Title: Birds and Nature, Vol. 12 No. 3 [August 1902]

Author: Various

Editor: William Kerr Higley

Release date: January 5, 2015 [eBook #47883]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper, Stephen Hutcheson,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

BIRDS AND NATURE. | ||

| ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vol. XII. | OCTOBER, 1902. | No. 3. |

Ere, in the northern gale,

The summer tresses of the trees are gone,

The woods of Autumn, all around our vale,

Have put their glory on.

The mountains that infold,

In their wide sweep, the colored landscape round,

Seem groups of giant kings, in purple and gold,

That guard the enchanted ground.

I roam the woods that crown

The uplands, where the mingled splendors glow,

Where the gay company of trees look down

On the green fields below.

My steps are not alone

In these bright walks; the sweet southwest, at play,

Flies, rustling, where the painted leaves are strown

Along the winding way.

And far in heaven, the while,

The sun, that sends that gale to wander here,

Pours out on the fair earth his quiet smile—

The sweetest of the year.

—William Cullen Bryant.

Darlings of children and of bard,

Perfect kinds by vice unmarred,

All of worth and beauty set

Gems in Nature’s cabinet:

These the fables she esteems

Reality most like to dreams.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Nature.”

The sun-birds bear a similar relation to the oriental tropics that the humming birds do to the warmer regions of the Western hemisphere. Both have a remarkably brilliant plumage which is in harmony with the gorgeous flowers that grow in the tropical fields. It is probable that natives of Asia first gave the name sun-birds to these bright creatures because of their splendid and shining plumage. By the Anglo-Indians they have been called hummingbirds, but they are perching birds while the hummingbirds are not. There are over one hundred species of these birds. They are graceful in all their motions and very active in their habits. Like the hummingbirds, they flit from flower to flower, feeding on the minute insects which are attracted by the nectar, and probably to some extent on the honey, for their tongues are fitted for gathering it. However, their habit while gathering food is unlike that of the hummingbird, for they do not hover over the flower, but perch upon it while feeding. The plumage of the males nearly always differs very strongly from that of the females. The brilliantly colored patches are unlike those of the hummingbirds for they blend gradually and are not sharply contrasted, though the iridescent character is just as marked. The bills are long and slender, finely pointed and curved. The edges of the mandibles are finely serrated.

The nests are beautiful structures suspended from the end of a bough or even from the underside of a leaf. The entrance is near the top and usually on the side. Over the entrance a projecting portico is often constructed. The outside of the nest is usually covered with coarse materials, apparently to give the effect of a pile of rubbish. Two eggs are usually laid in these cozy homes, but in rare instances three have been found. The Philippine Sun-bird of our illustration is a native of the Philippines and is found on nearly all the islands from Luzon to Mindanao. The throat of the male has a beautiful iridescence shaded with green, while that of the female, shown on the nest, is yellow.

Fly, white butterflies, out to sea,

Frail pale wings for the winds to try;

Small white wings that we scarce can see

Here and there may a chance-caught eye

Fly.

Note, in a score of you, twain or three

Brighter or darker of tinge or dye;

Some fly light as a laugh of glee,

Some fly soft as a long, low sigh:

All to the haven where each would be—

Fly.

—Swinburne.

PHILIPPINE YELLOW-BREASTED SUN-BIRD.

(Cinnyris jugularis).

Life-size.

FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES.

Days and weeks of busy preparation rolled around and promptly at the appointed time the Animals’ Fair opened in splendor.

A large football field had been secured for the show, and a striking sight met the eyes of curious men, women and children, who crowded through the gates on the opening day.

Two immense St. Bernard dogs had been appointed gatekeepers, and the human crowd were uncommonly respectful and subdued as they paid their entrance fee of a handful of grain or a juicy bone and passed these representatives of animal law.

The first thing to attract the eye as one entered the Fair was a large band stand which was occupied by a band of monkeys in red coats and caps, who made up in quantity what their music lacked in quality, and went through their performance with a decorum unexcelled by more musical organizations.

The monkeys found themselves more at home in their booth, which, was near the grand stand, the entrance fee to which was a small sack of peanuts. Here the delighted human audience watched an unequaled show of daring rope and trapeze performances, of acrobatic feats which none but “four-handed” artists were able to accomplish, and of comical antics such as only monkeys can go through. The excited children screamed with laughter and showered peanuts upon the performers, who, following their instincts, forgot their scheduled program and joined in a wild rush and squabble over the unexpected treat. Such little episodes were soon over, however, and the entertainment and forgotten dignity were resumed together.

Next to the monkeys’ booth was one occupied by geese, ducks and peacocks, and was one which deserves especial mention. It was elaborately decorated with garlands of feather flowers dyed in all the colors of the rainbow, hung against a background of snowy white feathers. On each side stood a peacock with gorgeous tail outspread, showing to lovely effect against the white walls behind them. Pillows and cushions of softest feathers, festoons of snowy down trimmings, quills and wings and breasts for millinery purposes, feather boas, feather brushes and dusters, quill pens and quill toothpicks were displayed to greatest advantage and offered for sale for a small sum of wheat or corn.

The hogs came next with a large and elaborate display, which included strings of sausages and Dewey hams, huge glass jars of snowy lard, hams and bacon put up in fancy ways, and piles of canned pork and deviled ham. In another part of the booth were brushes of all kinds made from hog bristles, soaps manufactured from otherwise unsalable parts of hog anatomy, saddles and other leather goods made from the hides, and—in a conspicuous position—a great pile of inflated pigskin footballs, which caught the eye of every schoolboy who came near the booth.

“Young man,” grunted one of the boothkeepers to a boy who was examining this pile of balls, “young man, never despise a hog nor deride him for his slowness. There is nothing more lively than a pigskin when properly inflated. It is a thing for the possession of which the representatives of the largest colleges are proud to contend, and he is the hero of the day who carries the pigskin to a winning touchdown. Why, college students will leave their books behind them, will cast aside the cultivation of their brains for the glory of chasing the pigskin over a muddy field. They will sacrifice life itself in its pursuit 102 and count broken limbs and bloody noses as badges of honor. Take my advice. Buy a pigskin football and enter at once upon the path of glory.”

It is hardly necessary to add that this sale, and many like it, were made during the progress of the Fair.

The booth of the wild birds was the most beautiful one in the whole display. It was gotten up to represent a forest glade, with shadowy aisles and leafy retreats. Its carpet was made of grasses and moss and ferns and flowers. A little fountain cast its waters into a tiny pool, where birds dipped their wings or quenched their thirst. Dainty nests were built in many curious ways, some hanging from the branches, others hiding beneath the grasses or sheltered by the leaves. A myriad of brilliant birds flitted through this miniature paradise, the bluebird, the redbird, the orange and black oriole, the scarlet tanager, golden canaries and many others, making up a flashing bouquet of color.

Then there were solos, and duets, and grand concerts, when thrush and lark and canary and redbird and warbler joined their voices in a great gush of melody through which ran the liquid trills and cadenzas of mocking-bird and nightingale. The quail piped his “Bob White” from the ferns and grasses; and the parrot—as clown of the occasion—imitated the human voice in comically jerky efforts.

Along the front of the booth were displayed rows of bottles filled with every imaginable kind of bug and worm which the industrious birds had gathered from orchards and fields, and which were exhibited as proof of the invaluable aid which the birds give to man.

The cattle display was next on the list—a notable one, and attractive to every man and woman. There were noble representatives from every breed of cattle, with the most beautiful, gentle-eyed calves that were ever seen. There was a tempting display of great glass jars of rich milk and yellow cream, huge cheeses and golden butter balls, daintily molded curds and glasses of whey. There was a free tank of delicious iced buttermilk, which was continually surrounded by a thirsty crowd who drank as if they had never tasted buttermilk before.

Then there were countless varieties of fancy articles made from horn and bone, pots of glue, cans of neatsfoot oil, and leather goods of every possible description.

There was dressed beef, and jerked beef, and dried beef, and potted and canned and corned and deviled and roasted. There was oxtail soup, and blood pudding, and cakes of suet, and stacks of tallow candles. There were hides tanned into soft carriage robes and rugs; there were bottles of rennet tablets; there were fancy colored bladders, and bunches of shoestrings. In short, the articles contained in this display were beyond enumeration in a short account like this.

The dogs came next with a wonderful display of fancy breeds, of trick dogs and trained dogs, of dogs little and big, varying from the shaggy Eskimo to the skinny little hairless Mexican, and from the huge St. Bernard to the tiny terrier. The Newfoundlands gave a life-saving exhibition every day, wherein monkeys dressed as people were rescued from the water or from buildings supposed to be on fire.

The St. Bernards dragged frozen traveler monkeys from snowbanks of cotton and carried them on their backs to places of safety.

Cute puppies and clumsy puppies went through their antics for the amusement of the children and rolled unconcernedly over beautiful carriage rugs which were labeled “Japanese Wolfskin.”

The sheep and goats had a booth together, wherein was a marvelous display of wools and woolen goods, yarns, pelts, angora furs, kid gloves, kid shoes, rugs, carpets and blankets.

There were ropes of goats’ hair which water could not destroy, and wigs which were destined to cover the heads of learned judges and barristers.

There was a wonderful red tally-ho coach, drawn by four snow-white goats driven by a monkey dressed as a coachman, which made the circuit of the Fair grounds every afternoon, while monkey passengers made the air lively and cleared the way by the loud notes of their tin horns. This exhibition set the children wild, and parents were daily 103 teased to buy the charming turnout for the use of their little human monkeys.

The cats had a display which met with the highest favor from their little girl visitors. Here were beautiful pussies of every kind and color, with coats as soft and shiny as silk. There were numbers of the cunningest kittens, which rolled and tumbled and went through their most graceful motions to the unending delight of the little spectators.

This booth was gaily festooned with strings of mice and rats, caught up here and there by small rabbits, gophers and moles.

There was a string band that played in this booth every afternoon to demonstrate the superiority of cat-gut strings over those made of silk or wire, as used on violins, mandolins, guitars and all other stringed instruments. They never failed to announce that their bows were strung with the finest of horsehair which had been supplied by the horses whose booth was farther down the grounds.

The horses attracted every eye and aroused much discussion among the visitors as to whether horses would ever be entirely superseded by automobiles and electric engines.

The children went into ecstacies over the Shetland ponies, and the ladies declared the Arabian horses “too lovely for anything.”

Every boy who visited this booth was presented with a baseball covered with the best of horsehide leather.

But time fails me to tell of all the wonderful things which this Fair presented to the eyes of admiring men. On one point only was dissatisfaction expressed by the visitors—there was no Midway. President Monkey, when interviewed by a representative of the Associated Press in regard to the omission, made the following remarkable statement:

“No, it was not a matter of oversight. The camel volunteered to bring some of his Arabs to establish the Streets of Cairo, and some of the monkeys were anxious to put in a Gay Paris display. The lions wished to bring some trained Wild Men of Borneo for a Hagenbeck show, and the snakes wanted to do jugglery. You can see that there was no lack of what misguided people call ‘attractions.’

“The management discussed the Midway from every point of view, and decided that it was entirely too low grade for a first-class entertainment such as we desired to make. We felt that it would only attract a rough class of visitors, whose presence we did not desire. And so the unanimous decision was, ‘We will have a good, clean, respectable show or we will have no show at all.’

“No, sir. Say emphatically in your dispatches that the Midway was intentionally omitted. Such things may do for men, but beasts will have none of them.”

The Fair was in every way a success, being carried through without disturbance of any kind and coming out free of debt and with much legal tender in the treasury.

Men were so much impressed by the obligations which they owed to the animal world that there was a decided improvement in their treatment of its various representatives. While this state of affairs cannot be expected to last long, the animals have learned how to arouse such respect and have decided to make the Animal Fair an annual attraction.

Mary McCrae Culter.

In the morning the path by the river

Sent me a messenger bird,—

“I’m all by myself and lonely,

Come,” as I waked I heard.

I walked the path by the water,

Till a daisy spoke and said,

“I am so tired of shining;

Why don’t you pat my head?”

So I kissed and fondled the daisy,

Till the clover upon the lea

Said, “It is time for eating,

Spread your luncheon on me.”

But first I went to the orchard,

And gathered the fruit that hung,

Before I answered the green-sward,

Where the clovery grasses swung.

Then the rocks on the hill-side called me,

And the flowers beside the way,

And I talked with the oaks and maples

Till Night was threatening Day.

Then I knelt at the foot of the sunset,

And laid thereon my prayer,

And the angels, star-crowned, hurried

To carry it up the stair.

And this was the plea I put there:

Make me so pure and good

That I shall be worthy the friendship

Of river, and field, and wood.

Lucia Belle Cook.

GREAT GRAY OWL.

(Scotiaptex cinerea).

⅓ Life-size.

FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES.

Through Mossy and viny vistas

Soaked ever with deepest shade,

Dimly the dull owl stared and stared

From his bosky ambuscade.

—James Whitcomb Riley, “A Vision of Summer.”

The Great Gray or Cinereous Owl is the largest of the American owls. The appearance of great size, however, is due to its thick and fluffy plumage. Its body is very small being only slightly larger than those of the barred or hoot owl. The eggs are also said to be small when compared with the size of the bird.

The range of this handsome Owl is practically confined to the most northern regions of North America, where it breeds from the latitude of Hudson Bay northward as far as forests extend. In the winter it is more or less migratory, the distance that it travels southward seeming to depend solely on the severity of the season. It has been captured in several of the northern United States, from the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans. It is related in “The Hawks and Owls of the United States,” that “Dr. Dall considers it a stupid bird and states that sometimes it may be caught in the hands. Its great predilection for thick woods, in which it dwells doubtless to the very limit of trees, prevents it from being an inhabitant of the barren grounds or other open country in the north. It is crepuscular or slightly nocturnal in the southern parts of its range, but in the high north it pursues its prey in the daytime. In the latter region, where the sun never passes below the horizon in summer, it is undoubtedly necessity and not choice that prompts it to be abroad in the daylight.” Its yellow eyes are very small and would indicate day-hunting proclivities.

Dr. A. K. Fisher states that its “food seems to consist principally of hares, mice and others of the smaller mammals as well as small birds.” Dr. W. H. Dall has taken “no less than thirteen skulls and other remains of red-poll linnets from the crop of a single bird.” Specimens in captivity are reported to have relished a diet of fish.

Its nest is described as a coarse structure built in the taller trees and composed of twigs and lined with moss and feathers. The note of this great bird is said to be “a tremulous, vibrating sound, somewhat resembling that of the screech owl.”

The Great Gray Owl is also known as the Great Sooty Owl and the Spectral Owl. Its generic title, Scotiaptex, is from two Greek words, one meaning darkness and the other to frighten.

The dignified mien of this great bird may well have been the inspiration that caused the poet to say,

Art thou, grave bird! so wondrous wise indeed?

Speak freely, without fear of jest or gibe—

What is thy moral and religious creed?

And what the metaphysics of thy tribe?

I spent last summer in a quiet, old country place where my only near neighbors were the birds, rabbits and squirrels, but I formed many pleasant acquaintances among these, and the dearest among them was a pair of little goldfinches that built their nest in the topmost bough of a young pear tree that overshadowed the porch where I spent a great part of my time.

I did not discover the nest until the little ones were already hatched. The early June days had been cloudy and cool and had kept me shut in, so I did not have the pleasure of watching my little neighbors build their home. The nest was so carefully hidden among the leafy boughs that no one would have suspected it was there. My attention was first arrested to it one morning by the faint cries of young birds, and on looking up I saw a little goldfinch perched on the topmost bough of the pear tree, bending fondly over what I knew must be the nest. She lingered but a moment and then darted away to an apple tree near by, where I discovered her mate. He was a tiny little fellow, not much larger than she, but his jacket seemed a brighter yellow and his head and the tips of his wings a glossier black. They rested a moment, seemingly in earnest conversation, then both darted away to a thicket of tall grass and weeds that grew along the banks of a creek that ran near by.

It was but a few moments until the little mother was back again and in her tiny yellow beak I saw the dainty morsel she was carrying to the hungry little family.

All day long, back and forth, from the nest to the thicket she flew, but the hungry little ones never seemed to be satisfied. The father bird did not come very often, and I wondered if he was spending his time in idleness or seeking pleasure for himself, while the poor, little mother was working so arduously for the support of the family. But I hardly think this was the case, for he always came from this same thicket and they always seemed confidential and happy. He would rest himself daintily on some branch overlooking the nest, and with many quips and turns watch the mother as she fed the hungry little ones. Sometimes he would bring food himself and then they would fly away together. I think he was searching for the food and probably gathering it, for sometimes Mistress Goldfinch would be gone but a moment until she would return with the food.

Every day the same scenes were repeated, only the cries of the little ones grew more clamorous, and I could see their gaping mouths as they stretched their necks, each one trying to convince the mother that he was the hungriest bird in the nest. The little mother was always patient and loving—what a lesson to us who so often chafe and fret under the petty trials of every day life! As the days went by the young birds grew bolder and I could see their little yellow bodies as they fluttered and pushed themselves near the edge of the nest, and I knew that there would soon be an empty nest in the pear tree.

It was one afternoon, about ten days after I discovered the nest, that the lessons in flying began. The father and mother would fly from the nest to some twig a few feet from the nest and then back again, then from twig to twig with many little chirps as if saying, “Don’t you see how easy it is? All you have to do is to try.” Then the boldest little fellow would perch himself on the edge of the nest, flutter his little wings, sit still for a minute, and then roll back into the nest as if it was too much for him. Then the father and mother would repeat 109 the lesson, but all in vain that afternoon, so they finally gave up and went in search of food. The next morning the lessons began in earnest, and then the bold little youngster, who had made so many pretentions the afternoon before, grew bolder and with a nervous little flutter and a sidewise plunge landed on a twig some few feet below the nest. He rested a few moments and then, with a few encouraging chirps from his parents, tried it again with better results. One by one the other timid fledglings were induced to follow him. There were many tumbles and falls, but the little mother was always there to encourage and help, and by afternoon the little home was deserted. They staid a few days in the trees near by and then flew away to seek new homes, and all that was left to remind me of the happy family was the empty nest in the leafy bough.

Ellen Hampton Dick.

The dove, bearing an olive branch, is, in Christian art, an emblem of peace. The early churches used vessels of precious metal fashioned in the shape of a dove in which to place the holy sacrament, no doubt because the Holy Spirit descended upon Christ in the form of a dove.

Noah’s dove, of still older fame, was immortalized as a constellation in the sky.

The plaintive “coo” of the dove has also added to the sentiment about it. The poets delight to refer to it as a sorrowful bird. One of them says:

“Oft I heard the tender dove

In fiery woodlands making moan.”

The dove, “most musical, most melancholy,” is the singer whom the mocking bird does not attempt to imitate.

There is a Philippine legend that of all birds only the dove understands the human tongue. The pigeon tribe is noted for its friendliness to man—

“Of all the feathered race

Alone it looks unscared on the human face.”

The word dove means “diver” and refers to the way this bird ducks its head.

It has purposely designed “wing whistles” and often strikes the wings together when beginning to fly.

The broken wing dodge it often practices tends to prove that its ancestors built on the ground.

The nest of the dove has no architectural beauty and it is not a good housekeeper, and is something of a gad-about. Indeed, doves are not so gentle in character as they are usually portrayed. They are sometimes impolite to each other and occasionally indulge in a family “scrap.” But as nothing in this world is quite perfect, the dove with its fine form, and beautiful quaker-like garb, may be accepted as one of the most interesting of our birds.

Belle Paxson Drury.

The Green-crested or Acadian Flycatcher is a frequent summer resident in the eastern United States, and through the valley of the Mississippi river it migrates as far northward as Manitoba, where it is said to be quite common.

This bird exhibits no haste in its northward spring journey, for it is one of the latest species to arrive on its breeding grounds in the higher latitudes and as winter approaches, it leaves the United States entirely and winters in Mexico, Central America and northern South America.

If we would make the acquaintance of the Green-crested Flycatcher, we must seek it in woodlands in the vicinity of some stream or other body of water. Its favorite haunts are “deep, shady, second-growth hardwood forests, on rather elevated ground, especially beech woods with little undergrowth, or bottom lands not subject to periodical overflow.” It is not an over shy bird, yet it is rather difficult to find, for its colors are in perfect harmony with its surroundings as it passes from tree to tree through the dark foliage of the lower limbs. So perfect is this color-harmony that Major Charles Bendire said, “I have several times failed to detect the bird when I was perfectly certain it was within twenty feet of me,” and Neltje Blanchan likens its movements to “a leaf that is being blown about, touched by the sunshine flittering through the trees, and partly shaded by the young foliage casting its first shadows.”

Like its sister flycatchers the Green-crested is not a good natured bird and will even quarrel with individuals of its own species. Even its voice is fretful, especially when from its perch it is waiting for an insect to pass by. It seldom perches higher than from fifteen to twenty feet from the ground, and while standing constantly twitches its tail and frequently utters a note that Mr. Chapman describes as a single spee or peet.

It is a beneficial bird, for its food consists of insects except in the fall when it feeds to a limited extent on wild berries. It will occasionally visit orchards where it has learned there may be found a plentiful supply of food to its liking. When an insect is sighted, like the other flycatchers, except that it chooses a low rather than a high perch from which to watch, it flies outward and with an upward sweep seldom fails to catch its prey in its open bill, which is suddenly closed with a notably loud click that seems like an expression of satisfaction over the result of its efforts.

The drooping branches of several kinds of trees and shrubs are selected by the Green-crested Flycatchers as suitable sites for their unpretentious homes. The nests are semipensil, being attached by the rim to the fork of a small limb or to two parallel limbs. They are shallow and so loosely constructed that frequently the eggs may be seen from the underside. As this Flycatcher breeds nearly throughout its range, the materials used in the construction of the nests varies greatly. In southern states where Spanish moss is common it is one of the chief constituents of the nest. In more northern district, stems of plants, small roots and fibrous materials are used. These are loosely woven with blades of grass, dry flowers and the catkins of the willow. Not infrequently the hanging catkins, decayed fibres and the loose ends of stems and blades of grass give an untidy appearance to the home of this useful and interesting bird.

GREEN-CRESTED FLYCATCHER.

(Empidonax virescens).

Life-size.

In a delightful article called “Character in Birds,” Mr. Torrey gives many instances of bird traits that show distinct differences of nature in various species, and which lead one to recall others that have fallen under observation. Mr. Torrey does not mention, for instance, a peculiarity of the redeyed vireo, which is as marked as its persistent and rather tiresome note; that is, its almost intolerable curiosity and fussiness, qualities which it carries to such an extreme that they become absolutely comic. I think I have never seated myself to watch the nest of any bird, that a redeyed vireo has not appeared on the scene and scolded me; and the moment a bird utters a cry of alarm a redeyed vireo is sure to appear with his fretful air of “Oh, dear, what is the matter now?” ready and willing to take a hand in any rows that may be going and quite sure to make more fuss than the really aggrieved party; and oddly enough seeming, in one instance at least, even to resent the noise that the troubled bird was making, for one day when an indigo bird, that I had tormented by watching its nest, had chippered and chattered until he had brought every bird in the neighborhood to see what was the matter, a redeyed vireo, after prancing around for a time, flew at the distracted indigo bird with a very cross squawk, which said as plainly as words, “Do be quiet, can’t you?”

The vireo’s action in this case was in marked contrast to that of a thistle bird which came up warbling and gave me a careless glance, and then flew away still singing, but as the noise continued he came back presently and perching on a twig above me, bent his bright head to look at me, saying, “swee-et” in a long-drawn, inquiring way, with a little break in his voice which was singularly endearing, as are all the ways of these charming creatures; after inspecting me again he disappeared, but at a renewed outcry from the indigo birds he came warbling back once more. This time he paid little attention to me, having apparently satisfied his curiosity on that point on his former visit; but seeming to divine that there must be some reason why the indigo bird should make so much fuss, he began to examine the tree which held the nest. Suddenly he discovered the nest, and after a start which expressed surprise and interest, he flew up and hovered over it for an instant and then flitted away, warbling. Redeyed vireos seem to be always restless and irritable, and perfectly sure that you mean to do them or their nests some harm, and it is sometimes quite distracting to go into a certain piece of woods where they are very plentiful; the moment you enter it they begin their distressful “please, please,” uttered half pleadingly and half crossly. One is sure they must be near a vireo’s nest, yet may pass beneath it day after day, and though looking for it fail to find it, if there are no young ones, so skillful are they in concealing their beautiful nests. These are among the most fascinating of bird cradles, particularly in this piece of woods where there are many birch trees, from which the vireo obtains fine, silky shreds of the beautifully tinted bark and weaves into the nest with the most exquisite effect, giving unusual delicacy of color and texture. The redeye has also the most remarkable habit of arranging the nest so that it shall be quite hidden by the leaves, often with one leaf which serves as a roof and protects the young or eggs from sun and rain; and if they would only keep quiet they would usually be quite safe, but instead, the moment any one appears they make so much noise that attention is attracted to them at once, and you begin naturally to look for the cause. Even then it may be some time before the nest 114 is discovered, as there are usually only one or two points from which a view of it can be obtained and a single leaf will sometimes quite conceal it. Possibly there are circumstances in the life of a redeyed vireo which, if known, would account for his irritability and egotistical belief that all eyes are upon him with evil intent; but our eyes are dull, and one could wish at times that his trials, whatever they may be, might sweeten his temper. I do know, at least, that redeyed vireos are much tormented by that plague of bird life, the cowbunting, which delights in laying her eggs in the redeye’s nest; and nowhere could they be placed where they would cause more discomfort, for the vireo’s nest is a delicate structure and none too large for its own nestlings. I think the cowbird often injures the nest when she lays her egg, as she probably gets in and out of it with more or less haste, being hurried by the aggrieved owners, for not only do the young vireos fall out of the nest, but even the interloping cowbird sometimes falls out before he is able to fly and meets his death by a tumble before he is prepared to leave the nest.

One summer I was watching a hawk’s nest and was always greeted by the angry cries of the redeyed vireos, who never ceased to scold at me and the hawk, and so upset a nervous, but well meaning at least, flycatcher that it, too, joined in the abuse. Sometimes when the hawk flew away the vireos would follow him for quite a distance through the trees, scolding in the most dismal manner and showing little fear of the great, fierce creature, who they seemed to know could not catch them among the thick branches of the trees. But one day I was amazed to see a redeyed vireo actually on the lower part of the hawk’s nest. To be sure the hawk was absent, but he had a swift and silent way of returning that made it seem a rather dangerous bit of bravado. The redeye often has a most uncomfortable habit not only of quarreling with any neighbor that will quarrel but also of squabbling with each other even during the time that they are engaged in caring for the young. One summer a pair of them, having a nest in a tree near the house, were so quarrelsome and kept up such a persistent clatter that they became really tiresome. It must be admitted, however, that in this particular case they had cause for being irritable, for they were trying to bring up a cowbunting besides their own family, and perhaps each thought the other was to blame for the misfortune. Indeed it took little imagination to think that their perpetual squabbles were caused by mutual recriminations in regard to their voracious foster nestling. Poor vireos! They fought with each other and everyone else, but particularly with a phœbe which had a nest near by, and was also tired and fretful from overwork and perhaps fond of a row himself, for he had an aggravating habit of coming into a little tree just below the vireos’ nest and twitching his tail in the rather inane manner peculiar to phœbes, and that was all that was needed to throw the vireos into a perfect fume, and they responded instantly, flying at him wrathfully and were promptly met by a kindred spirit. It was a most unreasonable business, as neither wanted anything that the other had, and seemed to prove that all they needed was an excuse to show their ill temper. These same vireos had a very real cause for rage and fear in the presence of the red squirrels, and they never failed to pursue and scold one the moment it appeared. Their whole life seemed so uncomfortable and their perpetual fussing was so wearisome that it was difficult to feel proper sympathy for them when their affairs ended tragically. But they were most devoted parents, and as such must have credit, though their domestic arrangements seemed squalidly inharmonious and were so pronounced that no one living in the vicinity could help knowing all about them.

Thistle birds, like the vireos, are very apt to appear in response to any call of alarm or annoyance from their neighbors, but their interest seems to have a sweet and kindly spirit, very different to the acidulated attitude of the redeyed vireo. In truth the most marked characteristic of these little beauties is a peculiar loveableness and their gentle cheeriness makes them ideal companions. They have a delightful habit of appearing in 115 June in flocks and congregating on the white sandy beach of the lake, reminding one of the clouds of yellow butterflies that come to the same place at certain times of the year. At this time the male thistle bird sings in a perfect ecstacy of joy and love; but of all their attractive qualities none is so endearing as a habit they have late in the fall of singing as they fly high up, mere specks, their exquisite ethereal notes drifting down sometimes with the first snowflakes as they go joyfully to meet the storm and the night.

Scarlet tanagers are often hardly more agreeable in their marital relations than the redeyed vireos, and though no doubt they vary greatly in this respect, those that I have noticed showed a decided coldness, occasionally varied by marked crossness. And the wooing of a scarlet tanager is sometimes most amusing, for the female is, or pretends to be, amazingly indifferent and it must take a courageous lover to persist in spite of her severe manner, but male tanagers are gifted with persistence and do not seem to go unmated, and they make most devoted parents, though it would hardly have been expected of them after their seeming indifference during the incubating. One pair of tanagers that had a nest close to the house, and so could be constantly watched, were never on really friendly terms with each other, sometimes quarreling outright, and only seeking each other’s society when some danger seemed to threaten their young ones. Then the female seemed glad of the presence of her mate. Young scarlet tanagers are very confiding and gentle in their ways, and do not seem to have much fear of man here. There are always several of these pretty creatures flitting about in the evergreens near the house at the season when they are old enough to begin to take care of themselves, and they often alight on the hammock ropes or sit on the branches quite near me, looking on with bright, interested eyes. They have little playful ways that are rather unusual in a young bird and remind one of kittens. Sometimes when a shred of the arbor vitæ bark hangs down above them they will play with it, using their beak as a kitten does its paws, and their voices have an almost plaintive sweetness that adds greatly to their attractions.

Next perhaps in fussiness to a redeyed vireo may be counted the phœbe; and there does not appear to be quite so much reason for the phœbe’s unhappy frame of mind, for on the whole their nests seem rather safer than those of most birds, built as they so often are in sheltered places about the houses and barns. But though the nests escape the young phœbes are very liable to come to grief, and their elders nearly wear themselves out when the young first leave the nest, which they often choose to do on a very stormy day. Phœbes are pugnacious, too, and carry on feuds among themselves year after year, those on the east side of the house always quarreling with those on the west side, and when they first come back in the spring there are frequent conflicts, noisily carried on in midair, which continue at intervals until both parties are too busy with their nests and young to attend to other things, though even then, if an idle moment occurs, they promptly take advantage of it to have a brush with each other. There never seems to be any particular advantage gained on either side; so dismal as they seem about it all they no doubt rather enjoy the excitement afforded by these little interludes.

Young phœbes show none of these aggressive qualities, and have the most gentle and attractive manners and a peculiar air of innocence that is most captivating. If the parent phœbe brings up an insect all the nestlings, who may be sitting in a row on a branch, wave their soft wings and squeak. The parent inspects them for a moment and then feeds one. The instant the old bird has decided which shall be fed the rest subside and wait quietly until her return. There is no pushing and crowding or following the parent.

The slate colored junco is another of the essentially cheerful spirits, yet has a remarkable sedateness and self-possession, such as one is sometimes surprised to find in people of particularly quiet and gentle dispositions. And he has one habit that has made him very dear, for he always appears in the fall and remains 116 until quite late in the season. During this time he haunts the evergreen trees in front of the house, coming back there every evening to sleep or to seek shelter from a storm, announcing his arrival with low twitterings and restless games of play. If one goes under the evergreens after dark and gently shakes a branch there will be a slight fluttering of wings and disturbed sleepy notes from the juncos. They love to feed in the drive which runs in front of the house and in the thickets of rose bushes that creep up to the windows, coming close to the veranda and eating any crumbs that are thrown out for them, and even on the wettest day looking trim and contented and bringing with them a sense of companionship which can be only appreciated by those who have lived much alone, when the different creatures come to be better known than they can be where there are people constantly distracting the attention.

The Kentucky cardinal, though I have known it but slightly, made a very vivid impression because of its gentle pensiveness. I once spent a few months in a little village in Florida and flocks of these exquisite creatures appeared from time to time in our garden and in different places that we visited. They were always rather tame, coming near us and feeding on the ground, uttering plaintive notes that reminded me of the cedar bird and which suggested a much smaller bird. The cardinal’s manner had something so sensitive and touching about it that it appealed to me at once and made the lovely strangers as dear as though they had been known a lifetime. They were never hurried or excited and I never heard a cross note or saw the slightest indication of any friction among them; but their whole manner was colored with sadness—a quiet, unobtrusive sadness. Even their song was tinged with it and it was curious how these brilliant creatures left on the mind a sense of “going quietly” and being subdued, which made them the greatest contrast to the absurd redwinged black birds with whom they often shared the umbrella tree.

Hundreds of other instances of bird character crowd into the mind, as one writes, and the air seems again full of airy creatures each with his or her small personality standing out from all the rest in bright contrast, some grave, some gay, some cross, and others kind, but all beautiful and full of interest.

Louise Claude.

Frowning, the owl in the oak complained him

Sore, that the song of the robin restrained him

Wrongly of slumber, rudely of rest.

“From the north, from the east, from the south and the west,

Woodland, wheat-field, corn-field, clover,

Over and over and over and over,

Five o’clock, ten o’clock, twelve or seven,

Nothing but robin-songs heard under heaven:

How can we sleep?”

—Sidney Lanier, “Owl Against Robin.”

LOUISIANA WATER-THRUSH.

(Seiurus motacilla).

Life-size.

FROM COL. CHI. ACAD. SCIENCES.

The Louisiana Water-thrush is a woodland bird with quite an extended range, which includes all of the eastern United States west to the plains and north to Massachusetts, Michigan and Minnesota. It winters in the region of the Gulf of Mexico and southward into South America. This bird seems to be burdened with long names, for it is also called the Large-billed Water-thrush and Large-billed Wagtail Warbler. The last name is quite appropriate for it, as well as the other water-thrushes, are warblers rather than thrushes. The name Wagtail well describes one of its most striking characteristics. It is a dignified bird, and as it moves with stately steps along the limb of a tree, or a log upon the ground, the tail moves up and down in rhythm with its step. It is a shy bird and its “never-ceasing alertness suggests the watchfulness of the savage.” When discovered and that will not be until it already knows of the intruder’s presence, it sounds an alarm and quickly flies to some distant perch where it watches every movement of the invader, its body constantly teetering as if with suppressed excitement.

When seeking a nesting site the Water-thrush shows a partiality for wild and favorable localities near a stream of water, especially “where dashing brooks leap down wooded hillsides.” At times, however, it will select a retired spot on the wooded banks of a lowland stream or of a lake. The nest is built in some secure retreat among the roots of an overturned tree, in the cavity of an old log or stump, or in the moss under a bank. An impenetrable thicket with a rank growth of ferns and moss, is the usual desideratum when seeking a place to locate its home.

The nests are bulky and constructed with dead leaves, often partly decayed, which are obtained from the muddy banks and with the mud still adhering to them. These, with twigs and rootlets, are laid together and when the mud dries all are cemented into a compact mass which forms the wall of the nest. This is lined with fine grasses, small roots, bark fibers and feathers or hair. The nest is so similar in color to that of its environment that it is not easily detected.

The Louisiana Water-thrush seldom utters its interesting song when on the ground, but from some higher perch or when flying. Audubon thought its song was equal to that of the European nightingale; that its notes were as powerful and mellow and not infrequently as varied. Dr. Ridgway says, “This may be true of the ecstatic love-song, heard on rare occasions, and uttered as the singer floats in perfect abandon of joy, with spread tail and fluttering wings, but it can hardly be true of the ordinary song, which, although rich, sweet and penetrating, and almost startling in the first impression it creates, is soon finished and the pleasing effect is somewhat transient. It cannot be denied, however, that its song is one of the richest to be heard in our forests.”

Another Writer speaks of its song as “a beautiful, wild, wayward effort,” and Mr. Chapman says, “As a songster the Water-thrush is without a rival. His song is not to be compared with the clear-voiced carol of the rose-breasted grosbeak, the plaintive chant of the field sparrow, or the hymnlike melody of the true thrushes; it is of a different kind. It is the untamable spirit of the bird rendered in music. There is an almost fierce wildness in its ringing notes. On rare occasions he is inspired to voice his passion in a flight-song, which so far exceeds his usual performance that even the memory of it is thrilling.”

When I was a small boy I lived with my parents in my grandfather’s home. Here was grandfather’s large dog Rouse. He was the constant companion of my uncle in his work on the farm. His great desire was to carry something in his mouth when the team started for the field. He was often given a singletree, with which he marched along, showing evident satisfaction. One day he concluded to cut across a field instead of going around the road. The fence was a high rail one and, burdened with the weight of the heavy singletree, he could not jump over. After several vain attempts he dropped his load, stood looking up and down the road. Then looking at the singletree for a moment picked it up and put it through between the rails. He then jumped over the fence, gathered up the singletree and trotted on.

One thing he absolutely refused to carry was an iron wedge unless it was put in a basket. On one occasion this same uncle lost the lash of the whip he was using in driving a yoke of oxen. He had another at the house, but it was nearly a mile distant. He wrote his want on a slip of paper and giving it to Rouse said, “Take this to mother.” He was soon scratching at the kitchen door. When the door was opened he dropped the note on the floor, was given the whip lash and hurried away to the field.

A certain dog belonged to a doctor. He often trotted along under the buggy when the doctor went to call on his patients. On one occasion the doctor rode horseback and hurriedly threw the bridle rein over a hitching post where the visit was made. The horse threw up his head, the bridle rein was freed from the post and the horse started down the road. The dog saw the move and started after him. After some little difficulty he caught the dangling rein, brought the horse back to the post and held him there until the doctor came out.

On another occasion a horse was tied to a post of the porch at the doctor’s house. He got restless and was soon standing with fore feet on the porch. The dog saw it and, catching him by the tail, pulled until he backed down and stood on the ground.

There is a big shepherd dog not far from where I live that watches for the evening train. As soon as it appears he runs to a certain place beside the track, where the mail clerk throws him a bundle of papers. He never fails to be at his post or on the way.

A dog who was utilized to run a dog power churn at last grew tired and resorted to various schemes to get out of the work. Just after the churn had been made ready one day the lady heard the vigorous bawling of a calf and looking out she saw the dog trying hard to get a calf into position to do the churning. After this it was necessary to tie his dog-ship the night before if he was to be used next day.

An Iowa dog who had suffered much from firecrackers on the Fourth always disappeared soon after midnight of the third at the first shot of an anvil or cannon cracker. He spent the day in the country far from town and never returned until the noise had ceased.

A friend who was a photographer had a large Newfoundland dog who had a great deal of curiosity about his make-up, as well as much sense. His face was always the first to appear at the village postoffice window when the mail was opened. The master was an oldtime photographer when stronger water ammonia was much used in the preparation of paper. There was an assistant in the gallery who liked to tease the dog and knowing the trait of desiring to investigate every box or bottle that was opened, played many tricks on him, but none of them seemed to cure him or to lessen this desire until he got a good full whiff of stronger ammonia, which laid him 121 full length on the floor and made him less anxious to look into everything with his nose.

His master had a book for the butcher and a different one for his account with the grocer. When meat or groceries were wanted it was only necessary to give him a book in which had been written the articles desired and a basket and away he went. He knew where to go by the color of the book. Often in coming home with meat he was set upon by other dogs who tried to rob him. One day a large hound tried several times to get the meat, but was kept away by very significant growls. Becoming more determined he made a final dash, when Newfoundland set the basket down and no hound ever got a sounder thrashing. Then with head and tail held high the basket was carried home in triumph.

Alvin M. Hendee.

Among some curios lately brought from Mexico, is a cake made of the eggs of water beetles.

This odd sort of edible resembles, outwardly, a biscuit made of coarse brown or oatmeal flour. In taste it is not unlike the same wholesome article of diet. As a matter of fact, water beetles hold a high place in the domestic economy of the poorer natives of Mexico.

Their collection is, therefore, quite an industry, and one in which the Indians, particularly, are adepts.

This is the plan of operation: Reeds are cut and placed along the margins of lakes and ponds. Soon these reeds are covered by an incredible number of eggs so minute that it is necessary to shake them on a cloth to gather them.

These eggs are then put in bags and pounded.

The result is a coarse flour, which may be cooked in a great variety of ways. All highly nutritious and stimulating. A vast number of beetles are also collected and used as food for chickens, but notwithstanding this immense demand, the supply suffers no appreciable diminution.

Louise Jamison.

Oh, golden days with cloudless skies—

When forests flame with gorgeous dyes;

A touch of wine seems in the air,

Fields are brown—pastures bare.

Deep purple wraps the distant hills,

Gray shadows fall upon the rills;—

Thro’ rustling corn the zephyrs sigh,

In grief to see fair summer die.

These are days of Nature’s glory,

Sung in song, and told in story.

—J. Mayne Baltimore.

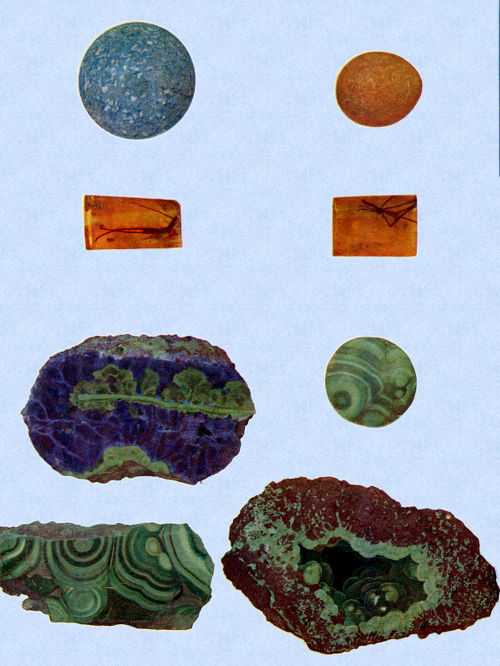

This stone was the sapphire of the Greeks, Romans and Hebrew Scriptures. Pliny likened it to the blue sky adorned with stars. Large quantities of worked pieces of it are found in early Egyptian tombs, and the Chinese have long held it in high esteem. Marco Polo visited Asiatic mines of the mineral in 1271 A. D., and these had doubtless been worked for a long time previous. Besides its value as a stone it was in former times used as a blue pigment, giving the ultramarine blue. In modern times not only has the esteem in which the stone is held for ornamental purposes declined but the mineral can be artificially made so as to give the desired blue color for paints and thus the use of the natural lapis lazuli has greatly diminished. It is still however carved to make vases, small dishes, brooches and ring stones and is used to a considerable extent for mosaic work. When, also, pieces of sufficient size and of a uniform color can be found, large carved objects may be made which command a high price.

The stone known as lapis lazuli as it occurs in nature is not a single mineral but a mixture of several, among which are calcite, pyrite and pyroxene. From these however it is possible to separate a mineral of uniform composition sometimes crystallized in dodecahedrons which is probably the essential ingredient of the stone. This mineral is known as lazulite and in composition is a silicate of soda and alumina with a small quantity of sodium sulphide. It is by making a substance of this composition that the artificial ultramarine is produced. The artificial is said to be as good as the natural for a pigment and can be produced for a three-hundredth part of the cost. The natural lapis lazuli has a hardness of 5½ and a specific gravity about like that of quartz. It is quite opaque. In color it is blue, varying from the prized ultramarine to paler, and at times is of a greenish shade. It is said the pale colored portions can be turned darker by heating to a red heat. When the variety from Chile is heated in the dark it emits a phosphorescent green light. The stone in Nature is often flecked with white calcite. Portions so affected are not considered as valuable as the uniform blue. Grains of pyrite are also usually scattered through the stone giving the “starry” effect referred to by Pliny.

Lapis lazuli usually occurs in limestone but in connection with granite so that it seems to be a product of the eruption of the granite through the limestone. The lapis lazuli of best quality comes from Asia, the mines being at Badakschan in the northeastern part of Afghanistan on the Oxus river. The mining is done by building great fires on the rocks and throwing water on them to break them. The yield at present is small, not over 1,500 pounds a year being obtained. The lapis lazuli from these mines is distributed all over Asia, going chiefly to China and Russia. The price realized is said to be from $50 to $75 per pound. Lapis lazuli of poorer quality comes from a region at the western end of Lake Baikal in Siberia. The only other important locality is in the Andes Mts. of Chile near the boundary of the Argentine Republic. This material is not much used at the present time on account of its poor quality but it was employed by the Incas for decorative purposes. One mass 24×12×8 in., doubtless from this locality is now in the Field Columbian Museum, and was found in a Peruvian grave. It is one of the largest masses of lapis lazuli known.

The walls of a palace at Zarskoe-Selo, Russia, built by order of Catherine II are entirely lined with slabs of lapis lazuli and amber. Pulverized the stone was used as a tonic and purgative by the Greeks and Romans. The name lapis lazuli means blue stone. Armenian stone is another term by which the stone is known in trade.

AMBER, MALACHITE, LAPIS-LAZULI AND AZURITE.

LOANED BY FOOTE MINERAL CO.

Few minerals have been longer in favor for ornamental purposes than amber. Among remains of the earliest peoples such as the Egyptians and Cave-dwellers of Switzerland it is found in carved masses indicating that it was highly prized. The Phenicians are said to have sailed to the Baltic for the purpose of procuring it, while the Greeks’ knowledge of it is indelibly preserved in our word electricity derived from their word elektron. The high favor in which the ancients regarded amber has hardly endured however to the present time. Were it not for its use for mouthpieces of pipes and other smokers’ articles and the occasional amber necklace to be seen, amber would hardly be known among the present generation in our country.

Amber is a fossil gum of trees of the genus Pinus and is thus a vegetable rather than mineral product. In color it is yellow, varying to reddish, brownish and whitish. Its hardness is 2 to 2.5, it being slightly harder than gypsum and softer than calcite. It cannot be scratched by the finger nail but easily and deeply with a knife. It is also brittle. Its specific gravity is scarcely greater than that of water, the exact specific weight being 1.050-1.096. It thus almost floats in water, especially sea water. It is transparent to translucent. On being heated it becomes soft at 150 degrees and at 250 degrees to 300 degrees melts. It also burns readily and at a low temperature, a fact which has given rise to the name of bernstein by which the Germans know it, and to one of the Roman names for it, lapis ardens. Rubbed with a cloth it becomes strongly electric, attracting bits of paper, etc. As already noted, our word electricity comes from the Greek for amber, this seeming to be one of the first minerals in which this property was noted. Amber being a poor conductor of heat feels warm rather than cold in the hand, contrary to most minerals. It is attacked but slowly by alcohol, ether and similar solvents, a property by which it may be distinguished from most modern gums and some other fossil ones. In composition it is an oxygenated hydrocarbon, the percentages of these elements being in an average sample, carbon 78.94, hydrogen 10.53 and oxygen 10.53. The mineralogical name of amber is succinite, a word derived from the Latin succum, juice. One of its constituents is the organic acid called succinic acid.

The present source of most of the amber of commerce is the Prussian Coast of the Baltic Sea, between Memel and Dantzig, although it is found as far west as Schleswig-Holstein and the Frisian Islands and even occasionally on the shores of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. From time immemorial pieces of amber have been cast upon the shore in these localities and their collection and sale has afforded a livelihood to coast dwellers. Such amber is called sea stone or sea amber and is superior to that obtained by mining, since it is usually of uniform quality and not discolored and altered on the surface. Owing to its lightness the amber is often found entangled in seaweed and the collectors are accustomed to draw in masses of seaweed and search them for amber. Amber so obtained is called scoopstone, nets being sometimes used to gather in the seaweed. In the marshy regions men on horse-back, called amber riders, follow the outgoing tide and search for the yellow gum. It is also searched for by divers to some extent. From the earliest times the title to this amber has vested in the State and its collecting has been done either under State control or as at present when a tax is levied by the government upon it. This tax is levied on the amber that is mined as well as that obtained from the sea and brings a revenue at the present time of about $200,000.

Up to 1860 the methods of procuring amber were largely confined to obtaining it in the manner above noted. As it was evident however that the sea amber came from strata underneath and that if either by dredging or mining these strata could be reached a much larger supply could be obtained, exploration was carried on by mining methods 126 with successful results, and the principal amount of the amber of commerce is now so obtained. The strata as shown in the mines of Samland, the rectangular peninsula of East Prussia where most of the mining is carried on, are: First, a bed of sand; below this a layer of lignite with sand and clay, and following this a stratum of greensand, fifty or sixty feet in thickness. While all these strata contain scattered pieces of amber, it is at the bottom of the greensand layer that the amber chiefly occurs, in a stratum four or five feet thick and of very dark color. It is called the “blue earth.” This stratum is of Tertiary age and there can be no doubt that its amber represents gum fallen from pines which grew at this period and whose woody remains are represented to some extent in the layer of lignite. It is probably true as Zaddach remarks that the amber has been collected here from older deposits. One of the most interesting proofs of the vegetable origin of amber is the occurrence in it of insects, sometimes with a leg or wing separated a little distance from the body, showing that it had struggled to escape. These insects include spiders, flies, ants and beetles, while the feather of a bird has even been found thus preserved. Indeed the amber deposits have furnished important contributions to our knowledge of Tertiary life. Inasmuch as the pieces bearing such remains are valued more highly than ordinary amber, unscrupulous persons have at times found profitable employment in boring cavities into pieces of amber, introducing flies or lizards into them and then filling up the hole with some modern gum of the same color. It is said that all amphibious or water animals seen in amber have been introduced in this way.

Besides the counterfeiting of the inclusions of amber there are several substitutes for the gum itself. These are chiefly celluloid and glass, the substitution of the former being dangerous if used for the embellishment of pipes, on account of its inflammatory character. Celluloid can be distinguished from amber by the fact that when rubbed it does not become electric and gives off an odor of camphor instead of the somewhat aromatic one of amber. It is also quickly attacked by alcohol or ether, and when scraped with a knife gives a shaving rather than a powder as amber does. Glass can be distinguished by its cold feeling and greater specific gravity.

Besides these substitutes it has been found possible by heating and pressing the scraps of amber not large enough for carving to make them into a homogeneous mass which is sometimes sold as amber and sometimes as amberoid. Amber is worked to desired shapes by turning it on lathes or by cutting by hand. By heating it in linseed oil it becomes soft so that it can be bent and often all opaque spots can be made to disappear by such treatment. The amber which is most highly prized of any in the world comes from Sicily. Eight hundred dollars have been paid for pieces of this no larger than walnuts, making their value nearly equal to that of diamonds. The beauty of the Sicilian amber consists in the variety of colors which it displays, blood red and chrysolite green being not uncommon, and the fact that these often exhibit a brilliant fluorescence, glowing within with a light of different color from the exterior. Chemically the Sicilian amber is not the same as the Prussian as it contains less succinic acid and is somewhat more soluble. In other respects it is not essentially different. It occurs chiefly on the eastern and southeastern coasts being washed up in a manner very similar to the Prussian amber.

Amber has been found in several places in the United States, but there is little of commercial value. It is mostly connected with the Cretaceous glauconitic or green sand deposits of New Jersey, fragments being frequently found there. This amber is of yellow color but not so compact or lustrous as foreign amber. Amber has also been reported from the marls of North Carolina, some of the coal beds of Wyoming and in connection with lignite in Alaska. In the latter region the natives are said to carve it into rude beads.

Amber occurs in small quantities in several countries of Europe, such as near Basel in Switzerland, near Paris in France, and near London in England. It is also found in many parts of Asia, these localities being a source of supply 127 to the Asiatic countries such as China and India. Occasionally amber is obtained from Mexico which has the beautiful fluorescence of the Sicilian article, though the exact locality whence it comes is not known. Specimens of carved amber are found among the relics of the Aztecs and it is probable that they used it for incense. The early use of amber by European peoples has already been referred to. There are references to it in the most ancient literature and worked masses of it are found among human relics of the greatest antiquity. Up to comparatively modern times it was an important article of commerce among widely scattered peoples and had much to do with bringing about communication between them. Together with tin it was one of the chief objects which led the Romans to penetrate the Gallic regions to the west and north of the Mediterranean and Pliny says that “it had been so highly valued as an object of luxury that a very diminutive human effigy made of amber had been known to sell at a higher price than living men, even in stout and vigorous health.” One of the most elaborate of the Greek myths is that which accounts for the origin of amber. It runs in this wise:—Phaethon, undertaking to drive the chariot of his sun god father, Helios, lost control of his steeds and approaching too near the earth set it on fire. Jupiter to stop him launched a thunder-bolt at Phaethon and he fell dead into the Eridanus. His sisters lamenting his death were changed into poplars and their tears became amber.

In the Odyssey one of Penelope’s admirers gives her an amber necklace, and Martial compares the fragrance of amber to the fragrance of a kiss. Milton writes of amber and Shakespeare mentions it both in “Love’s Labor Lost” and “The Taming of the Shrew.”

Necklaces of amber are popular wedding presents among the peasants of Prussia and they form an important feature of the ornaments worn by many African chiefs.

The properties assigned to amber both as a charm and as a medicine have been many. From the earliest times it has been used as an amulet, being supposed to bring good luck and to protect the wearer against the evil eye of an enemy. Necklaces of amber beads are used to this day as preventive or curative of sore throat and the Shah of Persia wears around his neck a cube of amber reported to have fallen from heaven in the time of Mohammed, which is supposed to have the power of rendering its wearer invulnerable. Amber was also taken internally in former times as a cure for asthma, dropsy, toothache and other diseases and to this day is prescribed by physicians in France, Germany and Italy for different ailments.

The use of amber for artistic and decorative purposes has declined considerably since the Middle Ages, but magnificent illustrations of its employment for these purposes are to be seen in many European museums, notably the Green Vaults of Dresden.

Though so soft and easily destructible a substance it endures with ordinary care as well as the hardest stone, and works of art formed from amber are as well preserved as any to be found.

Malachite is a green opaque mineral whose color indicates a salt of copper. It is a carbonate of copper containing water, the percentages being in the typical mineral, cupric oxide 71.9, carbon dioxide 19.9, and water 8.2. It is the common form which copper assumes when it or even its ores oxidize in the air. Many of the green stains on rocks or minerals can be correctly referred to malachite. It is only valued for ornamental purposes however when it occurs in compact masses usually exhibiting concentric layers. Malachite in this form takes a fine polish. Malachite is not a hard mineral, its hardness being between 3.5 and 4. It can therefore be scratched with a knife. It is comparatively heavy, weighing four times as much as an equal bulk of water. When heated before the blowpipe it fuses easily, coloring the flame green. By heating long enough on charcoal it can be made to yield a globule of copper. It is easily attacked by common acids, causing effervescence of carbon dioxide. This test can be used to distinguish it from the silicate of copper, chryscolla, which has the same color.

Besides its occurrence in massive forms 128 as noted above Malachite not uncommonly occurs in tufts and rosettes incrusting other minerals. This is an especially common occurrence in mines in Arizona and affords specimens of great beauty especially when the green tufts of malachite are seen upon brown limonite, for then the appearance of moss on wood is closely simulated. Such material is of course too fragile to be used for decorative purposes.

Malachite is prepared for ornamental use by sawing masses of the character of those previously referred to into thin strips which are then fastened as a veneer on vessels of copper, slate or other stone previously turned to the desired shape. Putting pieces together so that neither by their outlines nor color will it appear that they are patchwork requires a high degree of skill and such work is done almost exclusively in Russia. Table tops, vases and various other vessels are manufactured in this way and form objects of great beauty. The pillars of the Church of Isaac in St. Petersburg are of malachite prepared in this way and there are similar pillars in the Church of St. Sophia, Constantinople, said to have been taken from the Temple of Diana at Ephesus.

Occasionally the desired object can be turned from a single piece of malachite, but pieces of sufficient size for this purpose are rare. Bauer describes one piece found in the Gumeschewsk mines which was 17½ feet long, 8 feet broad and 3½ feet high and compact throughout. This is probably the largest single mass known.

Russia furnishes most of the malachite suitable for work of this kind and the art of cutting and fitting the stone is possessed almost exclusively in that country. Most of the Russian malachite has been obtained from the mines of Nischne-Tagilsk and Bogoslowsk in the northern Urals, or Gumeschewsk in the southern. The supply has gradually decreased till now only the Nischne-Tagilsk mines are productive. The malachite is said to occur there in veins in limestone.

Besides the Urals, fine malachite suitable for cutting comes from Australia. Burra Burra in New South Wales and Peak Downs in Queensland are localities whence good Australian malachite is obtained.

Malachite as a mineral is common in copper mines in the United States but it is only in Arizona that it is found of a quality suitable for cutting. A variety from Morenci, Arizona, consists of malachite and azurite and gives a combination of green and blue that is unique and pleasing. (See colored plate.) Less use has been made of such material for ornamental purposes than might have been for most of it has unfortunately been smelted as a copper ore.

Malachite is rarely used for rings or small jewels but is cut into earrings, bracelets, inkstands and similar objects. Art objects of malachite seem to have been in much favor with Russian emperors as gifts to contemporaneous sovereigns, and so bestowed are to be seen in numerous palaces in Europe. Perhaps the most famous of these gifts is the set of center tables, mantel pieces, ewers, basins and vases presented by the Emperor Alexander to Napoleon and still to be seen in an apartment of the Grand Trianon at Versailles.

Malachite was well known to the ancients and like other precious stones was worn as an amulet. It was called pseudo-emerald by Theophrastus. Its name is from the Greek malake, the word for mallows and was given doubtless on account of its green color.

Azurite, the blue mineral which often accompanies malachite is likewise a hydrous carbonate of copper and occasionally occurs so that it can be used with malachite for ornamental purposes.

Oliver Cummings Farrington.

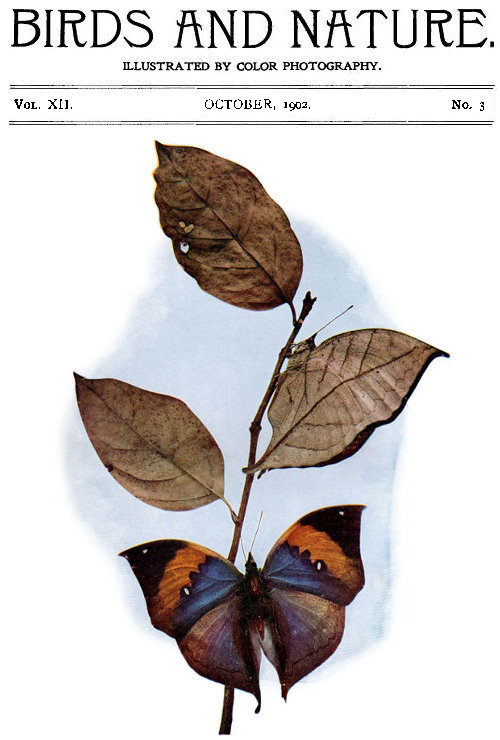

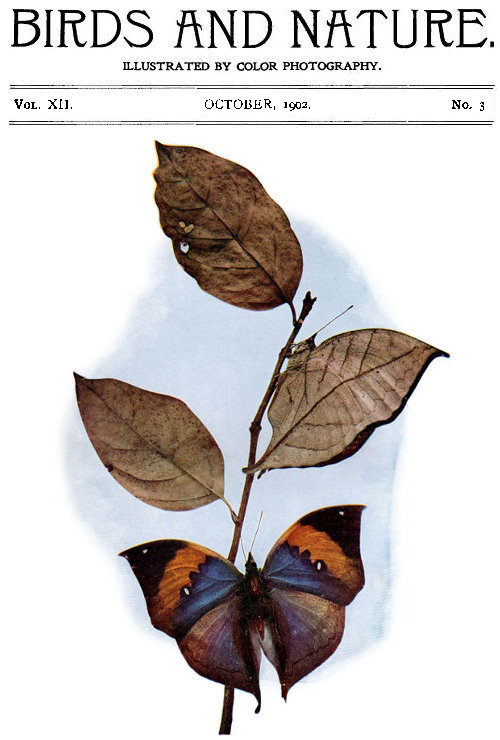

LEAF BUTTERFLY (INDIA).

(Kallima paralekta).

Life-size.

FROM COL. F. M. WOODRUFF.

There are many instances of protective imitation or mimicry in nature, but none are more pronounced, more perfect or more interesting than that shown by the leaf butterflies. Briefly defined, the phenomenon of mimicry is that relation which obtains when “a certain species of plants or animal possesses some special means of defense from its enemies and some other species inhabiting the same district or a part of it, and not itself provided with the same special means of defense, closely resembles the first species in all external points of form and color, though often very different in structure and unrelated in the biological order.” Many animals, such as some tree-lizards, resemble the colors of the environment in which they live, either for protection from enemies or in order that they may more easily catch their prey. Some arboreal snakes hang from the boughs of trees like the drooping ends of creeping vines.

The coloring of the under surface of the wings of the leaf butterflies very closely resembles the color of a dried leaf. As dried leaves vary in color and appearance, so do the butterflies vary in the color and markings of their wings. It is said that even in the same species, the under surface of the wings may be of various shades of brown, yellow, ash and red. But the imitation of the dried leaf does not alone rest on the color, for often, here and there, may be seen small groups of dark colored spots which strikingly resemble the patches of fungi that are so common on leaves. The mimicry of this butterfly is purely protective and not for the purpose of deceiving its prey.

Dr. Alfred Russel Wallace in his “Malay Archipelago” writes of this butterfly as he found it in its native element. He says, “This species was not uncommon in dry woods and thickets, and I often endeavored to capture it without success, for after flying a short distance it would enter a bush among dry or dead leaves, and however carefully I crept up to the spot, I could never discover it till it would suddenly start out again, and then disappear in a similar place. At length I was fortunate enough to see the exact spot where the butterfly settled, and though I lost sight of it for some time, I at length discovered that it was close before my eyes, but that in its position of repose it so closely resembled a dead leaf attached to a twig as almost certain to deceive the eye, even when gazing full upon it. I captured several specimens on the wing, and was able fully to understand the way in which this wonderful resemblance is produced.

“The ends of the upper wings terminate in a fine point, just as the leaves of many tropical shrubs and trees are pointed, while the lower wings are somewhat more obtuse, and are lengthened out into a short thick tail. Between these two points there runs a dark curved line, exactly representing the midrib of a leaf, and from this radiate on each side a few oblique marks, which well imitate the lateral veins. These marks are more clearly seen on the outer portion of the base of the wings and on the inner side toward the middle and apex, and they are produced by striae and markings which are very common in allied species, but which are here modified and strengthened so as to imitate more exactly the venation of a leaf.

“The habit of the species is always to rest on a dead twig and among dead or dried leaves, and in this position, with the wings closely pressed together, their 132 outline is exactly that of a moderately sized leaf, slightly curved or shrivelled. The tail of the hind wing forms a perfect stalk, and touches the stick while the insect is supported by the middle pair of legs, which are not noticed among the twigs and fibers that surround it. The head and antennae are drawn back between the wings, so as to be quite concealed, and there is a little notch hollowed out at the very base of the wings, which allows the head to be retracted sufficiently. All these varied details combine to produce a disguise that is so complete and marvellous as to astonish everyone who observes it; and the habits of the insects are such as to utilize all these peculiarities, and render them available in such a manner as to remove all doubt of the purpose of this singular case of mimicry, which is undoubtedly a protection to the insect. Its strong, swift flight is sufficient to save it from its enemies when on the wing, but if it were equally conspicuous when at rest, it could not long escape extinction owing to the attacks of the insectivorous birds and reptiles that abound in tropical forests.”

The waves come galloping up the shore,

The trees are flinging their arms about.

All night I have heard the wind’s loud roar,

And the surf call back with angry shout.

And after the wind a grieving rain

Comes sighing and sobbing past my door,

“The summer flowers I seek in vain,

Is my work of love forever o’er?”

One day ago and a soft sun shone,

Butterflies flitted through quiet air,

But now both they and the birds are gone

And soon will the trees be stripped and bare.

Though winds blow cold and the skies are gray,

The sun of summer still shines for me,

For naught can drive from my heart away,

The memory of bird and flower and tree.

Grace Wickham Curran.