Title: Dr. Lavendar's People

Author: Margaret Wade Campbell Deland

Illustrator: Lucius Wolcott Hitchcock

Release date: October 11, 2011 [eBook #34427]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

DR. LAVENDAR'S PEOPLE

BY

MARGARET DELAND

AUTHOR OF "OLD CHESTER TALES"

ILLUSTRATED BY

LUCIUS HITCHCOCK

NEW YORK AND LONDON

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

1903

Copyright, 1903, by HARPER & BROTHERS.

All rights reserved.

Published October, 1903.

TO

DR. FRANCIS B. HARRINGTON

These Stories are

Dedicated

CONTENTS

The Apotheosis of the Reverend Mr. Spangler

ILLUSTRATIONS

"I HAVE A PRESENT FOR YOU—A SISTER'" . . . Frontispiece

"SHE ALWAYS CAME INTO THE LIBRARY TO SAY GOOD-NIGHT TO HIM"

"LURCHED FORWARD INTO A CHAIR, BREATHING LOUDLY"

"MRS. BARKLEY ROSE, TAPPING THE TABLE WITH ALARMING LOUDNESS"

"MISS LYDIA, WATCHING HIM, GREW PALER AND PALER"

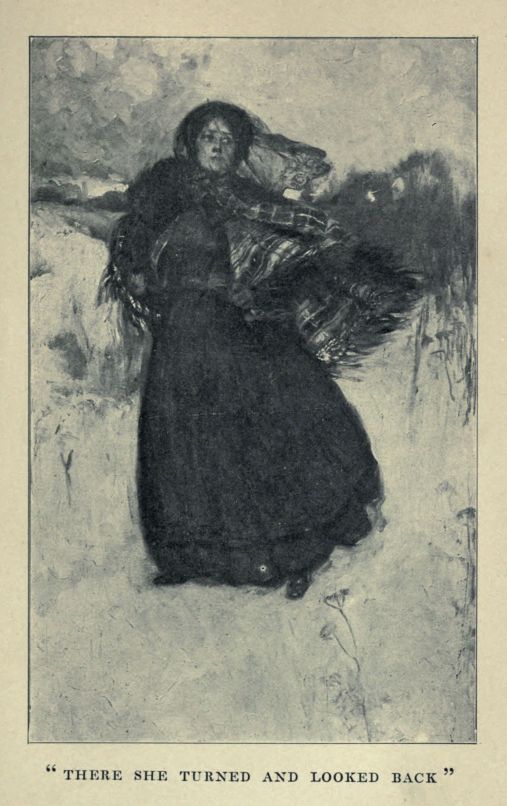

"THERE SHE TURNED AND LOOKED BACK"

"THOMAS DILWORTH GOT ON HIS FEET AND SWORE"

"'WHAT IS THE NAME OF THE KIND PERSON?'"

"SHE KNELT DOWN, AS USUAL, AT THE BIG CHINTZ-COVERED WINGED CHAIR"

MISS HARRIET WAS LEANING FORWARD

"'A HAPPY SLEEP,' MISS ANNIE REPEATED"

THE APOTHEOSIS

OF THE

REVEREND MR. SPANGLER

I

Miss Ellen Baily kept school in the brick basement of her old frame house on Main Street.

The children used to come up a flagstone path to the side door, and then step down two steps into an entry. Two rooms opened on this entry; in one the children sat at small, battered desks and studied; in the other Miss Baily heard their lessons, sitting at a table covered with a red cloth, which had a white Grecian fret for a border and smelled of crumbs. On the wall behind her was a faded print of "Belshazzar's Feast"; in those days this was probably the only feasting the room ever saw—although on a thin-legged sideboard there were two decanters (empty) and a silver-wire cake-basket which held always three apples. Both rooms looked out on the garden—the garden and, in fine weather, Mr. David Baily! ... Ah, me—what it was, in the dreary stretches of mental arithmetic, to look across the flower-beds and see Mr. David—tall and dark and melancholy—pacing up and down, sometimes with a rake, oftener with empty hands; always with vague, beautiful eyes fixed on some inner vision of heart-broken memory. Miss Ellen's pupils were confident of this vision because of a tombstone in the burial-ground which recorded the death of Maria Hastings, at the romantic age of seventeen; and, as everybody in Old Chester knew, Mr. Baily had been in love with this same seventeen-year-old Maria. To be sure, it was thirty years ago; but that does not make any difference, "in real love," as any school-girl can tell you. So, when David Baily paced up and down the garden paths or sat in the sunshine under the big larch we all knew that he was thinking of his bereavement.

In the opinion of the older girls, grief had wrecked Mr. David's life; he had intended to be a clergyman, but had left the theological school because his eyes gave out. "He cried himself nearly blind," the girls told each other with great satisfaction. After that he tried one occupation after another, but somehow failed in each; which was proof of a delicacy of constitution induced by sorrow. Furthermore, he seemed pursued by a cruel fortune—"Fate," the girls called it. Elderly, unromantic Old Chester did not use this fine word, but it admitted pursuing disaster.

For instance: there was the time that David undertook the charge of a private library in Upper Chester, and three months afterwards the owner sold it! Then Mr. Hays found a job for him, and just as he was going to work he was laid up with rheumatism. And again Tom Dilworth got him a place as assistant book-keeper; and David, after innumerable tangles on his balance-sheet, was obliged to say, frankly, that he had no head for figures. But he was willing to do anything else—"any honest work that is not menial," he said, earnestly. And Tom said, why, yes, of course, only he'd be darned if he knew what to suggest. But he added, in conjugal privacy, that David ought to be hided for not turning his hand to something. "Why doesn't he try boot-blacking? Only, I suppose, he'd say he couldn't make the change correctly. He doesn't know whether two and two make five or three—like our Ned."

"Why, they make four, Tom," said Mrs. Dilworth. And Thomas stared at her, and said, "You don't say so!"

There had been no end of such happenings; "and none of them my brother's fault," Miss Ellen told the sympathetic older girls, who glanced sideways at Mr. David and wished that they might die and be mourned as Mr. David mourned Maria.

The fact was, the habit of failure had fastened upon poor David; and in the days when Miss Ellen's school was in its prime (before the new people told our parents that her teaching was absurdly inadequate), he was depending on his sister for his bread-and-butter. That Miss Ellen supported him never troubled the romantic souls of Miss Ellen's pupils any more than it troubled Miss Ellen—or Mr. David. "Why shouldn't she?" the girls would have demanded if any such rudely practical question had been asked; "he is so delicate, and he has a broken heart!" So that was how it happened that the pupils were able to have palpitating glimpses of him, walking listlessly about the garden, or dozing in a sunny window over an old magazine, or doing some pottering bit of carpentering for Miss Ellen, but never losing his good looks or the grieved melancholy of his expression.

Miss Ellen had been teaching for twenty years.

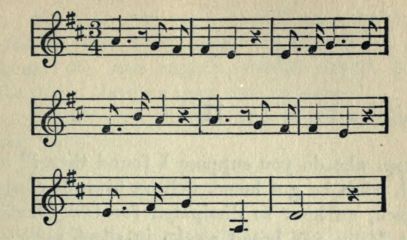

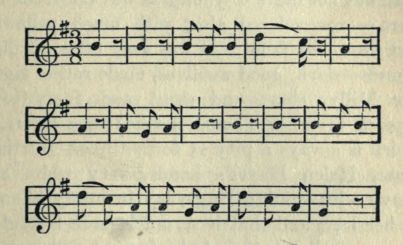

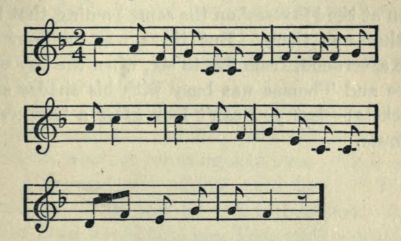

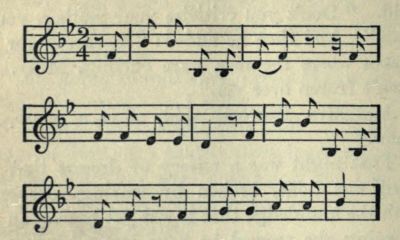

It is useless to deny that, unless one has a genius for imparting knowledge, teaching is a drudgery. It was drudgery to Ellen Baily, but she never slighted it on that account. She was conscientious about the number of feet in the highest mountain in the world; she saw to it that her pupils could repeat the sovereigns of England backward. Besides these fundamentals, the older girls had Natural Philosophy every Friday; it was not, perhaps, necessary that young ladies should know that the air was composed of two gases (the girls who had travelled and seen the lighted streets of towns knew what gas was), nor that rubbing a cat's fur the wrong way in the dark would produce electric sparks—such things were not necessary. But they were interesting, and, as Mrs. Barkley said, if they did not go too far and lead to scepticism, they would do no harm. However, Miss Ellen counteracted any sceptical tendencies by reading aloud, every Saturday morning, Bishop Cummings on the Revelation, so that even Dr. Lavendar was not wiser than Miss Ellen's girls as to what St. John meant by "a time, and a time, and a half of a time," or who the four beasts full of eyes before and behind stood for. For accomplishments, there was fine sewing every Wednesday afternoon; and on Mondays, with sharply pointed pencils, we copied trees and houses from neat little prints; also, we had lessons upon the piano-forte, so there was not one of us who, when she left Miss Ellen's, could not play at least three pieces, viz., "The Starlight Valse," "The Maiden's Prayer," and "The Last Rose of Summer."

Ah, well, one may smile. Compared to what girls know nowadays, it is, of course, very absurd. But, all the same, Miss Ellen's girls knew some things of which our girls are ignorant: reverence was one; humility was another; obedience was a third. And poor, uneducated folk (compared with our daughters) that we of Old Chester may be, we are, if I mistake not, glad that we were taught a certain respect for our own language, which, though it makes the tongue of youth to-day almost unintelligible, does give us a joy in the wells of English undefiled which our children do not seem to know; and for this, in our dull Old Chester way, we are not ungrateful. However, this may all be sour grapes....

At any rate, for twenty painstaking years Miss Ellen's methods fed and clothed Mr. David. Then came the winter of Dr. Lavendar's illness, and the temporary instalment of the Reverend Mr. Spangler, and Ellen Baily realized that there were other things in the world than David's food and clothes.

Dr. Lavendar, cross, unbelieving, protesting, was to be hustled down South by Sam Wright; and the day before he started Mr. Spangler appeared. That was early in February, and Dr. Lavendar was to come back the first of May.

"Not a day sooner," said Sam Wright.

"I'll come when I see fit," said Dr. Lavendar. He didn't believe in this going away, he said. "Home is the best place to be sick in. The truth is, Willy King doesn't want me to die on his hands—it would hurt his business," said Dr. Lavendar, wickedly; "I know him!"

But to Mr. Spangler Dr. Lavendar said other things about Willy, and Sam Wright, too; in fact, about all of them. And he pulled out his big, red silk pocket-handkerchief with a trembling flourish and wiped his eyes. "I don't deserve it," he said. "I'm a dogmatic old fogy, and I won't let the new people have their jimcrackery; and I preach old sermons, and I've had a cold in my head for three months. And yet, look at 'em: A purse, if you please! And Sam Wright is going down with me. Sam ought to be ashamed of himself to waste his time; he's a busy man. No, sir; I don't deserve it. And, if you take my advice, you'll pray the Lord that your people will treat you as you don't deserve."

Mr. Spangler, a tall, lean man, very correctly dressed, who was depended upon in the diocese as a supply, made notes solemnly while Dr. Lavendar talked; but he sighed once or twice, patiently, for the old man was not very helpful. Mr. Spangler wanted to know what Sunday-school teachers could be relied upon, and whether the choir was very thin-skinned, and which of the vestry had chips on their shoulders.

"None of 'em. I knocked 'em all off, long ago," said Dr. Lavendar. "Don't you worry about that. Speak your mind."

"I have," said Mr. Spangler, coughing delicately, "an iron hand when I once make up my mind in regard to methods; firmness is, I think, a clergyman's duty, and duty, I hope, is my watchword; but I think it best to canvass a matter thoroughly before making up my mind."

"It is generally wise to do so," said Dr. Lavendar, very meekly.

"Of course," Mr. Spangler said, kindly, "you belong to a somewhat older period, and do not, perhaps, realize the value of our modern ways of dealing with a parish—I mean in regard to firmly carrying out one's own ideas. I suppose these good people do pretty much as they please, so far as you are concerned?"

"Perhaps they do," said Dr. Lavendar, very, very meekly.

"So, not wishing to offend, I will ask a few questions: I have heard that the parish is perhaps a little old-fashioned in regard to matters of ritual? I have wondered whether my cassock would be misunderstood?"

"Cassock?" said Dr. Lavendar. "Bless your heart, wear a pea-jacket if it helps you to preach the Word. It will only be for ten Sundays," he added, hopefully.

The Reverend Mr. Spangler smiled at that; and when he smiled one saw that his face, though timid, was kind.

So Dr. Lavendar, growling and scolding, fussing about Danny and his little blind horse Goliath, and Mr. Spangler's comfort, was bundled off; and Mr. Spangler settled down in the shabby rectory. His iron will led him to preach in his surplice, and it was observed that a silver cross dangled from his black silk fob. "But it's only for ten weeks," said Old Chester, and asked him to tea, and bore with him, and did nothing more severe than smile when he bowed in the creed—smile, and perhaps stand up a little straighter itself.

This, of the real Old Chester. Of course the new people were pleased; and one or two of the younger folk liked it. Miss Ellen Baily was not young, but she liked the surplice better than Dr. Lavendar's black gown and bands, and the sudden sparkle of the cross when Mr. Spangler knelt gave her a pang of pleasure. David, too, was not displeased. To be sure, David was rarely stirred to anything so positive as pleasure. But at least he made no objections to the cross; and he certainly brightened up when, on Saturday afternoon, Mr. Spangler called. He even talked of Gambier, to which he had gone for a year, and of which, it appeared, the clergyman was an alumnus. Miss Ellen had a pile of compositions on the table beside her, and she glanced at one occasionally so that she might not seem to expect any share in the conversation. But, all the same, Mr. Spangler noticed her. He was not drawn to the brother; still, he talked to him about their college, for Mr. Spangler believed that being agreeable was just as much a clergyman's duty as was changing the bookmarks for Advent or Lent; and duty, as Mr. Spangler often said, was his watchword. Furthermore, he was aware that his kindness pleased the silent, smiling woman seated behind the pile of compositions.

It pleased her so much that that night, after David had gone to bed, she went over to Mrs. Barkley's to talk about her caller.

"Well, Ellen Baily," Mrs. Barkley said, briskly, as Miss Baily came into the circle of lamplight by the parlor-table, "so you had a visitor to-day? I saw him, cross and all."

"It was a very small one," Miss Baily protested, "and only silver."

"Would you have had it diamonds?" demanded Mrs. Barkley, in a deep bass. "Oh, well; it doesn't really matter; there are only nine more Sundays. But Sam Wright says he shall mention it when he writes to Dr. Lavendar."

"I suppose Dr. Lavendar saw it before he went away," Ellen said, with some spirit.

"Well, if he doesn't take his religion out in crosses, I suppose it's all right. But he's not a very active laborer in the vineyard. I suppose you know about him?"

"Why, no," Ellen said; "nothing except that he supplies a good deal."

"Supplies? Yes, because his mother left him a house in Mercer, and enough to live on in a small way; so he likes supplying better than taking a charge where he'd have to work hard and couldn't have his comforts."

"Why doesn't he take a charge where he could have his comforts?"

"Can't get the chance," Mrs. Barkley explained, briefly. "Not enough of a preacher. And, besides, he likes his ease in Zion. Rachel Spangler's old house, and her Mary Ann, and his father's library, and—well, the flesh-pots of Mercer!—and supplying, just enough to buy him his ridiculous buttoned-up coats. That's what he likes. I suppose he uses the same old sermons over and over. Doesn't ever have to write a new one. However, he's here, and maybe Old Chester will do him good. Ellen Baily, did you know that we have a new-comer in Old Chester? A widow. I don't like widows. Her name's Smily. Foolish name! She's staying at the Stuffed Animal House. She's Harriet Hutchinson's cousin, and she's come down on her for a visit."

"Maybe she'll make her a present when she goes away," said Ellen, hopefully.

"Present! She needs to have presents made to her. She hasn't a cent but what her husband's brother gives her. He's a school-teacher, I understand; and you know yourself, Ellen Baily, how much a school-teacher can do in that way?"

Miss Ellen sighed.

"Well," proceeded Mrs. Barkley, "I just thought I'd tell you about her, because if we all invite her to tea, turn about, it will be a relief to Harriet—(she isn't well, that girl; I'm really uneasy about her). And I guess the Smily woman won't object to Old Chester food, either," said Mrs. Barkley, complacently. "I've asked her for Tuesday evening, and I thought I'd throw in Mr. Spangler and get him off my mind."

"David likes him so much," Miss Ellen began.

"Does he?" said Mrs. Barkley. "Well, tell him to come; he can talk to Mr. Spangler. I'm afraid I might hurt the man's feelings if I had to do all the talking. I seem to do that sometimes. Did you ever notice, Ellen, that the truth always hurts people's feelings? But I knew his mother, so I don't want to do anything to wound him. I won't ask you, Ellen; I don't like five at table. But just tell David to come, will you?"

And Miss Baily promised, gratefully. David was not often asked out in Old Chester.

II

The supper at Mrs. Barkley's was a great occasion to David Baily. Right after dinner he went up to the garret, and Ellen heard him shuffling about overhead, moving trunks. After a while he came down, holding something out to his sister.

"Guess I'll wear this," he said, briefly. It was an old black velvet waistcoat worked with small silk flowers, pink and blue and yellow.

"I haven't seen gentlemen wear those waistcoats lately," Miss Ellen said, doubtfully.

Mr. David spread the strange old garment across his narrow breast, and regarded himself in the mirror above the mantel. "Father wore it," he said.

Then he retired to his own room. When he reappeared he wore the waistcoat. His old black frock-coat, shiny on the shoulders and with very full skirts, hung so loose in front that the flowered velvet beneath was not conspicuous; but Mr. David felt its moral support when, at least ten minutes before the proper time, he started for Mrs. Barkley's.

His hostess, putting on her best cap before her mirror, glanced down from her window as he came up the path. "Ellen ought not to have sent him so early," she said, with some irritation. "Emily!" she called, in her deep voice, "just go to the front door and tell Mr. Baily to go home. I'm not ready for him. Or he can sit in the parlor and wait if he wants to. But he can't talk to me."

Emily, a mournful, elderly person, sought, out of regard for her own feelings, to soften her mistress's message; but David instantly retreated to walk up and down the street, keeping his eye on Mrs. Barkley's house, so that he could time his return by the arrival of Mr. Spangler.

"He'll come at the right hour, I presume," he said to himself. Just then he saw Mrs. Smily stepping delicately down the street, her head on one side, and a soft, unchanging smile on her lips. As they met she minced a little in her step, and said:

"Dear me! I'm afraid I've made a mistake. I'm looking for Mrs. Barkley's residence."

"Mrs. Barkley resides here," said Mr. David, elegantly.

She looked up into his sad, dark eyes with a flurried air. "Dear me," she said, "I fear I am late."

"Oh, not late," said poor David. "Perhaps we might walk up and down for a minute longer?"

Mrs. Smily, astonished but flattered, tossed her head, and said, Well, she didn't know about that! But, all the same, she turned, and they walked as far as the post-office.

"I'm afraid you are very attentive to the ladies," Mrs. Smily said, coquettishly, when David had introduced himself; and David, who had never heard a flirtatious word (unless from Maria), felt a sudden thrill and a desire to reply in kind. But from lack of experience he could think of nothing but the truth. He had been too early, he said, and had come out to wait for Mr. Spangler—"and you, ma'am," he added, in a polite after-thought. But his hurried emphasis made Mrs. Smily simper more than ever. She shook her finger at him and said:

"Come, come, sir!" And David's head swam.

At that moment Mr. Spangler, buttoned to his chin in a black waistcoat, came solemnly along, and, with his protection, David felt he could face Mrs. Barkley.

But, indeed, she met her three guests with condescension and kindness. "They are all fools in their different ways," she said to herself, "but one must be kind to them." So she made Mrs. Smily sit down in the most comfortable chair, and pushed a footstool at her. Then she told Mr. Spangler, good-naturedly, that she supposed he found Old Chester very old-fashioned. "Don't you be trying any candles on us," she threatened him, in a jocular bass. As for David, she paid no attention to him except to remark that she supposed time didn't count with him. But her bushy eyebrows twitched in a kindly smile when she said it. Then she began to talk about Dr. Lavendar's health. "It is a great trial to have him away," she said. "Dear me! I don't know what we will do when the Lord takes him. I wish he might live forever. Clergymen are a poor lot nowadays."

"Why, I heard," said Mrs. Smily, "that he didn't give entire satisfaction."

"What!" cried Mrs. Barkley. "Who has been talking nonsense to you? Some of the new people, I'll be bound."

Mrs. Smily, very much frightened, murmured that no doubt she was mistaken. Wild horses would not have drawn from her that she had heard Annie Shields that was, say that Dr. Lavendar had deliberately advised some one she knew to be bad; and that he had refused to help a very worthy man to study for the ministry; and that the Ferrises said he ought to be tried for heresy (or something) because he married Oscar King to their runaway niece; and that he would not give a child back to its repentant (and perfectly respectable) mother—"And a mother's claim is the holiest thing on earth," Mrs. Smily said—and that he had encouraged Miss Lydia Sampson in positively wicked extravagance. After hearing these things, Mrs. Smily had her opinion of Dr. Lavendar; but that was no reason why she should let Mrs. Barkley snap her head off. So she only murmured that no doubt she had made a mistake.

"I think you have," said Mrs. Barkley, dryly; and rose and marshalled her company in to supper. "She's a perfect fool," she told herself, "but I hope the Lord will give me grace to hold my tongue." Perhaps the Lord gave her too much grace, for, for the rest of the evening, she hardly spoke to Mrs. Smily; she even conversed with David rather than look in her direction.

For the most part the conversation was a polite exchange of views upon harmless topics between Mrs. Barkley and Mr. Spangler, during which Mrs. Smily cheered up and murmured small ejaculations to David Baily. She told him that she was scared nearly to death of the stuffed animals at Miss Harriet's house.

"They make me just scream!" she said.

David protectingly assured her that they were harmless.

"But they are so dreadful!" Mrs. Smily said. "Isn't it strange that my cousin likes to—to do that to animals? It isn't quite ladylike, to my mind."

Mr. Baily thought to himself how ladylike it was in Mrs. Smily to object to taxidermy. He noticed, too, that she ate almost nothing, which also seemed very refined. It occurred to him that such a delicate creature ought not to go home alone; the lane up to Miss Harriet's house was dark with overhanging trees, and, furthermore, half-way up the hill it passed the burial-ground. In a burst of fancy David saw himself near the low wall of the cemetery, protecting Mrs. Smily, who was shivering in her ladylike way at the old head-stones over in the grass. He began (in his own mind) a reassuring conversation: "There are no such things as spectres, ma'am. I assure you there is no occasion for fear." And at these manly words she would press closer to his side. (And this outside the burial-ground—oh, Maria, Maria!)

But this flight of imagination was not realized, for later Emily announced that Miss Harriet's Augustine had come for Mrs. Smily.

"Did she bring a lantern?" demanded Mrs. Barkley. "That lane is too dark except for young folks."

Augustine had a lantern, and was waiting with it at the front door for her charge; so there was no reason for Mr. David to offer his protection. He and Mr. Spangler went away together, and David twisted his head around several times to watch the spark of light jolting up the hill towards the burial-ground and the Stuffed-Animal House. When the two men said good-night, Mr. Spangler had a glimpse of a quickly opened door and heard an eager voice—"Come in, dear brother. Did you have a delightful evening?"

"How pleasing to be welcomed so affectionately!" said the Reverend Mr. Spangler to himself.

III

The gentle warmth of that welcome lingered persistently in Mr. Spangler's mind.

"I suspect that she kissed him," he said to himself; and a little dull red crept into his cheeks.

Miss Ellen, dark-eyed, gentle, with soft lips, made Mr. Spangler suddenly think of a spray of heliotrope warm in the sunshine. "That is a very poetical thought," he said, with a sense of regret that it probably could not be utilized in a sermon. But when he entered the study he banished poetry, because he had a letter to write. It was in answer to an offer of the secretaryship of a church publishing-house in a Western city.

Dr. Lavendar, it appeared, had mentioned Mr. Spangler's name to one Mr. Horatius Brown, stating that in his opinion Mr. Spangler was just the man for the place—"exact, painstaking, conscientious," Mr. Brown quoted in his letter; but forbore to add Dr. Lavendar's further remark that Mr. Spangler would never embarrass the management by an original idea. "He'll pick up pins as faithfully as any man I know," said Dr. Lavendar, "and that's what you religious newspapers want, I believe?" Mr. Spangler was not without a solemn pride in being thus sought out by the ecclesiastical business world, especially when he reflected upon the salary which Mr. Brown was prepared to offer; but acceptance was another matter. To leave his high calling for mere business! A business, too, which would involve exact hours and steady application;—Compared with that, and with the crude, smart bustle of the Western city, the frugal leisure of his placid days in Mercer assumed in his mind the sanctity of withdrawal from the world, and his occasional preaching took on the glow of missionary zeal. "No," said Mr. Spangler, "mercenary considerations do not move me a hair's-breadth." Mr. Spangler did not call his tranquil life in Mercer, his comfortable old house, his good cook, his old friends, his freedom from sermon-writing, mercenary considerations. On the contrary, he assured himself that his "circumstances were far from affluent; but I must endure hardness!" he used to add cheerfully. And very honestly his declination seemed to him something that Heaven would place to his credit. So he wrote to the publishing-house that he had given the proposition his most prayerful consideration, but that he believed that it was his duty to still labor at the sacred desk—and duty was, he hoped, the watchword of his life. And he was Mr. Brown's "obedient servant and brother in Christ—Augustus Spangler."

Then he settled down in Dr. Lavendar's armchair by the fire in the study; but he did not read the ecclesiastical paper which every week fed his narrow and sincere mind. Instead he wondered how often Dr. Lavendar called upon his female parishioners. Would twice in a fortnight be liable to be misunderstood? Mr. Spangler was terribly afraid of being misunderstood. Then he had a flash of inspiration: he ought, as rector, to visit the schools. That was only proper and could not possibly be misunderstood. "For an interest in educational affairs is part of a priest's duty," Mr. Spangler reflected.

If he was right, it must be admitted that Dr. Lavendar was very remiss. So far as we children could remember, he had never visited Miss Ellen's school and listened to recitations and heard us speak our pieces. Whether that was because he did not care enough about us to come, or because he saw us at Collect class and Sunday-school and church, and in the street and at the post-office and at home, until he knew us all by heart, so to speak, may be decided one way or the other; but certainly when Mr. Spangler came, and sat through one morning, and told us stories, and said we made him think of a garden of rosebuds, and took up so much of Miss Ellen's time that she could not hear the mental arithmetic, it was impossible not to institute comparisons. Indeed, some hearts were (for the moment) untrue to Mr. David. When Miss Ellen called on us to speak our pieces, we were so excited and breathless that, for my part, I could not remember the first line of "Bingen on the Rhine," and had to look quickly into the Fourth Reader; but before I could begin, Lydia Wright started in with "Excelsior," and she got all the praise; though I'm sure I—well, never mind! But Dr. Lavendar wouldn't have praised one girl so that all the others wanted to scratch her! All that first half, the pupils, bending over their copy-books, writing, "Courtesy to inferiors is true gentility," glanced at the visitor sideways, and if they caught his eye, looked down, blushing to the roots of their hair—which was not frizzled, if you please, or hanging over their eyes like the locks of Skye-terriers, but parted and tied with a neat ribbon bow on the tops of all the small heads. But Mr. Spangler did not look often at the pupils; instead he conversed in a low voice with Miss Ellen. Nobody could hear what he said, but it must have been very interesting, for when Miss Ellen suddenly looked at the clock she blushed, and brought her hand hurriedly down on the bell on her desk. It was ten minutes after the hour for recess!

For the rest of that day Miss Ellen Baily moved and looked as one in a dream. Her brother, however, did not seem to notice her absent-mindedness. Indeed, he was as talkative as she was silent.

"Sister," he said, as they sat at tea, "I need a new hat. One with a blue band about it might be—ah—becoming."

"Blue is a sweet color," said Miss Ellen, vaguely.

"Mrs. Smily remarked to me that before her affliction made it improper, she was addicted to the color of blue."

"Was she?" Ellen said, absently.

"Don't you think," David said, after a pause, "that my coat is somewhat shabby? You bought it, you may remember, the winter of the long frost."

"Is it?" Miss Ellen said.

"Yes; and the style is obsolete, I think. Not that I am a creature of fashion, but I do not like to be conspicuous in dress."

"You are not that, dear David," Miss Ellen protested. "On Sunday I often think nobody looks as handsome as you."

David blushed. "You are partial, Ellen."

"No, I'm not," cried Miss Ellen, coming out of her reveries. "Only yesterday I heard some one say that you were very fine-looking."

"Who said it?"

"Never mind," Ellen said, gayly.

"Do tell me, sister," he entreated; "that's a good girl."

"It was somebody whose opinion you care a great deal about."

"I think you might tell me," said Mr. David, aggrieved. "Not that I care, because it isn't true, and was only said to please you. People know how to get round you, Ellen. But I'd just like to know."

"Guess," said Miss Ellen.

"Well, was it—Mrs. Smily?"

"Oh, dear, no! It was somebody very important in Old Chester. It was Mrs. Barkley."

"Oh," said Mr. David.

"A compliment from her means so much, you know," Miss Ellen reminded him.

David was silent.

"But all the same," Ellen said, "you do need a coat, dear brother. I'm afraid I've been selfish not to notice it."

Mr. David made no reply.

Miss Ellen beamed at him. "You always look well, in my eyes: but it pleases me to have you well dressed, too."

"Well, then, to please you, I'll dress up," said Mr. David, earnestly.

IV

"Does not Mr. Baily take any part whatever in his sister's work?" Mr. Spangler said. He was calling upon Mrs. Barkley, and the conversation turned upon the guests whom he had met at the tea-party.

"That is a very foolish question," said Mrs. Barkley; "but of course you don't know poor David, or you wouldn't have asked it. David means well, but he has no mind. Still, he has tried, poor fellow." Then she recited the story of David's failures. "There is really nothing that he is capable of doing," she ended, thoughtfully; "though I think, if his eyes hadn't given out, he might have made a good minister. For David is a pious man, and he likes to visit."

A faint red came into Mr. Spangler's cheeks; although he had been in Old Chester nearly a month, he had not yet become acclimated to Mrs. Barkley. The watchword of duty made him call, but he closed her front door behind him with an emphasis which was not dutiful.

"That's done!" he said; and thought to himself how much pleasanter than parochial visits were educational matters.

Mr. Spangler felt their importance so deeply that he spent two more mornings watching Miss Ellen's pupils work out examples on the blackboard and hearing them read, turn about, in the Fourth Reader. In fact, the next month was a pretty happy time for Miss Ellen's girls.

"I skipped to the bottom of the page in 'Catiline's Reply,'" Lydia Wright said, giggling, "and she never knew it!"

The girls were tremendously interested but not very sympathetic, for "she's so dreadfully old!" they told each other. Had Miss Ellen been Maria's age and had a beau (by this time they called Mr. Spangler Miss Ellen's beau, the impudent little creatures!), how different it would have been! But Miss Ellen was forty. "Did you ever know anything so perfectly absurd?" said the older girls. And the second-class girls said they certainly never did. So when Mr. Spangler came and listened to recitations we poked one another, and put out our tongues behind our Readers, and made ourselves extremely obnoxious—if dear Miss Ellen had had the eyes to see it, which, indeed, she had not. She was very absent in those days; but she did her work faithfully, and saw to David's new coat, and asked Mrs. Smily to tea, not only to help out Miss Harriet at the Stuffed-Animal House, but because David told her a piteous tale of Mrs. Smily's loneliness and general forlornness. David had had it directly from Mrs. Smily herself, and had been greatly moved by it; she had told him that this was a sad and unfriendly world.

"But I am sure your brother-in-law's family is much attached to you?" David said, comfortingly.

Then poor Mrs. Smily suddenly began to cry. "Yes; but I am afraid I can't live at my brother-in-law's any longer. His wife is—is tired of me," said the poor little creature.

David was thunderstruck. "Tired? Of you! Oh, impossible!"

Then she opened her poor foolish heart to him. And David was so touched and interested that he could hardly wait to get home to pour it all into Ellen's ears. Ellen was very sympathetic, and made haste to ask Mrs. Smily to tea; and when she came was as kind and pitiful as only dear, kind Ellen could be. But perhaps she took Mrs. Smily's griefs a little less to heart than she might have done had she heard the tale a month before. Just then she was in the whirl of Old Chester hospitality; she was asked out three times in one week to meet the Supply!—and by that time the Supply had reached the point of hoping that he was going to meet Miss Ellen.

Yet, as Mr. Spangler reflected, this was hardly prudent on his part. "For I might become interested," he said to himself, and frowned and sighed. Now, as everybody knows, the outcome of "interest" is only justified by a reasonable affluence. "And," Augustus Spangler reminded himself, "my circumstances are not affluent." Indeed, that warm, pleasant old house in Mercer, and Mary Ann, and his books, and those buttoned-up coats needed every penny of his tiny income. "Therefore," said Mr. Spangler, "it is my duty to put this out of my head with an iron hand." But, all the same, Ellen Baily was like a spray of heliotrope.

For a week, the second week in April, while Old Chester softened into a mist of green, and the crown-imperials shook their clean, bitter fragrance over the bare beds in the gardens—for that week Mr. Spangler thought often of his income, but oftener of Miss Ellen. Reason and sentiment wrestled together in his lazy but affectionate heart; and then, with a mighty effort, sentiment conquered....

"It seems," said Mr. Spangler, nervously, "a little premature, but my sojourn in Old Chester is drawing to a close; I shall not tarry more than another fortnight; so I felt, my dear friend, that I must, before seeking other fields of usefulness, tell you what was in my mind—or may I say heart?"

"You are very kind," Ellen Baily said, breathlessly.

.... Mr. Spangler had invited Miss Ellen to walk with him on Saturday afternoon at four. Now, as everybody knows in Old Chester, when a gentleman invites you to walk out with him, you had better make up your mind whether it is to be "yes" or "no" before you start. As for poor Ellen, she did not have to make up her mind; it was made up for her by unconquerable circumstances. If she should "seek other fields of usefulness," she could not take David with her. It was equally clear that she could not leave him behind her. Where would he find his occasional new coat, or even the hat with the blue band, if there were no school in the basement? Compared to love-making and romance, how sordid are questions about coats! Yet, before starting on that Saturday-afternoon walk, poor, pretty Miss Ellen, tying the strings of her many-times retrimmed bonnet under her quivering chin, asked them, and could find no answer except that if he should "say anything," why, then, she must say "no"; but, of course, he wasn't going to say anything. So she tied her washed and ironed brown ribbons into a neat bow, and started down the street with the Reverend Mr. Spangler.

David Baily, watching them from the gate, ruminated over obvious possibilities. Mrs. Barkley had opened his eyes to the fact that Mr. Spangler "was taking notice," and David was not without a certain family pride in a ministerial proposal. "He'll do it this afternoon," said David; and went pottering back into the empty school-room to mend a bench that Ellen told him needed a nail or two. But the room was still and sunny, and Ellen's chair was comfortable; and sitting there to think about the bench, he nodded once or twice, and then dozed for an hour. When he awoke it seemed best to mend the bench the next day; then, yawning, and staring vacantly out of the window, he saw Mrs. Smily, and it seemed only friendly to go out and tell her (confidentially) what was going to happen.

"It will make quite a difference to you, won't it?" Mrs. Smily said.

"Oh," David said, blankly, "that hadn't occurred to me. However," he added, with a little sigh, "my sister's happiness is my first thought."

Mrs. Smily clasped her hands. "Mr. Baily, I do think you are real noble!" she said.

Mr. David stood very erect. "Oh, you mustn't flatter me, ma'am."

"Mr. Baily, I never flatter," Mrs. Smily said, gravely. "I don't think it's right."

And David thought to himself how noble Mrs. Smily was. Indeed, her nobility was so much in his mind that, strangely enough, he quite forgot Ellen's exciting afternoon. He remembered it the next morning, but when he essayed a little joke and a delicate question, the asperity with which the mild Ellen answered him left him gaping with astonishment. Evidently Mr. Spangler had not spoken. David would have been less (or more) than a human brother if he had not smiled a very little at that. "Ellen expected it," he said to himself. "Well, I did myself, and so did Mrs. Barkley." It never occurred to him that the Reverend Mr. Spangler might also have had expectations which left him disappointed and mortified. Yet when a gentleman of Mr. Spangler's age—one, too, whose income barely suffices for his own comfort, and who, added to this, has had his doubts whether the celibacy of the clergy may not be a sacrament of grace—when such a gentleman does make up his mind to offer himself—to offer himself, moreover, to a lady no longer in her first youth, who is pleasing perhaps to the eye, but not, certainly, excessively beautiful, and whose fortune is merely (and most meritoriously, of course) in her character and understanding—it is a blow to pride to be refused. Mr. Spangler found it hard to labor at the sacred desk that morning; yet no one would have thought it, to see the fervor with which, as Old Chester said, he "went through his performances."

But he read the service, hot at heart and hoping that Miss Baily observed how intensely his attention was fixed on things above. When he stood in the chancel waiting for the collection-plates, and saying, in a curious sing-song, absolutely new to Old Chester, "Zaccheus stood forth, and said, Behold, Lord—" his glance, roving over the congregation, rested once on Ellen Baily, and was as carefully impersonal as though she were only a part of the pew in which she sat. Miss Ellen thrilled at that high indifference; it occurred to her that even had David's circumstances been different, she could scarcely have dared to accept the hand of this high creature.

"—the half of all my goods—" said Mr. Spangler. Yes, it was inconceivable, considering what he was offering her, that Ellen Baily could let her brother stand in the way!

All that long, pleasant spring Sunday, Augustus Spangler was very bitter. All that week he was distinctly angry. He said to himself that he was glad that Dr. Lavendar was soon to return; he would, after making his report of the parish, shake the dust of Old Chester from off his feet as witness against Miss Baily, and depart. By the next Sunday he had ceased to be angry, but his pride was still deeply wounded. By Wednesday he had softened to melancholy; he was able to say that it all came from her sense of duty. Unreasonable, of course, but still duty. Then, on Thursday, suddenly, he was startled by a question in his own mind: Was it unreasonable? If she gave up her teaching—"what would that fellow live on?"

That was a very bad moment to the Reverend Mr. Spangler. Pride vanished in honest unhappiness. He began to think again about his income; he had known that to marry a wife meant greater economy; but sacrifices had not seemed too difficult considering that that wife was to be Miss Ellen Baily. But if the wife must be Miss Baily plus—"that fellow"!

"It is out of the question," said poor Mr. Spangler, and arose and paced up and down the study. He was very miserable; and the more miserable he became, the more in love he knew himself to be. "But it is madness to think of the matter further," he told himself, sternly—"madness!"

Yet he kept on thinking of it—or of Miss Ellen's dark eyes, and her smile, and the way her hair curled in little rings about her temples. "But it's impossible—impossible!" he said. Then, absently, he made some calculations: To meet the support of David Baily he would have to have an increase of so much in his income or a decrease of so much in his expenses. "Madness!" said Augustus Spangler, firmly. "But how her eyes crinkle up when she smiles!"

Yet it took another day before the real man conquered. His expenses should be decreased, and David should live with them.

Yes, it would mean undeniable pinching; he must give up this small luxury and that; his Mary Ann could not broil his occasional sweetbread; and the occasional new book must be borrowed from the library, not purchased for his own shelves. He must push about to get more supplying. He had meant to come down one step when he got married; well, he would have to come down two—yes, or three. But he would have Miss Baily. And warmed with this tender thought, he sat down, then and there, at nearly midnight, and wrote Miss Ellen a letter. It was a beautiful letter, full of most beautiful sentiments expressed with great elegance and gentility. It appreciated Miss Ellen's devotion to her family, and acknowledged that a sense of duty was a part of the character of a Christian female. It protested that it was far from the Reverend Mr. Spangler to interfere with that sense of duty; on the contrary, he would share it; nay more, he would assist it, for duty was, he hoped, the watchword of his life. If Miss Baily would consent to become his wife, Mr. Baily, he trusted, would make his home with his sister.

Mr. Spangler may have been addicted to petticoats (in his own toilet) and given to candles and other emblems of the Scarlet Woman, but his letter, beneath its stilted phrase, was an honest, manly utterance, and Ellen Baily read it, thrilling with happiness and love.

That was Friday, and she had only time to read those thin, blue pages and thrust them into the bosom of her dress, when it was time to go to school and hear her girls declare that the Amazon was the largest river in South America; but we might have said it was the largest river in Pennsylvania, and Miss Ellen would have gone on smiling at us. At recess we poured out into the garden, eager to say, "Goodness! do you suppose he's popped?" The older girls were especially excited, but they took their usual furtive look about the garden before sitting down on the steps to eat their luncheons. Alas, He was not there!

"Perhaps," said Lydia Wright, "he has gone to the tomb."

This, for the moment, was deliciously saddening; but, after all, real live love-making, even of very old people, is more fascinating than dead romance. Through the open window we could see Miss Ellen sitting at her desk, writing. There were some sheets of blue paper spread out in front of her, and she would glance at them, and then write a little, and then glance back again, and smile, and write. But she did not look troubled, or "cross," as the girls called it; so we knew it could not be an exercise that she was correcting. But when she came out to us, and said, in a sweet, fluttered voice, "Children, will one of you take this letter to the post-office?" we knew what it meant—for it was addressed to the Reverend Mr. Spangler. How we all ran with it to the post-office!—giggling and palpitating and sighing as our individual temperaments might suggest. In fact, I know one girl who squeezed a tear out of each eye, she was so moved. When we came back, there was Miss Baily still sitting at her desk, her cheek on one hand, her smiling eyes fastened on those sheets of blue paper. "Gracious," said the girls, "what a long recess!" and told each other to be quiet and not remind her to ring the bell.

Then suddenly something happened....

An old carry-all came shambling along the road; there were two people in it, and one of them leaned over from the back seat and said to the driver: "This is my house. Stop here, please." The girls, clustering like pigeons on the sunny doorstep, began to fold up their luncheon-boxes, and look sidewise, with beating hearts, towards the gate—for it was He! How graceful he was—how elegant in his manners! Ah, if our mothers had bidden us have manners like Mr. David!—but they never did. They used to say, "Try and behave as politely as Miss Maria Welwood," or, "I hope you will be as modest in your deportment as Miss Sally Smith." And there was this model before our eyes. It makes my heart beat now to remember how He got out of that rattling old carriage and turned and lifted his hat to a lady inside, and gave her his hand (ah, me!) and held back her skirts as she got out, and bowed again when she reached the ground. She was not much to look at; she was only the lady who was visiting at the Stuffed-Animal House, and she was dressed in black, and her bonnet was on one side. They stood there together in the sunshine, and Mr. David felt slowly in all his pockets; then he turned to us, sitting watching him with beating hearts.

"Little girls," he said—he was near-sighted, and, absorbed as he always was with sorrow, we never expected him to know our names—"little girls, one of you, go in and ask my sister for two coach fares, if you please."

We rose in a body and swarmed back into the school-room—just as Miss Ellen with a start looked at the clock and put out her hand to ring the bell. "Mr. David says, please, ma'am, will you give him money for two coach fares?"

Miss Ellen, rummaging in her pocket for her purse, said: "Yes, my love. Will you take this to my brother?" Just why she followed us as we ran out into the garden with her purse perhaps she hardly knew herself. But as she stood in the doorway, a little uncertain and wondering, Mr. David led the shabby, shrinking lady up to her.

"My dear Ellen," he said, "I have a present for you—a sister."

Then the little, shabby lady stepped forward and threw herself on Miss Ellen's shoulder.

"A sister?" Ellen Baily said, bewildered.

"We were married this morning in Upper Chester," said Mr. David, "and I have brought her home. Now we shall all be so happy!"

V

That evening Dr. Lavendar came home. Of course all the real Old Chester was on hand to welcome him.

When the stage came creaking up to the tavern steps, the old white head was bare, and the broad-brimmed shabby felt hat was waving tremulously in the air.

"Here I am," said Dr. Lavendar, clambering down stiffly from the box-seat. "What mischief have you all been up to?"

There was much laughing and hand-shaking, and Dr. Lavendar, blinking very hard, and flourishing his red silk pocket-handkerchief, clapped Mr. Spangler on the shoulder.

"Didn't I tell you about 'em? Didn't I tell you they were the best people going? But we mustn't let 'em know it; makes 'em vain," said Dr. Lavendar, with great show of secrecy. "And look here, Sam Wright! You fellows may congratulate yourselves. Spangler here has had a fine business offer made him, haven't you, Mr. Spangler? and it's just your luck that you got him to supply for you before he left this part of the country. A little later he wouldn't have looked at Old Chester. Hey, Spangler?"

"Oh, that's settled," Mr. Spangler said. "I declined—"

"Oh," said Dr. Lavendar, "have you? Well, I'm sorry for 'em."

And Augustus Spangler smiled as heartily as anybody. He had a letter crushed up in his hand; he had read it walking down from the post-office to the tavern, and now he was ready to say that Old Chester was the finest place in the world. He could hardly wait to get Dr. Lavendar to himself in the rectory before telling him his great news and giving him a little three-cornered note from Ellen Baily which had been enclosed in his own letter.

"Well, well, well," said Dr. Lavendar.

He had put on a strange dressing-gown of flowered cashmere and his worsted-work slippers, and made room for his shaggy old Danny in his leather chair, and lighted his pipe. "Now tell us the news!" he said. And was all ready to hear about the Sunday-school teachers, and the choir, and Sam Wright's Protestantism, and many other important things. But not at all:—

"I'm engaged to be married."

"Well, well, well," said Dr. Lavendar, blinking and chuckling with pleasure; then he read Ellen's little note. "I had to tell you myself," Ellen wrote him, "because I am so happy." And then there were a dozen lines in which her heart overflowed to this old friend. "Dear child, dear child," he murmured to himself. To no one but Dr. Lavendar—queer, grizzled, wrinkled old Dr. Lavendar, with never a romance or a love-affair that anybody had ever heard of—could Miss Ellen have showed her heart. Even Mr. Spangler did not know that heart as Dr. Lavendar did when he finished Ellen's little letter.—And Dr. Lavendar didn't tell. "I am so happy," said Miss Ellen. Dr. Lavendar may have looked at Mr. Spangler and wondered at the happiness. But, after all, wonder, on somebody's part, is a feature of every engagement. And if the wonder is caused only by the man's coat, and not by his character, why be distressed about it? Mr. Spangler was an honest man; if his mind was narrow, it was at least sincere; if his heart was timid, it was very kind; if his nature was lazy, it was clean and harmless. So why shouldn't Ellen Baily love him? And why shouldn't Dr. Lavendar bubble over with happiness in Ellen's happiness?

"She's the best girl in the world," he told Mr. Spangler. "I congratulate you. She's a good child—a good child."

Mr. Spangler agreed, in a somewhat solemn manner.

"But David—how about David?"

"My house shall always be open to Mrs. Spangler's relatives," said Mr. Spangler, with Christian pride.

"You are a good fellow, Spangler," Dr. Lavendar said; and listened, chuckling, to Mr. Spangler's awkward and correct expressions of bliss. For indeed he was very happy, and talked about Miss Ellen's virtues (which so eminently qualified her to become his wife), as fatuously as any lover could.

"Hi, you, Danny," said Dr. Lavendar, after half an hour of it, "stop growling."

"There's somebody at the door," said Augustus Spangler, and went into the entry to see who it was. He came back with a letter, which he read, standing by the table; then he sat down and looked white. Dr. Lavendar, joyously, was singing to himself:

"'Ten-cent Jimmy and his minions

Cannot down the Woolly Horse.'

"Spangler, we must drink to your very good health and prospects. Let's have Mary bring the glasses."

"I fear," said Mr. Spangler—he stopped, his voice unsteady. "I regret—"

"Hullo!" said Dr. Lavendar, looking at him over his spectacles; "what's wrong?"

"I'm extremely sorry to say," said poor Mr. Spangler, "that—it can't be."

"A good glass of wine," said Dr. Lavendar, "never hurt—"

"I refer," said Mr. Spangler, sighing, "to my relations with Miss Ellen Baily."

Dr. Lavendar looked at him blankly.

"I have just received a letter," the poor man went on, "in which she informs me that it can never be." His lip trembled, but he held himself very straight and placed the letter in his breast-pocket with dignity.

"Spangler, what are you talking about?"

"It appears," said Mr. Spangler, "that her brother—"

"Fiddlesticks!" said Dr. Lavendar. "Has Ellen started up some fantastic conscientiousness? Spangler, women's consciences are responsible for much unhappiness in this world. But I won't have it in my parish! I'll manage Ellen; trust me." He pulled at his pipe, which had gone out in these moments of agitation. "I tell you, sir," he said, striking a match on the bottom of his chair, "these saintly, self-sacrificing women do a fine work for the devil, if they only knew it, bless their hearts."

"You misapprehend," said Mr. Spangler, wretchedly; and then told Miss Ellen's news. It was brief enough, this last letter; there was no blame of David; indeed, he had displayed, Miss Baily said, "a true chivalry; but of course—" "Of course," said Mr. Spangler.

But Dr. Lavendar broke out so fiercely that Danny squeaked and jumped down out of the chair. "Upon my word; upon my word, Spangler, what were you thinking of to let it go on? If I had been at home, it would never—upon my word!" This was one of the times that Dr. Lavendar felt the limitations of his office in regard to language. Mr. Spangler, his elbows on his knees, his chin on hands, was staring miserably at the floor.

"I shall, I trust, meet it in the proper spirit," he said.

Dr. Lavendar nodded. "Of course," he said. "Fortunately, she is dealing with a man who has backbone—perhaps."

Mr. Spangler sighed. "I regret to say that her presence in her school under the circumstances does seem imperative."

Dr. Lavendar lighted his pipe. "Do you mean on account of money, Spangler?"

"The support of Mr. David Baily and this—this female, must be met, I suppose, by Miss Baily's school."

"You are not so situated that you—" began Dr. Lavendar, delicately.

"My circumstances," said Augustus Spangler, "are not affluent. I have my residence in Mercer; and I supply, as you know. But my income barely suffices for one. Four—would be out of the question."

Dr. Lavendar looked at Ellen's little, happy note, lying half open on the table. "Poor old jack-donkey of a David!" he groaned.

"His selfishness," said Augustus Spangler, between his teeth, his voice suddenly trembling with anger, "is perfectly incomprehensible to me—perfectly incomprehensible! I endeavor always to exercise charity in judging any human creature; but—really, really!"

"It isn't selfishness as much as silliness. David hasn't mind enough to be deliberately selfish. The poor fellow never thought. He never has thought. Ellen has always done the thinking for the family. Well, the harm's done. But, Spangler—" the old man stopped and glanced sharply at the forlorn and angry man opposite him. Yes, he certainly seemed very unhappy;—and as for Ellen! Dr. Lavendar could not bear that thought. "Spangler, I'll stand by you. I won't let her offer you up as well as herself. There must be some way out."

Mr. Spangler shook his head hopelessly. "The support of four persons on my small stipend is impossible."

"Spangler, my boy!" said Dr. Lavendar, suddenly, "there is a way out. What an old fool I am not to have thought of it! My dear fellow"—Dr. Lavendar leaned over and tapped Mr. Spangler's knee, chuckling aloud—"that secretaryship!"

"Secretaryship?" Mr. Spangler repeated, vaguely.

"You declined it? I know. But I don't believe Brown's got a man yet. I heard from him on another matter, yesterday, and he didn't say he had. Anyway, it's worth trying for. We can telegraph him to-morrow," said Dr. Lavendar, excitedly.

Mr. Spangler stared at him in bewilderment. "But," he said, breathlessly, "I—I don't think—I fear I am not fit." He felt as if caught in a sudden wind; his face grew red with agitation. "I declined it!" he ended, gasping.

"Fit?" said Dr. Lavendar. "My dear man, what fitness is needed? There's nothing to it, Spangler, I assure you." Dr. Lavendar was very much in earnest; he sat forward on the edge of his chair and gesticulated with his pipe. "Don't be too modest, my boy."

"Business entails such responsibilities," Mr. Spangler began, in a frightened voice.

"Oh, but this is mere routine," Dr. Lavendar interrupted; "they want a clergyman—somebody with tact. There's a good deal of church politics in it, I suppose, and they've got to have somebody who would never step on anybody's toes."

"I would never do that," said Mr. Spangler, earnestly, "but—"

"No," said Dr. Lavendar, abruptly, his voice changing—"no, Spangler, you never would." Then he was silent for a moment, pulling on his pipe, wondering perhaps, in spite of himself, at Ellen. "No, you never would. You see, you are just the man for the place. Brown said they wanted somebody who was presentable; he said they didn't need any particular abil—I mean any particular business ability."

"But," said Mr. Spangler, "to give up my sacred calling—"

"Spangler, come now! you don't 'call' very loudly, do you? There, my dear boy, let an old fellow have his joke. I merely mean you don't preach as often as if you had a regular parish. And you can supply, you know, there just as well as here."

"The Master's service is my first consideration," said Augustus Spangler.

Dr. Lavendar looked at him over his spectacles. "Mr. Spangler, the Christian business-man serves the Master just as well as we do."

"I should wish to reflect," said Mr. Spangler.

"Of course."

"Miss Baily would, I fear, object to going so far away."

"If the place is still open, I'll manage Ellen," said Dr. Lavendar; but he looked at Mr. Spangler narrowly. "And your own entreaties will, of course, weigh with her if you show determination. I think you told me you were pretty determined?"

"I have," said Mr. Spangler, "an iron will; but that would not justify me in insisting if Miss Baily—" His voice trailed off; it rose before him—the far-off, bustling city, the office, the regular hours, the people whose toes must not be stepped upon, the letters to write and read, the papers to file, all the exact minutiae the position involved. And his comfortable old house? his leisure? his ease? And Mary Ann? Mary Ann would never consent to go so far! "I—I really—" he began.

Dr. Lavendar frowned. "Mr. Spangler, I would not seem to urge you. Ellen is too dear to us for that. But if you appreciate her as I suppose you do—"

"I do indeed!" broke in poor Augustus Spangler, fervently.

"The way is probably open to you."

"But—" said Mr. Spangler, and then broke out, with marked agitation; "I—I really don't see how I could possibly—" Yet even as he spoke he thought of Ellen's sweet eyes. "Good Heavens!" said Mr. Spangler, passionately; "what shall I do?"

But Dr. Lavendar was silent. Mr. Spangler got up and began to walk about.

"My affection and esteem," he said, almost weeping, "are unquestioned. But there are other considerations."

Dr. Lavendar said nothing.

"It is a cruel situation," said Mr. Spangler.

Dr. Lavendar looked down at his pipe.

There was a long silence. Augustus Spangler walked back and forth. Dr. Lavendar said never a word.

"A man must consider his own fitness for such a position," Mr. Spangler said, pleadingly.

"Perhaps," Dr. Lavendar observed, mildly, "Ellen's affections are not very deeply engaged? It will be better so."

"But they are!" cried Mr. Spangler. "I assure you that they are! And I—I was so happy," said the poor man; and sniffed suddenly, and tried to find the pocket in his coat-tails.

Dr. Lavendar looked at him out of the corner of his eye.

Mr. Spangler stood stock-still; he opened and shut his hands, his lips were pressed hard together. He seemed almost in bodily pain, for a slight moisture stood out on his forehead. He was certainly in spiritual pain. The Ideal of Sacrifice was being born in Mr. Spangler's soul. His mild, kind, empty face grew almost noble; certainly it grew very solemn.

"Dr. Lavendar," he said, in a low voice, "I will do it."

Dr. Lavendar was instantly on his feet; there was a grip of the hand, and, for a moment, no words.

"I'll telegraph Mr. Brown," said Mr. Spangler, breathlessly.

"So will I!" said Dr. Lavendar.

Mr. Spangler was scarlet with heroism. "It means giving up my house and my very congenial surroundings, and I fear Mary Ann will feel too old to accompany me; but with—with Ellen!"

"She's worth six Mary Anns, whoever Mary Ann may be," said Dr. Lavendar.

"You may have thought me hesitant," said Mr. Spangler, "but I felt that I must weigh the matter thoroughly."

"Why, certainly, man. It was your duty to think what was best for Ellen."

"Exactly," Mr. Spangler said, getting his breath again, and beginning to feel very happy. "And duty is, I hope, my watchword; but I had to reflect," he ended, a little uncomfortably.

But Dr. Lavendar would not let him be uncomfortable. They sat down again, and Dr. Lavendar filled another pipe, and until long after midnight they talked things over—the allowance to be made to David and his bride, the leasing of the house in Mercer, the possible obduracy of Mary Ann, and, most of all, the fine conduct of the Reverend Mr. Spangler.

But when they had said good-night, Dr. Lavendar sat awhile longer by his fireside, his pipe out, his old white head on his breast.

"The minute I get back," he said to himself after a while, sheepishly—"the minute I get back I poke my finger into somebody else's pie. But I think 'twas right: Ellen loves him; and he's not a bad man.—And Brown don't want brains."

Then he chuckled and got up, and blew out the lamp.

THE NOTE

I

Of course everybody in Old Chester knew that there was something queer about Mary Gordon's marriage—not the mere fact of the man, queer as he was; for, to Old Chester's ideas, he was very queer.... A "travelling-man," to begin with—and the Gordons had a line of scholars and professional men behind them—a drummer, if you please. In theory, Old Chester was religiously democratic; it plumed itself upon its Christian humility, and every Sunday it publicly acknowledged that Old Chesterians were like the rest of humanity to the extent of being miserable sinners. But, all the same, that Mary Gordon should marry a "person" of that sort—

"Dear me!" said Old Chester.

However, travelling-men may be worthy; they need not necessarily use perfumery or put pomade upon their shiny, curly, black hair. But Mr. Algernon Keen was obviously not worthy, and he was saturated with perfumery, and his black, curly hair was sleek with oil. Furthermore, he was very handsome: his lips were weak and pouting and red; his eyes liquid and beautiful; his plump cheeks slightly pink. One may believe that such physical characteristics do not imply moral qualities; but only youth has such a belief. When one has lived a little while in the world, one comes to know that a human soul prisoned in such pretty flesh is piteously hampered. Yet Mary Gordon, meeting this poor creature by chance, fell deeply in love with him. Of course such falling in love was queer—it was inexplainable; for Mary was a nice girl—not, of course, of the caliber of some Old Chester girls; she had not the mind of Alice Gray nor the conscience of Sally Smith; but she was a quiet, biddable, good child—at least so far as anybody knew. But nobody knew much about her. In the first place, the Gordons lived just far enough out of Old Chester to miss its neighborliness. Mary was not often seen in town, and in her own home her brother Alex's loud personality crushed her into a colorless silence. Her father did not crush her—he merely did not notice her; but he was fond of her—at least he had the habit of indifferent affection. She always came into the library to say good-night to him; and he, sitting by the fire in a big, winged chair, a purple silk handkerchief spread over his white locks, to keep off possible draughts, would turn his cheek up to her mechanically; but the soft touch of her lips never made him lift his eyes from his book. She never kissed Alex good-night; she was openly afraid of him. Alex was rude to her and made her wait on him, throwing her a curt "thank you" once in a while, generally coupled with some sarcastic reference to her slowness or stupidity—for, indeed, the child was both slow and stupid. Perhaps, had she been loved— But no one can tell now how that would have been. At any rate, there was a pathetic explanation of loneliness to account for the fact that she was drawn to this Algernon Keen, who had nothing to recommend him except a cheap and easy kindliness that cost him no effort and was bestowed on everybody.

Of course the two men, her father and brother, refused to consider Keen as Mary's suitor at all. Alex nearly had a fit over it; in his rage and mortification he took all Old Chester into his confidence. He went to the Tavern—this was the day after Mary had, trembling and crying, told her little love affair to her father and begged his consent—Alex went to the Tavern and ordered the snickering, perfumed youth out of town.

"Well, I guess not," said Algy. "This town doesn't belong to you, does it?"

Alex stammered with passion: "If—if you dare to address Miss Gordon again, I'll—I'll—I'll horsewhip you," he said, his pale eyes bulging from his crimsoning face.

"I guess Mary has a right to let me talk to her if she wants to; this is a free country," the other blustered. And Alex, loudly, on the Tavern steps, cursed him for a skunk, a— Well, Old Chester was never able to quote Alex. He came to his senses after this dreadful exhibition of himself, and was horribly mortified. But post-mortification cannot undo the deed, and before night everybody in Old Chester knew that Mary Gordon had fallen in love with—"the person who brings samples to Tommy Dove's apothecary shop."

Old Chester was truly sorry for Mary; "for," as Mrs. Barkley said, "love's love, whether it's suitable or not; and Mary has such a lonely life, poor child! Well, it will take time for her to get over it."

It seemed to take a good deal of time. That winter she grew pale and was often ill. The poor little thing seemed to creep into her shell to brood over her blighted hopes. Once she was downright sick for a week, and Mr. Gordon sent for William King. Willy said at first that Mary had something on her mind (which certainly Mary's family did not need to be told).

"I believe she's thinking about that scoundrel yet," said Alex. "But she has just got to understand that we'll never allow it, Willy. You may as well make that clear to her, and let her get over her moping."

William King looked thoughtful and said he would call again.

However, any of us Old Chester girls could have enlightened the doctor. "Mary was pining away for her lover;" that was all there was to it. But the lover never appeared, being engaged in offering samples of pomade and perfumery to apothecary stores in other regions. And then, suddenly, the queer thing happened....

The Globe announced: "Married—by Dr. Lavendar, Mary Gordon to Algernon Keen"—and the date, which was the night before.

"What!" said Old Chester at the breakfast-table, and gaped out of its windows to see Mary, crying very much, get into the stage, not at her father's house, but at the Tavern door, if you please, and drive away with the Person. What did it mean? "Was Alex at home? Did he consent?" demanded Old Chester; for Alex had been away from home for a week. By noon it was decided that Alex had consented; for it came out that he had returned to Old Chester the previous afternoon, and with him, shrinking into the corner of the stage, was Mr. Algy Keen.

"Get out," Alex said to him when the stage drew up at the Gordon house. The man got out, shambling and stumbling, with a furtive look over his shoulder, for Alex Gordon walked behind him to the front door, his right hand gripped upon his walking-stick, his left clinched at his side.

"He kep' just behind the feller," the stage-driver told Van Horn at the Tavern afterwards—"just behind him, like as if he was afraid the feller'd run away from him. But the feller, he stopped right at the steps, and he turned around, and he says, 'Mind you,' he says (mad as a hatter)—'mind you,' he says, 'I'm not brought, I've come';—whatever that means," the stage-driver ruminated.

So much Old Chester knew the day after Mary Gordon's wedding. And it naturally sought to know a little more.

"I suppose her father feels it very much?" ventured Mrs. Barkley to Dr. Lavendar.

"Any man feels the marriage of his only girl," said Dr. Lavendar, briefly. And Mrs. Barkley held her tongue. But Mrs. Drayton, who was just then anxious about her soul and found it necessary to consult Dr. Lavendar as to the unpardonable sin—Mrs. Drayton was not so easily squelched. "My Jean says that the Gordon's Rachel told her that Alex brought the man into the house by the ear, and then sent her for you, running, and—"

"She didn't bring me into the house by the ear," said Dr. Lavendar.

"But why, do you suppose, was it all so sudden?" said Mrs. Drayton; "it almost looks—"

"How do you know it was sudden?" said Dr. Lavendar.

"Well, my Jean said—"

"It may have been sudden to Jean," said the old man; "possibly Mary had not taken Jean into her confidence. Some folks don't confide in servants, you know."

But Mrs. Drayton was proof against so delicate a thrust. "Well, I only hope she won't repent at her leisure;—if there's nothing but haste to repent of. If there's anything else—"

"I'll say good-day, Mrs. Drayton," interrupted Dr. Lavendar; "and as for your question about the unpardonable sin, ma'am, why, just be ready to forgive other folks and you needn't be afraid of the unpardonable sin for yourself."

He took his hat and stick and went thumping down-stairs. In the hall he met William King going up to see the invalid, and said, with a gasp: "Willy, my boy, a good, honest murderer is easier to deal with than some milder kinds of wrong-doing."

"Dr. Lavendar," said William, "I'd rather have a patient with small-pox than treat some lighter ills that I could name."

As for Mrs. Drayton, she told her daughter that Dr. Lavendar was very unspiritual, and did not understand the distress of a sensitive temperament. "Even the slightest error fills me with remorse," said Mrs. Drayton. "Dear me! I should think Mary Gordon would know what remorse is—for, of course, there is only one thing to think."

II

Old Chester thought the one thing. No evasions of Dr. Lavendar's, no miserable silence on the part of the disgraced father and the infuriated brother, could banish that one thought. But nothing definite was known. "Although," as everybody said to everybody else, "of course, Dr. Lavendar knows the whole thing, and probably Willy King does, too." If they did, they kept their knowledge to themselves. But Dr. Lavendar went often to the Gordon house that winter. "They're pretty lonely, those two men," he told Willy once—perhaps six months afterwards.

"Would either of them have softened if the baby had lived, do you think, sir?" William said. And Dr. Lavendar shook his head.

"Perhaps her father might. But Alex will never forgive her, I'm afraid."

And Alex never did forgive her—not even when she died, as, happily, she did six or seven years later. She died; and life closed over the miserable little tragedy as water closes, rippling, over some poor, broken thing flung into its depths.

"Thank God!" Alex said, when he heard she was gone.

"You may thank God for her," Dr. Lavendar said, turning upon him sternly, "but ask mercy for yourself, because this door of opportunity is shut upon you forever."

Dr. Lavendar had brought them the news. They did not ask how it had come to him; it was enough to hear it. The two men, Mary's father and brother, listened while he told them, briefly: "She died yesterday. The funeral will be to-morrow, at twelve."

"Thank God!" Alex said, hoarsely, and lifted his hand and cursed the man who had dishonored them.

And Dr. Lavendar turned upon him in solemn anger. "Your opportunity is gone—so far as she is concerned. There yet remains, however, the poor, foolish sinner whom she loved—"

"Damn him!" said Alex.

"—and who loved her."

Old Mr. Gordon dropped his face in his hands and groaned.

"Who loved her," Dr. Lavendar repeated.

"For that, at least, he cannot be indifferent to us, whatever he has made us suffer."

Neither of his listeners spoke. It was growing dark in the long room, walled to the ceiling with books and lighted only by a fire sputtering in the grate. Mr. Gordon, sitting in his big, winged chair close to the hearth, said, after a long pause: "You said—to-morrow, Edward? Where?"

"In Mercer. I shall go up on the morning stage."

Again the silence fell. Alex got up and walked to the window and looked out. "Why didn't you bring Danny in, Dr. Lavendar?" he said, carelessly; "the little brute will freeze out there in your buggy. I'll call him in." He turned to leave the room, and then stopped.

"Alexander, sit down," said Dr. Lavendar.

Alex sat down with involuntary quickness; then he threw his legs out in front of him and thrust his hands down into his pockets. "Dr. Lavendar, this is our affair. I'm obliged to you for your kind intentions; but this is our affair. You've told your news, and we have listened respectfully—if I should say gladly you might be shocked. So I only say respectfully. But you have spoken; we have listened. That is all there is to it. The thing is finished. The book is closed. I say thank God! I don't know what my father says. If he takes my advice, for I've been a good son to him; I never gave him any cause to be ashamed;—if he takes my advice, he'll forget the whole affair. That's what I mean to do. The book is closed. I shall never think of it again." He got up and walked about with affectation of vast indifference.

"Alex, you will probably never think of anything else," Dr. Lavendar said, half pitifully; and then, sternly, again: "I can't make you accept the opportunity that still is open to you; but I will point it out to you: Come up to Mercer to-morrow with your father and me."

"Mercer!" the younger man cried out, furiously; "you mean to see her buried? To dance on her grave and pull the man out and spit in his face and—" He stopped, his face suddenly purpling, his light eyes staring and rolling; then he stumbled and jerked himself together, and lurched forward into a chair, breathing loudly. The two old men, trembling with horror, ran to him. "Oh, Edward," John Gordon said—"oh, Edward, why did you rouse him? He can't speak of it, he can't think of it. Alex—there!—we'll say no more about it."

Alex stared at them with glassy eyes, in silence; his father kept bemoaning himself and imploring his old friend to say no more. "You won't speak of it again, Edward? He goes out of his head with rage. Promise me not to speak of it any more."

"No, John; no," Dr. Lavendar said, sadly; and as Alex's eyes cleared into bewildered consciousness, the old minister stood a little aside while the father helped the son to his feet and led him away. When he came back, shuffling feebly down the long, darkening room, Dr. Lavendar was still sitting by the fire. "He's quiet now; I—I think he's ashamed. I hope so. But he won't come out of his room."

Dr. Lavendar nodded.

John Gordon spread his purple handkerchief over his white locks, with shaking hands, and then sat down, tumbling back in his chair in a forlorn heap. "Edward," he said, feebly, "tell me about it. It was on Thursday? Had she been sick long?" Then, in a low voice, "She—didn't lack for comforts?"

"No; I think not. The man was as tender with her as—as you might have been. She was sick—I mean in bed—two weeks. She had been ailing for a long time; you remember I spoke to you about it about a month ago. And again last week."

"You—saw her?"

"Yes."

"More than once?"

"Oh, many times," Dr. Lavendar said, simply; "many times, of course."

John Gordon put out his hand; Dr. Lavendar shook it silently. Then suddenly the old man broke out, in weak, complaining anger: "He wouldn't let me write to her. I would have sent her some money. He wouldn't hear of it. He was awful, Edward. I—I didn't dare."

Dr. Lavendar was silent. It had grown so dark that he could not see the father's face. Suddenly, from behind the leafless trees at the foot of the garden, a smouldering yellow glow of sunset broke across the gloom of the room, and touched the purple cowl and the veined hands covering the aged face. Dr. Lavendar sighed.

"What can I do, Edward? I can't go to-morrow. You see I can't."

"Yes, you can, John."

"He would die; he'd have another attack. His heart is bad, Edward."

"Oh, I'm afraid it is, I'm afraid it is. But John, you do your duty. Never mind Alex's heart. That isn't your affair."

"Oh, I couldn't possibly go—not possibly," the father protested, nervously.