Title: The Men Who Wrought

Author: Ridgwell Cullum

Release date: July 24, 2011 [eBook #36836]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Andrew Sly, Al Haines and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

THE

MEN WHO WROUGHT

By

RIDGWELL CULLUM

Author of "The Night Riders," "The Way of

the Strong," "The Law Breakers," etc.

PHILADELPHIA

GEORGE W. JACOBS & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1916, by

George W. Jacobs & Company

All rights reserved

Printed in U. S. A.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Golden Woman

The Law-Breakers

The Way of the Strong

The Twins of Suffering Creek

The Night-Riders

The One-Way Trail

The Trail of the Axe

The Sheriff of Dyke Hole

The Watchers of the Plains

CONTENTS

| I. | The Danger |

| II. | A Strange Meeting |

| III. | The Mystery |

| IV. | Mr. Charles Smith |

| V. | The Lure |

| VI. | The Old Mill Cove |

| VII. | On the Grey North Sea |

| VIII. | Borga |

| IX. | The Friendly Deep |

| X. | The Future |

| XI. | Back at Dorby Towers |

| XII. | Kuhlhafen |

| XIII. | News |

| XIV. | "Kamerads" |

| XV. | The Ineradicable Strain |

| XVI. | Enemy Movements |

| XVII. | The Crouch of the Tiger |

| XVIII. | From Beneath the Waters |

| XIX. | The Tiger Springs |

| XX. | Bar-Leighton |

| XXI. | Enemy Movements |

| XXII. | A Means of Escape |

| XXIII. | The Wreck at Dorby |

| XXIV. | Ruxton Arrives at a Great Decision |

| XXV. | The Sweetness of Life |

| XXVI. | Ruxton Wins a Trick |

| XXVII. | The Week-End Begins |

| XXVIII. | The Week-End |

| XXIX. | The Close of the Week-End |

| XXX. | Gazing Upon a New World |

| XXXI. | After Twelve Months |

ILLUSTRATIONS

He moved a step nearer the rail . . . . . . . . . Frontispiece

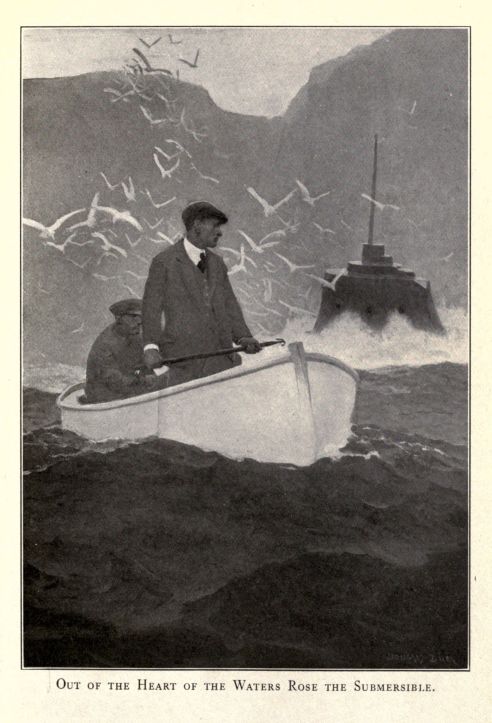

Out of the grey waters rose the submersible

THE MEN WHO WROUGHT

"Amongst the many uncertainties which this deplorable, patched-up peace has brought us, there is, at least, one significant certainty, my boy. It's the inventor. He's buzzing about our heads like a fly in summer-time, and he's just about as—sticky."

Sir Andrew Farlow sighed. His sigh was an expression of relief; relief at the thought that he and his son, dining together at Dorby Towers for the first time since the dissolution of Parliament had released the latter from his political duties, had at last reached the end of a long discussion of the position brought about by the hopelessly patched-up peace, which, for the moment, had suspended the three years of terrible hostilities which had hurled the whole of Europe headlong over the precipice of ruin.

The great ship-owner toyed with the delicate stem of his liquor glass. There was a smile in his keen blue eyes. But it was a smile without lightness of heart to support it.

"Yes, I know. They've been busy enough throughout the war—and to some purpose. Now we have a breathing space they'll spread like a—plague."

Ruxton Farlow sipped his coffee. The weight of the recent discussion was still oppressing him. His mind was full of the appalling threat which the whole world knew to be overshadowing the future.

The dinner was drawing to its close. The butler, grown old in Sir Andrew's service, had finally withdrawn. The great Jacobean dining-hall of Dorby Towers, with its aged oak beams and beautifully carved panelling, was lost in the dim shadows cast by the carefully shaded table lights. Father and son were occupying only the extreme end of the dining-table, which had, at some far-distant age, served to bear the burden of the daily meals of half a hundred monks. There were no other lights in the room, and even the figures of the two diners were only illuminated by the reflected glow from the spotless damask on the table, a fashion to which the conservative habits of the household still ardently clung. It was a fitting setting for such a meeting as the present.

Sir Andrew Farlow, Baronet, was one of the greatest magnates of shipping and ship-building in the country, and was also one of the greatest sufferers by the German submarine warfare during the late war. His extreme wealth, and the fact of the enormous Government contracts in his ship-building yards, had left him practically immune from the consequences of his losses, but the losses to his fleet had been felt by the man, who was, before all things in the world, a shipmaster.

His son, and only partner, had spent those past three years in the service of his country. Not in the actual fighting line but in the work of organization, an important position which his wealth and capacity had entitled him to.

Sir Andrew pierced and lit a cigar.

"We mustn't ridicule them, though," he said, in his hearty Yorkshire way. "We've laughed at 'em too often in the past. It's a laugh which cost our country a couple of thousand millions, and a world-wide suffering which mankind will never forget." Then his manner lightened. "Henceforth the inventor must be to us a rare and precious orchid. We must spend hundreds of thousands of pounds on him, the same as I spend thousands on my orchid houses. I count myself well repaid if I succeed in raising one single perfect bloom on some rare plant. That is, if my rivals have failed with the same plant. The inventor is the orchid of modern civilization, and the perfect blooms he produces are very, very precious and—rare."

"You are thinking of those diabolical engines of destruction which were prepared for this war."

Ruxton helped himself to a cigar.

"On the contrary, I am thinking of the defence, not the offence, of this old country of ours."

The younger man nodded as he lit his cigar.

"That is it. We must prepare—prepare. We have only a breathing space for it."

"There must be no more slumbering."

"And no more sacrificing the country to self-seeking demagogues."

"Yes, and no more slavery to Party prejudices, as antique as the timbers of this house."

"Nor the knaveries of men who seek power through dividing the country into classes, and setting each at the other's throat."

"Nor must we ever again allow the nation's security, economic or military, to be hurled into the cockpit of Party politics."

"Gad! It makes me shiver when I think how near—how near——"

"We were to destruction," added Sir Andrew gravely.

It was again a moment of intense thought. Each man was regarding from his own view-point that intangible threat inspired by the unsatisfactory termination of the war, which left the Teutonic races in a position to brew further mischief with which to flood the world.

The pucker of thought, the drawn brows, completed the likeness of Sir Andrew Farlow to England's national symbolic figure. His broad shoulders and shortish figure; his round, strong, Yorkshire face, with its crowning of snow-white, curly hair, and the old-fashioned, crisp side whiskers made him a typical John Bull, even in his modern evening dress.

In the case of his son Ruxton it was almost in every respect an antithesis.

No foreigner would have taken Ruxton Farlow for anything but an Englishman, just as no Englishman but would have charged him with possessing foreign blood in his veins. And the Englishman would have been right.

Sir Andrew Farlow had spent a brief married life of a few months over one year with one of the most beautiful women amongst the Russian nobility, and the birth of his son left him a widower.

From his mother young Ruxton had inherited all those characteristics which foreign Europe assigns to the British born; his great size, his fair, waving hair and his darkly serious eyes. These things all came from his Russian mother, who had possessed them herself in a marked degree. Furthermore he inherited other qualities which could never be claimed for his Yorkshire father. The boy from his earliest childhood was an idealist: an idealist of but a single purpose which developed into a brilliant specimen of the modern product of an old-fashioned patriotism.

But he brought more to bear upon his patriotism than the mere passionate devotion to his country. He was a fine product of public school and university with the backing of a keen, well-balanced brain, and a natural aptitude for statecraft in relation to the rest of the world. He saw with eyes wide open to those interests dearest to his heart, and clearly, without one single smudge of the fog of personal self-interest.

"It's never out of my thoughts, Dad," Ruxton said at last. "It is with me at all times. It is the purpose of my life to devote myself to, and associate myself with, only those who will place their country before all else in life."

"An ideal difficult to realize in Great Britain," observed his father drily.

"Do you think that? Do you really think that?"

Sir Andrew stirred impatiently.

"It is not what I think. It is not what any of us think. It is what we see and hear—and know. This war has shown up so many weaknesses in the armor of our social economy as well as the psychology of our people that one hardly knows where to hurl one's condemnation the most forcefully. So many weaknesses and failures stand out crying aloud for the bitter castigations of national conscience that it is difficult to point out one worthy feature. Oh, you think that too sweeping," cried the baronet with flushed rugged cheeks and brow, as his son raised questioning eyes in his direction. "That is what every other man and woman in the country would say in their purblind vanity. But it is true. True of the country. True of us all. There is one thing which appeals to me as our greatest failure, however. One failure preëminent over all others that has sunk deep down in my heart, and the scar of which can never be obliterated. I was brought up in the early Victorian days when patriotism was no mere head-line in a sensation-loving press. It was something real. Something big. Something which gripped the sense of duty and made our men and women yearn for active participation when danger threatened our Empire, even to the sacrifice of all they held dear in life. That national spirit was sick to death when this war broke out. Our press was divided, our politicians were divided, and, yes, our people were largely indifferent. But for the strength of a few of our leaders, men who have deserved far better of our country than our country has ever yielded them, thanks to indifference and Party politics, the end of this war would have come with even more terrible consequences to our Empire than all that is signified by the position, almost approaching in status quo ante, in which we now find ourselves. The ramifications of our lack of national spirit are so multifarious that it is impossible to go into them as a whole. One or two, however, are so prodigious, and have been so pronouncedly marked, that the veriest optimist has not failed to observe. One which stood out remarkably was the attitude of the reigning Government when war was declared. Every newspaper cried aloud that our ranks had closed up to meet the peril. They did close up, as far as the will of the country was concerned, but our machinery was geared to certain movement, a machine built through years of partizanship in politics. The result was pitiful. When the party in power was faced with Labor troubles which threatened our downfall in the war, they dared not face their task of drastic remedy because they saw in the dim future the loss of votes which would return their opponents to power at the next election. Hence the political crisis, at a time when we could ill afford such crises, and the formation of a coalition. Ten months were thus lost in drifting while Labor played, and our soldiers, inadequately armed, went to their deaths. The press, a divided press, mark you, sought a scapegoat in the individual, when they, no less than our national machinery, were to blame for the disaster. Is such a condition conceivable in a fervent Latin race, or an iron-shod Teuton? No, no. Is it right to blame Labor, who, for the past decade and more, has been coddled and pampered into the belief that like any baby in its cradle it has only to cry loud enough to obtain the alleviating fluid? It at least has cunning enough to realize that its weight of vote in the country is sufficient to control the destiny of the demagogues who seek place and power through its ignorance. Man, but it makes me sweat to think of it. National spirit? Faugh! Look at the manufacturers. Patriotism? They were full of newspaper patriotism until those who were executing Government contracts discovered that their profits were to be limited. The Army? Our voluntary system? The Army was all right. Oh, yes, the Army was great. But the system? The system was probably the most painful among all our national systems. The most hopelessly inadequate. And, from a national spirit view, was hideously grotesque. But the men who joined and shed their blood upon those terrible battle-fields abroad were as the worker in the vineyard who engaged for one penny. They gave their all, and made up in the execution of their duty for those who sheltered behind the skirts of their womenkind, and the race of shopkeepers they left behind. The spirit of our country when the war broke out was a sordid commercial spirit. 'Business as usual' was the cry. Then our press, our wonderful divided press, said the country was not awake. It was slumbering! I tell you it was a lie!" The old man banged his fist upon the table and set the glasses jumping. "Our country was not asleep. Every man, woman, and child capable of common understanding realized our peril from the start. It was the hateful commercial mind seeking to make gain out of the disaster which had overtaken the world, that mind that has acquired for us the detestable sobriquet of 'a race of shopkeepers,' that hindered and deterred us. We were not slumbering. We were awake. Wide awake! To think that I have lived to see the day when our women's fair hands should be called upon to distribute the white feather. Our present-day musicians and our national bards will tell you that the old songs of England are out of date. They are right. Our girls and boys look askance at your Marryats, your Dickenses, your Thackerays, your Stevensons, and all those great masters who found their strength in our country's greatest ages. When war broke out we were floundering in the mire of sensualism brought about by the years of peace and security, and so we bred the cult of the sensualist writers on sex problems, and all the accompaniment of the other arts to match."

The white-haired veteran, who had spent his early youth fighting his country's battles on the Empire's frontiers, and, in later days, had devoted all his energies to the furthering of Britain's supremacy on the seas, passed one strong hand over his lined brow. He swallowed like a man choking back an emotion threatening to overwhelm him. Then the flush died out of his rugged cheeks, and he smiled at the son he loved, and who was his one remaining relative. "Forgive me, my boy, but—but all I've said is true. I don't think many will deny it. Anyway those who do are lying to their own consciences, or—or are purblind in their insane egoism."

Ruxton smiled responsively and thrust back his chair.

"There's no forgiveness needed, Dad," he said. "You have quoted but a few of the hundred signs, of which we all have proof, that when war broke out patriotism had only the smallest possible part in the life of this country. From the beginning to the end of this war England has had to pay out of her coffers, to those of her people whose services she needed, a price so extortionate that one wonders if it is not all some hideous nightmare and in truth unreal. But tell me, Dad," he went on after a pause, "you spoke just now of inventors, and your manner suggested that there was something—important."

Sir Andrew rose from the table and led the way towards the distant folding doors.

"Well, I don't know if it will prove to be anything—worth while."

He fumbled at an inner pocket of his dinner coat, and produced a letter written on thin paper. When they reached the great hall and stood under the brilliant electrolier he unfolded it and held it out for his son's perusal.

"I get lots of them," he said almost apologetically, "and few enough turn out worth while. This one reads a little different. That's all."

"Sir,

"You are a great shipmaster. You owned a fleet of merchant shipping when war broke out of forty-two coastwise and thirty-five ocean-going ships. At the end of the war you owned thirteen coastwise and twenty-one ocean-going traders. I have a means of saving you any such loss by submarine in the future. May I be permitted to show you my invention?

"Truly yours,

"Charles Smith.

"P.S.—Absolute secrecy is necessary. A simple 'yes' addressed by wire to Veevee, London, will be sufficient."

"The wording of it is so unusual that it—interested me," Sir Andrew went on, as Ruxton began to read the letter a second time.

Presently the younger man looked up from his reading.

"That's your imagination working, Dad," he said, smiling. Then he added: "Let it work. Let it run riot. That's what we want in England—now. I should see this man. I think he is a foreigner—in spite of his English name."

The John Bull face of the elder man wreathed into a warm smile as he looked up at his towering son.

"I had decided to," he said quietly.

Ruxton handed him back the letter. Then he moved across to the great mullioned window and looked out upon the perfect summer night. The moon was shining at its full and not a cloud was visible anywhere.

"I have some letters to write, my boy," Sir Andrew went on. "If you want me I shall be in the library. What are you going to do?"

"I think I shall take a stroll along the cliffs. It'll do me good, Dad. I want to feel our beloved Yorkshire cliffs under my feet again, and make sure they're—still there."

Ruxton laughed.

"The General Election is on August 21st, isn't it?" his father enquired presently. "You've got seven weeks in which to recuperate, and get the cobwebs blown off you."

"I always get rid of bad fancies up here in my native air," Ruxton said lightly. "I'm glad we haven't a strenuous campaign."

"No. We shall win all right."

"Win?" Ruxton laughed. "The National Party will sweep the polls. Labor will be opposed to us as Labor will oppose any party. They will always be with us. But even if the extreme Radicals were to link forces with them, they couldn't obtain a twenty-five per cent. representation. No, Dad, whatever the country failed to realize during the first two years of war, it's been all brought home to it now. The English housewife has been driven to a sweeping and garnishing of her home. We've driven her to that, and the National Party is—going to see she does it thoroughly."

The younger man's enthusiasm drew an approving smile from his father. Also a world of pride in this great, fair-haired idealist shone in his eyes.

"Sweep and garnish. That's it, boy," he said ardently. "And what a sweeping, what a garnishing is needed. I wonder. Can it be done?"

"That is what we intend to test. It is to that great effort my colleagues have pledged their lives. I have pledged mine to another. I tell you, Dad, that the sweeping and garnishing isn't sufficient. That is only the moral side of the campaign that lies before us, and without it the other side can never be achieved. But all my future is to be given up to the material security side of the problem. It may be only my dreaming, but I seem to see a terrible threat sweeping up over the eastern horizon. A threat so appalling for us as to make the late war almost insignificant. Some day, if you have the patience to listen to a dreamer, I will tell you of the dread that persistently haunts me. Meanwhile we have that—breathing space."

Without troubling himself to get a hat Ruxton Farlow passed through the entrance hall, out into the brilliant, warm summer night, and strode on towards his destiny.

The peace of the night knocked vainly at the heart of the man as he moved along over the grass-grown cart track, which skirted those fields abutting on the pathway marking the broken line of the lofty Yorkshire cliffs.

The warmth of the July air left him utterly forgetful of the light evening clothes in which he was clad, just as the grass-grown track failed to remind him that the shoes he wore had never been intended for country rambles. The soft sea breeze fanned his cheeks, and the bracing air added vigor of body if it left his mental feelings wholly uninspired.

For the time, at least, Ruxton Farlow was living within himself. His mental digestion was devouring hungrily of that force which had come to make his contemporaries realize that here was a man of that unusual calibre which must ultimately make him a leader of men in whatever walk of life he chose for that strenuous journey.

The full moon, shedding a ghostly glory on every hand, yielded him the necessary guidance for his footsteps. It served his purpose, but its beauty for once left him unimpressed. The diamond-studded sky suggested no jewel-bedecked cloak of mysterious night as at other times it was wont to appeal. All romance was dead for the time, as though the shutter of his mental camera had been closed with a slam for the development of the plates within which held those living, grim pictures of the life he felt himself surrounded by on every hand.

He passed the last stile and faced the open sea. That smooth limitless expanse, sighing and restless, as it gently rocked its bosom like some aged crone nursing the infant she was too old to bear herself. He flung himself full length upon a rustling bed of heather. His head was towards the sea, and craning over the very edge of the dizzy cliff. There was no thought in his mind of the dangerous proximity. He had known these cliffs almost from his birth up. They were the friends of his whole life, and their possible latent treachery was unthinkable to him. He propped his face between his two hands and sank his elbows deep into the heather. Then, like some schoolboy, his feet were raised behind him, and crossed, while his eyes searched that mysterious horizon lost in the shadows of a perfect night.

It has been said that Ruxton Farlow was an idealist. But let there be no misapprehension about it. His idealism was practical and full of sanity. He was no visionary. His mind was ever groping for the material welfare of his country. The moral welfare, he felt, should be in hands far more capable in that direction than his life and learning had made his. It had been his habit of life to feed his mind upon hard and incontrovertible facts which bore upon the goal of his ideals. He accepted nothing which was merely backed by academic logic. He demanded the logic of practice. Theory was impossible to him, unless that theory was demonstrated in practice. Thus it was he kept his mind alert for facts—and again facts.

The facts which concerned him at the moment were many, and he found in them all, when arranged in due order, one stream like some rushing river which raced on its tempestuous way to the wide sea of disaster beyond.

The starting-point of his facts was the truth that no modern combination of force, however superlative its effort, could crush out of international existence the power of two peoples with aggregate populations of virile strength of some hundred and odd million souls. The war had proved that. And the only possible peace resulting from it had added the conviction that, from a peace point of view, the war had proved utterly useless and damaging. Besides the enormous expenditure of treasure and the vast sacrifices of human life, it had given the world a nominal peace backed by an aggravation of international hatred and spleen a thousand times greater than had ever been known in history since the days of bare-limbed savagery.

What then was the outlook? The man stirred with that nervous suggestion of a disturbed mind. War—war! On every hand war—again. Once again all the moral development of the human race towards those higher planes of light, learning, and religious ideals was shadowed by the spectre which during the last three years had flung men back to the shadows of an ancient savagery and barbarism.

The savage mind of the Teuton had broken out into a fierce conflagration of barbarism. Again it would smoulder, like some slumbering volcano, only to break out again when the arrogance of the German heart told it that the time was ripe to avenge the indignity of its earlier failure.

Ruxton Farlow accepted this as his basis of fact, and followed the river down its turbulent course towards that sea of disaster which he already saw looming ahead. It required no imagination. The course was a straight one, straight as the crow flies. For that passion of hatred which inspired the flood brooked no obstruction to its course. It clamored for its goal and swept all side issues out of its path. Great Britain lay in that sea beyond. Great Britain, who, in German eyes, owned the earth, and incidentally had snatched even those inadequate colonies from her bosom, which, through long years of diplomatic trickery, she had contrived to acquire. The Prussian passion for conquest had been changed through the late war to the passionate national hatred of the German people against Great Britain. This was clear. So clear that the light which shone upon it was painful to his mental vision.

What then was the resulting position of the country he loved? The lessons of the war were many—so many. Yet preëminently outstanding was one fact which smothered all others in its significance, and reduced them all almost to nothingness. His father had dwelt upon the lack of national spirit when war broke out. That had been remedied. The country had changed during those three years of suffering and sacrifice. No, his father had missed the great lesson. Yet it was so simple—so simple.

The man raised his head higher, and folded his arms under him as a support. He gazed down at the calm summer moonlit sea. So calm, so peaceful, so—seductive to the straining mind.

He began to realize the yearning of the suicide for the peace beyond life. How easy to solve all problems. How easy to rid oneself of the duties, the harassing, cruel duties imposed by the Creator of all life. The soft murmur of the breaking swell upon the beach below. One plunge beneath that shimmering surface and—nothing. In that instant there flashed through his mind a memory of just such another sea. The perfect summer sea. The great ship, one of the wonders of the age. A stealing trail of foam across the glass-like surface. An explosion. Then fifteen hundred souls solve the problem of that—nothing! Ah, that was it. That was the Danger. He knew. Every thinking human being knew that if Germany had begun war with a fleet of some three or four hundred submarines, three weeks would have terminated the war so far as Britain was concerned.

He moved over on to his side, and his movement was a further expression of nervous tension. He propped his head upon one hand with his eyes fixed on the vague horizon beyond which the Teutonic giant was peacefully slumbering, and his thought was spoken aloud.

"Is he slumbering?" he asked of the sea. "Is he? Will he ever sleep again? No, I think not. Not at least while there is a chance that his intelligence behind the machine can render an island home untenable."

"Night claims from the overburdened soul the truth which daylight is denied."

Ruxton Farlow sat up with a jolt. His dark, searching eyes were turned from the sea. They were turned in the direction whence the voice, which had answered him, had proceeded. In the brilliant moonlight he saw the outline of a figure standing upon the footpath which ran parallel to the coast-line. The figure was not quite distinct, but it was clearly a woman's, which corroborated the conviction he had received at the sound of the voice.

"But for once she has betrayed her—trust," he said, and a feeling of irritation swept over him that he had permitted himself to respond to the challenge of this stranger, who was probably something in the nature of one of life's vagrants, wandering homeless over the deserted ways of the countryside.

Then he discovered to his further annoyance that his response had brought forth its logical result. The figure was moving towards him, and as it drew near he became aware of that delightful feminine rustle which no man ever yet found unseductive.

The woman made no verbal reply until she was standing before him. Ruxton was still sitting on the heather, but his eyes were wide with astonished admiration, and his clean-shaven lips were parted, which added to his whole expression of incredulous amazement.

The woman standing before him was no vagrant, unless a vagrant could possess a queenly presence, and an attire which suggested the best efforts of London or Paris. He stared, stared as might some schoolboy budding into manhood at the sight of a perfect womanhood. Then, in a moment, questions raced through his head. Who was she, and where—where did she come from? What freak of fortune had set her wandering those cliffs alone—and at night?

She was beautifully tall and crowned with a royal wealth of hair which remained hatless. Its color was not certain in the moonlight, but Ruxton felt that it must be red-gold. He could think of no other color which could match such a presence. Her figure, sharply outlined in the moonlight, was superb. It suggested all he had ever seen in those ardent dreams of youth. Her face possessed something of the reflected glory of the moon lit by eyes whose color was hidden from him, but which shone like great dull jewels full of a living fire.

All these things he realized in one swift comprehensive glance. But in another moment his whole attention was absorbed by the rich voice, the tones of which were like the softest music of some foreign southern land.

"It is scarcely fair to blame the night," she said, in smiling protest.

All unprepared for the encounter Ruxton had nothing but a stupid monosyllable to offer.

"No," he said, and a sigh somehow escaped him.

Then, in a moment, the blood was set swiftly pulsating through his veins.

"May I sit down?" the woman enquired. "I have had a long walk, and am a little tired," she added in explanation.

But she waited for no permission. And somehow Ruxton felt that her expression of weariness was far below the mark. She appeared quite exhausted.

"You are more than a little tired," he said, with urgent solicitude.

Now that her face was nearer to his level he could see that she was indeed very, very beautiful. Her eyes were large and almost oriental in their shape. Her cheeks were as delicate as the petals of a lily. The contour of her whole face was a perfect oval with just sufficient lengthening to give it character.

She did not deny him. But a smile lit her eyes.

"This is delicious," she said, with a sigh of content, turning her face towards the sea, and drinking in deep draughts of fresh, salt air.

Ruxton endeavored to gather his faculties, which had been completely scattered by the thrilling shock of the encounter. He felt himself to be like a callow youth of seventeen rather than a man of over thirty-five, a man whose public life had made intercourse with women of society a matter of every day.

"You have had a long walk?" he enquired wonderingly. "But at night? On these cliffs? You are ten miles from Dorby, and there is no habitation between—except Dorby Towers. Beyond this there is a village or two, but no railway for miles." He had made up his mind that she did not belong to this district. Her costume was still in his thoughts.

"I did not come from Dorby. Nor from any of those villages. Still, I have had a long walk. I have been on my feet nearly three hours."

As she offered no further explanation Ruxton urged her.

"Will you not explain—more?"

"Is it needed?"

The woman faced round, and her Eastern eyes were smiling frankly into his.

Ruxton had no alternative. He desired none. The situation had suddenly gripped him. He was caught in its toils, and delighted that it was so. This woman's beauty, her frank unconventionality, were wholly charming. He asked nothing better than that she should satisfy her whim, and sit there, beside him, talking—talking of what she pleased so long as he listened to the rich music in her voice, and could watch the play of her beautiful, mobile features.

"No," he said deliberately. "There is no need." Then he made a comprehensive gesture with one hand. "The night is beautiful, it is a night of romance and adventure. Let us forget there are such things as conventionality, and just—talk. Let us talk as this silver night prompts. Let us try and forget that painful thought which daylight brings us all. As you say, the night is the time of truth, while daylight demands the subterfuge which conceals it."

But the woman did not respond to his invitation. A little pucker of sudden distress marred her brows.

"Conventionality. I had forgotten," she said. Then her manner became suddenly earnest. She leant slightly forward, and her shining eyes warned Ruxton of the genuineness of their appeal. "Yes, I had truly forgotten," she went on. "Will you—will you forget for the moment there is the difference of sex between us? Will you forget that I am a woman who has wilfully thrust her presence upon a man, a stranger, and laid herself open to a dreadful interpretation of her actions? Will you simply regard me as some one who is striving to unravel those tangled skeins, which, just now, seem to be enveloping a helpless humanity, and, in her effort, has sought out the only man whom she feels can help her—Mr. Ruxton Farlow, the man who will one day rise to be a great ruler in his country?"

"You sought me out?" enquired Ruxton, ignoring the tribute so frankly spoken.

"That is why I have been on my feet for three hours. Will you do as I have asked?"

The charm of this beautiful creature was greater than the man knew. The situation, as she put it, was wholly impossible. Yet her fascination was such that he was impelled to hold out his hand.

"For the time, at least, we are comrades in a common cause," he said, smiling. "My hand on it."

The woman laid a white-gloved hand in his, and the thought in the man's mind was regret at the necessity for gloves.

Ruxton stretched himself out on the heather again. This time he was on his side, supporting his head upon his hand and facing her. The moon was shining full down upon her uncovered hair, and illuminating the perfect features which held the man's gaze.

"And now for the tangled skein," he said with attempted lightness, while his eyes lit whimsically.

"Ruxton Farlow doesn't need a woman to point the dreadful tangle in which humanity is involved—just now. He knows more of the threads than perhaps any man of his country. He was thinking of them when he was run to earth here upon this scented waste of Nature's riot. He was probably pulling apart the wretched threads himself, seeking hope in his endeavor, hope for the future, hope for the future of this land we both love, and for its people. Doubtless he, as others, has found the task something more than arduous, and no doubt he has searched the scene that lies below him, yearning for that peace of mind which oblivion has yielded in recent days to so many souls which have passed beneath the shining surface which encircles this iron-bound coast."

Ruxton's eyes devoured the entrancing animation which accompanied the words. An added amazement had leapt within him. She had fathomed his secret feelings as his eyes had searched the surface of the shimmering summer sea. Her understanding was even more uncanny than had been her sudden apparition. Who was she? he kept reiterating to himself. Who? And where did she come from?

"I felt all that," he found himself saying.

"I know. I have felt it all, too. But your feeling had no inspiration in cowardice. It is the mind of the imaginative that sees an exaggeration in all that offends the sensibilities. It is the mind that distorts with painful fancy the threat which has not yet fallen. It is the mind which is inspired by a heart strong with hope, which in its turn owes its inspiration to a spirit possessed of a great power to do. Of such spirit are the leaders of men. Their mental agony is theirs alone, they suffer and do for those others who do not possess power to do for themselves."

The woman's eyes were turned upon the distant horizon again. Their gaze was introspective, and she talked as she thought, regardless for the time of the man beside her.

But he was more mindful. No word of hers was lost upon him. He was marvelling at her depth of understanding, he was marvelling at her simplicity of expression. And, through it all, he was noting and endeavoring to place that suggestion of foreign intonation in her perfect English accent. More and more was this splendid creature becoming an enigma. More and more was he becoming absorbed in her, and more surely was his promise of simple comradeship becoming an impossibility.

"And the threat—which inspires these phantasms?" he said, as the musical tones ceased, and the murmur of the sea came up to them in their eyrie.

"It is a reality."

Ruxton stirred. He sat up once more, and his gaze, for the moment, left the beautiful profile, and wandered towards the eastern horizon.

"I know," he said simply.

"I have seen," came the impressive rejoinder.

Ruxton's eyes came back to the woman's face.

"Will you tell me?"

His request was made without a shadow of excitement. That was his way when confronted with a crisis. Now he understood why she had worn herself to weariness for three hours on her feet. But for all the interest of the moment his mind was still questioning—Who?

"The telling would be worthless. It would convey simply—words. There is better than telling."

"But the world is at peace now," Ruxton suggested.

"It was at peace before, when—the telling came from all ends of the world."

"And no one listened."

"Those who could have helped refused to hear. And those who heard were powerless."

"So now you come——?"

"To one who, eschewing all that his wealth and position could give him of life's leisure and delight, has dedicated his whole future to the land I—have learned to love."

"And what would you have me do?" Ruxton was smiling, but behind his smile was a brain searching and hungry.

"Do? Ah, that is it." The woman turned swiftly. All her calm had been caught up in a hot emotion. Her eyes were wide and shining as she leant towards him and searched his fair face and dark eyes. "There is peace as you said. But it is only words written upon paper with ink that is manufactured, and by a pen also manufactured. The whole peace is only manufactured. There is no peace in the hearts of the leaders of nations, only hate, which has inspired a passionate yearning for revenge, a passion which has intensified a thousandfold all effort towards the destruction of the hated. Need I tell you of the Teuton feelings? Ruined, blasted as has been that great machine, both military and industrial, there is still the Teuton mind ready and yearning for such a revenge as will stagger all conscious life. Well may the sensitive imagination distort and magnify the threat that cannot yet be grasped. Well may the straining mind contemplate with ecstasy the oblivion gained by those poor creatures on the Lusitania. But for those who would learn, and know, and see, there is a better, braver death to die than the bosom of the ocean can offer. I tell you there is work for every true Briton, man and woman. Work that can offer little else than the reward of a conscience that, maybe, is rendered easy in death. The men who would lead Britain must be men with eyes, and ears, and mind wide open. The time has gone by when England's politicians may sit down in luxurious offices and enjoy the liberal salaries this country so generously dispenses. They must learn first hand of the dangers which threaten these impregnable shores. Impregnable? That has been the fetish which has been the ruin of Britain's national spirit. But I tell you, as surely as the sun will rise to-morrow I can prove to you that impregnability can never again be applied to these splendid shores. Remember, these are the days when victories and destruction are wrought by thought in peace time. The days of simple brute strength have died for all time. And that is why I have travelled far to seek Ruxton Farlow."

"You have sought me to tell me all this that I have thought for months. That I have felt. That in my heart I have known as surely as that night follows day. You have sought me," he added reflectively.

The stranger leant still further towards him, and the man thrilled at the contiguity. So close was she that her breath fanned his cheek, and he found himself gazing into the eager, beautiful eyes.

"And have I not done right? Have I not done right to come to you, who have felt, and thought, and known these things for months—if I can show you even more than in your worst moments you have ever dreamed of?"

It was an intense moment. Its intensity for the man was well-nigh overpowering. Was this wonderful creature some brilliant siren luring him to destruction for very wantonness, or in the interest of others? Was she just as she represented, just an ardent patriot, to whom chance had revealed some damaging secret of his country's enemies, or was she merely a woman endowed with superlative beauty exercising her attraction in those enemies' interests? These things flashed through his brain, even as those feelings of sex stirred his blood and made for denial. For a moment the mental side of him rose dominant.

"You are a foreigner," he challenged, in a voice he hardly recognized as his own.

"I am a Pole."

The admission came promptly.

"You speak English—perfectly," he persisted in the same voice.

"I am—glad."

"Where were you—during the war?"

"In England."

The questions and answers flew back and forth without a semblance of hesitation.

"Yes, yes." Then the man mused. "There were thousands of foreigners at large in England—then."

"But not all were—spies."

The man lowered his eyes. A flush stole up to his brow. It was a flush of shame.

"I—I beg your pardon," he said. The mind had yielded to the man.

"Why should you? Your country should be first in your thoughts. You have not hurt me."

Ruxton passed one hand across his broad, fair forehead.

"But you—a Pole. It seems——"

"It seems that I must have some motive other than I have stated. I have." A bitter laugh accompanied the admission. Quite suddenly she threw her arms wide in a dramatic gesture. "Look at me," she cried. "You see a Pole, but before all things you see a woman. Give riot to your heart, and leave your head for other things. Then you will understand my motives. I have lived through centuries of horror during that terrible war. A horror that even you, who know the horrors committed, will never be able to understand. The innocent women and children in Belgium and France, and my own country, on your own shores, on the high seas. O God," she buried her face in her hands. Then, in a moment, she looked up. "Think—think, if at some future time the Teuton demons overrun this beautiful land I love. The past, those horrors of which I have spoken are nothing to that which will be committed here in England. Now do you understand? Now—will you let me show you what—I can show you?"

"I think I understand—now."

"And you will grant my request?" The urgency was intense. But in a moment the woman went on in a changed tone. A soft smile accompanied her next words. "But no. Don't answer now. It would not be fair to yourself. It would not be fair to your country. It would even deny all that I believe of you. Keep your answer. You will give it to me—later. I will not let you forget. Now I must go."

She rose to her feet, and Ruxton watched her with stirring feelings as she occupied herself with that truly feminine process of smoothing out the creases of the costume which had suffered by contact with the heather.

At last she held out her white-gloved hand, and Ruxton sprang to his feet. He realized that she was about to vanish out of his life as swiftly and mysteriously as she had entered it.

"You are going?" he said quickly.

"Yes. But you will be reminded."

The man held the gloved hand a shade longer than was necessary.

"But on these cliffs? Alone?" Somehow her going had become impossible to him.

But the woman laughed easily.

"It will be only a few moments on these cliffs. It is nothing. Remember I have been wandering about for three hours—alone."

"But—Good-bye!"

The man made his farewell regretfully. He had been about to ask her how, with ten miles to Dorby, and a considerable distance to other villages, she would only be on the cliffs a few moments. But he felt that her coming and her going were her secret, and he had no right to pry into it—yet.

"Good-bye."

The woman turned away, but was promptly arrested by a swift question.

"May I not know your name?"

The stranger faced him once more, and her smile lit up her radiant features till Ruxton felt that never in his life had he seen anything to equal her beauty.

"My name? Yes—why not? It is Vladimir. Vita Vladimir."

Then, in a moment, the man stood gazing after her, as the brilliant moonlight outlined the perfect symmetry of her receding figure.

Ruxton Farlow's return home was even more preoccupied than had been his going. An entirely new sensation was stirring within him. Before, his thoughts had been flowing along the troubled channel of affairs, all of which bore solely upon the purpose of his life. Now their flow had been further confused by the addition of an emotion, which, under ordinary circumstances, might well have leavened the most gloomy forebodings. Instead, however, it was rather like an artist engaged on painting a picture of tragic significance who suddenly discovers that another hand has added some detail, which, while it is still a part of the subject portrayed, yet renders the whole a masterpiece of incongruity.

The coming of a woman into the affairs of his life seemed to him as incongruous as it was pleasant, and, in the circumstances, justified. It was an element all unconsidered before. His association with women until now had been the simple parrying of the feminine shafts levelled at him in the process of ordinary social intercourse in the position he occupied in life. He was by no means a man who took no delight in women's society. On the contrary. But his purpose in life had always been too big as yet to permit his dwelling upon those pleasures which no real manhood can ever ignore.

Women were to him part of the most exalted side of a man's life. His ideals in that direction were as wholly unworldly as his ideals were practical in every other direction. From his earliest youth, due to the death of his mother at his birth, he had never experienced a woman's influence upon his life, and thus he had been left to the riot of imagination, which, in very truth, had been his safeguarding against the operation of the matrimonial market of social London in the midst of which he had found himself plunged.

Now, under conditions wholly robbed of every convention, he had suddenly been confronted by a wonderful creature, who, to his vivid imagination, appealed as the most beautiful of all her beautiful sex. Furthermore the contact had been brought about through those very ideals and purposes to which he had devoted his life. And, moreover, the wonder of it all was that his purpose was apparently her purpose, and she had sought him because this was so. Herein lay the extraordinary incongruity of a sex attraction brought about by the threatened tragedy overshadowing them all.

Vita Vladimir!

It was a name such as he might have discovered anywhere amongst the foreign colony in Soho. His attraction towards the woman afforded no glamor to the name. None at all. He told himself frankly it did not fit her. Furthermore it left him unconvinced that it truly belonged to her. Yet she said she was a Pole. And somewhere in the back cells of memory there was a sort of hazy recollection that "Vladimir" had some connection with Polish history.

However, the question of her name left him cold. Only the vivid picture of her personality remained in his mind. Her charm, her ardor, her beauty, and that extraordinary suggestion of mystery, conveyed in her costume, and the evasion of the details of her coming and going—these things had caught the imagination and the youth in him, and acted upon them like champagne.

He strove to thrust aside these things and consider her only through the purpose on which she had sought him out. She knew, and had seen, the realities of the threat which he believed to be hanging over his country. She could, and would, show him these things.

Suddenly on the impulse of a reasonable incredulity he asked himself if he were dreaming. The whole thing must be a mere phantasm, the outcome of all the troubled thought which had occupied him for so long. But she had told him he would hear from her again, and then that tiny white-gloved hand. He felt its clasp now, as it had lain in his strong palm. No, it was no dream. She was real—and she was very, very beautiful.

By the time he reached the great colonnade which formed the entrance porch of his home the woman's personality had dominated all his endeavor to regard the incident from any other point of view. The woman had absorbed all that was in him, and a curious, deep, thrilling sensation of delight at the encounter had completely thrust into the background the purpose which had brought it about. All that which we in our consideration of the affairs of life are apt to despise, and even leave out of our reckoning altogether, had asserted itself. It was the sex instinct, which no power of human mentality can resist.

Ruxton had no wish to meet his father again that night. He wanted solitude. He wanted to think and dream, as all youth desires to think and dream, when the floodgates of sex are opened, and it finds itself caught in the first rush of its tide.

Glancing at his watch he discovered it to be close upon midnight. But the hour had no significance in his present mood. His father would have retired, and the library would be empty, so he passed up the oak stairway with the determination to smoke a final cigar, and let his thoughts riot over the delectable banquet the evening had provided for them.

But that particular pleasure was definitely denied him. When he entered the library the lights were still on, and he beheld his father's curly white head still bent over the table at which he was wont to attend to his private correspondence.

The old man looked up as the other walked down the long book-lined room towards him. His deep-set eyes were smiling as they were ever ready to smile upon the companion of his wifeless life.

"Finished your ramble?" he enquired pleasantly.

Ruxton returned the smile and flung himself upon a long old settle before he replied.

"The ramble is finished," he said, preparing to light a cigar.

Their eyes met. The father knew there remained something as yet unspoken behind the reply. He waited. But Ruxton's decision was not yet taken.

"Finished your letters yet?" he enquired from behind a cloud of smoke.

The bright blue eyes surveying him twinkled.

"One more," his father said.

"Go ahead then."

Sir Andrew knew by the tone that ultimately the unspoken word was to come. He glanced down at his papers with a sigh.

"I believe, after all, I shall have to break with some of my old-fashioned habits. It is an awful thing to contemplate at my time of life. I think I must be getting old. The burden of private correspondence begins to weigh. I have always held that a private secretary for such a purpose is waste of money, and the undesirable admission of another into one's private life."

Ruxton stretched out his long legs. His bulk almost completely filled the settle.

"It's hard work for Yorkshire to change its habit. A feature applying pretty generally to the Briton. I only wonder a man of your vast fortune has clung to such habits so long. I, who possess but a twentieth of the fortune you possess, find I cannot do without one."

"But then you are a political man," his father smiled drily.

Ruxton nodded. "And in consequence I am saved much heartburning."

"Yes." Sir Andrew gathered up a sheaf of sealed envelopes and flung them into his post basket. "Twenty-five letters. Answers to cranks. Answers to those philanthropists who love to do good with other folks' money. Answers to beggars, to would-be blackmailers, to public institutions whose chief asset is a carefully compiled list of likely subscribers, and then—those whom we have decided to encourage—the inventors. Here is our friend Charles Smith." He picked up the last letter remaining to be dealt with. "What am I going to say to him?"

The old man scratched one shaggy eyebrow with the point of his penholder—one of his signs of doubt and perplexity.

"This secrecy business adds importance to the reply," he added.

Ruxton held out his hand.

"Let's read it again," he said.

His father passed the letter across, and sat watching the concentrated brows of his son, while the latter re-perused the contents.

The watching man was about to turn back to his desk when his eyes abruptly widened questioningly. Ruxton had suddenly sat bolt upright, and a quick flush of suppressed excitement spread over his strong expressive features.

"Veevee, London!" he exclaimed. "A code address which is obviously a word made out of initial letters. V. V." Then he looked across at his startled parent. "I say, Dad, there's mystery here all right—mystery everywhere to-night. V. V. Those initials fit Vita Vladimir exactly."

"Precisely. Also Vivian Vansittart," smiled his father. "Or any other high-sounding names beginning with V."

Ruxton passed the letter back with a laugh. Then he flung himself back on the settle.

"Wait until I have told you what happened to me to-night. Then write to that man and give him a definite appointment at some time when you can devote several hours to him—if necessary."

Sir Andrew pushed his high-backed chair well away from the desk and helped himself to a cigar.

"This is one more than I have any right to to-night, Rux," he said, as he crossed his stout legs, "but go ahead."

Ruxton seemed in no hurry to begin his story. The truth was he felt reluctant to let any one share his secret. Furthermore he was doubtful, in the light of cold words, if that which he had to tell would carry the conviction which possessed him. It seemed impossible; and then the personality of Vita. No. But he felt that the story must be told, if only in justification of his demand for Mr. Charles Smith.

"Look here, Dad," he began at last. "I know you regard me as a bit of a dreamer, but on more than one occasion you have been pleased to say you consider my judgment pretty sound. Perhaps it is. I don't know. Maybe to-night I have been unduly affected by feelings which don't usually carry me away; but, even so, I think I have retained sufficient of our Yorkshire phlegm to get a right estimate of things, and the things which have happened to-night I am convinced are connected with the V. V. in that letter. I was on the cliffs, lying on the heather, looking out to sea, when a woman came along who had been endeavoring to hunt me out for three hours. She was the most beautiful creature I have ever seen. She does not belong to Dorby, or the neighborhood. She was dressed to perfection, and was hatless, and her name was Vita Vladimir. I tell you these details because they are all significant, and I want you to understand that first."

"Go on," his father nodded.

"Go on?" Ruxton gave a short laugh. "It's easier to say than to do—adequately. Anyway this is the whole story."

Both men's cigars had been entirely consumed by the time Ruxton Farlow had finished his long recital. He told his story of his meeting with Vita Vladimir with all the simple force which was part of the Russian nature in him. And, in spite of his fears to the contrary, none of its dramatic significance was lost in the telling.

His father read in the story all his son wanted him to read. But he read deeper even than that, and the depth of his reading was a trespass upon the ground which Ruxton fondly believed he had kept to himself. The shrewd Yorkshire mind probed deep to the vivid impression this Vita Vladimir had made upon his only son, and as yet he was not sure that he shared the boy's enthusiasm. However, long years of understanding had convinced him of Ruxton's clarity of judgment in vital matters, and his earnest recital of the woman's warning and promises carried the conviction that, in spite of the boy's attraction, his judgment in this matter had remained unimpaired. He accepted the facts, but, to himself, deplored the means by which they had been conveyed.

"It is quite remarkable, boy, quite remarkable," was his only comment at the conclusion of the story. Then he held the man Smith's letter in his hand and glanced at the postscript.

But Ruxton was not satisfied with such comment. He was anxious that his hard-headed father should see eye to eye with him.

"But what do you think of it?" he demanded, with suppressed feeling.

The great ship-owner took some moments formulating his reply.

"One's impression from your telling is the honesty of the woman," he said deliberately at last. "There are three possibilities in the matter. First that she is honest. Second that she—belongs to our enemies. Third that she is a—crank. But the second and third I think can be dismissed. Why should our enemies make such an extraordinary proposal to you, or to anybody, short of a man important enough to be done away with? The suggestion of 'crank' is quite dispensable, in view of the significance of the story as it bears on all the possibilities of the future we have discussed. Accepting her honesty, I should say that the answer to this letter will be received by her for—transmission. Well?"

"Then answer that letter in the affirmative, and see this Charles Smith, Dad," cried Ruxton, rising and pacing the floor. "I am going to probe this matter to the bottom." Then he came to a halt before the desk, and gazed down into his father's serious eyes. "There is mystery abroad, Dad. There is more than mystery. There is something tangible. A great and threatening danger which must be nullified. We don't know what it is yet. We can only surmise, but surmise is futile. We must go and find out, as she said. We must learn these things first hand. I shall go."

"That is what I felt you had—decided." The old man sighed. "I can't disguise my regret, my boy, but it is—in the light of your life's purpose—your duty to go. I will do my part. I will see this—Charles Smith."

The General Election had come and gone like a hurricane of emotion sweeping the country from one end to the other. Passionate opinion had been stirred, it had been brought to a feverish surface and had been hurled from lip to lip in that spirit of contention, than which no more bitter feeling can be roused in the affairs of modern life. For once, however, Britain was far less divided than usual. Even prejudice, that blind, unreasoning, unthinking prejudice which usually characterizes the voter, who claims for himself "good citizenship," had somehow been shaken to its foundations. It was an almost awakened Britain which marched on the polls and registered its adhesion and support to the men who, out of the muckhole of demagoguery, had risen superior even to themselves and yielded to the real needs of the country.

And the voice of the new Britain had been heard like a clarion across the Empire, so that, at the close of the polls, the world knew that, as Ruxton Farlow had said, the British housewife had determined upon that sweeping and garnishing so sadly needed, and that once and for all she had decided to bolt and bar the back door through which for so long she had been assailed by her enemies.

Ruxton Farlow was on his way to his little old Georgian house in Smith Square, Westminster. He was returning from Downing Street, where he had been summoned hastily and urgently by the new Prime Minister. He had found that electrical individual busily engaged in superintending the removal of his effects, aided by his equally energetic secretary, from one house in Downing Street to that Mecca of all political aspirations, "No. 10."

Ruxton had avoided the vehicles and packing-cases at the door and was conducted to the great little man's library. And on his entry the secretary had been promptly dismissed. The interview was brief. It was so brief that Ruxton, who understood and preferred such methods, was not a little disconcerted. There had been a hearty hand-shake, a few swiftly spoken compliments and a quick assurance, and once more the big man found himself picking his way amongst the debris on the doorsteps.

But this time he had scarcely seen the obstructions he had to avoid. He dodged them almost mechanically. His heart was beating high with a quiet exultation, for he had left the presence of the wonderful little man, who seemed to live his whole life on the edge of his nervous system, with the assurance of a junior Cabinet rank in the new Ministry.

But the first rush of his tumultuous feelings quickly subsided, as was his way, and he remembered that which was at once his duty and desire. So he turned into a post-office and despatched a code wire to his father in Yorkshire that he might be the first person in the world to learn of his early triumph. Yes, he wanted his to be the first congratulations. He smiled to himself as he left the post-office. The entire press had been devoting itself to forecasting the personnel of the new Cabinet, but not in one single instance had his name been included in the lists.

It was with a sense bordering on perfect delight that he turned into the calm backwater of Smith Square. And for once the dingy atmosphere took on a reflected glory from his feelings. The square church, with its four squat towers, handsome enough in its architecture but drab of hue, might have been some structure of Gothic splendor. Even the impoverished trees which surrounded it had something of the verdant splendor of spring in them on this late summer afternoon. The sparrows and the pigeons failed even to bring home to him the greyness of life in a London square. For the moment those mental anxieties which had haunted him ever since the Great War were powerless to depress his outlook. Life was very good—very good indeed.

He crossed the square and let himself into his house with a latch-key. He crossed the panelled hall and flung his hat and cane upon a table and hurried up the stairway to his study. He had been interrupted in his correspondence by the Prime Minister's summons, and now he was anxious to be done with it, and be free to contemplate the new situation in the light of those many purposes he had in view.

As he sat down at his desk the door in the oak panelling at the far end of the room was thrust open and his secretary appeared. In a few moments these two were absorbed in their work with a thoroughness which was characteristic of Ruxton. Thus for two hours and more the memory of his promotion was completely thrust into the background.

The butler had just brought him in a tray of afternoon tea, and the two men took the opportunity to abandon their work for a few minutes' leisure.

Ruxton leant back in his chair and lit a cigar, while the secretary lit a cigarette and poured out the tea.

"Our labors have borne fruit, Heathcote," said Ruxton, seizing the moment to impart his good news. "We are raised from the rank and file. Our future lies on the front benches."

"The Cabinet?"

"Yes, the Cabinet."

Nor could Ruxton quite control the delight surging through him.

"Now we begin to see the development of all those long-laid plans we have so ceaselessly worked upon, Heathcote," he went on. "Now we are getting nearer to the position which will enable us to bring about something of that security for this old country for which we both so ardently long. Now—Heathcote—now!"

There was a passionate triumph underlying the idealist's words which found ample reflection in the dark eyes of the keen-faced secretary.

The Honorable Harold Heathcote, a younger son in an old English family, had been Ruxton's secretary from the beginning of his political career; he was a brilliant youngster who had determined upon a political career for himself, and had, with considerable shrewdness, pinned his faith to the banner which, from the beginning of his career, Ruxton Farlow had unfurled for himself. These two men were working for a common purpose.

"I knew it would come, Mr. Farlow," said Heathcote with cordial enthusiasm. "And there'll be more to follow, or I have no understanding of the times. I am glad. Very glad."

At that moment there was a knock at the door, and Heathcote rose to answer it. When he returned he handed two telegrams to his chief.

"Telegrams," he said laconically, and returned to his seat and to his tea.

Ruxton ran a paper knife through the envelopes. The first message was from his father. It was brief, cordial, but urgent.

"Heartiest congratulations. Immensely delighted. Must see you at once. Inventor turned out most important as well as mysterious.—Farlow."

Ruxton read the message over two or three times. Then he deliberately tore it up into small pieces and dropped it in the waste-paper basket.

He opened the second message with a preoccupied air. He was thinking—thinking deeply. But in a moment all his preoccupation vanished as he glanced over its contents. He hungrily devoured the words written on the tinted paper.

"Am delighted at your promotion. I anticipated it. My most heartfelt good wishes. Do not let this success make you forget our meeting. Dare I hope that you may find your way to 17, Streamside Mansions, Kensington?—Vita Vladimir."

It was some moments before Ruxton's eyes left that message. A world of unsuspected emotion was stirring within him. He had not forgotten. He was never likely to forget. But in the midst of his emotion some freak of mind had caught and held the significance of this mysterious creature's congratulations. How—how had she learned of—his promotion, when no one but himself and the Prime Minister knew of it?

Suddenly he bestirred himself. He carefully refolded Vita's message, and placed it in his pocket. Then he turned to Heathcote.

"I shall have to go to Dorby to-night. My father wants me. It is rather important. Fortunately things here will not require me just now. But you must notify me of anything important happening. Meanwhile give orders to have my things got ready, and look me out a train. I must run out to send a wire."

"Can't I send it for you?"

"No-o. I think not, thanks."

A profound silence reigned in the library at Dorby Towers.

The pungent aroma of cigars weighed upon the atmosphere in spite of the wide proportions of the apartment. Considerable light was shed from the antique sconces upon the walls, as also by the silver candelabra upon the long refectory table which ran down the centre of the room. But withal it was powerless to dispel the dark suggestion of the old bookcases which lined the walls of the room.

Two men were occupying one side of the table, and Ruxton Farlow sat alone at the other. The eyes of all three were focussed intently upon the object lying upon the table, which was a ten-foot model of a strange-looking water craft.

The first to break the spell of the burden of silence was Sir Andrew Farlow, who, with a bearded stranger, occupied the side of the table opposite his son. But his was no attempt at speech. He merely leant forward with an elbow on the polished oak, and his fingers softly stroking his square chin and tightly compressed lips. He was humming softly, an expression of an intently occupied mind. The fixity of his gaze suggested a desire to bore a way to the heart of the secrets the strange model contained.

The bearded stranger was watching him closely while his eyes appeared to be focussed upon the object of interest, and presently, as though the psychological moment had arrived, he, too, leant forward, and, with an arm stretched out, terminating in a long, lean, tenacious-looking hand, he pressed a button on the side of the model. Instantly the whole interior of it was lit electrically, and the light shone through a series of exquisitely finished glass-covered port-holes extending down the vessel's entire sides.

He spoke no word, but sat back in his chair and went on smoking, while he closely watched for any sign of impression which the two interested spectators displayed.

The moments slipped by. The patient stranger sat on with his long lean legs crossed, and a benevolent smile in his large eyes. After a while Ruxton sat back in his chair. Then Sir Andrew abandoned his inspection, and turned to the man beside him.

It seemed to be the cue awaited, for the stranger promptly leant forward again and released a spring by the movement of a switch. Instantly the model split in half, and, opening much in the fashion of a pea-pod, displayed the longitudinal sections of its interior.

Simultaneously the two men whose lives had been hitherto given up to ship construction rose to their feet, and pored over the wonderful and delicate mechanism and design the interior revealed.

Then it was that Sir Andrew verbally broke the silence.

"Will you explain, Mr. Smith?"

The inventor removed his cigar.

"You know—marine mechanism?" he enquired.

Sir Andrew nodded.

"Yes, unless there is a new principle here."

"It is the perfected submarine principle which was used towards the end of the war. There is no fresh detail in that direction."

"We have a complete knowledge of that principle," said Ruxton. "We have been constructing for the Admiralty throughout the war."

"Good."

There was a distinct "T" at the end of the word as Mr. Smith spoke it.

Ruxton shot a quick glance in his direction. The man's whole personality was an unusual one. He was very tall, and very thin. His intellectual head, quite nobly formed, was crowned by a shock of snow-white hair closely hogged, as might be a horse's mane. His features were almost as lean as his body. But the conformation of a magnificent forehead and the gently luminous eyes, beneath eyebrows almost as bushy as a well-grown moustache, made one forget the fact. Then, too, the carefully groomed, closely cut snow-white beard and moustache helped to disguise it still more. It was the face of a man of great mentality and lofty emotions, a face of simplicity and kindliness. It was, in fact, a face which demanded a second scrutiny, and one which inspired trust and liking.

To the rest must be added certain details which seemed a trifle extraordinary in view of his profession. If his tailor did not trade in Bond Street then he certainly must have served his apprenticeship in those select purlieus. Perfect cut and excellence of material marked every detail of his costume, which was of the "morning" order.

"Then there is little enough to explain, except for the architectural side of the matter," Mr. Smith went on, with a peculiarly back-of-the-throat tone in his speech, which also possessed a shadow of foreign accent. "I am not offering you a submarine principle. That is established now all over the world. I please to call my invention a submersible merchantman. You will observe the holds for merchandise. You will see the engine-rooms," he went on, rising and pointing out each detail as he enumerated it. "There are the stateroom decks, with the accompaniment of saloon and kitchens, and baths, and—and all the necessities of passenger traffic. Everything is there on a lesser scale such as you will find on a surface liner. Its speed and engine power will compare favorably with any liner afloat up to ten thousand tons. Thus it has the speed of a surface craft on the surface, with the added advantages of a submarine. In addition to these I have a light, in the course of production, which will serve to render the submarine immune from the dangers of submersion. I call it the 'U-rays.'"

"The U-rays?" Ruxton's enquiry came like a shot.

"Just so."

Mr. Smith replied quite unhesitatingly, and Ruxton's obvious suspicion was disarmed.

"This vessel," the inventor went on, quite undisturbed, "solves the last problem of sea traffic under—all conditions."

The light of enthusiasm was shining in the man's luminous eyes as he made his final pronouncement. It was as though the thought had filled him with a profound hope of the fulfillment of some ardent desire. It suggested to the more imaginative Ruxton that he cared more for the purpose of his invention than for its commercial aspect to himself.

"You speak, of course, of—war," Ruxton said.

The large eyes of the stranger widened with horror and passion.

"I speak of—international murder!" he cried fiercely.

Sir Andrew turned from the model at the tone of the reply. Ruxton would have pursued the subject, but Mr. Smith gave him no opportunity.

"Your pardon, gentlemen," he said with a sudden, exquisite smile of childlike simplicity. "Memories are painful. I have much that I remember, and—but let us keep to the business in hand."

"Memories are painful to us all—here in England," said Ruxton gently. "But—this is a beautiful model. Perfect in every detail."

"It was made in my own shops," returned the inventor simply.

"And you say this," indicating the model, "has been tested on a constructed vessel?"

"I have travelled more than ten thousand miles in just such a vessel. I have travelled on the surface at twenty-four knots, and under the surface at fifteen. I have carried mixed cargoes, and I have carried certain passengers. All these things I have done for experiment, so that the principle should be perfected. You can judge for yourselves. A vessel of this type awaits your pleasure at any hour. A vessel of two thousand tons."

"Two thousand?" The incredulous ejaculation escaped Sir Andrew before he was aware of it.

"It is nothing," exclaimed Mr. Smith, turning quickly. "A vessel of ten thousand tons can just as easily be constructed."

The sweeping assertion spoken with so simple a confidence had the effect of silence upon his audience. It was overwhelming even to these men who had witnessed the extraordinary development of invention during the war.

After awhile Ruxton broke the silence.

"In your original communication to us you assured us of a means of avoiding the losses we endured during the war from submarine attack. This I understand is the—means. Will you point its uses? I see it in my own way, but I should like to hear another mind on the subject."

Mr. Smith folded his arms and settled himself in his chair. Ruxton was not seeking information on the subject of the boat. His imagination told him all he wanted to know in that direction. It was the man he wanted to study. It was the man he was not certain of. He was convinced that this man was a foreigner, for all his British name. He desired to fathom the purpose lying behind this stranger's actions.

"A great Admiral just before the war," said the inventor, "declared that the future of naval warfare lay under the water, and not on the surface, as we have always believed. He was right. But he did not go as far as he might have gone. The whole future of shipping lies as much under water as on the surface. I tell you, gentlemen, that this boat, here, will afford untold blessings to humanity. To an island country it affords—existence. Think. This country, Britain, is not self-supporting. Is it not so? It could not keep its people alive for more than months. It depends upon supplies from all ends of the earth. All roads upon the high seas lead to Britain. And every helpless surface vessel, carrying life to the island people at home, is a target for the long-distance submarine. If an enemy possesses a great fleet of submarines he does not need to declare a war area about these shores. Every high sea is a war area where he can ply his wanton trade. With the submarine as perfect as it is to-day, Britain, great as she is in naval armaments, can never face another war successfully. That thought is in the mind of all men already." The man paused deliberately. Then with a curious foreign gesture of the hands he went on. "But there is already established an axiom. Submarine cannot fight submarine—under the surface." He shrugged. "It is so simple. How can an enemy attack my submersible? The moment a submarine appears, the submersible submerges and the enemy is helpless. An aerial warship will become a spectacle for the amused curiosity to the ocean traveller. In peace time storms will have small enough terror, and on the calm summer seas we shall speed along at ever-increasing mileage. I tell you, gentlemen, the days of wholly surface boats are gone. The days of clumsy blockades are over, just as are the starvation purposes of contraband of war. With the submersible how is it possible to prevent imports to a country which possesses a seaboard? That is the proposition I put to the world in support of my submersible."

Father and son sat silently listening to the easy, brief manner of the man's explanation. Nor was it till he spoke of the futility of a war submarine's efforts against his submersible did any note of passion and triumph find its way into the man's manner. At that point, however, a definite uplifting made itself apparent. His triumph was in the new depth vibrating in his musical voice. There was a light in his eyes such as is to be found in the triumphant gaze of the victor.