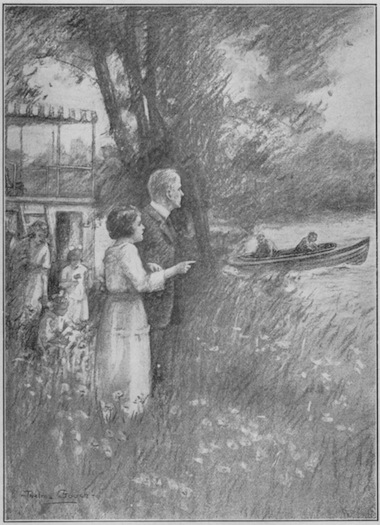

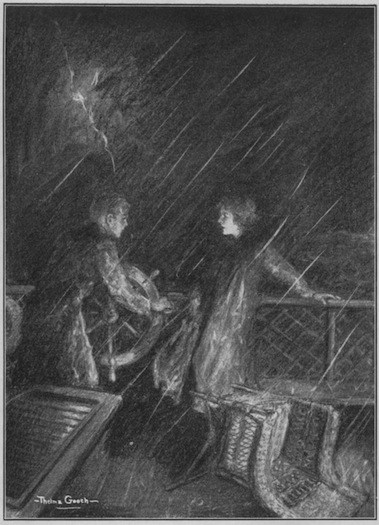

“There they are!” cried Ruth, clasping Mr. Howbridge’s arm in her excitement. “The same two men!”

Title: The Corner House Girls on a Houseboat

Author: Grace Brooks Hill

Illustrator: Thelma Gooch

Release date: January 18, 2012 [eBook #38609]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

“There they are!” cried Ruth, clasping Mr. Howbridge’s arm in her excitement. “The same two men!”

THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS

ON A HOUSEBOAT

|

HOW THEY SAILED AWAY WHAT HAPPENED ON THE VOYAGE AND WHAT WAS DISCOVERED |

BY

GRACE BROOKS HILL

Author of “The Corner House Girls,” “The

Corner House Girls Snowbound,” etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

THELMA GOOCH

NEW YORK

BARSE & HOPKINS

PUBLISHERS

BOOKS FOR GIRLS

By Grace Brooks Hill

The Corner House Girls Series

12mo. Cloth. Illustrated.

|

THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS AT SCHOOL THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS UNDER CANVAS THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS IN A PLAY THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS’ ODD FIND THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS ON A TOUR THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS GROWING UP THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS SNOWBOUND THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS ON A HOUSEBOAT |

BARSE & HOPKINS

Publishers, New York

Copyright, 1920,

by Barse & Hopkins

The Corner House Girls on a Houseboat

Printed in U. S. A.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS ON A HOUSEBOAT

Delicious and appetizing odors filled the kitchen of the old Corner House. They were wafted even to the attic, were those whiffs and fragrant zephyrs. Some of them even escaped through the open windows, causing Uncle Rufus to cease his slow and laborious task of picking up some papers from the newly cut lawn.

“Dat suah smells mighty good—mighty good!” murmured the old darkey to himself, as he straightened up by the process of putting one hand to the small of his back and pressing there, as though a spring needed adjusting. “Dat suah smells mighty good! Mrs. Mac mus’ suah be out-doin’ of herse’f dish yeah mawnin’!”

He turned his wrinkled face toward the Corner House, again sniffing deeply.

A pleased and satisfied look came over his countenance as the cooking odors emanating from the kitchen became more pronounced.

“Dey’s suah to be some left—dey suah is, ’cause hit’s Miss Ruth’s party, an’ she’s always gen’rus wif de eatin’s. She suah is. Dey’s suah to be some left.”

He removed his hand from the small of his back, thereby allowing himself to fall forward again in the proper position for picking up papers, and went on with his work.

Inside the kitchen, where the odors were even more pronounced, as one might naturally expect to find them, two girls and a pleasant-faced woman were busy; though not more so than a fresh-appearing Finnish maid, who hummed an air full of minor strains as she opened the oven door now and then, thereby letting out more odors which were piled upon, mingled with, and otherwise added to those already bringing such a delicious sensation to Uncle Rufus.

“Aren’t you planning too much, Ruth?” asked her sister Agnes, as the girl addressed carefully placed a wondrously white napkin over a plate of freshly baked macaroons. “I mean the girls will never eat all this,” and she waved her hand to include a side table on which were many more plates, some empty, awaiting their burden from the oven, while others were covered with white linen like some mysterious receptacles under a stage magician’s serviette.

“Oh, don’t worry about that!” laughed Ruth. “My only worry is that I shall not have enough.”

“Well, for the land’s sake! how many do you expect?” demanded Agnes Kenway.

“Six. But there will be you and me and—”

“Then Mr. Howbridge is coming!” cried Agnes, as if there had been some question about it, though this was the first time his name had been mentioned that morning.

“He may come,” answered Ruth quietly.

“He may! Oh my stars! As if you didn’t know he was coming!” retorted Agnes. “Is it in—er—his official capacity?”

“I asked Mr. Howbridge to come to advise us about forming the society,” Ruth said. “I thought it best to start right. If we are going to be of any use as a Civic Betterment Club in Milton we must be on a firm foundation, and—”

“Hear! Hear!” interrupted Agnes, banging on the table with an agate mixing spoon, and thereby bringing from a deep pantry the form and face of Mrs. MacCall, the sturdy Scotch housekeeper.

“Please don’t do that!” begged Ruth.

“Hoots! Whut’s meanin’ wi’ the rattlin’ an’ thumpin’?” demanded Mrs. MacCall.

“Oh, some nonsense of Agnes’,” answered Ruth. “I was just telling her that I had asked the girls to luncheon, to talk over the new Civic Betterment Club, and that Mr. Howbridge is coming to advise us how to get a charter, or incorporate, or whatever is proper and—”

“I was only applauding after the fashion in the English Parliament,” interrupted Agnes. “They always say ‘Hear! Hear!’ away down in their throats.”

“Well, they don’t bang on tables with granite spoons,” retorted Ruth, as she handed a pie to Linda, the humming Finnish maid, who popped it into the oven, quickly shutting the door, to allow none of the heat to escape.

“Hoot! I would not put it past ’em, I would not!” murmured Mrs. MacCall. “What those English law makers do—I wouldna’ put it past them!” and, shaking her head, she retired into the deep pantry again.

“Well, you’re going to have enough of sweets, I should say;” observed Agnes, “even as fond as Mr. Howbridge is of them. For the land’s sake, aren’t you going to stop?” she demanded, as Ruth poured into a dish the cake batter she had begun to stir as soon as the pie was completed.

“This is the last. You don’t need to stay and help me any longer if you don’t want to, dear. Run out and play,” urged Ruth sweetly.

“Run out and play! As if I were Dot or Tess! I like that! Why, I was thinking of asking you to let me join the society!”

“Oh, of course you may, Agnes! I didn’t think you’d care for it. Why, certainly you may join! We want to get as many into it as we can. Do come to the meeting this afternoon. Mr. Howbridge is going to explain everything, and I thought we might as well make it a little social affair. It was very good of you to help me with the baking.”

“Oh, I like that. And I believe I will come to the meeting. Now shall we clean up?”

“I do him,” interposed Linda. “I wash him all up,” and a sweep of her muscular arm indicated the pots, pans, dishes and all the odds and ends left from the rather wholesale baking.

“Oh, I shall be so glad if you will!” exclaimed Ruth. “I want to go over the parlor and library again. And I wonder what has become of Dot and Tess. I asked them to get me some wild flowers, but they have been gone over an hour and—”

The voice of Mrs. MacCall from the deep pantry interrupted.

“Hi, Tess! Hi, Dot!” she called. “Where ha’ ye been? Come ye here the noo, and be for me waukrife minnie.”

“What in the world does she mean?” asked Agnes, for sometimes, well versed as she was in the Scotch of the housekeeper, there were new words and phrases that needed translating. Especially as it seemed to the girls that more and more Mrs. MacCall was falling back into her childhood speech as she grew older—a speech she had dropped during her younger life except in moments of excitement.

This time, however, it was beyond even the “ken” of Ruth, who rather prided herself on her Highland knowledge. But Mrs. MacCall herself had heard the question. Out she came from the pantry, smiling broadly.

“Ye no ken ‘waukrife minnie’?” she asked. “Ah, ’tis a pretty little verse o’ Rabbie Burns. I’ll call it o’er the noo.”

Then she gave them, with all the burring of which her tongue was capable:

“Whare are you gaun, my bonnie lass,

Whare are you gaun, my hinnie?

She answered me right saucilie,

An errand for my minnie.”

Coming down to earth again, Mrs. MacCall shot back into the pantry and from an open window in the rear that looked out in the orchard she called:

“Hi, Tess! Hi, Dot! Come ye here, and be for me the lassies that’ll gang to the store.”

“Are Tess and Dot there?” asked Ruth. “I’ve been wondering where they had disappeared to.”

“They be coming the noo,” answered Mrs. MacCall. “Laden in their arms wi’ all sorts of the trash.” And then she sang again:

“O fare thee well, my bonnie lass,

O fare thee well, my hinnie!

Thou art a gay an’ a bonnie lass,

But thou has a waukrife minnie.”

“What in the world is a ‘waukrife minnie’?” asked Agnes, but there was no chance to answer, for in the kitchen, making it more busy than ever, trooped the two younger members of the Corner House girls quartette—Tess and Dot.

Their arms were filled with blossoms of the woods and fields, and without more ado they tossed them to a cleared place on the table, whence Linda had removed some of the pans and dishes.

“Oh, what a lovely lot of flowers!” cried Ruth. “It’s just darling of you to get them for me. Now do you want to help me put them into vases in the library?”

Dot shook her head.

“Why not?” asked Ruth gently.

“I promised my Alice-doll to take her down by the brook, and I just have to do it,” answered Dot. “And Tess is going to help me; aren’t you, Tess?” she added.

“Yes,” was the answer. “I’m going to take Almira.”

“Then you must take her kittens, too!” insisted Dot. “She’ll feel bad if you don’t.”

“I won’t take ’em all—I’ll take one kitten,” compromised Tess. “There she is, now!” And Tess darted from the room to pounce on the cat, which did not seem to mind very much being mauled by the children.

“Will ye gang a’wa’ to the store the noo?” asked Mrs. MacCall, with a warm smile as she came from the pantry. “There’s muckle we need an’—”

“I’ll go if you give me a cookie,” promised Dot.

“So’ll I,” chimed in Tess, coming in on the tribute. “We can take Almira and your Alice-doll when we come back,” she confided to her sister.

“Yes, I think they’ll wait. I know Alice-doll will, but I’m not so sure about Almira,” and Dot seemed rather in doubt. “She may take a notion to carry her kittens up in the bedroom—”

“Don’t dare suggest such a thing!” cried Ruth.

“I’m to have company this afternoon, and if that cat and her kittens appear on the scene—”

“Oh, I wasn’t going to carry them in!” interrupted Dot, with an air of injured innocence. “They’re Almira’s kittens, and she can do what she likes with them, I suppose,” she added as an afterthought. “Only I know that every once in a while she takes a notion to plant them in a new place. Once Uncle Rufus found them in his rubber boots, and they scratched him like anything when he put his foot inside.”

“Well, if you have to go to the store for Mrs. MacCall you won’t have any time to help me arrange the flowers,” observed Ruth, anxious to put an end to the discussion about the family cat and kittens, for she knew Dot had a fund of stories concerning them.

“Yes, traipse along now, my bonnie bairns,” advised the Scotch housekeeper, and, bribed by two cookies each, a special good measure on Saturday, Dot and Tess were soon on their way, or at least it was so supposed.

Linda was helping Mrs. MacCall clear away the baking utensils, and Ruth and Agnes were in the parlor and library, tastefully arranging the wild flowers that Dot and Tess had gathered.

“Isn’t Dot queer to cling still to her dolls?” remarked Agnes, as she stepped back to get the effect of a bunch of red flowers against a dark brown background in one corner of the room.

“Yes, she is a strange child. And poor Almira! Really I don’t see how that cat stands it here, the way Tess and Dot maul her.”

“They aren’t as bad as Sammy Pinkney. Actually I caught him yesterday tying the poor creature to the back of Billy Bumps!”

“Not on the goat’s back!” cried Ruth.

“Really, he was. I sent him flying, though!”

“What was his idea?”

“Oh, he said he’d heard Neale tell how, in a circus, a little dog rode on a pony’s back and Sammy didn’t see why a cat couldn’t ride on a goat.”

“Well, if he put it that way I suppose she could,” assented Ruth. “But Almira seems to take herself very seriously with all those kittens. We really must get rid of them. Vacation will soon be here, and with Tess and Dot around the house all day, instead of just Saturdays, I don’t know what we shall do.”

“Have you made any vacation plans at all?”

“Not yet, Agnes. I thought I’d wait until I saw Mr. Howbridge at the club meeting this afternoon.”

“What has he to do with our vacation—unless he’s going along?”

“Oh, no, I didn’t mean that, at all! But the financial question does enter into it; and as he is our guardian and has charge of our money, I want to know just how much we can count on spending.”

“Why, have we lost any money?”

“Not that I know of. I hope not! But I always have consulted him before we made any summer plans, and I don’t see why we should not now.”

“Well, I suppose it’s all right,” assented Agnes, as she took up another bunch of flowers. “But I wonder—”

She never finished that sentence. From somewhere, inside or outside the house, a resounding crash sounded. It shook the walls and floors.

“Oh, my! what’s that?” cried Ruth, dropping the blossoms from her hands and hastening to the hall.

Deep, and perhaps portentous, silence had succeeded the crash. But both Ruth and Agnes knew enough of the goings and comings in the Corner House not to take this silence for serenity. It meant something, as the crash had.

“What was it?” murmured Ruth again, and she fairly ran out into the hall, followed by her sister.

Then came a series of bumps, as if something of no small size was rolling down the porch steps. By this time it was evident that the racket came from without and not from within. Then a voice cried:

“Hold it! Hold it! Don’t let it roll down!”

“That’s Dot!” declared Ruth.

And then a despairing voice cried:

“I can’t! I can’t hold it! Look out!”

Once again the rumbling, rolling, bumping sound came, and with it was mingled the warning of the Scotch housekeeper and the wail of Dot who cried:

“Oh, she’s dead! She’s smashed!”

“Something really has happened this time!” exclaimed Ruth, and her face became a little pale.

“If only it isn’t serious,” burst out Agnes. “Oh, dear, what those youngsters don’t think of for trouble!”

“They don’t mean to get into trouble, Agnes. It’s only their thoughtlessness.”

“Well then, they ought to think more. Oh, listen to that, will you!” Agnes added, as another loud bumping reached the two sisters’ ears.

“It’s something that’s sure,” cried Ruth, and grew paler than ever.

The happening was not really as tragic as it seemed, yet it was sufficiently momentous to cause a fright to the two older girls. Especially to Ruth, who felt herself to be, as she literally was, a mother to the other three; though now that Agnes was putting up her hair and putting down her dresses a new element had come into the household.

While yet in tender years the responsibilities of life had fallen on the shoulders of Ruth Kenway. In their former home—a city more pretentious in many ways than picturesque Milton, their present home—the Kenways had lived in what, literally, was a tenement house. Their father and mother were dead, and the small pension granted Mr. Kenway, who had been a soldier in the Spanish war, was hardly sufficient for the needs of four growing girls.

Then, almost providentially, it seemed, the Stower estate had come to Ruth, Agnes, Dot and Tess. Uncle Peter Stower had passed away, and Mr. Howbridge, the administrator of the estate, had discovered the four sisters as the next of kin, to use his legal phrase.

Uncle Peter Stower had lived for years in the “Corner House” as it was called. The mansion stood opposite the Parade Ground in Milton, and there Uncle Rufus, the colored servant of his crabbed master, had spent so many years that he regarded himself as a fixture—as much so as the roof.

At first no will could be found, though Mr. Howbridge recalled having drawn one; but eventually all legal tangles were straightened out, and the four sisters came to live in Milton, as related in the first book of the series, entitled “The Corner House Girls.”

There was Ruth, the oldest and the “little mother,” though she was not so very little now. In fact she had blossomed into a young lady, a fact of which Mr. Howbridge became increasingly aware each day.

So the four girls had come to live at the Corner House, and that was only the beginning of their adventures. In successive volumes are related the happenings when they went to school, when they had a jolly time under canvas, and when they took part in a school play.

The odd find made in the garret of the Corner House furnished material for a book in itself and paved the way for a rather remarkable tour in an auto.

In those days the Corner House girls became acquainted with a brother and sister, Luke and Cecile Shepard. Luke was a college youth, and the friendship between him and Ruth presently ripened into a deep regard for each other. But Luke had to go back to college, so Ruth saw very little of him, though the young folks corresponded freely.

All this was while the Corner House girls were “growing up.” In fact, it became necessary to tell of that in detail, so that the reason for many things that happened in the book immediately preceding this, which is called “The Corner House Girls Snowbound,” could be understood.

In that volume the Corner House girls become involved in the mysterious disappearance of two small twins, and after many exciting days spent in the vicinity of a lumber camp a clue to the mystery was hit upon.

But now the memory of the blizzard days spent in the old Lodge were forgotten. For summer had come, bringing with it new problems, not the least of which was to find a place where vacation days might be spent.

Ruth proposed to speak of that when her guardian called this Saturday afternoon. As she had hinted to Agnes, Ruth had invited a number of girl friends to luncheon. It was the plan to form a sort of young people’s Civic Club, to take up several town matters, and Ruth was the moving spirit in this, for she loved to work toward some definite end.

This Saturday was no exception in being a busy one at the Corner House.

In pursuance of her plans she had enlisted the whole household in preparing for the event, from Mrs. MacCall, who looked after matters in general, Linda, who helped with the baking, Uncle Rufus, who was cleaning the lawn, down to Dot and Tess, who had been sent for flowers.

And then had come the bribing of Dot and Tess to go to the store and, following that, the crash.

“What can it be?” murmured Ruth, as she and Agnes hastened on. “Some one surely must be hurt.”

“I hope not,” half whispered Agnes.

From the side porch came the sound of childish anguish.

“She’s all flatted out, that’s what she is! She’s all flatted out, my Alice-doll is, and it’s all your fault, Tess Kenway! Why didn’t you hold the barrel?”

“I couldn’t, I told you! It just rolled and it rolled. It’s a good thing it didn’t roll on Almira!”

“Gracious! did you hear that?” cried Agnes. “What can they have been doing?”

The two older sisters reached the porch together, there to find Mrs. MacCall holding to Tess, whom she was brushing off and murmuring to in a low voice, filled with much Scotch burring.

Dot stood at the foot of the steps holding a rather crushed doll out at arm’s length, for all who would to view. And stalking off over the lawn was Almira, the cat, carrying in her mouth a wee kitten. Uncle Rufus was hobbling toward the scene of the excitement as fast as his rheumatism would allow. Scattered on the ground at the foot of the steps was a collection of odds and ends—“trash” Uncle Rufus called it. The trash had come from an overturned barrel, and it was this barrel rolling down the steps and off the porch that had caused the noise.

“What happened?” demanded Ruth, breathing more easily when she saw that the casualty list was confined to the doll.

“It was Tess,” declared Dot. “She tipped the barrel over and it rolled on my Alice-doll and now look at her.”

Dot referred to the doll, not to her sister, though Tess was rather a sight, for she was covered with feathers from an old pillow that had been thrown into the barrel and had burst open during the progress of the accident.

At first Tess had been rather inclined to cry, but finding, to her great relief, that she was unhurt, she changed her threatened tears into laughter and said:

“Ain’t I funny looking? Just like a duck!”

“What were you trying to do, children?” asked Ruth, trying to speak rather severely in her capacity as “mother.”

“I was trying to put Almira and one of her kittens into the barrel,” explained Tess, now that Mrs. MacCall had got off most of the feathers. “I leaned over to put Almira in the barrel, soft and easy like, down on the other pillow, and it upset—I mean the barrel did. It began to roll, and I couldn’t stop it and it rolled right off the porch and—”

“Right over my Alice-doll it rolled, and she’s all squashed!” voiced Dot.

“Oh, be quiet! She isn’t hurt a bit,” cried Tess. “Her nose was flat, anyhow.”

“Did the barrel roll over you?” asked Agnes, smiling now.

“Almost,” said Tess. “But I got out of the way in time, and Almira grabbed up her kitten and ran. Where is she?” she asked.

“Never mind the cat,” advised Ruth. “She’s caused enough excitement for one Saturday morning. Why were you putting her in the barrel, anyhow, Tess?”

“So I’d know where she was when I came back. I wanted her and one kitten to play with if Dot is going to play with her Alice-doll when we get back from the store. But I guess I leaned too far over.”

“I guess you did,” assented Ruth. “Well, I’m glad it was no worse. Is your doll much damaged, Dot?”

“Maybe I can put a little more sawdust or some rags in her and stuff her out. But she’s awful flat. And look at her nose!”

“Her nose was flat, anyhow, before the barrel rolled over her,” said Tess. “But I’m sorry it happened. I guess Almira was scared.”

“We were all frightened,” said Ruth. “It was a terrible racket. Now let the poor cat alone, and run along to the store. Oh, what a mess this is,” and she looked at the refuse scattered from the trash barrel. “And just when I want things to look nice for the girls. It always seems to happen that way!”

Uncle Rufus shuffled along.

“Doan you-all worry now, honey,” he said, speaking to all the girls as one. “I’ll clean up dish yeah trash in no time. I done got de lawn like a billiard table, an’ I’ll pick up dish yeah trash. De ash man ought to have been along early dis mawnin’ fo’ to get it. I set it dar fo’ him.”

That explained the presence on the side porch of the barrel of odds and ends collected for the ash man to remove. He had not called, and seeing the receptacle there, with an old feather pillow among the other refuse, Tess thought she had her opportunity.

“Run along now, my bonny bairns! Run along!” counseled the old Scotch woman. “’Tis late it’s getting, and the lassies will be here to lunch before we know it.”

“Yes, do run along,” begged Ruth. “And then come back to be washed and have your hair combed. I want you to look nice if, accidentally, you appear on the scene.”

Thus bidden, and fortified with another cookie each, Tess and Dot hurried on to the store, Dot tenderly trying to pinch into shape the flattened nose of her Alice-doll.

Rufus got a broom and began to clean the scattered trash to put back into the barrel, and Mrs. MacCall hurried into her kitchen, where Linda was humming a Finnish song as she clattered amid the pots and pans.

“Oh, we must finish the parlor and library,” declared Ruth. “Do come and help, Agnes.”

“Coming, Ruth. Oh, here’s Neale!” she added, pausing to look toward the gate through which at that moment appeared a sturdy lad of pleasant countenance.

“He acts as though he had something on his mind,” went on Agnes, as the youth broke into a run on seeing her and her sister on the steps. “Wait a moment, Ruth. He may have something to tell us.”

“The fates forbid that it is anything more about Tess and Dot!” murmured Ruth, for the children had some minutes before disappeared down the street.

“News!” cried Neale O’Neil, as he swung up the steps. “I’ve got such news for you! Oh, it’s great!” and his face fairly shone.

“Just a minute now, Neale,” said Ruth, in the quiet voice she sometimes had to use when Tess and Dot, either or both, were engaged in one of their many startling feats. “Quiet down a bit, please, before you tell us.”

The boy had reached the porch, panting from his run, and he had been about to burst out with the news, which he could hardly contain, when Ruth addressed him.

“What’s the matter? Don’t you want to hear it?” he asked, fanning himself vigorously with his hat.

“Oh, yes, it isn’t that,” said Agnes, with a smile, which caused Neale’s lips to part in an answering one, showing his white teeth that made a contrast to his tanned face. “But we have just passed through rather a strenuous time, Neale, and if you have anything more startling to tell us about Tess and Dot—”

“Oh, it isn’t about them!” laughed Neale O’Neil. “They’re all right. I just saw them going down the street.”

“Thank goodness!” murmured Ruth. “I thought they had got into more mischief. Well, go on, Neale, and tell us the news. Is it good?”

“The best ever,” he answered, sobering down a little. “The only trouble is that there isn’t very much of it. Only a sort of rumor, so to speak.”

“Sit down,” said Agnes, and she herself suited her action to the words. “Uncle Rufus has the spilled trash cleaned up now.”

“Yes’m, it’s done all cleaned up now,” murmured the old colored servant as he departed, having made the side porch presentable again. “But I suah does wish dat trash man’d come ’roun’ yeah befo’ dem two chilluns come back. Dey’s gwine to upsot dat barrel ag’in, if dey gets a chanst; dey suah is!” and he departed, shaking his head woefully enough.

“What happened?” asked Neale. “An accident?”

“You might call it that,” assented Ruth, sitting down beside her sister. “It was a combination of Tess, Dot, Alice-doll and Almira all rolled into one.”

“That’s enough!” laughed the boy, to whom readers of the previous volumes of the series need no introduction.

Neale O’Neil had once been in a circus. He was known as “Master Jakeway” and was the son of James O’Neil. Neale’s uncle, William Sorber, was the ringmaster and lion tamer in the show billed as “Twomley & Sorber’s Herculean Circus and Menagerie.” Some time before the opening of the present story, Neale had left the circus and had come to Milton to live, making his home with Con Murphy, the town cobbler.

“Well, go on with your news, Neale,” said Ruth gently, as she gazed solicitously at the boy. She was beginning to have more and more something of a feeling of responsibility toward him. This was due to the fact that Ruth was growing older, as has been evidenced, and also to the fact that Neale was also, and at times, she thought, he showed the lack of the care of a loving mother.

“Yes, I want to hear it,” interposed Agnes. “And then we simply must get the house in shape, if the girls aren’t to find us with smudges of dust on our noses.”

“Is there anything I can do?” asked Neale eagerly. “Are you going to have a party?”

“Some of Ruth’s young ladies are coming to lunch,” explained Agnes. “I don’t suppose I may be classed with them,” and she looked shyly at her sister.

“I don’t see why not,” came the retort from the oldest Kenway girl. “I’d like to have you come to the meeting, Agnes.”

“No, thank you, civics are not much in my line. I hated ’em in school. Though maybe I’ll come to the eats. But let’s hear Neale’s news. It may spoil from being kept.”

“Not much danger of that,” said the boy, with another bright smile. “But are you sure there isn’t anything I can do to help?”

“Perfectly sure, Neale,” answered Ruth. “The two irrepressibles brought me the flowers I wanted to decorate with, and it only remains to put them in vases. But now I’m sure we have chattered enough about ourselves. Let us hear about you.”

“It isn’t so much about me; it’s about—father,” and Neale’s voice sank when he said that. He spoke in almost a reverent tone. And then his face lighted up again as he exclaimed:

“I have some news about him! That’s why I ran to tell you. I knew you’d be glad.”

“Oh, Neale, that’s fine!” cried Agnes, clasping him by the arm. “After all these years, really to have news of him! I’m so glad!”

“Is he really found?” asked Ruth, who was of a less excitable type than her sister, though she could get sufficiently worked up when there was need for it.

“No, he isn’t exactly found,” went on Neale. “I only wish he were. But I just heard, in a roundabout way, that he may not be so very far from here.”

“That is good news,” declared Ruth. “How did you hear it?”

“Well, you know my father was what is called a rover,” went on the boy. “I presume I don’t need to tell you that. He wouldn’t have been in the circus business with Uncle Bill, and he wouldn’t have had me in the circus—along with the trick mules—unless he had loved to travel about and see the country.”

“That’s a safe conclusion,” remarked Agnes. To her sister and herself Neale’s circus experiences were an old story. He had often told them how, when a small boy, he had performed in the sawdust ring.

“Yes, father was a rover,” went on Neale. “At least that’s the conclusion I’ve come to of late. I really didn’t know him very well. He left the circus when I was still small and told Uncle Bill to look after me. Well, Uncle Bill did, I’ll say that for him. He was as kind as any boy’s uncle could be.”

“Anyhow, as you know, father left the circus, gave me in charge of Uncle Bill, and went off to seek his fortune. I suppose he realized that I would be better off out of a circus, but he knew he had to live, and money is needed for that. So that’s why he quit the ring, I imagine. He’s been seeking his fortune for quite a while now, and—”

“Neale, do you mean to say he has come back?” cried Agnes.

“Not exactly,” was the answer. “At least if he has come back I haven’t seen him. But I just met a man—a sort of tramp he is, to tell you the truth—and he says he knew a man who saw my father in the Alaskan Klondike, where father had a mine. And this man—this tramp—says my father started back to the States some time ago.”

“With a lot of gold?” asked Ruth, her eyes gleaming with hope for Neale.

“This the man didn’t know. All he knew was that there was a rumor that my father had struck it fairly rich and had started back toward civilization. But even that news makes me feel good. I’m going to see if I can find him. I always had an idea, and so did Uncle Bill, that it was to Alaska father had gone, and this proves it.”

“But who is this man who gave you the news, and why doesn’t he know where your father can be found?” asked Ruth. “Also is there anything we can do to help you, Neale?”

“What a lot of questions!” exclaimed Agnes.

“I think I can answer them,” Neale said. He was calmer now, but his face still shone and his eyes sparkled under the stress of the happy excitement. “The man, as I said, is a tramp. He asked me for some money. He was driving a team of mules on the canal towpath, and I happened to look at one of the animals. It reminded me of one we had in the circus—a trick mule—but it took only a look to show me it wasn’t the same sort of kicker. I got to talking to the man, and he said he was broke—only had just taken the job and the boss wouldn’t advance him a cent until the end of the week. I gave him a quarter, and we got to talking. Then he told me he knew men who had been in the Klondike, and, naturally, I asked him if he had ever heard of a man named O’Neil. He said he had, and then the story came out.”

“But how can you be sure it was your father?” asked Ruth, wisely not wanting false hopes to be raised.

“That was easily proved when I mentioned circus,” said Neale. “This tramp, Hank Dayton, he said his name was, remembered the men speaking of my father talking about circuses, and saying that he had left me in one.”

“That does seem to establish an identity,” Ruth conceded. “Where is this man Dayton now, Neale?”

“He had to go on with the canal boat. But I learned from him all I could. It seems sure that my father is either back here, after some years spent in Alaska, or that he will come here soon. He must have been writing to Uncle Bill, and so have learned that I came here to live. Uncle Bill knows where I am, but I don’t know where he is at this moment, though I could get in touch with him. But I’ll be glad to see my father again. Oh, if I could only find him!”

Neale seemed to gaze afar off, over the fields and woods, as if he visualized his long-lost father coming toward him. His eyes had a dreamy look.

“Can’t we do something to help you?” asked Ruth.

“That’s what I came over about as soon as I had learned all the mule driver could tell me,” went on the boy. “I thought maybe we could ask Mr. Howbridge, your guardian, how to go about finding lost persons. There are ways of advertising for people who have disappeared.”

“There is,” said Agnes. “I’ve often seen in the paper advertisements for missing persons who are wanted to enable an estate to be cleared up, and the last time I was in Mr. Howbridge’s office I heard him telling one of the clerks to have such an advertisement prepared.”

“Then that’s what I’ve got to have done!” declared Neale. “I’ve got some money, and I can get more from Uncle Bill if I can get in touch with him. I’m going to see Mr. Howbridge and start something!”

He was about to leave the porch, to hasten away, when Ruth interposed.

“Mr. Howbridge is coming here this afternoon,” said the girl. “You might stay and see him, if you like, Neale.”

“What, with a whole Civic Betterment Club of girls coming to the Corner House! No, thank you,” he laughed. “I’ll see him afterward. But I have more hope now than I ever had before.”

“I’m very glad,” murmured Ruth. “Mr. Howbridge will give you any help possible, I’m sure. Shall I speak to him about it when he comes to advise us how to form our Civic Betterment Club?”

“Oh, I think not, thank you,” answered Neale. “He’ll have enough to do this afternoon without taking on my affair. I can tell him later. But I couldn’t wait to tell you.”

“Of course you couldn’t!” said Agnes. “That would have been a fine way to treat me!” Neale, who was Agnes’ special chum, in a way seemed like one of the family—at least as much so as Mrs. MacCall, the housekeeper, Uncle Rufus, or Sammy Pinkney, the little fellow who lived across Willow Street, on the opposite side from the Corner House.

“Well, I feel almost like another fellow now,” went on Neale, as he started down the walk. “Not knowing whether your father is alive or not isn’t much fun.”

“I should say not!” agreed Agnes. “I wish I could ask you to stay to lunch, Neale, but—”

“Oh, gee, Aggie!” The boy laughed, and off down the street he hastened, his step light and his cheery whistle ringing out.

“Isn’t it wonderful!” exclaimed Agnes, as she followed her sister into the house.

“Yes, if only it proves true,” returned the older girl, more soberly.

From the kitchen came the clatter of pans and dishes as Linda disposed of the clutter incidental to making cakes and dainties for a bevy of girls. Mrs. MacCall could be heard humming a Scotch song, and as Tess and Dot returned from the store she raised her voice in the refrain:

“Thou art a gay an’ bonnie lass,

But thou hast a waukrife minnie.”

“What in the world is a waukrife minnie?” demanded Agnes again, pausing in her task.

“It’s ‘wakeful mother,’” answered Ruth. “I remember now. It’s in Burns’ poem of that name. But do hurry, please, Aggie, or the girls will be here before we can change our dresses!”

“The fates forbid!” cried her sister, and she hastened to good advantage.

The lunch was over and the “Civic Betterment League” was in process of embryo formation, under the advice of Mr. Howbridge, and Ruth was earnestly presiding over the session of her girl friends in the library of the Corner House, when, from the ample yard in the rear of the old mansion, came a series of startled cries.

There was but one meaning to attach to them. The cries came from Dot and Tess, and mingled with them were the unmistakable yells of Sammy Pinkney.

At the same time Mrs. MacCall added her remonstrances to something that was going on, while Uncle Rufus, tottering his way along the hall, tapped at the door of the library and said:

“’Scuse me, Miss Ruth, but de chiluns done got cotched in de elevator!”

“The elevator!” Agnes screamed. “What in the world do you mean?”

“Yas’um, dat’s whut it is,” said the old colored man. “Tess an’ Dot done got cotched in de elevator!”

Mr. Howbridge had been making an address to Ruth’s assembled girl chums when the interruption came. He had been telling them just how to go about it to organize the kind of society Ruth had in mind. In spite of her half refusal to attend the session, Agnes had decided to be present, and she was sitting near the door when Uncle Rufus made his statement about the two smallest Kenways being “cotched.”

“But how can they be in an elevator?” demanded Agnes. “We haven’t an elevator on the place—there hardly is one in Milton.”

“I don’t know no mo’ ’bout it dan jest dat!” declared the old colored man. “Sammy he done say dey is cotched in de elevator an’—”

“Oh, Sammy!” cried Agnes. “If Sammy has anything to do with it you might know—”

She was interrupted by a further series of cries, unmistakably coming from Tess and Dot, and, mingled with their shouts of alarm, was the voice of Mrs. MacCall saying:

“Come along, Ruth! Oh, Agnes! Oh, the poor bairns! Oh, the wee ones!” and then she lapsed into her broadest Scotch so that none who heard understood.

“Something must have happened!” declared Ruth.

“It is very evident,” added Agnes, and the two sisters hurried out, brushing past Uncle Rufus in the hall.

“Can’t we do something?” asked Lucy Poole, one of the guests.

“Yes, we must help,” added Grace Watson.

“I think perhaps it will be best if you remain here,” said Mr. Howbridge. “I don’t imagine anything very much out of the ordinary has happened, from what I know of the family,” he said with a smile. “I’ll go and see, and if any more help is needed I shall let you young ladies know. Unless it is, the fewer on the scene the better, perhaps.”

“Especially if any one is hurt,” murmured Clo Baker. “I never could stand the sight of a child hurt.”

“They don’t seem to have lost their voices, at any rate,” remarked Lucy. “Listen:”

As Mr. Howbridge followed Agnes and Ruth from the room, there was borne to the ears of the assembled guests a cry of:

“Let me down! Do you hear, Sammy Pinkney! Let me down!”

And a voice, undoubtedly that of the Sammy in question, answered:

“I’m not doing anything! I can’t get you down! It’s Billy Bumps. He did it!”

“Two boys in mischief,” murmured Lucy.

“No, Billy is a goat, so I understand,” said Clo. “I hope he hasn’t butted one of the children down the cistern.”

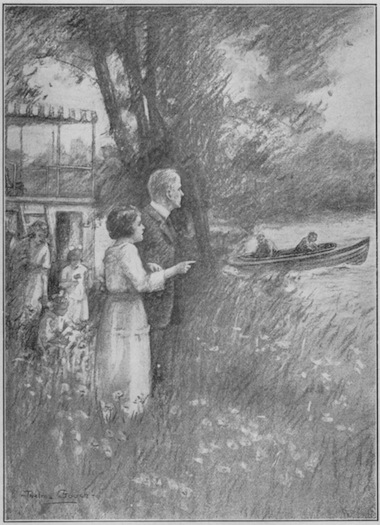

And while the guests were vainly wondering what had happened, Ruth, Agnes and Mr. Howbridge saw suspended in a large clothes basket, which was attached to a rope that ran over the high limb of a great oak tree in the back yard, Tess and Dot. They were in the clothes basket, Dot with her Alice-doll clasped in her hands; and both girls were looking over the side of the hamper.

Attached to the ground end of the rope, where it was run through a pulley block, was a large goat, now contentedly chewing grass, and near the animal, with a startled look on his face, was a small boy, who, when he felt like it, answered to the name Sammy Pinkney.

“Get us down! Get us down!” cried Dot and Tess in a chorus, while Mrs. MacCall stood beneath them holding out her apron as if the two little girls were ripe apples ready to fall.

“How did you get up there?” demanded Ruth, her face paling as she saw the danger of her little sisters, for Tess and Dot were too high up for safety.

“Get us down!” cried Dot and Tess in a chorus, while Mrs. MacCall

stood beneath them holding out her apron.

“Sammy elevatored us up,” explained Dot.

“Well, you wanted to go!” replied the small boy in self justification.

The goat kept on eating grass, of which there was an ample supply in the yard of the Corner House.

“What shall we do?” cried Agnes.

“Run into the house and get a strong blanket or quilt,” advised Mr. Howbridge quickly, but in a quiet, insistent voice which seemed to calm the excitement of every one. “Bring the blanket here. We will hold it beneath the basket like a fire net, though I do not believe there is any immediate danger of the children falling. The rope seems to be firmly caught in the pulley block.”

His quick eye had taken in this detail of the “elevator.” The rope really had jammed in the block, and, as long as it held, the basket could not descend suddenly. Even if the rope should be unexpectedly loosened, there would still be the weight of the attached goat to act as a drag on the end of the cable, thus counterbalancing, in a measure, the weight of the girls in the clothes basket.

“But I don’t want to take any chances,” explained the lawyer. “We’ll take hold and extend the blanket under them, in case they should fall.”

“I have my apron ready now!” cried Mrs. MacCall. “Oh, the puir bairns! What ever possit it ye twa gang an’ reesk their lives this way, ye tapetless one?” she cried to Sammy angrily, suddenly, in her excitement, using the broadest of Scotch.

“Well, they wanted to ride in an elevator, an’ I—I made one,” he declared.

And that is just what he had done. Whether it was his idea or that of Tess and Dot did not then develop. What Sammy had done was to take the largest clothes basket, getting it unobserved when Mrs. MacCall and Linda were busy over Ruth’s party. He had fastened the basket to a long rope, which had been thrown over the high limb of the oak tree. Then Sammy had passed the rope through a pulley block, obtained no one knew where, and had hitched to the cable the goat, Billy Bumps.

By walking away from the tree Billy had pulled on the rope. The straightaway pull was transformed, by virtue of the pulley, into an upward motion, and the basket ascended. It had formed the “elevator” to which Uncle Rufus alluded.

And, really, it did elevate Dot and Tess. They had been pulled up and had descended as Sammy made the goat back, thus releasing the pull on the rope. All had gone well for several trips until the rope jammed in the pulley, thus leaving the two girls suspended in the basket at the highest point. Their screams, the fright of Sammy, the alarms of Uncle Rufus and Mrs. MacCall had followed in quick succession.

“Here’s the blanket!” cried Agnes speeding to the scene with a large woolen square under her arm. “Have they fallen yet?”

Behind her came stringing the guests. It had been impossible for them to remain in the library with their minds on civic betterment ideas when they heard what had happened.

“Well, did you ever!” cried one of the number in astonishment.

“What can it mean?” burst out a second.

“Looks to me like an amateur circus,” giggled a third. She was a lighthearted girl and had not taken much of an interest in the rather dry meeting.

“Those children will be hurt,” cried a nervous lady. “Oh, dear, why did they let them do such an awful thing as that?”

“I think they did it on their own account,” said another lady. “Our Tommy is just like that—into mischief the minute your back is turned.”

“I’m glad they came!” said Mr. Howbridge. “They may all take hold of the edges of the blanket and extend it as firemen do the life net. You may stand aside now, Mrs. MacCall, if you will,” he told the Scotch housekeeper, and not until then did she lower her apron and move out from under the swaying basket, murmuring as she did so something about Sammy being a “tapetless gowk” who needed a “crummock” or a good “flyte,” by which the girls understood that the boy in question was a senseless dolt who needed a severe whipping or a good scolding.

Ruth, Agnes and the guests took hold of the heavy blanket and held it under the basket as directed by Mr. Howbridge. Then, seeing there would be little danger to the children in case the basket should suddenly fall, the lawyer directed Sammy to loosen the goat from the rope.

“He’ll run if I do,” objected Sammy.

“Let him run, you ninnie!” cried Mrs. MacCall. “An’ if ever ye fetchet him yon again I’ll—I’ll—”

But she could not call up a sufficiently severe punishment, and had to subside.

Meanwhile the mischievous boy had led Billy Bumps off to one side, by the simple process of loosening the rope from the wagon harness to which it was fastened. Mr. Howbridge then took a firm hold of the cable and, after loosening it from where it had jammed in the pulley block, he braced his feet in the earth, against the downward pull of the basket, and so gently lowered Tess and Dot to the ground.

“I’m never going to play with you again, Sammy Pinkney!” cried Tess, climbing out of the basket and shaking her finger at the boy.

“Nor me, either!” added Dot, smoothing out the rumpled dress of her Alice-doll.

“Well, you asked me to make some fun and I did,” Sammy defended himself.

“Yes, and you made a lot of excitement, too,” added Ruth. “You had better come into the house now, children,” she went on. “And, Sammy, please take Billy away.”

“Yes’m,” he murmured. “But they asked me to elevator ’em up, an’ I did!”

“To which I shall bear witness,” said Mr. Howbridge, laughing.

Mrs. MacCall “shooed” Tess and Dot into the house, murmuring her thanks to providence over the escape, and, after a while, the excitement died away and Ruth went on with her meeting.

The Civic Betterment League was formed that afternoon and eventually, perhaps, did some good. But what this story is to concern itself with is the adventure on a houseboat of the Corner House girls. Meanwhile about a week went by. There had been no more elevator episodes, though this does not mean that Sammy did not make mischief, nor that Tess and Dot kept out of it. Far from that.

One bright afternoon, when school was out and the pre-supper appetites of Dot and Tess had been appeased, the two came running into the room where Ruth and Agnes sat.

“He’s here! He’s come!” gasped Tess.

“And he’s got, oh, such a dandy!” echoed Dot.

“Who’s here, and what has he?” asked Agnes, flying out of her chair.

“You shouldn’t say anything is a ‘dandy,’” corrected Ruth to her youngest sister.

“Well it is, and you told me always to tell the truth,” was the retort.

“It’s Mr. Howbridge and he’s out in front with a—the—er the beautifulest automobile!” cried Tess. “It’s all shiny an’ it’s got wheels, an’—an’ everything! It’s newer than our car.”

Ruth was sufficiently interested in this news to look from the window.

“It is Mr. Howbridge,” she murmured, as though there had been doubts on that point.

“And he must have a new auto,” added Agnes. “Oh, he has!” she cried.

A moment later they were welcoming their guardian at the door, while the smaller children formed an eager and anxious background.

“What has happened?” asked Agnes, while Ruth, remembering her position as head of the family, asked:

“Won’t you come in?”

“I’d much rather you would come out, Miss Ruth,” the man responded. “It is just the sort of day to be out—not in.”

“Especially in such a car as that!” exclaimed Agnes. “It’s a—”

“Be careful,” murmured Ruth, with an admonishing glance from Agnes to the smaller girls. “Little pitchers, you know—”

“It’s a wonderful car!” went on Agnes. “Is it yours?”

“Well, I sometimes doubt a little, when I recall what it cost me,” her guardian answered with a laugh. “But I am supposed to be the owner, and I have come to take you for a ride.”

“Oh, can’t we go?” came in a chorus from Tess and Dot.

“Yes, all of you!” laughed Mr. Howbridge. “That’s why I waited until school was out. They may come, may they not, Miss Ruth?” he asked. Always he was thus deferential to her when a question of family policy came up.

“Yes, I think so,” was the low-voiced answer. “But we planned to have an early tea and—”

“Oh, I promise to get you back home in plenty of time,” the lawyer said, with a laugh. “And after that, if you like, we might take another ride.”

“How wonderful!” murmured Agnes.

“Won’t you stay to tea?” asked Ruth.

“I was waiting for that!” exclaimed Mr. Howbridge. “I shall be delighted. Now then, youngsters, run out and hop in, but don’t touch anything, or you may be in a worse predicament than when you were in the clothes basket elevator.”

“We won’t!” cried Tess and Dot, running down the walk.

“You must come back and be washed!” cried Ruth. It was a standing order—that, and the two little girls knew better than to disobey.

But first they inspected the new car, walking all around it, and breathing in, with the odor of gasoline, the awed remarks of some neighboring children.

“That’s part our car,” Dot told these envious ones, as she and Tess started back toward the house. “We’re going for a ride in it, and don’t you dare touch anything on it or Mr. Howbridge’ll be awful mad!”

“Um, oh, whut a lubly auto,” murmured Alfredia Blossom, who had come on an errand to her grandfather, Uncle Rufus. “Dat’s jest de beatenistest one I eber see!”

“Yes, it is nice,” conceded Tess, proudly, airily and condescendingly.

A little later the two younger children and Agnes sat in the rear seat, while Ruth was beside Mr. Howbridge at the steering wheel. Then the big car purred off down the street, like a contented cat after a saucer of warm milk.

“It was very good of you to come and get us,” said Ruth, when they were bowling along. “Almost the christening trip of the car, too, isn’t it?” she asked.

“The very first trip I have made in it,” was the answer. “I wanted it properly christened, you see. There is a method in my madness, too. I have an object in view, Martha.”

Sometimes he called Ruth this, fancifully, with the thought in mind that she was “cumbered with many cares.”

Again he would apply to her the nickname of “Minerva,” with its suggestion of wisdom. And Ruth rather liked these fanciful appellations.

“You have an object?” she repeated.

“Yes,” he answered. “As usual, I want your advice.”

“As if it was really worth anything to you!” she countered.

“It will be in this case, I fancy,” he went on with a smile. “I want your opinion about a canal boat.”

Ruth stole a quick glance at the face of her guardian. There was a silence between them for a moment, broken only by the purr of the powerful machine and the suction of the rubber tires on the street. Agnes, Dot and Tess were having a gay time behind the two figures on the front seat.

“A canal boat?” murmured Ruth, as if she had not heard aright.

“Perhaps I had better qualify that statement,” went on Mr. Howbridge in his courtroom voice, “by saying that it is, at present, Minerva, on the canal. And a boat on the canal is a canal boat, is it not? I ask for a ruling,” and he laughed as he slowed down to round a corner.

“I don’t know anything about your legal phraseology,” answered Ruth, entering into the bantering spirit of the occasion, “but I don’t see why a boat on the canal becomes a canal boat any more than a cottage pudding becomes a house. The pudding has no cottage in it any more than a club sandwich has a club in it and—”

“I am completely at your mercy,” Mr. Howbridge broke in with. “But, speaking seriously, this boat is on the canal, though strictly it is not a canal boat. You know what they are, I dare say?”

“I used to have to take Tess and Dot down to the towpath to let them watch them often enough when we first came here,” said Ruth, with a laugh. “They used to think canal boats were the most wonderful objects in the world.”

“Are we going on a canal boat?” asked Tess, overhearing some of the talk on the front seat. “Oh, are we?”

“Oh, I hope we are!” added Dot. “My Alice-doll just loves canal boats. And wouldn’t it be splendiferous, Tess, if we could have a little one all to ourselves and Scalawag or maybe Billy Bumps to pull it instead of a mule?”

“That would be a sight on the towpath!” cried Agnes. “But what is this about canal boats, Mr. Howbridge?”

“Has some one opened a soda water store on board one?” asked Dot suddenly.

“Not exactly. You’ll see, presently. But I do want your opinion,” he went on, speaking directly to Ruth now, “and it has to do with a boat on a canal.”

“I still think you are joking,” she told him. “And except for the fact that we have a canal here in Milton I should think you were trying to fool me.”

“Impossible, Minerva,” he replied, soberly enough.

As Ruth had said, Milton was located on both the canal and a river, the two streams, if a canal can be called a stream, joining at a certain point, so that boats could go from one to the other. Gentory River, which acted as a feeder to one section of the canal, also connected with Lake Macopic, a large body of water. The lake contained many islands.

The automobile skirted the canal by a street running parallel to it, and then Mr. Howbridge turned down a rather narrow street, on which were situated several stores that sold supplies to the canal boats, and brought his machine to a stop on the bank of the waterway beside the towpath, as it is called from the fact that the mules or horses towing the boats walk along that level stretch of highway bordering the canal and forming part of the canal property.

At this part of the canal, the stream widened and formed a sort of harbor for boats of various kinds. It was also a refitting station; a place where a captain might secure new mules, hire helpers, buy grain for his animals and also victuals for himself and family; for the owners of the canal boats often lived aboard them. This place, known locally as “Henderson’s Cove,” was headquarters for all the canal boatmen of the vicinity.

“Here is where we disembark, to use a nautical term,” said Mr. Howbridge, with a smile at the younger children.

“Is this where we take the boat?” asked Dot eagerly.

“You might call it that,” said Mr. Howbridge, with another genial smile. “And now, Martha, to show that I was in earnest, there is the craft in question,” and he pointed to an old hulk of a canal boat, which had seen its best days.

“That! You want my opinion on that?” cried the girl, turning to her guardian in some surprise.

“Oh, no, the one next to it. The Bluebird.”

Ruth changed her view, and saw a craft which brought to her lips exclamations of delight, no less than to the lips of her sisters. For it was not a “rusty canaler” they beheld, but a trim craft, a typical houseboat, with a deck covered with a green striped awning and set with willow chairs, and a cabin, the windows of which, through their draped curtains, gave hint of delights within.

“Oh, how lovely!” murmured Agnes.

“A dream!” whispered Ruth. “But why do you bring us here to show us this?” she asked with much interest.

“Because,” began Mr. Howbridge, “I want to know if you would like—”

Just then an excited voice behind the little party burst out with:

“Oh, Mr. Howbridge, I’ve been looking everywhere for you!” Neale O’Neil came hurrying along the towpath, seemingly much excited.

“I hope that Supreme Court decision hasn’t gone against me,” Ruth heard her guardian murmur. “If that case is lost—”

And then Neale began to talk excitedly.

“They told me at your office you had come here, Mr. Howbridge,” said Neale. “And I hurried on as fast as I could.”

“Did they send you here to find me?” asked the lawyer.

“Yes, sir.”

“With any message?” As Mr. Howbridge asked this Ruth noticed that her guardian seemed very anxious about something.

“Yes, I have a message,” went on Neale. “It’s about—”

“The Jackson case?” interrupted the lawyer. “Is there a decision from the court and—”

“Oh, no, this isn’t anything about the Jackson case or any other,” Neale hastened to say. “It’s about my father. And—”

Ruth and Agnes could not help gasping in surprise. As for the two smaller Kenway children all they had eyes for was the houseboat.

“Oh, your father!” repeated Mr. Howbridge. “Have you found him, Neale?” There was very evident relief in the lawyer’s tone.

“No, sir, I haven’t found him. But you know you told me to come to you as soon as I had found that tramp mule driver again, and he’s back in town once more. He just arrived at the lower lock with a grain boat, and I hurried to tell you.”

“Yes, that was right, Neale,” said Mr. Howbridge. “Excuse me, Miss Ruth,” he went on, turning to the girl, “but I happen to be this young man’s legal adviser, and while I planned this for a pleasure trip, it seems that business can not be kept out of it.”

“Oh, we don’t mind!” exclaimed Ruth, with a smile at Neale. “Of course we know about this, and we’d be so glad if you could help find Mr. O’Neil.”

“All right then, if the young ladies have no objection,” said the lawyer, “we’ll combine business with pleasure. Suppose we go aboard the Bluebird. I want Miss Ruth’s opinion of her and—”

“I don’t see why in the world you want my opinion about this boat,” said the puzzled girl. “I’m almost sure there’s a joke in it, somewhere.”

“No, Martha, no joke at all, I do assure you,” answered her guardian. “You’ll understand presently. Now, Neale, you say this mule driver has come back?”

“Yes, sir. You know I went to you as soon as he gave me a hint that my father might have returned from Alaska, and you said to keep my eyes open for this man.”

“I did, Neale, yes. You of course know this story, don’t you, Miss Ruth?” he asked.

“Yes, I believe we were the first Neale told about it.”

“Well,” went on Mr. Howbridge, while Tess and Dot showed signs of impatience to get on board the boat, “I told Neale we must find out more from this Hank Dayton, the mule driver, before we could do anything, or start to advertise for Mr. O’Neil. And now, it seems, he is here again. At first, Neale, when I saw you hurrying along, excited, I was afraid I had lost a very important law case. I am glad you did not bring bad news.”

Ruth stole a glance at her guardian’s face. He was more than usually quiet and anxious, she thought, though he tried to be gay and jolly.

“We’ll have a look at this boat,” said Mr. Howbridge, as they advanced toward it. “I’ll get Minerva’s opinion, and then we’ll try to find Hank Dayton.”

“I know where to find him,” said Neale. “He’s going to bunk down at the lower lock for a while. I made him promise to stay there until he could have a talk with you.”

“Very good,” announced the lawyer. “Now come on, youngsters!” he cried with a gayer manner, and he caught Dot up in his arms and carried her aboard the boat, Neale, Ruth and the others following.

It was a typical houseboat. That is, it was a sort of small house built on what would otherwise have been a scow. The body of the boat was broad beamed forward and aft, as a sailor would say. That is, it was very wide, whereas most boats are pointed at the bow, and only a little less narrow at the stern.

“It’s like a small-sized canal boat, isn’t it?” remarked Agnes, as they went down into the cabin.

“But ever so much nicer,” said Ruth.

“Oh, look at the cute little cupboards!” cried Dot. “I could keep my dolls there.”

“And here’s a sweet place for the cats!” added Tess, raising the cover of a sort of box in a corner. “It would be a crib.”

“That’s a locker,” explained Mr. Howbridge, with a smile.

“Oh, I wouldn’t want to lock Almira in there!” exclaimed the little girl. “She might smother, and how could she get out to play with her kittens?”

“Oh, I don’t mean that it can be locked,” explained the lawyer. “It is just called that on a boat. Cupboards on the wall and the window seats on the floor are generally called lockers on board a ship.”

“Is this a ship?” asked Dot.

“Well, enough like one to use some of the same words,” replied Mr. Howbridge. “Now let’s look through it.”

This they did, and each step brought forth new delights. They had gone down a flight of steps and first entered a small cabin which was evidently intended for a living room. Back of that was very plainly the dining room, for it contained a table and some chairs and on the wall were two cupboards, or “lockers” as the lawyer said they must be called.

“And they have real dishes in them!” cried Tess, flattening her nose against one of the glass doors.

“Don’t do that, dear,” said Ruth in a low voice.

“But I want to see,” insisted Tess.

“So do I!” chimed in Dot, and soon the two little sisters, side by side, with noses pressed flat against the doors, were taking in the sights of the dishes. Mr. Howbridge silently motioned to Ruth to let them do as they pleased.

“Oh, what a lovely dolls’ party we could have here!” sighed Dot, as she turned away from the dish locker.

“And couldn’t Almira come?” asked Tess, appealing to Agnes. “And bring one of her kittens?”

“Yes, we’ll even allow you two kittens, for fear one would get lonesome,” laughed Mr. Howbridge. “But come on. You haven’t seen it all yet.”

There was a small kitchen back of the dining room, and both Ruth and Agnes were interested to see how conveniently everything was arranged.

“It would be ever so much easier to get meals here than in the Corner House,” was Ruth’s opinion.

“Do you think so?” asked the lawyer.

“Yes, everything is so handy. You hardly have to take a step to reach anything,” added Agnes. “You only have to turn from the stove to the sink, and another turn and you have everything you want, from a toasting fork to an egg beater,” and she indicated the different kitchen utensils hanging in a rack over the stove.

“I’m glad you like it,” said Mr. Howbridge, and Ruth found herself wondering why he said that.

They passed into the sleeping quarters where small bunks, almost like those in Pullman cars, were neatly arranged, even to a white counterpane and pillow shams on each one.

“Oh, how lovely.”

“And how clean and neat!”

“It’s just like a sleeping car on the railroad.”

“Yes, or one of those staterooms on some steamers.”

“A person could sleep as soundly here as in a bed at home,” was Ruth’s comment.

“Yes, unless the houseboat rocked like a ship,” said Agnes.

“I don’t think it could rock much on the canal.”

“No, but it might on a river, or a lake. I guess a houseboat like this can go almost anywhere.”

There were two sets of sleeping rooms, one on either side of a middle hall or passageway. Then came a small bathroom. And back of that was something that made Neale cry out in delight.

“Why, the boat has an engine!” exclaimed the boy. “It runs by motor!”

“Yes, the Bluebird is a motor houseboat,” said Mr. Howbridge, with a smile. “It really belongs on Lake Macopic, but to get it there through the canal mules will have to be used, as this boat has such a big propeller that it would wash away the canal banks. It is not allowed to move it through the canal under its own power.”

“That’s a dandy engine all right!” exclaimed Neale, and he knew something about them for one summer he had operated a small motor craft on the Gentory River, as well as running the Corner House girls’ automobile for them. “I wish I could run this,” he went on with a sigh, “but I don’t suppose there’s any chance.”

“I don’t know about that,” said the lawyer, musingly. “That is what I brought Minerva here to talk about. Let’s go back to the main cabin and sit down.”

“I’m going to sit on one of the lockers!” cried Tess, darting off ahead of the others.

“I want to sit on it, too!” exclaimed Dot.

“There are two lockers on the floor—one for each,” laughed Mr. Howbridge.

As the little party moved into the main cabin, Ruth found herself wondering more and more what Mr. Howbridge wanted her opinion on. She was not long, however, in learning.

“Here is the situation,” began the lawyer, when they were all seated facing him. His tone reminded Ruth of the time he had come to talk to them about their inheritance of the Corner House. “This boat, the Bluebird, belongs to an estate. The estate is being settled up, and the boat is going to be sold. A man living at the upper end of Lake Macopic has offered to buy it at a fair price if it is delivered to him in good condition before the end of summer. As the legal adviser of the estate I have undertaken to get this boat to the purchaser. And what I brought you here for, to-day, Minerva,” he said, smiling at Ruth, “is to ask your opinion about the best way of getting the boat there.”

“Do you really mean that?” asked the girl.

“I certainly do.”

“Well, I should say the best plan would be to start it going, and steer it up the canal to the river, through the river into the lake and up the lake to the place where it is to be delivered,” Ruth answered, smiling.

“But Mr. Howbridge said the boat couldn’t be moved by the motor on the canal,” objected Agnes.

“Well, have mules tow it, then,” advised Ruth. “That is very simple.”

“I am glad you think so,” replied the lawyer. “And the next matter on which I wish your advice is whether to start the boat off alone on her trip, or just in charge of, say, the mule driver.”

“Oh, I wouldn’t want to trust a lovely houseboat like this to only a mule driver!” exclaimed Ruth.

“That’s what I thought,” went on her guardian, with another smile. “It needs some one on board to look after it, doesn’t it?”

“Well, yes, I should say so.”

“Then how would you like to take charge?” came the unexpected question.

“Me?” cried Ruth. “Me?”

“You, and all of you!” went on the lawyer. “Listen. Here is the situation. I have to send this houseboat to Lake Macopic. You dwellers of the Corner House need a vacation. You always have one every summer, and I generally advise you where to go. At least you always ask me, and sometimes you take my advice.

“This time I advise you to take a houseboat trip. And I make this offer. I will provide the boat and all the needful food and supplies, such as gasoline and oil when you reach the river and lake. Everything else is on board, from beds to dishes. I will also hire a mule driver and engage some mules for the canal trip. Now, how does that suit you?”

“Oh! Oh!” exclaimed Agnes, and it seemed to be all she could say for a moment. She just looked at Mr. Howbridge with parted lips and sparkling eyes.

“How wonderful!” murmured Ruth.

“Can we go?” cried Tess.

“The whole family, including Neale,” said Mr. Howbridge.

“Oo-ee!” gasped Dot, wide-eyed.

Agnes and Neale stared entranced at each other, Agnes, for once, speechless.

“Well, now I have made the offer, think it over, and while you are doing that I’ll give a little attention to Neale’s case,” went on Mr. Howbridge. “Now, young man, suppose we go and find this mule driver who seems to know something of your father.”

“Oh, wait! Don’t go away just yet!” begged Ruth. “Let’s talk about the trip some more! Do you really think we can go?”

“I want you to go. It would be doing me a favor,” said the lawyer. “I must get this boat to Lake Macopic somehow, and I don’t know a better way than to have Martha and her family take it,” and he bowed formally to his ward.

“And did you really mean I may go, too?” asked Neale.

“If you can arrange it, and Miss Ruth agrees.”

“Of course I will! But, oh, there will be such a lot to do to get ready. We’d have to take Mrs. MacCall along, too,” she added.

“Of course,” assented Mr. Howbridge. “By all means!”

“And would you go too?” asked Ruth.

“Would you like me to?” the lawyer countered.

“Of course. We’d all like it.”

“I might manage to make at least part of the trip,” was the reply. “Then you have decided to take my offer?”

“Oh, I think it’s perfectly wonderful!” burst out Agnes.

As for Tess and Dot, it could be told what they thought by just looking at them.

“Very well then,” said the guardian, “we’ll consider it settled. I’ll have to see about mules and a driver for the canal part of the trip and—”

An exclamation from Neale interrupted him.

“What is it?” asked the lawyer.

“Why couldn’t we hire Hank Dayton for a mule driver?” Neale asked. “He’s rough, but I think he’s a decent man and honest, and he knows a lot about the canal and boats and mules.”

“It might not be a bad idea,” assented Mr. Howbridge. “We’ll find him and ask him, Neale. And it would be killing two birds with one stone. He could help you in your search for your father. Yes, I think that will be a good plan. Girls, I’ll leave you here to look over the Bluebird at your leisure while Neale and I go to interview the mule driver.”

“And I hope he will be able to tell you how to find your father, Neale,” said Agnes, in a low voice.

“I hope so, too,” added the boy. “You don’t know, Aggie, how much I’ve wanted to find father.”

“Of course I do, Neale. And you’ll find him, too!”

Neale went on with Mr. Howbridge, somewhat cheered by Agnes’ sympathy.

Left to themselves on the Bluebird, Ruth, Agnes, Dot and Tess went over every part of it again, from the engine room to the complete kitchen and living apartments.

“Neale will just love fussing around that motor,” said Agnes.

“You speak as if we had already decided to make the trip,” remarked Ruth, with a bright glance at her sister.

“Why, yes, haven’t you?” Agnes countered. “I thought you and Mr. Howbridge had fixed it up between you when you were chatting up on the front seat of the auto.”

“He never said a word to me about it,” declared Ruth.

“He must have said something,” insisted her sister.

“Oh, of course we talked, but not about this,” and Ruth swept her hands about to indicate the Bluebird. “I was as much surprised as you to have him ask us if we would take her up to the lake.”

“Well, it will be delightful, don’t you think?”

“Yes, I think it will. But of course it depends on Mrs. MacCall.”

“I don’t see why!” exclaimed Agnes quickly and reproachfully.

“Of course you do. She’ll have to go along to act as chaperone and all that. We may have to tie up at night in lonely places along the canal or river and—”

“We’ll have Neale and Mr. Howbridge! And how about asking Luke Shepard and his sister Cecile?” went on Agnes.

Ruth flushed a little.

“I don’t believe Cecile and Luke can go,” she replied slowly. “Cecile has got to go home to take care of her Aunt Lorena, who is sick, and Luke wrote me that he had a position offered to him as a clerk in a summer hotel down on the coast, and it is to pay so well that he would not dream of letting the opportunity pass.”

“Oh, that’s too bad, Ruth. You won’t see much of him.”

“I am not sure I’ll see anything of him.” And Ruth’s face clouded a little.

“Well, anyway, as I said before, we’ll have Neale and Mr. Howbridge,” continued Agnes.

“Neale. But Mr. Howbridge is not sure he can go—at least all the way. However, we’ll ask Mrs. MacCall.”

“I think she’ll be just crazy to go!” declared Agnes. “Come on, let’s go right away and find out.”

“But we must wait for Mr. Howbridge to come back. He told us to.”

“Well, then we’ll say we’re already living on board,” said Agnes. “Oh, won’t it be fun to eat on a houseboat!” and she danced off to the dining room, took her seat at the table, and exclaimed: “I’ll have a steak, rare, with French fried potatoes, plenty of gravy and a cup of tea and don’t forget the pie à la mode.”

Tess and Dot laughed and Ruth smiled. They then went all over the boat again, with the result that they grew more and more enthusiastic about the trip. And when Mr. Howbridge and Neale came back in the automobile a little later, beaming faces met them.

“Well, what about it, Minerva?” Mr. Howbridge asked Ruth. “Are you going to act as caretakers for the boat to help me settle the estate?”

“Since you put it that way, as a favor, I can not refuse,” she answered, giving him a swift smile. “But, as I told the girls, it will depend on Mrs. MacCall.”

“You leave her to me,” laughed the lawyer. “I’ll recite one of Bobby Burns’ poems, and if that doesn’t win her over nothing will. Neale, do you think you can manage that motor?”

“I’m sure of it,” said the boy. “It isn’t the same kind I had to run before, but I can get the hang of it all right.”

“Is there any news about your father?” asked Ruth, glancing from her guardian to the boy.

“Nothing very definite,” answered the lawyer. “We found Hank Dayton, and in spite of his rough and ragged clothes I discovered him to be a reliable fellow. He told us all he knew about the rumor of Mr. O’Neil having returned from the Klondike, and I am going to start an inquiry, with newspaper advertising and all that. And I may as well tell you that I have engaged this same Hank Dayton to drive the mules that will draw the Bluebird on the canal part of the trip.”

“Oh!” exclaimed Agnes. “I thought Neale said this man was a tramp!”

“He is, in appearance,” said Mr. Howbridge, with a smile. “A person can not wear an evening suit and drive canal mules. But Hank seems to be a sterling chap at the bottom, and with Neale and Mrs. MacCall to keep him straight, you will have no trouble.

“It is really necessary,” he went on, “to have some man who understands the canal, the mules, and the locks to look after the boat, and I think this Dayton will answer. He has just finished a trip, and so Neale and I hired him. It will be well for Neale to keep in touch with him, too, for through Hank we may get more news of Mr. O’Neil. And now, if you have sufficiently looked over the Bluebird, we may as well go back.”

“It would be a good while before I could see enough of her!” exclaimed Agnes. “I’m just in love with the craft, and I know we shall have a delightful summer on her. Only the trip will be over too soon, I’m afraid.”

“There is no necessity for haste,” the lawyer assured her. “The purchaser of the boat does not want her until fall, and you may linger as long as you like on the trip.”

“Good!” exclaimed Agnes.

A family council was held the next day at which Mr. Howbridge laid all the facts before Mrs. MacCall. At first the Scotch housekeeper would not listen to any proposal for the trip on the water. But when Ruth and Agnes had spoken of the delights of the boat, and when the housekeeper had personally inspected the Bluebird, she changed her mind.

“Though I never thought, in my old age, I’d come to bein’ a houseboat keeper,” she chuckled. “But ’tis all in the day’s work. I’ll gang with ye ma lassies. A canal boat is certainly more staid than an ice-boat, and I went alang with ye on that.”

“Hurray!” cried Agnes, unable to restrain her joy. “All aboard for Lake Macopic!”

The door opened and Aunt Sarah Maltby came in.

“I thought I heard some one calling,” she said anxiously.

“It was Agnes,” explained Ruth. “She’s so excited about the trip.”

“Fish? What fish? It isn’t Friday, is it?” asked the old lady, who was getting rather deaf.

“No, Auntie dear, I didn’t say fish—I said trip.” And Ruth spoke more loudly. “We are going to make a trip on a houseboat for our summer vacation. Would you like to come along?”

Aunt Sarah Maltby shook her head, as Tess pulled out a chair for her.

“I’m getting too old, my dear, to go traipsing off over the country in one of those flying machines.”

“It’s a houseboat—not a flying machine,” Agnes explained.

“Well, it’s about the same, I reckon,” returned the old lady. “No, I’ll stay at home and look after things at the Corner House. It’ll need somebody.”

“Yes, there’s no doubt of that,” Ruth said.

So it was arranged. Aunt Sarah Maltby would stay at home with Linda and Uncle Rufus, while Mrs. MacCall accompanied the Corner House girls on the houseboat.

There was much to be done before the trip could be undertaken, and many business details to arrange, for, as inheritors of the Stower estate, Ruth and her sisters received rents from a number of tenants, some of them in not very good circumstances.

“And we must see that they will want nothing while we are gone,” Ruth had said.

It was part of her self-imposed duties to play Lady Bountiful to some of the poorer persons who rented Uncle Peter Stower’s tenements.

“Well, as long as you don’t go to buying ‘dangly jet eawin’s’ for Olga Pederman it will be all right,” said Agnes, and they laughed at this remembrance of the girl who, when ill with diphtheria, had asked for these ornaments when Ruth called to see what she most wanted.

Eventually all the many details were arranged and taken care of. A mechanic had gone over the motor of the Bluebird and pronounced it in perfect running order, a fact which Neale verified for himself. He had made all his plans for going on the trip, and between that and eagerly waiting for any news of his missing father, his days were busy ones.

Mr. Howbridge had closely questioned Hank Dayton and had learned all that rover could tell, which was not much. But it seemed certain that Mr. O’Neil had started from Alaska for the States.