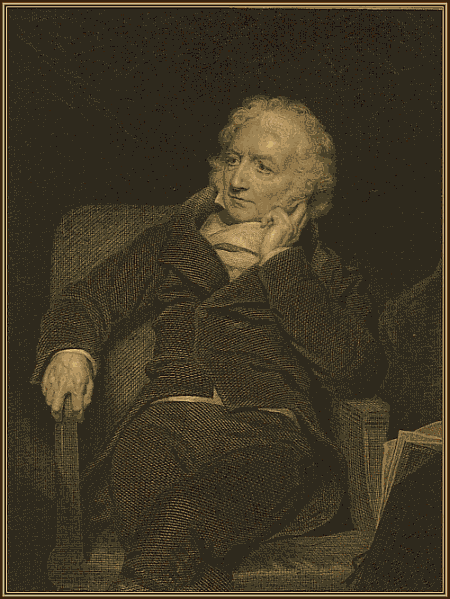

HENRY FUSELI ESQre

Title: The Life and Writings of Henry Fuseli, Volume 1 (of 3)

Author: Henry Fuseli

Editor: John Knowles

Release date: January 16, 2012 [eBook #38591]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Margo Romberg, Karl Eichwalder and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

KEEPER, AND PROFESSOR OF PAINTING TO THE

ROYAL ACADEMY IN LONDON; MEMBER OF THE FIRST CLASS

OF THE ACADEMY OF ST. LUKE AT ROME.

"Animo vidit, ingenio complexus est, eloquentiâ illuminavit."

Velleius Paterculus in Ciceronem.

MADAM,

I feel a degree of diffidence in dedicating to your Ladyship the Life and Posthumous Works of Henry Fuseli; because, with regard to the former, no one is better acquainted with the extent of his talents, or can form a more accurate opinion of the powers of his conversation, and the excellent qualities of his head and heart, than yourself. In giving some account of his life and pursuits, I have endeavoured to speak of him as he was, and to become his[iv] "honest chronicler." How far I have succeeded, it is for your Ladyship to form a judgment. Had it ever occurred to me, during his lifetime, that it would be my lot to become his Biographer, I should have kept a Journal, and thus have been enabled to present to you, and to the world, a more copious and rich view of his colloquial powers. But as this is not the case, if the Memoir bring to your remembrance the general power of his genius, or give an adumbration of his professional merit; if it convey impressions of his profound classical attainments and critical knowledge, and recall with them the simplicity of his domestic habits, my end is fully answered.

It is not for me to make an apology for sending to the public, under the high support of your Ladyship's name, the posthumous works of my friend; as these, I know, will be acceptable to you; and many of them have already received the highest encomiums, when delivered as Lectures before the Members of the Royal Academy of Arts.

I am fully certain that if the mind which dictated these works, could now be conscious of the fact, no circumstance would give to it greater satisfaction, than the knowledge of their appearing under the sanction of your patronage.

I have the honour to subscribe myself,

Madam,

Your Ladyship's most obedient,

And obliged humble servant,

JOHN KNOWLES.

4, Osnaburgh Street, Regent's Park,

24th March, 1830.

In offering to the public the Life and a complete edition of the literary Works of Henry Fuseli, I feel myself called upon to state the sources whence the former has been drawn.

The daily intercourse and sincere friendship which subsisted for many years between this great artist and myself, afforded me the opportunity of witnessing his domestic habits, hearing many of the incidents of his life, and watching his career as an artist; and, being executor to his will, his professional as well as private papers came into my possession. Independently of these advantages, I have been in correspondence with the nearest branches of [viii] his family, (at Zurich, in Switzerland,) and from their kindness have obtained many particulars of his early life, together with the correction of some previously inaccurate dates. Whatever estimate, therefore, may be formed of my work, as a literary production, the particulars have been gathered from the most authentic and unquestionable sources.

With respect to his works, it may be necessary to state that the first Six Lectures were published in a quarto volume under Mr. Fuseli's own superintendence, and were printed in a more extended form than that in which they were delivered; additional observations having been inserted for the press, and notes added to indicate the authorities whence his opinions were derived. They are now reprinted from a copy in my possession, in which are noted some corrections by the author.

The remaining Six Lectures are published from the manuscripts in his own hand-writing, without any addition, omission, or alteration.

The Aphorisms were collated, and re-copied fairly some years before the death of the[ix] author: these are printed verbatim as he intended they should come before the public.

The History of the Italian Schools of Art will be found to contain the professional lives of Michael Angelo, Raffaelle, Titian, Correggio, and other great masters, with the author's criticisms on their works. Most of the observations on Art were made by Fuseli while in Italy and France, after a close inspection of the frescoes, pictures, or works in sculpture, which he describes or criticises; and the particulars of the lives of the artists were deduced from a careful perusal and comparison of the most elaborate and esteemed works in which they have been recorded.

The reader will notice, that, in a few instances, the same notions and expressions are repeated; a circumstance which occasioned from an eminent artist, (the late Sir Thomas Lawrence,) for whose opinion and talents I had great respect, a recommendation to "use the pruning-knife." But it appeared to me, after due consideration, to be preferable that I should print the manuscripts as they came into my hands; for to have omitted these [x] passages might have disturbed the connexion of the reasoning and rendered the author's ideas less apparent to the reader; I therefore present his works to the world without any omission, alteration, or addition on my part.

John Knowles.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Fuseli's birth and family.—Passion for drawing manifested in his childhood.—His destination for the Church.—Singular cause of ambidexterity.—Fuseli's early fondness for entomology.—He enters the Collegium Carolinum at Zurich.—His associates there: Lavater, Usteri, Tomman, Jacob and Felix Hess.—Professors Bodmer and Breitinger.—His partiality for Shakspeare, &c.—His turn for satire called forth at the College.—He courts the Poetic Muse.—Enters into holy orders at the same time with Lavater.—State of Pulpit oratory in Zurich.—Fuseli and Lavater become champions of the public cause against a magistrate of Zurich.—Quits Zurich | Page 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The friends are accompanied in their journey by Professor Sulzer.—They visit Augsburgh and Leipsic.—Arrive at Berlin.—Fuseli furnishes some designs for Bodmer's work.[xii]— Baron Arnheim.—Fuseli visits Barth, in Pomerania, where he pursues his studies for six months under Professor Spalding.—Motives which induce him to visit England, where he arrives in 1763, under the protection of Sir Andrew Mitchell.—Lord Scarsdale: Mr. Coutts: Mr. Andrew Millar: Mr. Joseph Johnson.—Fuseli receives engagements from the booksellers.—His first residence in London: becomes acquainted with Smollet: Falconer: A. Kauffman: Mrs. Lloyd: Mr. Cadell: Garrick.—Fuseli accepts, and shortly after relinquishes the charge of travelling tutor to the son of Earl Waldegrave.—His first interview with Sir Joshua Reynolds.—His earliest production in oil painting.—He visits Liverpool.—Takes part in Rousseau's quarrel with Hume and Voltaire, (1767) and exerts his pen in the cause of his countryman | 22 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Fuseli leaves England for Italy in the society of Dr. Armstrong.—They quarrel, and separate at Genoa.—Fuseli arrives at Rome (1770).—His principle of study there.—He suffers through a fever, and repairs to Venice for his health.—Visits Naples.—Quits Rome (1778) for Switzerland.—Letter to Mr. Northcote.—Fuseli renews his classical studies.—Visits his family at Zurich.—Engages in an unsuccessful love-affair.—Arrives again in London | 46 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Fuseli settles in London.—Interview with Mr. Coutts.—Reconciliation with Dr. Armstrong.—Professor Bonnycastle.—Society at Mr. Lock's.—Mr. James Carrick Moore and Admiral Sir Graham Moore.—Sir Joshua Reynolds.—Mr. West.—Anecdote of Fuseli and West.—The popular picture[xiii] of "The Nightmare."—Death of Fuseli's Father.—Visit to Mr. Roscoe at Liverpool.—Fuseli's singular engagement to revise Cowper's Iliad.—Three Letters from Mr. Cowper.—Anecdotes of Fuseli and Dr. Geddes | 57 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Subjects painted by Fuseli for Boydell's "Shakspeare Gallery."—His assistance towards the splendid Edition of "Lavater's Physiognomy."—His picture for Macklin's "Poets' Gallery."—His contributions to the Analytical Review.—His critique on Cowper's Homer | 77 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Fuseli's proficiency in Italian History, Literature, and the Fine Arts, exemplified in his Criticism on Roscoe's Lorenzo de' Medici | 110 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Fuseli's Marriage.—His inducements to associate himself with the Royal Academy.—He translates Lavater's "Aphorisms on Man."—Remarks on his own "Aphorisms on Art."—Particulars of Fuseli's acquaintance with Mrs. Wollstonecraft | 158 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Milton.—First notion of the "Milton Gallery" hence suggested.—Letter to Mr. Roscoe from Fuseli and Mr. Johnson.—Circumstances attending Fuseli's Election as a Royal Academician.—Sir Joshua Reynolds's temporary secession connected with that event.—Fuseli's progress in the pictures for the "Milton Gallery."[xiv]—Controversy between Fuseli and the Rev. Mr. Bromley.—Subjects painted for Woodmason's "Illustrations of Shakspeare."—Subscription towards the completion of the Milton Gallery.—Letter from Mr. Roscoe.—Fuseli contributes to Seward's "Anecdotes."—His Visit to Windsor with Opie and Bonnycastle.—Anecdotes connected with that Visit.—Letter from Mr. Roscoe.—Mr. Johnson's Imprisonment, and Fuseli's adherence to him.—Anecdote of Lord Erskine.—Exhibition of the "Milton Gallery," and List of the Works composing it, with incidental Comments, &c.—Letter to Fuseli from his brother Rodolph.—Letter from Fuseli to Mr. Lock | 171 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Fuseli's Lectures at the Royal Academy.—Letters respecting them from Mr. Farington.—Letter from Sir Henry Englefield, on the subject of the ancient Vases.—Death of Fuseli's friend Lavater.—Fuseli's Visit to Paris in 1802.—His Letter from thence to Mr. James Moore.—His acquaintance with the French Painters David and Gerard.—Results of his Visit.—Letter from Mr. Roscoe.—Fuseli's Remarks on some of the Paintings in the Louvre.—Letter from Mr. Smirke.—Fuseli elected Keeper of the Royal Academy.—Incidental Anecdote.—Letter to Mr. Joseph Johnson | 239 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| The Biographer's Introduction to Fuseli.—New Edition of Pilkington's Dictionary of Painters, superintended by Fuseli.—Establishment of the British Institution, and Fuseli's limited Contributions to the Exhibition there.—Subject from Dante.—Fuseli's Remarks on Blake's Designs.—His Lectures on Painting renewed.—Tribute of esteem from the Students of the Academy.—Letter.—Death of Mr. Johnson, and Fuseli's[xv] sympathy on the occasion.—Fuseli re-elected to the Professorship of Painting at the Royal Academy | 287 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Fuseli's prefatory Address to his resumed Lectures.—His second Edition of Pilkington.—He suffers from a nervous fever, and visits Hastings in company with the Biographer.—His Picture of Marcus Curius, and Letter relative to it.—Letter from Mr. Roscoe.—Canova's Intercourse with Fuseli.—Anecdotes of Fuseli and Harlow.—Letters from Fuseli to the Biographer.—Republication of his Lectures, with additions.—Death of Professor Bonnycastle, and Anecdote concerning him.—Death of Fuseli's friend and patron Mr. Coutts.—An agreeable party at Fuseli's house | 304 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Decline of Fuseli's Health.—Letter from Mr. James C. Moore.—Fuseli's Bust by Baily, and Portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence.—His last Academical Lectures.—Particulars of his Illness and Death.—Proceedings relative to his interment, with an account of the ceremony—Copy of his Will | 329 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Fuseli's personal appearance and habits.—Existing Memorials of him in Pictures and Busts.—His method of dividing his time.—Anecdotes exemplifying his irritability.—His attainments in classical and in modern Languages.—Instances of his Powers of Memory.—His intimate knowledge of English Poetry and Literature.—His admiration of Dante.—His Passion for Entomology.—His opinions of some contemporary Artists.—His conversational powers, and Anecdotes.—His deficient acquaintance with the pure Physical Sciences | 350 |

| CHAPTER XIV.[xvi] | |

| Fuseli's inherent shyness of disposition.—His opinion of various noted individuals, viz. Dr. Johnson, Sterne, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Gibbon, Horne Tooke, and Thomas Paine.—His cultivation of English notions and habits.—His attachment to civil and religious Liberty.—His intimacy with theatrical matters.—His adventure at a Masquerade.—His powers as a Critic, both in Literature and Art, with various illustrative examples.—His impressions of Religion.—One of his Letters on Literature | 371 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Character of Fuseli as an Artist.—His early style.—His ardent pursuit of excellence in design.—His neglect of mechanical means, particularly as regards Colours.—His professional independence, unmixed with obstinacy.—His pre-eminent faculty of invention, and success in the portraiture of the ideal.—His deficiencies as to correctness, and disinclination to laborious finish.—Causes of his limited popularity as a Painter.—His felicity in Likenesses.—His colour and chiar-oscuro.—His quality as a Teacher of the Fine Arts.—His ardent love of Art.—Arrangements as to the disposal of his Works, &c.—List of his Subjects exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1774 to 1825 | 395 |

| APPENDIX. | |

| On the character of Fuseli as an Artist, by W. Y. Ottley, Esq.—Verses to Fuseli on his series of Pictures from the Poetical Works of Milton, by W. Roscoe, Esq.—Ode to Fuseli on seeing Engravings from his Designs, by H. K. White, Esq.—"A Vision,"—verses in which Fuseli's principal productions are briefly noticed [xvii] | 419 |

Fuseli's birth and family.—Passion for drawing manifested in his childhood.—His destination for the Church.—Singular cause of ambidexterity.—Fuseli's early fondness for entomology.—He enters the Collegium Carolinum at Zurich.—His associates there: Lavater, Usteri, Tomman, Jacob and Felix Hess.—Professors Bodmer and Breitinger.—His partiality for Shakspeare, &c.—His turn for satire called forth at the College.—He courts the poetic Muse.—Enters into holy orders at the same time with Lavater.—State of pulpit oratory in Zurich.—Fuseli and Lavater become champions of the public cause against a magistrate of Zurich.—Quits Zurich.

As there is a natural wish in mankind to be made acquainted with the history of those men who have distinguished themselves by any extraordinary exertion of talent, so we always[2] experience regret when we look to the biography of a celebrated man, if we find the details scanty, or the particulars respecting him resting for their accuracy upon the uncertainty of oral communication, made after a lapse of several years.

Although the mind of an author may, at a remote period, be appreciated by a perusal of his works, and the capacity and talents of an artist be judged of by the powers of invention which he has displayed,—by the harmony of his colour and the style and correctness of his lines; yet these do not completely satisfy; we wish the more to see him in his closet, to pursue him into familiar life, and to be made acquainted with the paths which he trod and the mode of study which he adopted to arrive at eminence. Who does not feel this impulse when he peruses the meagre accounts we have received of Shakspeare or Correggio? although the utmost efforts of industry have been employed to collect facts relating to these extraordinary men.

It is with such feelings that I attempt to give some particulars of the life and professional career of Henry Fuseli, while they are fresh on the memory; for if the biography of any[3] particular man be not written during his lifetime, or shortly after his decease, we recollect perhaps only a few circumstances, and fill up the record by guessing at the rest.

Many of the incidents which I am about to relate respecting Mr. Fuseli were communicated by himself; for I had the happiness of enjoying his friendship uninterruptedly for twenty years, and was almost in the daily habit of seeing and conversing with him until the last period of his existence. Other particulars I have collected from some of his relations and friends, and gleaned much from his private papers, which fell into my possession, as executor to his will. The facts may therefore be relied upon, and they will, at least, assist some future biographer: for I feel the difficulties under which I must unavoidably labour, in attempting to display the powers of a highly gifted man, and an eminent professor in an art which requires the study of years, nay of a whole life, to understand in any competent degree.

Henry Füessli (for such is the family name), the second son of John Caspar Füessli, was born on the 7th February, 1741, N.S. at Zurich, in Switzerland, which city had been the native place of his family for many generations.

His father, John Caspar, a painter of portraits and sometimes of landscapes, was distinguished for his literary attainments; when young, he had travelled into Germany, and became a pupil of Kupetzky, the most celebrated portrait painter of his time. He then resided for some time at Rastadt, as portrait painter to that court; and afterwards went to Ludswigsbourg, with letters of recommendation to the Prince of Wirtemberg, and was particularly patronized by him.

In the war of 1733, a French army having entered Germany, threw every thing there into confusion, on which Füessli withdrew from the scene of military operations, to Nuremberg, and remained in that city for six months, in expectation of a termination of hostilities; but hearing of the fall of his patron, the Prince of Wirtemberg, in the field of battle, he returned to Zurich, and settled in Switzerland for life.

Shortly after his return to his native city, he married Elizabeth Waser, an excellent woman, but of retired habits, who confined her attention to the care of her house and family, and to the perusal of religious books. By this marriage he had eighteen children, three of whom only arrived at the age of manhood;—Rodolph, who followed his father's profession as a painter, and[5] afterwards, settling at Vienna, became librarian to the Emperor of Germany; Henry, the subject of this Memoir; and Caspar, well known for his able and discriminative works on entomology.

Although John Caspar Füessli, the father, had travelled much, and was not unacquainted with the manners of courts, and could practise, when he thought proper, those of a courtier, yet he had assumed the carriage of an independent man of the world, and acquired an abrupt and blunt manner of speaking. Yet, as he was endowed with learning and possessed of talents, his house was frequented by men the most eminent in literature and in the arts, in Zurich and its neighbourhood. He was also an author, and, among other works, published the Lives of the Helvetic Painters, in which he received considerable assistance, both in its arrangement and style, from his son Henry. This he was enabled to do, notwithstanding, to use his own words, "in boyhood, when the mind first becomes capable of receiving the rudiments of knowledge, he had not the advantage of the amalgamating tuition of a public school."[1]

Henry Fuseli not only profited in his early years by the instruction of his parents, but also by the society which his father kept; indeed, he may be said to have been rocked in his cradle by the Muses,—for Solomon Gessner was his godfather. This poet and painter was the intimate friend of the elder Fuseli, and addressed to him an elaborate letter on landscape-painting, which is published in his works. But it was to his mother that Henry considered himself chiefly indebted for the rudiments of his education: she, it appears, was a woman of superior talents, and possessed, in a high degree, the affection and gratitude of her children. Even in the latter days of his life, when Fuseli has spoken of his mother, I have seen tears start into his eyes.

Henry Fuseli showed, very early, a predilection for drawing, and also for entomology; but the former was checked by his father, who knowing, from his own pursuits, the difficulty of arriving at any eminence in the fine arts, except a man's whole mind and attention be given to them; and having designed his son[7] Henry for the clerical profession, under the expectation of advantageous preferment for him in the church, he considered that any pursuit requiring more than ordinary attention would draw his mind from those studies which appertain to theology, and thus be injurious to his future prospects. Perhaps, too, his dislike to his son's being an artist may also have arisen from the notion, that he would never excel in the mechanical part of painting; for, in youth, he had so great an awkwardness of hands, that his parents would not permit him to touch any thing liable to be broken or injured. His father has often exclaimed, when such things were shown to his visitors, "Take care of that boy, for he destroys or spoils whatever he touches."

Although the love which Fuseli had for the fine arts might be checked, yet it was not to be diverted altogether; this pursuit, which was denied him by parental authority, was secretly indulged,—for he bought with his small allowance of pocket-money, candles, pencils, paper, &c., in order to make drawings when his parents believed him to be in bed. These he sold to his companions; the produce of which enabled him either to purchase materials for the execution of other drawings, or to add articles[8] to his wardrobe, such as his parents might withhold, from prudential motives.

Many of his early sketches are still preserved, one of which is now in my possession,—"Orestes pursued by the Furies." The subjects which he chose were either terrific or ludicrous scenes: in both these, he at all periods of life excelled: although his early works are incorrect in point of drawing, yet they generally tell the story which they intend to represent, with a wonderful felicity, particularly when it is considered that several of them proceeded from the mind of a mere child, scarcely eleven years of age.

The work which most engrossed Fuseli's juvenile attention was Tobias Stimmer's field-sports: these subjects he copied diligently, either with a pen or in Indian ink, as well as the sketches of Christopher Maurer, Gotthard Ringgli, Jobst Ammann, and other masters of Zurich. These artists, it must be acknowledged, possessed great powers of invention, and had a firm and bold outline, yet their figures are not to be commended for proportions or elegance, and the mannerism of their works was a dangerous example for a student to follow. It is not surprising, therefore, that we find an imitation of their faults in the early drawings of[9] Fuseli; in which short and clumsy figures are generally draped in the old Swiss costume.

Although the father seldom or ever attended public worship, yet he was not ignorant of the principles of religion, and knew what would be expected from his son when he entered upon the clerical profession: in order, therefore, to initiate him in the doctrines which he intended he should teach, he employed a clergyman to assist him in these as well as to instruct him in the classics. From this gentleman he borrowed the most esteemed religious books, which it was his practice, in the evenings, to read aloud to Henry. But while the father was reading the paraphrases of Doddridge, or the sermons of Götz or Saurin, the son was not unfrequently employed in making drawings; and the better to escape observation, he used his left hand for that purpose. This practice made him ambidextrous during his life.

The tutor soon perceived the bent of his pupil's inclination, who, instead of making his themes, or attending to other studies, was caricaturing those about him; and he told his father that, although he had an uncommon capacity for whatever he undertook with ardour, yet he was so wayward in his disposition, and[10] so bent upon drawing, that it was doubtful whether he would ever become a scholar.

The health of Mrs. Füessli being in a very delicate state, the family removed a few miles from the city, for the benefit of the air. Henry was at this time about twelve years of age. A residence in the country opened to his active mind a new field for contemplation, in the study of nature; and he now found great delight in what he had before in a degree pursued,—entomology. This study his father allowed him to prosecute, as he considered that the attempt to gain a knowledge of a science

would be advantageous to his future walk in life; he therefore indulged his wish, encouraged him to proceed, and furnished him with books by which he could get information respecting the genera of insects, and their habits.[2] And in the pursuit of entomology he was usually accompanied by his younger brother, Caspar, who has written so ably upon this science; and I have often heard Henry enlarge, in glowing terms, upon the pleasurable sensations which he experienced, when a boy, from [11] the freshness of the air, at the dawn of day, when he had been creeping through hedge-rows in search of the larvæ of insects, or in pursuit of the disturbed and escaping moth or butterfly.

After a residence of two or three years in the country, Henry had arrived at that age when he required and was likely to profit by more profound instructions than he had hitherto received; with the view of affording these, his family resumed their residence at Zurich, and he was placed as a student in the Collegium Carolinum, in which he was matriculated, and finally took the degree of Master of Arts.

The secluded life which Fuseli's parents led, particularly while they resided in the country, had confined his juvenile acquaintances to a M. Nüscheler,[3] and to those youths who received occasional instructions from his father in painting. A college was therefore a new and imposing scene. Although he was then a novice in society, and had from nature a degree of shyness, which was increased by seclusion; yet his acute and discerning mind soon discovered those students who possessed the greatest talents, and with whom [12] he could therefore with the more pleasure associate. Accordingly, he formed an acquaintance, which ripened into lasting friendship, with Lavater, Usteri, Tomman, Jacob, and Felix Hess; names well known in German literature.

At this time, the celebrated Bodmer and Breitinger were professors in the Caroline College; they were the intimate friends of the elder Füessli, (who has transmitted their likenesses to posterity,) and in consequence of this intimacy, they paid more than ordinary attention to the young student. These learned men were, in addition to their other studies, actively engaged in reforming the German language, and in this respect correcting the taste of their countrymen, and they constantly urged their pupils to pursue the same course; for at this period a pure and elegant style was very rare, and therefore considered no mean acquirement.

A naturally strong constitution, with considerable elasticity of mind, enabled Fuseli to pursue his studies for many hours in each day without interruption. In fact, he was capable of any mental labour, however severe. He attended diligently the usual routine of college studies, and being possessed of a very retentive memory, these were attained or performed without[13] difficulty. He therefore found time to gain a considerable knowledge of the English, French, and Italian languages. He was attracted to these, not only by the desire of travelling at some future period, but that he might be enabled to read some of the most celebrated authors in their own tongues.

He was enamoured with the plays of Shakspeare, and attempted a translation of Macbeth into German. The novels of Richardson, particularly his Clarissa, made a powerful and lasting impression upon his mind.[4] The works of Rousseau were eagerly devoured by him. And the poetic flights of Dante not only aroused his feelings, but afforded subjects for his daring pencil, which, notwithstanding his numerous studies, was not laid aside.

Mixing in society naturally gives to an observing mind a knowledge of men and manners. After Henry Fuseli had attended for some time the college studies, and acquired some degree of confidence in his own powers, he discovered and exposed weak points in some of the professors and tutors who had been held up as examples to the students, and also brought forward the merit and latent qualities of others, who from their modesty had remained without notice, and thus drew them from obscurity. If he could not attain his object by satire, in which he was very powerful, he sometimes resorted to caricature, a weapon not less formidable in his hands. The wounded pride of some of the masters induced them to draw up a formal complaint against him, and he was threatened with expulsion by the president, which was only a menace to intimidate him, as the heads of the college admired his talents, and were pleased with his assiduity.

In reading the Holy Scriptures (which he did diligently), the classics, or the modern historians or poets, Fuseli's mind was most powerfully attracted by those incidents or expressions which are out of the ordinary course, and he frequently embodied them with his pencil. Bodmer perceiving this bent of his mind, recommended him to try his powers in poetry, and[15] gave him, as models for imitation, the works of Klopstock and Weiland. The former were considered by Henry to be master-pieces; he caught the inspiration, and published, in a weekly journal called the "Freymüthigen Nachrichten,"[5] an ode to Meta. This was so much in the spirit, and so near an imitation of Klopstock's style, that the ardent admirers of this great poet attributed it to him, and which was believed by all who were not in the secret. He also attempted a tragedy from the Bible, "The Death of Saul," which was also highly commended.

It is but reasonable to suppose, that Bodmer would endeavour to instil into the mind of a favourite pupil a love for the abstract sciences, in the knowledge of which he was himself so eminently skilled: but for these Fuseli showed an utter distaste, which continued during the whole of his life. He has more than once exclaimed to me, "Were the angel Gabriel sent expressly to teach me the mathematics, he would fail in his mission." And he has frequently dilated upon the annoyance which he felt, when discovered by any one of the tutors to be engaged in some favourite pursuit, by his putting, in Latin, an abrupt and unexpected question in physics, such as, [16] "Quid est calor, Henrice Füessli?"

In the year 1761, Fuseli and his intimate friend Lavater entered into holy orders. The state of pulpit oratory, at this time, in Zurich, is thus described by a kinsman[6] of the former: "The Dutch method of analyzing was at this time in vogue in our pulpits. By aiming at popularity, the language was often reduced to the lowest strain, and to mere puerilities. The subjects were chiefly dogmatical; and if a moral theme was introduced, their sermons betrayed no knowledge of mankind: they were mostly common-place declamation, deficient in precision and just discrimination. Exaggeration prevented the backslider from applying the description to himself; and as the way to reformation was neither intelligibly nor mildly pointed out, he was rather irritated than corrected.

"Even the most distinguished preachers lost themselves in long and tiresome discourses, wandering either through the barren fields of scholastic or academic exercises, of little interest to a common audience; or else they spun out labyrinthine allegories.

"Others tried to excite the feelings by doctrines that bordered on mysticism or Moravianism; and there were those who made simplicity their aim, not the noble but the coarser species, descending to vulgarity and meanness to flatter the popular taste, and endeavouring to disguise vacuity and sameness by low comparisons, little tales, and awkward imagery.

"Some were to be found who, in their zeal for doctrinal faith, abused morality and philosophy, and bestowed the nickname of "Taste-tellers" on those who took a different course, and aimed at a better mode of address."

Klopstock, Bodmer, Weiland, Zimmerman, S. Gessner, and some others, feeling how defective pulpit oratory was at Zurich, had laboured to bring about a better style of preaching, but without much effect. Fuseli, upon entering into holy orders, determined to regulate his efforts, and by the advice of these learned men, he chose Saurin's sermons as models of manner and arrangement; but with the view of conveying[18] his sentiments so as to produce the greatest effect upon his audience, adopted the more inflated language of Klopstock and of Bodmer.

As his reputation stood high at college, and as his society was coveted for the power which he displayed in conversation, and for his deep knowledge in the classics and in sacred and profane history; so, a great degree of curiosity was excited among his friends, as to the success of his probationary sermon, which he knowing, with characteristic humour, took his text from the 17th chapter of the Acts of the Apostles, 18th verse, "What will this babbler say?" and preached against the passion of curiosity.

The new mode of preaching which Fuseli adopted and carried into many of the pulpits of Zurich; the novelty of the style, the originality of the ideas, and the nervous language which he used, pleased "the judicious few;" but it was "caviare to the general;" and hence the youthful preacher gained no great degree of popular applause. His friends, and Bodmer in particular, prompted him to persevere in the course which he had commenced, assuring him, that, in the end, it would be crowned with success; but at this time an incident happened, which gave a turn to his pursuits in life.

The works of Rousseau, Voltaire, and others,[19] who were then endeavouring by their writings to bring about a reform in the political and moral conditions of society, warmed his imagination, and he, Lavater, Jacob and Felix Hess, (who were not less influenced,) were determined to exert themselves, to benefit those of their native city. An opportunity was soon presented to their active minds. Rumour had been for some time busy with the character of a ruling magistrate, the high land-bailiff Grebel, ascribing to him various acts of tyranny and oppression, and among others, that of appropriating to himself property, and bidding defiance to the rightful owners. This he considered he might do with impunity, not only by the power which he possessed from his high situation, but also from that which he derived from his father-in-law, who was the burgomaster of Zurich.

The young friends made diligent inquiries into these charges, and found that there were ample grounds to justify the reports which were current. Their indignation was aroused, and they sent an anonymous letter to the magistrate, threatening him with instant exposure if he did not restore the property. Grebel, relying too much upon the feeling of security which power creates, took no notice[20] of this letter. Upon which Fuseli, and Lavater in particular, excited farther by his contempt, resolved to make the cause of the injured party their own, and accordingly wrote a pamphlet, entitled, "The Unjust Magistrate, or the Complaint of a Patriot," in which they detailed, in forcible and glowing terms, the acts of oppression which had been committed, and called upon the Government to examine into the facts, and punish the offender.

This pamphlet they industriously circulated, and took care that it should fall into the hands of all the principal members of the government. The manly tone in which it was written, and the facts adduced in support of the accusation, made such an impression on the council of Zurich, that it was stated from authority, if the author would avow himself, all the circumstances should be inquired into, and the facts carefully examined.

Upon this, Fuseli and Lavater, who were the ostensible persons, boldly stepped forward, and acknowledged themselves the authors. Evidence was taken, and the truth of the accusation established to its utmost extent. An upright judgment was awarded; the property restored; and the guilty magistrate then absconded, to avoid the personal punishment so justly due to his crimes.

Of this incident, which perhaps was the most important of Fuseli's life, as it was the cause of his quitting his native country, and changing his profession, he very seldom spoke; and during the whole term of our acquaintance, never mentioned the particulars but once, and then remarked, "Although I cannot but reflect with some degree of satisfaction upon the correctness of our feeling, and the courage which we displayed, yet, situated as we and our families then were, it evinced precipitation on our part, and a want of knowledge of the world."

This spirited act, on the part of Fuseli and his friends, was for some time the theme of public conversation at Zurich, and their patriotism was greatly applauded. But the disgrace which had fallen, by their means, on the accused, was felt by his powerful family, who considered, that, from their connexion with him, a part of the ignominy fell upon themselves. The tendency and natural consequences of such feelings were properly appreciated by the respective families of the young men, and they considered it prudent to recommend them to withdraw for a time from the city.

The friends are accompanied in their journey by Professor Sulzer.—They visit Augsburgh and Leipsic.—Arrive at Berlin.—Fuseli furnishes some designs for Bodmer's work.—Baron Arnheim.—Fuseli visits Barth, in Pomerania, where he pursues his studies for six months under Professor Spalding.—Motives which induce him to visit England, where he arrives in 1763, under the protection of Sir Andrew Mitchell.—Lord Scarsdale: Mr. Coutts: Mr. Andrew Millar: Mr. Joseph Johnson.—Fuseli receives engagements from the booksellers.—His first residence in London: becomes acquainted with Smollet: Falconer: A. Kauffman: Mrs. Lloyd: Mr. Cadell: Garrick.—Fuseli accepts, and shortly after relinquishes the charge of travelling tutor to the son of the Earl of Waldegrave.—His first interview with Sir Joshua Reynolds.—His earliest production in oil painting.—He visits Liverpool.—Takes part in Rousseau's quarrel with Hume and Voltaire, (1767) and exerts his pen in the cause of his countryman.

It was fortunate for Fuseli and his friends, that the learned Sulzer, who held the situation of professor of mathematics in the Joachimsthel College, at Berlin, was at Zurich at this time, having obtained leave from the King of Prussia to visit his native country, to endeavour to dissipate his grief for the loss of a beloved wife. Sulzer, who had taken a lively interest in the[23] cause which these young men had advocated, was about to return to Berlin, and offered to take them with him: this opportunity was not to be neglected; and he, Fuseli, Lavater, Jacob and Felix Hess, set out on their journey, early in the year 1763, accompanied by a numerous train of friends and admirers, who attended them as far as Winterthur, at which place they were welcomed with fervour, as the enemies of oppression.

Sulzer justly and properly appreciated what would probably be felt by young men who, for the first time, leave home and those connexions which make home dear to them; and he therefore, in order to dissipate any unpleasant feelings, determined to remain for some days at those cities or towns on the road, where there was any thing to be seen worthy of attention. The change, however, was less felt by Fuseli than by his companions; the profession in which he had been employed was not one of his choice; he had always entertained a strong desire to travel, and he had lost, a few years previously, an affectionate mother[7] to whom he was tenderly attached.

The first city of note at which they tarried was Augsburgh: here Fuseli showed his predilection for art, in giving, by letter to his friends at Zurich, a florid description of the sensations which he experienced on seeing the colossal figure of St. Michael over the gateway of the arsenal, the work of a Bavarian sculptor, Reichel. In the churches and senate-house of this city, the paintings of Tintoretto, Schönfeld, and Rothenhamer, attracted his particular attention; and he expressed his regret at the neglect which appeared to attend the works of the last-named master, (whom he eulogizes as "one of the most able painters of Germany,") as his pictures were then falling into rapid decay.

At Leipsic, they were introduced by Sulzer to Ernesti, Gellert, Weisse, and other literati. From the description which Fuseli gave of the two former, it is evident that he, as well as Lavater, had paid early in life a sedulous attention to physiognomy. Of Ernesti, he says, "although he spoke of the liberality of all classes in Saxony, his countenance did not agree with his words; on the contrary, he seems to be growing intolerant from knowledge and from authorship." Of Gellert, he remarks, "he has an expressive mouth, it turns on one side with[25] a sensible easy smile; he is so gentle, so accustomed to express simplicity in his very countenance, and yet so quick-sighted, that he was disturbed by being looked at, and inquired whether I was displeased with him; he has certainly a tendency to hypochondria."

On their arrival at Berlin, Sulzer commenced (according to a promise made at Zurich) arrangements for publishing a splendid and improved edition of his friend Bodmer's "Noachide," which was to be embellished with engravings. B. Rhode, of Berlin, was employed to make the designs for the first four cantos; those for the remaining eight were furnished by Fuseli, who, not only to raise his own credit, but to show his gratitude to Bodmer, exerted his utmost ability upon that work. Comparing these with his former drawings, it is evident that the St. Michael, at Augsburgh, was the standard for the stupendous forms which he introduced against a murky sky, in the terrible scenes of the destruction of the primeval inhabitants of the earth. In these subjects he succeeded beyond expectation. In the more lovely scenes of the poem he was not equally happy; for, "instead of repose and cheerfulness, his female figures had a degree of wantonness bordering somewhat upon voluptuousness."

The popularity of the cause which induced Fuseli and his companions to leave Zurich travelled before them, and they were caressed not only by the friends and acquaintances of Sulzer, at Berlin, but by all those who were enemies to oppression from whatever quarter it might spring. Among these, was the then Baron Arnheim, who was so much pleased with the recital of the transaction, and struck with the appearance and conversation of Fuseli and Lavater, that he had a picture painted, representing their first interview, which is still preserved by his family.

After remaining a short time at Berlin, Sulzer placed his young friends with Professor Spalding, who resided at Barth, in Hither Pomerania. Fuseli here pursued his classical studies with eagerness, and did not neglect the fine arts, for we find that he drew the portrait of the Professor's daughter, and also added to the decorations of her summer-house by his pencil.

During a residence of six months at Barth, he gained the highest estimation for talents with all those who knew him, and the esteem of Spalding, but he left his friends there, being recalled to Berlin by Sulzer.

The cause of Fuseli's return to the capital[27] was, that, at this time, some of the literati of Germany and Switzerland had it in contemplation to establish a regular channel of literary communication between those countries and England. Fuseli's tutors and friends, Bodmer, Breitenger, and Sulzer, felt a lively interest in this project, and took an active part in carrying the design into execution. These philosophers thought, that there was no person better qualified than Fuseli to conduct the business. He was possessed of great mental and bodily activity; they had the highest opinion of his talents; and they considered that his extensive knowledge of modern languages would facilitate their project. In making the proposal, Sulzer represented that it would be inconvenient, if not dangerous, for him to go back, within a limited time, to Zurich; for it was well known to the family of Grebel, that he had taken the most active part in the affair against their relation: and moreover that, although his companions might, under this circumstance, from their powerful connexions, return at no distant period with impunity, yet Fuseli, not so happily situated, would suffer from all the effects of tyranny which power could exercise. This reasoning had its due effect upon the mind[28] of Fuseli; he however asked the opinion of his father, which being in favour of his accepting the offer of Sulzer, made him determine to visit England.

Sir Andrew Mitchell was at this time the British minister at the court of Prussia: he was a friend of Sulzer's, who accordingly introduced Fuseli to him. At his house he improved much in English conversation, and he met several men of literary note, among whom was Dr. Armstrong, who was then physician to the British forces in Germany; and with this gentleman he became intimately acquainted.

Sir Andrew Mitchell was about to return to England; and being pleased with the society of Fuseli, and wishing to give every facility to the views of Sulzer, he liberally made the offer to the latter that his young friend should accompany him to London, and promised that he would give him his protection when there, and such introductions as should be useful in effecting the object of his mission. This offer was not to be refused: Fuseli, therefore, set out with Sir Andrew, and arrived in England at the close of the year 1763.

Before he quitted Prussia, he took leave of Lavater, his early and devoted friend, who, at parting, put into his hands a paper, which he[29] previously had framed and glazed, on which was written, in German, "Thue den siebenden theil von dem was du thun kannst."[8] "Hang this in your bed-chamber, my dear friend," said he; "look at it occasionally, and I foresee the result."

Sir Andrew Mitchell fully performed his promise, for, on their arrival in London, he was anxious to introduce his protégé to men distinguished either for rank, property, or talents: among these were the late Lord Scarsdale and Mr. Coutts, the banker. Sir Andrew, knowing, however, that booksellers of respectability and probity are the best patrons of literary characters, strongly recommended him to Mr. Andrew Millar and Mr. Joseph Johnson. The former was well known as an opulent man, and an old and established publisher; the latter had but recently begun business on his own account, but he had already acquired the character which he retained during life,—that of a man of great integrity, an encourager of literary men as far as his means extended, and an excellent judge of their productions. With these persons Fuseli kept up a friendly intercourse during their lives.

Fuseli took lodgings in the house of a Mrs. Green, in Cranbourn Street, then called Cranbourn Alley. He lived here from prudential motives,—those of economy, as well as being near to the house of a gentleman (Mr. Coutts) to whom he had been introduced, who resided at this time in St. Martin's Lane. No sooner was he fixed in this place, than he wrote to his father, to give him an account of his voyage and journey from Berlin to London, and of the prospects which appeared to be open to him. Stranger as he was in the great metropolis of England, separated from his family, and nearly unknown to any of its inhabitants, his sensitive feelings were aroused, and in a gloomy state of mind he sallied forth, with the letter in his hand, in search of a post-office.

At this period there was much greater brutality of demeanour exercised by the lower orders of the English towards foreigners than there is at present. Meeting with a vulgar fellow, Fuseli inquired his way to the post-office, in a broad German pronunciation: this produced only a horse-laugh from the man. The forlorn situation in which he was placed burst on his mind;—he stamped with his foot, while tears trickled down his cheeks. A gentleman who saw the transaction, and felt for[31] Fuseli, apologised for the rudeness which he had received, explained its cause, and told him that, as a foreigner, he must expect to be so treated by the lower orders of the people: after this he shewed him where he might deposit his letter. This kindness from a stranger, in some degree, restored tranquillity to his agonised feelings.

Finding that his name was difficult of pronunciation to an Englishman, he shortly after altered the arrangement of the letters, and signed "Fusseli."

He kept up a constant correspondence with Bodmer and Sulzer. This was not, however, conducted in those terms of respectful diffidence in which a pupil generally addresses his tutors; but with that manly independence of spirit which he inherited from his father, and with that originality of thought so peculiar to himself; which, although he frequently differed in opinion with them, and expressed his notions with asperity, was somewhat pleasing to these eminent men, particularly to Bodmer, whose constant advice to his pupils was, "Think and act for yourselves."

The independent spirit of Fuseli would not allow him to be under the pecuniary obligations which his friends offered; he therefore laboured[32] hard, and fortunately got ample employment from the booksellers, in translating works from the French, Italian, and German languages into English; and some popular works from the English into German,—among others the letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montague.

In 1765, he published (with his name affixed) a translation of the Abbé Winkelmann's "Reflections on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks," which was dedicated to his friend and patron, Lord Scarsdale. The dedication is dated the 10th April, 1765. Much to the credit of Mr. Millar, he took every opportunity of forwarding the sale of this work, and gave Fuseli the whole proceeds, after deducting only the expenses of paper and printing.

At this time he visited very frequently Smollet, and also Falconer, the author of "the Shipwreck," and other works. The latter then was allowed to occupy apartments in old Somerset House, and Fuseli always represented him as a man of mild and inoffensive manners, although far from being happy, in consequence of the pressure of his pecuniary circumstances. For Doctor Smollet he made several drawings of scenes in his novel of Peregrine Pickle, which were engraved and published in an early edition[33] of that well-known work. This edition is now very scarce.

Mr. Cadell having, in the year 1766, succeeded to the business of Mr. Millar, as a bookseller and publisher, he also kept up the connexion with Fuseli, and gave him constant employment.

A taste for the fine arts had been recently awakened in England, and some of the principal painters, sculptors, and architects, had formed themselves into a society for promoting them; from which circumstance, high expectations were raised of the encouragement likely to be afforded to artists by the public. Fuseli was stimulated by these to fresh exertions of his pencil, and all his leisure hours were devoted to drawing or etching historical subjects.

About this period he became acquainted with two artists his countrymen, Mr. Moser, who on the establishment of the Royal Academy was appointed Keeper, and Mr. Kauffman, chiefly known, at present, as the father of the more celebrated Angelica Kauffman, who, considered as a female artist, even now ranks high as an historical painter.

With Miss Kauffman, it appears, Fuseli was much enamoured; and although he did not at[34] any time hold her professional talents in high esteem, yet he always spoke of her in terms of regard, and considered her as a handsome, lively, and engaging woman.

The youth, fine manly countenance and conversational talents of Fuseli made a deep impression upon most female hearts and minds: hence, Miss Mary Moser (now better known as Mrs. Lloyd), the daughter of Mr. Moser, who was in almost the daily habit of seeing and conversing with him, also experienced their influence; and she flattered herself that the feelings which she had were mutual.

If Fuseli ever had any affection for this lady while he was in England, it was soon dissipated by change of scene and the pleasures which he pursued when in Italy. The two following letters, which are extracted from Mr. J. T. Smith's Life of Nollekens, tend to show the disposition of both parties towards each other.

"If you have not forgotten at Rome those friends whom you

remembered at Florence, write to me from that nursery of arts

and raree-show of the world, which flourishes in ruins: tell me

of pictures, palaces, people, lakes, woods, and rivers; say if

Old Tiber droops[35] with age, or whether his waters flow as clear,

his rushes grow as green, and his swans look as white, as those

of Father Thames; or write me your own thoughts and reflections,

which will be more acceptable than any description of any thing

Greece and Rome have done these two thousand years.

"I suppose there has been a million of letters sent to Italy with an account of our Exhibition, so it will be only telling you what you know already, to say that Reynolds was like himself in pictures which you have seen; Gainsborough beyond himself in a portrait of a gentleman in a Vandyke habit; and Zoffany superior to every body, in a portrait of Garrick in the character of Abel Drugger, with two other figures, Subtle and Face. Sir Joshua agreed to give a hundred guineas for the picture; Lord Carlisle half an hour after offered Reynolds twenty to part with it, which the Knight generously refused, resigned his intended purchase to the Lord, and the emolument to his brother artist. (He is a gentleman!) Angelica made a very great addition to the show; and Mr. Hamilton's picture of Brisëis parting from Achilles, was very much admired; the Brisëis in taste, à l'antique, elegant and simple. Coates, Dance, Wilson,[36] &c. as usual. Mr. West had no large picture finished. You will doubtless imagine, that I derived my epistolary genius from my nurse; but when you are tired of my gossiping, you may burn the letter, so I shall go on. Some of the literati of the Royal Academy were very much disappointed, as they could not obtain diplomas; but the Secretary, who is above trifles, has since made a very flattering compliment to the Academy in the Preface to his Travels: the Professor of History is comforted by the success of his "Deserted Village," which is a very pretty poem, and has lately put himself under the conduct of Mrs. Hornick and her fair daughters, and is gone to France; and Dr. Johnson sips his tea, and cares not for the vanity of the world. Sir Joshua, a few days ago, entertained the Council and Visitors with calipash and calipee, except poor Coates, who last week fell a sacrifice to the corroding power of soap-lees, which he hoped would have cured him of the stone: many a tear will drop on his grave, as he is not more lamented as an artist than a friend to the distressed. (Ma poca polvere sono che nulla sente!) My mamma declares that you are an insufferable creature, and that she speaks as good English as your mother did High-German. Mr. Meyer laughed[37] aloud at your letter, and desired to be remembered. My father and his daughter long to know the progress you will make, particularly

Mary Moser,

Who remains sincerely your friend, and believes you will exclaim or mutter to yourself, 'Why did she send this d——d nonsense to me?'"

Henry Fuseli, Esq. à Roma.

"Rome, April 27, 1771.

"madam,

"I am inexcusable. I know your letter by heart, and have never answered it; but I am often so very unhappy within, that I hold it matter of remorse to distress such a friend as Miss Moser with my own whimsical miseries;—they may be fancied evils, but to him who has fancy, real evils are unnecessary, though I have them too. All I can say is, that I am approaching the period which commonly decides a man's life with regard to fame or infamy; if I am distracted by the thought, those who have passed the Rubicon will excuse me, and you are amongst the number.

"Mr. Runciman, who does me the favour to carry these lines, my friend, and, in my opinion, the best Painter of us in Rome, has desired me[38] to introduce him to your family; but he wants no other introduction than his merit. I beg my warmest compliments to papa and mamma, and am unaltered,

"Madam,

""Your most obliged servant and friend,

"Fuseli."

"To Miss Moser,

Craven Buildings, Drury Lane."

Mrs. Lloyd was a painter of flowers, which she grouped with taste, and coloured with truth and brilliancy; in this department of the art she experienced patronage from her late Majesty Queen Charlotte, who employed her pencil not only on pictures, but also to decorate a room in the palace at Frogmore. This lady always held the talents of Fuseli in the highest respect. Being invited by the late Mr. Angerstein to view the superb collection of pictures in his house in Pall Mall, then belonging to him, but subsequently sold by his heirs to the Nation, she left him by expressing her gratitude for the treat which his kindness had afforded her, but she added, "In my opinion, Sir, your finest pictures are on the staircase," alluding to those which he purchased of Fuseli,[39] and which had formed a part of the Milton Gallery.

At this time, Garrick was in the height of his reputation; and as Fuseli considered the theatre the best school for a foreigner to acquire the pronunciation of the English language, and Garrick's performance an excellent imitation of the passions, which would give him a lesson essential to historical designs; he never missed the opportunity of seeing him act, and he was generally to be found in the front row of the pit: to obtain which, he often used much personal exertion, and put himself in situations of hazard and inconvenience. And he has often dwelt with delight upon the performances of the man who represented so well the stormy passions of Richard, or the easy libertinism of Ranger; and then could descend to the credulous Abel Drugger, and, in the character of the silly tobacconist, so alter the expression of his countenance as scarcely to be recognised as the person who had delineated the higher character in the histrionic art. As a proof of the strong impression which Garrick's acting made at this period upon Fuseli, there are now in the possession of the Countess of Guilford, two drawings, which he presented[40] to the late Alderman Cadell; the one representing Garrick and Mrs. Pritchard as Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, from the passage,

the other, Garrick as Richard the Third, making love to Lady Anne, over the corse of her father-in-law, Henry the Sixth. These, according to an inscription on the second, were made in London, in 1766. And although they have the faults of most of his early productions, yet they are drawn with characteristic truth and spirit.

At the end of the year (1766) an advantageous offer was made to Fuseli, to undertake the situation of travelling tutor to Viscount Chewton, the eldest son of Earl Waldegrave, which, after consulting Professor Sulzer, he accepted. For this charge, it was considered, his extensive knowledge of languages and eminent literary talents fully qualified him. His lordship was young, and, when in France, showed an impatience of control common to a youth of his age and rank in life, the latter of which he thought should exempt him from the authority and constraint which his tutor considered it his duty to exert. This disposition, on the part of the pupil, naturally[41] excited the irritable feelings of Fuseli, and on a second refusal to obey, a severe blow was given. Considering that, after this, his services would be of no avail to a youth by whom they were not properly appreciated, he, to use his own words, "determining to be a bear-leader no longer," wrote in nearly those terms to Earl Waldegrave, and returned to England. He left, however, some written instructions with Lord Chewton, showing how he might profit by travelling. On his return to this country, Earl Waldegrave, so far from condemning (as Fuseli expected) his conduct, told him that he had acted with a proper degree of spirit; but Fuseli's family, and most of his friends, blamed him in the strongest terms for his impetuosity, as they considered that a want of forbearance on his part had ruined those prospects in life which naturally would arise from forming a connexion with a family of such consequence as that of Earl Waldegrave. To Bodmer he explained all the circumstances of the case, with the state of his feelings; and his venerable tutor wrote him a letter of consolation. In reply to this, Fuseli spoke in florid terms of the agonies which he had felt while residing in that noble family, when he considered himself obliged to say Yes, when No[42] "stuck in the throat;"—and thus showed, that he was not framed to live with courtiers. In after-life he used to remark jocosely to his friends, "The noble family of Waldegrave took me for a bear-leader, but they found me the bear."

On Fuseli's return to England, in 1767, there was every prospect that the society which had been formed for the promotion of the fine arts would receive royal protection and patronage, and become a chartered body.[9] And it was then the general opinion, that great public encouragement would be given to artists. This still increased his wish to become a painter. He sought for and obtained an introduction to Mr. (afterwards Sir Joshua) Reynolds, to whom he showed a portfolio of drawings, and some small etchings, which he had recently made from subjects in the Bible, and an etching on a large scale from Plutarch,—"Dion seeing a female spectre sweep his hall." Sir Joshua,[43] who was much struck with the style, grandeur, and original conception of his works, asked him how long he had been from Italy? Fuseli answered, "he had never seen that favoured country;" at which the former expressed much surprise; and, to mark how highly he estimated his talents, requested permission to have some of the drawings copied for himself. This was readily granted, and he was induced, by the solicitations of Fuseli, to accept some of the etchings. The interview ended by Reynolds assuring him, that "were he at his age, and endowed with the ability of producing such works, if any one were to offer him an estate of a thousand pounds a-year, on condition of being any thing but a painter, he would, without the least hesitation, reject the offer."

Having received such encouragement and flattering encomiums from the greatest painter of the age, Fuseli directed nearly the whole of his attention to drawing; and at the recommendation of Reynolds, afterwards tried oil colours. The first picture he produced was "Joseph interpreting the dreams of the butler and baker of Pharaoh." On showing this to Reynolds, he encouraged him to proceed, remarking, "that he might, if he would, be a colourist as well as a draughtsman." This picture,[44] now in the possession of the Countess of Guilford, fully justifies the opinion of Sir Joshua, as it is remarkably well coloured, and, as a first attempt in oil colours, may be considered a surprising production.

From the time of Fuseli's first arrival in England, he had been a constant visitor at Mr. Johnson's house, and, in common with all those who were acquainted with him, was a great admirer of his steady, upright character. In the summer of 1767, he was prevailed upon to accompany him to Liverpool, which was Johnson's native town. From this, and subsequent visits, Fuseli became acquainted with men who, in after-life, were the greatest patrons of his pencil.

The attention of the public was at this time much engaged by the constant attacks made by Hume and Voltaire on the works of Rousseau. Fuseli advocated the cause of his countryman, and published anonymously, during the year 1767, a thin duodecimo volume, entitled "Remarks on the Writings and Conduct of J. J. Rousseau." But he never wished it to be considered that he was the author of this work. To speak of it as a literary production, it abounds with wit and sarcasm; and although, in style, it cannot be considered strictly English, yet there is novelty in the remarks, and great power of[45] language throughout the book. It also shows him to be well read in the works of Rousseau, whom at this time he idolized, and to be perfectly acquainted with the nature of the disputes in all their bearings. Perhaps the reasons for not wishing it to be considered a work of his, although he never denied it, were, that there are in several instances coarseness of language and indelicacies of expression which disfigure the pages of the book, and that in more advanced life the high opinion which he had formed of Rousseau, was in a degree abated. Fuseli gave the design for the frontispiece, which represents in the foreground, Voltaire booted and spurred, riding upon man, who is crawling upon the earth: in the back of the picture, Justice and Liberty are gibbeted. Rousseau is witnessing Voltaire's pranks, and by his attitude seems to threaten disclosure. This work is rarely to be met with, as the greater part of the impression was destroyed shortly after it was printed, by an accidental fire which took place in Mr. Johnson's house, who then resided in Paternoster Row.

Fuseli leaves England for Italy in the society of Dr. Armstrong.—They quarrel, and separate at Genoa.—Fuseli arrives at Rome (1770).—His principle of study there.—He suffers through a fever, and repairs to Venice for his health.—Visits Naples.—Quits Rome (1778) for Switzerland.—Letter to Mr. Northcote.—Fuseli renews his classical studies.—Visits his family at Zurich.—Engages in an unsuccessful love-affair.—Arrives again in London.

Fuseli had now determined to relinquish the pen for the pencil, and to devote his life to painting; his wishes were therefore directed to Rome, the seat of the fine arts.

Having at Mr. Coutts' table renewed the intimacy with Dr. Armstrong, which formerly subsisted at Berlin, and as the Doctor considered it necessary to pass the winter in the milder climate of Italy, to relieve a catarrhal complaint, under which he was then labouring, Fuseli was tempted to accompany him thither, and they left London the end of November 1769, with the intention of going to Leghorn by sea.

Their voyage, from adverse winds and tempestuous weather, was long and tedious; the monotony of a life at sea, and the qualms which generally affect landsmen in such a situation, were not fitted to allay the naturally irritable tempers of Armstrong and his companion: they at first became dissatisfied with their situation, then with each other, and finally quarrelled about the pronunciation of an English word; Fuseli pertinaciously maintaining that a Swiss had as great a right to judge of the correct pronunciation of English as a Scotsman.

After a tedious passage of twenty-eight days, the ship was driven by a gale of wind into Genoa, where Fuseli and Armstrong parted in a mood far from friendly. Armstrong took the direct road to Florence, where he intended to reside. Fuseli went first to Milan; here he remained a few days to examine the works of art, and then passed a short time at Florence, on his way to Rome, where he arrived on the 9th of February 1770.

Shortly after he had taken up his abode in "the eternal city," he again changed the spelling of his name; this he did to accommodate it to the Italian pronunciation; and always afterwards signed, "Fuseli."

His views now were to see the stores of art, which had been collected in, or executed at[48] Rome; and subsequently, to examine with care each particular specimen, for his future improvement. He did not spend his time in measuring the proportion of the several antique statues, or in copying the fresco or oil pictures of the great masters of modern times; but in studying intensely the principles upon which they had worked, in order to infuse some of their power and spirit into his own productions.

Although he paid minute attention to the works of Raphael, Correggio, Titian, and the other great men whom Italy has produced, yet, he considered the antique and Michael Angelo as his masters, and formed his style upon their principles.

To augment his knowledge, he examined living models, sometimes attended the schools of anatomy, and used the dissecting knife, in order to trace the origin and insertion of the outer layer of muscles of the human body. But he was always averse to dissecting, believing the current story, that his idol, Michael Angelo, had nearly lost his life from a fever got by an anatomical examination of a human body in a state of putrefaction.

By such well-directed studies, and by great exertion, his improvement was rapid, and he[49] soon acquired a boldness and grandeur of drawing which surprised the Italian artists, one of whom was so struck with some of his compositions, that, in reference to their invention, he immediately exclaimed, "Michael Angelo has come again!"

In the year 1772, his progress was impeded by a fever, which enfeebled his nervous system. This illness he attributed to the heat of the climate, and to having, in a degree, departed from those regular and very abstemious habits which marked the early part of his life. The fever changed his hair, originally of a flaxen, to a perfectly white colour, and caused a tremulous motion in the hands, which never left him, but increased with age. He has more than once told me, that this indisposition drove his mind into that state, which Armstrong so forcibly describes in "The Art of preserving Health:"

Being advised to change the air and scene, he went to Venice, and remained there until he had thoroughly examined the works of art in that city, and regained sufficient strength of[50] body and mind to resume with effect his studies and labours at Rome.

Although he got much employment from those Englishmen who resided at or visited Rome, yet he saved no money, being always negligent of pecuniary concerns. His friends in England were unacquainted with his progress in the arts until the year 1774, when he sent a drawing to the exhibition of the Royal Academy, the subject of which was, "The death of Cardinal Beaufort," from Shakspeare.

In 1775, he visited Naples, studied the works of art in that city, and examined the excavations at Herculaneum and Pompeii.

In 1777, he sent from Rome to England a picture in oil, representing a scene in "Macbeth," for the annual exhibition at the Royal Academy.

In 1778, he took a farewell of Rome, and left his friends there with regret. As a nation, however, he was not very partial to the modern Italians, who, he said, "were lively and entertaining, but there was the slight drawback of never feeling one's life safe in their presence." This he exemplified by the following fact: "When I was one day preparing to draw from a woman selected by artists for a model, on account of her fine figure, on altering the[51] arrangement of her dress, I saw the hilt of a dagger in her bosom, and on inquiring, with astonishment, what it meant, she drew it, and quaintly answered, 'Contro gl' impertinenti.'"

On his way to Switzerland, he stayed some time at Bologna, Parma, Mantua, Milan, Lugano, and Belanzona. At Bologna, he remained with Sir Robert Smyth, Bart. who, while at Rome, had given him considerable employment. Thence he proceeded to Lugano, from which place he wrote the following letter to Mr. Northcote, who was then studying at Rome:—

"Lugano, 29th Sept. 1778.

"dear northcote,

"You may, and must think it unfriendly for me to have advanced to the borders of Switzerland without writing to you; but what would have been friendly to you was death to me; and self-preservation is the first duty of the eighteenth century. Madness lies on the road I must think over to come at you; and at the sound of Rome, my heart swells, my eye kindles, and frenzy seizes me.

"I have lived at Bologna as agreeably and as happily as my lacerated heart and boiling brains would let me, with Sir Robert and his lady.

"You, whose eye diverges not, will make the use of Bologna I have not, or at least but very imperfectly: much more than what is thought of, may be made of that place. What I admire, and what I frequented most,—what indeed suited my melancholy best, are the cloisters of St. Michael, in Bosco, near the city. The fragments of painting there are by Ludovico Caracci and his school, and, in my opinion, superior for realities to the Farnese gallery. There is a figure[10] in one of the pictures which my soul has set her seal upon: 'tis to no purpose to tell you what figure—if you find it not, or doubt, it was not painted for you; and if you find it, you will be obliged for the pleasure to yourself only. Still in that, and all I have seen since my departure, Hesiod's paradox gains more and more ground with me,—'that the half is fuller than the whole,' or, if you will, full of the whole.

"At Mantua I have had emotions which I had not apprehended from Julio Romano, at Rome: but the post going, I have not time to enter into so contradictory a character.

"The enclosed[11] I shall re-demand at your hands in England. Take need of the mice. Of Rome, you may tell me what you please. Those I should wish to know something about, you know not. I have written to Navina in the Bolognese palace; pray give her my best compliments e dille che quando sarò in Inghilterra troverò qualche opportunità di provare, prima del mio ritorno in Italia, che non sono capace di scordarmi dell' amicizia sua. To Mr. Hoare I shall write next post.

"Love me,

"Fuseli.

"P.S. I have been here (at Lugano) these eight days, at the house of an old schoolfellow of mine, who is governor of this place.

"À Mons. James Northcote, à Roma."

In Italy he became acquainted with David and other artists of note, as well as with several Englishmen distinguished either for rank or talents. With the Hon. George Pitt (the late Lord Rivers,) he there became very intimate, and he was flattered by his friendship and patronage, which he enjoyed during the whole of his life.

The necessary employment of his time in painting, and studying works of art, during several of the first years of his residence in Italy, was such as to leave little opportunity for other occupations, and he found, to his regret, that he had either lost a great deal of his knowledge of the Greek language, or, what is more probable, that he had never possessed it in that degree which he flattered himself he had attained while at college. Determined, however, to regain or acquire this, he now studied sedulously the Grecian poets, made copious extracts of fine passages from their works, and thus gained, in the opinion of the best judges, what may be called, at least, a competent knowledge of that language.

Although Fuseli's professional talents were much admired, and highly appreciated in Italy, yet, as he did not court it, he never obtained a diploma, or other honour, from any academy in those cities in which he resided, or occasionally visited. Indeed, he refused all overtures which were made to him on this subject; for he considered that the institution of academies "were symptoms of art in distress."

Having arrived at Zurich the end of October 1778, after an absence of sixteen years, his father, who had taken great pains, in early life, to[55] check his love for the fine arts, and to prevent his being an artist, was now gratified by witnessing the great proficiency he had attained: and he knew enough of the state of the arts in Europe to feel that his son did then rank, or would shortly, among the first painters of his time. During a residence of six months with his family, he painted some pictures; among them "The Confederacy of the Founders of Helvetian liberty," which he presented to, and which is still preserved in, the Senate-house at Zurich. Lavater, however, did not consider this picture a good specimen of his friend's powers, particularly as to colouring, and expressed his distaste to this in such strong terms, as were by no means gratifying to him.

Fuseli was always very susceptible of the passion of love. But when at Zurich, in the year 1779, his affections were gained in an extraordinary degree by the attractions of a young lady, then in her twenty-first year, the daughter of a magistrate, who resided in the "Rech" house of Zurich. This lady, whom he calls in his correspondence, "Nanna," had a fine person, lively wit, and great accomplishments, and among the latter, her proficiency in music was considerable, which is celebrated in a poem by Göethe. It appears that she was not indifferent[56] to him; but her father, who was opulent, considered that her marriage with a man dependent upon the caprice of the public for his support, was not a suitable connexion for his daughter, and he therefore withheld his consent to their union. This disappointment drove Fuseli from Zurich earlier than he intended; and it would appear by his letters, that his mind, even after his arrival in England, was almost in a state of phrenzy. He, some time after, however, received the intelligence that "Nanna" had given her hand to a gentleman who had long solicited it, Mons. le Consieller Schinz, the son of a brother of Madame Lavater; and thus his hopes in that quarter terminated.

In April 1779, he took a last farewell of his native country and family, and returned to settle again in London. On his way to England, in order to improve his knowledge in art, he travelled leisurely through France, Holland, and the Low Countries, examining in his route whatever was worthy of notice.

Fuseli settles in London.—Interview with Mr. Coutts.—Reconciliation with Dr. Armstrong.—Professor Bonnycastle.—Society at Mr. Lock's.—Mr. James Carrick Moore and Admiral Sir Graham Moore.—Sir Joshua Reynolds.—Mr. West.—Anecdote of Fuseli and West.—The popular picture of "The Nightmare."—Death of Fuseli's Father.—Visit to Mr. Roscoe at Liverpool.—Fuseli's singular engagement to revise Cowper's Iliad.—Three Letters from Mr. Cowper.—Anecdotes of Fuseli and Dr. Geddes.