalize postoffice, courthouse, poorhouse, council chamber, armory, cadets, police court, women's parlors.

White House, referring to President's residence, should be capitalized.

Capitalize only the distinguishing words if two or more names are connected, as the Wabash and Missouri Pacific railroad companies. (In singular form, Wabash Railroad Co.)

Do not capitalize the seasons of the year unless they are personified.

Do not capitalize a. m. and p. m. except in headlines.

Capitalize O. K., write it with periods, and form present tense, O. K.'s and past tense, O. K.'d.

Capitalize Boy Scouts (referring to organization). Make Campfire (referring to the girls' organization) one word, capitalized.

Capitalize Constitution referring to that of the United States. But state constitution (lower-case).

A series of three or more words takes commas except before conjunctions, as: There were boxes of guns, bayonets, cartridges and bandages. Separate members of the series with semicolons if there are commas within the phrase, as: There were boxes of guns, bayonets and cartridges; casks of powder, high explosives and chemicals; and many other prohibited articles.

Use asterisks to indicate that part of quoted matter has been omitted, as, He said: "I favor all measures that * * * will help the people."

Use leaders to indicate a pause in the thought.

He said he would never return . . . . . .

When the news reached his mother, she fainted.

Commas set off an explanatory phrase but not a restrictive phrase of inclusive qualification. One writes: Poe, a poet of America, wrote "The Raven." But one writes: Poe the poet is a finer craftsman than Poe the fiction writer.

Use commas before conjunctions in a sentence made up of separate clauses, each with its own subject nominative, as, The horse is old, but it is still willing. If the same subject, write it: The horse is old but willing.

Use no period after letters used in place of numbers, as, B Company. (Companies of soldiers are designated as B Company, not Company B.)

Use hyphen and no apostrophe when dates are joined, as, 1861-65.

Write the caliber of a revolver or rifle with a period, as .22.

Use no commas in years and street numbers, as, 1904, not 1,904; and 2452 High street. But write: 2,156 persons and $1,560.

Follow this style in date lines: CHICAGO, May 10.—

BROWNSVILLE, Mich., May 10.—

Avoid this form as hackneyed: His wealth (?) has disappeared.

Place a comma or a colon after said, remarked and similar words when quoted matter follows.

Writes the Duke of Argyll: I have always held that clear thinking will find its own expression in clear writing. As to mere technical rules, there are very few that occur to me, except such as these—first, to aim at short sentences, without involution or parenthetical matter; second, to follow a logical order in construction of sentences, and in the sequence of them; third, to avoid absolutely such phrases as "the former" and "the latter," always preferring repetition to the use of such tiresome references. The last rule, and in some measure the other, I learned from Macaulay, and have found it of immense use. There is some mannerism in his style, but it is always clear as crystal, and this rule of repetition contributed much to this.

Quotation marks are not needed when matter is indented, thus: The speaker said in part:

I do not believe that, etc.

Sometimes marks of punctuation belong inside quotation marks and sometimes outside, as: "Did you hear him say, 'I am here'?" But in this case: "I heard him say, 'Are you here?'" Continental usage permits this form: "Are you shot!?" but it is not in good use on this side.

Use no quotation marks with slang of your own writing.

Use no quotes in writing testimony with question and answer. This is the style:

Q.—What is your name?

A.—John Jones.

Observe the style on quotes within quotes: The witness said: "I asked him, 'Where is my copy of "Paradise Lost"?'"

Writes Arnold Bennett: One is curious about one's fellow-creatures: therefore one watches them. And generally the more intelligent one is, the more curious one is, and the more one observes. The mere satisfaction of this curiosity is in itself a worthy end, and would alone justify the business of systemized observation. But the aim of observation may, and should, be expressed in terms more grandiose. Human curiosity counts among the highest social virtues (as indifference counts among the basest defects), because it leads to a disclosure of the causes of character and temperament and thereby to a better understanding of the springs of human conduct. Observation is not practiced directly with this high end in view (save by prigs and other futile souls); nevertheless it is a moral act and must inevitably promote kindliness—whether we like it or not. It also sharpens the sense of beauty. An ugly deed—such as a deed of cruelty—takes on artistic beauty when its origin and hence its fitness in the general scheme begin to be comprehended. In the perspective of history we can derive esthetic pleasure from the tranquil scrutiny of all kinds of conduct—as well, for example, of a Renaissance Pope as of a Savonarola. Observation endows our day and our street with the romantic charm of history, and stimulates charity—not the charity which signs cheques, but the more precious charity which puts itself to the trouble of understanding. The condition is that the observer must never lose sight of the fact that what he is to see is life, is the woman next door, is the man in the train—and not a concourse of abstractions. To appreciate all this is the first inspiring preliminary to sound observation.

Watch for nouns ending in -ics. Many of them are singular, such as politics, mathematics, ethics.

Make sums of money singular: Five dollars was spent, unless individual pieces of money are meant, as: Five silver dollars were placed on the table. Write moneys, not monies.

Remember that data, memoranda, phenomena, paraphernalia, bacteria and strata are plural.

Distinguish between majority and plurality. Majority means the lead of a candidate over all other candidates. Plurality means the lead of a candidate over one other candidate.

Event, incident, affair, occurrence, happening, circumstance do not mean the same things. Look them up.

Use preventive, not preventative.

Distinguish between ambassador, minister, consul, envoy.

Avoid feminine forms of such words as author, artist, dancer, violinist, pianist, poet. It may be necessary occasionally to change more than the spelling. For example, the world's greatest pianiste may not mean the world's greatest pianist.

Prefer motorist to automobilist and autoist.

Sewer is a drain. Sewage is what goes through it. Sewerage is a system of drains.

Don't use divine as a noun.

Don't write couple unless you mean two things joined and not merely two.

Don't write party for person, nor people for persons.

Don't use citizens when you mean simply persons.

Don't write a large per cent of when speaking of persons when you mean a large proportion.

When nouns are attended by participles, two constructions are possible. One may say either I know of John's being there, or I know of John being there; The fact of the battle's having been lost, or The fact of the battle having been lost. The possessive is to be preferred with proper names and in most simple constructions; it is altogether to be preferred with pronouns when the principal idea is in the participle. One says: I saw him going, I heard them singing; but I heard of his going; I urged his going; I advised their attending; I objected to his staying; I opposed their going; the fact of his being there made a difference; On his saying this the people shouted; With their consenting the thing was settled; He spoke of my setting out as already agreed to; He found fault with our accepting the place, etc.

[25]Collective nouns are usually singular, as, The club has increased its membership. However, a collective noun, when it is used to refer more particularly to individuals than to the mass, is plural, as The crowd was orderly, but, The crowd threw up their hats. In using collective nouns beware of mixing the number. Do not write, The audience was in their seats, but The audience was seated, or The audience were in their seats.

I believe in the profession of journalism.

I believe that the public journal is a public trust; that all connected with it are, to the full measure of their responsibility, trustees for the public; that acceptance of lesser service than the public service is betrayal of this trust.

I believe that clear thinking and clear statement, accuracy and fairness are fundamental to good journalism.

I believe that a journalist should write only what he holds in his heart to be true.

I believe that suppression of the news for any consideration other than the welfare of society is indefensible.

I believe that no one should write as a journalist what he would not say as a gentleman; that bribery by one's own pocketbook is as much to be avoided as bribery by the pocketbook of another; that individual responsibility may not be escaped by pleading another's instruction or another's dividends.

I believe that advertising, news and editorial columns should alike serve the best interests of the readers; that a single standard of helpful truth and clearness should prevail for all; that the supreme test of good journalism is the measure of its public service.

I believe that the journalism which succeeds best—and best deserves success—fears God and honors man; is stoutly independent, unmoved by pride of opinion or greed of power; constructive, tolerant, but never careless; self controlled, patient; always respectful of its readers, but always unafraid; is quickly indignant at injustice; is unswayed by the appeal of privilege or the clamor of the mob; seeks to give every man a chance and, as far as law and honest wages and recognition of human brotherhood can make it so, an equal chance; is profoundly patriotic, while sincerely promoting international good will and cementing world comradeship; is a journalism of humanity, of and for today's world.

Never use I in referring to yourself except in a signed article.

Avoid the use of he or she and his or her. The use of either phrase is seldom required for clearness' sake. When a noun is used which may refer indifferently to both sexes, the accepted practice is to use the masculine pronoun. For example, say: Let the teacher do his duty and he need not fear criticism, not Let the teacher do his or her duty and he or she need not fear criticism.

Similarly after indefinite singulars like each, every, somebody, anybody, use the masculine singular pronoun. Thus, Everyone should do his duty and he should do it every day. Here one is not only to avoid the use of he or she and his or her, but also particularly and constantly to be on guard against they and their. Sentences like Nobody knows what they can do till they try; Everyone is urged to come and bring their pocketbooks with them, are frequently heard and often get into print.

Do not use the same for a third personal or a demonstrative pronoun. The farmer brought a load of wheat to town and sold it (not the same) at the mill.

Do not make such a pronoun, except in the phrase such as. He has fruits of all sorts and his prices for such are unreasonable, is the sort of use to be avoided.

Distinguish between its, possessive pronoun, and it's, contraction of it is.

Use either or neither only of two, any one or none of more than two, as: In one group are Russia, Germany and Austria, in another France and England. Any one of the first group acting with either of the second could determine the question. (As conjunctions, either and neither may introduce the first of a series of particulars consisting of three or more. It is correct to say Neither this nor that nor the other thing; but when used as pronouns, either and neither should be rigidly confined to use with reference to two only.)

Prefer always no one and nobody to not any one or not anybody, as It is no one's (or nobody's) business, not, It is not any one's (or not anybody's) business.

Do not use apiece for each of persons. Say: The men each took an apple or took an apple each, not The men took an apple apiece. But they might have bought the apples at so much apiece.

Be careful not to say these sort of things, these kind of men, for this sort of things or this kind of men.

In questions direct or indirect be careful to use whom when the objective[28] case is required. Do not say, Who did you see there? or, I do not know who he meant.

The relative who should be used only of persons (or of beasts or things personified). Do not say: The dog whom you saw or He drove the horse who made the best record. The relative which should be used only of beasts and inanimate objects. Do not say: The women and children which were numerous then came trooping in.

The relative that may be used regardless of gender and the antecedent.

That should be used after a compound antecedent mentioning both persons and animals or things, as, The soldiers, the ambulances and the pack mules that were recaptured, were sent to the rear.

Be careful of the case of who if a parenthetical sentence intervenes between it and its verb. He said that Gen. Harrison, whom, everybody well knew, had long been interested in the case, would make the closing argument. Such faulty objective is often heard in daily speech and not infrequently gets into the papers. Of course who should be used. But whom should be used when the infinitive follows: He said that Gen. Harrison, whom everybody admitted to be profoundly versed in the law, would discuss the point.

It is proper to omit the relative pronoun on occasion when it is the object of the following verb, as He was among the men (whom) I saw.

Never use like as a conjunction. John may look like James or act like James or speak like James, but he never looks, acts or speaks like James looks, acts or speaks; he never looks like he wanted to do something, nor conducts himself like he thought he owned the earth, or like he was crazy. Like (as in the first example) may be followed by an objective case of a substantive, with which the construction is completed: You are like me in this; You, like me, believe this; He conducted himself like a crazy man. When a clause is demanded, as if should be used: He looks as if he wanted something; he acts as if he were crazy.

Do not use if for whether in introducing indirect questions: I doubt whether (not if) this is true; I asked whether (not if) he would go.

Do not use as for that. Not I do not know as this is so, but I do not know that this is so.

Do not use without for unless. We cannot go unless (not without) he comes.

Do not use but what for but that or that. I do not doubt that (or but that) he will come, not but what he will come; They did not know but that (not but what) they might accept it.

Do not use while for although, as, while it is probable. While refers to time.

The verb should agree with its subject in person and number. It ought not to be necessary to give this obvious rule, but hardly a day passes without violation of it in almost every paper. Its violation is especially common in the inverted sentence, introduced with there. There is likely to be some changes; There is, at the present writing, some hopes of peace; There seems to be, in view of all the conditions, many objections to this plan, are examples of the faulty usage.

The to should not be separated from the infinitive by word or phrase. The modifier should precede the to or follow the verb. Do not say to promptly act, but to act promptly or promptly to act. Such use as in the example just given is bad enough, but it is not so offensive as the intrusion of time adverbs and negatives as, for example, He decided to now go, or He expected to not only go but to stay, or He preferred to not stay.

Do not end a sentence with the to of an omitted infinitive; as: He could not speak but tried to; but He refused to go but he ought to go, or He ought to go but he refuses.

Subordinate infinitives and participles take their time from the verb in the principal clause. They should therefore be the simple so-called present forms. Do not say: I intended to have gone, or I intended having gone, but I intended to go, I intended going; not He had expected to have been present, but He had expected to be present; not He would have liked to have seen you; but He would have liked to see you; not I was desirous to have gone, but I was desirous to go.

With the verbs appear (in the sense of seem to be) and feel, look, smell and sound (used intransitively) use an adjective and not an adverb, i. e., The rose smells sweet; Miss Coghlan as Lady Teazle looked charming; She appeared happy. But appear in the same sense of behave is followed by an adverb, as He appears well; and the other verbs used transitively of course take an adverb, as He looked sharply at the man.

When one wishes to imply doubt or denial in a condition of present or indefinite time, the imperfect subjunctive should be used, as If the book were here, I should show you—but the book is not here; If it were true, you would long ago have heard it—but it is not true. But if one is referring to past time, the imperfect indicative must be used, as, If he was here yesterday, I did not know it.

Be careful to distinguish between lay and lie, raise and rise, set and sit. The first of each pair is transitive, and always requires an object; the second is intransitive and never takes an object. (The only exception is sit used of a[30] rider, as, He sits his horse well.) One lays or sets a thing down and raises it up. One lies or sits down and rises from one's place. Land lies this way or that. (But we speak of the lay of the land.)

Especially pains must be taken to keep straight the past tenses and past participles of lay and lie. Of lay past tense and participle are alike laid. He laid or he has laid the case before the authorities. The past tense of lie is lay (the same as the present tense of the transitive verb), the past participle is lain. These forms are seldom if ever used for parts of lay; but for them laid is very often used, as, He laid or he has laid down to take a nap, where the correct usage is He lay or he has lain down, etc.

Prices rise, wages rise, bread rises, bread is set to rise; men raise prices or wages; He rose and raised his hand. Clothing of every sort sits well or ill, it does not set. The corresponding noun, however, is set; He admired the set of the garment. You set a hen, but the hen sits and is a sitting hen. The heavenly bodies set, but that is another word, which means to sink or to settle.

Inanimate objects are not injured but damaged.

Use wish to mean simple desire, as, I wish to see him. Use want to mean acute need, as, I want food.

Only moving objects collide. Two automobiles may collide, but an automobile does not collide with a fence.

Things of a general class are compared with each other to bring out points of similarity or dissimilarity. One thing is compared to another of a different class. He compared Detroit with Cleveland. He compared Detroit to a busy hive of bees.

Things occur or happen by chance and take place by design. An accident happens or occurs; a pre-arranged act takes place.

Except in legal papers use proved instead of proven.

Transpire does not mean to take place but to leak out, as, They tried to keep their deliberations secret, but it transpired that * * *

Enthuse is not a good word. Say become enthusiastic.

Medicine, laws and oaths are administered; blows and punishment are dealt.

Allege is used only in referring to formal charges and not as a synonym for say or assert.

The past tense and past participle of dive are dived. Don't use dove.

[31]The past tense and past participle of forecast are forecast. Don't use forecasted.

The past tense and past participle of hang are hung, except in reference to an execution; then write, He was hanged.

The past tense and past participle of plead are pleaded and not plead or pled. Don't write, He plead guilty, but He pleaded guilty.

The past tense of swim is swam, and the past participle is swum.

Newspaper men can read with profit this list of words and phrases to be avoided, compiled by Charles A. Dana for his associates on the New York Sun:

Mark Twain in "A Tramp Abroad" wrote: "Harris said that if the best writer in the world once got the slovenly habit of 'doubling up his have's,' he could never get rid of it; that is to say, if a man gets the habit of saying 'I should have liked to have known more about it' instead of saying 'I should have liked to know more about it,' his disease is incurable."

Great liberty may be exercised in placing the adverb according to the emphasis desired. In general it should be placed near the word or phrase it modifies to express the thought most clearly. One should not say, Not only he spoke forcefully but eloquently; nor He was rather forceful than eloquent, but He was forceful rather than eloquent.

Note particularly that when the adverb is placed within the verb, it should regularly follow the first auxiliary. For example: This can truthfully be said, not This can be truthfully said; He will probably have set out by noon, not He will have probably, etc.; It has long been expected, not It has been long expected.

If the adverb is intended to modify the whole sentence, it very properly stands first, as, Decidedly, this is not true; Assuredly, he does not mean that. In such sentences the adverb really modifies some verb understood, as, I say decidedly this is not true.

Do not use this, that and some as adverbs. Never say this high, this long, that broad, that good, this much, that much, some better, some earlier. Say thus or so whenever tempted to use this or that in such connections, and use somewhat instead of some.

Do not say a man is dangerously ill; say alarmingly or critically. Never use illy; you might as well say welly.

After a negative use so in a comparison. This is as good as that, but This is not so good as that.

Say as far as, as long as, etc.; not so far as, so long as. Thus, As far as I know, this is true; As long as I stay here, you may use my book.

Use previously to, agreeably to, consistently with, etc., instead of the adjective forms, in such expressions as Previously to my arrival, he had been informed; We acted agreeably to the instructions.

Beware of only. Better not use it unless you are sure it is correctly placed. Observe the difference in the meaning here: I have only spoken to him. I have spoken only to him.

Don't use liable when you mean likely. A man is likely to park his automobile so he will be liable to arrest.

Don't use painfully cut and similar expressions. One is not pleasantly cut.

Occasionally means on occasion. So don't write very occasionally, but very seldom or infrequently.

Farther is used to denote distance; further in other senses, as, I told him further that I walked farther than he.

Be sparing in the use of epithets and of adjectives and adverbs generally. Especially avoid the use of superlatives. Superlatives are seldom true. Rarely is a man the most remarkable man in the country in any particular; rarely is an accident the worst in the history of the city. Better understate than overstate; better err on the side of moderation than excess. William Cobbett says: "Some writers deal in expletives to a degree that tires the ear and offends the understanding. With them everything is excessively, or immensely, or extremely, or vastly, or surprisingly, or wonderfully, or abundantly, or the like. The notion of such writers is that these words give strength to what they are saying. This is a great error. Strength must be found in the thought or it will never be found in the words. Big sounding words, without thoughts corresponding, are effort without effect."

Be sure to remember that nee means born. It is of course impossible then to speak of Mrs. Doe, nee Mary Roe, as one is never born with a Christian name, but Mrs. Doe, nee Roe. And, of all things when a widow has remarried, do not write Mrs. Richard Roe, nee Mrs. John Doe.

Adjectives, if wisely used, give desirable color to a story. A thesaurus will brighten up a reporter's adjectival vocabulary. These are suggestions for possible substitutions of fresh words for more or less hackneyed words:

Prefer agreeable to nice, which means accurate; and long to lengthy.

Words like perfect and unique cannot be compared. Never write, more perfect, most perfect, most unique.

Eschew the word very. It seldom strengthens a sentence.

It is better to use such words as feline, bovine, canine, human as adjectives only.

Prefer several or many to a number of.

[35]Healthy means possessing health, as, a healthy man. Healthful means conducive to health, as, healthful climate, surroundings, employment. Do not use healthful in speaking of food, but wholesome.

Parlous is archaic. Don't use the phrase in these parlous times. The word in good usage is perilous.

Nobody has explained the difference between actual photographs and photographs.

Awful means inspiring awe, fearful inspiring fear, and terrible inspiring terror.

Anxious implies anxiety. Say eager if you mean it.

The first meaning of hectic is habitual. The second meaning is fevered. It connotes heat more particularly than red.

Great care is needed in using these three words: livid, lurid and weird. Livid means primarily black and blue. It also means a grayish blue or lead color, as flesh by contusion. It doesn't mean anything else. Lurid means a pale yellow, ghastly pale, wan; figuratively it means gloomy or dismal, grimly terrible or sensational. When used in its first sense it is properly applicable to the yellow flames seen through smoke. It does not mean fiery red. In its figurative sense it can be used to describe a series of incidents calculated to shock or to stun by the enormity of them. Weird means primarily pertaining to witchcraft and is used in reference to the witches in "Macbeth." It also means unearthly, uncanny, eerie. A green light might be called weird. It must not be used to mean peculiar, as, She wore a weird hat.

Says Irvin S. Cobb: I'd rather have my work read by thousands of people throughout the country than be the author of the greatest classic that ever mouldered on a shelf.

In my opinion, the masses are worth our art. If we believe in a democratic form of government we should believe in a democratic attitude toward the art of the short story, and I, for one, frankly admit that I write for the shop girl and business man rather than for the high-brow critic. That does not mean you must necessarily choose between them, but if I had to choose I would let the critic go.

Be careful to use the proper prepositions in all connections.

Say different from, not different to.

We say a man lives on, not in, a street, an avenue, etc. Children play in the street, but on the pavement.

One writes under, not over, a signature. The preposition has no reference to the place of the signature.

Do not overwork on the part of. This phrase is often used where by or among is to be preferred, as, Much patriotism is displayed on the part of the Greeks.

Say off, not off from or off of. He fell off his horse, or He fell from his horse.

Discriminate carefully between beside and besides. The first is always a preposition and means either by the side of, as, He stood beside me, or aside from, or out of, as, This is beside our present purpose; He was beside himself for joy. Besides is either preposition or adverb: as the former it means in addition to, as Several others were present besides those you saw; as adverb it means moreover or more than that, as There were, besides, many pompous volumes.

Be careful with between and among; between is used with reference to two persons, parties or things; among with reference to many: In this city Democrats and Republicans divide the offices between them; in some cities they are distributed among all the parties.

Distinguish between in and into. Into implies action. A man goes into his house and then he is in the house.

A person dies of typhoid fever rather than from typhoid fever.

Distinguish between consist in and consist of. Virtue consists in right living. The family consists of seven persons.

A book is illustrated with sketches and it is illustrated by the artist who made the sketches.

Omit from from the phrases from hence, from thence, from whence.

Use an article with every noun of a series unless the nouns are so closely related that one concept is implied. Say, The bread and jam was good, but The bread and the jam were good. Say, A horse and buggy, but A man and a woman.

Do not repeat an article before each adjective of a series when all modify the same noun. Say, A red, white and blue flag. If you mean three flags, say, A red, a white, and a blue flag.

Do not write a or an after sort of and kind of. Make it: He is the right sort of man for mayor.

The definite article is used too often when it might better be omitted, as in this sentence: The study of the dictionary is helpful. Write it: Study of the dictionary.

The general rule on The News is that all numbers above nine shall be written in figures, and that all numbers below 10 shall be spelled out. There are, of course, many exceptions to this rule. Figures are always used for degrees of latitude and longitude, degrees of temperature, per cent, prices, racing time, scores, definite sums of money, time, votes, dates (as Sept. 27), ages, street numbers and tabulated statistics.

Spell out indefinite figures, as about a dollar's worth.

Use Roman numerals in writing of kings, as George V, and then without a period. Do not use Roman numerals in designating centuries. Write it fourteenth century, not XIVth century.

Write Monday at 8 a. m., not at 8 o'clock on Monday morning.

Spell out such expressions as the early seventies.

Use figures in dimensions when written thus: a lot 4×6 feet.

All ages shall be written thus: John Smith, 8 years old. Do not write it: John Smith, aged 8, or aged eight. It will be easy to remember the rule if you observe that in writing it thus: John Smith, aged 18, 48 Jones street, you are opening an opportunity for an error easily made. It may appear: John Smith, aged 184, 8 Jones street.

All ordinals are spelled out. Write it thirtieth, not 30th. Write a date: Feb. 6, not February 6th, or February sixth.

Do not use both numerals and figures spelled out in one phrase. Write it: Eight feet eleven inches. If in a phrase a number over 10 precedes a number under 10, express both in figures, thus 18 hours 4 minutes. If vice versa, express it thus: two hours eighteen minutes.

| I | 1 | XIX | 19 | CL | 150 |

| II | 2 | XX | 20 | CC | 200 |

| III | 3 | XXX | 30 | CCC | 300 |

| IV | 4 | XL | 40 | CCCC | 400 |

| V | 5 | L | 50 | D | 500 |

| VI | 6 | LX | 60 | DC | 600 |

| VII | 7 | LXX | 70 | DCC | 700 |

| VIII | 8 | LXXX | 80 | DCCC | 800 |

| IX | 9 | XC | 90 | DCCCC | 900 |

| X | 10 | C | 100 | M | 1,000 |

The metric system is the system of measurement of which the meter is the fundamental unit. It was first adopted in France and is now in general use in most civilized countries except the English-speaking countries. The system is now used throughout the world for scientific measurements. Its use was legalized in the United States in 1866.

The meter, the unit of length, was intended to be one ten-millionth part of the earth's meridian quadrant and is nearly so. Its length is 39.370 inches. The unit of surface is the are, which is 100 square meters. The theoretical unit of volume is the stere, which is a cubic meter. The unit of volume for the purposes of the market is the liter, which is the volume of one kilogram of distilled water at its maximum density and is intended to be one cubic decimeter. For 10 times,[41] 100 times, 1,000 times and 10,000 times one of these units, the prefixes, deca-, hecto-, kilo- and myria- are used. For 1-10, 1-100 and 1-1,000 of the units, the prefixes deci-, centi- and milli- are used.

In this table the equivalents are measures common in the United States and are not to be confused with British measures, which in some cases vary slightly.

| 1 myriameter | 5.4 nautical miles or 6.21 statute miles. |

| 1 kilometer | 0.621 statute mile or nearly 5/8 mile. |

| 1 hectometer | 109.4 yards. |

| 1 decameter | 1.988 rods. |

| 1 meter | 39.37 inches or about 1 yard 3 inches. |

| 1 decimeter | 3.937 inches. |

| 1 centimeter | 0.3937 inch. |

| 1 millimeter | 0.03937 inch. |

| 1 hectare | 2.471 acres. |

| 1 are | 119.6 square yards. |

| 1 centiare (square meter) | 10.764 square feet. |

| 1 decastere | 13 cubic yards or about 2¾ cords. |

| 1 stere (cubic meter) | 1.308 cubic yards or 35.3 cubic feet. |

| 1 decistere | 3½ cubic feet. |

| 1 hectoliter | 26.4 gallons. |

| 1 decaliter | Little more than 2 gallons 5 pints. |

| 1 liter | 1 quart 1/2 gill. |

| 1 deciliter | 0.845 gill. |

| 1 millier | 2,204.6 pounds avoirdupois. |

| 1 kilogram | Little more than 2 pounds 3 ounces. |

| 1 hectogram | Little more than 3 ounces 8 drams. |

| 1 decagram | 154.32 grains troy. |

| 1 gram | 15.43234 grains. |

| 1 decigram | 1.543234 grains. |

| 1 centigram | 0.154323 grains. |

| 1 milligram | 0.015432 grains. |

This is the style of The News on abbreviating the names of states and territories:

Do not abbreviate Port to Pt.

Abbreviate Fort to Ft., whether a city or a post.

Abbreviate Mount to Mt. in names like Mt. Vernon.

Do not abbreviate names of cities, as Kazoo, Frisco, St. Joe.

Do not use state with names of well-known cities, such as Chicago, Cleveland, Denver, etc.

Follow a firm name as the firm writes it, except in the capitalization of the, as the Ford Motor Co. Later in the story the name may appear as the Ford company. It is the J. L. Hudson Company. However, one may say, after writing the firm name, that the Hudson company will, etc.

[43]Use Mich. after the names of all places in the state except:

Beware of the names of cities in other states identical with those in Michigan. Also watch for the names of cities identical with those in other states, as Portland, Me., and Portland, Ore. A few cities that should carry a state designation because there are places of the same name in Michigan are:

Do not abbreviate Attorney to Atty. before a name.

Do not abbreviate first names except in reproducing signatures, as, Wm. H. Taft, if Mr. Taft wrote it that way.

Abbreviate senior and junior with commas on each side, as John Jones, Jr., spoke.

Do not make Tom, Dan, Ben, Joe, etc., abbreviations unless you are sure they are. Alex Dow is written without the period.

Write S O S and similar telegraphic abbreviations, and I O U without periods.

Use Bros. only when firm name is so written.

Use ampersand (&) in firm name only when the firm uses it.

Abbreviate number when followed by numerals, as No. 10.

[44]Spell out United States except in addresses or in army and navy phrases. Military and naval titles should be written thus:

Class of '08 may be used for Class of 1908.

Abbreviate degrees after a name.

Book sizes, 4to, 8vo, 12mo, should be written without periods.

Use only abbreviations that will surely be understood, such as Y. M. C. A., W. C. T. U., etc., in referring to organizations.

Never write Xmas.

These abbreviations should be used:

Abbreviate saint and saints in proper names, as St. Louis, Sault Ste. Marie, Ste. Anne's, SS. Peter and Paul's church.

Write scriptural texts Gen. xiv, 24; II Kings viii, 11-15.

Abbreviate names of political parties only thus, Smith (Rep.) defeated Jones (Dem.) for alderman.

Do not abbreviate street, avenue, boulevard, place or other designation of a thoroughfare.

Abbreviate clock time when immediately connected with figures to a. m. and p. m.

Prefer for example to e. g.

Prefer namely to viz.

Prefer that is to i. e.

Write English money £5 4s 6d, without commas.

Abbreviate the months thus:

Use don't only when you may substitute do not. Perhaps you have seen the advertisement which reads: "Hand Made Tobacco Don't Bite the Tongue."