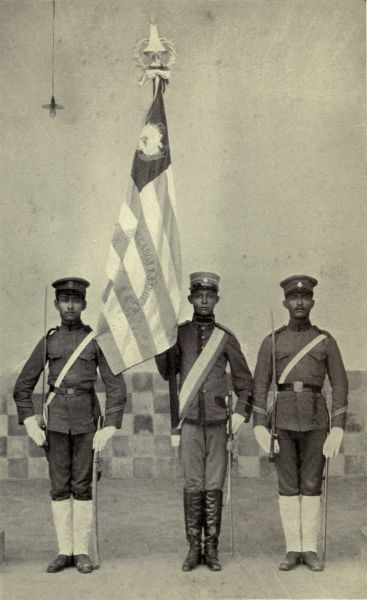

"The Colours."

The Salvadorean Flag, Supported by Cadets of the School for Corporals And

Sergeants.

Title: Salvador of the Twentieth Century

Author: Percy F. Martin

Release date: March 9, 2014 [eBook #45102]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Adrian Mastronardi, Julia Neufeld and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

SALVADOR OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

WORKS BY

PERCY F. MARTIN, F.R.G.S.

————

MEXICO OF

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

With Map, and more than 100 Illustrations. 2 Vols.

Demy 8vo. 30s. net.

"Will take its place as a standard work of reference on the country."—Truth.PERU OF

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

With Map, and 43 Illustration. I Vol. 15s. net.SALVADOR OF

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

With Map, and 48 Illustrations. 1 Vol. 15s. net.

LONDON : EDWARD ARNOLD

BY

AUTHOR OF

"THROUGH FIVE REPUBLICS OF SOUTH AMERICA," "MEXICO OF THE TWENTIETH

CENTURY," "PERU OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY," ETC.

NEW YORK

LONGMANS, GREEN & CO.,

LONDON: EDWARD ARNOLD

1911

[All rights reserved]

While it is quite reasonable to hope for a consistent improvement among the Central American nations, and as easy to discern the extent of amelioration which has already occurred, it is necessary to bear in mind some of the causes which have hitherto conduced to the turbulence and the tragedies which have characterized government by some of these smaller Latin Republics.

Many writers, who can know but little of the Spanish race, have attributed the early failures of the States which broke away from the Motherland, not only to lack of stability, but to a radical psychological defect in the national character. This is a decided mistake, for the Spanish people, both in their individual and in their collective character, are fully as capable of exercising the rights, and of enjoying rationally the benefits, of self-government as any other nation of the world. The patriots and heroes who distinguished themselves in the early days of these young Republics, while themselves descendants of the Spaniards, generally speaking, and having only in a few cases Indian blood in their veins, had to combat against all the ambition and avarice, all the pride[vi] and prejudices, of the Church-ridden land which had set its grip upon New Spain, and meant, if possible, to keep it there. But it was not possible, and in a few decades was witnessed their complete expulsion as rulers from the countries which had been won by the flower of Spain's soldiery, and lost by the exercise of Spain's oppression and greed.

While the early history of the Latin-American Republics contains much to distress, and even to depress, the reader, it is impossible to avoid paying a tribute to the band of gallant men who fought so desperately in the cause of freedom, and eventually won it. It is not just to say, as so many historians have said, that the highest incentives of these men to action were the favours of artificial and hereditary greatness, with the accumulation, by whatsoever means, of that wealth by which such favours might be purchased. Undoubtedly some mercenary motives were at work, as they usually are in political upheavals of this nature. Does anyone imagine, for instance, during the disturbances which occurred in Mexico early in the present year, and which were personally assisted by United States citizens, that low mercenary motives were lacking? Does anyone imagine that the numerous North American filibusters who took part in the fighting, first on the Texas borders, and then in Mexico itself, had any idea of assisting a persecuted people to free themselves from the yoke of a tyrant? Or was it not the glamour of golden lucre to be paid to them, and the promise of the much-coveted land across the Rio Grande del Norte, that impelled these young Yankees to throw in their lot with the rebels, trusting to their own complacent Government at Washington to see them through—as it actually did—any[vii] trouble which might happen to them if they proved to be upon the losing side?

It would perhaps be equally correct to describe the early Spanish conquerors as greedy adventurers, since they never had any ideas of benefiting the countries or the people whom they afflicted so sorely. It is true that they encountered fearful dangers, displayed unheard-of bravery, overturned empires, and traversed with bloody steps an entire continent; but it was to aggrandize the Crown of Spain and to fill their own empty pockets with golden spoil, which, once secured, witnessed the fulfilment of their ambitions.

It was, moreover, from this veritable horde of greedy tyrants that in later days the peoples of these nations sought to obtain, and finally did obtain, their freedom; their experiences of the Spanish Viceroys, with their courts more brilliant and more corrupt than that at Madrid itself; the persecutions of the Church, which has left a record in Latin-America more bloody and more barbarous than even in Europe; the deafness shown by the Spanish Crown whenever an appeal for consideration or clemency was addressed to it—all these things conduced to that upheaval which has taken over one hundred years to consummate and fructify.

It was, then, against all this that the people of Central America were called upon to fight. Can anyone be surprised at the demoralization which occurred in their own ranks when their efforts to secure their freedom from Spain were once crowned with success? History shows many other such instances; indeed, bad as is the record of the earliest days of Latin-American self-government, it by no means stands without parallel. The objects—beyond[viii] a desire to be free from the brutal tyranny of the Spanish Viceroys—of the Latin-American revolutionists were never very clearly defined or well understood. Neither was any preconceived or organized plan ever made or carried out in connection with the French Revolution.

Some historians are of opinion that the revolutionists of Central America originally contemplated the establishment of an independent Kingdom or Monarchy which should comprise the ancient Vice-Royalty, or, as it was called, the "Kingdom of Guatemala." But there is little evidence that any such notion was generally popular. Among the body of office-seekers and hangers-on of royal Courts it may, of course, have been regarded with favour. But the Provisional Junta, which was convoked immediately after the separation from Spain, showed a great majority of Liberals, who, in spite of the pressure brought to bear upon them, and the personal danger in which they stood, proceeded boldly to administer the oath of absolute independence, and to convoke an assembly of patriots which should organize the country on the basis of Republican institutions. The effort which was made later on through French machinations to establish a monarchy in Mexico failed dismally, as had the previous efforts put forward by the Mexicans themselves, when Iturbide was made—or, to be more correct, made himself—Emperor for a very brief period.

The people of Central America were but few in number, and were widely distributed over the face of the country. It took several weeks to get into communication with some of the outlying districts, and the diffusion of the newly-created voters prevented them from becoming in any way a united people, or[ix] even cognizant of what was being done in their name. In fact, while anxiously awaiting the intelligence that their Junta was about to issue the long-looked-for Republican Charter, the people of Salvador received the startling and disastrous news that their country was to be incorporated into the Mexican Empire. They had been basely betrayed, and it is small wonder that they stood aghast at the colossal nature of that betrayal.

Terrible indeed was the position for the newly-arisen Republic of Salvador. The men whom they had sent to attend the Junta at Guatemala City were met and overawed by armed bands; their deliberations were forcibly interrupted and suspended; some of them, such as Bedoya, Maida, and others, were ruthlessly assassinated, while their own leader and President of the Provisional Junta, one Gainza, turned traitor and went over to the enemy under promise of a high post in the new royal Government.

Salvador was the nearest province to Guatemala, and the centre of Liberalism. It was not long before the patriots of this country took up arms in the defence of their newly-acquired freedom, and when they did theirs was practically the first battle which was fought upon Central American territory by Central Americans among themselves. Unfortunately, it was by no means the last; and history bristles with instances of terrible internecine warfare—of father arrayed against son, brother against brother, and of whole families, once united in bonds of love, wrenched asunder, never again to be reconciled this side of the grave. For years following, the soil of this beautiful land was drenched with human blood, its energies crippled, its resources abandoned. Are we justified in supposing that the[x] end has come? I verily believe that, if it has not actually arrived, it is at least in sight.

It must be remembered that the people of Central America are no longer an uneducated and unduly excitable race, except, perhaps, where their personal honour and independence are concerned; they possess an exceedingly clear and precise knowledge of their prospective or immediate requirements; they have as enlightened leaders among them as ever their powerful Northern neighbour possessed or possesses: all that they ask, and all that they should be granted, is the freedom to manage their own affairs in their own way and in their own time. A well-known writer upon Central America, who visited these countries some five-and-fifty years ago, declared: "Even as it was no one, whatever his prejudices, could fail to perceive the advance in the manners and customs, and the change in the spirit, of the people of Central America during the ten years of freedom which the Constitution secured." If that was true then, it is doubly, trebly true to-day, when education and foreign travel have served to open the minds and broaden the tolerance of these people, who may reasonably be permitted, and even earnestly encouraged, to work out their own salvation. By free and unrestricted intercourse with the nations of the world this can best be effected, and day by day is proving the truth of the saying of Dr. Johnson: "The use of travelling is to regulate imagination by reality, and, instead of thinking how things may be, see them as they are."

October, 1911.

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGES | |

Discovery of Salvador—Scenery—Volcanoes—Separation of Salvador from Spanish dominion—Central American Confederation—Attempts to reconstruct it—General Barríos—Lake Ilopango—Earthquake results—Remarkable phenomena—Public roads—Improvement under Figueroan Government | 1-12 |

| CHAPTER II | |

Government—Executive power—Chamber of Congress—The Cabinet—Justice—The courts—Prisons and prisoners—Employment and treatment—Police force—How distributed—Education—Colleges and schools—State-aided education—Teaching staffs—Primary education—Posts and telegraphs—Improved interstate parcels post | 13-35 |

| CHAPTER III | |

Biographical—The President, Dr. Manuel E. Araujo—The ex-President, General Figueroa—The Cabinet—Dr. don Francesco Dueñas, Minister for Foreign Affairs—Dr. don Teodosio Corranza, Home Affairs—Dr. Gustavo Baron, Public Instruction—Ingeniero Peralta Lagos—Dr. Castro V.—Don Eusebio Bracamonte—Don Miguel Dueñas—Department of Agriculture—Señor Carlos Garcia Prieto, Finance and Public Credit | 36-48 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

Government finances—London Market appreciation of Salvador bonds—History of foreign debt—Salvador Railway security—Central American Public Works Company—Changing the guarantee—Financial conditions to-day—Public debt at end of 1909—Budget for 1910-11—Small deficit may be converted into surplus—Summary | 49-60 |

| CHAPTER V | |

[xii]Salvador versus Honduras and Nicaragua—Attitude of the President—Proclamation to the people—Generals Rivas and Alfaro—Invasion of Salvador—Ignominious retreat of enemy—Conciliatory conduct of General Figueroa—Character of Salvadorean people—Treachery of Zelaya | 61-73 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

Outbreak of hostilities between Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Guatemala—Discreditable conduct of Nicaragua proved—Failure of United States and Mexican intervention—Dignified and loyal attitude of General Figueroa—Warning to Honduras—President Davila used as Zelaya's cat's-paw—The former's subsequent regret—Central American Court of Justice trial of claim for damages and result of judgment | 74-85 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

The Army—Division of forces—Active reserve—Auxiliary—Republic's fighting strength—Military education—Strict training—Excellent discipline—Schools and polytechnics—Manual exercise—Workshops and output—Economies in equipments—Garrison services—Barracks—Destruction of Zapote Barracks—New constructions at Capital, Santa Ana, Santa Tecla, Sitio-del-Niño, Ahuachapán, Cojutepeque, San Miguel—Annual expenditure | 86-95 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

British Minister to Salvador—Lionel Edward Gresley Carden—British Legation hospitality—Mrs. Carden—Government indifference to valuable services—British Vice-Consul—No report for twenty years—Foreign Office neglect—United States Minister—Valuable trade information from American Legation—Salvadorean relations with Washington | 96-109 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

United States information for traders—Improved Consular services—United States and Salvador Government—Bureau of Pan-American Republics—Mr. Mark J. Kelly—Exceptional services—The American Minister, Major W. and Mrs. Heimké—Salvadorean Minister to U.S.A., Señor Federico Mejía—Central American Peace Conference and the United States | 110-119 |

| CHAPTER X | |

Latin-American trade and British diplomacy—Serious handicap inflicted by the British Government—Sacrificing British interests—Why British trade has been lost to Salvador—United States trade with Salvador—German competition—Teutonic characteristics—Britain's free trade principles—Severe American rivalry—United States Steel Company's methods | 120-136 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| [xiii] British trade declines—Suggested remedy—Distributing centres—Trading companies and branches—Unattractive cheap goods—Former hold on Salvadorean markets—Comparative statistics between Great Britain, Germany, and the United States—Woollen and cotton goods—Absence of British bottoms from Salvadorean ports—Markets open to British manufacturers—Agricultural implements | 137-149 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

British fire apparatus—Story of a British installation—Coffee and sugar machinery—Cane-mills—Fawcett, Preston and Co.'s installations—High reputation enjoyed by British firms—United States coffee equipment—German competition—Methods of German commercial travellers—Openings for British trade—Effect of Panama Canal—Libel upon Salvador manufacturers—Salvador Chamber of Commerce | 150-165 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

Systems of business—Long credits—British and United States methods versus German—Making "good" stock losses—Question of exchange—Effect upon business—Drafts and speculators—Customary terms of payment—Central American banks as agents—Prominent Salvadorean banks—The Press of the Republic—Prominent newspapers—Some of their contributors—Central American Press Conference | 166-180 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

Mining—Ancient workings—Precious metals found—Copper deposits—Iron ores—Treatment of ores in England—Difficulties of transport—Some deceased authorities—Mines in operation—Butters' Salvador mines—History of undertaking—Large profits earned—Directorial policy—Machinery and equipment—Butters' Divisadero Mines—Butters' cyaniding plant | 181-195 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

Transportation—Salvador Railway Company—Early construction—Gauge—Bridges—Locomotives—Rolling-stock—Personnel of railway—Steamship service—Extensions—Increasing popularity—Exchange and influence on railway success—Importers versus planters—Financial conditions—Projected extensions—Geological survey—Mr. Minor C. Keith's Salvador concession | 196-215 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

Ports and harbours—La Unión—Population—Railway extensions—Lack of British bottoms—Carrying trade—H.B.M. Vice-Consul—Port of Triunfo—Improving the entrance—Proposed railway—Acajutla—Loading and unloading cargoes—Proposed improvements—Salvador Railway connections—La Libertad—Commandante and garrison—Loading and unloading cargoes—Cable station and the service provided by Government—The staff of operators | 216-227 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| [xiv] Agriculture—Government support and supervision—Annual productions—Agricultural schools—Cattle-breeding—Coffee—Sugar—Tobacco—Forestry—Rice—Beans—Cacao—Balsam—Treatment by natives | 228-246 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

Departments: Capital cities—Population—Districts—Salvador Department—City of San Salvador—Situation—Surroundings—Destruction in 1854 by earthquake—Description of catastrophe—Loss of life actually small—Evacuation of city—Recuperative faculty of the people | 247-255 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

City of San Salvador—San Salvador as place of residence—Theatres—Parks—Streets—Hotels—Domestic servants—Hospitality of residents—Societies and associations—Educational establishments—Government buildings—Religion and churches—Casino—Hospitals and institutions—Disastrous conflagrations—Public monuments | 256-275 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

Department of Chalatenango—Rich agricultural territories—Annual fair—Generally prosperous conditions—Department of Cuscutlán—City of Cojutepeque—Industries—Cigar factories—Volcanoes—Lake of Cojutepeque—Department of Cabañas—Scenic features—Feast of Santa Barbara—Department of San Vicente—Public buildings and roads | 276-286 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

Department of La Libertad—Physical characteristics—Balsam Coast—Santa Tecla—Department of Sonsonate—Life and hotels—Department of Ahuachapán—City of Ahuachapán—Public buildings and baths—Projected railway extension—Department of Santa Ana—Chief city—Generally prosperous conditions | 287-299 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

Department of La Paz—Characteristics—Zacatecoluca—Population—Former proportions—Districts—Towns—Principal estates—Santiago—Nonualco—San Juan Nonualco—Climate—Water-supply—Santa Maria Ostuma—Mercedes la Ceiba—San Pedro Mashuat—Some minor estates—Small property holdings | 300-305 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

Department of San Miguel—Postless coast—Indigo plantations—City of San Miguel—Cathedral—Water-supply—Archæological interests—Projected railway connections | 306-310 |

Department of Morazán—City of Gotéra—Mountains and fertile plains—Agricultural produce | 310-311 |

Department of La Unión—Boundaries—Scenery—Guascorán River—Industries—Commerce | 311-313 |

Department of Usulután—Physical characteristics—Volcanic curiosities—Surrounding villages—Populations—El Triunfo—Santiago de Maria | 313-316 |

| Conclusion | 317-320 |

| Index | 321-328 |

| FACING PAGE | |

| "The Colours" | Frontispiece |

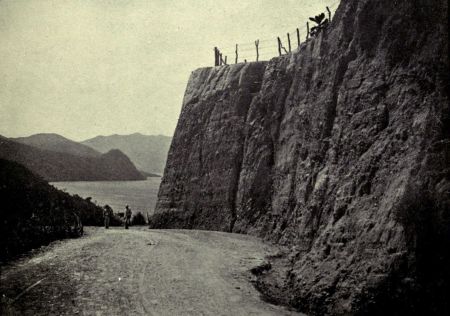

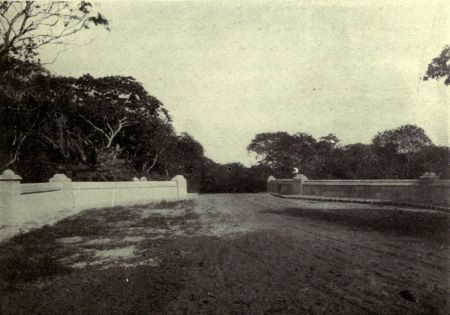

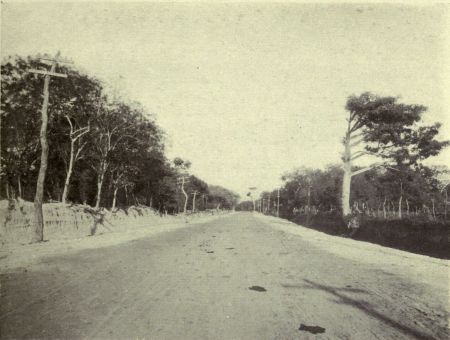

| Views on New National Road, between San Vicente and Ilopango | 8 |

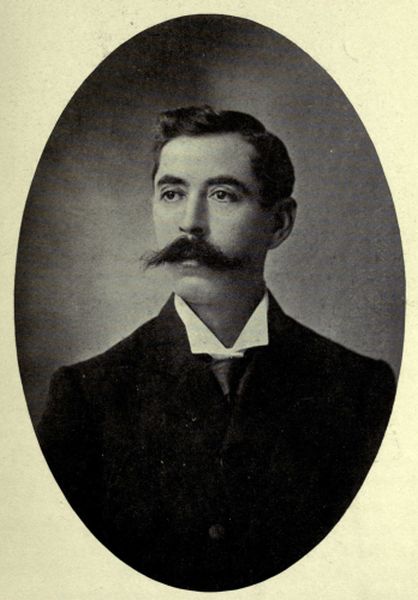

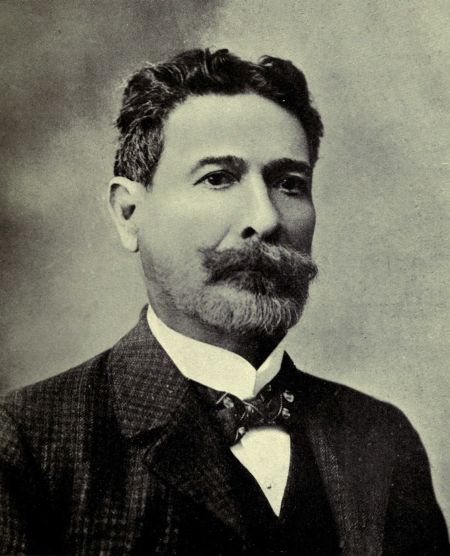

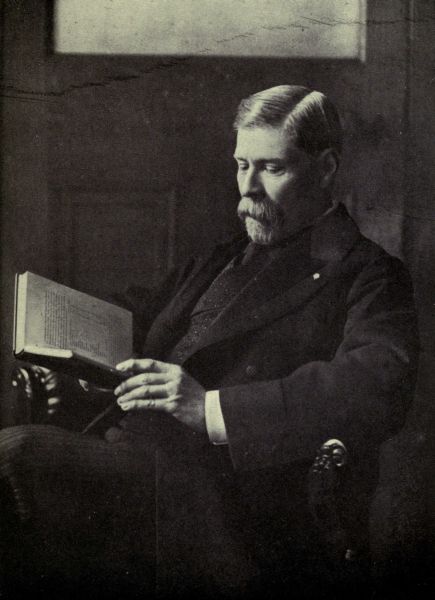

| H. E. Dr. Manuel Enrique Araujo, President of the Republic of Salvador 1911-1915 | 18 |

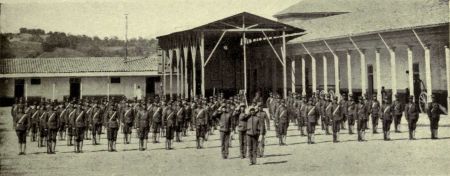

| The 3rd Company, Sergeants' School, in Review Order | 28 |

| Company in Line, Sergeants' School | 28 |

| Section of Riflemen kneeling, Sergeants' School | 28 |

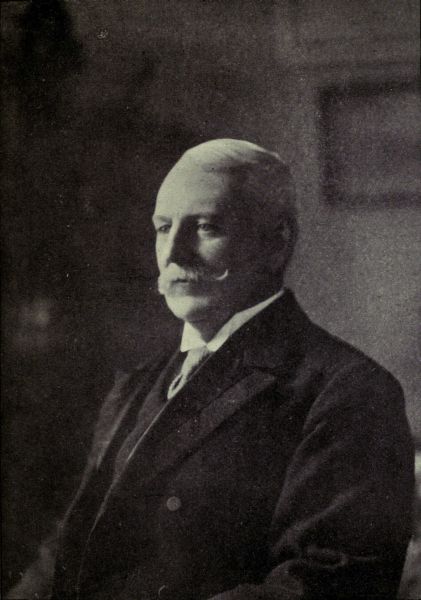

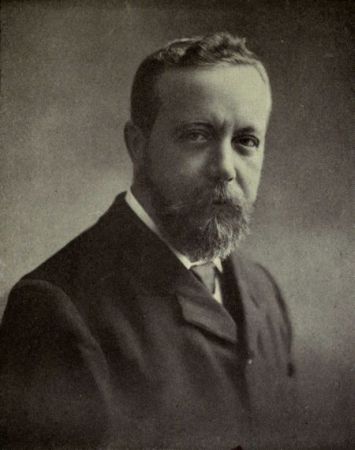

| General Fernando Figueroa, President of the Republic of Salvador 1907-1911 | 38 |

| Dr. Artúro Ramón Ávila, Consul-General for the Republic of Salvador to Great Britain, appointed May, 1911 | 46 |

| Artillery on Parade-Ground, San Salvador Barracks | 60 |

| Colonel's Quarters, School of Sergeants | 70 |

| Officers' Club-Room, School of Sergeants | 70 |

| Penitentiary at San Salvador | 78 |

| Officers' Club-Room, Military Polytechnic School | 78 |

| Colonel, Adjutant, and Captains of Company | 86 |

| Cadet Corps, School of Sergeants | 86 |

| Mr. Lionel Edward Gresley Carden, C.M.G., H.B.M. Minister-Resident at Salvador (as well as at Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Honduras) | 98 |

| Front of Sergeants' School, San Salvador | 108 |

| Typical Street in San Salvador, showing Style of One-Storey Houses | 108 |

| Mr. Mark Jamestown Kelly, F.R.G.S., for Fifteen Years Consul-General in Great Britain for Salvador (retired June, 1911), and Chairman of the Salvador Railway Company, Limited | 114 |

| Side-view of "El Rotulo" Bridge | 118 |

| The National Road leading to La Libertad, showing "El Rotulo" Bridge | 118 |

| Entrance to Avenida La Ceiba at San Salvador | 130 |

| [xvi]The Famous Avenida under Construction | 130 |

| View of the New Avenida leading to San Salvador, taken from the North | 140 |

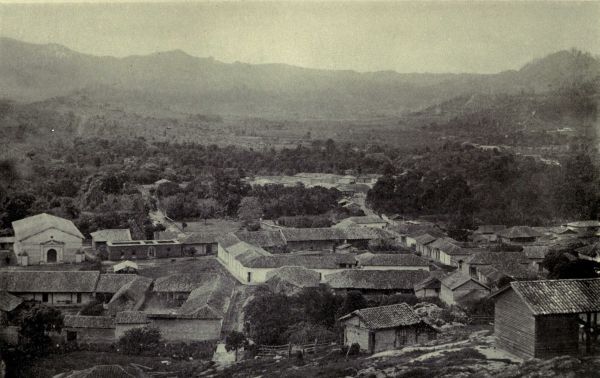

| View of the Picturesque Town of Marcala | 150 |

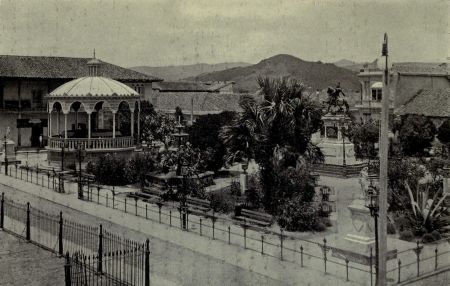

| El Parque Barríos, one of the most Beautiful Public Resorts in Central America | 162 |

| Government Building ("Casa Blanca"), San Salvador | 178 |

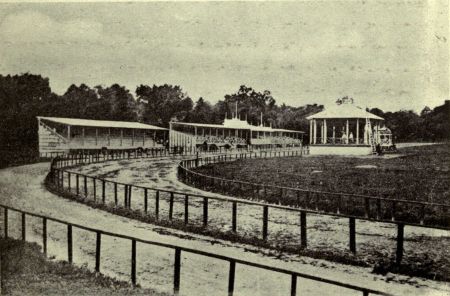

| Campo de Marte (Racecourse), San Salvador | 178 |

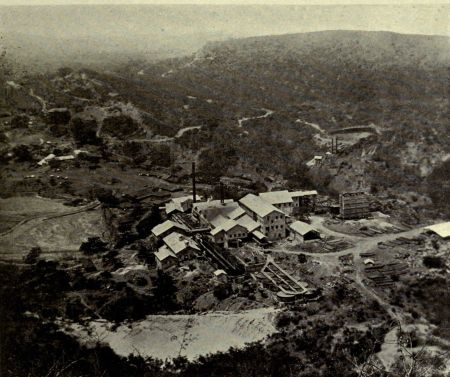

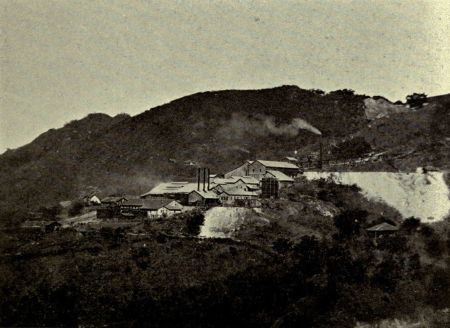

| 1. View of Butters' Divisadero Mines, Department of Morazán, Salvador | 188 |

| 2. Butters' Salvador Mines, Santa Rosa, Department of La Unión, Salvador | 188 |

| Map of the Salvador Railway | 198 |

| Deck Bridge on Salvador Railway | 206 |

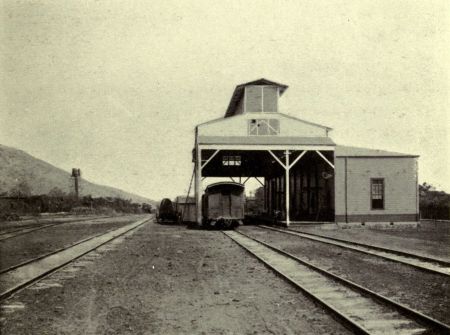

| Station Building at Santa Ana on the Salvador Railway | 206 |

| Mr. Charles T. Spencer, General Manager of the Salvador Railway, appointed May, 1911 | 222 |

| Don Juan Amaya, Governor of the Department of Cuscutlán | 222 |

| Native Habitation in the Hot Country | 232 |

| Native making Sugar from a Primitive Wooden Mill | 232 |

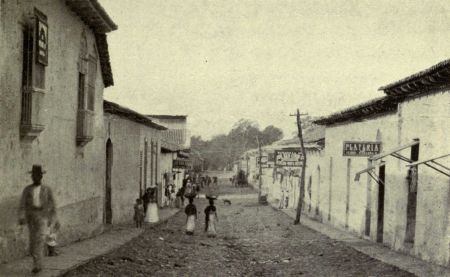

| A Street in Sonsonate (Calle de Mercado) | 242 |

| Type of "Quinta" or Country-House in Santa Tecla (New San Salvador) | 242 |

| Public Park in San Salvador, where Throngs of Well-dressed People assemble in the Evening to listen to an Excellent Military Band | 258 |

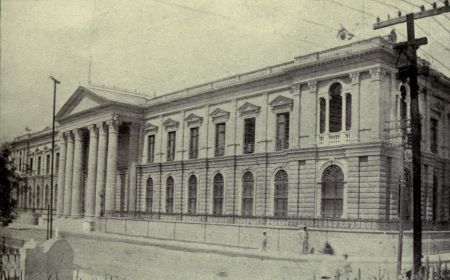

| New National Palace at San Salvador | 268 |

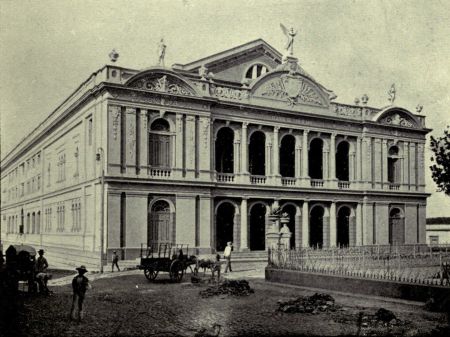

| Theatre at Santa Ana, Department of Santa Ana | 268 |

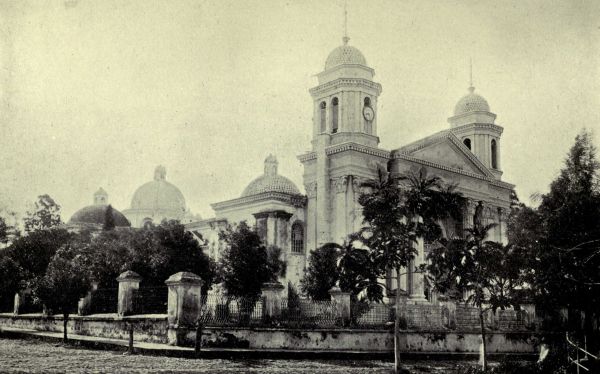

| Cathedral of Sonsonate, Department of Sonsonate | 274 |

| Public Park at Cojutepeque, Department of Cuscutlán | 284 |

| Barracks at Cojutepeque, Department of Cuscutlán | 284 |

| Municipal Palace at Sonsonate, Department of Sonsonate | 294 |

| Group of Salvadoreans of the Superior Working-Class | 314 |

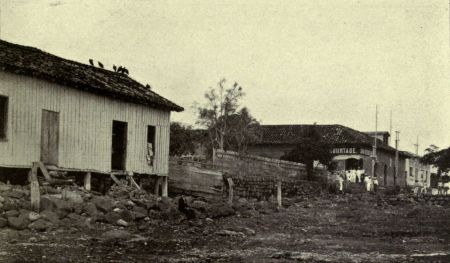

| The "Stately" Offices of His Britannic Majesty's Vice-Consul at La Unión, one of the Principal Ports in Salvador | 306 |

| Barracks at Santa Tecla (New San Salvador) | 306 |

| Map of the Republic of Salvador | At end |

Discovery of Salvador—Scenery—Volcanoes—Topographical features—Mountain ranges—Natural fertility—Lake Ilopango—Earthquake results—Remarkable phenomena—Disappearance of islands—Public roads improvement and construction under Figueroa government.

It was in the year 1502 that Christopher Columbus, that remarkable and noble-minded Genoese, undeterred by the shameful treatment meted out to him by his adopted countrymen in Spain, sailed away to the East Indies in search of a new passage; and it was in consequence of the mutiny among his ruffianly followers that, putting into Hispaniola, Salvador was discovered. For something over 300 years Spain ruled, and ruled brutally; the history of her government here—as elsewhere through Latin America—being one long series of oppressions, cruelties and injustices practised upon the unfortunate natives and the Spanish residents alike. The ill-treatment extended to Columbus is but a case in point.

Lying on the Pacific Ocean, between the parallels of 13° and 14° 10' N. latitude, and the meridians of 87° and 90° W. longitude, Salvador has a coast-line of about 160 miles, extending from the Bay of Fonseca to the River Paz, which is one of the boundaries between[2] this Republic and the neighbouring State of Guatemala. While Salvador is the smallest of the five different countries forming the Central American group, boasting of but 9,600 square miles, it not alone possesses some of the richest and most beautiful territory, but has the densest population as well as the most considerable industry and the most important commerce.

Very remarkable are the topographical features of Salvador, and very profound is the impression created upon the traveller's mind as he approaches it for the first time through the beautiful Bay of Fonseca, with its wealth of tropical scenery, the romantic islands and the background of noble mountains, afforested to the tops of their numerous peaks, and filling the mind with awe at the memory of their numerous destructive eruptions through the centuries.

The coast here presents, for the greater part, a belt of low-lying, richly wooded alluvial land, varying in width from ten to twenty miles. Behind this, and displaying an abrupt face seawards, rises a noble range of coast mountains—or rather a broad plateau—having an average elevation of 2,000 feet, and relieved by numerous volcanic peaks. It is not the height of these mountains that lends so much dignity and beauty, for, as mountains go, they would be considered as anything but remarkable. It is their extraordinary formation, their almost terrible proximity, and their long and terrifying history, which challenge the attention of the individual who gazes upon them for the first time.

Between the range and the great primitive chain of the Cordilleras beyond, lies a broad valley varying in width from twenty to thirty miles, and being over 100[3] miles in length. Very gently the coastal plateau subsides towards this magnificent valley, which is drained and abundantly watered by the River Lempa, and is unsurpassed for natural beauty and fertility by any equal extent of country in the tropics.

The northern border of this terrestrial paradise—so far as the eye can judge it—rests upon the flank of the mountains of Honduras, which tower skywards about it to the height of 6,000 to 8,000 feet, broken and rugged to the very summits. To the south of the Lempa, however, the country rises from the immediate and proper valley of the river, first in the form of a terrace with a very abrupt face, and afterward by a gradual slope to the summit of the plateau.

Then comes another curious physical feature—a deep, green, and wooded basin of altogether unique scenic beauty and fertility, formed by the system of numerous small rivers which rise in the western part of the country around the feet of the volcano Santa Ana, falling finally into the sea near Sonsonate. This formation is in the shape of a triangle, the base resting on the sea, and the apex defined by the volcano. A second and even a larger basin is that of the River San Miguel, lying transversely to the valley of the River Lempa, in the eastern division of the State, and separated only by a number of smaller detached mountains from the Bay of Fonseca.

Approaching the Salvadorean coast upon any of the steamers which run there, one is confronted with no fewer than eleven great volcanoes, which literally bristle along the east of the plateau which has been mentioned as intervening between the valley of the Lempa and the sea. As a boy and a keen philatelist, I always wondered why Salvador postage-stamps had[4] a group of three active and terrible-looking volcanoes upon their faces. When I visited that country for the first time I understood. The long row of sentinels, grim, yet extraordinarily beautiful, form a right line from north-west to south-east, accurately coinciding with the great line of volcanic action which is clearly defined from Mexico to Peru. Commencing on the side of Guatemala their order is as follows: Apaneca, Santa Ana, Izalco, San Salvador, San Vicente, Usulután, Tecapa, Zacatecoluca, Chinameca, San Miguel, and Conchagua. There are others of lesser note, besides a family of extinct volcanoes, whose craters are sometimes filled with water, as well as numerous volcanic vents or "blow-holes," which the natives not inaptly call infiernillos, i.e., "little hells!" Even the apparently harmless and beautiful island of Tigre, which occupies the centre of the Bay of Fonseca, and a veritable picture of scenic grandeur, is a slumbering volcano, and has a history at once interesting and terrifying. The memorable Cosieguina, El Viejo, Felica, and Momotombo, in Nicaragua, face El Tigre on the other side.

The most beautiful of the Republic's many volcanic lakes is that of Ilopango, on the borders of which is situated the village of the same name, with a scattered population of between 1,400 and 1,500 people. The lake is some 6·85 miles long from west to east, about 5·11 miles wide, with an area of 25·1 square miles and a developed shore-line of 28·8 miles. The late President of the Republic, General Fernando Figueroa, was kind enough to place a steam-launch at my disposal, which enabled me to see the lake under the most favourable auspices, and in company with his nephew, Señor Angulo, I spent several interesting hours upon its[5] calm, deep green surface. This lake has been the scene of numerous remarkable volcanic phenomena, the most recent of which took place a few weeks after my visit, and resulted in the centre islands, which were one of its most charming features, completely disappearing beneath the surface of its waters.

In January, 1880, the lake had also been the scene of a severe earthquake, which shook the entire surrounding country. Upon this occasion the waters suddenly rose about 4 feet above their usual level, and, flowing into the bed of the Jibóa—a stream which forms the usual outlet from the lake—increased it to the proportions of a broad and raging river, which soon made for itself a channel from 30 to 35 feet in depth. A rapid subsidence in the level of the lake was thus produced, and by March 6 in the same year the surface was 34 feet below its maximum. It was then that the rugged and stony island, about 500 feet in diameter, and which I have mentioned above, suddenly rose over the waters, reaching to a height of 150 feet above the level of the lake and being surrounded by several smaller islands, the waters all around becoming intensely hot. Previous to this extraordinary phenomenon, the bottom of the lake, so I was informed, had been gradually rising, and so violent was the flood when it occurred, that the small village of Atuscatla, near the outlet, was entirely destroyed.

Some years afterwards—namely, in February, 1892—while some severe earthquakes were taking place in Guatemala, their reflex was felt in the same spot—Atuscatla, on Lake Ilopango—Lieutenant Hill, who was then making investigations in Salvador on behalf of the United States Government, declaring that a[6] shock was felt lasting fifteen seconds, and then continued with gradually decreasing force for a further one minute and five seconds.

When I was a visitor to Ilopango, there were two extremely comfortable hotels to be found on the banks, both having some very convenient bathing facilities to offer, and each having a beautiful garden attached. During the hot season, and upon Sundays and all holidays, these hotels are crowded with visitors from San Salvador, who ride out in parties, there being no other mode of reaching the lake. The road is a truly beautiful one, travellers crossing numerous streams and passing through shady, blossom-covered woods, containing many magnificent trees. By moonlight this route appears remarkably picturesque, and many people prefer to make the journey thus. Ilopango is some four hours' ride from the capital, and the journey across the lake usually occupies another two or three hours in an electric or naphtha launch. The hotels and bathing establishments, however, are located upon the side of the lake nearest to San Salvador.

The outline of the beautiful Ilopango Lake, when last surveyed, was quite accurately determined by means of intersections from the various topographical stations. Its surface in January, 1893, was found to be 1,370 feet (417·6 metres) above the sea. Its actual depth the surveyors had no means of ascertaining; its basin, however, is far below the general level of the surrounding ridges, which are all volcanic. Those to the north and east are formed of layers of sand and ashes partially compacted, yellowish in colour, and throwing out spurs towards the lake, terminating in steep bluffs. West of the lake the ground rises to the San Jacinto Hills; but the soft material composing[7] it has been eroded into a maze of sharp ridges and deep gulches. The eastern hills are also broken into a succession of knife-like ridges.

Professor Goodyear, a famous American geologist, has said that the southern hills consist entirely of volcanic materials, but are of a much harder and firmer structure than those of the north and east, being composed largely of conglomerates containing boulders well cemented together. The lake is situated upon the volcanic axis of the country, and has long been the seat of numerous earthquakes and active volcanic phenomena, the most violent of recent times being those of 1879 and 1880. According to the same Professor Goodyear, there was a series of earthquake shocks, some of great violence, extending from December 22 to January 12, 1880, followed by a period of quiet until the night of January 20, when, after a series of loud reports and explosions, followed by violent hissings and dense clouds of steam, a mass of volcanic rock rose from the centre of the lake to a height of 58 feet (17·7 metres). Previous to this the bottom of the lake had been gradually rising until January 11, and the waters had been lifted to maximum height of 5·2 feet above their usual level. This sudden rise converted the outlet from a small stream—not over 20 feet wide and a foot deep, and with a current of two or three miles per hour—into a raging torrent discharging as much water as a great river. So violent was the flood that the small village of Atuscatla, situated near the outlet, was as stated, destroyed, and the channel was so widened and deepened that the waters of the lake fell 38·6 feet (11·75 metres) from the highest point reached, or 33·4 feet (10·17 metres) below their original level.[8] During the time of this flood the Rio Jibóa, which carries off the waters of the lake, was enormously swollen and became very muddy, and in the lower portion overflowed its banks, flooding broad tracts of the plain. By the middle of February, 1880, the lake adjusted itself to the new conditions, and since that time, until the visitation of last year (1910), there had been no great change in its level; the variations at present going on are due to the excess of precipitation during the rainy months over that which is prevalent in the dry season.

Anyone who had seen Salvador, say, ten years ago, and who revisited it to-day, would assuredly be impressed by the great improvement which has taken place in, and the extension of, both the main and sub-roads of the Republic. Whereas in former times the roads were only passable in the dry season, and were even then very trying to travellers on account of the dust encountered, while in the wet season they became mere morasses, to-day they are in the majority of cases so well built and so carefully maintained that even in the wet season of the year it is quite possible to use them.

This great improvement has been brought about mainly by the enterprise of the late President, General Fernando Figueroa, who evinced a keen and consistent interest in opening up new means of communication by making public roadways of enduring worth, his excellent work being actively continued by his present successor.

Views on New National Road, between San Vicente and Ilopango.

The main routes of communication in Salvador run longitudinally through the country, from Rio Paz and the city of Ahuachapán on the west, to La Unión and the Rio Guascorán on the east. From this central[9] line, which connects all the important cities and towns of the interior, other roads run out like spurs to the towns and the cities to the northward, or to those of the coast to the southward. Thus, from Santa Ana there is a road north to Metapán, and one south to Sonsonate and Acajutla. Ahuachapán also has a road to Sonsonate via Ataco and Apaneca, two towns which are located high up in the mountains. At Sitio de Niño, on the Salvador Railway line, there is a road northward to Opico. Here, also, the main road to the city of San Salvador divides, one branch going north to the volcano of that name, and the other to the south of it via the famous Guarumál Ravine and Santa Tecla. From the city of San Salvador there are roads north to Chalatenango via Tonacatepeque, and south to the port of La Libertad via Santa Tecla.

Cojutepeque is connected by road to the towns of Ilobasco and Sensuntepeque to the north-east. San Vicente has a road to the port of La Libertad, running south-west via Zacatecoluca. At San Vicente the main east and west road separates, one branch going to the north of the Tecapa-San Miguel group of volcanoes, via the cities of Jucuapa and Chinameca to San Miguel, and the other south via the city of Usulután. San Miguel has several roads leading in all directions. There is one north to the town of Gotera, another north-east to the Mining District via Jocoró and Santa Rosa, which continues to the principal crossings of the Rio Guascorán; and there is yet another, running nearly due east to La Unión, on the Gulf of Fonseca.

I was in the country while construction was proceeding in connection with the Ilopango-San Vicente road improvements, and I was much impressed with the thoroughness of the work being undertaken. The new[10] construction was some 40 kilometres long by 61⁄2 to 7 metres in width (say 20 to 25 feet). It was commenced in 1906, and it will be finished by the end of next year (1912). It is estimated to cost not less than 350,000 pesos. It is a purely Government undertaking, and ranks as one of the most important highways in the Republic. At first over 250 men were employed, but as the work progressed this number was reduced to 200. The highest part of the road is cut through the side of the mountain at 210 metres (say 700 feet) above the shore of Lake Ilopango. The steepest gradient is 7 per cent., and the minimum radius 20 feet. The most expensive part was that between Kilometre 14 and Kilometre 13, where extremely hard rocks have had to be cut through. At one point ten men were engaged for a period of nine months upon the most difficult part, and they were suspended from above by ropes, in order to reach and to cut down the massive timber trees obstructing progress.

The Chief Engineer engaged by the Government to undertake this contract is Señor Don Juan Luis Buerón, a German by birth, having seen the light at Königsberg; but he is a United States citizen by adoption. Señor Buerón is now seventy-eight years of age, and although he is getting rather beyond active hard work, his valuable experience and shrewd judgment are much appreciated by the Government in all such matters as road construction. He has built many public roads in North America, he told me, and was also responsible for laying the track of the Havana (Cuba) tramways. This interesting old engineer had also gained some experience in Mexico before the days of Maximilian (1857-1869). He now occupies a position of comfort, and enjoys the deep respect of the hundreds[11] of peons who call him master. Señor Juan Buerón junior, the son, is an equally capable road engineer, and assists his father in his work for the Government of Salvador.

Another road deserving of mention is that which has been put under the charge of the official engineer, Don Guillermo Quirós, and one which unites the town of Santiago-de-María with the port of Linares, on the River Lempa, passing through Alegría. The section from Santiago-de-María to Alegría has been completed, and it was officially inaugurated while I was in the Republic; the journey from Berlín to the River Lempa can now be continued with much greater celerity. Very considerable are the advantages that this highway has brought to that part of the country, in which are situated the most valuable coffee plantations, whose owners now find far greater conveniences for bringing the berry to the port of El Triunfo, since the road leading to this place has also been repaired and widened to facilitate the transit by beasts of burden. The official engineer, Don Manuel Aragón, has been occupied with the planning and opening of a road from Citalá, in the department of Chalatenango, to Metapán, in the department of Santa Ana. The road leading from this capital to the port of La Libertad is likewise the object of attention. The official engineer, Don Andrés Soriano, with a gang of foremen and labourers, have been working for several months past repairing it.

This highroad continually needs very large sums of money for maintenance. The repairs which in former years have been carried out have proved anything but lasting, owing to the serious mistakes in construction of an engineer who put into practice certain untried experiments, which completely failed.

It is necessary now to remedy this mistake, and drains and aqueducts have had to be constructed on the road where none previously existed, to avoid, in the rainy season, destruction by the strong currents of water rushing over it. The official engineer, Don Alberto Pinto, was occupied during a good part of the year 1908 upon road works, having made many alterations, improvements and widenings in the roads of the Departments of San Miguel, La Unión, Usulután, Chalatenango, Santa Ana and Cabañas.

On the way from Mercedes to Jucuapa, and also upon the road to San Miguel, it is proposed to construct a bridge of stone and mortar, at the place called Barrancas de Jucuapa; the chief engineer, Señor Pinto, has already made an estimate and sent in the corresponding plans. The cost will amount to a little more or a little less than $10,000.

Early Days of independence—"Central American Federation"—Constitutional Presidents—Executive power—Chamber of Congress—The Cabinet—Justice—The courts—Prisons and prisoners—Employment and treatment—Police force—How distributed—Education—Colleges and schools—State-aided education—Teaching staffs—Primary education—Posts and telegraphs—Improved interstate parcels post.

The breaking away from Spanish dominion (although the seeds of revolution were laid as far back as 1811) did not take place until ten years later, and coincided with the successful termination of the struggle for liberty which occurred in Mexico under the patriot priest Hidalgo. Salvador gained its freedom, comparatively speaking, without bloodshed; and on September 15, 1821, it was declared a free and independent State. In the year following an attempt was made to annex the country to the Mexican Empire, under the rule of the ambitious and unscrupulous Emperor Agustin Yturbide, during his very brief reign, in 1822. As history relates, this presumptuous Mexican was born in Valladolid (now known as Morelia) on September 27, 1783, and he was sentenced to death and shot on July 19, 1824.

It is to the credit of Salvador that it was the one Central American State which firmly resisted the invasion of the Mexican troops; but in the end it had to submit to a far superior force, commanded by General Filisola, and was then formally incorporated[14] into the Mexican Empire. This humiliation endured, however, for a very brief time, since in the following year Yturbide met his violent death, after which a Constitutional Convention was called, and in 1824 a Federal Republic was declared bearing the name of the "Central American Federation." This was composed of the five States—Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica—the first President being General Manuel José Arce.

Party jealousies and personal ambitions, however, soon brought about disintegration, and in spite of the efforts of some far-seeing patriots, who considered that in union alone lay the hope of peace, security and prosperity for their country, the form of government proved wholly impracticable. Nevertheless it continued for a few years to struggle along, General Francisco Morazán, doing his best to maintain order and to save the union from disruption. Notwithstanding all his efforts, the Federation was dissolved in 1839, and the five States again became independent Sovereign Republics. Three years later General Morazán unwisely made another effort to reunite the countries; but his attempt was treacherously rewarded by a conspiracy against his life, followed by his execution in San José, Costa Rica, in the month of September, 1842.

Since his death various attempts have been made from time to time, to reunite the several Republics, the last effort of this kind having been prosecuted by General Zelaya, perhaps one of the most unscrupulous and dishonest, as well as one of the cruellest, Spanish-Americans who has ever attained supreme power. Whatever chances of success a United Central America might have had, under the auspices of a[15] Zelaya it could have never met with anything but failure. General Zelaya, in spite of frantic efforts to maintain his position, was himself chased from Nicaragua in 1909, and is now said to be living in Europe upon the proceeds of the money which he is declared to have filched from his country during his long and oppressive reign.

In the year 1885, General Justo Rufino Barríos, President of Guatemala, had sought to accomplish what Morazán had failed to do; but his efforts ended equally in disaster. On August 13, 1886, the Constitution which is at present in force was promulgated, and General Menéndez was elected as first President under that Constitution by popular vote in 1887, for the term ending in 1890. He was succeeded by General Carlos Ezeta, who was inaugurated on March 1, 1891. The third President was General Rafael Gutierrez. Then followed General Tomás Regaládo; Don Pedro José Escalón; General Fernando Figueroa; and the ruling President, Doctor Manuel Enrique Araujo.

The form of government in vogue is that of a free, sovereign and independent Republic—that is to say, democratic, elective, and representative. The Constitution now in existence is contained in a code of articles. The Government is divided into Legislative, Executive, and Judicial sections. The Legislative power is vested in the National Assembly, which is composed of one Chamber, and having the title of the National Chamber of Deputies. This consists of 42 members, three Deputies being elected for each Department by direct popular vote for a term of one year, the right to vote being vested in every male citizen who is over eighteen years of age. It is to be[16] observed that every Salvadorean is not only privileged, but is compelled to vote, thus doing his duty to the State.

The Executive consists of a President and a Vice-President, who are elected by popular vote for a term of four years. In addition to being Chief Magistrate, the President is also Commander-in-Chief of the Army. In the event of a failure to elect the Executive, a President is chosen by a majority of votes in the Congress from among the three candidates having polled the largest number of votes in the popular election. He is not eligible for re-election either as President or as Vice-President until four years shall have elapsed. The date of the Executive's inauguration is on March 1 following the election, which is usually held in the month of November.

The administration of each of the fourteen different Departments is in the hands of a Governor, who is selected by the President from personal knowledge of both his capacity and temperament. Besides administering the civil affairs of the territory under his jurisdiction, this official is usually either a military man or one possessed of adequate military knowledge; and he is thus Commandant of the military of his Department.

It was my pleasure to meet, and spend some considerable time in the company of, many of the Governors of the different Departments, and I was deeply impressed with their general thoroughness of purpose, their keen desire in all cases to further the interests of their Departments, and to apply to their benefit any and every advantage which could be adapted from the governments of other countries.

The municipalities, on the other hand, are managed entirely by their own officials, all of whom are elected[17] by the people themselves. The officials comprise an Alcade, or Mayor, a Syndic and several Regidores, or Aldermen, these being numbered according to the size of the population. A good deal of competition exists for office, and at the time of election much amusement is derived from watching the canvassing in progress. There is a decidedly healthy appearance of municipal enterprise in most of the towns of Salvador, and, taking these as a whole, they seem to be uncommonly well administered. In the accepted sense of the word, there is no real poverty, no slums, no crying "graft" scandal demanding redress, as in our much-vaunted civilization, and such charities as are rendered necessary in the form of hospital relief and medical attention are rendered cheerfully and as a matter of course, entailing neither a favour nor a dependence upon either party.

In Salvador, as in all the Latin-American Republics, the President is a reality, and not a mere figure-head. He makes his presence felt, and yet, in a perfectly constitutional manner; he associates the form of a democracy with the reality of government. For many years past the people have had, and have to-day, an excellent example of a thoroughly sensible and dignified Chief Executive, who has firmly upheld the good name of the country and piloted it with a strong, and even masterly, hand through a maze of difficulties. Of General Fernando Figueroa as of Doctor don Manuel Enrique Araujo, it may truthfully be said that they have kept before them a lofty ideal of the honour of their nation, and one which has been the one incentive in guiding their policy. The whole demeanour of these distinguished men has been productive of the country's esteem, while their real qualities for administration[18] have not been denied even by their most determined political opponents.

The personnel of the present Ministry in Salvador reflects the best intelligence and the greatest administrative ability of that country, the President having selected from among the former members of the Cabinet, and added to their number, such persons as enjoy the confidence of the majority of the Congress; and he has retained them as his advisers and his coadjutors so long as, and not longer than, that confidence continues. The present Cabinet consist of the following:

Ministers or Secretaries of State.

Foreign Affairs, Justice and Beneficence: Doctor don Francisco Dueñas. Interior, Industry ("Fomento"), Public Instruction and Agriculture: Doctor don Teodosio Corranza. Finances and Public Credit: Don Rafael Guirola, D.

Sub-Secretaries of State.

Foreign Affairs: Doctor don Manuel Castro, R. Justice and Beneficence: Doctor don José Antonio Castro, V. Interior: Doctor Cecilio Bustamente. Industry ("Fomento"): Ingeniéro José Maria Peralta Lagos. Public Instruction: Doctor Gustavo Baron. Agriculture: Don Miguel Dueñas. Finance and Public Credit: Don Carlos G. Prieto. War and Marine: Don Eusebio Bracamonte.

H. E. Dr. Manuel Enrique Araujo;

President of the Republic of Salvador 1911-1915.

Perhaps it is the Ministry of the Interior which is charged with the most numerous and most important sections. Upon this Department depend the General Direction of the Post-Office; the General Direction of the Telegraph and Telephones; the General Direction of Police; the Direction of the National Printing Establishment; the Direction of the Superior Council of Health; the General Direction of Vaccination, as well as of the Municipal Treasury and many other small[19] offices that complete the establishments included in the public administration.

The number of measures carried out by this one Ministry during the years 1907 and 1908 amounted, more or less, to 3,600. The subjects that came under the jurisdiction of the Secretaryship of State are also many and complex; and in order to attain results they demand both constant attention and an intimate knowledge of the administrative laws, the many special regulations, the numerous statutes and dispositions which exist, as well as any quantity of minor laws.

The Judicial Power is vested in a Supreme Court, which holds its sittings in the city of San Salvador; two District Courts, which are also held in the city; District Courts which are held in the cities of Santa Ana, San Miguel, and Cojutepeque, as well as periodical Circuit Courts held in different districts; and there is a long list of Justices of the Peace.

The Justices of the Supreme Court are elected by the National Assembly for a term of two years, while the Judges of the First and Second Instance are appointed by the Supreme Court for a term of two years. The Justices of the Minor Courts are elected by popular vote.

As in most Latin-American countries, the course of justice is not always speedy, all depositions, no matter how trivial the case under trial may be, nor whether it be civil or criminal, having to be laboriously written out, "examination-in-chief" and "cross-examination" being practices little known. Naturally, an immense amount of valuable time is thus consumed, and the results are anything but conclusive.

To a considerable extent the administration of[20] justice in Central America is based upon the same principles as those in force in the United States, and it is generally admitted, especially by those who have suffered from them, that these are far from perfect. The theory of Latin-American justice is excellent, such theory being that every man is entitled to justice speedily and without delay, freely and without price. We all know that this is not the experience of litigants generally, and in no part of Latin America can the administration of justice be considered entirely perfect. Salvador is not worse off than any of its neighbours in this respect, while, on the other hand, there is a decided amount of respect entertained for the judiciary, and few verdicts have been given which have called forth any protest, nor many rulings handed down which have excited conflict among the public.

Travellers in Latin-American countries, more often than not such as pay but a very superficial visit to those lands, are in the habit of drawing pitiful pictures of the cruelty practised upon prisoners and injustice shown towards litigants, and they indulge in harrowing accounts of "nauseating filth," "poisonous stenches," "germs of disease," "bad food," and numerous other, blood-curdling horrors. However true such descriptions of some countries are, and I rather imagine that most of them are the outcome of vivid imagination on the one hand and of blind prejudice upon the other, it is certain that nothing of this kind can be truthfully said about Salvador.

It would be ridiculous to suppose that this Republic more than any other builds luxuriously-equipped and comfortable prison-houses, to act as an encouragement for the committing of crime. The object of punishment, we are told, is prevention of evil, and we all[21] know that under no circumstances can it be made incentive to good. The punishments inflicted upon Salvadorean prisoners are based upon much about the same scale as in other countries; but the physical condition of the prisoners as a whole is infinitely better than that which is to be met with in any other Latin-American country, with the two exceptions of Peru and Mexico.[1] Of all three countries I may say with every justice that the present prison system is of a much more lenient and humane nature than that of any other country in either the old or new world. I state this deliberately and after having visited most of the prisons in Latin-American Republics, as well as many of those to be found in Europe and the United States.

It is the object of the Government of Salvador to make as much use of prisoners' services as is legitimate, and at the same time to find for them intelligent and useful occupations. While hard work is not always compulsory, and is not always an accompaniment of a sentence to imprisonment, every encouragement is offered to prisoners to engage themselves in some kind of work; and in many instances substantial payments are derived from some of the work thus undertaken, all such payments being carefully preserved for the use of the prisoners, and handed over to them at the time of their release. Thus, for instance, in the Penitenciaría Central, at San Salvador, which is the chief penal establishment in the Republic, many of the prisoners are engaged in making furniture for the public offices, as well as military and police uniforms, boots, etc., likewise for use in the army and the police[22] force. I am not sure whether any payment is made to prisoners for this kind of contribution; but in other penal establishments which I visited I observed that the prisoners were making baskets, mats, toys, and other small articles, which were offered to visitors for a trifling sum, and in other cases were sent to the public market for sale.

At the Penitenciaría at Santa Ana the same method was in vogue with regard to employing prisoners, some remarkably good furniture, police clothing, and military boots and shoes, being turned out here also. In this establishment, as well as in others, the utmost cleanliness prevails. The long rows of airy and well-ventilated cells are well lighted, the walls and ceilings being whitewashed and the floors, built of red brick, kept scrupulously clean. No furniture of any kind is allowed to remain in the cells during the day, but at night mattresses with clean blankets are thrown down side by side, and the prisoners sleep with their day-clothes folded up and placed under their heads or deposited under the mattresses.

In other cells there are light canvas or wooden cots of an easily detachable nature, which are folded up and put away during the daytime, so that the cells are always free from encumbrances of any kind. Prisoners are allowed to move about freely (unless under very severe punishment due to violence) from the cells to the yard, and most of them are engaged during the daytime in weaving baskets, sewing materials, or doing some other kind of work which may be congenial to them. They are not compelled to wear any special form of clothing nor a degrading uniform, while some are even permitted to smoke.

Although strictly guarded by armed soldiers, I did[23] not, when I visited these establishments, witness a single instance of brutality or overbearing demeanour on the part of these guardians; on the other hand, there seemed to be a sort of fraternity between them and their wards, chatting and laughter proceeding, apparently, without objection upon the part of the Governor or Superintendents.

The area of the prison cells was in no case less than 10 feet by 6 feet, and in some instances it was found to be considerably larger. All ablutionary exercises take place in the paved yard of the prison, and prisoners are compelled to bathe at least once a week in the open air; those who are so inclined may take a bath once every day. The food, which I had the opportunity of tasting, seemed thoroughly wholesome and plentiful, meat being provided in quantities as well as boiled maize, beans (frijoles), and coffee of excellent quality.

I can only repeat that, from close personal observation, I am unable to endorse any of the harrowing descriptions of prison barbarities, which I have referred to above, as applying in any way to Salvadorean penitentiaries.

Considerable attention has been paid to the establishment and maintenance of a thoroughly efficient Police Force, by the late Director-General, General Enrique Bará, who has studied the question of Police administration in Europe and the United States, and has applied most of the good points which he found existing there to the Police organization in the Republic of Salvador.

All Police are under the control of the Minister of the Interior—Ministerio de Gobernación—although the organization itself is a military one. The severest[24] discipline is maintained, and the men are moderately well paid. They seem, moreover, to be drawn from the better classes instead of from the worst, as is so often, unfortunately, the case in some parts of Latin America.

All the larger towns, such as Santa Ana, San Miguel, Sonsonate, La Unión, etc., have their own well-organized Police Force, each placed under a responsible officer, but all of them directly dependent upon, and subject to control from, the Capital. Especial care is taken to organize both the day and night corps, and, as a consequence of the strictness which is maintained, very few robberies, and scarcely any murders, take place nowadays in the Capital or chief towns.

The Superior Officers of the Police Force consist of the following:

1 Director-General.

1 Sub-Director.

1 Secretario de la Dirección (Secretary to the Director-General).

1 Tesorero Específico (Special Treasurer).

1 Instructor.

1 Ayudante de la Dirección (Adjutant to the Director).

1 Juez Especial de Policia (Special Police Magistrate).

1 Secretario del Juzgado de Policia (Secretary to the Police Magistrate).

1 Guarda-Almacén (Storekeeper).

1 Escribiente de la Dirección (Amanuensis to the Director).

1 Escribiente del Juzgado (Amanuensis to the Magistrate).

1 Escribiente de la Comandancia (Amanuensis to the Commandant).

1 Medico del Cuerpo (Doctor to the Corps).

1 Practicante (Assistant-Surgeon).

1 Telegrafista (Telegraphist).

3 Barberos (Barbers).

2 Asistentes (Assistants).

The present Director-General of the Police is General Gregorio Hernández A., who was appointed in the month of May last (1911).

The Capital is divided up into seven different districts or zones, each zone being policed as follows:

Zone 1: 1 Comandante (Chief Superintendent in Charge), 1 Sergeant,

4 Inspectors, and 60 Policemen.

Zone 2: Same as Zone 1.

Zone 3: 1 Comandante, 1 Sergeant, 3 Inspectors, and 60 Policemen.

Zone 4: 1 Comandante, 1 Sergeant, 2 Inspectors, and 64 Policemen.

Zone 5: 1 Comandante, 1 Sergeant, 2 Inspectors, and 64 Policemen.

Zone 6: 1 Comandante, 1 Sergeant, 2 Inspectors, and 56 Policemen.

Zone 7: 1 Comandante, 1 Sergeant, 2 Inspectors, and 40 Policemen.

In this last zone the policemen are mounted.

The different Departments are also well policed, as follows:

New San Salvador (Santa Tecla), having 1 Comandante (Superintendent and Director), 2 Inspectors, and 40 Policemen.

Sonsonate: 1 Comandante (Superintendent and Director), 1 Sub-Director, 1 Secretario, 3 Inspectors, and 32 Policemen.

Cojutepeque: 1 Director, 2 Inspectors, and 25 Policemen.

Atiquizaya: 1 Director, 1 Inspector Secretario, 1 Sub-Inspector (or Second Inspector), and 15 Policemen.

San Vicente: 1 Comandante (Director), 3 Inspectors, and 21 Policemen.

Ahuachapán: 1 Director, 1 Secretario, 3 Inspectors, and 27 Policemen.

Chalchuápa has two Zones, which are policed as follows: First: 1 Director, 2 Inspectors, and 27 Policemen. Second: 1 Director, 2 Inspectors, and 18 Policemen.

Santa Ana: 1 Director, 1 Sub-Director, 1 Secrétario, 1 Guarda-Almacen, 2 Escribientes, 150 Policemen, 1 Comandante de Dragones, 1 Sergeant, and 40 Mounted Men.

San Miguel: 1 Director, 1 Sub-Director, 4 Inspectors, and 57 Policemen.

La Unión: 1 Director, 1 Sub-Director, 3 Inspectors, and 40 Policemen.

Zacatecoluca: 1 Director, 2 Inspectors, and 18 Policemen.

The total personnel of the Salvadorean Police Force is as follows:

| In the Capital (including the Superior Officers above mentioned) | 454 | men. |

| New San Salvador (Santa Tecla) | 43 | " |

| Sonsonate | 38 | " |

| Cojutepeque | 28 | " |

| Atiquizaya | 18 | " |

| San Vicente | 25 | " |

| Ahuachapán | 32 | " |

| Chalchuapa | 20 | " |

| Usulután | 21 | " |

| Santa Ana | 174 | " |

| San Miguel | 63 | " |

| La Unión | 51 | " |

| Zacatecoluca | 21 | " |

| Total | 988 | men. |

The Government of Salvador are of opinion, and very rightly so to my thinking, that inasmuch as education is compulsory it ought to be free, since the State, by depriving parents of the labour of their children, entails some sacrifices on them. It has also relieved them of the burden of paying any kind of school fees; and this in a country like Salvador, which possesses naturally a great proportion of humble inhabitants, to whom the payment of even the lightest fees would appear an immense taxation, means a great deal. To organize a system of collecting fees from among the people living long distances from the Capital would also have been onerous; and the Government saves all this, and many other outlays, while procuring the best results from its educational system. The benefits arising, moreover, will be reaped by future generations, since a liberal education is a matter in which all citizens are interested; and there is certainly no hardship in calling upon all to contribute by means of a moderate tax towards that end.

As I have said, the happiest results have been achieved by the Government's broad and comprehensive system of education in Salvador. The authorities combine with the municipalities in carrying out their arrangements, and the teachers of both sexes are drawn from among the best and most cultured classes of the community.

There has been established since July, 1907, a Board of Education (Junta de Educación), which is subject to the directorship of a specially-appointed Minister and Sub-Secretario of Public Instruction. In the month of November, 1907, an important conference was summoned, and held meetings at the Capital, at which[27] the curriculum to be adopted was fully discussed, and the plans for the carrying on of all places of private and public education was entirely reorganized. The whole system of conducting elementary, normal, and advanced schools, holding day and night classes, granting scholarships and holding periodical examinations, has now been placed upon a thoroughly sound and comprehensive basis; and it is only just to say that in this respect the Republic of Salvador compares most favourably with any country in Europe, or with any educational system in the United States of America.

The education of the sexes is conducted in the same elementary schools, and not only is this found an economy, but the feminine mind is found here (as in Scotland and elsewhere) to become strengthened when put through the curriculum given to boys and men. Competition is greater between the sexes than between rivals of the same sex, and a correspondingly higher standard of achievement is obtained. It has been found in Latin America, where until recent years women were kept in ignorance and were denied the attainment of any but social positions in the community, that constant intercourse between the sexes had led to a more perfect development of character, and had materially diminished shyness. Marriages are now made of a safer kind, and a new and more intelligent class of citizen is springing up, all of which facts will tend in due course to bring about a more complete political settlement and the introduction of permanent order among the people. Although by no means as yet extinct, the conventual existence for the women of Salvador is fast diminishing, and they are commencing to realize the advantages and pleasures[28] of living under freer and less morbid conditions than formerly.

Santa Ana seems to be essentially the educational centre of the Republic; for whereas schools, colleges, and Universities are to be found in all of the Departments, in Santa Ana there are no fewer than thirty-three such establishments, besides several private schools and seminaries. San Salvador has between 6 and 7 important educational institutes, and many small private schools; Cuscutlán has 8 or 9; La Paz, 7 or 8; Sonsonate, 5 or 6; while Ahuachapán, Chalatenango, Cabañas, San Vicente, La Unión, Morazán, and La Libertad, are all similarly well provided.

The teaching staff at present employed under Government control numbers something over 1,100, and is divided up into Directors, Sub-Directors, Auxiliary Professors, these being composed of both the male and the female sex. These latter are in a small minority, but, still, there are over 278 Lady Directors, over 120 Sub-Directors, and 100 Professors.

The 3rd Company, Sergeants' School, in Review Order.

Company in line, Sergeants' School.

Section of Riflemen kneeling, Sergeants' School.

The proportion of pupils matriculating is extremely high, and in this respect the girls come very close in point of number, as also in the number of marks obtained, to the boys. The Government provides all the necessary books, stationery, models, apparatus, etc., for the use of the pupils, and these latter are not put to one penny expenditure for anything that they may require. It is considered absolutely proper and consistent with the dignity of the family for a Salvadorean child to receive a Government free education; and as this is divorced from all compulsory religious instruction, children of all denominations, or of none, can participate. As a matter of fact, practically all attending are of the Roman Catholic faith, but no dogmatic[29] teaching is resorted to in any establishment under Government control.

Mention should be made of the very useful and successful educational establishments which the Government has organized and supported since 1907, such as the Medical and Surgical College, Chemistry and Dental Schools, Commerce and Industry College, as well as the National University, which has been entirely remodelled and reorganized since December 15, 1907.

Upon several occasions the Government has found the necessary money to send a particularly promising pupil to Europe or to the United States, for the purposes of study and receiving the finest training that the world of art and letters can offer. The last pupil to be sent to study music at the expense of the Government was Señorita Natalia Ramos, who left for Italy in the month of May (1911), and is now making good progress there. In every sense of the word the Salvadorean Government has proved a "paternal Government" in these respects; and many a genius has been rescued from probable obscurity, and much dormant talent has been fostered and encouraged for the benefit of the community at large as well as to the lasting advantage of the individual.

Attention on the part of the Government is now being given to a further modification in the system of primary instruction; and this is being effected gradually, it being proposed as a preliminary to establish several high schools throughout the country. A School of Agriculture, with all necessary elements and machinery, was inaugurated during the year 1908. Mixed primary schools in the country now number 132, with a total number of registered pupils amounting to[30] 34,752. Expenditures for 1907 under this head were nearly $400,000, and in addition there are many private institutions where primary instruction only is given. Academic teaching is in the charge of the National University of San Salvador, embracing schools of law, medicine, pharmacy, dentistry, civil engineering, etc.

In no other part of the Government service has greater improvement been manifested than in the Department of Posts. This Department is supported out of its own revenues, and the service during the past few years has been extended to a very considerable extent, while the credit of the Central Office has been maintained by punctuality in the payments of the foreign postal service. Among the more notable Conventions celebrated have been those with the Republic of Mexico for the exchange of parcels and money orders, and a triweekly postal service introduced to the neighbouring Republic of Guatemala via Jerez; a postal service has also been established with the same country via Zacapa. It is satisfactory to be able to state that since the inauguration of these additional services, which took place early in 1907, scarcely any interruptions have occurred, not even in the rainiest weather, a fact which may be attributed to the zeal and ability of the officials and employés of the Postal Department.

The annual expenditure of this branch of the public service has increased from $87,084 in 1902, $102,787 in 1903, $121,756 in 1904, $142,855 in 1905, $161,662 in 1906, to over $200,000 in 1910. The regularity and rapidity with which the house-to-house postal deliveries take place in the Capital and principal cities of the Republic have frequently been noticed, and[31] favourably commented upon, by foreigners sojourning in Salvador. Honesty among the employés is no less a feature of the postal arrangements in this Republic, where all public servants are reasonably paid and are as diplomatically handled, so that general contentment obtains among the large class of public servants employed.

The Parcel Post Department is also exhibiting from year to year notable increases, as the following figures will show: $44,613.55 in 1901; $58,096.27 in 1902; $68,467.30 in 1903; $88,557.60 in 1904; $90,662.72 in 1905; $93,295.80 in 1906; and for the first six months in 1907 the figures given are $51,654.86, or at the rate of $103,000 for the whole year.

A Postal Convention for the exchange of money orders between Salvador and Great Britain was signed in London on June 27, 1907, in San Salvador on the following August 27, 1907, and, after being approved by the President, General Figueroa, took effect on September 5, 1907, the exchange offices being situated at San Salvador and London respectively.

The telegraph and telephone service has also increased consistently, especially since 1903, at which time as an economic measure, and for the convenience of the public, a considerable reduction took place in the amounts of the charges. There has been a large increase in telephonic connections, and several new offices have been established, while the old ones have been considerably improved, necessitating large outlays for this purpose, as well as for works and materials. Many hundreds of miles of new telephone and telegraph lines have been added to the system, of late there has been a marked increase in the telephone and telegraph apparatus, and the personnel of the system[32] has been proportionately augmented. There have been two handsome towers constructed at San Salvador, and another at Santa Ana, for the introduction of wires to the Central Offices, and the system in vogue leaves little to be desired either in regard to efficiency or completeness. The general budget for telegraphs and telephones has risen steadily, from a little over $260,000, in 1902, to over $500,000, in 1910.

During the year 1910 the number of cablegrams received in the Republic were as follows: Cables sent from Salvador, 7,877; received in the Republic, 8,723. In those transmitted there were used 61,727 words, and in those received 75,950. Total of cables sent and received, 16,600 = 137,677 words. The amount represented in cost was $96,450.47, and of this the Government received $23,994.27.

Considerable progress has been made in Salvador in connection with wireless telegraphy, this being one of the first—if not the first—of the Central American Republics to adopt the new system of communication. By the time these pages are in the hands of the reading public, the Government will have completed two additional wireless stations, one at Planes de Renderos, near the Capital (San Salvador), and the other at the Port of La Libertad. With the completion of these stations, wireless communication will have been established between the Capital and all the ports of the Republic.

The electric light service used and supported by the Government has also increased. In 1902 the total cost was barely $25,000, whereas to-day it amounts to over $50,000, exclusive of the value of subventions by which several of the electric light companies have been aided by the Government.

In connection with the recently-held Central American Conference convened in Guatemala City, and at which representatives of all five Central American States were present, great improvements were resolved upon in reference to the postal arrangements between these States. It was determined, for instance, to introduce a much more comprehensive parcels post; and although the dimensions of articles which may be sent were not much extended, the character of the commerce carried through the post was considerably broadened, with beneficial results to all of the different States. It was, among other things, decided to prevent any libellous or indecent publications passing through the Post-Office; and here a distinct improvement has been made upon British Post-Office methods, which permit of the carrying of any sort of literature so long as it is covered from inspection. The Central American postal authorities reserve the right—and exercise it—to open and retain anything which they suspect to be of a dangerous or wrongful nature, and thus they act with more intelligence than some of their European brethren.

The Regulation for the Control of the Postal Service, as passed by the Government on September 26, 1893, was found wholly unfit for this important branch; and from that date to the present, continual reforms have been introduced into the postal service, which now stands among the best regulated in Central America. In the Fiscal Estimate of the year 1907, passed by the National Congress, several notable economies were introduced, such as the suppression of some of the too numerous employés, and reduction of the salaries of others; while these measures seemed opportune, they did not work well in practice, neither[34] did they give good results. The Ministry was obliged, therefore, to again make alterations in order to insure permanent order in the postal department.