MASTERPIECES IN COLOUR

EDITED BY—T.

LEMAN HARE

GIOVANNI BELLINI

In the Same Series

|

| Artist. | Author. |

| VELAZQUEZ. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| REYNOLDS. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| TURNER. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| ROMNEY. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| GREUZE. | Alys Eyre Macklin. |

| BOTTICELLI. | Henry B. Binns. |

| ROSSETTI. | Lucien Pissaro. |

| BELLINI. | George Hay. |

| FRA ANGELICO. | James Mason. |

| REMBRANDT. | Josef Israels. |

| LEIGHTON. | A. Lys Baldry. |

| RAPHAEL. | Paul G. Konody. |

| HOLMAN HUNT. | Mary E. Coleridge. |

| TITIAN. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| MILLAIS. | A. Lys Baldry. |

| CARLO DOLCI. | George Hay. |

| GAINSBOROUGH. | Max Rothschild. |

| TINTORETTO. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| LUINI. | James Mason. |

| FRANZ HALS. | Edgcumbe Staley. |

| VAN DYCK. | Percy M. Turner. |

| LEONARDO DA VINCI. | M. W. Brockwell. |

| RUBENS. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| WHISTLER. | T. Martin Wood. |

| HOLBEIN. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| BURNE-JONES. | A. Lys Baldry. |

| VIGÉE LE BRUN. | C. Haldane MacFall. |

| CHARDIN. | Paul G. Konody. |

| FRAGONARD. | C. Haldane MacFall. |

In Preparation |

| J. F. MILLET. | Percy M. Turner. |

| MEMLINC. W. H. | James Weale. |

| ALBERT DÜRER. | Herbert Furst. |

| CONSTABLE. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| RAEBURN. | James L. Caw. |

| BOUCHER. | C. Haldane MacFall. |

| WATTEAU. | C. Lewis Hind. |

| MURILLO. | S. L. Bensusan. |

| JOHN S. SARGENT, R.A. | T. Martin Wood. |

And Others. |

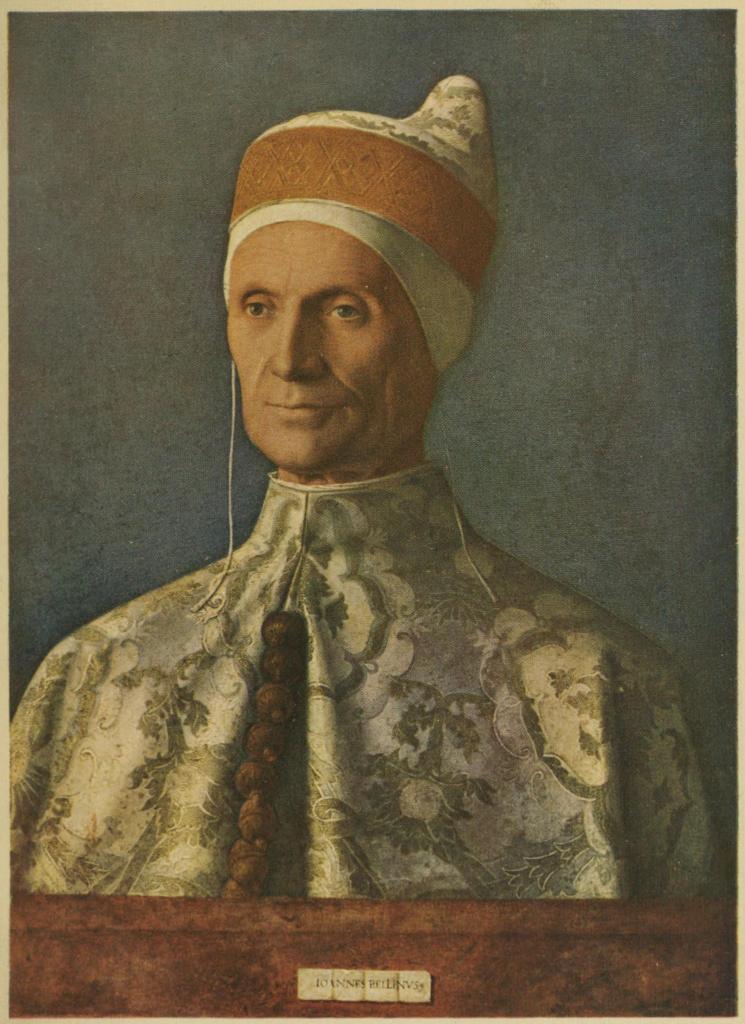

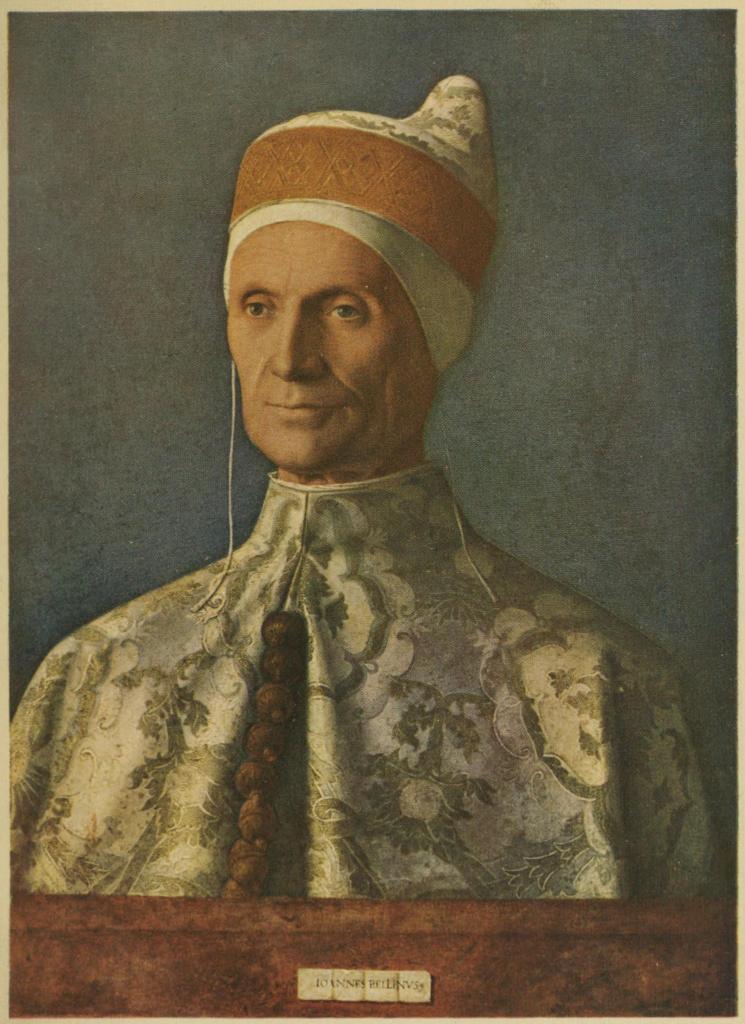

PLATE I.—VIRGIN AND CHILD. (Frontispiece)

This picture is interesting, apart from its fine colour and

drawing, on account of the landscape background. It will be

remembered that Bellini was one of the first artists to introduce

landscape into his pictures of the Virgin. In the Academy at

Venice.

BELLINI

BY GEORGE HAY

ILLUSTRATED WITH EIGHT

REPRODUCTIONS IN COLOUR

LONDON: T. C. & E. C. JACK

NEW YORK: FREDERICK A. STOKES CO.

[7]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Plate |

| I. | Virgin and Child | Frontispiece |

| In the Academy at Venice |

| | Page |

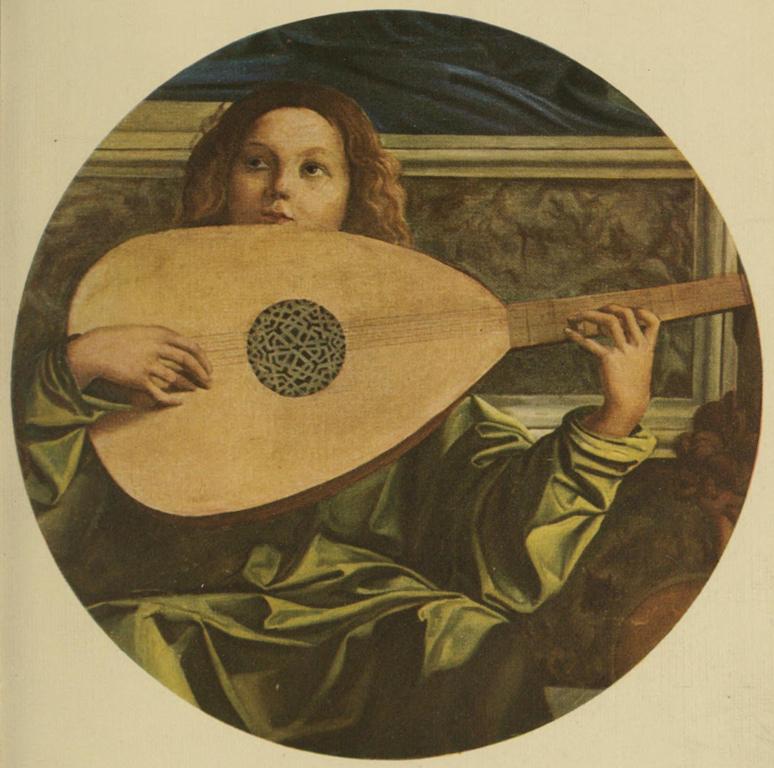

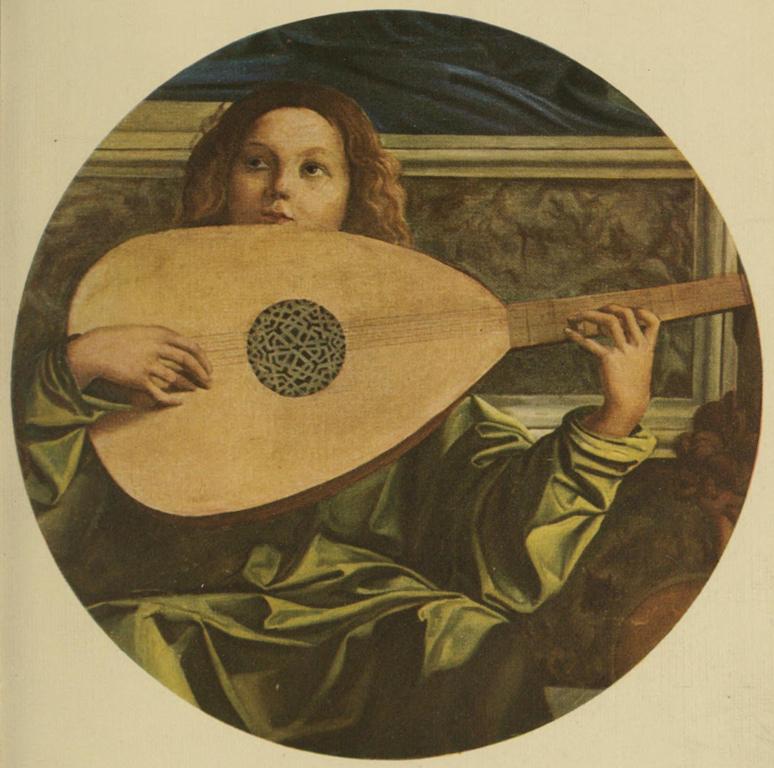

| II. | The Doge Loredano | 14 |

| In the National Gallery, London |

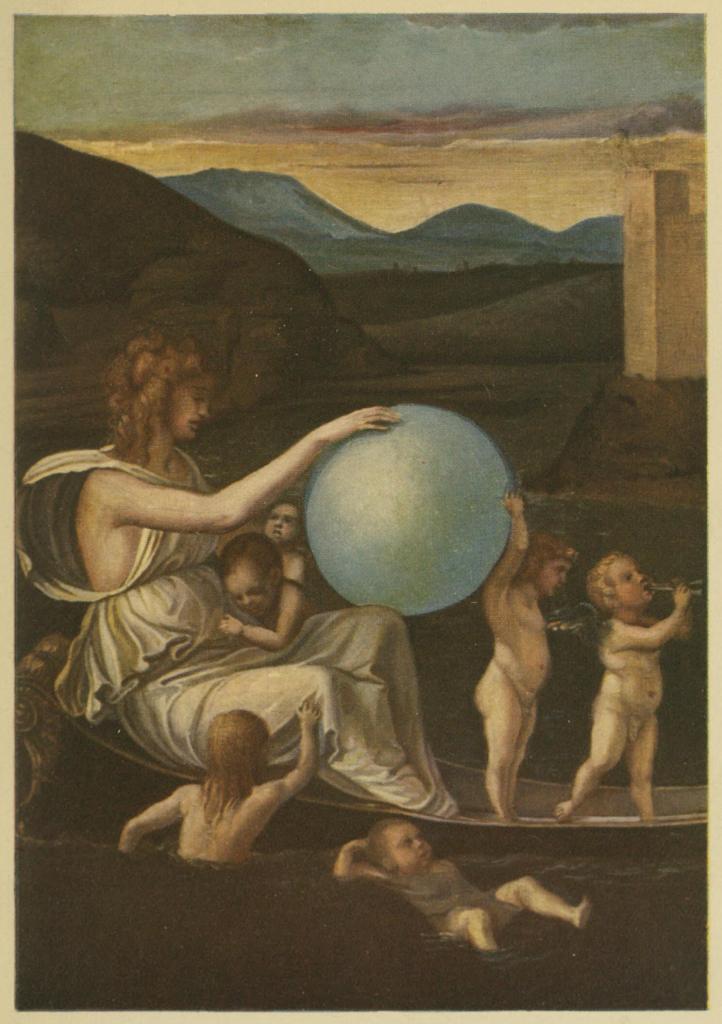

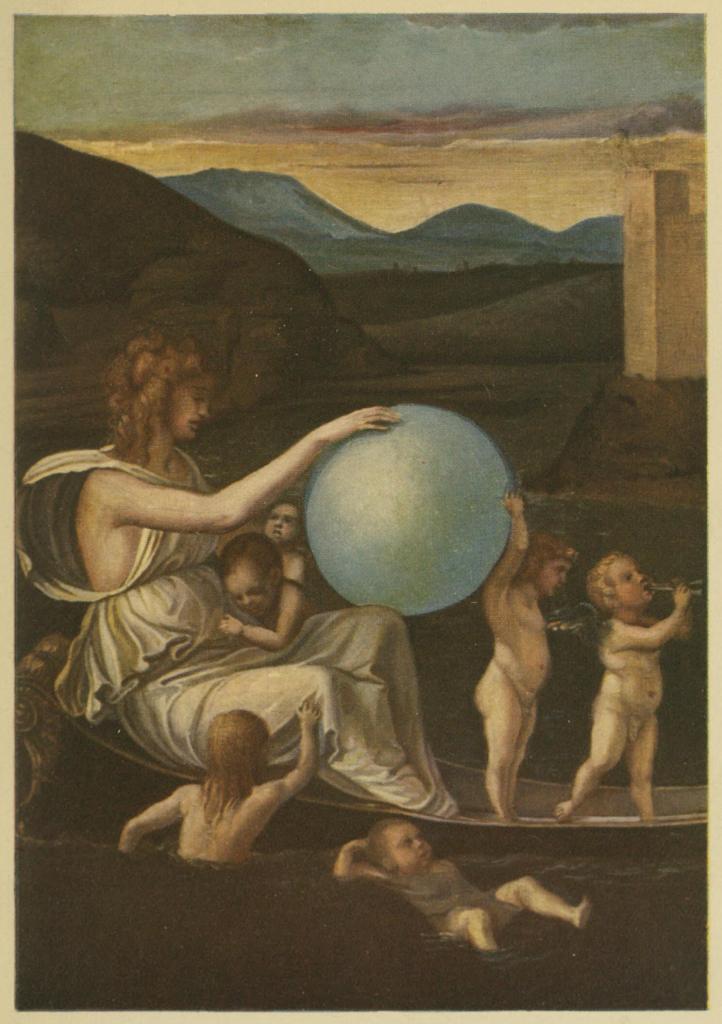

| III. | Angel playing a Lute | 24 |

| In the Academy at Venice |

| IV. | Madonna with the Holy Child Asleep | 34 |

| In the Academy at Venice |

| V. | Pieta | 40 |

| In the Brera Gallery at Milan |

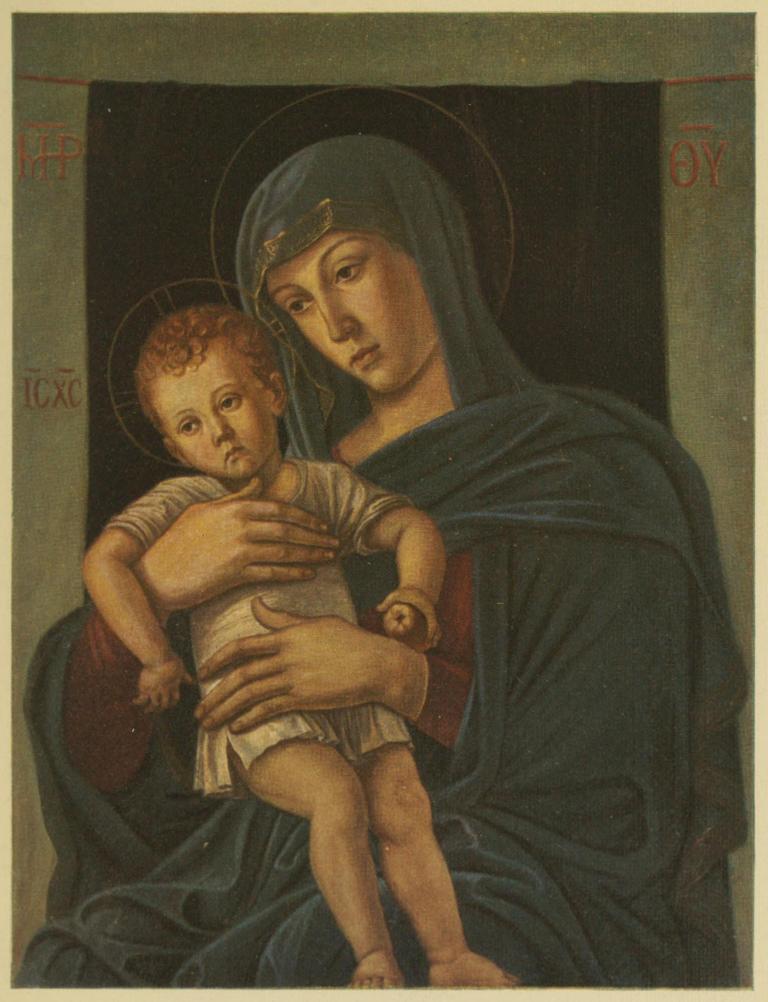

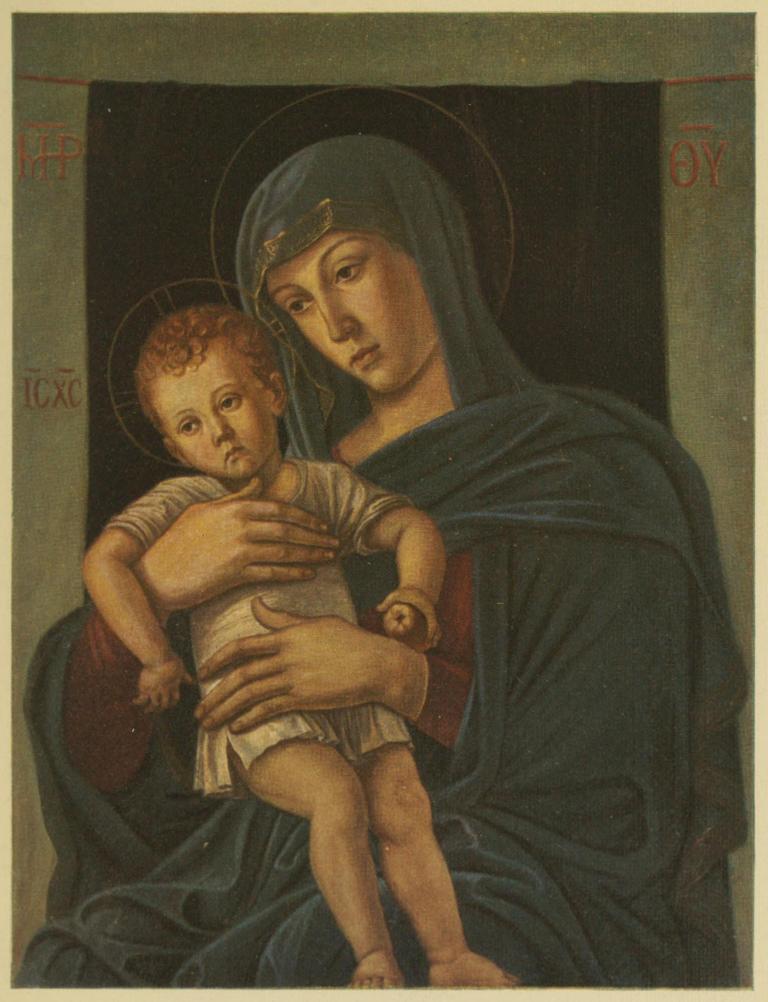

| VI. | Allegory: The Barque of Love | 50 |

| In the Academy at Venice |

| VII. | Madonna and Child | 60 |

| In the Academy at Venice |

| VIII. | Madonna and Child | 70 |

| In the Brera Gallery at Milan |

[8]

[9]

INTRODUCTION

From the standpoint of the biographer,

it is to be regretted that more of the

great Italian artists of the fifteenth century

were not associated with the Church. In

the days of the most interesting activity of

painters and sculptors, the capacity to write[10]

was rarely met beyond the monasteries

and few people took the trouble to record

any impression of notable men in the early

years of their career. We are apt to forget

that, for one artist whose name is preserved

to us to-day, there are a score of men whose

work has perished, whose very names are

forgotten. In middle life, or in old age,

when commissions from Popes or Emperors

had attracted the attention of the world at

large to the best men of the time, there

might be some chronicler found to make

passing but invaluable reference to those

of his contemporaries whose names were

common in men’s mouths, but such notes

were made in very haphazard fashion, they

were not necessarily accurate, and might

be founded upon personal observation or

rumour, or even upon the prejudice that

was inevitable when Italy was a congerie

[11]of opposing states. Latter-day historians

grope painfully and conscientiously after the

scanty records of great painters, searching

the voluminous writings of men who have

little to say, and very little authority for

saying anything about the great personalities

of the art world of their time. It is

not surprising, under these circumstances,

that despite much search the record of

many lives that must have been fascinating

cannot be found. We learn more of the

man from his work than we can hope to

learn from any written record and, as the

taste for studying pictures grows, so all

the internal evidence of a man’s thought

and ways of life accumulates and the

message that underlies canvas and stands

revealed in colour and line to the trained

eye, is translated for the benefit of a

curious generation. We learn to know[12]

what manner of man the painter was from

the models he chose, the portraits he

painted, the qualities and nature of his

landscape, the expression of his joy in

light and air, his feeling for flowers and

birds. By a process of synthetical reasoning

we come to see, though it be as in a

glass, darkly, the picture that every man

paints, from the years of his activity to the

last year of his sojourn among mortals—that

is the portrait of himself. Doubtless

we are often misled, because as each critic,

artist or layman, finds in the picture a reflection

of what he takes there, it remains

difficult to arrive at definite conclusions

upon which all men can agree about any

painter. Happily the effort pleases our own

generation, and as there are many great

men who flourished in the fifteenth century

and have left their pictures to be their sole

[15]

monument, there is no lack of work.

Naturally in this curious and inquisitive

age there are some who would rather discover

a well authenticated story about an

artist’s life than an unexpected masterpiece

from his hand, but then the appeal of

letters is always more widespread than

that of paint. It is always pleasant to

endeavour to supply a want, but it is only

fair to remember that in writing about

people whose life story was not preserved

by their contemporaries, the path is strewn

with pitfalls.

PLATE II.—THE DOGE LOREDANO

This picture, which is of bust length and life size, is one of the

ten examples of Giovanni Bellini in the National Gallery, and is

perhaps the most important example of the artist as a portrait

painter. The Doge wears his state robes and cap of office, and

the picture is signed on a cartellino.

In dealing with the Italians from the days

of Cimabue to Clovio, it has been the custom

to depend very largely upon the works of

Giorgio Vasari, and to rely for later and

more accurate information upon the volumes

written by Crowe and Cavalcaselle, passing

from them to Morelli and Berenson.[16]

Vasari, to whom the students of Italian art,

down to the middle of the sixteenth century,

are so deeply indebted, was born in 1512,

and lived for more than sixty years. He

was a painter and architect, related to

Luca Signorelli, and engaged for a great

part of his life upon work in Arezzo. He

was a great copyist, a painstaking writer,

and never did critic wield a milder pen if

he chanced to be writing of Florentine art,

or a more prejudiced one if he dealt with

things of Venice. He was first a patriot

and then a critic. One night, he tells us,

a friend of Monsignore Giovio expressed a

wish to add to his library a treatise on

men who had distinguished themselves

in the arts of design, from the time of

Cimabue down to the year of the conversation.

Vasari undertook the work and

founded it, he says, upon notes and memo[17]randa

which he had made from the time

when he was a boy. The compilation was

finished about the year 1547, it was written

at a time when the painter was very busy

with commissions. He did his best in a

certain prejudiced fashion, and the result

for all its defects is very valuable. Naturally

enough Vasari had not too large a share

of the gifts required for his task, nor had

he the necessary facts before him for writing

really reliable history. Much that he wrote

was accepted faute de mieux, but modern

researches have necessitated a revision of

very many estimates that Vasari formed

for us, together with a considerable portion

of his facts, and we have learned to understand

something of the source and direction

of his prejudices.

The literary union of Crowe and Cavalcaselle,

who started their joint work in the[18]

latter half of the nineteenth century, with

better equipment of facts and a larger

measure of critical insight, has been far more

valuable, and a complete popular edition of

their work revised by sympathetic and well

qualified writers is greatly to be desired;

but in no case can we regard a volume

devoted to the biographies of scores of

artists as being altogether reliable. The

spirit of study is abroad, to-day men will

devote more time to the life story of a comparatively

obscure artist than they would

have given fifty years ago to half-a-dozen

painters of European reputation. It is not

easy, one might almost say it is not possible,

to tell succinctly the story of men who

have left no clear record and were not regarded

by their contemporaries as fit and

proper subjects for a biography. At best

we can study the available sources of in[19]formation,

and use such measure of judgment

as is in us to construct a reasonable and

likely narrative. To delve in all manner of

likely and unlikely places, to study and

make allowances for the prejudices of the

time, to rely upon the painted canvas to

confirm or confute the printed word—these

are the tasks of the conscientious biographer

who must not be ill content if, after sifting

an intolerable amount of chaff, he can find

a few forgotten grains of corn.

I

GIAN BELLINI’S YOUTH

Giovanni, or Gian Bellini as he is

generally called, the subject of this brief

record and appreciation, is one of the most

fascinating painters of the fifteenth century.[20]

He has left many a lovely picture to the

world, but alas he was no diarist, he had

no Boswell, and there are gaps in the

history of his life that will never be filled

up. In the vast and unexplored region of

Italian archives there may be some facts

that research will bring to light, but at present

we know very little, and can only be

grateful that the story of his life is not

shrouded altogether in the mist that obscures

so much of the personal history of

eminent Venetians in the fifteenth century.

“When zealous efforts are supported by

talent and rectitude, though the beginning

may appear lowly and poor, yet do they

proceed constantly upwards by gradual

steps, never ceasing nor taking rest until

they have finally attained to the summit

of distinction.” In this fashion Giorgio

Vasari, who in those admirable but unre[21]liable

“Lives,” seldom fails to speak kindly

and enthusiastically of artists whom neither

he nor his friends had occasion to dislike,

begins his account of the house of Bellini.

He passes on to deal in detail with Jacopo

Bellini, the father of that Giovanni with

whose life and work it is proposed to deal

briefly in this place. Of the father little is

known, but he is said to have lived in the

shadow of St. Mark’s great Cathedral in

Venice, and to have worked under some of

the Umbrian masters in the Ducal Palace.

He must have served and studied in the

studio of Gentile da Fabriano in days when

Fra Angelico had not reached the Convent

of San Marco; there is evidence, too, that

he travelled and painted portraits. The

date of his death is as uncertain as the

year of his birth. It is said that the new

paganism held more attractions for him[22]

than the old faith, and that the most of

his commissions were from the great and

flourishing secular institutions of the Republic.

Little is left of his pictures, but

a few delightful sketches are preserved in

Paris and London and, but for the larger

fame of his sons, Jacopo Bellini would

doubtless have been forgotten to-day, and

such work as is left would be attributed by

leading critics to different masters.

Gentile Bellini seems to have been born

between 1425 and 1430 and the date of

Giovanni’s birth is not known definitely.

It may be associated with the year 1430.

PLATE III.—ANGEL PLAYING A LUTE

This is a detail from an altar-piece formerly in the Church of

San Giobbé. The work is now in the Academy of Venice.

At this time it must be remembered

that Venice was on the road to her ultimate

decline. Costly wars with Milan and

Florence had seriously damaged the Exchequer,

the fratricidal sea-fights with Genoa

had cost a wealth of human life and treasure

[25]

and, although Venice had annexed nearly a

dozen provinces in half a century, the outlay

had been out of proportion to the results.

At the same time, the Venetians did not

know that their splendid state was on the

downward road. The new route to India

was unknown. Columbus and Diaz had yet

to withdraw the sea-borne commerce of the

world from Venice to Spain, and so bring

about the commercial ruin of the Republic,

and the Republic, with her maritime trade

and her wealth of spoils from the East, could

furnish endless material for the artists who

were rising in her midst. Everywhere there

was colour in abundance, the “Purple East”

cast a broad shadow upon the Adriatic.

Then, again, it is worth remarking that the

Venetian painters did not concern themselves,

as their Florentine brothers did, with

matters lying beyond the scope of their[26]

canvas, they did not dally with architecture

or sculpture in the intervals of picture

painting. In short, pictures represented

the tribute of Venice to the arts, and this

concentration was not without its influence

upon the work done. Literature did not

flourish, because the city reared few literary

men and the tendency of the citizens was

towards pleasure rather than study. All

could admire a picture at a time when few

could read a book, and the spirit of the

Renaissance, fluttering over the Venetian

Republic, had done little more than waken

its people to a sense of the beauty of the

human form. Although in the days when

Gian Bellini was a little boy, the terror of

the Turkish invasion was upon the eastern

end of the Mediterranean, it had hardly

reached Venice or, if it had, only through

the medium of envoys and kings who came[27]

to ask the assistance of the Republic to

keep the Turk from Constantinople. To

these appeals the response of Venice in

those days could not be very efficacious,

but the envoys added a more flamboyant

note to the city’s colouring, and served an

artistic if not a political purpose.

Vasari tells us that Jacopo Bellini painted

his pictures not on wood, but on canvas.

“In Venice,” he writes naïvely, “they do

not paint on panel, or if they do use it

occasionally they take no other wood but

that of the fir, which is most abundant in

that city, being brought along the river

Adige in large quantities from Germany.

It is the custom then in Venice to paint

very much upon canvas, either because

this material does not so readily split, is

not liable to clefts, and does not suffer

from the worm, or because pictures on[28]

canvas may be made of such size as is

desired, and can also be sent whithersoever

the owner pleases, with little cost and

trouble.” Perhaps Vasari overlooked the

effect of sea air upon open frescoed walls,

although that effect was clear enough to

the Venetians. But Jacopo, for all that he

painted upon canvas, and was employed by

some of the leading Venetian guilds, makes

no outstanding figure upon the page of the

art history of Venice. He seems to have

lived prosperously, honourably, and intelligently,

to have caught the earliest possible

reflection of the growing spirit of paganism,

thereby incurring the anger and mistrust

of the Church party that had regarded

painting as the proper intermediary between

faith and the general public, to have

pleased his state employers in Venice and

Padua, and then to have died rather outside[29]

the odour of sanctity, leaving an honourable

name behind him, and children who were

destined to spread its fame far and wide.

Students of Gian Bellini’s life and work

can see that only a part of the father’s

teaching fell upon fruitful soil. Jacopo

Bellini, as we have seen, was a man in

whom the early religious spirit that the

Renaissance did much to cloud over was

of small account, but the pagan revival

that found so many adherents in Florence

and Venice, towards the close of the fifteenth

century, left young Gian Bellini

almost untouched. We shall see that the

commissions offered by wealthy patrons,

who had no love for sacred subjects, were

either rejected, or were accepted and not

fulfilled. It is surely permissible to believe

that the teaching of early days had a

lasting influence upon the outlook of the[30]

two Bellinis, and strengthened them in the

determination to do work that appealed as

much to their heart as to their hand. Certainly

they followed conscience where it led

them. In the case of Gian Bellini, with whom

we are mostly concerned here, it is interesting

to see that his long life, passed as it

was in the very critical time that embraced

the fall of Constantinople and the League

of Cambrai, was completely free from cloud.

His mind was formed very early. He worked

strenuously, carefully, and in the fashion that

pleased his conscience, till within a very

short time of his death, and the serenity of

his spirit, clearly revealed in a series of

exquisite pictures, was untouched by all

that happened in the world around him.

Changes came thick and fast upon Venice

in the years when Bellini was hard at work,

and new ideas were receiving acceptance[31]

on every hand. The Renaissance, with its

revival of pagan thought in the train of

learning, scattered new ideas throughout the

Venetian studios. Bellini’s pupil and successor

Titian could depict pagan goddess

and Christian Deity with equal facility.

Giorgione was travelling along the same

paths when death overtook him, but Gian

Bellini, while he continued to make progress

in his art, refused to make any concession

to the pagan spirit, and with one possible

exception in the case of the Bacchanals, a

picture painted for the Duke of Ferrara,

now in the Alnwick Castle Collection, his

last pictures were as devout in thought and

feeling as the first.

It seems strange, perhaps, to express

doubts about a picture that bears the painter’s

signature, and has been freely accepted as

the work of his hands, but we must not forget[32]

that the fifteenth-century painters in Italy

were the directors of a school as well as

the tenants of a studio. The Bellini and

Vivarini families were at the head of Venetian

painters, and consequently the best students

of the time were attracted to their studios,

content to mix colours, prepare canvases, and

paint the less important parts of a commissioned

picture. After a time they even

painted pictures, and signed them with the

master’s name. We have certain facts in

connection with the Ferrara picture, and

few facts are to be found in the case of any

others. It is on record that Bellini took an

unfinished picture to Ferrara, completed it

under the eye of the Duke, and received

eighty-five ducats for it. The question

becomes whether this is the picture now at

Alnwick that Titian finished, because those

who know it say that the background has

[35]

a landscape of the familiar Titian kind, with

glimpses of Cadore and Pieve, where the

younger painter was born. We are left, then,

with the almost certain knowledge that Titian

painted a part of the “Bacchanal” picture,

and that the other part is opposed in sentiment

to Bellini’s theories of art. So the sceptics

do not lack a measure of justification.

PLATE IV.—MADONNA WITH THE HOLY CHILD ASLEEP

This is one of the most beautiful of the painter’s studies of a

familiar theme, and appeals to the spectator from the literary as

well as the artistic side. The original is in the Venice Academy.

In the latter days of his life Bellini’s

studio became something like a factory, and

there seems very little reason to doubt that

some of his clever pupils like Bondinelli,

Bissolo, Marconi, Catena and others were

allowed to sign, with the master’s name,

“Ioannes Bellinus,” pictures that had no

more than the slightest acquaintance with

the master’s brush. One of the most distinguished

of our modern critics, Mr. Bernhard

Berenson, attended an exhibition of Venetian

pictures held in London a few years ago, and[36]

found that the great majority of the pictures

attributed to Bellini were by his pupils. He

pointed out then that the signature upon

which the unfortunate owners were accustomed

to lean was no better than a broken

reed. Bellini, of course, was not the only

offender in this respect. His great pupil

Titian copied the master’s fault, and there

is on record a letter from Frederic, Duke of

Mantua, asking Titian to send out work that

has his touch as well as his signature. With

these facts before us, it becomes permissible

to doubt whether Bellini, in the last years of

a long life devoted to sacred work, elected

to turn aside, and yield deliberately to the

pagan movement he had opposed so long.

We can find no other work of his hand

that is directly opposed to his theories

of religious art, though it is fair to remember

that he had a very active mind,[37]

and even responded to the influence of his

own great pupils Titian and Giorgione.

II

MIDDLE LIFE

It is not easy to say how far a great

painter reflects his time and how far he

influences it. Tradition and surroundings

must needs count for much, but their exact

value is not easy to estimate. Indeed the

influence of a man is often strongest upon

the generations that succeed to his own, for

no hints are left of the doubts and difficulties

that beset the master. The attitude of

the Venetians towards art in the fifteenth

century, when Gian Bellini started his work,

differed from that of the Florentines by

reason of the splendid isolation of Venice.[38]

The State was a law to herself; she instituted

her own customs, she ruled her

own life. Her wars had less effect than

her commercial victories upon those of her

citizens who turned their thoughts towards

art, the stress and strife beyond her boundaries

left her artists comparatively untouched.

The wider significance of the

Renaissance hardly reached her, her people

were not only pleasure-loving, but self-centred.

Happily, Jacopo Bellini was by

way of being a traveller and his experiences

were not lost upon his children. He knew

Florence and worked in the city at a time

when her great men were beginning to

rise in all their lasting glory, he may have

seen Brunelleschi himself at work upon the

Duomo. He knew Padua, where the tradition

of Giotto was very strong, though that

great master himself had long passed away,

[41]

and so he brought to the art he practised

in his own city something of the technique

of the new movement, as well as the very

definite touch of the pagan sentiment that

was to be developed in all its beauty by his

son’s pupils Titian and Giorgione. The

effect of his travels, limited though they

were, was very lasting, and though Gian

Bellini did not see life as his father had seen

it, his work paved the way for the masters

whose work was in some aspects greater

than his. In his early days Venice had no

very distinctive art. What there was seems

to have been ecclesiastical in thought and

extremely formal in design. It was the appeal

of the clericals to a people who could

neither write nor read, but although a State

may erect boundaries and may devote itself

to the enjoyment of prosperity, those who

care for the claims of art cannot escape[42]

altogether from the forces that are at work

in surrounding cities. One of the chief

forces at work in Northern Italy was the

revival of learning that seems to have

marched side by side with the discovery of

personal beauty. The Church had kept

beauty in the background, the Renaissance

brought it to the canvas of every artist.

Bellini turned the discovery of personal

beauty to the service of the Madonna.

PLATE V.—PIETA

This fine example of the master’s art may be seen at the

Brera Gallery in Milan.

Students of the life of Fra Angelico know

that a Dominican preacher exercised a very

great effect upon the painter’s life, and was

responsible for sending him, at a very early

age, to the great Convent of the Dominicans

at Fiesole. There he was received as a

brother, and from the shelter of the cloister

he gave his art message to the world, his

story being preserved to us at the same

time because the progress of the Dominicans[43]

was recorded. A few years later Giovanni

Bellini, then a boy newly in his teens, would

seem to have fallen under a very similar

influence. He was not fourteen when St.

Bernardino came to Padua and preached

the doctrine of godliness and Jew-baiting

to a people who were not ill-disposed towards

asceticism. In the fifteenth century

a boy of fourteen was a man. The Pope

made Cardinals of lads who were still younger

and many, who have left their names written

large in Italian history, were married when

they were fifteen. Gian Bellini would have

been assisting his father in the decoration

of the Gattemelata Chapel of Padua at

the time and there is no doubt that St.

Bernardino’s addresses impressed him very

deeply. To be sure he did not go into a

religious house after the fashion of Fra

Angelico, but he turned his thoughts towards[44]

religion, and for the rest of his long life his

brush was kept almost exclusively for the

service of sacred art. The tendencies towards

paganism that his father is known

to have shown held no attraction for him.

He sought to express the beauty of the

New Testament stories, and it is hard to

find throughout all Italy an artist whose

achievements in that direction can vie

with his, for Gian Bellini brought sensuous

beauty and rare qualities of emotion to

canvas for the first time in the history of

painting.

In those early days of the middle century

there were two acknowledged leaders of

painting in the world that young Bellini

knew. The first was his father, who is said

to have studied in the studios of Gentile da

Fabriano (1370 to 1450), and that of Pisanello

who was born somewhere about the same[45]

time as da Fabriano, and died a year later.

It is worth noting that Jacopo Bellini called

one of his sons Gentile after his earliest

master, though whether Gentile or Giovanni

was the elder son remains uncertain. Mr.

Roger Fry, who writes with great authority

upon the subject, is of opinion that Gian

may have been a natural son of Jacopo, and

in those days when Popes had “nephews” in

abundance, and the marriage vow was more

honoured in the breach than the observance,

very little stigma attached to illegitimacy.

The other great painter of Gian Bellini’s

time was the Paduan painter Squarcione,

who presided over a large and flourishing

school in his native city, and did work that

was quite as good as that of his contemporaries.

He adopted as his son a lad from

Padua or Mantua named Andrea Mantegna,

who was destined to take such high rank[46]

among the painters of the Venetian

School.

Although Padua and Venice were in a

sense rivals, there seems to have been a

very friendly understanding for many years

between Squarcione and Jacopo Bellini, so

that Gian and Gentile were able to watch

the progress of the Paduan master and his

pupils, and to decide for themselves how

much they would accept, and what they

would reject of the teaching. In early years

these influences must have been of great

value to the painter, but happily they were

not destined to be lasting, for when Gian’s

sister married Andrea Mantegna, Squarcione

quarrelled with his adopted son, and the

intimacy with the Bellini family came to an

end. This is as it should have been in the

best interests of Gian Bellini’s art, for when

he returned to Venice and settled down[47]

there permanently, he was able to follow his

own ideas, and free himself from what was

bad in the influence of the stiff, formal, and

lifeless school of Padua.

Venice must have been a remarkable city

in those years. To-day it stimulates the

imagination as few cities in Europe can do,

then it must have been one of the wonders

of the world. There are some striking

accounts of the city written in the latter

part of the fifteenth century, and though

space does not permit any quotation at

length, one brief paragraph will not be out

of place. Philippe de Comines, envoy of

Charles VIII., came to Venice in 1494, and

recalled his impressions of that city in his

memoirs. “I was taken along the High

Street,” he writes, “they call it the Grand

Canal, and it is very broad, galleys cross it;

and it is the fairest street, I believe, that may[48]

be in the whole world, and fitted with the

best houses; the ancient ones are painted,

and most have a great piece of porphyry

and serpentine on the front. It is the most

triumphant city I have ever seen, and doth

most honour to ambassadors and strangers.

It doth most wisely govern itself,

and the service of God is most solemnly

performed. Though the Venetians have

many faults, I believe God has them in

remembrance for the reverence they pay

in the service of His Church.” This brief

tribute to the charm of Venice is of special

value because it helps us to understand why

the Venetians were not strenuous seekers

after knowledge, why their painters did no

more than paint, and why their response to

the humanities was so small. It explains

the decorative quality of Bellini’s pictures,

the splendour of their colours. Pageantry

[51]

and ceremonial were the great desires of

Venetian life, the man who could add to

the lustre of a State procession along the

splendid water-way of the Grand Canal

was more to them than the scholar who

had written a treatise that moved the more

learned Florentines to admiration. Life was

so full of pleasure, so varied in its appeals,

that the Venetians could not spare time, or

even develop the will to study. They had

raised the old cry “panem et circenses” and,

in the days of Gian Bellini, there was no

lack of either. History is full of records

that reveal other nations in a similar light,

philosophers have drawn the inevitable conclusions—and

the trend of life is no wise

altered.

PLATE VI.—ALLEGORY: THE BARQUE OF LOVE

This is one of a little series of panel pictures by Bellini that

may be seen in the Academy at Venice. The others depict Evil,

Fate, Luxury, and Zeal, and Prudence. This picture is sometimes

called “Venus ruling the World,” but such a title seems rather

foreign to the painter’s own attitude.

Under Bellini, painting lost the conventions

that had been regarded as correct or

inevitable in Squarcione’s studio, and Gian’s[52]

pictures bear the same relation to those of

the Paduan, and his pupil, as Newman’s

writing bears to bad eighteenth-century

English prose. But despite all developments

in the technique of his art, Gian Bellini’s

painting remained quite constant to the

mood that St. Bernardino had induced.

Doubtless, had his gifts been of another kind,

he would have entered the Church, he would

have dreamed dreams and seen visions that

would not have found such world-wide expression

while, being an artist, inheriting

artistic traditions from his father, living in

the centre of the small world of Venetian

and Paduan painters, he expressed his

beautiful emotions in fashion that has not

weakened its claim upon us in more than

four hundred years. The glamour of Venetian

life, the extraordinary beauty of the

city that was his home, the splendour and[53]

the pageants that were part of a Venetian

life, the intensity of the colour that surrounded

him on all sides—some of it belonging

to Venice by right, and even more,

brought to her shores by the ceaseless traffic

of the sea—all these things developed and

deepened the emotion that was to find so

exquisite an expression from his brush. To

him, as to Fra Angelico, faith was a real and

living thing, and like the great monk who

died at ripe age while he was yet a boy,

Gian Bellini became a lover of the world in

its most picturesque aspect, accepting without

hesitation the traditional explanation of

its creation.

Naturally enough his appeal to the artist

is founded upon a dozen considerations,

mostly technical, his appeal to the layman

is direct and spontaneous. A countryman

who has never seen a studio can respond to[54]

the exquisite beauty of Bellini’s Virgins and

Children, can feel the charm of the sunshine

that fills the air and lights sea and land,

can recognise the infinite glamour of the

roads that wind away into the mysterious

distance of the background, can enjoy the

rich, almost sensuous, colouring. Perhaps

had Bellini taken the vows, a great part of

these beauties would have been lost, the

infinite variety of lovely women and children

could hardly have been secured. As a

Venetian, and a pleasure lover, he could

not have responded, as Fra Angelico did,

to the restricted life and rigid discipline

of a religious order.

It was not easy for Gian Bellini to

devote himself entirely to sacred subjects

if he wished to earn a living by his brush,

because his father had stood outside the

Church. In those days, too, the best church[55]work

was in the hands of one family, the

Vivarini, whose monopoly was hardly likely

to be disturbed by an artist who could

show no better credentials than a connection,

legitimate or illegitimate, with a painter

whose feeling was distinctly pagan. Jacopo

Bellini, for all that he was a most admired

artist, had no claims upon the Church, and

does not seem to have received many commissions

from it. Various wealthy societies

in Venice had been accustomed to employ

him to decorate their halls with work that,

as we have said before, has been lost, and

their guilds or scuole would doubtless have

given Gian all the work he wished to do

had he been satisfied to do it.

He could not choose for himself. St.

Bernardino had chosen for him in those

years when his mind was most impressionable.

Gian Bellini’s hand was doubtless[56]

to be seen in Padua where he assisted

his father, and his earliest independent

work is to be found in the Casa Correr

at Venice, where one finds a “Transfiguration,” a

“Crucifixion,” and two “Pietas.”

He painted portraits, one from our own

National Gallery is to be seen here. This is

a picture of the Doge, Leonardo Loredano,

who held office from 1501 to 1521.

The early pictures reveal Bellini at the

parting of the ways. His figures have many

of the defects of the School of Padua. His

knowledge of anatomy is decidedly small,

he lacks confidence in himself, and yet it

is not difficult to recognise that the painter

is moving into a new country, that his

presentation of sacred subjects is developing

on lines that must add considerably to

their artistic value and to the permanence

of their appeal.[57]

An amusing story is told of the way in

which young Bellini acquired his knowledge

of oil painting. He is said to have

assumed the dress of a Venetian nobleman,

and to have gone to the studio of a popular

artist of the time, under pretext of having

his portrait painted. While the artist, one

Antonello of Messina, was busily engaged

upon his portrait, Bellini is said to have

watched the process very carefully and to

have secured the much needed lesson. It is

more than likely that the story is untrue, but

it has obtained a large measure of credence.

His first big altar-piece is said to have

been done for the altar of St. Catherine of

Sienna, and after one or two other church

paintings had been accomplished, Giovanni

was commissioned to decorate the great

Council Hall of Venice with historical

paintings. But it is well to remember that[58]

altar painting never ceased to interest him,

his greatest achievements having been accomplished

for churches. There are few

things in art more beautiful than Gian

Bellini’s altar-pieces. Ruskin has paid a

special tribute to the “Virgin and Four

Saints” in the church dedicated to St.

Zaccaria, father of the Baptist. He says

that the Zaccaria altar-piece, and the one

in the Frari, by the same master, are the

two finest pictures in the world. Of the big

works, however, nothing remains, Gentile

being the only one of the family who is represented

to-day by pictures painted on a very

large scale. Vasari tells us that Gian painted

four pictures in fulfilment of a commission,

one representing the Pope Alexander III.

receiving Frederic Barbarossa after the

abjuration of the Schism of 1177, the next

showing the Pope saying Mass in San Marco,

[61]

another representing his Holiness

in the act of presenting a canopy to the

Doge, and the last in which the Pontiff is

presented with eight standards and eight

silver trumpets by clergy assembled outside

the gates of Rome. These subjects or some

of them had been painted by one Gueriento

of Verona when Marco Corner was Doge.

Petrarch had written the inscriptions for

them, but they had faded, and in later years

Tintoretto painted his “Paradiso” over the

damaged frescoes. There is a story to the

effect that Giovanni and Gentile Bellini had

promised the councillors that their pictures

should last two hundred years; as a matter

of fact, they would seem to have been

destroyed by fire within half that period.

PLATE VII.—MADONNA AND CHILD

This picture shows the centre figures of a very famous painting

by Bellini in the Academy at Venice in which the Madonna and

Child are seen between St. Catherine and St. Mary Magdalen.

The faces most delightfully painted are full of spiritual grace and

the colouring is exquisite.

The style of the picture commissioned

makes its own significant commentary upon

the times. It was always considered advis[62]able

to stir in the Venetians appreciation for

State ceremonial, which encouraged so much

of the pageantry associated with Venetian

life and, even if Giovanni Bellini had no

keen taste for such work, he could not

refuse a commission that would establish

his name among his fellow countrymen.

To-day the Sala del Maggior Consiglio

holds pictures by Titian, Paul Veronese,

and other artists who followed closely upon

Gian Bellini’s era.

III

THE LATTER DAYS

Shortly after the Council Hall pictures

had been undertaken, in 1479, to be exact,

the Sultan, Mohammed II., conqueror of

Constantinople, wished to have his portrait[63]

painted, and applied to the Doge of Venice

to send him a competent artist to do the

work. It should be remembered that the

Sultan had been waging a successful war

upon Venice, and that in January 1479 the

State had ceded Scutari, Stalimene, and

other territory and had agreed to pay an indemnity

of 200,000 ducats, with a tribute of

10,000 ducats a year for trading rights and

the exercise of consular jurisdiction in Constantinople.

Naturally the success of the

Turks, who had taken Constantinople in

1454, was making a very great impression

throughout Europe, and Venice had striven

to the uttermost to rouse the Powers to concerted

action, but in those days nobody was

anxious to trust the Republic. These are

matters, of course, that pertain to history

rather than art, but it is curious to remember

that throughout the times when[64]

the watchers from St. Mark’s Tower saw

the reflected glare of burning cities, when

the security of Christian Europe was

threatened seriously, when plagues were

devastating Venice, Gian Bellini seems to

have gone on his way all undisturbed,

painting his pictures in the most leisurely

fashion, and the fact that art stood right

above politics and strife is clearly shown

in the action of the Sultan in sending to

Venice for a good artist as soon as peace

had been restored. There seems to have

been some question of sending Gian because

his brother was busily engaged on

other work in the Ducal Palace, but after

a while it was decided to send Gentile, who

painted a portrait of the Sultan that found

its way afterwards into the Layard Collection

in Venice. Some surprise has been

expressed that the Sultan should have[65]

allowed any one to paint his portrait, because

portrait painting is forbidden by the

Koran[1], but Mohammed II. was a man of

very advanced ideas and he not only gave

sittings to Gentile Bellini, but treated him

with the greatest favour, dismissing him

with many marks of approval and great

gifts. Among the presents brought back

to Venice by the painter were the armour

and sword of the great Doge Dandolo, who

had been buried in the year 1205 in the

private chapel in St. Sophia. Mohammed II.

had caused the great tomb to be destroyed,

but he sent the great patriot’s armour back

to its native land. Vasari tells us that the

meeting between the brothers on Gentile’s

return to Venice was most affectionate.

This journey to Constantinople would[66]

seem to have added to the reputation of the

house of Bellini, and to have increased the

demand for portraits by both brothers. This,

in its way, would doubtless have led to the

multiplying of school pieces. History has

very little to tell of the progress of the

brothers during the years that followed.

We know that the Doge Loredano, whose

portrait has been painted by Gian Bellini,

succeeded to his high office in 1501, that

Titian would have been working in Bellini’s

studio then, and that Bellini himself was in

the enjoyment of what was known as a

broker’s patent, and was official painter to

the State. His was the duty of painting the

portrait of every Doge who succeeded to the

control of Venetian affairs during his term

of office, and he also painted any historical

picture in which the Doge had to figure.

There was a salary attached to the office,[67]

and the work was quite light. As far as we

can tell Gian Bellini was still averse from

painting secular subjects. He was now an

old man, but he had made great progress in

his work, conquering many of the difficulties

of perspective, shadow, and colouring that

had baffled his predecessors. The pageants

demanded by the great Mutual Aid Societies

(Scuole) from the artists in their employ, he

would seem to have left to his brother

Gentile, for these pictures had a big political

purpose to serve, and they demanded the

travel, the experience, and the mood that

Gian lacked. His brush was sufficiently

occupied with altar-pieces and portraits of

distinguished Venetians, now, alas, lost to

the world.

One incident that is not without its instructive

side in this connection is recorded

in the year 1501, when Isabella, Duchess of[68]

Mantua, sent her agent in Venice to Gian

Bellini to arrange with him to paint a secular

subject. The old painter, now in the neighbourhood

of his seventieth year, accepted

money on account, and then turned his

thoughts to other things. The agent worried

him from time to time with little or no effect,

and wrote despairing letters to the Duchess

to convey Bellini’s various excuses. Not

until 1504, when the Duchess was proposing

to take legal action, was the picture finished,

and then it does not seem to have been what

was required. At the same time it must

have been a work of great merit, because a

year later we find the Duchess commissioning

another picture, and asking for a secular

subject, which the old painter after much

hesitation refused to paint.[69]

PLATE VIII.—MADONNA AND CHILD

This picture is from the Brera Gallery in Milan and is held by

many of the painter’s admirers to be his finest presentment of the

Mother and the Son. It is certainly a work of most enchanting

beauty, one to which the eye turns again and again.

Happily Isabella d’Este was not only a

voluminous letter writer, but her correspondence

[71]

has been preserved, and some forty

letters were written in connection with the

Bellini picture, by the lady whom Cardinal

Bembo called “the wisest and most fortunate

of women,” and of whom a poet wrote,

“At the sound of her name all the Muses

rise and do reverence.” She had seen Bellini’s

work, and had admired it in Venice,

before she asked a friend, one Signor

Vianello, to secure a picture for her camerino.

At first the old painter raised objections,

says Vianello. “I am busy working

for the Signory in the Palace,” he said,

“and I cannot leave my work from early

morning until after dinner.” Then he asked

for 150 ducats and said he would make

time, then he came down to 100 ducats

and accepted 25 on account Then as has

been explained, he declared that he could

not undertake the class of subject that the[72]

Duchess wanted, and Isabella wrote to say

that she would accept anything antique that

had a fine meaning. Vianello writes in reply

to say that Bellini has gone to his country

villa and cannot be reached, and the correspondence

and the years pass, until at last

the Duchess gets quite cross and writes,

“We can no longer endure the villainy of

Giovanni Bellini,” and goes on to instruct

her agent to make application to the Doge,

Leonardo Loredano, the one whose portrait,

painted by Giovanni Bellini, is in our National

Gallery, to commit the old painter for fraud.

To this action Bellini responds by showing

Vianello that he has a “Nativity” three parts

finished, and after a time he sends it to the

Duchess together with a very humble letter

of apology, that the lady is good enough to

accept. She even writes, “Your ‘Nativity’

is as dear to us as any picture we possess.”[73]

In 1506 Albert Dürer was in Venice where

he declares that he found the Venetians

very pleasant companions, and adds with

sly sarcasm that some of them knew how

to paint. At the same time he records his

fear lest any of them should put poison in

his food, but speaks in high terms and

without suspicion of Gian Bellini who had

praised his work and offered to buy a

picture. All these things are small matters

enough, but unhappily the records of

Bellini’s life are so scanty that it is hard

to find anything more until the year 1513

when Gian Bellini, well over eighty, found

his position as official painter challenged by

his pupil Titian, who presented a petition

to the Council of Ten, stating inter alia

that he was desirous of a little fame rather

than of profit, that he had refused to serve

the Pope, and that he wanted the first[74]

broker’s patent that should be vacant in

the Fondaco de’ Tedeschi on the same conditions

as those granted to Messer Zuan

Bellin.[1] The work that was being done

was the restoration of the Great Hall of

the Council, and the painting had been in

progress for some forty years, Gian Bellini

and two pupils being now engaged upon it.

There is no doubt that this application by

Titian annoyed Bellini’s friends and pupils,

and even to us it seems a little unreasonable

and in bad form to clamour so eagerly for

a place that was already occupied. But it

would seem to have been the custom of the

time to apply early for any privilege of this

kind, for we find in later years that Tintoretto

applied for Titian’s place long before

the older master’s capacity for working had

come to an end.

Bellini’s friends were successful, although

it would appear that the old painter’s progress

had been too slow completely to

satisfy the Council of Ten. In the following

year Titian, who had been allowed to start

work, was told that he must wait until older

claims were satisfied, the expenses of his

assistants were disallowed, and his commission

came to an end. In the autumn of

that year Titian brought another petition to

the Council, asking once more for the first

vacant broker’s patent, and mentioning the

fact that Bellini’s days could not be long in

the land. Just about this time the Venetian

authorities seem to have held an inquiry into

the progress of the work that was being

done in the Hall of the Great Council, only

to find that the amount of money they

had spent should have secured them a far

larger amount of work than had been[76]

accomplished. It is hardly surprising that

these inquiries should have become necessary,

there must have been a great laxity

in the State departments in the years following

the working out of the plans that

had been made by France, Austria, Spain,

and the Pope at Cambrai. In the last few

years Venice had been fighting for her life,

Lombardy had passed out of her hands,

Verona, Vicenza, and Padua had followed.

The Republic had even been forced to seek

aid from the Sultans of Turkey and Egypt,

and although Venice was destined to emerge

from her troubles and light the civilised

world a little longer there is small cause

for wonder if, in the times of exceptional

excitement, her statesmen had not given

their wonted attention to the progress of

the arts. Doubtless Gian Bellini’s leisurely

methods and failing strength were account[77]able

for the slow progress of the pictures

in the Council Hall, and Titian took advantage

of the fact to send in a third petition,

offering to finish some work at his own

expense, but he had no occasion to take

much more trouble.

On November 29, 1516, Gian Bellini died,

well on the road to his ninetieth year, “and

there were not wanting in Venice,” says

Vasari, “those who by sonnets and epigrams

sought to do him honour after his

death as he had done honour to himself

and his country during his life.” One cannot

help thinking that half-a-dozen pages

of biography would have been worth a

bushel of sonnets.

With Gian Bellini the last great painter

of purely religious subjects passed away.

He had stood between art and paganism.

Perhaps the younger men found him narrow[78]

and pedantic, but it is certain that so long

as Gian Bellini was the leading painter of

Venice it was not easy for pictures to respond

to the ever growing demands that

followed the Renaissance. Now the road

was clear, painting was to reach its highest

point in the work of Giorgione and Titian,

and was then to decline almost as rapidly

as it had risen.

Gian Bellini for all the wide influence

that he exerted, not only upon contemporary

painting, but upon sculpture too, sent

very little work out of Venice. Examples

are to be seen in cities that are comparatively

close at hand, Rimini, Pesaro,

Vicenza, Bergamo, and Turin, but his

genius seems to have been too completely

recognised in his own city for his work to

travel far afield, and the portrait of himself

in the Uffizi Gallery is no more than a[79]

pupil’s work with a studio signature. One

of his last undisputed paintings was for

the altar of St. Crisostom in Venice. It

is said that he painted it at the age of

eighty-five. After death his fame suffered

by the rise of those stars of Venetian

painting, Titian, Giorgione, and Tintoretto,

and throughout three centuries his work

was held in comparatively small esteem,

perhaps because it was often judged by the

studio pictures with the forged signatures.

As late as the middle of the nineteenth

century nobody seemed quite to know the

real pictures from the false ones, but with

the rise of critics like Crowe, Morelli, and

Berenson a much better state of things

has been established. Copies and student

works have been separated from the originals,

careful study of technique and mannerism

has made clear a large number of[80]

points that were doubtful and in dispute,

and although the process of separating the

sheep from the goats has reduced considerably

the number of works that can be

accepted as genuine, the gain to the artist’s

reputation atones for the loss.

The plates are printed by Bemrose Dalziel, Ltd., Watford

The text at the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh