Title: The Life of Isaac Ingalls Stevens, Volume 2 (of 2)

Author: Hazard Stevens

Release date: August 31, 2013 [eBook #43590]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by KD Weeks, Jana Srna, Bryan Ness, Jennie Gottschalk, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by the Google Books Library Project (http://books.google.com)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Life of Isaac Ingalls Stevens, Volume II (of 2), by Hazard Stevens

| Note: |

Images of the original pages are available through

Google Books Library Project. See

http://books.google.com/books?id=yfABAAAAMAAJ Project Gutenberg has the other volume of this work. Volume I: see http://www.gutenberg.org/files/43589/43589-h/43589-h.htm |

Several of the double- and triple-page maps are accessible in a larger size by using the “Larger image” link below each caption.

BY HIS SON

HAZARD STEVENS

WITH MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOL. II

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

1900

COPYRIGHT, 1900, BY HAZARD STEVENS

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

| CHAPTER XXVI THE CHEHALIS COUNCIL | |

| Graphic account by Judge James G. Swan—Indians assemble on lower Chehalis River—The camp and scenes—Method of proceeding—Indians object to leaving their wonted resorts—Tleyuk, young Chehalis chief, proves recusant and insolent—Governor Stevens rebukes him—Tears up his commission before his face—Dismisses the council—His forbearance, and desire to assist the Indians—Treaty made with Quenaiults and Quillehutes next fall as result of this council | 1 |

| CHAPTER XXVII PERSONAL AND POLITICAL.—SAN JUAN CONTROVERSY | |

| Death of George Watson Stevens—Governor Stevens keeps Indians in order—Visits Vancouver—Confers with Superintendent Palmer, of Oregon—Firm stand against British claim to San Juan Archipelago—Purchases Taylor donation claim—Democratic convention to nominate delegate in Congress—Governor Stevens a candidate—Effect of speech before convention: “If he gets into Congress, we can never get him out”—J. Patton Anderson nominated | 10 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII INDIANS OF THE UPPER COLUMBIA | |

| Manly Indians—Ten Great Tribes—Nez Perces—Missionary Spalding—His work—Abandons mission—Escorted in safety by Nez Perces—Intractable Cuyuses—Religious rivalry—Dr. Whitman—Yakimas, Spokanes, Cœur d’Alenes, Flatheads, Pend Oreilles, Koutenays—Upper country free from settlers—Indian jealousy—Conspiracy to destroy whites discovered by Major Alvord—Warnings disregarded—Governor Stevens thrown in gap—Prepares for council—Walla Walla valley chosen by Kam-i-ah-kan—Journey to Dalles—Incidents—Unfavorable outlook—Escort secured—Trip to Walla Walla—“Call yourself a great chief and steal wood?”—Council ground—Scenes—General Palmer arrives—Programme for treaty—Officers—Lieutenant Gracie, Mr. Lawrence Kip, and escort arrive—Governor Stevens urges General Wool to establish post there | 16 |

| CHAPTER XXIX THE WALLA WALLA COUNCIL | |

| Nez Perces arrive—Savage parade—Head chief Hal-hal-tlos-sot or Lawyer, an Indian Solon—Cuyuses, Walla Wallas, Umatillas arrive—Pu-pu-mox-mox—Feasting the chiefs—Fathers Chirouse and Pandosy arrive—Kam-i-ah-kan—Four hundred mounted braves ride around Nez Perce camp—Young Chief—Spokane Garry—Palouses fail to attend—Timothy preaches in Nez Perce camp—Yakimas arrive—Commissioners visit Lawyer—Spotted Eagle discloses Cuyuse plots—Council opened—Treaties explained—Five thousand Indians present—Horse and foot races—Young Chief asks holiday—Pu-pu-mox-mox’s bitter speech—Lawyer discloses conspiracy of Cuyuses to massacre whites—Moves his lodge into camp to put it under protection of Nez Perces—Governor Stevens prepares for trouble—Determines to continue council—Invites Indians to speak their minds—Lawyer favorable—Kam-i-ah-kan scornful—Pathetic speech of Eagle-from-the-Light—Steachus wants reservation in his own country—General Stevens’s tent flooded—Lawyer accepts treaty—Young Chief and others refuse—Governor Stevens’s pointed words—Separate reservations for Cuyuses, Walla Wallas, and Umatillas—Sudden arrival of Looking Glass—His indignation—Orders Nez Perces to their lodges—Night conference with Yakimas—Stormy council—Lawyer goes to his lodge—Kam-i-ah-kan, Pu-pu-mox-mox sign treaties—Lawyer’s advice—Nez Perces and Cuyuses counsel by themselves—Lawyer’s authority confirmed—Last day of treaty—Both tribes sign—Eagle-from-the-Light presents his medicine, a grizzly bear’s skin, to Governor Stevens—Satisfactory ending great relief—Delegations to Blackfoot council—Nez Perce scalp-dance—Treachery of other tribes—Outbreak—Compelled to live under treaties—Provisions of treaties—Benefits of council—Present prosperity | 34 |

| CHAPTER XXX CROSSING THE BITTER ROOTS | |

| Party for Blackfoot council—Crossing Snake River—Red Wolf and Timothy thrifty chiefs—Traverse fine country—Cœur d’Alene Mission—Council with Indians—Wrestling match—Crossing the Bitter Root Mountains—Rafting the Bitter Root River—Bitter Root or St. Mary’s valley—Reception by the Flatheads and Pend Oreilles—Victor complains of the Blackfeet | 66 |

| CHAPTER XXXI THE FLATHEAD COUNCIL | |

| Chiefs unwilling to unite on one reservation—Alexander dreads strictness of the white man’s rule—Big Canoe—What need of treaty between friends?—Let us live together—Protracted debates—Indians feast and counsel among themselves—No result—Victor leaves the council—Two days’ intermission—Governor Stevens accepts Victor’s proposition and concludes treaty—Moses refuses to sign treaty—“The Blackfeet will get his hair” | 81 |

| CHAPTER XXXII MARCH TO FORT BENTON.—MARSHALING THE TRIBES | |

| Nez Perces and Flatheads to hunt south of Missouri pending council—Prairie Plateau on summit of Rocky Mountains—Elk for supper—Lewis and Clark’s Pass—Management of train—Traverse the plains—Abundant game—Bewildering buffalo trails—Reach Fort Benton—Governor Stevens meets Commissioner Cumming on Milk River—Boats belated—Provisions exhausted—Leathery jerked meat—Pemmican two years old—Hunting buffalo on Judith—Bighorn at Citadel Rock—Metsic, the hunter—Two thousand western Indians fraternizing with Blackfeet—Stolen horses—Doty recovers them—Cumming claims sole authority—Forced to subside into proper place—He stigmatizes Blackfeet and country—Disagrees on all points—Governor Stevens’s views—A million and a half buffalo find sustenance on these plains | 92 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII THE BLACKFOOT COUNCIL | |

| Twelve thousand Indians kept in hand for months—Nez Perces and Snakes move to Yellowstone for food—Adams and Tappan seek Crows—Delay of boats imperils council—Indians summoned—Council changed to mouth of Judith River—Remarkable express service—Three thousand five hundred Indians assemble—Best feeling—Treaty concluded—Peace established—Terms well kept by Blackfeet—Scenes at council ground—Grand chorus of one hundred Germans—Homeric feasts—Disgruntled commissioner | 107 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV CROSSING THE MOUNTAINS IN MIDWINTER.—SURPRISE OF THE CŒUR D’ALENES AND SPOKANES | |

| The start homeward—The haggard expressman brings news of Indian outbreak—How Pearson ran the gauntlet of hostile Indians—Governor Stevens disregards warning dispatches—Resolves to force his way back by the direct route—Sends to Fort Benton for arms and ammunition—Hastens ahead of train to Bitter Root valley—Confers with Flatheads and Nez Perces—Alarming reports—Procures fresh animals—Nez Perce chiefs join the party—Taking the unexpected route—Crossing the snowy Bitter Roots—Ten dead horses—The surprise of the Cœur d’Alenes—“Peace or war?”—Craig and the Nez Perces take direct route home—Surprise of the Cœur d’Alenes—Rescue of blockaded miners—Indians called to council—The Stevens Guards and Spokane Invincibles organized | 120 |

| CHAPTER XXXV STORMY COUNCIL WITH THE SPOKANES | |

| Disaffected Indians—Kam-i-ah-kan’s emissaries and falsehoods—Governor Stevens’s firm front preserves friendship—Looking Glass’s treachery discovered and frustrated—Dubious speeches—Indians’ friendship gained—Light marching order—Four days’ march in driving storm to the Nez Perce country | 133 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI THE FAITHFUL NEZ PERCES | |

| Two thousand assemble in council—Offer two hundred and fifty warriors to force way through hostiles—Battle of Oregon volunteers—The way cleared—The Nez Perce guard of honor—March to Walla Walla—Capture of Ume-how-lish—Reception by the volunteers—Governor Stevens’s speech—Winter campaign—Letter to General Wool—His inaction and mistaken views—In camp, 27° below zero—The Nez Perces dismissed— Governor Stevens pushes on to the Dalles in advance of train—Crossing the gorged Deschutes—By trail down the Columbia to Vancouver—The sail at night in the storm—Arrival at Olympia after nine months’ absence—Mrs. Stevens and children visit Whitby Island—In danger from northern Indians | 143 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII PROSTRATION.—RESCUE | |

| Country utterly prostrated—Settlers take refuge in towns—Abandon farms—General Wool disbands volunteers, takes the defensive, and maligns the people—Review of war— Kam-i-ah-kan, leading spirit—Treacherous chiefs, fresh from signing treaties, incite war—Miners massacred—Agent Bolon murdered—Major Haller’s repulse—Settlers driven from Walla Walla—Massacre on White River—Volunteers raised— Lieutenant Slaughter killed—Impenetrable forests and swamps—Cascades afford hidden resorts—Fruitless march of Major Rains to Yakima—Governor Stevens addresses legislature—His measures of relief—Calls out volunteers— Visits lower Sound—Enlists Indian auxiliaries—Settlers return to farms—Build blockhouses—Organization of volunteers | 156 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII WAGING THE WAR ON THE SOUND | |

| Volunteers form Northern, Central, and Southern battalions—Plan of campaign—Cooperation sought with regulars—Memoir of information sent General Wool and Colonel Wright—Campaign east of Cascades suggested—Wool’s flying visit to Sound—Demands virtual disbanding of volunteers—Governor Stevens’s caustic letter of refusal—Pat-ka-nim fights hostiles—Naval forces—Battle of Connell’s prairie—Scouring the forests and swamps amid rains and storms—-Red allies—Massacre at Cascades—Two companies of rangers called out to reassure settlers—Unremitting warfare—Hostiles surrender or flee across Cascades—Posts and blockhouses turned over to regulars—Volunteers on Sound disbanded | 171 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX THE WAR IN THE UPPER COUNTRY | |

| Fruitless movements of Oregon volunteers—Colonel Wright marches to Yakima valley in May—Parleys instead of fighting—Governor Stevens proposes joint movement across Cascades—Colonel Casey declines—Colonel Shaw crosses Nahchess Pass—Marches to Walla Walla—Governor Stevens journeys to Dalles—Dispatches Goff’s and Williams’s companies to Walla Walla—Seeks coöperation with Colonel Wright—Warns him against amnesty to Sound murderers—Three columns reach Walla Walla the same day—Shaw defeats hostiles in Grande Ronde—His victory restrains disaffected Nez Perces—Governor Stevens invites Colonel Wright to attend peace council in Walla Walla—That officer fooled by the Yakimas—His abortive campaign—Ow-hi’s diplomacy | 194 |

| CHAPTER XL THE FRUITLESS PEACE COUNCIL | |

| Governor Stevens, assured of support by Colonel Wright, revokes call for additional volunteers—Council with Klikitats—Refuses to receive Indian murderers on reservation—Pushes forward to Walla Walla—Indians take pack-train—Steptoe arrives with four companies—Indians assemble—Manifest hostility—Steptoe moves off—Volunteers start for Dalles—Steptoe refuses guard—Governor Stevens recalls volunteers—Hostile and threatening Indians—Steptoe refusing support, Governor Stevens moves to his camp— Disaffected chiefs demand that treaties be abrogated, whites leave the country—Governor Stevens demands submission—Terminates council—Starts for Dalles—Attacked on march—The fight—Moves back to Steptoe’s camp—Indians attack it—Repulsed—Blockhouse built—One company left—Both commands march to Dalles—Steptoe’s change of views—Demand on Colonel Wright to deliver up Sound murderers, who gives order—Cleverly evaded—Colonel Wright marches to Walla Walla—Counsels with hostile chiefs—Yields to their demands—Whites ordered out of the country—Shameful betrayal of duty—Governor Stevens’s indignant letters to the War and Indian departments—Pernicious influence of missionaries and Hudson Bay Company—Governor Stevens’s views finally adopted—Steptoe’s defeat—Wright defeats hostiles—Summary executions—Fate of Ow-hi and Qualchen | 206 |

| CHAPTER XLI DISBANDING THE VOLUNTEERS | |

| Entire force disbanded—Their character, discipline—Public property sold—So many captured animals that more were sold than purchased—Transportation cost nothing—Anecdote of Captain Henness—Thirty-five forts built by volunteers, twenty-three by settlers, seven by regulars—Colonel Casey refuses demand for surrender of murderers—Governor Stevens insists—Sharply rebukes Colonel Casey’s slurs—Leschi surrendered for trial—Is finally hanged—Qui-e-muth killed | 232 |

| CHAPTER XLII MARTIAL LAW.—DIFFICULTIES OVERCOME | |

| Hudson Bay Company’s ex-employees remain in Indian country—Suspected of aiding enemy—Governor Stevens orders them to the towns—Five return to farms, at instigation of trouble-makers—Arrested and thrown in jail Judge Lander issues writ of habeas corpus—Martial law proclaimed in Pierce County—Colonel Shaw arrests judge and clerk, who are taken to Olympia and released—Lawyers pass condemnatory resolutions—Judge Lander holds court in Olympia—Issues writs—Martial law in Thurston County—Judge Lander arrested—Held prisoner at Camp Montgomery until end of war—Martial law abrogated—Governor Stevens fined fifty dollars—His action in proclaiming martial law disapproved by the President—Dishonorable discharge used to maintain discipline—Company A refuse to take field—Pass contumacious resolutions—Are dishonorably discharged—Control of disaffected Indians—Agents in constant danger—Summary dealing with whiskey-sellers—Agents men of high qualities—-Statement of temporary reserves—Indians and agents—Northern Indians depredate on Sound—Captain Gansevoort severely punishes them at Port Gamble, and sends them north—Colonel Ebey falls victim to their revenge | 242 |

| CHAPTER XLIII LEGISLATIVE CENSURE.—POPULAR VINDICATION | |

| Governor Stevens’s habits of labor—Adopts costume of the country—Builds home—Housewarming—Fourth message to legislature—Renders account of Indian war—Resolutions censuring Governor Stevens, for dismissing Company A and proclaiming martial law, pooled and passed—Indignation of the people—Governor Stevens nominated for Congress— Canvasses the Territory—Elected by two thirds vote— Resigns as governor—Death of James Doty—Turns over governorship to Governor McMullan; Indian affairs, to Superintendent Nesmith—Return journey East—Incidents | 260 |

| CHAPTER XLIV IN CONGRESS.—VINDICATING HIS COURSE | |

| Passing Superintendent Nesmith’s accounts—Obtaining funds for Indian service—President recommends confirmation of the treaties—Welcomed back by old friends—General Lane a tower of strength—Demands that military deliver Yakima murderers to punishment—They abandon their protégés—Takes house and moves family to Washington—Mr. James G. Swan, secretary—Circular letter to emigrants—Appeals to Indian Department to establish farms promised Blackfeet—Has Lieutenant John Mullan placed in charge of building wagon-road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla—Exposes memoir of Captain Cram—Convinces Senate Indian committee that treaties ought to be confirmed—Advocates Northwestern boundary commission—Speeches on Indian war—Pacific Railroad—Defends Nesmith—Matters engaging attention—Resists exactions of Hudson Bay Company in memoir to Secretary of State—Steptoe’s defeat—Colonel Wright punishes Indians—General Harney placed in command of Washington and Oregon departments—He revokes Wool’s order excluding settlers from upper country—Address on Northwest—Walter W. Johnson, private secretary—Treaties all confirmed March 8, 1859—Dictates his final report on Northern route before breakfast | 271 |

| CHAPTER XLV SAVING SAN JUAN | |

| Returns to Puget Sound—Guest of General Harney—Close relations with—Renominated for Congress—The canvass—Elected—Death of Mr. Mason—San Juan dispute waxes warm over a pig—General Harney advised by Governor Stevens—Sends Captain Pickett to occupy the island—British fleet blockade—Reinforcements sent to Pickett—British powerless on land—Thousands of American miners in Victoria and on Fraser River—Governor Gholson guided by Governor Stevens—Offers support of militia to General Harney, who places ammunition at his disposal—General Scott pacifies British lion—Governor Stevens’s influence in saving the archipelago | 288 |

| CHAPTER XLVI THE STAND AGAINST DISUNION | |

| Governor Stevens becomes chief exponent and authority on Northern route—Letter to Vancouver railroad convention— Contending for the Northern route—Governor Stevens lives down prejudice—Gains respect—Great influence with President and departments—His habits—Rebuke of self-seekers—Political issues—Governor Stevens a national man—Sustained constitutional rights of South, as matter of justice and to defeat disunion—Patriotism of men of this view—Attends Charleston and Baltimore Democratic conventions—Supports General Lane—Split in party—Governor Stevens accepts as chairman of executive committee of National Democracy—Writes address in a single night—Labors hard—Hopes of success—Abraham Lincoln elected President—Act to pay Indian war debt passed—W.W. Miller appointed Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Washington Territory—Governor Stevens’s achievements in seven years—His firm Union sentiments—Denounces secession—Strengthens the hands of the President | 296 |

| CHAPTER XLVII THE OFFER OF SWORD AND SERVICES | |

| Governor Stevens returns to Washington Territory—Recommends supporting the government and arming the militia—Elected captain of Puget Sound Rifles of Olympia—Democratic convention meets—Governor Stevens withdraws his name as candidate for delegate—His speech—Offers services—Hastens to Washington—Meets cold reception—Accepts colonelcy of 79th Highlanders—Governors Andrew and Sprague offer regiments | 313 |

| CHAPTER XLVIII THE 79TH HIGHLANDERS.—THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC | |

| The Highland Guard, a New York city militia battalion, volunteer as the 79th Highlanders—Splendid material—Severe losses at Bull Run—Promised to be sent home to recruit—Disappointed— Colonel Stevens takes command—Breaks unworthy officers—The mutiny and its suppression—Colonel Stevens enforces discipline—Marches through Washington with band playing the dead march—Removes camp guards and appeals to honor of the regiment—Crossing the Potomac into Virginia—Colonel Stevens’s brief speech at midnight—Building Fort Ethan Allen—Digging forts and felling forests—Picket alarms—The reconnoissance of Lewinsville—General McClellan meets returning column; his anxiety to avoid a general engagement— Colonel Stevens deprived of his brigade and given three green regiments—President Lincoln reminded, directs appointment of Colonel Stevens as brigadier-general; says delay is owing to General McClellan’s advice—Hazard Stevens appointed adjutant 79th Highlanders—Colonel Stevens appointed brigadier-general— Moves forward four miles to Camp of the Big Chestnut—The recusant wagon-master—The unexpected rebuke—McClellan’s passive-defensive—General Stevens ordered to Annapolis—Bids farewell to the Highlanders—Whole line cries, “Tak’ us wi’ ye!”—Secures appointment of his son as captain and assistant adjutant-general—Condemns McClellan’s management—Predicts disaster—Reaches Annapolis—Applies for Highlanders—McClellan objects, but President Lincoln overrules him and sends them | 321 |

| CHAPTER XLIX THE PORT ROYAL EXPEDITION | |

| General Thomas W. Sherman—His army—General Stevens’s brigade—The embarkation—Fleet assemble off Fortress Monroe—Boat’s crew of Highlanders—Lively scenes—Sailing out to sea—Storm scatters the fleet—Opening sealed orders—Sail for Port Royal—The rebel defenses—Commodore Dupont’s attack—The enemy’s flight—Landing of the troops—Demoralized by sweet-potato field—General Stevens alone urges advance inland—Constructs a mile of defensive works—Sickness—Life on Hilton Head | 341 |

| CHAPTER L BEAUFORT.—ACTION OF PORT ROYAL FERRY | |

| General Stevens occupies Beaufort, the Newport of the South—Abandoned by white population—Sacked by negroes; their ignorance, habits, condition—Faint attack on the pickets—General Stevens advances across Port Royal Island—Pickets outer side, throwing enemy on the defensive—Enemy close the Coosaw River—General Stevens’s plan to dislodge them authorized—Reinforcement by two regiments and gunboats—Flatboats assembled in a hidden creek—Troops embark at midnight, cross Coosaw, and effect landing—March in echelon toward Port Royal Ferry—The action—The enemy’s hasty retreat—The Ferry occupied—The forts destroyed—Troops bivouac for the night—Cross the ferry and march to Beaufort in triumph—Thanked in general orders for the victory of Port Royal Ferry | 353 |

| CHAPTER LI BEAUFORT.—CAMPAIGN PLANNED AGAINST CHARLESTON | |

| General Stevens restores public library—It is confiscated by Treasury agents against his protest—The Gideonites come to elevate the freedmen—General Stevens moderates their zeal; wins their gratitude—Other visitors—Thorough course of drill and discipline—Twenty-five-mile picket line—Detachment of 8th Michigan defeat 13th Georgia regiment on Wilmington Island—Death of Mr. Caverly—Governor Stevens’s views on military situation—General Stevens’s force a menace to Charleston and Savannah Railroad—Six miles trestle bridges—General Robert E. Lee’s defensive measures—General Stevens eager to cross swords with Lee—Plans movement to destroy railroad and hurl whole army on Charleston—Captain Elliott’s scouting trips—General Sherman adopts plan—Commodore Dupont to coöperate—General Hunter supersedes General Sherman—Fort Pulaski taken—General Hunter proclaims negroes forever free, then impresses them as soldiers—General Stevens’s views on the negro soldier—He is confirmed as brigadier-general | 367 |

| CHAPTER LII JAMES ISLAND CAMPAIGN AGAINST CHARLESTON | |

| Enemy abandon lower part of Stono River and batteries—General Benham plans movement on Charleston by way of James Island—General Stevens lands on James Island—Drives back enemy in sharp action—Takes three guns—Cautions Benham of need of a day’s preparation before attacking—Incompetent commanders—Wright joins, a week later, with his division—Organization of the army—Enemy strengthening works across island—Fort Lamar, strong advanced work—General Stevens erects counter-battery—Reconnoissances | 387 |

| CHAPTER LIII BATTLE OF JAMES ISLAND | |

| General Benham’s precipitate determination to assault Fort Lamar—Protests of his generals—He orders General Stevens to assault at dawn, Wright and Williams to support—Attacking column—Forms at two P.M.—Drives in and follows hard on enemy’s pickets—Enters field in front of fort at daylight—Rushes on the work in column of regiments—The fight over the parapet—Deadly fire from enemy’s reserves in rear of the work—Troops withdrawn in good order and reformed—General Williams attacks on left—General Wright takes position to protect left and rear—General Stevens about to assault a second time, when General Benham suddenly gives up the fight and orders both columns to retreat—Forces and losses—Causes of the repulse—Highlanders’ revenge at Fort Saunders—Benham deprived of command and sent North | 399 |

| CHAPTER LIV RETURN TO VIRGINIA | |

| The Highlanders present General Stevens with a sword—His response—Death of Daniel Lyman Arnold—General Stevens’s letters to his wife—Holds Benham to account—General Wright succeeds to command on Benham’s arrest—James Island evacuated—Troops uselessly harassed—Jean Ribaut’s fort—Voyage to Virginia—General Stevens’s letter to President Lincoln recommending such movement—His views of military situation—Lands at Newport News—Ninth corps formed, General Stevens commanding first division—Meets General Cullum | 416 |

| CHAPTER LV POPE’s CAMPAIGN | |

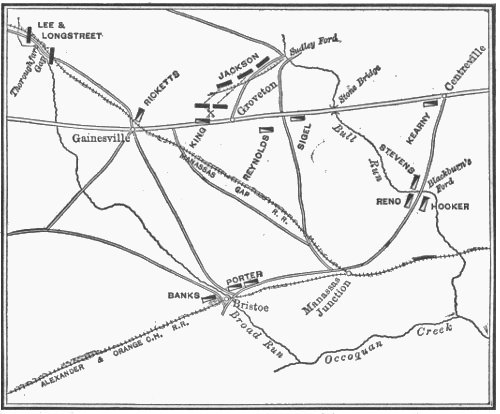

| General Stevens moves to Fredericksburg—Division in three brigades, and joined by two light batteries—Stevens and Reno’s division, march up the Rappahannock; join Pope’s army at Culpeper Court House—General Stevens stops straggling and marauding—Battle of Cedar Mountain—Army of Virginia—Pope advances to Rapidan—General Stevens holds Raccoon Ford—Lee leaves McClellan—Concentrates against Pope, who withdraws behind Rappahannock—General Stevens’s action at Kelly’s Ford—Marching up the river to head off Lee—Benjamin silences enemy’s gun with a single shot—Reinforcements arrive from Army of the Potomac—Jackson marches around right flank and falls on rear—Positions and movements, August 26, 27, 28—Description of Bull Run battlefield—Jackson withdraws from Manassas and takes position there—Movements of Pope’s forces—Fiasco of McDowell and Sigel—Jackson attacks—Stubborn fight of General Gibbon near Groveton—Generals King and Ricketts march away from the enemy—Pope reiterates order to attack | 425 |

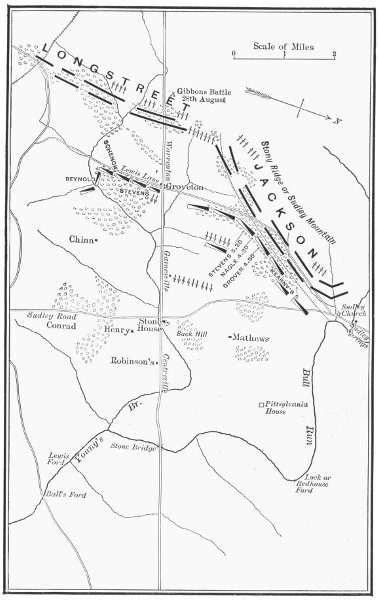

| CHAPTER LVI THE SECOND BATTLE OF BULL RUN | |

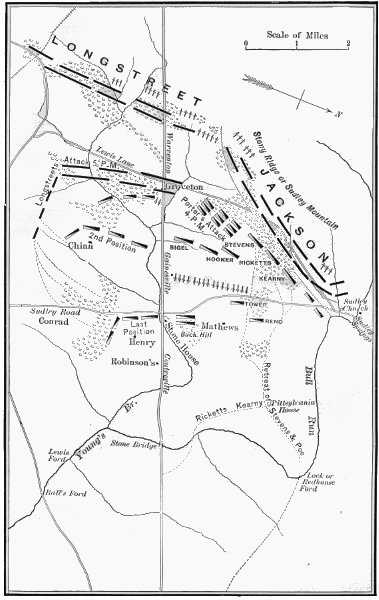

| Jackson resumes his position—Sigel’s troops move forward slowly and become engaged—Reynolds, on left, advances, but falls back—Troops of right wing arrive, scattered to meet Sigel’s cries for reinforcements—General Stevens advances with small force to Groveton—Unexpectedly fired on by enemy’s skirmishers—Benjamin maintains unequal artillery combat—Sigel and Schenck withdraw troops from key-point—Jackson forces back Milroy and Schurz—General Porter’s movement—Inactive all day—Pope hurls disconnected brigades on Jackson’s corps—Attacks by Grover, Reno, Kearny, Stevens, all repulsed—King’s division slaughtered—General Stevens collects his scattered division—Union attacks repulsed the first day—Lee master of the situation—August 30, second day—Pope sure the enemy had retreated—General Stevens expresses contrary view—Captain John More finds enemy in force—Pope’s fatuous Order of pursuit—Porter slowly forms column in centre—Pope’s faulty dispositions— Whole army bunched in centre—Wings stripped of troops— Porter’s attack—General Stevens joins in it—The repulse— Lee’s opportunity—Longstreet’s onslaught—The battle on left and centre—The right firmly held—General Stevens’s remark—Pope orders retreat—General Stevens withdraws deliberately—Checks pursuit—Capture of Lieutenant Heffron—Crosses Bull Run at Lock’s Ford—Bivouac for night—Battle lost by incompetent commander—Troops fought bravely | 446 |

| CHAPTER LVII THE BATTLE OF CHANTILLY | |

| Retreat to Centreville—Rear-guard—Bivouac on Centreville heights—Counting stacks—Two thousand and twelve muskets left—Loss nearly one half—General Stevens’s last letter—Sudden orders—March to intercept Jackson—Battle of Chantilly—General Stevens’s charge—He falls, bearing the colors—The enemy driven from his position—Sudden and furious thunderstorm bursts over the field | 477 |

| CHAPTER LVIII THE BATTLE OF CHANTILLY | |

| Progress of the fight—General Kearny responds to General Stevens’s summons with Birney’s brigade—His death—Three of Reno’s regiments engaged—Night ends the contest—Sixteen Union regiments against forty-eight Confederate—Respective losses and forces—General Stevens averted great disaster | 487 |

| CHAPTER LIX FINAL SCENE | |

| General Stevens’s body borne from battle to Washington—President considering placing him in command at time of his death— Burial in Newport, R.I.—City erects monument—Inscription— Poem—General Stevens’s descendants | 498 |

| Appendix—Census of Indians | 503 |

| Index | 507 |

| PAGE | |

| Arrival of Nez Perce Cavalcade at the Council | 34 |

| Feasting the Chiefs | 36 |

| Kam-i-ah-kan, Head Chief of the Yakimas | 38 |

| U-u-san-male-e-can: Spotted Eagle, a chief of the Nez Perces | 40 |

| Walla Walla Council | 42 |

| Pu-pu-mox-mox: Yellow Serpent, Head Chief of the Walla Wallas | 46 |

| We-ah-te-na-tee-ma-ny: Young Chief, Head Chief of the Cuyuses | 50 |

| She-ca-yah: Five Crows, a Chief of the Cuyuses | 52 |

| Appushwa-hite: Looking Glass, War Chief of the Nez Perces | 54 |

| Hal-hal-tlos-sot: The Lawyer, Head Chief of the Nez Perces | 58 |

| The Scalp Dance | 60 |

| Ow-hi, a Chief of the Yakimas | 64 |

| The Flathead Council | 82 |

| The Blackfoot Council | 112 |

| Group of Blackfoot Chiefs—Ha-ca-tu-she-ye-hu, Star Robe, Chief of the Gros Ventres; Th-ke-te-pers, The Rider, Great War Chief of the Gros Ventres; Sak-uis-tan, Heavy Shield, Great Warrior of the Blood Indians; Stam-yekh-sas-ci-cay, Lame Bull, Piegan Chief | 114 |

| Blackfoot Chiefs—Tat-tu-ye, The Fox, Chief of the Blood Indians; Mek-ya-py, Red Dye, Piegan Warrior | 116 |

| Group: Commissioner Alfred Cumming, Alexander Culbertson, William Craig, Delaware Jim, James Bird | 118 |

| Crossing the Bitter Roots in Midwinter | 126 |

| Cœur d’Alene Mission | 128 |

| Spokane Garry: Head Chief of the Spokanes | 140 |

| Ume-how-lish, War Chief of the Cuyuses | 148 |

| Homestead in Olympia | 260 |

| Letter offering Sword and Services (facsimile) | 316 |

| Captain Hazard Stevens at the age of 19, from a photograph | 340 |

| Headquarters at Beaufort | 372 |

| General Stevens and Staff: Captain B.F. Porter, Lieutenant William T. Lusk, Captain Hazard Stevens, Lieutenant Abraham Cottrell, General Stevens, Major George S. Kemble, Lieutenant Benjamin R. Lyons | 386 |

| Headquarters on James Island | 398 |

| Camp of General Stevens’s Division at Newport News | 422 |

| Headquarters at Newport News | 424 |

| The Monument | 502 |

The portraits of Indian chiefs were made by Gustavus Sohon, a private soldier of the 4th infantry, an intelligent and well-educated German, who had great skill in making expressive likenesses. He also made the views of the councils and expedition. These portraits, with many others taken by the same artist, were intended by General Stevens to be used to illustrate a complete account of his treaty operations. The views of camps and headquarters were sketched by E. Henry, E Company, 79th Highlanders.

| The Interior from Cascade Mountains to Fort Benton. Made on reduced scale from Governor Stevens’s map of April 30, 1857, sent to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Routes traversed by Governor Stevens taken from maps accompanying his final report of the Northern Pacific Railroad route. See Appendix for marginal notes | 16 |

| Theatre of Indian War of 1855–56 on Puget Sound and West of Cascade Mountains. Made on reduced scale from map sent by Governor Stevens to the Secretary of War with report of March 21, 1856 | 172 |

| Reconnoissance of Lewinsville, September 11, 1862 | 330 |

| Port Royal and Sea Islands of South Carolina | 352 |

| Action at Port Royal Ferry, January 1, 1862 | 358 |

| Battle of James Island, June 16, 1862 | 402 |

| Virginia—Potomac to Rapidan River | 426 |

| Positions of forces August 26, 1862, 9 P.M. | 432 |

| Positions of forces August 27, 9 P.M. | 433 |

| Positions of forces August 28, 9 P.M. | 443 |

| Second Battle of Bull Run, August 29 | 446 |

| Second Battle of Bull Run, August 30 | 464 |

| Jackson’s flank march, August 31 | 480 |

| Battle of Chantilly, September 1 | 482 |

THE LIFE OF ISAAC INGALLS STEVENS

While treating with the Sound Indians, the governor sent William H. Tappan, agent for the southwestern tribes, Henry D. Cock, and Sidney Ford to summon the Chinooks, Chehalis, and coast Indians to meet in council on the Chehalis River, just above Gray’s Harbor, on February 25, and on returning to Olympia dispatched Simmons and Shaw on the same duty. On the 22d he left Olympia on horseback, rode to the Chehalis, thirty miles, and the following day descended that stream in a canoe to the treaty ground. Among other settlers who attended the council at the governor’s invitation was James G. Swan, then residing on Shoalwater Bay, and since noted for his interesting writings on the Pacific Northwest, and for the valuable collections of Indian implements and curiosities, and monographs of their languages, customs, and history that he has made for the Smithsonian Institution. Judge Swan gives the following graphic and lively account of this council in his “Three Years’ Residence in Washington Territory.” He describes how he and Dr. J.G. Cooper, accompanied by twenty canoe-loads of Indians, paddled up the Chehalis one cold, damp morning, without waiting for breakfast, finding it difficult to keep warm:—

“But the Indians did not seem to mind it at all; for, excited with the desire to outvie each other in their attempts to be first to camp, they paddled, and screamed, and shouted, and laughed, and cut up all kinds of antics, which served to keep them in a glow. As we approached the camp we all stopped at a bend in the river, about three quarters of a mile distant, when all began to wash their faces, comb their hair, and put on their best clothes. The women got out their bright shawls and dresses, and painted their faces with vermilion, or red ochre and grease, and decked themselves out with their beads and trinkets, and in about ten minutes we were a gay-looking set; and certainly the appearance of the canoes filled with Indians dressed in their brightest colors was very picturesque, but I should have enjoyed it better had the weather been a little warmer.

“The camp ground was situated on a bluff bank of the river, on its south side, about ten miles from Gray’s Harbor, on the claim of Mr. James Pilkington. A space of two or three acres had been cleared from logs and brushwood, which had been piled up so as to form an oblong square. One great tree, which formed the southern side to the camp, served also as an immense backlog, against which our great camp-fire and sundry smaller ones were kindled, both to cook by and to warm us. In the centre of the square, and next the river, was the governor’s tent; and between it and the south side of the ground were the commissary’s and other tents, all ranged in proper order. Rude tables, laid in open air, and a huge framework of poles, from which hung carcasses of beef, mutton, deer, elk, and salmon, with a cloud of wild geese, ducks, and smaller game, gave evidence that the austerities of Lent were not to form any part of our services.

“Around the sides of the square were ranged the tents and wigwams of the Indians, each tribe having a space allotted to it. The coast Indians were placed at the lower part of the camp; first the Chinooks, then the Chehalis, Quen-ai-ult, and Quaitso, Satsop, upper Chehalis, and Cowlitz. These different tribes had sent representatives to the council, and there were present about three hundred and fifty of them, and the best feeling prevailed among all.

“The white persons present consisted of only fourteen, viz., Governor Stevens, George Gibbs (who officiated as secretary to the commission), Judge Ford, with his two sons, who were assistant interpreters, Lieutenant-Colonel B.F. Shaw, the chief interpreter, Colonel Simmons and Mr. Tappan, Indian agents, Dr. Cooper, Mr. Pilkington, the owner of the claim, Colonel Cock, myself, and last, though by no means the least, Cushman, our commissary, orderly sergeant, provost marshal, chief story-teller, factotum, and life of the party,—‘Long may he wave.’ Nor must I omit Green McCafferty, the cook, whose name had become famous for his exploits in an expedition to Queen Charlotte’s Island to rescue some sailors from the Indians. He was a good cook and kept us well supplied with hot biscuit and roasted potatoes.

“Our table was spread in the open air, and at breakfast and supper was pretty sure to be covered with frost, but the hot dishes soon cleared that off, and we found the clear, fresh breeze very conducive to a good appetite. After supper we all gathered round the fire to smoke our pipes, toast our feet, and tell stories.

“The next morning the council was commenced. The Indians were all drawn up in a large circle in front of the governor’s tent, and around a table on which were placed the articles of treaty and other papers. The governor, General Gibbs, and Colonel Shaw sat at the table, and the rest of the whites were honored with camp-stools, to sit around as a sort of guard, or as a small cloud of witnesses.

“Although we had no regimentals on, we were dressed pretty uniform. His Excellency the Governor was dressed in a red flannel shirt, dark frock coat and pants, and these last tucked in his boots, California fashion; a black felt hat, with, I think, a pipe stuck through the band; and a paper of fine-cut tobacco in his coat pocket. We also were dressed like the governor, not in ball-room or dress-parade uniform, but in good, warm, serviceable clothes.

“After Colonel Mike Simmons, the agent, and, as he has been termed, the Daniel Boone of the Territory, had marshaled the savages into order, an Indian interpreter was selected from each tribe to interpret the jargon of Shaw into such language as their tribes could understand. The governor then made a speech, which was translated by Colonel Shaw into jargon, and spoken to the Indians, in the same manner the good old elders of ancient times were accustomed to deacon out the hymns to the congregation. First the governor spoke a few words, then the colonel interpreted, then the Indians; so that this threefold repetition made it rather a lengthy operation. After this speech the Indians were dismissed till the following day, when the treaty was to be read. We were then requested by the governor to explain to those Indians we were acquainted with what he had said, and they seemed very well satisfied. The governor had purchased of Mr. Pilkington a large pile of potatoes,--about a hundred bushels,—and he told the Indians to help themselves. They made the heap grow small in a short time, each taking what he required for food; but lest any one should get an undue share, Commissary Cushman and Colonel Simmons were detailed to stand guard on the potato pile, which they did with the utmost good feeling, keeping the savages in a roar of laughter by their humorous ways.

“At night we again gathered around the fire, and the governor requested that we should enliven the time by telling anecdotes, himself setting the example. Governor Stevens has a rich fund of interesting and amusing incidents that he has picked up in his camp life, and a very happy way of relating them. We were all called upon in turn. There were some tales told of a wild and romantic nature, and Judge Ford and Colonel Mike did their part. Old frontiersmen and early settlers, they had many a legend to relate of toil, privation, fun, and frolic; but the palm was conceded to Cushman, who certainly could vie with Baron Munchausen or Sindbad the Sailor in his wonderful romances. His imitative powers were great, and he would take off some speaker at a political gathering or a camp-meeting in so ludicrous a style that even the governor could not preserve his gravity, but would be obliged to join the rest in a general laughing chorus. Whenever Cushman began one of his harangues, he was sure to draw up a crowd of Indians, who seemed to enjoy the fun as much as we, although they could not understand a word he said. He usually wound up by stirring up the fire; and this, blazing up brightly and throwing off a shower of sparks, would light the old forest, making the night look blacker in the distance, and showing out in full relief the dusky, grinning faces of the Indians, with their blankets drawn around them, standing up just outside the circle where we were sitting. Cushman was a most capital man for a camp expedition, always ready, always prompt and good-natured.

“The second morning after our arrival the terms of the treaty were made known. This was read line by line by General Gibbs, and then interpreted by Colonel Shaw to the Indians. The provisions of the treaty were these: They were to be placed on a reservation between Gray’s Harbor and Cape Flattery, and were to be paid forty thousand dollars in different installments. Four thousand dollars in addition was also to be paid them, to enable them to clear and fence in land and cultivate. No spirituous liquors were to be allowed on the reservation; and any Indian who should be guilty of drinking liquor would have his or her annuity withheld.

“Schools, carpenters’ and blacksmiths’ shops were to be furnished by the United States; also a sawmill, agricultural implements, teachers, and a doctor. All their slaves were to be free, and none afterwards to be bought or sold. The Indians, however, were not to be restricted to the reservation, but were to be allowed to procure their food as they had always done, and were at liberty at any time to leave the reservation to trade with or work for the whites.

“After this had all been interpreted to them, they were dismissed till the next day, in order that they might talk the matter over together, and have any part explained to them which they did not understand. The following morning the treaty was again read to them after a speech from the governor, but although they seemed satisfied, they did not perfectly comprehend. The difficulty was in having so many tribes to talk to at the same time, and being obliged to use the jargon, which at best is a poor medium of conveying intelligence. The governor requested any one of them that wished, to reply to him. Several of the chiefs spoke, some in jargon and some in their own tribal language, which would be interpreted into jargon by one of their people who was conversant with it; so that, what with this diversity of tongues, it was difficult to have the subject properly understood. But their speeches finally resulted in one and the same thing, which was that they felt proud to have the governor talk with them; they liked his proposition to buy their land, but they did not want to go to the reservation. The speech of Narkarty, one of the Chinook chiefs, will convey the idea they all had. ‘When you first began to speak,’ said he to the governor, ‘we did not understand you; it was all dark to us as the night; but now our hearts are enlightened, and what you say is clear to us as the sun. We are proud that our Great Father in Washington thinks of us. We are poor, and can see how much better off the white men are than we are. We are willing to sell our land, but we do not want to go away from our homes. Our fathers and mothers and ancestors are buried there, and by them we wish to bury our dead and be buried ourselves. We wish, therefore, each to have a place on our own land where we can live, and you may have the rest; but we can’t go to the north among the other tribes. We are not friends, and if we went together we should fight, and soon we would all be killed.’ This same idea was expressed by all, and repeated every day. The Indians from the interior did not want to go on a reservation with the coast or canoe Indians. The whole together only numbered 843 all told, as may be seen by the following census, which was taken on the ground:—

| Lower Chehalis | 217 |

| Upper Chehalis | 216 |

| Quenaiults | 158 |

| Chinooks | 112 |

| Cowlitz | 140 |

| 843 |

“But though few in numbers, there were among them men possessed of shrewdness, sense, and great influence. They felt that though they were few, they were as much entitled to a separate treaty as the more powerful tribes in the interior. We all reasoned with them to show the kind intentions of the governor, and how much better off they would be if they could content themselves to live in one community; and our appeals were not altogether in vain. Several of the tribes consented, and were ready to sign the treaty, and of these the Quenaiults were the most prompt, evidently, however, from the fact that the proposed reservation included their land, and they would consequently remain at home.

“I think the governor would have eventually succeeded in inducing them all to sign, had it not been for the son of Carcowan, the old Chehalis chief. This young savage, whose name is Tleyuk, and who was the recognized chief of his tribe, had obtained great influence among all the coast Indians. He was very willing at first to sign the treaty, provided the governor would select his land for the reservation, and make him the grand Tyee, or chief, over the whole five tribes; but when he found he could not effect his purpose, he changed his behavior, and we soon found his bad influence among the other Indians, and the meeting broke up that day with marked symptoms of dissatisfaction. This ill-feeling was increased by old Carcowan, who smuggled some whiskey into the camp, and made his appearance before the governor quite intoxicated. He was handed over to Provost Marshal Cushman, with orders to keep him quiet till he got sober. The governor was very much incensed at this breach of his orders, for he had expressly forbidden either whites or Indians bringing one drop of liquor into the camp.

“The following day Tleyuk stated that he had no faith in anything the governor said, for he had been told that it was the intention of the United States government to put them all on board steamers and send them away out of the country, and that the Americans were not their friends. He gave the names of several white persons who had been industrious in circulating these reports to thwart the governor in his plans, and most all of them had been in the employ of the Hudson Bay Company. He was assured that there was no truth in the report, and pretended to be satisfied, but in reality was doing all in his power to break up the meeting. That evening the governor called the chiefs into his tent, but to no purpose, for Tleyuk made some insolent remarks, and peremptorily refused to sign the treaty, and with his people refused to have anything to do with it. That night in his camp they behaved in a very disorderly manner, firing off guns, shouting, and making a great uproar.

“The next morning, when the council was called, the governor gave Tleyuk a severe reprimand, and, taking from him his paper, which had been given to show that the government recognized him as chief, he tore it to pieces before the assemblage. Tleyuk felt this disgrace very keenly, but said nothing. The paper was to him of great importance, for they all look on a printed or written document as possessing some wonderful charm. The governor then informed them that as all would not sign the treaty it was of no effect, and the camp was then broken up.

“Throughout the whole of the conference Governor Stevens evinced a degree of forbearance, and a desire to do everything he could for the benefit of the Indians. Nothing was done in a hurry. We remained in the camp a week, and ample time was given them each day to perfectly understand the views of the governor. The utmost good feeling prevailed, and every day they were induced to some games of sport to keep them good humored. Some would have races on the river in their canoes, others danced, and others gambled; all was friendly till the last day, when Tleyuk’s bad conduct spoiled the whole.”

That was an intrepid and resolute act of Governor Stevens, thus to tear up the turbulent chief’s commission before his face, surrounded by three hundred and fifty Indians and supported by only fourteen whites; but it effectually cowed the insolent young savage, and preserved the respect of the Indians.

The council was by no means abortive, for in consequence of it the following fall Colonel Simmons obtained the assent and signature of the chiefs of the Quenaiult and Quillehute coast tribes to the treaty so carefully explained to them at the Chehalis council, and it was signed by Governor Stevens at Olympia, January 25, 1856, on his return from the Blackfoot council, and duly confirmed with the other treaties on March 8, 1859. These Indians were given $25,000 in annuities, and $2500 to improve the reservation, the selection of which was left to the President. A reservation of ten thousand acres was set off at the mouth of the Quenaiult River, including their principal village and salmon fishery, renowned as yielding the richest and finest salmon on the coast, a fish of medium size, deep, rich color, and exquisite flavor. The other provisions were the same as those secured to the Sound Indians.

Tah-ho-lah and How-yatl, head chiefs of the two tribes, and twenty-nine other chiefs signed the treaty, and it was witnessed by M.T. Simmons, general Indian agent; H.A. Goldsborough, surveyor; B.F. Shaw, interpreter; James Tilton, surveyor-general; F. Kennedy, J.Y. Miller, and H.D. Cock.

These two tribes numbered four hundred and ninety-three, a number greatly in excess of the census given in Swan’s account. In their distrust the Indians invariably reported less than their actual numbers, and nearly every tribe was found to be larger than the first estimate. The numbers of the Chinook, Chehalis, and Cowlitz Indians were reported by Governor Stevens in 1857 as one thousand one hundred and fifteen.

Including the Quenaiults and the Cowlitz, and other Indians not on reservations, they now number some seven hundred, and are in about the same condition as the Sound Indians.[1]

Just before going to the Chehalis council, Governor Stevens and his family suffered a sad and severe affliction in the death of his young kinsman, George Watson Stevens, who was drowned on February 16 at the debouch of the Skookumchuck Creek into the Chehalis River, as he was returning from Portland, whither he had gone to cash some government drafts. He was accompanied on the journey by A.B. Stuart, the mail and express carrier, who, as they approached the stream, had occasion to stop at a settler’s house, while George Stevens kept on, and, although cautioned by Stuart, lost his life in the attempt to cross by the usual ford. The Skookumchuck empties into the Chehalis at right angles, and although ordinarily a stream of moderate size, becomes, when swollen by rains, a mighty and furious flood, which, encountering the rapid current of the Chehalis, forms a dangerous whirlpool in the centre of that river. Not realizing the danger, and anxious to reach his journey’s end that day, he forced his horse into the raging torrent, and was swept, man and steed, into the whirlpool below, where, although a fine swimmer and a strong, vigorous man, he met his death. Stuart reached the ford soon afterwards, and finding it impassable and his companion nowhere visible, rightly concluded that he was lost, and hastened to Olympia with the sad tidings.

Governor Stevens with a party hastened to the scene, and diligently searched for the missing one. The governor caused a band of horses to be driven into the stream to test its power, but all were instantly swept down into the larger river, several of them clear to the whirlpool, although the water had fallen considerably. The unfortunate youth’s horse swam ashore, and was found with the saddle and saddle-bags soaked with water, and a few days later his remains were found in the river a mile below the whirlpool. This sad event cast a deep gloom upon the family, and indeed all the community, for he was a young man of great promise, noble traits, and only twenty-two years of age. The governor said of him:—

“His whole character was an admirable blending of strength and gentleness. He was essentially a man of great resolution, daring, enterprise, and purpose, who adhered with great inflexibility to his determinations; yet he was so gentle, so kindly, so courteous, and so disinterested that his strength did not fully appear in ordinary intercourse. To his friends his death is a sad bereavement, which time only can obliterate. His memory will be precious, his life an example, his bright and pure spirit is now in the heavenly mansion.”

“He was a brother in the house,” wrote Mrs. Stevens to her mother; “evenings he always spent at home, and took an interest in everything about the house, played with the children, seemed to be happy just staying in our society. Here is my garden he made, and the flowers he set out, and marks of him all about us.”

It was a sad time when his remains were brought in, and the little toys and candy he had thoughtfully purchased for the children were found in his pockets and saddle-bags. He was buried on the beautiful green Bush Prairie, amid the scenes of mountain, prairie, and forest he loved so well. His intimate friends, Mason and Doty, were soon to be laid at rest by his side.

In a letter to a sister Mrs. Stevens relates another instance of the governor’s firmness and fearlessness in dealing with the Indians:—

“There are three different tribes of Indians in Olympia now, all different,—the Nisquallies, Chissouks, and northern Fort Simpson Indians. A curious sight it is to see them. They are all gambling, their mats spread on the ground; and you will see groups of fifty seated on the ground, and playing all day and night. The town is full of them. Mr. Stevens has them right under his thumb. They are as afraid as death of him, and do just what he tells them. He told the chiefs of the tribes he would not let them disturb the whites. That night they kept up an awful howling and singing, making night hideous like a pack of wolves. Mr. Stevens got up, took a big club, and went right in among them, and talked to them, and told them that the first man that opened his lips he would knock down. The chief said, ‘Close’ (All right), and not another sound came from them that night. When he came back, he said the biggest lodge was full of men sitting in a circle around a big fire, smoking and singing.”

Returning from the Chehalis council, Governor Stevens remained the next two months in Olympia, hard at work with his multifarious duties, reviewing legislative acts, preparing reports of the councils and treaties, instructing the Indian agents, and attending to the unceasing cares and questions arising from the Indians, and preparing for the trip east of the mountains. In April he made the arduous horseback and river trip to Vancouver, and there met Superintendent Joel Palmer, of Oregon, by appointment, having previously invited him, in order to arrange with him in regard to the proposed council with the Indians of the upper country, some of whom were within General Palmer’s superintendency.

This spring began the San Juan Island controversy with Great Britain, which came near involving the two countries in war, and lasted with various phases for eighteen years, until it was finally decided in favor of the United States by Emperor William I., of Germany.

By the treaty of 1846 the main ship-channel which separates the continent from Vancouver Island was fixed as the boundary from the point where the 49th parallel intersects the Gulf of Georgia, in order to give the whole of that island to Great Britain, for the parallel intersects it. It happens, however, that there are two channels, with a valuable group of islands between them, answering this description. The Americans claimed the western-most, the Canal de Haro, which runs next to Vancouver Island, and is the shorter, broader, and deeper, in every respect the main ship-channel, while the English insisted that the eastern channel, Rosario Straits, was the proper boundary. The shrewd and aggressive officers of the Hudson Bay Company at Victoria, Sir James Douglass at their head, originated the British claim, which otherwise had never arisen, so little merit had it, and in order to gain a foothold on, and claim possession of, these valuable islands, placed a flock of sheep on San Juan, and stationed there a petty official of the company. The island was included in Whatcom County by act of the Washington legislature, the property thereon became subject to taxation, and the sheriff of the county levied upon and seized a number of the sheep in default of payment of taxes.

Sir James Douglass thereupon addressed Governor Stevens, complaining of the seizure, and demanding to know if the sheriff’s proceedings were authorized or sanctioned in any manner by the executive officer of Washington Territory. The governor promptly replied, May 12, 1855, and firmly and uncompromisingly asserted the American right, and justified the sheriff. After reciting the acts of Oregon and Washington assuming jurisdiction over the islands, he continued:—

“The sheriff, in proceeding to collect taxes, acts under a law directing him to do so. Should he be resisted in such an attempt, it would become the duty of the governor to sustain him to the full force of the authority vested in him.

“The ownership remains now as it did at the execution of the treaty of June 11, 1846, and can in no wise be affected by the alleged ‘possession of British subjects.’”

The correspondence was communicated to the Secretary of State, who in reply deprecated any action by the territorial authorities pending a settlement of the question by the respective governments, and the dispute remained in abeyance until excited some years afterwards by another British act of aggression. Had our government firmly asserted its undoubted right at this time, the matter would have been settled. To the resolute and patriotic stand of Governor Stevens on this occasion, and his subsequent course in defense of this American territory, as will be seen hereafter, were due the ultimate defeat of the persistent and hard-fought British demands.

At this time the governor purchased of William Taylor for $2000 his donation claim, a fine tract of half a section, 320 acres, six miles southwest of Olympia, and in the northwestern corner of Bush Prairie. It comprised a few acres of prairie, over a hundred acres of heavy meadow, and the remainder in heavy fir timber. A small house and a field fenced off the prairie were the only improvements. The governor always took great interest and pleasure in the soil, in gardening and farming. He soon put a man on the place, and laid out extensive plans of improving it.

In April the Democratic convention met in Olympia to nominate a candidate for delegate in Congress, to succeed Judge Lancaster. The delegates assembled in a large store building on the southwest corner of Main and First streets, belonging to George A. Barnes. Governor Stevens was a candidate for the nomination. He was desirous, after completing his treaty operations and returning from the Blackfoot council, to represent the Territory in Congress, and there push forward his plans for the public service, further railroad surveys, wagon roads, mail routes, steamer service, Indian treaties and policy, and, above all, the Northern Pacific Railroad. Many of the first settlers were strong in his support, recognizing how much such a man in Congress could accomplish for the Territory. There were two other candidates, Judge Columbia Lancaster, very anxious to succeed himself, and J. Patton Anderson, United States marshal, who had traveled all over the Territory in taking the census the previous year, and, it was said, had diligently improved his opportunities as census-taker by paying court to all the women, kissing all the babies, and pledging all the men to support him for delegate. He was a man of good appearance, cordial, pleasant Southern manners, and well calculated to make friends. The convention divided between the three candidates, and balloted an entire day without result. In the evening the candidates were invited to address the convention. Colonel Shaw, who was one of the governor’s supporters, although not a member of the convention, says that he advised the governor not to accept the invitation, lest the friends of the other candidates, hearing him speak, should become alarmed at his ability and power, and combine against him. Such advice was the very last that the governor, with his straightforward and positive character, would relish. He went before the convention, and in a forcible and patriotic speech, without reference to himself, set forth the needs of the Territory, and the public measures required for its advancement, so ably and clearly that his friends were delighted, and felt sure that he would be chosen on the next ballot. But it turned out as Shaw feared. Although he gained votes, his opponents combined on Anderson, and nominated him, some of them exclaiming, “It won’t do to nominate the governor, for if he once gets into Congress, we can never get him out again.”

The Indians of the upper Columbia, with whom Governor Stevens was next to treat, presented a far more pressing and difficult problem than the reduced tribes of the Sound. They numbered fourteen thousand souls, comprised in ten powerful tribes, viz., Nez Perces, Cuyuses, Umatillas, Walla Wallas, Yakimas, Spokanes, Cœur d’Alenes, Flatheads, Pend Oreilles, and Kootenais.[2] They were a manly, athletic race, still uncontaminated by the vices and diseases which so often result from contact with the whites, and far superior in courage and enterprise, as well as in form and feature, to the canoe Indians of the Sound and coast. Each tribe possessed its own country, clearly defined by well-known natural boundaries, within whose limits their wanderings were restrained, save when they “went to buffalo,” or attended some grand council or horse-race with a neighboring tribe. The chase, the salmon fishery, the root ground, the numerous bands of horses and cattle, furnished easy and ample sustenance. It was estimated that the Nez Perces owned twenty thousand head of these animals, and the Cuyuses, Umatillas, and Walla Wallas not less than fifteen thousand. The Yakimas and Spokanes also possessed great numbers.

Of all these tribes, the Nez Perces or Sahaptin were the most numerous and progressive. They numbered 3300, and occupied the country along the western base of the Bitter Root Mountains for over two hundred miles, and a hundred miles in width, including both banks of the Snake and its tributaries, the Kooskooskia or Clearwater, Salmon, Grande Ronde, Tucañon, etc. Yearly, in the spring or fall, their war chief would lead a strong party across the Rocky Mountains to hunt the buffalo on the plains of the Missouri, and many were the bloody encounters they had with the dreaded Blackfeet, the Arabs of the plains. They owned great numbers of horses, and the advent of the horse among them, about the middle of the eighteenth century, obtained from the Spaniards of New Mexico or California, of which they preserved the tradition, was the chief cause of their prosperous condition. From the days of Lewis and Clark, the first of the white race to meet their astonished gaze, they were famed as the firm friends of the white man. During all the fur-hunting and trading epoch the “mountain men,” as the trappers and voyageurs delighted to call themselves, were welcome in the lodges of the Nez Perces. Together they wintered in safety on the banks of the Kooskooskia, and together they hunted the buffalo on the plains of the Missouri, and made common cause against the Blackfeet. Among the most noted of the numerous encounters in which they were allied against their common foe was the stubborn fight of Pierre’s Hole in 1832, so graphically described by Washington Irving in his “Bonneville Adventures.” It was in this fight that Lawyer, then a promising young brave, and afterwards for many years the powerful head chief of the Sahaptin, received a severe wound in the hip, which never entirely healed, and doubtless hastened his death.

In 1836 Rev. H.H. Spalding with his wife was sent out by the Presbyterians, and settled as a missionary on the Lapwai, a branch on the southern side of the Kooskooskia, twelve miles above its confluence with the Snake. Here he was preceded by William Craig, a Virginian, one of the best type of mountain men, who had married a Nez Perce maiden and made his home among her people. Aided by Craig’s knowledge of the Nez Perce tongue and character, and of the Indians themselves, Mr. Spalding taught the whole tribe a simple Christian faith, made a dictionary of their language, and translated and had printed in the native tongue a hymn-book, catechism, and New Testament, taught a number of the young men to read and write their own language, built a saw and grist mill, and labored to induce them, not without success, to till the soil. Yet, after all this achievement, he was in the end led to abandon his mission. In an unhappy hour he opened a store and went to trading with the Indians. In their experience a trader was the personification of greed and falsehood. To them the union of the trader, all selfishness and fraud, and the preacher of morality and truth was monstrous, nay, impossible. Mr. Spalding, too, was hard and exacting in his dealings, and offended in that way. With all his zeal and energy, he evidently lacked knowledge of Indian nature, perhaps of human nature. What wonder that some of the Nez Perces, seeing that the trading-post was a fact, concluded that his preaching was a fraud, and warned him out of their country! The massacre of the devoted missionary, Dr. Marcus Whitman, and his family, by the Cuyuses, in 1847, had just occurred, and Mr. Spalding, fearing a like fate if he remained after the warning, abandoned the mission where he had done so much. The majority of the Nez Perces, however, desired him to remain; and when he decided upon going, they formed a strong party of warriors, and escorted him with his family and effects unharmed through the hostile Indians to the frontier settlement. They magnanimously refused the large reward offered them, saying, “We will not sell Mr. Spalding; he left our country of his own free will, and we escorted him as his friends.” In the war which ensued they remained the firm friends of the whites, and the officers of the Oregon volunteers engaged in it presented them with a fine, large American flag, in which they took great pride. It was their boast that “We are the friends of the white man. The white man is our brother. His blood has never stained our hands.” Craig remained among them in perfect safety, and was treated with undiminished kindness. Although abandoned by Mr. Spalding, they by no means discarded the good he had taught them. They maintained, unaided, their simple religious worship, and held services regularly every Sabbath, with preaching, singing of hymns, and reading of the Bible, all in their own language, with the books translated and printed for them by the devoted missionary. They prided themselves upon their superior intelligence, upon having young men who could read and write, and upon their ancient and fast friendship with the whites. This friendship indeed was not merely a matter of sentiment. They were shrewd enough to turn it to good account. Large emigrations crossed the plains to Oregon during the period from 1843 to 1855; and the Nez Perces used to go down to the emigrant road on the Grande Ronde or Umatilla, with bands of fat, sleek, handsome ponies, and exchange them with the emigrants for their worn-out horses, oxen, and sometimes a cow, clothing, groceries, ammunition, etc. The Pikes, as the Missourians who comprised the majority of the emigrants were called, “allowed that the Nez Perces could beat a Yankee on a trade.” By these means they were beginning to obtain cattle as well as horses, were learning to wear blankets and shirts instead of skins, and individuals were even beginning to set out fruit trees, and plant corn and potatoes, and in a word the Nez Perces were making rapid strides toward civilization. There is no more interesting and instructive example of the amelioration of a savage tribe by the introduction of domestic animals, and its steady growth from abject barbarism, than that afforded by the Nez Perces. But little more than a century ago they were a tribe of naked savages, engaged in a perpetual struggle against starvation. Their country afforded but little game, and they subsisted almost exclusively on salmon, berries, and roots. The introduction of the horse enabled them to make long journeys to the buffalo plains east of the Rocky Mountains, where they could lay in great abundance of meat and furs; furnished them with a valuable animal for trading with other less favored tribes; soon raised them to comparative affluence, and developed in their hunting and trading expeditions a manly, enterprising, shrewd, and intelligent character. They had improved and profited still more from their intercourse with the whites, until there seemed every prospect that, with the introduction of cattle, they might lay aside their nomadic habits, and become a pastoral and then an agricultural people.

The Cuyuses were the most disaffected and intractable of all the tribes. But little is known of their early history. They are said to have come from the east many years ago. No tribe could resist their prowess, and when they settled on the Umatilla and Walla Walla rivers, having driven out the original inhabitants, none dared molest them; since which, wars and pestilence had reduced their numbers to but five hundred, and continual intermarriages with the neighboring tribes had caused their own language to fall into disuse. But they still maintained their separate independence, and were as haughty and arrogant as ever. The Jesuits established a mission on the Umatilla and made some progress in their conversion, and then Dr. Whitman came among them, establishing his mission in the Walla Walla valley, and for several years possessed their confidence and accomplished much good. The rivalry between Jesuit and Protestant missionary was carried to a high pitch. Pictorial cards were issued by each party, representing its opponents descending into the fiery depths of the infernal regions, where Satan and his imps, with red-hot pitchforks, were impatiently waiting to receive their prey, while the converts to the true faith were ascending to heaven up a broad flight of stairs with winged angels on either side. This hostile and bigoted attitude of the missionaries towards each other must have weakened the respect and confidence of the Indians, and contributed not a little to the troubles that followed.

Dr. Whitman was accustomed to attend the Indians when sick, and these labors, undertaken in the purest benevolence, were ultimately the cause of his death; for, the measles having broken out among them, and great numbers, especially of the children, dying, their suspicions were directed towards this devoted and able missionary.

In the war which ensued the Cuyuses suffered severely, were deprived of great numbers of horses, compelled to relinquish their white captives, and to surrender to well-deserved death some of the most active in the massacre. Their head chief was known as the Young Chief, and next in rank and influence was the Five Crows.

The Walla Wallas and Umatillas numbered upwards of one thousand, and inhabited the banks of the rivers which bear their names, and those of the Columbia. Their head chief was Pu-pu-mox-mox or the Yellow Serpent, a man of great intelligence and force of character, but well stricken in years.

The Yakimas, including outlying bands,[3] were over 3900 strong, and occupied the large region between the Columbia and the Cascades, with their principal abodes in the Yakima valley. One band, the Palouses, lived on the Palouse River, on the north side of the Snake and east of the Columbia, next the Nez Perce country. Large bands of the Yakimas had crossed the Cascades and were pressing on the feebler races on the west, by whom they were appropriately termed “Klik-i-tats” or robbers. The Jesuits had a mission on the Ah-ti-nam Creek, on the Yakima, but do not seem to have acquired much influence over them.

The Spokanes numbered 2200, including the Colvilles, 500, and Okinakanes, 600, and held the country north of Snake River to Pend Oreille Lake and the 49th parallel, and extending west from the Nez Perce country, and that occupied by the Cœur d’Alenes at the base of the Bitter Root Mountains, to the Columbia River. A Presbyterian mission was also established among them under Rev. E. Walker and G.C. Eells, and abandoned about the same time as that of Mr. Spalding.

Immediately east of the Spokanes, under the western slope of the Bitter Roots, lived the Cœur d’Alenes, a tribe of about five hundred. There was a Catholic mission among them presided over by Father Ravalli, and they had been converted to the ancient faith, and their material condition greatly improved by the good fathers.

The Flatheads, Pend Oreilles, and Koutenays lived in the mountain valleys between the main range of the Rockies and the Bitter Roots, upon the tributaries of Clark’s Fork chiefly, and depended largely upon the buffalo for their subsistence. They, too, like the Nez Perces, were distinguished as the constant friends of the whites, and were exposed to the unceasing forays of the Blackfeet. They numbered 2250. They termed themselves the Salish, and the Spokanes and Cœur d’Alenes were of the same stock.

There were also some small independent bands along the Columbia, who subsisted chiefly on salmon. Five sixths of the Indians lived within the Washington superintendency,—all, indeed, except the Cuyuses, Umatillas, Walla Wallas, and a small number of the Nez Perces, who dwelt or roamed in both territories, and the small bands about the Dalles and on the Columbia, Des Chutes, and John Day’s rivers, who lived wholly in Oregon.

The whole vast region occupied by these numerous, brave, and manly Indians was still free from the intrusion of white settlers, save a handful in the Walla Walla valley and about Colville. But year after year they saw the long trains of emigrants pass through their country and settle, like swarming bees, upon the fertile plains of the Wallamet. They saw the Indians there dispossessed of their hunting grounds, and rapidly dying off the face of the earth. The tale of every Indian wronged or aggrieved, or who thought himself wronged or aggrieved, was borne with startling rapidity to their ears. Thus far their intercourse with the whites had been of immense benefit to them. The fur traders supplied them with superior weapons, blankets, and many articles of comfort, and had greatly improved their condition. Devoted missionaries had labored among them for years, and with marked success. By trade with the emigrants they were growing rich in cattle. But the actual occupation of the soil by the settlers filled them with alarm. Amid all these benefits, the fear was fast growing into conviction that the fate of the Chinooks and the Wallamets was the presage of their fate, and that the whites would sooner or later pour with increasing numbers into their country, and appropriate it for themselves. The Flatheads, Pend Oreilles, and Koutenays, remote from the settlements, retained their ancient friendship for the whites. But among the other tribes the desperate resolution was extending and deepening itself to rise and wipe out the dreaded invaders ere it was too late. For several years the bold and turbulent spirits among them had been enlisting the disaffected Indians far and wide in a great combination designed to crush the unsuspecting whites simultaneously at all points by one sudden and mighty blow. In 1853 the wild rumors of impending outbreaks, the forerunners of every Indian war, but which have been invariably unheeded by the over-confident whites, were flying about the land. Yet outwardly all was serene. The great tribes of the upper country, from whom alone danger was to be feared, were as yet unmolested by settlers, had reaped only benefits from the whites, and were as friendly as ever to all appearance. Both authorities and people were lulled into a sense of complete security, and disregarded with contempt the warnings of the few who foresaw the danger. In truth, a similar state of affairs has preceded nearly all our great Indian wars. They have not been caused by petty acts of aggression, stinging whole tribes to frenzied revenge. Indians who undergo such treatment are usually too degraded and helpless to resist. But powerful tribes, unbroken by too long contact with the whites, fired and led by their master spirits, have from time to time risen in arms, and vainly striven to arrest and drive back the white race ere it overwhelmed them, as it had overwhelmed their kindred. Many chiefs have shown profound sagacity in foreseeing the danger menacing their race, and the highest talents and bravery in their bloody struggles to avert it. The Nez Perces saw the danger, but they alone realized the hopelessness of averting it by war. The Nez Perces alone discerned that their only safety was to “follow the white man’s road,” and that his mode of life was better than their own. Under the wise guidance of Lawyer, they had become imbued with these convictions, by which their traditional friendship to the whites was strengthened and confirmed, and the time was fast approaching when their fidelity was to save many a valuable life, and preserve the settlements from destruction.

In the spring of 1853 General Benjamin Alvord, then a major and commanding the military post at the Dalles, heralded among the Indians the approach of Governor Stevens with the exploring parties, and in reply was visited by a delegation of chiefs of the Yakimas, Cuyuses, and Walla Wallas, who said that “they always liked to have gentlemen, Hudson Bay Company men, or officers of the army, or engineers, pass through their country, to whom they would extend every token of hospitality. They did not object to persons merely hunting, or those wearing swords, but they dreaded the approach of the whites with ploughs, axes, and shovels in their hands.” Major Alvord had largely dealt with and studied these Indians, and moreover he had confidential sources of information from the Catholic priests of the Yakima Mission. He became so impressed with the danger of an outbreak that he reported the facts and rumors to his superior, General Hitchcock, commanding the Pacific Department, by whom they were discredited, and Major Alvord was soon afterwards relieved from the Dalles. Events were soon to prove that the magnitude and imminence of the danger were even greater than he apprehended. Says General Alvord:[4]—

“I informed Governor Stevens of these threatened Indian difficulties, and of the gigantic scale of their proposed insurrection. What should he do? Was he to remain idle and let the storm come? No, he set to work to provide for the inevitable. As the whites would come as five or six, or ten thousand would come every summer, he did his best to get the Indians to sell their Indian titles.”