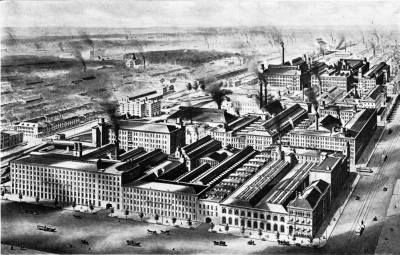

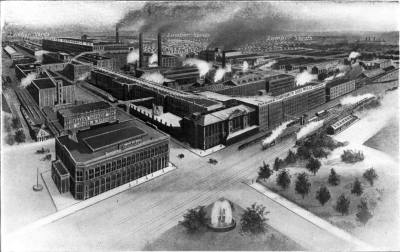

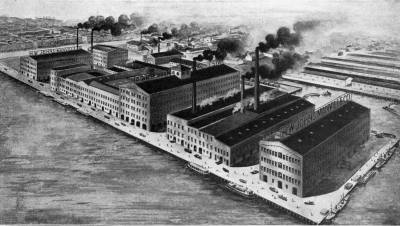

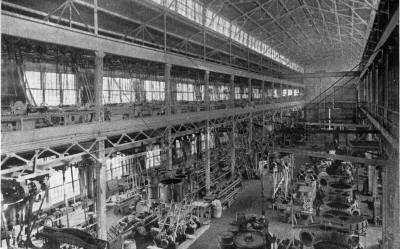

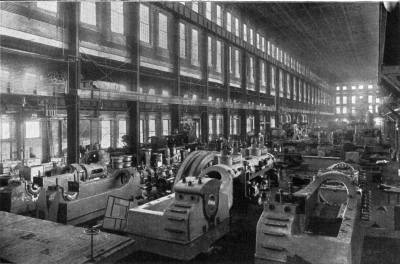

BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF THE BALDWIN LOCOMOTIVE WORKS, PHILADELPHIA, PENNA.

Cyclopedia

of

Commerce, Accountancy,

Business Administration

Volume 2

A General Reference Work on

ACCOUNTING, AUDITING, BOOKKEEPING, COMMERCIAL LAW, BUSINESS

MANAGEMENT, ADMINISTRATIVE AND INDUSTRIAL ORGANIZATION,

BANKING, ADVERTISING, SELLING, OFFICE AND FACTORY

RECORDS, COST KEEPING, SYSTEMATIZING, ETC.

Prepared by a Corps of

AUDITORS, ACCOUNTANTS, ATTORNEYS, AND SPECIALISTS IN BUSINESS METHODS AND MANAGEMENT

Illustrated with Over Two Thousand Engravings

TEN VOLUMES

CHICAGO

AMERICAN TECHNICAL SOCIETY

1910

Copyright, 1909

BY

AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CORRESPONDENCE

Copyright, 1909

BY

AMERICAN TECHNICAL SOCIETY

Entered at Stationers' Hall, London

All Rights Reserved

Authors and Collaborators

JAMES BRAY GRIFFITH, Managing Editor.

Head. Dept. of Commerce, Accountancy, and Business Administration, American School of Correspondence.

ROBERT H. MONTGOMERY

Of the Firm of Lybrand, Ross Bros. & Montgomery, Certified Public Accountants.

Editor of the American Edition of Dicksee's Auditing.

Formerly Lecturer on Auditing at the Evening School of Accounts and Finance of the University of Pennsylvania, and the School of Commerce, Accounts, and Finance of the New York University.

ARTHUR LOWES DICKINSON, F. C. A., C. P. A.

Of the Firms of Jones, Caesar, Dickinson, Wilmot & Company, Certified Public Accountants, and Price, Waterhouse & Company, Chartered Accountants.

WILLIAM M. LYBRAND, C. P. A.

Of the Firm of Lybrand, Ross Bros. & Montgomery, Certified Public Accountants.

F. H. MACPHERSON, C. A., C. P. A.

Of the Firm of F. H. Macpherson & Co., Certified Public Accountants.

CHAS. A. SWEETLAND

Consulting Public Accountant.

Author of "Loose-Leaf Bookkeeping," and "Anti-Confusion Business Methods."

E. C. LANDIS

Of the System Department, Burroughs Adding Machine Company.

HARRIS C. TROW, S. B.

Editor-in-Chief, Textbook Department, American School of Correspondence.

CECIL B. SMEETON, F. I. A.

Public Accountant and Auditor.

President, Incorporated Accountants' Society of Illinois.

[iv]Fellow, Institute of Accounts, New York.

JOHN A. CHAMBERLAIN, A. B., LL. B.

Of the Cleveland Bar.

Lecturer on Suretyship, Western Reserve Law School.

Author of "Principles of Business Law."

HUGH WRIGHT

Auditor, Westlake Construction Company.

GLENN M. HOBBS, Ph. D.

Secretary, American School of Correspondence.

JESSIE M. SHEPHERD, A. B.

Associate Editor, Textbook Department, American School of Correspondence.

GEORGE C. RUSSELL

Systematizer.

Formerly Manager, System Department, Elliott-Fisher Company.

OSCAR E. PERRIGO, M. E.

Specialist in Industrial Organization.

Author of "Machine-Shop Economics and Systems," etc.

DARWIN S. HATCH, B. S.

Assistant Editor, Textbook Department, American School of Correspondence.

CHAS. E. HATHAWAY

Cost Expert.

Chief Accountant, Fore River Shipbuilding Co.

CHAS. WILBUR LEIGH, B. S.

Associate Professor of Mathematics, Armour Institute of Technology.

L. W. LEWIS

Advertising Manager, The McCaskey Register Co.

MARTIN W. RUSSELL

[v]Registrar and Treasurer, American School of Correspondence.

HALBERT P. GILLETTE, C. E.

Managing Editor, Engineering-Contracting.

Author of "Handbook of Cost Data for Contractors and Engineers."

R. T. MILLER, JR., A. M., LL. B.

President, American School of Correspondence.

WILLIAM SCHUTTE

Manager of Advertising, National Cash Register Co.

E. ST. ELMO LEWIS

Advertising Manager, Burroughs Adding Machine Company.

Author of "The Credit Man and His Work" and "Financial Advertising."

RICHARD T. DANA

Consulting Engineer.

Chief Engineer, Construction Service Co.

P. H. BOGARDUS

Publicity Manager, American School of Correspondence.

WILLIAM G. NICHOLS

General Manufacturing Agent for the China Mfg. Co., The Webster Mfg. Co., and the Pembroke Mills.

Author of "Cost Finding" and "Cotton Mills."

C. H. HUNTER

Advertising Manager, Elliott-Fisher Co.

FRANK C. MORSE

Filing Expert.

Secretary, Browne-Morse Co.

H. E. K'BERG

Expert on Loose-Leaf Systems.

Formerly Manager, Business Systems Department, Burroughs Adding Machine Co.

EDWARD B. WAITE

Head, Instruction Department, American School of Correspondence.

Authorities Consulted

The editors have freely consulted the standard technical and business literature of America and Europe in the preparation of these volumes. They desire to express their indebtedness, particularly, to the following eminent authorities, whose well-known treatises should be in the library of everyone interested in modern business methods.

Grateful acknowledgment is made also of the valuable service rendered by the many manufacturers and specialists in office and factory methods, whose coöperation has made it possible to include in these volumes suitable illustrations of the latest equipment for office use; as well as those financial, mercantile, and manufacturing concerns who have supplied illustrations of offices, factories, shops, and buildings, typical of the commercial and industrial life of America.

JOSEPH HARDCASTLE, C. P. A.

Formerly Professor of Principles and Practice of Accounts, School of Commerce, Accounts, and Finance, New York University.

Author of "Accounts of Executors and Testamentary Trustees."

HORACE LUCIAN ARNOLD

Specialist in Factory Organization and Accounting.

Author of "The Complete Cost Keeper," and "Factory Manager and Accountant."

JOHN F. J. MULHALL, P. A.

Specialist in Corporation Accounts.

Author of "Quasi Public Corporation Accounting and Management."

SHERWIN CODY

Advertising and Sales Specialist.

Author of "How to Do Business by Letter," and "Art of Writing and Speaking the English Language."

FREDERICK TIPSON, C. P. A.

Author of "Theory of Accounts."

CHARLES BUXTON GOING

Managing Editor of The Engineering Magazine.

Associate in Mechanical Engineering, Columbia University.

Corresponding Member, Canadian Mining Institute.

F. E. WEBNER

Public Accountant.

Specialist in Factory Accounting.

[vii]Contributor to The Engineering Press.

AMOS K. FISKE

Associate Editor of the New York Journal of Commerce.

Author of "The Modern Bank."

JOSEPH FRENCH JOHNSON

Dean of the New York University School of Commerce, Accounts, and Finance.

Editor, The Journal of Accountancy.

Author of "Money, Exchange, and Banking."

M. U. OVERLAND

Of the New York Bar.

Author of "Classified Corporation Laws of All the States."

THOMAS CONYNGTON

Of the New York Bar.

Author of "Corporate Management," "Corporate Organization," "The Modern Corporation," and "Partnership Relations."

THEOPHILUS PARSONS, LL. D.

Author of "The Laws of Business."

E. ST. ELMO LEWIS

Advertising Manager, Burroughs Adding Machine Company.

Formerly Manager of Publicity, National Cash Register Co.

Author of "The Credit Man and His Work," and "Financial Advertising."

T. E. YOUNG, B. A., F. R. A. S.

Ex-President of the Institute of Actuaries.

Member of the Actuary Society of America.

Author of "Insurance."

LAWRENCE R. DICKSEE, F. C. A.

Professor of Accounting at the University of Birmingham.

Author of "Advanced Accounting," "Auditing," "Bookkeeping for Company Secretary," etc.

FRANCIS W. PIXLEY

Author of "Auditors, Their Duties and Responsibilities," and "Accountancy."

CHARLES U. CARPENTER

General Manager, The Herring-Hall-Marvin Safe Co.

Formerly General Manager, National Cash Register Co.

[viii]Author of "Profit Making Management."

C. E. KNOEPPEL

Specialist in Cost Analysis and Factory Betterment.

Author of "Systematic Foundry Operation and Foundry Costing," "Maximum Production through Organization and Supervision," and other papers.

HARRINGTON EMERSON, M. A.

Consulting Engineer.

Director of Organization and Betterment Work on the Santa Fé System.

Originator of the Emerson Efficiency System.

Author of "Efficiency as a Basis for Operation and Wages."

ELMER H. BEACH

Specialist in Accounting Methods.

Editor, Beach's Magazine of Business.

Founder of The Bookkeeper.

Editor of The American Business and Accounting Encyclopedia.

J. J. RAHILL, C. P. A.

Member, California Society of Public Accountants.

Author of "Corporation Accounting and Corporation Law."

FRANK BROOKER, C. P. A.

Ex-New York State Examiner of Certified Public Accountants.

Ex-President, American Association of Public Accountants.

Author of "American Accountants' Manual."

CLINTON E. WOODS, M. E.

Specialist in Industrial Organization.

Formerly Comptroller, Sears, Roebuck & Co.

Author of "Organizing a Factory," and "Woods' Reports."

CHARLES E. SPRAGUE, C. P. A.

President of the Union Dime Savings Bank, New York.

Author of "The Accountancy of Investment," "Extended Bond Tables," and "Problems and Studies in the Accountancy of Investment."

CHARLES WALDO HASKINS, C. P. A., L. H. M.

Author of "Business Education and Accountancy."

JOHN J. CRAWFORD

Author of "Bank Directors, Their Powers, Duties, and Liabilities."

DR. F. A. CLEVELAND

Of the Wharton School of Finance, University of Pennsylvania.

Author of "Funds and Their Uses."

Foreword

With the unprecedented increase in our commercial activities has come a demand for better business methods. Methods which were adequate for the business of a less active commercial era, have given way to systems and labor-saving ideas in keeping with the financial and industrial progress of the world.

Out of this progress has risen a new literature—the literature of business. But with the rapid advancement in the science of business, its literature can scarcely be said to have kept pace, at least, not to the same extent as in other sciences and professions. Much excellent material dealing with special phases of business activity has been prepared, but this is so scattered that the student desiring to acquire a comprehensive business library has found himself confronted by serious difficulties. He has been obliged, to a great extent, to make his selections blindly, resulting in many duplications of material without securing needed information on important phases of the subject.

In the belief that a demand exists for a library which shall embrace the best practice in all branches of business—from buying to selling, from simple bookkeeping to the administration of the financial affairs of a great corporation—these volumes have been prepared. Prepared primarily for[9] use as instruction books for the American School of Correspondence, the material from which the Cyclopedia has been compiled embraces the latest ideas with explanations of the most approved methods of modern business.

Editors and writers have been selected because of their familiarity with, and experience in handling various subjects pertaining to Commerce, Accountancy, and Business Administration. Writers with practical business experience have received preference over those with theoretical training; practicability has been considered of greater importance than literary excellence.

In addition to covering the entire general field of business, this Cyclopedia contains much specialized information not heretofore published in any form. This specialization is particularly apparent in those sections which treat of accounting and methods of management for Department Stores, Contractors, Publishers and Printers, Insurance, and Real Estate. The value of this information will be recognized by every student of business.

The principal value which is claimed for this Cyclopedia is as a reference work, but, comprising as it does the material used by the School in its correspondence courses, it is offered with the confident expectation that it will prove of great value to the trained man who desires to become conversant with phases of business practice with which he is unfamiliar, and to those holding advanced clerical and managerial positions.

In conclusion, grateful acknowledgment is made to authors and collaborators, to whose hearty coöperation the excellence of this work is due.

Table of Contents

(For professional standing of authors, see list of Authors and Collaborators at front of volume.)

VOLUME II

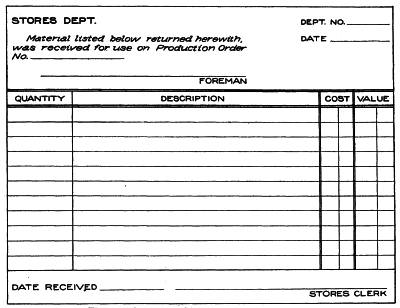

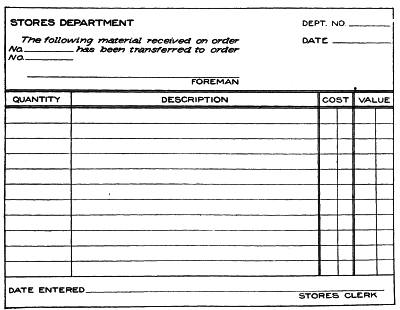

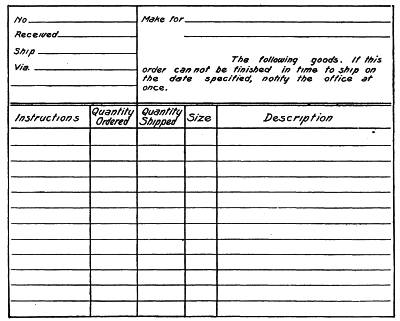

| Purchasing and Stores Department | By James B. Griffith | Page 11 |

| Lists of Dealers—Catalogue Filing and Indexing—Special Quotations—Department Routine—Requisitions—Purchase Orders—Receipts and Invoices—The Stores Department—Organization—Taking Inventory—Installing a Stores System—Record Files—Materials and Supplies—Parts and Finished Stores—Machinery and Equipment Records | ||

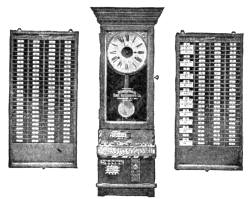

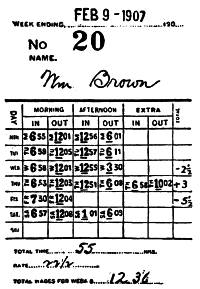

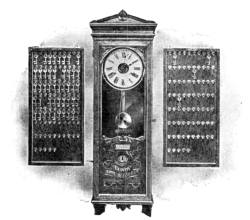

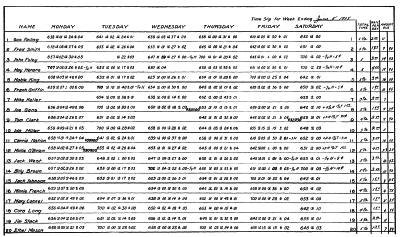

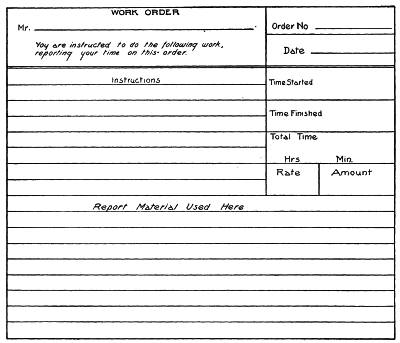

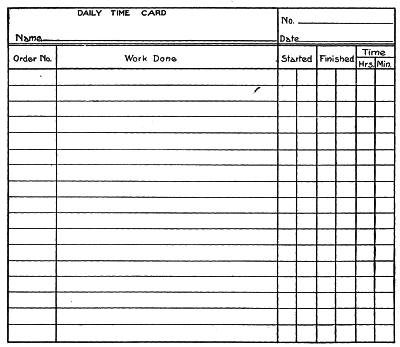

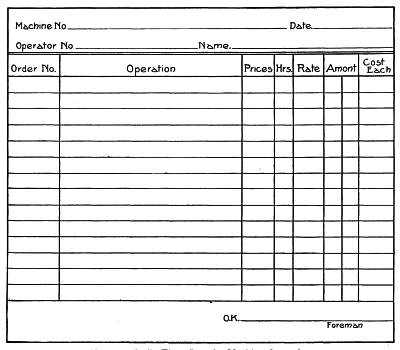

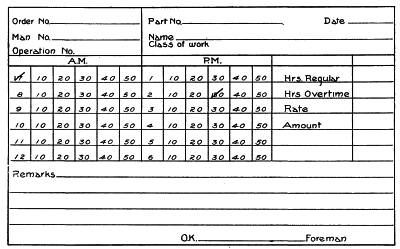

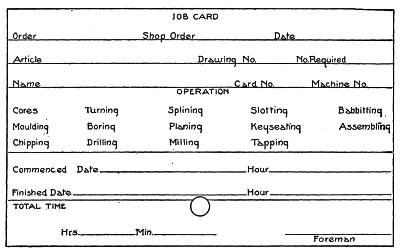

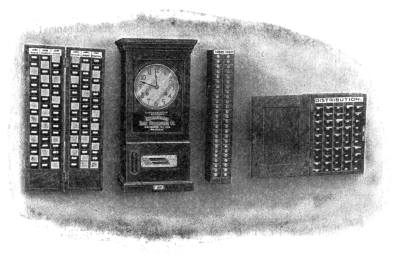

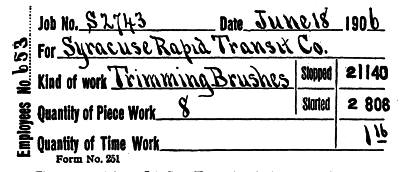

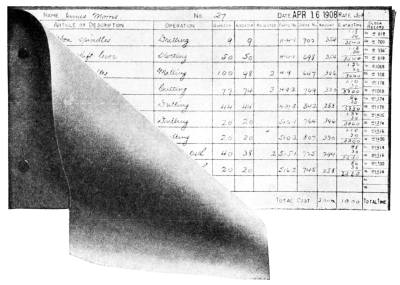

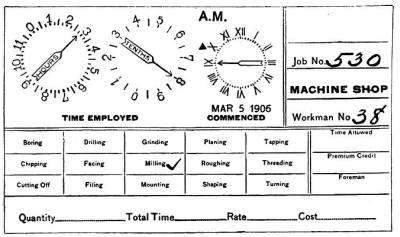

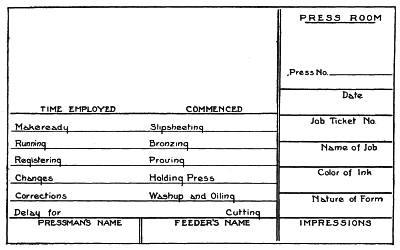

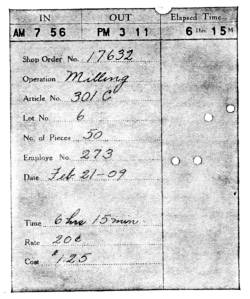

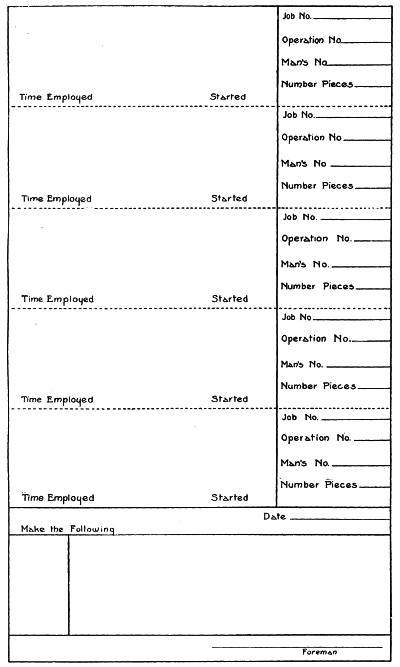

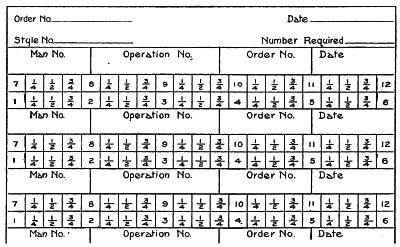

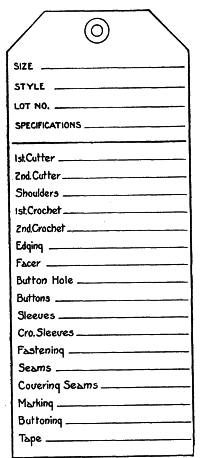

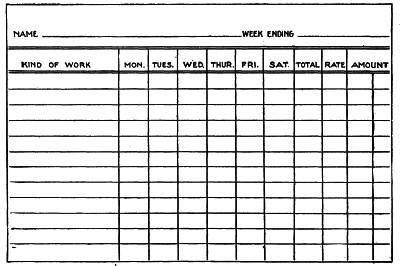

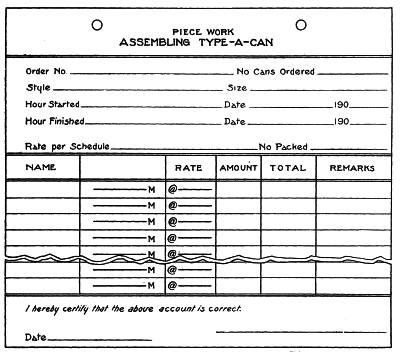

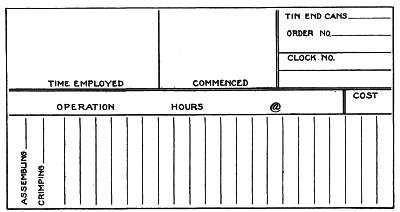

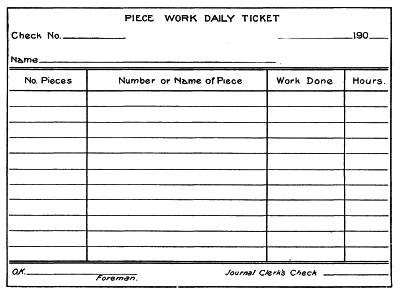

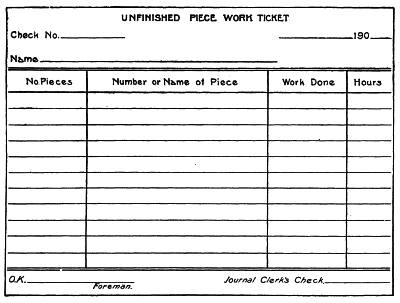

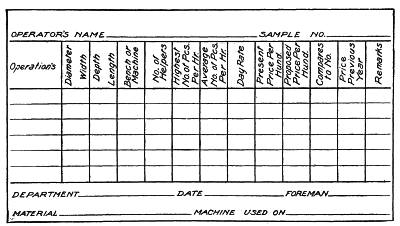

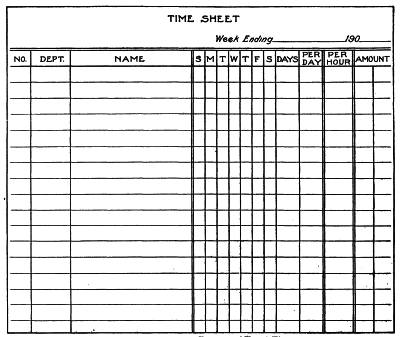

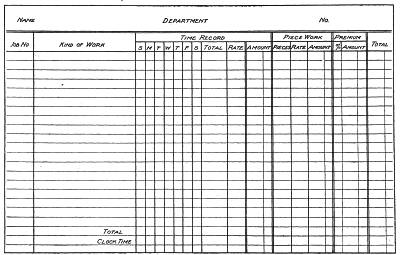

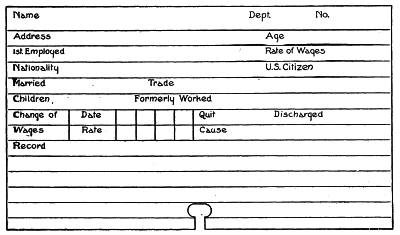

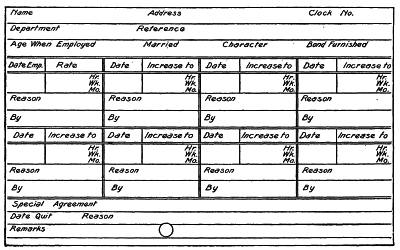

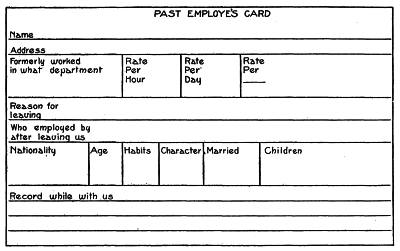

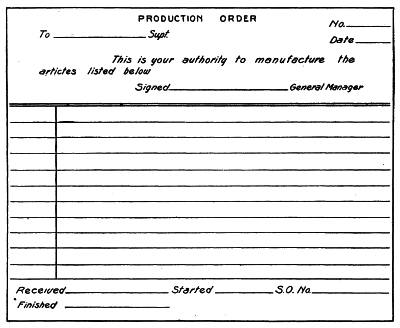

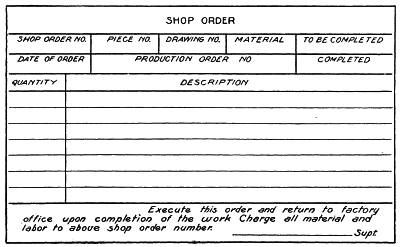

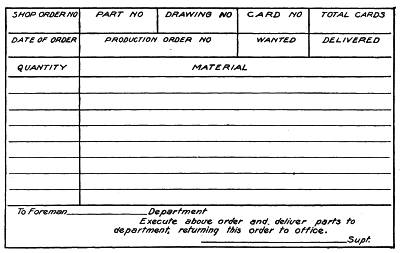

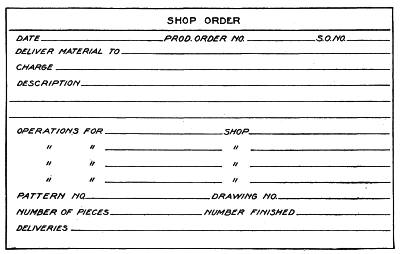

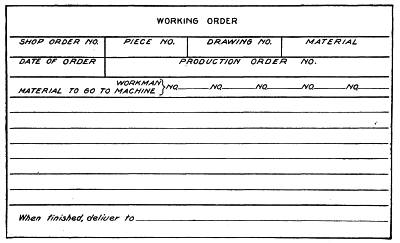

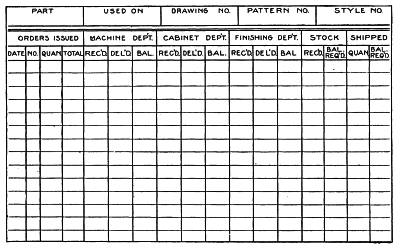

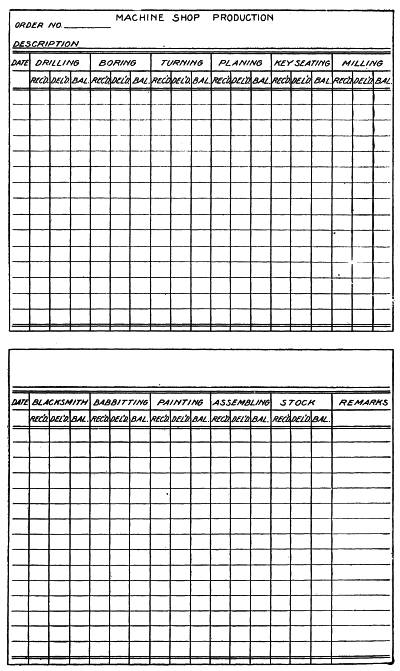

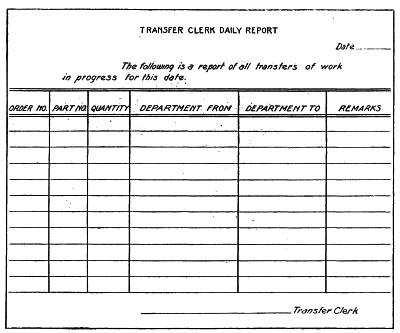

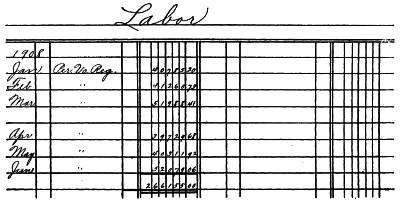

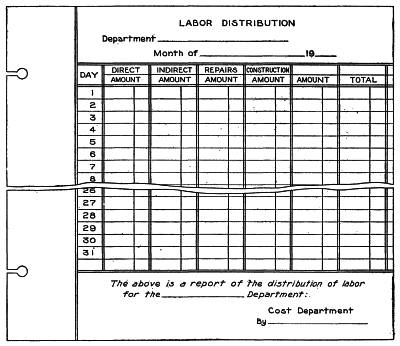

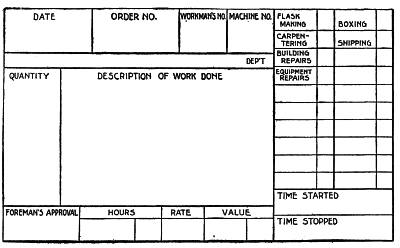

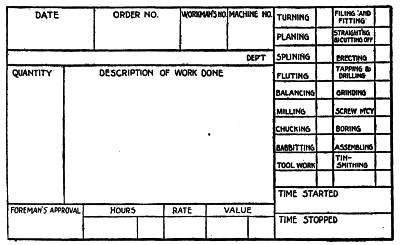

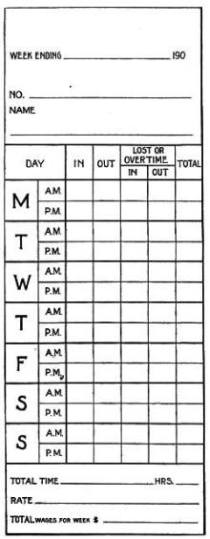

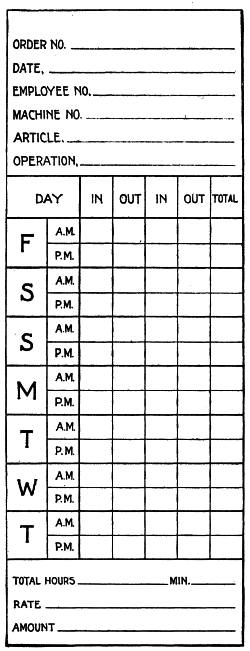

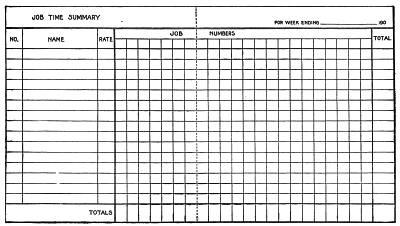

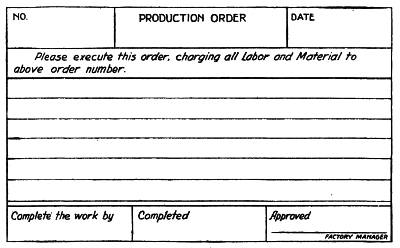

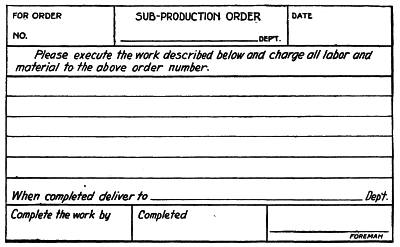

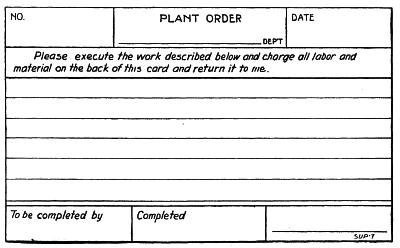

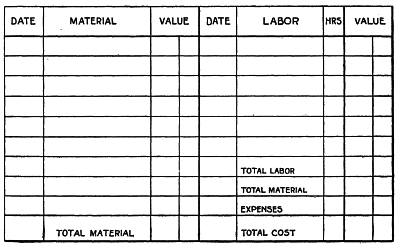

| Records of Labor and Manufacturing Orders | By James B. Griffith | Page 65 |

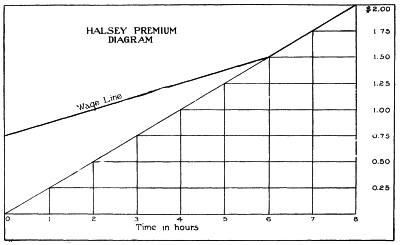

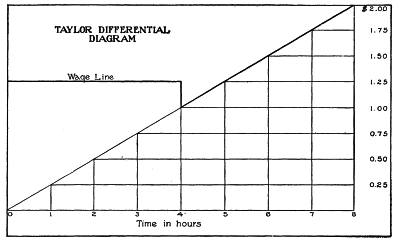

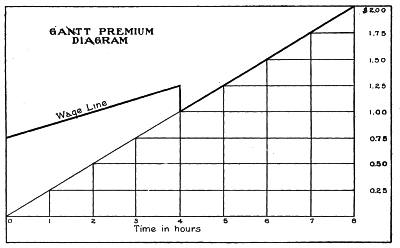

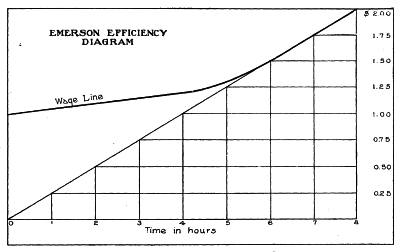

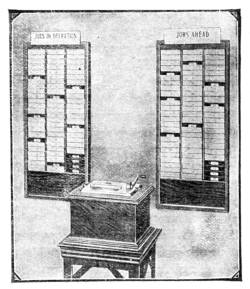

| Labor Records—Wage Systems—Day Wage—Piece Rates—Premium Systems—Efficiency Systems—Time-Keeping Systems—Time Clocks—Production Time Records—Time Cards—Mechanical Time Recorders—Piece-Work Records—Production Orders—Shop Orders—Order Register—Tracing the Order | ||

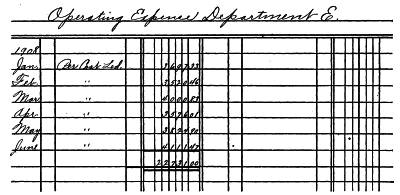

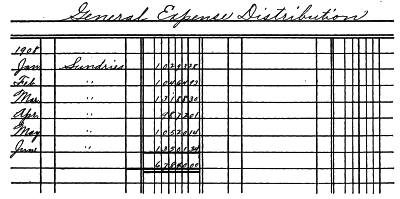

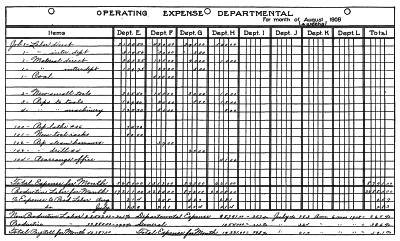

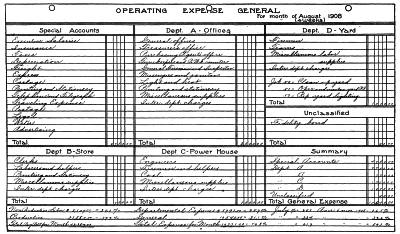

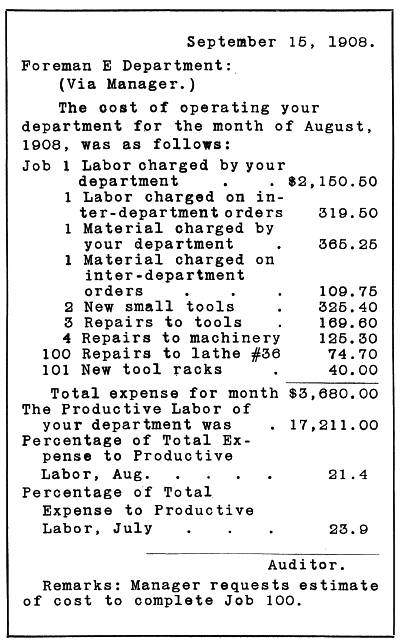

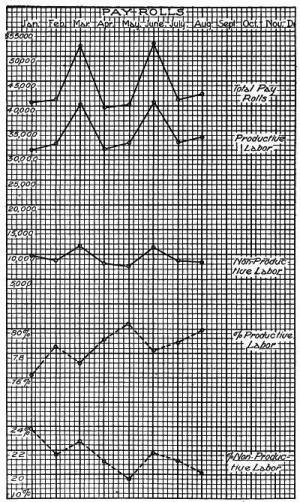

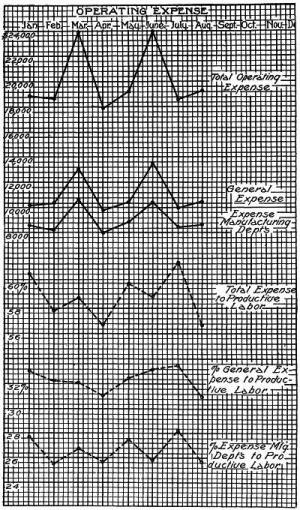

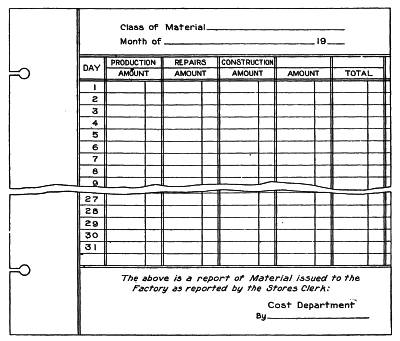

| General Expense | By Chas. E. Hathaway | Page 127 |

| Expense Distribution—True Cost—Selling Expense—Methods of Distribution—The Man-Hour-Rate Method—The Machine-Hour-Rate Method—The Percentage Method—Productive and Non-Productive Labor—Expense and Production Cost Ledgers—Departmental Expenses—General Expense—How to Use Percentages—Operating Expense Statements—What the Statement Should Show—Comparative Figures—General Expense Statements—Charts | ||

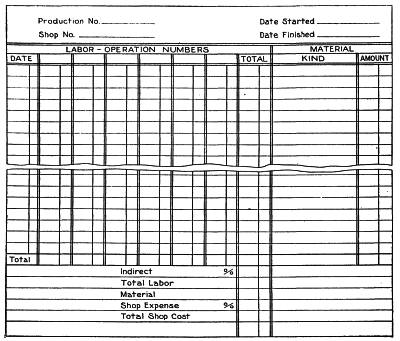

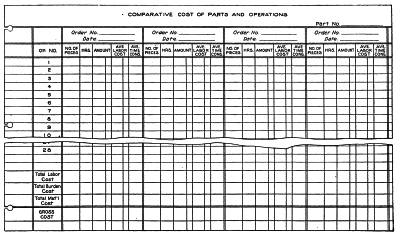

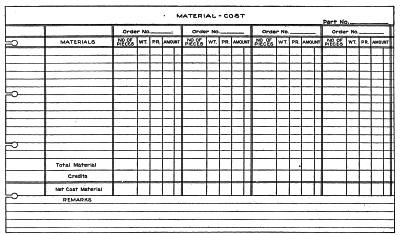

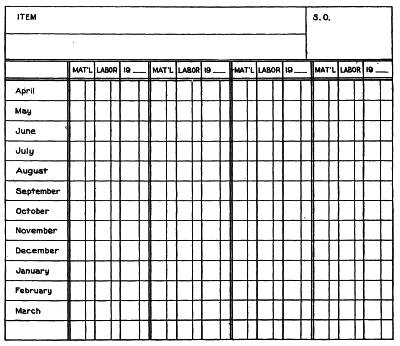

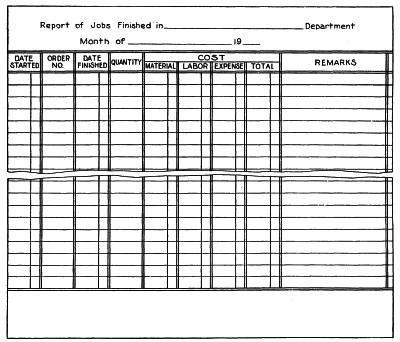

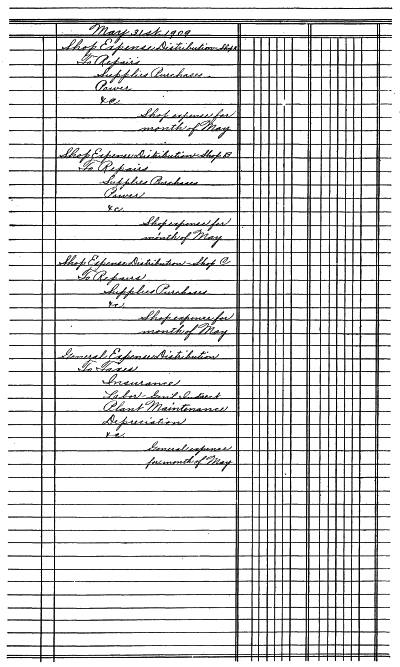

| Cost Summaries | By James B. Griffith | Page 165 |

| Collecting Cost Data—Material Cost Records—Labor Cost—Job Cost—Comparative Cost Records—By-Products—Production Records—Controlling Accounts | ||

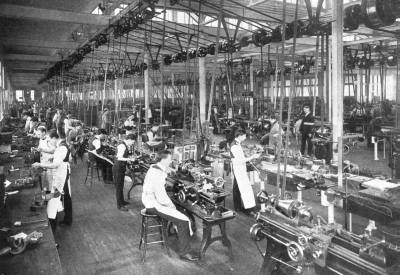

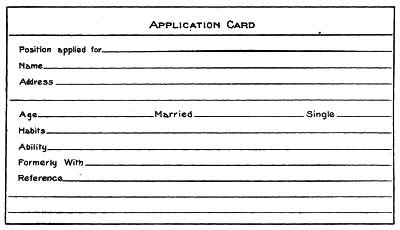

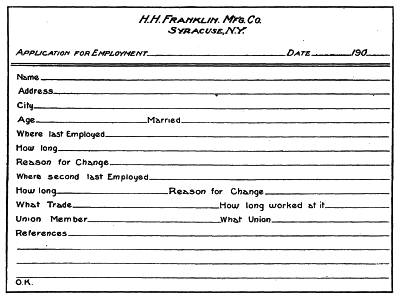

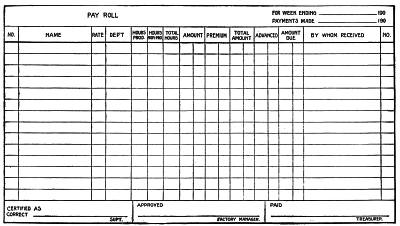

| Machine-Shop Management | By Oscar E. Perrigo | Page 193 |

| Methods of Modern Manufacturing—Organization of Manufacturing Plant—Official Communications—Successful Management—Shop Methods and Records—The Employment Agency—Time Keeping—Time Cards—Paying Employes—Production Orders—Plant Orders—Storing and Issuing Stock and Materials | ||

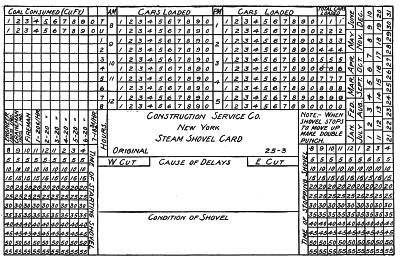

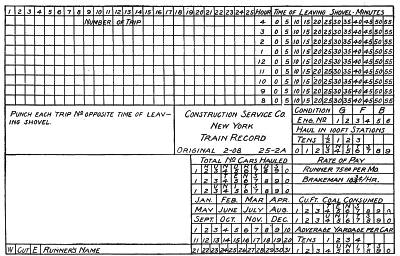

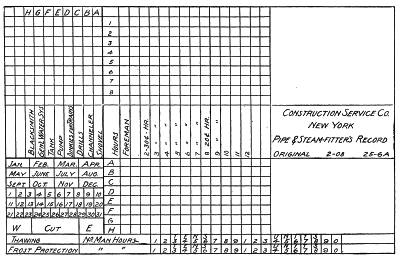

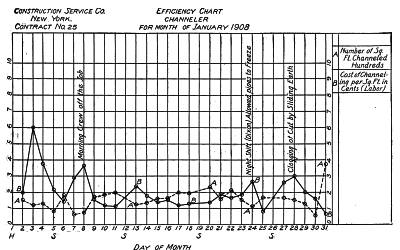

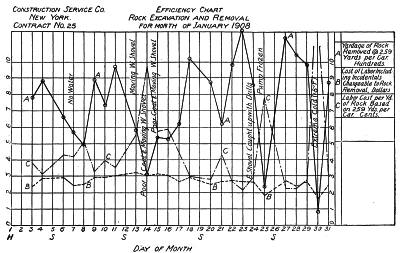

| Cost-Analysis Engineering | By R. T. Dana and H. P. Gillette |

Page 251 |

| The Science of Management—Subdivision of Duties—Cost Getting—Punch-Cards—Cost Distribution—Process Cost Subdivision—Output—Checking up Charts—Cost Reduction—Bonus System—Labor Saving Devices—Chronological Charts | ||

| Review Questions | Page 319 | |

| Index | Page 331 | |

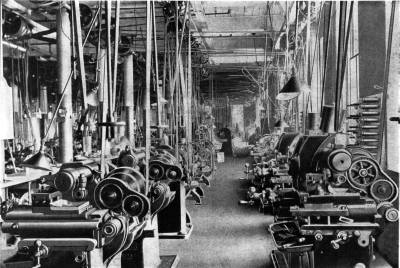

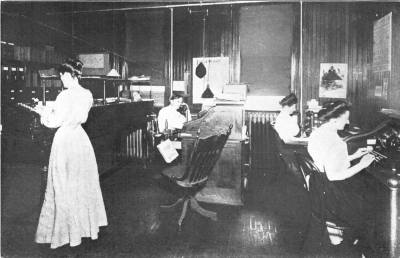

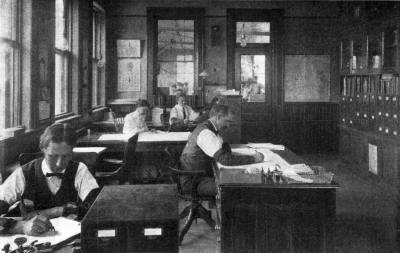

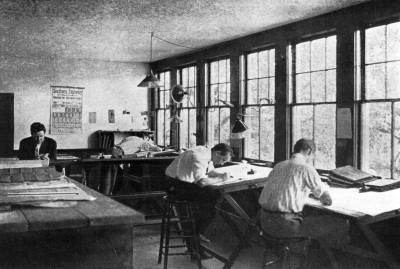

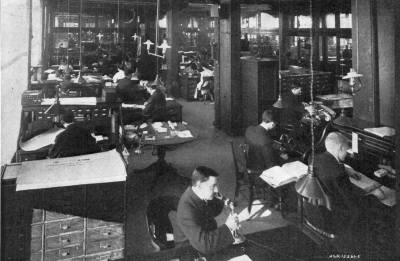

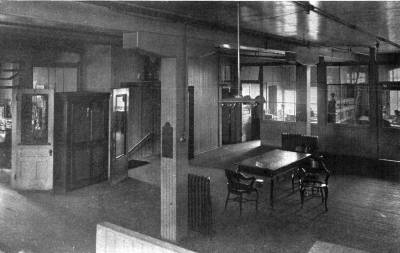

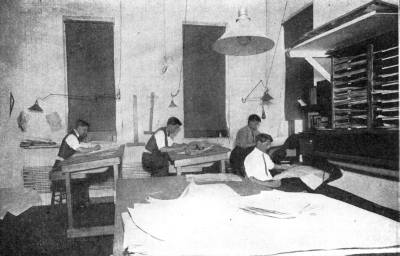

SHOP OFFICE, WESTERN ELECTRIC COMPANY, NEW YORK CITY

PURCHASING AND STORES DEPARTMENT

PURCHASING DEPARTMENT

1. If the old axiom, "Goods well bought are half sold," holds true, the purchasing department may well be considered one of the most important in any business. In referring to the purchasing department we have in mind that department, or division of the business, whose duty it is to attend to the buying. In a large industrial enterprise this may mean a department headed by a purchasing agent with several assistants; in a department store, the buyers for the several departments; in a small retail business, the member of the firm who buys the goods. No matter whether the department be an extensive one, or one requiring but a part of the time of one man, the principle is the same.

Perhaps no other head of a department has greater need of complete information and systematic records of his department, than does the buyer. A man may have every qualification for a successful purchasing agent, but, unless he has the most detailed information to aid him in judging qualities and prices, his cannot be considered a successful department. On the other hand, many a man, with no other qualification than common sense, has built up a most successful purchasing department because his work was thoroughly systematized.

We will consider the purchasing department from two standpoints: The information required, and the routine work to be performed. Under the first head the requirements may be stated as:

1. List of dealers.

2. Full information about lines carried by each dealer or manufacturer.

3. Records of special quotations.

4. Information about qualities supplied by various dealers, to be obtained from records of past purchases.

LIST OF DEALERS

2. The purchasing agent will have no difficulty in securing a list of dealers. Even a new business is usually well supplied with[12] circulars, catalogues, and other information showing which dealers handle certain lines. The principal concern of the purchasing agent is to so record this information that it will be instantly available.

In some cases it is found necessary to make special lists of dealers, and these are usually made on cards. A card is used for each article or class of material that may be of interest, and the name of the class is written at the top of the card. Below this are listed the names and addresses of dealers and manufacturers supplying that particular class of material. Since in most concerns this information can be combined with the system of catalogue indexing, we do not show a special form for this record.

CATALOGUE FILING AND INDEXING

3. A purchasing agent must necessarily gather much of the information required in the operation of his department from catalogues supplied by manufacturers. These catalogues are his technical library, in many cases supplying the only available information relative to a particular class of goods. Needless to say, some method must be provided for carefully preserving these catalogues. They must be filed in such a manner that they can be located quickly.

While every office has plenty of opportunities to accumulate an oversupply of catalogues, resulting in a tendency to discard all except those in which the purchasing agent may be interested at the time, it is better to err on the side of a liberal supply. A catalogue that comes in to-day may be of no immediate value, but it may become useful a little later. It would be impracticable to keep every catalogue and circular that reaches the office, but, if it is from a new concern, or offers any new ideas, it should be kept, even though the subject is not of especial interest at the moment.

Many systems of catalogue filing have been devised, and there are almost as many styles of catalogue files on the market as there are manufacturers of such equipment. No one system or style of filing will answer the requirements in every concern. Each must build up a filing system that will conform to existing conditions.

Though a system of universal application cannot be laid down, some general suggestions may prove of value. No matter what the style of receptacle used, catalogues are filed according to one of two methods: The alphabetical, or the numerical. The alphabetical[13] method consists in the arrangement of catalogues in bookcases or other suitable devices, according to the names of the publishers. For a small number of catalogues, this is a very satisfactory system, for the very reason that a purchasing agent soon becomes familiar with the catalogues of different manufacturers, recognizing them by their size, shape, or color.

A modification of the alphabetical system is one in which the catalogues are arranged alphabetically by classes; that is, the lines of goods in which the purchasing agent is interested are divided into specific classes. In each of these divisions, the catalogues of all manufacturers listing that class of goods are arranged in alphabetical order. This method is also very satisfactory for a limited number of catalogues.

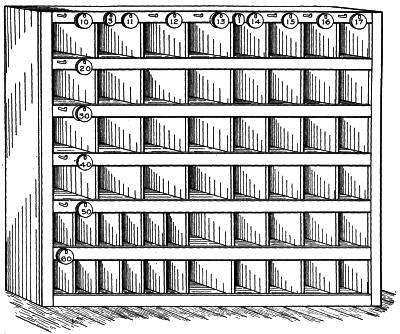

For a large catalogue file the numerical system will prove the most satisfactory. By this system each catalogue is given a number which should be plainly shown on the back of the catalogue. All catalogues of a specific class are placed in one group, and a series of numbers is set aside for the group. To illustrate, we might have machinery catalogues, numbers 1 to 100. All machinery catalogues would then be given a number in that series. If the number be increased beyond 100, the numbering system would be repeated by using 1a, 2a, etc.

With the numerical system, the catalogues of each group must be arranged in exact numerical order, so that any catalogue may be instantly located.

4. Files. As has already been stated, the style of file, as well as the method of filing, or indexing, must conform to the conditions in each individual office. However, the experience of the past is the best guide for the future. As a general rule, sectional bookcases will be found the most satisfactory for catalogues in bound form, that is, those with substantial covers, and particularly those that will readily stand on edge. An advantage of the sectional bookcase is that all catalogues can plainly be seen, and even though a numerical system be used, a man soon learns to recognize catalogues of certain manufacturers without referring to any number or indexing system.

In every catalogue file will be found pamphlets, circulars, and price lists which are not easily cared for in bookcases. For these a section of a vertical file is recommended, and in many cases this file[14] has been used successfully for filing all sorts of miscellaneous catalogues. It may be expanded to any capacity, and can be used with equal success for either the alphabetical or numerical system of indexing.

Which is the better depends upon the circumstances, but in nearly every case either the sectional bookcase or the vertical file, or perhaps a combination of the two, will be found most satisfactory.

5. Catalogue Indexing. The principal value of a file of catalogues lies in the index. A miscellaneous lot of catalogues is of very little value unless it be properly indexed. True, most catalogues contain an index, but this is not the sort of index required by the purchasing agent. He does not care for an itemized list of every article manufactured by John Jones & Co., but he does want an index that will show him where he can find descriptions and prices of machines of a certain class. A catalogue may list thousands of articles in which the purchasing agent has no interest, where it lists ten that are of use to him. These ten articles are the ones which should be shown in his index.

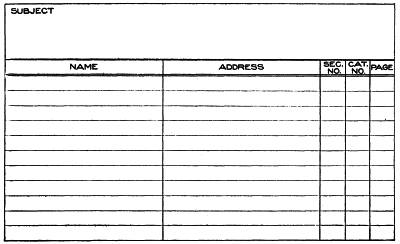

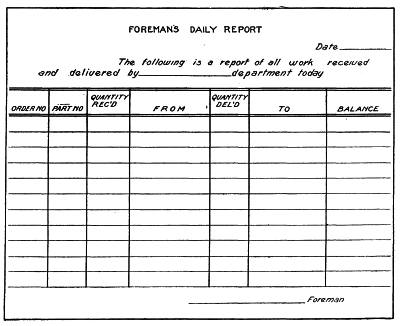

Fig. 1. Subject Card for Catalogue Index

The principal index of the catalogue file is one arranged by subjects. A card used for this purpose is shown in Fig. 1. At the top of the card is listed the subject. Below this is given the names and addresses of all manufacturers supplying the goods listed. In the columns at the right are recorded the section number,[15] catalogue number, and page. The section number refers to the section in the file where the catalogue will be found; the catalogue number to the catalogue itself; and the page to the number of the page in the catalogue. In making up such an index, it is unnecessary to include a long list of articles of no especial interest, but simply those which the concern is obliged to purchase. If an entirely new subject comes up, it can then be listed after suitable investigation.

These cards are filed alphabetically, according to the name of the subject. While in some large concerns a more elaborate file will be necessary, this index can usually be kept in a small card tray in a desk drawer.

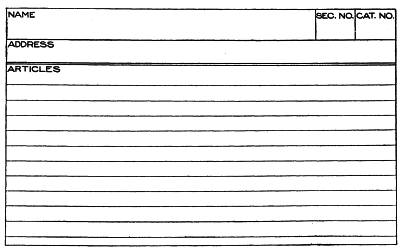

Fig. 2. Title Card for Catalogue Index

When the numerical system of filing is used, another index is necessary to locate the catalogues by name. In most cases our chief concern would be to locate the catalogue by subject, but there are times when it becomes necessary to locate a catalogue by name. To provide for this cross-index, the card shown in Fig. 2 is used. It will be noted that the arrangement of this card is just the opposite of the subject index, the name and address of the manufacturer being given at the top of the card together with the reference to the section and catalogue numbers. On the lower half of the card are listed the names of articles, made by that manufacturer, in which we are interested. This card is also filed alphabetically, but, of course, under the name of the manufacturer. When the number of cards is limited,[16] both forms can be filed in the same index by using contrasting colors. For instance, a buff color might be used for the subject index, and salmon for the name index.

SPECIAL QUOTATIONS

6. Every purchasing agent receives, in addition to published price lists, many special quotations on material and supplies in which he is interested. Very frequently quotations are received at a time when he is not in the market for the particular material offered, but they are nevertheless of value for possible future use, and should be carefully preserved.

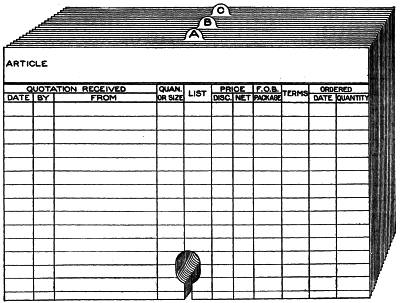

Fig. 3. Card Form for Special Quotations

One method of handling special quotations is to set aside a special file, or a drawer, or a section of the regular file, to be used exclusively for quotations. The quotations, when such a file is used, are usually filed alphabetically according to the name of the material offered. This method of filing necessitates a cross-index to locate the letters by names of firms and is not entirely satisfactory, owing to the difficulty of locating the most advantageous quotations. There may be a dozen or more letters from different firms quoting prices on the same material, and, to find which is the lowest, all must be examined.[17] Again, a firm will make quotations on several lines in the same letter, which necessitates copying a part of the items or reorganizing the filing system.

In a business receiving many such quotations, it is advisable to reserve a special file for them, but we recommend their being filed according to the names of firms. To provide an accessible record of special quotations, the use of a special form, either on cards or loose leaves, is recommended. While no form universally applicable can be devised, the several forms herein presented are very good examples of forms in use and offer some valuable points for study.

Fig. 3 is a conventional form. This is a card, at the top of which is provided space for recording the name of the article or class of material. Below this is a record of all quotations received, giving date, name of the firm from whom the quotation is received, and initials of the salesman making the quotation, when made in this manner. The columns following are for quantity, or size on which the quotation is based, the list price, discount, net, whether f. o. b. or delivered, and terms. The last two columns are for a record of orders placed.

One of these cards is used for each article or class of material on which special quotations are received. Every quotation is recorded, no matter from whom, and when the card is filled a new one is added. Whenever records on any one card become obsolete, the card can be destroyed, keeping the file up to date.

The cards are filed according to the names of the articles or classes of material. When the number of classes is limited, it will be satisfactory to index the cards by means of a straight alphabetical index. In this case quotations on bolts and all other articles, the names of which commence with b, would be filed back of the B index. If the number of articles is large, it is advisable to use blank index guides and write the names of classes of material. As an illustration, in some lines of manufacture, bolts will be used in all sizes. On the index would be written the word Bolts, and back of this the cards would be filed according to sizes, one card being used for each size of bolt. The same plan can be carried out for each class of material. It is also advisable, in a manufacturing business, to subdivide the file as, between materials—representing materials which actually enter into the construction of the product manufactured—and supplies—representing all classes of factory supplies.

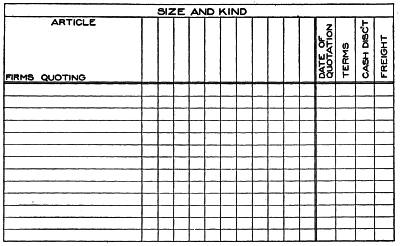

A card especially designed for a record of quotations on articles which are listed in several sizes is shown in Fig. 4. The special feature of this form is the inclusion of several columns in which to record prices on a number of different sizes of the same article. This form would be especially applicable in recording prices on such articles as bolts, mentioned in the preceding paragraph.

Fig. 4. Quotation Card for Records of Prices of Several Sizes

ORDERS PLACED

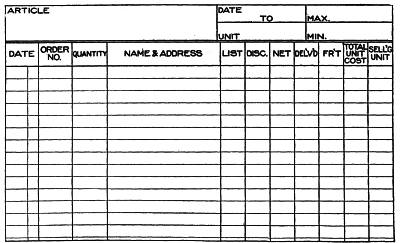

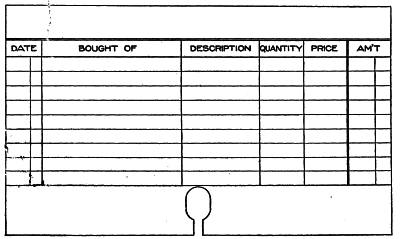

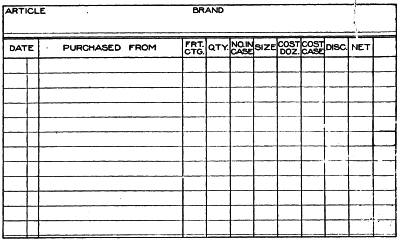

7. Of equal importance is a record of orders placed. A purchasing agent needs to know where orders for a given article have been placed in the past, prices paid, promptness of delivery, and general character of goods received. A convenient method of recording this information is to use a card similar to the illustration, Fig. 5, which shows a form used for recording purchases of a given article between specified dates. The record itself shows the order number, quantity, name of vendor, and full information about prices, including total cost per unit. These cards are filed alphabetically, according to the name of the article, exactly as described for the records of special quotations.

Fig. 6 omits some of the details, but provides for notations relative to quantities, etc., under the heading, description. This form also shows total amount, thus furnishing a record of the gross investment in material of a given class.

Fig. 5. Detailed Record of Orders Placed

Fig. 6. Record of Orders, Including Price and Amount

Fig. 7 is used in a manufacturing business, and is intended to provide a record of orders placed which will prevent a duplication of orders. At the extreme right of this form is a column headed purpose. In many manufacturing businesses, orders for certain materials are placed after contracts have been received, and the material is specified for use on a certain contract or order. In other establishments several lines of goods are manufactured, but certain materials enter into the manufacture of all lines. The purchasing agent may receive requisitions[20] from different sources for material required in these various lines, and his records should show for what lines or departments orders have been placed. Both of these contingencies are provided for in this form, as the purpose of each order is plainly stated.

Fig. 7. Order Record of a Manufacturer, Showing Purpose for Which the Goods are Required

Fig. 8. Record of Orders Providing for Details of Each Order

Fig. 8 is another special form, designed for use where certain particulars are required. In devising a form, it should be made as simple as possible, but, at the same time, provision should be made for recording all particulars that may be of especial value in the business[21] in which it is to be used. The forms shown are presented, not as being ideal for use in all cases, but for their suggestive value.

It is immaterial whether these forms be on cards or in loose-leaf form. That is a question of individual preference, and can only be decided by the person who is to make use of the system.

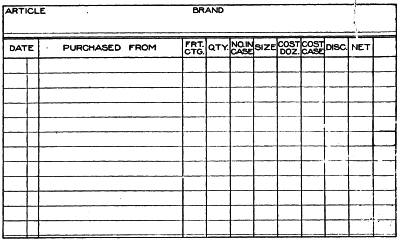

A good example of a form designed especially for use in a loose-leaf system is shown in Fig. 9. This gives full information about both orders and receipts, furnishing complete information relative to quantities of any particular line handled.

Fig. 9. A Loose-Leaf Record of Goods Ordered and Received

The manner of filing is the same as with the card system, except that these sheets are arranged between suitable indexes in a loose-leaf binder. If desired, the order records and special quotations can be filed together. By using forms of different colors the two can be filed in the same index. This is a very convenient arrangement, for then all records of both quotations and orders are found together. In some cases all of the information required will be found on the order records. When special quotations are received they can be filed in front of, or immediately back of, this record.

While in some offices other special records may be advisable, all necessary information for the average office relative to sources of supply, prices, etc., are provided by catalogues and records of quotations and prices described. Any other information required can be provided for by a modification of the forms referred to.

DEPARTMENT ROUTINE

8. Any discussion of the routine duties of the purchasing department is necessarily more or less theoretical and any method of procedure laid down is subject to such modification as will reduce it to a practical working basis for the individual establishment. To present the subject in a practical manner, therefore, this discussion will be confined to the needs of an average manufacturing business. As has been stated elsewhere in these papers, it is much less difficult to modify a system designed to care for all details in a large establishment than to expand the simple systems of a small business.

The duties of the purchasing agent in respect to the actual purchase of goods may be classified as follows:

1. Receiving requisitions, or orders for materials and supplies required for stock or in different departments.

2. Placing and following up orders.

3. Checking receipt of goods.

4. Checking invoices for prices.

5. Filing order copies and requisitions.

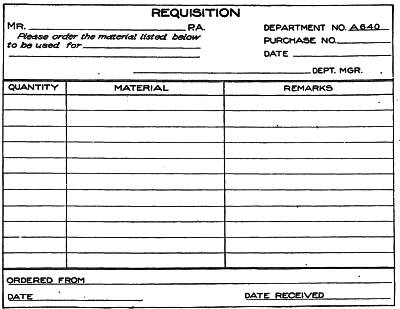

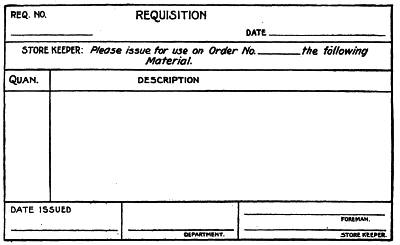

9. Requisitions. Under ordinary circumstances the purchasing agent will place no orders until he has first received a requisition from either the stores department or the department that requires the material. The requisition should in every case state the purpose for which the material or supplies is required, as well as by whom wanted.

Each department should be supplied with its own requisition blanks, and, to make them distinctive, a different color should be adopted for each department. Each department should also be identified by a letter which will be printed on the requisition blank in connection with a serial number. Thus the requisition numbers of one department will start with A1, another B1, etc.

A positive rule should be laid down that all requisitions issued by one department are to be signed by one person, usually the foreman. This rule must be rigidly enforced and no requisitions honored without the proper signature.

While requisitions should be drafted in a form to meet individual requirements, Fig. 10 is given as a typical example that will be found suitable in a large majority of offices.

The requisition, as a rule, is made in duplicate. The original goes to the purchasing agent and the duplicate is retained by the foreman. In some of the larger establishments a triplicate form is[23] used, the original and duplicate being sent to the purchasing agent. The duplicate is then returned to the foreman with proper notations to show that the order has been placed.

There are very few cases, however, where this is necessary. It is not a good plan to require the foreman to keep records that can be eliminated, and the average foreman does not care when or where the order is placed; all he wants is the material. He has no interest in going back of the purchasing agent on whom he has made requisition.

When the factory is located at a distance from the office, requisitions should be in triplicate and bear the O. K. of the superintendent or factory manager. The duplicate will then be filed in the factory office pending the receipt of the goods.

Fig. 10. A Typical Form of Requisition Blank

Foremen who make requisitions on the purchasing agent will retain their copies until the material is received.

On receipt of the requisition, the purchasing agent first investigates to find if the material, or some other that will answer the same purpose, is in stock. If not, he looks up his sources of supply and prices, and then he is ready to place the order. When a large investment is involved, it is usually necessary to obtain special quotations, and sometimes samples, before the order can be placed.

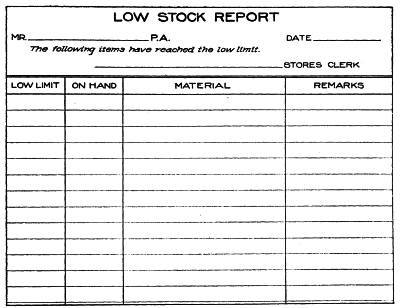

10. Low Stock Report. Another form of requisition is the low stock report furnished by the stores clerk. Every article and class of material in stock is given a low limit. When this limit is reached the stores clerk makes a report, Fig. 11, to the purchasing agent. This is recognized as a notice to purchase. The report shows the low limit and quantity in stock. It is important that the low limit be included, for in some cases it will be found advisable to change the limit. Material formerly used in large quantities may now be in so little demand that it will be thought best to reduce the limit. At other times it will be necessary to increase the limit.

Fig. 11. The Stores Clerk's Report of Low Stock

The report is made in duplicate, a copy being retained by the stores clerk until advised that the order has been placed. There is no special need for keeping these reports permanently; all information that they would supply may be had from copies of purchase orders.

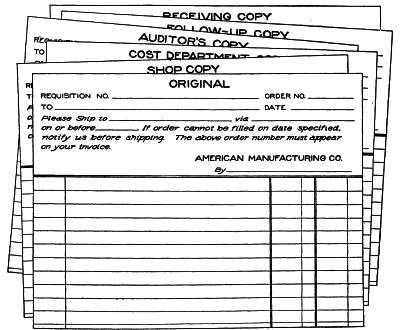

11. Purchase Orders. When an order is placed, it is of course necessary to keep one or more copies. The best practice is to make purchase orders in manifold, providing as many copies as may be required. Modern typewriters and carbon paper render it possible to make all necessary copies at one writing.

The number of copies will be governed by the requirements of the business. In a small business where the goods are received by the purchasing agent, one copy is sufficient. When a receiving clerk is employed, a second copy will be needed by him to check the receipt of goods.

The illustration, Fig. 12, shows a set of six blanks, the original and five copies, which will meet the requirements of the average manufacturing business. These copies will be used as follows:

Fig. 12. Typical Form of Manifold Order Blanks

Original. This is to be mailed or delivered to the vendor.

Follow-Up Copy. This copy is retained by the purchasing agent to follow up the order. It is first filed in a tickler, or date file, back of the date when an acknowledgment should be received. If no acknowledgment is received, the vendor is followed up and the order filed ahead.

The order is next filed under the date when the invoice should be received. After the invoice is received, the order copy can be used to follow up the transportation company for delivery.

Receiving Copy. This copy goes to the receiving clerk who files[26] it according to the name of the vendor. When the goods are received, he checks the items against the copy and returns it to the purchasing agent. In some cases he reports the receipt of goods by means of a receiving slip, which will be explained later.

Auditor's Copy. In a highly organized business a copy of every order is given to the comptroller or auditor. The principal use of this copy is to furnish information in respect to obligations incurred, that finances may be provided in advance.

Cost Department Copy. The copy furnished the cost department is to post the cost clerks in prices. In many large factories complete files of all orders placed are kept in the cost office. This is an excellent plan since it provides a complete price record.

Shop Copy. This is intended for the special use of the factory when located at a distance from the office. It is filed in the office of the factory manager, under the name of the vendor, and supplies him with a record of all orders placed for the factory.

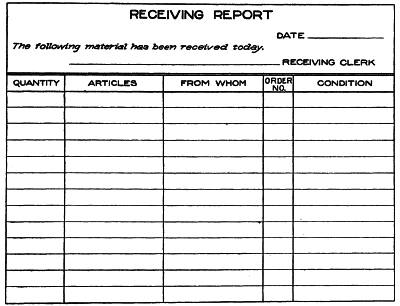

12. Checking Receipts. The purchasing agent will be advised of the receipt of goods by the return of the receiving clerk's copy of the order, properly checked. Or, in some cases, it may be advisable to have all goods reported on a special form, Fig. 13.

Fig. 13. A Form of Report of Goods Received

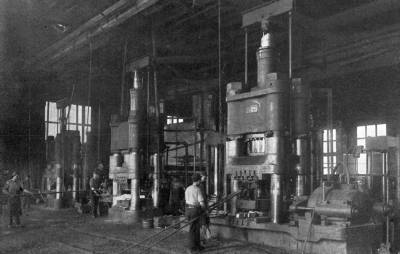

SURPLUS TOOLS GATHERED FROM OVER-EQUIPMENT AT LOCAL SHOPS AND RETURNED TO CENTRAL STORES ON THE SANTA FE SYSTEM

The Reapportionment of Work, Concentrating all Manufacturing Operations at Topeka, Made it Possible to Return to General Stock Many

Small Tools, to be Used as Needed Instead of Held in Unnecessary or Excess Local Reserve

Courtesy of the Engineering Magazine

In those factories where a receiving clerk, as well as a stores clerk, is employed, the receiving slip should be made in duplicate. One copy will go to the stores clerk with the goods and will later be sent to the purchasing agent, furnishing a double check on the goods. The purchasing agent will send one copy to the cost clerk, first noting the account to be charged. This gives the cost clerk the necessary information for charging out material when used.

One argument in support of this plan is that, having no record of quantities ordered, the receiving clerk will be compelled to carefully count and list all articles received. But it is also true that he is obliged to make a detailed copy instead of merely checking the items against his copy of the order.

Another point in connection with the work of the receiving clerk that has caused much discussion, is the wisdom of furnishing him with a record of prices. The prevailing opinion among manufacturers seems to be that this should not be done. This need not interfere with the operation of our system, for prices can be left off the receiving clerk's copy by using a short carbon. This will keep all blanks uniform in size.

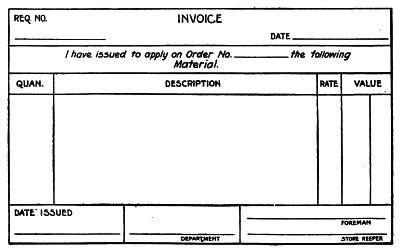

13. Checking Invoices. It may be laid down as a rule that invoices should first go to the purchasing agent, not for audit, but to be checked for quantities and prices. The purchasing agent will check the invoice, note on it the purpose, or the department for which the goods were purchased, and forward it to the auditor. The transaction is then closed so far as the purchasing agent is concerned.

14. Filing. After the O. K.'d invoice has been forwarded to the auditor, the following papers remaining in the purchasing department are to be filed:

Follow-up copy of the order, filed alphabetically under the name of the vendor.

Receiving clerk's copy of the order, filed with the original requisition.

Requisition from the department requesting the goods, filed numerically according to the departmental serial number; that is, all requisitions from Dept. A will be filed together in numerical sequence.

When a record of goods received has been made on the forms prescribed, the purchasing agent's records will be complete.

THE STORES DEPARTMENT

15. In this discussion, the stores department, or stock department as it is frequently called, is treated as a subordinate division of the purchasing department. Properly organized, it becomes one of the most valuable from a profit-making standpoint. Without organization it may degenerate into one of the most useless.

To attain the state of efficiency of which it is capable, the organization and system of operation of the stores department must be of the highest order, otherwise it cannot be expected to fulfill its mission. So much has been written about the failure of stores departments and stores systems to produce desired results, that a statement of what is meant by stores department seems to be demanded before we can arrive at intelligent conclusions regarding its functions and operation.

Broadly, the stores department is that department of a business which has the custody of its stock in trade, materials, supplies, and other physical property, except real estate. Reduced to a concrete example, in a trading business the term means that department which is responsible for the storage and proper care of the goods purchased for resale; also the materials and appliances required in the operation of the business. There may be no department known by this name; there may be no one man whose duty it is to supervise the work; nevertheless, the department exists. Every clerk in a small retail store may be a receiving clerk, a salesman, and a stores clerk; or in a larger establishment several men may be employed as stockkeepers; but in both cases the responsibilities of the stores department are shouldered by some one, perhaps by several people.

Like every other department of a business, the organization of a stores department depends largely upon the nature of the business. To furnish an illustration that can be readily understood, we will treat the organization and operation of the stores department from the standpoint of a manufacturer.

ORGANIZATION

16. The stores department is properly under the direct supervision of the purchasing agent. In the last analysis he is the man who is responsible for the maintenance of a stock of materials and supplies which will at all times be adequate for the business. It is proper,[29] therefore, that he should have supervision over the receipt, storage, and delivery of the goods which he has purchased.

In the actual operation of the stores department, the purchasing agent will delegate his authority to the chief stores clerk, who will in turn be assisted by the necessary number of stock men and a receiving clerk. It will be the duty of the chief stores clerk to see that all materials are properly stored, to maintain the records prescribed, and to furnish such reports as may be necessary regarding the movement of the stock. He will have general supervision over the entire department. In the actual physical operations of the department, he will be assisted by stock men who are subject to his orders.

In small establishments the stores clerk also acts as receiving clerk, but in the larger enterprises, a separate receiving clerk is required. He will check the receipt of all goods, deliver them to the storage places prescribed by the chief stores clerk, and make such reports as may be prescribed. While he is, generally speaking, under the orders of the chief stores clerk, he also makes certain reports direct to the purchasing agent.

TAKING AN INVENTORY

17. Before a stores department can be successfully organized an inventory must be taken, for this inventory will be the basis on which the records of the stores department are founded.

Stores record systems are quite commonly referred to as perpetual inventories, and, occasionally, such a system is pointed to as a failure for the reason that at the end of the year, or other fiscal period, the inventory, that is, the actual physical inventory of the stock, does not check with the records. The fact that systems of stores records have been regarded as inventories in fact, is responsible for most so-called failures. Regarded in its proper relation, a perpetual inventory is nothing more nor less than an accurate accounting of all goods that come into and go out of the establishment, these records to be checked by an actual physical inventory with such regularity and frequency that the accounts can safely be considered as exhibiting a correct inventory. In considering the question, how to take an inventory, we refer, therefore, to an actual physical inventory, that is, a count of every article in stock. When once this inventory is taken and properly recorded, it is entirely possible to install and maintain[30] systems which will make it unnecessary to inventory all of the physical property at any one time.

It has been the general custom in a large manufacturing establishment to shut down for a period of greater or less duration, running all the way from two or three days to as many weeks, for the purpose of taking an inventory. Since it has been considered necessary to shut down for this purpose, inventories have, as a rule, been taken but once a year. All this is unnecessary, for, with proper methods, it is possible to take even a complete inventory without perceptible interruption of the operation of the plant. The first step is to decide, at just what time the inventory is to be taken, and to have all foremen get their shops in readiness. This means a general cleaning up which will make it easy to locate and count, weigh, or measure the materials, tools, supplies, and work in process. Then, at a specified time the work of taking the inventory should be started simultaneously in every shop.

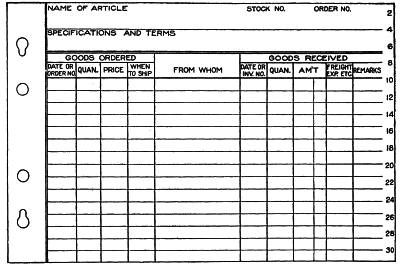

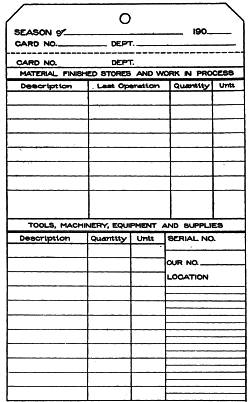

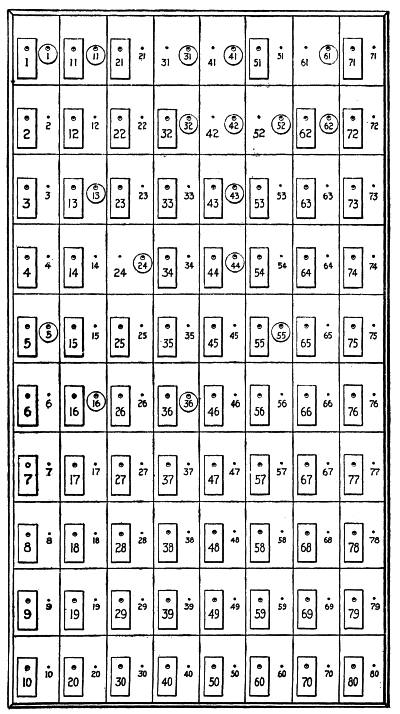

The making of the necessary records will be in charge of a clerk who will be assisted by the foremen and as many helpers as may be required. Each clerk is given a supply of tags, ruled as shown in Fig. 14. These are made in the form of shipping tags, but larger than the usual sizes used for that purpose. It will be noted that the tag is perforated near the top. The portion above the perforation shows the season and date of inventory, the card number, and the department. The card number and the department are repeated on the lower part of the card, which is also divided into two parts. The upper half is for an inventory of material, finished stores, and work in process, divided as to description, name of last operation, the quantity, and the unit. The lower half is for an inventory of tools, machinery, equipment, and supplies, with provision for the description, quantity, unit, numbers, and location. By unit is meant the unit in which the material or supplies are priced, as pounds, yards, dozen, gross, etc.

The first operation is to attach one of these cards, which are consecutively numbered, to each machine, tool, bin, rack, or pile of material. Then the clerk and his assistants will go through the shop and weigh and count the material represented by each tag, recording the items on the tag itself. As this is done, the lower half of the tag is torn off. Since a record is kept of the card numbers given to each clerk, it will be necessary for him to turn in every one, and if care is[31] used in placing the tag on every article before the count has begun, there is no possibility of material being overlooked. As a further precaution against the loss of cards, the remaining part of the tag is afterward removed and sent to the office for checking against the main record. As the tag is used merely to insure a record of quantities of all property, it is unnecessary to include prices.

Fig. 14. Labor-Saving Inventory Tag

With this method an inventory can be taken in a very short time. There are cases on record where an inventory in the largest industrial enterprises has been taken by this method without shutting down the plant in any department for a longer period than two days.

18. Inventory Records. When the physical inventory has been taken, the next step is to record quantities and prices, and make the extensions that the record may show total values. The records of the inventory should be classified; that is, all material or equipment of a certain class should be recorded on the same form, so that the total value of each class can be ascertained.

For a manufacturing business, the inventory is subdivided as follows:

Machinery and Equipment.

Machine Tools.

Small Tools.

Drawings and Patterns.

Materials and Supplies.

Parts and Finished Stores.

Work in Process.

Manufactured Goods.

One form might be made to answer the purpose for all these inventories, but as certain special information is needed in each case, it is considered the better plan to use special forms. We, accordingly, illustrate forms for each of these classes.

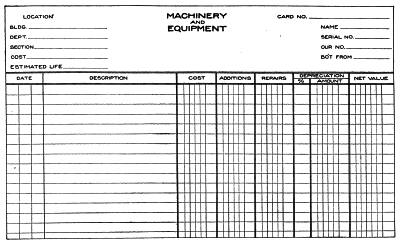

Machinery and Equipment. Under this heading is listed all machinery, furniture, office appliances, and equipment of all classes required in the operation of the business. The form for the inventory is shown in Fig. 15, this being a loose-leaf form, about 10 x 12 inches in size.

For this section, a sheet is used for each specific class of equipment, and, where the same class of equipment is required in different buildings or departments, a sheet is used for each department. For instance, all typewriters used in a given department will be inventoried on one sheet, and no other equipment will be inventoried on the same sheet.

The information given at the head of the sheet includes the location, cost, estimated life, name, series number, our number, and from whom purchased. The form provides for a record of date (meaning date purchased), and description of the equipment, original cost, cost of additions and repairs, per cent and amount of depreciation, and the net value. Reference to this record shows the exact number of machines of a given class in use and just where they are being used.

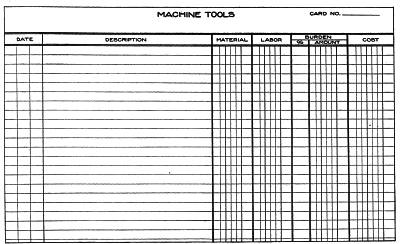

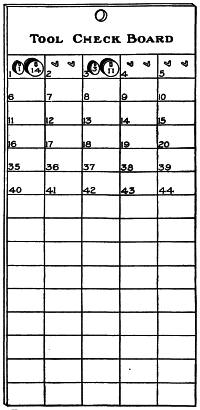

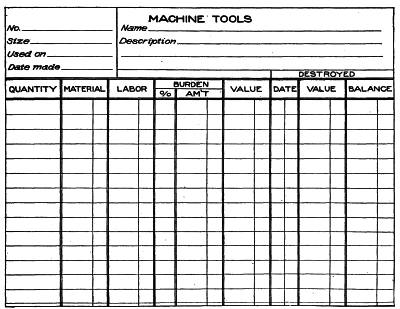

Machine Tools. Under the head of machine tools, an inventory covers all tools of this character, whether purchased or manufactured in the plant. Since large plants usually manufacture their own machine tools, this form is used to show date of manufacture or purchase, description, cost of material and labor, per cent, and amount added to cover the factory burden, and the total cost. Like the form used for machinery and equipment, all machine tools of a given class should be inventoried on the same sheet, Fig. 16.

Fig. 15. Loose-Leaf Form for an Inventory of Machinery and Equipment

Fig. 16. Inventory Form for Machine Tools

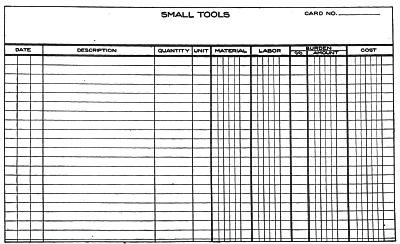

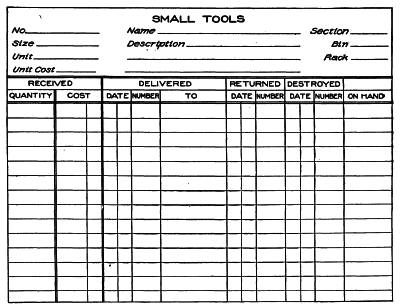

Fig. 17. Inventory Record of Small Tools

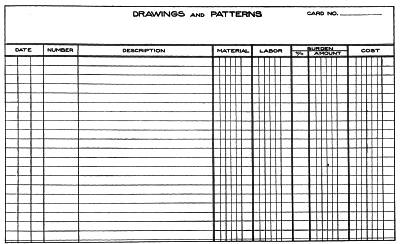

Fig. 18. Form of Inventory Sheet for Drawings and Patterns

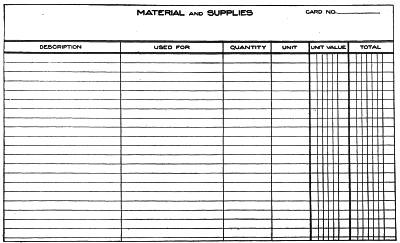

Fig. 19. Form of Inventory Sheet for Materials and Supplies

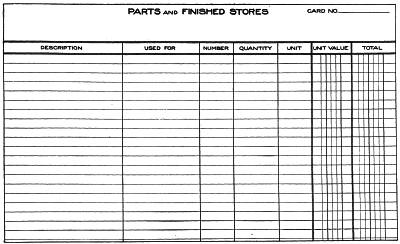

Fig. 20. An Inventory of Parts and Finished Stores

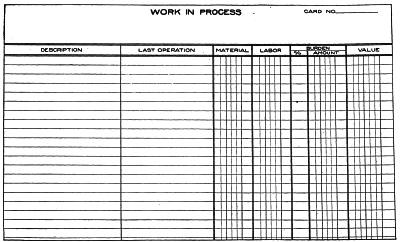

Fig. 21. Special Form for Inventory of Work in Process

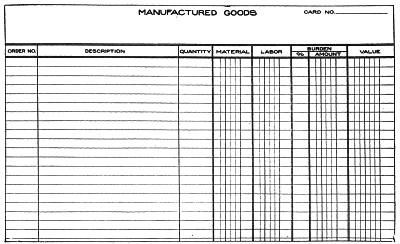

Fig. 22. Sheet for an Inventory of Manufactured Goods

Small Tools. Most small tools are purchased, but some of them may be made in the plant. These tools may be purchased singly, or in lots of one dozen, or in other quantities. To meet these conditions the form, Fig. 17, provides for a record of date of purchase, description, quantity, unit, material and labor costs, per cent and amount of burden, and total cost. When the tools are purchased ready for use, only the last money column is used.

Drawings and Patterns. This inventory includes all drawings and patterns that are in use or of value to the business. In placing a value on this property, conservatism is necessary. A new pattern is supposedly worth what it cost to manufacture it. But a pattern may become obsolete in a very short time. It is necessary, therefore, when taking the inventory, to estimate the probable life of all patterns, basing this estimate not only on wear and tear, but on the probability of their being replaced by later models. The cost of drawings and patterns should be entirely absorbed in the cost of the goods manufactured, and to cover this a very liberal rate of depreciation must be provided. In the inventory form we do not show the depreciation, as we consider it more practicable to take a complete inventory, and make a new appraisal of drawings and patterns at the end of each fiscal period. The form given for this inventory, Fig. 18, shows date put in stock, the number, description, and details of cost.

Material and Supplies. The inventory of material and supplies includes all material which goes into the construction of the goods and all supplies required in the operation of the plant.

In recording this inventory, supplies and material should be kept separate, and each should be thoroughly classified. One sheet should show but one special class; that is, if one of the items is hardware, nothing but the hardware inventory should be included on the same sheet. This form, shown in Fig. 19, gives the description, the purpose for which the material is used, quantity in stock, unit of measure, unit value, and total value.

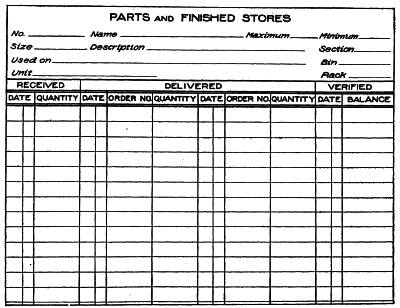

Parts and Finished Stores. This section is intended to include all finished parts in a plant manufacturing parts to be later assembled into complete machines, also any finished stores or semi-completed parts. Under the latter head would come such items as castings,[42] which are made in advance, to be used as needed. This inventory is recorded on the form shown in Fig. 20, giving the description, for what used, the number of the part, quantity, unit, unit value, and total value.

Work in Process. Under the head of work in process is included all partially completed orders in the plant at the time of inventory. If an efficient cost system has been maintained, it will not be a difficult matter to arrive at accurate costs of all such material. Without a cost system it is necessary to use extreme care in estimating the cost of material and labor to date.

One of the most important items of information in this inventory is the last operation, which means the last completed operation. It is necessary to have this information before we can figure the actual cost. The form for this inventory, Fig. 21, includes description, name of last operation, cost of material, cost of labor, per cent and amount of burden, and total value.

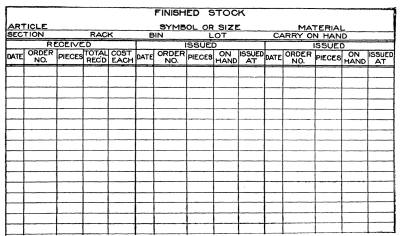

Manufactured Goods. The inventory of manufactured goods includes all goods completed ready for the market. In a trading business this would include the regular stock in trade. Fig. 22 shows a form for the inventory of manufactured goods, which, with slight changes, would answer the purpose for the stock in a trading business. The form shows the order number (meaning the shop order number on which the goods were manufactured), the description, the quantity, the material and labor costs, the burden, and total value.

When these inventories are completed, and the extensions made, it will be seen that a complete record of values of all physical property is provided. From these records the ledger accounts should be adjusted so that all records will correspond. The records also furnish the necessary information from which to make the stores record, which is necessary when installing the system.

These inventory sheets may be filed either in the drawers of a vertical file or in a loose-leaf binder, though the latter is preferred. The sheets for each class should be kept by themselves and classified as explained above. The index may be alphabetical, or blank indexes, on which the names of the classes are written, may be used. The sheets in each class should be numbered consecutively and kept in numerical sequence.

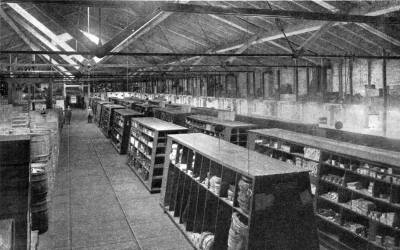

A CORNER IN THE GENERAL OFFICES OF THE DOBIE FOUNDRY & MACHINE CO., NIAGARA FALLS, N. Y.

STORES DEPARTMENT A MONEY SAVER

19. Although a stores department is the first essential in the operation of a cost accounting system, manufacturers sometimes hesitate to install such a department on the ground of expense. Without considering its valuable features, the claim is made that the operation of this department involves a larger expenditure than is warranted by the results. But such claims are not borne out by the experience of manufacturers who have tested the efficiency of the department. Where results are found which appear to support this claim, investigation will invariably reveal faulty installation or faulty operation, or both.

Opposed to this claim, the experiences of many manufacturers show that the stores department is an actual money saver. If anything like an efficient cost-accounting system is to be maintained, a stores department is an absolute necessity; but even if there is no cost system, a stores department can be made profitable. An adequate system of records in a well-organized stores department will show at all times the exact condition of the stock, and this alone should justify the maintenance of such a department. Slow moving stocks are pointed out, so that a greater effort may be made to move them; if a stock is running low, the records give warning before the danger point is reached. All this applies with the same force to a trading business as to a manufacturing enterprise. By showing the volume of stock on hand, by pointing out its movements, a stores-record system prevents the accumulation of dead stock, yet makes it possible to maintain active stocks at the lowest volume consistent with safety, and thereby saves money by keeping the investment at the lowest possible point.

Surprising results in money saving through stores-record systems have been shown by some manufacturers. In one case which came within the writer's observation, a reduction of more than $10,000.00 in the average investment was made. A certain manufacturer of machinery, who had an inadequate stores system, found that his stock of material averaged $30,000.00, while the business required a stock of not more than $20,000.00. He engaged a competent man to install and operate the system, paid him a liberal salary, and at the end of a year found that his stock averaged less than $20,000.00. Moreover, the stock was clean—there being nothing in it that was not needed—was[44] well arranged, and in every respect in a more satisfactory condition than before. That meant a saving of the earnings of $10,000.00, and by using it in extending his business, the money was worth 20% to him.

INSTALLING A STORES SYSTEM

20. When the inventory has been completed, the next important step in the organization of a stores department is to provide the necessary storage places for all materials and supplies and see that these are properly stored.

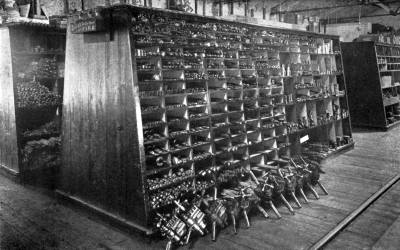

The question, as to what is a proper storage place is one which must be worked out to fit conditions as found in the individual establishment. Generally speaking, in a manufacturing business, materials should be located as closely as possible to the departments in which they will be used. In a large plant it is usually necessary to have several storerooms to accommodate the various classes of material, and in order that they may be located conveniently. The question of proper storage is a vitally important one in every business, and especially so in a manufacturing plant. Ideal conditions are impossible to obtain in all plants, but the first consideration should be to have a definite storage place for every class of material, and to always keep the material in that especial place. Go into a plant having no well-defined system of storage, and you will find workmen spending more time looking for materials needed than would have been required to take the same material to a stockroom and withdraw it as needed. In trading businesses the necessity for systematic stock keeping has long been recognized. Wholesale houses have their stock arranged in departments and stored on different floors of the warehouse with special men in charge of stock keeping. A retailer, no matter whether he is operating a department store or dealing exclusively in one class of merchandise, has his goods arranged by departments. But in too many manufacturing plants the question of storage for raw material and supplies has received little consideration. A manufacturer will invest dollars in raw material and keep no record of it; yet the same man would regard as preposterous the suggestion that he should keep no record of cash. As a matter of fact, the material should be as well cared for, and as strictly accounted for, as cash. Every dollar's worth of material should be regarded in the same light as a dollar in gold.

Next in importance to the location of the storerooms is the question of the storage of the material itself. The storerooms should be equipped with such bins, racks, shelves, boxes, and drawers as may be required for the proper care of the material. In storing the material the question of its size and weight, and the frequency with which it will be needed, should be considered. Extremely heavy articles should not be stored on the floor, but should be raised to about the height of a truck, thus saving labor both in unloading and loading. Material which is constantly being called for should be kept on shelves that are within easy reach. The top shelves and inaccessible corners can be reserved for articles seldom called for. As far as possible, all articles of the same class should be kept in the same section of the storeroom. Above all, a given article should always be kept in the same place. In some storerooms it is not uncommon to find, hidden away in some dark corner, articles which are not supposed to be in stock, all because no definite storage place has been provided. The record system can be of little value unless the articles are to be found in the sections allotted to them.

All of this but emphasizes the importance of having the storeroom and stores system under the exclusive control of one man. No one should be allowed to interfere with the work of the chief stores clerk. If there is any cause for criticism it should be taken to his superior. Suggestions from foremen and others who are obliged to make use of the storeroom, should, and probably will, be welcomed by the average stores clerk, but no foreman should instruct one of his men to place material in the storeroom except as instructed by its head.

Aside from the storeroom proper, the stores clerk will have charge of material stored outside of the plant. Lumber, fuel, and heavy castings are examples of material coming under this head. Nevertheless, his records should include all of this material, and he should have general supervision over its storage in order that he may more readily determine, or more closely estimate, quantities in stock.

21. Receiving. In the organization of the stores department, it is necessary to provide for a record of the receipt of all material and supplies. The system must be so constructed that it will not only insure a record of all goods coming into the establishment, but prevent the acceptance of goods which should not be received.

All receiving should, therefore, be in charge of one man. In the larger industrial enterprises, a receiving clerk is employed, whose duty is to receive and receipt for all goods coming into the establishment, and to deliver them to the storeroom or the department in which they are to be used. The stores clerk may, in a small concern, perform all of the functions of the receiving clerk.

When goods come in, the receiving clerk will refer to his file of purchase order copies to find if the goods have been ordered. It will be remembered that an alphabetical file has been recommended for these orders, which are to be filed under the name of the shipper. The reason for this is that the package does not always show the nature of its contents, while the name of the shipper is almost invariably shown somewhere on the package or on the shipping tag.

Goods should not be accepted by the receiving clerk unless he has an order. To do so is liable to cause trouble. As an illustration, we will suppose that the concern has made a contract for material on which deliveries are to be made at stated intervals. The first shipment received shows that the material is not up to specifications and the contract is cancelled. Pending an adjustment, the receiving clerk is instructed to accept no more material on the contract. If he does so, the concern will very likely be obliged to pay for it, and it may even have a bearing on the entire contract.

Another class of shipments which must be carefully watched is the return of goods by customers of the concern. In some businesses, this question is not important; in others, great care must be exercised to insure proper credit. In a manufacturing or a trading business other than retail, the customer will usually notify the house that he is returning goods. When such a notice is received, instructions should be given to the receiving clerk whether to accept or refuse them.

One class of business in which the receipt of returned goods must be handled with extreme care is the installment business. Most installment contracts vest title to the goods in the seller until all payments are made. To avoid payment, a customer may return goods without notice. Acceptance by the seller cancels the contract at once. A safe rule to follow, therefore, is to accept no returned goods until authorized to do so by one in authority.

The receiving slip, Fig. 13, Page 16, is to be filled out by the receiving clerk. One copy will go to the purchasing agent and the[47] other to the stores clerk. From these reports the stores clerk makes his record of material received. In some cases material ordered for the use of a particular department is to be sent direct to the department and not to the storeroom. A third copy of the report should be made which will be sent to the department, from whence it will go to the stores clerk, properly receipted.

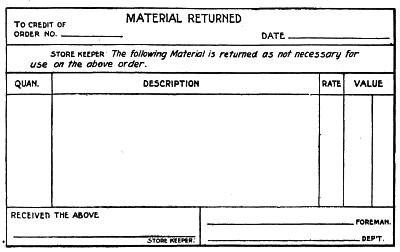

22. Deliveries. The stores clerk, being in custody of all stock, is responsible not alone for its safe keeping but for deliveries. He must be in a position to show what stock has been delivered, to whom, and for what purpose.

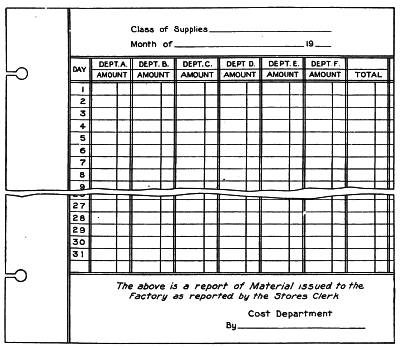

There is but one method that will insure an accurate record of deliveries and that is, to deliver no goods without a written order or requisition, signed by one having authority to authorize withdrawals.

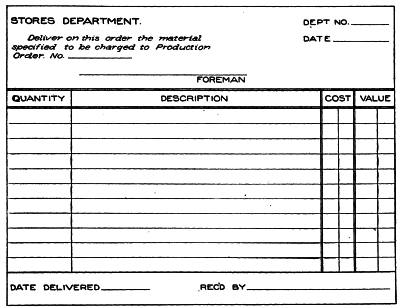

Each department, or shop, should be supplied with storeroom requisitions, numbered consecutively with the department number or letter; that is, a requisition from one shop might be numbered B 100, another C 100. These requisitions should be made in duplicate or triplicate. When the duplicate form is used, the original is sent to the stores clerk and the duplicate retained by the foreman. When the stores clerk has completed his records and the foreman has received the material, both copies are to be sent to the cost department. One copy acts as a check against the other, making it impossible for either the stores clerk or foreman to make false returns. To make identification easy, the two blanks should be printed on paper of contrasting colors. In the cost department one copy should be filed according to the department in which the requisition originated, keeping the numbers consecutive, and the other under the production or job order number. On completion of the order, the latter copy can be destroyed as it will no longer be needed. The departmental copies may also be destroyed, say at the end of a three months' period.

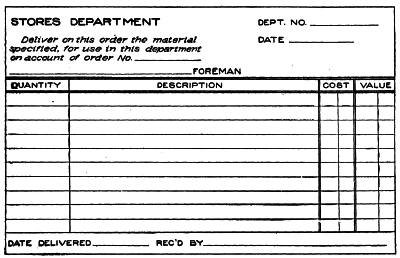

Sometimes it will be found advisable for the stores clerk to retain a copy of the requisition, in which event the triplicate form will be used, two copies being sent to him. He will file his copy by production order numbers, if for material, or by departmental numbers, if for supplies.

All requisitions should provide for a record of prices and values, these to be entered in the cost department. If this is omitted it will[48] be necessary for the cost clerk to enter the items and extend cost on another blank; when included, he can post values direct from the requisition to the permanent cost records. Place should also be provided on the requisition for the signature of the one who receives the material.

Fig. 23. Requisition for Material to be Used on a Production Order

A form of requisition adapted to the use of the average manufacturing enterprise is shown in Fig. 23. This form shows the department number, the date, the production order number, quantity, description, cost, and value. At the bottom the necessary form of receipt is provided. Usually this form will be found adequate for both material and supplies. When used for supplies, the purpose for which they are intended is to be inserted in place of the production order number. Special forms for supplies and repair material are used in some plants. These should differ in color from the material requisitions. A form of this character is illustrated in Fig. 24.

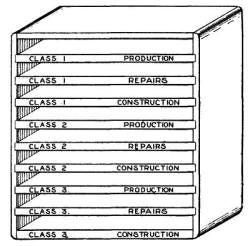

STORES RECORDS

23. The installation of a stores-record system calls for the exercise of judgment of the highest order, for the record of material and[49] supplies is of no less importance than the record of cash. As has already been stated, material should be accounted for with the same fidelity as cash; a dollar's worth of material should be regarded as a dollar in gold.

The stores record system should be an integral part of the accounting system of a business; it should be checked as carefully as any account in the ledger. Only by making the stores record a part of the accounting system can it be operated successfully.

Fig. 24. Special Departmental Requisition for Material

Stores records may be divided into two classes—one recording both quantities and values, and one recording quantities only. Frequently both classes are used in one establishment. In the storeroom a system is maintained which records quantities without prices; in the cost department a record of values and quantities may be kept.

The records kept in the storeroom are primarily intended to show quantities on hand, or rather quantities that should be on hand. Sometimes these records show prices, but there appears to be no good reason why this should be done. It is better to have all accounting of values done in the accounting department.

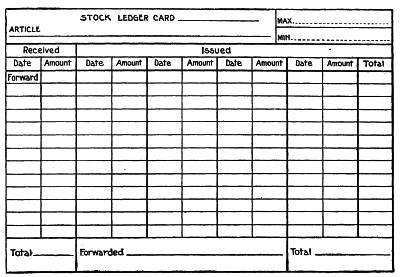

The records under consideration are those of the storeroom. These records must show quantities received and quantities issued, from which a record of the quantity on hand can be obtained. To supply the necessary information, the records must show quantities[50] of each article or kind of material in stock, which necessitates a system of units. Some articles will move much more rapidly than others; therefore, a bound book is not practical. Either cards or loose leaves can be used successfully, a card or sheet being used for the record of each article.

In order that the records may be instantly available, they must be properly classified. The classifications should follow the same lines as the ledger accounts, which will correspond with the classifications adopted in recording the original inventory. Records of material and supplies should be separated, and each divided into classes. The cards or loose leaves should be filed and indexed according to these classifications.

For example, we will suppose that one division of the material account is hardware. On one index will be written the word Hardware, the index forming a main division. Back of the index all cards or sheets recording articles that come in the hardware classification will be filed, these records also being properly classified and subdivided. In the hardware stock will be found screws of several classes, as round-head bright, round-head blued, flat-head bright, flat-head blued. In the S section, back of Hardware, one index will be headed Screws. This division will be subdivided by indexes headed with the names of the classes or kinds of screws. The stores record cards or sheets will then be filed back of these subdivision indexes in the order of sizes. A card or sheet may be used for each size, or several sizes may be recorded on the same sheet.

24. Verification of Stores Records. When indexed in this manner the stores record of any article can be quickly located, and the sectional divisions will assist greatly in verifying the records. While the stores records are intended merely as records of material in stock, their accuracy must be verified by an actual inventory, just as the cash account is verified by a count of cash on hand. However, if thoroughly classified, it is not necessary to verify all of the stores records at one time; they can be verified by sections, or the record of a single article can be verified by an article inventory, without regard to other records.

Accounts in the ledger should be arranged to correspond with the stores classifications, that is, purchase accounts should be carried with materials forming the main divisions of the stores records; as[51] Hardware, Bar Steel, Foundry Material, Foundry Supplies, and Factory Supplies. When the stock of one class, as hardware, is inventoried, the result should be recorded on the regular inventory sheet, priced, and extended, and the total compared with the hardware purchase account in the ledger. Any discrepancies should be adjusted at once, but if the records are carefully kept, and an inventory of each class is taken two or three times a year, the discrepancies should be practically nil.

If the routine prescribed is faithfully followed, there is no theoretical reason why stores records should not check as closely as cash, with the possible exception of bulk stores, like fuel and ores, where estimates are necessary. Even then, if inventories are taken when these stores are at the lowest point, there should be little difficulty in arriving at accurate results. However, the greatest responsibility rests on the chief stores clerk. He must not let a single pound of material leave the storeroom without an order, for it is on the accuracy of his records that all of the accounts are based. The order copies received in the cost department furnish the basis for all material charges. Here prices are entered and extensions are made. The chief cost clerk will transmit to the chief accountant weekly or monthly recapitulations of all material charged out. The chief accountant will credit his purchase accounts and debit Manufacturing, Maintenance, Repair, or Expense accounts as the case may be. Purchase accounts thus become controlling accounts of the stores records, and the latter takes its legitimate place as an integral part of the accounting system.

RECORD FORMS

25. All forms for stores records, no matter what the class of material recorded, possess certain characteristics in common; yet the information required about each special class is usually of such nature that a special form is advisable. This may mean the use of several forms in the same establishment.

When installing any system, however, it is more economical to invest more money in printing and have forms that fit exactly, than to attempt to make special records conform to forms prepared for other purposes. If certain specific information is required, the form should be designed to exhibit just that information, and if the form[52] is properly designed, the saving of time both in recording and consulting the record will much more than offset the slight additional cost of special printing.

The number of forms must not be so large as to cause confusion, but against the opposite extreme the cost of time must be considered. It will be found that the value of clerks' time is greater than the cost of printing.

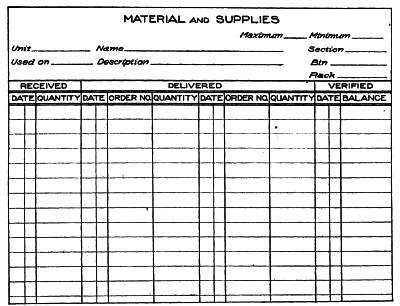

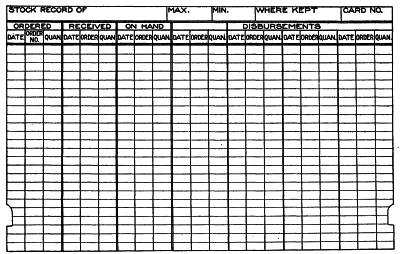

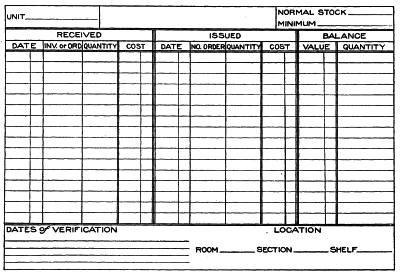

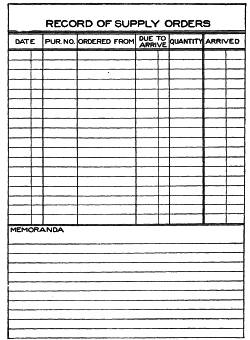

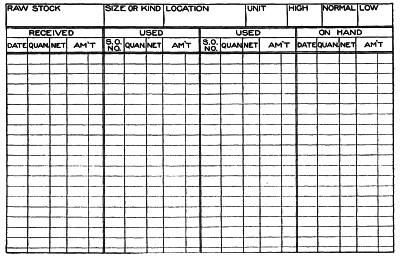

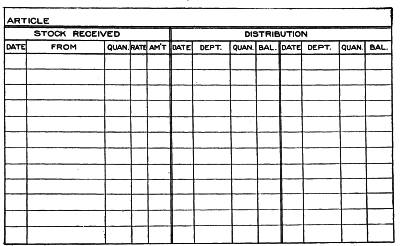

Fig. 25. Form for a Stock Record of Materials and Supplies