Title: Down the Columbia

Author: Lewis R. Freeman

Release date: December 9, 2011 [eBook #38249]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Pat McCoy, Greg Bergquist and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

[Pg i]

[Pg ii]

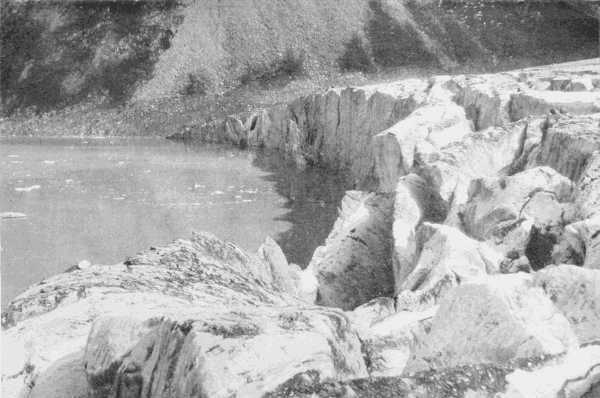

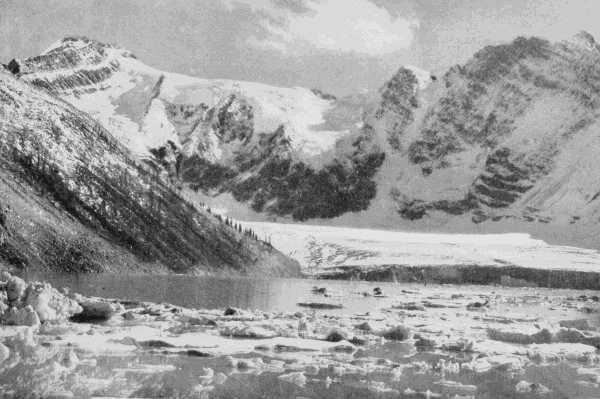

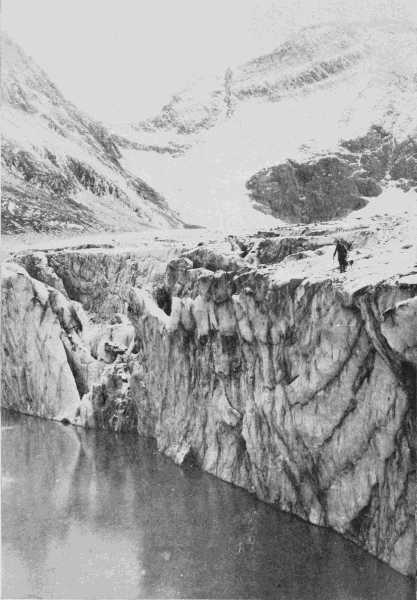

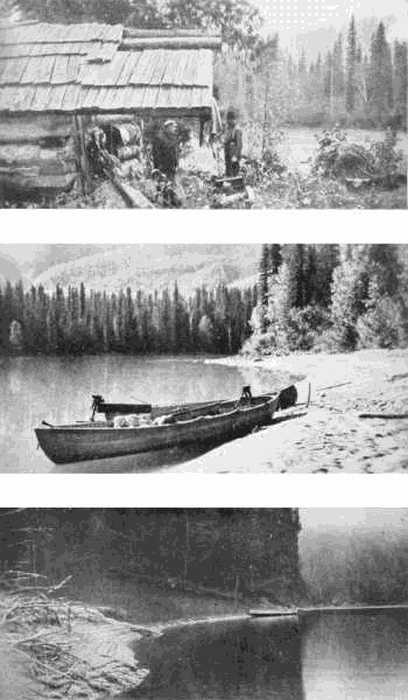

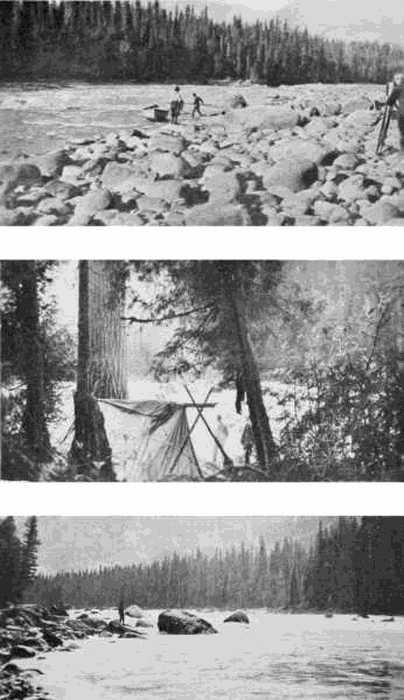

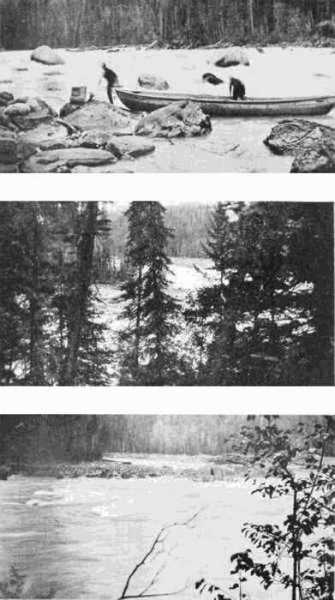

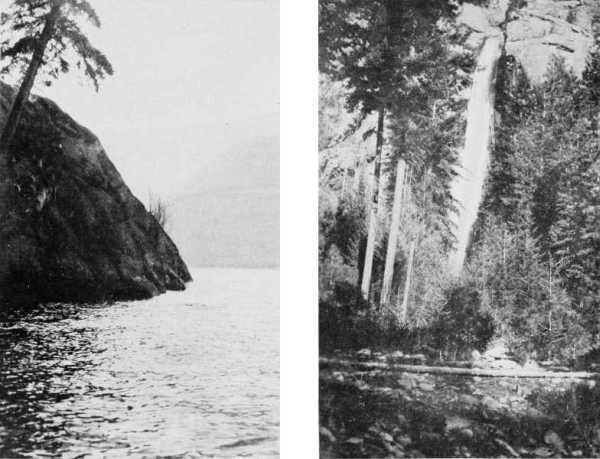

Courtesy of Byron Harmon, Banff

Courtesy of Byron Harmon, Banff[Pg iii]

AUTHOR OF “IN THE TRACKS OF THE TRADES,”

“HELL’S HATCHES,” ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

NEW YORK

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

1921

[Pg iv]

Copyright 1921

By DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY, Inc.

The Quinn & Boden Company

BOOK MANUFACTURERS

RAHWAY NEW JERSEY

[Pg v]

TO

C. L. CHESTER

Hoping he will find in these pages some compensation for the fun he missed in not being along.

[Pg vi]

[Pg vii]

The day on which I first conceived the idea of a boat trip down the Columbia hangs in a frame all its own in the corridors of my memory. It was a number of years ago—more than a dozen, I should say. Just previously I had contrived somehow to induce the Superintendent of the Yellowstone National Park to grant me permission to attempt a winter journey on ski around this most beautiful of America’s great playgrounds. He had even sent a Government scout along to keep, or help, me out of trouble. We were a week out from the post at Mammoth Hot Springs.

Putting the rainbow revel of the incomparable Canyon behind, we had crossed Yellowstone Lake on the ice and fared onward and upward until we came at last to the long climb where the road under its ten feet of snow wound up to the crest of the Continental Divide. It was so dry and cold that the powdery snow overlying the crust rustled under our ski like autumn leaves. The air was diamond clear, so transparent that distant mountain peaks, juggled in the wizardry of the lens of the light, seemed fairly to float upon the eyeball.

At the summit, where we paused for breath, an old Sergeant of the Game Patrol, letting down a tin can on a string, brought up drinks from an air-hole which he claimed was teetering giddily upon the very ridge-pole of North America.

“If I dip to the left,” he said, suiting the action to[Pg viii] the word, “it’s the Pacific I’ll be robbing of a pint of Rocky Mountain dew; while if I dip to the right it’s the Atlantic that’ll have to settle back a notch. And if I had a string long enough, and a wing strong enough, to cast my can over there beyond Jackson’s Hole,” he went on, pointing southeasterly to the serrated peaks of the Wind River Mountains, “I could dip from the fount of the Green River and keep it from feeding the Colorado and the Gulf of California by so much.”

That led me to raise the question of boating by river from the Great Divide to the sea, and the Scout, who knew something of the Madison, Jefferson and Gallatin to the east, and of the Salmon, Clearwater and Snake to the west, said he reckoned the thing could be done in either direction provided a man had lots of time and no dependent family to think of and shake his nerve in the pinches.

The old Sergeant agreed heartily. River boating was good, he said, because it was not opposed to Nature, like climbing mountains, for instance, where you were bucking the law of gravity from start to finish. With a river it was all easy and natural. You just got into your boat and let it go. Sooner or later, without any especial effort on your part, you reached your objective. You might not be in a condition to appreciate the fact, of course, but just the same you got there, and with a minimum of hard work. Some rivers were better for boating than others for the reason that you got there quicker. The Snake and the Missouri were all very well in their way, but for him, he’d take the Columbia. There was a river that[Pg ix] started in mountains and finished in mountains. It ran in mountains all the way to the sea. No slack water in all its course. It was going somewhere all the time. He had lived as a kid on the lower Columbia and had trapped as a man on the upper Columbia; so he ought to know. There was a “he” river if there ever was one. If a man really wanted to travel from snowflake to brine and not be troubled with “on-wee” on the way, there was no stream that ran one-two-three with the Columbia as a means of doing it.

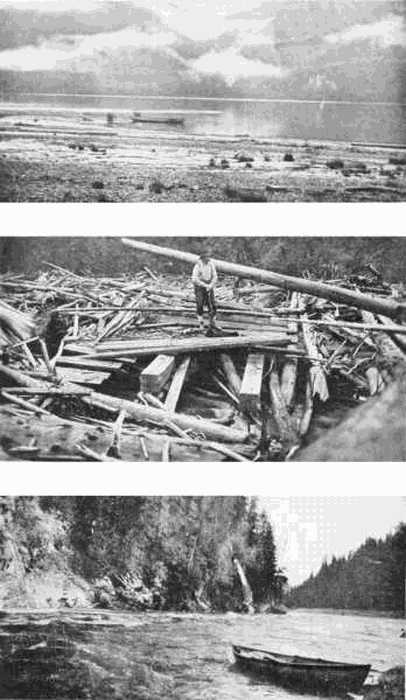

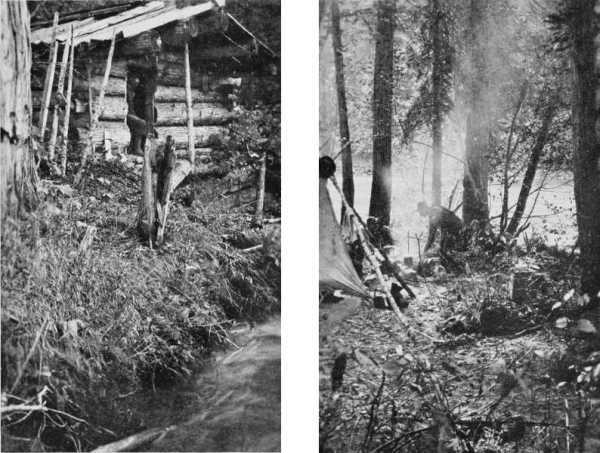

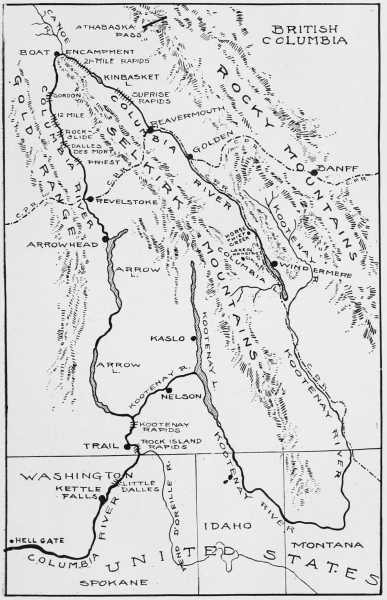

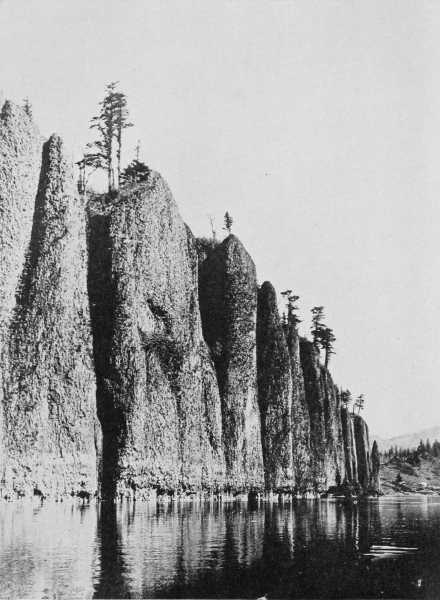

That night, where we steamed in the black depths of a snow-submerged Government “Emergency” cabin, the Sergeant’s old Columbia memories thawed with the hunk of frosted beef he was toasting over the sheet-iron stove. He told of climbing for sheep and goat in the high Kootenay, of trailing moose and caribou in the valleys of the Rockies, and finally of his years of trapping on the creeks and in the canyons that run down to the Big Bend of the Columbia; of how he used to go down to Kinbasket Lake in the Fall, portaging or lining the three miles of tumbling cascades at Surprise Rapids, trap all winter on Sullivan Creek or Middle River, and then come out in the Spring to Revelstoke, playing ducks-and-drakes with his life and his scarcely less valuable catch of marten, mink and beaver running the riffles at Rock Slide, Twelve Mile and the terrible Dalles des Morts. He declared that there were a hundred miles of the Big Bend of the Columbia that had buffaloed to a fare-ye-well any equal stretch on any of the great rivers of North America for fall, rocks and wild rip-rarin’ water generally. But the dread Rapids of Death and the[Pg x] treacherous swirls and eddies of Revelstoke Canyon were not the last of swift water by a long shot. Just below the defile of the Arrow Lakes the white caps began to rear their heads again, and from there right on down through the seven hundred miles and more to tide-water below the Cascade Locks in Oregon there was hardly a stretch of ten miles without its tumble of rapids, and mostly they averaged not more than three or four miles apart.

“She’s sure some ‘he’ river,” the old chap concluded as he began to unroll his blankets, “going somewhere all the time, tumbling over itself all the way trying to beat itself to the finish.”

Confusing as the Sergeant was with his “he” and “she” and “it” as to the gender of the mighty Oregon, there was no question of the fascination of the pictures conjured up by his descriptions of that so-well-called “Achilles of Rivers.” Before I closed my eyes that night I had promised myself that I should take the first opportunity to boat the length of the Columbia, to follow its tumultuous course from its glacial founts to the salt sea brine, to share with it, to jostle it in its “tumble to get there first.”

I held by that resolve for more than a dozen years, although, by a strange run of chance, I was destined to have some experience of almost every one of the great rivers of the world before I launched a boat upon the Columbia. My appetite for swift water boating had grown by what it fed on. I had come more and more to the way of thinking of my Yellowstone companion who held that boating down rivers was good because it was not opposed to Nature, “like mountain climb[Pg xi]ing, for instance, where you bucked the law of gravity all the way.” In odd craft and various, and of diverse degree of water worthiness, I had trusted to luck and the law of gravity to land me somewhere to seaward of numerous up-river points of vantage to which I had attained by means of travel that ranged all the way from foot and donkey-back to elephant and auto. The Ichang gorges of the Yangtze I had run in a sampan manned by a yelling crew of Szechuan coolies, and the Salween and Irawadi below the Yunnan boundary in weird Burmese canoes whose crews used their legs as well as their arms in plying their carved paddles. I had floated down the Tigris from Diarbekir to Mosul on a kalek of inflated sheepskins, and the Nile below the Nyanzas in a cranky craft of zebra hide, whose striped sides might have suggested the idea of modern marine camouflage. On the middle Niger I had used a condemned gunboat’s life-raft, and on the Zambesi a dugout of saffron-tinted wood so heavy that it sank like iron when capsized. And it had been in native dugouts of various crude types that I had boated greater or lesser lengths of the swifter upper stretches of the Orinoco, Amazon and Parana.

But through it all—whether I was floating in a reed-wrapped balsa on Titacaca or floundering in a pitch-smeared gufa on the Euphrates—pictures conjured up by remembered phrases of the old ex-trapper keep rising at the back of my brain. “The big eddy at the bend of Surprise Rapids, where you go to look for busted boats and dead bodies;” “the twenty-one mile of white water rolling all the way from Kinbasket Lake to Canoe River;” “the double[Pg xii] googly intake at the head of Gordon Rapid;” “the black-mouthed whirlpool waiting like a wild cat at the foot of Dalles des Morts”—how many times had I seen all these in fancy! And at last the time came when those pictures were to be made real—galvanized into life.

It was well along toward the end of last summer that my friend C. L. Chester, whose work in filming the scenic beauties of out-of-the-way parts of the world has made the name Chester-Outing Pictures a byword on both sides of the Atlantic, mentioned that he was sending one of his cameramen to photograph the sources of the Columbia in the Selkirks and Rockies of western Canada. Also that he was thinking of taking his own holiday in that incomparably beautiful region. He supposed I knew that there were considerable areas here that had barely been explored, to saying nothing of photographed. This was notably so of the Big Bend country, where the Columbia had torn its channel between the Rockies and Selkirks and found a way down to the Arrow Lakes. He was especially anxious to take some kind of a boat round the hundred and fifty miles of canyon between Beavermouth and Revelstoke and bring out the first movies of what he had been assured was the roughest stretch of swift water on any of the important rivers of the world. Was there, by any chance, a possibility that my plans and commitments were such that I would be free to join him in the event that he made the trip personally?

As a matter of fact there were several things that should have prevented my breaking away for a trip to[Pg xiii] the upper Columbia in September, not the least among which was a somewhat similar trip I had already planned for the Grand Canyon of the Colorado that very month. But the mention of the Big Bend was decisive. “I’ll go,” I said promptly. “When do you start?”

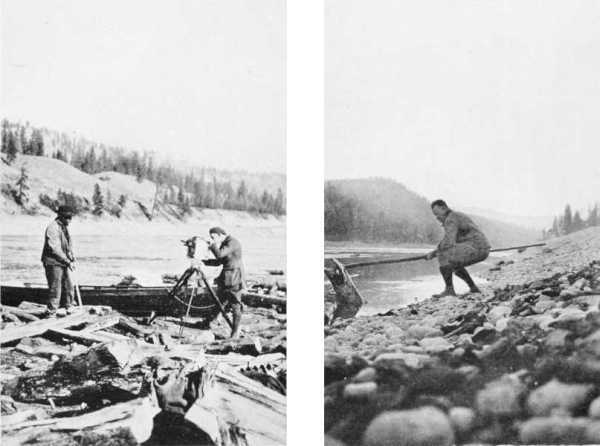

It was finally arranged that I should go on ahead and engage men and boats for the Big Bend part of the trip, while Chester would endeavour to disentangle himself from business in Los Angeles and New York in time to join his cameraman and myself for a jaunt by packtrain to the Lake of the Hanging Glaciers. The latter is one of the high glacial sources of the Columbia in the Selkirks, and Chester, learning that it had never been photographed, desired especially to visit it in person. Returning from our visit to the source of the river, we planned to embark on the boating voyage around the Big Bend. It was not until business finally intervened to make it impossible for Chester to get away for even a portion of the trip which he had been at such trouble to plan, that I decided to attempt the voyage down the Columbia as I had always dreamed of it—all the way from the eternal snows to tide-water. At Chester’s suggestion, it was arranged that his cameraman should accompany me during such portion of the journey as the weather was favourable to moving picture work.

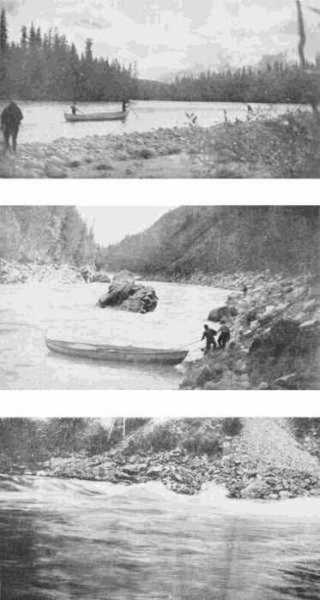

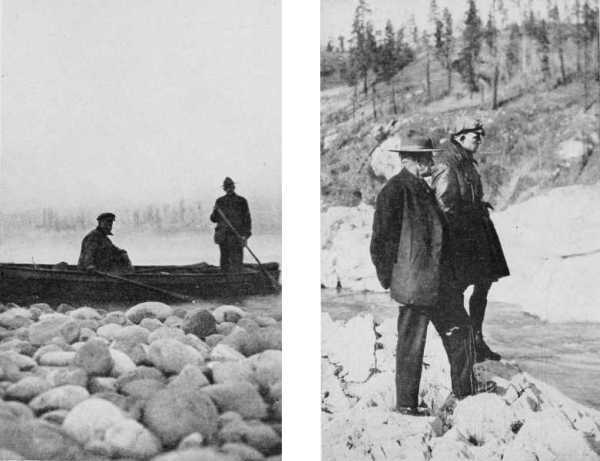

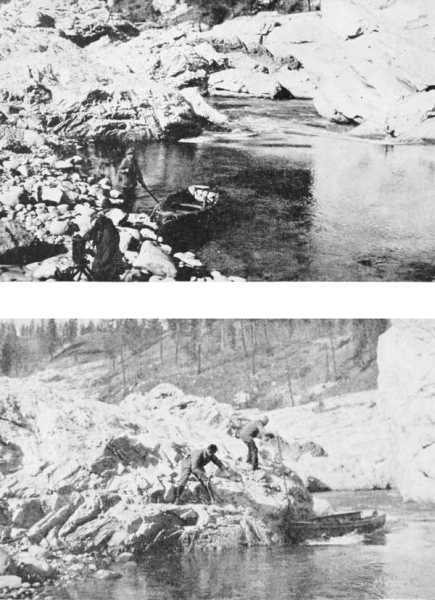

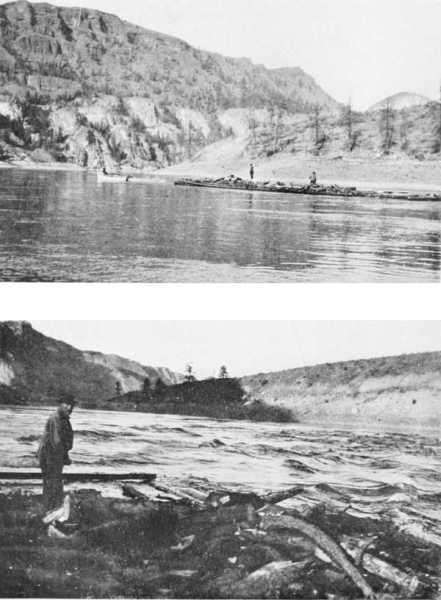

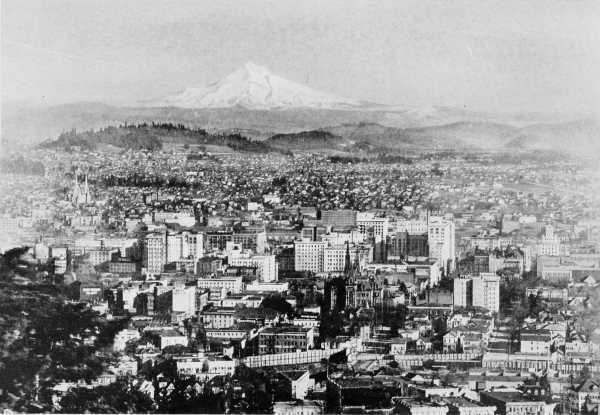

Our preliminary work and exploration among the sources of the river over (this was carried on either on foot or by packtrain, or in runs by canoe over short navigable stretches of the upper river), we pushed off from Beavermouth, at the head of the Big Bend.[Pg xiv] For this most arduous part of the voyage there were four in the party, with a big double-ended boat specially built for rough water. Further down, for a considerable stretch, we were three, in a skiff. Then, for a couple of hundred miles, there were four of us again, manning a raft and a towing launch. After that we were two—just the cameraman and myself, with the skiff. Him I finally dropped at the foot of Priest Rapids, fifty miles above Pasco, and the last two hundred and fifty miles down to Portland I rode alone. This “solo” run—though a one-man boat crew is kept rather too busy in swift water to have much time for enjoying the scenery—was far from proving the least interesting period of the journey.

So far as I have been able to learn, my arrival in Portland marked the end of the first complete journey that has been made from the glacial sources of the Columbia to tide-water. David Thompson, scientist and explorer for the Northwest Company, racing against the Astor sea expedition to be first to establish a post at the mouth of the Columbia, boated down a very large part of the navigable part of the river over a hundred years ago. I have found no evidence, however, that he penetrated to the glacial fields in the Selkirks above Windermere and Columbia Lake from which spring the main feeders of the upper river. Thompson’s, and all of the other voyages of the early days of which there is authentic record, started from Boat Encampment, where the road from the plains and Montreal led down to the Columbia by the icy waters of Portage River, or, as it is now called, Wood River. Thus all of the old Hudson Bay and North[Pg xv]west voyageurs ran only the lower seventy-five miles of the Big Bend, and avoided what is by far its worst water—Surprise Rapids and the twenty-one miles of cascades below Kinbasket Lake. Ross Cox, Alexander Ross and Franchiere, whose diaries are the best commentaries extant upon early Columbia history, had no experience of the river above Boat Encampment. Lewis and Clark, and Hunt, with the remnants of the Astor transcontinental party, boated the river only below the Snake, and this was also true of Whitman and the other early missionaries and settlers. Frémont made only a few days’ journey down the river from the Dalles.

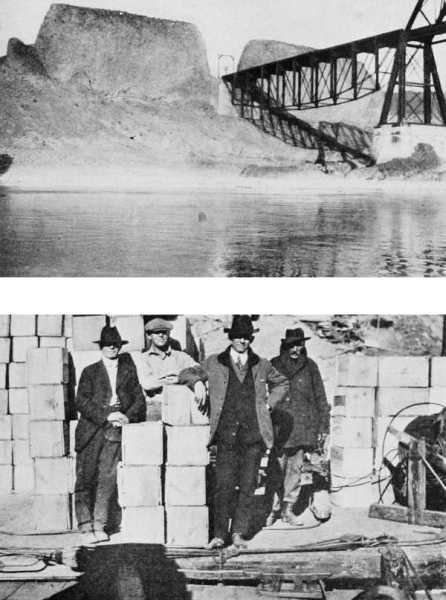

Of recent down-river passages, I have been able to learn of no voyageur who, having rounded the Big Bend, continued his trip down to the lower Columbia. The most notable voyage of the last three or four decades was that of Captain F. P. Armstrong and J. P. Forde, District Engineer of the Department of Public Works of Nelson, British Columbia, who, starting at the foot of the Lower Arrow Lake in a Peterboro canoe, made the run to Pasco, just above the mouth of the Snake, in ten days. As Captain Armstrong already knew the upper Columbia above the Arrow Lakes from many years of steamboating and prospecting, and as both he and Mr. Forde, after leaving their canoe at Pasco, continued on to Astoria by steamer, I am fully convinced that his knowledge of that river from source to mouth is more comprehensive than that of any one else of the present generation. This will be, perhaps, a fitting place to acknowledge my obligation to Captain Armstrong (who[Pg xvi] accompanied me in person from the mouth of the Kootenay to the mouth of the Spokane) for advice and encouragement which were very considerable factors in the ultimate success of my venture. To Mr. Forde I am scarcely less indebted for his courtesy in putting at my disposal a copy of his invaluable report to the Canadian Government on the proposal to open the Columbia to through navigation to the Pacific Ocean.

Compared to the arduous journeys of the old Astorian and Hudson Bay voyageurs on the Columbia, my own trip—even though a considerably greater length of river was covered than by any of my predecessors—was negligible as an achievement. Only in rounding the Big Bend in Canada does the voyageur of to-day encounter conditions comparable to those faced by those of a hundred, or even fifty years ago who set out to travel on any part of the Columbia. For a hundred miles or more of the Bend, now just as much as in years long gone by, an upset with the loss of an outfit is more likely than not to spell disaster and probably tragedy. But in my own passage of the Big Bend I can claim no personal credit that those miles of tumbling water were run successfully. I was entirely in the hands of a pair of seasoned old river hands, and merely pulled an oar in the boat and did a few other things when I was told.

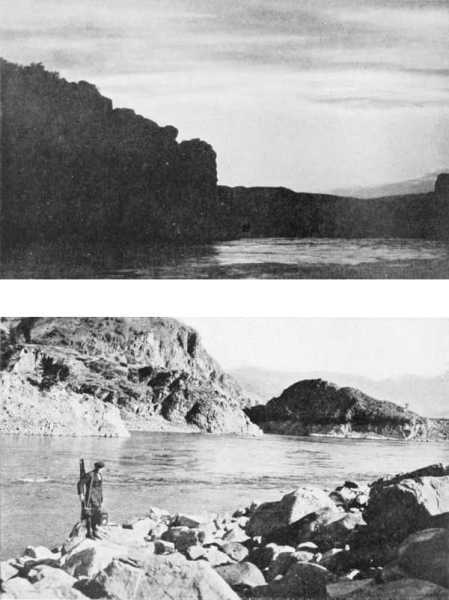

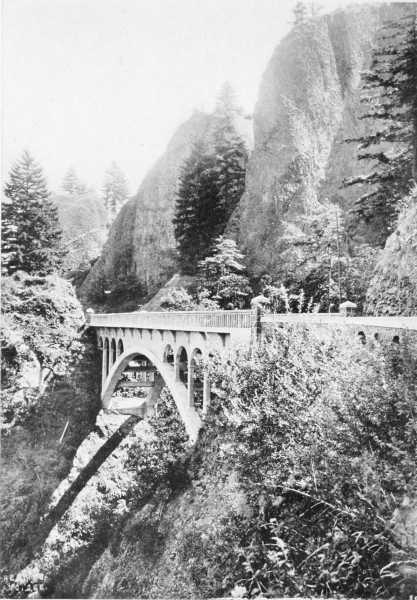

But it is on the thousand miles of swiftly flowing water between the lower end of the Big Bend and the Pacific that conditions have changed the most in favour of the latter day voyageur. The rapids are, to be sure, much as they must have appeared to Thompson,[Pg xvii] Ross, Franchiere and their Indian contemporaries. The few rocks blasted here and there on the lower river in an attempt to improve steamer navigation have not greatly simplified the problems of the man in a rowboat or canoe. Nor is an upset in any part of the Columbia an experience lightly to be courted even to-day. Even below the Big Bend there are a score of places I could name offhand where the coolest kind of an old river hand, once in the water, would not have one chance in ten of swimming out. In half a hundred others he might reckon on an even break of crawling out alive. But if luck were with him and he did reach the bank with the breath in his body, then his troubles would be pretty well behind him. Below the Canadian border there is hardly ten miles of the river without a farm, a village, or even a town of fair size. Food, shelter and even medical attention are not, therefore, ever more than a few hours away, so that the man who survives the loss of his boat and outfit is rarely in serious straits.

But in the case of the pioneers, their troubles in like instance were only begun. What between hostile Indians and the loss of their only means of travel, the chances were all against their ever pulling out with their lives. The story of how the vicious cascade of the Dalles des Morts won its grisly name, which I will set down in its proper place, furnishes a telling instance in point.

It is a callous traveller who, in strange lands and seas, does not render heart homage to the better men that have gone before him. Just as you cannot sail the Pacific for long without fancying that Cook and[Pg xviii] Drake and Anson are sharing your night watches, so on the Columbia it is Thompson and Cox and Lewis and Clark who come to be your guiding spirits. At the head of every one of the major rapids you land just as you know they must have landed, and it is as through their eyes that you survey the work ahead. And when, rather against your better judgment, you decide to attempt to run a winding gorge where the sides are too steep to permit lining and where a portage would mean the loss of a day—you know that the best of the men who preceded you must have experienced the same hollowness under the belt when they were forced to the same decision, for were they not always gambling at longer odds than you are? And when, elate with the thrill of satisfaction and relief that come from knowing that what had been a menacing roar ahead has changed to a receding growl astern, you are inclined to credit yourself with smartness for having run a rapid where Thompson lined or Ross Cox portaged, that feeling will not persist for long. Sooner or later—and usually sooner—something or somebody will put you right. A broken oar and all but a mess-up in an inconsiderable riffle was all that was needed to quench the glow of pride that I felt over having won through the roughly tumbling left-hand channel of Rock Island Rapids with only a short length of lining. And it was a steady-eyed old river captain who brought me back to earth the night I told him—somewhat boastfully, I fear—that I had slashed my skiff straight down the middle of the final pitch of Umatilla Rapids, where Lewis and Clark had felt they had to portage.

[Pg xix]“But you must not forget,” he said gently, with just the shadow of a smile softening the line of his firm lips, “that Lewis and Clark had something to lose besides their lives—that they had irreplaceable records in their care, and much work still to do. It was their duty to take as few chances as possible. But they never let the risk stop them when there wasn’t any safer way. When you are pulling through Celilo Canal a few days from now, and being eased down a hundred feet in the locks, just remember that Lewis and Clark put their whole outfit down the Tumwater and Five-Mile Rapids of the Dalles, in either of which that skiff of yours would be sucked under in half a minute.”

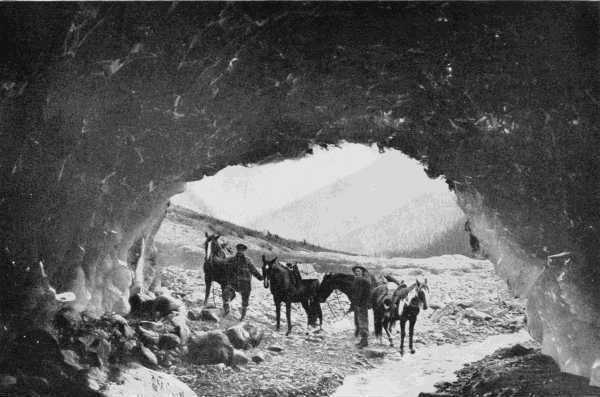

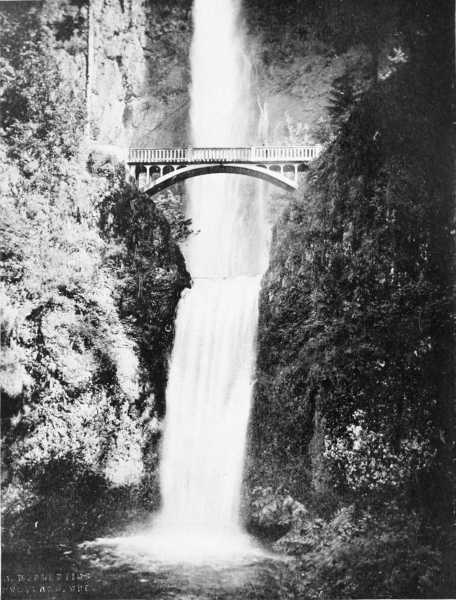

Bulking insignificantly as an achievement as does my trip in comparison with the many Columbia voyages, recorded and unrecorded, of early days, it still seems to me that the opportunity I had for a comprehensive survey of this grandest scenically of all the world’s great rivers gives me warrant for attempting to set down something of what I saw and experienced during those stirring weeks that intervened between that breathless moment when I let the whole stream of the Columbia trickle down my back in a glacial ice-cave in the high Selkirks, and that showery end-of-the-afternoon when I pushed out into tide-water at the foot of the Cascades.

It is scant enough justice that the most gifted of pens can do to Nature in endeavouring to picture in words the grandest of her manifestations, and my own quill, albeit it glides not untrippingly in writing of lighter things, is never so inclined to halt and sputter[Pg xx] as when I try to drive it to its task of registering in black scrawls on white paper something of what the sight of a soaring mountain peak, the depth of a black gorge with a white stream roaring at the bottom, or the morning mists rising from a silently flowing river have registered on the sensitized sheets of my memory. Superlative in grandeur to the last degree as are the mountains, glaciers, gorges, waterfalls, cascades and cliffs of the Columbia, it is to my photographs rather than my pen that I trust to convey something of their real message.

If I can, however, pass on to my readers some suggestion of the keenness of my own enjoyment of what I experienced on the Columbia—of the sheer joie de vivre that is the lot of the man who rides the running road; it will have not been in vain that I have cramped my fingers and bent my back above a desk during several weeks of the best part of the California year. Robert Service has written something about

Shall I need to confess to my readers that the one cloud on the seaward horizon during all of my voyage down the Columbia was brooding there as a consequence of the presentiment that, sooner or later, I should have to do my own babbling?

Pasadena, July, 1921.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Introduction | vi | |

| I. | Preparing for the Big Bend | 1 |

| II. | Up Horse Thief Creek | 20 |

| III. | At the Glacier | 48 |

| IV. | The Lake of the Hanging Glaciers | 63 |

| V. | Canal Flats to Beavermouth | 77 |

| VI. | Through Surprise Rapids | 92 |

| VII. | Kinbasket Lake and Rapids | 134 |

| VIII. | Boat Encampment to Revelstoke | 160 |

| IX. | Revelstoke to the Spokane | 192 |

| X. | Rafting Through Hell Gate | 235 |

| XI. | By Launch Through Box Canyon | 267 |

| XII. | Chelan to Pasco | 286 |

| XIII. | Pasco to the Dalles | 323 |

| XIV. | The Home Stretch | 360 |

FACING PAGE

DOWN THE COLUMBIA

The itinerary of our Columbia trip as originally planned in Los Angeles called, first, for an expedition to the source of the river, next, a voyage by boat around the Big Bend from Beavermouth to Revelstoke, and, finally, if there was time and good weather held, a voyage of indefinite length on toward the sea. As the trip to the glaciers was largely a matter of engaging a good packer well in advance, while there was no certainty of getting any one who would undertake the passage of the Big Bend, it was to the latter that we first directed our attention. Chester wired the Publicity Department of the Canadian Pacific and I wrote friends in various parts of British Columbia. The C. P. R. replied that they had requested their Sub-Divisional Superintendent at Revelstoke to institute inquiries for boatmen in our behalf. The only one of my friends who contributed anything tangible stated that “while the Columbia above Golden and below Revelstoke was admirably suited to pleasure boating, any attempt to run the Big Bend between those points would result in almost certain disaster.”

As this appeared to be about the extent of what we[Pg 2] were likely to learn from a distance, I decided to start north at once to see what could be arranged on the ground. Victoria yielded little save some large scale maps, and even these, they assured me in the Geographic Department of the B. C. Government where I secured them, were very inaccurate as to detail. The Big Bend region, it appeared, had never been surveyed north of the comparatively narrow zone of the C. P. R. grant. Several old hunting friends whom I met at the Club, although they had ranged the wildernesses of the Northwest from the Barren Lands to Alaska, spoke of the Big Bend as a veritable terra incognita.

“It’s said to be a great country for grizzly,” one of them volunteered, “but too hard to get at. Only way to get in and out is the Columbia, and that is more likely to land you in Kingdom Come than back in Civilization. Best forget about the Big Bend and go after sheep and goat and moose in the Kootenays.”

At Kamloops I was told of an Indian who had gone round the Big Bend the previous May, before the Spring rise, and come out not only with his own skin, but with those of seven grizzlies. I was unable to locate the Indian, but did find a white man who had made the trip with him. This chap spent half an hour apparently endeavouring to persuade me to give up the trip on account of the prohibitive risk (my experience on other rivers, he declared, would be worse than useless in such water as was to be encountered at Surprise, Kinbasket and Death Rapids) and about an equal amount of time trying to convince me that my life would be perfectly safe if only I would en[Pg 3]gage him and his Indian and confide it to their care. As the consideration suggested in return for this immunity figured out at between two and three times the rate we had been expecting to pay for boatmen, I had to decline to take advantage of it.

Finally, in Revelstoke, through the efforts of T. C. McNab of the Canadian Pacific, who had been at considerable trouble to line up possible candidates for a Big Bend trip, I met Bob Blackmore. After that things began moving toward a definite end.

“You won’t find old Bob Blackmore an active church-worker,” I was told in Revelstoke, “and at one time he had the reputation of being the smoothest thing in the way of a boot-legger in this part of B. C. But he drinks little himself, is a past-master of woodcraft, a dead shot, and has twice the experience of swift-water boating of any man on the upper Columbia. In spite of the fact that he has undergone no end of hardship in his thirty years of packing, hunting, prospecting, trapping and boating all over the West, he’s as hard to-day at fifty odd as most men are at thirty. Because he dished a boatload of freight last year somewhere up river, there are a few who are saying that old Bob Blackmore is losing his grip. Don’t believe it. He was never better in his life than he is right now, and if you can persuade him to run your show round the Big Bend you’re in luck. Once you start, you’ll come right on round to Revelstoke all right. No fear on that score. But if you have old Bob Blackmore you’ll stand a jolly lot better chance of arriving on top of the water.”

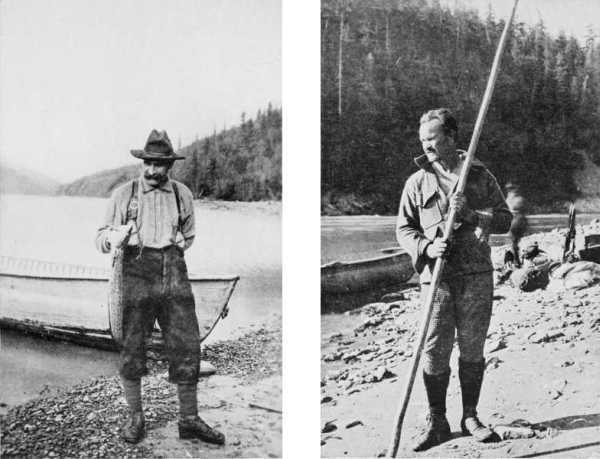

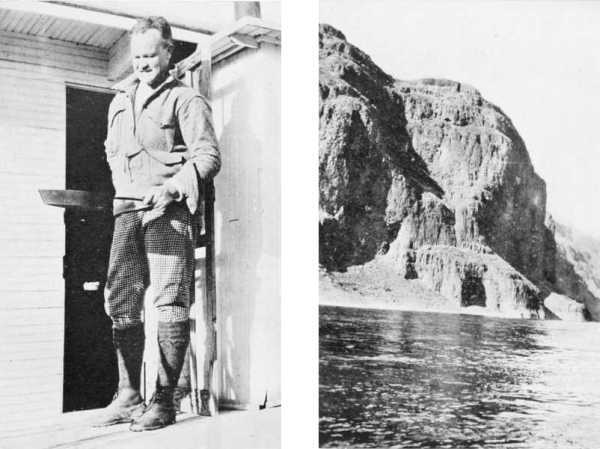

I found Bob Blackmore at his river-side home in the[Pg 4] old town—what had been the metropolitan centre of Revelstoke in the days when it was the head of navigation of steamers from below the Arrow Lakes, and before the railway had come to drag settlement a mile northeastward and away from the Columbia. He was picking apples with one hand and slapping mosquitoes with the other—a grey-haired, grey-eyed man of middle height, with a muscular torso, a steady stare, and a grip that I had to meet half way to save my fingers. He might have passed for a well-to-do Middle Western farmer except for his iron-grey moustaches, which were long and drooping, like those affected by cowboy-town sheriffs in the movies.

I knew at once that this was the man I wanted, and my only doubt was as to whether or not he felt the same way about me. They had told me in town that Blackmore, having some means and being more or less independent, never went out with a man or an outfit he did not like. I felt that it was I who was on approval, not he. I need not have worried, however. In this instance, at least, Bob Blackmore’s mind was made up in advance. It was the movies that had done it.

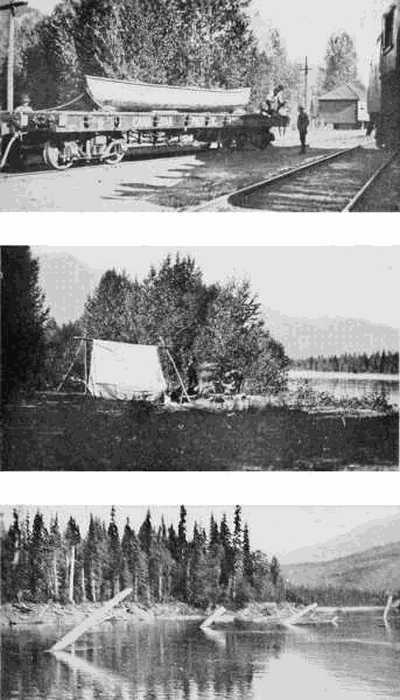

“The C. P. R. people wrote me that you might be wanting me for the Bend,” he said genially after I had introduced myself, “and on the chance that we would be hitching up I have put my big boat in the water to give her a good soaking. I’ve figured that she’s the only boat on the upper river that will do for what you want. I reckon I know them all. She’ll carry three or four times as much as the biggest Peterboro. Besides, if you tried to go round in canoes,[Pg 5] you’d be portaging or lining in a dozen places where I would drive this one straight through. With any luck, and if the water doesn’t go down too fast, I’d figure on going the whole way without taking her out of the river at more’n one place, and maybe not there.”

“So you’re willing to go ahead and see us through,” I exclaimed delightedly. “They told me in the town that you’d probably need a lot of persuading, especially as you’ve been saying for the last two or three years that you were through with the Bend for good and all.”

Blackmore grinned broadly and somewhat sheepishly. “So I have,” he said. “Fact is, I’ve never yet been round the Bend that I didn’t tell myself and everybody else that I’d never try it again. I really meant it the last time, which was three or four years ago. And I’ve really meant it every time I said it right up to a few days back, when I heard that you wanted to take a movie machine in there and try and get some pictures. If that was so, I said to myself, it was sure up to me to do what I could to help, for there’s scenery in there that is more worth picturing than any I’ve come across in thirty years of knocking around all over the mountain country of the West. So I’m your man if you want me. Of course you know something of what you’re going up against in bucking the Bend?”

“Yes,” I replied a bit wearily. “I’ve been hearing very little else for the last week. Let’s talk about the scenery.”

“So they’ve been trying to frighten you out of it,” he said with a sympathetic smile. “They always do[Pg 6] that with strangers who come here to tackle the Bend. And mostly they succeed. There was one chap they couldn’t stop, though. He was a professor of some kind from Philadelphia. Fact is, he wasn’t enough frightened. That’s a bad thing with the Columbia, which isn’t to be taken liberties with. I buried him near the head of Kinbasket Lake. We’ll see his grave when we come down from Surprise Rapids. I’ll want to stop off for a bit and see if the cross I put up is still standing. He was....”

“Et tu Brute,” I muttered under my breath. Then, aloud: “Let’s look at the boat.”

Already this penchant of the natives for turning the pages of the Big Bend’s gruesome record of death and disaster was getting onto my nerves, and it was rather a shock to find even the quiet-spoken, steady-eyed Blackmore addicted to the habit. Afterwards, when I got used to it, I ceased to mind. As a matter of fact, the good souls could no more help expatiating on what the Big Bend had done to people who had taken liberties with it than an aviator who is about to take you for a flight can help leading you round back of the hangar and showing you the wreckage of his latest crash. It seems to be one of the inevitable promptings of the human animal to warn his brother animal of troubles ahead. This is doubtless the outgrowth of the bogies and the “don’ts” which are calculated to check the child’s explorative and investigative instincts in his nursery days. From the source to the mouth of the Columbia it was never (according to the solicitous volunteer advisers along the way) the really dangerous rapids that I had put behind me.[Pg 7] These were always somewhere ahead—usually just around the next bend, where I would run into them the first thing in the morning. Luckily, I learned to discount these warnings very early in the game, and so saved much sleep which it would have been a real loss to be deprived of.

Blackmore led the way back through his apple orchard and down a stairway that descended the steeply-sloping river bank to his boat-house. The Columbia, a quarter of a mile wide and with just a shade of grey clouding its lucent greenness to reveal its glacial origin, slid swiftly but smoothly by with a purposeful current of six or seven miles an hour. A wing-dam of concrete, evidently built to protect the works of a sawmill a bit farther down stream, jutted out into the current just above, and the boat-house, set on a raft of huge logs, floated in the eddy below.

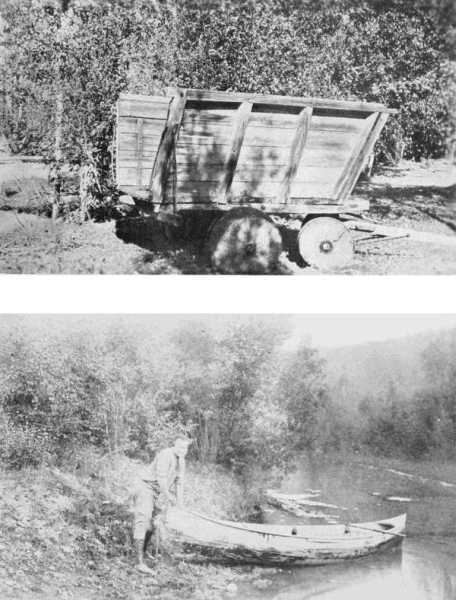

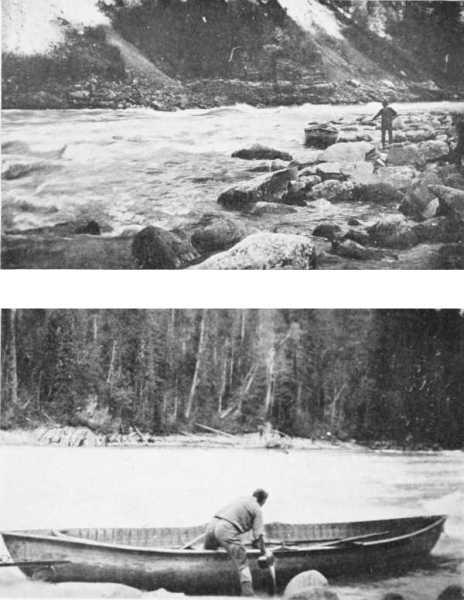

There were two boats in sight, both in the water. Blackmore indicated the larger one of the pair—a double-ender of about thirty feet in length and generous beam—as the craft recommended for the Big Bend trip. “I built her for the Bend more than fifteen years ago,” he said, tapping the heavy gunwale with the toe of his boot. “She’s the only boat I know that has been all the way round more than once, so you might say she knows the road. She’s had many a hard bump, but—with any luck—she ought to stand one or two more. Not that I’m asking for any more than can be helped, though. There’s no boat ever built that will stand a head-on crash ’gainst a rock in any such current as is driving it down Surprise or Kinbasket or Death Rapids, or a dozen other runs of[Pg 8] swift water on the Bend. Of course, you’re going to hit once in a while, spite of all you can do; but, if you’re lucky, you’ll probably kiss off without staving in a side. If you’re not—well, if you’re not lucky, you have no business fooling with the Bend at all.

“Now what I like about this big boat of mine,” he continued, taking up the scope of the painter to bring her in out of the tug of the current, “is that she’s a lucky boat. Never lost a man out of her—that is, directly—and only one load of freight. Now with that one (indicating the smaller craft, a canoe-like double-ender of about twenty feet) it’s just the other way. If there’s trouble around she’ll have her nose into it. She’s as good a built boat as any on the river, easy to handle up stream and down—but unlucky. Why, only a few weeks ago a lad from the town borrowed her to have a bit of a lark running the ripple over that dam there. It’s covered at high water, and just enough of a pitch to give the youngsters a little excitement in dropping over. Safe enough stunt with any luck at all. But that boat’s not lucky. She drifted on sidewise, caught her keel and capsized. The lad and the two girls with him were all drowned. They found his body a week or two later. All his pockets were turned wrong-side-out and empty. The Columbia current most always plays that trick on a man—picks his pockets clean. The bodies of the girls never did show up. Probably the sand got into their clothes and held them down. That’s another little trick of the Columbia. She’s as full of tricks as a box of monkeys, that old stream there, and you’ve got to[Pg 9] keep an eye lifting for ’em all the time if you’re going to steer clear of trouble.”

“It won’t be the first time I’ve had my pockets picked,” I broke in somewhat testily. “Besides, if you’re going to charge me at the rate that Indian I heard of in Kamloops demanded, there won’t be anything left for the Columbia to extract.”

That brought us down to business, and I had no complaint to make of the terms Blackmore suggested—twelve dollars a day for himself and boat, I to buy the provisions and make my own arrangements with any additional boatmen. I already had sensed enough of the character of the work ahead to know that a good boatman would be cheap at any price, and a poor one dear if working only for his grub. Blackmore was to get the big boat in shape and have it ready to ship by rail to Beavermouth (at the head of the Bend and the most convenient point to get a craft into the river) when I returned from the source of the Columbia above Windermere.

Going on to Golden by train from Revelstoke, I looked up Captain F. P. Armstrong, with whom I had already been in communication by wire. The Captain had navigated steamers between Golden and Windermere for many years, they told me at C. P. R. headquarters in Revelstoke, and had also some experience of the Bend. He would be unable to join me for the trip himself, but had spoken to one or two men who might be induced to do so. In any event his advice would be invaluable.

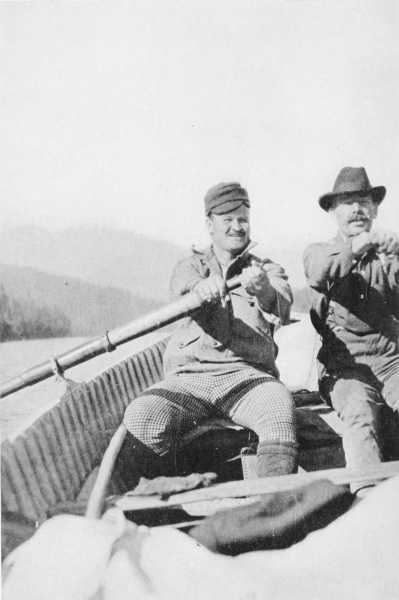

I shall have so much to say of Captain Armstrong in the account of a later part of my down-river voy[Pg 10]age that the briefest introduction to a man who has been one of the most picturesque personalities in the pioneering history of British Columbia will suffice here. Short, compactly but cleanly built, with iron-grey hair, square, determined jaw and piercing black eyes, he has been well characterized as “the biggest little man on the upper Columbia.” Although he confessed to sixty-three years, he might well have passed for fifty, a circumstance which doubtless had much to do with the fact that he saw three years of active service in the transport service on the Tigris and Nile during the late war. Indeed, as became apparent later, he generally had as much reserve energy at the end of a long day’s paddling as another man I could mention who is rather loath to admit forty.

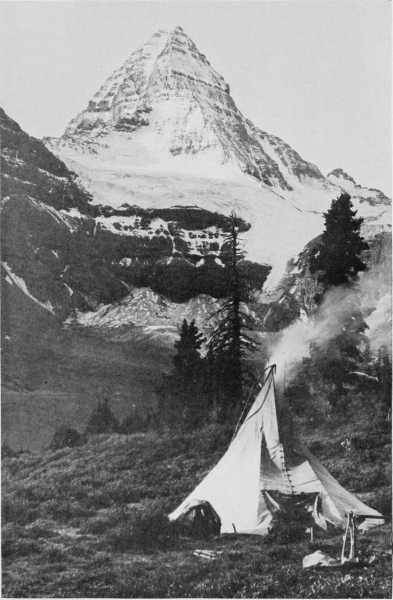

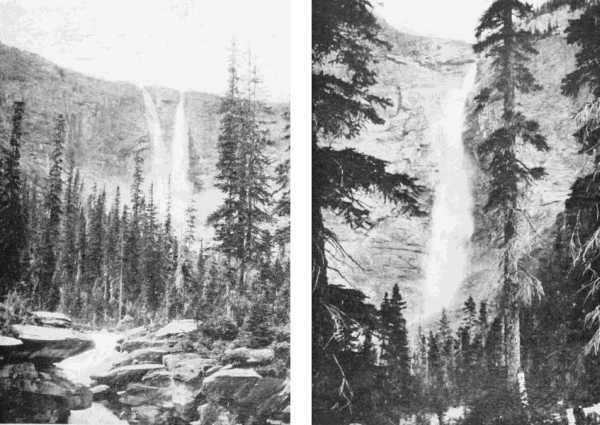

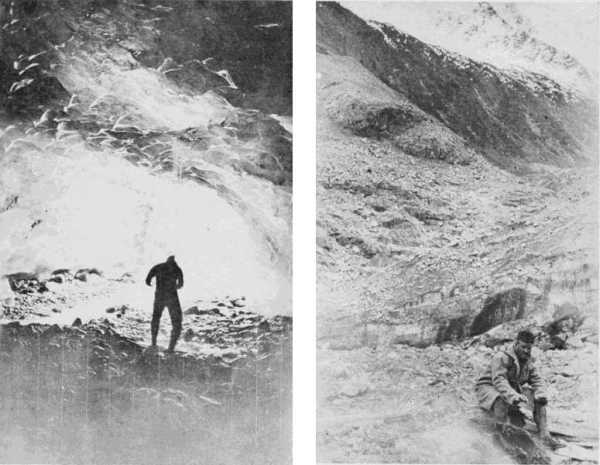

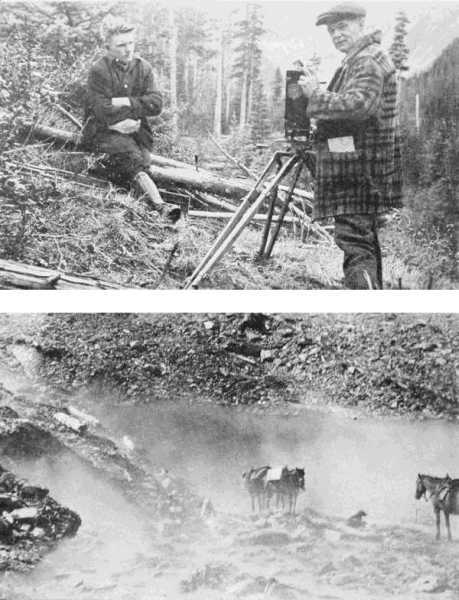

Courtesy of Byron Harmon, Banff

Courtesy of Byron Harmon, Banff TWIN FALLS (left)

TWIN FALLS (left)Captain Armstrong explained that he was about to close the sale of one of his mines on a tributary of the upper Columbia, and for that reason would be unable to join us for the Big Bend trip, as much as he would have enjoyed doing so. In the event that I decided to continue on down the Columbia after circling the Bend, it was just possible he would be clear to go along for a way. He spoke highly of Blackmore’s ability as a river man, and mentioned one or two others in Golden whom he thought might be secured. Ten dollars a day was the customary pay for a boatman going all the way round the Bend. That was about twice the ordinary wage prevailing at the time in the sawmills and lumber camps. The extra five was partly insurance, and partly because the work was hard and really good river men very scarce. It was [Pg 11]fair pay for an experienced hand. A poor boatman was worse than none at all, that is, in a pinch, while a good one might easily mean the difference between success and disaster. And of course I knew that disaster on the Bend—with perhaps fifty miles of trackless mountains between a wet man on the bank and the nearest human habitation—was spelt with a big D.

So far as I can remember, Captain Armstrong was the only one with whom I talked in Golden who did not try to dramatize the dangers and difficulties of the Big Bend. Seemingly taking it for granted that I knew all about them, or in any case would hear enough of them from the others, he turned his attention to forwarding practical plans for the trip. He even contributed a touch of romance to a venture that the rest seemed a unit in trying to make me believe was a sort of a cross between going over Niagara in barrel and a flight to one of the Poles.

“There was a deal of boot-legging on the river between Golden and Boat Encampment during the years the Grand Trunk was being built,” he said as we pored over an outspread map of the Big Bend, “for that was the first leg of the run into the western construction camps, where the sale of liquor was forbidden by law. Many and many a boatload of the stuff went wrong in the rapids. This would have been inevitable in any case, just in the ordinary course of working in such difficult water. But what made the losses worse was the fact that a good many of the bootleggers always started off with a load under their belts as well as in their boats. Few of the bodies were ever[Pg 12] found, but with the casks of whisky it was different, doubtless because the latter would float longer and resist buffeting better. Cask after cask has kept turning up through the years, even down to the present, when B. C. is a comparative desert. They are found in the most unexpected places, and it’s very rare for a party to go all the way round the Bend without stumbling onto one. So bear well in mind you are not to go by anything that looks like a small barrel without looking to see if it has a head in both ends. If you have time, it will pay you to clamber for a few hours over the great patch of drift just below Middle River on Kinbasket Lake. That’s the one great catch-all for everything floatable that gets into the river below Golden. I’ve found just about everything there from a canary bird cage to a railway bridge. Failing there (which will only be because you don’t search long enough), dig sixteen paces northwest by compass from the foundation of the west tower of the abandoned cable ferry just above Boat Encampment.”

“How’s that again!” I exclaimed incredulously. “Sure you aren’t confusing the Big Bend with the Spanish Main?”

“If you follow my directions,” replied the Captain with a grin, “you’ll uncover more treasure for five minutes’ scratching than you’d be likely to find in turning over the Dry Tortugas for five years. You see, it was this way,” he went on, smiling the smile of a man who speaks of something which has strongly stirred his imagination. “It was only a few weeks after Walter Steinhoff was lost in Surprise Rapids[Pg 13] that I made the trip round the Bend in a Peterboro to examine some silver-lead prospects I had word of. I had with me Pete Bergenham (a first-class river man; one you will do well to get yourself if you can) and another chap. This fellow was good enough with the paddle, but—though I didn’t know it when I engaged him—badly addicted to drink. That’s a fatal weakness for a man who is going to work in swift water, and especially such water as you strike at Surprise and the long run of Kinbasket Rapids. The wreckage of Steinhoff’s disaster (Blackmore will spin you the straightest yarn about that) was scattered all the way from the big whirlpool in Surprise Rapids down to Middle River, where they finally found his body. We might easily have picked up more than the one ten-gallon cask we bumped into, floating just submerged, in the shallows of the mud island at the head of Kinbasket Lake.

“I didn’t feel quite right about having so much whisky along; but the stuff had its value even in those days, and I would have felt still worse about leaving it to fall into the hands of some one who would be less moderate in its use than would I. I knew Pete Bergenham was all right, and counted on being able to keep an eye on the other man. That was just where I fell down. I should have taken the cask to bed with me instead of leaving it in the canoe.

“When the fellow got to the whisky I never knew, but it was probably well along toward morning. He was already up when I awoke, and displayed unwonted energy in getting breakfast and breaking camp. If I had known how heavily he had been tip[Pg 14]pling I would have given him another drink before pushing off to steady his nerve. That might have held him all right. As it was, reaction in mind and body set in just as we headed into that first sharp dip below the lake—the beginning of the twenty-one miles of Kinbasket Rapids. At the place where the bottom has dropped out from under and left the channel blocked by jagged rocks with no place to run through, he collapsed as if kicked in the stomach, and slithered down into the bottom of the canoe, blubbering like a baby. We just did manage to make our landing above the cascade. With a less skilful man than Bergenham at the stern paddle we would have failed, and that would have meant that we should probably not have stopped for good before we settled into the mud at the bottom of the Arrow Lakes.

“Even after that I could not find it in my heart to dish for good and all so much prime whisky. So I compromised by burying it that night, after we had come through the rapids without further mishap, at the spot I have told you of. That it was the best thing to do under the circumstances I am quite convinced. The mere thought that it was still in the world has cheered me in many a thirsty interval—yes, even out on the Tigris and the Nile, when there was no certainty I would ever come back to get it again.

“And now I’m going to tell you how to find it, for there’s no knowing if I shall ever have a chance to go for it myself. If you bring it out to Revelstoke safely, we’ll split it fifty-fifty, as they say on your side of the line. All I shall want to know is who your other boatmen are going to be. Blackmore is all right, but if[Pg 15] any one of the men whom he takes with him is a real drinker, you’d best forget the whole thing. If it’s an ‘all-sober’ crew, I’ll give you a map, marked so plainly that you can’t go wrong. It will be a grand haul, for it was Number One Scotch even when we planted it there, and since then it has been ageing in wood for something like ten years. I suppose you’ll be keen to smuggle your dividend right on down into the ‘The Great American Desert’?” he concluded with a grin.

“Trust me for that,” I replied with a knowing shake of my head. “I didn’t spend six months writing up opium smuggling on the China Coast for nothing.” Then I told him the story of the Eurasian lady who was fat in Amoy and thin in Hongkong, and who finally confessed to having smuggled forty pounds of opium, three times a week for five years, in oiled silk hip- and bust-pads.

“You must have a lot of prime ideas,” said the Captain admiringly. “You ought to make it easy, especially if you cross the line by boat. How would a false bottom ... but perhaps it would be safer to float it down submerged, with an old shingle-bolt for a buoy, and pick it up afterwards.”

“Or inside my pneumatic mattress,” I suggested. “But perhaps it would taste from the rubber.” By midnight we had evolved a plan which could not fail, and which was almost without risk. “The stuff’s as good as in California,” I told myself before I went to sleep—“and enough to pay all the expenses of my trip in case I should care to boot-leg it, which I won’t.”

Captain Armstrong’s mention of the Steinhoff disaster was not the first I had heard of it. The chap[Pg 16] with whom I had talked in Kamloops had shown me a photograph of a rude cross that he and his Indian companion had erected over Steinhoff’s grave, and in Revelstoke nearly every one who spoke of the Bend made some reference to the tragic affair. But here in Golden, which had been his home, the spectacularity of his passing seemed to have had an even more profound effect. As with everything else connected with the Big Bend, however, there was a very evident tendency to dramatize, to “play up,” the incident. I heard many different versions of the story, but there was one part, the tragic finale, in which they all were in practical agreement. When his canoe broke loose from its line, they said, and shot down toward the big whirlpool at the foot of the second cataract of Surprise Rapids, Steinhoff, realizing that there was no chance of the light craft surviving the maelstrom, coolly turned round, waved farewell to his companions on the bank, and, folding his arms, went down to his death. Canoe and man were sucked completely out of sight, never to be seen again until the fragments of the one and the battered body of the other were cast up, weeks later, many miles below.

It was an extremely effective story, especially as told by the local member in the B. C. Provincial Assembly, who had real histrionic talent. But somehow I couldn’t quite reconcile the Nirvanic resignation implied by the farewell wave and the folded arms with the never-say-die, cat-with-nine-lives spirit I had come to associate with your true swift-water boatman the world over. I was quite ready to grant that the big sockdolager of a whirlpool below the second pitch[Pg 17] of Surprise Rapids was a real all-day and all-night sucker, but the old river hand who gave up to it like the Kentucky coons at the sight of Davy Crockett’s squirrel-gun wasn’t quite convincing. That, and the iterated statement that Steinhoff’s canoe-mate, who was thrown into the water at the same time, won his way to the bank by walking along the bottom beneath the surface, had a decidedly steadying effect on the erratic flights to which my fancy had been launched by Big Bend yarns generally. There had been something strangely familiar in them all, and finally it came to me—Chinese feng-shui generally, and particularly the legends of the sampan men of the portage villages along the Ichang gorges of the Yangtze. The things the giant dragon lurking in the whirlpools at the foot of the rapids would do to the luckless ones he got his back-curving teeth into were just a slightly different way of telling what the good folk of Golden claimed the Big Bend would do to the hapless wights who ventured down its darksome depths.

Now that I thought of it in this clarifying light, there had been “dragon stuff” bobbing up about almost every stretch of rough water I had boated. Mostly it was native superstition, but partly it was small town pride—pride in the things their “Dragon” had done, and would do. Human nature—yes, and river rapids, too—are very much the same the world over, whether on the Yangtze, Brahmaputra or upper Columbia.

That brought the Big Bend into its proper perspective. I realized that it was only water running down hill after all. Possibly it was faster than any[Pg 18]thing I had boated previously, and certainly—excepting the Yukon perhaps—colder. A great many men had been drowned in trying to run it; but so had men been drowned in duck-ponds. But many men had gone round without disaster, and that would I do, Imshallah. I always liked that pious Arab qualification when speaking of futurities. Later I applied the name—in fancy—to the skiff in which I made the voyage down the lower river.

Yes, undoubtedly the most of the yarns and the warnings were “dragon stuff” pure and simple, but Romance remained. A hundred miles of river with possible treasure lurking in every eddy, and one place where it had to be! I felt as I did the first time I read “Treasure Island,” only more so. For that I had only read, and now I was going to search for myself—yes, and I was going to find, too. It was a golden sunset in more ways than one the evening before I was to leave for the upper river. Barred and spangled and fluted with liquid, lucent gold was the sky above hills that were themselves golden with the tints of early autumn. And in the Northwest there was a flush of rose, old rose that deepened and glowed in lambent crimson where a notch between the Selkirks and Rockies marked the approximate location of historic Boat Encampment. “Great things have happened at Boat Encampment,” I told myself, “and its history is not all written.” Then: “Sixteen paces northwest by compass from the foundation of the west tower of the abandoned cable ferry....” Several times during dinner that evening I had to check myself from humming an ancient song. “What’s that[Pg 19] about, ‘Yo, ho, ho and a bottle of rum’?” queried the mackinaw drummer from Winnipeg who sat next me. “I thought you were from the States. I don’t quite see the point.”

“It’s just as well you don’t,” I replied, and was content to let it go at that.

When I started north from Los Angeles toward the end of August Chester, held up for the moment by business, was hoping to be able to shake free so as to arrive on the upper Columbia by the time I had arrangements for the Big Bend voyage complete. We would then go together to the Lake of the Hanging Glaciers before embarking on the Bend venture. Luck was not with him, however. The day I was ready to start on up river from Golden I received a wire stating that he was still indefinitely delayed, and that the best that there was now any chance of his doing would be to join me for the Bend. He had ordered his cameraman to Windermere, where full directions for the trip to the glaciers awaited him. He hoped I would see fit to go along and help with the picture, as some “central figure” besides the guides and packers would be needed to give the “story” continuity. I replied that I would be glad to do the best I could, and left for Lake Windermere by the next train. Few movie stars have ever been called to twinkle upon shorter notice.

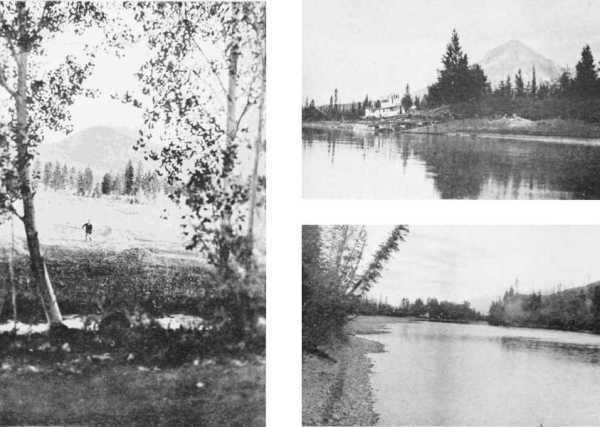

One is usually told that the source of the Columbia is in Canal Flats, a hundred and fifty miles above Golden, and immediately south of a wonderfully lovely mountain-begirt lake that bears the same name as the river. This is true in a sense, although, strictly speak[Pg 21]ing, the real source of the river—the one rising at the point the greatest distance from its mouth—would be the longest of the many mountain creeks which converge upon Columbia Lake from the encompassing amphitheatre of the Rockies and Selkirks. This is probably Dutch Creek, which rises in the perpetual snow of the Selkirks and sends down a roaring torrent of grey-green glacier water into the western side of Columbia Lake. Scarcely less distant from the mouth of the Columbia are the heads of Toby and Horse Thief creeks, both of which bring splendid volumes of water to the mother river just below Lake Windermere.

It was the presence of the almost totally unknown Lake of the Hanging Glaciers near the head of the Horse Thief Creek watershed that was responsible for Chester’s determination to carry his preliminary explorations up to the latter source of the Columbia rather than to one slightly more remote above the upper lake. We had assurance that a trail, upon which work had been in progress all summer, would be completed by the middle of September, so that it would then be possible for the first time to take pack-horses and a full moving-picture outfit to one of the rarest scenic gems on the North American continent, the Lake of the Hanging Glaciers. To get the first movies of what is claimed to be the only lake in the world outside of the polar regions that has icebergs perpetually floating upon its surface was the principal object of Chester in directing his outfit up Horse Thief Creek. My own object was to reach one of the several points where the Columbia took its rise in the[Pg 22] glacial ice, there to do a right-about and start upon my long-dreamed-of journey from snowflake to brine.

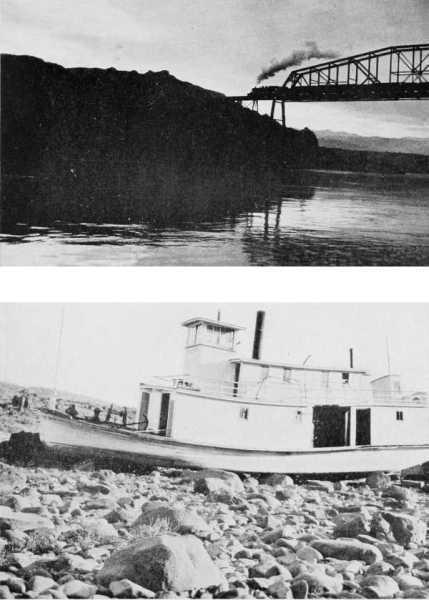

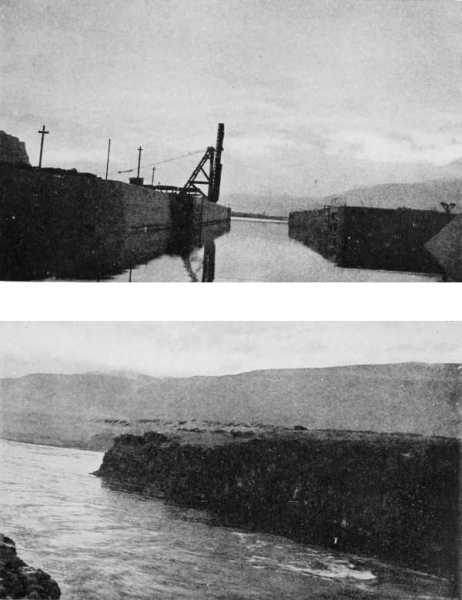

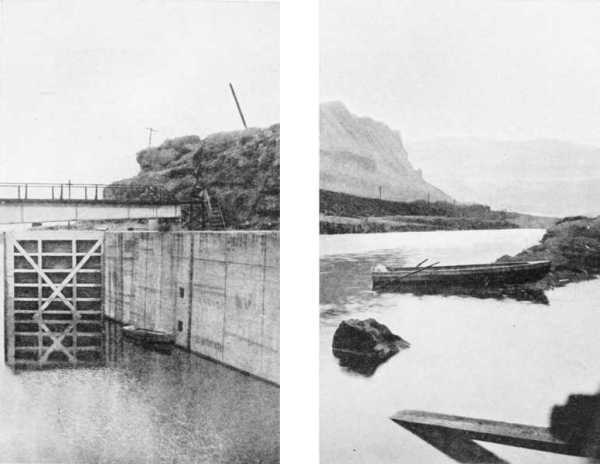

It is a dozen years or more since one could travel the hundred miles of the Columbia between Golden and Lake Windermere by steamer. The comparatively sparse population in this rich but thinly settled region was not sufficient to support both rail and river transport, and with the coming of the former the latter could not long be maintained. Two or three rotting hulks on the mud by the old landing at Golden are all that remain of one of the most picturesque steamer services ever run, for those old stern-wheelers used to flounder up the Columbia to Windermere, on through Mud and Columbia Lakes to Canal Flats, through a log-built lock to the Kootenay watershed, and then down the winding canyons and tumbling rapids of that tempestuous stream to Jennings, Montana. Those were the bonanza days of the upper Columbia and Kootenay—such days as they have never seen since nor will ever see again. I was to hear much of them later from Captain Armstrong when we voyaged a stretch of the lower river together.

There is a train between Golden and Windermere only three times a week. It is an amiable, ambling “jerk-water,” whose conductor does everything from dandling babies to unloading lumber. At one station he held over for five minutes to let me run down to a point where I could get the best light on a “reflection” picture in the river, and at another he ran the whole train back to pick up a basket of eggs which had been overlooked in the rush of departure. The[Pg 23] Canadian Pacific has the happy faculty of being all things to all men. Its main line has always impressed me as being the best-run road I have ever travelled on in any part of the world, including the United States. One would hardly characterize its little country feeders in the same words, but even these latter, as the instances I have noted will bear out, come about as near to being run for the accommodation of the travelling public as anything one will ever find. There is not the least need of hurrying this Golden-Windermere express. It stops over night at Invermere anyway, before continuing its leisurely progress southward the next morning.

Chester’s cameraman met me with a car at the station, and we rode a mile to the hotel at Invermere, on the heights above the lake. His name was Roos, he said—Len H. Roos of N. Y. C. It was his misfortune to have been born in Canada, he explained, but he had always had a great admiration for Americans, and had taken out his first papers for citizenship. He could manage to get on with Canadians in a pinch, he averred further; but as for Britishers—no “Lime-juicers” for him, with their “G’bly’me’s” and afternoon teas. I saw that this was going to be a difficult companion, and took the occasion to point out that, since he was going to be in Canada for some weeks, it might be just as well to bottle up his rancour against the land of his birth until he was back on the other side of the line and had completed the honour he intended to do Uncle Sam by becoming an American citizen. Maybe I was right, he admitted thoughtfully; but it would be a hard thing for him to do, as he[Pg 24] was naturally very frank and outspoken and a great believer in saying just what he thought of people and things.

He was right about being outspoken. He had also rather a glittering line of dogma on the finer things of life. Jazz was the highest form of music (he ought to know, for had he not played both jazz and grand opera when he was head drummer of the Galt, Ontario, town band?); the Mack Sennett bathing comedy was his belle ideal of kinematic art; and the newspapers of William Hearst were the supreme development of journalism. This latter he knew, because he had done camera work for a Hearst syndicate himself. I could manage to make a few degrees of allowance for jazz and the Mack Sennett knockabouts under the circumstances, but the deification of Hearst created an unbridgeable gulf. I foresaw that “director” and “star” were going to have bumpy sledding, but also perceived the possibility of comedy elements which promised to go a long way toward redeeming the enforced partnership from irksomeness, that is, if the latter were not too prolonged. That it could run to six or seven weeks and the passage of near to a thousand miles of the Columbia without turning both “director” and “star” into actual assassins, I would never have believed. Indeed, I am not able to figure out even now how it could have worked out that way. I can’t explain it. I merely state the fact.

Walter Nixon, the packer who was to take us “up Horse Thief,” had been engaged by wire a week previously. His outfit had been ready for several days,[Pg 25] and he called at the hotel the evening of my arrival to go over the grub list and make definite plans. As there were only two of us, he reckoned that ten horses and two packers would be sufficient to see us through. The horses would cost us two dollars a day a head, and the packers five dollars apiece. The provisions he would buy himself and endeavour to board us at a dollar and a half apiece a man. This footed up to between thirty-five and forty dollars a day for the outfit, exclusive of the movie end. It seemed a bit stiff offhand, but was really very reasonable considering present costs of doing that kind of a thing and the thoroughly first-class service Nixon gave us from beginning to end.

Nixon himself I was extremely well impressed with. He was a fine up-standing fellow of six feet or more, black-haired, black-eyed, broad-shouldered and a swell of biceps and thigh that even his loose-fitting mackinaws could not entirely conceal. I liked particularly his simple rig-out, in its pleasing contrast to the cross-between-a-movie-cowboy-and-a-Tyrolean-yodeler garb that has come to be so much affected by the so-called guides at Banff and Lake Louise. Like the best of his kind, Nixon was quiet-spoken and leisurely of movement, but with a suggestion of powerful reserves of both vocabulary and activity. I felt sure at first sight that he was the sort of a man who could be depended upon to see a thing through whatever the difficulties, and I never had reason to change my opinion on that score.

It was arranged that night that Nixon should get away with the pack outfit by noon of the next day, and[Pg 26] make an easy stage of it to the Starbird Ranch, at the end of the wagon-road, nineteen miles out from Invermere. The following morning Roos and I would come out by motor and be ready to start by the time the horses were up and the packs on. That gave us an extra day for exploring Windermere and the more imminent sources of the Columbia.

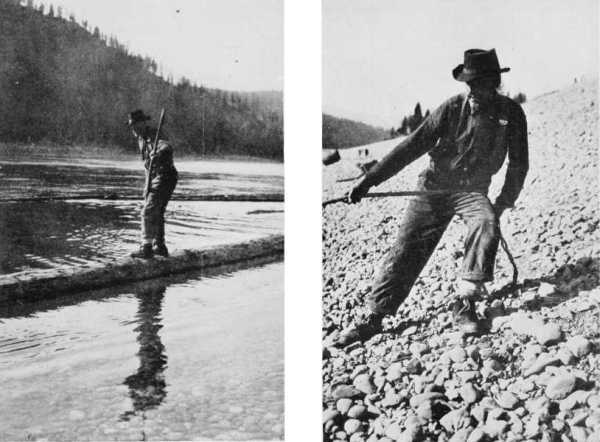

Roos’ instructions from Chester called for a “Windermere Picture,” in which should be shown the scenic, camping, fishing and hunting life of that region. The scenic and camping shots he had already made; the fish and the game had eluded him. I arrived just in time to take part in the final scurry to complete the picture. The fish to be shown were trout, and the game mountain sheep and goat, or at least that was the way Roos planned it at breakfast time. When inquiry revealed that it would take a day to reach a trout stream, and three days to penetrate to the haunts of the sheep and goats, he modified the campaign somewhat to conform with the limited time at our disposal. Close at hand in the lake there was a fish called the squaw-fish, which, floundering at the end of a line, would photograph almost like a trout, or so the hotel proprietor thought. And the best of it was that any one could catch them. Indeed, at times one had to manœuvre to keep them from taking the bait that was meant for the more gamy and edible, but also far more elusive, ling or fresh-water cod. As for the game picture, said Roos, he would save time by having a deer rounded up and driven into the lake, where he would pursue it with a motor boat and shoot the required hunting pictures. He would like[Pg 27] to have me dress like a tourist and do the hunting and fishing. That would break me in to adopting an easy and pleasing manner before the camera, so that a minimum of film would be spoiled when he got down to our regular work on the Hanging Glacier picture. It wouldn’t take long. That was the advantage of “news” training for a cameraman. You could do things in a rush when you had to.

Mr. Clelland, secretary of the Windermere Company, courteously found us tackle and drove us down to the outlet of the lake to catch the squaw-fish. Three hours later he drove us back to the hotel for lunch without one single fragment of our succulent salt-pork bait having been nuzzled on its hook. I lost my “easy and pleasing manner” at the end of the first hour, and Roos—who was under rather greater tension in standing by to crank—somewhat sooner. He said many unkind things about fish in general and squaw-fish in particular before we gave up the fight at noon, and I didn’t improve matters at all by suggesting that I cut out the picture on a salmon can label, fasten it to my hook, and have him shoot me catching that. There was no sense whatever in the idea, he said. You had to have studio lighting to get away with that sort of thing. He couldn’t see how I could advance such a thing seriously. As I had some doubts on that score myself, I didn’t start an argument.

In the afternoon no better success attended our effort to make the hunting picture,—this because no one seemed to know where a deer could be rounded up and driven into the lake. Again I discovered a way[Pg 28] to save this situation. On the veranda of the country club there was a fine mounted specimen of Ovis Canadensis, the Canadian mountain sheep. By proper ballasting, I pointed out to Roos, this fine animal could be made to submerge to a natural swimming depth—say with the head and shoulders just above the water. Then a little Evinrude engine could be clamped to its hind quarters and set going. Forthwith the whole thing must start off ploughing across the lake just like a live mountain sheep. By a little manœuvring it ought to be possible to shoot at an angle that would interpose the body of the sheep between the eye and the pushing engine. If this proved to be impossible, perhaps it could be explained in a sub-title that the extraneous machinery was a fragment of mowing-machine or something of the kind that the sheep had collided with and picked up in his flight. Roos, while admitting that this showed a considerable advance over my salmon-label suggestion of the morning, said that there were a number of limiting considerations which would render it impracticable. I forget what all of these were, but one of them was that our quarry couldn’t be made to roll his eyes and register “consternation” and “mute reproach” in the close-ups. I began to see that there was a lot more to the movie game than I had ever dreamed. But what a stimulator of the imagination it was!

As there was nothing more to be done about the hunting and fishing shots for the present, we turned our attention to final preparations for what we had begun to call the “Hanging Glacier Picture.” Roos[Pg 29] said it would be necessary to sketch a rough sort of scenario in advance—nothing elaborate like “Broken Blossoms” or “The Perils of Pauline” (we hadn’t the company for that kind of thing), but just the thread of a story to make the “continuity” ripple continuously. It would be enough, he thought, if I would enact the rôle of a gentleman-sportsman and allow the guides and packers to be just their normal selves. Then with these circulating in the foreground, he would film the various scenic features of the trip as they unrolled. All the lot of us would have to do would be to act naturally and stand or lounge gracefully in those parts of the picture where the presence of human beings would be best calculated to balance effectively and harmoniously the composition. I agreed cheerfully to the sportsman part of my rôle, but demurred as to “gentleman.” I might manage it for a scene, but for a sustained effort it was out of the question. A compromise along this line was finally effected. I engaged to act as much like a gentleman as I could for the opening shot, after which I was to be allowed to lapse into the seeming of a simple sportsman who loved scenery-gazing more than the pursuit and slaying of goat, sheep and bear. Roos observed shrewdly that it would be better to have the sportsman be more interested in scenery than game because, judging from our experience at Windermere, we would find more of the former than the latter. He was also encouragingly sympathetic about my transient appearance as a gentleman. “I only want about fifty feet of that,” he said as he gave me[Pg 30] a propitiating pat on the back; “besides, it’s all a matter of clothes anyhow.”

Before we turned in that night it transpired that Chester’s hope of being the first to show moving pictures of the Lake of the Hanging Glaciers to the world was probably doomed to disappointment, or, at the best, that this honour would have to be shared with an equally ambitious rival. Byron Harmon, of Banff, formerly official photographer for the Canadian Pacific, arrived at Invermere and announced that he was planning to go “up Horse Thief” and endeavour to film a number of the remarkable scenic features which he had hitherto tried to picture in vain. His schedule was temporarily upset by the fact that we had already engaged the best packtrain and guides available. Seasoned mountaineer that he was, however, this was of small moment. A few hours’ scurrying about had provided him with a light but ample outfit, consisting of four horses and two men, with which he planned to get away in the morning. He was not in the least perturbed by the fact that Roos had practically a day’s start of him. “There’s room for a hundred cameramen to work up there,” he told me genially; “and the more the world is shown of the wonders of the Rockies and the Selkirks, the more it will want to see. It will be good to have your company, and each of us ought to be of help to the other.”

I had some difficulty in bringing Roos to a similarly philosophical viewpoint. His “Hearst” training impelled him to brook no rivalry, to beat out the other man by any means that offered. He had the better packtrain, he said, to say nothing of a day’s start.[Pg 31] Also, he had the only dynamite and caps available that side of Golden, so that he would have the inside track for starting avalanches and creating artificial icebergs in the Lake of the Hanging Glaciers. I would like to think that it was my argument that, since it was not a “news” picture he was after, the man who took the most time to his work would be the one to get the best results, was what brought him round finally. I greatly fear, however, it was the knowledge that the generous Harmon had a number of flares that did the trick. He had neglected to provide flares himself, and without them work in the ice caves—second only in interest to the Lake of the Hanging Glaciers itself—would be greatly circumscribed. At any rate, he finally agreed to a truce, and we took Harmon out to the end of the road in our car the following morning. Of the latter’s really notable work in picturing the mountains of western Canada I shall write later.

The horses were waiting, saddled and packed, as we drove up to the rendezvous. The packer was a powerfully built fellow, with his straight black hair and high cheek bones betokening a considerable mixture of Indian blood. His name was Buckman—Jim Buckman. He was the village blacksmith of Athalmere, Nixon explained. He was making plenty of money in his trade, but was willing to come along at a packer’s wage for the sake of the experience as an actor. The lure of the movies was also responsible for the presence of Nixon’s fourteen-year-old son, Gordon, who had threatened to run away from home if he wasn’t allowed to come along. He proved a useful acquisition—more than sufficiently so, it seemed to[Pg 32] me, to compensate for what he did to the jam and honey.

Roos called us around him and gave instructions for the “business” of the opening shot. Nixon and Jim were to be “picked up” taking the last of the slack out of a “diamond hitch,” Gordon frolicking in the background with his dog. When the car drove up, Nixon was to take my saddle horse by the bridle, walk up and shake hands with me. Then, to make the transition from Civilization to the Primitive (movie people never miss a chance to use that word) with a click, I was to step directly from the car into my stirrups. “Get me!” admonished Roos; “straight from the running board to the saddle. Don’t touch the ground at all. Make it snappy, all of you. I don’t want any of you to grow into ‘foot-lice.’”

My saddle horse turned out to be a stockily-built grey of over 1200 pounds. He looked hard as nails and to have no end of endurance. But his shifty eye and back-laid ears indicated temperamentality, so that Nixon’s warning that he “warn’t exactly a lady’s hawss” was a bit superfluous. “When you told me you tipped the beam at two-forty,” he said, “I know’d ‘Grayback’ was the only hawss that’d carry you up these trails. So I brung him in, and stuffed him up with oats, and here he is. He may dance a leetle on his toes jest now, but he’ll gentle down a lot by the end of a week.”

Whether “Grayback” mastered all of the “business” of that shot or not is probably open to doubt, but that he took the “Make it snappy!” part to heart there was no question. He came alongside like a[Pg 33] lamb, but the instant I started to make my transition from “Civilization to the Primitive with a click” he started climbing into the car. The only click I heard was when my ear hit the ground. Roos couldn’t have spoiled any more film than I did cuticle, but, being a “Director,” he made a good deal more noise about it. After barking his hocks on the fender, “Grayback” refused to be enticed within mounting distance of the car again, so finally, with a comparatively un-clicky transition from Civilization to the Primitive, I got aboard by the usual route from the ground.

The next shot was a quarter of a mile farther up the trail. Here Roos found a natural sylvan frame through which to shoot the whole outfit as it came stringing along. Unfortunately, the “Director” failed to tell the actors not to look at the camera—that, once and for all, the clicking box must be reckoned as a thing non-existent—and it all had to be done over again. The next time it was better, but the actors still had a wooden expression on their faces. They didn’t look at the camera, but the expression on their faces showed that they were conscious of it. Roos then instructed me to talk to my companions, or sing, or do anything that would take their minds off the camera and make them appear relaxed and natural. That time we did it famously. As each, in turn, cantered by the sylvan bower with its clicking camera he was up to his neck “doing something.” Nixon was declaiming Lincoln’s Gettysburg speech as he had learned it from his phonograph, Gordon was calling his dog, Jim was larruping a straggling pinto and cursing it in fluent local idiom, and I was singing[Pg 34] “Onward, Christian Soldiers!” We never had any trouble about “being natural” after that; but I hope no lip reader ever sees the pictures.

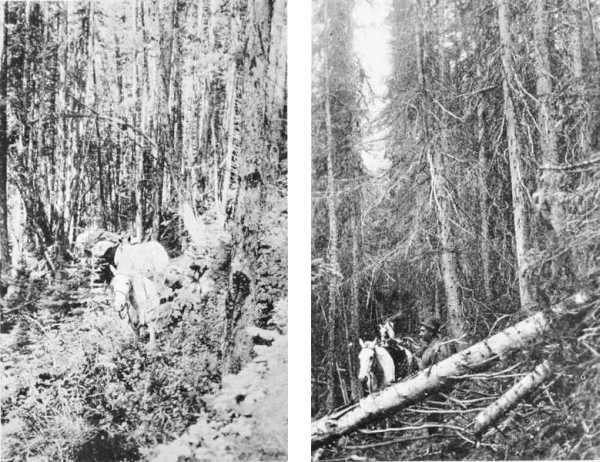

After picking up Roos and his camera we made our real start. One pack-horse was reserved for the camera and tripod, and to prevent him from ranging from the trail and bumping the valuable apparatus against trees or rocks, his halter was tied to the tail of Nixon’s saddle animal. Except that the latter’s spinal column must have suffered some pretty severe snakings when the camera-carrier went through corduroy bridges or lost his footings in fords, the arrangement worked most successfully. The delicate instrument was not in the least injured in all of the many miles it was jogged over some of the roughest trails I have ever travelled.

The sunshine by which the last of the trail shots was made proved the parting glimmer of what had been a month or more of practically unbroken fair weather. Indeed, the weather had been rather too fine, for, toward the end of the summer, lack of rain in western Canada invariably means forest fires. As these had been raging intermittently for several weeks all over British Columbia, the air had become thick with smoke, and at many places it was impossible to see for more than a mile or two in any direction. Both Roos and Harmon had been greatly hampered in their work about Banff and Lake Louise by the smoke, and both were, therefore, exceedingly anxious for early and copious rains to clear the air. Otherwise, they said, there was no hope of a picture of the Lake of the Hanging Glaciers that would be worth[Pg 35] the film it was printed on. They must have rain. Their prayer was about to be answered, in full measure, pressed down and running over—and then some.

We had been encountering contending currents of hot and cold air all the way up the wagon-road from Invermere and the lower valley. Now, as we entered the mountains, these became more pronounced, taking the form of scurrying “dust-devils” that attacked from flank and van without method or premonitory signal. The narrowing gorge ahead was packed solid with a sullen phalanx of augmenting clouds, sombre-hued and sagging with moisture, and frequently illumined with forked lightning flashes discharged from their murky depths. Nixon, anxious to make camp before the storm broke, jogged the horses steadily all through the darkening afternoon. It was a point called “Sixteen-mile” he was driving for, the first place we would reach where there was room for the tent and feed for the horses. We were still four miles short of our destination when the first spatter of ranging drops opened up, and from there on the batteries of the storm concentrated on us all the way.

We made camp in a rain driving solidly enough to deflect the stroke of an axe. I shall not enlarge upon the acute discomfort of it. Those who have done it will understand; those who have not would never be able to. It was especially trying on the first day out, before the outfit had become shaken down and one had learned where to look for things. Nixon’s consummate woodcraftsmanship was put to a severe test, but emerged triumphant. So, too, Jim, who proved himself as impervious to rain as to ill-temper. The[Pg 36] fir boughs for the tent floor came in dripping, of course, but there were enough dry tarpaulins and blankets to blot up the heaviest of the moisture, and the glowing little sheet-iron stove licked up the rest. A piping hot dinner drove out the last of the chill, and we spent a snug, comfy evening listening to Nixon yarn about his mountaineering exploits and of the queer birds from New York and London whom he had nursed through strange and various intervals of moose and sheep-hunting in the Kootenays and Rockies. We slept dry but rather cold, especially Roos, who ended up by curling round the stove and stoking between shivers. Nixon and Jim drew generously on their own blanket rolls to help the both of us confine our ebbing animal heat, and yet appeared to find not the least difficulty in sleeping comfortably under half the weight of cover that left us shaking. It was all a matter of what one was used to, of course, and in a few days we began to harden.