Title: The Heart of the Wild: Nature Studies from Near and Far

Author: S. L. Bensusan

Release date: May 24, 2014 [eBook #45745]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Roger Frank, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Heart of the Wild, by S. L. (Samuel Levy) Bensusan

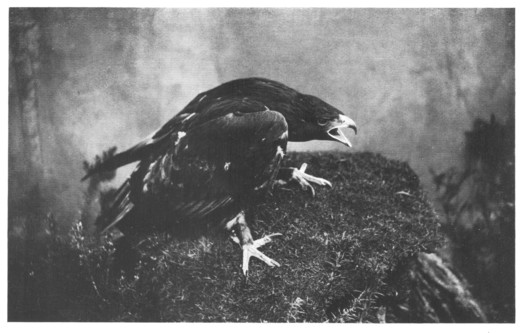

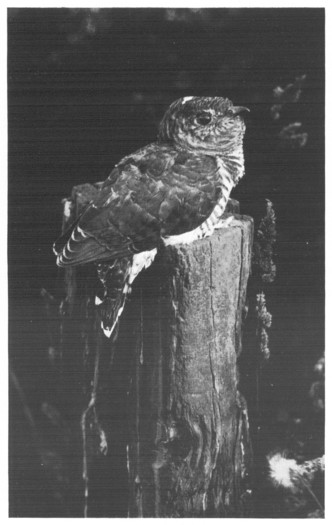

GOLDEN EAGLE [Photo by C. Reid]

Dear Sir Robert,

I have but one regret in offering to you and to some small section of lovers of wild life this bundle of stories, a regret that for the most part they end with the violent death of the bird or beast whose life-story is set out. One of my friendliest and most charming critics, whom I would not willingly hurt or offend, told me lately that she will read no more of my stories of bird and beast unless I promise to make them end happily. I quoted Omar the Tentmaker in extenuation, and pointed out that if we could shatter the sorry scheme of things and remould it “nearer to the hearts desire” the lion and the lamb would lie down side by side and the big game shooter would confine his skill to the target. Then I added that for the time being the battle is to the strong, and the explosive bullet and the hammerless ejector are to the sportsman, but from the depth of a twelve year knowledge of the world and a deep love of the life that is entrusted to our care, she turned away declaring in great distress that I am “very horrid”. Certainly I was greatly abashed, even though I could not wish her to read this book.

You, no unworthy son of one who was a mighty hunter before the Lord, know that these stories are true in substance if not in form, and that such cruelty as is set out in its proper place is of the kind that man has dealt in some way or another to the brute creation since the dim far-off days when first he learned to fashion hatchet and spear and knife. His excuse has passed, but the old-time savagery lingers. I have done no more than set down what I have seen, though I have gifted bird and beast with an intelligence they are not allowed to possess. You at least will grant that there is some foundation for my lapse from the grace in which serious naturalists thrive even to the second and third edition of volumes that become works of reference to those who refuse to admit imagination to their councils. You have seen much of the strange camaraderie that exists in the African forest and on the heather-clad hills of your native land, and you know that the philosophy of the orthodox professor has not yet fashioned even in dreams all the wonders of life in the heavens above and on the earth beneath and in the waters under the earth. I am presumptuous enough to think that those of us who have camped out under the canopy of the stars in the world’s waste places, and have followed the track for days and nights together, not without privation, have caught glimpses of an order and union in the wild life around us that will some day be recognised and investigated by those who speak and write with more authority than I have even the ambition to command. I must even confess, with all due humility, that I am beyond the reach of rebuke for my attitude towards bird and beast so long as it does not come from those, like yourself, whose experience of the fauna and avi-fauna of North Africa, Southern Europe and the Scottish Highlands is greater than my own.

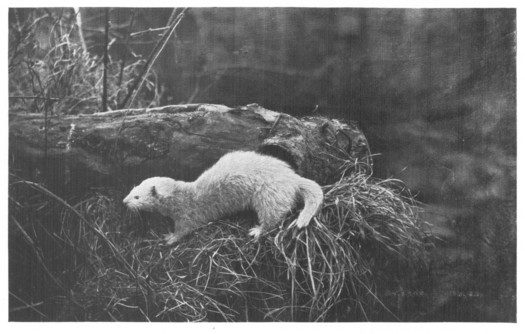

It is not easy to explain how the Red Fox and the Golden Eagle came to be friends. Perhaps there were hours in the months of his extreme loneliness when the great bird was pleased to unbend, and the fox was the only living creature that was neither to be eaten nor feared. Then they were near neighbours. From the rocky ledge upon which the eagle’s eyrie was set you could throw a stone to the fox earth. The Golden Eagle, king of the air and monarch of all the wild life he surveyed, could well afford to feel generously disposed to the fox in this wild highland country, for poor Reynard by no means cut the gallant figure of his brethren in Leicestershire and other homes of grass land. He went dejected and lived poorly, liable to be shot on sight, no more than vermin in the eyes of gamekeepers and foresters.

It was early morning, from his vantage-ground the King of the Air surveyed his splendid hunting grounds. All round as far as the eye could see there were hills, the heather that covered their lower sides glowed faintly in the morning light. The air had a nipping freshness that dwellers in town cannot imagine. Even the fox appreciated it, though he had been on the prowl all night. He was preparing to sleep, and only kept one eye open to watch his patron.

The golden eagle stood erect, his keen eyes piercing the distance from Ben Hope to Ben Hiel and south to the valleys that ended with Ben Loyal. It was his territory, bird and beast paid him tribute over all the land his far-seeing eye could reach, even to the distant sea. Then the joy of morning and of power came to him. He flapped his wings and screamed, the sound of his triumph echoed among the hills.

“Good-morning, my lord,” said the fox obsequiously.

“Oh, it’s you, is it?” replied the eagle with good-natured contempt. “Don’t you wish you could fly on a morning like this?” Once again he flapped his wings that must have measured six feet from tip to tip, and the rising light caught the orange-coloured feathers that lay sharp and pointed along his neck, gilded the yellow cere at the base of bill, and set the gold iris of his deep-set eyes aflame. Even the fox found his fear mingled with admiration when he looked from the black claws to the bill that was straight at base and hooked at the point, a weapon that could tear life out of any wild thing that lived in the Highlands.

In the sun the deep brown feathers of the eagle’s body were turned to purple, the muscles stood out like whipcord on the yellow legs feathered to the toes. Those talons, nearly three inches long, could catch and kill any game bird in the Highlands, from the capercailzie that lives among the dark woods upon the shoots of the larch and pine, down to the ptarmigan of the barren hill-tops, or his red cousin of the heather and ling.

“It is so fine that I must enjoy the view before I start,” continued the eagle. “I suppose you supped late?”

“Yes, my lord,” replied the fox nervously, “I found a couple of dead——”

“Faugh!” interrupted the eagle in great disgust. “Carrion: I can’t enjoy anything that I haven’t struck down for myself. Sometimes, when the snow is on the ground, and I have flown some hundreds of miles in search of a dinner, I may have to content myself with a stillborn lamb, or even with frozen birds, but I couldn’t make a rule of it, or ever thrive on such fare.”

“Do you fly for hundreds of miles literally and truly?” asked the astonished fox. “Why, if I go over ten miles of ground, in the spring for example, I expect my vixen to say quite a number of flattering things; and in the winter, when I’m living solitary, I would never think of going so far as that unless I were starving.”

“My speed is about one hundred miles an hour,” said the eagle solemnly, “and I can increase it for a short distance. And now I’ll bid you good-morning.” He gave another wild exultant cry and flung himself into space. Before the fox could open the other eye, the bird was a speck of brown without definite shape, rapidly disappearing.

“Well, well,” soliloquised the fox, “if I can’t fly, I don’t have to travel hundreds of miles to find a meal.” So saying, he retired to his earth.

But the Golden Eagle had not far to fly on this occasion. For the first few moments he soared higher and higher, rejoicing in the vast spaces of the sky, in the illimitable freedom of life, in the caress of the morning. Only when the ecstasy had passed did he look below, far below, where men and beasts live cribbed, cabined and confined to the surface of mother earth. Below the hill-tops, where the ptarmigan in their winter garb were invisible even to his keen eyes amid the surrounding snow, past long ranges of moor where fur and feather lay low amid the heather in an agony of apprehension, he saw a great blackcock sunning himself on a rock by the side of a plantation of Scotch firs. The guns had all gone south, the artful bird had baffled them time and again, though some of his brothers, and his sister the grey hen, had gone to bag. Now, careless of danger, the bronze-plumaged bird sat sunning himself in the sunlight, spreading his handsome white tail feathers and thinking of the days that were not far away when he would do battle with his brethren for the grey hens. Around him fur and feather crouched low and shut eyes; little birds that had come down from the high lying moors checked their song, a shadow seemed to drop across the wintry sun. Too late the blackcock looked up, saw his terrible enemy literally dropping upon him, saw the huge wings and the tail feathers open like a fan to break the impending fall, was conscious of a sudden blow—and knew no more. In a moment the Golden Eagle’s talons had pierced the blackcock to the heart, and all that remained on the rock was a handful of bronze feathers, as the captor rose with a shrill cry of triumph. He made straight for a bare rock some mile or more away, and then with one foot upon the dead bird he plucked it rapidly with his beak, scattering the feathers on all sides. This done, he tore the skin open and feasted ravenously on the still warm flesh.

His meal over, he preened himself, and with sudden movement rose from the rock and resumed his flight, still hungry. This time he went in the direction of the moorland, and instead of floating over it at a great height travelled low, as though he had been an owl. The place was solitary at all times, undrained and seldom shot, and he knew it for a place where white hares might be found. Nor was he disappointed, for he started one unfortunate puss, and laughing at her feverish attempts to escape, dropped heavily upon her. In that moment the poor hare screamed and died. The terrible talons had gone right through her lungs, and at the same instant the curved beak delivered a stunning blow upon her head. Looking hastily round, the eagle saw a piece of high flat ground by the side of a wood, and rose in flight towards it, carrying his prey in his talons without any apparent effort. But as he lifted it, and before he had put the dead hare in the best position for his attack, two ravens came suddenly from a neighbouring corrie and flew screaming towards him, calling him all manner of insulting names for daring to poach on their preserves. Without waiting to argue with them, he gripped the hare again and flew away, followed for a long distance by the black, angry birds, whose language will not bear repetition. Finally they tired of pursuit, or perhaps remembered that he might lose command of his temper and turn upon them. But to do that with any effect he must have dropped the hare, and they knew well enough that he would be by no means anxious to do that. So they abused him until they were tired, and then returned to their corrie, feeling certain that their reputation would be enhanced by what had taken place.

Then the Golden Eagle sought another rock, and devoured the hare at his leisure—very angrily withal, for he hated being made ridiculous by contemptible eaters of carrion like ravens. But the rich repast comforted him, and when he left the rock and ascended high in air, it was to seek a river or loch. That was soon found, and he dropped slowly by its edge, with more grace and less force than he had used when falling upon the blackcock. His wings and tail were spread sooner than before, and he came to anchor as a fine sailing yacht might come to rest with all her canvas fluttering down. By the edge of the loch he washed with great care, removing the bloodstains from talons, beak and cere, but he did not drink. Thirst seldom troubled him.

His hunger satiated at last, and there being no little ones to provide for, the Golden Eagle rose high, and sailed in leisurely fashion for miles, keeping a watchful eye on the earth, where he saw fear-stricken birds and beasts seeking what shelter the land afforded. But he was not hungry enough to take anything that offered, and preferred to wait until some dainty morsel was put directly in his way. And it happened that a red grouse, hit in the wing during the last drive of the season, was to be seen fluttering vainly over the moorland, and the eagle fell on this unfortunate, bringing the gift of instant death. Perhaps he was unintentionally kind. Not being hungry, he was content to eat the dainty parts that pleased him best, and leave the rest for fox or stoat, or any vermin that might come along. Once again he washed with scrupulous care, and then, rising high, turned in the direction of home. He was many miles away, but before the widespread sweep of his wings miles disappeared, and the thirty or forty that he had covered took less than half an hour to race through. With his familiar scream of triumph he lighted on his home rock, surveyed the world, and knew that it was good.

The fox had had a very long nap. He, too, had washed in his own half-hearted fashion, and was preparing for his evening prowl.

“I hope you have had a good day, my lord,” he said rather anxiously. He had a vague fear that the hour might come when a succession of bad days would make the great bird too careless or too hungry to regard foxes with his present indifference.

“I’ve done very well, thank you,” replied the Golden Eagle with the graciousness born of a full meal. “Good luck to your hunting.” So saying he stretched himself to his fullest extent, then gradually drew his feathers closely together, allowed the bright eyes that had never winked at December’s sun to close, and the alert, vigorous head to sink slowly down. And so he slept.

He had but one care. His mate, who had built and lived with him for five long years, had disappeared a month before, and he could find no trace of her. In vain he had travelled as far as Caithness on the east, and to Foula among the Shetlands in the north, and down south as far as Perthshire, screaming the old love-cry as he went that she might hear and answer him. She had left the eyrie as usual one morning; they never hunted together, and he had not seen her again. Nor would he, for she had failed to find food and had been tempted by carrion. The carrion—a dead chicken—covered a steel fox-trap, and though, in her frenzied fight for liberty, she had torn the controlling staple from the ground, a keeper had passed within shot before she could get clear of the wood, and now her skin was being stuffed by a Perth taxidermist, and she would presently appear under a glass case in the hall of the shooting lodge by the loch side.

One day differed only from another by reason of the success or failure of its hunting. If rabbits and grouse—red, black, or white—were plentiful, the Golden Eagle sought no other food and returned to his eyrie at peace with all the world. But there were days in the winter season when nothing was to be found, or more often still when the quarry got to cover, and then the eagle would come home screaming with rage, and the red fox would slink to his earth and remain until he was well assured that the great bird was asleep.

Towards January’s end the Golden Eagle fasted for two days, and on the third rose in the air, feeling strangely weak and ill at ease. Happily the mist, that had been lying all over the land and had helped to keep him hungry, was growing thin and yielding altogether in places where the sun struck boldly at it. So the bird winged his way to one of the wildest forests in Sutherlandshire, a place seldom disturbed for nine months out of the twelve. The last stalker had left with October, the monarchs of the herd had long ceased from “belling” and had been forced to the lowlands and the root-crop fields by the stress of severe weather. With keen eyes, and a rage born of hunger in his heart, the Golden Eagle saw a small herd of young stags and hinds disappear into a wood where he could not hope to follow them, and then he skirted a few corries and came to a wild glen where rocks lay strewn haphazard as though there had been a battle of giants there in the days of old. But the eagle only saw one rock—a high one standing at the brow of the glen and bathed in sudden sunshine. A young fawn not a year old had left its herd and was basking in the light. With a scream of triumph the Golden Eagle swooped down upon the luckless little animal, drove the cruel talons deep into its back, and buffeted its head with his heavy wings. Dazed by the suddenness of the attack and blinded by the blows from the bird’s strong pinions, the poor fawn staggered to the edge of the rock, the eagle released his grip, and his victim fell headlong on to a rock below, striking it with a force that broke its neck and ended its sufferings.

The dead body was too heavy for the bird to carry off, so he stayed by its side and tore and ate ravenously, until all the hunger that troubled him was forgotten. It was a very difficult task to rise from the heavy meal, but he made way at once to the nearest stream in order to wash in the icy water, and only then turned heavily towards home, feeling very little inclined after the long fast and the heavy meal to move in any but leisurely fashion. But he had to forget his inclinations. Two large peregrine falcons spied their rival a long way off, and seeing that he was not in a fit state to face their onslaught, made a furious attack upon him. Could he have reached either of them it would have gone hard with the one caught; but he was like a merchantman pursued by a couple of fast cruisers, and while they could turn and twist and use their wings in any direction they fancied, he had to follow a steady course, and content himself with uttering threats of what he would do if he caught one of them then or thereafter. When at last, having done all it was safe to do without getting quite within reach of the terrible beak or talons, the falcons flew screaming to their homes, the eagle was left with a very bad indigestion. Had he been carrying his food in his talons he must have dropped it, and the swift enemies would have caught it in the air and made off beyond hope of recovery, for they could cover three miles to his two.

Doubtless the crows and other eaters of carrion would soon leave nothing of the carcase from which he had torn his meal.

Shortly after this day, a touch of mildness that seemed a forerunner of spring came to the Highlands, and the Golden Eagle took a sudden flight to the north-east. He passed beyond the limits of the land and the home of the sea eagles, and moved swiftly in the direction of the desolate island of Foula, beyond the larger group of the Shetlands. And on the following day he turned to the south again, but not alone, his new mate came with him, a beautiful creature, larger, heavier and even more fierce than he. She had come from Norway to Foula Island, and consented gladly enough to share his home in the wild hills of Sutherlandshire.

Through the slowly lengthening days of February the two eagles, while hunting independently, worked together to restore the nest on the rock. It was a very big and rough affair, six feet across at the base, built of sticks taken from the Scotch fir and the larch and the thick twigs of heather. Inside it was soft with grass and fern and mosses, and when it was complete the mother eagle laid three eggs, each three inches long and nearly as big round the broader end. They were purple, with red-brown blotches and streaks of yellow and black. It was March before the first egg was laid, and as the other two came at intervals of several days, the first nestling came before the other eggs were hatched. He was an ugly little fellow with big mouth, staring eyes, and grey down in place of feathers.

Then the other two nestlings made their appearance, and the fox, whose vixen had given him a litter of cubs, was more uneasy than ever. It was apparently impossible to satisfy the appetite of the eaglets. The father and mother birds thought less for the time being of their own wants than of the requirements of their babies. For miles round all the weaklings and cripples among the game birds were destroyed, and one afternoon the mother eagle came to the eyrie with a young lamb in her claws. She had snatched the new-born creature from the hill-side, and would have been delighted to feed regularly on lamb, but the shepherd had seen her, and when she paid her next visit to the hills on the following morning he was waiting with a shot-gun. Anxiety made him fire too soon, a handful of feathers came fluttering down, and the mother eagle received a couple of pellets in her side and several through the outer edge of the primaries of one wing. Thereafter she left the lambs alone. Her alarm was the greater because she had never heard a gun before, and the shock of the charge, though well-nigh spent before it reached her, was very severe.

“What fools these men are,” said the Golden Eagle angrily to the Red Fox some days after the accident to his mate, “they grudge us the food for our little ones. And yet if they had but the wit to understand, we serve their purposes as well as our own. The strong birds and beasts that are useful in the world can get away from us, the weak ones are taken. But if they were not taken they would soon spoil the race. Why, I have taken hundreds of crippled birds from these moors and valleys since men began to shoot in these parts.”

“Do you remember the place before shooting began?” asked the fox in great wonderment.

“Not perhaps before the gun began to be used,” replied the eagle, “but my memory goes back to times when there was very little shooting indeed. The moors were all undrained, the forests were sheep farms for the most part, and the deer were not preserved. The Highland boys used to load their old guns with slugs and black powder pushed in with a ramrod, and would wait at the springs for the deer, and if they shot one would salt it for winter eating. Then the lairds were poor men, and shared their deer with the poachers. I was a young bird in those days, though I shall never be old. The eagle renews his youth, and I expect to record a hundred years. Now I must be off, here comes my mate.”

The mother bird was a black speck in the distance, but her mate’s loving eye could find her out, and he sailed away to meet her as she came heavily towards the nest, a young pig in her claws. She found a farmhouse, and dropped on to the pig-sty, where mother sow had presented her owners with a litter of seven. Six had managed to get within cover, the seventh, a weakly little animal, had paid the penalty, and was already pork. The farmer’s wife had seen the outrage, but her husband and sons were working on another part of the land and could not be reached. So the eaglets had a splendid meal of sucking-pig, and there was enough for the parents too.

In a few weeks the down on the eaglets’ bodies had turned to feathers, and they were completely fledged, handsome birds, like their parents in all respects save that they had a white ring on the tail feathers. One morning after they had learned to fly and were beginning to enjoy the exercise, the Golden Eagle addressed them seriously.

He and his mate had just come from the farmhouse where they had surprised a couple of hens.

“Look here, my children,” he said as he plucked one dead fowl with wonderful rapidity, “eat well to-day, for from to-morrow you will have yourselves to look after.” His children eyed him curiously, so did the Red Fox who sat solemnly outside his lair. “I mean it,” continued the Golden Eagle seriously. “You will hunt for yourselves after to-day, and if you come poaching on the hunting-grounds of your mother and myself there will be trouble and you will be in the midst of it. Down to now we have raised and fed you, your wants have been our worry, but now that time is up, and after to-day you are no more to us than if you didn’t exist. We don’t want to see you again, and if you are wise you will take care that we don’t.” And on the following morning the young eaglets departed, flew some way together, and then chose their respective kingdoms.

They did not thrive, and of the three only one reached maturity. The first lighted on a stoat in a ditch and could not strike it with the sharp talons before the angry little beast had jumped at its throat and bitten through the external jugular vein. Another, not heeding his parents’ warnings, set out for the farm whence the sucking-pig had come and was shot. But the parent birds remained together in their eyrie and knew no trouble save when storms were brewing. They could see storms rising out of the Atlantic, and when one was on the way to their beloved hills they would grow nervous and restless and fill the air with their screams.

August came round and the Golden Eagle’s joy of life knew no bounds. Never had the moors been so full of delicious red grouse, never before in all his long life had he fed so well.

One afternoon he sat on a rock at the head of a wild corrie. Below him went the stalker and his master, two hundred yards away and quite invisible.

“A fine day, Donald,” said the sportsman; “my best achievement since I came to the Highlands.” To be sure he was only a Sassenach, but he had shot a grouse, and caught a salmon in the morning, and an hour ago, after a long stalk, he had grassed a ten-pointer that was on its way to the lodge strapped to a pony’s back.

“Best kill that de’il yonder,” grumbled Donald, taking a huge pinch of snuff preparatory to launching into a long account of the Golden Eagle’s misdeeds.

Some unaccountable impulse brought the eagle to his wings. Ignorant of his danger, he floated lazily down the valley until the barrel of a mannlicher rifle gleaming from below caught his quick eye. He seemed to see right into it. As though conscious of imminent danger, he screamed defiance and rose higher with loud flapping of his heavy wings. The rifle cracked....

“How terribly the Mother Eagle has been screaming,” said the Red Fox to himself as he made cautious way down the hill that night. “Thank goodness she has gone to sleep at last. My nerves were giving out.”

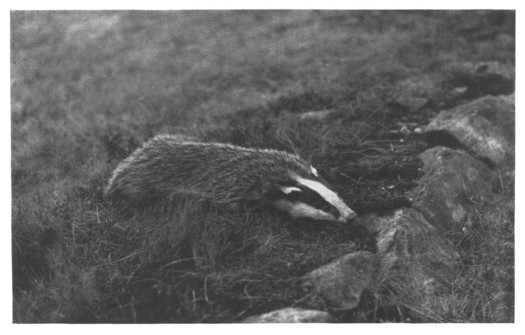

Even the residents hardly knew the part of the forest that the badger called his own, the tourists and callers from the nearest seaside town had never seen it. From June to September there were visitors in plenty; they came along the white dusty roads in coaches, carriages and motor-cars; they walked, or rode on bicycles, held picnics in the shadow of beech and oak trees, and often left assortments of glass bottles and paper to mark the spot they had delighted to honour. Sometimes on his nightly rounds Brock would pass one of these places, and would make haste to get away from the neighbourhood, for his scent was exceedingly keen, and he knew the number of the visitors as certainly as though he had been out during the daytime. The fear of man had come to him quite naturally, it was part of his life to dread and avoid this relentless enemy, just as it was his rule to range the woods by night and to retire to his earth when the sun came out of the east heralded by the pageant of the morning twilight.

He had few friends; only the brown owl sometimes paused in her work to pass the time of night, or the fox, whose earth was close at hand amid the thick-growing gorse, would hold a little converse after a good hunting expedition that had closed before dawn woke the rest of the woodland. Then in the moment when sleepy birds were trying their earliest notes and wondering why those strange visitors the cuckoo and nightingale would sing all the night through, when the wood-pigeons were tumbling heavily from their perches, and the shy kingfisher was standing by the edge of his home in the bank of the stream, the brown owl would seek his hollow tree, and badger and fox would seek their homes. The badger’s abode was quite palatial. Just where the gorse ended and the trees asserted themselves again, the soil was very light, and there were patches of broom and bushes of pink thorn and hazel. Clear of the roots, the first passage began, with a rather steep slope to a well-cleared chamber in which the badger slept. Beyond this apartment there was an upward slope from which two or three tracks branched to the right, and at the end of the slope was another chamber used as a storeroom only a few feet below ground. To the right of this was another dip that went to the open air, or offered a road by yet another gallery to a point just above the sleeping-chamber. In times of stress the grandparents and more remote ancestors of the badger had been accustomed to use the chamber that was nearest the second entrance, for they could then hear the lightest human footfall. But in the old bad days even this precaution had availed them nothing. Dogs and tongs had been employed by their pursuers, and they had been butchered to give idle folk a few hours’ amusement.

When the badger had found the earth in the autumn following his birth, he did not know that it should have been the home of his house. He had wandered across miles of country when his family broke up. His parents had separated, his two sisters had chosen their own road, and the earth in which he was born remained in the sole possession of his father. Once he had assured himself that he would enjoy undisputed occupation, the badger explored and renovated all the tunnelled passages, stopped up all entrances save one by raising sandy mounds with his feet, and prepared to enjoy a solitary existence. Thoughtful, sober and introspective he had no desire for companionship just then.

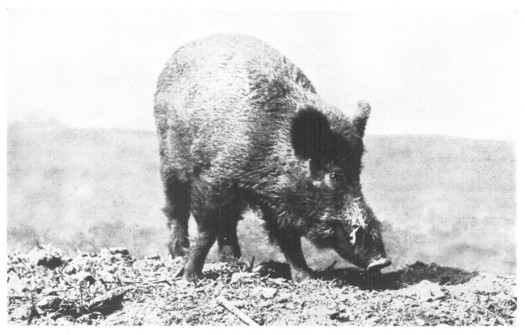

“I had as fine a family of cubs as you could wish to see,” said father fox, when they had known one another for a few weeks, “but the hunt drew the gorse and two of them were killed. The others have gone away, so has my vixen, and if the hunt comes again I’ll go too.”

The badger stirred uneasily, and traversed all his passages again to make sure that every possible precautions had been taken. Though he had stopped the bolt holes, it was only by way of hiding them from prying eyes; a few minutes’ work would suffice him to open them again in time of need. Even when he went out at night he would cover his point of exit in the most careful fashion, using hind and fore-feet with equal ease. Only when the hole was screened would he set out in search of what the wood might yield. Sometimes he would go down to the marshy ground by the river and take toll of frogs and insects, he would even stray into the nearest orchards and eat the fallen apples, pears and plums. Failing these he would root up plants and fungi and carry away what he did not want, for storing; but whether he ate in the wildest part of the wood or comparatively near the haunts of man the enemy, he never forgot the need for guarding against surprise. Like Agag of old he walked delicately, and his hearing, like that of the wild boar, was only suspended when his jaws were actually working. So he would pause with a mouthful of food, or stop half-way in the work of grubbing up a root to scent the breeze, though the forest held no foe within its ample boundaries.

In the early autumn, after his arrival, the young badger cleared away the bed of dry fern and grasses in the sleeping-chamber. His methods were peculiar, for he collected what he could in his forepaws and then shuffled out of the earth backwards. Many journeys were necessary to accomplish this task which was pursued by night, after a meal had been taken; and when the work was ended, he moved to certain parts of the wood where he had torn up ferns and grasses which were now dry. He took these to the sleeping-chamber in the awkward fashion already described, and though much was lost in transit he had a warm and pleasant bed at last. Feeling at his ease he ranged the woods in search of wounded game, making many a hearty meal off fur and feather that should have been retrieved. Later on, the wind and the rain entered the wood together and removed all traces that marked the badger’s journey to and fro, while the badger, finding his bed warm and his house free from draughts, set up a barrier by the entrance and went to sleep. Like the porcupine and squirrel he refused to face the severe weather, though it is more than likely that he responded to warm spells and came out on certain winter nights in search of roots, or the wasp-nests that were in the river bank. But his capacity for sleep robbed winter of half its terrors and kept him in good condition. The food stores supported him if he woke in time of snow, the troubles that proved fatal to so much of the woodland’s life never reached him, and when he resumed his normal activity in March he was no worse for the protracted rest.

The new life that stirred the forest could not rouse him to any great ecstasy. The season did no more than endow him with a funny little grunt and an unwonted measure of playfulness. He loved to stand on his hind-legs and sharpen his fore-paws against the rough oak tree-trunks, and in April evenings he would sometimes be astir before his usual time, generally after light showers of rain. He often went lumbering through the wood with a curious swaying movement, and sometimes walking backward as though by way of expressing his playful humour. There was great joy in the uncouth body, but he had none to share it with him. Even the fox found a vixen; their loving cries resounded through the woods as they hunted together by night, and in the heart of the earth there were four little cubs that would sometimes come to the edge of the gorse and play with the rabbits.

Brock was now to be ranked among the adults; he had shed his four premolar teeth, and from tip of tail to tip of nose must have been very nearly three feet long. He stood about a foot high and the rough skin lay loosely on his body. His jaws were uncommonly strong—no other animal of equal size could boast such a pair—and no dog that had not been trained to bait badgers could have attacked him with impunity. For the present, however, he had no enemies to face, and his lines were cast in pleasant places, among the birds’ nests that were scattered in profusion through the wood. Where the nests were built low the badger would not be denied—the eggs of partridge, thrush, blackbird and wild pheasant supplied him with many a meal, and sometimes he was quick enough to add the parent bird to his meal. The animal that could rob wild bees of their honey had nothing to fear from birds, and even the stoats, weasels and snakes that pursued birds’ nests would not wait to argue their claims with Brock. He soon learned that some birds deprived of one clutch will even lay another, and was delighted to observe their industry, and profit by it in due season. At the same time it must be remarked that he did very little real harm. His neighbour the fox was pursuing an active campaign against all the outlying poultry-yards with so much success that he could afford to leave the rabbits in peace; the badger did no more than help to reduce the overwhelming number of common birds. Since game preserving had been practised on the estates that joined the wood, ceaseless war had been waged against hawks, falcons and other birds; ignorant keepers had dealt with the kestrel and the owl as severely as with the carrion crow, and the tendency of birds like blackbirds and thrushes was to justify Mr. Malthus by increasing beyond the capacity of the food supply. In helping to counteract this tendency the badger was doing good work; it was better for the eggs to be eaten than for the young birds to be born and starved.

Summer waned, and at the time when the stags in Highland forests were seeking the hinds, Brock found the trail of one of his own species and felt the pangs of love. He grunted and yelped as though the spring had come again, and followed the track of the loved one for miles, night after night. Perhaps the unknown, whose scent would have been equally keen, knew that she was pursued and assumed the virtue of shyness; perhaps she was really shy. In either case she was hard to find, and on many a morning the badger was forced to beat a very hurried retreat to his home, hungry, footsore and disappointed, compelled to draw upon his winter stores of roots and grasses for a meal. At last he found his love. She had stayed to hunt for frogs in the river bed, and in rather grudging fashion accepted his attentions. Between wooing and winning a great gulf was fixed, but after nights of pleasant companionship, the well-beloved one agreed to become Mrs. Brock. Had there been other males in the neighbourhood, a fight for supremacy might have been necessary, but the nearest badgers were many miles away and this pair had the district to themselves. Until the storms came they roamed the woods together, finding in addition to roots and berries, wounded game and an occasional nest of wasps or wild bees, which they would root out and eat as it stood, comb, honey, insects and grubs. With the first break up of the weather each retired to its home. She lived across the river but swimming presented no difficulty to either.

When the winter waned, and the first warm dry days called the woodland to renewed life, the badger was early astir. Once again his bed was scattered to the winds, and a fresh one was made in the fashion already described; once again he tested the entrance and exits and made what effort he could to obliterate his own tracks. Then he swam across the river and, returning with his lady-love, conducted her to her new home where she was quite happy. For awhile they travelled together, then he walked alone, and in his clumsy fashion brought some fresh roots and bulbs down to the warm earth where three blind baby badgers shared the fern leaf couch with his mate. They were quite blind and helpless, but while they were awake their mother was with them, and while they slept she foraged for herself. As long as he was in the neighbourhood of the earth her lord would hunt with her, but when he wished to go far afield he went alone, she would not travel a long way from her little ones.

Later, Brock would lead the baby badgers on their first rambles, in the days when they were learning to look after themselves. He showed them how and where food must be sought, warned them of the sound and scents that portended danger, and taught them their share of forest lore. This was his duty now that their mother had gone back to her own quarters across the river and the little ones must face the world alone. With the coming of autumn he sought his mate once more, but she had gone, and for all his efforts he never found her again. But, ranging a part of the wood to which he had never penetrated before, he met a badger philosopher, an old fellow who had seen six or seven summers and grown grey with accumulated wisdom.

This philosopher, whose search for a mate had been equally unavailing, declared that the contemplative life was best of all, remarked that the old badger run he tenanted was not far removed from an unoccupied earth and suggested that they should hunt together. The younger one accepted the suggestion, and started making a bed in the new earth without delay.

It was about this time that he was called upon to give battle. Without knowing it he had moved into a district that was favoured by one or two daring poachers. Stray pheasants from a neighbouring estate were tempted into open spaces by judicious display of raisins, hares and rabbits were plentiful, and the main road was less than a mile away. One poacher had a valuable lurcher that would start off into the wood at a given signal and never return without a rabbit. Coming down a glade at top speed in hot pursuit of a hare the lurcher saw the badger, and forgetful of his safer quarry turned to the attack. It was quite a short contest. To be sure, the dog secured a good grip, but he had forgotten or never known the extraordinary elasticity of the badger’s skin. He only realised it when the animal he had attacked so unceremoniously had fastened on his throat with a grip nothing could relax. In little more time than is required to set the statement down the lurcher lay dead and terribly mangled by the badger whose terror had given place to rage.

All in vain the poacher called and called, until the coming of the morning light warned him to make his way home and return, without the impedimenta of his calling, to go through the wood in the guise of a peaceful pedestrian. To one whose knowledge of woodcraft was so complete it was no hard task to find the spot where the lurcher lay, and a very brief examination of the shattered head indicated clearly enough the author of the deed. Only the badger’s merciless jaws could have bitten through the lurcher’s skull as though it had been a wooden match-box.

The poacher was a dull fellow, an idle loafer who knew the county gaol intimately, ill-treated his wife and gave long hours to the ale-house. And yet for all his unprepossessing ways he was not without some measure of affection, and it had been given to the dead lurcher. Never Arab loved his well-tried horse better than this wastrel loved his dog—it had possessed an intelligence that was almost human, and had been the one living thing that loved him without change of mood. In the silence of the wood the poacher cried like a little child, hid his friend under the ferns until he could return and bury him, and then turned on the badger’s track.

Men who have been long brought up in the woodland and learned all the tricks of the poacher’s trade are hard to baffle. As the poacher moved along all his gifts so long latent, stimulated by grief and rage, he became for the time one with the wood and its denizens. He heard the ceaseless under-song, and could analyse it as the skilled critic of music can analyse the component parts of a symphony; almost instinctively he knew the shy fearful birds that were peeping at him through many a screen of leaves, the grass snake and adder that were gliding away from him. In those hours of wrath and exaltation his eyes were opened; without haste on the one hand or delay on the other he found the badger’s earth, never losing for long the track of the five toes and the sharp nails.

Down in the darkness where his bed was strewn, Brock realised the coming of his enemy; the horror of man so long dormant in him was revived. He stood up noiselessly and heard the unseen feet move deliberately in search of the entrance to the earth. Against this man who, in clear-headed hours, could read Nature’s stories as though they were set in printed page before him, a badger must fight hard for life. It would be a contest of wits.

The footsteps passed; the hidden animal heard the slow and regular decline; the normal sounds of the woodland were resumed. By night, he thought, he would creep away and leave the place, he would go back to his old haunts below the river where there was safety. The afternoon turned towards sunset, and then Brock, who was in a passage close to the ground, heard the tramp, tramp that had startled him in the morning. The man was coming back, was moving from one part of the ground to the other, sounding the entrance and the bolt holes. Already he seemed to know them all. What was he doing?

Presently the dull thud of a spade was heard by the mouth of the run, and the purpose of the poacher was clear. He had blocked each entrance and was going to dig until he had found the destroyer of his companion. Had he stayed till the following day the quarry would have passed. He knew this well enough so he had brought gun and food, trenching-spade, lantern and tobacco, and was about to dig down foot by foot to the badger’s lair.

Quite undismayed now that the risk of invasion had yielded to certainty, the hunted animal prepared to defend himself. At the foot of the first slope he started to pile the loose earth using his hind-feet as readily as the others, and before the poacher was half-way down the barrier was strong enough to have kept a dog at bay. But the man was depending upon his own exertions, he had no dog, and when his spade encountered the defence it was speedily broken down.

By this time the badger had retreated past his bedroom into one of the deepest passages, the one that commanded a double route. He had already gone to two of the exits that were intended for emergency, but the human taint was strong at each, and he feared to let the issue of the contest depend upon a chance flight. Perhaps it was as well, for the strongly pegged netting that was ranged round each hole must have given him a pause that would have sufficed the poacher.

The lantern was lighted now and the pipe was out; the poacher, flabby and out of condition, was deaf to the call of his tired limbs. Passion sustained him in the pursuit of a task that few sane men would have attempted. The task would have been relatively easy if additional assistance had been to hand, but the poacher had no friends. He had reached the bedroom now, the soil had responded to the sharp spade edge, and with savage glee he broke up the soft couch of ferns and grass, and then set the lantern down and mopped his forehead and thought deeply. Two passages led from this chamber, without counting the one he had followed; he piled the dry bed by one of them and set it alight, in hope that the smoke might enter and make the fugitive bolt. But though the material was dry and burnt well the air was windless and the fumes ascended.

“Curse you,” he cried, as though he knew Brock was in hearing and thought he could follow his words. “I’ll dig till I find you, if I dig up the whole earth.”

Once again the spade work was resumed, the eerie silence of the night was broken by the recurrent thud. The poacher was drunk with passion; the impenetrable dignity of the night and the silence of his foe seemed to set his blood on fire. All sense of fatigue had gone; he hardly knew how his temples were throbbing or realised that his breath was coming in short painful gasps until, after another frenzied spell of work, he turned to survey the long trench that marked his progress, and shout out a gibe at the unseen badger.

At that moment his light was extinguished, the candle had burnt itself out, the darkness enveloped him almost with a sense of physical force. By the junction of the two paths some ten feet away Brock heard the sound of a heavy fall, the following silence was long and deep. For some quarter of an hour the badger did not move, then he moved cautiously to the right along a seldom-used passage and came to a forgotten crossway. Down one side of it a current of air came clean and pure. He followed it, along a track he had not used before until he reached an opening under a bank. All seemed safe. His sharp ears could not catch the sound of human breath, there was no taint of humanity by the bush that hid the entrance. The night was still profoundly dark. He slipped noiselessly into the shadows.

BADGER [Photo by C. Reid]

The old snake-catcher passing down the woodland clearing in the morning found the poacher lying at peace, his spade gripped tightly in one hand. A coroner’s jury was told by the doctor that sudden and unaccustomed exertion had brought about a failure of the heart’s action and a painless death. And twelve good men and true wondered greatly that the deceased should have exerted himself so greatly. Trained terriers had been put into the earth under the various nets and had returned quite silently to their owners. “He must have been insane,” said the enlightened jurymen.

But the snake-catcher, who believed in fairies, knew better. “He tried to dig a badger by night,” he said, “and that disturbed the little people. So they killed him.”

When Abdullah, the slave dealer, led the long file of loaded camels towards the desert on the bright April morning, only one of his animals remained in the fandak. Within a week she had a companion, her little baby camel who came into the world as though to give her his company during the long, hot months of summer when, at the sun’s bidding, the caravan that had just set out would cease from its labours and rest in the far-off city of Timbuctoo.

The fandak was a large rectangular enclosure open to the sky everywhere save in the cloisters round the inside walls. It was filthily dirty, and full of flies and insects, but Basha the baby camel noted none of these things. He passed his early days wandering round the cloisters to look at the half-starved mules and donkeys that were brought in there for their much needed rest, and when the heat was greatest and the flies most insistent, he would lie contentedly by his mother’s side. For all the fandak’s limitations Basha had been born in fortunate hour. His mother’s services were not required in field or city, heavy spring rains had made food plentiful and cheap, so that she was well fed, and the little one, who by the way was two feet odd inches high when he was born, enjoyed an unfailing supply of milk. Had he come into the world at another time or place, his mother might have been put to work hard before he was three months old, her milk might have been required for cheese, and he would have pined and died as so many baby camels do. Even when the summer waned and the autumn rains starred the fields with flowers of bewildering beauty, Basha stayed with his mother on a farm outside the city gates. The caravan came back in the season of cool weather and in place of the merchandise they had taken to the South, the camels brought slaves for the Sok el Abeed, but they could not go out again. Between them and the Soudan the fierce veiled Touaregs of the desert were in arms, and in the direction of the coast the chief camel road was held by the braves of a tribe that was in open revolt against Morocco’s Sultan.

So, while Abdullah swore strange oaths by the Prophet’s beard, and declared that the men of the desert were descended from devils and the men of the western province from apes, little Basha grew strong and unshapely, and life was an affair of sunshine and good milk. Day by day the farmer spread his mother’s food before her on a cloth; dried beans, crushed date stones and a very small measure of corn and chopped hay, and Basha would sniff at it with very little interest. If the farmer himself was absent the cloth might be forgotten, and then Mother Camel would make an angry noise in her throat and refuse to eat, and little Basha would suffer accordingly.

“Why must you have a cloth to eat from?” he asked her one day, when she was gurgling indignantly while the rats made merry at her expense, and she made no attempt to check their depredations.

“It is Camel Law,” replied his mother. “If we were to eat our food from the bare ground we should take all manner of dirt into our mouths, and in a little while it would make us ill, perhaps fatally. Our inside arrangements are very delicate and complicated. In the fandak two camels and no more will feed from one mat or cloth, and it is right that there should be precedence at meal-times. The most important camels should be fed first. That is etiquette, and we set a great store by it. Indeed, if this consideration is overlooked we let our masters know about it.”

“But when you leave your food, I get less milk,” remonstrated Basha.

“You can’t begin too early,” explained the Mother Camel, “to understand that all camels must suffer. It is part of our life to work hard, to endure ill-treatment and to be deprived of our fair share of good things. Down to the present your good luck has been astonishing. Your brother and sister, one born seven years ago and the other four, died of starvation before they had lived through one summer. I myself was born in the country of the black men south of the Atlas mountains, and had to come here with my mother across the desert before I was six months old.”

Basha took small account of these warnings. He could do no more than judge life as he found it, and do credit to his environment by growing to be a fine specimen of his race. When at length he was taken from his mother he was fully a year old, and he enjoyed some idle months on the farm land, living for the most part upon green herbage, and straying far and wide in search of camel thorn, r’tam, tamarisk and mimosa. When he had found his favourite bush, he would run his upper lip over the leaves as though to assure himself that they were what he sought, but if he knew what he liked he did not know what was good for him. A wandering Bedouin shepherd came upon him one morning just as he was beginning to sniff with appreciation at some leaves that would have finished his career at once, and thereafter Basha’s liberty was curtailed and he had his first experience of the manacles. They were made of steel and fitted round each fore-leg above the ankle. This was a most effective device, for a camel walks moving both legs on the same side simultaneously, and the steel was capable of arresting the walk altogether. He had to endure many long and painful hours in this confinement.

As he was quite unconscious of having done anything to deserve such treatment, and knew nothing of his own stupidity, Basha was full of indignation and kicked with his hind-legs at all passers, exhibiting early signs of bad temper. Then the first evil days came to him, and in the picturesque language of his master he “ate the stick” until he knew fear and understood the virtue of docility. But in after days when he was goaded beyond endurance he always kicked out with his hind-legs, and he learned that many camels do the same when they are angry, although their fore limbs are much stronger than the hind ones. Perhaps the early use of the shackles accounts for this tendency, which is common to the most of African camels.

If his training in those early days was cruel, Basha was no worse off than his fellows. He had to learn to endure the saddle and the pack, to kneel at word of command, and to go with the other camels on short journeys carrying some light load in preparation for the trying days to come. He grew very slowly but managed to preserve a good condition, clearly to be seen in the rising hump and in the well-covered skin. Camels that were overworked or underfed lost their hump, and if they had any serious illness, their skin looked like a moth-eaten fur.

In his fifth year when he was reckoned fit for the full measure of work Basha was a very finely developed beast, even though his ugliness was undeniable. His long, thick upper lip was divided in two, and this peculiarity accounted in part for his perpetual sneer; his eyes, the one redeeming feature of his head, were shaded by heavy brow and coarse eyelashes; his ears were very small and round and he acquired the curious power of compressing his nostrils that was to be so serviceable in days to come. His legs were long and thin, and the great shapeless feet in which they terminated looked very absurd; his walk was little better than an awkward flat-footed shuffle. His tail was short and stumpy, and his mode of resting had brought well-defined hard growths to his chest and knees. He could travel without fatigue over endless miles of level ground, but hills tired him at once; and he could swim sturdily though nothing but the most severe thirst would make him drink of running water. His early-day nervousness had gone though he was still restive when taken from his companions. He seldom called as he had been in the habit of doing when he was young, but with manhood, if the term be permissible, he had developed a violent temper, and there were seasons of the year when only Abdullah dare approach him. At these times he would grow very excited, he would repeat the horrid gurgling noise that his mother had made, and would go about with a hideous pink bladder hanging from one side of his mouth. At the first sign of this state among his male camels Abdullah would seek to reduce their rage by bloodletting. The camels would be hobbled in turn and told to sit down, and after a cord had been tied tightly round the neck two small incisions would be made just below the cord. This was an effective cure for ferocity, but was not always a possible remedy when the camels were on the march, for it left them very weak.

In the first year of his complete strength Basha was hired with two other camels by a Moor who traded between the Atlantic coast and Marrakesh, the far southern capital of the Moorish Empire. The work was hard and the loads were heavy, but the Moor did not spare himself. The start from coast or capital would be made in the very early morning hours. The camels would be loaded in skilful fashion, the weight being put as high on the ribs as possible, because the hind limbs were so much weaker than the others. If there was any mistake or the weight was unfairly heavy, the camels would gurgle angrily and refuse to rise. Then some fresh adjustment was necessary for Abd el Karim knew better than to waste his time in trying to force an ill-loaded or over-strained animal to his feet. Once a camel had risen and started he would go until he dropped, but no animal would rise before being satisfied that he was being fairly handled. In those early hours the beasts would be fed with cakes made of crushed grain and dates, mixed for choice with camel milk or, failing that, with water. The meal over, the little procession would start out well in advance of sunrise, and when the first halt was called it would be to avoid the midday sun and give the weary men a little time to repose. When the journey was resumed it would be kept up until night was falling and it was no longer safe to be found on any one of the broad tracks that served the southern countries for a road. Then Abd el Karim would seek an ensala, a piece of bare ground next some village, fenced round with cactus thorn and prickly pear. He would pay the equivalent of a few pence for admission, and once there the headman of the village would be responsible to the nearest country governor for the safety of the little company. The camels would be unloaded, watered and fed, three or four pounds of grain being the maximum supply for each beast, and they would enjoy some six hours’ rest. But as soon as the false dawn appeared in the sky and Abd el Karim had said the early morning prayer that is called the fejer, and comes with the third cock-crow, loads would be replaced and the journey resumed. Basha plodded along with seeming content, but in his heart he hated his new master. It was not that he had any special unkindness to complain about, the ill-treatment was quite impartial, he hated all humans, and Abd el Karim stood for him as the type of the tyrants who inflicted such base servitude upon the camel world. He had no pet grievance, and would most certainly have resented any special act of kindness as an impertinence. Whatever kindly feelings he might have had were kept under so severely that his face had but two expressions. He looked upon the world with indignation and contempt in turn. When he walked through the narrow streets of Marrakesh carrying a pack that weighed between three and four hundred pounds upon his shoulders, he would turn neither to the right nor to the left; horses, mules and pedestrians had perforce to make way for him. Not only was he prepared to walk over anything that stood in his way, he was ready to turn round and bite any passer who came within reach of his mouth. From nose to tail he could not have been less than eight feet long in those days, and he stood more than six feet high from hump to ground. In brief, Basha was an ill-natured, sulky beast, but his powers of endurance gave him a value for which all his little failings were forgiven.

In the camel fandak at Marrakesh where he had first seen the daylight he would join the rest of Abdullah’s animals from time to time and hear of their adventurous journeys to the Soudan. His mother was still at work among them and had lost another son since Basha was born. She was ageing now under the combined influences of hard work and insufficient food, and the sight of her condition roused her son to a state of anger in which pity took no part. He had no affection for her, but her state increased the bitterness of his feelings against the enemy man. From time to time he noted the disappearance of animals he had known and asked about them.

“He fell,” replied his mother once, referring to a camel of his own age, “and then you know the old cry.”

“I don’t,” confessed Basha, “what do you mean?”

“It has passed into the proverbs of our masters,” said his mother slowly. “‘When the camel falls,’ runs their adage, ‘out with your knives.’ It is a recognition of our undying pluck. So long as we can endure we keep up and when we fall we are beaten and done for. No rest can cure us. Our masters know that, and when we fall in our tracks their knives are out—sometimes before we are dead.”

Basha turned away, sick with anger. This then was the end of things, to labour through the heat of day, to toil until the last store of strength was exhausted, and then die a dishonourable death under the curved daggers of brutal masters. How he hated them, one and all.

It was on account of his recent losses that Abdullah decided to include Basha in the next caravan that left Marrakesh for the South, and so it happened that he made one of a string of fifty beasts that filed out of the city by way of the Dukala Gate on a fine September morning. For some weeks past the camels had rested and had been tended with an approach to care. Before a final selection was made each animal was examined with care and a few were rejected on account of ailments that were plain to the practical eyes of Abdullah and his assistants. Chief of these disqualifying symptoms was a foot disease brought on by overwork, and the fate of Basha’s mother hung in the balance for she was beginning to show signs of the unending labour imposed upon her. But there was a fair sporting chance for her, and Abdullah took it. The unaccustomed rest of the past three weeks and the regular food had almost restored her strength.

Although he was now in his tenth year Basha had not crossed the Sahara. He had not finished growing but was immensely strong, and the journey had no terrors for him. For the first few days the land was one vast oasis and the camels went unwatered, feeding in the very early morning before the dew was off the autumn greenery, and so storing enough moisture to last them through the day. They were well fed at night, and Basha began to think that the difficulties of which his companions spoke after supper when they sat in a great group, had been exaggerated. Then the caravan reached the real desert beyond the Draa country, and he understood. The sun was like molten copper above, and the sands seemed white-hot underneath. Vegetation ceased. No man spoke, and at night the hours of respite from the heat seemed to fly. A reserve stock of water was carried in goat-skin barrels on some of the camels, but Abdullah made a detour in order to reach the oases that lay scattered here and there. And when the wells at one of these oases were found to be dry, the real troubles of the journey commenced. Supplies were reduced all round as they moved towards the next oasis, and on the second morning following the reduction the desert was swept by a dust-storm.

Long before Abdullah and his companions could note its approach, the leading camels saw the advancing columns of the storm, and with one accord they dropped to their knees and crouched with their long necks stretched out and their nostrils firmly closed to face the coming trouble. The men shrouded themselves in their haiks and crouched on the ground, taking refuge with Allah from Satan and his legions, for they knew well that the sand columns were really djinoon, who went about the desert seeking whom they might devour. When the legions of the storm had passed, and men and beasts arose to continue the journey, the terror of the desert lay heavily upon one and all.

The caravan had a mournful appearance as it laboured across the desert in the tracks of the storm. Camels shuffled along with the hopeless, listless energy of creatures attuned to suffering in its every form; the men, riding or walking, seemed to have yielded to the depression that the Sahara knows so well. Shifting sand and raging wind had hidden the tracks, but Abdullah and Abd el Karim, who was acting as his lieutenant, had rare eyes, and they corrected their bearings by the stars at night. For perhaps the first time in his life Basha realised the cunning economy of his body. His stomach had four compartments, to say nothing of cells, that served for the preservation of the water-supply, and he could regulate the flow of food and water in manner that took the keen edge from his sufferings. Men suffered more than beasts, but they had the consolation of their faith. “Mektub,” they muttered, when Abdullah pointed out the need for diminished rations lest the next oasis should fail them, “it is written”. If their safe arrival in the far-off Abaradiou of Timbuctoo was decreed, no dust storm would avail to stay them; if they were to be one of the caravans that the pitiless Sahara swallows up, no complaint would avail to avert the evil decree.

At night when the packs were removed and the men smoked the forbidden haschish over their scanty supper, or took council with the star Sohail that served to guide them to the South, the camels held converse after their own fashion.

“The end is upon me,” cried Basha’s mother one evening, “My feet are worn away. It is not for me to see the Niger’s bank or to eat the camel thorn in the woods beyond the Mosque of Sankoréh”.

“It is well, mother,” said the camel crouched by her side; “you will rest at least. We shall go on, and your load will be added to ours. Rejoice then in the end of the day’s work.” And late on the following afternoon, at the hour when the sun first appeared to relent of his pitiless severity, Basha saw his mother stoop slowly to the earth.

“A camel falls,” cried Abd el Karim, who walked by his side, “out with your knives.” He leapt forward, Basha saw the red stain in the white sand, and then passed on with averted eyes. A few camels gurgled to express sympathy or indignation, three or four were stopped by Abdullah’s orders and the burden of the dead beast was divided among them. Then the march was resumed, and in the evening an oasis was reached where there were date palms in plenty, and a well untouched by drought. Far into the night the water was poured into the puddled troughs from the goat-skin bucket that served the well, each of the camels receiving ten or twelve gallons—enough to quench their raging thirst and give them a store for two or even three days.

Half of the party remained at the oasis, the other half under Abdullah’s guidance turned aside to El Djouf, the desert city where the merchandise of the camels would be exchanged for the great blocks of salt that were worth their weight in gold, and slaves in far-off villages beyond Timbuctoo. Basha was one of the camels that remained behind, and he sat through the night with sleepless eyes seeing ever before him the dead body of his mother, and hearing Abd el Karim’s horrid cry. It was anger with the living rather than pity for the dead that fed his growing wrath. A light breeze stirred the palm leaves, he heard the far-off cry of a jackal and then the patter of little feet. This last sound came nearer until a company of desert antelope ran in view. Undisturbed by the camels they ranged in search of green food, and drank of the water remaining in the puddled troughs as though indifferent to the proximity of the sleeping men.

One, who seemed to be the leader of the deer, paused by Basha’s side.

“Little master,” said the camel, “whence come you, and what have you seen?”

“We range the sands,” replied the stranger, “from the oasis that is tended by man even to the far-off spring that only the gazelles have seen. And to-night we fly from El Kebeer, the great jackal, who has brought his pack in search of meat.”

“Where is he now?” asked Basha, shuddering.

“All are together now,” said the gazelle. “They have found the body of an old mother camel fallen by the way. Until the morning comes they will hardly leave the spot, and ere then we shall be miles from here. We shall seek green places that the desert hides from all save us, we shall rejoice in our freedom and our peaceful lives. Farewell.”

He slipped noiselessly into the shadows and was gone. But Basha sat wakeful and watchful through the night.

With the break of day the most of the camels in the oasis rose to search for the young green growths that held the dew, but Basha sat silent.

“Fool,” cried Abd el Karim, staggering from his tent, the haschish dreams still clouding his brain; “art thou too among the sick? Shall I kill thee, or wilt thou eat, O thrice cursed beast?”

“Leave me while there is time,” growled Basha, but Abd el Karim heard no more than the usual angry gurgle, and drawing off one of his slippers he struck Basha across the mouth.

With a curious cry like a trumpet-call Basha shuffled to his feet, and Abd el Karim, realising that some awful change had come to his charge, turned and ran.

In long slanting strides, with outstretched neck, lowered head and open mouth, Basha pursued noisily. The other camels were feeding behind the palm grove, their guardians with them, Abd el Karim had run towards the desert. But the drug he favoured had made his feet unsteady; in the hour of his direst need he slipped and fell. Basha’s teeth closed on the white haik that enveloped his master, and then he came down slowly to a sitting position and thrust the man, senseless now from fright, between the smooth rock and the bony ridge of his chest.

When he rose and ran towards the open desert he was mad, doomed to run until he dropped and died. But the man he had left prone on the rock that had tripped him would never, never rise again.

Many days later, in the great fandak of the Abaradiou beyond the gates of Timbuctoo, Abdullah told his friend the slave-merchant of the journey. “We had two anxious days,” he said, “but the grace of Allah was upon all save Abd el Karim. One of the camels that had never known the desert broke down and went mad. Perhaps the man had ill-treated him, perhaps even strove to stop him. Who shall say more than that Abd el Karim’s hour had come? May Allah have pardoned him.”

When he woke to being, and left the warm shelter of his mother’s feathers to take a look at the world around him, the sun was smiling upon the purple heather, and a light wind was stirring the leaves of birch and mountain-ash in the plantation below. He was no more than a tiny ball of yellow fluff with some dark-brown marks on back and sides, and a chestnut patch on his head, and there were eight brothers and sisters exactly like each other, waiting for him by the side of the heather tuft under which his mother had been hatching her eggs.

His father sat on another tuft a few yards away, spreading his plumage in the sunlight, and the little grouse thought he was fortunate in having such a handsome parent. The head, neck, breast and sides of Father Grouse were of a very bright chestnut colour, with black lines across, his lower feathers were darker, but tipped with white, to show his pure Highland breeding.

“Kok-kok,” said Father Grouse. “What a fine family I have to be sure. The stupid gamekeeper put his foot in our first nest and we had to make another one. So you are all very late. June is already here, the other birds on the moor can fly by now. Kok-kok.”

Then he and his wife broke off the tiny fresh tops of the heather, and the little bird, having been fed with his brothers and sisters, ran about in the sun till it went down, and then crept back to the nest where the shells of broken eggs had been lying, pale cream shells covered with heavy blotches of red. The little grouse, warm under his mother’s feathers and above the moss that lined the nest, slept quite happily, dreaming of the days when he would be able to fly over the moor. He woke with a start hearing his father crying:—

“Who goes there? Who goes there? my sword, my sword.”

“Don’t be frightened,” said Mother Grouse reassuringly, as the little ones nestle closer to her, “he says that every morning.”

The newcomer soon became accustomed to be called at daybreak by this startling cry, and he learned as soon to hide from the buzzard, the peregrine falcon and the carrion crows that, between them, eventually managed to secure all his brothers, because they would not listen to their father’s warning. Mrs. Grouse had decided at last that the last big egg, which was as broad at one end as at the other, held no son or daughter, and as soon as she had made up her mind about that she put on her summer dress; it was buff-coloured and marked with irregular bars of black. When the family had admired it they flew together across the heather. Father Grouse had no summer dress; he did not change his costume before autumn.

The family kept to the moor, where they met many very pleasant relatives with children quite grown up, so much like their mothers that it was hard to tell the difference, and while they were together Father Grouse gave his only son a lot of useful information.

“We keep to the heather,” he said. “It is our own. On the hills beyond,” and he pointed to the mountain behind the moor, “you find our cousins, the ptarmigan. In the plantation below the hills where there are birch, hazel, ash and juniper trees and where the roebuck hides in the ferns, you have another cousin, the blackcock. He feeds with us sometimes. We have not much to do with either of them, though we are not unfriendly. Kok-kok.”

It was a very fine summer, the heather was fresh and sweet to eat, and very warm to lie on. The little grouse soon lost the yellow down that had covered him, and his plumage became very much like his mother’s. The family would fly about in a group, father and mother leading, and they often went off the heather to eat the grass and early berries.

“I have lived more than one whole year,” said Father Grouse, “but I was born in a very bad season. The heather was bitten by the frost, the rain was unceasing, we could not get enough food, and it was terribly cold on the wet ground. Hundreds died—but lie down, somebody is coming.”

The family crouched low in the heather and saw the landlord’s factor walking up the hill-side with a stout gentleman who wore an unbecoming coat and a waistcoat with a heavy watch chain across it. The stout gentleman passed a handkerchief across his forehead. “It is a fine view,” he gasped, “and what are the limits of the bag?”

“Eight hundred brace of grouse may be shot and forty stags but the laird is not a hard man and might make it a thousand brace and fifty stags,” said the factor, who had forgotten how to blush.

“Now,” whispered Father Grouse, and uttering a challenge, he rose within three yards of the stout gentleman, closely followed by wife and family.

“You see,” said the factor, “the moor is packed with birds, you can almost walk over them.”

“Why did you show yourself like that, my dear?” said Mother Grouse, when they had settled after a long easy flight.

“Ah,” replied her husband, “you leave me to attend to my own business. I like to see men like that on the moor, they do no harm. It is the young, slender men who are never tired and are always shooting that I object to. You can’t get away from them, Kok-kok.”

“Did you hear the factor,” continued Father Grouse, after as near an approach to a chuckle as a red grouse can achieve. “He said the bag was limited to eight hundred brace, though the laird might make the limit up to a thousand. Now there are not two hundred and fifty brace on the moor. As for the stags, fancy a man like that trying to stalk them; well, let us go and eat some heather-tops—such talk makes me feel weak.”

They were glorious days that led to the middle of August. The young grouse was becoming quite big; he could take long flights without fatigue, could accomplish a small call, was an adept at finding good food and soft sleeping places, and he never allowed his attentions to stray from his feathered enemies.

He had some narrow escapes; on one occasion the peregrine falcon struck down one of his sisters as she was flying by his side; on another the great Golden Eagle, coming from his eyrie on the mountain top, was circling over him, but suddenly saw a young deer calf on a rock not far away. The rock looked over the bare hill-side, and the eagle, lighting on the poor calf’s back, buffeted its face so heavily with his wings that it fell off the rock and, tumbling down, was killed on the hill-side. The Golden Eagle made his meal, the fox and the carrion crow took what was left. It was a sad sight, and the Golden Eagle was more unpopular than ever on the moor and in the forest.

The young grouse made the acquaintance of the biggest deer on the hill, a king of stags, with brow, bay and tray antlers, who explained that he was a stag royal. This acquaintance was made one afternoon in early August when the grouse family were feeding on some succulent grasses by the side of the burn where the stag came to drink.

“I am more than pleased to meet you again,” said the stag. “I wish you and your family as sure an escape from the shot gun as I hope to get from the rifle.” So saying he trotted off, and Father Grouse spread his feathers just as though he had been a blackcock in a juniper tree, and challenged as loudly as he could.

“Last September,” he said, turning to his wondering son, “after my parents had met with misfortune passing over the butts, I found myself on some high ground near the big corrie. The royal stag you saw just now was resting there with his family, and he had been seen by the stalker. I was sitting on a heather tuft thinking that now I had lost my parents I should have to join the grouse pack, when I saw the stalker and the man who shoots the stags, crawling along the ground in my direction. They wanted to get behind the stag and shoot him as he sat head to wind.

“I can see them now—the stalker very cool, and the shooter very tired. As I looked I thought I recognised him as the man who had shot my parents. I did not hesitate, but rose up when they were almost near enough to touch me, flew within hearing of the stag and called out:—

“Who goes there? The gun, the gun.”