Title: Scenes and Characters of the Middle Ages

Author: Edward Lewes Cutts

Release date: May 27, 2013 [eBook #42824]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (http://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Scenes and Characters of the Middle Ages, by Edward Lewes Cutts

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/scenescharacters00cuttuoft |

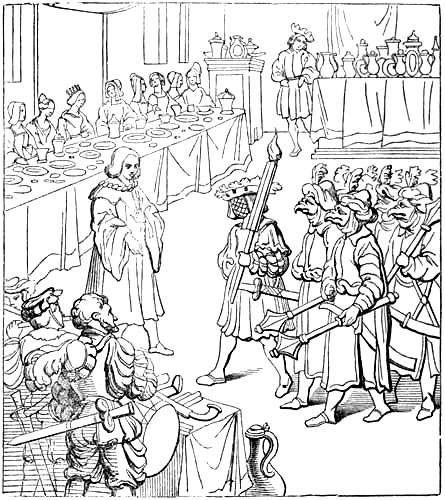

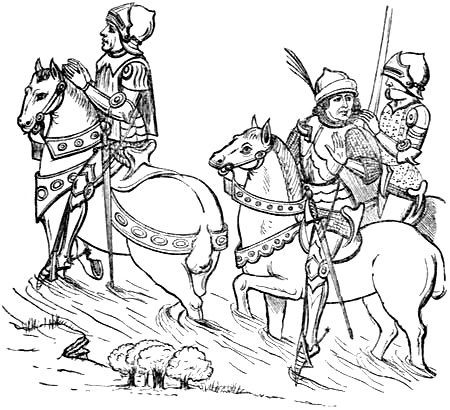

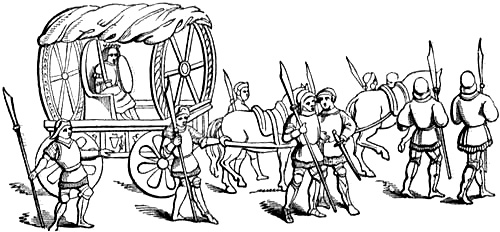

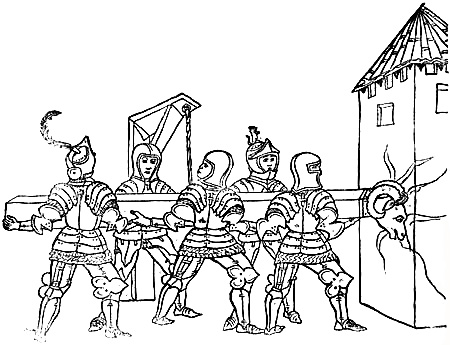

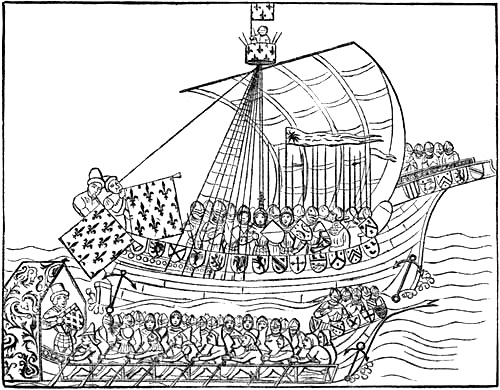

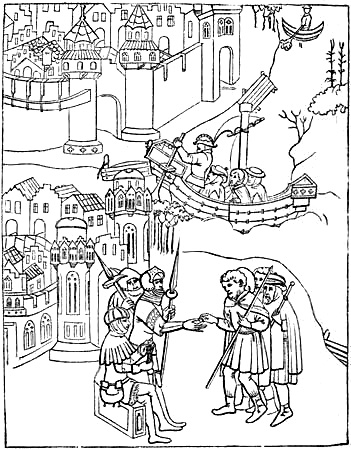

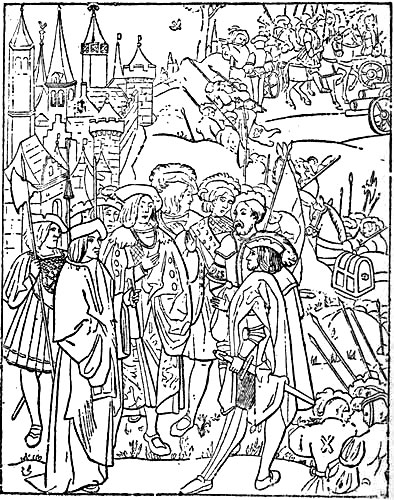

King Henry the Eighth’s Army.

SCENES & CHARACTERS

OF THE MIDDLE AGES

By the Rev. EDWARD L. CUTTS, B.A.

LATE HON. SEC. OF THE ESSEX ARCHÆOLOCICAL SOCIETY

WITH ONE HUNDRED AND EIGHTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS

THIRD EDITION

LONDON: ALEXANDER MORING LIMITED

THE DE LA MORE PRESS 32 GEORGE STREET

HANOVER SQUARE W 1911

| THE MONKS OF THE MIDDLE AGES. | ||

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | The Origin of Monachism | 1 |

| II. | The Benedictine Orders | 6 |

| III. | The Augustinian Order | 18 |

| IV. | The Military Orders | 26 |

| V. | The Orders of Friars | 36 |

| VI. | The Convent | 54 |

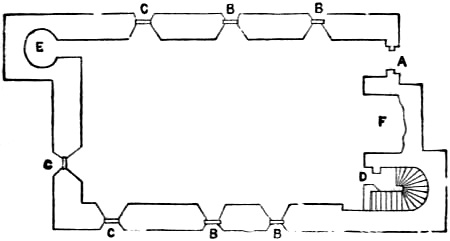

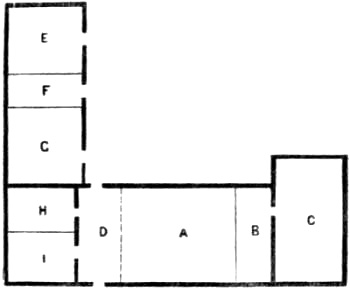

| VII. | The Monastery | 70 |

| THE HERMITS AND RECLUSES OF THE MIDDLE AGES. | ||

| I. | The Hermits | 93 |

| II. | Anchoresses, or Female Recluses | 120 |

| III. | Anchorages | 132 |

| IV. | Consecrated Widows | 152 |

| THE PILGRIMS OF THE MIDDLE AGES. | ||

| I. | Pilgrims | 157 |

| II. | Our Lady of Walsingham and St. Thomas of Canterbury | 176 |

| [Pg viii] | ||

| THE SECULAR CLERGY OF THE MIDDLE AGES. | ||

| I. | The Parochial Clergy | 195 |

| II. | Clerks in Minor Orders | 214 |

| III. | The Parish Priest | 222 |

| IV. | Clerical Costume | 232 |

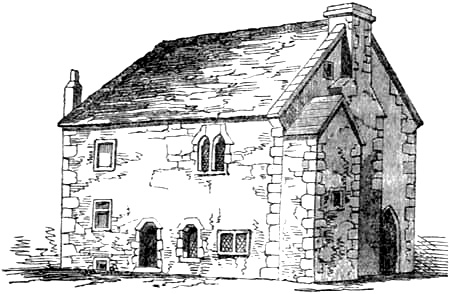

| V. | Parsonage Houses | 252 |

| THE MINSTRELS OF THE MIDDLE AGES. | ||

| I. | 267 | |

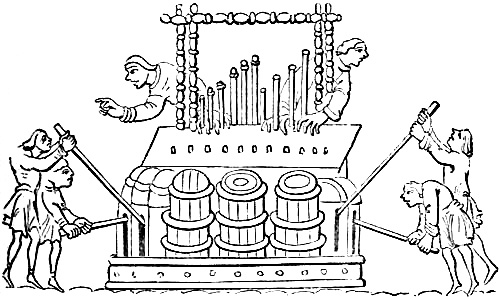

| II. | Sacred Music | 284 |

| III. | Guilds of Minstrels | 298 |

| THE KNIGHTS OF THE MIDDLE AGES. | ||

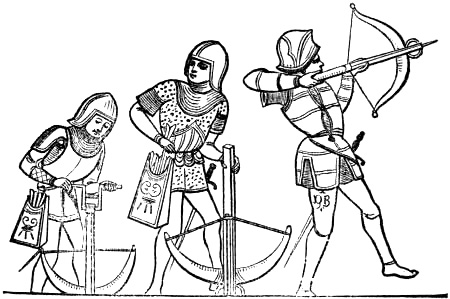

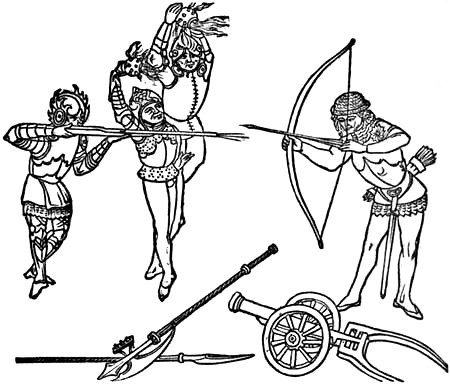

| I. | Saxon Arms and Armour | 311 |

| II. | Arms and Armour, from the Norman Conquest downwards | 326 |

| III. | Armour of the Fourteenth Century | 338 |

| IV. | The Days of Chivalry | 353 |

| V. | Knights-Errant | 369 |

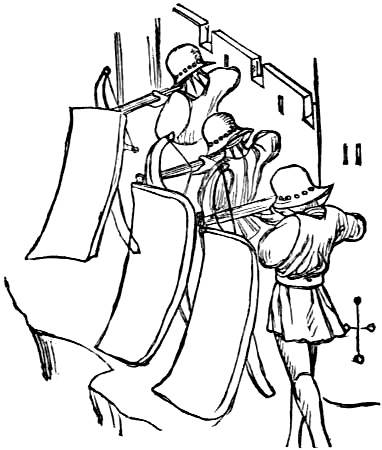

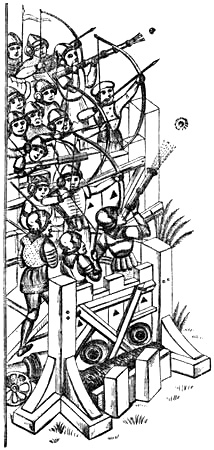

| VI. | Military Engines | 380 |

| VII. | Armour of the Fifteenth Century | 394 |

| VIII. | The Knight’s Education | 406 |

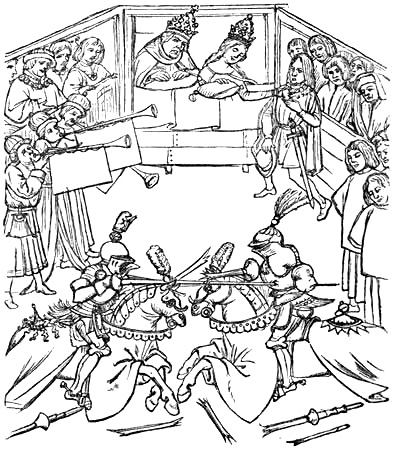

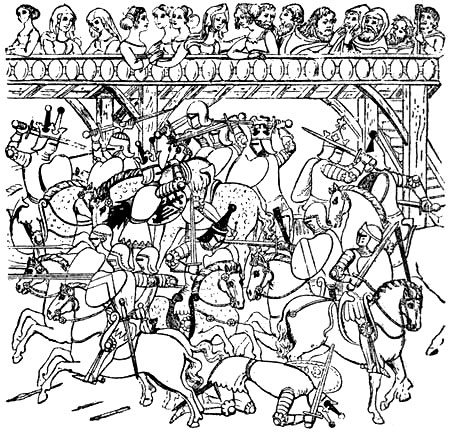

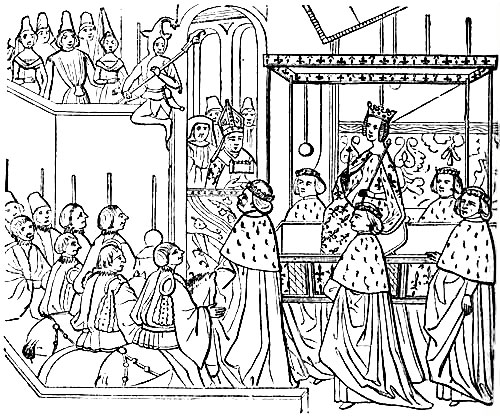

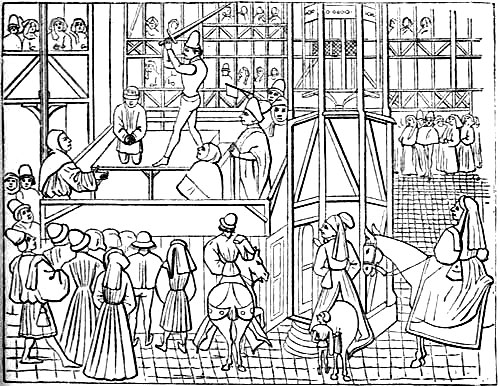

| IX. | On Tournaments | 423 |

| X. | Mediæval Bowmen | 439 |

| XI. | Fifteenth Century and later Armour | 452 |

| THE MERCHANTS OF THE MIDDLE AGES. | ||

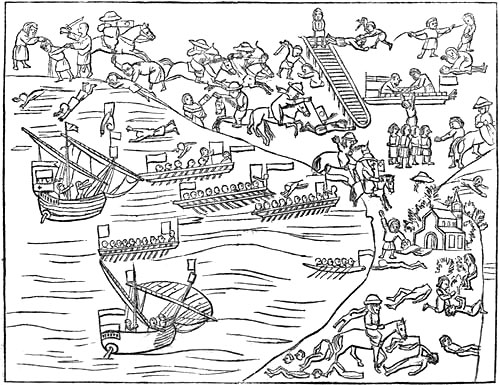

| I. | Beginnings of British Commerce | 461 |

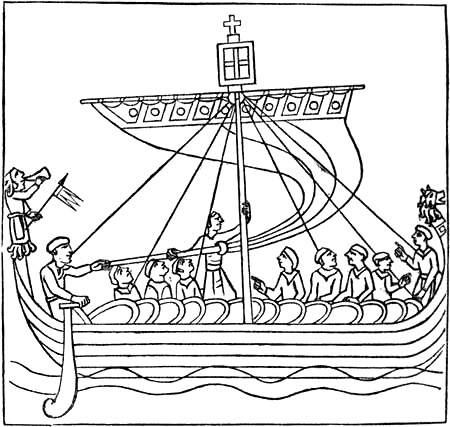

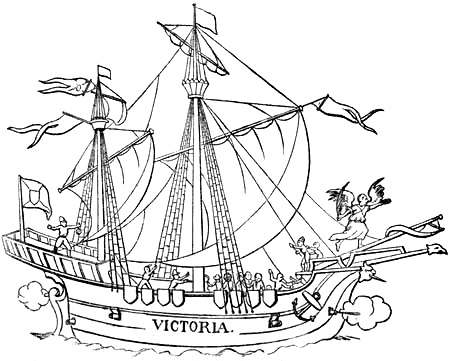

| II. | The Navy | 475 |

| III. | The Social Position of the Mediæval Merchants | 487 |

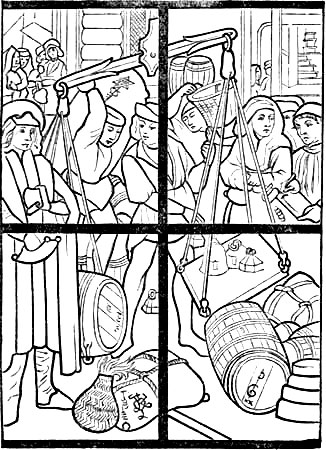

| IV. | Mediæval Trade | 503 |

| V. | Costume | 518 |

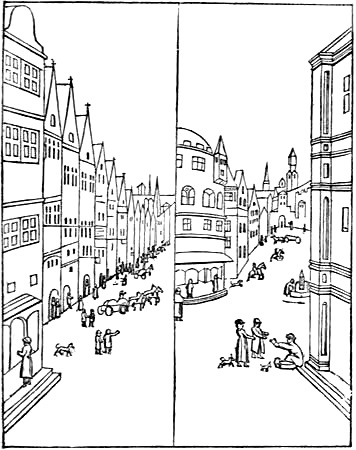

| VI. | Mediæval Towns | 529 |

THE MONKS OF THE MIDDLE AGES.

THE ORIGIN OF MONACHISM.

e do not aim in these chapters at writing general history, or systematic

treatises. Our business is to give a series of sketches of mediæval life

and mediæval characters, looked at especially from the artist’s point of

view. And first we have to do with the monks of the Middle Ages. One

branch of this subject has already been treated in Mrs. Jameson’s “Legends

of the Monastic Orders.” This accomplished lady has very pleasingly

narrated the traditionary histories of the founders and saints of the

orders, which have furnished subjects for the greatest works of mediæval

art; and she has placed monachism before her readers in its noblest and

most poetical aspect. Our humbler task is to give a view of the familiar

daily life of ordinary monks in their monasteries, and of the way in which

they enter into the general life without the cloister;—such a sketch as

an art-student might wish to have who is about to study that picturesque

mediæval period of English history for subjects for his pencil. The

religious orders occupied so important a position in mediæval society,

that they cannot be overlooked by the historical student; and the flowing

black robe and severe intellectual features of the Benedictine monk, or

the coarse frock and sandalled feet of the mendicant friar, are too

characteristic and too effective, in contrast with the gleaming armour[Pg 2]

and richly-coloured and embroidered robes of the sumptuous civil costumes

of the period, to be neglected by the artist. Such an art-student would

desire first to have a general sketch of the whole history of monachism,

as a necessary preliminary to the fuller study of any particular portion

of it. He would wish for a sketch of the internal economy of the cloister;

how the various buildings of a monastery were arranged; and what was the

daily routine of the life of its inmates. He would seek to know under what

circumstances these recluses mingled with the outer world. He would

require accurate particulars of costumes and the like antiquarian details,

that the accessories of his picture might be correct. And, if his monks

are to be anything better than representations of monkish habits hung upon

“lay figures,” he must know what kind of men the Middle Age monks were

intellectually and morally. These particulars we proceed to supply as

fully as the space at our command will permit.

e do not aim in these chapters at writing general history, or systematic

treatises. Our business is to give a series of sketches of mediæval life

and mediæval characters, looked at especially from the artist’s point of

view. And first we have to do with the monks of the Middle Ages. One

branch of this subject has already been treated in Mrs. Jameson’s “Legends

of the Monastic Orders.” This accomplished lady has very pleasingly

narrated the traditionary histories of the founders and saints of the

orders, which have furnished subjects for the greatest works of mediæval

art; and she has placed monachism before her readers in its noblest and

most poetical aspect. Our humbler task is to give a view of the familiar

daily life of ordinary monks in their monasteries, and of the way in which

they enter into the general life without the cloister;—such a sketch as

an art-student might wish to have who is about to study that picturesque

mediæval period of English history for subjects for his pencil. The

religious orders occupied so important a position in mediæval society,

that they cannot be overlooked by the historical student; and the flowing

black robe and severe intellectual features of the Benedictine monk, or

the coarse frock and sandalled feet of the mendicant friar, are too

characteristic and too effective, in contrast with the gleaming armour[Pg 2]

and richly-coloured and embroidered robes of the sumptuous civil costumes

of the period, to be neglected by the artist. Such an art-student would

desire first to have a general sketch of the whole history of monachism,

as a necessary preliminary to the fuller study of any particular portion

of it. He would wish for a sketch of the internal economy of the cloister;

how the various buildings of a monastery were arranged; and what was the

daily routine of the life of its inmates. He would seek to know under what

circumstances these recluses mingled with the outer world. He would

require accurate particulars of costumes and the like antiquarian details,

that the accessories of his picture might be correct. And, if his monks

are to be anything better than representations of monkish habits hung upon

“lay figures,” he must know what kind of men the Middle Age monks were

intellectually and morally. These particulars we proceed to supply as

fully as the space at our command will permit.

Monachism arose in Egypt. As early as the second century we read of men and women who, attracted by the charms of a peaceful, contemplative life, far away from the fierce, sensual, persecuting heathen world, betook themselves to a life of solitary asceticism. The mountainous desert on the east of the Nile valley was their favourite resort; there they lived in little hermitages, rudely piled up of stones, or hollowed out of the mountain side, or in the cells of the ancient Egyptian sepulchres, feeding on pulse and herbs, and water from the neighbouring spring.

One of the frescoes in the Campo Santo, at Pisa, by Pietro Laurati, engraved in Mrs. Jameson’s “Legendary Art,” gives a curious illustration of this phase of the eremitical life. It gives us a panorama of the desert, with the Nile in the foreground, and the rock caverns, and the little hermitages built among the date-palms, and the hermits at their ordinary occupations: here is one angling in the Nile, and another dragging out a net; there is one sitting at the door of his cell shaping wooden spoons. Here, again, we see them engaged in those mystical scenes in which an over-wrought imagination pictured to them the temptations of their senses in visible demon-shapes—beautiful to tempt or terrible to affright; or materialised the spiritual joys of their minds in angelic or divine visions: Anthony driving out with his staff the beautiful demon from his cell, or[Pg 3] rapt in ecstasy beneath the Divine apparition.[1] Such pictures of the early hermits are not infrequent in mediæval art—one, from a fifteenth century MS. Psalter in the British Museum (Domit. A. xvii. f. 4 v), will be found in a subsequent chapter of this book.

We can picture to ourselves how it must have startled the refined Græco-Egyptian world of Alexandria when occasionally some man, long lost to society and forgotten by his friends, reappeared in the streets and squares of the city, with attenuated limbs and mortified countenance, with a dark hair-cloth tunic for his only clothing, with a reputation for exalted sanctity and spiritual wisdom, and vague rumours of supernatural revelations of the unseen world; like another John Baptist sent to preach repentance to the luxurious citizens; or fetched, perhaps, by the Alexandrian bishop to give to the church the weight of his testimony to the ancient truth of some doctrine which began to be questioned in the schools.

Such men, when they returned to the desert, were frequently accompanied by numbers of others, whom the fame of their sanctity and the persuasion of their preaching had induced to adopt the eremitical life. It is not to be wondered at that these new converts should frequently build, or select, their cells in the neighbourhood of that of the teacher whom they had followed into the desert, and should continue to look up to him as their spiritual guide. Gradually, this arrangement became systematised; a number of separate cells, grouped round a common oratory, contained a community of recluses who agreed to certain rules and to the guidance of a chosen head; an enclosure wall was generally built around this group, and the establishment was called a laura.

The transition from this arrangement of a group of anchorites occupying the anchorages of a laura under a spiritual head, to that of a community[Pg 4] living together in one building under the rule of an abbot, was natural and easy. The authorship of this cœnobite system is attributed to St. Anthony, who occupied a ruined castle in the Nile desert, with a community of disciples, in the former half of the fourth century. The cœnobitical institution did not supersede the eremitical; both continued to flourish together in every country of Christendom.[2]

The first written code of laws for the regulation of the lives of these communities was drawn up by Pachomius, a disciple of Anthony’s. Pachomius is said to have peopled the island of Tabenne, in the Nile, with cœnobites, divided into monasteries, each of which had a superior, and a dean to every ten monks; Pachomius himself being the general director of the whole group of monasteries, which are said to have contained eleven hundred monks. The monks of St. Anthony are represented in ancient Greek pictures with a black or brown robe, and often with a tau cross of blue upon the shoulder or breast.

St. Basil, afterwards bishop of Cesaræa, who died A.D. 378, introduced monachism into Asia Minor, whence it spread over the East. He drew up a code of laws founded upon the rule of Pachomius, which was the foundation of all succeeding monastic institutions, and which is still the rule followed by all the monasteries of the Greek Church. The rule of St. Basil enjoins poverty, obedience, and chastity, and self-mortification. The habit both of monks and nuns was, and still is, universally in the Greek Church, a plain, coarse, black frock with a cowl, and a girdle of leather, or cord. The monks went barefooted and barelegged, and wore the Eastern tonsure, in which the hair is shaved in a crescent off the fore part of the head, instead of the Western tonsure, in which it is shaved in a circle off the crown. Hilarion is reputed to have introduced the Basilican institution into Syria; St. Augustine into Africa; St. Martin of Tours into France; St. Patrick into Ireland, in the fifth century.

The early history of the British Church is enveloped in thick obscurity, but it seems to have derived its Christianity (indirectly perhaps) from an Eastern[Pg 5] source, and its monastic system was probably derived from that established in France by St. Martin, the abbot-bishop of Tours. One remarkable feature in it is the constant union of the abbatical and episcopal offices; this conjunction, which was foreign to the usage of the church in general, seems to have obtained all but universally in the British, and subsequently in the English Church. The British monasteries appear to have been very large; Bede tells us that there were no less than two thousand one hundred monks in the monastic establishment of Bangor in the sixth century, and there is reason to believe that the number is not overstated. They appear to have been schools of learning. The vows do not appear to have been perpetual; in the legends of the British saints we constantly find that the monks quitted the cloister without scruple. The legends lead us to imagine that a provost, steward, and deans, were the officers under the abbot; answering, perhaps, to the prior, cellarer, and deans of Benedictine institutions. The abbot-bishop, at least, was sometimes a married man.

THE BENEDICTINE ORDERS.

n the year 529 A.D., St. Benedict, an Italian of noble birth and great

reputation, introduced into his new monastery on Monte Cassino—a hill

between Rome and Naples—a new monastic rule. To the three vows of

obedience, poverty, and chastity, which formed the foundation of most of

the old rules, he added another, that of manual labour (for seven hours a

day), not only for self-support, but also as a duty to God and man.

Another important feature of his rule was that its vows were perpetual.

And his rule lays down a daily routine of monastic life in much greater

detail than the preceding rules appear to have done. The rule of St.

Benedict speedily became popular, the majority of the existing monasteries

embraced it; nearly all new monasteries for centuries afterwards adopted

it; and we are told, in proof of the universality of its acceptation, that

when Charlemagne caused inquiries to be made about the beginning of the

eighth century, no other monastic rule was found existing throughout his

wide dominions. The monasteries of the British Church, however, do not

appear to have embraced the new rule.

n the year 529 A.D., St. Benedict, an Italian of noble birth and great

reputation, introduced into his new monastery on Monte Cassino—a hill

between Rome and Naples—a new monastic rule. To the three vows of

obedience, poverty, and chastity, which formed the foundation of most of

the old rules, he added another, that of manual labour (for seven hours a

day), not only for self-support, but also as a duty to God and man.

Another important feature of his rule was that its vows were perpetual.

And his rule lays down a daily routine of monastic life in much greater

detail than the preceding rules appear to have done. The rule of St.

Benedict speedily became popular, the majority of the existing monasteries

embraced it; nearly all new monasteries for centuries afterwards adopted

it; and we are told, in proof of the universality of its acceptation, that

when Charlemagne caused inquiries to be made about the beginning of the

eighth century, no other monastic rule was found existing throughout his

wide dominions. The monasteries of the British Church, however, do not

appear to have embraced the new rule.

St. Augustine, the apostle of the Anglo-Saxons, was prior of the Benedictine monastery which Gregory the Great had founded upon the Celian Hill, and his forty missionaries were monks of the same house. It cannot be doubted that they would introduce their order into those parts of England over which their influence extended. But a large part of Saxon England owed its Christianity to missionaries of the native church sent forth from the great monastic institution at Iona and afterwards at Lindisfarne, and these would doubtless introduce their own monastic system. We find,[Pg 7] in fact, that no uniform rule was observed by the Saxon monasteries; some seem to have kept the rule of Basil, some the rule of Benedict, and others seem to have modified the ancient rules, so as to adapt them to their own circumstances and wishes. We are not surprised to learn that under such circumstances some of the monasteries were lax in their discipline; from Bede’s accounts we gather that some of them were only convents of secular clerks, bound by certain rules, and performing divine offices daily, but enjoying all the privileges of other clerks, and even sometimes being married. Indeed, in the eighth century the primitive monastic discipline appears to have become very much relaxed, both in the East and West, though the popular admiration and veneration of the monks was not diminished.

In the illuminations of Anglo-Saxon MSS. of the ninth and tenth centuries, we find the habits of the Saxon monks represented of different colours, viz., white, black, dark brown, and grey.[3] In the early MS. Nero C. iv., in the British Museum, at f. 37, occurs a very clearly drawn group of monks in white habits; another group occurs at f. 34, rather more stiffly drawn, in which the margin of the hood and the sleeves is bordered with a narrow edge of ornamental work.

About the middle of the ninth century, however, Archbishop Dunstan reduced all the Saxon monasteries to the rule of St. Benedict; not without opposition on the part of some of them, and not without rather peremptory treatment on his part; and thus the Benedictine rule became universal in the West. The habit of the Benedictines consisted of a white woollen cassock, and over that an ample black gown and a black hood. We give here an excellent representation of a Benedictine monk, from a book which formerly belonged to St. Alban’s Abbey, and now is preserved in the British Museum (Nero D. vii. f. 81). The book is the official catalogue which each monastery kept of those who had been benefactors to the house, and who were thereby entitled to their grateful remembrance and their prayers. In many cases the record of a benefaction is accompanied by an illuminated portrait of the benefactor. In the present case, he is[Pg 8] represented as holding a golden tankard in one hand and an embroidered cloth in the other, gifts which he made to the abbey, and for which he is thus immortalised in their Catalogus Benefactorum. Other illustrations of Benedictine monks, of early fourteenth century date, may be found in the Add. MS. 17,687, at f. 3; again at f. 6, where a Benedictine is preaching; and again at f. 34, where one is preaching to a group of nuns of the same order; and at f. 41, where one is sitting writing at a desk (as in the scriptorium, probably). Yet again in the MS. Royal 20 D. vii., is a picture of St. Benedict preaching to a group of his monks. A considerable number of pictures of Benedictine monks, illustrating a mediæval legend of which they are the subject, occur in the lower margin of the MS. Royal 10 E. iv., which is of late thirteenth or early fourteenth century date. A drawing of Abbot Islip of Westminster, who died A.D. 1532, is given in the “Vetusta Monumenta,” vol. iv. Pl. xvi. In working and travelling they wore over the cossack a black sleeveless tunic of shorter and less ample dimensions.

Benedictine Monk.

The female houses of the order had the same regulations as those of the monks; their costume too was the same, a white under garment, a black gown and black veil, with a white wimple around the face and neck. They had in England, at the dissolution of the monasteries, one hundred and twelve monasteries and seventy-four nunneries.[4] For illustration of an abbess see the fifteenth century MS. Royal 16 F. ii. at f. 137.

The Benedictine rule was all but universal in the West for four centuries; but during this period its observance gradually became relaxed.[Pg 9] We cannot be surprised if it was found that the seven hours of manual labour which the rule required occupied time which might better be devoted to the learned studies for which the Benedictines were then, as they have always been, distinguished. We should have anticipated that the excessive abstinence, and many other of the mechanical observances of the rule, would soon be found to have little real utility when simply enforced by a rule, and not practised willingly for the sake of self-discipline. We are not therefore surprised, nor should we in these days attribute it as a fault, that the obligation to labour appears to have been very generally dispensed with, and some humane and sensible relaxations of the severe ascetic discipline and dietary of the primitive rule to have been very generally adopted. Nor will any one who has any experience of human nature expect otherwise than that among so large a body of men—many of them educated from childhood[5] to the monastic profession—there would be some who were wholly unsuited for it, and some whose vices brought disgrace upon it. The Benedictine monasteries, then, at the time of which we are speaking, had become different from the poor retired communities of self-denying ascetics which they were originally. Their general character was, and continued throughout the Middle Ages to be, that of wealthy and learned bodies; influential from their broad possessions, but still more influential from the fact that nearly all the literature, and art, and science of the period was to be found in their body. They were good[Pg 10] landlords to their tenants, good cultivators of their demesnes; great patrons of architecture, and sculpture, and painting; educators of the people in their schools; healers of the sick in their hospitals; great almsgivers to the poor; freely hospitable to travellers; they continued regular and constant in their religious services; but in housing, clothing, and diet, they lived the life of temperate gentlemen rather than of self-mortifying ascetics. Doubtless, as we have said, in some monasteries there were evil men, whose vices brought disgrace upon their calling; and there were some monasteries in which weak or wicked rulers had allowed the evil to prevail. The quiet, unostentatious, every-day virtues of such monastics as these were not such as to satisfy the enthusiastical seeker after monastical perfection. Nor were they such as to command the admiration of the unthinking and illiterate, who are always more prone to reverence fanaticism than to appreciate the more sober virtues, who are ever inclined to sneer at religious men and religious bodies who have wealth, and are accustomed to attribute to a whole class the vices of its disreputable members.

The popular disrepute into which the monastics had fallen through their increased wealth, and their departure from primitive monastical austerity, led, during the next two centuries, viz., from the beginning of the tenth to the end of the eleventh, to a series of endeavours to revive the primitive discipline. The history of all these attempts is very nearly alike. Some young monk of enthusiastic disposition, disgusted with the laxity or the vices of his brother monks, flies from the monastery, and betakes himself to an eremitical life in a neighbouring forest or wild mountain valley. Gradually a few men of like earnestness assemble round him. He is at length induced to permit himself to be placed at their head as their abbot, requires his followers to observe strictly the ancient rule, and gives them a few other directions of still stricter life. The new community gradually becomes famous for its virtues; the Pope’s sanction is obtained for it; its followers assume a distinctive dress and name; and take their place as a new religious order. This is in brief the history of the successive rise of the Clugniacs, the Carthusians, the Cistercians, and the orders of Camaldoli and Vallombrosa and Grandmont; they all sprang[Pg 11] thus out of the Benedictine order, retaining the rule of Benedict as the groundwork of their several systems. Their departures from the Benedictine rule were comparatively few and trifling, and need not be enumerated in such a sketch as this: they were in fact only reformed Benedictines, and in a general classification may be included with the parent order, to which these rivals imparted new tone and vigour.

The following account of the foundation of Clairvaux by St. Bernard will illustrate these general remarks. It is true that the founding of Clairvaux was not technically the founding of a new order, for it had been founded fifteen years before in Citeaux; but St. Bernard was rightly esteemed a second founder of the Cistercians, and his going forth from the parent house to found the new establishment at Clairvaux was under circumstances which make the narrative an excellent illustration of the subject.

“Twelve monks and their abbot,” says his life in the “Acta Sanctorum,” “representing our Lord and his apostles, were assembled in the church. Stephen placed a cross in Bernard’s hands, who solemnly, at the head of his small band, walked forth from Citeaux.... Bernard struck away to the northward. For a distance of nearly ninety miles he kept this course, passing up by the source of the Seine, by Chatillon, of school-day memories, till he arrived at La Ferté, about equally distant between Troyes and Chaumont, in the diocese of Langres, and situated on the river Aube. About four miles beyond La Ferté was a deep valley opening to the east. Thick umbrageous forests gave it a character of gloom and wildness; but a gushing stream of limpid water which ran through it was sufficient to redeem every disadvantage. In June, A.D. 1115, Bernard took up his abode in the valley of Wormwood, as it was called, and began to look for means of shelter and sustenance against the approaching winter. The rude fabric which he and his monks raised with their own hands was long preserved by the pious veneration of the Cistercians. It consisted of a building covered by a single roof, under which chapel, dormitory, and refectory were all included. Neither stone nor wood hid the bare earth, which served for floor. Windows scarcely wider than a man’s hand admitted a feeble light. In this room the monks took their frugal meals of herbs and water. Immediately above the refectory was the[Pg 12] sleeping apartment. It was reached by a ladder, and was, in truth, a sort of loft. Here were the monks’ beds, which were peculiar. They were made in the form of boxes or bins of wooden planks, long and wide enough for a man to lie down in. A small space, hewn out with an axe, allowed room for the sleeper to get in or out. The inside was strewn with chaff, or dried leaves, which, with the woodwork, seem to have been the only covering permitted.... The monks had thus got a house over their heads; but they had very little else. They had left Citeaux in June. Their journey had probably occupied them a fortnight, their clearing, preparations, and building, perhaps two months; and thus they would be near September when this portion of their labour was accomplished. Autumn and winter were approaching, and they had no store laid by. Their food during the summer had been a compound of leaves intermixed with coarse grain. Beech-nuts and roots were to be their main support during the winter. And now to the privations of insufficient food was added the wearing out of their shoes and clothes. Their necessities grew with the severity of the season, till at last even salt failed them; and presently Bernard heard murmurs. He argued and exhorted; he spoke to them of the fear and love of God, and strove to rouse their drooping spirits by dwelling on the hopes of eternal life and Divine recompense. Their sufferings made them deaf and indifferent to their abbot’s words. They would not remain in this valley of bitterness; they would return to Citeaux. Bernard, seeing they had lost their trust in God, reproved them no more; but himself sought in earnest prayer for release from their difficulties. Presently a voice from heaven said, ‘Arise, Bernard, thy prayer is granted thee.’ Upon which the monks said, ‘What didst thou ask of the Lord?’ ‘Wait, and ye shall see, ye of little faith,’ was the reply; and presently came a stranger who gave the abbot ten livres.”

William of St. Thierry, the friend and biographer of St. Bernard, describes the external aspect and the internal life of Clairvaux. We extract it as a sketch of the highest type of monastic life, and as a corrective of the revelations of corrupter life among the monks which find illustration in these pages.

“At the first glance as you entered Clairvaux by descending the[Pg 13] hill you could see it was a temple of God; and the still, silent valley bespoke, in the modest simplicity of its buildings, the unfeigned humility of Christ’s poor. Moreover, in this valley full of men, where no one was permitted to be idle, where one and all were occupied with their allotted tasks, a silence deep as that of night prevailed. The sounds of labour, or the chants of the brethren in the choral service, were the only exceptions. The order of this silence, and the fame that went forth of it, struck such a reverence even into secular persons that they dreaded breaking it—I will not say by idle or wicked conversation, but even by pertinent remarks. The solitude, also, of the place—between dense forests in a narrow gorge of neighbouring hills—in a certain sense recalled the cave of our father St. Benedict, so that while they strove to imitate his life, they also had some similarity to him in their habitation and loneliness.... Although the monastery is situated in a valley, it has its foundations on the holy hills, whose gates the Lord loveth more than all the dwellings of Jacob. Glorious things are spoken of it, because the glorious and wonderful God therein worketh great marvels. There the insane recover their reason, and although their outward man is worn away, inwardly they are born again. There the proud are humbled, the rich are made poor, and the poor have the Gospel preached to them, and the darkness of sinners is changed into light. A large multitude of blessed poor from the ends of the earth have there assembled, yet have they one heart and one mind; justly, therefore, do all who dwell there rejoice with no empty joy. They have the certain hope of perennial joy, of their ascension heavenward already commenced. In Clairvaux they have found Jacob’s ladder, with angels upon it; some descending, who so provide for their bodies that they faint not on the way; others ascending, who so rule their souls that their bodies hereafter may be glorified with them.

“For my part, the more attentively I watch them day by day, the more do I believe that they are perfect followers of Christ in all things. When they pray and speak to God in spirit and in truth, by their friendly and quiet speech to Him, as well as by their humbleness of demeanour, they are plainly seen to be God’s companions and friends. When, on the other hand, they openly praise God with psalmody, how pure and fervent are[Pg 14] their minds, is shown by their posture of body in holy fear and reverence, while by their careful pronunciation and modulation of the psalms, is shown how sweet to their lips are the words of God—sweeter than honey to their mouths. As I watch them, therefore, singing without fatigue from before midnight to the dawn of day, with only a brief interval, they appear a little less than the angels, but much more than men....

“As regards their manual labour, so patiently and placidly, with such quiet countenances, in such sweet and holy order, do they perform all things, that although they exercise themselves at many works, they never seem moved or burdened in anything, whatever the labour may be. Whence it is manifest that that Holy Spirit worketh in them who disposeth of all things with sweetness, in whom they are refreshed, so that they rest even in their toil. Many of them, I hear, are bishops and earls, and many illustrious through their birth or knowledge; but now, by God’s grace, all acceptation of persons being dead among them, the greater any one thought himself in the world, the more in this flock does he regard himself as less than the least. I see them in the garden with hoes, in the meadows with forks or rakes, in the fields with scythes, in the forest with axes. To judge from their outward appearance, their tools, their bad and disordered clothes, they appear a race of fools, without speech or sense. But a true thought in my mind tells me that their life in Christ is hidden in the heavens. Among them I see Godfrey of Peronne, Raynald of Picardy, William of St. Omer, Walter of Lisle, all of whom I knew formerly in the old man, whereof I now see no trace, by God’s favour. I knew them proud and puffed up; I see them walking humbly under the merciful hand of God.”

The first of these reformed orders was the Clugniac, so called because it was founded, in the year 927, at Clugny, in Burgundy, by Odo the Abbot. The Clugniacs formally abrogated the requirement of manual labour required in the Benedictine rule, and professed to devote themselves more sedulously to the cultivation of the mind. The order was first introduced into England in the year 1077 A.D., at Lewes, in Sussex; but it never became popular in England, and never had more than twenty houses here, and they small ones, and nearly all of them founded before the reign[Pg 15] of Henry II. Until the fourteenth century they were all priories dependent on the parent house of Clugny; though the prior of Lewes was the High Chamberlain, and often the Vicar-general, of the Abbot of Clugny, and exercised a supervision over the English houses of the order. The English houses were all governed by foreigners, and contained more foreign than English monks, and sent large portions of their surplus revenues to Clugny. Hence they were often seized, during war between England and France, as alien priories. But in the fourteenth century many of them were made denizen, and Bermondsey was made an abbey, and they were all discharged from subjection to the foreign abbeys. The Clugniacs retained the Benedictine habit. At Cowfold Church, Sussex, still remains a monumental brass of Thomas Nelond, who was prior of Lewes at his death, in 1433 A.D., in which he is represented in the habit of his order.[6]

Carthusian Monk.

In the year 1084 A.D., the Carthusian order was founded by St. Bruno, a monk of Cologne, at Chartreux, near Grenoble. This was the most severe of all the reformed Benedictine orders. To the strictest observance of the rule of Benedict they added almost perpetual silence; flesh was forbidden even to the sick; their food was confined to one meal of pulse, bread, and water, daily. It is remarkable that this the strictest of all monastic rules has, even to the present day, been but slightly modified; and that the monks have never been accused of personally deviating from it. The order was numerous on the Continent, but only nine houses of the order were ever established in England. The principal of these was the Charterhouse (Chartreux), in London, which, at the dissolution, was rescued by Thomas Sutton to serve one at least of the purposes of its original[Pg 16] foundation—the training of youth in sound religious learning. There were few nunneries of the order—none in England. The Carthusian habit consisted of a white cassock and hood, over that a white scapulary—a long piece of cloth which hangs down before and behind, and is joined at the sides by a band of the same colour, about six inches wide; unlike the other orders, they shaved the head entirely.

The representation of a Carthusian monk, on previous page, is reduced from one of Hollar’s well-known series of prints of monastic costumes. Another illustration may be referred to in a fifteenth century book of Hours (Add.), at f. 10, where one occurs in a group of religious, which includes also a Benedictine and a Cistercian abbot, and others.

Cistercian Monk.

In 1098 A.D., arose the Cistercian order. It took the name from Citeaux (Latinised into Cistercium), the house in which the new order was founded by Robert de Thierry. Stephen Harding, an Englishman, the third abbot, brought the new order into some repute; but it is to the fame of St. Bernard, who joined it in 1113 A.D., that the speedy and widespread popularity of the new order is to be attributed. The order was introduced into England at Waverly, in Surrey, in 1128 A.D. The Cistercians professed to observe the rule of St. Benedict with rigid exactness, only that some of the hours which were devoted by the Benedictines to reading and study, the Cistercians devoted to manual labour. They affected a severe simplicity; their houses were to be simple, with no lofty towers, no carvings or representation of saints, except the crucifix; the furniture and ornaments of their establishments were to be in keeping—chasubles of fustian, candlesticks of iron, napkins of coarse cloth, the cross of wood, and only the chalice might be of precious metal. The amount of manual labour[Pg 17] prevented the Cistercians from becoming a learned order, though they did produce a few men distinguished in literature; they were excellent farmers and horticulturists, and are said in early times to have almost monopolised the wool trade of the kingdom. They changed the colour of the Benedictine habit, wearing a white gown and hood over a white cassock; when they went beyond the walls of the monastery they also wore a black cloak. St. Bernard of Clairvaux is the great saint of the order. They had seventy-five monasteries and twenty-six nunneries in England, including some of the largest and finest in the kingdom.

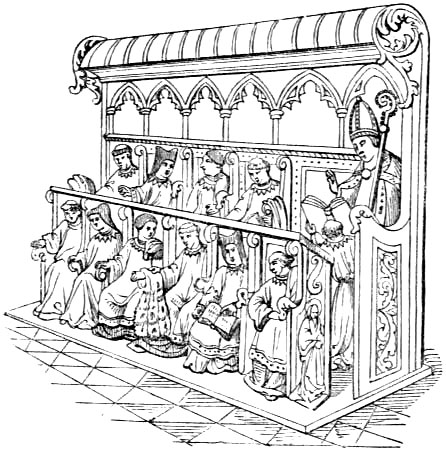

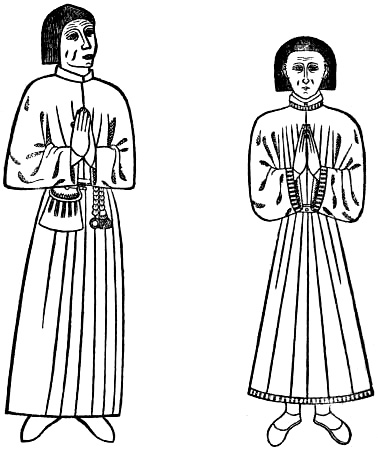

The cut represents a group of Cistercian monks, from a MS. (Vitellius A. 13) in the British Museum. It shows some of them sitting with hands crossed and concealed in their sleeves—an attitude which was considered modest and respectful in the presence of superiors; some with the cowl over the head. It will be observed that some are and some are not bearded.

Group of Cistercian Monks.

The Cistercian monk, whom we give in the opposite woodcut, is taken from Hollar’s plate.

Other reformed Benedictine orders which arose in the eleventh century, viz., the order of Camaldoli, in 1027 A.D., and that of Vallombrosa, in 1073 A.D., did not extend to England. The order of the Grandmontines had one or two alien priories here.

The preceding orders differ among themselves, but the rule of Benedict is the foundation of their discipline, and they are so far impressed with a common character, and actuated by a common spirit, that we may consider them all as forming the Benedictine family.

THE AUGUSTINIAN ORDERS.

e come next to another great monastic family which is included under the

generic name of Augustinians. The Augustinians claim the great St.

Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, as their founder, and relate that he

established the monastic communities in Africa, and gave them a rule. That

he did patronise monachism in Africa we gather from his writings, but it

is not clear that he founded any distinct order; nor was any order called

after his name until the middle of the ninth century. About that time all

the various denominations of clergy who had not entered the ranks of

monachism—priests, canons, clerks, &c.—were incorporated by a decree of

Pope Leo III. and the Emperor Lothaire into one great order, and were

enjoined to observe the rule which was then known under the name of St.

Augustine, but which is said to have been really compiled by Ivo de

Chartres from the writings of St. Augustine. It was a much milder rule

than the Benedictine. The Augustinians were divided into Canons Secular

and Canons Regular.

e come next to another great monastic family which is included under the

generic name of Augustinians. The Augustinians claim the great St.

Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, as their founder, and relate that he

established the monastic communities in Africa, and gave them a rule. That

he did patronise monachism in Africa we gather from his writings, but it

is not clear that he founded any distinct order; nor was any order called

after his name until the middle of the ninth century. About that time all

the various denominations of clergy who had not entered the ranks of

monachism—priests, canons, clerks, &c.—were incorporated by a decree of

Pope Leo III. and the Emperor Lothaire into one great order, and were

enjoined to observe the rule which was then known under the name of St.

Augustine, but which is said to have been really compiled by Ivo de

Chartres from the writings of St. Augustine. It was a much milder rule

than the Benedictine. The Augustinians were divided into Canons Secular

and Canons Regular.

The Canons Secular of St. Augustine were in fact the clergy of cathedral and collegiate churches, who lived in community on the monastic model; their habit was a long black cassock (the parochial clergy did not then universally wear black); over which, during divine service, they wore a surplice and a fur tippet, called an almuce, and a four-square black cap, called a baret; and at other times a black cloak and hood with a leather girdle. According to their rule they might wear their beards, but from the thirteenth century downwards we find them usually shaven. In the Canon’s Yeoman’s tale, from which the following extract is taken, Chaucer[Pg 19] gives us a pen-and-ink sketch of a canon, from which it would seem that even on a journey he wore the surplice and fur hood under the black cloak:—

“Ere we had ridden fully five mile,

At Brighton under Blee us gan atake [overtake]

A man that clothed was in clothes blake,

And underneath he wered a surplice.

*****

And in my hearte wondren I began

What that he was, till that I understood

How that his cloak was sewed to his hood,[7]

For which when I had long avised me,

I deemed him some chanon for to be.

His hat hung at his back down by a lace.”

The hat which hung behind may have been like that of the abbot in a subsequent woodcut; but he wore his hood; and Chaucer, with his usual humour and life-like portraiture, tells us how he had put a burdock leaf under his hood because of the heat:—

“A clote-leaf he had laid under his hood

For sweat, and for to keep his head from heat.”

Chaucer rightly classes the canons rather with priests than monks:—

“All be he monk or frere,

Priest or chanon, or any other wight.”

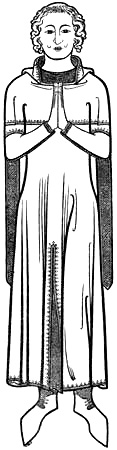

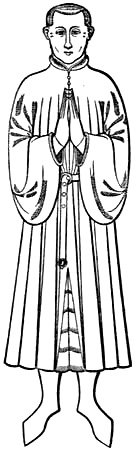

The canon whom we give in the wood-cut over-leaf, from one of Hollar’s plates, is in ordinary costume. An engraving of a semi-choir of canons in their furred tippets from the MS. Domitian xvii, will be found in a subsequent chapter on the Secular Clergy.

There are numerous existing monumental brasses in which the effigies of canons are represented in choir costume, viz., surplice and amice, and often with a cope over all; they are all bareheaded and shaven. We may mention specially that of William Tannere, first master of Cobham College (died 1418 A.D.), in Cobham Church, Kent, in which the almuce, with its[Pg 20] fringe of bell-shaped ornaments, over the surplice, is very distinctly shown; it is fastened at the throat with a jewel. The effigy of Sir John Stodeley, canon, in Over Winchendon Church, Bucks (died 1505), is in ordinary costume, an under garment reaching to the heels, over that a shorter black cassock, girded with a leather girdle, and over all a long cloak and hood.

The Canons Regular of St. Augustine were perhaps the least ascetic of the monastic orders. Enyol de Provins, a minstrel (and afterwards a monk) of the thirteenth century, says of them: “Among them one is well shod, well clothed, and well fed. They go out when they like, mix with the world, and talk at table.” They were little known till the tenth or eleventh century, and the general opinion is, that they were first introduced into England, at Colchester, in the reign of Henry I., where the ruins of their church, of Norman style, built of Roman bricks, still remain. Their habit was like that of the secular canons—a long black cassock, cloak and hood, and leather girdle, and four-square cap; they are distinguished from the secular canons by not wearing the beard. According to Tanner, they had one hundred and seventy-four houses in England—one hundred and fifty-eight for monks, and sixteen for nuns; but the editors of the last edition of the “Monasticon” have recovered the names of additional small houses, which make up a total of two hundred and sixteen houses of the order.

Canon of St. Augustine.

The Augustinian order branches out into a number of denominations; indeed, it is considered as the parent rule of all the monastic orders and religious communities which are not included under the Benedictine order; and retrospectively it is made to include all the distinguished recluses and clerics before the institution of St. Benedict, from the fourth to the sixth century.

[Pg 21]The most important branch of the Regular Canons is the Premonstratensian, founded by St. Norbert, a German nobleman, who died in 1134 A.D.; his first house, in a barren spot in the valley of Coucy, in Picardy, called Pré-montre, gave its name to the order. The rule was that of Augustine, with a severe discipline superadded; the habit was a coarse black cassock, with a white woollen cloak and a white four-square cap. Their abbots were not to use any episcopal insignia. The Premonstratensian nuns were not to sing in choir or church, and to pray in silence. They had only thirty-six houses in England, of which Welbeck was the chief; but the order was very popular on the Continent, and at length numbered one thousand abbeys and five hundred nunneries.

Under this rule are also included the Gilbertines, who were founded by a Lincolnshire priest, Gilbert of Sempringham, in the year 1139 A.D. There were twenty-six houses of the order, most of them in Lincolnshire and Yorkshire; they were all priories dependent upon the house of Sempringham, whose head, as prior-general, appointed the priors of the other houses, and ruled absolutely the whole order. All the houses of this order were double houses, that is, monks and nuns lived in the same enclosure, though with a rigid separation between their two divisions. The monks followed the Augustinian rule; the nuns followed the rule of the Cistercian nuns. The habit was a black cassock, a white cloak, and hood lined with lambskin. The “Monasticon” gives very effective representations (after Hollar) of the Gilbertine monk and nun.

The Nuns of Fontevraud was another female order of Augustinians, of which little is known. It was founded at Fontevraud in France, and three houses of the order were established in England in the time of Henry II.; they had monks and nuns within the same enclosure, and all subject to the rule of an abbess.

The Bonhommes were another small order of the Augustinian rule, of little repute in England; they had only two houses here, which, however, were reckoned among the greater abbeys, viz., Esserug in Bucks, and Edindon in Wilts.

The female Order of our Saviour, or, as they are usually called, the Brigittines, were founded by St. Bridget of Sweden, in 1363 A.D. They[Pg 22] were introduced into England by Henry V., who built for them the once glorious nunnery of Sion House. At the dissolution, the nuns fled to Lisbon, where their successors still exist. Some of the relics and vestments which they carried from Sion House have been carefully preserved ever since, and are now in the possession of the Earl of Shrewsbury.[8] Their habit was like that of the Benedictine nuns—a black tunic, white wimple and veil, but is distinguished by a black band on the veil across the forehead.

Other small offshoots of the great Augustinian tree were those which observed the rule of St. Austin according to the regulations of St. Nicholas of Arroasia, which had four houses here; and those which observed the order of St. Victor, which had three houses.

We may refer the reader to two MS. illuminations of groups of religious for further illustration of their costumes. One is in the beautiful fourteenth century MS. of Froissart in the British Museum (Harl. 4,380, at f. 18 v). It represents a dying pope surrounded by a group of representative religious, cardinals, &c. Among them are one in a brown beard, and with no appearance of tonsure (? a hermit); another in a white scapular and hood (? a Carthusian); another in a black cloak and hood over a white frock (? a Cistercian); another in a brown robe and hood, tonsured. Again, in the MS. Tiberius B iii. article 3, f. 6, the text speaks of “Convens of monkys, chanons and chartreus, celestynes, freres and prestes, palmers, pylgreymys, hermytes, and reclus,” and the illuminator has illustrated it with a row of religious—first a Benedictine abbot; then a canon with red cassock and almuce over surplice; then a monk with white frock and white scapular banded at the sides, as in Hollar’s cut given above, is clearly the Carthusian; then comes a man in brown, with a knotted girdle, holding a cross staff and a book, who is perhaps a friar; then one in white surplice over red cassock, who is the priest; then a hermit, in brown cloak over dark grey gown; and in the background are partly seen two pilgrims and a monk. Other illustrations of monks are frequent in the illuminated MSS.

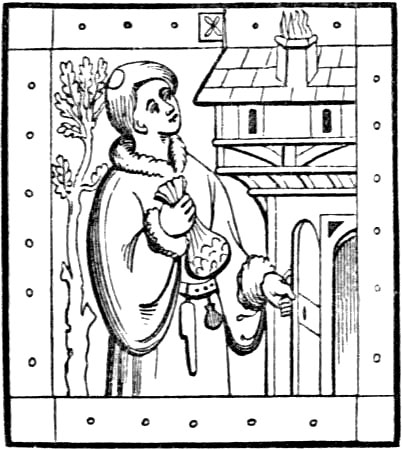

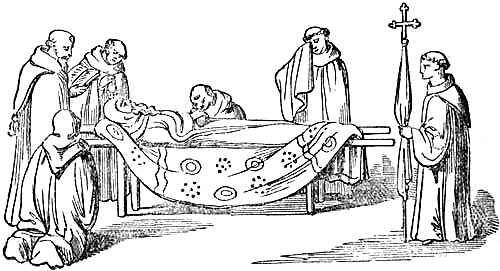

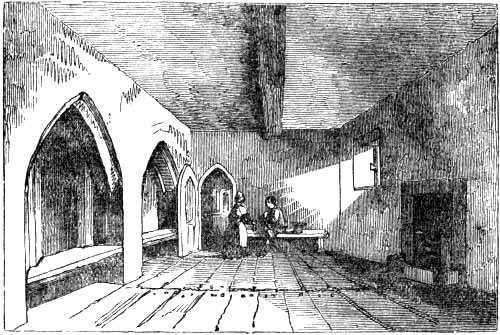

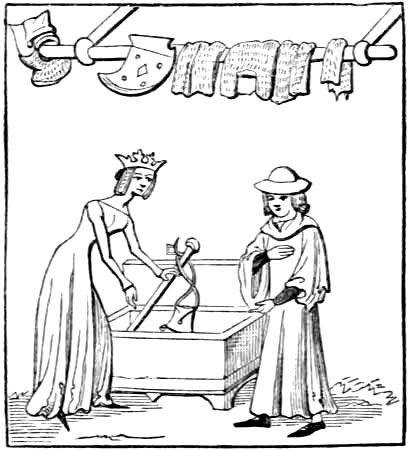

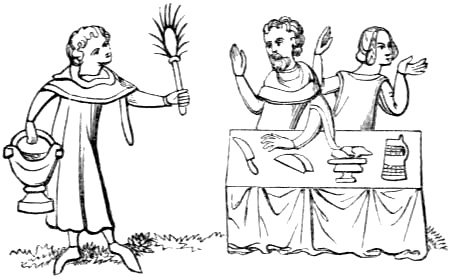

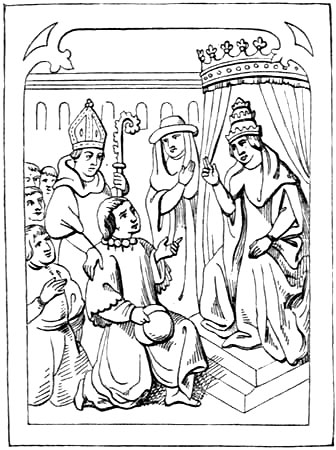

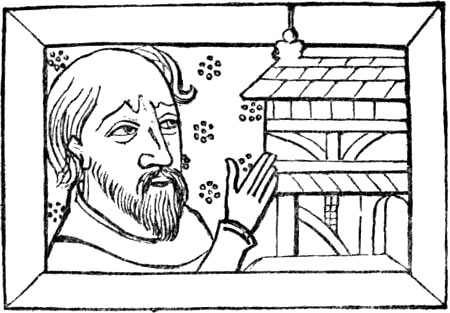

[Pg 23]The HOSPITALS of the Middle Ages deserve a more extended notice than we can afford them here. Some were founded at places of pilgrimage and along the high roads, for the entertainment of poor pilgrims and travellers. Thus at St. Edmund’s Bury there was St. John’s Hospital, or God’s House, without the south gate; and St. Nicholas Hospital, without the east gate; and St. Peter’s Hospital, without the Risley gate; and St. Saviour’s Hospital, without the north gate—all founded and endowed by abbots of St. Edmund. At Reading there was the Hospital of St. Mary Magdalene, for twelve leprous persons and chaplains; and the Hospital of St. Lawrence, for twenty-six poor people and for the entertainment of strangers and pilgrims—both founded by abbots of Reading; one at the gate of Fountains Abbey, for poor persons and travellers; one at Glastonbury, under the care of the almoner, for poor and infirm persons; &c., &c. Indeed, they were scattered so profusely up and down the country that the last edition of the “Monasticon” enumerates no less than three hundred and seventy of them. Those for the poor had usually a little chamber for each person, a common hall in which they took their meals, a chapel in which they attended daily service. They usually were under the care and government of one or more clergymen; sometimes in large hospitals of a prior and bretheren, who were Augustinian canons. The canons of some of these hospitals had special statutes in addition to the general rules, and were distinguished by some peculiarity of habit; for example, the canons of the Hospital of St. John Baptist at Coventry wore a cross on the breast of their black cassock, and a similar one on the shoulder of their cloak. The poor people were also under a simple rule, and were regarded as part of the community. The accompanying woodcut enables us to place a group of them before the eye of the reader. It is from one of the initial letters of the deed (Harl. 1,498) by which Henry VII.[Pg 24] founded a fraternity of thirteen poor men (thirteen was a favourite number for such hospitals) in Westminster Abbey, who were to be under the governance of the monks, and to repay the king’s bounty by their prayers. The group represents the abbot and some of the monks, and behind them some of the bedesmen, each of whom has the royal badge—the rose and crown—on the shoulder of his habit, and holds in his hand his rosary, the symbol of his prayers. Happily some of these ancient foundations have continued to the present day, and the brethren may be seen yet in coats of antique fashion, with a cross or other badge on the sleeve. Examples of the architecture of the buildings may be seen in the Bede Houses in Higham Ferrers Churchyard, built by Archbishop Chechele in 1422; St. Thomas’s Hospital, Northampton; Wyston’s Hospital, Leicester; Ford’s Hospital, Coventry; the Alms Houses at Sherborne; the Leicester Hospital at Warwick, &c. Mr. Turner, in the “Domestic Architecture,” says that there exists a complete chronological series from the twelfth century downwards.

Bedesmen. Temp. Hen. VII.

Hospitals were also established for the treatment of the sick, of which St. Bartholomew’s Hospital is perhaps our most illustrious instance. It was founded to be an infirmary for the sick and infirm poor, a lying-in hospital for women—there were sisters on the hospital staff, and if the women happened to die in hospital their children were taken care of till seven years of age. The staff usually consisted of a community living under monastic vows and rule, viz., a prior and a number of brethren who were educated and trained to the treatment of sickness and disease, and one or more of whom were also priests; a college, in short, of clerical physicians and surgeons and hospital dressers, who devoted themselves to the service of the sick poor as an act of religion, and had always in mind our Lord’s words, “Inasmuch as ye do it to one of the least of these my brethren, ye do it unto me.” In the still existing church of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, in Smithfield, is a monument of the founder “Rahere, first canon and prior,” which is, however, of much later date, probably of about 1410 A.D.; his recumbent effigy, and the kneeling figures of two of his canons beside him, afford good authorities for costume. They have been engraved in the “Vetusta Monumenta,” vol. ii. Pl. xxxvi.

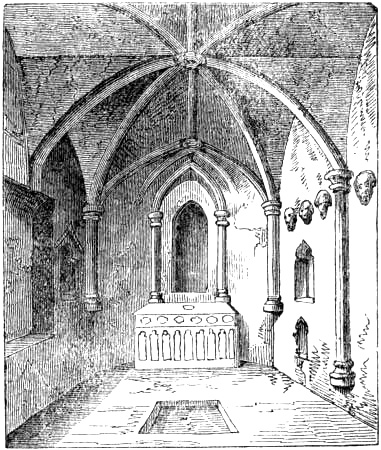

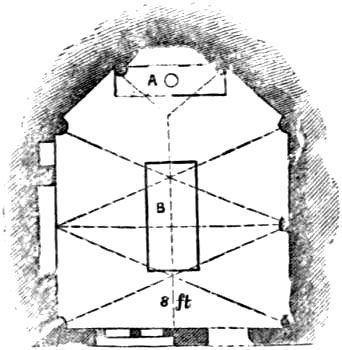

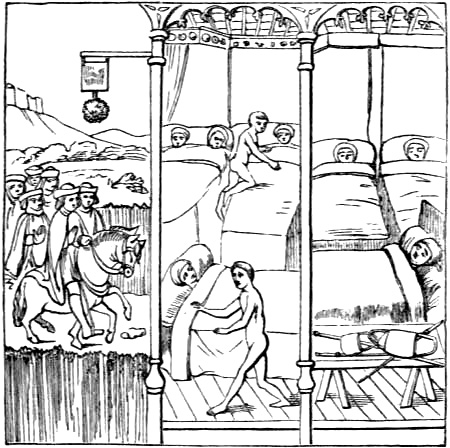

[Pg 25]The building usually consisted of a great hall in which the sick lay, a chapel for their worship, apartments for the hospital staff, and other apartments for guests. We are not aware of any examples in England so perfect as some which exist in other countries, and we shall therefore borrow some foreign examples in illustration of the subject. The commonest form of these hospitals seems to have been a great hall divided by pillars into a centre and aisles, in which rows of beds were arranged; with a chapel in a separate building at one end of the hall, and other buildings irregularly disposed in a courtyard; as at the Hôtel Dieu of Chartres, a building of 1153 A.D.,[9] and the Salle des Morts at Ourscamp.[10] At Tonerre we find a modification of the above plan. The hospital is still a vast hall, but is divided by timber partitions along the side walls into little separate cells. Above these cells, against the side walls, and projecting partly over the cells, are two galleries, along which the attendants might walk and look down into the cells. At the east end of this hall two bays were screened off for the chapel, so that they who were able might go up into the chapel, and they who could not rise from their beds could still take part in the service.[11] At Tartoine, near Laon la Fère, is a hospital on a different plan: a hall, with cells on one side of it, is placed on one side of a square courtyard, and the chapel and lodgings for the brethren on another side of the court.[12]

THE MILITARY ORDERS.

e have already sketched the history of the rise of monachism in the

fourth century out of the groups of Egyptian eremites, and the rapid

spread of the institution, under the rule of Basil, over Christendom; the

adoption in the west of the new rule of Benedict in the sixth century; the

rise of the reformed orders of Benedictines in the tenth and eleventh

centuries; and the institution in the eleventh and twelfth centuries of a

new group of orders under the milder discipline of the Augustinian rule.

We come now to a class of monastics who are included under the Augustinian

rule, since that rule formed the basis of their discipline, but whose

striking features of difference from all other religious orders entitle

them to be reckoned as a distinct class, under the designation of the

Military Orders. When the history of the mendicant orders which arose in

the thirteenth century has been read, it will be seen that these military

orders had anticipated the active religious spirit which formed the

characteristic of the friars, as opposed to the contemplative religious

spirit of the monks. But that which peculiarly characterises the military

orders, is their adoption of the chivalrous crusading spirit of the age in

which they arose: they were half friars, half crusaders.

e have already sketched the history of the rise of monachism in the

fourth century out of the groups of Egyptian eremites, and the rapid

spread of the institution, under the rule of Basil, over Christendom; the

adoption in the west of the new rule of Benedict in the sixth century; the

rise of the reformed orders of Benedictines in the tenth and eleventh

centuries; and the institution in the eleventh and twelfth centuries of a

new group of orders under the milder discipline of the Augustinian rule.

We come now to a class of monastics who are included under the Augustinian

rule, since that rule formed the basis of their discipline, but whose

striking features of difference from all other religious orders entitle

them to be reckoned as a distinct class, under the designation of the

Military Orders. When the history of the mendicant orders which arose in

the thirteenth century has been read, it will be seen that these military

orders had anticipated the active religious spirit which formed the

characteristic of the friars, as opposed to the contemplative religious

spirit of the monks. But that which peculiarly characterises the military

orders, is their adoption of the chivalrous crusading spirit of the age in

which they arose: they were half friars, half crusaders.

The order of the Knights of the Temple was founded at Jerusalem in 1118 A.D., during the interval between the first and second crusades, and in the reign of Baldwin I. Hugh de Payens, and eight other brave knights, in the presence of the king and his barons, and in the hands of the Patriarch, bound themselves into a fraternity which embraced the fundamental monastic vows of obedience, poverty, and chastity; and, in[Pg 27] addition, as the special object of the fraternity, they undertook the task of escorting the companies of pilgrims from the coast up to Jerusalem, and thence on the usual tour to the Holy Places. For the open country was perpetually exposed to the incursions of irregular bands of Saracen and Turkish horsemen, and death or slavery was the fate which awaited any caravan of helpless pilgrims whom the infidel descried as they swept over the plains, or whom they could waylay in the mountain passes. The new knights undertook besides to wage a continual war in defence of the Cross against the infidel. The canons of the Temple at Jerusalem gave the new fraternity a piece of ground adjoining the Temple for the site of their home, and hence they took their name of Knights of the Temple; and they gradually acquired dependent houses, which were in fact strong castles, whose ruins may still be seen, in many a strong place in Palestine. Ten years after, when Baldwin II. sent envoys to Europe to implore the aid of the Christian powers in support of his kingdom against the Saracens, Hugh de Payens was sent as one of the envoys. His order received the approval of the Council of Troyes, and of Pope Eugene III., and the patronage of St. Bernard, who became the great preacher of the second crusade; and when Hugh de Payens returned to Palestine, he was at the head of three hundred knights of the noblest houses of Europe, who had become members of the order. Endowments, too, for their support flowed in abundantly; and gradually the order established dependent houses on its estates in nearly every country of Europe. The order was introduced into England in the reign of King Stephen; at first its chief house, “the Temple,”[13] was on the south side of Holborn, London, near Southampton Buildings; afterwards it was removed to Fleet Street, where the establishment still remains, long since converted to other uses; but the original church, with its round nave, after the form of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre at Jerusalem,[14] still continues a monument of the[Pg 28] wealth and grandeur of the ancient knights. They had only five other houses in England, which were called Preceptories, and were dependent upon the Temple in London.

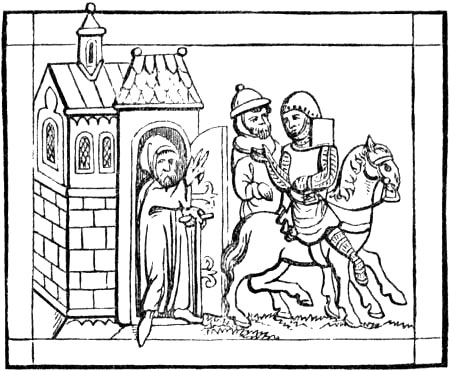

The knights wore the usual armour of the period; but while other knights wore the flowing surcoat of the twelfth or thirteenth centuries, or the tight-fitting jupon of the fourteenth, or the tabard of the fifteenth, of any colour which pleased their taste, and often embroidered with their armorial bearings, the Knights of the Temple were distinguished by wearing this portion of their equipment of white, with a red cross over the breast; and over all a long flowing white mantle, with a red cross on the shoulder; they also wore the monastic tonsure. In the early fourteenth century MS. in the British Museum, Royal 1,696, at f. 335, is a representation of Eracles, Prior at Jerusalem, the Prior of the Hospital, and the Master of the Temple, sent to France to ask for succour. The illumination shows us the King of France sitting on his throne, and before him is standing a religious in mitre and crozier, who is no doubt Eracles, and another in a peculiarly shaped black robe, with a cross patee on the left shoulder, who is either Hugh de Payens the Templar, or Raymond de Puy the Hospitaller, but which it is difficult to determine. Again, in the fine fourteenth[Pg 29] century MS., Nero E. 2, at f. 345 v, is a representation of the trial of the Templars: there are three of them standing before the Pope and the King of France, dressed in a grey tunic, and over that a black mantle with a red cross on the left breast, and a pointed hood over the shoulders. Folio 350 represents the Master of the Temple being burnt to death in presence of the king and nobles. Again, in the fine MS. Royal 20, c. viii., of the time of our Richard II., at f. 42 and f. 48, are representations of the same scenes. Folio 42 is a group of Templars habited in long black coat, fitting close up to the neck, like the ordinary civil robes of the time, with a pointed hood (like that with which we are familiar in the portraits of Dante), with a cross patee on the right shoulder; the hair is tonsured. At f. 45 is the burning of a group of Templars (not tonsured), and at f. 48 the burning of the Master of the Temple and another (tonsured). Their banner was of a black and white striped cloth, called beauseant, which word they adopted as a war-cry. The rule allowed three horses and a servant to each knight. Married knights were admitted, but there were no sisters of the order. The order was suppressed with circumstances of gross injustice and cruelty in the fourteenth century, and the bulk of their estates was given to the Hospitallers. The knight here given, from Hollar’s plate, is a prior of the order, in armour of the thirteenth century.

A Knight Templar.

The Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, or the Knights Hospitallers, originally were not a military order; they were founded about 1092 by the merchants of Amalfi, in Italy, for the purpose of affording hospitality to pilgrims in the Holy Land. Their chief house, which was called the Hospital, was situated at Jerusalem, over against the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; and they had independent hospitals in other places in the Holy Land, which were frequented by the pilgrims. Their kindness to the sick and wounded soldiers of the first crusade made them popular, and several of the crusading princes endowed them with estates; while many of the crusaders, instead of returning home, laid down their arms, and joined the brotherhood of the Hospital. During this period of their history their habit was a plain black robe, with a linen cross upon the left breast.

[Pg 30]At length their endowments having become greater than the needs of their hospitals required, and incited by the example of the Templars, a little before established, Raymond de Puy, the then master of the hospital, offered to King Baldwin II. to reconstruct the order on the model of the Templars. From this time the two military orders formed a powerful standing army for the defence of the kingdom of Jerusalem.

When Palestine was finally lost to the Christians, the Knights of St. John passed into the Isle of Cyprus, afterwards to the Isle of Rhodes, and, finally, to the Isle of Malta,[15] maintaining a constant warfare against the infidel, and doing good service in checking the westward progress of the Mohammedan arms. In the latter part of their history, and down to a recent period, they conferred great benefits by checking the ravages of the corsairs of North Africa on the commerce of the Mediterranean and the coast towns of Southern Europe. They patrolled the sea in war-galleys, rowed by galley-slaves, each of which carried a force of armed soldiers—inferior brethren of the order, officered by its knights. They are not even now extinct.

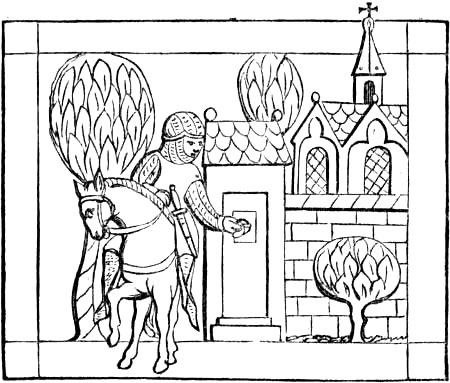

The order was first introduced into England in the reign of Henry I., at Clerkenwell; which continued the principal house of the order in England, and was styled the Hospital. The Hospitallers had also dependent houses, called Commanderies, on many of their English estates, to the number of fifty-three in all. The houses of the military knights in England were only cells, erected on the estates with which they had been endowed, in order to cultivate those estates for the support of the order, and to form depôts for recruits; i.e. for novices, where they might be trained, not in learning like Benedictines, or agriculture like Cistercians, or preaching like Dominicans, but in piety and in military exercises. A plan and elevation of the Commandery of Chabburn, Northumberland, are engraved in Turner’s “Domestic Architecture,” vol. iii. p. 197. The superior of the order in England sat in Parliament, and was[Pg 31] accounted the first lay baron. When on military duty the knights wore the ordinary armour of the period, with a red surcoat marked with a white cross on the breast, and a red mantle with a white cross on the shoulder. Some of their churches in England possibly had circular naves, like the church of the Temple in Jerusalem; out of the four “round churches,” which remain, one belonged to the Knights of the Hospital. The chapel at Chabburn is a rectangular building. There were many sisters of the order, but only one house of them in England.

One of two earlier representations of knights of the order may be noted here. In a MS. in the Library at Ghent, of the date of our Edward IV., is a picture of John Lonstrother, prior of the order; he wears a long sleeveless gown over armour. It is engraved in the “Archælogia,” xiii. 14. The MS. Add. 18,143 in the British Museum is said in a note at the beginning of the volume to have been the missal of Phillippe de Villiers de l’Isle Adam, the famous Grand Master of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem from 1521 to 1534. In the frontispiece is a portrait of the Grand Master in a black robe lined with fur, and a cross patee on the breast. On the opposite page is another portrait of him in a robe of different fashion, with a cross rather differently shaped. The monument of the last English Prior, Sir Thomas Tresham, in his robes as prior of the order, still remains in Rushton Church, Northants. A fine portrait of a Knight of Malta is in the National Gallery. The Hospitaller given on the[Pg 32] preceding page, from Hollar’s plate, is a (not very good) representation of one in the armour of the early part of the fourteenth century, with the usual knight’s chapeau, instead of the mail hood or the basinet, on his head.

A Knight Hospitaller.

It will be gathered from the authorities of the costume of the Knights of the Temple and of the Hospital here noted, that when we picture to ourselves the knights on duty in the Holy Land or elsewhere, it should be in the armour of their period with the uniform surcoat of their order; but when we desire to realise their appearance as they were to be ordinarily seen, in chapel or refectory, or about their estates, or forming part of any ordinary scene of English life, it must be in the long cassock-like gown, with the cross on the shoulder, and the tonsured head, described in the above authorities, which would make their appearance resemble that of other religious persons.

Other military orders, which never extended to England, were the order of Teutonic Knights, a fraternity similar to that of the Templars, but consisting entirely of Germans; and the order of Our Lady of Mercy, a Spanish knightly order in imitation of that of the Trinitarians.

One other order of religious—the Trinitarians—we have reserved for this place, because while by their rule they are classed among the Augustinian orders, the object of their foundation gives them an affinity with the military orders, and their mode of pursuing that object makes their organisation and life resemble that of friars. The moral interest of their work, and its picturesque scenes and associations, lead us to give a little larger space to them than we have been able to do to most of the other orders. It is difficult for us to realise that the Mohammedan power seemed at one time not unlikely to subjugate all Europe; and that after their career of conquest had been arrested, the Mohammedan states of North Africa continued for centuries to be a scourge to the commerce of Europe, and a terror to the inhabitants of the coasts of the Mediterranean. They scoured the Great Sea with their galleys, and captured ships; they made descents on the coasts, and plundered towns and villages; and carried off the captives into slavery, and retreated in safety[Pg 33] with their booty, to their African harbours. It is only within quite recent times that the last of these strongholds was destroyed by an English fleet, and that the Greek and Italian feluccas have ceased to fear the Algerine pirates. We have already briefly stated how the Hospitallers, after their original service was ended by the expulsion of the Christians from the Holy Land, settled first at Cyprus, then at Rhodes, and did good service as a bulwark against the Mohammedan progress; and lastly, as Knights of Malta, acted as the police of the Mediterranean, and did their best to oppose the piracies of the Corsairs. But in spite of the vigilance and prowess of the knights, many a merchant ship was captured, many a fishing village was sacked, and many captives, men, women, and children of all ranks of society, were carried off into slavery; and their slavery was a cruel one, exaggerated by the scorn and hatred bred of antagonism in race and religion, and made ruthless by the recollection of ages of mutual injuries. The relations and friends of the unhappy captives, where they were people of wealth and influence, used every exertion to rescue those who were dear to them, and their captors were ordinarily willing to set them to ransom; but hopeless indeed was the lot of those—and they, of course, were the great majority—who had no friends rich enough to help them.

The miserable fate of these helpless ones moved the compassion of some Christ-like souls. John de Matha, born, in 1154, of noble parents in Provence, with Felix de Valois, retired to a desert place, where, at the foot of a little hill, a fountain of cold water issued forth; a white hart was accustomed to resort to this fountain, and hence it had received the name of Cervus Frigidus, represented in French by (or representing the French?) Cerfroy. There, about A.D. 1197, these two good men—the Clarkson and Wilberforce of their time—arranged the institution of a new Order for the Redemption of Captives. The new order received the approval of the Pope Innocent III., and took its place among the recognised orders of the church. This Papal approval of their institution constituted an authorisation from the head of the church to seek alms from all Christendom in furtherance of their object. Their rules directed that one-third of their income only should be reserved for their own maintenance, one-third[Pg 34] should be given to the poor, and one-third for the special object of redeeming captives. The two philanthropists preached throughout France, collecting alms, and recruiting men who were willing to join them in their good work. In the first year they were able to send two brethren to Africa, to negotiate the redemption of a hundred and eighty-six Christian captives; next year, John himself went, and brought back a thankful company of a hundred and ten; and on a third voyage, a hundred and twenty more; and the order continued to flourish,[16] and established a house of the order in Africa, as its agent with the infidel. They were introduced into England by Sir William Lucy of Charlecote, on his return from the Crusade; who built and endowed for them Thellesford Priory in Warwickshire; and subsequently they had eleven other houses in England. St. Rhadegunda was their tutelary saint. Their habit was white, with a Greek cross of red and blue on the breast—the three colours being taken to signify the three persons of the Holy Trinity, viz., the white, the Eternal Father; the blue, which was the transverse limb of the cross, the Son; and the red, the charity of the Holy Spirit.

The order were called Trinitarians, from their devotion to the Blessed Trinity, all their houses being so dedicated, and hence the significance of their badge; they were commonly called Mathurins, after the name of their founder; and Brethren of the Order of the Holy Trinity for the Redemption of Captives, from their object.

Before turning from the monks to the friars, we must devote a brief sentence to the Alien Priories. These were cells of foreign abbeys, founded upon estates which English proprietors had given to the foreign houses. After the expenses of the establishment had been defrayed, the surplus revenue, or a fixed sum in lieu of it, was remitted to the parent house abroad. There were over one hundred and twenty of them when Edward I., on the breaking out of the war with France, seized upon them,[Pg 35] in 1285, as belonging to the enemy. Edward II. appears to have pursued the same course; and, again, Edward III., in 1337. Henry IV. only reserved to himself, in time of war, what these houses had been accustomed to pay to the foreign abbeys in time of peace. But at length they were all dissolved by act of Parliament in the second year of Henry V., and their possessions were devoted for the most part to religious and charitable uses.

THE ORDERS OF FRIARS.

e have seen how for three centuries, from the beginning of the tenth to

the end of the twelfth, a series of religious orders arose, each aiming at

a more successful reproduction of the monastic ideal. The thirteenth

century saw the rise of a new class of religious orders, actuated by a

different principle from that of monachism. The principle of monachism, we

have said, was seclusion from mankind, and abstraction from worldly

affairs, for the sake of religious contemplation. To this end monasteries

were founded in the wilds, far from the abodes of men; and he who least

often suffered his feet or his thoughts to wander beyond the cloister was

so far the best monk. The principle which inspired the Friars was that of

devotion to the performance of active religious duties among mankind.

Their houses were built in or near the great towns; and to the majority of

the brethren the houses of the order were mere temporary resting-places,

from which they issued to make their journeys through town and country,

preaching in the parish churches, or from the steps of the market-crosses,

and carrying their ministrations to every castle and every cottage.

e have seen how for three centuries, from the beginning of the tenth to

the end of the twelfth, a series of religious orders arose, each aiming at

a more successful reproduction of the monastic ideal. The thirteenth

century saw the rise of a new class of religious orders, actuated by a

different principle from that of monachism. The principle of monachism, we

have said, was seclusion from mankind, and abstraction from worldly

affairs, for the sake of religious contemplation. To this end monasteries

were founded in the wilds, far from the abodes of men; and he who least

often suffered his feet or his thoughts to wander beyond the cloister was

so far the best monk. The principle which inspired the Friars was that of

devotion to the performance of active religious duties among mankind.

Their houses were built in or near the great towns; and to the majority of

the brethren the houses of the order were mere temporary resting-places,

from which they issued to make their journeys through town and country,

preaching in the parish churches, or from the steps of the market-crosses,

and carrying their ministrations to every castle and every cottage.