Title: Tennyson and his friends

Editor: Baron Hallam Tennyson Tennyson

Release date: December 27, 2011 [eBook #38420]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO

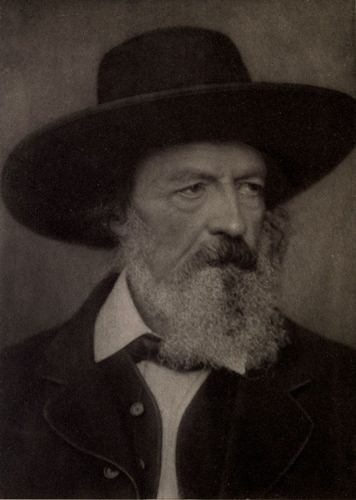

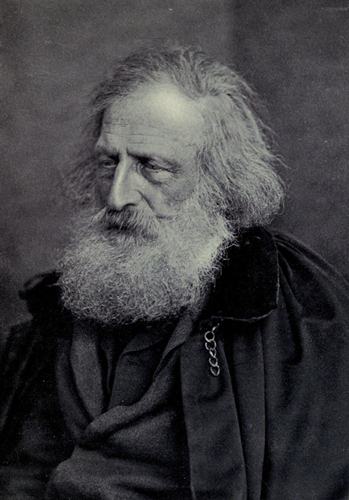

Barraud, photographer Emery Walker, Ph.sc.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson

(in his 80th year)

TENNYSON AND HIS

FRIENDS

EDITED

BY

HALLAM, LORD TENNYSON

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

ST. MARTIN’S STREET, LONDON

1911

Dedicated

TO

THE FRIENDS OF TENNYSON

BY

HIS SON

To those who have contributed to this volume their memories of my father, criticisms of his work, or records of his friends, I owe a deep debt of gratitude. Three of the writers, Henry Butcher, Sir Alfred Lyall, and Graham Dakyns, have lately, to my great loss, passed away—into that fuller “light of friendship”—

| “a clearer day Than our poor twilight dawn on earth.” |

TENNYSON.

[The following chapters about my father are arranged, as far as possible, according to the sequence of his life. Further reminiscences by the Duke of Argyll, Gladstone, Jowett, Lecky, Locker-Lampson, Palgrave, Lord Selborne, Tyndall, Aubrey de Vere, and other friends, will be found in Tennyson, a Memoir.]

| PAGE | |

| Recollections of my Early Life. By Emily, Lady Tennyson | 3 |

| Tennyson and Lincolnshire. By Willingham Rawnsley— | |

| I. Tennyson’s Country | 8 |

| II. The Somersby Friends | 18 |

| Tennyson and his Brothers, Frederick and Charles. By Charles Tennyson | 33 |

| Tennyson on his Cambridge Friends— | |

| Arthur Henry Hallam | 71 |

| To James Spedding | 72 |

| To Edward FitzGerald | 75 |

| To John Mitchell Kemble | 78 |

| To J. W. Blakesley | 78 |

| To R. C. Trench | 79 |

| To the Rev. W. H. Brookfield | 80 |

| To Edmund Lushington | 81 |

| Charles Tennyson-Turner | 86 |

| Tennyson and Lushington. By Sir Henry Craik, K.C.B., M.P. | 89 |

| Tennyson, FitzGerald, Carlyle, and other Friends. By Dr. Warren, President of Magdalen College, Oxford, and now Professor of Poetry | 98 |

| Some Recollections of Tennyson’s Talk from 1835 to 1853. By Edward FitzGerald | 142 |

| Tennyson and Thackeray. By Lady Ritchie | 148 |

| Tennyson on his Friends of Later Life— | |

| To W. C. Macready | 157 |

| To the Rev. F. D. Maurice | 157 |

| To Sir John Simeon | 159 |

| [Pg x]To Edward Lear on his Travels in Greece | 160 |

| To the Master of Balliol | 161 |

| To the Duke of Argyll | 162 |

| To Gifford Palgrave | 162 |

| To the Marquis of Dufferin and Ava | 165 |

| To W. E. Gladstone | 167 |

| To Mary Boyle | 168 |

| W. G. Ward | 171 |

| To Sir Richard Jebb | 171 |

| To General Hamley | 172 |

| Lord Stratford de Redcliffe | 173 |

| General Gordon | 173 |

| G. F. Watts, R.A. | 173 |

| Tennyson and Bradley (Dean of Westminster). By Margaret L. Woods | 175 |

| Notes on Characteristics of Tennyson. By the late Master of Balliol (Professor Jowett) | 186 |

| Tennyson, Clough, and the Classics. By Henry Graham Dakyns | 188 |

| Recollections of Tennyson. By the Rev. H. Montagu Butler, D.D., Master of Trinity College, Cambridge | 206 |

| Tennyson and W. G. Ward and other Farringford Friends. By Wilfrid Ward | 222 |

| Tennyson and Aldworth. By Sir James Knowles, K.C.V.O. | 245 |

| The Funeral of Dickens | 253 |

| Fragmentary Notes of Tennyson’s Talk. By Arthur Coleridge | 255 |

| Music, Tennyson, and Joachim. By Sir Charles Stanford | 272 |

| The Attitude of Tennyson towards Science. By Sir Oliver Lodge, F.R.S. | 280 |

| Tennyson as a Student and Poet of Nature. By Sir Norman Lockyer, F.R.S. | 285 |

| Memories. By E. V. B. | 292 |

| Tennyson and his Talk on some Religious Questions. By the Right Rev. the Bishop of Ripon | 295 |

| [Pg xi]Tennyson and Sir John Simeon, and Tennyson’s Last Years. By Louisa E. Ward | 306 |

| Sir John Simeon. By Aubrey de Vere | 321 |

| Tennyson. By Arthur Sidgwick, Fellow of Corpus Christi, Oxford, and sometime Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge | 322 |

| Tennyson: His Life and Work. By the Right Hon. Sir Alfred Lyall, G.C.B. | 344 |

| Tennyson: The Poet and the Man. By Professor Henry Butcher | 385 |

| James Spedding. By W. Aldis Wright, Vice-Master of Trinity College, Cambridge | 393 |

| Arthur Henry Hallam. By Dr. John Brown | 441 |

| APPENDICES | |

| A. The Comments of Tennyson on one of his later Ethical Poems | 475 |

| B. “Hands all Round,” set to music by Emily, Lady Tennyson | 481 |

| C. Miscellaneous Letters from Unknown Friends | 485 |

| D. Tennyson’s Arthurian Poem | 498 |

| FACE PAGE | |

| IN PHOTOGRAVURE | |

| Alfred, Lord Tennyson (in his 80th year) | Frontispiece |

| Emily, Lady Tennyson. From a drawing by G. F. Watts, R.A. | 3 |

| IN BLACK AND WHITE | |

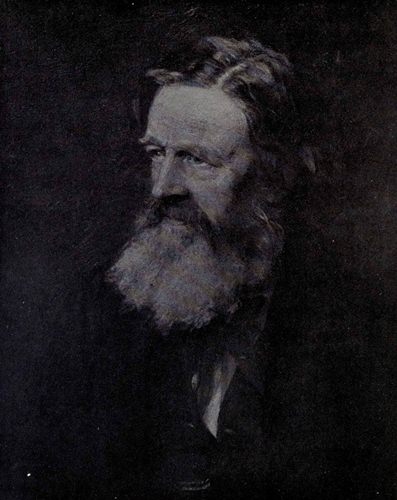

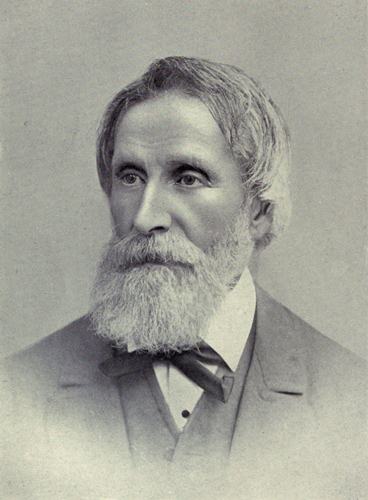

| Frederick Tennyson | 33 |

| Charles Tennyson-Turner | 58 |

| A. H. H. | 71 |

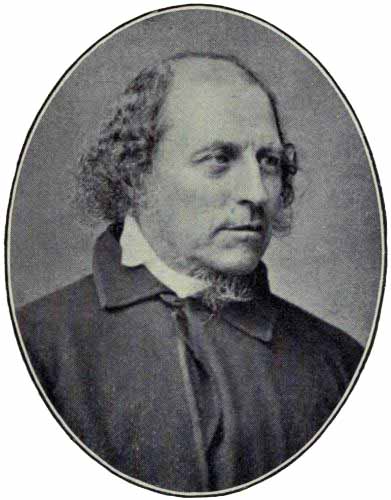

| Edmund Lushington | 89 |

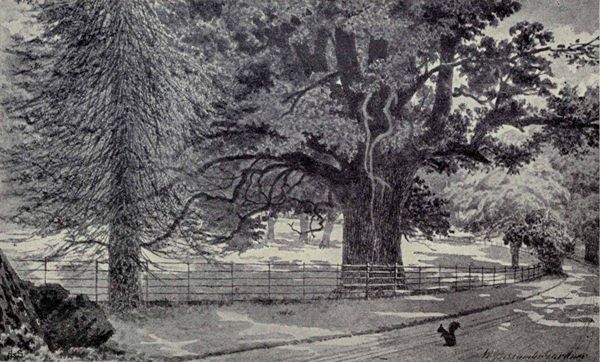

| The Drive at Farringford, showing on the left the “Wellingtonia” planted by Garibaldi | 163 |

| Tennyson and his two Sons | 188 |

| Arthur Tennyson | 222 |

| Horatio Tennyson | 229 |

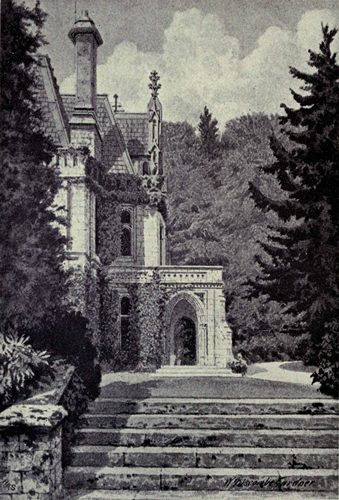

| The South Side of Entrance from below the Terrace, Aldworth | 245 |

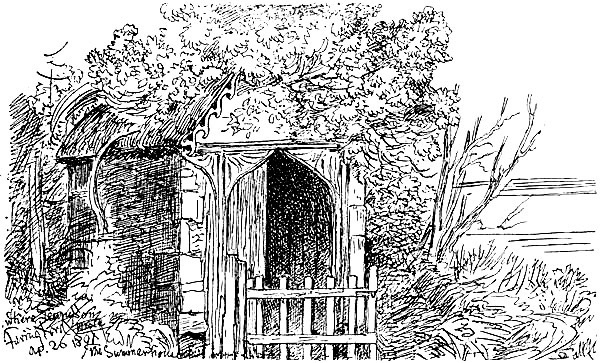

| Summer-house at Farringford, where “Enoch Arden” was written | 292 |

| The Corner of the Study at Farringford where Tennyson wrote, with his Deerhound “Lufra” and the Terrier “Winks” in the foreground | 306 |

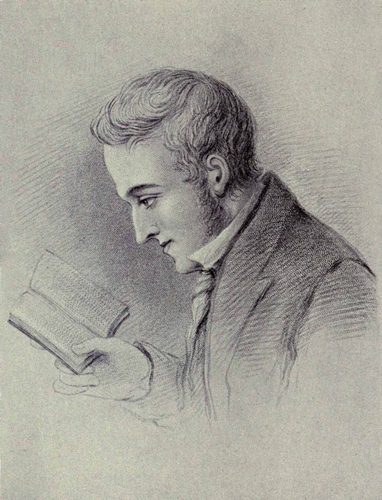

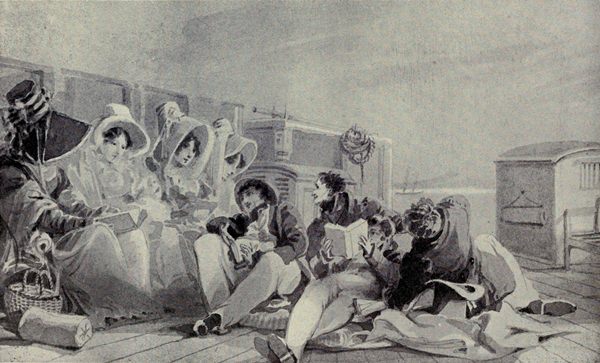

| Arthur Hallam reading “Walter Scott” aloud on board the “Leeds,” bound from Bordeaux to Dublin, Sept. 9, 1830 | 441 |

TENNYSON AND HIS FRIENDS

(Dedication of “The Death of Œnone” to Emily, Lady Tennyson)

| There on the top of the down, The wild heather round me and over me June’s high blue, When I look’d at the bracken so bright and the heather so brown, I thought to myself I would offer this book to you, This, and my love together, To you that are seventy-seven, With a faith as clear as the heights of the June-blue heaven, And a fancy as summer-new As the green of the bracken amid the gloom of the heather. |

Emery Walker, Ph.sc.

Emily Lady Tennyson

from a drawing by G. F. Watts, R.A.

By Emily, Lady Tennyson

Written for her son in 1896

You ask me to tell you something of my life before marriage at Horncastle in Lincolnshire. It would be hard indeed not to do anything you ask of me if within my power. To say the truth, this particular thing you want is somewhat painful. The first thing I remember of my father[1] is his looking at me with sad eyes after my mother’s[2] death. Her I recollect, passing the window in a velvet pelisse, and then in a white shawl on the sofa, and then crowned with roses—beautiful in death. I recollect, too, being carried to her funeral; but I asked what they were doing, and in all this had no idea of death.

My life before marriage was in many ways sad: in one, however, unspeakably happy. No one could have had a better father, or been happier with her two sisters, Anne and Louisa. Although, if we were too merry and noisy in the mornings, we were summoned by my Aunt Betsy (who lived with us) all three into her room, to hold out our small hands for stripes from a certain little riding-whip; or if, later in the day, our needlework was not well done we had our fingers pricked with a needle, or if the lessons were not finished, we had fools’ caps put on our heads, and were banished to a corner of the room. My aunt’s nature was by no means cruel; she was, on the whole, kind and dutiful to us, yet no[Pg 4] doubt with effort on her part, for she had no instinctive love of children.

Among our neighbours we had as friends the Tennysons, the Rawnsleys, the Bellinghams, and the Massingberds. The death of my cousin, Mr. Cracroft, was among my early tragedies. He had been on public business at Lincoln: and on his return to Horncastle, was seized at our house with Asiatic cholera, a solitary case, which proved fatal. Ourselves and his daughters heard of it in a strange way. We were in a tent at a sheep-shearing, the great rustic festival of that day. A village boy came into our tent, and swarmed up the pole, saying to us, “I know something; your father is dead.” We hurried home, and we, three sisters, were put by my aunt (to keep us quiet) to the hitherto-unwonted task of stoning raisins. This made me so indignant that I threw my raisins over the edge of the bowl, and forthwith my aunt caught me up, and—so rough was the treatment of children then—banged my head against the door of our old wainscoted rooms, until I called out for my father, crying aloud, “Murder”; when he rushed in and saved me.

My next memory of my father is his giving me Latin lessons; and at this time I somehow came across a copy of Cymbeline, which I read with great delight. Then we had our first riding-lessons. I well recall my dislike of riding, when my pony was fastened to a circus stake, which I had to go round and round. Unfortunately, much as my father wished it, I never became a good horsewoman. He himself was so good a rider, when all the gentlemen of the county were volunteers, that he could ride horses which no one else could ride—so my grandmother would tell me with pride—adding, “Your father and his brother (both six foot three) were the handsomest men among them all.” At that time he kept guard with his fellow-volunteers[Pg 5] over the French prisoners, who, he said, were always cheerful and always singing their patriotic songs.

But to return to my sisters and myself. For exercise we generally took long walks in the country, and I remember that when staying at my father’s house in Berkshire[3] we often used to wander up to a tower among our woods where a gaunt old lady lived, called Black Jane, who told our fortunes. We had our favourite theatricals, too, like other children. Our dramatic performances were frequent, and our plays were, some of them, drawn from Miss Edgeworth’s tales. I was always fond of music, and used to sing duets with my soldier cousin, Richard Sellwood.

At eight years old I was sent, with my sisters, to some ladies for daily lessons, and later to schools in Brighton and London, for my father disliked having a governess in the house. So, much as he objected to young girls being sent from home, school in our case seemed the lesser evil. My sisters liked school; to me it was dreadful. As soon as I reached the Brighton seminary, I remember that for weeks I appeared to be in a horrible dream, and the voices of the mistresses and the girls around me seemed to be all thin, like voices from the grave. I could not be happy away from my father, who was my idol, though after a while I grew more accustomed to the strange life. My father would never let us go the long, cold journey[Pg 6] at Christmas time from Brighton to Horncastle, but came up to town for the vacation, and took us for treats to the National Gallery, and other places of interest. Great was the joy, when the summer holidays arrived, and after travelling by coach through the day and night, we three sisters saw Whittlesea-mere gleaming under the sunrise. It seemed as if we were within sight of home.

When I was eighteen, my Aunt Betsy left us to live by herself alone. We spent rather recluse lives, but we were perfectly happy, my father reading to us every evening from about half-past eight to ten, the hour at which we had family prayers. Most delightful were the readings; for instance, all of Gibbon that could be read to us, Macaulay’s Essays, Sir Walter Scott’s novels. For my private reading he gave me Dante, Ariosto, and Tasso, Molière, Racine, Corneille. Later I read Schiller, Goethe, Jean Paul Richter; and for English—Pearson, Paley’s Translation of the Early Fathers, Coleridge’s works, Wordsworth, and of course Milton and Shakespeare. We had walks and drives and music and needlework. Now and again we dined in the neighbourhood, and some of the neighbours dined with us; and once a year my father asked all the legal luminaries of Horncastle to dinner with him.

Before my sister Louy married your Uncle Charles (Tennyson-Turner) in 1836, my cousin, Catherine Franklin, daughter of Sir Willingham Franklin, took up her abode with us, and we had several dances at our house. Two fancy-dress dances I well remember. Louy and I disliked visiting in London and in country-houses, and so we always refused, and sent Anne in our stead. My first ball, I thought an opening of the great portals of the world, and I looked forward to it almost with awe. It is rather curious that at one of my very few balls, Mr. Musters (Jack Musters his intimates called[Pg 7] him), who married Byron’s Mary Chaworth, should have asked for, and obtained, an introduction to me.

In 1842 came Catherine’s marriage to our true friend, Drummond Rawnsley, the parson of the Rawnsley family; and then my sister Anne married Charles Weld. After this my father and I lived together alone. The only change we had from our routine life was a journey, one summer, to Tours, with Anne and Charles Weld, and his brother Isaac Weld, the accomplished owner of Ravenswell, near Bray, in Ireland.

At your father’s home, Somersby, we used to have evenings of music and singing. Your Aunt Mary played on the harp as her father used to do. She was a splendid-looking girl, and would have made a beautiful picture. Then your Aunt Emily (beloved of Arthur Hallam) had wonderful eyes—depths on depths they seemed to have—and a fine profile. “Testa Romana” an old Italian said of her. She had more of the colouring of the South, inherited, perhaps, from a member of Madame de Maintenon’s family who married one of the Tennysons. Your father had also the same kind of colouring. All, brothers and sisters, were fair to see. Your father was kingly, masses of fine, wavy hair, very dark, with a pervading shade of gold, and long, as it was then worn. His manner was kind, simple, and dignified, with plenty of sportiveness flashing out from time to time. During my ten years’ separation from him the doctors believed I was going into a consumption, and the Lincolnshire climate was pronounced to be too cold for me; and we moved to London, to look for a home in the south of England. We found one at last at Hale near Farnham, which was called by your father “my paradise.” The recollection of this delightful country made me persuade your father eventually to build a house near Haslemere. We were married on June 13, 1850, at Shiplake on the Thames.

By Willingham Rawnsley

I

Tennyson’s Country

| Calm and deep peace on this high wold, And on these dews that drench the furze, And all the silvery gossamers That twinkle into green and gold. Calm and still light on yon great plain That sweeps with all its autumn bowers, And crowded farms and lessening towers, To mingle with the bounding main. |

Lincolnshire is a big county, measuring seventy-five miles by forty-five, but it is perhaps the least well known of all the counties of England. The traveller by the Great Northern main line passes through but a small portion of its south-western fringe near Grantham; and if he goes along the eastern side from Peterborough to Grimsby or Hull, he gains no insight into the picturesque parts of the county, for the line takes him over the rich flat fenlands with their black vegetable mould devoid of any kind of stone or pebble, and intersected by those innumerable dykes or drains varying from 8 to 80 feet across, which give the southern division of Lincolnshire an aspect in harmony with its Batavian name “the parts of Holland.”

The Queen of this flat fertile plain is Boston, with her wonderful church-tower and lantern 280 feet high, a[Pg 9] marvel of symmetry when you are near it, and visible for more than twenty miles in all directions. Owing to its slender height it seems, from a distance, to stand up like a tall thick mast or tree-trunk, and is hence known to all the countryside as “Boston stump.”

At this town, the East Lincolnshire line divides: one section goes to the left to Lincoln; the other, following the bend of the coast at about seven miles’ distance from the sea, turns when opposite Skegness and runs, at right angles to its former course, to Louth,—Louth whose beautiful church spire was painted by Turner in his picture of “The Horse Fair.”

The more recent Louth-to-Lincoln line completes the fourth side of a square having Boston, Burgh, Louth, and Lincoln for its corners, which contains the fairest portion of the Lincolnshire wolds, and within this square is Somersby, Tennyson’s birthplace and early home. It is a tiny village surrounded by low green hills; and close at hand, here nestling in a leafy hollow, and there standing boldly on the “ridgèd wold,” are some half a dozen churches built of the local “greensand” rock, from whose towers the Poet in his boyhood heard:

The Christmas bells from hill to hill

Answer each other in the mist—

the mist which lay athwart those “long gray fields at night,” and marked the course of the beloved Somersby brook.

If we go past the little gray church with its perfect specimen of a pre-Reformation cross hard by the porch, and past the modest house almost opposite, which was for over thirty years the home of the Tennysons, we shall come at once to the point where the road dips to a little wood through which runs the rivulet so lovingly described by the Poet when he was leaving the home of his youth:

[Pg 10]Flow down, cold rivulet, to the sea

Thy tribute wave deliver:

No more by thee my steps shall be,

For ever and for ever.

and again:

Unloved, by many a sandy bar,

The brook shall babble down the plain,

At noon or when the lesser wain

Is twisting round the polar star;

Uncared for, gird the windy grove,

And flood the haunts of hern and crake;

Or into silver arrows break

The sailing moon in creek and cove.

Northward, beyond the stream, the white road climbs the wold above Tetford, and disappears from sight. These wolds are chalk; the greensand ridge being all to the south of the valley, except just at Somersby and Bag-Enderby, where the sandrock crops up by the roadside, and in the little wood by the brook.

This small deep channelled brook with sandy bottom—over which one may on any bright day see, as described in “Enid,”

a shoal

Of darting fish, that on a summer morn...

Come slipping o’er their shadows on the sand,

But if a man who stands upon the brink

But lift a shining hand against the sun,

There is not left the twinkle of a fin

Betwixt the cressy islets white with flower—

was very dear to Tennyson. When in his “Ode to Memory” he bids Memory

Come from the woods which belt the gray hillside,

The seven elms, the poplars four

That stand beside my father’s door,

he adds:

And chiefly from the brook that loves

To purl o’er matted cress and ribbèd sand,

Or dimple in the dark of rushy coves,

Drawing into his narrow earthen urn

In every elbow and turn,

The filter’d tribute of the rough woodland,

O! hither lead thy feet!

[Pg 11]If we follow this

pastoral rivulet that swerves

To left and right thro’ meadowy curves,

That feed the mothers of the flock,

we, too, shall hear

the livelong bleat

Of the thick fleecèd sheep from wattled folds

Upon the ridgèd wolds.

And shall see the cattle in the rich grass land, and mark on the right the green-gray tower of Spilsby, where so many of the Franklin family lived and died, the family of whom his future bride was sprung.

Still keeping by the brook, we shall see, past the tower of Bag-Enderby which adjoins Somersby, “The gray hill side” rising up behind the Old Hall of Harrington, and

The Quarry trenched along the hill

And haunted by the wrangling daw,

above which runs the chalky “ramper” or turnpike-road which leads along the eastern ridge of the wold to Alford, whence you proceed across the level Marsh to the sea at Mablethorpe.

The Marsh in Lincolnshire is a word of peculiar significance. The whole country is either fen, wold, or marsh. The wolds, starting from Keal and Alford, run in two ridges on either side of the Somersby Valley, one going north to Louth and onwards, and one west by Spilsby and Horncastle to Lincoln. Here it joins the great spine-bone of the county on which, straight as an arrow for many a mile northwards, runs the Roman Ermine Street; and but for the Somersby brook these two ridges from Louth and Lincoln would unite at Spilsby, whence the greensand formation, which begins at Raithby, sends out two spurs, one eastwards, ending abruptly at Halton, while the other pushes a couple of miles farther south, until at Keal the road drops suddenly[Pg 12] into the level fen, giving a view—east, south, and west—of wonderful extent and colour, ending to the east with the sea, and to the south with the tall pillar of Boston Church standing up far above the horizon. This flat land is the fen; all rich cornland and all well drained, but with few habitations, and with absolutely no hill or even rise in the ground until, passing Croyland or Crowland Abbey, which once dominated a veritable land of fens only traversable by boats, you come, on the farther side of Peterborough, to the great North Road. Such views as this from Keal, and the similar one from Lincoln Minster, which looks out far to the south-west over a similar large tract of fen, are not to be surpassed in all the land.

But the Poet’s steps from Somersby would not as a rule go westwards. The coast would oftener be his aim; and leaving Spilsby to the right, and the old twice-plague-stricken village of Partney, where the Somersby rivulet becomes a river, he would pass from “the high field on the bushless pike” to Miles-cross-hill, whence the panorama unfolds which he has depicted in Canto XI. of “In Memoriam”:

Calm and still light on yon great plain,

That sweeps with all its autumn bowers,

And crowded farms and lessening towers,

To mingle with the bounding main.

Thence descending from the wold he would go through Alford, and on across the sparsely populated pasture-lands, till he came at last to

Some lowly cottage whence we see

Stretched wide and wild the waste enormous marsh,

Where from the frequent bridge,

Like emblems of infinity,

The trenchèd waters run from sky to sky.

This describes the third section of Lincolnshire called the Marsh, a strip between five and eight miles wide,[Pg 13] running parallel with the coast from Boston to Grimsby, and separating the wolds from

the sandbuilt ridge

Of heaped hills that mound the sea.

This strip of land is not marsh in the ordinary sense of the word, but a belt of the richest grass land, all level and with no visible fences, each field being surrounded by a broad dyke or ditch with deep water, hidden in summer by the tall feathery plumes of the “whispering reeds.” Across this belt the seawind sweeps for ever. The Poet may allude to this when, in his early poem, “Sir Galahad,” he writes:

But blessed forms in whistling storms

Fly o’er waste fens and windy fields;

and “the hard grey weather” sung by Kingsley breeds a race of hardy gray-eyed men with long noses, the manifest descendants of the Danes who peopled all that coast, and gave names to most of the villages there, nine-tenths of which end in “by.”

This rich pasture-land runs right up to the sand-dunes,—Nature’s own fortification made by the winds and waves which is just outside the Dutch and Roman embankments, and serves better than all the works of man to keep out the waters of the North Sea from the low-lying levels of the Marsh and Fen.

The lines in the “Lotos-Eaters”:

They sat them down upon the yellow sand

Between the sun and moon upon the shore,

describes what the Poet might at any time of full moon have seen from that “sand-built ridge” with the red sun setting over the wide marsh, and the full moon rising out of the eastern sea; and “The wide winged sunset of the misty marsh” recalls one of the most noticeable features of that particular locality, where, across the limitless windy plain, the sun would set in[Pg 14] regal splendour; and when “cold winds woke the gray-eyed morn” his rising over the sea would be equally magnificent in colour.

Having crossed the “Marsh” by a raised road with deep wide dykes on either side, and no vestige of hedge or tree in sight, except where a row of black poplars or aspens form a screen from the searching wind round a group of the plainest of farm buildings, red brick with roofing of black glazed pan-tiles, you come to the once tiny village of Mablethorpe, sheltering right under the sea-bank, the wind-blown sands of which are held together by the penetrating roots of the tussocks of long, coarse, sharp-edged grass, and the prickly bushes of sea buckthorn, gray-leaved and orange-berried.

You top the sand-ridge, and below, to right and left, far as eye can see, stretch the flat, brown sands. Across these the tide, which at the full of the moon comes right up to the barrier, goes out for three-quarters of a mile; of this the latter half is left by the shallow wavelets all ribbed, as you see it on the ripple-marked stone of the Horsham quarries, and shining with the bright sea-water which reflects the low rays of the sun; while far off, so far that they seem to be mere toys, the shrimper slowly drives his small horse and cart, to the tail of which is attached the primitive purse net, the other end of it being towed by the patient, long-haired donkey, ridden by a boy whose bare feet dangle in the shallow wavelets. Farther to the south the tide ebbs quite out of sight. This is at “Gibraltar Point,” near Wainfleet Haven, where Somersby brook at length finds the sea, a place very familiar to the Poet in his youth. The skin of mud on the sands makes them shine like burnished copper in the level rays of the setting sun, which here have no sandbank to intercept them, but at other times it is a scene of dreary desolation, such as is aptly described in “The Passing of Arthur”:

[Pg 15]a coast

Of ever-shifting sand, and far away

The phantom circle of a moaning sea.

It was near this part of the shore that, as a young man, he often walked, rolling out his lines aloud or murmuring them to himself, a habit which was also that of Wordsworth, and led in each case to the peasants supposing the Poet to be “craäzed,” and caused the Somersby cook to wonder “what Mr. Awlfred was always a-praying for,” and caused also the fisherman, whom he met on the sands once at 4 A.M. as he was walking without hat or coat, and to whom he bid good-morning, to reply, “Thou poor fool, thou doesn’t knaw whether it be night or daä.”

But at Mablethorpe the sea does not go out nearly so far, and at high tide it comes right up to the bank with splendid menacing waves, the memory of which furnished him, five and thirty years after he had left Lincolnshire for ever, with the famous simile in “The Last Tournament”:

as the crest of some slow-arching wave,

Heard in dead night along that table shore,

Drops flat, and after the great waters break

Whitening for half a league, and thin themselves,

Far over sands marbled with moon and cloud,

From less and less to nothing.

This accurately describes the flat Lincolnshire coast with its “interminable rollers” breaking on the endless sands, than which waves the Poet always said that he had never anywhere seen grander, and the clap of the wave as it fell on the hard sand could be heard across that flat country for miles. Doubtless this is what prompted the lines in “Locksley Hall”:

Locksley Hall, that in the distance overlooks the sandy tracts,

And the hollow ocean-ridges roaring into cataracts.

“We hear in this,” says the “Lincolnshire Rector,”[4][Pg 16] writing in Macmillan’s Magazine of December 1873, “the mighty sound of the breakers as they fling themselves at full tide with long-gathered force upon the slope sands of Skegness or Mablethorpe on the Lincolnshire coast, nowhere is ocean grander in a storm; nowhere is the thunder of the sea louder, nor its waves higher, nor the spread of their waters on the beach wider.”

It is not only of the breakers that the Poet has given us pictures. Along these sands it was his wont, no doubt, as it has often been that of the writer,

To watch the crisping ripples on the beach,

And tender curving lines of creamy spray,

and it is still Skegness and Mablethorpe which may have furnished him with his simile in “The Dream of Fair Women”:

So shape chased shape as swift as, when to land

Bluster the winds and tides the self-same way,

Crisp foam-flakes scud along the level sand,

Torn from the fringe of spray.

Walking along the shore as the tide goes out, you come constantly on creeks and pools left by the receding waves,

A still salt pool, lock’d in with bars of sand,

Left on the shore; that hears all night

The plunging seas draw backward from the land

Their moon-led waters white.[5]

or little dimpled hollows of brine, formed by the wind-swept water washing round some shell or stone:

As the sharp wind that ruffles all day long

A little bitter pool about a stone

On the bare coast.[6]

Many characteristics of Lincolnshire scenery and of Somersby in particular are introduced in “In Memoriam.”

[Pg 17]In Canto LXXXIX. the poet speaks of the hills which shut in the Somersby Valley on the north:

Nor less it pleased in lustier moods

Beyond the bounding hill to stray.

In XCV. he speaks of the knolls, elsewhere described as “The hoary knolls of ash and haw,” where the cattle lie on a summer night:

Till now the doubtful dusk reveal’d

The knolls once more where, couch’d at ease,

The white kine glimmer’d, and the trees

Laid their dark arms about the field:

and in Canto C. he calls to mind:

The sheepwalk up the windy wold,

and many other features seen in his walks with Arthur Hallam at Somersby.

In “Mariana” we have:

From the dark fen the oxen’s low

Came to her: without hope of change,

In sleep she seem’d to walk forlorn,

Till cold winds woke the gray-eyed morn,

About the lonely moated grange.

But no picture is more complete and accurate and remarkable than that of a wet day in the Marsh and on the sands of Mablethorpe:

Here often when a child I lay reclined:

I took delight in this fair strand and free:

Here stood the infant Ilion of the mind,

And here the Grecian ships all seem’d to be.

And here again I come, and only find

The drain-cut level of the marshy lea,

Gray sand-banks, and pale sunsets, dreary wind,

Dim shores, dense rains, and heavy-clouded sea.

From what we have said it will be clear to the reader that while it is the fen land only that the railway traveller sees, it is the Marsh and the Wolds—and particularly in Lord Tennyson’s mind the Wolds—that[Pg 18] make the characteristic charm of the county, a charm of which so many illustrations are to be found throughout his poems. Certainly in her wide extended views, in the open wolds with the villages and their gray church towers nestling in the sheltered nooks at the wold foot, and also (to quote again from the “Lincolnshire Rector”) “in her glorious parish churches and gigantic steeples, Lincolnshire has charms and beauties of her own. And as to fostering genius, has she not proved herself to be the ‘meet nurse of a poetic child’? for here, be it remembered, here in the heart of the land, in Mid-Lincolnshire, Alfred Tennyson was born, here he spent all his earliest and freshest days; here he first felt the divine afflatus, and found fit material for his muse:

The Spirit of the Lord began to move him at times in the Camp of Dan between Zorah and Eshtaol.”

II

The Somersby Friends

| We leave the well-beloved place Where first we gazed upon the sky; The roofs, that heard our earliest cry, Will shelter one of stranger race. ······· I turn to go: my feet are set To leave the pleasant fields and farms; They mix in one another’s arms To one pure image of regret. |

It is no wonder that the Tennysons loved Somersby. They were a large family, and here they grew up together, making their own world and growing ever more fond of the place for its associations. “How[Pg 19] often have I longed to be with you at Somersby!” writes Alfred Tennyson’s sister, Mary,[7] thirteen years after leaving the old home. “How delightful that name sounds to me! Visions of sweet past days rise up before my eyes, when life itself was new,

And the heart promised what the fancy drew.”

Here, when childhood’s happy days were over, the Tennyson girls rejoiced in the society of their brothers’ Cambridge friends, and, though the village was so remote that they only got a post two or three times a week,[8] here they not only drank in contentedly the beauty of the country, but also passed delightful days with talk and books, with music and poetry, and dance and song, when, on the lawn at Somersby, one of the sisters

brought the harp and flung

A ballad to the brightening moon.

Here, as Arthur Hallam said, “Alfred’s mind was moulded in silent sympathy with the everlasting forms of Nature.”

I have said that they made their own world; and they were well able to do it, for they were a very remarkable family. The Doctor was a very tall, dark man, very strict with his boys, to whom he was schoolmaster as well as parent. He was a scholar, and unusually well read, and possessed a good library. Clever, too, he was with his hands, and carved the stone chimney-piece in the dining-room, which his man Horlins built under his direction. He and his wife were a great contrast, for she was very small and gentle and highly sensitive.

Edward FitzGerald speaks of her as “one of the most innocent and tender-hearted ladies I ever saw”; and the[Pg 20] Poet depicts her in “Isabel,” where he speaks of her gentle voice, her keen intellect and her

Sweet lips whereon perpetually did reign

The summer calm of golden charity.

Mary was the letter-writer of the family, and a very clever woman, and her letters show that she knew her Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Keats, and Coleridge as well as her brother’s poems.

They were a united family, but Charles and Alfred were nearest to her in age. She writes to one of her great friends: “O my beloved, what creatures men are! my brothers are the exception to this general rule.” Accordingly, of Charles she writes: “If ever there was a sweet delightful character it is that dear Charley,” and of Alfred: “A. is one of the noblest of his kind. You know my opinion of men in general is much like your own; they are not like us, they are naturally more selfish and not so affectionate.” She adds:

Alfred is universally beloved by all his friends, and was long so before he came to any fame....

We look upon him as the stay of the family; you know it is to him we go when anything is to be done. Something lately occurred here which was painful; we wrote to Alfred and he came immediately, after, I am told, not speaking three days scarcely to any one from distress of mind, and that not for himself, mind, but for others. Did this look like selfishness?

After leaving Somersby she felt the loss of these brothers sorely.

Alfred’s devotion to his mother was always perfect. In October 1850 Mary writes from Cheltenham:

Yesterday, Mamma, I, and Fanny went to look for houses, as Alfred has written to say that he should like to live by his Mother or in the same house with us, if we could get one large enough, and he would share the rent, which would be a great deal better. He wishes us to take a house in the neighbourhood of London, if we can give up ours, with him, or to take[Pg 21] a small house for him and Emily[9] on the outskirts of Cheltenham till we can move; so what will be done I know not, but this I know that Alfred must come here and choose for himself, so we have written to him to come immediately, and we are daily expecting him.

But though life at Cheltenham when the brothers were all away was dull for Mary, it had not been so at Somersby; for there they had home interests sufficient to keep them always occupied, and they were not without neighbours. Ormsby was close at hand, to the north, where lived as Rector, Frank Massingberd, afterwards Chancellor of Lincoln, a man of cultivation and old-world courtesy. His wife Fanny was one of the charming Miss Barings of Harrington, which was but a couple of miles off to the east. Her sister Rosa was that “sole rose of beauty, loveliness complete,” to whom the Poet wrote such charming little birthday verses; and sixty-five years afterwards Rosa, then Mrs. Duncombe Shafto, still spoke with enthusiasm of those happy days. Mrs. Baring had married for her second husband, Admiral Eden, a man of great conversational powers, and with a very large circle of interesting friends. He took the old Hall of Harrington, with its fine brick front, from the Cracrofts, who moved to Hackthorn near Lincoln, and thus the families at Harrington and Somersby saw a great deal of one another.

There were two Eden daughters, the strikingly handsome Dulcibella and her sister, who looked after the house and its guests. Hence their nicknames of “Dulce” and “Utile.”

A mile or two beyond Harrington was Langton, where Dr. Johnson came to visit his friend Bennet Langton, who died only seven years before Dr. Tennyson came to Somersby. But, though the Langtons were friends of the Doctor’s, this was not a house the young people[Pg 22] much frequented. Mary, having come back to the old neighbourhood, writes from Scremby: “I am going to Langton to-morrow to spend a few days with the Langtons, don’t you pity me? I hope I shall get something more out of Mrs. Langton than Indeed, Yes, No!”

Adjoining Langton the Tennysons had friends in the Swans of Saucethorpe, and a little farther eastwards was Partney, where George Maddison and his mother lived. He was a hero, of whom tales were told of many courageous deeds, such as his going single-handed and taking a desperate criminal who, being armed, had barricaded himself in an old building and set all the police at defiance. It was a question whether people most admired the courage of the man or the beauty of his charming wife, Fanny, one of the three good-looking daughters of Sir Alan Bellingham, who all found husbands in that neighbourhood. In the Lincolnshire poem, “The Spinster’s Sweet-Arts,” the Poet has immortalized their name:

Goä to the laäne at the back, and loök thruf Maddison’s gaäte!

From Partney the hill rises to Dalby, where lived John Bourne, whose wife was an aunt of the young Tennysons, and here they would meet the handsome Miss Bournes of Alford; one, Margaret, was dark, the other was Alice, a beautiful fair girl. They married brothers, Marcus and John Huish. Mrs. John Bourne was the Doctor’s sister Mary, and the young Tennysons would have been oftener at Dalby had it been their Aunt Elizabeth Russell[10] who lived there, of whom they always spoke in terms of the strongest affection.

The old house at Dalby was burnt down in 1841. About this Mr. Marcus Huish tells me that his mother wrote in a diary at the time:

[Pg 23]Jan. 5, 1841.—On this day Dalby House, the seat of the Bournes, and round whose simple Church, standing embosomed in trees, my family, including my dear sister Mary Hannah, lie buried, was burnt to the ground;

and on the 7th Mrs. Huish wrote:

I have this morning received intelligence that the dear House at Dalby was on Tuesday night burnt down, and is now a wreck. I feel very deeply this disastrous circumstance, endeared as it was to me by ties of time and association. Mr. Tennyson has written to me as follows on this catastrophe.

The letter was a long one, two pages being left for it in the diary, but unfortunately it was never copied in.

The villages here are very close together, and going from Partney, two miles eastward, you come to Skendleby, where Sir Edward Brackenbury lived, whose elder brother Sir John was Consul at Cadiz, and used to send over some good pictures and some strong sherry, known by the diners-out as “the Consul’s sherry.” The Rector of the next village of Scremby was also a Brackenbury, and here Mary Tennyson most loved to visit. Mrs. Brackenbury, whom she always calls “Gloriana,” was adored by all who knew her. Mary says, “She is so sweet a character, and she has always been so kind and so anxious for our family ... I look upon her as already a saint.” Two of the Rectors of Halton had also been Brackenburys—a father and son in succession, and they were followed by two generations of Rawnsleys—Thomas Hardwicke and his son Drummond.

Adjoining Scremby is Candlesby, where Tennyson’s genial friend, John Alington, who had married another of the beautiful Miss Bellinghams, was Rector; and within half a mile is Gunby, the delightful old home of the Massingberds. In Dr. Tennyson’s time Peregrine Langton, who had married the heiress of the Massingberds and taken her name, was living there.

It was from Gunby that Algernon Massingberd disappeared, going to America and never being heard[Pg 24] of again, which gave rise to a romance in “Novel” form, that came out many years later called The Lost Sir Massingberd. Going on eastward still, by Boothby, where Dr. Tennyson’s friends the Walls family lived, in a house to which you drove up across the grass pasture, the sheep grazing right up to the front door, a thing still common in the Lincolnshire Marsh, you come to Burgh, with its magnificent Church tower and old carved woodwork. Here was the house of Sir George Crawford, and here from the edge of the high ground on which the Church stands you plunge down on to the level Marsh across which, at five miles’ distance, is Skegness, at that time only a handful of fishermen’s cottages, with “Hildred’s Hotel,” one good house occupied by a large tenant farmer, and a reed-thatched house right on the old Roman sea bank, built by Miss Walls, only one room thick, so that from the same room she could see both the sunrise and the sunset. Here all the neighbourhood at different times would meet, and enjoy the wide prospect of sea and Marsh and the broad sands and the splendid air. When the tide was out the only thing to be seen, as far as eye could reach, were the two or three fishermen, like specks on the edge of the sea, and the only sounds were the piping of the various sea-birds, stints, curlews, and the like, as they flew along the creeks or over the gray sand-dunes. Mablethorpe was nearer to Somersby, but had no house of any size at which, as here, the dwellers on the wold knew that they were always welcome.

But we have other houses to visit, so let us return by Burgh and Bratoft, where above the chancel arch of the ugly brick Church is a remarkable picture of the Spanish Armada, represented as a huge red dragon, with the ships of Effingham’s fleet painted in the corner of the picture.

Passing Bratoft, the next thing we come to is the[Pg 25] Somersby brook, which is here “the Halton River,” and on the greensand ridge, overlooking the fen as far as “Boston Stump,” stands the fine Church of Halton Holgate. In this Church, as at Harrington, Alfred as a boy must have seen the old stone effigy of a Crusader as described in “Locksley Hall Sixty Years After”

with his feet upon the hound,

Cross’d! for once he sailed the sea to crush the Moslem in his pride.

The road ascends the “hollow way” cut through the greensand, and a timber footbridge is flung across it leading from the Church to the Rectory. Dr. Tennyson could tell the story of how his old friend T. H. Rawnsley, the Rector, and Mr. Eden, brother of the Admiral, being in London, looked in at the great Globe in Leicester Square and heard a man lecturing on Geology. They listened till they heard “This Greensand formation here disappears” (he was speaking of Sussex) “and crops up again in an obscure little village called Halton Holgate in Lincolnshire.” “Come along, Eden!” said the Rector; “this is a very stupid fellow.”

Halton was the house, and Mr. and Mrs. Rawnsley the people, whom Dr. Tennyson most loved to visit. She had been previously known to him as the beautiful Miss Walls of Boothby. The Rector was the most genial and agreeable of men, and her charm of look and manner made his wife a universal favourite.

Here are two characteristic letters from Dr. Tennyson to Mr. Rawnsley:

Tuesday 28th, 1826.

Dear Rawnsley—In your not having come to see me for so many months, when you have little or nothing to do but warm your shins over the fire while I, unfortunately, am frozen or rather suffocated with Greek and Latin, I consider myself as not only slighted but spifflicated. You deserve that I should take no notice of your letter whatever, but I will comply with your invitation partly to be introduced to the agreeable and clever lady, but more especially to have the[Pg 26] pleasure of seeing Mrs. Rawnsley, whom, you may rest assured, I value considerably more than I do you. Mrs. T. is obliged by your invitation, but the weather is too damp and hazy, Mr. Noah,—so I remain your patriarchship’s neglected servant,

G. C. Tennyson.

This letter was addressed to the Rev. T. H. Rawnsley, Halton Parsonage. The next was addressed to Halton Palace, and runs thus:

Somersby, Monday.

Dear Rawnsley—We three shall have great pleasure in dining with you to-morrow. We hope, also, that Mr. and Mrs. Clarke and yourselves will favour us with their and your company to dinner during their stay. I like them very much, and shall be very happy to know more of them.—Very truly yours,

G. C. Tennyson.

P.S.—How the devil do you expect that people are to get up at seven o’clock in the morning to answer your notes? However, I have not kept your Ganymede waiting.

The friendship between the families, which was further cemented when the Rector’s son Drummond married Kate Franklin, whose cousin, Emily Sellwood, afterwards became the Poet’s wife, has been maintained for three generations. Alfred shared his father’s opinion of Halton, and often wrote both to the Rector and his wife. In one letter to her, after pleading a low state of health and spirits as his reason for not joining her party at Halton, he says: “At the same time, believe me it is not without considerable uneasiness that I absent myself from a house where I visit with greater pleasure than at any other in the country, if indeed I may be said to visit any other.”

After leaving Somersby, he wrote on Jan. 28, 1838, from High Beech, Epping Forest:

My dear Mrs. Rawnsley—I have long been intending to write to you, for I think of you a great deal, and if I had not a kind of antipathy against taking pen in hand I would write to you oftener; but I am nearly as bad in this way as[Pg 27] Werner, who kept an express (horse and man) from his sister at an inn for two months before he could prevail upon himself to write an answer to her, and her letter to him was, nevertheless, on family business of the last importance. But my chief motive in writing to you now is the hope that I may prevail upon you to come and see us as soon as you can. I understood from some of my sisters that Mr. Rawnsley was coming in February to visit his friend Sir Gilbert. Now I trust that you and Sophy will come with him—of course he would not pass without calling, whether alone or not. I was very sorry not to have seen Drummond. I wish he would have dropt me a line a few days before, that I might have stayed at home and been cheered with the sight of a Lincolnshire face; for I must say of Lincolnshire, as Cowper said of England,

With all thy faults I love thee still.

You hope our change of residence is for the better. The only advantage in it is that one gets up to London oftener. The people are sufficiently hospitable, but it is not in a good old-fashioned way, so as to do one’s feelings any good. Large set dinners with stores of venison and champagne are very good things of their kind, but one wants something more; and Mrs. Arabin seems to me the only person about who speaks and acts as an honest and true nature dictates: all else is artificial, frozen, cold, and lifeless.

Now that I have said a good word for Lincolnshire and a bad one for Essex, I hope I have wrought upon your feelings, and that you will come and see us with Mr. Rawnsley. Pray do. You could come at the same time with Miss Walls when she pays her visit to the Arabins, and so have all the inside of the mail to yourselves; for though you were very heroic last summer on the high places of the diligence, I presume that this weather is sufficient to cool any courage down to zero.—Believe me, with love from all to all, always yours,

A. Tennyson.

Beech Hill, High Beech, Loughton, Essex.

To this letter Mrs. Tennyson, the Poet’s mother, adds a postscript, though she complains that Alfred has scarcely left her room to do so. The letter is dated in her hand.

[Pg 28]The Halton family consisted of Edward, Drummond, and Sophy. The latter, with Rosa Baring, were two of Alfred’s favourite partners at the Spilsby and Horncastle balls. Sophy Rawnsley became Mrs. Ed. Elmhirst; she often talked of the old Halton and Somersby days. “He was,” she said, “so interesting, because he was so unlike other young men; and his unconventionality of manner and dress had a charm which made him more acceptable than the dapper young gentleman of the ordinary type at ball or supper party. He was a splendid dancer, for he loved music, and kept such time; but you know,” she would say, “we liked to talk better than to dance together at Horncastle, or Spilsby, or Halton; he always had something worth saying, and said it so quaintly.” Rosa at eighty-three recalled the same times with animation, and said to me, “You know we used to spoil him, for we sat at his feet and worshipped him; and he read to us, and how well he read! and when he wrote us those little poems we were more than proud. Ah, those days at Somersby and Harrington and Halton, how delightful they were!”

The Halton family were a decade younger than Charles, Alfred, and Mary Tennyson, but Drummond married eight years before Alfred. Emily Sellwood, just before her marriage with Alfred, wrote to Mrs. Drummond Rawnsley:

My dearest Katie—You and Drummond are among the best and kindest friends I have in the world, and let me not be ungrateful, I have some very good and very kind—Thy loving sister

Emily.

The use of the thy is very frequent with the Sellwoods, and in all Mary Tennyson’s letters too.

It was at Halton, in the time of its next Rector, Drummond Rawnsley, that the farmer Gilbey Robinson gave his son Canon H. D. Rawnsley the famous advice[Pg 29] which the Poet has preserved in his Lincolnshire poem “The Churchwarden and the Curate”:

But creeäp along the hedge bottoms an thou’ll be a Bishop yit.

And it was at Halton that Mr. Hoff, a large tenant farmer, lived of whom Dr. Tennyson heard many a story from the Rector. He was quite a character, and the Lord Chancellor Brougham was brought over by Mr. Eden from Harrington to see and talk with him. I knew Mr. Hoff, and have heard the Rector describe the lively afternoon they had. Farming was one of Lord Brougham’s hobbies, and he talked of farming to his heart’s content, and was delighted with the old fellow’s shrewdness and independence, and his racy sayings in the Lincolnshire dialect, the kind of sayings which Tennyson has preserved in his “Northern Farmer.” The farmer, too, was pleased with his visitor, but he said to the Rector afterwards, “He is straänge cliver mon is Lord Brougham, and he knaws a vast, noä doubt, but he knaws nowt about ploughing.” It was the same farmer who was introduced by the Rector to the leading Barrister at the Spilsby sessions, where both the Rector and Dr. Tennyson were always in request to dine with the bar, when the Judge was at Spilsby, for the charm of their presence and the brightness of their conversation. Mr. Hoff had seen “Councillor Flowers” in Court in his wig and gown, but meeting him now in plain clothes, and finding him a very small man, he said to him straight out, “Why, you’re nobbut a meän-looking little mon after all.” These tenant farmers, whether in the Marsh, wold, or fen, were very considerable people in days when agriculture was at its best. In the Marsh, one in particular, Marshal Heanley, was always termed the Marsh King. He it was who at the Ram-show dinner at Halton, when Ed. Stanhope, the Minister for War, had spoken of the future which was opening for the[Pg 30] great agriculturists, and, after alluding to Lord Brougham’s visit to the Shire and the sending of some farmers’ sons to the Bar, had suggested the possibility of one of them arriving at the top of the tree and sitting some day on the Woolsack. The “Marsh King” got up and said, “I allus telled yer yer must graw wool; but when you’ve grawed it, yer mustn’t sit on it, yer must sell it.”

There was a good deal of humour and also of characteristic independence about both the farmers and their men in those days; the Doctor’s own man, when found fault with, had flung the harness in a heap on the drawing-room floor, saying, “Cleän it yersen then.” And at Halton Rectory an old Waterloo cavalryman was coachman, who kept in the saddle-room the sword he had drawn at Quatre-Bras, a delight to us boys to see and hear about. He had a way of thinking aloud, and when, driving once at Skegness, he saw the Halton schoolmaster, his particular aversion, Mrs. Rawnsley heard him say, “If there ain’t that conceäted aäpe of ourn.” On a later occasion, when, at a rent-day dinner, he was handing round the beer, and the schoolmaster asked, “Is it ale or porter?” in a voice heard by all the table he replied, “It’s näyther aäle nor poörter, but very good beer, much too good for the likes o’ you, so taäke it and be thankful.” Perhaps his most famous saying was addressed to my younger brother who, when attempting to copy his elders who always jumped the quickset hedge opposite the saddle-room as a short cut to the house, had stuck in the thorns and cried, “Grayson, Grayson, come and help me out!” The old man slowly wiped his hands, and with his usual deliberation said, “Yis, I’m a-coming.” “But look sharp, confound you, it’s pricking me.” “Oh, if you’re going to sweër you may stay theër, and be damned to you.”

From Halton the way is short to Spilsby, the market[Pg 31] town where the Franklins had lived, and the statue of Sir John resting his hand on an anchor looks down every Monday on the chaffering Market folk at one end of the Market Place, whilst the women still crowd round the old Butter-cross at the other end. In the Church is the Willoughby chapel, full of interesting monuments.

Many of the Franklin family lie in the Churchyard, and on the Church wall are three tablets to the three most distinguished brothers,—James, the soldier, who made the first ordnance survey of India; Sir Willingham, the Judge of the Supreme Court of Madras; and Sir John, the discoverer of the North-West Passage. Hundleby adjoins Spilsby where Mr. John Hollway lived, of whom the Poet wrote: “People say and I feel that you are the man with the finest taste and knowledge in literary matters here.” Next to Hundleby comes Raithby, the home of the Edward Rawnsleys, where the Poet was a frequent visitor, and thence passing Mavis-Enderby on the left, the road runs on the Ridge of the Wold through Hagworthingham to Horncastle, the home of the Sellwoods. Mavis-Enderby is referred to in Jean Ingelow’s poem, “The High Tide on the Coast of Lincolnshire, 1571”:

Play uppe, play uppe, O Boston bells!

······

The brides of Mavis Enderby.

After a visit to Raithby in 1874 Alfred wrote to Mrs. Edward Rawnsley:

My dear Mary—I stretch out arms of love to you all across the distance,—all the Rawnsleys are dear to me, and you, though not an indigenous one, have become a Rawnsley, and I invoke you in the same embrace of the affection, tho’ memory has not so much to say about you.

At Keal, east of Mavis-Enderby, the Cracrofts, whom the Doctor knew well, were living; and below the[Pg 32] far-famed Keal Hill, in the flat fen, lay Hagnaby Priory, the home of Thomas Coltman, whose nephews Tom and George were often there. George, a genial giant of the heartiest kind, became Rector of Stickney, half-way between Keal and Boston; he was one of the Poet’s closest friends. In a letter to the Rector of Halton he says, “Remember me to all old friends, particularly to George Coltman”; and in after years he seldom met a Lincolnshire man without asking, “How is George Coltman? He was a good fellow.” Agricultural depression has altered things in Lincolnshire. Among the farmers the larger holders have disappeared in many places, and in the pleasant homes of Halton and Somersby, such men as the Rectors in those Georgian and early Victorian days, Nature does not repeat.

The departure of the Tennyson family made a blank which could never be filled. The villagers whom they left behind never forgot them, and even in extreme old age they were still full of memories of the family, and talked of the learning and cleverness of “the owd Doctor,” the fondness of the children for their mother and, most noticeable of all, their “book-larning,”

And boöks, what’s boöks? thou knaws thebbe naither ’ere nor theer.

The old folk all seemed to think that “to hev owt to do wi boöks” was a sign of a weak intellect. “The boys, poor things! they would allus hev a book i’ their hands as they went along.” A few years ago there was still one old woman in Somersby who remembered going, seventy-one years back, when she was eleven years old, for her first place to the Tennysons. What she thought most of was “the young laädies.” She was blind, but she said, “I can see ’em all now plaän as plaän; and I would have liked to hear Mr. Halfred’s voice ageän—sich a voice it wer.”

Frederick Tennyson.

By Charles Tennyson[11]

My uncle Frederick lived near St. Heliers, and my father and I visited him (1887) in his house, overlooking the town and harbour of St. Heliers, Elizabeth Castle, and St. Aubyn’s Bay. The two old brothers talked much of bygone days; of the “red honey gooseberry,” and the “golden apples” in Somersby garden, and of the tilts and tourneys they held in the fields; of the old farmers and “swains”; of their college friends; and of the waste shore at Mablethorpe: and then turned to later days, and to the feelings of old age. My father said of Frederick’s poems that “they were organ-tones echoing among the mountains.” Frederick told Alfred as they parted that “not for twenty years had he spent such a happy day.”—Tennyson: a Memoir, by his Son.

| To C. T. |

| True poet, surely to be found When Truth is found again. |

Of all the brothers of Alfred Tennyson the closest akin to him were Frederick and Charles. The three were born in successive years, Frederick in 1807, Charles in 1808, and Alfred in 1809. They slept together in a little attic under the roof of the old white Rectory at Somersby, they played together, read together, studied together under the guidance of their father, and all three left home to go together to the school at Louth, which Alfred and Charles at least held in detestation until their latest years. Frederick was the first to break up the[Pg 34] brotherhood, for, in 1817, he left Louth for Eton, but to the end of his long life—he outlived all his brothers—he seems to have looked back on the days of his childhood through the medium of this fraternal trinity. Years afterwards he wrote of their common submission to the influence of Byron, who “lorded it over them, with an immitigable tyranny,” and a fire at Farringford in 1876 brings to his mind the destruction of their Aunt Mary’s house at Louth, in the gardens of which he wrote: “I, and Charles, and Alfred, enthusiastic children, used to play at being Emperors of China, each appropriating a portion of the old echoing garden as our domain, and making them reverberate our tones of authority.”

At school the brothers seem to have kept much to themselves; they took little interest in the school sports, in which their great size and strength would have well qualified them to excel, and passed their time chiefly in reading and wandering over the rolling wold and flat shores of their native Lincolnshire. They began at an early age their apprenticeship to poetry. Alfred, at least, had written a considerable volume of verse by the time he was fourteen, and all three contributed to the Poems by Two Brothers, which were published at Louth in 1827, when Frederick, the author of four of the poems, had just entered St. John’s, Cambridge (his father’s old College). Charles used to tell how, when the tiny volume was published, he and Alfred hired a conveyance out of the £10 which the publisher had given them, and drove off for the day to their favourite Mablethorpe, where they shouted themselves hoarse on the shore as they rolled out poem by poem in one another’s ears. The notes and headings to the poems give some idea of the breadth and variety of reading for which the brothers had found opportunity in their quiet country life, for the volume contains twenty quotations from Horace, eight from Virgil, six from Byron, five[Pg 35] from Isaiah, four from Ossian, three from Cicero, two apiece from Moore, Xenophon, Milton, Claudian, and the Book of Jeremiah, with others from Addison, John Clare, Juvenal, Ulloa’s Voyages, Beattie, Rennel’s Herodotus, Savary’s Letters, Tacitus’ Annals, Pliny, Suetonius’ Lives of the Caesars, Gibbon’s Decline and Fall, Racine, the Mysteries of Udolpho, La Auruncana, the Songs of Jayadeva, Sir William Jones (History of Nadir Shah, Eastern Plants, and Works, vol. vi.), Cowper, Ovid, Burke on the Sublime and Beautiful, Dr. Langhorne’s Collins, Mason’s Caractacus, Rollin, Contino’s Epitaph on Camoens, Hume, Scott, the Books of Joel and Judges, Berquin, Young, Sale’s Koran, Apollonius of Rhodes, Disraeli’s Curiosities of Literature, Sallust, Terence, Lucretius, Coxe’s Switzerland, Rousseau, the Ranz des Vaches, Baker on Animalculae, Spenser, Shakespeare, Chapman and various old English ballads, while many notes give odd scraps of scientific, geographical, and historical learning.

Alfred and Charles followed Frederick to Cambridge in 1828 and entered Trinity, whither their elder brother had just migrated from John’s. All the three brothers attained a certain amount of rather unconventional distinction at the University; Frederick, who had taken a high place on his entrance into Eton and subsequently became Captain of the Oppidans, obtained the Browne Gold Medal for a Greek Ode (in Sapphic metre) on the Pyramids, the last cadence of which, “ὀλλυμένων γὰρ ἄχθων ἐξαπολειται,” is the only fragment which tradition has preserved. Charles obtained a Bell Scholarship in 1829, chiefly through the beauty of his translations into English (one line, “And the ruddy grape shall droop from the desert thorn,” was always remembered by Alfred), and the youngest brother secured, as is well known, the University Prize for English Verse with his “Timbuctoo.” None of the brothers, however, attained[Pg 36] great distinction in the schools, though Frederick and Charles graduated B.A. in 1832. With the end of their Cambridge careers the brotherhood finally dissolved. It was at first proposed that all three should (in deference to the wish of their grandfather), become clergymen. Frederick had always shown a certain independence and intractability of character. At Eton, though a skilful and ardent cricketer, he acquired a reputation for eccentricity, and Sir Francis Doyle describes him as “rather a silent, solitary boy, not always in perfect harmony with Keate,”—a gentleman with whom most spirits, however ardent, generally found it convenient to agree.

Sir Francis recounts one typical incident: Frederick, then in the sixth form, had returned to school four days late after the Long Vacation. Keate sent for him and demanded an explanation. None was forthcoming. Keate stormed in his best manner, his prominent eyebrows shooting out, and his Punch-like features working with fury, Frederick remaining all the while cynically calm. Finally the fiery doctor insists with many objurgations on a written apology from the boy’s father, whereupon the culprit leisurely produces a crumpled letter from his pocket and hands it coolly to the head-master. A fresh tirade follows, accusing Frederick of every defect of character and principle known to ethics, and concluding, “and showing such a temper too”!

How little Frederick regarded himself as fitted for Holy Orders may be judged from a letter he wrote in 1832 to his friend John Frere: “I expect,” he says, “to be ordained in June, without much reason, for hitherto I have made no kind of preparation, and a pretty parson I shall make, I’m thinking.” The grandfather came apparently to share this conclusion, for the ordination never took place.

It must have been about this time that Frederick[Pg 37] made the acquaintance of Edward FitzGerald, who was two years his junior. The pair maintained a close correspondence for many years, and “Fitz” became godfather to one of his friend’s sons and left a legacy to be divided among his three daughters.

Frederick’s fine presence and frank, tempestuous, independent nature seem to have made a powerful appeal to the younger man, for he had the great height, noble proportions, and dome-like forehead of the Tennyson family, and was so robustly built that it is said that in later years, when he lived in Florence, a new servant girl, on seeing him for the first time speeding up his broad Italian staircase in British knee-breeches, fell back against the wall in astonishment, exclaiming, “Santissima Madonna, che gambe!” Unlike his brothers, however, his hair (which he wore rather longer than was common even at that time) was fair and his eyes blue.

“I remember,” wrote Fitz in 1843, “the days of the summer when you and I were together quarrelling and laughing.... Our trip to Gravesend has left a perfume with me. I can get up with you on that everlastingly stopping coach on which we tried to travel from Gravesend to Maidstone that Sunday morning: worn out with it we got down at an Inn and then got up on another coach, and an old smiling fellow passed us holding out his hat—and you said, “That old fellow must go about as Homer did,” and numberless other turns of road and humour, which sometimes pass before me as I lie in bed.”

And in the next year he writes:

How we pulled against each other at Gravesend! You would stay—I wouldn’t—then I would—then we did. Do you remember that girl at the bazaar ... then the gentleman who sang at Ivy Green?

And seven years later Gravesend and its ἀνήριθμοι shrimps are still in his memory.

Very soon, however, after leaving Cambridge,[Pg 38] Frederick, who had inherited a comfortable property at Grimsby, set out for Italy, and in Italy and near the Mediterranean he remained, with the exception of an occasional visit to England, until 1859.

He was passionately fond of travel, which, as he used to say, “makes pleasure solemn and pain sweet,” and even his marriage in 1839 to Maria Giuliotti, daughter of the chief magistrate of Siena, could not induce him to make a settled home. In 1841 we hear of him (through “Fitz”) in Sicily, playing a cricket match against the crew of the Bellerophon on the Parthenopaean Hills, and “sacking the sailors by ninety runs.” “I like that such men as Frederick should be abroad,” adds the writer, “so strong, haughty, and passionate,” and in 1842 “Fitz” pictures him “laughing and singing, and riding into Naples with huge self-supplying beakers full of the warm South.” All the while he continued to write to FitzGerald “accounts of Italy, finer” (says the latter) “than any I ever heard.”

Once he describes himself coming suddenly upon Cicero’s Formian villa, with its mosaic pavement leading through lemon gardens down to the sea, and a little fountain bubbling up “as fresh as when its silver sounds mixed with the deep voice of the orator sitting there in the stillness of the noonday, devoting the siesta hours to study.” FitzGerald replies with letters full of affection; he sighs for Frederick’s “Englishman’s humours”—for their old quarrels: “I mean quarrel in the sense of a good, strenuous difference of opinion, supported on either side by occasional outbursts of spleen. Come and let us try,” he adds, “you used to irritate my vegetable blood.” “I constantly think of you,” he writes, “and as I have often sincerely told you, with a kind of love I feel towards but two or three friends ... you, Spedding, Thackeray, and only one or two more.” And again: “It is because there are so few F. Tennysons in the[Pg 39] world that I do not like to be wholly out of hearing of the one I know.... I see so many little natures that I must draw to the large.”

All this time Frederick was writing verse and Fitz constantly urges him to publish. “You are now the only man I expect verse from,” he writes in 1850, after he had given Alfred up as almost wholly fallen from grace. “Such gloomy, grand stuff as you write.” Again: “We want some bits of strong, genuine imagination.... There are heaps of single lines, couplets, and stanzas that would consume the ——s and ——s like stubble.”

Much of their correspondence is taken up with the discussion of music. They both agree in placing Mozart above all other composers. Beethoven they find too analytical and erudite. Original, majestic, and profound, they acknowledge him, but at times bizarre and morbid.

“We all raved about Byron, Shelley, and Keats,” wrote Frederick long after, in 1885, “but none of them have retained their hold on me with the same power as that little tone poet with the long nose, knee-breeches, and pigtail.” Indeed he was at different times told by two mediums that the spirit of Mozart in these same knee-breeches and pigtail accompanied him, invisibly to the eye of sense, as a familiar. Music was the passion of Frederick Tennyson’s life. It was said among his friends that when he settled in Florence (as he did soon after 1850), he lived in a vast Hall designed by Michael Angelo, surrounded by forty fiddlers, and he used to improvise on a small organ until he was over eighty years of age.

“After all,” he wrote in 1874, “Music is the Queen of the Arts. What are all the miserable concrete forms into which we endeavour to throw ‘thoughts too deep for tears’ or too rapturous for mortal mirth, compared with the divine, abstract, oceanic utterances of that voice which can multiply a thousandfold and exhaust in infinite echoes the passions that[Pg 40] on canvas, in marble, or even in poesy (the composite style in aesthetics), so often leave us cold and emotionless! I believe Music to be as far above the other Arts as the affections of the soul above the rarest ingenuity of the perfect orator! Perhaps you are far from agreeing with me. Indeed the common charge brought against her by her sisters among the Pierides—and by the transcendentalists and philosophical Critics—is that She has no type like the other Arts on which to model her creations and to regulate her inspirations. I say her inexhaustible spring is the soul itself, and its fiery inmost—the chamber illuminated from the centre of Being—as the finest and most subtle ethers are begotten of, and flow nearest to the Sun.”

Frederick lived at Florence till 1857 and found there, after years of wandering, his first settled home. The idea of settling tickled his humour, and in 1853 he writes: “I am a regular family man now with four children (the last of whom promises to be the most eccentric of a humorous set) and an Umbrella.” In Florence he came in contact with Caroline Norton and her son Brinsley, of the latter of whom he writes an amusing account:

Young Norton has married a peasant girl of Capri, who, not a year ago, was scampering bare-footed and bare-headed over the rocks and shingles of that island. He has turned Roman Catholic among other accomplishments—being in search, he said, of a “graceful faith.”... Parker has just published a volume of his which he entitled “Pinocchi: or Seeds of the Pine,” meaning that out of this small beginning he, Brin, would emerge, like the pine, which is to be “the mast of some great Admiral,” from its seedling. He is quite unable to show the applicability of this title, and, seeing that the book has been very severely handled in one of the periodicals under the head of “Poetical Nuisances,” some are of opinion that “Pedocchi” would have been a more fitting name for it. However, to do him no injustice, he has sparks of genius, plenty of fancy and improvable stuff in him, and is, moreover, a young gentleman of that irrepressible buoyancy which, to use the language of the Edinburgh Review, “rises by its own[Pg 41] rottenness....” As I said, he is not more than three-and-twenty, but is very much in the habit of commencing narrative in this manner: “In my young days when I used to eat off gold plate!” to which I reply, “Really a fine old gentleman like you should have more philosophy than to indulge in vain regrets.”

While we were located at Villa Brichieri, up drove one fine day the famous Caroline, his mother, who, not to speak of her personal attractions, is really, I should say, a woman of genius, if only judged by her novel, Stuart of Dunleath, which is full of deep pathos to me. I asked Brin one day what his mother thought of me. He stammers very much, and he said, “She th-th-th-thinks very well of you, but I d-d-don’t think she likes your family.” “Good heavens! here’s news,” I said. Well, afterwards she told me of having met Alfred at Rogers’, and of having heard that he had taken a dislike to her. “Why, Mrs. Norton,” I said, “that must be nearly thirty years ago, and do you harbour vindictive feelings so long?” “Oh!” she said, “why, I’m not thirty!”

Again, one day we met her in a country house where we were invited to meet her, and soon after she had shaken hands with me she said, with a dubious kind of jocosity, “I should like to see all the Tennysons hung up in a row before the Villa Brichieri.” Upon the whole, I thought her a strange creature, and she has not yet lost her beauty—a grand Zenobian style certainly, but, like many celebrated beauties, she seems to have won the whole world. Among other things she said in allusion to some incident, “What mattered it to me whether it was an old or a young man—I who all my life have made conquests?” It seemed to me that to dazzle in the great world was her principal ambition, and literary glory her second.[12]

But Frederick was too much of a man of moods to care for society. He used to describe himself as a “person of gloomy insignificance and unsocial monomania.” Society he dismissed contemptuously as “Snookdom,” and would liken it gruffly to a street row. The “high-jinks of the high-nosed” (to use another phrase of his) angered him, as did all persons “who go about with[Pg 42] well-cut trousers and ill-arranged ideas.” The consequence was that his acquaintance in Florence long remained narrow. In 1854, shortly after the birth of his second son, he wrote:

Sponsors I have succeeded in hooking, one in this manner: A friend of mine called yesterday and introduced a Mr. Jones. “Sir,” said I, “happy to see you. Like to be a godfather?” “Really,” he said, not quite prepared for the honour, “do my best.” “Thank you, then I’ll call for you on my way to the church”; so Mr. Jones was booked.

One hears, however, of a visit of Mrs. Sartoris (Adelaide Kemble) in 1854. “I had not seen her for twenty years,” writes Frederick; “she is grown colossal, but all her folds of fat have not extinguished the love of music in her.” But one friendship which Frederick made in Florence was destined to be a lifelong pleasure to him. In 1853 he writes:

The Brownings I have but recently become acquainted with. They really are the very best people in the world, and a real treasure to that Hermit, a Poet. Browning is a wonderful man with inexhaustible memory, animal spirits, and bonhomie. He is always ready with the most apropos anecdote, and the happiest bon mot, and his vast acquaintance with out-of-the-way knowledge and the quaint Curiosity Shops of Literature make him a walking encyclopaedia of marvels. Mrs. B., who never goes out—being troubled like other inspired ladies with a chest—is a little unpretending woman, yet full of power, and, what is far better, loving-kindness; and never so happy as when she can get into the thick of mysterious Clairvoyants, Rappists, Ecstatics, and Swedenborgians. Only think of their having lived full five years at Florence with all these virtues hidden in a bushel to me!

In 1854 he published his first volume of verse, Days and Hours. The book was, on the whole, well received. Charles Kingsley (whose early and discriminating recognition of the merits of George Meredith places him high among the critics of his day) wrote: “The poems are[Pg 43] the work of a finished scholar, of a man who knows all schools, who has profited more or less by all, and who often can express himself, while revelling in luxurious fancies, with a grace and terseness which Pope himself might have envied.” There was, however, a good deal of adverse criticism, and it was probably mainly owing to his irritation at many of the strictures (often futile enough) which were passed upon him at this time that he kept silence for the next thirty-six years. At any rate, he was always ready to the end of his life for a growl or a thunder at the critics.