Title: Memorials of the Life of Amelia Opie

Author: Amelia Opie

Editor: C. L. Brightwell

Release date: December 8, 2014 [eBook #47595]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Delphine Lettau, Cindy Beyer, Rcool and the

Project Gutenberg team at

http://www.pgdpcanada.net

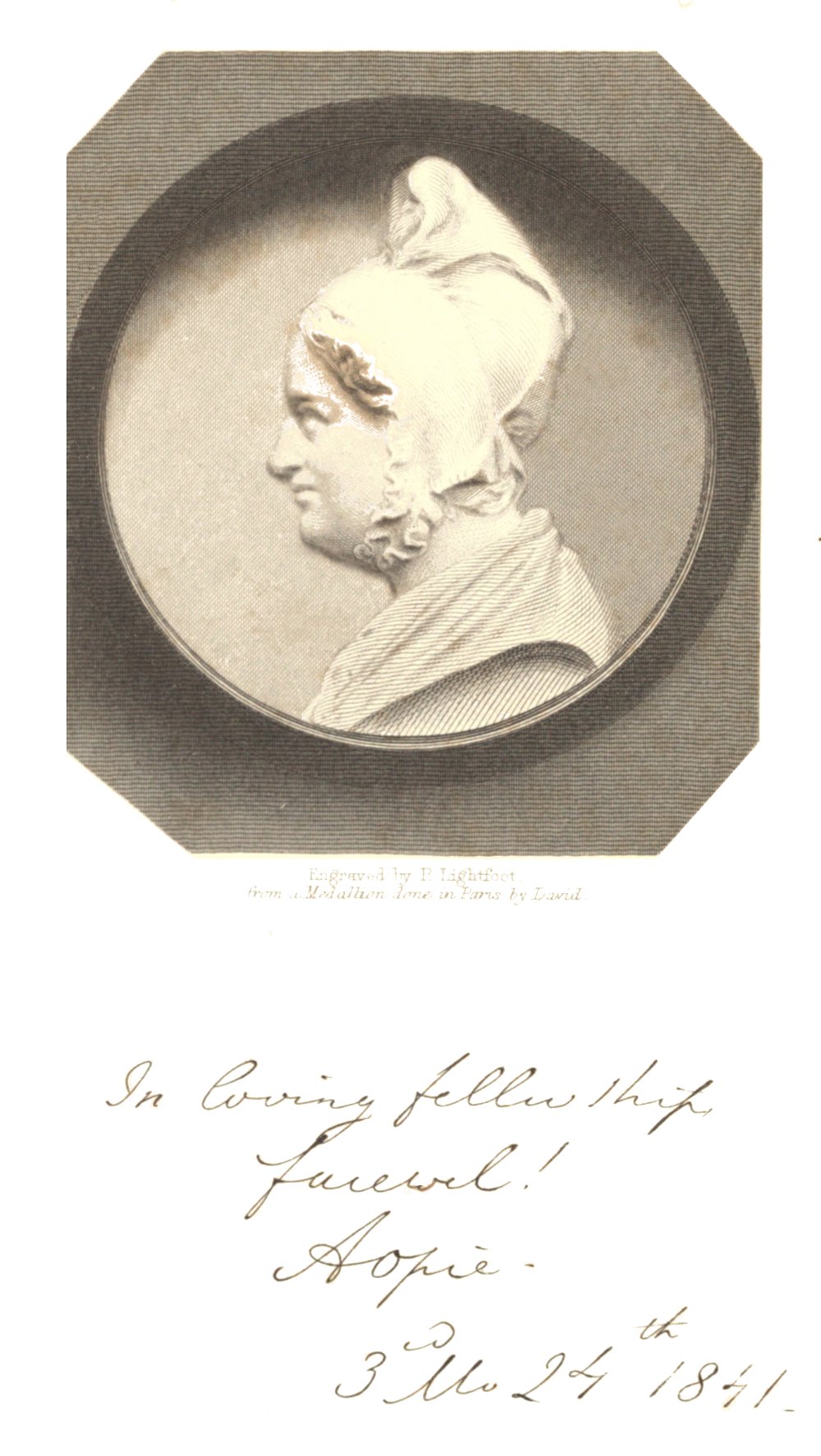

In loving fellowship farewel! A Opie. 3rd Mo 24th 1841.

MEMORIALS

OF THE

LIFE OF AMELIA OPIE,

SELECTED AND ARRANGED

BY

CECILIA LUCY BRIGHTWELL.

NORWICH:

FLETCHER AND ALEXANDER;

LONDON: LONGMAN, BROWN, & Co.

MDCCCLIV.

PREFACE.

In the preparation of these Memoirs for publication, the principal part of the labour has been undertaken by my daughter; the pressure of other engagements having only permitted me to undertake the general direction and supervision of the whole.

As the Executor of Mrs. Opie, her papers and letters came into my hands; and it devolved on me to decide in what way to dispose of them. There had been, (I believe,) a general impression among her friends, that she would herself prepare an account of her Life; but although she seems to have made some efforts at commencing the task, and the subject was often affectionately recommended, and even urged upon her, she has left it a matter of regret to her friends, (and especially so to the compilers of these memoirs,) that no “Autobiography” was found among her papers. Nor did Mrs. Opie ever distinctly give any directions as to the publication of her MSS. or any Memoir of her Life; but we have, we think, strong presumptive evidence, that she anticipated, if not desired, that it should be done.

Not long before she died, she said, that her Executor would have no light task with her papers; and a few days before she breathed her last, when she could no longer hold a pen, she called her attendant to her, and dictated a most touching and affectionate farewell address, to me and my daughter, directing the delivery of various small articles as remembrances to a few most intimate friends, and requesting us to complete what she had left undone; adding, that she had confidence in our judgment, and believed that we should “do everything for the best.”

It has been with an earnest desire to justify this trust, and to perfect, as far as in our power, that which she had, in fact commenced, but left incomplete, that these pages have been put to the press.

It will be seen, in the course of these Memoirs, that the materials from which they are compiled, are principally Papers, Letters, and Diaries, of Mrs. Opie’s own writing; a few Letters preserved by her, and judged to be of general interest, and bearing upon her history, we have thought it well to give. It would have been no difficult task, to have greatly extended these Memoirs, had it been deemed expedient to make a free use of the Letters received by her, and of which a very large number were found among her papers; but we have not felt ourselves at liberty to adopt such a course, and we trust there will be found in this Volume few (may we say we hope no) violations of private and confidential communications.

My acquaintance with the subject of these Memoirs, commenced nearly forty years ago; and well do I remember the first impressions made on me by her frank and open manner, the charm of her fine and animated countenance, her artless cheerfulness and benevolence, and the extraordinary powers of her conversation. But it was not till the time of Dr. Alderson’s last illness, that my acquaintance with Mrs. Opie ripened into confidential friendship. From that period to the time of her decease, I had the happiness to enjoy much of her society, and to hear her recollections of her earlier days, and her graphic descriptions of the scenes and characters, which had been subjects of interest to her during the course of her long life; and she subsequently often read me a large portion of the correspondence she continued to maintain.

Gifted with an extraordinary memory, a reverence for truth, extending even to the minutest details, a disposition to look at the best side of everything and everybody, and with almost dramatic power in the exhibition of character and manners; Mrs. Opie when she entered into any details of her former life, painted the whole scene with such truthfulness and power, as to make it live before her hearers, and fix it in their memory.

As an Author, her works have undergone the ordeal of public criticism, and some additional testimony is afforded by these Memoirs, to the favourable impression they made. It will be seen that Sir Walter Scott, Dr. Chalmers, Southey, and other men of note, alike agreed in paying their tribute of admiration to her power of touching the heart, and awakening the softer passions.

The great leading feature of Mrs. Opie’s character was pure, christian benevolence; charity in its highest sense. None that knew her could fail to observe this. Unwearied in her efforts to relieve the distresses of others, and limited in her own means, she was almost ingenious in some of the methods she devised for doing so, and made it matter of duty to avail herself of her influence with her wealthier friends to induce them to assist her endeavours. Her patience in dealing with the incessant importunities of persons who applied for her aid, was almost more than exemplary: but she found a blessing in doing good; and, in her parting address, before alluded to, she has not failed to urge “the remembrance of the poor, so as to be blessed by them.”

Of her religion, the latter part of this Memoir will best speak, and especially the short extracts from her private Journals. These, speaking from the depths of her own heart, shew how holily and humbly she walked before her God; how strictly she called herself to account day by day; and how firmly she relied on the atonement of the Lord Jesus Christ as her hope in life and support in death.

Mrs. Opie had no liking for religious controversy, and seemed to me always desirous of avoiding it. I believe she disliked dogmatic theology altogether. Her religion was the “shewing out of a good conversation her works, with meekness of wisdom.”

She ever deemed her union with “the Friends” the happiest event of her life; and she did honour to her profession of their principles, by shewing that they were not incompatible with good manners and refined taste. She met with some among them who have always appeared to me to come the nearest to the standard of christian perfection; these were her dearest friends on earth, and she is now, with them, numbered among the blessed dead who have died in the Lord, who have ceased from their labours, and whose works do follow them.

THOMAS BRIGHTWELL.

Norwich, May, 1854.

A Second Edition of this work having been speedily called for, the Author has found but little opportunity for making additions to it, and the present is, therefore, excepting some trifling omissions, and the introduction of a few additional lines, simply a reprint of the former volume.

C. L. BRIGHTWELL.

Norwich, July, 1854.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I.

Birth and Parentage; her Father; her Mother’s Family; her Mother; Sonnet to her Mother’s Memory; Early Reminiscences; Early Terrors and their Cure; the Black Man; Crazy Women; Bedlam; Visits to the Inmates; Early Training; the Female Sailor; Abrupt Conclusion 1

CHAPTER II.

First Sorrow; the Assizes; Sir Henry Gould; the Usury Cause; “Christian;” Mr. Bruckner; Girlish Days; her Friendship with Mrs. Taylor; Mrs. T.’s Memoir of her 22

CHAPTER III.

Norfolk and Norwich, and their Inhabitants; Young Love; the Drama; Song writing and Cromer; Politics; Visit to London; Letters from thence; the Old Bailey Trials 34

CHAPTER IV.

French Emigrants; Letter to Mrs. Taylor; Letter of the Duke d’Aiguillon; Visit to London and Letter from thence; London again; Letter from Mrs. Wollstonecroft; First introduction to Mr. Opie; Mr. Opie’s early history; Return to Norwich; Preparations for Marriage 51

CHAPTER V.

Marriage; Early Ménage; Authorship; Lay on portrait of Mrs. Twiss; Letter to Mrs. Taylor; Visit to Norwich; Letter from Mr. Opie; Mrs. Opie to Mrs. Taylor; Mr. Opie’s Mother 68

CHAPTER VI.

“The Father and Daughter;” Critique in the Edinburgh; three Letters to Mrs. Taylor; volume of “Poems;” “Go, youth beloved;” Letter from Sir J. Mackintosh; S. Smith’s Lecture 79

CHAPTER VII.

The Trials of Genius; Domestic Troubles; Letters to Mrs. Taylor; Journey to France; Arrival at Paris; the Louvre; the First Consul; Charles James Fox; The Soirée; Kosciusko 91

CHAPTER VIII.

The Review and Buonaparte; “Fesch;” General Massena; Return to England; Letter to Mrs. Colombine Visit to Norwich; “Adeline Mowbray;” Letter to Mrs. Taylor; Mr. Erskine 108

CHAPTER IX.

Prosperity; “Simple Tales;” Visit to Southill; Lady Roslyn; Mr. Opie’s “Lectures;” his Illness; his Death 125

CHAPTER X.

Return to Norwich; “Poems;” Memoir of her Husband; Letter from Lady Charleville; from Mrs. Inchbald; Visit to London; Party at Lady E. Whitbread’s; Visit to Cromer; “Temper;” “Tales of Real Life;” Soirée at Madame de Staël’s 135

CHAPTER XI.

Letters of Mrs. Opie to Dr. Alderson, written during her visit in London in the year 1814 146

CHAPTER XII.

Friendship with the Gurney family; two Letters from Mr. J. J. Gurney; Death of his Brother; Mrs. Opie’s Return from London; Early Religious Opinions; Mrs. Roberts; Recollections of Sir W. Scott; Visit to Edinburgh; “Valentine’s Eve;” Visit to Mr. Hayley; “Tales of the Heart;” Letter to Mr. Hayley; Letter from Mrs. Inchbald; her death 167

CHAPTER XIII.

Illness of Dr. Alderson; His Daughter’s anxiety; Priscilla Gurney; Bible and Anti-Slavery Meetings; “Madeline;” Letter from Southey; “Lying;” Letters to Mrs. Fry; Mrs. Opie joins the Society of Friends; Dr. Alderson’s Decline and Death 183

CHAPTER XIV.

Consolation in Sorrow; Letter to a Friend; Journal for the year 1827 197

CHAPTER XV.

Yearly Meetings; Letter from London; Letters from Ladies Cork and Charleville; “Detraction Displayed;” Letter from Archdeacon Wrangham; Cromer; Diary for 1829 212

CHAPTER XVI.

Visit to Paris; Journal during her Stay there; Letter from thence; Return to England; Letter from Lafayette; Sonnet “on seeing the Tricolor;” Southey's “Colloquies;” Letter from Mrs. Fry; “Nursing Sisters” 229

CHAPTER XVII.

Revolution of “the Three Days;” Mrs. Opie goes to Paris again; her Journal there 245

CHAPTER XVIII.

Letter on the Distribution of Prizes at the Catholic Schools; Continuation of Journal; Letter giving an Account of her Visit to the French Court 264

CHAPTER XIX.

Influence of Christian Fellowship; Mrs. Opie Returns to England; gives up Housekeeping; Journey into Cornwall; Letters and Journal during her Residence there 284

CHAPTER XX.

Return to Norwich; Extracts from her Diary; Dr. Chalmers and Mrs. Opie at Earlham; Lines addressed by Mrs. Opie to Dr. Chalmers; “Lays for the Dead;” Visit to London; Journey to Scotland; her Journal there; The Highlands; her Visit to Abbotsford 302

CHAPTER XXI.

Journey to Belgium; Visit to Ghent; Journal of her Travels; Letter from the Rhine Falls; Homeward Journey; Arrival at Calais 317

CHAPTER XXII.

Mrs. Opie’s Removal to Lady’s Lane; Letters, Visitors, and Writing; Spring Assizes of 1838; Memoirs of Sir W. Scott; Visits to London and Northrepps; Death of Friends; Anti-Slavery Convention; Winter and Spring of 1840-41; Visits to Town and Letters from thence in 1842-43; Illness; Close of 1843; Letter of Reminiscences of Thomas Hogg 333

CHAPTER XXIII.

Death of Mr. Briggs; Summer Assizes, 1844; “Reminiscences of Judges Courts;” “Reminiscences of George Canning” 353

CHAPTER XXIV.

The Seventy-fifth year; Notes and Incidents in the years 1845-46; Deaths of Mr. J. J. Gurney and of Dr. Chalmers; Letter from Cromer; Death of Mrs. E. Alderson; Mrs. Opie’s Visit to London in the Spring of 1848; Letter from thence 366

CHAPTER XXV.

The Castle Meadow house; Indisposition; Increase of Crime; Rush’s Trial; Summer Assizes of 1849; Death of Bishop Stanley; Summer and Autumn of 1850; Farewell Visit to London; the Great Exhibition; Summer of 1852; Rheumatic Gout; Notes; last Visit to Cromer; the Spring and Summer of 1853; Sudden Illness, October 23rd; Patience and Cheerfulness; Increasing Sickness; Leave Taking; Death 382

Conclusion 404

MEMORIALS

OF THE

LIFE OF AMELIA OPIE.

BIRTH AND PARENTAGE; HER FATHER; HER MOTHER’S FAMILY; HER MOTHER; SONNET TO HER MOTHER’S MEMORY; EARLY REMINISCENCES; EARLY TERRORS AND THEIR CURE; THE BLACK MAN; CRAZY WOMEN; BEDLAM; VISITS TO THE INMATES; EARLY TRAINING; THE FEMALE SAILOR; ABRUPT CONCLUSION.

Amelia Opie, the only child of James Alderson, M.D., and of Amelia, his wife, was born the 12th of November, 1769, in the parish of St. George, Norwich; she was baptized by the Rev. Samuel Bourn, then the Presbyterian Minister of the Octagon chapel, in that city. Her father was one of a numerous family, the children of the Rev. Mr. Alderson, of Lowestoft, of whom some account is given in Gillingwater’s History of that “ancient town.” From this we gather that “Mr. Alderson was a very worthy, well-disposed man, of an exceeding affable and peaceable disposition, much esteemed by the whole circle of his acquaintance, and, as he lived much respected, so he died universally lamented.” His death happened in 1760. In a note the following account of his family is added: “Four sons and two daughters survive him; the sons are all distinguished for their industry and ability, and are eminent in their several professions; James, an eminent surgeon, at Norwich; John, a physician, at Hull, Thomas, a merchant, at Newcastle; and Robert, a barrister, at Norwich. Of the two daughters, Judith is married to Mr. Woodhouse, and Elizabeth unmarried.”

This was written in 1790. Were the historian now to add a supplementary notice, with how much satisfaction would he record, that, in the third generation, this family numbered among its descendants, Amelia Opie and Sir E. H. Alderson; the former the child of the eldest brother, the latter the son of the youngest.

The tender attachment borne by Mrs. Opie to her father was perhaps her most prominent characteristic. They were companions and friends through life; and when, at length, in a good old age, he was taken from her, she wept with a sorrow which no time could obliterate, and for which there was no solace but in the hope of rejoining him in a better world. Deeply touching are the evidences of the love which prompted her pen in its most successful efforts, influenced her in all the steps she took throughout her career, and rendered her indefatigable in cheering and soothing him through the long years of his declining age. Best of all, she was enabled to direct his mind towards those great truths of the gospel, which she had learned to love, and in which she found her support, when the arm of her earthly friend was about to relax its hold, and leave her alone to pursue in solitude the remainder of her pilgrimage.

Probably the early loss of the wife and mother was one cause which drew more close the bond of union between the “Father and Daughter.” It naturally followed that when, at the age of fifteen, she took the head of her father’s table, and the management of his domestic arrangements, she should endeavour, as much as possible, to supply the place which had been left vacant, and that her young affections should cling more fondly around her remaining parent. There was also much in the father calculated to draw to him the love of his child. He was of fine person and attractive manners, and to these external advantages was joined something better and more enduring—a kind-hearted and generous sympathy for the sufferers whom his skill relieved, and a charity to the poor, which induced him freely to give them his valuable advice and assistance. His daughter says, “He prescribed for about four or five hundred persons at his house every week. The forms in our large hall in a morning were so full from half-past eight till eleven, that I could scarcely pass; and this he did till the end of the year 1820, or rather perhaps to the beginning of 1821, when, unable to go down-stairs, he received the people, at my earnest desire, in my little drawing-room, till he said he could receive no one again. Oh! it was the most bitter trial he or I ever experienced, when he was forced to give up this truly Christian duty; and I was obliged to tell the afflicted poor people that their kind physician was no longer well enough to open his house to receive them, and try to heal their diseases again. He wept, and so did I; and they were bitter tears, for I feared he would not long survive the loss of his usefulness.” Those acts of kindness are not yet forgotten in his native city; an aged woman, being told the other day of the death of Mrs. Opie, recalled to mind the days of her father, “the doctor,” and the time when he was “very good to the poor folks, that is, he gaw’n ’em his advice for nothing; and that was a true charity, lady.”

Mrs. Opie’s mother, Amelia, was the daughter of Joseph Briggs, of Cossambaza, up the Ganges, (eldest son of Dr. Henry Briggs, rector of Holt, Norfolk, and Grace, his wife,) and of Mary, daughter of Captain Worrell, of St. Helena. In an old pocket book, Mrs. Opie has entered the following memoranda concerning this branch of her maternal ancestors.

Account of my great, great, great grandfather, Augustine Briggs, M.P., for Norwich. (From the pedigree of the Briggs’ in Blomefield’s “History of Norfolk.”) An ancient family of Salle, in Norfolk, who before the reign of Edward the First assumed the surname of De Ponte, or Pontibus, i.e. at Brigge or Brigges; as the ancient family of the Fountaines of the same place assumed theirs, of De Fonte or Fontibus, much about the same time, one we presume dwelling by the bridge or bridges, the other by the springs or fountains’ heads. The eldest branch of both families continued in Salle till they united in one. William Atte Brigge, of Salle, called in some deeds W. de Fonte de Salle, was living at Salle in 1334. John Atte Brigge, his second son, was alive in 1385. Thomas Brigge, of Holt, the fourth brother, was alive in 1400; and, in 1392, went to the Holy Sepulchre of our Lord, an account of which pilgrimage written by himself is still extant, in a manuscript in Caius College Library. Augustine Briggs, mayor, alderman, and member for Norwich in four Parliaments, was turned out of the Corporation by the rebels, and restored at the king’s restoration. He joined the Earl of Newcastle’s forces at the siege of Lynn, in 1643. There is a long sword in the family, with a label in Augustine Briggs’ own hand writing tied to it. “This I wore at the siege of Linn, in the servis of the royal martyr, K. Charles ye First, A. Briggs.” He lies buried in a vault in the church of St. Peter’s Mancroft, built by himself, but he alone of the family lies there. It has been since appropriated by the Dean and Chapter to another family, as it was supposed no one was alive to claim it; but I, A. Opie, am the lineal descendant and representative of this excellent man, and the vault was my property. The following is a translation of part of the Latin inscription on his mural monument in St. Peter’s church:—“He was indeed highly loyal to his king, and yet a studious preserver of the ancient privileges of his country; was also firm and resolute for upholding the Church of England, and assiduous and punctual in all the important trusts committed to him, whether in the august assembly of Parliament, his honourable commands in the militia, or his justiciary affairs on the bench: gaining the affections of the people by his hospitality and repeated acts of kindness, which he continued beyond his death, leaving the following charities by his will, as a more certain remembrance to posterity, than this perishing monument erected by his friends, which his posterity endeavours by this plate to continue to further ages.” He died in 1684, aged 67. He lived in the Briggs’ Lane, called after him, which lane is now (1839) widening, and is to be called D’Oyley Street, a proper tribute of respect to the public spirited individual who subscribed £1600 to further this improvement.[1]

Augustine Briggs was also a public benefactor to this, his native city, for he left “estates and monies to increase the revenue of the Boys’ and Girls’ Hospital, and for putting out two poor boys to trades every year, as can read and write, and have neither father nor mother to put them forth to such trades.” My cousin, Henry Perronet Briggs, R.A.,[2] his male representative, has a very fine picture of him, a half-length, in his military dress, painted, he believes, by a pupil of Vandyke. I have a tolerably good three-quarter picture of him,[3]—Amelia Opie. I have also a portrait of his daughter-in-law, Hannah Hobart, heiress of Edmund Hobart, son of the Lord Chief Justice Hobart, afterwards ennobled, and wife of Dr. W. Briggs, M.D., of the University of Cambridge, a man of great science and learning, and an eminent physician.

* * * * * *

Of the mother of Mrs. Opie but few memorials remain. She was of a delicate constitution, and appears to have cherished the habits of retirement, so naturally preferred by an invalid. Her early death bereaved her daughter of a mother’s care and guidance at the most critical period of woman’s life; and we may perhaps trace some features of Mrs. Opie’s character to this event. From the occasional glimpses we catch of the mother in her daughter’s short record of her own early days, it is evident that she was possessed of firm purpose and high principle; a true-hearted woman, and somewhat of a disciplinarian. Her steady hand would have curbed the high spirit of her child, and softened those ebullitions of youthful glee, which made the young Amelia such an impetuous, mirthful creature: she would have been more demure and decorous had her mother lived, but perhaps less charming and attractive. Speedily as the mother’s influence was withdrawn, it left, notwithstanding, some indelible traces in the memory of her daughter, who frequently referred to her, even in her latter days, and usually with reference to some bad habit from which she had warned her, or some good one which she had inculcated. Mrs. Alderson died on the 31st of December, 1784, in the 39th year of her age.

A series of Letters referring to the death of Mr. Joseph Briggs and his wife, and the transfer of their little orphan daughter to England, still exist. They are principally written by Mr. William Briggs, the second son of Dr. Henry Briggs, who having died in 1748, (just about the time of his eldest son’s decease in India,) the family affairs were committed to the care of his next surviving son. He writes thus:—

Several years ago my elder brother, Joseph Briggs, went over to Bengal as a writer in the Company’s service; he married Miss Mary Worrell; he died in May, 1747, and his widow in the December following; leaving behind one child, Amelia. Captain James Irwin, out of friendship to my brother, took care of his little daughter after the death of her mamma. The latter end of May, 1749, the child arrived here in England, and is now in perfect health.

To this kind friend of the orphan, Captain Irwin, the grateful uncle writes:—

London, August 23rd, 1749.

Worthy sir, your letter of December 24th, 1748, and my very dear niece, Amelia Briggs, came safe to England the latter end of May last, praised be God! My honoured father dying in May 1748, yours to him came to me with one directed for myself, in both which you give very uncommon proofs of real friendship. Friendship in prosperity is common; but in adversity none are true friends but the pious.

Your great care of my niece has given very sensible pleasure to all her relations, and all unite with me to return you sincere and hearty thanks; at present we can only express our gratitude in words, but should you ever be pleased to give us an opportunity, I doubt not but you will find us ready to testify our thanks by useful deeds. I believe you will meet with a reward more substantial and durable from our gracious God.

My very great affection for my dear brother Joseph naturally leads me to love and care for the little orphan as if it was my own. She will never want whilst I have it in my power to assist her. She will be a burden to none of her relations; for, before she will have any occasion for it, she will be in possession of a very handsome annuity. At present she is with my mother in Norfolk, one hundred miles from London. She is a charming child, and the country agrees very well with her. The black girl, her nurse, is not reconciled to England; and, thinking she never shall be so, she is determined to return to Bengal by the Christmas ships. As my mother will give her entire liberty to be at her own disposal, I believe her design is to enter into service, as other free women do. If it be in your power, you are very much desired by all my niece’s friends to prevent Savannah’s being bought or sold as a negro.

May the God of all grace and consolation keep and bless you, dear sir, and all your family, with everything necessary to make your short passage easy and agreeable through time into a happy eternity, is the sincere wish and prayer of,

Dear Sir,

Your most obliged humble servant,

W. B.

Seven years after her mother’s death, (1791,) she addressed to her memory the following sonnet.

ON VISITING CROMER FOR THE FIRST TIME SINCE THE DEATH

OF MY MOTHER, WITH WHOM I USED FREQUENTLY TO VISIT IT.

Scenes of my childhood, where, to grief unknown,

And, led by Gaiety, I joy’d to rove,

’Ere in my breast Care fix’d her ebon throne,

And her pale rue, with Fancy’s roses wove.

No more, alas! your wonted charms I view,

Ye speak of comforts I can know no more;

The faded tints of Memory ye renew,

And wake of fond regret the tearful power.

But would ye bid me still the beauties prize

That on your cliff-crowned shores in state abide,

Bid, aim’d in awful pomp, yon billows rise

And seek the realms where Night and Death reside;

Unusual empire bid them there assume,

And force departed goodness from the tomb!

Many years after, among her “Lays for the Dead,” appeared some further lines dedicated to her mother, and, as they have several references to the recollections she retained of her, and are in themselves very sweet and full of earnest tenderness of regret, they are reprinted here:—

IN MEMORY OF MY MOTHER.

An orphan’d babe, from India’s plain

She came, a faithful slave her guide!

Then, after years of patient pain,

That tender wife and mother died.

Where gothic windows dimly throw

O’er the long aisles a dubious day,

Within the time-worn vaults below

Her relics join their kindred clay—

And I, in long departed days,

Those dear though solemn precincts sought,

When evening shed her parting rays,

And twilight lengthening shadows brought—

There long I knelt beside the stone

Which veils thy clay, lamented shade!

While memory, years for ever gone,

And all the distant past pourtray’d!

I saw thy glance of tender love!

Thy check of suffering’s sickly hue!

Thine eye, where gentle sweetness strove

To look the ease it rarely knew.

I heard thee speak in accents kind,

And promptly praise, or firmly chide;

Again admir’d that vigorous mind

Of power to charm, reprove, and guide.

Hark! clearer still thy voice I hear!

Again reproof, in accents mild,

Seems whispering in my conscious ear,

And pains, yet soothes, thy kneeling child!

Then, while my eyes I weeping raise,

Again thy shadowy form appears;

I see the smile of other days,

The frown that melted soon in tears!

Again I’m exiled from thy sight,

Alone my rebel will to mourn;

Again I feel the dear delight

When told I may to thee return!

But oh! too soon the vision fled,

With all of grief and joy it brought;

And as I slowly left the dead,

And gayer scenes, still musing sought,

Oh! how I mourn’d my heedless youth

Thy watchful care repaid so ill,

Yet joy’d to think some words of truth

Sunk in my soul, and teach me still;

Like lamps along life’s fearful way

To me, at times, those truths have shone,

And oft, when snares around me lay,

That light has made the danger known.

Then, how thy grateful child has blest

Each wise reproof thy accents bore!

And now she longs, in worlds of rest,

To dwell with thee for evermore!

* * * * * *

Mrs. Opie evidently designed, at one time, to write a record of the most interesting events of her life; she commenced the task, but abruptly broke off when she reached the age of early youth. This interesting fragment was clearly written at a late period of her life, it commences thus:—

“Ce n’est que le premier pas qui coûte,” says the proverb, and when I have once begun to put down my recollections of days that are gone, with a view to their meeting other eyes besides my own, the difficulty of the task will, I trust, gradually disappear.

But I should be afraid that my garrulities, as I may call them, would not be so interesting to others as I have thought they might be, had I not observed such a hunger and thirst in the world in general for anecdotes, whether biographical or otherwise, and had I not experienced, and seen others evince, such interest and amusement while reading of persons and things; and I am thus encouraged to record my recollections of those distinguished persons with whom I have had the privilege of associating, from my youth upwards, to the present day. Therefore, without further delay or apology, I mean to relate a few “passages” in my very early days, in order to make my readers acquainted with the preparation for my future life and occupations, which these days so evidently afforded.

One of my earliest recollections is of gazing on the bright blue sky as I lay in my little bed, before my hour of rising came, and listening with delighted attention to the ringing of a peal of bells. I had heard that heaven was beyond those blue skies, and I had been taught that there was the home of the good, and I fancied that those sweet bells were ringing in heaven. What a happy error! Neither illusion nor reality, at any subsequent period of my life, ever gave me such a sensation of pure, heartfelt delight, as I experienced when morning after morning I looked on that blue sky, and listened to those bells, and fancied that I heard the music of the home of the blest, pealing from the dwelling of the most high. Well do I remember the excessive mortification I felt when I was told the truth, and had the nature of bells explained to me; and, though I have since had to awake often from illusions that were dear to my heart, I am sure that I never woke from one with more pain than I experienced when forced to forego this sweet illusion of my imaginative childhood.

I believe I was naturally a fearful child, perhaps more so than other children; but I was not allowed to remain so. Well do I remember the fears, which I used to indulge and prove by tears and screams, whenever I saw the objects that called forth my alarm. The first was terror of black beetles, the second of frogs, the third of skeletons, the fourth of a black man, and the fifth of madmen.

My mother, who was as firm from principle, as she was gentle in disposition, in order to cure me of my first fear, made me take a beetle in my hand, and so convince myself it would not hurt me. As her word was law, I obeyed her, though with a shrinking frame; but the point was carried, and when, as frequently happened, I was told to take up a beetle and put it out of the way of being trodden upon, I learnt to forget even my former fear.

She pursued the same course in order to cure me of screaming at sight of a frog; I was forced to hold one in my hand, and thence I became, perhaps, proud of my courage to handle what my playfellows dared not touch.

The skeleton of which I was afraid was that of a girl, black, probably, from the preparation it had undergone; be that as it may, I was induced to take it on my lap and examine it, and at last, calling it my black doll, I used to exhibit it to my wondering and alarmed companions. Here was vanity again perhaps.

The African of whom I was so terribly afraid was the footman of a rich merchant from Rotterdam, who lived opposite our house; and, as he was fond of children, Aboar (as he was called) used to come up to speak to little missey as I stood at the door in my nurse’s arms, a civility which I received with screams, and tears, and kicks. But as soon as my parents heard of this ill behaviour, they resolved to put a stop to it, and missey was forced to shake hands with the black the next time he approached her, and thenceforward we were very good friends. Nor did they fail to make me acquainted with negro history; as soon as I was able to understand, I was shewn on the map where their native country was situated; I was told the sad tale of negro wrongs and negro slavery; and I believe that my early and ever-increasing zeal in the cause of emancipation was founded and fostered by the kindly emotions which I was encouraged to feel for my friend Aboar and all his race.

The fifth terror was excited by two poor women who lived near us, and were both deranged though in different degree. The one was called Cousin Betty, a common name for female lunatics; the other, who had been dismissed from bedlam as incurable, called herself “Old Happiness,” and went by that name. These poor women lived near us, and passed by our door every day; consequently I often saw them when I went out with my nurse, and whether it was that I had been told by her, when naughty, that the mad woman should get me, I know not; but certain it is, that these poor visited creatures were to me objects of such terror, that when I saw them coming (followed usually by hooting boys) I used to run away to hide myself. But as soon as my mother was aware of this terror she resolved to conquer it, and I was led by her to the door the next time one of these women was in sight; nor was I allowed to stir till I had heard her kindly converse with the poor afflicted one, and then I was commissioned to put a piece of money into her hand. I had to undergo the same process with the other woman; but she tried my nerves more than the preceding one, for she insisted on shaking hands with me, a contact not very pleasing to me: however, the fear was in a measure conquered, and a feeling of deep interest, not unmixed with awe, was excited in my mind, not only towards these women, but towards insane persons in general; a feeling that has never left me, and which, in very early life, I gratified in the following manner:—

When able to walk in the street with my beloved parents, they sometimes passed the city asylum for lunatics, called the bedlam, and we used to stop before the iron gates, and see the inmates very often at the windows, who would occasionally ask us to throw halfpence over the wall to buy snuff. Not long after I had discovered the existence of this interesting receptacle, I found my way to it alone, and took care to shew a penny in my fingers, that I might be asked for it, and told where to throw it. A customer soon appeared at one of the windows, in the person of a man named Goodings, and he begged me to throw it over the door of the wall of the ground in which they walked, and he would come to catch it. Eagerly did I run to that door, but never can I forget the terror and the trembling which seized my whole frame, when, as I stood listening for my mad friend at the door, I heard the clanking of his chain! nay, such was my alarm, that, though a strong door was between us, I felt inclined to run away; but better feelings got the mastery, and I threw the money over the door, scarcely staying to hear him say he had found the penny, and that he blessed the giver. I fully believe that I felt myself raised in the scale of existence by this action, and some of my happiest moments were those when I visited the gates of bedlam; and so often did I go, that I became well known to its inmates, and I have heard them say, “Oh! there is the little girl from St. George’s” (the parish in which I then lived.) At this time my mother used to send me to shops to purchase trifling articles, and chiefly at a shop at some distance from the bedlam, which was as far again from my home. But, when my mother used to ask me where I had been, that I had been gone so long, the reply was, “I only went round by bedlam, mamma.”

But I did not confine my gifts to pence. Much of my weekly allowance was spent in buying pinks and other flowers for my friend Goodings, who happened to admire a nosegay which he saw me wear; and as my parents were not inclined to rebuke me for spending my money on others, rather than on myself, I was allowed for some time to indulge in this way the interests which early circumstances, those circumstances which always give the bias to the character through life, had led me to feel in beings whom it had pleased the Almighty to deprive of their reason. At this period, and when my attachment to this species of human woe was at its height, a friend of ours hired a house which looked into the ground named before, and my father asked the gentleman to allow me to stand at one of the windows, and see the lunatics walk. Leave was granted and I hastened to my post, and as the window was open I could talk with Goodings and the others; but my feelings were soon more forcibly interested by an unseen lunatic, who had, they told me, been crossed in love, and who, in the cell opposite my window, sang song after song in a voice which I thought very charming.

But I do not remember to have been allowed the indulgence of standing at this window more than twice. I believe my parents thought the excitement was an unsafe one, as I was constantly talking of what I had said to the mad folks, and they to me; and it was so evident that I was proud of their acquaintance, and of my own attachment to them, that I was admonished not to go so often to the gates of the bedlam; and dancing and French school soon gave another turn to my thoughts, and excited in me other views and feelings. Still, the sight of a lunatic gave me a fearful pleasure, which nothing else excited; and when, as youth advanced, I knew that loss of reason accompanied distressed circumstances, I know that I was doubly eager to administer to the pecuniary wants of those who were awaiting their appointed time in madness as well as poverty. Yet, notwithstanding, I could not divest myself entirely of fear of these objects of my pity; and it was with a beating heart that, after some hesitation, I consented to accompany two gentlemen, dear friends of mine, on a visit to the interior of the bedlam. One of my companions was a man of warm feelings and lively fancy, and he had pictured to himself the unfortunate beings, whom we were going to visit, as victims of their sensibility, and as likely to express by their countenances and words the fatal sorrows of their hearts; and I was young enough to share in his anticipations, having, as yet, considered madness not as occasioned by some physical derangement, but as the result, in most cases, of moral causes. But our romance was sadly disappointed, for we beheld no “eye in a fine phrensy rolling,” no interesting expression of sentimental woe, sufficient to raise its victims above the lowly walk of life in which they had always moved; and I, though I knew that the servant of a friend of mine was in the bedlam who had been “crazed by hopeless love,” yet could not find out, amongst the many figures that glided by me, or bent over the winter fire, a single woman who looked like the victim of the tender passion.

The only woman, who had aught interesting about her, was a poor girl, just arrived, whose hair was not yet cut off, and who, seated on the bed in her new cell, had torn off her cap, and had let the dark tresses fall over her shoulders in picturesque confusion! This pleased me; and I was still more convinced I had found what I sought, when, on being told to lie down and sleep, she put her hand to her evidently aching head, as she exclaimed, in a mournful voice, “Sleep! oh, I cannot sleep!” The wish to question this poor sufferer being repressed by respectful pity, we hastened away to other cells, in which were patients confined in their beds; with one of these women I conversed a little while, and then continued our mournful visits. “But where (said I to the keeper) is the servant of a friend of mine (naming the patient) who is here because she was deserted by her lover?” “You have just left her,” said the man. “Indeed,” replied I, and hastened eagerly back to the cell I had quitted. I immediately began to talk to her of her mistress and the children, and called her by her name, but she would not reply. I then asked her if she would like money to buy snuff? “Thank you,” she replied. “Then give me your hand.” “No, you must lay the money on my pillow.” Accordingly I drew near, when, just as I reached her, she uttered a screaming laugh, so loud, so horrible, so unearthly, that I dropped the pence, and rushing from the cell, never stopped till I found myself with my friends, who had themselves been startled by the noise, and were coming in search of me. I was now eager to leave the place; but I had seen, and lingered behind still, to gaze upon a man whom I had observed from the open door at which I stood, pacing up and down the wintry walk, but who at length saw me earnestly beholding him! He started, fixed his eyes on me with a look full of mournful expression, and never removed them till I, reluctantly I own, had followed my companions. What a world of woe was, as I fancied, in that look! Perhaps I resembled some one dear to him! Perhaps—but it were idle to give all the perhapses of romantic sixteen—resolved to find in bedlam what she thought ought to be there of the sentimental, if it were not. However, that poor man and his expression never left my memory; and I thought of him when, at a later period, I attempted to paint the feelings I imputed to him in the “Father and Daughter.”

On the whole, we came away disappointed, from having formed false ideas of the nature of the infliction which we had gone to contemplate. I have since then seen madness in many different asylums, but I was never disappointed again.

Faithful to the views with which I began this little sketch of my childhood and my early youth, I will here relate a circumstance which was romantic enough to add fresh fuel to whatever I had already of romance in my composition; and therefore is another proof that, from the earliest circumstances with which human beings are surrounded, the character takes its colouring through life. Phrenologists watch certain bumps on the head, indicative, they say, of certain propensities, and assert that parents have a power to counteract, by cultivation, the bad propensities, and to increase the good. This may be a surer way of going to work; but, as yet, the truth of their theory is not generally acknowledged. In the meanwhile, I would impress on others what I am fully sensible of myself; namely, that the attention of parents and instructors should be incessantly directed to watching over the very earliest dispositions and tastes of their children or pupils, because, as far as depends on mere human teaching, whatever they are in disposition and pursuit in the earliest dawn of existence, they will probably be in its meridian and its decline.

When I was scarcely yet in my teens, a highly respected friend of mine, a member of the Society of Friends, informed me that she had a curious story to relate to me and her niece, my favourite friend and companion; she told us that her husband had received a letter from a friend at Lynn, recommending to his kindness a young man, named William Henry Renny, who was a sailor, just come on shore from a distant part, and wanted some assistance on his way (I think) to London. My friend, who was ever ready to lend his aid when needed, and was sure his correspondent would not have required it for one unworthy, received the young man kindly, and ordered him refreshments in the servants’ hall; and, as I believe, prepared for him a bed in his own house. But before the evening came, my friend had observed something in the young man’s manner which he did not like; he was too familiar towards the servants, and certainly did not seem a proper inmate for the family of a Friend. At length, in consequence of hints given him by some one in the family, he called the stranger into his study, and expressed his vexation at learning that his conduct had not been quite correct. The young man listened respectfully to the deserved rebuke, but with great agitation and considerable excitement, occasioned perhaps, as my candid friend thought, by better meals than he had been used to, and which was therefore a sort of excuse for his behaviour; but little was my friend prepared for the disclosure that awaited him. Falling on his knees, the young man, with clasped hands, conjured his hearer to forgive him the imposition he had practised. “Oh, sir,” cried he, “I am an impostor, my name is not William Henry R. but Anna Maria Real, I am not a man, but a woman!” Such a confession would have astounded any one; judge then how it must have affected the correct man whom she addressed! who certainly did not let the woman remain in her abject position, but desired immediately to hear a true account of who and what she was. She said, that her lover, when very young, had left her to go to sea, and that she resolved to follow him to Russia, whither he was bound; that she did follow him, disguised as a sailor, and had worked out her passage undetected. She found her lover dead, but she liked a sailor’s life so well, that she had continued in the service up to that time, when (for some reason which I have forgotten) she left the ship, and came ashore at Lynn, not meaning to return to it, but to resume the garb of her sex. On this latter condition, my friend and his wife were willing to assist her, and endeavour to effect a reformation in her. The first step was to procure her a lodging that evening, and to prevent her being seen, as much as they could, before she had put on woman’s clothes. Accordingly, she was sent to lodgings, and inquiries into the truth of her story were instituted at Lynn and elsewhere.

But what an interesting tale was this for me, a Miss just entered into her teens! Of a female soldier’s adventures I had some years previously heard, and once had seen Hannah Snelling, a native of Norfolk, who had followed her lover to the wars. Here was a female sailor added to my experience. Every opportunity of hearing any subsequent detail was eagerly seized. What a romantic incident! The romance of real life too! How I wanted to see the heroine; and I was rather mortified that my sober-minded friend would not describe her features to me. Might I (I asked) be at last allowed to see her? and as my parents gave leave, I, accompanied by a young friend, called at the adventurer’s lodgings, who was at home! Yes,—she was at home, and to our great consternation we found her in men’s clothes still, and working at a trade which she had acquired on board ship, the trade of a tailor! Nor did she leave off though we were her guests, but went on stitching and pulling with most ugly diligence, though ever and anon casting her large, dark, and really beautiful, though fierce eyes, over our disturbed and wondering countenances, silently awaiting to hear why we came. We found it difficult to give a reason, as her appearance and employment so totally extinguished any thing like sentiment in our young hearts, upon this occasion. However, we broke the ice at last, and she told us something of her story: which, however touching in the beginning, as that of a disguise and an enterprize prompted by youthful love, became utterly offensive when persisted in after the original motives for it had ceased. Her manner too was not pleasant: I wore a gold watch in my girdle, with a smart chain and seals, and the coveting eye with which she gazed, and at length clapped her hand upon them, begging to see them near, gave me a feeling of distaste; and, as I watched her almost terrible eyes, I fancied that they indicated a deranged mind; therefore, hastening to give her the money which I had brought for her, I took my leave, with my friend, resolving not to visit her again. Out of respect to our friends, she went to the Friends’ meeting with them, and they were pleased to see her there in her woman’s attire; but when she walked away, with the long strides and bold seeming of a man, it was anything rather than satisfactory, to observe her.

I once saw her walk, and though this romance of real life occupied the minds of my young friend and myself, and was afterwards discussed by us, still the actress in it was becoming, justly, an object with whom we should have loathed any intercourse.

I do not recollect how long she remained under the care of my excellent friends, but I think much of her story was authenticated by the answers to the inquiries made. All that I know with certainty is, that a collection of wild beasts came to town, the showman of which turned out to be Maria Real’s husband, and with him she left Norwich!

* * * * * *

Thus abruptly does Mrs. Opie’s narrative of her early days break off. Had she turned the next leaf in that history it must have been to record her first sorrow.

|

For all that it is Briggs’ Street still!—Ed. |

|

Since deceased. |

|

This portrait is the first of those which she apostrophizes in her “Lays for the Dead,” and begins— “There hangs a Soldier in a distant age, Call’d to his doom—my honour’d ancestor.” |

FIRST SORROW; THE ASSIZES; SIR HENRY GOULD; THE USURY CAUSE; “CHRISTIAN;” MR. BRUCKNER; GIRLISH DAYS; HER FRIENDSHIP WITH MRS. TAYLOR; MRS. T.’s MEMOIR OF HER.

In one of his letters to a friend, Southey remarks:—

“Few autobiographies proceed much beyond the stage of boyhood. So far all our recollections of childhood and adolescence, though they call up tender thoughts, excite none of the deeper feeling with which we look back upon the time of life when wounds heal slowly, and losses are irreparable. This is, no doubt, the reason why so many persons who have begun to write their own lives have stopped short when they got through the chapter of their youth.”

The poet elsewhere observes, that the wounded spirit, which shrinks from such a record of past griefs, finds solace in breathing out its regret in the tender strains of verse. And so it was in the present instance. The loss of her mother was deplored in pathetic numbers; and no other record of this event is given.

Another passage in the history of her earlier days is found in her note book, a few pages after the former, shewing how early she manifested a predilection, in the gratification of which she found so much enjoyment in after life. It should be mentioned before we proceed further, that the house in which Mrs. Opie was born was situated in Calvert Street, immediately opposite a handsome mansion, once the residence of an individual of note in his day, and after whom the street was named. This house Dr. Alderson afterwards inhabited for some years; but in the interim, he removed from the one in which his daughter was born, to another, opposite St. George’s church, and in which they were living at the time referred to in the following pages:—

To a girl fond of excitement it will easily be believed that the time of Assizes was one of great interest. As soon as I was old enough to enjoy a procession, I was taken to see the judges come in; and, as youthful pages in pretty dresses ran, at that time of day, by the side of the high sheriff’s carriage in which the judges sat, while the coaches drove slowly, and with a solemnity becoming the high and awful office of those whom they contained, it was a sight which I, the older I grew, delighted more and more to witness: with reverence ever did I behold the judges’ wigs, the scarlet robes they wore, and even the white wand of the sheriff had an imposing effect on me.

As years advanced, I began to wish to enter the assize court; and as soon as I found that ladies were allowed to attend trials, or causes, I was not satisfied till I had obtained leave to enjoy this indulgence. Accordingly some one kindly undertook to go with me, and I set off for court: it was to the nisi prius court that I bent my way, for I could not bear the thoughts of hearing prisoners tried, as the punishment of death was then in all its force; but I was glad to find myself hearing counsel plead and judges speak where I had no reason to apprehend any fearful consequences to the defendants. By some lucky chance I also soon found myself on the bench, by the side of the judge. Although I could not divest myself of a degree of awful respect when I had reached such a vicinity, it was so advantageous a position for hearing and seeing, that I was soon reconciled to it, especially as the good old man, who sat then as judge, seemed to regard my fixed attention to what was going forward with some complacency.

Sir Henry Gould was the judge then presiding, and he was already on the verge of eighty; but the fire of his fine eye was not quenched by age, nor had his intellect as yet bowed before it; on the contrary, he is said while in Norwich to have delivered a charge to the jury, after a trial that had lasted far into the night, in a manner that would have done credit to the youngest judge on the bench.

This handsome and venerable old man, surprised probably at seeing so young a listener by his side, was so kind at last as to enter into conversation with me. Never, I think, had my vanity been so gratified, and when, on my being forced to leave the court, by the arrival of my dinner hour, he said he hoped I was sufficiently pleased to come again, I went home much raised in my own estimation, and fully resolved to go into court again next day. As I was obliged to go alone, I took care to wear the same dress as I wore the preceding day, in hopes that if the judge saw me he would cause way to be made for me. But being obliged to go in at a door where the crowd was very great, I had little hopes of being seen, though the door fronted the judge; at last I was pushed forward by the crowd, and gradually got nearer to the table. While thus struggling with obstacles, a man, not quite in the grade of a gentleman, pushed me back rather rudely, and said, “there miss, go home—you had better go away, what business have you here? this is no place for you; be advised—there go, I tell you!” But miss was obstinate and stood her ground, turning as she did so towards the judge, who now perceived and recognized her, and instantly ordered one of the servants of the court to make way for that young lady; accordingly way was made, and at his desire I took my place again by the judge’s side. It was not in nature, at least not in my weak nature, to resist casting a triumphant glance on my impertinent reprover, and I had the satisfaction of seeing that he looked rather foolish. I do not remember that on either of these days I heard any very interesting causes tried, but I had acquaintances amongst the barristers, and I liked to hear them plead, and I also liked to hear the judge sum up: in short, all was new, exciting, and interesting. But I disliked to hear the witnesses sworn. I was shocked at the very irreverent manner in which the oath was administered and repeated; and evidently the Great Name was spoken with as much levity as if it had been merely that of a brother mortal, not the name of the great King of kings. This was the drawback to my pleasure, but not a sufficient one to keep me from my now accustomed post, and a third time, but early enough to have my choice of places, I repaired to court, and seated myself near the extremity of the bench, hoping to be called to my accustomed seat when my venerable friend arrived. It was expected that the court would be that day crowded to excess, for the cause coming on was one of the deepest interest. One of our richest and oldest aldermen was going to be proceeded against for usury, and the principal witness against him was a gentleman who owed him considerable obligation. The prosecutor was unknown to me; the witness named above I knew sufficiently to bow to him as he passed our house, which he did every day; and he was reckoned a worthy and honourable man. These circumstances gave me an eager desire to be a witness of the proceedings, and I was gratified at being able to answer some questions which the judge asked me when, as before, he had beckoned me to sit by him.

The cause at length began, and it was so interesting that I listened with almost breathless attention, feeling, for the first time, what deep and agitating interest a court of justice can sometimes excite, and what a fearful picture it can hold up to the young of human depravity; for, as this cause went on, the witness for the accused, and the witness for the accuser, both swore in direct opposition to each other! One of them therefore was undoubtedly perjured! and I had witnessed the commission of this awful crime!

Never shall I forget that moment; as it seemed very soon to be the general conclusion, that my acquaintance was the person perjured. I felt a pain wholly unknown before, and though I rejoiced that my friend, the accused, was declared wholly innocent of the charge brought against him, I was indeed sorry that I should never be able to salute my old acquaintance with such cordiality in future, when he passed my window, as this stain rested on his reputation; but that window he was never to pass again!

The next morning before I was up, (for beginning influenza confined me to my bed,) the servant ran into the room to inform me that poor —— had been found dead in his bed, with strong suspicions of suicide by poison!

Instantly I dressed myself, forgetting my illness, and went in search of more information. Well do I remember the ghastly expression of the wretched man’s countenance as he left the court. I saw his bright grey eye lifted up in a sort of agony to heaven, with, as I supposed, the conviction that he was retiring in disgrace, and I had been told what his lips uttered, while his eyes so spoke. “What! are you going,” said a friend to him. “Yes; why not? What should I stay for now?” and his tone and manner bore such strong evidence of a desponding mind, that these words were repeated as confirming the belief that he had destroyed himself.

I never can forget with what painful feelings I went back to my chamber, the sensation of illness forgotten, by the sufferings of my mind!

What would I not have given to hear that the poor man who had thus rushed unbidden into the presence of his heavenly judge, urged by the convictions of having been condemned in the presence of an earthly one, was innocent of this second crime! It had been terrible to believe him guilty of the first.

My mind was so painfully full of this subject, that it was always uppermost with me; and, to increase my suffering, the unhappy man’s grave was dug immediately opposite our windows; and although I drew down the blinds all day long, I heard the murmuring voices of the people talking over the event, some saying he was an injured man, and venting curses on the heads of those who had brought him to that pass. The verdict having been that “he was found dead in his bed,” the interment took place in the usual manner; and it did so early in the morning. I took care to avoid the front of the house till all was over; and when the hour in the following morning arrived, at which I used to go to the window, and receive the bow and smile of our neighbour, I remembered with bitter regret that I should see him no more, as he lay beneath the wall before me.

Even while I am writing, the whole scene in the court, and the frightful results, live before me with all the vividness of early impressions; and I can scarcely assert, that, at any future stage of life, I ever experienced emotions more keen or more enduring.

Judge Gould came to Norwich again the next year, and as I heard he had inquired for me, I was not long in going to court. One of his first questions was concerning the result of the Usury cause, which he had found so interesting, and he heard with much feeling what I had to impart. I thought my kind friend seemed full a year older; and when I took leave of him I did not expect to see him again. Perhaps the invitation which he gave me, was a proof of a decay of faculties; for he said that if ever I came to London, he lived in such a square, (I forget the place,) and should be pleased to introduce me to his daughter Lady Cavan. I did go to London before he died, but I had not courage enough to call on Sir Henry Gould; I felt it was likely that he had forgotten me, and that he was unlikely to exclaim, like my friends at the bedlam, “Oh! here’s the young girl from St. George’s!”

It may be remembered that in the short memorial of her earlier days, given in the preceding chapter, Mrs. Opie says that her attention was drawn away from an interest that was becoming too absorbing in the unhappy inmates of the bedlam, by new sources of occupation and interest. “Dancing and French school,” she says, “soon gave another turn to my thoughts, and excited in me other views and feelings.” The master who first instructed her to thread the gay mazes of the dance was one, “Christian,” a man well skilled in his art, and who attained such celebrity in it, that the room in which he taught is still called after him, “Christian’s room.” Here the young Amelia received her first lessons in dancing; and in after years she was wont to refer to those days, and would close her recollections of the worthy Christian, by telling how on one occasion, when she and her husband were in Norwich, they accompanied a friend to see the Dutch Church. “The two gentlemen were engaged in looking around and making their observations; and I, finding myself somewhat cold, began to hop and dance upon the spot where I stood. Suddenly, my eyes chanced to fall upon the pavement below, and I started at beholding the well-known name of ‘Christian,’ graved upon the slab; I stopped in dismay, shocked to find that I had actually been dancing upon the grave of my old master—he who first taught me to dance!”

The gentleman who gave her instruction in the French language was a remarkable man, and one for whom she entertained an affectionate respect which continued during the remainder of his life. As he is frequently referred to in her letters and elsewhere, it may not be irrelevant here to give some particulars respecting him, which are principally gathered from an article in “the Monthly Magazine,” written by the late Mr. Wm. Taylor. It appears that in 1752, Mr. Colombine, one of a French refugee family, then residing in Norwich, was entrusted by the members of the Walloon church, in that city, on occasion of his going over to Holland, to seek out for them a suitable pastor. In the execution of this commission, he applied to Mr. Bruckner, then holding a pastorship at Leyden. This gentleman, who had been educated for the theological profession, was of eminent literary acquirements; he read the Hebrew and the Greek, composed correctly, and was able to preach in four languages: Latin, Dutch, French, and English. He listened favourably to the invitation of the Norwich church; and in 1753 settled amongst them, and continued to officiate during 51 years with increasing satisfaction: about the year 1766, Mr. B. also undertook the charge of the Dutch church, of which the duties had become almost nominal, in consequence of the diminished numbers of Dutch families, and the gradual disuse of that language.

The French was Mr. Bruckner’s favourite tongue; and in it he gave lessons, both public and private, to the young people of his adopted city, for many years: he also cultivated music, and delighted in practising upon the organ. He was, besides, an author, and published a work entitled “Théorie du Systême Animal,” and, under an assumed name, a pamphlet entitled “Criticisms on the Diversions of Purley.” His death took place in the month of May, 1804; at his house in St. Benedict’s street. Mr. Opie painted an admirable likeness of him, which appeared in the London Exhibition of 1800. This picture was in the possession of Mrs. Opie at the time of her death, and is the subject of one of her “Lays.” There was a very singular expression in the eyes, and on one occasion a visitor who was calling upon her, gazing on the picture, remarked, that he was painfully affected by this look, as he remembered to have seen the same strange appearance in the countenance of a person who committed suicide. This remark forcibly struck Mrs. Opie, and no wonder, as it was the fact that her poor master died by his own hands! A gradual failure of spirits overtook him in his old age; sleep forsook his eyelids, and the fatal stroke terminated his existence, to the regret of all who had known him; for he was much beloved for his kindliness and affability, and his society was courted to the last, as his conversation shewed good sense, humour, and information. A small piece of paper, written in her delicate and minute characters, and found among her letters, proves that his friend and pupil continued to think of him after the lapse of more than half a century.

Lines, addressed to me by my dear friend and French master, John Bruckner, a Flemish Clergyman, on my requesting him to let my husband paint a portrait of him for me.

Pourquoi me demander, aimable Amélie

De ce front tout ridé, le lugubre portrait?

Pour être contemplé jamais il ne fut fait,

Assez il a déplu—Permettez qu’ on l’oublie!

John Bruckner, 1800.

Translation in prose:—

Why do you ask of me, amiable Amelia, the gloomy portrait of this wrinkled brow? It was never meant to be contemplated. It has enough displeased—Let it now be forgotten.—A. O. 1852.

To this amiable man and accomplished scholar Mrs. Opie was indebted, not only for instruction in French, but for much general information, which he was well qualified to impart.

The premature death of Mrs. Alderson occasioned (as we have seen) the introduction of her daughter into society at a very early age. Her father delighted to make her his constant companion, and introduced her to the company of the friends with whom he visited, and whom he welcomed to his house. Hence, at a time when girls are usually confined to the school room, she was presiding as mistress of his household, and mingling in the very gay society of the Norwich circles of that day. The period of which we write was shortly before the breaking out of the French revolution, and was one of great commercial prosperity, in which the merchant-manufacturers of the old town shared, in an extraordinary degree. This state of things lasted until the troubles consequent upon that event disturbed the commercial relations of the continent; when the trade declined, and a season of unparelleled depression ensued. But at the time of which we speak, it was a thriving and prosperous city, and abounded in gaiety and amusements of various sorts.

A young girl placed in such circumstances must have greatly needed the counsel and friendship of a wise female friend; and such an one Miss Alderson happily found in Mrs. John Taylor, a lady distinguished for her extensive knowledge and many excellencies. She was living at that time in Norwich, not far from Mr. Alderson’s, and an intimacy was early formed between the two ladies, which appears to have lasted uninterruptedly through life. After Mrs. Opie’s marriage, she continued to correspond with this friend of her early days, and happily many of her letters to Mrs. T. have been preserved.

Frequent mention is made of Mrs. Taylor in Sir James Mackintosh’s life, and she is spoken of as one of the principal attractions amid the circle of friends whose society he sought, when carried by his professional duties to Norwich. Mr. Montague, his companion on some of these occasions, says:—

“N. was always a haven of rest to us, from the literary society with which that city abounded. Dr. Sayers we used to visit, and the high-minded and intelligent Wm. Taylor; but our chief delight was in the society of Mrs. John Taylor, a most intelligent and excellent woman, mild and unassuming, quiet and meek, sitting amidst her large family, occupied with her needle and domestic occupations, but always assisting, by her great knowledge, the advancement of kind and dignified sentiment and conduct.

Manly wisdom and feminine gentleness were in her united with such attractive manners, that she was universally loved and respected. In ‘high thoughts and gentle deeds’ she greatly resembled the admirable Lucy Hutchinson, and in troubled times would have been equally distinguished for firmness in what she thought right. In her society we passed every moment we could rescue from the court.”[4]

How dear must such a friend have been to one whom she so tenderly loved! When some years later a portrait of Mrs. Opie was brought out in “The Cabinet,” a periodical of the day, Mrs. Taylor drew up a short notice of her friend, to accompany this likeness. This paper was written about the time of Mr. Opie’s death, but it principally refers to the early part of Mrs. Opie’s life. After speaking of the circumstances of her birth, of the early death of her mother, and of the proofs she gave, even in childhood, of poetical genius and taste, the writer continues:—

“Mrs. Opie’s musical talents were early cultivated. Her first master was Mr. Michael Sharp, of Norwich, who possessed a degree of love for his profession which comparatively few, employed in the drudgery of teaching, evince. Mrs. O. never arrived at superiority as a player, but she may be said to have been unrivalled in that kind of singing in which she more particularly delighted. Those only who have heard her can conceive the effect she produced in the performance of her own ballads; of these, ‘The poor Hindoo’ was one of her chief favourites, and the expression of plaintive misery and affectionate supplication which she threw into it, we may safely say has very seldom been equalled. She may fairly be said to have created a style of singing of her own, which, though polished and improved by art and cultivation, was founded in that power, which she appears so pre-eminently to possess, of awakening the tender sympathies and pathetic feelings of the mind.”

After enumerating some further accomplishments possessed by her friend, Mrs. Taylor closes her tribute of affectionate regard, by speaking of the excellencies of a heart and mind “distinguished by frankness, probity, and the most diffusive kindness;” and appeals to the many who could bear witness from experience, to those sympathies which “made the happiness of her friends her own, and to the unremitting ardour with which she laboured to remove the miseries that came within her knowledge and influence.”

|

See Life of Sir James Mackintosh. |

NORFOLK AND NORWICH, AND THEIR INHABITANTS; YOUNG LOVE; THE DRAMA; SONG WRITING AND CROMER; POLITICS; VISIT TO LONDON; LETTERS FROM THENCE; THE OLD BAILEY TRIALS.

Mr. Holcroft, in his Autobiography, writes thus of East Anglia:—

“I have seen more of the county of Norfolk than of its inhabitants; of which county I remark, that, to the best of my recollection, it contains more churches, more flints, more turkeys, more turnips, more wheat, more cultivation, more commons, more cross roads, and from that token probably more inhabitants, than any county I ever visited. It has another distinguishing and paradoxical feature, if what I hear be true; it is said to be more illiterate than any other part of England, and yet, I doubt, if any county of like extent have produced an equal number of famous men.”

The praises of Norwich were written thus, in old monkish rhymes in days of yore;

“Urbs speciosa situ, nitidis pulcherrima tectis,

Grata peregrinis, deliciosa suis.”

If common fame speak true, the Inhabitants of the old City have been noted for three peculiarities—the resolute purpose and strongly marked character of her men; the fair looks of her women; and the deep-rooted attachment which is entertained for her by those born and bred within her walls. The subject of this memoir certainly shared largely in this love for the city of her birth. During the eight and twenty years of her life which preceded her marriage, with the exception of occasional visits to London and elsewhere, she remained in her native town and in her father’s house; and when, at the expiration of nine years, she became a widow, she returned to live under her father’s roof again; nor at his death did she manifest a desire to quit the place endeared to her by the recollections of so many long and happy years.

At the period to which we have arrived in her history, she possessed the advantages of a pleasing personal appearance. Her friend, Mrs. Taylor, delicately alludes to the graces of “person, mind, and manner,” so happily united in her; and Mr. Opie’s portraits fully bear testimony to the truth of these friendly representations. Her countenance was animated, bright, and beaming; her eyes soft and expressive, yet full of ardour; her hair was abundant and beautiful, of auburn hue, and waving in long tresses; her figure was well formed; her carriage fine; her hands, arms, and feet, well shaped;—and all around and about her was the spirit of youth, and joy, and love. What wonder if she early loved, and was beloved! She used to own that she had been guilty of the “girlish imprudence” of love at sixteen. From the following lines in one of her poems, it should seem that this fancy of her youth was but a day-dream destined to pass away like the rest!

I’ve gazed on the handsome, have talked with the wise,

With the witty have laugh’d, untouched by love’s power,

And tho’ long assailed by young Corydon’s eyes,

They charmed for a day, and were thought of no more!

But once, I confess, (t’was at tender sixteen,)

Love’s agents were busy indeed round my heart,

And nought but good fortune’s assistance I ween,

Could ere from my bosom have warded the dart.

Numerous admirers, indeed, seem to have paid her homage, and courted her favour in those days. Some perhaps enjoyed a short season of hope, and there were two or three, whose rapturous effusions were committed to some secret receptacle, there to await a season of leisure when their claims might be considered. But alas! none such came; they lay forgotten; and only came to light when she, whose bright young charms they told of, had closed a long life.

High spirits, uninterrupted health, a lively fancy, and poetic talent, were hers; and she fully enjoyed and exercised these natural advantages.

One of her earliest tastes was a love of the drama, and Mr. Capel Lofft, writing to her in 1808, observes, “Your uncle, the barrister, was saying yesterday evening, how struck he was, almost in your childhood, with your power of dramatic diction and recitation, and that he had never thought it equalled by any one.” This taste she cultivated; and, when not more than eighteen years of age, wrote a tragedy, entitled “Adelaide,” which is still extant. It was acted for the amusement of her friends; she herself performing the heroine’s part, while Mr. Robert Harvey played the rôle of “the old father.”

It should seem from an expression in one of her letters, that this was not a solitary effort in theatrical composition, and that she even aspired to see some of her plays performed in public. It was probably this taste which early introduced her to an acquaintance with the Kemble family; as she says, in a very early letter to her father, signing herself ‘Euridice,’ “My claim to this name was revived in my mind the other day, by Mr. Kemble coming up to me, saying, ‘Euridice, the woods, Euridice, the floods,’ &c.” She ever entertained an ardent admiration for the illustrious Mrs. Siddons; an admiration mingled with a warm sentiment of personal regard. This was manifested in a touching and natural manner after the death of that lady, when, as she was one day visiting the Soanian museum, (in company with the friend who now records the fact,) happening unexpectedly to see a cast of Mrs. Siddons’ face, taken after death, and unable to control her emotion, she burst into a passionate flood of tears!

Mrs. Taylor was probably right in her judgment when she said to Mrs. Opie, “You ought to rest your fame upon song writing.” Many of the most popular songs she published after her marriage had been early productions of her pen; and were, perhaps, not excelled by any efforts of that kind in her later years. Some of them first appeared separately in newspapers and magazines, and a few in a periodical miscellany called “The Cabinet.”

The Lay to the memory of her mother was written (as we have said) at Cromer, in the year 1791; and is the first in an old manuscript book containing her earlier poems, many of which she afterwards published. They were produced in this and the following year, and are inscribed “Verses written at Cromer.” This place seems to have been, throughout life, very dear to her; owing no doubt, in part, to the fact that she had frequently spent the summer season there with her mother in her childhood; hence it became associated in her mind with these earliest recollections.

There she indulged in fond memories and fancies, spending the long summer days roving along the shore, and weaving her thoughts into verse, grave or gay. She deplores her fate when compelled to leave

These scenes belov’d upon whose tranquil shores,

Thoughtless of ill, I breathed my earliest songs,

While childish sports and hopes—a joyous throng—

In soft enchantment bound the guiltless hours.

And concludes,

Here I would wander, from day’s earliest dawn,

Till o’er the western summit steals dark night;

And from the rugged cliff or dewy lawn,

Reluctant fades the last pale gleam of light.