The Riverside Biographical Series

NUMBER 5

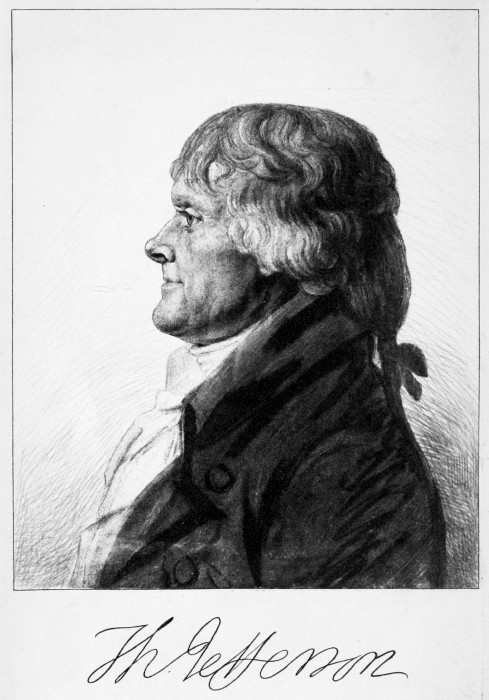

THOMAS JEFFERSON

BY

HENRY CHILDS MERWIN

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

Boston: 4 Park Street; New York: 11 East Seventeenth Street

Chicago: 378-388 Wabash Avenue

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

COPYRIGHT, 1901, BY HENRY C. MERWIN

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

CONTENTS

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | Youth and Training | 1 |

| II. | Virginia in Jefferson’s Day | 16 |

| III. | Monticello and its Household | 28 |

| IV. | Jefferson in the Revolution | 36 |

| V. | Reform Work in Virginia | 45 |

| VI. | Governor of Virginia | 59 |

| VII. | Envoy at Paris | 71 |

| VIII. | Secretary of State | 82 |

| IX. | The Two Parties | 98 |

| X. | President Jefferson | 114 |

| XI. | Second Presidential Term | 130 |

| XII. | A Public Man in Private Life | 149 |

THOMAS JEFFERSON

I

YOUTH AND TRAINING

Thomas Jefferson was born upon a frontier estate in Albemarle County, Virginia, April 13, 1743. His father, Peter Jefferson, was of Welsh descent, not of aristocratic birth, but of that yeoman class which constitutes the backbone of all societies. The elder Jefferson had uncommon powers both of mind and body. His strength was such that he could simultaneously “head up”—that is, raise from their sides to an upright position—two hogsheads of tobacco, weighing nearly one thousand pounds apiece. Like Washington, he was a surveyor; and there is a tradition that once, while running his lines through a vast wilderness, his assistants gave out from famine and fatigue, [pg 2]and Peter Jefferson pushed on alone, sleeping at night in hollow trees, amidst howling beasts of prey, and subsisting on the flesh of a pack mule which he had been obliged to kill.

Thomas Jefferson inherited from his father a love of mathematics and of literature. Peter Jefferson had not received a classical education, but he was a diligent reader of a few good books, chiefly Shakespeare, The Spectator, Pope, and Swift; and in mastering these he was forming his mind on great literature after the manner of many another Virginian,—for the houses of that colony held English books as they held English furniture. The edition of Shakespeare (and it is a handsome one) which Peter Jefferson used is still preserved among the heirlooms of his descendants.

It was probably in his capacity of surveyor that Mr. Jefferson made the acquaintance of the Randolph family, and he soon became the bosom friend of William Randolph, the young proprietor of Tuckahoe. The Randolphs had been for ages a family of con[pg 3]sideration in the midland counties of England, claiming descent from the Scotch Earls of Murray, and connected by blood or marriage with many of the English nobility. In 1735 Peter Jefferson established himself as a planter by patenting a thousand acres of land in Goochland County, his estate lying near and partly including the outlying hills, which form a sort of picket line for the Blue Mountain range. At the same time his friend William Randolph patented an adjoining estate of twenty-four hundred acres; and inasmuch as there was no good site for a house on Jefferson’s estate, Mr. Randolph conveyed to him four hundred acres for that purpose, the consideration expressed in the deed, which is still extant, being “Henry Weatherbourne’s biggest bowl of Arrack punch.”

Here Peter Jefferson built his house, and here, three years later, he brought his bride,—a handsome girl of nineteen, and a kinswoman of William Randolph, being Jane, oldest child of Isham Randolph, then Adjutant-General of Virginia. She was born in [pg 4]London, in the parish of Shadwell, and Shadwell was the name given by Peter Jefferson to his estate. This marriage was a fortunate union of the best aristocratic and yeoman strains in Virginia.

In the year 1744 the new County of Albemarle was carved out of Goochland County, and Peter Jefferson was appointed one of the three justices who constituted the county court and were the real rulers of the shire. He was made also Surveyor, and later Colonel of the county. This last office was regarded as the chief provincial honor in Virginia, and it was especially important when he held it, for it was the time of the French war, and Albemarle was in the debatable land.

In the midst of that war, in August, 1757, Peter Jefferson died suddenly, of a disease which is not recorded, but which was probably produced by fatigue and exposure. He was a strong, just, kindly man, sought for as a protector of the widow and the orphan, and respected and loved by Indians as well as white men. Upon his deathbed he left two injunctions regarding his son [pg 5]Thomas: one, that he should receive a classical education; the other, that he should never be permitted to neglect the physical exercises necessary for health and strength. Of these dying commands his son often spoke with gratitude; and he used to say that if he were obliged to choose between the education and the estate which his father gave him, he would choose the education. Peter Jefferson left eight children, but only one son besides Thomas, and that one died in infancy. Less is known of Jefferson’s mother; but he derived from her a love of music, an extraordinary keenness of susceptibility, and a corresponding refinement of taste.

His father’s death left Jefferson his own master. In one of his later letters he says: “At fourteen years of age the whole care and direction of myself were thrown on myself entirely, without a relative or a friend qualified to advise or guide me.”

The first use that he made of his liberty was to change his school, and to become a pupil of the Rev. James Maury,—an ex[pg 6]cellent clergyman and scholar, of Huguenot descent, who had recently settled in Albemarle County. With him young Jefferson continued for two years, studying Greek and Latin, and becoming noted, as a schoolmate afterward reported, for scholarship, industry, and shyness. He was a good runner, a keen fox-hunter, and a bold and graceful rider.

At the age of sixteen, in the spring of 1760, he set out on horseback for Williamsburg, the capital of Virginia, where he proposed to enter the college of William and Mary. Up to this time he had never seen a town, or even a village, except the hamlet of Charlottesville, which is about four miles from Shadwell. Williamsburg—described in contemporary language as “the centre of taste, fashion, and refinement”—was an unpaved village, of about one thousand inhabitants, surrounded by an expanse of dark green tobacco fields as far as the eye could reach. It was, however, well situated upon a plateau midway between the York and James rivers, and was swept by breezes [pg 7]which tempered the heat of the summer sun and kept the town free from mosquitoes.

Williamsburg was also well laid out, and it has the honor of having served as a model for the city of Washington. It consisted chiefly of a single street, one hundred feet broad and three quarters of a mile long, with the capitol at one end, the college at the other, and a ten-acre square with public buildings in the middle. Here in his palace lived the colonial governor. The town also contained “ten or twelve gentlemen’s families, besides merchants and tradesmen.” These were the permanent inhabitants; and during the “season”—the midwinter months—the planters’ families came to town in their coaches, the gentlemen on horseback, and the little capital was then a scene of gayety and dissipation.

Such was Williamsburg in 1760 when Thomas Jefferson, the frontier planter’s son, rode slowly into town at the close of an early spring day, surveying with the outward indifference, but keen inward curiosity of a countryman, the place which was to be his [pg 8]residence for seven years,—in one sense the most important, because the most formative, period of his life. He was a tall stripling, rather slightly built,—after the model of the Randolphs,—but extremely well-knit, muscular, and agile. His face was freckled, and his features were somewhat pointed. His hair is variously described as red, reddish, and sandy, and the color of his eyes as blue, gray, and also hazel. The expression of his face was frank, cheerful, and engaging. He was not handsome in youth, but “a very good-looking man in middle age, and quite a handsome old man.” At maturity he stood six feet two and a half inches. “Mr. Jefferson,” said Mr. Bacon, at one time the superintendent of his estate, “was well proportioned and straight as a gun-barrel. He was like a fine horse, he had no surplus flesh. He had an iron constitution, and was very strong.”

Jefferson was always the most cheerful and optimistic of men. He once said, after remarking that something must depend “on the chapter of events:” “I am in the habit [pg 9]of turning over the next leaf with hope, and, though it often fails me, there is still another and another behind.” No doubt this sanguine trait was due in part at least to his almost perfect health. He was, to use his own language, “blessed with organs of digestion which accepted and concocted, without ever murmuring, whatever the palate chose to consign to them.” His habits through life were good. He never smoked, he drank wine in moderation, he went to bed early, he was regular in taking exercise, either by walking or, more commonly, by riding on horseback.

The college of William and Mary in Jefferson’s day is described by Mr. Parton as “a medley of college, Indian mission, and grammar school, ill-governed, and distracted by dissensions among its ruling powers.” But Jefferson had a thirst for knowledge and a capacity for acquiring it, which made him almost independent of institutions of learning. Moreover, there was one professor who had a large share in the formation of his mind. “It was my great good for[pg 10]tune,” he wrote in his brief autobiography, “and what probably fixed the destinies of my life, that Dr. William Small, of Scotland, was then professor of mathematics; a man profound in most of the useful branches of science, with a happy talent of communication and an enlarged liberal mind. He, most happily for me, soon became attached to me, and made me his daily companion when not engaged in the school; and from his conversation I got my first views of the expansion of science, and of the system of things in which we are placed.”

Jefferson, like all well-bred Virginians, was brought up as an Episcopalian; but as a young man, perhaps owing in part to the influence of Dr. Small, he ceased to believe in Christianity as a religion, though he always at home attended the Episcopal church, and though his daughters were brought up in that faith. If any theological term is to be applied to him, he should be called a Deist. Upon the subject of his religious faith, Jefferson was always extremely reticent. To one or two friends only did he disclose [pg 11]his creed, and that was in letters which were published after his death. When asked, even by one of his own family, for his opinion upon any religious matter, he invariably refused to express it, saying that every person was bound to look into the subject for himself, and to decide upon it conscientiously, unbiased by the opinions of others.

Dr. Small introduced Jefferson to other valuable acquaintances; and, boy though he was, he soon became the fourth in a group of friends which embraced the three most notable men in the little metropolis. These were, beside Dr. Small, Francis Fauquier, the acting governor of the province, appointed by the crown, and George Wythe. Fauquier was a courtly, honorable, highly cultivated man of the world, a disciple of Voltaire, and a confirmed gambler, who had in this respect an unfortunate influence upon the Virginia gentry,—not, however, upon Jefferson, who, though a lover of horses, and a frequenter of races, never in his life gambled or even played cards. Wythe was then just beginning a long and honorable [pg 12]career as lawyer, statesman, professor, and judge. He remained always a firm and intimate friend of Jefferson, who spoke of him, after his death, as “my second father.” It is an interesting fact that Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, and Henry Clay were all, in succession, law students in the office of George Wythe.

Many of the government officials and planters who flocked to Williamsburg in the winter were related to Jefferson on his mother’s side, and they opened their houses to him with Virginia hospitality. We read also of dances in the “Apollo,” the ball-room of the old Raleigh tavern, and of musical parties at Gov. Fauquier’s house, in which Jefferson, who was a skillful and enthusiastic fiddler, always took part. “I suppose,” he remarked in his old age, “that during at least a dozen years of my life, I played no less than three hours a day.”

At this period he was somewhat of a dandy, very particular about his clothes and equipage, and devoted, as indeed he remained through life, to fine horses. Virginia im[pg 13]ported more thoroughbred horses than any other colony, and to this day there is probably a greater admixture of thoroughbred blood there than in any other State. Diomed, winner of the first English Derby, was brought over to Virginia in 1799, and founded a family which, even now, is highly esteemed as a source of speed and endurance. Jefferson had some of his colts; and both for the saddle and for his carriage he always used high-bred horses.

Referring to the Williamsburg period of his life, he wrote once to a grandson: “When I recollect the various sorts of bad company with which I associated from time to time, I am astonished I did not turn off with some of them, and become as worthless to society as they were.... But I had the good fortune to become acquainted very early with some characters of very high standing, and to feel the incessant wish that I could ever become what they were. Under temptations and difficulties, I would ask myself what would Dr. Small, Mr. Wythe, Peyton Randolph do in this situation? What course in it will as[pg 14]sure me their approbation? I am certain that this mode of deciding on my conduct tended more to correctness than any reasoning powers that I possesed.”

This passage throws a light upon Jefferson’s character. It does not seem to occur to him that a young man might require some stronger motive to keep his passions in check than could be furnished either by the wish to imitate a good example or by his “reasoning powers.” To Jefferson’s well-regulated mind the desire for approbation was a sufficient motive. He was particularly sensitive, perhaps morbidly so, to disapprobation. The respect, the good-will, the affection of his countrymen were so dear to him that the desire to retain them exercised a great, it may be at times, an undue influence upon him. “I find,” he once said, “the pain of a little censure, even when it is unfounded, is more acute than the pleasure of much praise.”

During his second year at college, Jefferson laid aside all frivolities. He sent home his horses, contenting himself with a mile [pg 15]run out and back at nightfall for exercise, and studying, if we may believe the biographer, no less than fifteen hours a day. This intense application reduced the time of his college course by one half; and after the second winter at Williamsburg he went home with a degree in his pocket, and a volume of Coke upon Lytleton in his trunk.

II

VIRGINIA IN JEFFERSON’S DAY

To a young Virginian of Jefferson’s standing but two active careers were open, law and politics, and in almost every case these two, sooner or later, merged in one. The condition of Virginia was very different from that of New England,—neither the clerical nor the medical profession was held in esteem. There were no manufactures, and there was no general commerce.

Nature has divided Virginia into two parts: the mountainous region to the west and the broad level plain between the mountains and the sea, intersected by numerous rivers, in which, far back from the ocean, the tide ebbs and flows. In this tide-water region were situated the tobacco plantations which constituted the wealth and were inhabited by the aristocracy of the colony. Almost every planter lived near a river and had his own [pg 17]wharf, whence a schooner carried his tobacco to London, and brought back wines, silks, velvets, guns, saddles, and shoes.

The small proprietors of land were comparatively few in number, and the whole constitution of the colony, political and social, was aristocratic. Both real estate and slaves descended by force of law to the eldest son, so that the great properties were kept intact. There were no townships and no town meetings. The political unit was the parish; for the Episcopal church was the established church,—a state institution; and the parishes were of great extent, there being, as a rule, but one or two parishes in a county.

The clergy, though belonging to an establishment, were poorly paid, and not revered as a class. They held the same position of inferiority in respect to the rich planters which the clergy of England held in respect to the country gentry at the same period. Being appointed by the crown, they were selected without much regard to fitness, and they were demoralized by want of supervision, for there were no resident bishops, and, [pg 18]further, by the uncertain character of their incomes, which, being paid in tobacco, were subject to great fluctuations. A few were men of learning and virtue who performed their duties faithfully, and eked out their incomes by taking pupils. “It was these few,” remarks Mr. Parton, “who saved civilization in the colony.” A few others became cultivators of tobacco, and acquired wealth. But the greater part of the clergy were companions and hangers-on of the rich planters,—examples of that type which Thackeray so well describes in the character of Parson Sampson in “The Virginians.” Strange tales were told of these old Virginia parsons. One is spoken of as pocketing annually a hundred dollars, the revenue of a legacy for preaching four sermons a year against atheism, gambling, racing, and swearing,—for all of which vices, except the first, he was notorious.

This period, the middle half of the eighteenth century, was, as the reader need not be reminded, that in which the English church sank to its lowest point. It was the [pg 19]era when the typical country parson was a convivial fox-hunter; when the Fellows of colleges sat over their wine from four o’clock, their dinner hour, till midnight or after; when the highest type of bishop was a learned man who spent more time in his private studies than in the duties of his office; when the cathedrals were neglected and dirty, and the parish churches were closed from Sunday to Sunday. In England, the reaction produced Methodism, and, later, the Tractarian movement; and we are told that even in Virginia, “swarms of Methodists, Moravians, and New-Light Presbyterians came over the border from Pennsylvania, and pervaded the colony.”

Taxation pressed with very unequal force upon the poor, and the right of voting was confined to freeholders. There was no system of public schools, and the great mass of the people were ignorant and coarse, but morally and physically sound,—a good substructure for an aristocratic society. Wealth being concentrated mainly in the hands of a few, Virginia presented striking contrasts of [pg 20]luxury and destitution, whereas in the neighboring colony of Pennsylvania, where wealth was more distributed and society more democratic, thrift and prosperity were far more common.

“In Pennsylvania,” relates a foreign traveler, “one sees great numbers of wagons drawn by four or more fine fat horses.... In the slave States we sometimes meet a ragged black boy or girl driving a team consisting of a lean cow and a mule; and I have seen a mule, a bull, and a cow, each miserable in its appearance, composing one team, with a half-naked black slave or two riding or driving as occasion suited.” And yet between Richmond and Fredericksburg, “in the afternoon, as our road lay through the woods, I was surprised to meet a family party traveling along in as elegant a coach as is usually met with in the neighborhood of London, and attended by several gayly dressed footmen.”

Virginia society just before the Revolution perfectly illustrated Buckle’s remark about leisure: “Without leisure, science is impos[pg 21]sible; and when leisure has been won, most of the class possessing it will waste it in the pursuit of pleasure, and a few will employ it in the pursuit of knowledge.” Men like Jefferson, George Wythe, and Madison used their leisure for the good of their fellow-beings and for the cultivation of their minds; whereas the greater part of the planters—and the poor whites imitated them—spent their ample leisure in sports, in drinking, and in absolute idleness. “In spite of the Virginians’ love for dissipation,” wrote a famous French traveler, “the taste for reading is commoner among men of the first rank than in any other part of America; but the populace is perhaps more ignorant there than elsewhere.” “The Virginia virtues,” says Mr. Henry Adams, “were those of the field and farm—the simple and straightforward mind, the notions of courage and truth, the absence of mercantile sharpness and quickness, the rusticity and open-handed hospitality.” Virginians of the upper class were remarkable for their high-bred courtesy,—a trait so inherent that it rarely disappeared [pg 22]even in the bitterness of political disputes and divisions. This, too, was the natural product of a society based not on trade or commerce, but on land. “I blush for my own people,” wrote Dr. Channing, from Virginia, in 1791, “when I compare the selfish prudence of a Yankee with the generous confidence of a Virginian. Here I find great vices, but greater virtues than I left behind me.” There was a largeness of temper and of feeling in the Virginia aristocracy, which seems to be inseparable from people living in a new country, upon the outskirts of civilization. They had the pride of birth, but they recognized other claims to consideration, and were as far as possible from estimating a man according to the amount of his wealth.

Slavery itself was probably a factor for good in the character of such a man as Jefferson,—it afforded a daily exercise in the virtues of benevolence and self-control. How he treated the blacks may be gathered from a story, told by his superintendent, of a slave named Jim who had been caught stealing [pg 23]nails from the nail-factory: “When Mr. Jefferson came, I sent for Jim, and I never saw any person, white or black, feel as badly as he did when he saw his master. The tears streamed down his face, and he begged for pardon over and over again. I felt very badly myself. Mr. Jefferson turned to me and said, ‘Ah, sir, we can’t punish him. He has suffered enough already.’ He then talked to him, gave him a heap of good advice, and sent him to the shop.... Jim said: ‘Well I’se been a-seeking religion a long time, but I never heard anything before that sounded so, or made me feel so, as I did when Master said, “Go, and don’t do so any more,” and now I’se determined to seek religion till I find it;’ and sure enough he afterwards came to me for a permit to go and be baptized.... He was always a good servant afterward.”

Another element that contributed to the efficiency and the high standard of the early Virginia statesman was a good, old-fashioned classical education. They were familiar, to use Matthew Arnold’s famous expression, [pg 24]“with the best that has ever been said or done.” This was no small advantage to men who were called upon to act as founders of a republic different indeed from the republics of Greece and Rome, but still based upon the same principles, and demanding an exercise of the same heroic virtues. The American Revolution would never have cut quite the figure in the world which history assigns to it, had it not been conducted with a kind of classic dignity and decency; and to this result nobody contributed more than Jefferson.

Such was Virginia in the eighteenth century,—at the base of society, the slaves; next, a lower class, rough, ignorant, and somewhat brutal, but still wholesome, and possessing the primitive virtues of courage and truth; and at the top, the landed gentry, luxurious, proud, idle and dissipated for the most part, and yet blossoming into a few characters of a type so high that the world has hardly seen a better. Had he been born in Europe, Jefferson would doubtless have devoted himself to music, or to [pg 25]architecture, or to literature, or to science,—for in all these directions his taste was nearly equally strong; but these careers being closed to him by the circumstances of the colony, he became a lawyer, and then, under pressure of the Revolution, a politician and statesman.

During the four years following his graduation, Jefferson spent most of the winter months at Williamsburg, pursuing his legal and other studies, and the rest of the year upon the family plantation, the management of which had devolved upon him. Now, as always, he was the most industrious of men. He lived, as Mr. Parton remarks, “with a pen in his hand.” He kept a garden book, a farm book, a weather book, a receipt book, a cash book, and, while he practiced law, a fee book. Many of these books are still preserved, and the entries are as legible now as when they were first written down in Jefferson’s small but clear and graceful hand,—the hand of an artist. Jefferson, as one of his old friends once remarked, hated superficial knowledge; and he dug to the roots of [pg 26]the common law, reading deeply in old reports written in law French and law Latin, and especially studying Magna Charta and Bracton.

He found time also for riding, for music, and dancing; and in his twentieth year he became enamored of Miss Rebecca Burwell, a Williamsburg belle more distinguished, tradition reports, for beauty than for cleverness. But Jefferson was not yet in a position to marry,—he even contemplated a foreign tour; and the girl, somewhat abruptly, married another lover. The wound seems not to have been a deep one. Jefferson, in fact, though he found his chief happiness in family affection, and though capable of strong and lasting attachments, was not the man for a romantic passion. He was a philosopher of the reasonable, eighteenth-century type. No one was more kind and just in the treatment of his slaves, but he did not free them, as George Wythe, perhaps foolishly, did; and he was even cautious about promulgating his views as to the folly and wickedness of slavery, though he did his [pg 27]best to promote its abolition by legislative measures. There was not in Jefferson the material for a martyr or a Don Quixote; but that was Nature’s fault, not his. It may be said of every particular man that there is a certain depth to which he cannot sink, and there is a certain height to which he cannot rise. Within the intermediate zone there is ample exercise for free-will; and no man struggled harder than Jefferson to fulfill all the obligations which, as he conceived, were laid upon him.

III

MONTICELLO AND ITS HOUSEHOLD

In April, 1764, Jefferson came of age, and his first public act was a characteristic one. For the benefit of the neighborhood, he procured the passage of a statute to authorize the dredging of the Rivanna River upon which his own estate bordered in part. He then by private subscriptions raised a sum sufficient for carrying out this purpose; and in a short time the stream, upon which before a bark canoe would hardly have floated, was made available for the transportation of farm produce to the James River, and thence to the sea.

In 1766, he made a journey to Philadelphia, in order to be inoculated for smallpox, traveling in a light gig drawn by a high-spirited horse, and narrowly escaping death by drowning in one of the numerous rivers which had to be forded between Charlottes[pg 29]ville and Philadelphia. In the following year, about the time of his twenty-fourth birthday, he was admitted to the bar, and entered almost immediately upon a large and lucrative practice. He remained at the bar only seven years, but during most of this time his professional income averaged more than £2500 a year; and he increased his paternal estate from 1900 acres to 5000 acres. He argued with force and fluency, but his voice was not suitable for public speaking, and soon became husky. Moreover, Jefferson had an intense repugnance to the arena. He shrank with a kind of nervous horror from a personal contest, and hated to be drawn into a discussion. The turmoil and confusion of a public body were hideous to him;—it was as a writer, not as a speaker, that he won fame, first in the Virginia Assembly, and afterward in the Continental Congress.

In October, 1768, Jefferson was chosen to represent Albemarle County in the House of Burgesses of Virginia; and thus began his long political career of forty years. A [pg 30]resolution which he formed at the outset is stated in the following letter written in 1792 to a friend who had offered him a share in an undertaking which promised to be profitable:—

“When I first entered on the stage of public life (now twenty-four years ago) I came to a resolution never to engage, while in public office, in any kind of enterprise for the improvement of my fortune, nor to wear any other character than that of a farmer. I have never departed from it in a single instance; and I have in multiplied instances found myself happy in being able to decide and to act as a public servant, clear of all interest, in the multiform questions that have arisen, wherein I have seen others embarrassed and biased by having got themselves in a more interested situation.”

During the next few years there was a lull in political affairs,—a sullen calm before the storm of the Revolution; but they were important years in Mr. Jefferson’s life. In February, 1770, the house at Shadwell, where he lived with his mother and sisters, [pg 31]was burned to the ground, while the family were away. “Were none of my books saved?” Jefferson asked of the negro who came to him, breathless, with news of the disaster. “No, master,” was the reply, “but we saved the fiddle.”

In giving his friend Page an account of the fire, Jefferson wrote: “On a reasonable estimate, I calculate the cost of the books burned to have been £200. Would to God it had been the money,—then had it never cost me a sigh!” Beside the books, Jefferson lost most of his notes and papers; but no mishap, not caused by his own fault, ever troubled his peace of mind.

After the fire, his mother and the children took temporary refuge in the home of an overseer, and Jefferson repaired to Monticello,—as he had named the elevated spot on the paternal estate where he had already begun to build the house which was his home for the remainder of his life.

Monticello is a small outlying peak, upon the outskirts of the mountainous part of Virginia, west of the tide-water region, and [pg 32]rising 580 feet above the plain at its foot. Upon its summit there is a space of about six acres, leveled partly by nature and partly by art; and here, one hundred feet back from the brow of the hill, Jefferson built his house. It is a long, low building,—still standing,—with a Grecian portico in front, surmounted by a cupola. The road by which it is approached winds round and round, so as to make the ascent less difficult. In front of the house three long terraces, terminating in small pavilions, were constructed; and upon the northern terrace, or in its pavilion, Jefferson and his friends used to sit on summer nights gazing off toward the Blue Ridge, some eighty miles distant, or upon the nearer peaks of the Ragged Mountains. The altitude is such that neither dew nor mosquitoes can reach it.

To this beautiful but as yet uncompleted mountain home, Jefferson, in January, 1772, brought his bride. She was Martha Skelton, who had been left a widow at nineteen, and was now twenty-two, a daughter of John Wayles, a leading and opulent lawyer. [pg 33]Martha Skelton was a tall, beautiful, highly educated young woman, of graceful carriage, with hazel eyes, literary in her tastes, a skillful performer upon the spinnet, and a notable housewife whose neatly kept account books are still preserved. They were married at “The Forest,” her father’s estate in Charles City County, and immediately set out for Monticello.

Two years later, in 1774, died Dabney Carr, a brilliant and patriotic young lawyer, Jefferson’s most intimate friend, and the husband of his sister Martha. Dabney Carr left six small children, whom, with their mother, Jefferson took under his wing, and they were brought up at Monticello as if they had been his own children. Jefferson loved children, and he had, in common with that very different character, Aaron Burr, an instinct for teaching. While still a young man himself, he was often called upon to direct the studies of other young men,—Madison and Monroe were in this sense his pupils; and the founding of the University of Virginia was an achievement [pg 34]long anticipated by him and enthusiastically performed.

Jefferson was somewhat unfortunate in his own children, for, of the six that were born to him, only two, Martha and Maria, lived to grow up. Maria married but died young, leaving one child. Martha, the first-born, was a brilliant, cheerful, wholesome woman. She married Thomas Mann Randolph, afterward governor of Virginia. “She was just like her father, in this respect,” says Mr. Bacon, the superintendent,—“she was always busy. If she wasn’t reading or writing, she was always doing something. She used to sit in Mr. Jefferson’s room a great deal, and sew, or read, or talk, as he would be busy about something else.” John Randolph of Roanoke once toasted her—and it was after his quarrel with her father—as the sweetest woman in Virginia. She left ten children, and many of her descendants are still living.

To her, and to his other daughter, Maria, who is described as being more beautiful and no less amiable than her sister, but not [pg 35]so intellectual, Jefferson owed the chief happiness of his life. Like many another man who has won fame and a high position in the world, he counted these things but as dust and ashes in comparison with family affection.

IV

JEFFERSON IN THE REVOLUTION

Shortly after Mr. Jefferson’s marriage, the preliminary movements of the Revolution began, and though he took an active part in them it was not without reluctance. Even after the battle of Bunker Hill, namely, in November, 1775, he wrote to a kinsman that there was not a man in the British Empire who more cordially loved a union with Great Britain than he did. John Jay said after the Revolution: “During the course of my life, and until the second petition of Congress in 1775, I never did hear any American of any class or description express a wish for the independence of the colonies.”

But these friendly feelings were first outraged and then extinguished by a long series of ill-considered and oppressive acts, covering, with some intermissions, a period of [pg 37]about twelve years. Of these the most noteworthy were the Stamp Act, which amounted to taxation without representation, and the impost on tea, which was coupled with a provision that the receipts should be applied to the salaries of officers of the crown, thus placing them beyond the control of the local assemblies. The crown officers were also authorized to grant salaries and pensions at their discretion; and a board of revenue commissioners for the whole country was established at Boston, and armed with despotic powers. These proceedings amounted to a deprivation of liberty, and they were aggravated by the king’s contemptuous rejection of the petitions addressed to him by the colonists. We know what followed,—the burning of the British war schooner, Gaspee, by leading citizens of Providence, and the famous tea-party in Boston harbor.

Meanwhile Virginia had not been inactive. In March, 1772, a few young men, members of the House of Burgesses, met at the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg. They were Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee and his [pg 38]brother, Thomas Jefferson, and a few others. They drew up several resolutions, the most important of which called for the appointment of a standing committee and for an invitation to the other colonies to appoint like committees for mutual information and assistance in the struggle against the crown. A similar resolution had been adopted in Massachusetts two years before, but without any practical result. The Virginia resolution was passed the next day by the House of Burgesses, and it gave rise to those proceedings which ushered in the Revolution.

The first Continental Congress was to meet in Philadelphia, in September, 1774; and Jefferson, in anticipation, prepared a draft of instructions for the delegates who were to be elected by Virginia. Being taken ill himself, on his way to the convention, he sent forward a copy of these instructions. They were considered too drastic to be adopted by the convention; but some of the members caused them to be published under the title of “A Summary View of the Rights of America.” The pamphlet was extensively [pg 39]read in this country, and a copy which had been sent to London falling into the hands of Edmund Burke, he had it reprinted in England, where it ran through edition after edition. Jefferson’s name thus became known throughout the colonies and in England.

The “Summary View” is in reality a political essay. Its author wasted no time in discussing the specific legal and constitutional questions which had arisen between the colonies and the crown; but he went to the root of the matter, and with one or two generalizations as bold and original as if they had been made by Rousseau, he cut the Gordian knot, and severed America from the Parliament of Great Britain. He admitted some sort of dependence upon the crown, but his two main principles were these: (1) that the soil of this country belonged to the people who had settled and improved it, and that the crown had no right to sell or give it away; (2) that the right of self-government was a right natural to every people, and that Parliament, therefore, had no authority to [pg 40]make laws for America. Jefferson was always about a century in advance of his time; and the “Summary View” substantially anticipated what is now the acknowledged relation of England to her colonies.

Jefferson was elected a member of the Continental Congress at its second session; and he made a rapid journey to Philadelphia in a chaise, with two led horses behind, reaching there the night before Washington set out for Cambridge. The Congress was composed mainly of young men. Franklin, the oldest member, was seventy-one, and a few others were past sixty. Washington was forty-three; John Adams, forty; Patrick Henry, a year or two younger; John Rutledge, thirty-six; his brother, twenty-six; John Langdon and William Paca, thirty-five, John Jay, thirty; Thomas Stone, thirty-two, and Jefferson, thirty-two.

Jefferson soon became intimate with John Adams, who in later years said of him: “Though a silent member of Congress, he was so prompt, frank, explicit, and decisive upon committees and in conversation—not [pg 41]even Samuel Adams was more so—that he soon seized upon my heart.”

Jefferson, as we have seen, was not fitted to shine as an orator, still less in debate. But as a writer he had that capacity for style which comes, if it comes at all, as a gift of nature; which needs to be supplemented, but which cannot be supplied, by practice and study. In some of his early letters there are slight reminders of Dr. Johnson’s manner, and still more of Sterne’s. Sterne indeed was one of his favorite authors. However, these early traces of imitation were absorbed very quickly; and, before he was thirty, Jefferson became master of a clear, smooth, polished, picturesque, and individual style. To him, therefore, his associates naturally turned when they needed such a proclamation to the world as the Declaration of Independence; and that document is very characteristic of its author. It was imagination that gave distinction to Jefferson both as a man and as a writer. He never dashed off a letter which did not contain some play of fancy; and whether he was inventing a [pg 42]plough or forecasting the destinies of a great Democracy, imagination qualified the performance.

One of the most effective forms in which imagination displays itself in prose is by the use of a common word in such a manner and context that it conveys an uncommon meaning. There are many examples of this rhetorical art in Jefferson’s writings, but the most notable one occurs in the noble first paragraph of the Declaration of Independence: “When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.”

Upon this paragraph Mr. Parton eloquently observes: “The noblest utterance of the whole composition is the reason given for making the Declaration,—‘A decent [pg 43]respect for the opinions of mankind.’ This touches the heart. Among the best emotions that human nature knows is the veneration of man for man. This recognition of the public opinion of the world—the sum of human sense—as the final arbiter in all such controversies is the single phrase of the document which Jefferson alone, perhaps, of all the Congress, could have originated; and in point of merit it was worth all the rest.”

Franklin and John Adams, who were on the committee with Jefferson, made a few verbal changes in his draught of the Declaration, and it was then discussed and reviewed by Congress for three days. Congress made eighteen suppressions, six additions, and ten alterations; and it must be admitted that most of these were improvements. For example, Jefferson had framed a paragraph in which the king was severely censured for opposing certain measures looking to the suppression of the slave trade. This would have come with an ill grace from the Americans, since for a century New England had been enriching herself by that trade, and the southern colonies had subsisted upon the labor [pg 44]which it brought them. Congress wisely struck out the paragraph.

The Declaration of Independence was received with rapture throughout the country. Everywhere it was read aloud to the people who gathered to hear it, amid the booming of guns, the ringing of bells, and the display of fireworks. In Philadelphia, after the reading, the late king’s coat of arms was burned in Independence Square; in New York the leaden statue, in Bowling Green, of George III. was “laid prostrate in the dust,” and ordered to be run into bullets. Virginia had already stricken the king’s name from her prayer-book; and Rhode Island now forbade her people to pray for the king, as king, under a penalty of one hundred thousand pounds! The Declaration of Independence, both as a political and literary document, has stood the test of time. It has all the classic qualities of an oration by Demosthenes; and even that passage in it which has been criticised—that, namely, which pronounces all men to be created equal—is true in a sense, the truth of which it will take a century or two yet to develop.

V

REFORM WORK IN VIRGINIA

In September, 1776, Jefferson, having resigned his seat in Congress to engage in duties nearer home, returned to Monticello. A few weeks later, a messenger from Congress arrived to inform him that he had been elected a joint commissioner with Dr. Franklin and Silas Deane to represent at Paris the newly formed nation. His heart had long been set upon foreign travel; but he felt obliged to decline this appointment, first on account of the ill health of his wife, and secondly, because he was needed in Virginia as a legislator. Not since Lycurgus gave laws to the Spartans had there been such an opportunity as then existed in the United States. John Adams declared: “The best lawgivers of antiquity would rejoice to live at a period like this when, for the first time in the history of the world, [pg 46]three millions of people are deliberately choosing their government and institutions.”

Of all the colonies, Virginia offered the best field for reform, because, as we have already seen, she had by far the most aristocratic political and social system; and it is extraordinary how quickly the reform was effected by Jefferson and his friends. In ordinary times of peace the task would have been impossible; but in throwing off the English yoke, the colonists had opened their minds to new ideas; change had become familiar to them, and in the general upheaval the rights of the people were recognized. A year later, Jefferson wrote to Franklin: “With respect to the State of Virginia, in particular, the people seem to have laid aside the monarchical and taken up the republican government with as much ease as would have attended their throwing off an old and putting on a new set of clothes.”

Jefferson’s greatness lay in this, that he was the first statesman who trusted the mass of the people. He alone had divined the fact that they were competent, morally and [pg 47]mentally, for self-government. It is almost impossible for us to appreciate Jefferson’s originality in this respect, because the bold and untried theories for which he contended are now regarded as commonplace maxims. He may have derived his political ideas in part from the French philosophical writers of the eighteenth century, although there is no evidence to that effect; but he was certainly the first statesman to grasp the idea of democracy as a form of government, just as, at a later day, Walt Whitman was the first poet to grasp the idea of equality as a social system. Hamilton, John Adams, Pinckney, Gouverneur Morris, even Washington himself, all believed that popular government would be unsafe and revolutionary unless held in check by a strong executive and by an aristocratic senate.

Jefferson in his lifetime was often charged with gross inconsistency in his political views and conduct; but the inconsistency was more apparent than real. At times he strictly construed, and at times he almost set aside the Constitution; but the clue to [pg 48]his conduct can usually be found in the fundamental principle that the only proper function of government or constitutions is to express the will of the people, and that the people are morally and mentally competent to govern. “I am sure,” he wrote in 1796, “that the mass of citizens in these United States mean well, and I firmly believe that they will always act well, whenever they can obtain a right understanding of matters.” And Jefferson’s lifelong endeavor was to enable the people to form this “right understanding” by educating them. His ideas of the scope of public education went far beyond those which prevailed in his time, and considerably beyond those which prevail even now. For example, a free university course for the most apt pupils graduated at the grammar schools made part of his scheme,—an idea most nearly realized in the Western States; and those States received their impetus in educational matters from the Ordinance of 1787, which was largely the product of Jefferson’s foresight.

Happily for Virginia, she did not become [pg 49]a scene of war until the year 1779, and, meanwhile, Jefferson and his friends lost no time in remodeling her constitution. There were no common schools, and the mass of the people were more ignorant and rough than their contemporaries in any other colony. Elections were scenes of bribery, intimidation, and riot, surpassing even those which Hogarth depicted in England. Elkanah Watson, of Massachusetts, describes what he saw at Hanover Court House, Patrick Henry’s county, in 1778: “The whole county was assembled. The moment I alighted, a wretched, pug-nosed fellow assailed me to swap watches. I had hardly shaken him off, when I was attacked by a wild Irishman who insisted on my swapping horses with him.... With him I came near being involved in a boxing-match, the Irishman swearing, I ‘did not trate him like a jintleman.’ I had hardly escaped this dilemma when my attention was attracted by a fight between two very unwieldy fat men, foaming and puffing like two furies, until one succeeded in twisting [pg 50]a forefinger in a sidelock of the other’s hair, and in the act of thrusting by this purchase his thumb into the latter’s eye, he bawled out, ‘King’s Cruise,’ equivalent in technical language to ‘Enough.’ ”

Quakers were put in the pillory, scolding women were ducked, and it is said that a woman was burned to death in Princess Anne County for witchcraft. The English church, as we have seen, was an established church; and all taxpayers, dissenters as well as churchmen, were compelled to contribute to its support. Baptist preachers were arrested, and fined as disturbers of the peace. The law of entail, both as respects land and slaves, was so strict that their descent to the eldest son could not be prevented even by agreement between the owner and his heir.

In his reformation of the laws, Jefferson was supported by Patrick Henry, now governor, and inhabiting what was still called the palace; by George Mason, a patriotic lawyer who drew the famous Virginia Bill of Rights; by George Wythe, his old pre[pg 51]ceptor, and by James Madison, Jefferson’s friend, pupil, and successor, who in this year began his political career as a member of the House of Burgesses.

Opposed to them were the conservative party led by R. C. Nicholas, head of the Virginia bar, a stanch churchman and gentleman of the old school, and Edward Pendleton, whom Jefferson described as “full of resource, never vanquished; for if he lost the main battle he returned upon you, and regained so much of it as to make it a drawn one, by dexterous manœuvres, skirmishes in detail, and the recovery of small advantages, which, little singly, were important all together. You never knew when you were clear of him.”

Intense as the controversy was, fundamental as were the points at issue, the speakers never lost that courtesy for which the Virginians were remarkable; John Randolph being perhaps the only exception. Even Patrick Henry—though from his humble origin and impetuous oratory one might have expected otherwise—was never guilty [pg 52]of any rudeness to his opponents. What Jefferson said of Madison was true of the Virginia orators in general,—“soothing always the feelings of his adversaries by civilities and softnesses of expression.”

Jefferson struck first at the system of entail. After a three weeks’ struggle, land and slaves were put upon the same footing as all other property,—they might be sold or bequeathed according to the will of the possessor. Then came a longer and more bitter contest. Jefferson was for abolishing all connection between church and state, and for establishing complete freedom of religion. Nine years elapsed before Virginia could be brought to that point; but at this session he procured a repeal of the law which imposed penalties for attendance at a dissenting meeting-house, and also of the law compelling dissenters to pay tithes. The fight was, therefore, substantially won; and in 1786, Jefferson’s “Act for establishing religion” became the law of Virginia.1

[pg 53]Another far-reaching law introduced by Jefferson at this memorable session of 1776 provided for the naturalization of foreigners in Virginia, after a two years’ residence in the State, and upon a declaration of their intention to become American citizens. The bill provided also that the minor children of naturalized parents should be citizens of the United States when they came of age. The principles of this measure were afterward embodied in the statutes of the United States, and they are in force to-day.

At this session Jefferson also drew an act for establishing courts of law in Virginia, the royal courts having necessarily passed out of existence when the Declaration of Independence was adopted. Moreover, he set on foot a revision of all the statutes of Virginia, a committee with him at the head being appointed for this purpose; and finally he procured the removal of the capital from Williamsburg to Richmond.

[pg 54]All this was accomplished, mainly by Jefferson’s efforts; and yet the two bills upon which he set most store failed entirely. These were, first, a comprehensive measure of state education, running up through primary schools and grammar schools to a state university, and, secondly, a bill providing that all who were born in slavery after the passage of the bill should be free.

This was Jefferson’s second ineffectual attempt to promote the abolition of slavery. During the year 1768, when he first became a member of the House of Burgesses, he had endeavored to procure the passage of a law enabling slave-owners to free their slaves, He induced Colonel Bland, one of the ablest, oldest, and most respected members to propose the law, and he seconded the proposal; but it was overwhelmingly rejected. “I, as a younger member,” related Jefferson afterward, “was more spared in the debate; but he was denounced as an enemy to his country, and was treated with the greatest indecorum.”

In 1778 Jefferson made another attempt:[pg 55]—he brought in a bill forbidding the further importation of slaves in Virginia, and this was passed without opposition. Again, in 1784, when Virginia ceded to the United States her immense northwestern territory, Jefferson drew up a scheme of government for the States to be carved out of it which included a provision “that after the year 1800 of the Christian Era, there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in any of the said States, otherwise than in punishment of crimes.” The provision was rejected by Congress.

In his “Notes on Virginia,” written in the year 1781, but published in 1787, he said: “The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism, on the one part, and degrading submission on the other. Our children see this, and learn to imitate it.... With the morals of the people their industry also is destroyed. For in a warm climate no one will labor for himself who can make another labor for him.... Indeed, I tremble for my country [pg 56]when I reflect that God is just; that his justice cannot sleep forever.... The Almighty has no attribute which can take sides with us in such a contest.”

When the Missouri Compromise question came up, in 1820, Jefferson rightly predicted that a controversy had begun which would end in disruption; but he made the mistake of supposing that the Northern party were actuated in that matter solely by political motives. April 22, 1820, he wrote: “This momentous question, like a fire-bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union.... A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper.... The cession of that kind of property, for so it is misnamed, is a bagatelle which would not cost me a second thought if, in that way, a general emancipation and expatriation could be effected; and gradually and with due sacrifices I think it might be. [pg 57]But as it is, we have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.”

And later, he wrote of the Missouri Compromise, as a “question having just enough of the semblance of morality to throw dust into the eyes of the people.... The Federalists, unable to rise again under the old division of Whig and Tory, have invented a geographical division which gives them fourteen States against ten, and seduces their old opponents into a coalition with them. Real morality is on the other side. For while the removal of the slaves from one State to another adds no more to their numbers than their removal from one country to another, the spreading them over a larger surface adds to their happiness, and renders their future emancipation more practicable.”

These misconceptions as to Northern motives might be ascribed to Jefferson’s advanced age, for, as he himself graphically expressed it, he then had “one foot in the grave, and the other lifted to follow it;” but [pg 58]it would probably be more just to say that they were due, in part, to his prejudice against the New England people and especially the New England clergy, and in part to the fact that his long retirement in Virginia had somewhat contracted his views and sympathies. Jefferson was a man of intense local attachments, and he took color from his surroundings. He never ceased, however, to regard slavery as morally wrong and socially ruinous; and in the brief autobiography which he left behind him he made these predictions: “Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate than that these people are to be free. Nor is it less certain that the two races, equally free, cannot live in the same government.”

History has justified the second as well as the first of these declarations, for, excepting that brief period of anarchy known as “the carpet-bag era,” it cannot be maintained that the colored race in the Southern States have been at any time, even since their emancipation, “equally free,” in the sense of politically free, with their white fellow citizens.

VI

GOVERNOR OF VIRGINIA

For three years Jefferson was occupied with the legislative duties already described, and especially with a revision of the Virginia statutes, and then, in June, 1779, he succeeded Patrick Henry as governor of the State. It has often been remarked that he was, all through life, a lucky man, but in this case fortune did not favor him, for the ensuing two years proved to be, so far as Virginia was concerned, by much the worst period of the war.

The French alliance, though no doubt an ultimate benefit to the colonies, had at first two bad effects: it relaxed the energy of the Americans, who trusted that France would fight their battles for them; and it stimulated the British to increased exertions. The British commissioners announced that henceforth England would employ, in the prosecu[pg 60]tion of the war, all those agencies which “God and nature had placed in her hands.” This meant that the ferocity of the Indians would be invoked, a matter of special moment to Virginia, since her western frontier swarmed with Indians, the bravest of their race.

The colony, it must be remembered, was then of immense extent; for beside the present Virginia and West Virginia, Kentucky and the greater part of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois were embraced in it. It stretched, in short, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River. Upon the seaboard Virginia was especially vulnerable, the tide-water region being penetrated by numerous bays and rivers, which the enemy’s ships could easily ascend, for they were undefended by forts or men. The total navy of the colony was four vessels, mounting sixty-two guns, and a few armed boats. The flower of the Virginia soldiery, to the number of ten thousand, were in Washington’s army, and supplies of men, of arms, of ammunition and food were urgently called for by General [pg 61]Gates, who was battling against Cornwallis in North Carolina. The militia were supposed to number fifty thousand, which included every man between sixteen and fifty years of age; but this was only one man for every square mile of territory in the present State of Virginia, and of these militiamen it was estimated that, east of the Blue Ridge, only about one in five was armed with a gun. The treasury was practically bankrupt, and there was a dearth of every kind of warlike material.

Such was the situation which confronted, as Mr. Parton puts it, “a lawyer of thirty-six, with a talent for music, a taste for art, a love of science, literature, and gardening.” The task was one calling rather for a soldier than a statesman; but Mr. Jefferson faced it with courage, and on the whole with success. In retaliating the cruel measures of the British, he showed a firmness which must have been especially difficult for a man of his temperament. He put in irons and confined in a dungeon Colonel Henry Hamilton and two subordinate officers who had com[pg 62]mitted atrocities upon American prisoners. He caused a prison-ship, like the ships of infamous memory which were employed as prisons by the British at New York, to be prepared; and the exchange of captives between Virginia and the British was stopped. “Humane conduct on our part,” wrote Jefferson, “was found to produce no effect. The contrary, therefore, is to be tried. Iron will be retaliated by iron, prison-ships for prison-ships, and like for like in general.” But in November, 1779, notice was received that the English, under their new leader, Sir Henry Clinton, had adopted a less barbarous system of warfare; and fortunately Jefferson’s measures of reprisal became unnecessary.

Hampered as he was by want of men and money, Jefferson did all that he could to supply the needs of the Virginia soldiers with Washington, of the army in North Carolina, led by Gates, and of George Rogers Clarke, the heroic commander who put down the Indian uprising on the western frontier, and captured the English officer who instigated [pg 63]it,—that same Colonel Hamilton of whom mention has already been made. The story of Clarke’s adventures in the wilderness,—he was a neighbor of Jefferson, only twenty-six years old,—of his forced marches, of his masterful dealing with the Indians, and finally of his capture of the British force, forms a thrilling chapter in the history of the American Revolution.

Many indeed of Jefferson’s constituents censured him as being over-zealous in his support of the army of Gates. He stripped Virginia, they said, of troops and resources which, as it proved afterward, were needed at home. But if Cornwallis were not defeated in North Carolina, it was certain that he would overrun the much more exposed Virginia. If he could be defeated anywhere, it would be in the Carolinas. Jefferson’s course, it is sufficient to say, was that recommended by Washington; and his exertions in behalf of the Continental armies were commended in the highest terms not only by Washington, but also by Generals Gates, Greene, Steuben, and Lafayette. The mili[pg 64]tia were called out, leaving behind only so many men as were required to cultivate the land, wagons were impressed, including two belonging to the governor, and attempts were even made—extraordinary for Virginia—to manufacture certain much-needed articles. “Our smiths,” wrote Jefferson, “are making five hundred axes and some tomahawks for General Gates.”

Thus fared the year 1779, and in 1780 things went from bad to worse. In April came a letter from Madison, saying that Washington’s army was on the verge of dissolution, being only half-clothed, and in a way to be starved. The public treasury was empty and the public credit gone. In August occurred the disastrous defeat of General Gates at Camden, which left Virginia at the mercy of Cornwallis. In October a British fleet under Leslie ravaged the country about Portsmouth, but failing to effect a juncture with Cornwallis, who was detained in North Carolina by illness among his troops, did no further harm. Two months later, however, Benedict Arnold sailed up the James River [pg 65]with another fleet, and, after committing some depredations at Richmond, sailed down again, escaping by the aid of a favorable wind, which hauled from east to west just in the nick of time for him.

In June, 1781, Cornwallis invaded Virginia, and no one suffered more than Jefferson from his depredations. Tarleton was dispatched to seize the governor at Monticello; but the latter was forewarned by a citizen of Charlottesville, who, being in a tavern at Louisa when Tarleton and his troop swept by on the main road, immediately guessed their destination, and mounting his horse, a fleet Virginia thoroughbred, rode by a short cut through the woods straight to Monticello, arriving there about three hours ahead of Tarleton.

Jefferson took the matter coolly. He first dispatched his family to a place of safety, sent his best horse to be shod at a neighboring smithy, and then proceeded to sort and separate his papers. He left the house only about five minutes before the soldiers entered it.

[pg 66]Two slaves, Martin, Mr. Jefferson’s body servant, and Cæsar, were engaged in hiding plate and other articles under the floor of the portico, a single plank having been raised for that purpose. As Martin, above, handed the last article to Cæsar under the floor, the tramp of the approaching cavalry was heard. Down went the plank, shutting in Cæsar, and there he remained, without making any outcry, for eighteen hours, in darkness, and of course without food or water. One of the soldiers, to try Martin’s nerve, clapped a pistol to his breast, and threatened to fire unless he would tell which way his master had fled. “Fire away, then,” retorted the black, fiercely answering glance for glance, and not receding a hair’s breath.

Tarleton and his men scrupulously refrained from injuring Jefferson’s property. Cornwallis, on the other hand, who encamped on Jefferson’s estate of Elk Hill, lying opposite Elk Island in the James River, destroyed the growing crops, burned all the barns and fences, carried off—“as was to be expected,” [pg 67]said Mr. Jefferson—the cattle and horses, and committed the barbarity of killing the colts that were too young to be of service. He carried off, also, about thirty slaves. “Had this been to give them freedom,” wrote Jefferson, “he would have done right; but it was to consign them to inevitable death from the smallpox and putrid fever, then raging in his camp.”

“Some of the miserable wretches crawled home to die,” Mr. Randall relates, “and giving information where others lay perishing in hovels or in the open air, by the wayside, these were sent for by their generous master; and the last moments of all of them were made as comfortable as could be done by proper nursing and medical attendance.”

These dreadful scenes, added to the agitation of having twice been obliged, at a moment’s notice, to flee from the enemy, to say nothing of the anxieties which she must have endured on her husband’s account, were too much for Mrs. Jefferson’s already enfeebled constitution. She died on September 6, 1782.

[pg 68]Six slave women who were household servants enjoyed for thirty years a kind of humble distinction at Monticello as “the servants who were in the room when Mrs. Jefferson died;” and the fact that they were there attests the affectionate relations which must have existed between them and their master and mistress. “They have often told my wife,” relates Mr. Bacon, “that when Mrs. Jefferson died they stood around the bed. Mr. Jefferson sat by her, and she gave him directions about a good many things that she wanted done. When she came to the children, she wept, and could not speak for some time. Finally she held up her hand, and, spreading out her four fingers, she told him she could not die happy if she thought her four children were ever to have a stepmother brought in over them. Holding her other hand in his, Mr. Jefferson promised her solemnly that he would never marry again;” and the promise was kept.

After his wife’s death Jefferson sank into what he afterward described as “a stupor of [pg 69]mind;” and even before that he had been, for the first and last time in his life, in a somewhat morbid mental condition. He was an excessively sensitive man, and reflections upon his conduct as governor, during the raids into Virginia by Arnold and Cornwallis, coming at a time when he was overwrought, rankled in his mind. He refused to serve again as governor, and desiring to defend his course when in that office, became a member of the House of Burgesses in 1781, in order that he might answer his critics there; but not a voice was raised against him. In 1782, he was again elected to the House, but he did not attend; and both Madison and Monroe endeavored in vain to draw him from his seclusion. To Monroe he replied: “Before I ventured to declare to my countrymen my determination to retire from public employment, I examined well my heart to know whether it were thoroughly cured of every principle of political ambition, whether no lurking particle remained which might leave me uneasy, when reduced within the limits of mere private [pg 70]life. I became satisfied that every fibre of that passion was thoroughly eradicated.”

Jefferson was an impulsive man,—in some respects a creature of the moment; certainly often, in his own case, mistaking, as a permanent feeling, what was really a transitory impression. His language to Monroe must, therefore, be taken as the sincere deliverance of a man who, at that time, had not the remotest expectation of receiving, or the least ambition to attain, the highest offices in the gift of the American people.

VII

ENVOY AT PARIS

Two years after his wife’s death, namely, in 1784, Jefferson was chosen by Congress to serve as envoy at Paris, with John Adams and Benjamin Franklin. The appointment came at an opportune moment, when his mind was beginning to recover its tone, and he gladly accepted it. It was deemed necessary that the new Confederacy should make treaties with the various governments of Europe, and as soon as the envoys reached Paris, they drew up a treaty such as they hoped might be negotiated. It has been described as “the first serious attempt ever made to conduct the intercourse of nations on Christian principles;” and, on that account, it failed. To this failure there was, however, one exception. “Old Frederick of Prussia,” as Jefferson styled him, “met us [pg 72]cordially;” and with him a treaty was soon concluded.

In May, 1785, Franklin returned to the United States, and Jefferson was appointed minister. “You replace Dr. Franklin,” said the Count of Vergennes when Jefferson announced his appointment. “I succeed,—no one can replace him,” was the reply.

Jefferson’s residence in Paris at this critical period was a fortunate occurrence. It would be a mistake to suppose that he derived his political principles from France:—he carried them there; but he was confirmed in them by witnessing the injustice and misery which resulted to the common people from the monarchical governments of Europe. To James Monroe he wrote in June, 1785: “The pleasure of the trip [to Europe] will be less than you expect, but the utility greater. It will make you adore your own country,—its soil, its climate, its equality, laws, people, and manners. My God! how little do my countrymen know what precious blessings they are in possession of and which no other people on earth [pg 73]enjoy! I confess I had no idea of it myself.”

To George Wythe he wrote in August, 1786: “Preach, my dear sir, a crusade against ignorance; establish and improve the law for educating the common people. Let our countrymen know that the people alone can protect us against these evils; and that the tax which will be paid for this purpose is not more than the thousandth part of what will be paid to kings, priests, and nobles, who will rise up among us if we leave the people in ignorance.” To Madison, he wrote in January, 1787: “This is a government of wolves over sheep.” Jefferson took the greatest pains to ascertain the condition of the laboring classes. In the course of a journey in the south of France, he wrote to Lafayette, begging him to survey the condition of the people for himself. “To do it most effectually,” he said, “you must be absolutely incognito; you must ferret the people out of their hovels, as I have done; look into their kettles; eat their bread; loll on their beds on pretense of resting your[pg 74]self, but in fact to find if they are soft. You will feel a sublime pleasure in the course of the investigation, and a sublimer one hereafter, when you shall be able to apply your knowledge to the softening of their beds, or the throwing a morsel of meat into their kettle of vegetables.”

These excursions among the French peasantry, who, as Jefferson well knew, were ruinously taxed in order to support an extravagant court and an idle and insolent nobility, made him a fierce Republican. “There is not a crowned head in Europe,” he wrote to General Washington, in 1788, “whose talents or merits would entitle him to be elected a vestryman by the people of America.”

But for the French race Jefferson had an affinity. He was glad to live with people among whom, as he said, “a man might pass a life without encountering a single rudeness.” He liked their polished manners and gay disposition, their aptitude for science, for philosophy, and for art; even their wines and cookery suited his taste, and his preference in this respect was so well known that [pg 75]Patrick Henry once humorously stigmatized him as “a man who had abjured his native victuals.”

Jefferson’s stay in Paris corresponded exactly with the “glorious” period of the French Revolution. He was present at the Assembly of the Notables in 1787, and he witnessed the destruction of the Bastille in 1789.

“The change in this country,” he wrote in March, 1789, “is such as you can form no idea of. The frivolities of conversation have given way entirely to politics. Men, women, and children talk nothing else ... and mode has acted a wonderful part in the present instance. All the handsome young women, for example, are for the tiers étât, and this is an army more powerful in France than the 200,000 men of the king.”

The truth is that an intellectual and moral revolution preceded in France the outbreak of the populace. There was an interior conviction that the government of the country was excessively unjust and oppressive. A love of liberty, a feeling of [pg 76]fraternity, a passion for equality moved the intellect and even the aristocracy of France. In this crisis the reformers looked toward America, for the United States had just trodden the path upon which France was entering. “Our proceedings,” wrote Jefferson to Madison in 1789, “have been viewed as a model for them on every occasion.... Our [authority] has been treated like that of the Bible, open to explanation, but not to question.”

Jefferson’s advice was continually sought by Lafayette and others; and his house, maintained in the easy, liberal style of Virginia, was a meeting place for the Revolutionary statesmen. Jefferson dined at three or four o’clock; and after the cloth had been removed he and his guests sat over their wine till nine or ten in the evening.

In July, 1789, the National Assembly appointed a committee to draught a constitution, and the committee formally invited the American minister to assist at their sessions and favor them with his advice. This function he felt obliged to decline, as being [pg 77]inconsistent with his post of minister to the king. No man had a nicer sense of propriety than Jefferson; and he punctiliously observed the requirements of his somewhat difficult situation in Paris.

What gave Mr. Jefferson the greatest anxiety and trouble, was our relations with the piratical Barbary powers who held the keys of the Mediterranean and sometimes extended their depredations even into the Atlantic. It was a question of paying tribute or going to war; and most of the European powers paid tribute. In 1784, for example, the Dutch contributed to “the high, glorious, mighty, and most noble, King, Prince, and Emperor of Morocco,” a mass of material which included thirty cables, seventy cannon, sixty-nine masts, twenty-one anchors, fifty dozen sail-needles, twenty-four tons of pitch, two hundred and eighty loaves of sugar, twenty-four China punch-bowls, three clocks, and one “very large watch.”

Jefferson ascertained that the pirates would require of the United States, as the [pg 78]price of immunity for its commerce, a tribute of about three hundred thousand dollars per annum. “Surely,” he wrote home, “our people will not give this. Would it not be better to offer them an equal treaty? If they refuse, why not go to war with them?” And he pressed upon Mr. Jay, who held the secretaryship of foreign affairs, as the office was then called, the immediate establishment of a navy. But Congress would do nothing; and it was not till Jefferson himself became President that the Barbary pirates were dealt with in a wholesome and stringent manner. During the whole term of his residence at Paris he was negotiating with the Mediterranean powers for the release of unfortunate Americans, many of whom spent the best part of their lives in horrible captivity.

Mr. Jefferson’s self-imposed duties were no less arduous. He kept four colleges informed of the most valuable new inventions, discoveries, and books. He had a Yankee talent for mechanical improvements, and he was always on the alert to obtain anything of this nature which he thought might be [pg 79]useful at home. Jefferson himself, by the way, invented the revolving armchair, the buggy-top, and a mould board for a plough. He bought books for Franklin, Madison, Monroe, Wythe, and himself. He informed one correspondent about Watt’s engine, another about the new system of canals. He smuggled rice from Turin in his coat pockets; and he was continually dispatching to agricultural societies in America seeds, roots, nuts, and plants. Houdin was sent over by him to make the statue of Washington; and he forwarded designs for the new capitol at Richmond. For Buffon he procured the skin of an American panther, and also the bones and hide of a New Hampshire moose, to obtain which Governor Sullivan of that State organized a hunting-party in the depth of winter and cut a road through the forest for twenty miles in order to bring out his quarry.