Title: The Opium Monopoly

Author: Ellen N. La Motte

Release date: August 21, 2010 [eBook #33479]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries (http://www.archive.org/details/toronto)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries. See http://www.archive.org/details/opiummonopoly00lamouoft |

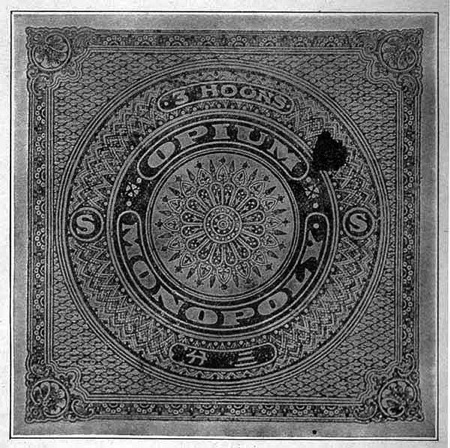

Wrapper of packet of opium, as sold in licensed opium shops of Singapore. Each packet contains enough opium for about six smokes.

"If this was our battle, if these were our ends,

Which were our enemies, which were our friends?"

Witter Bynner, in The Nation.

CONTENTS

| Chapter | Page | |

| Introduction | ix | |

| I. | Great Britain's Opium Monopoly | 1 |

| II. | The Indian Opium Monopoly | 6 |

| III. | Japan as an Opium Distributor | 11 |

| IV. | Singapore | 18 |

| V. | The Straits Settlements Opium Commission | 23 |

| VI. | Opium in Siam | 26 |

| VII. | Hongkong | 30 |

| VIII. | Sarawak | 35 |

| IX. | Shanghai | 37 |

| X. | India | 44 |

| XI. | Turkey and Persia | 54 |

| XII. | Mauretius | 56 |

| XIII. | British North Borneo | 58 |

| XIV. | British Guiana | 62 |

| XV. | History of the Opium Trade in China | 65 |

| XVI. | Conclusion | 73 |

INTRODUCTION

We first became interested in the opium traffic during a visit to the Far East in 1916. Like most Americans, we had vaguely heard of this trade, and had still vaguer recollections of a war between Great Britain and China, which took place about seventy-five years ago, known as the Opium War. From time to time we had heard of the opium trade as still flourishing in China, and then later came reports and assurances that it was all over, accompanied by newspaper pictures of bonfires of opium and opium pipes. Except for these occasional and incidental memories, we had neither knowledge of, nor interest in the subject. On our way out to Japan, in the July of 1916, we met a young Hindu on the boat, who was outspoken and indignant over the British policy of establishing the opium trade in India, as one of the departments of the Indian Government. Of all phases of British rule in India, it was this policy which excited him most, and which caused him most ardently to wish that India had some form of self-government, some voice in the control and management of her own affairs, so that the country could protect itself from this evil. Without this, he declared, his country was powerless to put a stop to this traffic imposed upon it by a foreign government, and he greatly deplored the slow, but steady demoralization of the nation which was in consequence taking place. As he produced his facts and figures, showing what this meant to his people—this gradual undermining of their moral fiber and economic efficiency—we grew more and more interested. That such conditions existed were to us unheard of, and unbelievable. It seemed incredible that in this age, with the consensus of public opinion sternly opposed to the sale and distribution of habit-forming drugs, and with legislation to curb and restrict such practices incorporated in the laws of all ethical and civilized governments, that here, on the other side of the world, we should come upon opium traffic conducted as a government monopoly. Not only that, but conducted by one of the greatest and most highly civilized nations of the world, a nation which we have always looked up to as being in the very forefront of advanced, progressive and humane ideals. So shocked were we by what this young Hindu told us, that we flatly refused to believe him. We listened to what he had to say on the subject, but thinking that however earnest he might be, however sincere in his sense of outrage at such a policy, that he must of necessity be mistaken. We decided not to take his word for it, but to look into the matter for ourselves.

We did look into the matter. During a stay in the Far East of nearly a year, in which time we visited Japan, China, Hongkong, French Indo-China, Siam and Singapore, we looked into the matter in every country we visited. Wherever possible we obtained government reports, and searched them carefully for those passages giving statistics concerning the opium trade—the amount of opium consumed, the number of shops where it was sold, and the number of divans where it was smoked. We found these shops established under government auspices, the dealers obtaining their supplies of opium from the government, and then obtaining licenses from the government to retail it. In many countries, we visited these shops and divans in person, and bought opium in them freely, just as one goes to a shop to buy cigarettes. We found a thorough and complete establishment of the opium traffic, run by the government, as a monopoly. Revenue was derived through the sale of opium, through excise taxes upon opium, and through license fees paid by the keepers of opium shops and divans. A complete, systematic arrangement, by which the foreign government profited at the expense of the subject peoples under its rule. In European countries and in America, we find the governments making every effort to repress the sale of habit-forming drugs. Here, in the Far East, a contrary attitude prevails. The government makes every effort to encourage and extend it.

Two notable exceptions presented themselves. One was Japan. There are no opium shops in Japan, and the Japanese Government is as careful to protect its people from the evils and dangers of opium as any European country could be. It must be remembered, however, that Japan is a free and independent country. It has never been conquered by a European country, and perhaps one explanation as to why the Japanese are a powerful, virile people, is because Japan is the one Oriental nation that has never been dominated by a European power, and in consequence, never drugged.

The other exception is our own possession of the Philippines, which although a subject country, has never had the opium traffic established as part of the machinery of an alien government.

On our return to America, we were greatly exercised over these facts which we had unearthed. We continued our researches as to the opium traffic in the New York Public Library, and in the Library of Congress, in Washington, in both of which places there is a rich and abundant literature on the subject. We obtained ready access to official blue books and government reports, issued by the British Government, and it is from these sources that the material in this book is largely drawn. We were somewhat hampered in our investigations by the fact that because of the war, these blue books have not always been of recent date, some of them being two or three years old. For this reason, it has not always been possible to give the most recent figures as to opium consumption and distribution in the various countries. However, we feel that we have obtained enough information to uphold our case, and in any event, there is no doubt that the opium traffic, as fostered by the British Government, still continues. In looking over the list of British colonies where it is established, we may find here and there a diminution in the amount of opium consumed, but this is probably due to the exigencies of war, to the lack of shipping and transportation, rather than to any conscientious scruples or moral turnover; because the revenue derived from the opium trade is precious. In some instances, as in the case of the Straits Settlements, the local British Government derives from forty to fifty per cent of its revenue from this source. Yet, taken in relation to the whole, it is not large. However valuable it may be, however large the percentage in the case of any particular colony, it can surely never be large enough to compensate for the stigma attached. It is a blot upon the honor of a great nation to think that she deliberately runs her colonies on opium. No revenue, whether large or small, can be justified when coming from such a source as this.

In all these blue books and official reports, the question of the Opium Monopoly, as it is called, is dealt with freely. There is no attempt to hide or suppress the facts. The subject is reported frankly and fully. It is all there, for any one to read who chooses. How then, does it happen that we in America know nothing about Great Britain's Opium Monopoly? That the facts are new to us and come to us as a shock? One is because of our admiration for Great Britain. Those who know—and there are a few—hesitate to state them. Those who know, feel that it is a policy unworthy of her. We hesitate to call attention to the shortcomings of a friend. There are other reasons also for this conspiracy of silence—fear of international complications, fear of endangering the good feeling between the two countries, England and America. Consequently England has been able to rely upon those who know the facts to keep silent, either through admiration or through fear. Also the complete ignorance of the rest of us has been an additional safeguard. Therefore, for nearly a century, she has been running her Opium Monopoly undisturbed. It began as a private industry, about the time of the East India Company, but later on passed out of the hands of private individuals into the department of Opium Administration, one of the branches of the colonial government. But, loyal as we have been all these years, we can remain silent no longer. The time is now rapidly approaching when the two countries, England and America, are to become closely united. How can we become truly united, however, when on such a great moral question as this we stand diametrically opposed?

There is still another reason why we should break silence. The welfare of our own country is now at stake. The menace of opium is now threatening America, and our first duty is to ourselves. Little by little, surreptitiously, this drug has been creeping in over our borders, and to-day many thousands of our young men and young women are drug addicts, habituated to the use of one of the opium derivatives, morphia or heroin. The recent campaign against drug users, conducted by the New York Department of Health, has uncovered these addicts in great numbers; has brought them before us, made us see, in spite of ourselves, that thousands of them exist and that new ones are being created daily. The question arises, how do they obtain the drug? It was the fortune of the writer to be present during the first week of the opening of the Health Department Clinic for Drug Addicts, and her work consisted in taking the histories of these pitiful, abject wrecks of men and women who swarmed to the clinic in hundreds, seeking supplies of the drug which they could not obtain elsewhere. The history of these patients was almost invariably the same—there was a monotony in their tragic, pathetic recital as to how they became victims, how they first became acquainted with the drug. As a rule, they began in extreme youth, generally between fifteen and twenty years of age, one boy having begun at the age of thirteen. In nearly every case they had tried it as a lark, as an experiment. At "parties," they said, when some one of the company would pass round a box full of heroin, inviting them to snuff it. To snuff it, these children, very much as a small boy goes behind the barn to try his first cigarette. In many instances those who produced the box were peddlers, offering it as a gift at first, knowing that after a dose or two the fatal habit would be formed and another customer created. These peddlers doubtless obtained their supplies from smugglers. But that takes us back to our argument, namely, the part played by that great nation which grows and distributes opium to the world. For that nation produces an over-supply of opium, far more than is needed by the medical profession for the relief of pain. Opium is not profitable in its legitimate use. It is only profitable because of the demands of addicts, men and women deliberately debauched, either through the legalized machinery of colonial governments, or through the illegal activities of smugglers. A moral sentiment that will balk at this immense over-production, the sole object of which is to create drug victims, is the only weapon to fight it. In giving this book to the public, we are calling upon that moral sentiment. We feel that we shall number among our staunchest supporters that great body of men and women in England who have for years been vainly fighting the opium traffic. No more bitter opponents of this policy are to be found than amongst the English people themselves. From time to time, in Parliament, sharp debates have arisen as to the advisability of continuing it, and some of the greatest men in England have been steadfastly opposed. The great Gladstone has described it as "morally indefensible." The time has now come for us, people of both countries, to unite to stop it.

THE OPIUM MONOPOLY

I

GREAT BRITAIN'S OPIUM MONOPOLY

In a book shop in Shanghai, we came upon a small book with an arresting title, "Drugging a Nation," by Samuel Merwin. It was published in 1908, eight years before we chanced upon it, shabby and shop worn, its pages still uncut. The people of Shanghai, the great International Settlement of this largest city and most important seaport of China, did not have to read it. They knew, doubtless, all that its pages could disclose. We, however, found it most enlightening. In it there is this description of the British Opium Monopoly:

"In speaking of it as a 'monopoly' I am not employing a cant word for effect. I am not making a case. That is what it is officially styled in a certain blue book on my table which bears the title, 'Statement Exhibiting the Moral and Material Progress of India during the year 1905-'6,' and which was ordered by the House of Commons to be printed, May 10, 1907.... Now to get down to cases, just what this Government Opium Monopoly is, and just how does it work? An excerpt from the rather ponderous blue book will tell us. It may be dry but it is official and unassailable. It is also short.

"'The opium revenue'—thus the blue book—'is partly raised by a monopoly of the production of the drug in Bengal and the United provinces, and partly by the levy of a duty on all opium imported from native states.... In these two provinces, the crop is grown under the control of a government department, which arranges the total area which is to be placed under the crop, with a view to the amount of opium required.'

"So much for the broader outline. Now for a few of the details: 'The cultivator of opium in these monopoly districts receives a license, and is granted advances to enable him to prepare the land for the crop, and he is required to deliver the whole of the product at a fixed price to opium agents, by whom it is dispatched to the government factories at Patna and Ghazipur.'

"The money advanced to the cultivator bears no interest. The British Indian government lends money without interest in no other cases. Producers of crops other than opium are obliged to get along without free money.

"When it has been manufactured, the opium must be disposed of in one way and another; accordingly: 'The supply of prepared opium required for consumption in India is made over to the Excise Department ... the chests of "provision" opium, for export, are sold at monthly sales, which take place at Calcutta.' For the meaning of the curious term, 'provision opium' we have only to read on a little further. 'The opium is received and prepared at the government factories, where the out-turn of the year included 8,774 chests of opium for the Excise Department, about three hundred pounds of various opium alkaloids, thirty maunds of medical opium; and 51,770 chests of provision opium for the Chinese market.' There are about 140 pounds in a chest.... Last year the government had under poppy cultivation 654,928 acres. And the revenue to the treasury, including returns from auction sales, duties and license fees, and deducting all 'opium expenditures' was nearly $22,000,000."

As the blue book states, this opium is auctioned off once a month. At that point, the British Government, as a government, washes its hands of the business. Who buys the opium at these government auctions, and what afterwards becomes of it? "The men who buy in the opium at these monthly auctions and afterwards dispose of it are a curious crowd of Parsees, Mohammedans, Hindoos and Asiatic Jews. Few British names appear in the opium trade to-day. British dignity prefers not to stoop beneath the taking in of profits; it leaves the details of a dirty business to dirty hands. This is as it has been from the first. The directors of the East India Company, years and years before that splendid corporation relinquished the actual government of India, forbade the selling of its specially-prepared opium direct to China, and advised a trading station on the coast whence the drug might find its way 'without the company being exposed to the disgrace of being engaged in illicit commerce.'"

"So clean hands and dirty hands went into partnership. They are in partnership still, save that the most nearly Christian of governments has officially succeeded the company as party of the first part."

You will say, if the British Government chooses to deal in opium, that is not our concern. It is most emphatically our concern. Once a month, at these great auction sales, the British Government distributes thousands of pounds of opium, which are thus turned loose upon the world, to bring destruction and ruin to the human race. The buyers of this opium are not agents of the British Government. They are merely the distributors, through whom this drug is directed into the channels of trade. The British Government derives a certain portion of its revenue from the sale of opium, therefore depends upon these dealers to find a market for it. They are therefore, as distributors, the unofficial agents of the British Government, through whom it is sold legitimately, or smuggled around the world. In seeking to eradicate the drug evil, we must face the facts, and recognize clearly that the source of supply is the British Government, through whose agents, official and unofficial, it is distributed.

America, so they tell us, is now menaced by the drug evil. Now that prohibition is coming into effect, we are told that we are now confronted by a vice more terrible, far more deteriorating and dangerous. If that is true, then we must recognize our danger and guard against it. Some of the opium and morphia which reaches this country is smuggled in; the rest is imported by the big wholesale drug houses. There is an unlimited supply of it. As we have seen, the British Government encourages poppy production, even to the extent of lending money without interest to all those who are willing to raise this most profitable crop. The monopoly opium is sold once a month to the highest bidders, and some of these highest bidders are unscrupulous men who must find their markets how and where they can. That fact, of course, is of no moment to the British Government. It is of deepest concern to Americans, however. To the north of us we have the Dominion of Canada. To the south, the No-Man's Land of Mexico. At the present moment, the whole country is alarmed at the growing menace of the drug habit, which is assuming threatening proportions.

II

THE INDIAN OPIUM MONOPOLY

Let us quote from another dry official record, of unimpeachable veracity—the Statesman's Year-Book, for 1916. On page 140, under the heading of The British Empire: India and Dependencies, we read: "Opium. In British territory the cultivation of the poppy for the production of opium is mainly restricted to the United Provinces, and the manufacture of the opium from this region is a State monopoly. A limited amount is also grown in the Punjab for local consumption and to produce poppy seeds. In the monopoly districts the cultivator receives advances from Government to enable him to prepare the land for the crop, and he is bound to sell the whole of the produce at a fixed price to Government agents, by whom it is despatched to the Government factory at Ghazipur to be prepared for the market. The chests of manufactured opium are sold by auction in Calcutta at monthly sales. A reserve is kept in hand to supply the deficiencies of bad seasons, and a considerable quantity is distributed by the Indian excise departments. Opium is also grown in many of the Native States of Rajputana and Central India. These Native States have agreed to conform to the British system. No opium may pass from them into British territory for consumption without payment of duty.

"The bulk of the exports of opium from India has been to China. By arrangements with that country, the first one being in 1907, the exports from India have been limited, and provision made for the cessation of the export to China when the native Chinese production of opium shall be suppressed. The trade with China is now practically suspended."

The important things to notice in the above statement are these: The growing of poppies, the manufacture of opium, and the monthly auction sales continue. Also, the opium trade with China is practically at an end. The history of the opium traffic in China is a story complete in itself and will be dealt with in another chapter. At present, we must notice that the trade with China is practically suspended, but that the British Government is still auctioning off, once a month at Calcutta, great quantities of opium. Where does this opium go—who are the consumers? If not to China, then where?

The same reliable authority, the Statesman's Year-Book for 1918, has this to say on the subject. On page 130 we read: "Opium: In British territory the cultivation of the poppy for the production of opium is practically confined to the United Provinces, and the manufacture of opium from this region is a State monopoly. The bulk of the exported opium is at present either sent to the United Kingdom, or supplied direct to the Governments of consuming countries in the Far East; a certain quantity is also sold by auction in Calcutta at monthly sales. Opium is also grown in many of the Native States of Rajputana and Central India, which have agreed to conform to the British system." The following tables, taken from most reliable authority, give some idea of the exports to the "consuming countries of the Far East." Note that Japan began buying opium in 1911-12. We shall have something to say about the Japanese smuggling later. Also note that it was in 1907 that Great Britain and China entered into agreement, the outcome to be the suppression of the opium trade in China. But see the increasing imports into the treaty ports; up till almost the very last moment British opium being poured into China. In the second table, observe the increasing importation into England, (United Kingdom), synchronous with the increased exports to Japan, which will be discussed later.

STATISTICAL ABSTRACT RELATING TO BRITISH INDIA 1903-4 TO 1912-13

EXPORTS OF OPIUM

|

1903-4

£ |

1904-5

£ |

1905-6

£ |

1906-7

£ |

1907-8

£ |

1908-9

£ |

1909-10

£ |

1910-11

£ |

1911-12

£ |

1912-13

£ |

|

|

China

Treaty Ports |

1,610,296 | 1,504,604 | 1,130,372 | 1,031,065 | 1,215,147 | 2,703,871 | 1,234,432 | 2,203,670 | 3,614,887 | 3,242,902 |

| Hongkong | 3,576,431 | 4,036,436 | 3,775,826 | 3,771,409 | 3,145,403 | 2,230,755 | 3,377,222 | 3,963,264 | 3,019,858 | 2,400,084 |

|

Straits

Settlements |

1,365,743 | 1,262,834 | 1,163,529 | 1,150,506 | 1,169,018 | 1,032,220 | 1,234,763 | 1,692,053 | 1,099,801 | 704,870 |

| Java | 63,402 | 78,383 | 70,960 | 78,117 | 113,343 | 88,410 | 138,035 | 386,825 | 362,120 | 383,408 |

| Siam | 93,323 | 58,000 | 47,062 | 30,150 | 4,383 | 17,533 | 0 | 10,217 | 190,657 | 263,177 |

| Macao | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 236,420 |

| Japan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 76,817 | 129,545 |

|

French

Indo-China |

212,247 | 76,333 | 50,345 | 52,673 | 84,742 | 118,933 | 207,287 | 207,722 | 325,500 | 99,018 |

|

Other

Countries |

58,668 | 65,705 | 76,418 | 82,361 | 49,616 | 41,107 | 17,366 | 45,565 | 36,420 | 15,659 |

| Total | 6,980,110 | 7,082,295 | 6,314,512 | 6,205,281 | 5,781,652 | 6,232,829 | 6,209,105 | 8,509,316 | 8,726,060 | 7,481,088 |

| Page 196 | Table 170 | Congressional Library HA 1713-A3-Ref. |

From Statistical Abstract Relating to British India, 1905-6 to 1911-15.

Page 181. Table 164. Exports of Opium to Various Countries.

| 1910-11 | 1911-12 | 1912-13 | 1913-14 | 1914-15 | ||

| French Indo-China | £129,502 | 291,425 | ||||

| Java | 472,199 | 282,252 | ||||

| Siam | 164,030 | 204,328 | ||||

| China-Hongkong | 1,084,093 | 110,712 | ||||

| Straits Settlements | 226,500 | 80,572 | ||||

| United Kingdom | 927 | 2,907 | 1,180 | 18,433 | 58,148 | |

| Treaty Ports, China | 27,833 | 0 | ||||

| Macao | 18,295 | 0 | ||||

| Japan | 119,913 | 100,659 | ||||

| Other countries | 19,223 | 47,543 | ||||

| Total | £2,280,031 | 1,175,639 | ||||

III

JAPAN AS AN OPIUM DISTRIBUTOR

In an article which appeared in the New York Times, under date of February 14, 1919, we read: "A charge that the Japanese Government secretly fosters the morphia traffic in China and other countries in the Far East is made by a correspondent in the North China Herald in its issue of December 21st last. The correspondent asserts that the traffic has the financial support of the Bank of Japan, and that the Japanese postal service in China aids, although 'Japan is a signatory to the agreement which forbids the import into China of morphia or of any appliances used in its manufacture or application.'

"Morphia no longer can be purchased in Europe, the correspondent writes. The seat of industry has been transferred to Japan, and morphia is now manufactured by the Japanese themselves. Literally, tens of millions of yen are transferred annually from China to Japan for the payment of Japanese morphia....

"In South China, morphia is sold by Chinese peddlers, each of whom carries a passport certifying that he is a native of Formosa, and therefore entitled to Japanese protection. Japanese drug stores throughout China carry large stocks of morphia. Japanese medicine vendors look to morphia for their largest profits. Wherever Japanese are predominant, there the trade flourishes. Through Dairen, morphia circulates throughout Manchuria and the province adjoining; through Tsingtao, morphia is distributed over Shantung province, Anhui, and Kiangsu, while from Formosa morphia is carried with opium and other contraband by motor-driven fishing boats to some point on the mainland, from which it is distributed throughout the province of Fukien and the north of Kuangtung. Everywhere it is sold by Japanese under extra-territorial protection."

The article is rather long, and proves beyond doubt the existence of a well-organized and tremendous smuggling business, by means of which China is being deluged with morphia. In the body of the article we find this paragraph:

"While the morphia traffic is large, there is every reason to believe that the opium traffic upon which Japan is embarking with enthusiasm, is likely to prove even more lucrative. In the Calcutta opium sales, Japan has become one of the considerable purchasers of Indian opium.... Sold by the Government of India, this opium is exported under permits applied for by the Japanese Government, is shipped to Kobe, and from Kobe is transshipped to Tsingtao. Large profits are made in this trade, in which are interested some of the leading firms of Japan."

This article appears to be largely anti-Japanese. In fact, more anti-Japanese than anti-opium. Anti-Japanese sentiment in America is played upon by showing up the Japanese as smugglers of opium. The part the British Government plays in this traffic is not emphasized. "In the Calcutta opium sales, Japan has become one of the considerable purchasers of Indian opium ... sold by the Government of India." We are asked to condemn the Japanese, who purchase their stocks of opium as individuals, and who distribute it in the capacity of smugglers. We are not asked to censure the British Government which produces, manufactures and sells this opium as a State monopoly. We are asked to denounce the Japanese and their nefarious smuggling and shameful traffic, but the source of supply, which depends upon these smugglers as customers at the monthly auctions, is above reproach. A delicate ethical distinction.

However, there is no doubt that the Japanese are ardent smugglers. In an article in the March, 1919, number of "Asia" by Putnam Weale, we find the following bit: 1 "At all ports where Japanese commissioners of Maritime Customs (in China) hold office, it is undeniable that centres of contraband trade have been established, opium and its derivatives being so openly smuggled that the annual net import of Japanese morphia (although this trade is forbidden by International Convention) is now said to be something like 20 tons a year—sufficient to poison a whole nation."

Mr. Weale is an Englishman, therefore more anti-Japanese than anti-opium. We do not recall any of his writings in which he protests against the opium trade as conducted by his Government, nor the part his Government plays in fostering and encouraging it.

However, there are other Englishmen who see the situation in a more impartial light, and who are equally critical of both Great Britain and Japan. In his book, "Trade Politics and Christianity in Africa and the East," by A. J. Macdonald, M.A., formerly of Trinity College, Cambridge, we find the facts presented with more balance. Thus, on page 229: "... In the north of China another evil is springing up. The eradication of the opium habit is being followed by the development of the morphia traffic.... The morphia habit in northern China, especially Manchuria, is already widespread. The Chinese Government is alert to the evil, but their efforts to repress it are hampered by the action of traders, mainly Japanese, who elude the restrictions imposed by the Chinese and Japanese Governments.... China is being drenched with morphia. It is incredible that anything approaching the amount could possibly be devoted to legitimate purposes. It is said that in certain areas coolies are to be seen 'covered all over with needle punctures.' An injection of the drug can be obtained for three or four cents. In Newchang 2,000 victims of the morphia habit died in the winter of 1914-15. Morphia carries off its victims far more rapidly than opium.... Morphia is not yet manufactured in any appreciable quantities in the East, and certainly even Japan cannot yet manufacture the hypodermic injectors by means of which the drug is received. The bulk of the manufacture takes place in England, Germany and Austria.... In this traffic, two firms in Edinburgh and one in London are engaged. The trade is carried on through Japanese agents. The Board of Trade returns show that the export of morphia from Great Britain to the East has risen enormously during the last few years—

| 1911 | 5½ | tons | |

| 1912 | 7½ | " | |

| 1913 | 11¼ | " | |

| 1914 | 14 | " |

"... The freedom which allows three British firms to supply China with morphia for illicit purposes is a condemnation of English Christianity."

This book of Mr. Macdonald's was published in 1916. Mr. Weale's article was published in 1919, in which he speaks of an importation of about twenty tons of morphia. Apparently the three British firms which manufacture morphia, two in Edinburgh and one in London are still going strong. Japan, however, appears to be growing impatient with all this opprobrium cast upon her as the distributor of drugs, especially since much of the outcry against this comes from America. Our own country seems to be assisting in this traffic in a most extensive manner. The Japan Society Bulletin No. 60 calls attention to this:

NEW TURN IN MORPHIA TRAFFIC

The morphia traffic in China has taken a new turn, according to the Japan Advertiser. It quotes Putnam Weale to the effect that whilst in recent years the main distributors have been Japanese, the main manufacturers have been British. The morphia has been exported in large quantities from Edinburgh to Japan, but as the result of licensing the exports of this drug from Great Britain, the shipments to Japan dropped from 600,229 ounces in 1917 to one-fourth that amount in 1918. The Japan Chronicle, speaking from "absolutely authentic information," states that 113,000 ounces of morphia arrived in Kobe from the United States in the first five months of 1919. These figures are not given as the total shipments received in Kobe, but merely as the quantity of which The Chronicle has actual knowledge. It states further that this morphia is being transhipped in Kobe harbor to vessels bound for China. Dr. Paul S. Reinsch, who has resigned his post as Minister to China, has stated that he will use every resource in his power to stop the shipment from America of morphia intended for distribution in China, in defiance of the international convention which prohibits the sale of the drug in that country.

If sufficient publicity is cast upon the distributors, Japanese, English and American, public sentiment may in time take cognizance of the source of all this mischief, namely, the producer.

1 "A Fair Chance for Asia," by Putnam Weale, page 227.

IV

SINGAPORE

In January, 1917, we found ourselves at Singapore, a British dependency, situated at the end of the Malay Peninsula, and one of the greatest seaports of the Orient. We were stopping at the Hotel de l'Europe, a large and first class hotel. The first morning at breakfast, the waiter stood beside us, waiting for our order. He was a handsome young Malay, dressed in white linen clothes, and wearing a green jade bracelet on one wrist. We gave him our order and he did not move off. He continued to stand quietly beside our chairs, as in a trance. We repeated the order—one tea, one coffee, two papayas. He continued to stand still beside us, stupidly. Finally he went away. We waited for a long time and nothing happened. At last, after a long wait, he returned and set before us a teapot filled with hot water. Nothing else. We repeated again—tea, coffee, papayas. We said it two or three times. Then he went away and came back with some tea. We repeated again, coffee and fruit. Eventually he brought us some coffee. Finally, after many endeavors, we got the fruit. It all took a long time. We then began to realize that something was the matter with him. He could understand English well enough to know what orders we were giving him, but he seemed to forget as soon as he left our sight. We then realized that he was probably drugged. It was the same thing every day. In the morning he was stupid and dull, and could not remember what we told him. By evening his brain was clearer, and at dinner he could remember well enough. The effects of whatever he had been taking had apparently worn off during the day.

We learned that the opium trade was freely indulged in, at Singapore, fostered by the Government. Singapore is a large city of about 300,000 inhabitants, a great number of which are Chinese. It has wide, beautiful streets, fine government buildings, magnificent quays and docks—a splendid European city at the outposts of the Orient. We found that a large part of its revenue is derived from the opium traffic—from the sale of opium, and from license fees derived from shops where opium may be purchased, or from divans where it may be smoked. The customers are mainly Chinese.

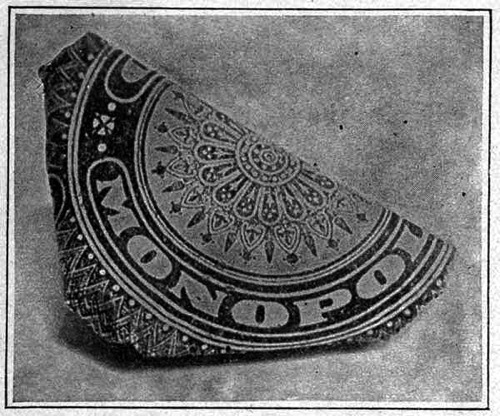

I wanted to visit these Government-licensed opium shops and opium dens. A friend lent me two servants, as guides. We three got into rickshaws and went down to the Chinese quarter, where there are several hundred of these places, all doing a flourishing business. It was early in the afternoon, but even then, trade was brisk. The divans were rooms with wide wooden benches running round the sides, on which benches, in pairs, sharing a lamp between them, lay the smokers. They purchased their opium on entering, and then lay down to smoke it. The packages are little, triangular packets, each containing enough for about six smokes. Each packet bears a label, red letters on a white ground, "Monopoly Opium."

In one den there was an old man—but you can't tell whether a drug addict is old or not, he looked as they all do, gray and emaciated—but as he caught my eye, he laid down the needle on which he was about to cook his pill, and glanced away. I stood before him, waiting for him to continue the process, but he did not move.

"Why doesn't he go on?" I asked my guide. "He is ashamed to have you see him," came the reply.

"But why should he be ashamed?" I asked, "The British Government is not ashamed to sell to him, to encourage him to drug himself, to ruin himself. Why should he be ashamed?"

"Nevertheless, he is," replied the guide. "You see what he looks like—what he has become. He is not quite so far gone as the others—he is a more recent victim. He still feels that he has become degraded. Most of them do not feel that way—after a while."

So we went on and on, down the long street. There was a dreadful monotony about it all. House after house of feeble, emaciated, ill wrecks, all smoking Monopoly Opium, all contributing, by their shame and degradation, to the revenues of the mighty British Empire.

Packet of opium, actual size, as sold in licensed opium shop in Singapore. The local government here derives from forty to fifty per cent of its revenue through the sale of opium.

That evening after dinner, I sat on the wide verandah of the hotel, looking over a copy of the "Straits Times." One paragraph, a dispatch from London, caught my eye. "Chinese in Liverpool. Reuter's Telegram. London, January 17, 1917. Thirty-one Chinese were arrested during police raids last night on opium dens in Liverpool. Much opium was seized. The police in one place were attacked by a big retriever and by a number of Chinese, who threw boots and other articles from the house-top."

Coming fresh from a tour of the opium-dens of Singapore, I must say that item caused some mental confusion. It must also be confusing to the Chinese. It must be very perplexing to a Chinese sailor, who arrives in Liverpool on a ship from Singapore, to find such a variation in customs. To come from a part of the British Empire where opium smoking is freely encouraged, to Great Britain itself where such practices are not tolerated. He must ask himself, why it is that the white race is so sedulously protected from such vices, while the subject races are so eagerly encouraged. It may occur to him that the white race is valuable and must be preserved, and that subject races are not worth protecting. This double standard of international justice he must find disturbing. It would seem, at first glance, as if subject races were fair game—if there is money in it. Subject races, dependents, who have no vote, no share in the government and who are powerless to protect themselves—fair game for exploitation. Is this double-dealing what we mean when we speak of "our responsibility to backward nations," or of "the sacred trust of civilization" or still again when we refer to "the White Man's burden"?

Pondering over these things as I sat on the hotel verandah, I finally reached the conclusion that to print such a dispatch as that in the "Straits Times" was, to say the least, most tactless.

V

THE STRAITS SETTLEMENTS OPIUM COMMISSION

From time to time, certain people in England apparently have qualms as to Great Britain's opium traffic, and from time to time questions are raised as to whether or not such traffic is morally defensible. In February, 1909, apparently in answer to such scruples and questionings on the part of a few, a very interesting report was published, "Proceedings of the Commission appointed to Enquire into Matters Relating to the Use of Opium in the Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay States. Presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of His Majesty." This document may be found in the New York Public Library and is well worth careful perusal.

This Commission consisted of about a dozen men, some English, some natives of the Straits Settlements. They apparently made an intensive and exhaustive study of the subject, carefully examining it from every angle. Countless witnesses appeared before them, giving testimony as to the effects of opium upon the individual. This testimony is interesting, in that it is of a contradictory nature, some witnesses saying that moderate opium indulgence is nothing worse than indulgence in alcoholic beverages, and like alcohol, only pernicious if taken to excess. Other witnesses seemed to think that it was most harmful. The Commission made careful reports as to the manner of licensing houses for smoking, the system of licensing opium farms, etc., and other technical details connected with this extensive Government traffic. Finally, the question of revenue was considered, and while the harmfulness of opium smoking was a matter of divided opinion, when it came to revenue there was no division of opinion at all. As a means of raising revenue, the traffic was certainly justifiable. It was proven that about fifty per cent of the revenues of the Straits Settlements and the Federated Malay States came from the opium trade, and, as was naïvely pointed out, to hazard the prosperity of the Colony by lopping off half its revenues, was an unthinkable proceeding.

The figures given are as follows.

| 1898 | Revenue derived from Opium | 45.9 per cent |

| 1899 | 44.8 | |

| 1900 | 43.3 | |

| 1901 | 53.2 | |

| 1902 | 48.3 | |

| 1903 | 47.1 | |

| 1904 | 59.1 | |

| 1905 | 46. | |

| 1906 | 53.3 |

There was one dissenting voice as to the conclusions reached by this Opium Commission, that of a Bishop who presented a minority report. But what are moral scruples against cold facts—that there's money in the opium trade?

This Commission made its report in 1909. But the opium business is apparently still flourishing in the Straits Settlements. Thus we read in the official Blue Book for 1917, "Colony of the Straits Settlements" that of the total revenue for the year, $19,672,104, that $9,182,000 came from opium.

What per cent is that?

VI

OPIUM IN SIAM

Bangkok, Siam, January, 1917. Siam, an independent kingdom. As a matter of fact, "protected" very sternly and thoroughly by Great Britain and France, so that its "independence" would about cover an oyster cracker. However, it is doubtless protected "benevolently" for what protectorate is anything but benevolent? The more rigorous the protectorate, the more benevolent its character. The Peace Conference seems to have given us a new word in "mandatory." We do not know as yet what adjective will be found to qualify mandatory, but it will doubtless be fitting and indicative of idealism—of sorts. Therefore, all will be well. Our suspicions will be lulled. It is high time that a substitute was found for "benevolent protectorate."

The particular form of benevolence noted in Siam was the total inability of the Siamese to exclude British opium. They are allowed, by the benevolent powers, to impose an import duty on all commodities imported—except opium. That is free. The treaty between Siam and Great Britain in 1856 says so. We rather fancy that Great Britain had more to say about this in 1856 than Siam, but maybe not. Anyway, poor old Siam, an independent kingdom, is bound to receive as much opium as may be imported, and is quite powerless, by the terms of this treaty, to enact laws to exclude it. In the last year or two, the Government of Siam has been obliged to put the opium traffic under government control, in order to minimize the worst evils in connection with it, although to restrict and regulate an evil is a poor substitute for the ability to abolish it.

All this, you will see, is rather tough on the Siamese, but good business for the British Empire.

However, opium is not bad for one. There are plenty of people to testify to that. We Americans have a curious notion to the contrary, but then, we Americans are so hysterical and gullible. An Englishman whom we met in Bangkok told me that opium was not only harmless, but actually beneficial. He said once that he was traveling through the jungle, into the interior somewhere. He had quite a train of coolies with him, carrying himself and his baggage through the dense forests. By nightfall, he found his coolies terribly exhausted with the long march. But he was in a hurry to press on, so, as he expressed it, he gave each of them a "shot" of morphia, whereupon all traces of fatigue vanished. They forgot the pain of their weary arms and legs and were thus enabled to walk all night. He said that morphia certainly knocked a lot of work out of men—you might say, doubled their capacity for endurance.

The night we left Bangkok, we got aboard the boat at about nine in the evening. The hatch was open, and we looked into the hold upon a crowd of coolies who had been loading sacks of rice aboard the ship. There they lay upon the rice sacks, two or three dozen of them, all smoking opium. Two coolies to a lamp. I rather wondered that a lamp did not upset and set the boat on fire, but they are made of heavy glass, with wide bottoms, so that the chances of overturning them are slight. So we leaned over the open hatch, looking down at these little fellows, resting and recuperating themselves after their work, refreshing themselves for the labor of the morrow.

Opium is wonderful, come to think of it. But why, since it is so beneficial and so profitable, confine it to the downtrodden races of the world? Why limit it to the despised races, who have not sense enough to govern themselves anyway?

The following figures are taken from the Statistical Year Books for the Kingdom of Siam:

Foreign trade and navigation of the port of Bangkok, imports of opium:

| 1911-12 | 1,270 | chests of opium |

| 1912-13 | 1,775 | |

| 1913-14 | 1,186 | |

| 1914-15 | 2,000 | Imported from India and Singapore. |

| 1915-16 | 2,000 | |

| 1916-17 | 1,100 | |

| 1917-18 | 1,850 | |

Also, from the same source, we find the number of retail opium shops:

| 1912-13 | 2,985 |

| 1913-14 | 3,025 |

| 1914-15 | 3,132 |

| 1915-16 | 3,104 |

| 1916-17 | 3,111 |

VII

HONGKONG

"The Crown Colony of Hongkong was ceded by China to Great Britain in January, 1841; the cession was confirmed by the treaty of Nanking in August, 1842; and the charter bears date April 5, 1843. Hongkong is the great center for British commerce with China and Japan, and a military and naval station of first-class importance."

Thus the Statesman's Year Book. This authority, however, omits to mention just exactly how this important piece of Chinese territory came to be ceded to Great Britain. It was the reward that Great Britain took unto herself as an "indemnity" following the successful prosecution of what is sometimes spoken of as the first opium war—a war of protest on the part of China against Great Britain's insistence on her right to deluge China with opium. China's resistance was in vain—her efforts to stem the tide of opium were fruitless—the might, majesty, dominion and power of the British Empire triumphed, and China was beaten. The island on which Hongkong is situated was at that time a blank piece of land; but strategically well placed—ninety miles south of the great Chinese city of Canton, the market for British opium.

The opposite peninsula of Kowloon, on the mainland, was ceded to Great Britain by treaty in 1861, and now forms part of Hongkong. By a convention signed at Peking in June, 1898, there was also leased to Great Britain for 99 years a portion of Chinese territory mainly agricultural, together with the waters of Mirs Bay and Deep Bay, and the island of Lan-tao. Its area is 356 square miles, with about 91,000 inhabitants, exclusively Chinese. Area of Old Kowloon is 3 square miles. Total area of colony, 391 square miles.

The population of Hongkong, excluding the Military and Naval establishments, and that portion of the new territory outside New Kowloon, was according to the 1911 census, 366,145 inhabitants. Of this number the Chinese numbered 354,187.

This colony is, of course, governed by Great Britain, and is not subject to Chinese control. Here is situated a Government opium factory, and the imports of Indian opium into Hongkong for the past several years are as follows:

| 1903- 4 | 3,576,431 | pounds sterling |

| 1904- 5 | 4,036,436 | |

| 1905- 6 | 3,775,826 | |

| 1906- 7 | 3,771,409 | |

| 1907- 8 | 3,145,403 | |

| 1908- 9 | 2,230,755 | |

| 1909-10 | 3,377,222 | |

| 1910-11 | 3,963,264 | |

| 1911-12 | 3,019,858 | |

| 1912-13 | 2,406,084 | |

| 1913-14 | 1,084,093 | |

| 1914-15 | 110,712 |

These figures are taken from "Statistical Abstract Relating to British India, 1905-6 to 1911-15," and "Statistical Abstract Relating to British India, 1903-4 to 1912-13." The falling off in imports of opium noticed in 1914-15 may be due to the war, lack of shipping, etc., or to the fact that the China market was due to close on April 1, 1917. The closing of the China market—400,000,000 of people destined no longer to have opium supplied to them (except illegally, by smuggling, etc.) is naturally a big blow to the British opium interests. That is where the menace to the rest of the world comes in. Opium has been proved such a profitable commodity, that if one market is shut off, others must be found as substitutes. The idea of closing the trade altogether naturally does not appeal to those who profit by it. Therefore, what we should hail at first sight as a welcome indication of a changed moral sentiment, is in reality but the pause which proceeds the casting about for new markets, for finding new peoples to drug.

The Colonial Report No. 972, Hongkong Report for 1917, gives the imports and exports of opium: Page 7—

"The imports and exports of certified opium during the year as follows:

| Imports | 7 | chests |

| Export | 224 | chests |

Of these, however, the imports all come from Shanghai, and of the total export of 224 chests, 186 went to Shanghai."

Opium received from other sources than Shanghai makes a better showing. "Seven hundred and forty chests of Persian opium imported during the year, and seven hundred and forty-five exported to Formosa. Nine hundred and ten chests of uncertified Indian opium were imported: Four hundred and ten chests by the Government Monopoly, and the remaining five hundred for the Macao opium farmer."

Macao is a small island off the coast of China, near Canton—a Portuguese settlement, owned by Portugal for several centuries, where the opium trade is in full blast. But somehow, one does not expect so much of Portugal. The most significant feature of the above paragraph, however, lies in the reference to the importation of Persian opium. "Seven hundred and forty chests of Persian opium imported." Query, who owns Persia?

Nevertheless, in spite of this poor showing, in spite of the decrease in opium importation as compared with the palmy days, all is not lost. The Crown Colony of Hongkong still continues to do an active trade. In the Colonial Office List for 1917, on page 218, we read:

"Hongkong. Revenue: About one-third of the revenue is derived from the Opium Monopoly."

VIII

SARAWAK

Near British North Borneo. Area, 42,000 square miles, many rivers navigable. The government of part of the present territory was obtained in 1842 by Sir James Brooke from the Sultan of Brunei. Various accessions were made between 1861, 1885, and 1890. The Rajah, H.H. Sir Charles Johnson Brooke, G.C.M.G., nephew to the late Rajah, born June 3, 1829, succeeded in 1868. Population estimated at 500,000, Malays, Dyaks, Kayans, Kenyahs, and Muruts, with Chinese and other settlers.

Thus the Statesman's Year Book, to which we would add a paragraph from an article in the National Geographic Magazine for February, 1919. Under the title: "Sarawak: The Land of the White Rajahs" we read: "With the recent death of Sir Charles Brooke, G.C.M.G., the second of the white rajahs of Sarawak, there came to an end one of the most useful and unusual careers among the many that have done credit to British rule in the Far East. For nearly 49 years he governed, as absolute sovereign, a mixed population of Chinese, Malays, and numerous pagan tribes scattered through the villages and dense jungles of an extensive territory on the northwest coast of Borneo.

"Constant solicitude for the welfare of his people won the sympathy and devotion which enabled this white man, supported by an insignificant army and police, to establish the peaceful occupations of civilization in place of barbarous tyranny and oppression." How thoroughly this "civilizing" process was accomplished may be judged somewhat by turning to the Colonial Office List for 1917, where on page 436 we read: "Sarawak: The principal sources of revenue are the opium, gambling, pawn shops, and arrack, producing:

| 1908 | $483,019 |

| 1909 | 460,416 |

| 1910 | 385,070 |

| 1911 | 420,151 |

| 1912 | 426,867 |

| 1913 | 492,455 |

In the Statesman's Year Book for 1916 we find the total revenue for this well-governed little colony as follows, given however in pounds sterling, instead of dollars, as in the above table. Thus:

| Revenue— | 1910 | 221,284 pounds sterling |

| 1911 | 159,456 | |

| 1912 | 175,967 | |

| 1913 | 210,342 | |

| 1914 | 208,823 |

It would seem as if forty-nine years of constant solicitude for the welfare of a people, establishing the peaceful occupations of civilization, might have resulted in something better than a revenue derived from opium, gambling, pawn shops and arrack.

IX

SHANGHAI

In the New York Library there is an interesting little book, about a quarter of an inch thick, and easy reading. It is entitled: "Municipal Ethics: Some Facts and Figures from the Municipal Gazette, 1907-1914. An Examination of the Opium License policy of the Shanghai Municipality. In an Open Letter to the Chairman of the Council, by Arnold Foster, Wuchang. For 42 years Missionary to the Chinese."

Shanghai, being a Treaty Port, is of two parts. The native or Shanghai city, under the control and administration of the Chinese. And the foreign concessions, that part of the city under the control and administration of foreigners. This is generally known as the International Settlement (also called the model settlement), and the Shanghai Municipal Council is the administrative body. Over this part the Chinese have no control. In 1907, when China began her latest fight against the opium evil, she enacted and enforced drastic laws prohibiting opium smoking and opium selling on Chinese soil, but was powerless to enforce these laws on "foreign" soil. In the foreign concessions, the Chinese were able to buy as much opium as they pleased, merely by stepping over an imaginary line, into a portion of the town where the rigid anti-opium laws of China did not apply.

Says Mr. Arnold, in his Open Letter: "It will be seen that the title of the pamphlet, Municipal Ethics, describes a situation which is a complex one. It concerns first the actual attitude of the Shanghai Municipal Council towards the Chinese national movement for the suppression of the use of opium. This, we are assured by successive Chairmen of the Council, has been one of "sincere sympathy," "the greatest sympathy," and more to the same effect. Certainly no one would have guessed this from the facts and figures reproduced in this pamphlet from the columns of the "Municipal Gazette."

"The second element in the ethical situation is the actual attitude of the Council not only towards the Chinese national movement, but also towards its own official assurances, protestations and promises.

"It is on this second branch of the subject before us that I specially desire to focus attention, and for the facts here stated that I would bespeak the most searching examination. The protestations of the Council as to its own virtuous attitude in regard to opium reform in China are made the more emphatic, and also the more open to criticism, by being coupled with some very severe insinuations made at the time, as to the insincerity and unreliability of the Chinese authorities in what they were professing, and in what they were planning to do in the same matter of opium reform. It so happens, as the event proves, that these sneers and insinuations were not only quite uncalled for, but were absolutely and utterly unjust. When a comparison is instituted between (a) 'official pronouncements' made two years ago by the Chinese authorities as to what they then intended to do for the suppression of the opium habit, and (b) the 'actual administrative results' that in the meanwhile have been accomplished, the Chinese have no cause to be ashamed of the verdict of impartial judges. What they have done may not always have been wise, it may sometimes have been very stern, but the outcome has been to awaken the astonishment and admiration of the whole civilized world! When, on the other hand, a comparison is instituted between (a) the fine professions and assurances of the Shanghai Municipal Council made six or seven years ago as to its own attitude towards the 'eradication of the opium evil' and (b) the 'actual administrative results' of the Council's own proceedings, the feelings awakened are of very different order. Here, not to mention any other consideration, two hard facts stare one in the face: First, in October, 1907, there were eighty-seven licensed opium shops in the International Settlement. In May, 1914, there were six hundred and sixty-three. In 1907 the average monthly revenue from opium licenses, dens and shops combined, was Taels 5,450. In May, 1914, the revenue from licenses and opium shops alone was Taels 10,995. The Council will not dispute these figures."

At the beginning of the anti-opium campaign in 1907, there were 700 dens (for smoking) in the Native City, and 1600 in the International Settlement. The Chinese closed their dens and shops at once. In the Settlement, the dens were not all closed until two years later, and the number of shops in the Settlement increased by leaps and bounds. Table I shows an outline of the Municipal opium-shop profits concurrent with the closing of the opium houses—and subsequently:

| Year | Month | Dens | Shops | Monthly revenue, shops only |

| 1908 | Jan. | 1436 | 87 | Taels, 338 |

| Oct. | 1005 | 131 | 623 | |

| 1909 | Jan. | 599 | 166 | 1,887 |

| Oct. | 297 | 231 | 2,276 | |

| 1910 | Oct. | Closed | 306 | 5,071 |

| 1911 | Oct. | 348 | 5,415 | |

| 1912 | Nov. | 402 | 5,881 | |

| 1913 | Dec. | 560 | 8,953 | |

| 1914 | March | 628 | 10,188 | |

| April | 654 | 10,772 |

Mr. Arnold quotes part of a speech made by the Chairman of the Municipal Council, in March, 1908. The Chairman says in part: "The advice which we have received from the British Government is, in brief, that we should do more than keep pace with the native authorities, we should be in advance of them, and where possible, encourage them to follow us." It must have been most disheartening to the native authorities, suppressing the opium traffic with the utmost rigor, to see their efforts defied and nullified by the increased opportunities for obtaining opium in that part of Shanghai over which the Chinese have no control. A letter from a Chinese to a London paper, gives the Chinese point of view: "China ... is obliged to submit to the ruthless and heartless manner in which British merchants, under the protection of the Shanghai 'Model Settlement' are exploiting her to the fullest extent of their ability."

There is lots of money in opium, however. The following tables compiled by Mr. Arnold show the comparison between the amount derived from opium licenses as compared with the amount derived from other sorts of licenses.

| 1913. | Wheelbarrows | Taels, | 38,670 | ||

| Carts | 22,944 | ||||

| Motor cars | 12,376 | ||||

| Cargo boats | 5,471 | ||||

| Chinese boats | 4,798 | ||||

| Steam launches | 2,221 | Total, | 86,480 | ||

| Opium shops | 86,386 | Opium, | 86,386 |

Another table shows the licensed institutions in Shanghai representing normal social life (chiefly of the Chinese) as compared with revenue from opium shops:

| 1913. | Tavern | Taels, | 16,573 | |

| Foreign liquor seller | 19,483 | |||

| Chinese | wine shop | 28,583 | ||

| " | tea shop | 9,484 | ||

| " | theater | 8,714 | ||

| " | club | 3,146 | ||

| Total | 85,983 | |||

| Opium shops | 86,386 | |||

Treaty Ports are those cities in China, in which the foreign powers have extra-territorial holdings, not subject to Chinese jurisdiction. Shanghai is one of them, the largest and most important. The Statistical Abstract Relating to British India for 1903-4 to 1912-13 shows the exports of British opium into these Treaty Ports.

| 1903- 4 | 1,610,296 pounds sterling | ||

| 1904- 5 | 1,504,604 | ||

| 1905- 6 | 1,130,372 | ||

| 1906- 7 | 1,031,065 | ||

| 1907- 8 | 1,215,142 | ||

| 1908- 9 | 2,703,871 | ||

| 1909-10 | 1,234,432 | ||

| 1910-11 | 2,203,670 | ||

| 1911-12 | 3,614,887 | ||

| 1912-13 | 3,242,902 |

It was in 1907 that China began her great fight against the opium evil, and enacted stringent laws for its prohibition on Chinese soil. On page 15 of his little book, Mr. Arnold quotes from Commissioner Carl, of Canton: "The 1912 figure (for the importation of foreign opium) is the largest on record since 1895. The great influx of Chinese into the foreign concessions, where the anti-opium smoking regulations cannot be enforced by the Chinese authorities, and where smoking can be indulged in without fear of punishment, no doubt accounts for the unusual increase under foreign opium."

X

INDIA

India is the source and fount of the British opium trade, and it is from Indian opium that the drug is chiefly supplied to the world. As we have said before, it is a government monopoly. Cultivators, who wish to plant poppies, may borrow money from the Government free of interest, the sole condition being that the crop be sold back to the Government again. It is manufactured into opium at the Government factory at Ghazipur, and once a month, the Government holds auctions at Calcutta, by means of which the drug finds its way into the trade channels of the world—illicit and otherwise. 2

The following facts are taken from "Statistics of British India. Financial Statistics, Volume II, Eighth Issue," to be found at the New York Public Library:

Area under Poppy Cultivation

| Acreage: | 1910-11 | 362,868 | |

| 1911-12 | 200,672 | ||

| 1912-13 | 178,263 | ||

| 1913-14 | 144,561 | ||

| 1914-15 | 164,911 | ||

| 1915-16 | 167,155 | ||

| 1916-17 | 204,186 |

In the hey-day of the China trade, 613,996 acres were under cultivation in the years 1905-6, consequently this is a drop in the extent of acreage. But, as we have said before, the closing of the China market simply means that other outlets must be found, and apparently they are being found, since from 1914 onwards, the acreage devoted to poppy planting is slowly increasing again.

The opium manufactured in the Government factory is of three kinds—provision opium for export; excise opium, for consumption in India, and medical opium, for export to London. It is this latter form of opium which, according to Mr. MacDonald, in his "Trade Politics and Christianity in Africa and the East" is being manufactured into morphia by three British firms, two in Edinburgh and one in London, which morphia the Japanese are buying and smuggling into North China.

The "Statistics of British India" shows the countries into which Indian opium has been exported: we will take the figures for the last five years, which show the number of chests sent out.

| 1912-13 | 1913-14 | 1914-15 | 1915-16 | 1916-17 | |

| China | 19,575 | 4,061 | 1,000 | 734 | 500 |

| Straits Settlements | 5,098 | 1,537 | 755 | 605 | 239 |

| United Kingdom | 11 | 115 | 498 | 199 | 0 |

| Mauretius | 10 | 19 | 23 | 65 | 120 |

| Ceylon | 50 | 105 | 80 | 65 | 80 |

| Cochin-China | 805 | 875 | 2,690 | 2,035 | 3,440 |

| Java | 3,010 | 3,265 | 2,650 | 1,835 | 1,965 |

| Other countries | 2,815 | 1,929 | 3,160 | 3,248 | 2,366 |

| Total | 31,374 | 11,906 | 10,858 | 8,786 | 8,710 |

In some countries we see a falling off, as in China. Cochin-China, the French colony, shows a considerable increase—the little Annamites, Tonquinese, Cambodgians and other inhabitants of this colony of the French Republic being shown what's what. Mauretius, a British Colony five hundred miles off the coast of Madagascar, in the Indian ocean, seems to be coming on. The falling off in shipments to the United Kingdom may possibly have been due to the war and the scarcity of ships. "Other countries" seem to be holding their own. With the end of the war, the increase in ships, and general trade revival, we may yet see compensation for the loss of China. With the increase of drug addicts in the United States, it may be that in time America will no longer be classed under "other countries" but will have a column all to itself.

In another table we find a comparison as to the number of chests of provision or export opium and of excise opium, or that intended for consumption in India. Thus:

| Provision Opium | Excise Opium | |||

| 1910-11 | 15,000 | chests | 8,611 | chests |

| 1911-12 | 14,000 | 9,126 | ||

| 1912-13 | 7,000 | 9,947 | ||

| 1913-14 | 12,000 | 8,307 | ||

| 1914-15 | 10,000 | 8,943 | ||

| 1915-16 | 12,000 | 8,391 | ||

| 1916-17 | 12,000 | 8,732 | ||

Each chest contains roughly about one hundred and forty pounds.

Revenue

The revenue of India is derived from various sources, and is classified under eight heads. Thus: for 1916-17.

| I. | Land | |||

| Forest | ||||

| Tribute from Native States | Total | £25,124,489 | ||

| II. | Opium | 3,160,005 | ||

| III. | Taxation: | |||

| 1. Salt | ||||

| 2. Stamps | ||||

| 3. Excise | ||||

| 4. Customs | ||||

| 5. Provincial rates | ||||

| 6. Income tax | ||||

| 7. Registration | 32,822,976 | |||

| IV. | Debt Services | 1,136,504 | ||

| V. | Civil Services | 2,364,985 | ||

| VI. | Military Services | 1,575,946 | ||

| VII. | Commercial: | |||

| 1. Post | ||||

| 2. Telegraph | ||||

| 3. Railways | ||||

| 4. Irrigation | 51,393,566 | |||

| VIII. | Miscellaneous Receipts | 1,221,497 | ||

| Grand total | £118,799,968 |

Out of these eight classifications, opium comes fourth on the list.

But in addition to the direct opium revenue, we must add another item, Excise, which is found under the third heading, taxation. In the "India Office List for 1918" we find "Excise" explained as follows: Page 383: "Excise and Customs: Excise duties in India are levied with the two fold object of raising revenue and restricting the use of intoxicants and narcotics." In the same book, on page 385, we also read: "Excise and Customs Revenues: The total of the excise and customs revenues on liquors and drugs in 1915-16 was in round figures ten million pounds. This total gives an average of rather more than ninepence a head on the whole population of British India as the revenue charge on drink and drugs during the year."

These excise duties are collected on spirits, beer, opium and intoxicating drugs, such as ganja, charas, and bhang, all forms or preparations of Indian hemp (Cannabis Indica), known in some countries as hashish. In 1917-18 there were 17,369 drug shops throughout India. The excise duties collected from these sources was pretty evenly distributed. Excise revenue for a period of years is as follows:

| Excise | Opium | Total Revenue | |

| 1907- 8 | £6,214,210 | £5,244,986 | £ 88,670,329 |

| 1908- 9 | 6,389,628 | 5,884,788 | 86,074,624 |

| 1909-10 | 6,537,854 | 5,534,683 | 91,130,296 |

| 1910-11 | 7,030,314 | 7,521,962 | 97,470,114 |

| 1911-12 | 7,609,753 | 5,961,278 | 100,580,799 |

| 1912-13 | 8,277,919 | 5,124,592 | 106,254,327 |

| 1913-14 | 8,894,300 | 1,624,878 | 105,220,777 |

| 1914-15 | 8,856,881 | 1,572,218 | 101,534,375 |

| 1915-16 | 8,632,209 | 1,913,514 | 104,704,041 |

| 1916-17 | 9,215,899 | 3,160,005 | 118,799,968 |

The "Statistics of British India for 1918" has this to say on the subject of Excise (page 218): "Revenue: During the ten years ending with 1916-17 the net receipts from Excise duties increased ... at the rate of 47 per cent. The receipts from opium (consumed in India, not exported) being at the rate of 44 per cent. The net receipts from liquors and from drugs other than opium ... the increase at the rate of 48 per cent. This large increase is due not merely to the expansion of consumption, but also to the imposition of progressively higher rates of duty and the increasingly extensive control of the excise administration. The revenue from drugs, (excluding opium) has risen in ten years ... the increase being at the rate of 67 per cent."

A national psychology that can review these figures with complacency, satisfaction and pride is not akin to American psychology. A nation that can subjugate 300,000,000 helpless people, and then turn them into drug addicts—for the sake of revenue—is a nation which commits a cold-blooded atrocity unparalleled by any atrocities committed in the rage and heat of war. The Blue Book shows no horror at these figures. Complacent approval greets the increase of 44 per cent of opium consumption, and the increase of 67 per cent in the use of other habit-forming drugs. Approval, and a shrewd appreciation of the possibilities for more revenue from "progressively higher rates of duty," knowing well that drug addicts will sell soul and body in order to procure their daily supply.

2 This description of the Opium Department is to be found in Statistics of British India, Financial Statistics, Vol. II, 8th Issue, page 159:

OPIUM. The region in which the poppy was cultivated in 1916-17 for the manufacture of "Bengal opium" comprises 32 districts of the United Provinces of Agra and Ouhd. The whole Department has, with effect from the 29th September, 1910, been under the control of one Opium Agent, with headquarters at Ghazipur. At Ghazipur there is a Government factory where the crude opium is manufactured into the form in which it passes into consumption. The cultivation of the poppy and the manufacture of opium are regulated by Act XIII of 1857, as amended by Act I of 1911, and are under the general control of the Lieutenant Governor and the Board of Revenue of the United Provinces, and the immediate supervision of the Opium Agent at Ghazipur. The possession, transport, import and export of opium are regulated by rules framed under the Indian Opium Act. Cultivation is permitted only under licenses granted under the authority of the Opium Agent. The area to be cultivated is fixed by the license, and the cultivator is bound to sell the whole of his production to the Opium Department at the rate fixed by Government.... Advances, on which no interest is charged, are given to licensed cultivators at the time of executing the agreement and from time to time (though ordinarily no more than two advances are given) until final delivery. In March, April and May the opium is made over to the officers of the Department, and weighed and tested, and as soon as possible afterwards each cultivator's accounts are adjusted, and the balance due is paid him. After weighment the opium is forwarded to the Government factory at Ghazipur, where it is manufactured in 3 forms—(a) opium intended for export to foreign countries, departmentally known as "provision opium"—(b) opium intended for consumption in India and Burma, departmentally known as "excise opium" and (c) medical opium for export to London. Provision opium is made up in the form of balls or cakes, each weighing 3.5 lbs., and is packed in chests, each chest containing forty cakes, weighing 1401/7 lbs. It is generally of 71° efficiency. Excise opium is made up in cubical packets, each weighing one seer, 60 of which are packed in a case. It is of higher consistency than the "provision opium." Medical opium is made up into cakes weighing 2 lbs. Provision opium is sold by public auction in Calcutta. A notification is published annually, generally about the month of June, stating the number of chests which will be put up for sale in each month of the next calendar year, and the quantities so notified are not altered without three months notice. Sales are conducted month by month by the Bengal Government; 7,000 chests were notified for sale in 1917 for shipment to non-China markets. The number of chests actually sold was 4,615. In addition to this, 4,500 chests were sold to the Government of the Straits Settlements, 2,200 to the Government of Netherland Indies, and 410 to the Government of Hongkong. The duty levied by Government on each chest may be taken to be the difference between the average price realized and the average cost.

XI

TURKEY AND PERSIA

Next to India, the greatest two opium-producing countries in the world are Turkey and Persia. The Statesman's Year Book for 1918 has this to say about it. On page 1334: "The principal exports from Turkey into the United Kingdom ... in two years were:

| 1915 | 1916 | |

| Barley | £ 156,766 | £ 49,413 |

| Raisins | 127,014 | 34,003 |

| Dried fruit | 375,519 | 540,633 |

| Wool | 36,719 | 143,216 |

| Tobacco | 149,100 | 3,711 |

| Opium | 262,293 | 48,090 |

These are the only articles mentioned in this list of chief exports. There are others, doubtless, but the Statesman's Year Book is a condensed and compact little volume, dealing only with the principal things exported. In 1915 we therefore notice that the opium export was second on the list, being exceeded by but one other, dried fruit. In 1916, the third year of the war, the opium export is decidedly less, as are all the other articles exported, except dried fruit and wool—which were articles probably more vital to the United Kingdom at that time even than opium.

PERSIA

The same authority, the Statesman's Year Book for 1918, gives a table on page 1162, showing the value of the chief exports from Persia. The values are given in thousands of kran, sixty kran equaling one pound sterling.

| 1914-15 | 1915-16 | ||

| Opium | 41,446 kran | 41,732 kran |

Since the war, both Turkey and Persia are more or less under control of the British Empire, which gives Great Britain virtual control of the world's output of opium. With this monopoly of the opium-producing countries, and with a million or so square miles added to her immense colonial Empire, one wonders what use Great Britain will make of the mandatory powers she has assumed over the lives and welfare of all these subject peoples! Will she find these helpless millions ready for her opium trade? Will she establish opium shops, and opium divans, and reap half the costs of upkeep of these newly acquired states by means of this shameful traffic?

XII

MAURETIUS

Another British colony is Mauretius, acquired by conquest in 1810, and formally ceded to Great Britain by the Treaty of Paris in 1814. This island is in the Indian Ocean, 500 miles east of Madagascar, with an area of about 720 square miles. The population is about 377,000, of which number 258,000 are Indian, and 3,000 Chinese. Opium appears to be sold in the colony, since the Blue Book mentions that licenses are required for opium sellers. As far as we can discover, by perusal of these Government Reports, the sale of opium is not conducted by the Government itself, as in India, the Straits Settlements, Hongkong, etc., but is carried on by private dealers who obtain licenses before they can open opium shops. A part of the revenue, however, is derived from opium; thus, according to the Blue Book for the Colony of Mauretius for 1915, page V 73, we read that the imports of opium for the year amounted to 1,353 kilos, with a duty collected of 54,126 rupees. The Blue Book for 1916 shows a gratifying increase. Thus, the import of crude opium from India amounted to 5,690 kilos, with a duty collected of 227,628 rupees. (See page V 64.)

| 1915 | 1916 | |

| Imports of opium | 1,353 kilos | 5,690 kilos |

| Duty on opium | 54,126 rupees | 227,628 rupees |

| Total duty on all imports | 3,765,677 rupees | 4,143,085 rupees |

Statistics for British India, Eighth Issue, gives these figures:

Opium exported to Mauretius

| 1912-13 | 10 | chests |

| 1913-14 | 19 | " |

| 1914-15 | 23 | " |

| 1915-16 | 65 | " |

| 1916-17 | 120 | " |

This is a poor little colony, but has its possibilities. The consumption of opium appears to be increasing steadily in a most satisfactory manner. Congratulations all round.

XIII

BRITISH NORTH BORNEO

British North Borneo occupies the northern part of the island of Borneo. Area, about 31,000 square miles, with a coast line of over 900 miles. Population (1911 census), 208,000, consisting mainly of Mohammedan settlers on the coast and aboriginal tribes inland. The Europeans numbered 355; Chinese 26,000; Malays, 1,612; East Indians about 5,000 and Filipinos 5,700. The number of natives cannot be more than approximately estimated, but is placed at about 170,000. The territory is under the jurisdiction of the British North Borneo Company, being held under grants from the Sultans of Brunei and Sulu (Royal Charter in 1881).

Like many other British colonies, opium is depended upon for part of the revenue. The Statesman's Year Book for 1916 observes on page 107: "Sources of revenue: Opium, birds' nests, court fees, stamp duty, licenses, import and export duties, royalties, land sales, etc. No public debt."