Larger Image

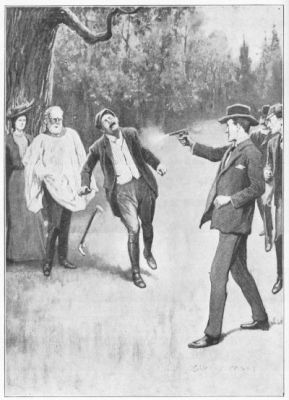

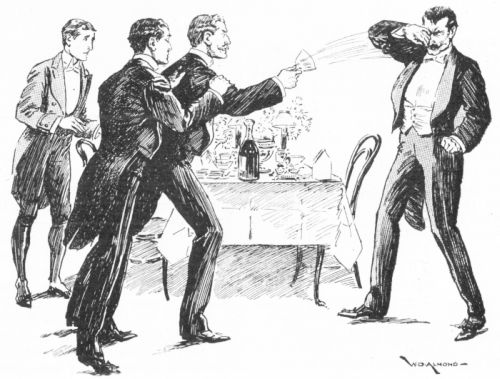

"HE SPUN ROUND WITH A SCREAM AND FELL UPON HIS BACK."

(See page 11.)

Title: The Strand Magazine, Vol. 27, January 1904, No. 157

Author: Various

Release date: November 5, 2013 [eBook #44113]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jane Robins, Jonathan Ingram and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Page | |

| THE RETURN OF SHERLOCK HOLMES. By A. Conan Doyle. | 3 |

| HAPPY EVENINGS. | 15 |

| THE CONVERSION OF AUNT SARAH. By Archibald Marshall. | 24 |

| HOW A CROMO-LITHOGRAPH IS PRINTED. By L. Gray-Gower. | 33 |

| SADI THE FIDDLER. By Max Pemberton. | 40 |

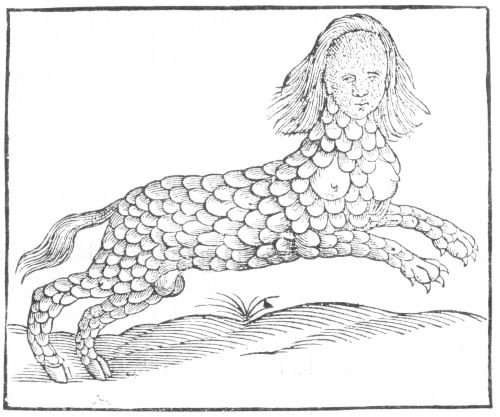

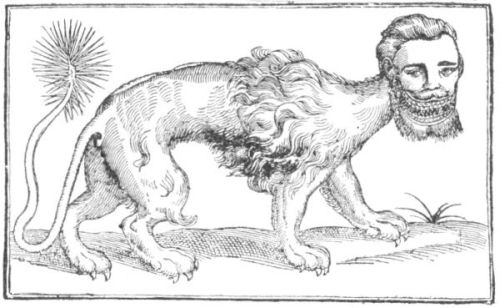

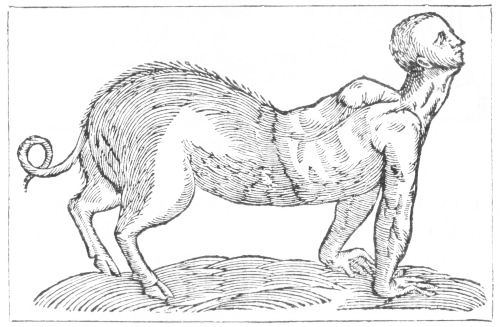

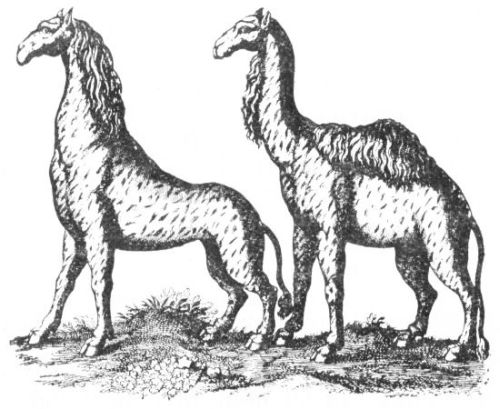

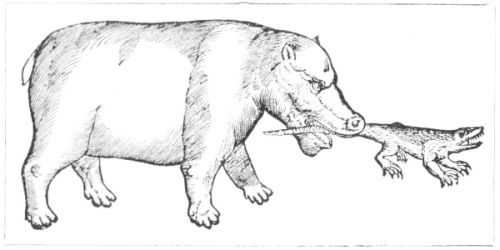

| PRINCE HENRY'S BEAST BOOK. | 49 |

| DIALSTONE LANE. By W. W. Jacobs. | 55 |

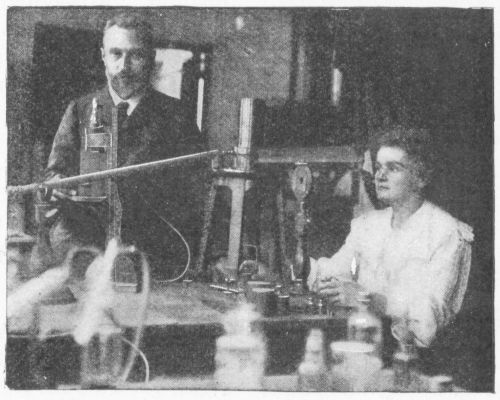

| Illustrated Interviews. LXXX—M. CURIE, THE DISCOVERER OF RADIUM. By Cleveland Moffett. | 65 |

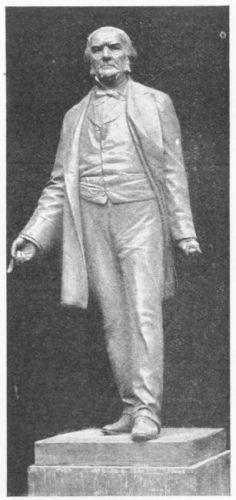

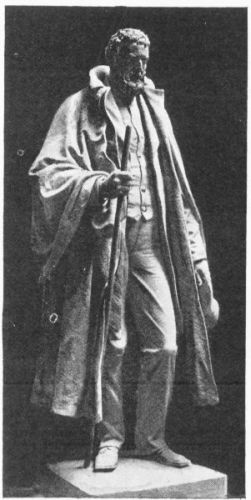

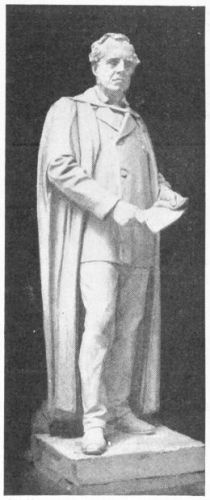

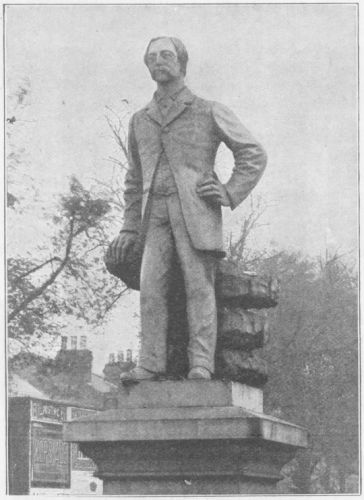

| TROUSERS IN SCULPTURE. By Ronald Graham. | 74 |

| THE COILS OF FATE. By L. J. Beeston. | 81 |

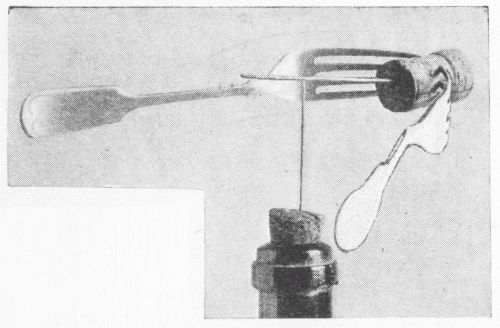

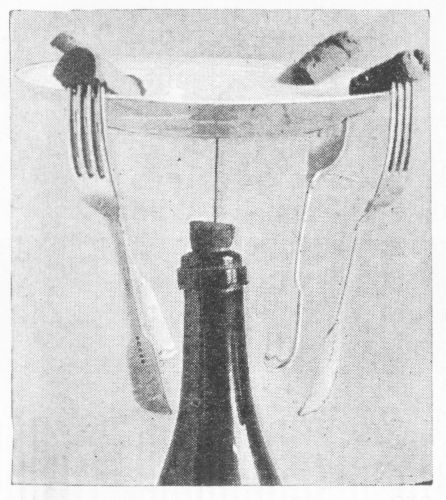

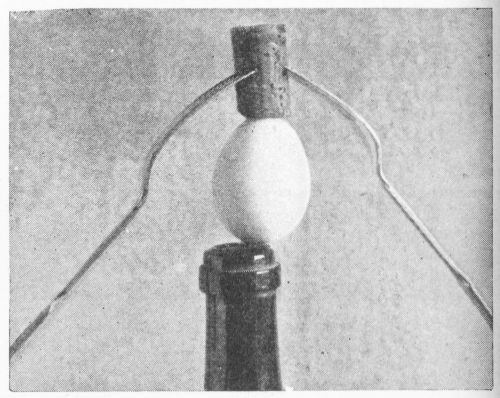

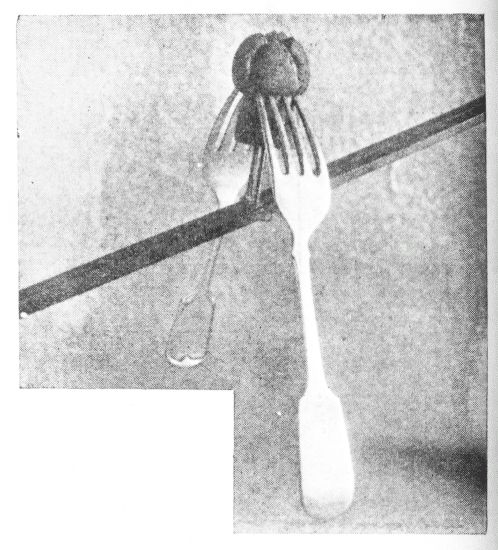

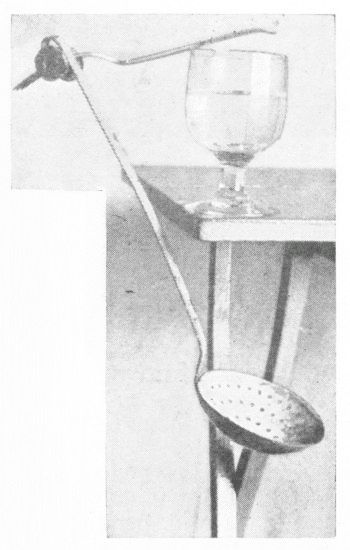

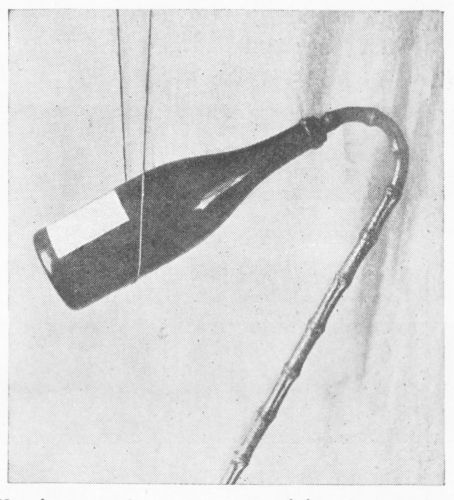

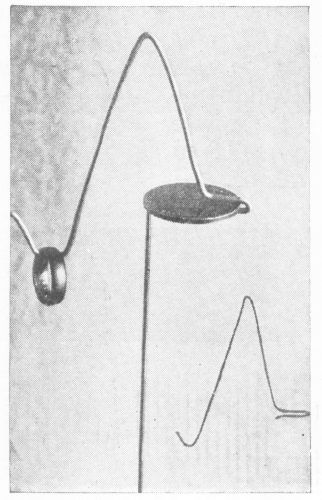

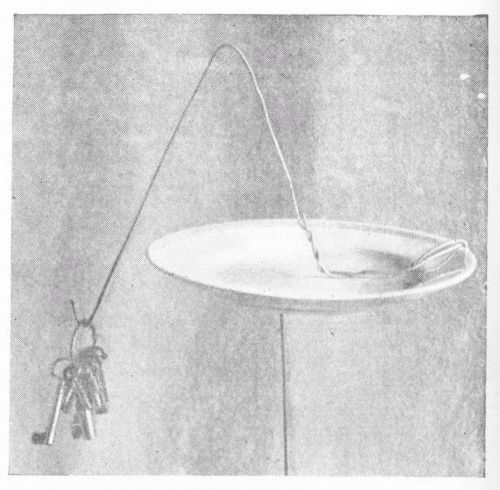

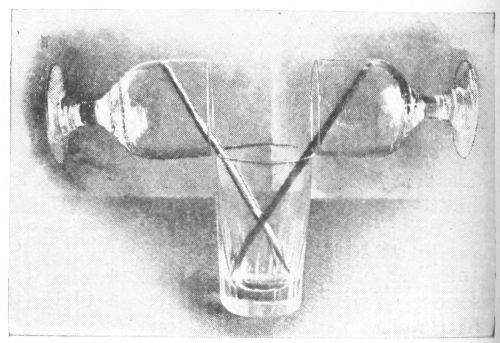

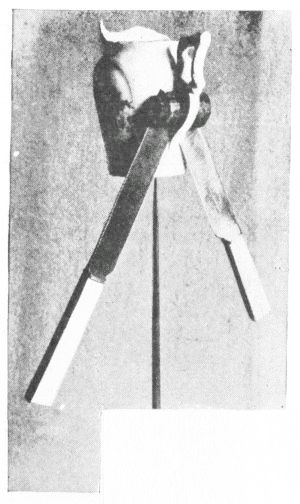

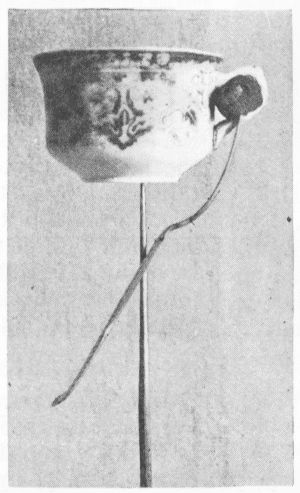

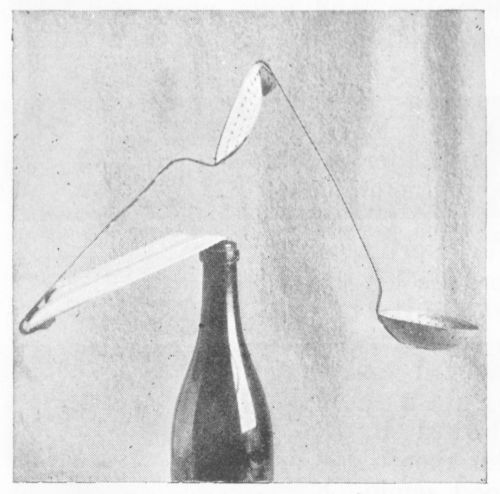

| ECCENTRICITIES OF EQUILIBRIUM. By Louis Nikola. | 91 |

| MISS CAIRN'S COUGH-DROPS. By Winifred Graham. | 97 |

| Solutions to the Puzzles in the December Number. | 104 |

| THE PHŒNIX AND THE CARPET. By E. Nesbit. | 108 |

| CURIOSITIES. | 116 |

Copyright, 1904, by A. Conan Doyle in the United States of America.

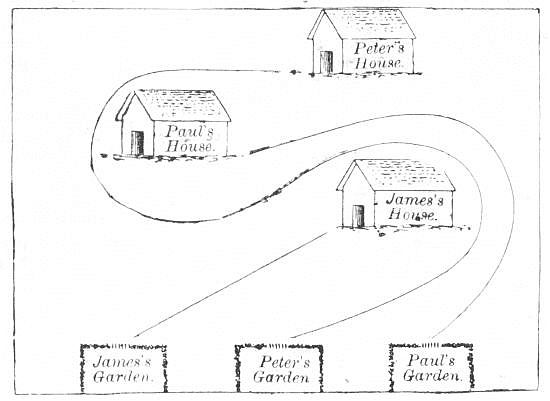

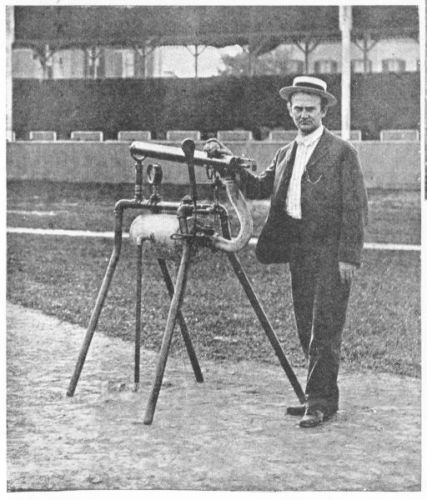

From the years 1894 to 1901 inclusive Mr. Sherlock Holmes was a very busy man. It is safe to say that there was no public case of any difficulty in which he was not consulted during those eight years, and there were hundreds of private cases, some of them of the most intricate and extraordinary character, in which he played a prominent part. Many startling successes and a few unavoidable failures were the outcome of this long period of continuous work. As I have preserved very full notes of all these cases, and was myself personally engaged in many of them, it may be imagined that it is no easy task to know which I should select to lay before the public. I shall, however, preserve my former rule, and give the preference to those cases which derive their interest not so much from the brutality of the crime as from the ingenuity and dramatic quality of the solution. For this reason I will now lay before the reader the facts connected with Miss Violet Smith, the solitary cyclist of Charlington, and the curious sequel of our investigation, which culminated in unexpected tragedy. It is true that the circumstances did not admit of any striking illustration of those powers for which my friend was famous, but there were some points about the case which made it stand out in those long records of crime from which I gather the material for these little narratives.

On referring to my note-book for the year 1895 I find that it was upon Saturday, the 23rd of April, that we first heard of Miss Violet Smith. Her visit was, I remember, extremely unwelcome to Holmes, for he was immersed at the moment in a very abstruse and complicated problem concerning the peculiar persecution to which John Vincent Harden, the well-known tobacco millionaire, had been subjected. My friend, who loved above all things precision and concentration of thought, resented anything which distracted his attention from the matter in hand. And yet without a harshness which was foreign to his nature it was impossible to refuse to listen to the story of the young and beautiful woman, tall, graceful, and queenly, who presented herself at Baker Street late in the evening and implored his assistance and advice. It was vain to urge that his time was already fully occupied, for the young lady had come with the determination to tell her story, and it was evident that nothing short of force could get her out of the room until she had done so. With a resigned air and a somewhat weary smile, Holmes begged the beautiful intruder to take a seat and to inform us what it was that was troubling her.

"At least it cannot be your health," said he, as his keen eyes darted over her; "so ardent a bicyclist must be full of energy."

She glanced down in surprise at her own feet, and I observed the slight roughening of the side of the sole caused by the friction of the edge of the pedal.

"Yes, I bicycle a good deal, Mr. Holmes, and that has something to do with my visit to you to-day."

My friend took the lady's ungloved hand and examined it with as close an attention and as little sentiment as a scientist would show to a specimen.

"You will excuse me, I am sure. It is my business," said he, as he dropped it. "I nearly fell into the error of supposing that you were typewriting. Of course, it is[4] obvious that it is music. You observe the spatulate finger-end, Watson, which is common to both professions? There is a spirituality about the face, however"—he gently turned it towards the light—"which the typewriter does not generate. This lady is a musician."

"Yes, Mr. Holmes, I teach music."

"In the country, I presume, from your complexion."

"Yes, sir; near Farnham, on the borders of Surrey."

"A beautiful neighbourhood and full of the most interesting associations. You remember, Watson, that it was near there that we took Archie Stamford, the forger. Now, Miss Violet, what has happened to you near Farnham, on the borders of Surrey?"

The young lady, with great clearness and composure, made the following curious statement:—

"My father is dead, Mr. Holmes. He was James Smith, who conducted the orchestra at the old Imperial Theatre. My mother and I were left without a relation in the world except one uncle, Ralph Smith, who went to Africa twenty-five years ago, and we have never had a word from him since. When father died we were left very poor, but one day we were told that there was an advertisement in the Times inquiring for our whereabouts. You can imagine how excited we were, for we thought that someone had left us a fortune. We went at once to the lawyer whose name was given in the paper. There we met two gentlemen, Mr. Carruthers and Mr. Woodley, who were home on a visit from South Africa. They said that my uncle was a friend of theirs, that he died some months before in great poverty in Johannesburg, and that he had asked them with his last breath to hunt up his relations and see that they were in no want. It seemed strange to us that Uncle Ralph, who took no notice of us when he was alive, should be so careful to look after us when he was dead; but Mr. Carruthers explained that the reason was that my uncle had just heard of the death of his brother, and so felt responsible for our fate."

"Excuse me," said Holmes; "when was this interview?"

"Last December, four months ago."

"Pray proceed."

"Mr. Woodley seemed to me to be a most odious person. He was for ever making eyes at me—a coarse, puffy-faced, red-moustached young man, with his hair plastered down on each side of his forehead. I thought that he was perfectly hateful—and I was sure that Cyril would not wish me to know such a person."

"Oh, Cyril is his name!" said Holmes, smiling.

The young lady blushed and laughed.

"Yes, Mr. Holmes; Cyril Morton, an electrical engineer, and we hope to be married at the end of the summer. Dear me, how did I get talking about him? What I wished to say was that Mr. Woodley was perfectly odious, but that Mr. Carruthers,[5] who was a much older man, was more agreeable. He was a dark, sallow, clean-shaven, silent person; but he had polite manners and a pleasant smile. He inquired how we were left, and on finding that we were very poor he suggested that I should come and teach music to his only daughter, aged ten. I said that I did not like to leave my mother, on which he suggested that I should go home to her every week-end, and he offered me a hundred a year, which was certainly splendid pay. So it ended by my accepting, and I went down to Chiltern Grange, about six miles from Farnham. Mr. Carruthers was a widower, but he had engaged a lady-housekeeper, a very respectable, elderly person, called Mrs. Dixon, to look after his establishment. The child was a dear, and everything promised well. Mr. Carruthers was very kind and very musical, and we had most pleasant evenings together. Every week-end I went home to my mother in town.

"The first flaw in my happiness was the arrival of the red-moustached Mr. Woodley. He came for a visit of a week, and oh, it seemed three months to me! He was a dreadful person, a bully to everyone else, but to me something infinitely worse. He made odious love to me, boasted of his wealth, said that if I married him I would have the finest diamonds in London, and finally, when I would have nothing to do with him, he seized me in his arms one day after dinner—he was hideously strong—and he swore that he would not let me go until I had kissed him. Mr. Carruthers came in and tore him off from me, on which he turned upon his own host, knocking him down and cutting his face open. That was the end of his visit, as you can imagine. Mr. Carruthers apologized to me next day, and assured me that I should never be exposed to such an insult again. I have not seen Mr. Woodley since.

"And now, Mr. Holmes, I come at last to the special thing which has caused me to ask your advice to-day. You must know that every Saturday forenoon I ride on my bicycle to Farnham Station in order to get the 12.22 to town. The road from Chiltern Grange is a lonely one, and at one spot it is particularly so, for it lies for over a mile between Charlington Heath upon one side and the woods which lie round Charlington Hall upon the other. You could not find a more lonely tract of road anywhere, and it is quite rare to meet so much as a cart, or a peasant, until you reach the high road near Crooksbury Hill. Two weeks ago I was passing this place when I chanced to look back over my shoulder, and about two hundred yards behind me I saw a man, also on a bicycle. He seemed to be a middle-aged man, with a short, dark beard. I looked back before I reached Farnham, but the man was gone, so I thought no more about it. But you can imagine how surprised I was, Mr. Holmes, when on my return on the Monday I saw the same man on the same stretch of road. My astonishment was increased when the incident occurred again, exactly as before, on the following Saturday and Monday. He always kept his distance and did not molest me in any way, but still it certainly was very odd. I mentioned it to Mr. Carruthers, who seemed interested in what I said, and told me that he had ordered a horse and trap, so that in future I should not pass over these lonely roads without some companion.

"The horse and trap were to have come this week, but for some reason they were not delivered and again I had to cycle to the station. That was this morning. You can think that I looked out when I came to Charlington Heath, and there, sure enough, was the man, exactly as he had been the two weeks before. He always kept so far from me that I could not clearly see his face, but it was certainly someone whom I did not know. He was dressed in a dark suit with a cloth cap. The only thing about his face that I could clearly see was his dark beard. To-day I was not alarmed, but I was filled with curiosity, and I determined to find out who he was and what he wanted. I slowed down my machine, but he slowed down his. Then I stopped altogether, but he stopped also. Then I laid a trap for him. There is a sharp turning of the road, and I pedalled very quickly round this, and then I stopped and waited. I expected him to shoot round and pass me before he could stop. But he never appeared. Then I went back and looked round the corner. I could see a mile of road, but he was not on it. To make it the more extraordinary, there was no side road at this point down which he could have gone."

Holmes chuckled and rubbed his hands. "This case certainly presents some features of its own," said he. "How much time elapsed between your turning the corner and your discovery that the road was clear?"

"Two or three minutes."

"Then he could not have retreated down the road, and you say that there are no side roads?"

"None."

"Then he certainly took a footpath on one side or the other."

"It could not have been on the side of the heath or I should have seen him."

"So by the process of exclusion we arrive at the fact that he made his way towards Charlington Hall, which, as I understand, is situated in its own grounds on one side of the road. Anything else?"

"Nothing, Mr. Holmes, save that I was so perplexed that I felt I should not be happy until I had seen you and had your advice."

Holmes sat in silence for some little time.

"Where is the gentleman to whom you are engaged?" he asked, at last.

"He is in the Midland Electrical Company, at Coventry."

"He would not pay you a surprise visit?"

"Oh, Mr. Holmes! As if I should not know him!"

"Have you had any other admirers?"

"Several before I knew Cyril."

"And since?"

"There was this dreadful man, Woodley, if you can call him an admirer."

"No one else?"

Our fair client seemed a little confused.

"Who was he?" asked Holmes.

"Oh, it may be a mere fancy of mine; but it has seemed to me sometimes that my employer, Mr. Carruthers, takes a great deal of interest in me. We are thrown rather together. I play his accompaniments in the evening. He has never said anything. He is a perfect gentleman. But a girl always knows."

"Ha!" Holmes looked grave. "What does he do for a living?"

"He is a rich man."

"No carriages or horses?"

"Well, at least he is fairly well-to-do. But he goes into the City two or three times a week. He is deeply interested in South African gold shares."

"You will let me know any fresh development, Miss Smith. I am very busy just now, but I will find time to make some inquiries into your case. In the meantime take no step without letting me know. Good-bye, and I trust that we shall have nothing but good news from you."

"It is part of the settled order of Nature that such a girl should have followers," said Holmes, as he pulled at his meditative pipe, "but for choice not on bicycles in lonely country roads. Some secretive lover, beyond all doubt. But there are curious and suggestive details about the case, Watson."

"That he should appear only at that point?"

"Exactly. Our first effort must be to find who are the tenants of Charlington Hall. Then, again, how about the connection between Carruthers and Woodley, since they appear to be men of such a different type? How came they both to be so keen upon looking up Ralph Smith's relations? One more point. What sort of a ménage is it which pays double the[7] market price for a governess, but does not keep a horse although six miles from the station? Odd, Watson—very odd!"

"You will go down?"

"No, my dear fellow, you will go down. This may be some trifling intrigue, and I cannot break my other important research for the sake of it. On Monday you will arrive early at Farnham; you will conceal yourself near Charlington Heath; you will observe these facts for yourself, and act as your own judgment advises. Then, having inquired as to the occupants of the Hall, you will come back to me and report. And now, Watson, not another word of the matter until we have a few solid stepping-stones on which we may hope to get across to our solution."

We had ascertained from the lady that she went down upon the Monday by the train which leaves Waterloo at 9.50, so I started early and caught the 9.13. At Farnham Station I had no difficulty in being directed to Charlington Heath. It was impossible to mistake the scene of the young lady's adventure, for the road runs between the open heath on one side and an old yew hedge upon the other, surrounding a park which is studded with magnificent trees. There was a main gateway of lichen-studded stone, each side pillar surmounted by mouldering heraldic emblems; but besides this central carriage drive I observed several points where there were gaps in the hedge and paths leading through them. The house was invisible from the road, but the surroundings all spoke of gloom and decay.

The heath was covered with golden patches of flowering gorse, gleaming magnificently in the light of the bright spring sunshine. Behind one of these clumps I took up my position, so as to command both the gateway of the Hall and a long stretch of the road upon either side. It had been deserted when I left it, but now I saw a cyclist riding down it from the opposite direction to that in which I had come. He was clad in a dark suit, and I saw that he had a black beard. On reaching the end of the Charlington grounds he sprang from his machine and led it through a gap in the hedge, disappearing from my view.

A quarter of an hour passed and then a second cyclist appeared. This time it was the young lady coming from the station. I saw her look about her as she came to the Charlington hedge. An instant later the man emerged from his hiding-place, sprang upon his cycle, and followed her. In all the broad landscape those were the only moving figures, the graceful girl sitting very straight upon her machine, and the man behind her bending low over his handle-bar, with a curiously furtive suggestion in every movement. She looked back at him and slowed her pace. He slowed also. She stopped. He at once stopped too, keeping two hundred yards behind her. Her next movement was as unexpected as it was spirited. She suddenly whisked her wheels round and dashed straight at him! He was as quick as she, however, and darted off in desperate flight. Presently she came back up the road again, her head haughtily in the air, not deigning to take any further notice of her silent attendant. He had turned also, and still kept his distance until the curve of the road hid them from my sight.

I remained in my hiding-place, and it was well that I did so, for presently the man reappeared cycling slowly back. He turned in at the Hall gates and dismounted from his machine. For some few minutes I could see him standing among the trees. His hands were raised and he seemed to be settling his necktie. Then he mounted his cycle and rode away from me down the drive towards the Hall. I ran across the heath and peered through the trees. Far away I could catch glimpses of the old grey building with its bristling Tudor chimneys, but the drive ran through a dense shrubbery, and I saw no more of my man.

However, it seemed to me that I had done a fairly good morning's work, and I walked back in high spirits to Farnham. The local house agent could tell me nothing about Charlington Hall, and referred me to a well-known firm in Pall Mall. There I halted on my way home, and met with courtesy from the representative. No, I could not have Charlington Hall for the summer. I was just too late. It had been let about a month ago. Mr. Williamson was the name of the tenant. He was a respectable elderly gentleman. The polite agent was afraid he could say no more, as the affairs of his clients were not matters which he could discuss.

Mr. Sherlock Holmes listened with attention to the long report which I was able to present to him that evening, but it did not elicit that word of curt praise which I had hoped for and should have valued. On the contrary, his austere face was even more severe than usual as he commented upon the things that I had done and the things that I had not.

"Your hiding-place, my dear Watson,[8] was very faulty. You should have been behind the hedge; then you would have had a close view of this interesting person. As it is you were some hundreds of yards away, and can tell me even less than Miss Smith. She thinks she does not know the man; I am convinced she does. Why, otherwise, should he be so desperately anxious that she should not get so near him as to see his features? You describe him as bending over the handle-bar. Concealment again, you see. You really have done remarkably badly. He returns to the house and you want to find out who he is. You come to a London house-agent!"

"What should I have done?" I cried, with some heat.

"Gone to the nearest public-house. That is the centre of country gossip. They would have told you every name, from the master to the scullery-maid. Williamson! It conveys nothing to my mind. If he is an elderly man he is not this active cyclist who sprints away from that athletic young lady's pursuit. What have we gained by your expedition? The knowledge that the girl's story is true. I never doubted it. That there is a connection between the cyclist and the Hall. I never doubted that either. That the Hall is tenanted by Williamson. Who's the better for that? Well, well, my dear sir, don't look so depressed. We can do little more until next Saturday, and in the meantime I may make one or two inquiries myself."

Next morning we had a note from Miss Smith, recounting shortly and accurately the very incidents which I had seen, but the pith of the letter lay in the postscript:—

"I am sure that you will respect my confidence, Mr. Holmes, when I tell you that my place here has become difficult owing to the fact that my employer has proposed marriage to me. I am convinced that his feelings are most deep and most honourable. At the same time my promise is, of course, given. He took my refusal very seriously, but also very gently. You can understand, however, that the situation is a little strained."

"Our young friend seems to be getting into deep waters," said Holmes, thoughtfully, as he finished the letter. "The case certainly presents more features of interest and more possibility of development than I had originally thought. I should be none the worse for a quiet, peaceful day in the country, and I am inclined to run down this afternoon and test one or two theories which I have formed."

Holmes's quiet day in the country had a singular termination, for he arrived at Baker Street late in the evening with a cut lip and a discoloured lump upon his forehead, besides a general air of dissipation which would have made his own person the fitting object of a Scotland Yard investigation. He was immensely tickled by his own adventures, and laughed heartily as he recounted them.

"I get so little active exercise that it is always a treat," said he. "You are aware that I have some proficiency in the good old British sport of boxing. Occasionally it is of service. To-day, for example, I should have come to very ignominious grief without it."

I begged him to tell me what had occurred.

"I found that country pub which I had already recommended to your notice, and there I made my discreet inquiries. I was in the bar, and a garrulous landlord was giving me all that I wanted. Williamson is a white-bearded man, and he lives alone with a small staff of servants at the Hall. There is some rumour that he is or has been a clergyman; but one or two incidents of his short residence at the Hall struck me as peculiarly unecclesiastical. I have already made some inquiries at a clerical agency, and they tell me that there was a man of that name in orders whose career has been a singularly dark one. The landlord further informed me that there are usually week-end visitors—'a warm lot, sir'—at the Hall, and especially one gentleman with a red moustache, Mr. Woodley by name, who was always there. We had got as far as this when who should walk in but the gentleman himself, who had been drinking his beer in the tap-room and had heard the whole conversation. Who was I? What did I want? What did I mean by asking questions? He had a fine flow of language, and his adjectives were very vigorous. He ended a string of abuse by a vicious back-hander which I failed to entirely avoid. The next few minutes were delicious. It was a straight left against a slogging ruffian. I emerged as you see me. Mr. Woodley went home in a cart. So ended my country trip, and it must be confessed that, however enjoyable, my day on the Surrey border has not been much more profitable than your own."

The Thursday brought us another letter from our client.

"You will not be surprised, Mr. Holmes," said she, "to hear that I am leaving Mr. Carruthers's employment. Even the high pay cannot reconcile me to the discomforts [9]of my situation. On Saturday I come up to town and I do not intend to return. Mr. Carruthers has got a trap, and so the dangers of the lonely road, if there ever were any dangers, are now over.

"As to the special cause of my leaving, it is not merely the strained situation with Mr. Carruthers, but it is the reappearance of that odious man, Mr. Woodley. He was always hideous, but he looks more awful than ever now, for he appears to have had an accident and he is much disfigured. I saw him out of the window, but I am glad to say I did not meet him. He had a long talk with Mr. Carruthers, who seemed much excited afterwards. Woodley must be staying in the neighbourhood, for he did not sleep here, and yet I caught a glimpse of him again this morning slinking about in the shrubbery. I would sooner have a savage wild animal loose about the place. I loathe and fear him more than I can say. How can Mr. Carruthers endure such a creature for a moment? However, all my troubles will be over on Saturday."

"So I trust, Watson; so I trust," said Holmes, gravely. "There is some deep intrigue going on round that little woman, and it is our duty to see that no one molests her upon that last journey. I think, Watson, that we must spare time to run down together on Saturday morning, and make sure that this curious and inconclusive investigation has no untoward ending."

I confess that I had not up to now taken a very serious view of the case, which had seemed to me rather grotesque and bizarre than dangerous. That a man should lie in wait for and follow a very handsome woman is no unheard of thing, and if he had so little audacity that he not only dared not address her, but even fled from her approach, he was not a very formidable assailant. The ruffian Woodley was a very different person, but, except on the one occasion, he had not molested our client, and now he visited the house of Carruthers without intruding upon her presence. The man on the bicycle was doubtless a member of those week-end parties at the Hall of which the publican had spoken; but who he was or what he wanted was as obscure as ever. It was the severity of Holmes's manner and the fact that he slipped a revolver into his pocket before leaving our rooms which impressed me with the feeling that tragedy might prove to lurk behind this curious train of events.

A rainy night had been followed by a glorious morning, and the heath-covered country-side with the glowing clumps of flowering gorse seemed all the more beautiful to eyes which were weary of the duns and drabs and slate-greys of London. Holmes and I walked along the broad, sandy road[10] inhaling the fresh morning air, and rejoicing in the music of the birds and the fresh breath of the spring. From a rise of the road on the shoulder of Crooksbury Hill we could see the grim Hall bristling out from amidst the ancient oaks, which, old as they were, were still younger than the building which they surrounded. Holmes pointed down the long tract of road which wound, a reddish yellow band, between the brown of the heath and the budding green of the woods. Far away, a black dot, we could see a vehicle moving in our direction. Holmes gave an exclamation of impatience.

"I had given a margin of half an hour," said he. "If that is her trap she must be making for the earlier train. I fear, Watson, that she will be past Charlington before we can possibly meet her."

From the instant that we passed the rise we could no longer see the vehicle, but we hastened onwards at such a pace that my sedentary life began to tell upon me, and I was compelled to fall behind. Holmes, however, was always in training, for he had inexhaustible stores of nervous energy upon which to draw. His springy step never slowed until suddenly, when he was a hundred yards in front of me, he halted, and I saw him throw up his hand with a gesture of grief and despair. At the same instant an empty dog-cart, the horse cantering, the reins trailing, appeared round the curve of the road and rattled swiftly towards us.

"Too late, Watson; too late!" cried Holmes, as I ran panting to his side. "Fool that I was not to allow for that earlier train! It's abduction, Watson—abduction! Murder! Heaven knows what! Block the road! Stop the horse! That's right. Now, jump in, and let us see if I can repair the consequences of my own blunder."

We had sprung into the dog-cart, and Holmes, after turning the horse, gave it a sharp cut with the whip, and we flew back along the road. As we turned the curve the whole stretch of road between the Hall and the heath was opened up. I grasped Holmes's arm.

"That's the man!" I gasped.

A solitary cyclist was coming towards us. His head was down and his shoulders rounded as he put every ounce of energy that he possessed on to the pedals. He was flying like a racer. Suddenly he raised his bearded face, saw us close to him, and pulled up, springing from his machine. That coal-black beard was in singular contrast to the pallor of his face, and his eyes were as bright as if he had a fever. He stared at us and at the dog-cart. Then a look of amazement came over his face.

"Halloa! Stop there!" he shouted, holding his bicycle to block our road. "Where did you get that dog-cart? Pull up, man!" he yelled, drawing a pistol from his side pocket. "Pull up, I say, or, by George, I'll put a bullet into your horse."

Holmes threw the reins into my lap and sprang down from the cart.

"You're the man we want to see. Where is Miss Violet Smith?" he said, in his quick, clear way.

"That's what I am asking you. You're in her dog-cart. You ought to know where she is."

"We met the dog-cart on the road. There was no one in it. We drove back to help the young lady."

"Good Lord! Good Lord! what shall I do?" cried the stranger, in an ecstasy of despair. "They've got her, that hellhound Woodley and the blackguard parson. Come, man, come, if you really are her friend. Stand by me and we'll save her, if I have to leave my carcass in Charlington Wood."

He ran distractedly, his pistol in his hand, towards a gap in the hedge. Holmes followed him, and I, leaving the horse grazing beside the road, followed Holmes.

"This is where they came through," said he, pointing to the marks of several feet upon the muddy path. "Halloa! Stop a minute! Who's this in the bush?"

It was a young fellow about seventeen, dressed like an ostler, with leather cords and gaiters. He lay upon his back, his knees drawn up, a terrible cut upon his head. He was insensible, but alive. A glance at his wound told me that it had not penetrated the bone.

"That's Peter, the groom," cried the stranger. "He drove her. The beasts have pulled him off and clubbed him. Let him lie; we can't do him any good, but we may save her from the worst fate that can befall a woman."

We ran frantically down the path, which wound among the trees. We had reached the shrubbery which surrounded the house when Holmes pulled up.

"They didn't go to the house. Here are their marks on the left—here, beside the laurel bushes! Ah, I said so!"

As he spoke a woman's shrill scream—a scream which vibrated with a frenzy of horror—burst from the thick green clump of bushes in front of us. It ended suddenly on its highest note with a choke and a gurgle.

"This way! This way! They are in the bowling alley," cried the stranger, darting through the bushes. "Ah, the cowardly dogs! Follow me, gentlemen! Too late! too late! by the living Jingo!"

We had broken suddenly into a lovely glade of greensward surrounded by ancient trees. On the farther side of it, under the shadow of a mighty oak, there stood a singular group of three people. One was a woman, our client, drooping and faint, a handkerchief round her mouth. Opposite her stood a brutal, heavy-faced, red-moustached young man, his gaitered legs parted wide, one arm akimbo, the other waving a riding-crop, his whole attitude suggestive of triumphant bravado. Between them an elderly, grey-bearded man, wearing a short surplice over a light tweed suit, had evidently just completed the wedding service, for he pocketed his prayer-book as we appeared and slapped the sinister bridegroom upon the back in jovial congratulation.

"They're married!" I gasped.

"Come on!" cried our guide; "come on!" He rushed across the glade, Holmes and I at his heels. As we approached, the lady staggered against the trunk of the tree for support. Williamson, the ex-clergyman, bowed to us with mock politeness, and the bully Woodley advanced with a shout of brutal and exultant laughter.

"You can take your beard off, Bob," said he. "I know you right enough. Well, you and your pals have just come in time for me to be able to introduce you to Mrs. Woodley."

Our guide's answer was a singular one. He snatched off the dark beard which had disguised him and threw it on the ground, disclosing a long, sallow, clean-shaven face below it. Then he raised his revolver and covered the young ruffian, who was advancing upon him with his dangerous riding-crop swinging in his hand.

"Yes," said our ally, "I am Bob Carruthers, and I'll see this woman righted if I have to swing for it. I told you what I'd do if you molested her, and, by the Lord, I'll be as good as my word!"

"You're too late. She's my wife!"

"No, she's your widow."

His revolver cracked, and I saw the blood spurt from the front of Woodley's waistcoat. He spun round with a scream and fell upon his back, his hideous red face turning suddenly to a dreadful mottled pallor. The old man, still clad in his surplice, burst into such a string of foul oaths as I have never heard, and pulled out a revolver of his own, but before he could raise it he was looking down the barrel of Holmes's weapon.

"Enough of this," said my friend, coldly. "Drop that pistol! Watson, pick it up! Hold it to his head! Thank you. You, Carruthers, give me that revolver. We'll have no more violence. Come, hand it over!"

"Who are you, then?"

"My name is Sherlock Holmes."

"Good Lord!"

"You have heard of me, I see. I will represent the official police until their arrival. Here, you!" he shouted to a frightened groom who had appeared at the edge of the glade. "Come here. Take this note as hard as you can ride to Farnham." He scribbled a few words upon a leaf from his note-book. "Give it to the superintendent at the police-station. Until he comes I must detain you all under my personal custody."

The strong, masterful personality of Holmes dominated the tragic scene, and all were equally puppets in his hands. Williamson and Carruthers found themselves carrying the wounded Woodley into the house, and I gave my arm to the frightened girl. The injured man was laid on his bed, and at Holmes's request I examined him. I carried my report to where he sat in the old tapestry-hung dining-room with his two prisoners before him.

"He will live," said I.

"What!" cried Carruthers, springing out of his chair. "I'll go upstairs and finish him first. Do you tell me that that girl, that angel, is to be tied to Roaring Jack Woodley for life?"

"You need not concern yourself about that," said Holmes. "There are two very good reasons why she should under no circumstances be his wife. In the first place, we are very safe in questioning Mr. Williamson's right to solemnize a marriage."

"I have been ordained," cried the old rascal.

"And also unfrocked."

"Once a clergyman, always a clergyman."

"I think not. How about the license?"

"We had a license for the marriage. I have it here in my pocket."

"Then you got it by a trick. But, in any case a forced marriage is no marriage, but it is a very serious felony, as you will discover before you have finished. You'll have time to think the point out during the next ten years or so, unless I am mistaken. As to you, Carruthers, you would have done better to keep your pistol in your pocket."

"I begin to think so, Mr. Holmes; but when I thought of all the precaution I had taken to shield this girl—for I loved her, Mr. Holmes, and it is the only time that ever I knew what love was—it fairly drove me mad to think that she was in the power of the greatest brute and bully in South Africa, a man whose name is a holy terror from Kimberley to Johannesburg. Why, Mr. Holmes, you'll hardly believe it, but ever since that girl has been in my employment I never once let her go past this house, where I knew these rascals were lurking, without following her on my bicycle just to[13] see that she came to no harm. I kept my distance from her, and I wore a beard so that she should not recognise me, for she is a good and high-spirited girl, and she wouldn't have stayed in my employment long if she had thought that I was following her about the country roads."

"Why didn't you tell her of her danger?"

"Because then, again, she would have left me, and I couldn't bear to face that. Even if she couldn't love me it was a great deal to me just to see her dainty form about the house, and to hear the sound of her voice."

"Well," said I, "you call that love, Mr. Carruthers, but I should call it selfishness."

"Maybe the two things go together. Anyhow, I couldn't let her go. Besides, with this crowd about, it was well that she should have someone near to look after her. Then when the cable came I knew they were bound to make a move."

"What cable?"

Carruthers took a telegram from his pocket.

"That's it," said he.

It was short and concise:—

"The old man is dead."

"Hum!" said Holmes. "I think I see how things worked, and I can understand how this message would, as you say, bring them to a head. But while we wait you might tell me what you can."

The old reprobate with the surplice burst into a volley of bad language.

"By Heaven," said he, "if you squeal on us, Bob Carruthers, I'll serve you as you served Jack Woodley. You can bleat about the girl to your heart's content, for that's your own affair, but if you round on your pals to this plain-clothes copper it will be the worst day's work that ever you did."

"Your reverence need not be excited," said Holmes, lighting a cigarette. "The case is clear enough against you, and all I ask is a few details for my private curiosity. However, if there's any difficulty in your telling me I'll do the talking, and then you will see how far you have a chance of holding back your secrets. In the first place, three of you came from South Africa on this game—you Williamson, you Carruthers, and Woodley."

"Lie number one," said the old man; "I never saw either of them until two months ago, and I have never been in Africa in my life, so you can put that in your pipe and smoke it, Mr. Busybody Holmes!"

"What he says is true," said Carruthers.

"Well, well, two of you came over. His reverence is our own home-made article. You had known Ralph Smith in South Africa. You had reason to believe he would not live long. You found out that his niece would inherit his fortune. How's that—eh?"

Carruthers nodded and Williamson swore.

"She was next-of-kin, no doubt, and you were aware that the old fellow would make no will."

"Couldn't read or write," said Carruthers.

"So you came over, the two of you, and hunted up the girl. The idea was that one of you was to marry her and the other have a share of the plunder. For some reason Woodley was chosen as the husband. Why was that?"

"We played cards for her on the voyage. He won."

"I see. You got the young lady into your service, and there Woodley was to do the courting. She recognised the drunken brute that he was, and would have nothing to do with him. Meanwhile, your arrangement was rather upset by the fact that you had yourself fallen in love with the lady. You could no longer bear the idea of this ruffian owning her."

"No, by George, I couldn't!"

"There was a quarrel between you. He left you in a rage, and began to make his own plans independently of you."

"It strikes me, Williamson, there isn't very much that we can tell this gentleman," cried Carruthers, with a bitter laugh. "Yes, we quarrelled, and he knocked me down. I am level with him on that, anyhow. Then I lost sight of him. That was when he picked up with this cast padre here. I found that they had set up house-keeping together at this place on the line that she had to pass for the station. I kept my eye on her after that, for I knew there was some devilry in the wind. I saw them from time to time, for I was anxious to know what they were after. Two days ago Woodley came up to my house with this cable, which showed that Ralph Smith was dead. He asked me if I would stand by the bargain. I said I would not. He asked me if I would marry the girl myself and give him a share. I said I would willingly do so, but that she would not have me. He said, 'Let us get her married first, and after a week or two she may see things a bit different.' I said I would have nothing to do with violence. So he went off cursing, like the foul-mouthed blackguard that he was, and swearing that he would have her yet. She was leaving me this week-end, and I had got a[14] trap to take her to the station, but I was so uneasy in my mind that I followed her on my bicycle. She had got a start, however, and before I could catch her the mischief was done. The first thing I knew about it was when I saw you two gentlemen driving back in her dog-cart."

Holmes rose and tossed the end of his cigarette into the grate. "I have been very obtuse, Watson," said he. "When in your report you said that you had seen the cyclist as you thought arrange his necktie in the shrubbery, that alone should have told me all. However, we may congratulate ourselves upon a curious and in some respects a unique case. I perceive three of the county constabulary in the drive, and I am glad to see that the little ostler is able to keep pace with them; so it is likely that neither he nor the interesting bridegroom will be permanently damaged by their morning's adventures. I think, Watson, that in your medical capacity you might wait upon Miss Smith and tell her that if she is sufficiently recovered we shall be happy to escort her to her mother's home. If she is not quite convalescent you will find that a hint that we were about to telegraph to a young electrician in the Midlands would probably complete the cure. As to you, Mr. Carruthers, I think that you have done what you could to make amends for your share in an evil plot. There is my card, sir, and if my evidence can be of help to you in your trial it shall be at your disposal."

In the whirl of our incessant activity it has often been difficult for

me, as the reader has probably observed, to round off my narratives, and

to give those final details which the curious might expect. Each case

has been the prelude to another, and the crisis once over the actors

have passed for ever out of our busy lives. I find, however, a short

note at the end of my manuscripts dealing with this case, in which I

have put it upon record that Miss Violet Smith did indeed inherit a

large fortune, and that she is now the wife of Cyril Morton, the senior

partner of Morton and Kennedy, the famous Westminster electricians.

Williamson and Woodley were both tried for abduction and assault, the

former getting seven years and the latter ten. Of the fate of Carruthers

I have no record, but I am sure that his assault was not viewed very

gravely by the Court, since Woodley had the reputation of being a most

dangerous ruffian, and I think that a few months were sufficient to

satisfy the demands of justice.

Ordinarily the High Street fairly stewed with juvenile humanity. But to-night, for a wonder, the High Street, Plimsoll Lane, Byles's Rents, and all the adjacent squalid courts and avenues were deserted. Something more than a mild fog was needed to effect such a transformation out of school hours. Neither was there evidence, ocular or auricular, of any hand-organ, or a trained bear, or a free fight enlivening the neighbourhood. How was it possible to account for the peaceful condition of the streets? Surely the ordinary denizens of the gutter couldn't be at school? Well, not exactly at school, but at the school-house. A ragged little urchin of seven volunteered to be our pilot.

"'Appy evenin'? Yessir, I'm goin' there myself. I'll show you."

"What's your name, my boy?"

"Saunders, sir; but they allers calls me 'Magsie,' all along o' my twin-sister wot uz named Marguerite."

"And why isn't your little sister with you to-night?"

"'Cos she got scarlet fever."

"Scarlet fever? Good gracious, boy!"

"An' she died—more'n a year ago."

"Oh, I see."

"The lidy wot we calls the Countess 's goin' to be at the 'Appy Evenin' to-night. Look! That's 'er—see—with the 'at an' the little black fevvers."

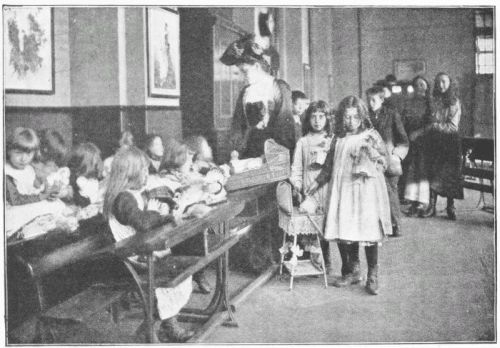

We proved to be just in time. Several ladies and gentlemen had doffed their furs and overcoats, and stood smiling at one end of a large school-room, whilst in the middle some two or three hundred meanly-clad, but clean and happy-looking, children of all ages under twelve or thirteen trooped along merrily to the notes of a piano in the corner.

"This is our overture," explained the gentle-eyed lady with the "fevvers." "We always begin this way and they seem to enjoy it." She raised her jewelled finger and the music stopped. So did the promenaders. There was a silence, punctuated by giggles, as the Countess observed, "And now for our games this evening. What girls for the quiet room?"

Twenty hands went up instantly.

"What boys?"

Half-a-dozen—not more—two of whom were cripples.

"And the noisy room? And the fairy-tale room? And the toy room? And the painting room? And the dolls' room?"

Thus were these denizens of the gutter in one of the most notorious slums of London granted their hearts' wishes for this evening. As they made a choice, so they were marched off under the wing of a lady or gentleman to a separate room, and the music struck up again for a Sir Roger de Coverley.

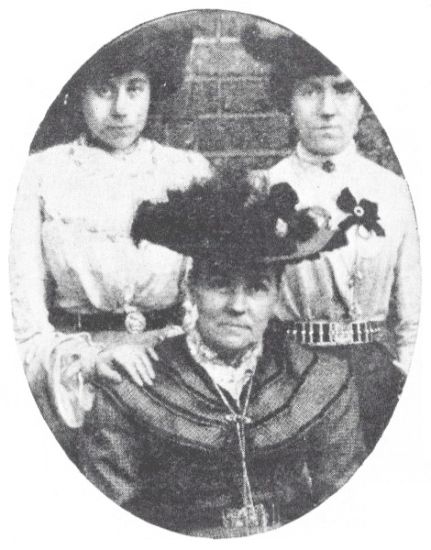

THE COUNTESS OF JERSEY—PRESIDENT OF THE COUNCIL.

From a Photo. by Gillman, Oxford.

"There is no use," explains one of the ladies, "forcing a child to romp if it doesn't want to romp. Perhaps its tastes are in quite another direction—indeed, we know that there are thousands of wretched little mites in London who pine for quiet and seclusion. Then there are kiddies who are passionately fond of fairy stories. They could listen to them by the hour—perhaps by the day—yet possibly outside of a Happy Evening they never hear one that really interests them. Our girls' fairy-teller here, I may tell you, has a wonderful gift. She really mesmerizes the children. Would you like to be mesmerized, too?"

"With all the pleasure in life," we reply, and the handle of the fairy-tale room is slowly turned. We may mention it for a fact, and as a tribute to the lady's powers, that the noise of our entrance is absolutely without effect on this little audience. Oh, what would not a pulpit orator, a politician, a lecturer—yes, even a great actor—give to hold his auditors' minds thus in the hollow of his hand? They see nothing, hear nothing but the speaker.

"'So, so,' cried the Genie, in an angry voice; 'if that is the case then you must quickly step upon this strip of carpet.' And he laid a piece of red and yellow carpet on the ground.

"'What for?' asked the young Prince. You see, he didn't know about the magic in the carpet—nobody had ever told him.

"'What for?' replied the Genie. 'Why, because——' and he told him then and there. And he put on his hat and stepped upon the carpet, and like a flash——"

We stole out at this juncture, leaving the children open-mouthed and open-eyed, oblivious of our presence and retreat, and ascending a flight of steps found ourselves ushered into a totally different scene. The uproar was terrific, which was not surprising considering that a hundred and fifty boys were yelling at the top of their lungs.

"Punch 'im, 'Magsie'; 'it 'im on the nob!"

And "Magsie," suiting the action to the word, actually landed his opponent one on the "nob." It was a boxing match—presided over by a peer's son. Physically the combatants were most unequally matched, one lad being nearly thirteen and the other—my original cicerone of the evening—only seven. But they equalize these matters at the Happy Evenings, and "Pokey" was on his knees, while Billy was the possessor of much pugilistic science. With each fairly-planted blow the yelling was terrific, but nobody objected; they encouraged it, if anything. What's the good of being happy if you can't yell? And so the hundred and fifty yelled. They have a proper contempt for girls. Girls only giggle and scream.

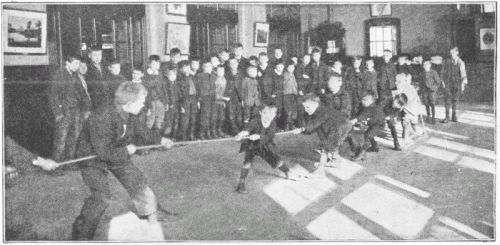

THE GREAT CONTEST: THORPE'S MEWS v. BYLES'S RENTS.

From a Photo. by][George Newnes, Ltd.

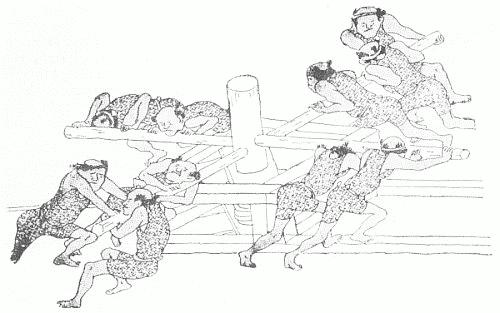

But the chief event of the evening among the juvenile male section was the tug-of-war—the denizens of Thorpe's Mews versus Byles's Rents, a truly Homeric contest, as it would have appeared to Liliput. Powerfully-built tatterdemalions boasting fully three feet of stature were matched against a lesser number of giants of four feet six. The rope swayed now this side—now[18] that—of the chalked line. Was ever so much sinew built up of stale bread-crusts and fried fish before? But the Byles's Rents men—pale, perspiring, and panting—ultimately pulled their rivals across the line and on to their knees pell-mell, and the ceiling threatened to splinter and send down pounds of plaster upon the heads of the spectators at shouts over this triumph. It was thrice repeated, and then, lo! a few steps and the scene had changed and we were in the dolls' room.

"PLEASE, LADY, MAY I 'AVE THE FAIRY DOLL NEXT TIME?"

From a Photo. by][George Newnes, Ltd.

Every year in November there is a brave show of dolls dressed for the Happy Evenings children at Bath House, Piccadilly, and some of these dolls were here now, tended, oh, so gently, almost worshipped, as they are taken out of their cupboard resting-places and dressed and undressed.

"Please, lady, may I 'ave the fairy doll next time?" pleaded a golden-haired little child, with an earnest, wistful look.

"Yes, if your hands are the cleanest.[19] The little girl with the very cleanest hands shall dress the fairy doll."

There is a buzz of pleased anticipation, and then a small voice is heard:—

"Oh, Kitie Jimes, will your mother lend my mother your kike o' smellin' soap next Tuesday evenin', an' you can 'ave our fryin'-pan?"

In the girls' noisy room they were playing "London Bridge" and "Kiss-in-the-Ring," but it was tame work in comparison with the uproarious diversions of the stern sex below. When the boys' boxing contest was over they had a sack race, but a small group of youngsters were observed making for the door.

"W'ere you goin', 'Arry?" asked a friend.

"Me? Oh. I'm goin' with Johnson."

"W'ere's Johnson goin'?"

"Darnstairs. Johnson's father's a 'ouse-painter, and 'e knows something, Johnson does. We promised to go an' see Millie White paint in the paintin' room. You orter see 'er dror a 'orse. I promised to 'old her cup an' Johnson's 'oldin' her paints. P'r'aps, if you come, she'll let you 'ave a brush to 'old."

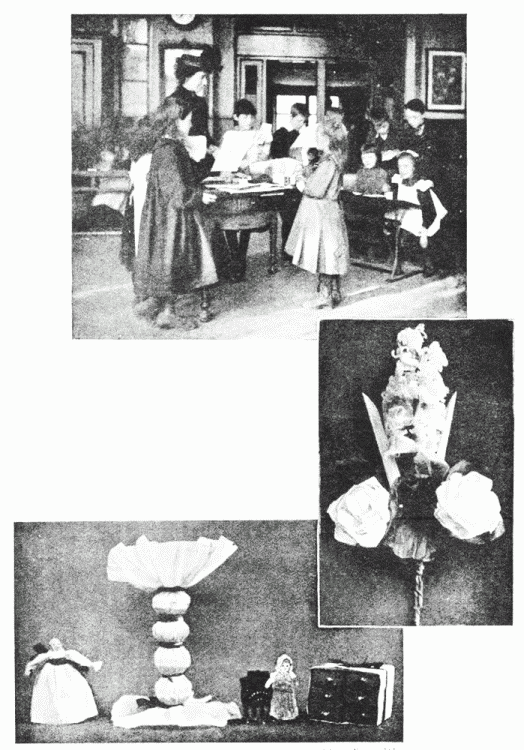

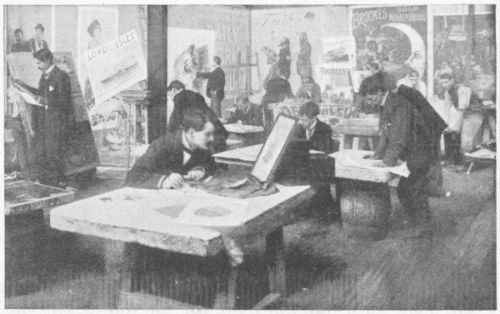

This is gallantry and this is appreciation of art. Five minutes later, after seeing the champion of Byles's Rents again victorious in the sack race, we descend to the painting room to find Miss Millie White (ætat eight), the celebrated animal painter, daughter of Larry White; the well-known Shoreditch navvy, surrounded by her admirers. In another part of the same room we come upon quite an animated group of talented colourists. Some of the[20] designs done by these children of the slums are most creditable, and at least their faces are radiant with happiness, which is the chief thing after all. The articles produced in the toy-making room are vastly ingenious. Out of the most unpromising materials—such as reels of cotton and match-boxes, fortified by cardboard and coloured paper—the most delectable toys are produced.

THE PAINTING ROOM.

From a Photo. by George Newnes, Ltd.

ARTIFICIAL FLOWERS

MADE BY THE CHILDREN.

From a Photo. by George Newnes, Ltd.

ARTICLES MADE BY THE CHILDREN.

From a Photo. by]

[George Newnes, Ltd.

As the famous chef, Brillat-Savarin, could create an exquisite soup out of a kid glove and a pint of boiling water, so these tiny artisans manage to manufacture butchers' shops, chests of drawers, tables, sofas, Christmas crackers, and luxuriant flowers out of the meanest ingredients. One of the favourite diversions of the smaller children is cutting out and colouring fashion-plates, decapitating the heads and[21] fitting on instead portraits of their favourite "great ladies" of the Happy Evenings Association which they have found in the newspapers. These are afterwards stiffened with cardboard and made to stand up in a group, which at a distance gives a very good idea of a swell reception amongst the "hupper suckles"—if it did not more nearly suggest a wax-work gathering at Madame Tussaud's. Two of these figures we photographed for The Strand—Lady Northcote and Lady Margaret Rice—both indefatigable workers of the Children's Happy Evenings Association.

LADY NORTHCOTE.

As constructed by the children.

And what—the reader may ask at this stage—what is the Happy Evenings Association? Well, it is a body of kind-hearted ladies and gentlemen—numbering some of the highest and noblest names that you will find in "Burke" or "Debrett"—who take a pleasure in going down amongst the slums of London and teaching the slum waifs how to play. For the London guttersnipe doesn't know how to play. As a rule, he or she can maunder about and fight and scream and exchange badinage and throw stones in the gutter, but of true games the gamin is as ignorant as his parents are of entrées or Euclid. Before the association was started in 1891 there was no one to teach them the mysteries of battledore and shuttlecock, sack races, kiss-in-the-ring, picture-books, dolls, and doll dressmaking. As their motto expressed it, the association, whose first efforts began at the Waterloo Road Schools, was "to put a thought beneath their rags to ennoble the heart's struggle."

LADY MARGARET RICE.

As constructed by the children.

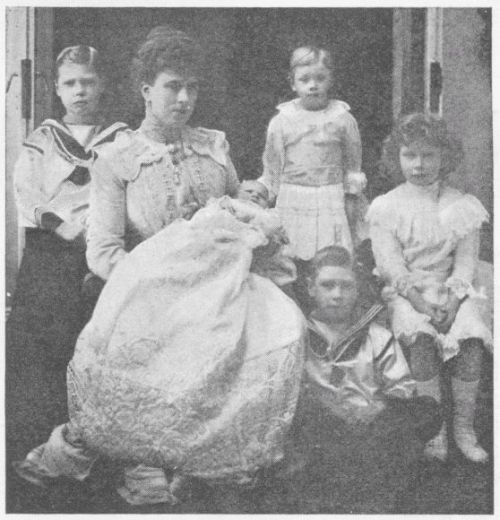

THE PRINCESS OF WALES AND HER FAMILY—THE PRINCESS IS THE PRESIDENT OF THE ASSOCIATION.

From a Photo. by Wilkinson & Co., Norwich. Published by the London Stereoscopic Co.

The gutters were full—the Board schools after school-hours were empty. Why not get permission to use these empty Board schools for the little ones to play in? And so in a modest fashion the first of the Happy Evenings was carried out by Miss Heather Bigg at Waterloo Road Schools in January, 1891. The association grew and workers came forward until now it is one of the most influential, as it is the "smartest," charity in London. It has for its president that mother of so many little children—the Princess of Wales; its chief of council is the Countess[22] of Jersey, and among its helpers are the Marchioness of Zetland, Lady Ludlow, Lady Cadogan, Lady Iddesleigh, Mrs. Bland-Sutton, etc. Moreover, the children of the rich are brought to serve the children of the poor, the example being set by children no less highly placed than the little Princes and the little Princess at Marlborough House, whose dolls and toys find their way into the Happy Evenings gatherings. When little Prince Edward first heard of the Happy Evenings he turned to his Royal mamma and said:—

MRS. BLAND-SUTTON—HON. SECRETARY OF THE ASSOCIATION.

From a Photo. by E. W. Evans.

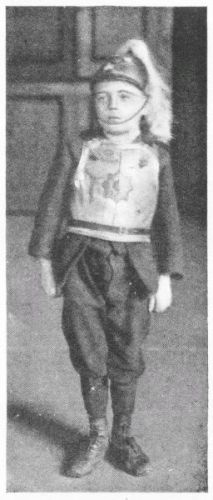

"Mayn't I give my helmet and breast-plate? It's such good fun to dress up as a soldier. I'm sure those little boys would like it." And so a little gamin was pointed out to us at a Happy Evening, prancing about in the martial and metallic raiment which had lately enclosed the person of another boy—the future King of England.

PRINCE EDWARD'S ARMOUR.

From a Photo. by George Newnes, Ltd.

Some wag has called these gatherings "Juvenile Parties for Guttersnipes," and although the secretary naturally resents the terms of such description, yet perhaps, on the whole, it gives a fair idea to the average observer of what these gatherings really mean. "We do not, however, aim at making our Happy Evenings a juvenile party. We try and make the pastimes of the children approximate closely to those of a well-ordered nursery or school-room, and the children are encouraged to vary their amusements on their own initiative, and to choose by preference those games which involve co-operation."

EAST-END CHILDREN IN LADY JERSEY'S CHILD-DRAMA

"ST. GEORGE."

From a Photo. by W. S. Bradshaw & Sons.

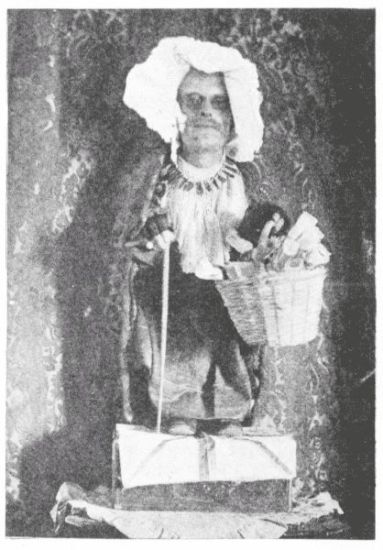

Occasionally the elder children get together[23] and arrange rough-and-ready presentments of historic incidents, such as the Battle of Cressy, the Execution of Mary Queen of Scots, the Indian Mutiny, Alfred and the Cakes, the Landing of the Pilgrim Fathers, etc. The Mayflower, in this last tableau, was represented by a large newspaper boat capable of holding the two feet of one child comfortably. The other Pilgrim Fathers apparently preferred to wade.

The picture on page 22 shows a party of East London children in Lady Jersey's play, "St. George of England," and in their brave costumes they certainly compare very favourably with any equal body of children from more fashionable regions.

A DAY IN THE COUNTRY.

From a Photo. by[Lady Margaret Rice.]

But perhaps the greatest event of the whole year for the children of the Happy Evenings occurs in summer, when each branch president invites them for a merry day in the country. Somehow or other the girls manage to rake up cheap cotton frocks for the occasion of various tints and degrees of wear—and the boys are carefully washed, brushed, and patched; and then off to one of the stately homes of England, where they may romp in the grass or in the woods and pick wild flowers to their hearts' content. You would scarcely recognise these half-fed, prematurely old London children in the laughing faces and buoyant forms of this picture taken at Osterley Park.

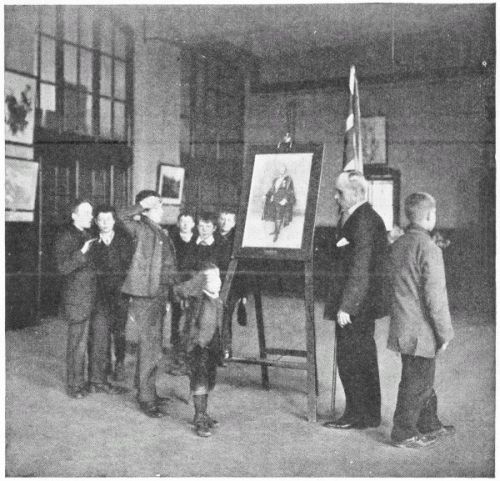

A HAPPY EVENING CONCLUDED—SALUTING HIS MAJESTY.

From a Photo. by George Newnes, Ltd.

One other picture taken has a special interest as showing that lessons of loyalty are inculcated at the Happy Evenings. It represents the conclusion of the sports and games; the boys are seen filing before a portrait of His Majesty and the Union Jack and saluting as they pass, while the piano plays "God Save the King."

When young Lord Otterburn vowed before the altar of Grace Church, 114th Avenue, Chicago, to endow Miss Sadie M. Cutts with all his worldly goods, that fortunate young lady obtained a husband of attractive appearance, agreeable manners, and a sweet temper; a coronet, a beautiful but dilapidated castle in Northumberland, surrounded by an unproductive estate, and a share in the family attentions of Aunt Sarah. In exchange for these blessings she brought, as her contribution to the happiness of the married state, a warm appreciation of her husband's good qualities, a dowry which, when reckoned in dollars, touched seven figures, a frank and fearless character, and a total ignorance of the importance of Aunt Sarah in the domestic well-being of the noble house of Otterburn.

She was not left long in ignorance on this point. She had only had time to refurnish the whole of Castle Gide, to instal electric light, to rebuild the stables, adapting part of them to the requirements of a stud of motor-cars, to take the gardens in hand, and to relet most of the farms, when Aunt Sarah was upon the newly-married couple with a proposal for a visit.

"And who is Aunt Sarah, anyway?" inquired Lady Otterburn, when her husband handed her that lady's letter over the breakfast-table.

"Aunt Sarah," replied Otterburn, "is the bane of the existence of all the members of my family who can afford to keep their heads above water."

"Sounds kind of cheering," observed her ladyship. "How does she get her clutch in?"

"She proposes herself for short visits, and has never been known to leave any house where the cooking is decent and the beds comfortable under a month. She is my Uncle Otterburn's widow, and, having been left exceedingly poor, exercises the right of demanding bed and board from members of my family in rotation as often as it is convenient to her."

"If she's poor," said Lady Otterburn, "it won't harm us to give her a shake-down and a sandwich or two as often as she wants 'em. I apprehend she'll make herself agreeable in return."

"That's where you make a mistake," replied Otterburn. "Aunt Sarah has never been known to make herself agreeable in her life. In fact, she prides herself upon doing the reverse. She'll tell you before you have[25] known her two minutes that she always says what she thinks. And she won't be telling you a lie."

"Two can play at that game," said Lady Otterburn. "Most times I say what I think myself."

"But you only think pleasant things," replied her husband. "My flower of the prairie!"

Now, Chicago is not exactly a prairie, but the young Countess of Otterburn was pretty and graceful enough to deserve the most high-flown compliments, and appreciated them when they came from her husband. She therefore graciously accepted his latest flight of imagination, and told him to write to Aunt Sarah and invite her to come to Castle Gide and stay as long as she found it convenient.

Aunt Sarah came a week later with a considerable amount of luggage, but no maid. The motor-omnibus was sent to the station to meet her, in spite of her nephew's warnings.

"She'll arrive as cross as can be," he said. "She hates motors of every description, and I don't suppose has ever been on one in her life."

"Then it's time she tried it," said Lady Otterburn. "There isn't a horse in the place that could draw a buggy fourteen miles to the depôt and back and bring her here in time for dinner."

"Well, you'll see," said Otterburn. "She'll tell us what she thinks of us when she gets here."

She did. The powerful motor-omnibus drew up before the door of Castle Gide—at which Lord and Lady Otterburn were standing to receive their guest—having completed the seven-mile journey from the station in about five-and-twenty minutes. The driver and the footman beside him wore expressions of apprehensive discomfort, and the latter jumped down off his seat to open the door at the back of the vehicle with some alacrity.

There emerged a tall and formidable-looking old lady, with an aquiline nose and abundant, well-arranged grey hair. She wore an imposing bonnet and a dress not of the latest fashion, which rustled richly. There was a cloud on her magnificent brow, her mouth was firmly closed, and she showed no signs of agreeable feeling at arriving thus at her journey's end.

"How do you do, Aunt Sarah?" said Otterburn, hastening down the steps to greet her. "Very pleased to see you again. Hope the old 'bus brought you along comfortably."

"No, Edward," replied Aunt Sarah, rigidly, "the old 'bus, as you term it, did not bring me along comfortably. I had vowed never to trust myself to one of these detestable new inventions, and I am surprised at your sending such a contrivance to meet me. This, I suppose, is your wife. How do you do, my lady? I shall probably be able to tell better how I like your appearance when[26] I have recovered from the perilous journey to which I have been subjected. I should like to be shown at once to my room. I am much too upset by my late experience to think of joining you downstairs to-night."

"Why, certainly," said Lady Otterburn. "I'll take you upstairs, and you shall have your supper just when and how you please—right here and now if you prefer it. I want that you should make yourself at home in this house."

Aunt Sarah transfixed her with a haughty glare.

"Considering that this house was my home for five-and-thirty years," she said, "I think I can promise to do that. Thank you, Lady Otterburn. I will not detain you any longer. This was the third best bachelor's room in my day; I know my way about it well. No doubt you have other more important guests for whom the better rooms are reserved. I will wish you good-night."

"My!" said the Countess of Otterburn, on the other side of a firmly-closed door. "She's a peach!"

The most consistently disagreeable people are not without their moments of relenting, and Aunt Sarah came downstairs about noon of the following day in a far better humour than she had carried to her room on her arrival at Castle Gide. In the first place she had discovered that the erstwhile bachelor rooms had been converted into a perfect little suite, with the appointments of which even a luxury-loving old lady determined to find fault with everything could hardly quarrel. During her voluntary seclusion she had been made as comfortable and waited on as well as if she were a rich woman in her own house, and the little dinner which had been served to her in the privacy of her own bijou salon was far superior to any meal that had ever been served to her before in Castle Gide, even when she had been mistress of it. Morning tea, therefore, found Aunt Sarah mollified, a dainty breakfast served to put her almost into an attitude of peace and goodwill towards mankind, and a glass of pale sherry and a dry biscuit after her toilet had been made and the morning papers read sent her downstairs with the definite intention of being civil to her nephew's wife, whom she had come to Castle Gide prepared cordially to hate.

This frame of mind lasted for several hours. Lady Otterburn devoted herself to the old lady's entertainment, and, to her husband's unconcealed astonishment, roused more than once a grim chuckle of amusement, as she rattled her clever Transatlantic tongue across the luncheon-table. Aunt Sarah pleased! Aunt Sarah laughing! Aunt Sarah allowing someone else to monopolize the conversation! He had known her all his life, but such a spectacle had hitherto been denied him.

"My dear, you're a marvel," he said to his American countess when luncheon was over and Aunt Sarah had retired to her own apartments, still in high good-humour. "You bowled me over the first time we met. That was nothing. But Aunt Sarah! I couldn't have believed it possible. I wish I had asked all my uncles and aunts and cousins to see it."

"You don't know enough to run when you're in a hurry," replied Lady Otterburn. "You'd find her a real beautiful woman if you all took her the right way."

"Well, we shall see," said Otterburn. "You've had a grand success so far, but the experience of years teaches me that seasons of calm in Aunt Sarah's life are not lasting. Much depends on the afternoon nap."

Alas! Aunt Sarah's afternoon nap was a troubled one. It may have been the lobster salad, of which she had eaten too largely; it may have been the iced hock-cup, of which she had drunk too freely, that disturbed her slumbers. Whatever it was she came down again what time the tea-table was spread in the hall with her usual inclination to make herself disagreeable strongly in the ascendant, and, if possible, augmented by the reaction from her previous state of amiability. The first audacious sally made by her hostess, which would have been received with tolerant amusement at the luncheon-table, only drew a scandalized glare from Aunt Sarah, and the ominous words: "I must ask you to remember in whose presence you find yourself, if you please."

Lady Otterburn may have been surprised at this sudden change of atmosphere, but she seemed entirely unconcerned, and took no notice of her husband's surreptitious kick underneath the tea-table, which said as plain as speech, "I told you so." She talked with gay wit, but gave no opportunity for a further rebuke. But Aunt Sarah's twisted temper was not to be softened by the most searching tact, and her next contribution to the sociability of the occasion was the remark, "This tea is positively not fit to drink. In my day Withers would not have dared to keep such stuff in his shop."

"He don't keep it now," answered her hostess. "I have it bought in China and shipped overland. It costs four dollars the pound."

"I have no doubt it is expensive," retorted Aunt Sarah, "although there is no occasion to poke your money down my throat. It is the way it is made. No servant can be trusted to make tea. I always have two teapots and make it myself. I find it is never fit to drink unless I do so."

"I'd just love to have you make some for yourself," said Lady Otterburn. "I'll ring the bell for two more teapots. It's too bad you shouldn't have it as you like it."

Aunt Sarah, who was secretly rather ashamed of having mistaken caravan-borne tea for that sold by the village grocer, suffered herself to be softened again, and became almost amiable when her hostess insisted upon drinking from the fresh brew which was presently made, and declared that it was a great improvement on the old.

"I think it is better," admitted Aunt Sarah. "I may say that I have never yet met anyone who could make tea as I can. You will excuse me for having commented on yours, but, as Edward knows, I always say what I think."

Edward did know it to his cost. But again he was astonished at the sight of Aunt Sarah charmed back to good-humour when apparently in one of her most relentless moods, and with further astonishment he reminded himself that his experience did not afford a precedent for her apologizing for any word of blame that may have fallen from her lips. But he had no time to ponder on these things. Developments were proceeding.

"You find it a good plan always to say what you think?" asked Lady Otterburn, sweetly.

"It is the only honest plan," replied Aunt Sarah. "If everybody would do it instead of telling lies on all occasions, great or small, there would be a good deal less hypocrisy in the world than there is now."

"Well, I guess you are right," said Lady Otterburn. "I guess I'll commence right away and follow your example. And so will Edward. Now, mind, Edward, don't you dare to say a single word that you don't mean, and just you tell your Aunt Sarah exactly what you think as long as she's with us. And so will I. And all the people who are coming this evening shall be told to do the same."

"Eh? What?" exclaimed Aunt Sarah.

When Aunt Sarah came down into the great hall at twenty minutes to nine that evening she found it full of young men and women who had arrived about an hour before, and whom she had kept waiting ten minutes for their dinner. She did not apologize for her[28] late appearance. That was not her custom. She singled out a young man of the company and said, "How do you do, Henry? I am pleased to see you at Castle Gide again. You used to come here frequently in happier times."

"They were not happier times for me, Aunt Sarah," replied the young man, rather nervously. "My chief recollection of them is that I was generally sent to bed before dinner for getting into mischief."

"Ah!" said Aunt Sarah. "That is the way to treat mischievous boys. And you don't bear malice."

"I am afraid I do," said the young man. "I was treated most unjustly."

"By whom, pray?" inquired Aunt Sarah, beginning to bridle.

"Very occasionally by Uncle Otterburn," said the young man. "Invariably by you."

"Upon my word!" exclaimed Aunt Sarah. "That is a pretty way to talk!"

"He must say what he thinks, you know," said Lady Otterburn. "We are all going to play at that as long as we are together. Anybody who is convicted of an insincere speech is to pay half a crown to the hospital fund. Here is the box. It contains a contribution from Edward, who told Lady Griselda that she was not at all late when she came down five minutes ago. Edward, take Aunt Sarah in to dinner. She has kept us waiting for nearly a quarter of an hour."

"Have I got into a company of lunatics?" inquired Aunt Sarah, as she took her nephew's arm.

No member of the party with the exception of Aunt Sarah had reached middle-age. Most of the men were contemporaries of Otterburn's, the years of whose pilgrimage were thirty. Some of them were married and had their wives with them, but the majority were unattached, and there were several girls, some English and some American. Otterburn's grouse-moors were the ostensible excuse for their finding themselves collected at Castle Gide, but they were so well mixed that they would probably have succeeded in enjoying themselves even if there had been no shooting to occupy the days. There was a regular hubbub of conversation round the dinner-table on this first evening, and loud peals of laughter, rising above the din and clatter of twenty tongues all moving at once, seemed to indicate that Lady Otterburn's game was adding to the gaiety of the occasion.

"No," said a demure young lady, in answer to a request from her neighbour. "I will not play accompaniments for you after dinner. It is quite true, as you say, that I read music extraordinarily well. I have always politely denied it before, but I know I do. Your singing, however, is so distasteful to me that I am sorry I cannot oblige you."

"I have got a good voice," said her neighbour, "and I have studied under the best masters."

"You have not profited by your studies," replied the lady; "and your voice, so far from being good, is very thin and of no quality whatsoever."

"I guess," said a fair American, surveying the company, "that we're a good-looking crowd round this table. And, among all the women, I have a conviction that I go up for the beauty prize. I have had to hug that conviction in secret for a very long time, and now it's out."

Thus and thus was the House of Truth built up stone by stone, and Aunt Sarah's position was pitiable. Hitherto she had made her mark in whatever society she found herself by sheer insistence on her right to be frankly and critically disagreeable. On any ordinary occasion she would have had the whole tableful of young people prostrate under the terror of her biting tongue, and not a whit would she have cared for consequent unpopularity so long as she had made herself acknowledged as the dominating spirit of the assembly. Now she was met and foiled by the dexterous use of the very weapons which she had wielded so long and so unmercifully, and no arrogant speech could she make but its sting was removed by an equally outspoken reply.

Thus, to her right-hand neighbour, a young man with smooth black hair and a preternaturally solemn face: "I don't know who you are, but by your long upper lip I should judge you to be a Mortimer."

"My name and appearance are both undoubtedly Mortimer," he replied, gravely. "My character, I am happy to say, is not."

"Perhaps you do not know," said Aunt Sarah, "that I am a Mortimer?"

"I am perfectly aware of it," was the answer. "It would cost me half a crown to congratulate you on the fact."

"And may I ask what fault you have to find with the family whose name you have the honour of bearing?"

"They are insufferably cantankerous and domineering."

"Not all of them," interrupted Otterburn, anxious above all desire for unsullied truth to avert the impending storm which was gathering around him. "You must not take his criticisms as personal, Aunt Sarah."

"Pass the box this way," said the solemn young man. "Otterburn will contribute another half-crown."

Before dinner was half-way through Aunt Sarah was in as black a rage as had ever darkened even her Olympian brow. By the time the ladies left the room she had delivered herself of as many insulting speeches as it usually took her a day to achieve, and her average output was no small one. But it was all to no purpose. Her most ambitious efforts, instead of striking a chill of terror to the hearts of her listeners, were warmly applauded, with an air of the utmost politeness, and from every quarter she received as good as she gave. It took her some time to realize that she was affording considerable amusement to her nephew's guests, but when she did arrive at that state of knowledge she could hardly command herself sufficiently to leave the room without doing bodily hurt to someone.

"I will not stand this insolent behaviour any longer," she said to Lady Otterburn when the door of the dining-room had been closed behind them. "How dare you treat me in this way?"

"Why, bless me, Aunt Sarah," exclaimed Lady Otterburn, in well-feigned surprise, "you said yourself that if everyone spoke the truth always, as you pride yourself on doing, it would be a real lovely thing. We are all speaking the truth under a penalty, and you are speaking it so well that you haven't been fined once."

"Psshtschah!" is the nearest possible orthographic rendering of the exclamation of contempt and disgust that forced itself from Aunt Sarah's lips. "I have had enough of this insensate folly," she continued. "I shall go straight to my room, and if I do not receive more respectful treatment in this house, where I so long reigned as undisputed mistress, I shall leave it to-morrow. Do you understand me?"

"I understand you very well," said Lady Otterburn. "And I will ask you to try and understand me. The respect which you demanded as mistress of this house is now due to me, and I look to receive it from my guests. If you discover that it is not within your power to grant it I shall not press you to prolong your visit."

Aunt Sarah again gave vent to the exclamation indicated above, and sailed up the broad staircase to her own apartments with anger and disgust marked on every line and curve of her figure.

Aunt Sarah had never been so angry before in her life. She was an extraordinarily disagreeable old woman—disagreeable in a masterly, cold-blooded, incisive way, partly because disagreeable speech was a genuine expression of her nature, partly because she had discovered in the course of years that she gained more by being disagreeable, which came easy to her, than by being pleasant, which did not. One of the weapons of her armoury was the feigning of anger, and few could stand upright before her wrath. But for this very reason she had seldom been opposed in such a way as to make her really angry, and now that this had happened to her she was almost beside herself with rage.