WOMEN of SLAVONIA.

Title: Austria

Author: Frederic Shoberl

Release date: May 28, 2013 [eBook #42826]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Sandra Eder, Matthew Wheaton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

AUSTRIA.

WOMEN of SLAVONIA.

ILLUSTRATED BY

TWELVE COLOURED ENGRAVINGS.

The proper study of mankind is man.—Pope.

Philadelphia:

PUBLISHED BY C. S. WILLIAMS.

W. Brown, Printer.

1828.

On turning over the pages of this work, some readers may possibly be surprised to find that so large a proportion of the engravings belong to one of the countries composing the Austrian empire. When, however, it is considered that a high degree of civilization tends to assimilate the manners, amusements, and dress of the great mass of the inhabitants of those countries in which it prevails; and that the people of the German states of this empire are scarcely, if at all surpassed in that respect by any nation in Europe; it will be evident that they must exhibit fewer of those peculiar characteristics which it is the object of this work to collect and delineate.

Hungary stands in a very different predicament. Peopled by tribes belonging to many different nations, whose distinctive habits, manners, and prejudices have not been melted down by refinement and cultivation, it affords much more ample materials for the pencil than Austria, properly so called. For this reason, by far the greater part of the embellishments have been selected from among the singular, picturesque and romantic costumes of that kingdom and its dependant provinces.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | Provinces of the Austrian Empire—Their Extent and Population | 1 |

| II. | Of the different Nations of the Austrian Dominions—The Jews—The Germans—The Slavonians, including the Bohemians—The Slowacks—The Wendes and the Rascians of Illyria—The Magyares or Hungarians—The Walachians—The Zingares or Gipsies—The Armenians—The Greeks, Turks, &c. | 2 |

| III. | Religions—Roman Catholics—Greek Church—Armenians—Protestants—Socinians—Jews—Mahometans | 9 |

| IV. | Character of the People of Austria | 12 |

| AUSTRIA, LOWER AND UPPER. | ||

| V. | Inhabitants of Lower Austria—Manners of the People of Vienna—Amusements—Houses—Population and Mortality—Shops—Paved Streets—The Fire-Watch—Costumes of Upper Austria | 16 |

| STYRIA. | ||

| VI. | Costume of the Inhabitants—The Johannæum at Grätz | 26 |

| BOHEMIA. | ||

| VII. | Costumes of the Bohemians | 28 |

| MORAVIA. | ||

| VIII. | Costumes of the Inhabitants—Account of the Haunacks—Peasants of the Frontiers | 30 |

| THE TYROL. | ||

| IX. | Migrations of the Tyrolese—Their Frankness—Their Attachment to the House of Austria—Anecdote of the Archduchess Elizabeth—Literary Turn of the Tyrolese—Their Extraordinary Honesty—Fondness for Pugilistic Exercises and the Chase—Ancient Practice—Moral Character—Superstition—Mechanical Genius—Persons and Costumes—National Songs—Custom of visiting the Graves of Relations—Marriage Ceremonies of the Tyrolese | 32 |

| HUNGARY. | ||

| X. | Extent—Division—Constitution—Vast Estates of the Magnats—State of the Peasantry—Their Indolence—Thievish Disposition of the Herdsmen—Punishments—Hungarian Prison—General Appearance of the Peasants and their Habitations in different Counties—Horned Cattle—Sheep—Village Herdsmen—Ravages of Wolves—Granaries—Costumes | 49 |

| TRANSYLVANIA. | ||

| XI. | Extent of Population—Manners of the Walachians—The Gipsies—Costumes | 70 |

| BUKOWINA. | ||

| XII. | Transfer of the Country to Austria—Extent—Population—Costumes | 81 |

| THE MILITARY FRONTIERS. | ||

| XIII. | Military Constitution—Carlstadt Frontier—Banal Frontier—Slavonia—Banat Frontier | 86 |

| GALICIA, OR AUSTRIAN POLAND. | ||

| XIV. | Extent and Nature of the Country—Benefits resulting to the People from the Partition of Poland—Cruelty and Injustice of the Ancient System—Superior Degree of Security enjoyed under the Austrian Government—Mode of Building—Appearance of a Polish Village—Inns—Jews—Uncleanliness of the Poles | 100 |

| 1. | Clementinian Women of Slavonia, | Frontispiece |

| 2. | Peasant of Egra in Winter dress, | to face page 28 |

| 3. | Peasant of the Mountains of Moravia | 31 |

| 4. | Tyrolese Hunter | 37 |

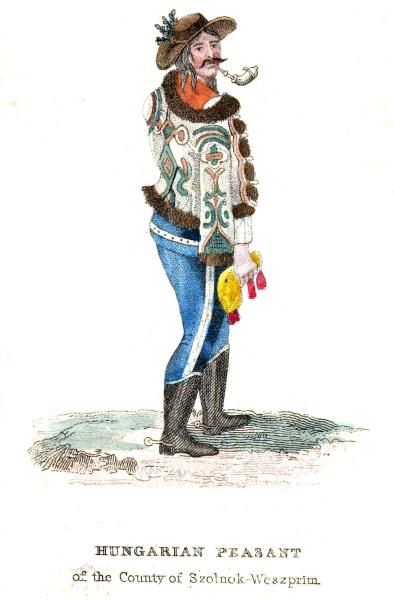

| 5. | Hungarian Peasant of the County of Weszprim | 64 |

| 6. | Armed Plajash | 80 |

| 7. | Boyar of Szered | 82 |

| 8. | Unmarried Female of Jackobeny | 84 |

| 9. | Female Peasant of Philippowan | 85 |

| 10. | Tanaszia Dorojevich, Vice Haram-Bassa of the Szeressans | 88 |

| 11. | Unmarried Female of Ottochacz | 93 |

| 12. | Unmarried Female of Glina | 94 |

PROVINCES OF THE AUSTRIAN EMPIRE—THEIR EXTENT AND POPULATION.

The empire of Austria, one of the most extensive and powerful of the states of Europe, is composed of provinces situated in Germany, Poland and Italy, and embraces the whole of Hungary.

The German dominions of this monarchy consist of Upper and Lower Austria, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, Bohemia, Moravia, part of Silesia, and the Tyrol and Salzburg.

In Poland it possesses the kingdom of Galicia.

The Hungarian states are: Hungary proper, Slavonia, Croatia, Dalmatia, Transylvania and the Bukowina.

In Italy, Venice and the Milanese form the Lombard-Venetian kingdom, one of the brightest jewels in the crown of Austria.

The extent and population of these provinces is shown in the subjoined table.

EXTENT AND POPULATION OF THE PROVINCES OF THE AUSTRIAN EMPIRE.

| German Square miles. | Inhabitants. | |

| The kingdom of Bohemia | 956.80 | 3,203,222 |

| The Margravate of Moravia The duchy of Silesia |

417.64 86.85 |

1,680,935 |

| Austria below the Enns | 363.65 | 1,048,324 |

| Austria above the Enns, including the circles of the Inn and Hausruck and Salzburg | 344.32 | 756,897 |

| The duchy of Styria | 398.98 | 799,056 |

| The duchy of Carinthia | 190.90 | 278,500 |

| Illyria and part of Croatia | 250.95 | 467,836 |

| The Littorale, or Coast District | 176.18 | 422,861 |

| Tyrol and Voralberg | 520.44 | 717,542 |

| The Lombard-Venetian kingdom | 867.50 | 4,111,535 |

| The government of Dalmatia | 274.94 | 295,089 |

| The kingdom of Galicia | 1526.12 | 3,755,454 |

| Civil Hungary, Croatia and Slavonia | 4097.06 | 8,200,000 |

| Civil Transylvania Transylvanian Military Frontiers |

1118.70 | 1,510,000 138,284 |

| Banat Frontiers | 186.00 | 171,657 |

| Slavonian Frontiers | 139.40 | 230,079 |

| Warasdin Military government | 67.40 | 107,217 |

| Carlstadt Military government | 166.40 | 188,906 |

| Banal Regiments | 54.20 | 95,442 |

| —————- | —————— | |

| 12,204.48 | 28,178,836 |

OF THE DIFFERENT NATIONS IN THE AUSTRIAN DOMINIONS—THE JEWS—THE GERMANS—THE SLAVONIANS, INCLUDING THE BOHEMIANS—THE SLOWACKS—THE WENDES AND THE RASCIANS OR ILLYRIANS—THE MAGYARES OR HUNGARIANS—THE WALACHIANS—THE ZIGANIS OR GIPSIES—THE ARMENIANS—THE GREEKS, &c.

The population of the Austrian dominions is composed of different races, each having particular manners and even a peculiar language. All these nations are far from being actuated by the same spirit, or feeling the same attachment for the state to which they belong. This is one of the great causes of the political weakness of Austria; a weakness which has been sensibly manifested in all the wars of invasion. United within a longer or a shorter period under[Pg 3] the authority of one and the same prince, they do not form one compact whole. Thus the different inhabitants of the Austrian states have neither the same interests nor the same feelings. The Hungarians, the Bohemians and the Tyrolese, people extremely jealous of their independence, do not consider themselves as being of the same nation as the Austrians, whom most of them in fact deem beneath them, because in general they possess greater vivacity and a more strongly marked character. There is no spirit of unity among them, though all are subject to the same sceptre.

The principal nations distributed over the spacious dominions of Austria are the Germans, the Slavonians, and the Magyares or Hungarians properly so called. We also meet with Walachians, Ziganis or gypsies, Greeks, and a few Armenians, French and Walloons; but these form no important part of the population. There is another race, which, though of foreign extraction, is widely spread over these provinces as throughout every country in Europe, and that is the Jews. These people, who form a distinct nation amidst all other nations, swarm in the various provinces of the Austrian monarchy, with the exception of Styria, Carinthia and upper Austria. Bohemia, Moravia, Hungary and Galicia contain great numbers of them. Thus it is calculated that there are 170,000 of them in Galicia, 130,000 in Hungary, 50,000 in Bohemia, and 30,000 in Moravia. They are likewise very numerous in Transylvania.

It is very generally supposed in other countries that the greatest part of the population of Austria consists of Germans: but this is by no means the case. Austria, properly so called, is the only province that is entirely peopled by Germans; all the others are more or less inhabited by Slavonians, and the other races mentioned above. The Germans are also diffused over Styria and Carinthia. In Bohemia, there is but one circle, that of Ellbogen, which is entirely peopled by them. Of Moravia they occupy only the part situated on the confines of Austria and Silesia, as well as the districts to the south of the circles of Znaim and Brunn. Still less numerous in Hungary, they are scarcely met with excepting in certain villages in the[Pg 4] counties of Zips, Wieselburg, Œdenburg, Scharosch and Eisenburg. In Transylvania there are more of them: but their number there is inferior to that of the natives. In Galicia, if we except several of the principal towns, we find no Germans but in a few villages whither they have been sent by the government to introduce improvements into the system of agriculture. Thus most of the wealthy citizens of Cracow are Germans, of Saxon or Silesian extraction.

The most numerous of all the races spread over the territories subject to Austria is the Slavonian, now but little known by this generic name, on account of the immense extent of country which it inhabits. Interesting for more than one reason, the Slavonians are worthy alike of the meditation of the philosopher and the researches of the historian, as well on account of the vast space they occupy, as the uniformity of manners which they have preserved in all ages, notwithstanding the vicissitudes experienced by the governments to which they were subject. The numerous traces left by their language in various idioms in which we should never expect to meet with words of Slavonic origin, render the study of it of great importance.

The Slavonian race is divided into an infinite number of branches, some of which are found exclusively in Russia and Poland, and others in the Austrian dominions. To the latter belong the Tshechs, or Bohemians, the Slowacks, the Poles, the Wendes, the Rascians, and the Croats.

The Bohemian language, spoken in Bohemia and Moravia, is but a dialect of the Slavonian; but surrounded by German provinces, their inhabitants have adopted an alphabet which differs very little from that used in Germany. The Bohemian dialect is remarkable for its richness, the softness of its pronunciation, and the facility with which it adapts itself to the inflexions of song. It is daily undergoing a change, however, from its mixture with the German; and hence many words of the primitive Bohemian idiom are no longer understood by the common people. The Bohemians are accounted one of the most civilized of all the Slavonian races in the Austrian empire. The Moravians also are distinguished for their mild and gentle manners and their extraordinary industry.

The Slowacks, the relics of the Moravian monarchy, which comprehended Moravia and the north-western part of Hungary, are nearly confined to those two countries. There are nevertheless some of them in Bohemia. To those people particularly applies the observation of Schwartner, who remarks, that of all the inhabitants of Hungary the Slowacks multiply fastest. Wherever they settle, the Germans and Magyares gradually disappear. Thus in the 14th century the mountainous part of the county of Gömör was entirely inhabited by Germans, whereas at present the population consists exclusively of Slowacks.

The Wendes, who are found in Carinthia, Carniola and Lower Styria, as far as the frontiers of Hungary, belong also to the Slavonians. But among all the Slavonian tribes, the Croatians have retained most of their primitive manners and character. Originally of Bosnian extraction, they are spread not only in Croatia, but also in Hungary. At once soldiers and husbandmen, their religion and customs closely resemble those of their neighbours the Transylvanians and Slavonians. They form excellent light troops, and are fond of serving in the corps of Hulans.

The Rascians or Illyrians, the last branch of the Slavonians, appear to be descended from the ancient Scythians. The name of Srbi which they give to themselves, seems to indicate that they formerly inhabited Dacia, the modern Servia. They principally inhabit Transylvania and Hungary. There are many of them also in the county of Warasdin, as well as in Croatia, where they form nearly a third of the population.

The language of the Slavonians is soft, sonorous and pleasing to the ear. Though spoken by people who have not made any great progress in the arts and sciences, it has nevertheless been brought to a high degree of perfection. It has even assumed all the characters of a modern language, and may claim a distinguished rank among those of the most civilized nations. The turns of which it is susceptible, and the inversions which it has in common with the Greek and German, render it equally expressive and energetic. Copious and harmonious, it may vie with the Italian in melody and softness, especially when it is sung.

This language is more widely extended than any other language of Europe. It is spoken throughout all Transylvania, Galicia, Hungary, Moravia, Bohemia, and generally in all the provinces of Austria. It is also very common in Lusatia, Silesia, Poland, Lithuania, Prussia, Russia, Moscovy, and even in Sweden. It is met with along the whole coast of the Adriatic, in Croatia, Slavonia, Bosnia, Dalmatia, Bulgaria and Turkey in Europe. It should however be observed, that though all the inhabitants of these different countries speak the same language, yet their various dialects differ not only in the pronunciation and signification of many words; but also in a great number of radical words which are not to be found in the neighbouring dialects. The difference of these dialects is not governed, as might be supposed, by the intercourse between nation and nation, since the signification of words used by contiguous tribes frequently differs in the most striking manner. Hence neighbouring nations do not perhaps understand one another; whereas those which are wide asunder have no difficulty to comprehend each other’s meaning. Thus the Russian and Cossack dialects vary but little from those spoken by the Bosnians and the inhabitants of Ragusa, whose language differs so widely from that of their neighbours, the Dalmatians, and the people of Carniola. In like manner, the Russian idiom differs much from that of the Poles, though the Russians are neighbours to that nation as the Bosnians are to the Dalmatians.

Next to the Slavonians and Germans, the Magyares or Hungarians are the race most widely spread in the Austrian monarchy. They probably derive their origin from Asia; and this conjecture seems to be strengthened by the traces of Asiatic manners which they still retain. Unenlightened and disliking the arts and commerce, they indulge that indolence and apathy in which the people of Asia place their happiness. In this respect then the character of the Magyares differs widely from that of the Germans and Slavonians, who engage with ardour in all sorts of speculations as well as retail trades. Hungary, therefore, which they inhabit, would be a very poor country did not the fertility[Pg 7] of the soil confer on them an affluence which they never would derive from their own exertions.

The Magyares are spread as far as the coasts of the Adriatic: a small tribe of them, known by the appellation of Szythes, is found near Fiume living peaceably among the Illyrians. The great mass of the nation, however, exists in Hungary, where the number of the Magyares is estimated at about three millions and a half.

The Walachians appear to be with the Slavonians the most ancient inhabitants of the country watered by the Danube. In number, though very much inferior to the latter, they equal the Magyares; at least in the countries situated eastward of the Theiss. Naturally vain, these people pretend to be descendants of the Roman colonists, who settled from time to time in ancient Germany. They accordingly style themselves Rumani, to indicate this noble origin. It is, however, more probable that they proceed from a mixture of the ancient Dacians, Romans and Slavonians. Their language in fact is composed of terms more or less altered, which manifestly belonged to those different nations. But a circumstance which shows that the groundwork of their language is not derived from the Latin is, that their declensions and conjugations have no resemblance to those of the latter: neither do the terminations of the majority of their words correspond with those generally observed in the Latin.

Without arts, and almost without religion and civilization, the Walachian peasants know no other wants and pleasures but those of a roving life. They are in general suspicious, vindictive and disposed to hate other nations; hence the Hungarians and Transylvanians treat them exactly like slaves. The Walachians, like the Slavonians multiply fast; and it is perhaps on this account that they are deemed dangerous by the Hungarians among whom they live.

The Ziganis or Ziguener, a roving or rather vagabond race, are very numerous in the Bukowina, Hungary, Galicia, and Transylvania. In the latter province they amount to more than sixty thousand; and out of seventy thousand inhabitants who composed the population of the Bukowina, when it was ceded to Austria in 1778, more than 10,000[Pg 8] were Ziganis. Of the origin of these people, whose manners, habits and way of life, perfectly correspond with those of the gipsies, nothing is known with certainty; but the arguments of Grellman seem to render it probable, that they are the descendants of the Hindoos expelled from India at the time of Tamerlane’s invasion in 1408 and 1409. Of the period of their arrival in Hungary we are not informed, but they were known in that country so early as 1417, about which time probably they began to introduce themselves into Transylvania. The Ziganis in general manifest more attachment to the Hungarians than to any other nation, either because the manners of the latter approach nearest to their own, or because they afford them more protection.

The Armenians in the Austrian dominions are descended from those who, towards the conclusion of the seventeenth century, removed from Asia and settled in Transylvania, where there are now upwards of eleven hundred families. Most of them dwell in the towns of Armienstadt and Ebesfalva, the first of which was named after them. In the sequel others of this nation fixed their abode in Hungary, where there is not found any considerable community of of them excepting at Neusatz, in the country of Bartsch. In Galicia also they are so numerous as to have an archbishop at Lemberg, the capital of that province.

The same causes which have transferred Armenians into Austria have also brought thither Greeks, Macedonians and Albanians. The people of these different nations indeed are not numerous, there being scarcely six hundred families of them in Transylvania, in which province most of them reside. Naturally industrious, these foreigners have proved very useful to Austria, and the city of Cronstadt is indebted to them for the establishment of several important manufactures.

It is in Moravia alone that we find a few of those Walloon families, who serve to remind the spectator of the glorious period when the crowns of Austria and Spain were united on the same head.

RELIGIONS—ROMAN CATHOLICS—GREEK CHURCH—ARMENIANS—PROTESTANTS—SOCINIANS—JEWS—MAHOMETANS.

All the sects of the Christian religion are to be found in Austria, and the Jews, Armenians, and Greeks, are more or less numerous in the different provinces. Such a diversity of religious opinions cannot fail to have a considerable influence on the minds and manners of the inhabitants.

The Roman Catholic is the religion both of the sovereign and of the state. The great majority of the inhabitants of Austria profess this religion, which was long the only one tolerated in the provinces composing this empire. Joseph II. however, sensible of the injustice of proscribing persons on account of their religious opinions, issued an edict granting toleration to the professors of all creeds. Since that time the different Christian sects, the Jews and even the Mahometans, have enjoyed liberty of conscience in the Austrian dominions.

The archbishop of Vienna is the head of the civil, and the archbishop of St. Pölten, of the military clergy. The latter alone has a right to recommend to the emperor’s nomination, persons qualified for military ecclesiastical appointments, such as the chaplaincies of regiments and fortresses. The archbishop and bishops are all members of the metropolitan chapter. On the death of one of their number, the chapter has a right to propose a successor for the nomination of the emperor, who approves or rejects as he thinks proper, without allowing any sort of interference on the part of the pope. Hence several of the sees are at present vacant, as the government has found it convenient to appropriate the large revenues attached to many of them to the exigencies of the state.

It would be difficult to state with accuracy the number of Catholics in Austria; but so much is certain, that they[Pg 10] compose at least two-thirds of the population of the empire. The Protestants are not numerous, excepting in Bohemia on the frontiers of Saxony.

With the exception of Russia and Turkey, no country in Europe contains so many professors of the Greek faith, as the dominions of Austria. Some of these are termed united, as they acknowledge the pope for their supreme head, while others have refused to become thus united with the Catholics. They are chiefly to be met within Galicia, Hungary, Croatia, and Transylvania.

The Armenian christians have chosen Galicia in preference for their new abode; but there are some also in Hungary and Transylvania. Almost all of them are engaged in commerce. These people are remarkable for their activity and industry, and such of them as do not make a profession of the arts or trade, pursue agriculture with truly laudable perseverance. Almost all those who have settled in Hungary have adopted the latter: and the pains they have bestowed on a soil naturally excellent, have been rewarded with such abundant crops, that almost all of them have acquired in a short time a competence and even wealth.

Since the time of Joseph II. the Protestants, both Lutherans and Calvinists, have enjoyed the free exercise of their religion in the imperial dominions. The number of the former is estimated at about one million and a half, and that of the latter two millions and a half. Bohemia, Hungary, and Moravia are the countries in which they are most numerous. Almost all of them are remarkable for their industry.

There are many other religious sects in Austria. The province of Transylvania alone is computed to contain upwards of forty-five thousand Socinians or Unitarians, who enjoy the same rights and privileges as the Catholics and Protestants. Most of these Socinians are Hungarians or Szeklers, and their number throughout Hungary is so considerable that they have founded one hundred and sixty churches. Hungary has also afforded an asylum to the Mennonites and Anabaptists, but though they are tolerably numerous there, as well as in Transylvania, still[Pg 11] they form but a small part of the population of those two countries.

The Jews in the Austrian states are not, as we have seen, so numerous as it might be imagined. They amount to about three hundred thousand. In order to make real citizens of them, the sovereigns conferred on them the same prerogatives with the rest of their subjects. This wise measure, however, has not excited in them any genuine love for their country, or inspired them with the least zeal for the welfare of the state. The Jews, as in the other countries of Europe, live insulated amidst the nation to which they belong; and continue to form a separate people, who never will mingle with any other race. Self is their ruling principle, and private interest their sole study. Without love to their sovereign, without concern for their country, they are indifferent to every thing excepting money, which is the god of their idolatry. Leading, wherever they are found, a wandering life, they consider themselves rather as travellers than as citizens, whose fortunes are dependent on the prosperity of their native land.

The Austrian sovereigns, after conferring upon them the rights of citizens, deemed it but fair that the Jews should, like all the other classes of society, furnish soldiers for the public defence. This just requisition they resisted, and it was necessary to employ force to compel submission to this general measure. It was not without great difficulty that fifteen hundred were levied in Galicia: some of them served in the ranks, and others in the artillery and wagon-train.

The active commerce subsisting between Austria and Turkey, brings a great number of Turks into the former empire. All or nearly all of them are merchants. The advantages which they enjoy gradually induce them to settle in the country; but they are not yet sufficiently numerous to have mosques. These Turks therefore are content to practise their religion within their own houses; and when they do meet, it is not so much to worship God as to smoke and chat together. The coffee-houses of the Prater, and of Leopoldstadt, at Vienna, are commonly full of these foreigners, who carelessly seated on handsome divans, surrounded by sherbet and other liquors, and smoking[Pg 12] long cigars, exhibit a picture of oriental manners amidst a European population. The stranger is equally struck by the splendour of their dress, the fashion of which is so different from that of the close garments of Europe.

CHARACTER OF THE PEOPLE OF AUSTRIA IN GENERAL.

The south of Germany would be the most fortunate country in Europe, if the government to which it is subject had not shown in many circumstances a weakness that but ill accords with the wisdom of its views. Temperate in its climate, fertile from the nature of its soil, and happy in its institutions, it remains invariably in a monotonous state of well-being, which is prejudicial to the activity of the mind alone, not to the happiness of the citizens. The inhabitants of this peaceful and fertile country have but one wish, that is, to live to-morrow as they lived yesterday. This tranquillity which in Austria pervades all classes of society is surely preferable to that agitation and thirst of wealth which torment almost all ranks in other countries. Thus industry, ease and domestic enjoyments are more highly valued in Austria than elsewhere: there every thing is done rather out of duty than for fame; and no man looks for the reward of his actions in the empty popularity which merely flatters pride and vanity, without ever gratifying the heart.

A nation which has no other motive than a love of its duties must be essentially a generous and an upright nation. What nation displays, on the whole, more integrity and generosity than the Austrians? They carry the love of their sovereigns to the highest pitch, and that because they regard this love as the most sacred of duties. Let their rulers be ever so unfortunate, their attachment is but the stronger, and the greatest sacrifices seem to cost them nothing.

The Germans in general, and the Austrians in particular, possess a sincerity and a probity that are proof against[Pg 13] every thing. These valuable qualities originate as much in the excellence of their institutions as of their hearts. Their tranquil and peaceful disposition as well as their domestic habits, encourage in them a love of order and union from which they never deviate.

In consequence of this love of order the Austrians are remarkably neat in their dress, so that you seldom see among them, as in other countries, wretches in rags by the side of elegance and luxury. There is not an Austrian peasant but possesses a decent suit of clothes, boots, and a furred great coat for winter. Enter their habitations and you will find the same neatness and cleanliness which are conspicuous in their habiliments. In these rustic dwellings nothing announces affluence, but on the other hand there is nothing to denote poverty and indigence. When the lower classes of a nation are well dressed, who can doubt its wealth and its prosperity?

The Austrians have been generally considered as ceremonious, and as attaching too much importance to the formalities of etiquette. Foreigners have been apt to ridicule them on this account, without reflecting that this adherence to forms and ceremonies is a result of their love of order and decorum. It must nevertheless be confessed that, if etiquette and the forms of politeness are more strictly observed in Germany than in other countries, this is partly owing to the prerogatives enjoyed there by the nobility. Though the line between the classes is much more strongly marked than elsewhere, still there is nothing offensive in that demarcation. The differences of rank are confined to a few court privileges, and the right of admittance to certain assemblies, which afford too little pleasure to deserve much regret. In fact the grandees of Vienna, who are the most magnificent and wealthy in Europe, are so far from abusing the advantages they possess, that in the streets they suffer the meanest vehicles to stop their brilliant equipages. The emperor himself, and his brothers, when they go abroad drive quietly along in the file of hackney-coaches, and take delight to appear in their amusements as private individuals.

As to the national character, there is but little opportunity for its development in Austria, since the different[Pg 14] nations who inhabit the various provinces of that empire do not form a compact whole, and are not all actuated by the same spirit. Two great causes, however, might give a certain stimulus to the public mind, and also excite patriotism in Austria; these are, the love of the country and of the sovereign; and the felicity which all the inhabitants enjoy under protecting laws. Husbandmen rather than traders, the Austrians are for this very reason more attached to their native soil. The interests of the country are in fact more closely connected with those of the cultivator of the soil, than of the merchant, whose almost only object is the success of his speculations, on which his precarious existence depends. Agriculture is honoured in Austria, and the most illustrious of its princes, as well as the sovereign himself, are fully sensible of its importance to an empire possessing so fertile a soil.

The Austrian nation is perhaps the most upright and the most moral of any in Europe. There is not an Austrian, with the exception of the higher class of society, but feels that morality is the genuine source of domestic happiness and the guarantee of the peace of families. The sacred ties of marriage are still respected; and how indeed could it well be otherwise in a country where woman is devoted to her conjugal duties and finds the reward of this devotedness in the scrupulous fidelity of him who is its object! Conjugal love always leads to maternal affection; and the Austrian women are all, or nearly all, excellent mothers. They are not more ostentatious in their attachment to their children than in their love for their husbands: so that the name of her who sacrifices herself for the object of a pure and tender affection remains for ever unknown to the world. Divorce, which introduces a kind of anarchy into families, has never been sanctioned by the laws of Austria, and this is not one of the least important benefits that it owes to its legislation.

The fair sex in Austria have in general auburn hair, delicate complexions and large blue eyes, the united effect of which there would be no withstanding, did not their modesty and simplicity command respect, and temper by the charm of virtue the too powerful impression of their beauty. They delight by their sensibility, as they interest[Pg 15] by their imagination. Without being too much addicted to the cultivation of literature and the fine arts, they are no strangers to the best productions of either; and when you have once gained their confidence you are astonished at their knowledge, which they never display but in spite of themselves. The Austrian ladies speak with equal fluency all the languages of Europe; and in company they possess in general a marked superiority over the men.

These observations apply particularly to the women of the higher classes: as to those of inferior rank, they can scarcely be surpassed for goodness of disposition and purity of morals. The maternal love of these rustics is too strong not to preserve them from those faults which are unhappily too common among females of the same condition in many other countries. Labour and the exercises of religion occupy them entirely, and exempt them from those vices which are generated by idleness. They are, however, charged, at least those of some districts, with being too much addicted to spirituous liquors, and with impairing by this indulgence their circumstances and their health.

The men are in general tall, well proportioned, and of a ruddy complexion: but though few ordinary persons are to be found among them, it is rarely that you meet with forms distinguished by that higher sort of manly beauty which is frequently seen in the south of Europe, and which furnished models for the finest statues of antiquity. The Germans still answer the description given by Tacitus of their ancestors: they are almost all fair and light complexioned: and their souls do not possess the energy which their stature and strength would seem to denote.

INHABITANTS OF LOWER AUSTRIA—MANNERS OF THE PEOPLE OF VIENNA—AMUSEMENTS—HOUSES—POPULATION AND MORTALITY—SHOPS—PAVED STREETS—THE FIRE-WATCH—COSTUMES OF UPPER AUSTRIA.

The inhabitants of Lower Austria, in which the capital of the empire is situated, are, with the Hungarians, the most fortunate of the subjects of the imperial sceptre. Cultivating a fertile soil, and not having, like the Styrians and the Tyrolese, to struggle incessantly against an inclement climate, they are happy in their geographical position; and they are in general deserving of it by the excellence of their disposition. Harbouring none but the milder sentiments, they have more gentleness than energy, and more good nature than elevation. The Austrians are a simple and a hospitable nation; and the same observation applies to their nobles, who never assume the German or rather the Austrian pride, unless when they would enforce the prerogatives of birth. A stranger has least to suffer from this narrow-mindedness, which is becoming the less common, the more the education of the higher classes is improved, and the more they learn that true nobility ought to display itself in exalted sentiments alone.

It is natural to suppose that there must be a great difference between the manners, customs and dress of the inhabitants of Lower Austria, according as they reside in the country or in cities, or belong to the working classes which, in Austria, as in other countries, have manners peculiar to themselves.

The manners of the higher classes in Vienna and in the other towns of Lower Austria, are in general mild and simple; and they are found in harmony with that good nature which is the most distinguishing feature in the Austrian character. Though the nobility are not free from the imputation of haughtiness and of attaching too much value to titles[Pg 17] and honorary distinctions, it cannot be denied that much hospitality prevails among them as among the wealthy tradesmen. Many of the upper classes keep open tables; and in many houses visitors are permitted at all hours of the day and even until midnight, to partake alike of every repast that is served up and of the conversation.

It is alleged, and not without reason, that the people of Vienna are rather too fond of good cheer. This is a general propensity of all classes; so that those whose means will not permit them to have delicacies are sure to indemnify themselves by the abundance of their viands. The lower ranks always mingle with this indulgence a fondness for other amusements, such as dancing and walking. The tradesman of the capital takes great delight on a Sunday in a little country excursion with his family; and as the parks of the grandees are open to all comers, these are generally the places of rendezvous. He also frequents the Prater and the public places of the metropolis; he looks and listens with interest to all that passes, provided he is not watched; for instead of wishing, like a Frenchman, for instance, to attract attention, he feels uncomfortable as soon as he is noticed. His whole happiness centres in himself and his numerous family, from which he never likes to be parted. This picture of the happiness of the people of Vienna is the more pleasing since it is not chequered, as in most of the great cities of Europe, with the appearance of squalid misery. In fact you can there distinguish but two classes, the nobles and the citizens; all below them being blended by a certain degree of luxury and ease with the latter.

In winter, companies do not assemble about the stoves as round our fire-places. The equable heat diffused by these stoves admits of their breaking into groups in the different apartments, which thus assume the appearance of a coffee-house. Servants in party-coloured liveries hand round all sorts of refreshments and sometimes the mistress of the house does the honours of it herself with an engaging attention that charms a stranger. In general, however, she takes this duty on herself only when she wishes to honour in a particular manner persons of distinction or eminent travellers; at other times, leaving every visitor to[Pg 18] amuse himself as he pleases. In these societies, you observe numbers of ribbons of all colours, and chamberlains’ keys at all pockets; these distinctions are so common that a person who has none is almost a singularity. What renders these companies rather irksome is the practice which prevails of not calling any one by his name but only by his title. Thus you hear the persons about you greeted by the appellations of baron, director, inspector, captain, duke, or general; and remain ignorant of their real names unless some friend takes the trouble to tell you who they are.

The ladies, on these occasions, are almost always ranged in a circle, chatting together or engaged in various works of embroidery, frequently to the number of thirty or forty. The young men of Vienna never make their appearance at these parties: hence their manners have not the polish which the habit of keeping good company imparts, nor do they pay those attentions which are due to the sex. In these companies you only meet with a few young Austrian or foreign princes, who but too frequently imagine that their rank exempts them from that delicate politeness which virtuous women inspire and can duly appreciate.

It is not to the want of accomplishments in the Austrian ladies, that the indifference of the young men in regard to them must be attributed, but to the unsociable habits of the latter. Their education having been in general neglected, riding and hunting occupy all the leisure which they do not pass at the coffee-houses, in smoking and play. The rest of their time is devoted to the pleasures of the table. With such a way of life and such habits, how is it possible to keep up that tone of decency which it is necessary to maintain in a select company? Nothing seems to them so difficult and so irksome, and to avoid this unpleasant restraint, they keep away from such societies altogether.

Being thus left to themselves, the ladies of Vienna can do no other than seek the company of the foreigners whom they find possessed of amiable manners and information. Flattered by their attentions, and tired of the society of men, which is generally monotonous enough in Austria, the stranger exerts himself still more to please. He feels a deeper interest in studying their character; the better[Pg 19] he becomes acquainted with it, the more he esteems them; and he is astonished that females so gentle, so lovely, and so fascinating, should be forsaken by those whom they are so well qualified to delight.

The young men of rank at Vienna, having in general no occupation, and as we have seen shunning company, are but too apt to yield to the seductions of the gaming-table. Numerous instances of the fatal effects of this baneful passion might be related; but circumstances of this nature are too common in most other civilized countries to appear extraordinary.

The picture of the manners and amusements of the higher classes at Vienna, drawn by Dr. Bright, is interesting.

Morning calls, says that traveller, are not considered of the same importance in Vienna as in London. When a stranger has been properly introduced into a family, he usually receives a general invitation, of which he is expected to avail himself. Accordingly he calls in the evening; and if the lady of the house or any of the family be at home, he is admitted, and then, as it happens, meets others, or is the only visitor. Easy conversation or cards, music and tea, chess or enigmas, fill up the evening; or if the party be numerous, dances and refreshments, the rehearsal of poetry, or other exercises of mind or body, enliven the visit and dispel the unpleasant restraints of society.

The evening amusements in Germany are very various, and sometimes almost fall under the denomination of puerile. Not content with requesting young ladies to recite verses, they will sometimes invert the natural order of things and compel children to act plays, while grown people will play cross-questions and crooked answers; or standing in a circle, and holding a cord in their hands, pass a ring from one to the other, while some one of the party is required to discover in whose possession it is to be found.

Acting riddles is a favourite game, and one which is well calculated to amuse those who are wisely resolved to be amused when they can. A certain portion of the company retire into an adjoining room, where they concert together how best to represent by action the different syllables which compose a word, and the meaning of the[Pg 20] whole word. They presently return, and carrying on their preconcerted action, require the company to resolve the riddle. Thus, for instance, on one occasion the word determined upon was Jumeaux. Some of the actors, coming from their retirement, began to squeeze a lemon into a glass, calling the attention of the company very particularly to it by their action, thus representing Ju. Others came forward imitating the various maladies and misfortunes of life, thus acting the syllable of meaux. Then finally tottered into the circle an Italian duke and a Prussian general, neither less than six feet in height, dressed in sheets and leading-strings, a fine bouncing emblem of Jumeaux.

Dinner-parties, though not the regular every day amusements of life in Vienna, are not uncommon. There is much similarity in the style of dinners throughout Germany, and it has some points of peculiar excellence. The table is generally round or oval; so that each guest has means of intercourse with the whole party, even when it is large. It is covered for the greater part with a tasteful display of sweets or fruits; two places only being left near the middle for the substantial dishes. Each person is provided with a black bottle of light wine, and every cover, even at a table d’hote, is furnished with a napkin and silver forks. The first dishes which occupy the vacant spaces are always soups; they are quickly removed to the side-tables and distributed by the servants. In the mean time, the next dish is placed upon the table, taken off, carved, and carried round to the guests in precisely the same manner; and so on till every thing has been served. The plates are carefully changed, but the knives and forks very generally remain throughout the greater part of the dinner, or, at best, are only wiped and returned. The dishes are so numerous and the variety so great, that, as every body eats a little of every thing, they seldom take twice of the same.

The succession of luxuries is not exactly as with us. An Englishman is somewhat surprised to see a joint of meat followed by a fish, or a savoury dish usurp the place of one that was sweet. To conclude the ceremony, each servant takes one of the sweetmeat ornaments off the table,[Pg 21] and carries it, as he has done with the other dishes, to all the guests.

During all this time the conversation is general and lively, and beyond a doubt much more interesting than that which is heard on similar occasions and in similar society in England, where its current is perpetually interrupted by the attention which every one is bound to pay to the wants and wishes of persons at the most distant part of the table. While the sweetmeats are served, a few glasses of some superior kinds of wine, which have likewise been distributed at intervals during the dinner, are carried round; and then the company, both ladies and gentlemen, rise at the same time by a kind of mutual consent, which, as the rooms are seldom carpeted, occasions no inconsiderable noise. To this succeeds a general bowing and compliment from every one to each of the company individually, each hoping that the other has eaten a good dinner. This peculiar phrase is precisely the counterpart of another always employed on the parting of friends about mid-day, each expressing a sincere hope that the other will eat a hearty dinner. This is the most usual form of civility in Vienna.

The party then adjourns to another apartment, where coffee is served and where it is frequently joined by other visitors, chiefly men, who come without particular invitation, to pay their respects or to converse on business, in the manner of a morning call, and who prolong their stay as the movements of the first party indicate: for an invitation to dinner by no means necessarily implies that you are to spend the evening or any part of it at the house or that the family has no other engagement as soon as dinner is concluded and the guests have taken their coffee and liquors.

As the dinner is early, being always between twelve and five, the remainder of the evening is employed in various pursuits. A drive in the Prater or to some place of public resort, a visit to the theatre, or a succession of the calls just described, employ the evening; or, if the dinner has been very early, the party resumes the occupations and business of the day.

The time and duration of the performances at the theatres are very convenient. They begin about six and conclude[Pg 22] a little after nine. The greatest decorum prevails during the representation, the police-military, that is police-officers, in a particular kind of livery and wearing swords, being stationed in all the avenues. Thus a person going with a wish to hear the play is not disappointed by those brawls which scarcely ever fail to interrupt the performance in our English theatres; nor is there any part of the house to which a party of the most delicate females might not resort with the greatest propriety.

The theatrical performances are continued throughout the whole year, with the exception of the days prohibited by the Catholic calendar, on many of which, however, concerts, public rehearsals, and a species of exhibition called a Tableau are permitted. The latter amusement, being scarcely known in this country, requires some notice.

The object of these exhibitions is, to represent by groups of living figures the compositions of celebrated sculptors or painters. With this view that part of the apartment or theatre, beyond which the Tableau is to be placed, is darkened, and on raising a curtain, the figures are discovered dressed in the costume which the painter has given them, and firmly fixed in the attitude prescribed by his pencil. The light is skilfully introduced and other objects arranged so as to give as nearly as possible the effect of the original painting. After some time the curtain drops to give the performers time to rest, and to relieve themselves from the painful attitudes which they are frequently obliged to preserve; and the curtain again drawn up discovers them still in their characteristic postures. When the spectators are supposed to be satisfied with one picture another is introduced, and thus several are exhibited in succession. This generally forms only part of the evening’s amusement, and is either accompanied by a theatrical performance, or if in private by dancing or music.

An interesting variety of this entertainment was witnessed by Dr. Bright. In the midst of a brilliant assembly, the folding-doors of another room were suddenly thrown open, and what appeared to be a beautiful collection of wax-figures was displayed to the delighted eye. They were placed on pedestals, in recesses, or in groups around the room. They represented heathen deities, or the gnomes[Pg 23] and fairies with which the poets have peopled the regions of imagination, with all their emblematical accompaniments, and their dresses, which were selected with the greatest taste. These figures were represented by persons whom nature had favoured in a distinguished manner; they preserved an unmoved firmness of attitude, and nothing interrupted the illusion they intended to create but the animation of their eyes, and the smile which sometimes dimpled the cheek even of the rooted Daphne. To assert that this exhibition was beautiful were to degrade its charms; it seemed to throw a magic spell over the spectators, and the great difficulty was to induce them to retire when it was actually necessary to relieve the figures from the painful position in which they stood.

The houses of Vienna are in general rather small than large; the palaces of the grandees alone being spacious. Most of the houses are of brick or wood covered with slate, and some with shingles. As a measure of precaution, however, the police forbids the use of the latter; so that whenever a house is repaired it must be roofed with slate or tiles. The houses in the city only are from four to six stories high: those of the suburbs occupy more ground but are not so lofty. Here the mansions of the great, of very simple and sometimes very whimsical architecture, have handsome gardens attached to them. The interior is not so commodiously arranged as it might be. The walls are more commonly painted in fresco than papered. The furniture is not in general costly, excepting in the palaces of princes or the mansions of bankers or wealthy merchants, whose opulence enables them to command all the elegances as well as the conveniences of life. Simplicity, neatness and perfect cleanliness, which are far to be preferred to tawdry magnificence, are every where observable.

Fire-places are almost unknown in the private houses of Vienna, and a stranger is surprised not to find any even in the kitchens.

Vienna is composed of two distinct parts, the city properly so called and the suburbs, the latter being separated from the former by large ditches and high walls. The total population is about 225,000 souls. It is at present on the increase, in consequence of the important advantages[Pg 24] derived by Austria from the late wars. This city, however, is not a healthy residence, notwithstanding the high winds which usually prevail there, and which tend to promote salubrity. Instances of longevity are much more rare in this than in other capitals. In general the mortality is as one to fifteen annually, which is nearly three times as great as that of the British metropolis. Though this effect may be partly owing to the attachment to the pleasures of the table for which the people of Vienna are proverbial, yet, it must also be in part ascribed to the climate, which is extremely variable, frequently changing in the course of few hours from the extreme of heat to that of cold, and the air, unless ventilated daily by a breeze about two hours before noon is said to become pestilential. The spring water also is insalubrious, being apt to occasion bowel complaints to strangers; and the water of the Danube is so thick and muddy that it cannot be drunk unless filtered.

The numerous benevolent institutions in Vienna and the comforts enjoyed by the lower classes seem to argue that this great mortality is owing rather to the climate than to any other cause. The humane mind is not here shocked by the appearance of that squalid misery which excites as much disgust as pity, and the number of mendicants with which most other large cities are infested. But if the lower classes here are better off than in some other countries, it is chiefly owing to their superior morality and good conduct, which secure them from indigence and want.

The shops of Vienna are not decorated with that profusion and luxury which are displayed in those of London and Paris. They are neat and simple; and though they may contain a considerable variety of goods, yet frequently a square glazed case of patterns hanging at the door is the only mark by which the nature of a shopkeeper’s dealings is estimated. The shops, therefore, contribute but little to the embellishment of the streets in which they are situated.

The streets of the city properly so called are paved with a light gray sienite brought from Hungary and Bohemia, or with a very hard species of granite furnished by the mountains of Upper Austria. Both these species of stone are susceptible of a high polish, and they are wrought into a variety of ornamental articles, particularly snuff-boxes.[Pg 25] The streets of the suburbs, being unpaved, are in winter almost impassable on account of the mud, and not the most pleasant in summer, owing to the clouds of dust raised by the winds which sweep through them.

Vienna possesses the advantage of being traversed in all directions by subterraneous canals, which run into the Danube, and into which all the impurities of the city are carried by regular drains and sewers. It is well lighted at night, when a horse and foot patrole are employed to protect the lives and properties of the citizens, a duty in which they are ably seconded by the fire-watch, chiefly consisting of invalid soldiers, who are not capable of active military service. Armed with long staves, they walk through the streets of Vienna, crying the hour, and at twelve o’clock adding, put out your fires and shut your doors! A hat of tin slouched behind and turned up before, covers the head, and that the wearer may be known again, it is marked with a particular number or letters. In this manner it is easy to ascertain any individual who may have neglected his duty or exceeded his orders. A loose drab coat is also marked by a number. Pantaloons, boots or gaiters according to the season, a leathern apron, and a leathern bucket, slung behind to be ready in case of fire, complete the costume of one of these watchmen.

The inhabitants of the villages surrounding Vienna have nearly the same manners and costume as those of the capital following similar professions. The remark is equally applicable to the people of Upper Austria. Among the peasantry in both, the men universally wear low broad-brimmed hats, as a protection both from rain and sun, and a kind of half-boots. The breeches, usually of a dark colour, are suspended by coloured braces put on over the waistcoat, and a broad belt encircles the waist. A jacket of dark-coloured cloth covers all; a black handkerchief is worn round the neck, and the stockings are blue, a colour for which these people appear to have a predilection.

The handkerchief which covers the head and over which the hat is put, is a peculiarity in the costume of the women of these provinces.

COSTUME OF THE INHABITANTS—THE JOANNÆUM AT GRATZ.

In Styria the costume of both sexes is singular. The head-dress of the women of its capital, Grätz, and the neighbouring villages, such as maid-servants and daughters of inferior tradesmen or small farmers, generally consists of a cap of heavy gold lace, in the shape of a helmet, not unlike that worn by women of the same class in Vienna. In their forms these caps vary a little, the sides being frequently very broad, and opening wide backward almost in the manner of a butterfly’s wings. The gold is often richly varied with alternate stripes of embossed silver lace, or with embroidered figures: others wear a cap of the same form, made of black silk and lace, while others again have the black silk richly worked with flowers.

Most of the female peasants in the surrounding country wear broad hats of light coloured felt, nearly resembling those of Holland in shape, and like them lined with linen, which is brought over to cover half of the upper surface of the brim. This lining is generally of some dark colour. All wear double handkerchiefs about the neck and shoulders, and a tight bodice of some gay colour cut low in the back, with a triangular false cape running in a point nearly to the waist.

The countrymen likewise wear broad hats encircled by a ribbon or a wide gold lace; a coloured silk handkerchief about the neck, and a fancy waistcoat, with ornamented braces on the outside, by which the dark-coloured breeches are suspended. Their stockings are blue, and they wear neat half-boots lacing before in a point. On week-days they have jackets, but on holidays wear long frock coats of some dark cloth, generally green, and ornamented with many large shining buttons.

We cannot quit this province without directing the[Pg 27] the attention of the reader to an institution of recent establishment, which Dr. Bright pronounces to be the most interesting at Grätz; this is the Joannæum, which takes its name from the archduke John, its founder. This prince, who has distinguished himself by his love of knowledge perhaps above any prince in Europe, and who is truly worthy of the high situation in which his birth has placed him, and of the estimable imperial family of which he forms a part, had pursued with unceasing assiduity an investigation into the resources both natural and political of Styria. He had himself surveyed every romantic scene, gathered every mountain flower, estimated the capability of every rich valley, and drawn his conclusions as to what was excellent and what still remained to be improved; and wishing to make the stores he had collected and the information he had gained of substantial use to the country, he determined to present his valuable collections and library to the inhabitants of the capital, that they might afford the means of instruction to the people, and prove an encouragement to further research. The Archduke accordingly gave the whole of this treasure, consisting of an herbal which contained fourteen thousand specimens, and a large store of minerals, an extensive library, philosophical instruments and manufactured produce to the town of Grätz. These were deposited in a large building, formerly a private house, purchased for the purpose, and in the course of a year or two lectures on chemistry, botany, mineralogy, astronomy and manufactures, were established; a reading room was likewise opened and supplied with above fifty different periodical scientific publications. The example of the Archduke soon induced several other persons to contribute towards completing so desirable an object; and among other liberal contributors, Count von Egger presented his library and a valuable cabinet of natural history.

At this institution lectures are given on mineralogy, botany and chemistry, astronomy, mechanics and the means of resuscitating persons apparently drowned. This last course of lectures has lately been appointed to be held in all the institutions for the higher branches of education in the Austrian dominions, and is frequently delivered on[Pg 28] Sunday. Although the Joannæum was originally quite unconnected with the public education of the country, the students of medicine have lately been permitted to avail themselves of certificates from the professors, to forward their claims to academic honours at Vienna.

COSTUMES OF THE BOHEMIANS.

The name of Bohemia is derived from that of the Boji, a Celtic nation which inhabited this country at the period to which the earliest historical records of it relate. Notwithstanding the numerous resources possessed by the inhabitants in the fertility of the soil, in the mines, the forests and the different manufactures established in the course of the last century, the country is not very flourishing. The peasantry being reduced to the state of serfs, the apathy and indolence consequent on servitude, cause Bohemia to swarm with mendicants and vagabonds.

Among these are a great number of gipsies, who in some parts of Europe are erroneously denominated Bohemians.

The costumes of Bohemia differ considerably from those of Austria, properly so called. The annexed engraving represents a young peasant of the environs of Egra. These are a handsome race of men, with fine open countenances.

Their dress combines simplicity and elegance. Wide trowsers in the Turkish fashion, reaching to the middle of the leg, contrast by their dark colour as well as by their amplitude, with the short, tight waistcoats. The under-waistcoat, or rather a sort of stomacher, which is left uncovered by the two open upper waistcoats, is the article of their dress in regard to which they are most particular.

In winter these villagers wear over all a long brown cloth surtout. The hat has a broad brim and a low crown, [Pg 29]round which is tied a coloured ribbon. From their earliest childhood they are habituated to smoking, and they are seldom seen without pipes in their mouths, especially in winter.

PEASANT of EGRA IN WINTER DRESS.

The wives and daughters of peasants in general employ dark-coloured stuffs only for their apparel. In cold weather they wear a cap of fur, or of woollen, round which a muslin handkerchief is tied behind. Their stockings are of a dark colour; the shoes are black with red heels: the quarters are bordered with a piece of the latter colour, which turns down over the instep.

The principal piece of finery in the dress of these women is the girdle, in which they are particularly studious of elegance and richness. It fastens both before and behind, and from the middle hangs a broad band of the same material and similarly ornamented, which passes in a semicircle sometimes to the right, at others to the left.

The wedding apparel of the young female peasants of this part of Bohemia is remarkable. Everywhere else a wedding is an occasion of rejoicing and gaiety not only to the new-married couple, but also to such of their relations and friends as are invited. Not so at Egra. There the bride would be deemed guilty of an act of unpardonable indecorum, if she were to appear in a white dress, or to give additional splendour to her apparel by pearls, jewels, or laces. Marriage, being considered in this country as the most important and solemn act of life, is celebrated with the utmost gravity. Every thing, therefore, that bears the resemblance of ostentation is avoided: the bride is attired in her usual black dress, to which is added a cloak of the same colour, reaching to the knees and not unlike that used in the rest of Europe at funerals. She holds in one hand a rosary, and in the other a veil which is to cover her during the ceremony; and in the most modest and devout attitude she proceeds to the church.

In summer the inhabitants of these parts go very lightly clothed. The men have but one open waistcoat, which leaves the bosom exposed; the women wear a corset without sleeves, a petticoat, a blue apron and a handkerchief of the same colour about the neck. The head is covered with a white handkerchief, which is tied behind.

COSTUMES OF THE INHABITANTS—ACCOUNT OF THE HAUNACKS—PEASANTS OF THE FRONTIERS.

The costume of the inhabitants of Moravia resembles more or less that of the people of the contiguous countries. In the centre of the province the men generally wear jacket, waistcoat, and pantaloons of one colour, hussar boots, and a hat, the broad brim of which is cocked behind and slouched before.

The women dress nearly in the style of the Austrian peasants, but in winter they wear over the laced corset and gown a sort of hussar jacket of cloth bordered with fur, while gaiters or boots defend their feet and legs from cold and damp.

Near Olmütz there is a small tract of country, extending about five square German miles, and inhabited by a tribe of people called Haunacks, or Haunachians, who are supposed by the native statistical writers to be the pure descendants of the aboriginal inhabitants of Moravia. They derive their name from the small river Hauna. Their history is rather obscure, but they are undoubtedly a Slavonic tribe.

In stature they are short, but strong and muscular; and being simple, temperate, and plain in their habits, they attain in general a very advanced age. By the neighbouring Germans they are reproached as being slothful and averse to bodily labour; while they themselves boast of the fertility of their soil, and look down with contempt upon the other inhabitants of Moravia as an inferior set of beings, to whom nature has been more niggardly of her gifts. Their mode of living is frugal and highly primitive. The flesh of the hog joined with hasty-pudding is their favourite viand, and beer their only beverage.

The young women are remarkable for the grace and ele[Pg 31]gance of their forms, and the neat adjustment of their dresses, which are extremely picturesque and show off to great advantage the considerable share of personal beauty with which the wearers are gifted. Their summer dress consists of a large white linen cap, the lappets of which, bordered with lace and embroidered with red silk, fall over their shoulders. Their long hair is suffered to float in tresses; or, when the cap is laid aside, is gracefully twisted and tied over the head with knots of ribbons. A coloured corset, laced before shows the shape to advantage. Their well turned ankles are set off with white or red stockings, and black shoes with red heels.

PEASANT of the MOUNTAINS of MORAVIA.

The dress of the men consists of a round hat adorned with ribbons of various colours; a waistcoat commonly green, embroidered with red silk, encompassed by a broad leathern girdle, with brown pantaloons attached to the vest by means of large buckles; and boots. This is their summer costume, but in winter they cover the head with a large and singularly shaped fur cap, and throw over their shoulders an undressed sheep or wolf-skin, in the absence of which they wear a brown woollen cloak with a large hood, like that of a Capuchin Friar.

On the frontiers of Hungary the costume of the peasant of Moravia partakes of the style of dress usual in the former country. A broad-brimmed, low-crowned hat covers his head; the short coat, which in shape resembles the surcoat of the ancient knights, is girt round the waist by a leathern girdle: and he carries his bundle slung behind him from a shoulder-belt. He wears tight pantaloons, and stockings, round which are twisted the strings that fasten his sandals, as represented in the engraving.

MIGRATIONS OF THE TYROLESE—THEIR FRANKNESS—THEIR ATTACHMENT TO THE HOUSE OF AUSTRIA—ANECDOTE OF THE ARCHDUCHESS ELIZABETH—LITERARY TURN OF THE TYROLESE—THEIR EXTRAORDINARY HONESTY—FONDNESS FOR PUGILISTIC EXERCISES AND THE CHASE—ANCIENT PRACTICE—MORAL CHARACTER—SUPERSTITION—MECHANICAL GENIUS—PERSONS AND COSTUMES—NATIONAL SONGS—CUSTOM OF VISITING THE GRAVES OF RELATIONS—MARRIAGE CEREMONIES OF THE TYROLESE.

The most striking feature in the character of the Tyrolese is their love of independence and their attachment to their native land. The intense cold, however, that prevails in the elevated valleys, in general compels their inhabitants to quit them in winter, when they repair to the neighbouring towns to pursue their different professions. Thus villages, nay even whole valleys are at times nearly deserted, except by the aged men, the women and the children. At stated periods, therefore, these mountaineers emigrate in bodies of thirty or forty, and spread themselves over Italy, Bavaria, and Austria. Some of them become excellent carpenters, others skilful smiths, and it is seldom that they do not follow more than one trade. They are particularly addicted to the mechanical arts. The young lads hire themselves to tend cattle. On the return of summer and the approach of harvest-time, these mountaineers set out for their respective hamlets, joyfully carrying with them their little savings. They collect in companies and march to the sound of the bagpipe, which at a distance announces their coming. All run out to meet them, and they rarely pass through a village without being supplied with refreshments. In this manner they travel forward till they reach their humble homes, where they[Pg 33] forget their hardships and fatigues in the affectionate embraces of their wives, children and relations.

The industry of the Tyrolese does not suffer them to be content with these migrations occasioned by the inclemency of the climate. They travel all over Germany with aromatic and medicinal plants, carpets, gloves, chamois-skins, steel trinkets, or wooden wares carved with the utmost delicacy. These commodities they carry chiefly to Vienna, being encouraged by the favourable reception given to them by the inhabitants, who are delighted with their frankness and good humour. The Tyrolese always speak what they think without reserve or disguise. Like our Quakers they address every one, not excepting the emperor himself, in the second person singular; and they question the sovereign without the least ceremony respecting his intentions in regard to their country. When these plans do not harmonize with their ideas, they censure them with the utmost freedom. There have been instances of their carrying their complaints to the foot of the throne, and remonstrating with a liberty which to courtiers must appear very extraordinary.

To the honour of the sovereigns of the house of Austria, it must be confessed that any of their subjects may obtain a private audience of them with less difficulty than in other states an interview can be gained with a minister. If I were to select, says a British traveller, from among the eulogies which have been passed on monarchs, the most glowing traits, assisted by the warmest efforts of imagination, I might not, perhaps make a deeper impression upon the mind of the reader, than by the simple recital of the fact, that it is the habit of the Austrian ruler to admit into his presence and to personal interview every individual of his realm. One day in every week is devoted to this sacred duty; when the emperor, with the first dawning of the morning, attends in a private apartment to receive petitions and complaints from the mouths of even the poorest of his subjects. He listens to them freely, and though he seldom judges finally at the moment, shows his sympathy and declares his feeling in their behalf.

The known frankness and intrepidity of the Tyrolese induced Austria to grant them great liberty. Never, indeed,[Pg 34] was government more paternal than that of Austria in regard to the Tyrol. Hence all the inhabitants went into mourning when the fortune of war transferred them a few years since to another power, which, by its ill-judged measures, only strengthened their attachment to their former sovereign. The struggle which they made in his behalf against the united force of France and Bavaria shows what exertions a nation fighting for independence is capable of making, and will occupy a conspicuous place in the history of those wars which have lately distracted Europe. The general peace which put an end to these hostilities, crowned the wishes of the faithful Tyrolese, and replaced them under the Austrian sceptre.

As the most trivial circumstances frequently impart a clearer insight into the character of an individual or a nation than those of more importance, the following authentic anecdote may be worth recording. The archduchess Elizabeth, aunt to the present emperor of Austria, who was so much beloved that the people of Vienna always called her Unsere Liese, (Our Bess) took a particular fancy to milk with her own hands the beautiful cows which she had collected at Schönbrunn. She had heard the Tyrolese highly extolled for their skill and cleverness in this operation, and therefore had several herdsmen brought from the Tyrol, that they might instruct her in the milking and general management of cattle. The first who arrived, seeing the princess engaged in milking her cows, gazed at her in silence for a few moments, and then burst out into the exclamation: “Get thee gone, thou awkward baggage! why, thou wouldst not earn salt to thy porridge!” After he had thus politely driven away the princess, he fell to work and milked the whole herd in less time than the archduchess would have done a single cow. During the course of this extraordinary instruction, these men never could be persuaded to soften their language or to use less frankness in their expressions. So far, however, from displeasing by their freedom, they had some difficulty to obtain permission to return to their native mountains.

The Tyrolese who travel into Germany, to carry on a little traffic in drugs and peltry, have in general several partners. At any rate the husband never goes without his[Pg 35] wife, nor the brother without his sister. It is very rarely that a man is seen by himself disposing of his commodities. They have not failed to observe that the costume of their women excites the curiosity of strangers, and they judiciously avail themselves of it that they may find a better market for their merchandise. When they settle at Vienna, almost all of them adopt the trades of carpenter or mason.

A singular fact, and which serves to show the natural bent of this nation, is, that there is scarcely a Tyrolese peasant but has his library, however small. Though it contains perhaps no more than thirty or forty volumes, still it affords proof of a fondness for study. The Bible, the Lives of the Saints, a history of their country, or of Austria, together with a few geographical works, compose the generality of these rustic libraries. So strong is their hankering for news, that many of those in easy circumstances take in the Inspruck newspaper; which, in the long winter evenings, furnishes them with subjects for discussion and comments, in which their own country is not forgotten.

Theft and robbery are so uncommon in Tyrol, that locks are almost unknown, at least in the villages. The doors of their habitations have no other guard than the mutual integrity of the inmates. The peasants therefore have merely a latch, which is raised by means of a bit of packthread, and this method of closing the entrance to their cottages is adopted solely to keep the cattle out of them. A hundred times, says a traveller, have I stopped at inns where there was no key whatever, and yet I never lost any thing. At Vienna, and in other parts of Germany also, the Tyrolese bear the highest character for honesty and integrity, and there is no instance of any of them having abused the confidence reposed in him.

Such is their respect for the memory of deceased relatives and friends, that they scarcely ever go out of mourning for them. A person who should violate this custom would be considered as degenerate. It is not uncommon to see a widow wear mourning all her life for her husband, or a daughter for a mother. If this practice attests the excellence of their hearts, the mourning assumed by them on account of the misfortunes which befall their country equally proves the ardour of their patriotism.[Pg 36] When I visited the Tyrol, says a French traveller, after the war in 1809, I asked a peasant why the people were all in mourning. “Look at our towns,” replied he, “you see that they are in ashes; and can you still ask why we are in mourning?” A nation endowed with such qualities, cannot fail to be deeply interesting to every enlightened mind and to every generous heart.

The Tyrolese peasants are mostly robust, and attach more value to vigour of body than to beauty of form. From their infancy they addict themselves to exercises best calculated to increase the strength and suppleness of their limbs. Some, after the example of the ancient Greeks, are professed wrestlers, and pursue the exercise with such ardour, that if they were to neglect it for some time their health would suffer. Hence they seldom pass a week without challenging other champions, and they will go many miles either to be actors in, or witnesses of such matches.

Pugilistic exercises have in consequence become an amusement inseparable from rustic weddings, fairs and parish festivals. They were formerly frequent in the vicinity of Inspruck, the capital of the country; but the police took advantage of the quarrels which they occasioned, to apprehend the combatants and force them to enlist in the army for life: so that it is only in the remote districts that they can indulge without fear in their favourite diversion.