Transcriber’s Note:

This text includes characters that require UTF-8 (Unicode) file

encoding:

‘ ’ “ ” (curly quotation marks)

œ (oe ligature)

διορθῶσαι (Greek)

ñ (n with tilde)

ç (c with cedilla)

+ - (mathematics symbols)

If any of these characters do not display properly,

make sure your text reader’s “character set” or “file encoding” is set

to Unicode (UTF-8). You may also need to change the default font.

Additional notes are at the end of the book.

THE WORKS OF HENRY HALLAM.

INTRODUCTION

TO THE

LITERATURE OF EUROPE

IN THE FIFTEENTH, SIXTEENTH,

AND

SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES.

BY

HENRY HALLAM, F.R.A.S.,

CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE ACADEMY OF MORAL AND POLITICAL SCIENCES

IN THE FRENCH INSTITUTE

VOLUME II.

WARD, LOCK & CO.,

LONDON: WARWICK HOUSE, SALISBURY SQUARE, E.C.

NEW YORK: BOND STREET.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. |

|---|

| ON THE GENERAL STATE OF LITERATURE IN THE MIDDLE AGES TO THE END OF THE

FOURTEENTH CENTURY. |

| Page |

| Retrospect of Learning in Middle Ages Necessary | 1 |

| Loss of learning in Fall of Roman Empire | 1 |

| Boethius—his Consolation of Philosophy | 1 |

| Rapid Decline of Learning in Sixth Century | 2 |

| A Portion remains in the Church | 2 |

| Prejudices of the Clergy against Profane Learning | 2 |

| Their Uselessness in preserving it | 3 |

| First Appearances of reviving Learning in Ireland and England | 3 |

| Few Schools before the Age of Charlemagne | 3 |

| Beneficial Effects of those Established by him | 4 |

| The Tenth Century more progressive than usually supposed | 4 |

| Want of Genius in the Dark Ages | 5 |

| Prevalence of bad Taste | 5 |

| Deficiency of poetical Talent | 5 |

| Imperfect State of Language may account for this | 6 |

| Improvement at beginning of Twelfth Century | 6 |

| Leading Circumstances in Progress of Learning | 6 |

| Origin of the University of Paris | 6 |

| Modes of treating the Science of Theology | 6 |

| Scholastic Philosophy—its Origin | 7 |

| Roscelin | 7 |

| Progress of Scholasticism; Increase of University of Paris | 8 |

| Universities founded | 8 |

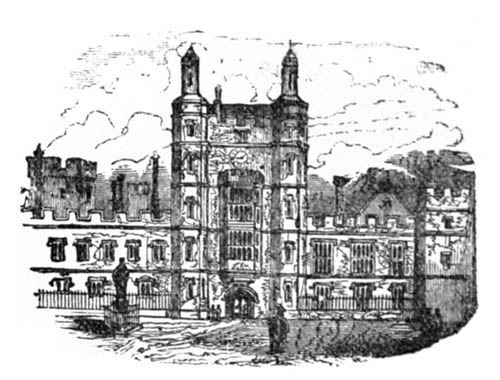

| Oxford | 8 |

| Collegiate Foundations not derived from the Saracens | 9 |

| Scholastic Philosophy promoted by Mendicant Friars | 9 |

| Character of this Philosophy | 10 |

| It prevails least in Italy | 10 |

| Literature in Modern Languages | 10 |

| Origin of the French, Spanish, and Italian Languages | 10 |

| Corruption of colloquial Latin in the Lower Empire | 11 |

| Continuance of Latin in Seventh Century | 12 |

| It is changed to a new Language in Eighth and Ninth | 12 |

| Early Specimens of French | 13 |

| Poem on Boethius | 13 |

| Provençal Grammar | 14 |

| Latin retained in use longer in Italy | 14 |

| French of Eleventh Century | 14 |

| Metres of Modern Languages | 15 |

| Origin of Rhyme in Latin | 16 |

| Provençal and French Poetry | 16 |

| Metrical Romances—Havelok the Dane | 18 |

| Diffusion of French Language | 19 |

| German Poetry of Swabian Period | 19 |

| Decline of German Poetry | 20 |

| Poetry of France and Spain | 21 |

| Early Italian Language | 22 |

| Dante and Petrarch | 22 |

| Change of Anglo-Saxon to English | 22 |

| Layamon | 23 |

| Progress of English Language | 23 |

| English of the Fourteenth Century—Chaucer, Gower | 24 |

| General Disuse of French in England | 24 |

| State of European Languages about 1400 | 25 |

| Ignorance of Reading and Writing in darker Ages | 25 |

| Reasons for supposing this to have diminished after 1100 | 26 |

| Increased Knowledge of Writing in Fourteenth Century | 27 |

| Average State of Knowledge in England | 27 |

| Invention of Paper | 28 |

| Linen Paper when first used | 28 |

| Cotton Paper | 28 |

| Linen Paper as old as 1100 | 28 |

| Known to Peter of Clugni | 29 |

| And in Twelfth and Thirteenth Century | 29 |

| Paper of mixed Materials | 29 |

| Invention of Paper placed by some too low | 29 |

| Not at first very important | 30 |

| Importance of Legal Studies | 30 |

| Roman Laws never wholly unknown | 31 |

| Irnerius—his first Successors | 31 |

| Their Glosses | 31 |

| Abridgements of Law—Accursius’s Corpus Glossatum | 31 |

| Character of early Jurists | 32 |

| Decline of Jurists after Accursius | 32 |

| Respect paid to him at Bologna | 33 |

| Scholastic Jurists—Bartolus | 33 |

| Inferiority of Jurists in Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries | 34 |

| Classical Literature and Taste in dark Ages | 34 |

| Improvement in Tenth and Eleventh Centuries | 34 |

| Lanfranc and his Schools | 35 |

| Italy—Vocabulary of Papias | 36 |

| Influence of Italy upon Europe | 36 |

| Increased copying of Manuscripts | 36 |

| John of Salisbury | 36 |

| Improvement of Classical Taste in Twelfth Century | 37 |

| Influence of increased Number of Clergy | 38 |

| Decline of Classical Literature in Thirteenth Century | 38 |

| Relapse into Barbarism | 38 |

| No Improvement in Fourteenth Century—Richard of Bury | 39 |

| Library formed by Charles V. at Paris | 39 |

| Some Improvement in Italy during Thirteenth Century | 40 |

| Catholicon of Balbi | 40 |

| Imperfection of early Dictionaries | 40 |

| Restoration of Letters due to Petrarch | 40 |

| Character of his Style | 41 |

| His Latin Poetry | 41 |

| John of Ravenna | 41 |

| Gasparin of Barziza | 42 |

| CHAPTER II. |

|---|

| ON THE LITERATURE OF EUROPE FROM 1400 TO 1440. |

| Zeal for Classical Literature in Italy | 42 |

| Poggio Bracciolini | 42 |

| Latin Style of that Age indifferent | 43 |

| Gasparin of Barziza | 43 |

| Merits of his Style | 43 |

| Victorin of Feltre | 44 |

| Leonard Aretin | 44 |

| Revival of Greek Language in Italy | 44 |

| Early Greek Scholars of Europe | 44 |

| Under Charlemagne and his Successors | 45 |

| In the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries | 45 |

| In the Twelfth | 46 |

| In the Thirteenth | 46 |

| Little Appearance of it in the Fourteenth Century | 47 |

| Some Traces of Greek in Italy | 47 |

| Corruption of Greek Language itself | 47 |

| Character of Byzantine Literature | 48 |

| Petrarch and Boccace learn Greek | 48 |

| Few acquainted with the Language in their Time | 49 |

| It is taught by Chrysoloras about 1395 | 49 |

| His Disciples | 49 |

| Translations from Greek into Latin | 50 |

| Public Encouragement delayed | 51 |

| But fully accorded before 1440 | 51 |

| Emigration of learned Greeks to Italy | 52 |

| Causes of Enthusiasm for Antiquity in Italy | 52 |

| Advanced State of Society | 52 |

| Exclusive Study of Antiquity | 53 |

| Classical Learning in France low | 53 |

| Much more so in England | 53 |

| Library of Duke of Gloucester | 54 |

| Gerard Groot’s College at Deventer | 54 |

| Physical Sciences in Middle Ages | 55 |

| Arabian Numerals and Method | 55 |

| Proofs of them in Thirteenth Century | 56 |

| Mathematical Treatises | 56 |

| Roger Bacon | 57 |

| His Resemblance to Lord Bacon | 57 |

| English Mathematicians of Fourteenth Century | 57 |

| Astronomy | 58 |

| Alchemy | 58 |

| Medicine | 58 |

| Anatomy | 58 |

| Encyclopædic Works of Middle Ages | 58 |

| Vincent of Beauvais | 59 |

| Berchorius | 59 |

| Spanish Ballads | 59 |

| Metres of Spanish Poetry | 60 |

| Consonant and assonant Rhymes | 60 |

| Nature of the Glosa | 61 |

| The Cancionero General | 61 |

| Bouterwek’s Character of Spanish Songs | 61 |

| John II. | 62 |

| Poets of his Court | 62 |

| Charles, Duke of Orleans | 62 |

| English Poetry | 62 |

| Lydgate | 63 |

| James I. of Scotland | 63 |

| Restoration of Classical Learning due to Italy | 63 |

| Character of Classical Poetry lost in Middle Ages | 64 |

| New School of Criticism in Modern Languages | 64 |

| Effect of Chivalry on Poetry | 64 |

| Effect of Gallantry towards Women | 64 |

| Its probable Origin | 64 |

| It is shown in old Teutonic Poetry; but appears in the Stories of Arthur | 65 |

| Romances of Chivalry of two Kinds | 65 |

| Effect of Difference of Religion upon Poetry | 66 |

| General Tone of Romance | 66 |

| Popular Moral Fictions | 66 |

| Exclusion of Politics from Literature | 67 |

| Religious Opinions | 67 |

| Attacks on the Church | 67 |

| Three Lines of Religious Opinions in Fifteenth Century | 67 |

| Treatise de Imitatione Christi | 68 |

| Scepticism—Defences of Christianity | 69 |

| Raimond de Sebonde | 69 |

| His Views misunderstood | 69 |

| His real Object | 70 |

| Nature of his Arguments | 70 |

| CHAPTER III. |

|---|

| ON THE LITERATURE OF EUROPE FROM 1440 TO THE CLOSE OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY. |

| The year 1440 not chosen as an Epoch | 71 |

| Continual Progress of Learning | 71 |

| Nicolas V. | 71 |

| Justice due to his Character | 72 |

| Poggio on the Ruins of Rome | 72 |

| Account of the East, by Conti | 72 |

| Laurentius Valla | 72 |

| His Attack on the Court of Rome | 72 |

| His Treatise on the Latin Language | 73 |

| Its Defects | 73 |

| Heeren’s Praise of it | 73 |

| Valla’s Annotations on the New Testament | 73 |

| Fresh Arrival of Greeks in Italy | 74 |

| Platonists and Aristotelians | 74 |

| Their Controversy | 74 |

| Marsilius Ficinus | 75 |

| Invention of Printing | 75 |

| Block Books | 75 |

| Gutenberg and Costar’s Claims | 75 |

| Progress of the Invention | 76 |

| First printed Bible | 76 |

| Beauty of the Book | 77 |

| Early printed Sheets | 77 |

| Psalter of 1547—Other early Books | 77 |

| Bible of Pfister | 77 |

| Greek first taught at Paris | 78 |

| Leave unwillingly granted | 78 |

| Purbach—his Mathematical Discoveries | 78 |

| Other Mathematicians | 78 |

| Progress of Printing in Germany | 79 |

| Introduced into France | 79 |

| Caxton’s first Works | 79 |

| Printing exercised in Italy | 79 |

| Lorenzo de’ Medici | 80 |

| Italian Poetry of Fifteenth Century | 80 |

| Italian Prose of same Age | 80 |

| Giostra of Politian | 80 |

| Paul II. persecutes the Learned | 81 |

| Mathias Corvinus | 81 |

| His Library | 81 |

| Slight Signs of Literature in England | 81 |

| Paston Letters | 82 |

| Low Condition of Public Libraries | 83 |

| Rowley | 83 |

| Clotilde de Surville | 83 |

| Number of Books printed in Italy | 83 |

| First Greek printed | 84 |

| Study of Antiquities | 84 |

| Works on that Subject | 84 |

| Publications in Germany | 85 |

| In France | 85 |

| In England, by Caxton | 85 |

| In Spain | 85 |

| Translations of Scripture | 85 |

| Revival of Literature in Spain | 86 |

| Character of Labrixa | 86 |

| Library of Lorenzo | 87 |

| Classics corrected and explained | 87 |

| Character of Lorenzo | 87 |

| Prospect from his Villa at Fiesole | 87 |

| Platonic Academy | 88 |

| Disputationes Camaldulenses of Landino | 88 |

| Philosophical Dialogues | 89 |

| Paulus Cortesius | 89 |

| Schools in Germany | 89 |

| Study of Greek at Paris | 91 |

| Controversy of Realists and Nominalists | 91 |

| Scotus | 91 |

| Ockham | 92 |

| Nominalists in University of Paris | 92 |

| Low State of Learning in England | 92 |

| Mathematics | 93 |

| Regiomontanus | 93 |

| Arts of Delineation | 93 |

| Maps | 94 |

| Geography | 94 |

| Greek printed in Italy | 94 |

| Hebrew printed | 95 |

| Miscellanies of Politian | 95 |

| Their Character, by Heeren | 95 |

| His Version of Herodian | 96 |

| Cornucopia of Perotti | 96 |

| Latin Poetry of Politian | 96 |

| Italian Poetry of Lorenzo | 97 |

| Pulci | 97 |

| Character of Morgante Maggiore | 97 |

| Platonic Theology of Ficinus | 98 |

| Doctrine of Averroes on the Soul | 98 |

| Opposed by Ficinus | 99 |

| Desire of Man to explore Mysteries | 99 |

| Various Methods employed | 99 |

| Reason and Inspiration | 99 |

| Extended Inferences from Sacred Books | 99 |

| Confidence in Traditions | 100 |

| Confidence in Individuals as inspired | 100 |

| Jewish Cabbala | 100 |

| Picus of Mirandola | 101 |

| His Credulity in the Cabbala | 101 |

| His Literary Performances | 102 |

| State of Learning in Germany | 102 |

| Agricola | 103 |

| Renish Academy | 103 |

| Reuchlin | 104 |

| French Language and Poetry | 104 |

| European Drama | 104 |

| Latin | 104 |

| Orfeo of Politian | 105 |

| Origin of Dramatic Mysteries | 105 |

| Their early Stage | 105 |

| Extant English Mysteries | 105 |

| First French Theatre | 106 |

| Theatrical Machinery | 107 |

| Italian Religious Dramas | 107 |

| Moralities | 107 |

| Farces | 107 |

| Mathematical Works | 107 |

| Leo Baptista Alberti | 108 |

| Lionardo da Vinci | 108 |

| Aldine Greek Editions | 109 |

| Decline of Learning in Italy | 110 |

| Hermolaus Barbarus | 111 |

| Mantuan | 111 |

| Pontanus | 111 |

| Neapolitan Academy | 112 |

| Boiardo | 112 |

| Francesco Bello | 113 |

| Italian Poetry near the End of the Century | 113 |

| Progress of Learning in France and Germany | 113 |

| Erasmus—his Diligence | 114 |

| Budæus—his early Studies | 114 |

| Latin not well written in France | 115 |

| Dawn of Greek Learning in England | 115 |

| Erasmus comes to England | 116 |

| He publishes his Adages | 116 |

| Romantic Ballads of Spain | 116 |

| Pastoral Romances | 117 |

| Portuguese Lyric Poetry | 117 |

| German popular Books | 117 |

| Historical Works | 118 |

| Philip de Comines | 118 |

| Algebra | 118 |

| Events from 1490 to 1500 | 119 |

| Close of Fifteenth Century | 119 |

| Its Literature nearly neglected | 119 |

| Summary of its Acquisitions | 119 |

| Their Imperfection | 120 |

| Number of Books printed | 120 |

| Advantages already reaped from Printing | 120 |

| Trade of Bookselling | 121 |

| Books sold by Printers | 121 |

| Price of Books | 122 |

| Form of Books | 122 |

| Exclusive Privileges | 122 |

| Power of Universities over Bookselling | 123 |

| Restraints on Sale of Printed Books | 124 |

| Effect of Printing on the Reformation | 124 |

| CHAPTER IV. |

|---|

| ON THE LITERATURE OF EUROPE FROM 1500 TO 1520. |

| Decline of Learning in Italy | 125 |

| Press of Aldus | 125 |

| His Academy | 126 |

| Dictionary of Calepio | 126 |

| Books printed in Germany | 126 |

| First Greek Press at Paris | 126 |

| Early Studies of Melanchthon | 127 |

| Learning in England | 127 |

| Erasmus and Budæus | 128 |

| Study of Eastern Languages | 128 |

| Dramatic Works | 128 |

| Calisto and Melibœa | 128 |

| Its Character | 129 |

| Juan de la Enzina | 129 |

| Arcadia of Sanazzaro | 129 |

| Asolani of Bembo | 130 |

| Dunbar | 130 |

| Anatomy of Zerbi | 130 |

| Voyages of Cadamosto | 130 |

| Leo X., his Patronage of Letters | 131 |

| Roman Gymnasium | 131 |

| Latin Poetry | 132 |

| Italian Tragedy | 132 |

| Sophonisba of Trissino | 132 |

| Rosmunda of Rucellai | 132 |

| Comedies of Ariosto | 132 |

| Books printed in Italy | 133 |

| Cælius Rhodiginus | 133 |

| Greek printed in France and Germany | 133 |

| Greek Scholars in these Countries | 134 |

| College at Alcala and Louvain | 134 |

| Latin Style in France | 135 |

| Greek Scholars in England | 135 |

| Mode of Teaching in Schools | 136 |

| Few Classical Works printed here | 137 |

| State of Learning in Scotland | 137 |

| Utopia of More | 137 |

| Inconsistency in his Opinions | 138 |

| Learning restored in France | 138 |

| Jealousy of Erasmus and Budæus | 138 |

| Character of Erasmus | 139 |

| His Adages severe on Kings | 139 |

| Instances in illustration | 140 |

| His Greek Testament | 142 |

| Patrons of Letters in Germany | 142 |

| Resistance to Learning | 143 |

| Unpopularity of the Monks | 145 |

| The Book excites Odium | 145 |

| Erasmus attacks the Monks | 145 |

| Their Contention with Reuchlin | 145 |

| Origin of the Reformation | 146 |

| Popularity of Luther | 147 |

| Simultaneous Reform by Zwingle | 147 |

| Reformation prepared beforehand | 147 |

| Dangerous Tenets of Luther | 148 |

| Real Explanation of them | 149 |

| Orlando Furioso | 150 |

| Its Popularity | 150 |

| Want of Seriousness | 150 |

| A Continuation of Boiardo | 150 |

| In some Points inferior | 151 |

| Beauties of its Style | 151 |

| Accompanied with Faults | 151 |

| Its Place as a Poem | 152 |

| Amadis de Gaul | 152 |

| Gringore | 152 |

| Hans Sachs | 152 |

| Stephen Hawes | 153 |

| Change in English Language | 153 |

| Skelton | 154 |

| Oriental Languages | 154 |

| Pomponatius | 155 |

| Raymond Lully | 155 |

| His Method | 155 |

| Peter Martyr’s Epistles | 156 |

| CHAPTER V. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF ANCIENT LITERATURE IN EUROPE FROM 1520 TO 1550. |

| Superiority of Italy in Taste | 157 |

| Admiration of Antiquity | 158 |

| Sadolet | 158 |

| Bembo | 159 |

| Ciceronianus of Erasmus | 159 |

| Scaliger’s Invective against it | 160 |

| Editions of Cicero | 160 |

| Alexander ab Alexandro | 160 |

| Works on Roman Antiquities | 161 |

| Greek less Studied in Italy | 161 |

| Schools of Classical Learning | 161 |

| Budæus—his Commentaries on Greek | 161 |

| Their Character | 162 |

| Greek Grammars and Lexicons | 162 |

| Editions of Greek Authors | 163 |

| Latin Thesaurus of R. Stephens | 163 |

| Progress of Learning in France | 164 |

| Learning in Spain | 165 |

| Effects of Reformation on Learning | 165 |

| Sturm’s Account of German Schools | 165 |

| Learning in Germany | 166 |

| In England—Linacre | 166 |

| Lectures in the Universities | 166 |

| Greek perhaps Taught to Boys | 167 |

| Teaching of Smith at Cambridge | 167 |

| Succeeded by Cheke | 168 |

| Ascham’s Character of Cambridge | 168 |

| Wood’s Account of Oxford | 168 |

| Education of Edward and his Sisters | 169 |

| The Progress of Learning is still slow | 169 |

| Want of Books and Public Libraries | 169 |

| Destruction of Monasteries no Injury to Learning | 169 |

| Ravisius Textor | 170 |

| Conrad Gesner | 170 |

| CHAPTER VI. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF THEOLOGICAL LITERATURE IN EUROPE FROM 1520 TO 1550. |

| Progress of the Reformation | 171 |

| Interference of Civil Power | 171 |

| Excitement of Revolutionary Spirit | 172 |

| Growth of Fanaticism | 172 |

| Differences of Luther and Zwingle | 172 |

| Confession of Augsburg | 173 |

| Conduct of Erasmus | 173 |

| Estimate of it | 174 |

| His Controversy with Luther | 174 |

| Character of his Epistles | 176 |

| His Alienation from the Reformers increases | 176 |

| Appeal of the Reformers to the Ignorant | 176 |

| Parallel of those Times with the Present | 177 |

| Calvin | 177 |

| His Institutes | 177 |

| Increased Differences among Reformers | 178 |

| Reformed Tenets spread in England | 178 |

| In Italy | 178 |

| Italian Heterodoxy | 179 |

| Its Progress in the Literary Classes | 180 |

| Servetus | 180 |

| Arianism in Italy | 181 |

| Protestants in Spain and Low Countries | 181 |

| Order of Jesuits | 181 |

| Their Popularity | 181 |

| Council of Trent | 182 |

| Its Chief Difficulties | 182 |

| Character of Luther | 182 |

| Theological Writings—Erasmus | 183 |

| Melanchthon—Romish Writers | 183 |

| This Literature nearly forgotten | 184 |

| Sermons | 184 |

| Spirit of the Reformation | 184 |

| Limits of Private Judgment | 185 |

| Passions instrumental in Reformation | 185 |

| Establishment of new Dogmatism | 186 |

| Editions of Scripture | 186 |

| Translations of Scripture | 186 |

| In English | 187 |

| In Italy and Low Countries | 187 |

| Latin Translations | 187 |

| French Translations | 188 |

| CHAPTER VII. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF SPECULATIVE, MORAL, AND POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY, AND OF JURISPRUDENCE, IN

EUROPE, FROM 1520 TO 1550. |

| Logic included under this head | 188 |

| Slow Defeat of Scholastic Philosophy | 188 |

| It is sustained by the Universities and Regulars | 188 |

| Commentators on Aristotle | 188 |

| Attack of Vives on Scholastics | 189 |

| Contempt of them in England | 189 |

| Veneration for Aristotle | 189 |

| Melanchthon countenances him | 189 |

| His own Philosophical Treatises | 190 |

| Aristotelians of Italy | 190 |

| University of Paris | 190 |

| New Logic of Ramus | 190 |

| It meets with unfair treatment | 191 |

| Its Merits and Character | 191 |

| Buhle’s account of it | 191 |

| Paracelsus | 191 |

| His Impostures | 192 |

| And Extravagancies | 192 |

| Cornelius Agrippa | 192 |

| His pretended Philosophy | 193 |

| His Sceptical Treatise | 193 |

| Cardan | 193 |

| Influence of Moral Writers | 194 |

| Cortegiano of Castiglione | 194 |

| Marco Aurelio of Guevara | 194 |

| His Menosprecio di Corte | 194 |

| Perez d’Oliva | 195 |

| Ethical Writings of Erasmus and Melanchthon | 195 |

| Sir T. Elyot’s Governor | 195 |

| Severity of Education | 196 |

| He seems to avoid Politics | 196 |

| Nicholas Machiavel | 196 |

| His motives in writing the Prince | 197 |

| Some of his Rules not immoral | 197 |

| But many dangerous | 197 |

| Its only Palliation | 198 |

| His Discourses on Livy | 198 |

| Their leading Principles | 198 |

| Their Use and Influence | 199 |

| His History of Florence | 199 |

| Treatises on Venetian Government | 199 |

| Calvin’s Political Principles | 199 |

| Jurisprudence confined to Roman Law | 200 |

| The Laws not well arranged | 200 |

| Adoption of the entire System | 200 |

| Utility of General Learning to Lawyers | 200 |

| Alciati—his Reform of Law | 201 |

| Opposition to him | 201 |

| Agustino | 201 |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF THE LITERATURE OF TASTE IN EUROPE FROM 1520 TO 1550. |

| Poetry of Bembo | 201 |

| Its Beauties and Defects | 202 |

| Character of Italian Poetry | 202 |

| Alamanni | 202 |

| Vittoria Colonna | 202 |

| Satires of Ariosto and Alamanni | 203 |

| Alamanni | 203 |

| Rucellai | 203 |

| Trissino | 203 |

| Berni | 203 |

| Spanish Poets | 204 |

| Boscan and Garcilasso | 204 |

| Mendoza | 204 |

| Saa di Miranda | 205 |

| Ribeyro | 205 |

| French Poetry | 205 |

| Marot | 206 |

| Its Metrical Structure | 206 |

| German Poetry | 206 |

| Hans Sachs | 206 |

| German Hymn | 206 |

| Theuerdanks of Pfintzing | 206 |

| English Poetry—Lyndsay | 206 |

| Wyatt and Surrey | 207 |

| Dr. Nott’s Character of them | 207 |

| Perhaps rather exaggerated | 208 |

| Surrey improves our versification | 208 |

| Introduces Blank Verse | 208 |

| Dr. Nott’s Hypothesis as to his Metre | 208 |

| It seems too extensive | 209 |

| Politeness of Wyatt and Surrey | 209 |

| Latin Poetry | 210 |

| Sannazarius | 210 |

| Vida | 210 |

| Fracastorius | 210 |

| Latin Verse not to be disdained | 210 |

| Other Latin Poets in Italy | 211 |

| In Germany | 211 |

| Italian Comedy | 211 |

| Machiavel | 211 |

| Aretin | 211 |

| Tragedy | 212 |

| Sperone | 212 |

| Cinthio | 212 |

| Spanish Drama | 212 |

| Torres Naharro | 212 |

| Lope de Rueda | 212 |

| Gil Vicente | 213 |

| Mysteries and Moralities in France | 213 |

| German Theatre—Hans Sachs | 213 |

| Moralities and Similar Plays in England | 214 |

| They are turned to religious Satire | 214 |

| Latin Plays | 214 |

| First English Comedy | 215 |

| Romances of Chivalry | 215 |

| Novels | 215 |

| Rabelais | 216 |

| Contest of Latin and Italian Languages | 216 |

| Influence of Bembo in this | 217 |

| Apology for Latinists | 217 |

| Character of the Controversy | 217 |

| Life of Bembo | 217 |

| Character of Italian and Spanish Style | 218 |

| English Writers | 218 |

| More | 218 |

| Ascham | 218 |

| Italian Criticism | 218 |

| Bembo | 218 |

| Grammarians and Critics in France | 219 |

| Orthography of Meigret | 219 |

| Cox’s Art of Rhetoric | 219 |

| CHAPTER IX. |

|---|

| ON THE SCIENTIFIC AND MISCELLANEOUS LITERATURE OF EUROPE FROM 1520 TO 1550. |

| Geometrical Treatises | 220 |

| Fernel Rhœticus | 220 |

| Cardan and Tartaglia | 220 |

| Cubic Equations | 220 |

| Beauty of the Discovery | 221 |

| Cardan’s other Discoveries | 221 |

| Imperfections of Algebraic Language | 222 |

| Copernicus | 222 |

| Revival of Greek Medicine | 223 |

| Linacre and other Physicians | 223 |

| Medical Innovators | 224 |

| Paracelsus | 224 |

| Anatomy | 224 |

| Berenger | 224 |

| Vesalius | 224 |

| Portal’s Account of him | 225 |

| His Human Dissections | 225 |

| Fate of Vesalius | 225 |

| Other Anatomists | 225 |

| Imperfection of the Science | 225 |

| Botany—Botanical Gardens | 226 |

| Ruel | 226 |

| Fuchs | 226 |

| Matthioli | 226 |

| Low State of Zoology | 226 |

| Agricola | 227 |

| Hebrew | 227 |

| Elias Levita—Pellican | 227 |

| Arabic and Oriental Literature | 227 |

| Geography of Grynæus | 228 |

| Apianus | 228 |

| Munster | 228 |

| Voyages | 228 |

| Oviedo | 228 |

| Historical Works | 228 |

| Italian Academies | 229 |

| They pay regard to the Language | 229 |

| Their fondness for Petrarch | 229 |

| They become numerous | 229 |

| Their Distinctions | 230 |

| Evils connected with them | 230 |

| They succeed less in Germany | 230 |

| Libraries | 230 |

| CHAPTER X. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF ANCIENT LITERATURE IN EUROPE FROM 1550 TO 1600. |

| Progress of Philology | 231 |

| First Editions of Classics | 231 |

| Change in Character of Learning | 232 |

| Cultivation of Greek | 232 |

| Principal Scholars—Turnebus | 232 |

| Petrus Victorius | 233 |

| Muretus | 233 |

| Gruter’s Thesaurus Criticus | 234 |

| Editions of Greek and Latin Authors | 235 |

| Tacitus of Lipsius | 235 |

| Horace of Lambinus | 235 |

| Of Cruquius | 236 |

| Henry Stephens | 236 |

| Lexicon of Constantin | 237 |

| Thesaurus of Stephens | 237 |

| Abridged by Scapula | 238 |

| Hellenismus of Caninius | 239 |

| Vergara’s Grammar | 239 |

| Grammars of Ramus and Sylburgius | 239 |

| Camerarius—Canter—Robortellus | 240 |

| Editions by Sylburgius | 241 |

| Neander | 241 |

| Gesner | 241 |

| Decline of Taste in Germany | 242 |

| German Learning | 242 |

| Greek Verses of Rhodomanu | 242 |

| Learning Declines | 243 |

| Except in Catholic Germany | 243 |

| Philological Works of Stephens | 243 |

| Style of Lipsius | 244 |

| Minerva of Sanctius | 244 |

| Orations of Muretus | 244 |

| Panegyric of Ruhnkenius | 244 |

| Defects of his Style | 245 |

| Epistles of Manutius | 245 |

| Care of the Italian Latinists | 245 |

| Perpinianus—Osorius—Maphœus | 246 |

| Buchanan—Haddon | 246 |

| Sigonius, De Consolatione | 246 |

| Decline of Taste and Learning in Italy | 247 |

| Joseph Scaliger | 247 |

| Isaac Casaubon | 248 |

| General Result | 249 |

| Learning in England under Edward and Mary | 249 |

| Revival under Elizabeth | 249 |

| Greek Lectures at Cambridge | 250 |

| Few Greek Editions in England | 250 |

| School Books enumerated | 250 |

| Greek taught in Schools | 251 |

| Greek better known after 1580 | 251 |

| Editions of Greek | 252 |

| And of Latin Classics | 252 |

| Learning lower than in Spain | 252 |

| Improvement at the End of the Century. | 253 |

| Learning in Scotland | 253 |

| Latin little used in Writing | 253 |

| Early Works on Antiquities | 254 |

| P. Manutius on Roman Laws | 254 |

| Manutius, De Civitate | 254 |

| Panvinius—Sigonius | 255 |

| Gruchius | 255 |

| Sigonius on Athenian Polity | 256 |

| Patrizzi and Lipsius on Roman Militia | 256 |

| Lipsius and other Antiquaries | 256 |

| Saville on Roman Militia | 257 |

| Numismatics | 257 |

| Mythology | 257 |

| Scaliger’s Chronology | 258 |

| Julian Period | 258 |

| CHAPTER XI. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF THEOLOGICAL LITERATURE IN EUROPE FROM 1550 TO 1600. |

| Diet of Augsburg in 1555 | 259 |

| Progress of Protestantism | 259 |

| Its Causes | 260 |

| Wavering of Catholic Princes | 260 |

| Extinguished in Italy and Spain | 260 |

| Reaction of Catholicity | 260 |

| Especially in Germany | 261 |

| Discipline of the Clergy | 261 |

| Influence of Jesuits | 261 |

| Their Progress | 262 |

| Their Colleges | 262 |

| Jesuit Seminary at Rome | 262 |

| Patronage of Gregory XIII. | 262 |

| Conversions in Germany and France | 263 |

| Causes of this Reaction | 263 |

| A rigid Party in the Church | 264 |

| Its Efforts at Trent | 264 |

| No Compromise in Doctrine | 265 |

| Consultation of Cassander | 265 |

| Bigotry of Protestant Churches | 266 |

| Tenets of Melanchthon | 266 |

| A Party hostile to him | 267 |

| Form of Concord, 1576 | 267 |

| Controversy raised by Baius | 267 |

| Treatise of Molina on Free will | 268 |

| Protestant Tenets | 268 |

| Trinitarian Controversy | 268 |

| Religious Intolerance | 270 |

| Castalio | 270 |

| Answered by Beza | 271 |

| Aconcio | 271 |

| Minus Celsus, Koornhert | 271 |

| Decline of Protestantism | 272 |

| Desertion of Lipsius | 272 |

| Jewell’s Apology | 272 |

| English Theologians | 272 |

| Bellarmin | 273 |

| Topics of Controversy changed | 273 |

| It turns on Papal Power | 274 |

| This upheld by the Jesuits | 274 |

| Claim to depose Princes | 274 |

| Bull against Elizabeth | 274 |

| And Henry IV. | 275 |

| Deposing Power owned in Spain | 275 |

| Asserted by Bellarmin | 275 |

| Methods of Theological Doctrine | 275 |

| Loci Communes | 275 |

| In the Protestant and Catholic Church | 276 |

| Catharin | 276 |

| Critical and Expository Writings | 276 |

| Ecclesiastical Historians | 277 |

| Le Clerc’s Character of them | 277 |

| Deistical Writers | 277 |

| Wierus, De Præstigiis | 278 |

| Scot on Witchcraft | 278 |

| Authenticity of Vulgate | 278 |

| Latin Versions and Editions by Catholics | 278 |

| By Protestants | 279 |

| Versions into Modern Languages | 279 |

| CHAPTER XII. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF SPECULATIVE PHILOSOPHY FROM 1550 TO 1600. |

| Predominance of Aristotelian Philosophy | 279 |

| Scholastic and genuine Aristotelians | 280 |

| The former class little remembered | 280 |

| The others not much better known | 280 |

| Schools of Pisa and Padua | 280 |

| Cesalpini | 280 |

| Sketch of his System | 280 |

| Cremonini | 281 |

| Opponents of Aristotle | 281 |

| Patrizzi | 281 |

| System of Telesio | 281 |

| Jordano Bruno | 282 |

| His Italian Works—Cena de li Ceneri | 282 |

| Della Causa, Principio ed Uno | 282 |

| Pantheism of Bruno | 283 |

| Bruno’s other Writings | 284 |

| General Character of his Philosophy | 285 |

| Sceptical Theory of Sanchez | 286 |

| Logic of Aconcio | 286 |

| Nizolius on the Principles of Philosophy | 286 |

| Margarita Antoniana of Pereira | 287 |

| Logic of Ramus—its Success | 288 |

| CHAPTER XIII. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF MORAL AND POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY AND OF JURISPRUDENCE FROM 1550 TO 1600. |

| Soto, De Justitia | 289 |

| Hooker | 290 |

| His Theory of Natural Law | 290 |

| Doubts felt by others | 290 |

| Essays of Montaigne | 290 |

| Their Characteristics | 290 |

| Writers on Morals in Italy | 293 |

| In England | 293 |

| Bacon’s Essays | 293 |

| Number of Political Writers | 294 |

| Oppression of Governments | 294 |

| And Spirit generated by it | 294 |

| Derived from Classic History | 294 |

| From their own and the Jewish | 294 |

| Franco Gallia of Hossoman | 295 |

| Vindiciæ of Languet | 295 |

| Contr’Un of Boetie | 295 |

| Buchanan, De Jure Regni | 296 |

| Poynet, on Politique Power | 296 |

| Its liberal Theory | 296 |

| Argues for Tyrannicide | 297 |

| The Tenets of Parties swayed by Circumstances | 297 |

| Similar Tenets among the Leaguers | 298 |

| Rose on the Authority of Christian States over Kings | 298 |

| Treatise of Boucher in the same Spirit | 299 |

| Answered by Barclay | 299 |

| The Jesuits adopt these Tenets | 299 |

| Mariana, De Rege | 299 |

| Popular Theories in England | 300 |

| Hooker | 300 |

| Political Memoirs | 301 |

| La Noue | 301 |

| Lipsius | 301 |

| Botero | 301 |

| His Remarks on Population | 301 |

| Paruta | 302 |

| Bodin | 302 |

| Analysis of his Treatise called the Republic | 302 |

| Authority of Heads of Families | 302 |

| Domestic Servitude | 303 |

| Origin of Commonwealths | 303 |

| Privileges of Citizens | 303 |

| Nature of Sovereign Power | 304 |

| Forms of Government | 304 |

| Despotism and Monarchy | 304 |

| Aristocracy | 305 |

| Senates and Councils of State | 305 |

| Duties of Magistrates | 305 |

| Corporations | 305 |

| Slaves, part of the State | 305 |

| Rise and Fall of States | 306 |

| Causes of Revolution | 306 |

| Astrological Fancies of Bodin | 306 |

| Danger of sudden Changes | 307 |

| Judicial Power of the Sovereign | 307 |

| Toleration of Religions | 307 |

| Influence of Climate on Government | 307 |

| Means of obviating Inequality | 308 |

| Confiscations—Rewards | 308 |

| Fortresses | 308 |

| Necessity of Good Faith | 309 |

| Census of Property | 309 |

| Public Revenues | 309 |

| Taxation | 309 |

| Adulteration of Coin | 310 |

| Superiority of Monarchy | 310 |

| Conclusion of the Work | 310 |

| Bodin compared with Aristotle and Machiavel | 310 |

| And with Montesquieu | 310 |

| Golden Age of Jurisprudence | 311 |

| Cujacius | 311 |

| Eulogies bestowed upon him | 311 |

| Cujacius, an Interpreter of Law rather than a Lawyer | 312 |

| French Lawyers below Cujacius—Govca and others | 312 |

| Opponents of the Roman Law | 313 |

| Faber of Savoy | 313 |

| Anti-Tribonianus of Hottoman | 313 |

| Civil Law not countenanced in France | 314 |

| Turamini | 314 |

| Cau Law | 314 |

| Law of Nations; its early State | 314 |

| Francis a Victoria | 314 |

| His Opinions on Public Law | 315 |

| Ayala, on the Rights of War | 315 |

| Albericus Gentilis on Embassies | 316 |

| His Treatise on the Rights of War | 317 |

| CHAPTER XIV. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF POETRY FROM 1550 TO 1600. |

| General Character of Italian Poets in this Age | 318 |

| Their usual Faults | 318 |

| Their Beauties | 318 |

| Character given by Muratori | 318 |

| Poetry of Casa | 318 |

| Of Costanzo | 319 |

| Baldi | 319 |

| Caro | 319 |

| Odes of Celio Magus | 319 |

| Coldness of the Amatory Sonnets | 320 |

| Studied Imitation of Petrarch | 320 |

| Their Fondness for Description | 320 |

| Judgment of Italian Critics | 320 |

| Bernardino Rota | 320 |

| Gaspara Stampa; her Love for Collalto | 321 |

| Is ill-requited | 322 |

| Her Second Love | 322 |

| Style of Gaspara Stampa | 322 |

| La Nautica of Baldi | 322 |

| Amadigi of Bernardo Tasso | 323 |

| Satirical and burlesque Poetry; Aretin | 323 |

| Other burlesque Writers | 324 |

| Attempts at Latin Metres | 324 |

| Poetical Translations | 324 |

| Torquato Tasso | 324 |

| The Jerusalem excellent in Choice of Subject | 324 |

| Superior to Homer and Virgil in some Points | 324 |

| Its Characters | 325 |

| Excellence of its Style | 325 |

| Some Faults in it | 325 |

| Defects of the Poem | 326 |

| It indicates the peculiar Genius of Tasso | 326 |

| Tasso compared to Virgil | 326 |

| To Ariosto | 326 |

| To the Bolognese Painters | 327 |

| Poetry Cultivated under Charles and Philip | 327 |

| Luis de Leon | 328 |

| Herrera | 328 |

| General Tone of Castilian Poetry | 329 |

| Castillejo | 329 |

| Araucana of Ercilla | 329 |

| Many epic Poems in Spain | 329 |

| Camœns | 330 |

| Defects of the Lusiad | 330 |

| Its Excellencies | 330 |

| Mickle’s Translation | 330 |

| Celebrated Passage in the Lusiad | 331 |

| Minor Poems of Camœns | 331 |

| Ferreira | 331 |

| Spanish Ballads | 331 |

| French Poets numerous | 332 |

| Change in the Tone of French Poetry | 333 |

| Ronsard | 333 |

| Other French Poets | 334 |

| Du Bartas | 334 |

| Pibrac; Desportes | 335 |

| French Metre and Versification | 335 |

| General character of French Poetry | 335 |

| German Poetry | 336 |

| Paradise of Dainty Devices | 336 |

| Character of this Collection | 336 |

| Sackville’s Induction | 336 |

| Inferiority of Poets in early years of Elizabeth | 337 |

| Gascoyne | 337 |

| Spenser’s Shepherd’s Kalendar | 337 |

| Sydney’s Character of Contemporary Poets | 338 |

| Improvement soon after this Time | 338 |

| Relaxation of Moral Austerity | 339 |

| Serious Poetry | 339 |

| Poetry of Sydney | 339 |

| Epithalanium of Spenser | 340 |

| Poems of Shakspeare | 340 |

| Daniel and Drayton | 340 |

| Nosce Teipsum of Davies | 340 |

| Satires of Hall, Marston, and Donne | 341 |

| Modulation of English Verse | 341 |

| Translations of Homer by Chapman | 341 |

| Of Tasso by Fairfax | 342 |

| Employment of Ancient Measures | 342 |

| Number of Poets in this Age | 342 |

| Scots and English Ballads | 343 |

| The Faery Queen | 343 |

| Superiority of the First Book | 343 |

| The succeeding Books | 344 |

| Spenser’s Sense of Beauty | 344 |

| Compared to Ariosto | 344 |

| Style of Spenser | 345 |

| Inferiority of the latter Books | 345 |

| Allegories of the Faery Queen | 346 |

| Blemishes in the Diction | 346 |

| Admiration of the Faery Queen | 346 |

| General Parallel of Italian and English Poetry | 347 |

| Decline of Latin Poetry in Italy | 347 |

| Compensated in other Countries | 347 |

| Lotichius | 347 |

| Collections of Latin Poetry by Gruter | 348 |

| Characters of some Gallo-Latin Poets | 348 |

| Sammarthanus | 349 |

| Belgic Poets | 349 |

| Scots Poets—Buchanan | 349 |

| CHAPTER XV. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF DRAMATIC LITERATURE FROM 1550 TO 1600. |

| Italian Tragedy | 350 |

| Pastoral Drama | 351 |

| Aminta of Tasso | 351 |

| Pastor Fido of Guarini | 352 |

| Italian Opera | 352 |

| The National Taste revives in the Spanish Drama | 353 |

| Lope de Vega | 353 |

| His Extraordinary Fertility | 353 |

| His Versification | 354 |

| His Popularity | 354 |

| Character of his Comedies | 354 |

| Tragedy of Don Sancho Ortiz | 355 |

| His Spiritual Plays | 356 |

| Numancia of Cervantes | 356 |

| French Theatre—Jodelle | 357 |

| Garnier | 357 |

| Comedies of Larivey | 358 |

| Theatres in Paris | 358 |

| English Stage | 359 |

| Gammar Gurton’s Needle | 359 |

| Gorboduc of Sackville | 359 |

| Preference given to the Irregular Form | 359 |

| First Theatres | 360 |

| Plays of Whetstone and Others | 360 |

| Marlowe and his Contemporaries | 360 |

| Tamburlaine | 361 |

| Blank Verse of Marlowe | 361 |

| Marlowe’s Jew of Malta | 361 |

| And Faustus | 361 |

| His Edward II. | 361 |

| Plays whence Henry VI. was taken | 361 |

| Peele | 362 |

| Greene | 362 |

| Other Writers of this Age | 363 |

| Heywood’s Woman Killed with Kindness | 363 |

| William Shakspeare | 364 |

| His First Writings for the Stage | 364 |

| Comedy of Errors | 365 |

| Love’s Labour Lost | 365 |

| Taming of the Shrew | 365 |

| Midsummer Night’s Dream | 365 |

| Its Machinery | 366 |

| Its Language | 366 |

| Romeo and Juliet | 366 |

| Its Plot | 367 |

| Its Beauties and Blemishes | 367 |

| The Characters | 367 |

| The Language | 367 |

| Second Period of Shakspeare | 368 |

| The Historical Plays | 368 |

| Merchant of Venice | 368 |

| As You Like It | 369 |

| Jonson’s Every Man in his Humour | 369 |

| CHAPTER XVI. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF POLITE LITERATURE IN PROSE FROM 1550 TO 1600. |

| Italian Writers | 369 |

| Casa | 369 |

| Tasso | 370 |

| Firenzuola | 370 |

| Character of Italian Prose | 370 |

| Italian Letter Writers | 370 |

| Davanzati’s Tacitus | 371 |

| Jordano Bruno | 371 |

| French Writers—Amyot | 371 |

| Montaigne; Du Vair | 371 |

| Satire Menippée | 372 |

| English Writers | 372 |

| Ascham | 372 |

| Euphues of Lilly | 373 |

| Its Popularity | 373 |

| Sydney’s Arcadia | 374 |

| His Defence of Poesie | 374 |

| Hooker | 374 |

| Character of Elizabethan Writers | 374 |

| State of Criticism | 375 |

| Scaliger’s Poetics | 375 |

| His Preference of Virgil to Homer | 375 |

| His Critique on Modern Latin Poets | 376 |

| Critical Influence of the Academics | 376 |

| Dispute of Caro and Castelvetro | 377 |

| Castelvetro on Aristotle’s Poetics | 377 |

| Severity of Castelvetro’s Criticism | 377 |

| Ercolano of Varchi | 378 |

| Controversy about Dante | 378 |

| Academy of Florence | 378 |

| Salviati’s Attack on Tasso | 379 |

| Pinciano’s Art of Poetry | 379 |

| French Treatises of Criticism | 379 |

| Wilson’s Art of Rhetorique | 379 |

| Gascoyne; Webbe | 380 |

| Puttenham’s Art of Poesie | 380 |

| Sydney’s Defence of Poesy | 380 |

| Novels of Bandello | 380 |

| Of Cinthio | 381 |

| Of the Queen of Navarre | 381 |

| Spanish Romances of Chivalry | 381 |

| Diana of Monte-Mayor | 382 |

| Novels in the Picaresque Style | 382 |

| Guzman d’Alfarache | 382 |

| Las Guerras de Granada | 383 |

| Sydney’s Arcadia | 383 |

| Its Character | 383 |

| Inferiority of other English Fictions | 384 |

| CHAPTER XVII. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF PHYSICAL AND MISCELLANEOUS LITERATURE FROM 1500 TO 1600. |

| Tartaglia and Cardan | 385 |

| Algebra of Pelletier | 385 |

| Record’s Whetstone of Wit | 385 |

| Vieta | 385 |

| His Discoveries | 386 |

| Geometers of this Period | 388 |

| Joachim Rhœticus | 388 |

| Copernican Theory | 388 |

| Tycho Brahe | 389 |

| His System | 389 |

| Gregorian Calendar | 390 |

| Optics | 390 |

| Mechanics | 390 |

| Statics of Stevinus | 391 |

| Hydrostatics | 392 |

| Gilbert on the Magnet | 392 |

| Gesner’s Zoology | 392 |

| Its Character by Cuvier | 392 |

| Gesner’s Arrangement | 393 |

| His Additions to known Quadrupeds | 393 |

| Belon | 394 |

| Salviani and Rondelet’s Ichthyology | 394 |

| Aldrovandus | 394 |

| Botany—Turner | 395 |

| Maranta—Botanical Gardens | 395 |

| Gesner | 396 |

| Dodœns | 396 |

| Lobel | 396 |

| Clusius | 396 |

| Cæsalpin | 396 |

| Dalechamps—Bauhin | 397 |

| Gerard’s Herbal | 397 |

| Anatomy—Fallopius | 397 |

| Eustachius | 397 |

| Coiter | 398 |

| Columbus | 398 |

| Circulation of the Blood | 398 |

| Medicinal Science | 398 |

| Syriac Version of New Testament | 399 |

| Hebrew Critics | 399 |

| Its Study in England | 399 |

| Arabic begins to be Studied | 399 |

| Collection of Voyages by Ramusio | 400 |

| Curiosity they awakened | 400 |

| Other Voyages | 401 |

| Accounts of China | 401 |

| India and Russia | 401 |

| English Discoveries in the Northern Seas | 401 |

| Geographical Books—Ortelius | 401 |

| Guicciardini | 402 |

| French Memoirs | 403 |

| Universities in Italy | 403 |

| In other Countries | 403 |

| Libraries | 403 |

| Collections of Antiquities in Italy | 404 |

| Pinelli | 404 |

| Italian Academies | 405 |

| Society of Antiquaries in England | 405 |

| New Books and Catalogues of them | 406 |

| Literary Correspondence | 406 |

| Bibliographical Works | 406 |

| Restraints on the Press | 407 |

| Index Expurgatorius | 407 |

| Its Effects | 407 |

| Restrictions in England | 407 |

| Latin more employed on this account | 408 |

| Influence of Literature | 408 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF ANCIENT LITERATURE IN EUROPE FROM 1600 TO 1650. |

| Learning of 17th Century less Philological | 409 |

| Popularity of Comenius | 409 |

| Decline of Greek Learning | 410 |

| Casaubon | 410 |

| Viger de Idiotismis | 411 |

| Weller’s Greek Grammar | 411 |

| Labbe and Others | 411 |

| Salmasius de Lingua Hellenistica | 412 |

| Greek Editions—Savile’s Chrysostom | 412 |

| Greek Learning in England | 413 |

| Latin Editions—Torrentius | 413 |

| Gruter | 413 |

| Heinsius | 413 |

| Grotius | 414 |

| Rutgersius—Reinesius—Barthius | 414 |

| Other Critics—English | 414 |

| Salmasius | 415 |

| Good Writers of Latin | 415 |

| Scioppius | 416 |

| His Philosophical Grammar | 416 |

| His Infamia Famiani | 416 |

| Judicium de Stylo Historico | 416 |

| Gerard Vossius, de Vitiis Sermonis | 417 |

| His Aristarchus | 417 |

| Progress of Latin Style | 418 |

| Gruter’s Collection of Inscriptions | 418 |

| Assisted by Scaliger | 419 |

| Works on Roman Antiquity | 419 |

| Geography of Cluversius | 420 |

| Meursius | 420 |

| Ubbo Emmius | 420 |

| Chronology of Lydiat—Calvisius | 420 |

| Petavius | 421 |

| Character of this Work | 421 |

| CHAPTER XIX. |

|---|

| HISTORY Of THEOLOGICAL LITERATURE IN EUROPE FROM 1600 TO 1650. |

| Temporal Supremacy of Rome | 422 |

| Contest with Venice | 423 |

| Father Paul Sarpi | 423 |

| History of Council of Trent | 424 |

| Gallican Liberties—Richter | 424 |

| Perron | 425 |

| Decline of Papal Power | 425 |

| Unpopularity of the Jesuits | 426 |

| Richelieu’s Care of Gallican Liberties | 426 |

| Controversy of Catholics and Protestants | 426 |

| Increased respect for the Fathers | 426 |

| Especially in England—Laud | 427 |

| Defections to the Catholic Church | 427 |

| Wavering of Casaubon | 428 |

| And of Grotius | 429 |

| Calixtus | 434 |

| His Attempts at Concord | 434 |

| High Church Party in England | 435 |

| Daillé on the Right Use of the Fathers | 435 |

| Chillingworth’s Religion of Protestants | 436 |

| Character of this Work | 436 |

| Hales on Schism | 438 |

| Controversies on Grace and Free will—Augustinian Scheme | 438 |

| Semi-pelagian Hypothesis | 439 |

| Tenets of the Reformers | 439 |

| Rise of Arminianism | 440 |

| Episcopius | 440 |

| His Writings | 440 |

| Their Spirit and Tendency | 440 |

| Great Latitude allowed by them | 441 |

| Progress of Arminianism | 441 |

| Cameron | 441 |

| Rise of Jansenism | 441 |

| Socinus—Volkelius | 442 |

| Crellius—Ruarus | 442 |

| Erastianism maintained by Hooker | 443 |

| And Grotius | 444 |

| His Treatise on Ecclesiastical Power of the State | 444 |

| Remark upon this Theory | 446 |

| Toleration of Religious Tenets | 446 |

| Claimed by the Arminians | 446 |

| By the Independents | 447 |

| And by Jeremy Taylor | 447 |

| His Liberty of Prophesying | 447 |

| Boldness of his Doctrines | 447 |

| His Notions of Uncertainty in Theological Tenets | 448 |

| His low Opinion of the Fathers | 448 |

| Difficulty of Finding out Truth | 449 |

| Grounds of Toleration | 449 |

| Inconsistency of One Chapter | 450 |

| His General Defence of Toleration | 450 |

| Effect of this Treatise | 451 |

| Its Defects | 451 |

| Great Erudition of this Period | 452 |

| Usher—Petavius | 452 |

| Sacred Criticism | 452 |

| Grotius—Coccejus | 452 |

| English Commentators | 453 |

| Style of Preaching | 453 |

| English Sermons | 453 |

| Of Donne | 454 |

| Of Jeremy Taylor | 454 |

| Devotional Writings of Taylor and Hall | 454 |

| In the Roman | 455 |

| And Lutheran Church | 455 |

| Infidelity of some Writers—Charron—Vanini | 455 |

| Lord Herbert of Cherbury | 456 |

| Grotius de Veritate | 457 |

| English Translation of the Bible | 457 |

| Its Style | 457 |

| CHAPTER XX. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF SPECULATIVE PHILOSOPHY FROM 1600 TO 1650. |

| Subjects of this Chapter | 458 |

| Aristotelians and Ramists | 458 |

| No improvement till near the End of the Century | 459 |

| Methods of the Universities | 459 |

| Scholastic Writers | 459 |

| Treatises on Logic | 460 |

| Campanella | 460 |

| His Theory taken from Telesio | 460 |

| Notion of Universal Sensibility | 461 |

| His Imagination and Eloquence | 461 |

| His Works Published by Admai | 462 |

| Basson | 463 |

| Berigard | 463 |

| Magnen | 463 |

| Paracelsists | 463 |

| And Theosophists | 463 |

| Fludd | 464 |

| Jacob Behmen | 464 |

| Lord Herbert de Veritate | 464 |

| His Axioms | 465 |

| Conditions of Truth | 465 |

| Instinctive Truths | 466 |

| Internal Perceptions | 466 |

| Five Notions of Natural Religion | 466 |

| Remarks of Gassendi on Herbert | 467 |

| Gassendi’s Defence of Epicurus | 468 |

| His chief Works after 1650 | 468 |

| Preparation for the Philosophy of Lord Bacon | 468 |

| His Plan of Philosophy | 468 |

| Time of its Conception | 469 |

| Instauratio Magna | 470 |

| First Part—Partitiones Scientiarum | 470 |

| Second Part—Novum Organum | 470 |

| Third Part—Natural History | 470 |

| Fourth Part—Scala Intellectûs | 471 |

| Fifth Part—Anticipationes Philosophiæ | 471 |

| Sixth Part—Philosophia Secunda | 471 |

| Course of studying Lord Bacon | 472 |

| Nature of the Baconian Induction | 472 |

| His Dislike of Aristotle | 474 |

| His Method much required | 474 |

| Its Objects | 474 |

| Sketch of the Treatise De Augmentis | 474 |

| History | 474 |

| Poetry | 475 |

| Fine Passage on Poetry | 475 |

| Natural Theology and Metaphysics | 475 |

| Form of Bodies might sometimes be inquired into | 475 |

| Final Causes too much slighted | 476 |

| Man not included by him in Physics | 476 |

| Man—in Body and Mind | 476 |

| Logic | 476 |

| Extent given it by Bacon | 476 |

| Grammar and Rhetoric | 477 |

| Ethics | 477 |

| Politics | 477 |

| Theology | 478 |

| Desiderata enumerated by him | 478 |

| Novum Organum—First Book | 478 |

| Fallacies—Idola | 478 |

| Confounded with Idols | 478 |

| Second Book of Novum Organum | 479 |

| Confidence of Bacon | 479 |

| Almost justified of late | 480 |

| But should be kept within Bounds | 481 |

| Limits to our Knowledge by Sense | 481 |

| Inductive Logic—whether confined to Physics | 481 |

| Baconian Philosophy built on Observation and Experiment | 482 |

| Advantages of the latter | 482 |

| Sometimes applicable to Philosophy of Human Mind | 483 |

| Less so to Politics and Morals | 483 |

| Induction less conclusive on these Subjects | 483 |

| Reasons for this Difference | 484 |

| Considerations on the other Side | 484 |

| Result of the whole | 485 |

| Bacon’s Aptitude for Moral Subjects | 486 |

| Comparison of Bacon and Galileo | 487 |

| His Prejudice against Mathematics | 488 |

| Bacon’s Excess of Wit | 488 |

| Fame of Bacon on the Continent | 489 |

| Early Life of Descartes | 491 |

| His beginning to philosophise | 491 |

| He retires to Holland | 491 |

| His Publications | 492 |

| He begins by doubting all | 492 |

| His First Step in Knowledge | 492 |

| His Mind not Sceptical | 493 |

| He arrives at more Certainty | 493 |

| His Proof of a Deity | 493 |

| Another Proof of it | 494 |

| His Deductions from this | 494 |

| Primary and Secondary Qualities | 495 |

| Objections made to his Meditations | 495 |

| Theory of Memory and Imagination | 496 |

| Seat of Soul in Pineal Gland | 497 |

| Gassendi’s Attacks on the Meditations | 497 |

| Superiority of Descartes | 497 |

| Stewart’s Remarks on Descartes | 498 |

| Paradoxes of Descartes | 499 |

| His Just Notions and Definitions | 500 |

| His Notion of Substances | 501 |

| Not Quite Correct | 501 |

| His Notions of Intuitive Truth | 501 |

| Treatise on Art of Logic | 502 |

| Merits of his Writings | 502 |

| His Notions of Free will | 502 |

| Fame of his System, and Attacks upon it | 503 |

| Controversy with Voet | 503 |

| Charges of Plagiarism | 504 |

| Recent Increase of his Fame | 505 |

| Metaphysical Treatises of Hobbes | 505 |

| His Theory of Sensation | 506 |

| Coincident with Descartes | 506 |

| Imagination and Memory | 506 |

| Discourse or Train of Imagination | 507 |

| Experience | 507 |

| Unconceivableness of Infinity | 507 |

| Origin of Language | 508 |

| His Political Theory interferes | 508 |

| Necessity of Speech exaggerated | 509 |

| Use of Names | 509 |

| Names Universal not Realities | 509 |

| How imposed | 510 |

| The Subject continued | 510 |

| Names differently imposed | 511 |

| Knowledge | 511 |

| Reasoning | 512 |

| False Reasoning | 512 |

| Its frequency | 513 |

| Knowledge of Fact not derived from Reasoning | 514 |

| Belief | 514 |

| Chart of Science | 515 |

| Analysis of Passions | 515 |

| Good and Evil relative Terms | 515 |

| His Paradoxes | 515 |

| His Notion of Love | 516 |

| Curiosity | 516 |

| Difference of Intellectual Capacities | 516 |

| Wit and Fancy | 517 |

| Differences in the Passions | 517 |

| Madness | 517 |

| Unmeaning Language | 517 |

| Manners | 517 |

| Ignorances and Prejudice | 518 |

| His Theory of Religion | 518 |

| Its supposed Sources | 518 |

| CHAPTER XXI. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF MORAL AND POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY AND OF JURISPRUDENCE FROM 1600 TO 1650. |

| Casuistical Writers | 521 |

| Importance of Confession | 521 |

| Necessity of Rules for the Confessor | 521 |

| Increase of Casuistical Literature | 521 |

| Distinction of subjective and objective Morality | 522 |

| Directory Office of the Confessor | 522 |

| Difficulties of Casuistry | 522 |

| Strict and Lax Schemes of it | 523 |

| Convenience of the latter | 523 |

| Favoured by the Jesuits | 523 |

| The Causes of this | 523 |

| Extravagance of the strict Casuists | 524 |

| Opposite Faults of Jesuits | 524 |

| Suarez, De Legibus | 524 |

| Titles of his Ten Books | 524 |

| Heads of the Second Book | 525 |

| Character of such Scholastic Treatises | 525 |

| Quotations of Suarez | 525 |

| His Definition of Eternal Law | 526 |

| Whether God is a Legislator | 526 |

| Whether God could permit or commend wrong Actions | 527 |

| English Casuists—Perkins—Hall | 527 |

| Selden, De Jure Naturali Juxta Hebræos | 528 |

| Jewish Theory of Natural Law | 528 |

| Seven Precepts of the Sons of Noah | 528 |

| Character of Selden’s Work | 528 |

| Grotius and Hobbes | 528 |

| Charron on Wisdom | 529 |

| La Mothe le Vayer—his Dialogues | 529 |

| Bacon’s Essays | 529 |

| Their Excellence | 530 |

| Feltham’s Resolves | 530 |

| Browne’s Regligio Medici | 531 |

| Selden’s Table Talk | 532 |

| Osborn’s Advice to his Son | 532 |

| John Valentine Andrax | 532 |

| Abandonment of Anti-Monarchical Theories | 533 |

| Political Literature becomes historical | 533 |

| Bellenden De Statu | 534 |

| Campanella’s Politics | 534 |

| La Mothe le Vayer | 534 |

| Naude’s Coups d’Etat | 534 |

| Patriarchal Theory of Government | 534 |

| Refuted by Suarez | 535 |

| His Opinion of Law | 535 |

| Bacon | 536 |

| Political Economy | 536 |

| Serra on the Means of obtaining Money without Mines | 537 |

| His Causes of Wealth | 537 |

| His Praise of Venice | 537 |

| Low Rate of Exchange not essential to wealth | 587 |

| Hobbes.—His Political Works | 538 |

| Analysis of his Three Treatises | 538 |

| Civil Jurists of this period | 543 |

| Suarez on Laws | 544 |

| Grotius—De Jure Belli et Pacis | 544 |

| Success of this Work | 544 |

| Its Originality | 545 |

| Its Motive and Object | 545 |

| His Authorities | 545 |

| Foundation of Natural Law | 546 |

| Positive Law | 546 |

| Perfect and Imperfect Rights | 546 |

| Lawful Cases of War | 546 |

| Resistance by Subjects unlawful | 547 |

| All Men naturally have Right of War | 547 |

| Right of Self-Defence | 548 |

| Its Origin and Limitations | 548 |

| Right of Occupancy | 549 |

| Relinquishment of it | 549 |

| Right over Persons—By Generation | 549 |

| By Consent | 549 |

| In Marriage | 549 |

| In Commonwealths | 549 |

| Right of Alienating Subjects | 549 |

| Alienation by Testament | 550 |

| Rights of Property by Positive Law | 550 |

| Extinction of Rights | 550 |

| Some Casuistical Questions | 550 |

| Promises | 550 |

| Contracts | 551 |

| Considered ethically | 551 |

| Promissory Oaths | 552 |

| Engagements of Kings towards Subjects | 552 |

| Public Treaties | 552 |

| Their Interpretation | 553 |

| Obligation to repair Injury | 553 |

| Rights by Law of Nations | 554 |

| Those of Ambassadors | 554 |

| Right of Sepulture | 554 |

| Punishments | 554 |

| Their Responsibility | 555 |

| Insufficient Causes of War | 556 |

| Duty of avoiding it | 556 |

| And Expediency | 556 |

| War for the sake of other Subjects | 556 |

| Allies | 556 |

| Strangers | 556 |

| None to Serve in an Unjust War | 556 |

| Rights in War | 557 |

| Use of Deceit | 557 |

| Rules and Customs of Nations | 557 |

| Reprisals | 557 |

| Declarations of War | 557 |

| Rights by law of nations over Enemies | 558 |

| Prisoners become Slaves | 558 |

| Rights of Postliminium | 558 |

| Moral Limitation of Rights in War | 558 |

| Moderation required as to spoil | 559 |

| And as to Prisoners | 559 |

| Also in Conquest | 559 |

| And in Restitution to right Owners | 559 |

| Promises to Enemies and Pirates | 559 |

| Treaties concluded by competent Authority | 560 |

| Matters relating to them | 561 |

| Truces and Conventions | 561 |

| Those of Private persons | 561 |

| Objections to Grotius made by Paley unreasonable | 561 |

| Reply of Mackintosh | 561 |

| Censures of Stewart | 562 |

| Answer to them | 562 |

| Grotius vindicated against Rousseau | 565 |

| His Arrangement | 565 |

| His Defects | 565 |

| CHAPTER XXII. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF POETRY FROM 1600 TO 1650. |

| Low Estimation of the Seicentisti | 566 |

| Not quite so great as formerly | 566 |

| Praise of them by Rubbi | 566 |

| Also by Salfi | 566 |

| Adone of Marini | 567 |

| Its Character | 567 |

| And Popularity | 567 |

| Secchia Rapita of Tassoni | 568 |

| Chiabrera | 569 |

| His Followers | 569 |

| The Styles of Spanish Poetry | 570 |

| The Romances | 570 |

| The Brothers Argensola | 570 |

| Villegas | 571 |

| Quevedo | 571 |

| Defects of Taste in Spanish Verse | 571 |

| Pedantry and far-fetched Allusions | 572 |

| Gongora | 572 |

| The Schools formed by him | 573 |

| Malherbe | 573 |

| Criticisms upon his Poetry | 574 |

| Satires of Regnier | 574 |

| Racan—Maynard | 574 |

| Voiture | 574 |

| Sarrasin | 575 |

| Low state of German Literature | 575 |

| Literary Societies | 575 |

| Opitz | 575 |

| His Followers | 576 |

| Dutch Poetry | 576 |

| Spiegel | 576 |

| Hooft-Cats-Vondel | 577 |

| Danish Poetry | 577 |

| English Poets numerous in this age | 577 |

| Phineas Fletcher | 577 |

| Giles Fletcher | 578 |

| Philosophical Poetry | 578 |

| Lord Brooke | 578 |

| Denham’s Cooper’s Hill | 579 |

| Poets called Metaphysical | 579 |

| Donne | 580 |

| Crashaw | 580 |

| Cowley | 580 |

| Johnson’s Character of him | 580 |

| Narrative Poets—Daniel | 580 |

| Drayton’s Polyolbion | 581 |

| Browne’s Britannia’s Pastorals | 581 |

| Sir John Beaumont | 582 |

| Davenant’s Gondibert | 582 |

| Sonnets of Shakspeare | 582 |

| The person whom they address | 583 |

| Sonnets of Drummond and others | 584 |

| Carew | 584 |

| Ben Jonson | 585 |

| Wither | 585 |

| Habington | 585 |

| Earl of Pembroke | 585 |

| Suckling | 586 |

| Lovelace | 586 |

| Herrick | 586 |

| Milton | 586 |

| His Comus | 586 |

| Lycidas | 587 |

| Allegro and Penseroso | 587 |

| Ode on the Nativity | 588 |

| His Sonnets | 588 |

| Anonymous Poetry | 588 |

| Latin Poets of France | 588 |

| In Germany and Italy | 588 |

| In Holland—Heinsius | 589 |

| Casimir Sarbievius | 589 |

| Barlæus | 589 |

| Balde—Greek Poems of Heinsius | 590 |

| Latin Poets of Scotland—Jonston’s Psalms | 590 |

| Owen’s Epigrams | 590 |

| Alabaster’s Roxana | 590 |

| May’s Supplement to Lucan | 590 |

| Milton’s Latin Poems | 591 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF DRAMATIC LITERATURE FROM 1600 TO 1650. |

| Decline of the Italian Theatre | 591 |

| Filli de Sciro | 592 |

| Translations of Spanish Dramas | 592 |

| Extemporaneous Comedy | 593 |

| Spanish Stage | 593 |

| Calderon—Number of his Pieces | 593 |

| His Comedies | 593 |

| La Vida es Sueno | 594 |

| A Secreto agravio secreta vengança | 595 |

| Style of Calderon | 595 |

| His Merits sometimes overrated | 596 |

| Plays of Hardy | 596 |

| The Cid | 597 |

| Style of Corneille | 598 |

| Les Horaces | 598 |

| Cimia | 598 |

| Polyeucte | 599 |

| Rodogune | 599 |

| Pompey | 599 |

| Heraclius | 599 |

| Nicomède | 600 |

| Faults and Beauties of Corneille | 600 |

| Le Menteur | 600 |

| Other French Tragedies | 600 |

| Wenceslas of Rotron | 600 |

| Popularity of the Stage under Elizabeth | 601 |

| Number of Theatres | 601 |

| Encouraged by James | 601 |

| General Taste for the Stage | 601 |

| Theatres closed by the Parliament | 602 |

| Shakspeare’s Twelfth Night | 602 |

| Merry Wives of Windsor | 603 |

| Measure for Measure | 604 |

| Lear | 604 |

| Timon of Athens | 604 |

| Pericles | 605 |

| His Roman Tragedies—Julius Cæsar | 606 |

| Antony and Cleopatra | 606 |

| Coriolanus | 606 |

| His Retirement and Death | 607 |

| Greatness of his Genius | 607 |

| His Judgment | 607 |

| His Obscurity | 608 |

| His Popularity | 608 |

| Critics on Shakspeare | 609 |

| Ben Jonson | 609 |

| The Alchemist | 609 |

| Volpone, or The Fox | 610 |

| The Silent Woman | 610 |

| Sad Shepherd | 611 |

| Beaumont and Fletcher | 611 |

| Corrupt State of their Text | 611 |

| The Maid’s Tragedy | 611 |

| Philaster | 612 |

| King and no King | 613 |

| The Elder Brother | 613 |

| The Spanish Curate | 613 |

| The Custom of the Country | 613 |

| The Loyal Subject | 613 |

| Beggar’s Bush | 613 |

| The Scornful Lady | 614 |

| Valentinian | 614 |

| The Two Noble Kinsmen | 615 |

| The Faithful Shepherdess | 615 |

| Rule a Wife, and have a Wife | 616 |

| Some other Plays | 616 |

| Origin of Fletcher’s Plays | 616 |

| Defects of their plots | 616 |

| Their Sentiments and Style Dramatic | 617 |

| Their Characters | 617 |

| Their Tragedies | 617 |

| Inferior to their Comedies | 618 |

| Their Female Characters | 618 |

| Massinger—Nature of his Dramas | 619 |

| His Delineations of Character | 619 |

| His Subjects | 619 |

| Beauty of His Style | 620 |

| Inferiority of his Comic Powers | 620 |

| Some of his Tragedies particularized | 620 |

| And of his other Plays | 620 |

| Ford | 621 |

| Shirley | 621 |

| Heywood | 622 |

| Webster | 622 |

| His Duchess of Malfy | 622 |

| Vittoria Corombona | 622 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF POLITE LITERATURE IN PROSE FROM 1600 TO 1650. |

| Decline of Taste in Italy | 623 |

| Style of Galileo | 624 |

| Bentivoglio | 624 |

| Boccalini’s News from Parnassus | 624 |

| His Pietra del Paragone | 625 |

| Terrante Pallavicino | 625 |

| Dictionary Delia Crusca | 625 |

| Grammatical Works—Buonmattei—Bartoli | 626 |

| Tassoni’s Remarks on Petrarch | 626 |

| Galileo’s Remarks on Tasso | 626 |

| Sforza Pallavicino | 626 |

| And other Critical Writers | 626 |

| Prolusiones of Strada | 627 |

| Spanish Prose—Gracian | 627 |

| French Prose—Du Vair | 627 |

| Balzac | 628 |

| Character of his Writings | 628 |

| His Letters | 628 |

| Voiture—Hotel Rambouillet | 629 |

| Establishment of French Academy | 630 |

| Its objects and Constitution | 630 |

| It publishes a Critique on the Cid | 631 |

| Vaugelas’s Remarks on the French Language | 631 |

| La Mothe le Vayer | 632 |

| Legal Speeches of Patru | 632 |

| And of Le Maistre | 632 |

| Improvement in English Style | 633 |

| Earl of Essex | 633 |

| Knolles’s History of the Turks | 634 |

| Raleigh’s History of the World | 635 |

| Daniel’s History of England | 635 |

| Bacon | 635 |

| Milton | 636 |

| Clarendon | 636 |

| The Icon Basilice | 636 |

| Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy | 637 |

| Earle’s Characters | 637 |

| Overbury’s Characters | 637 |

| Jonson’s Discoveries | 637 |

| Publication of Don Quixote | 638 |

| Its Reputation | 638 |

| New Views of its Design | 638 |

| Probably erroneous | 638 |

| Difference between the two Parts | 639 |

| Excellence of this Romance | 639 |

| Minor Novels of Cervantes | 639 |

| Other Novels—Spanish | 639 |

| And Italian | 639 |

| French Romances—Astrée | 639 |

| Heroic Romances—Gomberville | 640 |

| Calprenède | 640 |

| Scuderi | 641 |

| Argenis of Barclay | 641 |

| His Euphormis | 643 |

| Campanella’s City of the Sun | 643 |

| Few Books of Fiction in England | 643 |

| Mundus Alter et Idem of Hall | 644 |

| Godwin’s Journey to the Moon | 644 |

| Howell’s Dodona’s Grove | 644 |

| Adventures of Baron de Fænesle | 644 |

| CHAPTER XXV. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF MATHEMATICAL AND PHYSICAL SCIENCE FROM 1600 TO 1650. |

| State of Science in 16th Century | 645 |

| Tediousness of Calculations | 645 |

| Napier’s Invention of Logarithms | 645 |

| Their Nature | 645 |

| Property of Numbers discovered by Stifelius | 645 |

| Extended to Magnitudes | 646 |

| By Napier | 646 |

| Tables of Napier and Briggs | 646 |

| Kepler’s New Geometry | 647 |

| Its Difference from the Ancient | 647 |

| Adopted by Galileo | 648 |

| Extended by Cavalieri | 648 |

| Applied to the Ratios of Solids | 648 |

| Problem of the Cycloid | 648 |

| Progress of Algebra | 649 |

| Briggs—Girard | 649 |

| Harriott | 649 |

| Descartes | 650 |

| His Application of Algebra to Curves | 650 |

| Suspected Plagiarism from Harriot | 650 |

| Fermat | 651 |

| Algebraic Geometry not successful at first | 652 |

| Astronomy—Kepler | 652 |

| Conjectures as to Comets | 652 |

| Galileo’s Discovery of Jupiter’s Satellites | 653 |

| Other Discoveries by him | 653 |

| Spots of the Sun discovered | 653 |

| Copernican System held by Galileo | 654 |

| His Dialogues, and Persecution | 654 |

| Descartes alarmed by this | 655 |

| Progress of Copernican System | 655 |

| Descartes denies General Gravitation | 655 |

| Cartesian Theory of the World | 655 |

| Transits of Mercury and Venus | 656 |

| Laws of Mechanics | 656 |

| Statics of Galileo | 657 |

| His Dynamics | 657 |

| Mechanics of Descartes | 658 |

| Law of Motion laid down by Descartes | 658 |

| Also those of Compound Forces | 659 |

| Other Discoveries in Mechanics | 659 |

| In Hydrostatics and Pneumatics | 659 |

| Optics—Discoveries of Kepler | 660 |

| Invention of the Telescope | 660 |

| Of the Microscope | 660 |

| Antonio de Dominis | 660 |

| Dioptrics of Descartes—Law of Refraction | 661 |

| Disputed by Fermat | 661 |

| Curves of Descartes | 661 |

| Theory of the Rainbow | 661 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF SOME OTHER PROVINCES OF LITERATURE FROM 1600 TO 1650. |

| Aldrovandus | 662 |

| Clusius | 662 |

| Rio and Marcgraf | 662 |

| Jonston | 662 |

| Fabricius on the Language of Brutes | 663 |

| Botany—Columna | 664 |

| John and Gaspar Bauhin | 664 |

| Parkinson | 664 |

| Valves of the Veins discovered | 665 |

| Theory of the Blood’s Circulation | 665 |

| Sometimes ascribed to Servetus | 665 |

| To Columbus | 666 |

| And to Cæsalpin | 666 |

| Generally unknown before Harvey | 667 |

| His Discovery | 667 |

| Unjustly doubted to be Original | 667 |

| Harvey’s Treatise on Generation | 668 |

| Lacteals discovered by Asellius | 668 |

| Optical Discoveries of Scheiner | 669 |

| Medicine—Van Helmont | 669 |

| Diffusion of Hebrew | 669 |

| Language not studied in the best method | 669 |

| The Buxtorfs | 670 |

| Vowel Points rejected by Cappel | 670 |

| Hebrew Scholars | 671 |

| Chaldee and Syriac | 671 |

| Arabic | 671 |

| Erpenius | 671 |

| Golius | 671 |

| Other Eastern Languages | 672 |

| Purchas’s Pilgrim | 672 |

| Olearius and Pietro della Valle | 672 |

| Lexicon of Ferrari | 672 |

| Maps of Blaew | 672 |

| Davila and Bentivoglio | 673 |

| Mendoza’s Wars of Granada | 673 |

| Mezeray | 673 |

| English Historians | 673 |

| English Histories | 673 |

| Universities | 673 |

| Bodleian Library founded | 674 |

| Casaubon’s Account of Oxford | 674 |

| Catalogue of Bodleian Library | 674 |

| Continental Libraries | 675 |

| Italian Academies | 675 |

| The Lincei | 675 |

| Prejudice for Antiquity diminished | 676 |

| Browne’s Vulgar Errors | 677 |

| Life and Character of Peiresc | 677 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF ANCIENT LITERATURE IN EUROPE FROM 1650 TO 1700. |

| James Frederic Gronovius | 678 |

| James Gronovius | 679 |

| Grævius | 679 |

| Isaac Vossius | 679 |

| Decline of German Learning | 679 |

| Spanheim | 679 |

| Jesuit Colleges in France | 679 |

| Port-Royal Writers—Lancelot | 679 |

| Latin Writers—Perizonius | 680 |

| Delphin Editions | 680 |

| Le Fevre and the Daciers | 680 |

| Henry Valois—Complaints of Decay of Learning | 680 |

| English Learning—Duport | 681 |

| Greek not much studied | 681 |

| Gataker’s Cinnus and Antoninus | 681 |

| Stanley’s Æschylus | 682 |

| Other English Philologers | 682 |

| Bentley | 682 |

| His Epistle to Mill | 682 |

| Dissertation on Phalaris | 682 |

| Disadvantages of Scholars in that Age | 683 |

| Thesauri of Grævius and of Gronovius | 683 |

| Fabretti | 684 |

| Numismatics, Spanheim—Vaillant | 684 |

| Chronology—Usher | 684 |

| Pezron | 685 |

| Marsham | 685 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. |

|---|

| HISTORY OF THEOLOGICAL LITERATURE FROM 1650 TO 1700. |

| Decline of Papal Influence | 685 |

| Dispute of Louis XIV. with Innocent XI. | 686 |

| Four Articles of 1682 | 686 |

| Dupin on the ancient Discipline | 686 |

| Dupin’s Ecclesiastical Library | 687 |

| Fleury’s Ecclesiastical History | 687 |

| His Dissertations | 687 |

| Protestant Controversy in France | 688 |

| Bossuet’s Exposition of Catholic Faith | 688 |

| His Conference with Claude | 688 |

| Correspondence with Molanus and Leibnitz | 689 |

| His Variations of Protestant Churches | 690 |

| Anglican Writings against Popery | 690 |

| Taylor’s Dissuasive | 690 |

| Barrow—Stillingfleet | 690 |

| Jansenius | 691 |

| Condemnation of his Augustinus in France | 691 |

| And at Rome | 691 |

| The Jansenists take a Distinction | 692 |

| And are Persecuted | 692 |

| Progress of Arminianism | 692 |

| Courcelles | 693 |

| Limborch | 693 |

| Le Clerc | 693 |

| Sancroft’s Fur Prædestinatus | 693 |

| Arminianism in England | 694 |

| Bull’s Harmonia Apostolica | 694 |

| Hammond—Locke—Wilkins | 694 |

| Socinians in England | 695 |

| Bull’s Defensio Fidei Nicenæ | 695 |