Title: Highway Pirates; or, The Secret Place at Coverthorne

Author: Harold Avery

Release date: September 9, 2010 [eBook #33680]

Most recently updated: January 6, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

| I. | A Day of Trouble |

| II. | The Knocking on the Wall |

| III. | Men in Hiding |

| IV. | The Singing Ghost |

| V. | Nicholas Coverthorne Shows his Hand |

| VI. | A Mad Prank |

| VII. | Tried and Sentenced |

| VIII. | My Journey Begins |

| IX. | The Rising |

| X. | Highway Pirates |

| XI. | The Last of the "True Blue" |

| XII. | Within the Cavern |

| XIII. | The Brandy Kegs |

| XIV. | Abandoned |

| XV. | In Desperate Straits |

| XVI. | The Subterranean Tunnel |

| XVII. | Daylight at Last |

| XVIII. | A Further Find |

| XIX. | Brought to Bay |

"They've seen us! Run for it!"

My chosen friend, Miles Coverthorne, was the speaker. He sprang to his feet as he uttered the words, and darted like a rabbit into the bushes, I myself following hard at his heels. The seasons seem to have come earlier in those days, and though May was not out, the woods and countryside appeared clothed with all the richness of leafy June.

At headlong speed we dashed through the underwood, stung by hazel switches which struck us across the face like whips, and staggering as our feet caught in thick tufts of grass.

"Who is it—keepers?" I inquired.

"No; 'Eagles'!" was the quick reply.

If anything had been needed to quicken my pace, this last word would have served the purpose. We both rushed wildly onward, as though our very lives were at stake.

It may be guessed that Miles did not mean to imply that a number of real eagles were swooping down upon us with the intention of bearing us away to some rocky crags, there to form an appetizing repast for their young; the word had, in this case, a special meaning, to explain which a slight digression will be necessary.

Many things have altered since the year 1830, and in no direction are greater changes manifested than in the schools and school life of that period compared with those of the present day. What the modern boy at Hobworth's School (so called after its worthy founder) would think of the place if suddenly transferred back to the days when I went there as a boarder, I cannot imagine. Whole chapters might be devoted to a comparison of the past with the present, but for the purposes of our story only one point need be considered, and that is the great difference in the style and character of recreation out of school hours.

Though organized games, such as cricket, no doubt existed in the big public schools, they were unknown at Hobworth's. Such sports as prisoner's base, marbles, and an elaborate form of leap-frog called—if I remember rightly—"fly-the-garter," we certainly indulged in; but, as might be expected, such amusements did not always satisfy the bolder spirits—the result being that these found vent for their adventurous inclinations in various expeditions, which more than once landed them in serious trouble with farmers and gamekeepers.

I cannot say that there was any vicious intention in these raids and forays. It was perhaps difficult for us boys to see the justice of certain men claiming all the birds' eggs, squirrels, or hazel-nuts in the neighbourhood, especially as these things were of no value to their avowed owners. Again, if pheasants were disturbed, or fences broken, or perhaps a rabbit knocked over for the joy of subsequently cooking it surreptitiously in a coffee-pot, it was, after all, a very small matter, and not worth making a fuss about. So, at least, the youngster of that period would have argued.

Those were not happy times for the small and weak. Brute force was far too highly esteemed, and the champion fighter of a school was thought as much or even more of than the leading cricket or football player is to-day. It was an unpardonable sin for a small boy to sneak, but the cruelty and oppression of the more evil-minded of his elders was hardly deemed worthy of censure. Out of school hours very little notice was taken by masters of how their pupils employed their time, and as long as the latter refrained from bringing the place about their ears with any acts of particularly flagrant mischief, they were left pretty much to their own devices.

Partly for mutual protection against the violence of their fellows, and partly in pursuit of the questionable forms of recreation already referred to, the boys had formed themselves into a number of "tribes," each under the leadership of some heavy-fisted chieftain to whom they swore allegiance, at the same time sharing all their worldly possessions with the other members of the band.

In course of time these various small communities became gradually absorbed into two large rival bands known as the "Foxes" and the "Eagles," the peculiarity of name being due to an exciting story of adventure among the Indians which had been going the round of the school; for books of that kind were, in those days, a rare and highly-prized possession.

Skirmishes between parties of the two tribes were of frequent occurrence, and expeditions with various objects, and not unfrequently exciting endings, were indulged in almost every half-holiday afternoon. Miles and myself were numbered among the "Foxes," while at the head of the "Eagles" was a notorious bully named Ben Liddle, who possessed all the nature and none of the nobility of the actual savage. This leader had lately laid claim to all the woods and country on the north side of the road which passed the school, as the hunting-ground of the "Eagles," and had thrown out dark hints of a terrible vengeance which should be meted out to any luckless "Fox" who should be captured encroaching on this preserve.

As this meant nothing less than calmly appropriating all the places where any good sport could be obtained, the claim was naturally resented by the "Foxes;" and though Kerry, our chief, had not as yet made any public pronouncement on the subject, it was understood that before long the matter would be discussed, probably in a grand pitched battle between the tribes, when this and other causes of disagreement would be settled once for all.

But even Ben Liddle's threats were not sufficient to keep enterprising "Foxes" on the south side of the road. Miles and I had already made several expeditions into the forbidden territory, perhaps rather enjoying the extra risk of capture by "Eagles," added to the chance of being chased by keepers. On this particular Saturday afternoon we had penetrated into the depths of a favourite haunt named Patchley Wood. The arms of an "Indian" at such times, I might explain, were a big catapult, a pocketful of pebbles, and a short stick with a lump of lead at the end, in shape somewhat resembling a life-preserver. This weapon—known to us as a "squaler"—was capable of being flung with great force and precision. With the whole of this outfit we were duly provided.

We had been in the woods perhaps half an hour, and had lain down to rest at the foot of a tree, when my companion's quick eye detected the approach of the enemy, with the result that we immediately took flight in the manner which has already been described.

At headlong speed we dashed off through the bushes, regardless of the noise we made; for any hope we might hitherto have entertained of escaping unobserved had been dispelled by the shout sent up by the "Eagles" the moment we moved. On we ran, the enemy following hard in pursuit, crashing through the underwood, while Liddle's voice rang out yelling directions to his followers, heedless of the risk he ran of attracting the notice of the keepers. If captured by the rival chief, we knew we might expect no mercy; and though the pair of us were pretty swift-footed, we felt that nothing short of a stroke of luck would save us, for among the "braves" now in pursuit were some of the best runners in the school.

To lessen still more our hope of escape, before us rose a gentle slope, on which the underwood grew so sparse and thin as to render it certain that we should be seen by our pursuers as we breasted the rise. We laboured on up the hill, gasping for breath as we neared the top; then a yell of triumph from behind, as our pursuers caught sight of us, goaded us to pull ourselves together in one last effort to escape.

Plunging into the thickets, which now became again more dense, we had not gone twenty yards when Miles caught his foot in a root, and came down headlong. He recovered himself immediately from the shock of the fall, and attempted to scramble to his feet, but sank down again with a smothered cry of pain.

"I'm done for," he said. "I've twisted my ankle. Go on; don't wait!"

Anxious as I was to outdistance the "Eagles," I had certainly no thought of leaving Miles to their tender mercies, and glancing round I saw, close at hand, the trunk of a large tree which had recently been felled, together with a large heap of branches which had been lopped off by the woodcutters. Though a very poor one, it was our only chance; so, half carrying Miles, I got him to the spot. We flung ourselves down in a little vacant space between the trunk and the pile of wood, and at the same moment heard Liddle and the foremost of his band gain the summit of the slope, and come bursting through the bushes.

Possibly if we had had a better start, the "Eagles" might have searched for and found us; as it was, they never thought we should pull up with them so close at our heels, and the wood pile was such a poor place of concealment that it did not seem to attract their attention or arouse their suspicion. They rushed on, whooping as they went; and those following behind, no doubt thinking that their comrades in front had us in view, paid no heed to anything but the headlong chase. Thus it came about that, much to our surprise, as we lay panting on the ground we had the satisfaction of hearing the last of our pursuers go racing past, leaving us unmolested to recover our wind and make off in another direction.

"I thought my ankle was broken," muttered Miles, "but it's only a sharp twist. I think I can hobble along; and we'd better get out of this as soon as we can, for they may find they've overrun us, and turn back."

We paused for a moment to get our bearings.

"The road must be close here," I remarked. "Once across it we shall be in our own territory, and can easily escape."

Taking the lead, and with my companion hobbling along in the rear, I headed for the edge of the wood. Fortune seemed to be favouring us, for we found a gap in the hedge through which Miles was able to scramble in spite of his disabled foot. I followed with a jump, and we were just congratulating ourselves on having outwitted the hostile "tribe," when a long-drawn yell, which we at once recognized as their war-cry, caused us to turn our heads. Away down the road stood a solitary "brave," who had evidently been sent there by Liddle to give warning if we should break out of the wood. The yell was immediately answered by others, and a moment later several of our foes came bursting through the hedge, though at a spot some distance beyond the post occupied by their scout.

Escape seemed out of the question. It was impossible for Miles, with his wrenched ankle, to scramble over ditches and hedges, and we had no choice but to keep on the road. In despair we turned and ran towards the school, Coverthorne hobbling and hopping along as best he could, with clenched teeth and subdued groans. Then suddenly, as we turned a corner, we came face to face with a gentleman on horseback, who on seeing us abruptly reined in his steed.

My first fearful thought was that this must be Squire Eastman, the owner of the woods in which we had been trespassing; but a second glance showed me that I was mistaken, and at the same time I heard Miles exclaim,—

"Hullo, young man!" remarked the horseman; "you seem in a hurry. What's the matter? Late for school?"

"No, thank you, uncle," gasped the boy; "it's only—only a game."

Mr. Nicholas Coverthorne was a hard-featured man, with cold gray eyes and a rather harsh voice. He rode a big black horse, and seemed to control the animal with a wrist of iron. Something in his manner and appearance caused me to take an instinctive dislike to him, though at the time of this our first meeting I certainly had reason to feel grateful for his opportune appearance, which was undoubtedly the means of delivering us out of the hands of our enemies. As the leading "braves" turned the corner, they promptly wheeled about and fled back the way they had come, shouting out to their comrades that we had been caught by the squire, at which intelligence the band quickly dispersed over the fields, and made their way back to the school by different routes.

A few more sentences passed between uncle and nephew, and though not any more observant of such things than most boys, it struck me at once that the relationship between them did not appear to be very cordial. Mr. Coverthorne explained that he had been over to see a neighbouring farmer about the sale of a horse.

"I'm going to stay with a friend at Round Green to-night," he said. "It's rather too far to get here from home and back in the same day, though I daresay Nimrod would take me all the way if I let him."

The speaker laughed in a mirthless manner, and after a few more questions as to how his nephew was getting on at school, and when the holidays began, wished us good-bye, and, with a parting nod, went on his way.

Miles seemed glad to get the interview ended, and turned to me with what seemed almost a sigh of relief as the horseman disappeared round the bend in the road.

"Come on," he said. "The 'Eagles' may be hiding somewhere, and rush out as soon as the horse has passed them. That was my uncle Nicholas," he continued, as he hobbled along. "I don't think I ever told you about him. He's my father's only brother, but they quarrelled some years ago, and now they never meet or speak."

"Why was that?" I asked.

"Oh, it was about the property. My grandfather left Coverthorne and almost all the land to my father, and Uncle Nicholas had only a small farm called Stonebank; but before that he'd had a lot of money to enable him to start in business, and he lost it all in speculation. He said at my grandfather's death that the property and land ought to have been divided, but my father told him he had already had his share in money."

"Your people have lived at Coverthorne an awful time, haven't they?" I asked.

"Oh yes. It's a dear old house, with low rooms and big latticed windows with stone mullions, and a broad oak staircase. There's an old sundial in the garden which was put there in Queen Elizabeth's reign; and what's more, the house has a secret place which nobody can find."

"A secret place! what's that?" I inquired, pricking up my ears.

"Why, it's a little secret chamber or hiding-place which has been made somewhere in the building years and years ago, when there might be chances of people having to be concealed to save their lives. There is a rule in our family, handed down from one generation to another, that the whereabouts of the secret place must only be known to the owner of the house, and be told by him to the heir when he is twenty-one."

"Then you yourself don't know where it is?"

"No; my father will tell me when I come of age. Of course if he were dying, or were going on a long journey from which he might never return, or anything of that kind were to happen, he would tell me at once, else the secret might be lost for ever."

"Is it big enough for a man to get into?"

"Oh yes—big enough for two people to stand in, so father says."

"Then surely it must be easy to find. I can't see how it's possible for there to be a little room in a house without people knowing it is there. I believe I could find it for you if you gave me the chance."

Miles laughed.

"You'd better come over and try," he answered. "Now, that's a good idea. You must come and stay with me for part of the summer holidays, and we'll have heaps of fun. It would be jolly to have you, for I often find it dull with no cousins or friends of my own age."

The proposal struck me as most delightful. During the last few moments I had been picturing up the ancient house, with its old-world associations and romantic hidden chamber, and comparing it, in my mind, with the prosaic red-brick building in which my own parents lived. Moreover, Coverthorne, I knew, was situated on the sea-coast, and only about a quarter of a mile from the summit of the rugged cliffs. I had often listened with envy to my friend's tales of wrecks and smugglers, and longed to have an opportunity of wandering over the wide headlands, climbing the rocks and exploring the caves. Now the prospect of such treats being actually in store made me feel quite a thrill of delightful anticipation.

I had not finished thanking Miles and telling him how much I should like to come, when we reached the school. Passing through a side door we entered the playground, and were almost immediately surrounded by a crowd of "Foxes," who had somehow got wind of our escape from the "Eagles," and were eager to have a detailed account of the adventure.

Telling our story, and receiving the congratulations of the other members of our "tribe," so much occupied our attention that we hardly noticed the sound of a horse galloping down the road and stopping in front of the schoolhouse; but a few moments later Sparrow, the porter, crossed the playground and, addressing Miles, told him he was wanted at once by Dr. Bagley.

A message of that kind from the headmaster usually meant that there was trouble in the wind.

"Hullo!" exclaimed a boy named Seaton, "what's the row, I wonder? He'll want you next, Eden. You must have been seen in the woods, and the squire has sent some one over to complain."

Reluctantly Miles followed the porter. In no very enviable frame of mind I waited, expecting every minute to be ordered to appear before the doctor in his study. Still no such message came, nor did Miles return to inform us of his fate. We heard the horseman ride away again, but the height of the playground wall prevented our seeing whether he really were one of the men-servants from the Hall. A little later Liddle returned with a band of his "braves;" but the "Foxes" being also present in force, he could only shake his fist at me, and repeat his former threats of what he would do if he caught us on the hunting-ground of the "Eagles." At length the bell rang, and we moved towards the house.

Hardly had I entered the door when I met Sparrow.

"Have you heard the news, Master Eden?" he exclaimed. "Dreadful—dreadful! Poor Master Coverthorne! His father's been shot—mortally wounded—and is most probably dead by this time. It's a great question if the young gentleman will ever see him alive."

"What!" I cried—"Mr. Coverthorne shot! How did it happen?"

"It's true enough," answered Sparrow. "I had it all from the messenger himself. Mr. Coverthorne was out shooting with a party, and a gen'leman's gun went off by accident as he was climbing a hedge. Mr. Coverthorne was shot in the breast. They got a trap, and took him to the Crown at Welmington, and sent for a surgeon. He wanted particular to see his son, so one of the postboys rode over; but it's hardly likely the young gentleman will get there in time."

"What a dreadful thing!" I muttered. "Poor Miles! I wish I could have seen him before he went."

The news of this terrible blow which had so suddenly fallen on my companion shocked me almost as much as if the trouble had been my own. When adventuring together into the woods that afternoon, how little he imagined what the immediate future had in store!

I sat down with the rest in the long, bare dining-room, but had little heart to eat; the thought of Miles being hurried along the country road, not knowing whether he would find his father alive or dead, weighed down my spirits. If his father died, the only relative he would have in the world, besides his widowed mother, would be his uncle Nicholas; and remembering the latter's hard face and harsh voice, and the story of the brothers' quarrel, my mind was filled with dark forebodings for the future of my friend.

It was ten days before I saw Miles again; then he returned to school for the last three weeks of the half. Seeing him dressed in black, and noticing the unaccustomed look of sadness on his usually cheerful face, boylike I felt for a moment shy of meeting him; but with the first hearty hand-grip all feeling of restraint vanished, and I was able to give him the assurance of my sympathy and friendship. Then it was that I heard for the first time how he had arrived at Welmington too late to see his father alive—a fact which must have added greatly to the heaviness of the blow and the keenness of his grief.

Naturally, for the time, he had no heart to join in our usual amusements; and his rough, though for the most part good natured, schoolboy comrades showed their sympathy in allowing him to go his own ways. Just then "Foxes" and "Eagles" had buried the hatchet, owing to the fact that a spell of hot weather had set in, and the members of both "tribes" went amicably, nearly every day, to bathe in a neighbouring stream.

The majority of the boarders were thus engaged one afternoon, and Miles and I had the playground to ourselves. We were sitting on a seat under a shady tree, and something perhaps in the restful quiet of the place encouraged my companion to unburden himself and take me into his confidence. I had noticed a troubled look on his face, and inquired whether anything was weighing on his mind.

"Yes," he replied. "Look here, Sylvester, old fellow, I'm sure there's something wrong at home that I don't quite understand. Mr. Denny, our lawyer, has been there with my mother, and they haven't told me what is the matter, but they seem to be afraid of something or somebody, and I believe it's Uncle Nicholas."

"Why? has he shown any signs of ill-will?"

"No; if anything, he's appeared more friendly than he has been since I can remember. He came over to Coverthorne the day after the funeral, and said he was sorry that he and my father had quarrelled; that there had probably been mistakes on both sides, but he was glad now to think that all the misunderstanding had been cleared away before James's death, and that they had mutually agreed the past should be forgiven and forgotten. My uncle must have noticed the surprised look on my mother's face, as she knew of no such reconciliation; and he went on to explain that he and my father had agreed not to make it public till next Christmas Day, when they intended to dine together. 'There's another matter which was to have been mentioned then,' he went on. 'I won't broach the subject now. After the terrible shock, you aren't in a fit state to be bothered with business. We'll leave it for a few weeks.'"

"I must say I didn't like the look of that man when I saw him," I muttered; "his face seemed hard and cruel."

"My mother mistrusts him too, and so does Mr. Denny. I can tell that by the way in which they speak about him."

For some moments Miles remained silent, scraping patterns in the gravel with the heel of his boot.

"Look here. You're an old friend whom I know I can trust, Sylvester," he exclaimed suddenly. "I'm sure if I tell you what I think you won't let it go any farther?"

I at once gave him the promise he desired.

"Soon after Uncle Nicholas's visit," he began, "Mr. Denny came to stay with us for three days, spending most of his time going through my father's papers. My mother would be closeted with him for an hour at a time. I could hear their voices talking together in low tones as I passed the door; and when they came out there was always a worried, anxious look on their faces. I had heard it mentioned that my father's will and some other documents were missing; but hitherto Mr. Denny had not treated the loss as a very serious thing, at all events as far as I could gather. I don't think I should have troubled my head any more about the matter, but for what I am going to describe. It was on the last day of Mr. Denny's visit. I had gone to bed rather early, as I was tired, and had been asleep some hours, when I was awakened by a sound like a muffled knocking. I lay for a few minutes, thinking it must have been my fancy; then the sound was repeated. The thought occurred to me at once that it must be some one who had come to the house for some reason or other, and was knocking at the back door to try and waken one of the servants. I got up, leaned out of my window, and called out, 'Who's there?' No reply was given, nor could I see any one in the yard. Once more I thought my fancy had deceived me; then thump—thump—thump! it came again. 'It must be some one at the front door,' I thought; so I threw a coat over my shoulders and went out of my room, down a passage, and across the landing to a window that looks out on the front of the house. I opened it, and once more asked who was there, but got no answer.

"The horses in the stables often make curious noises at night, but this rapping was too regular to have been caused by them. I walked slowly back, and just as I reached the middle of the landing it came again, knock—knock—knock! I expect you'll think me a coward, but I must own that a chill went all down my back. People say that Coverthorne is haunted, and this strange rapping in the middle of the night, long after every one else had gone to bed, reminded me of all the stories I had often heard the servants telling each other round the kitchen fire. If you'll believe me, I was more than half inclined to bolt for my room and stick my head under the bedclothes. The sound came from somewhere downstairs, and, as far as I could judge, from the direction of the very room which is supposed to be particularly favoured by the ghost. It was like some one rapping slowly and deliberately with his knuckles on the panel of a door. I stood irresolute and holding my breath; then I heard something tinkle like metal falling on stone. That seemed to break the spell, and my heart beat fast. I no longer feared a ghost, but thought it must be robbers. What I intended doing I hardly know, but I think I must have had some vague idea of trying to slip across the kitchen to the servants' quarters, and there rouse the men. I went slowly and carefully down the stairs, my bare feet making no sound. The knocking was repeated. I could tell now exactly from what part of the house it came, and a strong desire seized me to get a sight of the thieves and see what they were about. Old houses like ours have all kinds of funny twists and turns. I crept along to one of these, and peeped round the corner. What I saw astonished me more than if I had been confronted by a whole band of robbers. I was looking down a long, narrow passage, the walls of which are panelled with oak: at the farther end stood my mother and Mr. Denny. She was carrying a candle, while he held in his hands a hammer and small chisel; the latter it was which he must have dropped a few moments before, when I heard the chink of its fall on the flagstones. What they were doing I could not imagine. I saw Mr. Denny rap on the wall with the handle of the hammer, at the same time turning his ear to listen, as though he almost expected some one on the other side of the panelling to say 'Come in!' Then it dawned on me in a moment that they were searching for the secret place."

Miles paused as he said this, and I listened breathlessly for what was coming next.

"Of course," continued my companion, "I guessed at once that my mother and Mr. Denny were searching then, instead of in the daytime, because they thought it best for the servants not to see and go gossiping in the village. As they evidently did not want me with them, I turned and crept quietly back to bed again; but I couldn't help lying awake listening for the tap of the hammer, and from that I knew they continued searching most of the night. Try as I would, I could not rest till my curiosity was in some measure satisfied; so on the following day, after Mr. Denny had gone back home, I told my mother what I knew, and begged her to give me an explanation. Even then she wouldn't tell me plainly what was the matter. She said Mr. Denny had heard a rumour which made him uneasy about our future, and that he wanted to find some letters and papers which he thought it possible my father might have stowed away in the secret place. She warned me to be sure and not mention this to the servants, and, above all, to Uncle Nicholas."

My companion's story reawakened all the former interest which I had felt in the old house. It seemed to me a place which must be abounding in mystery, and almost as romantic as the enchanted castle of a fairy tale.

"I should like to help to search, and see if I couldn't find the secret place," I blurted out.

"So you shall," answered Miles. "It was understood that you were to stay with me at Coverthorne." Then seeing that I hesitated, regretful at having reminded him of a promise which had been made before the sad circumstance of his father's death—"Oh yes," he added, "I'm quite expecting you to come back with me. Mother wishes it too, for she thinks it will do me good to have some companion of my own age, to cheer me up. It will be fine," he went on, his face growing brighter than I had seen it since his return to the school. "We'll shoot rabbits, and bathe, and go down to Rockymouth, and go fishing in one of the boats. There'll be heaps to do, if only we get fine weather."

All these projects were delightful to contemplate, but the thought of searching for that mysterious hidden chamber was what still appealed most strongly to my imagination.

"What a pity your father wasn't able to tell you the secret before you came of age!" I remarked.

"I daresay he would have," answered Miles sadly, "if only I had arrived in time to see him alive."

"Haven't you been able to find any clue that would help you in the search?"

"No; the secret has been so well kept, and handed on from father to son, that, outside our family, many people who have heard the story think there is no such place."

"Has it ever been used for anything?"

"Not that I know of, except, I believe, years ago. When there was the scare of a French invasion, my grandfather, who was alive then, hid all his silver and valuables there. About a year ago my father went to London, and Mr. Denny thinks it possible that before he started he might have wanted to find a safe place for his papers, put them in the secret chamber, and not troubled to take them out again when he came back."

It seems to me that in my young days the prospect of breaking up and going home for the holidays was a period which occasioned a greater amount of rejoicing and excitement than it does among the younger generation of the present time. For one thing, the contrast between school and home was greater then; and again, the half-year was longer than the term, and the end of it the more eagerly awaited. Now, my grandchildren appear to be no sooner packed off to school than they are back again. In addition to all this, when that particular vacation drew near, the prospect of returning home with Miles for a fortnight at Coverthorne made me long all the more for the few remaining days to pass; and when at length we flung our dog-eared school books into our desks for the last time, and rushed out into the playground to give vent to our feelings with three rousing cheers, I know I shouted till I was hoarse.

Owing to the limited accommodation on the coaches, we had two actual breaking-up days—half of the boys going home on the one and half on the other, those whose progress in school work had been most satisfactory being allowed to start first.

Miles and I had the good fortune to be numbered among the latter, and I don't think I shall ever forget that bright summer morning when, together with several more companions, we started to walk to the little village of Round Green, through which the coach passed about nine o'clock. Our luggage had already preceded us in a cart, to be transferred to the boot of the Regulator, the guard of which, George Woodley by name, was a prime favourite with us boys.

Shutting my eyes for a moment, I can imagine myself standing again outside the Sportsman Inn at Round Green, waiting with boyish eagerness for the first distant note of the horn which—this being the end of a stage—was sounded to give the hostlers warning to bring out the fresh horses. What music ever was so sweet on a bright summer morning as that gay call, coupled with the brisk clattering of the hoofs, when it sounded in the ears of a boy returning home from school? How we held our breath and strained our ears to listen for the approaching vehicle! I could almost imagine I heard that far-off fanfare now, forgetful of the fact that the gulf of a long life divides me from that time, that the railway has long displaced the Regulator, and that coachman, guard, and most of their young passengers know now a greater secret than the one which, during the coming holidays, I hoped to fathom.

When in actual sight of the two things I had most longed to see, I can hardly say which of them more strongly attracted my attention—the sea glistening like a sheet of silver in the distance, or the old house nestling down among the trees, with its mullioned windows, gray, lichen-covered walls, and the funny little cupola surmounting the roof, and containing the bell which was rung to summon the farm hands to their meals. The coach had put us down at a spot on the highroad known as Tod's Corner, where an old servant had met us, and driven us the rest of the way in a light trap which was just large enough to hold us and our luggage.

Even at the first glance Coverthorne quite realized my expectations. The house and farm buildings formed a quadrangle, while the windows of the sitting-rooms looked out into a quiet, old walled garden, with fruit-trees, box-edged paths, beds of old-fashioned flowers, and a big mulberry tree, in the shade of which was a rustic seat. Inside the building was a large stone-flagged hall, in which, except on special occasions, we had our meals. The rooms were low and cool, the steps of the staircase were shallow and broad, flanked with a ponderous balustrade of dark oak, while panelling of the same material covered the walls of the best rooms and some of the passages. The whole place seemed characteristic of a peaceful old age, and it was almost impossible to think that within its walls anything could ever occur to disturb its restful quiet with any jarring note of violence or fear.

Mrs. Coverthorne gave me a kindly welcome, though it was evident that she had not yet recovered from the shock of her husband's death. Her quiet voice and motherly smile at once won my affections; but often, when her face was in repose, it bore a sad and harassed expression which did not escape my notice, and which brought back to my mind a remembrance of the hints which Miles had given me at school, of some trouble, in addition to his father's death, which overshadowed the family.

We arrived early in the afternoon, and after a hearty meal, for which the long ride in the fresh air had given us an appetite, we hurried out of doors, to go the round of the place, and visit all Miles's favourite haunts. To the neighbouring pond and water-wheel, the orchard, the stables and dog-kennels—to these and a score of other places my friend rushed, eager to discover whether any changes had taken place; and after he had satisfied his curiosity on these points, we went farther afield, roaming over the estate, which on that side included all the land between Coverthorne and the sea. In those days, when people did comparatively little travelling, the sight of the ocean was more of a novelty to an inland-bred boy than it would be now; and standing on the summit of a headland, listening to the surging of the waves against the foot of the precipice over which we gazed, I caught my breath, thrilled with a feeling which was almost one of awe. Away to our left was the little coast village of Rockymouth, and as we looked we could see a tiny fishing-boat beating up against the wind to make the harbour, while on either hand the formidable line of frowning cliffs stretched away, headland beyond headland, till lost in the blue and hazy distance. To me the view was like a scene from some stirring romance, and I drank it in, little thinking under what different circumstances I should one day renew my acquaintance with that sea and shore.

So many things there were to occupy our attention during that first afternoon and evening that, for the time being, our resolve to search for the secret place was banished from our minds; but after we had finished breakfast on the following morning, I reminded Miles of our project.

"D'you want to begin at once?" he asked, smiling.

"Why not!" I returned; "it won't take us long."

"Won't it?" answered my companion. "Don't you be so cocksure till you've tried.—By the way," he continued, his face changing from gay to grave, "we'd better not let my mother know what we're doing; it would only revive unpleasant thoughts in her mind."

"Would she be vexed if she found out we were searching for the hiding-place?" I asked.

"Oh no! it's the loss of the papers she troubles so much about."

It was easy to make an excuse for wandering about the house, and together we examined every nook and corner, from the cold, gloomy cellars to dark and stuffy holes in the roof. More than once I thought I had made some wonderful discovery when I came across mysterious little doors in some of the bedrooms opening into dark cupboards or closets in the wall; but Miles in every case damped my enthusiasm by saying that these were already well known to the whole household. I must confess that in my own mind I had fondly imagined I should discover the secret chamber without much difficulty, but soon I began to realize that it was not such an easy task as I had expected, and at the end of a couple of hours I came near to owning myself beaten.

"This is where I saw old Denny sounding the walls with the hammer," said Miles. As my companion spoke, we were passing down the narrow wainscoted passage which he had described to me at school. I struck the boarding myself once or twice with my knuckles as we moved along, but produced no sound which might betoken the presence of a hollow cavity behind the oak. Arriving at length at an old square-panelled doorway, we entered a room which I at once realized I had not been inside before. Save for a plain wooden chair and table, it was empty and destitute of furniture. There was nothing specially remarkable about the place, yet the appearance of its interior seems so vividly impressed on my mind, that I can see it now as though at this moment I were once more crossing the threshold.

The apartment was evidently intended for a sort of morning room or second parlour. The walls were panelled with oak, and a carved mantelpiece, of massive though not elaborate design, framed the wide, open hearth. There was a curious earthy smell about the place, probably owing to the fact that it was never used; which seemed strange, for it had a pleasant outlook into the garden.

"What a jolly room!" I exclaimed. "Why isn't it used?"

Miles gave a short laugh.

"There's no need," he answered; "we've got enough without it."

We crossed the bare floor and sat down in the deep window-seat. I still went on talking, but, though I hardly noticed it at the time, my companion grew quieter than before. He returned absent-minded replies to my questions, and seemed, from the position of his head, as though he half expected to hear something in the passage or the garden. We may have sat like this for ten minutes or longer, when suddenly an intent expression on Miles's face caused me to break off abruptly in what I was saying. Then, for the first time, I became aware of a curious sound, faint and subdued, as though some one were humming with the mouth closed. At first it seemed far away; then it might have been in the room, though in what part it was impossible to say. I was listening idly and with no particular wonder to the noise, when Miles rose to his feet.

"Come on," he said abruptly.

For a moment I hesitated, not understanding this sudden move; then seeing my friend already half-way across the room, I rose and followed.

"Where are you going?" I asked.

"Oh, anywhere," he answered, almost snappishly, and I wondered what could have upset his temper.

A boy's thoughts turn quickly from one point to another, like a weather-vane in a changing wind, and that afternoon our search for the secret chamber was abandoned in favour of another form of amusement. Miles had already learned to shoot, and promised to take me out with him that evening in the hope that we might get a few rabbits. I was, of course, eager for the expedition, though my own part in it would be the comparatively humble one of carrying the flasks for powder and shot. What a clumsy thing that old flintlock fowling-piece would appear now beside the modern breechloader! Yet how I envied my friend its possession while I watched him cleaning it, as we sat in the garden, sheltered from the hot sun by the thick foliage of the old mulberry tree!

"There!" said Miles at length, as he threw aside the oiled rag and brought the weapon to his shoulder; "with a charge well rammed home, I'll warrant her to kill as far as any gun in the county!"

The heat of the day was past when we set out, and the landscape appeared bathed in warm evening sunshine. I wished that the "Foxes" and "Eagles" could see us sallying forth armed with a real gun; and when about two fields away from the house we halted to load and prime the piece, I felt almost as though I were actually embarked on one of the wild adventures of the hunter heroes of our Indian tales.

As far as actual sport went, we tramped a long way with very little result. We should see rabbits feeding out in the fields as we crept up under the hedges, but before we got within range they would suddenly prick up their ears and scamper back to their holes.

"The ground is so hard in this hot weather that they hear us coming," muttered Miles; but he managed to get a few shots, and, much to my delight, killed two, which he handed to me to carry.

So we went on, walking across the open, or creeping cautiously along under the shadow of hedges and bushes, until we reached the summit of the cliffs, where we sat down to rest.

"How many ships can you see?" asked Miles.

"Two," I replied.

"I can make out a third!" he answered, pointing with his finger. "My eyes, I expect, are sharper than yours. It's a great deal a matter of practice. You'd be surprised what keen sight some of the men have here who've been sailors. Old Lewis, for instance—he can tell a ship's nationality when she appears only a speck on the horizon, and I believe he can see almost as well in the dark as he can in the daylight. He's a curious old fellow. Some afternoon we'll go out fishing with him in his boat."

We sat looking out over the vast expanse of ocean till the sun sank like a huge ball of fire below the horizon; then my companion rose once more to his feet.

"It's time we went back to supper," he said, "or mother will be getting anxious, and think we've met with an accident. She's been very nervous since father's death."

Crossing a stretch of common land, we found ourselves looking down on a little sheltered valley, through which ran a tiny stream, winding its way towards a little cove where I knew my friend often went to bathe. Worn out, no doubt, in the course of ages by the water, this gully narrowed down as it neared the sea, but where we stood it was some little distance across, and the farther side was covered with quite a thick copse of trees and bushes.

"I wish I'd brought the dog with me," said Miles. "There is any quantity of rabbits here. Still, we may be able to get a shot. If we creep along till we reach that corner," he continued, as we entered the fringe of the wood, "we may find some of them sitting out in the open."

Bending down, we moved forward in single file, avoiding any dry twigs which might crack beneath our feet. In this manner we had proceeded some distance, when I was startled by a rustling in the bushes, and a big brown dog went bounding across our path.

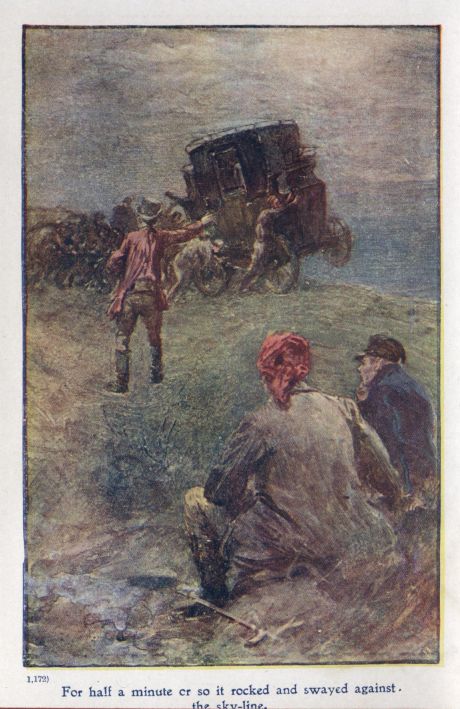

"You poaching rascal!" exclaimed Miles, and raised his gun to his shoulder. He was, I am sure, too kind-hearted to have actually shot the dog; it was more of an angry gesture, or he might have intended to send the charge a few yards behind the animal's tail to give it a fright. Anyway, before he could have had time to pull the trigger, to my astonishment a man suddenly rose up close to us, as though out of the ground.

"Don't shoot, Master Miles!" he cried. "It be only old Joey, and he's doing no harm."

The speaker was clad in a dilapidated hat, a blue jersey, and a pair of old trousers stuffed into a fisherman's boots. I set him down at once as a poacher, and was astonished at the friendly tone in which he addressed the owner of the property on which he was found trespassing. I was still further surprised when Miles, instead of showing any signs of resentment, merely turned and said in an almost jocular tone,—

"Hullo! what are you up to? It's a mercy I didn't mistake you for a fox or a rabbit, and put a charge of shot into your whiskers."

"Just out for an evening stroll, sir, and lay down to rest," replied the man, whistling the dog to his side. There was a funny twinkle in his piercing gray eyes as he spoke, the meaning of which Miles seemed to fathom, for his own face relaxed into a grin.

"Begging your pardon, sir," the fellow continued, "I don't think you're likely to find any rabbits in this copse to-night. They're all gone to bed early, or perhaps old Joey may have frightened them."

For another moment Miles and the man stood looking into each other's faces, and once more the meaning smile passed between them; then the former uncocked his gun, and slung it over his shoulder.

"All right!" he answered.—"Come on, Sylvester; it's time we went back to supper."

There was no hedge to the copse. We stepped out from among the trees and underwood, and had not gone far when the man came running after us.

"Master Miles," he said, "if ever you want to go a-fishing, you can come down to Rockymouth and have the boat, sir; and if you'll give me a call, I'll go with you."

I hardly heard what he said, for glancing into the wood, something caught my eye which immediately riveted my attention. Projecting from behind a clump of bushes were a pair of heavy boots, and as I looked one of them moved, which showed conclusively that they were not empty. I waited till we had got some little distance beyond the copse, and then seized my companion's arm.

"Miles," I whispered, "there's another man hiding in the wood."

"Is there?" he answered carelessly. "Some friend of old Lewis, I suppose."

"Is that the old sailor you were talking about?" I asked. "What's he doing in your wood at this time in the evening? Lying down, too, concealed among the bushes. He must be poaching."

Miles only smiled, and shook his head.

"He's all right. The chap wouldn't harm a stick of our property; in fact, he'd just about murder any one who did."

Though more mystified than ever with this explanation, it was the only one I could get, and we walked on talking of other matters until we came within a field of the house. The darkness had almost fallen by this time, though back across the undulating country I could just see the dark ridge where the tree tops rose above the side of the valley.

"I'm going to fire," said Miles; "it saves the bother of drawing the charge."

The report of the piece rang out, and echoed over the quiet country, and as though in answer to the sound there came out of the distance the sharp bark of a dog. It was evident that the man Lewis was still enjoying his evening stroll in the wood.

"Master Joe's getting out of training, I fancy," muttered Miles, as though speaking to himself. "I say," he added aloud, "you needn't mention anything to mother about our meeting those men in the wood. They aren't up to any harm, but it might make her more nervous; she gets frightened at anything now."

"But what are they doing?" I asked. "Surely they can't be loitering out there for fun?"

Miles laughed.

"It's fun of a sort," he answered. "I'll tell you some day. Now come on in to supper."

It was one of those hot, still nights when it seems impossible to sleep, and tired though I was with my long ramble in the open air, I lay tossing from side to side, now and again dozing off into an uneasy slumber, only to once more suddenly find myself broad awake. At length, feeling very thirsty, I got up and groped my way across to the washstand for a drink of water. A delicious cool breeze had just begun to come in at the window. I went over and leaned out. The sky was gray and wan with the first pale light of dawn, and the country over which I gazed looked ghostly and strange in the twilight. With my arms folded on the sill, I remained for some time drawing in the fresh morning air in deep breaths, and fascinated by the solemn silence which still reigned over the sleeping world, when to my ear came suddenly an unexpected sound—the clatter of a closing gate.

Wondering who could be about at that early hour, I gazed across the neighbouring field, and so doing saw the figures of two men emerge from the deep shadow of the farthest hedge. At a peculiar jog-trot they crossed the open till a slope in the ground once more hid them from my view. The light was not strong enough to allow of my making out anything beyond the outline of their figures, but it seemed to me that each carried on his back something which I thought resembled a soldier's knapsack. It was impossible, I say, for me to recognize their faces, but following close at the heels of the first I distinctly saw a dog, and immediately decided in my own mind that the man must be Lewis, whom I had seen a few hours before hiding in the wood. What the men could be doing, or whither they were going, I had not the faintest idea, but it struck me that they were up to no good, and that their errand was one which they would not have performed in broad daylight. No other person crossed the field, and at length, greatly perplexed, I returned to bed.

I began to think there were other mysteries to be solved at Coverthorne besides the whereabouts of the secret chamber.

Though I longed to tell Miles of what I had seen in the early morning, yet on second thoughts I decided to let the matter drop. The vague replies which he had given to my questions of the previous evening showed clearly that he was not disposed to give me a true explanation of the fisherman's presence in the wood. I must own that this puzzled me not a little, for, certain as I felt of my comrade's uprightness and honour, it was firmly impressed on my mind that there was something very questionable in old Lewis's conduct; and if this were so, it was difficult to understand why Miles should tolerate underhand doings on what was now practically his own estate. It was, however, after all, no business of mine; and I determined to restrain my curiosity till my friend chose to explain, or a good opportunity occurred for me to broach the subject again, and ask him further questions.

At odd times we continued our search for the secret place, but without any further success than before. Miles became inclined to treat the matter as a joke, but I had some reason to believe that, though our search and the various incidents connected with it were often highly amusing, the loss of the papers, which it was possible had been placed in the hidden chamber, might prove more serious than my school friend fully understood.

What suggested this thought to my mind was part of a conversation which I chanced to overhear under circumstances which were briefly as follows. On about the fourth day of my visit Mr. Denny put in an appearance at the house. I did not know of his arrival, but on going into the parlour for something I found him there with Mrs. Coverthorne, turning out the contents of an old bureau which stood against the wall. I merely entered the room and went out again, but that was long enough for me to see that not only were the table and the window-seat littered with the contents of pigeonholes and drawers, but that all the books had been removed from the shelves above, and were undergoing a careful examination, as though it were thought possible that some paper of importance might be found between their leaves.

At dinner I sat opposite the lawyer. He was a thin, dry little man, with very bright eyes and quick, jerky movements which reminded me of a bird. He spoke kindly to us boys, cracked jokes, and spoke about our school life and our holiday amusements; but in spite of this I could not help thinking that his gaiety was rather forced. Mrs. Coverthorne, too, looked more anxious than usual; and though she also made attempts to be cheerful, I felt sure that the lawyer's business with her had not been of a pleasant or reassuring nature.

Almost directly after the meal was finished Miles started off on an errand to Rockymouth—Mr. Denny, who lived there, having arranged to return later in the afternoon. Left to myself, I climbed into the old mulberry tree, and discovering a most comfortable perch among the branches, read a book until I fell asleep.

As a combined result of the strong sea air and an unusual amount of outdoor exercise, I must have slept pretty soundly; but I was at length aroused by the sound of voices, and looking down through the leafy branches saw Mrs. Coverthorne and the lawyer walking down the garden path towards the gate. They did not see me, and I could not help overhearing what they said, though the only words which reached my ears were those which they spoke as they were passing close to the tree.

"Don't be too downhearted, ma'am," Mr. Denny was saying in his brisk manner; "there's still that one chance I spoke of. We haven't had an opportunity to compare the dates yet, and that's an important matter."

"I cannot bring myself to think it possible that my dear husband could have done such a thing—at least without telling me of his intentions. There must be some great mistake. We mustn't tell Miles, not just yet, for I had so wished to make these holidays specially happy."

A few moments later, as the speaker was returning alone to the house, I saw that she was weeping. A great longing filled my heart to understand her trouble, and to render her and Miles some assistance. It seemed a vain and hopeless wish, for of what use could I, a mere schoolboy and comparative stranger, possibly be to them? Yet the unexpected often happens, and the queer cross-currents on the sea of life bring about unlooked-for meetings with equally strange results.

Two days later a respectable working-man made his appearance at Coverthorne. We heard that he was a master-builder, and that he had come to give some advice about repairs. He went all over the house, even going so far as to climb more than half-way up two of the big chimneys. It was, I say, given out that he was to ascertain whether certain of the walls and parts of the roof needed repair, but I hazarded a shrewd guess that he had been employed by Mr. Denny in a confidential manner to apply his practical knowledge of building and architecture in a further attempt to find the secret chamber. If this were so, the man was not any more successful than we boys had been. Granted that such a hiding-place really existed, it was constructed in some most unlikely place, or concealed in an unusually skilful manner.

Miles and I sought it again more than once; but gradually, when the novelty of the idea had worn off and the quest appeared hopeless, I must confess that I began to lose interest in the matter, and to devote my attention to more attractive amusements.

There was certainly no lack of these at Coverthorne. We shot rabbits, bathed from the beach of the little sheltered cove, and went out to sea and fished for whiting and pollack. In pursuit of this last-named form of sport we usually made use of a boat which belonged to the man Lewis. He seemed very willing for us to have it, often came out with us himself, teaching us how to row and to use the sail, and refusing to accept any money in return.

In addition to the fact of having seen him under circumstances which naturally excited my curiosity, there was something about the man which roused my interest in a special degree. As a boy he had served in the navy, having been present at the battle of the Nile; and how eagerly we listened to accounts of those great fights with the French on sea and land, the memory of which was still fresh in men's minds when I was a lad! The brown dog almost always accompanied its master. It was a very intelligent animal, and however far from home, if given anything and told to carry it back to its master's cottage, it would do so with the greatest certainty and promptitude.

Though past middle age, and round-shouldered like many old sailors, Lewis was wonderfully active, and sprang from one boat to another in the harbour or climbed the rocks with the agility of a cat. It was really this which, by accident, led to my making some further discoveries with regard to the old salt. We had been out for a sail, and Lewis, after taking leave of us, was running along the village street to overtake some friend whom he saw in the distance.

"The old beggar can cover the ground at a good pace still," remarked Miles.

"I saw him from my bedroom window the other night," I remarked unthinkingly, "cutting across your field with something which looked like a soldier's knapsack on his back. He must have a good wind."

"Soldier's knapsack!" blurted out Miles with a laugh. "More like a keg of French brandy, with another on his chest to keep the balance."

"What?" I exclaimed.

Taken off his guard, Miles had gone a bit too far to refuse a further explanation.

"I don't suppose it matters if I tell you," he remarked, with a glance over his shoulder to make sure that no one else was listening. "Old Lewis goes in a bit for what used to be known as the 'free trade,' but what you now hear of as smuggling."

"I thought smugglers were men who owned ships and sailed across from France with tobacco, and lace, and spirits—" I began.

"So they do," interrupted Miles; "but there are smugglers on land as well as on sea. The men who bring the stuff across from France only do part of the work; when it is put ashore it has to be taken inland and sold, and often it has to be hidden away somewhere till the preventive men are off their guard. Bless you, I know all about it, and you would too if you'd lived as long as I have on the coast."

"And was that what he was up to the night we found him in the little wood by the cliffs?" I asked, a light suddenly breaking in on my mind.

"Yes," answered Miles. "I saw at a glance what was afoot. You noticed another man hiding behind a bush. I daresay there were a dozen more of them in the copse."

"But what were they doing there?"

"Well, it would take a long time to explain it all in detail: but to put it in a few words, what happens is something like this. Somebody—probably old Lewis or another man—arranges with the owner of a lugger to bring some brandy from France, the spirit being sent over in little tubs or ankers. It is, of course, all arranged beforehand just when and where the stuff is to be landed, and preparations are made accordingly. Lewis gets a number of men, farm labourers and others, to act as what are termed 'carriers,' and these meet and lie hidden somewhere close to the place on the coast where the run is to take place. The tubs are all fastened to a long rope, so that, as soon as ever the lugger brings to, the end of this rafting line can be conveyed to the beach, and the whole 'crop' dragged on shore. With the same cords by which the tubs are fastened to the ropes they are then tied together in such a way that the carriers can sling them over their shoulders. Each man takes two ankers, and then they scatter, and dash off inland to some meeting-place already agreed upon. In this way, when the men are up to their work, it takes only a few minutes for the lugger to discharge her cargo, while the carriers get clear of the beach and disappear."

I must own to being rather shocked at the careless and even jocular tone in which my companion described a traffic which I had always heard spoken of as a crime.

"But, Miles," I began, "it's against the law!"

"Oh, of course it is!" he answered, laughing; "but who's going to interfere with a few poor men turning a penny now and then? The only result is that people round about get better brandy than they otherwise would have done, and a good bit cheaper. Of course people like us don't have any share in the business, but when we know anything is happening we just look the other way."

The weak points in my comrade's arguments may be patent enough to the present-day reader of this story; but it is due to him to say that in those times, especially along the coast, defrauding the revenue was hardly looked upon as a crime, and in the still earlier times of "free trade" this idea had an even greater hold on the minds of the common people, who were always ready to regard the smuggler as a hero, and the exciseman as a villain. Old ideas die hard in country places, and Miles had listened to the talk of the fisher folk since childhood, and had been accustomed to regard the matter from their point of view.

I had always imagined the smuggler as a picturesque sort of villain, sailing the seas in a saucy craft, with a belt stuck full of knives and pistols, and I must own to something like a feeling of disappointment when brought face to face with the original.

"Don't they ever have fights with the coast-guards?" I asked.

"Not if they can help it," was the reply. "You see if they resisted and wounded the officers it would be a serious thing, and might mean transportation for some of them. There's been a lively chase once or twice. I'm very much afraid, though, that there'll be an ugly row some day if they are caught; for old Lewis and some of his men are determined fellows, and as likely as not would show fight before allowing their kegs to be taken."

The remainder of the way home was beguiled with further tales of the doings of the smugglers.

"Look here," Miles concluded, as we came in sight of the house. "Of course mother doesn't know all this, or I expect she'd object to our going out so much with Lewis. All I do is what I did the other night: if I know the men are on our ground, I look the other way. It's no business of mine to meddle with their doings, and there isn't one of them who would take a single rabbit or forget to shut a gate behind him. If he did, he'd soon hear of it from the others."

The remainder of my stay at Coverthorne passed pleasantly if uneventfully, nothing of any note happening until the last day of my visit, when an incident occurred which I have good reason always to remember.

The day was wet and stormy. Miles was engaged doing something for his mother, and having nothing particular with which to occupy my attention, I strolled from one part of the house to another, and at length found my way to the empty room which I have already described, and which I discovered by this time was spoken of as the west parlour. This morning the curious earthy smell which I had remarked there before seemed stronger than usual; but in spite of this and its bare and neglected appearance, the room struck me as one which would have been pleasant and cosy if properly furnished.

I strolled over to the window-seat, and sat gazing round at the dark oak panelling, wondering vaguely why the place was never used. If occupied in no other way, it surprised me that Miles did not appropriate it for a sort of private den or workshop. I was lolling back, idly poking a straw into a crevice of the woodwork, when suddenly the same strange sound broke on my ear which I had heard before. I sat up to listen. It was like some one humming without any regard to tune. At one time it seemed to come from a distant part of the house, and then it appeared to be actually in the room.

One glance was sufficient to show that the chamber itself was empty. I listened with awakened curiosity, but with no sensation of uneasiness or fear. What could it be?

Rising to my feet I walked across the room, stepped into the open fireplace, and stared up the wide chimney. Some spots of rain fell on my upturned face, but nothing was to be seen except the gray sky overhead. I stepped back into the room, and still the muffled drone continued, rising and falling, and then ceasing altogether.

"It must be the wind in the chimney," I thought, and moved once more into the open hearth; but now the sound seemed in the room, and was certainly not in the stone shaft above my head. I next opened the window and looked out into the walled garden. No noise, however, was to be heard there but the patter of the raindrops on the leaves of the trees. Perplexed and rather astonished, I now crossed the floor, opened the door, and went out into the passage, only to find it empty. Once more, as I stood undecided what to do next, the crooning notes fell on my ear, and I began to think that some one was playing me a trick. It was just as I had arrived at this conclusion that I heard Miles calling me; and a moment later, in obedience to my answering hail, he joined me in the empty room.

"I keep hearing that funny noise," I said, "and I can't make out where it comes from."

He made no reply, but stood at my side listening till the sound came again, this time a long, mournful wail like that of some one in pain. I turned, and was surprised to find that Miles's face was almost bloodless. He slipped his arm within mine, and drew me towards the door.

"What can it be?" I asked.

"No one will ever know for certain," he answered, speaking almost in a whisper. "The room is haunted!"

"Haunted!" I cried, stopping short as I gained the passage. "You don't believe in ghosts?"

"I believe in that one," he answered. "I've heard it too often to have any doubt. That's the reason we never use the room; only mother doesn't like it talked about, because it only frightens the servants. People have tried to make out it was the wind; but though we've blocked up the chimney, and have stopped every crack and hole we could find, it makes no difference to the sound, and no one can tell from what part of the room it comes. Besides, the story is that my great-grandfather died there. When he was an old man he always went about humming to himself, and making just the same sort of noise that has been heard in the room ever since his death. All the people round know about it, and they call it the Singing Ghost of Coverthorne."

"O Miles," I began, "you don't believe such stuff as that?"

"I know you'll think me a coward," he interrupted. "I'm not afraid of most things, but I own frankly I hate to go near that horrid room. Mother had it furnished, and tried to use it one winter; but at the end of a month she got so frightened of the noise that she declared she'd never sit there again."

"I don't mind your ghost," I exclaimed, laughing. "You wait here, and I'll go back and listen to it again."

I entered the room, closed the door behind me, and stood waiting in a corner of the floor. I tried to persuade myself that I was not in the least frightened, but my heart beat faster than usual, and I strained my ears with almost painful intentness to catch the slightest sound. Within the last few moments the place seemed to have grown more cold, damp, and earthy than before; it felt like standing in a vault. Then, whether from the floor, ceiling, or solid oak panelling on the walls, I could not tell, came once more that mysterious sound, as though a person were humming with closed lips. I cast one hasty glance round the room, and made hurriedly for the door. Miles was still waiting in the passage.

"You didn't stay very long," he remarked with a quiet smile.

In due course the summer holidays came to an end, and Miles and I met again at school. I had not been in his company five minutes before I noticed that his face wore a different look from when I had seen him last at Coverthorne; indeed, he seemed once more as sad and dejected as he had appeared immediately after his father's funeral.

"What's the matter with you? Have you been ill?" I asked; but he only shook his head and gave evasive replies.

The first day of the half was always one of excitement. The reunion of old friends, the appearance of new boys and masters, the changes of classes and dormitories, all aroused our lively interest; but Miles seemed in no mood to join in our fun. He slipped out of the playground as soon as work was finished, and went off for a walk alone.

Thinking that his return to school had in some way recalled the consciousness of his bereavement, I allowed him for a time to go his own way; but when tea was over I determined to find him, and at least offer him some expression of sympathy. After a little search I discovered him standing with his back against a tree moodily chewing a piece of straw.

"There is something the matter with you," I said. "Why won't you tell me? Is it private?" My arm seemed naturally to slip through his as I asked the question, and perhaps the action, simple as it was, gave him a fresh assurance of my friendship, and influenced him to unburden himself of what was on his mind.

"There's no harm in my telling you, Sylvester," he replied. "I know you won't let it go any further. I'm upset by what's happened at home."

"Something that has happened since I stayed with you?" I asked.

"Well, yes," he answered—"that is, it's come to a head since your visit. I daresay while you were with us you noticed that there was something wrong, and that my mother often seemed worried and depressed. It was not till after you'd gone that I found out what was really the matter."

He paused as though expecting me to speak, but I made no interruption.

"As I've already told you, my father made a will about two years ago," continued Miles. "He signed it at Mr. Denny's office, and took it away with him; but now it can't be found. My mother always thought that it was in the secret drawer of the bureau; but it proved to be empty when she went to look. Then, as I've mentioned before, the idea occurred to her and Mr. Denny that it had been put away for safety in the secret place. If that's the case, then goodness knows if either the papers or the hidden chamber will ever be discovered. At least so far all attempts have proved a failure. Mr. Denny even goes so far as to suggest that the so-called hiding-place may be nothing but a small cavity in the wall behind some sliding panel; though he admits that, from a remark he once heard my father make, he had always believed it was a place large enough to conceal a man. If it's only a little hole somewhere in the stonework, we might pull the house down before we found it."

"But see here," I interrupted. "I don't understand anything about lawyers' business; but even if your father's will were lost, I suppose the property will come to you all the same, seeing that you are his only son."

"Wait a moment till I have finished the story," continued my companion. "When I talked to you about this once before, I described how my uncle came to Coverthorne soon after my father's funeral, and spoke to my mother about a secret reconciliation between the brothers, and hinted at a matter of business which he would discuss at some future time, when she should have recovered somewhat from the shock of her loss. My mother was surprised, and thought it very strange, as she had heard no word from her husband to lead her to suppose that he had made up the quarrel with his brother. The matter, I say, puzzled her a good bit, but did not cause her any actual uneasiness till Mr. Denny came one day and told her privately of an extraordinary rumour he had heard in Rockymouth, to the effect that Uncle Nicholas had told some one that my father had made a will leaving him half the property, that being the fair share which he ought to have had after my grandfather's death. This rumour, coupled with what my uncle had already said to her, caused my mother to begin to fear that something was wrong. She wanted to write to Uncle Nicholas right away; but Mr. Denny advised her to say nothing till she heard from him. In the meantime they made further attempts to find the will which my father had signed in the lawyer's office, Mr. Denny knowing the terms of this one, and hoping it would bear a more recent date than any other which my father might have made. You see, if a man makes more than one will it's the last that counts, and the others are worth nothing."

I nodded to show that I understood this explanation.

"About a week or ten days after you left," went on Miles, "one afternoon Uncle Nicholas called, and out came the whole affair. He produced the will of which we had already heard the rumour, and said that my father had executed it at the time that they had made up their quarrel. The terms were exactly what Mr. Denny had already hinted—that if my father died first, half the estate was to go to Nicholas; in case, however, Nicholas did not survive his brother, the whole property would come to my mother and myself. Having read the paper, he once more described how my father had been prompted to take this step out of a sense of justice; and then he added that, after all, it would make very little difference to any of us, since he himself had no children, and I should be his heir. He would only enjoy his share during the rest of his life, which at most would not be many years. From the first my mother was amazed and incensed at this disclosure. Though she saw the signature at the foot of the document, and recognized it as my father's handwriting, yet she could not but regard the whole thing as an unfair and wicked attempt on my uncle's part to rob us of our possessions. My father had been so open in his dealings, and she had always shared his confidence; it seemed, therefore, almost impossible that he should have taken such a step without at least telling her of his intentions. The interview soon became a stormy one. Uncle Nicholas, in a cold, half-ironical manner, said he felt sure that my mother would not oppose her dead husband's wishes; and gave as the reason for our not finding another will that my father had no doubt destroyed the first before making the second. He pooh-poohed the idea of any document being deposited in the hidden chamber, saying that the so-called secret place was merely a hole in one of the chimneys, which had been built up in my grandfather's time to prevent the birds building there and making a mess. My mother, however, would not be convinced, though this fresh will was clearly of a later date than the one for which she had been searching. She would not admit the justice of my uncle's claims, reminding him that he had received his portion from his father in money. She accused him of attempting to deprive his brother's widow and only son of their heritage, and at length refused to discuss the subject any further, directing him to communicate in future with our lawyer, Mr. Denny.

"'Very well,' answered my uncle shortly. 'If you are determined not to listen to reason, I can say no more; but I had much rather have settled the matter amicably between ourselves without creating a public scandal.' His face was black as thunder as he left the house, and I could see at once that all his former pleasant manners had been simply put on for the time being to suit his own purpose. Two days later Mr. Denny called to see us, and he and my mother had a long talk in the dining-room. I wasn't present myself, but I learned afterwards that my uncle had gone straight from us to the lawyer. The latter had seen the will, and was obliged to confess that it seemed genuine and in order, and was dated at least eighteen months after the one executed at his office. I think old Denny was as much surprised at my father's conduct as my mother had been, and he questioned her closely to find out whether anything had ever happened which could in any way have brought my father into Nicholas's power, so that he might have been induced by threats of any kind to make such a disposition of his property. Of course my mother knew nothing of the kind; but in calling to mind everything she could remember, she recollected that a few months back she had seen my father address and send a large sealed envelope to his brother, and as this would have been just about the time when Nicholas asserted that the reconciliation had taken place, it seemed possible that this very letter might have contained the will. The document, I should say, was witnessed by a housekeeper of my uncle's who had since died, and by a sea captain who had often stayed at Stonebank, but whose vessel had foundered in a storm, with all hands. The fact that both of the witnesses were dead seemed suspicious, but there was no flaw in the signatures, and Nicholas had a witness who could prove that my father and Rhodes, the master-mariner, had met at Stonebank on the day the will was signed."

"Then what is going to be done?" I asked.

"What can be done?" returned Miles, with a shrug of his shoulders. "My uncle poses as a model of forbearance, and says he will allow us to remain in possession of the whole estate till the beginning of the New Year, at which date the property will be duly divided."

"At least you'll have the old house," I remarked, not knowing what else to say.

"Yes; but look here, Sylvester," my friend exclaimed. "We shall never be able to live on at Coverthorne as we're doing now if half the property is taken away from us. I believe Uncle Nicholas knows that," continued the speaker excitedly. "He wants to force us to leave, and then he'll raise or borrow money from somewhere, and so come to be owner of the whole place. He's a bad man—you can see it in his face—and how ever he induced my father to make the will I can't imagine."

"I can't either," I replied. "I disliked your uncle the first time I saw him. I believe he's a villain."