Title: The Secret Service Submarine: A Story of the Present War

Author: Guy Thorne

Release date: August 25, 2012 [eBook #40581]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mark C. Orton, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from scanned images of public domain

material from the Google Print project.)

NEW YORK

SULLY & KLEINTEICH

1915

The verses used as preface appeared in the issue of Truth for 4th November 1914. They are reproduced here by special and courteous permission of the Editor. The verses were published anonymously, but the author has kindly allowed me to mention his name. He is Mr. William Booth.

| IX. | Out in the North Sea. Preparing for Action | 145 |

| X. | The Spear of Foam | 154 |

| XI. | The Submarine Fights for England | 164 |

| XII. | The last Chapter—in two parts— | |

| Doris and Marjorie have a late Visitor | 177 | |

| Return of the Seven Heroes | 184 |

On thinking it over, I date the extraordinary affairs which so thrilled England and brought me such undeserved good fortune from the day on which I tried to enlist.

The position was this. My father was an engineer with a small, but apparently thriving, foundry at Derby. My mother died and my father sent me to Oxford, my younger brother, Bernard Carey, being an officer in the Navy. At Oxford, I was one of that perennial tribe of young asses who play what used to be called the "Giddy Goat" in those days with the greatest aplomb and satisfaction to themselves. I was at a good college—Exeter—for originally we were west-country people, and all sons of Devon and Cornwall go to Exeter.

I was immensely strong and healthy. I did not row, but played Rugby football, being chosen to play in the Freshmen's match, and subsequently got my "Blue." I did no reading whatever. My father gave me a more than sufficient allowance, and in my second year, having sprained myself badly, I bought a motor car—an expensive Rolls-Royce—on credit, and became a "blood." I could not play games any more, though I was healthy enough, so I used to go constantly to London "to see my dentist," which, of course, meant dinner at the Café Royal, too many cocktails at the Empire, and a wild rush home in the car to get to College before twelve o'clock at night.

When any musical comedy company visited Oxford, I, in company with my friends, used to invite the ladies of the chorus to tea. I did all the silly things possible, got sent down for a term, and eventually only just managed to scrape through a pass degree, after being ploughed several times in this or that "Group."

Then my father died, and it was found that he had nothing whatever to leave us. His works were in the hands of his creditors—it seems that things had been going wrong for years—and there was I, with a game leg, an excellent taste in such dubious vintages as the Oxford wine merchants provide, a somewhat exact knowledge of ties, waist-coats, and socks, a smattering of engineering which I had picked up from my father purely from a liking of the subject, and, when my bills were paid, exactly £14, 7s. 3d.

Knowing nothing whatever of the slightest value to anybody, myself included, I naturally decided to devote my attention to the education of youth. My "Blue," short as the time was that I enjoyed it, would be an asset, I imagined; and, for the rest, to teach urchins their Latin grammar for a few hours a day could not be a very arduous occupation.

Accordingly, I went to see a suave gentleman in the Strand, who received me courteously, but without enthusiasm. This gentleman was one of the mediums by which those who would instruct the young find a field for their activities. I paid him a guinea, I think it was, and he then took down my qualifications.

When I mentioned my "Blue" with pride, he shook his head.

"My dear sir, 'Blues' are now a drug in the market," he said. "Surely you read the daily papers, especially the Daily Wire"?

"No," I replied, "I am no bookworm."

He coughed rather nastily and I began to get irritated with the fellow.

"Then I must explain," he continued, "that there has been a great outcry against over-athleticism in the public schools, in all schools, in fact, and I fear your 'Blue' is not worth ..."

"Quite so," I broke in; "'not worth a damn,' you were going to say."

"I was going to say no such thing, Mr. Carey," he replied stiffly. "At any rate, we will do our best for you. You cannot hope for more than a private school at first, and your success in the profession you have—er—chosen, will depend entirely upon your success in a comparatively humble sphere."

A week afterwards, I received two or three little forms telling me to apply to various headmasters.

Prospects were not cheering, and the salaries offered would about have kept me in cigarettes at Oxford. To cut a long story short, I eventually became third master—there were only three of us—in Morstone House School in Norfolk, at a salary of eighty pounds a year and all found—except washing.

Morstone House School was a sort of discreet modern edition of Dotheboys Hall. I do not mean to say, of course, in these enlightened days, that the boys were starved or ill-treated. But everything was cut down to the very margin—to the margarine, as my colleague Lockhart, who was a cripple, and a wit—the Head got him cheap for that—would occasionally remark.

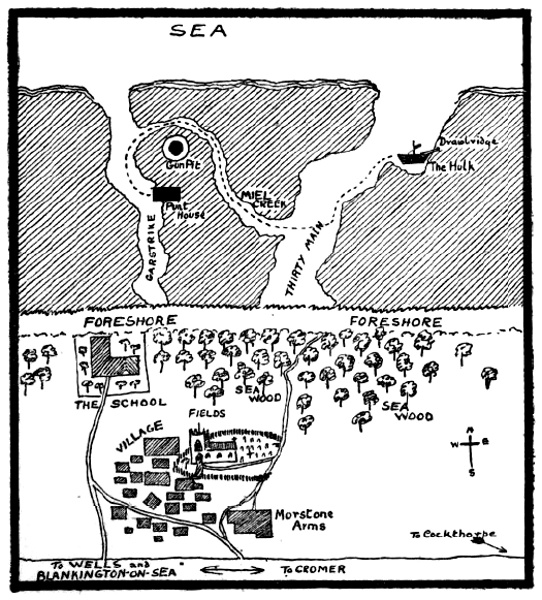

For two years I remained at Morstone, a miserable enough life for an ex-blood, you will say—only there were consolations. One of them, and to me it was a very great one indeed, was that Morstone was situated in a remote village on the east coast, on the edge of vast saltings or sea marshes intersected by great creeks of sullen, tidal water. It was five miles to the nearest little town, Blankington-on-Sea, and as lonely a place as well could be conceived. Nevertheless, these vast marshes stretching for many miles on either side formed one of the finest wild-fowl districts in the whole of England. I was, and always had been, passionately fond of shooting. I had saved my guns from the wreck, and the whole of my leisure time in winter was taken up with perhaps the most fascinating of all sports.

The wild geese would fly at night over the lonely mud-flats with a noise like a pack of hounds in the sky. Duck of all sorts abounded, teal, widgeon, mallard, and the rarer pintail and even the crested grebe. There were plenty of snipe, stint, golden plover and shank—in short, it was a paradise for the sportsman. I kept fit and well from the first day of August to the last day of February. My work at the school was easy enough, and I had an absolutely absorbing pursuit to take me out of myself and make me forget what a very sorry part I was playing in the battle of life—for I think it only due to myself to remark that I was a young ass without being a fool. This is a nice distinction, but there are those who will understand my meaning.

The second consolation—I do not put it second because it was the lesser of the two, but from a somewhat natural reluctance to speak of it until the last necessary moment—was Doris.

This brings me to that extraordinary man, my chief. I am not going to discount the interest of this narrative by saying too much of this gentleman at the outset. His name is familiar enough to England now. I will merely describe him and his surroundings.

The Headmaster of Morstone House School was Doctor Upjelly. His qualifications for the position he held were, to say the least of it, peculiar. He was "Doctor" by virtue of a German degree obtained during what must have been a singularly misspent youth—they are coarse brutes at these German universities, or I should be the last to refer to early indiscretions!—at Heidelberg. Love of teaching he had none. Love of money seemed to be his predominating characteristic, though he was as keen on wild-fowling as I was myself. This was the only thing that made me regard him as human—that is to say, at the beginning.

What Doctor Upjelly's early life had been, nobody knew. He had travelled much abroad, at any rate, and spoke French, German, and Italian fluently. He had been in England for a great many years, the last six of which he had spent at Morstone House. He had purchased the school from the decayed clergyman who ran it before him, and seemed to be perfectly contented with his life, though he often made visits to London and occasionally entertained visitors at Morstone. He had married an Englishwoman in Germany, we always understood, a lady with two daughters by a former marriage, Doris and Marjorie Joyce. Doris was twenty-two and Marjorie twenty-one. They lived at Morstone and kept house for their stepfather, supervised the school accounts, and generally did work which ought to have been done by the matron, a sinister old hag called Mrs. Gaunt, and apparently the only person in whom Doctor Upjelly ever confided.

To say that Doris and Marjorie hated their stepfather would be to put it with extreme mildness. They were both young and high-spirited girls, and they would have left him like a shot had it not been for some promise extorted from them by their dying mother, which they felt bound to observe. This was Mrs. Joyce's only bequest to her daughters, and, like most promises given to a semi-conscious person probably quite unaware of what she is saying, about as cruel and immoral a thing as ever bound quixotic inexperience.

Old Upjelly was a tyrant. He did not interfere in the affairs of the school much—that was to his daughters' and the masters' gain, to say nothing of the wretched boys. But the girls were forced to lead a semi-monastic life. They were not allowed to accept invitations to tennis parties at local rectories, or even to play duets at the nasty little schoolroom concerts which were always being got up by fussy parsons' wives. And most of all, they were not allowed to have anything to do with the assistant masters.

Now, as both Doris and Marjorie, of whom I naturally saw a great deal, confided to me, they had never wished to have anything to do with the assistant masters until my arrival. This did not make me vain, in view of my two other colleagues and of some who had preceded me and of whom I had heard.

The first master, who lived in a cottage in the village with a wife as senile and decrepit as himself, was the Reverend Albert Pugmire. In dim and distant days, he had held various curacies, from which he had been politely requested to retire owing to a somewhat excessive fondness for Old Tom Gin. I understand there had never been any actual inhibition on the part of a justly outraged bishop, but Mr. Pugmire, at any rate, had become chief drudge to Doctor Upjelly.

Pugmire was about sixty-two. In appearance he was exactly like one of those tapers with which one lights the gas, thin, white, ghostly, except for one vivid splash of colour, a nose resembling nothing so much as a piece of coral, which he averred was the result of indigestion. He really was a classical scholar of remarkable attainments. He would even teach a boy who wanted to learn, and once, when the son of a local clergyman with a taste for the classics wormed his way into the horrid old man's confidence, I remember with what a thunderclap of amazement it came upon us all when this young Philips gained an open scholarship at Magdalen. The event was so unprecedented that I saw Doctor Upjelly at a loss for the first time in his life. He did not know what to say, and that night old Pugmire had to be carried home. The affair, however, soon sank into oblivion and was never mentioned.

The second master, who taught such mathematics as each imp condescended to learn, was poor little Lockhart, a misshapen bundle of bones, as hollow and bitter as a dried lemon. When a baby, his nurse, during a heated altercation with the cook, had thrown him at the latter lady, and the poor chap had never known any happiness since. He had an income of his own of about a hundred a year and was able enough in his way, but he was too acid for ordinary intercourse—though, as will presently appear, he had unsuspected qualities.

Then I came, the ex-Blue with the game leg.

Having said so much, it will be fairly obvious that the second consolation I have mentioned in my life was Doris.

The Great War broke out and, in common with every other decent Englishman of my own age, I heard the call of the country. I am not going to sentimentalise about this—there is no necessity—but, of course, I was keen as mustard to go.

I was exactly six feet high; my eyesight was far above the average—the man who does most of his shooting at twilight, by moonlight, or in early dawn and at long ranges, has far keener sight than most men. My teeth were so good that I could eat Upjelly's mutton with ease, if not with satisfaction. As far as personal strength went, I was as strong as a bull—indeed, if the music halls had remained in their pristine simplicity and had not been given over to the elaborate spectacle, I could have earned a living as a weight-lifter in a leopard skin and pink tights; but, and here was the thing that made me lie awake at night grinding my teeth and cursing fate—not knowing what she had in store for me—there was my leg.

Now, I could walk and outwalk most men I knew on the marshes, the most difficult form of progression probably known to man, as anyone who has tramped the thick, black mud and the marrum grass well knows. No professional wild-fowler from Stiffkey or Cockthorpe could outdo me. Yet, when I went to Norwich and offered myself for the East Norfolk Territorial Battalion, a fool of a doctor in goggles, with whom I wouldn't have cleaned my ten-bore, rejected me at once, despite all I could say or do—and, what is more, told me that I would have no possible chance elsewhere. I told him what I thought of him, and nearly cried. Then I went out into an adjacent pub, had some beer, and cursed bitterly, until the recruiting sergeant whom I had first interviewed, likewise in search of beer, happened to come into the private bar. He was a decent sort of johnny and told me a few eye-opening things about doctors. He said that he would be proud to have me in his company, and he gave me an invaluable tip. Finding out that I knew something about engineering, he suggested that I should go to London and try and get into the Royal Naval Flying Corps. At that time, the great fleet of armoured motor cars was being got ready. I could drive a car with any man and I was a fairly good motor mechanic.

My brother, Bernard, was, as I said, in the Navy. He was, by this time, Lieutenant-Commander in the submarine section, and he was in London, having been shot in the arm during a little scrap off Heligoland.

I got leave from old Upjelly, who, for some queer reason or other, did not seem to take to the idea of my enlisting—though, heaven knows, he had never shown any appreciation of my services—and went up to town. I found Bernard just out of hospital. He had to rest for another month, and, as he had hardly any money beyond his pay and special allowances, he wanted to do it on the cheap. I suggested that he should come down to Morstone and stay in the village pub. He was as keen on shooting as I, and he hailed the idea with joy.

He took me to the then depôt of the R.N.F.C., at the big Daily Mail air-ship shed at Wormwood Scrubbs, and he used every possible bit of influence he had got to get me in.

The naval people were all awfully jolly, but regulations were strict, and though they moved heaven and earth for me, it could not be done.

I said good-bye to my brother, who was to come down to Morstone almost immediately, and one dull, bitter afternoon in the middle of December, I found myself in a third-class carriage going home—once more a hopeless failure.

I could see old Upjelly's mocking sneer, I could hear little Lockhart's titter; old Pugmire would say, "A gin and soda is clearly indicated in this crisis." And Doris—what would Doris say?

Well, Doris, poor Doris, would weep. She would know it was not my fault, dear little girl, but she would weep. And for many days I should read my newspaper, which arrived in the evening, over the fire in my sitting-room in the north wing at the end of the dormitory, and if I did not weep too, it would be because I was a man and not a girl. Other people would be doing glorious things. Two-thirds of the men of my own college were already either at the front or in training. Some smug, who could not get into the second fifteen at Exeter, would become D.S.O. or V.C. Morstone would be full of farm lads, who had gone out louts and come back wounded heroes. And for me, only what some priggish hymn or other describes as "the daily round, the common task," how damnably common, only I myself knew.

The afternoon, as I have said, was dark and lowering, and as I changed at Heacham for the local train, a bitter wind, which cut like a knife, swept over the vast flats, straight from Heligoland, the Kiel Canal, and the tossing wastes of the North Sea.

We crawled along slowly, stopping at half a dozen stations, until, with a groan, the train drew up in the God-forsaken little terminus of Blankington-on-Sea. The sea was two miles away over the mud flats, and Blankington consisted of an enormous church, five maltsters' yards, a few fly-blown shops, and seventeen public-houses, where the townspeople and labourers on the weekly market day defied the marsh fogs with ardent spirits.

Wordingham, the husband of the woman who kept the Morstone Inn, was waiting with his dog-cart. I hoisted in my kit-bag and jumped up beside him and we started off. It was pitch dark, and we had five miles to go along a level road.

On the right were huge fields of barley stubble, all in the great shoot of the Earl of Blankington, whose yearly head of "birds," as partridges are called in Norfolk, to say nothing of pheasants, was second only to that of Sandringham itself, not so very far away. To the left were a few more fields where some plovers wailed mysteriously, "it's dark and late," or "it's late and dark," and beyond, the vast creeks and saltings towards the ocean. Even as we got out of the little town, I heard the great boom of a double ten-bore far away. Well, I could at least go back to my wild-fowling, and Wordingham told me that the geese were working backwards and forwards in skeins of at least a hundred, right over the Morstone miels.

We bowled along through the night, and I turned up the collar of my thick ulster, for it was bitterly cold.

"Well," I said, "any news, Wordingham?"

Wordingham was a big, strong, nut-brown, silent man, who took time before he spoke. At last he did so, but without replying to my question.

"My missus," he said slowly, "has got the parlour behind the bar ready for your brother, sir. It is a snug, ship-shape little place, and we will do our best to make him comfortable. And if you and I can't show the Captain a bit of sport, well, there's no one in this part of the country who can."

"Good," I said. "My brother has still got a month to get thoroughly fit before he goes back to join the North Sea Squadron. I want him to have as much shooting as possible."

Wordingham nodded and flicked up his horse. He was a well-known wild-fowler in East Norfolk and, if report spoke true, a very skilful poacher too. The marshes were free to everyone, right up to where the sea came on rare spring tides. Wordingham had an excellent mahogany punt, with a long, black-powder gun, and he would often get as many as thirty brace of duck at a single shot after hours of cautious water-stalking.

But, apart from the wild birds of the saltings, Morstone was in the very heart of one of the most famous shoots in England. The villagers were poachers to a man, and it was well known that fast motor cars often made sudden appearances at night, whereby the poulterers of Leadenhall Market were greatly enriched next morning. Many and many were the "old things" that found their way into the capacious side-pockets of my friend—"old thing" being the local name for hare, a word which is never spoken aloud in a Norfolk village by those who find it "their delight of a moonlight night," &c. &c.

I thought none the worse of Sam Wordingham for that. I had no big shoot and no expensive machinery of game-keepers and night-watchers to keep up. I, myself, was a bit of an Ishmael, to say nothing of a lover of sport.

"I am sure we can do my brother very well," I said. "It is a fine fowling year with all this cold, and there are a lot of worthy fowl about, as many as I have ever seen. But has there been no news in the village since I left?"

"You will be surprised to hear as the Doctor himself dropped in to the private bar yesterday evening."

"Doctor Upjelly?"

Sam nodded. "It was about nine o'clock. Mr. Pugmire was settin' by the fire, not to say boozed, but as is usual about nine o'clock. 'Muzzy' is how I put it. Thinks I, 'Here's the Doctor come after Mr. Pugmire,' though I never knew such a thing in all these years before, and everyone knows Mr. Pugmire's little failings, the Doctor included."

"Was it that?"

"No, it weren't," and Sam turned his big, brown face toward me.

I knew Sam. Many and many a midnight had we spent together waiting for flighting time. I forbore in anticipation.

"'E sets himself down and 'e calls for a bottle of strong, old ale—fowlers' tipple. 'E nods quite pleasant to Mr. Pugmire, what was looking at him like a cat looks when you catch it stealin' cream. 'Pugmire,' says he, 'you will join me in a little refreshment?' But the old gentleman, he was too scairt, and 'e mumbles something and shuffles off 'ome—and I'll lay that's the first time Mr. Pugmire has been 'ome partly sober this year. Then the Doctor, he makes 'imself very pleasant, 'e does. My missus comes in and he begins asking about—what do you think 'e arst about, sir?"

"I haven't an idea."

"About the Captain, about your brother."

I was startled. I hadn't told the Doctor that my brother was coming to stay in the village—it was no business of his, and we had few confidences on any subject. Lockhart knew and, of course, Doris and her sister, but they were not likely to have said anything.

"What did he want to know?" I asked.

"Where he was sleeping, and if we were going to make the gentleman comfortable, and if he had a taste for shooting, had I heard? Regular lot of questions!"

"Well, it's very kind of the Doctor to take an interest in my brother," I replied.

"Very, sir," Wordingham answered dryly. "Mr. Jones, he came down last night at ten o'clock, came down from London in his motor car, 'e did. He's at the school now, or leastways, with this tide and the moon getting up in an hour or so, he will be out on the marshes with the Doctor. I heard tell that they was to be out all night. Bill Jack Pearson, from the school, 'e told me."

Again there was silence, while I thought over this little bit of information, for anything is news in such a stagnant hole as Morstone. Mr. Jones was a friend of the Doctor's who often came to see him. He was a short, sturdy, red-faced man with bright blue eyes and a very reserved manner. We always understood that he was in business in the city, and well-to-do. Like the Doctor, he had a passion for wild-fowling, or that, at any rate, was supposed to be the reason for his visits, though Doris had more than once hinted to me that she thought Marjorie, her younger sister, was a bit of an attraction too.

"Ever been out with Mr. Jones, sir?" Wordingham asked.

"Not I. Why, I've only been out with the Doctor once in all the time I've been at Morstone. He seems to prefer to be alone."

"Aye, he's a solitary man, is the Doctor. On that time you went out with him, did you get anything, sir?"

"I got a couple of brent geese, but the Doctor was not in form at all and missed his one chance when they came over."

"Now, would you be surprised, sir, if I was to tell you that the Doctor is one of the worst shots in the parish?"

"I should be very surprised indeed. Why? He gets awfully good bags night after night—whenever he goes out, in fact."

"You know Jim Long up at Cockthorpe?"—he was mentioning a famous professional wild-fowler who lived by supplying the markets with duck and taking out sportsmen from London over the difficult and intricate marshes at night.

"Of course I do. Been out with him lots of times."

"Well, sir, don't say as I told you, don't mention it to Jim and don't mention it to a living soul, but I found out only last month, accidental like, that Jim's been supplying the Doctor with teal and widgeon and grey geese and plover and what not for goodness knows 'ow long. 'E leaves a nice little bag in the Doctor's old hulk in Thirty Main Creek, and the Doctor finds 'em there and brings 'em home. And, what's more, Mr. Jones, 'e can't shoot for nuts, neither. I've see'd 'im firing off their guns, to get 'em dirty, from the deck of the hulk!"

At this I began to laugh, though the news was a bit of a shock to me, for I had always regarded the Doctor and his friend as true sportsmen. I saw no reason to disbelieve what Wordingham had said, for he was not a man who spoke rashly, and, comic though the business was, I could not help that sort of odd discomfort one feels when an illusion is shattered. The only good thing I knew of Upjelly was now a thing of the past. Of course, I had heard of the type of sportsman who buys a creel of trout at the fishmonger's on his way home, or gets his pheasants at the poulterer's—about the cheapest and nastiest form of vanity that exists, I should think. But I had never heard of anything of the sort in connection with wild-fowling; and indeed, a man who, night after night, will go through the extraordinary discomforts, the freezing cold, the occasional real danger, the weary hours of waiting in the dark, merely to get a reputation as a fowler, must be king and skipper of all the humbugs and pretenders since Mr. Pecksniff himself.

I had little more conversation with Sam, his news occupied all my thoughts and for a time I forgot my own troubles. I remember thinking, in a childish sort of way, what a rag it would be to stalk old Upjelly one night, and catch him in the very act. What a hold I should have over him afterwards!

We approached the village. The wind cried in the chimneys of the houses with a strange, wailing note. The moon just peeped out behind the gaunt church tower, amid the scud of ghostly clouds, and its light grew brighter as we turned to the left towards the school itself. At the same moment, the wind, smelling salt of the marshes and of the open sea a mile beyond, and carrying particles of sand, struck me with its full force, so that I had to bow my head.

In three minutes we were at Morstone House School. It was a long, low building of considerable extent, shaped like the letter L. The shorter arm was three storeys high and was the Doctor's own quarters, together with his cook, housemaid, and the old matron, Mrs. Gaunt. The longer wing contained the schoolrooms on the ground floor, a bare apartment known as the dining-hall, and two dormitories in each of which there were about fifteen boys, the whole school consisting of some fifty boys, thirty of whom were boarders. This part of the building was only two storeys high, save at one end, where there was a small tower. Just outside each dormitory was a master's sitting-room and bedroom. One of these was mine—the top one—the other, down below, that of Lockhart.

There were three main entrances to the school. One, the front door, in the middle of the longer portion of the building, another, a small door in the angle, used only by the masters, and the Doctor's private entrance, opening out into his garden on the other side of the block.

It was just ten o'clock as I drove through the playing fields and on to the gravel sweep in front of the house. Bill Jack Pearson, the school porter, opened the masters' door and took my bag. He was a pleasant, cheery fellow, who liked me.

"Well, Bill Jack," I said, "everything all right?"

"Everything all right, Mr. Carey. The Doctor and Mr. Jones, who came last night, have gone out towards Cockthorpe. The geese are working there, and they won't be back till dawn. There's some supper in your room, and I've lit the fire."

Then I asked a question which the porter quite understood.

"And Mrs. Gaunt?"

"The old cat's gone to bed, sir," he said in a lower voice. "I've just come from the Doctor's kitchen, and Cook told me."

I passed through the little paved lobby which led to the long corridor of class-rooms, and hurried up the bare, wooden stairs. There was a good fire in my room and the lamp was lit upon the supper-table, where a jug of beer flanked a cold wild goose—and ordinary mortals who have not tasted that delicacy have missed a lot.

I took off my coat, went into my bedroom and washed my hands, peeped into the dormitory, where only a single lamp was burning dimly and all the boys seemed asleep, and then returned.

As I closed the door and saw my own familiar things around me, the remembrance of what had happened came over me in a great flood. I groaned aloud. Upon the walls, washed with terra-cotta, were my college groups, reminding me of Oxford and happier days. There were some silver cups upon a shelf. In a glass-fronted cupboard by the side of the fireplace were my guns. Over the mirror on the mantelpiece was a faded blue cap, and on the writing-table was a pile of filthy, dogs-eared, little exercise books, in which reluctant urchins had been scribbling attempts at Latin prose.

I bit my lip hard and sat down to supper, which did not take more than five or six minutes. Then I prepared myself for something that was yet to come.

Against the wall by the window was a bookshelf containing the few volumes I possessed and such schoolbooks as I used in my work. I took down Smith's classical dictionary, and Liddell and Scott's Greek ditto, and, inserting my hand in the place this left, withdrew a pleasant little instrument which I had bought for twenty-seven-and-six—see advertisement in the Strand Magazine—from a scientific toy-shop in Holborn. This was known as "Our Portable House Telephone," and, not to elaborate the mystery, a little wire ran out of my window, through the ivy, and round the angle of the building to the Doctor's block, where it found unobtrusive entry through another window. At this end was an instrument exactly like the one I held in my hand, but which rested in a hole made in the plaster of the wall and was concealed by that touching engraving, "The Soul's Awakening." I had fixed up the whole thing myself some two months before, when the Doctor was away in London, Mrs. Gaunt at market in Blankington-on-Sea, and the boys engaged in a paper chase.

Doris was waiting, of course.

"Dearest, so you've got back—I heard the trap!"

"Yes; can you come?"

"In a minute. The connecting door to the school is locked, but I made Bill Jack lend me his key."

"Right-O!"—and I waited breathlessly for Doris.

I daresay such a proceeding as this may strike the ultra-proper with dismay. But we loved each other, there was no harm in it, and, besides, what the deuce were we to do? It was the only way we could meet at all, and even then, it only happened now and again.

The door of my sitting-room opened without a sound and Doris entered. Doris's hair is dark red, and, when it is down, it reaches almost to her heels. Titian red, I believe, is the right name for it, though I'm sure I don't know why. Her eyes are dark blue, like the blue on the wing of a freshly killed mallard—I am not good at this sort of thing, but she is a ripper. Directly she had closed the door, which she did noiselessly, she saw from my face what had happened. I felt a rotten tout, I can tell you, to stand there, chucked again.

"Well, here I am," I said, "returned empty, declined with thanks, His Majesty having no use for my services! Same old game, Doris dear, and if they lose the war now, they can't blame me!" I spoke bitterly, but lightly also; yet when Doris put her arms round my neck and I held her close, when I could feel warm tears upon my cheek, I was as near breaking down as I have ever been in my life.

"Never mind, Johnny darling, never mind," she whispered, "I love you just the same—you've always got me—and it isn't your fault. You've tried as hard as you possibly can to go."

She could only stay a quarter of an hour; it wasn't safe longer. Marjorie was keeping cave, for the sisters occupied the same room. I told her everything as shortly as I could, and with a sigh, we both agreed that we must make the best of it. She wanted me to go, she longed for me to go, I knew that. What patriotism there was in Morstone House School was confined to the boys and to the Doctor's stepdaughters. Upjelly himself seemed to take very little interest in the conflagration of the world, or, if he did, he never showed it. But I knew as well as I knew anything that Doris would rather have had me go to the Front and get a bullet through my head than that I should stay at home; which, I may remark, is the right sort of girl.

"Well," she said at length, "let us hope the Germans invade us—it will be somewhere about here, I suppose, if they do—and then you can have a smack at them with your single eight-bore, Johnny; that would be something, wouldn't it?"

She told me the news of the school, such as it was, and then, with a final kiss, we separated and I was left alone.

The bitterness was still in my heart, a deep sort of fire at the bottom of everything which I can't put into words—like the gentlemen in the boys' historical novels, who always begin: "I am but a plain, unlettered yeoman, and more handy with the sword than with the pen"—you know what I mean. Still, I was a man and a strong one, and an Englishman whose brother was fighting for his King. I did not know before that life could hurt so badly as it was hurting now. For nearly an hour, I suppose, I walked up and down my room, until the fire grew low and the wailing of the wind outside seemed to speak of disaster and complete the innuendo of the time.

And then, quite suddenly, I do not know what it was, my spirits began to clear. It was like a thick sea-mist on the marshes, which hangs like a dull, grey blanket for hours, with the birds calling all round, only you cannot get a shot at them. Suddenly the sun, or a puff of wind, makes the whole thing roll up like a curtain, and you see a herd of curlew or a wisp of snipe quite close to you. That is how I felt. I caught sight of my face in the glass, and I was surprised. It was positively glowing—just as if I had been made Commander-in-Chief of the R.N.F.C. and Admiral Jellicoe had asked me to come and have a drink.

I am not used to analysing my feelings, which seem to me like chemicals—the more you analyse them, the worse they smell; so I could not account in the least for this sudden change.

Well, I was wondering at it and thinking that I had better turn in before I got the black dog on my shoulders again, when there was a tap at the door, and in shuffled little Lockhart. He had a bottle of whisky under one arm and a syphon under the other, and he looked, as usual, like a plucked spring chicken that had not been properly fed—bones sticking out everywhere.

"Thought perhaps you hadn't any whisky," he said—and then, "Hallo! pulled it off this time?" He was looking at my face.

I started, because there was something in his voice I had not heard before, and something in his eyes I had not seen.

"My dear chap," he went on, banging down the whisky on the table and holding out his hand. "I can't tell you how glad I am!"

Well, this made it rather hard. Of course, I had to tell him that I had got the kick out again, but I didn't feel the depression coming back, all the same. What I did feel, though, was a sudden liking for the odd little fellow who was my colleague. We had always got on well enough together, never had rows or anything of that sort, but he was too cynical for me as a rule. In five minutes, however, I found myself sitting on one side of the fire—which we made up—with Lockhart on the other, talking away as if we had been intimate friends for years.

By Jove, how the little fellow came out! If his body was maimed and crippled, he had a big soul, if ever a man had. I can recognise beautiful English when I hear it or read it. This man seemed inspired. His talk of England and what we were going through and of what we still had to go through was like that wonderful passage in Richard II which I had been trying to make my idiot boys learn for rep. He was so awfully kind and sympathetic, too. He said all that Doris had said, though in quite another way. It was like a wise man, who had known and done everything, comforting one.

When he had finished, and sat looking at the fire, I had to tell him what I felt.

"I'm awfully indebted to you, Lockhart," was what I said. "You've pulled me together and made a man of me again, and I can't thank you enough. I'm afraid we haven't been such friends as we ought to have been"—and I held out my hand. He took it and there was a strained smile upon his wizened little face.

"Carey," he said, "don't you be downhearted, for you are going to have your chance yet, unless I am very much mistaken."

"What do you mean?" I asked, for there was obviously something behind his words.

For answer, he did a curious thing. He slipped out of his arm-chair, hopped across the room like a sparrow, and as quietly, and opened the door, looking into the passage. Then he closed it and came back into the middle of the room.

"In the first place, John Carey," he said, "I mean that there is something very wrong about this house."

I had just finished my tub the next morning, and was about to shave, when there was a knock at my bedroom door. The school porter came in with a message—"the Doctor sends his compliments, sir, and will you give him the pleasure of your company at breakfast this morning?"

This was quite unusual on the part of my chief. He always breakfasted alone in his own house; even his daughters did not share the meal with him. Lockhart and myself breakfasted with the boys—that is to say, we sat at a table at one end of the room, while old Mrs. Gaunt, the matron, presided over the bread-and-scrape and the urn of wishy-washy tea which was all the boarders got, unless they provided delicacies for themselves.

About half-past eight, I went downstairs, round the rectangular wing, into the Doctor's garden, and knocked at his front door. I was almost immediately shown into the breakfast-room, a comfortable place, with a good many books and a fine view over the marshes.

Old Upjelly was standing upon the hearthrug as I entered, and I must describe for you a very remarkable personality indeed.

The Doctor was six feet high and proportionately broad. He was not only broad from shoulder to shoulder, but thick in the chest, a big, powerful man of fifty years of age. His face was enormous, as big as a ham almost, and it was of a uniform pallor, rather like badly-cooked tripe, as I once heard Lockhart describe it. A parrot-like nose projected in the centre of this fleshy expanse; small, but very bright eyes, sunk in caverns of flesh, looked out under bushy, black brows which squirted out—there is no other word. He was clean-shaved and his mouth was large, firm and curiously watchful, if I may so express it. Upjelly could make his eyes say anything he pleased, but I have always thought that the mouth is the feature in the human face which tells more than any other. And if Upjelly's mouth revealed anything, it was secretiveness, while there was a curious Chinese insensitiveness about it. Lockhart, who had rather a genius for description, used to say that he could conceive Doctor Upjelly locking himself up in his study and sitting down to spend a quiet and solitary afternoon torturing a cat.

He greeted me with his soft, rather guttural voice and with something meant for an expansive smile.

"Ah, here we are," he said, "and tell me at once, Mr. Carey, if you have been successful in your application."

Of course, I was quite prepared for this question and briefly related the facts of the case, explaining that even my brother's influence had failed to secure my entry into the Royal Naval Flying Corps.

"I am truly sorry," he said, with the unctuous manner he reserved for parents, "truly sorry; but you must remember, Mr. Carey, that 'they also serve who only stand and wait.'" And as he said it, or was it my fancy, there came a curious gleam into those little bits of glistening black glass he called his eyes.

A minute or two afterwards, and just as the maid was bringing in various hot dishes, the door opened and Mr. Jones entered.

I had been introduced to Mr. Jones some months before, though neither he nor Upjelly had ever invited me to shoot with them. I had only met him for a few minutes and had never formed a very definite opinion about him one way or the other.

He shook hands with me kindly enough, and I noticed how extremely firm and capable his grip was. It was not at all the sort of grip one would expect from the ordinary city man, though, of course, nowadays everybody plays golf or does something of the kind, even in business circles.

Mr. Jones' face was clean-shaved, too, and rather pleasant than otherwise, though it was somewhat heavy. His eyes were bright blue, his hair, thinning a little at the top, a light yellowish colour. He walked with a slight roll or, shall I say swagger?—I really hardly know how to describe it—which somehow or other seemed reminiscent, and he spoke almost pedantically good English. When I say good English, I mean to say that he chose his words with more care than most Englishmen do—almost as if he were writing it down.

We sat down to breakfast, and I saw at once that neither Doris nor her sister were to be there. The meal was elaborate; I had no idea Upjelly did himself in such style, for except at Oxford or Cambridge, or in big country houses, breakfast is not generally a very complicated affair in an ordinary English family. The coffee was excellent—there was no tea—and there was a succession of hot dishes. I noticed, however, that Mr. Jones took nothing but coffee, French rolls—I suppose the Doctor's cook knew how to make them—and a little butter. And I noticed also that, after all, he could not be of very great importance or good breeding, because he tucked his table-napkin into his collar round his chin, an odd proceeding enough!

We began about the war, of course. Upjelly asked me my impressions of London, and was most interested when I told him of all I had seen going on at the R.N.F.C. Depôt at Wormwood Scrubbs, especially about the great Rolls-Royce cars and the guns they were mounting on them. I never thought the man took such an interest in anything outside his food and his shooting—if indeed he took an interest even in shooting, which Wordingham's story of last night led me to doubt.

Somehow or other, I was convinced that Upjelly did not care either way about my failure to enlist. He said the conventional things, but I knew he was inwardly indifferent. It was not the same with Mr. Jones, whom I began to like. He seemed genuinely sorry.

"I can understand, Mr. Carey," he said, "that you have been extremely disappointed. I can sympathise with you most thoroughly. It is the duty and the privilege of every man who is capable of bearing arms to fight for the Fatherland which has given him birth."

Of course, this was a bit highfalutin, but he meant well.

"Thank you," I said, "it certainly has been pretty rotten, but perhaps I may get something to do yet. I would give anything just to have one go at those swines of Germans! You saw what they did yesterday at the little village of Oostcamp, in Belgium?"

"We must not believe all we read in the papers, Mr. Carey," Upjelly said, wagging his head and piling his plate with ham—the beast ate butter with his ham!

"I know," I replied; "of course, it is not all true, but there have been enough atrocities absolutely proved to show what utter soulless beasts the Germans are. It is a pity that we are not at war with a nation of gentlemen, like the French, if we have to be at war at all!"

The Doctor flushed a little. I suppose he thought I was too outspoken. "I have lived much in Germany in my youth," he said, "and always found them most hospitable and kind. You must not condemn a nation for the deeds of a few."

"Well, you may have been in Germany," I thought, "but you can't explain away Louvain, for instance, or lots of other places!"

Still, it was not my place to shove my oar in too much, and I turned to Jones.

"What do you think, Mr. Jones?" I asked.

He hesitated for two or three seconds, as if he was trying to make up his mind. "No one deplores certain incidents in Belgium more than I do," he said at length, "but we must hope that, as Doctor Upjelly says, there is a brighter side to the picture. You must remember that even a German probably loves his country just as much as an Englishman."

Well, of course I knew that was all rot. I had never been in Germany, but people who let a chap like the Kaiser rule them and who live on sausages and beer about as interesting as ditchwater, must be thorough blighters! However, I changed the subject.

"Now, the Navy," I said, "from all accounts, are quite a decent lot of chaps. What a sportsman von Müller was till we bagged the Emden. He behaved like a white man all through, and we let him keep his sword, which I think we were quite right in doing."

Mr. Jones smiled suddenly, revealing a row of very white and even teeth. "You," he began, "I mean we, are an arrogant people, we English!" and he chuckled as if he were amused at what I had said. "I quite agree with you, however," he went on, "that the German naval officer is a fine fellow. Your brother, by the way, is in our Navy, isn't he?"

"Yes," I said; "he was wounded in a little affair off Heligoland the other day. But he is getting fit now. Oh, by the way, Doctor, he is coming down here to get some shooting. He is going to stay at the Morstone Arms."

"So I heard," Upjelly answered—the old fox, I thought I was going to catch him out!—"I went in there last night, a thing I don't often do, in order to see if I could find old Mr. Pugmire, and I heard from Mrs. Wordingham. I shall hope to have the pleasure of making his acquaintance when I return."

"You are going away, Doctor?"

"Yes. That was one of the things I wanted to see you about. Mr. Jones is very kindly going to drive me up to town in his car this morning, and I shall be away for a couple of days. I want to leave you in charge as my representative."

"But Lockhart——" I began.

"Mr. Lockhart is not quite as capable of keeping discipline in the school as you are, Carey."

"Thank you very much, sir," I replied; "I will do my best."

The meal continued and we all got on very well. Upjelly seemed really interested in my brother and, after a cigarette, when I rose to go into school, both he and Jones shook me very cordially by the hand.

As I was leaving the room, I noticed one curious thing. There was a little writing-table by the door and on it I distinctly saw the Navy List for that month, obviously fresh from London. What old Upjelly could want with a Navy List, a book which, of course, I had upstairs, I could not conceive, and it gave me food for thought, especially in view of what I shall have to relate very shortly.

At the eleven o'clock break, when the boys had come out and were punting about a soccer ball in front of the school, I saw Mr. Jones' big green car, with himself at the wheel and the Doctor by his side, come round the house and start off for London.

I felt as if a great oppression was removed. My brother would arrive that afternoon; Upjelly was out of the way; I was in charge of the whole place. It would be hard if I did not see more of Doris than I had been able to do for months past.

We went into school again. I was taking what, in a pitiful attempt at persuading ourselves we were a public school, we called the Sixth Form, in Virgil. My boys, there were about ten of them, were a pleasant enough set of lads, ranging from fifteen to the two eldest boys, both of whom were seventeen. They were twins, Dickson max. and Dickson major, the sons of a poor clergyman near Norwich, who could not afford to send them to a better school. They had tried for entrance scholarships at Repton and at Denstone, but had failed, and at all that concerns books or learning were rather duffers. Yet they were clever boys in their way, good sportsmen and, despite a perfectly abnormal talent for mischief, could be depended on in the main. I liked them both and I was sorry for them. Their one hope was that the war would last long enough for them to enlist, for their father was too poor even to pay the necessary expenses to send them into the Public Schools Corps, where lads of such physique and cheery manners could have been sure of a welcome.

"Per varios casus, per tot discrimina rerum," droned out Dickson max., in painful endeavour to bury a dead language in the very stiff clay of his mind. "Through various causes ..."

"Now how can you say 'causes,' Dickson? You know perfectly well what it is that Aeneas is saying. He is exhorting his followers to press towards Rome against all sorts of bad luck. 'Casus' should have been translated 'chances.' 'Per tot discrimina rerum' is, of course, 'through so many changes of fortune.' Imagine Aeneas is Sir John French, pressing onwards to Berlin."

It was fatal; that gave the signal.

"Sir," said Dickson major instantly, "did you see any of the Royal Naval Flying Corps in London?"

Dickson max. put down his Virgil. "Is it true, sir, that they have got a hundred armoured motor cars, each one with a maxim gun on it?"—questions from eager faces were fired at me from all parts of the room.

I trust I am no precisian, as the people in Stevenson's stories are always saying, and I confess that, for the next quarter of an hour I held forth in an animated fashion about all that I had seen and done in London. After all, it is the duty of a schoolmaster to encourage patriotism, isn't it? I was just describing some of the new aerial guns that we are mounting on some of the principal London buildings for the defence of the city against Zeppelins, when there was a most appalling crash and howl outside in the corridor.

There was dead silence for an instant, then I jumped down from my desk and rushed out. An unpleasant, almost a terrifying spectacle met my eyes. Old Mrs. Gaunt, the matron, was rolling upon the flags of the corridor like a wounded ostrich, yelping, there is really no other word for it, as if in agony. Her face was pale as linen and her mouth was twisted. She was obviously in great pain.

"Whatever has happened?" I said, trying to help her, but as I lifted the old thing by the shoulder she shrieked loudly and I had to lay her down again.

"My leg's broken!" she cried, "my leg's broken! One of those filthy boys left his ball about, and I trod on it"—and indeed I saw, a few yards away, the white fives ball which had been the cause of her disaster.

The porter was summoned, we improvised an ambulance somehow, and took the poor old thing to her room in the Doctor's wing, Doris and Marjorie attending to her, while the porter rushed off on his bicycle for the nearest doctor.

In about an hour the doctor came. It was perfectly true, Mrs. Gaunt had broken her leg. It was a simple fracture and, as the Doctor told me afterwards, the woman was as tough as an old turkey, but she would be confined to her bed for a fortnight at least, and the injured limb was already encased in plaster of Paris.

It was strictly against the rules for any boy to leave a fives ball about. An accident had nearly happened once before for the same reason. At lunch, I conducted a stern inquisition as to the culprit's identity. It was Dickson max., who owned up at once, and I told him to come to my room after the meal.

I could not very well cane a boy of seventeen who would have been at Sandhurst if his people could have afforded. Besides, I was too inwardly grateful to him to have the slightest wish to do anything of the sort. I gave him a thousand Latin lines and told him to stay in that afternoon, which was a half-holiday, and on three subsequent halves, and I am sorry to say that he grinned in my face as I did so. It was not an impudent grin, or I should have known how to deal with it, but it was one of perfect comprehension, and I fear I blushed as I told the young beggar to clear out as quickly as possible.

Certainly the fates were working well for me, though I had, even then, not the least idea of what an eventful day this was to prove. Nothing came to tell me that I was already embarked upon the greatest enterprise of my life. I was to know more before night.

Now one of my most cherished possessions at that time was a motor bicycle. It was of an antiquated pattern and more often in the workshop than on the road. Fortunately, such engineering knowledge as I had enabled me to tinker at it for myself. To-day, though it had recently been running with a most horrid cacophony resembling the screams of a dying elephant and a machine gun alternately, it would still get along, and I mounted it for Blankington-on-Sea to meet my brother Bernard.

I put it up at the hotel—I saw the yard attendant wink at the stable boy as he housed it—ordered a trap and went to the station. The train came in to time and my brother descended from a first-carriage. I had seen him in London only a day before, and despite his natural annoyance at the failure to get me into the R.N.F.C., he had been particularly cheery. As we shook hands and the porter took his kit-bags and gun-cases to the trap, I saw that he had something on his mind. He hardly even smiled. I jumped to a wrong conclusion.

"Bernard," I said, "would you like a whisky-soda before we start? You look as if you had been enjoying yourself too much last night."

He shook his head. "No peg for me, thanks; let us get on the road."

We went out of the station together and as we came into the yard he said in a low voice: "I have a deuce of a lot to tell you, but not now."

Then we started for Morstone.

Little more than an hour later we were seated in the parlour at the inn. A comfortable fire glowed upon the hearth and sent red reflections round the homely room, lighting up the stuffed pintail in its case, the old-fashioned, muzzle-loading marsh gun over the mantelpiece, the gleaming lustre ware upon a dresser of old oak, and an engraving of old Colonel Hawker himself, the king of wild-fowlers and a name to conjure with in East Anglia. Upon the table was a country tea, piping hot scones made by good Mrs. Wordingham, a regiment of eggs, a Gargantuan dish of blackberry jam.

"By Jove, this is a good place!" Bernard said. "Two lumps and lots of cream, please. Look at this egg! Upon my word, I would like to shake by the hand the fowl that laid it!"

We made an enormous meal and then, as he pulled out a blackened "B.B.B." and filled it with "John Cotton," my brother began to talk.

"We are quite safe here, I suppose?" he said; "nobody can overhear us?"

"Safe as houses."

"Very well, then; now look here, old chap, you noticed I seemed a bit off colour when you met me. Well, I'm not off colour, but I've had some very serious news and, what is more, a sort of commission in connection with it. After I saw you off yesterday I went to the Army and Navy Club. There I found a letter from Admiral Noyes, written at the Admiralty and asking me to call at once. I was shipmate with Noyes when he was captain of the old Terrific, and he has helped me a lot in my service career. It was he who got me transferred into Submarines—where, you know, I have made a bit of a hit. Well, now Noyes is Chief of the Naval Intelligence Department. He sent for me and asked me a lot of questions, specially about Kiel and the Frisian Islands. I was at Kiel for the manœuvres two years ago and I know all that coast like my hat. I didn't quite see the drift of his questions until he told me what was going on. It seems"—and here Bernard's voice sank very low—"it seems that, recently, there has been a tremendous leakage of information to the enemy—Naval information, I mean. We have our people on the look-out, and there is no doubt whatever that, during the last two months, over and over again the German ships have got information about our movements."

"I know. There is a whole lot about it in the Daily Wire: flash signals from the Yorkshire coast at night, round about Whitby, and so on."

"Oh yes, I saw that too; but the leakage is not there, my boy. That's newspaper talk. The Admiralty know to a dead certainty that the leakage is going on in East Norfolk, round about here."

I whistled. "I don't see how that can be," I said. "There is no wireless station anywhere near. The few boats that come into Blankington-on-Sea are only small coasters and they are very carefully scrutinised; and as for flash signals, I am out on the marshes nearly every night, the foreshore is patrolled by sentries, and nothing of the sort has ever been hinted at."

"Exactly; that is the point. But that there is a leakage and that it is doing irreparable harm, you may take as an absolute certainty. Noyes knew that I was coming down to Norfolk for a rest and for some shooting. When I applied for leave, I had to state my destination and so forth. Noyes got hold of it by chance and sent for me, knowing he could trust me. The long and short of it is, Johnny, that I have got a roving commission to keep my eyes very wide open indeed, to see if I can't find something out. Don't mistake me. This is not a mere trifling matter. It is one of the gravest things and one of the most perfectly organised systems that has happened during the war. Why," he said, bringing his fist down upon the table so that the cups rattled, his face set and stern, "the safety of the whole of England may depend upon this being discovered and stopped!"

"But surely," I asked, "they have had people down here already?"

Bernard nodded. "Oh yes," he said, "the coastguards are specially warned, there have been thorough searches, quietly carried out, reports are constantly made from every village by accredited agents—and the Admiralty has not a single clue. Now, old chap, if you can help me, and if we can do anything together, well, here's our chance! There won't be any difficulty about your getting into the R.N.F.C., or any other corps you like, if we can only throw light upon this dark spot."

I caught fire from his words. "By Jove!" I cried, "if only there was a chance! I would do anything! But I know every man, woman, and child in this village and the surrounding ones. There is not one of them capable of acting as a spy. There are no suspicious strangers. Even the wild-fowlers who come down here are all regular and known visitors, above suspicion." I said this in all good faith, and then, suddenly, a light came to me like a flash of lightning, and I rose slowly from my chair. Bernard told me afterwards that I had grown paper-white and was trembling.

"What is it?" he said quickly.

"I hardly dare say," I replied. "It seems wild foolishness and yet——"

He waited very patiently, and still I could not bring myself to speak. Then it was his turn to take away my breath. He leant forward on the table and pulled out a pocket-book.

"Supposing, John," he said, "that you have been living in a fool's paradise for months. Supposing that, by some means unknown to me and the Admiralty, unknown to anyone, you are actually living in the centre of a cunningly woven web of espionage, whose strands reach from Berlin to Wilhelmshaven, from Kiel to London!"

He took a piece of paper from his pocket-book. I saw that there were figures upon it, not letters, but he read it as if they were print.

"'Paul Upjelly,'" he said, "'Paul Upjelly, Ph.D.; English subject; possessed of private means; has been for eight years headmaster of Morstone House School; habits'—h'm—h'm—you know all about his habits, John—'man whose past cannot be traced for more than ten years; known to have lived in Germany in youth; no suspicion at present attaches.'"

"What on earth does this mean?" I gasped.

"It only means that in this pocket-book I have lists of forty or fifty people round these coasts who might or might not be in the pay of Germany. There is not the slightest suspicion attaching to any one of them, but I saw you stand up suddenly and grow pale—well, I played into your strong suit, that was all. Was I right?"

"Last night," I said, "I had a very curious and significant talk with a brother-master of mine, whose name is Lockhart."

"Get him to come here and have a chat as soon as possible."

"That isn't necessary, because Upjelly is away in London and an old beast of a housekeeper he keeps, who tells him everything, is in bed with a broken leg. We can go up to the school all right, and I particularly want to introduce you to Miss Joyce, who is—er——"

He nodded. "I know," he said. "You bored me to tears about the young lady last time I saw you. Delighted to meet her. We will toddle up to the school as soon as ever you like and I will hear what Mr. Lockhart has got to say. I suppose you can trust him?"

"I am absolutely certain of it," and, with that, things began to fall together in my mind as the glass pieces in a kaleidoscope fall and make a pattern. I mentioned the Navy List that I had seen at breakfast that morning, and I told Bernard what Wordingham had told me concerning the Doctor's knowledge of his visit.

A gleam came into his eyes. "Ah!" he said, very softly, and that was all.

We got up to go, and as Bernard walked across the room to find his overcoat, for night had fallen and it was bitter cold, I exclaimed aloud. I knew what had puzzled me at breakfast when Mr. Jones came into the room. He walked exactly like my brother. If you go to Chatham, Portsmouth, or Plymouth, almost every other man in the street walks like that.

We went straight to the school, only a quarter of a mile away, and entered by the masters' door. I lit the lamp in my sitting-room, put on some coals, and rang a bell which communicated with the upper boys' room, where they were now at preparation. In a minute, there was a knock at the door and Dickson max. entered.

"Dickson," I said, "I want you to find Mr. Lockhart and ask him if he would be so very kind as to come to my room—oh and, by the way, this is my brother, Commander Carey, Dickson."

The boy grew pale for an instant and then flushed a deep, rosy red. He was a cool young wretch as a rule and I had never seen him so excited before. I loved him for it. The boys knew all about my brother. They had read of his exploits in the Submarine E8. I was always being pestered with questions about him.

Bernard shook hands. "I am glad to meet you," he said.

Dickson was tongue-tied, but he gazed with an almost painful reverence at Bernard.

"Oh, sir," he stammered, "oh, sir"—and then could get no further. In desperation he turned to me. "I've done five hundred of the lines, sir," he said.

"Oh well, you needn't do any more," I answered.

"And please, sir, I've taken some more snapshots which I think you might like"—and with that the lad pulled out a little bundle of recently developed and printed photographs—he had a small kodak—and laid them on the table. Then he bolted and we could hear him leaping downstairs, bursting with the great news.

"He's got it badly," I remarked—"hero worship."

"Jolly good thing," my brother answered. "Lord, I remember when I was a midshipman of signals, how I worshipped the flag-lieutenant. I ran after him like a little dog, and I thought he was God. Healthy!"

We sat without speaking, waiting for Lockhart. My brother took up the little bundle of snapshots and looked through them. Then we heard a shuffling footstep in the passage and Lockhart entered. I introduced him and we shut and locked the door. Bernard looked the little man up and down for a minute or two, talking on indifferent subjects. And then, as if satisfied, he plunged into business. He didn't tell my colleague all that he had told me, but he told him enough to set Lockhart quivering with eagerness and excitement.

"You shall hear all I know, Commander Carey," he said. "After all, it isn't much, though"—he hesitated for a moment and then began:

"This man, Upjelly, our chief, is absolutely unfitted to be a schoolmaster. He takes not the slightest interest in the school. John, here, has found out, what I long more than suspected, that the Doctor's wild-fowling is really a colossal pretence."

"Does the school pay?" my brother asked.

"Just about. There may be a small profit, but not enough to keep any man tied down here if he has the slightest ambition or is anybody at all. And, you haven't met the Doctor, but you may take it from me that he is no ordinary man. There has always been an air of mystery and secretiveness about him. He neither asks nor gives confidences. It struck me from the very first that he was a man with an absorbing mental interest of some sort or other. What was it?—that is what I asked myself.

"Three weeks ago, the Doctor had a guest. It was a Mr. Jones, who frequently visits him, apparently for the shooting. My bedroom is on the floor below this. As you see, I am a cripple and an invalid. I often pass nights of pain, when I cannot sleep. On one such night, three weeks ago, the window of my bedroom was open and I lay in the dark. About half-past three in the morning I heard footsteps on the gravel outside, and the Doctor's voice. The night was quite still, though pitch dark. Then I heard another voice which I recognised as that of the man Jones.

"The voices drew nearer until the men were almost underneath my window. They were coming back from the marshes. I only know a few words of German, but I recognise the language when I hear it. They were speaking German."

My brother nodded.

"That Jones," I put in, "I have already told you, Bernard, was here when I arrived last night. He left for London this morning, taking the Doctor up with him in his car."

"Four days ago," Lockhart continued, "I wanted some waste paper to wrap up a pair of boots I was sending to be mended. I was in my room and I told one of the boys of my dormitory to go downstairs and get some. It was about nine o'clock at night. The boy brought back two or three newspapers. One of them was the Cologne Gazette, very crumpled and torn, but with the date of only five days before. I have got it locked up in my writing-desk.

"To-day, being a half-holiday, I thought I would go out for a walk upon the foreshore. An overcoat rather impedes my movements, though I have to wear one sometimes. I thought I would take a scarf instead. I went into the hall, knowing that my scarf was in the pocket of my overcoat, and felt for it. The hall is rather dark and I could not see very well what I was doing. What I brought out of the pocket in which I felt was not my scarf, but—this!"

Lockhart quietly laid something upon the table, and we bent over to look at it. To me, at any rate, it was an extraordinary object. It was a sort of cross between a large watch and a compass, with a curious little handle. There were letters or figures, for a moment I could not say which, in a double row round the dial.

"Can you tell me what it is?"

My brother was shaken from his calm at last. He gave an exclamation.

"Yes, I can!" he said. "I know very well. But first, when was this photograph taken?"

With dramatic suddenness, he held out one of Dickson's prints. It was a picture of Mr. Jones' motor, with that gentleman at the wheel and the Doctor sitting on the far side, taken that very morning as they left for London.

"This morning," I said. "That is the Doctor and Mr. Jones going off to town."

"Mr. Jones at the wheel?" my brother asked.

"Yes, that is the fellow."

"Let me get it quite clear. The man, you say, walks like me?"

"Yes."

"Ah!" said my brother again, and his eyes had the look of a bloodhound on a leash. "And now I will proceed to explain to you the use of this pretty thing."

"This," said my brother, "is what is known as Charles Wheatstone's Cipher Instrument. It is a machine for writing in cipher. You see it has a sort of watch-face, which has the alphabet inscribed round its outer margin in the usual order, plus a blank space. A second alphabet is written on a card or paper and attached to the watch-face within the first alphabet. This has no blank space, and so there are but twenty-six divisions as against twenty-seven in the outer ring. Two hands are attached which travel at different speeds when the handle is turned. Accordingly, each time the long hand is carried forward to the blank space at the end of a word, the short hand will have moved forward one division on the inner ring of letters. Then a word is chosen as a key, written down in separate letters and the remaining letters of the alphabet are written in order beneath it. I'll show you. Suppose, for example, we choose the word 'English,' thus." He took a pencil and scribbled for a moment upon the back of one of Dickson's photographs:

"Now, if you read these letters downwards, you get this arrangement:

"This cryptographic alphabet is written on the inner card of the instrument, beginning at a point previously agreed on. Then, when a despatch is to be translated into cipher, the long hand is moved to that letter in the outer alphabet, and the letter to which the short hand points in the inner ring is written down. I need not go on, but I am sure the principle will be clear to you. These machines are in use in our Secret Service. But what I should like to point out to you in regard to this example is that the alphabet here is in German."

We all looked at each other in silence.

"That is conclusive proof," I said at length. "Of course, you will have Doctor Upjelly arrested directly he comes back."

"And thank you!" said my brother. "So kind of you to put up your little turn, Johnny! Will you have a cigar or a cocoanut? My dear boy, if we had this man arrested, ten to one his tracks would be absolutely covered and we could prove nothing. Don't you see, what we want to do is to catch him in the act, to find out what he does and how he does it. No such rough and ready methods!"—his voice became very grave and stern.

"Quarter-deck!" I thought to myself.

"This has not got to be taken lightly," he went on. "I believe that fate has put my finger upon the very pulse of what has been puzzling the Admiralty for weeks. I honestly believe that here, in this lonely house, is hidden the intellect of the Master Spy of Germany. We are up against it. We must work in silence and in the dark. The slightest slip would be fatal. I cannot exaggerate the importance of this affair, nor," he concluded, looking keenly at Lockhart and myself, "nor the danger."

Little Lockhart's face positively brightened at this. "Danger!" he cried, as if someone had made him a present. "Then I shall be able to do something to help! We shall all be able to do something and——"

Lockhart started and broke off. At that moment, from behind Smith's classical dictionary and Liddell and Scott's Greek ditto there came a faint, muffled whirr.

"Good God, what's that?" said Lockhart.

"Oh, it's all right," I answered, and I expect I looked about as big an ass as I felt. "That is—er—a little contrivance of my own. By the way, you fellows must keep it absolutely dark."

To say that they watched me with interest is to put it mildly. I withdrew "Our House Telephone, Not a Toy, 27s. 6d. net" from its hiding place. Doris was speaking. She knew that my brother had come and she was dying to meet him. Old Mrs. Gaunt was sleeping peacefully; in fact I fear, so prone are all of us to error, that Doris had administered just twice the amount of opiate that the doctor had prescribed.

Doris suggested that she and Marjorie should come at once to my room. They also suggested that we should dine there, with the connivance of a friendly housemaid. I told her to hold the line for a minute, and explained.

My brother's face lost all preoccupation. He was a naval officer, you will remember, and, though a distinguished one, was as young gentlemen in that Service usually are in both age and inclination.

"Can a duck swim?" said my brother.

"Well, I'll go," Lockhart remarked, with just a trace of his old bitterness.

"You sit where you are, old soul," I told him. "Bernard, both the girls are only stepdaughters of the Doctor, who, they have told me, did not treat their mother very well and who is a perfect tyrant to them. They're as true as steel; I can answer for them. They will be of tremendous help."

"Leave it all to me," he replied. "I am skipper of this from now onwards. You follow my lead."

A minute or two afterwards the girls came in. Doris, as I have already explained, was as pretty as Venus, Cleopatra, and Gertie Millar all in one, and she only beat Marjorie by a short head. All the other girls I've ever met were simply "also ran."

Marjorie's hair was black. She was a brunette with olive-coloured skin and green eyes, like very dark, clear emeralds. She was extraordinarily lovely. Indeed, all three of us had seriously considered starting a picture postcard firm, with the girls as models and I to manage it, so that Doris and I could get married and have Marjorie to live with us. Rather a good scheme, only it would have needed at least two hundred pounds capital, which we hadn't got! Doris had on her engagement ring, which she generally wore on a string round her neck, underneath her blouse. I had put thirty shillings each way on "Baby Mine" for the Grand National and it had come off—hence the ring.

"Let me introduce you to my fiancée, Miss Joyce," I said to Bernard.

He took her hand and bowed over it, looking out of the corner of his eyes at Marjorie.

Little Lockhart gasped. "Babe that I am!" he said, "blind mole! To think that I have lived in this house with young John Carey for so long, the house honeycombed with secret wires, and an illicit engagement in progress under my nose, and I knew nothing of it!"

"Well, you are not the only person, Mr. Lockhart," Marjorie said. "And now I am going to fetch up dinner. Cook is out for the evening. Amy is in the plot. We've got soup—only tinned, but quite nice; there's a round of cold beef; and we will make an omelette on John's fire."

"I'll come and help you carry the things," said my brother, and they left the room as friendly as if they had known each other for years.

"Well, what do you think of my brother?" I asked Doris. I'm afraid my arm was round her waist and I had forgotten Lockhart.

"I'm decidedly of the opinion," she said, "that Commander Carey knows more than enough to come indoors when it rains."

Lockhart here revealed qualities of an unsuspected nature—I had never really appreciated Lockhart until the night before.

"I happen to have, locked up in the cupboard of my sitting-room," he said, "a bottle of claret wine and a bottle of sherry wine. I will go and fetch them to grace this feast."

"You nasty, horrid villain, so you drink in secret, do you?" I remarked.

"Only Bovril, but please don't let it be known," was the reply, and then Doris and I were alone.

I have never been one of those people who kiss and tell, so I will pass over the next minute; but after some business of no importance, she put her hands on my shoulders and looked me straight in the face.

"John," she said, "there is something up!"

"What do you mean?"

"I don't exactly know, but there is something up. I can feel it—and something has happened, too, that I have got to tell you about. Before the Doctor left this morning, he told Marjorie that Mr. Jones had fallen in love with her and that she would have to marry him after the war was over, when he has straightened out his business affairs."

"Good Lord!" I said, "that thing? Why——"

"What have you got against him?" she asked quickly. "He's wealthy, the Doctor says, he has got good manners; of course, he's older than Marjorie, but he's not an old man. I thought you said you rather liked him?"

"I did say so, and I liked him better than ever after meeting him this morning. You know I had breakfast with the Doctor?"

"I know, and there is something up. Something to do with your brother—I am certain of it. But why do you object to Mr. Jones for Marjorie?"

"What does Marjorie say herself?"

"She told the Doctor"—the girls would never call the Doctor "Father"—"that if Mr. Jones had a million a minute and was the last man left on earth after a second flood, she would rather spend her life in the garden eating worms than marry him!"

"Marjorie's plenty of pluck," I answered, "and is obviously of romantic temperament. Anyone else in the wind?"

"Anyone else?" she said, with a bitter note in her voice, "whom do we ever see? We live as prisoners here, as you very well know, Johnny, and if it were not for you I should long ago have jumped into Thirty Main Creek and ended it all."

I held her close to me. "Dear," I said, "it will all come right, I am certain. Somehow or other, we shall be able to be married soon, and then you need never see Morstone or the Doctor any more."