Drawn & Etched by A. Hervieu.

MUSEUM DES CURIOSITES HISTORIQUES

LE PUBLIC EST PRIÉ DE

NE TOUCHER À AUCUN

DE CES OBJETS.

Title: Paris and the Parisians in 1835 (Vol. 2)

Author: Frances Milton Trollope

Release date: May 16, 2012 [eBook #39710]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

Page 46: The phrase "find out if he can any single" seems to be missing a word.

Page 384: The phrase starting "swarm _au sixième_" has no closing quotation mark.

Preparing for publication, by the same Author,

In 3 vols. post 8vo. with 15 Characteristic Engravings.

THE LIFE AND ADVENTURES

OF

JONATHAN JEFFERSON WHITLAW;

OR,

SCENES ON THE MISSISSIPPI.

Paris and the Parisians,

in 1835.

VOL. 2.

Drawn & Etched by A. Hervieu.

MUSEUM DES CURIOSITES HISTORIQUES

LE PUBLIC EST PRIÉ DE

NE TOUCHER À AUCUN

DE CES OBJETS.

London:

Richard Bentley, New Burlington Street,

Publisher in Ordinary to His Majesty.

1835.

AUTHOR OF "DOMESTIC MANNERS OF THE AMERICANS,"

"TREMORDYN CLIFF," &c.

"Le pire des états, c'est l'état populaire."—Corneille.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

RICHARD BENTLEY, NEW BURLINGTON STREET,

Publisher in Ordinary to His Majesty.

1836.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY SAMUEL BENTLEY,

Dorset Street, Fleet Street.

Peculiar Air of Frenchwomen.—Impossibility that an Englishwoman should not be known for such in Paris.—Small Shops.—Beautiful Flowers, and pretty arrangement of them.—Native Grace.—Disappearance of Rouge.—Grey Hair.—Every article dearer than in London.—All temptations to smuggling removed.Page 1

Exclusive Soirées.—Soirée Doctrinaire.—Duc de Broglie.—Soirée Républicaine.—Soirée Royaliste.—Partie Impériale.—Military Greatness.—Dame de l'Empire.11

L'Abbé Lacordaire.—Various Statements respecting him.—Poetical description of Notre Dame.—The Prophecy of a Roman Catholic.—Les Jeunes Gens de Paris.—Their omnipotence.22

Palais Royal.—Variety of Characters.—Party of English.—Restaurant.—Galerie d'Orléans.—Number of Loungers.—Convenient abundance of Idle Men.—Théâtre du Vaudeville.49

Literary Conversation.—Modern Novelists.—Vicomte d'Arlincourt.—His Portrait.—Châteaubriand.—Bernardin de Saint Pierre.—Shakspeare.—Sir Walter Scott.—French familiarity with English Authors.—Miss Mitford.—Miss Landon.—Parisian passion for Novelty.—Extent of general Information.62

Trial by Jury.—Power of the Jury in France.—Comparative insignificance of that vested in the Judge.—Virtual Abolition of Capital Punishments.—Flemish Anecdote.75

English Pastry-cooks.—French horror of English Pastry.—Unfortunate experiment upon a Muffin.—The Citizen King.85

Parisian Women.—Rousseau's failure in attempting to describe them.—Their great influence in Society.—Their grace in Conversation.—Difficulty of growing old.—Do the ladies of France or those of England manage it best?92

La Sainte Chapelle.—Palais de Justice.—Traces of the Revolution of 1830.—Unworthy use made of La Sainte Chapelle.—Boileau.—Ancient Records.105 vii

French ideas of England.—Making love.—Precipitate retreat of a young Frenchman.—Different methods of arranging Marriages.—English Divorce.—English Restaurans.116

Mixed Society.—Influence of the English Clergy and their Families.—Importance of their station in Society.132

Le Grand Opéra.—Its enormous Expense.—Its Fashion.—Its acknowledged Dulness.—'La Juive.'—Its heavy Music.—Its exceeding Splendour.—Beautiful management of the Scenery.—National Music.143

The Abbé Deguerry.—His eloquence.—Excursion across the water.—Library of Ste. Geneviève.—Copy-book of the Dauphin.—St. Etienne du Mont.—Pantheon.156

Little Suppers.—Great Dinners.—Affectation of Gourmandise.—Evil effects of "dining out."—Evening Parties.—Dinners in private under the name of Luncheons.—Late Hours.166

Hôpital des Enfans Trouvés.—Its doubtful advantages.—Story of a Child left there.177

Procès Monstre.—Dislike of the Prisoners to the ceremony of Trial.—Société des Droits de l'Homme.—Names given to viii the Sections.—Kitchen and Nursery Literature.—Anecdote of Lagrange.—Republican Law.201

Memoirs of M. Châteaubriand.—The Readings at L'Abbaye-aux-Bois.—Account of these in the French Newspapers and Reviews.—Morning at the Abbaye to hear a portion of these Memoirs.—The Visit to Prague.212

Jardin des Plantes.—Not equal in beauty to our Zoological Gardens.—La Salpêtrière.—Anecdote.—Les Invalides.—Difficulty of finding English Colours there.—The Dome.232

Expedition to Montmorency.—Rendezvous in the Passage Delorme.—St. Denis.—Tomb prepared for Napoleon.—The Hermitage.—Dîner sur l'herbe.241

George Sand.258

"Angelo Tyran de Padoue."—Burlesque at the Théâtre du Vaudeville.—Mademoiselle Mars.—Madame Dorval.—Epigram.270

Boulevard des Italiens.—Tortoni's.—Thunder-storm.—Church of the Madeleine.—Mrs. Butler's "Journal."292 ix

A pleasant Party.—Discussion between an Englishman and a Frenchman.—National Peculiarities.302

Chamber of Deputies.—Punishment of Journalists.—Institute for the Encouragement of Industry.—Men of Genius.313

Walk to the Marché des Innocens.—Escape of a Canary Bird.—A Street Orator.—Burying-place of the Victims of July.323

A Philosophical Spectator.—Collection of Baron Sylvestre.—Hôtel des Monnaies.—Musée d'Artillerie.335

Concert in the Champs Elysées.—Horticultural Exhibition.—Forced Flowers.—Republican Hats.—Carlist Hats—Juste-Milieu Hats.—Popular Funeral.347

Minor French Novelists.360

Breaking-up of the Paris Season.—Soirée at Madame Récamier's.—Recitation.—Storm.—Disappointment.—Atonement.—Farewell.371

POSTSCRIPT379

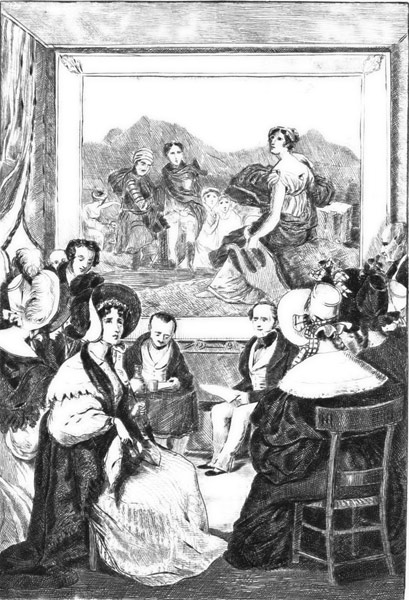

SoiréePage 20

Le Roi Citoyen88

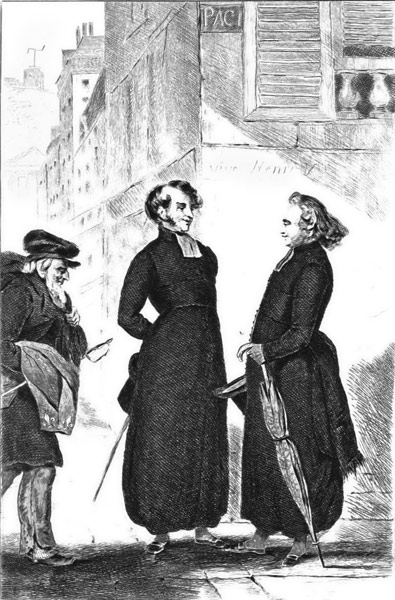

Prêtres de la Jeune France158

Lecture à l'Abbaye-aux-Bois228

Boulevard des Italiens294

"V'là les restes de notre Révolution de Juillet"328

PARIS

AND THE PARISIANS

IN 1835.

Peculiar Air of Frenchwomen.—Impossibility that an Englishwoman should not be known for such in Paris.—Small Shops.—Beautiful Flowers, and pretty arrangement of them.—Native Grace.—Disappearance of Rouge.—Grey Hair.—Every article dearer than in London.—All temptations to smuggling removed.

Considering that it is a woman who writes to you, I think you will confess that you have no reason to complain of having been overwhelmed with the fashions of Paris: perhaps, on the contrary, you may feel rather disposed to grumble because all I have hitherto said on the fertile subject of dress has been almost wholly devoted to the historic and fanciful costume of the republicans. Personal appearance, and all that concerns it, is, however, a very important feature in the 2 daily history of this showy city; and although in this respect it has been made the model of the whole world, it nevertheless contrives to retain for itself a general look, air, and effect, which it is quite in vain for any other people to attempt imitating. Go where you will, you see French fashions; but you must go to Paris to see how French people wear them.

The dome of the Invalides, the towers of Notre Dame, the column in the Place Vendôme, the windmills of Montmartre, do not come home to the mind as more essentially belonging to Paris, and Paris only, than does the aspect which caps, bonnets, frills, shawls, aprons, belts, buckles, gloves,—and above, though below, all things else—which shoes and stockings assume, when worn by Parisian women in the city of Paris.

It is in vain that all the women of the earth come crowding to this mart of elegance, each one with money in her sack sufficient to cover her from head to foot with all that is richest and best;—it is in vain that she calls to her aid all the tailleuses, coiffeuses, modistes, couturières, cordonniers, lingères, and friseurs in the town: all she gets for her pains is, when she has bought, and done, and put on all and everything they have prescribed, that, in the next shop she enters, she hears one grisette behind the counter mutter to another, "Voyez ce que désire cette dame anglaise;"—and 3 that, poor dear lady! before she has spoken a single word to betray herself.

Neither is it only the natives who find us out so easily—that might perhaps be owing to some little inexplicable freemasonry among themselves; but the worst of all is, that we know one another in a moment. "There is an Englishman,"—"That is an Englishwoman," is felt at a glance, more rapidly than the tongue can speak it.

That manner, gait, and carriage,—that expression of movement, and, if I may so say, of limb, should be at once so remarkable and so impossible to imitate, is very singular. It has nothing to do with the national differences in eyes and complexion, for the effect is felt perhaps more strongly in following than in meeting a person; but it pervades every plait and every pin, every attitude and every gesture.

Could I explain to you what it is which produces this effect, I should go far towards removing the impossibility of imitating it: but as this is now, after twenty years of trial, pretty generally allowed to be impossible, you will not expect it of me. All I can do, is to tell you of such matters appertaining to dress as are open and intelligible to all, without attempting to dive into that very occult part of the subject, the effect of it.

In milliners' phrase, the ladies dress much less in Paris than in London. I have no idea that 4 any Frenchwoman, after her morning dishabille is thrown aside, would make it a practice, during "the season," to change her dress completely four times in the course of the day, as I have known some ladies do in London. Nor do I believe that the most précieuses in such matters among them would deem it an insufferable breach of good manners to her family, did she sit down to dinner in the same apparel in which they had seen her three hours before it.

The only article of female luxury more generally indulged in here than with us, is that of cashmere shawls. One, at the very least, of these dainty wrappers makes a part of every young lady's trousseau, and is, I believe, exactly that part of the présent which, as Miss Edgeworth says, often makes a bride forget the futur.

In other respects, what is necessary for the wardrobe of a French woman of fashion, is necessary also for that of an English one; only jewels and trinkets of all kinds are more frequently worn with us than with them. The dress that a young Englishwoman would wear at a dinner party, is very nearly the same as a Frenchwoman would wear at any ball but a fancy one; whereas the most elegant dinner costume in Paris is exactly the same as would be worn at the French Opera.

There are many extremely handsome "magasins 5 de nouveautés" in every part of the town, wherein may be found all that the heart of woman can desire in the way of dress; and there are smart coiffeuses and modistes too, who know well how to fabricate and recommend every production of their fascinating art: but there is no Howell and James's wherein to assemble at a given point all the fine ladies of Paris; no reunions of tall footmen are to be seen lounging on benches outside the shops, and performing to the uninitiated the office of signs, by giving notice how many purchasers are at that moment engaged in cheapening the precious wares within. The shops in general are very much smaller than ours,—or when they stretch into great length, they have uniformly the appearance of warehouses. A much less quantity of goods of all kinds is displayed for purposes of show and decoration,—unless it be in china shops, or where or-molu ornaments, protected by glass covers, form the principal objects: here, or indeed wherever the articles sold can be exhibited without any danger of loss from injury, there is very considerable display; but, on the whole, there is much less appearance of large capital exhibited in the shops here than in London.

One great source of the gay and pretty appearance of the streets, is the number and elegant arrangement of the flowers exposed for sale. Along 6 all the Boulevards, and in every brilliant Passage (with which latter ornamental invention Paris is now threaded in all directions), you need only shut your eyes in order to fancy yourself in a delicious flower-garden; and even on opening them again, if the delusion vanishes, you have something almost as pretty in its place.

Notwithstanding the multitudinous abominations of their streets—the prison-like locks on the doors of their salons, and the odious common stair which must be climbed ere one can get to them—there is an elegance of taste and love of the graceful about these people which is certainly to be found nowhere else. It is not confined to the spacious hotels of the rich and great, but may be traced through every order and class of society, down to the very lowest.

The manner in which an old barrow-woman will tie up her sous' worth of cherries for her urchin customers might give a lesson to the most skilful decorator of the supper-table. A bunch of wild violets, sold at a price that may come within reach of the worst-paid soubrette in Paris, is arranged with a grace that might make a duchess covet them; and I have seen the paltry stock-in-trade of a florist, whose only pavilion was a tree and the blue heavens, set off with such felicity in the mixture of colours, and the gradations of shape and form, as made me stand to gaze longer 7 and more delightedly than I ever did before Flora's own palace in the King's Road.

After all, indeed, I believe that the mystical peculiarity of dress of which I have been speaking wholly arises from this innate and universal instinct of good taste. There is a fitness, a propriety, a sort of harmony in the various articles which constitute female attire, which may be traced as clearly amongst the cotton toques, with all their variety of brilliant tints, and the 'kerchief and apron to match, or rather to accord, as amongst the most elegant bonnets at the Tuileries. Their expressive phrase of approbation for a well-dressed woman, "faite à peindre," may often be applied with quite as much justice to the peasant as to the princess; for the same unconscious sensibility of taste will regulate them both.

It is this national feeling which renders their stage groups, their corps de ballet, and all the tableaux business of their theatres, so greatly superior to all others. On these occasions, a single blunder in colour, contrast, or position, destroys the whole harmony, and the whole charm with it: but you see the poor little girls hired to do angels and graces for a few sous a night, fall into the composition of the scene with an instinct as unerring, as that which leads a flight of wild geese to cleave the air in a well-adjusted triangular phalanx, instead of scattering themselves to every 8 point of the compass; as, par exemple, our figurantes may be often seen to do, if not kept in order by the ballet-master as carefully as a huntsman whistles in his pack.

It is quite a relief to my eyes to find how completely rouge appears to be gone out of fashion here. I will not undertake to say that no bright eyes still look brighter from having a touch of red skilfully applied beneath them: but if this be done, it is so well done as to be invisible, excepting by its favourable effect; which is a prodigious improvement upon the fashion which I well remember here, of larding cheeks both young and old to a degree that was quite frightful.

Another improvement which I very greatly admire is, that the majority of old ladies have left off wearing artificial hair, and arrange their own grey locks with all the neatness and care possible. The effect of this upon their general appearance is extremely favourable: Nature always arranges things for us much better than we can do it for ourselves; and the effect of an old face surrounded by a maze of wanton curls, black, brown, or flaxen, is infinitely less agreeable than when it is seen with its own "sable silvered" about it.

I have heard it observed, and with great justice, that rouge was only advantageous to those who did not require it: and the same may be said with 9 equal truth of false hair. Some of the towering pinnacles of shining jet that I have seen here, certainly have exceeded in quantity of hair the possible growth of any one head: but when this fabric surmounts a youthful face which seems to have a right to all the flowing honours that the friseur's art can contrive to arrange above it, there is nothing incongruous or disagreeable in the effect; though it is almost a pity, too, to mix anything approaching to deceptive art with the native glories of a young head. For which sentiment messieurs les fabricans of false hair will not thank me;—for having first interdicted the use of borrowed tresses to the old ladies, I now pronounce my disapproval of them for the young.

Au reste, all I can tell you farther respecting dress is, that our ladies must no longer expect to find bargains here in any article required for the wardrobe; on the contrary, everything of the kind is become greatly dearer than in London: and what is at least equally against making such purchases here is, that the fabrics of various kinds which we used to consider as superior to our own, particularly those of silks and gloves, are now, I think, decidedly inferior; and such as can be purchased at the same price as in England, if they can be found at all, are really too bad to use.

The only foreign bargains which I long to bring home with me are in porcelain: but this our custom-house 10 tariff forbids, and very properly; as, without such protection, our Wedgewoods and Mortlakes would sell but few ornamental articles; for not only are their prices higher, but both their material and the fashioning of it are in my opinion extremely inferior. It is really very satisfactory to one's patriotic feelings to be able to say honestly, that excepting in these, and a few other ornamental superfluities, such as or-molu and alabaster clocks, etcætera, there is nothing that we need wish to smuggle into our own abounding land.

Exclusive Soirées.—Soirée Doctrinaire.—Duc de Broglie.—Soirée Républicaine.—Soirée Royaliste.—Partie Impériale.—Military Greatness.—Dame de l'Empire.

Though the salons of Paris probably show at the present moment the most mixed society that can be found mingled together in the world, one occasionally finds oneself in the midst of a set evidently of one stamp, and indeed proclaiming itself to be so; for wherever this happens, the assembly is considered as peculiarly chosen and select, and as having all the dignity of exclusiveness.

The picture of Paris as it is, may perhaps be better caught at a glance at a party collected together without any reference to politics or principles of any kind; but I have been well pleased to find myself on three different occasions admitted to soirées of the exclusive kind.

At the first of these, I was told the names of most of the company by a kind friend who sat near me, and thus became aware that I had the honour of being in company with most of King Philippe's present ministry. Three or four of these 12 gentlemen were introduced to me, and I had the advantage of seeing de près, during their hours of relaxation, the men who have perhaps at this moment as heavy a weight of responsibility upon their shoulders as any set of ministers ever sustained.

Nevertheless, nothing like gloom, preoccupation, or uneasiness, appeared to pervade them; and yet that chiefest subject of anxiety, the Procès Monstre, was by no means banished from their discourse. Their manner of treating it, however, was certainly not such as to make one believe that they were at all likely to sink under their load, or that they felt in any degree embarrassed or distressed by it.

Some of the extravagances of les accusés were discussed gaily enough, and the general tone was that of men who knew perfectly well what they were about, and who found more to laugh at than to fear in the opposition and abuse they encountered. This light spirit however, which to me seemed fair enough in the hours of recreation, had better not be displayed on graver occasions, as it naturally produces exasperation on the part of the prisoners, which, however little dangerous it may be to the state, is nevertheless a feeling which should not be unnecessarily excited. In that amusing paper or magazine—I know not which may be its title—called the "Chronique de Paris," 13 I read some days ago a letter describing one of the séances of the Chamber of Peers on this procès, in which the gaiety manifested by M. de Broglie is thus censured:—

"J'ai fait moi-même partie de ce public privilégié que les accusés ne reconnaissent pas comme un vrai public, et j'ai pu assister jeudi à cette dramatique audience où la voix tonnante d'un accusé lisant une protestation, a couvert la voix du ministère public. J'étais du nombre de ceux qui ont eu la fièvre de cette scène, et je n'ai pu comprendre, au milieu de l'agitation générale, qu'un homme aussi bien élevé que M. de Broglie (je ne dis pas qu'un ministre) trouvât seul qu'il y avait là sujet de rire en lorgnant ce vrai Romain, comparable à ces tribuns qui, dans les derniers temps de la république, faisaient trembler les patriciens sur leurs chaises curules."

"Ce vrai Romain," however, rather deserved to be scourged than laughed at; for never did any criminal when brought to the bar of his country insult its laws and its rulers more grossly than the prisoner Beaune on this occasion. If indeed the accounts which reach us by the daily papers are not exaggerated, the outrageous conduct of the accused furnishes at every sitting sufficient cause for anger and indignation, however unworthy it may be of inspiring anything approaching to a feeling of alarm: and the calm, dignified, and 14 temperate manner in which the Chamber of Peers has hitherto conducted itself may serve, I think, as an example to many other legislative assemblies.

The ministers of Louis-Philippe are very fortunate that the mode of trial decided on by them in this troublesome business is likely to be carried through by the upper house in a manner so little open to reasonable animadversion. The duty, and a most harassing one it is, has been laid upon them, as many think, illegally; but the task has been imposed by an authority which it is their duty to respect, and they have entered upon it in a spirit that does them honour.

The second exclusive party to which I was fortunate enough to be admitted, was in all respects quite the reverse of the first. The fair mistress of the mansion herself assured me that there was not a single doctrinaire present.

Here, too, the eternal subject of the Procès Monstre was discussed, but in a very different tone, and with feelings as completely as possible in opposition to those which dictated the lively and triumphant sort of persiflage to which I had before listened. Nevertheless, the conversation was anything but triste, as the party was in truth particularly agreeable; but, amidst flashes of wit, sinister sounds that foreboded future revolutions grumbled every now and then like distant thunder. Then there was shrugging of shoulders, and shaking 15 of heads, and angry taps upon the snuff-box; and from time to time, amid the prattle of pretty women, and the well-turned gentillesses of those they prattled to, might be heard such phrases as, "Tout n'est pas encore fini".... "Nous verrons ... nous verrons".... "S'ils sont arbitraires!" ... and the like.

The third set was as distinct as may be from the two former. This reunion was in the quartier St. Germain; and, if the feeling which I know many would call prejudice does not deceive me, the tone of first-rate good society was greatly more conspicuous here than at either of the others. By all the most brilliant personages who adorned the other two soirées which I have described, I strongly suspect that the most distinguished of this third would be classed as rococo; but they were composed of the real stuff that constitutes the true patrician, for all that. Many indeed were quite of the old régime, and many others their noble high-minded descendants: but whether they were old or young,—whether remarkable for having played a distinguished part in the scenes that have been, or for sustaining the chivalric principles of their race, by quietly withdrawing from the scenes that are,—in either case they had that air of inveterate superiority which I believe nothing on earth but gentle blood can give.

There is a fourth class still, consisting of the 16 dignitaries of the Empire, which, if they ever assemble in distinct committee, I have yet to become acquainted with. But I suspect that this is not the case: one may perhaps meet them more certainly in some houses than in others; but, unless it be around the dome of the Invalides, I do not believe that they are to be found anywhere as a class apart.

Nothing, however, can be less difficult than to trace them: they are as easily discerned as a boiled lobster among a panier full of such as are newly caught.

That amusing little vaudeville called, I think, "La Dame de l'Empire," or some such title, contains the best portrait of a whole clique, under the features of an individual character, of any comedy I know.

None of the stormy billows which have rolled over France during the last forty years have thrown up a race so strongly marked as those produced by the military era of the Empire. The influence of the enormous power which was then in action has assuredly in some directions left most noble vestiges. Wherever science was at work, this power propelled it forward; and ages yet unborn may bless for this the fostering patronage of Napoleon: some midnight of devastation and barbarism must fall upon the world before what he has done of this kind can be obliterated. 17

But the same period, while it brought forth from obscurity talent and enterprise which without its influence would never have been greeted by the light of day, brought forward at the same time legions of men and women to whom this light and their advanced position in society are by no means advantageous in the eyes of a passing looker-on.

I have heard that it requires three generations to make a gentleman. Those created by Napoleon have not yet fairly reached a second; and, with all respect for talent, industry, and valour be it spoken, the necessity of this slow process very frequently forces itself upon one's conviction at Paris.

It is probable that the great refinement of the post-imperial aristocracy of France may be one reason why the deficiencies of those now often found mixed up with them is so remarkable. It would be difficult to imagine a contrast in manner more striking than that of a lady who would be a fair specimen of the old Bourbon noblesse, and a bouncing maréchale of Imperial creation. It seems as if every particle of the whole material of which each is formed gave evidence of the different birth of the spirit that dwells within. The sound of the voice is a contrast; the glance of the eye is a contrast; the smile is a contrast; the step is a contrast. Were every feature of a dame de l'Empire 18 and a femme noble formed precisely in the same mould, I am quite sure that the two would look no more alike than Queen Constance and Nell Gwyn.

Nor is there at all less difference in the two races of gentlemen. I speak not of the men of science or of art; their rank is of another kind: but there are still left here and there specimens of decorated greatness which look as if they must have been dragged out of the guard-room by main force; huge moustached militaires, who look at every slight rebuff as if they were ready to exclaim, "Sacré nom de D* * *! je suis un héros, moi! Vive l'Empereur!"

A good deal is sneeringly said respecting the parvenus fashionables of the present day: but station, and place, and court favour, must at any rate give something of reality to the importance of those whom the last movement has brought to the top; and this is vastly less offensive than the empty, vulgar, camp-like reminiscences of Imperial patronage which are occasionally brought forward by those who may thank their sabre for having cut a path for them into the salons of Paris. The really great men of the Empire—and there are certainly many of them—have taken care to have other claims to distinction attached to their names than that of having been dragged out of heaven knows what profound obscurity by Napoleon: I 19 may say of such, in the words of the soldier in Macbeth—

"If I say sooth, I must report they were

As cannon overcharged with double cracks."

As for the elderly ladies, who, from simple little bourgeoises demoiselles, were in those belligerent days sabred and trumpeted into maréchales and duchesses, I must think that they make infinitely worse figures in a drawing-room, than those who, younger in years and newer in dignity, have all their blushing honours fresh upon them. Besides, in point of fact, the having one Bourbon prince instead of another upon the throne, though greatly to be lamented from the manner in which it was accomplished, can hardly be expected to produce so violent a convulsion among the aristocracy of France, as must of necessity have ensued from the reign of a soldier of fortune, though the mightiest that ever bore arms.

Many of the noblest races of France still remain wedded to the soil that has been for ages native to their name. Towards these it is believed that King Louis-Philippe has no very repulsive feelings; and should no farther changes come upon the country—no more immortal days arise to push all men from their stools, it is probable that the number of these will not diminish in the court circles.

Meanwhile, the haut-ton born during the last 20 revolution must of course have an undisputed entrée everywhere; and if by any external marks they are particularly brought forward to observation, it is only, I think, by a toilet among the ladies more costly and less simple than that of their high-born neighbours; and among the gentlemen, by a general air of prosperity and satisfaction, with an expression of eye sometimes a little triumphant, often a little patronizing, and always a little busy.

It was a duchess, and no less, who decidedly gave me the most perfect idea of an Imperial parvenue that I have ever seen off the stage. When a lady of this class attains so very elevated a rank, the perils of her false position multiply around her. A quiet bourgeoise turned into a noble lady of the third or fourth degree is likely enough to look a little awkward; but if she has the least tact in the world, she may remain tranquil and sans ridicule under the honourable shelter of those above her. But when she becomes a duchess, the chances are terribly against her: "Madame la Duchesse" must be conspicuous; and if in addition to mauvais ton she should par malheur be a bel esprit, adding the pretension of literature to that of station, it is likely that she will be very remarkable indeed.

My parvenue duchess is very remarkable indeed. She steps out like a corporal carrying a message: 21 her voice is the first, the last, and almost the only thing heard in the salon that she honours with her presence,—except it chance, indeed, that she lower her tone occasionally to favour with a whisper some gallant décoré, military, scientific or artistic, of the same standing as herself; and moreover, she promenades her eyes over the company as if she had a right to bring them all to roll-call.

Notwithstanding all this, the lady is certainly a person of talent; and had she happily remained in the station in which both herself and her husband were born, she might not perhaps have thought it necessary to speak quite so loud, and her bons mots would have produced infinitely greater effect. But she is so thoroughly out of place in the grade to which she has been unkindly elevated, that it seems as if Napoleon had decided on her fate in a humour as spiteful as that of Monsieur Jourdain, when he said—

"Votre fille sera marquise, en dépit de tout le monde: et si vous me mettez en colère, je la ferai duchesse."

L'Abbé Lacordaire.—Various Statements respecting him.—Poetical description of Notre Dame.—The prophecy of a Roman Catholic.—Les Jeunes Gens de Paris—Their omnipotence.

The great reputation of another preacher induced us on Sunday to endure two hours more of tedious waiting before the mass which preceded the sermon began. It is only thus that a chair can be hoped for when the Abbé Lacordaire mounts the pulpit of Notre Dame. The penalty is really heavy; but having heard this celebrated person described as one who "appeared sent by Heaven to restore France to Christianity"—as "a hypocrite that set Tartuffe immeasurably in the background"—as "a man whose talent surpassed that of any preacher since Bossuet"—and as "a charlatan who ought to harangue from a tub, instead of from the chaire de Notre Dame de Paris,"—I determined upon at least seeing and hearing him, however little I might be able to decide on which of the two sides of the prodigious chasm that yawned between his friends and enemies the truth was 23 most likely to be found. There were, however, several circumstances which lessened the tedium of this long interval: I might go farther, and confess that this period was by no means the least profitable portion of the four hours which we passed in the church.

On entering, we found the whole of the enormous nave railed in, as it had been on Easter Sunday for the concert (for so in truth should that performance be called); but upon applying at the entrance to this enclosure, we were told that no ladies could be admitted to that part of the church—but that the side aisles were fully furnished with chairs, and afforded excellent places.

This arrangement astonished me in many ways:—first, as being so perfectly un-national; for go where you will in France, you find the best places reserved for the women,—at least, this was the first instance in which I ever found it otherwise. Next, it astonished me, because at every church I had entered, the congregations, though always crowded, had been composed of at least twelve women to one man. When, therefore, I looked over the barrier upon the close-packed, well-adjusted rows of seats prepared to receive fifteen hundred persons, I thought that unless all the priests in Paris came in person to do honour to their eloquent confrère, it was very unlikely that this uncivil arrangement should be found necessary. 24 There was no time, however, to waste in conjecture; the crowd already came rushing in at every door, and we hastened to secure the best places that the side aisles afforded. We obtained seats between the pillars immediately opposite to the pulpit, and felt well enough contented, having little doubt that a voice which had made itself heard so well must have power to reach even to the side aisles of Notre Dame.

The first consolation which I found for my long waiting, after placing myself in that attitude of little ease which the straight-backed chair allowed, was from the recollection that the interval was to be passed within the venerable walls of Notre Dame. It is a glorious old church, and though not comparable in any way to Westminster Abbey, or to Antwerp, or Strasburg, or Cologne, or indeed to many others which I might name, has enough to occupy the eye very satisfactorily for a considerable time. The three elegant rose-windows, throwing in their coloured light from north, west, and south, are of themselves a very pretty study for half an hour or so; and besides, they brought back, notwithstanding their miniature diameter of forty feet, the remembrance of the magnificent circular western window of Strasburg—the recollection of which was almost enough to while away another long interval. Then I employed myself, not very successfully, 25 in labouring to recollect the quaint old verses which I had fallen upon a few days before, giving the dimensions of the church, and which I will herewith transcribe for your use and amusement, in case you should ever find yourself sitting as I was, bolt upright, as we elegantly express ourselves when describing this ecclesiastical-Parisian attitude, while waiting the advent of the Abbé Lacordaire.

"Si tu veux savoir comme est ample

De Notre Dame le grand temple,

Il y a, dans œuvre, pour le seur,

Dix et sept toises de hauteur,

Sur la largeur de vingt-quatre,

Et soixante-cinq, sans rebattre,

A de long; aux tours haut montées

Trente-quatre sont comptées;

Le tout fondé sur pilotis—

Aussi vrai que je te le dis."

While repeating this poetical description, you have only to remember that une toise is the same as a fathom,—that is to say, six feet; and then, as you turn your head in all directions to look about you, you will have the satisfaction of knowing exactly how far you can see in each.

I had another source of amusement, and by no means a trifling one, in watching the influx of company. The whole building soon contained as many human beings as could be crammed into it; and the seats, which we thought, as we took them, were very so-so places indeed, became accomodations 26 for which to be most heartily thankful. Not a pillar but supported the backs of as many men as could stand round it; and not a jutting ornament, the balustrade of a side altar, or any other "point of 'vantage," but looked as if a swarm of bees were beginning to hang upon it.

But the sight which drew my attention most was that displayed by the exclusive central aisle. When told that it was reserved for gentlemen, I imagined of course that I should see it filled by a collection of staid-looking, middle-aged, Catholic citizens, who were drawn together from all parts of the town, and perhaps the country too, for the purpose of hearing the celebrated preacher: but, to my great astonishment, instead of this I saw pouring in by dozens at a time, gay, gallant, smart-looking young men, such indeed as I had rarely seen in Paris on any other religious occasion. Amongst these was a sprinkling of older men; but the great majority were decidedly under thirty. The meaning of this phenomenon I could by no means understand; but while I was tormenting myself to discover some method of obtaining information respecting it, accident brought relief to my curiosity in the shape of a communicative neighbour.

In no place in the world is it so easy, I believe, to enter into conversation with strangers as in 27 Paris. There is a courteous inclination to welcome every attempt at doing so which pervades all ranks, and any one who wishes it may easily find or make opportunities of hearing the opinions of all classes. The present time, too, is peculiarly favourable for this; a careless freedom in uttering opinions of all kinds being, I think, the most remarkable feature in the manners of Paris at the present day.

I have heard that it is difficult to get a tame, flat, short, matter-of-fact answer from a genuine Irishman;—from a genuine Frenchman it is impossible: let his reply to a question which seeks information contain as little of it as the dry Anglicism "I don't know," it is never given without a tone or a turn of phrase that not only relieves its inanity, but leaves you with the agreeable persuasion that the speaker would be more satisfactory if he could, and moreover that he would be extremely happy to reply to any further questions you may wish to ask, either on the same, or any other subject whatever.

It was in consequence of my moving my chair an inch and a half to accommodate the long limbs of a grey-headed neighbour, that he was induced to follow his "Milles pardons, madame!" with an observation on the inconvenience endured on the present occasion by the appropriation of all the best places to the gentlemen. It was 28 quite contrary, he added, to the usual spirit of Parisian arrangements; and yet, in fact, it was the only means of preventing the ladies suffering from the tremendous rush of jeunes gens who constantly came to hear the Abbé Lacordaire.

"I never saw so large a proportion of young men in any congregation," said I, hoping he might explain the mystery to me. What I heard, however, rather startled than enlightened me.

"The Catholic religion was never so likely to be spread over the whole earth as it is at present," he replied. "The kingdom of Ireland will speedily become fully reconciled to the see of Rome. Le Sieur O'Connell desires to be canonized. Nothing, in truth, remains for that portion of your country to do, but to follow the example we set during our famous Three Days, and place a prince of its own choosing upon the throne."

I am persuaded that he thought we were Irish Roman Catholics: our sitting with such exemplary patience to wait for the preaching of this new apostle was not, I suppose, to be otherwise accounted for. I said nothing to undeceive him, but wishing to bring him back to speak of the congregation before us, I replied,

"Paris at least, if we may judge from the vast crowd collected here, is more religious than she has been of late years."

"France," replied he with energy, "as you 29 may see by looking at this throng, is no longer the France of 1823, when her priests sang canticles to the tune of "Ça ira." France is happily become most deeply and sincerely Catholic. Her priests are once more her orators, her magnates, her highest dignitaries. She may yet give cardinals to Rome—and Rome may again give a minister to France."

I knew not what to answer: my silence did not seem to please him, and I believe he began to suspect he had mistaken the party altogether, for after sitting for a few minutes quite silent, he rose from the place into which he had pushed himself with considerable difficulty, and making his way through the crowd behind us, disappeared; but I saw him again, before we left the church, standing on the steps of the pulpit.

The chair he left was instantly occupied by another gentleman, who had before found standing-room near it. He had probably remarked our sociable propensities, for he immediately began talking to us.

"Did you ever see anything like the fashion which this man has obtained?" said he. "Look at those jeunes gens, madame! ... might one not fancy oneself at a première représentation?"

"Those must be greatly mistaken," I replied, "who assert that the young men of Paris are not among her fidèles." 30

"Do you consider their appearing here a proof that they are religious?" inquired my neighbour with a smile.

"Certainly I do, sir," I replied: "how can I interpret it otherwise?"

"Perhaps not—perhaps to a stranger it must have this appearance; but to a man who knows Paris...." He smiled again very expressively, and, after a short pause, added—"Depend upon it, that if a man of equal talent and eloquence with this Abbé Lacordaire were to deliver a weekly discourse in favour of atheism, these very identical young men would be present to hear him."

"Once they might," said I, "from curiosity: but that they should follow him, as I understand they do, month after month, if what he uttered were at variance with their opinions, seems almost inconceivable."

"And yet it is very certainly the fact," he replied: "whoever can contrive to obtain the reputation of talent at Paris, let the nature of it be of what kind it may, is quite sure that les jeunes gens will resort to hear and see him. They believe themselves of indefeasible right the sole arbitrators of intellectual reputation; and let the direction in which it is shown be as foreign as may be to their own pursuits, they come as a 31 matter of prescriptive right to put their seal upon the aspirant's claim, or to refuse it."

"Then, at least, they acknowledge that the Abbé's words have power, or they would not grant their suffrage to him."

"They assuredly acknowledge that his words have eloquence; but if by power, you mean power of conviction, or conversion, I do assure you that they acknowledge nothing like it. Not only do I believe that these young men are themselves sceptics, but I do not imagine that there is one in ten of them who has the least faith in the Abbé's own orthodoxy."

"But what right have they to doubt it?... Surely he would hardly be permitted to preach at Notre Dame, where the archbishop himself sits in judgment on him, were he otherwise than orthodox?"

"I was at school with him," he replied: "he was a fine sharp-witted boy, and gave very early demonstrations of a mind not particularly given either to credulity, or subservience to any doctrines that he found puzzling."

"I should say that this was the greatest proof of his present sincerity. He doubted as a boy—but as a man he believes."

"That is not the way the story goes," said he. "But hark! there is the bell: the mass is about to commence." 32

He was right: the organ pealed, the fine chant of the voices was heard above it, and in a few minutes we saw the archbishop and his splendid train escorting the Host to its ark upon the altar.

During the interval between the conclusion of the mass and the arrival of the Abbé Lacordaire in the pulpit, my sceptical neighbour again addressed me.

"Are you prepared to be very much enchanted by what you are going to hear?" said he.

"I hardly know what to expect," I replied: "I think my idea of the preacher was higher when I came here, than since I have heard you speak of him."

"You will find that he has a prodigious flow of words, much vehement gesticulation, and a very impassioned manner. This is quite sufficient to establish his reputation for eloquence among les jeunes gens."

"But I presume you do not yourself subscribe to the sentence pronounced by these young critics?"

"Yes, I do,—as far, at least, as to acknowledge that this man has not attained his reputation without having displayed great ability. But though all the talent of Paris has long consented to receive its crown of laurels from the hands of her young men, it would be hardly reasonable to 33 expect that their judgment should be as profound as their power is great."

"Your obedience to this beardless synod is certainly very extraordinary," said I: "I cannot understand it."

"I suppose not," said he, laughing; "it is quite a Paris fashion; but we all seem contented that it should be so. If a new play appears, its fate must be decided by les jeunes gens; if a picture is exhibited, its rank amidst the works of modern art can only be settled by them: does a dancer, a singer, an actor, or a preacher appear—a new member in the tribune, or a new prince upon the throne,—it is still les jeunes gens who must pass judgment on them all; and this judgment is quoted with a degree of deference utterly inconceivable to a stranger."

"Chut! ... chut!" ... was at this moment uttered by more than one voice near us: "le voilà!" I glanced my eye towards the pulpit, but it was still empty; and on looking round me, I perceived that all eyes were turned in the direction of a small door in the north aisle, almost immediately behind us. "Il est entré là!" said a young woman near us, in a tone that seemed to indicate a feeling deeper than respect, and, in truth, not far removed from adoration. Her eyes were still earnestly fixed upon the door, and continued 34 to be so, as well as those of many others, till it reopened and a slight young man in the dress of a priest prepared for the chaire appeared at it. A verger made way for him through the crowd, which, thick and closely wedged as it was, fell back on each side of him, as he proceeded to the pulpit, with much more docility than I ever saw produced by the clearing a passage through the intervention of a troop of horse.

Silence the most profound accompanied his progress; I never witnessed more striking demonstrations of respect: and yet it is said that three-fourths of Paris believe this man to be a hypocrite.

As soon as he had reached the pulpit, and while preparing himself by silent prayer for the duty he was about to perform, a movement became perceptible at the upper part of the choir; and presently the archbishop and his splendid retinue of clergy were seen moving in a body towards that part of the nave which is immediately in front of the preacher. On arriving at the space reserved for them, each noiselessly dropped into his allotted seat according to his place and dignity, while the whole congregation respectfully stood to watch the ceremony, and seemed to

"Admirer un si bel ordre, et reconnaître l'église."

It is easier to describe to you everything which 35 preceded the sermon, than the sermon itself. This was such a rush of words, such a burst and pouring out of passionate declamation, that even before I had heard enough to judge of the matter, I felt disposed to prejudge the preacher, and to suspect that his discourse would have more of the flourish and furbelow of human rhetoric than of the simplicity of divine truth in it.

His violent action, too, disgusted me exceedingly. The rapid and incessant movement of his hands, sometimes of one, sometimes of both, more resembled that of the wings of a humming-bird than anything else I can remember: but the hum proceeded from the admiring congregation. At every pause he made, and like the claptraps of a bad actor, they were frequent, and evidently faits exprès: a little gentle laudatory murmur ran through the crowd.

I remember reading somewhere of a priest nobly born, and so anxious to keep his flock in their proper place, that they might not come "between the wind and his nobility," that his constant address to them when preaching was, "Canaille Chrétienne!" This was bad—very bad, certainly; but I protest, I doubt if the Abbé Lacordaire's manner of addressing his congregation as "Messieurs" was much less unlike the fitting tone of a Christian pastor. This mundane apostrophe was continually repeated throughout the 36 whole discourse, and, I dare say, had its share in producing the disagreeable effect I experienced from his eloquence. I cannot remember having ever heard a preacher I less liked, reverenced, and admired, than this new Parisian saint. He made very pointed allusions to the reviving state of the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland, and anathematized pretty cordially all such as should oppose it.

In describing the two hours' prologue to the mass, I forgot to mention that many young men—not in the reserved places of the centre aisle, but sitting near us, beguiled the tedious interval by reading. Some of the volumes they held had the appearance of novels from a circulating library, and others were evidently collections of songs, probably less spiritual than spirituels.

The whole exhibition certainly showed me a new page in the history of Paris as it is, and I therefore do not regret the four hours it cost me: but once is enough—I certainly will never go to hear the Abbé Lacordaire again.

La Tour de Nesle.

It is, I believe, nearly two years ago since the very extraordinary drama called "La Tour de Nesle" was sent me to read, as a specimen of the outrageous school of dramatic extravagance which had taken possession of all the theatres in Paris; but I certainly did not expect that it would keep its place as a favourite spectacle with the people of this great and enlightened capital long enough for me to see it, at this distance of time, still played before a very crowded audience.

That this is a national disgrace, is most certain: but the fault is less attributable to the want of good taste, than to the lamentable blunder which permits every species of vice and abomination to be enacted before the eyes of the people, without any restraint or check whatever, under the notion that they are thereby permitted to enjoy a desirable privilege and a noble freedom. Yet in this same country it is illegal to sell a deleterious drug! There is no logic in this. 38

It is however an undeniable fact, as I think I have before stated, that the best class of Parisian society protest against this disgusting license, and avoid—upon principle loudly proclaimed and avowed—either reading or seeing acted these detestable compositions. Thus, though the crowded audiences constantly assembled whenever they are brought forward prove but too clearly that such persons form but a small minority, their opinion is nevertheless sufficient, or ought to be so, to save the country from the disgrace of admitting that such things are good.

We seem to pique ourselves greatly on the superiority of our taste in these matters; but let us pique ourselves rather on our theatrical censorship. Should the clamours and shoutings of misrule lead to the abolition of this salutary restraint, the consequences would, I fear, be such as very soon to rob us of our present privilege of abusing our neighbours on this point.

While things do remain as they are, however, we may, I think, smile a little at such a judgment as Monsieur de Saintfoix passes upon our theatrical compositions, when comparing them to those of France.

"Les actions de nos tragédies," says he, "sont pathétiques et terribles; celles des tragédies angloises sont atroces. On y met sous les yeux du spectateur les objets les plus horribles; un mari qui 39 discourt avec sa femme, qui la caresse et l'étrangle."

Might one not think that the writer of this passage had just arrived from witnessing the famous scene in the "Monomane," only he had mistaken it for English? But he goes on—

"Une fille toute sanglante...." (Triboulet's daughter Blanche, for instance.)—"Après l'avoir violée...."

He then proceeds to reason upon the subject, and justly enough, I think—only we should read England for France, and France for England.

"Il n'est pas douteux que les arts agréables ne réussissent chez un peuple qu'autant qu'ils en prennent le génie, et qu'un auteur dramatique ne sauroit espérer de plaire si les objets et les images qu'il présente ne sont pas analogues au caractère, au naturel, et au goût de la nation: on pourroit donc conclure de la différence des deux théâtres, que l'âme d'un Anglais est sombre, féroce, sanguinaire; et que celle d'un Français est vive, impatiente, emportée, mais généreuse même dans sa haine; idolatrant l'honneur"—(just like Buridan in this same drama of the Tour de Nesle—this popular production of la Jeune France—la France régénérée)—"idolatrant l'honneur, et ne cessant jamais de l'apercevoir, malgré le trouble et toute la violence des passions."

Though it is impossible to read this passage 40 without a smile, at a time when it is so easy for the English to turn the tables against this patriotic author, one must sigh too, while reflecting on the lamentable change which has taken place in the moral feeling of revolutionised France since the period at which it was written.

What would Saintfoix say to the notion that Victor Hugo had "heaved the ground from beneath the feet of Corneille and Racine"? The question, however, is answered by a short sentence in his "Essais Historiques," where he thus expresses himself:—

"Je croirois que la décadence de notre nation seroit prochaine, si les hommes de quarante ans n'y regardoient pas Corneille comme le plus grand génie qui ait jamais été."

If the spirit of the historian were to revisit the earth, and float over the heads of a party of Parisian critics while pronouncing sentence on his favourite author, he might probably return to the shades unharmed, for he would only hear "Rococo! Rococo! Rococo!" uttered as by acclamation; and unskilled to comprehend the new-born eloquence, he would doubtless interpret it as a refrain to express in one pithy word all reverence, admiration, and delight.

But to return to "La Tour de Nesle." The story is taken from a passage in Brantôme's history "des Femmes Galantes," where he says, 41 "qu'une reine de France"—whom however he does not name, but who is said to have been Marguérite de Bourgogne, wife of Louis Dix—"se tenoit là (à la Tour de Nesle) d'ordinaire, laquelle fesant le guet aux passans, et ceux qui lui revenoient et agréoient le plus, de quelque sorte de gens que ce fussent, les fesoit appeler et venir à soy, et après ... les fesoit précipiter du haut de la tour en bas, en l'eau, et les fesoit noyer. Je ne veux pas," he continues, "assurer que cela soit vrai, mais le vulgaire, au moins la plupart de Paris, l'affirme, et n'y a si commun qu'en lui montrant la tour seulement, et en l'interrogeant, que de lui-même ne le die."

This story one might imagine was horrible and disgusting enough; but MM. Gaillardet et * * * * * (it is thus the authors announce themselves) thought otherwise, and accordingly they have introduced her majesty's sisters, the ladies Jeanne and Blanche of Burgundy, who were both likewise married to sons of Philippe-le-Bel, the brothers of Louis Dix, to share her nocturnal orgies. These "imaginative and powerful" scenic historians also, according to the fashion of the day among the theatrical writers of France, add incest to increase the interest of the drama.

This is enough, and too much, as to the plot; and for the execution of it by the authors, I can only say that it is about equal in literary merit 42 to the translations of an Italian opera handed about at the Haymarket. It is in prose—and, to my judgment, very vulgar prose; yet it is not only constantly acted, but I am assured that the sale of it has been prodigiously great, and still continues to be so.

That a fearful and even hateful story, dressed up in all the attractive charm of majestic poetry, and redeemed in some sort by the noble sentiments of the personages brought into the scenes of which it might be the foundation—that a drama so formed might captivate the imagination even while it revolted the feelings, is very possible, very natural, and nowise disgraceful either to the poet, or to those whom his talent may lead captive. The classic tragedies which long served as models to France abound in fables of this description. Alfieri, too, has made use of such, following with a poet's wing the steady onward flight of remorseless destiny, yet still sublime in pathos and in dignity, though appalling in horror. In like manner, the great French dramatists have triumphed by the power of their genius, both over the disgust inspired by these awful classic mysteries, and the unbending strictness of the laws which their antique models enforced for their composition.

If we may herein deem the taste to have been faulty, the grace, the majesty, the unswerving 43 dignity of the tragic march throughout the whole action—the lofty sentiments, the bursts of noble passion, and the fine drapery of stately verse in which the whole was clothed, must nevertheless raise our admiration to a degree that may perhaps almost compete with what we feel for the enchanting wildness and unshackled nature of our native dramas.

But what can we think of those who, having ransacked the pages of history to discover whatever was most revolting to the human soul, should sit down to arrange it in action, detailed at full length, with every hateful circumstance exaggerated and brought out to view for the purpose of tickling the curiosity of his countrymen and countrywomen, and by that means beguiling them into the contemplation of scenes that Virtue would turn from with loathing, and before which Innocence must perish as she gazes? No gleam of goodness throughout the whole for the heart to cling to,—no thought of remorseful penitence,—no spark of noble feeling; nothing but vice,—low, grovelling, brutal vice,—from the moment the curtain rises to display the obscene spectacle, to that which sees it fall between the fictitious infamy on one side, and the real impurity left on the other!

As I looked on upon the hideous scene, and remembered the classic horrors of the Greek tragedians, 44 and of the mighty imitators who have followed them, I could not help thinking that the performance of MM. Gaillardet et * * * * * was exceedingly like that of a monkey mimicking the operations of a man. He gets hold of the same tools, but turns the edges the wrong way; and instead of raising a majestic fabric in honour of human genius, he rolls the materials in mud, begrimes his own paws in the slimy cement, and then claws hold of every unwary passenger who comes within his reach, and bespatters him with the rubbish he has brought together. Such monkeys should be chained, or they will do much mischief.

It is hardly possible that such dramas as the "Tour de Nesle" can be composed with the intention of producing a great tragic effect; which is surely the only reason which can justify bringing sin and misery before the eyes of an audience. There is in almost every human heart a strange love for scenes of terror and of woe. We love to have our sympathies awakened—our deepest feelings roused; we love to study in the magic mirror of the scene what we ourselves might feel did such awful visitations come upon us; and there is an unspeakable interest inspired by looking on, and fancying that were it so with us, we might so act, so feel, so suffer, and so die. But is there 45 in any land a wretch so lost, so vile, as to be capable of feeling sympathy with any sentiment or thought expressed throughout the whole progress of this "Tour de Nesle"? God forbid!

I have heard of poets who have written under the inspiration of brandy and laudanum—the exhalations from which are certainly not likely to form themselves into images of distinctness or beauty; but the inspiration that dictated the "Tour de Nesle" must have been something viler still, though not less powerful. It must, I think, have been the cruel calculation of how many dirty francs might be expressed from the pockets of the idle, by a spectacle new from its depth of atrocity, and attractive from its newness.

But, setting aside for a moment the sin and the scandal of producing on a public stage such a being as the woman to whom MM. Gaillardet et * * * * * have chosen to give the name of Marguérite de Bourgogne, it is an object of some curiosity to examine the literary merits of a piece which, both on the stage and in the study, has been received by so many thousands—perhaps millions—of individuals belonging to "la grande nation" as a work deserving their patronage and support—or at least as deserving their attention and attendance for years; years, too, of hourly progressive intellect—years during which the 46 march of mind has outdone all former marches of human intelligence—years during which Young France has been labouring to throw off her ancient coat of worn-out rococoism, and to clothe herself in new-fledged brightness. During these years she has laid on one shelf her once-venerated Corneille,—on another, her almost worshipped Racine. Molière is named but as a fine antique; and Voltaire himself, spite of his strong claims upon their revolutionary affections, can hardly be forgiven for having said of the two whom Victor Hugo is declared to have overthrown, that "Ces hommes enseignèrent à la nation, à penser, à sentir, à s'exprimer; leurs auditeurs, instruits par eux seuls, devinrent enfin des juges sévères pour eux mêmes qui les avaient éclairés." Let any one whose reason is not totally overthrown by the fever and delirium of innovation read the "Tour de Nesle," and find out if he can any single scene, speech, or phrase deserving the suffrage which Paris has accorded to it. Has the dialogue either dignity, spirit, or truth of nature to recommend it? Is there a single sentiment throughout the five acts with which an honest man can accord? Is there even an approach to grace or beauty in the tableaux? or skill in the arrangement of the scenes? or keeping of character among the demoniacal dramatis personæ which MM. Gaillardet et * * * * * have brought together? 47 or, in short, any one merit to recommend it—except only its superlative defiance of common decency and common sense?

If there be any left among the men of France; I speak not now of her boys, the spoilt grandchildren of the old revolution;—but if there be any left among her men, as I in truth believe there are, who deprecate this eclipse of her literary glory, is it not sad that they should be forced to permit its toleration, for fear they should be sent to Ham for interfering with the liberty of the press?

It is impossible to witness the representation of one of these infamous pieces without perceiving, as you glance your eye around the house, who are its patrons and supporters. At no great distance from us, when we saw the "Tour de Nesle," were three young men who had all of them a most thoroughly "jeunes gens" and republican cast of countenance, and tournure of person and dress. They tossed their heads and snuffed the theatrical air of "la Jeune France," as if they felt that they were, or ought to be, her masters: and it is a positive fact that nothing pre-eminently absurd or offensive was done or said upon the stage, which this trio did not mark with particular admiration and applause.

There was, however, such a saucy look of determination to do what they knew was absurd, 48 that I gave them credit for being aware of the nonsense of what they applauded, from the very fact that they did applaud it.

It is easy enough sometimes to discover "le vrai au travers du ridicule;" and these silly boys were not, I am persuaded, such utter blockheads as they endeavoured to appear. It is a bad and mischievous tone, however; and the affecting a vice where you have it not, is quite as detestable a sort of hypocrisy as any other.

Some thousand years hence perhaps, if any curious collectors of rare copies should contrive among them to preserve specimens of the French dramas of the present day, it may happen that while the times that are gone shall continue to be classed as the Iron, the Golden, the Dark, and the Augustan ages, this day of ours may become familiar in all men's mouths as the Diabolic age,—unless, indeed, some charitable critic shall step forward in our defence, and bestow upon it the gentler appellation of "the Idiot era."

Palais Royal.—Variety of Characters.—Party of English.—Restaurant.—Galerie d'Orléans.—Number of Loungers.—Convenient abundance of Idle Men.—Théâtre du Vaudeville.

Though, as a lady, you may fancy yourself quite beyond the possibility of ever feeling any interest in the Palais Royal, its restaurans, its trinket-shops, ribbon-shops, toy-shops &c. &c. &c. and all the world of misery, mischief, and good cheer which rises étage after étage above them; I must nevertheless indulge in a little gossip respecting it, because few things in Paris—I might, I believe, say nothing—can show an aspect so completely un-English in all ways as this singular region. The palace itself is stately and imposing, though not externally in the very best taste. Corneille, however, says of it,—

"L'univers entier ne peut voir rien d'égal

Au superbe dehors du Palais Cardinal,"

as it was called from having been built and inhabited 50 by the Cardinal de Richelieu. But it is the use made of the space which was originally the Cardinal's garden, which gives the place its present interest.

All the world—men, women and children, gentle and simple, rich and poor,—in short, I suppose every living soul that enters Paris, is taken to look at the Palais Royal. But though many strangers linger there, alas! all too long, there are many others who, according to my notions, do not linger there long enough. The quickest eye cannot catch at one glance, though that glance be in activity during a tour made round the whole enclosure, all the national characteristic, picturesque, and comic groups which float about there incessantly through at least twenty hours of the twenty-four. I know that the Palais Royal is a study which, in its higher walks and profoundest depths, it would be equally difficult, dangerous, and disagreeable to pursue: but with these altitudes and profundities I have nothing to do; there are abundance of objects to be seen there, calculated and intended to meet the eyes of all men, and women too, which may furnish matter for observation, without either diving or climbing in pursuit of knowledge that, after all, would be better lost than found.

But one should have the talent of Hogarth to describe the different groups, with all their varied 51 little episodes of peculiarity, which render the Palais Royal so amusing. These groups are, to be sure, made up only of Parisians, and of the wanderers who visit la belle ville in order to see and be seen in every part of it; yet it is in vain that you would seek elsewhere the same odd selection of human beings that are to be found sans faute in every corner of the Palais Royal.

How it happens I know not, but so it is, that almost every person you meet here furnishes food for speculation. If it be an elegant well-appointed man of fashion, the fancy instantly tracks him to a salon de jeu; and if you are very good-natured, your heart will ache to think how much misery he is likely to carry home with him. If it be a low, skulking, semi-genteel moustache, with large, dark, deep-set eyes rolling about to see whom he can devour, you are as certain that he too is making for a salon, as that a man with a rod and line on his shoulder is going to fish. That pretty soubrette, with her neat heels and smart silk apron, who has evidently a few francs tied up in the corner of the handkerchief which she holds in her hand—do we not know that she is peering through the window of every trinket-shop to see where she can descry the most tempting gold ear-rings, for the purchase of which a quarter's wages are about to be dis-kerchiefed? 52

We must not overlook, and indeed it would not be easy to do so, that well-defined domestic party of our country-folks who have just turned into the superb Galerie d'Orléans. Father, mother, and daughters—how easy to guess their thoughts, and almost their words! The portly father declares that it would make a capital Exchange: he has not yet seen La Bourse. He looks up to its noble height—then steps forward a pace or two, and measures with his eye the space on all sides—then stops, and perhaps says to the stately lady on his arm, (whose eyes meanwhile are wandering amidst shawls, gloves, Cologne bottles, and Sèvres china, first on one side and then on the other,)—"This is not badly built; it is light and lofty—and the width is very considerable for so slight-looking a roof; but what is it compared to Waterloo-bridge!"

Two pretty girls, with bright cheeks, dove-like eyes, and "tresses like the morn," falling in un-numbered ringlets, so as almost to hide their curious yet timid glances, precede the parent pair; but, with pretty well-taught caution, pause when they pause, and step on when they step on. But they can hardly look at anything; for do they not know, though their downcast eyes can hardly be said to see it, that those youths with coal-black hair, favoris and imperials, are spying at them with their lorgnettes? 53

Here too, as at the Tuileries, are little pavilions to supply the insatiable thirst for politics; and here, too, we could distinguish the melancholy champion of the elder branch of the Bourbons, who is at least sure to find the consolation of his faithful "Quotidienne," and the sympathy of "La France." The sour republican stalks up, as usual, to seize upon the "Réformateur;" while the comfortable doctrinaire comes forth from the Café Véry, ruminating on the "Journal des Débats," and the chances of his bargains at Tortoni's or La Bourse.

It was in a walk taken round three sides of the square that we marked the figures I have mentioned, and many more too numerous to record, on a day that we had fixed upon to gratify our curiosity by dining—not at Véry's, or any other far-famed artist's, but tout bonnement at a restaurant of quarante sous par tête. Having made our tour, we mounted au second at numéro—I forget what, but it was where we had been especially recommended to make this coup d'essai. The scene we entered upon, as we followed a long string of persons who preceded us, was as amusing as it was new to us all.

I will not say that I should like to dine three days in the week at the Palais Royal for quarante sous par tête; but I will say, that I should have 54 been very sorry not to have done it once, and moreover, that I heartily hope I may do it again.

The dinner was extremely good, and as varied as our fancy chose to make it, each person having privilege to select three or four plats from a carte that it would take a day to read deliberately. But the dinner was certainly to us the least important part of the business. The novelty of the spectacle, the number of strange-looking people, and the perfect amenity and good-breeding which seemed to reign among them all, made us look about us with a degree of interest and curiosity that almost caused the whole party to forget the ostensible cause of their visit.

There were many English, chiefly gentlemen, and several Germans with their wives and daughters; but the majority of the company was French; and from sundry little circumstances respecting taking the places reserved for them, and different words of intelligence between themselves and the waiters, it was evident that many among them were not chance visitors, but in the daily habit of dining there. What a singular mode of existence is this, and how utterly inconceivable to English feelings!... Yet habit, and perhaps prejudice, apart, it is not difficult to perceive that it has its advantages. In the first place, there is no management in the world, not even that of Mrs. Primrose 55 herself, which could enable a man to dine at home, for the sum of two francs, with the same degree of luxury as to what he eats, that he does at one of these restaurans. Five hundred persons are calculated upon as the daily average of company expected; and forty pounds of ready money in Paris, with the skilful aid of French cooks, will furnish forth a dinner for this number, and leave some profit besides. Add to which, the sale of wine is, I believe, considerable. Some part of the receipts, however, must be withdrawn as interest upon the capital employed. The quantity of plate is very abundant, not only in the apparently unlimited supply of forks and spoons, but in furnishing the multitude of grim-looking silver bowls in which the potage is served.

On the whole, however, I can better understand the possibility of five hundred dinners being furnished daily for two francs each, by one of these innumerable establishments, than I can the marvel of five hundred people being daily found by each of these to eat them. Hundreds of these houses exist in Paris, and all of them are constantly furnished with guests. But this manner of living, so unnatural to us, seems not only natural, but needful to them. They do it all so well—so pleasantly! Imagine for a moment the sort of tone and style such a dining-room would take in London. I do not mean, if limited to the same 56 price, but set it greatly beyond the proportion: let us imagine an establishment where males and females should dine at five shillings a-head—what din, what unsocial, yet vehement clattering, would inevitably ensue!—not to mention the utter improbability that such a place, really and bonâ fide open to the public, should continue a reputable resort for ladies for a week after its doors were open.

But here, everything was as perfectly respectable and well arranged as if each little table had been placed with its separate party in a private room at Mivart's. It is but fair, therefore, that while we hug ourselves, as we are all apt to do, on the refinement which renders the exclusive privacy of our own dining-rooms necessary to our feelings of comfort, we should allow that equal refinement, though of another kind, must exist among those who, when thrown thus promiscuously together, still retain and manifest towards each other the same deference and good-breeding which we require of those whom we admit to our private circle.

At this restaurant, as everywhere else in Paris, we found it easy enough to class our gens. I feel quite sure that we had around us many of the employés du gouvernement actuel—several anciens militaires of Napoleon's—some specimens of the 57 race distinguished by Louis Dix-huit and Charles Dix—and even, if I do not greatly mistake, a few relics of the Convention, and of the unfortunate monarch who was its victim.

But during this hour of rest and enjoyment all differences seem forgotten; and however discordant may be their feelings, two Frenchmen cannot be seated near each other at table, without exchanging numberless civilities, and at last entering into conversation, so well sustained and so animated, that instead of taking them for strangers who had never met before, we, in our stately shyness, would be ready to pronounce that they must be familiar friends.

Whether it be this causant, social temper which makes them prefer thus living in public, or that thus living in public makes them social, I cannot determine to my own satisfaction; but the one is not more remarkable and more totally unlike our own manners than the other, and I really think that no one who has not dined thus in Paris can have any idea how very wide, in some directions, the line of demarcation is between the two countries.

I have on former occasions dined with a party at places of much higher price, where the object was to observe what a very good dinner a very good cook could produce in Paris. But this experiment 58 offered nothing to our observation at all approaching in interest and nationality to the dinner of quarante sous.

In the first place, you are much more likely to meet English than French society at these costly repasts; and in the second, if you do encounter at them a genuine native gourmet of la Grande Nation, he will, upon this occasion, be only doing like ourselves,—that is to say, giving himself un repas exquis, instead of regaling himself at home with his family—

"Sur un lièvre flanqué de deux poulets étiques."

But at the humble restaurant of two francs, you have again a new page of Paris existence to study,—and one which, while it will probably increase your English relish for your English home, will show you no unprofitable picture of the amiable social qualities of France. I think that if we could find a people composed in equal proportions of the two natures, they would be as near to social perfection as it is possible to imagine.