THE HEROES OF ASGARD

THE

HEROES OF ASGARD

TALES FROM SCANDINAVIAN MYTHOLOGY

BY A. & E. KEARY

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY HUARD

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., LTD.

1909

All rights reserved

New edition September, 1906. Reprinted July, 1909.

Norwood Press:

Berwick & Smith Co., Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

PREFACE.

In preparing the Second Edition of this little volume

of tales from the Northern Mythology for the press,

the Authors have thought it advisable to omit the

conversations at the beginning and end of the

chapters, which had been objected to as breaking the

course of the narrative. They have carefully revised

the whole, corrected many inaccuracies and added

fresh information drawn from sources they had not

had an opportunity of consulting when the volume

first appeared. The writers to whose works the

Authors have been most indebted, are Simrock,

Mallet, Laing, Thorpe, Howitt and Dasent.

CONTENTS.

| | | |

PAGE |

|---|

| INTRODUCTION, |

9 |

CHAPTER I.

THE ÆSIR. |

| PART |

I. | — |

A GIANT—A COW—AND A HERO, |

41 |

| II. | — |

AIR THRONE, THE DWARFS, AND THE LIGHT ELVES, |

51 |

| III. | — |

NIFLHEIM, |

59 |

| IV. | — |

THE CHILDREN OF LOKI, |

67 |

| V. | — |

BIFRÖST, URDA, AND THE NORNS, |

72 |

| VI. | — |

ODHÆRIR, |

81 |

CHAPTER II.

HOW THOR WENT TO JÖTUNHEIM. |

| PART | I. | — |

FROM ASGARD TO UTGARD, |

109 |

| II. | — |

THE SERPENT AND THE KETTLE, |

130 |

CHAPTER III.

FREY. |

| PART | I. | — |

ON TIPTOE IN AIR THRONE, |

147 |

| II. | — |

THE GIFT, |

152 |

| III. | — |

FAIREST GERD, |

157 |

| IV. | — |

THE WOOD BARRI, |

163 |

CHAPTER IV.

THE WANDERINGS OF FREYJA. |

| PART | I. | — |

THE NECKLACE BRISINGAMEN, |

169 |

| II. | — |

LOKI—THE IRON WOOD—A BOUNDLESS WASTE, |

177 |

| III. | — |

THE KING OF THE SEA AND HIS DAUGHTERS, |

185 |

CHAPTER V.

IDŪNA'S APPLES. |

| PART | I. | — |

REFLECTIONS IN THE WATER, |

191 |

| II. | — |

THE WINGED-GIANT, |

198 |

| III. | — |

HELA, |

212 |

| IV. | — |

THROUGH FLOOD AND FIRE, |

218 |

CHAPTER VI.

BALDUR. |

| PART | I. | — |

THE DREAM, |

231 |

| II. | — |

THE PEACESTEAD, |

240 |

| III. | — |

BALDUR DEAD, |

247 |

| IV. | — |

HELHEIM, |

250 |

| V. | — |

WEEPING, |

256 |

CHAPTER VII.

THE BINDING OF FENRIR. |

| PART | I. | — |

THE MIGHT OF ASGARD, |

263 |

| II. | — |

THE SECRET OF SVARTHEIM, |

272 |

| III. | — |

HONOUR, |

279 |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

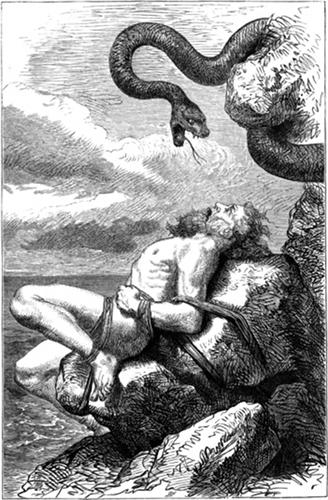

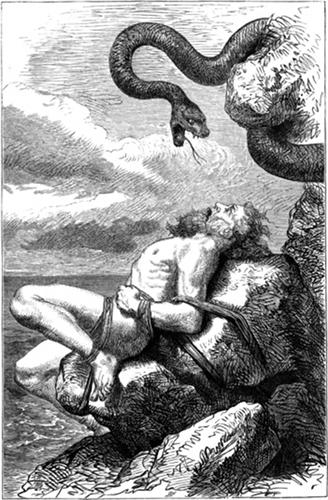

| THE PUNISHMENT OF LOKI, |

285 |

CHAPTER IX.

RAGNARÖK. |

| OR, THE TWILIGHT OF THE GODS, |

295 |

| INDEX OF NAMES, WITH MEANINGS, |

315 |

List of Illustrations.

PAGE

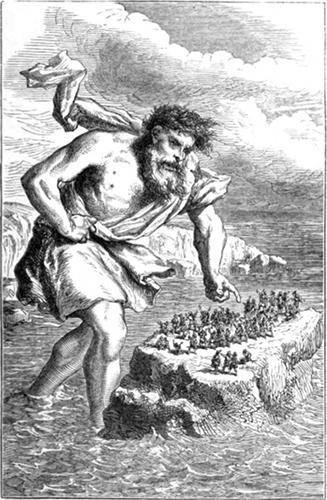

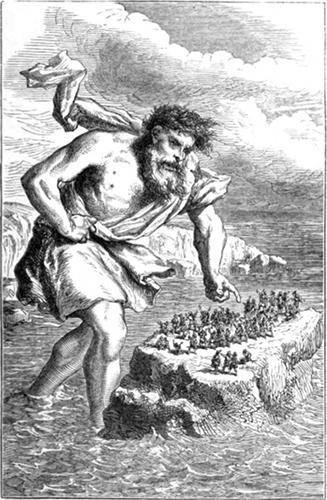

- GIANT SUTTUNG AND THE DWARFS, 86

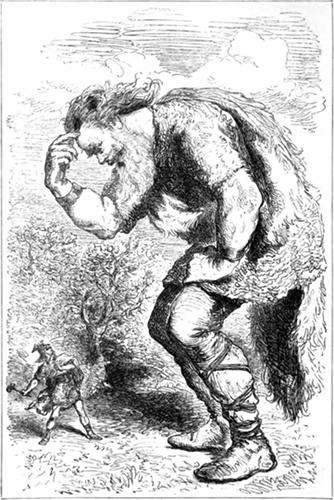

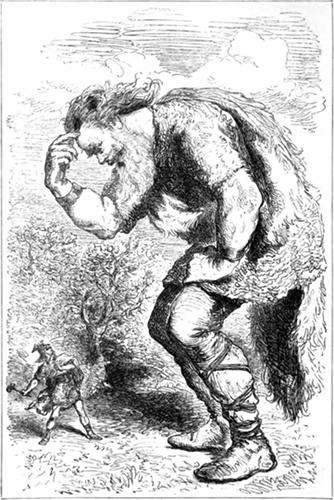

- GIANT SKRYMIR AND THOR, 115

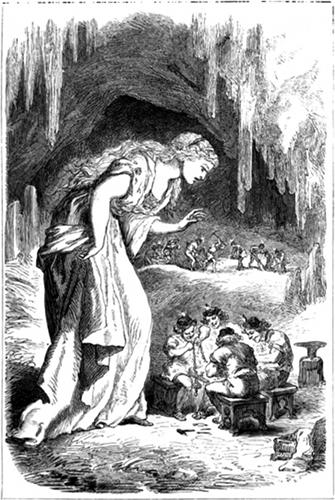

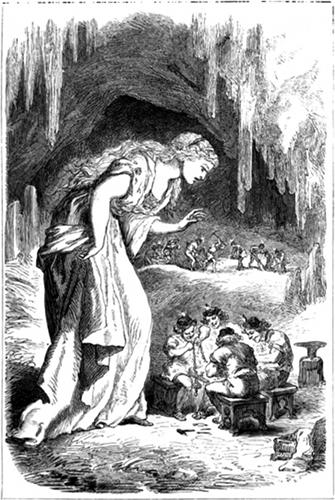

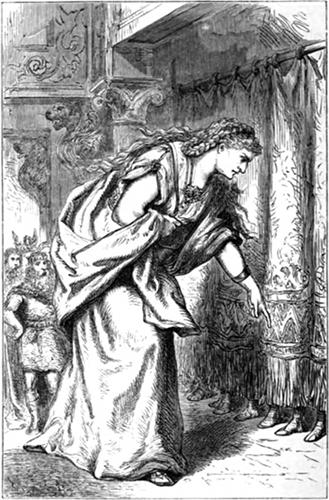

- FREYJA IN THE DWARFS' CAVE, 172

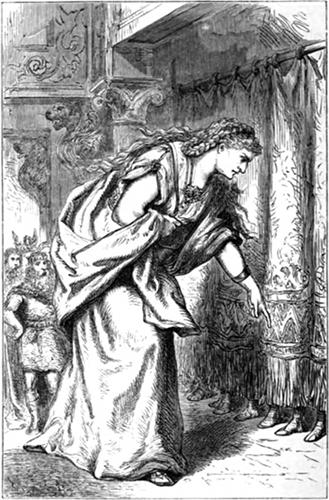

- IDUNA GIVING THE MAGIC APPLES, 195

- SKADI CHOOSING HER HUSBAND, 227

- TYR FEEDING FENRIR, 265

- THE PUNISHMENT OF LOKI, 292

THE HEROES OF ASGARD.

INTRODUCTION.

If we would understand the religion of the ancient

Scandinavians, we ought to study at the same

time the myths of all Teutonic nations. A drawing

together of these, and a comparison of one

with another, has been most beautifully effected

by Simrock, in his Handbuch der Deutschen

Mythologie, where he tells us that whilst the

Scandinavian records are richer and more definite,

they are also younger than those of Germany,

which latter may be compared to ancient half

choked-up streams from which the fuller river

flows, but which, it is to be remarked, that

river has mingled in its flowing. Grimm says that

both religions—the German and the Northern—were

in the main identical, though in details

they varied; and as heathenism lingered longer in

Scandinavia than in any other part of Europe,

it is not surprising that there, rather than

anywhere else, we should find the old world

wants and hopes and fears, dark guesses, crude

imaginings, childlike poetic expressions, crystallised

into a pretty definite system of belief

and worship. Yes, we can walk through the

glittering ice halls of the old frozen faith, and

count its gems and wonder at its fearful

images; but the warm heart-reachings from which

they alike once flowed, we can only darkly feel,

at best but narrowly pry into here and there.

Ah! if we could but break up the poem again

into the syllables of the far off years.

The little tales which follow, drawn from the

most striking and picturesque of the Northern

myths, are put together in the simplest possible

form, and were written only with a design to

make the subject interesting to children. By-and-bye,

however, as we through their means become

in a slight degree acquainted with the characters

belonging to, and the parts played by, the various

deities of this mythology, it will not be uninteresting

to consider what their meaning may be, and to

try if we can trace the connection of one with

another. At present it seems best, as an introduction

to them—and without it they would be

scarcely intelligible—to give a very slight sketch

of the Northern mythology, as it is gathered from

the earliest Scandinavian sources, as well as a

short account of the sources from which it is

gathered.

Laing, in the introduction to his Translation

of the Heimskringla Saga, says,—"A nation's literature

is its breath of life, without which a nation

has no existence, is but a congregation of individuals.

During the five centuries in which the

Northmen were riding over the seas, and conquering

wheresoever they landed, the literature of the

people they overcame was locked up in a dead

language, and within the walls of monasteries. But

the Northmen had a literature of their own, rude

as it was." Songs and sagas, mythical and heroic,

were the staple of this literature of the north; and

these appear to have been handed down by word of

mouth from skald to skald until about the beginning

of the twelfth century. Then Sæmund the Learned,

and others, began to commit them to writing.

Sæmund the Learned was born in Iceland about

the year 1057, fifty years after Christianity had

been positively established in that island. He

passed his youth in Germany, France, and Italy,

studying at one time with a famous master, "by

whom he was instructed in every kind of lore."

So full, indeed, did Sæmund's head become of all

that he had learnt, that he frequently "forgot the

commonest things," even his own name and

identity, so that when asked who he was, he

would give the name of any one he had been

reading about. He was also said to be an astrologer,

and a charming little anecdote is related of him in

this capacity, which, however, would be out of

place here. When he went back to Iceland, he

became priest of Oddi, instructed the people about

him, studied the old religion, and, besides writing

a history of Norway and Iceland, which has been

lost, transcribed several of the mythic and heroic

songs of the North, which together form a collection

known by the name of the Poetic, Elder, or

Sæmund's Edda. The songs themselves are supposed

to date from about the eighth century;

Sæmund wrote them down in the twelfth. The

oldest copy of his original MS. is of the fourteenth

century, and this copy is now in the Royal

Library of Copenhagen. A few years ago they

were translated into English by B. Thorpe. So

much for the history of the Elder Edda—great-grandmother

the name is said to mean, but after

all she scarcely seems old enough to be called a

great-grandmother. We have traced her growing

up, and seen how she has dressed herself, and we

begin to think of her almost as a modern young

lady. When we listen to the odd jumble of tales

she tells us, too, we are more than half inclined

to quarrel with her, though without exactly knowing

whether it is with her youth or her age that

we find fault. You are too young to know what

you are talking about, great-grandmother, we complain;

but, oh dear! you mumble so and make

use of such odd old-fashioned words we can scarcely

understand you. Sæmund was not the only man

who wrote down songs and sagas; he had some

contemporaries, many successors; and, about fifty

years after his death, we hear of Snorro Sturleson,

a rich man, twice Supreme Magistrate of the

Icelandic Republic, who also lived for some time

at Oddi, and who has left many valuable additions

to the stock of Icelandic written lore. Laing says

of him—"Snorro Sturleson has done for the

history of the Northmen, what Livy did for the

history of the Romans." Amongst other things, he

wrote a sort of commentary or enlargement of

Sæmund's Edda, probably drawn from MSS. of

Sæmund and of others, which were preserved at Oddi.

This is called the Prose, Younger, or Snorro's

Edda, and was translated many years ago by M.

Mallet into French. Added to these two sources

of information respecting the Scandinavian mythology,

there are many allusions to the myths

scattered through the heroic lays with which

Northern literature abounds.

The Poetic Edda consists of two parts—the

mythological and the heroic. The mythological

songs contain an account of the formation and

destruction of the world, of the origin, genealogies,

adventures, journeys, conversations of the gods,

magic incantations, and one lay which may be

called ethical. This portion of the Edda concludes

with a song called "The Song of the

Sun," of which it is supposed Sæmund himself

was the author. Thorpe, the English translator,

says, "It exhibits a strange mixture of Christianity

and heathenism, whence it would seem that the

poet's own religion was in a transition state. We

may as well remark here that the only allusion

to Christianity in the Elder Edda, with the exception

of this last song, which stands quite alone, is a

single strophe in an incantation:—

"An eighth I will sing to thee,

If night overtake thee,

When out on the misty way,

That the dead Christian woman

No power may have to do thee harm."

Which savours curiously of the horror which

these heathens then evidently felt of the new

faith.

The Younger Edda is a very queer old lady

indeed. She begins by telling a sort of story. She

says "there was once a King called Gylfi, renowned

for his wisdom and skill in magic;" he being seized

with a desire to know all about the gods, and

wishing also to get his information first-hand, sets

off on a journey to Asgard itself, the gods' own

abode. When he gets there he finds a mysterious

Three seated upon three thrones—the High, the

Equally High, and the Third. The story-teller is

supposed to have taken this picture from a temple at

Upsal, where the thrones of Odin, Thor, and Frey

were placed in the same manner, one above another.

Gylfi introduces himself as Gangler, a name for

traveller (connected with the present Scotch word

gang), and proceeded to question the Three upon the

origin of the world, the nature and adventures

of the gods, &c., &c. Gangler's questions, and

the answers which he receives, will, with reference

to the Elder Edda tales, help us to get just the

short summary we want of the Scandinavian mythology—the

mythology grown up and old, and

frozen tight, as we find it in the Eddas.

"What was the beginning of things?" asks Gangler;

and Har (the highest of the Three), replying in the

words of an ancient poem, says,—

"Once was the age

When all was not—

No sand, nor sea,

No salt waves,

No earth was found,

Nor over-skies,

But yawning precipice

And nowhere grass."

This nothingness was called Ginnungagap, the gap

of gaps, the gaping of the chasms: and Har goes on

to relate what took place in it. On the north side of

Ginnungagap, he says, lay Niflheim, the shadowy

nebulous home of freezing cold and gathering gloom;

but on the south lay the glowing region of Muspellheim.

There was besides a roaring cauldron

called Hvergelmir, which seethed in the middle of

Niflheim, and sent forth twelve rivers called the

strange waves; these flowed into the gap and froze

there, and so filled the gap with ice: but sparks

and flakes of fire from Muspellheim fell upon the

ice. Ginnungagap on the north side was now

filled with ice and vapour and fleeting mists and

whirlwinds, but southwards with glowing radiancy,

with calm and light and wind—still air; and so,

continues Har, the heat met the frost, the frost

melted into drops, the drops quickened into life,

and there was a human form called Ymir, a giant.

"Was he a god?" asks Gangler. "Oh! dear no,"

answers Har; "we are very far indeed from believing

him to have been a god; he was wicked and the

father of all the Frost Giants." "I wonder what he

ate?" said Gangler. "There was a cow," Har went

on to explain; "she was made out of the drops,

too, and the giant fed upon her milk." "Good,"

answered Gangler; "but what fed the cow?" "She

licked the stones of Ginnungagap, which were

covered with salt hoar frost;" and then Har goes

on to relate how by degrees a man, Bur, grew up

out of the stones as the cow licked them, good,

not like Ymir, but the father of the gods; and here

we may remark that the giant and the god equally

were the sole progenitors of their immediate descendants.

Ymir was the father of the first giant, Bur

had a son called Bör. But after that the races mix

to a certain extent, for Bör married a giantess and

became the father of three sons, Odin, Vili and Ve.

"Was there any degree of good understanding

between these two races?" asks Gangler. "Far

from it," replies Har; and then he tells how the

sons of the god slew all the frost giants but one,

dragged the body of old Ymir into the middle of

Ginnungagap, made the earth out of it,—"from his

blood the seas, from his flesh the land, from his

bones the mountains, of his hair the trees, of his

skull the heavens and of his brains the clouds.

Then they took wandering flakes from Muspellheim,

and placed them in the heavens." Until this time,

says the Völuspá.

"The sun knew not

Where she a dwelling had,

The moon knew not

What power he possessed,

The stars knew not

Where they had a station."

About this time it happened that the sons of

the god took a walk along the sea-beach, and there

found two stems of wood which they fashioned into

the first man and woman:—

"Spirit gave them Odin

Sense gave Hœnir

Blood gave Lodin (Loki)

And goodly colour."

After this it is said that the all-holy gods, the

Æsir, the Lords, went to their judgment seats, held

council, and gave names to the "night and to the

waning moon, morn, midday, afternoon, and eve

whereby to reckon years." Then they built a city

called Asgard in the middle of the earth, altars and

temples, "made furnaces, forged tongs and fabricated

tools and precious things;" after which they stayed

at home and played joyously with tables. This

was the golden age of the gods; they were happy.

"To them," says the old song, "was naught the

want of gold, until there came three maids all

powerful from the giants."

In some mysterious way it appears that a desire

for gold seized upon the gods in the midst of their

innocent golden play. Then they formed the dwarfs,

in order that these might get gold for them out of the

earth. The dwarfs till then had been just like maggots

in Ymir's dead flesh, but now received human

likeness. A shadow begins to creep over the earth,

the golden age is past. At the same time three

things happen. The gods discover the use or

want of gold; the first war breaks out, as it is said,

"Odin hurled his spear amid the people, and then

was the first war;" and the three all-powerful giant

maids appear. "Gold," says the old song (and calls

her by a name as if she were a person), "they pierced

with lances,—

"And in the High one's Hall

Burnt her once,

Burnt her thrice,

Oft not seldom,

Yet she still lives.

Wolves she tamed,

Magic arts she knew, she practised,

Ever was she the joy

Of evil people."

The three giant maidens are the three Fates—the

sisters,—Past, Present and Future. They came

from giant land, which in this place typifies the

first mixed cause of all things; they came at the

moment when the golden age was disappearing; they

stand upon the very edge of its existence, at once

the bringers and the avengers of evil. "The golden

age ceased when gold was invented," is an old

saying. "After the golden age, time begins," is

another, or, in the words of a German proverb,

"To the happy no hour strikes." And now let

us see what sort of looking world these giants, gods,

men, dwarfs and fateful maids whom Har has been

talking about were living in.

"Round without," Har says so; but a flat round.

The outmost circle a frozen region full of frost

giants; inside that circle, the sea; in the middle of

the sea, the earth in which men live, called Midgard,

and made out of Ymir's eyebrows; in the midst of

the earth Asgard, the city of the gods. It seems

to be rather a disputed point whether or not Asgard

was on the top of a hill. Heavenly mountains are

mentioned in the Edda, but they are placed at the

edge of heaven under one end of the rainbow, not

at all near Asgard, if Asgard was in the middle of

the earth. However, to make the city more conspicuous

we have placed it on the summit of a hill

in the picture of the Scandinavian World which

stands at the beginning of this chapter, and here

remark that this picture must not be looked at

exactly in a geographical light even from a Scandinavian

point of view. It is rather an expression of

ideas than of places, for we have tried to figure by

it what is said about the great World Tree Yggdrassil

and its three roots. "That ash," says Har, which

was indeed the earth-bearer, "is the greatest and

best of all trees." Its branches spread over the

whole world and even reach above heaven. It

has three roots, very wide asunder. One of them

goes down to Ginnungagap. The frost giants live

over it, and over this root is a deep well which we

shall hear more of by-and-bye. In the picture this

root could not be shown, but the branches which

encircle the ice region are supposed to spring from

it. Another root extends to Niflheim, the old roaring

cauldron lies under it, a great snake called Nidhögg

gnaws it night and day as the old lay says.

"Yggdrasil's ash suffers greater hardship than

men know of. Nidhögg tears it." Under this root

also lies Helheim, a home of the dead. The third

root is in heaven: gods and men live under it, in

Asgard and Midgard; the giant fate-sisters also live

under it, at the top of the Rainbow's arch in their

palace very beauteous, which stands by the Holy

Urda Fount. They water the tree every day with

the holy water, so that ever "it stands green over

Urda's Fount."

These maidens are called Norns;—they fix the

destinies of men, Har says; "but besides them,"

he adds, "there are a great many other norns—indeed,

for each man that is born there is a norn

to decide his fate."

"Methinks, then," says Gangler, "that these Norns

were born far asunder; they are not of the same

race." "Some belong to the Æsir, some come

from the Elves, and some are dwarfs' daughters."

Besides these wonders, we are told that an eagle

perched amongst the highest branches of Yggdrasil

with a hawk between his eyes, four harts ran

amongst the branches and bit off the buds, and a

squirrel called Ratatösk or branch borer ran up

and down, carrying messages between the Eagle

and Nidhögg, as one account says, causing strife

between them—a kind of typical busybody, in fact.

Such is the myth of Yggdrasil, of which Jacob

Grimm remarks "it bears the stamp of a very

high antiquity, but does not appear to be fully

unfolded." Of course, it was only the symbol of

a thought, the Scandinavians could not have believed

that there was such a tree. But of what thought

was it the symbol? The editor of Mallet's Northern

Antiquities says, "We are inclined to regard

this mythic Tree as the symbol of ever-enduring

time, or rather of universal nature, ever varying

in its aspects but subsisting throughout eternity."

It is called somewhere "Time's hoary nurse," and

we see the principles of destruction and of renovation

acting upon it. One root in the formless elemental

abyss, one in the formed ice-frozen-over giant land,

its branches spreading over the whole world; one

reaching up to the unseen. Its name means "Ygg"—terror,

horror, fear—"drasil"—horse or bearer—and

the first syllable is one of the names of Odin

the chief god. We must not omit to mention that

our Maypoles and the German Christmas trees are

offshoots of Yggdrasil, "that ash, the greatest and

best of trees."

"But who is the first and eldest of the gods?"

Gangler asks. "We call him Allfather," says Har,

"but besides this he has twelve names."

Allfather, Odin or Woden, the eldest son of

Bör by a giantess, is the chief god of the Eddas,

and it is quite true, as Har says, that he has many

names. He was called Allfather—the father of gods

and men, and Valfather or the chooser, because he

chose which of the slain in battle should come and

live with him in heaven; he called himself by many

names when he travelled, he was known as Ygg,

but generally, chiefly, he was Odin. The meaning

of the first syllable of this last name is terror (like

Ygg), or violent emotion. Simrock says that air

in calm or storm lies at the root of Odin's being;

from this he grew up to be a god of the spirit, a

king of gods, "as in the simple ideas of the people,"

he says, "nature and spirit are inseparable; he became

as much a commander of the spirits of men as of

the forces of nature." Air, widespread and most

spiritual of the elements, how naturally akin it seems

to that wind, blowing where it listeth, which moves

in hidden ways the spirits of men. Inspiration,

madness, poetry, warrior-rage, the storm of wind,

the storm of mind—we find Odin in them all. Thor

the thunder-god stood next in importance to Odin.

Odin was his father, and he had a giantess mother,

Jörd (the earth). Besides these Har enumerates

Baldur, Tyr, Vidar, Vali, Hödur, Bragi, all called

sons of Odin;—we shall hear the stories that belong

to them by-and-bye.

All these were of the race of the Æsir or Asgard

gods; there were other deities counted amongst them,

and yet kept a little distinct—the Vanir gods and

goddesses. These were of a different race, and it

is not clear how and when they became mixed with

the Æsir. What the Eddas say about it is simply

this, that the Æsir made peace with the Vanir and

exchanged hostages with them. Amongst these we

find Niörd a kind of sea-coast god, the original

of Nipen still known in Norway, his son and

daughter Frey and Freyja, "beauteous and mighty,"—Frey

presiding over rain, sunshine, and the fruits

of the earth; Freyja goddess of the beautiful year

and of love, and Heimdall, a god who lived upon

the heavenly hills at one end of the rainbow. A

sea-king called Ægir, whose nature is not quite

defined whether he belonged to the god or the giant

is occasionally mentioned in the Edda tales, and

also a wise giant Mimer. But there is besides a

mysterious being whom we name last because he

requires a little explanation. This is Loki. He

was one of the Æsir; we read of his being with

Odin when that god took his fateful walk along the

seashore and made man, he helped Odin in the

work; we come upon him frequently travelling with

the gods, sometimes at least as a friend, and

yet it is evident that Loki was looked upon as an

evil being. "Some call him the calumniator of

the gods," says Har, "the contriver of all fraud and

mischief, the disgrace of gods and men. Loki is

handsome," he adds, "and well made, but of a very

fickle mood and most evil disposition. He surpasses

all beings in those arts called cunning and

perfidy." Simrock says that fire lies at the root of

Loki's being as air lies in that of Odin,—fire

which has good and evil in it, but most outwardly

destructive power; hence the beginning of the idea

of his evil-heartedness. From simple nature myths,

it is quite easy to conceive that the moral principle,

as it grew up in a people, would develop spiritual

ones, and the character of the gods would materially

alter with the growth of the religion. Good and

evil are scarcely conceptions which the wars of the

elements give birth to. By the law is the knowledge

of sin. The name of Loki, it is said, may mean the

bright element.

Amongst the goddesses who were called Asyniur,

Frigga stands out chief in the Eddas as Odin's wife,

but several others are named, and also the Valkyrior,

swayers of the battle and heavenly serving maidens.

The peace between the Æsir and the Vanir, and

the perceptible difference between these races of gods,

points to an amalgamation of the religions of two

tribes of Teutons in very early times: their faiths

would be similar, drawn indeed from one source,

but would have been modified by the circumstances

and requirements of the divergent tribes. Simrock

supposes that the Vanir worshippers may have been

dwellers by the sea, and have had a special reverence

for wind and water deities—mild, wide, beneficent

airs. Their gods are a little milder in nature than

those of Asgard, they are also more purely nature

deities, with less of the moral element in their characters,

which looks as if the two faiths had joined at different

stages of development, at different levels one

may say, so that the line between them is still

discernible. We have seen how Har explains to

Gangler the formation of the universe in Ginnungagap

out of the strange ice waves; primeval giant;

beneficent might of the gods; its endurance,

rooted in the mighty Tree, that reached from depth

to height,—

"Laved with limpid water,

Gnawed by more serpents

Than any one would think

Of witless mortals."

He had also something to say concerning the

future of the world. "What hast thou to tell me

about it?" said Gangler; and Har replied,—"In

the first place there will come a winter;" and

then he described the destruction of the world—flood

and storm, and ice and fire, and warfare, a

supreme conflict; all the powers of evil, the

chaotic powers—primeval chaos surging again out

of Niflheim and Muspellheim—on one side, the

gods, the forming orderly principle of the course

of the universe, on the other—all rage within,

and through the mighty ash, which itself trembles,

"Groans that aged tree." Monsters and gods

alike fall, killing each other, and one cannot say

with whom the victory lies; for though the sun,

moon, and stars are made away with, and the

earth sinks into the flood, it soon emerges again,

"beauteously green," destined, as it would seem,

to run a second course. Brighter, purer? The

account is so mixed that one cannot say, and

why should we puzzle over it; perhaps they

knew as little what they thought and hoped as

we know about them—those old song-singers and

myth-spinners of days gone by, as one of them

says,—

"Few may see

Further forth

Than when Odin

Meets the wolf."

Notwithstanding, we cannot help feeling, as we

contemplate this myth, that there was something

noble, very grimly courageous in its fatalism.

Simrock says, "the course of Northern mythology

is like a drama." The world's beginning, the

golden years, the first shadow of evil, evil that

came with times, evil fated to come, the troubles

of various kinds, all death shadows which fell

upon the gods (we shall trace them in the

following tales); and above all, hanging over all,

crowning all, the twilight, the struggle, the end,

the renewing; for it is not, be it observed, the

end of the world, of time, of succession of events

that is recorded in this myth (called the Ragnarök

Myth), but rather of the struggling powers that

had been brought by these, that had formed

these. Looking through this drama two things

chiefly strike us, fatalism and combat. The two

do not contradict one another. The gods fight

the giants from the earliest times; they go on

fighting them in a thousand ways, even though

they know that their own final defeat and

destruction are fixed—they ward off the evil day

as far as possible, hoping through its shadow

again and again, dauntless to the end. It is

impossible to help admiring the impulses which

led to the building up, and dictated the worship

of this idea,—the worship of the gods who were

to die, who were, in spite of most courageous

defiance of it, after all but the servants of the

inevitable. Of course it was perfectly simple and

natural that this conception of unceasing strife,

of the alternate victory and defeat of light and

darkness, cold and heat, should arise in the

minds of any worshippers of the natural world,

but it must, one would think, have acquired

some moral significance to these heathen Northmen

by the time that Odin had come to be

Allfather, even Valfather, and Frigga, through the

nourishing earth, the lady of married love and

of the hearth. A good deal of this courageous

spirit of conflict and self-surrender comes

into the Scandinavian myths and heroic tales.

We read of one of the gods' messengers, who,

when implored to desist from an undertaking because

danger threatened, replied, "For one day

was my age decreed and my whole life determined."

In a lay of Odin, it says, "We ourselves

die, but the fair fame never dies of him who

has earned it;" and this reminds us of the

Scandinavian custom of engraving the records of

their warlike deeds upon their shields. "When a

young warrior was at first enlisted," it is said,

"they gave him a white and smooth buckler,

which was called the 'shield of expectation,'

which he carried until he had earned its record."

It is related of one of the celebrated Jomsburg

sea-rovers called Bui, that finding himself defeated

in an engagement, and seeing that all further

resistance was fruitless, he took his treasure—two

chests full of gold—and, calling out "Overboard

all Bui's men," plunged into the sea and perished.

But better far is the following:—"A warrior

having been thrown upon his back in wrestling

with his enemy, and the latter finding himself

without arms, the vanquished person promised to

wait without changing his posture while the other

fetched a sword to kill him, and he faithfully

kept his word."

Such traits as these lie on the light side of the

Northern character, pity that the other side is such a

dark one. Craft, avarice, cruelty—we cannot shut

our eyes to them—cropping up everywhere, in the

stories of the gods, and still more frequently in the

sagas whose details are sometimes most revolting.

Amongst other stories, we have one of a young sea-rover,

called Sigurd, by-the-bye, a son of that very

Bui mentioned above. Sigurd and his companions

had been taken prisoners, and were condemned to

be beheaded. They were all seated on a log of wood,

and one after another had his head struck off, whilst

king Hakon their capturer looked on; the account

says, that he came out after breakfast to watch the

execution. The sea-rovers all met their fate with

unflinching courage, and as the executioner asked

each one, before he struck the blow, what he thought

of death, each gave some fierce mocking answer;

but when it came to Sigurd's turn, and he was asked

what he thought of death, he answered, "I fear not

death, since I have fulfilled the greatest duty of life,

but I must pray thee not to let my hair be touched

by a slave, or stained with my blood." The story

tells us he had long fair hair, as fine as silk,

flowing in ringlets over his shoulders. One of the

cruel king Hakon's followers, being moved, it

seems, either with pity for Sigurd's hair or admiration

of his courage, stept forward and held the ringlets

whilst the executioner struck, upon which Sigurd

twitched his head forward so strongly that the warrior

who was holding his hair had both his hands cut off,

"and this practical joke so pleased the king's son,"

continues the tale, "that he gave Sigurd his life."

"Thou tellest me many wonderful things," said

Gangler; "what are the names of the Homesteads

in heaven?" In answer, Har tells him about Odin's

halls, and Thor's, and Baldur's, and Frigga's, and

many another bounteous, wide-spreading, golden-roofed

mansion; amongst them of Valhalla, which Odin had

prepared especially for warriors who fell in battle

and who were thenceforth to be his sons, called

Einherjar, heroes, champions. "Methinks," said

Gangler, "there must be a great crowd in Valhalla,

and often a great press at the door among such a

number of people constantly thronging in and out."

"Why not ask," says Har, "how many doors there

are?—

"Five hundred doors

And forty eke

I think are in Valhall.

"But what does Odin give the warriors to eat?"

asked Gangler. "The flesh of the good boar Sæhrimnir,

and this is more than enough (though few know

how much is required for heroes), for in spite of its

being eaten every day it becomes whole again every

night; truly it is the best of flesh." "And what have

the heroes to drink?" asked Gangler "for they must

require a plentiful supply; do they drink only water?"

"A silly question that," replied Har; "dost thou

imagine that Allfather would invite kings and jarls

and other great men and give them nothing to drink

but water? In that case the heroes would think

they had paid dearly to get to Valhall, enduring

great hardships and receiving deadly wounds; they

would find they had paid too great a price for water

drink. No, no, the case is quite otherwise, in

Valhall there is a famous goat that supplies mead

enough for all the heroes and to spare." "Mighty

things these," said Gangler; "but how do the heroes

amuse themselves when they are not drinking?"

"Every day they ride into the court and fight till

they cut each other in pieces, this is their pastime;

but when meal-tide approaches they return to drink

in Valhall." "Odin is great and mighty," answered

Gangler, "as it is said in one of the Æsir's own

poems,—

"The ash Yggdrasill

Is the first of Trees,

As Skidbladnir of ships,

Odin of Æsir

Sleipnir of steeds,

Bifrost of bridges,

Bragi of Bards,

Habrok of hawks

And Garm of hounds is."

"But do all the dead go to Valhalla?" No; down

below in Niflheim there was another home of the

dead which was ruled over by the underworld

goddess Hela, and called after her Helheim. Coldness

and discomfort, according to one account,

were rather its characteristics than actual suffering;

and as all the dead were said to go there who died

of sickness or old age, it was probably at one time

regarded more as a place of misfortune than of

punishment. The cold, hidden-away condition of

the dead, separated from the bright, warm life of

the upper world, would naturally suggest their being

consigned to the keeping of some under-world deity,

unless, indeed, they could lay claim to a second higher

life by virtue of any great warlike deed done up

here. By degrees misfortune must have deepened

into suffering; and, as the moral sense quickened,

the idea would arise of there being a retribution for

misdeeds done on earth as well as an emptiness of

its missed glories. There is a description given of

some place of punishment—it is not quite clear what

place it refers to—in these words,—

"A hall standing

Far from the sun

In Nastrond,

Its doors turn northward,

Venom drops fall

Through its apertures;

The Hall is twined

With serpents' backs.

There she saw wading,

Through sluggish streams,

Bloodthirsty men

And perjurers;

There Nidhög sucks

The corpse of the dead

The wolf tears men—

Understand ye yet, or what?"

"Now," says Har; that was when he had finished

his description of Ragnarök, "If thou, Gangler, hast

any more questions to ask, I know not who can

answer thee, for I never heard tell of any one who

could relate what will happen in the other ages of

the world." "Upon which," the story says, "Gangler

heard a terrible noise all round him; he looked

everywhere, but could see neither palace, nor city,

nor any thing save a vast plain. He therefore set

out on his return home." And so disappears king

Gylfi.

But we, who are not so presumptuous as to enquire

into the future of the ages, and are neither learned

nor over inquisitive like king Gylfi, will go on

listening to the great-grandmothers' stories, giant

stories and god stories—a little bit that one remembers,

and a little bit that another remembers, and so

on; and all the time we will try to make the story

tellers clear to one another and to ourselves as they

go on, translating their old fashioned words into our

own common every day words and modes of speech,

so that we may have at least a chance of understanding

them.

CHAPTER I.

THE ÆSIR.

PART I. A GIANT—A COW—AND A HERO.

In the beginning of ages there lived a cow, whose

breath was sweet, and whose milk was bitter. This

cow was called Audhumla, and she lived all by

herself on a frosty, misty plain, where there was

nothing to be seen but heaps of snow and ice

piled strangely over one another. Far away to the

north it was night, far away to the south it was

day; but all around where Audhumla lay a cold,

grey twilight reigned. By-and-by a giant came out

of the dark north, and lay down upon the ice near

Audhumla. "You must let me drink of your milk,"

said the giant to the cow; and though her milk

was bitter, he liked it well, and for him it was

certainly good enough.

After a little while the cow looked all round her

for something to eat, and she saw a very few grains

of salt sprinkled over the ice; so she licked the

salt, and breathed with her sweet breath, and then

long golden locks rose out of the ice, and the

southern day shone upon them, which made them

look bright and glittering.

The giant frowned when he saw the glitter of the

golden hair; but Audhumla licked the pure salt

again, and a head of a man rose out of the ice.

The head was more handsome than could be

described, and a wonderful light beamed out of

its clear blue eyes. The giant frowned still more

when he saw the head; but Audhumla licked the

salt a third time, and then an entire man arose—a

hero majestic in strength and marvellous in beauty.

Now, it happened that when the giant looked

full in the face of that beautiful man, he hated him

with his whole heart, and, what was still worse, he

took a terrible oath, by all the snows of Ginnungagap,

that he would never cease fighting until either

he or Bur, the hero, should lie dead upon the

ground. And he kept his vow; he did not cease

fighting until Bur had fallen beneath his cruel blows.

I cannot tell how it could be that one so wicked

should be able to conquer one so majestic and so

beautiful; but so it was, and afterwards, when the

sons of the hero began to grow up, the giant and

his sons fought against them, too, and were very

near conquering them many times.

But there was of the sons of the heroes one of

very great strength and wisdom, called Odin, who,

after many combats, did at last slay the great old

giant, and pierced his body through with his keen

spear, so that the blood swelled forth in a mighty

torrent, broad and deep, and all the hideous giant

brood were drowned in it excepting one, who ran

away panting and afraid.

After this Odin called round him his sons, brothers,

and cousins, and spoke to them thus: "Heroes,

we have won a great victory; our enemies are dead,

or have run away from us. We cannot stay any

longer here, where there is nothing evil for us to

fight against."

The heroes looked round them at the words of

Odin. North, south, east, and west there was no

one to fight against them anywhere, and they called

out with one voice, "It is well spoken, Odin; we

follow you."

"Southward," answered Odin, "heat lies, and

northward night. From the dim east the sun

begins his journey westward home."

"Westward home!" shouted they all; and westward

they went.

Odin rode in the midst of them, and they all paid

to him reverence and homage as to a king and

father. On his right hand rode Thor, Odin's strong,

warlike, eldest son. On his left hand rode Baldur,

the most beautiful and exalted of his children; for

the very light of the sun itself shone forth from his

pure and noble brow. After him came Tyr the

Brave; the Silent Vidar; Hödur, who, alas! was

born blind; Hermod, the Flying Word; Bragi,

Hœnir, and many more mighty lords and heroes;

and then came a shell chariot, in which sat Frigga,

the wife of Odin, with all her daughters, friends,

and tirewomen.

Eleven months they journeyed westward, enlivening

the way with cheerful songs and conversation,

and at the twelfth new moon they pitched their

tents upon a range of hills which stood near the

borders of an inland sea. The greater part of one

night they were disturbed by mysterious whisperings,

which appeared to proceed from the sea-coast,

and creep up the mountain side; but as Tyr, who

got up half a dozen times, and ran furiously about

among the gorse and bushes, always returned

saying that he could see no one, Frigga and her

maidens at length resigned themselves to sleep,

though they certainly trembled and started a good

deal at intervals. Odin lay awake all night, however;

for he felt certain that something unusual

was going to happen. And such proved to be the

case; for in the morning, before the tents were

struck, a most terrific hurricane levelled the poles,

and tore in pieces the damask coverings, swept

from over the water furiously up the mountain

gorges, round the base of the hills, and up again

all along their steep sides right in the faces of the

heroes.

Thor swung himself backwards and forwards, and

threw stones in every possible direction. Tyr sat

down on the top of a precipice, and defied the winds

to displace him; whilst Baldur vainly endeavoured

to comfort his poor mother, Frigga. But Odin

stepped forth calm and unruffled, spread his arms

towards the sky, and called out to the spirits of the

wind, "Cease, strange Vanir (for that was the name

by which they were called), cease your rough play,

and tell us in what manner we have offended you that

you serve us thus."

The winds laughed in a whispered chorus at the

words of the brave king, and, after a few low titterings,

sank into silence. But each sound in dying

grew into a shape: one by one the strange, loose-limbed,

uncertain forms stepped forth from caves,

from gorges, dropped from the tree tops, or rose

out of the grass—each wind-gust a separate Van.

Then Niörd, their leader, stood forward from the

rest of them, and said, "We know, O mighty Odin

how you and your company are truly the Æsir—that

is to say, the lords of the whole earth—since you

slew the huge, wicked giant. We, too, are lords,

not of the earth, but of the sea and air, and we

thought to have had glorious sport in fighting one

against another; but if such be not your pleasure,

let us, instead of that, shake hands." And, as he

spoke, Niörd held out his long, cold hand, which

was like a windbag to the touch. Odin grasped

it heartily, as did all the Æsir; for they liked the

appearance of the good-natured, gusty chief, whom

they begged to become one of their company, and

live henceforth with them.

To this Niörd consented, whistled good-bye to

his kinsfolk, and strode cheerfully along amongst

his new friends. After this they journeyed on

and on steadily westward until they reached the

summit of a lofty mountain, called the Meeting

Hill. There they all sat round in a circle, and

took a general survey of the surrounding neighbourhood.

As they sat talking together Baldur looked up

suddenly, and said, "Is it not strange, Father Odin,

that we do not find any traces of that giant who

fled from us, and who escaped drowning in his

father's blood?"

"Perhaps he has fallen into Niflheim, and so

perished," remarked Thor.

But Niörd pointed northward, where the troubled

ocean rolled, and said, "Yonder, beyond that sea,

lies the snowy region of Jötunheim. It is there

the giant lives, and builds cities and castles, and

brings up his children—a more hideous brood even

than the old one."

"How do you know that, Niörd?" asked Odin.

"I have seen him many times," answered Niörd,

"both before I came to live with you, and also

since then, at night, when I have not been able to

sleep, and have made little journeys to Jötunheim,

to pass the time away."

"This is indeed terrible news," said Frigga;

"for the giants will come again out of Jötunheim

and devastate the earth."

"Not so," answered Odin, "not so, my dear

Frigga; for here, upon this very hill, we will build

for ourselves a city, from which we will keep guard

over the poor earth, with its weak men and women,

and from whence we will go forth to make war

upon Jötunheim."

"That is remarkably well said, Father Odin,"

observed Thor, laughing amidst his red beard.

Tyr shouted, and Vidar smiled, but said nothing;

and then all the Æsir set to work with their

whole strength and industry to build for themselves

a glorious city on the summit of the mountain.

For days, and weeks, and months, and years they

worked, and never wearied; so strong a purpose

was in them, so determined and powerful were they

to fulfil it. Even Frigga and her ladies did not

disdain to fetch stones in their marble wheelbarrows,

or to draw water from the well in golden

buckets, and then, with delicate hands, to mix the

mortar upon silver plates. And so that city rose by

beautiful degrees, stone above stone, tower above

tower, height above height, until it crowned the hill.

Then all the Æsir stood at a little distance, and

looked at it, and sighed from their great happiness.

Towering at a giddy height in the centre of

the city rose Odin's seat, called Air Throne, from

whence he could see over the whole earth. On

one side of Air Throne stood the Palace of Friends,

where Frigga was to live; on the other rose the

glittering Gladsheim, a palace roofed entirely with

golden shields, and whose great hall, Valhalla, had

a ceiling covered with spears, benches spread with

coats of mail, and five hundred and forty entrance-gates,

through each of which eight hundred men

might ride abreast. There was also a large iron

smithy, situated on the eastern side of the city,

where the Æsir might forge their arms and shape

their armour. That night they all supped in

Valhalla, and drank to the health of their strong,

new home, "The City of Asgard," as Bragi, their

chief orator, said it ought to be called.

PART II. AIR THRONE, THE DWARFS, AND THE LIGHT ELVES.

In the morning Odin mounted Air Throne, and

looked over the whole earth, whilst the Æsir

stood all round waiting to hear what he thought

about it.

"The earth is very beautiful," said Odin, from

the top of his throne, "very beautiful in every

part, even to the shores of the dark North Sea;

but, alas! the men of the earth are puny and

fearful. At this moment I see a three-headed

giant striding out of Jötunheim. He throws a

shepherd-boy into the sea, and puts the whole of

the flock into his pocket. Now he takes them out

again one by one, and cracks their bones as if

they were hazel-nuts, whilst, all the time, men

look on, and do nothing."

"Father," cried Thor in a rage, "last night I

forged for myself a belt, a glove, and a hammer,

with which three things I will go forth alone to

Jötunheim."

Thor went, and Odin looked again.

"The men of the earth are idle and stupid,"

said Odin. "There are dwarfs and elves, who live

amongst them, and play tricks which they cannot

understand, and do not know how to prevent. At

this moment I see a husbandman sowing grains of

wheat in the furrows, whilst a dwarf runs after

him, and changes them into stones. Again, I see

two hideous little beings, who are holding under

water the head of one, the wisest of men, until he

dies; they mix his blood with honey; they have

put it into three stone jars, and hidden it

away."

Then Odin was very angry with the dwarfs, for

he saw that they were bent on mischief; so he

called to him Hermod, his Flying Word, and

despatched him with a message to the dwarfs and

light elves, to say that Odin sent his compliments,

and would be glad to speak with them, in his palace

of Gladsheim, upon a matter of some importance.

When they received Hermod's summons the

dwarfs and light elves were very much surprised,

not quite knowing whether to feel honoured or

afraid. However, they put on their pertest manners,

and went clustering after Hermod like a

swarm of ladybirds.

When they were arrived in the great city they

found Odin descended from his throne, and sitting

with the rest of the Æsir in the Judgment Hall

of Gladsheim. Hermod flew in, saluted his master,

and pointed to the dwarfs and elves hanging like

a cloud in the doorway to show that he had fulfilled

his mission. Then Odin beckoned the little people

to come forward. Cowering and whispering they

peeped over one another's shoulders; now running

on a little way into the hall, now back again, half

curious, half afraid; and it was not until Odin had

beckoned three times that they finally reached his

footstool. Then Odin spoke to them in calm, low,

serious tones about the wickedness of their mischievous

propensities. Some, the very worst of

them, only laughed in a forward, hardened manner;

but a great many looked up surprised and a little

pleased at the novelty of serious words; whilst the

light elves all wept, for they were tender-hearted

little things. At length Odin spoke to the two

dwarfs by name whom he had seen drowning the

wise man. "Whose blood was it," he asked,

"that you mixed with honey and put into jars?"

"Oh," said the dwarfs, jumping up into the air,

and clapping their hands, "that was Kvasir's blood.

Don't you know who Kvasir was? He sprang up

out of the peace made between the Vanir and yourselves,

and has been wandering about these seven

years or more; so wise he was that men thought

he must be a god. Well, just now we found him

lying in a meadow drowned in his own wisdom; so

we mixed his blood with honey, and put it into

three great jars to keep. Was not that well done,

Odin?"

"Well done!" answered Odin. "Well done!

You cruel, cowardly, lying dwarfs! I myself saw

you kill him. For shame! for shame!" and then

Odin proceeded to pass sentence upon them all.

Those who had been the most wicked, he said,

were to live, henceforth, a long way underground,

and were to spend their time in throwing fuel upon

the great earth's central fire; whilst those who had

only been mischievous were to work in the gold

and diamond mines, fashioning precious stones and

metals. They might all come up at night, Odin

said; but must vanish at the dawn. Then he

waved his hand, and the dwarfs turned round,

shrilly chattering, scampered down the palace-steps,

out of the city, over the green fields, to their unknown,

deep-buried earth-homes. But the light

elves still lingered, with upturned, tearful, smiling

faces, like sunshiny morning dew.

"And you," said Odin, looking them through

and through with his serious eyes, "and you——"

"Oh! indeed, Odin," interrupted they, speaking

all together in quick, uncertain tones; "Oh! indeed,

Odin, we are not so very wicked. We have never

done anybody any harm."

"Have you ever done anybody any good?"

asked Odin.

"Oh! no, indeed," answered the light elves,

"we have never done anything at all."

"You may go, then," said Odin, "to live

amongst the flowers, and play with the wild bees

and summer insects. You must, however, find

something to do, or you will get to be mischievous

like the dwarfs."

"If only we had any one to teach us," said the

light elves, "for we are such foolish little people."

Odin looked round inquiringly upon the Æsir;

but amongst them there was no teacher found for

the silly little elves. Then he turned to Niörd,

who nodded his head good-naturedly, and said,

"Yes, yes, I will see about it;" and then he strode

out of the Judgment Hall, right away through the

city gates, and sat down upon the mountain's

edge.

After awhile he began to whistle in a most

alarming manner, louder and louder, in strong

wild gusts, now advancing, now retreating; then

he dropped his voice a little, lower and lower,

until it became a bird-like whistle—low, soft, enticing

music, like a spirit's call; and far away

from the south a little fluttering answer came,

sweet as the invitation itself, nearer and nearer

until the two sounds dropped into one another.

Then through the clear sky two forms came

floating, wonderfully fair—a brother and sister—their

beautiful arms twined round one another,

their golden hair bathed in sunlight, and supported

by the wind.

"My son and daughter," said Niörd, proudly,

to the surrounding Æsir, "Frey and Freyja,

Summer and Beauty, hand in hand."

When Frey and Freyja dropped upon the hill

Niörd took his son by the hand, led him gracefully

to the foot of the throne, and said, "Look

here, dear brother Lord, what a fair young instructor

I have brought for your pretty little elves."

Odin was very much pleased with the appearance

of Frey; but, before constituting him king and

schoolmaster of the light elves, he desired to know

what his accomplishments were, and what he considered

himself competent to teach.

"I am the genius of clouds and sunshine,"

answered Frey; and as he spoke, the essences of

a hundred perfumes were exhaled from his breath.

"I am the genius of clouds and sunshine, and if

the light elves will have me for their king I can

teach them how to burst the folded buds, to set

the blossoms, to pour sweetness into the swelling

fruit, to lead the bees through the honey-passages

of the flowers, to make the single ear a stalk of

wheat, to hatch birds' eggs, and teach the little

ones to sing—all this, and much more," said Frey,

"I know, and will teach them."

Then answered Odin, "It is well;" and Frey

took his scholars away with him to Alfheim, which

is in every beautiful place under the sun.

PART III. NIFLHEIM.

Now, in the city of Asgard dwelt one called Loki,

who, though amongst the Æsir, was not of the Æsir,

but utterly unlike to them; for to do the wrong, and

leave the right undone, was, night and day, this wicked

Loki's one unwearied aim. How he came amongst

the Æsir no one knew, nor even whence he came.

Once, when Odin questioned him on the subject,

Loki stoutly declared that there had been a time

when he was innocent and noble-purposed like the

Æsir themselves; but that, after many wanderings

up and down the earth, it had been his misfortune,

Loki said, to discover the half-burnt heart of a

woman; "since when," continued he, "I became

what you now see me, Odin." As this was too

fearful a story for any one to wish to hear twice

over Odin never questioned him again.

Whilst the Æsir were building their city, Loki,

instead of helping them, had been continually running

over to Jötunheim to make friends amongst

the giants and wicked witches of the place. Now,

amongst the witches there was one so fearful to

behold in her sin and her cruelty, that one would

have thought it impossible even for such an one

as Loki to find any pleasure in her companionship:

nevertheless, so it was that he married her, and

they lived together a long time, making each

other worse and worse out of the abundance of

their own wicked hearts, and bringing up their

three children to be the plague, dread, and misery

of mankind. These three children were just what

they might have been expected to be from their

parentage and education. The eldest was Jörmungand,

a monstrous serpent; the second Fenrir,

most ferocious of wolves; the third was Hela, half

corpse, half queen. When Loki and his witch-wife

looked at their fearful progeny they thought

within themselves, "What would the Æsir say if

they could see?" "But they cannot see," said

Loki; "and, lest they should suspect Witch-wife, I

will go back to Asgard for a little while, and salute

old Father Odin bravely, as if I had no secret

here." So saying, Loki wished his wife good-morning,

bade her hide the children securely in-doors,

and set forth on the road to Asgard.

But all the time he was travelling Loki's children

went on growing, and long before he had reached

the lofty city Jörmungand had become so large,

that his mother was obliged to open the door to

let his tail out. At first it hung only a little way

across the road; but he grew, Oh, how fearfully

Jörmungand grew! Whether it was from sudden

exposure to the air, I do not know; but, in a single

day he grew from one end of Jötunheim to the

other, and early next morning began to shoot out

in the direction of Asgard. Luckily, however, just

at that moment Odin caught sight of him, when,

from the top of Air Throne, the eyes of this vigilant

ruler were taking their morning walk. "Now,"

said Odin, "it is quite clear, Frigga, that I must

remain in idleness no longer at Asgard, for monsters

are bred up in Jötunheim, and the earth has need

of me." So saying, descending instantly from

Air Throne, Odin went forth of Asgard's golden

gates to tread the earth of common men, fighting

to pierce through Jötunheim, and slay its

monstrous sins.

In his journeyings Odin mixed freely with the

people of the countries through which he passed;

shared with them toil and pleasure, war and grief;

taught them out of his own large experience, inspired

them with his noble thoughts, and exalted

them by his example. Even to the oldest he could

teach much; and in the evening, when the labours

of the day were ended, and the sun cast slanting

rays upon the village green, it was pleasant to

see the sturdy village youths grouped round that

noble chief, hanging open mouthed upon his words,

as he told them of his great fight with the

giant of long ago, and then pointing towards

Jötunheim, explained to them how that fight was

not yet over, for that giants and monsters grew

round them on every side, and they, too, might

do battle bravely, and be heroes and Æsir of

the earth.

One evening, after thus drinking in his burning

words they all trooped together to the village

smithy, and Odin forged for them all night arms

and armour, instructing them, at the same time,

in their use. In the morning he said, "Farewell,

children; I have further to go than you can come;

but do not forget me when I am gone, nor how

to fight as I have taught you. Never cease to be

true and brave; never turn your arms against one

another; and never turn them away from the giant

and the oppressor."

Then the villagers returned to their homes and

their field-labour, and Odin pressed on, through

trackless uninhabited woods, up silent mountains,

over the lonely ocean, until he reached that strange,

mysterious meeting-place of sea and sky. There,

brooding over the waters like a grey sea fog, sat

Mimer, guardian of the well where wit and wisdom

lie hidden.

"Mimer," said Odin, going up to him boldly,

"let me drink of the waters of wisdom."

"Truly, Odin," answered Mimer, "it is a great

treasure that you seek, and one which many have

sought before, but who, when they knew the price

of it, turned back."

Then replied Odin, "I would give my right

hand for wisdom willingly."

"Nay," rejoined the remorseless Mimer, "it is

not your right hand, but your right eye you must

give."

Odin was very sorry when he heard the words

of Mimer, and yet he did not deem the price too

great; for plucking out his right eye, and casting

it from him, he received in return a draught of

the fathomless deep. As Odin gave back the horn

into Mimer's hand he felt as if there were a

fountain of wisdom springing up within him—an

inward light; for which you may be sure he never

grudged having given his perishable eye. Now,

also, he knew what it was necessary for him to do

in order to become a really noble Asa,[1] and that

was to push on to the extreme edge of the earth

itself, and peep over into Niflheim. Odin knew

it was precisely that he must do; and precisely

that he did. Onward and northward he went over

ice-bound seas, through twilight, fog, and snow,

right onward in the face of winds that were like

swords until he came into the unknown land, where

sobs, and sighs, and sad, unfinished shapes were

drifting up and down. "Then," said Odin, thoughtfully,

"I have come to the end of all creation,

and a little further on Niflheim must lie."

Accordingly he pushed on further and further

until he reached the earth's extremest edge, where,

lying down and leaning over from its last cold peak,

he looked into the gulf below. It was Niflheim. At

first Odin imagined that it was only empty darkness;

but, after hanging there three nights and

days, his eye fell on one of Yggdrasil's mighty

stems. Yggdrasil was the old earth-tree, whose

roots sprang far and wide, from Jötunheim, from

above, and this, the oldest of the three, out of

Niflheim. Odin looked long upon its time-worn,

knotted fibres, and watched how they were for ever

gnawed by Nidhögg the envious serpent, and his

brood of poisonous diseases. Then he wondered

what he should see next; and one by one spectres

arose from Naströnd, the Shore of Corpses—arose

and wandered pale, naked, nameless, and without

a home. Then Odin looked down deeper into the

abyss of abysses, and saw all its shapeless, nameless

ills; whilst far below him, deeper than Naströnd,

Yggdrasil, and Nidhögg, roared Hvergelmir,

the boiling cauldron of evil. Nine nights and days

this brave wise Asa hung over Niflheim pondering.

More brave and more wise he turned away from

it than when he came. It is true that he sighed

often on his road thence to Jötunheim; but is it

not always thus that wisdom and strength come

to us weeping.

PART IV. THE CHILDREN OF LOKI.

When, at length, Odin found himself in the land of

giants—frost giants, mountain giants, three-headed

and wolf-headed giants, monsters and iron witches

of every kind—he walked straight on, without

stopping to fight with any one of them, until he

came to the middle of Jörmungand's body. Then

he seized the monster, growing fearfully as he

was all the time, and threw him headlong into

the deep ocean. There Jörmungand still grew,

until, encircling the whole earth, he found that

his tail was growing down his throat, after which

he lay quite still, binding himself together;

and neither Odin nor any one else has been

able to move him thence. When Odin had thus

disposed of Jörmungand, henceforth called the

Midgard Serpent, he went on to the house of

Loki's wife. The door was thrown open, and the

wicked Witch-mother sat in the entrance, whilst on

one side crouched Fenrir, her ferocious wolf-son,

and on the other stood Hela, most terrible of

monsters and women. A crowd of giants strode

after Odin, curious to obtain a glance of Loki's

strange children before they should be sent away.

At Fenrir and the Witch-mother they stared with

great eyes, joyfully and savagely glittering; but

when he looked at Hela each giant became as

pale as new snow, and cold with terror as a mountain

of ice. Pale, cold, frozen, they never moved again;

but a rugged chain of rocks stood behind Odin, and

he looked on fearless and unchilled.

"Strange daughter of Loki," he said, speaking to

Hela, "you have the head of a queen, proud forehead,

and large, imperial eyes; but your heart is

pulseless, and your cruel arms kill what they

embrace. Without doubt you have somewhere a

kingdom; not where the sun shines, and men

breathe the free air, but down below in infinite

depths, where bodiless spirits wander, and the cast-off

corpses are cold."

Then Odin pointed downwards towards Niflheim,

and Hela sank right through the earth, downward,

downward, to that abyss of abysses, where she

ruled over spectres, and made for herself a home

called Helheim, nine lengthy kingdoms wide and

deep.

After this, Odin desired Fenrir to follow him,

promising that if he became tractable and obedient,

and exchanged his ferocity for courage, he should

not be banished as his brother and sister had been.

So Fenrir followed, and Odin led the way out of

Jötunheim, across the ocean, over the earth, until

he came to the heavenly hills, which held up the

southern sky tenderly in their glittering arms.

There, half on the mountain-top and half in air,

sat Heimdall, guardian of the tremulous bridge

Bifröst, that arches from earth to heaven.

Heimdall was a tall, white Van, with golden teeth,

and a wonderful horn, called the Giallar Horn, which

he generally kept hidden under the tree Yggdrasil;

but when he blew it the sound went out into all

worlds.

Now, Odin had never been introduced to Heimdall—had

never even seen him before; but he

did not pass him by without speaking on that

account. On the contrary, being altogether much

struck by his appearance, he could not refrain

from asking him a few questions. First, he requested

to know whom he had the pleasure of

addressing; secondly, who his parents were, and

what his education had been; and thirdly, how

he explained his present circumstances and occupation.

"My name is Heimdall," answered the guardian

of Bifröst, "and the son of nine sisters am I.

Born in the beginning of time, at the boundaries

of the earth, I was fed on the strength of the earth

and the cold sea. My training, moreover, was so

perfect, that I now need no more sleep than a

bird. I can see for a hundred miles around me

as well by night as by day; I can hear the grass

growing and the wool on the backs of sheep. I

can blow mightily my horn Giallar, and I for ever

guard the tremulous bridge-head against monsters,

giants, iron witches, and dwarfs."

Then asked Odin, gravely, "Is it also forbidden to

the Æsir to pass this way, Heimdall? Must you

guard Bifröst, also, against them?"

"Assuredly not," answered Heimdall. "All

Æsir and heroes are free to tread its trembling,

many-coloured pavement, and they will do well to

tread it, for above the arch's summit I know that

the Urda fountain springs; rises, and falls, in a

perpetual glitter, and by its sacred waters the

Nornir dwell—those three mysterious, mighty

maidens, through whose cold fingers run the golden

threads of Time."

"Enough, Heimdall," answered Odin. "Tomorrow

we will come."

PART V. BIFRÖST, URDA, AND THE NORNS.

Odin departed from Heimdall, and went on his

way, Fenrir obediently following, though not now

much noticed by his captor, who pondered over the

new wonders of which he had heard. "Bifröst,

Urda, and the Norns—what can they mean?"

Thus pondering and wondering he went, ascended

Asgard's Hill, walked through the golden

gates of the City into the palace of Gladsheim, and

into the hall Valhalla, where, just then, the Æsir

and Asyniur[2] were assembled at their evening meal.

Odin sat down to the table without speaking, and,

still absent and meditative, proceeded to carve the

great boar, Sæhrimnir, which every evening eaten,

was every morning whole again. No one thought of

disturbing him by asking any questions, for they

saw that something was on his mind, and the Æsir

were well-bred. It is probable, therefore, that the

supper would have been concluded in perfect

silence if Fenrir had not poked his nose in at the

doorway, just opposite to the seat of the lovely

Freyja. She, genius of beauty as she was, and

who had never in her whole life seen even the

shadow of a wolf, covered her face with her hands,

and screamed a little, which caused all the Æsir

to start and turn round, in order to see what was

the matter. But Odin directed a reproving glance

at the ill-mannered Fenrir, and then gave orders

that the wolf should be fed; "after which," concluded

he, "I will relate my adventures to the

assembled Æsir."

"That is all very well, Asa Odin," answered

Frey; "but who, let me ask, is to undertake the

office of feeding yon hideous and unmannerly

animal?"

"That will I, joyfully," cried Tyr, who liked

nothing better than an adventure; and then, seizing

a plate of meat from the table, he ran out of the

hall, followed by Fenrir, who howled, and sniffed,

and jumped up at him in a most impatient, un-Æsir-like

manner.

After the wolf was gone Freyja looked up again,

and when Tyr was seated once more, Odin began.

He told them of everything that he had seen, and

done, and suffered; and, at last, of Heimdall, that

strange white Van, who sat upon the heavenly

hills, and spoke of Bifröst, and Urda, and the

Norns. The Æsir were very silent whilst Odin

spoke to them, and were deeply and strangely

moved by this conclusion to his discourse.

"The Norns," repeated Frigga, "the Fountain

of Urd, the golden threads of time! Let us go,

my children," she said, rising from the table, "let

us go and look at these things."

But Odin advised that they should wait until

the next day, as the journey to Bifröst and

back again could easily be accomplished in a

single morning.

Accordingly, the next day the Æsir and Asyniur all

rose with the sun, and prepared to set forth. Niörd

came from Noatun, the mild sea-coast, which he had

made his home, and with continual gentle puffings

out of his wide, breezy mouth, he made their

journey to Bifröst so easy and pleasant, that they

all felt a little sorry when they caught the first

glitter of Heimdall's golden teeth. But Heimdall

was glad to see them; glad, at least, for their

sakes. He thought it would be so good for them

to go and see the Norns. As far as he himself

was concerned he never felt dull alone. On the top

of those bright hills how many meditations he had!

Looking far and wide over the earth how much he

saw and heard!

"Come already!" said Heimdall to the Æsir,

stretching out his long, white hands to welcome

them; "come already! Ah! this is Niörd's doing.

How do you do, cousin," said he; for Niörd and

Heimdall were related.

"How sweet and fresh it is up here!" remarked

Frigga, looking all round, and feeling that it would

be polite to say something. "You are very happy,

Sir," continued she, "in having always such fine

scenery about you, and in being the guardian of

such a bridge."

And in truth Frigga might well say "such a

bridge;" for the like of it was never seen on the

ground. Trembling and glittering it swung across

the sky, up from the top of the mountain to

the clouds, and down again into the distant sea.

"Bifröst! Bifröst!" exclaimed the Æsir, wonderingly;

and Heimdall was pleased at their surprise.

"At the arch's highest point," said he, pointing

upward, "rises that fountain of which I spoke.

Do you wish to see it to-day?"

"That do we, indeed," cried all the Æsir in a

breath. "Quick, Heimdall, and unlock the bridge's

golden gate."

Then Heimdall took all his keys out, and fitted

them into the diamond lock till he found the right

one, and the gate flew open with a sound at the