Title: My Friend Annabel Lee

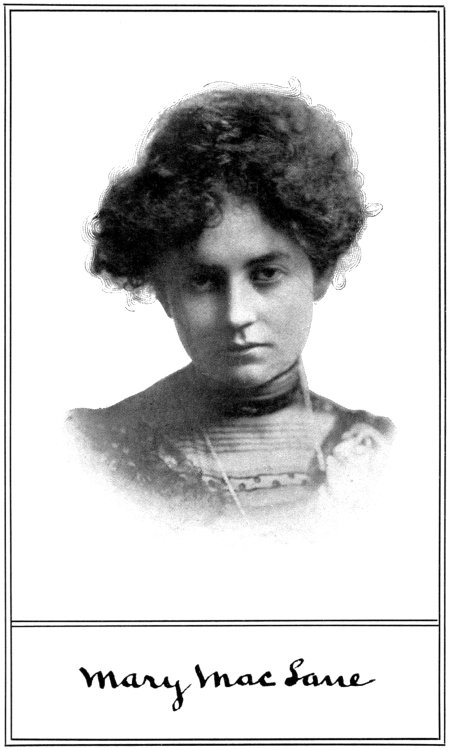

Author: Mary MacLane

Release date: September 2, 2013 [eBook #43624]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marie Bartolo from page images made available

by the Internet Archive: American Libraries

My Friend Annabel Lee

Chicago

Herbert S. Stone and Company

MCMIII

COPYRIGHT, 1903

BY

HERBERT S. STONE & COMPANY

Issued September 1, 1903

TO

LUCY GRAY, IN CHICAGO

THIS BOOK

AND ONE PALE LAVENDER FLOWER OF AMARANTH

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | The Coming of Annabel Lee | 1 |

| II. | The Flat Surfaces of Things | 7 |

| III. | My Friend Annabel Lee | 13 |

| IV. | Boston | 15 |

| V. | A Small House in the Country | 29 |

| VI. | The Half-Conscious Soul | 35 |

| VII. | The Young-Books of Trowbridge | 43 |

| VIII. | “Give Me Three Grains of Corn, Mother” | 55 |

| IX. | Relative | 61 |

| X. | Minnie Maddern Fiske | 69 |

| XI. | Like a Stone Wall | 81 |

| XII. | To Fall in Love | 89 |

| XIII. | When I Went to the Butte High School | 97 |

| XIV. | “And Mary MacLane and Me” | 113 |

| XV. | A Story of Spoon-Bills | 131 |

| XVI. | A Measure of Sorrow | 153 |

| XVII. | A Lute with no Strings | 163 |

| XVIII. | Another Vision of my Friend Annabel Lee | 173 |

| XIX. | The Art of Contemplation | 183 |

| XX. | Concerning Little Willy Kaatenstein | 193 |

| XXI. | A Bond of Sympathy | 225 |

| XXII. | The Message of a Tender Soul | 233 |

| XXIII. | Me to My Friend Annabel Lee | 241 |

| XXIV. | My Friend Annabel Lee to Me | 255 |

| XXV. | The Golden Ripple | 257 |

My Friend Annabel Lee

BUT the only person in Boston town who has given me of the treasure of her heart, and the treasure of her mind, and the touch of her fair hand in friendship, is Annabel Lee.

Since I looked for no friendship whatsoever in Boston town, this friendship comes to me with the gentleness of sunshowers mingled with cherry-blossoms, and there is a human quality in the air that rises from the bitter salt sea.

Years ago there was one who wrote a poem about Annabel Lee—a different [2]lady from this lady, it may be, or perhaps it is the same—and so now this poem and this lady are never far from me.

If indeed Poe did not mean this Annabel Lee when he wrote so enchanting a heart-cry, I at any rate shall always mean this Annabel Lee when Poe’s enchanting heart-cry runs in my mind.

Forsooth Poe’s Annabel Lee was not so enchanting as this Annabel Lee.

I think this as I gaze up at her graceful little figure standing on my shelf; her wonderful expressive little face; her strange white hands; her hair bound and twisted into glittering black ropes and wound tightly around her head.

Were you to see her you would say that Annabel Lee is only a very pretty little black and terra-cotta and white statue of a Japanese woman. And forthwith you would be greatly mistaken.

It is true that she had stood in extremely [3]dusty durance vile, in a Japanese shop in Boylston street, for months before I found her. It is also true that I fell instantly in love with her, and that on payment of a few strange dollars to the shop-keeper, I rescued her from her surroundings and bore her out to where I live by the sea—the sea where these wonderful, wide, green waves are rolling, rolling, rolling always. Annabel Lee hears these waves, and I hear them, at times holding our breath and listening until our eyes are strained with listening and with some haunting terror, and the low rushing goes to our two pale souls.

For though my friend Annabel Lee lived dumbly and dustily for months in the shop in Boylston street, as if she were indeed but a porcelain statue, and though she was purchased with a price, still my friend Annabel Lee is exquisitely human.

There are days when she fills my life with herself.

She gives rise to manifold emotions which do not bring rest.

It was not I who named her Annabel Lee. That was always her name—that is who she is. It is not a Japanese name, to be sure—and she is certainly a native of Japan. But among the myriad names that are, that alone is the one which suits her; and she alone of the myriad maidens in the world is the one to wear it.

She wears it matchlessly.

I have the friendship of Annabel Lee; but for her love, that is different.

Annabel Lee is like no one you have known. She is quite unlike them all. Times I almost can feel a subtle, conscious love coming from her finger-tips to my forehead. And I, at one-and-twenty, am thrilled with thrills.

Forsooth, at one-and-twenty, in spite of [5]Boston and all, there are moments when one can yet thrill.

But other times I look up and perchance her eyes will meet mine with a look that is cold and penetrating and contemptuous and confounding.

Other times I look up and see her eyes full of indifference, full of tranquillity, full of dull deadly quiet.

Came Annabel Lee from out of Boylston street in Boston. And lo, she was so adorable, so fascinating, so lovable, that straightway I adored her; I was fascinated by her; I loved her.

I love her tenderly. For why, I know not. How can there be accounting for the places one’s loves will rest?

Sometimes my friend Annabel Lee is negative and sometimes she is positive.

Sometimes when my mind seems to have wandered infinitely far from her I realize suddenly that ’tis she who holds it [6]enthralled. Whatsoever I see in Boston or in the vision of the wide world my judgment of it is prejudiced in ways by the existence of my friend Annabel Lee—the more so that it’s mostly unconscious prejudice.

Annabel Lee’s is an intense personality—one meets with intense personalities now and again, in children or in bull-dogs or in persons like my friend Annabel Lee.

And I never tire of looking at Annabel Lee, and I never tire of listening to her, and I never tire of thinking about her.

And thinking of her, my mind grows wistful.

“THERE are moments,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “when, willy nilly, they must all come out upon the flat surfaces of things.

“They look deep into the green water as the sun goes down, and their mood is heavy. Their heart aches, and they shed no tears. They look out over the brilliant waves as the sun comes up, and their mood is light-hearted and they enjoy the moment. Or else their heart aches at the rising and their mood is light-hearted at the setting. But let it be one or the other, there are bland moments when they see nothing but flat surfaces. If they find all at once, by a little accident, that their best-loved is a traitor friend, [8]and they go at the sun’s setting and gaze deep into the green water, and all is dark and dead as only a traitor best-beloved can make it, and their mood is very heavy—still there is a bland moment when their stomach tells them they are hungry, and they listen to it. It is the flat surface. After weeks, or it may be days, according to who they are, their mood will not be heavy—yet still their stomach will tell them they are hungry, and they will listen. If their best-loved cease to be, suddenly—that is bad for them, oh, exceeding bad; they suffer, and it takes weeks for them to recover, and the mark of the wound never wears away. But with time’s encouraging help they do recover. But if,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “their stomach should cease to be, not only would they suffer—they would die—and whither away? That is a flat surface and a very truth. And when they [9]consider it—for one bland moment—they laugh gently and cease to have a best-loved, entirely; they cease to fill their veins with red, red life; they become like unto mice—mice with long slim tails.

“For one bland moment.

“And, too, the bland moment is long enough for them to feel restfully, deliciously, but unconsciously, thankful that there are these flat surfaces to things and that they can thus roll at times out upon them.

“They roll upon the flat surfaces much as a horse rolls upon the flat prairie where the wind is.

“And when for the first time they fall in love, if their belt is too tight there will come a bland moment when they will be aware that their belt is thus tight—and they will not be aware of much else.

“During that bland moment they will loosen their belt.

“When they were eight or nine years old and found a fine, ripe, juicy-plum patch, and while they were picking plums a balloon suddenly appeared over their heads, their first delirious impulse was to leave all and follow the balloon over hill and dale to the very earth’s end.

“But even though a real live balloon went sailing over their heads, they considered this: that some other kids would get our plums that we had found. A balloon was glorious—a balloon was divine—but even so, there was a bland moment in which the thought of some vicious, tow-headed Swede children from over the hill, who would rush in on the plums, came just in time to make the balloon pall on them.

“But,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “by the same token, in talking over the balloon after it had vanished down the sky, there would come another bland moment [11]when the plums would pall upon them—pall completely, and would appear hateful in their eyes for having kept from them the joy of following the divine balloon. That is another aspect of the flat surfaces of things. And they must all come out upon the flat surfaces, willy-nilly.

“And,” said Annabel Lee, glancing at me as my mind was dimly wistful; “not only must they come out upon the flat surfaces of things, but also you and I must come, willy-nilly.

“And since we must come, willy-nilly,” added the lady, “then why not stay out upon the flat surfaces? Certainly ’twill save the trouble of coming next time. Perhaps, however, it’s all in the coming.”

MY FRIEND Annabel Lee never fails to fascinate and confound me.

Much as she gives, there is in her infinitely more to get.

My relation with her never goes on, and it never goes back. It leads nowhere. She and I stop together in the midst of our situation and look about us. And what we see in the looking about is all and enough to consider.

And considering, I write of it.

YESTERDAY the lady was in her most amiable mood, and we talked together—about Boston, it so happened.

“Do you like Boston?” she asked me.

“Yes,” I replied; “I am fond of Boston. It fascinates me.”

“But not fonder of it than of Butte, in Montana?”

“Oh, no,” said I, hastily. “Butte in Montana is my first love. There are barren mountains there—they are with me always. Boston doesn’t go to my heart in the least, but I like it much. I like to live here.”

“I am fond of Boston—sometimes,” Annabel Lee observed. “Here by the sea [16]it is not quite Boston. It is everything. This sea washes down by enchanted purple islands and touches at the coast of Spain. But if one can but turn one’s eyes from it for a moment, Boston is a fine and good thing, and interesting.”

“I think it is—from several points of view,” I agreed.

“Tell me what you find that interests you in Boston,” said my friend Annabel Lee.

“There are many things,” I replied. “I have found a little corner down by the East Boston wharf where often I sit on cold days. The sun shines bright and warm on a narrow wooden platform between two great barrels, and I can be hidden there, but I can watch the madding crowd as it goes. The crowd is very madding down around East Boston. And I do not lack company—sometimes brave, sharp-toothed rats venture out on the [17]ground below me. They can not see the madding crowd, but they can enjoy the sunshine and hunt mice among the rubbish.

“The dwellers in East Boston—they are the poor we have always with us. They are not the meek, the worthy, the deserving poor. They are the devilish, the ill-conditioned—one with the wharf rats that hunt for mice. Except that the rats do occasionally try to clean their soft, gray coats by licking them with their little red tongues; whereas, the poor—But why should the poor wash? Are they not the poor?

“As I rest me between my two great barrels and watch this grewsome pageant, I think: It seems a quite desperate thing to be poor in Boston, for Boston is said to be of the best-seasoned knowledge and to carry a lump of ice in its heart. From between my two barrels in East Boston I [18]have seen humanity, oh, so brutal, oh, so barbarous as ever it could have been in merrie England in the reign of good old Harry the Eighth.——

“And so then that is very interesting.”

“In truth it is so,” said my friend Annabel Lee.

“Boston is fair, and very fair.—Tell me more.”

“And times,” I said, “I sit in one of the window-seats on the stairway of the Public Library. And I look at the walls. A Frenchman with a marvelous fancy and great skill in his finger-ends has worked on those walls. He painted there the emblems of all the world’s great material things of all ages. And over them he painted a thin gray veil of those things that are not material, that come from no age, that are with us, around us, above us—as they were with the children of Israel, with the dwellers in Pompeii, with [19]the fair cities of Greece and the inhabitants thereof.

“I have looked at the paintings and I have been dazzled and transported. What is there not upon those walls!

“I have seen, in truth, ‘the vision of the world and all the wonder that shall be.’

“I have seen the struggling of the chrysalis-soul and its bursting into light; I have seen the divinity that doth sometime hedge the earth; I have looked at a conception of Poetry and I have heard the thin, rhythmic sounds of shawms and stringed instruments; and I have heard low, voluptuous music from within the temple—human voices like sweet jessamine; I have seen the fascinating idolatry of pagans—and I have seen, pale in the evening by the light of a star, the wooden figure of the Cross; I have leaned over the edge of a chasm and beheld the things of old—the army of Hannibal before [20]Carthage—the Norsemen going down to the sea in ships—the futile, savage fighting of Goths and Vandals; I have seen science and art within the walled cities, and I have seen frail little lambs gamboling by the side of the brook; I have seen night-shades lowering over occult works, and I have seen bees flying heavy-laden to their hives on a fine summer’s morning; I have heard a lute played where a tiny cataract leaps, and the pipes of Pan mingled with the bubbling notes of a robin in mint meadows; I have seen pages and pages of printed lines that reach from world’s end to world’s end; I have seen profound words written centuries ago in inks of many colors; I have seen and been overwhelmed by the marvels of scientific things bristling with the accurate kind of knowledge that I shall never know; withal, I have seen the complete serenity of the world’s face, as shown [21]by the brush of the Frenchman Chavannes.

“And over all, the nebulous conception of the long, ignorant silence.

“What is there not upon those wonderful walls!

“I sit in semi-consciousness in the little window-seat and these things swim before my two gray eyes. My mind is full of the vision of murmuring, throbbing life.

“But what a thing is life, truly—for marvelous as are these pictures, those that I have seen, times, down where the rats forage among the rubbish, are more marvelous still.”

“Truly,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “there is much, much, in Boston. Tell me more.”

“Well, and there is the South Station,” I went on. “Oh, not until one has ambled and idled away a thousand hours in that place of trains and varied peoples can one [22]know all of what is really to be found within its waiting-rooms.

“I have found Massachusetts there—not any Massachusetts that I had ever read about, but the Massachusetts that comes in from Braintree and Plymouth and Middleboro carrying a Boston shopping-bag; the Massachusetts that is intellectual and thrusts its forefinger through the handle of its tea-cup; the Massachusetts that eats soup from the end of its spoon; the Massachusetts that is good-hearted but walks funny; the Massachusetts that takes all the children and goes down to Providence for a day—each of the children with a thick, yellow banana in its hand; the Massachusetts that has its being because the world wears shoes—for it is intellectual and can make shoes.

“And in the South Station, furthermore, there are people from the wide world around. Actors and authors and artists [23]are to be seen coming in and going out and sitting waiting in the waiting-rooms. Some mightily fine and curious persons have sat waiting in those waiting-rooms, as well as dingy Italians with strings of beads around their necks.

“And in the South Station there are so many, many people, that, once in a long while, one can meet with some of those tiny things that one has waited for for centuries. In among a multitude of faces there may be a young face with lines of worn and vivid life in it, and with alert and much-used eyes, and with soft dull hair above it. In a flash one recognizes it, and in a flash it is gone. It is a face that means beautiful things and one has known it and its divineness a long, long time. And here in the South Station in Boston came the one gold glimpse of it.

“And I have seen in the South Station a strange scene: that of a mild Jew man [24]bearing the brunt of caring for his large family of small children, while their child-weary mother was allowed for once in her life to rest completely, sitting with her eyes closed and her hands folded. She might well rest tranquil in the thought that in giving birth to that small Hebraic army she had done her share of this dubious world’s penance.

“And in the South Station, as much as anywhere, one feels the air of Boston.

“The air of Boston, too, is wonderful—and ’tis not free for all to breathe. ’Tis for the anointed—the others must content them with the untinted, unscented air that blows wild from mountain-tops and north seas. But for me, I have eyes wherewith to see—and since the air of Boston has color, I can see it. And I have ears wherewith to hear—and since the air of Boston has musical vibrations, I can hear it. And I have sensibility—[25]wherefore all that is pungent in the air of Boston, and all that is fine, and all that is art, and all that is beautiful, and all that is true, and all that is benign, and particularly all that is very cool and all that is bitterly contemptuous—are not wholly lost upon me.

“If all the persons who go to and fro at the South Station were heroes and breathed the air there and left their dim shadows behind them—as they do—I presume the South Station would be hallowed ground. They all are not heroes, but they breathe the air and leave their dim shadows, whatever they may be, and ever after the air of the South Station is tinctured. And since more than a half of these people are of Boston, the air is tinctured therewith.

“If you are civilized and conventional you may know and breathe this air. If you are not—well, at least you may stand [26]and contemplate it. And always one can bide one’s time.

“My contemplation of it has interested me.

“The air of Boston is a mingling of very ancient and very modern things and ways of thinking that are picturesque and at times lead to something. The ancient things date back to Confucius and others of his ilk—and the modern ones are tinted with Lilian Whiting and newspapers and the theater.

“One is half-conscious of this as one contemplates, and one’s thought is, ‘Woe is me that I have my habitation among the tents of Kedar!’ One exclaims this not so much that one considers oneself benighted, but that one is very sure that the air of Boston considers one so. To be sure, it ought to know, but, somehow, as yet one is content to bide one’s time.

“But yes. There is a beatified quality [27]in the air of Boston. It is tinted with rose and blue. It sounds, remotely, of chimes and flutes. You feel it, perchance, when you sit within the subdued, brilliant stillness of Trinity church—when you walk among the green and gold fields about Brookline and Cambridge, where orchids are lifting up their pale, soft lips—when you are in the Museum of Fine Arts and see, hanging on the wall, a small dull-toned picture that is old—so old!

“Music is in the air of Boston. It pours into the heart like fire and flood—it awakens the soul from its dreaming—it sends the human being out into the many-colored pathways to see, to suffer, it may be—yes, surely to suffer—but to live, oh, to live!

“One can see in the mists the slender, gray figure of one’s own soul rising and going to mingle with all these. In spite of the clouds about it, one knows its going and that it is well. It was long since said: [28]‘My beloved has gone down into her garden to the bed of spices, to feed in the gardens and to gather lilies.’ And now again is the beloved in the garden, and in those moments, oh, life is fair”——

My friend Annabel Lee opened her lips—her lips like damp, red quince-blooms in the spring-time—and told me that there were times when I interested her, times when I amused her mightily, and times when in me she made some rare discoveries.

But which of the three this time was, she has not told.

BUT Boston—or even Butte in Montana—is not to be compared to a lodging-place far down in the country: a tiny house by the side of a fishy, mossy pond, in summer-time, with the hot sun shining on the door-step, and a clump of willows and an oak-tree growing near; on the side of the house where the sun is bright in the morning, some small square beds of radishes, and pale-green heads of lettuce, and straight, neat rows of young onions, with the moist earth showing black between the rows; and a few green peas growing by a small fence; and on the other side of the little house grass will grow—tall rank grass and some hardy weeds, and perhaps a tiger-lily or two [30]will come up unawares. The fishy pond will not be too near the house, nor too far away—but near enough so that the singing of the frogs in the night will sound clear and loud.

Rolling hills will be lying fair and green at a distance, and cattle will wander and graze upon them in the shade of low-hanging branches. On still afternoons a quail or a pheasant will be heard calling in the woods.

The air that will blow down the long gentle uplands will be very sweet. The message that it brings, as it touches my cheeks and my lips and my forehead, will be one of exceeding deep peace.

I would live in the little house with a friend of my heart—a friend in the shadows and half-lights and brilliances. For if the hearts of two are tuned in accord the harmony may be of exquisite tenor.

In the very early morning I would sit [31]on the doorstep where the sun shines, and my eyes would look off at the prospect. Life would throb in my veins.

In the middle of the forenoon I would be kneeling in the beds of radishes and slim young onions and lettuce, pulling the weeds from among them and staining my two hands with black roots.

In the middle of the day I would sit in the shade, but where I could see the sunshine touching the brilliant greenness, near the house and afar. And I could see the pond glaring with beams and motes.

In the late afternoon I, with the friend of my heart, would walk down among the green valleys and wooded hills, by fences and crumbling stone walls, until we reached a point of vantage where we could see the sea.

In the night, when the sun had gone and the earth had cooled and the dark, dark gray had fallen over all, we would [32]sit again on the doorstep. It would be lonesome there, with the sound of the frogs and of night-birds—and there would be a cricket chirping. We would speak to each other with one or two words through long stillnesses.

Presently would come the dead midnight, and we would be in heavy sleep beneath the low, hot roof of the little house.

Mingled with the dead midnight would be memories of the day that had just gone. In my sleep I would seem to walk again in the meadows, and the green of the countless grass-blades would affect me with a strange delirium—as if now for the first time I saw them. Each little grass-blade would have a voice and would shout: Mary MacLane, oh, we are the grass-blades and we are here! We are the grass-blades, we are the grass-blades, and we are here!

And yes. That would be the marvelous thing—that they were here. And would not the leaves be upon the trees?—and would not tiny pale flowers be growing in the ground?—and would not the sky be over all? Oh, the unspeakable sky!

In the dead midnight sleep would leave me and I would wake in a vision of beauty and of horror, with fear at my heart, with horrible fear at my heart.

Then frantically I would think of the little radish-beds outside the window—how common and how satisfying they were. Thus thinking, I would sleep again and wake to the sun’s shining.

“You would not,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “stay long in such a place.”

I looked at her.

“Its simplicity and truth,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “would deal you [34]deep wounds and scourge you and drive you forth as if you were indeed a money-changer in the temple.”

ANNABEL LEE leaned her two elbows on the back of a tiny sandalwood chair and looked down at me.

We regarded each other coldly, as friends do, times.

“You,” said Annabel Lee, “have a half-conscious soul. Such a soul that when it hears a strain of music can hear away to the music’s depths but can understand only one-half of its meaning; but because it is half-conscious it knows that it understands only the half, and must need weep for the other half; such a soul that when it wanders into the deep green and meets there a shadow-woman, with long, dark hair and an enchanting voice, it feels to its depths the spirit of the green and the [36]voice of the shadow-woman, but can understand only one-half of what they tell: but because it is half-conscious it knows that it understands only the half, and must need weep for the other half; such a soul that when it is bound and fettered heavily, it knows since it is half-conscious, that it is bound and fettered, but knows not why nor wherefore nor whether it is well, which is the other half—and it must need weep for it; such a soul that when it hears thunderings in the wild sky will awaken from sleep and listen—listen, but since it is half-conscious it can only hear, not know—and it sounds like an unknown voice in an unknown language, telling the dying speech of its best-loved—it is frantic to know the translation which is the other half; such a soul that when life gathers itself up from around it and stands before it and says, Now, contemplate life, it contemplates, since it is [37]half-conscious, but it for that same reason strains its eyes to look over life’s shoulders into the dimness—which is an impossible thing, and the other half; such a soul that when it finds itself mingling in love for its friend, and all, it enjoys, oh, vividly in all moments but the crucial moments, when it aches in torment and doubt—for it is half-conscious and so knows its lacking.

“Desolate is the way of the half-conscious soul,” said Annabel Lee.

“The wholly conscious soul receives into itself things in their entirety without question or wonder: the half-conscious soul receives the half of things, and knowing that there is another half, it wonders and questions till all’s black.

“The wholly conscious soul is different from the wholly unconscious soul in that the former is positive whilst the latter is negative—and they both in their nature [38]can find rest: but the half-conscious soul knows that it is half-conscious, still it knows not at what points it is conscious and at what points unconscious—for when it thinks itself conscious, lo, it is unconscious, and when it thinks itself unconscious it is heavily, bitterly conscious—and nowhere can it find rest.

“The wholly conscious soul holds up before its eyes a mirror and gazes at itself, its color, its texture, its quality, its desires and motives, without flinching, in the strong light of day; the wholly unconscious soul knows not that it is a soul, and never uses a mirror: but the half-conscious soul looks into its glass in the gray light of dusk—it sees its color, its texture, its quality, its desires—but its motives are hidden. Its eyes are wide in the gray light to learn what those, its own motives, are. It can not know, but it can never rest for trying to know.

“The wholly conscious soul knows its love, its sorrow, its bitterness, its remorse.

“The half-conscious soul knows its love—and wonders why it loves, and wonders if it really can love any but itself, and wonders that it cares for love; the half-conscious soul knows its sorrow—and marvels that it should have sorrow since it can grasp not truth; the half-conscious soul knows its bitterness, and realizes at once its right to and its reason for bitterness—but, thinking of it, the arrow is turned in the wound; the half-conscious soul knows its remorse, but it is convinced that it has no right to remorse, since it does its unworthy acts with infinite forethought.

“The wholly conscious soul is a chastened spirit and so has its measure of happiness; the wholly unconscious soul is an unchastened spirit, for it deserves no [40]chastisement—neither has it any happiness, for it knows not whether it is happy or otherwise: but the half-conscious soul is chastised where it is not deserving of it, and goes unchastised where it is richly deserving of it—and so has no happiness, but instead, unhappiness.

“Woe to the half-conscious soul,” said Annabel Lee.

“How brilliantly does the emerald sea flash in the sunshine before the eyes of the half-conscious soul!—but burns it with mad-fire.

“How melting-sweet is the perfume of the blue anemone to the sense of the half-conscious soul!—but burns it with mad-fire.

“How beautiful are the bronze lights in the eyes of its friend to the half-conscious soul!—that burn it with mad-fire.

“How joyous is the half-conscious soul [41]at the sounds of singing voices on water!—that burn it with mad-fire.

“How surely come the wild, sweet meanings of the outer air into the depths of the half-conscious soul!—but burn it with mad-fire.

“How madly happy is the half-conscious soul in still hours at sight of a solitary pine-tree upon the mountain-top!—that burns it with mad-fire.

“How tenderly comes Truth to the half-conscious soul in the dead watches of the night!—but burns it with mad-fire.

“Life is vivid, alert, telling to the half-conscious soul,” said Annabel Lee.

“You,” said Annabel Lee, “with your half-conscious soul, when you sit where the gray waves wash the sea-wall at high-tide, when you sit listening with your head bent and your hands dead cold, you think you realize your life—you think you know its hardness—you think you have [42]measured the cruelty they will give you; but you do not know. You know but half—you weep for the other half, though it be horror.

“Still, though you are but half-conscious, though you weep for the other half, when you sit listening with your head bent and your hands dead cold, where the gray waves wash the sea-wall at high-tide—yet you know some of each one of the things that are around you.

“Wonderful in conception is the half-conscious soul,” said Annabel Lee.——

I looked hard at my friend Annabel Lee. Was she teasing me? Was she laughing at me? For she does tease me and she does laugh at me. And was she at either of these pastimes, with all this about a half-conscious soul?

But here again she left me ignorant of her thought, and there is no way of knowing.

THERE are two writers, among them all, to whom I owe thanks for countless hours of complete pleasure. Not the pleasure that stirs and fires one, but the pleasure which enters into the entire personality, and rests and satisfies a common, unstrained mind. ’Tis the same pleasure that comes with eating all by myself—eating peaches and a fine, tiny lamb chop in the middle of the day.

One of these two writers is J. T. Trowbridge who has written young-books.

Often I have thought, Life would be different, and duller colored, and less thickly sprinkled with marigolds-and-cream, had I never known my Trowbridge.

Often I have thanked the happy fate that put into my hands my first young-book of Trowbridge. ’Twas when I was fourteen—one day in October, when I lived in a flat, windy town that was named Great Falls, in Montana. Since that time I have never been without the young-books of J. T. Trowbridge. There have but seven years passed since then, but when seven years more, and seven years again, up to threescore, have gone, I still shall spend one-half my rest-hours, my pleasure-hours, my loosely-comfortable, unstrained hours with the young-books of Trowbridge.

When I go to a theater I enjoy it thoroughly. A theater is a good thing, and the actor is a stunning person—but how eagerly and gladly I come back into my own room where there is a faithful, little, tan deer standing waiting, all so pathetic and sweet, upon the desk.

When I go out into two crowded rooms among some fascinating persons that I have heard of before—women with fine-wrought gowns—I like that, too, and I wouldn’t have missed it—but how utterly restful and adorable it is to come back to my own room where there is my comfortable quiet friend in a rusty black flannel frock, sitting waiting—and her hands so soft and good to feel.

When I read gold treasures of literature—Vergil, it may be, or a Browning, or Kipling—I am enchanted and enthralled. I marvel at these people and how they can write. I think how marvelous is writing, at last—but how gladly and thankfully, after two hours or three, I return back to these my young-books of Trowbridge.

They are about people living on farms, and they are written so that you know that red-root grows among wheat-spears, [46]and must be weeded out, and that the farmer’s boys have to milk the cows mornings before breakfast and evenings after supper. For they have supper in the Trowbridge books—and it is even attractive and tastes good.

When the lads go to gather kelp to spread on the land, and are gone for the day by the seashore, they eat roasted ears of corn, and cold-boiled eggs, and bread-and-butter, and three bottles of spruce beer—and if you really know the Trowbridge books you can eat of these with them, and with a wonderful appetite.

When a slim boy of sixteen goes to hunt for his uncle’s horse that had been stolen in the night (because the boy left the stable door unlocked), along pleasant country roads and smiling farms in Massachusetts—if you really know the Trowbridge books—the slim boy of sixteen is not more anxious to find the horse than [47]you are. When the boy and the reader first start after the horse they are far too wretched and anxious to eat—for the crabbed uncle told them they needn’t come back to the farm without that horse. But long before noon they are glad enough that they have a few doubled slices of buttered bread to eat as they go. When at last they come upon the horse calmly feeding under a cattle-shed at a county fair twenty miles away, they are quite hungry, and in their joy they purchase a wedge of pie and some oyster crackers, so that they needn’t be out of sight of the horse while they eat. And the reader—if he really knows the Trowbridge books—would fain stop here, for there is trouble ahead of him. He would fain—but he can not. He must go on—he must even come in crucial contact with Eli Badger’s hickory club—he must go with the boy until he sees him and the [48]horse at last safely back at Uncle Gray’s farm, the horse placidly munching oats in his own stall, and the boy eating supper once more with appetite unimpaired, and the crabbed uncle once more serene. And—if you know Trowbridge’s books—you can eat, too, tranquilly.

When a boy is left alone in the world by the death of his aunt and starts out to find his uncle in Cincinnati—if you know Trowbridge’s books—you prepare for hardship and weariness, but still occasional sandwiches and doughnuts (but not the greasy kind). And always you know there must be a haven in the house of the uncle in Cincinnati. Only—if you know the Trowbridge books—you are fearful when you get to the uncle’s door, and you would a little rather the boy went in to meet him while you waited outside. Trowbridge’s uncles are apt to be so sour as to heart, and so bitter as to tongue, and [49]so sarcastic in their remarks relating to boys who come in from the country to the city in order that they—the uncles—may have the privilege of supporting them. Though you know—if you know the Trowbridge books—that Trowbridge’s boys never come into the city for that purpose. The heavy-tempered uncles, too, are made aware of this before long, and change the tenor of their remarks accordingly—and after some just pride on the part of the nephews, all goes well. Whereupon your feeling of satisfaction is more than that of the boy, of the uncle, of Trowbridge himself.

But these roasted ears of corn and cold-boiled eggs are among the lesser delights of the young-books of Trowbridge. The most fascinating things in them are the conversations. They are so real that you hear the voices and see the expressions of the faces.

Trowbridge is one of the kind that listens twice and thrice to persons talking, so that he hears the key-note and the detail, and his pen is of the kind that can write what he hears. It is never too much, never too little; it is not noticeable at all, because it is all harmony.

It is entirely and utterly common.

And it is real.

In the young-books of Trowbridge, and nowhere else, I have heard boys talking together so that I knew how their faces looked, and how carelessly and loosely their various collars were worn, and their dubious hats. I have heard a grasping, grouty old man pound on the kitchen floor with his horn-headed cane—he had come over while the family were at breakfast to inform them that their dog had killed five of his sheep, and to demand the dog’s life. I have heard the lessons and other things they said in a country [51]school-room sixty years ago, where boys were sometimes obliged, for punishment, to sit on nothing against the door. I have heard the extreme discontent in the voice of another grouty, grasping farmer when it became evident to him that he would be obliged to give up a horse that had been stolen before he bought him. But here I must quote, as nearly correctly as I can without the book:

“‘And sold him to this Mr. Badger’ (said Kit) ‘for seventy dollars.’

“‘Seventy gim-cracks!’ exclaimed Uncle Gray, aghast. ‘I should think any fool might know he’s worth more than that.’

“He was thinking of Brunlow, but Eli applied the remark to himself.

“‘I did know it,’ he growled. ‘That’s why I bought him. And mighty glad I am now I didn’t pay more.’

“‘Sartin!’ replied Uncle Gray; ‘but didn’t it occur to you ’t no honest man [52]would want to sell an honest hoss like that for any such sum?’

“‘I didn’t know it,’ said Eli, groutily. ‘He told a pooty straight story. I got took in, that’s all.’

“‘Took in!’ repeated Uncle Gray. ‘I should say, took in! I know the rogue and I’m amazed that any man with common sense and eyes in his head shouldn’t ’a’ seen through him at once.’

“‘Maybe I ain’t got common sense, and maybe I ain’t got eyes in my head,’ said Eli, with a dull fire in the place where eyes should have been if he had had any. ‘But I didn’t expect this.’

“Kit hastened to interpose between the two men.”

Always I have been sorry that the boy interposed just there.

I have read the book surely seven-and-seventy times. Each time this talk over the horse comes exceeding pungent to my [53]ears. How impossible it is to weary of Trowbridge, because there is no effort in the writing, and no effort in the reading, and because of a deep-reaching, never-failing sense of humor.——

How flat seem these words!

The young-books of Trowbridge can not be set down in words. What with the simplicity, what with the quality of naturalness, what with a delicate tenderness for all human things, what with the rare, rare quality of commonness that is satisfying and quieting as the vision of a little green radish-bed, what with an inner sympathy between Trowbridge and his characters and, above all, an inner sympathy with his readers, what with Truth itself and the sweet gift of portraying the sunshiny days as they are—why talk of Trowbridge?

Is it not all there written?

Can one not read and rest in it?

“NO,” SAID my friend Annabel Lee, “I can’t really say that I care for Trowbridge. All that you have said is true enough, but he fails to interest me.”

“What do you like in literature?” I asked, regarding her with interest, for I had never heard her say. It must need be something characteristic of herself.

“I like strength, and I like simplicity, and I like emotion, and I like vital things always. And I like poetry rather than prose. Just now,” said Annabel Lee, “I am thinking of an old-fashioned bit of verse that to me is all that a poem need be. To have written it is to have done [56]enough in the way of writing, because it’s real—like your Trowbridge.”

“Oh, will you repeat it for me!” I said.

“It is called, ‘Give Me Three Grains of Corn, Mother.’ It is of a famine in Ireland a great many years ago—a lad and his mother starving.”

And then she went on:

“What do you think,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “is it not full of power and poetry and pathos?”

“Yes, it could not in itself be better,” I replied. “And it has the simplicity.”

“And pretends nothing,” said Annabel Lee.

“And who wrote it?” I asked.

“Oh, some forgotten Englishwoman,” said Annabel Lee. “I believe her name was Edwards. She perhaps wrote a poem, now and then, and died.”

“And are the poems forgotten, also?” I inquired.

“Yes, forgotten, except by a few. But when they remember them, they remember them long.”

“Then which is better, to be remembered, and remembered shortly, by the multitudes; or to be forgot by the multitudes and remembered long by the one or two?”

“It is incomparably better to be remembered long by the one or two,” said Annabel Lee. “To be forgotten by any one or anything that once remembered you is sorely bitter to the heart.”

“DO YOU think, Annabel Lee,” I said to her on a day that I felt depressed, “that all things must really be relative, and that those which are not now properly relative will eventually become so, though it gives them acute anguish?”

The face of Annabel Lee was placid, and also the sea. The one glanced down upon me from the shelf, and the other spread away into the distance.

Were that face and that sea relative? Surely they could not be, since those two things in their very nature might go ungoverned. Do not universal laws, in extreme moments, give way?

“Relative!” said Annabel Lee. “Nothing [62]is relative. I tell you nothing is relative. I am come out of Japan. In Japan, when I was very new to everything, there was an ugly frog-eyed woman who washed me and anointed me and dressed me in silk, the while she pinched my little white arms cruelly, so that my little red mouth writhed with the pain. Also the frog-eyed woman looked into my suffering young eyes with her ugly frog-eyes so that my tiny young soul was prodded as with brad-nails. The frog-eyed woman did these things to hurt me—she hated me for being one of the very lovely creatures in Japan. She was a vile, ugly wretch.

“That was not relative. I tell you that was not relative,” said Annabel Lee.

“If I had been an awkward, overgrown, bloodless animal and that frog-eyed woman had pinched my little white arms—[63]still she would have been a vile, ugly wretch.

“If I had been a vicious spirit and that frog-eyed woman had looked into my vicious eyes with her ugly frog-eyes—still she would have been a vile, ugly wretch.

“If I had been a hateful little thing, instead of a gently-bred, gently-living, pitiful-to-the-poor maiden, and that frog-eyed woman had hated me with all her frog-heart—still she would have been a vile, ugly wretch.

“If that frog-eyed woman had stood alone in Japan with no human being to compare her to—still the frog-eyed woman would have been a vile, ugly wretch.

“She has left her horrid frog-mark on my fair soul. Not anything beneath the worshiped sun can ever blot out the horrid frog-mark from my fair soul. A thousand [64]curses on the ugly, frog-eyed woman,” said Annabel Lee, tranquilly.

“Then that, for one thing, is not relative,” I said. “But perhaps that is because of the power and the depth of your eyes and your fair soul. Where there are no eyes and no fair souls—at least where the eyes and the fair souls can not be considered as themselves, but only as things without feeling for life—then are not things relative?”

“Nothing is relative,” said Annabel Lee. “If your dog’s splendid fur coat is full of fleas and you caress your dog with your hands, then presently you may acquire numbers of the fleas. You love the dog, but you do not love the fleas. You forgive the fleas for the love of the dog, though you hate them no less. So then that is not relative. If that were relative you would love the fleas a little for the same reason that you forgive them: for [65]love of your dog. Forgiveness is a negative quality and can have no bearing on your attitude toward the fleas.”

Having said this, Annabel Lee gazed placidly over my head at the sea.

When her mood is thus tranquil, she talks graciously and evenly and positively, and is beautiful to look at.

My mind was now in much confusion upon the subject in question. But I felt that I must know all that Annabel Lee thought about it.

“What would you say, Annabel Lee,” said I, “to a case like this: If a soul were at variance with everything that touches it, everything that makes life, so that it must struggle through the long nights and long days with bitterness, is not that because the soul has no sense of proportion, and has not made itself properly relative to each and everything that is?—relative, so that when one hard thing [66]touches it, simultaneously one soft thing will touch it; or when it mourns for dead days, simultaneously it rejoices for live ones; or when its best-loved gives it a deep wound, simultaneously its best enemy gives it vivid pleasure.”

“Nothing is relative,” again said Annabel Lee. “Nothing can be relative. Nothing need be relative. If a soul is wearing itself to small shreds by struggling days and nights, that is a matter relating peculiarly to the soul, and to nothing else, nothing else. If a soul is wearing itself to small shreds by struggling, the more fool it. It is struggling because of things that would never, never struggle because of it. In truth, not one of them would move itself one millionth of an inch because of so paltry a thing as a soul.”

I looked at Annabel Lee, her hair, her hands and her eyes. As I looked, I was reminded of the word “eternity.”

A human being is a quite wonderful thing, truly—and great—there’s none greater.

Annabel Lee is a person who always says truth, for, for her, there is nothing else to say.

She has reached that marvelous point where a human being expects nothing.

“If the days of a life, Annabel Lee,” I said, “are made bright because of two other lives that are dear to it, and if the life happens upon a day when the thought of the two whom it loves makes its own heart like lead, then what can there be to smooth away its weariness, in heaven above, in the earth beneath, or in the waters under the earth?”

“Foolish life,” said my friend Annabel Lee. “There is no pain in Japan like what comes of loving some one or some thing. And if the some one or the some thing is the only thing the life can call its [68]own, then woe to it. The things it needs are three: a Lodging Place in heaven above; a Bit of Hardness in the earth beneath; a Last Resort in the waters under the earth. These three—but no life has ever had them.”

“In the end,” I said, “when all wide roadways come together, and all heavy hearts are alert to know what will happen, then will there not indeed be one grand adjustment, and life and all become at once magnificently relative?”

“Never; it can’t be so. Nothing is relative,” said Annabel Lee, on a day that I felt depressed.

TO-DAY my friend Annabel Lee and I went to the theater and we saw a wonderful and fascinating woman with long dark-red hair upon the stage.

She is attractive, that red-haired woman—adorably attractive. And she reminds one of many things.

Annabel Lee was greatly interested in her acting, and was charmed with herself—and so was I.

“Do you suppose she finds life very delightful?” I said to my friend.

“I don’t suppose,” my friend replied, “she is of the sort that considers whether or not life is delightful. Probably her work is hard enough to keep her out of mischief of any kind.”

Whereupon we both fell to thinking how fortunate are they whose work is hard enough to keep them out of mischief of any kind.

“But there must be,” I said, “some months, perhaps in the summer, when she doesn’t work. I have heard that some actors take houses among the mountains and do their own housework for recreation.”

“I,” said Annabel Lee, “can not quite imagine this woman with the red hair making bread and scouring pans and kettles for pleasure. But very likely she sometimes goes into the country for vacations, and I can fancy her doing the various small enjoyable things that celebrities can afford to do—like wading barefooted in a narrow brooklet, or swinging high and recklessly in a barrel-stave hammock.”

“And since she is so adorable on the [71]stage,” I exclaimed, “how altogether enchanting she would be wading in the brooklet or swinging in the barrel-stave hammock—she with the long, red hair! Perhaps it would even be braided down her back in two long tails.”

It is a picture that haunts me—Mrs. Fiske in the midst of her vacation doing the small enjoyable things.

“Of course,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “we don’t know that she doesn’t spend her vacations in a fine, conventional, stupid yacht, or at some magnificent, insipid American or English country house. We can only give her the benefit of the doubt.”

“Yes, the benefit of the doubt,” I replied.

How fascinating she was, to be sure, with her personality merged in that of Mary Magdalene!

The Magdalene is no longer a shadowy [72]ideal with a somewhat buxom body, scantily draped, with indefinite hair and with the lifeless beauty that the old masters paint. Nor is she quite the woman of the scriptures who is presented to one’s mind without that quality which is called local coloring, and with too much of the quality that is ever present with the women in the scriptures—a something between uncleanness and final complete redemption.

No, Mary Magdalene is Mrs. Fiske, a slight woman still in the last throes of youth, with two shoulders which move impatiently, expressing indescribable emotions of aliveness and two lips which perform their office—that of coloring, bewitching, torturing, perfuming, anointing the words that come out of them. Apart from these lips, Mary Magdalene’s face has a wonderfully round and childish look, and her two round eyes at first sight [73]give one an idea of positive innocence. In the Magdalene’s face—and in that of an actor of Mrs. Fiske’s range—these are a beautifully delicate incongruity.

And my friend Annabel Lee has told me that the strongest things are the delicate incongruities—the strongest in all this wide world. Because they make you consider—and considering, you wait.

With such a pair of round, innocent eyes of some grayish color—who can blame Mary Magdalene?

In the latter acts of the play these eyes go one step farther than innocence: they do hunger and thirst after righteousness. And, ah, dear heaven (you thought to yourself), how well they did it! To hunger and thirst after righteousness—not herself, but her eyes. That was this Mary Magdalene’s art.

This Mary Magdalene, though she is indeed in the last throes of youth—without [74]reference to the years she may know—has yet beneath her chin a very charming roundness of flesh which one day obviously will become a double chin. Just now it is enchanting. There are feminine children of seven and eight with round faces, who have just that fullness beneath the chin, and beneath the chin of Mary Magdalene—and added to her eyes—it carries on the idea of innocence and inexperience to a rare good degree. Any other woman actor would have long since massaged this fullness away. Forsooth, perhaps this is the one woman actor who could wear such a thing with beauty.

Mary Magdalene’s hair in its deep redness is scornful and aggressive in the first acts of the play. In the latter acts it assumes a marvelous patheticness. And, if you like, there is a world of patheticness in red hair.

If Mary Magdalene’s hair were of a different color—if the bronze shadows were yellow, or gray, or black, or brown shadows—her lips and her shoulders were in vain.

On the stage Mary Magdalene stands with her back to her audience—she stands, calm and placid, for three or four minutes before the rising and falling curtain, graciously permitting all to admire and feast their eyes upon the red of her hair.

“She knows,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “that she can make her face bewitching—and she knows also that her hair is bewitching without being so made. And she chooses that the world at large shall know it, too.”

She has will-power, has Mary Magdalene. It is her will, her strength, her concentration of all her power to herself that makes her thus bewitching—and [76]that seduces the brains of those who sit watching her as she moves upon the stage.

She controls all her mental and physical features with metallic precision—except her hair, and that she leaves uncontrolled to do its own work. It does its work well.

She has cultivated that mobileness of her lips, probably with hard work and infinite patience—and she makes them damp and brilliant with rouge. She rubs the soft, thick skin of her face with layers of grease. She loads her two white arms with limitless powder. And the two childish eyes are exceeding heavy-laden as to lid and lash with black crayon. One experiences a revulsion as one contemplates them through a glass. Her voice in the days of her youth had drilled into it the power to thrill and vibrate, and to become exquisitely tender upon occasion, [77]and now it does the bidding of its owner with docility and skill. Since its owner has forcefulness and a power of selfish concentration, the voice is mostly magnetic and cold and strong. It is magnetic and cold and strong and contemptuous when its owner says, “My curse upon you!” When its owner’s eyes do hunger and thirst after righteousness the voice brings a miserable, anguished feeling to the throats of those who sit listening. Every emotion that the voice betrays is transmitted to the seduced brains of those who sit listening. The red-haired woman works her audience up to some torturing pitches—the while herself blandly and cold-bloodedly earning an honest livelihood by the sweat of her brow.

Forsooth, it’s always so.

If all the red-haired woman’s scorn and anguish were real, the audience would sit unmoved. If the red-haired woman’s [78]scorn and anguish were real it would strike inward—instead of outward toward the audience—and the audience would not know. If the red-haired woman’s scorn and anguish were real, it would not seem real and would be very uninteresting. And that very likely is the reason why the scorn and anguish of other red-haired women—and of black-haired, and brown-haired, and yellow-haired, and gray-haired, and pale-haired women, who are not working on the stage—is so uninteresting and ineffectual. It is real, and they can not act it out, and so it doesn’t seem real—and you don’t have to pay money to see it done.

To make it seem real they must need go at it cold-bloodedly, and work it up, and charge you a round price for it.

Mary Magdalene isn’t here to do this, but Mrs. Fiske takes her place and does it for her.

She does it exquisitely well.

Could Mary Magdalene herself—she of the Bible—be among those who sit watching, she would surely marvel and admire.

Meanwhile, for myself, I have two visions of this Mary Magdalene.

One—in one of the acts wherein her eyes do hunger and thirst after righteousness—when she sits before a small table and lifts her pathetic, sweet voice with the words, “When the dawn breaks, and the darkness shall flee away”; and then she stands and the red hair is equally pathetic and twofold bewitching, and she says again, “When the dawn breaks, and the darkness shall flee away.” And the other vision is of her in the country in the midst of a summer day, under a summer sky, swinging high and recklessly in a barrel-stave hammock.

MY FRIEND Annabel Lee has told me there are bitterer things in store for me than I have known yet.

Times I have wondered what they can be.

“When you have come to them,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “they will be so bitter and will fit so well into your life that you will wonder that you did not always know about them, and you will wonder why you did not always have them.”

“The bitterest things I have known yet,” I said, “have had to do with the varying friendship of one or another whom I have loved.”

“Varying friendship?” said Annabel Lee. “But friendship does not vary.”

“No, that is true,” I rejoined. “I mean the varying deception I have had from some whom I have loved.”

“In time,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “you will love more, and your deceiving will be all at once, and bitterer. It will be a rich experience.”

“Why rich?” I inquired.

“Because from it,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “you will learn to not see too much, to not start out with faith, in fact, to take the goods that the gods provide and endeavor to be thankful for them. Your other experiences have been poverty-stricken in that respect. They leave you with rays of hope, without which you would be better off. They are poor and bitter. What is to come will be rich and bitterer. Their bitterness will prevent you from appreciating the richness of [83]them—until perhaps years have come and taken them from immediately before your eyes. As soon as they are where you can not see them, you can consider them and appreciate their richness.”

“Whatever they may be,” I made answer, “I do not think I shall ever be able to appreciate their richness.”

“Then you will be very ungrateful,” said my friend Annabel Lee.

I looked hard at her—and she looked back at me. There are times when my friend Annabel Lee is much like a stone wall.

“Yes,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “if you ever feel to express proper gratitude for the good things of this life, be sure that you express your gratitude for the right thing. Very likely you will not have a great deal of gratitude, and you must not waste any of it—but what you do have will be of the most excellent [84]quality. For it will accumulate, and the accumulation will all go to quality. And the things for which you are to be grateful are the bitternesses you have known. If you have had it in mind ever to give way to bursts of gratitude for this air that comes from off the salt sea, for that line of pearls and violets that you see just above the horizon, for the health of your body, for the sleep that comes to you at the close of the day, for any of those things, then get rid of the idea at once. Those things are quite well, but they are not really given to you. They are merely placed where any one can reach them with little effort. The kind fates don’t care whether you get them or not. Their responsibility ends when they leave them there. But the bitternesses they give to each person separately. They give you yours, Mary MacLane, for your very own. Don’t say they never think of you.”

“I’ve no intention of saying it,” said I.

“You will find,” said my friend Annabel Lee—without noticing my interruption, and with curious expressions in her voice and upon her two red lips—“you will find that these bitternesses come from time to time in your life, like so many milestones. They are useful as such—for of course you like to take measurements along the road, now and again, to see what progress you have made. Along some parts of the road you will find your progress wonderful. If you are appreciative and grateful, at the last milestone you have come to thus far you will express your measure of gratitude to the kind fates. That is, no—” said my friend Annabel Lee, “you will not do this at the milestone, but after you have passed it and have turned a corner, and so can not see it even when you look back.”

“But why shall I express gratitude [86]there?” I inquired in a tone that must have been rather lifeless.

“Why?” repeated my friend Annabel Lee. “Because you will have grown in strength on account of these milestones; because you will have learned to take all things tranquilly. Why, after the very last milestone I daresay you would be able to sit with folded hands if a house were burning up about your ears!”

“Which must indeed be a triumph,” said I.

“A triumph?—a victory!” said my friend Annabel Lee—with still more curious expressions. “And the victories are not what this world sees”—which reminded me of things I used to hear in Sunday-school ever so many years ago. “You remember the story of the Ten Virgins? Taking the story literally,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “the lot of the five Foolish Virgins is much the more fortunate. [87]There was a rare measure of bitterness for them when they found themselves without oil for their lamps at a time when oil was needed. They gained infinitely more than they lost. As for the five Wise Virgins—well, I wouldn’t have been one of them under any circumstances,” said my friend Annabel Lee. “Fancy the miserable, mean, mindless, imaginationless, selfish natures that could remain unmoved by the simplicity of the appeal, ‘Give us of your oil, for our lamps are gone out.’ It must now,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “be a hundred times bitterer for them to think of being handed down in endless history as demons of selfishness—and they are now where they can not, presumably, measure their bitterness by milestones of progress.”

“So then, yes,” said my friend Annabel Lee—“whatever else you may do as you [88]go through life, remember to save up your gratitude for the bitternesses you have known—and remember that for you the bitterest is yet to come.”

“Have you, Annabel Lee,” I asked, “already known the bitterest that can come—and can you sit with your hands folded in the midst of a burning house?”

“Not I!” said my friend Annabel Lee, and laughed gayly.

Again I looked hard at her—and she looked back at me.

Certainly there are times when my friend Annabel Lee is like a stone wall.

“I LOVED madly,” said my friend Annabel Lee. “There came one down out of the north country that was dark and strong and brave and full of life’s fire. All my short life had been bathed in summer. I had dreamed my thirteen years beneath cherry-blossoms upon a high hill.

“But at the coming of this man from the north country I opened my two sloe-eyes, and the world turned white—exquisite, rapturous, divine white.

“And afterward all was heavy gray.

“Away from the high hill of the cherry-blossoms there lay a stretch of red barren waste with towering rocks—and beyond that a quiet, quiet sea that was only blue.

“At the left of the high hill of the cherry-blossoms there was a mountain covered with green ivy—dark green ivy that defined its own green shape against the brilliant yellow sky behind it. Green and yellow, green and yellow, green and yellow, said the sky and the mountain covered with ivy.

“The high hill of the cherry-blossoms was colored with all the colors of Japan.

“I lived there with people—my mother and my father and some others—all with pale faces and sloe-eyes.

“But some of them were very ugly.

“Then came one down out of the north country that was dark and strong and brave and full of life’s fire.

“He was ugly, but his face was perfect.

“Straightway I fell in love with this one. Of all things in Japan, what a thing it is to fall in love!

“Where the red barren waste lay spread [91]below me I saw manifold softnesses, like a dove’s breast, like a fawn’s eyes, like melted lilies, and the towering, gloomy rocks were the home of violet dreams.

“In the deep green of the ivy mountain my soul found rest at nightfall among mystery and shadow. It wandered there in marvelous peace. And the coolness and damp and the low muttering of the wind and the night birds went into it with a stirring, powerful influence. Also the voices out of the very long ago came from among the green, dark ivy, and from the crevices of gray stones beneath it, and they told me true things in the stillness.

“From the deepness of the brilliant yellow sky—the yellow of burnished brass—there came legion earth-old contradictions. And wondrous paradox and parallel that had not been among the cherry-blossoms appeared to me as my [92]mind contemplated these. I said, Am I thus in love because that I am weak, or that I am strong? For I see here that it is both weakness and strength. And I said, Am I myself when I do this thing? or was that I who lived among the cherry-blossoms? I said, Who am I? What am I?

“Below all there was the blue, broad sea. This sea gave out a white mist that rose and spread over the earth. I knew that I was in love, once and for all.

“The world was white. The world was beautiful. The world was divine.

“Life shone out of the mist unspeakable in its countless possibilities. Voices spoke near me and infinite voices called to me from afar—they sounded clear and faint and maddening-soft and tender, and the soul of me answered them with deafening, joyous silent music.

“He from the north country that was dark and strong and brave and full of [93]life’s fire came, some days, to the high hill of the cherry-blossoms. He spoke often and of many things. He spoke to people—to my mother and to my father, and to others. And rarely he spoke to me. Rarely he looked at me. He had been in the great world. He knew wonderful women and wonderful men. He had been touched with all things.

“What a human being was he!

“And of all things in Japan, what a thing it is to fall in love!

“When three days had gone my heart knew rapture beyond any that it had dreamed. It knew the mysteries and the fullnesses.

“After three days the world turned to that divine white, and was white for seven days.

“And afterward all was heavy gray.

“The one from the north country returned back to the north country.

“Of all things in Japan, what a thing it is to fall in love!

“I was not in love with this one because he was a man, or because he was strange and fascinating—but because he was a glorious human being.

“My heart was not turned to this one to marry him. Marrying and giving in marriage are for such as are in love unconsciously.

“To see this one from the north country—to hear his voice—that was life and all for me—life and all.

“But he was gone.

“He left a silence and a weariness.

“These came and crowded out the white from my heart, and themselves found lodgment there.

“And all was heavy gray.

“The picture of life and the mystery and shadow that was revealed to me when the world was white has never [95]gone. It has filled me in the days of my youth with an old terror.

“Of all things in Japan, what a thing it is to fall in love!

“To fall in love!”—said my friend Annabel Lee, the while her two eyes and her two white hands, in their expression, their position, told of a thing that is heart-breaking to see.

“THERE was a time,” I said to my friend Annabel Lee, “when I went to the Butte High School. I think of it now with mingled feelings.”

“You were younger then,” said my friend Annabel Lee.

“I was younger, and in those days I still looked upon life as something which would one day open wide and display wondrous and beautiful things for me. And meanwhile I went every day to the Butte High School. I found it a very interesting place—much more interesting than I have since found the broad world. I was sixteen and seventeen and eighteen, and things were not brilliantly colored, [98]and so I made much with a vivid fancy of all that came in my path.”

“And what do you, now that you are one-and-twenty?” said my friend Annabel Lee.

“I sit quietly,” I replied, “and wish not, and wait not—and look back upon the days in the Butte High School with mingled feelings.”

“Also unawares,” said my friend Annabel Lee, “you still think things relating to that which is one day to open wondrously for you. But, never mind,” she added hastily, as I was about to say something, “tell me about the Butte High School.”

“’Twas a place,” said I, “where were gathered together manifold interesting phenomena, and where I studied Vergil, and grew fond of it, and was good in it; and where I studied geometry, and was fond of it, and knew less about it each day that I studied it;—and always I [99]studied closely the persons whom I met daily in the Butte High School. I recall very clearly each member of the class of ninety-nine. My memory conjures up for me some quaint and fantastic visions against picturesque backgrounds that appeal to my sense of delicate incongruity, especially so since viewed in this light and from this distance.”

“What are some of them?” said my friend Annabel Lee.

“There is one,” said I, “of a girl whom always in my mind I called The Shad, for that she was so bland, and so flat, and so silent,—and she had a bad habit of asking me to write her Latin exercises, which perhaps was not so much like a shad as like a person; and there is one of a girl who spent the long hours of the day in writing long, long letters to her love, but knew painfully little about the lessons in the class-rooms; and there is one of a girl [100]who brought to school every day a small flask of whiskey to cheer her benighted hours,—she was daily called back and down by the French teacher on account of her excessively bad French, and life had looked dull for her were it not for the flask’s pungent contents; there is one of a strange-looking, tawny-headed girl who sat across the narrow aisle from me in the assembly-room during my last year in school, who kept her desk neatly piled with the works (she called them works) of Albert Ross—and after she had read them, very kindly she would lean over and repeat the stories, with quotations verbatim, for my benefit;—her standing in her classes was not brilliant, but in Albert Ross she was thorough; there is one of a clever, pretty girl who was malicious—exquisitely malicious in all her ways and deeds, and seemingly no thought entered her head that was not [101]fraught with it,—she was malicious in algebra, malicious in literature, malicious in ancient history, malicious in physical culture, malicious in the writing of short themes—and when it so chanced that I made a failure in a recitation, or was stupid, she would look up at me and smile very sweetly and maliciously; and there is one of a girl whose quaint and voluble profanity haunts me still. And especially there is in my memory a picture of all these on our graduating day, receiving each a fine white diploma rolled up and neatly tied with the class colors—a picture of these and the others,—we were fifty-nine in all. And the diplomas stated tacitly, in heavily engrossed letters, that we had all been good for four years and had fulfilled every requirement of the Butte High School. So we had, doubtless—but how much some of us had done for which in our diplomas we were not [102]given credit! In truth, nothing was stated in them, in engrossed lettering, about courses in love-letters, or profanity, or malice, and Albert Ross was not in the curriculum.

“And the president of the school board doled out those diplomas, with a short, set speech for each, one wet June day—but he was not aware how insignificant they were.

“And my mind likewise conjures up a vision of two with whom I used to take what we called tramps, during our last year in the High School—far down and out of Butte, on Saturdays and other days when school was not. I remember those two and those tramps exceeding well—nor can I think with but four years gone that the two themselves have forgotten. One of these was an individual whose like I have not since known. She reminded me sometimes of Cleopatra and [103]sometimes of Peg of Limmavaddy. She was of Irish ancestry and had a long black mane of hair braided down behind, and two conscious and lurid eyes of the kind that is known as Irish blue. She had brains enough within her head, but did not study overmuch. Her ways of going through life were often very dubious. She weighed a great many pounds. Her experience of the world was large, and to me she was fascinating. For herself, she was always rather afraid of me—so much afraid, in truth, that if I said a funny thing she must need laugh—with a forced and fictitious merriment; if I told her she had no soul, she must need agree with me abjectly, though she was a good Catholic; if I frowned upon her, she shivered and was silent. Fanciful names and frocks (though this lady’s frocks were always fanciful in ways) were selected for these tramping expeditions. This one’s [104]fanciful name was called Muddled Maud. For no particular reason, I believe—but she wore it well. The other member of our trio was of a less extraordinary type. She was stout as to figure, and she knew a great deal about some things. She was very good in history, and at home she could make pie and cake and bread. It is true that her cake sometimes stuck, and sometimes sank in the middle, and when she carved a fowl she could not always hit the joints. And she was one of the kind that always pronounces picture, “pitcher.” She was also known as a very sensible girl. I can see her now with a purple ribbon around her neck and a brown rain-coat on coming into the High School on a wet morning. When we went tramping she usually wore an immense gray-white, mother-hubbard gown, belted in at the waist, and a wide flat hat, which made her look rather like [105]a toad-stool. Her fanciful name was Emancipated Eva. Emancipated, in truth, she was. In the High School she was dignified and sedate, but on our tramps she would frequently skip like a young lamb, and frisk and gambol down there in the country.

“She who was called Muddled Maud likewise frisked and gamboled—and always she personified my idea of the French noun abandon.

“Also I frisked and gamboled in those days far down in the country.

“The fanciful name selected for me was Refreshment Rosanna—and I can not tell why. But it was thought a good name for a lady tramp. We started on these tramps at six in the morning. We would rise from our beds at five, and at ten minutes before six I would meet Muddled Maud at the corner of Washington and Quartz streets, below her house. Together [106]we would go down east Park street to the home of Emancipated Eva. Then we walked seven miles or eight away into the open and the wild.

“We took things along to eat—sometimes a great many things and sometimes a few. Times Muddled Maud would have but a curious-looking jelly-roll, and Emancipated Eva would come laden with hard bits of beef, and I could show but a plate of fudge. But other times there were tarts and meat-pies and turnovers, and deviled ham and deviled chicken and deviled veal and deviled tongue and deviled fish of divers kinds, and some bottles of nut-brown October ale, and sardines a l’huile, and green, green olives. Only the more there was, the harder to carry. But, times, Muddled Maud would carry much with little effort—she would adorn herself with the luncheon—a long bit of sausage-link about her neck like a [107]chain, and upon her hat, held securely with bonnet-pins, fat yellow lemons, and two bananas crossed in front like the tiny guns on a soldier’s hat, and bunches of Catawba grapes scattered here and there, and pears hanging by their little stems behind.

“The too early morning prevented all from being seen by the inhabitants of Butte, and we did not venture home again until came the friendly darkness.

“Those were fascinating expeditions—and whose was the glory? Mine was the glory. ’Twas I who invented them. ’Twas I who knew there was none so fitted for a so delicate absurdity as she we called Muddled Maud; and after her, none so fitted as the fair, the good-natured, the Emancipated; and together with them both, I. And I led them forth, and I led them back, and I said things should be thus and so, and straightway [108]they were thus and so. And we enjoyed it, and clear air was in our lungs and life was in our veins, for we had each but eighteen years and were full of youth. But most of all ’twas fascinating because we were three of three widely differing manners of living and methods of reasoning. For I was not like Emancipated Eva, nor yet like Muddled Maud; and Emancipated Eva was not like me, nor yet like Muddled Maud; and Muddled Maud was not like Emancipated Eva, nor yet like me.

“To be sure, there were some things in my ordering which neither the one nor the other found enchanting. Why should the MacLane do all the ordering? they murmured between themselves, but they dared not openly revolt, so all went well.

“But now these are gone.

“The three of us were graduated from the Butte High School with the fifty-nine [109]others of ninety-nine, and had each a fine white diploma, and went our ways.

“She who was like Cleopatra and Peg of Limmavaddy is teaching a school, according to the last that I heard, in the north of Montana; and she that was Emancipated Eva has long since gone to California, and is married, and keeps a house; and for me—I am here, far off from Butte, with you, Annabel Lee, some things having been done meanwhile.

“But though the two are gone, I warrant they have not forgotten. They have not forgotten the Butte High School, nor the class of ninety-nine, nor the tramps we went, nor their tyrant, me.