Title: Cruise of the 'Alert'

Author: R. W. Coppinger

Release date: August 16, 2013 [eBook #43483]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Bergquist, Stephen Blundell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

In preparing the following pages for the press, I have endeavoured to give a brief account, divested as much as possible of technicalities, of the principal points of interest in Natural History which came under observation during the wanderings of a surveying ship; while at the same time I have done my utmost, at the risk of rendering the narrative disconnected, to avoid trenching on ground which has been rendered familiar by the writings of travellers who have visited the same or similar places. And if in a few instances I have given some rather dry details regarding the appearance and surroundings of certain zoological specimens, it has been my intention, by an occasional reference to the more striking forms of life met with in each locality, to afford some assistance to those amateurs who, like myself, may desire to avail themselves of the opportunities afforded by the surveying ships of the British Navy for performing, although with rude appliances and very few books of reference, some useful and interesting work.

Large collections of zoological specimens were made, and as these accumulated on board, they were from time to time sent[viii] home to the Admiralty, whence they were transmitted to the British Museum, the authorities of that institution then submitting them to specialists for systematic description. For much kindly aid in making these arrangements, as well as for advice and encouragement received during the progress of the cruise, I am indebted to Dr. Albert Günther, F.R.S., Keeper of Zoology in the British Museum.

I take this opportunity to thank Mr. Frederick North, R.N., for the use of a collection of photographs which were taken by him during the cruise under circumstances of peculiar difficulty, and of which most of the engravings in this work are reproductions.

I am also under obligations to all the other officers for assistance rendered to me in various ways; and especially to those officers who acted successively as Senior Lieutenants, for the consideration with which they tolerated those parts of my dredging operations that necessarily interfered with the maintenance of good order and cleanliness on the ship's decks.

Finally, I have to thank my friend, Mr. R. Bowdler Sharpe, the distinguished ornithologist of the British Museum, by whose advice and encouragement I was induced to submit these pages to the public, for his assistance in perusing my MS., and offering some useful suggestions.

R. W. C.

| INTRODUCTION. | |

| PAGE | |

| Object of the Voyage—Former Surveys of Straits of Magellan—Change of Programme—Selection of Ship—Equipment—Arrangements for Natural History Work—Change of Captain—List of Officers | 1-4 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Departure from England—Storm Petrels—A Sparrow-hawk at Sea—Collecting Surface Organisms with Tow-net—Water-kite—Wire Sounding Apparatus—Land-swallow at Sea—Gulfweed—Phosphorescence of Sea-water—Arrive at Madeira—Curious Town—Dredging Work—A Pinery—Discoloured Sea-water—Petrels again—St. Vincent—Cape de Verde—Pelagic Animals—Sounding near Abrolhos Bank—Dredging over Hotspur Bank—Dredging over Victoria Bank—Moths and Butterflies on the Ocean—Extraordinary Vitality of Sphinx Moths—Arrive at Monte Video—Gauchos—Trip into Interior of Uruguay—Buenos Ayres—Dr. Burmeister's Museum—Arrive at the Falklands—"Stone Runs" | 5-33 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| We enter Straits of Magellan—Reach Sandy Point—Gold and Coal—Surrounding Country—Elizabeth Island—Dredging—Fuegians at Port Famine—We enter Smyth's Channel—Canoe "Portage" at Isthmus Bay—Arrive at Tom Bay—A Fuegian Family—Trinidad Channel—Climate of Western Patagonia—Flora—Rock Formation—Soilcap—Natives—The Channel Tribe of Fuegians—Scarcity of Old People—Water-birds of Tom Bay—Sea Otters—A Concealed "Portage"—Habits of Gulls and Shags—Steamer-ducks—Land-shells—Fresh-water Fish—Deer | 34-65 |

| CHAPTER III.[x] | |

| Trinidad Channel gouged out by Glaciers—Port Henry—Trumpet-shells—Native Camp—Wolsey Sound—"Cache Diablo"—"Ripple-marked" Limestone—Fuegian Burial-place—Marine Animals—Strange Capture of Fish—Whales Abundant—Exploration of Picton Channel—Attack on Sealers—Signs of Old Ice Action—"Hailstone" Rock—Soil motion—We proceed Northward to Refit—English Narrows—Gulf of Peñas | 66-80 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Arrival at Valparaiso—War between Chili, Peru, and Bolivia—Sir George Nares returns to England—Captain Maclear joins—Coquimbo—Shell Terraces—Trip to Las Cardas—Habits of Pteroptochus—Island of St. Ambrose—Habits of Petrels—Flight of the Albatross—Santiago de Chilé—Natural History Museum—Santa Lucia—Church of La Compania—Heights of Montenegro—A Fly-trap Plant—Copper mines of Brillador—Peculiarities of Chilian Mines—Talcahuano—Outbreak of Small-pox—Isla de los Reyes—Shooting a "Coypo"—Railway Trip to Araucanian Territory—Our Locomotive—Incidents of the Journey—Fossil Tree-trunk at Quiriquina Island | 81-102 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| We return to Patagonian Waters—Gulf of Peñas—Spring in the Trinidad Channel—Gephyrean at Cockle Cove—Diving Petrel—Tree Cormorants—Magellan Kingfisher—A Curious Moss—Wind-swept Bushes—Gull, Cormorant, and Skua—Examination of Brazo del Norte—Black-necked Swan—A Sealer's Yarn—Fur-seal Trade—Hardships of Seal-hunting—Otter Skins—Experiment with Condor—Fuegians at Tilly Bay—Flaking Glass Arrow-heads—List of Fuegian Words—The Maranhense—A Magellan Glacier—Native Fish-weirs—The Magellan Nutria | 103-126 |

| CHAPTER VI.[xi] | |

| We proceed towards Skyring Water—Otway Water—Canal of Fitzroy Terrace-levels—Plants and Animals—Bay of the Mines—Previous Explorers—The Coal Mines—Altamirano Bay—Prospects of the Settlement—A Seal "Rookery"—Puerto Bueno—We proceed Northwards—Port Riofrio—Gray Harbour—Sailing for Coast of Chili—Small-pox amongst the Chilians—Discoloured Sea-water—Habits of Ant Thrush | 127-143 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Early History of Tahiti—Otaheite and Tahiti—Its appearance from Seaward—Harbour of Papiété—Produce—Matavai Bay—Tahiti annexed to France—Prince Tamitao—Annexation Festivities—King Pomare V.—Coral growing on Ship's Bottom—Nassau Island—Danger Islands—Tema Reef—Union Group—Nukunono—Oatáfu—Natives afflicted with a Skin Disease—Stone Implements—Religious Scruples—Metal Fish-hooks not appreciated—Capriciousness of Sharks—Lalla Rookh Bank | 144-158 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

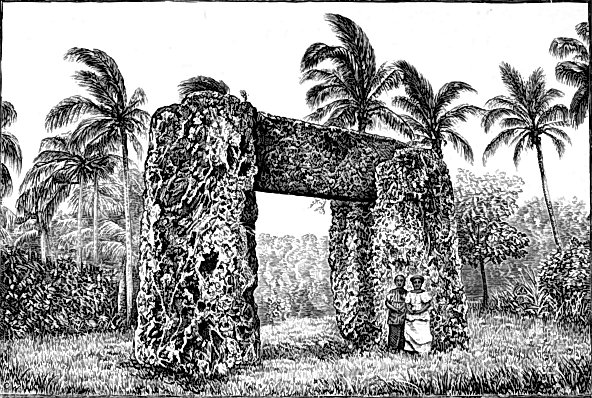

| Arrival at Fiji—Levuka—Ratu Joe comes on Board—Excursion to Bau in Viti Levu—We visit King Cacobau—A Native Feast—Lalis—Tapa—The Bure Kalou—Bakola—Old Fijian Atrocities—Double Canoe—Stone Adzes now becoming rare—Angona Drinking—Sir Arthur Gordon—Walk across Ovalau—The Kaicolos—An Imprudent Settler—Pine-apple Cultivation—Periophthalmus—Suva—Site of Future Capital—Sail towards Tonga Islands—Pelagic Animals—Early History of Tonga—Missionaries—Nukualofa—A Costly Pair of Gates—Visit to Bea—Davita—Evidence of Elevation of Island—King George of Tonga—Wellington Gnu—Curious Stone Monument—Trip to Village of Hifo—We are entertained by the Natives—Famous Caves—Eyeless Fish—Swifts behaving like Bats—Searching for Reefs—Discolouration of Sea-water—Return to Levuka—Voyage to Australia—Surface Life | 159-179 |

| CHAPTER IX.[xii] | |

| Refitting Ship at Sydney—Mr. Haswell joins us—We proceed Northwards along East Coast of Australia—Port Curtis, Queensland—A "Labour Vessel"—Mr. Eastlake—Marine Fauna abundant—Festivities at Gladstone—Birds—Percy Islands—Survey of Port Molle—Queensland Aborigines—"Black Police"—"Dispersing" Black fellows—Dredging Operations—A Parasitic Shell-fish—Port Denison—Visit to a Native Camp—Throwing the Boomerang—A Beche-de-mer Establishment at Lizard Island—Hostility of the Natives—Drawings by Aborigines at Clack Island—Albany Island, North-Eastern Australia | 180-193 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Settlement at Thursday Island—Torres Straits Islanders—Pearl-Shell Fisheries—Value of the Shell—Pearls not abundant—Neighbouring Islands—Lizards—Land-crab—Land-shells—Ferns—Birds—Booby Island—Arrive at Port Darwin, North-Western Australia—Submarine Cables—Trans-continental Telegraph—Palmerston—Northern Territory Gold-fields—Aborigines at Port Darwin—Marine Fauna—Birds—Geese perching on Trees | 194-208 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Voyage from Port Darwin to Singapore—Through the Eastern Archipelago—We arrive at Singapore—Oceanic "Tiderips"—Bird Island, Seychelles—Sea-birds on Land—Port Mahé, Seychelles—The Coco-de-Mer—Gigantic Tortoise—Produce of the Islands—Vanilla—A Primitive Crushing-mill—Dredging Operations—Periophthalmus—The Seychelles, of Granitic Structure—We visit the Amirante Group—African Islands—Abundance of Orbitolites—Crabs pursued by Eels—Eagle Island—Partridge shooting—Young Lizards—Darros Island—Casuarinas—Dredging—Poivre Island—Trees and Shrubs—Isle des Roches—Flora scanty—Land-birds—General Remarks on the Amirantes as a Group—"Fringing Reefs," but no "Barrier Reefs"—Signs of Elevation—Weather and Lee Sides contrasted | 209-229 |

| CHAPTER XII.[xiii] | |

| Alphonse Island—Pearl-shell—Providence Island—Method of planting Cocoa-nuts—Edible Turtle—Flora—Red Coral—Cerf Islets—St. Pierre—Du Lise Island—Flora and Fauna—Erratic Stones on Coral Reef—Glorioso Island—We sail for Mozambique Island—And sight East Coast of Africa—Trade at Mozambique—Inhabitants—Caju—Shells of Foreshore—The Survey concluded—Homeward Bound—Cape of Good Hope—Egg of the Epiornis—Arrival at Plymouth | 230-245 |

| General Index | 246 |

| Index of Natural History Terms | 253 |

| Facing | |

| H.M.S. "Alert" at anchor in Tom Bay, West Coast of Patagonia | title |

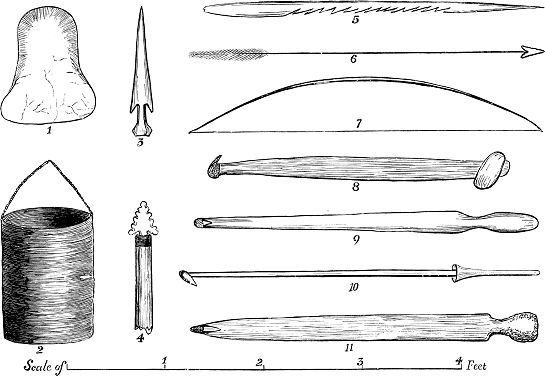

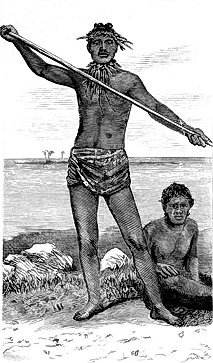

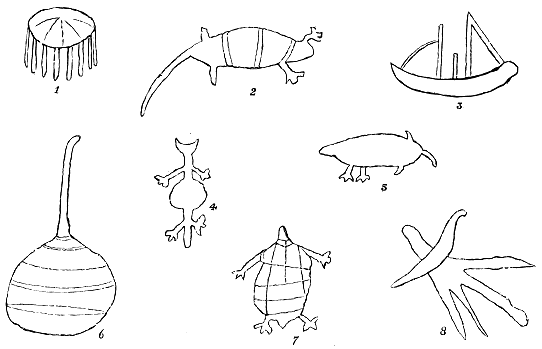

| Fuegian and Australian Implements | 34 |

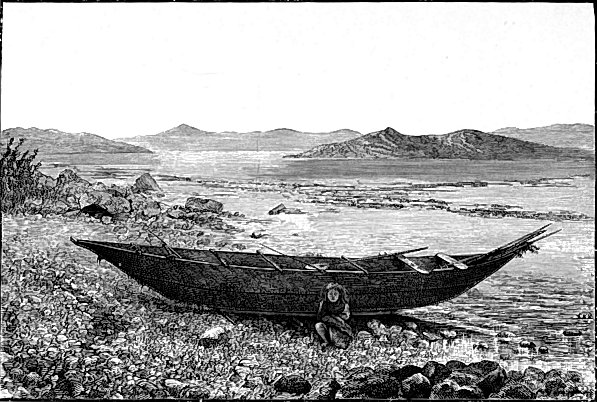

| Canoe of Channel Fuegians | 50 |

| Fuegian "Portage" for Transport of Canoes Overland | 60 |

| Fuegians Offering their Children for Barter | 65 |

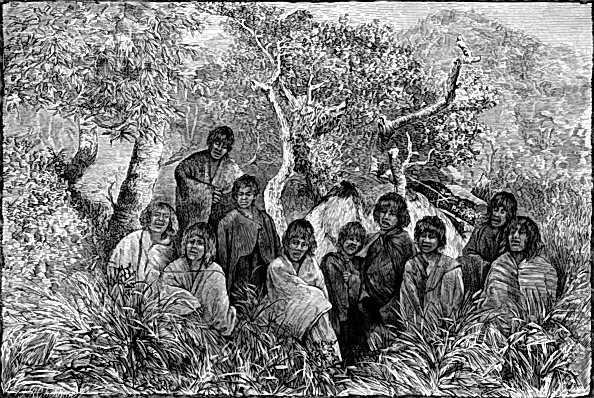

| Our Fuegian Friends at Tilly Bay, Straits of Magellan | 104 |

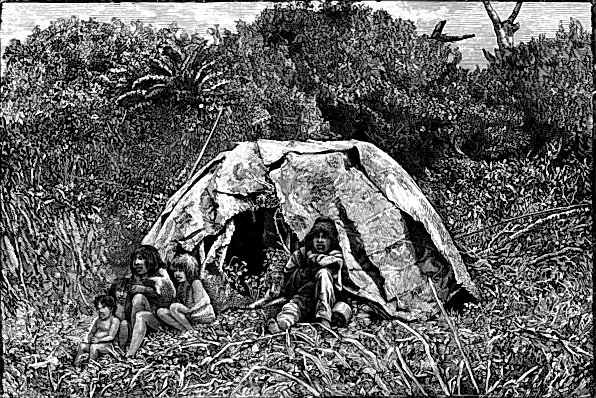

| Fuegian Hut at Tilly Bay | 120 |

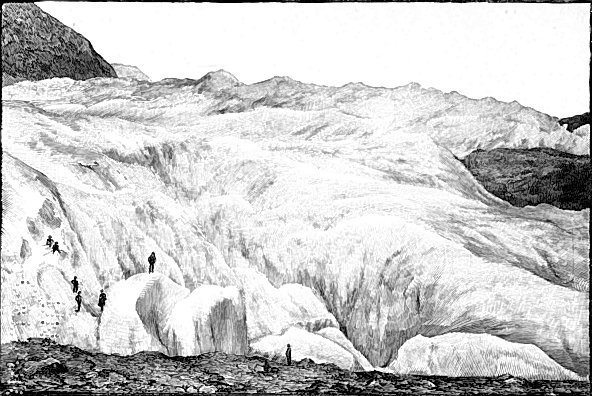

| Foot of Glacier, at Glacier Bay, Straits of Magellan | 124 |

| Fish-hooks of Union Islanders | 143 |

| Woman of Tahiti | 144 |

| Fisherman of Tahiti | 148 |

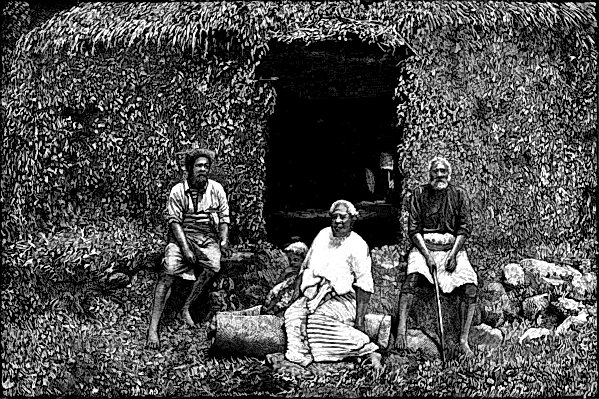

| King Cacobau of Fiji, Wife, and Ratu Joe | 160 |

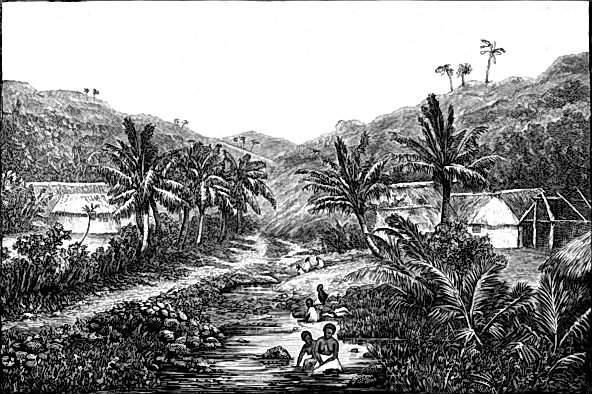

| Totoonga Valley, Ovalau, Fiji | 166 |

| Ancient Stone Monument at Tongatabu | 174 |

| Facsimiles of Drawings by Australian Aborigines | 192 |

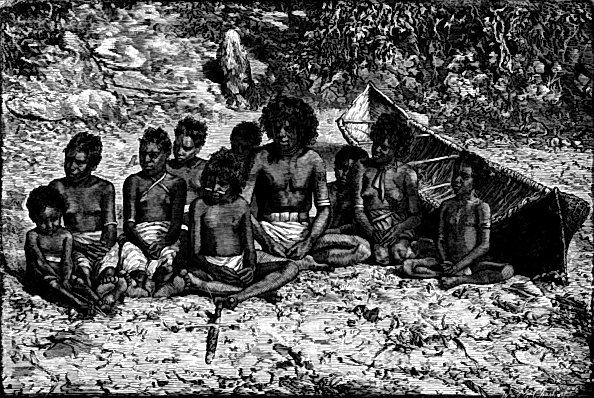

| Aborigines of North-West Australia | 204 |

| "Travellers' Trees" in Gardens at Singapore | 210 |

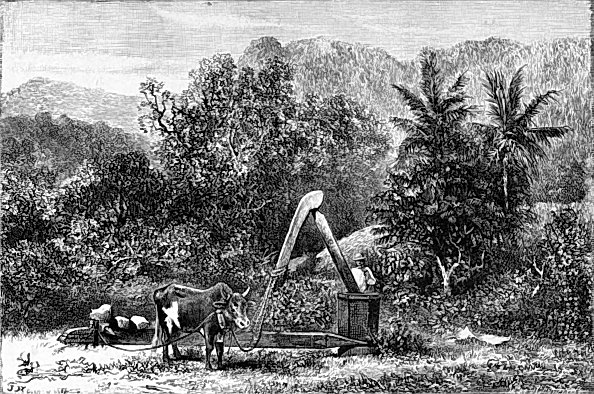

| "Copra" Crushing Mill at Seychelles | 218 |

In the summer of 1878 it was decided by the Lords of the Admiralty to equip a vessel for the threefold purpose of continuing the survey of the Straits of Magellan, of investigating the nature and exact position of certain doubtful reefs and islands in the South Pacific Ocean, and of surveying a portion of the northern and western coasts of Australia. The special object of the Magellan portion of the work was to make such a detailed survey of the sheltered channels extending southward from the Gulf of Peñas to Port Tamar as would enable vessels to pass from the Straits to the Pacific, and vice versâ, without having to encounter the wild and inhospitable outer coasts presented by the chain of desolate islands here fringing the western coasts of South America. It was also desirable that additional anchorages should be found and surveyed, where vessels might lie in safety while waiting for the cessation of a gale, or for a favourable tide to help them through the straits. The surveys made by the Adventure and Beagle in 1826-36, and by the Nassau in 1866-9, were excellent so far as they went, and so far as the requirements of their times were concerned; but the great increase of ocean navigation within the last few years had rendered it necessary that the charts should contain more minute surveys of certain[2] places which were not formerly of importance. The South Pacific portion of our survey was to be mainly in connection with the recently acquired colony of the Fiji Islands, and was to be devoted to an exploration of the eastern passages leading to this group, with an investigation of the doubtful dangers reported in the vicinity of the great shipping tracts. Finally, on completing the above, and arriving at Australia, we were to spend a year and a half, or thereabouts, in surveying the line of reefs which fringe its whole western seaboard, the ill-defined position of which is a serious obstacle to the now extensive trade between Western Australia and the Dutch islands of the Malay Archipelago.

The latter part of the orders was subsequently changed, inasmuch as we were directed to omit the survey of the western shores of Australia, and were ordered instead, on completing the North Australian work, to proceed to Singapore, in the Straits of Malacca, to refit. Thence we were to return home by the Cape of Good Hope, stopping on our way at the Seychelles, Amirante Islands, and Mozambique, in order to fix astronomically the position of the Amirante Group, and, as opportunities occurred, to take a line of soundings off the east coast of Africa.

The vessel selected for this special service was the Alert, a man-of-war sloop of 751 tons measurement and 60 horse-power nominal; and the command of the expedition was given to Capt. Sir George Nares, K.C.B. By a happy coincidence the same stout craft which had already done such good service in the Arctic Expedition of 1875-6, and which bears the honour of having attained the highest northern latitude, was selected as the ship in which Sir George Nares was now about to proceed on a voyage of exploration in high southern latitudes. She was officially commissioned on the 20th of August, with a complement of 120 officers and men, her equipments including apparatus for conducting deep sea sounding and dredging operations, and a miscellaneous collection of instruments not usually supplied to H.M.'s ships.

It being the wish of the enterprising hydrographer of the navy—Captain, now Sir Frederick Evans, K.C.B.—that the opportunities which this expedition would afford of making a valuable natural history collection in regions little known to science should not be thrown away, and Sir George Nares warmly seconding him in this wish, the Admiralty determined on appointing as surgeon an officer who, in addition to his duties as medical officer of the ship, would be inclined to devote his spare time to the cause of natural science. Sir George Nares, knowing my fondness for natural history, with characteristic kindness gave my application his support, and I had therefore the good fortune to be appointed as medical officer of the Alert, on the understanding that (so far as my medical duties permitted) I would not lose sight of the advantages which would accrue to science from a collection of natural-history objects illustrative of the fauna and flora of the countries visited in the course of the voyage.

During the four years over which my narrative extends, many changes took place in the personnel of the expedition. Scarcely a year had elapsed from the date of our departure from England, when we had to regret the loss of Sir George Nares, who left us at Valparaiso, and returned to England by mail-steamer, in order to enter upon his duties as Director of the Marine Department of the Board of Trade. We were fortunate, however, in having as his successor Captain John Maclear—formerly of the Challenger exploring expedition—to whom I take this opportunity of expressing my thanks for the unvarying kindness which I have always experienced at his hands, as well as for much assistance and encouragement in the prosecution of our zoological work.

The following is a list of the officers:—

Captain Sir George S. Nares, K.C.B., F.R.S.; succeeded by Captain John Maclear, F.R.M.S.

Lieut. George R. Bethell; succeeded by Lieut. James Deedes.

Lieut. the Hon. Foley C. P. Vereker; succeeded by Lieut. George Rooper.

Lieut. Gordon S. Gunn (subsequently became senior lieutenant).

Nav. Lieut. William H. Petley.

Sub-Lieut. James H. C. East (subsequently served as lieutenant).

Sub-Lieut. Charles W. de la P. Beresford (left the ship at Singapore).

Staff-Surgeon Richard W. Coppinger, M.D.

Paymaster Frederick North.

Engineer, John Dinwoodie.

Engineer, William Cook.

Boatswain, Alfred Payne.

(Lieut. Grenfell joined the ship at Singapore, and remained until the close of the commission.)

After various delays, owing to defects in machinery, we finally bade adieu to the shores of England on the 25th of September, 1878, taking our departure from Plymouth.

On the second day at sea the little storm petrels appeared over our wake, and accompanied us, off and on, for most of our way to Madeira. These seemed to be of two kinds, the Thalassidroma pelagica and Thalassidroma leachii, the latter being sufficiently recognizable from their having forked tails, in which respect they differ from other species of the genus. Many attempts were made to catch them by means of hooks baited with fat, skeins of thread, etc., but all to no purpose; and I rather fancy that in this thoroughfare of the ocean the wily creatures have had too much experience of the arts of man, and are therefore not to be caught so easily as their more ignorant brethren of the southern hemisphere.

On the 28th of September, when 155 miles to the westward of Cape Finisterre, and during a fresh easterly breeze, a sparrow-hawk made his appearance, at first hovering round the ship, and ultimately settling on the rigging. It had probably strayed too far from the shore in the pursuit of some tempting prey, and had then lost its reckoning, being eventually blown to seaward. At all events, it had travelled some long distance, as it evinced its weariness by resting quietly and contentedly on the main-topgallant rigging, until one of the seamen, who had managed to[6] climb up unobserved, suddenly laid hands on it. On placing it in a meat-safe, which we extemporised as a cage, it ate ravenously, as well it might after its long journey.

When in the latitude of Lisbon, and 180 miles to the westward of the Portuguese coast, a large "sea-flier" bird paid us a visit, soaring over the waves in our vicinity, and evidently on the look-out for garbage from the ship. The plumage of the upper surface of wings and body was of a dusky brown colour, the under surface of the body was whitish, and the wings were long and pointed; in mode of flight he resembled a large tern. He did not long remain with us, probably not finding it a sufficiently productive hunting-ground. I may here mention that on the 6th of October, when a hundred miles from Madeira, we sighted a bird answering the same description.

All opportunities of plying the tow-net were duly availed of, but owing to the unusually rapid speed of the ship, these were few. However, we succeeded in capturing many specimens of living Foraminifers (mostly of the genus Orbitolites), stalk-eyed Crustaceans, Radiolarians, an Ianthina, a few Salpæ, and the pretty little Pteropod Mollusc, the Criseis aciculata, besides many other organisms which the rapid motion of the net through the water had rendered unrecognizable. As it is usually found that these minute pelagic organisms are to be obtained from the surface in most abundance at night-time, and during the day retreat for some fathoms from the glare of the sunlight, I constructed a wooden apparatus on the principle of a kite, which I attached to the towing line at some three or four yards from the net, and which had the effect of dragging down the net some yards below the surface, and then retaining it at a uniform depth. It of course required to be adjusted each time to suit the required depth and the rate of the vessel, but it had this great advantage over the usual system of employing heavy weights, that the strain not being nearly so great, a light and manageable rope could be used; and that, moreover, the adjustment for depth could be[7] readily made by altering the trim of this water-kite. When I first tried this apparatus, and before I had succeeded in trimming it satisfactorily, it caused great amusement to the bluejackets by the playful manner in which it manœuvred under our stern, now diving deeply towards our rudder post (the shimmer of the white wood in the deep blue water reminding one of a dolphin), and now whimsically rising rapidly to the surface with an impetus that shot it fully six feet out of the water.

On the 4th of October, the captain made some experiments with the "Lucas deep-sea sounder." It consists of a strong brass drum carrying 2,000 fathoms of fine steel wire, and fitted with a cyclometer which registers on a dial the number of fathoms of wire run out. The sinker, which weighs 20 lbs., is made of lead, and has at its lower extremity a bull-dog snapper, which, on striking the ground, shuts up suddenly, so as to enclose a sample of the sea bottom. The apparatus is supposed to be capable of sounding to a depth of 500 fathoms in a vessel going 5 knots, and to 50 fathoms when going 12 knots. It is said to be a modification of an invention of Sir W. Thompson's. We subsequently used this largely, and found it to be a most convenient and expeditious method of sounding to depths of 500 fathoms, with the ship almost stationary. The wire could be wound up again while the ship was under way.

During the forenoon of this same day we saw, to our astonishment, a land swallow, which flew about the ship for a few minutes, and then went on his way rejoicing. He would have had to travel 254 miles to make the nearest land, which was the island of Porto Santo.

An erratic fragment of gulfweed (Sargassum bacciferum) was entangled in the tow-net on the 5th of October, when we were 105 miles north-east of Madeira, a circumstance which is of interest as regards the distribution of the plant, the locality cited being considerably beyond the northern limit of the great eddy between the Gulf Stream and the Atlantic equatorial current, commonly[8] called the Sargasso Sea. It was encrusted with a delicate white Polyzoon (Membranipora), and among other organisms carried on its fronds a pretty little Spirorbis shell, and several entomostracous Crustaceans of a deep-blue colour.

The phosphorescence of the sea is a trite subject, and one about which a very great deal has been written; but nevertheless, of its actual cause, or of the purposes which it is intended to serve, really very little is positively known. The animals to which it would seem mainly due are the small stalk-eyed Crustacea, the Pyrocystis noctiluca, and the Tunicate Molluscs. I have sometimes observed, when occupied at night in sifting the contents of a tow-net, that these organisms, as they were being sucked through the nozzle of the dip-tube, emitted flashes of light, so brilliant, that they could be distinctly seen even in a well-lighted room. During the voyage from England to Madeira, the wake of the ship was every night, with one exception, phosphorescent. The exception alluded to was on the night previous to our arrival at Madeira, when probably the unusual brilliancy of the moonlight caused the light-emitting creatures to retreat a few yards from the surface, as happens in the day-time. I have often noticed that while the phosphorescence of the comparatively still water abeam of the ship and on her quarter usually seems to emanate from large spherical masses of about a foot in diameter (commonly called "globes of fire"), yet the luminosity of the broken water in the vessel's immediate wake comes apparently from innumerable minute points. I have rarely captured any of the larger jellyfishes in the tow-net; and on those nights when I have observed the water lighted up the most brilliantly, the prevailing organisms have proved to be the small entomostracous Crustaceans.

The morning of the 7th of October broke cool and hazy, as we steamed up and dropped anchor in Funchal Roads, on the south side of the island of Madeira. Crowds of native boats, with their half-naked occupants, quickly thronged around; remaining, however, at a respectful distance, until the boat containing the[9] haughty pratique officer came alongside. On the present occasion this portentous individual was contented with a very superficial inquiry into our sanitary condition, and after a few formal questions as to our tonnage, complement of crew, number of guns, and general condition, shoved off with the laconic exclamation, "All right!" We soon availed ourselves of this permission to visit the shore.

The most conspicuous objects in Funchal, as seen from the anchorage, are the "Loo Rock" (used as a fort and lighthouse), on the west side of the town, and on the centre of the crescent-shaped beach which fronts the town a remarkable and lofty cylindrical tower of dark-brown stone. This tower, we were informed, was built about the year 1800, and was intended as a support for a huge crane, which was to facilitate the loading and disembarkation of the cargo of merchant ships. The tower as it stands is about eighty feet in height, and as its base is now about forty yards distant from high-water mark on the beach, as an article of utility it is quite effete. Our surveyors have ascertained that the land has not been elevated since the first admiralty surveys. This they arrive at by a comparison of old and recent charts with known marks on the shore, and we are therefore inclined to believe that the beach has been silted up by accumulations of basaltic rubble brought down by the two adjoining rivers, and here washed inshore by the sea. The tower is now without any appearance of the crane, and raises its plain cylindrical body in gloomy grandeur, reminding one of the old round towers of Ireland; and, as in their case, its origin will probably some years hence be veiled in obscurity.

Madeira was considered to be looking unusually dingy, on account of a long season of drought, rain not having fallen for nine months. But some two or three days after our arrival a great religious ceremony took place at the village of Machico, eight miles to the eastward of Funchal. The object was to offer up prayers for rain; and, sure enough, two days afterwards, rain fell abundantly!

During our stay here the dredge was several times brought into requisition. On the 8th of October, a party, consisting of the captain, Lieut. Vereker, some seamen, and myself, started in the steam-cutter on a dredging expedition to the bay of Santa Cruz, which is distant about eight miles from Funchal. As we steamed along the coast, we had excellent opportunities of observing the sections exhibited by the cliffs of the varieties of volcanic rock of which the upper crust of the island is mainly formed. At Point Garajas (Brazen Head), of which Lieut. Vereker made a good sketch, the north-east face of the cliff presents a magnificent dyke—a nearly vertical seam of dark lava, about three feet in width and two hundred feet in height, extending from summit to water line, and sealing up this long fissure in the older trachytic rock of the head. Farther on, masses of basalt resting unconformably on variously arranged layers of laterite tuff and trachyte, the latter in many places honeycombed in weird fantastic caverns, afforded a fertile subject for geological reveries into the early history of this now beautiful island. On reaching the bay of Santa Cruz, we lowered the dredge in thirty-five fathoms, finding, as we had half anticipated, that it was altogether too heavy to ride on the mass of sand that here forms the sea bottom. It buried itself like an anchor, and it was not without great difficulty that we could succeed in dislodging it. On bringing it up, we found it to contain some shells of the genera Cardium, Pecten, Cypræa, Oliva, and Dentalium, a few small Echini, a Sertularian Polyp, several Annelids—among others, a Nereis—and Alcyonarians. We returned on board soon after dusk, having spent a most enjoyable, if not materially profitable, day. On subsequently dredging in fifty fathoms in the same bay, our work was more satisfactory; but besides some Crustaceans, an Ophiocoma, and an Asterias of a brilliant orange colour, obtained few specimens of any interest. On another day we tried the coast to the westward of Funchal; and as we moved along in the steam-cutter, obtained, by means of the tow-net, several specimens[11] of gulfweed entangling small sponges. The dredge, being put over in seven fathoms, procured for us many specimens of a Cidaris, studded with black spines three to four inches long, and whose oblate spheroidal tests of about two inches diameter were of a beautiful smalt colour. Off the same coast, in forty fathoms, the bottom was found to consist of black basaltic sand crowded with tooth-shells. This fine black sand seemed to form the sea-bottom along the south coast of the island as far out as the fifty fathom line, and from our experience does not prove a favourable berth for our friends the Mollusca and Annulosa.

Among the Crustaceans obtained in the above dredgings was a species of Glaucothöe new to science, which has since been described by Mr. E. J. Miers, of the British Museum, under the title of "Glaucothöe rostrata."

On the afternoon of the 12th of October, in company with Sir George Nares, and under the guidance of Dr. Grabham, a British doctor for many years resident in Madeira, we had an opportunity of inspecting a "pinery," established within the last two years by a Mr. Holloway, and by which he expects to amass a considerable fortune. This establishment, which lies to the north-east of the town, at an altitude of about three hundred feet, consists of a series of long, low hothouses with sloping glass roofs, painted white, and facing to the southward, and is heated entirely by the sun's rays. The material in which the pines are planted consists of the branches of the blackberry plant chopped to fragments, and spread out in a thick layer, and in this substitute for mould the young pines are placed, at intervals of about eighteen inches apart. They grow to an enormous size, as we ourselves witnessed; and being cut when they show the least sign of ripening, and packed carefully in well-ventilated boxes, are shipped to London, where they fetch prices varying from twenty-five to thirty shillings each.

Dr. Grabham was kind enough to give us much interesting information concerning the natural history of the island, which,[12] from his long experience and constant observation, was most valuable. He pointed out to us a considerable tract of land in the vicinity of the town which used to be thickly planted with vines, but which is now only devoted to the cultivation of sweet potatoes. During the last seven years the vine crops have been steadily decreasing, owing to the ravages of the Phylloxera vastatrix, and wine-making is now at a low ebb. The number of trees in the island was also rapidly diminishing, owing to the demand for fuel; and although efforts are made, by the cultivation of pine forests, to supply that want, the demand yet exceeds the supply. In a few years Madeira will no longer be, as its name implies, a land of wood. Although so late in the season, numbers of flowers were still in full bloom; the Bougainvillea with its dark-red bracts, and the yellow jasmine adorning the trellis-work; further up the hill the belladonna lily attracted attention, and on the heights were the old familiar furze blossoms, reminding us of the land we had left behind us.

On October 12th we weighed anchor, and proceeded to the southward. All that night and the following day we steamed quietly along in smooth water, with a long, shallow ground swell (of which, however, the old craft took advantage to display her extraordinary rolling powers), and late in the afternoon, just before dark, caught sight of Palmas, one of the Canary Islands, whose peak, 7,000 feet high, loomed conspicuously through a light bank of clouds. It was distant seventy miles. On the morning of the 15th we experienced for the first time the influence of the north-east trade wind, which wafted us along pleasantly at the rate of about seven knots. Up to this the only sign of animal life had been a solitary storm petrel, but on the following day a shoal of flying fish (Exocetus volitans) appeared, to pay their respects and greet us on our approach to the tropical zone. During the night, the wind, which had hitherto only behaved tolerably, fell light; and as the morning of the 17th dawned, we found ourselves flapping about in almost a complete[13] calm. There were several merchant vessels in sight, with one of which, a fine-looking full-rigged clipper ship, we communicated by signal, when the usual dumb interchange of civilities took place; she informing us that she was the Baron Collinson, seventeen days out from Liverpool, and we in return giving the latest news we were aware of, viz., the failure of the Glasgow Bank. During the afternoon, a shark, which seemed to be the Squalus glaucus, hovered about our stern. It was accompanied by at least four "pilots" (Naucrates ductor), whose conspicuous dark-blue body stripes showed out in striking contrast to the sombre hues of the shark, whose body formed the background.

It is during those tropical calms, usually so wearisome to the seaman, that the lover of natural history reaps his richest harvest. On the present occasion the tow-net brought up quantities of a minute conferva consisting of little bundles of delicate straw-coloured fibres, about one-eighth of an inch in length, and resembling, on a small scale, the familiar bundles of "faggots" as one sees them hawked in the streets. Under a high magnifying power the individual fibres composing these bundles were seen to consist of jointed segments marked with dots and transverse striæ as a diatom. When placed in spirit, they at once broke up into a shapeless fluffy mass. The surface water was thickly impregnated with them, yet not so as to impart any obvious discolouration. About dusk the trade wind suddenly returned, and a heavy shower of rain brought to a close a day of great interest.

On the 18th of October, many of us fore and aft were diligently expending our ingenuity in fishing for bonitoes, of which several (apparently the Thinnus pelamis) were to be seen about the ship; but, to our great chagrin, only one, a small specimen, was captured. The tow-net still brought up quantities of the conferva before mentioned, and multitudes of minute unattached specimens of the Spirorbis nummulites.

On the following day, as we lay all but becalmed, the storm petrels (Thalassidroma pelagica) appeared in great numbers, settling[14] on the water close to our stern, in flocks of twelve or fourteen, and feeding greedily on the rubbish thrown overboard. It seems that the natural food of these birds (which probably consists of the minute surface organisms) is not within their reach when the surface of the water is unbroken, and hence during calms they are more than commonly anxious to avail themselves of any offal thrown overboard. It was most interesting to observe the neat and graceful way in which they plant their webbed feet on the water, as with outstretched wings and legs erect they maintain a stationary attitude while pecking at the object of their fancy. They appeared to scrupulously avoid wetting the tarsi, and still to use the feet as a means of maintaining a fixed position on the surface of the water. I had never previously observed those untiring little navigators at rest in mid-ocean, but on this occasion we all saw them, with wings closed, floating as placidly on the water as ducks in a millpond. The old idea of their following ships only before and during stormy weather is, I believe, now quite exploded. I think that within the tropics, at all events, they are most numerous in the vicinity of ships during calm weather. Finding animal life scarce at the surface, I tried the tow-net sunk to a depth of about three fathoms, and having previously raked the surface, was enabled to institute a comparison; the result being that similar species were captured in both situations, but that a far greater number of individuals were present in the deeper water. During the day-time we obtained a number of Crustaceans, several Atlanta shells, Globigerina bulloides, and the same conferva as on the previous day. After dark I got a great quantity of highly phosphorescent Crustaceans, and one small cuttle-fish.

On the 20th the trade wind returned in full force, and the monotony of an otherwise uneventful day was varied by the appearance of a shoal of porpoises, which accompanied us for some time, moving along abreast of us and about two hundred yards off on our starboard beam, and making themselves conspicuous by their usual frisky behaviour.

On the afternoon of the 22nd the high land of San Antonio, the most northerly of the Cape de Verde Islands, hove in sight, far away on our starboard bow; but the evening closing in thick and dark, and this group being almost without lighthouses, the captain decided on laying-to until next morning. When about twenty miles off, we received a visit from a good-sized hawk, evidently out on a foraging tour; he hovered for a while about our mastheads, reconnoitring our decks, and then soared away.

As we sailed along the east coast of San Antonio (the largest island of the Cape de Verde group), we observed a small outlying island rock, composed of closely packed vertical columnar masses of rock (probably basaltic), which, from their artificial appearance, reminded one forcibly of the Giant's Causeway, or of the Staffa Columns. The hills of the main island, which sloped up majestically from a low rocky beach to peaks five or six thousand feet high, were clothed with herbage, whose varying tints of green, to which the shadows of the secondary peaks added dusky patches of brown, created a most pleasing landscape.

We reached the harbour of Porto Santo, St. Vincent, on the afternoon of the 23rd of October, and soon after the anchor was dropped, those of us who could leave the ship proceeded to land. As we approached the beach, we were greatly struck by a contrivance, new to most of us, for carrying coals from the yard where it is stowed to the shipping wharves, a distance of nearly a quarter of a mile,—a row of posts, like those used for telegraph wires, placed about four yards apart, and supporting on iron rollers a long endless wire, to which are hung at intervals large metal buckets containing the coal. There is an incline from the depôt to the wharf, and consequently, as the full buckets travel down to the lower end of the circuit, and are canted so as to discharge their contents, the empty buckets pass up the incline back to the coal-yard, and so a circuit is completed. Most of the large passenger-steamers traversing the South Atlantic find St. Vincent a convenient place to stop at to replenish their[16] bunkers, and it is to this coal trade that the island owes its importance.

After a cursory inspection of the little town, which presented a very neat and orderly appearance, we strolled out into the country, following the direction of the western shore of the bay. The country exhibited a tolerably green appearance, and we were informed that vegetation had been exceptionally good during the previous two years, owing to the rainfall having been much above the average. Of trees of course there were none to be seen, and of shrubs only a few stunted representatives, scattered singly or in patches. A species of rank grass, however, flourished, and here and there a rather stately fungus raised its head as if in defiance of its otherwise sterile surroundings, the blown sand of the foreshore supplying sufficient nutriment for its humble wants. Of dead shells a great variety were picked up on the beach between tide marks, including representatives of the genera Arca, Patella, Cardium, Harpa, Littorina, and Strombus; a very perfect Spirula shell was also noticed. The blown-sand ridges above high-water mark were everywhere perforated by the burrows of a very active grey-coloured crab (Remipes scutellatus), whose feet terminated in sharp incurved claws admirably adapted for the creature's mining operations. Its burrows extended obliquely downwards, and to a depth of two feet from the surface of the blown-sand ridges. A couple of grasshoppers were the only other additions made on this occasion to our zoological collection.

The afternoon of the next day (24th October) I was enabled to devote to dredging operations, working over the bay at depths varying from two to twelve fathoms. From these I obtained some large and active specimens of a large wing-shell, the Strombus pugilis, whose gymnastic performances, when subsequently placed in a vessel of sea-water, excited general interest. Armed with his long powerful foot, he struck out boldly in all directions, the operculated extremity acting like a sword blade, and alarming me for the safety of the seaweeds and other more delicate[17] organisms which occupied the same vessel. When disposed to turn about, it protruded the foot so as to half encircle the shell, and by then rapidly straightening the organ the desired change of position was effected. It was very interesting to see the complete control which the animal thus exercised over its heavy and apparently unwieldy shell. In twelve fathoms of water we came upon a great quantity of blue-spined Echini, the tangles of the dredge in one short haul bringing up about two dozen. Fishing-lines were also brought into requisition, resulting in the capture of some fishes of a pale crimson colour, belonging to the blenny family.

In the evening of this day (24th October) we sailed from St. Vincent. Up to the 29th instant the north-east trade wind proved fairly propitious, but it now failed us completely; and as we were at this time in latitude 8° N., and there were otherwise unmistakable indications of our having arrived at the "Doldrums" (the region of equatorial calms), steam was had recourse to. Under this artificial stimulus we proceeded at a rate of from five to six knots, a speed unfortunately too great for the use of the tow-net; and on this occasion the circumstance was all the more vexatious, as the surface water seemed peculiarly rich in animal life. Ultimately, however, determining on sacrificing some bunting in the cause of science, I put a tow-net over the stern, and the captain aided me materially by towing from the end of the lower studding-sail boom a ten-foot trawl-net. Between the two we succeeded in capturing some water insects of the genus Halobates, several beautiful large Ianthinæ, but unfortunately with their fragile shells partly broken and severed from their rafts; also a Physalia, a small free-swimming Actinia, some discophorous Medusæ, and several Pteropod Molluscs of the genus Hyalea. For several consecutive days the surface water after dusk was thronged with the above-mentioned Medusæ, whose tough gelatinous discs, of three inches diameter, continually clogged up the meshes of the tow-net. On the 2nd of November[18] we obtained some Globigerina forms, several Crustaceans, some minute Pteropods of the genus Cuvieria, and a host of minute Confervæ, of the kind met with previously to the northward of Madeira. On the afternoon of the 5th of November, when we were about a hundred miles from St. Paul's Rocks, we noticed that the little petrels, which for weeks had accompanied us in great numbers, were now feebly represented, and in the evening were completely gone. Perhaps they had found out their proximity to terra firma, and were gone for a run on shore. It is very strange how these birds, which follow ships over the ocean for thousands of miles, can manage to time their journeys so as to reach land for their breeding season. That the same individuals do follow ships for such great distances we have good evidence; for Captain King, in his voyage of the Adventure and Beagle, mentions a case in which the surgeon of a ship, coming home from Australia, having caught a Cape pigeon (Daption capensis), which had been following the ship, tied a piece of ribbon to it as a mark, and then set it free. The bird, recognized in this way, was observed to follow them for a distance of no less than 5,000 miles.

From the last date to the 9th of November, but little of interest occurred. One day a petrel (Thalassidroma pelagica) had been caught with a skein of thread; and on opening the body the crop was found to contain a number of stony particles, bits of cinders, minute shells, and otolites of fishes. In the tow-net we caught a number of Rhizopods, of 1⁄20 inch diameter, which kept continually unfolding and shutting up their bodies in telescopic fashion. When quiescent, the animal is egg-shaped, and about the size of a mustard seed; but when elongated, it is twice that length, and exhibits a tubular sort of proboscis armed with an irregular circle of vibrating cilia. We also obtained a Pteropod resembling the Criseis aciculata, an Ianthina, and some hyaline amœbiform bodies, which were entirely beyond my powers of recognition. On the following day we got more of the pretty[19] violet shells (Ianthina fragilis), several Crustaceans, including a large and perfect Glass-crab (Phyllosoma), and several large Salpæ and Medusæ.

On the 12th of November we entered the north limit of our surveying ground, being in latitude 17° S., and in the vicinity of the Abrolhos Bank. Here, in latitude 17° 18′ S., longitude 35° 34′ W., we made a cast with Bailie's deep-sea sounding apparatus; reaching bottom in 1,975 fathoms, and finding it to consist of "Globigerina mud," of a pasty tenacity, tinged with red, and containing a great mass of Globigerina tests, whole and fragmentary. Later in the day, when in latitude 17° 32′ S., longitude 35° 46′ W., we again sounded, getting bottom in 700 fathoms, and bringing up a sort of light-grey ooze. Towards evening we struck soundings in thirty-five fathoms, over the Hotspur Bank. There we made a successful haul of the dredge, finding the bottom composed of dead coral encrusted with Nullipores, Polyzoa, and slimy Algæ, and containing in its crevices some Crustaceans of the genera Actæa and Corallana, and a few Annelids. The stony masses of coral which we brought up were pierced in all directions by boring molluscs; and one specimen of a long elaborately woven sponge (which has since been described by Mr. S. O. Ridley, of the British Museum, as a new variety of Cladochalina armigera) was found attached to a lump of coral.

The next day we sounded in latitude 18° 4′ S., longitude 36° 1′ W., using the Lucas wire sounder. We reached bottom in 300 fathoms, the bull-dog apparatus bringing up fragments of coral rock encrusted with calcareous Algæ. In the afternoon we passed into deeper water, sounding over the Globigerina ooze area, in 1,395 and 2,025 fathoms. The surface water again exhibited the same conferva-like bodies which were so abundantly obtained near Madeira. The Pyrocystis noctiluca was also largely represented; and in the evening the tow-net was found to contain small cuttle-fish, some dead spirorbis shells, specimens of the Criseis aciculata, Cleodora pyramidata, and of[20] a species of Hyalea, and a thick fleshy Pteropod, a species of Pneumodermon, small globe fishes, many long, transparent, stalk-eyed Crustaceans, and other minute members of the same class of Arthropoda.

On the 14th of November we sounded in latitude 19° 43′ S., longitude 36° 5′ W., the bottom consisting of a pale chocolate-coloured tenacious mud. Towards evening we reached the position of the Montague Bank, which is indicated on the chart as a bank about three miles long, and in one part covered by only thirty-six fathoms of water. We sounded for this bank repeatedly, but in vain, nowhere getting bottom with 470 fathoms of line. The ship was now allowed to drift during the night-time, soundings being made from time to time; and towards morning we filled our sails to a northerly breeze, and stood on for the Victoria Bank. In the afternoon we met with a large school of sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus), displaying to advantage, as usual, their huge cylindrical snouts, and alternately their great spreading tails; this circling exercise appearing to be a favourite amusement of theirs.

On reaching the Victoria Bank, we hauled the dredge in thirty-nine fathoms, but dropping on a rugged coral bottom, the bag was torn to pieces; however, the tangles contained numbers of an oval-shaped sponge, varying in length from a quarter of an inch to an inch, and studded with beautiful glassy spicules (determined by Mr. Ridley to be a new species of Chalina), and also numbers of the genera Vioa, Nardoa, Aphroceras, and Grantia. Among Polyzoa, the genera Canda, Membranipora, Cribrillina, Gigantopora, Rhyncopora, Smittia, and Cellepora were represented. Our operations in the Abrolhos region being now at an end, we shaped a course for Monte Video.

On the 22nd of November, when we were a hundred miles from the Brazilian coast, and in about the latitude of Rio, great numbers of moths appeared, hovering about the ship, and settling on the rigging. The wind was at the time blowing freshly from the westward; but the moths appeared, strange to say, as if[21] coming up from the south-eastward. Conspicuous among them by their great numbers as well as by their formidable appearance, were the Sphinx moths. These large insects seemed gifted with marvellous powers of flight; for although the wind amounted to a fresh breeze, I noticed that they were not only able to hold their own, but even to make headway against it. We concluded, however, that nearer in shore the wind was much stronger, perhaps reaching us so as an upper current, and that it had consequently blown them off the land. Later in the day the Lepidoptera were represented in still greater variety, so that altogether the ship exhibited an unusually sportive appearance; men and officers alike striking out with their caps here and there, as they pursued the objects of their fancy. In the course of the day I collected no less than seventeen species, of which fourteen were moths, and the remainder butterflies. As illustrating the great tenacity of life of the Sphinx moths, I may mention that, in the case of one refractory individual, it was only after employing all the deadly resources at the time at my command, viz., prussic acid, ammonia, oxalic acid, chloroform, crushing the thorax, etc., that I could succeed in removing all the ordinary manifestations of life. However, as, after long incarceration in a bottle filled with the fumes of chloroform, he at length appeared to have succumbed, I proceeded to remove the contents of his large fleshy body. This done, I filled in the body with cotton wadding, and placing the specimen on one side, proceeded to operate on another. But no sooner had I put down the specimen thus prepared, than it proceeded to kick about in a most vigorous way, and otherwise gave unmistakable signs of vitality. On turning it on its legs, it crawled about, clung to my finger, and seemed to imply that it could get on just as well with a cotton interior as with the whole complicated apparatus of intestine and so forth, which it had given me so much trouble to remove.

It was a strange coincidence, that among the contents of the tow-net on this occasion was a large black Chrysalis. It also[22] contained a great number of little phosphorescent spheres, which, under a high magnifying power, proved to be similar to the bodies described by Sir Wyville Thompson, under the term Pyrocystis noctiluca. On the same day we entered the Albatross region, one large white bird (Diomedea exulans) and several sooties (Diomedea fuliginosa) soaring around our ship. Some land-birds were also seen, one of which, a species of finch (?) was captured and preserved.

On the 24th of November we approached within eighty miles of the Brazilian coast, and on getting soundings in forty-eight fathoms, immediately put the dredge overboard. The hempen tangles contained starfishes of three or four species, and the bag brought up a mass of bluish tenacious mud, which, on sifting, was found to contain some Crustaceans and tube-building Annelids, and many small shells, living and dead, of the genera Dentalium, Hyalea, Arca, and others. About the same time a turtle was observed floating on the water.

On the forenoon of the 26th, land—the coast of Uruguay—was in view on our starboard beam, a long low line of beach, whose uniform outline was broken by a conspicuous tall lighthouse, which stamped the locality as Cape Santa Maria. A few hours later we obtained a view of Lobos Island, a bare-looking uninviting mass of rock, situated just off Maldonado Point; and as we now fairly entered the estuary of the Plate, a number of large gulls (apparently of the genus Dominicanus) joined us, eagerly picking up any offal cast overboard.

We arrived at Monte Video on the 27th of November, and stayed until the 14th of December, during this time making several trips into the country.

On one occasion I went by train to a place called Colon, about ten miles to the N.W. of Monte Video. Starting from the central station of the Northern Railway, I took my seat in a clean well-fitted carriage, with two other passengers, one of whom, my vis-à-vis, might have realized one's ideas of a Guy Fawkes. In the[23] course of the journey, this individual somewhat surprised me by diving his hand into a back coat pocket, and producing therefrom a formidable-looking silver-sheathed dagger, which, however, to my relief, he quietly laid down beside him on the seat, perhaps that he might the more conveniently stretch himself out; possibly because he thought me a suspicious companion, and wished to show in time that he was not unprepared in case of an attack.

About Colon the country was open enough, presenting to the eye a great bare tract of weedy-looking land varied by gently undulating hills, and studded with oxen innumerable; the farm-houses, low structures disposed about half a mile apart, hardly breaking the monotony of the landscape. Here and there a gaily caparisoned Gaucho cantered about, apparently without any fixed object, except to enjoy his liberty, and gave a picturesque character to the scene. These Gauchos are really fine-looking fellows, well mounted, and most excellent horsemen. They have about them a certain air of well-fed contentment, which, in spite of their known ferocity, almost elicits admiration. It is a popular error to apply the term "Gaucho" indiscriminately to all the horse-riding community of the lower classes, for the term is properly only applicable to those homeless wandering horse-riders whose sole worldly possession consists of a horse and its trappings, who roam about from place to place, picking up whatever they can appropriate by fair means or foul, and who, consequently, do not enjoy a very high reputation among the settled inhabitants. The word "Gaucho" is looked upon as a term of reproach, and an honest, self-respecting peasant so addressed would reply, "No, Señor, no soy Gaucho, soy Paysano." By a clever stroke of policy the present dictator of Uruguay, Señor Letore, has almost succeeded in putting a stop to the infamous practice of "cattle lifting," formerly so common among the "Gauchos." Their equipment usually includes a long strip of hide, ostensibly carried as a tether for the horse, but frequently turned to account as a lasso. A law has now been enacted, and is rigidly enforced, restricting the length of this rope[24] to five "brazeros," i.e., five arm spans; and as it is in consequence much too short to answer the purpose of a lasso, these mounted tramps are no longer able to capture stray bullocks for the sole pleasure of gouging out the tongue as a dainty dish. Indeed, a gentleman of Durazno, for many years resident in the country, informed me that it was now no uncommon thing to see a Gaucho carrying a hempen rope instead of a thong, the want of a lasso leaving him without the means of helping himself to a cowhide.

About Colon the prevailing plants were a large thistle and a purple-flowered Echium, and these so predominated as at a distance to seem to cover the entire surface of the ground. A light fall of rain, and a puffy breeze, combined to make it a bad day for insect hunting, and accordingly very few of these creatures were seen or captured. Of birds, the cardinal grosbeak, partridges, and pigeons, were abundant.

Some days subsequently we received, through the courtesy of the directors of the railway company, permission to travel free to the extremity of their line, and of this indulgence we availed ourselves so far as to make a trip to Durazno, the northern terminus of the railway. Accordingly, a party consisting of the captain and four of us ward-room officers started by a train leaving the central terminus at seven in the morning. This railway, which has been for eleven years in existence, and for a long time struggling against unfavourable circumstances (rebellion and so forth), is now gradually assuming a prosperous condition, and has been extended so far that it now pierces the republic of Uruguay in a northern direction, to a distance of 128 miles from Monte Video. As we emerged from the precincts of the town, and passed through a hamlet called "Bella-Vista," on the shores of the bay, we noticed here and there woods of the eucalyptus tree growing in great luxuriance to a height of eighty and even a hundred feet, the foliage of adjoining trees being so interlocked as to afford considerable patches of shelter from the sun's rays. Sir George Nares, who has had some experience of these trees in Australia, where they are indigenous,[25] said that he had rarely seen them clad with so dense a foliage. We were told that these trees had been imported and planted only twelve years previously; yet such is their rapidity of growth, that they are now of the magnitude of forest trees. On reaching a distance of about twelve miles from Monte Video, the number of trees (none of which, except the willows, were indigenous) had so far decreased, that the few solitary representatives which dotted the landscape served only to render the paucity of the race the more remarkable. The surface configuration of the land was everywhere the same—a gently undulating grass-covered plain, where the depths from crest to hollow averaged about thirty feet, admitting a range of vision of about twelve miles from the summit of each rise. Of ravines, fissures, or gullies, there were none; and as the railway track had evaded the difficulties of levelling by pursuing a most meandering course, not even a cutting was to be seen to afford means for arriving at a geological examination of the district. About the station of Independencia, rock was to be seen for the first time, consisting of a coarse-grained (apparently felspathic) granite, showing itself through the alluvial soil in the shape of low rounded masses, or as boulders disseminated in streams directed radially from the outcropping source. At the next station, appropriately named "Las Piedras" (the stones), the rock was in greater proportion; and during the remainder of our journey north, perhaps once in every ten miles, the wide expanse of grass-land would be varied by an odd-looking outcrop of granite. Stone was evidently a rare commodity in these parts, most of the huts being built of sticks and mud.

As far as Santa Lucia, a station about forty miles from Monte Video, the land (divided into fields by hedgerows of aloes) was studded thickly enough with large prickly thistles of a very coarse description; but to the northward of this position the prominent features of the landscape underwent a change. Trees disappeared altogether, and except along the river banks, where some bushes resembling bog-myrtle eked out an existence, no[26] shrubs were to be seen. Thistles were still present, but in very small numbers, and indeed there was little to meet the eye but a wide expanse of grass-land dotted here and there with herds of oxen, sheep, and horses (which seemed in very small proportion to the acreage), and exhibiting, at distances of about two miles apart, small one-storied huts. For ploughing and other agricultural work, oxen seemed to be used, to the exclusion of horses; which is all the more strange, as the latter here exist in great abundance, and are so cheap as to create that equestrian peasantry which to a European visitor is, I think, the most striking characteristic of the country.

As one of the up-trains passed by us at the station of Joashim Suarez, we noticed several trucks piled up with ox skulls and other bones, and on enquiry ascertained that they were for exportation to England, to be used in sugar-refining factories: the bones were piled up so high on the trucks as to tower above the engine, so that as the train approached us end-on, they formed a ghastly sort of figure-head.

At Santa Lucia the train stopped half an hour for refreshments, and all hands adjourned to an hotel close by the railway station, where a good breakfast, consisting of many courses (including beefsteak and potatoes), was satisfactorily disposed of. The charge for this repast was moderate, being only six reals = 3s. 6d. a head.

Of birds a great many were to be seen as we travelled along. Looking forward from the carriage windows, we could see ground doves of a dull slate colour, rising from the track, and sheering off to either side in great flocks, as the train advanced. A species of lapwing, with bluish-grey plumage barred with white across the wings, and displaying a pair of long red legs, kept us continually alive to its presence by its harsh double cry. Partridges were also abundant. These birds are strictly preserved all over Uruguay, and during the breeding season, from September to March, no shooting of any kind is allowed without special[27] permission. We saw one flock of ostriches stalking about unconcernedly among the cattle. We were subsequently told that the ostriches in this district were all allowed to run wild, the value of the feathers not repaying the cost of farming. Of deer, the largest indigenous mammal, we saw only one individual, browsing quietly among a herd of cattle. They are allowed to come or go as they please, not being sought after or utilized by the inhabitants.

On arriving at Durazno we were most hospitably received and entertained by Mr. Ware, the engineer of the railway, under whose guidance we inspected the sights of this dilapidated country town, and then proceeded to explore the banks of the river Yi, a tributary of the Rio Negro, where a great variety of animal life was to be seen. There was here a large lagoon bordered with low bushes, a favourite haunt of the largest living rodent, the capybara or "carpincho," as the natives call it, and also largely stocked with birds. Snipe and dottrel were here so tame as to allow one to approach within a few yards of them. In the course of the day we had the good fortune to meet a Mr. Edye, an Englishman, who, during thirteen years' residence in the Plate, had acquired a considerable insight into the natural history of the country. He told us that a great variety of birds inhabit the low bushes of the "Monte" (as they call the shallow valley of the river), including three species of the cardinal, one humming bird, the calandria or South American nightingale, etc. With reference to the tucutuco (Ctenomys), he assured us, contrary to the opinion expressed by Dr. Darwin, in his "Journal of a Naturalist," as to the animals never coming to the surface, that the little rodents were commonly to be seen near their holes about the time of dusk, and that they invariably retreated to the burrows on the near approach of a human being. He considered it almost impossible to catch them, but had no doubt about their habit of coming to the surface. As we strolled along the river banks, we saw and[28] captured a black snake about two and a half feet long, which was swimming gracefully from bank to bank, with its head elevated about two inches from the top of the water. We also got some living specimens of a river mussel, which is here used as fish bait.

Everywhere among the English-speaking community we heard the same gloomy accounts of the dulness of trade, arising from the yet unsettled state of the country. All agreed that the present Dictator was managing the country admirably, but expressed their fears that he would some day be "wiped out," as others had been before him, and that the country would again relapse into a state of anarchy and brigandage.

Some days later I had an opportunity of visiting Buenos Ayres, the capital of the Argentine Republic, situated on the opposite or south shore of the river Plate. Accompanied by Lieut. Gunn, I started from Monte Video on the evening of the 9th of December, taking passage on board one of the river-steamers (Villa de Salto), then plying daily between the two cities. The distance, 120 miles, is usually traversed at night-time, and in this arrangement sight-seers lose nothing, as, owing to the lowness of the banks and the great width of the river, the opposite shores are barely visible from a position in mid-channel. Our fellow-passengers, about eighty in number, represented Spanish, Italian, and English nationalities, and among the latter we were fortunate enough to meet two gentlemen residing in the country, to whom, as well as to the captain, a jovial, hospitable American, we were indebted for much interesting information concerning the men and manners of the country. After dinner—a long, ponderous affair—had been disposed of, a general dispersion took place, the gentlemen to smoke, and the ladies to their cabins; but in an hour or so the latter again appeared in the saloon, arrayed in evening dress of a more gay and airy character than that worn at dinner, and they now applied themselves diligently to the luxury of maté drinking. The fluid[29] known as maté is an infusion of the leaves of the Ilex paraguayensis, commonly called Paraguay tea, and is usually sucked through metal tubes about ten inches long, from a gracefully carved globular wooden receptacle about the size of an orange. One stock of "yerba" seemed to stand a great many waterings and sugarings, the necessary manipulations for which furnished the ladies with a suitable occupation. It was amusing to watch the eagerness with which the latter sucked away at their maté tubes, the attitude reminding one of a boy using a decoy whistle.

We anchored off the town of Buenos Ayres at an early hour the next morning, and here the inefficiency of the landing arrangements were made unpleasantly manifest. Three different means of locomotion were resorted to, in order to convey us from the steamer to the shore. We were pulled in a small boat for a portion of the way; then, as the boat grounded, the rowers got out, and, wading alongside, dragged it on for a few hundred yards more. We were then transferred, with our baggage, to a high-wheeled cart, drawn by two horses, which brought us through the last quarter of a mile of shallow water fringing the shore. The cost of effecting a landing was no inconsiderable item in the expense of our trip, and was moreover one calculated to prejudice unfavourably one's first impression of Buenos Ayres.

After securing rooms at the Hotel Universal, and breakfasting at the Strangers' Club, where we were most kindly received by the secretary, Mr. Wilson, we proceeded in search of the museum, so celebrated for its collection of fossil remains of the extinct South American mammals, arranged under the direction of Dr. Burmeister. We found the learned Professor enveloped in white dust, and busily engaged in restoring with plaster of Paris the spinous process of the vertebra of one of his specimens; and on explaining the object of our visit, he kindly drew our attention to the principal objects of interest in his collection. This museum has already been fully described, and I need hardly allude to the splendid specimens which it possesses of the Glyptodon, Machairodont,[30] Toxodon, Mylodon, and other fossils; its beautiful specimens of the Chlamydophorus retusus (a mole-like armadillo), the leathery turtle (Sphargis coriacea), the epiodon, etc. The Professor pointed with great pride to a recent specimen of armadillo, with the young one attached to its hind-quarters in a peculiar manner.

On the same day we inspected the Anthropological Museum, which is in a large building in the Plaza Victoria, opposite the old market, where we saw a fine collection of Tehuelche and Araucanian skulls, recently made by Señor Moreno in his travels through Patagonia. Among others was the skull of "Sam Slick," a son of the celebrated Casimiro, the Patagonian cacique, so well known for many years in the vicinity of Magellan Straits. We also saw a mummified specimen of a Patagonian, recently found in a cave at Punta Walichii, near the head waters of the Santa Cruz river.

In the course of the day we called upon Mr. Mulhall, the enterprising and courteous editor of the Buenos Ayrean Standard, and from him we acquired much valuable information as to the condition of the country. On taking up the Standard next morning, we found ourselves treated to an editorial notice chronicling our visit to the Argentine capital, and referring to the past and present services of H.M.S. Alert.

Coming fresh from so neat and trim a town as Monte Video, Buenos Ayres was not to be expected to impress one very favourably. It seemed, indeed, to be a great straggling town that, having arrived at a certain degree of civilization, had now for some years back considered itself entitled to rest on its laurels, and gradually fall into decay. Streets, plazas, and tramways were in a wretched state of neglect; and such were the great ruts which time and traffic had made in the streets, that baggage-carts might be seen brought to a dead lock, even in the principal thoroughfares. Buenos Ayres can boast of several fine old public buildings, among which the cathedral, with its classic[31] front, stands pre-eminent; and although there are some fine pieces of modern architecture, such as the Bolsa, or Exchange, the latter are so stowed away among lofty houses in narrow streets, that they require to be specially looked for to be noticed at all. I must qualify the above observations by mentioning that these are the impressions of only two days' sojourn in Buenos Ayres.

Some days later, His Excellency the Governor of the Falkland Islands (Mr. Callaghan) and his wife arrived at Monte Video, en route for his seat of government; and as the sailing schooner, which was the only regular means of communication between Monte Video and the Falklands, was then crowded with passengers, the Governor gladly accepted Sir George Nares's kind invitation to take him as his guest on board the Alert.

We left Monte Video on the 14th of December, and on the 26th, amid a furious storm of wind and hail, anchored in Stanley Harbour, Falkland Islands. Here we found that the great topic of conversation was a landslip of peat, which had occurred about a month previous to our arrival, laying waste a portion of the little settlement. On the summit of a hill above the east end of the town, a circular patch of turf, about two hundred yards in diameter, had collapsed; and at the same time a broad stream, four feet high, of semi-fluid peat, flowed down the hillside to the sea, in its course sweeping away walls and gardens, and partly burying the houses. This phenomenon, occurring at night, caused great consternation among the inhabitants of such an uneventful little place; but after the people had shaken themselves together somewhat, and recovered from their surprise, they found that after all no great damage had been done. The appearance of the peat avalanche, as seen from the ship, was very peculiar, and in many respects the whole occurrence resembled a lava flow.

On the evening of our arrival, we were most hospitably entertained at Government House, where we had also the pleasure of meeting all the rank and fashion of this part of the colony.

The next day, being fine, I determined to devote to an inspection of the "stone runs," which have been rendered so famous in the geology of the Falklands by the writings of Darwin, Wyville Thompson, and others. In this excursion I was fortunate in having the assistance of Dr. Watts, the colonial surgeon, a gentleman who, from his long experience of the group, was well acquainted with all the salient points in its natural history. The "run" which we visited lay in the hollow of a winding valley, situated about two miles to the westward of the settlement of Stanley. The rocks, heaped together confusedly, formed a so-called "stone river," varying in width from fifty to two hundred yards, and extending up the valley as a single "stream" for about one mile and a half, to a point where it seemed as if originated by a confluence of tributary streams flowing from the surrounding hills. The stones, composed of quartzite, presented a roughly rounded appearance, which was seemingly due to excessive weathering; and they were so covered with lichens, as to appear of a uniform grey colour. Those which lay below the surface were of a rust colour, and, by all accounts, the upturned stones required an exposure of many years to assume the uniform grey tint of the surface layer. The margin of the "run" was distinctly defined by an abrupt edge of swampy soil, with its tangled vegetation of diddle-dee, tea-plant, and balsam bog. Now, why are the stones of the "run" so entirely destitute of soil? and why do they exhibit a margin so sharp and well defined, yet without the elevated, rounded appearance of a river bank? Sir Wyville Thompson's theory, it seems to me, falls short of explaining this. I have as yet seen too little of the country to justify me in forming a fixed opinion; but I am, so far, inclined to think that these "streams of stones" are of a date anterior to the existence of peat on the island, and that the peat has been approaching the valleys from the elevated land by growth and slippage, and in its descent has encountered difficulty in obtaining a footing in those places where the stones are large, and being[33] heaped to a great depth, act like a gigantic drain, and so prevent any soil from forming. As far as I can ascertain, no attempt has ever been made to estimate the rate of movement (if any) of these "runs," and there is no evidence whatever of their motion during the present century. There is not sufficient land comprised by the watershed to form torrents capable of removing the dense mass of peaty soil, which, according to Sir W. Thompson's theory, would have been necessary for the transportation of the large blocks of stone that are here accumulated. The inhabitants remark, and I think with truth, that the summits of the hills and the upper slopes are as a rule more wet and boggy than the hollows below. This supports my view of the drainage being greatest in the valleys where the big stones were originally packed to a greater depth, and towards which the peat is now encroaching. It is worthy of remark that the surface of the stream is tolerably flat, and does not indicate a process of accumulation by flow from either side.

To Dr. Watts, my guide on this occasion, I was also indebted for a skin of the Falkland Island fox, an animal now almost extinct, a skull of the sea elephant, and a dried specimen of the petrel, which is known here as the "fire bird," from its habit of dashing itself against the lantern of the lighthouse, at whose base dead specimens are occasionally found.

We left the Falkland Islands on the evening of the 27th, and sailed to the westward. On the morning of the 1st of January, 1879, we entered the eastern entrance of the Straits of Magellan, passing within easy sight of Cape Virgins and Dungeness Point. As we approached the latter, we noticed a herd of guanacos browsing quietly near the beach, as if a passing ship were an object familiar to their eyes. This, our first impression of the famous Straits, was certainly favourable. A winding channel, the glassy smoothness of whose surface was only broken by the splashing of cormorants, steamer-ducks, and other sea-birds, stretched away to the westward. On the north side were the low undulating plains of Patagonia, covered with their summer mantle of greenish-yellow vegetation; while to the southward a few widely separated wreaths of blue smoke, ascending from the gloomy shores of Tierra del Fuego, marked out the dwelling-place of one of the most remarkable varieties of the human species. Favoured by the tide, we passed rapidly through the first Narrows, and at 6.30 in the evening had got as far as Cape Gregory. Here the flood-tide setting strongly to the westward, fairly brought us to a standstill, so we steamed in towards the north shore, and anchored close under Cape Gregory. A party of us who were bent on exploring soon landed, and proceeded in various directions in quest of game, and in the few remaining hours of daylight we succeeded in getting several[35] ducks, some small birds, and a young fox. The ground was for the most part covered with a sort of rank grass, through which bushes of the Berberry, Empetrum rubrum, and Myrtus nummularia, grew luxuriantly. A very pretty dwarf calceolaria was also abundant. The only quadruped seen was a fox, but the tucutucos (Ctenomys) must have been very numerous, for the ground was riddled in all directions by their burrows. Some of our party, who strolled along the beach towards Gregory Bay, found a small settlement of Frenchmen, who, it seemed, had recently come out here to try their hands at farming. After our arrival on board, one of the men brought me a specimen of a Myxine, which had come up on his fishing line, not attached to the hook, but adhering by its viscid secretion to the line at some distance above the hook. Of this curious fish I subsequently obtained many specimens in the western Patagonian channels.

FUEGIAN IMPLEMENTS 1-7.—AUSTRALIAN "WOOMERAHS" 8-11.