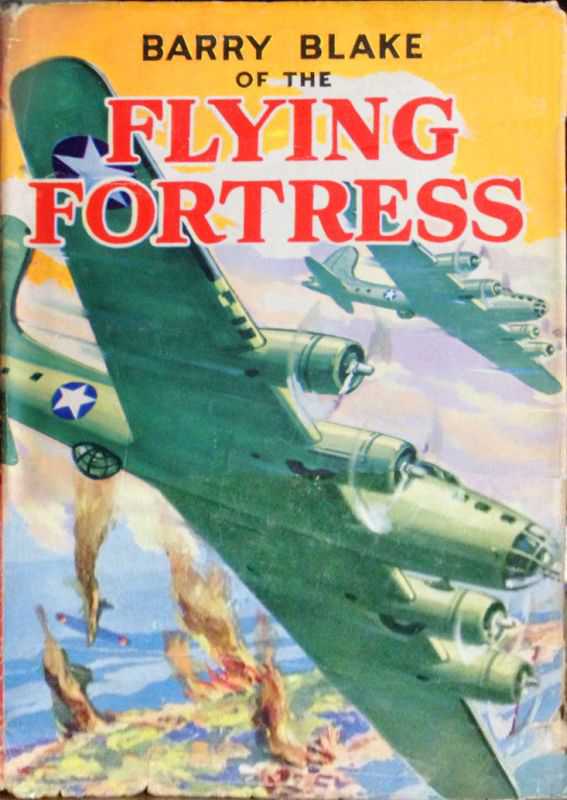

Title: Barry Blake of the Flying Fortress

Author: Gaylord Du Bois

Illustrator: J. R. White

Release date: December 18, 2014 [eBook #47696]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Stephen Hutcheson, Rick Morris, Rod Crawford, Dave Morgan, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Barry Blake of the Flying Fortress, by Gaylord Du Bois, Illustrated by J. R. White

FIGHTERS FOR FREEDOM Series

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | Randolph Field | 9 |

| II | Two Kinds of Rats | 17 |

| III | Jeep Jitters | 26 |

| IV | Lieutenant Rip Van Winkle | 33 |

| V | Sweet Rosy O’Grady | 41 |

| VI | Submarines to the Right | 51 |

| VII | Raid on Rabaul | 60 |

| VIII | Flying Wreckage | 71 |

| IX | Night Attack | 82 |

| X | Hand to Hand | 93 |

| XI | Lieutenant in White | 110 |

| XII | New Guinea Gardens | 118 |

| XIII | Mysterious Island | 129 |

| XIV | Dogfighting Fortress | 137 |

| XV | Slaughter From the Air | 149 |

| XVI | Secret Mission | 170 |

| XVII | Out of the Fog | 184 |

| XVIII | Adrift | 198 |

| XIX | The Catamaran | 212 |

| XX | Floating Wreckage | 225 |

| XXI | Patched Wings in the Dawn | 238 |

Barry and Chick Were Among the First to Leave

The bus from San Antonio pulled in to the curb and stopped. The door snapped open. Half a dozen uniformed upperclassmen wearing grim expressions moved closer to the vehicle.

“Roll out of it, you Misters!” bawled their leader in a voice of authority. “Shake the lead out of your shoes! Pop to it!”

Barry Blake and Chick Enders were among the first out of the bus, but they were not quick enough to suit the reception committee.

“Are you all crippled?” rasped the spokesman of the upperclass “processors.” “Come alive and fall in—here, on this line. Dress right! I said dress—don’t stick your necks out. Atten-shun! Hope you haven’t forgotten all the military drill you learned at primary. You, Mister! Rack it back. Eyes on a point. And out with your chest if you have any. Keep those thumbs at your trouser seams.... All right! Here’s your baggage tag. Write your name on it. Tag your baggage—and make it snappy. Stand at attention when you’ve finished. Hurry! That’s it.... Take baggage in left hand—left, not right. And wipe off your smile, Mister! ’Sbetter.... Mister Danvers, you will now take charge of these dum-dums.”

Barry was sweating. The blazing Texas sun was in his eyes. His chest ached for a normal, relaxed breath; yet he dared not move. Mister Danvers’ barking command came as a sharp relief.

“Right face.... Forward, march! Hup! Hup! Hup! Pull those chins back. Hup! Hup! Eyes on a point! And hold your right hands still—this isn’t a goose-step. Hup! Hup! Shoulders back—grab a brace—you’re in the Army now! Hup! Hup! Dee-tachment, halt!”

For more strained moments the new arrivals stood on the arched stoop of the Cadet Administration Building and listened to acid instructions. The talk dealt with the proper manner of reporting for duty. The tone of it, however, showed the processor’s profound doubt of the “dum-dums’” ability to do anything properly. It was deliberately maddening.

Barry Blake felt a wave of hot resentment sweep over him. A second later cool reason met it and drove it back.

“They’re just trying to see if we underclassmen can take it,” he told himself. “A cadet’s got to learn how to be an officer and a gentleman, in any situation. They’re teaching us the quick, hard way, that’s all!”

Barry held his tough, well-proportioned muscles a little less stiffly. He wondered how Chick Enders was taking the processor’s verbal jabs. From where he stood he could see Chick’s short, bandy-legged figure quiver under the barrage of upperclass sarcasm. Chick’s good-natured mouth was a hard line, and his eyes were pale blue slits above his pug nose. The homely cadet was having a hard job trying not to explode.

Suddenly he relaxed, and Barry, seeing it, chuckled inwardly. He had known Chick Enders since they were both in kindergarten. When he got angry, the kid’s blond bristles would stick up like the fuzz of a newly hatched chick. That always meant a fight, unless Chick’s sense of humor got the upper hand, as it had just now.

While the processor’s stinging remarks continued, Barry’s memory flashed back to the day that he and Chick had graduated from the Craryville High School. Barry had been valedictorian of the class, and Chick, he recalled, had been prouder of the fact than anyone.

There was an almost hound-like loyalty in the homely youth’s soul, and his hero was Barry Blake. From their earliest snow-ball battles to high school and varsity games where Barry carried the ball and Chick ran interference, it had always been the same. Both had enlisted at the same time and later applied for flying cadet training.

“I’m glad we’re still together,” Barry thought, with another glance at his friend’s freckled profile. “If he’d been sent to any other basic training school than Randolph Field, I’m afraid it would have broken Chick’s heart. We’ll be together here for nine weeks. After that—well, there’s a war on. We’ll train and fight wherever we’re sent, with no complaints....”

“All right, you Misters!” the upperclassman’s voice broke in on Barry’s thoughts. “Right, face! Column right, march! You’ll receive your company and room assignments upstairs. Try not to forget them!”

Still under a running fire of orders and caustic comments, the suffering “dum-dums” were taken to the supply room. Here each new cadet proceeded to draw a full outfit of bedding, clothing, and equipment.

“I feel like a walking department store!” Chick Enders muttered as he joined the line behind Barry. “They must have figured out scientifically just how much a guy can carry if he uses his ten fingers, his elbows and his teeth....”

“Roll up your flaps, Mister!” snapped a keen-eared processor, taking a step toward Chick. “You’ll get your chance to sound off soon enough!”

Just in time Chick caught and straightened out an apologetic grin. He had a hunch that any smile just now would be asking for trouble. Pulling his freckled face even longer than usual, he stepped out at Barry’s heels, and hoped that none of his assorted burdens would slip.

At the barracks, while changing into coveralls and new shoes, Barry and Chick were able to exchange a few hurried words.

“I’d heard that these upperclassmen were pretty unsympathetic,” the homely cadet remarked, “but I never thought they’d lay it on quite so heavy. I guess they stay awake nights inventing ways to make a dum-dum sweat.”

“Don’t let it get under your skin, Chick,” Barry laughed. “There’s no meanness behind their processing. It’s intended to make soldiers out of us. The first thing they do is to prick our balloons—take the conceit out of us, if we have any.”

“And the next thing is to toughen us up,” grinned Hap Newton, their roommate. “Don’t worry—in five weeks we’ll be processing a new bunch of dum-dums, and making ’em like it!”

Before they had finished changing clothes the processor in charge bellowed another order.

“Hit the ramp, you Misters!” he shouted. “On the double! Leave your powder and lipstick till tonight.”

Barry Blake grabbed his cap. He headed for the doorway, tightening his belt as he went.

“Come on, Chick,” he said. “I don’t know what the ramp is yet, but I aim to hit it hard and quick.”

“Me too,” his friend grunted, “even if I lose a shoe.... Mine aren’t laced up yet.”

The ramp, they discovered, was the broad stretch of concrete just outside the cadet barracks. Pouring out of the door, the dum-dums were greeted by rapid-fire commands:

“Fall in! Dress, right! Straighten-that-line-d’you-think-this-is-a- ring-around-the-rosy? ’Ten-shun! Count off! Forwar-r-rd, march! Hup, hup, hup! Column right, march! Column left, march! By the right flank, march! To the re-ar-r-r, march! Squa-a-ad, halt! Left, face! About, face! Forward, march!”

To Barry and Chick, both assigned to Squad 17, these maneuvers were a welcome change. Having mastered close-order drill at primary school, they now went through it automatically. Their taut nerves relaxed. The stiff soles of their new issue shoes were just beginning to smart, when a hollow voice boomed through the air.

“’Tenshun all squads now drilling!” whooped the invisible giant. “Squad 26! Take Squad 26 to the tailor shop.... Squad 17. Take Squad 17 to the barber shop. That is all.”

It was the voice of the Field’s public address system. Instantly the processors in charge of the two squads named marched them off the drilling area. As Squad 17 entered the shop, six barbers stood waiting by their chairs. Barry got a quick mental picture of sheep being driven to the shearing pen.

First in line was a sulky-looking youth, whose name-tag proclaimed him to be Glenn Cardiff Crayle. He had a sleek black pompadour, and a habit of passing his hand caressingly over it.

“Just trim the sides and neck, please,” Barry heard him mutter to the wielder of the shears.

The barber exchanged winks with the upperclassman in charge. He slipped expert fingers under a long lock of Crayle’s hirsute pride.

“Maybe you’d better have it regulation, sir,” he suggested with heavy emphasis.

Snip-snip-snip went the shears. Cadet Crayle writhed as if they were a savage’s scalping knife, but he knew he was helpless. Barry Blake chuckled inwardly. “Regulation length” would mean no loss to his own short, wavy hair, or to Chick’s blond bristles.

Six barbers and ten minutes for a haircut! In little more than a quarter of an hour, Squad 17 was marching back to the drilling area. Another half hour of close-order drill—then dinner formation.

Scarcely were they seated in the big cadet mess hall, when the nervous dum-dums found their worst suspicions realized. Mealtime was just another opportunity for hazing by the upperclassmen. Placed at the foot of a table seating eleven men, Barry and Chick discovered that they were the “gunners” of the group. That is, they must pass—“gun” or “shoot”—food and drink up the table whenever asked.

Two minutes after the meal began, the “table commander” at the upper end sent down his coffee cup for re-filling.

“A cup of coffee for Mr. Danvers,” murmured the lowerclassman nearest him.

“A cup of coffee for Mr. Danvers,” repeated Hap Newton as he passed the cup.

“A cup of coffee for Mr. Danvers,” Barry Blake solemnly announced, as he filled it and passed it back.

“You, Mister!” the table commander barked, looking straight at Chick Enders. “The potato dish is empty. You will signal the waiter by holding it up—like this.”

With his upper arm horizontal and his forearm vertical, the upperclassman demonstrated the proper gesture. Hap Newton giggled.

“Silence!” snapped the processor. “What’s your name? Newton? Sit forward on your chair, Mister—on the first four inches. Chin up, get some altitude. And take your left hand off the table. And remember—for a dum-dum to laugh, smile or chortle at mess is an inexcusable breach of manners.”

“Yes, sir,” mumbled Hap Newton, so meekly that Chick Enders nearly dropped the potato dish, trying not to laugh.

Dinner ended all too soon for most of the hungry new cadets. The food was ample, but so excellent that the time seemed too short to do it justice. At the close of the noon hour, Squad 17 was issued rifles, and plunged into the monotonous manual of arms. Not until evening did the weary dum-dums have time to relax.

Their first day at Randolph Field had been a full one—crammed with new impressions that would whirl through their dreams that night.

The weeks that followed were more crowded than any Barry Blake had known. Drills, monotonous, tiring, but excellent for physical “tone,” occupied the first few days. On Monday of the second week the regular training schedule began.

Mornings were devoted to Ground School. Barry and Chick put their best into it, knowing that study was vital to passing later tests. There were five subjects: Airplane and Engine Operation, Weather, Military Law, Navigation, and Radio Code. Of them all, Barry Blake preferred the first. His hobby had been flying model planes since he was in short pants.

The classroom in Hangar V with its blueprints, charts, takedown and working models made him feel at home. Here he “ate up” every lecture on Fuel Systems, Motors, Electric Systems, Engine Instruments, Wheels, and Brakes. The floor of the great hangar itself Barry found still more fascinating. Here were displayed the real planes and their parts, with cutaway and breakdown views. They gave him his first intimate contact with the powerful, fighting ships that he hoped soon to fly.

Flight instruction, in the BT-9 and BT-14 training planes, was always a mixture of anxieties and thrills. There was much to learn, and little time to learn it. In these ships, twice as big as the primary school “kites,” the speeds were higher, the controls more quickly responsive. The gadgets on the instrument panels were just double in number. And the instructors—!

“Lieutenant Baird has it in for me, Barry,” Chick Enders confided, as they headed down the concrete apron toward their ships. “No matter what I do, he just sits back and sulks. All the encouragement I’ve had from him is a grunt or a glare—ever since the day I taxied into the wrong stall with my flaps down.”

A step or two behind him, Barry glanced down at Chick’s short legs twinkling below the bobbing bustle of his ’chute. In spite of himself Barry chuckled. The idea that anybody could “have it in for” a fellow as homely and likeable as Chick was just too funny.

“Perhaps Lieutenant Baird has other troubles,” he suggested. “Remember, when your flight period begins he has already spent an hour with a hot pilot by the name of Glenn Crayle. That lad is enough to curdle the milk of human kindness in any instructor. I wouldn’t worry about it, Chick. You passed your twenty-hour test all right, didn’t you?”

“Yeah,” Chick admitted. “Maybe it is Crayle, more than I, who’s responsible for the lieutenant’s sour puss. Crayle’s a born show-off and a sorehead as well. Even the processors couldn’t prick his bubble, and they tried—oh-oh! G-gosh! I—er—hello, Crayle! I—uh—didn’t see you coming.”

Walking fast, Cadet Crayle passed the two friends with a glare. They turned and watched him disappear into the Operations Office. Chick Enders let out his breath in a long whistle.

“He must have heard all we said about him before he zoomed past us,” Barry said, with a dry smile. “Oh, well! It’s the truth, and it may do him good when he thinks it over.”

Practicing his chandelles that afternoon, Chick gave less thought to his instructor’s sour mood. As a result he did better than usual. Barry Blake, for his part, forgot the incident completely. It was not until special room inspection, the following Saturday morning, that he recalled Crayle’s ugly look.

Barry Blake was room orderly that week. This meant that he alone was responsible for the general neatness of the quarters he shared with Chick and Hap Newton. For ordinary morning and evening inspection the preparations were simple. Beds must be made, the room must be swept and dusted, and everything had to be in its proper place.

On Saturday, however, all three roommates pitched into the work. Everything must be in perfect, regulation order—each blanket edge laid just so, each speck of dust wiped up. Shoes, clothing, equipment must be spotless, or demerits would fall like rain.

To make sure that Barry had overlooked nothing in his dusting, Chick and Hap went over the furniture with their fingers, searching for a smear of dust. They found none, until Hap tried the bottom of the waste basket.

“Two ‘gigs’ for you, Mister Blake—if the inspecting officer had found that,” he remarked, with a wink at Chick.

“You’re dead right, Hap,” Chick spoke up, wiping his finger over the same spot. “The inspecting officer will do it with white gloves, you know. And if he gets a smear—”

“Aw, drive it in the hangar, fellows!” Barry protested with a grin. “Give me that waste basket and a rag. And then go wash your own hands.”

“Okay—but not in the washbowl I’ve just finished cleaning!” retorted Hap. “It’s too near inspection time. I’m going down the hall.... Coming, Chick?”

Barry polished the bottom of the waste basket as if it were brass. As he put the cleaning rag away, he glanced about him.

“If this room were to be any cleaner, it would have to be sterilized,” he declared. “Bring on your white gloves, and let’s see what they can find now. Guess I’ll have just time to join Chick and Hap down the hall and get back before inspection.”

The three roommates had figured almost too close. They were just starting back to their room when call to quarters sounded. As they hurried into the hall, a uniformed figure darted across the farther end.

“Say!” hissed Chick Enders. “Didn’t that mister come from our room?”

“I thought so,” muttered Barry. “He looked like Glenn Crayle! I wonder....”

There was no time for more speculation then. Official footsteps were approaching. The three cadets were just able to reach their room and stiffen at attention by their beds before the inspecting party came in view.

The officer in charge was Captain Branch, whose piercing black eyes had never been known to miss a spot of dirt. Square-jawed, quick-moving, he entered the room accompanied by a cadet officer with notebook and pencil. His thin, sensitive nostrils sniffed the air.

“Who,” he asked sharply, “has been smoking here within the last few minutes? The room smells foul!”

A tense, five-second silence followed. Barry Blake broke it.

“I don’t know, sir,” he managed to say. “It was none of us three. We don’t use tobacco.”

The muscles of the captain’s jaw bulged. The thin line of his lips hardened.

“What is your idea in leaving rolls of dust under your bed at inspection?” he demanded bitterly. “And dirty soap on your washbowl? And that can of foot powder on the desk? And that drawer—”

He broke off, to stride across the room. From the crack of a drawer in Barry’s desk drifted a tiny feather of smoke. Captain Branch jerked it open. There, on a charred paper, lay a smouldering cigar.

With his face like a marble mask, the officer tossed the cigar into the washbowl.

“Gentlemen,” he said heavily. “This is an idiotic defiance of authority. Unless you can clear yourselves immediately in a written report, appropriate punishment must follow. That is all.”

Not until the captain was out of hearing did the roommates dare to look about. Then, with a sigh that told more than words, Barry stooped and picked up two big, fuzzy “rats” of dust. Wordless, Chick Enders took the can of foot powder from the desk and wiped up what had been spilled.

Hap Newton groaned.

“It was Crayle, all right,” he declared. “I recognized him by the way he carries his head.... But why? Why should he want to sabotage us?”

“I think I know,” said Barry. “Two days ago he overheard Chick and me talking about him. What we said was true enough, as this frame-up proves—that Crayle is a sorehead, with an inflated ego.”

“Inflated and inflamed, both!” Chick Enders exclaimed. “He’s always trying to tell what a hot pilot he is. He hates anybody who shows him up.”

A hard grin stretched Hap’s wide, good-natured mouth.

Smoke Drifted Through a Crack in the Drawer

“We’ll show him up for a sneaking rat,” he said. “Nose up to the desk, fellows, and we’ll get busy on that written report....”

“Pull out of it, Hap!” Barry Blake interrupted. “We’ll only do a ground loop that way. Our best maneuver is to say nothing about Crayle and take our medicine. We can’t prove a thing against him, anyhow.”

Hap Newton’s jaw dropped. He sat down hard on his chair.

“You-you’re crazy, Blake!” he gasped. “We’re likely to be dismissed from Randolph for what’s happened this morning. Why should we sacrifice our wings, our reputation—everything we value here—to protect a yellow snake-in-the-grass like Crayle? That’s what it will mean!”

“We’ve circumstantial evidence that Crayle did it,” Chick Enders put in. “He had no business in our quarters. And it would have been idiotic for us to stand inspection in a room as raunchy as this, if we could help it. That ought to be plain to anybody. Get your pen and paper out, Barry.”

Seated at the desk, Barry Blake shook his head.

“We won’t make anything plain by accusing Glenn Crayle, fellows,” he stated. “That mister may be a fool in some ways, but he’s covered his tracks. Remember, we only thought that he came from our room. And, from the captain’s viewpoint, it would be natural for us to accuse someone else if we were guilty.”

Barry let those points sink into his roommates’ minds for a full minute.

“On the other hand,” he went on, “suppose we face the music. That is what Captain Branch would expect us to do if we were innocent and had no proof. We’ll pay a stiff penalty, of course, but I don’t think we’ll be dismissed from the Field.”

Hap Newton rose and stared out of the window. Chick Enders passed nervous fingers through his short, tow-colored hair.

“You’re right as always, Barry,” the homely cadet said finally. “There’s a paragraph in ‘Compass Headings’ that says: ‘Flying Cadets do not make excuses.’ I have a hunch we’ll be doing punishment tours for the rest of our course, but I’m ready to suffer in silence.”

Hap Newton grumbled and fumed, but he, too, gave in.

“I’ll get even with Crayle,” he added vengefully. “I’ll fix him—”

“No you won’t, Hap,” Barry cut in, “unless you’re willing to fly at his level. The ceiling’s zero down there. Come out of the clouds, fella! And help us clean this room for the second time today.”

Tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp! Up the long concrete ramp—halt—about face—and back again. One hundred and twenty steps to the minute, thirty inches to each step—a fast walk, in civilian life. But these three, covering a prescribed beat at widely spaced intervals, marching in silence and without pause, are not civilians. Not by a long shot!

They are Flying Cadets Blake, Enders, and Newton, wearing the uniform of the day, with field belt, bayonet scabbard and white gloves. Their penalty for a dirty room is posted on the company bulletin board: five tours and six “gigs,” or demerits, apiece. That’s a lot easier than they expected. Still, a “tour” lasts one hour and covers almost four miles. They have three hours still to go.

“And Glenn Crayle’s enjoying ‘open post’! Right now that mister is doubtless disporting himself with some sweet young thing at a tea dance in the San Antonio Flying Cadet Club.... Tramp, tramp, tramp.... Here’s where the ‘gig’ dodger ought to be! One of these days, he’ll slip up....”

Glenn Crayle never became a “touring cadet,” however. In small, clever ways he continued to work out his grudge against Chick and Barry. One of his bright tricks was to dust itching powder over the stick of the “Jeep,” or Link Trainer, knowing that Chick Enders would be the next to handle it.

The “Jeep” is a marvellous device to teach aviation cadets the art of flying by instruments—without ever leaving the ground. Entering it, the fledgling pilot finds himself in a cockpit like that of a real plane. Before him is an instrument panel. Above him an opaque canopy shuts off his view of everything else. In his closed cockpit are all the familiar controls. His situation is the same as if he were flying through clouds at night.

Poor Chick had a case of “Jeep jitters” from the moment he started his “flight” under the hood. The little moving ball and the two queer little needles simply would not stay in place. According to his instruments he dropped one wing and went into a “spit curl” or side slip that cost him precious altitude. Correcting it, he over-controlled. Dangerously close to Mother Earth, according to the Jeep’s altimeter, he zoomed, stalled, and theoretically crashed.

Climbing (in theory) to five thousand feet, Chick attempted once more to conquer the “jeepkrieg.” For some moments he succeeded. Then, without warning, his hand on the stick began to itch. He stood it as long as he dared, let go for one second of frantic scratching—and was lost.

Fifty feet from the theoretical ground he pulled out of his dive. He hedge-hopped over some imaginary trees, caught the stick between his knees, and tried to climb while scratching. Result—a third crash.

“I give up!” gurgled Chick, slamming back the canopy and bouncing out to the surprise of his instructor. “The thing has given me hives on my hands, sir. I’ve committed suicide three times by the altimeter, and I’m afraid I’ll do it in earnest!”

The instructor glanced at Chick’s reddened palm and snorted.

“Very well, Mister,” he snapped. “Spin off and get control of your nerves. You can try it again tomorrow when you’re out of the storm. But you’ll never learn instrument flying by mauling the stick the way you did just now.”

Within the week Chick had mastered the art of level “flight” in a “Jeep.” Yet he knew that his itch-inspired tantrum stood against his record as a prospective pilot of warplanes. The men who fly the Army’s fighting ships must have nerves of chilled steel. Those who might crack under the strain of air combat must be weeded out.

Second thought told Chick that Glenn Crayle must have doctored the “Jeep’s” stick. No hive ever itched as wickedly as his palm; and Crayle was using the trainer just before him.

“I’ll call that rat out for boxing practice, and work him over,” the angry cadet told Barry. “Crayle may outweigh me, but I’ll whittle him down to my size.”

“If you did,” Barry Blake pointed out, “he’d still win, according to his twisted way of thinking. Crayle knows that open grudges are frowned on here at the Field. If you let yourself get mad enough to beat him up, your supervising officer will put that down to poor control, too, Chick. Another show of nerves might wash you out as a pilot—for good. Stick it out, man! The sixty-hour test is only a week away.”

The sixty-hour progress test is a landmark, warning the Randolph Field Cadet that his basic training is nearly over. Sixty hours of flight training have been accomplished. All fundamental flying movements have been mastered, of course, at primary flying school. At Randolph Field they have become still more familiar. Climbing turns, steep turns, “lazy eights,” and forced landings have been learned and practiced thoroughly. Now the pilot’s ability to fly by instruments alone is to be judged.

Both Barry and Chick Enders had worked hard to perfect themselves in flying “under the hood.” The test should have held no terrors for either of them. Yet, as the hour approached, Chick grew nervous. He knew that his instructors were watching him for signs of another explosion.

“I’ll have to be extra good today,” he told his roommates, as the three donned their coveralls that afternoon. “Captain Branch just had me in the office for a little talk. I’m worried, fellows.”

“I noticed that you were sort of ‘riding the beam’ when you came into the locker room,” Hap Newton said, picking up his parachute. “Eyes fixed on vacancy, expression of a calf in a butcher’s cart, and all that. ’Smatter, Chick—did he bawl you out?”

“No, Hap, he was kind—too kind entirely. Reminded me of a sympathetic executioner. He’s flying with me on this test—in his own washing machine. If he so much as coughs when we get ‘upstairs’ I’ll probably reef back the stick and go into a stall.... Well, wish me happy landings. I’m taking off.”

Barry Blake shook his head gloomily at Chick’s departing figure.

“The kid’s in a storm already,” he muttered to Hap. “If Chick were the best gadgeteer on the Field he’d never pass a test under the hood with that case of jitters.”

“Instrument flying will show jumpy nerves every time,” Hap agreed. “It’s tough, Barry. The whole thing started when Glenn Crayle doped the ‘Jeep’ stick with itching powder. Of all the lowdown, squirmy tricks, that was the worst! And he’ll be tickled half to death if Chick is washed out.”

Barry Blake was so upset about his friend that his own nerves were none too steady. When he stepped into the cockpit, however, he took a firm grip on himself. Glenn Crayle, he vowed, should not have the laugh on two of them.

Barry was a born flier. Once in the air, he lost every trace of jitters. His performance was better than ever. He passed the test with a high mark, and brought his instructor back smiling. Hap Newton, who landed soon after, also passed without difficulty.

“Where’s Chick?” the latter asked, the moment they were alone.

“Still flying,” Barry said shortly. “There comes his ship. Flight Commander Branch must have been giving him an extra-thorough test.”

The two friends watched Chick’s ship come in for the landing. With engine cut off, it glided down. The wheels bumped—bounced—came down again.

“He’s heading for the hay,” Hap Newton yelled, as Chick’s plane slewed around. “Give her the gun, Chick!”

As if his frantic shout had actually been heard, Chick’s engine roared into life. The ship leaped into the air, and climbed like a cat with a dog after her.

“That washing machine must have developed a wobbly tail wheel,” Barry muttered; “or maybe it was a freak breeze that caught him.”

“Shucks, Barry,” Hap answered unhappily. “There’s no use making excuses for him. Chick’s still got the jeep jitters. He’s as good as washed out now.”

“Not if he lands okay this time,” Barry said.

Chick’s plane banked, turned, and came down the base leg with open throttle. The engine cut out. A wing dropped slightly, to counteract the drift of the light wind. So far, Chick was handling her nicely. At just the right second he lifted her nose a little to make a three-point landing. The tires touched....

And then it happened. The tail swung sharply. Chick, feeling it, cracked open his throttle, but he was a split second too late. The plane swapped ends, pivoting on a wing. Dust spurted from the runway. With a splintering, ripping crash the wing gave way. The plane nosed over, propeller biting the dirt.

Barry groaned, and started running before the dust began to settle. From West B. Street came the clanging of the ambulance and the crash truck. From the length of the West Flying Line men were running, each with an ugly picture in his mind’s eye—fire!

But neither smoke nor flame appeared. Instead, two helmeted figures crawled out of the wreckage. For a moment they stared at each other. Then, shaking his head, the Flight Commander walked away.

Barry Blake caught Chick roughly by the arm.

“Snap out of it, man!” he whispered. “Crayle’s here in the crowd, laughing himself sick. Reef back and gain some altitude! Chin up!”

Except for Crayle, few of the cadets about the plane were laughing. From the look that Captain Branch had given Enders, they sensed that this was no ordinary ground-loop that would qualify Chick for the Stupid Pilot’s Trophy. It was the tragedy that all cadet pilots dread—the wash-out.

Chick’s actual elimination from basic training school did not occur for a few days. Captain Branch’s recommendation had to be confirmed by the Stage Commander, who first flew with the unhappy cadet in a final test. His report, duly filed with those of Chick’s instructors and his Flight Commander, must be reviewed at the next meeting of the elimination board. All this took time.

On the evening before Chick was to hear the verdict, Barry and Hap made a special effort to cheer him up.

“Being ‘washed out’ is no disgrace, fella,” Barry told him. “It doesn’t mean that you’re kicked out of the Air Forces—only that you can’t be a pilot. You’ll get your officer’s commission just the same, in some other classification. So why worry?”

Chick’s homely face cracked in a wan smile. He had not regained his natural color since the ground-loop that wrecked his plane. The freckles stood out more plainly than usual on his snub nose.

“I hope you’re right, Barry,” he said huskily. “It’s only ‘under the hood’ that I go to pieces. Ever since that time I got the itch in the Link Trainer, instrument flying gives me the jitters. If it doesn’t carry over to advanced training school....”

“It won’t, Chick,” Hap Newton assured him stoutly. “What course have you picked for a first choice—Photography, Navigation, or Communications? You’re better than most in ‘buzzer’ code. Why don’t you ask for the advanced course in radio?”

“That would be my second choice, Hap,” Enders replied. “Bombardment’s my preference, though. Next to being a pilot, I’d like to dish it out to the enemy in big, explosive chunks. I’ve already told Captain Branch. He’ll put in a good word for me. And, listen, you bums! Don’t think I haven’t appreciated the way you’ve helped. A man’s got no right to be downhearted with a couple of friends like you.”

The next day Chick came into the room with a broad grin.

“Bombardment school for me!” he announced. “I’m leaving tonight. The board didn’t question Captain Branch’s recommendation. Now it’s all settled, I’m almost as happy as if I’d passed all my pilot tests. Only thing I hate is leaving you fellows, and—and the grand bunch of officers that we’ve had here at the Field. They tried to make me feel as if they didn’t like to say good-by, either.”

“They meant it, Chick!” Barry Blake exclaimed softly. “Student pilots aren’t just so much grist through the mill—not as our teaching officers see us. They’re real and personal friends of each cadet who’ll meet them halfway. It’s a big honor to know men like that!”

Parting with Chick Enders was a hard wrench for his roommates. As he boarded the bus for San Antonio that evening, they realized that they might be seeing him for the last time. In a world war of many fronts only a rare coincidence would bring them all together again.

“Happy landings, you goons!” Chick gulped as he gripped their hands.

“Pick your targets, fella—and remember us when you’re dropping block-busters on Tokyo!” Barry replied.

“Yeh, we’ll be right behind you with some more of ’em!” grinned Hap Newton, as the bus door slammed shut.

A few days after Chick’s departure for bombardier school, graduation separated the two remaining roommates. Barry, whose cool, quick brain and steady nerves would have fitted him for either fighter or bombardment flying, was allowed to choose the latter. Hap Newton’s one hundred and eighty-five pounds removed him automatically from the pursuit class. Recommended to twin engine school at Ellington Field, he said good-by to Barry in the Flying Cadets’ Club in San Antonio.

“We’ll keep in touch, Hap,” Barry promised. “And there’s just a chance we’ll meet up before this war is over. Keep eager, you stick-mauler! I’m taking off for Kelly Field now!”

“Set ’em down easy, you old sky-jazzer!” Hap smiled. “If you don’t, I’ll come along and lay an egg right on your tail assembly.”

Barry Blake strode away with a lump in his throat. He’d have to get used to parting with good friends, he told himself. The Air Forces were like that. Sometimes a flier had to watch his squadron members torch down under enemy fire. That was a lot tougher than shaking hands for the last time, with a grin and a wisecrack. Time to lay a new course, now—for Kelly Field and a pair of silver wings!

For Barry, the nine weeks at Kelly Field passed even more swiftly than those at Randolph. His acquaintance among his fellow cadets widened considerably. Yet, perhaps unconsciously, he avoided making friends so intimate that good-bys would be painful.

From training planes he graduated to handling the steady, reliable B-25 bombers. Taking off, flying and landing these medium bombers presented problems quite different from those he had met at Randolph Field. Barry caught on quickly. Gathering every scrap of skill he had ever learned, his mind “sensed” the right maneuver, the correct touch on each control.

Barry Learned the Correct Touch on Each Control

“You’re cut out for a Fortress pilot, Blake,” his instructor told him. “You’re naturally methodical. At the same time you’re as quick to grasp a new emergency as any cadet I’ve ever seen. Tomorrow you’ll shift to the old B-17. She has no tail turret, but for training purposes she handles like the newer types.”

Barry was more thrilled than he cared to show. Since pre-flight school, he had envied the pilots who flew the big flying forts—the famous B-17F’s. When the hour came that he actually sat at the controls of his Fortress, he knew beyond all doubt that these were the ships for him. The quadruple thunder of the bomber’s 4,800 horses was sweeter in his ears than a pipe-organ fugue.

First, in the co-pilot’s seat, he learned the exact touch needed on the throttles, the turbos, the r.p.m. adjustment, to keep the winged giant’s airspeed constant. This, for accurate bombing, would be a most important factor. Next, he learned exactly how to follow the Boeing’s P. D. I., or pilot director indicator, which kept the ship straight on her course with not the slightest change of altitude, while the bombardier sighted his target.

His final lessons included setting down and taking off on small, rough fields. Under war conditions many a bomber pilot has escaped destruction by knowing just what his ship can do in a pinch. Barry Blake was now as ready as any training school could make him.

What he longed for now was actual combat—the take-off before dawn on a real bombing mission—the swift descent on the enemy city, camp, or convoy—the blasting of his bombs on the target—the sight of enemy fighter planes falling apart before his ship’s guns.

But where would it be? Europe, Africa, the South Pacific, or the Aleutian chain?

Barry had hoped for a few days’ furlough after receiving his commission. A week at home would be like a taste of paradise after these seven crowded months. Even five days with Dad and Mom and the kid sister would be worth the heartache of saying good-by again. Yet, at the last moment, he learned that this was not to be.

Like a flooding tide the mighty crest of America’s war effort was sweeping everything before it. More planes than ever were needed at the fighting front. More planes were going there—and that meant more pilots. Twenty-four hours was the limit of Barry Blake’s time at home.

It was all like a dream. Walking up Craryville’s old main street, Barry felt like a beardless Rip Van Winkle. He had left there a green kid of eighteen. Now, an inch taller and ten pounds heavier, he passed neighbors who didn’t know him—until he spoke. And, speaking to them, he hardly knew himself. Professor Blake’s gangling offspring, who’d been the high school valedictorian, who had jerked sodas on Saturdays in the corner drug store—what had that self-conscious kid in common with Lieutenant Barry Blake, pilot of multi-engined bombing planes?

There was Mom and Dad. He’d never be different to them, or they to him. To the kid sister, he was a hero, of course, but Betty was only fourteen. She’d changed, too, in the past seven months. Barry wondered what in the world she’d be like when he came back again, after the war ... if he did come back. There wasn’t time for such thoughts, though. Half of his twenty-four hour visit was gone already!

When the train pulled out of Craryville next morning, Barry the high school kid was only a dim memory in the mind of Lieutenant Blake. His orders were to report at Seattle, Washington, where he would join the crew of a new B-17F as co-pilot. It was better, far better, to keep his thoughts fixed on that. Otherwise, recalling the good-bys just ended would be a bit too much to bear.

His pulses pounding with excitement, Barry Blake gazed across the long runways of Boeing Field at his first fighting ship. The great Flying Fortress seemed to perch lightly on the ground, despite her twenty-odd tons. Her propellers were turning slowly, glinting in the sun like the blades of four gigantic sword dancers.

Despite her drab coat of Army paint Barry thought her beautiful. The slim, torpedo-like profile, the high, strong sweep of her tail assembly—even the fishy grin produced by her bombardier’s window and forward gun ports—thrilled her young co-pilot to the core. This was the ship of his dreams. Her name, Sweet Rosy O’Grady, was painted just above her transparent nose.

Hurrying forward, he saluted the long-legged, lean-faced pilot who stood by the Rosy’s armed tail.

The lengthy captain looked up from the postcard he was scribbling. He lifted a nonchalant hand.

“You’re Lieutenant Blake?” he said with a Texas drawl. “The rest of our crew are all here, getting acquainted with the ship. I was just dashing off a card to the real Rosy O’Grady—my wife. It’s finished. Come in and meet the others. Then we’ll be ready to take off.”

Inside the big bomber, Captain O’Grady introduced Barry to the six other members of the crew.

“Meet Lieutenant Aaron Levitt, better known as Curly,” the skipper invited. “He’s the smartest, and probably the handsomest, ex-lawyer in the Air Forces. Born in Manhattan.”

“Lower East Side,” Levitt added, giving Barry a cordial handclasp and a keen look. “Happy that you’re going to be one of us, Lieutenant.”

“... and this gent is our bombardier, Sergeant Daniel Hale. He’s of the old time Texas breed, in spite of hailing from Arizona and looking more like a shorthorn bull. His great-granddad died fighting in the Alamo.”

Barry pulled what was left of his hand from Sergeant Hale’s bone-crushing grip and turned to “Sergeant Fred Marmon of Glens Falls, New York—the head nurse in charge of Rosy’s roaring quadruplets.” The red-haired engineer-gunner chuckled as he acknowledged Barry’s greeting.

“Boy!” he exclaimed. “And do those 1200 horsepower babies keep a man busy! Some of ’em, that is. One engine will run like a dream for fifty or a hundred hours. Another will develop more ailments than a motherless child. I’m hoping these new engines will be the first kind, Lieutenant. If not—well, here are Sergeants Cracker Jackson and Soapy Babbitt to help me out. They’re our top-turret and belly gunners, but they know a lot about aerial power plants, too.”

Last of all, Barry Blake met Tony Romani, the pint-sized tail gunner. The little corporal was as friendly as could be, but his sad, Latin eyes seemed to hold all the cares and worries which his crew mates laughingly discarded.

He was already hurrying back to his turret when Captain Tex O’Grady said, “Okay, boys! We’ll take her upstairs! I’ll mail this postcard to Mrs. O’Grady from Salt Lake City. If you have any letters to send you can drop them there. We’re heading west to the Orient.”

The Rosy’s four big engines deepened their song of power as she rushed down the runway. She was a living, throbbing organism, but her personality was yet to be learned. Newly fledged from Boeing’s great hatchery of warbirds, she had still to get acquainted with her crew, and they with her.

Barry Blake sat alert in his co-pilot’s seat, checking the instruments, as the runway dropped away below him. At the skipper’s nod, he touched the lever that retracted the landing gear. He heard the wheels wind up with a smooth mechanical whine, and noted the time it took in seconds. Again he moved the lever, letting the wheels down and raising them back in place. He tested the action of the flaps, the engines’ response to their throttles, the revolutions-per-minute of the props. In everything the Rosy O’Grady behaved as sweetly as any lady with such a name should do.

At Salt Lake City there was a short stop; then on they flew to San Antonio. Again Barry glimpsed the familiar countryside over which he and Chick Enders and Hap Newton had flown. The perfect green pattern of Randolph Field, with three or four flights of planes swinging over it, brought a homesick pang.

“We’ll never forget that scene, Mister,” the voice of Captain O’Grady broke into Barry’s thoughts. “I graduated from Randolph ten years ago, but it’s just like yesterday when I look back.”

“Those were the happiest weeks of my life,” Barry replied with a choke in his voice. “I know it now, though at the time it seemed a tough grind.”

Captain O’Grady turned one of his warm Irish grins on the young co-pilot.

“The real, tough grind,” he said, “will come when we reach our South Pacific base, I reckon. Barring accidents, the life of a fortress is about five or six months on the battlefront. Before it’s over we’ll all feel like graybeards, kid.”

The Rosy made one more stop at Tampa, Florida, where her engines were thoroughly checked and her tanks filled. Ahead of her stretched the long hop to Trinidad, off the northern coast of South America. If anything should go wrong, there were island bases in the Caribbean Sea where an emergency landing might be made. But in aviation, an ounce of prevention is worth many pounds of cure.

That evening in Tampa the crew had their last big restaurant meal for months to come. The following afternoon they took off despite storm warnings. There was no long last look at their native land. A few moments after the Rosy’s wheels had left the runway she was climbing through a heavy overcast of clouds.

As they roared over the southeastern tip of Cuba the weather cleared. Below them the Windward Passage lay, deep blue in the sunlight. Ahead rose the rugged mountain tops of Haiti.

Barry Blake felt a strange thrill as he gazed down into the jungle-clad valleys where not so many years ago United States Marines had hunted murderous voodoo worshipers. Somewhere in those dark gorges bloody voodoo rites were probably being performed at this very moment.

Invisible from the air the Haitian border was left behind. The dark green ranges of the Dominican Republic flowed past beneath the Rosy’s wings. Again the blue Caribbean stretched ahead of her.

Crossing the long thousand miles between Haiti and Trinidad they struck the worst weather yet encountered. At ten thousand feet the Fortress slammed into a black storm front.

It was worse than anyone had expected. The tumbling masses of air were like giant fists pummeling the big ship. She bucked like a frightened horse, reared, stood on her nose, and shuddered.

Something struck the right wing from beneath, flipping the Rosy over on her side, and off course. It was only air, though it felt to Barry like a collision with an express train. Tex O’Grady fought the controls with every ounce of strength in his big body. Muscles stood out in bunches on his lean jaw. In a flash of lightning Barry saw sweat streaming down the pilot’s face.

He glanced behind him. Lieutenant Levitt’s teeth showed in a fixed smile below his little moustache. In the lightning flashes the whites of his eyes showed clearly. Sergeant Hale’s big mouth was closed like a steel trap. Only Fred Marmon, the red-headed engineer, seemed to be enjoying himself. Meeting Barry’s eyes he winked, and waggled his fingers in a mocking gesture.

At that moment lightning struck the ship. Every light went off. The fuselage might have been the belly of a blasted submarine, pitch dark and battered by ceaseless depth charges. A beam of light touched the instrument panel. Barry Blake felt the cool barrel of a flashlight pressed into his hand.

“That will help you keep a check on your instruments!” Fred Marmon’s shout sounded in his ear.

Barry was grateful for his first chance to do something, however small, to help Tex. He watched the altimeter register a drop of five hundred feet, a steady climb of eight thousand, then another drop. In this fashion an hour passed.

All at once they were out of the storm. Clear moonlight shone through the plastic windows of the cockpit. The crew raised a hoarse cheer.

“Take over, Barry,” drawled Tex O’Grady’s voice. “I want to find out if I am still in one piece. When Rosy starts bucking like that she’s tougher than any bronc I ever forked on my daddy’s ranch in Texas!”

Unfastening his safety belt, Captain O’Grady heaved his lanky frame out of the seat and went back to talk with the navigator. Barry swept his glance over the instrument board. He tried the controls, to feel out any possible storm damage. Satisfied that there was none, he looked below.

A sea of rolling, silvery clouds lay in every direction. It was beautiful, but menacing. The ceiling below that overcast, Barry judged, would be zero. It might hide either land or sea, hills or marshes, for all that anyone knew. The storm had carried the Rosy O’Grady a number of miles off her course.

The four big engines’ steady drone of power sounded reassuring, until Barry remembered the last reading of the gas gauge before the lightning had knocked it out. There wasn’t enough left for fooling around, while the Rosy found out where she was.

After a few minutes, Captain Tex O’Grady loafed back to the cockpit.

“The radio’s out,” he told Barry. “That means we can’t get cross bearings to find our position. Curly Levitt is getting a fix now on some stars. Trouble is, he’s afraid his octant may have been knocked out of kilter when it fell off the navigation table, back there in the storm. Why don’t you go back and cheer him up?”

Barry thanked the lanky pilot and unfastened his safety belt. He suspected that O’Grady was just giving him an opportunity to stretch his legs. If a fellow needed cheering up, nobody could do a better job of it than “Old Man” O’Grady himself.

Lieutenant Curly Levitt was up in the top turret sighting through his instrument when Barry stepped back.

“Three stars is enough for a fix,” he shouted above the engines’ thunder. “Just wait till I shoot Venus.”

“Better not—it might really be Sirius!” punned Barry. “Anything I can do to help?”

“Thanks,” replied the navigator, as he prepared to step down, “Just open your mouth again and I’ll put my foot in it.”

Barry dodged, just in time to tumble over Fred Marmon who “accidentally” happened to be crouched just behind him. As he picked himself up, even sad-eyed Tony Romani laughed. The crew’s tense nerves were relaxing. Whistling a few bars from Pagliacci, the mustachioed navigator went back to his desk.

Curly Levitt was still a bit worried, however. On the accuracy of his reckoning depended the life of every man on board. If he failed, the chances were excellent that Sweet Rosy O’Grady would plunge to a watery grave the moment her gas supply gave out. At best she would crash in the Venezuelan jungle—unless, of course, the clouds broke up farther on and showed her crew a landing field.

“Check this reckoning with me, will you, Blake?” Levitt invited. “Then if there should be an error we can blame it on the wallop my octant took in the storm.”

“Okay!” Barry agreed. “If your octant is off, we’ll probably find it out too late to help ourselves. So don’t worry.”

Reckoning the fix is really a simple matter. At a given time only one point on the earth’s surface can be directly under any star. Using his octant, the navigator “shoots” or measures the elevation of two or more stars, and then figures out just where each “substellar” point is on the earth’s surface.

His next step is still easier. With his substellar points located on the map, he draws circles around them. One of the places where these circles intersect is the place where his plane was at the time the stars were “shot.” There is no real difficulty in guessing which intersection is the right one: the others are apt to be thousands of miles from his last known position.

Everything, of course, depends upon the accuracy of the star-shooting octant. This expensive and delicate instrument will not always stand abuse such as Curly Levitt’s had taken. There was reason for the young ex-lawyer to be worried. He slipped on his headset and switched on the interphone. The click in his ears told him that it still worked.

“Pilot from navigator,” he said. “If I’m right we’re fifty miles due north of Cayo Grande. Our present compass course would take us just past the southern tip of Trinidad. That checks pretty well with my dead reckoning. I haven’t had an accurate drift reading since we banged into that front.”

“Navigator from pilot,” came the drawling reply. “Rosy says she’ll take your word for it. She likes your style, hombre, even if you are a lily-fingered product of the effete East. A man who can keep any sort of dead reckoning in a storm like the one we just rode through will do to cross the river with.”

For the next hour Barry flew the big bomber, while her “Old Man” dozed in his seat. Below them the clouds continued unbroken. The moonlight on their gleaming crests and ridges gave the young co-pilot a queer sensation. It was hard not to believe that he was guiding a fantastic ship over the surface of a strange planet, thousands of light-years from Earth. In the lightless cockpit nothing seemed real.

“You fool—snap out of it!” Barry found himself muttering. “You’re heading into dreamland with your throttles wide. And that blur on the window isn’t imagination—it’s oil!”

“A cracked cylinder!” was Fred Marmon’s verdict, the minute he saw the oil spray on the window. “How near are we to landing, navigator?”

“Less than an hour,” Lieutenant Levitt answered, “provided there’s enough ceiling under those clouds.”

“I think there will be,” Captain O’Grady told them. “See! There’s a break in the overcast, dead ahead. We’ll go downstairs for a look.”

Taking over the controls, he nosed the Rosy downward through the black hole in the clouds. A moment later Barry could see moonlight glinting on the wave crests.

At a thousand feet the Fortress leveled out. Above her the cloud scuff was breaking up rapidly.

“Got that radio damage located yet, Babbitt?” O’Grady asked through the interphone. “We really ought to let Trinidad know that we’re on our way in, so they won’t be throwing up a lot of flak at us.”

“I’ll have the trouble fixed in about five minutes, sir,” Soapy replied. “Good thing we have plenty of spare parts. What that freak lightning bolt did to us was a caution!”

Just ahead a dark land mass rose out of the sea.

“That’s the upper jaw of the ‘Dragon’s Mouth,’” O’Grady remarked. “Trinidad is just beyond. I’m going upstairs again, until Soapy gets our radio working.”

The big bomber nosed sharply upward. For a few moments she clawed her way in almost pitch darkness through a cloud. Then the moonlight shone clear through the windows.

Suddenly a shaft of brilliant light burst through a rent in the scuff below them. Other searchlights stabbed upward. A sharp detonation jarred the Fortress.

“Antiaircraft shell!” grunted Rosy’s Old Man. “Evidently they don’t like unidentified planes cruising over the airfield. We’d better spin off.”

WHAMM! BLAMM!

Two shells, still closer than the first, made the big plane rock. Tex O’Grady pulled the stick back between his knees and gave the engine full throttle.

“Guess those hombres mean business, Blake,” he chuckled. “How do you like being under fire for the first time?”

“I don’t know,” replied Barry with a forced grin. “Somehow it doesn’t seem quite real, being shot at by your own ground forces. The trouble is that those shells would hurt just as much as Jap flak.”

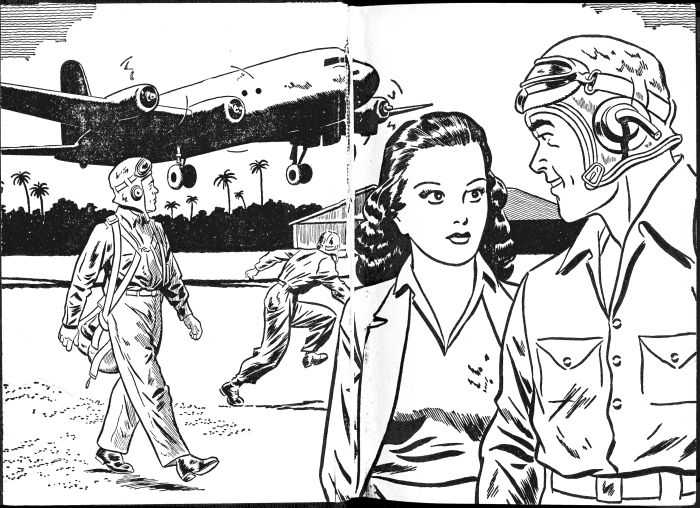

“Radio’s Okay, Sir!” Came Soapy Babbitt’s Voice

“Radio’s okay, sir!” came Soapy Babbitt’s voice. “What’ll I send?”

“Identification signals first,” the Old Man replied. “Explain what happened to our radio and lights. Then tell ’em to switch on the floodlights, so we can land before the oil from that cracked engine cylinder drowns us.”

Soapy was still talking into his radio when the searchlights behind them switched off. O’Grady nosed down. In a moment floodlights lighted up the field a few miles distant. The Rosy landed lightly for all her massiveness, and braked to a smooth stop.

“Yahoo! Me for some hot coffee!” whooped her Old Man, reaching for the entrance hatch. “Last man to the office buys for the whole bunch!”

Six days were spent in Trinidad, replacing the cracked cylinder and repairing the lightning’s damage to the electrical system. On the seventh day Rosy hopped off on her long trip across the Atlantic to Freetown, Africa.

This time she carried a few bombs. It was Sergeant Hale’s hope that they might sight a Nazi U-boat on the crossing. The chance, of course, was one in a million. However, watching for a target would help to dispel the monotony of the trip.

The weather was perfect—not a single bump in the air. With “George,” the automatic gyro, taking care of their flying, the pilots had little to do. By turns, they napped, lunched, listened to the radio, played games with the others of the crew. Even Fred Marmon had a soft snap, for Rosy’s hungry “quadruplets” were sucking their gas without a whimper.

Only Sergeant Hale, the bombardier, refused to join his crewmates in killing time. Stretched at full length in the plane’s transparent nose, he stared fixedly at the sea.

“Danny is a born hunter,” the Old Man observed. “Reckon he learned his patience from the Texas Apaches. They’ll lie ten hours in one spot without moving, waiting for a deer to pass a runway.”

They were just six hours out from Trinidad when Hale gave a bellow of discovery. Gazing down and ahead, Barry saw a convoy of twenty merchant ships, escorted by two destroyers and three corvettes. The intensified Nazi submarine attacks had made heavy protection necessary, he reasoned.

“We’ll go down and say hello to them,” said the captain, fastening his safety belt. “Maybe it will cheer them up to see Sweet Rosy O’Grady dropping them a curtsy, even if she can’t stick around.”

With engines throttled down, the bomber dropped toward the crawling convoy. Fascinated, Barry Blake watched the toy-like ships grow larger. Now he could make out the British flags and the tiny figures of the antiaircraft gun crews in their tin nests on the superstructures.

“I hope no cockeyed gunner takes us for an enemy and cuts loose,” he thought. “That wouldn’t be any fun at all—”

“Submarines to the right!” yelled Sergeant Danny Hale. “I can see their shadows just under the surface, Captain. And look—they’ve just fired two torpedoes! Let’s smash ’em!”

“You bet your sweet neck we will!” answered the Old Man. “Take over the throttles, Blake. Watch your r.p.m. We’ll give Hale a target he can’t miss.... Sergeant Babbitt, signal the convoy that we’re not bombing them!”

The Fortress leveled out at 500 feet. Glancing down, Barry saw the deck of a freighter immediately beneath him. He could almost catch the expressions on the upturned faces of her crew. His eyes came back to his instruments and clung to them.

“Bombs away!” yelled Hale’s voice in the interphone. “Give me a run at the other one, Captain.”

WHOOM! BR-ROOM!

As the Fortress zoomed sharply, the two bomb explosions buffeted her. She staggered, gained altitude, banked, and turned.

WHAMM! A torpedo had struck. Flame blossomed from the sides of the freighter. Another ship was dodging the second “tin fish.”

Searching the water for the submarines’ shadows, Barry spotted one, but it looked misshapen, seen through the spreading ring of the bomb burst. Then he found the other. It was less distinct, evidently diving at top speed. That was the next target.

Between it and the convoy, a destroyer was circling like an excited hound. She was waiting, Barry realized, for Rosy’s next run. The corvettes were threading their way through the mass of slower freighters, to be in at the kill.

“Steady, Blake—here we go again!” warned Captain O’Grady. “If that Hun is too deep for our bombs to hurt him, the explosion will spot his dive for the destroyer. Her depth charges will get him for sure.”

WHR-R-ROOM! BOOM!

The Rosy’s second run was still lower. The explosions made her aluminum skin crackle like an empty oil can. Suddenly Barry glimpsed the mast of a freighter spearing up at the bomber’s nose. He gave her full throttle. The mast flashed beneath—seemingly with mere inches of clearance.

“Upstairs” again, the fortress’s crew had a grandstand view of the submarine’s finish. The destroyer raced toward the mark left by Rosy’s last bombs. She dumped a depth charge off her stem. Her Y-guns pitched two more “ash cans,” bracketing the spot. A fourth and last depth charge completed the square.

Behind her, the corvettes darted to the oil slick that now spread over Sergeant Hale’s first target, and dropped two more charges for good measure.

“Pilot from radioman,” Soapy Babbitt’s voice crackled on the interphone. “The destroyer’s commander sends us his congratulations and thanks. He thinks we bagged the second sub, too. Wishes we could stay with him for the rest of the voyage.”

“I reckon he’s telling the truth,” chuckled Rosy’s Old Man. “Those undersea wolves have been hanging right at the heels of every convoy lately. They hunt in packs. We’ll just swing around the outskirts of this floating freight train and see if Danny Hale can spot any more suspicious shadows.”

The Fortress banked slightly in a slow turn, describing a twenty-mile circle around the convoy. As she swung back again, Barry could see the result of one torpedo hit.

The freighter had been struck on the starboard side near the bow. She was slightly down by the head. Smoke was still rising from her forecastle, but she still kept her place in line. Her life-boats were in place, with nobody near them. Evidently her crew had no other thought than to take her to port.

“There’s the second oil slick, Captain!” Hale called. “We got both those U-boats. Yip-yip-yippee!”

As the bombardier’s coyote howl shrilled in his earphones, Barry Blake laughed outright. Like every man on board he felt pretty cocky. Already their ship had been under fire. Now she had drawn first blood, sinking at least one enemy submarine without help. The world was their oyster, waiting to be cracked wide open when they reached the battlefront.

With a final waggle of their broad wings, Sweet Rosy O’Grady turned her back on the convoy and headed eastward on her course. A chorus of grateful whistles followed her. Owing to the thunder of her own engines, her crew could not hear the freighter’s salutes, but Tony Romani in the tail turret reported seeing the puffs of white steam.

The sinking of the subs provided conversation to last Barry and his companions for most of the trip. They were still comparing notes when the sun set. That put an end to Sergeant Hale’s sea-gazing.

Supper was supplied from thermos jugs and a box of sandwiches. Afterwards, Curly Levitt took a fix from the stars, and made a slight correction in their compass course. The engines were behaving so beautifully that their red-headed nurse, Fred, began to be bored. He roamed from tail turret to cockpit playing small practical jokes on everyone, until the Old Man told him to spin off.

By midnight everyone but Captain O’Grady was dozing. His co-pilot was sound asleep in his seat. He was waked by the first red beams of the sun rising over Africa. That was another thrill for Barry Blake—watching the shoreline of a foreign continent loom up out of the horizon. He slapped on his earphones in time to hear Curly Levitt giving the Old Man another change of course—this time to the north.

A few minutes later the deep harbor of Freetown took shape beneath them. Soapy Babbitt, contacting the RAF field, received permission to come in and land. The first of their long, transoceanic hops was safely ended.

The stop at Freetown was brief—chiefly for gas and a bit of rest for Rosy’s crew. Shortly after noon the big bomber took off again, headed for Accra, six hundred miles to the eastward. There the Pan American Lines had everything to do a complete servicing job. Captain O’Grady landed his ship just before the sudden equatorial night shut down.

A two-day rest put Rosy in first-class shape. Her engines were thoroughly broken in. Her mighty framework had been tested in action. Now it remained for her guns and gun turrets to be tried out under combat conditions.

And her crew! As Captain Tex O’Grady glanced at their keen, confident young faces, he knew he could depend on them. They’d meet danger with a grin of defiance and their cool efficiency would whittle down any odds they might meet.

Six thousand miles still remained between them and the Indian battlefront to which they had been ordered. The route would lie across Nigeria to Lake Tchad, then northwest to the Egyptian Sudan and down the Nile to Cairo. From there they would fly eastward in easy hops over Iran and India, till they reached their assigned base.

That was the plan; but in wartime the plans of mice and men are especially subject to change. A few hours before his take-off from Accra, radioed orders reached Captain O’Grady to head for Australia and the South Pacific. Heavy bombers were more urgently needed there, it appeared. And that meant Sweet Rosy O’Grady!

The new orders involved a greatly changed route. From now on Captain O’Grady and his crew would be flying below the equator. Heading southeast, they would have to cross the great Belgian Congo into East Africa before stopping to refuel. As soon as Fred Marmon learned that, he gave his “quadruplets” an extra careful inspection. A forced landing in those all but trackless jungles was something he hated to contemplate.

From Accra the Flying Fortress took off with all gas tanks full. Nine hundred miles across the Gulf of Guinea she roared to Libreville, where the Fighting French made up her depleted fuel. In the air again, she swept in a few hours over the vast territory that took H. M. Stanley years to explore. Twice she crossed the mighty Congo River. Then the five-hundred-mile expanse of Lake Tanganyika lay below.

“Watch out for elephants and giraffes, boys,” came the Old Man’s humorous drawl. “This is the country all the animal crackers come from. I’ll take Rosy down low enough so that you can see them.”

There was a general laugh, but as Captain O’Grady nosed his ship down to a thousand feet the crew really started to look. Perhaps the Old Man wasn’t kidding after all.

The dense masses of green forest broke up into small patches. Lush grazing lands appeared, with here and there a clump of trees. Farther on stretched a dry plain, spotted with the green of an occasional water hole. As they neared one of these, Barry Blake gave a shout.

“There are your elephants, Captain!” he exclaimed. “We interrupted their drink. I see a bunch of ostriches on the run, too—”

“Ostriches—ha, ha!” Tex O’Grady chuckled. “We’re not that near to Australia, Bub. Those long-necked critters you see are giraffes. Want me to prove it to you?”

He shoved the stick forward. As the giant plane dipped down to within two hundred feet of them, the frightened giraffes scattered like sheep. Barry could see their long, pathetic necks swaying like masts as they turned this way or that. Seconds later the herd was far behind.

“When we reach Australia, Lieutenant,” Curly Levitt’s voice murmured in the headphones, “I’ll buy you a beautiful, big picture book, and you can learn that G stands for Giraffe, and E for Elephant and M for the little Monkey who didn’t know which was which.”

A howl of merriment from the others who were listening in made Barry’s ears tingle.

“Okay, okay, I asked for it!” he admitted ruefully; and for the next hour he felt like a high school kid who has pulled the prize “boner” of the week in class.

The sensation wasn’t comfortable. Yet it went farther than anything that had happened yet to make him feel at one with the other members of the crew. These men, he realized, weren’t simply a detachment of non-coms and officers. They were a team, a family, an organism knit together by closer bonds than their assigned duties. Every last one of them was a brother to the rest, regardless of race or rank.

It was dark when the Flying Fortress reached Dar-es-Salam on the east coast. The next day, after servicing, the Rosy O’Grady hopped off across the Mozambique Channel. That same afternoon she landed at Tananarivo, Madagascar’s mountain capital, where the Fighting French had recently improved the landing field to take care of heavy planes.

“This is the last land we’ll see for three thousand-odd miles,” O’Grady informed his crew. “Next stop will be Broome, Australia. Marmon and Jackson, you will make an especially close check on the engines. Take your time about it. Better to spend an extra day here than a month on rubber rafts somewhere in the Indian Ocean.”

By noon of the third day, Fred and Cracker had checked and re-checked everything. Some of the care they took was really unnecessary. When they had finished, however, the bomber’s power plant was as perfect as human skill could make it. The fuel tanks were full. Food and water for a thirty-hour trip were aboard, but no bombs. To allow a safe margin in case of bad weather, the ship must fly as light as possible and save her gas.

They took off just at dawn. Soon they were out of sight of land, and from then on the trip became a long fight against boredom. Half of the way they flew on two engines, to economize on gas. The big bomber loafed along at five thousand feet, except on two occasions when she sighted squalls and had to dodge them. Before the trip was ended most of the Rosy’s crew would have welcomed a storm to break the monotony.

They landed at Broome, on Australia’s southwest tip, with plenty of gas to spare. The next day they headed northeastward, across the continent. Stopping at an American base in northern Queensland, they gassed up and hopped off on the last leg of their long flight to the battle zone.

Their base, when they found it, was still being carved out of the New Guinea jungle with the help of native labor. On the dirt runway Old Man O’Grady set his ship down like a cat on velvet. The moment she stopped he let out an old-time “rebel” yell.

When Barry and Fred Marmon climbed out last, after making their final checks, the Rosy’s red-haired engineer looked scornfully around him. In mock disgust, he stared at a group of men filling in a big, raw hole with shovels.

“Look, Lieutenant!” he snorted. “This is what we came three quarters of the way around the globe to find—a potato patch in the back woods!”

“Yes?” retorted Barry with a grim smile. “Those boys aren’t planting spuds, Fred; they’re filling in a new shell hole. The Japs must have dropped a few of Tojo’s calling cards just a little before we landed.”

The Japs called again that night. This time the “cards” that they dropped were shells from a cruiser that had sneaked close to the shore, in the dark hours. Five miles away, she let loose with her heaviest guns. Her aim was surprisingly accurate. To the Rosy O’Grady’s crew, the stuff seemed to be exploding all around their tent.

The screaming of shells, each followed instantly by an earth-shaking blast, produced a nightmare of horror for the unseasoned men. Not one of them gave way to fear, however. The most upset man in the tent was Tex O’Grady, who paced up and down between the cots, worrying about his ship and fighting mosquitoes. He couldn’t get Rosy into the air, because the field had no lights as yet.

“If I knew this confounded field better,” he fumed, “I’d take off and get her safe upstairs. But except for those shell flashes it’s as dark as the inside of a cow. I’d only ground loop—”

WHANG!

A shell burst, nearer than any before it; tossed chunks of earth through the open flap. Some dirt must have struck O’Grady in the mouth, Barry guessed, from the way the Old Man sputtered and spat.

“Better get your head down, Captain,” Curly Levitt spoke up. “You’re not as big a target as Rosy, but you’ll be safer on your cot.”

The shelling stopped as suddenly as it had started. Later Barry learned that a pair of motor torpedo boats had routed the Jap cruiser, with two gaping holes below her waterline.

The damage to ships on the flying field was comparatively light. One bomber had received a direct hit. Three more were damaged by shell fragments. Sweet Rosy O’Grady had escaped without a scratch. The worst tragedy was the killing of a twin-engined bomber’s crew when a shell exploded in their tent. Seven men had been sleeping there. All that was found of them was buried the next day in a single grave.

The attack was the last thing needed to make Barry and his friends ready for a raid of their own. Every man in the field was fighting mad. When O’Grady brought them the news that they were scheduled for a bombing mission that day, the Rosy’s crew cheered like maniacs.

“We’re going with the squadron to lay eggs on Rabaul,” the Old Man told them. “High-altitude stuff. You gunners will probably get your chance at a few Zero fighters, so make sure you load up with ammunition before we leave. Here come the carts to bomb us up now.”

Before Rosy had taken her last five-hundred pound egg on board the squadron commander was racing his Fortress down the runway. The other ten followed. Last of all, Old Man O’Grady took his ship up to her assigned position at the end of the right wing.

Looking ahead, Barry Blake thrilled at the sight of the other mighty Fortresses flying in a perfect V of V’s. To his mind they spelled irresistible, smashing power—force which must, in the long run, blast all the little yellow invaders out of the Pacific.

As the 600-mile distance to Rabaul narrowed, a tense expectancy gripped pilots and gunners. The squadron was flying at high bombing altitude, 25,000 feet. Every man was in his place, for at any time now a swarm of enemy planes might appear.

The Japs were struggling grimly to keep their grip on New Britain, Barry knew. Many of their best fighter squadrons had been shifted there from other fronts, in the past few weeks.

“Sixty miles still to go!” Curly Levitt’s warning came over the interphone.

O’Grady turned his head to glance at his co-pilot.

“The Nips’ aircraft detectors have heard us by now,” he drawled. “They’re manning their guns, and sweating some, too, I reckon. A bunch of Zero fighters will be taking off to bother us on the way in.... How do you feel about it, Blake?”

“As if I’d like a gun in my hands—or the lever that releases the bombs,” Barry laughed. “I feel just a little useless.”

Tex O’Grady’s smile faded out. He gazed straight ahead.

“You won’t be useless if anything happens to me, son,” he replied, gravely. “Keep your eyes peeled on every side now.... Those Zeros may not show up until after we’ve made our run, but you never can tell.”

Sergeant Hale in the bomber’s nose began counting aloud through the interphone.

“—thirteen—fourteen—fifteen Zeros dead ahead, and a flight of three more just above them. Here they come!”

“Flights two, three and four, pull in closer!” barked the command radio. “Wing men will step up—the others down—ready to repel attacking planes.”

Glancing up and to the right, Barry caught sight of still another enemy flight arrowing down at the Fortresses. He nudged O’Grady and pointed with his finger. The Old Man merely nodded. Keeping Rosy in her place in the tight protective formation was his only task for the moment.

Sergeant Hale Counted Aloud Through the Interphone

BR-R-R-R-R-R-R-R-R!

With a chattering roar that cut through the engines’ thunder, Rosy’s nose, top turret, and side guns went into action. From the squadron’s .50-caliber machine guns burst a storm of white tracer bullets. These mingled briefly with the fire of the diving enemy. Then most of the Zeros were below the flying forts.

Rosy O’Grady’s belly turret opened up, followed by Tony Romani’s fire from the “stinger” turret in the tail. As it ceased, the thought came to Barry Blake: “We’ve knocked them out of the sky! I thought those Japs were tough fighters, but this was like shooting clay pigeons. There’s nothing in sight but three Zeros torching down below—”

A slamming explosion jarred the fuselage. Then the side gun manned by Curly Levitt chattered harshly. Out of the corner of his eye, Barry saw the nearest Fortress stagger out of place in the V.

“Pilot from top gunner!” Soapy Babbitt’s report came through the phones. “Turret damaged by enemy shells. Machine guns still fire, but can’t aim.”

“Are you hurt, Soapy?” the Old Man asked.

“My left shoulder won’t work right,” came Babbitt’s reply. “Nothing to worry about. I’ll keep watch for more diving Zeros.”

“Ready, Blake!” O’Grady spoke sharply. “Watch your throttles—we’re nearing our targets now.”

Barry glued his eyes to the r.p.m. indicator. He forced his nerves to ignore the antiaircraft shells that burst closer and closer. This was the big moment of the whole raid—when the bombs were about to plummet down.

Cold air from the open bomb-bay doors rushed into the big ship’s belly. There came the welcome whistle of a falling bomb; then another, and another. A moment afterward the harbor of Rabaul swept beneath. It was out of sight before Barry could spot the bomb hits.

KRANG!

An antiaircraft burst rocked the big bomber like a cradle. Her right inboard engine sputtered and quit. Looking out at the wing, Barry glimpsed a jagged shrapnel hole in the cowling. He glanced to the left. Another Fortress had been hit. She was falling out of formation.

“Never mind, boys, Rosy O’Grady can toddle home all right on three engines,” the Old Man declared. “All you’ve got to do is to smack down every Zero you see....”

“Here come three of ’em, straight down at us!” yelped Soapy Babbitt from the jammed top turret. “If only I could aim these guns!”

“Maybe a Jap will cross your sights, Soapy!” the Old Man grunted, as he reefed back on the wheel. “I’ll try to give Hale a shot.”

Rosy’s nose came up. Her forward guns cut loose at the trio of diving planes. One spun away, smoking; another changed direction. The third kept coming, with his tracer bullets feeling for the Flying Fortress. When they touched her the Jap pilot pulled the trigger of his cannon.

A stunning blast threw Barry hard against his safety belt. Something—it felt like a hard-thrown baseball—struck his head. He felt himself falling into a black void.

Someone was shaking him, none too gently. A voice, Curly Levitt’s, pierced through his dulled consciousness.