Title: Harper's Round Table, June 11, 1895

Author: Various

Release date: June 28, 2010 [eBook #33010]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie McGuire

Copyright, 1895, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| PUBLISHED WEEKLY. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, JUNE 11, 1895. | FIVE CENTS A COPY. |

| VOL. XVI.—NO. 815. | TWO DOLLARS A YEAR. |

"Han'some," said Farmer Joe, having stretched himself on the shady side of the forecastle-deck and set his pipe going, "it 'pear's to me that it's about time we heard what happened to you after you got back to your own ship."

"You mean on my whaling voyages, I suppose," said Handsome.

"That's a right peert guess," responded Farmer Joe.

Handsome blew a whirling cloud of smoke that went swiftly out to leeward under the swelling foot of the fore-staysail. He watched it in a meditative manner until it disappeared, and then said:

"I was pretty glad to get back to my own ship, the Ellen Burgee, because, in spite of the fact that they treated us very well aboard the Two Cousins, you see I had a pretty good lay on the Ellen, and I didn't want to lose it. Of[Pg 594] course nobody ever gets rich by going to sea, but a fellow likes to stick fast to all he gets. Well, we didn't stay very long in the bay in company with the Two Cousins. We got to sea again, and laid our course for a bit of cruising-ground away to the southward, where our Captain said he believed the whaling was good. The voyage down there was as stupid as a Sunday-afternoon sermon in hot weather, and for the matter of that so was the cruising for two days, because we didn't raise a single spout. On the third day, however, we were gladdened by the welcome cry of 'There she blows!' There were half a dozen whales in sight, and the old man had great hopes of getting at least two of them. But that was not to be our luck that day. The first mate got fast to one big fellow, and killed him, but the rest of us returned to the ship empty-handed.

"Now I haven't told you anything about what's done with a whale after you get him; but as this story depends on that, I'll have to explain. The first job is to get the whale alongside the ship."

"Why not sail the ship alongside the whale?" asked one of the listeners.

"That ain't wholly practicable," answered Handsome, "because you might run into him and sink him. The ship does sail as close as she dares, but the boats must do their share. Two boats take the ends of a light line, with a weight slung on the bight so as to sink it, and they pass this under the whale's tail and around his 'small,' as the slimmest part of him is called. By means of this line, the ends being passed aboard the ship, a chain is run in a slip-noose around the 'small,' and Mr. Whale is hauled alongside and kept there. Next comes the business of cutting-in, which means cutting off the blubber and bone that are wanted. Stages, such as ships' painters use, are slung over the side of the vessel, and the first-class cutters, generally the ship's officers, stand on these stages with long-handled spades. The cutting-in begins at the place where the backbone joins the head, and the first strip taken off there is called the blanket piece. The pieces of blubber are hauled up with tackles, and these rip them off while the spades cut. It's a long and tough job, and it makes a new hand pretty sick. But it's child's play to what comes next, which is the trying-out. Say, I'd rather be a green hand again than have another job at trying-out."

"Well, tell us about it, anyhow," said Farmer Joe.

"It ain't any use to make a long yarn of that," continued Handsome. "The try-works, as they call them, are a sort of Dutch oven, built of bricks, and situated amidships. A couple of big iron pots stand on top of the oven, and the blubber, minced up, is put into them. You start a fire in the oven, and that boils out the oil, which is ladled out into casks, and then all hands turn to and pick out the pieces of fat and scraps so as to have nothing put pure oil. Well, to heave ahead with the yarn, we had our whale alongside overnight, and the next morning we started at cutting-in. About the time we'd got ready for trying-out, and started the fires, the breeze began to freshen up, and it looked rather dirty up to windward. The Captain said we must shake a leg with the trying-out.

"'Boys,' says he, 'we got to boil this oil with stu'ns'ls set, because before we get it done we'll be under a close-reefed maintops'l.'

"Well, bless you, he hadn't much more than got the words out of his mouth than the mast-head fellow lets out a yell:

"'There she blows! And there she breaches!'

"Now it wouldn't make any difference to a whaler if he thought the world was a-going to come to an end in ten minutes, he'd lower away if he saw a spout. So the Captain gave orders for two boats to get under way in chase of the new whales. One of the boats was the one I belonged to, and the next thing I knew I was sitting on my thwart. The sail was hoisted, and we went scudding down to leeward at a rattling gait. Say, it wasn't altogether agreeable to sit in that boat and notice the width and height of the sea that was getting up. But we soon forgot all about it in the excitement of going on.

"'It's a-going to be a tough job getting this whale alongside,' says one of the crew.

"'Wait till we get him first,' says Bacon.

"Well, it was our chance, and Bacon slung the iron into him with a vim. Up went flukes and down went whale. He soon came up and began to swim to windward at a fearful speed. The seas thundered against the bow of our boat, and great sheets of water came tumbling inboard.

"'Bale there, bale!' yelled Bacon, 'or the boat'll fill and sink!'

"You can bet we didn't need to be told twice. We hadn't fairly got started when the whale sounded, and we could tell by the trend of the line that he was coming back toward the boat.

"'Look out!' shouted Bacon.

"The next second the brute shot clear out of the water not fifty feet off the starboard beam of our boat, and raised such a wave when he fell back into the sea that he nearly swamped us.

"'For goodness' sake," says one of the men, 'cut the line and let him go.'

"'We'll never get back to the ship alive,' says another; 'look at the sea. It's blowing a gale.'

"Well, it was blowing in a bit of a squall just then, but Bacon's blood was up, and he was bound to have that whale.

"'Pull me up to him!' he shouted.

"We obeyed orders, and Bacon drove the lance right into his life.

"'Starn all!' he yelled, and we didn't get out of the way a second too quick, for the monster went into his flurry, and beat the sea into an acre of foam with his immense flukes. However, there he was dead enough, and in the mean time the ship had worked down to leeward of us, and was close at hand. It was a pretty troublesome piece of work to pass the line around his small in such a nasty sea; we managed to do it after four or five trials, and he was hauled alongside the ship just as it began to grow dark. Now I tell you what, lads, it was a very uncommon sight. There was the ship beginning to roll uneasily in the rising sea, with a blazing, smoking furnace amidships, looking for all the world as if she was on fire, and a whale on each side of her. The boats were hauled up, and then the Captain looked about him.

"'Cut the old whale adrift,' says he; 'we can't tow the two of them in this weather, and we've got about the best of his oil.'

"So we cut the carcass adrift, and it went rolling off down to leeward. It hadn't got fifty yards from the ship before all the water around it was black with sharks' fins, and the next instant a dozen of these wolves of the sea appeared, leaping and thrashing the water in their mad struggles to get at the remains of the whale. They seemed like regular demons, so fiercely did they attack the carcass, ripping away the remaining shreds of flesh, and smashing the bones in their powerful jaws. In five minutes the body was torn to pieces and the sharks disappeared, leaving us to imagine what would have happened to some of us if a boat had happened to capsize in the chase. Well, the gale increased in strength, and the sea rose more and more. The Captain didn't want to lose the whale, so he hove the ship to with the dead monster under our lee, where he rode pretty well, except that once in a while when we rolled heavily he would come up against the side of the ship with a thump that threatened to shake the timbers apart. However, the Captain said he was going to hang on till he found it was a case of life or death. All of a sudden we were startled by a terrible cry,

"'Fire!'

"Every man looked in the direction from which the cry came, and we saw a small but lively flame stealing up near the foot of the mainmast.

"'It's from the try-works!' shouted Bacon.

"Sure enough the gale had taken up every one's attention so that we all forgot about the fire in the try-works. It hadn't been put out, and now a coal or a spark or something had fallen on the deck, and the damage was done."

"'Why didn't you put it out?' asked one of the listeners.

"Put it out!" exclaimed Handsome: "why, man alive, don't you know the condition a whale ship is in when trying-out[Pg 595] is going on? She was simply afloat with whale oil. The deck was running with it; every plank and bit of loose rigging was soaked with it. Put it out! Why, we did all that mortal man could think of. The Captain ordered us to get up all the tarpaulins and spare canvas, and try to smother it, but, bless you, as soon as we threw them over the fire they soaked up the oil and began to burn. We fought the fire with the energy of desperate men, for we knew that if we had to take to the boats the chances of our ever seeing land again in such a sea would be pretty slim. Finally the Captain said he would try a desperate scheme. As yet the flames were around the decks and lower masts. What he proposed to do was to let the ship fall off into the trough of the sea in hopes that a big wave would sweep her deck and drown out the fire. Everything was made ready, and then with a face full of sorrow he gave the order to cut loose the carcass of the whale. He was afraid to let it hang there with the ship broadside on. We cut it loose, and then he ordered the helm to be put up, and all hands to take to the rigging. We went up with a good deal of misgiving. The ship fell off into the trough and wallowed there. The seas broke over her here and there, but not in sufficient volume to drown the fire, which was gaining headway all the time, and was now beginning to send tongues of flame up the rigging, as if in a mad attempt to drive us poor fellows out of our refuge.

"'It won't do,' says the Captain; 'we must lay down, lads, and take to the boats.'

"We all started for the deck, when suddenly Bacon uttered a fearful cry:

"'Look! Look!'

"He was pointing to windward, and looking in that direction, we all saw a tremendous wave rolling down upon the ship with the speed of an express train. We stopped where we were, and clung with an intense grip to the rigging. The wave came. It pitched the vessel up as if she were a chip of wood, and flung her over on her beam ends. There was a crashing and rending of wood, and several wild shrieks from the men as the foremast went by the board. There were half a dozen fellows on it, and they were plunged into that raging sea. I never saw them again. The rest of us were hanging on as best we could, when the very next wave that came put out the fire sure enough, for it turned the Ellen Burgee bottom up."

Handsome paused for a moment, as if overcome by the dreadful recollection.

"Well," he continued, "when she went over, I let go of the rigging and threw myself into the sea. I made up my mind it was all over with me, yet it turned out that this was not to be the case. I was buried under a ton or two of foaming water, but I came to the surface again, and found myself a long distance off from the overturned ship, which was fast settling in the water. I struck out, as a man will even when he doesn't know what use it is, and kept myself afloat for several minutes, the waves all the time driving me to leeward. Suddenly I saw a dark mass tumbling on the seas a short distance away. I thought it must be one of our boats that had got loose when the ship went over, and so I struck out for it. I was growing weak, blind, and dazed in the heavy seas, when I was caught up by a wave and flung squarely on top of the floating object. I grabbed wildly, and caught hold of something hard and slimy. I clung to it, though, and to my great amazement I found I was hanging to the flipper of the dead whale. You know they float on their sides when dead, with one flipper up in the air and the other under water. Well, it wasn't much of a life-raft, as you may well suppose, but a man in such a fix as I was will take anything he can get. I hung on there all right, the dead whale jumping and tumbling under me like a live fish. Toward morning the wind shifted, and at sunrise the gale broke. The sea began to go down right away, but a great swell was running. When the sun got fairly up I realized what a terrible position I was in. The heat was intense, and the gases from the carcass nearly overwhelmed me. But that was nothing. The air was filled with the discordant cries of hungry sea-birds. They swooped down from every direction, and pecked at the carcass. They beat at me with their wings, and acted as if they knew I was a doomed man, and the sooner they could drive me into the sea the better for me. But I fought them off, and sitting with one leg on each side of the flipper and clasping it with one arm, I clung to my dreadful life-buoy.

"And now came a new horror. Sharks appeared and began to fight around the whale, snapping and biting and tearing off pieces of the flesh. I realized that if this continued my life-buoy would be destroyed; but I was helpless. Then thirst began to torture me. All day long I tossed on that dead whale, with the birds and the sharks around me. At nightfall a gentle shower came, and by holding my mouth open I managed to relieve my thirst a little. As soon as it became dark the birds and the sharks left me, and presently, utterly exhausted, I fell asleep, leaning against the flipper. I remember that I was quite conscious of the danger of falling off my perch into the sea and drowning; but I didn't care. How long I slept I do not know. It must have been five or six hours. I was awakened by a heavy shock, and I found myself plunged into the sea. Involuntarily I uttered a scream for help.

"'Great Scott! there's a man,' I heard a voice say. 'Hang on there, lad. Catch this.'

"Plump came a circular white life-buoy into the sea, luckily falling within my reach. A few minutes later a boat had been lowered away, and I learned that my dead whale had been run down in the darkness by the ship Full Moon, bound for Liverpool from Hong-Kong. And so I was taken to England, with a pretty clear determination in my head never to go whaling again."

Here and there a daisy?

And now and then a clover?

And once a week a buttercup,

And so the whole land over?

A rose within the garden?

A lily in the sun?

Does dear old Mother Nature

Count flowers one by one?

No; daisies by the acre,

And clovers millionfold,

The meadows pink with blushing,

The pastures white and gold.

And roses, like the children,

Abloom at every door,

And buttercups as countless

As the sand upon the shore.

Dear Mother Nature scatters

Her flowers on road-side edge;

She carpets every forest,

And curtains every ledge.

And then she sets us dancing

To such a merry tune,

For all the world is laughing,

And, darlings, this is June!

"Harry, here are three apples; now suppose I wanted you to divide them equally between James, John, and yourself, how would you do it.'"

"I'd give them one and keep the others."

"Why, how do you make that out?"

"Well, you see, it would be one for those two, and one for me, too."[Pg 596]

HON. C. F. CRISP, SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE.

HON. C. F. CRISP, SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE.

It is not easy to describe in a short article an average day in the House of Representatives. The great days are exceptional, and a single historic scene gives no idea of the every-day work of the House. Moreover, if history is made on the days when excitement runs high, the business of carrying on the government is done every day, and it is about the latter that you wish to learn. By way of beginning, let me say a word about the place where this work is done. The House of Representatives holds its sessions in the southern wing of the Capitol at Washington. The House is very large, right angled, and rigid, with little ornament, and without beauty of proportion. The walls go up for about fifteen feet, and from that point the galleries slant back until they reach the next floor of the building. The roof is a vast expanse of glass, with the arms of each State painted on the square panels. The general effect is grayness of color and a size which can be measured in acres better than in feet. Against the southern wall is placed a high white marble dais or tribune, where the Speaker or presiding officer sits. Below the Speaker's desk and in descending tiers, also of white marble, sit the clerks of the House and the official reporters. Facing the Speaker, and ranged in a semicircle, are 360 desks, with a corresponding number of chairs, which are, or ought to be, occupied by the 350 Representatives and the four Territorial delegates.

Such is the place, but it would require a volume, and a very uninteresting one, too, to explain the machinery used in transacting the business for which this great hall is provided. Nevertheless, it is possible, perhaps, to give you in a general way some idea of an ordinary day's work in the lower branch of Congress. In theory, the House ought to take up its calendars on each day and dispose of each article in its order. But the great beauty of the calendars is that in practice they are never taken up at all.

How then, you will ask, is business done if the House never takes up the list of measures prepared for its consideration? It is done by a system of special rules. The Committee on Rules brings in a rule that the House shall take up, let us say the tariff, on a certain day, shall debate it a certain length of time, and shall then vote. This rule is adopted, the bill selected is taken from the calendar, and everything else gives way until the tariff is disposed of. Appropriation bills are privileged, because they provide the money necessary to carry on the government, and require no rule to be brought up. But all the other business of the House is done practically under special rules; in other words, the Committee on Rules selects out of the mass of business presented a small portion which the House shall consider, and to that small selection all the time of the House is devoted.

Imagine, then, that the House as you watch it from the gallery has come to the end of the morning hour, and has taken up the special order of the day made for it by its Committee on Rules. If it is the first time the subject has come up, the chairman of the committee making the report opens the debate. In any event, when the business of the day is thus laid before the House the debate begins. To any one who comes into the House gallery for the first time, the scene on the floor is one of apparently hopeless confusion. Members are reading, writing, talking, and moving about the chamber. There is an incessant murmur and buzz of conversation along the aisles and in the galleries. You who are looking on see a member rise and begin to talk, sometimes quietly, more often with great violence and excitement, not because he is really excited, but because he wishes to be heard above the din. Your ears are not accustomed to the noise, and you do not hear what is said. Still less can you guess what it is all about, and yet business is not proceeding by chance, and there are men on that confused floor who know exactly what is happening, and how the business is going on. You may have been unlucky in your day, and no measure of great interest being up, it may seem as if it were useless to stay, but if you will be patient, and bear with the confusion for the time, or perhaps come back another day, you will have your reward. You will see the House reach an exciting point in a debate, or some subject of great popular interest will come up, and then a sharp contest will follow between different members, which will be full of interest.

AN EXCITING MOMENT IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES.

AN EXCITING MOMENT IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES.

Instead of reading and writing and talking and moving about, you will see the members gather about the man who is speaking and those who are debating with him. Silence will come on the floor and in the galleries, broken by bursts of applause, as one member makes a sharp point or retorts quickly on his opponent. Nothing is more interesting than good debate of this kind, when men who are fencing or sparring with their wits instead of their hands. You will be surprised to see how easy it now is to know what is going on. You will be glad that you came to the gallery, for every wholesome-minded being likes to see a fair contest, whether of brains or muscles, and incidentally you will see how we English-speaking people have hammered out by discussion the laws under which we live, and have gained the liberty we enjoy. On the other hand, let us suppose that you are fortunate enough to get into the gallery on a day of great debate, when set speeches are to be made by the leaders on either side. A man arises near the middle of the House, a man whose face is familiar to you, because you have seen it so often in the illustrated papers, and all in a moment the House is hushed, and every word that the speaker says[Pg 597] falls distinctly upon your ear. Then, again, you feel rewarded, for you are hearing a party leader speak and are seeing a man about whom you have read. If it is the day upon which a great debate closes, the last speeches are made by the two leaders of the opposite sides, the galleries are crowded, but as every one is eager to hear, there is no difficulty in catching every word. The leader of the minority delivers his last assault upon the bill, the leader of the majority replies to him, and then the Speaker of the House says: "The hour having arrived at which the House has ordered that the debate be closed, the vote will now be taken upon the bill and amendments." Then comes the voting, a dreary process for everybody, for each roll-call occupies half an hour, and when it is done the Speaker announces the vote, and declares the bill passed or defeated as the case may be. If it is then more than five o'clock one of the leaders of the majority moves that the House adjourn, the Speaker declares the motion carried, and then the House stands adjourned until the next morning at twelve o'clock.

Such in very rough outline is a day in the House of Representatives when some subject which awakens differences spring up, or when a great debate closes or some important bill is passed. But there are many other days when no conclusion is reached, and still others which are consumed in roll-calls and motions designed to waste time, and to stop all action. If you chance to come on a day of that kind, the sooner you go away the better for your own comfort. The members must stay, but you need not.

It would, however, take a great deal more space than I have here to give you a description of the various scenes which occur in the House of Representatives, but the rough sketch which I have drawn may help you to some idea of what happens in the great popular body which with the Senate makes laws for the people of the United States. It is a good deal better, however, that every American boy and girl should come to Washington if they can possibly manage it, and try to learn from observation what their government is, and how it is carried on. They will have some dull hours if they pass many in the galleries of the House of Representatives, but they may have some minutes of great interest, which they will always be glad to remember, and they are certain to go away with a greater ability to judge intelligently their public men, and in this way be of better service themselves as American citizens responsible for the government of their country. If you cannot get to Washington, try to see your own Legislature in session, or your own city and town government. You will learn a great deal that will be useful to you when you come of age, and therefore responsible for your vote or influence for the government of the United States, which is always in the long-run what the people themselves make it.

I don't care much for the postage-stamps

Themselves—'tween me and you;

The fun I get collecting comes

From sticking 'em in with glue.

[Pg 598]

The recent war between China and Japan, which now seems to be practically over, fortunately, was watched by all the military and naval men in the world with a great deal of interest, for it was the first real war in which many of the modern inventions in war-ships and army accoutrements were given a fair trial. To be sure, China had little that was modern in her army and navy, though some of the ships of her navy were of recent European build, and were manned by capable seamen and good fighting-men. But the Japanese certainly did have many of the modern inventions in their cruisers, and they made most effective use of them.

The correspondents of the great papers of the world, however, seem to have suffered, and whether this is a development of modern warfare, or because the Japanese and Chinese did not understand and appreciate their position, does not appear to have been settled. At all events, the correspondents from Japan and China, as well as those from European and American countries, went about their always dangerous business at their peril, and were in constant danger of being captured and hung or murdered by either party. Some of these bright and daring men did lose their lives there, and no one takes the trouble to sing a requiem over them in verse or prose, but others, in spite of all the opposition, got to and remained at the front, and succeeded in sending out accurate news to their papers.

PHOTOGRAPHER AT WORK.

PHOTOGRAPHER AT WORK.

It was one of these successful newspaper men, and a Japanese at that, who originated the idea of using a balloon to help him get to the front, as well as to keep him safely out of the reach of both contestants. He procured a balloon, several, in fact—and had a peculiar metal frame-work constructed, which held him firmly in place under the balloon, and left his arms free, so that he could use them to write, or to work a huge camera that was also attached and supported by the same iron frame. By means of straps over his shoulders and about his body he could keep himself moderately firm in his position, and his camera reasonably stationary, except, of course, for the movements of the balloon itself, which he could not regulate.

Several times this correspondent was sent up in his balloon, and held by an assistant with the help of a long rope far above houses, and even hills, so that he could take photographs on his huge lens of the general view of a battle, while he himself was either too far away or too unimportant at the moment to the combatants to tempt them to fire upon him. In this way he succeeded in securing some astonishing views. They were, of course, very far removed from the scene of action, too far to give much of the small details, but they presented a bird's-eye view of the whole battle, which proved of great interest. Occasionally, because of a sudden movement of the balloon, he "took" the sky or a distant landscape instead of the raging battle beneath him, but these little mistakes were insignificant when on being hauled down, he discovered two or three views that showed charges of cavalry here, repulses of infantry there, and smoke and strife, bursting shells and burning houses, everywhere.

Sometimes the photographer would go up in his camera-balloon without being held to the earth by a rope, and then he might drift with the wind over the battle-field, or quietly drift away without getting a chance to "shoot." As a rule, however, calculations were pretty well made before the rope was dropped, and then the balloon was allowed to float where it would, with the comparative certainty that it would pass over, or nearly over, the scene of action.

Here is a chance for photographers who want to take new scenes and original things with their cameras. The earth at a few hundred feet distance would look like a big bowl covered with many little roofs, laced with white roads, along which funny little animals would be seen crawling along at a snail's pace.

Fling it from mast and steeple,

Symbol o'er land and sea,

Of the life of a happy people,

Gallant and strong and free.

Proudly we view its colors,

Flag of the brave and true,

With the clustered stars and the steadfast bars,

The red, the white, and the blue.

Flag of the fearless-hearted,

Flag of the broken chain,

Flag in a day-dawn started,

Never to pale or wane.

Dearly we prize its colors,

With the heaven light breaking through,

The clustered stars and the steadfast bars,

The red, the white, and the blue.

Flag of the sturdy fathers,

Flag of the loyal sons,

Beneath its folds it gathers

Earth's best and noblest ones.

Boldly we wave its colors,

Our veins are thrilled anew;

By the steadfast bars, the clustered stars,

The red, the white, and the blue.

Margaret E. Sangster.

A wise old doctor, for the benefit of his health, travelled around the country in a caravan, in which he lived, stopping for short periods at the larger towns. He had a young lad for an assistant, who was more or less quick and intelligent, but rather inclined to jump at conclusions. The doctor taught him a little medicine whenever he could spare the time, and he learned considerable, but diagnosis were to him still a mystery, especially in some cases, when the wise old doctor had used his eyes to detect the source of the illness.

They were staying for a few days in the town of B——, and the doctor had been in some demand, having at a previous visit secured a reputation by some apparently marvellous cures. His young assistant accompanied him on one occasion, when the doctor had pronounced the patient sick from eating too many oysters. This puzzled the lad, and when they left the house he asked his master how he knew the patient had been eating oysters. "Very simple," his master replied, "I saw a lot of oyster shells in the fireplace, and the answers to a few questions were all I needed to make a diagnosis."

One day, his master being away when a call came, he determined to answer it, and see if he could diagnose the case. He returned shortly after, and triumphantly told the doctor that the man was sick from eating too much horse.

"A horse, you stupid fool!" cried the irate doctor. "What do you mean?"

"Why, master, it couldn't be anything else, because I saw a saddle and stirrups under the bed."[Pg 599]

I don't believe that Mr. Henry ever thought what a queer combination of nicknames his son would have when he named him Thomas Richard. Some called him "Tom," some "Dick," and others, instead of calling him by his last name, Henry, changed that, too, to "Harry," so he became Tom, Dick, and Harry rolled into one.

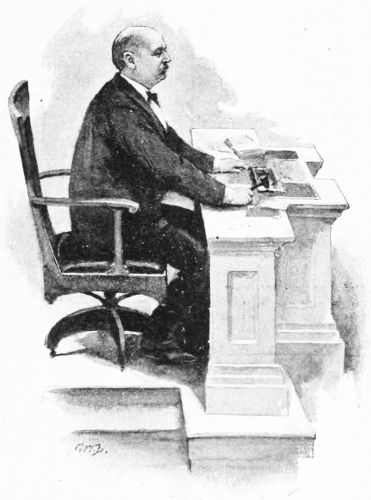

Mr. Henry was a great sportsman, and many a time had Tom listened to his father and one of his friends plan out a day's shooting. Tom had often made his little plans, only to be carried out in his dreams. But at last, one September evening, in his twelfth year, dreams could no longer satisfy him. As he sat in his father's "den" after supper, looking for the hundredth time through the book of colored sporting incidents and game-birds, taking occasional long glances at the little sixteen-bore which hung over his father's head, as he sat at his desk reading the Forest and Stream, Tom was really developing a plan. He must go shooting, and with a real gun of some kind. "Sling-shots" he was done with; then he knew if he asked permission, what the answer would be, and therefore he decided that his hunting-trip must be made "on the sly," and this alone was one cause for the rather restless night which followed. As he turned the pages of the big book he began to imagine himself in the place of the tall man in the picture just taking a partridge from his dog's mouth, and on the next page he was the short thick-set man in brown hunting-coat walking up to his dogs, who were "stiff" and "stanch" on a covey of quail, which in pictures you can always see hiding in the clump of bushes.

Now, Tom, Dick, and Harry had a friend, and that friend had a Flobert rifle, and on that friend's willingness to lend he was counting strongly. The game did not seem to worry him; he kept thinking of a certain patch of blackberry bushes just outside a small piece of woods, where he had often started up an old cock partridge, in fact, he knew so much about that partridge that once he crept up on him, and almost got a shot at him with the now-to-be-despised "sling-shot"; and with a Flobert—even if his father had said that no true sportsman would shoot a bird on the "sit"—he felt sure he could get him, and if he did he'd come home, own up, and trust to luck for the rest, but he was somewhat doubtful as to the reception he would meet.

The morning was bright and clear as Tom left the house to go down and "see what Jim Vail was going to do that day," and once outside the gate excitement again got hold of him, and he broke into a run; it was well he did, for about ten minutes later, as he turned into Mr. Vail's place, Jim was on the point of mounting his bicycle to start for a ride.

"Say, Jim," he shouted, "wait a second; I want to ask you something."

"Well, Tommy," he answered, "what can I do for you to-day? I'm going to get some exercise and get in shape for football at school; I got a letter from Ted yesterday, and he asked me to. I guess he's written to the rest of last year's team to do the same thing. I suppose you're going to ride your pony. But, really, what do you want?"

"Jim," said Tom, "I'm going to ask a favor of you. But first I want you to say you won't tell anybody anything about it. You won't, will you?"

"Of course not; but what it is?" replied Jim.

"Well," said Tom, slowly, "I'm going shooting, and I want you to lend me your Flobert rifle; you don't use it very much since your father gave you that beauty gun. I'll be careful, and I'll clean it all up for you when I'm done. Say, will you do it?"

Jim saw a chance for a little lecture, and came near giving it, but he thought of his popularity with the small boys and resisted.

"But, Tom," he answered, "how are you going to work it? I'll lend it to you, of course, but I don't want to get into any scrape with your father, and you'd better be careful, too. Now, what's your plan?"

Tom had this all arranged the moment he had seen Jim and the bicycle.

"I've got that all fixed," said Tom. "Say, you don't mind where you ride, do you? Now, I tell you what you do; just give me some cartridges, and then you start off with the rifle on your 'bike' and ride down the hill by 'Daddy Wilson's'—that's where I'm going to go shooting. When you get to the bridge, get off just a minute, and go down under the bridge and leave it on top the highest log under the boards on this side the brook, and then ride on and forget all about it. Catch?"

Jim "caught," and after another word of warning to be very careful, both in regard to the rifle and getting caught, he started, having left a box of Flobert cartridges with Tom.

HE CAUGHT A GLIMPSE OF A CERTAIN FAMILIAR WHITE HORSE.

HE CAUGHT A GLIMPSE OF A CERTAIN FAMILIAR WHITE HORSE.

"Daddy Wilson's" was quite a mile and a half from Jim's house; but it did not take Tom long to cover the distance, and in a very short time he was under the bridge and out again on the other side with the rifle under his arm. His experience had been very limited with firearms, but he had a natural gift of being "handy" with almost anything, and he acted as though hunting were an old pastime, and the gun a companion of years. However, he thought it best to try and see how it went, and was just taking aim at a little yellow chipmunk, when the sound of an approaching carriage made him change his mind, and dart under the bridge and wait; he had caught a glimpse of a certain familiar white horse, and as it trotted over the bridge, shaking a little stream of dust through the cracks and down his neck, he realized he had had a narrow escape. After it had gone by, he tried his aim on an old green frog, and laid him out "flatter'n a pan-cake," as he said to himself. Two or three more trials were made, and he started through the woods for his blackberry patch, first walking very carefully, and finally creeping on all fours; but whatever the reason, that wily cock partridge had had his breakfast and declined to be found, and Tom was disappointed and cast down; he had counted on that bird to ease the reception he would meet at home, and now he would have to return empty handed. However, he made up his mind "he'd shoot something," and for an hour or more be popped ineffectually at chipmunks and small birds, and was really enjoying the sport, when it struck him that late to dinner would require an explanation, and thus greatly increase the chances of the very thing which he now wanted to avoid. So he hurried towards home, and went in through the place by a back way, intending to leave the rifle at the stable. The coachman was a good friend of his, and would clean and return it, and everything would be all right again. Now it happened that Mr. Henry was having built a small shed and tool-house behind his house, and, as luck would have it, he was watching its progress at the very moment when Tom emerged from behind some bushes, and unconsciously was walking down this back road towards the stable with the Flobert held close along his leg on the side farthest away from the house, so that "no one could guess he had anything." All looked smooth sailing. Suddenly he was startled by a familiar voice,

"Hey, Tom!" it called; "what you got there?"

There was no escape.

"A rifle, sir," replied Tom, in a rather muffled voice.

"A what!" cried the voice.

"A rifle, sir," replied Tom, again.

"Bring it here," was the short reply, and over across the field went Tom to his doom.

"Go back there and get one of those carpenters to give you a good sized shingle," said Mr. Henry, "and give me the gun."

"Well," said Tom to himself, "I knew I was taking risks," and he returned in a moment with the shingle, and looking his father straight in the eye waited the next command.

"Now," said Mr. Henry, in his severest tones, "take that shingle and put it up against that big tree, and give me a cartridge."

Surprise and wonder are no names for the feelings that ran through Tom's mind; it made him tingle up and down his backbone—he couldn't say a single word; but there were more surprises to follow.

"What you been shooting, Tommy? Elephants, hey?"[Pg 600] said Mr. Henry, after firing all the cartridges Tom had left; "or was it only small game—a panther or lynx—you were after this morning?"

Tom's courage began to return, and as he found his father in such a splendid mood he was not going to allow himself to be bluffed.

"I went out after partridges, sir," he said, "and I thought I'd have one for supper to-night for mamma; but he wasn't there. I was sure I'd get one."

In a short time Mr. Henry had the whole story, and not a word of fault was found, and Tom thought he had the finest father in the world; he thought so before, but after this incident there was no doubt about it.

On the evening of the same day Tom was again devouring the "bird book," as he had always called it. Mr. Henry, who had been writing at his desk, pushed himself back, and looking at Tom, a smile crept over his face. His son was exactly as he had been at that age, and the reason of his lenient treatment of what many fathers would have given a severe punishment for was because he knew a good deal of the world, and especially how to treat a boy who had inherited a sportsman's love of woods and guns, and was not to blame for it. Tom was bending close over the book to see whether it was a woodcock or a quail the dog was pointing, when Mr. Henry startled him as he said with a laugh,

"My boy, did you really think you'd get a partridge? Why, Dr. Carver himself couldn't shoot a partridge with a rifle; why didn't you come and ask me for my gun?"

"'Cause I didn't think you'd lend it to me," said Tom, "and I was afraid you'd suspect something. I'll come to you to-morrow," he added, as a quiet joke on his father.

But the way his father took his little joke nearly made him "have a fit," as he told Jim Vail afterwards.

"All right, Tommy," said Mr. Henry, "come to me after breakfast and I'll fix you out."

Another restless night followed by another beautiful morning, and down across the field trudged Tom, Dick, and Harry, but it looked like a brown shooting-coat walking by itself with two setters following after it through curiosity. There went Tom with a real gun—the little sixteen-bore—a real hunting-coat, sleeves rolled up and pinned to hold them, and down below his knees, to be sure; real cartridges in his pocket, and to make it complete two real bird-dogs. He was going to be the man in the "bird book," and best of all there was no "on the sly" about it.

Down back of the place beyond the "muck pond," where Tom had often caught live bait for his father, and had slaughtered many a fine fat frog, to say nothing of the turtles and lizards which had been the starting of a small museum of which he was sole proprietor, down beyond this pond he struck into the woods and let "Jet" the Gordon and "Bang" the Irish setter run. He followed them closely. Soon they came to a point, and he walked towards them. But here's where there was a difference between the picture and his position at that moment; he looked in vain for the bird; in the picture he could see it, but, try his best, he could not see it in life. The dogs worried a little, he stepped on a twig which cracked; whir! and up got Mr. Partridge from the bushes—not exactly where Tom had expected—and whirled off, Tom crouching down to see where he lit, to try him again. Time and again the same thing happened, but Tom never could seem to see the bird till he got up, and he never thought to try him flying. The dogs got tired of this kind of shooting and came in "to heel," and finally, rather discouraged and decidedly tired, Tom sat down to decide whether he would go home or not. He was sitting under a large pine-tree and thinking what his father would say, when out of the branches above his head sailed, with a quiet, subdued whir, the very bird he had been chasing so long. It settled not more than thirty yards off on the roots of an upturned birch-tree and began a gentle cluck, spreading its fanlike tail and shaking its feathers, but only for a moment. Tom's chance had come. A hurried and excited aim, a loud bang, and the partridge was fluttering on the ground, and Tom was stooping over it; the gun was back where he had shot from; he had gotten to the bird before the dogs. What he wanted was a partridge in his coat pocket; he did not seem so anxious to have the dogs hand it to him, as his dreams had made him.

Tell the truth, Tom ran most of the way home. He met his father on the driveway, and a sudden composure took hold of him.

"Say, Pop," he said, "it ain't so easy as one thinks, is it?"

"I'll bet you didn't get anything, not even a chipper bird," said Mr. Henry; "now did you?"

Tom braced himself, his heart was beating fast, and the shivers were again making him jump and wriggle.

"I only got one decent shot," replied Tom, beginning very coolly, "but I got him, and mamma'll have that bird I didn't get yesterday to-night for supper. Look at that!" he shouted the last part of his sentence, and swinging the bird in front of his father's face, darted past to show and tell all in the house, leaving Mr. Henry in blank astonishment. What he was saying to himself was:

"I'll get that boy the prettiest gun in the city for Christmas, that's what I'll do; he'll be giving me points before long."[Pg 601]

The position in which Phil now found himself was certainly a perplexing one. By the very simple process of getting lost he had discovered Cree Jim's cabin, but was appalled to consider what else he had found at the same time. He now knew that the remainder of their journey, its most difficult and dangerous portion, must be undertaken without a guide. Not only this, but they must be burdened with a child so young as to be practically helpless. In the mean time, what was to be done with those silent and motionless forms whose dread presence so pervaded that lonely cabin? And how was he to communicate with his friends? There was no back trail to follow, for the snow had wiped it out. He did not even know in which direction camp lay, for in the ardor of his chase the evening before he had taken no note of course nor distance.

There was the stream, though, on whose bank the cabin was perched. It must flow into the river. Yes, that was his only hope. But the river might be miles away, and the camp as much farther, if, indeed, it could still be found where he had left it. But of course it would be! So long as Serge Belcofsky and Jalap Coombs had life and strength to search for him that camp would remain a permanent fixture until he returned to it. Phil was absolutely sure of that, and he now realized, as never before, the priceless value of a friendship whose loyalty is beyond doubt.

So the plan was formed. He would go down the stream and up the river until he found camp. Then he would bring Serge and a sledge back with him. In the mean time the child must be left where he was, for Phil doubted if he could carry him over the weary miles that he knew must lie between the cabin and camp, while for the little fellow to walk that distance was out of the question.

Phil sat on a stool before the fire while doing all this thinking. As he rose to carry out his plan, Nel-te, who was becoming terrified at his mother's silence in spite of his efforts to attract her attention, slipped from the bed, ran to his new friend, and thrusting a cold little hand into one of his, looked up with a smile of such perfect trust that Phil snatched him in his arms and kissed him, at the same time giving him a great hug.

Then he said: "Now, Nel-te, brother Phil is going away for a little while to get some doggies for you to play with, and you must stay here like a good boy, and not open the door until he comes back. Do you understand?"

"Yes; me go get doggies. Nel-te like doggies. Good doggies." And almost before Phil knew what the child was about he had slipped from his arms, run to the door, and was putting on the tiny snow-shoes that had been left outside. Then with an engaging smile, he called, cheerily: "Come. Nel-te say come. Get doggies."

"All right, little chap. I expect your plan is as good as mine, after all," replied Phil, into whose mind had just flashed the promise made to that dead mother, never to desert her baby. "And here I was, about to begin by doing that very thing," he reflected as he glanced at the marble face overspread by an expression of perfect content that his promise had brought.

Moved by a sudden impulse he picked up the boy, and, bringing him back, held him so that he might kiss the peaceful face. This the child did with a soft cooing that served to convey both love and pity. Then he ran to the stalwart figure that still lay on the floor, and, patting its swarthy cheek, said something in the Cree tongue that Phil did not understand.[Pg 602]

After that Phil carefully closed the door to prevent the intrusion of wild beasts, and the two, whose fortunes had become so strangely interwoven, set forth together down the white surface of the forest-bordered stream, on whose bank Nel-te had been born and passed his few years of life. He was happily but unconsciously venturing on his first "little journey into the world," while his companion was filled with a sense of manliness and responsibility from the experiences through which he had just passed that the mere adding of years could never have brought.

Phil wondered at the ease with which the little fellow managed his snow-shoes, until he reflected that the child had probably been taught to use them from the day of taking his first step. So the two fur-clad figures, ridiculously contrasted in size, trudged along side by side down the winding stream, the one thoughtfully silent and the other chattering of "doggies," until he began to lag behind and give signs that the pace was telling on his slender strength.

"Poor little chap," said Phil. "But I had been expecting it, and now we will try another scheme." So, slinging the tiny snow-shoes across the child's back, he picked him up and set him astride his own broad shoulders; when Nel-te clutched his head, and shouted with glee at this delightful mode of travel.

After they had gone a mile or so in this fashion they rounded a sharp bend, and came so suddenly upon poor Serge, who was making his way up the stream in search of some trace of his friend, that for a moment he stood motionless and speechless with amazement. He could make nothing of the approaching apparition until Phil shouted, cheerily:

"Hurrah, old man! Here we are, safe and sound, and awfully glad to see you."

"Oh, Phil!" cried Serge, while tears actually stood in his honest blue eyes, "I can hardly believe it! It seems almost too good to be true. Are you sure you are not wounded nor frozen nor hurt in any way? Haven't you suffered terribly? If you haven't, we have. I don't believe Mr. Coombs slept a wink last night, and I know I didn't. But I am happy enough at this minute to make up for it all, a hundred times over. Oh, Phil!"

"I have suffered a little from anxiety, and been a trifle hungry, and had some sad experiences, but I haven't suffered half so much as I deserved for my carelessness in getting lost. I found Cree Jim, though; but—"

"And brought him with you?" interrupted Serge, smiling for the first time in many hours, as he glanced at the quaint little figure perched on Phil's shoulders.

"Not exactly," replied the other, soberly. "You see this little chap is his son, and I've adopted him for a sort of a brother, and he is going with us."

"You've done what?" cried Serge.

"Adopted him. That is, you see I promised my aunt Ruth to bring her something from Alaska that was unique in the way of a curio, and it seems to me that Nel-te here will please her about as well as anything. Don't you think so?"

"Perhaps so," assented Serge, doubtfully. "But was his father willing that you should have him?"

"Oh yes, perfectly. That is, you know he is dead, and so is the mother; but I promised her to take care of the little chap, and as there wasn't anything else to be done, why, here we are."

"Of course it's all right if you say so," agreed Serge, "and I don't care, so long as you are safe, if you carry a whole tribe back to your aunt Ruth; but now don't you think we'd better be getting along to camp? It was all I could do to persuade Mr. Coombs to stay behind and look out for things; he is so anxious. The only way I could induce him to was by suggesting that you might come in tired and hungry, and would feel awfully if no one was there to welcome you. But he is liable to set out on a hunt for you at any moment."

"Certainly, we must get there as quickly as possible," replied Phil. "How far is it?"

"Not more than one mile up the river from the mouth of this creek, which is only a few rods below here. But oh, Phil, to think that I have found you! When I had almost given up all hope of ever again seeing you alive too. I have been down as far as our first camp on the river this morning, and this creek was my last hope. I wouldn't have left the country without you, though, or at any rate without knowing what had become of you. Neither would Mr. Coombs. We settled that last night while we talked over what had best be done."

"I was sure you wouldn't, old fellow," replied Phil, with something like a choke in his voice.

At the camp they were hailed by Jalap Coombs, who almost hugged Phil in his revulsion of feeling and unaffected joy at the lad's return.

"But you don't do it again, Philip, my son!" he cried. "That is, the next time you feels inclined to wander from home and stay out nights, ye may go, of course, but you'll have to take me along. So ef you gits lost, I gets lost likewise; for, as my old friend Kite Roberson useter say consarning prodergal sons, 'It's allers toughest on them as is left behind.' But Phil, what be ye doing with that furry little beggar? Is he the pilot ye went sarching for?"

"Yes," laughed Phil, lifting Nel-te down from his shoulders. "He is the pilot who is to lead us from this wilderness, and if you have got anything to eat, you'd better give it to him before he devours one of the dogs, which he seems inclined to do. I can answer for it, that he has been on short rations for several days, and is properly hungry."

"Have I got anything to eat?" cried the other. "Waal, rather! How does fresh steaks, and roasts, and chops, and stews strike your fancy?" With this he pointed to one side of the camp, where, to their astonishment, the boys saw a quantity of fresh meat, much of which was already cut into thin strips for freezing and packing.

"Where did it come from?" queried Phil, looking at Serge; but the latter only shook his head.

"It's jest a bit of salvage that I raked in as it went drifting by," explained Jalap Coombs, his face beaming with gratified pride. "It's some kind of deer-meat, and for a deer he was pretty nigh as big as one of those elephants back yonder in the moss cave. You see, he came cruising along this way shortly after Serge left, and the dogs give chase and made him heave to. When I j'ined 'em he surrendered. Then I had my hands full in a hurry, driving off the dogs and lashing 'em fast so as they couldn't eat him, horns and all, and cutting of him up. I hain't more'n made a beginning with him, either, for there's pretty nigh a full cargo left.

"But how did you kill him? There wasn't any gun in camp?" asked Phil, utterly bewildered.

"Of course there warn't no gun," answered Jalap Coombs, "and likewise I didn't need one. Sich things I leave for boys. How did I kill him, say you? Why, I jest naturally harpooned him like I would any other whale."

"Harpooned a moose!" cried Phil and Serge together; for they had by this time discovered the nature of the sailor's "big deer." "And where did you get the harpoon?" asked the former.

"Found it, leaning agin a tree while I were out after firewood," replied Jalap Coombs, at the same time producing and proudly exhibiting a heavy A-yan spear, such as were formerly used by the natives of the Pelly River valley. "It were a trifle rusty, and a trifle light in the butt," he added, "but it come in mighty handy when it were most needed, and for an old whaler it are not a bad sort of a weepon. I'm free to say, though, that I might have had hard luck in tackling the beast with it ef he hadn't been already wounded. I didn't know it till after he were dead, but when I come to cut him up, I saw where he'd been bleeding pretty free, and then I found this bullet in his innards. Still, I don't reckin you'd have called him a mouse, nor yet a rat, if ye'd seed him like I did under full sail, with horns set wing and wing, showing the speed of a fifty-ton schooner. If I hadn't had the harpoon I'd left him severely alone; but I allowed that a weepon as were good[Pg 603] enough for a whale would do for a deer, even ef he were bigger than the sun."

"It's a rifle-bullet, calibre forty-four," said Phil, who was examining the bit of lead that Jalap Coombs had taken from his "big deer." "I wonder if it can be possible that he is the same moose I wounded, and without whose lead I should never have found Cree Jim's cabin. It seems incredible that he should have come right back to camp to be killed, though I suppose it is possible. Certainly good fortune, or good luck, does seem to be pretty steadily on our side, and without the aid of the fur-seal's tooth either," he added, with a sly glance at Serge.

As soon as breakfast was finished, Phil and Serge slipped away, taking a sledge, to which was lashed a couple of axes, with them. They were going back to bury the parents of the child, who was so happily oblivious of their errand that he did not even take note of their departure.

The lads had no idea of how they should accomplish their sorrowful task. Even with proper tools they knew it would be impossible to dig a grave in the frozen ground, and as they had only axes with which to work, this plan was dismissed without discussion.

They had not settled on any plan when they rounded the last bend of the little stream and gained a point from which the cabin should have been visible. Then they saw at a glance that the task they had been dreading had been accomplished without their aid. There was no cabin, but a cloud of smoke rising from its site, as from an altar, gave ample evidence of its fate. A blazing log from the fire Phil left in its hearth must have rolled out on to the floor directly after his departure. Now only a heap of ashes and glowing embers remained to mark Nel-te's home.

"It is best so," said Phil, as the two lads stood beside the smouldering ruins of what had been a home and was now become a sepulchre. "And oh, Serge! think what might have been the child's fate if I had left him behind, as I at first intended. Poor little chap! I realize now, as never before, how completely his past is wiped out and how entirely his future lies in our hands. It is a trust that came without our seeking, but I accepted it; and now beside his mother's ashes I swear to be true to the promise I gave her."

"Amen!" said Serge, softly.

They planted a rude wooden cross, the face of which was chipped to a gleaming whiteness, close in front of the smouldering heap, and near it Serge fastened a streamer of white cloth to the tip of a tall young spruce. Cutting off the limbs as he descended, he left it a slender pole, and thus provided the native symbol of a place of burial.

"A FLYING-FISH-CATCHER FROM OLD HONG-KONG—YO HO! ROLL A

MAN DOWN!"

"A FLYING-FISH-CATCHER FROM OLD HONG-KONG—YO HO! ROLL A

MAN DOWN!"

As they approached the camp they were astonished to hear Jalap Coombs singing in bellowing tones the rollicking old sea chant of "Roll a Man Down!"

"A flying-fish-catcher from old Hong-Kong—

Yo ho! roll a man down—

A flying-fish-catcher comes bowling along;

Give us some time to roll a man down,

Roll a man up and roll a man down,

Give us some time to roll a man down.

From labbord to stabbord away we go—

Yo ho! roll a man down."

Jalap's voice was not musical, but it possessed a mighty volume, and as the quaint sea chorus roared and echoed through the stately forest, the very trees appeared to be listening in silent wonder to the unaccustomed sounds. Even Musky, Luvtuk, big Amook, and the other dogs seemed by their dismal howlings to be expressing either appreciation or disapprobation of the sailor-man's efforts.

The performers in this open-air concert were too deeply intent on their own affairs to pay any heed to the approach of the returning sledge party, who were thus enabled to come within full view of a most extraordinary scene unnoticed. Just beyond the camp, in a semicircle, facing the fire, a dozen dogs, resting on their haunches, lifted both their voices and sharp-pointed noses to the sky. On the opposite side of the fire sat Jalap Coombs holding Nel-te in his arms, rocking him to and fro in time to the chorus that he was pouring forth with the full power of his lungs, and utterly oblivious to everything save his own unusual occupation of putting a baby to sleep.

"Ha, ha, ha! Ho, ho, ho!" roared Phil and Serge, unable to restrain their mirth a moment longer. "Oh my! Oh my! Oh, Mr. Coombs, you'll be the death of me yet! What ever are you doing? Didn't know you could sing! What a capital nurse you make! What a soft voice for lullabies! The dogs, too! Oh dear! I shall laugh at the thought of this if I live to be a hundred! Don't mind us, though. Keep right on. Please do!"

But the concert was ended. Jalap Coombs sprang to his feet with a startled yell, and dropped the child, who screamed with the fright of his sudden awakening. The dogs, whose harmonious howlings were so abruptly interrupted, slunk away with tails between their legs, and hid themselves in deepest shadows.

"There, there, little chap. Don't be frightened," cried Phil, darting forward and picking up the child, though still shaking with laughter. "It's all right now. Brother Phil will protect you, and not let the big man frighten you any more."

"I frighten him indeed!" retorted Jalap Coombs, indignantly. "He was sleeping quiet and peaceful as a seal pup; and I were just humming a bit of a ditty that useter be sung to me when I were a kid, so's he'd have something pleasant to dream about. Then you young swabs had to come creeping up and yell like a couple of wild hoodoos, and set the dogs to howling and scare the kid, to say nothing of me, which ef I had ye aboard ship I'd masthead ye both till ye larnt manners. Oh, ye may snicker! But I have my opinion all the same of any man as'll wake a sleeping child, specially when he's wore out with crying, all on account of being desarted. And I'm not the only one nuther. There was old Kite Roberson who useter clap a muzzle onto his wife's canary whenever she'd get the kids to sleep, for fear the critter'd bust inter singing. But it's all right. You will know how it is yourselves some day."

Phil, seeing that, for the first time since he had known him, the mate was thoroughly indignant, set out to smooth his ruffled feelings.

"Why, Mr. Coombs," he said, "we didn't mean to startle you, but those wretched dogs kept up such a howling that we couldn't make ourselves heard as we neared camp. I'm sure I don't see how you could think we were laughing at you. It was those absurd dogs, and you'd have laughed yourself if you'd looked up and seen them. I'm sure it was awfully good of you to take so much trouble over this little fellow, and put him so nicely to sleep with your sing— I mean with your humming, though I assure you we didn't hear a hum."

"Waal," replied Jalap Coombs, greatly mollified by Phil's attitude. "I warn't humming very loud, not nigh so loud as I had been at fust. Ye see, I were kinder tapering off so as to lay the kid down, and begin to get supper 'gainst you kim back."

"Yes, I see," said Phil, almost choking with suppressed laughter. "But how did it happen that you were compelled to act as nurse? The little chap seemed happy enough when we went away."

"So he were, till he found you was gone. Then he begun to pipe his eye and set storm signals, and directly it come on to blow a hurricane with heavy squalls. So I had to stand by. Fust off I thought the masts would surely go; but I took a reef here and there, and kinder got things snugged down, till after a whilt the sky broke, the sun kim out, and fair weather sot in once more."

"Well," said Phil, admiringly, "you certainly acted with the judgment of an A No. 1 seaman, and I don't believe even your esteemed friend Captain Robinson could have done better. We shall call on you whenever our little pilot gets into troubled waters again, and feel that we are placing him in the best possible hands."

At which praise Jalap Coombs was greatly pleased, and said as how he'd be proud at all times to stand by the kid. Thus on the same day that little Nel-te McLeod lost his parents he found a brother and two stanch friends.

"Here, boys, is a piece of legislation which will add a new series of stamps to your collections," said Mr. Copeland, as he glanced up from his morning paper. "The bill transferring the printing of stamps to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing has just become a law, and hereafter Uncle Sam will manufacture his own stamps, as well as his own paper money."

"Why, father, if they make them here, we can see just how it's done!" exclaimed Donald, the eldest of the Copeland boys, who, with his brothers Jack and Ezra, was now experiencing the severest stage of the "stamp fever."

"Huh!" grunted the latter—nicknamed "The Parson," from his old-fashioned ways and a solemn assumption of wisdom. "Perhaps they'll not let you know anything at all about it. Bobby Simonds told me that the big company in New York that has always made 'em is awful particular about letting people see their machinery and things; and Bobby ought to know 'cause his uncle's an engraver there."

"Are they going to make all the stamps here in Washington?" broke in May, the baby of the family. "That'll be nice for you boys,'cause you can get 'em cheaper at the factory, can't you?"

"That's just like a girl," laughed Jack. "Anybody would think they were going to sell stamps by the yard."

"Well, my boy," said Mr. Copeland, "your sister is right, in a sense, as under this act the Post-office Department will buy its stamps wholesale from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, at a nominal price per thousand, without reference to their face value. I think you also are mistaken, Parson, as the public will doubtless be as free to inspect the manufacture of stamps as they now are to see the process of bank-note-making. When the stamp-printing plant is established, there should be a great deal in it to interest you youngsters. What do you say to a tour of investigation some Saturday?"

Their father's suggestion delighted the children, who waited eagerly for the fulfilment of the promise.

This came on a bright October morning, when the little party climbed the hill beyond the towering Washington Monument, and reached the grim brick building which is known as the Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

Here they were shown into a small reception-room, and kept waiting, with a throng of other sight-seers, until a card from the chief procured for them a special guide through the building. As she led them through a long corridor, this lady explained something of the complete and ingenious system which is in force here to prevent fraud or loss to the government. No visitor is permitted inside the building without one of the guides especially detailed for this service, while the work of each of the hundreds of employé's is so carefully checked and recorded that even the most insignificant error is readily traceable. Ink, paper, the engravers' dies, the printers' plates, are all given out on properly signed receipts, and until all are accounted for, even to the tiniest scrap of paper, the employés who have handled them are not permitted to leave the building; so that only by a widespread plot could all these safeguards be successfully eluded.

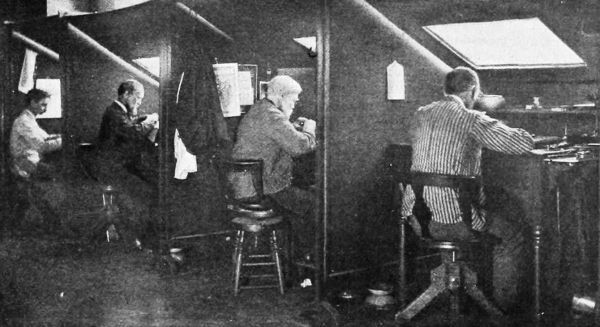

THE ENGRAVING-ROOM.

THE ENGRAVING-ROOM.

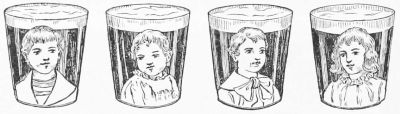

The little party was now shown into a very long room, at one end of which was ranged a row of compartments like sentry-boxes. In each of these sat a silent engraver, bent over the small square of steel upon which he was cutting some part of the design for paper money or stamps. The plates from which the stamps were formerly printed are the property of the government, so that the old designs, with a slight modification, are still in use. This modification consists of a trefoil mark placed in the upper corner of the new stamps, which will serve to distinguish them from the old issues printed by the American Bank-note Company. The work of the engravers is necessarily so painstaking and slow that the original dies are considered too expensive to use in the printing-presses. Thus, after the engraver has completed a die, it is subjected to a hardening process, and the design multiplied indefinitely upon soft steel plates by what is known as the transfer-press. The children were shown a long row of these presses, as well as the great vaults where all the designs, dies, and plates are locked up after the day's work. From the silence of the engravers' department they were led into the din and clatter of the press-room below. Here they found the new steam-presses as well as old-fashioned hand-presses in operation, and were able to see every detail of the actual printing of stamps.

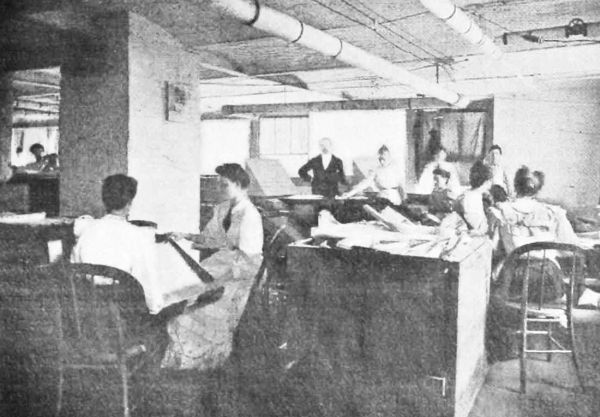

TAKING SHEETS OFF THE PRESSES.

TAKING SHEETS OFF THE PRESSES.

The hand-presses are worked by a plate-printer and one assistant, the printer first inking and polishing the engraved plate over a series of small gas-jets, after[Pg 605] which it is placed on the press. His assistant now lays a dampened sheet of paper upon the plate, the printer gives the press a turn, and a sheet of bright new stamps is drawn out at the other side. This work is done quickly and accurately, but it is a very slow process compared with that of the steam-presses, which turn out sheets of four hundred stamps each at the rate of one hundred thousand stamps an hour. The steam-presses carry four plates on an endless chain around the sides of a large square, in the circuit of which the plates are automatically heated to the proper temperature, inked, wiped off, and printed. The blank paper is laid on the plates by one assistant, while a second helper takes out the printed sheet. The printer in charge of the press has the most difficult part of the work, which consists in polishing the plate with his bare palms after it has been mechanically inked. This must be done so delicately as to leave neither too much nor too little ink upon the plate, but only just enough to give a clean, fine impression.

The presses clattered and clanked, and the children watched with breathless interest while a great stack of the dampened paper disappeared rapidly, sheet by sheet, through the press, reappearing again to be stacked in a second neat pile in the form of thousands upon thousands of new red two-cent stamps.

Besides the ordinary issues, the young investigators were much interested in seeing the printing of revenue stamps, of the long-strip stamps for cigar-boxes, and other tobacco stamps, and particularly the new two-cent stamps for playing-cards.

Having watched to their entire satisfaction the various movements of the great presses, the children began to feel that the object of their visit had been realized, and that there was nothing more to see. They were therefore somewhat surprised to learn that the printing of the stamps is merely the beginning of the work upon them, and that a number of very important things must happen to these small squares of red, blue, brown, and purple before they are ready to be sold through the little window in the post-office. After they are printed the sheets must be dried and pressed out, gummed, dried and pressed again, the sheets perforated and cut apart, trimmed, and, in addition, carefully counted before and after each of these operations.

In the early days of postage-stamps, and for several years after they first came into use, two serious difficulties presented themselves—i.e., the gumming and separating of the stamps. For a time a thick muddy mucilage was used, which curled up the sheets in a very inconvenient way. Then, again, before the ingenious device of perforation was hit upon, it was necessary to cut the stamps apart with a pair of scissors. Imagine a post-master in these busy days supplying his customers by the scissors method!

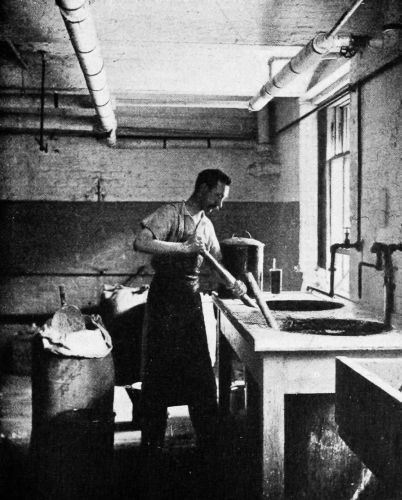

IN THE DRYING-ROOM.

IN THE DRYING-ROOM.

Fortunately a clever Frenchman conceived the plan of punching a series of small holes between the stamps, and his invention was promptly introduced into this country. The children were now eager to see the finishing processes of stamp-making, and so followed their guide into a large room, where they were greeted by a rush of warm air. Here their guide showed them the method of gumming the stamps and the curious apparatus used for the purpose. Along the entire length of the room, with a narrow passage between, are ranged a series of[Pg 606] wooden boxes, quite sixty feet in length. These are heated by steam, and through each box passes a sort of double endless chain. The sheets are fed, face down, into this queer machine, and passed under a roller, which allows the escape of just enough gum to coat the sheet thinly and evenly. The sheet is now caught on the endless chain by two automatic clamps, and carried into the long hot-box. It takes only a few moments for the journey through, but the sheets appear at the other end perfectly dried, and ready to be trimmed and perforated.

As the method of gumming stamps used by the various bank-note companies has been a carefully guarded and secret process, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing has been forced to invent its own machine for this purpose. The sheets are gummed at the rate of about eighteen a minute, which is certainly a vast improvement over the old method of putting on the gum by hand with a brush.

MIXING THE GLUE.

MIXING THE GLUE.

When the children were weary of watching the funny little brass fingers move along and hurry the sheets off into the hot-box, they turned to a corner where a workman was busy over a series of vats and buckets mixing the gum, which looked very clean and nice, and is made of dextrine, a vegetable product. The guide now showed them how the gummed sheets are pressed smooth for perforation, and then led them into a room where a score or more of odd little machines were in swift operation. Each machine is tended by two workwomen, most of whom wear fantastic caps of paper to shade their eyes, as the sheets must be fed into the machines with absolute accuracy in order that the perforations shall come in the right place. Each sheet has register lines printed in the margin, which must be adjusted exactly under a black thread fastened across the feeding-table. A quick whir of the wheels puts a neat line of pin-holes lengthwise between the stamps, cutting the sheet in half at the same time. The next machine perforates the sheet crosswise, and again cuts it in two, so that the sheets are now divided up into the regulation size of one hundred stamps each.

The children thought the minute disks of paper punched out by the perforators too insignificant to be considered, and were accordingly much surprised to learn that the sheets again have to be smoothed out, under great pressure, to reduce their bulk and remove the "burr" caused by the perforation.

After inspecting the final process of making up the stamps into packages, to be mailed to the postmasters all over the country, the children were taken by their father to the office of the chief of the bureau. Here they received a cordial welcome, and learned many interesting and curious details about stamps and stamp-making. About 3,000,000,000 stamps are annually furnished the Post-office Department by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, at the rate of five cents a thousand. Ninety per cent. of these are the two-cent stamps, and according to the last Post-office report the revenue from the sale of stamps is a little over $6,000,000 a month.

"By-the-way," observed the chief, "you young people should be very much interested in the Report of the Third Assistant Postmaster-General for 1893, which contains a carefully prepared and elaborately descriptive list of every stamp and postal card issued by the United States government. It must seem hard to you stamp collectors that the most beautiful stamps issued—the newspaper and periodical stamps—are not permitted to be sold to the public. One of the chief reasons for this is that the values of these small squares of paper run up to such high figures, viz., $24, $36, $48, and $60, that they would offer a great field in counterfeiters if generally circulated. There are some queer denominations among these stamps, notably the $1.92 stamp, which is about to be discontinued, and some very pretty colors. That reminds me—did they show you our ink-mills in your tour of inspection?"

Mr. Copeland explained that they had not seen the mills, so the children had the pleasure of being escorted by the chief himself into the grimy region which is seldom penetrated by the public. Here they saw the colors ground and mixed in small mills, from which the workmen—smeared from top to toe in a rainbow of colors—gathered the thick greasy ink by the bucketful. About one hundred thousand pounds of dry color is used annually for the two-cent stamps alone, the color being mixed with an equal quantity of burnt linseed oil, making two hundred thousand pounds of ink. Of course a large percentage of this color is lost in inking and polishing the plate.

The tour was now ended, and leaving the oily little wheels to their ceaseless grinding, the children, with a grateful good-by to their new friend, went home with their young heads full of the interesting things they had seen in Uncle Sam's stamp factory.

This Department is conducted in the interest of Girls and Young Women, and the Editor will be pleased to answer any question on the subject so far as possible. Correspondents should address Editor.

Girls who are terrified by thunder and lightning lose a great deal of enjoyment during the summer, when we have storms as well as sunshine. It may not be quite possible for every one to help being afraid when the sky is black with clouds and the lightning's flash, but it is within the power of most people to control the expression of fright. Once or twice having resolutely refrained from showing your terror, you will be surprised and pleased to find the terror itself lessening.

I know persons who go through life in a sort of bondage to fear of various kinds. They tremble and turn pale, or grow hysterical and cry, when the dark clouds gather and the thunders roll. There is a pretty German hymn which begins,

"It thunders, but I tremble not,

My trust is firm in God,

His arm of strength I've ever sought

Through all the way I've trod."