Title: Our Little Siamese Cousin

Author: Mary Hazelton Blanchard Wade

Illustrator: L. J. Bridgman

Release date: October 8, 2013 [eBook #43908]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, Beth Baran and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from images made available by the HathiTrust

Digital Library.)

| Our Little African Cousin |

| Our Little Alaskan Cousin |

| By Mary F. Nixon-Roulet |

| Our Little Arabian Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little Argentine Cousin |

| By Eva Cannon Brooks |

| Our Little Armenian Cousin |

| Our Little Australian Cousin |

| By Mary F. Nixon-Roulet |

| Our Little Belgian Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little Bohemian Cousin |

| By Clara V. Winlow |

| Our Little Brazilian Cousin |

| By Mary F. Nixon-Roulet |

| Our Little Canadian Cousin |

| By Elizabeth R. MacDonald |

| Our Little Chinese Cousin |

| By Isaac Taylor Headland |

| Our Little Cuban Cousin |

| Our Little Danish Cousin |

| By Luna May Innes |

| Our Little Dutch Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little Egyptian Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little English Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little Eskimo Cousin |

| Our Little French Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little German Cousin |

| Our Little Grecian Cousin |

| By Mary F. Nixon-Roulet |

| Our Little Hawaiian Cousin |

| Our Little Hindu Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little Hungarian Cousin |

| By Mary F. Nixon-Roulet |

| Our Little Indian Cousin |

| Our Little Irish Cousin |

| Our Little Italian Cousin |

| Our Little Japanese Cousin |

| Our Little Jewish Cousin |

| Our Little Korean Cousin |

| By H. Lee M. Pike |

| Our Little Malayan (Brown) Cousin |

| Our Little Mexican Cousin |

| By Edward C. Butler |

| Our Little Norwegian Cousin |

| Our Little Panama Cousin |

| By H. Lee M. Pike |

| Our Little Persian Cousin |

| By E. C. Shedd |

| Our Little Philippine Cousin |

| Our Little Polish Cousin |

| By Florence E. Mendel |

| Our Little Porto Rican Cousin |

| Our Little Portuguese Cousin |

| By Edith A. Sawyer |

| Our Little Russian Cousin |

| Our Little Scotch Cousin |

| By Blanche McManus |

| Our Little Siamese Cousin |

| Our Little Spanish Cousin |

| By Mary F. Nixon-Roulet |

| Our Little Swedish Cousin |

| By Claire M. Coburn |

| Our Little Swiss Cousin |

| Our Little Turkish Cousin |

Our Little

|

||

Many years ago there came to America two young men who were looked upon as the greatest curiosities ever seen in this country.

They belonged to another race than ours. In fact, they were of two races, for one of their parents was a Chinese, and therefore of the Yellow Race, while the other was a Siamese, belonging to the Brown Race.

These two young men left their home in far-away Siam and crossed the great ocean for the purpose of exhibiting the strange way in which nature had joined them together. A small band of flesh united them from side to side.

Thus it was that from the moment they were born to the day of their death the twin[vi] brothers played and worked, ate and slept, walked and rode, at the same time.

Thousands of people became interested in seeing and hearing about these two men. Not only this, but they turned their attention to the home of the brothers, the wonderful land of Siam, with its sacred white elephants and beautiful temples, its curious customs and strange beliefs.

Last year the young prince of that country, wishing to learn more of the life of the white people, paid a visit to America. He was much interested in all he saw and heard while he was here.

Now let us, in thought, return his visit, and take part in the games and sports of the children of Siam.

We will attend some of their festivals, take a peep into the royal palace, enter the temples, and learn something about the ways and habits of that far-away eastern country.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The First Birthday | 9 |

| II. | Little Chie Lo | 25 |

| III. | Night on the River | 36 |

| IV. | Work and Play | 47 |

| V. | New Year's | 55 |

| VI. | White Elephants | 61 |

| VII. | In the Temple | 67 |

| VIII. | The Legend of the Peace-Offering | 78 |

| IX. | Queer Sights | 87 |

| X. | The Queen's City | 98 |

| XI. | The Monsoon | 104 |

| PAGE | |

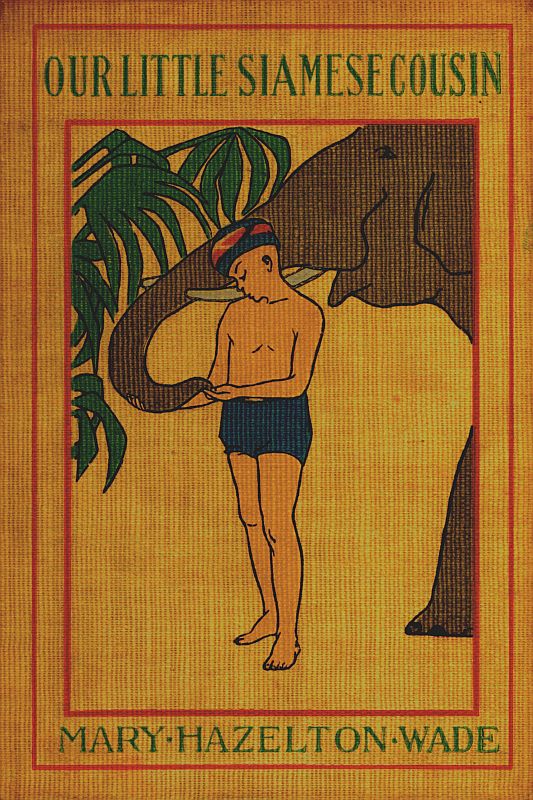

| Chin | Frontispiece |

| Chin's Home | 29 |

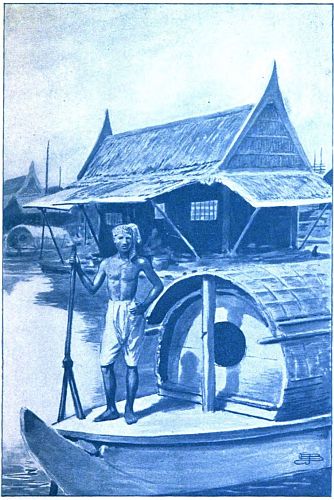

| The Great Temple at Bangkok | 40 |

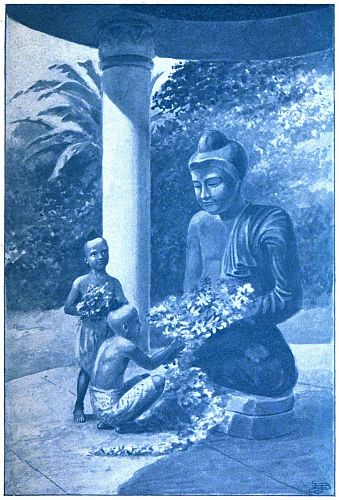

| "They carried some of their flowers to the statue of Buddha" | 57 |

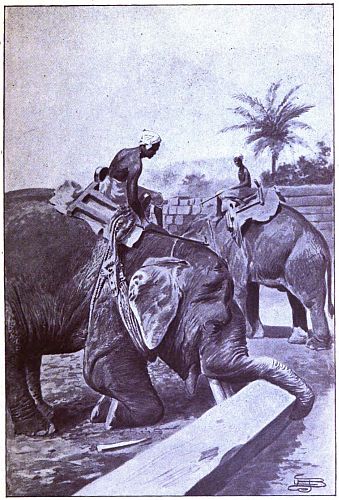

| "'They would pick up the logs with their trunks'" | 63 |

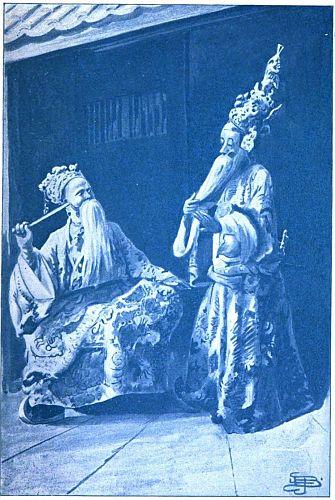

| Siamese Actors | 92 |

If you had seen Chin when he was born, you would have thought his skin yellow enough to suit anybody.

But his mother wasn't satisfied, for the baby's nurse was told to rub him with a queer sort of paste from top to toe. This paste was made with saffron and oil, and had a pleasant odour. It made Chin's skin yellower and darker than ever.

It did not seem to trouble him, however, for he closed his big brown eyes and went[10] to sleep before the nurse had finished her work.

After this important thing had been done, the tiny baby was laid in his cradle and covered over. This does not appear very strange until you learn that he was entirely covered. Not even the flat little nose was left so the boy could draw in a breath of fresh air.

It is a wonder that he lived, for his home is very near the equator and the weather is extremely warm there all the time. But he did live, and grew stronger and healthier every day. Each morning he was rubbed afresh and stowed away under the covers of his crib.

He had one comfort, although he did not realize it. The mosquitoes could not reach him, and that was a greater blessing than you can, perhaps, imagine. There are millions of these insects in Siam,—yes, billions, trillions,—and the people of that country are not willing to kill one of them!

"Destroy the life of a living creature! It is a dreadful idea," Chin's mother would exclaim. "Why, it is against the laws of our religion. I could never think of doing such a thing, even if my darling boy's face were covered with bites."

If she were to see one of Chin's American cousins killing a fly or a spider, she would have a very sad opinion of him.

She was only fourteen years old when Chin was born. People in our country might still call her a little girl, yet she kept house for her husband, and cooked and sewed and spun, and watched over her new baby with the most loving care.

The father was only a little older than the mother. He was so glad that his first baby was a boy that he hardly knew what to do. He was quite poor and had very little money, but he said:

"I am going to celebrate as well as I can.[12] Rich people have grand parties and entertainments at such times. I will hire some actors to give a little show, at any rate."

He invited his friends, who were hardly more than boys themselves, to come to the show. The actors dressed themselves up in queer costumes, and went through with a play that was quite clever and witty. Every one laughed a great deal, and when it was over the guests told the new father they had enjoyed themselves very much.

After a few months, Chin had grown strong enough to walk alone. He did not need to be covered and hidden away any longer. His straight black hair was shaved off, with the exception of a round spot on the top of his head, and he was allowed to do as he pleased after his morning bath in the river was over.

The bath did not last long, and was very pleasant and comfortable. There was no[13] rubbing afterward with towels, for the hot sunshine did the drying in a few moments.

Nor was there any dressing to be done, for the brown baby was left to toddle about in the suit Dame Nature had given him. It was all he could possibly desire, for clothing is never needed in Siam to keep one from catching cold.

Chin's mother herself wears only a wide strip of printed cloth fastened around her waist and hanging down to the knees. Sometimes, but not always, she has a long scarf draped across her breast and over one shoulder.

There are no shoes on her little feet, nor is there a hat on her head except in the hottest sunshine. There are many ornaments shining on her dark skin, even though she is not rich; and baby Chin did not have his toilet made till a silver bracelet had been fastened on his arms, and rings placed on his fingers.

After a year or two the boy's ears were bored so that gilt, pear-shaped earrings could be worn there. Soon after that a kind relative made him a present of silver anklets, and then he felt very much dressed indeed. Few boys as poor as he could boast of as much jewelry.

Chin was born on the river Meinam in a house-boat. There was nothing strange about that, for the neighbours and friends of the family had homes like his. It was cool and pleasant to live on the water. It was convenient when one wished to take a bath, and it was easy for the children to learn to swim so near home.

Yes, there were many reasons why Chin's parents preferred to make their home on the water. Perhaps the strongest one of all was that they did not have to pay any rent for the space taken up by the boat. A piece of land would have cost money. Then, again, if they[15] should not like their neighbours, they could very easily move to a new place on the river.

Chin's father built the house, or the boat, just before he was married. He had some help from his friends, but it was not such hard work that he could not have done it all alone.

A big raft of bamboo was first made. This served as the floating platform on which the house should stand. The framework of the little home was also made of bamboo, which could be got from the woods not far away, and was very light and easy to handle.

How should the roof be protected from the heavy rains that fell during a portion of the year? That could be easily managed by getting quantities of the leaves of the atap palm-tree for thatching. These would make a thick, close covering, and would keep out the storms for a long time if they were carefully cemented with mud.

The broad, overhanging eaves would give[16] shade to baby Chin when he was old enough to play in the outdoor air, and yet not strong enough to bear the burning sunshine.

Of course, there were many windows in the little house, you would think. There were openings in the walls in the shape of windows, certainly, but they were openings only, for they were not filled with glass, nor any other transparent substance. Chin's father would say:

"We must have all the air we can get. At night-time, when the rain falls heavily, we can have shutters on the windows. They are easily taken down whenever we wish."

Why, the whole front of the house was made so it could be opened up to the air and sunshine, as well as the view of passers-by. The family have few secrets, and do not mind letting others see how they keep house.

At this very moment, perhaps, Chin's mother is sitting on the edge of the bamboo[17] platform, washing her feet in the river; his grandmother may be there preparing the vegetables for dinner; or, possibly, Chin himself is cleaning his teeth with a stick of some soft wood.

The boy's mother has taught him to be very careful of his teeth. It is a mark of beauty with her people to have them well blacked. They will tell you, "Any dog can have white teeth." But there is nothing they admire more than bright red gums showing plainly with two rows of even, dark-coloured teeth.

How do they make their gums such a fiery red? It is caused by chewing a substance called betel, obtained from a beautiful kind of palm-tree very common in Siam.

Many of Chin's brown cousins chew betel, as well as the people of his own land. It is even put in the mouths of babies. Betel-chewing grows to be such a habit with them[18] that they become unhappy and uncomfortable if long without it. Even now, although Chin is only ten years old, he would say:

"I can go without food for a long time, if need be, but I must have my betel."

Let us go back to the boy's home.

If we should count the windows, we should find their number to be uneven. The Siamese believe something terrible would be sure to happen if this were not so. They seem to think "There is luck in odd numbers," for not only the steps leading to the houses, but the stairs leading from one floor to another must be carefully counted and made uneven.

There are three rooms in Chin's home. First, there is the sitting-room, where friends are received, although there is much less visiting done in Siam than in many other countries. It took little time and money to furnish the room. There are no pictures or ornaments here. There are two or three mats on which[19] one may sit, and there is a tray filled with betel from which every one is invited to help himself.

If callers should arrive and the betel were not offered to them, they would feel insulted and would go away with the intention of never coming to that house again.

The second room is that set apart for sleeping. Very little furniture is found here, as well, for all that Chin's father had to prepare was a number of long, narrow mattresses, stuffed with tree-cotton. Some pillows were made in the shape of huge bricks. They were also packed full of tree-cotton, and were stiff, uncomfortable-looking things; but Chin and his parents like them, so we should certainly not find fault.

You remember there are great numbers of mosquitoes in the country. How do they manage to sleep when the air around them is filled with the buzzing, troublesome creatures?[20] Coarse cotton curtains hang from the roof down over the beds. While these keep the mosquitoes away from the sleepers, they also keep out the air, so it is really a wonder that one can rest in any comfort.

When Chin is in the house during the day, he spends most of his time in the kitchen, which is also the eating-room. But, dear me! it is a smoky place, for the boy's father never thought of building a chimney.

The cooking is done over a little charcoal stove and, as the flames rise, the smoke rises, too, and settles on the ceiling and walls. Chin has had many good meals cooked over the little fire, and eaten as the family squatted around the tiny table.

Just think! It stands only four inches above the floor, and is not large enough to hold many dishes. That does not matter, for each one has his own rice-bowl on the floor in front of him. Chin has been brought[21] up so that he is satisfied with one or two things at a time. The little table is quite large enough to hold the dish of curried fish or meat from which each one helps himself.

Chin is a very nice boy, yet I shall have to confess that he usually eats with his fingers! Yes, not only he, but his father and mother and sister, and even grandmother, do the same thing. One after another helps himself from the same dish and thinks nothing of it.

People who are a little richer use pretty spoons of mother-of-pearl; Chin's mother owns one of these useful articles herself, but of course, that won't serve for five persons, so it is seldom seen on the table. As for knives and forks, she never even saw any.

One of her friends once watched a stranger from across the great ocean eating with these strange things. She laughed quietly when she told of it, and said:

"It must take a long, long time before one[22] can get used to them. They are very clumsy."

As Chin squats at his dinner he can look down through the split bamboos and see the water of the river beneath the house. It does not matter if he drops some crumbs or grains of rice. They can be easily pushed through the cracks, when down they will fall into the water to be seized by some waiting fish.

The good woman doesn't even own a broom. Her house-cleaning is done in the easiest way possible. Anything that is no longer useful is thrown into the river, while the dirt is simply pushed between the wide cracks of the floor.

The dish-washing is a simple matter, too. Each one has his own rice-bowl, and after the meal is over it is his duty to clean it and then turn it upside down in some corner of the kitchen. It is left there to drain until it is needed again.

Chin's mother cooks such delicious rice that he wonders any one can live without it. He needs no bread when he can have that, for it is a feast in itself. When poured out, it looks like a mountain of snow; each grain is whole and separate from the others.

It is cooked in an earthen pot with the greatest care, and, when it is done, never fails to look beautiful and delicate. Chin's mother would think herself a very poor housekeeper if she should make a mistake in preparing the rice.

When a dish of rat or bat stew is added to the meal, Chin feels that there is nothing more in the world that he could wish. He knows that the rich people in the city often have feasts where twenty or thirty different dainties are served. But he does not envy them. A person can taste only one thing at a time, and nothing can be better than a stew with plenty of curry and vegetables to flavour it. We[24] don't need to think of the rats and bats if it is an unpleasant idea.

As for Chin, if he had seen you shudder when they were spoken of, he could not have imagined what was the matter.

"Chie Lo! Chie Lo! come out quickly, or you won't see it before it passes," called Chin to his sister.

She was playing with her dolls in the sitting-room, but when she heard Chin calling she put them down and came out on the platform where her brother sat dangling his feet in the water and holding his pet parrot.

"Chie Lo! Chie Lo!" screamed the parrot, when she appeared. He was a bright-looking bird with a shining coat of green feathers and a red tuft on his head. He must have loved Chie Lo, for he reached up for her to pat him as she squatted beside her brother.

"Look, look," said Chin, "isn't that grand?"

The boy pointed to a beautiful boat moving rapidly down the river.

"It is the king's, you know," he whispered. "Do you see him there under the canopy, with his children around him?"

"Yes, yes, Chin, but don't talk; I just want to look."

It was no wonder that Chie Lo wished to keep still, for it was a wonderful sight. The boat was shaped like a huge dragon, whose carved head, with its fierce eyes, could be seen reaching out from the high bow. The stern was made in the shape of the monster's tail. The sides of the royal barge were covered with gilded scales, inlaid with pearls, and these scales shone and sparkled in the sunlight.

A hundred men dressed in red were rowing the splendid boat, and they must have had[27] great training, for they kept together in perfect time.

"Isn't the canopy over the king the loveliest thing you ever saw?" said Chin, who could not keep still. "It is made of cloth-of-gold, and so are the curtains. Look at the gold embroidery on the king's coat. Oh, Chie Lo, it doesn't seem as though he could be like us at all. I feel as though he must be a god.

"The young prince who took the long journey across the ocean last year is there with him," Chin went on. "Father told me that he visited strange lands where all the people have skins as white as pearls, and that he has seen many wonderful sights. But, Chie Lo, there is nothing in the world grander than our king and his royal boat, I'm sure."

As the barge drew nearer, the children threw themselves face downward on the platform until it had passed down the river. It was[28] their way of showing honour to the ruler of the land.

In the olden times all who came into the presence of the king, did so in one way only. They crawled. Even his own little children were obliged to do this. No one dared to stand in his presence.

But such things have been changed now. The king loves his people and has grown wiser since he has learned the ways of other countries. When he was a little boy, an English lady was his teacher for a long time, and she taught him much that other Kings of Siam had never known.

It is partly because of this that he is the best ruler Chin's people have ever had.

The royal barge was decorated with beautiful white and yellow umbrellas, many stories high. There was also a huge jewelled fan, such as no boat was allowed to carry except the king's.

Other dragon-shaped boats followed the[29] royal barge, but they were smaller and less beautiful. They were the king's guard-boats, and moved along in pairs.

Many other interesting sights could be seen on the river this morning. Vessels were just arriving from distant lands, while here and there Chinese junks were scattered along the shores. Chin and his sister can always tell such boats from any others. An eye is always painted on the bow.

A Chinaman who was once asked why he had the eye there, answered, "If no have eye, how can see?"

It is so much pleasanter outside, it is no wonder that Chin and his sister do not spend much time indoors.

After the royal procession had passed out of sight, Chie Lo went into the house and brought out her family of dolls. Of course they did not look like American dolls; you wouldn't expect it.

Some of them were of baked mud and wore no clothes. Others were of stuffed cotton and made one think of the rag dolls of Chie Lo's white cousins. The father and mother dolls were dressed in strips of cloth wound around their bodies, just like the real grown-up people of Siam, but the baby dolls had no more clothes than the children of the country.

Chie Lo talked to her dolls and sang queer little songs to them. She "made believe" they were eating, just as other little girls play, far away across the great ocean. Then she kissed them and put them to bed on tiny mattresses under the shady eaves of the house.

Perhaps you wouldn't have known that Chie Lo was kissing them, however, for the fashions of Siam are quite different from those of our country. She simply touched the dolls' noses with her own little flat one and drew in a long breath each time she did so. That was[31] her way of showing her love,—gentle little Chie Lo.

Chin didn't laugh, of course. He was used to seeing his sister playing with her dolls, and as for the kissing, that was the only way of doing it that he knew himself.

"Chie Lo, I saw some beautiful dolls in a store yesterday," he said, as he stopped working for a minute. He was making a new shuttlecock for a game with his boy friends the next day.

"What kind were they, Chin?" asked his sister.

"They were lovely wooden ones. Only rich children could buy them, for they cost a great deal. I wish I could get one for you, Chie Lo, but you know I haven't any money."

"What else did you see, Chin?"

"There were doll-temples in the store, and boats filled with sailors, and lovely ivory furniture[32] for the doll-houses. You must see the things yourself."

Chie Lo went on with her play. She finished putting her own toy house in order. It was one Chin had made for her. It looked like her own home,—it stood on a bamboo platform, it had a high, slanting roof, covered with palm leaves, and there were three rooms inside. Chin was a good boy to make it. All brothers were not as kind as he.

"Yes, I should like to see all those things," Chie Lo answered, after awhile. "But I am happy here with my own toys. I must row up the river to-morrow and sell some fruit for father. I won't have any time for play then."

"Come to dinner, children," called their mother. "Chin, take this jug and get some fresh water before you come in."

She handed a copper jug to Chin. He quickly filled it by reaching over the platform,[33] and followed his sister into the kitchen a moment later.

Every one was thirsty, and the jug was passed from one to another for each to help himself. There were no tumblers nor cups. Chin had made small dishes for his mother by cutting cocoanuts in halves and scooping out the delicious cream from the inside; but they did not use them for drinking the water.

Nor did they put their lips to the jug. Each one cleverly twisted a palm leaf into the shape of a funnel and received the water through this. It was done more quickly than I can tell you about it.

Chin and his sister thought it was a fine dinner. The evening dews were falling, and a gentle breeze came floating down the river. The terrible heat of the day was over and it was the very time to enjoy eating.

In the first place, there was the dish of steaming rice. There was also a sort of stew[34] made of meat chopped very fine and seasoned with red pepper. If you had tasted it, you would probably have cried:

"Oh dear, my mouth is burnt; give me a drink of water at once."

But Chin and Chie Lo thought it very nice indeed, and not a bit too hot.

"Isn't this pickled turnip fine?" said Chin's mother. "I bought it this morning from a passing store."

What could she mean by these words? It was a very common thing for these little brown cousins to see not only houses but stores moving past them down the river. The storekeepers were always ready to stop and sell their goods to any one who wished them.

Chin's mother never made bread, nor pies, nor cake, nor puddings. She bought most of the vegetables already cooked from the floating stores, so you can see she had quite an easy time in preparing her meals.

But to-day, after the rice and stew had been cooked, she laid bananas to roast in the hot coals, and these were now taken out and handed to her family as they squatted on the mats around the table.

If the children had no bread with their dinner, they ought to have had milk, you think. But they never drink it. The cows of Siam are not milked at all, and so the rich children of the country are brought up in the same way as Chin and his sister.

When the meal was finished, Chie Lo did not forget that her dear pussy must still be fed. It was an odd-looking little creature. Although it was a grown-up cat, yet its eyes were as blue as those of a week-old American kitten. It had a funny little tail twisted up into a knot. It was better off than many other cats of Siam, however, who go about with none at all.

After Chie Lo had watched her pussy eat all the fish she could possibly wish, the children went outdoors again to sit in the cool evening air.

The night was already pitch-dark, for there was no moon, and there is no long twilight in the tropics at any season of the year.

But what a beautiful sight now met the children's eyes! It seemed almost like fairy-land, there were so many lights to be seen in every direction.

Their home stood just below the great city of Bangkok, and along the shores of the river the houses and palaces and temples could be seen almost as plainly as in the daytime.[37] Floating theatres were passing by, each one lighted with numbers of coloured paper lanterns.

"Look! look!" cried Chin. "There are some actors giving a show outside. They want to tempt people to stop and come in to the play. See the beautiful pointed finger-nails on that one. What fine care he must take of them!"

It is no wonder Chin noticed the man's finger-nails, for they were at least five inches long.

"See the wings on the other actor, Chin," said his sister. "I suppose he represents some strange being who does wonderful deeds. I should like to go to the play. Look! there is a party of people who are going on board of the theatre."

The children now turned their eyes toward the small boat of a Chinaman who was calling aloud to the passers-by:

"Come here and buy chouchou; it is a fine dish, indeed."

A moment afterward he was kept so busy that he had no time to call. His canoe was fairly surrounded by other boats, for many people were eager to taste the delicious soup he served from an odd little stove in front of him.

It is hard to tell how chouchou is made. Many kinds of meat and all sorts of vegetables are boiled down to jelly and seasoned with salt and pepper. He must have had a good recipe, for every one that tasted his chouchou seemed to like it and want more.

"Listen to the music, Chie Lo," said her brother, as he turned longingly away from the chouchou seller.

It seemed more like noise than music. Two men stood on a bamboo raft causing loud, wailing sounds to come from some queer reed instruments. A third player was making the[39] loudest noise of all. He sat in the middle of a musical wheel, as it is called. This wheel is made of metal cups of different sizes placed next each other in a circle.

It seems strange that Chin and his sister should enjoy such "music," and stranger still that the grown-up people should also like it; but they seemed to do so. Were they doing it for their own pleasure? Oh no, they had dainties to sell as well as the chouchou maker, and this was their way of attracting attention.

New sights could be seen constantly. Here were the beautifully-trimmed boats of the rich people taking a ride for pleasure after the heat of the day. There were the canoes of the poor, who were also out to enjoy the sights, for Bangkok is a city built upon the water.

The river Meinam flows through its very centre. The name of the river means "Mother of Waters," just as the name of our own Mississippi means "The Father[40] of Waters." It is well named, for many canals reach out from it in different directions.

If a person is going to a temple to worship, if he has shopping to do, or a visit to make, he does not take a car or carriage, nor does he often walk. He steps into a boat, and after a pleasant sail or row, he finds himself at his journey's end.

"Let's go down the river before we go to bed," said Chin, who had grown tired of sitting still.

He stepped from the platform into his own little canoe and Chie Lo followed him.

The children looked very much alike. Their faces were of the same shape, their eyes were of the same colour, and the two little round heads were shaved in exactly the same way. A tuft of hair had been left on the top of each and was coiled into a knot.

When Chin grew a little older there would[41] be a great celebration over the shaving of his tuft. It would mark his "coming of age," but that would not be for two or three years yet. He was only eleven years old now and was left to do much as he pleased.

The little canoe made its way in and out among the big boats and soon left the city behind. Tall palm-trees lined the banks of the river and waved gently in the evening breeze.

Suddenly there was a loud sound, like a big drum, in the water directly under the boat. "Tom, tom! Tom, tom!" It startled Chie Lo, and she exclaimed:

"What is it, Chin? What is it?"

"It must be a drum-fish, Chie Lo. Nothing else could make a sound like that."

"Of course, Chin. It was all so quiet, and then the sound was so sudden, I didn't think for a moment what it could be."

They had often seen this ugly-looking fish,[42] which is never eaten by the people of their country. It is able to make a loud noise by means of a sort of bladder under its throat, and it is well called the "drum-fish."

The children still went onward, keeping time with their sculls. Suddenly the air around them blazed with countless lights, and a moment afterward the darkness seemed blacker than ever. Then, again the lights appeared, only to be lost as suddenly, while Chin and his sister held their oars and watched.

"Aren't they lovely?" said Chie Lo. "I never get tired of looking at the fireflies."

It is no wonder she thought so. The fireflies of Siam are not only very large and brilliant, but they are found in great numbers. And, strange to say, they seem fond of gathering together on certain kinds of trees only. There they send forth their light and again withdraw it at exactly the same moment.[43] It seems as though they must be under the orders of some leader. How else do they keep together?

"I can hear the trumpeter beetle calling along the shore," said Chin, as the boat floated about. "He makes a big noise for his size, and takes his part in the song of the night. There must be hundreds of lizards singing up there among the bushes, too, and I don't know what else."

"I suppose the parrots are asleep in the tree-tops by this time, as well as the monkeys. Don't you love to go about in the woods, Chin?"

"It is almost the best fun in the world, I think. Oh, Chie Lo, I saw something the other day I didn't tell you about. You made me think of it when you spoke of the monkeys. Father and I had gone a long way up the river in the canoe to get wild bananas. We had just turned to come home when I[44] saw a crocodile ahead of us, lying close to the shore. His wicked mouth was wide open and his eyes were glittering.

"All at once I saw what was the matter. A chain of monkeys was hanging from a tree-top above him. They were having sport with the monster. The lowest monkey would suddenly strike out with his paw and touch the crocodile's head when he was off his guard. Then the whole chain of monkeys would swing away as quick as a flash, and the crocodile would snap too late.

"Oh, he did get so angry after awhile, it made me laugh, Chie Lo. The monkeys grew bolder after awhile, and chattered more and more loudly.

"Then the crocodile began to play a game himself. He shut his eyes and pretended to be asleep. Down swung the monkeys, straight over his head. His jaws opened suddenly in time to seize the little fellow who had been[45] teasing him. That was the last of the silly little monkey, whose brothers and sisters fled up into the tree-tops as fast as they could go. I didn't see them again, but we could hear them crying and wailing as long as we stayed near the place."

"I wish I had been there," sighed Chie Lo. "It must have made you laugh to watch the monkeys before they were caught. But they are easily scared. I shouldn't be afraid of monkeys anywhere."

Chin smiled when his sister said these words.

"If there were enough monkeys together, Chie Lo, and if they were all angry and chasing you, I don't think you would exactly enjoy it.

"Father told me of a time when he was off with a party of men in a deep forest. They caught a baby monkey, and one of the men was going to bring it home. It made the mother wild to have her child taken from her.[46] She raised a loud cry and started after the men. Her friends and relatives joined her, crying and screaming.

"But this was not all, for every other monkey in the forest seemed to get the idea of battle. On they came by the hundreds and the thousands. Do you think those men weren't scared? They hurried along as fast as they could, stumbling over bushes and floundering in the mud. They were only too glad to reach the bank of the river, where they jumped into the canoes and paddled quickly away. The monkeys crowded on the shore and screamed at them. I wish I could have seen them."

Chin lay back and laughed as he finished the story.

"We mustn't stop to talk any more, for it is getting late," said Chie Lo. "But I love to hear you tell these stories, Chin. I hope you will remember some more to-morrow night. Now we must paddle home as fast as we can go."

The next morning the children were awakened early by the cawing of large flocks of crows. These noisy birds were leaving their resting-places in the trees near by, and starting out to search for breakfast in the fields and gardens of the country.

Chie Lo and her brother jumped out of bed, and a moment afterward were taking a refreshing swim in the waters of the river. The water felt cool and pleasant before the hot sunshine had warmed it.

"Come to breakfast," called their mother, as they were in the midst of a game of chase around the platform. "Come and eat the[48] fine hoppers I have just bought from the baker."

The children did not need to be called twice, for they loved the delicious cakes made of rice flour and cocoanut milk. The breakfast was soon eaten, and then Chin and his sister made haste to load Chie Lo's boat with the fruit she must sell on the river.

The mangosteens were placed in the first pile. They would surely be sold, because they were not only beautiful to look at, but fragrant to smell and delicious to taste. You may look for them in many parts of the world, but you will fail to find them unless you visit Chin and Chie Lo in their own country, or go to the islands near by.

The rind is of a brownish purple that changes its tints in the sunlight. Cut the fruit carefully in halves and you will find a creamy, white pulp, with a dark-red rim.

"They look too good to eat," you say.[49] But if you have once tasted them, you will long for more.

Chin and his sister are very fond of mangosteens, and so is nearly every person who has the pleasure of eating them.

But Chie Lo likes the durions better still. When she sorted the boat-load this morning, she was very careful to place this fruit so it should not touch any other kind. What an odour came from it! Ugh! It makes one think of bad eggs and everything else unpleasant.

But people who stop to-day to buy from the little girl will not consider that. If they have lived in the country for only a short time, they have grown to think of it as the finest of all fruits.

Picture the nicest things you have ever eaten,—walnuts, and cream and strawberries, and a dozen other delicious things,—they are all mingled together in the flavour of the durion.

Besides the durions and the mangosteens, there were great luscious oranges, noble pineapples, mangoes and bananas, breadfruit and sour-sops. Chie Lo would certainly have no trouble in selling her goods.

When she had rowed away from the house, Chin went inside and got his shuttlecock. He must find his boy friends and have a game before the day grew too hot. You mustn't blame him for letting his sister work while he played. It is the way of his people, and the idea never entered his head that girls should have, at least, as easy a life as boys. Yet this cousin of ours is gentle and good-natured and loving.

An hour after Chie Lo had gone away, Chin and his friends were having a lively game in the shade of some tall palm-trees, near the bank of the river. It was great sport. The shuttlecock was made of bamboo and was very light and easy to toss. But it[51] took great skill to keep it moving through the air for ten minutes at a time. The boys did not once touch it with their hands. As it came bounding toward Chin, he held the sole of his foot to receive it, and kicked it off in another direction. Perhaps the next boy struck at it with his heel, and the next with the side of his ankle or his knee. Forward and back it flew from one to another.

These naked boys of Siam were wonderfully graceful in their play. They must have spent many days of their short lives in gaining such skill as this.

There was little noise about it. There are places in the world where children think they are not having much fun unless there is a good deal of shouting and yelling. Siam is not such a country, and Chin is not that kind of a boy. He has many good times and many pleasures, although he enjoys them in a quiet manner.

How was Chie Lo getting along with her load of fruit this morning? She paddled down the river among the vessels which had come to anchor there.

"Fine oranges! Ripe durions!" her sweet voice called. And the people on the decks of the English steamers and the queer Chinese boats looked down at the little girl in her canoe.

Many of them smiled at the tiny fruit-seller, and beckoned to her to bring some of her fruit on board.

By noontime her wares were all sold and Chie Lo started homeward with a bag of odd-looking coins to give her father. It was very hot and the sunlight was so bright as it sparkled on the river that the little girl kept shutting her eyes.

All at once she felt a tremendous thump and the next moment she found herself far down under the surface of the water. The[53] boat had been overturned and was bobbing around over her head.

Do you suppose she tried to scream, or that she lost her senses from fright? Certainly not. As soon as she got her breath, she began to swim with one arm; with the other she reached out for the boat and quickly righted it.

After half a dozen strokes, she was able to spring into the canoe, and was soon paddling homeward as if nothing had happened.

What had caused her boat to upset? A passing fisherman had carelessly run into her. The accident did not seem to worry him, however. He did not even stop to see if Chie Lo needed help, but kept straight on his way. He did not mean to be unkind. He simply did not think there was any danger to the little girl. And there was none, for swimming is as natural as walking to the children of Siam, who have no fear of the water.

All that Chie Lo thought of was her precious coins, and those were safe in the little bag hanging around her neck. The next day would be a holiday and she knew her father would wish the money to spend.

It was the 27th of March, but to Chin and his sister it was the first day of a new year.

They woke up happy and smiling, for they would have much fun for three whole days. It is all very well for some people to be satisfied with a festival which lasts only twelve hours, but it is not so with the Siamese. They think they cannot do justice to such a joyful time unless they frolic and feast three times as long as that, at least.

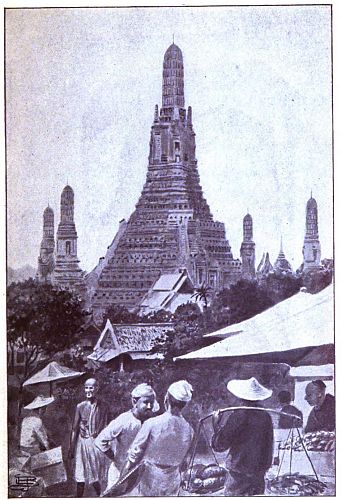

On the first day the children must go to the temple and carry offerings. This duty should certainly not be forgotten. But before they left home that morning they helped their mother give dishes of rice to the yellow-robed[56] priests who rowed slowly down the river as the sun was rising.

These priests in their long yellow gowns looked alike. Each one held before him a begging-bowl. He did not ask for food or money. It was the duty of the people to feed him and give what was needed to keep him from want.

This was what Chin and those of his country believed. And so, when each night was over, the priests left their cells and entered their boats. They passed along the river and through the canals. Some people gave to one, and some to another; some gave money, and some, food. But each one thought as he gave, "I am gaining merit by this deed of kindness." And he felt better for doing so.

When the priests had passed along, Chin and his sister began to think of their friends. They had presents of sweetmeats for them. They had saved all their spare coins for many[57] days to buy them. These sweetmeats looked very tempting as they divided them up and placed them in tiny baskets they had woven out of grasses.

Some of them were made of sugar and cocoanut. Others were rich with glutinous rice and peanuts. Their friends would be delighted with their gifts.

Before the day was over, Chin and Chie Lo had received many presents themselves, for the poorest people in the country manage to remember the New Year's festival.

The day was noisier than usual. The children laughed and shouted more than Siamese children commonly do. They danced and they sang. They went into the country and gathered flowers. They made wreaths and garlands. They carried some of their flowers to the statue of Buddha and placed them in the open palms of their saint.

They played tricks on each other. Chin[58] and Chie Lo were both caught by their playmates before the day was over and their faces blackened, and then they were shoved into the river. But they took the joke with perfect good nature, and laughed over it as merrily as their friends.

The best sport of the day was with their dear old grandmother. As she sat on the platform by the water's edge, Chin came up suddenly and dashed water all over her. After that, he sprinkled her with perfume and a sweet-smelling powder.

But this was not all, for he ran into the house and brought her out a new waist-cloth and a scarf to throw over her old shoulders. At the same time Chie Lo pressed two silver coins into her hand, and shouted with delight at the smile on the dear grandmother's face.

Without doubt the New Year's festival was very merry. Best of all, the children were allowed to do just as they pleased for the three[59] long, happy days. It is no wonder they were sorry when it was over.

"It is even better than the Swing Days," Chie Lo said to her brother, as they settled themselves for a good night's rest.

"Yes, I think so, too, yet we have a great deal of fun then," answered her brother, sleepily.

Girls never take part in the exercises of the Swing Days, but Chin had been training for two or three years to try his skill when he should be a little older.

A part of the city is set aside for the entertainment, and it is there that the swings are set up on high poles. A short distance away stands another pole marked with a waving banner. Just below this banner hangs a purse filled with gold.

Each person who enters the swing is allowed to work it back and forth till he brings himself near the precious purse. He has one[60] chance given him to reach out and seize it in his mouth. If he succeeds, it is his to keep, and he goes down to the ground on a rope ladder by the side of the pole, while the bystanders greet him with shouts and cheers.

If he fails, however, he is obliged to jump from the swing and slide down to the ground on the pole, while every one joins in a laugh at his awkwardness.

On Swing Days there are many processions through the streets. Banners and flags are waving everywhere, no work is done, and every one is gaily dressed and full of joy.

"I never rode on an elephant in my life," said Chie Lo with a sigh.

Chin had just been telling her of a trip he had made with his father. He had gone into the teak forest, and had travelled every bit of the way on an elephant.

"Perhaps you wouldn't like it if you had a chance to try," answered her brother. "You would feel safe enough, and the howdah is big enough for you to lie down in and take a nap. But the elephant swings from side to side as he walks, and the motion might make you feel sick until you get used to it."

"It looks comfortable, anyway," said Chie Lo. "A howdah looks like a tiny house, and[62] the bamboo top keeps off the hot sun nicely. Doesn't it ever slip on the elephant's back, Chin?"

"Of course not. It is fastened behind by a crupper that goes under the tail, while it is held in front by a band of rattan passed around the neck. So it is perfectly safe."

"Elephants are very wise animals, and I love them. Mother told me that a long time ago there was an elephant in the city that used to ladle out rice to the priests as they came out of the temple. He did it every morning, and was as careful about it as any person could be. He made no mistakes, for he never gave the rice to any people unless they were priests. Wasn't that wonderful, Chin?"

"It was very wise, at any rate, Chie Lo. But, of course, he could tell the priests because of their long yellow robes. I've heard more wonderful stories than that, though.

"I've watched elephants at work in a lumber[63] yard, myself. They would pick up the logs with their trunks, and carry them to the place where they were to be piled up. Then they would lay them down, one on top of another, and each time they would place them in such good order that the ends of the pile would be kept perfectly even. They are very careful workers; men couldn't do any better."

"Weren't you afraid when you crossed the river on the elephant's back, Chin? I heard you speaking about it to father when you got home."

"Not the least bit. The water grew deeper until at last only my howdah and the animal's head were above the surface. But he went on slowly and surely, and as he felt safe, I did, too. In a few minutes we were on dry land again, and climbed up the steep bank without stopping to rest.

"It was great fun whenever we went down hill. The big clumsy fellow knelt on his fore[64] legs, and actually slid down, with his hind legs dragging behind him."

"What good times you have, Chin. I wish I were a boy!" and Chie Lo sighed again.

"They say that the white elephants are going to march through the streets to-day. Let's go up in the city to see them," said Chin.

He was always glad to have his sister go about with him.

The home of our Siamese cousins is a strange country. It is often spoken of as the "Land of the White Elephant." You shall hear the reason.

Whenever a white elephant is seen in the forests, word is at once sent to the king, and parties of hunters go forth to secure him. He is looked upon as a sacred animal, for many of the people believe that the soul of some great and wise person has come back to dwell for a while in his body.

In the olden times there was a great celebration after a white elephant had been caught and was brought into the city. The king and his nobles, as well as hundreds of priests, went out to meet him with bands of music. He was led to the royal stables, and large pictures of the forests were hung around him, so he should not grow lonesome and long for his home in the jungle.

It is even said that he was fed from golden dishes, and that only the sweetest sugar-cane, the ripest bananas, and the tenderest grasses were given him as food. He was loaded with gifts.

The ways of the people are changing now, however, and both the king and his people are wiser than they used to be. Yet the white elephants are still treated with honour, and kept in the royal stables, while on great days they march in state through the streets of the city.

It is hardly right, however, to speak of them as white. Some of them are of a pale, pinkish gray colour. Others are ashy gray. Their eyes look washed-out and dull. They are not nearly as grand and noble-looking as their brothers, for it seems as though Mother Nature were tired and had not finished her work, when one looks at them.

After the children had watched the procession of white elephants, Chin said:

"Let us go to the temple, Chie Lo. It will be a pleasant walk. And, besides, father said we ought to go to-day. He gave me these coins to carry there." Chin held up two pieces of silver. "One of them is for you, Chie Lo, and the other is for me."

The place where the temple stood had been set apart from the rest of the city. It was divided up into large fields surrounded by walls. In each of these fields there was at least one large temple, and several small ones, besides the buildings where the priests lived with their pupils. Such a place is called a wat.

As Chin and his sister drew near one of these wats, they found many little stands from which men were busily selling gold-leaf to those who were on their way to the temples.

What would the people do with this gold-leaf, you wonder.

They would use it to cover any bare spots on their favourite images. It would "make merit" for them, as they would say; or, in other words, they would at some time be rewarded for the act of goodness.

It is in this way that the images are kept richly gilded, and many of them are fairly loaded with the precious stuff.

"We can't buy any to-day," said Chin, "we haven't money enough. But I wish I could get one of those rings that man is selling. They are made of hairs out of the manes and tails of the sacred horses. It would bring good fortune, I'm sure."

Poor ignorant Chin! As though anything[69] but his own honest little heart and good deeds would bring him happiness and success.

And now the children passed through the gateway and into the beautiful grounds. Stately trees grew on every side, and flowering plants were to be seen in every direction. Here and there stood large stone statues. They were ugly-looking figures, but were supposed to be the guardians of this holy place.

"After we come out, let's have a game of hide-and-seek with those children," said Chin.

He pointed to some boys and girls playing among the trees and statues, and having a merry time.

As the children turned toward the buildings, they passed under some trees from whose branches hung pieces of wood, stone, and porcelain.

"People hung those offerings there because they are going to build a home," said Chin.[70] "Or perhaps they are just married, and are beginning housekeeping."

"I know that, of course," answered Chie Lo.

As the boy and girl entered the temple, they stopped at the cistern of water near the door. Wooden dippers were handed to them, which they were to fill. They must wash their hands and rinse their mouths before they dared to draw near the statue of the holy Buddha or knelt in prayer. They must do it as a symbol that their tongues were pure.

After this was done, they threw their coins into a large money-box, and passed into the main part of the temple. There were no seats, but the worshippers sat together on the floor in little circles.

The altar was beautifully carved, and built up in the shape of a pyramid. Many offerings could be seen lying upon it. There were[71] lovely flowers, luscious fruits, and piles of snow-white rice. These had all been brought here to-day by those who had come to worship and to pray. Behind the altar were high panels on which the life of Buddha was pictured.

Chin and his sister loved to study these pictures and dream of the Holy One in whom they believed.

Their mother had taught them that long ago a great being lived in this world. He was born in a palace, and was the son of a king. He knew only joy and comfort until one day, when he met a poor old man. His heart went out in pity to him, and he said to himself:

"I will not live in comfort any longer if others in the world suffer and are poor."

He went out from the palace and spent the rest of his life teaching and giving help.

Chin and his sister did not stop to look at[72] the pictures now. They joined one of the groups sitting cross-legged upon the floor. A moment afterward their heads were bent, and their small hands were pressed together in prayer.

From time to time, one of the worshippers rose and stepped over to a big bronze bell, and rung it violently. This was because he felt that his prayers were not heard, and he wished to call attention.

Listen! A priest is reading from a palm-leaf book; and now he chants a prayer with his face hidden behind a big fan. He keeps time by striking a bell, or beating on a block of wood. The people rise upon their knees and bow to the ground as he chants. There is no music in the strange service.

As Chin got up to go away, he turned to Chie Lo and whispered:

"I love to look at the bronze elephants carved on the walls. They look very wise[73] and strong. They are the symbols of the Buddha, who taught men to be patient and faithful."

"I always love to look at the flag of our country, too," answered Chie Lo. "The great white elephant pictured on the red cloth makes me think of the same thing."

"I believe I shall like it when I am old enough to come here to study with the priests," her brother went on. "I shall like to serve them, and they will teach me many good things. But I don't believe I shall ever be a priest myself."

It is the custom of Chin's country for all the boys to live awhile in the wats, as soon as they are old enough to have their heads shaved. They help the priests in the temples, and serve them in different ways. They are also taught to write and cipher. After they have stayed a certain time, they may choose for themselves what they will do. They may[74] study to become priests themselves, or they may go back to their homes and choose some kind of work.

As for Chie Lo, what would she do when Chin went away from home? Her parents were too poor to send her to a school for girls. She would sell fruits and vegetables in her little boat until she was old enough to get married.

Poor little child! She turned to her brother as they left the temple, and said:

"I wish, Chin, that I could go to school and be able to recite poems and stories."

For in that strange country of Siam, few girls learn either to read or write, even if they are able to go to school.

Their teacher recites some lines and the pupils repeat them after him until the whole piece is learned. Then another is taken up in the same way, and still another. But every child must be sure of one thing: she must[75] know an odd number of pieces when she has finished.

You remember the Siamese seem to be afraid of even numbers in anything whatsoever.

As for geography, or history, or any other pleasant study, such as you have, very few of the children of that country have even heard of them. I doubt if Chin and his sister know anything about the great, beautiful country on the other side of the world, where their American cousins are living.

But Siam is slowly changing, and, as I have already said, the king who now rules is wiser than those before him. He will help his people to become wiser, too.

As the children went on their way home, they fell to talking about their ruler. They spoke of him as "The Lord of the Celestial Elephant," and other queer titles.

"He worships in the temple of the Emerald[76] Buddha," Chin told his sister. He had heard others describe the beautiful place.

"It seems as though I could almost see it," the boy declared. "It must be wonderful. Just think, Chie Lo, the floor is paved with bricks of brass, and the walls are covered with paintings. The altar is several times as high as our house. It is loaded with images from the bottom to the very top. They are covered with gold, except the Emerald Buddha itself, which is above all the rest.

"Its hair is made of solid gold, in which are diamonds and rubies and many other kinds of precious gems. I wish I could look at it just once, although it is so high up, a person can hardly see it as he stands on the floor."

"Mother said nobody made that statue," said Chie Lo when her brother had finished. "It was a miracle, and suddenly appeared in the world after a visit of Buddha."

"Mother and father know a great deal," replied Chin. "When we get home to-night, let's ask them to tell us the story of how gold and silver came to be in the world."

It was a beautiful moonlight night. The stars shone faintly in the clear sky.

"They do not look as though they felt as happy as usual," said Chin to Chie Lo, who sat beside him on the platform of the house. "They are jealous because the moon is hiding them by her brightness. Here comes father; now we can ask him."

"Father, will you tell us the story of Rosy Dawn?" said his son, as the boat drew up beside the platform and the man jumped out.

"As soon as I fill my betel-box, Chin," was the answer.

Five minutes afterward, the family gathered around the story-teller by the side of the quiet river.

"Once upon a time," he began, "Father Sun was much nearer the earth than he is now. He was ever ready to advise his younger brother, the king of our country, and would even order his officers, the stars, to do anything which might help this blessed land.

"It was long, long ago that all this happened. Everything was so different then from what it is now, that there was no sickness nor sorrow in the land. People lived to be hundreds of years old. Why, my children, the King of Siam himself was looked upon as a very young man, although he was at least one hundred and sixty years old.

"His father, the old king, was still alive, but had grown tired of ruling after two hundred years of such work. He had given it into his son's hands, and now took his ease.

"His only daughter, a beautiful maiden named Rosy Dawn, spent most of her time in cheering him and making his life happy. No one had ever looked upon her sweet face except her own family. She was as good and simple as she was beautiful. Her days must have passed very quietly, for her only amusements were singing her old father to sleep and wandering alone through the fields and woods.

"A sad thing happened about this time. The naughty stars grew jealous of their lord, the Sun. They did not like it because he chose to keep awake all the time, and was having such pleasure with the earth and its people that he never thought of sleeping.

"Day and night, summer and winter, he gave his bright light to the world; he seemed afraid that something ill might happen to his young brother the king, if he left him for a moment. Of course, the stars had no chance of showing[81] their own beauty, and this was what put them out of temper. They said to each other:

"'Our lord has some reason for not sleeping which we do not understand. We will watch him, and set a snare for him.'

"So, when they themselves should have been sound asleep, for it was now bright noonday, they set to watch the jolly, laughing Sun.

"It happened at this very time that Rosy Dawn left her sleeping father's side and went out for a frolic in the woods. She picked the wild flowers and made them into wreaths; she softly sang sweet songs to herself, and she watched the squirrels and lizards as they played about among the trees.

"All at once she spied a beautiful butterfly move past her. It was larger and more brilliant than any she had ever seen before. She said to herself:

"'I must have the lovely creature,' and ran after it.

"On flitted the butterfly, faster and faster; on sped Rosy Dawn after it. But it was in vain. For after a long chase, and just as she thought she was about to succeed, the butterfly rose up into the air, higher and higher above her head.

"Now the fair maiden turned back toward home, and for the first time she thought of how tired she was. Her dainty feet fairly ached from the long chase, and she stopped at a refreshing brook to bathe.

"Just at this moment, the Sun's glorious chariot appeared over the hilltop. The warm light fell upon Rosy Dawn and made her feel quiet and restful. At the same time the Sun himself looked down upon the beautiful maiden and he fell in love with her then and there.

"When she had finished her bath, Rosy Dawn left the stream and entered a shady cavern near by, where she might rest.

"The Sun's great chariot flew through the heavens as his noble steeds were spurred onward. It seemed as though he could not wait a moment longer before he should come to the charming girl he had just seen.

"You ask me if he won Rosy Dawn's love in return. Ah, yes! And, sad to say, trouble followed after.

"You remember that the jealous stars were watching their lord's movements. After a while they discovered that he was making love to Rosy Dawn. They followed him one day when the two were fondly talking together in their favourite resting-place, the cavern.

"Alas! the chariot was outside. The wicked stars seized it and carried it off, and the frightened steeds ran away. They did not turn their heads until they had reached home.

"The angry stars did not stop here. They raised a great shout against their ruler, and[84] declared they would be his subjects no longer. The poor old Sun began to tremble, and shed tears of gold.

"The mountains were truly sorry for him. They opened up a passageway through which he might return home. They promised him that he might drive through this cavern every day and be perfectly safe. Again he wept, and more plentifully still.

"At last he started on his way homeward, and, as he journeyed along, his tears fell and formed pools of gold. Those pools are now the gold mines of Siam.

"It took twelve hours for Old Sol to reach home, after which he went out every day; but he came back regularly at night-time by way of the cavern that the mountains had given him.

"After this poor Rosy Dawn wandered sadly about through the caves and mountains. She, too, wept, and her tears were very plentiful.[85] Wherever they fell you will now find the silver mines of our country.

"But you must not think her joy was at an end. The wicked stars at last made an agreement with their lord, the Sun. They said he might live with Rosy Dawn for one-half the month, if they were allowed to look at her beautiful face for the other half.

"Ever since that time the Sun meets Rosy Dawn at the mouth of the cave where he first saw her, and carries her home to stay with him for two weeks out of each month."

"You didn't mention one important thing," said Chin, as his father ended the story. "You forgot to say that the stars insisted on the Sun's never kissing Rosy Dawn when any one can see him. We know hers is another name for the Moon; and the Sun breaks his agreement with the stars once in a great while, whenever there is an eclipse."

"Yes, that is why the people beat drums[86] and fire off guns at such times," said the children's mother. "It is to shame the Sun, and to make him stop such conduct at once. Of course it takes some time for the sounds to reach him, but as soon as he hears, he seems to be ashamed, for the eclipse soon passes by."

"When I was a boy, I went on a pilgrimage to the very cavern where the Sun first met Rosy Dawn," said the father. "I was careful to carry both a silver coin and a gold one. When we reached the place, I threw the money into the cavern. Every one else did likewise. We offered these coins in hopes of making merit for ourselves."

"I am going to the city to-day to buy a new waist-cloth," said Chin's father one morning. "Chin, you may go with me, if you like."

A few moments afterward the two were paddling down the river past the temples and palaces which lined the shore.

Besides the homes of the rich, surrounded by stately palm-trees and beautiful gardens, there were other houses belonging to poorer people. These last were built close to the river's edge, but were raised high up above the water, on posts.

This was a wise thing to do for several reasons. In the first place, the river would rise after the fall rains began, and the houses[88] might float away,—or, at least, the people inside would be flooded, unless they had been careful to build high enough to prepare for such times.

The fine houses were of brick or wood, but the poorer ones were much like Chin's house-boat, woven of bamboo and thatched with leaves.

The boy and his father soon left the main part of the river and turned into one of the canals. They were now in a part of the city where a good deal of business was going on. They left the boat, after fastening it to the bank, and walked along through the narrow street.

The fronts of the houses here were all open and everything within could be plainly seen. In this one was a big counter, almost filling the room, and the merchant himself sat cross-legged upon it with his goods around him.

There was a bakery where the cakes and[89] bread were made and baked in sight of everyone who passed. Chin liked to stop and look at the various workmen. There was much to see and learn. The metal-workers were pounding and hammering away, and, as the boy watched them, he could see bracelets and anklets shaped, and sheets of copper formed into various dishes.

In many places the families of the storekeepers lived in the one room that was both store and dwelling, but they did not seem to be troubled when they noticed Chin's black eyes following them.

In one store a hammock hung from the ceiling and a baby was swinging there. What did he care if he was brought up on the street, as one might say? Care! He seemed to think the coming and going of so many people was meant all for him, and he laughed and crowed at each new face.

"Do look, father," said Chin, as they[90] passed a barber's shop. "There is a Chinaman having his head and eyebrows shaved. He won't be satisfied until his eyelashes have been pulled out. Other people have strange fashions, don't they?"

His father smiled. "Yes, Chin, we are all different from each other in this world. But I know one thing in which we are like the Chinese. We love kites, don't we?"

Chin's eyes sparkled. "Yes, indeed, father. There is a kite store, now. Let us go in and look around. The kites there are beautiful."

It is no wonder Chin longed to stop. All sorts of kites were there to tempt the passer-by. They were in the shapes of flowers and boats, dragons and elephants, and I can't tell how many other odd or lovely patterns. Chin's father was as much interested as his son, and a half-hour was spent before they finally decided on buying a kite in the form of a butterfly.

"We will have great sport in flying it this afternoon," said Chin. "Chie Lo must enjoy it with us."

He had finished speaking when he caught sight of a procession coming in that direction. A moment before there had been so many children, dogs, and cats in the street they seemed to block the way of everything else; but now the children quickly turned aside and ran into the doorways.

As the procession drew near, a great shouting and beating of drums could be heard.

"Father, look quickly," said Chin. "The men are carrying a statue of Buddha on a litter. Isn't it beautiful? It is all covered with gilt. I wonder where they will carry it. Oh, now I see; they have stopped at that open place and are going to have a play. There are the actors themselves."

"Some rich man is doing this," said Chin's father. "He has probably hired the actors,[92] and the show will be free to all. He is making merit for himself, without doubt. We will join the crowd."

By this time the gilded statue had been set up on a sort of throne, and sticks of incense were lighted and placed on the rough altar in front of it.

The strangest part came now, for the actors began to put on their queer costumes right before the people who had gathered around the show. Then came the play.

There was neither stage nor curtain; nor was there any scenery, except that of the place itself. But Chin and his father enjoyed it as well as the other onlookers. They laughed and looked sad, in turn, and seemed to forget that it was only a play, and not real life, that was pictured before them.

When the play was over, Chin's father said:

"We must go back to the stores, for I have not bought my waist-cloth yet."

The place they soon entered was different from any dry-goods store you ever saw. The room was fitted with pigeonholes, in each of which was folded a strip of cloth one yard wide, and three yards long. Some of these pa-nungs, or waist-cloths, were of silk, and others of cotton. Some were striped, and others figured. They form, as you know, the principal part of the dress of both men and women in Siam.

After Chin's father had looked at a number of the cotton waist-cloths, he finally decided on one that was gaily striped. It was of no use for him to examine anything made of silk. It would cost more than the poor man could afford.

"Now, for the tailor's," he said. "I must buy thread and needles."

A few steps brought them to the tiny shop where the tailor sat, working busily, but on the watch for customers at the same time. He[94] held the cloth on which he was sewing between his toes! That did not seem strange to Chin. He had often watched carpenters use their toes to hold boards in place. As to himself, his own toes were put to every possible use, so that you would almost call him four-handed.

As his feet were always bare, why shouldn't he make them useful in other ways than walking and running, swimming and playing games? There was no reason at all.

"I'm getting hungry, and we are a good ways from home, father. I wish we could buy some cakes."

Chin looked longingly at a stand under a stone archway where two men stood in front of a movable furnace. Square griddles were on the furnace, and the men were busily baking cakes. Each one was made in the shape of the figure 8. Curlicue cakes, they were called.

A crowd of boys was standing as near to the furnace as possible, watching the men. Some were buying the cakes as they came from the hot griddle; others had no money and could only look on.

Each of the bakers held in his hand a terra-cotta bottle with a small hole in the end. He kept the bottle horizontal while he filled it with the batter. When the griddle was hot enough, he held the bottle upright for a moment with his finger over the hole, then, taking his finger away, he passed it quickly over the griddle with the motion you would use in making the figure 8. A minute afterward, a delicious curlicue cake was ready for a customer.

"You may treat yourself here, Chin," said his father, "while I go to the betel stand yonder, to get my box filled."

It was now noon-time, and the sun was very hot. The street, which had been crowded all the morning, was nearly empty.[96] Almost every one in the city, except the poorer people, was now taking a midday nap in the shadow of some tree or veranda.

"We must go home, Chin, for I am warm and tired," said his father, but he smiled pleasantly, for he had enjoyed the morning as much as his son.

On their way to the boat they passed some jugglers treading fire and climbing a ladder of sharp knives with their bare feet. At most times, a large crowd would have been gathered around them, but there were few people now. It was too hot, and even Chin was glad to leave the city street and get into his little boat once more.

Perhaps you wonder if there are no carriages in this strange city of the East. There are not many, since, as you remember, most of the travelling is done on the water. But once in a while one sees a queer sort of vehicle called a jinrikisha.

It is much like an open buggy on two wheels and is drawn by men. It is more common in the land of Chin's Japanese cousins, however, than in his country.

Then, again, if any of Chin's people are in a great hurry (but that very seldom happens), they may hire gharries, which are very light and have canvas tops. These are drawn by small horses brought from China.

"The gharries are strange things," thinks Chin's father; "the idea of using them must have been given by those queer white people, who do not seem to enjoy life as we Siamese do. They move so much faster, and are not satisfied to do things in the quiet, happy way of my countrymen."

"I have had a lovely time to-day, too," said Chie Lo, when Chin had told her of his walk through the city.

"I sold my fruit in an hour or two, and then Pome Yik and I went off in my canoe to have a good time by ourselves."

Chin laughed when his sister mentioned Pome Yik. She was a curly-headed playmate of Chie Lo's. The Siamese think that straight, wiry hair is the only beautiful kind in the world, and make fun of any one whose hair is even wavy. So the little girl spoken of came to have the nickname Pome Yik, which means curly-head.

Her real name was almost forgotten, but, poor child, she didn't enjoy hearing herself called Pome Yik any more than if it had been "double-toe" or "hunchback," or the name given to any kind of deformed person by the people of her country.

"We went several miles before we stopped," Chie Lo went on. "We passed that big rice plantation, Chin, where you often go on errands for father. Then we came to a field flooded with water and covered with lotus blossoms. They had been raised for market and the people were busy gathering them.

"See, Chin, they gave me these to bring home. Aren't they beautiful?"

Chie Lo held up a bunch of the great, delicate lilies for her brother to admire. Their hearts were golden; the petals, which were of a faint pink near the centre, were of a deep, bright red toward the tips.

The flower had a great meaning to these[100] children of Siam. It told the story of life, and was sacred to the Buddha, who was often pictured sitting on the lotus. Why should it mean so much? Let us see.

The root of the plant lies embedded in the mud. That represents our weak human nature. As the long stems grow, they reach up through the deep water toward the sunlight. That is what we all do, is it not? for we long to do right and seek the light of love and wisdom.

At length a wondrous blossom appears on the surface of the water. It is perfect in shape, and beautiful in colour, while its heart is golden, we remember. That is the blossoming of a whole life. The lotus is a fine symbol, we have to admit.

But Chie Lo spoke of the people gathering the lotus for market. Of course the flowers could be readily sold, but that was not all. The Chinese in the city would be glad to[101] buy the seeds, which they grind and make into cakes. The stems could be cooked and served as a delicious vegetable; the fibres of the leaf-stalks would furnish lamp-wicks. The plant has many uses in the country where it is raised.

"Father says the king has beautiful lotus ponds in the grounds near the palace," said Chin, as he smelled the flowers. "He has seen them, as well as the fountains and statues and lovely gardens."

"It must be a grand thing to be a king," replied Chie Lo, thoughtfully. "They say that the palace is even more wonderful than the grounds around it.

"Just think of it! the floors are paved with marble and the tables are also of marble. There are all sorts of couches to lie and sit on. These are covered with silks and satins of beautiful colours, and there are pictures on the walls that have been painted to look just like[102] people the king has known. Ah! what a sight it must be!"

Chie Lo shut her eyes, as though she might then be able to see what she had been describing.

"The city of the royal women is inside all the rest of the king's grounds," said Chin. "You know that one must pass through three walls before one can enter it. No man can go there except the king and the priests."

"Yes, mother has told me about it," answered Chie Lo. "It is a real city, too, for it contains stores and temples, theatres and markets. There are all sorts of lovely trees and plants, ponds and summer houses. The children must have a fine time in such a lovely place. It must be a grand thing to be born in a king's family." Chie Lo sighed.

"Tell me what else you saw beside the lily-fields this morning," said Chin, who was quite[103] satisfied to be a free, careless, happy boy, and envied nobody.