Title: At the Court of the Amîr: A Narrative

Author: John Alfred Gray

Release date: December 9, 2013 [eBook #44395]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Henry Flower and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

AT THE COURT OF THE AMÎR

BY

JOHN ALFRED GRAY, M.B. Lond.

Late Surgeon to H.H. The Amîr of Afghanistan

LONDON

RICHARD BENTLEY AND SON

Publishers in Ordinary to Her Majesty the Queen

1895

[All Rights Reserved]

I would not have thought of inflicting a book on my long-suffering fellow-countrymen, but for the wish expressed by my publishers: for

In Afghanistan however, difficult of access, and hence comparatively unknown, there have been, since that strong man Amîr Abdurrahman ascended the Throne, such remarkable changes in the administration of the country, and such strides towards civilization, that it was thought a narrative of life there, throwing, possibly, some light on the personality of the Monarch, and on the “bent” of the people, might be of general interest.

The book has been written in the intervals of professional work, and, with its shortcomings of diction and style, the only merit it can claim—that of “local colour”—is due to the fact that it was compiled from the letters I wrote from Afghanistan to her who is now my wife.

Wadham Lodge,

Uxbridge Road,

Ealing, W.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| On the Road to Kabul | 1 |

| The start and the wherefore. Unsettled condition of Afghanistan. Departure from Peshawur. Jumrûd Fort and the Watch-tower. The Afghan guard. The Khyber defile. Eccentricities of Rosinante. Lunch at Ali Musjid. Pathan villages. Pathans, their appearance and customs. Arrival at Landi-Kotal Serai. The Shenwari country. Caravan of Traders. Dakka. Dangers of the Kabul River. Mussaks. Camp at Bassawal. Chahardeh. Mountain road by the river. Distant view of Jelalabad. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Arrival at Kabul | 16 |

| Arrival at Jelalabad, Reception by the Governor. The Palace. The Town. The Plain. Quarters in the Guest Pavilion. The friendly Khan. Tattang and the gunpowder factory. The Royal gardens at Nimla. The Suffêd Koh Mountains. Arboreal distribution in Afghanistan. Gundamuk. Assassination of Cavagnari: details of the plot. The “Red bridge.” Commencement of mountainous ascent to Kabul. Jigdilik. Massacre of British in 1837. Former dangers of the valley of Katasang. Enterprising peasants. Tomb in the Sei Baba valley. Burial customs. The Lataband Pass and the Iron Cage. Distant view of Kabul. The Amîr’s projected road at Lataband. The approach to Kabul. The Lahore Gate. | |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Reception | 31 |

| Position of Kabul. Its defences. Amîr’s opinion of the Founders of his Capital. Entry into Kabul. Aspect of the Townsmen. Arrival at the Arm Foundry. Visit of the Afghan Official. His appearance. Absence of Amîr. To be received at the Palace by the Princes. The approach to the Palace. The Amîr’s Pavilion. Page boys. The Princes Habibullah and Nasrullah. The Reception. Internal arrangement of Pavilion. The earthquake. [viii]Abrupt ending of the Reception. Other buildings in the Palace. | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Afghan Hospitals | 41 |

| The first attendance at an Afghan Hospital. Its arrangement. The drugs and instruments. The Patients. An Interpreter presents himself. Dispensers. Marvellous recovery of the Page boy. Its effect. Buildings near the Hospital. The Durbar Hall and Guest House. The Sherpûr Military Hospital. Lord Roberts and the Sherpûr Cantonment. Adventure with an Afghan soldier. Arrangement of the In-patient Hospital. Diet of Patients. Attendance of Hakims. Storekeepers and their ways. | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Afghan Dwellings | 53 |

| The Residential streets of Kabul. Their appearance and arrangement. The Police. Criminal Punishments. The Houses. Their internal arrangement. Precautions to ensure privacy. Manner of building for the rich and for the poor. Effect of rain and earthquake. The warming of houses in winter. Afternoon teas. Bath-houses. The Afghan bath. | |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The Kabul Bazaars | 68 |

| The unpopular Governor and his toothache. The meeting in the Erg Bazaar. Appearance of the Kabul Bazaars. The shops and their contents. Boots, shoes, and cobblers. Copper workers. The tinning of cooking pots. Impromptu tobacco pipes. Tobacco smoking by the Royal Family. Silk and cotton. “Bargaining.” “Restaurants.” Tea drinking. Confectioners. The baker’s oven. Flour mills. The butcher’s shop. Postîns and their cost. Furs. Ironmongers. Arms. “The German sword.” The Afghan tulwar. Rifles and pistols. Bows. Silver and gold-smiths. Caps and turbans. Embroidery. Grocers: tea, sugar, soap, and candles, and where they come from. Fruiterers. Tailors. “The Railway Guard.” Costume of the Kabuli townsmen. Personal effect of the Amîr on costume. Drug shops. | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Ethics | 90 |

| Sir S. Pyne’s adventure in the Kabul river. The Tower on the bank. Minars of Alexander. Mahomedan Mosques. The cry of the Priest. Prayers and Religious Processions. Afghan conception of God. Religious and non-Religious Afghans. The schoolhouse and the lessons. Priests. Sêyids: descendants of the Prophet. The lunatic Sêyid. The Hafiz who [ix]was fined. The Dipsomaniac. The Chief of the Police and his ways. Danger of prescribing for a prisoner. “The Thing that walks at night.” The end of the Naib. Death-bed services. The Governor of Bamian. Courtship and weddings among the Afghans. The formal proposal by a Superior Officer. The wedding of Prince Habibullah. Priests as healers of the sick. The “Evil Eye.” Ghosts. | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Afghan Surgeons and Physicians | 115 |

| Accidents from machinery in motion. The “dressers of wounds” in Afghanistan. Their methods of treating wounds, and the results of the same. The “Barber surgeons.” Tooth drawing and bleeding. The Hindustani “Doctors.” “Eye Doctors” and their work. The Hakims or Native Physicians. Treatment of disease by the People. Aspect in which European Physicians are viewed by the different Classes. | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The March to Turkestan | 129 |

| Jealousy and its results. Sport among the Afghans. The “Sportsmen” among the mountains. Order to join the Amîr in Turkestan. Preparations. Camp at Chiltan. The Banquet. The Nautch dance. Among the Hindu Kush mountains. The camp in the Hazara country. Courtesy of Jan Mahomed. Mountain paths. Iron spring. The underground river and the Amîr’s offer. The Red mountain and the Deserted City. Camp in the Valley of Bamian. The English prisoners of 1837. The Petrified Dragon. The Colossal Idols: The Cave-dwellers. The Pass of the “Tooth-breaker.” Ghuzniguk. Story of Ishak’s rebellion. Tash Kurghán: the Shave and the Hospital. “The Valley of Death.” The Plains of Turkestan and the heat thereof. The Mirage. Arrival at Mazar. The House. Story of the death of Amîr Shere Ali. | |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| The Amîr | 157 |

| To be “presented.” The Palace Gardens. The Amîr. Questions asked by His Highness. Punishment of rebellious in Afghanistan. Asiatic motives from European standpoint. Amîr’s arrangement for my safety. Bazaars and houses of Mazar. The Suburbs. The Military Hospital. The Patients. Afghan appreciation of European medical treatment. The two chief Hakims. Hindustani intrigue. Amîr’s sense of Justice. The Trial. A Courtier’s influence. The guard of the Amîr’s table. | |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Life in Turkestan | 176 |

| General Nassir Khan. The Belgian’s Request. Escape of Allah Nûr: his Capture. The Amîr’s Decision. The Turkestan Commander-in-Chief. [x]Operation on Allah Nûr. The Armenian’s Comments. Illness of Hadji Jan Mahomed. Excursion to Takh-ta-Pûl. Fortune-telling among the Afghans. The Policeman-cook and the Lunch. Balkh. The Mosque at Mazar-i-Sherif and its Miracles. Called to His Highness. The Cool-air Pavilion. Illness of the British Agent: the Armenian’s advice: the Answer from the Amîr. Brigadier Hadji-Gul Khan. Afghan Endurance of Suffering. Euclid and Cards. | |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| The Inhabitants of Afghanistan | 193 |

| Slaves in Kabul: prisoners of war and others. The frequent rebellions. The different nationalities in Afghanistan. Origin of the Afghan race. The Turk Sabaktakin. Mahmûd of Ghuzni. Buddhism displaced by Mahomedanism. Border Afghans. Duranis. Ghilzais. Founding of a Dynasty of Afghan Kings. Ahmad Shah. Timûr Shah. The Sons of Timûr. Zaman Shah. The Afghan “Warwick.” Execution of Paînda. Rebellion of the Shah’s brother. Mahmûd Shah. Another brother rebels. Shujah-ul-Mulk crowned: deposed by the Barakzai chief. Exile of Shujah. The Koh-i-nûr. The Puppet-king and the Barakzai Wazir. Murder of the Wazir. The Wazir’s brother becomes Amîr. The first Afghan War. Rule of Dôst Mahomed: A Standing Army established. Accession of Shere Ali. Amîr Afzal Khan. Abdurrahman. The Ghilzais. Border Pathans, Afridis, Shinwaris. The Hazaras. Turkomans, Usbàks. The Christian Church. | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Birth of Prince Mahomed Omer | 210 |

| Hazara slaves, Kaffir slaves, and others. Court Pages. High positions occupied by slaves. Price of slaves. Wife and children of Hazara Chief in slavery. Illness of the Hostage of an Afghan Chief. Abdur Rashid down with fever. Own illness and the aches thereof. The British Agent’s postal arrangements. Postage in Afghanistan. Power of annoying possessed by Interpreters. The Chief Bugler. The Page boy and the Sirdar. The Page boy and the Amîr. The uproar on September 15th. Congratulations to the Sultana. The crowd outside the Harem Serai. The Sultana’s reply. Matter of succession complicated. Surgical operations. The Priest with a blemish: his request. The Amîr’s reply. The operation. The Mirza’s comments. | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Rearing of the Infant Prince | 225 |

| The Amîr’s autograph letter. Medical consultation concerning the rearing of the Prince. Conflicting customs of the Orient and the Occident. Conservative nurses. The “Hakim fair to see”: the patient. Lessons in Persian and in English. Portrait painting. Dietary difficulties. Gracious acts of His Highness. Amîr’s letter of condolence. The Royal visit by deputy. Congratulations of the British Agent. Accident to the favourite [xi]Page. The khirgar. Attempt upon the life of the Amîr. An earthquake. Afghan appreciation of pictures and jokes. Generosity of the Amîr. The first winter Durbar. The Royal costume. The Amîr’s question: the Parable. The dining-room. The guests. The breakfast. The press of State business. Amîr’s thoughtful kindness. Visit to the Commander-in-Chief. The ride to the Hospital. Adventure with the “fool horse.” Hospital patients in winter. “Two much and three much.” | |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| The Amîr’s Conversation | 251 |

| Sent for to the Palace. Fragility of Europeans. The Amîr’s postîn. The Bedchamber. The King’s evening costume. The guests. The Amîr’s illness. School in the Durbar-room. The Amîr’s conversation. Khans: the water supply of London: plurality of wives. The Amîr is bled. His Highness a physician in Turkestan. Drawing. The Amîr’s portrait. Amîr’s choice of costume. The Shah of Persia. Portraits of the Shah. The rupee and the Queen’s portrait. Cigar holders. Concerning Afghan hillmen. Dinner. The Amîr’s domestic habits. Amîr’s consideration for subordinates. European customs. The new Kabul. Native drugs. Soup and beef tea. The paper trick. The Kafir Page. European correspondence. Vaccination of Prince Mahomed Omer. Afghan women. The Prince’s house. The Prince. The operation. Abdul Wahid. Afghan desire for vaccination. The Armenian’s useful sagacity. An Afghan superstition. The Agent’s secretary. His comments upon Bret Harte: the meaning of “By Jove.” European “divorce” from an Oriental point of view. | |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The First Sitting | 272 |

| Morning prayers. Early tea. Breakfast. The first sitting for the Amîr’s portrait. The Courtier’s criticism. The Amîr’s rebuke. The Deputation. Conversation with the Amîr: the climate of England and Australia. Awe of the Courtiers. The favourite Page boy’s privileges. Serious incident at a sitting. The Captain’s toothache. Present of a rifle from the Amîr. The shooting expedition and its dangers. Courage of the “Burma policeman.” The eccentric rider. The singing Afghan. The scenery of Mazar. Salutations in the market place. The meeting with Prince Amin Ullah. | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| The Amîr As an Art Critic | 282 |

| The “villain” cook. Mental effect of a cold in the head. Portrait of the infant Prince. The Amîr’s reflection in the window. The Amîr as an Art Critic. Salaams to the King’s Portrait. The Amîr’s toilet. A shooting expedition. The mud of Mazar. The Armenian’s comments. The [xii]sample case of cigars. The Amîr’s handwriting. A sunset. | |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| The Levee on New Year’s Day | 293 |

| The Mahomedan New Year’s Eve. Presents. The “Izzat” medal. Coinage of Afghanistan: Rupees: Pice: the “Tilla.” Levee on New Year’s Day. The guests: Maleks and Governors: the British Agent. Presents to the Amîr. Chess as played in Afghanistan. The Amîr as a Pathologist. The steam-engine pony. Sight-seeing with the Princes. The Temple of Mazar. The booths at the entrance to the Temple. The Park of Mazar. Native music. The Afghan dance. Kabuli wrestling. | |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| The Young Princes | 308 |

| Infant Prince as the Sultana’s Deputy. Reception by the Prince: the pavilion: the guard: costume. Visit to Prince Hafiz Ullah. Her Majesty’s photograph. Lunch with the Prince in the Palace Gardens. The “Royal manner.” The mother of Prince Hafiz Ullah. A drawing of the Prince. Adventure with the fat General. The power of the Amîr’s name. The Amîr as a Consulting Surgeon. The Fast of Ramazàn. Overdose of tobacco. The Evening Durbar. Danger if a King fasts; “Marazàn.” The Durbar. The surgical operation: attempted vendetta. Flowers in the Palace. The Usbàk’s artistic design. The Amîr’s diary. The present of sugar. Official notice of return march to Kabul. The “Cracker.” End of Ramazàn. The guard of Amazons. | |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| The Return Journey to Kabul | 324 |

| Loading up. The first camp. Tropical heat: the whirlwind. The Amîr’s khirgar. Scanty rations. Midnight marching. Dangers in the pitchy darkness. Impure water. Daybreak. The second camp. Lost on the plains. Naibabad: the rain. The march to Tash Kurghan. The Khulm Pass. Sight seeing from the house tops. The Durbar. Punishment of the unjust townsfolk. The Amîr’s health. The eclipse of the sun. On the march again: the dust: jammed in the valleys. Ghuzniguk. An Afghan “Good Samaritan.” A poisonous sting: the Amîr’s remedy. A block on the road. The tiger valley. Haibuk. Adventure with the elephant: the somnolent Afghan. The aqueduct. Discomforts of a camp in an orchard. | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| The Arrival in Kabul | 345 |

| The Durbar in Haibuk. “Rustom’s throne.” The ancient caves. The wounded Governor: Kabul dentistry. The erring Hakim. Courtesy of [xiii]His Highness. “Microbes.” Elephant riding. A grateful peasant. Dangerous passes. The Durbar at Shush-Bûrjah: the hot river. Accidents on the “Tooth-breaker.” Akrab-Abad. The camp of the camels. A pet dog. Evil results of “temper.” A cheap banquet. Coal. Arrival of Englishmen. Durbar at Kalai Kasi. The Amîr again as a physician. Approach to Kabul. Reception by the Princes. The “High garden.” The Pavilion. Malek the Page. Arrival of the Amîr. The Reception. Arrival at the Workshops. Hospitality. | |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Life in Kabul | 361 |

| The Îd festival: salaam to the Amîr: the educating of Afghans. Products of the Workshops. Royal lunch at Endekki: the Invitation: the Brougham: the Palace: the Drawing-room: the Piano. Evening illumination of gardens: dinner. The unreliable Interpreter. A night at the Palace. Commencement of intrigue. Gifts to the Amîr. The rebuke to Prince Nasrullah. Noah’s Ark: the nodding images. Illness again: the Amîr’s advice. An afternoon call. Illness of the Amîr: the visit: His Highness’s question: the Amîr’s good breeding. An earthquake. Report on Kabul brandy: Mr. Pyne’s opinion: the Amîr’s perplexity. The Hindu’s objection. The mysterious midnight noise: the solution of the mystery. Mumps. The wedding of Prince Nasrullah: invitation from the Sultana: the Fête: a band of pipers. The Prince and his bride. Overwork at the Hospital. One of the troubles of a Ruler. Scenery near Bala Hissar. The Amîr duck shooting. The sick chief: his imprudence: his amusements. The will of the clan. | |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| The Amîr’s Illness | 381 |

| Sent for to the Palace. The Amîr’s health: the Liniment. Questions in chemistry. Early breakfast at the Palace. A courtier as a waiter. Called to Prince Aziz Ullah: his illness. Illness of the Deputy Commander-in-Chief. A visit to Prince Mahomed Omer. The Queen’s brougham: her Reverend Uncle. The Jelalabad official and his promise. Dinner with Mr. Pyne. Death of Prince Aziz Ullah. The Chief ill again. The weather. The silence at the Palace. December 2nd: the Call. The town at night. Illness of the Amîr: former treatment. The Amîr’s prayer. Bulletins. Called to the Sultana. The Harem. The Sultana’s illness. A poisonous dose. Improvement of Amîr: and of Sultana. The innocent plot. A present. Musicians. Amîr and Sultana as patients. Annoyances by an interpreter. A shock. The Sultana’s letter. News from Malek, the Page. In the Harem: the Armenian’s [xiv]comments. Quarters in the Prince’s quadrangle. The Amîr’s relapse. | |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Royal Patients | 399 |

| The Hindustani Interpreter. The Amîr as a host: the Sultana as hostess. The Amîr’s photograph. The Sultana’s name. Sirdar, the girl-boy. The sleeping draught. The tea cup and the thermometer. The Christmas Dinner: the guests: the menu: music. The Amîr’s fainting attack: the remedy: effect on the physician: the substituted remedy: further effect on the physician; the Amîr’s prescription. The Amîr’s alarming nervous symptoms. Hospital cases. Duties of the Princes Habibullah and Nasrullah. | |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| A Kabul Winter | 410 |

| Hindustani intrigue: information from the British Agent: offer of assistance: measures for protection: further intrigue. The “Royal manner.” The two factions: Habibullah: Mahomed Omer. The question of succession. Return to the City House and English Society: the cold of Kabul. The naked beggar boy. The old Kabul bridge. The question of “bleeding.” Disbanding of a Shiah regiment. Amîr’s advice to his sons. Improvement in Amîr’s health. The Hindustani again: Sabbath. The Afghan noble as workshop superintendent. New Year sports. The grand stand: the crowd: refreshments. Horse-racing: collisions. Tent pegging and its dangers. Lemon slicing. Displays of horsemanship. Amîr’s absence from the sports. The Naû Rôz levee. Salaam to the Sultana. Amîr in the Salaam Khana: reception of the Maleks and merchants: presents. The Princes standing before the Amîr. Reception of the English engineers: the “White-beard:” his age: the Amîr’s surprise. | |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| A Kabul Spring | 426 |

| Spring clothing: a grateful Afghan. Poison bowls. A haunted house: the skeleton in the garden. Increase of patients. Called to the Palace: Amîr’s costume. Troubles of a Ruler: Secretary in disgrace. Amîr’s plans for the future. Geologists in the service. Occidental v. Oriental. Mercantile commissions. The Armenian’s leave. The locusts. Prince Mahomed Omer and his Lâla. The Palace gardens. A military Durbar. Amîr’s thoughtfulness. A portrait. Amîr’s opinion of his people: education of his soldiers. The arrest: murder of the prisoner: the Amîr’s decision. Ramazàn. Rising of the river. The Íd Festival. The Physician’s plans: the Amîr’s comment. [xv]Prince Habibullah’s portrait: Prince Nasrullah’s portrait: his remark. | |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| On Leave | 442 |

| The last Durbar: the Amîr’s remark: a wedding present. The journey down. An awful day: “difficult hot.” Exhaustion. The work of the locusts. The breeding establishment: a study in colour. An illegal march. Simla. The Despatch. Dinners and dances. The study of character. The Armenian in London. Return to India. | |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| The Welcome to Kabul | 454 |

| Pathan rifle thieves. Dacca. The midnight alarm: the melée. “Bally rascals.” The next morning. The terror of the Amîr’s name. Running postmen. Kabul post. Armenian’s opinion of London. Changes in the English “staff.” Visitors: letters. Lady doctor’s application. Salaam to the Amîr. His Highness’s welcome. The military Durbar. Presents. The new British Agent. Visit to the Sultana. Salaam to Prince Habibullah. Another visit to the Amîr: his appreciation of scenic effect. His answer to the lady doctor’s application. | |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| The Cholera | 465 |

| Ramazàn. The outbreak of Cholera. Precautions. Notices in the bazaars. Rapid spread. European medicine. The overwhelming dread. Processions to the Mosque. Oriental fatalism. The shadow of death. Removal of the Court to the mountains. Closure of the workshops. The Armenian as an Inspector. The Prince’s chamberlain. Death of the Dabier-ul-Mulk. The mortality. An incident. Afghan appreciation of British motives. Arrival of an Englishman with thoroughbred horses. Dying out of the Cholera. Visit to Paghman. The soldiers in chains. Anger of the Amîr. An earthquake: the Amîr as a scientist. Illness of the “Keeper of the Carpets.” Arrival of Mr. Pyne and other Englishmen. Another visit to the Amîr. His Highness’s description of a Royal illness. Dinner from the Palace: the sealed dishes. | |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| Another Winter | 479 |

| A political Durbar: tact of the Amîr: a friendly soldier. The banquet. Return of the Cholera. Essay on “Precautionary measures.” Health of the English in Kabul. Report to the Amîr: His Highness’s kindness. Visit [xvi]to Prince Nasrullah: a “worm-eaten” tooth: the operation. Erring Englishmen: the Amîr’s remedy. Amîr as a chess-player. The far-sighted Armenian: winter quarters. End of the Cholera. Invasion of Small-pox and Erysipelas. To Paghman: Portrait of Prince Mahomed Omer: present from the Sultana. The sketch of the Prince: resemblance to the Amîr: his costume: arrangement of the group. Present of a slave boy. A lesson in courtesy to the Page boys. Native dinners. Visit of Mr. Pyne: the sandali. Completion of the portrait. The Amîr’s remark. Sultana’s gift to the Paghmanis: Afghan mode of slaughtering. Ride to Kabul: the mud. The Afghan Agent: the “Gnat.” Sent for to the Palace: a Landscape Commission: postponement of leave; disappointment: the Amîr’s remedy. Christmas dinner at the shops. The “Health of Her Majesty.” | |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| Adieu to Kabul | 497 |

| Afghan artists. Presentation of the little Prince’s portrait. His quarters at the Palace. The Prince as a host. A walk in the Kabul Bazaars. Before the Amîr: landscapes. A fresh commission. The “Gnat’s” interpreting. The Amîr’s answer. Art pupils before the Amîr. The Amîr’s kindly remark. The miner’s dog: shattered nerves and surgical operations. The worries of Kabul life. To Paghman: the glens: the spy. Sketches. Before the Amîr. A fresh Commission. Adieux. | |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| The Argument | 512 |

| Afghan court life from an English standpoint. The Afghan Courtier. Untrustworthiness. Intrigue. Question of “cause” or “consequence.” Possibility of raising the moral plane. The Amîr’s obvious opinion. His Highness’s great work. Certain evils. Former condition of the middle classes: present condition: opening of the eyes: comparison with similar class in India. Progress in Afghanistan. Civilizing effect of the Amîr. Dôst Mahomed’s rule: comparison with Abdurrahman. Altered condition of country. The Amîr’s civilizing measures: drastic measures. Peaceful measures: education: the teaching of handicrafts: of art: the spreading of knowledge: prizes for good or original work. Personal fascination of the Amîr. | |

| Trophy of Afghan Arms | On the cover. |

| Portrait of His Highness the Amîr (from a Painting by the Author) | Frontispiece. |

| Obverse of Hand-made Cabul Rupee of the Present Reign | On the title page. |

| Colossal Figure “Sa-mama” in the Bamian Valley (from a Photograph by Arthur Collins, F.G.S.) | To face page 144. |

| The Author and the Armenian Interpreter (from a Photograph by Van der Weyde) | To face page 230. |

| Prince Mahomed Omer and his “Commander-in-Chief” (from a Photograph by Arthur Collins, F.G.S.) | To face page 412. |

At the Court of the Amîr.

The start and the wherefore. Unsettled condition of Afghanistan. Departure from Peshawur. Jumrûd Fort and the Watch-tower, The Afghan guard. The Khyber defile. Eccentricities of Rosinante. Lunch at Ali Musjid. Pathan villages. Pathans, their appearance and customs. Arrival at Landi Kotal Serai. The Shenwari country. Caravan of Traders. Dakka. Dangers of the Kabul River, Mussaks. Camp at Bassawal. Chahardeh. Mountain road by the river. Distant view of Jelalabad.

It was with no small amount of pleasurable excitement that I donned the Afghan turban, and with Sir Salter (then Mr.) Pyne and two other English engineers, started from Peshawur for Kabul to enter the service of the Amîr.

I had made the acquaintance of Mr. Pyne in London, where I was holding a medical appointment. He had returned to England, after his first short visit to Kabul, with orders from the Amîr to buy machinery, procure engineering assistants, and engage the services of an English surgeon.

I gathered from his yarns that, for Europeans at the present day, life among the Afghans was likely to be a somewhat different thing from what it was a few years ago.

In the reigns of Dost Mahomed and Shere Ali it was simply an impossibility for a European to[2] take up a permanent residence in Afghanistan; in fact, except for occasional political missions, none was allowed to enter the country.

We do, indeed, hear of one or two, travelling in disguise, who managed to gather valuable facts concerning the country and its inhabitants, but we learn from their narratives that the hardships they were forced to undergo were appalling. For ages it has been a proverb among the natives of India that he who goes to Kabul carries his life in his hand. They say, “Trust a cobra, but never an Afghan;” and there is no denying the fact that the people of Afghanistan have had the credit from time immemorial of being a turbulent nation of highway robbers and murderers. If there were any chance of plunder they spared not even their co-religionists, and, being fanatical Mahomedans, they were particularly “down” on any unfortunate traveller suspected of being a Feringhi and an infidel.

A busy professional life following upon the engrossing studies of Hospital and University, had given me neither time nor any particular inducement to read about Afghanistan, so that when I left England I knew very little about the country. However, on reaching India I found plenty of people ready enough to enlighten me.

I heard, from officers who had been on active service in Afghanistan in 1880, of the treacherous and vindictive nature of the people; of the danger when they were in Kabul of walking in the town except in a party of six or seven; of the men who, even taking this precaution, had been stabbed. I[3] heard, too, a great deal about the assassination of the British envoy in Kabul, Sir Louis Cavagnari, in 1879; of the highway dangers of the two hundred mile ride from the British frontier to Kabul, and, remembering that we were about to trust our lives absolutely for some years to the good faith of these proverbially treacherous Afghans, it struck me we were in for an experience that was likely to be exciting.

What actually happened I will relate.

We were all ready to start from Peshawur one day in March, 1889. The Amîr’s agent, a stout and genial old Afghan, named Abdul Khalik Khan, had provided us with turbans, tents, and horses; we had received permits from the Government to cross the frontier, and our baggage was being loaded on the pack-horses when a telegram arrived directing us to await further orders. We were informed that there was fighting among the Pathans in the Khyber, and we were to postpone our departure till it was over. This seemed a healthy commencement.

Three days afterwards, however, we were allowed to proceed. The first day’s march was short, simply from the cantonment across the dusty Peshawur plain to Jumrûd fort: about nine miles. The fort, originally built by the Sikhs in 1837, has been repaired and strengthened by the British, who now hold it. It is said, however, to be of no very great value: one reason being because of the possibility of its water supply being cut off at any time by the Afghan hillmen.

The servants, with the pack-horses and tents, took up their quarters in the courtyard, but we four[4] accompanied the officer in charge up to his rooms in the watch-tower. From here we had an extensive view over the Peshawur valley. The entry to the Khyber was about three miles off to the west. We had left the cantonment early in the afternoon, and soon after our arrival it became dark. We dined, and were thinking of turning in to prepare for our long hot ride on the morrow, when we found, instead, that we should have to turn out.

The fort was not an hotel, and had no sleeping accommodation to offer us. I looked at Pyne. The baggage was down there in the courtyard, somewhere in the dark, and our bedding with it. Should we——? No! we would roll up our coats for pillows, throw our ulsters over us, and sleep on the platform outside the tower. We were proud to do it. But—the expression “bed and board” appealed to my feelings ever afterwards.

We had an early breakfast.

In the morning we found the guard of Afghan cavalry waiting for us in the travellers’ caravansary near the fort. There were about forty troopers—“the Amîr’s tag-rag,” as the British subalterns disrespectfully called them.

They were rough-looking men, dressed more or less alike, with turbans, tunics, trousers, and long boots. Each had a carbine slung over his shoulder and a sword at his side. A cloak or a rug was rolled up in front of the saddle and a couple of saddle bags strapped behind. They carried no tents. I cannot say they looked smart, but they looked useful. Of the individual men some were rather Jewish in type, good-looking fellows—these were Afghans; and one[5] or two had high cheek-bones and small eyes—they were Hazaras. All were very sunburnt, and very few wore beards. This last fact surprised me; I had thought that Mahomedans never shaved the beard.

It is, however, not at all an uncommon thing for soldiers and officers in the Afghan army to shave all but the moustache; but I learnt that in a Kabul court of law, when it is necessary in swearing to lay the hand upon the beard, that a soldier’s oath is not taken: he has no beard to swear by.

The baggage was sent off under a guard of about a dozen troopers. We followed with the rest and entered the gorge of the Khyber. It is a holiday trip now-a-days to ride or drive into the Pass. You obtain a permit from the Frontier Political Officer, and are provided with a guard of two native cavalrymen, who conduct you through the Pass as far as Landi Kotal. This is allowed, however, on only two days in the week, Mondays and Thursdays—the Koffla, or merchant days. The Khyber Pathans have entered into an agreement with the Government that for the payment of a certain subsidy they will keep the Pass open on those two days: will forbear to rob travellers and merchants. Doubtless it is an act of great self-denial on their part, but they keep faith.

Riding along the Pass one sees posted at intervals, on rock or peak, the Pathan sentry keeping guard. He is a fine-looking man, as he stands silently in his robes: tall, with black beard and moustache. His head may be shaven or his long hair hang in ringlets over his shoulders. He wears a little skull cap with, may be, a blue turban wound carelessly round it: a loose vest reaching the knee is confined at the[6] waist by the ample folds of the cummerbund, or waist shawl. In this is thrust a pistol or two and a big ugly-looking knife. The short trousers of cotton, reaching half-way down the leg, are loose and not confined at the ankle like the townsman’s “pyjamas.” On the feet he wears the Afghan shoe with curved up toe: the ornamental chapli or sandal of leather: or one neatly made of straw. Draped with classical beauty around the shoulders is the large blue cotton lûngi, or cloak. If the morning is cold the sheepskin postîn is worn, the sleeves of which reach to the elbow. If it rain the postîn is reversed, and the wool being outside shoots the wet off. The next day’s sun dries it.

The rifle he has may be an old English musket, a Martini-Henry or a native jezail, but, whatever it be, in the Pathan’s hands it is deadly.

The scenery in the Khyber is rugged and wild, the only vegetation being stunted bushes and trees at the bottom of the gorge. The rocky cliffs rise precipitously on either side, and gradually closing in, are, at a little distance from the entry, not more than three or four hundred feet apart. The road at one time leads by the stream at the bottom of the gorge, and later creeping up the mountain it winds in and out round the spurs or fissures half-way up the face of the cliff. It is a good broad road, made, and kept in excellent repair, by the British. Nevertheless, I was far from happy: my mare, accustomed to a town, was frightened by the rocks, the sharp turns, and the precipices, and desired to escape somewhere, anywhere—and there was no parapet.

By-and-bye, however, we descended and were in a stony valley, for the Pass varies in width from ten or twelve feet to over a hundred yards. Mr. Pyne suggested a canter. A canter! I knew the mare by this time, and I had on only a hunting bit. Off we went. Pyne had a good horse, a Kataghani that had been given him in Kabul, but we swept ahead, my bony mare and I, much to Pyne’s disgust—and mine, for I couldn’t hold her. Roads! what were roads to her? Away she went straight up the valley, and such a valley! The ground was covered with pebbles and big stones, and cut up by dry water-courses wide and narrow. The narrower gulleys she cleared at a bound, the wider she went headlong into and out of before I had time to hope anything. I soon was far ahead of the guard, only the Captain managed to keep somewhere in my wake, shouting, “Khubardar,” “Take care!” I yearned to khubardar with a great yearn, for in addition to the danger of breaking my neck was that of being shot. Sawing at the reins did not check her, and at last I flung myself back, caught the cantle of the saddle with my right hand, and jerked at the curb. I was tossed in the air at every stride, and my loaded revolver thumped my hip at each bound, but her speed diminished, and at last she gave in and stopped, panting and snorting. Then the Captain came clattering up, and I was obliged to turn the mare round and round or she would have been off again. The Captain smiled and said, “Khob asp,” “It is a good horse.”

“Bally,” I said, which means “Yes.”

We adjusted the saddle and waited till the others[8] came up. Pyne remonstrated with me and told me I ought not to have done such a thing, it was not safe! He viewed it as a piece of eccentricity on my part.

About eight miles from Jumrûd, and where the defile is narrow and precipitous, is the Ali Musjid fort. This is built on a high, nearly isolated, rocky hill to the left or south of the road. The small Musjid, or Mosque, from which the place takes its name, stands by the stream at the bottom of the defile. It was erected, according to tradition, by the Caliph Ali. The fort, which is called the key of the Khyber, has at different times been in possession of Afghans and British. We hold it now. The last man we dislodged was General Gholam Hyder Khan, Orak zai, who was then in the service of Amîr Yakûb Khan. He is now Commander-in-Chief of the Amîr’s army in Kabul and Southern Afghanistan. He is a big stout man, about six feet three inches in height. When I saw him in Kabul he did not seem to bear any malice on account of his defeat. There is another General Gholam Hyder, a short man, who is Commander-in-Chief in Turkestan, and of whom I shall have occasion to speak hereafter.

At Ali Musjid we sat by the banks of the streamlet and hungrily munched cold chicken and bread; for Mr. Pyne had suggested at breakfast our tucking something into our holsters in case of necessity: he had been there before.

Beyond Ali Musjid the narrow defile extended some distance, and then gradually widening out we found ourselves on an elevated plateau or table-land, bounded by not very high hills. The plain was some miles in extent, and we saw Pathan villages dotted[9] here and there, with cornfields surrounding them. The villages were fortified. They were square, surrounded by a high wall with one heavy gate, and with a tower at one or all four corners. The houses or huts were arranged inside in a row against the wall, and being flat roofed and the outer wall loopholed there was at once a “banquette” ready for use in case the village should be attacked.

The mountains and valleys of the Khyber range and of the other Indian frontier mountains are inhabited by these semi-independent Afghans called, collectively, Pathans or Pukhtana. There are many learned and careful men among the Government frontier officers who are at present investigating the origin and descent of the Pathan tribes.

The Khyberi Pathan whom I have described as the “guard” of the Pass is a fair type of the rest. The men are quarrelsome, are inveterate thieves, but are good fighters. Many of them enter the British service and make excellent soldiers. They are divided into a great number of different tribes, all speaking the same language, Pukhtu, or Pushtu, and bound by the same code of unwritten law, the Pukhtanwali. The neighbouring tribes, however, are jealous of one another and rarely intermarry. There is the vendetta, or law of retaliation, among them, and almost always an ancient feud exists between neighbouring villages. The women, unlike the Mahomedan townswomen, are not closely veiled; the head is covered by a blue or white cotton shawl, which, when a stranger approaches, is drawn across the lower part of the face. They wear a long dark-blue robe reaching midway between knee and ankle,[10] decorated on the breast and at the hem with designs in red. The feet are generally bare, and the loose trousers are drawn tight at the ankle. Their black hair hangs in two long plaits, the points being fastened with a knot of many-coloured silks.

When one considers the nature of these mountaineers—hereditary highway robbers and fighters, crack shots, agile and active, and when one observes the unlimited possibility they have among rocks, valleys, and passes of surprising a hostile army and of escaping themselves—the advantage of a “subsidy” becomes apparent.

At the distant or west extremity of the plateau, where we saw the Pathan villages, is the Landi Kotal serai. An ordinary caravansary in Afghanistan is a loopholed enclosure with one gate, and is very like the forts or villages I have described. At Landi Kotal, in addition to the native serai, is one built by the Government. It is strongly fortified, with bastion, embrasure, and banquette, and any part of the enclosure commanded by the adjoining hills is protected by a curtain or traverse.

Hot, tired, and thirsty, we four rode into the fort, and were received by the British officer in charge. The Afghan guard took up their quarters in the native serai outside. Good as the road was it had seemed an endless journey. Winding in and out in the heat we had seemed to make but little progress, and the unaccustomed weight of the turban and the dragging of the heavy revolver added considerably to our fatigue; but the march, after all, was not more than five-and-twenty miles.

This time there was ample accommodation for[11] us, and after an excellent dinner, the last I had in British territory for many a long month, we turned in.

After Landi Kotal, the Khyber narrows up. We wound in and out round the fissures and water channels in the face of the mountain, and climbed up and down as before; but presently the guard unslung their carbines and closed in round us. It was the Shenwari country we were now traversing, and these Pathans, even by the Amîr’s soldiers, are considered dangerous; for what says the proverb, “A snake, a Shenwari, and a scorpion, have never a heart to tame.” The Amîr had, however, partly subjugated them even then, and a tower of skulls stood on a hill outside Kabul.

Then we came to a series of small circular dusty valleys surrounded by rocky mountains. There was nothing green, and the heat was very great, it seemed to be focussed from the rocks. Further on we caught up with a caravan of travelling merchants with their camels and pack-horses.

These men belong almost entirely to a tribe of Afghans called Lohani. They come from the mountains about Ghazni. In the autumn they travel down to India with their merchandise and go about by rail and steamer to Bombay, Karachi, Burma, and other places for the purposes of trade. In the spring they go northward to Kabul, Herat, and Bokhara. Under the present Amîr they can travel in Afghanistan without much danger, but in the reigns of Shere Ali and Dost Mahomed they had practically to fight their way.

They go by the name of Povindia, from the[12] Persian word Parwinda, “a bale of merchandise.” When I was in Turkestan I became acquainted with one of these men. He was a white bearded old Afghan who had been, he told me, to China, Moscow, and even to Paris. He tried to sell me a small nickel-plated Smith and Wesson revolver.

We rode by the caravan of traders and reached Dakka, on the banks of the Kabul river. This is the first station belonging to the Amîr. The Colonel commanding came out to receive us, and conducted us to a tent on the bank, where we sat and drank tea. We were much interested in watching some Afghans swimming down the river buoyed up by inflated skins—“mussaks.” Grasping the skin in their arms they steered with their legs, the force of the current carrying them rapidly along. Two men took a donkey across. They made a raft by lashing four or five skins to some small branches; and tying the donkey’s legs together, they heaved him sideways on to the raft. Clinging to the skins they pushed off, and, striking out with the legs, they were carried across in a diagonal direction. By-and-bye some men floated by on a rough raft made of logs. They were taking the wood to India for sale.

The river here, though not very deep, is dangerous, on account of the diverse currents.

In the centre, to the depth of three or four feet, the current runs rapidly down the river; deeper it either runs up the river or goes much slower than the surface water.

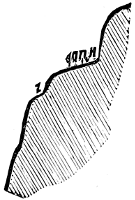

A few years later I was travelling past here, one hot summer, with Mr. Arthur Collins, recently geologist to the Amîr, and we determined to bathe.[13] Mr. Collins, who was a strong swimmer, swam out into the middle: I paddled near the bank where the current was sweeping strongly up stream. Mr. Collins, out in the middle, was suddenly turned head over heels and sucked under. He could not get to the surface, and, therefore, swam under water, happily in the right direction, and he came up very exhausted near the bank.

After resting, we rode on through some hot pebbly valleys, with no sign of vegetation, until we reached Bassawal, where we camped. The tents were put up, sentries posted, and the servants lit wood fires to prepare dinner. It soon became dark, for the twilight is very short. We were advised to have no light in our tent, lest the tribes near might take a shot at us; and we dined in the dark. It was the first night I had ever spent in a tent, and to me it seemed a mad thing to go to bed under such circumstances. I remember another night I spent near here some years afterwards, but that I will speak of later.

On this occasion the night passed quietly.

The next morning they woke us before daybreak. The cook had lit a fire and prepared breakfast—fried eggs, tinned tongue, and tea. As soon as we were dressed the tents were struck, and while we were breakfasting the baggage was loaded up. We had camp chairs and a little portable iron table, but its legs became bent, and our enamelled iron plates had a way of slipping off, so that we generally used a mule trunk instead. The baggage was sent off, and we sat on the ground and smoked. Starting about an hour afterwards, we rode along through fertile[14] valleys with cornfields in them: here water for irrigation could be obtained. In March the corn was a foot high. Then we rode across a large plain covered with a coarse grass. It was not cultivated because of the impossibility of obtaining water. We camped further on in the Chahardeh valley, which was partly cultivated and partly covered with the coarse grass. The tents were put up near a clump of trees, where there was a well. Unfortunately, there was also the tomb of some man of importance, and other graves, near the well. The water we had from it tasted very musty and disagreeable. Next day we went through other cultivated valleys to the mountains again. The river here made a curve to the south, and the mountains came close up to the bank. The road, cut out of the face of the mountain, ran sometimes level with the bank, sometimes a hundred feet or more above it. It was much pleasanter than the Khyber Pass, for to the north (our right) there was the broad Kabul river, with cultivated fields on its northern bank, and though the scorching heat of the sun was reflected from the rocks there was a cool breeze blowing. I thought it was a wonderfully good road for native make, but I found, on enquiry, that it had been made by the British during the Afghan war.

After rounding a shoulder of the mountain, where the road was high above the river, we could see in the distance the Jelalabad Plain and the walled city of Jelalabad. However, it was a long way off and we had to ride some hours before we reached it.

When on a journey in Afghanistan it is not usual to trot or canter, in fact, the natives never trot.[15] They ride at a quick shuffling walk: the horse’s near-side feet go forward together, and his off-side feet together—a camel’s walk. It is an artificial pace, but very restful.

There was a shorter route which we could have taken from Bassawal, avoiding Jelalabad altogether, but it was mostly over pebbly hills and desert plains, and was exceeding hot. From Dacca we had kept fairly close to, though not actually in sight of, the Kabul river. It makes a vast difference to one’s comfort in a tropical or semi-tropical country to travel through cultivated land where, if only at intervals, there is something green to be seen. Few things are more fatiguing than the glare of a desert and the reflected heat from pebbles and rocks; we, therefore, chose the longer but pleasanter route.

Arrival at Jelalabad. Reception by the Governor. The Palace. The Town. The Plain. Quarters in the Guest Pavilion. The friendly Khan. Tattang and the gunpowder factory. The Royal gardens at Nimla. The Suffêd Koh mountains. Arboreal distribution in Afghanistan. Gundamuk. Assassination of Cavagnari: details of the plot. The “Red bridge.” Commencement of mountainous ascent to Kabul. Jigdilik. Massacre of British in 1837. Former dangers of the valley of Katasang. Enterprising peasants. Tomb in the Sei Baba valley. Burial customs. The Lataband Pass and the Iron Cage. Distant view of Kabul. The Amîr’s projected road at Lataband. The approach to Kabul. The Lahore Gate.

We arrived at Jelalabad about the middle of the afternoon. The town is fortified; surrounded by a high wall, with bastions and loopholes; and is in a good state of repair. We entered one of the massive gates, rode through the bazaars to the Palace. The bazaars, like those of Kabul, are roughly roofed over to keep out the glare of the sun.

The Governor of Jelalabad received us in the Palace gardens: seats were placed in the shade: fans were waved by the page boys to keep off the flies; and a crowd of people stood around. Sweets were brought—chiefly sugared almonds—then tea and cigarettes, and bouquets of flowers.

We rested for a while, and as we smoked the Governor made the usual polite Oriental speeches. Then he invited us to see the interior of the Palace.[17] It is a large white building, standing in the midst of well laid out gardens, in which are many varieties of Eastern and European fruit-trees and flowers. The Palace was semi-European in its internal decoration. It was unfinished at this time. There was a large central hall with a domed roof, and smaller rooms at the side: a separate enclosure was built for the ladies of the harem: near by were kitchens, rooms for the Afghan bath, and a Guest house or pavilion in a garden of its own.

The town of Jelalabad is between ninety and a hundred miles from the Indian frontier town Peshawur, and contains, in the summer, a population of from three to four thousand inhabitants. There is one chief bazaar or street with shops. The other streets are very narrow. Though much smaller it resembles in style the city of Kabul, which I will describe presently.

The spot was chosen by Bâber Bâdshah, the Tartar king, founder of the Mogul dynasty of Afghanistan and India. He laid out some gardens here, but the town of Jelalabad was built by his grandson, Jelaluddin Shah, also called Akbar, in 1560 A.D., just about the time when Queen Elizabeth came to the throne. The place is interesting to us from the famous defence of Sir Robert Sale during the first Afghan war, when he held the town from November, 1841, to April, 1842.

The river which runs near the town is here broad and rapid, though shallow and with low banks. All along the river for miles the plain is marshy and overgrown with reeds. In the summer when the swamp is more or less dried up, one rides through[18] the reeds rather than keep to the glare and heat of the road. The plain of Jelalabad, nearly two thousand feet above the sea, is about twenty miles long, that is, from east to west, and four or five miles wide. Wherever it can be irrigated from the Kabul river it is delightfully fertile, but everywhere else it is hot barren desert. The climate of Jelalabad is much more tropical than that of Kabul—more resembling the climate of Central India; and in the winter the nomadic Afghans of the hills in the Kabul province pack their belongings on donkeys or bullocks, and with their whole families move down to Jelalabad, so that the winter population of the town is enormously greater than that of the summer.

Palm trees and oranges grow out in the gardens: pomegranates and grapes in great quantities; and there are many kinds of tropical as well as sub-tropical flowers. His Highness the Amîr had an idea a short time ago of establishing a tea plantation here. It is doubtful, however, whether it would be successful, for in the summer there is the dust storm and the scorching wind—the simûm.

After taking leave of the Governor we were shown into the Guest pavilion in its enclosed garden. Here arrangements had been made for us to spend the night. On the north side, where the pavilion overlooks the Kabul river, was a stone colonnade or verandah with pillars. A sentry was stationed here and also at the gate of the garden. One of the Khans had asked permission to entertain us at dinner, and with Afghan hospitality he provided also for the guard, servants, and horses. He did not dine with us but came in afterwards for a chat. I noticed that[19] in spite of being a Mahomedan he did not refuse a cigarette and some whiskey. This gentleman we were told had considerable power in the neighbourhood of Gundamuk, and we were advised, in case it should ever be necessary to escape from Kabul, to remember his friendliness; for though Gundamuk is a long way from Kabul, one could ride there in a day.

Next day we had a gallop through the fertile part of the valley. I had changed my mare for a steadier horse and my mind was peaceful. Away to the south it was stony and bare, and in the distance we could see the snow-capped range of the Suffêd Koh or White Mountains. We did not go very many miles, but put up at the village of Tattang. Some of the villages are built entirely as forts, resembling those in the Khyber district. In others there is a similar but smaller fort, which is occupied by the Malek or some rich man with his immediate retainers; the other houses, flat topped and built of sun-dried bricks, are clumped irregularly together near the fort. But the windows, for safety and to ensure privacy, generally open into a walled garden or yard, so that even these have the appearance of being fortified. The villages are surrounded by orchards and fields.

At Tattang the Amîr has a gunpowder factory, and the superintendent showed us over it. The machinery is of wood, roughly made, and is worked by water power. The water is obtained from a stream rising in the Suffêd Koh mountains, and is led by broad channels to the water wheels. Along the channels, and indeed along most of the irrigation canals that one sees in the country, are planted poplars or willows; these protect the canal banks[20] from injury, and possibly lessen by their shade the rapid evaporation of water that takes place in a dry hot climate. The gunpowder is not for sale, and severe penalties are inflicted on those detected selling or stealing any.

The following day we left the cultivated part of the valley and rode through a stony desert and over pebbly mountains to Nimla. Contrasted with the pleasant ride through the fields of the day before, the heat and glare were most oppressive. The Nimla valley is, however, an oasis in the desert. In it there is a very beautiful garden enclosed within a high wall. It was made by Shah Jehangir about 1610 A.D., and has been repaired by the present Amîr. One can see the garden a great way off, the deep green of its cypress trees being a striking piece of colour among the blue greys and reds of the mountainous barren landscape. There is an avenue of these trees about one hundred feet wide, and between them, from one end of the garden to the other, rushes a broad stream with three cascades artificially made and enclosed within a stone embankment. The water is brought from a stream rising in the Suffêd Koh mountains, and rushes on to join the Surkhâb, a branch of the Kabul river.

At one end of the avenue is a pavilion surrounded by flowers. Here we put up for the night. Soldiers were sent off to the nearest villages to buy provisions, and our Hindustani cook, having dug a shallow hole in the ground in which to build his wood fire, placed a couple of stones on each side to support his pots, and sent us an excellent dinner of soup, roast fowl, and custard pudding.

We started off early next morning. Leaving the Nimla valley we had a rough road, often no more than a dry watercourse which led up over rocky mountains and across stony plains for many miles. As we were travelling westward, on our left hand, that is to the south, could be seen the great range of mountains called the Suffêd Koh, on the other side of which is the Kurram valley, now occupied by the British. This range forms the southern boundary of the Kabul province, and extending from the Khyber mountains had been on our left the whole way. Our route, however, had been somewhat north-west, for we had kept fairly close to although not on the banks of the Kabul river, but at Jelalabad we branched off from the river south-west, and came much closer to the Suffêd Koh.

This range, unlike the other mountains we saw, is covered with great forests of trees. In the whole country the arboreal distribution is peculiar. The forests are confined entirely to the main ranges of mountains and their immediate offshoots. The more distant prolongations are bare and rocky. I remember once in travelling from Turkestan to Kabul, everyone stopped and stared, for there on a mountain a solitary tree could be seen; it looked most extraordinary. In the valleys there are poplars and willows, which have been planted by the peasants for use afterwards as roofing beams, and there are orchards of fruit-trees, but I never saw a forest, a wood, nor even a spinney. The species of tree on those mountains where they are to be found, varies, of course, according to the height you find them growing. For instance, high up, there are the cone-bearing trees, the various kinds of pine[22] and fir. Then come the yew and the hazel, the walnut and the oak. Lower down—to 3,000 feet—are wild olives, acacias, and mimosas. On the terminal ridges you find simply shrubs and herbs.

We passed Gundamuk, where in May, 1879, the “Treaty of Peace” was signed by the reigning Amîr Yakoub and by Sir Louis Cavagnari. Four months later, in September, Cavagnari, while British Resident in Kabul, was assassinated with the connivance of the same Amîr. I heard the whole plot of the assassination when I was in Kabul.

The story was this. Cavagnari had been holding Durbars, giving judgment in cases of dispute brought to him by the natives, and had been distributing money freely, till the Sirdars, coming to Amîr Yakoub, said, “No longer is the Amîr King of Afghanistan, Cavagnari is King.” Yakoub therefore took counsel with his Sirdars as to the best course to adopt. They said, “To-morrow the Herati regiments come for their pay—send them to Cavagnari.” It was crafty advice—they knew the hot fiery nature of the Heratis. The following day, when the troops appeared, unarmed, as is the custom on these occasions, Amîr Yakoub sent word, “Go to Cavagnari—he is your King.” Off rushed the soldiers tumultuously, knowing the Englishman had been lavish with money. The Sikh sentry at the Residency Gate, seeing a great crowd rushing to the Bala Hissar, challenged them. The excited shouts of the crowd being no answer, he fired. At once their peaceable though noisy excitement changed to anger, and they retaliated with a shower of stones. The Residency guard were called out, some of the Afghans rushed back for their rifles, and soon all[23] were furiously fighting, though no one but Yakoub and his Sirdars knew why. Messages were sent to Amîr Yakoub, and the answer he returned was, “If God will, I am making preparations.” The end was the massacre of the British Envoy and all with him.

About ten miles beyond Gundamuk was Surkh pul, or “The Red Bridge.” This is an ancient brick bridge built over the river Surkâb, which runs into the Kabul river near Jelalabad. The bridge is built high up at a wild looking gorge between precipitous red mountains, and the river comes roaring out into the valley. The water of the river is reddish, or dark-brown, from the colour of the mud in suspension; however, the Afghans said it was good water, and while we sat in the shade of a fakir’s hut there, the servants boiled some of the water and gave us tea. Then we crossed the bridge and rode on again. From here, almost to the Kabul valley, the road is through a very wild and desolate mountainous region; you gradually rise higher and higher, to nearly 8,000 feet, but just before you reach Kabul, descend some 2,000 feet, the valley of Kabul being 6,000 feet above the sea. It is, of course, a very great deal colder in this region than in Jelalabad; in fact, while the harvest is being reaped in Jelalabad, the corn at Gundamuk, only twenty-five miles further on, is but an inch or two above the ground. It would, perhaps, be more accurate to say that the ascent commences at Nimla. We rode some miles between two ranges of hills—the long narrow valley being cut across by spurs from the mountains; then climbed a very long steep ascent, with precipitous walls of rock on either side, and descended a narrow winding gorge[24] which appeared to have been once the bed of a river. On either side of this gorge there was brushwood growing, some stunted holly trees, and what looked like twisted boxwood trees. Then we climbed the mountain, on the top of which is the Jigdilik serai. This is 6,200 feet high, and the scenery from the serai is the abomination of desolation—range after range of barren mountains. It felt bitterly cold up there, after the heat we had been through.

They found us a room over the gateway of the serai, lit a blazing wood fire, and we stayed there till the next day. In the first Afghan war in 1837, during the winter retreat of the British army, of the 5,000 soldiers and 11,000 camp followers who left Kabul, only 300 reached Jigdilik, and of these only one, Dr. Brydon, reached Jelalabad, the others were shot down by the Afghans, or died of cold and exposure.

The village of Jigdilik is not on the hill where the serai is situated, but in the valley at the foot. Here three gorges meet. One was the road by which the ill-fated army came in their retreat from Kabul through the Khurd Kabul Pass. We took another road to the north-west. We climbed up and down over steep mountains and through narrow defiles hemmed in by bare rocks. In the valleys it was rare to see anything but stones, rocks, and pebbles. There was one valley at Katasung where there was a little stream with grass growing by it. This valley, a short time ago, was very dangerous to travel through on account of the highway robberies and murders of a tribe living near. It is safer now, for the Amîr has killed some of them, imprisoned others, and dispersed the rest. We camped at Sei Baba, a narrow valley of pebbles,[25] with a small stream trickling through it. An enterprising peasant, finding water there, had picked all the pebbles off a narrow strip of ground, piled them in a ring round his field, led the water by a trench to it, and had planted some corn. He, however, was nowhere to be seen, nor was there any house or hut there.

We occasionally came across these patches among the mountains wherever there was a trickle of water to be obtained. Sometimes they were more extensive than this one, and, if made on the slope of the mountain, the ground was carefully dug and built up into terraces, so that irrigation was possible. In the middle of the Sei Baba valley was a tomb with a low wall all round it, and a solitary tree was growing by. On the tomb were placed two or three pairs of horns of the wild goat. This is done as a mark of great respect. Every passer by, too, throws a stone on a heap by the grave, and strokes his beard while he mutters a prayer. The heap of stones, or “tsalai,” is supposed to be piled only over the graves of holy men or martyrs; but they are heaped over any grave that happens to be apart from others, and by the wayside. The peasants, not knowing, assume it is the grave of a holy man. The custom is said by some to originate by imitation from an act of Mahomed, in which the form but not the spirit of the ceremony, has been retained; for Mahomed, fleeing for refuge to Mecca from Medina, threw stones at the city and cursed it. By others, these heaps of stones are supposed to be representative of the Buddhist funeral pillars, the custom having remained extant since the days when Buddhism was the[26] dominant religion of the people inhabiting this country. The latter seems the more likely explanation.

By the side of some of these tombs a small shrine, “ziyârat,” is built. If the tomb is that of a known holy man, the passer by, in addition to adding a stone and saying his prayer, calls upon the name of the saint, and tears a small piece of rag off his garment which he hangs on the nearest bush or tree. The shred is to remind the holy man that the wearer has prayed him to intercede on his behalf with the prophet Mahomed. On the grave, too, is generally planted a pole with an open hand, cut out of zinc or tin, fixed on the top. If the deceased has fallen in battle a red rag is fixed on the pole as well. What the open hand pointing to the sky represents I never heard.

When we arrived at Sei Baba we found that a party of peasants on the tramp had halted there—one of their number died just as we arrived. Seeing that we had a cavalcade of horsemen and much baggage, and there being no village nearer than seven or eight miles, they came to us to beg a little calico for a winding sheet. It struck me that ten yards, the amount they asked for, was rather much for that purpose. Possibly they thought the living men required it quite as much as the dead man.

Next day we had a high and stony range of mountains to climb—the Lataband Pass, nearly eight thousand feet above the sea. This part of the journey between Lataband and Chinár, with the winding rocky road curving high up round the spurs or plunging into narrow ravines, always seems to me the wildest and most weird of all. The mountains are so huge and rocky, the ravines so precipitous, and the silence[27] so appalling. A few years ago the Pass was dangerous not only in itself—the road in one place runs on a ledge of rock overhanging a seemingly bottomless precipice—but it was infested with Afghan highway robbers. Being comparatively near the capital this was particularly exasperating to the Amîr. Finding ordinary punishments of no avail he determined to make an example of the next man apprehended. As we were riding along we could see fixed on one of the highest peaks something that looked in the distance like a flagstaff. The road winding on we drew nearer, and saw it was not a flag, it was too globular, and it did not move in the wind. When we got right under the peak we saw it was a great iron cage fixed on the top of a mast. The robber had been made an example of. There was nothing left in the cage but his bones. I never heard of there being any more highway robbery or murder near here.

From this pass you get the first view of Kabul. In the distance it seems a beautiful place, and after the long desolate march the sight of it lying in the green Kabul valley is delightful. We reached the foot of the mountains, rode some miles along a stony and barren plain till we reached a village called Butkhak, where we camped. The next day the cultivated part of the Kabul valley lay before us. First were the fields surrounding Butkhak, then we crossed a small dilapidated brick bridge over the Logar river, which runs north to join the Kabul river. We had quite lost sight of our old friend the Kabul river since we left Jelalabad: he was away somewhere to the north of us, cutting a path for himself among the mountains. The Amîr has spent[28] several thousands of pounds—or rather lacs of rupees—in trying to make a road in the course of the river from Kabul to Jelalabad, but it was found quite impracticable among the mountains in the Lataband and Chinár district. The object, of course, was to avoid the climb over the Lataband Pass. I have never been the route through the Khurd Kabul Pass to Jigdilik, but I have heard that the road is not very good.

After crossing the Logar bridge we mounted a range of low pebbly hills, which run irregularly east across the valley, cutting it in two. From the elevated ground we could see on our left a large reed grown marsh surrounded by meadow land, which ran right up to the foot of the mountains, forming the south boundary of the valley. We were much nearer to the southern than to the northern limit. The mountains curved round in front of us and we could see the gap or gorge between the Asmai and Shere Derwaza mountains. From this the Kabul river emerged and took its course in a north-easterly direction across the valley.

On the south bank of the river near the gorge and at the foot of the Shere Derwaza lay the city. Jutting out north-east from the Shere Derwaza into the valley, about a mile south of the gorge, was the spur of the Bala Hissar, and the city seemed, as it were, to be tucked into the corner between the Shere Derwaza, its Bala Hissar spur, and the Asmai mountain. On our right, about a mile and a half north of the city, was the Sherpur cantonment or fortification, backed by two low hills—the Bemaru heights.

We descended the elevated ground, from which we had a birds-eye view of the valley, and found ourselves riding along excellent roads fringed with poplar trees. The cultivated fields separated by irrigation channels lay to the left of us. On the right were the pebbly hills we had crossed lower down, continued irregularly west. On the last hill nearest the town, “Siah Sang,” was a strong fort, built by the British when Lord Roberts was in Kabul. It is called Fort Roberts.

We rode along the avenues of poplar and plane trees right up to the Bala Hissar spur. In the time of the Amîr Shere Ali, on the high ground of the spur stood the royal residence and the fort, and when Yakoub was Amîr this was the Residency where Cavagnari lived. It is now almost all in ruins or demolished. The gateway stands, and a part of the old palace. This is used as a prison for women, political prisoners, Hazaras, and others. The wall and the moat exist, and inside, some rough barracks have been built for a few troops. The native fort on the higher ground of the Bala Hissar seems to be in good repair. I have never been inside. It is used as a magazine for powder.

We passed the Bala Hissar, leaving it on our left, and the road led through a plantation of willows extending from the Bala Hissar some distance north, skirting the east suburb of the city. The willows in the plantation were arranged in rows about ten yards apart with a water trench or ditch under each row of trees, and the shaded space between was green with grass—an unusual sight in Afghanistan. The trees were planted by Amîr Shere Ali, whose idea[30] was to camp his soldiers here in the summer without tents. The willow branches are used now to make charcoal for gunpowder.

We entered the gate of the city called the Lahore Gate. It was rather dilapidated, but looked as though it might once have been strong. There were heavy wooden doors studded with iron, and large loopholes in the upper brickwork of the gate which were guarded by brick hoods open below, a species of machicoulis gallery. Possibly the loopholes were once used for the purpose of pouring boiling water on the heads of an attacking enemy.

Position of Kabul. Its defences. Amîr’s opinion of the Founders of his Capital. Entry into Kabul. Aspect of the Townsmen. Arrival at the Arm Foundry. Visit of the Afghan Official. His appearance. Absence of Amîr. To be received at the Palace by the Princes. The approach to the Palace. The Amîr’s Pavilion. Page boys. The Princes Habibullah and Nasrullah. The Reception. Internal arrangement of Pavilion. The earthquake. Abrupt ending of the Reception. Other buildings in the Palace.

The city of Kabul, 5,780 feet above the sea, lies then at the foot of the bare and rocky mountains forming the west boundary of the Kabul valley, just at the triangular gorge made by the Kabul river. Through this gorge runs the high road to Turkestan and Ghuzni. An ancient brick wall, high, though somewhat ruined, with towers at intervals, leads up on each side of the gorge to the summit of the Asmai and Shere Derwaza mountains, along the latter to the Bala Hissar spur, where it joins the fort. From the Asmai a line of hills extends west to the Paghman range. Formerly the wall was taken across the gorge, bridging the Kabul river. Remains of it are to be seen on a small island in the middle. The city, therefore, was well protected on the western side—the side of danger from invasion of the Tartars: it is comparatively unprotected on the east, except by the Bala Hissar fort; for in those days little danger of invasion was apprehended from India.

The city extends a mile and a-half from east to west, and one mile from north to south. Hemmed in as it is by the mountains, there is no way of extending it, except in a northerly direction towards the Sherpur cantonment. It is here midway between the city and Sherpur on the north side of the river that the Amîr has built his palace.

His Highness speaks derisively of the founders of his capital, “Dewanas,” he calls them, “Fools to build a city of mud huts cramped into a corner among the mountains.” One of his ambitions has been to build a new Kabul in the fertile Chahardeh valley to the west of the Shere Derwaza and Asmai mountains, between them and the Paghman hills. Amîr Shere Ali had also the intention of building a new Kabul, and “Shere pur,” the “City of Shere Ali,” was begun. However, he got no further than three sides of the wall round it.

The desire to build a new Kabul is not surprising when one has seen the present city. The first thing that strikes you on entering it is the general look of dilapidation and dirtiness. Closer acquaintance shows you how inexpressibly unclean and unhealthy an ancient Oriental city can become.

We rode through the narrow badly-paved streets, and through the bazaars, which were crowded with turbanned Afghans and Hindus robed in bright colours. They moved out of the way of our rather large cavalcade, but very few showed any appearance of curiosity; and we rode on to the garden or orchard in the gorge between the Shere Derwaza and Asmai mountains, where, by the side of the Kabul river, the Amîr’s European Arm foundry has been estab[33]lished. This is protected on one side by the river, on the three other sides by high walls.

The entrance was through a large double wooden gate, where some soldiers were on guard. Inside there were built along the walls a series of rooms where tin workers, brass workers, and others practised their handicraft. In one of the larger of these rooms Mr. Pyne and myself were located, and an adjoining one was prepared for the two English engineers, Messrs. Stewart and Myddleton, who had accompanied us.

In the centre of the ground three or four large buildings were in course of erection. These had been commenced by Mr. Pyne during his first short visit to Kabul. The walls were nearly completed. To finish them were the corrugated iron roofs which Mr. Pyne had brought out from England, and the machinery, some of which was lying around packed in cases in two hundredweight pieces: the rest arrived on strings of camels a few days or weeks after we did.

In our room we found a large table loaded with sweets, cakes, kaimaghchai, or cream and tea, and various other eatables. We set to, but were presently visited and salaamed by some score or so of Hindustani mistris, whom Mr. Pyne had engaged and sent on from India. There was a very fair carpet on the earth-beaten floor. Our beds, bedding, and chairs we had brought with us. A soldier was posted on guard at our door and another on the roof.

In the space inside the enclosure unoccupied by buildings, there grew a great many mulberry trees, and outside the walls were large beds of flowers, vines trailed over upright poles, and a fountain. This plot[34] of ground had once been the garden of a wealthy Afghan gentleman.

On the day after our arrival in Kabul it rained hard, but on the following day we received a ceremonial visit from Jan Mahomed Khan, the treasury officer, who was accompanied by a large retinue of servants. This gentleman was of medium height and slightly built. He had a rather dark skin, but a very pleasant face, and was charming in his manner. His costume was brilliant. It consisted of a black astrakhan hat of the globular Russian shape, a purple velvet tunic embroidered with gold, a belt and sword, both highly ornamented with beaten gold, trousers and patent leather boots. The sword was not of the European shape. It was made with a slight curve, had no hand guard, and slipped almost entirely into the scabbard. Mr. Pyne was acquainted with this gentleman, having met him during his first visit to Kabul. I, therefore, was introduced. After the usual compliments and polite speeches, it was intimated to us that Prince Habibullah, the eldest son of the Amîr, would receive us at the Palace that day.

We learnt that His Highness the Amîr himself was away in Turkestan, where he had been fighting his rebellious cousin Ishak.

After Jan Mahomed Khan had politely asked permission to depart, we got ready to go to the Palace. Our horses were brought to the door, and we rode, accompanied by our guard and an interpreter, to the Erg Palace. This Palace is situated outside the town, about midway between it and the Sherpur cantonment. We rode from the workshops some little distance along the Kabul river, then skirted the[35] Government buildings which are built on the south and east sides of the Palace gardens, and arrived at the east entrance, a big arched gateway in which, however, there were no gates. Here we left our horses. Entering the gateway we walked across the gardens, the guard unceremoniously clearing out of our way the clerks, pages, and petitioners who were walking along the paths. We saw in front of us the ramparts, moat, and bridges of the Palace. The flame-shaped battlements of the walls, and the decorated gateway set in a semicircular recess flanked by bastions, had a quaint Oriental appearance.

On the wall over the gateway was a small cupola sheltering what appeared to be a telescope, but may have been a machine gun. From this tower issues at sunrise and sunset the wild native music of drums and horns, which is the invariable “Salaam i subh” and “Salaam i shām” of Oriental kings. Many a morning in after years was I woke up at daybreak by the weird monotonous howl of the horns and the distant rattle of the drums.

We crossed the bridge in front of us and entered the decorated gateway, the wooden gates of which—massive and studded with iron—were open. Inside was the guard-room, large and high, with passages leading off from it, and the soldiers of the guard were grouped idly about.