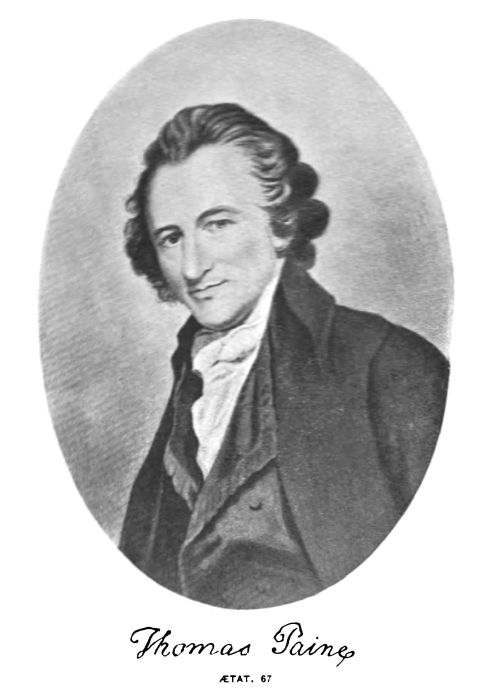

Title: The Life Of Thomas Paine, Vol. 1. (of 2)

Author: Moncure Daniel Conway

Contributor: William Cobbett

Release date: October 10, 2011 [eBook #37701]

Most recently updated: March 18, 2013

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger

CHAPTER V. LIBERTY AND EQUALITY

CHAPTER VII. UNDER THE BANNER OF INDEPENDENCE

CHAPTER VIII. SOLDIER AND SECRETARY

CHAPTER IX. FRENCH AID, AND THE PAINE-DEANE CONTROVERSY.

CHAPTER X. A STORY BY GOUVERNEUR MORRIS

CHAPTER XI. CAUSE, COUNTRY, SELF

CHAPTER XII. A JOURNEY TO FRANCE

CHAPTER XIII. THE MUZZLED OX TREADING OUT THE GRAIN.

CHAPTER XIV. GREAT WASHINGTON AND POOR PAINE

CHAPTER XV. PONTIFICAL AND POLITICAL INVENTIONS

CHAPTER XVI. RETURNING TO THE OLD HOME

CHAPTER XVII. A BRITISH LION WITH AN AMERICAN HEART

CHAPTER XVIII. PAINE'S LETTERS TO JEFFERSON IN PARIS

CHAPTER XIX. THE KEY OF THE BASTILLE

CHAPTER XX. "THE RIGHTS OF MAN"

Part I. of "The Rights of Man" was printed by Johnson in time for the

CHAPTER XXI. FOUNDING THE EUROPEAN REPUBLIC

CHAPTER XXII. THE RIGHT OF EVOLUTION

CHAPTER XXIII. THE DEPUTY FOR CALAIS IN THE CONVENTION

CHAPTER XXIV. OUTLAWED IN ENGLAND

In the Preface to the first edition of this work, it was my painful duty to remark with severity on the dissemination of libels on Paine in a work of such importance as Mr. Leslie Stephen's "History of English Thought in the Eighteenth Century." The necessity of doing so was impressed on me by the repetition of some of Mr. Stephen's unfounded disparagements in Mr. O. B. Frothingham's "Recollections and Impressions." I have now the satisfaction of introducing this edition with retractations by both of those authors. Mr. Frothingham, in a letter which he authorizes me to use, says: "Your charge is true, and I hasten to say peccavi The truth is that I never made a study of Paine, but took Stephen's estimates. Now my mistake is clear, and I am willing to stand in the cold with nothing on but a hair shirt Your vindication of Paine is complete." Mr. Frothingham adds that in any future edition of his work the statements shall be altered. The note of Mr. Leslie Stephen appeared in The National Reformer, September 11, 1892, to which it was sent by a correspondent, at his desire; for it equally relates to strictures in a pamphlet by the editor of that journal, Mr. John M. Robertson.

"The account which I gave of Paine in the book upon the Eighteenth Century was, I have no doubt, erroneous. My only excuse, if it be an excuse, was the old one, 'pure ignorance.' I will not ask whether or how far the ignorance was excusable.

"Mr. Conway pointed out the error in an article contributed, I think, to the Fortnightly Review at the time. He has, no doubt, added, since then, to his exposure of my (and other people's) blunders, and I hope to read his book soon. Meanwhile, I must state that in consequence of the Fortnightly article, I altered the statements in the second edition of my book. I have no copy at hand [Mr. S. writes from the country] and cannot say what alterations precisely I made, though it is very possible that they were inadequate, as for certain reasons I was unable to attend properly to the revision. If a third edition should ever be required, I would go into the question more thoroughly. I have since that time read some letters upon Paine contributed by Mr. Conway to the New York Nation. I had seen the announcement of his new publication, and had made up my mind to take the first opportunity of going into the question again with Mr. Conway's additional information. I hope that I may be able to write Paine's life for the Dictionary of National Biography, and if so, shall have the best opportunity for putting on record my final judgment It will be a great pleasure to me if I find, as I expect to find, that he was greatly maligned, and to make some redress for my previous misguided remarks."

It is indeed to be hoped that Mr. Stephen will write the Life in the Dictionary, whose list of subjects for the coming volume, inserted in the Athenæum since his above retraction, designates Thomas Paine as an "infidel" writer. Mr. Stephen can do much to terminate the carefully fostered ignorance of which he has found himself a victim. In advance of his further treatment of the subject, and with perfect confidence in his justice, I here place by the side of my original criticism a retraction of anything that may seem to include him among authors who have shown a lack of magnanimity towards Paine.

The general statement (First Preface, p. xvi) must, however, remain; for recent discussions reveal a few unorthodox writers willing to throw, or to leave, "a traditionally hated head to the orthodox mob." On the other hand, some apology is due for this phrase. No orthodox mob is found. Here and there some halloo of the old Paine hunt is heard dying away in the distance, but the conservative religious and political press, American and English, has generally revised the traditional notions, and estimated the evidence with substantial justice. Nearly all of the most influential journals have dealt with the evidence submitted; their articles have been carefully read by me, and in very few are the old prejudices against Paine discoverable. Were these estimates of Paine collected with those of former times the volume would measure this century's advance in political liberty, and religious civilization.

My occasionally polemical treatment of the subject has been regretted by several reviewers, but its necessity, I submit, is the thing to be regretted. Being satisfied that Paine was not merely an interesting figure, but that a faithful investigation of his life would bring to light important facts of history, I found it impossible to deal with him as an ordinary subject of inquiry. It were vain to try and persuade people to take seriously a man tarred, feathered, pilloried, pelted. It was not whitewashing Paine needed, but removal of the pitch, and release from the pillory. There must first of all be an appeal against such sentence. And because the wrongs represented a league of prejudices, the pleadings had to be in several tribunals—moral, religious, political, social,—before the man could be seen at all, much less accorded the attention necessary for disclosure of the history suppressed through his degradation. Paine's personal vindication would still have required only a pamphlet, but that it was ancillary to the historic revelations which constitute the larger part of this work. A wiser writer—unless too wise to touch Paine at all—might have concealed such sympathies as those pervading this biography; but where sympathies exist the reader is entitled to know them, and the author subjects himself to a severer self-criticism if only in view of the vigilance he must excite. I have no feeling towards Paine inconsistent with recognition of his faults and errors. My vindication of him has been the production of evidence that removed my own early and baseless prejudices, and rendered it possible for me to study his career genuinely, so that others might do the same. The phantasmal Paine cleared away, my polemic ends. I have endeavored to portray the real Paine, and have brought to light some things unfavorable to him which his enemies had not discovered, and, I believe, could never have discovered.

The errata in the first edition are few and of slight importance. I wish to retract a suggestion made in my apology for Washington which I have discovered to be erroneous. It was suggested (vol. ii., pp. 173 and 382) that Washington's failure to answer Paine's private letter of September 20,1795, asking an explanation of his neglect while he (Paine) was in prison and his life in peril, may have been due to its interception by Pickering (who had by a suppression of documents sealed the sad fate of his predecessor in office, Edmund Randolph). I have, however, discovered that Paine's letter did reach Washington.

I would be glad if my own investigations, continued while preparing an edition of Paine's works, or any of my reviewers, had enabled me to relieve the shades with which certain famous names are touched by documentary facts in this history. The publication of those relating to Gouverneur Morris, while American Minister in France, was for personal reasons especially painful to myself. Though such publication was not of any importance to Paine's reputation, it was essential to a fair judgment of others—especially of Washington,—and to any clear comprehension of the relations between France and the United States at that period. As the correspondence between Gouverneur Morris and the French Minister concerning Paine, after his imprisonment, is in French, and the originals (in Paris) are not easily accessible to American and English readers, I have concluded to copy them here.

À Paris le 14 février 1794 26 pluviôse.

Le Ministre plénipotentiaire des États Unis de l'Amérique près la République française au Ministre des Affaires Étrangères.

Monsieur:

Thomas Paine vient de s'addresser à moi pour que je le reclame comme Citoyen des États Unis. Voici (je crois) les Faits que le regardent. Il est né en Angleterre. Devenu ensuite Citoyen des États Unis il s'y est acquise une grande célébrité par des Écrits révolutionnaires. En consequence il fut adopté Citoyen français et ensuite élu membre de la Convention. Sa conduite depuis cette Epoque n'est pas de mon ressort J'ignore la cause de sa Détention actuelle dans la prison du Luxembourg, mais je vous prie Monsieur (si des raisons qui ne me sont pas connues s'opposent à sa liberation) de vouloir bien m'en instruire pour que je puisse les communiquer au Gouvernement des États Unis.

J'ai l'honneur d'être, Monsieur,

Votre très humble Serviteur,

Gouv. Morris.

Paris, 1 Ventôse l'An 2d. de la Républic une et indivisible.

Le ministre des Affaires Étrangères au Ministre Plénipotentiaire des-États Unis de l'Amérique près la République Française.

Par votre lettre du 26 du mois dernier, vous réclames la liberté de Thomas Paine, comme Citoyen américain. Né en Angleterre, cet ex-deputé est devenu successivement Citoyen Américain et Citoyen français. En acceptant ce dernier titre et en remplissant une place dans le corps législatif, il s'est soumis aux lois de la République et il a renoncé de fait à la protection que le droit des gens et les traités conclus avec les États Unis auraient pu lui assurer.

J'ignore les motifs de sa détention mais je dois présumer qu'ils sont bien fondés. Je vais néanmoins soumettre au Comité de Salut public la demande que vous m'avez adressée et je m'empresserai de vous faire connaître sa decision.

DEFORGES.

The translations of these letters are on page 120, vol ii., of this work. No other letters on the subject between these Ministers are known. The reader may judge whether there is anything in the American Minister's application to warrant the opening assertion in that of Deforgues. Morris forwarded the latter to his government, but withheld his application, of which no copy exists in the State Archives at Washington.

At Hornsey, England, I saw a small square mahogany table, bearing at its centre the following words: "This Plate is inscribed by Thos. Clio Rickman in Remembrance of his dear friend Thomas Paine, who on this table in the year 1792 wrote several of his invaluable Works."

The works written by Paine in Rickman's house were the second part of "The Rights of Man," and "A Letter to the Addressers." Of these two books vast numbers were circulated, and though the government prosecuted them, they probably contributed largely to make political progress in England evolutionary instead of revolutionary. On this table he set forth constitutional reforms that might be peacefully obtained, and which have been substantially obtained And here he warned the "Addressers," petitioning the throne for suppression of his works: "It is dangerous in any government to say to a nation, Thou shalt not read. This is now done in Spain, and was formerly done under the old government of France; but it served to procure the downfall of the latter, and is subverting that of the former; and it will have the same tendency in all countries; because Thought, by some means or other, is got abroad in the world, and cannot be restrained, though reading may."

At this table the Quaker chieftain, whom Danton rallied for hoping to make revolutions with rose-water, unsheathed his pen and animated his Round Table of Reformers for a conflict free from the bloodshed he had witnessed in America, and saw threatening France. This little table was the field chosen for the battle of free speech; its abundant ink-spots were the shed blood of hearts transfused with humanity. I do not wonder that Rickman was wont to show the table to his visitors, or that its present owner, Edward Truelove—a bookseller who has suffered imprisonment for selling proscribed books,—should regard it with reverence.

The table is what was once called a candle-stand, and there stood on it, in my vision, Paine's clear, honest candle, lit from his "inner light," now covered by a bushel of prejudice. I myself had once supposed his light an infernal torch; now I sat at the ink-spotted candle-stand to write the first page of this history, for which I can invoke nothing higher than the justice that inspired what Thomas Paine here wrote.

The educated ignorance concerning Paine is astounding. I once heard an English prelate speak of "the vulgar atheism of Paine." Paine founded the first theistic society in Christendom; his will closes with the words, "I die in perfect composure, and resignation to the will of my Creator, God." But what can be expected of an English prelate when an historian like Jared Sparks, an old Unitarian minister, could suggest that a letter written by Franklin, to persuade some one not to publish a certain attack on religion, was "probably" addressed to Paine. (Franklin's "Writings," vol. x., p. 281.) Paine never wrote a page that Franklin could have so regarded, nor anything in the way of religious controversy until three years after Franklin's death. "The remarks in the above letter," says Sparks, "are strictly applicable to the deistical writings which Paine afterwards published." On the contrary, they are strictly inapplicable. They imply that the writer had denied a "particular providence," which Paine never denied, and it is asked, "If men are so wicked with religion, what would they be without it?" Paine's "deism" differed from Franklin's only in being more fervently religious. No one who had really read Paine could imagine the above question addressed to the author to whom the Bishop of Llandaff wrote: "There is a philosophical sublimity in some of your ideas when speaking of the Creator of the Universe." The reader may observe at work, in this example, the tiny builder, prejudice, which has produced the large formation of Paine mythology. Sparks, having got his notion of Paine's religion at secondhand, becomes unwittingly a weighty authority for those who have a case to make out. The American Tract Society published a tract entitled "Don't Unchain the Tiger," in which it is said: "When an infidel production was submitted—probably by Paine—to Benjamin Franklin, in manuscript, he returned it to the author, with a letter from which the following is extracted: 'I would advise you not to attempt unchaining the Tiger, but to burn this piece before it is seen by any other person.'" Thus our Homer of American history nods, and a tract floats through the world misrepresenting both Paine and Franklin, whose rebuke is turned from some anti-religious essay against his own convictions. Having enjoyed the personal friendship of Mr. Sparks, while at college, and known his charity to all opinions, I feel certain that he was an unconscious victim of the Paine mythology to which he added. His own creed was, in essence, little different from Paine's. But how many good, and even liberal, people will find by the facts disclosed in this volume that they have been accepting the Paine mythology and contributing to it? It is a notable fact that the most effective distortions of Paine's character and work have proceeded from unorthodox writers—some of whom seem not above throwing a traditionally hated head to the orthodox mob. A recent instance is the account given of Paine in Leslie Stephen's "History of English Thought in the Eighteenth Century." On its appearance I recognized the old effigy of Paine elaborately constructed by Oldys and Cheetham, and while writing a paper on the subject (Fortnightly Review, March, 1879) discovered that those libels were the only "biographies" of Paine in the London Library, which (as I knew) was used by Mr. Stephen. The result was a serious miscarriage of historical and literary justice. In his second edition Mr. Stephen adds that the portrait presented "is drawn by an enemy," but on this Mr. Robertson pertinently asks why it was allowed to stand? ("Thomas Paine: an Investigation," by John M. Robertson, London, 1888). Mr. Stephen, eminent as an agnostic and editor of a biographical dictionary, is assumed to be competent, and his disparagements of a fellow heretic necessitated by verified facts. His scholarly style has given new lease to vulgar slanders. Some who had discovered their untruth, as uttered by Paine's personal enemies, have taken them back on Mr. Stephen's authority. Even brave O. B. Frothingham, in his high estimate of Paine, introduces one or two of Mr. Stephen's depreciations (Frothingham's "Recollection and Impressions," 1891).

There has been a sad absence of magnanimity among eminent historians and scholars in dealing with Paine. The vignette in Oldys—Paine with his "Rights of Man" preaching to apes;—the Tract Society's picture of Paine's death-bed—hair on end, grasping a bottle,—might have excited their inquiry. Goethe, seeing Spinoza's face de-monized on a tract, was moved to studies of that philosopher which ended in recognition of his greatness. The chivalry of Goethe is indeed almost as rare as his genius, but one might have expected in students of history an historic instinct keen enough to suspect in the real Paine some proportion to his monumental mythology, and the pyramidal cairn of curses covering his grave. What other last-century writer on political and religious issues survives in the hatred and devotion of a time engaged with new problems? What power is confessed in that writer who was set in the place of a decadent Satan, hostility to him being a sort of sixth point of Calvinism, and fortieth article of the Church? Large indeed must have been the influence of a man still perennially denounced by sectarians after heretical progress has left him comparatively orthodox, and retained as the figure-head of "Freethought" after his theism has been abandoned by its leaders. "Religion," said Paine, "has two principal enemies, Fanaticism and Infidelity." It was his strange destiny to be made a battle-field between these enemies. In the smoke of the conflict the man has been hidden. In the catalogue of the British Museum Library I counted 327 entries of books by or concerning Thomas Paine, who in most of them is a man-shaped or devil-shaped shuttlecock tossed between fanatical and "infidel" rackets.

Here surely were phenomena enough to attract the historic sense of a scientific age, yet they are counterpart of an historic suppression of the most famous author of his time. The meagre references to Paine by other than controversial writers are perfunctory; by most historians he is either wronged or ignored. Before me are two histories of "American Slavery" by eminent members of Congress; neither mentions that Paine was the first political writer who advocated and devised a scheme of emancipation. Here is the latest "Life of Washington" (1889), by another member of Congress, who manages to exclude even the name of the man who, as we shall see, chiefly converted Washington to the cause of independence. And here is a history of the "American Revolution" (1891), by John Fiske, who, while recognizing the effect of "Common Sense," reveals his ignorance of that pamphlet, and of all Paine's works, by describing it as full of scurrilous abuse of the English people,—whom Paine regarded as fellow-sufferers with the Americans under royal despotism.

It may be said for these contemporaries that the task of sifting out the facts about Paine was formidable. The intimidated historians of the last generation, passing by this famous figure, left an historic vacuum, which has been filled with mingled fact and fable to an extent hardly manageable by any not prepared to give some years to the task. Our historians, might, however, have read Paine's works, which are rather historical documents than literary productions. None of them seem to have done this, and the omission appears in many a flaw in their works. The reader of some documents in this volume, left until now to slumber in accessible archives, will get some idea of the cost to historic truth of this long timidity and negligence. But some of the results are more deplorable and irreparable, and one of these must here be disclosed.

In 1802 an English friend of Paine, Redman Yorke, visited him in Paris. In a letter written at the time Yorke states that Paine had for some time been preparing memoirs of his own life, and his correspondence, and showed him two volumes of the same. In a letter of Jan. 25, 1805, to Jefferson, Paine speaks of his wish to publish his works, which will make, with his manuscripts, five octavo volumes of four hundred pages each. Besides which he means to publish "a miscellaneous volume of correspondence, essays, and some pieces of poetry." He had also, he says, prepared historical prefaces, stating the circumstances under which each work was written. All of which confirms Yorke's statement, and shows that Paine had prepared at least two volumes of autobiographic matter and correspondence. Paine never carried out the design mentioned to Jefferson, and his manuscripts passed by bequest to Madame Bonneville. This lady, after Paine's death, published a fragment of Paine's third part of "The Age of Reason," but it was afterwards found that she had erased passages that might offend the orthodox. Madame Bonneville returned to her husband in Paris, and the French "Biographical Dictionary" states that in 1829 she, as the depositary of Paine's papers, began "editing" his life. This, which could only have been the autobiography, was never published. She had become a Roman Catholic. On returning (1833) to America, where her son, General Bonneville, also a Catholic, was in military service, she had personal as well as religious reasons for suppressing the memoirs. She might naturally have feared the revival of an old scandal concerning her relations with Paine. The same motives may have prevented her son from publishing Paine's memoirs and manuscripts. Madame Bonneville died at the house of the General, in St. Louis. I have a note from his widow, Mrs. Sue Bonneville, in which she says: "The papers you speak of regarding Thomas Paine are all destroyed—at least all which the General had in his possession. On his leaving St. Louis for an indefinite time all his effects—a handsome library and valuable papers included—were stored away, and during his absence the store-house burned down, and all that the General stored away were burned."

There can be little doubt that among these papers burned in St. Louis were the two volumes of Paine's autobiography and correspondence seen by Redman Yorke in 1802. Even a slight acquaintance with Paine's career would enable one to recognize this as a catastrophe. No man was more intimately acquainted with the inside history of the revolutionary movement, or so competent to record it. Franklin had deposited with him his notes and papers concerning the American Revolution. He was the only Girondist who survived the French Revolution who was able to tell their secret history. His personal acquaintance included nearly every great or famous man of his time, in England, America, France. From this witness must have come testimonies, facts, anecdotes, not to be derived from other sources, concerning Franklin, Goldsmith, Ferguson, Rittenhouse, Rush, Fulton, Washington, Jefferson, Monroe, the Adamses, Lees, Morrises, Condorcet, Vergennes, Sievès, Lafayette, Danton, Genet, Brissot, Robespierre, Marat, Burke, Erskine, and a hundred others. All this, and probably invaluable letters from these men, have been lost through the timidity of a woman before the theological "boycott" on the memory of a theist, and the indifference of this country to its most important materials of History.

When I undertook the biography of Edmund Randolph I found that the great mass of his correspondence had been similarly destroyed by fire in New Orleans, and probably a like fate will befall the Madison papers, Monroe papers, and others, our national neglect of which will appear criminal to posterity. After searching through six States to gather documents concerning Randolph which should all have been in Washington City, the writer petitioned the Library Committee of Congress to initiate some action towards the preservation of our historical manuscripts. The Committee promptly and unanimously approved the proposal, a definite scheme was reported by the Librarian of Congress, and—there the matter rests. As the plan does not include any device for advancing partisan interests, it stands a fair chance of remaining in our national oubliette of intellectual desiderata.

In writing the "Life of Paine" I have not been saved much labor by predecessors in the same field They have all been rather controversial pamphleteers than biographers, and I have been unable to accept any of their statements without verification. They have been useful, however, in pointing out regions of inquiry, and several of them—Rickman, Sherwin, Linton—contain valuable citations from contemporary papers. The truest delineation of Paine is the biographical sketch by his friend Rickman. The "Life" by Vale, and sketches by Richard Carlile, Blanchard, and others, belong to the controversial collectanea in which Paine's posthumous career is traceable. The hostile accounts of Paine, chiefly found in tracts and encyclopaedias, are mere repetitions of those written by George Chalmers and James Cheetham.

The first of these was published in 1791 under the title: "The Life of Thomas Pain, Author of 'The Rights of Men,' with a Defence of his Writings. By Francis Oldys, A.M., of the University of Pennsylvania. London. Printed for John Stock-dale, Pickadilly." This writer, who begins his vivisection of Paine by accusing him of adding "e" to his name, assumed in his own case an imposing pseudonym. George Chalmers never had any connection with the University of Philadelphia, nor any such degree. Sherwin (1819) states that Chalmers admitted having received L500 from Lord Hawksbury, in whose bureau he was a clerk, for writing the book; but though I can find no denial of this I cannot verify it. In his later editions the author claims that his book had checked the influence of Paine, then in England, and his "Rights of Man," which gave the government such alarm that subsidies were paid several journals to counteract their effect. (See the letter of Freching, cited from the Vansitart Papers, British Museum, by W. H. Smith, in the Century, August, 1891.) It is noticeable that Oldys, in his first edition, entitles his work a "Defence" of Paine's writings—a trick which no doubt carried this elaborate libel into the hands of many "Paineites." The third edition has, "With a Review of his Writings." In a later edition we find the vignette of Paine surrounded by apes. Cobbett's biographer, Edward Smith, describes the book as "one of the most horrible collections of abuse which even that venal day produced." The work was indeed so overweighted with venom that it was sinking into oblivion when Cobbett reproduced its libels in America, for which he did penance through many years. My reader will perceive, in the earlier chapters of this work, that Chalmers tracked Paine in England with enterprise, but there were few facts that he did not manage to twist into his strand of slander.

In 1809, not long after Paine's death, James Cheetham's "Life of Thomas Paine" appeared in New York. Cheetham had been a hatter in Manchester, England, and would probably have continued in that respectable occupation had it not been for Paine. When Paine visited England and there published "The Rights of Man" Cheetham became one of his idolaters, took to political writing, and presently emigrated to America. He became editor of The American Citizen, in New York. The cause of Cheetham's enmity to Paine was the discovery by the latter that he was betraying the Jeffersonian party while his paper was enjoying its official patronage. His exposure of the editor was remorseless; the editor replied with personal vituperation; and Paine was about instituting a suit for libel when he died. Of Cheetham's ingenuity in falsehood one or two specimens may be given. During Paine's trial in London, for writing "The Rights of Man," a hostile witness gave testimony which the judge pronounced "impertinent"; Cheetham prints it "important" He says that Madame de Bonneville accompanied Paine on his return from France in 1802; she did not arrive until a year later. He says that when Paine was near his end Monroe wrote asking him to acknowledge a debt for money loaned in Paris, and that Paine made no reply. But before me is Monroe's statement, while President, that for his advances to Paine "no claim was ever presented on my part, nor is any indemnity now desired." Cheetham's book is one of the most malicious ever written, and nothing in it can be trusted.

Having proposed to myself to write a critical and impartial history of the man and his career, I found the vast Paine literature, however interesting as a shadow measuring him who cast it, containing conventionalized effigies of the man as evolved by friend and foe in their long struggle. But that war has ended among educated people. In the laborious work of searching out the real Paine I have found a general appreciation of its importance, and it will be seen in the following pages that generous assistance has been rendered by English clergymen, by official persons in Europe and America, by persons of all beliefs and no beliefs. In no instance have I been impeded by any prejudice, religious or political. The curators of archives, private collectors, owners of important documents bearing on the subject, have welcomed my effort to bring the truth to light. The mass of material thus accumulated is great, and its compression has been a difficult task. But the interest that led me to the subject has increased at every step; the story has abounded in thrilling episodes and dramatic surprises; and I have proceeded with a growing conviction that the simple facts, dispassionately told, would prove of importance far wider than Paine's personality, and find welcome with all students of history. I have brought to my task a love for it, the studies of some years, and results of personal researches made in Europe and America: qualifications which I countless than another which I venture to claim—the sense of responsibility, acquired by a public teacher of long service, for his words, which, be they truths or errors, take on life, and work their good or evil to all generations.

The history here undertaken is that of an English mechanic, of Quaker training, caught in political cyclones of the last century, and set at the centre of its revolutions, in the old world and the new.

In the church register of Euston Parish, near Thetford, England, occurs this entry: "1734. Joseph Pain and Frances Cocke were married June 20th." These were the parents of Thomas Paine. The present rector of Euston Church, Lord Charles Fitz Roy, tells me that the name is there plainly "Pain," but in the Thetford town-records of that time it is officially entered "Joseph Paine."

Paine and Cocke are distinguished names in the history of Norfolk County. In the sixteenth century Newhall Manor, on the road between Thetford and Norwich, belonged to a Paine family. In 1553 Thomas Paine, Gent., was, by license from Queen Mary, trustee for the Lady Elizabeth, daughter of Henry VIII., by Queen Anne Bullen. In St. Thomas Church, Norwich, stands the monument of Sir Joseph Paine, Knt, the most famous mayor and benefactor of that city in the seventeenth century. In St. John the Baptist Church is the memorial of Justice Francis Cocke (d. 1628). Whether our later Joseph and Thomas were related to these earlier Paines has not been ascertained, but Mr. E. Chester Waters, of London, an antiquarian especially learned in family histories, expressed to me his belief that the Norfolk County Paines are of one stock. There is equal probability that John Cocke, Deputy Recorder of Thetford in 1629, pretty certainly ancestor of Thomas Paine's mother, was related to Richard Cock, of Norwich, author of "English Law, or a Summary Survey of the Household of God upon Earth" (London, 1651). The author of "The Rights of Man" may therefore be a confutation of his own dictum: "An hereditary governor is as inconsistent as an hereditary author." One Thomas Payne, of the Norfolk County family, was awarded L20 by the Council of State (1650) "for his sufferings by printing a book for the cause of Parliament." Among the sequestrators of royalist church livings was Charles George Cock, "student of Christian Law, of the Society of the Inner Temple, now (1651) resident of Norwich." In Blomefields "History of Norfolk County" other notes may be found suggesting that whatever may have been our author's genealogy he was spiritually descended from these old radicals.

At Thetford I explored a manuscript—"Freeman's Register Book" (1610-1756)—and found that Joseph Paine (our author's father) was made a freeman of Thetford April 18, 1737, and Henry Cock May 16,1740. The freemen of this borough were then usually respectable tradesmen. Their privileges amounted to little more than the right of pasturage on the commons. The appointment did not imply high position, but popularity and influence. Frances Cocke had no doubt resided in Euston Parish, where she was married. She was a member of the Church of England and daughter of an attorney of Thetford. Her husband was a Quaker and is said to have been disowned by the Society of Friends for being married by a priest. A search made for me by official members of that Society in Norfolk County failed to discover either the membership or disownment of any one of the name. Joseph's father, a farmer, was probably a Quaker. Had the son (b. 1708) been a Quaker by conversion he would hardly have defied the rules of the Society at twenty-six.

Joseph was eleven years younger than his wife. According to Oldys he was "a reputable citizen and though poor an honest man," but his wife was "a woman of sour temper and an eccentric character." Thomas Paine's writings contain several affectionate allusions to his father, but none to his mother. "They say best men are moulded out of faults," and the moulding begins before birth.

Thomas Paine was born January 29, 1736-7, at Thetford. The plain brick house was in Bridge Street (now White Hart) and has recently made way for a pretty garden. I was inclined to adopt a more picturesque tradition that the birthplace was in old Heathen man Street, as more appropriate for a paien (no doubt the origin of Paine's name), who also bore the name of the doubting disciple. An appeal for allowances might be based on such a conjunction of auspices, but a manuscript of Paine's friend Rickman, just found by Dr. Clair J. Grece, identifies the house beyond question.

Thomas Paine is said by most of his biographers to have never been baptized. This rests solely on a statement by Oldys:

"It arose probably from the tenets of the father, and from the eccentricity of the mother, that our author was never baptized, though he was privately named; and never received, like true Christians, into the bosom of any church, though he was indeed confirmed by the bishop of Norwich: This last circumstance was owing to the orthodox zeal of Mistress Cocke, his aunt, a woman of such goodness, that though she lived on a small annuity, she imparted much of this little to his mother.

"As he was not baptized, the baptism of Thomas Pain is not entered on the parish books of Thetford. It is a remarkable fact, that the leaves of the two registers of the parishes of St. Cuthbert's and St. Peter's, in Thetford, containing the marriages, births, and burials, from the end of 1733, to the beginning of 1737, have been completely cut out. Thus, a felony has been committed against the public, and an injury done to individuals, by a hand very malicious and wholly unknown. Whether our author, when he resided in Thetford in 1787, looked into these registers for his own birth; what he saw, or what he did, we will not conjecture. They contain the baptism of his sister Elizabeth, on the 28th of August, 1738."

This is Oldysian. Of course, if there was any mischief Paine did it, albeit against his own interests. But a recent examination shows that there has been no mutilation of the registers. St Peter's and St. Cuthbert's had at the time one minister. In 1736, just before Paine's birth, the minister (John Price) died, and his successor (Thomas Vaughan) appears to have entered on his duties in March, 1737. A little before and during this interregnum the registers were neglected. In St Cuthbert's register is the entry: "Elizabeth, Daughter of Joseph Payne and Frances his wife of this parish, was born Aug't the 29th, 1738, baptized September ye 20, 1738." This (which Oldys has got inaccurately, suo more) renders it probable that Thomas Paine was also baptized. Indeed, he would hardly have been confirmed otherwise.

The old historian of Norfolk County, Francis Blomefield, introduces us to Thetford (Sitomagus, Tedford, Theford, "People of the Ford") with a strain of poetry:

"No situation but may envy thee,

Holding such intimacy with the sea,

Many do that, but my delighted muse

Says, Neptune's fairest daughter is the Little Ouse."

After reading Blomefield's history of the ancient town, and that of Martin, and after strolling through the quaint streets, I thought some poet should add to this praise for picturesqueness some tribute on Thetford's historic vistas. There is indeed "a beauty buried everywhere," as Browning says.

Evelyn, visiting his friend Lord Arlington at Euston in September, 1677, writes:

"I went to Thetford, the Burrough Towne, where stand the ruines of a religious house; there is a round mountaine artificially raised, either for some castle or monument, which makes a pretty landscape. As we went and returned, a tumbler shew'd his extraordinary addresse in the Warren. I also saw the Decoy, much pleas'd with the stratagem."

Evelyn leaves his own figure, his princely friends, and the tumbler in the foreground of "a pretty landscape" visible to the antiquarian all around Thetford, whose roads, fully followed, would lead past the great scenes of English history. In general appearance the town (population under five thousand) conveys the pleasant impression of a fairly composite picture of its eras and generations. There is a continuity between the old Grammar School, occupying the site of the ancient cathedral, and a new Mechanics' Institute in the old Guildhall. The old churches summon their flocks from eccentric streets suggestive of literal sheep-paths. Of the ignorance with which our democratic age sweeps away as cobwebs fine threads woven by the past around the present, Thetford showed few signs, but it is sad to find "Guildhall" effacing "Heathenman" Street, which pointed across a thousand years to the march of the "heathen men" (Danes) of Anglo-Saxon chronicles.

"A. 870. This year the [heathen] army rode across Mer-cia into East Anglia, and took up their winter quarters in Thetford; and the same winter King Edmund fought against them, and the Danes got the victory, and slew the king, and subdued all the land, and destroyed all the ministers which they came to. The names of their chiefs who slew the king were Hingwar and Habba."

If old Heathenman Street be followed historically, it would lead to Bury St. Edmunds, where, on the spot of his coronation, the young king "was placed in a goodly shrine, richly adorned with jewels and precious stones," and a royal saint added to the calendar. The blood of St. Edmund reconsecrated Thetford.

"A. 1094. Then at Candlemas the king [William Rufus] went to Hastings, and whilst he waited there for a fair wind he caused the monastery on the field of battle to be consecrated; and he took the staff from Herbert Losange, bishop of Thetford."

The letters of this Bishop Herbert, discovered at Brussels, give him an honorable place in the list of Thetford authors; wherein also occur the names of Richard of Thetford, author of a treatise on preaching, Jeffrey de Rocherio, who began a history of the monarchy, and John Brame, writer and translator of various treatises. The works of these Thetford authors are preserved at Cambridge, England.

Thetford was, in a way, connected with the first newspaper enterprise. Its member of Parliament, Sir Joseph Williamson, edited the London Gazette, established by the Crown to support its own policy. The Crown claimed the sole right to issue any journal, and its license was necessary for every book. In 1674 Sir Joseph, being Secretary of State (he bought the office for L5,000), had control of the Gazette and of literature. In that year, when Milton died, his treatise on "Christian Doctrine" was brought to Williamson for license. He said he could "countenance nothing of Milton's writings," and the treatise was locked up by this first English editor, to be discovered a hundred and forty-nine years later.

On his way to the Grammar School (founded by bequest of Sir Richard Fulmerston, 1566) Paine might daily read an inscription set in the Fulmerston almshouse wall: "Follow peace and holines with all men without the which no man shall see the Lord." But many memorials would remind him of how Williamson, a poor rector's son, had sold his talent to a political lord and reached power to buy and sell Cabinet offices, while suppressing Milton. Thomas Paine, with more talent than Williamson to dispose of, was born in a time semi-barbaric at its best, and savage at its worst. Having got in the Quaker meeting an old head on his young shoulders, he must bear about a burden against most things around him. The old churches were satanic steeple-houses, and if he strolled over to that in which his parents were married, at Euston, its new splendors were accused by surrounding squalor.

Mr. F. H. Millington of Thetford, who has told Williamson's story,* has made for me a search into Paine's time there.

"In Paine's boyhood [says Mr. Millington in a letter I have from him] the town (about 2,000 inhabitants) possessed a corporation with mayor, aldermen, sword-bearers, macemen, recorder. The corporation was a corrupt body, under the dominance of the Duke of Grafton, a prominent member of the Whig government. Both members of Parliament (Hon. C. Fitzroy, and Lord Augustus Fitzroy) were nominees of Grafton. The people had no interest and no power, and I do not think politics were of any account in Paine's childhood. From Paine's 'Rights of Man' (Part ii., p. 108) it is clear that his native town was the model in his mind when he wrote on charters and corporations. The Lent Assizes for the Eastern Circuit were held here, and Paine would be familiar with the procedure and pomp of a court of justice. He would also be familiar with the sight of men and women hung for trivial offences. Thetford was on the main road to London, and was a posting centre.

* "Sir Joseph Williamson, Knt., A.D. 1630-1701. A Page in

the History of Thetford." A very valuable contribution to

local history.

Paine would be familiar with the faces and equipages of some of the great Whig nobles in Norfolk. Walpole might pass through on his way to Houghton. The river Ouse was navigable to Lynn, and Paine would probably go on a barge to that flourishing seaport. Bury St. Edmunds was a provincial capital for the nobility and gentry of the district. It was twelve miles from Thetford, and in closest connection with it The religious life of Thetford would be quiet. The churches were poor, having been robbed at the reformation. The Quakers were the only non-conformists in the town. There is a tradition that Wesley visited the town; if he did Paine would no doubt be among his hearers. On the whole, I think it easy to trace in Paine's works the influence of his boyhood here. He would see the corrupting influence of the aristocracy, the pomp of law, the evils of the unreformed corporations; the ruins of great ecclesiastical establishments, much more perfect than now, would bring to his mind what a power the church had been. Being of a mechanical turn of mind no doubt he had often played about the paper-mill which was, and is, worked by water-power."

When Paine was a lad the grand gentlemen who purloined parks and mansions from the Treasury were sending children to the gallows for small thefts instigated by hunger. In his thirteenth year he might have seen under the shadow of Ely Minster, in that region, the execution of Amy Hutchinson, aged seventeen, for poisoning her husband. "Her face and hands were smeared with tar, and having a garment daubed with pitch, after a short prayer the executioner strangled her, and twenty minutes after the fire was kindled and burnt half an hour." (Notes and Queries, 27 September, 1873.) Against the prevailing savagery a human protest was rarely heard outside the Quaker meeting. Whether disowned or not, Paine's father remained a Quaker, and is so registered at burial; and his eminent son has repeatedly mentioned his own training in the principles of that Society. Remembering the extent to which Paine's Quakerism had influenced his political theories, and instances of their bearing on great events, I found something impressive in the little meeting-house in Cage Lane, Thetford. This was his more important birthplace. Its small windows and one door open on the tombless graveyard at the back,—perhaps that they might not be smashed by the mob, or admit the ribaldry of the street. The interior is hardly large enough to seat fifty people. Plymouth Brethren have for some years occupied the place, but I was told that the congregation, reduced to four or five, would soon cease to gather there. Adjoining the meeting-house, and in contact with it, stands the ancient Cage, which still remains to explain the name "Cage Lane." In its front are two arches, once iron-grated; at one stood the pillory, at the other the stocks,—the latter remembered by some now living.

On "first day," when his schoolmates went in fine clothes to grand churches, to see gay people, and hear fine music, little Thomas, dressed in drab, crept affrighted past the stocks to his childhood's pillory in the dismal meeting-house. For him no beauty or mirth, no music but the oaths of the pilloried, or shrieks of those awaiting the gallows, There could be no silent meeting in Cage Lane. Testimonies of the "Spirit" against inhumanity, delivered beside instruments of legal torture, bred pity in the child, who had a poetic temperament. The earliest glimpses we have of his childhood are in lines written on a fly caught in a spider's web, and an epitaph for a crow which he buried in the garden:

"Here lies the body of John Crow,

Who once was high, but now is low;

Ye brother Crows take warning all,

For as you rise, so must you fall."

This was when he was eight years of age. It seems doubtful whether the child was weeping or smiling, but the humor, if it be such, is grim, and did not last long. He had even then already, as we shall see, gained in the Quaker meeting a feeling that "God was too good" to redeem man by his son's death, as his Aunt Cocke instructed him, and a heart so precocious was a sad birthright in the Thetford of that day. We look in vain for anything that can be described as true boyhood in Paine. Oldys was informed, no doubt rightly, that "he was deemed a sharp boy, of unsettled application; but he left no performances which denote juvenile vigour or uncommon attainments." There are, indeed, various indications that, in one way and another, Thetford and Quakerism together managed to make the early years of their famous son miserable. Had there been no Quakerism there had been no Thomas Paine; his consciousness of this finds full recognition in his works; yet he says:

"Though I reverence their philanthropy, I cannot help smiling at the conceit, that if the taste of a Quaker had been consulted at the creation, what a silent and drab-coloured creation it would have been! Not a flower would have blossomed its gaieties, nor a bird been permitted to sing."

There is a pathos under his smile at this conceit. Paine wrote it in later life, amid the flowers and birds of his garden, which he loved, but whose gaieties he could never imitate. He with difficulty freed himself from his early addiction to an unfashionable garb; he rarely entered a theatre, and could never enjoy cards.

By the light of the foregoing facts we may appreciate the few casual reminiscences of his school-days found in Paine's writings:

"My parents were not able to give me a shilling, beyond what they gave me in education; and to do this they distressed themselves.

"My father being of the Quaker profession, it was my good fortune to have an exceeding good moral education, and a tolerable stock of useful learning. Though I went to the grammar school (the same school, Thetford in Norfolk, that the present counsellor Mingay went to, and under the same master), I did not learn Latin, not only because I had no inclination to learn languages, but because of the objection the Quakers have against the books in which the language is taught. But this did not prevent me from being acquainted with the subjects of all the Latin books used in the school The natural bent of my mind was to science. I had some turn, and I believe some talent, for poetry; but this I rather repressed than encouraged, as leading too much into the field of imagination.

"I happened, when a schoolboy, to pick up a pleasing natural history of Virginia, and my inclination from that day of seeing the western side of the Atlantic never left me."

Paine does not mention his proficiency in mathematics, for which he was always distinguished. To my own mind his "turn" for poetry possesses much significance in the light of his career. In excluding poets from his "Republic" Plato may have had more reasons than he has assigned. The poetic temperament and power, repressed in the purely literary direction, are apt to break out in glowing visions of ideal society and fiery denunciations of the unlovely world.

Paine was not under the master of Thetford School (Colman), who taught Latin, but under the usher, Mr. William Knowler, who admitted the Quaker lad to some intimacy, and related to him his adventures while serving on a man-of-war. Paine's father had a small farm, but he also carried on a stay-making business in Thetford, and his son was removed from school, at the age of thirteen, to be taught the art and mystery of making stays. To that he stuck for nearly five years. But his father became poorer, his mother probably more discontented, and the boy began to dream over the adventures of Master Knowler on a man-of-war.

In the middle of the eighteenth century England and France were contending for empire in India and in America. For some service the ship Terrible, Captain Death, was fitted out, and Thomas Paine made an effort to sail on her. It seems, however, that he was overtaken by his father on board, and carried home again. "From this adventure I was happily prevented by the affectionate and moral remonstrances of a good father, who from the habits of his life, being of the Quaker profession, looked on me as lost." This privateer lost in an engagement one hundred and seventy-five of its two hundred men. Thomas was then in his seventeenth year. The effect of the paternal remonstrances, unsupported by any congenial outlook at Thetford, soon wore off, and, on the formal declaration of war against France (1756), he was again seized with the longing for heroic adventure, and went to sea on the King of Prussia, privateer, Captain Mendez. Of that he soon got enough, but he did not return home.

Of Paine's adventures with the privateer there is no record. Of yet more momentous events of his life for some years there is known nothing beyond the barest outline. In his twentieth year he found work in London (with Mr. Morris, stay-maker, Hanover Street, Longacre), and there remained near two years. These were fruitful years. "As soon as I was able I purchased a pair of globes, and attended the philosophical lectures of Martin and Ferguson, and became afterwards acquainted with Dr. Bevis, of the society called the Royal Society, then living in the Temple, and an excellent astronomer."

In 1758 Paine found employment at Dover with a stay-maker named Grace. In April, 1759, he repaired to Sandwich, Kent, where he established himself as a master stay-maker. There is a tradition at Sandwich that he collected a congregation in his room in the market-place, and preached to them "as an independent, or a Methodist" Here, at twenty-two, he married Mary Lambert. She was an orphan and a waiting-woman to Mrs. Richard Solly, wife of a woollen-draper in Sandwich. The Rev. Horace Gilder, Rector of St. Peter's, Sandwich, has kindly referred to the register, and finds the entry: "Thomas Pain, of the parish of St. Peters, in the town of Sandwich, in Kent, bachelor, and Mary Lambert, of the same parish, spinster, were married in this church, by licence, this 27th day of Sept., 1759, by me William Bunce, Rector." Signed "Thomas Pain, Mary Lambert In the presence of Thomas Taylor, Maria Solly, John Joslin."

The young couple began housekeeping on Dolphin Key, but Paine's business did not thrive, and he went to Margate. There, in 1760, his wife died, Paine then concluded to abandon the stay-making business. His wife's father had once been an exciseman. Paine resolved to prepare himself for that office, and corresponded with his father on the subject. The project found favor, and Paine, after passing some months of study in London, returned to Thetford in July, 1761. Here, while acting as a supernumerary officer of excise, he continued his studies, and enjoyed the friendship of Mr. Cock-sedge, the Recorder of Thetford. On 1 December, 1762, he was appointed to guage brewers' casks at Grantham. On 8 August, 1764, he was set to watch smugglers at Alford.

Thus Thomas Paine, in his twenty-fifth year, was engaged in executing Excise Acts, whose application to America prepared the way for independence. Under pressure of two great hungers—for bread, for science—the young exciseman took little interest in politics. "I had no disposition for what is called politics. It presented to my mind no other idea than is contained in the word jockey-ship." The excise, though a Whig measure, was odious to the people, and smuggling was regarded as not only venial but clever. Within two years after an excise of £1 per gallon was laid on spirits (1746), twelve thousand persons were convicted for offences against the Act, which then became a dead letter. Paine's post at Alford was a dangerous one. The exciseman who pounced on a party of smugglers got a special reward, but he risked his life. The salary was only fifty pounds, the promotions few, and the excise service had fallen into usages of negligence and corruption to which Paine was the first to call public attention. "After tax, charity, and fitting expenses are deducted, there remains very little more than forty-six pounds; and the expenses of housekeeping in many places cannot be brought under fourteen pounds a year, besides the purchase at first, and the hazard of life, which reduces it to thirty-two pounds per annum, or one shilling and ninepence farthing per day."

It is hardly wonderful that Paine with his globes and scientific books should on one occasion have fallen in with the common practice of excisemen called "stamping,"—that is, setting down surveys of work on his books, at home, without always actually travelling to the traders' premises and examining specimens. These detective rounds were generally offensive to the warehouse people so visited, and the scrutiny had become somewhat formal. For this case of "stamping," frankly confessed, Paine was discharged from office, 27 August, 1765.*

* I am indebted to Mr. G. J. Holyoake for documents that

shed full light on an incident which Oldys has carefully

left in the half-light congenial to his insinuations. The

minute of the Board of Excise, dated 27 August, 1765, is as

follows:

"Thomas Paine, officer of Alford (Lincolnshire), Grantham collection, having on July 11th stamped the whole ride, as appears by the specimens not being signed in any part thereof, though proper entry was shown in journal, and the victuallers stocks drawn down in his books as if the same had been surveyed that day, as by William Swallow, Supervisor's letter of 3rd instant, and the collector's report thereon, also by the said Paine's own confession of the 13th instant, ordered to be discharged; that Robert Peat, dropped malt assistant in Lynn collection, succeed him."

The following is Paine's petition for restoration:

"London, July 3, 1766. Honourable Sirs,—In humble obedience to your honours' letter of discharge hearing date August 29, 1765, I delivered up my commission and since that time have given you no trouble. I confess the justice of your honours' displeasure and humbly beg to add my thanks for the candour and lenity with which you at that unfortunate time indulged me. And though the nature of the report and my own confession cut off all expectations of enjoying your honours' favour then, yet I humbly hope it has not finally excluded me therefrom, upon which hope I humbly presume to entreat your honours to restore me. The time I enjoyed my former commission was short and unfortunate—an officer only a single year. No complaint of the least dishonesty or intemperance ever appeared against me; and, if I am so happy as to succeed in this, my humble petition, I will endeavour that my future conduct shall as much engage your honours' approbation as my former has merited your displeasure. I am, your honours' most dutiful humble servant, Thomas Paine."

Board's minute: "July 4, 1766. Ordered that he be restored on a proper vacancy."

Mr. S. F. Dun, for thirty-three years an officer of excise, discovered the facts connected with Paine's discharge, and also saw Paine's letter and entry books. In a letter before me he says: "I consider Mr. Paine's restoration as creditable to him as to the then Board of Excise."

After Paine's dismission he supported himself as a journeyman with Mr. Gudgeon, a stay-maker of Diss, Norfolk, where he is said to have frequently quarrelled with his fellow-workmen. To be cast back on the odious work, to be discharged and penniless at twenty-eight, could hardly soothe the poor man's temper, and I suppose he did not remain long at Diss. He is traceable in 1766 in Lincolnshire, by his casual mention of the date in connection with an incident related in his fragment on "Forgetfulness." He was on a visit at the house of a widow lady in a village of the Lincolnshire fens, and as they were walking in the garden, in the summer evening, they beheld at some distance a white figure moving. He quitted Mrs. E. and pursued the figure, and when he at length reached out his hand, "the idea struck me," he says, "will my hand pass through the air, or shall I feel anything?" It proved to be a love-distracted maiden who, on hearing of the marriage of one she supposed her lover, meant to drown herself in a neighboring pond.

That Thomas Paine should sue for an office worth, beyond its expenses, thirty-two pounds, argues not merely penury, but an amazing unconsciousness, in his twenty-ninth year, of his powers. In London, for some months there stood between him and starvation only a salary of twenty-five pounds, given him by a Mr. Noble for teaching English in his academy in Goodman's Fields. This was the year 1766, for though Paine was restored to the excise on July 11th of this year no place was found for him. In January, 1767, he was employed by Mr. Gardiner in his school at Kensington. Rickman and others have assigned to this time Paine's attendance of lectures at the Royal Society, which I have however connected with his twentieth year. He certainly could not have afforded globes during this pauperized year 1766. In reply to Rickman's allusion to the lowly situations he had been in at this time, Paine remarked: "Here I derived considerable information; indeed I have seldom passed five minutes of my life, however circumstanced, in which I did not acquire some knowledge."

According to Oldys he remained in the school at Kensington but three months. "His desire of preaching now returned on him," says the same author, "but applying to his old master for a certificate of his qualifications, to the bishop of London, Mr. Noble told his former usher, that since he was only an English scholar he could not recommend him as a proper candidate for ordination in the church." It would thus appear that Paine had not parted from his employer in Goodman's Fields in any unpleasant way. Of his relation with his pupils only one trace remains—a letter in which he introduces one of them to General Knox, September 17, 1783: "Old friend, I just take the opportunity of sending my respects to you by Mr. Darby, a gentleman who was formerly a pupil of mine in England."

Oldys says that Paine, "without regular orders," preached in Moorfields and elsewhere in England, "as he was urged by his necessities or directed by his spirit." Although Paine's friendly biographers have omitted this preaching episode, it is too creditable to Paine's standing with the teacher with whom he had served a year for Oldys to have invented it. It is droll to think that the Church of England should ever have had an offer of Thomas Paine's services. The Quakerism in which he had been nurtured had never been formally adopted by him, and it offered no opportunities for the impulse to preach which seems to mark a phase in the life of every active English brain.

On May 15, 1767, Paine was appointed excise officer at Grampound, Cornwall, but "prayed leave to wait another vacancy." On February 19, 1768, he was appointed officer at Lewes, Sussex, whither, after a brief visit to Thetford, he repaired.

Not very unlike the old Norfolk borough in which Paine was born was Lewes, and with even literally an Ouse flowing through it Here also marched the "Heathen Men," who have left only the legend of a wounded son of Harold nursed into health by a Christian maiden. The ruined castle commands a grander landscape than the height of Thetford, and much the same historic views. Seven centuries before Paine opened his office in Lewes came Harold's son, possibly to take charge of the excise as established by Edward the Confessor, just deceased.

"Paine" was an historic name in Lewes also. In 1688 two French refugees, William and Aaron Paine, came to the ancient town, and found there as much religious persecution as in France. It was directed chiefly against the Quakers. But when Thomas Paine went to dwell there the Quakers and the "powers that be" had reached a modus vivendi, and the new exciseman fixed his abode with a venerable Friend, Samuel Ollive, a tobacconist. The house then adjoined a Quaker meetinghouse, now a Unitarian chapel. It is a quaint house, always known and described as "the house with the monkey on it." The projecting roof is supported by a female nondescript rather more human than anthropoid. I was politely shown through the house by its occupant, Mr. Champion, and observed in the cellar traces of Samuel Ollive's—afterward Paine's—tobacco mill. The best room upstairs long bore on its wall "Tom Paine's study." The plaster has now flaked off, but the proprietor, Mr. Alfred Hammond, told me that he remembers it there in 1840. Not far from the house is the old mansion of the Shelleys,—still called "The Shelleys,"—ancestors of a poet born with the "Rights of Man," and a child of Paine's revolution. And—such are the moral zones and poles in every English town—here in the graveyard of Jireh Chapel—is the tomb of William Huntington S. S. [Sinner Saved] bearing this epitaph:

"Here lies the Coalheaver, beloved of God, but abhorred of men: the omniscient Judge, at the grand assize, shall ratify and confirm that to the confusion of many thousands; for England and its metropolis shall know that there hath been a prophet among them. W. H: S. S."

While Paine was at Lewes this Hunt alias Huntington was a pious tramp in that part of England, well known to the police. Yet in his rubbish there is one realistic story of tramp-life which incidentally portrays an exciseman of the time. Huntington (born 1744), one of the eleven children of a day-laborer earning from seven to nine shillings a week in Kent, was sent by some friends to an infant school.

"And here I remember to have heard my mistress reprove me for something wrong, telling me that God Almighty took notice of children's sins. It stuck to my conscience a great while; and who this God Almighty could be I could not conjecture; and how he could know my sins without asking my mother I could not conceive. At that time there was a person named Godfrey, an exciseman in the town, a man of a stern and hard-favoured countenance, whom I took notice of for having a stick covered with figures, and an ink-bottle hanging at the button-hole of his coat. I imagined that man to be employed by God Almighty to take notice, and keep an account of children's sins; and once I got into the market-house, and watched him very narrowly, and found that he was always in a hurry by his walking so fast; and I thought he had need to hurry, as he must have a deal to do to find out all the sins of children. I watched him out of one shop into another, all about the town, and from that time eyed him as a most formidable being, and the greatest enemy I had in all the world."

To the shopkeepers this exciseman was really an adversary and an accuser, and one can well believe that his very physiognomy would be affected by such work, and the chronic consciousness of being unwelcome. We may picture Paine among the producers of Lewes—with but four or five thousand people, then a notorious seat of smugglers—with his stick and ink-bottle; his face prematurely aged, and gathering the lines and the keen look which mask for casual eyes the fundamental candor and kindliness of his face.

Paine's surveys extended to Brighton; the brilliant city of our time being then a small fishing-town known as Brighthelmston. It was scarce ten miles distant, and had no magistrates, offenders being taken to Lewes. There was a good deal of religious excitement in the neighborhood about the time Paine went there to reside, owing to the preaching of Rev. George Whitefield, chaplain of Lady Huntingdon, at a chapel built by her ladyship at Brighthelmston. Lady Huntingdon already had a quasi-miraculous fame which in Catholic times would have caused her to be honored as St. Selina. In those days a pious countess was more miraculous than the dream that foretold about Lady Huntingdon's coming. Surrounded by crowds, she had to send for her chaplain, Whitefield, who preached in a field till a chapel was built. At the time when Lady Huntingdon was exhorting the poor villagers of Brighton, two relatives of hers, Governor Shirley of Massachusetts and his aide-de-camp Colonel George Washington, were preparing the way for the great events in which Paine was to bear a part.

When Paine went on his survey he might have observed the Washington motto, possibly a trace of the pious countess, which long remained on a house in Brighton: Exitus acta probat. There was an ancient Washington who fought at the battle of Lewes; but probably if our exciseman ever thought of any Washington at all it was of the anomalous Colonel in Virginia founding a colonial association to disuse excisable articles imported from England. But if such transatlantic phenomena, or the preaching of Whitefield in the neighborhood, concerned Paine at all, no trace of their impression is now discoverable. And if there were any protest in him at that time, when the English government had reached its nadir of corruption, it cannot be heard. He appears to have been conventionally patriotic, and was regarded as the Lewes laureate. He wrote an election song for the Whig candidate at New Shoreham, for which the said candidate, (Rumbold by name) paid him three guineas; and he wrote a song on the death of General Wolfe, which, when published some years later, was set to music, and enjoyed popularity in the Anacreontic and other societies. While Britannia mourns for her Wolfe, the sire of the gods sends his messengers to console "the disconsolate dame," assuring her that her hero is not dead but summoned to lead "the armies above" against the proud giants marching against Heaven.

The ballad recalls Paine the paien, but the Thetford Quaker is not apparent. And, indeed, there are various indications about this time that some reaction had set in after the preaching phase.

"Such was his enterprise on the water," says Oldys, "and his intrepidity on the ice that he became known by the appellation of Commodore" William Carver (MS.) says he was at this time "tall and slim, about five feet eight inches."

At Lewes, where the traditions concerning Paine are strong, I met Miss Rickman, a descendant of Thomas "Clio" Rickman—the name Clio, under which his musical contributions to the Revolution were published, having become part of his name. Rickman was a youth in the Lewes of Paine's time, and afterwards his devoted friend. His enthusiasm was represented in children successively named Paine, Washington, Franklin, Rousseau, Petrarch, Volney. Rickman gives an account of Paine at Lewes:

"In this place he lived several years in habits of intimacy with a very respectable, sensible, and convivial set of acquaintance, who were entertained with his witty sallies and informed by his more serious conversations. In politics he was at this time a Whig, and notorious for that quality which has been defined perseverance in a good cause and obstinacy in a bad one. He was tenacious of his opinions, which were bold, acute, and independent, and which he maintained with ardour, elegance, and argument. At this period, at Lewes, the White Hart evening club was the resort of a social and intelligent circle who, out of fun, seeing that disputes often ran very warm and high, frequently had what they called the 'Headstrong Book.' This was no other than an old Greek Homer which was sent the morning after a debate vehemently maintained, to the most obstinate haranguer in the Club: this book had the following title, as implying that Mr. Paine the best deserved and the most frequently obtained it: 'The Headstrong Book, or Original Book of Obstinacy.' Written by ———— ——— of Lewes, in Sussex, and Revised and Corrected by Thomas Paine.

"'Immortal Paine, while mighty reasoners jar, We crown thee General of the Headstrong War; Thy logic vanquish'd error, and thy mind No bounds but those of right and truth confined. Thy soul of fire must sure ascend the sky, Immortal Paine, thy fame can never die; For men like thee their names must ever save From the black edicts of the tyrant grave.'

"My friend Mr. Lee, of Lewes, in communicating this to me in September, 1810, said: 'This was manufactured nearly forty years ago, as applicable to Mr. Paine, and I believe you will allow, however indifferent the manner, that I did not very erroneously anticipate his future celebrity.'"

It was probably to amuse the club at the White Hart, an ancient tavern, that Paine wrote his humorous poems.

On the 26 March, 1771, Paine married Elizabeth, daughter of Samuel Ollive, with whom he had lodged. This respected citizen had died in July, 1769, leaving in Lewes a widow and one daughter in poor circumstances. Paine then took up his abode elsewhere, but in the following year he joined the Ollives in opening a shop, and the tobacco-mill went on as before. His motive was probably compassion, but it brought him into nearer acquaintance with the widow and her daughter. Elizabeth is said to have been pretty, and, being of Quaker parentage, she was no doubt fairly educated. She was ten years younger than Paine, and he was her hero. They were married in St. Michael's Church, Lewes, on the 26th of March, 1771, by Robert Austen, curate, the witnesses being Henry Verrall and Thomas Ollive, the lady's brother.

Oldys is constrained to give Paine's ability recognition. "He had risen by superior energy, more than by greater honesty, to be a chief among the excisemen." They needed a spokesman at that time, being united in an appeal to Parliament to raise their salaries, and a sum of money, raised to prosecute the matter, was confided to Paine. In 1772 he prepared the document, which was printed, but not published until 1793.* Concerning the plea for the excisemen it need only be said that it is as clear and complete as any lawyer could make it. There was, of course, no room for originality in the simple task of showing that the ill-paid service must be badly done, but the style is remarkable for simplicity and force.

Paine put much time and pains into this composition, and passed the whole winter of 1772-3 trying to influence members of Parliament and others in favor of his cause. "A rebellion of the excisemen," says Oldys, "who seldom have the populace on their side, was not much feared by their superiors." Paine's pamphlet and two further leaflets of his were printed. The best result of his pamphlet was to secure him an acquaintance with Oliver Goldsmith, to whom he addressed the following letter:

* The document was revived as a pamphlet, though its subject

was no longer of interest, at a time when Paine's political

writings were under prosecution, and to afford a vehicle for

an "introduction," which gives a graphic account of Paine's

services in the United States. On a copy of this London

edition (1793) before me, one of a number of Paine's early

pamphlets bearing marks of his contemporary English editor,

is written with pencil: "With a preface (Qy. J. Barlow)."

From this, and some characteristics of the composition, I

have no doubt that the vigorous introduction was Barlow's.

The production is entitled, "The Case of the Officers of

Excise; with remarks on the qualifications of Officers;

and of the numerous evils arising to the Revenue, from the

insufficiency of the present salary. Humbly addressed to the

Hon. and Right Hon. Members of both Houses of Parliament."

"Honored Sir,—Herewith I present you with the Case of the Officers of Excise. A compliment of this kind from an entire stranger may appear somewhat singular, but the following reasons and information will, I presume, sufficiently apologize. I act myself in the humble station of an officer of excise, though somewhat differently circumstanced to what many of them are, and have been the principal promoter of a plan for applying to Parliament this session for an increase of salary. A petition for this purpose has been circulated through every part of the kingdom, and signed by all the officers therein. A subscription of three shillings per officer is raised, amounting to upwards of £500, for supporting the expenses. The excise officers, in all cities and corporate towns, have obtained letters of recommendation from the electors to the members in their behalf, many or most of whom have promised their support. The enclosed case we have presented to most of the members, and shall to all, before the petition appear in the House. The memorial before you met with so much approbation while in manuscript, that I was advised to print 4000 copies; 3000 of which were subscribed for the officers in general, and the remaining 1000 reserved for presents. Since the delivering them I have received so many letters of thanks and approbation for the performance, that were I not rather singularly modest, I should insensibly become a little vain. The literary fame of Dr. Goldsmith has induced me to present one to him, such as it is. It is my first and only attempt, and even now I should not have undertaken it, had I not been particularly applied to by some of my superiors in office. I have some few questions to trouble Dr. Goldsmith with, and should esteem his company for an hour or two, to partake of a bottle of wine, or any thing else, and apologize for this trouble, as a singular favour conferred on His unknown

"Humble servant and admirer,

"Thomas Paine.

"Excise Coffee House,

"Broad Street, Dec. 21, 1772.

"P. S. Shall take the liberty of waiting on you in a day or two."'

* Goldsmith responded to Paine's desire for his acquaintance.

I think Paine may be identified as the friend to whom

Goldsmith, shortly before his death, gave the epitaph first

printed in Paine's Pennsylvania Magaritu, January, 1775,

beginning,

"Here Whitefoord reclines, and deny it who can,

Though he merrily lived he is now a grave man."

In giving it Goldsmith said, "It will be of no use to me

where I am going."

I am indebted for these records to the Secretary of Inland

Revenue, England, and to my friend, Charles Macrae, who

obtained them for me.

To one who reads Paine's argument, it appears wonderful that a man of such ability should, at the age of thirty-five, have had his horizon filled with such a cause as that of the underpaid excisemen, Unable to get the matter before Parliament, he went back to his tobacco-mill in Lewes, and it seemed to him like the crack of doom when, 8 April, 1774, he was dismissed from the excise. The cause of Paine's second dismission from the excise being ascribed by his first biographer (Oldys) to his dealing in smuggled tobacco, without contradiction by Paine, his admirers have been misled into a kind of apology for him on account of the prevalence of the custom. But I have before me the minutes of the Board concerning Paine, and there is no hint whatever of any such accusation. The order of discharge from Lewes is as follows: