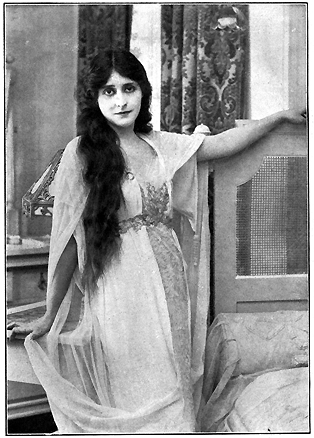

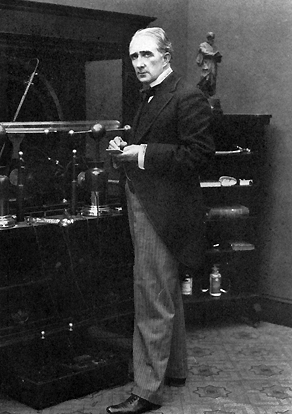

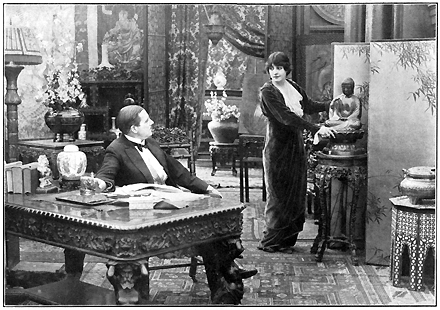

CLARA KIMBALL YOUNG AS “LOLA.”

Title: Lola

Author: Owen Davis

Release date: December 22, 2010 [eBook #34724]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Barbara Tozier, Brian Kerr, Bill Tozier and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net

CLARA KIMBALL YOUNG AS “LOLA.”

BY

AUTHOR OF “SINNERS,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED WITH SCENES FROM THE PHOTO-PLAY PRODUCED AND COPYRIGHTED BY THE WORLD FILM CORPORATION

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

PAGE

World Film Corporation Presents

CLARA KIMBALL YOUNG

in “LOLA” by Owen Davis

A SHUBERT FEATURE

PHOTO-PLAY IN FIVE ACTS

CAST OF CHARACTERS

| Lola | Clara Kimball Young | |

| Dr. Barnhelm, her father | Alec B. Francis | |

| Dr. Crossett, her friend | Edward M. Kimball | |

| Dick Fenway | } in love with Lola { | James Young |

| John Dorris | Frank Holland | |

| Mrs. Harlan | Olga Humphreys | |

| Stephen Bradley | Edward Donneley | |

| Julia Bradley | Irene Tams | |

| Marie | Mary Moore | |

| Mrs. Mooney | Julia Stuart | |

| Nellie Mooney | Baby Esmond | |

| Dr. Mortimer | Lionel Belmore | |

| Life-Saver | Cecil Rejan | |

The old man lay back in his chair asleep. The morning sun beat against the drawn window shades, filling the room with a dim, almost cathedral light. An oil lamp, which had performed its duty faithfully through the night, now seemed to resent its neglect, and spluttered angrily. There was the usual sound of the busy city’s street outside the window, for the morning was advancing, but here in the room it was very quiet. A quaint little Dutch clock ticked away regularly, and the tired man’s soft breathing came and went, peacefully, for his sleep was untroubled, his heart was full of happiness.

Presently the door opened, and a young girl came into the room, and seeing him, there in the chair, she stopped, afraid for a moment, then stepped forward and bent over him. She smiled as she straightened up, and turning called out softly:

“Coming, Maria,” the answer came in a clear, fresh young voice; for a moment the sleeper hesitated, about to awake, then thought better of it, and dreamed a dream of the triumph that was to be his.

“Hush!” Maria spoke softly as Lola came into the room, and Lola, following the girl’s pointed finger, smiled lovingly as she crossed and stood beside her father’s chair.

There was a strong contrast between these two girls as they stood there for a moment, side by side, young and good-looking as both undoubtedly were.

Lola was the sleeper’s daughter. Maria, their servant. Maria was strong and rugged; Lola delicate and blond. Maria’s splendid young body had been developed by hard work, while her mind had been stunted by a miserable childhood of neglect and abuse. Lola, since her mother’s death, had been her father’s constant companion, and had seemed to catch from him something of his grave and scholarly outlook upon life, lightened, however, by the impulses of a naturally sweet and sunny disposition, and the brave happiness of youth.

“He hasn’t been to bed at all!” exclaimed Maria, as Lola stooped and put her hand lightly on the sleeper’s arm.

“Father!” she called softly. “Father! It is morning!”

He awoke, startled, for a moment rather bewildered, then added his smile to theirs, and said brightly, “I am very happy, Lola.”

“I’m sure you haven’t any right to be, and, of course, you know that you ought to be scolded?”

“Perhaps so,” he returned, looking with pride at a complicated electric apparatus on the table beside him, “but I have worked it all out! I am sure of it this time!”

“Put that dreadful lamp out, and open the window!” called out Lola to Maria, as she started to pick up from the floor bits of broken glass and pieces of wire.

“I do wish you would use the electric lights, father. That lamp isn’t enough, even if you could be trusted to refill it, which you can’t!”

“You can’t teach an old dog new tricks, my dear,” smiled the Doctor, as he rose, rather stiffly. “The big thoughts won’t come by electric light, at least not to an old fellow who learned to do his thinking under an old-fashioned student’s lamp.”

“Oh, I don’t mind, not really,” answered Lola. “And, besides, the lamp saves money.”

She was turning away when the Doctor’s low chuckle of amusement stopped her. “Are you laughing at me, father?” she questioned, with pretended sternness.

“Just a little perhaps, my dear, because after this you need not think of little savings. You shall give up your school-teaching; you shall have new dresses every day of your life, and hats—— La! Never mind, you shall see.”

“You really think so, father?”

“I know it! After last night I shall never doubt it again. I did not dare to stop until my work was done, and then I sat there, dreaming, until I fell asleep.”

He looked again at his apparatus with such pride and confidence that even Lola, who knew nothing of the details of his experimental work, was thrilled with the hope of his success, and rested her hand tenderly upon his arm as she stood beside him.

They were much alike, these two, as they stood there together, the tall, rather delicate old man, and the fragile, sensitive girl. Dreamers both, one had but to look at them to see that, and they started apart, almost guiltily, as the little clock on the mantel struck eight.

“Eight o’clock! Oh, Maria! Eight o’clock! We must hurry!” Lola called out to Maria, who was busily arranging the breakfast table in the adjoining room.

“Come, father!” she continued. “Run and get yourself ready for breakfast, and the very minute we get through I am going to put you to bed.”

“Not to-day, my dear,” he answered gaily; “this is to be my busy day!”

As he left the room, smiling and happy, Maria looked after him anxiously.

“He’ll be sick if you don’t look out, Miss Lola. He don’t know no more about takin’ care of himself than one of my sister’s babies.”

Lola laughed cheerfully as she looked with approval over the neatly arranged breakfast table.

“I think he is perfectly well, Maria, and quite delighted with himself this morning. He feels sure that he has made a wonderful discovery, something he has been working on for years. I know that he thinks it is going to be a fine thing for all the world and for us, Maria; he says it is going to make us rich.”

“I hope so, I’m sure. There’s lots of little things we’re needing in the kitchen,” said Maria practically. “Anyway, he’s the best doctor in the world, and he ought to have the most money!”

“Don’t get his egg too hard.”

“No, Miss, it will be just like he wants it.”

When the Doctor returned he found everything ready for his breakfast, and he stopped to greet Maria kindly, as he always did, for aside from his habit of rather old-fashioned courtesy she was a great favorite of his.

“Would you like a pan-cake, Doctor?” she inquired anxiously, as she stood beside the table. “There’s a Dutch lady boarding with my brother’s wife. She showed me how to make real German ones.”

“I can’t have you spoiling father,” reproved Lola gently. “Besides German pan-cakes are not supposed to be eaten for breakfast.”

“She knows no more about German food,” said the Doctor, “than an Irishman’s pig! You shall make me one of your pan-cakes to-night.”

Maria smiled gratefully at him, and leaving the apartment ran down stairs to the letter-box in the hall, returning a moment later with the morning mail, which she put beside Lola’s plate.

“Four letters,” said Lola, glancing over them. “One for me, a bill! Two for you, father.” She pushed them across the cloth. “And, Maria! Oh, Maria! This is for you. Oh, Maria! You’re blushing. Who do you suppose it’s from,” she teased, as Maria stepped forward eagerly and took the letter.

“I guess, Miss,” said Maria in confusion, “I guess it’s from a friend of mine.”

Lola looked after her, as she hurried out of the room, the precious letter clutched tightly in her hand.

“Poor girl! That is from her sweetheart, the one she calls Mr. Barnes, and she can’t read it.”

“I thought you were to teach her,” remarked her father, as he helped himself to a second piece of toast.

“I am trying my best,” answered Lola, “but she never had a chance before, that’s what makes it so hard for her now.”

“She has done wonders since you found her, my dear girl. She has caught the spirit of this great New York, and she is growing very fast.”

“Hello!” he exclaimed, as he opened the first of his letters. “From Paul Crossett.”

Lola looked up, surprised and pleased, as her father hastily read the brief note, and continued.

“He is here, at last! Here in New York! And he is coming up this morning.”

“That’s fine!” exclaimed Lola, her face reflecting her father’s pleasure. “I have heard so much about him all my life, and now I am really going to see him.”

“I, myself,” said the Doctor, “have only seen him once in ten years, only twice in twenty. He is a great man now, rich and famous, but he was a scamp when I first knew him.” He laughed softly as his mind travelled back to the time when he and this successful French physician were boys together at the University.

“How was it?” inquired Lola, “that a Frenchman was your chum at Heidelberg?”

“He was,” her father replied, “even as a boy, a cynic, a philosopher, and he amused me. He had a big mind, and a big heart, and I loved him.”

As he spoke he opened the second letter, and after a moment’s reading looked up at Lola, his face reflecting an almost comic dismay. “Listen, Lola! ‘My dear Doctor,’” he read slowly, his voice betraying his surprise and growing distress, “‘I am going to call upon you to-morrow, and ask you to do me a great honor. I love your daughter——’” he stopped helplessly, almost like a child, afraid to continue.

Lola rose from the table, blushing furiously, but with a happy light underlying the guilty look in her eyes.

“Father!”

He looked at her for a moment, and gradually his look softened and the surprise gave way to a humorous tenderness.

“Let’s tear it up,” he suggested, holding the unwelcome paper out before him. “I think that would be the best way out of this.”

“Oh, no, father!” exclaimed Lola, catching his hand anxiously; “do go on, it’s very interesting.”

“Oh,” said the Doctor drily, “then we will proceed. ‘I love your daughter, and I want to ask you to let her become my wife.’”

“And to think,” said Lola, as he paused, “and to think that I didn’t know his handwriting.”

“So! So you know who had the impudence to write this,” assumed her father.

“Well,” replied Lola rather timidly, “I have my suspicions.”

“Oh, this love business,” groaned the Doctor in great disgust; “just as I have everything fixed, this must come! It is Mr. Fenway, I suppose?”

“Father!” cried Lola, indignantly. “Mr. Fenway! The idea!”

The Doctor turned the page quickly and read the signature, then exclaimed to her in wonder, “John Dorris! And I thought he only came here to talk to me! Did you know anything of this?”

“Anything?” replied Lola. “Well, I—I told him to write to you.”

For just a moment he hesitated; they were alone together in the world, these two, and the bond between them had been very close, and now all was to be changed; this stranger, a man, whom a few months before they had never seen, had stepped into their lives, and never again would this man’s child be to him quite what she had been for so many peaceful, happy years.

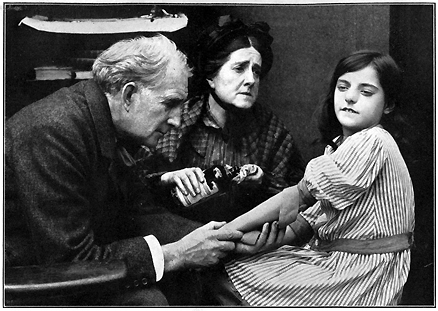

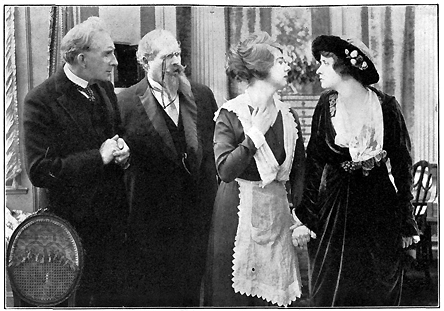

JAMES YOUNG AS DICK FENWAY.

Something of the bitterness of this thought must have become visible in his face, for Lola stepped to him anxiously, and he, generous and afraid of hurting any living creature as he always was, smiled at her tenderly and put his arm about her as he spoke gravely: “God bless you Lola, and if he is the right man, God bless you both.”

She nestled against him, reassured by his tone, and he continued, “John Dorris, a fine fellow, but I thought for a moment that it must be Dick Fenway.”

“Father,” she protested, “it isn’t at all like you to be so silly! Dick Fenway is nothing but—but a millionaire!”

“Am I supposed to sympathize with him for that?” inquired the Doctor gravely. “But, my dear,” he added, as he saw that she was mutely appealing for his sympathy, “I like your young man best, although he is like the rest of us; he isn’t half good enough for the woman he loves.”

He led her tenderly into the front room, and seating himself in his favorite old chair, drew her down upon one of its sturdy arms, and began to question her about John Dorris. At first she was conscious and embarrassed, but little by little, reassured by his sympathy, she opened her heart to him, and let him see that this new love that had come into her life was not a passing fancy, but a feeling so pure and tender that he sat awed before it, as all good men are awed when for a moment it is permitted them to read the secrets of a woman’s heart. He helped her greatly in that half hour, and as she clung to him, timid, half afraid even of her own happiness, he spoke to her of her mother and of what her love had been to him.

In all the world I think there is no stronger tie, no closer sympathy, than there is between a father and a daughter, and these two felt that then, and gloried in it, never dreaming of that awful thing that was so soon to come between them.

At last he left her, and went to change his clothes, and when Maria entered the room ten minutes later, she still sat there, her lover’s letter in her hand, her mind filled with strange, new thoughts, half happiness, half fear.

Maria went to her, and seeing the look on her face, and the open letter in her hand, said timidly, “That’s a letter from him?”

“Yes,” smiled Lola happily, “from him!”

“So is mine, Miss,” volunteered poor Maria, “but I can’t read it.” Lola turned quickly to her.

“Shall I read it for you?”

“Thank you, Miss, I knew you would, but I’d be ashamed to have him know it. He ain’t like most of the young fellars hanging around. He’s smart! He’s a sailor, on the Vermont, and he’s just fine!”

“This is from Boston,” said Lola, as she glanced at the open letter Maria handed to her. “I am glad to read it for you, of course, but before long I am going to have you so that you will be able to read his letters for yourself.”

“I hope so, Miss Lola, but I’m awful slow. I don’t know what I’d do if it wasn’t for you,” she continued gratefully; “there ain’t anybody else in the world I could bear to see reading his letters. I’d rather just keep them, without ever knowing what he said. It’s a lot just to know that a person wants to write to you.”

“‘Boston, June Third,’ began Lola. ‘Respected Friend: I write you these lines to say that I am well, and I hope you are the same. Boston is a fine City, with lots of people and many buildings. There is water here with ships and things in it, just like New York. I often think of you, and no girl seems like you to me, so no more from,

“‘Yours respectfully,

“‘Wm. Barnes.’”

“Ain’t that a fine letter?” said Maria, with great admiration. “Getting letters like that makes me more ashamed than ever. I’m afraid I’m too ignorant to appreciate all he tells about the countries he visits.”

“It is a very fine letter, I am sure, Maria, and he must be a fine fellow, and very fond of you?”

“Oh, yes, I’m sure he is,” replied Maria happily. “At first I wouldn’t have nothing to do with him, but he kept on coming around,—and now I’m glad he did. After what I saw at home I about made up my mind not to let any man come near me, but—but somehow he’s different. He wouldn’t act like father, or like my sister’s husband, I know; he’s the kind that seems to think a girl ought to be taken care of; that’s nice, when you never had anybody that thought that in all your life, isn’t it?”

“It’s very nice, Maria,” replied Lola, quite touched by the tone of real affection in Maria’s voice. “I am sure that it is the nicest thing in the world.” As she spoke a ring of the bell interrupted them, and Maria, hastily putting the precious letter in her apron pocket, went to the door and admitted a shabby little woman and a delicate child.

“Good morning, Mrs. Mooney,” said Lola, as she caught sight of them. “Good morning, Nellie! Come right in. Tell father, Maria!” she continued, and as Maria left the room she bent over little Nellie and kissed her tenderly, then turned to the anxious mother and did her best to put her at her ease.

“I’m afraid we’re too early, Miss,” began Mrs. Mooney, in that tired, colorless voice that tells its own story of hardship and hopelessness, “but Nellie couldn’t rest at all last night. We don’t want to be bothering your father, though; he’s been kind enough already.”

“He is quite ready for you, I’m sure,” replied Lola, “but I will go to him; he might need me to help him with his things.” As she left the room Nellie looked after her wistfully.

“There’s nobody I ever see like her,” she said, in that tone one often hears in children’s voices when they speak of those whom they have selected for that strange form of hero worship so common to the young. “When he hurts me, and I have to cry, I’ll see her with the tears in her eyes.”

“I know,” replied her mother gratefully; “it was she that first brought the Doctor to see you, and he’ll cure you yet, and if they do that——” She stopped for a moment and clutched at her breast, as though to tear away the dread and anguish that was there. “It’s all right, Nellie—it’s all right, I’m telling you! You’re going to be as good as any of ’em yet!”

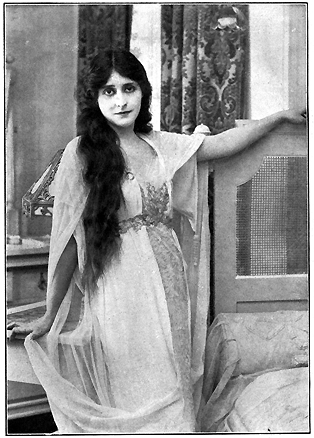

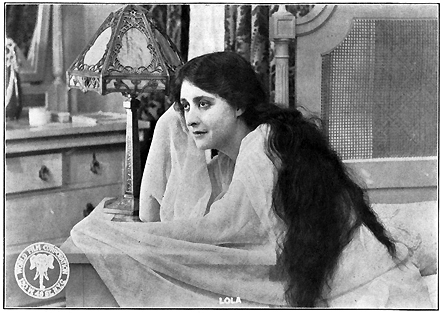

LOLA VISITS THE MOONEY FAMILY.

Doctor Martin Barnhelm had for over twenty years practised medicine in New York. Aside from the fact that he was thoroughly qualified for his profession, he had a gentle, kindly manner that made him popular with all his patients. His might have been an unusual success, but of late years he had devoted more and more of his time to research work. He had a growing reputation in the medical world, as an expert in the development of electro-medical apparatus, and unknown to anyone he was devoting all his energies to the realization of a theory, which to his mind at least promised to be the most important medical discovery since the introduction of antiseptic surgery. In the front room of his apartment he carried on his experiments, and so complete was his devotion to the object of his ambition that he scarcely allowed himself time to earn, by his profession, even the modest sum necessary for the household expenses. Lola saw that his heart was wholly set upon this one idea, and without in the least understanding its purpose, aided him by rigid economy, and had even, against his rather faint protest, begun to add to the family income by teaching in a settlement school.

Although the Doctor had so jealously guarded his time that he had lost most of his wealthy patients, he had never been able to deny his professional aid to those unfortunates from whom no other fee than gratitude could be expected. Nellie Mooney was one of these. She had inherited from a vicious father the tainted blood and the weakened constitution, which, helped on by the bad air and insufficient nourishment of the poor of the crowded tenement district, had resulted in a tubercular disease of the bone of her right arm.

Mrs. Mooney brought the child twice a week for treatment, but of late the disease had been gaining headway, and in spite of the Doctor’s best efforts, she was in constant agony. He was treating her now in the little alcove he used as his office, and outside, with the curtains drawn, Lola was doing her best to soothe the almost frantic mother.

The treatment, in spite of all the Doctor’s gentleness, was painful in the extreme, and Lola was anxious to spare the poor woman the sight of her daughter’s suffering, but at the sound of a stifled cry from behind the curtains, Mrs. Mooney was unable to restrain herself, and rushed toward the next room with a cry of agony.

“Please,” said Lola, as she gently stopped her. “They are better without you.”

“I’m going to her,” exclaimed the mother, quite unable to withstand the thought of her child suffering alone. “You don’t know what it is, Miss Lola; I’ve got to go.”

As she spoke she drew the curtain aside, and entered the alcove, and Lola would have followed had not a ring of the bell made her pause and go to the door. It was still early in the forenoon, and as Lola opened the door she fully expected to be greeted by another of the Doctor’s patients, but in place of that a young man stood smiling on the threshold.

“John!” she exclaimed happily, then stopped shyly as he stepped eagerly forward and put his arm around her. It was only the night before that he had told her of his love, and she was still afraid of him, but he, manlike, refused to give up an advantage already won, and drew her to him, holding her closely until she, of her own accord, raised her lips to his.

“Did he read my letter?” he asked eagerly and rather nervously.

Now she had him at an advantage, for however great his fear was of her father, she had none at all.

“Oh, yes,” she replied, smiling, “and he is perfectly furious.”

As she saw his face fall she would have reassured him, but just then a moan of anguish from the alcove made him turn his head inquiringly.

“It is the little Mooney girl,” she answered, in reply to his unspoken question. “It is some dreadful disease of the bone, but father hopes to be able to help her.”

“Poor little girl,” said John, as he offered her a cluster of gorgeous roses that he had brought with him.

Lola took the flowers with a word of thanks, as the Doctor threw open the curtains and entered with his arm about Nellie, and followed by Mrs. Mooney.

“There,” he exclaimed, “it is over now. You are a brave girl, Nellie. You must bring her again on Saturday, Mrs. Mooney.”

“You are not faint, are you, Nellie?” said Lola, alarmed at the child’s paleness.

“Oh, no, Miss,” replied Nellie bravely, her eyes fastened with wondering admiration on the beautiful roses.

“Take them,” said Lola impulsively, holding them out to her, but she shrank back, afraid.

“Oh, no! Why, you just got them yourself.”

“He doesn’t mind, do you?” Lola demanded of John, and he answered so pleasantly and cordially that the child was persuaded to accept them, and was taken home by her mother in such a glow of gratitude that for the moment, at least, her pain was forgotten.

American Beauty roses, at a dollar each, on the window-sill of a wretched tenement! An extravagance, no doubt, and yet I wonder if they would have better fulfilled their destiny had they met the usual fate of their fellows and been trampled under foot upon the floor of some crowded ball room.

As Lola closed the door after Nellie and Mrs. Mooney, she turned to see John and her father eyeing one another, with the consciousness of the necessary interview showing in their faces. She laughed happily and, crossing to the Doctor, pointed to John, who stood rather stiffly beside the table.

“There is John, father.”

“Humph,” said he, coldly, determined at least that the young man’s path should not be made too easy, “so I see.”

“I—I,” began John, rather lamely, “I—er——”

Lola laughed merrily, and catching one by each hand drew them together, looking up at them, her face so radiant that in a moment their stiffness was forgotten, and they joined in her laugh.

“No use trying to be formal, John, while she is laughing at us.”

“No, sir,” replied John heartily, as he accepted the other’s proffered hand; “all that I am going to say is that I shall do my best to make her happy.”

“You won’t have any great trouble there, my boy. She has always been happy, and always will be if—if you will always love her.”

“I think I may safely promise that,” said John, smiling confidently. “It doesn’t seem to be difficult.”

“You are very happy, you two,” continued the Doctor, glancing from one to the other, “and will you believe an old man when he tells you that it is the only happiness that is real? A happiness so great that even if death comes, the memory is still the dearest feeling in your hearts. I have no sermon for you. God bless you, and help you, so long as you shall live.”

“We are having a little trouble already, Doctor, and I want your help,” said John boldly. “I want you to tell her that she must marry me at once.”

“John,” cried Lola, indignantly, “I haven’t any idea at all of being married for months!”

“Ah!” smiled the Doctor hopefully. “Perhaps, if you quarrel with him about it, we may get rid of him yet. That would be good news for me, yes, and for poor Dick Fenway!”

“Don’t tease,” protested Lola, “and, anyway, Mr. Fenway isn’t poor; he is a millionaire.”

“I suppose,” said John, “that it is rather an obvious thing for me to say, but I don’t like that man. It isn’t that I am jealous. I was once, I will admit, but after last night I am not afraid of him. But he isn’t on the level. I have the right to tell you now, Lola,” he continued, turning to her. “I knew him in Cleveland two years ago. He comes here to your house, and takes you to theatres and concerts.”

Lola looked at him, surprised. “Surely I am not going to make the sudden discovery that I have bound myself to a jealous old Ogre, am I?” she inquired.

“Fenway,” said John bluntly, “has a wife in Cleveland.”

The Doctor’s face grew stern, and Lola looked both shocked and distressed.

“John!” she exclaimed in dismay, for she liked young Fenway, and more than either of the others knew that, if this thing were true, he had done his best to deceive her.

“He married a telephone girl in one of the big hotels,” went on John, anxious to get the unpleasant story over, for he had a man’s feeling of loyalty to his sex, and hated to be placed in the position of a tale bearer.

“He has been trying ever since to get a divorce, but she won’t let him. It isn’t a thing a fellow likes to talk about, but it’s true.”

“Thank you,” said the Doctor gravely; “my home is not large enough to hold that sort of man. I shall tell him so if he calls again.”

“I am sorry, very sorry,” said Lola. “There was something about him I always liked, and it hurts me to think that he tried to deceive me as he did.”

“Bah!” protested the Doctor. “The world is full of men like that, but once you know them, they are harmless. Don’t look sad, my dear; it is so easy to forget all about him.”

It was not so easy, however, for Lola to forget Dick Fenway’s deceit as her father fancied. Only a few weeks before he had told her that he loved her, and when she had gently refused him he had shown such bitter disappointment that she had been quite touched, and had ever since done her best to be kind to him. Now the thought that at the time he had spoken of his love for her he had had a wife filled her with amazement. Lola knew little of the evil of the world, but she felt that here there was something wrong, and it disturbed her. Long after John had gone to his business, and her father had left to meet his old friend, Doctor Crossett, she sat thinking it over, and the more she thought the more distressed she became.

Dick Fenway had been brought to the house by a friend of John’s, and from the first she had been attracted by his gayety and recklessness. He was a great contrast to the men she had known. Careless, rich and happy, and there was something about the young man that had made a strong appeal to the maternal feeling that is in every woman, however young or unworldly she may be. Fenway’s habit of depending upon her for advice, his very confession of careless helplessness, had put him somewhat in the position of a child whom she felt it her duty to help with advice and counsel.

At first, when a little later Maria told her that he was waiting for her in the front room, she decided not to go to him, but, on second thought, she changed her mind, and thinking it best to have the whole matter definitely settled, she entered the room gravely, perhaps a little sadly.

KIND HEARTED DOCTOR BARNHELM ATTENDS THE SICK CHILD OF MRS. MOONEY.

“Good morning, Miss Barnhelm,” said Fenway, as he rose to meet her. “I know it’s too early for a call, but I wanted you to come for a ride in my new car. It’s downstairs.”

“No, thank you, Mr. Fenway.”

“Oh, but you’ve got to try it. She’s a corker. Why, I was thinking of you when I bought it.”

“Were you?” said Lola coldly.

“Yes, honestly. Why, you know, Lola, that——”

“How long is it since you have heard from your wife in Cleveland?” interrupted Lola.

For a moment his surprise silenced him; then he turned upon her angrily.

“Who’s been telling you my business?” he demanded, almost roughly.

“Do you think,” asked Lola gently, “that she would share in your desire for me to try your new car?”

“I didn’t want you to know about her,” he answered, a queer expression of mingled shame and determination on his face. “It happened a long time ago. I was a fool, more even of a fool than usual, when I married her. I haven’t seen her in almost two years, and—and I’m never going to see her again.”

“Father was angry when he heard that you were married,” said Lola, looking at him calmly, and with no expression of anger in her face. “He thought that you had not been quite honest about it.”

“What did you think?” questioned Fenway.

“I was very much surprised and a little hurt. Father is going to ask you not to come here again. That is why I was glad to speak to you before he did.”

“Then you won’t let it quite queer me with you?” exclaimed the young man eagerly. “She’s bound to give me a chance to divorce her, sooner or later. I’m having her watched, every breath she draws. Even if your father won’t let me come here you’ll see me sometimes, won’t you?”

“No, Mr. Fenway, I shan’t see you again. Father is right about that, but I am glad you came here to-day. Surely we have been good friends enough for me to ask you, for your own sake, to be worthy of the better side that I know is in you. This girl is your wife; you yourself say that she has not done anything wrong. Wouldn’t it be better to——”

“Don’t talk about her,” said Dick, savagely.

“I’m afraid that we can’t talk at all, unless we talk about her. A man with as kind a heart as yours couldn’t have meant to wrong her, or me, or any other girl. I hoped that I was enough your friend to be able to ask you to go back to her, if you can, and if you can’t, to tell you that you ought to be honest with the persons who trust you! There! I’ve said it!” And she stood looking at him for a moment. Then, softening, she extended her hand.

“Good-bye!”

He stood looking at her, then stepped forward boldly and took her hand.

“Lola,” and as he spoke there was a tone of passion in his voice that frightened her, “I love you!”

She looked him in the face and answered gently, “I am going to marry John Dorris.”

“Not—not because of this—this damned story you heard about me?”

“No,” replied Lola quietly. “Because I love him.”

He stepped back, dropping her hand, and for the first time since she had known him a look of real sadness came into his face.

“I—I guess there’s nothing for me to do but go. I have usually had most everything I wanted in this world, but now if I’m going to lose you I’m getting the worst of things, after all.”

“I am sorry,” began Lola, but he shook his head impatiently and crossed to the door. “I haven’t any use for your sympathy. You say you are going to marry John Dorris, but you haven’t done it yet. You say that you are not going to see me again. I don’t believe that, Lola. You don’t love me. I know, but you don’t love him either. You don’t know what love is, and when you learn it won’t be from John Dorris.”

He closed the door behind him, and she heard him running down the stairs as she stood there with a strange dread in her heart.

From her window, a few hours later, Lola could see her father as he turned in from Eighth Avenue and walked briskly toward the house. With him was a rather short, extremely animated, and perfectly groomed gentleman, whom she at once knew to be Doctor Paul Crossett. Even from that distance she could plainly see that, although she knew him to be a man of her father’s age, he had the look of one much younger.

It would be a bold man who would dare to state that married life and the atmosphere of a home do more to bring about grey hairs and wrinkles than the emptiness of a bachelor’s existence, but in this case, at least, the contrast was startling.

Paul Crossett, quite fifty, had, and looked to have, all the enthusiasms of youth. He was a Frenchman, and to a close observer he was perhaps rather freer in gesticulations than our somewhat stiff New Yorkers, but he was far from being the Frenchman of the comic supplement. Indeed, Paul Crossett was a real citizen of the world, quite as much at home in New York, London or Berlin as he was in Paris. He was one of the best known authorities on nervous disorders in the medical world, besides being a surgeon of international reputation. As he entered the room with her father a moment later, Lola advanced to meet him with a smile, but, to her surprise, at the sight of her he stopped, and a look of deep sorrow, almost of fear, came into his face.

“This is Lola, Paul,” said the Doctor proudly.

In a moment the look on Dr. Crossett’s face changed to one of eager welcome, and he stepped forward and took both of her extended hands in his.

“You are as your mother was,” he said gently, then as he stooped to kiss her saying softly, “My age permits,” she saw a tear on his smooth, almost boyish cheek, and with a woman’s quick intuition she understood and loved him for the love he had had for her mother, whom he had not seen since his early manhood, but whom he had never forgotten, and never could forget.

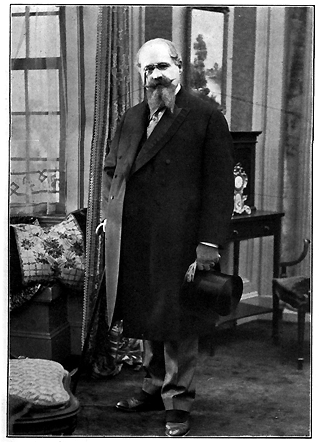

E. M. KIMBALL AS DOCTOR CROSSET.

In that moment grew up between those two an affection and an understanding that under happier circumstances would have lasted all their lives. In the awful time, now so rapidly approaching, he was to be her truest friend. His love and sympathy was to outlast that of lover and father. He gave to her the place in his heart that her mother had always had, the same blind love and devotion, and it was hers until the end.

“I am glad to know you, Doctor Crossett,” said Lola, a little timidly, as he stepped away from her, now smiling merrily.

“So,” he replied heartily, as he looked around the room curiously. “So! this is one of your famous New York apartments?”

“No, Paul,” said Dr. Barnhelm, rather ruefully, “this is a flat.”

“But what is the difference?”

“About a hundred dollars a month.”

“But surely you are not poor, Martin, you, with your mind?”

“My dear Paul, it takes twenty-four hours a day to make a good living here in New York, and I could not spare the time.”

“I see,” exclaimed Dr. Crossett, as his keen eyes fell upon the complicated electrical apparatus on the table. “You had a better use for it.” He crossed and bent over the affair with deep professional interest.

“So? A high frequency, a most peculiar and most powerful interrupter. Not for the X-ray? No, then for what?”

“I am going to tell you all about it. There is no man in America, and only one other in Europe, who could judge of it as you could judge. It is ten years’ work, Paul; it has meant poverty to both of us, but it is a big thing.”

“Tell me,” said Dr. Crossett eagerly.

“Tell him, father,” interrupted Lola, “while I run to the store. I will only be a few moments, and you won’t miss me. When I come back, Doctor Crossett,” she smiled at him frankly, “I am going to make you explain to me all about it. Father never would.”

She left them, in spite of Dr. Crossett’s offers to accompany her, and as the door closed behind her he stood for a moment looking after her, and from her to a framed picture of her mother that hung on the wall.

“Nine years, Martin,” he laid his slender, powerful hand gently on his old friend’s shoulder; “nine years since you wrote me that her mother——”

They stood together for a moment in silence before the Doctor answered: “Yes, Paul, nine years.”

“I was with you in my heart,” the Frenchman continued, “but, tut—tut—! Come, you have discovered—what?”

As he turned away the bell rang, and with a word of excuse Dr. Barnhelm stepped to the door and admitted John Dorris.

“Lola told me to wait for her here,” said the young man cheerfully. “She wouldn’t let me go with her, to tell the truth; I am taking a little holiday, and I don’t quite know what to do with myself.”

The Doctor turned to his friend, smiling.

“Each of us, Doctor Crossett, as we grow older accumulate troubles. Will you let me present my worst, Mr. John Dorris?”

“I am pleased,” said the Frenchman, bowing, “but shall I confess that I do not understand?”

“I am going to marry Lola,” said John frankly, as he stepped forward and offered his hand.

“Ah! Now I do understand,” responded Dr. Crossett. “Then Dr. Barnhelm has my sympathy, and you my approval. You have at least, good taste.”

“Thank you, Doctor—am I in the way?” inquired John, turning to Dr. Barnhelm.

“Not at all. I was about to explain my pet hobby; as you will often have to hear about it, it might be a good thing if you were to listen now. I will spare you the technical description, John; you would not understand, and you, Paul, are of course familiar with this apparatus. This, then, is an instrument by which, if I am right, and I am convinced that there is no doubt of that, I can restore life to a person who has been dead for many hours.”

“Doctor!” cried John, horrified and anxious; and he turned to Dr. Crossett, expecting him to share in his belief that long hours of brooding over his experiments had turned the old man’s brain, but, to his intense surprise, he read nothing but eager interest in the Frenchman’s face, as the latter bent over the instrument and inquired earnestly: “Many hours, Martin?”

“Five,” replied Dr. Barnhelm; “perhaps six, possibly seven!”

“That has not been claimed before?”

“I can do it.”

“You can restore the dead to life?” demanded John with such disbelief and distress in his voice that Dr. Crossett turned to him with a kindly smile and said gently, “You need not look at your future father-in-law in horror, my dear young friend. He is not mad. I have studied these things, as perhaps you know. In Paris I have seen the experiment tried. I have seen the heart action cease and later be resumed. I have seen muscular activity stimulated and the patient, whom I myself had pronounced dead, rise and walk unaided from the operating room. But”—he stopped and for a moment eyed his old friend keenly—“but only has this been done in my peculiar case, and never more than five minutes after the last flutter of the pulse!”

“My theory is right,” replied Dr. Barnhelm with deep conviction. “My instrument is right! As yet I have been unable to demonstrate it upon a human being for want of a subject, but I have succeeded always with the lower animals.”

“You claim what, Martin?” continued Dr. Crossett. “That you can restore the heart action to those who die, of what?”

The Doctor smiled slightly as he replied:

“Death is what? When the heart ceases to beat! Life is what? When it beats on, untroubled. I can take the body of a man whose pulse has not fluttered in hours, and I can bring the beating of his heart back! I can bring him back to life!”

He looked almost in triumph into the earnest, sympathetic face of his friend, then turned to John, but his smile left him at what he saw in the young man’s eyes.

“Don’t say that, Doctor,” begged John, earnestly. “I can’t believe that it is true, and if it is, it is horrible!”

“I do not claim to give life,” explained the older man gently, “only to restore it. For how long depends upon the nature of the disease of which the patient dies. Old age must always have its victims. I cannot check decay, nor cancer, nor tuberculosis. There are many cases where, if I were to bring my patient back to life, it would be but to die again, but there are many, many times when I can, and will, restore life to those who die by accident, by drowning, by heart failure, by shock!”

“It is sacrilege!” cried John in horror. “Suppose that a man dies, and his body is brought to you. Do you claim that you will give him back his life?”

“I do,” answered the Doctor firmly.

“What of his soul?”

“John,” exclaimed the doctor, startled and offended by the question.

“When a man dies,” continued John earnestly, “more than the throbbing of his pulse leaves him. The thing we call a soul, whatever it may be, wherever it may be, goes out with his life, out of his body to a life everlasting. In God’s name, how dare you talk of bringing that empty shell back into the living world?”

“I have lived for over twenty years in the dissecting room,” remarked Dr. Crossett, with rather a contemptuous smile. “I know the human body. They differ very little, each organ has its place, all is complete—I have not found a soul.”

“We do not think alike there, Paul,” said Dr. Barnhelm gravely. “There is something, a soul, an intelligence, call it what you will, but it is not tangible, and it is divine! I mean no sacrilege. Why, this theory of mine, the truth of which I am prepared to prove, has been my prayer, and now it has been granted. It is for the good of humanity.”

“I don’t like it,” replied John nervously. “You know best, I suppose, and I am going to try to take your word for it, but I don’t like it. If you don’t mind, I’ll go and meet Lola. It may be all right, I suppose it is, if you say so, but it gives me the fidgets.”

He left the room as he spoke, and as he closed the door and started down the stairs he heard them laughing together.

“He is not a physician,” said Dr. Crossett as soon as John was out of hearing.

“No,” replied Dr. Barnhelm. “He is a bank clerk.”

“Bank clerk! La! Then why try to make him understand? Come, tell me all about this,” and he looked critically at the apparatus before him.

“It is the theory,” began the Doctor, “of a tremendously interrupted electrical current applied to the heart. The high frequency in itself is not new.”

“No,” agreed Dr. Crossett. “Romanoff, Thailer, Woodstock, eh?”

“Yes, but the application is new, and also I have here a Mercury Turbine Interrupter of my own invention. I can get over thirty thousand more interruptions a second than were ever before obtained. With it I have never once failed. It was the great high frequency by which I won my battle. It is ready now to show to the world.”

“Ah! Your theory—it is pretty.”

“It is true.”

“Then,” exclaimed Dr. Crossett, “there need be no more of this.” He looked contemptuously around the shabby room and out through the window at the noisy, squalid neighborhood.

“To live as New York lives! It is not civilization. It is like the cave man, to live in a hole in a cliff. Bah! To sit on an ugly chair, and to look at nothing, out of dirty windows!”

“New York,” laughed Dr. Barnhelm, “is the great market place of the world. You can buy anything here, even beautiful surroundings.”

“Then you, Martin, shall buy them. This,” he touched the electrical apparatus almost tenderly, “will bring fame and wealth. Happiness you had before.”

“It has been selfish of me in a way, Paul,” began the Doctor, as though trying to find excuses to satisfy his own conscience, “but Lola has not minded. She is as Helen was. If she is surrounded by love and tenderness, she is content. She does not ask fortune for many of her favors.”

“She does not need them, Martin.”

As Dr. Crossett spoke, from below, through the open window, came the harsh clang of an ambulance bell, and these two surgeons both stopped and listened, their professional instinct unconsciously aroused.

“There is a sound, Martin,” he continued, “that is understood in every country in the world.”

“The ambulance stopped here at this house,” said Dr. Barnhelm, with a trace of nervousness, and he stepped to the window and looked out. “There is a crowd collecting. I wonder——”

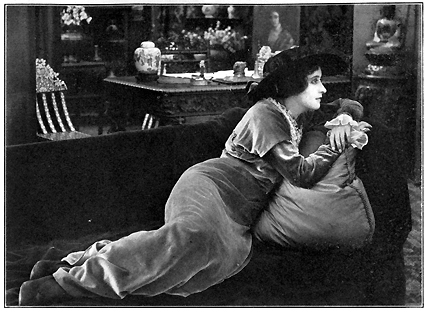

DOCTOR BARNHELM PERFECTS HIS MACHINE FOR RESTORING ANIMATION.

The door burst open, and John Dorris entered the room; as they saw his face, they knew at once that the news he brought was bad news, and both being brave men, they turned calmly and steadily to meet it.

“Doctor,” he panted hoarsely, “Lola—Lola!”

“Well, John?”

It was the father who spoke, and his cool, even tone did much to steady the boy.

“She,” he continued brokenly, “she—they—they are bringing her! There was an accident, she—she——” He stopped as Dick Fenway entered, so pale and wild, that Dr. Crossett, to whom he was a stranger, stepped forward, as though to offer to support him, but stopped suddenly as Fenway cried out: “I did it! It was my fault! As she crossed the Avenue I turned my car, thinking she would stop, but she hated me, and she wouldn’t stop, and—and—I killed her.”

There was silence for a moment in the room, broken only by Fenway’s sobs and by a low moan of anguish from the father. Then came a sound of stumbling footsteps, slowly, very slowly advancing up the stairs. The sound of men carrying a heavy burden.

“My friend! Be brave!” and Paul Crossett put his arm about his old friend’s shoulders. “We will fight for her life, you and I together, as life is not often fought for.”

The footsteps had grown nearer, in the room there was silence as the four men waited, in the court-yard below a street organ began to play, and the foolish, empty tune burned itself forever into their memories as they stood there.

The footsteps hesitated for a moment on the landing below, then began again, nearer, louder now, and suddenly a big, red-faced policeman stood in the doorway.

“Here?” he inquired, in that queer, impersonal voice that speaks of long acquaintance with the tragedies of life.

“Yes,” replied John, hoarsely, “here.”

An ambulance surgeon entered in response to the officer’s nod, and following him came another policeman and a white-coated driver; between them on a stretcher they bore a covered form, very quiet, so quiet that not even a movement stirred the blanket that covered it.

As they put their burden down gently on the worn old couch the young surgeon turned to Dr. Barnhelm, who stepped forward.

“It is no use, sir. You can’t do anything. It was the heart, I think. She was not crushed, but she died instantly. Can any of you give me the facts for my report?”

Maria had entered the adjoining room, attracted by the unusual sounds, and heard what he said, and as she heard she cried out pitifully. The sound seemed to add the finishing touch to the strain they were under, and they turned sharply.

“Go, Maria!” said the Doctor, coldly. “Answer any questions this gentleman asks of you. Compose yourself, please, and go.”

The girl turned without a word, and followed by the surgeon went out into the hall, the driver and one of the policemen joining them, while the other crossed and touched Dick Fenway on the arm.

“You’ll have to come with me, sir,” he said quietly.

Fenway for a moment looked at him bewildered, then stooped and picking up the hat he had dropped on the floor, slowly walked to the door. At the door he stopped and looked back at the covered figure on the couch, shuddered and went out, the officer following.

John closed the door softly behind them and turned back to where the two men stood, Paul Crossett’s hand on the father’s shoulder.

“Can’t—can’t you do anything,” he questioned, “anything at all?”

“Wait!” The word came like a command, sharply, from Dr. Barnhelm’s lips. “Paul! You know what I am going to do?”

Dr. Crossett nodded slightly. The meaning of it came suddenly to John, and he cried out in protest, “Doctor!”

“You see her there! Dead!” The father spoke slowly, calmly. “Well, I can bring her back! She is my daughter.” He turned quietly to John, but with a look in his eyes that few men would have dared oppose.

“Shall I let her die? I—who can save her?”

“No,” the young man spoke humbly, “no. I—I love her too.”

“Go—wait outside. Go—now!” and John went with just one look at the still form on the couch.

“I am ready, Martin,” said Dr. Crossett, when they were alone, and he threw off his coat and stepping to the table starting to connect the batteries and adjust his instrument with the practical hand of an expert. For just one moment the father faltered.

“It is only a theory, Paul. It may fail.”

“We are here,” replied his friend steadily, “to make that theory fact. You must direct me. Call the interruptions as you want them.”

The doctor crossed to the couch, and drawing aside the blanket stood looking down at Lola. In that moment all that this child of his meant to him came into his mind, and the thought gave him strength. The fear and grief died, and in their place came firmness, confidence. He knelt and deftly unfastened her dress and bared her girlish breast, then crossing to the table took in each hand a glass electrode connected by long wires to the powerful machine, and slowly returned to where his daughter lay.

“Now, Paul!”

A touch of Dr. Crossett’s practised hand and the great machine came to life. Back and forth in the coil violet sparks jumped, flashing, sparkling. From the electrodes in his strong hands a million tiny specks of light sprang angrily, and when for a moment he held them close together these specks became a solid bar of violet light, almost a flame. The noise was deafening, the solid crash of the leaping current, as Dr. Crossett gradually moved his index up to its full strength, rang through the little room and echoed back from the walls, the vibrations so close that to any but a practiced ear they sounded like one steady roar.

Once again he paused beside the couch, and an electrode in each hand, the violet light dancing all about him, he raised his eyes in a short prayer. “God help me,” he said, his voice half buried in the riot of sound. “Don’t hold my pride against me. I ask it, not as the inventor, but as the father.”

He did not speak again, nor did the friend who stood watchfully beside the spluttering, crashing machine. Three times he held the electrodes to her body, one over her heart, one against her back, but there was no movement, no sign of life. The leaping sparks seemed to pass through her tender frame, but she lay there still, with that awful stillness of the dead. The man, working over her, the father no longer, but the physician, the inventor, did not hesitate. Again and again she was enfolded in the bright beams of violet light. Again and again he held the leaping current to her heart, and at last, when, for what seemed to be the hundredth time he drew back and looked at her, his whole body suddenly stiffened, a hoarse cry burst from him, and he fell crashing to the floor.

Dr. Crossett shut off the current and sprang to him. He had fainted, and turning from him to Lola, Paul Crossett saw what the father had seen. A soft color slowly stealing back into that white face and a slow, steady rising and falling of her breast as her heart began again to beat.

On the following day the papers devoted a few lines to the accidental injury of a young girl, “Lola Barnhelm, daughter of Dr. Martin Barnhelm, a physician in good standing in the neighborhood.” The fact that “the automobile by which the young lady was injured belonged to Richard Fenway, the well-known Wall Street broker, son of old Dick Fenway of Cleveland, and a well-known figure in the life of the ‘Broadway crowd,’” seemed to be of more general interest than the account of her injury, but two of the papers noted the fact that “she was at first pronounced dead and later found to be merely suffering from shock.”

What Dr. Barnhelm and Dr. Crossett said to one another no one besides themselves ever knew. To John, after the moment when Dr. Crossett went to him, white-faced, and awed, and told him that Lola was alive, they said nothing.

John was content. He loved her, and she had come back to him! Had she for those few moments been really dead, or had the young ambulance surgeon been mistaken? What did it matter? Late that night they had allowed him to creep softly to her chamber door, and looking in he had seen her sleeping quietly, and they assured him that, aside from a probable nervous shock, she was quite unharmed.

In the days that followed the nervous shock turned out to be more serious than was at first supposed. Physically, Lola seemed to be in good condition, but for the first time in her life she was unjust, irritable, and jealous. Dr. Crossett claimed this to be a fine symptom of returning health.

“Temper,” he remarked cheerfully, “is the copyright trade-mark of the convalescent,” but to John her sudden, unreasonable fits of anger and a feeling that in anyone but Lola he would have described as selfishness amazed and alarmed him.

Dr. Barnhelm, too, seemed changed, but in his case the change was for the better. He was closeted all day, and often almost all night with his machine, and its low throbbing penetrated the whole building and brought indignant protests from the other tenants, protests that were received by the Doctor with a slow smile of contempt and at once forgotten.

From the moment when he was assured of his daughter’s safety, he buried himself in his work, calm and happy, with little thought for anything but this great discovery of his—this wonderful invention that was to do so much for suffering humanity.

Dr. Crossett left them after the first few days to keep some important engagement in the West, but before he left he had insisted upon advancing Dr. Barnhelm a sum of money sufficient for his needs, enough to allow him freedom to complete his experiments and prepare the elaborate models necessary for a demonstration before the Medical Society.

At first Dr. Barnhelm had refused to accept the favor, but Lola, greatly to his surprise, had sided against him, and more to please her than for any other reason he had taken the money on the understanding that it was to be repaid out of the first profits of his invention. At the time there seemed little reason to doubt his ability to repay his friend. Fame and success mean much to a physician’s income, and after the proof he had so lately had how could he consider anything but success possible? He gave up his practice, excepting only a few of his old charity patients, and turning the borrowed money over to Lola, who had for a long time been in the habit of controlling the family purse, he buried himself in his work.

For over two months Dr. Crossett travelled, first to Chicago, then to Denver, and from there to San Francisco. Everywhere he was received with the honors due to a man of his high standing in the medical world, and allowed full opportunity to compare the treatment of nervous disorders with the methods of the best physicians of his own country. He had come as the representative of the French society, of which he was president, and it was his object to gather enough information to aid him in the writing of a book upon this subject. He heard once from Dr. Barnhelm, notifying him of a change in their address from upper Eighth Avenue to an apartment on Riverside Drive. No explanation for the change was offered, the rest of the letter being a long account of the progress of his work and a few words about Lola, that she had quite recovered her health and seemed to be in unusually high spirits.

For some weeks after this he had been travelling almost constantly, but on his return to Chicago he found a short note waiting for him at his hotel. In this note Dr. Barnhelm simply stated that he was in trouble and anxious to see him. That it was nothing that need cause him to cut short his stay in the West, but that the matter was a delicate one, and that he was anxious to see him immediately upon his return.

Dr. Crossett was rather alarmed by the whole tone of his old friend’s letter. Of Lola there was no mention, but he could not free himself of a vague suspicion that she must be the cause of her father’s evidently deeply troubled mind, and he brought his business affairs to an abrupt end and caught the next fast train to New York.

It had been Spring when Dr. Crossett landed in America; it was now Summer, and, as his taxi ran smoothly up Fifth Avenue to the Park, the boarded-up fronts of the houses suggested to him a plan for forcing a brief extension of his vacation and spending a week or two with Lola and her father at some of the famous American watering-places of which he had often heard. His own splendid health and superb vitality he owed, in part, to his habit of allowing himself frequent intervals of mental rest and outdoor exercise, and as he thought of how Lola would be benefited by a change from the hot, stale air of the city to some beautiful seashore or mountain resort, he smiled to himself happily.

The cab stopped, and as he got out and turned to pay the driver he noticed with surprised approval the unbroken row of stately apartment houses facing the green of Riverside Park and the wide expanse of the Hudson. His old friend was growing wise he thought to himself; here at least were grass, and trees, and fresh air.

Maria admitted him, and showing him through a wide foyer-hall into a pretty and well-furnished parlor, turned to leave him, but he called her back anxiously.

“Miss Lola! Tell me, Maria?”

There was just a trace of hesitation as she answered.

“Very well, I think, sir. I never saw her looking better in my life.”

“Good! Good! Ah! The times, they have changed,” and he looked around the daintily furnished apartment smilingly. “It is not as it was two months ago.”

“No, sir.”

“You also,” as he noticed her neat black dress and white cap and apron; “you are a very pretty girl, Maria.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Do not thank me,” he replied with a chuckle. “I share in the pleasure it causes you. Now, Maria, don’t blush. I am old enough to be your father, and I like you because you are good to those two who are so dear to me. I am happy to see all these signs of prosperity. The Doctor’s practice must have increased?”

“I don’t think so, sir,” said Maria. “No patients ever come here, leastways none but the poor ones who don’t pay nothin’.”

“So? And yet he has not given the news of his discovery to the world. I do not comprehend.”

Maria hesitated for a moment, then faced him anxiously as though to say something, but after a moment’s pause she recovered herself and said respectfully:

“The Doctor is out, sir. Miss Lola is dressing. She will be here in a moment.”

“I am in no hurry,” he replied, “now that you tell me that all is well here. I am content to share in the happiness of my friend. His daughter well; a fine home; one could not hope for this two months ago! Poverty, death! Pish!” and he snapped his fingers contemptuously. “They are gone! It is indeed the age of miracles.”

“Coming back like she did, sir,” retorted Maria, “after everyone thought she was dead, ain’t a thing that does a body any good! You couldn’t expect her to be quite so happy and so sweet as she used to be, could you, Doctor?”

In the girl’s voice was so much of anxious inquiry, such a tone of real sadness and regret, that he turned to her alarmed, but at that moment Lola came into the room. In the few seconds it took her to cross to him, smiling, both hands extended in greeting, his practiced eye assured him that never in all his experience had he seen a young woman in such superb physical health. She was radiant! The simple little housedress in which he had first seen her had been exchanged for an elaborate afternoon costume. Her skin was clear, he had remembered her as being pale, even in the short time he had seen her before the accident; but now she had a high color and an eager, animated manner that spoke of an abundant reserve of vitality.

“There you are, Doctor,” she cried gaily, as he returned the warm pressure of her hands. “I wonder if you know how glad I am to see you?”

“No, my dear,” he answered, “not unless you are reflecting my own pleasure in seeing you like this. I was worrying about you, way off there in the West. Were you well? Were you happy? Now I have but to look at you.”

“You are a flatterer, Doctor.”

As Lola turned from him smiling, her eyes fell on Maria, who stood watching the Doctor’s face with a curious look of eager curiosity, her look changed, and she spoke sharply, almost cruelly.

“What are you doing here, Maria?”

Maria flushed and tears came to her eyes as she stammered, “I—I——”

“You may go.”

“Yes, Miss.”

Maria left the room and Lola turned to find Dr. Crossett looking at her in wonder. He knew of the real affection that there had been between these two, and his own tender heart told him how Lola’s tone must have hurt the girl who had so much reason to think of her with affection and gratitude. He made no effort to keep a look of reproof out of his eyes, but if Lola saw it there she gave no sign of it, but seated herself on a broad couch and motioned to him airily to seat himself beside her.

“Now, Dr. Crossett,” she began, “I want to talk with you before you see father. He is the dearest man in the world, but he knows nothing at all about business. He wrote to you?”

“Yes, that is why I am here.”

“It is about money; he is very poor.”

“Poor?” Dr. Crossett glanced about the expensively furnished room in surprise, but Lola continued without seeming to notice. “He did not want to write, but I made him. You are his friend. You love him. I am sure that you will be glad to help him.”

“What I have is his,” answered Dr. Crossett. “Surely there is no need to repeat that. If he wanted more, why did he not ask for it when I gave him my check before I left New York?”

“Oh, that money he borrowed from you he was going to use for his experiments; to perfect his machines, and to prepare to demonstrate them, but naturally I could not allow him to do that. If he’s to be a famous man he must, at least, live like a gentleman. I selected this apartment, and insisted upon his moving, and now he is so worried, and nervous, and cross, just because he has no more money.”

“He is my friend,” said the Doctor gravely. “I will gladly supply all he needs, but——”

“But——!” repeated Lola impatiently, and to him for a moment it sounded almost rudely. “Surely you are not going to say that I have been extravagant. Father has hinted it, so has John, and it wouldn’t be fair for you to join them against me. You won’t do that, will you?”

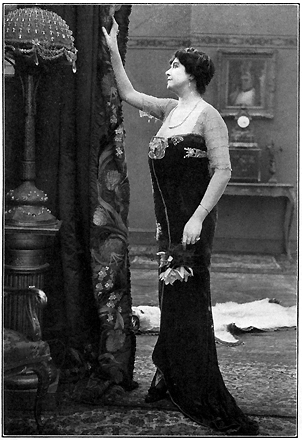

LOLA SHOCKS HER FATHER AND HIS FRIEND BY HER HEARTLESSNESS.

As she looked up at him shyly, yet confidently, it seemed to him that the last twenty years had been a dream, and that he was sitting beside that other young woman, so like her, and any trace of disappointment he had felt at her attitude fell away, and there was nothing but tenderness in his voice as he replied:

“It was more years ago than I can count that your mother came to me and looked up as you are looking now, and begged me not to side against her. She wanted to marry your father; and all were saying ‘no.’ I could not refuse her anything any more than I could you, although it hurt me to help bring about that marriage, for I loved her myself. So you see how helpless I am. I must fight your battles. I have no choice.”

“You’re a dear,” laughed Lola happily, “and if I had been mother—but there—I must not make you vain. I was sure that I could depend upon you. Now, let’s not talk about serious things any more. Come! Let me show you the view of the river from the windows. Isn’t it glorious here! Why, do you know, Doctor dear, that after Eighth Avenue this is like another world? Look!” She had dragged him to the window and with one hand on his shoulder, and her pretty, eager face flushed with an almost passionate enthusiasm, she stood pointing out to where the Drive curved majestically, flanked on one side by its stately buildings, on the other by the always beautiful Hudson and the distant Palisades.

“Look!” she repeated. “I was content once in that shabby, horrid flat. Perfectly content, and patient, and happy. Father said that I was content because I was good, but I know better; it was because I was ignorant; because the thing that was mine was the only thing I knew. He talks of going back! Threatens, because he is afraid, because he never spent money in his life, and is too old to learn now, to return to that squalid, shabby, dirty hole. I want you to talk to him,” and she turned him so that he faced her, and as he felt the nervous grasp on his arm he marvelled at her strength. “I want you to tell him what I have already told him, that, if he goes back there, he will go alone. I am out of it now, and there isn’t power enough in the world to drag me back.”

“My dear,” remonstrated the Doctor gravely, “you and John are to be married; he is young; surely while he is making his way in the world you will be willing to share whatever his fortune may be. Love is as sweet in poverty, Lola, as it is in a home like this.”

“That is a platitude, Doctor, a platitude invented by cowards who weren’t strong enough to win the good things of life, and who, because they couldn’t have them, were fools enough to try to blind themselves with stupid words. I am a woman! A woman’s only chance for all the beautiful things of life rests upon some man. When a man comes to me and says, ‘I want the only things you have, your youth, your love, your beauty,’ haven’t I the right to say, ‘What will you give me for them?’”

The Doctor drew back, deeply shocked. Her words, the deep earnestness of her voice, and the hard, selfish look in her eyes, surprised and hurt him. He was a sentimentalist and to him a woman’s whole existence should be in her love, and in the home her lover could provide for her. Modern as he was in his practice of medicine, advanced as he was in his psychological studies, at heart he was an old-fashioned man, with all of the old-fashioned man’s ideas of love and marriage. For a moment he felt a feeling of repulsion, almost of horror, and he looked coldly at this young girl, who seemed to be so greatly changed by a few short weeks of luxury, but as he looked he thought of the day, only so lately passed, when she had been brought to them, white and lifeless, and as he saw her now, defiant, rebellious, in all the vigor of her splendid health, he smiled at her tenderly. He knew, as few men know, the changes that some great nervous shock so often makes in a person’s character, and he resolved to devote himself to this girl until her nervous system fully recovered, to help her with gentle kindness until her old tranquil serenity was fully restored. It came into his mind that of all the many cases of hysteria which he had successfully treated here was one that would challenge his greatest skill, and he was glad of the fortune that had sent him to her, for his experienced eyes saw that she was to need his help, and in the confidence of a man to whom failure seldom came he felt secure in his ability to restore her to her old gentle self. He sat down beside her and talked quietly of her father and of the fame and fortune that was so sure to be his, and as he talked he watched her and saw just a young, happy, innocent girl, serene now, perfectly gentle, perfectly calm, and they laughed and talked merrily together until her father entered the room.

Dr. Crossett looked at his friend anxiously and found, as he was prepared to find, that the Doctor seemed nervous and depressed, but when, after a few moments, Lola left them together, he was hardly prepared for the look of shame and humiliation he saw on his face.

“You sent for me, Martin,” he said, trying to show in his voice the deep sympathy and friendship that he really felt.

“Paul,” the Doctor answered, after a moment’s hesitation, “the money I borrowed from you is gone! Gone! and not for the purpose for which you loaned it.”

“I made no condition, Martin. The loan was my own suggestion. I am not a poor man, and all that I have is at your service. It is not worth the tragedy in your face. With the fame that your discovery will bring to you, you can easily repay me. Come!” He put his arm affectionately over Dr. Barnhelm’s shoulder. “Let’s say no more about it. Just tell me of your work. It must be only a few days now before you demonstrate before the Medical Society.”

“To-morrow night,” replied the Doctor. “I have remedied the flaws in the construction of my apparatus, and Saturday Karn & Co. promised to deliver the new machine. They sent me a bill for eight hundred dollars. I”—he stopped, his face flushed with shame; then recovered himself with an effort—“I was unable to pay the amount, and they—they refused to give me credit.”

“But, Martin,” Dr. Crossett spoke gravely, “your life’s work was depending upon the delivery of your apparatus in time for demonstration to-morrow. Surely you should have set aside that sum, no matter what else you sacrificed.”

“I was selfish enough,” replied the Doctor, “to want my mind freed of every care. I allowed Lola to persuade me to place all of the loan in her hands. She knew that this bill was coming. Saturday I—I asked her for the money, and—and she told me that it was gone.”

“Yes.”

“How?”

The Doctor pointed, with a smile that almost brought the tears to his friend’s eyes, to the expensive furniture and rather elaborate window hangings.

“I—I blame myself,” he said quickly, as if to prevent any critical mention of his daughter. “She is young, and she doesn’t understand. I had grown used to trusting her with everything. Why, Paul! In these past years there have been times when I could not collect enough to pay our rent, little as it was. Not once did I even have to tell her of it. She always seemed to guess it for herself, and she would bring me what I needed, saved from her pitiful little housekeeping allowance, or earned by her teaching. All this selfish greed of pleasure and luxury is new to her. I do not like it. It is not like my girl!”

“Our fault,” agreed Dr. Crossett. “We spoke too much of the great success that was coming to you. It turned her head. Come, let us forget it.”

“Not yet, Paul; I want you to understand. I could not speak of her, as I am speaking now, to anyone but you. When she first insisted upon taking this apartment I knew that I did wrong not to forbid it, but she was in a peculiar nervous condition—she seemed morbid and unlike herself. I hardly dared to oppose her.”

“And the change?” inquired Dr. Crossett. “Has it done her good?”

“I hardly know,” the father answered, anxiously. “Her health seems to be satisfactory. In fact, she never, even as a child, seemed to be in such perfect physical condition, and yet——”

He stopped, seemingly unable to finish.

“It is the emotion,” exclaimed Dr. Crossett, “the love. Young girls before marriage often have serious nervous disorders. We must be patient. There is no need to worry. Marriage will restore her old poise. I speak with authority, Martin, for my practice has shown me much of the delicate nature of these nervous disorders; there is nothing here that need alarm you. Come! Tell me. When is this marriage to take place?”

“I cannot tell. It was to have been very soon after her recovery, but she has already postponed it twice. Young Dorris is almost out of patience.”

“Almost out of patience!” repeated Dr. Crossett scornfully. “A bad mood in which to begin a lifelong companionship with even the best of women. Come.” He put his hand almost playfully on the Doctor’s shoulder and shook him gently. “Facts! Always stick to the facts. We know her. She is a good girl. We love her. There is no more to say.”

“If it is money she wants,” exclaimed Dr. Barnhelm bitterly, “I will make it for her. It isn’t that I think anything money can buy too good for her, but for her to be selfish.”

“Hush,” said Paul very tenderly. “She has no mother; we must remember that. We are men, and we stand helpless before her womanhood, like children in the dark. Now! We will say no more. We will go to the bank to-day, while there is time. We will get that money, and to-morrow night, before the Medical Society, you shall make your name big, famous. Eh?”

“If I do,” exclaimed Dr. Barnhelm gratefully, “I shall have you to thank for it.”

“She shall thank me, Martin. You will tell her that part of the silks, and ribbons, and laces that you buy for her come from me. Eh? She will love me then. Come.”

Dr. Crossett allowed Dr. Barnhelm no time for remonstrance, but insisted so firmly that they should go at once to the bank that he was obliged to agree, and leaving a message for Lola that they would soon return, they descended in the elevator and walked briskly down the Drive, the Frenchman declaring that it was nothing short of a crime to ride on such a day, and he kept up such a flood of cheerful talk and happy reminiscence that, in spite of his deep humiliation, Dr. Barnhelm soon found himself laughing merrily.

In the meantime things were not going smoothly in Lola’s sitting room in the apartment. John Dorris had for some hour or more been doing his best to win Lola into a promise of an early marriage, and in spite of his best resolution he found himself rapidly growing impatient.

“It is no use, John!” Lola spoke almost angrily.

“The more we talk of it, the less we seem to agree. I do not care to be married before winter.”

“This is the third time you have changed the date,” remonstrated John. “I am beginning to think that——”

“Well?” She interrupted sharply and with so much of challenge in her manner that John had to curb his rising indignation as he replied.

“If I am not careful we will quarrel again, and we have done more than enough of that lately.”

“I am sure I can’t help it, John, if you choose to be cross and unreasonable.”

“Has it all been my fault?”

“No, of course not,” cried Lola, with one of the sudden changes of mood that had so often puzzled him of late. “I have been perfectly horrid, I know, and I won’t be any more. Just forgive me, John—and—and”—she looked up at him sweetly—“and kiss me, if you want to.”

John stooped and kissed her, and asked earnestly, “And we shan’t postpone the wedding again, shall we?”

“Only a little while, dear.”

He turned angrily away, but she caught his arm.

“Now, John! Can’t you trust me? Don’t you love me enough to give me my way in a little thing like this?”

As he stood rather coldly beside her, she suddenly threw both her arms about his neck and clung to him. Much as he loved her there was something in the utter abandon of her manner that shocked him, and for a moment he tried to draw away, but her delicate-looking arms were strong, and she clung all the tighter, laughing at his half-hearted effort to escape.

“Am I so dreadfully ugly, John, that you can’t bear to have me near you?”

“Lola!” he exclaimed passionately, “what are you doing? What is it that has changed you so? If you love me what reason have you for putting me off with one foolish excuse after another? What is it that you want?”

“I know that I ask a great deal, dear,” she replied tenderly, “but I want a love great enough for anything.”

“My love is great enough, Lola,” said John, as he once more tried gently to remove her arms from about his neck. “Please don’t try to make it any greater until you are ready to return it.”

She looked up again into his face and laughed at the cold expression she saw there, then suddenly drew him close, her arms straining about him, and kissed him, not as a young girl timidly kisses the man she loves, but with the kiss of a passionate woman. He was a man, like other men, and the man in him took fire in a moment, and he returned her kiss and would have drawn her still closer into his arms, but with a little low laugh she freed herself, and stepping back of the table shook her finger at him playfully.

“Now, John! You mustn’t be silly.”

She laughed lightly, mockingly, as he stood there, already ashamed of the sudden fierce feeling that had mastered him, and full of disgust of himself for the physical passion that had for the first time entered into any of his thoughts toward her.

“It is all right, John,” she continued, feeling that she had him at a disadvantage. “It is all settled. The marriage is postponed, but only for a little, little while. Now run along, and come back late this afternoon to see Dr. Crossett, and if you will promise to be very good you may stay to dinner.”

“I will, Lola, thank you,” replied John, “but—but I wish you would tell me what you are going to do this afternoon?”

“Why, I am going out.”

“Not—Lola! You are not going to that Harlan woman’s house?”

“Why, John! You know that you told me you didn’t like to have me go there?” She looked at him so innocently that he felt himself a brute to continue, but he forced himself to go on.

“The woman is hardly respectable, and the crowd she has hanging around her house are not proper acquaintances for a girl like you. I haven’t got over the shock of seeing you in that woman’s carriage yesterday.”

“Now, please,” cried Lola impatiently, “please don’t begin that all over again. You have been scolding about that all the afternoon.”

“But, if you have known this woman for months, why is it that you have never spoken of her? Would you have spoken of her at all if you had not known that I saw you with her?”

“If she is such a terrible person, how is it that you know her so well?”

“Lola! I am a man. Men are different! Surely you must see that?”

“Why are they different? I am not a child. I am a woman! Why shouldn’t I have a little fun once in a while? Why should men have everything?”

“Do you call it fun to live the life that woman lives? You don’t know what she is; if you did you would rather stay shut up in this room as long as you were alive than call yourself a friend of hers.”

“John! You are absurd.”

“No! I am not absurd. A girl like you, Lola, doesn’t even know what such women as that Mrs. Harlan are. It is your very innocence, dear, that makes you so bold.”