Title: Climbing on the Himalaya and Other Mountain Ranges

Author: Norman Collie

Release date: May 24, 2014 [eBook #45747]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Melissa McDaniel, Paul Marshall, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Climbing on the Himalaya and Other Mountain Ranges, by Norman Collie

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/climbingonhimala00collrich |

Printed at the Edinburgh University Press,

by T. and A. Constable,

FOR

DAVID DOUGLAS.

LONDON SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT AND CO., LTD.

CAMBRIDGE MACMILLAN AND BOWES.

GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS.

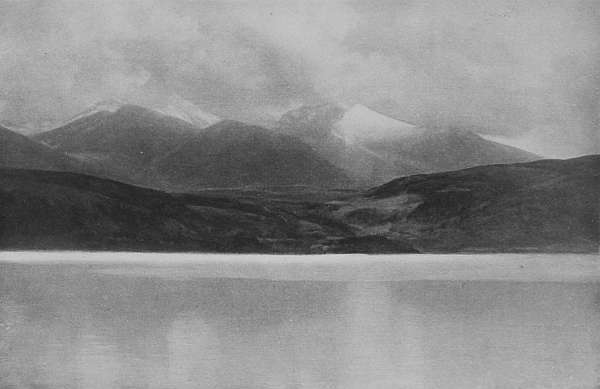

A Stormy Sunset.

CLIMBING ON

THE HIMALAYA

AND

OTHER MOUNTAIN RANGES

BY

J. NORMAN COLLIE, F.R.S.

MEMBER OF THE ALPINE CLUB

EDINBURGH

DAVID DOUGLAS

1902

All rights reserved

After a book has been written, delivered to the publisher, and the proofs corrected, the author fondly imagines that little or no more is expected of him. All he has to do is to wait. In due time his child will be introduced to the world, and perhaps an enthusiastic public, by judicious comments on the virtues of the youngster, will make the parent proud of his offspring.

Before, however, this much-desired event can take place, custom demands that a preface, or an introduction of the aforesaid youngster to polite society, must be written. Unfortunately also the parent has to compile a list or index of the various items of his progeny's belongings that are of interest; so that nothing be left undone that may be of service to the young fellow, what time he makes his bow before a critical audience. In books on travel, nowadays, it is customary often [Pg vi] somewhat to scamp this necessary duty, and, after a few remarks in the preface, on subjects not always of absorbing interest, to conclude with the hope that the reader will be as interested in the description of places he has never seen as the author has been in writing about them.

Of course, formerly these matters were better managed. In the 'Epistle Dedicatorie,' the author would at once begin with:—'To the most Noble Earle'—then with many apologies, all in the best English and most perfect taste, he, under the patronage of the aforesaid Noble Earle, would launch his venture on to the wide seas of publicity, or perhaps growing bolder, would put forth his wares with some such phrases as the following:—'And now, oh most ingenuous reader! can you find narrated many adventures, both on the high mountains of the earth, and in far countries but little known to the vulgar. Here are landscapes brought home, and so faithfully wrought, that you must confess, none but the best engravers could work them. Here, too, may'st thou find described diverse parts of thine own native land.' [Pg vii]

'Choose that which pleaseth thee best. Not to detain thee longer, farewell; and when thou hast considered thy purchase, may'st thou say, that the price of it was but a charity to thyself, so not ill spent.'

16 Campden Grove,

London, 24th March 1902

Four of the chapters in this book have appeared before in the pages of the Scottish Mountaineering Club Journal (A Chuilionn, Wastdale Head, A Reverie, and the Oromaniacal Quest). They all, however, have been partly rewritten, so the author trusts that he may be excused for offering to the public wares which are not entirely fresh.

The Fragment from a

Lost MS., and part of the chapter on the Lofoten Islands,

were first printed in the Alpine Journal.

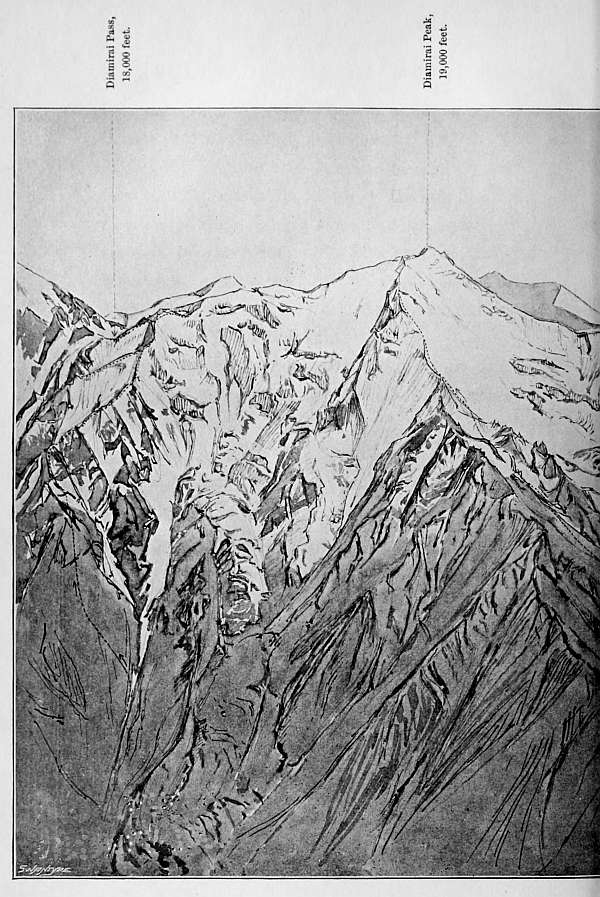

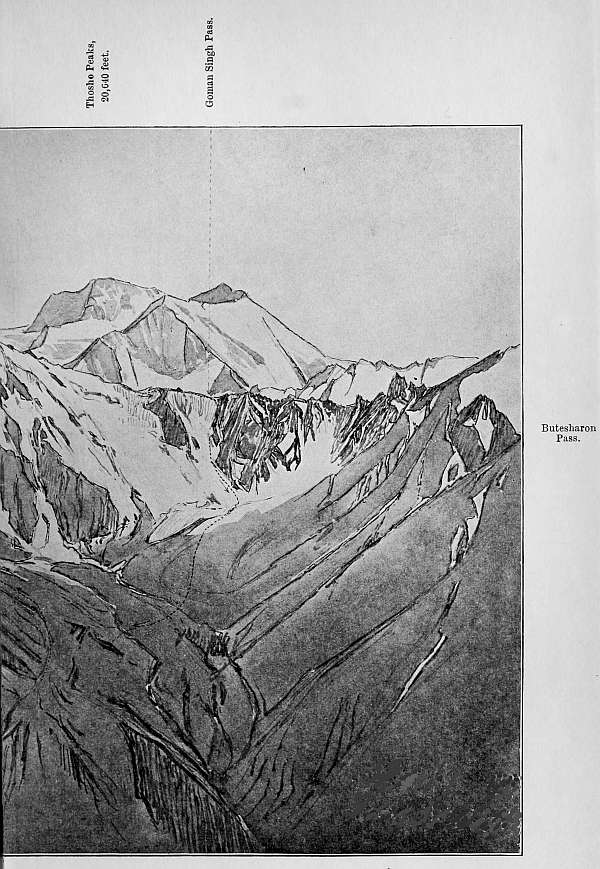

The author also takes this opportunity of thanking Mr. Colin

B. Phillip, first, for allowing photogravure reproductions to be

made of two of his pictures (The Coolin and the Macgillicuddy's

Reeks), and secondly, for the great trouble Mr. Phillip took

in producing the three sketches of the Himalayan mountains

which are to be found in the text.

CONTENTS.

The Himalaya— |

||

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | General History of Mountaineering in the Himalaya, | 1 |

| II. | Our Journey out to Nanga Parbat, | 25 |

| III. | The Rupal Nullah, | 38 |

| IV. | First Journey to Diamirai Nullah and the Diamirai Pass, | 57 |

| V. | Second Journey to Diamirai Nullah and Ascent to 21,000 feet, | 70 |

| VI. | Ascent of the Diamirai Peak, | 85 |

| VII. | Attempt to ascend Nanga Parbat, | 104 |

| VIII. | The Indus Valley and Third Journey to Diamirai Nullah | 118 |

| The Canadian Rocky Mountains, | 135 | |

| The Alps, | 165 | |

| The Lofoten Islands, | 185 | |

| A Chuilionn, | 211 | |

| The Mountains of Ireland, | 225 | |

| Prehistoric Climbing near Wastdale Head, | 245 | |

| A Reverie, | 263 | |

| The Oromaniacal Quest, | 283 | |

| Fragment from a Lost MS., | 299 | |

| Notes on the Himalayan Mountains, | 305 | |

| Index, | 311 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| A Stormy Sunset, | Frontispiece | |

| A Himalayan Camp, | To face page | 2 |

| A Himalayan Nullah | " " | 38 |

| The Diamirai Pass from the Red Pass, | " " | 62 |

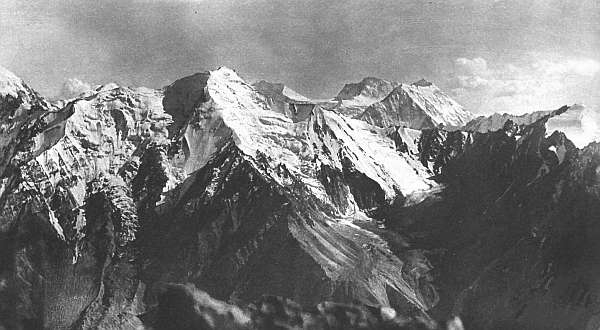

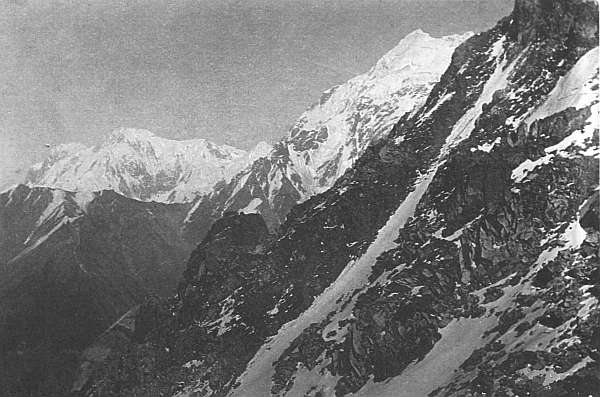

| The Mazeno Peaks from the Red Pass, | " " | 74 |

| The Diamirai Peak from the Red Pass, | " " | 88 |

| View of the Diamirai Peak from the Red Pass, | " " | 90 |

| On Nanga Parbat, from Upper Camp, | " " | 104 |

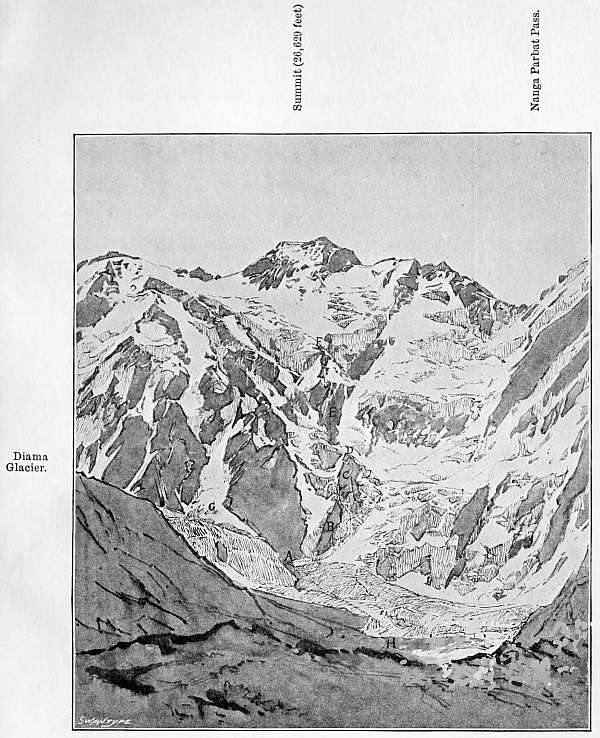

| Nanga Parbat from the Diamirai Glacier, | " " | 110 |

| Do. Do. Do., | " " | 112 |

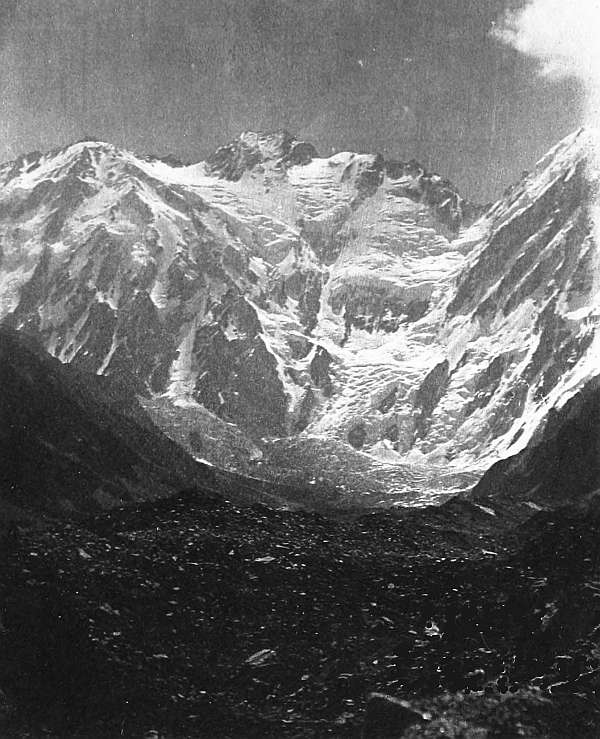

| View of Diama Glacier from Slopes of Diamirai Peak, | " " | 116 |

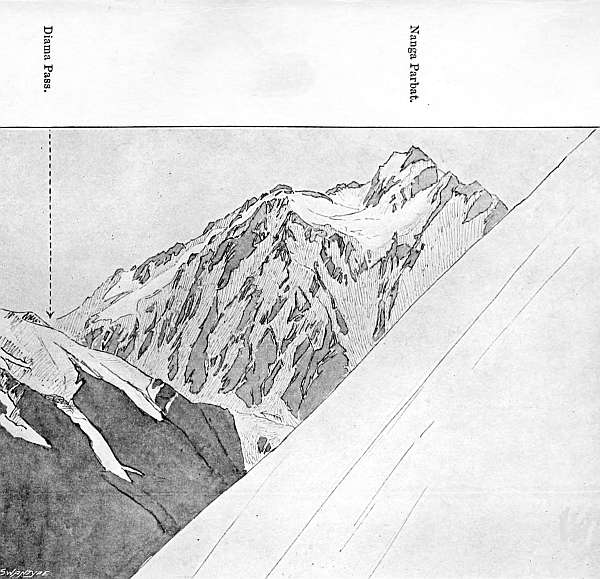

| The Diama Pass from the Rakiot Nullah, | " " | 120 |

| The Chongra Peaks from the Red Pass, | " " | 122 |

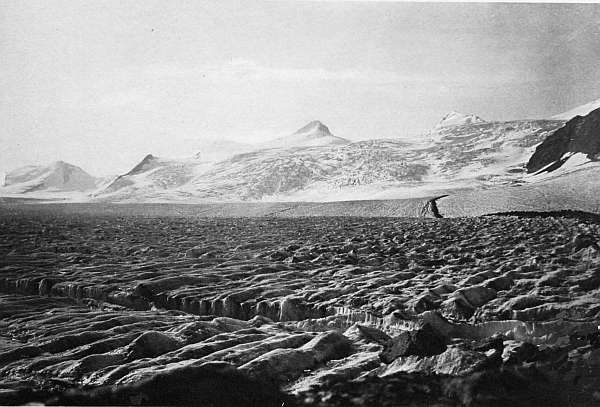

| The Freshfield Glacier, | " " | 148 |

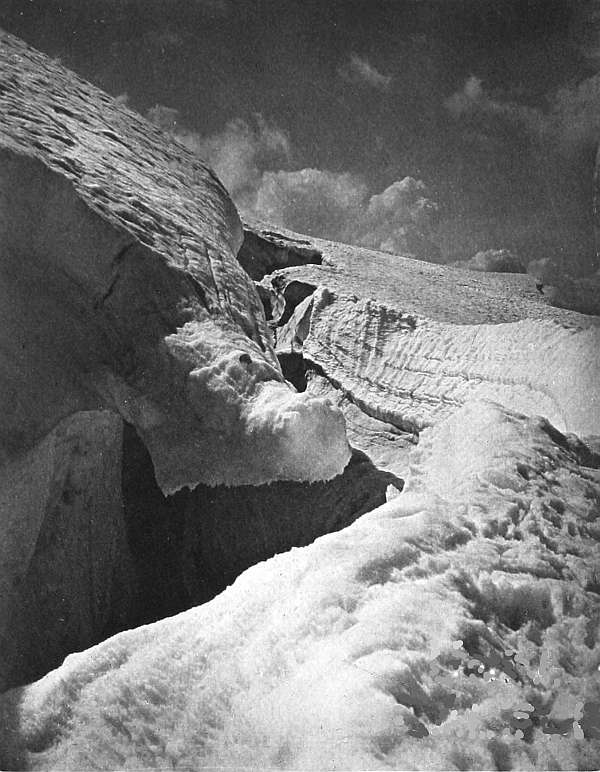

| A Crevasse on Mont Blanc, | " " | 166 |

| Lofoten, | " " | 186 |

| The Coolin, | " " | 212 |

| The Macgillicuddy's Reeks, | " " | 226 |

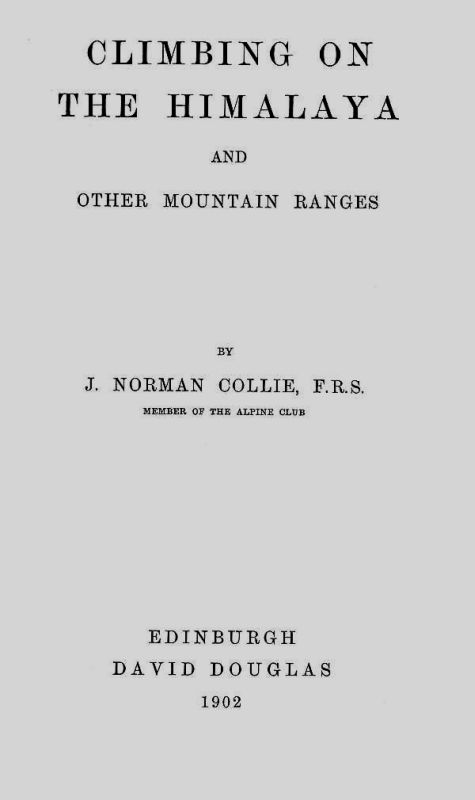

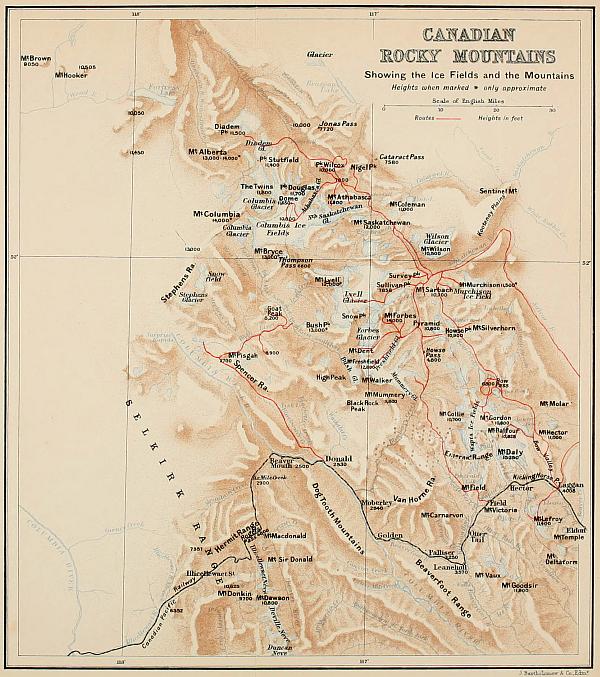

LIST OF MAPS

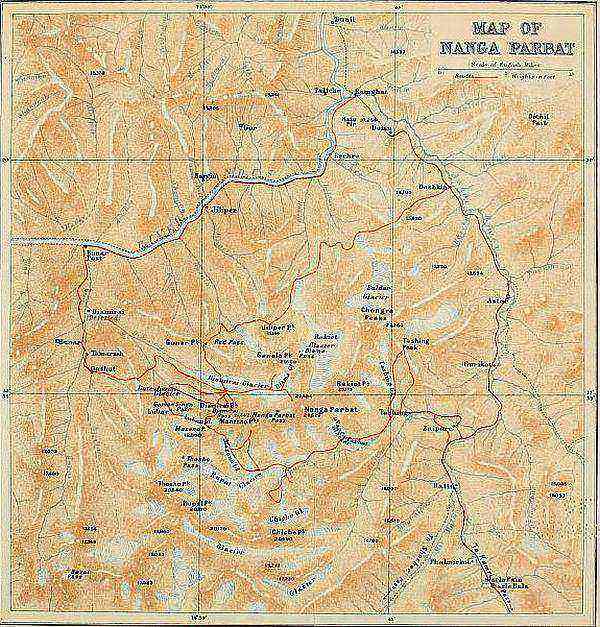

| Map of Kashmir, | To face page | 28 |

| Map of Nanga Parbat, | " " | 40 |

| Canadian Rocky Mountains. | ||

| Map of the Ice-fields and the Mountains, | " " | 144 |

GENERAL HISTORY OF MOUNTAINEERING IN THE HIMALAYA

At some future date, how many years hence who can tell? all the wild places on the earth will have been explored. The Cape to Cairo railway will have brought the various sources of the Nile within a few days' travel of England; the endless fields of barren ice that surround the poles will have yielded up their secrets; whilst the vast and trackless fastnesses of that stupendous range of mountains which eclipses all others, and which from time immemorial has served as a barrier to roll back the waves of barbaric invasion from the fertile plains of Hindustan—these Himalaya will have been mapped, and the highest points in the world above sea-level will have been visited by man. Most certainly that time will come. Yet the Himalaya, [Pg 2] although conquered, will remain, still they will be the greatest range of mountains on earth, but will their magnitude, their beauty, their fascination, and their mystery be the same for those who travel amongst them? I venture to think not: for it is unfortunately true that familiarity breeds contempt.

Be that as it may, at the present time an enormous portion of that country of vast peaks has never been trodden by human foot. Immense districts covered with snow and ice are yet virgin and await the arrival of the mountain explorer. His will be the satisfaction of going where others have feared to tread, his the delight of seeing mighty glaciers and superb snow-clad peaks never gazed upon before by human eyes, and his the gratification of having overcome difficulties of no small magnitude. For exploration in the Himalaya must always be surrounded by difficulties and often dangers. That which in winter on a Scotch hill would be a slide of snow, and in the Alps an avalanche, becomes amongst these giant peaks an overwhelming cataclysm shaking the solid bases of the hills, and capable with its breath alone of sweeping down forests.

A Himalayan Camp.

The man who ventures amongst the Himalaya in order that he may gain a thorough knowledge of them must of necessity be a mountaineer as well as a mountain traveller. He must delight not only in finding his way to the summits of the mountains, but also in the beauties of the green valleys below, in the bare hill-sides, and in the vast expanses of glaciers and snow and ice; moreover his curiosity must not be confined to the snows and the rock ridges merely as a means for exercising an abnormal craze for gymnastic performances, or he will show himself to be 'a creature physically specialised, perhaps, but intellectually maimed.'

For in order to cope with all the difficulties as they arise, and to guard against all the dangers that lurk amidst the snows and precipices of the great mountains, a high standard, mental as well as physical, will be required of him who sets out to explore the Himalaya: he must have had a long apprenticeship amidst the snow-peaks and possess, too, geographical instincts, common sense, and love of the mountains of no mean order.

During these latter years few sports have developed so rapidly as mountaineering; nor is this to be wondered at, for no sport is more in harmony with the personal characteristics of the Englishman. When he sets out to conquer unknown peaks, to spend his leisure time in fighting with the great mountains, it is usually no easy task he places in [Pg 4] front of himself; but in return there is no kind of sport that affords keener enjoyments or more lasting memories than those the mountaineer wrests from Nature in his playground amongst the hills.

Mountaineering, moreover, is a sport of which we as a nation should be proud, for it is the English who have made it what it is. There are many isolated instances of men of other nationalities who have spent their time in climbing snow-peaks and fighting their way through mountainous countries; but when we inquire into the records of discovery amongst the mountain ranges of the world—in the Alps, the frosty Caucasus, the mighty Himalaya, in the Andes, in New Zealand, in Norway, wherever there are noble snow-clad mountains to climb, wherever there are difficulties to overcome—it is usually Englishmen that have led the way.

For the pure love of sport they have fought with Nature and conquered; others have followed after; and the various Alpine Clubs which have been founded during the last twenty years are witnesses of the fact that mountaineering is now one of the pastimes of the world. It has taken its place amongst our national sports, and every year sees a larger number of recruits filling the ranks.

In one volume of that splendid collection of books which could have been produced nowhere [Pg 5] else but in England—the 'Badminton Library of Sports and Pastimes'—we find Mr. C. E. Mathews writing: 'I can understand the delight of a severely contested game of tennis or rackets, or the fascination of a hard-fought cricket-match under fair summer skies. Football justly claims many votaries, and yachting has been extolled on the ground (amongst others) that it gives the maximum of appetite with the minimum of exertion. I can appreciate a straight ride across country on a good horse, and I know how the pulse beats when the University boats shoot under Barnes bridge with their bows dead level, to the music of a roaring crowd; and yet there is no sport like mountaineering.' This was written for a book on mountaineering, but it may be truthfully said, without making distinctions between sports of various kinds, all of which have their votaries, that a sport that demands from those who would excel in its pursuit the utmost efforts, both physical and mental, not for a few hours only, but day after day in sunshine and in storm—a sport whose followers have the whole of the mountain ranges of the world for their playground, where the most magnificent scenery Nature can lavish is spread before them, where success means the keenest of pleasure, and defeat is unattended by feelings of regret; where friendships are [Pg 6] made which would have been impossible under other circumstances—for on the mountains the difficulties and the dangers shared in common by all are the surest means for showing a man as he really is—a sport which renews our youth, banishes all sordid cares, ministers to mind and body diseased, invigorating and restoring the whole—surely such a sport can be second to none!

But as access to the Alps and other snow ranges becomes easier year by year, the mountaineer, should he wish to test his powers against the unclimbed hills, must perforce go further afield. There are still, however, unclimbed mountains enough and to spare for many years yet to come.

In the Himalaya the peaks exceeding 24,000 feet in height, that have been measured, number over fifty,[A] whilst those above 20,000 feet may be counted by the thousand. Every year, officers of the Indian Army and others in search of game wander through the valleys which come down from the great ranges, but up to the present time only a few mountaineering expeditions have been made to this marvellous mountain land. For this there are many reasons. The distance of India from England precludes the busy man from spending his summer vacation there; the natural difficulties of the [Pg 7] country, the lack of provisions, the total absence of roads, and lastly, the disturbed political conditions, make any ordinary expedition impossible. Moreover, although the English are supposed to hold the southern slopes of the Himalaya, yet it is a curious fact that almost from the eastern end of this range in Bhutan to the western limit in the Hindu Kush above Chitral we are rigorously excluded. About the eastern portion of the Himalaya in Bhutan, and the mountains surrounding the gorge through which the Bramaputra flows, we know very little, as only some of the higher peaks have been surveyed from a distance. Next in order, to the westward, comes Sikkim, one of the few districts in the Himalaya where Europeans can safely travel under the very shadows of the great peaks. Next comes the native state of Nepaul, stretching for five hundred miles, the borders of which no white man can cross, except those who are sent by the Indian Government as political agents, etc., to the capital, Katmandu. It is evident at once to any one looking at the map of India, that Nepaul and Bhutan hold the keys of the doors through which Chinese trade might come south. The breaks in the main chain in many places allow of trade-routes, and in times gone by even Chinese armies have poured through these passes and successfully invaded Nepaul. [Pg 8]

The idea of establishing friendly relations between India and this Trans-Himalayan region was one of the many wise and far-reaching political aspirations of Warren Hastings. On it he spent much of his time and thought. His policy was carried out consistently during the time he was Governor-General of India, and commercial intercourse during that period seemed to be well established. Four separate embassies were sent to Bhutan, one of which extended its operations to Tibet. This first British Mission to penetrate beyond the Himalaya was that under Mr. George Bogle in 1774. But on the removal of Warren Hastings from India, these admirable methods of establishing a friendly acquaintance with the powers in Bhutan and Tibet were at once abandoned. It is true that a quarter of a century later, in 1811, Mr. Thomas Manning, a private individual, performed the extraordinary feat of reaching Lhasa, and saw the Dalai Lama, a feat that to this day has not been repeated by an Englishman. But when the guiding hand and head of Warren Hastings no longer ruled India, this commercial policy sank into complete oblivion. From that day to the present little intercourse of any kind seems to have been held between the [Pg 9] English Government and those states in that border land between India and China.[B]

On the west of Nepaul lie Kumaon, Garhwal, Kulu, and Spiti. Through most of these districts the Englishman can wander, which is also the case with Kashmir to a certain extent.

The sources of the rivers that emerge from these Himalayan mountains are almost unknown, except in the case of the Ganges, which rises in the Gangootri peaks in Garhwal. The upper waters of the Indus, the Sutlej, the Bramaputra (or Sanpu), and the numberless rivers emerging from Nepaul and flowing into the Ganges, in almost every case come from beyond the range we call the Himalaya. Their sources lie in that unknown land north of the so-called main chain. Whether there is a loftier and more magnificent range behind is at present doubtful, but reports of higher peaks further north than Devadhunga (Mount Everest) reach us from time to time. The Indian Government occasionally sends out trained natives from the survey department to collect information about these districts where Englishmen are forbidden to go, and it is to their efforts that the various details [Pg 10] we find on maps relating to these countries are due. Some day the lower ranges leading up to the great snow-covered mountains will be opened to the English. Sanatoria will be established, tea plantations will appear on the slopes of the Nepaulese hills, as is now the case at Darjeeling, and then only will the exploration of the mountains really begin, for which, at the present day, as far as Tibet and Nepaul are concerned, we have even less facilities than the Schlagintweits and Hooker had forty to fifty years ago.

From the mountaineer's point of view, little has been accomplished amongst the Himalaya, and of the thousands of peaks of 20,000 feet and upwards hardly twenty have been climbed. The properly equipped expeditions made to these mountains merely for the sport of mountaineering may be said to be less than half a dozen. Of course the officers in charge of the survey department have done invaluable work, which, however, often had to be carried out by men unacquainted (from a purely climbing point of view) with the higher developments of mountain craft. To this, however, there are exceptions, notably Mr. W. H. Johnson, who worked on the Karakoram range.

To omit work done by the earlier travellers, the first prominent piece of mountaineering seems to [Pg 11] have been achieved by Captain Gerard in the Spiti district. In the year 1818 he attempted the ascent of Leo Porgyul, but was unsuccessful after reaching a height of 19,400 feet (trigonometrically surveyed). Ten years later he made the first successful ascent of a mountain (unnamed) of 20,400 feet. Speaking of his wanderings in 1817-21, he says: 'I have visited thirty-seven places at different times between 14,000 and 19,400 feet, and thirteen of my camps were upwards of 15,000 feet.' During the years 1848-49-50 Sir Joseph Hooker made his famous journeys into the Himalaya from Darjeeling through Sikkim. Obtaining leave to travel in East Nepaul, he traversed a district that since then has been entirely closed to Europeans. By travelling to the westward of Darjeeling he crossed into Nepaul, explored the Tambur river as far as Wallanchoon, whence he ascended to the head of a snow pass, 16,756 feet, leading over to the valley of the Arun river, which rises far away northward of Kanchenjunga. On the pass he experienced his first attack of mountain sickness, suffering from headache, giddiness, and lassitude. At this point he was probably nearer to Devadhunga[C] (Mount Everest) than any European has ever been, the mountain being only fifty miles away. From the [Pg 12] summit of another pass in East Nepaul, the Choonjerma pass, 16,000 feet, he no doubt saw Devadhunga. From here he returned to Sikkim, and travelled to Mon Lepcha, immediately at the south-west of Kanchenjunga. During the next year he visited the passes on the north-east of Kanchenjunga leading into Tibet and ascended three of them, the Kongra Lama pass, 15,745 feet; the Tunkra pass, 16,083 feet; and the Donkia pass, 18,500 feet. From Bhomtso, 18,590 feet, the highest and most northerly point reached by him, a magnificent view to the northward into Tibet was obtained; and Dr. Hooker mentions having seen from this point two immense mountains over one hundred miles distant to the north of Nepaul. It was during his return to Darjeeling that he and Dr. Campbell were made prisoners by the Raja of Sikkim.

During the years 1854-58 the two brothers, Adolf and Robert Schlagintweit wandered through a large portion of the Himalaya. They were the first explorers who possessed any real knowledge of snow work, having gained their experience in the Alps. Starting from Nynee Tal they followed the Pindar river to its source, just under the southern slopes of Nanda Devi. Then crossing to the north-east by a pass about 17,700 feet high, they reached Milam on the Gori river, whence they [Pg 13] penetrated into Tibet over several passes averaging 18,000 feet. In this district, never since visited by Europeans, they made more than one glacier expedition, finally returning over the main chain, close to Kamet or Ibi Gamin (25,443 feet), on the slopes of which they remained for a fortnight, their highest camp being at 19,326 feet. An unsuccessful attempt was made on the peak, for they were forced to retreat after having reached an altitude of 22,259 feet. Returning over the Mana pass to the valley of the Sarsuti river, they descended to Badrinath. The upper valley of the Indus north of Kashmir was next explored, and Adolf, having crossed the Karakoram pass, was murdered at Kashgar.[D] In the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal (vol. xxxv.) will be found a paper by the two brothers on the 'Comparative Hypsometrical and Physical Features of High Asia, the Andes, and the Alps,' which deals in a most interesting manner with the respective features of these several mountain ranges.

In the years 1860-1865 Mr. W. H. Johnson, whilst engaged on the Kashmir Survey, established a large number of trigonometrical stations at a height of over 20,000 feet. One of his masonry [Pg 14] platforms on the top of a peak 21,500 feet high is said to be visible from Leh in Ladâk. The highest point he probably reached was during an expedition made from the district Changchenmo north of the Pangong lake in the year 1864. Travelling northwards he made his way through the mountains to the Yarkand road, and at one point, being unable to proceed, he found it necessary to climb over the mountain range at a height of 22,300 feet, where the darkness overtook him, and he was forced to spend the night at 22,000 feet. In the next year, 1865, on his journey to Khutan he was obliged to wait for permission to enter Turkestan; and being anxious to obtain as much knowledge of the country to the north as possible, he climbed three peaks—E57, 21,757 feet; E58, 21,971 feet; and E61, 23,890 feet (?). The heights of the first two mountains have been accurately determined by a series of trigonometrical observations, but there has probably been some error made in the height of the last, E61.

Mr. Johnson was a most enthusiastic mountaineer, and, owing to a suggestion made by him and Mr. Drew to the Asiatic Society of Bengal, efforts were made in 1866 to form a Himalayan Club, but through want of support and sympathy the club was never started. Mountaineering was [Pg 15] indeed in those days so little appreciated by the political department of India that this journey of Mr. Johnson's in 1865 was made the excuse for a reprimand, owing to which he left the Service and took employment under the Maharaja of Kashmir.

About the same time that Johnson was exploring the district to the north and north-east of Ladák, the officers of the survey, Captain T. G. Montgomerie, H. H. Godwin Austen, and others, were actively at work on the Astor Gilgit and Skardu districts. They pushed glacier exploration much further than had been done before; and it is quite remarkable how much they accomplished when one considers that in those days climbers had only just learned the use of ice-axes and ropes, and the knowledge of ice and snow even in the Alps was very limited. The exploration of the Baltoro glacier, the discovery of the second highest peak in the Himalaya—K2, 28,278 feet—and the peaks Gusherbrum and Masherbrum, by H. H. Godwin Austen, and his ascent of the Punmah glacier to the old Mustagh pass will remain as marvels of mountain exploration.

In the next ten or fifteen years but little mountaineering was done in the Himalaya. The Government Survey in Garhwal, Kumaon, and Sikkim was carried on, and more correct maps of [Pg 16] the mountain ranges in these parts were issued. On Kamet about 22,000 feet was reached. In Sikkim, Captain Harman, during his work for the survey, made several attempts to climb some of the loftier peaks. He revisited the Donkia pass, and, like Dr. Hooker, saw from it the two enormous peaks far away to the north of Nepaul. In order to measure their height trigonometrically, he remained on the summit of the pass (18,500 feet) all night, but unfortunately was so severely frost-bitten that ultimately he was invalided home.

In the year 1883 Mr. W. W. Graham started for India with the Swiss guide Joseph Imboden, on a purely mountaineering expedition; he first went to Sikkim, then attacked the group round Nanda Devi in Garhwal, and later returned to Sikkim and the mountains near Kanchenjunga.

This expedition of Graham's remains still the most successful mountaineering effort that has been made amongst the Himalaya. No less than seven times was he above 20,000 feet on the mountains, the three highest ascents being, Kabru (Sikkim), 24,015 feet, A21 or Mount Monal (Garhwal), 22,516 feet, and a height of 22,500-22,700 feet on Dunagiri (Garhwal). It is perhaps to be regretted that Graham did not write a book setting forth in detail all his experiences, though a short account of [Pg 17] his travels and ascents may be found in vol. xii. of the Alpine Club Journal.

Arriving at Darjeeling early in 1883, he and Imboden made their way to Jongri just under Kanchenjunga on the south-west, and climbed a peak, Kang La, 20,300 feet. The Guicho La (pass), 16,000 feet, between Kanchenjunga and Pundim, was ascended, but as the end of March was much too early in the year for climbing, they returned to Darjeeling, and Imboden then went back to Europe. It was not till the end of June that Graham was joined by Emil Boss and Ulrich Kauffmann, who came out from Grindelwald. They started from Nynee Tal to attack Nanda Devi, travelling to Rini on the Dhauli river, just to the westward of Nanda Devi. From Rini they proceeded up the Rishiganga, which runs down from the glaciers on the west of Nanda Devi, but they were stopped in the valley by an impassable gorge that had been cut by a glacier descending from the Trisuli peaks. Obliged to retreat, they next attacked Dunagiri, 23,184 feet; after climbing over two peaks, 17,000 and 18,000 feet, they camped at 18,400 feet, and finally got to a point from which they could see the top of A22, 21,001 feet over the top of A21, 22,516 feet, and must therefore have been at least at a height of 22,700 feet. Unfortunately [Pg 18] hail, wind, and snow drove Graham and Boss off the peak within 500 feet of the top—Kauffmann had given in some distance lower down—and it was only with difficulty that they were able to return to their camp, which was reached in the dark.

The weather then obliged them to return to Rini, from which place they again started for Nanda Devi. This time they went up the north bank of the Rishiganga. After illness, the desertion of their coolies, and all the sufferings produced by cold and wet weather, they reached the glacier in four days, only to find that again they were cut off from it by a perpendicular cliff of 200 feet, down which the glacier torrent poured. Their attempt to cross the stream was also fruitless; so, baffled for the second time, they were forced to return to their camping-ground under Dunagiri at Dunassau, from which place they climbed A21, 22,516 feet, by the western ridge, calling it Mount Monal. They then tried A22, 21,001 feet, but were stopped by difficult rocks after reaching a point about 20,000 feet. By the middle of August Graham was back again in Sikkim and got to Jongri by September 2. With Boss and Kauffmann he explored the west side of Kabru and the glacier which comes down from Kanchenjunga. But the weather was continuously bad; they started to climb Jubonu, but were turned back. Then they [Pg 19] crossed the Guicho La to ascend Pundim, but found it impossible; more bad weather kept them idle till the end of the month. They then managed to ascend Jubonu, 21,300 feet. A few days later they went up the glacier which lies on the south-east of Kabru, camping at 18,400 feet; and starting at 4.30 A.M. they succeeded, owing to a favourable state of the mountain, in reaching the summit, 24,015 feet (or rather, the summit being cleft into three gashes, they got into one of these, about 30 feet from the true top). It was not till 10 P.M. that they returned to their camp. The last peak they ascended was one 19,000 feet on the Nepaul side of the Kang La. Thus ended this most remarkable series of ascents, carried out often under the most difficult circumstances. Graham, from his account of his travels, was evidently not a man to talk about all the discomforts and hardships of climbing at these altitudes, and this lack of information about his feelings and sensations above 20,000 feet has been urged against him as a proof that he never got to 24,000 feet at all. But any one who will take the trouble to read his account of the ascent of Kabru, cannot fail to admit that he must have climbed the peak lying on the south-west of Kanchenjunga, viz. Kabru, for there is no other high peak there which he could have ascended [Pg 20] from his starting-point except Kanchenjunga itself; moreover, unless he had climbed Kabru, neither he nor Emil Boss could have seen Devadhunga nor the two enormous peaks to the north-west, which they distinctly state must be higher than Devadhunga. Now, if they climbed Kabru, they were at a height of 24,000 feet whether they had a barometer with them or not, for that is the height determined by the Ordnance Survey. The heights reached in all their other completed ascents are vouched for in the same way, for if a mountain has been properly measured by triangulation, its height is known with a greater degree of accuracy than can ever be obtained by taking a barometer to the summit.

The next real mountaineering expedition after that of Graham was in 1892, when Sir Martin Conway, together with Major Bruce, and M. Zurbriggen as guide, explored a large part of the Mustagh range. In all they made some sixteen ascents to heights of 16,000 feet and upwards, the highest being Pioneer peak, 22,600 feet.

Arriving at Gilgit in May, when much winter snow still lay low down on the mountains, they first explored the Bagrot nullah. Here they ascended several glaciers and surveyed the country. But huge avalanches continually falling entirely stopped [Pg 21] any high climbing. They therefore went into the Hunza Nagyr valley as far as Nagyr. In the meantime, as the weather was bad, they investigated first the Samayar and afterwards the Shallihuru glaciers. At the head of the former a pass was climbed, the Daranshi saddle, 17,940 feet, and a peak called the Dasskaram needle, 17,660 feet. They then returned to the Nagyr valley and reached the foot of the great Hispar glacier, 10,320 feet. From here they travelled to the Hispar pass, 17,650 feet, nearly forty miles, thence down the Biafo glacier, another thirty miles. The Hispar pass is therefore the longest snow pass traversed outside the Arctic regions. About half way up the Hispar glacier Bruce left Conway and climbed over the Nushik La, but joined him again later at Askole.

From Askole the Baltoro glacier was ascended. Near its head the summit of Crystal peak, 19,400 feet, on the north side of the valley, was reached. From the summit, the Mustagh tower, a rival in height to K2, 28,278 feet, was seen. To quote Conway's description: 'Away to the left, peering over a neighbouring rib like the one we were ascending, rose an astonishing tower. Its base was buried in clouds, and a cloud-banner waved on one side of it, but the bulk was clear, and the right-hand outline was a vertical cliff. We afterwards [Pg 22] discovered that it was equally vertical on the other side. This peak rises in the immediate vicinity of the Mustagh pass, and is one of the most extraordinary mountains for form we anywhere beheld.'

Two days later they made another climb on a ridge to the east, and parallel to the one previously climbed. From here they first saw K2. Amongst the magnificent circle of peaks that surrounded them at this spot, many of which were over 25,000 feet, one only seemed to offer any chance of being climbed. This was the Golden Throne. It stands at the head of the Baltoro glacier, differing greatly in form and structure from its neighbours; and of all the mountains it seemed most accessible.

Amongst, however, the enormous glaciers and snow-fields that eclipse probably those of any other mountains in ordinary latitudes, even to arrive at the beginning of the climbing was a problem of much difficulty. To again quote: 'We struggled round the base of the Golden Throne, up 2000 feet of ice-fall to a plateau where we camped; then we forced a camp on to a second, and again on to a third platform ... we got daily weaker as we ascended ... we finally reached the foot of the ridge which was to lead us, as we supposed, to the top of the Golden Throne. It was an ice-ridge, and not as we hoped of snow, [Pg 23] and it did not lead us to the top but to a detached point in the midst of the two main buttresses of the Throne.' This peak they named Pioneer peak, 22,600 feet. After this climb they returned to Kashmir.

Major Bruce, who accompanied Sir M. Conway in this expedition, has been climbing in the Himalaya for many years. In 1893, whilst at Chitral with Capt. F. Younghusband, he ascended Ispero Zorn. In July of the same year he made several ascents near Hunza on the Dhaltar peaks—the highest point reached being 18,000 feet. During August of the same year he climbed to 17,000 feet above Phekkar near Nagyr, with Captain B. E. M. Gurdon, and even in December, at Dharmsala, he had some mountaineering.

Major Bruce has done some excellent mountaineering in a district that may be said to be his alone, namely in Khaghan, a district south-west of Nanga Parbat and north of Abbottabad. Here, in company with Harkabir Thapa and other Gurkhas, a great deal of climbing has been accomplished, the district having been visited almost every year since 1894.

The best piece of climbing in Khaghan was the ascent of the most northern Ragee-Bogee peaks (16,700 feet), by Harkabir Thapa alone. This peak is close to the Shikara pass, though separated by one peak from it. [Pg 24]

Another district visited by Major Bruce in 1898 was in Ladák east of Kashmir—the Nun Kun range. Several new passes were traversed, and peaks up to 19,500 feet were climbed.[E]

There is certainly no mountaineer who has a record of Himalayan climbing to compare with Major Bruce's, ranging as it does from Chitral on the west to Sikkim on the east. In fact, to show how the mountains exercise a magnetic influence on him, in the summer of 1898 he saw, what no one had ever seen before, in the short space of two months, the three highest mountains in the world: Devadhunga, K2, and Kanchenjunga.

In 1898 Dr. and Mrs. Bullock Workman traversed several passes in Ladák, Nubra, and Suru; and in 1899, with M. Zurbriggen as guide, went to Askole and up the Biafo glacier to the Hispar Pass. Then they climbed the Siegfried Horn, 18,600 feet, and Mount Bullock-Workman, 19,450 feet, both near the Skoro La. Afterwards, returning to the Shigar valley, Mount Koser Gunge, 21,000 feet, was ascended.

The last mountaineering expedition to the Himalaya was that of Mr. Douglas Freshfield, who, in company with Signor V. Sella, Mr. E. Garwood, and A. Maquignaz as guide, made the tour of Kanchenjunga, crossing the Jonsong La, 21,000 feet.

OUR JOURNEY OUT TO NANGA PARBAT

Amongst mountaineers, who has not at some time or another looked at the map of India, wishing at the same time for an opportunity to visit the Himalaya? to see Kanchenjunga, Devadhunga, Nanda Devi, Nanga Parbat, or any of the hundreds of snow-clad mountains, every one of which is higher than the loftiest peaks of other lands? to wander through the valleys filled with tropical vegetation until the higher grounds are reached, where the great glaciers lie like frozen rivers amidst the white mountains, while the green pasturages and pine woods below bask in the sunshine? to travel through the land where all natural things are on [Pg 26] a big scale, a land of great rivers and mighty mountains, a land where even the birds and beasts are of larger size, a land that was peopled many centuries ago with civilised races, when Western Europe was in a state of barbarism? But these Himalaya are far away, and often as one may wish some day to start for this marvellous land, yet the propitious day never dawns, and less ambitious journeys are all that the Fates will allow. Although it had seemed most unlikely that I should ever be fortunate enough to visit the Himalaya, yet at last the time arrived when my dream became a reality. I have seen the great mountains of the Hindu Kush and the Karakoram ranges, from Tirach Mir over Chitral to K2 at the head of the Baltoro glacier; I have wandered in that waste land, the marvellous gorge of the Indus. I have stopped at Chilas, one of the outposts of civilisation in the wild Shinaki country, where not many years ago no white man could venture. I have passed through the defile at Lechre, where in 1841 a landslip from the northern buttress of Nanga Parbat dammed back the whole Indus for six months, until finally the pent-up masses of water, breaking suddenly through the thousands of feet of debris, burst with irresistible force down through that unknown mountain-land lying [Pg 27] below Chilas for many hundreds of miles, till at last the whirling flood, no longer hemmed in by the hills, swept out on to the open plains near Attock, and in one night annihilation was the fate of a whole Sikh army. Also I have seen the northern side of the mighty Nanga Parbat, the greatest mountain face in the whole world, rising without break from the scorching sands of the Bunji plain, first to the cool pine woods and fertile valleys five thousand feet above, next to the glaciers, and further back and higher to the ice-clad avalanche-swept precipices which ring round the topmost snows of Nanga Parbat itself, whose summit towers 26,629 feet above sea-level, and 23,000 feet above the Indus at its base: whilst further to the northward Rakipushi and Haramosh, both 25,000 feet high, seem only to be outlying sentinels of grander and loftier ranges behind.

It was in 1894 that the late Mr. A. F. Mummery and Mr. G. Hastings arranged that if they could obtain permission from the Indian Government to visit that part of Kashmir in which Nanga Parbat lies, they would start from England in June 1895, and attempt the ascent. Early in 1895 I made such arrangements (owing to the kindness of Professor Ramsay of London University College) that I was able to join the expedition. [Pg 28]

We left England on June 20, joining the P. and O. steamer Caledonia at Brindisi. The voyage was delightful till we left Aden—even in the Red Sea the temperature never rising above 90°,—but once in the Indian Ocean we experienced the full force of the monsoon; and it was exceedingly rough from there to Bombay, which we reached on July 5. Two days later we arrived at Rawul Pindi, having had a very hot journey on the railway, a maximum of 103° being experienced between Umballa and Rawul Pindi.

At the latter place the foothills of the Himalaya were seen for the first time, rising out of the plains of the Panjab. And that night, amidst a terrific thunderstorm, the breaking of the monsoon on the hills, we slept in dak bungalow just short of Murree. From Rawul Pindi to Baramula, in the vale of Kashmir, an excellent road exists, along which one is able to travel in a tonga. These strongly built two-wheel carriages complete the journey of about one hundred and seventy miles in two or three days. Owing, however, to the monsoon rain, we found the road in many places in a perilous condition. Bridges had been washed away, great boulders many feet thick had rolled down the mountain-side sometimes to find a resting-place in the middle of the road, sometimes to go crashing through it; in one place the whole mountain-side was slowly moving down, road and all, into the Jhelum river below at the bottom of the valley. But on the evening of July 9 we safely reached Baramula.

Beyond Baramula it is necessary to take a flat-bottomed boat or punt, called a dunga, traversing the vale of Kashmir by water. This valley of Kashmir, about which so much has been written, is beyond all adequate description. Situated as it is, 6000 feet above sea-level, in an old lake basin amongst the Himalaya, its climate is almost perfect. A land of lakes and waterways, splendid trees and old ruins, vines, grass-lands, flowers, and pine forests watered by cool streams from the snow ranges that encircle it, with a climate during the summer months like that of the south of France—no wonder this valley of Kashmir is beautiful.

In length about eighty miles, and twenty-five miles in breadth, it lies surrounded by giant peaks. Haramukh, 16,903 feet, is quite close; to the eastward rise the Nun Kun peaks, 23,447 feet; whilst to the north Nanga Parbat, 26,629 feet high, can be seen from the hill stations. The atmospheric colours in the clear air are for ever changing, and no better description of them can be given than one [Pg 30] by Walter R. Lawrence in his classical work on the Valley of Kashmir, where as settlement officer he spent several years. He says, 'In the early morning the mountains are often a delicate semi-transparent violet, relieved against a saffron sky and with light vapours clinging round their crests. Then the rising sun deepens shadows and produces sharp outlines and strong passages of purple and indigo in the deep ravines. Later on it is nearly all blue and lavender with white snow peaks and ridges under a vertical sun, and as the afternoon wears on these become richer violet and pale bronze, gradually changing to rose and pink with yellow and orange snow, till the last rays of the sun have gone, leaving the mountains dyed a ruddy crimson, with snows showing a pale creamy green by contrast. Looking downward from the mountains, the valley in the sunshine has the hues of the opal; the pale reds of the Karéwá, the vivid light greens of the young rice, and the darker shades of the groves of trees, relieved by sunlit sheets, gleams of water, and soft blue haze, give a combination of tints reminding one irresistibly of the changing hues of that gem. It is impossible to do justice to the beauty and the grandeur of the mountains of Kashmir, or to enumerate the lovely glades and forests visited by so few.' [Pg 31]

Nowadays Kashmir is a prosperous country. But before the settlement operations were taken in hand (1887) by Lawrence the country-people were suffering from every kind of abuse and tyranny. Now it is all changed, and under the rule of Maharaja Pratab Singh, who resolved that this settlement should be carried out and gave it his loyal support, the country-folk are contented and prosperous; the fields are properly cultivated, without fear that the harvest will be reaped by some extortionate official; the houses are rebuilt, and the orchards, gardens, and vineyards are well looked after. It was not till my return from the mountains that I had a chance of spending a few days in this fascinating valley.

After leaving Baramula our route lay for some time up the Jhelum river, which drains most of the vale of Kashmir; but soon we emerged on the Woolar lake, and in the grey morning light the hills that completely encircle the valley could be partly seen through the long streams of white mist that draped them. The lake was perfectly calm, and reflected on its surface the nearer hills. Soon we came to miles of floating water-lilies in bloom, whilst on the banks quaint mud houses and farms, encircled with poplar, walnut, and chenar trees, were visible; and, beyond, great distances of grass lands and orchards stretched back to the mountains. [Pg 32]

But we were not across the lake. From the westward a rain-cloud was approaching, and soon the whole face of nature was changed. Small waves arose; then a blast of wind swept down part of the matting which served as an awning to our boat, and in a moment we were in danger of being swamped. The rowers at once began to talk wildly, evidently in great fear of drowning. Several other dungas, which were near and in the same plight as our own, came up, so all the boats were lashed together by ropes. Meanwhile the women and children (for the Kashmiri lives on the dunga with his wife and family) were screaming and throwing rice on the troubled waters, presumably to propitiate the evil beings who were responsible for the perilous state of affairs, and seemingly this offering to the gods was effective, for the angry deity, the storm-cloud, passed on, the wind dropped, and without further adventure we made land at Bandipur on the northern shore of the lake in warm sunshine.

Here we found ponies which had been hired for us by Major C. G. Bruce of the 5th Gurkhas. He had travelled all the way from Khaghan to Kashmir in order to engage servants, ponies, etc., [Pg 33] and had spent a fortnight out of a month's leave in arranging these matters for us who were strangers to him. Since that time I have seen much more of Bruce, but I shall always remember this kindness. I may also say that during the whole of our expedition the military and political officers, and others whom we met, invariably helped us in every way possible.

On July 11 we loaded the ponies with our baggage and started for Nanga Parbat. Our route lay over the Tragbal or Raj Diangan pass, 11,950 feet. On the further side we descended to Kanjalwan in the valley of the Kishnganga river. Up this valley about twelve miles is the village of Gurais, where we were nearly stopped by the tahsildar, a most important village official. We wanted more ponies, which he of course promised, but next morning they were not forthcoming. Messages were useless, and seemingly persuasion also was of no avail, he assuring us that there were no ponies, and telling us every kind of lie with the utmost oriental politeness. Mummery was, however, equal to the occasion. He wrote out a telegram, which of course he never intended to send, the contents of which he had translated to the tahsildar. It was addressed to the British Resident at Srinagar, asking what should be done [Pg 34] with a miserable official at Gurais who would give us neither help nor ponies. The effect was magical. In less than ten minutes we had three times as many ponies as we wanted, and that too in a district where everything with four legs was being pressed into the service of the Gilgit commissariat. The tahsildar rode several miles up the valley with us, finally insisting that Mummery should ride his pony, and return it after two or three days when convenient.

Just above Gurais we left the valley of the Kishnganga, and turned to the left or north-east up the valley of the Burzil. From this valley two passes lead over the range into the country that drains down the Astor nullah to the Indus: the first is the Kamri, 12,438 feet, the second the Burzil or Dorikoon pass, 13,900 feet, over which the military road to Gilgit has been made. Both these passes ultimately lead to Astor. We chose the Kamri, for we were told that better forage for our ponies could be obtained on the northern slopes. We crossed the pass on July 14, finding still some of the winter snows unmelted on the top.

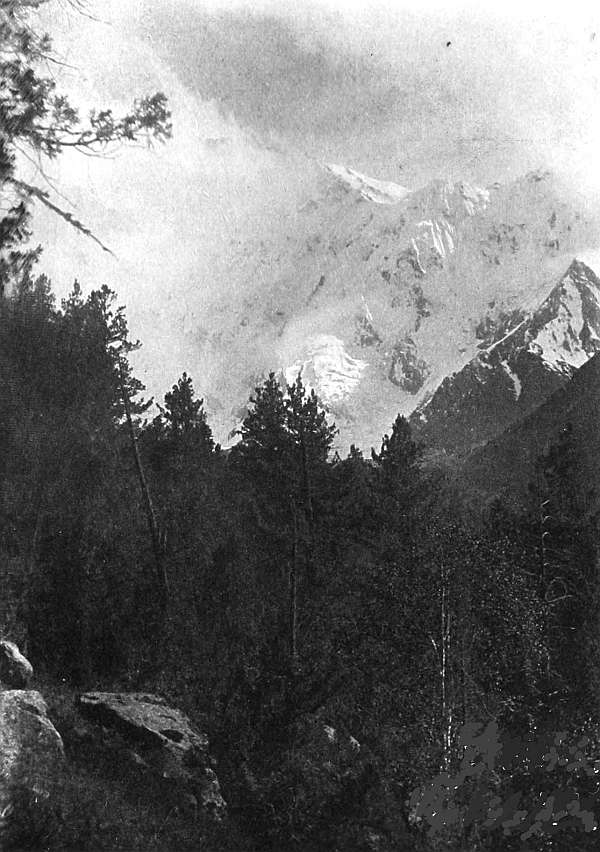

From the summit we had our first view of Nanga Parbat, over forty miles away, but rising in dazzling whiteness far above all the intervening ranges. There is nothing in the Alps that can at all [Pg 35] compare with it in grandeur, and although often one is unable to tell whether a mountain is really big, or only appears so, this was not the case with Nanga Parbat as seen from the Kamri. It was huge, immense; and instinctively we took off our hats in order to show that we approached in a proper spirit.

Two days later we camped at Rattu, where we found Lieutenant C. G. Stewart encamped with his mountain battery. He showed us the guns (weighing 2 cwt. each) which he had taken over the Shandur pass in deep snow when accompanying Colonel Kelly from Gilgit to the relief of Chitral. During this passage he became snow-blind.

The forcing of the Shandur pass was one of the hardest pieces of work in the whole of the relief of Chitral, and the moral effect produced was invaluable. For the Chitralis were under the impression that even troops without guns could not cross the pass. Imagine their consternation when a well-equipped force, together with a mountain battery, was at the head of the Mastuj river leading down to Chitral.

After we had been hospitably entertained by Lieutenant Stewart, and duly admired his splendid mule battery, we left the next day, July 16, and finally, in the dark that night, camped at the base [Pg 36] of Nanga Parbat. During the day the ponies that we had hired only came as far as a village named Zaipur, where we paid off our men, and sent them and the ponies back to Bandipur.

We did not, however, wish to camp at Zaipur, which lay on the south side of the Rupal torrent, but were anxious to cross to Chorit, a village opposite, and then go on to Tashing. How this was to be accomplished was not at first sight very plain. But the villagers were most willing to help, and those of the Chorit village came down on the further bank, in all about fifty to sixty men. Then bridge-building began; tons of stones and brushwood were built out into the raging glacier torrent; next pine trunks were neatly fixed on the cantilever system in these piers on both sides, and when the two edifices jutted far enough out into the stream, several thick pine trunks, about fifty feet long, were toppled across, and prevented from being washed down the stream by our Alpine ropes, which were tied to their smaller ends. Several of these trunks were then placed across between the two piers, and after three hours' hard work the bridge was finished. For this magnificent engineering achievement the headmen of the two villages were presented with two rupees. We did not camp at Tashing, but crossed the glacier [Pg 37] immediately above the village, and in a hollow amongst a grove of willows set up our tents.

We had taken twenty-seven days from London travelling continuously, but the weather was perfect. We were on the threshold of the unknown, and the untrodden nullahs round Nanga Parbat awaited us.

THE RUPAL NULLAH

'And thus these threatening ranges of dark mountain, which, in nearly all ages of the world, men have looked upon with aversion or with terror, are, in reality, sources of life and happiness far fuller and more beneficent than the bright fruitfulnesses of the plain.'—Modern Painters.

Our camp in the Rupal nullah was certainly most picturesque, pitched on a slightly sloping bank of grass, strewn with wildflowers and surrounded by a species of willow-tree which, during the hot midday sunshine, afforded most welcome shade. Firewood could be easily obtained in abundance from the dead stems and branches of the thicket, and water from a babbling stream which descended from the lower slopes of Nanga Parbat, almost within a stone's-throw of our tents.

Determined after our week's walk from Bandipur to make the most of our delightful camp, we spent the next day, July 17, in blissful laziness, doing hardly anything. We pretended now and again to busy ourselves with the tents and the baggage. A willow branch which hung in front of our tent door would need breaking off, or a rope tightening. But the day was really a holiday, and our most serious occupation was to bask in the warm sunshine and inhale the keen, bracing mountain air fresh from the snow-fields at the head of the Rupal nullah.

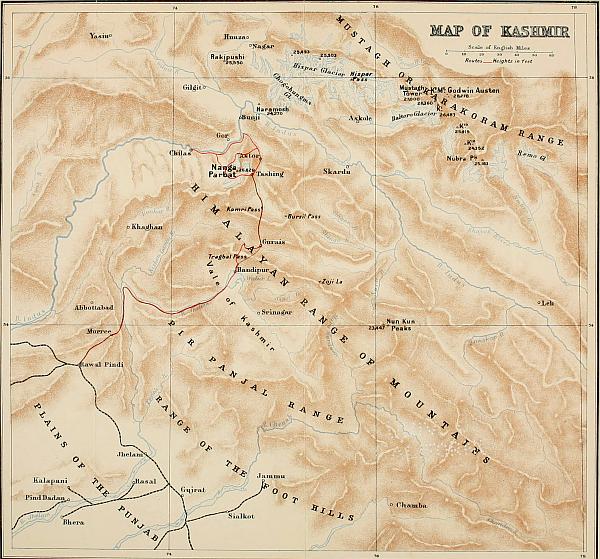

A Himalayan Nullah.

The sense of absolute freedom, of perfect contentment with our present lot, blessed gift of the mountains to their true and faithful devotees, was beginning to steal over us. Languidly we talked about the morrow, our only regret arising from our inability to catch a glimpse of that monarch of the mountains, Nanga Parbat, and the ice-fringed precipices which overhang his southern face.

The Rupal is the largest nullah close to Nanga Parbat. It runs eastwards from the peaks by the Thosho pass under the whole southern face of Nanga Parbat, till it joins the valley coming down from the Kamri pass, some eight miles below Tashing. The total length is about twenty-five miles in a straight line, but only those who have wandered in these Himalayan nullahs know how that twenty-five miles can be lengthened. The interminable ups and downs, which with endless repetition confront the traveller, now descending on to glaciers by steep moraine walls, now scrambling over loose stones and debris, or crossing from one side of the nullah to the other, all the variations [Pg 40] which a mountain path strews with such prodigality in the way, set measurement at defiance, and no man may tell the true length of a nullah twenty-five miles long. The inhabitants are wise; they speak only of a day's journey, and later we easily dropped into their ways, miles being hardly ever mentioned. In fact, to show how deceptive measurement by the map may be, when late in August we left the Diamirai nullah with the whole of our camp baggage to reach the next big nullah, the Rakiot, the traverse over two easy passes just below the snow-line took us no less than three days from early in the morning till late at night, though the distance as the crow flies is only ten miles.

Tashing, the village, which lay a few miles below us down the valley, is large and prosperous, the peasants owning many flocks and herds. Chickens, eggs, and milk are plentiful, and situated as it is some distance from the Gilgit road, any surplus stock of provisions is not depleted to the same extent as is the case with hamlets in the Astor valley. Sheep, which are small and not easy to obtain at Astor, may be purchased without difficulty at Tashing. Not many years ago Tashing used to be periodically raided by the Chilas tribesmen, who lived on the western slopes of the Nanga Parbat range. They, like the old border thieves, would swarm over the Mazeno and Thosho passes and lift all the sheep and goats they could find, sometimes even taking the women as well. This, however, is now completely stopped since we 'pacified' Chilas. Mountain robbers of course still harass the land, but they have been driven further to the westward, and now it is the Chilas folk themselves who are the victims. In fact we heard later that at the end of July the tribesmen from Kohistan and Thur (to the south-west of Chilas) were pillaging the country at the head of the Bunar and Barbusar nullahs, where they had killed several shepherds and driven away their flocks.

The Rupal nullah above Tashing is fairly fertile, the vegetation stretching up a considerable distance. Pine-trees and small brushwood flourish at the foot of the Rupal or main glacier, whilst for several miles further on the north side of the valley grass and dwarf rhododendron bushes grow. The glaciers from Nanga Parbat sweep across the valley much in the same way as the Brenva glacier sweeps across the Val Véni, cutting off the upper pasturages from the villages below. Of course the highest peak in the neighbourhood is Nanga Parbat itself. But those on the south-west of the Rupal nullah, rising as they do some 7000 to 8000 feet above the [Pg 42] floor of the valley, present a most magnificent spectacle. One especially (marked 20,730 feet) which stands alone at the head of the nullah, charms the eye with its beautiful form and exquisite lines of snow and rock. We christened it the Rupal peak, whilst its neighbour further west, almost its equal in size (20,640 feet), we named the Thosho peak.

Another summit (20,490 feet) to the eastward might, as it stands at the head of the Chiche nullah, appropriately be termed the Chiche peak, and the glacier which descends from it to the end of the Rupal glacier, the Chiche glacier. A very good idea of the relative size and form of the great main range of Nanga Parbat on the north side of the Rupal nullah may be obtained from the top of the Kamri pass. The ridge to the westward of the true summit of Nanga Parbat, stretching as far as the Mazeno La, does not culminate in any very pronounced peaks. The lowest point, probably 19,000 to 20,000 feet, lies a little over a mile directly west of the top of the mountain. We have called this dip in the ridge the Nanga Parbat pass, and two peaks marked 21,442 feet and 20,893 feet the Mazeno peaks. To the eastward of Nanga Parbat the Rakiot peak, a superb snow-capped mountain, rises to the height of 23,170 feet, and [Pg 43] here the main ridge turns considerably more to the north-east, ending in the twin Chongra peaks, 22,360 feet, which overlook Astor and the Chongra valley. Beyond these a sudden and abrupt fall in height of about 3000 feet occurs, and the ridge running more and more in a northerly direction, and never rising above 18,000 feet in height, constitutes the western boundary of the Astor valley.

The height of our camp in the Rupal nullah was calculated from observations made with a mercurial barometer. The difference in level between the two cisterns was 531 millimetres, from which observation it was 9900 feet above sea-level.[F]

We finally decided that it would be best to obtain a good view of the south face of Nanga Parbat before we made up our minds whether we should remain in the Rupal nullah. Two of us, Mummery and I, agreed to start the next day with the intention of combining business with pleasure; in fact, we had vague ideas about climbing the Chiche peak, 20,490 feet. [Pg 44]

On July 18 we set out early. Our route lay up the north side of the Rupal nullah through the fields of the small hamlet of Rupal. The morning light, the ripening crops waving in the sunshine, and the fields backed by pine woods, glaciers, and snow-peaks, were very beautiful. Unfortunately, as is usual in this part of the Rupal nullah, we were unable to obtain any view of the great peak of Nanga Parbat, our path taking us directly underneath it. Above the Rupal village the Nanga Parbat glacier sweeps across the valley from underneath the summit of the peak. This glacier, which owes its formation to avalanches perpetually falling down the southern face of the mountain, lies across the Rupal nullah almost at right angles, and forms a huge embankment varying from 500 to 800 feet high. The route up the nullah here turns off to the right, following a hollow which has been formed between the mountain-side and the true left bank of the glacier, and which we found well wooded, with a clear stream running down the centre. In all the larger nullahs the same conditions were conspicuous: usually for several miles up the valley above the end of the glacier a subsidiary valley would exist, between the side moraine of the glacier and the hill-side. These side moraines are often clothed with huge pine-trees, whilst below, birches [Pg 45] and willows, dwarf rhododendrons and wild roses, cover the pasturages.

A climb of about 200 feet is necessary to take one on to the Nanga Parbat glacier, which at this point is flush with the top of the moraine, and, like so many others in this district, is littered with stones of all sizes. Though much more uneven, it is similar to the lower end of glaciers such as the Zmutt or the Miage. On the west side of the glacier a steep descent must be made down on to the bottom of the Rupal nullah. The floor of the valley here is carpeted with masses of brushwood. As one proceeds up the nullah two more glaciers, similar to the Nanga Parbat glacier, descend at a steep angle from the big peak, but do not stretch quite across the valley, and can be passed by walking round between their ends and the Rupal torrent. Just below the Rupal glacier itself, a well-wooded stretch of pasture-land opens out, studded with pines and other trees. Here it was that we saw, or thought we saw, our first red bear; he was some way off, but the keen-eyed shikari saw the bushes moving, and assured us that the movement was due to a 'Balu,' and as there were traces of these animals in every direction, probably the shikari was right.

Having made up our minds to camp just at the end of the Chiche glacier, we tried to effect a crossing [Pg 46] over the Rupal torrent which looked quite shallow in several places, but these mountain streams are very deceptive. From a distance of a hundred yards nothing seems more easy than to wade across, but to any one in the swirling torrent the aspect of affairs is very different; ice-cold water with insecure and moving stones below is by no means conducive to a rapid crossing, and our shikari, who first essayed it, made but little advance. Ultimately he edged his way safely back to land, but still on the same side of the stream. Mummery, who was not to be beaten, next made a determined effort, but in his turn had to retreat after having been very nearly swept off his feet. There was, however, an alternative route. By ascending the valley to the end of the Rupal glacier a path would doubtless easily be found on the ice which would take us across to our camping-ground for the night. We were not disappointed, and soon found a spot where our tents could be pitched. The day had been more or less misty, but towards sunset the clouds began partially to roll off the peaks. Then in the gleaming gold of a Himalayan sunset we beheld the southern face of Nanga Parbat. Eagerly we scanned every ridge and glacier, as naturally we preferred to attack the peak if possible from the well-provisioned and hospitable Rupal [Pg 47] nullah. Should we be unable to find a feasible route on this side, then it would be necessary to move our base of operations over the range into the wild Chilas country, about which we knew very little, but where we were certain supplies would be difficult to obtain. Knight, who was at Astor in 1891, writes of the Chilas country as follows:—

'That white horizon so near me was the limit of the British Empire, the slopes beyond descending into the unexplored valleys of the Indus where dwell the Shinaka tribesmen. Had I crossed the ridge with my followers, the first human beings we met would in all probability have cut our heads off.'

Our survey of the south of Nanga Parbat was not very encouraging; directly above the Rupal nullah the mountain rose almost sheer for 14,000 to 15,000 feet. Precipice towered above precipice. Hanging glaciers seemed to be perched in all the most inconvenient places, whilst some idea of the average angle of this face may be obtained from the map. The height of the glacier directly under the summit is about 11,000 to 12,000 feet—that is to say, in about two miles or less, measured on the map, there is a difference in height of 15,000 feet. In the Alps one can only compare it in acclivity with the Mer de Glace face of the Charmoz and [Pg 48] Grépon. On the south face of the Matterhorn or of Mont Blanc a mile measured on the map would probably only make a difference in height of some 5000 and 7000 feet respectively. To come to more familiar instances, the top of the Matterhorn rises 8000 to 9000 feet above Zermatt, but it is distant some six or seven miles; whilst the summit of Mont Blanc, which is 12,000 feet higher than Chamounix, is about eight miles off.

One route however seemed to offer some hopes of success. By climbing a very steep rock buttress and then traversing an ice ridge, which looked like a very exaggerated copy of the one on the Brenva route up Mont Blanc, a higher snow-field could be gained, from which the Nanga Parbat pass seemed easy of access. But as the pass was not much over 20,000 feet, at least another 6000 feet would have to be ascended, and the rocky ridge which connected it with the summit would tax the climbers' powers to the utmost. An obvious question also arose as to the possibility of pushing camps with provisions up to 20,000 feet by this route, for we were agreed that our highest camp must at least be somewhere about that altitude.

But the evening mists again drifted over the magnificent range opposite and soon hid the upper part of the mountain. They did not finally disappear [Pg 49] till long after sunset. In the meantime we contented ourselves with planning our expedition for the morrow by the light of the camp fire. The height of the camp by mercurial barometer was 12,150 feet.

Before daylight next day we started up the middle of the Chiche glacier, accompanied by two of our Kashmiri servants. Stones without number covered the ice, and our lanterns only sufficed to show how unpleasant our path on the glacier was likely to prove. Soon the cold grey of the morning revealed the Chiche peak straight in front of us, a dim and colourless shadow. Quickly the dawn rose; we saw the bare precipitous ice slopes on its northern face, scored everywhere by avalanche grooves, and the loneliness of the scene impressed itself upon us. We were entering on a new land, a country without visible trace of man; probably we were the first who had ever ventured into its recesses. No breeze stirred, and the eastern sun slanting across the peaks threw jagged shadows over the snows; soon rising higher in the heavens, it topped the ridges and bathed us in its warm glow.

At once the glacier wakened into life, and as the stones on the surface were loosened from the frozen grip of night, those which were insecurely perched would ever and again fall down the slippery ice; [Pg 50] then would we hear a grating noise followed by a deep thud or booming splash. These luckless stones had 'left the warm precincts of the cheerful day,' and deep in the cavernous hollows of each crevasse or below the still green water of the glacier pools they rested, till such time as the crushing heel of the relentless ice should grind them slowly to powder.

Grand and solemn in the perfect summer's morning was my introduction to the snow world of the mighty Himalaya. The great hills were around me once more. The peaks, ridges, ice-clad gullies, and stupendous precipices encircling me, sent the blood tingling through my veins; I was free to climb where I listed, and the whole of a long July day was before me. To those whose paths lie in more civilised and inhabited regions, this enthusiasm about wild and desolate mountains may seem unwarranted, may, perhaps, even savour of an elevation of fancy, a vain belief of private revelation founded neither on reason nor common sense. They probably will agree with Dr. Johnson, who writes of the Western Highlands of Scotland: 'It will readily occur that this uniformity of barrenness can afford little amusement to the traveller; that it is easy to sit at home and conceive rocks, heaths, and waterfalls, and that these journeys are useless [Pg 51] labours which neither impregnate the imagination nor inform the understanding.' The 'saner' portion of humanity, on the whole, are of one mind with the great Doctor, at least if one can judge from their utterances, and the votary of the mountains is often looked upon with pity as one who, being carried away by a kind of frenzy, is hardly responsible for his actions.

A sport like mountaineering needs no apology. Moreover, it has been so often and so ably defended by writers with ample knowledge of their subject, that nothing remains for me to say to this 'saner portion,' unless perhaps I might be allowed to quote the following oracular remark: '"But it isn't so, no-how," said Tweedledum. "Contrariwise," continued Tweedledee, "If it was so it might be; and if it were so it would be; but as it isn't, it ain't. That's logic."'

There are, however, those who accuse the mountaineer of worse things than a foolish and misguided enthusiasm about the waste places of the earth. I have often been told that this ardent desire for wild and rugged scenery is an unhealthy mental appetite, the result of the restless and jaded palate of the age, which must be indulged by new sensations, no matter at what cost. Why cannot the mountaineer rest content with the fertile valleys, [Pg 52] the grass-clad ranges, and the noble forests with the streams flashing in the sunlight? Why cannot he be satisfied with these simpler and more homely pleasures? To what end is this eagerness for scenes where desolation and naked Nature reign supreme, where avalanches thunder down the mountain-sides, where man has never lived, nay, never could live?

To a few the knowledge of the hills is given. They can wander free in the great snow world relying on their mountain craft; and should their imagination not be impregnated nor their understanding informed, then are their journeys indeed useless. For Nature spreads with lavish hand before them some of the grandest sights upon which human eye can gaze. Delicate, white, ethereal peaks like crystallised clouds send point after point into the deep azure blue sky. Driven snow, marvellously moulded in curving lines by the wind, wreathes the long ridges; and in the deep crevasses the light plays flashing backwards and forwards from the shining beryl blue sides: sights such as these delight the soul of the mountaineer and tempt him always onward.

The ever-varying clouds, forming, dissolving, and again collecting on the mountains, show, here a delicate spire of rock, undiscernible until the white curling vapour shuts out the black background, [Pg 53] there a lesser snow-peak tipped by the sunlight floating slowly across it and rimmed by the white border of the morning mists.

But it is needless for the lover of the mountains to describe these sights; the mere stringing together of word-pictures carries little conviction. The sailor who spends his life on the ocean might just as well attempt to awaken enthusiasm for a seafaring life in the minds of inland country-folk, by describing the magnificence of a storm at sea, when the racing waves drive by the ship and the wind shrieks in the rigging, or by telling them of voyages through summer seas when the fresh breezes and the long rolling billows speed the ship on its homeward way through the ever-changing waters.

The subject, however, must not be taken too seriously. No doubt the average individual has most excellent reasons for abstaining from climbing hills, whilst the mountaineer is, as a rule, more competent to ascend peaks than to explain their attractions; and to quote from a fragment of a lost MS.,[G] probably by Aristotle: 'Now, concerning the love of mountain climbing and the excess and deficiency thereof, as well as the mean which is also a virtue, let this suffice.' [Pg 54]

But I have wandered far from the Chiche glacier. Whether it was owing to our tremendous burst of enthusiasm which reacted on our ambition, or to a lack of muscle necessary for a hard day's work, nevertheless it must be recorded that presently our anxiety to climb the Chiche peak gradually dwindled, and after several tentative suggestions we both eagerly agreed that from a smaller summit just as good a view of Nanga Parbat could be obtained as from one 20,490 feet high.

We therefore turned our attention to a spur on our right which ran in a northerly direction from the Chiche peak. As the day wore on even this proved too much for us, and after tediously floundering through soft snow, and cutting steps up a small couloir of ice, a strange and fearsome process to our Kashmiris, we sat down to lunch, at a height of 16,000 feet, and basely gave up any ideas of higher altitudes. We were hopelessly out of condition. Below us on our left lay a most enticing rock ridge, where plenty of fun and excitement could be had, and from its precipitous nature in several places, it would evidently take us the rest of the afternoon to get back to our camp.

Clouds persistently interfered with the view of Nanga Parbat, but now and again its summit would shine through the drifting vapours, showing precipice above precipice. The eastern face of the [Pg 55] Chiche peak, which we saw edgeways, was superb. Nowhere in the Alps is there anything with which one can compare the savage black corrie which nestled right in the heart of the mountain, showing dark, precipitous walls of rock, with here and there a shelf where isolated patches of snow rested. This corrie forms one of the heads of the Chiche nullah, which would be worth visiting for this solitary and savage view alone. As we descended our rock-ridge we had to put on the rope, and soon experienced all the pleasures of the initiated. Our bold and fearless Kashmir servants got more and more alarmed; and the peculiar positions they occasionally thought it necessary to assume made us feel how sweet is the joy of being able to accomplish something that an inexperienced companion regards as impossible. In many places it was only by very great persuasion that they were induced to move. Many were the things they told in Hindustani, which we understood but imperfectly, though we gathered in a general way that no self-respecting Kashmiri would ever attempt to climb down such places, and that even the ibex and markhor would find it an impossibility, a true enough assertion, seeing that many of the small rock faces to be negotiated were practically perpendicular for fifteen or twenty feet. [Pg 56]

We reached our tents late in the afternoon to find that Hastings had come up from the lower camp. A council of war was then held. Evidently we were not in condition to storm lofty peaks; and in order to get ourselves into proper training, a walk round to the other side of Nanga Parbat was considered necessary. Hastings as arranged had brought up plenty of provisions, thus enabling the party to brave the snows and uninhabited wilds in front of them. Our immediate movements decided upon, we sat round the camp fire, dined, smoked, talked, and finally, when the stars were shining brightly above the precipice-encircled summit of Nanga Parbat opposite, retired into our sleeping-bags for the night.

FIRST JOURNEY TO DIAMIRAI NULLAH AND THE DIAMIRAI PASS

Early the next morning, before the sun had risen, we started for the Mazeno La, which should lead us into the wild and unknown Chilas country. We soon experienced the kind of walking that afterwards we found to be more often than not the rule. Loose stones of every size and description lay piled between the edge of the glacier and the side of the valley, and it was useless to attempt to walk on the glacier itself, for not only was it buried deep with debris, but was crevassed as well. For some distance we followed the northern or left bank, passing by the snout of a small ice-fall that came down from the main range of Nanga Parbat, and then turned to the right up and over an intervening spur, which finally brought us to the level [Pg 58] of the glacier that lay immediately under the Mazeno La. Across this our path lay in the burning sun of the morning. Before us, about 1500 feet higher up, was the pass; first the glacier was crossed, and then partly by rocks and partly over soft snow the way led upwards. Within a few hundred feet of the summit (18,000 feet) I experienced a violent attack of mountain sickness, and was hardly able to crawl to the top. This was the only time any of the party suffered at all, and later a slight headache or lassitude was the only symptom that I ever felt, even when at heights up to 20,000 feet.

The western face of the pass is much more precipitous than the one we had ascended, but by making use of an easy rock arête we soon got down (2000 feet) to the more level glacier below. The Mazeno La on the western side somewhat resembles the Zinal side of the Triftjoch, but is not quite so difficult.

The more active of our coolies, together with servants, were sent on with the instructions to camp on the right-hand side of the glacier as soon as they should come to any bushes out of which a fire could be made, but we were not destined that evening to camp in any comfort. Caught on the glacier by the darkness we were forced to sleep [Pg 59] for the night on a small plot of grass on the edge of the side moraine, 13,400 feet, and not till the next morning did we rejoin our coolies about a mile and a half lower down the valley. After we had obtained sufficient to eat we started down beside the glacier, which I have named the Lubar glacier on account of the small shepherds' encampment of that name just below the end of it. On our arrival at Lubar we made our first acquaintance with the Chilas folk, some of whom looked very wild and unkempt, but throughout our expedition we found them to be friendly enough, and never experienced any difficulty with them. Some sour and particularly dirty goats' milk out of huge gourds was their offering to us, and a small sheep, price four rupees, was purchased.

Our destination, however, was the Diamirai nullah on the north-west of Nanga Parbat, so we did not stay long, and winding away up the hill-side, leaving the Lubar stream far below us on the left, we first traversed a beautiful wood of birch-trees, and later got out on to the bare hill-side.