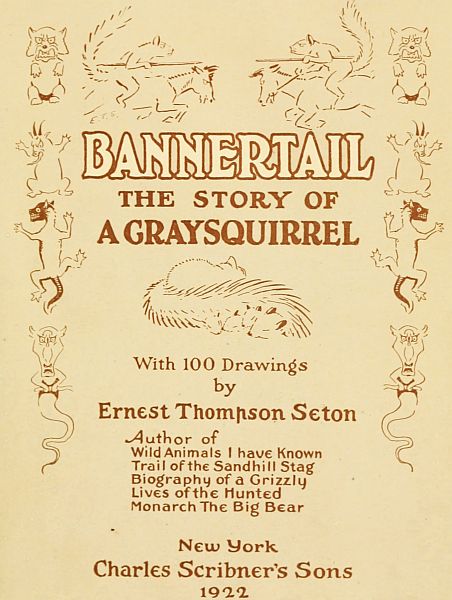

Title: Bannertail: The Story of a Graysquirrel

Author: Ernest Thompson Seton

Release date: May 28, 2013 [eBook #42827]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Heather Clark and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

These are the ideas that I have aimed to set forth in this tale.

1st. That although an animal is much helped by its mother's teaching, it owes still more to the racial teaching, which is instinct, and can make a success of life without its mothers guidance, if only it can live through the dangerous time of infancy and early life.

2d. Animals often are tempted into immorality—by which I mean, any habit or practice that would in its final working, tend to destroy the race. Nature has rigorous ways of dealing with such.

3d. Animals, like ourselves, must maintain[vi] ceaseless war against insect parasites—or perish.

4th. In the nut forests of America, practically every tree was planted by the Graysquirrel, or its kin. No squirrels, no nut-trees.

These are the motive thoughts behind my woodland novel. I hope I have presented them convincingly; if not, I hope at least you have been entertained by the romance.

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | The Foundling | 1 |

| II. | His Kittenhood | 9 |

| III. | The Red Horror | 15 |

| IV. | The New and Lonely Life | 19 |

| V. | The Fluffing of His Tail | 25 |

| VI. | The First Nut Crop | 31 |

| VII. | The Sun Song of Bannertail | 39 |

| VIII. | The Cold Sleep | 49 |

| IX. | The Balking of Fire-eyes | 57 |

| X. | Redsquirrel, the Scold of the Woods | 65 |

| XI. | Bannertail and the Echo Voice | 71 |

| XII. | The Courting of Silvergray | 77 |

| XIII. | The Home in the High Hickory | 85 |

| [viii]XIV. | New Rivals | 91 |

| XV. | Bachelor Life Again | 97 |

| XVI. | The Warden Meets an Invader | 103 |

| XVII. | The Hoodoo on the Home | 109 |

| XVIII. | The New Home | 117 |

| XIX. | The Moving of the Young | 125 |

| XX. | The Coming-out Party | 135 |

| XXI. | Nursery Days of the Young Ones | 141 |

| XXII. | Cray Hunts for Trouble | 147 |

| XXIII. | The Little Squirrels Go to School | 151 |

| XXIV. | The Lopping of the Wayward Branch | 157 |

| XXV. | Bannertail Falls into a Snare | 163 |

| XXVI. | The Addict | 173 |

| XXVII. | The Dregs of the Cup | 181 |

| XXVIII. | The Way of Destruction | 185 |

| XXIX. | Mother Carey's Lash | 191 |

| XXX. | His Awakening | 199 |

| [ix]XXXI. | The Unwritten Law | 205 |

| XXXII. | Squirrel Games | 213 |

| XXXIII. | When Bannertail Was Scarred for Life | 221 |

| XXXIV. | The Fight with the Black Demon | 229 |

| XXXV. | The Property Law among Animals | 243 |

| XXXVI. | Gathering the Great Nut Harvest | 251 |

| XXXVII. | And To-day | 261 |

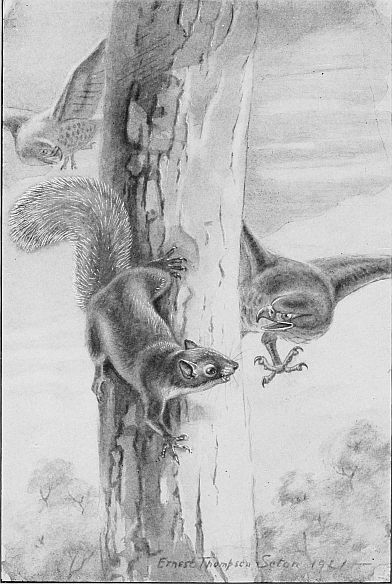

| Facing Page | |

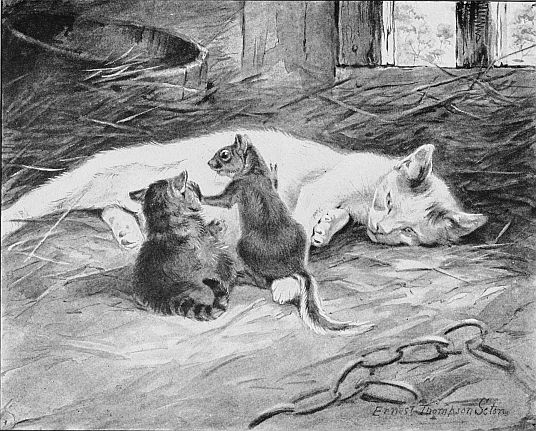

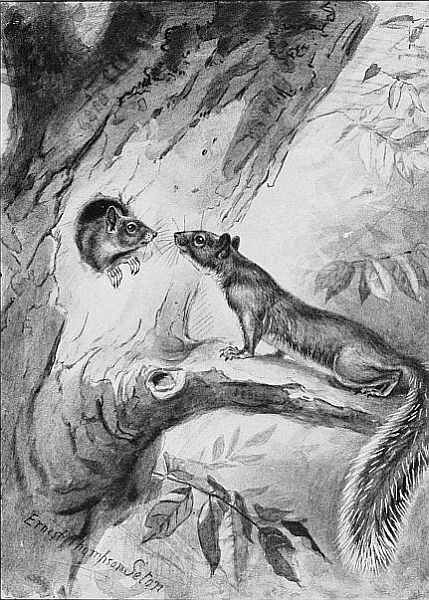

| His kittenhood | 12 |

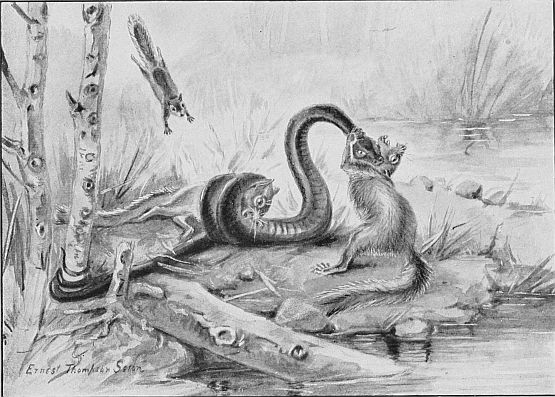

| Baffling Fire-eyes | 60 |

| They twiddled whiskers good night | 82 |

| With an angry "Quare!" Silvergray scrambled up again | 130 |

| The little squirrels at school | 154 |

| Cray sank—a victim to his folly | 160 |

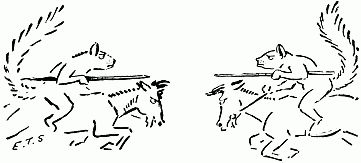

| A dangerous game | 226 |

| The battle with the Blacksnake | 238 |

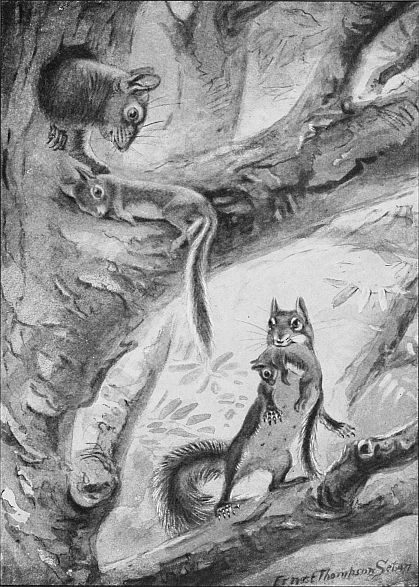

She appeared to have no mate; at least none was seen. No doubt the outlaw gunners could have told a tale, had they cared to admit that they went gunning in springtime; and now the widow was doing the best she could by her family in the big gnarled tree. All went well for a while, then one day, in haste maybe, she broke an old rule in Squirreldom; she climbed her nesting tree openly, instead of going up its neighbor, and then crossing to the den by way of the overhead branches. The farm boy who saw it, gave a little yelp of savage triumph; his caveman nature broke out. Clubs and stones were lying near, the whirling end of a stick picked off the mother Squirrel as she tried to escape with a little one in her mouth. Had he killed two dangerous enemies the boy could not have yelled louder. Then up the tree he climbed and found in the nest two living[5] young ones. With these in his pocket he descended. When on the ground he found that one was dead, crushed in climbing down. Thus only one little Squirrel was left alive, only one of the family that he had seen, the harmless mother and two helpless, harmless little ones dead in his hands.

Why? What good did it do him to destroy all this beautiful wild life? He did not know. He did not think of it at all. He had yielded only to the wild ancestral instinct to kill, when came a chance to kill, for we must remember that when that instinct was implanted, wild animals were either terrible enemies or food that must be got at any price.

The excitement over, the boy looked at the helpless squirming thing in his hand, and a surge of remorse came on him. He could not feed it; it must die of hunger. He wished that he knew of[6] some other nest into which he might put it. He drifted back to the barn. The mew of a young Kitten caught his ear. He went to the manger. Here was the old Cat with the one Kitten that had been left her of her brood born two days back. Remembrance of many Field-mice, Chipmunks and some Squirrels killed by that old green-eyed huntress, struck a painful note. Yes! No matter what he did, the old Cat would surely get, kill, and eat the orphan Squirrel.

Then he yielded to a sudden impulse and said: "Here it is, eat it now." He dropped the little stranger into the nest beside the Kitten. The Cat turned toward it, smelled it suspiciously once or twice, then licked its back, picked it up in her mouth, and tucked it under her arm, where half an hour later the boy found it taking dinner alongside its new-found foster-brother, while the motherly old[7] Cat leaned back with chin in air, half-closed eyes and purring the happy, contented purr of mother pride. Now, indeed, the future of the Foundling was assured.

The Kitten too grew up, and in midsummer was carried off to a distant farmhouse to be "their cat."

Now the Squirrel was over half-grown, and his tail was broadening out into a great banner of buff with silver tips. His life was with the old Cat; his food was partly from her dish. But many things there were to eat that delighted him, and that pleased her not. There was corn in the barn, and chicken-feed in the yard, and fruit in the garden. Well-fed and protected, he grew big and handsome, bigger and handsomer than his wild brothers, so the house-folk said. But of that he knew nothing; he had never seen his own people. The memory of his mother had faded out. So far as he knew, he was only a bushy-tailed Cat. But inside was an inheritance of instincts, as well as of blood and bone, that would surely take control and send him herding, if they happened near, with those and those alone of the blowsy silver tails.

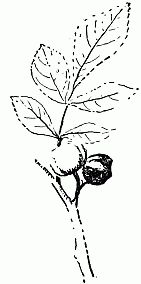

HIS KITTENHOOD

HIS KITTENHOOD

There was a growing, murmuring sound, then smoke from the barn, like that he had seen coming from the red mystery in the cook-house. But this grew very fast and huge; men came running, horses frantically plunging hurried out, and other living things and doings that he did not understand. Then when the sun was high a blackened smoking pile there was[18] where once had stood the dear old barn; and a new strange feeling over all. The old Cat disappeared. A few days more and the house-folk, too, were gone. The place was deserted, himself a wildwood roving Squirrel, quite alone, without a trace of Squirrel training, such as example of the old ones gives, unequipped, unaccompanied, unprepared for the life-fight, except that he had a perfect body, and in his soul enthroned, the many deep and dominating instincts of his race.

Food there was in abundance now, for it was early autumn; and who was to be his guide in this: "What to eat, what to let alone?" These two guides he had, and they proved enough: instinct, the[22] wisdom inherited from his forebears, and his keen, discriminating nose.

Scrambling up a rotten stub one day, a flake of bark fell off, and here a-row were three white grubs; fat, rounded, juicy. It was instinct bade him seize them, and it was smell that justified the order; then which, it is hard to say, told him to reject the strong brown nippers at one end of each prize. That day he learned to pry off flakes of bark for the rich foodstuffs lodged behind.

At another time, when he worked off a slab of bark in hopes of a meal, he found only a long brown millipede. Its smell was earthy but strange, its many legs and its warning feelers, uncanny. The smell-guide seemed in doubt, but the inborn warden said: "Beware, touch it not." He hung back watching askance, as the evil thing, distilling its strange pestilent gas, wormed Snake-like out of sight, and Bannertail[23] in a moment had formed a habit that was of his race, and that lasted all his life. Yea, longer, for he passed it on—this: Let the hundred-leggers alone. Are they not of a fearsome poison race?

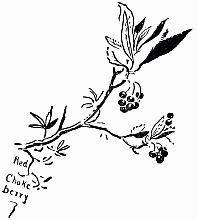

Thus he grew daily in the ways of woodlore. He learned that the gum-drops on the wounded bark of the black birch are good to eat, and the little faded brown umbrella in the woods is the sign that it has a white cucumber in its underground cellar; that the wild bees' nests have honey in them, and grubs as good as honey; but beware, for the bee has a sting! He learned that the little rag-bundle babies hanging from vine and twig, contain some sort of a mushy shell-covered creature that is amazingly good to eat; that the little green apples that grow on the oaks are not acorns, and are yet toothsome morsels of the lighter sort, while nearly every bush in the woods at[24] autumn now had strings of berries whose pulp was good to eat and whose single inside seed was as sweet as any nut. Thus he was learning woodcraft, and grew and prospered, for outside of sundry Redsquirrels and Chipmunks there were few competitors for this generous giving of the Woods.

Why? What the trunk is to the elephant and the paw to the monkey, the tail is to the Graysquirrel. It is his special gift, a vital part of his outfit, the secret of his life. The 'possum's tail is to swing by, the fox's tail for a blanket wrap, but the Squirrel's tail is a parachute, a "land-easy"; with that in perfect trim he can fall from any height in any tree and be sure of this, that he will[29] land with ease and lightness, and on his feet.

This thing Bannertail knew without learning it. It was implanted, not by what he saw in Kitten days, or in the woods about, but by the great All-Mother, who had builded up his athlete form and blessed him with an inner Guide.

October, the time of the nut harvest, came. Dry leaves were drifting to the ground, and occasional "thumps" told of big fat nuts that also were falling, sometimes of themselves and sometimes cut by harvesters; for, although no other[34] Graysquirrel was to be seen, Bannertail was not alone. A pair of Redsquirrels was there and half a dozen Chipmunks searching about for the scattering precious nuts.

Their methods were very different from those of the Graysquirrel race. The Chipmunks were carrying off the prizes in their cheek-pouches to underground storehouses. The Redsquirrels were hurrying away with their loads to distant hollow trees, a day's gathering in one tree. The Graysquirrels' way is different. With them each nut is buried in the ground, three or four inches deep, one nut at each place. A very precise essential instinct it is that regulates this plan. It is inwrought with the very making of the Graysquirrel race. Yet in Bannertail it was scarcely functioning at all. Even the strongest inherited habit needs a starter.

How does a young chicken learn to peck? It has a strong inborn readiness to do it, but we know that that impulse must be stimulated at first by seeing the mother peck, or it will not function. In an incubator it is necessary to have a sophisticated chicken as a leader, or the chickens of the machine foster-mother will die, not knowing how to feed. Nevertheless, the instinct is so strong that a trifle will arouse it to take control. Yes, so small a trifle as tapping on the incubator floor with a pencil-point will tear the flimsy veil, break the restraining bond and set the life-preserving instinct free.

Like this chicken, robbed of its birthright by interfering man, was Bannertail in his blind yielding to a vague desire to hide the nuts. He had never seen it done, the example of the other nut-gatherers was not helpful—was bewildering, indeed.

Confused between the inborn impulse and the outside stimulus of example, Bannertail would seize a nut, strip off the husk, and hide it quickly anywhere. Some nuts he would thrust under bits of brush or tufts of grass; some he buried by dropping leaves and rubbish over them, and a few, toward the end, he hid by digging a shallow hole. But the real, well-directed, energetic instinct to hide nut after nut, burying them three good inches, an arm's length, underground, was far from being aroused, was even hindered by seeing the Redsquirrels and the Chipmunks about him bearing away their stores, without attempting to bury them at all.

So the poor, skimpy harvest was gathered. What was not carried off was hidden by the trees themselves under a layer of dead and fallen leaves.

High above, in an old red oak, Bannertail[37] found a place where a broken limb had let the weather in, so the tree was rotted. Digging out the soft wood left an ample cave, which he gnawed and garnished into a warm and weather-proof home.

The bright, sharp days of autumn passed. The leaves were on the ground throughout the woods in noisy dryness and lavish superabundance. The summer birds had gone, and the Chipmunk, oversensitive to the crispness of the mornings, had bowed sedately on November 1, had said his last "good-by," and had gone to sleep. Thus one more voice was hushed, the feeling of the woods was "Hush, be still!"—was all-expectant of some new event, that the tentacles of high-strung wood-folk sensed and appraised as sinister. Backward they shrank, to hide away and wait.

This was the season of the shortest days, though no snow had come as yet to cover the brown-leaved earth. Few birds[42] were left of the summer merrymakers. The Crow, the Nuthatch, the Chickadee, and the Woodwale alone were there, and the sharp tang of the frost-bit air was holding back their sun-up calls. But Bannertail, a big Graysquirrel now, found gladness in the light, intensified, it seemed, by the very lateness of its coming.

"Qua, qua, qua, quaaaaaa," he sang, and done into speech of man the song said: "Hip, hip, hip, hurrahhh!"

He had risen from his bed in the hollow oak to meet and greet it. He was full of lusty life now, and daily better loved his life. "Qua, qua, qua, quaaaa!"—he poured it out again and again. The Chickadee quit his bug hunt for a moment to throw back his head and shout: "Me, too!" The Nuthatch, wrong end up, answered in a low, nasal tone: "Hear, hear, hear!" Even the sulky Crow joined in at[43] last with a "'Rah, 'rah, 'rah!" and the Woodwale beat a long tattoo.

"Hip, hip, hip, hurrah, hurrah, hurrah!" shouted Bannertail as the all-blessed glory rose clear above the eastern trees and the world was aflood with the Sun-God's golden smile.

A score of times had he thus sung and whip-lashed his tail, and sung again, exulting, when far away, among the noises made by birds, was a low "Qua, quaaa!"—the voice of another Graysquirrel!

His kind was all too scarce in Jersey-land, and yet another would not necessarily be a friend; but in the delicate meaningful modulations of sound so accurately sensed by the Squirrel's keen ear, this far-off "Qua, qua," was a little softer than his own, a little higher-pitched, a little more gently modulated, and Bannertail knew without a moment's guessing. "Yes, it was a Graysquirrel, and it[44] was not one that would take the war-path against him."

The distant voice replied no more, and Bannertail set about foraging for his morning meal.

The oak-tree in which he had slept was only one of the half-a-dozen beds he now claimed. It was a red oak, therefore its acorns were of poor quality; and it was on the edge of the woods. The best feeding-grounds were some distance away, but the road to them well known. Although so much at home in the trees, Bannertail travelled on the ground when going to a distance. Down the great trunk, across an open space to a stump, a pause on the stump to fluff his tail and look around, a few bounds to a fence, then along the top of that in three-foot hops till he came to the gap; six feet across this gap, and he took the flying leap with pride, remembering how, not so long ago,[45] he used perforce to drop to the ground and amble to the other post. He was making for the white oak and hickory groves; but his keen nose brought him the message of a big red acorn under the leaves. He scratched it out and smelled it—yes, good. He ripped off the shell and here, ensconced in the middle, was a fat white grub, just as good as the nut itself, or better. So Bannertail had grub on the half-shell and nuts on the side for his first course. Then he set about nosing for hidden hickory-nuts; few and scarce were they. He had not found one when a growing racket announced the curse-beast of the woods, a self-hunting dog. Clatter, crash, among the dry leaves and brush, it came, yelping with noisy, senseless stupidity when it found a track that seemed faintly fresh. Bannertail went quietly up a near elm-tree, keeping the trunk between himself and the beast.[46] From the elm he swung to a basswood, and finished his meal of basswood buds. Keeping one eye on the beast, he scrambled to an open platform nest that he had made a month ago, where he lazed in the sun, still keeping eyes and ears alert for tidings from the disturber below.

The huge brute prowled around and found the fresh scent up the elm, and barked at it, too, but of course he was barking up the wrong tree, and presently went off. Bannertail watched him with some faint amusement, then at last went rippling down the trunk and through the woods like a cork going down a rushing stream.

He was travelling homeward by the familiar route, on the ground, in undulated bounds, with pauses at each high lookout, when again the alarm of enemies reached him—a dog, sniffing and barking, and farther off a hunter. Bannertail[47] made for the nearest big tree, and up that he went, keeping ever the trunk between. Then came the dog—a Squirrel Hound—and found the track and yelped. Up near the top was a "dray," or platform nest, one Bannertail had used and partly built, and in this he stretched out contentedly, peering over the edge at the ugly brutes below. The dog kept yelping up the trunk, saying plainly: "Squirrel, squirrel, squirrel, up, up, up!" And the hunter came and craned his neck till it was cricked, but nothing he saw to shoot at. Then he did what a hunter often does. He sent a charge of shot through the nest that was in plain view. There were some heavy twigs in its make-up, and it rested on a massive fork, or the event might have gone hard with Bannertail. The timber received most of the shock of the shot, but a something went stinging through his ear tip that stuck[48] beyond the rim. It hurt and scared him, and he was divided between the impulse to rush forth and seek other shelter, and the instinct to lie absolutely still. Fortunately he lay still, and the hunter passed on, leaving the Squirrel wiser in several ways, for now he knew the danger of the dray when gunners came and the wisdom of "lay low" when in doubt.

For two days the storm raged, and[52] when the white flakes ceased to pile upon the hills and trees, a cutting blast arose that sent snow-horses riding across the fields and piled them up in drifts along the fences.

It made life harder for the Squirrel-Folk by hiding good Mother Earth from their hungry eyes; but in one way the wind served them, for it swept the snow from all the limbs that served the tree-folk as an over-way.

For two days the blizzard hissed. The third day it was very cold; on the fourth day Bannertail peeped forth on the changed white world. The wind, the pest of wild life in the trees, had ceased, the sky was clear, and the sun was shining in a weak, uncertain way. It evoked no enthusiasm in the Graycoat's soul. Not once did he utter his Sun-salute. He was stiff and sleepy, and a little hungry as he went forth. His hunger grew with the[53] exercise of moving. Had he been capable of such thought he might have said: "Thank goodness the wind has swept the snow from the branches." He galloped and bounded from one high over-way to another, till a wide gap between tree-tops compelled him to descend. Over the broad forest floor of shining white he leaped, and made for the beloved hickory grove. Pine-cones furnish food, so do buds of elm and flower-buds of maple. Red acorns are bitter yet eatable, white acorns still better, and chestnuts and beechnuts delicious, but the crowning glory of a chosen feast is nuts of the big shag hickory—so hard of shell that only the strongest chisel teeth can reach them, so precious that nature locks them up in a strong-box of stone, enwrapped in a sole-leather case; so sought after, that none of them escape the hungry creatures of the wood for winter use,[54] except such as they themselves have hidden for just such times. Bannertail quartered the surface of the snow among the silent bare-limbed trees, sniffing, sniffing, alert for the faintest whiff.

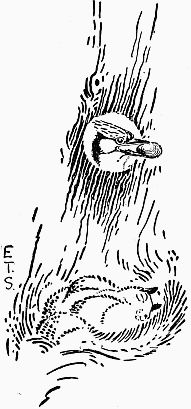

A hound would not have found it—his nose is trained for other game. Bannertail stopped, swung his keen "divining-rod," advanced a few hops, moved this way and that, then at the point of the most alluring whiff, he began to dig down, down through the snow.

Soon he was out of sight, for here the drift was nearly two feet deep. But he kept on, then his busy hind feet replacing the front ones as diggers for a time, sent flying out on the white surface brown leaves, then black loam. Nothing showed but his tail and little jets of leaf-mould. His whole arm's-length into the frosty ground did he dig, allured by an ever-growing rich aroma. At last he seized[55] and dragged forth in his teeth a big fat hickory-nut, one buried by himself last fall, and, bounding with rippling tail up a tree to a safe perch that was man-high from the ground, he sawed the shell adroitly and feasted on the choicest food that is known to the Squirrel kind.

A second prowl and treasure-hunt produced another nut, a third produced an acorn, a visit to the familiar ever-unfrozen spring quenched his thirst, and then back he undulated through the woods and over the snow to his cosey castle in the oak.

Now it was a race for the tall timber, and a close one, but Bannertail's hops were six feet long; his legs went faster than the eye could see. The deep snow was harder on him than on his ferocious enemy, but he reached the great rugged trunk of an oak, and up that, gaining a little. The Weasel followed close behind, up, up, to the topmost limbs, and out on a long, level branch to leap for the next tree. Bannertail could leap farther than Fire-eyes, but then he was heavier and had to leap from where the twigs were thicker. So Fire-eyes, having only half as far to go, covered the leap as well as the Squirrel did, and away they went as before.

Every wise Squirrel knows all the leaps

in his woods, those which he can easily

make, and those which will call for every

ounce of power in his legs. The devilish

pertinacity of the Weasel, still hard after

him, compelled him to adopt a scheme.

He made for a wide leap, the very limit

of his powers, where the take-off was the

end of a big broken branch, and racing

six hops behind was the Brown Terror.

Without a moment's pause went Bannertail

easily across the six-foot gap, to land

on a sturdy limb in the other tree. And the

Weasel! He knew he could not make it,

hung back an instant, gathered his legs

under him, snarled, glared redder-eyed

than ever, bobbed down a couple of times,

measured the distance with his eye, then

wheeled and, racing back, went down

the tree, to cross and climb the one

that sheltered the Squirrel. Bannertail

quietly hopped to a higher perch, and,

when the right time came, leaped back

again to the stout oak bough. Again the

Weasel, with dogged pertinacity, raced[61]

[62]

down and up, only to see the Graysquirrel

again leap lightly across the impassable

gulf. Most hunters would have

given up now, but there is no end to the

dogged stick-to-itiveness of the Weasel;

besides, he was hungry. And half-a-dozen

times he had made the long circuit

while his intended victim took the short

leap. Then Bannertail, gaining confidence,

hit on a plan which, while it may

have been meant for mere teasing, had

all the effect of a deep stratagem played

with absolute success.

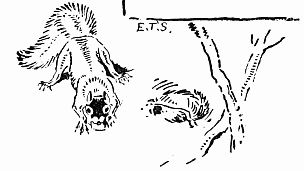

When next the little red-eyed terror came racing along the oak limb, Bannertail waited till the very last moment, then leaped, grasped the far-side perch, and, turning, "yipped" out one derisive "grrrf, grrrf, grrrf" after another, and craned forward in mockery of the little fury. This was too much. Wild with rage, the Weasel took the leap, fell far[63] short, and went whirling head over heels down seventy-five feet, to land not in the soft snow but on a hard-oak log, that knocked out his cruel wind, and ended for the day all further wish to murder or destroy.

"Qua, qua, qua, quaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa!" from a high perch. Ringing across the woodland it went, and the Woodwales drummed on hardwood drums, in keen responsiveness, to the same fair, vernal influence of the time.

Though he seemed only to sing for singing's sake, he was conscious lately of a growing loneliness, a hankering for company that had never possessed him all winter; indeed, he had resented it when any hint of visitors had reached him, but now he was restless and desireful, as well as bursting with the wish to sing.

"Qua, qua, qua, quaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa!" he sang again and again, and on the still, bright air were echoes from the hills.

"Qua, qua, quaaaaaaaaaaaaaa!" He poured it out again, and the echo came, "Qua, quaaaaa!" Then another call, and the echo, "Quaaa!"

Was it an echo?

He waited in silence—then far away he heard the soft "Qua, quaa" that had caught his ear last fall. The voice of another Graycoat, but so soft and alluring that it thrilled him. Here, indeed, was the answer to the hankering in his heart.

But even as he craned and strained to locate its very place, another call was heard:

On a log he stopped, with senses alert for new guidance. "Qua, qua, quaaa," came the soft call, and up the tree went Bannertail, a silvery tail-tip flashed behind the trunk, and now, ablaze with watchfulness, he followed fast. Then[76] came a lone, long "Qua, qua," then a defiant "Grrff," like a scream, and a third big Graysquirrel appeared, to scramble up after Bannertail.

In their combat rage they paid no heed to where they were. Their every clutch was on each other, none for the branch, and over they tumbled into open space.

Two fighting cats so falling would have[80] clutched the harder and hoped each that the other would be the one to land on the under side. Squirrels have a different way. Sensing the fall, at once they sprang apart, each fluffed his great flowing tail to the utmost—it is nature's own "land-easy"—they landed gently, wide apart, and quite unshaken even by the fall. Overhead was the Lady of the tourney, in plain view, and the two stout knights lost not a moment in darting up her tree; again they met on a narrow limb, again they clutched and stabbed each other with their chisel teeth, again the reckless grapple, clutch, and the drop in vacant air—again they shot apart, one landed on the solid ground, but the other—the echo voice—went splash, plunge into the deepest part of the creek! In ten heart-beats he was safely on the bank. But there is such soothing magic in cold water, such[81] quenching of all fires, be they of smoke or love or war, that the Echo Singer crawled forth in quite a different mood, and Bannertail, flashing up the great tree trunk, went now alone.

To have conquered a rival is a long step toward victory, but it is not yet victory complete. When he swung from limb to limb, ever nearer the Silvergray, he was stirred with the wildest hankering of love. Was she not altogether lovely? But she fled away as though she feared him; and away he went pursuing.

There is no more exquisite climbing action than that of the Squirrel, and these two, half a leap apart, winding, wending, rippling through the high roof-tree of the woods, were less like two gray climbing things than some long, silvery serpent, sinuating, flashing in and out in undulating coils with endless grace and certainty among the trees.

Now who will say that Silvergray really raced her fastest, and who will deny that he did his best? He was strong and swift, the race must end, and then she faced him with anger and menace simulated in her face and pose. He approached too near; her chisel teeth closed on his neck. He held still, limp, absolutely unresisting. Her clutch relaxed. Had he not surrendered? They stood facing each other, an armed neutrality established, nothing more.

Shyly apart and yet together, they drifted about that day, feeding at feed time. But she was ready to warn him that his distance he must keep.

By countless little signs they understood each other, and when the night came she entered a familiar hollow tree and warned him to go home.

THEY TWIDDLED WHISKERS GOOD NIGHT

THEY TWIDDLED WHISKERS GOOD NIGHT

Next day they met again, and the next, for there is a rule of woodland courtship—three times he must offer and be refused. Having passed this proof, all may be well.

Thus the tradition of the woods was fully carried out, and Bannertail with Silvergray was looking for a home.

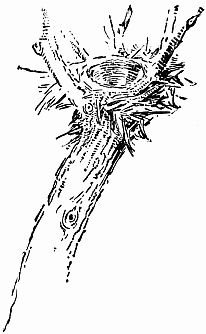

So the red oak den was then and there abandoned. Search in the hickory grove resulted in a find. A Flicker had dug[88] into the trunk of a tall hickory where it was dead. Once through the outer shell the inner wood was rotten punk, too easy for a Flicker to work in, but exactly right and easy for a Graysquirrel. Here, then, the two set to work digging out the soft rotten wood till the chamber was to their liking, much bigger than that the Woodpecker would have made.

March, the Wakening-moon, was spent in making the home and lining the nest. Bark strips, pine-needles, fine shreds of plants that had defied the wind and snow, rags of clothes left by winter woodmen, feathers, tufts of wool, and many twigs of basswood with their swollen buds, and slippery-elm, and one or two—yes, Silvergray could not resist the impulse—fat acorns found from last year's crop and hidden now deep in the lining of the nest. There can be no happier time for any wild and lusty live thing[89] than when working with a loving mate at the building and making of the nest. Their world is one of joy—fine weather, fair hunting, with food enough, overwhelming instincts at their flush of compulsion—all gratified in sanest, fullest measure. This sure is joy, and Bannertail met each yellow sun-up with his loudest song of praise, as he watched it from the highest lookout of his home tree. His "qua" song reached afar, and in its vibrant note expressed the happy time, and expressing it, intensified it in himself. There seemed no ill to mar the time. Even the passing snow-storms of the month seemed trifles; they were little more than landmarks on the joyful way.

And Bannertail, what could he do? Hurt, rebuffed, not wanted in the house he had made and loved, turned away perforce and glumly sought his bachelor home in the friendly old red oak.

Whatever was the cause, Bannertail knew that it was his part to keep away, at least to respond to her wishes. Next morning, after feeding, he swung to the nesting tree. Yes, there she was on a limb—but at once she retreated to the door and repeated the signal, "You are not wanted here." The next day it was the same. Then on the third day she was nowhere to be seen. Bannertail[95] hung about hoping for a glimpse, but none he got. Cautiously, fearfully, he climbed the old familiar bark-way; silently arriving at the door, he gently thrust in his head. The sweet familiar furry smell told him "yes, she was there."

He moved inward another step. Yes, there she lay curled up and breathing. One step more; up she started with an angry little snort. Bannertail sprang back and away, but not before he had seen and sensed this solving of the mystery. There, snuggling together under her warm body were three tiny little baby Squirrels.

For this, indeed, it was that Mother Nature whispered messages and rules of conduct. For this time it was she had dowered this untutored little mother Squirrel with all the garnered wisdom of the folk before. Nor did she leave them now, but sent the very message to Mother[96] Squirrel and Father Squirrel, and the little ones, too, at the very time when their own poor knowledge must have failed.

It was the unspoken hint from her that made the little mother-soon-to-be hide in the nesting-place some nuts with buds of slippery-elm, twigs of spice bush, and the bitter but nourishing red acorns. In them was food and tonic for the trying time. Water she could get near by, but even that called for no journey forth, it chanced that a driving rain drenched the tree, and at the very door she found enough to drink.

Another, wholly different food, was added to the list. With the bright spring days the yellow Sapsucker arrived from the South. He is a crafty bird and a lover of sweets. His plan is to drill with his sharp beak a hole deep through the bark of a sugar-maple, so the sap runs out and down the bark, lodging in the crevices; and not one but a score of trees he taps. Of course the sun evaporates the sap, so it becomes syrup, and even sugar on the edges. This attracts many spring insects, which get entangled in the sticky stuff, and the Sapsucker, going from tree to tree in the morning, feasts on a rich confection of candied bugs. But many other creatures of the woods delight in this primitive sweetmeat, and Bannertail did not hesitate to take it[101] when he could find it. Although animals have some respect for property law among their own kind, might is the only right they own in dealing with others.

Amusement aplenty Bannertail found in building "drays," or tree nests. These are stick platforms of the simplest open-work, placed high in convenient trees. Some are for lookouts, some for sleeping-porches when the night is hot, some are for the sun-bath that every wise Squirrel takes. Here he would lie on his back in the morning sun with his belly exposed, his limbs outsprawling, and let the healing sun-rays strike through the thin skin, reaching every part with their actinic power.

Bannertail did it because it was pleasant, and he ceased doing it when it no longer pleased him. Is not this indeed Dame Nature's way? Pain is her protest against injury, and soothingness in[102] the healthy creature is the proof that it is doing good. Many disorders we know are met or warded off by this sun-bath. We know it now. Not long ago we had no fuller information than had Bannertail on such things. We knew only that it felt good at the time and left us feeling better; so we took it, as he took it, when the need of the body called for it, and ceased as he did, when the body no longer desired it.

There never yet was feminine heart that withheld its meed of worship from her fighting champion coming home victorious—which reason may not have entered into it at all. But this surely counted: The young ones' eyes were opened, they were no longer shapeless lumps of flesh. They were fuzzy little Squirrels. The time had come for the father to rejoin the brood.

With the come-together instinct that follows fight, he climbed to the very doorway; she met him there, whisker to whisker. She reached out and licked his wounded shoulder; when she reentered the den he came in too; nosing[108] his brood to get their smell, just as a woman mother buries her nose in the creasy neck of her baby; he gently curled about them all, and the reunited family went sound asleep in their single double bed.

Then came another little shock. The Bluejay, the noisy mischief-maker, was prowling around the farmhouse, and high on a ledge he found a handful of big horse-chestnuts gathered by the boy "to throw at cats." Had he been hungry the Jay would have eaten them, but choice food was plentiful, so now his storage instincts took charge. The Bluejay nearly sprained his bill getting a hold on a nut, then carried it off, looking for a hollow tree in which to hide it, as is the custom of his kind. The hole he found was the[113] Squirrel's nest. He meant to take a good look in before dropping it, but the nut was big and heavy, smooth and round. It slipped from his beak plump into the sleeping family, landing right on Bannertail's nose. Up he jumped with a snort and rushed to the door. The Bluejay was off at a safe distance, and chortled a loud "Tooral, tooral, jay, jay!" in mischievous mockery, then flew away. Bannertail might have taken that nut for a friendly gift, but its coming showed that the den was over-visible. There was something wrong with it.

Later the very same day, the Bluejay did this same thing with another big chestnut. Evidently now he enjoyed the commotion that followed the dropping of the nut.

One day later came a still more disturbing event. A roving, prowling cur found the fresh Squirrel track up the tree, and[114] "yapped" so persistently that two boys who were leagued with the dog for all manner of evil, came, marked the hole and spent half an hour throwing stones at it, varying their volleys with heavy pounding on the trunk to "make the Squirrel come out."

Of course, neither Bannertail nor Silvergray did show themselves. That is very old wood-wisdom. "Lay low, keep out of sight when the foe is on the war-path." And at last the besiegers and their yap-colleague tramped away without having seen sign or hair of a Squirrel.

There was very little to the incident, but it sank deep into Silvergray's small brain. "This nest is ill-concealed. Every hostile creature finds it."

There was yet another circumstance that urged action. Shall I tell it? It is so unpicturesque. A Squirrel's nest is a breeding-ground for vermin; a nest that[115] is lined with soft grass, feathers, and wool becomes a swarming hive. Bannertail's farm upbringing had made him all too familiar with feathers and wool. His contribution to the home furnishing had been of the kind that guaranteed a parasitic scourge. This thing he had not learned—for it is instilled by the smell of their mother nest—cedar bark and sassafras leaves, with their pungent oils, are needed to keep the irritating vermin swarm away. And Silvergray, was she at fault? Only in this, the purifying bark and leaves were scarce. She was weak compared with Bannertail. His contributions had so far outpointed hers that the nest had become unbearable. Their only course was to abandon it.

Winter storm and beaming sun had purged and purified the rough old aerie; it was high on a most unclimbable tree, yet sheltered in the wood, and here Silvergray halted in her search. All about the nest and tree she climbed, and smelled to find the little owner marks, of musk or rasping teeth, if such there should be—the marks that would have warned her that this place was already possessed. But none there were. The place was without taint, bore only through and through the clean, sweet odor of the woods and wood.

And this is how she took possession: She rubbed her body on the rim of the nest, she nibbled off projecting twiglets, she climbed round and round the trunk[121] below and above, thus leaving her foot and body scent everywhere about, then gathered a great mouthful of springtime twigs, with their soft green leaves, and laid them in the Hawk nest for the floor-cloth of her own.

She went farther, and found a sassafras, with its glorious flaming smell of incense, its redolence of aromatic purity, and with a little surge of joy instinctive she gathered bundle after bundle of the sweet, strong twigs, spread them out for the rug and matting of the house. And Bannertail did the same, and for a while they worked in harmony. Then was struck a harsh, discordant note.

Crossing the forest floor Bannertail found a rag, a mitten that some winter woodcutter had cast away, and, still obsessed with the nursery garnish of his own farm-kitten days, he pounced on this and bore it gleefully to the nest that they were[122] abuilding. And Silvergray, what said she, as the evil thing was brought? She had no clear ideas, no logic from the other ill-starred home. She could not say: "There was hoodoo on it, and this ragged woollen mitt seems hoodoo-like to me." But these were her strange reactions. "The smell of that other nest was like this; that smell is linked with every evil memory. I do not want it here." Her instinct, the inherited wisdom of her forebears, indorsed this view, and as she sniffed and sniffed, the smell inspired her with intense hostility, a hostility that in the other nest was somewhat offset by the smell of her loved brood, but this was not—it was wholly strange and hostile. Her neck hair rose, her tail trembled a little, as, acting under the new and growing impulse of violent dislike, she hurled the offending rag far from the threshold of her nest. Flop it went to the ground[123] below. And Bannertail, not quite understanding, believed this to be an accident. Down he went as fast as his fast feet could carry him, seized on the ragged mitten, brought it again to the home-building. But the instinct that had been slow arousing was now dominant in Silvergray. With an angry chatter she hurled the accursed thing afar, and made it clear by snort and act that "such things come not there."

This was the strenuous founding of the new nest, and these were among the hidden springs of action and of unshaped thoughts that ruled the founding.

The nest was finished in three days. A rain roof over all of fresh flat leaves, an inner lining of chewed cedar bark, an abundance of aromatic sassafras, one or two little quarrels over accidental rags that Bannertail still seemed to think worth while. But the new nest was finished,[124] pure and sweet with a consecrating, plague-defying aroma of cedar and of sassafras to be its guardian angel.

The sun was up above the trees. The Bluejay sang "Too-root-el-too-root-el," which means, "all clear." And the glad[129] Red Singing-Hawk was wheeling in great rhythmic swoops to the sound of his own wild note, "Kyo-kyo-kyoooo." He wheeled and rejoiced in his song and his flight.

"All's clear! All's well!" sang Crow and Bluejay—these watchful ones, watchful, perforce, because their ways of rapine have filled the world with enemies. And Silvergray prepared a second time for the perilous trip. She took the nearest of her babies, gently but firmly, and, scrambling to the door, paused to look and listen, then took the final plunge, went scurrying and scrambling down the trunk. On the ground she paused again, looked forward and back, then to the old nest to see her mate go in and come out again with a young one in his mouth, as though he knew exactly what was doing and how his help was needed. With an angry "Quare!"[130] she turned and scrambled up again, bumping the baby she bore with many a needless jolt, and met Bannertail. Nothing less than rage was in her voice, "Quare, quare, quare!" and she sprang at him. He could not fail to understand. He dropped the baby on a broad, safe crotch, and whisked away to turn and gaze with immeasurable surprise. "Isn't that what you wanted, you hothead?" he seemed to say. "Didn't we plan to move the kids?" Her only answer was a hissing "Quare!" She rushed to the stranded little one, made one or two vain efforts to carry it, as well as the one already in her mouth, then bounded back to the old home with her own charge, dropped it, came rushing back for the second, took that home, too, then vented all her wrath and warnings in a loud, long "Qua!" which plainly meant: "You let the kids alone. I don't need your help. I wouldn't trust you. This is a mother's job."

WITH AN ANGRY "QUARE!" SILVERGRAY SCRAMBLED UP AGAIN

WITH AN ANGRY "QUARE!" SILVERGRAY SCRAMBLED UP AGAIN

She stayed and brooded over them a long time before making the third attempt. And this time the impulse came from the tickling crawlers in the bed. She looked forth, saw Bannertail sitting up high, utterly bewildered. She gave a great warning "Qua!" seized number one for the third time, and forth she leaped to make the great migration.

The wood was silent except for its

own contented life, and she got half-way

to the new nest, when high on a broad,

safe perch she paused and set her burden

down. Was it the maddening tickling of

a crawler that gave the hint, or was it

actual wisdom in the lobes behind those

liquid eyes? Who knows? Only this is

sure, she looked that baby over from end

to end. She hunted out and seized in her

teeth and ground to shreds ten of the[131]

[132]

plaguing crawlers. She combed herself,

she scratched and searched her coat from

head to tail, and on her neck, where she

could not see, she combed and combed,

till of this she was certain, no insects of

the tickling, teasing kind were going with

her to the new home. Then seizing her

baby by the neck-scruff, up she bounded,

and in ten heart-beats he was lying in

their new and fragrant bed.

For a little while she cuddled him there, to "bait him to it," as the woodsmen say. Then, with a parting licking of his head, she quit the nest and hied away for the rest of the brood.

Bannertail had taken the hint. He was still up high, watching, but not going near the old nest.

Silvergray took number two and did the very same with him, deloused him thoroughly on the same old perch, then left him with the first. The third went[133] through the same. And Silvergray was curled up with the three in the new high nest for long, before Bannertail, after much patient, watchful waiting, seeing no return of Silvergray, went swinging to the old nest to peep in, and realized that it was empty, cold, abandoned.

He sat and thought it over. On a high, sunny perch that he had often used, he made his toilet, as does every healthy Squirrel, thoroughly combed his coat and captured all, that is, one or two of the crawlers that had come from the old nest. He drank of the spring, went foraging for a while, then swung to the new-made nest and shyly, cautiously, dreading a rebuff, went slowly in. Yes, there they were. But would she take him in? He uttered the low, soft, coaxing "Er-er-er-er," which expresses every gentleness in the range of Squirrel thought and feeling. No answer. He made no move, but[134] again gave a coaxing "Er-er-er," a long pause, then from the hovering furry form in the nest came one soft "Er," and Bannertail, without reserve, glided in and curled about them all.

A Hawk came wheeling high over the tree tops. He was not hunting, for he wheeled and whistled as he wheeled. Silvergray knew him well, and marked his ample wings. She had seen a Redtail raid. This might not be of the bandit kind, but a Hawk is a Hawk. She gave a low, warning "Chik, chik" to the family, to which they paid not a whit of attention. So she seized each in turn by the handy neck-scruff, and bundled him indoors to safety.

Three times this took place on different days. Three times the mother's vigorous lug home was needed, and by now the lesson was learned. "Chik, chik" meant "Look out; danger; get home."

They were growing fast now. Their coats were sleek and gray. Their tails were as yet poor skimps of things, but their paws were strong and their claws were sharp as need be. They could[139] scramble all about the old Hawk nest and up and down the rugged bark of the near trunk. Their different dispositions began to show as well as their different gifts and make-up.

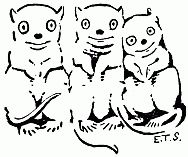

The third and smallest was a little girl-Squirrel, very shy and gentle. She loved to be petted and would commonly snuggle up to mother, whining softly, "Nyek, nyek," even when her brothers were playing, as well as at feeding-time. So in this sort they named themselves, Brownhead, Cray, and Nyek-nyek.

The first lesson in all young wild life is this, "Do as you are told"; the penalty of disobedience is death, not always immediate, not clearly consequent, but soon or late it comes. This indeed is the law, driven home and clinched by ages of experience: "Obey or die."

If the family is outstretched in the sun, and keen-eyed mother sees a Hawk, she says, "Chik, chik," and the wise little ones come home. They obey and live. The rebellious one stays out, and the Hawk picks him up, a pleasant meal.

If the family is scrambling about the tree trunk and one attempts to climb a long, smooth stretch, from which the bark has fallen, mother cries "Chik, chik," warning that he is going into danger. The obedient one comes back and lives. The unruly one goes on. There is no clawhold on such trunks. He falls far to the ground and pays the price.

If one is being carried from a place of danger, and hangs limp and submissive from his mother's mouth, he is quickly landed in a place of safety. But one that struggles and rebels, may be cut by mother's tightening teeth, or dropped by her and seized on by some enemy at[146] hand. There are always enemies alert for such a chance. Or if he swings to drink at the familiar spring and sees not what mother sees, a Blacksnake lurking on a log, or heeds not her sharp "Keep back," he goes, and maybe takes a single sip, but it is his last.

If one, misled by their bright color, persists in eating fruit of the deadly nightshade, ignoring mother's warning, "Quare, quare!" he eats, he has willed to eat; and there is a little Squirrel body tumbled from the nest next day, to claim the kindly care of growing plants and drifting leaves that will hide it from the view.

Yes, this is the law, older than the day when the sun gave birth to our earth that it might go its own way yet still be held in law: "Obey and live; rebel and die."

Last was Cray, quickest of them all, not so heavy as Brownhead, yet agile, inquisitive, full of energy, but a rebel all the time. He would climb that long, smooth column above the nest. His mother's warning held him not. And when the clawhold failed he slipped, but jumped and landed safe on a near limb.

He would go forth to investigate the loud trampling in the woods, and far below him watched with eager curiosity the big, two-legged thing that soon discovered him. Then there was a loud crack like a heavy limb broken by the wind, and the bark beside his head was splintered by a blow that almost stunned him with its shock, although it did not touch him. He barely escaped into the nest. Yes, he still escaped.

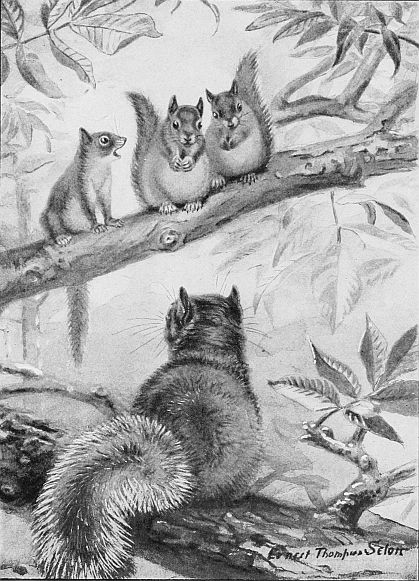

Clean your coat, and extra-clean your tail; fluff it out, try its trig suppleness, wave it, plume it, comb it, clean it; but ever remember it, for it is your beauty and your life.

When there is danger on the ground, such as the trampling of heavy feet, do not go to spy it out, but hide. If near a hole, pop in; if on a big high limb, lie[154] flat and still as death. Do not go to it. Let it come to you, if it will.

In the air, if there is danger near, as from Hawks, do not stop until you have at least got into a dense thicket, or, better still, a hole.

If you find a nut when you are not hungry, bury it for future use. Nevertheless this lesson counted for but little now, as all last year's nuts were gone, and this year's far ahead.

If you must travel on the ground, stop every little while at some high place to look around, and fail not then each time to fluff and jerk your tail.

When in the distant limbs you see something that may be friend or foe, keep out of sight, but flirt your white tail tip in his view. If it be a Graycoat, it will answer with the same, the wigwag: "I'm a Squirrel, too."

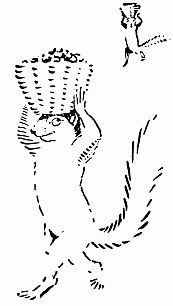

THE LITTLE SQUIRRELS AT SCHOOL

THE LITTLE SQUIRRELS AT SCHOOL

Learn and practise, also, the far jumps[155] from tree to tree. You'll surely need them some day. They are the only certain answer to the Red-eyed Fury that lives on Mice, but that can kill Squirrels, too, if he catches them; that climbs and jumps, but cannot jump so far as the Graycoats, and dare not fall from high, for he has no plumy tail, nothing but a useless little tag.

Drink twice a day from the running stream, never from the big pond in which the grinning Pike and mighty Snapper lie in wait. Go not in the heat of the day, for then the Blacksnake is lurking near, and quicker is he even than a Squirrel, on the ground.

Go not at dusk, for then the Fox and the Mink are astir. Go not by night, for then is the Owl on the war-path, silent as a shadow; he is far more to be feared than the swish-winged Hawk. Drink then at sunrise and before sunset, and[156] ever from a solid log or stone which affords good footing for a needed sudden jump. And remember ever that safety is in the tree tops—in this and in lying low.

These were the lessons they slowly learned, not at any stated time or place, but each when the present doings gave it point. Brownhead was quick and learned almost overfast; and his tail responding to his daily care was worthy of a grown-up. Lithe, graceful Nyek-nyek too, was growing wood-wise. Cray was quick for a time. He would learn well at a new lesson, then, devising some method of his own, would go ahead and break the rules. His mother's warning "Quare" held him back not at all. And his father's onslaught with a nip of powerful teeth only stirred him to rebellious fight.

The big Ground-beast below seized on

the quivering, warm young body, and[161]

[162]

yelled aloud: "Billy, Billee, I got him; a

great big Silvergray! Yahoo!"

But the meaning of that was unknown to the little mother and the rest. They only knew that a huge, savage Brute had killed their little brother, and was filling the woods with its hideous blood-curdling roars.

Swinging from tree to tree, leaping the familiar jump-ways, he left the family one early morning, drank deeply at the spring brook, went on aground "hoppity-hop" for a dozen hops, then stopped to look around and frisk his tail. Then on, and again a look around. So he left the hickory[166] woods, and swung a mile away, till at last he was on the far hillside where first he met the Redhead.

High in a tasselled pine he climbed and sat, and his fine nose took in the pleasant gum smells with the zest that came from their strangeness as much as from their sweetness.

As he sat he heard a rustling, racketty little noise in the thicket near. Flattening to the bough and tightening in his tail he watched. What should appear but his old enemy, the Redhead, dragging, struggling with something on the ground, stopping to sputter out his energetic, angry "Snick, snick," as the thing he dragged caught in roots and twigs. Bannertail lay very low and watched intently. The Redsquirrel fussed and worked with his burden, now close at hand. Bannertail saw that it was a flat, round thing, like an acorn-cup, only many times larger,[167] and reddish, with a big, thick stem on the wrong side—a stem that was white, like new-peeled wood.

Bannertail had seen such growing in the woods, once or twice; little ones they were, but his nose and his inner guide had said: "Let them alone." And here was this fiery little Redsquirrel dragging one off as though he had a prize! Sometimes he lifted it bodily and made good headway, sometimes it dragged and caught in the growing twigs. At last it got fixed between two, and with the energy and fury that so often go with red hair, the Redhead jerked, shoved, and heaved, and the brittle, red-topped toadstool broke in two or three crisp pieces. As he sputtered and Squirrel-cussed, there was a warning Bluejay note. Redhead ran up the nearest tree; as it happened, the one in which was Bannertail, and in an instant the enemies were face to face. "Scold and[168] fight" is the Redsquirrel's first impulse, but when Bannertail rose up to full height and spread his wondrous tail the Red one was appalled. He knew his foe again; his keen, discriminating nose got proofs of that. The memory of defeat was with him yet. He retreated, snick-sputtering, and finally went wholly out of sight.

When all was still, Bannertail made his way to the broken mushroom; rosy red and beautiful its cap, snowy white its stem and its crisp, juicy flesh.

But of this he took no count. The smelling of it was his great chemic test. It had the quaint, earthy odor of the little ones he had seen before, and yet a pungent, food-like smell, like butternuts, indeed, with the sharp pepper tang of the rind a little strong, and a whiff, too, of the many-legged crawling things that he had learned to shun. Still, it was alluring as food. And now was a crucial time,[169] a veritable trail fork. Had Bannertail been fed and full, the tiny little sense of repulsion would have turned the scale, would have reasserted and strengthened the first true verdict of his guides—"Bad, let it alone." But it had an attractive nut-like aroma that was sweetly appetizing, that set his mouth a-watering; and this thing turned the scale—he was hungry.

He nibbled and liked it, and nibbled yet more. And though it was a big, broad mushroom, he stopped not till it all was gone. Food, good food it surely was. But it was something more; the weird juices that are the earth-child's blood entered into him and set the fountains of his life force playing with marvellous power. He was elated. He was full of fight. He flung out a defiant "Qua!" at a Hen-hawk flying over. He rummaged through the pines to find that fighting[170] Redsquirrel. He leaped tree gaps that he would not at another time have dared. Yes, and he fell, too; but the ample silver plume behind was there to land him softly on the earth. He made a long, far, racing journey, saw hills and woods that were new to him. He came to a big farmhouse like the one his youth had known, but passed it by, and galloped to another hillside. From the top of a pine he vented his wild spirits in a boisterous song—the song of spring and fine weather, and the song of autumn time and vigor.

The sun was low when, feeling his elation gone, feeling dumb and drowsy, indeed, he climbed the homestead tree and glided into the old Hawk nest to curl in his usual place beside his family.

Silvergray sniffed suspiciously; she smelled his whiskers, she nibble-nibbled with tongue and lips at the odd-smelling specks of whitish food on his coat, and the[171] juices staining his face and paws. New food; it was strange, but pleased her not. A little puzzled, she went to sleep, and Bannertail's big tail was coverlet for all the family.

He did not move that day; he had no desire to move. The sun was low when at length he went forth and down. At the crystal spring he drank deep and drank again. Silvergray licked his fur when he came back with the youngsters to the nest. He was better now, and next sun-up was himself again, the big, boisterous, rollicking Squirrel of the plumy tail, the playmate of the young ones, the husband of his wife. And their merry lives went on, till one morning, on the bank of the creek that flowed from the high hill-country, he found a tiny, shiny fragment of the weird spellbinding mushroom. A table scrap, no doubt, flood-borne from a Redhead feast. He sniffed, as he sniffed all new, strange things. A moon back it would have been doubtful or repellent, but he had closed his ears to the first warning of the inner guide; so the warning now was very[177] low. He had yielded to the slight appetite for this weird taste, so that appetite was stronger. He eagerly gobbled the shining, broken bit, and, possessed of keen desire for more, went bounding and pausing and fluffing, farther, farther off, nor stopped till once more high in the hill-country, among the pines and the banks where the toadstools of black magic grew.

Very keen was Bannertail when he swung from the overhead highway of the pines to the ground, to gallop over banks with nose alert. Nor had he far to go. This was toadstool time, and a scattered band of these embodied earth-sprites was spotting a sunlit bank with their smooth and blushing caps.

Was there in his little soul still a warning whisper? Yes. Just a little, a final, feeble "Beware, touch it not!"—very faint compared with the first-time warning,[178] and now to be silenced by counter-doings, just as a single trail in the sand is wholly blotted out by a later trail much used that goes counterwise across it.

Just a little pause made he, when the sick smell of the nearest toadstool was felt and measured by his nose. The lust for that strong foody taste was overdominating. He seized and crunched and revelled in the flowing juices and the rank nut taste, the pepper tang, the toothsome mouthiness, and gobbled with growing unreined greed, not one, but two or three—he gorged on them; and though stuffed and full, still filled with lust that is to hunger what wounding is to soft caress. He rushed from one madcap toadstool to another, driving in his teeth, revelling in their flowing juices, like the blood of earthy gnomes, and rushed for joy up one tall tree after another. Then, sensing the[179] Redsquirrels, pursued them in a sort of berserker rage, eager for fight, desperate fight, any fight, fight without hate, that would outlet his dangerous, boiling power, his overflow of energy. Joy and power were possessing his small brain and lusty frame. He found another bank of madcap cups; he was too gorged to eat them, but he tossed and chewed the juicy cups and stems. He raced after a fearsome Water-snake on a sunny bank, and, scared by the fury of his onslaught, the Snake slipped out of sight. He galloped up a mighty pine-tree, on whose highest limbs were two great Flickers, clacking. He chased them recklessly, then, clinging to a bark flake that proved loose, he was launched into the air, a hundred feet to fall. But his glorious tail was there to serve, and it softly let him down to earth. It was well for him that he met no cat or dog that day, for the little earth-born[180] demon in his soul had cast out fear as well as wisdom.

And Mother Carey must have wept as she saw this very dear one take into his body and his brain a madness that would surely end his life. She loved him, but far more she loved his race. And just a little longer she would wait, and give him yet one chance. And if he willed not to be strong, then must he pay the price.

Not happy was his homecoming that night. Silvergray sniffed at his whiskers. She liked not his breath. There was no kindness in her voice, her only sound a harsh, low "Grrrff!"

And the family life went on.

Not that day did he go out, or wish to go. Sick unto death was he; so sick he did not care. The rest let him alone. They did not understand, and there was something about him which made them keep away. Next day he crawled forth slowly and drank at the spring. That[184] day he lay on the sunning dray and ate but little. More than one sun arose and set before he was again the strong, hale, hearty Bannertail, the father of his family, the companion and protector of his wife.

They knew only the sorrow of it. They had no knowledge of how it came or how to prevent its coming. But big and everywhere is the All-Mother, Mother Carey, the wise one who seeks to have her strong ones build the race. Twice had she[188] warned him. Now he should have one more chance.

The Thunder-moon, July, was dominating Jersey woods, when the lusty life force of the father Graycoat inevitably sent him roving to the woods of the madcaps. Plenty they were now, and many had been stored by the Redsquirrels for winter use, for this is the riddle of their being, that the Redsquirrels long ago have learned. On the bank, when they are rooted in the earth, their juices from the underworld are full of diabolic subtlety, are tempting in the mouth as they are deadly in the blood and sure destruction at the last. They must be uprooted, carried far from the ground and the underground, and high hung in the blessed purifying pine tops, where Father Sun can burn away their evil. There, after long months of sun and wind and rain purgation, their earth-born bodies[189] are redeemed, are wholesome Squirrel food. This was the lesson Mother Carey had taught the Redheads, for their country is the country of the fool-trap toadstools. But the Graycoats know it not. And Bannertail came again.

Their day was nearly over. They were now like old worn hags, whose beauty is[194] gone, and with it their power to please—hags who have become embittered and seek only to destroy. So the fool-trap toadstools waited, silently as hunters' deadfalls wait, until the moment comes to strike.

It was the same sweet piny woods, the same bright sparkling stream, and the Song-hawk wheeled and sang the same loud song, as Bannertail came once again to seek his earth-born food, to gratify his growing lust.

And Mother Carey led him on.

Plentifully strewn were the unholy madcaps, broad bent and wrinkled now, their weird aroma stronger and to a morbid taste more alluring. Even yet a tiny warning came as he sniffed their rancid, noxious aura. The nut allurement, too, was strong, and Bannertail rejoiced.

The feast was like the other, but shorter, more restrained. There were little[195] loathsome whiffs and acrid hints that robbed it of its zest. Long before half a meal, the little warden that dwells somewhere betwixt mouth and maw began to send offensive messages to his brain, and even with a bite between his teeth there set in strong a fearful devastating revulsion, a climax of disgust, a maw-revolt, an absolute loathing.

His mouth was dripping with its natural juice, something gripped his throat, the last morsel was there and seemed to stick. He tight closed his eyes, violently shook his head. The choking lump was shaken out. Pains shot through his body. Limbs and lungs were cramped. He lay flat on the bank with head down-hill. He jerked his head from side to side with violent insistence. His stomach yielded most of the fateful mass. But the poison had entered into his body, already was coursing in his veins.

Writhing with agony, overwhelmed with loathing, he lay almost as dead, and the smallest enemy he ever had might now and easily have wreaked the limit of revenge. It was accident so far as he was concerned that made him crawl into a dense thicket and like dead to lie all that day and the night and the next day. And dead he would have been but for the unusual vigor of his superb body. Good Mother Carey kept his enemies away.

Back at the home nest the mate and family missed him, not much or pointedly, as would folk of a larger brain and life, but they missed him; and from the tall, smooth shaft that afternoon the little mother sent a long "qua" call. But there was no answering "qua." She had no means of knowing; she had no way of giving help had she known.

The sun was low on Jersey hills that second day when poor broken Bannertail,[197] near-dead Bannertail, came to himself, his much-enfeebled self. His head was throbbing, his body was cramped with pain, his mouth was dry and burning. Down-hill he crawled and groped slowly to the running stream and drank. It revived him a little, enough so he could crawl up the bank and seek a dry place under a log to lie in peace—sad, miserable, moaning peace.

Three days he suffered there, but the fever had turned on that first night; from the moment of that cooling drink he was on the mend. For food he had no wish, but daily and deeply he drank at the stream.

On that third day he was well enough to scramble up the hill; he passed a scattering group of the earthy madcaps. Oh, how he loathed them; their very smell set his mouth a-dripping, refusing its own proper juice.

Good things there were to eat on the ground, but he had little appetite, though for three days he had not eaten. He passed by fat white grubs and even nuts, but when he found some late wild strawberries he munched them eagerly. Their acid sweetness, their fragrant saneness, were what his poor sick body craved. He rested, then climbed a leaning tree. He had not strength for a real climb. In an old abandoned Flicker hole he curled himself in safety, and strong, gentle Mother Nature, Mother Carey, loving ever the brave ones that never give up, now spread her kindly influence, protecting, round about him and gave him blessed, blessed sleep.

Next day he was up with the morning Robins, and now was possessed of the impulse to go home. Vague pictures of his mate and little ones, and the merry home tree, came on his ever-clearer brain. He set out with a few short hops, as he used to go, and, first sign of sanity, he stopped[202] to fluff his tail. He noticed that it was soiled with gum. Nothing can dethrone that needful basic instinct to keep in order and perfect the tail. He set to work and combed and licked each long and silvered hair; he fluffed it out and tried its billowy beauty, and having made sure of its perfect trim he kept on, cleaned his coat, combed it, went to the brook-side and washed his face and paws clean of every trace of that unspeakable stuff, and in the very cleansing gave himself new strength. Sleek and once more somewhat like himself he was, when on he went, bounding homeward with not short bounds, but using every little lookout on the way to peer around and fluff and jerk his tail.

Back at the home tree at last, nearly seven suns had come and gone since the family had seen him.

The first impulse of the little mother[203] was hostility. A stranger is always a hostile in the woods. But he flicked the white flag on his tail tip, and slowly climbed the tree. The youngsters in alarm had hidden in the nest at mother's "Chik, chik." She came cautiously forward. His looks were familiar yet strange. Here now was the time to use caution. He swung up nearly to the door. She stood almost at bay, uttered a little warning "Ggrrrfffhh." He crawled up closer. She spread her legs, clutched firmly on the bark above him. He wigwagged his silver tail-tip and, slowly drawing nearer, reached out. Their whiskers met; she sniffed, smell-tested him. No question now. A little changed, a little strange, but this was surely her mate. She wheeled and went into the nest. He came more slowly after, put in his head, gave a low, soft "Er." There was no reply and no hostile move.[204] He crawled right in, his silver plume was laid about them all, and the reunited family slept till the hour arrived for evening meal.

Many foods there are which are wholesome, except that they have in them a measure of poison.

For these the All-Mother has endowed the wild things' bodies with a subtle antidote, which continues self-replenishing so long as the containing flask is never wholly emptied. But if it so chance that in some time of fearful stress the flask is emptied, turned upside down, drained dry, it never more will fill. The small[208] alembic that distils it breaks, as a boiler bursts if it be fired while dry. Thenceforth the toxin that it overcame has virulence and power; that food, once wholesome, is a poison now.

A "surfeit" men call this breaking of the flask; all too well is it known. By this, unnumbered healthful foods—strawberries, ice-cream, jam, delicate meat, eggs, yes, even simple breads can by the devastating drain of one rash surfeit be turned into very foods of death. The poison always was there, but the secret, neutralizing chemical is gone, the elixir is destroyed, and by the working of the law its deadly power is loosed. As poor second now to this lost and subtle protection, the All-Mother endows the body with another, one of a lower kind. She makes that food so repellent to the unwise, punished creature that he never more desires it. She fills him with a[209] fierce repulsion, the bodily rejection that men call "nausea."

This is the law of surfeit. Bannertail had fallen foul of it, and Mother Carey, loving him as she ever loves her strong ones, had meted out the fullest measure of punishment that he, with all his strength, could bear and yet come through alive.

The Red Moon of harvest was at hand. The Graycoat family was grown, and happy in the fulness of their lives, and Bannertail was hale and filled with the joy of being alive, leading his family beyond old bounds, teaching them the ways of the farther woods, showing them new foods that the season brings. He, wise leader now, who once had been so unwise. Then Mother Carey put him to the proof. She led, he led them farther than they had ever gone before, to the remotest edge of the hickory woods. On[210] a bank half sunlit as they scampered over the leaves and down the logs, he found a blushing, shining gnome-cap, an earth-born madcap. Yes, the very same, for in this woods they came, though they were rare. One whiff, one identifying sniff of that Satanic exhalation, and Bannertail felt a horrid clutching at his throat, his lips were quickly dripping, his belly heaved, he gave a sort of spewing, gasping sound, and shrank back from that shining cap with eyes that bulged in hate, as though he saw a Snake. There is no way of fully telling his bodily revulsion. The thing that once was so alluring, was so loathsome that he could not stand its fetid odor on the wind. And the young ones were caught by the unspoken horror of the moment, they took it in; they got the hate sense. They tied up that horror in their memories with that rank and sickly smell. They turned away, Bannertail[211] to drink in the running brook, to partly forget in a little while, yet never quite to forget. He was saved, the great All-Mother had saved him, which was a good thing, but not in itself a great thing. This was the great thing, that in that moment happened—the loathing of the earth-born fiend was implanted in his race, and through them would go on to bless his generations yet to be.

Three kinds of big Hawks there are in the Squirrel woods in summertime: the[216] Hen-hawk that commonly sails high in the air, screaming or whistling, and that at other times swoops low and silent through the woods, and always is known by his ample wings and bright red tail; the gray Chicken-hawk that rarely soars, but that skims among the trees or even runs on the ground, whose feathers are gray-brown, and whose voice is a fierce crek, crek, creek; and the Song-hawk or Singer, who is the size of the Chicken-hawk, but a harmless hunter of mice and frogs, and known at all seasons by the stirring song that he pours out as he wheels like a Skylark high in the blue.

The inner guide had warned the boisterous Bannertail to beware of all of them. Experience taught him that they will attack, and yet are easily baffled, if one does but slip into a hole or thicket, or even around the bole of a tree.

Many times that summer did Bannertail[217] avoid the charge of Redtail or Chicken-hawk by the simple expedient of going through a fork or a maze of branches. There was no great danger in it, as long as he kept his head; and it did not disturb him, or cause his heart a single extra beat. It became a regular incident in his tree-top life, just as a stock man is accustomed to the daily danger of a savage Bull, but easily eludes any onset by slipping through a fence. It does not cause him a tremor, he is used to it; and men there are who make a sport of it, who love to tease the Bull, who enjoy his helpless rage as he vainly tries to follow. His mighty strength is offset by their cunning and agility. It is a pretty match, a very ancient game, and never quite loses zest, because the Bull does sometimes win; and then there is one less Bull-teaser on the stock-range.

This was the game that Bannertail[218] evolved. Sure of himself, delighting in his own wonderful agility, he would often go out to meet the foe, if he saw the Hen-hawk or the Chicken-hawk approaching. He would flash his silver tail, and shrill "Grrrff, grrrff," by way of challenge.

The Hen-hawk always saw. "Keen-eyed as a hawk" is not without a reason. And, sailing faster than a driving leaf, he would swish through the hickory woods to swoop at the challenging Squirrel. But just as quick was Bannertail, and round the rough trunk he would whisk, the Hawk, rebounding in the air to save himself from dashing out his brains or being impaled, would now be greeted on the other side by the head and flashing tail of the Squirrel, and another with loud, defiant "Ggrrrffhh, grggrrrffhh."

Down again would swoop the air bandit, quicker than a flash, huge black claws advanced, and Bannertail would wait till[219] the very final instant, rejoicing in his every nerve at tension, and just as those deadly grappling-irons of the Hawk were almost at his throat, he would duck, the elusive, baffling tail would flash in the Hawk's very face, and the place the Graycoat had occupied on the trunk was empty. The grapnels of the Hawk clutched only bark; and an instant later, just above, the teasing head and the flaunting tail of Bannertail would reappear, with loudly voiced defiance.

The Hawk, like the Bull, is not of gentle humor. He is a fierce and angry creature, out to destroy; his anger grows to fury after such defeat, he is driven wild by the mockery of it, and oftentimes he begets such a recklessness that he injures himself by accident, as he charges against one of the many sharp snags that seem ever ready for the Squirrel-kind's defense.

Yes, a good old game it is, with the zest of danger strong. But there is another side to it all.

Bannertail had an ancient feud with the big Hen-hawk, whose stick nest was only a mile away, high in a rugged beech. There were a dozen farmyards that paid[224] unwilling tribute to that Hawk, a hundred little meadows with their Mice and Meadowlarks, and one open stretch of marsh with its Muskrats and its Ducks. But the hardwood ridges, too, he counted on for dues. The Squirrels all were his, if only he could catch them. Many a game had he and Bannertail, a game of life and death.