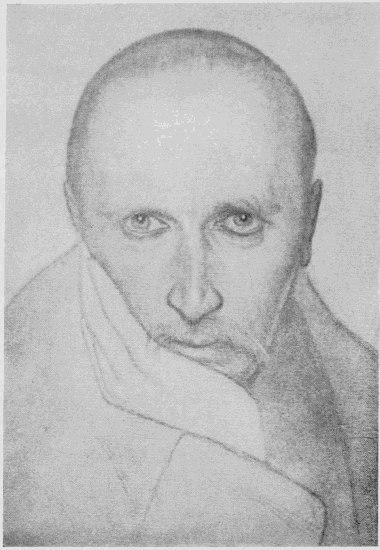

Romain Rolland after a drawing by Granié (1909)

Romain Rolland after a drawing by Granié (1909)

Title: Romain Rolland: The Man and His Work

Author: Stefan Zweig

Translator: Cedar Paul

Eden Paul

Release date: January 8, 2011 [eBook #34888]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif, University of Michigan Libraries

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

BY

STEFAN ZWEIG

TRANSLATED FROM THE ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPT

BY

EDEN and CEDAR PAUL

NEW YORK

THOMAS SELTZER

1921

Copyright, 1921, by

THOMAS SELTZER, Inc.

All rights reserved

PRINTED IN U. S. A.

Not merely do I describe the work of a great European. Above all do I pay tribute to a personality, that of one who for me and for many others has loomed as the most impressive moral phenomenon of our age. Modelled upon his own biographies of classical figures, endeavouring to portray the greatness of an artist while never losing sight of the man or forgetting his influence upon the world of moral endeavour, conceived in this spirit, my book is likewise inspired with a sense of personal gratitude, in that, amid these days forlorn, it has been vouchsafed to me to know the miracle of so radiant an existence.

IN COMMEMORATION

of this uniqueness, I dedicate the book to those few who, in the hour of fiery trial, remained faithful to

ROMAIN ROLLAND

AND TO OUR BELOVED HOME OF

EUROPE

| Dedication | PAGE | |

PART ONE: BIOGRAPHICAL | ||

| I. | Introductory | 1 |

| II. | Early Childhood | 3 |

| III. | School Days | 8 |

| IV. | The Normal School | 12 |

| V. | A Message From Afar | 18 |

| VI. | Rome | 23 |

| VII. | The Consecration | 29 |

| VIII. | Years of Apprenticeship | 32 |

| IX. | Years of Struggle | 37 |

| X. | A Decade of Seclusion | 43 |

| XI. | A Portrait | 45 |

| XII. | Renown | 48 |

| XIII. | Rolland As the Embodiment of the European Spirit | 52 |

PART TWO: EARLY WORK AS A DRAMATIST | ||

| I. | The Work and the Epoch | 57 |

| II. | The Will To Greatness | 63 |

| III. | The Creative Cycles | 67 |

| IV. | The Unknown Dramatic Cycle | 71 |

| V. | The Tragedies of Faith. Saint Louis, Aërt, 1895-1898 | 76 |

| VI. | Saint Louis. 1894 | 80 |

| VII. | Aërt, 1898 | 83 |

| VIII. | Attempt To Regenerate the French Stage | 86 |

| IX. | An Appeal to the People | 90 |

| X. | The Program | 94 |

| XI. | The Creative Artist | 98 |

| XII. | The Drama of the Revolution, 1898-1902 | 100 |

| XIII. | The Fourteenth of July, 1902 | 103 |

| XIV. | Danton, 1900 | 106 |

| XV. | The Triumph of Reason, 1899 | 110 |

| XVI. | The Wolves, 1898 | 113 |

| XVII. | The Call Lost in the Void | 117 |

| XVIII. | A Day Will Come, 1902 | 119 |

| XIX. | The Playwright | 123 |

PART THREE: THE HEROIC BIOGRAPHIES | ||

| I. | De Profundis | 133 |

| II. | The Heroes of Suffering | 137 |

| III. | Beethoven | 140 |

| IV. | Michelangelo | 144 |

| V. | Tolstoi | 147 |

| VI. | The Unwritten Biographies | 150 |

PART FOUR: JEAN CHRISTOPHE | ||

| I. | Sanctus Christophorus | 157 |

| II. | Resurrection | 160 |

| III. | The Origin of the Work | 162 |

| IV. | The Work without a Formula | 166 |

| V. | Key to the Characters | 172 |

| VI. | A Heroic Symphony | 177 |

| VII. | The Enigma of Creative Work | 181 |

| VIII. | Jean Christophe | 188 |

| IX. | Olivier | 195 |

| X. | Grazia | 200 |

| XI. | Jean Christophe and his Fellow Men | 203 |

| XII. | Jean Christophe and the Nations | 207 |

| XIII. | The Picture of France | 211 |

| XIV. | The Picture of Germany | 217 |

| XV. | The Picture of Italy | 221 |

| XVI. | The Jews | 224 |

| XVII. | The Generations | 229 |

| XVIII. | Departure | 235 |

PART FIVE: INTERMEZZO SCHERZO (COLAS BREUGNON) | ||

| I. | Taken Unawares | 241 |

| II. | The Burgundian Brother | 244 |

| III. | Gauloiseries | 249 |

| IV. | A Frustrate Message | 252 |

PART SIX: THE CONSCIENCE OF EUROPE | ||

| I. | The Warden of the Inheritance | 257 |

| II. | Forearmed | 260 |

| III. | The Place of Refuge | 264 |

| IV. | The Service of Man | 268 |

| V. | The Tribunal of the Spirit | 271 |

| VI. | The Controversy with Gerhardt Hauptmann | 277 |

| VII. | The Correspondence with Verhaeren | 281 |

| VIII. | The European Conscience | 285 |

| IX. | The Manifestoes | 289 |

| X. | Above the Battle | 293 |

| XI. | The Campaign against Hatred | 297 |

| XII. | Opponents | 304 |

| XIII. | Friends | 311 |

| XIV. | The Letters | 317 |

| XV. | The Counselor | 320 |

| XVI. | The Solitary | 324 |

| XVII. | The Diary | 327 |

| XVIII. | The Forerunners and Empedocles | 329 |

| XIX. | Liluli | 335 |

| XX. | Clerambault | 339 |

| XXI. | The Last Appeal | 348 |

| XXII. | Declaration of the Independence of the Mind | 351 |

| XXIII. | Envoy | 355 |

| Bibliography | 357 | |

| Index | 371 | |

[Click on any image to view it enlarged. (note from the etext producer.)]

| Romain Rolland after a drawing by Granié (1909) | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Romain Rolland at the Normal School | 12 |

| Leo Tolstoi's Letter | 20 |

| Rolland's Transcript of Francesco Provenzale's Aria from Lo Schiavo di sua Moglie | 34 |

| Rolland's Transcript of a Melody by Paul Dupin, L'Oncle Gottfried | 35 |

| Romain Rolland at the Time of Writing Beethoven | 142 |

| Romain Rolland at the Time of Writing Jean Christophe | 162 |

| Romain Rolland at the Time of Writing Above the Battle | 294 |

| Rolland's Mother | 324 |

| Original Manuscript of The Declaration of the Independence of the Mind | 352 |

The surge of the Heart's energies would not break in a mist of foam, nor be subtilized into Spirit, did not the rock of Fate, from the beginning of days, stand ever silent in the way.

Hölderlin.

THE first fifty years of Romain Rolland's life were passed in inconspicuous and almost solitary labors. Thenceforward, his name was to become a storm center of European discussion. Until shortly before the apocalyptic year, hardly an artist of our days worked in such complete retirement, or received so little recognition.

Since that year, no artist has been the subject of so much controversy. His fundamental ideas were not destined to make themselves generally known until there was a world in arms bent upon destroying them.

Envious fate works ever thus, interweaving the lives of the great with tragical threads. She tries her powers to the uttermost upon the strong, sending events to run counter to their plans, permeating their lives with strange allegories, imposing obstacles in their path—that they may be guided more unmistakably in the right course. Fate plays with them, plays a game with a sublime issue, for all experience is precious. Think of the greatest among our contemporaries; think of Wagner, Nietzsche, Dostoievsky, Tolstoi, Strindberg; in the case of each of them, destiny has superadded to the creations of the artist's mind, the drama of personal experience.

Notably do these considerations apply to the life of Romain Rolland. The significance of his life's work becomes plain only when it is contemplated as a whole. It was slowly produced, for it had to encounter great dangers; it was a gradual revelation, tardily consummated. The foundations of this splendid structure were deeply dug in the firm ground of knowledge, and were laid upon the hidden masonry of years spent in isolation. Thus tempered by the ordeal of a furnace seven times heated, his work has the essential imprint of humanity. Precisely owing to the strength of its foundations, to the solidity of its moral energy, was Rolland's thought able to stand unshaken throughout the war storms that have been ravaging Europe. While other monuments to which we had looked up with veneration, cracking and crumbling, have been leveled with the quaking earth, the monument he had builded stands firm "above the battle," above the medley of opinions, a pillar of strength towards which all free spirits can turn for consolation amid the tumult of the world.

ROMAIN ROLLAND was born on January 29, 1866, a year of strife, the year when Sadowa was fought. His native town was Clamecy, where another imaginative writer, Claude Tillier, author of Mon Oncle Benjamin, was likewise born. An ancient city, within the confines of old-time Burgundy, Clamecy is a quiet place, where life is easy and uneventful. The Rollands belong to a highly respected middle-class family. His father, who was a lawyer, was one of the notables of the town. His mother, a pious and serious-minded woman, devoted all her energies to the upbringing of her two children; Romain, a delicate boy, and his sister Madeleine, younger than he. As far as the environment of daily life was concerned, the atmosphere was calm and untroubled; but in the blood of the parents existed contrasts deriving from earlier days of French history, contrasts not yet fully reconciled. On the father's side, Rolland's ancestors were champions of the Convention, ardent partisans of the Revolution, and some of them sealed their faith with their blood. From his mother's family he inherited the Jansenist spirit, the investigator's temperament of Port-Royal. He was thus endowed by both parents with tendencies to fervent faith, but tendencies to faith in contradictory ideals. In France this cleavage between love for religion and passion for freedom, between faith and revolution, dates from centuries back. Its seeds were destined to blossom in the artist.

His first years of childhood were passed in the shadow of the defeat of 1870. In Antoinette, Rolland sketches the tranquil life of just such a provincial town as Clamecy. His home was an old house on the bank of a canal. Not from this narrow world were to spring the first delights of the boy who, despite his physical frailty, was so passionately sensitive to enjoyment. A mighty impulse from afar, from the unfathomable past, came to stir his pulses. Early did he discover music, the language of languages, the first great message of the soul. His mother taught him the piano. From its tones he learned to build for himself the infinite world of feeling, thus transcending the limits imposed by nationality. For while the pupil eagerly assimilated the easily understood music of French classical composers, German music at the same time enthralled his youthful soul. He has given an admirable description of the way in which this revelation came to him: "We had a number of old German music books. German? Did I know the meaning of the word? In our part of the world I believe no one had ever seen a German ... I turned the leaves of the old books, spelling out the notes on the piano, ... and these runnels, these streamlets of melody, which watered my heart, sank into the thirsty ground as the rain soaks into the earth. The bliss and the pain, the desires and the dreams, of Mozart and Beethoven, have become flesh of my flesh and bone of my bone. I am them, and they are me.... How much do I owe them. When I was ill as a child, and death seemed near, a melody of Mozart would watch over my pillow like a lover.... Later, in crises of doubt and depression, the music of Beethoven would revive in me the sparks of eternal life.... Whenever my spirit is weary, whenever I am sick at heart, I turn to my piano and bathe in music."

Thus early did the child enter into communion with the wordless speech of humanity; thus early had the all-embracing sympathy of the life of feeling enabled him to pass beyond the narrows of town and of province, of nation and of era. Music was his first prayer to the elemental forces of life; a prayer daily repeated in countless forms; so that now, half a century later, a week and even a day rarely elapses without his holding converse with Beethoven. The other saint of his childhood's days, Shakespeare, likewise belonged to a foreign land. With his first loves, all unaware, the lad had already overstridden the confines of nationality. Amid the dusty lumber in a loft he discovered an edition of Shakespeare, which his grandfather (a student in Paris when Victor Hugo was a young man and Shakespeare mania was rife) had bought and forgotten. His childish interest was first awakened by a volume of faded engravings entitled Galerie des femmes de Shakespeare. His fancy was thrilled by the charming faces, by the magical names Perdita, Imogen, and Miranda. But soon, reading the plays, he became immersed in the maze of happenings and personalities. He would remain in the loft hour after hour, disturbed by nothing beyond the occasional trampling of the horses in the stable below or by the rattling of a chain on a passing barge. Forgetting everything and forgotten by all he sat in a great armchair with the beloved book, which like that of Prospero made all the spirits of the universe his servants. He was encircled by a throng of unseen auditors, by imaginary figures which formed a rampart between himself and the world of realities.

As ever happens, we see a great life opening with great dreams. His first enthusiasms were most powerfully aroused by Shakespeare and Beethoven. The youth inherited from the child, the man from the youth, this passionate admiration for greatness. One who has hearkened to such a call, cannot easily confine his energies within a narrow circle. The school in the petty provincial town had nothing more to teach this aspiring boy. The parents could not bring themselves to send their darling alone to the metropolis, so with heroic self-denial they decided to sacrifice their own peaceful existence. The father resigned his lucrative and independent position as notary, which made him a leading figure in Clamecy society, in order to become one of the numberless employees of a Parisian bank. The familiar home, the patriarchal life, were thrown aside that the Rollands might watch over their boy's schooling and upgrowing in the great city. The whole family looked to Romain's interest, thus teaching him early what others do not usually learn until full manhood—responsibility.

THE boy was still too young to feel the magic of Paris. To his dreamy nature, the clamorous and brutal materialism of the city seemed strange and almost hostile. Far on into life he was to retain from these hours a hidden dread, a hidden shrinking from the fatuity and soullessness of great towns, an inexplicable feeling that there was a lack of truth and genuineness in the life of the capital. His parents sent him to the Lyceum of Louis the Great, a celebrated high school in the heart of Paris. Many of the ablest and most distinguished sons of France, have been among the boys who, humming like a swarm of bees, emerge daily at noon from the great hive of knowledge. He was introduced to the items of French classical education, that he might become "un bon perroquet Cornélien." His vital experiences, however, lay outside the domain of this logical poesy or poetical logic; his enthusiasms drew him, as heretofore, towards a poesy that was really alive, and towards music. Nevertheless, it was at school that he found his first companion.

By the caprice of chance, for this friend likewise fame was to come only after twenty years of silence. Romain Rolland and his intimate Paul Claudel (author of Annonce faite à Marie), the two greatest imaginative writers in contemporary France, who crossed the threshold of school together, were almost simultaneously, twenty years later, to secure a European reputation. During the last quarter of a century, the two have followed very different paths in faith and spirit, have cultivated widely divergent ideals. Claudel's steps have been directed towards the mystic cathedral of the Catholic past; Rolland has moved through France and beyond, towards the ideal of a free Europe. At that time, however, in their daily walks to and from school, they enjoyed endless conversations, exchanging thoughts upon the books they had read, and mutually inflaming one another's youthful ardors. The bright particular star of their heaven was Richard Wagner, who at that date was casting a marvelous spell over the mind of French youth. In Rolland's case it was not simply Wagner the artist who exercised this influence, but Wagner the universal poietic personality.

School days passed quickly and somewhat joylessly. Too sudden had been the transition from the romanticist home to the harshly realist Paris. To the sensitive lad, the city could only show its teeth, display its indifference, manifest the fierceness of its rhythm. These qualities, this Maelstrom aspect, aroused in his mind something approaching to alarm. He yearned for sympathy, cordiality, soaring aspirations; now as before, art was his savior, "glorious art, in so many gray hours." His chief joys were the rare afternoons spent at popular Sunday concerts, when the pulse of music came to thrill his heart—how charmingly is not this described in Antoinette! Nor had Shakespeare lost power in any degree, now that his figures, seen on the stage, were able to arouse mingled dread and ecstasy. The boy gave his whole soul to the dramatist. "He took possession of me like a conqueror; I threw myself to him like a flower. At the same time, the spirit of music flowed over me as water floods a plain; Beethoven and Berlioz even more than Wagner. I had to pay for these joys. I was, as it were, intoxicated for a year or two, much as the earth becomes supersaturated in time of flood. In the entrance examination to the Normal School I failed twice, thanks to my preoccupation with Shakespeare and with music." Subsequently, he discovered a third master, a liberator of his faith. This was Spinoza, whose acquaintance he made during an evening spent alone at school, and whose gentle intellectual light was henceforward to illumine Rolland's soul throughout life. The greatest of mankind have ever been his examples and companions.

When the time came for him to leave school, a conflict arose between inclination and duty. Rolland's most ardent wish was to become an artist after the manner of Wagner, to be at once musician and poet, to write heroic musical dramas. Already there were floating through his mind certain musical conceptions which, as a national contrast to those of Wagner, were to deal with the French cycle of legends. One of these, that of St. Louis, he was in later years indeed to transfigure, not in music, but in winged words. His parents, however, considered such wishes premature. They demanded more practical endeavors, and recommended the Polytechnic School. Ultimately a happy compromise was found between duty and inclination. A decision was made in favor of the study of the mental and moral sciences. In 1886, at a third trial, Rolland brilliantly passed the entrance examination to the Normal School. This institution, with its peculiar characteristics and the special historic form of its social life, was to stamp a decisive imprint upon his thought and his destiny.

ROLLAND'S childhood was passed amid the rural landscapes of Burgundy. His school life was spent in the roar of Paris. His student years involved a still closer confinement in airless spaces, when he became a boarder at the Normal School. To avoid all distraction, the pupils of this institution are shut away from the world, kept remote from real life, that they may understand historical life the better. Renan, in Souvenirs d'enfance et de jeunesse, has given a powerful description of the isolation of budding theologians in the seminary. Embryo army officers are segregated at St. Cyr. In like manner at the Normal School a general staff for the intellectual world is trained in cloistral seclusion. The "normaliens" are to be the teachers of the coming generation. The spirit of tradition unites with stereotyped method, the two breeding in-and-in with fruitful results; the ablest among the scholars will become in turn teachers in the same institution. The training is severe, demanding indefatigable diligence, for its goal is to discipline the intellect. But since it aspires towards universality of culture, the Normal School permits considerable freedom of organization, and avoids the dangerous over-specialization characteristic of Germany. Not by chance did the most universal spirits of France emanate from the Normal School. We think of such men as Renan, Jaurès, Michelet, Monod, and Rolland.

Although during these years Rolland's chief interest was directed towards philosophy, although he was a diligent student of the pre-Socratic philosophers of ancient Greece, of the Cartesians, and of Spinoza, nevertheless, during the second year of his course, he chose, or was intelligently guided to choose, history and geography as his principal subjects. The choice was a fortunate one, and was decisive for the development of his artistic life. Here he first came to look upon universal history as an eternal ebb and flow of epochs, wherein yesterday, to-day, and to-morrow comprise but a single living entity. He learned to take broad views. He acquired his pre-eminent capacity for vitalizing history. On the other hand, he owes to this same strenuous school of youth his power for contemplating the present from the detachment of a higher cultural sphere. No other imaginative writer of our time possesses anything like so solid a foundation in the form of real and methodical knowledge in all domains. It may well be, moreover, that his incomparable capacity for work was acquired during these years of seclusion.

Here in the Prytaneum (Rolland's life is full of such mystical word plays) the young man found a friend. He also was in the future to be one of the leading spirits of France, one who, like Claudel and Rolland himself, was not to attain widespread celebrity until the lapse of a quarter of a century. We should err were we to consider it the outcome of pure chance that the three greatest representatives of idealism, of the new poetic faith in France, Paul Claudel, André Suarès, and Charles Péguy, should in their formative years have been intimate friends of Romain Rolland, and that after long years of obscurity they should almost at the same hour have acquired extensive influence over the French nation. In their mutual converse, in their mysterious and ardent faith, were created the elements of a world which was not immediately to become visible through the formless vapors of time. Though not one of these friends had as yet a clear vision of his goal, and though their respective energies were to lead them along widely divergent paths, their mutual reactions strengthened the primary forces of passion and of steadfast earnestness to become a sense of all-embracing world community. They were inspired with an identical mission to devote their lives, renouncing success and pecuniary reward, that by work and appeal they might help to restore to their nation its lost faith. Each one of these four comrades, Rolland, Suarès, Claudel, and Péguy, has from a different intellectual standpoint brought this revival to his nation.

As in the case of Claudel at the Lyceum, so now with Suarès at the Normal School, Rolland was drawn to his friend through the love which they shared for music, and especially for the music of Wagner. A further bond of union was the passion both had for Shakespeare. "This passion," Rolland has written, "was the first link in the long chain of our friendship. Suarès was then, what he has again become to-day after traversing the numerous phases of a rich and manifold nature, a man of the Renaissance. He had the very soul, the stormy temperament, of that epoch. With his long black hair, his pale face, and his burning eyes, he looked like an Italian painted by Carpaccio or Ghirlandajo. As a school exercise he penned an ode to Cesare Borgia. Shakespeare was his god, as Shakespeare was mine; and we often fought side by side for Shakespeare against our professors." But soon came a new passion which partially replaced that for the great English dramatist. There ensued the "Scythian invasion," an enthusiastic affection for Tolstoi, which was likewise to be lifelong. These young idealists were repelled by the trite naturalism of Zola and Maupassant. They were enthusiasts who looked for life to be sustained at a level of heroic tension. They, like Flaubert and Anatole France, could not rest content with a literature of self gratification and amusement. Now, above these trivialities, was revealed the figure of a messenger of God, of one prepared to devote his life to the ideal. "Our sympathies went out to him. Our love for Tolstoi was able to reconcile all our contradictions. Doubtless each one of us loved him from different motives, for each one of us found himself in the master. But for all of us alike he opened a gate into an infinite universe; for all he was a revelation of life." As always since earliest childhood, Rolland was wholly occupied in the search for ultimate values, for the hero, for the universal artist.

During these years of hard work at the Normal School, Rolland devoured book after book, writing after writing. His teachers, Brunetière, and above all Gabriel Monod, already recognized his peculiar gift for historical description. Rolland was especially enthralled by the branch of knowledge which Jakob Burckhardt had in a sense invented not long before, and to which he had given the name of "history of civilization"—the spiritual picture of an entire era. As regards special epochs, Rolland's interest was notably aroused by the wars of religion, wherein the spiritual elements of faith were permeated with the heroism of personal sacrifice. Thus early do the motifs of all his creative work shape themselves! He drafted a whole series of studies, and simultaneously planned a more ambitious work, a history of the heroic epoch of Catherine de Medici. In the scientific field, too, our student was boldly attacking ultimate problems, drinking in ideas thirstily from all the streamlets and rivers of philosophy, natural science, logic, music, and the history of art. But the burden of these acquirements was no more able to crush the poet in him than the weight of a tree is able to crush its roots. During stolen hours he made essays in poetry and music, which, however, he has always kept hidden from the world. In the year 1888, before leaving the Normal School to face the experiences of actual life, he wrote Credo quia verum. This is a remarkable document, a spiritual testament, a moral and philosophical confession. It remains unpublished, but a friend of Rolland's youth assures us that it contains the essential elements of his untrammeled outlook on the world. Conceived in the Spinozist spirit, based not upon "Cogito ergo sum" but upon "Cogito ergo est," it builds up the world, and thereon establishes its god. For himself accountable to himself alone, he is to be freed in future from the need for metaphysical speculation. As if it were a sacred oath, duly sworn, he henceforward bears this confession with him into the struggle; if he but remain true to himself, he will be true to his vow. The foundations have been deeply dug and firmly laid. It is time now to begin the superstructure.

Such were his activities during these years of study. But through them there already looms a dream, the dream of a romance, the history of a single-hearted artist who bruises himself against the rocks of life. Here we have the larval stage of Jean Christophe, the first twilit sketch of the work to come. But much weaving of destiny, many encounters, and an abundance of ordeals will be requisite, ere the multicolored and impressive imago will emerge from the obscurity of these first intimations.

SCHOOL days were over. The old problem concerning the choice of profession came up anew for discussion. Although science had proved enriching, although it had aroused enthusiasm, it had by no means fulfilled the young artist's cherished dream. More than ever his longings turned towards imaginative literature and towards music. His most ardent ambition was still to join the ranks of those whose words and melodies unlock men's souls; he aspired to become a creator, a consoler. But life seemed to demand orderly forms, discipline instead of freedom, an occupation instead of a mission. The young man, now two-and-twenty years of age, stood undecided at the parting of the ways.

Then came a message from afar, a message from the beloved hand of Leo Tolstoi. The whole generation honored the Russian as a leader, looked up to him as the embodied symbol of truth. In this year was published Tolstoi's booklet What is to be Done?, containing a fierce indictment of art. Contemptuously he shattered all that was dearest to Rolland. Beethoven, to whom the young Frenchman daily addressed a fervent prayer, was termed a seducer to sensuality. Shakespeare was a poet of the fourth rank, a wastrel. The whole of modern art was swept away like chaff from the threshing-floor; the heart's holy of holies was cast into outer darkness. This tract, which rang through Europe, could be dismissed with a smile by those of an older generation; but for the young men who revered Tolstoi as their one hope in a lying and cowardly age, it stormed through their consciences like a hurricane. The bitter necessity was forced upon them of choosing between Beethoven and the holy one of their hearts. Writing of this hour, Rolland says: "The goodness, the sincerity, the absolute straightforwardness of this man made of him for me an infallible guide in the prevailing moral anarchy. But at the same time, from childhood's days, I had passionately loved art. Music, in especial, was my daily food; I do not exaggerate in saying that to me music was as much a necessary of life as bread." Yet this very music was stigmatized by Tolstoi, the beloved teacher, the most human of men; was decried as "an enjoyment that leads men to neglect duty." Tolstoi contemned the Ariel of the soul as a seducer to sensuality. What was to be done? The young man's heart was racked. Was he to follow the sage of Yasnaya Polyana, to cut away from his life all will to art; or was he to follow the innermost call which would lead him to transfuse the whole of his life with music and poesy? He must perforce be unfaithful, either to the most venerated among artists, or to art itself; either to the most beloved among men or to the most beloved among ideas.

In this state of mental cleavage, the student now formed an amazing resolve. Sitting down one day in his little attic, he wrote a letter to be sent into the remote distances of Russia, a letter describing to Tolstoi the doubts that perplexed his conscience. He wrote as those who despair pray to God, with no hope for a miracle, no expectation of an answer, but merely to satisfy the burning need for confession. Weeks elapsed, and Rolland had long since forgotten his hour of impulse. But one evening, returning to his room, he found upon the table a small packet. It was Tolstoi's answer to the unknown correspondent, thirty-eight pages written in French, an entire treatise. This letter of October 14, 1887, subsequently published by Péguy as No. 4 of the third series of "Cahiers de la quinzaine," began with the affectionate words, "Cher Frère." First was announced the profound impression produced upon the great man, to whose heart this cry for help had struck. "I have received your first letter. It has touched me to the heart. I have read it with tears in my eyes." Tolstoi went on to expound his ideas upon art. That alone is of value, he said, which binds men together; the only artist who counts is the artist who makes a sacrifice for his convictions. The precondition of every true calling must be, not love for art, but love for mankind. Those only who are filled with such a love can hope that they will ever be able, as artists, to do anything worth doing.

These words exercised a decisive influence upon the future of Romain Rolland. But the doctrine summarized above has been expounded by Tolstoi often enough, and expounded more clearly. What especially affected our novice was the proof of the sage's readiness to give human help. Far more than by the words was Rolland moved by the kindly deed of Tolstoi. This man of world-wide fame, responding to the appeal of a nameless and unknown youth, a student in a back street of Paris, had promptly laid aside his own labors, had devoted a whole day, or perhaps two days, to the task of answering and consoling his unknown brother. For Rolland this was a vital experience, a deep and creative experience. The remembrance of his own need, the remembrance of the help then received from a foreign thinker, taught him to regard every crisis of conscience as something sacred, and to look upon the rendering of aid as the artist's primary moral duty. From the day he opened Tolstoi's letter, he himself became the great helper, the brotherly adviser. His whole work, his human authority, found its beginnings here. Never since then, however pressing the demands upon his time, has he failed to bear in mind the help he received. Never has he refused to render help to any unknown person appealing out of a genuinely troubled conscience. From Tolstoi's letter sprang countless Rollands, bringing aid and counsel throughout the years. Henceforward, poesy was to him a sacred trust, one which he has fulfilled in the name of his master. Rarely has history borne more splendid witness to the fact that in the moral sphere no less than in the physical, force never runs to waste. The hour when Tolstoi wrote to his unknown correspondent has been revived in a thousand letters from Rolland to a thousand unknowns. An infinite quantity of seed is to-day wafted through the world, seed that has sprung from this single grain of kindness.

FROM every quarter, voices were calling: the French homeland, German music, Tolstoi's exhortation, Shakespeare's ardent appeal, the will to art, the need for earning a livelihood. While Rolland was still hesitating, his decision had again to be postponed through the intervention of chance, the eternal friend of artists.

Every year the Normal School provides traveling scholarships for some of its best pupils. The term is two years. Archeologists are sent to Greece, historians to Rome. Rolland had no strong desire for such a mission; he was too eager to face the realities of life. But fate is apt to stretch forth her hand to those who are coy. Two of his fellow students had refused the Roman scholarship, and Rolland was chosen to fill the vacancy almost against his will. To his inexperience, Rome still seemed nothing more than dead past, a history in shreds and patches, a dull record which he would have to piece together from inscriptions and parchments. It was a school task; an imposition, not life. Scanty were his expectations when he set forth on pilgrimage to the eternal city.

The duty imposed on him was to arrange documents in the gloomy Farnese Palace, to cull history from registers and books. For a brief space he paid due tribute to this service, and in the archives of the Vatican he compiled a memoir upon the nuncio Salviati and the sack of Rome. But ere long his attention was concentrated upon the living alone. His mind was flooded by the wonderfully clear light of the Campagna, which reduces all things to a self-evident harmony, making life appear simple and giving it the aspect of pure sensation. For many, the gentle grace of the artist's promised land exercises an irresistible charm. The memorials of the Renaissance issue to the wanderer a summons to greatness. In Italy, more strongly than elsewhere, does it seem that art is the meaning of human life, and that art must be man's heroic aim. Throwing aside his theses, the young man of twenty, intoxicated with the adventure of love and of life, wandered for months in blissful freedom through the lesser cities of Italy and Sicily. Even Tolstoi was forgotten, for in this region of sensuous presentation, in the dazzling south, the voice from the Russian steppes, demanding renunciation, fell upon deaf ears. Of a sudden, however, Shakespeare, friend and guide of Rolland's childhood, resumed his sway. A cycle of the Shakespearean dramas, presented by Ernesto Rossi, displayed to him the splendor of elemental passion, and aroused an irresistible longing to transfigure, like Shakespeare, history in poetic form. He was moving day by day among the stone witnesses to the greatness of past centuries. He would recall those centuries to life. The poet in him awakened. In cheerful faithlessness to his mission, he penned a series of dramas, catching them on the wing with that burning ecstacy which inspiration, coming unawares, invariably arouses in the artist. Just as England is presented in Shakespeare's historical plays, so was the whole Renaissance epoch to be reflected in his own writings. Light of heart, in the intoxication of composition he penned one play after another, without concerning himself as to the earthly possibilities for staging them. Not one of these romanticist dramas has, in fact, ever been performed. Not one of them is to-day accessible to the public. The maturer critical sense of the artist has made him hide them from the world. He has a fondness for the faded manuscripts simply as memorials of the ardors of youth.

The most momentous experience of these years spent in Italy was the formation of a new friendship. Rolland never sought people out. In essence he is a solitary, one who loves best to live among his books. Yet from the mystical and symbolical outlook it is characteristic of his biography that each epoch of his youth brought him into contact with one or other of the leading personalities of the day. In accordance with the mysterious laws of attraction, he has been drawn ever and again into the heroic sphere, has associated with the mighty ones of the earth. Shakespeare, Mozart, and Beethoven were the stars of his childhood. During school life, Suarès and Claudel became his intimates. As a student, in an hour when he was needing the help of sages, he followed Renan; Spinoza freed his mind in matters of religion; from afar came the brotherly greeting of Tolstoi. In Rome, through a letter of introduction from Monod, he made the acquaintance of Malwida von Meysenbug, whose whole life had been a contemplation of the heroic past. Wagner, Nietzsche, Mazzini, Herzen, and Kossuth were her perennial intimates. For this free spirit, the barriers of nationality and language did not exist. No revolution in art or politics could affright her. "A human magnet," she exercised an irresistible appeal upon great natures. When Rolland met her she was already an old woman, a lucid intelligence, untroubled by disillusionment, still an idealist as in youth. From the height of her seventy years, she looked down over the past, serene and wise. A wealth of knowledge and experience streamed from her mind to that of the learner. Rolland found in her the same gentle illumination, the same sublime repose after passion, which had endeared the Italian landscape to his mind. Just as from the monuments and pictures of Italy he could reconstruct the figures of the Renaissance heroes, so from Malwida's confidential talk could he reconstruct the tragedy in the lives of the artists she had known. In Rome he learned a just and loving appreciation for the genius of the present. His new friend taught him what in truth he had long ere this learned unawares from within, that there is a lofty level of thought and sensation where nations and languages become as one in the universal tongue of art. During a walk on the Janiculum, a vision came to him of the work of European scope he was one day to write, the vision of Jean Christophe.

Wonderful was the friendship between the old German woman and the Frenchman of twenty-three. Soon it became difficult for either of them to say which was more indebted to the other. Romain owed so much to Malwida, in that she had enabled him to form juster views of some of her great contemporaries; while Malwida valued Romain, because in this enthusiastic young artist she discerned new possibilities of greatness. The same idealism animated both, tried and chastened in the many-wintered woman, fiery and impetuous in the youth. Every day Rolland came to visit his venerable friend in the Via della Polveriera, playing to her on the piano the works of his favorite masters. She, in turn, introduced him to Roman society. Gently guiding his restless nature, she led him towards spiritual freedom. In his essay To the Undying Antigone, Rolland tells us that to two women, his mother, a sincere Christian, and Malwida von Meysenbug, a pure idealist, he owes his awakening to the full significance of art and of life. Malwida, writing in Der Lebens Abend einer Idealistin a quarter of a century before Rolland had attained celebrity, expressed her confident belief in his coming fame. We cannot fail to be moved when we read to-day the description of Rolland in youth: "My friendship with this young man was a great pleasure to me in other respects besides that of music. For those advanced in years, there can be no loftier gratification than to rediscover in the young the same impulse towards idealism, the same striving towards the highest aims, the same contempt for all that is vulgar or trivial, the same courage in the struggle for freedom of individuality.... For two years I enjoyed the intellectual companionship of young Rolland.... Let me repeat, it was not from his musical talent alone that my pleasure was derived, though here he was able to fill what had long been a gap in my life. In other intellectual fields I found him likewise congenial. He aspired to the fullest possible development of his faculties; whilst I myself, in his stimulating presence, was able to revive youthfulness of thought, to rediscover an intense interest in the whole world of imaginative beauty. As far as poesy is concerned, I gradually became aware of the greatness of my young friend's endowments, to be finally convinced of the fact by the reading of one of his dramatic poems." Speaking of this early work, she prophetically declared that the writer's moral energy might well be expected to bring about a regeneration of French imaginative literature. In a poem, finely conceived but a trifle sentimental, she expressed her thankfulness for the experience of these two years. Malwida had recognized Romain as her European brother, just as Tolstoi had recognized a disciple. Twenty years before the world had heard of Rolland, his life was moving on heroic paths. Greatness cannot be hid. When any one is born to greatness, the past and the present send him images and figures to serve as exhortation and example. From every country and from every race of Europe, voices rise to greet the man who is one day to speak for them all.

THE two years in Italy, a time of free receptivity and creative enjoyment, were over. A summons now came from Paris; the Normal School, which Rolland had left as pupil, required his services as teacher. The parting was a wrench, and Malwida von Meysenbug's farewell was designed to convey a symbolical meaning. She invited her young friend to accompany her to Bayreuth, the chief sphere of the activities of the man who, with Tolstoi, had been the leading inspiration of Rolland during early youth, the man whose image had been endowed with more vigorous life by Malwida's memories of his personality. Rolland wandered on foot across Umbria, to meet his friend in Venice. Together they visited the palace in which Wagner had died, and thence journeyed northward to the scene of his life's work. "My aim," writes Malwida in her characteristic style, which seldom attains strong emotional force, but is none the less moving, "was that Romain should have these sublime impressions to close his years in Italy and the fecund epoch of youth. I likewise wished the experience to be a consecration upon the threshold of manhood, with its prospective labors and its inevitable struggles and disillusionments."

Olivier had entered the country of Jean Christophe! On the first morning of their arrival, before introducing her friend at Wahnfried, Malwida took him into the garden to see the master's grave. Rolland uncovered as if in church, and the two stood for a while in silence meditating on the hero, to one of them a friend, to the other a leader. In the evening they went to hear Wagner's posthumous work Parsifal. This composition, which, like the visit to Bayreuth, is strangely interconnected with the genesis of Jean Christophe, is as it were a consecrational prelude to Rolland's future. For life was now to call him from these great dreams. Malwida gives a moving description of their good-by. "My friends had kindly placed their box at my disposal. Once more I went to hear Parsifal with Rolland, who was about to return to France in order to play an active part in the work of life. It was a matter of deep regret to me that this gifted friend was not free to lift himself to 'higher spheres,' that he could not ripen from youth to manhood while wholly devoted to the unfolding of his artistic impulses. But I knew that none the less he would work at the roaring loom of time, weaving the living garment of divinity. The tears with which his eyes were filled at the close of the opera made me feel once more that my faith in him would be justified. Thus I bade him farewell with heartfelt thanks for the time filled with poesy which his talents had bestowed on me. I dismissed him with the blessing that age gives to youth entering upon life."

Although an epoch that had been rich for both was now closed, their friendship was by no means over. For years to come, down to the end of her life, Rolland wrote to Malwida once a week. These letters, which were returned to him after her death, contain a biography of his early manhood perhaps fuller than that which is available in the case of any other notable personality. Inestimable was the value of what he had learned from this encounter. He had now acquired an extensive knowledge of reality and an unlimited sense of human continuity. Whereas he had gone to Rome to study the art of the dead past, he had found the living Germany, and could enjoy the companionship of her undying heroes. The triad of poesy, music, and science, harmonizes unconsciously with that other triad, France, Germany, and Italy. Once and for all, Rolland had acquired the European spirit. Before he had written a line of Jean Christophe, that great epic was already living in his blood.

THE form of Rolland's career, no less than the substance of his inner life, was decisively fashioned by these two years in Italy. As happened in Goethe's case, so in that with which we are now concerned, the conflict of the will was harmonized amid the sublime clarity of the southern landscape. Rolland had gone to Rome with his mind still undecided. By genius, he was a musician; by inclination, a poet; by necessity, a historian. Little by little, a magical union had been effected between music and poesy. In his first dramas, the phrasing is permeated with lyrical melody. Simultaneously, behind the winged words, his historic sense had built up a mighty scene out of the rich hues of the past. After the success of his thesis Les origines du théâtre lyrique moderns (Histoire de l'opéra en Europe avant Lully et Scarlatti), he became professor of the history of music, first at the Normal School, and from 1903 onwards at the Sorbonne. The aim he set before himself was to display "l'éternelle floraison," the sempiternal blossoming, of music as an endless series through the ages, while each age none the less puts forth its own characteristic shoots. Discovering for the first time what was to be henceforward his favorite theme, he showed how, in this apparently abstract sphere, the nations cultivate their individual characteristics, while never ceasing to develop unawares the higher unity wherein time and national differences are unknown. A great power for understanding others, in association with the faculty for writing so as to be readily understood, constitutes the essence of his activities. Here, moreover, in the element with which he was most familiar, his emotional force was singularly effective. More than any teacher before him did he make the science he had to convey, a living thing. Dealing with the invisible entity of music, he showed that the greatness of mankind is never concentrated in a single age, nor exclusively allotted to a single nation, but is transmitted from age to age and from nation to nation. Thus like a torch does it pass from one master to another, a torch that will never be extinguished while human beings continue to draw the breath of inspiration. There are no contradictions, there is no cleavage, in art. "History must take for its object the living unity of the human spirit. Consequently, history is compelled to maintain the tie between all the thoughts of the human spirit."

Many of those who heard Rolland's lectures at the School of Social Science and at the Sorbonne, still speak of them to-day with undiminished gratitude. Only in a formal sense was history the topic of these discourses, and science was merely their foundation. It is true that Rolland, side by side with his universal reputation, has a reputation among specialists in musical research for having discovered the manuscript of Luigi Rossi's Orfeo, and for having been the first to do justice to the forgotten Francesco Provenzale (the teacher of Alessandro Scarlatti who founded the Neapolitan school). But their broad humanist scope, their encyclopedic outlook, makes his lectures on The Beginnings of Opera frescoes of whilom civilizations. In interludes of speaking, he would give music voice, playing on the piano long-lost airs, so that in the very Paris where they first blossomed three hundred years before, their silvery tones were now reawakened from dust and parchment. At this date, while Rolland was still quite young, he began to exercise upon his fellows that clarifying, guiding, inspiring, and formative influence, which since then, increasingly reinforced by the power of his imaginative writings and spread by these into ever widening circles, has become immeasurable in its extent. Nevertheless, throughout its expansion, this force has remained true to its primary aim. From first to last, Rolland's leading thought has been to display, amid all the forms of man's past and man's present, the things that are really great in human personality, and the unity of all single-hearted endeavor.

It is obvious that Romain Rolland's passion for music could not be restricted within the confines of history. He could never become a specialist. The limitations involved in the career of such experts are utterly uncongenial to his synthetic temperament. For him the past is but a preparation for the present; what has been merely provides the possibility for increasing comprehension of the future. Thus side by side with his learned theses and with his volumes Musiciens d'autrefois, Haendel, Histoire de l'Opéra, etc., we have his Musiciens d'aujourd'hui, a collection of essays which were first published in the "Revue de Paris" and the "Revue de l'art dramatique," essays penned by Rolland as champion of the modern and the unknown. This collection contains the first portrait of Hugo Wolf ever published in France, together with striking presentations of Richard Strauss and Debussy. He was never weary of looking for new creative forces in European music; he went to the Strasburg musical festival to hear Gustav Mahler, and visited Bonn to attend the Beethoven festival. Nothing seemed alien to his eager pursuit of knowledge; his sense of justice was all-embracing. From Catalonia to Scandinavia he listened for every new wave in the ocean of music. He was no less at home with the spirit of the present than with the spirit of the past.

During these years of activity as teacher, he learned much from life. New circles were opened to him in the Paris which hitherto he had known little of except from the window of his lonely study. His position at the university and his marriage brought the man who had hitherto associated only with a few intimates and with distant heroes, into contact with intellectual and social life. In the house of his father-in-law, the distinguished philologist Michel Bréal, he became acquainted with the leading lights of the Sorbonne. Elsewhere, in the drawing-rooms, he moved among financiers, bourgeois, officials, persons drawn from all strata of city life, including the cosmopolitans who are always to be found in Paris. Involuntarily, during these years, Rolland the romanticist became an observer. His idealism, without forfeiting intensity, gained critical strength. The experiences garnered (it might be better to say, the disillusionments sustained) in these contacts, all this medley of commonplace life, were to form the basis of his subsequent descriptions of the Parisian world in La foire sur la place and Dans la maison. Occasional journeys to Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and his beloved Italy, gave him opportunities for comparison, and provided fresh knowledge. More and more, the growing horizon of modern culture came to occupy his thoughts, thus displacing the science of history. The wanderer returned from Europe had discovered his home, had discovered Paris; the historian had found the most important epoch for living men and women—the present.

ROLLAND was now a man of thirty, with his energies at their prime. He was inspired with a restrained passion for activity. In all times and scenes, alike in the past and in the present, his inspiration discerned greatness. The impulse now grew strong within him to give his imaginings life.

But this will to greatness encountered a season of petty things. At the date when Rolland began his life work, the mighty figures of French literature had already passed from the stage: Victor Hugo, with his indefatigable summons to idealism; Flaubert, the heroic worker; Renan, the sage. The stars of the neighboring heaven, Richard Wagner and Friedrich Nietzsche, had set or become obscured. Extant art, even the serious art of a Zola or a Maupassant, was devoted to the commonplace; it created only in the image of a corrupt and enfeebled generation. Political life had become paltry and supine. Philosophy was stereotyped and abstract. There was no longer any common bond to unite the elements of the nation, for its faith had been shattered for decades to come by the defeat of 1870. Rolland aspired to bold ventures, but his world would have none of them. He was a fighter, but his world desired an easy life. He wanted fellowship, but all that his world wanted was enjoyment.

Suddenly a storm burst over the country. France was stirred to the depths. The entire nation became engrossed in an intellectual and moral problem. Rolland, a bold swimmer, was one of the first to leap into the turbulent flood. Betwixt night and morning, the Dreyfus affair rent France in twain. There were no abstentionists; there was no calm contemplation. The finest among Frenchmen were the hottest partisans. For two years the country was severed as by a knife blade into two camps, that of those whose verdict was "guilty," and that of those whose verdict was "not guilty." In Jean Christophe and in Péguy's reminiscences, we learn how the section cut pitilessly athwart families, dividing brother from brother, father from son, friend from friend. To-day we find it difficult to understand how this accusation of espionage brought against an artillery captain could involve all France in a crisis. The passions aroused transcended the immediate cause to invade the whole sphere of mental life. Every Frenchman was faced by a problem of conscience, was compelled to make a decision between fatherland and justice. Thus with explosive energy the moral forces were, for all right-thinking minds, dragged into the vortex. Rolland was among the few who from the very outset insisted that Dreyfus was innocent The apparent hopelessness of these early endeavors to secure justice were for Rolland a spur to conscience. Whereas Péguy was enthralled by the mystical power of the problem, which would he hoped bring about a moral purification of his country, and while in conjunction with Bernard Lazare he wrote propagandist pamphlets calculated to add fuel to the flames, Rolland's energies were devoted to the consideration of the immanent problem of justice. Under the pseudonym Saint-Just he published a dramatic parable, Les loups, wherein he lifted the problem from the realm of time into the realm of the eternal. This was played to an enthusiastic audience, among which were Zola, Scheurer-Kestner, and Picquart. The more definitely political the trial became, the more evident was it that the freemasons, the anti-clericalists, and the socialists were using the affair to secure their own ends; and the more the question of material success replaced the question of the ideal, the more did Rolland withdraw from active participation. His enthusiasm is devoted only to spiritual matters, to problems, to lost causes. In the Dreyfus affair, just as later, it was his glory to have been one of the first to take up arms, and to have been a solitary champion in a historic moment.

Simultaneously, Rolland was working shoulder to shoulder with Péguy, and with Suarès the friend of his adolescence, in a new campaign. This differed from the championship of Dreyfus in that it was not stormy and clamorous, but involved a tranquil heroism which made it resemble rather the way of the cross. The friends were painfully aware of the corruption and triviality of the literature then dominant in Paris. To attempt a direct attack would have been fruitless, for this hydra had the whole periodical press at its service. Nowhere was it possible to inflict a mortal blow upon the many-headed and thousand-armed entity. They resolved, therefore, to work against it, not with its own means, not by imitating its own noisy activities, but by the force of moral example, by quiet sacrifice and invincible patience. For fifteen years they wrote and edited the "Cahiers de la quinzaine." Not a centime was spent on advertising it, and it was rarely to be found on sale at any of the usual agents. It was read by students and by a few men of letters, by a small circle growing imperceptibly. Throughout an entire decade, all Rolland's works appeared in its pages, the whole of Jean Christophe, Beethoven, Michel-Ange, and the plays. Though during this epoch the author's financial position was far from easy, he received nothing for any of these writings—the case is perhaps unexampled in modern literature. To fortify their idealism, to set an example to others, these heroic figures renounced the chance of publicity, circulation, and remuneration for their writings; they renounced the holy trinity of the literary faith. And when at length, through Rolland's, Péguy's, and Suarès' tardily achieved fame, the "Cahiers" had come into its own, its publication was discontinued. But it remains an imperishable monument of French idealism and artistic comradeship.

A third time Rolland's intellectual ardor led him to try his mettle in the field of action. A third time, for a space, did he enter into a comradeship that he might fashion life out of life. A group of young men had come to recognize the futility and harmfulness of the French boulevard drama, whose central topic is the eternal recurrence of adultery issuing from the tedium of bourgeois existence. They determined upon an attempt to restore the drama to the people, to the proletariat, and thus to furnish it with new energies. Impetuously Rolland threw himself into the scheme, writing essays, manifestoes, an entire book. Above all, he contributed a series of plays conceived in the spirit of the French revolution and composed for its glorification. Jaurès delivered a speech introducing Danton to the French workers. The other plays were likewise staged. But the daily press, obviously scenting a hostile force, did its utmost to chill the enthusiasm. The other participators soon lost their zeal, so that ere long the fine impetus of the young group was spent. Rolland was left alone, richer in experience and disillusionment, but not poorer in faith.

Although by sentiment Rolland is attached to all great movements, the inner man has ever remained free from ties. He gives his energies to help others' efforts, but never follows blindly in others' footsteps. Whatever creative work he has attempted in common with others has been a disappointment; the fellowship has been clouded by the universality of human frailty. The Dreyfus case was subordinated to political scheming; the People's Theater was wrecked by jealousies; Rolland's plays, written for the workers, were staged but for a night; his wedded life came to a sudden and disastrous end—but nothing could shatter his idealism. When contemporary existence could not be controlled by the forces of the spirit, he still retained his faith in the spirit. In hours of disillusionment he called up the images of the great ones of the earth, who conquered mourning by action, who conquered life by art. He left the theater, he renounced the professorial chair, he retired from the world. Since life repudiated his single-hearted endeavors he would transfigure life in gracious pictures. His disillusionments had but been further experience. During the ensuing ten years of solitude he wrote Jean Christophe, a work which in the ethical sense is more truly real than reality itself, a work which embodies the living faith of his generation.

FOR a brief season the Parisian public was familiar with Romain Rolland's name as that of a musical expert and a promising dramatist. Thereafter for years he disappeared from view, for the capital of France excels all others in its faculty for merciless forgetfulness. He was never spoken of even in literary circles, although poets and other men of letters might be expected to be the best judges of the values in which they deal. If the curious reader should care to turn over the reviews and anthologies of the period, to examine the histories of literature, he will find not a word of the man who had already written a dozen plays, had composed wonderful biographies, and had published six volumes of Jean Christophe. The "Cahiers de la quinzaine" were at once the birthplace and the tomb of his writings. He was a stranger in the city at the very time when he was describing its mental life with a picturesqueness and comprehensiveness which has never been equaled. At forty years of age, he had won neither fame nor pecuniary reward; he seemed to possess no influence; he was not a living force. At the opening of the twentieth century, like Charles Louis Philippe, like Verhaeren, like Claudel, and like Suarès, in truth the strongest writers of the time, Rolland remained unrecognized when he was at the zenith of his creative powers. In his own person he experienced the fate which he has depicted in such moving terms, the tragedy of French idealism.

A period of seclusion is, however, needful as a preliminary to labors of such concentration. Force must develop in solitude before it can capture the world. Only a man prepared to ignore the public, only a man animated with heroic indifference to success, could venture upon the forlorn hope of planning a romance in ten volumes; a French romance which, in an epoch of exacerbated nationalism, was to have a German for its hero. In such detachment alone could this universality of knowledge shape itself into a literary creation. Nowhere but amid tranquillity undisturbed by the noise of the crowd could a work of such vast scope be brought to fruition.

For a decade Rolland seemed to have vanished from the French literary world. Mystery enveloped him, the mystery of toil. Through all these long years his cloistered labors represented the hidden stage of the chrysalis, from which the imago is to issue in winged glory. It was a period of much suffering, a period of silence, a period characterized by knowledge of the world—the knowledge of a man whom the world did not yet know.

TWO tiny little rooms, attic rooms in the heart of Paris, on the fifth story, reached by a winding wooden stair. From below comes the muffled roar, as of a distant storm, rising from the Boulevard Montparnasse. Often a glass shakes on the table as a heavy motor omnibus thunders by. The windows command a view across less lofty houses into an old convent garden. In springtime the perfume of flowers is wafted through the open window. No neighbors on this story; no service. Nothing beyond the help of the concierge, an old woman who protects the hermit from untimely visitors.

The workroom is full of books. They climb up the walls, and are piled in heaps on the floor; they spread like creepers over the window seat, over the chairs and the table. Interspersed are manuscripts. The walls are adorned with a few engravings. We see photographs of friends, and a bust of Beethoven. The deal table stands near the window; two chairs, a small stove. Nothing costly in the narrow cell; nothing which could tempt to repose; nothing to encourage sociability. A student's den; a little prison of labor.

Amid the books sits the gentle monk of this cell, soberly clad like a clergyman. He is slim, tall, delicate looking; his complexion is sallow, like that of one who is rarely in the open. His face is lined, suggesting that here is a worker who spends few hours in sleep. His whole aspect is somewhat fragile—the sharply-cut profile which no photograph seems to reproduce perfectly; the small hands, his hair silvering already behind the lofty brow; his moustache falling softly like a shadow over the thin lips. Everything about him is gentle: his voice in its rare utterances; his figure which, even in repose, shows the traces of his sedentary life; his gestures, which are always restrained; his slow gait. His whole personality radiates gentleness. The casual observer might derive the impression that the man is debilitated or extremely fatigued, were it not for the way in which the eyes flash ever and again from beneath the slightly reddened eyelids, to relapse always into their customary expression of kindliness. The eyes have a blue tint as of deep waters of exceptional purity. That is why no photograph can convey a just impression of one in whose eyes the whole force of his soul seems to be concentrated. The face is inspired with life by the glance, just as the small and frail body radiates the mysterious energy of work.

This work, the unceasing labor of a spirit imprisoned in a body, imprisoned within narrow walls during all these years, who can measure it? The written books are but a fraction of it. The ardor of our recluse is all-embracing, reaching forth to include the cultures of every tongue, the history, philosophy, poesy, and music of every nation. He is in touch with all endeavors. He receives sketches, letters, and reviews concerning everything. He is one who thinks as he writes, speaking to himself and to others while his pen moves over the paper. With his small, upright handwriting in which all the letters are clearly and powerfully formed, he permanently fixes the thoughts that pass through his mind, whether spontaneously arising or coming from without; he records the airs of past and recent times, noting them down in manuscript books; he makes extracts from newspapers, drafts plans for future work; his thriftily collected hoard of these autographic intellectual goods is enormous. The flame of his labor burns unceasingly. Rarely does he take more than five hours' sleep; seldom does he go for a stroll in the adjoining Luxembourg; infrequently does a friend climb the five nights of winding stair for an hour's quiet talk; even such journeys as he undertakes are mostly for purposes of research. Repose signifies for him a change of occupation; to write letters instead of books, to read philosophy instead of poetry. His solitude is an active communing with the world. His free hours are his only holiday, stolen from the long days when he sits in the twilight at the piano, holding converse with the great masters of music, drawing melodies from other worlds into this confined space which is itself a world of the creative spirit.

WE are in the year 1910. A motor is tearing along the Champs Elysées, outrunning the belated warnings of its own hooter. There is a cry, and a man who was incautiously crossing the street lies beneath the wheels. He is borne away wounded and with broken limbs, to be nursed back to life.

Nothing can better exemplify the slenderness, as yet, of Romain Rolland's fame, than the reflection how little his death at this juncture would have signified to the literary world. There would have been a paragraph or two in the newspapers informing the public that the sometime professor of musical history at the Sorbonne had succumbed after being run over by a motor. A few, perhaps, would have remembered that fifteen years earlier this man Rolland had written promising dramas, and books on musical topics. Among the innumerable inhabitants of Paris, scarce a handful would have known anything of the deceased author. Thus ignored was Romain Rolland two years before he obtained a European reputation; thus nameless was he when he had finished most of the works which were to make him a leader of our generation—the dozen or so dramas, the biographies of the heroes, and the first eight volumes of Jean Christophe.

A wonderful thing is fame, wonderful its eternal multiplicity. Every reputation has peculiar characteristics, independent of the man to whom it attaches, and yet appertaining to him as his destiny. Fame may be wise and it may be foolish; it may be deserved and it may be undeserved. On the one hand it may be easily attained and brief, flashing transiently like a meteor; on the other hand it may be tardy, slow in blossoming, following reluctantly in the footsteps of the works. Sometimes fame is malicious, ghoulish, arriving too late, and battening upon corpses.

Strange is the relationship between Rolland and fame. From early youth he was allured by its magic; but charmed by the thought of the only reputation that counts, the reputation that is based upon moral strength and ethical authority, he proudly and steadfastly renounced the ordinary amenities of cliquism and conventional intercourse. He knew the dangers and temptations of power; he knew that fussy activity could grasp nothing but a cold shadow, and was impotent to seize the radiant light. Never, therefore, did he take any deliberate step towards fame, never did he reach out his hand to fame, near to him as fame had been more than once in his life. Indeed, he deliberately repelled the oncoming footsteps by the publication of his scathing La foire sur la place, through which he permanently forfeited the favor of the Parisian press. What he writes of Jean Christophe applies perfectly to himself: "Le succès n'était pas son but; son but était la foi." [Not success, but faith was his goal.]

Fame loved Rolland, who loved fame from afar, unobtrusively. "It were pity," fame seemed to say, "to disturb this man's work. The seeds must lie for a while in the darkness, enduring patiently, until the time comes for germination." Reputation and the work were growing in two different worlds, awaiting contact. A small community of admirers had formed after the publication of Beethoven. They followed Jean Christophe in his pilgrimage. The faithful of the "Cahiers de la quinzaine" won new friends. Without any help from the press, through the unseen influence of responsive sympathies, the circulation of his works grew. Translations were published. Paul Seippel, the distinguished Swiss author, penned a comprehensive biography. Rolland had found many devoted admirers before the newspapers had begun to print his name. The crowning of his completed work by the Academy was nothing more than the sound of a trumpet summoning the armies of his admirers to a review. All at once accounts of Rolland broke upon the world like a flood, shortly before he had attained his fiftieth year. In 1912 he was still unknown; in 1914 he had a wide reputation. With a cry of astonishment, a generation recognized its leader, and Europe became aware of the first product of the new universal European spirit.

There is a mystical significance in Romain Rolland's rise to fame, just as in every event of his life. Fame came late to this man whom fame had passed by during the bitter years of mental distress and material need. Nevertheless it came at the right hour, since it came before the war. Rolland's renown put a sword into his hand. At the decisive moment he had power and a voice to speak for Europe. He stood on a pedestal, so that he was visible above the medley. In truth fame was granted at a fitting time, when through suffering and knowledge Rolland had grown ripe for his highest function, to assume his European responsibility. Reputation, and the power that reputation gives, came at a moment when the world of the courageous needed a man who should proclaim against the world itself the world's eternal message of brotherhood.

THUS does Rolland's life pass from obscurity into the light of day. Progress is slow, but the impulsion comes from powerful energies. The movement towards the goal is not always obvious, and yet his life is associated as is none other with the disastrously impending destiny of Europe. Regarded from the outlook of fulfillment, we discern that all the ostensibly counteracting influences, the years of inconspicuous and apparently vain struggle, have been necessary; we see that every incident has been symbolic. The career develops like a work of art, building itself up in a wise ordination of will and chance. We should take too mean a view of destiny, were we to think it the outcome of pure sport that this man hitherto unknown should become a moral force in the world during the very years when, as never before, there was need for one who would champion the things of the spirit.

The year 1914 marks the close of Romain Rolland's private life. Henceforth his career belongs to the world; his biography becomes part of history; his personal experiences can no longer be detached from his public activities. The solitary has been forced out of his workroom to accomplish his task in the world. The man whose existence has been so retired, must now live with doors and windows open. His every essay, his every letter, is a manifesto. His life from now onward shapes itself like a heroic drama. From the hour when his most cherished ideal, the unity of Europe, seemed bent on its own destruction, he emerged from his retirement to become a vital element of his time, an impersonal force, a chapter in the history of the European spirit. Just as little as Tolstoi's life can be detached from his propagandist activities, just so little is there justification in this case for an attempt to distinguish between the man and his influence. Since 1914, Romain Rolland has been one with his ideal and one with the struggle for its realization. No longer is he author, poet, or artist; no longer does he belong to himself. He is the voice of Europe in the season of its most poignant agony. He has become the conscience of the world.

Son but n'était pas le succès; son but était la foi.

Jean Christophe, "La Révolte."

ROMAIN ROLLAND'S work cannot be understood without an understanding of the epoch in which that work came into being. For here we have a passion that springs from the weariness of an entire country, a faith that springs from the disillusionment of a humiliated nation. The shadow of 1870 was cast across the youth of the French author. The significance and greatness of his work taken as a whole depend upon the way in which it constitutes a spiritual bridge between one great war and the next. It arises from a blood-stained earth and a storm-tossed horizon on one side, reaching across on the other to the new struggle and the new spirit.

It originates in gloom. A land defeated in war is like a man who has lost his god. Divine ecstasy is suddenly replaced by dull exhaustion; a fire that blazed in millions is extinguished, so that nothing but ash and cinder remain. There is a sudden collapse of all values. Enthusiasm has become meaningless; death is purposeless; the deeds, which but yesterday were deemed heroic, are now looked upon as follies; faith is a fraud; belief in oneself, a pitiful illusion. The impulse to fellowship fades; every one fights for his own hand, evades responsibility that he may throw it upon his neighbor, thinks only of profit, utility, and personal advantage. Lofty aspirations are killed by an infinite weariness. Nothing is so utterly destructive to the moral energy of the masses as a defeat; nothing else degrades and weakens to the same extent the whole spiritual poise of a nation.