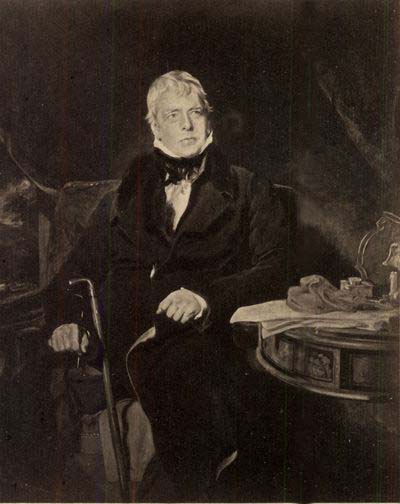

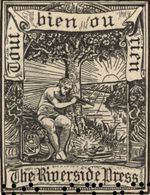

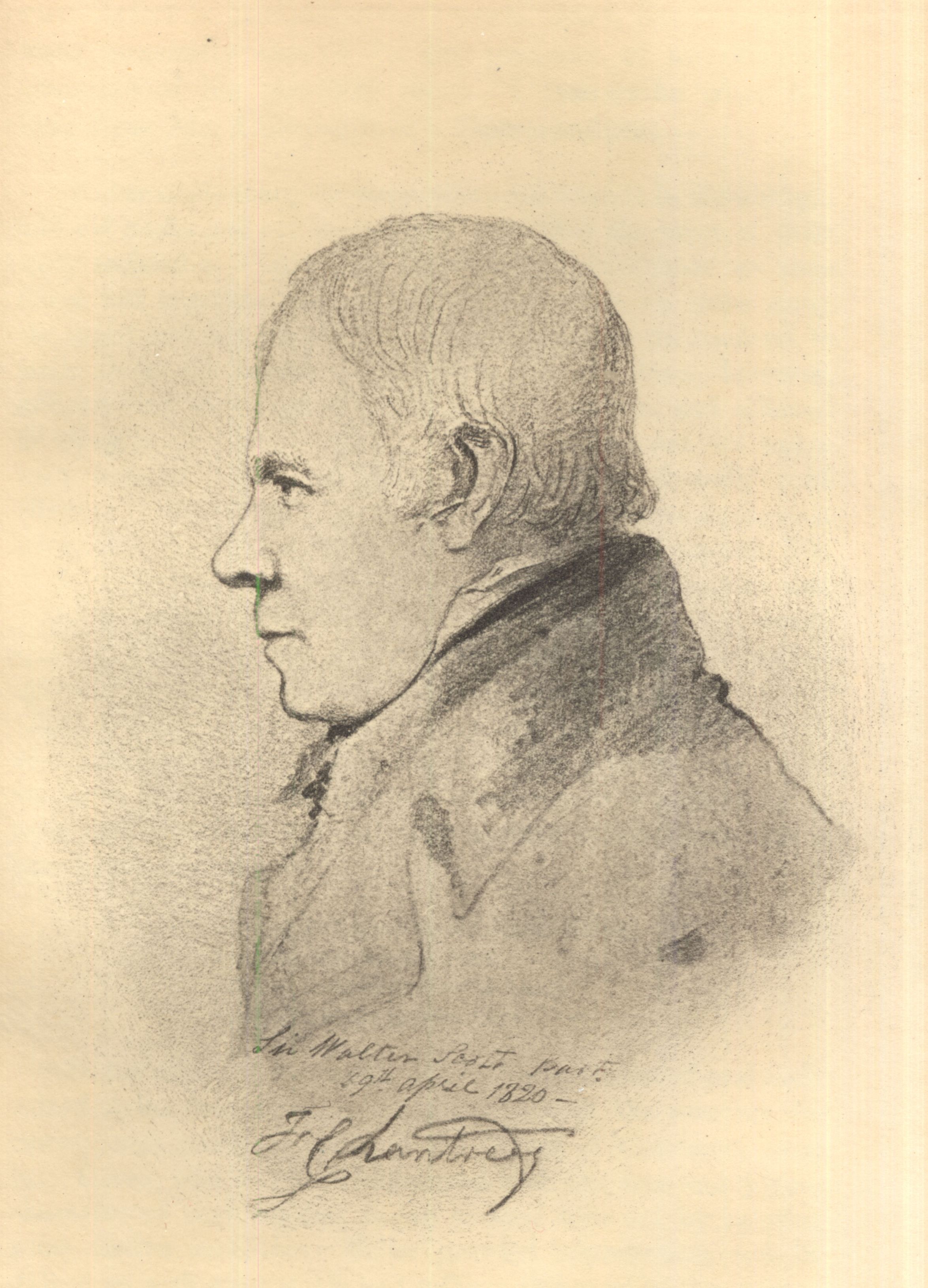

WALTER SCOTT IN 1820

From the painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence

Title: Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Volume 6 (of 10)

Author: J. G. Lockhart

Release date: October 5, 2011 [eBook #37631]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by D. Alexander, Christine P. Travers and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's note: Obvious printer's errors have been corrected, all other inconsistencies are as in the original. The author's spelling has been maintained.

Large-Paper Edition

COPIOUSLY ANNOTATED AND ABUNDANTLY ILLUSTRATED

IN TEN VOLUMES

VOL. VI

WALTER SCOTT IN 1820

From the painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence

BY

IN TEN VOLUMES

VOLUME VI

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

MCMI

COPYRIGHT, 1901

BY HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Six Hundred Copies Printed

Number,

DECLINING HEALTH OF CHARLES, DUKE OF BUCCLEUCH. — LETTER ON THE DEATH OF QUEEN CHARLOTTE. — PROVINCIAL ANTIQUITIES, ETC. — EXTENSIVE SALE OF COPYRIGHTS TO CONSTABLE AND CO. — DEATH OF MR. CHARLES CARPENTER. — SCOTT ACCEPTS THE OFFER OF A BARONETCY. — HE DECLINES TO RENEW HIS APPLICATION FOR A SEAT ON THE EXCHEQUER BENCH. — LETTERS TO MORRITT, RICHARDSON, MISS BAILLIE, THE DUKE OF BUCCLEUCH, LORD MONTAGU, AND CAPTAIN FERGUSON. — ROB ROY PLAYED AT EDINBURGH. — LETTER FROM JEDEDIAH CLEISHBOTHAM TO MR. CHARLES MACKAY.

1818-1819

I have now to introduce a melancholy subject—one of the greatest afflictions that ever Scott encountered. The health of Charles, Duke of Buccleuch was by this time beginning to give way, and Scott thought it his duty to intimate his very serious apprehensions to his noble friend's brother.

TO THE RIGHT HON. LORD MONTAGU, DITTON PARK, WINDSOR.

Edinburgh, 12th November, 1818.

My dear Lord,—I am about to write to you with feelings of the deepest anxiety. I have hesitated for two or three days whether I should communicate to your Lordship the sincere alarm which I entertain on account of the Duke's present state of health, but I have come (p. 2) to persuade myself, that it will be discharging a part of the duty which I owe to him, to mention my own most distressing apprehensions. I was at the cattle-show on the 6th, and executed the delegated task of toast-master, and so forth. I was told by **** that the Duke is under the influence of the muriatic bath, which occasions a good deal of uneasiness when the medicine is in possession of the system. The Duke observed the strictest diet, and remained only a short time at table, leaving me to do the honors, which I did with a sorrowful heart, endeavoring, however, to persuade myself that ****'s account, and the natural depression of spirits incidental to his finding himself unable for the time to discharge the duty to his guests, which no man could do with so much grace and kindness, were sufficient to account for the alteration of his manner and appearance. I spent Monday with him quietly and alone, and I must say that all I saw and heard was calculated to give me the greatest pain. His strength is much less, his spirits lower, and his general appearance far more unfavorable than when I left him at Drumlanrig a few weeks before. What ****, and indeed what the Duke himself, says of the medicine, may be true—but **** is very sanguine, and, like all the personal physicians attached to a person of such consequence, he is too much addicted to the placebo—at least I think so—too apt to fear to give offence by contradiction, or by telling that sort of truth which may controvert the wishes or habits of his patient. I feel I am communicating much pain to your Lordship, but I am sure that, excepting yourself, there is not a man in the world whose sorrow and apprehension could exceed mine in having such a task to discharge; for, as your Lordship well knows, the ties which bind me to your excellent brother are of a much stronger kind than usually connect persons so different in rank. But the alteration in voice and person, in features, and in spirits, all argue the decay of natural strength, and the (p. 3) increase of some internal disorder, which is gradually triumphing over the system. Much has been done in these cases by change of climate. I hinted this to the Duke at Drumlanrig, but I found his mind totally averse to it. But he made some inquiries of Harden (just returned from Italy), which seemed to imply that at least the idea of a winter in Italy or the south of France was not altogether out of his consideration. Your Lordship will consider whether he can or ought to be pressed upon this point. He is partial to Scotland, and feels the many high duties which bind him to it. But the air of this country, with its alternations of moisture and dry frost, although excellent for a healthy person, is very trying to a valetudinarian.

I should not have thought of volunteering to communicate such unpleasant news, but that the family do not seem alarmed. I am not surprised at this, because, where the decay of health is very gradual, it is more easily traced by a friend who sees the patient from interval to interval, than by the affectionate eyes which are daily beholding him.

Adieu, my dear Lord. God knows you will scarce read this letter with more pain than I feel in writing it. But it seems indispensable to me to communicate my sentiments of the Duke's present situation to his nearest relation and dearest friend. His life is invaluable to his country and to his family, and how dear it is to his friends can only be estimated by those who know the soundness of his understanding, the uprightness and truth of his judgment, and the generosity and warmth of his feelings.

I am always, my dear Lord, most truly yours,

Scott's letters of this and the two following months are very much occupied with the painful subject of the Duke of Buccleuch's health; but those addressed to his (p. 4) Grace himself are, in general, in a more jocose strain than usual. His friend's spirits were sinking, and he exerted himself in this way, in the hope of amusing the hours of languor at Bowhill. These letters are headed "Edinburgh Gazette Extraordinary," No. 1, No. 2, and so on; but they deal so much in laughable gossip about persons still living, that I find it difficult to make any extracts from them. The following paragraphs, however, from the Gazette of November the 20th, give a little information as to his own minor literary labors:—

"The article on Gourgaud's Narrative[1] is by a certain Vieux Routier of your Grace's acquaintance, who would willingly have some military hints from you for the continuation of the article, if at any time you should feel disposed to amuse yourself with looking at the General's most marvellous performance. His lies are certainly like the father who begot them. Do not think that at any time the little trumpery intelligence this place affords can interrupt my labors, while it amuses your Grace. I can scribble as fast in the Court of Session as anywhere else, without the least loss of time or hindrance of business. At the same time, I cannot help laughing at the miscellaneous trash I have been putting out of my hand, and the various motives which made me undertake the jobs. An article for the Edinburgh Review[2]—this for the love of Jeffrey, the editor—the first for ten years. Do., being the article Drama for the Encyclopædia—this for the sake of Mr. Constable, the publisher. Do. for the Blackwoodian Magazine—this for love of the cause I espoused. Do. for the Quarterly Review[3]—this for the love of myself, I believe, or, which is the same (p. 5) thing, for the love of £100, which I wanted for some odd purpose. As all these folks fight like dog and cat among themselves, my situation is much like the Suave mare magno, and so forth....

"I hope your Grace will never think of answering the Gazettes at all, or even replying to letters of business, until you find it quite convenient and easy. The Gazette will continue to appear as materials occur. Indeed I expect, in the end of next week, to look in upon Bowhill, per the Selkirk mail, about eight at night, with the hope of spending a day there, which will be more comfortable than at Abbotsford, where I should feel like a mouse below a firlot. If I find the Court can spare so important a person for one day, I shall order my pony up to meet me at Bowhill, and, supposing me to come on Friday night, I can easily return by the Blucher on Monday, dining and sleeping at Huntly Burn on the Sunday. So I shall receive all necessary reply in person."

Good Queen Charlotte died on the 17th of this month; and in writing to Mr. Morritt on the 21st, Scott thus expresses what was, I believe, the universal feeling at the moment:—

"So we have lost the old Queen. She has only had the sad prerogative of being kept alive by nursing for some painful weeks, whereas perhaps a subject might have closed the scene earlier. I fear the effect of this event on public manners—were there but a weight at the back of the drawing-room door, which would slam it in the face of w——s, its fall ought to be lamented; and I believe that poor Charlotte really adopted her rules of etiquette upon a feeling of duty. If we should suppose the Princess of Wales to have been at the head of the matronage of the land for these last ten years, what would have been the difference on public opinion! No man of experience will ever expect the breath of a court to be favorable to correct morals—sed si non caste caute (p. 6) tamen. One half of the mischief is done by the publicity of the evil, which corrupts those which are near its influence, and fills with disgust and apprehension those to whom it does not directly extend. Honest old Evelyn's account of Charles the Second's court presses on one's recollection, and prepares the mind for anxious apprehensions."

Towards the end of this month Scott received from his kind friend Lord Sidmouth, then Secretary of State for the Home Department, the formal announcement of the Prince Regent's desire (which had been privately communicated some months earlier through the Lord Chief Commissioner Adam) to confer on him the rank of Baronet. When Scott first heard of the Regent's gracious intention, he had signified considerable hesitation about the prudence of his accepting any such accession of rank; for it had not escaped his observation, that such airy sounds, however modestly people may be disposed to estimate them, are apt to entail in the upshot additional cost upon their way of living, and to affect accordingly the plastic fancies, feelings, and habits of their children. But Lord Sidmouth's letter happened to reach him a few days after he had heard of the sudden death of his wife's brother, Charles Carpenter, who had bequeathed the reversion of his fortune to his sister's family; and this circumstance disposed Scott to waive his scruples, chiefly with a view to the professional advantage of his eldest son, who had by this time fixed on the life of a soldier. As is usually the case, the estimate of Mr. Carpenter's property transmitted at the time to England proved to have been an exaggerated one; as nearly as my present information goes, the amount was doubled. But as to the only question of any interest, to wit, how Scott himself felt on all these matters at the moment, the following letter to one whom he had long leaned to as a brother, will be more satisfactory than anything else it is in my power to quote:—

(p. 7) TO J. B. S. MORRITT, ESQ., M. P., ROKEBY.

Edinburgh, 7th December, 1818.

My dear Morritt,—I know you are indifferent to nothing that concerns us, and therefore I take an early opportunity to acquaint you with the mixture of evil and good which has very lately befallen us. On Saturday last we had the advice of the death of my wife's brother, Charles Carpenter, commercial resident at Salem, in the Madras Establishment. This event has given her great distress. She has not, that we know of, a single blood-relation left in the world, for her uncle, the Chevalier de la Volere,[4] colonel of a Russian regiment, is believed to have been killed in the campaign of 1813. My wife has been very unwell for two days, and is only now sitting up and mixing with us. She has that sympathy which we are all bound to pay, but feels she wants that personal interest in her sorrow which could only be grounded on a personal acquaintance with the deceased.

Mr. Carpenter has, with great propriety, left his property in life-rent to his wife—the capital to my children. It seems to amount to about £40,000. Upwards of £30,000 is in the British funds; the rest, to an uncertain value, in India. I hope this prospect of independence will not make my children different from that which they have usually been—docile, dutiful, and affectionate. I trust it will not. At least, the first expression of their feelings was honorable, for it was a unanimous wish to give up all to their mother. This I explained to them was out of the question; but that, if they should be in possession at any time of this property, they ought, among them, to settle an income of £400 or £500 on their mother for her life, to supply her with a fund at her own uncontrolled disposal, for any indulgence (p. 8) or useful purpose that might be required. Mrs. Scott will stand in no need of this; but it is a pity to let kind affections run to waste; and if they never have it in their power to pay such a debt, their willingness to have done so will be a pleasant reflection. I am Scotchman enough to hate the breaking up of family ties, and the too close adherence to personal property. For myself, this event makes me neither richer nor poorer directly; but indirectly it will permit me to do something for my poor brother Tom's family, besides pleasing myself in "plantings, and policies, and biggings,"[5] with a safe conscience.

There is another thing I have to whisper to your faithful ear. Our fat friend, being desirous to honor Literature in my unworthy person, has intimated to me, by his organ the Doctor,[6] that, with consent ample and unanimous of all the potential voices of all his ministers, each more happy than another of course on so joyful an occasion, he proposes to dub me Baronet. It would be easy saying a parcel of fine things about my contempt of rank, and so forth; but although I would not have gone a step out of my way to have asked, or bought, or begged or borrowed a distinction, which to me personally will rather be inconvenient than otherwise, yet, coming as it does directly from the source of feudal honors, and as an honor, I am really gratified with it;—especially as it is intimated that it is his Royal Highness's pleasure to heat the oven for me expressly, without waiting till he has some new batch of Baronets ready in dough. In plain English, I am to be gazetted per se. My poor friend Carpenter's bequest to my family has taken away (p. 9) a certain degree of impecuniosity, a necessity of saving cheese-parings and candle-ends, which always looks inconsistent with any little pretension to rank. But as things now stand, Advance banners in the name of God and Saint Andrew. Remember, I anticipate the jest, "I like not such grinning honor as Sir Walter hath."[7] After all, if one must speak for himself, I have my quarters and emblazonments, free of all stain but Border theft and High Treason, which I hope are gentlemanlike crimes; and I hope Sir Walter Scott will not sound worse than Sir Humphry Davy, though my merits are as much under his, in point of utility, as can well be imagined. But a name is something, and mine is the better of the two. Set down this flourish to the account of national and provincial pride, for you must know we have more Messieurs de Sotenville[8] in our Border counties than anywhere else in the Lowlands—I cannot say for the Highlands. The Duke of Buccleuch, greatly to my joy, resolves to go to France for a season. Adam Ferguson goes with him, to glad him by the way. Charlotte and the young folks join in kind compliments.

Most truly yours,

A few additional circumstances are given in a letter of the same week to Joanna Baillie. To her, after mentioning the testamentary provisions of Mr. Carpenter, Scott says:—

My dear Friend,—I am going to tell you a little secret. I have changed my mind, or rather existing circumstances have led to my altering my opinions in a case of sublunary honor. I have now before me Lord Sidmouth's letter, containing the Prince's gracious and unsolicited intention to give me a Baronetcy. It will neither make me better nor worse than I feel myself—in (p. 10) fact it will be an incumbrance rather than otherwise; but it may be of consequence to Walter, for the title is worth something in the army, although not in a learned profession. The Duke of Buccleuch and Scott of Harden, who, as the heads of my clan and the sources of my gentry, are good judges of what I ought to do, have both given me their earnest opinion to accept of an honor directly derived from the source of honor, and neither begged nor bought, as is the usual fashion. Several of my ancestors bore the title in the seventeenth century; and were it of consequence, I have no reason to be ashamed of the decent and respectable persons who connect me with that period when they carried into the field, like Madoc—

"The crescent, at whose gleam the Cambrian oft,

Cursing his perilous tenure, wound his horn"—

so that, as a gentleman, I may stand on as good a footing as other new creations. Respecting the reasons peculiar to myself which have made the Prince show his respect for general literature in my person, I cannot be a good judge, and your friendly zeal will make you a partial one: the purpose is fair, honorable, and creditable to the Sovereign, even though it should number him among the monarchs who made blunders in literary patronage. You know Pope says:—

"The Hero William, and the Martyr Charles,

One knighted Blackmore, and one pensioned Quarles."[9]

So let the intention sanctify the error, if there should be one on this great occasion. The time of this grand affair is uncertain: it is coupled with an invitation to London, which it would be inconvenient to me to accept, unless it should happen that I am called to come up by the affairs of poor Carpenter's estate. Indeed, the prospects of my children form the principal reason for a change of sentiments upon this flattering offer, joined to my belief that, though I may still be a scribbler from inveterate habit, I shall hardly engage again in any work of consequence.

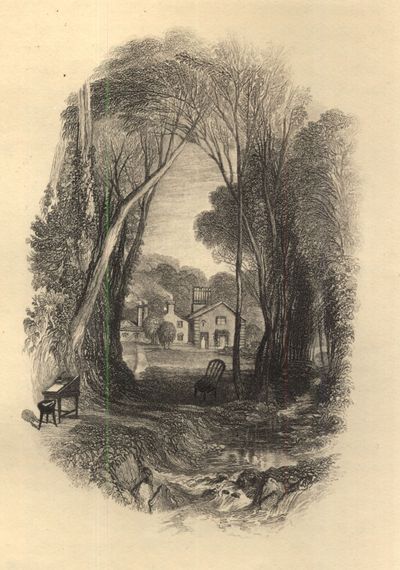

(p. 11) We had a delightful visit from the Richardsons, only rather too short. He will give you a picture of Abbotsford, but not as it exists in my mind's eye, waving with all its future honors. The pinasters are thriving very well, and in a year or two more Joanna's Bower will be worthy of the name. At present it is like Sir Roger de Coverley's portrait, which hovered between its resemblance to the good knight and to a Saracen. Now the said bower has still such a resemblance to its original character of a gravel pit, that it is not fit to be shown to "bairns and fools," who, according to our old canny proverb, should never see half-done work; but Nature, if she works slowly, works surely, and your laurels at Abbotsford will soon flourish as fair as those you have won on Parnassus. I rather fear that a quantity of game, which was shipped awhile ago at Inverness for the Doctor, never reached him: it is rather a transitory commodity in London; there were ptarmigan, grouse, and black game. I shall be grieved if they have miscarried.—My health, thank God, continues as strong as at any period in my life; only I think of rule and diet more than I used to do, and observe as much as in me lies the advice of my friendly physician, who took such kind care of me: my best respects attend him, Mrs. Baillie, and Mrs. Agnes. Ever, my dear friend, most faithfully yours,

In the next of these letters Scott alludes, among other things, to a scene of innocent pleasure which I often witnessed afterwards. The whole of the ancient ceremonial of the daft days, as they are called in Scotland, obtained respect at Abbotsford. He said it was uncanny, and would certainly have felt it very uncomfortable, not to welcome the new year in the midst of his family and a few old friends, with the immemorial libation of a het pint; but of all the consecrated ceremonies of the time, none gave him such delight as the visit which he received (p. 12) as Laird from all the children on his estate, on the last morning of every December—when, in the words of an obscure poet often quoted by him,

"The cottage bairns sing blithe and gay,

At the ha' door for hogmanay."

TO MISS JOANNA BAILLIE, HAMPSTEAD.

Abbotsford, 1st January, 1819.

My dear Friend,—Many thanks for your kind letter. Ten brace of ptarmigan sailed from Inverness about the 24th, directed for Dr. Baillie;—if they should have reached, I hope you would seize some for yourself and friends, as I learn the Doctor is on duty at Windsor. I do not know the name of the vessel, but they were addressed to Dr. Baillie, London, which I trust was enough, for there are not two. The Doctor has been exercising his skill upon my dear friend and chief, the Duke of Buccleuch, to whom I am more attached than to any person beyond the reach of my own family, and has advised him to do what, by my earnest advice, he ought to have done three years ago—namely, to go to Lisbon: he left this vicinity with much reluctance to go to Toulouse, but if he will be advised, should not stop save in Portugal or the south of Spain. The Duke is one of those retired and high-spirited men who will never be known until the world asks what became of the huge oak that grew on the brow of the hill, and sheltered such an extent of ground. During the late distress, though his own immense rents remained in arrears, and though I know he was pinched for money, as all men were, but more especially the possessors of entailed estates, he absented himself from London in order to pay with ease to himself the laborers employed on his various estates. These amounted (for I have often seen the roll and helped to check it) to nine hundred and fifty men, working at day wages, each of whom on a moderate average might maintain three persons, since the single men have (p. 13) mothers, sisters, and aged or very young relations to protect and assist. Indeed it is wonderful how much even a small sum, comparatively, will do in supporting the Scottish laborer, who is in his natural state perhaps one of the best, most intelligent, and kind-hearted of human beings; and in truth I have limited my other habits of expense very much since I fell into the habit of employing mine honest people. I wish you could have seen about a hundred children, being almost entirely supported by their fathers' or brothers' labor, come down yesterday to dance to the pipes, and get a piece of cake and bannock, and pence apiece (no very deadly largess) in honor of hogmanay. I declare to you, my dear friend, that when I thought the poor fellows who kept these children so neat, and well taught, and well behaved, were slaving the whole day for eighteen-pence or twenty-pence at the most, I was ashamed of their gratitude, and of their becks and bows. But, after all, one does what one can, and it is better twenty families should be comfortable according to their wishes and habits, than half that number should be raised above their situation. Besides, like Fortunio in the fairy tale, I have my gifted men—the best wrestler and cudgel-player—the best runner and leaper—the best shot in the little district; and as I am partial to all manly and athletic exercises, these are great favorites, being otherwise decent persons, and bearing their faculties meekly. All this smells of sad egotism, but what can I write to you about, save what is uppermost in my own thoughts: and here am I, thinning old plantations and planting new ones; now undoing what has been done, and now doing what I suppose no one would do but myself, and accomplishing all my magical transformations by the arms and legs of the aforesaid genii, conjured up to my aid at eighteen-pence a day. There is no one with me but my wife, to whom the change of scene and air, with the facility of easy and uninterrupted exercise, is of service. The young people (p. 14) remain in Edinburgh to look after their lessons, and Walter, though passionately fond of shooting, only stayed three days with us, his mind running entirely on mathematics and fortification, French and German. One of the excellencies of Abbotsford is very bad pens and ink; and besides, this being New Year's Day, and my writing-room above the servants' hall, the progress of my correspondence is a little interrupted by the Piper singing Gaelic songs to the servants, and their applause in consequence. Adieu, my good and indulgent friend: the best influences of the New Year attend you and yours, who so well deserve all that they can bring. Most affectionately yours,

Before quitting the year 1818, I ought to have mentioned that among Scott's miscellaneous occupations in its autumn, he found time to contribute some curious materials toward a new edition of Burt's Letters from the North of Scotland, which had been undertaken by his old acquaintance, Mr. Robert Jameson. During the winter session he appears to have made little progress with his novel; his painful seizures of cramp were again recurring frequently, and he probably thought it better to allow the story of Lammermoor to lie over until his health should be reëstablished. In the mean time he drew up a set of topographical and historical essays, which originally appeared in the successive numbers of the splendidly illustrated work, entitled Provincial Antiquities of Scotland.[10] But he did this merely to gratify his own love of the subject, and because, well or ill, he must be doing something. He declined all pecuniary recompense; but afterwards, when the success of the publication was secure, accepted from the proprietors some of the beautiful drawings by Turner, Thomson, and other artists, which had been prepared to accompany his (p. 15) text. These drawings are now in the little breakfast-room at Abbotsford—the same which had been constructed for his own den, and which I found him occupying as such in the spring of 1819.

In the course of December, 1818, he also opened an important negotiation with Messrs. Constable, which was completed early in the ensuing year. The cost of his building had, as is usual, exceeded his calculation; and he had both a large addition to it, and some new purchases of land, in view. Moreover, his eldest son had now fixed on the cavalry, in which service every step infers very considerable expense. The details of this negotiation are remarkable;—Scott considered himself as a very fortunate man when Constable, who at first offered £10,000 for all his then existing copyrights, agreed to give for them £12,000. Meeting a friend in the street, just after the deed had been executed, he said he wagered no man could guess at how large a price Constable had estimated his "eild kye" (cows barren from age). The copyrights thus transferred were, as specified in the instrument:—

| "The said Walter Scott, Esq.'s present share, being the entire copyright, of Waverley. | |||

| Do. | do | Guy Mannering. | |

| Do. | do | Antiquary. | |

| Do. | do | Rob Roy. | |

| Do. | do | Tales of My Landlord, | 1st Series. |

| Do. | do | do. | 2d Series. |

| Do. | do | do. | 3d Series. |

| Do. | do | Bridal of Triermain. | |

| Do. | do | Harold the Dauntless. | |

| Do. | do | Sir Tristrem. | |

| Do. | do | Roderick Collection, | |

| Do. | do | Paul's Letters. | |

| Do. | being one eighth of | The Lay of the Last Minstrel. | |

| Do. | being one half of | The Lady of the Lake. | |

| Do. | being one half of | Rokeby. | |

| Do. | being one half of | The Lord of the Isles." | |

The instrument contained a clause binding Messrs. Constable never to divulge the name of the Author of Waverley during his life, under a penalty of £2000.

(p. 16) I may observe, that had these booksellers fulfilled their part of this agreement, by paying off, prior to their insolvency in 1826, the whole bonds for £12,000, which they signed on the 2d of February, 1819, no interest in the copyrights above specified could have been expected to revert to the Author of Waverley: but more of this in due season.

He alludes to the progress of the treaty in the following letter to Captain Adam Ferguson, who had, as has already appeared, left Scotland with the Duke of Buccleuch. His Grace hearing, when in London, that one of the Barons of Exchequer at Edinburgh meant speedily to resign, the Captain had, by his desire, written to urge on Scott the propriety of renewing his application for a seat on that bench; which, however, Scott at once refused to do. There were several reasons for this abstinence; among others, he thought such a promotion at this time would interfere with a project which he had formed of joining "the Chief and the Aide-de-Camp" in the course of the spring, and accomplishing in their society the tour of Portugal and Spain—perhaps of Italy also. Some such excursion had been strongly recommended to him by his own physicians, as the likeliest means of interrupting those habits of sedulous exertion at the desk, which they all regarded as the true source of his recent ailments, and the only serious obstacle to his cure; and his standing as a Clerk of Session, considering how largely he had labored in that capacity for infirm brethren, would have easily secured him a twelve-month's leave of absence from the Judges of his Court. But the principal motive was, as we shall see, his reluctance to interfere with the claims of the then Sheriff of Mid-Lothian, his own and Ferguson's old friend and schoolfellow, Sir William Rae—who, however, accepted the more ambitious post of Lord Advocate, in the course of the ensuing summer.

(p. 17) TO CAPTAIN ADAM FERGUSON, DITTON PARK, WINDSOR.

15th January, 1819.

Dear Adam,—Many thanks for your kind letter, this moment received. I would not for the world stand in Jackie (I beg his pardon, Sir John) Peartree's way.[11] He has merited the cushion en haut, and besides he needs it. To me it would make little difference in point of income. The otium cum dignitate, if it ever come, will come as well years after this as now. Besides, I am afraid the opening will be soon made, through the death of our dear friend the Chief Baron, of whose health the accounts are unfavorable.[12] Immediate promotion would be inconvenient to me, rather than otherwise, because I have the desire, like an old fool as I am, courir un peu le monde. I am beginning to draw out from my literary commerce. Constable has offered me £10,000 for the copyrights of published works which have already produced more than twice the sum. I stand out for £12,000. Tell this to the Duke; he knows how I managed to keep the hen till the rainy day was past. I will write two lines to Lord Melville, just to make my bow for the present, resigning any claims I have through the patronage of my kindest and best friend, for I have no other, till the next opportunity. I should have been truly vexed if the Duke had thought of writing about this. I don't wish to hear from him till I can have his account of the lines of Torres Vedras. I care so little how or where I travel, that I am not sure at all whether I shall not come to Lisbon and surprise you, instead of going to Italy by Switzerland; that is, providing the state of Spain will allow me, without any unreasonable danger of my throat, to get from Lisbon to Madrid, and thence to Gibraltar. (p. 18) I am determined to roll a little about, for I have lost much of my usual views of summer pleasure here. But I trust we shall have one day the Maid of Lorn (recovered of her lameness), and Charlie Stuart (reconciled to bogs), and Sibyl Grey (no longer retrograde), and the Duke set up by a southern climate, and his military and civil aides-de-camp, with all the rout of younkers and dogs, and a brown hillside, introductory to a good dinner at Bowhill or Drumlanrig, and a merry evening. Amen, and God send it. As to my mouth being stopped with the froth of the title, that is, as the learned Partridge says, a non sequitur. You know the schoolboy's expedient of first asking mustard for his beef, and then beef for his mustard. Now, as they put the mustard on my plate, without my asking it, I shall consider myself, time and place serving, as entitled to ask a slice of beef; that is to say, I would do so if I cared much about it; but as it is, I trust it to time and chance, which, as you, dear Adam, know, have (added to the exertions of kind friends) been wonderful allies of mine. People usually wish their letters to come to hand, but I hope you will not receive this in Britain. I am impatient to hear you have sailed. All here are well and hearty. The Baronet[13] and I propose to go up to the Castle to-morrow to fix on the most convenient floor of the Crown House for your mansion, in hopes you will stand treat for gin-grog and Cheshire cheese on your return, to reward our labor. The whole expense will fall within the Treasury order, and it is important to see things made convenient. I will write a long letter to the Duke to Lisbon. Yours ever,

P. S.—No news here, but that the goodly hulk of conceit and tallow, which was called Macculloch, of the Royal Hotel, Prince's Street, was put to bed dead-drunk on Wednesday night, and taken out the next morning dead-by-itself-dead. Mair skaith at Sheriffmuir.

(p. 19) TO J. RICHARDSON, ESQ., FLUDYER STREET, WESTMINSTER.

Edinburgh, 18th January, 1819.

My dear Richardson,—Many thanks for your kind letter. I own I did mystify Mrs. **** a little about the report you mention; and I am glad to hear the finesse succeeded.[14] She came up to me with a great overflow of gratitude for the delight and pleasure, and so forth, which she owed to me on account of these books. Now, as she knew very well that I had never owned myself the author, this was not polite politeness, and she had no right to force me up into a corner and compel me to tell her a word more than I chose, upon a subject which concerned no one but myself—and I have no notion of being pumped by any old dowager Lady of Session, male or female. So I gave in dilatory defences, under protestation to add and eik; for I trust, in learning a new slang, you have not forgot the old. In plain words, I denied the charge, and as she insisted to know who else could write these novels, I suggested Adam Ferguson as a person having all the information and capacity necessary for that purpose. But the inference that he was the author was of her own deducing; and thus ended her attempt, notwithstanding her having primed the pump with a good dose of flattery. It is remarkable, that among all my real friends to whom I did not choose to communicate this matter, not one ever thought it proper or delicate to tease me about it. Respecting the knighthood, I can only say, that coming as it does, and I finding myself and my family in circumstances which will not render the petit titre ridiculous, I think there would be more vanity in declining than in accepting what is offered to me by the express wish of the Sovereign as a mark of favor and distinction. Will you be so kind as to inquire and let me know what the fees, etc., of a baronetcy amount to—for I must provide (p. 20) myself accordingly, not knowing exactly when this same title may descend upon me. I am afraid the sauce is rather smart. I should like also to know what is to be done respecting registration of arms and so forth. Will you make these inquiries for me sotto voce? I should not suppose, from the persons who sometimes receive this honor, that there is any inquiry about descent or genealogy; mine were decent enough folks, and enjoyed the honor in the seventeenth century, so I shall not be first of the title; and it will sound like that of a Christian knight, as Sir Sidney Smith said.

I had a letter from our immortal Joanna some fortnight since, when I was enjoying myself at Abbotsford. Never was there such a season, flowers springing, birds singing, grubs eating the wheat—as if it was the end of May. After all, nature had a grotesque and inconsistent appearance, and I could not help thinking she resembled a withered beauty who persists in looking youthy, and dressing conform thereto. I thought the loch should have had its blue frozen surface, and russet all about it, instead of an unnatural gayety of green. So much are we the children of habit, that we cannot always enjoy thoroughly the alterations which are most for our advantage.—They have filled up the historical chair here. I own I wish it had been with our friend Campbell, whose genius is such an honor to his country. But he has cast anchor I suppose in the south. Your friend, Mrs. Scott, was much cast down with her brother's death. His bequest to my family leaves my own property much at my own disposal, which is pleasant enough. I was foolish enough sometimes to be vexed at the prospect of my library being sold sub hasta, which is now less likely to happen. I always am, most truly yours,

On the 15th of February, 1819, Scott witnessed the first representation, on the Edinburgh boards, of the most (p. 21) meritorious and successful of all the Terryfications, though Terry himself was not the manufacturer. The drama of Rob Roy will never again be got up so well, in all its parts, as it then was by William Murray's company; the manager's own Captain Thornton was excellent—and so was the Dugald Creature of a Mr. Duff—there was also a good Mattie—(about whose equipment, by the bye, Scott felt such interest that he left his box between the acts to remind Mr. Murray that she "must have a mantle with her lanthorn;")—but the great and unrivalled attraction was the personification of Bailie Jarvie, by Charles Mackay, who, being himself a native of Glasgow, entered into the minutest peculiarities of the character with high gusto, and gave the west-country dialect in its most racy perfection. It was extremely diverting to watch the play of Scott's features during this admirable realization of his conception; and I must add, that the behavior of the Edinburgh audience on all such occasions, while the secret of the novels was preserved, reflected great honor on their good taste and delicacy of feeling. He seldom, in those days, entered his box without receiving some mark of general respect and admiration; but I never heard of any pretext being laid hold of to connect these demonstrations with the piece he had come to witness, or, in short, to do or say anything likely to interrupt his quiet enjoyment of the evening in the midst of his family and friends. The Rob Roy had a continued run of forty-one nights, during February and March; and it was played once a week, at least, for many years afterwards.[15] Mackay, of course, always selected it for his benefit;—and I now print from Scott's MS. a letter, which, no doubt, reached the mimic Bailie (p. 22) in the handwriting of one of the Ballantynes, on the first of these occurrences:—

TO MR. CHARLES MACKAY, THEATRE-ROYAL, EDINR.

(Private.)

Friend Mackay,—My lawful occasions having brought me from my residence at Gandercleuch to this great city, it was my lot to fall into company with certain friends, who impetrated from me a consent to behold the stage-play, which hath been framed forth of an history entitled Rob (seu potius Robert) Roy; which history, although it existeth not in mine erudite work, entitled Tales of my Landlord, hath nathless a near relation in style and structure to those pleasant narrations. Wherefore, having surmounted those arguments whilk were founded upon the unseemliness of a personage in my place and profession appearing in an open stage-play house, and having buttoned the terminations of my cravat into my bosom, in order to preserve mine incognito, and indued an outer coat over mine usual garments, so that the hue thereof might not betray my calling, I did place myself (much elbowed by those who little knew whom they did incommode) in that place of the Theatre called the two-shilling gallery, and beheld the show with great delectation, even from the rising of the curtain to the fall thereof.

Chiefly, my facetious friend, was I enamored of the very lively representation of Bailie Nicol Jarvie, in so much that I became desirous to communicate to thee my great admiration thereof, nothing doubting that it will give thee satisfaction to be apprised of the same. Yet further, in case thou shouldst be of that numerous class of persons who set less store by good words than good deeds, and understanding that there is assigned unto each stage-player a special night, called a benefit (it will do thee no harm to know that the phrase cometh from two Latin words, bene and facio), on which their friends (p. 23) and patrons show forth their benevolence, I now send thee mine in the form of a five-ell web (hoc jocose, to express a note for £5), as a meet present for the Bailie, himself a weaver, and the son of a worthy deacon of that craft. The which propine I send thee in token that it is my purpose, business and health permitting, to occupy the central place of the pit on the night of thy said beneficiary or benefit.

Friend Mackay! from one, whose profession it is to teach others, thou must excuse the freedom of a caution. I trust thou wilt remember that, as excellence in thine art cannot be attained without much labor, so neither can it be extended, or even maintained, without constant and unremitted exertion; and further, that the decorum of a performer's private character (and it gladdeth me to hear that thine is respectable) addeth not a little to the value of his public exertions.

Finally, in respect there is nothing perfect in this world,—at least I have never received a wholly faultless version from the very best of my pupils—I pray thee not to let Rob Roy twirl thee around in the ecstasy of thy joy, in regard it oversteps the limits of nature, which otherwise thou so sedulously preservest in thine admirable national portraiture of Bailie Nicol Jarvie.—I remain thy sincere friend and well-wisher,

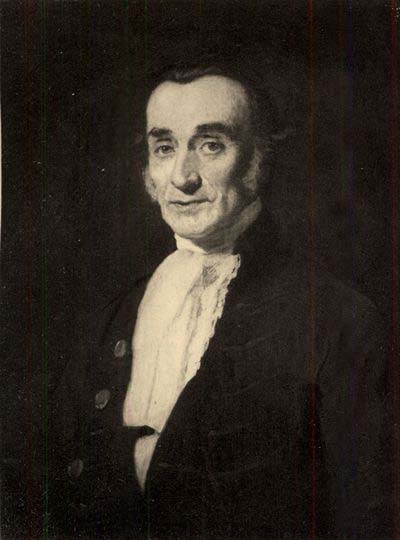

CHARLES MACKAY

From the painting by Sir D. Macnee

RECURRENCE OF SCOTT'S ILLNESS. — DEATH OF THE DUKE OF BUCCLEUCH. — LETTERS TO CAPTAIN FERGUSON, LORD MONTAGU, MR. SOUTHEY, AND MR. SHORTREED. — SCOTT'S SUFFERINGS WHILE DICTATING THE BRIDE OF LAMMERMOOR. — ANECDOTES BY JAMES BALLANTYNE, ETC. — APPEARANCE OF THE THIRD SERIES OF TALES OF MY LANDLORD. — ANECDOTE OF THE EARL OF BUCHAN.

1819

It had been Scott's purpose to spend the Easter vacation in London, and receive his baronetcy; but this was prevented by the serious recurrence of the malady which so much alarmed his friends in the early part of the year 1817, and which had continued ever since to torment him at intervals. The subsequent correspondence will show that afflictions of various sorts were accumulated on his head at the same period:—

TO THE LORD MONTAGU, DITTON PARK, WINDSOR.

Edinburgh, 4th March, 1819.

My dear Lord,—The Lord President tells me he has a letter from his son, Captain Charles Hope, R. N., who had just taken leave of our High Chief, upon the deck of the Liffey. He had not seen the Duke for a fortnight, and was pleasingly surprised to find his health and general appearance so very much improved. For my part, having watched him with such unremitting attention, I feel very confident in the effect of a change of air and of climate. It is with great pleasure that I find the (p. 25) Duke has received an answer from me respecting a matter about which he was anxious, and on which I could make his mind quite easy. His Grace wished Adam Ferguson to assist him as his confidential secretary; and with all the scrupulous delicacy that belongs to his character, he did not like to propose this, except through my medium as a common friend. Now, I can answer for Adam, as I can for myself, that he will have the highest pleasure in giving assistance in every possible way the Duke can desire; and if forty years' intimacy can entitle one man to speak for another, I believe the Duke can find nowhere a person so highly qualified for such a confidential situation. He was educated for business, understands it well, and was long a military secretary;—his temper and manners your Lordship can judge as well as I can, and his worth and honor are of the very first water. I confess I should not be surprised if the Duke should wish to continue the connection even afterwards, for I have often thought that two hours' letter-writing, which is his Grace's daily allowance, is rather worse than the duty of a Clerk of Session, because there is no vacation. Much of this might surely be saved by an intelligent friend, on whose style of expression, prudence, and secrecy, his Grace could put perfect reliance. Two words marked on any letter by his own hand would enable such a person to refuse more or less positively—to grant directly or conditionally—or, in short, to maintain the exterior forms of the very troublesome and extensive correspondence which his Grace's high situation entails upon him. I think it is Monsieur le Duc de Saint-Simon who tells us of one of Louis XIV.'s ministers qu'il avoit la plume—which he explains by saying that it was his duty to imitate the King's handwriting so closely, as to be almost undistinguishable, and make him on all occasions parler très noblement. I wonder how the Duke gets on without such a friend. In the mean time, however, I am glad I can assure him of Ferguson's (p. 26) willing and ready assistance while abroad; and I am happy to find still further that he had got that assurance before they sailed, for tedious hours occur on board of ship, when it will serve as a relief to talk over any of the private affairs which the Duke wishes to entrust to him.

I have been very unwell from a visitation of my old enemy, the cramp in my stomach, which much resembles, as I conceive, the process by which the deil would make one's king's-hood into a spleuchan,[16] according to the anathema of Burns. Unfortunately, the opiates which the medical people think indispensable to relieve spasms, bring on a habit of body which has to be counteracted by medicines of a different tendency, so as to produce a most disagreeable see-saw—a kind of pull-devil, pull-baker contention, the field of battle being my unfortunate præcordia. I am better to-day, and I trust shall be able to dispense with these alternations. I still hope to be in London in April.

I will write to the Duke regularly, for distance of place acts in a contrary ratio on the mind and on the eye: trifles, instead of being diminished, as in prospect, become important and interesting, and therefore he shall have a budget of them. Hogg is here busy with his Jacobite songs. I wish he may get handsomely through, for he is profoundly ignorant of history, and it is an awkward thing to read in order that you may write.[17] I give him all the help I can, but he sometimes poses me. For instance, he came yesterday, open mouth, inquiring (p. 27) what great dignified clergyman had distinguished himself at Killiecrankie—not exactly the scene where one would have expected a churchman to shine—and I found, with some difficulty, that he had mistaken Major-General Canon, called, in Kennedy's Latin Song, Canonicus Gallovidiensis, for the canon of a cathedral. Ex ungue leonem. Ever, my dear Lord, your truly obliged and faithful

Before this letter reached Lord Montagu, his brother had sailed for Lisbon. The Duke of Wellington had placed his house in that capital (the Palace das Necessidades) at the Duke of Buccleuch's disposal; and in the affectionate care and cheerful society of Captain Ferguson, the invalid had every additional source of comfort that his friends could have wished for him. But the malady had gone too far to be arrested by a change of climate; and the letter which he had addressed to Scott, when about to embark at Portsmouth, is endorsed with these words: "The last I ever received from my dear friend the Duke of Buccleuch.—Alas! alas!" The principal object of this letter was to remind Scott of his promise to sit to Raeburn for a portrait, to be hung up in that favorite residence where the Duke had enjoyed most of his society. "My prodigious undertaking," writes his Grace, "of a west wing at Bowhill, is begun. A library of forty-one feet by twenty-one is to be added to the present drawing-room. A space for one picture is reserved over the fireplace, and in this warm situation I intend to place the Guardian of Literature. I should be happy to have my friend Maida appear. It is now almost proverbial, 'Walter Scott and his Dog.' Raeburn should be warned that I am as well acquainted with my friend's hands and arms as with his nose—and Vandyke was of my opinion. Many of R.'s works are shamefully finished—the face studied, but everything else neglected. This is a fair opportunity of producing something really worthy of his skill."

(p. 28) I shall insert by and by Scott's answer—which never reached the Duke's hand—with another letter of the same date to Captain Ferguson; but I must first introduce one, addressed a fortnight earlier to Mr. Southey, who had been distressed by the accounts he received of Scott's health from an American traveller, Mr. George Ticknor of Boston—a friend, and worthy to be such, of Mr. Washington Irving.[18] The Poet Laureate, by the way, had adverted also to an impudent trick of a London bookseller, who shortly before this time announced certain volumes of Grub Street manufacture, as "A New Series of the Tales of my Landlord," and who, when John Ballantyne, as the "agent for the Author of Waverley," published a declaration that the volumes thus advertised were not from that writer's pen, met John's declaration by an audacious rejoinder—impeaching his authority, and asserting that nothing but the personal appearance in the field of the gentleman for whom Ballantyne pretended to act, could shake his belief that he was himself in the confidence of the true Simon Pure.[19] This affair gave considerable uneasiness at the time, and for a moment the dropping of Scott's mask seems to have been pronounced advisable by both Ballantyne and Constable. But he was not to be worked upon by such means as these. He calmly replied, "The author who lends himself to such a trick must be a blockhead—let them publish, and that will serve our purpose (p. 29) better than anything we ourselves could do." I have forgotten the names of the "tales," which, being published accordingly, fell still-born from the press. Mr. Southey had likewise dropped some allusions to another newspaper story of Scott's being seriously engaged in a dramatic work—a rumor which probably originated in the assistance he had lent to Terry in some of the recent highly popular adaptations of his novels to the purposes of the stage; though it is not impossible that some hint of the Devorgoil matter may have transpired. "It is reported," said the Laureate, "that you are about to bring forth a play, and I am greatly in hopes it may be true; for I am verily persuaded that in this course you might run as brilliant a career as you have already done in narrative—both in prose and rhyme;—for as for believing that you have a double in the field—not I! Those same powers would be equally certain of success in the drama, and were you to give them a dramatic direction, and reign for a third seven years upon the stage, you would stand alone in literary history. Indeed already I believe that no man ever afforded so much delight to so great a number of his contemporaries in this or in any other country. God bless you, my dear Scott, and believe me ever yours affectionately, R. S." Mr. Southey's letter had further announced his wife's safe delivery of a son; the approach of the conclusion of his History of Brazil; and his undertaking of the Life of Wesley.

TO ROBERT SOUTHEY, ESQ., KESWICK.

Abbotsford, 4th April, 1819.

My dear Southey,—Tidings from you must be always acceptable, even were the bowl in the act of breaking at the fountain—and my health is at present very totterish. I have gone through a cruel succession of spasms and sickness, which have terminated in a special fit of the jaundice, so that I might sit for the image of (p. 30) Plutus, the god of specie, so far as complexion goes. I shall like our American acquaintance the better that he has sharpened your remembrance of me, but he is also a wondrous fellow for romantic lore and antiquarian research, considering his country. I have now seen four or five well-lettered Americans, ardent in pursuit of knowledge, and free from the ignorance and forward presumption which distinguish many of their countrymen. I hope they will inoculate their country with a love of letters, so nearly allied to a desire of peace and a sense of public justice—virtues to which the great Transatlantic community is more strange than could be wished. Accept my best and most sincere wishes for the health and strength of your latest pledge of affection. When I think what you have already suffered, I can imagine with what mixture of feelings this event must necessarily affect you; but you need not to be told that we are in better guidance than our own. I trust in God this late blessing will be permanent, and inherit your talents and virtues. When I look around me, and see how many men seem to make it their pride to misuse high qualifications, can I be less interested than I truly am in the fate of one who has uniformly dedicated his splendid powers to maintaining the best interests of humanity? I am very angry at the time you are to be in London, as I must be there in about a fortnight, or so soon as I can shake off this depressing complaint, and it would add not a little that I should meet you there. My chief purpose is to put my eldest son into the army. I could have wished he had chosen another profession, but have no title to combat a choice which would have been my own had my lameness permitted. Walter has apparently the dispositions and habits fitted for the military profession, a very quiet and steady temper, an attachment to mathematics and their application, good sense, and uncommon personal strength and activity, with address in most exercises, particularly horsemanship.

(p. 31) —I had written thus far last week when I was interrupted, first by the arrival of our friend Ticknor with Mr. Cogswell, another well-accomplished Yankee—(by the bye, we have them of all sorts, e. g., one Mr. ****, rather a fine man, whom the girls have christened, with some humor, the Yankee Doodle Dandie). They have had Tom Drum's entertainment, for I have been seized with one or two successive crises of my cruel malady, lasting in the utmost anguish from eight to ten hours. If I had not the strength of a team of horses, I could never have fought through it, and through the heavy fire of medical artillery, scarce less exhausting—for bleeding, blistering, calomel, and ipecacuanha have gone on without intermission—while, during the agony of the spasms, laudanum became necessary in the most liberal doses, though inconsistent with the general treatment. I did not lose my senses, because I resolved to keep them, but I thought once or twice they would have gone overboard, top and top-gallant. I should be a great fool, and a most ungrateful wretch, to complain of such inflictions as these. My life has been, in all its private and public relations, as fortunate perhaps as was ever lived, up to this period; and whether pain or misfortune may lie behind the dark curtain of futurity, I am already a sufficient debtor to the bounty of Providence to be resigned to it. Fear is an evil that has never mixed with my nature, nor has even unwonted good fortune rendered my love of life tenacious; and so I can look forward to the possible conclusion of these scenes of agony with reasonable equanimity, and suffer chiefly through the sympathetic distress of my family.

—Other ten days have passed away, for I would not send this Jeremiad to tease you, while its termination seemed doubtful. For the present,

"The game is done—I've won, I've won,

Quoth she, and whistles thrice."[20]

(p. 32) I am this day, for the first time, free from the relics of my disorder, and, except in point of weakness, perfectly well. But no broken-down hunter had ever so many sprung sinews, whelks, and bruises. I am like Sancho after the doughty affair of the Yanguesian Carriers, and all through the unnatural twisting of the muscles under the influence of that Goule, the cramp. I must be swathed in Goulard and Rosemary spirits—probatum est.

I shall not fine and renew a lease of popularity upon the theatre. To write for low, ill-informed, and conceited actors, whom you must please, for your success is necessarily at their mercy, I cannot away with. How would you, or how do you think I should relish being the object of such a letter as Kean[21] wrote t'other day to a poor author, who, though a pedantic blockhead, had at least the right to be treated as a gentleman by a copper-laced, twopenny tearmouth, rendered mad by conceit and success? Besides, if this objection were out of the way, I do not think the character of the audience in London is such that one could have the least pleasure in pleasing them. One half come to prosecute their debaucheries, so openly that it would degrade a bagnio. Another set to snooze off their beef-steaks and port wine; a third are critics of the fourth column of the newspaper; fashion, wit, or literature, there is not; and, on the whole, I would far rather write verses for mine honest friend Punch and his audience. The only thing that could tempt me to be so silly, would be to assist a friend in such a degrading task who was to have the whole profit and shame of it.

Have you seen decidedly the most full and methodized collection of Spanish romances (ballads) published by the industry of Depping (Altenburgh and Leipsic), (p. 33) 1817? It is quite delightful. Ticknor had set me agog to see it, without affording me any hope it could be had in London, when by one of these fortunate chances which have often marked my life, a friend, who had been lately on the Continent, came unexpectedly to inquire for me, and plucked it forth par manière de cadeau. God prosper you, my dear Southey, in your labors; but do not work too hard—experto crede. This conclusion, as well as the confusion of my letter, like the Bishop of Grenada's sermon, savors of the apoplexy. My most respectful compliments attend Mrs. S.

Yours truly,

P. S.—I shall long to see the conclusion of the Brazil history, which, as the interest comes nearer, must rise even above the last noble volume. Wesley you alone can touch; but will you not have the hive about you? When I was about twelve years old, I heard him preach more than once, standing on a chair, in Kelso churchyard. He was a most venerable figure, but his sermons were vastly too colloquial for the taste of Saunders. He told many excellent stories. One I remember, which he said had happened to him at Edinburgh. "A drunken dragoon," said Wesley, "was commencing an assertion in military fashion, G—d eternally d—n me, just as I was passing. I touched the poor man on the shoulder, and when he turned round fiercely, said calmly, you mean God bless you." In the mode of telling the story he failed not to make us sensible how much his patriarchal appearance, and mild yet bold rebuke, overawed the soldier, who touched his hat, thanked him, and, I think, came to chapel that evening.

TO ROBERT SHORTREED, ESQ., SHERIFF-SUBSTITUTE, ETC., JEDBURGH.

Abbotsford, 13th April, 1819.

Dear Bob,—I am very desirous to procure, and as soon as possible, Mrs. Shortreed's excellent receipt for (p. 34) making yeast. The Duke of Buccleuch complains extremely of the sour yeast at Lisbon as disagreeing with his stomach, and I never tasted half such good bread as Mrs. Shortreed has baked at home. I am sure you will be as anxious as I am that the receipt should be forwarded to his Grace as soon as possible. I remember Mrs. Shortreed giving a most distinct account of the whole affair. It should be copied over in a very distinct hand, lest Monsieur Florence makes blunders.

I am recovering from my late indisposition, but as weak as water. To write these lines is a fatigue. I scarce think I can be at the circuit at all—certainly only for an hour or two. So on this occasion I will give Mrs. Shortreed's kind hospitality a little breathing time. I am tired even with writing these few lines. Yours ever,

TO HIS GRACE THE DUKE OF BUCCLEUCH, ETC., LISBON.

Abbotsford, 15th April, 1819.

My dear Lord Duke,—How very strange it seems that this should be the first letter I address to your Grace, and you so long absent from Scotland, and looking for all the news and nonsense of which I am in general such a faithful reporter. Alas, I have been ill—very—very ill—only Dr. Baillie says there is nothing of consequence about my malady except the pain—a pretty exception—said pain being intense enough to keep me roaring as loud as your Grace's ci-devant John of Lorn, and of, generally speaking, from six to eight hours' incessant duration, only varied by intervals of deadly sickness. Poor Sophia was alone with me for some time, and managed a half-distracted pack of servants with spirit, and sense, and presence of mind, far (p. 35) beyond her years, never suffering her terror at seeing me in a state so new to her, and so alarming, to divert her mind an instant from what was fit and proper to be done. Pardon this side compliment to your Grace's little Jacobite, to whom you have always been so kind. If sympathy could have cured me, I should not have been long ill. Gentle and simple were all equally kind, and even old Tom Watson crept down from Falshope to see how I was coming on, and to ejaculate "if anything ailed the Shirra, it would be sair on the Duke." The only unwelcome resurrection was that of old ****, whose feud with me (or rather dryness) I had well hoped was immortal; but he came jinking over the moor with daughters and ponies, and God knows what, to look after my precious health. I cannot tolerate that man; it seems to me as if I hated him for things not only past and present, but for some future offence, which is as yet in the womb of fate.

I have had as many remedies sent me for cramp and jaundice as would set up a quack doctor: three from Mrs. Plummer, each better than the other—one at least from every gardener in the neighborhood—besides all sorts of recommendations to go to Cheltenham, to Harrowgate, to Jericho for aught I know. Now if there is one thing I detest more than another, it is a watering-place, unless a very pleasant party be previously formed, when, as Tony Lumpkin says, "a gentleman may be in a concatenation." The most extraordinary recipe was that of my Highland piper, John Bruce, who spent a whole Sunday in selecting twelve stones from twelve south-running streams, with the purpose that I should sleep upon them, and be whole. I caused him to be told that the recipe was infallible, but that it was absolutely necessary to success that the stones should be wrapt up in the petticoat of a widow who had never wished to marry again; upon which the piper renounced all hope of completing the charm. I had need of a softer couch (p. 36) than Bruce had destined me, for so general was the tension of the nerves all over the body, although the pain of the spasms in the stomach did not suffer the others to be felt, that my whole left leg was covered with swelling and inflammation, arising from the unnatural action of the muscles, and I had to be carried about like a child. My right leg escaped better, the muscles there having less irritability, owing to its lame state. Your Grace may imagine the energy of pain in the nobler parts, when cramps in the extremities, sufficient to produce such effects, were unnoticed by me during their existence. But enough of so disagreeable a subject.

Respecting the portrait, I shall be equally proud and happy to sit for it, and hope it may be so executed as to be in some degree worthy of the preferment to which it is destined.[23] But neither my late golden hue (for I was covered with jaundice), nor my present silver complexion (looking much more like a spectre than a man), will present any idea of my quondam beef-eating physiognomy. I must wait till the age of brass, the true juridical bronze of my profession, shall again appear on my frontal. I hesitate a little about Raeburn, unless your Grace is quite determined. He has very much to do; works just now chiefly for cash, poor fellow, as he can have but a few years to make money; and has twice already made a very chowder-headed person of me. I should like much (always with your approbation) to try Allan, who is a man of real genius, and has made one or two glorious portraits, though his predilection is to the historical branch of the art. We did rather a handsome thing for him, considering that in Edinburgh we are neither very wealthy nor great amateurs. A hundred persons subscribed ten guineas apiece to raffle[24] for his fine picture (p. 37) of the Circassian Chief selling Slaves to the Turkish Pacha—a beautiful and highly poetical picture. There was another small picture added by way of second prize, and, what is curious enough, the only two peers on the list, Lord Wemyss and Lord Fife, both got prizes. Allan has made a sketch which I shall take to town with me when I can go, in hopes Lord Stafford, or some other picture-buyer, may fancy it, and order a picture. The subject is the murder of Archbishop Sharp on Magus Moor, prodigiously well treated. The savage ferocity of the assassins, crowding one on another to strike at the old prelate on his knees—contrasted with the old man's figure—and that of his daughter endeavoring to interpose for his protection, and withheld by a ruffian of milder mood than his fellows:—the dogged fanatical severity of Rathillet's countenance, who remained on (p. 38) horseback, witnessing, with stern fanaticism, the murder he did not choose to be active in, lest it should be said that he struck out of private revenge—are all amazingly well combined in the sketch. I question if the artist can bring them out with equal spirit in the painting which he meditates.[25] Sketches give a sort of fire to the imagination of the spectator, who is apt to fancy a great deal more for himself, than the pencil, in the finished picture, can possibly present to his eye afterwards.—Constable has offered Allan three hundred pounds to make sketches for an edition of the Tales of my Landlord, and other novels of that cycle, and says he will give him the same sum next year, so, from being pinched enough, this very deserving artist suddenly finds himself at his ease. He was long at Odessa with the Duke of Richelieu, and is a very entertaining person.

I saw with great pleasure Wilkie's sketch of your Grace, and I think when I get to town I shall coax him out of a copy, to me invaluable. I hope, however, when you return, you will sit to Lawrence. We should have at least one picture of your Grace from the real good hand. Sooth to speak, I cannot say much for the juvenile representations at Bowhill and in the library at Dalkeith. Return, however, with the original features in good health, and we shall not worry you about portraits. The library at Bowhill will be a delightful room, and will be some consolation to me who must, I fear, lose for some time the comforts of the eating-room, and substitute panada and toast and water for the bonny haunch and buxom bottle of claret. Truth is, I must make great restrictions on my creature-comforts, at least till my stomach recovers its tone and ostrich-like capacity of digestion. Our spring here is slow, but not unfavorable: the country looking very well, and my plantings for the season quite completed. I have planted quite up (p. 39) two little glens, leading from the Aide-de-Camp's habitation up to the little loch, and expect the blessings of posterity for the shade and shelter I shall leave, where, God knows, I found none.

It is doomed this letter is not to close without a request. I conclude your Grace has already heard from fifty applicants that the kirk of Middlebie is vacant, and I come forward as the fifty-first (always barring prior engagements and better claims) in behalf of George Thomson, a son of the minister of Melrose, being the grinder of my boys, and therefore deeply entitled to my gratitude and my good offices, as far as they can go. He is nearer Parson Abraham Adams than any living creature I ever saw—very learned, very religious, very simple, and extremely absent. His father, till very lately, had but a sort of half stipend, during the incumbency of a certain notorious Mr. MacLagan, to whom he acted only as assistant. The poor devil was brought to the grindstone (having had the want of precaution to beget a large family), and became the very figure of a fellow who used to come upon the stage to sing "Let us all be unhappy together." This poor lad George was his saving angel, not only educating himself, but taking on him the education of two of his brothers, and maintaining them out of his own scanty pittance. He is a sensible lad, and by no means a bad preacher, a stanch Anti-Gallican, and orthodox in his principles. Should your Grace find yourself at liberty to give countenance to this very innocent and deserving creature, I need not say it will add to the many favors you have conferred on me; but I hope the parishioners will have also occasion to say, "Weel bobbit, George of Middlebie." Your Grace's Aide-de-Camp, who knows young Thomson well, will give you a better idea of him than I can do. He lost a leg by an accident in his boyhood, which spoiled as bold and fine-looking a grenadier as ever charged bayonet against a Frenchman's throat. I think your Grace will (p. 40) not like him the worse for having a spice of military and loyal spirit about him. If you knew the poor fellow, your Grace would take uncommon interest in him, were it but for the odd mixture of sense and simplicity, and spirit and good morals. Somewhat too much of him.

I conclude you will go to Mafra, Cintra, or some of these places, which Baretti describes so delightfully, to avoid the great heats, when the Palace de las Necessidades must become rather oppressive. By the bye, though it were only for the credit of the name, I am happy to learn it has that useful English comfort, a water-closet. I suppose the armorer of the Liffey has already put it in complete repair. Your Grace sees the most secret passages respecting great men cannot be hidden from their friends. There is but little news here but death in the clan. Harden's sister is dead—a cruel blow to Lady Die,[26] who is upwards of eighty-five, and accustomed to no other society. Again, Mrs. Frank Scott, his uncle's widow, is dead, unable to survive the loss of two fine young men in India, her sons, whose death closely followed each other. All this is sad work; but it is a wicked and melancholy world we live in. God bless you, my dear, dear Lord. Take great care of your health for the sake of all of us. You are the breath of our nostrils, useful to thousands, and to many of these thousands indispensable. I will write again very soon, when I can keep my breast longer to the desk without pain, for I am not yet without frequent relapses, when they souse me into scalding water without a moment's delay, where I lie, as my old grieve Tom Purdie said last night, being called to assist at the operation, "like a haulded saumon." I write a few lines to the Aide-de-Camp, but I am afraid of putting this letter beyond the bounds of Lord Montagu's frank. When I can do anything for your Grace here, you know I am most (p. 41) pleased and happy.—Ever respectfully and affectionately your Grace's

TO CAPTAIN ADAM FERGUSON, ETC., ETC., ETC.

Abbotsford, April 16, 1819.

My dear Adam,—Having only been able last night to finish a long letter to the Chief, I now add a few lines for the Aide-de-Camp. I have had the pleasure to hear of you regularly from Jack,[27] who is very regular in steering this way when packets arrive; and I observe with great satisfaction that you think our good Duke's health is on the mending hand. Climate must operate as an alterative, and much cannot perhaps be expected from it at first. Besides, the great heat must be a serious drawback. But I hope you will try by and by to get away to Cintra, or some of those sequestered retreats where there are shades and cascades to cool the air. I have an idea the country there is eminently beautiful. I am afraid the Duke has not yet been able to visit Torres Vedras, but you must be meeting with things everywhere to put you in mind of former scenes. As for the Senhoras, I have little doubt that the difference betwixt your military hard fare and Florence's high sauces and jellies will make them think that time has rather improved an old friend than otherwise. Apropos of these ticklish subjects. I am a suitor to the Duke, with little expectation of success (for I know his engagements), for the kirk of Middlebie to George Thomson, the very Abraham Adams of Presbytery. If the Duke mentions him to you (not otherwise) pray lend him a lift. With a kirk and a manse the poor fellow might get a good farmer's daughter, and beget grenadiers for his Majesty's service. But as I said before, I dare say all St. Hubert's black pack are in full cry upon the living, and that he has little or no chance. It is something, however, to have tabled him, as better may come of it another day.

(p. 42) All at Huntly Burn well and hearty, and most kind in their attentions during our late turmoils. Bauby[28] came over to offer her services as sick-nurse, and I have drunk scarce anything but delicious ginger-beer of Miss Bell's brewing, since my troubles commenced. They have been, to say the least, damnable; and I think you would hardly know me. When I crawl out on Sibyl Grey, I am the very image of Death on the pale horse—lanthorn-jawed, decayed in flesh, stooping as if I meant to eat the pony's ears, and unable to go above a footpace. But although I have had, and must expect, frequent relapses, yet the attacks are more slight, and I trust I shall mend with the good weather. Spring sets in very pleasantly, and in a settled fashion. I have planted a number of shrubs, etc., at Huntly Burn, and am snodding up the drive of the old farmhouse, enclosing the Toftfield, and making a good road from the parish road to your gate. This I tell you to animate you to pick up a few seeds both of forest trees, shrubs, and vegetables; we will rear them in the hot-house, and divide honorably. Avis au lecteur. I have been a good deal entrusted to the care of Sophia, who is an admirable sick-nurse. Mamma has been called to town by two important avocations: to get a cook—no joking matter,—and to see Charles, who was but indifferent, but has recovered. You must have heard of the death of Joseph Hume, David's only son. Christ! what a calamity!—just entering life with the fairest prospects—full of talent, and the heir of an old and considerable family—a fine career before him: all this he was one day, or rather one hour—or rather in the course of five minutes—so sudden was the death—and then—a heap of earth. His disease is unknown; something about the heart, I believe; but it had no alarming appearance, nothing worse than a cold and sore throat, when convulsions came, and death ensued. It is (p. 43) a complete smash to poor David, who had just begun to hold his head up after his wife's death. But he bears it stoutly, and goes about his business as usual. A woeful case. London is now out of the question with me; I have no prospect of being now able to stand the journey by sea or land; but the best is, I have no pressing business there. The Commie[29] takes charge of Walter's matters—cannot, you know, be in better hands; and Lord Melville talks of gazetting quam primum. I will write a long letter very soon, but my back, fingers, and eyes ache with these three pages. All here send love and fraternity. Yours ever most truly,

P. S.—By the bye, old Kennedy, the tinker, swam for his life at Jedburgh, and was only, by the sophisticated and timid evidence of a seceding doctor, who differed from all his brethren, saved from a well-deserved gibbet. He goes to botanize for fourteen years. Pray tell this to the Duke, for he was

"An old soldier of the Duke's,

And the Duke's old soldier."

Six of his brethren, I am told, were in court, and kith and kin without end. I am sorry so many of the clan are left. The cause of quarrel with the murdered man was an old feud between two gypsy clans, the Kennedies and Irvings, which, about forty years since, gave rise to a desperate quarrel and battle on Hawick Green, in which the grandfathers of both Kennedy, and Irving whom he murdered, were engaged.

In the next of these letters there is allusion to a drama, on the story of The Heart of Mid-Lothian, of which Mr. Terry had transmitted the MS. to Abbotsford—and which ultimately proved very successful. Terry had, shortly before this time, become the acting manager of the Haymarket Theatre.

(p. 44) TO D. TERRY, ESQ., HAYMARKET, LONDON.

Abbotsford, 18th April, 1819.

Dear Terry,—I am able (though very weak) to answer your kind inquiries. I have thought of you often, and been on the point of writing or dictating a letter, but till very lately I could have had little to tell you of but distress and agony, with constant relapses into my unhappy malady, so that for weeks I seemed to lose rather than gain ground, all food nauseating on my stomach, and my clothes hanging about me like a potato-bogle,[30] with from five or six to ten hours of mortal pain every third day; latterly the fits have been much milder, and have at last given way to the hot bath without any use of opiates; an immense point gained, as they hurt my general health extremely. Conceive my having taken, in the course of six or seven hours, six grains of opium, three of hyoscyamus, near 200 drops of laudanum—and all without any sensible relief of the agony under which I labored. My stomach is now getting confirmed, and I have great hopes the bout is over; it has been a dreadful set-to. I am sorry to hear Mrs. Terry is complaining; you ought not to let her labor, neither at Abbotsford sketches nor at anything else, but to study to keep her mind amused as much as possible. As for Walter, he is a shoot of an Aik,[31] and I have no fear of him: I hope he remembers Abbotsford and his soldier namesake.